Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Developments and Prospects in Temperature Control Technique of Loop Heat Pipe for Spacecraft

National Key Laboratory of Spacecraft Thermal Control, Beijing Institute of Spacecraft System Engineering, Beijing, 100094, China

* Corresponding Author: Hongxing Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Recent Advances in Loop Heat Pipe)

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(4), 1261-1280. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.066473

Received 09 April 2025; Accepted 24 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

With the development of space-based remote sensing and deep space exploration technology, higher standards for temperature stability and uniformity of payloads have been proposed to spacecraft thermal control systems. As an efficient two-phase heat transfer device with active temperature control capabilities, the loop heat pipe (LHP) can be widely applied in spacecraft thermal control systems to achieve reliable temperature control under various operating modes and complex space thermal environments. This paper analyzes the fundamental theories of thermal switch-controlled, reservoir temperature-controlled, and bypass valve-controlled LHPs. The focus is on the theories and methods of achieving high-precision and high-reliability temperature control via active reservoir temperature control. Novel control techniques in recent years, such as non-condensable gas (NCG) control with a temperature stability of 0.01°C, are also briefly introduced as promising approaches to improve LHP performance. The on-orbit performance and characteristics of various LHP temperature control methods are provided and ranked in terms of control precision, energy consumption, complexity, and weight. Thermoelectric cooler (TEC)/electrical heater, as the foundation of reservoir temperature control, can achieve a temperature stability of ±0.2°C in space applications under a wide range of heat load. Microgravity model, control strategy, and operating mode conversion are three optimization directions that would hopefully further expand the application scenario of reservoir temperature control. Specific design principles and challenges for corresponding directions are summarized as guidance for researchers.Keywords

The major objective of a spacecraft thermal control system is to maintain the spacecraft and its payloads within a reasonable operating temperature range under complex and extreme space thermal environments. This is crucial for ensuring the realization of spacecraft functions and performance. In addition to absolute temperature levels, special payloads may impose requirements on temperature uniformity and stability. For temperature-sensitive payloads, destabilization of thermal noise caused by temperature fluctuations can make signal processing difficult, leading to reduced performance and unreliable output. In severe cases, such fluctuations can result in irreversible deformations on optical lenses, shortening their operational lifespan. For example, a specific optical detector module [1] has strict demands for temperature variation and stability. To improve imaging metrics such as signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and geometric accuracy, it requires minimal temperature changes and high stability throughout its entire operation cycle. Additionally, the laser altimeter on remote-sensing satellites requires that the temperature difference between lasers be less than ±1°C to ensure high mapping precision.

There are two key factors influencing payload temperatures: external heat flux variation from the space thermal environment, such as transient variations caused by solar radiation and planetary albedo while entering and exiting shadow zones [2]; and internal equipment switching between full-power operation and standby modes, causing transient heat dissipation changes. The thermal control system must achieve high-precision and high-stability temperature regulation for payloads under variable space thermal environments and working modes. LHP, as an efficient two-phase heat transfer device with active temperature control capabilities, possesses advantages such as strong heat dissipation, long heat transfer distance, simple structure, and flexible layout.

Many reviews on mathematical modeling, component design, and operational characteristics have been presented to improve LHP heat transfer capabilities [3–5]. The geometry of the evaporators and the presence of NCG directly affect LHP start-up behavior. Pore size, wettability, and micro-nano structure of wick have a significant impact on capillary driving force and heat transfer performance. However, most reviews neglect the temperature control principles and methods which are regarded as critical factors during LHP design for space application. This paper summarizes the basic principles and methods of thermal switch control, bypass valve control, and reservoir temperature control for LHP. Reservoir temperature control methods include thermoelectric cooler/electrical heater, phase change material, and high heat capacity coupling block. The corresponding performance and design parameters in space applications are the major evaluation principles in this paper. The advantages and disadvantages of temperature control methods and future development directions are analyzed in detail.

2 LHP Operating Temperature Control Methods

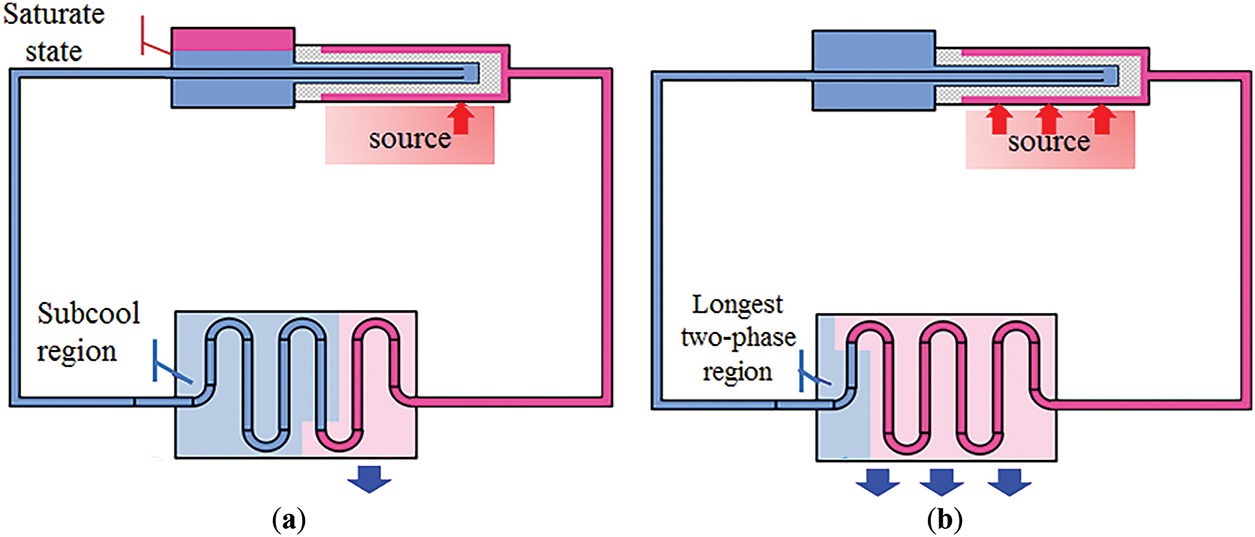

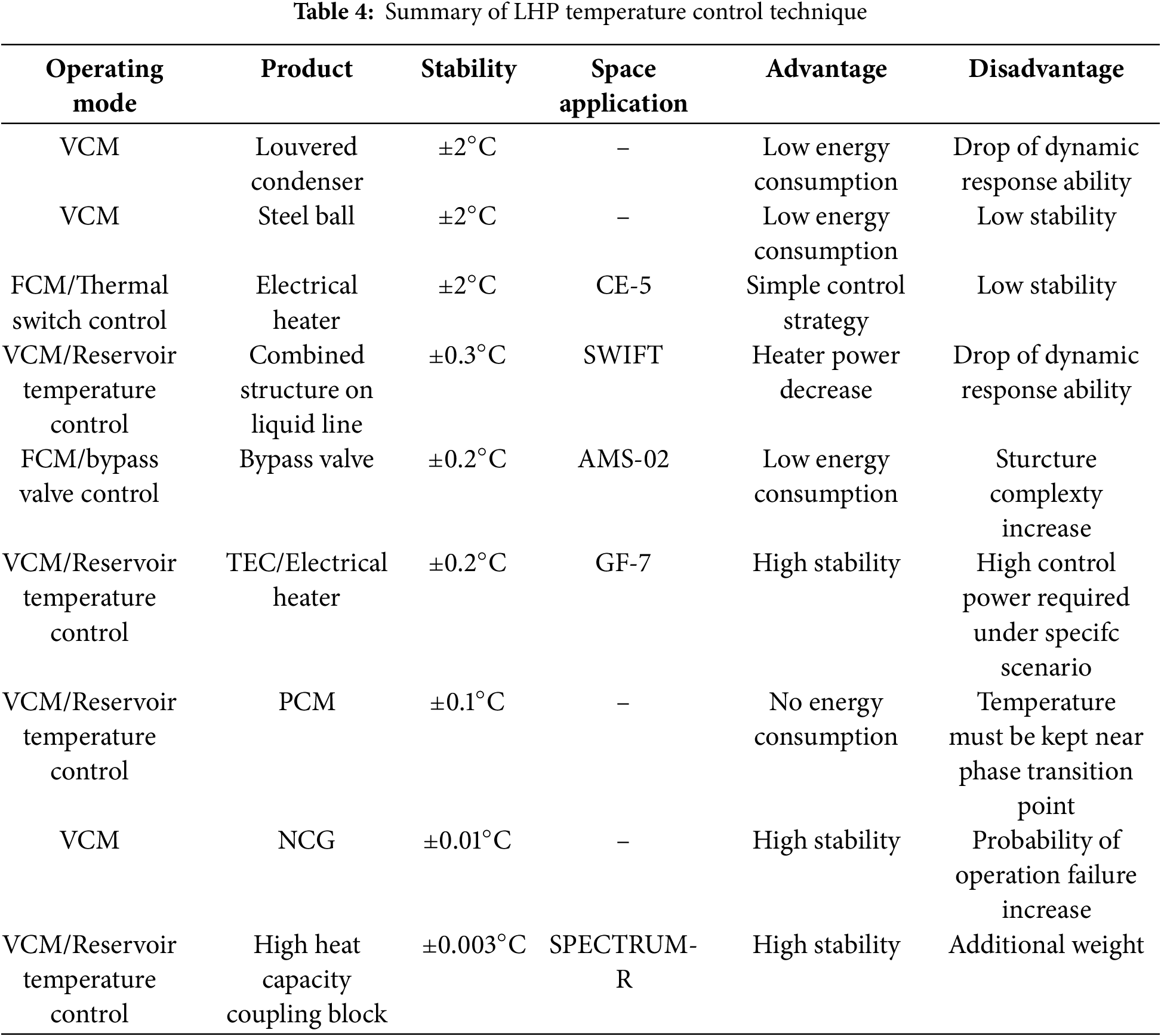

Before the choice of temperature control methods, it is recommended to check the LHP deprime limit to decide the allowable operating temperature range with sufficient margin and keep the electronics within a safe temperature limit. Factors such as NCG [6], working fluid [7], gravity [8], and wick property [9] have been investigated to judge the deprime limit under high heat flux application. The principles and methods for temperature control depend on LHP operating modes. As shown in Fig. 1, when the heat load is small, the reservoir is in a gas-liquid two-phase state, and the length of the two-phase region in the condenser changes with the heat load. In this case, the LHP operates in variable conductance mode (VCM), and the operating temperature can be controlled by regulating the temperature of the reservoir. When the length of the two-phase region in the condenser reaches its maximum and the reservoir is filled with subcooled liquid, the LHP operation converts into fixed conductance mode (FCM). In this mode, temperature control can be achieved through thermal switch control or bypass valve control.

Figure 1: Working fluid distribution under different operating mode (a) variable conductance mode (b) fixed conductance mode

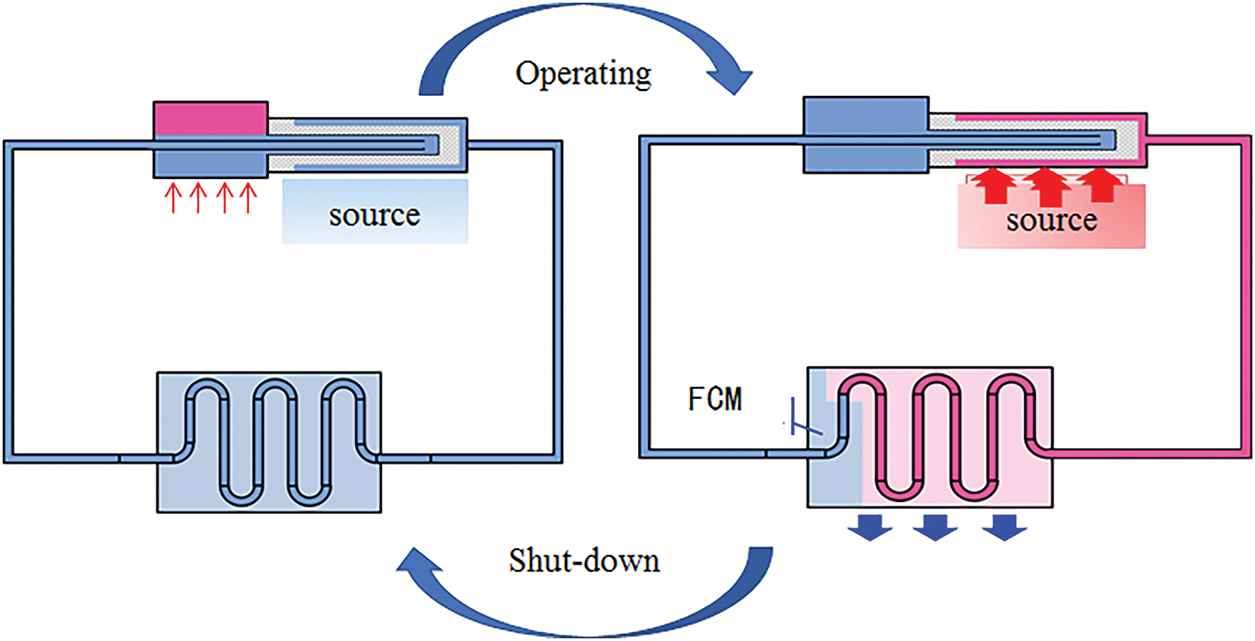

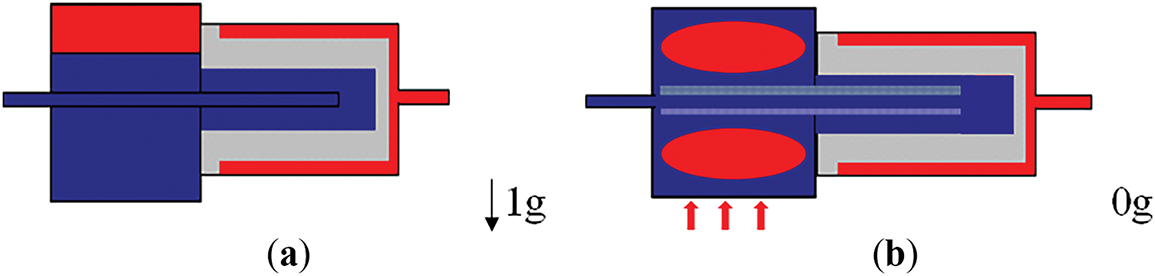

According to the operational status of the payload, LHP can simply achieve low-precision temperature control by switching between heat transfer mode and heat insulation mode. As shown in Fig. 2, when heat generated by equipment exceeds the upper threshold of the temperature control limit, LHP operates in fixed conductance mode to transfer heat to its full capacity. When the equipment temperature falls below the lower threshold of the control limit, the operation of LHP can be blocked by heating the reservoir to increase its saturation pressure. If the heat leak running through the stainless-steel tube of the LHP is small, heat transfer from the device to the cold wall could be insulated.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of thermal switch control

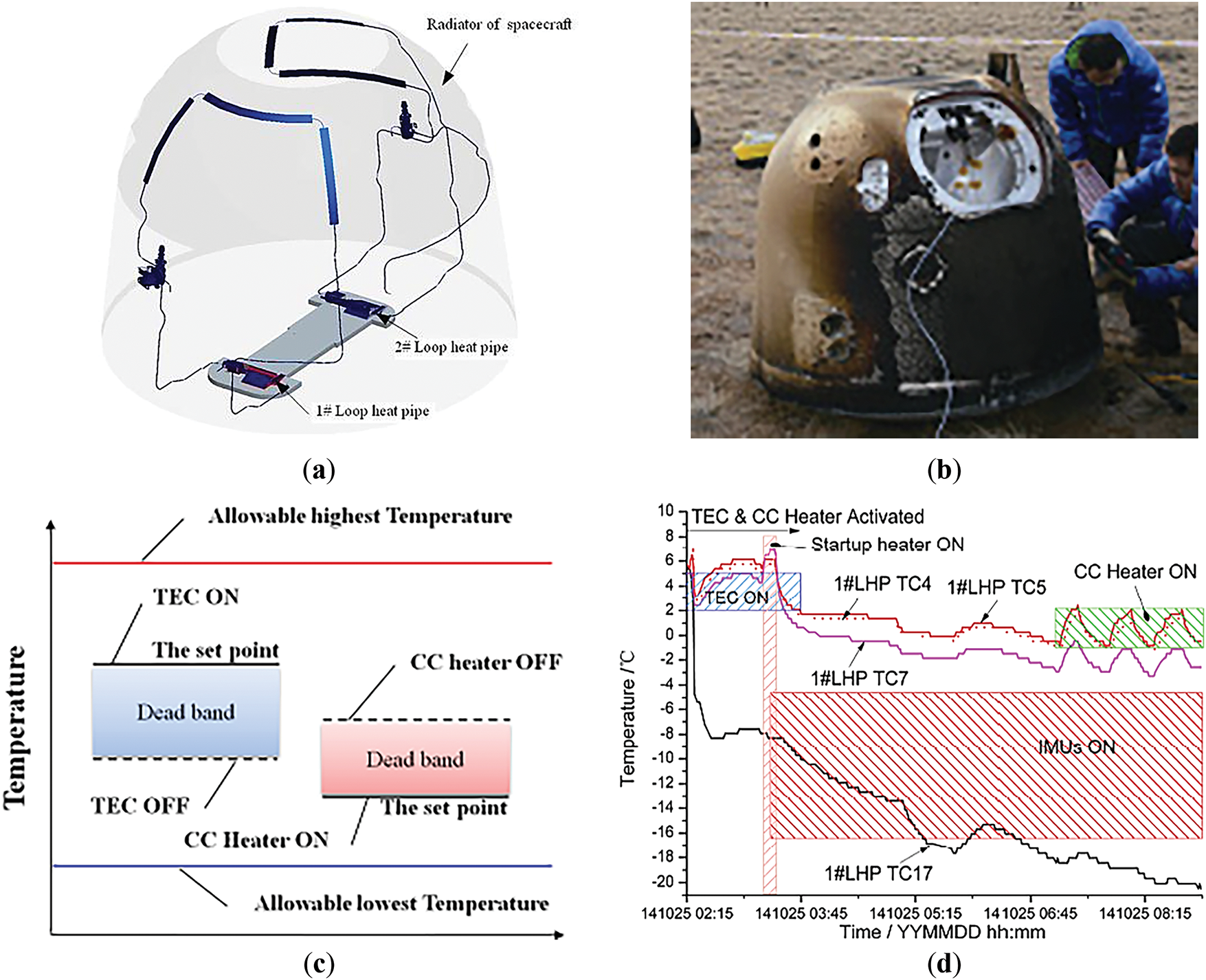

CE-5 Test Mission [10], launched in 2014, marked the first space application of Chinese LHP technology. The inertial measurement unit (IMU) in the return capsule utilized two sets of LHP as thermal switch control. During LHP operation, the actual heat transfer capacity exceeded 65 W, while the heat leakage in the insulation mode was less than 2 W, resulting in a thermal conductance ratio greater than 30. This effectively realized the thermal switch function. Fig. 3 illustrates the thermal switch control strategy of the LHP, while Fig. 3d shows the on-orbit operating temperature curve of the LHP. By LHP switched between heat transfer mode and heat insulation mode, temperatures of the two IMUs during operation were controlled within the ranges of 3.7°C to 7.6°C and 11.1°C to 12.8°C, respectively.

Figure 3: Thermal switch control for CE-5T1 (a) LHP structure (b) reentry capsule (c) control strategy (d) on-orbit temperature profile. Reprinted with permission from reference [10]

Table 1 summarizes typical space application cases of LHP with thermal switch control. Thermal switch control is simple and reliable, meeting the temperature control requirements for devices that require ordinary precision. However, it is difficult to achieve high-precision temperature control with this method.

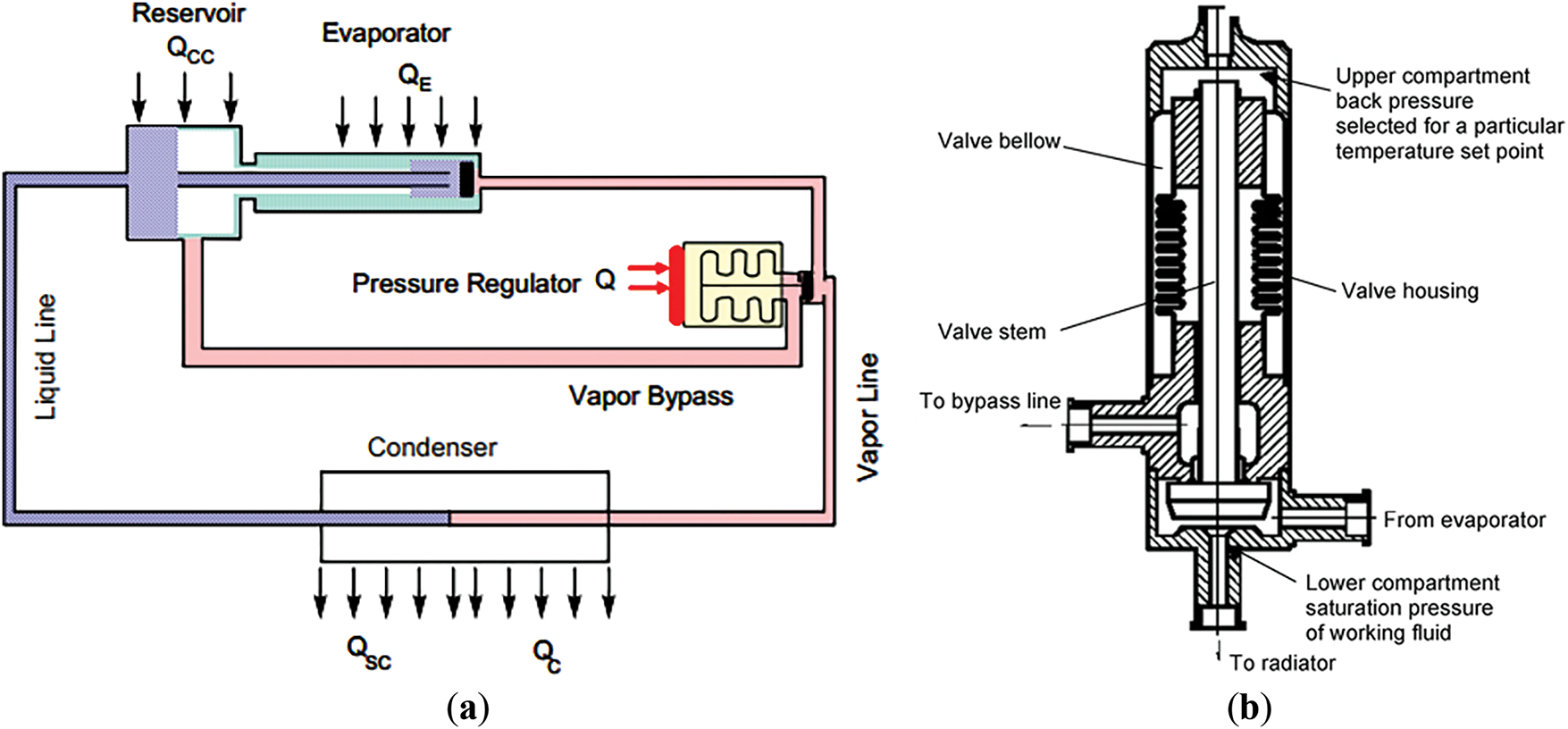

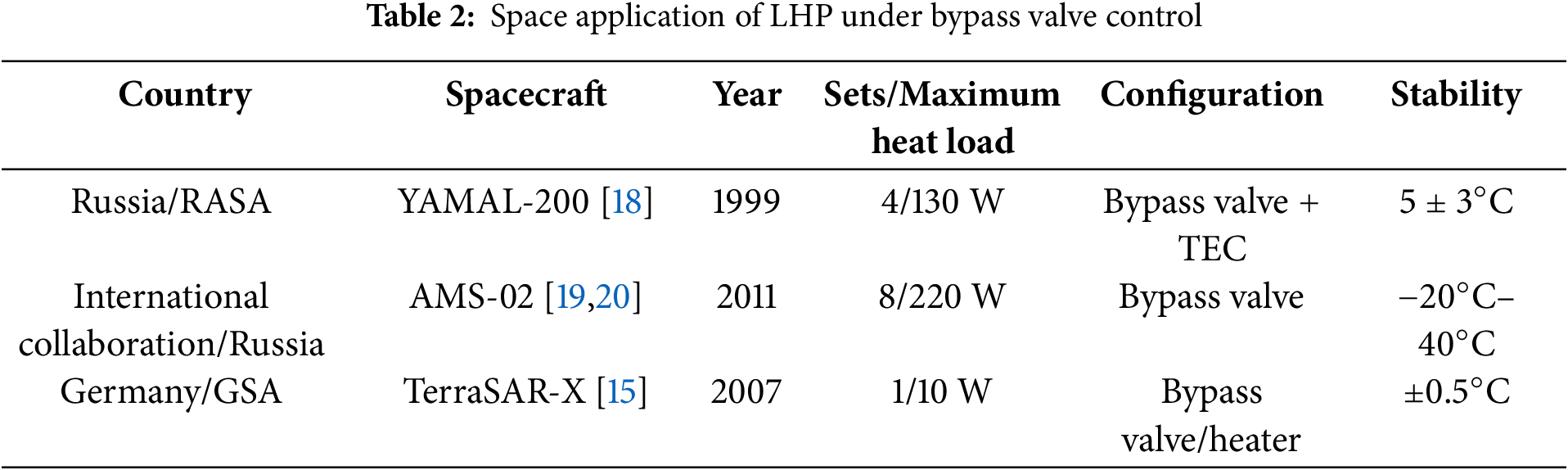

In cases where the heat load or external heat flux undergoes significant changes, the operating temperature of the LHP can fluctuate considerably. To address this issue, Russia’s Lavochkin Association proposed an LHP with a bypass and pressure regulating valve [14], as shown in Fig. 4. The bypass valve has three operational modes:

(1) On Mode: When the evaporator pressure is higher than the regulation pressure, the bypass valve remains fully open, with the valve stem at its highest position. No working fluid flows through the bypass line, and the operation is identical to that of a standard LHP without a bypass valve.

(2) Regulation Mode: When the evaporator pressure is lower than the regulation pressure, the bypass valve partially opens, allowing two-phase media to flow through both the bypass line and the condenser. In this mode, the bypass valve regulates the flow distribution.

(3) Off Mode: When the evaporator temperature falls below the set point temperature, no vapor-phase working fluid flows through the condenser, and the valve stem is at its lowest position. In this case, all vapor-phase working fluid flows entirely through the bypass line.

Figure 4: Schematic diagram of LHP under bypass valve control (a) LHP structure (b) pressure regulating valve. Reprinted with permission from reference [17]

Through the use of a bypass valve, fully passive temperature control can be achieved, ensuring stable performance of the LHP under varying thermal conditions.

By installing a heater on the bypass valve, active control of gas in the upper compartment can be achieved. Bodendieck et al. [15] proposed a set of governing equations to calculate the heating power applied to the bypass valve. In thermal vacuum tests, the temperature control accuracy of the LHP reached ±0.5°C. Nikitkin et al. [16] proposed that applying phase-change auxiliary materials to the bypass valve can improve the temperature control accuracy.

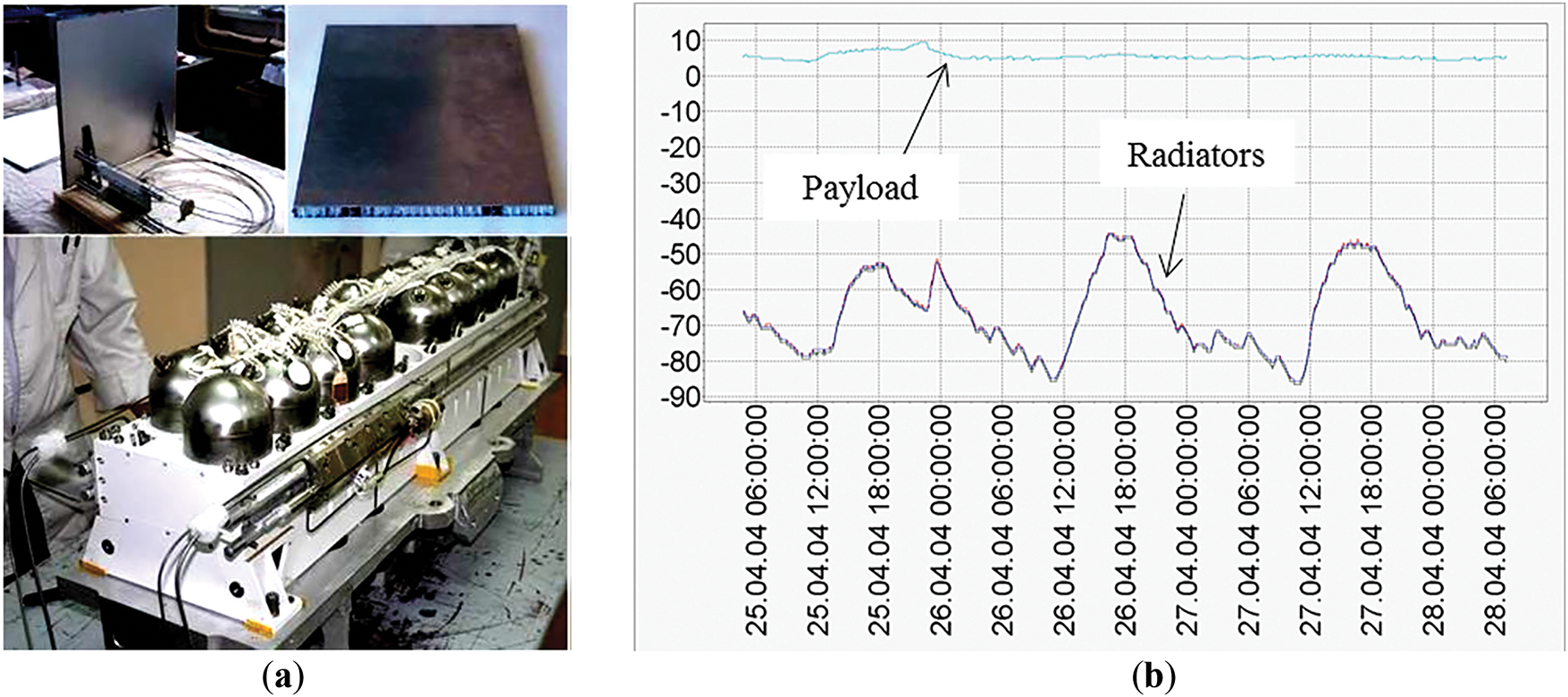

The Russian satellite YAMAL-200 [18] was the first to apply LHPs with bypass valves in space. YAMAL-200 used four sets of propylene-working-fluid LHPs to control the temperature of two groups of nickel-hydrogen batteries. Fig. 5a shows the layout of the LHP and batteries. Each set had a heat transfer capacity exceeding 125 W. The passive temperature control design of the LHP bypass valve achieved the goal of maintaining the nickel-hydrogen batteries within a temperature range of 5 ± 3°C as shown in Fig. 5b. This satellite not only validated the effectiveness of bypass valve temperature control through on-orbit data but also demonstrated the feasibility of using both electrical heaters and TECs installed on the reservoir for temperature control.

Figure 5: YAMAL-200 LHP under bypass valve control (a) LHP structure (b) on-orbit temperature profile. Reprinted with permission from reference [18]

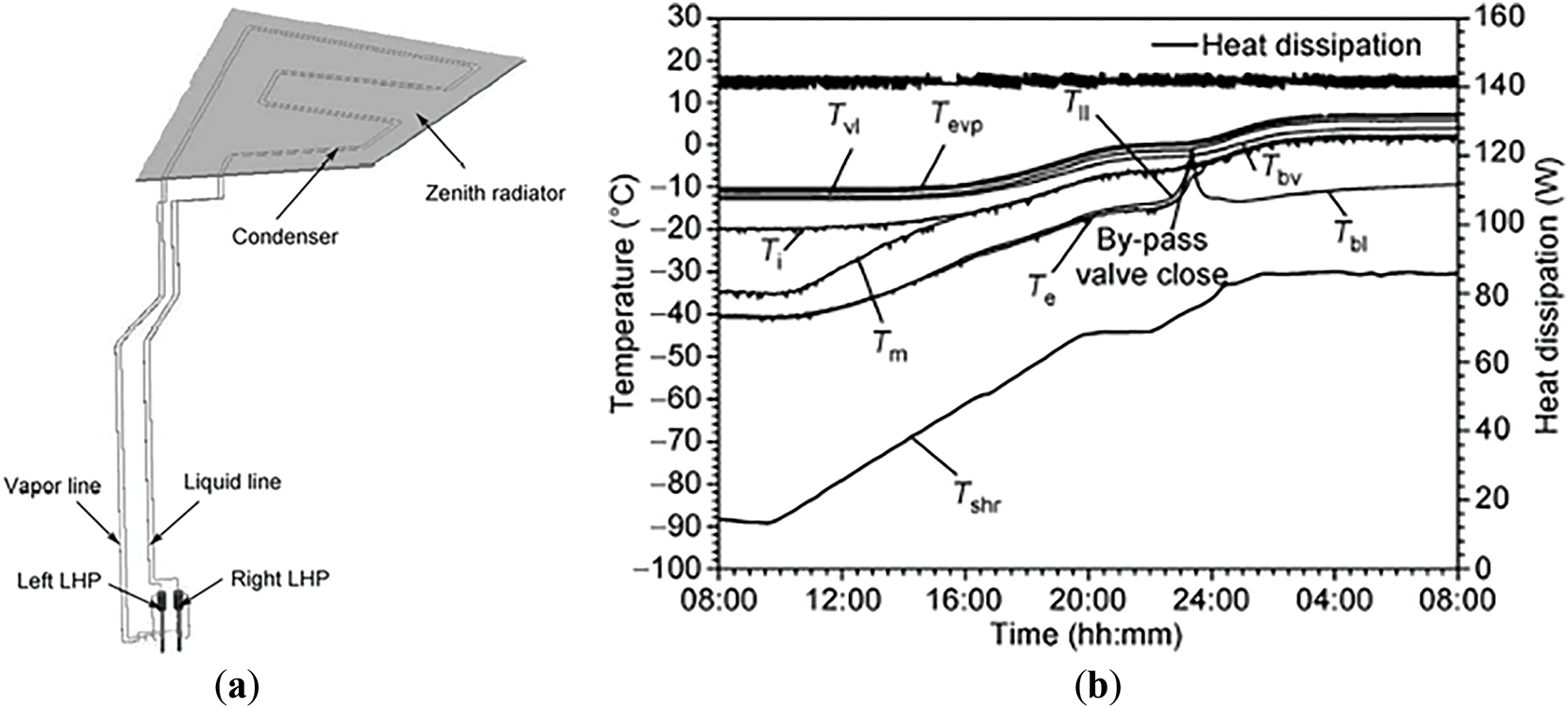

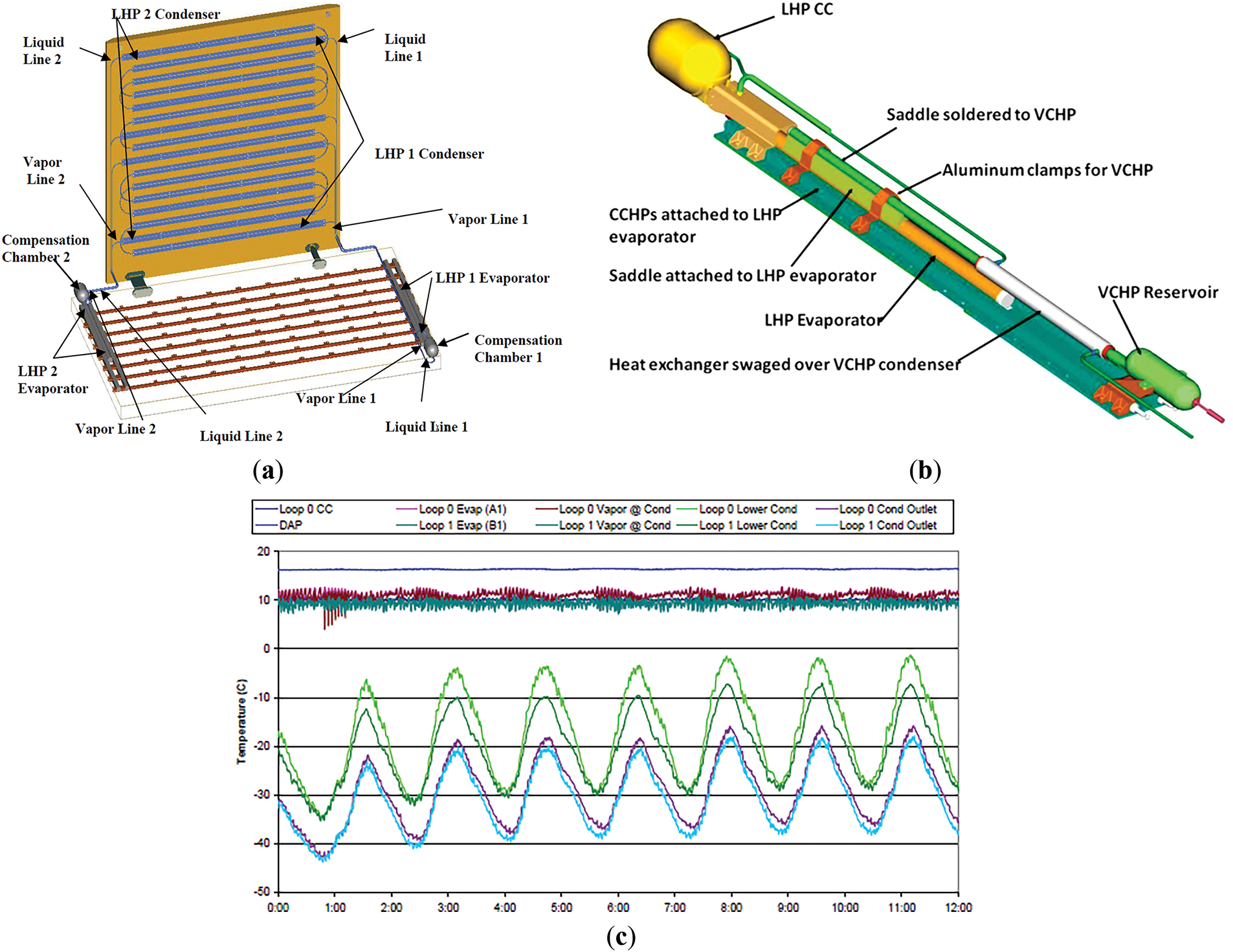

The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer 02 (AMS-02) [19,20], a large scientific instrument aboard the International Space Station, utilized eight propylene LHPs to transfer approximately 600 W of heat dissipation from four refrigerators. Fig. 6 shows the layout of the LHP and condenser panel. Each LHP could achieve a heat transfer capability of 220 W over a distance of 2.9 m. All LHPs featured a single-evaporator dual-loop structure. When the vapor pressure fell below the set point, the bypass valve directed part of the vapor into the reservoir, reducing the working fluid flow rate and heat exchange in the condenser to ensure that the refrigerator temperature remained above the lower limit of −20°C.

Figure 6: AMS-02 LHP under bypass valve control (a) LHP structure (b) temperature profile. Reprinted with permission from reference [19]

Table 2 summarizes typical space applications of LHP with bypass valve temperature control. The advantage of bypass valve control is that it is either fully passive or consumes minimal energy for temperature regulation. However, the addition of bypass lines and valves increases structural complexity and reduces system reliability.

2.3 Reservoir Temperature Control

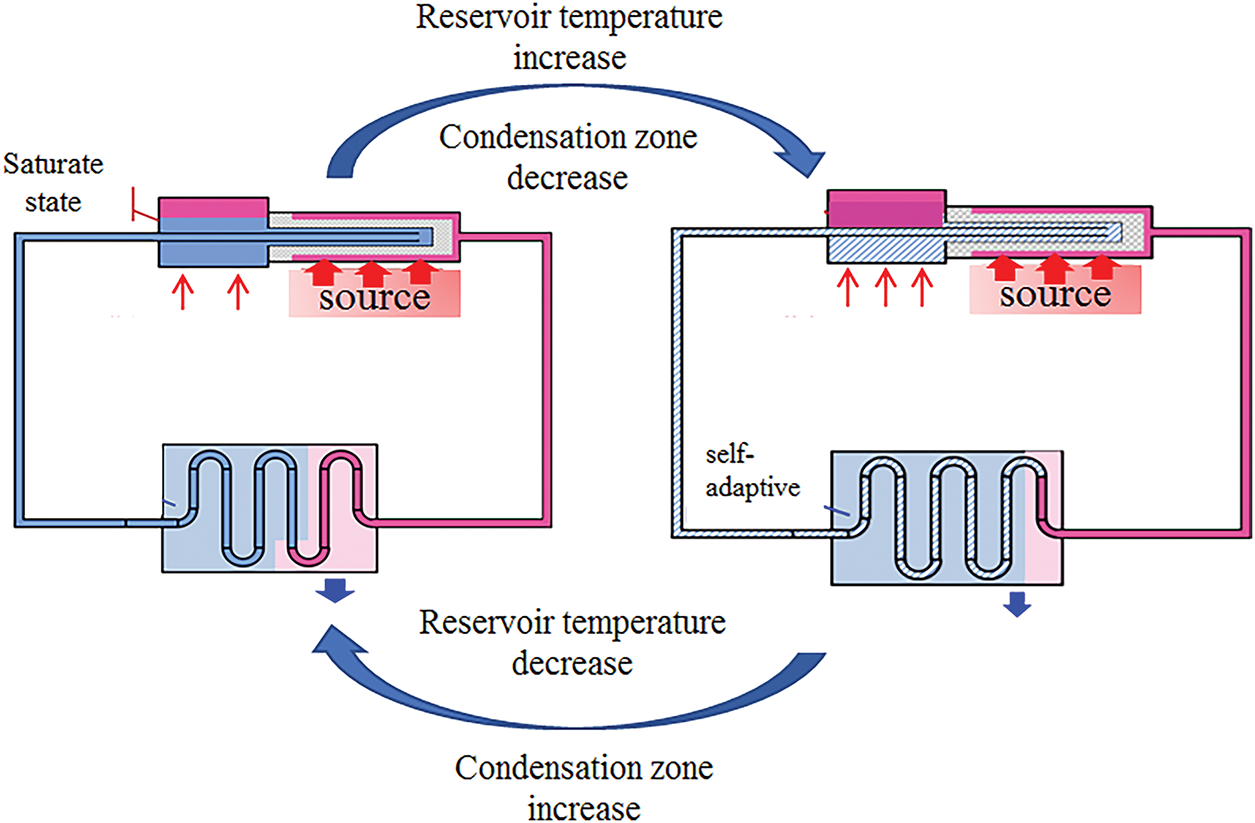

Reservoir temperature control is an active temperature control method. When the heat load on the evaporator or the external heat flux of the condenser varies over a wide range, applying a small compensation power to the reservoir in the gas-liquid two-phase state can achieve temperature control for the entire loop. The active temperature control capability of the LHP is a common characteristic of two-phase fluid loop systems. The saturated pressure difference and temperature difference between the evaporator and the reservoir, both in a saturated state, obey the Clausius-Clapeyron equation. When the reservoir temperature increases, the pressure rises, and the liquid is forced back into the condenser, reducing its effective condensation area, as shown in Fig. 7. Consequently, the saturation temperatures of the condenser and evaporator also increase. The opposite phenomenon is observed when the reservoir temperature decreases.

Figure 7: Schematic diagram of reservoir-temperature controlled LHP

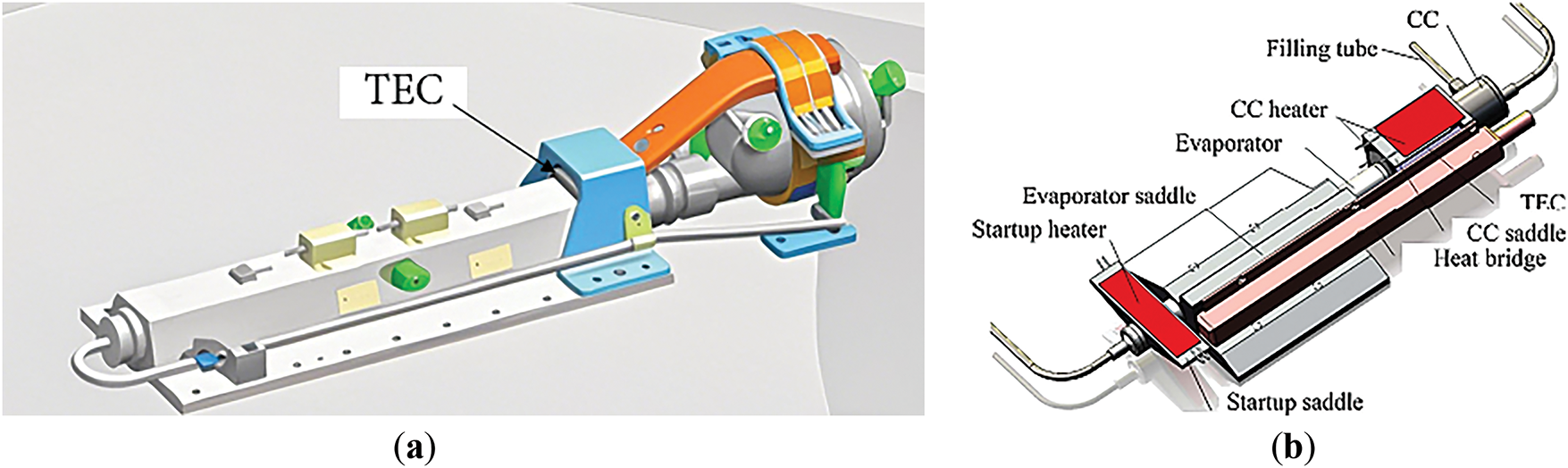

A TEC can control the temperature of the LHP reservoir by changing the direction of electric current to either heating or cooling. As shown in Fig. 8, the TEC can be installed on the reservoir or evaporator, and a high thermal conductivity bridge made of copper or a heat pipe is used to transfer heat between the TEC and the reservoir or evaporator.

Figure 8: Different methods of applying TEC (a) TEC on evaporator. Reprinted with permission from reference [13]. (b) TEC combined with electrical heater

TEC can also be combined with an electrical heater for reservoir temperature control. Fig. 8b shows a commonly used structure in Chinese space applications, where both the TEC and heater are mounted on the reservoir saddle. The cold side of the TEC is in direct contact with the reservoir, while a heat pipe thermal bridge transfers heat from the hot side of the TEC to the evaporator saddle.

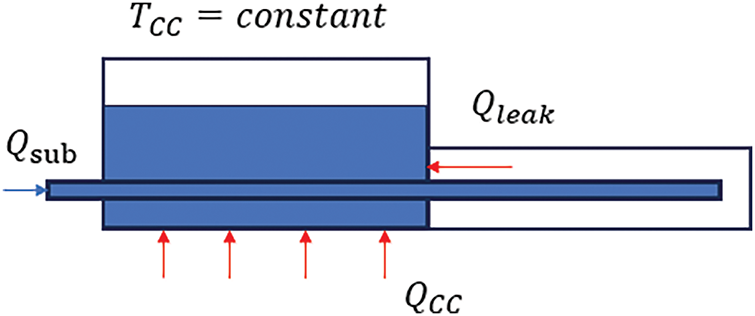

When the LHP reservoir is controlled by a TEC or electrical heater, the energy balance relationship of the reservoir is illustrated in Fig. 9. Here,

Figure 9: Energy balance relationship during reservoir control

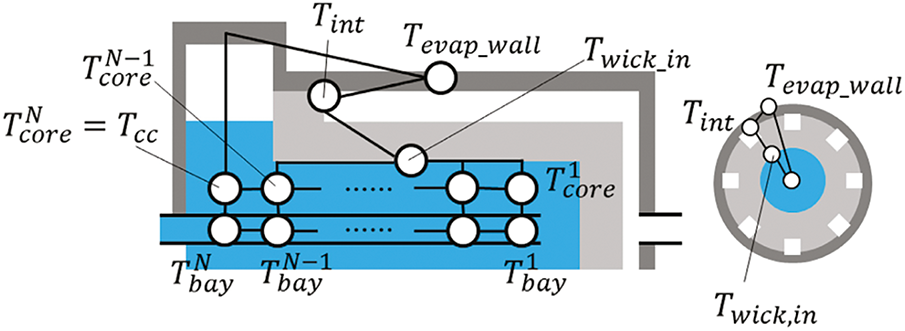

The ordinary model for calculating parasitic heat leakage between the evaporator and reservoir typically neglects the convective heat transfer occurring during the working fluid flow in the wick structure, considering only the conduction effect [21–24]. Zhou et al. [25] developed a heat leak model for LHP with liquid transport lines. This model accounts for nucleate boiling effects generated by the fluid flowing through the wick structure. In experiments using ammonia LHP, the saturation vapor temperature under various operating conditions was measured, showing that the new model significantly improves the accuracy of predicting the operating temperature of LHP in variable conductance mode compared to models considering only thermal conduction within the wick. Adachi et al. [26] proposed a model approximating the temperature distribution inside the wick using N nodes, as shown in Fig. 10, which can improve model accuracy. At higher heat inputs, there is vapor blanket formation that causes an increase in the evaporator temperature which is always higher than predicted temperature through models. Anand et al. [27] present a recession model based on the minimization of the difference between the predicted and measured evaporator wall temperatures to predict an equivalent vapor blanket thickness. It is worth noting that current LHP models have only been validated for natural operating states, lacking experimental data support for reservoir temperature control modes.

Figure 10: Thermal network using multiple nodes to approximate temperature in evaporator. Reprinted with permission from reference [26]

The effectiveness of TEC-based temperature control on the reservoir depends on the orientation of LHP. Reverse-gravity conditions for returning fluid flow are more favorable for TEC temperature control. Franzoso et al. [28] found that when the returning fluid flows against gravity, TEC cooling significantly increases the length of the two-phase region in the condenser, whereas this effect is less noticeable under gravity-assisted conditions. Pastukhov et al. [29] discovered that, under identical operating temperatures, the heating power required for TEC temperature control is much higher under gravity-assisted conditions than under reverse-gravity conditions.

Given the advantages of TEC for both startup and operation of LHP [30], Chinese space applications adopt the following temperature control strategy: during the blocked state of the LHP, TEC is turned off; during operation and standby states, the TEC remains on and performs only cooling while electrical heater set to on/off control algorithm. When the duty cycle of the electrical heater is high, TEC and heater often operate simultaneously, leading to energy waste. An alternative strategy involves both heating and cooling of the reservoir being achieved by reversing the voltage direction of the TEC. This approach avoids energy waste but frequent voltage changes may have a negative impact on the lifespan of TEC. Future research should focus on developing temperature control strategies that balance TEC lifespan and energy efficiency.

Electrical heater typically uses either PID algorithm or on/off control algorithm. Under normal circumstances, PID algorithm offers better temperature stability [31–33], but on/off control algorithm is simpler to design and highly reliable, making both widely used in practical engineering case depending on specific scenarios.

Ordinary control strategies require only the temperature of the control point as an input variable. Some scholars believe that incorporating multiple variables can enhance the dynamic stability of LHP. Gellrich et al. [34] proposed an improved PI controller that uses inputs including reservoir temperature, condenser outlet temperature, and heat load power. Numerical models show a significant reduction in reservoir temperature overshoot compared to traditional PI controllers. Gellrich et al. also proposed controllers based on reinforcement learning [35] and Kalman filters [36]. Numerical results indicate reduced absolute error and root mean square error during temperature control.

In microgravity environments, the position of the control point on the reservoir shell has neglectable effect on temperature control accuracy. However, in gravity environments, gas-liquid stratification occurs inside the reservoir and the choice of control point location—whether in the saturated vapor region or subcooled liquid region—significantly impacts control accuracy. Fang et al. [37] compared the performance of LHP under different orientations and control point configurations. When the control point is set in the saturated vapor region of the reservoir, the control accuracy reaches ±0.2°C, which is superior to when the control point is in the pure liquid phase region.

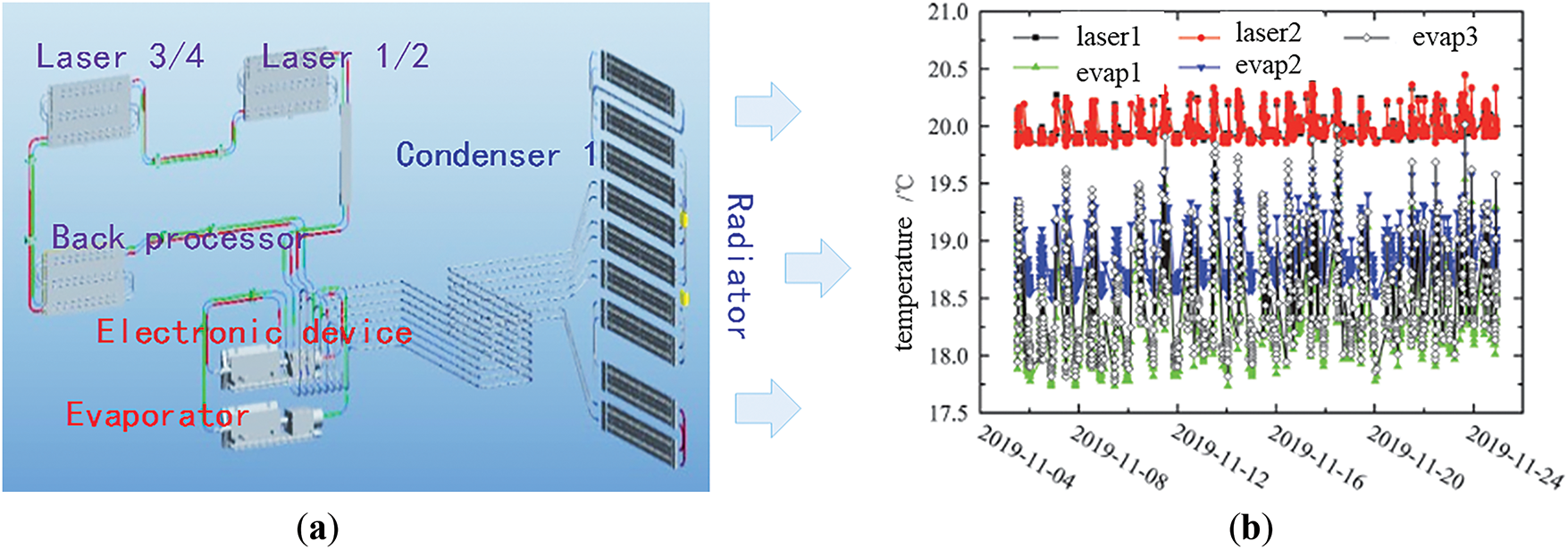

GF-7 satellite [38] uses LHP controlled by electrical heater/TECs. Heat sources include the front-end electronics, four lasers, and rear optical path electronics. LHP structure and heat sources are shown in Fig. 11a. To achieve the mission goal of height resolution better than 1 m, the laser altimeter must maintain good temperature stability and consistency. As shown in Fig. 11b, after entering orbit, the main LHP operating temperature stabilized at 19 ± 1°C, and the laser temperature was controlled within 19.8°C–20.4°C, meeting the design specifications.

Figure 11: GF-7 LHP designed for multiple heat source (a) LHP structure (b) on-orbit temperature profile

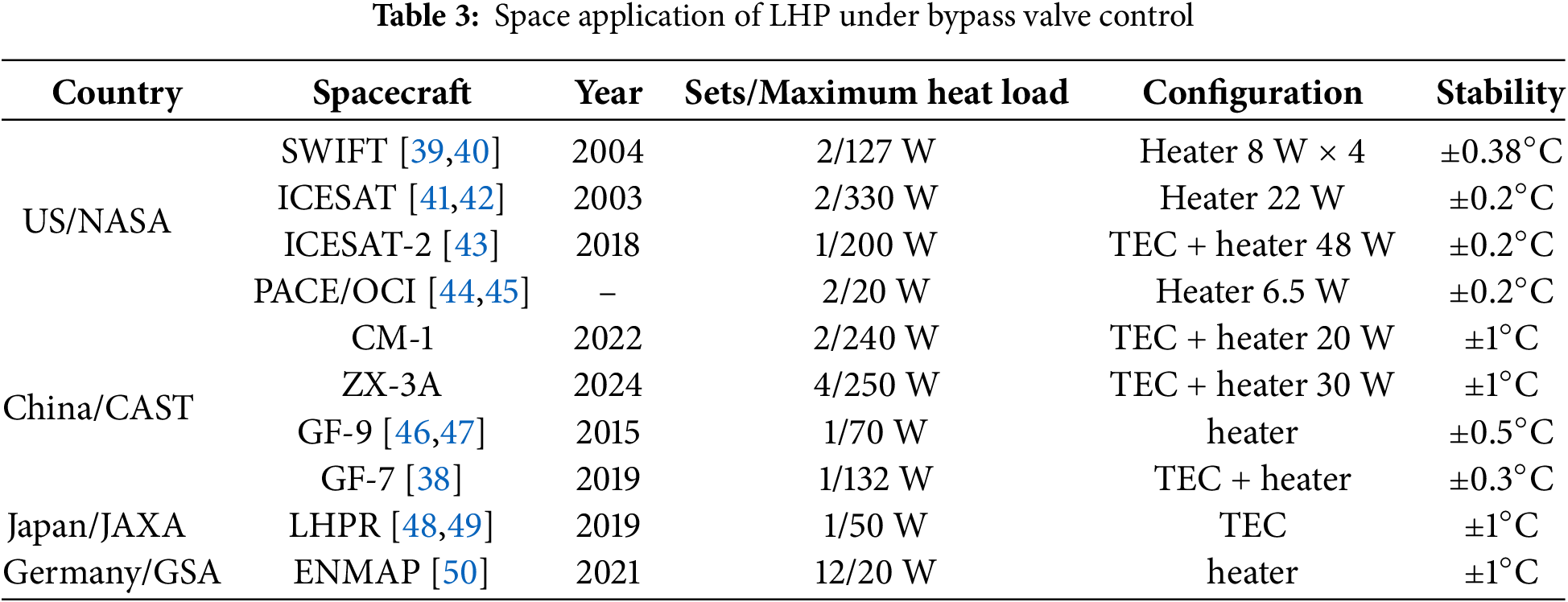

Table 3 summarizes space application cases of LHP using TEC/electrical heater for temperature control. This method can achieve relatively high temperature control precision but requires additional energy consumption for both the TEC and electrical heater.

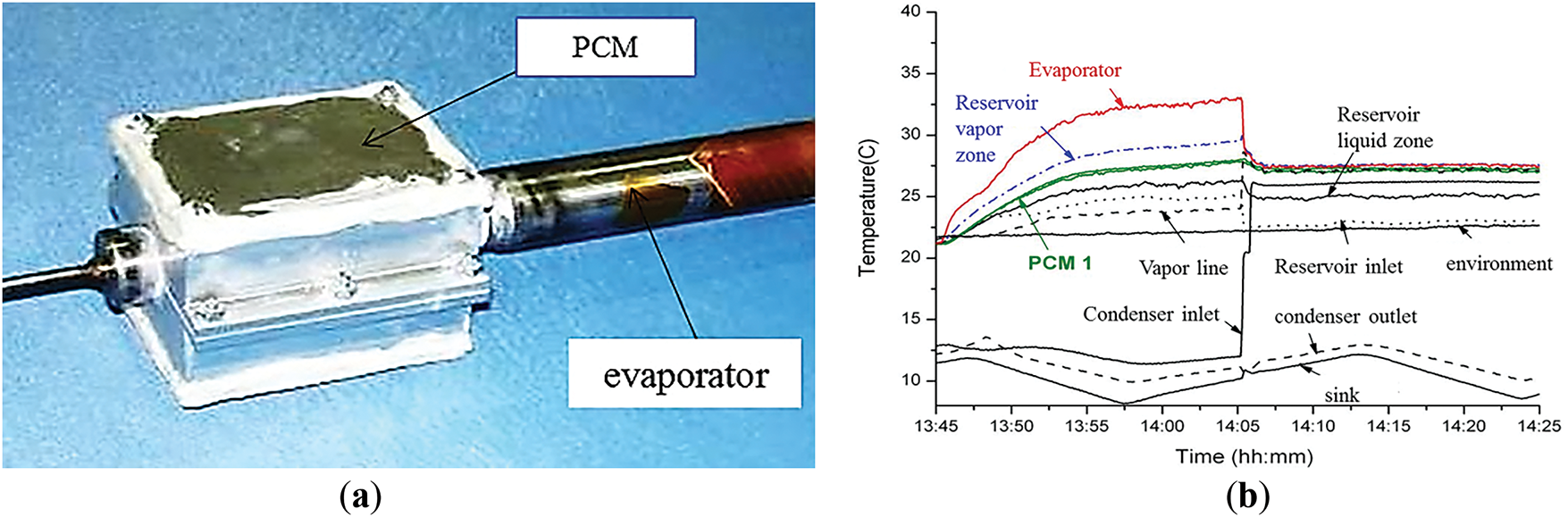

Zhang et al. [51] verified the feasibility of using phase change materials (PCM) for passive temperature control of the reservoir, as shown in Fig. 12a. When the external heat flux on the condenser or the power on the evaporator changes, the PCM can maintain the reservoir temperature near its phase transition point for a certain period by absorbing and releasing latent heat during solid-liquid phase transitions, thereby achieving passive temperature control. Fig. 12b shows the temperature curve where the reservoir temperature remains constant despite fluctuations in the heat sink temperature. It is worth noting that the PCM device can only maintain the reservoir temperature for a limited time and is effective only in scenarios where the external heat flux or load varies periodically.

Figure 12: Reservoir controlled under PCM (a) LHP structure (b) temperature profile

2.3.3 High Heat Capacity Coupling Block

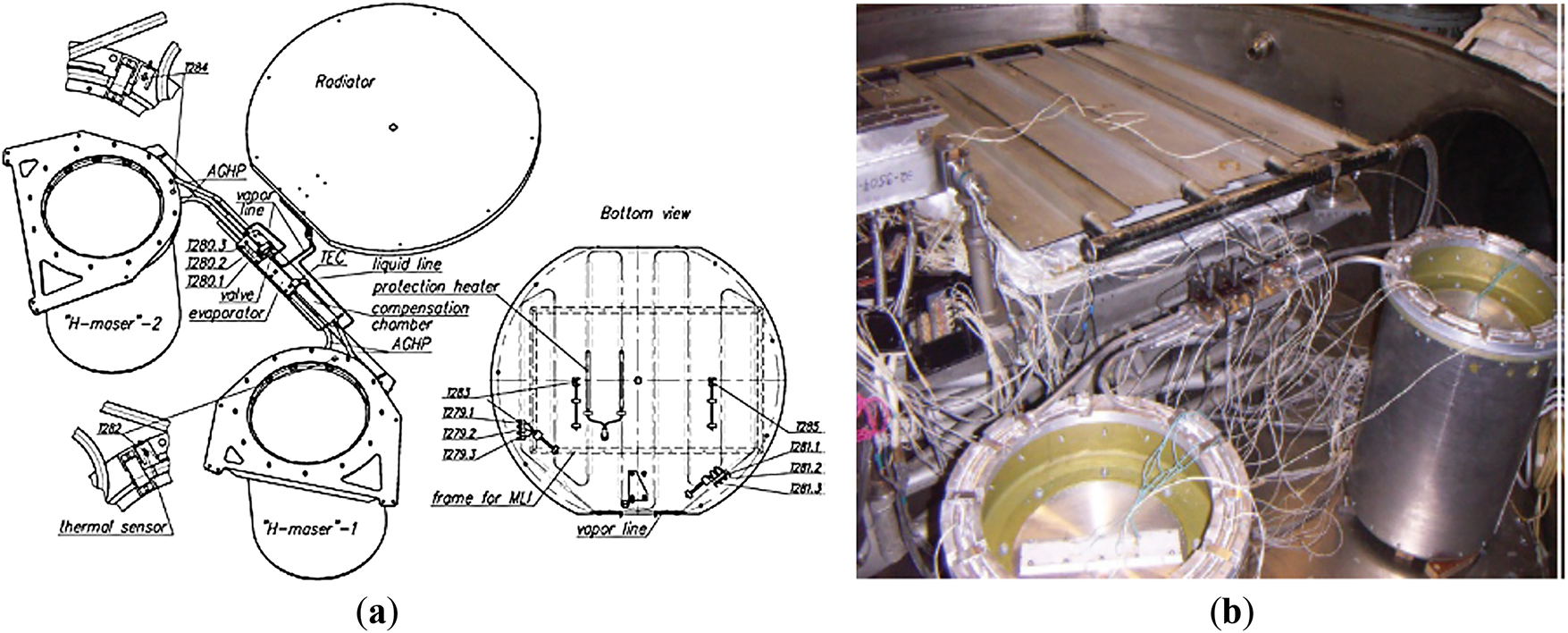

In 2011, Russian scientific experimental satellite Spectrum-R [52] used LHP to achieve high-precision and high-stability temperature control for a large radio telescope. The satellite had two microwave masers as backups for each other, with each generating 70 W of heat. Several heat pipes were coupled together to form a module, and the LHP evaporator was attached to these heat pipes as shown in Fig. 13. To suppress reservoir temperature fluctuations, a 1 kg aluminum block was installed on the reservoir. The price of this method is the additional weight while the advantage is extremely high temperature control accuracy and stability. Spectrum-R satellite achieved device temperature control with an accuracy of 0.1°C and an average temperature fluctuation of no more than 0.003°C over a period of 2400 s using LHP.

Figure 13: Reservoir controlled under high heat capacity coupling block (a) LHP structure (b) thermal vacuum test

2.3.4 Combined Structure on Liquid Line

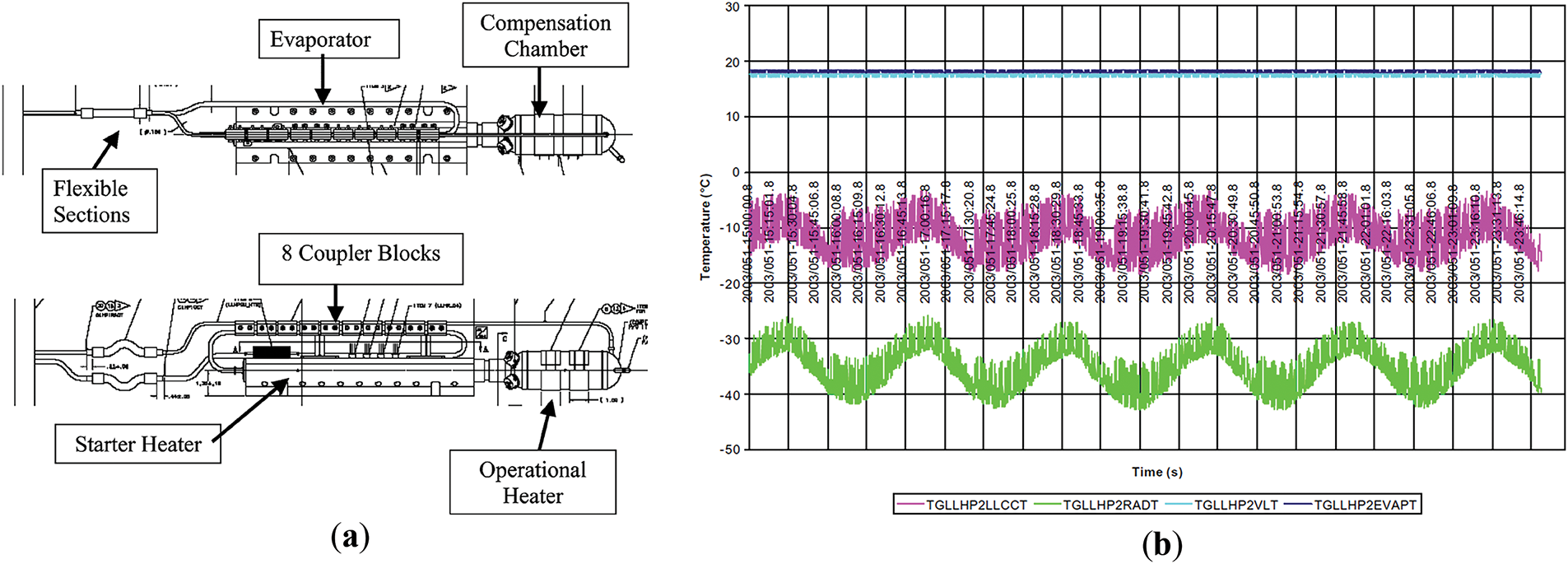

The thermal control system of the ICESAT, launched by the U.S., used two sets of propylene LHPs: one for dissipating heat from gyroscopes, power supplies, and other electronic devices with a heat load of approximately 330 W, and another for thermal control of a 120 W laser system. Each LHP reservoir was equipped with two heaters: an electrical heater (22 W) and a survival heater (22 W). The electrical heater regulated the reservoir temperature to 17 ± 0.2°C based on the set point. The structure of the LHP and its on-orbit temperature curve are shown in Fig. 14. To reduce the power consumption of the reservoir heaters for temperature control, NASA thermally coupled parts of the vapor and liquid lines of the LHPs using aluminum blocks. This heating of the vapor line reduced the subcooling of the returning liquid.

Figure 14: Liquid line combined with vapor line through coupling block (a) LHP structure (b) on-orbit temperature profile. Reprinted with permission from reference [42]

SWIFT is a scientific exploration satellite launched by NASA with an orbital height of 600 km. Its core payload, the Burst Alert Telescope, detects gamma-ray bursts in space. Eight ammonia groove heat pipes transferred heat to the evaporators of two propylene LHPs, which then directed the heat to the radiator panels. The structure of the LHP and its on-orbit temperature curve are shown in Fig. 15. The system employed a three-level temperature control strategy to suppress the temperature variation of the detector array within ±0.5°C: (1) Variable conductance heat pipe thermally coupled the LHP liquid line to the evaporator for coarse temperature control. When the returning liquid had a large degree of subcooling, part of the evaporator’s heat could be offset, reducing the power consumption of the reservoir electrical heater. (2) The electrical heater on the reservoir achieved precise temperature control of the LHP. (3) The electrical heater on the detector array board ensured uniform temperature across the board. A drawback of this method is that the variable conductance heat pipes respond slowly to changes in LHP operating conditions, leading to larger temperature fluctuations and reduced control accuracy.

Figure 15: Liquid line combined with evaporator through variable conductance heat pipes (a) BAT structure (b) LHP structure (c) on-orbit temperature profile. Reprinted with permission from reference [40]

Joung et al. [53,54] proposed a method to control the operating temperature of LHP by extracting or injecting NCG into the reservoir. Helium was used as the control gas, and distilled water served as the working fluid for the LHP. In steady-state operation tests, the temperature control accuracy of LHP reached 0.01°C. The authors noted a drawback of this method: when NCG is extracted, gaseous working fluid may also be removed from the reservoir, potentially causing LHP failure.

Khalili et al. [55] designed a LHP with a novel evaporator structure, where the operating temperature is controlled by the position of an iron ball inside the evaporator. The iron ball can be moved using an external magnet, which alters the parasitic heat leakage from the evaporator to the reservoir. A one-dimensional steady-state model was developed for the new LHP in a horizontal orientation. When the iron ball was in different positions, the predicted evaporator temperatures from the model showed a maximum error of no more than 5% compared to experimental data.

Dong et al. [56] proposed a temperature control method for LHP based on a louvered condenser. By adjusting the opening of louvers through a fuzzy control strategy, the radiation rate of the condenser board can be controlled, thereby controlling the length of condensation area in the LHP. The experiment adopted numerical simulation methods, and the results demonstrate that the louvered condenser can maintain the operating temperature of LHP under certain disturbances, although the dynamic response time is relatively long.

3 Challenge and Future Direction

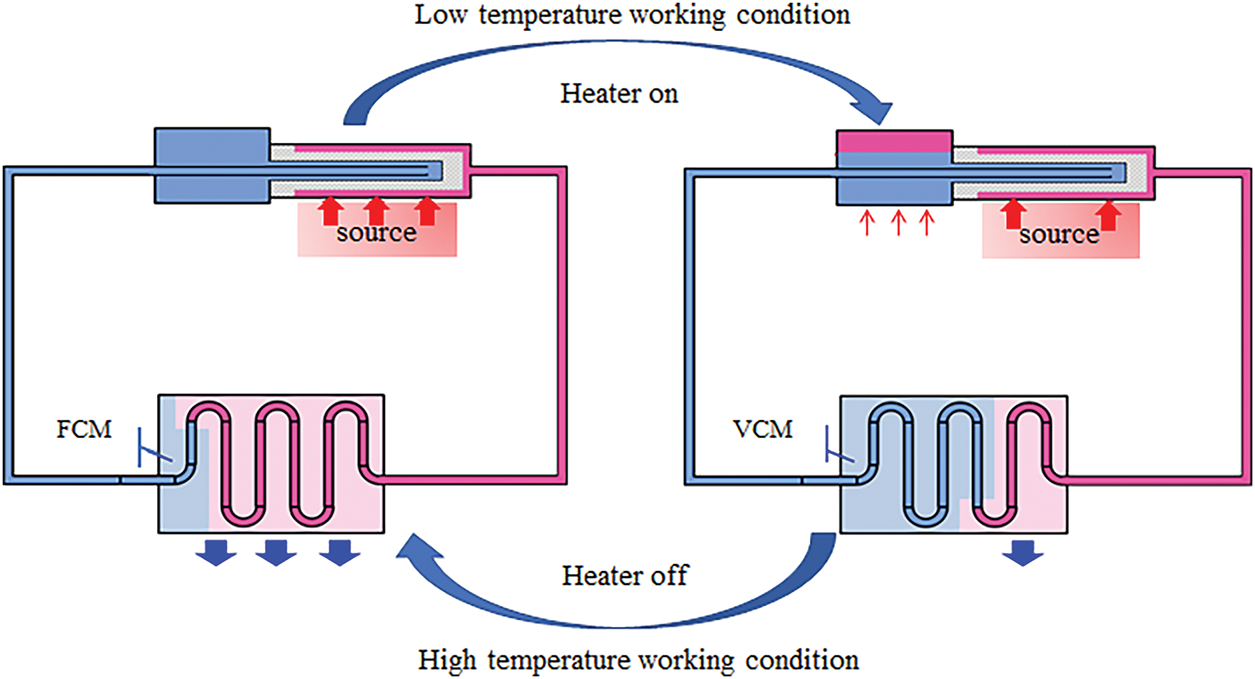

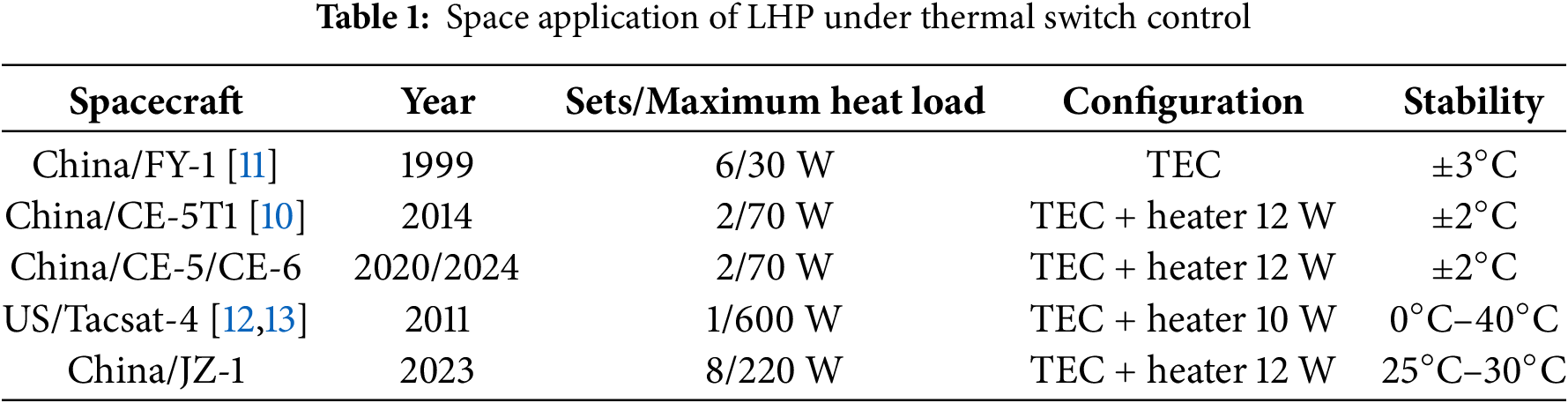

Table 4 summarizes the characteristics and advantages/disadvantages of diverse temperature control methods for LHP. It is evident that LHP with reservoir-based temperature control can achieve active high-precision and high-stability temperature regulation, meeting the temperature control requirements of various payloads on spacecraft.

Currently, space applications predominantly use TEC/electrical heater to regulate the temperature of LHP reservoir. However, several challenges remain unresolved:

(1) Mathematical models should be optimized for microgravity application. When operating in temperature control mode, LHP require heating or cooling after variation of external heat flux or payload operation modes. During this process, complex phase changes, heat transfer, and mass transfer occur within the two-phase state reservoir. Additionally, significant variations in gas-liquid interface distribution are observed under microgravity conditions [57] as shown in Fig. 16. To date, no precise mathematical model exists [58–60] that can reflect internal processes and predict heating or cooling power requirements for microgravity application, leading to an inaccuracy of temperature control.

(2) Reservoir temperature control should be improved to achieve higher stability and lower energy consumption. Existing space applications typically employ a strategy where TECs are always active while heaters provide additional temperature regulation. A portion of the heater’s power compensates for the refrigeration capacity of the TEC, leading to energy losses and placing additional heat loads on the heat dissipation surfaces. Moreover, excessive adjustment power from the heater can negatively impact the final temperature control accuracy.

(3) LHP should achieve reliable mode conversion on-orbit to address complex external thermal environments and variable payload operation modes as shown in Fig. 17. For high-temperature working condition requiring full-power operation, LHP function in fixed conductance mode to achieve maximum heat transfer capability. In contrast, for low-temperature working condition with partial-power operation, LHP switch to temperature control mode, maintaining operating temperatures using both heaters and TECs. However, research into the factors influencing transitions between fixed conductance mode and temperature control mode is insufficient. The system response to changes in heat loads and sinks is not sufficiently sensitive, affecting equipment temperature control accuracy.

Figure 16: Gas-liquid distribution in LHP (a) under 1 g gravity (b) under microgravity

Figure 17: Mode conversion of LHP under different working conditions

Based on the aforementioned analysis, the following research directions are proposed to address the challenges in reservoir temperature control for LHP in space applications:

(1) A steady-state computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model could be developed to characterize the internal processes between the evaporator and the reservoir. This model should predict the required temperature control power for various operating conditions under different attitudes on the ground. Peculiar microgravity phenomenon should also be considered in the model, such as natural convection disappearance and stratification effect. Through analysis of the flow, heat transfer, and phase change processes dominated by capillary and inertial forces within the reservoir and evaporator, factors such as the liquid inventory in LHP reservoir, magnitude of control power, heating and cooling locations could also be examined. Unlike one-dimensional model, the major challenge of a CFD model is the coupling effect of capillary force and evaporation process from which severe divergence may occur if not modeled appropriately. Multiphase models such as Volume of Fluid which have advantage on interface detection are recommended to solve this issue.

(2) The duty cycle of the electrical heater should serve as a criterion for decision-making. When the duty cycle exceeds a certain threshold, the refrigeration effect of the returning liquid alone can balance the energy requirements of the reservoir, allowing the TEC to be turned off. Conversely, when the duty cycle falls below the threshold, the TEC should be activated. Design guidelines for temperature control strategies should be proposed by considering factors such as spacecraft attitude, subcooling of the returning liquid, and control point location. In addition to pure active temperature control strategy, hybrid active-passive temperature control methods combining phase change materials with TECs or heaters should be explored through theoretical analysis and experimental verification. Optimization of reservoir structure and internal reflux pipeline is also a feasible solution to achieve a more energy-efficient, stable, and precise temperature control. Several design principles and optimization directions may be helpful, e.g., minimizing temperature field difference via an embedded control heater, minimizing reservoir mass while maximizing thermal capacitance, and minimizing liquid-vapor interface fluctuation inside reservoir via secondary wick.

(3) Experimental studies on the dynamic characteristics of LHP systems tailored to actual space application scenarios should be conducted. A system-level dynamic mathematical model reflecting the influence of heat sources and sinks on LHP performance should be established. The dynamic behavior during transitions between different operating modes, including initial temperature states, heat load conditions, and abrupt changes in heat sinks, should be analyzed. Combining dynamic modeling and experimental results, the reservoir structure and material should be optimized to improve the adaptability of LHP across wide temperature ranges and enhance their dynamic stability.

With the goal of addressing the high-precision, high-stability, and low-energy consumption temperature control requirements for payloads on spacecraft, this paper analyzes typical temperature control principles and methods of LHP, including thermal switch control, bypass valve control, and reservoir temperature control. Thermal switch control and bypass valve control are simple to apply, meeting the temperature control requirements for devices that require ordinary precision within ±2°C. However, it is difficult to achieve higher precision temperature control with these methods.

Current space applications of LHPs primarily use TEC/electrical heater for reservoir temperature control with an average temperature stability of ±0.2°C and energy consumption of 30 W. Passive reservoir control as PCM and coupling block can also achieve this level of stability but the application scenarios are restricted compared with TEC/electrical heater. LHP orientation, control strategy, and control point location are factors that should be taken into consideration while designing reservoir temperature control. Further improvement is possible if significant challenges listed below are resolved: (1) Lack of precise mathematical models for temperature control under microgravity scenario; (2) Inefficient temperature control strategies; (3) Insufficient understanding of mode conversion mechanisms between FCM and temperature control mode. To address these, future research should focus on: (1) Developing a steady-state CFD model to simulate internal processes under microgravity condition; (2) Optimizing active temperature control strategies using heater duty cycles to determine TEC operation, exploring hybrid active-passive thermal control methods, and improving reservoir structure for better efficiency and stability; (3) Conducting experimental studies on LHP dynamic characteristics under varying sink conditions and establishing a system-level dynamic model.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by National Outstanding Youth Foundation of China, grant number 2020-JCJQ-ZQ-042.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Chuxin Wang and Hongxing Zhang; formal analysis, Qi Wu and Ye Wang; investigation, Zenong Fang and Chang Liu; resources, Guoguang Li; writing—original draft preparation, Chuxin Wang; writing—review and editing, Zenong Fang, Hongxing Zhang and Jianyin Miao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jing YZ, Duan PF, Li BC, Wang WG, An N, Xia CH, et al. Design and system verification of the hyperspectral detector on the “Jumang” satellite. Chin J Space Sci. 2023;43(6):142–9. (In Chinese). doi:10.16708/j.cnki.1000-758X.2023.0093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhang BQ, Xiang YC, Xue SY, Zheng K, Zhong Q, Zhang YW. Analysis of the influence of Martian surface thermal environment on spacecraft thermal control. Chin J Space Sci. 2021;41(2):55–62. (In Chinese). doi:10.16708/j.cnki.1000-758X.2021.0022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ji X, Guo H, Xu J. Research and development of loop heat pipe—a review. Front Heat Mass Transf. 2020;14:1–16. doi:10.5098/hmt.14.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Szymanski P, Mikielewicz D, Fooladpanjeh S. Current trends in Wick structure construction in loop heat pipes applications: a review. Materials. 2022;15(16):5765. doi:10.3390/materials15165765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhao Y, Wei M, Dan D. Modeling, design, and optimization of loop heat pipes. Energies. 2024;17(16):3971. doi:10.3390/en17163971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Anand AR. Investigations on effect of noncondensable gas in a loop heat pipe with flat evaporator on deprime. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2019;143(9):118531. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2019.118531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Anand AR, Jaiswal A, Ambirajan A, Dutta P. Experimental studies on a miniature loop heat pipe with flat evaporator with various working fluids. Appl Therm Eng. 2018;144:495–503. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.11.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Nagano H, Ku J. Capillary limit of a miniature loop heat pipe with multiple evaporators and multiple condensers. In: Proceedings of the 9th AIAA/ASME Joint Thermophysics and Heat Transfer Conference; 2006 Jun 5–8; San Francisco, CA, USA. doi:10.2514/6.2006-3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Giraudon R, Lips S, Fabrègue D, Gremillard L, Maire E, Sartre V. Effect of the wick characteristics on the thermal behaviour of a LHP capillary evaporator. Int J Therm Sci. 2018;133:22–31. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2018.06.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang HX, Min M, Miao JY, Wang L, Chen Y, Ding T, et al. Development and on-orbit operation of loop heat pipes on Chinese circumlunar return and reentry spacecraft. J Mech Sci Technol. 2017;31(6):2597–605. doi:10.1007/s12206-017-0501-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Fang YK, Zhao XX, Tian M, editors. Thermal design and on-orbit temperature analysis of “Fengyun-1” C satellite. In: Proceedings of the 5th Space Thermal Physics Conference. Beijing, China: Chinese Society of Astronautics; 2000. p. 39–45. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

12. Dussinger PM, Sarraf DB, Anderson WG. Loop heat pipe for TacSat-4. In: Proceedings of the Space, Propulsion & Energy Sciences International Forum (SPESIF-2009); 2009 Feb 24–26; Huntsville, AL, USA. doi:10.1063/1.3115583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Hoang T, Armiger W, Baldauff R, Nguyen B, Mahony D, Robinson W. Performance of COMMx loop heat pipe on TacSat 4 spacecraft. In: Proceedings of the 42nd International Conference on Environmental Systems; 2012 Jul 15–19; San Diego, CA, USA. doi:10.2514/6.2012-3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Goncharov K, Kochetkov A, Buz V. Development of loop heat pipe with pressure regulator. SAE Tech Pap. 2006;1:2171. doi:10.4271/2006-01-2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Bodendieck F, Schlitt R, Romberg O, Goncharov K, Buz V, Hildebrand U. Precision temperature control with a loop heat pipe. In: Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Environmental Systems; 2005 Jul 11–14; San Francisco, CA, USA. Reston, VA, USA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics; 2005. p. 42–50. [Google Scholar]

16. Nikitkin M, Kotlyarov E, Serov G. Basics of loop heat pipe temperature control. In: Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Environmental Systems; 2000 Jul 10–13; Toulouse, France. Warrendale, PA, USA: Society of Automotive Engineers; 2000. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

17. Ku J. Methods of controlling the loop heat pipe operating temperature. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Environmental Systems: the SAE Brasil Congress and Exhibit; 2008 Oct 7–9; São Paulo, Brazil. Warrendale, PA, USA: Society of Automotive Engineers; 2008. p. 22942–54. [Google Scholar]

18. Goncharov K, Golikov A, Basov A. 10-year experience of operation of loop heat pipes mounted on board “yamal-200” satellite. Heat Pipe Sci Technol. 2014;5(1–4):539–46. doi:10.1615/heatpipescietech.v5.i1-4.620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang NH, Burger J, Luo F, Cui Z, Xin GM, Du WJ, et al. Operation characteristics of AMS-02 loop heat pipe with bypass valve. Sci China Tech Sci. 2011;54(7):13–1819. doi:10.1007/s11431-011-4417-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Xin G, Chen Y, Cheng L, Luan T, Song J, Molina M, et al. Simulation of a LHP-based thermal control system under orbital environment. Appl Therm Eng. 2009;29(13):2726–30. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2009.01.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Bai L, Guo J, Lin G, He J, Wen D. Steady-state modeling and analysis of a loop heat pipe under gravity-assisted operation. Appl Therm Eng. 2015;83(5):88–97. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2015.01.064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Jazebizadeh H, Kaya T. Numerical and experimental investigation of the steady-state performance characteristics of loop heat pipes. Appl Therm Eng. 2020;181:115577. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.115577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ramasamy NS, Kumar P, Wangaskar B, Khandekar S, Maydanik YF. Miniature ammonia loop heat pipe for terrestrial applications: experiments and modeling. Int J Therm Sci. 2018;124(7–8):263–78. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2017.10.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Meinicke S, Knipper P, Helfenritter C, Wetzel T. A lean approach of modeling the transient thermal characteristics of loop heat pipes based on experimental investigations. Appl Therm Eng. 2019;147:895–907. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhou L, Qu ZG, Chen G, Huang JY, Miao JY. One-dimensional numerical study for loop heat pipe with two-phase heat leak model. Int J Therm Sci. 2019;137(4):467–81. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2018.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Adachi T, Chang X, Nagai H. Numerical analysis of loop heat pipe using nucleate boiling model in evaporator core. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2022;195:123207. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2022.123207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Anand AR, Ambirajan A, Dutta P. Investigations on vapour blanket formation inside capillary wick of loop heat pipe. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2020;156(14):119685. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2020.119685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Franzoso A, Ruzzo P, Vettore C, Vettore C. TECLA: a TEC-enhanced loop heat pipe. In: Proceedings of the 43rd International Conference on Environmental Systems; 2013 Jul 14–18; Vail, Colorado, USA. Reston, VA, USA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics; 2013. p. 32–54. [Google Scholar]

29. Pastukhov VG, Maydanik YF. Experimental investigations of a loop heat pipe with active control of the operating temperature. Int J Therm Sci. 2022;172:107351. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2022.107351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yang R, Lin G, He J, Bai L, Miao J. Investigation on the effect of thermoelectric cooler on LHP operation with non-condensable gas. Appl Therm Eng. 2017;110:1189–99. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.08.070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Pastukhov VG, Maydanik YF. Temperature control of a heat source using a loop heat pipe integrated with a thermoelectric converter. Int J Therm Sci. 2023;184(5–6):108012. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2022.108012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Nagano H, Nishikawara M, Fukuyoshi F, Nagai H, Ogawa H. Thermal vacuum testing of a small loop heat pipe with a PTFE wick for spacecraft thermal control. Trans Jpn Soc Aeronaut Space Sci Aerosp Technol Jpn. 2012;10(ists28):Pc_27–33. doi:10.2322/TASTJ.10.PC_27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ku J, Paiva K, Mantelli M. Loop heat pipe transient behavior using heat source temperature for set point control with thermoelectric converter on reservoir. In: Proceedings of the 9th Annual International Energy Conversion Engineering Conference; 2011 Aug 16–18; Portland, OR, USA. Reston, VA, USA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics; 2011. p. 228–40. [Google Scholar]

34. Gellrich T, Meinicke S, Knipper P. Two-degree-of-freedom heater control of a loop heat pipe based on stationary modeling. In: Proceedings of the 48th International Conference on Environmental Systems; 2018 Jul 8–12; Albuquerque, NM, USA. Reston, VA, USA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics; 2018. p. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

35. Gellrich T, Min Y, Schwab S, Hohmann S. Model-free control design for loop heat pipes using deep deterministic policy gradient. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2020;53(2):1575–80. doi:10.1016/j.ifacol.2020.12.1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Gellrich T, Möller J, Schwab S, Hohmann S. Extended nonlinear dynamical modeling and state estimation for the temperature control of loop heat pipes. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Conference on Control Technology and Applications; 2020 Aug 24–26; Montreal, QC, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers; 2020. p. 1015–22. [Google Scholar]

37. Fang ZN, Liu C, Zhang CQ, Xu YW, Zhang HX, Miao JY. The influence factor analysis of loop heat pipe temperature controlling accuracy and capillary limit prediction. J Beijing Univ Aeronaut Astronaut. 2024;143:1–8. (In Chinese). doi:10.13700/j.bh.1001-5965.2022.0886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Huang JY, Pan FM, Fu WC. Thermal design and verification of laser altimeter for GF-7 satellite. Spacecr Eng. 2020;29(3):138–43. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1673-8748.2020.03.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Choi M. Swift BAT loop heat pipe thermal system characteristics and ground/flight operation procedure. In: Proceedings of the 1st International Energy Conversion Engineering Conference (IECEC); 2003 Aug 17–21; Portsmouth, VA, USA. [Google Scholar]

40. Choi MK. Swift BAT thermal recovery after loop heat pipe #0 secondary heater controller failure in october 2015. In: Proceedings of the 14th International Energy Conversion Engineering Conference; 2016 Jul 25–27; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. Reston, VA, USA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics; 2004. [Google Scholar]

41. Grob E, Baker C, McCarthy T. In-flight thermal performance of the geoscience laser altimeter system (GLAS) instrument. In: Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Environmental Systems; 2004 Jul 11–14; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Reston, VA, USA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics; 2004. [Google Scholar]

42. Baker C, Butler C, Jester P, Grob E. Geoscience laser altimetry system (GLAS) loop heat pipe anomaly and on orbit testing. In: Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Environmental Systems; 2011 Jul 17–21; Portland, OR, USA. [Google Scholar]

43. Ku J, Garrison M, Patel D. Loop heat pipe temperature oscillation induced by gravity assist and reservoir heating. In: Proceedings of the 45th International Conference on Environmental Systems; 2015 Jul 12–16; Seattle, WA, USA. Reston, VA, USA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics; 2014. p. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

44. Semenov SY, Patel D. Instrument level TVAC testing of the PACE OCI loop heat pipes. In: Proceedings of the 53rd International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES); 2024 Jul 21–25; Louisville, KY, USA. [Google Scholar]

45. Semenov S, Patel D, Hoang T, Stull C. Thermal ground testing of loop heat pipes for PACE OCI. In: Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Environmental Systems; 2022 Jul 10–14; Saint Paul, MN, USA. [Google Scholar]

46. Gao T, Yang T, Zhao SL, Meng QL. The design and application of temperature control loop heat pipe. In: Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium of Space Optical Instruments and Applications; 2017 Oct 16–18; Delft, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

47. Meng Q, Yang T, Yu Z, Zhao Z, Zhao Y, Yu F. Transient numerical simulation and on-orbit verification of loop heat pipe used for space remote sensor. J Beijing Univ Aeronaut Astronaut. 2020;46(11):2045–55. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

48. Okamoto A, Miyakita T, Nagano H. On-orbit experiment plan of loop heat pipe and the test results of ground test. Microgravity Sci Technol. 2019;31(3):327–37. doi:10.1007/s12217-019-9703-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Okamoto A, Miyakita T, Nagano H. Initial evaluation of on-orbit experiment of loop heat pipe on ISS. In: Proceedings of the 49th International Conference on Environmental Systems; 2019 Jul 7–11; Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

50. Lang D, Morgenroth L, Harms F, Sang B, Dandaleix L, Coquard T, et al. EnMAP hyper spectral instrument thermal design and test verification. In: Proceedings of the 49th International Conference on Environmental Systems; 2019 Jul 7–11; Vail, CO, USA. Reston, VA, USA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics; 2013. p. 351–67. [Google Scholar]

51. Zhang HX, Miao JY, Shao XG. Phase change material assisted LHP start-up experiment. J Astronaut. 2009;30(4):1732–37,43. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

52. Tulin DV, Vinogradov IS, Shabarchin AF, Privezentsev AS, Goncharov KA. System of maintaining the thermal regime of a space radio telescope. Cosm Res. 2014;52(5):386–90. doi:10.1134/s0010952514050098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Nam B, Park C, Joung W. Temperature uniformity of a hybrid pressure-controlled loop heat pipe with a heat pipe liner. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2024;156(3):107656. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2024.107656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Park C, Joung W. Effect of heat load on pneumatic temperature control characteristics of a pressure-controlled loop heat pipe. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2022;186(5):122472. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.122472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Khalili M, Abolmaali A, Mostafazade SH, Shafii MB. Experimental and analytical study of thermohydraulic performance of a novel loop heat pipe with an innovative active temperature control method. Appl Therm Eng. 2018;143:964–76. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.08.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Dong SJ, Li YZ, Wang J, Wang J. Fuzzy incremental control algorithm of loop heat pipe cooling system for spacecraft applications. Comput Math Appl. 2012;64(5):877–86. doi:10.1016/j.camwa.2012.01.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Matsuda Y, Nagano H, Okazaki S. Visualization of loop heat pipe with multiple evaporators under micro-gravity. In: Proceedings of the 45th International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES 2015); 2015 Jul 12–16; Bellevue, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

58. Shao B, Lin B, Li N, Liu L, Jiang Z, Dong D, et al. Numerical study on the effect of various working fluids on the performance of loop heat pipes based on two-dimensional simulation. J Therm Sci Eng Appl. 2025;17(3):1–17. doi:10.1115/1.4067630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Zhang Z, Cui H, Ma Z, Zhang Y, Liu Z, Liu W. Numerical study and parametric analysis of thermo-hydraulic behavior in a flat loop heat pipe at system scale. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;61:104874. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2024.104874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Wang HJ, Xu JY, Hong FJ. Developing of an open-source toolbox for liquid-vapor phase change in the porous wick of a LHP evaporator based on OpenFOAM. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2022;35(3):102068. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2022.102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools