Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Hybrid Nanofluids Mixed Convection inside a Partially Heated Square Enclosure with Driven Sidewalls

1 Laboratory LPCRI, Department of Physics, Sciences Faculty, 20 August 1955-Skikda University, Skikda, 21000, Algeria

2 Department of Technology, Faculty of Technology, 20 August 1955-Skikda University, Skikda, 21000, Algeria

3 Laboratoire LITE, Constantine 1 University, Constantine, 25000, Algeria

4 Unité de Recherche Appliquée en Energies Renouvelables URAER, Centre Développement des Energies Renouvelables CDER, Ghardaïa, 47133, Algeria

5 Laboratory of Mechanics, Amar Telidji University, BP 37G, Laghouat, 03000, Algeria

6 Faculty of Engineering and Pure Sciences, Mechanical Engineering Department, Istanbul Medeniyet University, Istanbul, 34730, Turkey

7 Department of Physics, Higher Normal School of Laghouat, Laghouat, 03000, Algeria

8 Laboratoire de Génie Civil et géo-Environnement (LGCgE), Université d’Artois, ULR 4515, Béthune, F-62400, France

* Corresponding Author: Aicha Bouhezza. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Computational Thermo-Fluids and Nanofluids)

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(4), 1323-1350. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.065254

Received 07 March 2025; Accepted 24 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

This study investigates laminar convection in three regimes (forced convection, mixed convection, and natural convection) of a bi-nanofluid (Cu-Al2O3-water)/mono-nanofluid (Al2O3-water) inside a square enclosure of sliding vertical walls which are kept at cold temperature and moving up, down, or in opposite directions. The enclosure bottom is heated partially by a central heat source of various sizes while the horizontal walls are considered adiabatic. The thermal conductivity and dynamic viscosity are dependent on temperature and nanoparticle size. The conservation equations are implemented in the solver ANSYS R2 (2020). The numerical predictions are successfully validated by comparison with data from the literature. Numerical simulations are carried out for various volume fractions of solid mono/hybrid-nanoparticles (), Richardson numbers (0.001 ≤ Ri ≤ 10), and hot source lengths (). Isothermal lines, streamlines, and average Nusselt numbers are analyzed. The thermal performance of nanofluids is compared to that of the base heat transfer fluid (water). Outcomes illustrate the flow characteristics significantly affected by the convection regime, hot source size, sidewall motion, and concentration of solid nanoparticles. In the case of sidewalls moving downward, using hybrid nanofluid (Cu-Al2O3-water) shows the highest heat transfer rate in the enclosure at Ri = 1, and volume fraction of φ = 5% where a significant increment (25.14%) of Nusselt number is obtained.Keywords

Energy efficiency is attracting extensive research to save energy and mitigate emissions. Manufacturing processes, thermal power plants, microelectronics, transportation, and other engineering applications generate significant amounts of heat. Efforts have been made to enhance the efficiency of thermal systems. Effective coolants have been developed to effectively dissipate heat [1].

Cooling methods can generally be divided into passive and active systems [2]-conventional coolants such as propylene glycol show limited thermal characteristics. One of the methods that improves the heat transfer characteristics is the insertion of highly conductive nano-additives [3,4]. Metals [5], metal oxides [6], metal nitrides [7], metal carbides [8], and carbonaceous materials [9] are the most widely used nanoparticles (NP). In general, the shape, size, stability of the dispersed NP, type of base fluid, the mass concentration of the fluid and NP, and other parameters all affect the thermal conductivity of the nanofluid (NF). NF has demonstrated superior thermal performance in various engineering applications compared with conventional fluids [10].

Numerous papers have investigated the thermal performance of nanofluids and reported potential enhancement effects, which make them alternatives to conventional heat transfer fluids. Said et al. [11] investigated the Magneto-Hydro-Convective of Cu-water NF inside a square porous cavity. The results showed that the heat transfer rate increases significantly when Re ≥ 250. In addition, the heat transfer enhancement is maximum at L = 0.25 for Re = 50 and Gr = 105. Ghasemi and Aminosadati [12] investigated nanofluid mixed convection in a triangular container. Heat transfer consistent with sliding vertical wall movement resulted in stronger flow and thus higher heat transfer rate. Bondarenko et al. [13] also analyzed the natural convection of Al2O3-water NF in a cavity in the presence of a heat-generating element. The outcomes indicated that adding NP increases the convective cooling process. Various nanofluid types were investigated in a cavity with partially heated walls [14], including Cu-water, Ag-water, Al2O3-water, and TiO2-water. The authors showed that increasing the volume fraction of NP and Rayleigh number increases the average Nu. In addition, among the investigated nanofluids, Cu-water was recommended due to its superior heat transfer rate. Zaydan et al. [15] presented a lid-driven square cavity filled with nanofluids made of different nanoparticles and different base fluids. A parametric study was conducted, including the effect of the nanoparticle’s shape and the Richardson number on the rate of heat transfer.

However, other studies indicated that the nanofluid concentration is a critical parameter. The effect of Al2O3 concentration was investigated [16]. Outcomes demonstrated that there is a critical concentration beyond which no significant performance improvement can be obtained. The optimal concentration was shown to be attained at a nanofluid concentration of 0.1%, which resulted in an enhancement up to 15%. Similarly, Sharipour et al. [17] utilized a nanofluid of various concentrations and investigated the thermal performance of TiO2-water nanofluid using nanoparticles of 50 nm average size to find the optimal concentration for thermal performance improvement. Various volume fractions were tested in the range of 0.05–0.8 Vol%. The investigated nanofluid was enclosed in an enclosure with cold and hot sidewalls while the bottom and top walls were kept adiabatic. Various Ra values were tested from 4.9 × 108 to 1.47 × 109. The results indicated an optimal volumetric concentration of ϕ = 0.05%, which enhanced the thermal performance by up to 8.2%. Yaseen et al. [18] indicated that Nu increased by 4.5% when using a flexible wall alone, but when the upper wall moved to the left, Nu increased by 28%.

Adding two different nano-additives in the same liquid [19], i.e., hybrid nanofluid (HNF), was addressed for improving fluids’ performance [20]. Several studies [21] utilized various combinations such as Al2O3-Cu [22], ceramic matrix nanocomposites like Al2O3-TiO2 [23], and polymeric nanomaterials such as polymer-CNT [24]. Moghadassi et al. [25] investigated HNF (Al2O3-water) and (Al2O3-Cu-water) for laminar forced convection in a horizontal pipe. Nanoparticle concentration was fixed at 0.1% considering particles of the average size of 15 nm. The study outcomes indicated a higher Nu number in the case of HNF outperforming that corresponding to the mono-nanofluid by 4.73%. Nwaokocha et al. [26] studied the HNF thermal performance in a square enclosure using MgO-ZnO nanoparticles dispersed in deionized water (DIW). Nanoparticle mass concentrations of 0.05 and 0.5 were investigated at various ratios ranging from 20 to 80%. A significant improvement in thermo-convection performance was achieved. Convective heat transfer was enhanced by 72.2%.

The performance of hybrid nanofluid has been tested in various enclosure shapes. Al-Mashaal et al. [27] numerically investigated 3D HNF convection. The findings indicated that increasing the CNT content significantly enhances heat transfer. Chamkha et al. [28] conducted a study considering HNF in a semicircular enclosure. The results indicated that the hybrid nanocomposites improved the heat transfer inside the enclosure. However, hybrid nanofluid does not always result in higher thermal performance according to Ghalambaz et al. [29]. The authors studied the HNF behavior in typical enclosures. Alsabery et al. [30] studied convective HNF in an enclosure partially divided having cold wavy sidewalls. The findings indicated that using HNF improved thermal performance. This study showed the critical effect of Ra. For low values Ra ≤ 105, increasing the nanoparticle loading enhanced the thermal performance whereas for higher Ra values lower effect was reported. A numerical study by Tayebi and Chamkha [31] examined heat enhancement of natural convection using an HNF in an elliptic annulus differentially heated for Ra values ranging between 103 and 3 105. Various nanoparticle volume fractions were tested in the range 0–0.12. The authors showed that utilizing HNF in confocal elliptic enclosures is more efficient than MNF. Heat transfer enhancement of HNF was reported for the case of porous trapeze [32]. Umar Ibrahim et al. [33] showed the outperformance of carbon-based in mixed convective HNF.

Hybrid nanofluids have been investigated in lid-driven cavities to understand their behavior and enhance their performance. Bouaraour [34], for instance, addressed the effect of various dimensionless parameters. The results showed that increasing the Ri from 0.01 to 1 increases the buoyancy effect and leads to higher Nu up to 4.5%. Furthermore, an NP increase of 8% resulted in a 9.8% performance improvement. Ali et al. [35] addressed the effect of various parameters, including Re, Ri, cavity size, and nanofluid concentration, for different directions of the moving walls. A significant increment in the heat transfer rate was reported. Increasing the volume fraction improved the thermal performance. When Re was set at high values, a large solid body increased the heat transfer rate. Additionally, performance decreased with the cavity length.

The above literature review shows that hybrid nanofluid mixed convection in partially heated enclosures with moving sidewalls has received less attention. This numerical study is aimed at investigating the combined effect of natural convection and forced convection of hybrid nanofluid in a square cavity with moving sidewalls and partially heated from the bottom wall. The thermal performance of hybrid nanofluid is compared with both mono-nanofluid and base fluid consisting of water. Isotherms, streamlines, and average Nusselt numbers are examined for various Ri values (0.001 ≤ Ri ≤ 10), nanoparticle volume fractions (

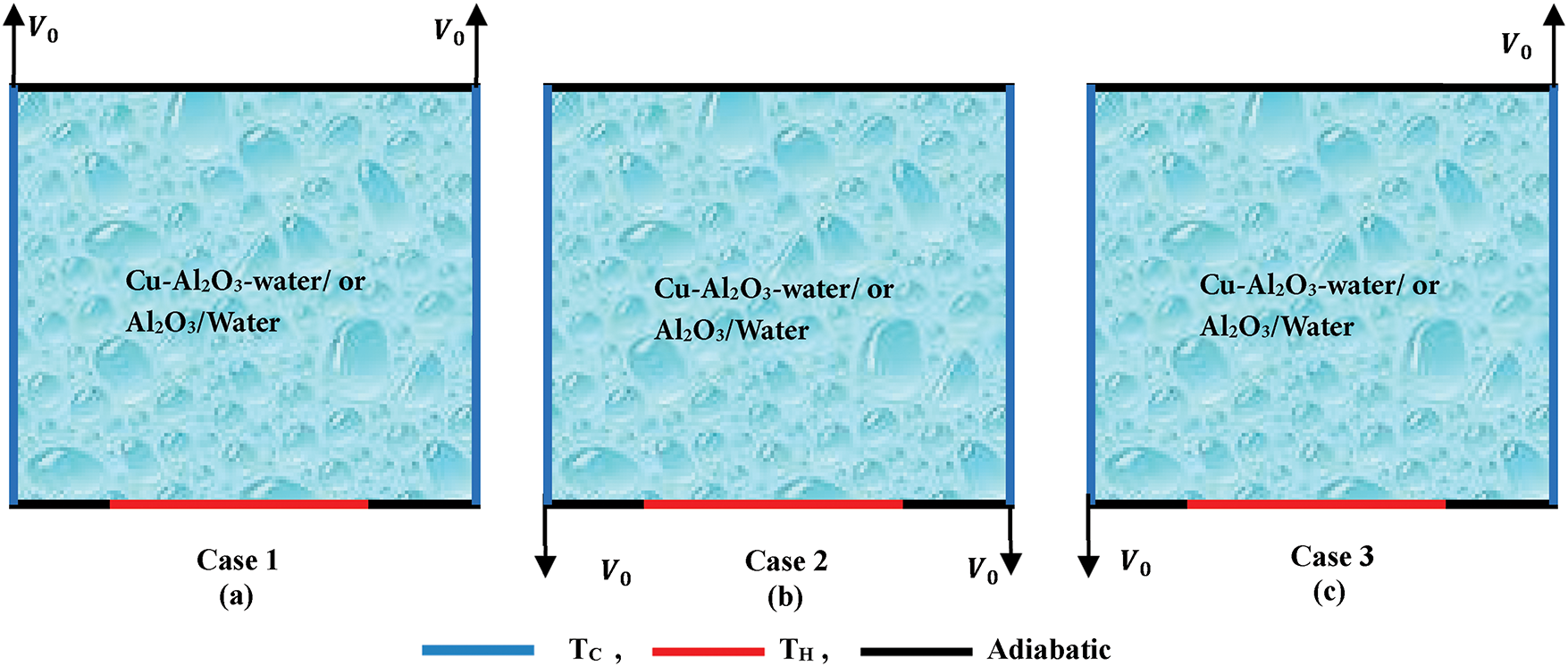

Consider a square cavity (Fig. 1) filled with an enhanced heat transfer fluid. Two types of HTF, i.e., Cu-Al2O3/Water (HNF) and Al2O3/Water (MNF) are examined to compare their performance with the base heat transfer fluid (water). The bottom wall of the cavity is partially heated at a constant temperature (TH). The vertical sidewalls move at a constant velocity (V0). The following assumptions are considered: 2D laminar and steady; Newtonian, incompressible, and homogenous fluid; viscous dissipation and work of pressure forces are neglected in the energy equation; no-slip solid particles in thermal equilibrium with the base fluid; constant thermophysical properties except density which follows the Boussinesq approach. The single-phase model is considered (SPM).

Figure 1: Sketch of the studied configurations: (a) Walls moving upward; (b) Walls moving downward; (c) Right wall moving upward and left wall moving downward

Three different cases of buoyancy-supported convective flows are considered based on the lateral velocity and thermal boundary conditions in the cavity shown in Fig. 1. to conduct a comprehensive comparative analysis between these cases based on thermal performance:

Case 1: Both sidewalls (left and right) of the cavity move in the same upward direction (i.e., against gravity) at a constant velocity V0.

Case 2: Both sidewalls move opposite to Case 1, i.e., in the same downward motion (gravity direction).

Case 3: The left wall moves downward and the right wall upward.

2D dimensional formulation is written as follows:

• Continuity

• Momentum

where

• Energy

where Cphnf and khnf are the specific heat and thermal conductivity of the hybrid nanofluid, respectively.

At y = 0

At y = H

At x = 0

Case 1:

Case 2:

Case 3:

At the right vertical wall: x = H

Case 1:

Case 2:

Case 3:

The dimensionless variables are obtained by:

The following nondimensional model is obtained:

Non-dimension parameters:

Reynolds number

Boundary conditions (no-dimensional):

At Y = 0

At Y=1

At X = 0

Case 1:

Case 2:

Case 3:

At X = 1

Case 1:

Case 2:

Case 3:

3.4 Thermophysical Properties of MNF and HNF

Density of MNF and HNF are obtained using the following formulas [36]:

where

As well, the heat capacity of MNF and HNF are determined [36]:

The thermal expansion effect of MNF and HNF is considered by utilizing the following expressions [36]:

while the viscosity of MNF and HNF is obtained by [37]:

where,

The thermal conductivity of MNF and HNF is evaluated using the following formula [37]:

where Pr is the Prandtl number while the Brownian motion Reynolds number is defined as:

where

while

The local and average Nusselt numbers are defined:

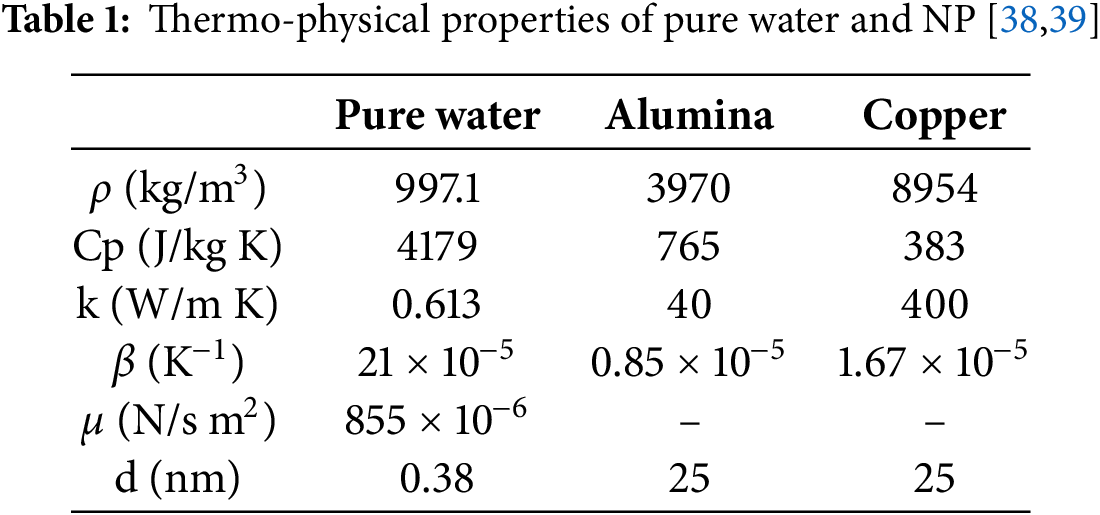

Table 1 illustrates the thermo-physical properties of pure water and NP employed.

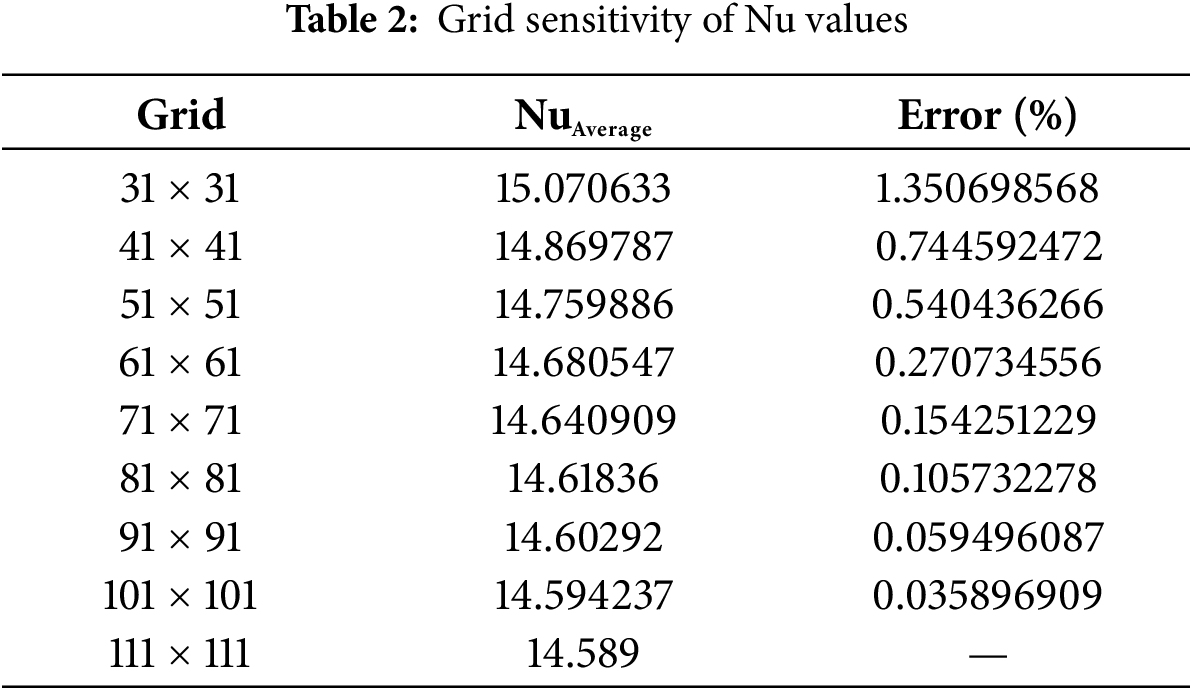

Numerical modeling is performed by solving 2D equations using ANSYS R2 (2020) software. The second-order discretization and second-order upwind are used for momentum and energy equations, respectively. A uniform structured grid is utilized in the simulations. The convergence criterion is set 10−5, for velocity and temperature, and 10−8 for the energy terms. Different grids are tested (31 × 31), (41 × 41), (61 × 61), (71 × 71), (81 × 81), (91 × 91), (101 × 101) and (111 × 111). Table 2 and Fig. 2 show a comparison of Nu for these configurations. Fig. 3 shows the vertical velocity along the middle x-plane for Ri = 10, in the Case 1 and with pure water. The results are grid-independent after 101 × 101 grid points. The optimal grid size is found to be (101 × 101) which is adopted in thefollowing simulations.

Figure 2: Average Nu variation for various tested grids

Figure 3: Mesh dependency study

To validate the numerical model, the predictions are compared with the results of three different studies (Sebdani et al. [40], Corvaro and Paroncini [41], and Fayz-Al-Asad et al. [42]). Fig. 4 depicts the average Nu variation with various NP volume fractions for Re = 1, 10, and 100 [40]. It is noted that the results agree well. Fig. 5 presents the comparison of isotherms double-exposure interferogram at Ra = 2.02 × 105, and the numerical streamlines at (Ra = 2 × 105) [41]. As well, the results are in good agreement. Finally, we compare the results obtained by Fayz-Al-Asad et al. [42] (Fig. 6) of the isotherms for various Gr at λ = 0.25 and A = 2.0 with the present results. The present predictions agree very well with these results, demonstrating the reliability of the present numerical model.

Figure 4: Comparison of Nu predictions with [40]

Figure 5: A comparison of the isotherms (a) double-exposure interferogram at Ra = 2.02 × 105, and (b) the numerical streamlines at (Ra = 2 × 105) with [41]

Figure 6: Comparison of the isotherms for various Gr at λ = 0.25 and A = 2.0. (a) results due to Fayz-Al-Asad et al. [42] and (b) predictions of the present study

Results are presented for heat transfer and flow patterns. Results are obtained for a Ri = 0.001 to 10, NP concentrations 0% to 5%, and hot source length values (ε = (1/5)H, (2/5)H, (3/5)H, (4/5)H) taking into account three different conditions (see Fig. 1, cases (1, 2, 3)).

5.1 Effect of Concentration of Solid Mono Nanoparticles/or Hybrid Nanoparticles

Case 1: Walls moving upward

Fig. 7 shows the isothermals and streamlines for MNF (Al2O3-water) and HNF (Cu-Al2O3-water). This figure presents recirculation zones because the boundary conditions are symmetrical, this for all volume fraction values changed from 0% to 5%. The intensity of the two cells increases with increasing the nanofluid concentration indicating a higher convective heat transfer rate. Furthermore, the temperature gradient increases with the volume fraction in the NF and hybrid fluid leading to higher overall heat transfer within the cavity, which makes the temperature contours more intense.

Figure 7: Impact of the NP concentration on the streamlines (left) and isotherms (right), for Ri = 1 and ε = (4/5)H (Al2O3-water) and (Cu-Al2O3-water) for (Case 1)

Case 2: Walls moving downward

Streamlines (left) and isotherms (right) are shown in Fig. 8 for MNF (Al2O3-water) and HNF (Cu-Al2O3-water). It is noted that the dynamic field consists of two counter-rotating cells for all volume fraction values. Increasing the NP concentration increases the dynamic field intensity and hence convective heat transfer. Viscous forces resulting from the downward movement of the sidewalls cause the descending fluid motion along the sidewalls, while buoyancy forces push the fluid upward along the center of the cavity. All the heat from the hot source spreads through the center of the cavity due to the higher heat transfer characteristics obtained by nanoparticle loadings. Heat diffusion increases with increasing particle concentration, which is better observed in the HNF than in MNF. The HNF shows a higher heat transfer rate in this configuration where walls are moving upward.

Figure 8: Effect of the NP concentration on the streamlines (left) and isotherms (right), for Ri = 1 and ε = (4/5)H (Al2O3-water) and (Cu-Al2O3-water) for (Case 2)

Case 3: Right wall moving upward and left wall moving downward

Fig. 9 shows the streamlines (left) and isotherms (right) for the third investigated case where the sidewalls are moving in opposite directions, i.e., the right wall is moving upward while the left wall is moving downward. The streamlines are represented by a single elliptical cell rotating counterclockwise, located in the middle to encompass the entire square cavity. These results are consistent with the experimental results resented by Blohm and Kuhlmann [43] and the numerical study presented by Oztop and Dagtekin [44] for incompressible fluid. The streamlines density increases with NP concentration. The thermal gradients also appear on the right side of the cavity, while on the left they are neglected. Increasing NP concentration creates steeper temperature gradients on the right sidewall. Since the wall motion corresponds to buoyancy forces, this lateral extension is more observed in MNF and HNF, which implies an increase in the thermal diffusivity.

Figure 9: Effect of the NP concentration on the streamlines (left) and isotherms (right), for Ri = 1 and ε = (4/5)H (Al2O3-water) and (Cu-Al2O3-water) for (Case 3)

Fig. 10 demonstrates the impact of the NP volume fraction (MNVF/or HNVF) on Nu for different values of Ri (0.01, 1 and 10) and ε = (4/5) H. The heat transfer rate increases with increasing MNVF/HNVF for all Ri values and all cases. By comparing the Nu number, it is noticed that the best thermal performance is observed in Case 2 where the highest values of Nu are obtained, and this is for all convection regimes. In Case 2, at Ri = 1 and volume fraction of φ = 5%, the use of (Cu-Al2O3-water) and (Al2O3-water) provides thermal performance improvements of 25.14% and 23.67%, respectively, compared to the thermal performance of water.

Figure 10: Effect of the MNP/HNP volume fraction on the averaged Nu when ε = (4/5)H and different Ri: (a) Ri= 0.01, (b) Ri = 1 and (c) Ri= 10

5.2 Effect of Richardson Number

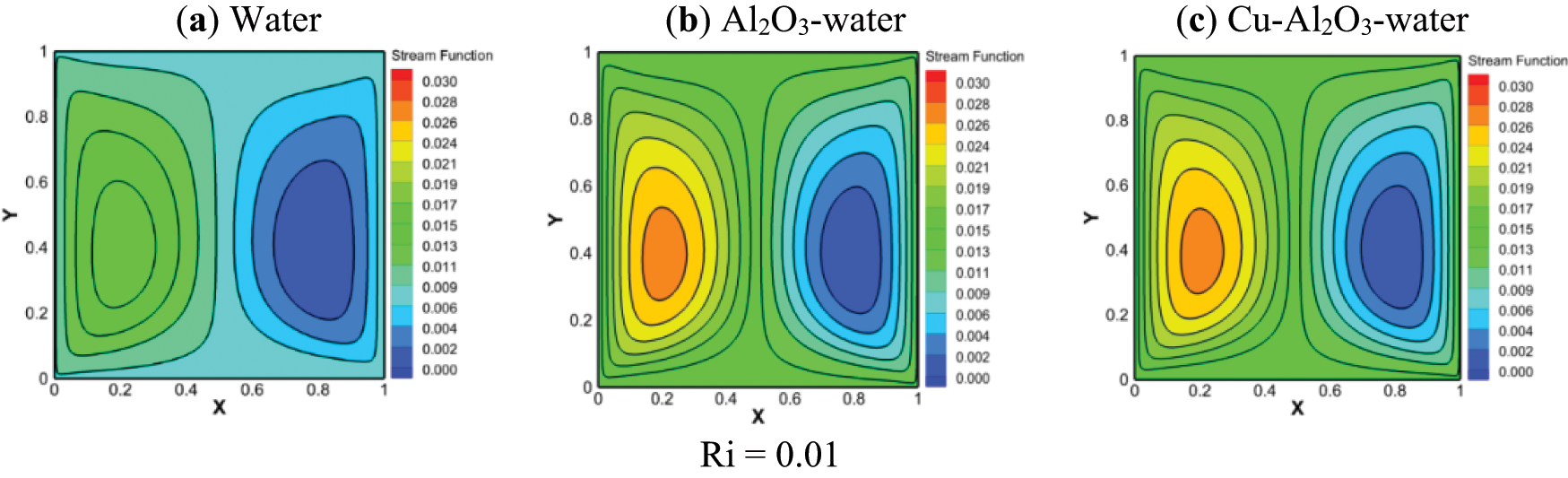

Fig. 11 shows the fluid circulation inside the cavity for various values of Ri when the heated source length is fixed at ε = (4/5)H and the nanoparticle concentration

Figure 11: Effect of the Ri on the streamlines (a) Water, (b) (Al2O3-water) and (c) (Cu-Al2O3-water), for ε = (4/5)H and

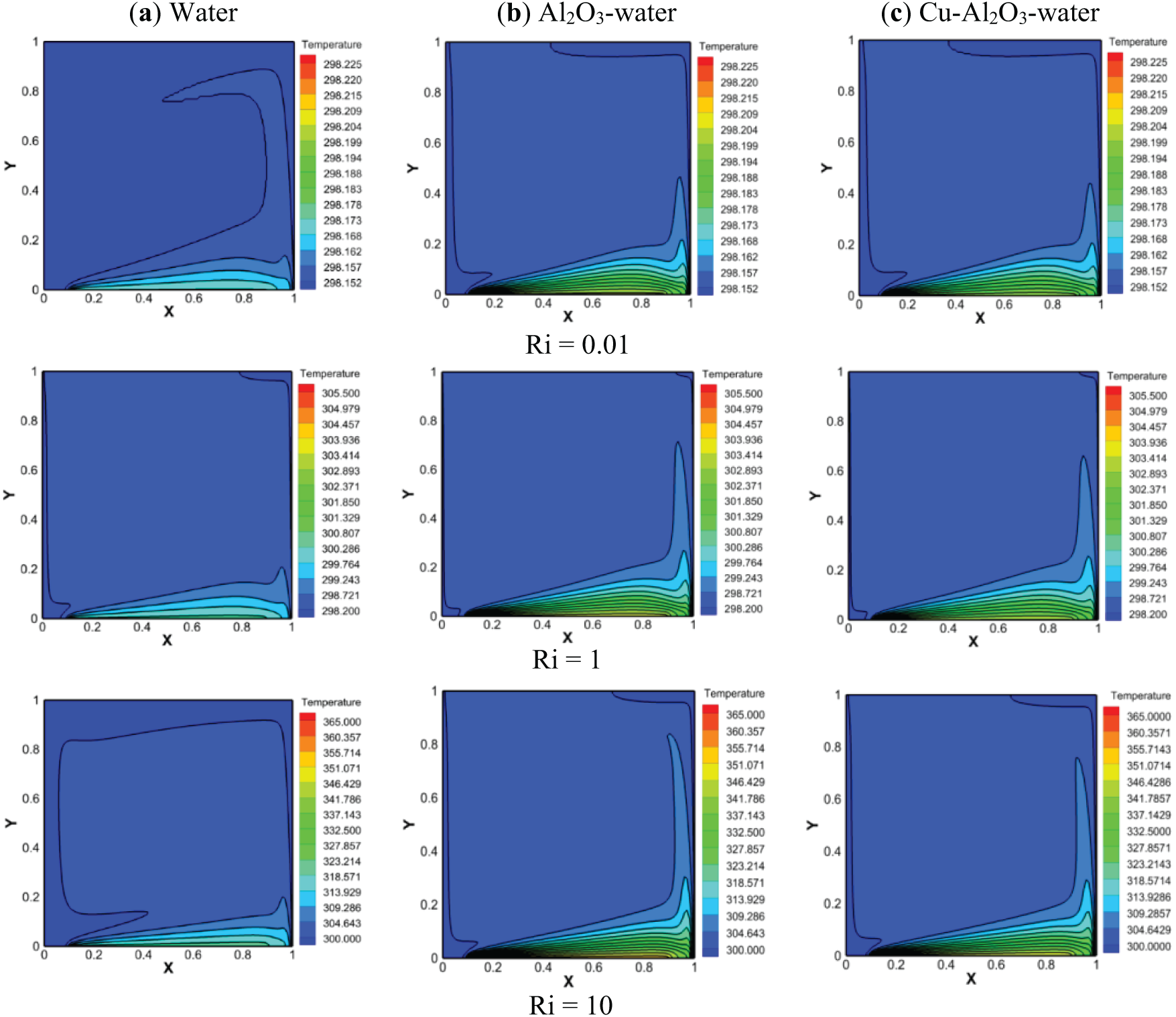

Figure 12: Effect of the Ri on the isotherms (a) Water, (b) (Al2O3-water), and (c) (Cu-Al2O3-water), for ε = (4/5)H and

Figs. 13 and 14 show the streamlines and isotherms inside the cavity for Case 2 and various values of Ri, when the heated source length is fixed at ε = (4/5)H for

Figure 13: Effect of the Ri on the streamlines (a) water, (b) (Al2O3-water) and (c) (Cu-Al2O3-water), for ε = (4/5)H and

Figure 14: Effect of the Ri on the isotherms (a) water, (b) (Al2O3-water) and (c) (Cu-Al2O3-water), for ε = (4/5)H and

Fig. 15 depicts the streamlines represented by a single central cell with an elliptical shape that gradually increases in size with increasing Ri. The movement of opposing sidewalls creates these vortices. For the temperature lines in Fig. 16, there is a clear deviation in the left half of the cavity, in contrast to the other half in which thermal diffusion is non-existent, which means that the upward velocity is responsible for the asymmetry. Since this velocity corresponds to the buoyancy forces of heat, heat transfer in the NF and the hybrid liquid, respectively, is better compared to pure water. Fig. 17 depicts the impact of Ri on Nu along the heated source for all cases, while the NP concentration is kept

Figure 15: Effect of the Ri on the streamlines (a) water, (b) (Al2O3-water) and (c) (Cu-Al2O3-water), when ε = (4/5)H and

Figure 16: Effect of the Ri on the isotherms (a) water, (b) (Al2O3-water) and (c) (Cu-Al2O3-water), when ε = (4/5)H and

Figure 17: Variation of the average Nu as a function of the Ri for three cases (a) Case 1, (b) Case 2, and (c) Case 3, and ε = (4/5) H and

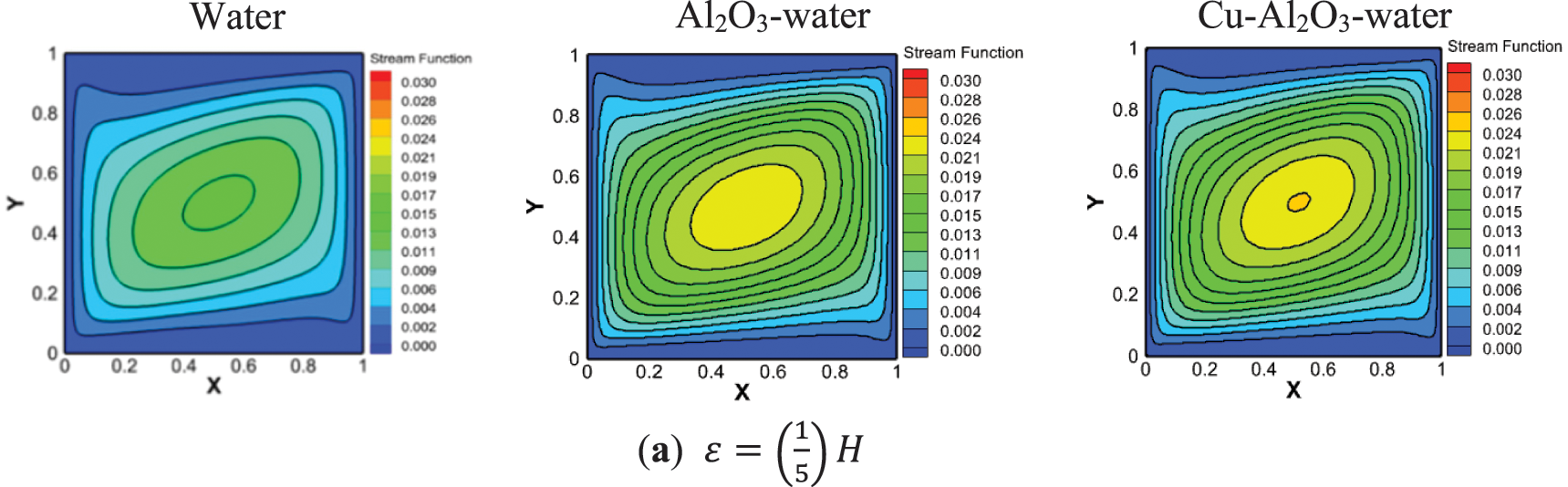

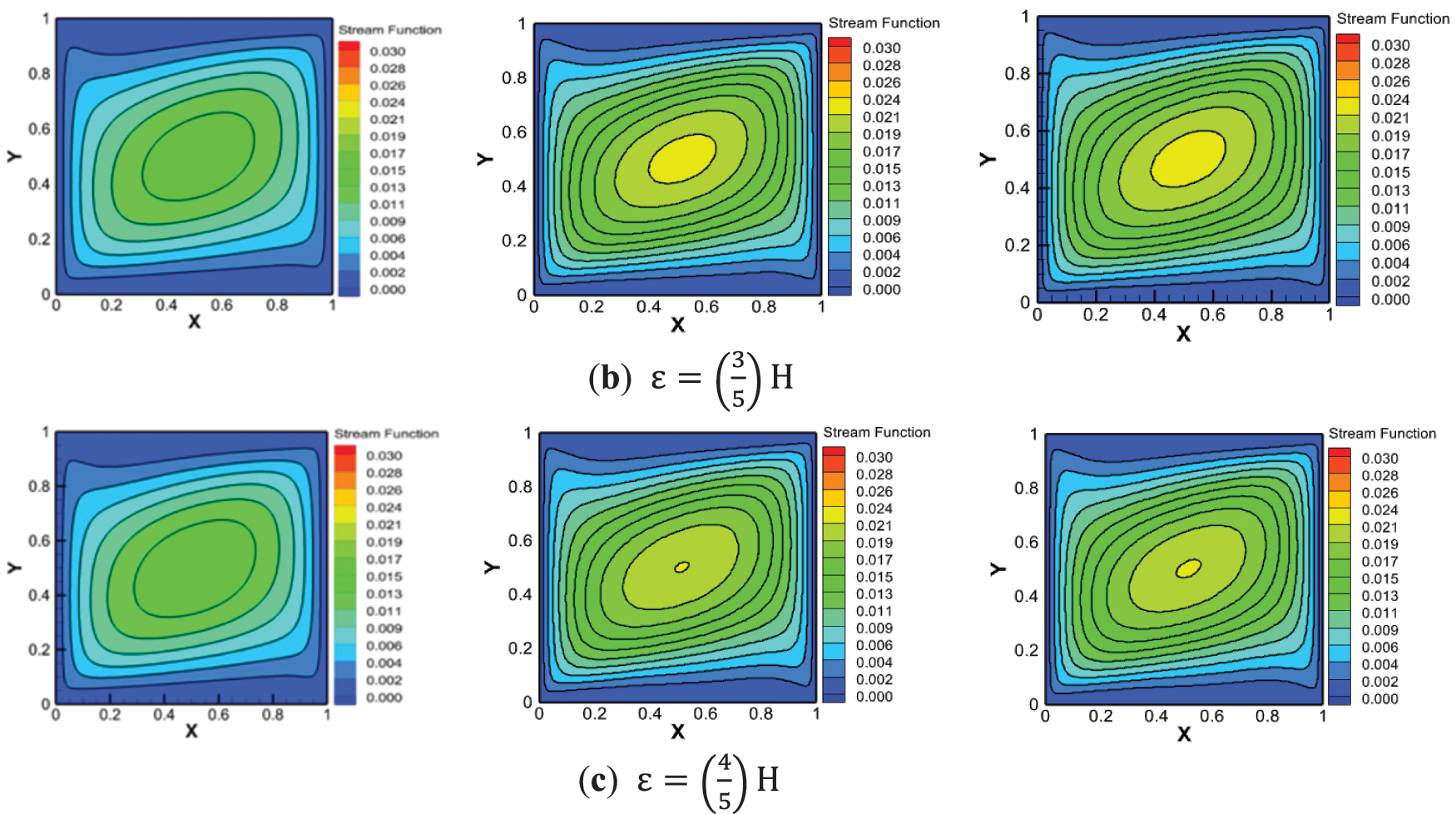

5.3 Effect of the Hot Source Length

The effect of the hot source length (HSL) on the isotherms and streamlines is illustrated in Figs. 18 and 19 for the three investigated cases. In Case 1, at Ri = 1, where both buoyancy force and shear stress are equal in value, the flow consists of two symmetrical vortexes rotating in opposite directions. This is for all fluids, as well as for all sizes of the hot source (HSLs). However, the intensity of the vortexes increases with increasing the HSL. However, as Ri increases (Ri = 10), the buoyancy force becomes important and overcomes the shear forces (natural convection prevails). Due to the temperature difference between the hot source and the cold vertical sidewalls of the cavity, the fluid at the bottom near the hot source becomes less dense and flows up and the cold fluid goes down. This enhances the fluid flow and two different asymmetric vortices are formed, one that includes most of the cavity near the left wall and the other vortex of small size near the right wall; this is for water, MNF, as well as HNF. However, as the HSL increases, the flow structure becomes different in MNF and HNF than in pure water, where in water the flow shape remains the same for all the HSLs, whereas in the MNF and HNF, at

Figure 18: Effect of the heated source length on the streamlines (a) (1/5)H (b) (3/5)H (c) (4/5)H for Ri = 10,

Figure 19: Effect of the heated source length on the isotherms (a) (1/5)H (b) (3/5)H (c) (4/5)H for Ri = 10,

Fig. 19 exhibits the effect of the HSL on the temperature distribution for Case 1. The isotherm lines are more intense near the hot source. This intensity increases in the presence of HNP, but as the HSL increases, the isotherm lines rise increasing distortion asymmetrically; this spread increases with the increase of the HSL. For water, heat spread near the left wall is better than the right wall for all lengths of the heat source. As for MNF and HNF, the heat transfer near the left wall is better than the right wall when

Fig. 20 displays the streamlines for Case 2. The flow inside the cavity consists of two symmetrical cells, which is valid for all three fluids. Increasing the length of the heat source and NP increases the flow intensity. The isotherm lines for the second case are represented in Fig. 21. These lines form a column in the center of the cavity, which confirms that heat is transferred in the center of the cavity by convection. It is noted that the length and thickness of the column increase with increasing the HSL and NP concentration.

Figure 20: Effect of the heated source length on the streamlines (a) (1/5)H (b) (3/5)H (c) (4/5)H for Ri = 10,

Figure 21: Effect of the heated source length on the isotherms (a) (1/5)H (b) (3/5)H (c) (4/5)H for Ri = 10,

Fig. 22 depicts the fluid flow for Case 3. The flow inside the cavity is created by both forced convection and natural convection, but the natural convection resulting from the hot source is dominant. Forced convection results from the downward movement of the left wall and the upward movement of the right wall, which leads to the formation of a single-cell vortex that rotates counterclockwise. The intensity of this vortex increases in the presence of NP and increases as well with the length of the hot source. The effect of the HSL on the isotherm lines for Case 3 is presented in Fig. 23. These lines are more intense around the heat source, they distort along the right wall, and their extension gradually increases with the size of the hot source in the MNF and HNF compared with pure water due to the heat characteristics enhanced in the presence of nanoparticles. On the left side, the temperature gradients show no change.

Figure 22: Effect of the heated source length on the streamlines (a) (1/5)H (b) (3/5)H (c) (4/5)H for Ri = 10,

Figure 23: Effect of the heated source length on the isotherms (a) 1/5 H (b) 3/5 H (c) 4/5 H for Ri = 10,

Fig. 24 illustrates the impact of the heated source length (ε) on Nu for the three cases and all fluids (water, MNF, and HNF). It is observed that the heat transfer rate increases with increasing HSL (ε) for all convection regimes and all working fluids; this applies to all cases and is consistent with previous studies [46–48]. A comparison of the average Nu values for the three cases reveals that the second case has the highest average Nu compared with Case 1 and Case 3. This is explained by the direction of the buoyancy forces and the shear forces, whereas in the second case, they have the same direction for both the right and left walls, which increases the heat transfer rate (potential cooling effect). The results show that Case 2 outperforms Cases 1 and 3. For example, at a length of ε =

Figure 24: Effect of the heated source length (ε) on the averaged Nu for all fluids and all cases, for

This paper presents a numerical investigation of mixed convective nanofluid flow in a cavity having sliding sidewalls and partially heated at the bottom wall with different boundary conditions. The thermal performance of hybrid nanofluid (Cu-Al2O3-water) is assessed based on average Nu and compared to that of mono-article nanofluid as well as base fluid (water). Various parameters are investigated including Ri, hot source length, and nanofluid concentration. The conclusions drawn are summarized as follows:

- The presence of solid HNP increases the heat transfer rate compared to the MNP case.

- When the walls are moving upward, i.e., opposite to the direction of the buoyancy forces, the results show the presence of flow structures that are symmetrical for forced and mixed convection and asymmetrical when natural convection is dominant.

- When the walls are moving downward, i.e., in the same direction as the buoyancy forces, the flow structures are symmetrical for each convection regime.

- For HNF and MNF, in the second case, increasing the length of the heat source affects the flow structure if the natural convection is dominant.

- Sidewall movement opposing buoyancy forces reduces the heat transfer rate in the cavity.

- Enhanced transfer is obtained inside the square cavity heated partially from the bottom and cooled symmetrically from the vertical sidewalls if the walls move downward (Case 2) for all NF and all convection regimes.

- In Case 2, the average Nu is enhanced by 17.83% compared to Case 3 and 23.72% compared to Case 1 for Ri = 1, ε = (4/5)H, and 5% HNP (Cu-Al2O3).

- Hybrid nanofluid shows a significant increment of Nusselt number up to 25.14% (Case 2) compared to the performance of the base fluid.

For future research concerns, investigation of the effect of inclination of this configuration could be addressed.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the support of the respective laboratories.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Meriem Bounib, Aicha Bouhezza: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing; Abdelkrim Khelifa: Investigation, Software, Validation, Visualization; Mohamed Teggar: Writing—review & editing; Hasan Köten, Aissa Atia, Yassine Cherif: Investigation, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| a | Thermal diffusivity, m2/s |

| Cp | Heat capacity, J/kg K |

| d | Nanoparticle mean diameter, m |

| g | Gravitational Acceleration, m/s2 |

| H | Cavity size, m |

| k | Thermal conductivity, W/m K |

| Nu | Nusselt number |

| Nuaverage | Average Nusselt number |

| p | Pressure, Pa |

| p | Dimensionless pressure |

| Re | Reynolds number |

| Renp | Brownian-motion Reynolds number |

| Pr | Prandtl number |

| Ri | Richardson number |

| T | Temperature, K |

| u, v | Components of velocity, m/s |

| U, V | Dimensionless velocity components |

| X, Y | Dimensionless Cartesian coordinates |

| x, y | Cartesian coordinates, m |

| List of Symbols | |

| Thermal expansion coefficient, K−1 | |

| Dynamic viscosity, N.s/m2 | |

| ν | Kinematic viscosity, m2/s |

| ρ | Mass Density, kg/m3 |

| ε | Hot source length |

| Volume fraction of nanoparticles (%) | |

| Subscripts | |

| 0 | Reference |

| bf | Base fluid |

| C | Cold |

| H | Hot |

| nf | Nanofluid |

| hnf | Hybrid-nanofluid |

| hnp | Hybrid-nanoparticle |

References

1. Zakaria IA, Mohamed WANW, Azid NHA, Suhaimi MA, Azmi WH. Heat transfer and electrical discharge of hybrid nanofluid coolants in a fuel cell cooling channel application. Appl Therm Eng. 2022;210(33):118369. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2022.118369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Senobar H, Aramesh M, Shabani B. Nanoparticles and metal foams for heat transfer enhancement of phase change materials: a comparative experimental study. J Energy Storage. 2020;32:101911. doi:10.1016/j.est.2020.101911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Atofarati EO, Sharifpur M, Huan Z. Nanofluids for heat transfer enhancement: a holistic analysis of research advances, technological progress and regulations for health and safety. Cogent Eng. 2024;11(1):2434623. doi:10.1080/23311916.2024.2434623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Kong M, Lee S. Performance evaluation of Al2O3 nanofluid as an enhanced heat transfer fluid. Adv Mech Eng. 2020;12(8):1687814020952277. doi:10.1177/1687814020952277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay S. Mixed convection flow of Cu-water nanofluid having differently shaped nanoparticles past a moving wedge. Forces Mech. 2022;9(4):100149. doi:10.1016/j.finmec.2022.100149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Abdulsahib AD, Alkhafaji D, Albayati IM. Optimizing heat sink performance by replacing fins from solid to porous inside various enclosures filled with a hybrid nanofluid. Front Heat Mass Transf. 2024;22(6):1777–804. doi:10.32604/fhmt.2024.057209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Luo Q, Lu C, Liu L, Zhu M. A review on the synthesis of transition metal nitride nanostructures and their energy related applications. Green Energy Environ. 2023;8(2):406–37. doi:10.1016/j.gee.2022.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kazem HA, Al-Waeli AHA, Chaichan MT, Sopian K. Numerical and experimental evaluation of nanofluids based photovoltaic/thermal systems in Oman: using silicone-carbide nanoparticles with water-ethylene glycol mixture. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2021;26(3):101009. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2021.101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Reddy PS, Sreedevi P, Reddy VN. Entropy generation and heat transfer analysis of magnetic nanofluid flow inside a square cavity filled with carbon nanotubes. Chem Thermodyn Therm Anal. 2022;6(9):100045. doi:10.1016/j.ctta.2022.100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Guo Z. A review on heat transfer enhancement with nanofluids. J Enh Heat Transf. 2020;27(1):1–70. doi:10.1615/jenhheattransf.2019031575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Said BO, Mebarek-Oudina F, Medebber MA. Magneto-hydro-convective nanofluid flow in porous square enclosure. Front Heat Mass Transf. 2024;22(5):1343–60. doi:10.32604/fhmt.2024.054164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ghasemi B, Aminossadati SM. Mixed convection in a lid-driven triangular enclosure filled with nanofluids. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2010;37(8):1142–8. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2010.06.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Bondarenko DS, Sheremet MA, Oztop HF, Ali ME. Natural convection of Al2O3/H2O nanofluid in a cavity with a heat-generating element. Heatline visualization. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2019;130(4):564–74. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.10.091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hosseini M, Mustafa MT, Jafaryar M, Mohammadian E. Nanofluid in tilted cavity with partially heated walls. J Mol Liq. 2014;199(3):545–51. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2014.09.051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zaydan M, Riahi M, Mebarek-Oudina F, Sehaqui R. Mixed convection in a two-sided lid-driven square cavity filled with different types of nanoparticles: a comparative study assuming nanoparticles with different shapes. Fluid Dyn Mater Process. 2021;17(4):789–819. doi:10.32604/fdmp.2021.015422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ghodsinezhad H, Sharifpur M, Meyer JP. Experimental investigation on cavity flow natural convection of Al2O3–water nanofluids. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2016;76:316–24. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2016.06.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sharifpur M, Solomon AB, Ottermann TL, Meyer JP. Optimum concentration of nanofluids for heat transfer enhancement under cavity flow natural convection with TiO2-water. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2018;98(8–9):297–303. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2018.09.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yaseen DT, Salih SM, Ismael MA. Effect of the lid-driven on mixed convection in an open flexible wall cavity with a partially heated bottom wall. Int J Therm Sci. 2023;188(5):108213. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2023.108213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Tayebi T, Chamkha AJ. Effects of various configurations of an inserted corrugated conductive cylinder on MHD natural convection in a hybrid nanofluid-filled square domain. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2021;143(2):1399–411. doi:10.1007/s10973-020-10206-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Rashidi MM, Sadri M, Sheremet MA. Numerical simulation of hybrid nanofluid mixed convection in a lid-driven square cavity with magnetic field using high-order compact scheme. Nanomaterials. 2021;11(9):2250. doi:10.3390/nano11092250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Minea AA. Challenges in hybrid nanofluids behavior in turbulent flow: recent research and numerical comparison. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;71(20):426–34. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.12.072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ahmed SE, Mansour MA, Mahdy A. Analysis of natural convection-radiation interaction flow in a porous cavity with Al2O3-Cu water hybrid nanofluid: entropy generation. Arab J Sci Eng. 2022;47(12):15245–59. doi:10.1007/s13369-021-06495-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Guo W, Zhai Y, Huang X, Li Z. Optimizing stability and enhancing flow boiling heat transfer performance of Al2O3-TiO2/water hybrid nanofluids. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2024;155(6):111177. doi:10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2024.111177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kolsi L, Adnan, Mir A, Muhammad T, Bilal M, Ahmad Z. Numerical simulation of heat and mass transfer through hybrid nanofluid flow consists of polymer/CNT matrix nanocomposites across parallel sheets. Alex Eng J. 2024;108(1):319–31. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2024.07.084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Moghadassi A, Ghomi E, Parvizian F. A numerical study of water based Al2O3 and Al2O3-Cu hybrid nanofluid effect on forced convective heat transfer. Int J Therm Sci. 2015;92(24):50–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2015.01.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Nwaokocha C, Momin M, Giwa S, Sharifpur M, Murshed SMS, Meyer JP. Experimental investigation of thermo-convection behaviour of aqueous binary nanofluids of MgO-ZnO in a square cavity. Therm Sci Eng Prog. 2022;28(2):101057. doi:10.1016/j.tsep.2021.101057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Almeshaal MA, Kalidasan K, Askri F, Velkennedy R, Alsagri AS, Kolsi L. Three-dimensional analysis on natural convection inside a T-shaped cavity with water-based CNT-aluminum oxide hybrid nanofluid. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2020;139(3):2089–98. doi:10.1007/s10973-019-08533-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Chamkha AJ, Miroshnichenko IV, Sheremet MA. Numerical analysis of unsteady conjugate natural convection of hybrid water-based nanofluid in a semicircular cavity. J Therm Sci Eng Appl. 2017;9(4):041004. doi:10.1115/1.4036203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ghalambaz M, Doostani A, Izadpanahi E, Chamkha AJ. Conjugate natural convection flow of Ag-MgO/water hybrid nanofluid in a square cavity. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2020;139(3):2321–36. doi:10.1007/s10973-019-08617-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Alsabery AI, Hashim I, Hajjar A, Ghalambaz M, Nadeem S, Saffari Pour M. Entropy generation and natural convection flow of hybrid nanofluids in a partially divided wavy cavity including solid blocks. Energies. 2020;13(11):2942. doi:10.3390/en13112942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Tayebi T, Chamkha AJ. Free convection enhancement in an annulus between horizontal confocal elliptical cylinders using hybrid nanofluids. Numer Heat Transf Part A Appl. 2016;70(10):1141–56. doi:10.1080/10407782.2016.1230423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Cimpean DS, Sheremet MA, Pop I. Mixed convection of hybrid nanofluid in a porous trapezoidal chamber. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2020;116(19):104627. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2020.104627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Umar Ibrahim I, Sharifpur M, Meyer JP. Mixed convection heat transfer characteristics of Al2O3-MWCNT hybrid nanofluid under thermally developing flow; effects of particles percentage weight composition. Appl Therm Eng. 2024;249(2):123372. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.123372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Bouaraour K. Mixed convection analysis of hybrid nanofluid in a lid-driven cavity with a hot block inside. J Mech Continua Math Sci. 2023;18(6):1–13. doi:10.26782/jmcms.2023.06.00001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ali IR, Alsabery AI, Bakar NA, Roslan R. Mixed convection in a double lid-driven cavity filled with hybrid nanofluid by using finite volume method. Symmetry. 2020;12(12):1977. doi:10.3390/sym12121977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Pak BC, Cho YI. Hydrodynamic and heat transfer study of dispersed fluids with submicron metallic oxide particles. Exp Heat Transf. 1998;11(2):151–70. doi:10.1080/08916159808946559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Corcione M. Heat transfer features of buoyancy-driven nanofluids inside rectangular enclosures differentially heated at the sidewalls. Int J Therm Sci. 2010;49(9):1536–46. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2010.05.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Usman M, Hamid M, Zubair T, Ul Haq R, Wang W. Cu-Al2O3/Water hybrid nanofluid through a permeable surface in the presence of nonlinear radiation and variable thermal conductivity via LSM. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2018;126(2):1347–56. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.06.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Rashad AM, Chamkha AJ, Ismael MA, Salah T. Magnetohydrodynamics natural convection in a triangular cavity filled with a Cu-Al2O3/water hybrid nanofluid with localized heating from below and internal heat generation. J Heat Transf. 2018;140(7):072502. doi:10.1115/1.4039213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Sebdani SM, Mahmoodi M, Hashemi SM. Effect of nanofluid variable properties on mixed convection in a square cavity. Int J Therm Sci. 2012;52:112–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2011.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Corvaro F, Paroncini M. A numerical and experimental analysis on the natural convective heat transfer of a small heating strip located on the floor of a square cavity. Appl Therm Eng. 2008;28(1):25–35. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2007.03.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Al-Asad MF, Alam MN, Tunç C, Sarker MMA. Heat transport exploration of free convection flow insideenclosure having vertical wavy walls. J Appl Comput Mech. 2021;7(2):520–7. doi:10.22055/jacm.2020.35381.2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Blohm C, Kuhlmann HC. The two-sided lid-driven cavity: experiments on stationary and time-dependent flows. J Fluid Mech. 2002;450:67–95. doi:10.1017/s0022112001006267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Oztop HF, Dagtekin I. Mixed convection in two-sided lid-driven differentially heated square cavity. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2004;47(8–9):1761–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2003.10.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Aydin O, Yang WJ. Natural convection in enclosures with localized heating from below and symmetrical cooling from sides. Int J Numer Meth Heat Fluid Flow. 2000;10(5):518–29. doi:10.1108/09615530010338196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Malkeson SP, Chakraborty N. Laminar natural convection of water-based alumina nanofluids in a square enclosure. Heat Transf Eng. 2024;45(14):1173–89. doi:10.1080/01457632.2023.2249727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Aydin O, Yang W. Mixed convection in cavities with a locally heated lower wall and moving sidewalls. Numer Heat Transf Part A Appl. 2000;37(7):695–710. doi:10.1080/104077800274037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Chen TH, Chen LY. Study of buoyancy-induced flows subjected to partially heated sources on the left and bottom walls in a square enclosure. Int J Therm Sci. 2007;46(12):1219–31. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2006.11.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools