Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Flow Boiling Heat Transfer and Pressure Gradient of R410A in Micro-Channel Flat Tubes at 25°C and 30°C

1 State Key Laboratory of Air-Conditioning Equipment and System Energy Conservation, Zhuhai, 519070, China

2 Guangdong Key Laboratory of Refrigeration Equipment and Energy Conservation Technology, Zhuhai, 519070, China

3 Gree Electric Appliances, Inc., Zhuhai, 519070, China

4 School of Intelligent Manufacturing Ecosystem, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, Suzhou, 215123, China

* Corresponding Author: Long Huang. Email:

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(2), 553-575. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.062851

Received 29 December 2024; Accepted 21 February 2025; Issue published 25 April 2025

Abstract

This study investigates the flow boiling heat transfer coefficient and pressure gradient of refrigerant R410A in micro-channel flat tubes. Experiments were conducted at saturation temperatures ranging from 25°C to 30°C, mass fluxes between 198 and 305 kg/m2s, and heat fluxes from 9.77 to 20.18 kW/m2, yielding 99 sets of local heat transfer coefficient data. The results show that increasing heat flux and mass flux enhances the heat transfer coefficient, although the rate of enhancement decreases with increasing vapor quality. Conversely, higher saturation temperatures slightly reduce the heat transfer coefficient. Additionally, the experimental findings reveal discrepancies in the accuracy of existing pressure drop and heat transfer coefficient prediction models under the studied conditions. This study recommends using the Kim and Mudawar correlation to predict pressure gradients within the tested range, with a Mean Error (ME) of −5.24% observed in this study. For heat transfer coefficients, the Cooper and Kandlikar correlations are recommended, achieving a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of approximately 22%. This research provides value for performance prediction and parameter selection of micro-channel technology in broader application scenarios within heating, ventilation and air-conditioning fields.Keywords

Nomenclature

| A | Heat transfer area (m2) |

| Bd | Bond number (–) |

| Bo | Boiling number (–) |

| Co | Convection number (–) |

| Cp | Specific Heat Capacity (J kg−1K −1) |

| d | Thickness of the wall |

| Dh | Hydraulic diameter (m) |

| Fr | Froude number (–) |

| G | Mass flux (kg m2s−1) |

| g | Gravitational acceleration (m2 s−1) |

| h | Enthalpy (kJ/kg) |

| k | Thermal conductivity (W m−1K−1) |

| Mass flow rate (kg/s) | |

| M | Molecular weight (g/mol) |

| MAE | Mean absolute error (–) |

| ME | Mean error (–) |

| Nconf | Confinement number (–) |

| Pr | Prandtl number (–) |

| P | Pressure (kPa) |

| PF | Wetted perimeter of channel (m2) |

| PH | Heated perimeter of channel (m2) |

| PR | Reduced pressure (–) |

| q | heat flux (kW m−2) |

| Heat flux based on heated perimeter of channel (kW m−2) | |

| Q | Heat transfer rate (W or kW) |

| Re | Reynolds number (–) |

| Su | Suratman number (–) |

| T | Temperature (K) |

| U | Heat loss coefficient (W/m2K) |

| We | Weber number (–) |

| X | Lockhart-Martinelli parameter |

| Greek Letters | |

| Void fraction (–) | |

| Dynamic viscosity, Uncertainty, Mean (kg m−1 s−1, –, /) | |

| Specific volume (m3 kg−1) | |

| Density (kg m−3) | |

| Surface tension, standard deviation (N m−1, /) | |

| Subscripts | |

| ami | Ambient |

| al | Aluminum |

| frict | Friction |

| in | Inlet |

| lo | Liquid only |

| l | Liquid |

| loss | Loss |

| mom | Momentum |

| out | Outlet |

| ref | Refrigerant |

| sat | Saturation |

| tp | Two-phase |

| total | Total |

| V | Vapor |

| vo | Vapor only |

| w,i | Inner wall |

| wall | Wall |

Refrigeration technology [1] plays a crucial role in modern society, significantly impacting our daily lives, various industries, and economic development. Particularly in the field of modern heat exchange technology, micro-channel multiport tubes have become a key component, widely used in advanced applications such as electronic cooling, automotive systems, air conditioning, heat pumps, and refrigeration systems. R410A is a widely used third-generation hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) blended refrigerant in air conditioning and heat pump systems [2,3]. Due to its high global market share, studying its performance holds significant industrial reference value. Despite the growing demand for eco-friendly refrigerants, R410A remains the mainstream choice in many regions during the regulatory transition period, and research into its improvement and optimization can provide technical support for a smooth transition between old and new refrigerants. This study aims to investigate the flow boiling heat transfer characteristics and pressure gradients of refrigerant R410A in micro-channel parallel flow tubes under varying saturation temperatures, mass fluxes, and heat fluxes. This design, owing to its exceptional efficiency and compact volume, significantly increases the surface area relative to the volume, this enhances heat transfer efficiency while reducing the overall equipment size. The automotive and aerospace industries have adopted smaller channel sizes to meet strict weight and size constraints, while the high-performance demands of the commercial and residential air-conditioners have led to the implementation of millimeter-sized channels to achieve higher heat transfer rates and improved efficiency [4]. By addressing the specific conditions and geometries of multi-port tubes, this research seeks to fill existing gaps and provide novel insights that contribute to the optimization of heat exchange systems.

Despite the broad application of mini-channel technology across various domains, research indicates that it still faces fundamental challenges in two-phase flow boiling. Qi et al. [5] optimized key design parameters of a household dehumidifier using R410A as the working fluid. The optimized schemes, obtained through non-dominated sorting, significantly enhanced heat transfer efficiency and two-phase mixing uniformity, fully demonstrating the potential of R410A in improving energy efficiency and system performance. Extensive literature surveys [6] highlight the lack of a mature classification system for the wide range of tube sizes reported. Recent studies by Kriz et al. [7] investigated the balance between surface tension and gravity by measuring liquid film thickness in channels, confirming that Co > 1.0 is an effective criterion for defining micro-channel flow. Additionally, the heat transfer behavior in small channels significantly differs from that in conventional channels, as demonstrated by studies such as Tanaka et al. [8], which reveals that the traditional flow boiling models are insufficient to fully explain the two-phase flow boiling phenomena of R1234yf in multiport tubes. One of the major challenges lies in the limited understanding of heat transfer mechanisms at elevated saturation temperatures, which are critical for applications such as heat pump dryers and solar-assisted heat pumps. Therefore, traditional Heat Transfer Coefficient (HTC) models like those proposed by Chen [9], which integrate nucleate and forced convective boiling, need to be reevaluated for the specific geometries and conditions of multiport tubes. Bediako et al. [10] examined the heat transfer behavior of R1234ze(E) in horizontal tubes with a hydraulic diameter of 2.07 mm under moderate to high saturation temperature conditions. Their findings revealed that the saturation temperature significantly influences the heat transfer coefficient, while variations in mass flux have a relatively weak impact. They identified nucleate boiling as the primary heat transfer mechanism and observed that with increasing saturation temperature, the dry-out point is reached earlier. Kandlikar et al. [11] discovered that convective processes become predominant with higher refrigerant vapor qualities characterized by a significant liquid-to-vapor density ratio. This condition induces an upward trend in the boiling HTC as vapor quality escalates. They noted that a substantial boiling number enhances the contribution of nucleate boiling, which diminishes with rising vapor quality, leading to a decline in the HTC as vapor quality increases. The flow boiling characteristics of refrigerant R410A in both smooth and finned tubes were examined by Wang et al. [12] and Ebisu et al. [13]. It was observed that the boiling HTC for R410A exceeded those of refrigerant R22, except at elevated vapor qualities. Furthermore, these coefficients were found to rise in response to increased heat and mass fluxes. However, comparative studies under varying higher saturation temperature conditions remain scarce, highlighting a significant research gap that this study aims to address. Kaew-On et al. [14] conducted studies on the evaporation HTC and pressure drop of R410A in aluminum multiport tube. The experimental results were obtained from tubes with a hydraulic diameter of 3.48 mm, mass fluxes vary from 200 to 400 kg/m2s, heat fluxes range between 5 and 14.25 kW/m2, and saturation temperatures within the range of 10°C to 30°C. The findings indicated that the mean HTC for R410A during evaporation increased with greater average quality, mass flux, and heat flux but decreased as the saturation temperature rose. Meanwhile, pressure drops escalated with an increase in mass flux but fell with rising saturation temperatures. The influence of heat flux on pressure drops was determined to be negligible.

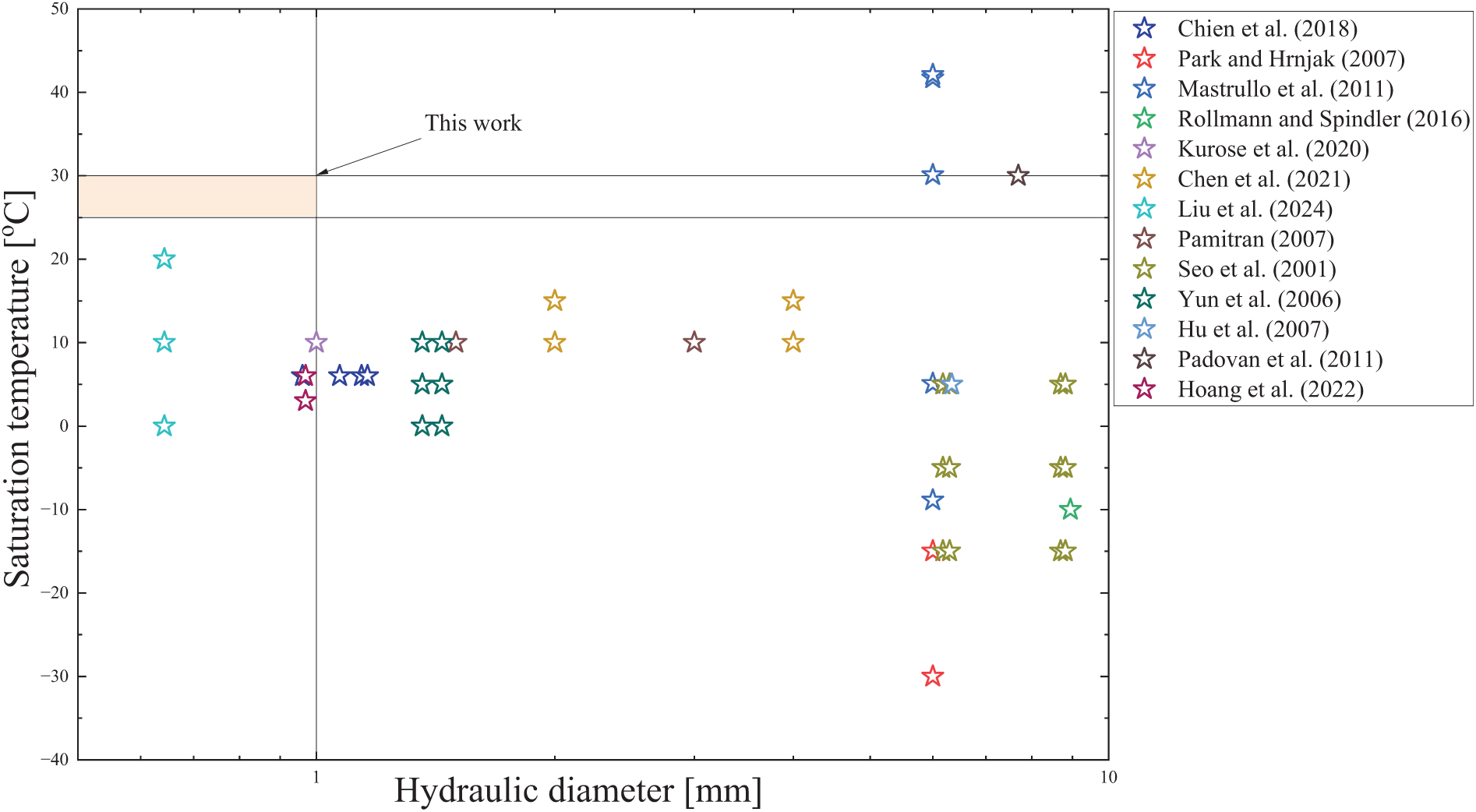

These findings underscore the importance of developing HTC covering wider range of geometries and operating conditions, thereby improving prediction accuracy and expanding understanding of the internal boiling heat transfer mechanisms. In particular, our study provides a comprehensive analysis of HTC across higher saturation temperatures, which have been underexplored in previous research. This integrated approach not only aids in enhancing equipment performance but also propels heat exchange technology toward greater efficiency and economic viability. Additionally, studies on two-phase flow boiling heat transfer and pressure drops for R410A and other refrigerants in mini-channel multiport tubes remain scarce. The majority of existing research on flow boiling within horizontal tubes involve datasets on halogenated refrigerants at low saturation temperatures (typically from −15°C to 20°C), which are typical conditions for refrigeration and air conditioning applications. However, particularly in the case of mini-channel tubes where data are scarce, there is still a need to validate existing heat transfer models at higher saturation temperatures. To address this gap, this study investigates flow boiling at saturation temperatures of 25°C and 30°C, providing a foundation for further research at even higher temperatures relevant to high-temperature heat pump systems. Our research provides experiment data and analysis at higher saturation temperatures, further validating the reliability and applicability of HTC models in broader practical scenarios. Fig. 1 summarizes the representative previous works on R410A.

Figure 1: A review survey on R410A tested flow boiling conditions (Chien et al. [15], Park et al. [16], Mastrullo et al. [17], Rollmann et al. [18], Kurose et al. [19], Chen et al. [20], Pamitran et al. [21], Liu et al. [22], Seo et al. [23], Yun et al. [24], Hu et al. [25], Padovan et al. [26], Hoang et al. [27])

Flow boiling data is primarily developed for conditions in air-condition, heat pumps and refrigeration systems. In such systems, the evaporator is a crucial component because it significantly impacts overall performance [28]. For example, heat pump clothes dryers that utilize HFC refrigerants extract heat from hot and humid air streams, achieving highly efficient heat recovery. These devices can reach higher saturation temperatures than typical air conditioning and refrigeration applications. According to research by Mancini et al. [29], the evaporating temperature can exceed 30°C, significantly enhancing drying efficiency and energy savings. Abou-Ziyan et al. [30] studied solar-assisted R134a heat pumps across a wide range of evaporating temperatures (0°C to 45°C). This research highlights the potential of solar energy as a renewable resource to enhance heat pump performance, particularly in regions with large variations in ambient temperature, where solar assistance can significantly improve operational efficiency and reliability.

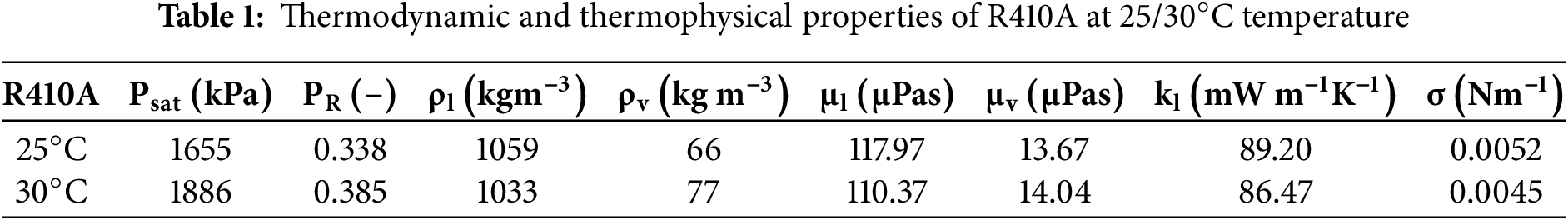

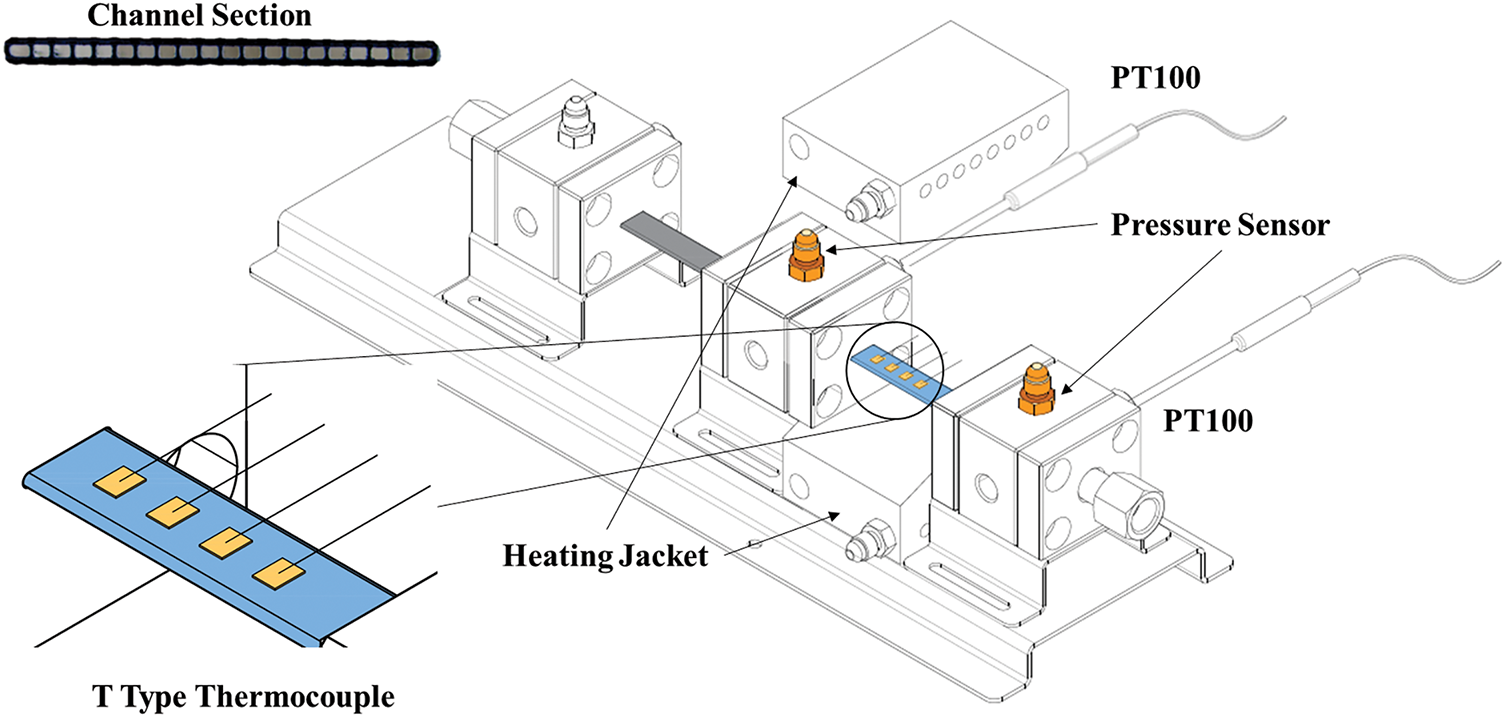

However, this study investigates the effects of saturation temperature, mass flux and heat flux on flow boiling heat transfer through measurements in micro-channel flat tubes, making it potentially useful for many other applications. Specifically, this study extends the understanding of HTC behavior across higher temperature ranges and varied mass flux conditions, which are particularly relevant to industrial applications beyond traditional HVAC systems. For thermophysical properties of the refrigerants under varying conditions, based on REFPROP 10.0 [31], please refer to Table 1. For instance, in the reboilers used in chemical and petrochemical processes, new data regarding the effect of temperature on the accuracy of predictive models would be extremely valuable. In these processes, controlling and optimizing boiling heat transfer is crucial not only for energy efficiency but also directly impacts production safety and economic benefits. Therefore, enhancing the theoretical basis for the design and operation of evaporators in these applications is vitally important.

Fig. 2 illustrates the schematic of the experimental setup, which consists of a refrigerant loop, two water loops (high and low temperature), and a data acquisition system. The refrigerant loop includes a gear pump, subcooler, mass flow meter, expansion valve, pre-heater, post-heater, test section (a flat tube micro-channel, as described in the Test Section chapter), condenser, and storage tank. During evaporation tests, the refrigerant is pumped by the gear pump to the test section. The mass flow rate of the refrigerant is measured by an OVAL mass flow meter and can be adjusted by changing the pump speed and the opening of the expansion valve. The vapor quality of the refrigerant at the inlet of the test section is controlled by the power consumption (circulating water volume and the temperature difference between inlet and outlet water) of the pre-heater. The test section is heated through the water loop, as depicted in the diagram. By controlling the mass flow rate and operating temperature of the water, the heat capacity can be varied. The post-heater is set to ensure that the refrigerant is in a superheated state after passing through, and the steam at the outlet of the post-heater is condensed by the condensing unit and then accumulates in the receiver, preparing for a new testing cycle. The experimental apparatus is insulated with foam and insulation cotton to minimize heat transfer between the system and the environment.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of the experimental setup [32]

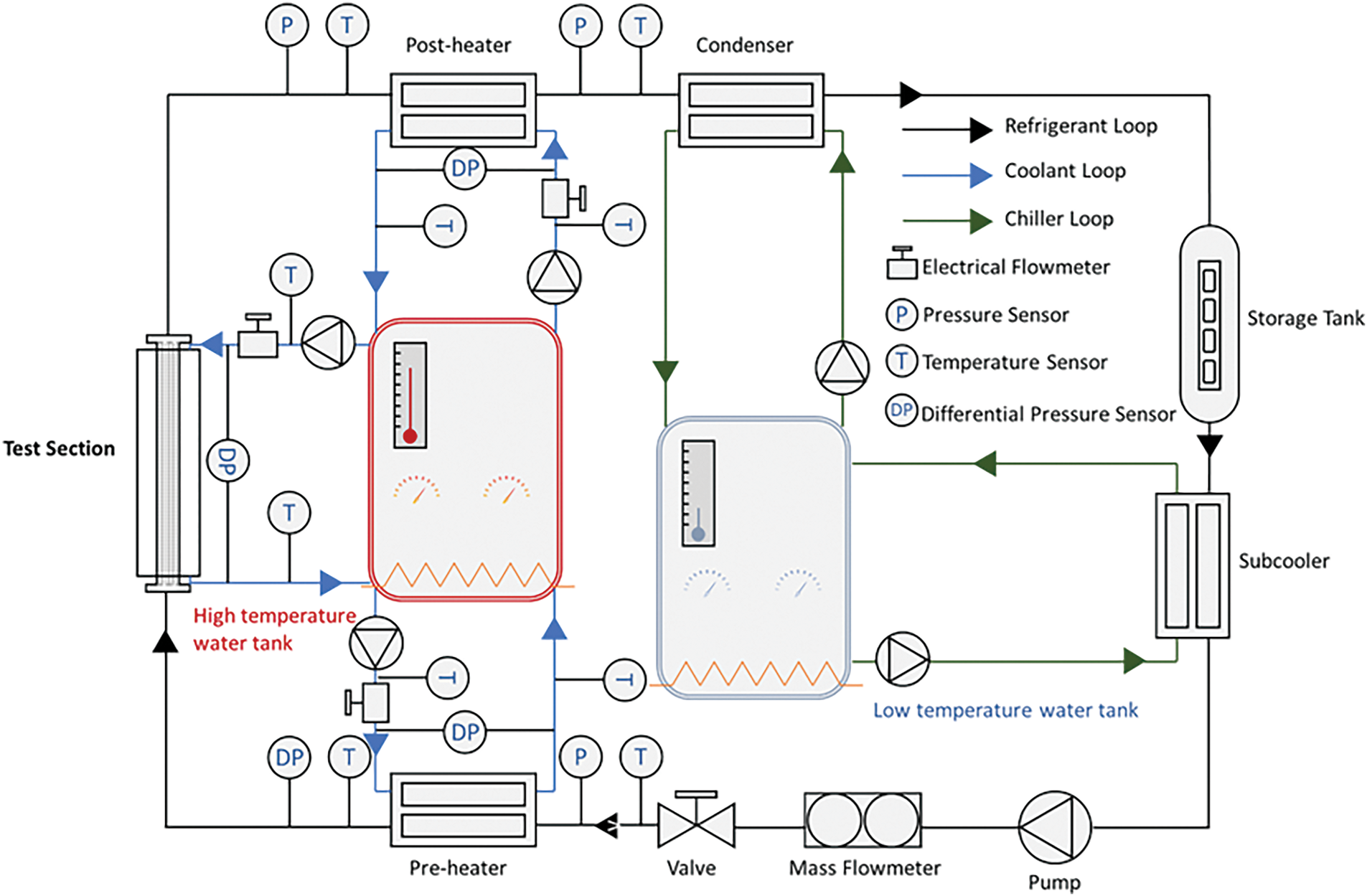

The overall configuration of the test setup includes a pair of Pt100, a pressure measurement system, heating component, and a parameter measurement assembly. The Pt100 sensors are assigned to monitor the temperatures at both the entry and exit points of the refrigerant, each thermometer being 15 cm in length. During operation, the pressure acquisition module is positioned directly above the sensor tips, ensuring that the pressure and temperature readings at the inlet and outlet are aligned. Inside the heating jacket, water is circulated and heat is evenly transferred to the micro-channel flat tube via aluminum, and due to external thermal influences, the pressure drop within the flat tube should be regarded as the aggregate of momentum and frictional pressure drops.

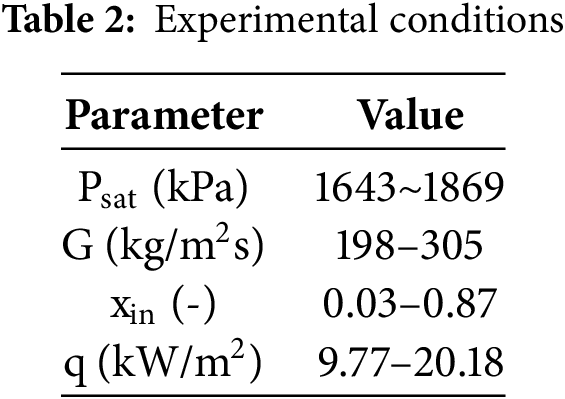

The test section (as shown in Fig. 3) consists of a single aluminum micro-channel tube, 400 mm in length, equipped with two independent hot water jackets. Consequently, the micro-channel tube is divided into a pre-section (250 mm long) and a heat transfer measurement section (150 mm long, shown in blue). In the pre-section, the refrigerant achieves a fully developed flow state, and its vapor quality is adjusted by the pre-heater. Measurements of the HTC are conducted within the heat transfer measurement section. It features 20 channels with smooth interiors and a hydraulic diameter of 0.632 mm. Wall temperature is measured using thermocouples, which are uniformly arranged in alternating patterns on both sides of the heat transfer measurement section, totaling 10 T-type thermocouple sets. The gaps between the thermocouples and the heating jacket are filled with thermally conductive silicone grease to ensure maximum heat exchange efficiency. Detailed test conditions are listed in Table 2.

Figure 3: Schematic diagram of test section

3 Measuring Technique and Data Reduction

The data were collected using Yokogawa data acquisition equipment and analyzed through a data reduction program. The physical properties of the refrigerant were sourced from REFPROP 10.0 [31]. All information, including testing conditions and real-time data, were monitored via a computer.

The heat transfer values were determined using Eq. (1a). Additionally, experimental data collected under various operating temperatures were utilized to calibrate heat losses, resulting in a functional relationship between temperature and heat loss (Eq. (1b)), which was then employed to calculate the convective heat transfer coefficient associated with heat losses.

The heat flow rate was calculated based on the mass flow rate and temperature change of the heated water flowing through the water jacket, as illustrated below:

In this formula,

The local HTC within the channel can be evaluated by the ratio of the heat flux to the difference between the saturation temperature and the inside wall temperature.

The inlet saturation temperature is determined based on the locally measured pressure, while the outlet saturation temperature is calculated by subtracting the pressure drop from the inlet value. In this study, there is a significant difference between the refrigerant’s saturation temperature and the wall temperature, and the change in saturation temperature due to the pressure drop is relatively small. Therefore, the variation in saturation temperature between the inlet and outlet can be derived as a linear relationship of two known values. The temperature of the inner tube wall,

The calculation method for the inlet vapor quality,

where

In this study, the total pressure drop of a two-phase fluid is calculated as the sum of the static head pressure drop

The static pressure head can be disregarded because the flow direction is horizontal. The refrigerant is presumed to evaporate from its liquid state at the saturation temperature, forming a vapor-liquid mixture at a vapor quality

For horizontal tubes, the void fraction α is defined by the Zivi’s [33] model.

The frictional pressure drop is then calculated as the difference between the total pressure drop and the momentum pressure drop:

By separating the frictional component in this manner, the study ensures an accurate representation of the contributions from both momentum and friction to the overall pressure drop.

3.3 Calibration Procedure and Experimental Uncertainty Analysis

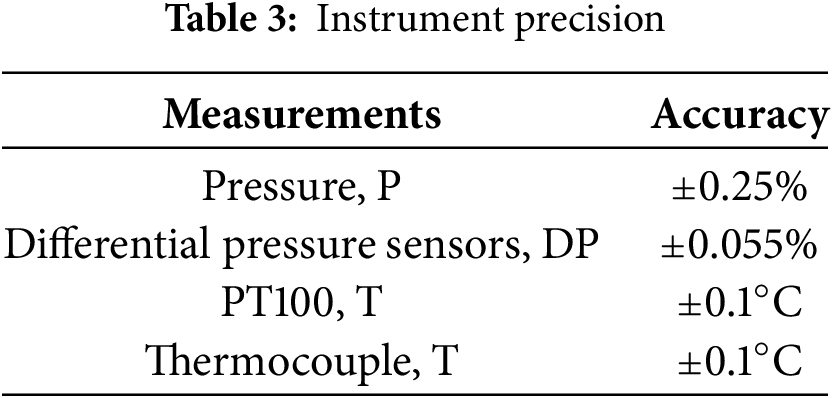

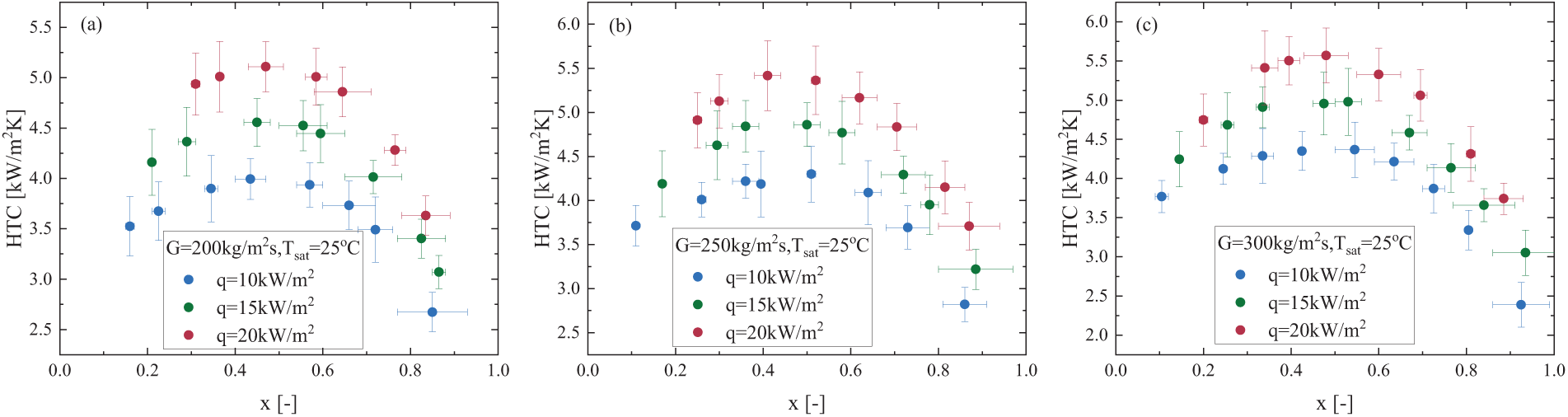

The system was calibrated to ensure the reliability of the study. The thermocouples were calibrated in an oil bath using a platinum resistance thermometer, ensuring an accuracy within 0.1 K. Calibration of the pressure sensors and flow meters was performed with standard pressure gauges and dedicated calibration instruments. To confirm the accuracy of the experiment, a heat balance was carried out by comparing the heat released by the refrigerant to the total heat absorbed by the cooling water, which was consistently under 9.6%, indicating effective thermal insulation and accurate measurement capabilities of the setup. Furthermore, the maximum uncertainties of indirect experimental parameters were assessed using the conventional method of error propagation analysis [34], this study divides the measurement accuracy of the experimental data and the calculated uncertainties into two separate tables: Table 3 summarizes the accuracy of the measuring instruments, while Table 4 lists the uncertainty ranges of the indirectly computed parameters.

4 R410A Two-Phase Flow Results

In the study, experimental data for the HTC were collected for R410A at saturation temperatures ranging from 25°C to 30°C, mass flux between 198 and 305 kg/m2s, and heat fluxes spanning 9.77 to 20.18 kW/m2. This section analyses the effects of heat flux, mass flux and saturations temperature on the HTC.

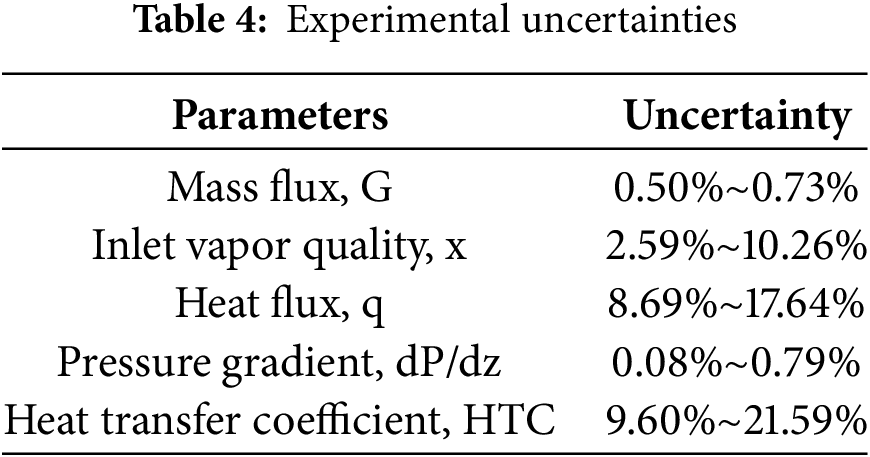

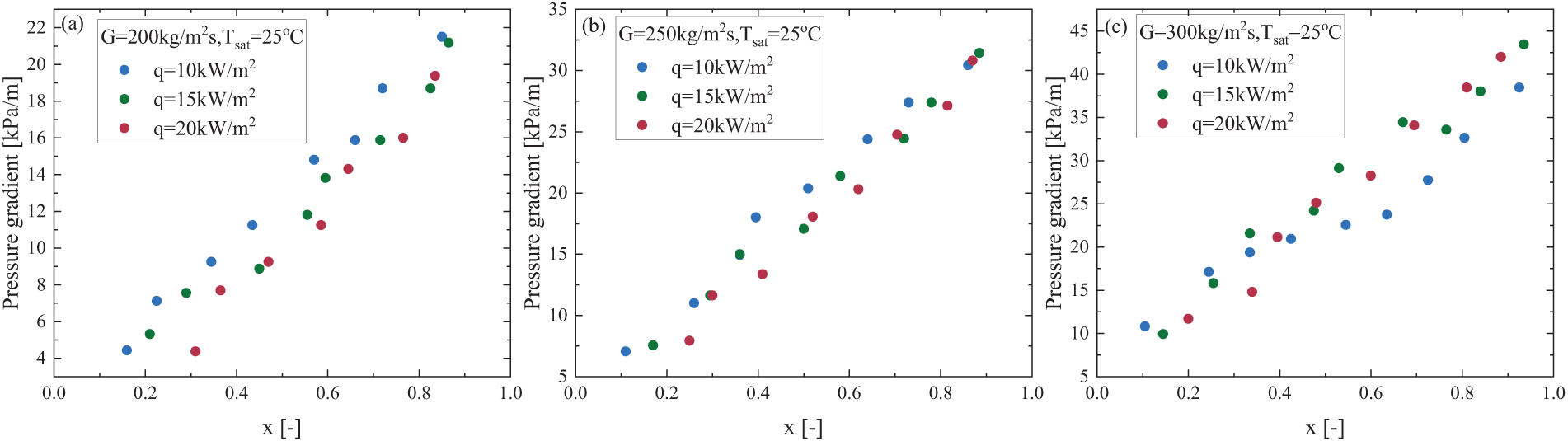

Fig. 4 illustrates the effect of heat flux on the HTC of R410A at a constant saturation temperature. It is clearly observed that the HTC increases with increasing heat flux. This phenomenon is expected, since it is typically linked to the more efficient activation of nucleation sites on the heated surface, which enhances bubble nucleation activity. Furthermore, when the vapor quality reaches a certain value, the HTC starts to decline. At higher heat flux, the contribution of the nucleate boiling heat transfer mechanism to the HTC becomes significantly more pronounced. The increase in heat flux causes a more substantial change between 10 and 15 kW/m2 compared to the change between 15 and 20 kW/m2. For instance, at a mass flux of G = 300 kg/m2s, when the heat flux increases from 10 to 15 kW/m2, the HTC increases by 14%, whereas when the heat flux rises from 15 to 20 kW/m2, the HTC only increases by 11%. Typically, when the vapor quality (x) exceeds approximately 0.5, the annular flow pattern predominates. However, experimental results indicate that even in the annular flow regime, nucleate boiling continues to play a significant role in heat transfer. As illustrated in Fig. 4, even when the vapor quality exceeds 0.6, the HTC still exhibits noticeable differences under the influence of the three different heat fluxes, with a maximum variation of up to 12%. This observation is consistent with the findings of Layssac et al. [35], who confirmed strong bubble nucleation activity during annular flow through the visualization of R245fa flow boiling at Tsat = 81°C in a 1.6 mm diameter sapphire ITO-coated tube. As shown in Fig. 5, there is no significant change in frictional pressure drop with varying heat flux, suggesting that the heat flux has relatively little or no clear effect on the frictional pressure drop in micro-channels. This is because the heat transfer process induced by heat flux exerts a more indirect influence on the instantaneous gas–liquid distribution in the micro-channel, thereby resulting in a relatively weak correlation between frictional pressure drop and heat flux.

Figure 4: Heat flux effect on the HTC for R410A at (a) G = 200 kg/m2s, Tsat = 25°C; (b) G = 250 kg/m2s, Tsat = 25°C and (c) G = 300 kg/m2s, Tsat = 25°C

Figure 5: Heat flux effect on the pressure gradient for R410A at (a) G = 200 kg/m2s, Tsat = 25°C; (b) G = 250 kg/m2s, Tsat = 25°C and (c) G = 300 kg/m2s, Tsat = 25°C

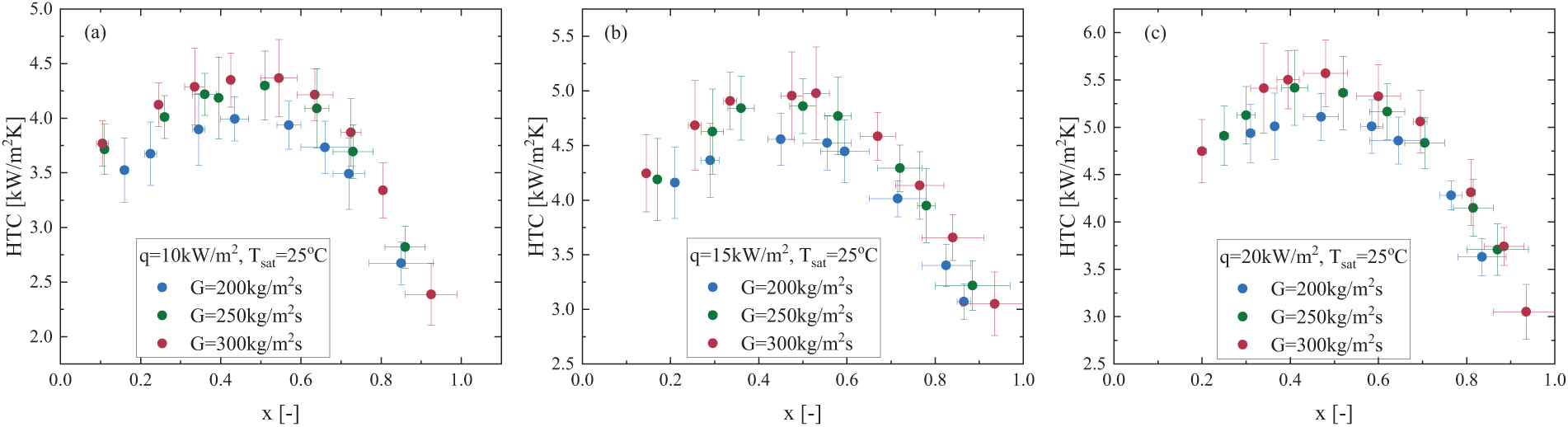

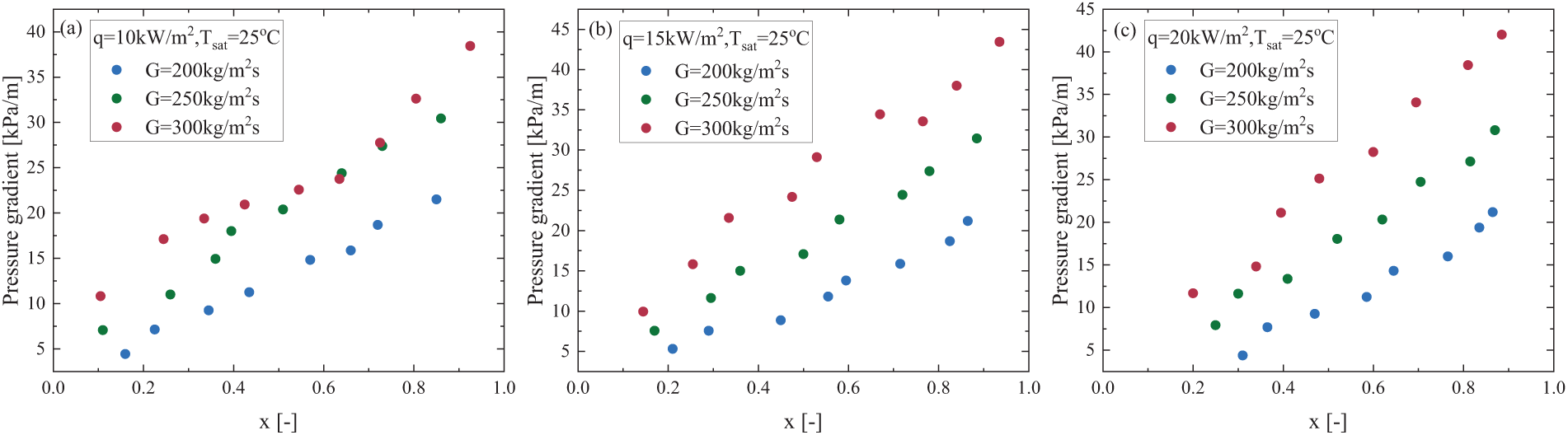

The impact of varying mass flux on the two-phase HTC trends was studied for three different mass flux values, while maintaining constant saturation temperature and heat flux conditions. Fig. 6 provides a detailed analysis of the impact of mass flux on the HTC. As seen in Fig. 6a–c, higher mass flux results in a higher HTC. The initial increase in the HTC is relatively short, likely due to the increase in inlet steam quality, which raises the bubble volume fraction and thereby increases the contact area between the bubbles and the liquid. This, in turn, enhances heat transfer by disturbing the temperature boundary layer through bubble break-up and coalescence processes, which disrupt the temperature gradient. However, the HTC shows a notable decrease when the vapor quality approaches 0.5. These shifts in slope are understood as transitions from nucleate boiling to convective boiling mechanisms. It is crucial to highlight that nucleation suppression effects are also observed in Fig. 6a. As the mass flux rises from 200 to 250 kg/m2s, the maximum HTC increases by about 8%. However, as the mass flux further rises from 250 to 300 kg/m2s, the maximum HTC only increases by about 2%. As indicated by the experimental results in Fig. 7, the frictional pressure drop increases with increasing mass flux. This is because, in micro-channels, a higher mass flux implies a higher flow velocity; under high-flow-velocity conditions, both the liquid and gas phases experience more pronounced shear stress and turbulence, leading to increased frictional losses between the channel walls and the two-phase flow.

Figure 6: Mass flux effect on the HTC for R410A at (a) q = 10 kW/m2, Tsat = 25°C; (b) q = 15 kW/m2, Tsat = 25°C and (c) q = 20 kW/m2, Tsat = 25°C

Figure 7: Mass flux effect on the pressure gradient for R410A at (a) q = 10 kW/m2, Tsat = 25°C; (b) q = 15 kW/m2, Tsat = 25°C and (c) q = 20 kW/m2, Tsat = 25°C

To further understand the fundamental mechanisms of boiling under high saturation temperature conditions, it is recommended that additional experimental studies be conducted. These studies should utilize high-speed infrared thermography to simultaneously capture the wall temperature field and two-phase flow images combined with high-speed video technology. Key parameters such as bubble frequency, bubble departure diameter, transient heat conduction in the heated wall, active nucleation site density, wet and dry regions of the heated surface, and liquid film thickness in the annular flow should be analyzed. Only with these experimental data will it be possible to more accurately characterize and validate the mechanisms involved in boiling processes and their effectiveness.

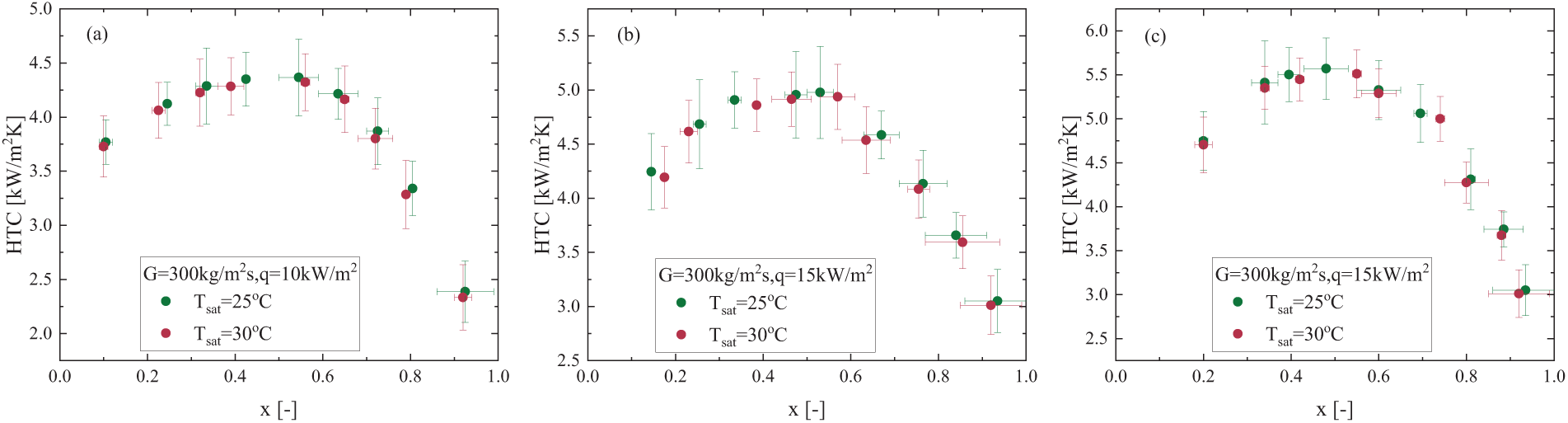

4.3 Effect of Saturation Temperature

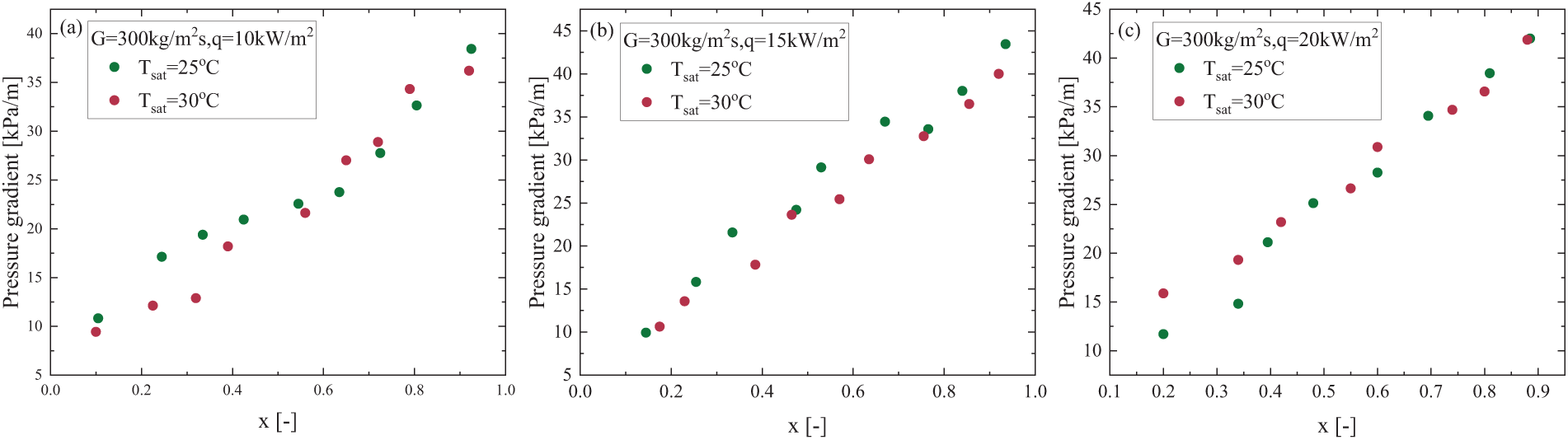

The effect of saturation temperature variation on the two-phase HTC trends was investigated under fixed mass flux and heat flux conditions, specifically at 25°C and 30°C, as shown in Fig. 8. From the figure, it can be observed that, after excluding the uncertainty range, the HTC decreases with increasing saturation temperature, regardless of the vapor quality range. However, the difference is not significant, with a maximum variation of only about 2%. This can be attributed to the decrease in the liquid thermal conductivity of R410A as the saturation temperature increases from 25°C to 30°C. Additionally, as the saturation temperature rises, the vapor density increases, but the liquid density decreases. Under the same mass flux and vapor quality, this results in a reduction in vapor velocity and an increase in liquid velocity, thereby reducing the gas-liquid velocity difference. As a result, the shear stress at the gas-liquid interface decreases, leading to an increase in liquid film thickness and a reduction in the HTC. The experimental results in Fig. 9 indicate that changes in saturation temperature have no significant impact on the frictional pressure drop. This may be attributed to the effect of saturation temperature on the thermophysical properties of the working fluid, such as viscosity, density, and surface tension. For instance, a rise in saturation temperature reduces liquid viscosity, which helps lower the frictional pressure drop, while changes in the liquid-gas density ratio influence heat transfer and phase distribution. However, in micro-channels, due to their small size and high flow velocity, the evolution of the two-phase interface is primarily governed by flow kinetic energy and local quality, which weakens the impact of thermophysical property changes induced by variations in saturation temperature. Additionally, flow patterns in micro-channels (e.g., slug flow, annular flow) and the distribution of gas and liquid phases have a more pronounced effect on pressure drop. Changes in saturation temperature within a moderate range are insufficient to significantly alter flow patterns. Consequently, the overall influence of saturation temperature on the frictional pressure drop in two-phase flow remains minimal.

Figure 8: Saturation temperature effect on the HTC for R410A at (a) G = 300 kg/m2s, q = 10 kW/m2, (b) 300 kg/m2s, q = 15 kW/m2 and (c) 300 kg/m2s, q = 20 kW/m2

Figure 9: Saturation temperature effect on the pressure gradient for R410A at (a) G = 300 kg/m2s, q = 10 kW/m2, (b) 300 kg/m2s, q = 15 kW/m2 and (c) 300 kg/m2s, q = 20 kW/m2

5.1 Database and the Evaluation Matrics

This study explores the heat transfer coefficient and pressure gradient during the flow boiling of R410A in a 20-port micro-channel tube. The mass flux was varied between 200 and 300 kg/m2s, and the heat flux ranged from 10 to 20 kW/m2. Two different saturation temperatures were tested: 25°C and 30°C. The experimental results were compared with existing correlations, and performance was evaluated based on key metrics, including the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Error (ME).

5.2 Pressure Gradient Prediction Methods Evaluation

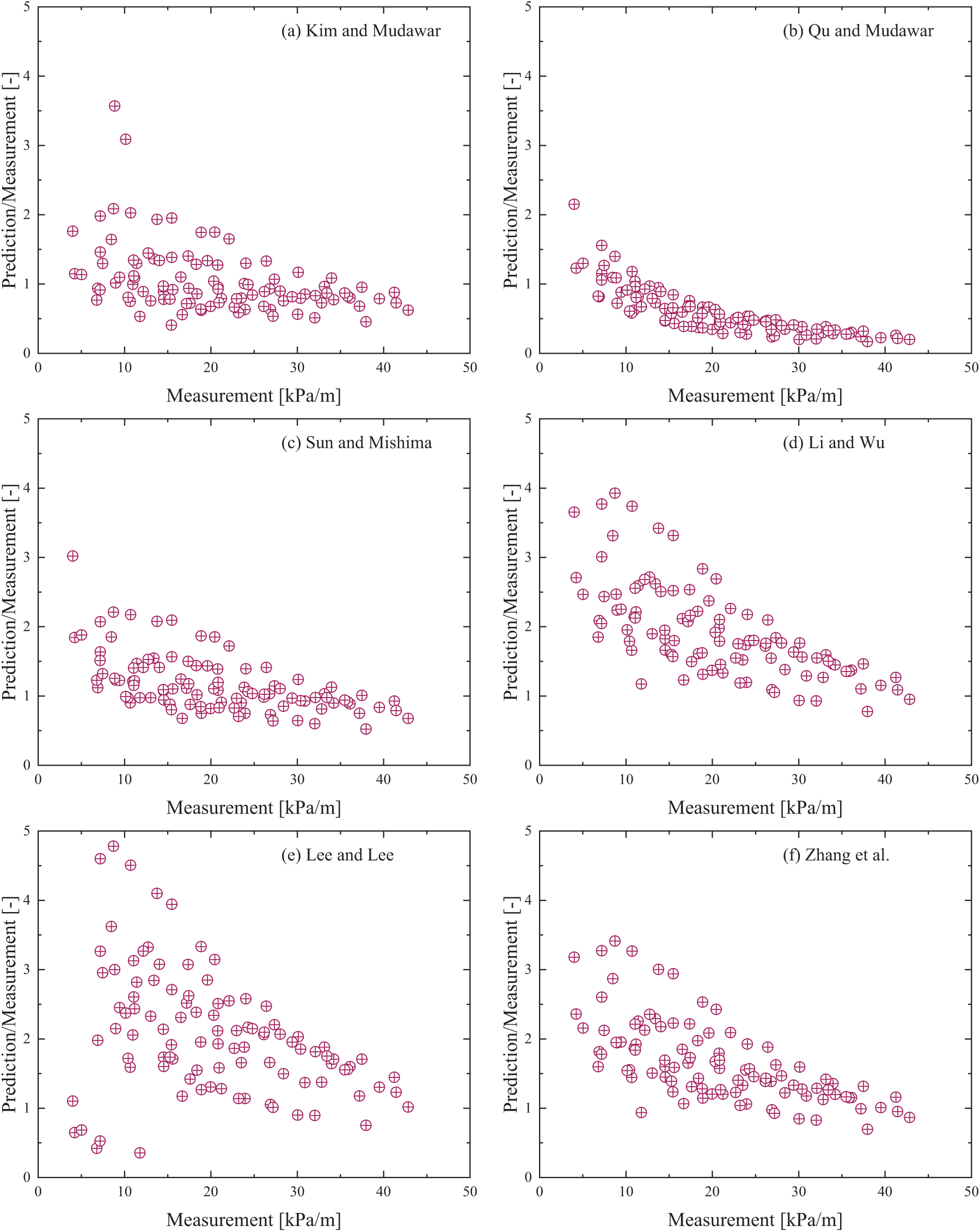

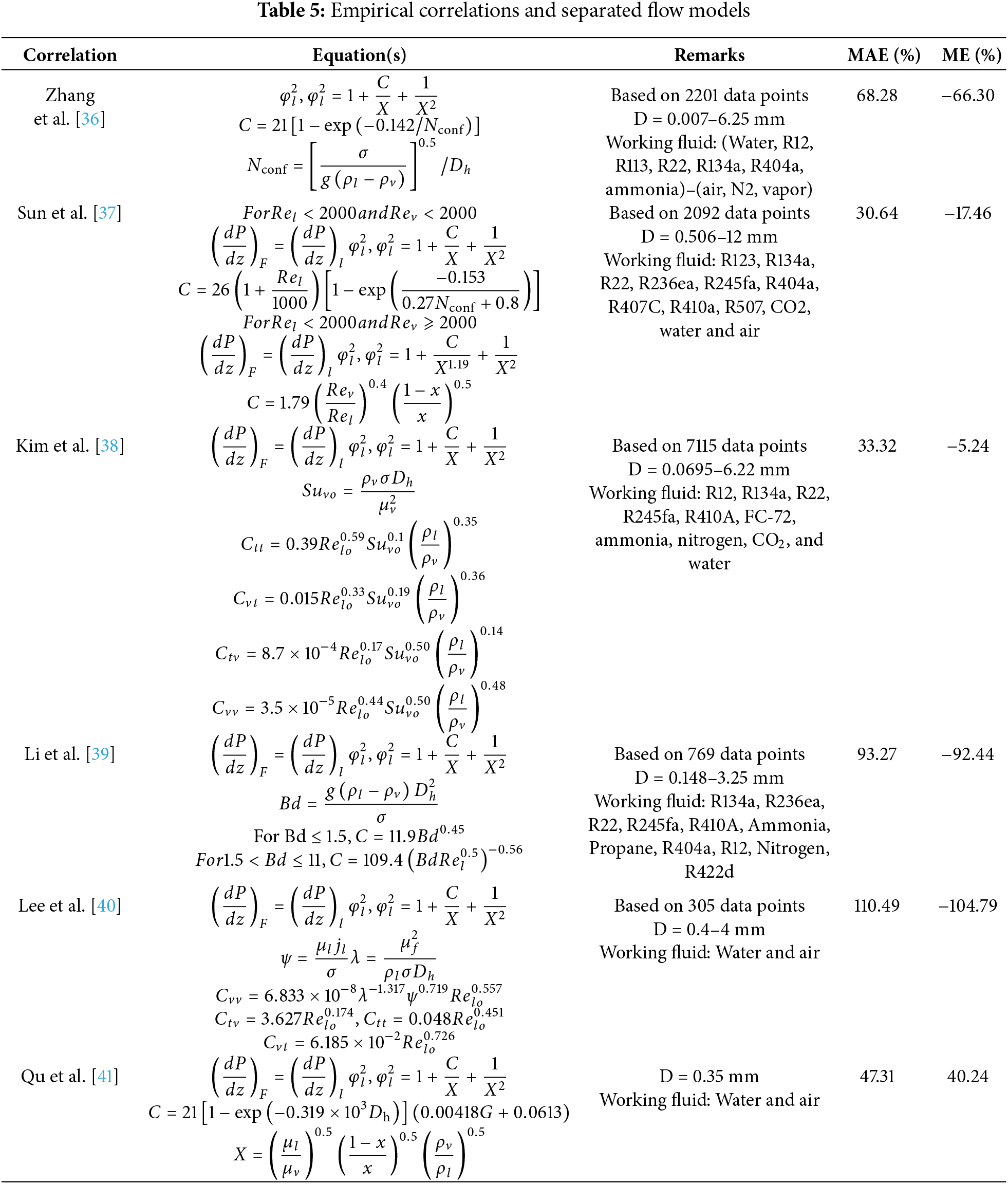

This study employed separated flow empirical correlation models to predict the pressure gradient in micro-channel tubes. Six widely recognized correlations were selected for investigation and evaluated by comparing their predictions with experimental results. Table 5 summarizes the derivation conditions of these models (e.g., hydraulic diameter and working fluid), equation forms, input parameters, and key characteristics to deepen the understanding of their predictive mechanisms. The model performance was quantitatively assessed using statistical metrics such as MAE and ME. Additionally, comparisons with related studies in the literature were conducted to analyze the differences in predictive performance under varying conditions. Fig. 10 illustrates the comparison between predicted and experimental values, providing a clear visual representation of the models’ accuracy and limitations. The results indicate that the existing correlations can accurately predict the pressure gradient of R410A in micro-channel tubes under specific operating conditions, though their performance is influenced by flow regimes and experimental parameters. This analysis validates the applicability of existing correlations while emphasizing the importance of refining models to accommodate specific conditions in micro-channel systems.

Figure 10: Comparison between experimental friction pressure coefficient and predictions according to (a) Kim et al. [38], (b) Qu et al. [41], (c) Sun et al. [37], (d) Li et al. [39], (e) Lee et al. [40], (f) Zhang et al. [36]

In these correlations, dimensionless parameters, such as the Martinelli parameter (X), the Bond number (Bd), and density-viscosity ratios, are commonly used to describe the effects of fluid properties, flow regimes, and channel geometry on two-phase flow pressure drops. Despite variations in empirical parameters and formulations, these models aim to quantitatively simplify complex phenomena like flow pattern transitions, liquid–vapor interactions, and flow confinement effects.

From the parameters and error analysis presented in Table 5, it is evident that there are notable differences in predictive accuracy among the various models. From the comparison of MAE and ME values, it is evident that all the examined models, except for that of Qu et al. [41], tend to overestimate the experimental results. Among these, the Kim et al. [38] model demonstrates relatively superior performance under the conditions of the present study, with an ME of only −5.24%. This advantage can likely be attributed to the model’s extensive database of over 7000 data points, which allowed the incorporation of both small-scale effects and diverse fluid properties within a unified, separated-flow framework. As a result, the model exhibits improved accuracy and applicability across a wide range of operating conditions, making it a recommended choice for predicting pressure gradients. In contrast, the Li et al. [39] and Lee et al. [40] models yield significantly larger MAE values of 93.27% and 110.49%, respectively. One possible reason for this discrepancy is that the Li et al. [39] database did not include R410A data, thereby preventing the optimal adjustment of their correlation when introducing the Bond number. Similarly, Lee et al. [40] used water and air as working fluids to calibrate the parameter C. When applied to conditions involving fluids with thermophysical properties substantially different from their test media, such as R410A, this calibration may lead to marked inaccuracies in the predicted results.

5.3 HTC Correlation Evaluation

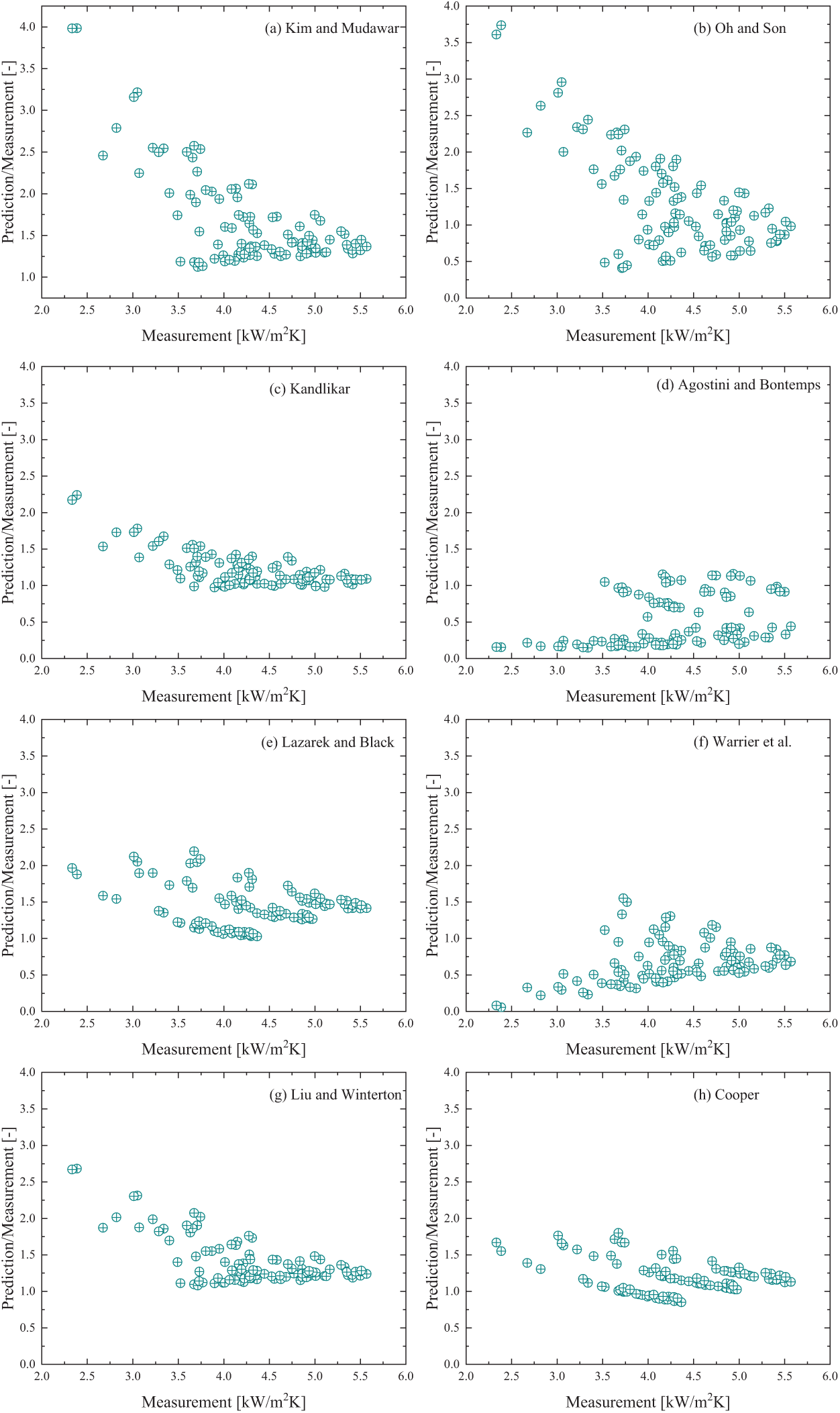

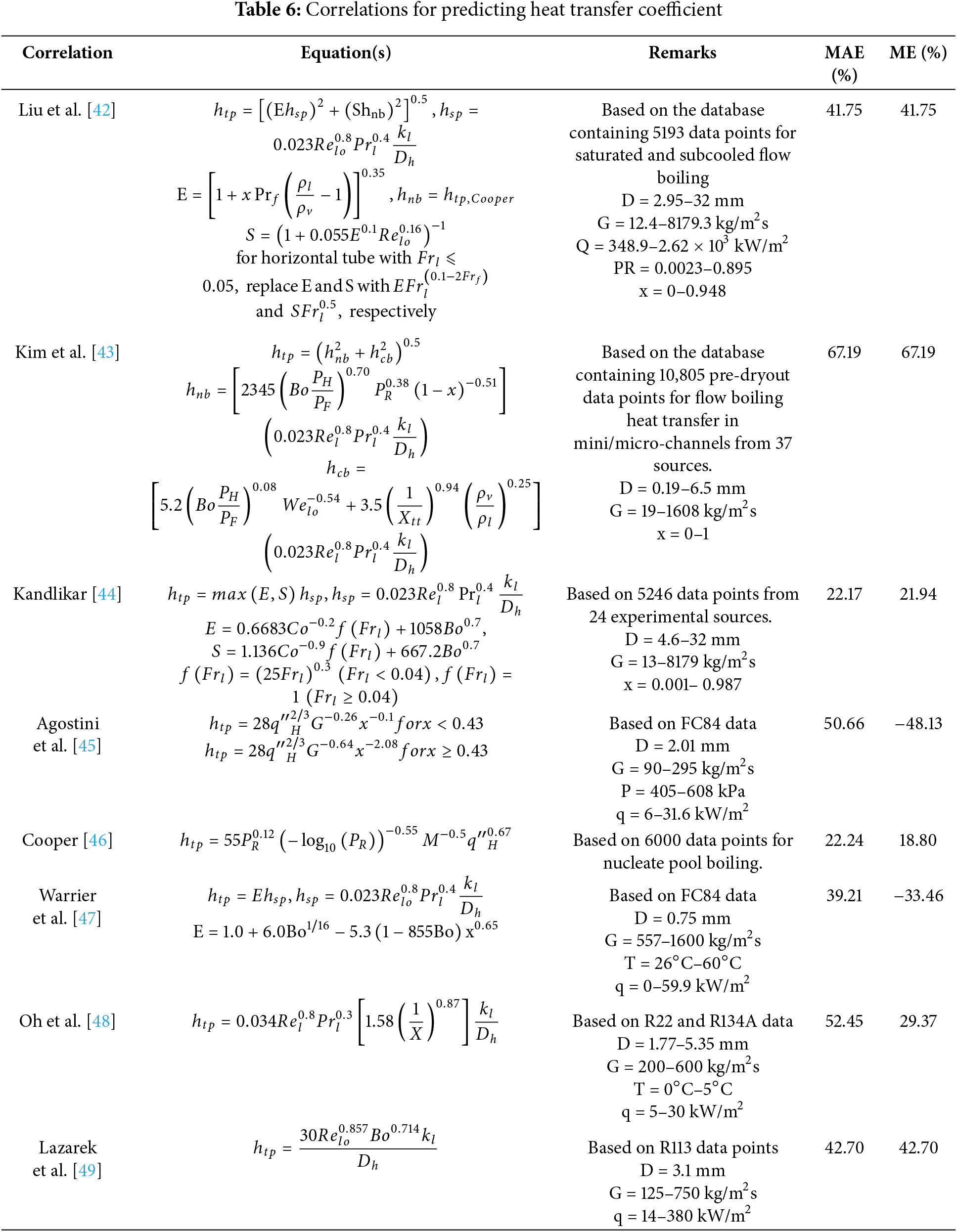

This subsection compares the experimental results of this study with eight commonly used correlations for predicting two-phase convective boiling heat transfer coefficients. As shown in Table 6, these correlations can be categorized into two types based on their mechanisms: empirical correlations derived from experimental data and hybrid correlations that combine theoretical and empirical approaches to account for both nucleate boiling and convective effects. Furthermore, based on their derivation methods, these correlations can be further classified into models developed for specific working fluids and models adjusted using compiled databases. Table 6 provides a brief overview of the derivation background and applicable scope of each correlation. By analyzing statistical metrics such as MAE and ME, the predictive accuracy of each model under the current experimental conditions is systematically evaluated. Fig. 11 visually compares the measured and predicted values, highlighting the strengths and limitations of each model. The in-depth analysis of these comparisons offers theoretical support and practical references for selecting or developing more accurate predictive tools under similar experimental conditions.

Figure 11: Comparison between experimental HTC and predictions according to (a) Kim et al. [43], (b) Oh et al. [48], (c) Kandlikar [44], (d) Agostini et al. [45], (e) Lazarek et al. [49], (f) Warrier et al. [47], (g) Liu et al. [42], (h) Cooper [46]

The results indicate that the Cooper correlation exhibits outstanding predictive performance within the studied operating range, with a MAE and ME of 22.24% and 18.8%, respectively. Although the Cooper [46] correlation was originally formulated for nucleate boiling conditions, subsequent investigations have successfully extended its applicability to flow boiling regimes under certain circumstances [50]. The findings of this analysis further support its broader potential for accurately predicting two-phase convective boiling heat transfer. In addition to the Cooper [46] correlation, the Kandlikar [44] model demonstrates similarly commendable predictive capabilities, achieving MAE and ME values of 22.17% and 21.94%, respectively. Unlike the Cooper [46] correlation, the Kandlikar [44] model was developed based on an extensive and diverse database comprising 5246 data points. By incorporating the dimensionless Fn number, this correlation extends its applicability and generality beyond the range of fluids and conditions represented in the original dataset. Such methodological advancement is particularly significant considering the inherent complexity of two-phase flow boiling phenomena, which involve interfacial dynamics, nucleate boiling mechanisms, flow regime transitions, fluid properties, mass flux, heat flux, channel geometry, and surface roughness. The Kandlikar [44] correlation’s more comprehensive data foundation and parametric considerations render it more universally applicable than simpler empirical formulations.

In summary, for R410A under the micro-channel heat transfer conditions considered, both the Cooper [46] correlation and the Kandlikar [44] model yields superior predictive accuracy. Therefore, these two correlations are suggested as reliable methods for estimating heat transfer coefficients within the studied operational range.

A comprehensive literature review of experimental studies on flow boiling reveals that many heat transfer coefficient data sets have been obtained for test sections with varying hydraulic diameters and different working fluids. Nevertheless, to date, no studies have simultaneously examined microchannel geometries, R410A as the working fluid, and saturation temperature conditions within relatively high saturation pressure ranges. Such data are critically important for further enhancing the design and performance optimization of evaporators in heat pump systems. To address this gap, the present study measures and analyzes local flow boiling heat transfer coefficients for R410A within a micro-channel across saturation temperatures, mass fluxes, and heat fluxes ranging from 25°C–30°C (corresponding to saturation pressures of 1643–1869 kPa and reduced pressures of 0.34–0.38), from 198–305 kg/m2s, and from 9.77–20.18 kW/m2, respectively. The experimental test section consisted of a rectangular micro-channel flattened tube with a Dh of 0.632 mm and a length of 0.15 m, which was heated by a water jacket to maintain stable thermal loads. Ultimately, 99 local flow boiling heat transfer coefficient data points were obtained under 12 distinct experimental conditions. This dataset provides a solid foundation for a deeper understanding of R410A flow boiling heat transfer characteristics in micro-channels, offering valuable insights for guiding the design and optimization of micro-channel heat exchangers in refrigeration and heat pump systems.

• The effect of heat flux: Under the same saturation temperature conditions, increasing the heat flux enhances the HTC, primarily due to intensified nucleate boiling. Although the HTC tends to decrease slightly at higher vapor qualities, nucleate boiling still makes a significant contribution to heat transfer, even in the high-quality region (x > 0.6).

• The effect of mass flux: Increasing the mass flux improves the HTC, but the rate of increase diminishes as the mass flux becomes higher. Around x = 0.5, the main heat transfer mechanism shifts from nucleate boiling to convective boiling, and nucleation suppression effects become apparent.

• The effect of saturation temperature: Under the same mass flux and heat flux conditions, raising the saturation temperature from 25°C to 30°C slightly reduces the HTC. This decrease is associated with changes in fluid thermophysical properties, as well as variations in gas-liquid two-phase velocities and interfacial shear stresses.

• Performance of pressure gradient prediction models: Except for the Qu et al. [41] model, other examined models tend to overpredict the results. Among these, the Kim et al. [38] model demonstrates the best performance for R410A conditions (ME approximately −5.24%). In contrast, the Li et al. [39] and Lee et al. [40] models exhibit large deviations under these conditions.

• Heat transfer coefficient prediction correlations: The Cooper [46] correlation and the Kandlikar [44] model both exhibit excellent predictive performance for R410A in micro-channel conditions (MAE around 22%), offering good suitability and accuracy. The Kandlikar [44] model, supported by a broad data foundation and parameterization, displays even greater general applicability. Therefore, these two correlations are suggested as reliable methods for estimating heat transfer coefficients within the studied operational range.

• The findings of this study provide a more accurate reference for predicting the heat transfer performance of R410A in micro-channel heat exchangers under high-pressure and high-temperature conditions. High heat flux significantly promotes nucleate boiling, which remains dominant even in regions with relatively high vapor quality. This suggests that adjusting the cross-sectional area or layout of flow channels can further enhance heat transfer in areas with high local heat loads. As the mass flux increases, the heat transfer coefficient improves but with diminishing returns, accompanied by higher pressure drops. Therefore, it is essential to comprehensively consider system efficiency and pressure drop when planning the pipe length, number of channels, and refrigerant circulation patterns.

In summary, this study experimentally analyzed the flow boiling heat transfer characteristics of R410A in microchannels, filling a data gap under high saturation pressure conditions. The results demonstrate that heat flux significantly enhances the heat transfer coefficient, with nucleate boiling dominating at high heat flux levels. While increasing mass flux improves heat transfer performance, the effect diminishes with higher fluxes and is accompanied by greater pressure drops. Higher saturation temperatures slightly reduce heat transfer efficiency. The Kim and Mudawar model showed the best performance in pressure drop prediction, while the Kandlikar model demonstrated strong applicability in predicting heat transfer coefficients. These findings provide valuable references for the design of microchannel heat exchangers and the optimization of heat pump systems.

Future research will focus on two main aspects: experimental studies and database development. On the experimental front, further validation or modification of existing models under higher saturation temperature conditions will be conducted. Additionally, other low-GWP or new refrigerants will be introduced, and advanced visualization techniques such as high-speed imaging and infrared thermography will be utilized to deeply investigate two-phase flow and bubble dynamics. These efforts aim to enhance the understanding of boiling mechanisms, improve heat transfer prediction models, and expand the potential applications of micro-channel heat exchangers under extreme operating conditions. In terms of database development, a systematic collection and integration of condensation data from existing literature will be carried out across five key dimensions: hydraulic diameter, saturation temperature, mass flux, heat flux, and mean vapor quality. This will allow for the evaluation and optimization of various correlations under different conditions, ultimately creating a tool with enhanced generality and predictive accuracy. Such a tool would provide comprehensive data support for future research and engineering design.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful for the support of State Key Laboratory of Air-Conditioning Equipment and System Energy Conservation.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52306026), and the State Key Laboratory of Air-Conditioning Equipment and System Energy Conservation Open Project (Project No. ACSKL2021KT01). The APC was covered by the Special Innovation Project Fund of the the State Key Laboratory of Air-Conditioning Equipment and System Energy Conservation Open Project (Project No. ACSKL2021KT01).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization was carried out by Bo Yu, Yuye Luo, Luyao Guo, and Long Huang; methodology was developed by Bo Yu and Luyao Guo; formal analysis was performed by Yuye Luo and Luyao Guo; investigation was conducted by Bo Yu, Yuye Luo, and Luyao Guo; data curation was managed by Bo Yu and Luyao Guo; the original draft was prepared by Bo Yu and Luyao Guo; review and editing were completed by Bo Yu, Luyao Guo, and Long Huang; supervision was provided by Long Huang; project administration was overseen by Long Huang; funding was secured by Long Huang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Given the presence of sensitive information and privacy considerations, the data presented in this study can be obtained upon request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Triki Z, Selloum A, Chiba Y, Tahraoui H, Mansour D, Amrane A, et al. Exergy analysis of a solar vapor compression refrigeration system using R1234ze(E) as an environmentally friendly replacement of R134a. Front Heat Mass Transfer. 2024;22(4):1107–28. doi:10.32604/fhmt.2024.052223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Booten CW, Nicholson SR, Mann MK, Abdelaziz O. Refrigerants: market trends and supply chain assessment. Golden, CO, USA: National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL); 2020. [Google Scholar]

3. Panato VH, Marcucci Pico DF, Bandarra Filho EP. Experimental evaluation of R32, R452B and R454B as alternative refrigerants for R410A in a refrigeration system. Int J Refrig. 2022;135:221–30. doi:10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2021.12.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Meng B, Wan M, Zhao R, Zou Z, Liu H. Micromanufacturing technologies of compact heat exchangers for hypersonic precooled airbreathing propulsion: a review. Chin J Aeronaut. 2021;34(2):79–103. doi:10.1016/j.cja.2020.03.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Qi X, Shi X, Liu Y. Modification and experimental verification of the performance improvement of domestic dehumidifiers. Front Heat Mass Transf. 2024;22(6):1661–78. doi:10.32604/fhmt.2024.058959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Guo L, Camm J, Hirokawa T, Li H, Huang L. A detailed review on the role of critical heat flux in micro-channel dryout phenomena and strategies for heat transfer enhancement. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2025;241(1):126740. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2025.126740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kriz A, Moghaddam S. Fundamentals of force balance in liquid films and transition from macro- to microchannels in flow boiling. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2023;202:123758. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2022.123758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Tanaka C, Dang C, Hihara E. Characteristics of flow boiling heat transfer in rectangular minichannels. In: Proceedings of the 15th International Heat Transfer Conference; 2014 Aug 10–15; Kyoto, Japan. Begellhouse. p. 2667–81. doi:10.1615/ihtc15.fbl.009589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chen JC. Correlation for boiling heat transfer to saturated fluids in convective flow. Ind Eng Chem Proc Des Dev. 1966;5(3):322–9. doi:10.1021/i260019a023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bediako EG, Rullière R, Marchetto DB, Dančová P, Revellin R, Vít T. Flow boiling heat transfer of R1234ze(E) in a horizontal mini-channel at medium and high saturation temperatures. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2024;226:125495. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2024.125495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kandlikar SG, Steinke ME. Flow boiling heat transfer coefficient in minichannels—correlation and trends. In: Proceeding of International Heat Transfer Conference 12; 2002 Aug 18–23; Grenoble, France; 2002. doi:10.1615/ihtc12.1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang CC, Yu JG, Lin SP, Ch Lu D. An experimental study of convective boiling of refrigerants R-22 and R-410A/Discussion. ASHRAE Transactions. 1998;104(2):1144–50. [Google Scholar]

13. Ebisu T, Torikoshi K. Heat transfer characteristics and correlations for R-410A flowing inside a horizontal smooth tube. ASHRAE Transactions. 1998;104(2):556–61. [Google Scholar]

14. Kaew-On J, Wongwises S. Experimental investigation of evaporation heat transfer coefficient and pressure drop of R-410A in a multiport mini-channel. Int J Refrig. 2009;32(1):124–37. doi:10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2008.06.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chien NB, Choi KI, Oh JT, Cho H. An experimental investigation of flow boiling heat transfer coefficient and pressure drop of R410A in various minichannel multiport tubes. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2018;127:675–86. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.06.145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Park CY, Hrnjak PS. CO2 and R410A flow boiling heat transfer, pressure drop, and flow pattern at low temperatures in a horizontal smooth tube. Int J Refrig. 2007;30(1):166–78. doi:10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2006.08.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Mastrullo R, Mauro AW, Thome JR, Vanoli GP. CO2 and R410A: two-phase flow visualizations and flow boiling measurements at medium (0.50) reduced pressure. Appl Therm Eng. 2012;49:2–8. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2011.10.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Rollmann P, Spindler K. New models for heat transfer and pressure drop during flow boiling of R407C and R410A in a horizontal microfin tube. Int J Therm Sci. 2016;103(3):57–66. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2015.11.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kurose K, Noboritate W, Sakai S, Miyata K, Hamamoto Y. An experimental study on flow boiling heat transfer of R410A in parallel two mini-channels heated unequally by high-temperature fluid. Appl Therm Eng. 2020;178(2):115669. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.115669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Chen CA, Li KW, Lin TF, Li WK, Yan WM. Study on heat transfer and bubble behavior inside horizontal annuli: experimental comparison of R-134a, R-407C, and R-410A subcooled flow boiling. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2021;24(3):100875. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2021.100875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Pamitran AS, Choi KI, Oh JT, Oh HK. Forced convective boiling heat transfer of R-410A in horizontal minichannels. Int J Refrig. 2007;30(1):155–65. doi:10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2006.06.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Liu H, Wu Z, Yuan C, Li H, Li H, Peng J, et al. Experimental study of R410A and its low GWP alternative R452B flow boiling in a multiport microchannel tube. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2024;230:125732. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2024.125732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Seo K, Kim Y, Lee KJ, Park YC. An experimental study on convective boiling of R-22 and R-410A in Horizontal smooth and micro-fin tubes. KSME Int J. 2001;15(8):1156–64. doi:10.1007/BF03185095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yun R, Hyeok Heo J, Kim Y. Evaporative heat transfer and pressure drop of R410A in microchannels. Int J Refrig. 2006;29(1):92–100. doi:10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2005.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Hu H, Ding G, Wei W, Wang Z, Wang K. Heat transfer characteristics of R410A-oil mixture flow boiling inside a 7 mm straight smooth tube. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2008;32(3):857–69. doi:10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2007.10.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Padovan A, Del Col D, Rossetto L. Experimental study on flow boiling of R134a and R410A in a horizontal microfin tube at high saturation temperatures. Appl Therm Eng. 2011;31(17–18):3814–26. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2011.07.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Hoang HN, Agustiarini N, Oh JT. Experimental investigation of two-phase flow boiling heat transfer coefficient and pressure drop of R448A inside multiport mini-channel tube. Energies. 2022;15(12):4331. doi:10.3390/en15124331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kim DS, Moretti I, Huber H, Monsberger M. Heat exchangers and the performance of heat pumps—analysis of a heat pump database. Appl Therm Eng. 2011;31(5):911–20. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2010.11.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Mancini F, Minetto S, Fornasieri E. Thermodynamic analysis and experimental investigation of a CO2 household heat pump dryer. Int J Refrig. 2011;34(4):851–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2010.12.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Abou-Ziyan HZ, Ahmed MF, Metwally MN, Abd El-Hameed HM. Solar-assisted R22 and R134a heat pump systems for low-temperature applications. Appl Therm Eng. 1997;17(5):455–69. doi:10.1016/S1359-4311(96)00045-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Lemmon EW, Bell IH, Huber M, McLinden M. NIST standard reference database 23: reference fluid thermodynamic and transport properties-REFPROP. Version 10.0. Gaithersburg: National Institute of Standards and Technology’, Standard Reference Data Program; 2018. [Google Scholar]

32. Guo L, Chen Y, Lin X, Huang L. Flow boiling heat transfer characteristics of R410A in microchannel exchangers: development of experimental facility. In: International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference at Purdue; 2024; West Lafayette, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

33. Zivi SM. Estimation of steady-state steam void-fraction by means of the principle of minimum entropy production. J Heat Transf. 1964;86(2):247–51. doi:10.1115/1.3687113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Moffat RJ. Describing the uncertainties in experimental results. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 1988;1(1):3–17. doi:10.1016/0894-1777(88)90043-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Layssac T, Lips S, Revellin R. Effect of inclination on heat transfer coefficient during flow boiling in a mini-channel. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2019;132:508–18. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.12.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhang W, Hibiki T, Mishima K. Correlations of two-phase frictional pressure drop and void fraction in mini-channel. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2010;53(1–3):453–65. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2009.09.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Sun LC, Mishima K. Evaluation analysis of prediction methods for two-phase flow pressure drop in mini-channels. In: 16th International Conference on Nuclear Engineering; 2008 May 11–15; Orlando, FL, USA; 2009. p. 649–58. doi:10.1115/ICONE16-48210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Kim SM, Mudawar I. Universal approach to predicting two-phase frictional pressure drop for adiabatic and condensing mini/micro-channel flows. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2012;55(11–12):3246–61. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2012.02.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Li W, Wu Z. A general correlation for adiabatic two-phase pressure drop in micro/mini-channels. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2010;53(13–14):2732–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2010.02.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Lee HJ, Lee SY. Pressure drop correlations for two-phase flow within horizontal rectangular channels with small heights. Int J Multiph Flow. 2001;27(5):783–96. doi:10.1016/S0301-9322(00)00050-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Qu W, Mudawar I. Measurement and prediction of pressure drop in two-phase micro-channel heat sinks. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2003;46(15):2737–53. doi:10.1016/S0017-9310(03)00044-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Liu Z, Winterton RHS. A general correlation for saturated and subcooled flow boiling in tubes and annuli, based on a nucleate pool boiling equation. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 1991;34(11):2759–66. doi:10.1016/0017-9310(91)90234-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kim SM, Mudawar I. Universal approach to predicting saturated flow boiling heat transfer in mini/micro-channels-Part II. Two-phase heat transfer coefficient. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2013;64(1972):1239–56. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2013.04.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Kandlikar SG. A general correlation for saturated two-phase flow boiling heat transfer inside horizontal and vertical tubes. J Heat Transf. 1990;112(1):219–28. doi:10.1115/1.2910348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Agostini B, Bontemps A. Vertical flow boiling of refrigerant R134a in small channels. Int J Heat Fluid Flow. 2005;26(2):296–306. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2004.08.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Cooper M. Saturation nucleate pool boiling-a simple correlation. In: First U.K. National Conference on Heat Transfer; 1984; Leeds, UK . p. 785–93. doi:10.1016/B978-0-85295-175-0.500138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Warrier GR, Dhir VK, Momoda LA. Heat transfer and pressure drop in narrow rectangular channels. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2002;26(1):53–64. doi:10.1016/S0894-1777(02)00107-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Oh HK, Son CH. Evaporation flow pattern and heat transfer of R-22 and R-134a in small diameter tubes. Heat Mass Transf. 2011;47(6):703–17. doi:10.1007/s00231-011-0761-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Lazarek GM, Black SH. Evaporative heat transfer, pressure drop and critical heat flux in a small vertical tube with R-113. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 1982;25(7):945–60. doi:10.1016/0017-9310(82)90070-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Piasecka M. Correlations for flow boiling heat transfer in minichannels with various orientations. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2015;81(2):114–21. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2014.09.063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools