Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Fluid Dynamics of Quantum Dot Inks: Non-Newtonian Behavior and Precision Control in Advanced Printing

School of Materials & Environmental Engineering, Shenzhen Polytechnic University, Shenzhen, 518055, China

* Corresponding Authors: Zhonghui Du. Email: ; Hongbo Liu. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(9), 2101-2129. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.068946

Received 10 June 2025; Accepted 12 September 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Quantum dot inks (QDIs) represent an emerging functional material that integrates nanotechnology and fluid engineering, demonstrating significant application potential in flexible optoelectronics and high-color gamut displays. Their wide applicability is due to a unique quantum confinement effect that enables precise spectral tunability and solution-processable properties. However, the complex fluid dynamics associated with QDIs at micro-/nano-scales severely limit the accuracy of inkjet printing and pattern deposition. This review systematically addresses recent advances in the hydrodynamics of QDIs, establishing scientific mechanisms and key technical breakthroughs from an interdisciplinary perspective. Current research has focused on three optimization directions: (1) regulating ligand structures to enhance colloidal stability, flow consistency, and anti-shear performance while mitigating nanoparticle aggregation; (2) incorporating low-viscosity or high-volatility solvents and surface tension modifiers to modify droplet dynamic characteristics and suppress the “coffee-ring” effect; (3) integrating advanced technologies such as electrohydrodynamic jetting and microfluidic targeted deposition to achieve submicron pattern resolution and high film uniformity, expanding adaptability in flexible electronics, biosensing, and anti-counterfeiting printing. A comparison of current technical routes and critical performance indicators has identified the dominant variables that influence QDI macroscopic/microscopic properties. A comprehensive analytical framework is presented which spans material structure, rheological behavior, manufacturing processes, and functional characteristics. Moreover, a proposed engineering ‘structure–parameter–behavior–performance’ serves to link core–shell structure, formulation parameters (e.g., viscosity and surface tension), fluidic behavior (e.g., shear thinning and Marangoni flow), and device performance (e.g., resolution and photoluminescence efficiency). The findings provide theoretical support and decision-making guidance for the large-scale application and interdisciplinary expansion of QDIs.Keywords

Quantum dot inks (QDIs) integrate nanotechnology and flexible manufacturing technology. As a functional fluid material with excellent photoelectric properties and solution processing ability, QDIs have broad applications in flexible displays, biosensors and high-resolution printing [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. However, the QI hydrodynamic behavior in micro-nano scale printing processes is complex and variable, and includes non-Newtonian rheological characteristics, interfacial wetting behavior, and particle agglomeration [9,10,11]. These features significantly affect the formation of ink droplets, flight stability and deposition uniformity, representing core bottlenecks that restrict practical application and industrial development [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Current review papers have discussed QDI synthesis, device structure and photoelectric properties [19,20,21], but a systematic study of the hydrodynamic characteristics has not been undertaken. Although material design and process application have been considered, the rheological behavior of ink under high shear conditions, the unsteady wetting process and the influence of key dimensionless parameters (such as the Ohnesorge and Weber numbers) on deposition behavior have not been examined in depth [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. A systematic framework from formulation to rheology to process to performance has not been proposed [30]. This review explicitly formulates a ‘structure–parameter–behavior–performance’ framework. The structure (e.g., core–shell configuration and particle size), formulation parameters (e.g., viscosity and surface tension), fluidic behavior during jetting (e.g., shear thinning, Marangoni flow, Ohnesorge and Weber numbers), and the device performance (e.g., resolution, uniformity and quantum efficiency) are systematically addressed to guide formulation and process optimization for high-performance printing. The dynamic characteristics and application of QDI are evaluated, focusing on the coupling of preparation method, physical and chemical characteristics, and shear thinning behavior. The analysis provides a systematic assessment of fluid response and performance optimization in inkjet printing, microfluidic sensing and precision patterning [31]. The Review establishes “structure-parameters-behavior-performance” from an engineering perspective, providing theoretical support and a technical basis for high-precision machining and multi-scenario adaptation.

2 Preparation and Characteristics of Quantum Dot Inks

The QDI represents a liquid functional material with quantum dot nanomaterials as its core functional component. These are compounded with solvents, surfactants, dispersants and other additives to facilitate printing and patterning [32]. The QDI delivers the fluidity and film-forming property of traditional ink, but also exhibits the optoelectronic characteristics of quantum dots, such as high brightness, narrow-band luminescence, adjustable emission wavelength and high quantum efficiency [33,34]. Consequently, QDI has wide application potential in many high-tech fields, such as quantum dot light emitting diodes (QLED), flexible displays, wearable devices, bioluminescent labels, solar cells and sensors [35,36]. However, the QDI performance depends to a large extent on the scientific and controllable preparation process. Different synthesis and preparation methods exhibit significant differences in stability, optoelectronic properties, environmental adaptability and expansibility [37,38]. A systematic analysis is warranted that compares current ink preparation technologies, and which examines the relationship between the physical and chemical characteristics and practical applications in order to facilitate QDI transfer from the laboratory to industrialization [39].

2.1 Principal Methods of Quantum Dot Ink Preparation

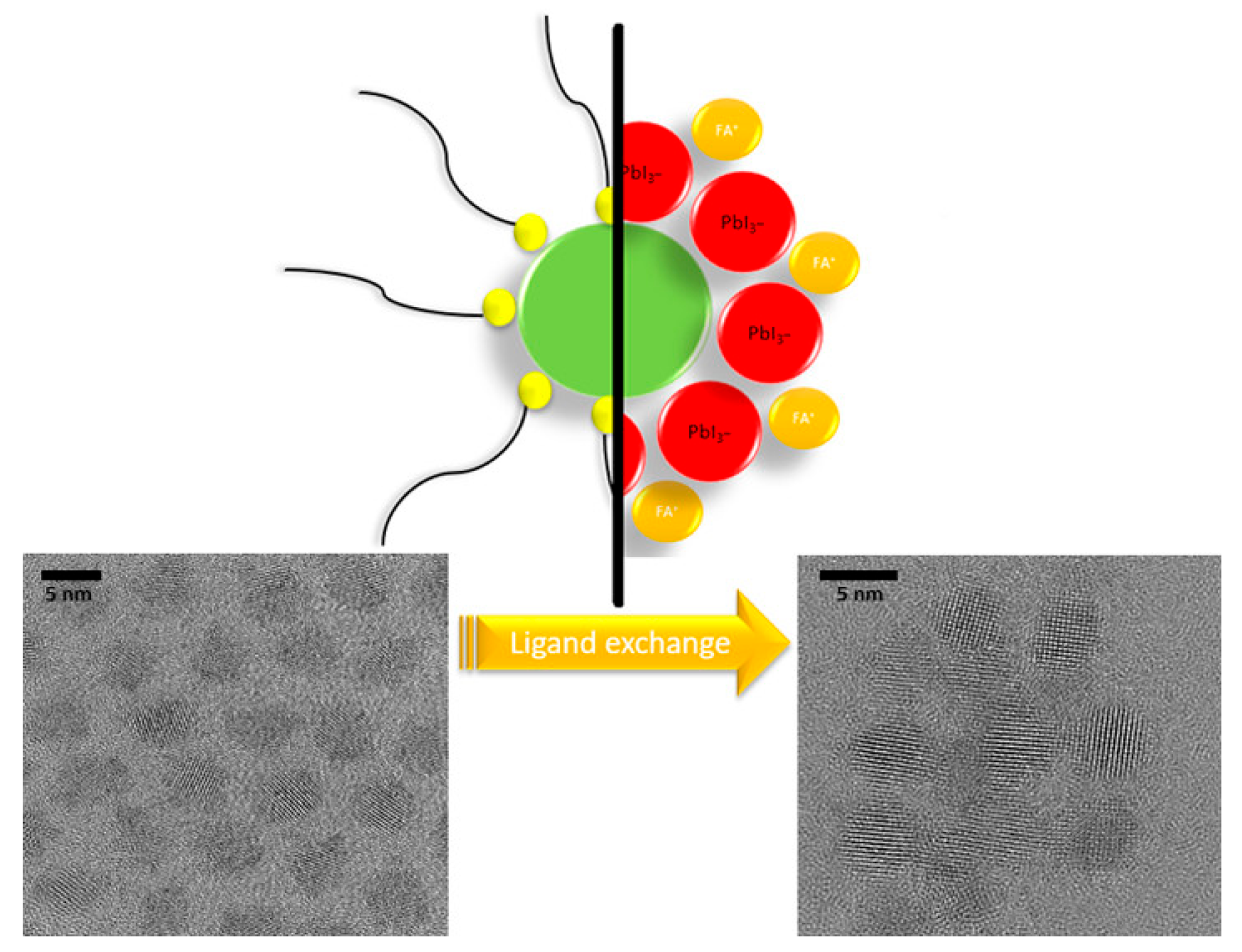

The solution phase method is the most widely used QDI preparation strategy in current research and industrial production [40,41]. In this method, quantum dots coated with organic ligands are utilized as raw materials, and dispersed in suitable organic solvents (toluene, chloroform, hexane, and n-butanol) or polar solvents (water, ethanol, and dimethyl sulfoxide). A small amount of dispersant or auxiliary ligands are added to improve the stability and dispersibility in solution [42]. By adjusting the quantum dot concentration, viscosity and solution tension, the resultant ink can meet the requirements of different printing technologies, such as inkjet printing, spin coating and self-assembly printing. This approach is highly dependent on the type of solvent, dispersion state and ligand, and the system ratio must be carefully controlled [43]. The process is illustrated in Fig. 1, which includes a schematic and real-image representation of colloidal PbS QDs, demonstrating the ligand exchange mechanism and how it affects dispersion stability [44]. The advantages and limitations of major QDI preparation methods are compared in Table 1 in terms of colloidal stability, process scalability, rheological tunability, and inkjet compatibility.

Figure 1: Schematic representation and photographic images of colloidal PbS QDs processed using the solution ligand exchange protocol. Adapted with permission from Ref. [43]. Copyright © 2020, American Chemical Society.

Table 1: Comparison of QDI preparation methods.

| Method | Stability (0–5) | Scalability (0–5) | Rheological Control (0–5) | Inkjet Compatibility (0–5) | Limitations |

| Solution-phase | 4.5 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | Toxic solvents, residual long-chain ligands |

| Phase-transfer | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | PL quenching risk, ligand mismatch |

| In-situ synthesis | 4.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | Scalability concerns, byproduct interference |

| Polymer encapsulation | 5.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | May hinder charge transport, increases viscosity |

| Colloidal self-assembly | 5.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | Sensitive to environment, low repeatability |

The solution phase method is easy to operate, the process conditions are mild, and it can be readily applied on a large scale. Moreover, the ink concentration and rheological properties can be controlled by the solvent ratio and binder, so it is suitable for different printing processes. In addition, this method can retain the luminescent characteristics and quantum efficiency of quantum dots, achieving good wetting and uniform film formation on various substrate surfaces. The latter is important in various printing and coating technologies, representing excellent process compatibility. Moreover, the method is particularly suitable for laboratory research and development, and can be used to rapidly verify the effects of different ligands, solvents and components on ink properties.

However, the solution phase method exhibits some disadvantages. Firstly, the majority of the organic solvents used are volatile and toxic, resulting in potential health risks to the operators and negative environmental impacts. Secondly, the surface organic ligands may hinder the injection and transmission of charges, which impedes the performance optimization of optoelectronic-devices. In addition, stability in long-term storage or use is an issue, where agglomeration and sedimentation can affect the consistency and reliability of the ink. In practical applications, the introduction of a polymer stabilizer, optimization of ligand length and structure, and improved packaging and storage methods are required.

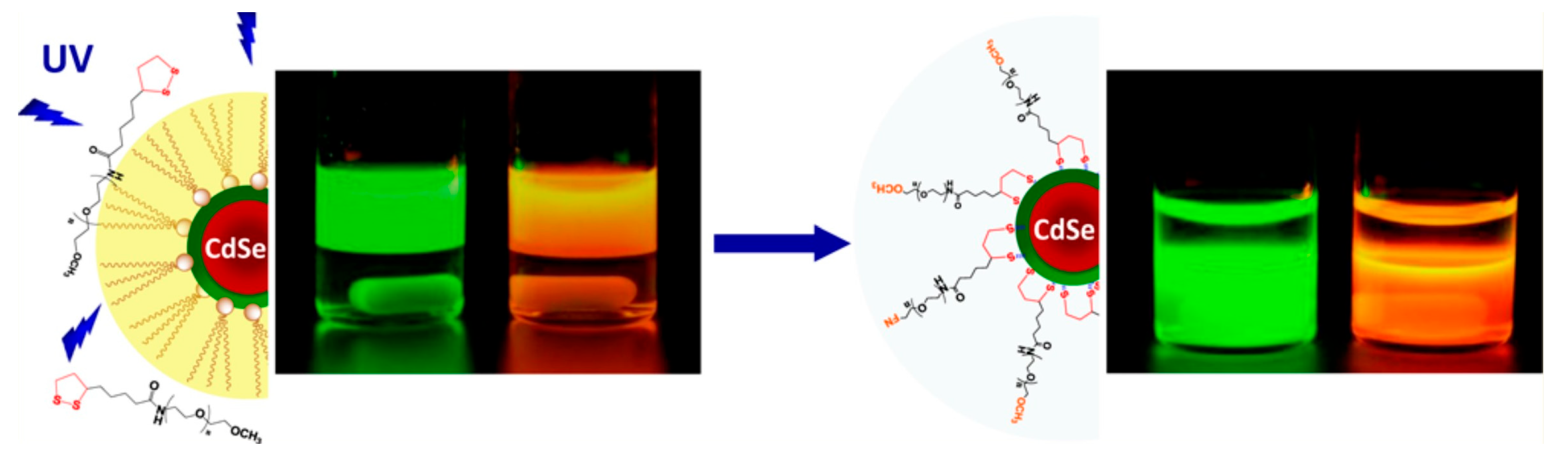

Phase transfer is a strategy used to facilitate the transfer of quantum dots from nonpolar solvent to polar solvent systems (particularly aqueous phases) by chemical modification [45,46]. This approach is utilized to enhance the stability of quantum dots synthesized in an oil phase when dispersed in polar solvents by ligand replacement or surfactant coating [47]. Common phase transfer methods include the use of ligands with polar functional groups such as mercaptoacetic acid, mercaptopropionic acid, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyethyleneimine (PEI) or polyethylene glycol (PEG) to partially or completely replace hydrophobic long-chain fatty acid ligands. This serves to alter the surface chemical properties of the quantum dots, enabling solvent compatibility. This process is normally conducted under the conditions of stirring, ultrasound or microwave assistance to ensure the completion and stability of the ligand exchange reaction. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the light-induced phase transfer process using water as the medium demonstrates enhanced quantum dot dispersion and fluorescent uniformity.

Figure 2: Light-induced phase transfer of quantum dots with water as the medium. Adapted with permission from Ref. [45]. Copyright © 2012, American Chemical Society.

This method can effectively expand the range of QDI applications in water-based systems, notably in biological imaging, medical diagnosis and low environmental impact electronic devices. When compared with the conventional oil-phase dispersion system, aqueous-phase ink has lower toxicity, higher biocompatibility and lower environmental impact, meeting the current demands of green manufacturing. In addition, the introduction of polar ligands improves wettability and adhesion of quantum dots on polar substrates, enabling subsequent patterning and device preparation.

The phase transfer process is often accompanied by a decline in fluorescence quantum efficiency, mainly due to an increase of surface defects or non-radiative recombination by new ligands. In addition, the new ligand may not match the quantum dot in terms of electronic structure, which results in lower charge injection efficiency. In some cases, quantum dots dispersed in the aqueous phase can exhibit poor dispersion for extended period due to electrostatic shielding, with possible precipitation, agglomeration or fluorescence quenching. Consequently, the nature of the ligand, exchange reaction conditions and post-treatment must be carefully controlled to improve biocompatibility and environmental sustainability, while retaining the requisite optoelectronic properties [48].

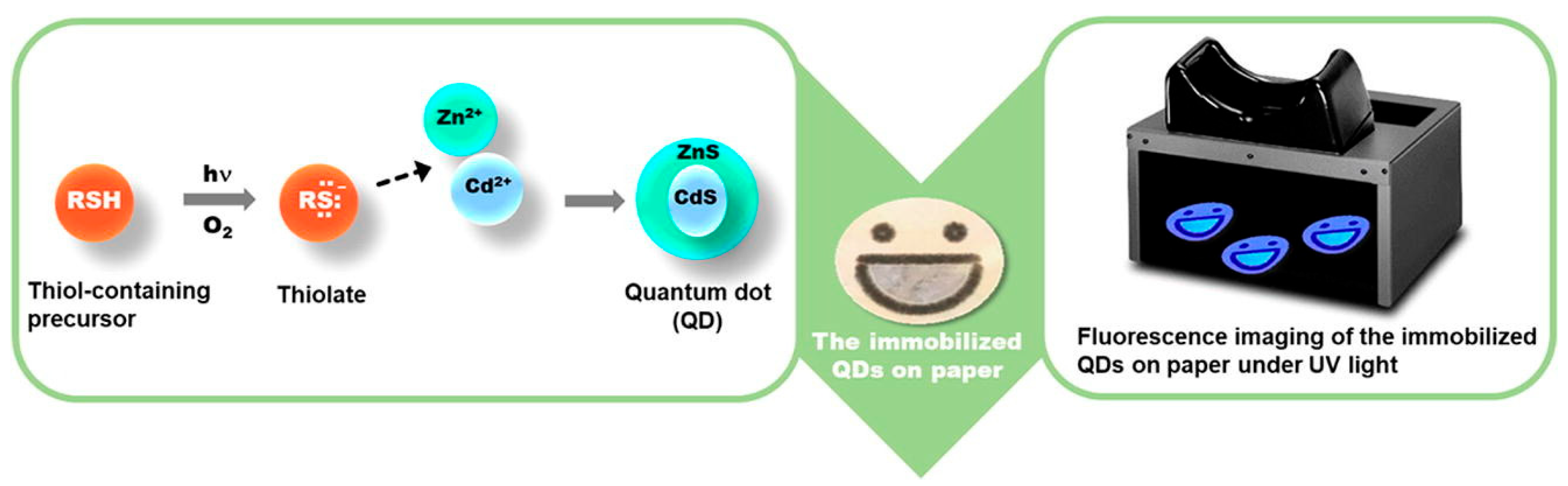

In-situ synthesis refers to the direct synthesis of quantum dots in the target solvent system and use in preparing ink [49]. This method circumvents the conventional “synthesis first, then dispersion” approach. By incorporating precursor materials (metal salts and sulfide/selenide precursors) and the necessary surface regulators in the ink formulation system, nano-quantum dots are generated in-situ at the appropriate temperature, pH and reaction time. This synthesis method is often used in the aqueous phase or polar organic systems, particularly in low-temperature rapid reactions assisted by inorganic stabilizers or polymers, which can improve overall efficiency and stability by simplifying the flow process. This is illustrated in Fig. 3, demonstrating how fluorescent ZnCd quantum dots are synthesized in-situ within a paper matrix using thiol-containing precursors and UV irradiation.

Figure 3: Fluorescent ZnCd QD preparation by in-situ synthesis in a paper matrix using thiol-containing precursors and irradiation by UV light. Adapted with permission from Ref. [49]. Copyright © 2022, SCOPUS.

The in-situ synthesis method exhibits advantages in terms of particle size control and dispersion stability [50]. As the quantum dots are present in the target ink environment at the initial stage of synthesis, the associated surface ligands are highly compatible with the solvent system, significantly reducing the risk of agglomeration. The method is simple to operate, and scale-up for continuous synthesis, enabling automatic and high-throughput preparation systems. Moreover, the mild reaction conditions facilitate the preparation of various functional materials, such as doped quantum dots and composite nano systems, expanding the QDI functional boundaries.

However, this method has some limitations. Firstly, the control of reaction conditions is demanding, where variations in temperature, reaction rate, precursor concentration and stirring speed can have a significant impact on the final particle size distribution and optical properties. Secondly, interference by impurity by-products due to non-ideal conditions can generate secondary phases that impact on optoelectronic properties. In addition, the stability of the synthesized quantum dots in ink requires further verification, where the debugging process of the formula is complicated, hampering industrial scale-up. This method is more suitable for scientific research and development or specific application scenarios, where further optimization is required to enable large-scale production.

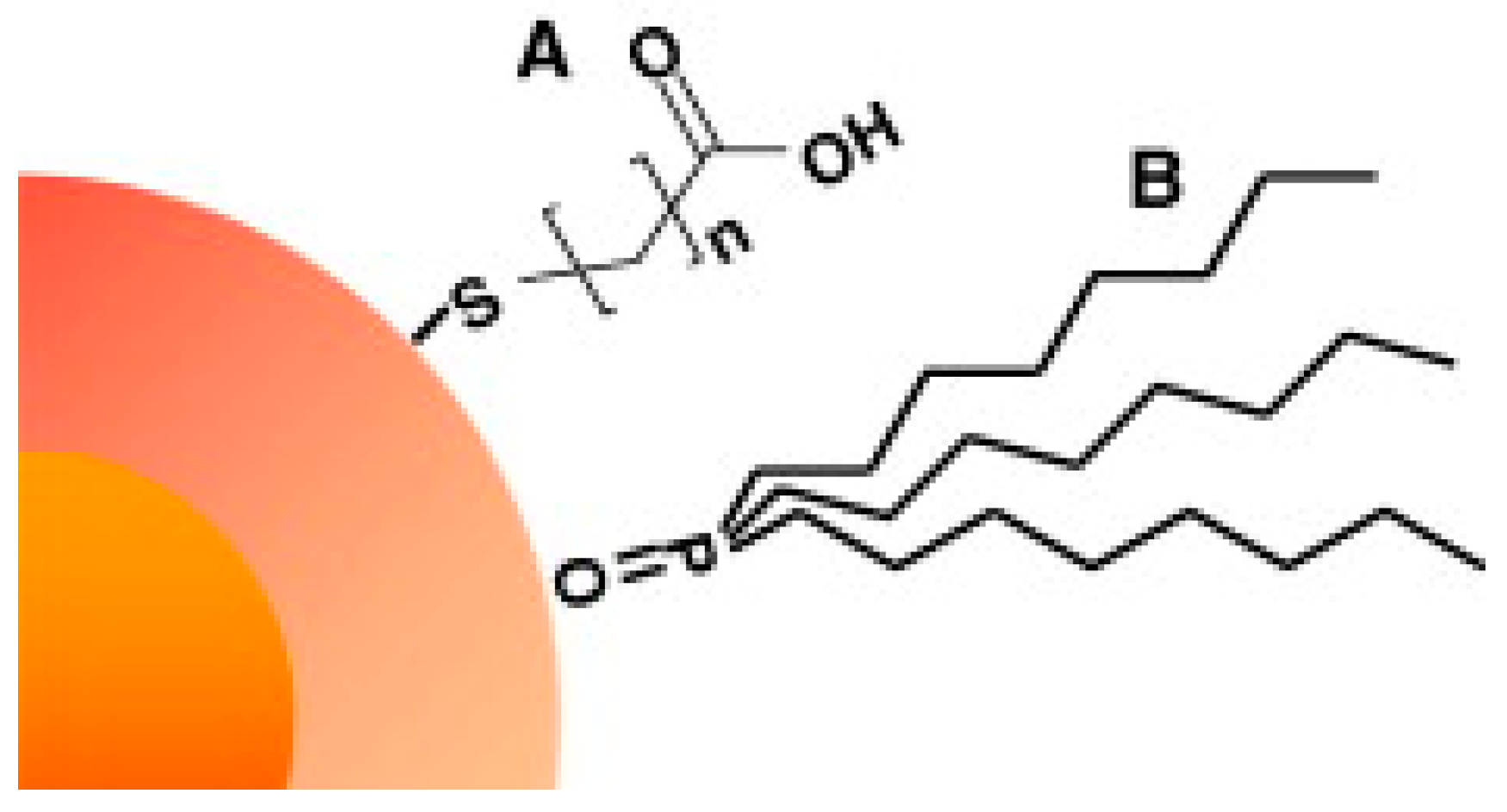

The polymer coating method is an effective means of QDI preparation by covering quantum dots with a functional polymer matrix to form composite nanostructures with good dispersibility and stability [51]. Common polymers such as polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polystyrene (PS) and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) have been utilized as coating materials. The stability of quantum dots in the ink is significantly improved by the effective film-forming property and physical barrier effect. In addition, block copolymers or amphiphilic polymers have been employed to control the interface coating, enhancing quantum dot dispersion and interface compatibility in aqueous or polar environments. The coating method can involve physical adsorption, interfacial self-assembly or chemical covalent grafting, which can match the target application. This concept is illustrated in Fig. 4, which shows how different terminal groups on amphiphilic ligands are tailored for solubility and surface compatibility in diverse environments.

Figure 4: Schematic representation of the quantum dot surface with (A) a hydrophilicmercaptoalkane acid applied for water-solubility, and (B) a lipophilic trioctylphosphine ligand. Adapted with permission from Ref. [52]. Copyright © 2022, Chemical Engineering Journal.

The principal advantage of this method is that it can significantly improve the QDI environmental stability, notably with respect to oxidation, damp heat and light aging resistance. The polymer coating can effectively prevent the penetration of oxygen, water vapor and harmful ions, alleviating fluorescence quenching or structural damage caused by surface defects. In addition, by adjusting the composition and molecular weight of polymer, the rheology, surface tension and wettability of the ink can be precisely controlled, enabling use in various printing technologies such as inkjet, flexography and screen printing.

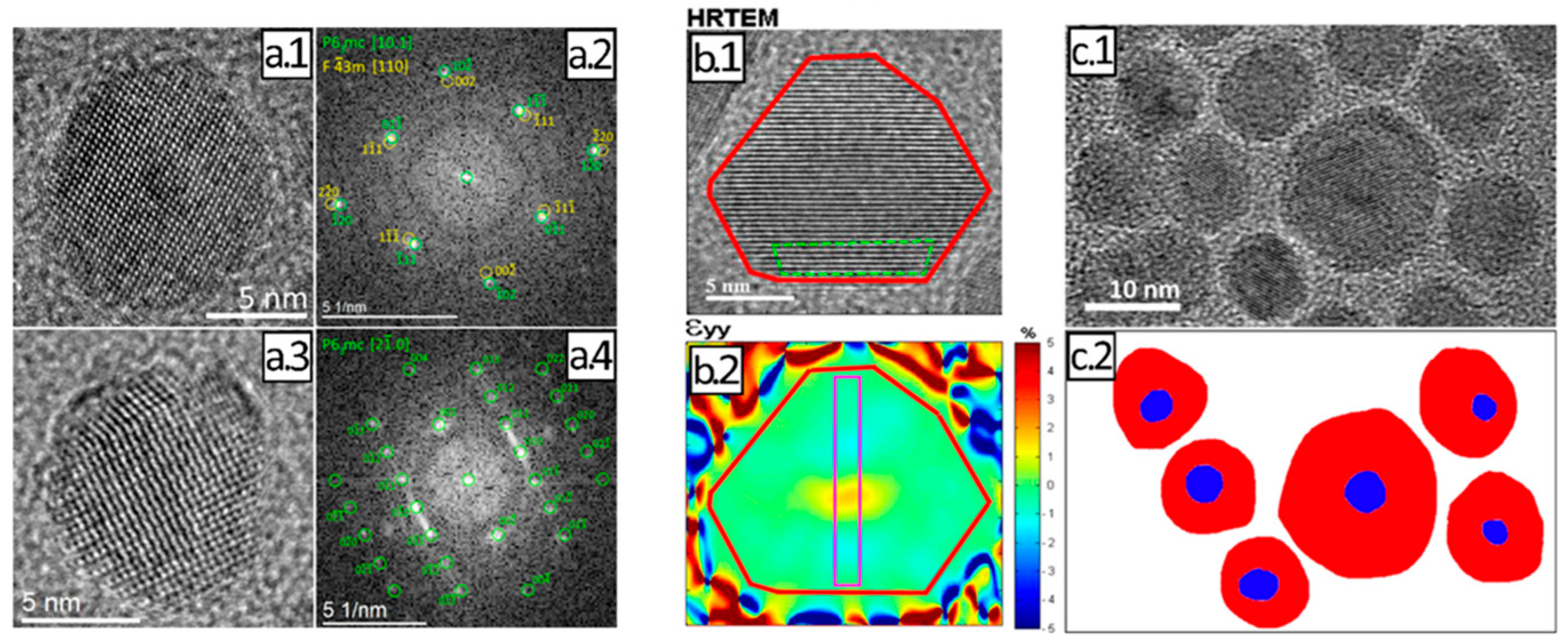

The crystallographic integrity and mechanical stability of the synthesized quantum dots is shown in Fig. 5, which includes high-resolution imaging and strain analysis. The observed lattice fringes and fast Fourier transform (FFT) patterns establish single-crystal characteristics with specific crystallographic orientations, which are essential for maintaining consistent optical and charge transport properties. The strain distribution mapping demonstrates controlled edge relaxation, circumventing excessive internal stress that can degrade colloidal or emission stability. The geometric and structural consistency observed across multiple QDs demonstrates formulation reliability and robustness under the high-shear and thermal conditions commonly encountered in inkjet printing.

Figure 5: High-resolution structural analysis of core–shell quantum dots; (a1,a3), HRTEM images; (a2,a4), corresponding FFT patterns; (b1), HRTEM image of a geometrically faceted QD particle; (b2), strain mapping derived from geometric phase analysis; (c1,c2), overview and schematic representation of multiple core–shell QDs. Adapted with permission from Ref. [53]. Copyright © 2020, Scientific Reports.

The polymer alone can provide the ink with additional functionality, such as self-repair, temperature and pH response, which facilitates intelligent printing and multifunctional device development [54].

While the polymer coating offers enhanced stability, it has some technical bottlenecks. Firstly, the polymer coating can inhibit electron/hole transport, which impacts on device charge injection and transport, limiting effective application in high-performance optoelectronic devices. Secondly, some polymers introduce shielding or absorption effects associated with the optical properties of quantum dots, which lowers luminous efficiency. Furthermore, the coating process may introduce residual reactants or by-products, which can pose potential risks to long-term device stability. Therefore, it is necessary to optimize the coating thickness, polymer type and interface compatibility in order to improve performance and stability.

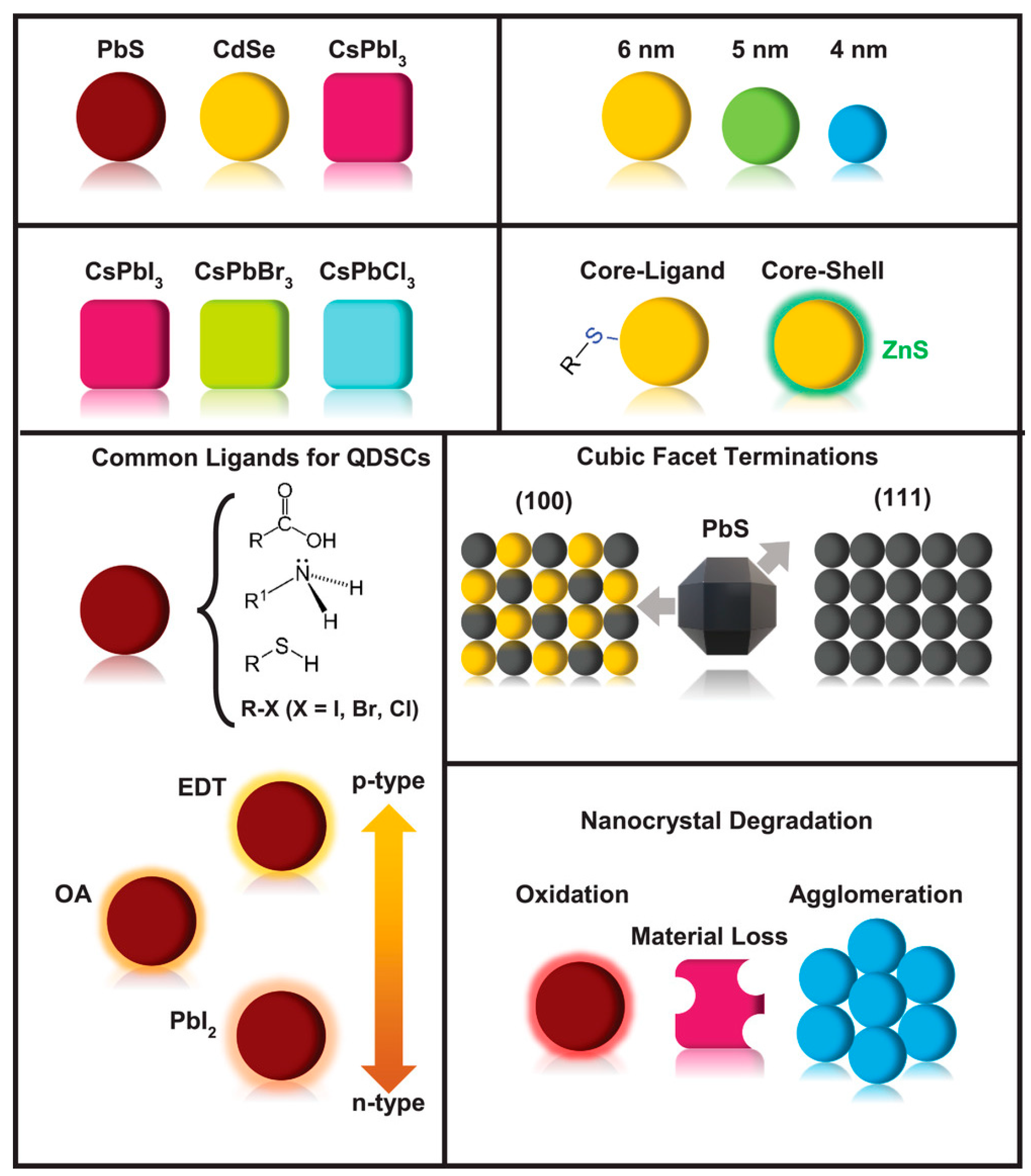

The colloidal self-assembly method enables a spatially ordered arrangement and structure construction based on non-covalent interactions between nanoparticles (van der Waals, electrostatic and hydrogen bonding). In this method, quantum dots are regulated by the action of specific solvents or external fields (electric, magnetic and surface tension gradient) to generate ink systems with specific structures during drying, annealing or solvent evaporation. This can include a monodisperse solution, two-dimensional monolayer film and three-dimensional superlattice. The self-assembly process is dependent on evaporation rate, solvent polarity, concentration gradient and surface tension, which can be controlled to deliver a target structure [55]. A broad overview of the quantum dot structures and surface ligands is provided in Fig. 6, including representative compositions, crystal facets, and common degradation pathways.

Figure 6: Representation of several colloidal QD materials. Adapted with permission from Ref. [56]. Copyright © 2021, Advanced Energy Materials.

This method enables a fine adjustment of the spatial arrangement and distribution of quantum dots, improving the uniformity and optical consistency of the entire film. This is particularly important in the preparation of monochromatic light-emitting devices, laser arrays and photonic crystals. A precise adjustment of the assembly structure can significantly enhance the charge transfer rate and optoelectronic coupling efficiency of the ink film. In addition, the self-assembly method does not require the inclusion of too many stabilizers, reducing interference by impurities, facilitating high-purity nano-material printing [55].

The colloidal self-assembly process requires extremely harsh experimental conditions and is highly sensitive to environmental disturbances (airflow, humidity and substrate cleanliness), which contributes to poor repeatability and low preparation efficiency. Moreover, the ordered structure is fragile and sensitive to the mechanical disturbance and heat treatment associated with the device manufacturing process, limiting practical application. In addition, if the spacing of quantum dots is too close in the assembly process, this can lead to fluorescence quenching or non-radiative recombination, which impacts on the optical properties. The development of a self-assembly control strategy with greater adaptability and higher fault tolerance is a high priority, where the use of template guidance or field control can improve assembly stability and efficiency.

2.2 QDI Physical and Chemical Characteristics, and Influencing Factors

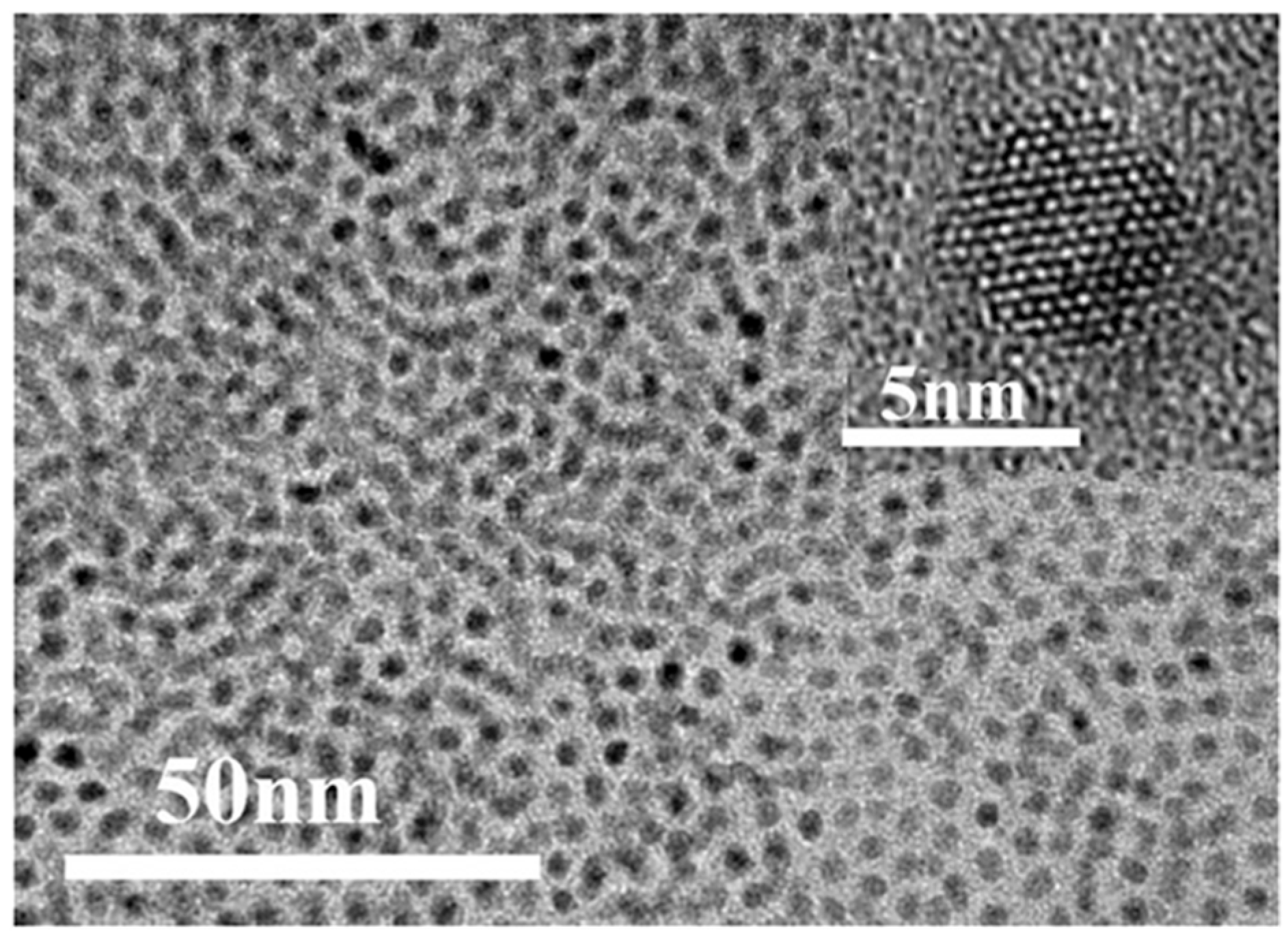

The QDI physical and chemical properties determine film-forming behavior and device adaptability, which are key in determining the quality and ultimate functional value of the ink. As shown in Fig. 7, the synthesized quantum dots exhibit a well-defined spherical morphology and a narrow size distribution, with average diameters in the 5–8 nm range. The absence of detectable agglomeration in the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image indicates a high level of colloid dispersion and surface ligand coverage [57]. This structural uniformity is crucial in avoiding sedimentation and shear-induced aggregation during storage and printing. Moreover, it ensures consistent jetting behavior and uniform deposition, which are critical for high-resolution patterning and film formation.

Figure 7: Low-magnification TEM image of core–shell quantum dots. The particles exhibit a uniform spherical morphology with an average diameter of 5–8 nm. The inset illustrates well-dispersed individual QDs without significant aggregation, indicating a high level of colloid stability and mono-dispersity, which are essential for ensuring jetting uniformity and rheological reproducibility in QDI formulations. Adapted with permission from Ref. [58]. Copyright © 2014, IEEE 40th Photovoltaic Specialist Conference.

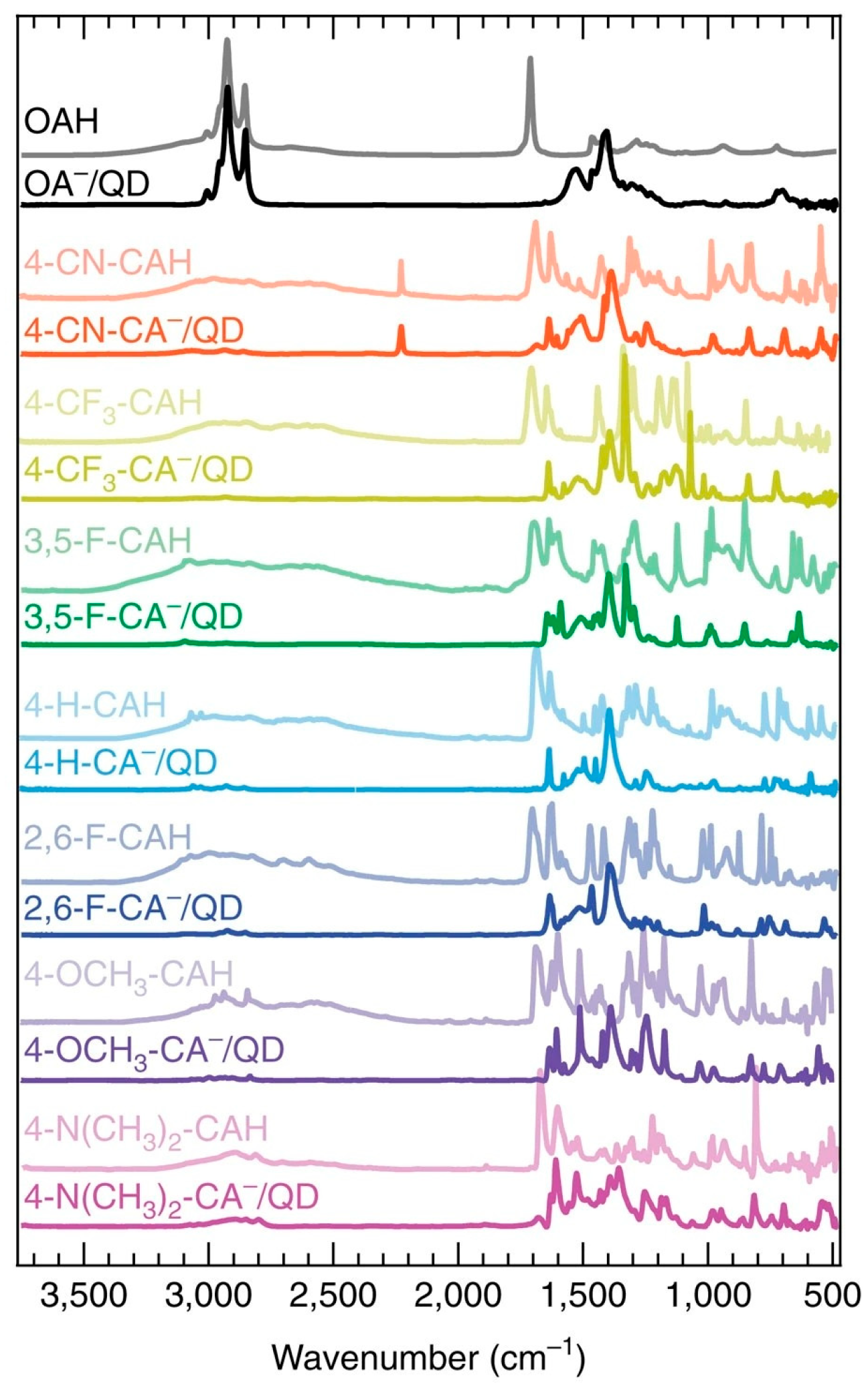

The important QDI features include dispersion, particle size (and distribution), surface charge, fluorescence quantum efficiency, stability (thermal, light and chemical), and rheological properties [59,60]. These properties are influenced by a number of internal and external factors, such as quantum dot composition, the type and density of surface ligands, solvents and additives, and environmental conditions (pH, ionic strength and temperature). The typical values of key parameters for QDI functionality and printability are: viscosity = 2–20 mPa·s for inkjet compatibility, but concentrated or high-molecular-weight formulations can reach 100–2000 mPa·s; surface tension = 30–50 mN/m, which can be lowered to ~28 mN/m by adding 0.1–0.5 wt% fluorinated or silicone-based surfactants [61]. The average colloidal quantum dot particle size is in the 2–10 nm range, with a standard deviation below 10% to ensure optical uniformity. The surface ligand density is typically maintained at 3–6 ligands nm−2, balancing colloidal dispersion and charge transfer efficiency. Stability benchmarks often demand >85% photoluminescence quantum yield retention over 30 days under ambient conditions (25°C). The Fourier transform-infrared (FTIR) spectra for various ligand-QD complexes are shown in Fig. 8, revealing chemical shifts associated with functional group interactions at the quantum dot surface.

Figure 8: FTIR spectra of the ligand (lighter profile) and ligand/QD complex (darker profiles) films. Adapted with permission from Refs. [59,60]. Copyright © 2017.

High-quality patterned printing requires an even distribution of quantum dots in the ink system, avoiding agglomeration. Dispersion depends on the chain length, polarity, density and steric effects associated with the surface ligands. Lipophilic ligands (octadecylamine and oleic acid) are suitable for nonpolar systems, whereas carboxyl-, hydroxyl- and amine-based ligands are more suitable for aqueous systems. Surface charge also affects the stability of the colloid. Charged quantum dots are dispersed in aqueous phase via electrostatic repulsion, but an excessively high ionic strength serves to compress the electric double layer and induce agglomeration [62].

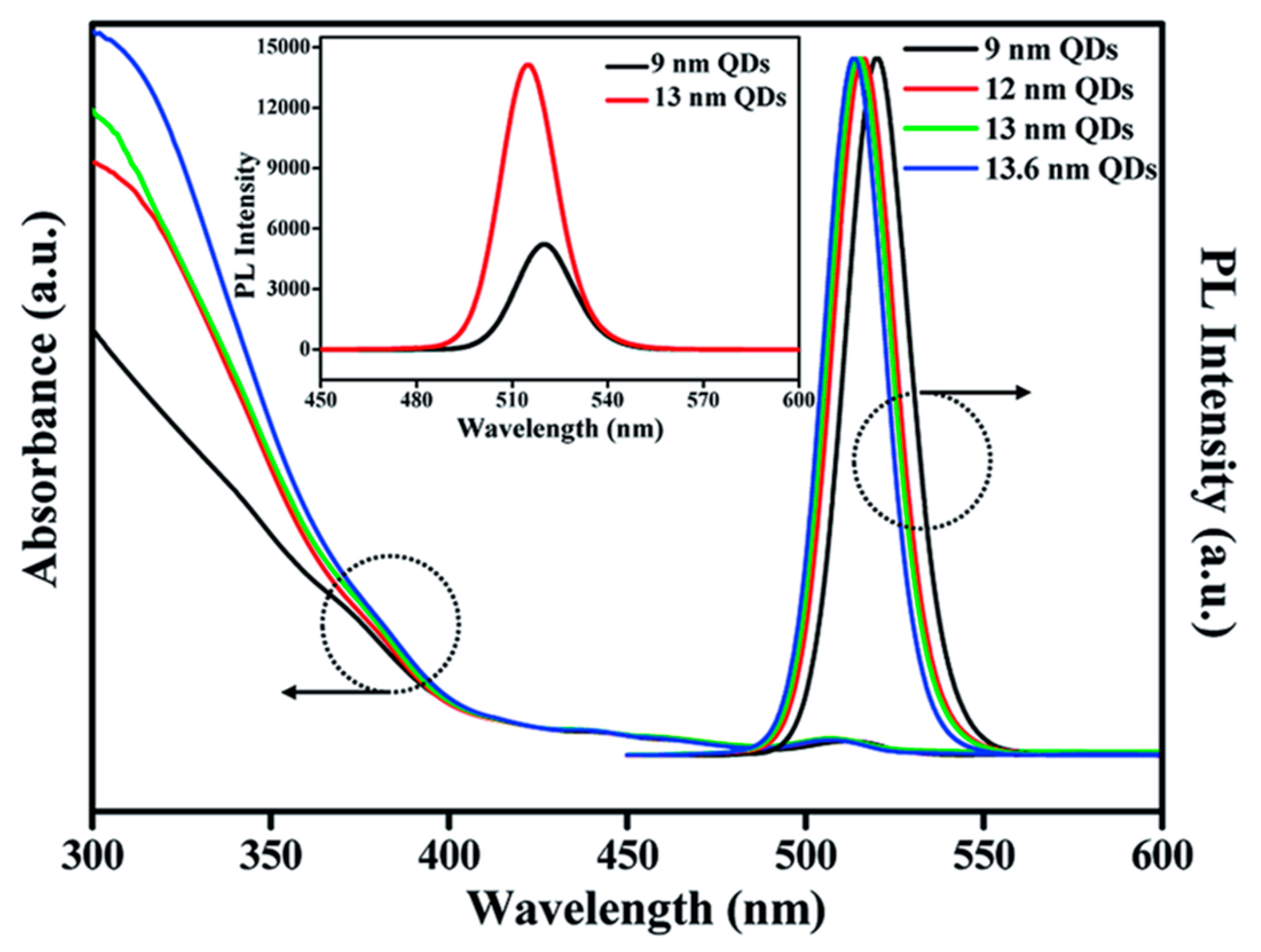

The quantum dot particle size directly affects the optical band gap and luminescence peak position [63]. The UV-Vis absorption and photoluminescence (PL) spectra of quantum dots with different diameters (9 nm, 12 nm, 13 nm and 13.6 nm) are shown in Fig. 9. The results show that, with an increase in particle size, the absorption edge and emission peak undergo significant red shifts, which is consistent with a quantum confinement effect. The smaller quantum dots have larger band gaps and shorter emission wavelengths. The narrow full width at half maximum (FWHM) and high intensity of the PL emission peaks indicate that the quantum dots exhibit good mono-dispersity and minimal trap states. These factors are crucial in ensuring color purity and luminous efficiency in quantum dot-based light-emitting and sensing applications. The magnified image in Fig. 9 compares the PL spectra of 9 nm and 13 nm quantum dots, demonstrating the shift in emission wavelength and enhancement of intensity. The narrower emission bandwidth indicates that the quantum dots have high mono-dispersity and an effective surface passivation effect, which is vital for high-efficiency light-emitting applications.

Figure 9: UV-Vis absorption and PL characterization of quantum dots with varying particle sizes. Adapted with permission from Ref. [64]. Copyright © 2017, RSC Advances.

The more uniform the particle size distribution, the greater the luminous color purity and quantum efficiency [63]. An uneven particle size results in a broadening of the luminescence bandwidth that affects the color performance and energy conversion efficiency of the device [65]. In addition, a smaller particle size promotes non-radiation recombination due to surface defects, which must be addressed by high-quality synthesis and effective surface passivation.

The nature of the ligand determines the ink solvent compatibility and affects charge transfer and device interface coupling. Short-chain or π-conjugated ligands can improve the charge migration rate, whereas long-chain ligands contribute to dispersibility, but may hinder charge flow [60]. Before device preparation, partial ligand replacement or heat treatment may be required to optimize the interface performance.

Quantum dots are extremely sensitive to oxygen, water vapor and ultraviolet light, and are prone to oxidation, ion dissolution or surface defects that result in fluorescence attenuation. The environmental stability can be enhanced by coating, crosslinking, doping or anti-oxidation treatment [66]. In terms of ink storage, it is necessary to monitor the factors that affect printability, such as precipitation and viscosity changes. Representative quantum dot ink systems are presented in Table 2, showing relevant correlations between material composition, fluid properties, and jetting behavior.

Table 2: Representative QD-solvent-ligand systems and associated rheological, stability, and printing properties.

| QD System | Solvents | Surface Ligand | Viscosity (mPa·s) | Surface Tension (mN/m) | Stability (PL after 30 Days @25°C) | Printability Performance (Jetting/Film) |

| CdSe/ZnS | Toluene + OA | Oleic acid (C18) | 3–5 | 33–38 | >85% | Jettable, slight CR effect |

| InP/ZnS | Hexane + BTA | Butylamine | 2–4 | 30–35 | >80% | Uniform film, low viscosity |

| PbS | NMP + PEG | PEG2000 | ~120 | ~32 | >90% | Requires preheating for smooth jet |

| CsPbBr3 | Toluene/dodecane | OA/OAm | 5–15 | 28–34 | ~70% | Good resolution, CR suppressed |

| Carbon QDs | Water + PVP | PVP-modified | 1.5–3.5 | 40–50 | >90% | High wettability, biocompatible |

2.3 Influence of Quantum Dot Ink Characteristics on Application Performance

The QDI physical and chemical characteristics determine stability and ultimate performance in specific applications. There are significant differences in ink requirements for different application scenarios. Therefore, in formulation design and performance optimization, the target use should be fully considered in order to achieve the best match between performance and technology [67].

In QLED operation, the PL quantum efficiency, particle size distribution and energy level structure of quantum dots in the ink are key factors that determine luminous efficiency, color purity and device lifetime [68]. Quantum dots with a high degree of uniformity can provide a narrow luminescent bandwidth and precise wavelength control, which facilitates a wide color gamut display. High surface passivation and low defect state density serve to suppress non-radiative recombination and improve the brightness and energy conversion efficiency of the device. The nature of the ligand and residual solvents in the ink also affect electron/hole injection efficiency and the interface carrier balance, which determine device performance. Therefore, in the preparation of QLED ink, short-chain ligand replacement, polar solvent selection and annealing optimization are often used to enhance charge transfer and optical coupling.

The QDI used for biomarkers and imaging should exhibit good water solubility, biocompatibility and light stability [69]. If the ink contains toxic ligands or unstable solvents, this will severely limit possible human applications. In addition, particle size at the nano-scale must be strictly controlled within the biofilm permeability range (<10 nm) to achieve effective cellular uptake and tissue penetration. The fluorescence wavelength should also be adapted to the biological window (650–900 nm) to reduce background interference and tissue absorption. Long-term dispersion and fluorescence intensity of the ink directly affect imaging clarity and diagnostic sensitivity. Therefore, in such applications, surface PEGylation, block polymer coating or multifunctional group modification strategies are often needed to enhance the targeting and physiological stability of the ink [70].

In optoelectronic devices, charge mobility, the light absorption coefficient and interface compatibility of QDI represent the principal performance bottlenecks [71]. If the ink contains a large number of organic ligands or highly viscous solvents, this may hinder the electron conduction, resulting in a lower open circuit voltage or reduction in the device response speed. By selecting highly conductive ligands (ethylene glycol and phenyl phosphonate) and thermally sensitive ligands, insulating components can be removed during sintering or annealing, with a consequent increase of film conductivity [72]. In addition, ink deposition affects film formation uniformity and crystal orientation, and has a direct impact on the device filling factor and stability. In order to improve device efficiency, it is often necessary to adjust the ink composition and optimize the interlayer electron/hole transport materials or interface buffer layers.

Flexible electronics equipment requires the ink to form a film at low temperature with excellent mechanical flexibility and stretchability [73]. The required ink should have suitable viscosity, low surface tension and good adhesion in order to adapt to large-scale manufacturing processes such as roll-to-roll printing and flexographic printing. The inclusion of polymer or elastomer additives can improve mechanical toughness, while circumventing negative effects on optoelectronic properties. Moreover, the ink should maintain long-term stability and oxidation resistance to avoid performance degradation during bending or long-term use. Therefore, it is often necessary to develop a special formulation for flexible electronics application, including low-temperature crosslinking agents, a cross-linkable polymer network and anti-cracking additives, ensuring functional integration and process adaptability [74].

Taking a process overview, QDI represents the key node in the integration of basic research and application. The preparation technology and performance optimization will decide the development pattern of the next generation of optoelectronic devices. The contribution of multidisciplinary collaboration and process innovation is anticipated to provide comprehensive breakthroughs with respect to display, energy, biology and intelligent manufacturing.

3 Hydrodynamic Properties, Effects and Regulation of Quantum Dot Inks

The hydrodynamic behavior of QDI is significantly different from that of conventional Newtonian fluids during processing. It has been reported that QDI often shows complex non-Newtonian fluid characteristics, such as shear-thinning and thixotropy [75].

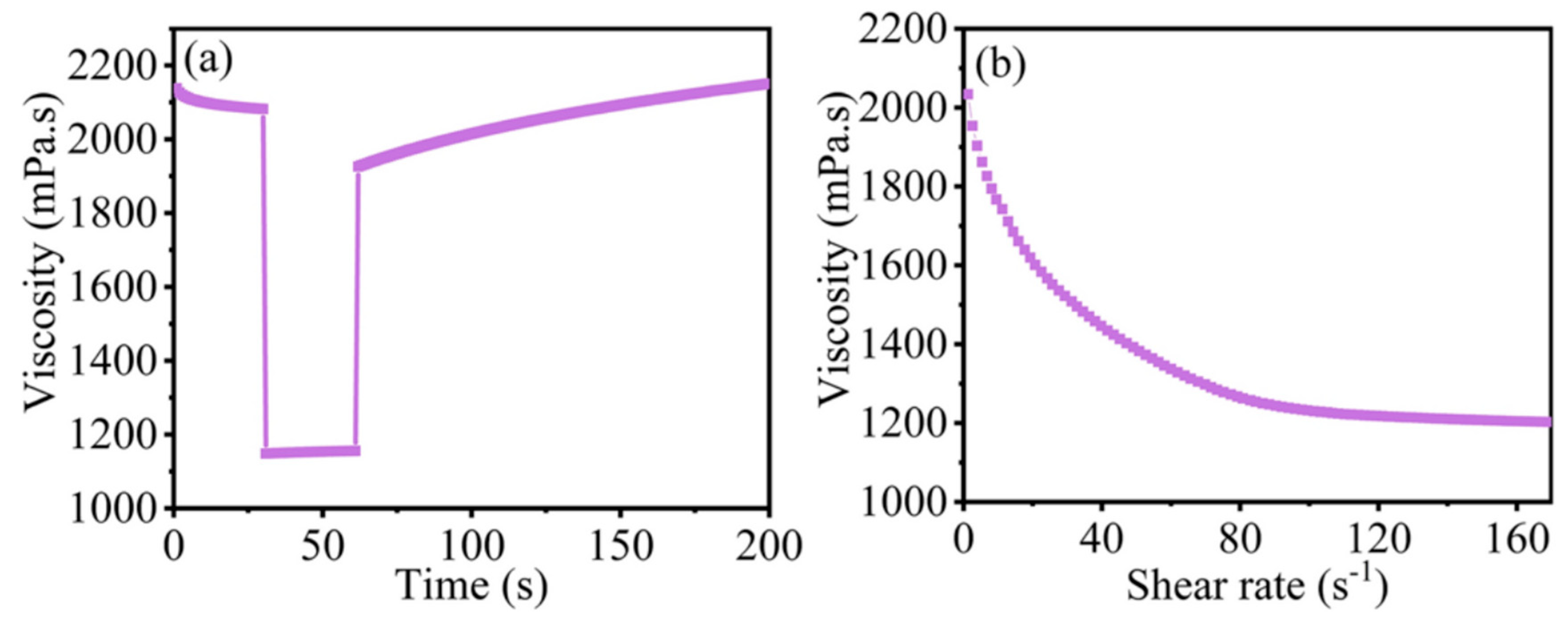

The viscosity curve for a ZnO quantum dot water-based ink with varying with shear rate and time in the process of simulated screen printing is shown in Fig. 10. The associated viscosity is high at low speed (0.1 s), and drops significantly at high speed (200 s), before gradually recovering following deceleration. The experimental data have shown that the ink viscosity decreased from approximately 2100 mPa·s to 1150 mPa·s (45% decrease) after high-speed shearing. The viscosity returned to the original level with time following shearing, exhibiting typical shear-thinning and thixotropy behavior. This means that the ink retains a high viscosity at low shear rate to maintain stability. At a high shear rate, the viscosity decreases, which is beneficial in terms of nozzle output and flow, notably in the operation of a printing nozzle. The viscosity range of a typical ink-jet ink is generally between 2 and 20 mPa·s, which can achieve a balance between colloid stability and printability. In addition, the surface tension must be adjusted to 30–50 mN/m to ensure good wetting of ink droplets on the substrate. For example, the addition of 0.1–0.5 wt% fluoro-surfactant can reduce the surface tension to ≈28 mN/m, without significantly reducing the optical quantum yield of the quantum dots.

Figure 10: Viscosity versus shear rate and time profile for a ZnO quantum dot water-based ink during simulated screen printing. (a) The rheological properties of the ZnO QDs water-based fluorescent ink during screen printing (25°C). (b) The shear properties of the ZnO QDs water-based fluorescent ink. Adapted with permission from Ref. [75]. Copyright © 2021, Scientific Reports.

3.1 Influence of Hydrodynamic Factors on Dispersion Stability

Shear rate is an important factor that affects the dispersion of quantum dots. Moderate shearing can promote ink mixing and short-term dispersion, but excessive shearing may lead to particle aggregation or phase change. When the shear rate exceeds ≈ 1000 s−1, the quantum dots may agglomerate, leading to a red shift of the PL peak [76,77]. This demonstrates that ultra-high speed stirring or spraying may undermine colloid stability and should controlled. Dimensionless parameters, such as the Ohnesorge number (Oh) and Weber number (We), are often used to characterize the behavior of ink in the inkjet process. An Oh number in the 0.1–1.0 range takes account of viscosity and surface tension effects, where maintaining low values avoids excessive satellite dripping or splashing [78]. Some studies have established the QDI rheological constitutive model, and revealed the critical stress (≈10 Pa) for aggregation at extremely high shear rates (104–106 s−1). Rheological models such as the power-law model and the Carreau-Yasuda model are commonly employed to quantitatively express QDI non-Newtonian behavior. The power-law model is expressed as η = K·

The Carreau-Yasuda model, defined as η(

Empirically, increasing quantum dot loading (e.g., from 5 to 20 wt%) results in a significant increase in η0 while reducing n. The ligand chain length and grafting density also serve to modulate λ and η0: short, compact ligands (butylamine) result in faster relaxation (low λ) and improved jetting, whereas bulky or long ligands (PEG2000) increase zero-shear viscosity and retard flow recovery. These observations enable rational ink design tailored to specific printing processes.

Based on these models, the printing optimization criteria can be proposed. When Oh ∈ [0.1, 1] and We < 4, the inkjet resolution is approximately 10 μm/m [79,80]. Combining inkjet printing with microfluidic technology and optimizing parameters such as the Weber and Reynolds numbers, it is possible to effectively suppress the “coffee-ring effect”, resulting in a significant improvement in film uniformity (to greater than 95%) [76].

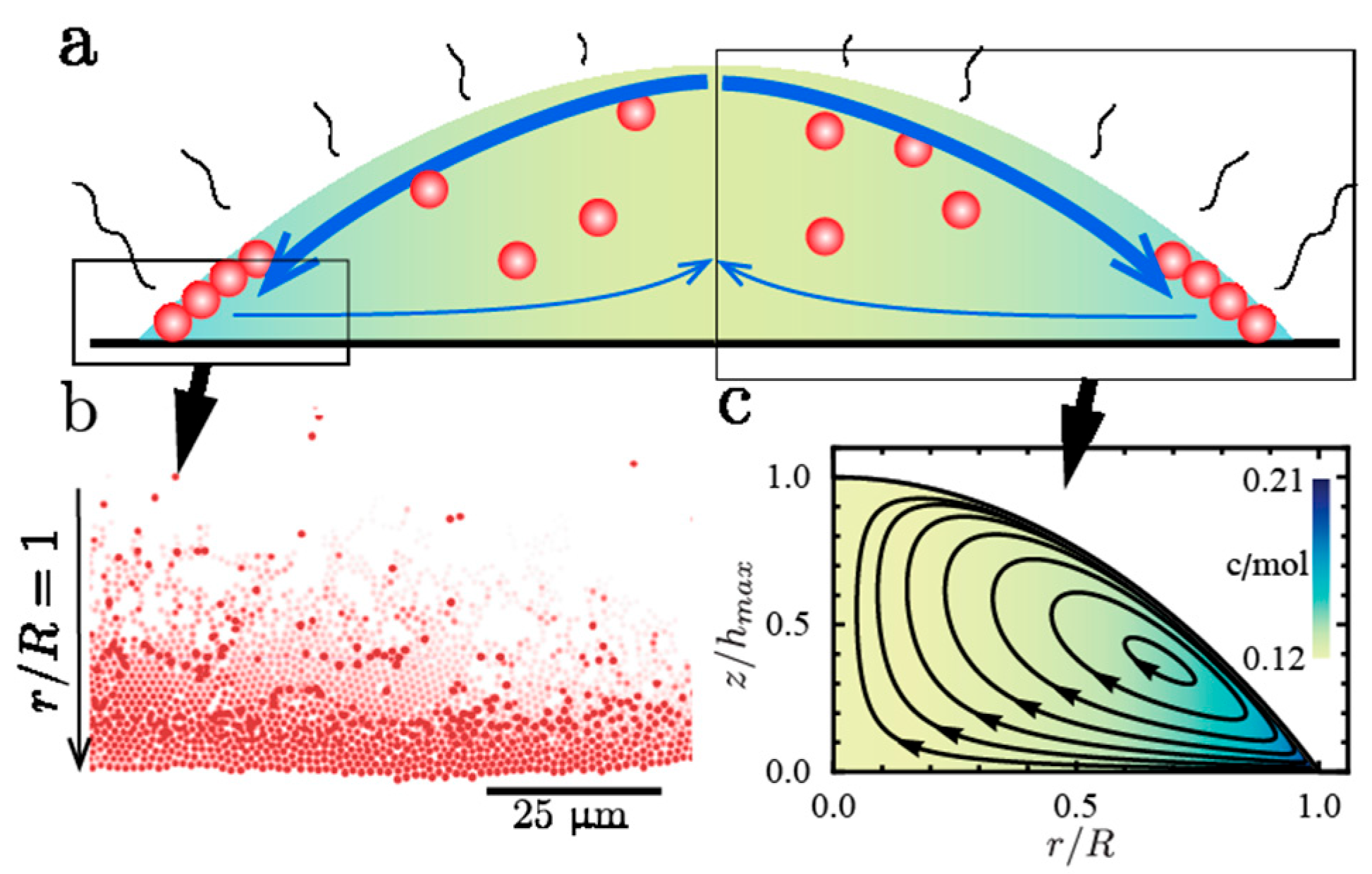

3.2 Influence of Interfacial Wetting and Drying Kinetics on Deposition

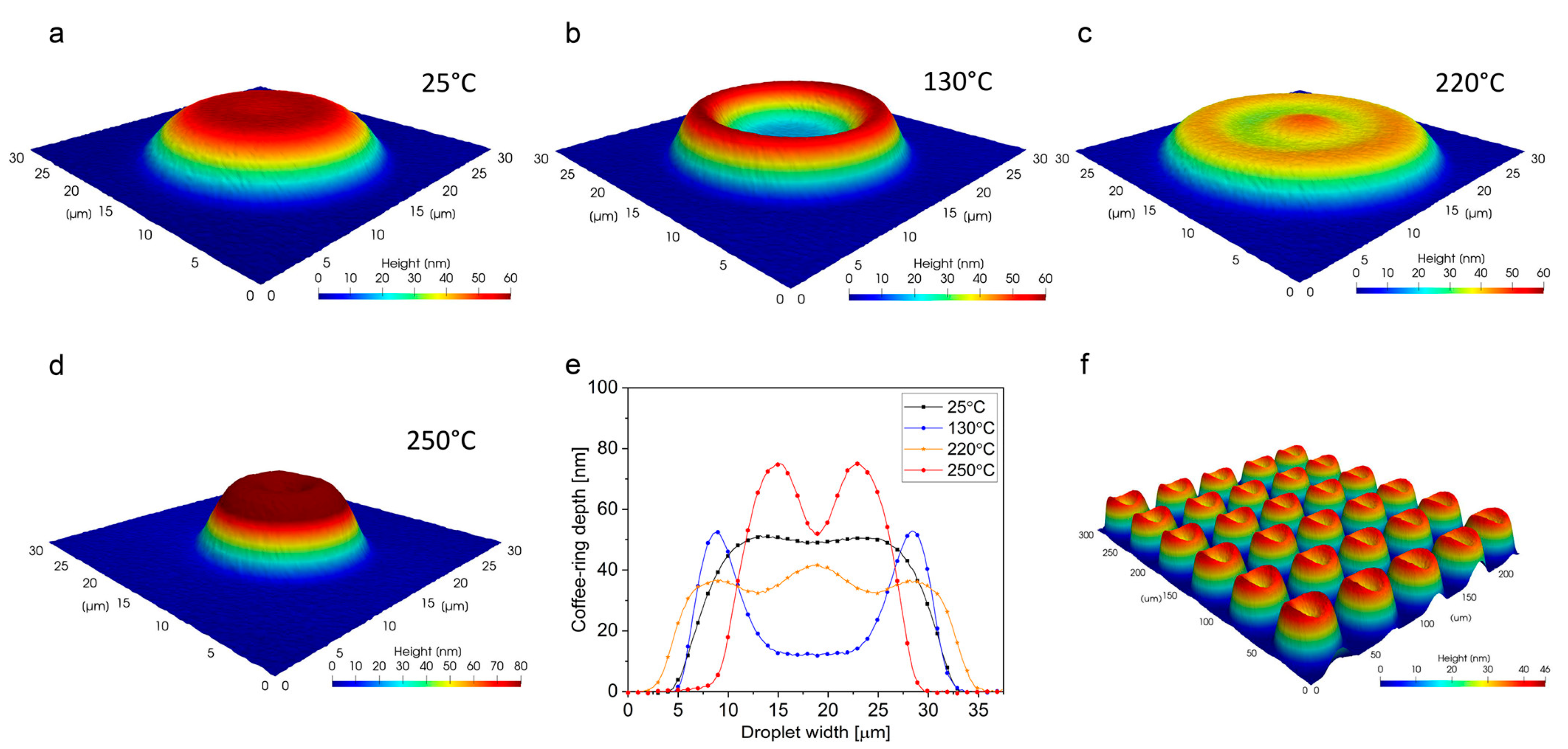

The wettability of the interface between the ink droplets and substrate and the drying process play important roles in determining deposition behavior. Good wettability (small contact angle) enables ink droplets to spread evenly on the substrate. Therefore, the ink surface tension is often adjusted by the surfactant to match the surface energy of the substrate [81,82]. In the drying process, the uneven rate of evaporation of the liquid film at the leading edge results in an outward capillary flow, which leads to the coffee-ring effect that causes an accumulation of particles at the edge of the ink droplets [83]. An inward Marangoni flow can be induced to balance the capillary flow and address this problem. A mixture of high and low boiling point solvents generates an evaporation rate gradient that produces inward Marangoni flow, effectively eliminating the coffee-ring. Gao et al. successfully printed a uniform (coffee-ring free) perovskite quantum dot microarray by mixing N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) with highly volatile butylbenzene and adjusting viscosity and surface tension, which generated an inward Marangoni flow [76]. In addition, adjusting the substrate temperature can promote ink evaporation and lock the contact line. Lin et al. found that an increase in substrate temperature and accompanying increase in evaporation rate served to pin the contact line and restrict the original outward capillary flow. The convex ink droplet geometry is transformed into a flat and uniform deposition [84]. The wetting behavior and drying kinetics can be significantly improved by adding surfactant, optimizing the solvent formulation and controlling printing environment, with an improved ink deposition quality. This enhancement in deposition is demonstrated in Fig. 11, which illustrates how the temperature-dependent coffee-ring behavior of PEDOT:PSS droplets directly influences the final film morphology and uniformity.

Figure 11: PEDOT:PSS droplet coffee-ring behavior at various temperatures. The images represent critical substrate temperatures from the perspective of the Leidenfrost effect: (a) Natural convection; (b) Nucleate boiling area where the critical heat flux occurs at 130°C: (c) Transition boiling where the Leidenfrost effect occurs with the associated Leidenfrost point at 220°C; (d) Film boiling temperature range where heat transfer increases significantly above 240°C; (e) Cross-sectional profiles of the droplets at the aforementioned points; (f) Controlled behavior of PEDOT:PSS droplets exhibiting a highly ordered nanopattern. Adapted with permission from Ref. [85,86]. Copyright © 2015, American Chemical Society.

3.3 Hydrodynamic Control Measures

- (i)Dispersant and polymer network: The addition of a polymer dispersant (polyvinyl alcohol and polyacrylate) can result in the formation of a colloidal structure network, which hinders the outflow and recombination of quantum dots. For example, the use of polyacrylate caused a change from a loose chain to a three-dimensional network structure in the ink, which effectively prevented particle spreading by shear flow [87].

- (ii)Surfactant: Fluorine-containing surfactant or silicone surfactant can significantly reduce the surface tension of ink, improving wettability. The addition of 0.1 wt% BD-3033H silicone surfactant to the ink served to trigger an inward Marangoni effect, where the quantum dots move towards the center of the ink droplet [88].

- (iii)Ligand engineering: By designing bifunctional ligands (such as mercapto-carboxylic acid) to increase the surface charge of quantum dots, the associated zeta potential can be increased to approximately –35 mV, inhibiting shear-induced agglomeration. Optimization of the ligands can improve colloid stability and enhance the tolerance of the ink to high temperature and high shear conditions [89].

- (iv)Mixed solvent system: The viscosity and drying rate can be optimized by utilizing mixed solvents with high and low boiling points (such as NMP/SBR system used by Sliz) or adding an ionic liquid mixture. Highly volatile components can contribute to rapid film formation, whereas less volatile solvents extend the wetting time, ensuring a smooth and uniform film structure [90].

- (v)Electrohydrodynamic (EHD) printing: In this case, the ink is driven by a high electric field (field strength = 5–10 kV/cm) to form Taylor cone and spray submicron droplets (1–2 μm), which exceed the resolution limit associated with conventional piezoelectric inkjets [86].

- (vi)Nozzle and driving parameters: The volume and speed of the ink droplets can be controlled by adjusting pulse voltage, nozzle geometry and trigger frequency. Optimizing the driving waveform and electric field direction can improve injection repeatability and accuracy [91].

- (vii)Control of the substrate and environment: Increasing substrate temperature to promote solvent evaporation and pinning the contact lines can improve deposition uniformity. Surface treatment of the substrate (hydrophilic or hydrophobic) enables an adjustment of wettability. Moreover, controlling the ambient humidity and temperature can reduce disturbances in the drying process and improve film quality [88].

- (viii)Microfluidic-assisted deposition: Before the ink drops reach the substrate, a microfluidic channel is used to enable particle distribution along the secondary flow (Dean flow), which can enable a uniform filling of quantum dots in complex structures. It has been reported that the efficiency of quantum dot deposition is improved by approximately 40% due to the Dean flow effect, and the distribution uniformity in micro-nano structures is significantly improved [92].

Establishing a reliable hydrodynamic model is very important in optimizing ink design and the printing process. On the one hand, the power law and Carreau models can be used to describe the shear-thinning behavior of ink and extract shear index and thixotropic parameters. On the other hand, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) can be used to simulate the flight, impact and evaporation of ink droplets, and simulate complex interface phenomena such as three-phase line pinning and Marangoni flow [93]. In addition, the introduction of multi-scale simulation technology (coupling molecular dynamics and finite element) and machine learning algorithms offers a new approach to predicting ink flow and deposition with high accuracy. Based on theoretical and experimental testing, the models can be optimized repeatedly, providing essential guidance for ink performance improvement and process development.

In the analysis of QDI hydrodynamic characteristics, several representative cases demonstrate how to achieve high-quality patterned deposition and optimize device performance by modulating the ink physical parameters and printing processes.

For instance, a study has developed a PbS QD ink based on an NMP solvent system. By incorporating 1 wt% n-butylamine (BTA) as the ligand, the colloidal stability and inkjet adaptability of the ink were markedly enhanced. During the inkjet printing process, the ink exhibited enhanced film-forming capabilities. The prepared infrared detector exhibited a detection gain exceeding 1012 Jones in the near-infrared region, indicating superior sensitivity and stability [94].

In another study, polyacrylate and silicone surfactant BD-3033H were added to the ink, effectively inducing a reverse flow in the ink droplets and successfully eliminating the coffee-ring effect. The uniformity and compactness of the film were further optimized by adjusting the ink formulation and substrate temperature, enhancing the optoelectronic performance of the device [88].

In the application of microfluidic technology, red and green QD patterns were printed using a static droplet array as the color conversion layer for full-color micro-LED displays. This approach achieved a high-resolution pattern with a minimum sub-pixel size of 20 μm. The brightness uniformity of the red and green arrays reached 98.58% and 98.72%, respectively, enabling high-precision display applications [95]. The optimal ranges for key dimensionless numbers and printing parameters are given in Table 3 for different QDIs and deposition techniques. This provides design references for tailoring rheology and droplet dynamics.

Table 3: Optimal range of values for the Ohnesorge number and Weber number, and associated process parameters for QDI applications.

| Application Type | QD Materials | Ohnesorge Number Oh | Weber Number We | Optimal Temperature (°C) | EHD field Strength (kV/cm) | Resolution (μm) |

| QLED Inkjet | CdSe/ZnS | 0.2–0.8 | <3 | 40–60 | N/A | 10–20 |

| Bio-Imaging | Carbon QD | 0.1–0.3 | <2 | RT | N/A | ~50 |

| EHD Printing | PbS | 0.4–0.7 | <4 | 60–80 | 5–10 | 1–2 |

| Microfluidic | InP | 0.3–0.6 | <3 | 25–40 | N/A | ~20 |

| Anti-counterfeit | CsPbBr3 | 0.25–0.7 | <3 | 50–80 | 3–6 | <10 |

4 QDI Application and Performance Optimization Based on Fluid Dynamic Properties

4.1 QDI Advantages and Application Scenarios

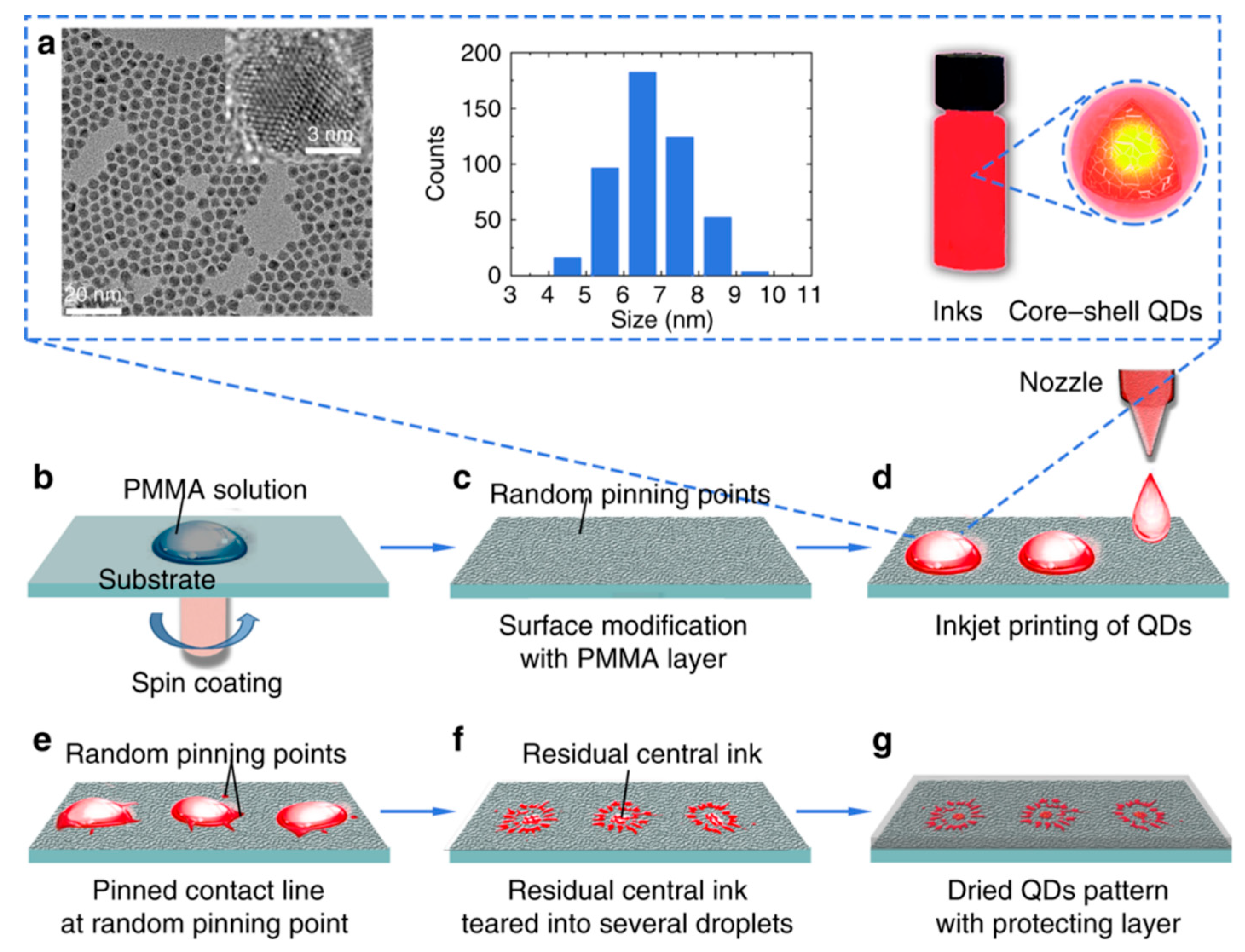

The QDI combines nano-scale size with unique optical characteristics. The quantum confinement effect with adjustable crystal size enables wide band absorption, narrow band emission, high photoluminescence quantum yield and good light stability. In addition, organic ligands on the surface of the quantum dots ensure stable colloidal dispersions in various solvents. Moreover, adjusting ink viscosity and surface tension can meet the requirements of inkjet printing [96]. Consequently, QDI exhibits distinct advantages in many applications. In inkjet printing, it can deliver full color, high brightness and wide color gamut pattern deposition that satisfy the requirements of high precision. In microfluidic and biosensors, the high luminous efficiency and stability support multi-channel fluorescence labeling and rapid detection [97]. In the case of flexible display, quantum dot light emitting devices exhibit wide color gamut, high brightness and low working voltage. Moreover, the devices are resistant to light attenuation, and can be used for ultra-thin, large-area and flexible screens [98]. Extremely small ink droplets are formed on the substrate by inkjet printing, and a unique “flower-shaped” quantum dot fluorescence pattern can be obtained by utilizing the interface pinning effect, with practical applications in high-security anti-counterfeiting labelling [99]. This approach takes advantage of the slow evaporation of QDI in a low volatile solvent environment, so that ink droplets are deposited at random pinning points on the substrate and split into multiple fluorescent dots, forming a complex and high-contrast pattern. These applications demonstrate that the combination of QDI physical and chemical advantages (high brightness, narrow band emission and excellent stability) and fluid processing characteristics (tunable fluid properties for jetting) support inkjet printing, microfluidic and wearable sensing.

As shown in the Fig. 12, the application of inkjet printing QDI can form a fluorescent pattern with a “flower-like” distribution on a surface-modified substrate. By controlling the wetting and evaporation of ink droplets, this method facilitates a uniform deposition of quantum dots and self-assembly into complex patterns. This serves to demonstrate the potential of QDI in anti-counterfeiting marking and high-resolution patterning [100].

Figure 12: Fluorescence pattern formed by inkjet-printed QDI on a surface-modified substrate, exhibiting a ‘flower-like’ distribution. (a) Typical TEM/HRTEM images (left), particle size distributions (middle), and ink for inkjet printing (right) of red core-shell quantum dots (QDs). (b) Surface modification of a substrate with partly dissolved PMMA solution by spin coating. (c) Substrate with random-distributed pinning points of PMMA nanoparticles on PMMA film after spin coating. (d) Inkjet printing of prepared QDs ink on the modified substrate. (e) Pinning process of QDs droplet contact line at random pinning points. (f) Residual central ink teared in to several smaller droplets in the final evaporation process. (g) A resulting security label composed of flower-like dot patterns, which are protected with a thin, optically transparent sticky gel film. Adapted with permission from Ref. [98]. Copyright © 2018.

4.2 Performance Evaluation Indicators in Typical Applications

Depending on the application, there are a number of QDI performance evaluation indices for quantum dot ink, which include:

- (i)Injectability: In order to evaluate the flow and droplet formation performance of ink in inkjet nozzles, dimensionless numbers (such as the Ohnesorge number, Oh) are used to quantify the effects of viscosity, density and surface tension. Stable injection generally requires an Oh number in the 0.1–1 range to avoid satellite droplets and nozzle blockage [85,86].

- (ii)Deposition accuracy and pattern resolution: The accuracy of the ink droplet deposition position and minimum achievable pattern scale can be expressed by a deposition error percentage and minimum line width (or dot diameter), where fine jet printing can reach the micron scale (<10 μm) [101].

- (iii)Uniformity of film formation: The uniformity of film thickness following ink droplet spreading and drying is influenced by the “coffee-ring effect”. The consistency of film formation can be significantly improved by optimizing solvent evaporation and the printing parameters [102]. An optimization of the solvent formulation has resulted in a highly uniform coating and no coffee ring associated with a printed perovskite QD microarray.

- (iv)Optical/optoelectronic efficiency: In optoelectronic devices, the external quantum efficiency (EQE) and brightness apply in light-emitting applications, whereas the optoelectronic conversion efficiency (PCE) is concerned with photovoltaic applications [103,104]. In recent years, the EQE of inkjet printer QLED has exceeded 16%, and the efficiency of quantum dot solar cells has exceeded 8.55%.

- (v)Chemical stability: The ability of ink and the associated film to maintain the target performance during long-term storage or processing is normally expressed by the fluorescence quantum yield or the device performance decay over time [105]. Passivated and high-quality QDI can significantly delay performance decay, while the PLQY of unoptimized CdSe/ZnS quantum dots drops sharply after storage in air for several weeks (from 90% to below 60%), which demonstrates the urgent need to improve stability.

4.3 Performance Optimization Strategy

Currently, research to optimize QDI performance has focused on such aspects as material, formulations and associated technology.

- (i)Optimization of formulation and ligand: By designing a core-shell structure and selecting an effective passivation ligand, the integrity of the electronic structure on the surface of quantum dots can be improved [68,106]. For example, double ionic bond ligands or inorganic halide ligands can be utilized for liquid phase exchange of quantum dots, which can significantly reduce the surface trap state density and improve luminous efficiency and stability. Atomic layer deposition and other technologies may be applied to accurately control the shell thickness, further enhancing the stability of quantum dot ink in the operating environment.

- (ii)Solvent and additive design: The evaporation rate, viscosity and surface tension of the ink can be controlled by matching high and low boiling point solvents. Gao et al. adjusted the ink properties by mixing dodecane (high boiling point) and toluene (low boiling point), successfully eliminating the coffee-ring effect after generating an appropriate Marangoni flow [107,108]. In addition, adding a small amount of surfactant or high volatility buffer can control the wetting and diffusion of ink droplets.

- (iii)Optimization of printing process parameters: The volume, speed and landing point of ink drops may be precisely controlled by adjusting the driving pulse waveform, piezoelectric voltage, frequency and moving speed of the nozzle. For example, the driving voltage or injection pressure can be lowered to reduce the ink droplet speed (Weber number < 4) to avoid splashing and dot crossing. In advanced technologies such as electro-jet printing (EHD), the electric field intensity (5–10 kV/cm) can be adjusted to obtain submicron ink droplets, achieving higher resolution deposition [109,110]. The internal flow and particle transport mechanisms within a sessile droplet are illustrated in Fig. 13, demonstrating how deposition patterns such as the coffee-ring effect arise during the drying process.

Figure 13: (a) Representation of a sessile droplet containing a non-saturated aqueous saline solution and a dilute dispersion of polymer microparticles. The blue lines indicate the direction of flow within the droplet. Note: a large portion of the liquid (close to the substrate) flows in the opposite direction, i.e., the classical “coffee-stain effect”. (b) Particles reach the contact line along the liquid-gas interface, forming a ring-shaped stain. (c) The inverted vortex flow profile is shown in the computed streamlines, which are also measured experimentally by particle tracking velocimetry. Adapted with permission from Ref. [109]. Copyright © 2019, Physical Review Fluids.

- (iv)Control of the interface and substrate: Surface treatment of the printed substrate can alter wettability or introduce micro-nano structural anchor points [111]. For example, spin-coating serves to partially dissolve polymers (PMMA nanoparticles) on the substrate to form random pinning points that can induce inkjet ink droplets to deposit at specific positions and generate predetermined patterns when drying. Plasma cleaning, ultraviolet ozone treatment and other methods are used to improve the substrate surface energy and enhance ink spreading and adhesion.

- (v)Environmental conditions control: Controlling the temperature, humidity and atmosphere of the printing environment by printing under constant temperature and humidity or in an inert gas, can avoid ink moisture absorption and oxidation, ensuring that each ink drop exhibits stable and consistent rheological characteristics. The film uniformity and optical properties can be further improved by adjusting the drying rate in a controlled environment.

The above optimization methods with experimental verification have resulted in significant advancements. Xiang et al. achieved an external quantum efficiency above 16% and a half-life exceeding 1.7 × 106 h for inkjet QD-LED devices via double ion ligand passivation and liquid-ligand exchange. Bawendi and co-workers increased the efficiency of passivated PbS quantum dot solar cells to 8.55%, and device performance was almost unchanged after storage in air for more than 150 days. These results demonstrate that the performance of QDI printing devices can be appreciably improved by optimizing materials and processes.

In practice, the optimization measures have resulted in a considerable performance improvement. Gao et al. obtained a highly uniform fluorescent film with no coffee rings when inkjet printing perovskite quantum dot microarrays, optimizing the ink formulation and printing process, which significantly enhanced film quality [76]. Xiang et al. reported an inkjet QD-LED EQE greater than 16% and improved device stability [103]. The Bawendi team have achieved an 8.55% efficiency for quantum dot solar cells by material passivation, maintaining this level of performance in air for an extended period [112]. These cases establish the effectiveness of optimization with respect to formulation design, ligand passivation and printing parameter adjustment, which can enable future industrial applications. Although the cited optimization strategies are effective, their suitability differs depending on the target use. For instance, ligand exchange using bifunctional or inorganic halide ligands is best suited for improving charge injection in QLEDs, whereas surfactant-mediated Marangoni tuning is applicable in achieving coffee-ring-free microarrays. Electrohydrodynamic (EHD) printing enables submicron resolution but suffers from throughput limitations. The strategies and target outcomes are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4: Strategic optimization approaches and application specificity.

| Strategy Type | Methods | Target Effect | Best Use Cases | Trade-Offs |

| Ligand Engineering | Short-chain/inorganic ligands | Improve charge transport, stability | QLEDs, PV, sensors | May reduce colloidal stability |

| Solvent/Additive Design | Mixed solvents, surfactants | Control Marangoni, suppress coffee-ring | Inkjet printing, displays | Volatility, component compatibility |

| Rheology Tuning | Polymer dispersants, viscosity control | Shear behavior optimization | Microfluidics, jetting systems | Possible increase in PL loss |

| Advanced Printing | EHD, microfluidic-assisted methods | High resolution, uniform deposition | Anti-counterfeit, nano-optics | Complexity, low throughput |

| Environmental Control | Temperature/humidity tuning | Film uniformity, repeatability | Roll-to-roll, flexible devices | Equipment-dependent |

5 Conclusions and Future Directions

This comprehensive review has systematically examined the intricate interplay between the preparation, hydrodynamic characteristics, and application performance of quantum dot inks (QDIs), highlighting their pivotal role in advancing next-generation printing and patterning technologies. The following key conclusions may be drawn:

- (a)Preparation Methods and Ink Characteristics: Diverse synthesis strategies, including solution-phase dispersion, phase transfer, in-situ synthesis, polymer coating, and colloidal self-assembly, offer distinct routes to QDI fabrication with inherent advantages and limitations. The optimized solution-phase method, involving thermal injection with dual-precursor techniques, currently represents the best option, achieving high mono-dispersity (<3% deviation), yield (~80%), and stability. The physicochemical properties of QDIs, such as colloidal stability, particle size distribution, ligand chemistry, rheological behavior (viscosity and surface tension) and optical efficiency, are fundamentally influenced by the preparation method and formulation engineering. These properties determine processability and the ultimate device performance.

- (b)Dominant Hydrodynamics and Impact: QDIs exhibit complex non-Newtonian fluid behavior, characterized by significant shear-thinning and thixotropy, which are critical in ink-jetting. Key dimensionless parameters, particularly the Ohnesorge number (optimal range = 0.1–1) and Weber number (preferably <4), govern droplet formation, flight stability, and deposition accuracy, enabling resolutions down to ~10 μm. The interplay between solvent evaporation-induced capillary flow and surfactant/Marangoni flow dictates deposition uniformity, where the “coffee-ring effect” poses a major challenge. Strategies employing mixed solvent systems, tailored surfactants, substrate temperature control, and surface energy modification have proven effective in suppressing this effect, achieving highly uniform films. Furthermore, QDIs exhibit sensitivity to environmental conditions, necessitating controlled printing environments or formulation adaptations.

- (c)Performance Optimization and Applications: Understanding and manipulating QDI hydrodynamics is essential for performance optimization across all applications. The strategies encompass: materials/formulation, involving ligand engineering (short-chain, bifunctional, or inorganic ligands) for enhanced stability and charge transport; solvent/additive design to control evaporation and flow dynamics; processing, involving advanced printing techniques like electrohydrodynamic (EHD) jetting that enable submicron resolution; precise control of jetting parameters (waveform, voltage, frequency, nozzle geometry and substrate motion); microfluidic-assisted deposition, leveraging secondary flows (Dean flow) for improved filling uniformity. In terms of interface/environment, substrate surface treatment/modification and environmental control (temperature, humidity and atmosphere) are critical. Optimization has yielded significant results: inkjet-printed QLEDs with EQE >16%, perovskite QD microarrays free of coffee-rings, QD solar cells with efficiencies >8.55% and enhanced air stability, and high-security anti-counterfeiting patterns with sub-20 μm features.

By reducing the QD particle size and tuning ligand structures, the viscosity and surface tension can be optimized to achieve stable jetting conditions (Oh = 0.1–1, We < 4), leading to high-resolution deposition (~10 μm) and suppression of the coffee-ring effect, which directly improves film uniformity and device efficiency. The systematic correlation of structure with performance facilitates rational engineering design in QDI ink formulation. This review has established a crucial “structure-parameters-behavior-performance” framework for QDIs. The framework serves to underscore that successful implementation hinges on a synergistic optimization of material design, rheological property control, hydrodynamic understanding, and tailored processing techniques.

The advancement of QDI technology hinges on addressing unresolved technical barriers that hinder practical applications. Future research must prioritize the following five critical challenges, each demanding interdisciplinary strategies and actionable innovation.

- 1.Material Stability and Scalable Formulation for Next-Generation QDs

While alternatives to conventional Cd-based QDs (e.g., InP, perovskite and carbon dots) offer reduced toxicity and sustainability benefits, colloidal stability and processability must be addressed. For instance, perovskite QDs exhibit rapid ion migration when exposed to moisture and UV, resulting in phase segregation and optical degradation. Carbon dots, despite the low associated cost, do not generate broad emission spectra, which limits high-color-purity applications. In order to address these challenges, surface passivation procedures using hybrid organic-inorganic ligands (e.g., ZnO-based capping agents) must be developed to suppress ion migration in perovskite QDs. In addition, standardized dispersion protocols for non-Cd QDs should incorporate solvent polarity thresholds for solubility and long-term stability evaluation, such as accelerated aging tests at 85°C/85% RH for 1000 h. Scalable synthesis routes for carbon dots, including microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass precursors, can further enable narrow emission tuning with reduced production costs.

- 2.Multiscale Modeling of Ink Deposition Dynamics

Current constitutive models (e.g., Carreau-Yasuda) do not adequately capture interfacial phenomena during printing, such as Marangoni instabilities or contact line pinning. Integrating molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of ligand-solvent interactions with mesoscale computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is essential to accurately predict deposition-induced aggregation. Furthermore, the development of hybrid machine learning (ML)-CFD frameworks requires high-resolution experimental datasets that link formulation variables (e.g., η0, λ and particle size distribution) with print behavior (e.g., droplet velocity and film thickness). Establishing an open-access database of QDI formulation parameters and print outcomes will accelerate model validation and training.

- 3.Biomedical and Environmental Applications: Bridging Performance and Compatibility

In order to expand QDIs into biomedical and environmental domains, a number of domain-specific hurdles must be addressed. Cytotoxic ligands (e.g., thiols and primary amines) compromise the long-term viability of QDI-based biomedical sensors, and atmospheric pollutants (e.g., ozone and acidic gases) degrade QDI-based environmental sensors. The design of biocompatible surface chemistries (e.g., zwitterionic ligands and PEGylated coatings) with in vitro (e.g., HEK293 cell viability at 10 μM QD concentration) and in vivo (e.g., murine subcutaneous implantation for 30 days) assays is critical. In environmental applications, antifouling coatings using cross-linked polymer networks (e.g., poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene)) can enhance sensor durability under oxidative stress. Collaborative research involving regulatory agencies should be directed at establishing safety benchmarks (e.g., ISO 10993 compliance) to facilitate clinical translation.

- 4.Intelligent QDIs: Stimuli-Responsive Functionality without Compromising Printability

Stimuli-responsive QDIs (e.g., pH-sensitive and photochromic) face practical limitations with respect to phase segregation between QDs and stimuli-sensitive polymers during jetting. Engineering covalent QD-polymer hybrids via click chemistry (e.g., azide-alkyne cycloaddition) can circumvent phase separation, while dynamic covalent bonds (e.g., Diels-Alder reversible linkers) enable stimuli-triggered rheological transitions. Validation in model printing processes, notably inkjet printing of pH-responsive inks with ±1 μm droplet diameter control or slot-die coating of thermo-responsive inks for temperature-dependent patterning will serve to demonstrate scalability.

- 5.Industrial Manufacturing: From Lab-Scale to High-Throughput Production

Current QDI formulations do not meet industrial demands for roll-to-roll (R2R) printing, which require shear-thinning behavior at

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Shenzhen Polytechnic Research Fund (6023310025K), Post-doctoral Later-stage Foundation Project of Shenzhen Polytechnic (6023271017K) and Horizontal Technology Development Project (6024260101K).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation: Zhen Gong, Siyu Chen, Zhenyu Feng and Dawang Li; data collection: Yanping Lin and Dan Jiang; validation, visualization, data interpretation: Caiyi Wu and Yichun Ke; figure preparation, visualization: Ning Zhao and Huixin Huang; original draft writing: Meiting Xu and Le Zhang; Zhonghui Du and Hongbo Liu supervised the project, secured funding, and revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data supporting this review are included within the article and its references. No new datasets were generated or analyzed. Materials preparation methods are described in the cited references.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Choi MK, Yang J, Kang K, Kim DC, Choi C, Park C, et al. Wearable red–green–blue quantum dot light-emitting diode array using high-resolution intaglio transfer printing. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7149. doi:10.1038/ncomms8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhang Q, Shao S, Chen Z, Pecunia V, Xia K, Zhao J, et al. High-resolution inkjet-printed oxide thin-film transistors with a self-aligned fine channel bank structure. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(18):15847–54. doi:10.1021/acsami.8b02390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Du Z, Zhang L, Du Y, Wei X, Du X, Lin X, et al. Controlling the polymer ink’s rheological properties to form single and stable droplet. Coatings. 2024;14(5):600. doi:10.3390/coatings14050600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Park SY, Lee S, Yang J, Kang MS. Patterning quantum dots via photolithography: a review. Adv Mater. 2023;35(41):2300546. doi:10.1002/adma.202300546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hou B, Mocanu FC, Cho Y, Lim J, Feng J, Zhang J, et al. Evolution of local structural motifs in colloidal quantum dot semiconductor nanocrystals leading to nanofaceting. Nano Lett. 2023;23(6):2277–86. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c04851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lee T, Kim BJ, Lee H, Hahm D, Bae WK, Lim J, et al. Bright and stable quantum dot light-emitting diodes. Adv Mater. 2022;34(4):2106276. doi:10.1002/adma.202106276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Meng T, Zheng Y, Zhao D, Hu H, Zhu Y, Xu Z, et al. Ultrahigh-resolution quantum-dot light-emitting diodes. Nat Photon. 2022;16(4):297–303. doi:10.1038/s41566-022-00960-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Rhee S, Jeong BG, Choi M, Lee J, Jung WH, Lim J, et al. Versatile use of 1,12-diaminododecane as an efficient charge balancer for high-performance quantum-dot light-emitting diodes. ACS Photonics. 2023;10(2):500–7. doi:10.1021/acsphotonics.2c01638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Soltman D, Subramanian V. Inkjet-printed line morphologies and temperature control of the coffee ring effect. Langmuir. 2008;24(5):2224–31. doi:10.1021/la7026847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Azzellino G, Freyria FS, Nasilowski M, Bawendi MG, Bulović V. Micron-scale patterning of high quantum yield quantum dot LEDs. Adv Mater Technol. 2019;4(7):1800727. doi:10.1002/admt.201800727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kim J, Roh J, Park M, Lee C. Recent advances and challenges of colloidal quantum dot light-emitting diodes for display applications. Adv Mater. 2024;36(20):2212220. doi:10.1002/adma.202212220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hadwen B, Broder GR, Morganti D, Jacobs A, Brown C, Hector JR, et al. Programmable large area digital microfluidic array with integrated droplet sensing for bioassays. Lab Chip. 2012;12(18):3305–13. doi:10.1039/C2LC40273D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jia Y, Li H, Guo N, Li F, Li T, Ma H, et al. Long-range order enhance performance of patterned blue quantum dot light-emitting diodes. Nat Commun. 2025;16:7643. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-62345-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kim DC, Karl M, Lee K, Ko D, Kim DH, Yang J, et al. Recent progress on the development of intrinsically stretchable electroluminescent devices. Small. 2025:e05099. doi:10.1002/smll.202505099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kim JM, Choi D, Lee N, Chae WS, Kim HS, Yu JH, et al. Role of conjugated structure of cross-linkers in patterned QLEDs. Nano Lett. 2025;25(26):10435–41. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.5c01926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tan C, Shan X, Ren T, Chen X, Zhang Z, Lin R, et al. Direct patterning and optical properties of quantum dot films based on UV micro-LEDs. Opt Express. 2025;33(12):24746. doi:10.1364/oe.558691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang W, Jiang P, Wu Z, Long R, Liu F, Du H, et al. Ligand-engineered quantum dots for photolithographic micro-LED color conversion. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Aspects. 2025;724:137505. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2025.137505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wu MX, Hsueh HW, Lu SH, Zeng BH, Huang YW, Fang CY, et al. Self-assembly of impact-resistant and shape-recoverable structures inspired by Taiwan rhinoceros beetles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2025;17(16):24630–43. doi:10.1021/acsami.5c03894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yang Z, Gao M, Wu W, Yang X, Sun XW, Zhang J, et al. Recent advances in quantum dot-based light-emitting devices: challenges and possible solutions. Mater Today. 2019;24:69–93. doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2018.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lee J, Jo H, Choi M, Park S, Oh J, Lee K, et al. Recent progress on quantum dot patterning technologies for commercialization of QD-LEDs: current status, future prospects, and exploratory approaches. Small Meth. 2024;8(7):2301224. doi:10.1002/smtd.202301224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Meng H. Patterning techniques for quantum dot light-emitting diodes (QDLED). In: Colloidal quantum dot light emitting diodes: materials and devices. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley Semiconductors; 2024. p. 361–71. doi:10.1002/9783527845149.ch14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wijshoff H. Structure- and fluid-dynamics in piezo inkjet printheads [dissertation]. Enschede, The Netherlands: University of Twente; 2008. doi:10.3990/1.9789036525824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kim DH, Hwang JH, Seo E, Lee K, Lim J, Lee D. Solution-processed thick hole-transport layer for reliable quantum-dot light-emitting diodes based on an alternatingly doped structure. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024;16(34):45139–46. doi:10.1021/acsami.4c07049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kim DH, Lee KJ, Hwang JH, Kwon H, Seo E, Lee J, et al. Thermally cross-linkable blended hole transport layer for solution-processed quantum dot light-emitting diodes. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2025;8(34):16727–35. doi:10.1021/acsanm.5c02714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kim Y, Yang J, Choi MK. Recent advances in transfer printing of colloidal quantum dots for high-resolution full color displays. Korean J Chem Eng. 2024;41(13):3469–82. doi:10.1007/s11814-024-00301-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lee N, Choi D, Ko KJ, Kim HS, Yu JH, Lee JS. Direct optical lithography using diazirine cross-linker for quantum dot light emitting diodes and enhancing photoluminescence quantum yield through post-treatment. ACS Nano. 2025;19(24):22253–61. doi:10.1021/acsnano.5c04130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xia D, Li J, Zhang Q, Shen S, Sheng C, Cong C, et al. Transferable self-assembled quantum dot microarrays for high-resolution luminescent applications. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2025;8(5):2493–9. doi:10.1021/acsanm.4c06769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Xu C, Chen M, Xu S, Geng C. Study of hybrid nanoscatterer for enhancing light efficiency of quantum dot-converted light-emitting diodes. J Lumin. 2024;276:120869. doi:10.1016/j.jlumin.2024.120869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zeng Q, Fan Y, Zhu Y, Guo T, Hu H, Li F. Electrohydrodynamic printing enables ultrahigh resolution quantum dot light-emitting diodes. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2025;46(1):64–7. doi:10.1109/LED.2024.3502469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yin Z, Huang Y, Bu N, Wang X, Xiong Y. Inkjet printing for flexible electronics: materials, processes and equipments. Chin Sci Bull. 2010;55(30):3383–407. doi:10.1007/s11434-010-3251-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Calvert P. Inkjet printing for materials and devices. Chem Mater. 2001;13(10):3299–305. doi:10.1021/cm0101632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Shirasaki Y, Supran GJ, Bawendi MG, Bulović V. Emergence of colloidal quantum-dot light-emitting technologies. Nature Photon. 2013;7(1):13–23. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2012.328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Klimov VI. Nanocrystal quantum dots. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

34. Chen O, Zhao J, Chauhan VP, Cui J, Wong C, Harris DK, et al. Compact high-quality CdSe–CdS core–shell nanocrystals with narrow emission linewidths and suppressed blinking. Nat Mater. 2013;12(5):445–51. doi:10.1038/nmat3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Kim TH, Cho KS, Lee EK, Lee SJ, Chae J, Kim JW, et al. Full-colour quantum dot displays fabricated by transfer printing. Nature Photon. 2011;5(3):176–82. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2011.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Medintz IL, Uyeda HT, Goldman ER, Mattoussi H. Quantum dot bioconjugates for imaging, labelling and sensing. Nature Mater. 2005;4(6):435–46. doi:10.1038/nmat1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Talapin DV, Murray CB. PbSe nanocrystal solids for n- and p-channel thin film field-effect transistors. Science. 2005;310(5745):86–9. doi:10.1126/science.1116703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Reiss P, Protière M, Li L. Core/shell semiconductor nanocrystals. Small. 2009;5(2):154–68. doi:10.1002/smll.200800841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Almeida G, Ubbink RF, Stam M, du Fossé I, Houtepen AJ. InP colloidal quantum dots for visible and near-infrared photonics. Nat Rev Mater. 2023;8(11):742–58. doi:10.1038/s41578-023-00596-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wichaiyo N, Wei Y, Ding C, Shi G, Yindeesuk W, Wang L, et al. Synthesis of p-type PbS quantum dot ink via inorganic ligand exchange in solution for high-efficiency and stable solar cells. J Semicond. 2025;46(4):042104. doi:10.1088/1674-4926/25030003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang C, Han D, Zhang X. PbS colloidal quantum dots: ligand exchange in solution. Coatings. 2024;14(6):761. doi:10.3390/coatings14060761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kowalik P, Bujak P, Penkala M, Pron A. Organic-to-aqueous phase transfer of alloyed AgInS2-ZnS nanocrystals using simple hydrophilic ligands: comparison of 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid, dihydrolipoic acid and cysteine. Nanomaterials. 2021;11(4):843. doi:10.3390/nano11040843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Aynehband S, Mohammadi M, Thorwarth K, Hany R, Nüesch FA, Rossell MD, et al. Solution processing and self-organization of PbS quantum dots passivated with formamidinium lead iodide (FAPbI3). ACS Omega. 2020;5(25):15746–54. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c02319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]