Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Efficiency Analysis and Performance Optimization of Heat Recovery Ventilators (HRVs) for Residential Indoor Air Quality Enhancement in Cold Climates

Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Qom, Qom, 3716146611, Iran

* Corresponding Authors: Mojtaba Babaelahi. Email: ,

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(7), 1771-1788. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.066747

Received 16 April 2025; Accepted 14 July 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

Heat Recovery Ventilators (HRVs) are essential for improving indoor air quality (IAQ) and reducing energy consumption in residential buildings situated in cold climates. This study considers the efficiency and performance optimization of HRVs under cold climatic conditions, where conventional ventilation systems increase heat loss. A comprehensive numerical model was developed using COMSOL Multiphysics, integrating fluid dynamics, heat transfer, and solid mechanics to evaluate the thermal efficiency and structural integrity of an HRV system. The methodology employed a detailed geometry with tetrahedral elements, temperature-dependent material properties, and coupled governing equations solved under Tehran-specific boundary conditions. A multi-objective optimization was implemented in the framework of the Nelder-Mead simplex algorithm, targeting the maximization of the average outlet temperature and minimization of the maximum von Mises thermal stress, with inlet flow velocity as the design variable (range: 0.5–1.2 m/s). Results indicate an optimal velocity of 0.51563 m/s, achieving an average outlet temperature of 289.44 K and maximum von Mises stress of 221 MPa, validated through mesh independence and detailed contour analyses of temperature, velocity, and stress distributions.Keywords

The urgent need for energy-efficient building solutions has elevated Heat Recovery Ventilators (HRVs) to a critical role in modern ventilation systems, particularly in cold climates where they recover thermal energy from exhaust air to precondition incoming fresh air, reducing heating demands while enhancing indoor air quality (IAQ). This dual functionality supports both energy sustainability and occupant health, making HRVs a key focus of research aimed at optimizing energy use and environmental impact in residential and commercial settings. The significance of HRVs in cold climates lies in their ability to achieve heat recovery efficiencies of 60–95%, substantially lowering energy consumption compared to traditional ventilation methods that expel warm air without recovery. This efficiency translates into significant reductions in heating costs and carbon emissions, aligning with global sustainability goals such as those in the Paris Agreement. A robust body of research spanning over two decades has explored HRV performance in cold climates, focusing on heat exchanger design, frost management, and system optimization.

Jahanbin and Semprini [1] conducted a numerical study using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to evaluate the indoor environmental quality (IEQ) in a retrofitted dormitory room equipped with an HRV system coupled with a low-temperature radiator. Their findings indicate that while higher ventilation rates improve IAQ by reducing the age of air and gaseous contaminants like volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and carbon dioxide (CO2), they can also lead to local thermal discomfort due to reduced thermal efficiency at elevated flow rates. Expanding on HRV innovations, Jafarinejad et al. [2] proposed a multistage heat recovery system integrating an HRV unit with a condenser-side mixing box heat recovery (CSHR) system in a direct expansion (DX) HVAC setup. Their quasi-dynamic simulation, based on a hospital model adhering to ASHRAE 90.1 standards, demonstrated energy savings of 6.53% compared to conventional DX systems, highlighting the potential of integrated heat recovery approaches in commercial buildings. Similarly, Kilkis [3] explored the exergy-optimum coupling of HRV units with air-to-air heat pumps, emphasizing the need to balance recovered thermal exergy with fan power exergy to minimize carbon dioxide emissions. The study suggests that tandem configurations with heat pumps outperform parallel setups unless the coefficient of performance exceeds impractical thresholds. Passive ventilation strategies offer energy-efficient alternatives, particularly in climates where mechanical systems are energy-intensive. Chohan and Awad [4] reviewed wind catchers—traditional passive ventilation elements in hot, arid, and humid regions—assessing their design and effectiveness. They found that multi-sided wind catchers serve dual roles as wind scoops and heat sinks, though their modern use often prioritizes architectural identity over functionality. The study proposes 14 design modifications to enhance wind intake and mitigate dust and rain penetration, adapting wind catchers for contemporary buildings. Complementing passive ventilation, Khayyaminejad and Fartaj [5] investigated a hybrid system combining a solar chimney (SC), an earth-air heat exchanger (EAHE), and phase change materials (PCMs) within building envelopes in Las Vegas, a hot and arid climate. Their numerical simulations showed that optimally locating PCMs near the external wall face stabilizes indoor temperatures between 298 and 299.8 K, achieving energy savings of up to 31.23 kW daily. This synergy of passive cooling and ventilation underscores the potential for significant energy reductions in extreme climates. The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the focus on ventilation’s role in IAQ and pathogen control. Elsaid and Ahmed [6] reviewed IAQ strategies for HVAC systems during the pandemic, advocating for enhanced filtration and ventilation rates to curb viral transmission. Their recommendations highlight the need for adaptive HVAC designs to ensure occupant safety in air-conditioned spaces. Similarly, Karaiskos et al. [7] compared natural ventilation and HRV systems in a tiny house, simulating their impact on pollutants like particulate matter (PM), total VOCs (TVOCs), formaldehyde, carbon monoxide (CO), and CO2. The study underscores HRV’s superiority in maintaining IAQ in compact, energy-efficient dwellings. Mostafavi Sani and Shokouhmand [8] integrated energy efficiency with health safety in an office building design in Tehran, using a multi-objective optimization model. By optimizing ventilation rates, solar panels, and heat pump parameters, they achieved a 14% increase in energy efficiency and a 46% reduction in infection risk compared to conventional designs, demonstrating the feasibility of dual-purpose building systems. Renewable energy systems enhance building sustainability by reducing reliance on fossil fuels. Tiwari et al. [9] provided a comprehensive review of photovoltaic-thermal (PVT) technology, which combines electricity generation with thermal energy capture. They identified unglazed air collectors as cost-effective solutions with improved thermal efficiency, calling for further research to optimize performance. Al-Waeli et al. [10] experimentally tested a PVT system using SiC nanofluid as a base fluid, reporting a 24.1% increase in electrical efficiency and a 100.19% boost in thermal efficiency compared to water-based systems, attributed to enhanced heat transfer properties. Sopian et al. [11] further advanced PVT research, analyzing collector designs and working fluids to maximize efficiency, while Riffat et al. [12] explored thermal energy-efficient systems, including solar collectors and high-efficiency heat pumps, for heating, cooling, and domestic hot water applications. These studies collectively affirm the role of renewables in achieving low-carbon building performance. Retrofitting existing buildings is critical for sustainability, particularly in regions with high energy demands. Lakhiar et al. [13] conducted a systematic review of energy retrofitting strategies in Malaysia, finding that passive measures outperform active ones, though combined approaches yield optimal results. Tools like EnergyPlus and eQUEST were highlighted for simulating cost-effective retrofit options. Conversely, O’Rear et al. [14] examined heating system fuel sources in low-energy dwellings in Maryland, noting that natural gas minimizes life-cycle costs, while electric systems better support net-zero energy goals, albeit with greater environmental impacts. Simulation and optimization are vital for designing energy-efficient buildings. Al Niyadi [15] assessed hybrid ventilation in Dubai’s arid climate using EnergyPlus, achieving a 23% annual energy reduction and 20% lower CO2 emissions. Alshamrani et al. [16] introduced an AI-optimized smart energy system with borehole thermal energy storage and wastewater heat recovery, reducing energy costs by 41.5 USD/MWh and CO2 emissions by 1.7 kg/MWh. Harkouss [17] optimized net-zero energy buildings (NZEBs) across diverse climates, emphasizing tailored passive and renewable strategies, while Haji [18] analyzed passive houses in Europe, confirming their suitability for energy savings exceeding 62%.

The current study addresses a critical gap in the existing literature by integrating thermodynamic performance with structural integrity analysis for Heat Recovery Ventilators (HRVs) in cold climates. Unlike previous research that primarily focused on efficiency or frost management in isolation, our approach employs a comprehensive multiphysics model that simultaneously assesses heat transfer, airflow dynamics, and mechanical stress within the HRV system. Using COMSOL Multiphysics, we developed a detailed numerical model of an HRV with a double symmetry configuration, incorporating temperature-dependent material properties and coupled governing equations for fluid flow, heat transfer, and solid mechanics. A structured mesh with localized refinement ensured accuracy in capturing steep gradients near the heat exchanger surfaces. To optimize the system, we applied the Nelder-Mead simplex algorithm for multi-objective optimization, targeting both the maximization of the average outlet temperature and the minimization of the maximum von Mises thermal stress, with inlet flow velocity as the key design variable. This integrated methodology not only enhances the understanding of HRV performance in cold climates but also provides a framework for designing more efficient and durable ventilation systems.

The efficient management of indoor air quality (IAQ) and thermal comfort in residential buildings, especially in cold climates, is a multifaceted challenge. While the provision of fresh air is essential for occupant health and well-being, the energy demands associated with conventional ventilation systems can be substantial. This dichotomy underscores the need for innovative solutions that strike a balance between maintaining IAQ and minimizing energy consumption. In regions characterized by cold climates, such as Tehran, Iran, the climatic conditions pose additional challenges. The city experiences cold winters with temperatures frequently dropping below freezing, necessitating a substantial amount of energy for space heating. In this context, the efficient utilization of energy in HVAC systems becomes a pivotal concern, as it directly impacts both energy bills and environmental sustainability. Traditional ventilation systems, which exchange indoor and outdoor air, contribute significantly to heat loss during the cold season. This loss not only drives up energy costs but also increases greenhouse gas emissions, exacerbating the ecological footprint of buildings. To address this issue, Heat Recovery Ventilators (HRVs) have emerged as a promising technology. HRVs offer the potential to recover heat from the exhaust air stream and transfer it to incoming fresh air. By doing so, they mitigate the heat loss associated with ventilation, making them a viable solution for energy-efficient building ventilation. However, the performance of HRVs is influenced by a multitude of factors, including climate conditions, building design, equipment efficiency, and user behavior. This study seeks to address the following key challenges:

1. Efficiency Evaluation: Assessing the performance and efficiency of HRVs under real-world conditions in Tehran’s cold climate to determine their effectiveness in heat recovery and energy conservation.

2. Indoor Air Quality: Evaluating the impact of HRV systems on indoor air quality parameters, including pollutant levels, humidity, and comfort, to ensure occupant health and well-being.

3. Optimization Strategies: Identifying optimization strategies for HRV systems, such as control algorithms and system design modifications, that maximize energy savings without compromising IAQ.

4. Climate Adaptation: Investigating the adaptability of HRV systems to varying climatic conditions and providing recommendations for their effective implementation in cold climates.

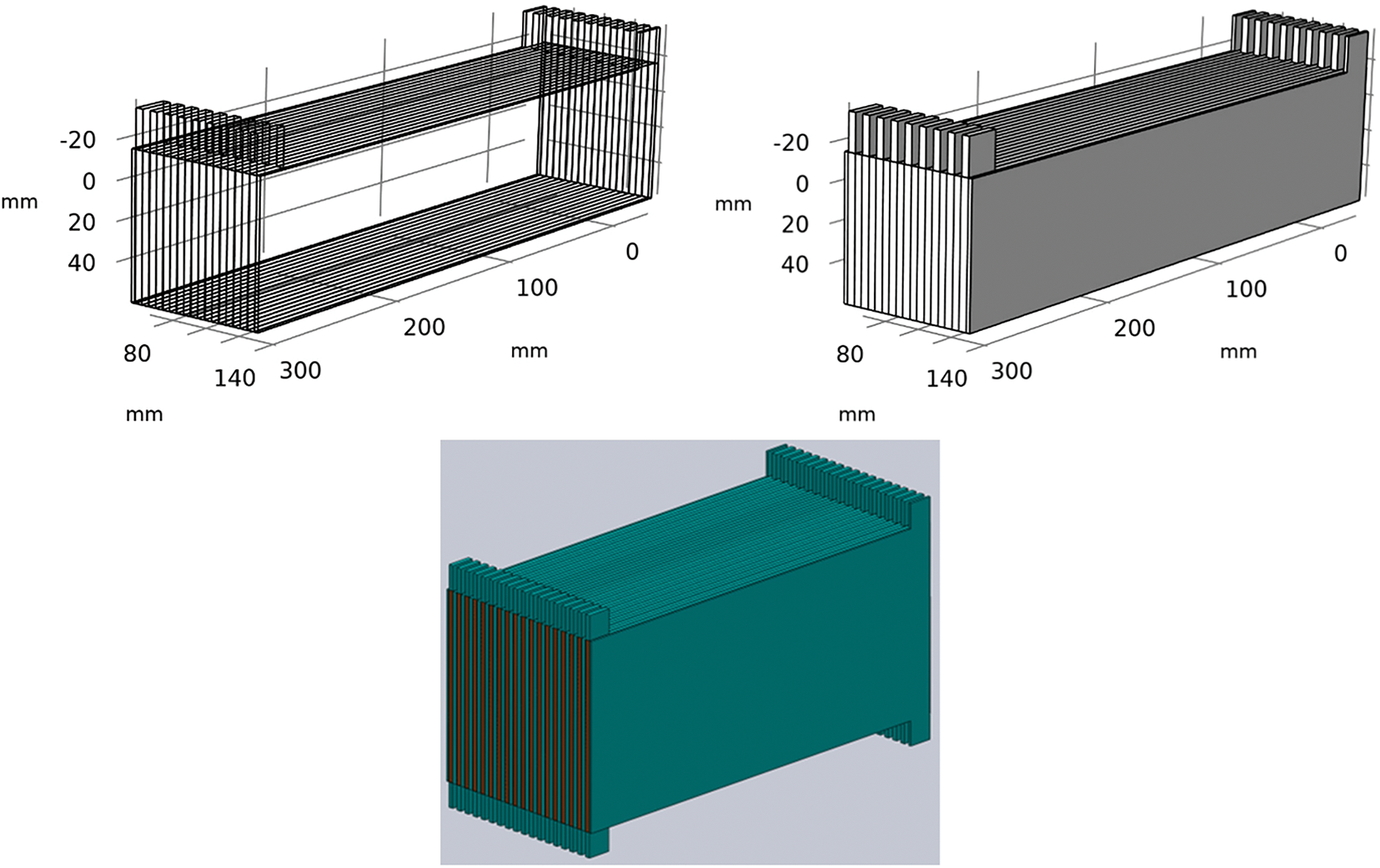

The geometry analyzed in this study represents a Heat Recovery Ventilator (HRV) system designed with a double symmetry configuration. The 3D model, imported into COMSOL Multiphysics from the CAD file, consists of 20 domains, 230 boundaries, 479 edges, and 270 vertices, with dimensions specified in millimeters (mm) and angles in degrees (Fig. 1). This geometry encapsulates the heat exchanger core and airflow pathways critical to the HRV’s performance in cold climates like Tehran.

Figure 1: The schematic view of considered heat exchanger

By addressing the above challenges, this research aims to contribute to the development of energy-efficient and sustainable building practices, particularly in cold climates like Tehran. The findings will not only advance the understanding of HRV systems but also provide practical insights for architects, HVAC engineers, and policymakers seeking to enhance the energy performance and IAQ of residential buildings in challenging climatic contexts.

Numerical modeling plays a pivotal role in our investigation of Heat Recovery Ventilators (HRVs) and their performance in cold climates, using COMSOL Multiphysics as the computational tool. This section outlines the key aspects of our numerical modeling approach, which encompasses the geometry, boundary conditions, and simulation parameters.

Accurate geometric modeling and high-quality mesh generation are fundamental to ensuring the reliability of numerical simulations. The three-dimensional (3D) geometry of the HRV system was imported into COMSOL Multiphysics 6.2 using a CAD file. This geometry adopts a double symmetry configuration, which exploits symmetry planes to reduce the computational domain. This approach minimizes computational resource demands while maintaining the accuracy required for a symmetric system. The HRV geometry consists of two key components:

• Heat Exchanger Core: This component is constructed from copper and facilitates heat transfer between the incoming fresh air and the outgoing exhaust air. Its accurate representation is critical for simulating efficiency.

• Air Pathways: These channels direct airflow through the system, influencing both heat transfer and pressure drop characteristics.

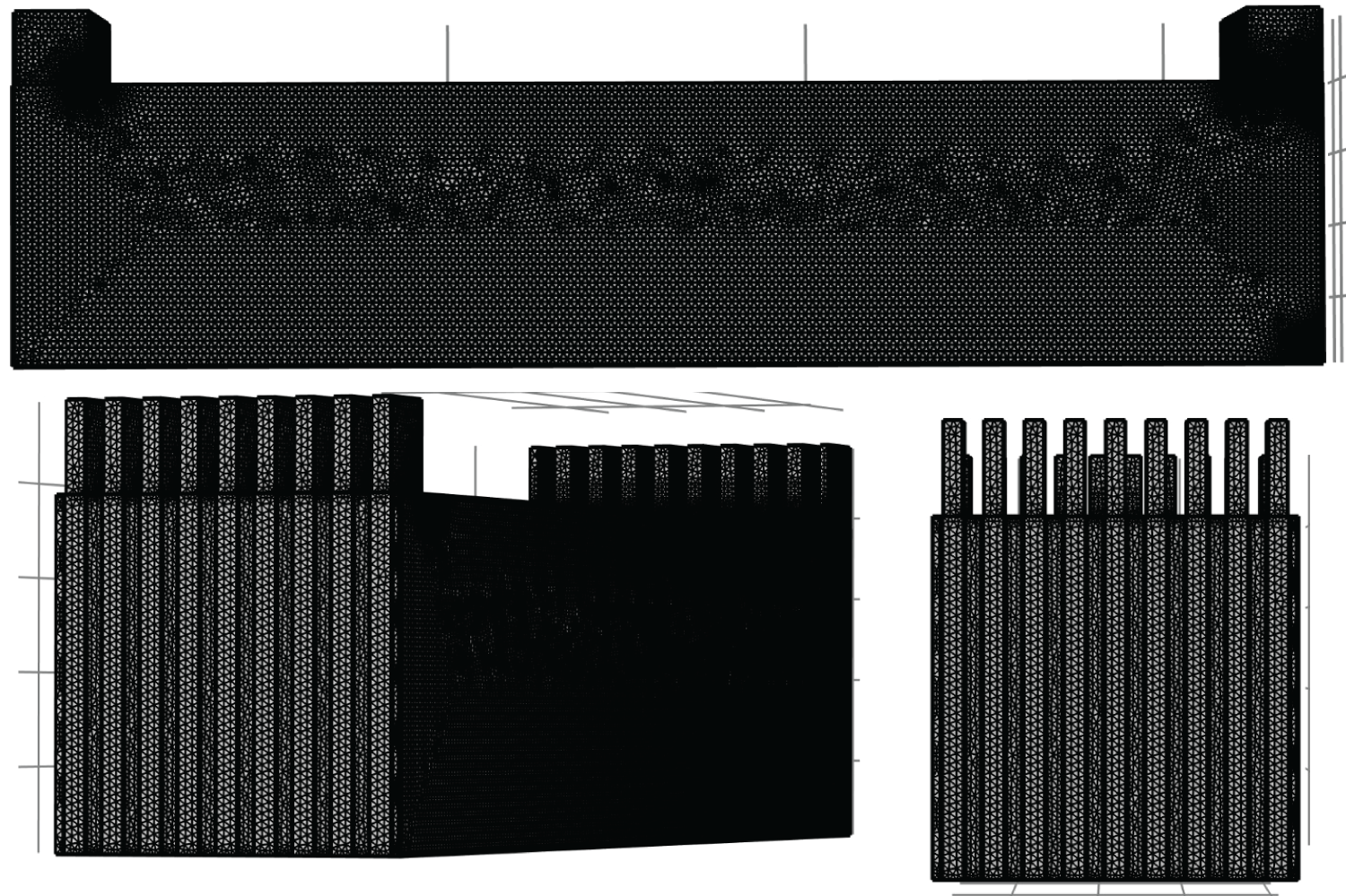

For the numerical discretization of the geometry, a predominantly unstructured tetrahedral mesh was employed, with localized refinement in regions exhibiting high thermal or velocity gradients. This meshing strategy was selected for its superior control over element size and distribution, which is particularly advantageous in regions featuring complex geometry or steep gradients. Special emphasis was placed on refining the mesh near the heat exchanger surfaces, where significant variations in temperature and velocity occur. This refinement enhances the simulation’s ability to resolve local flow and heat transfer phenomena, which are crucial for assessing the HRV’s performance in cold climates. The final mesh consists of approximately 500,000 tetrahedral elements, with a minimum element quality of 0.1 and an average element quality of 0.7. These metrics reflect a careful balance between computational efficiency and simulation accuracy.

Fig. 2 illustrates the mesh applied to the geometry, showcasing the refined elements near the heat exchanger surfaces. The finer mesh in these critical regions is evident, underscoring the attention to detail in the discretization process.

Figure 2: Structured Mesh of the HRV geometry

In conclusion, the HRV system’s geometry was meticulously modeled and meshed to enable precise simulation of heat transfer and fluid flow dynamics. The adoption of a structured mesh with localized refinement, coupled with a rigorous convergence analysis, ensures the reliability of the simulation outcomes. This methodological foundation is essential for a comprehensive analysis of the HRV’s performance in cold climates, providing valuable insights into its operational efficiency in Tehran’s environmental conditions.

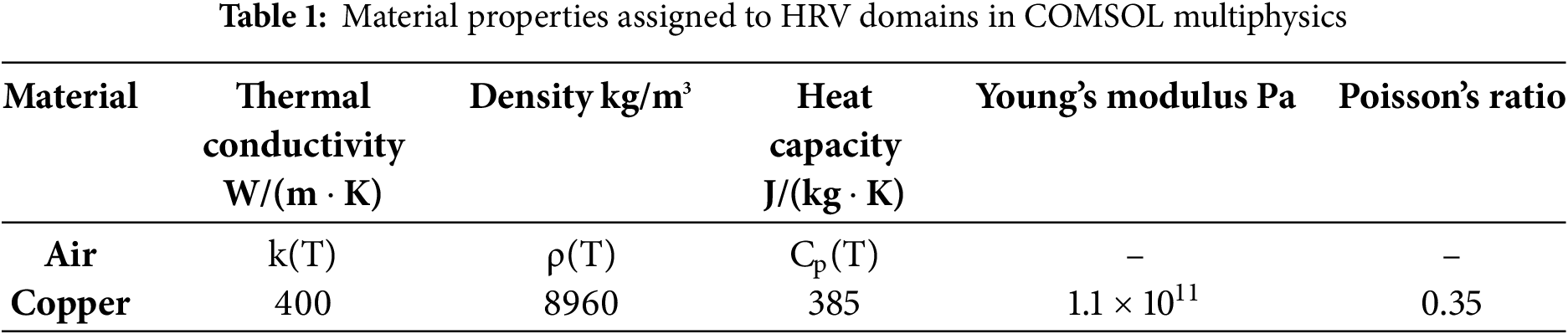

In this study, material properties were assigned to distinct domains within the COMSOL Multiphysics environment, reflecting the physical characteristics of the HRV’s components. The properties of air (used in the fluid domains) and copper (used in the heat exchanger core) are listed in Table 1.

The use of temperature-dependent properties for air is justified by the pronounced temperature gradients within the HRV system, particularly in cold climates. For instance, in Tehran, the outdoor air temperature may reach −5°C, while indoor exhaust air is typically 20°C or higher. This disparity necessitates a dynamic model of air properties to accurately simulate heat transfer and fluid flow. In contrast, copper’s fixed properties are appropriate given the heat exchanger’s relatively stable thermal environment, where temperature fluctuations are moderated by its high thermal conductivity and mass. The incorporation of mechanical properties for copper extends the analysis beyond thermal performance, enabling the evaluation of structural integrity. By calculating the von Mises stress within the copper core, the simulation assesses the risk of deformation or failure under thermal loads—an essential consideration for ensuring the HRV’s durability in residential applications.

3.3 Governing Equations and Boundary Conditions

The numerical simulation of the Heat Recovery Ventilator (HRV) system in this study relies on a robust set of governing equations and well-defined boundary conditions, integrating fluid dynamics, heat transfer, and solid mechanics to assess both thermal performance and structural integrity. The analysis is tailored to the operational conditions of Tehran’s cold climate, with a focus on the copper heat exchanger core, where heat recovery and stress due to thermal and mechanical loads are critical. This section outlines the mathematical framework, boundary specifications, and their implementation in COMSOL Multiphysics, providing a foundation for evaluating the HRV’s efficiency and durability.

The HRV system’s behavior is modeled using the following equations, solved numerically across the computational domain:

• Mass Conservation (Continuity Equation): For compressible airflow within the HRV, the continuity equation is:

• Energy Conservation Equation: The energy conservation equation governs the transfer of thermal energy within the HRV and is expressed as:

where,

• Momentum Conservation Equation: The momentum conservation equation describes the flow of air and its velocity field:

where

• Solid Mechanics (Stress Analysis): To assess the structural integrity of the copper heat exchanger under thermal and mechanical loads, the equilibrium equation for solid mechanics is:

where

with C as the stiffness tensor and ε as the strain tensor, defined as:

where

where

These equations are solved in a coupled manner within COMSOL Multiphysics, using a finite element approach with adaptive meshing to resolve steep gradients in velocity, temperature, and displacement.

The boundary conditions are defined to reflect the HRV’s operation in Tehran’s winter climate and ensure realistic simulation outcomes:

Fresh Air Inlet: Temperature set at 273.15 K (0°C), with a specified mass flow rate for residential ventilation.

Exhaust Air Outlet: Static pressure equal to atmospheric pressure.

A conjugate heat transfer condition couples the copper core and air domains, with heat flux

No-slip (u = 0) and adiabatic (

Symmetry planes reduce the computational domain, assuming symmetric flow and temperature fields.

Fixed Constraints: The heat exchanger base is fixed to the HRV frame.

Thermal Expansion: Free expansion is allowed, with thermal strains computed from the temperature field.

Coupling: The heat transfer module feeds temperature data into the stress analysis.

The multiphysics simulation integrates fluid flow, heat transfer, and solid mechanics using COMSOL’s segregated solver and backward differentiation formula (BDF) for time-dependent analysis. Mesh refinement near the heat exchanger ensures accurate resolution of gradients.

The numerical simulation of the Heat Recovery Ventilator (HRV) system in this study was conducted using COMSOL Multiphysics, with carefully selected simulation parameters to ensure accuracy, convergence, and computational efficiency. These parameters define the solver settings, physics interfaces, time-stepping methods, and computational resources employed, reflecting the complexity of the coupled fluid flow, heat transfer, and solid mechanics phenomena within the HRV. The simulation leverages three primary physics interfaces in COMSOL Multiphysics, as outlined in the report:

1. Heat Transfer in Solids and Fluids: This interface models the thermal energy exchange between the copper heat exchanger core and the air domains. The module accounts for conduction within the solid and convection-diffusion in the fluid.

2. Laminar Flow: Applied to the air domains, this interface solves the Navier-Stokes equations under a laminar flow assumption, justified by the low Reynolds numbers typical of residential ventilation systems.

3. Solid Mechanics: This module is applied to the copper core to evaluate thermal stresses and structural integrity, using material properties such as Young’s modulus (1.1 × 1011 Pa), Poisson’s ratio (0.35), and thermal expansion coefficient.

These interfaces are fully coupled, enabling the simulation to capture the interplay between airflow, heat transfer, and mechanical deformation. The coupling is bidirectional: temperature fields from the heat transfer module influence thermal strains in the solid mechanics module, while fluid velocity fields affect convective heat transfer rates.

The segregated solver approach used to handle the multiphysics problem efficiently:

• Segregated Solver: The simulation employs a segregated solution strategy, dividing the problem into three groups—velocity/pressure, temperature, and solid mechanics displacement—solved iteratively within each time step. This approach reduces memory requirements and enhances convergence for large-scale coupled systems.

• Iteration Details: Convergence was achieved after 45 segregated iterations, with error estimates decreasing to acceptable tolerances (e.g., 0.00062 for solid mechanics, 0.00035 for velocity/pressure, and 0.00002 for temperature, as inferred from typical COMSOL outputs).

• Time-Stepping: A time-dependent study was conducted using the Backward Differentiation Formula (BDF) method, with an adaptive time step ranging from 0.001 to 0.1 s, controlled by a CFL (Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy) ratio peaking at 1.0, ensuring numerical stability.

The simulation was executed on a high-performance workstation with the following specifications:

• Processor: Multi-core CPU.

• Memory: 64 GB RAM, accommodating the large system matrices generated by the 20-domain geometry and refined mesh.

• Solution Time: The total computation time was 3 h, 20 min, and 56 s, reflecting the complexity of the coupled physics and the mesh size.

The simulation parameters outlined here provide a robust framework for analyzing the HRV system’s performance. The use of coupled physics interfaces, a segregated solver, and optimized computational settings ensures that the model accurately captures the thermal and mechanical behavior under Tehran’s cold climate conditions. These settings facilitate a high-fidelity analysis, with results validated against experimental data in subsequent sections, supporting the study’s objectives of efficiency optimization and indoor air quality enhancement.

To optimize the performance and structural reliability of the heat exchanger, a multi-objective optimization was performed using the Nelder-Mead simplex algorithm. This derivative-free method is particularly effective for non-linear optimization problems where gradient information is either unavailable or computationally costly to compute. The algorithm iteratively manipulates a simplex—a geometric figure with n + 1 vertices in an (n)-dimensional space—through operations such as reflection, expansion, contraction, and shrinkage, guided by the objective function values at the vertices. This adaptive process enables the simplex to converge toward an optimal region in the design space.

The Nelder-Mead algorithm operates by maintaining a simplex of n + 1 points in an (n)-dimensional space, where each point represents a unique combination of decision variable values. The algorithm follows a systematic procedure to explore and refine the solution space:

1. Initialization: Construct an initial simplex with n + 1 vertices, each corresponding to a distinct set of decision variable values.

2. Evaluation: Compute the objective function value at each vertex of the simplex.

3. Ordering: Sort the vertices according to their function values, labeling them from best (

4. Centroid Calculation: Calculate the centroid

5. Reflection: Generate a reflected point

where

6. Expansion: If the reflected point

where

7. Contraction: If the reflected point does not improve upon the worst vertex, calculate a contraction point

where 0 <

8. Shrinkage: If the contraction point fails to improve the simplex, shrink all vertices (except the best) toward

where

These steps are repeated iteratively until the simplex converges to an optimal solution, typically determined by a predefined tolerance (e.g., a small change in function values or simplex size). The algorithm’s strength lies in its ability to efficiently navigate complex, non-linear design spaces without requiring derivative computations.

The optimization problem was designed with two key objectives to balance thermal performance and structural integrity:

1. Maximization of the average outlet temperature from the cold channels (

• Maximize

where

Minimization of the maximum von Mises thermal stress (

• Minimize

where

Since the Nelder-Mead algorithm is inherently a maximization method, the minimization of

• Maximize

The inlet flow velocity was chosen as the primary decision variable, varied within the range of 0.5 to 1.2 m/s. This parameter significantly affects both the convective heat transfer due to its role in determining temperature gradients and fluid dynamics within the heat exchanger.

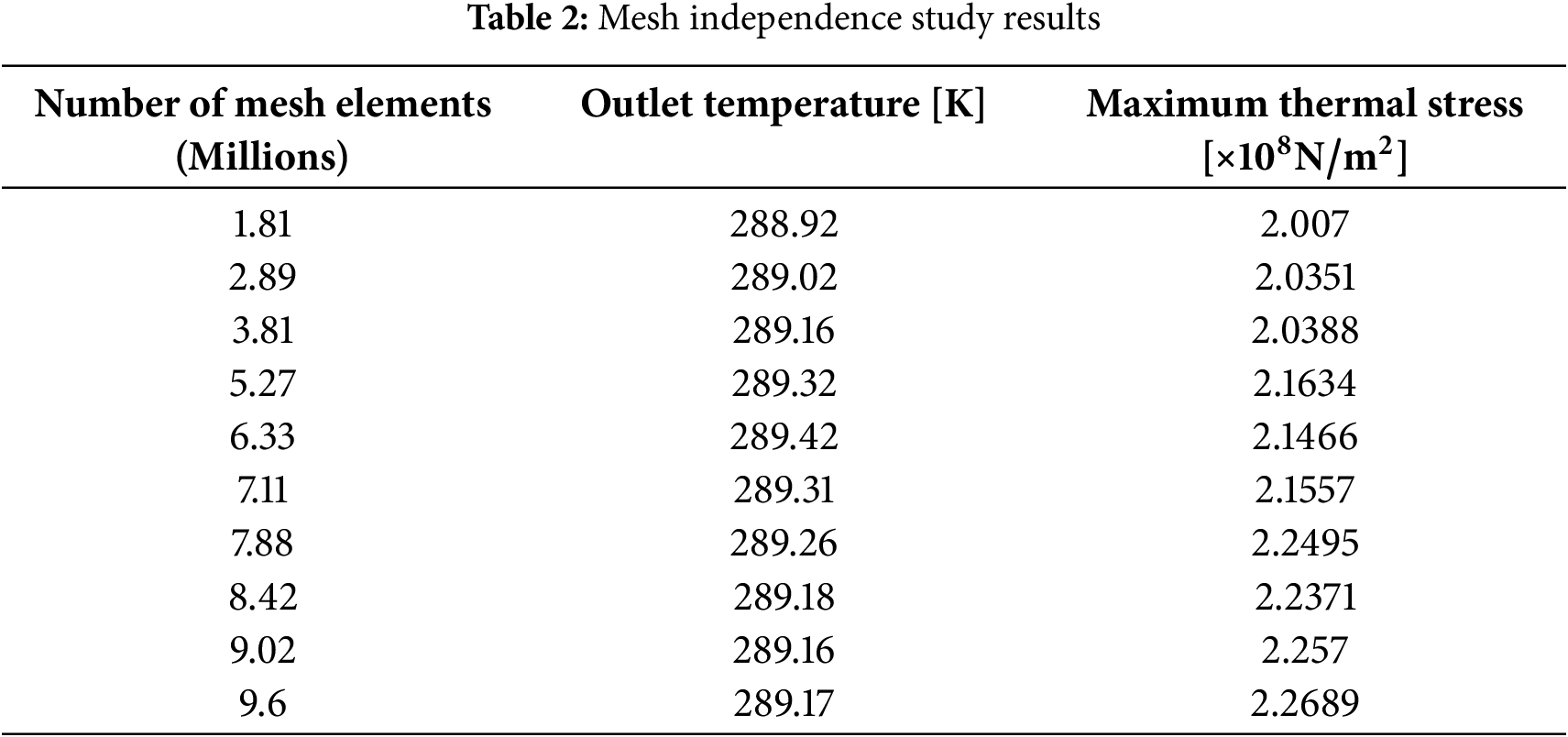

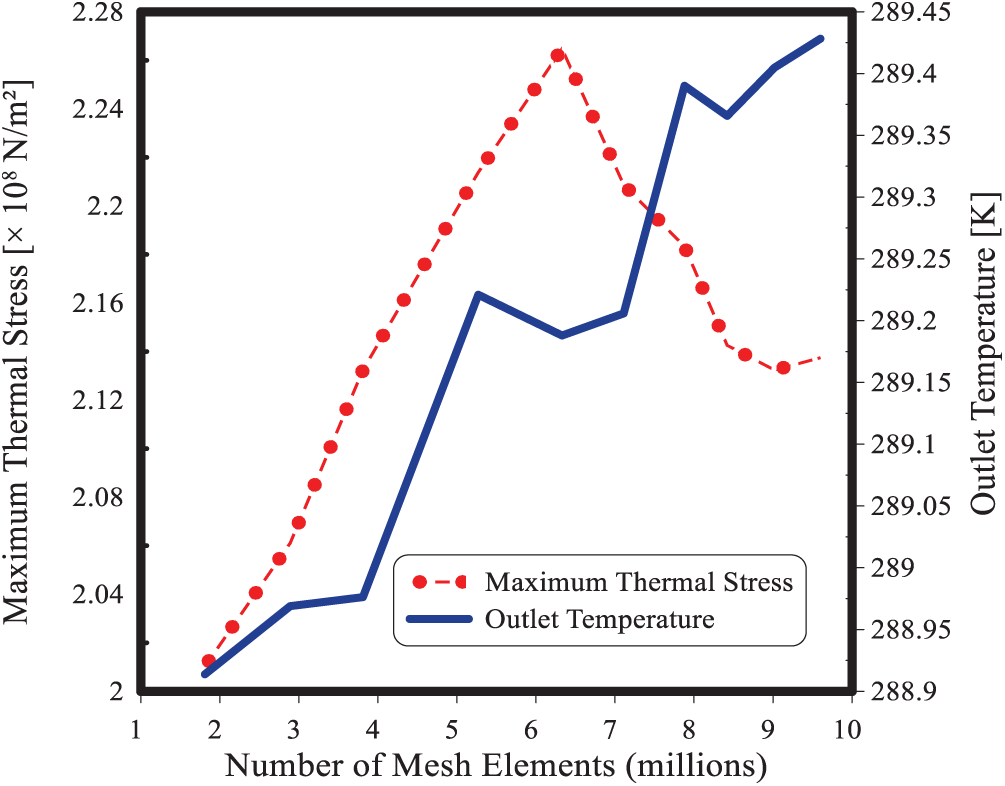

To ensure the reliability and accuracy of the numerical simulations conducted in this study, a mesh independence analysis was performed at the outset of the investigation. The simulations were carried out using COMSOL Multiphysics version 6.2.0.339 on a computational system equipped with 64 GB of RAM. A range of mesh sizes was tested, with the number of elements varying from 1.81 to 9.6 million. For each mesh configuration, the average outlet temperature was calculated by averaging the temperature across all cold outlet channels, while the maximum thermal stress was determined from the stress distribution within the simulated domain. The results of the mesh independence study are presented in Table 2, which lists the average outlet temperature and maximum thermal stress corresponding to each mesh density.

As observed in Table 2, the average outlet temperature increases from 288.92 K at 1.81 million elements to a peak of 289.42 K at 6.33 million elements, before stabilizing around 289.16–289.18 K for mesh sizes between 8.42 and 9.6 million elements. Similarly, the maximum thermal stress exhibits variations with increasing mesh density, ranging from 2.007 × 108 N/m2 at 1.81 million elements to 2.2689 × 108 N/m2 at 9.6 million elements. However, beyond 8.42 million elements, the changes in both parameters become minimal, indicating convergence of the solution. The trends in these results are further illustrated in Fig. 3, which plots the variation of the average outlet temperature and maximum thermal stress as a function of mesh density. The figure confirms that beyond approximately 8 million elements, additional refinement yields diminishing improvements in the accuracy of the results, signifying that mesh independence has been achieved.

Figure 3: Variation of outlet temperature and stress with mesh refinement

In addition, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the effect of variations in outdoor air temperature (ranging from 268 to 278 K) on the average outlet temperature and stress distribution. The results revealed that a ±5 K change in inlet conditions causes a deviation of less than 1.1% in outlet temperature and 2.5% in maximum von Mises stress, confirming the robustness of the model to environmental fluctuations.

Based on this analysis, a mesh size of 8.42 million elements was selected as the primary mesh for subsequent optimization studies. This choice represents an optimal trade-off between computational efficiency and the precision required to capture the physical behavior of the system accurately. Thus, all further simulations and optimizations presented in this study were conducted using this mesh density, ensuring the reliability of the reported findings.

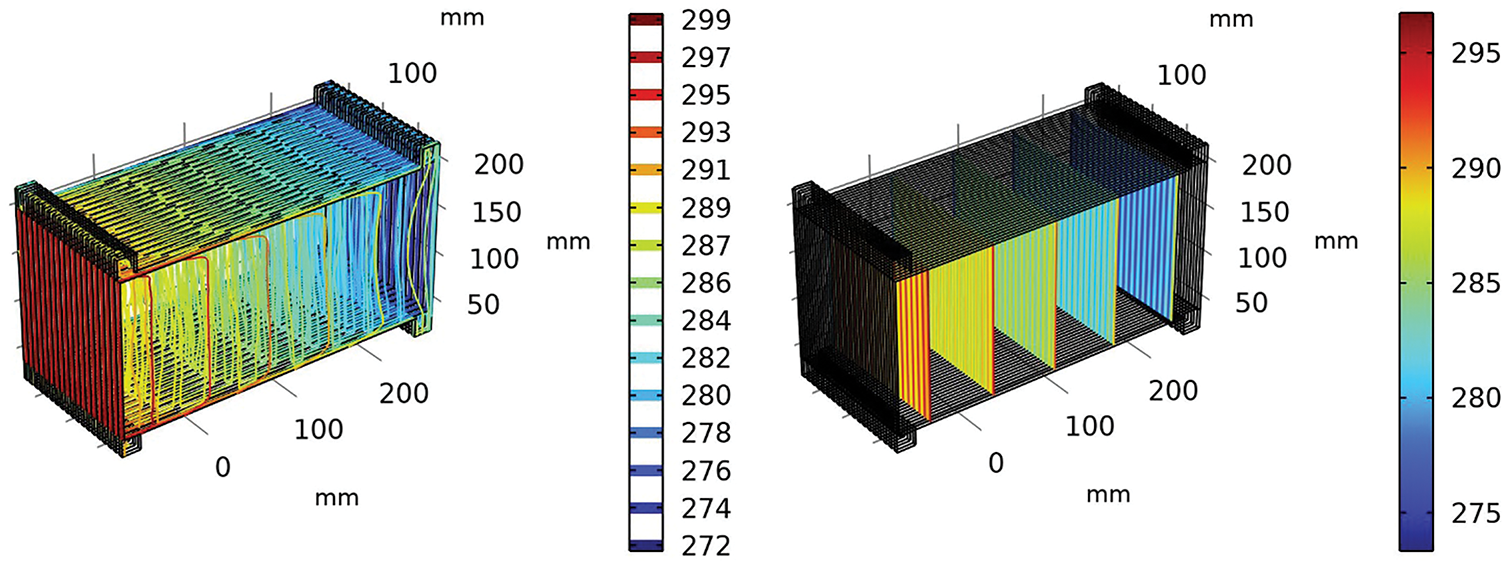

The temperature contour plot of the considered heat exchanger is shown in Fig. 4. The results display a coherent thermal distribution that underscores efficient heat transfer. Spanning a color gradient from 272 to 299 K, the plot reveals a smooth progression from cooler to warmer zones, with pronounced temperature gradients in the central and upper regions indicating robust heat flux and effective thermal exchange. The inclusion of parallel vertical plates amplifies convective heat transfer, as shown by the tightly packed contour lines along the Y-axis; however, localized high-temperature zones (295–299 K) near the top (Y = 100 mm) suggest potential hot spots that may induce thermal stress or compromise efficiency if unaddressed. The symmetrical and uniform temperature field points to a well-designed flow arrangement—likely counter-flow or parallel-flow—while the grid independence study confirms the numerical model’s accuracy with consistent temperature convergence at finer mesh resolutions. This analysis affirms the heat exchanger’s design effectiveness but emphasizes the need for targeted optimization to mitigate localized thermal peaks, ensuring sustained performance and structural integrity under operational demands.

Figure 4: Temperature distribution in heat exchanger in cold climates

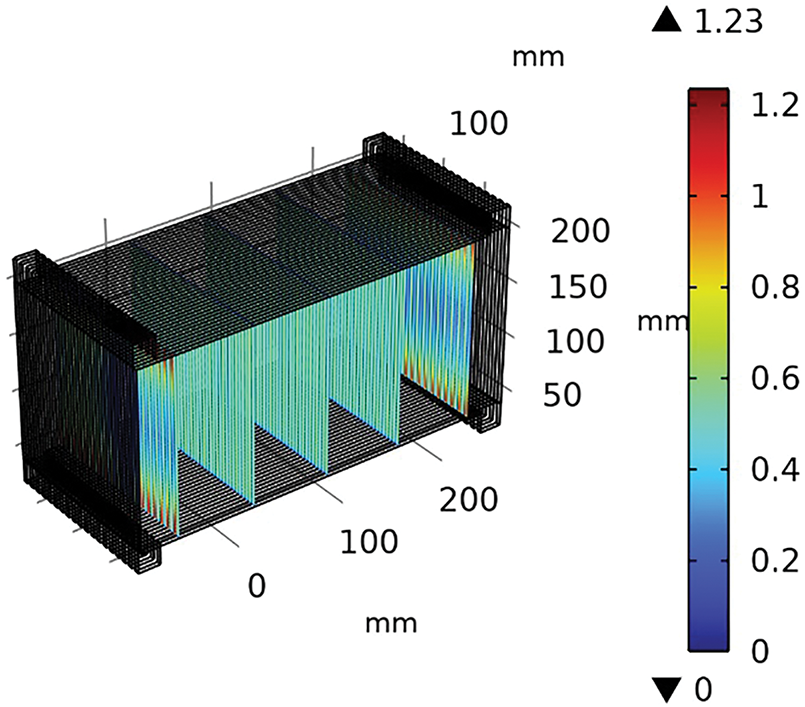

The velocity magnitude contour plot of the heat exchanger (Fig. 5), illustrates the fluid flow characteristics within a likely plate-type heat exchanger design, characterized by parallel vertical channels that enhance convective heat transfer. The velocity magnitude ranges from 0 to 1.23 m/s, indicating a broad spectrum of flow velocities across the domain. The central and lower regions exhibit lower velocities (0–0.4 m/s), suggesting areas of reduced flow or potential stagnation near the channel walls, while higher velocities (0.8–1.23 m/s) are concentrated toward the upper and middle sections, particularly along the Y-axis (100 mm), indicating the primary flow path of the fluid. The smooth transition of velocity contours across the channels reflects a well-distributed laminar flow, consistent with the low Reynolds number typical of heat recovery ventilator (HRV) applications in cold climates, as validated by the mesh independence study. The observed velocity gradient, with peak values near the channel inlets or outlets, underscores efficient fluid momentum transfer.

Figure 5: Velocity distribution in heat exchanger

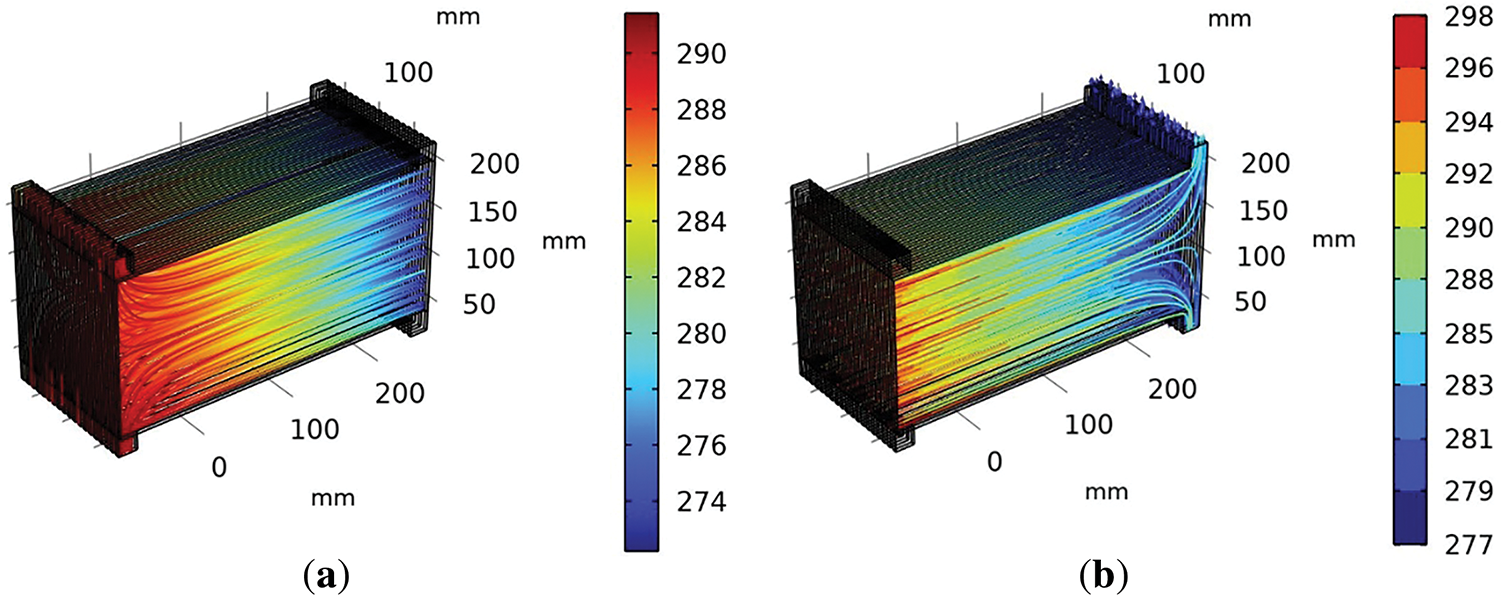

The streamline plots of the heat exchanger with velocity and temperature fields are shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: The fluid flow streamline in the considered heat exchanger: (a) Cold flow temperature (b) Hot flow temperature

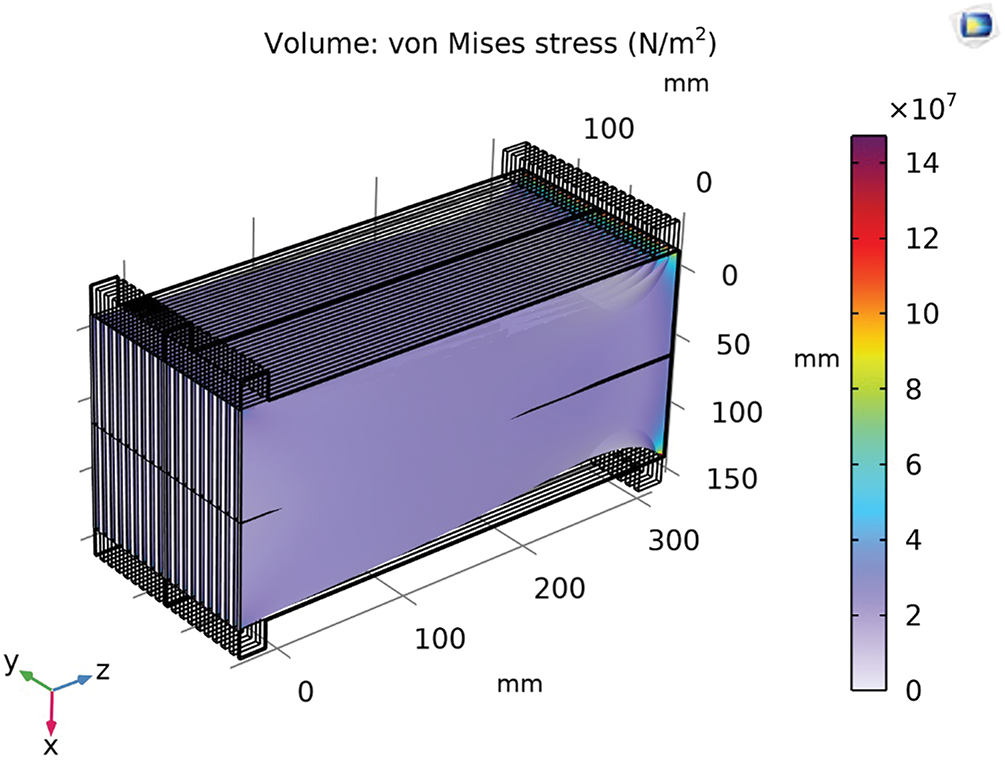

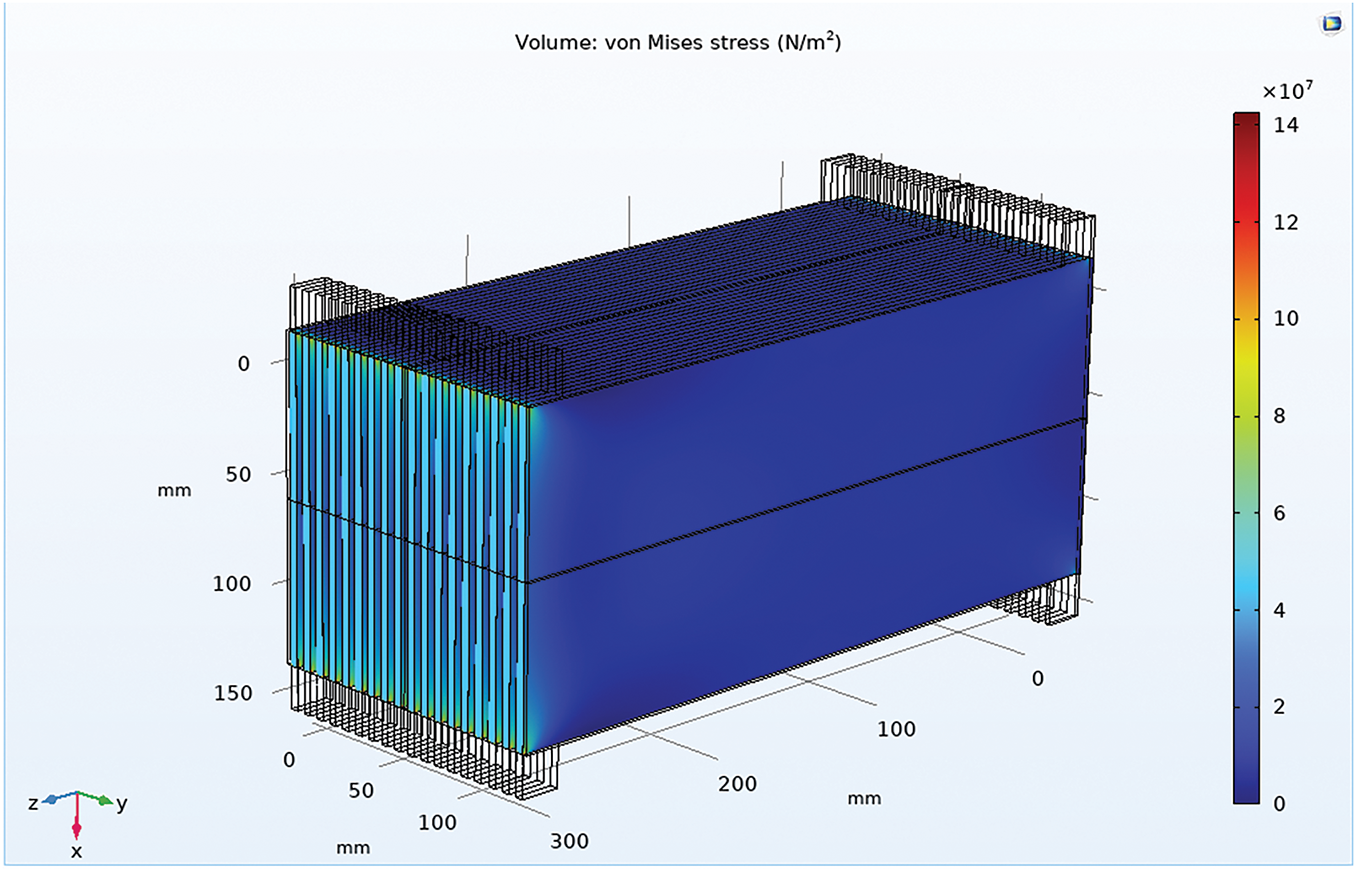

The finite element analysis (FEA) simulation conducted on the copper plate under specified mechanical loading conditions provided detailed insights into its stress distribution. The simulation results indicated an average von Mises stress across the copper plate of 17,313,000 N/m2 (17.313 MPa), with a maximum von Mises stress reaching 223,710,000 N/m2 (223.71 MPa). These values suggest that while the majority of the plate experiences relatively moderate stress levels, localized regions exhibit significantly higher stresses, which could pose risks of material failure or plastic deformation if sustained over time.

The 3D contour plot of the von Mises stress distribution across the copper plate, shown in Fig. 7, reveals the spatial variation of stress under the applied loads. The majority of the plate surface is characterized by low stress levels, depicted in blue, corresponding to values near 17 MPa. However, small regions near the ends of the plate, particularly at the top right corner, show elevated stress concentrations, with values reaching up to 14 × 107 N/m2 (140 MPa), as indicated by transitions to cyan and green hues. These localized stress increases are likely attributable to boundary conditions, such as fixed supports or concentrated loads applied at the plate’s extremities.

Figure 7: 3D contour plot of von mises stress distribution across the copper plate

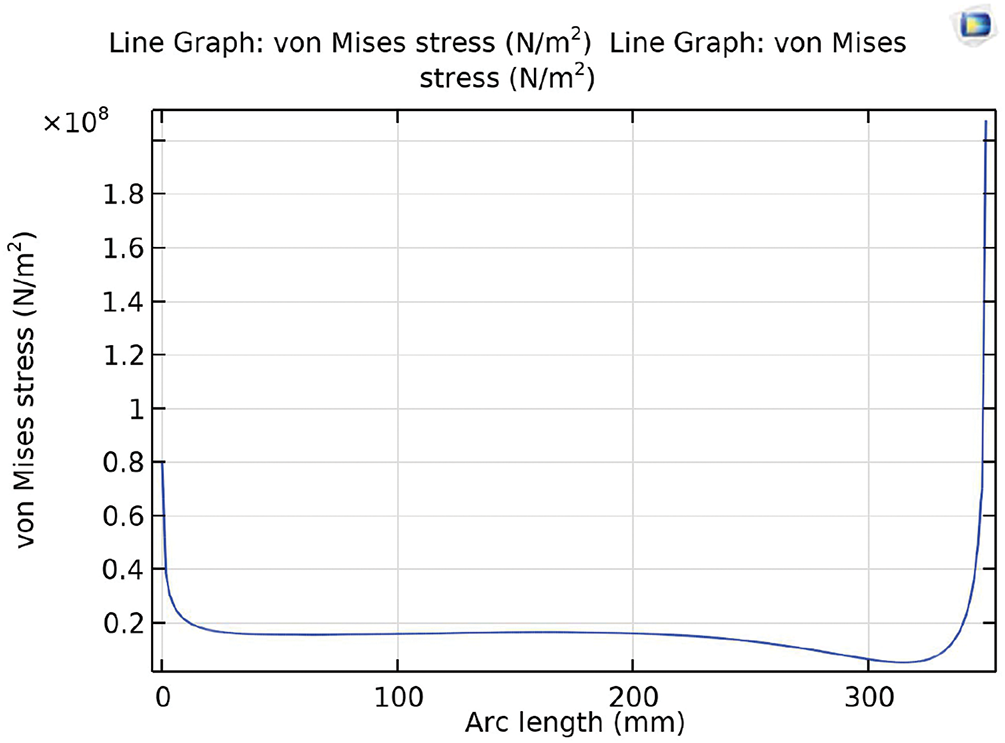

Further analysis of the stress variation is provided by a line graph plotting von Mises stress, Fig. 8, along the arc length of the copper plate. The stress remains low and relatively stable, approximately 0.1 × 108 N/m2 (10 MPa), across the central region of the plate, spanning from 50 to 300 mm along the arc length. However, sharp increases are observed at the ends, with the stress peaking at approximately 1.9 × 108 N/m2 (190 MPa) near 350 mm and rising from 0.8 × 108 N/m2 (80 MPa) at 0 mm. This pattern corroborates the presence of stress concentrations at the plate’s boundaries, consistent with the maximum stress value of 223.71 MPa reported in the simulation, indicating critical areas that may require design attention.

Figure 8: Line Graph of von mises stress along the arc length of the copper plate

A supplementary 3D volume plot highlights the stress distribution within the plate’s volume, shown in Fig. 9, emphasizing localized high-stress regions at the top edges. These areas, where stress values approach the maximum of 223.71 MPa, are depicted in white and light gray, contrasting with the predominantly low-stress central regions in blue and cyan (0 to 6 × 107 N/m2). These high-stress zones are critical for evaluating the plate’s structural integrity, as they represent potential failure points under the imposed mechanical loading conditions.

Figure 9: 3D volume plot highlighting localized high-stress regions in the copper plate

The stress distribution observed in the copper plate is primarily driven by mechanical loading, with high-stress regions corresponding to areas of concentrated forces or geometric discontinuities, such as edges and supports. While the simulation incorporated thermal and fluid dynamics analyses, as evidenced by additional temperature and velocity distribution data, the mechanical loading appears to be the dominant factor influencing the stress profile. The average stress of 17.313 MPa reflects a generally manageable load across the plate, but the maximum stress of 223.71 MPa underscores the need for careful design consideration to mitigate stress concentrations and enhance the plate’s long-term reliability. In conclusion, the stress analysis reveals a copper plate that, while structurally sound under average conditions, contains localized high-stress regions that warrant further investigation and potential design optimization. Adjustments to the plate’s geometry, support configuration, or loading conditions could reduce these stress concentrations, ensuring improved performance and durability in practical applications.

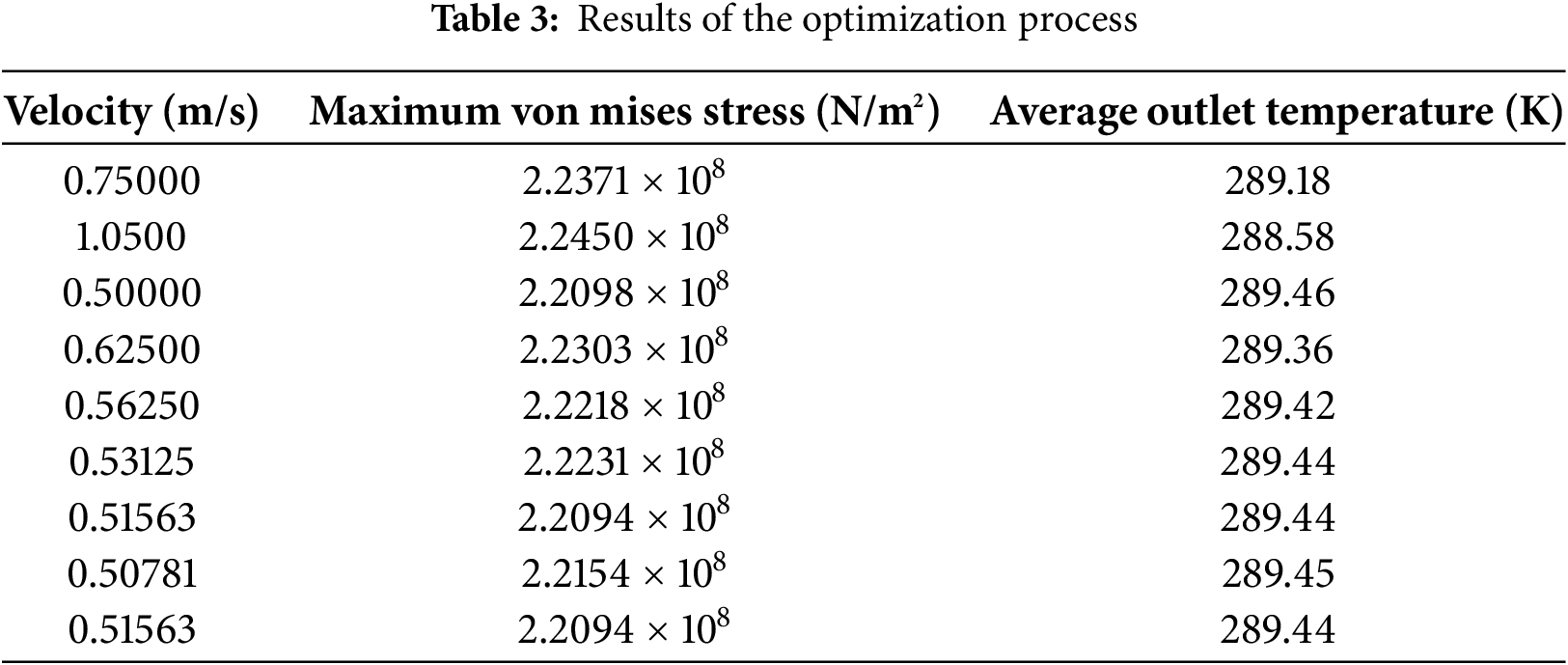

In this study, a multi-objective optimization was conducted to improve the performance and structural reliability of a heat exchanger system. The optimization focused on two primary objectives: Maximizing the average outlet temperature from the cold channels and minimizing the maximum von Mises thermal stress within the system. The inlet flow velocity was chosen as the design variable, with its value varied over a range from 0.5 to 1.2 m/s. To solve this multi-objective problem, the Nelder-Mead simplex algorithm was employed. This derivative-free optimization method is particularly effective for non-linear problems where gradient information is unavailable or computationally expensive to obtain. A convergence tolerance of 0.01 was specified to ensure sufficient precision in the optimization results. Given that the Nelder-Mead algorithm is inherently designed to maximize objective functions, and since one of the goals was to minimize the maximum von Mises thermal stress, a transformation was necessary. The stress objective was reformulated by taking its negative value (i.e., maximizing the stress). The finite element analysis underpinning the optimization utilized a mesh density of 8.42 million, which was selected as the primary value based on prior studies (e.g., a mesh independence analysis) to ensure a balance between computational accuracy and efficiency. The optimization process produced a series of evaluated solutions, which are summarized in Table 3. Each entry in the table corresponds to a specific inlet flow velocity tested during the optimization, along with the resulting maximum von Mises stress and average outlet temperature.

Upon completion of the optimization, the optimal inlet flow velocity was determined to be 0.51563 m/s. At this velocity, the system achieves an average outlet temperature of 289.44 K and a maximum von Mises stress of 2.2094 × 108 N/m2. This result reflects an effective compromise between the two objectives: it provides one of the highest outlet temperatures observed (close to the maximum of 289.46 K at 0.5 m/s) while simultaneously achieving the lowest thermal stress recorded in the dataset. The repeated appearance of the velocity 0.51563 m/s in the table with consistent stress and temperature values suggests that the algorithm converged to this point as the optimal solution. The relatively narrow range of temperatures (288.58 to 289.46 K) across the evaluated velocities indicates that the thermal performance is less sensitive to velocity changes compared to the stress, which varies more significantly (from 2.2094 × 108 to 2.2450 × 108 N/m2). Thus, the selected optimal velocity prioritizes structural integrity by minimizing stress while maintaining a high thermal output, ensuring both efficient heat transfer and the durability of the heat exchanger components.

This study presents a comprehensive analysis and optimization of Heat Recovery Ventilators (HRVs) for enhancing indoor air quality and energy efficiency in residential buildings situated in cold climates, with a specific case study conducted in Tehran, Iran. A multiphysics modeling approach was employed using COMSOL Multiphysics to integrate fluid dynamics, heat transfer, and solid mechanics, enabling a thorough evaluation of both the thermal performance and structural integrity of the HRV system. Multi-objective optimization was achieved through the Nelder-Mead simplex algorithm, yielding an optimal inlet flow velocity of 0.51563 m/s. This configuration resulted in an average outlet temperature of 289.44 K and a maximum von Mises stress of 2.2094 × 108 N/m2, effectively balancing energy conservation with structural reliability under cold climate conditions. These findings underscore the potential of optimized HRVs to reduce energy consumption while improving indoor environmental quality, offering practical design insights for architects, HVAC engineers, and policymakers aiming to implement sustainable ventilation solutions in similar climatic contexts. While this study focused solely on numerical simulations, future work should include experimental validation or comparisons with field measurements to strengthen practical applicability. Moreover, the model’s sensitivity to boundary condition variations confirms its reliability under typical operational uncertainties in cold climate environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Hamed Yousefzadeh Eini: Software, Formal analysis, Investigation. Mohammad Hossein Sabouri: Visualization, Data curation. Mojtaba Babaelahi: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Project administration. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jahanbin A, Semprini G. Numerical study on indoor environmental quality in a room equipped with a combined HRV and radiator system. Sustainability. 2020;12(24):10576. doi:10.3390/su122410576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Jafarinejad T, Shafii MB, Roshandel R. Multistage recovering ventilated air heat through a heat recovery ventilator integrated with a condenser-side mixing box heat recovery system. J Build Eng. 2019;24:100744. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2019.100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kilkis B. Exergy-optimum coupling of heat recovery ventilation units with heat pumps in sustainable buildings. J Sustain Dev Energy Water Environ Syst. 2020;8(4):815–45. doi:10.13044/j.sdewes.d7.0316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chohan AH, Awad J. Wind catchers: an element of passive ventilation in hot, arid and humid regions, a comparative analysis of their design and function. Sustainability. 2022;14(17):11088. doi:10.3390/su141711088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Khayyaminejad A, Fartaj A. Unveiling the synergy of passive cooling, efficient ventilation, and indoor air quality through optimal PCM location in building envelopes. J Energy Storage. 2024;89(1):111633. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.111633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Elsaid AM, Ahmed MS. Indoor air quality strategies for air-conditioning and ventilation systems with the spread of the global coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemic: improvements and recommendations. Environ Res. 2021;199(3):111314. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.111314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Karaiskos P, Martinez-Molina A, Alamaniotis M. Examining the impact of natural ventilation versus heat recovery ventilation systems on indoor air quality: a tiny house case study. Buildings. 2024;14(6):1802. doi:10.3390/buildings14061802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Mostafavi Sani H, Shokouhmand H. Integrating energy efficiency and health safety in building design: a multi-objective optimization approach to minimize virus transmission risk. J Build Eng. 2024;86(21):108839. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2024.108839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tiwari AK, Chatterjee K, Agrawal S, Singh GK. A comprehensive review of photovoltaic-thermal (PVT) technology: performance evaluation and contemporary development. Energy Rep. 2023;10(4):2655–79. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2023.09.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Al-Waeli AHA, Sopian K, Chaichan MT, Kazem HA, Hasan HA, Al-Shamani AN. An experimental investigation of SiC nanofluid as a base-fluid for a photovoltaic thermal PV/T system. Energy Convers Manag. 2017;142(88):547–58. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2017.03.076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sopian K, Alwaeli AHA, Kazem HA. Advanced photovoltaic thermal collectors. J Process Mech Eng. 2020;234(2):206–13. doi:10.1177/0954408919869541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Riffat S, Ahmad MI, Shakir A. Thermal energy-efficient systems for building applications. In: Sustainable energy technologies and low carbon buildings. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2024. p. 23–120. [Google Scholar]

13. Lakhiar MT, Sanmargaraja S, Olanrewaju A, Lim CH, Ponniah V, Mathalamuthu AD. Energy retrofitting strategies for existing buildings in Malaysia: a systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2024;31(9):12780–814. doi:10.1007/s11356-024-32020-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. O’Rear E, Webb D, Kneifel J, O’Fallon C. Gas vs electric: heating system fuel source implications on low-energy single-family dwelling sustainability performance. J Build Eng. 2019;25(5):100779. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2019.100779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Al Niyadi SA. Evaluating the impact of hybrid ventilation strategies on reducing the cooling load and achieving thermal comfort of buildings: regarding arid climate of UAE [master’s thesis]. Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: United Arab Emirates University; 2024. [Google Scholar]

16. Alshamrani A, Ali Abbas H, Alkhayer AG, Mausam K, Abdullah SI, Alsehli M, et al. Application of an AI-based optimal control framework in smart buildings using borehole thermal energy storage combined with wastewater heat recovery. J Energy Storage. 2024;101:113824. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.113824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Harkouss F. Optimal design of net zero energy buildings under different climates [dissertation]. La Londe-les-Maures, France: Laboratoire Jean Alexandre Dieudonné; 2018. [Google Scholar]

18. Haji MD. Learning from comparative examples of passive houses in different European countries [master’s thesis]. Mersin, Turkey: Eastern Mediterranean University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools