Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Spectral Quasi-Linearization Study of Variable Viscosity Casson Nanofluid Flow under Buoyancy and Magnetic Fields

1 PG and Research Department of Mathematics, Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda College, Mylapore, Chennai, 600004, India

2 Department of Mathematical Sciences, Saveetha School of Engineering, SIMATS, Chennai, 602105, Tamilnadu, India

3 Department of Pure and Applied Mathematics, School of Mathematical Sciences, Sunway University, Bandar Sunway, Petaling Jaya, 47500, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

4 Department of Physics, Faculty of Sciences, University of 20 Août 1955-Skikda, Skikda, 21000, Algeria

5 Department of Mathematical Sciences, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain, Abu Dhabi, P.O. Box 15551, United Arab Emirates

6 Department of Mathematics, Namal University, Mianwali, 42250, Pakistan

7 Department of Mathematics, Geethanjali College of Engineering and Technology, Cheeryal, 501301, India

8 Department of Mathematics and Computational Sciences, University of Zimbabwe, Mount Pleasant, Harare, P.O. Box MP167, Zimbabwe

* Corresponding Authors: Fateh Mebarek-Oudina. Email: ,

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(4), 1243-1260. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.066782

Received 17 April 2025; Accepted 14 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

The behavior of buoyancy-driven magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) nanofluid flows with temperature-sensitive viscosity plays a pivotal role in high-performance thermal systems such as electronics cooling, nuclear reactors, and metallurgical processes. This study focuses on the boundary layer flow of a Casson-based sodium alginate Fe3O4 nanofluid influenced by magnetic field-dependent viscosity and thermal radiation, as it interacts with a vertically stretching sheet under dissipative conditions. To manage the inherent nonlinearities, Lie group transformations are applied to reformulate the governing boundary layer equations into similarity forms. These reduced equations are then solved via the Spectral Quasi-Linearization Method (SQLM), ensuring high accuracy and computational efficiency. The analysis comprehensively explores the impact of key parameters—including mixed convection intensity, magnetic field strength, Casson fluid properties, temperature-dependent viscosity, thermal radiation, and viscous dissipation (Eckert number)—on flow characteristics and heat transfer rates. Findings reveal that increasing magnetic field-dependent viscosity diminishes both skin friction and thermal transport, while buoyancy effects enhance heat transfer but lower shear stress on the surface. This work provides critical insights into controlling heat and momentum transfer in Casson nanofluids, advancing the design of thermal management systems involving complex fluids under magnetic and buoyant forces.Keywords

The flow within the boundary layer that is generated by stretching a sheet is a significant engineering challenge that has a wide range of industrial applications, including plastic extrusion, melting and spinning, rolling and hot, drawing wire, producing glass fiber, manufacturing polymer and rubber sheets, and improved petroleum resource recovery. In stretching sheet problems, the heat transfer mechanism plays a pivotal role, as it shapes the thermal environment that ultimately governs the quality and consistency of the final product [1–3]. In light of these applications, Crane [4] pioneered the analysis of the Newtonian boundary layer in the sheet, stretched with a linear velocity. Subsequently, flow over a sheet stretched along the surface has emerged as a topic of intensive interest, prompting substantial research in this field [5–8]. Since Newtonian fluid viscosity is not dependent on external factors, the non-Newtonian fluids receive much attention because they can change their flow behavior in response to applied stress or shear rate [9–12]. Non-Newtonian fluids are categorized by their rheological behavior into shear-thinning and shear-thickening types. Among them, Casson fluids show a distinctive non-linear correlation between shear stress and shear rate. Examples include concentrated fruit liquids, coal tar, sauces, honey, jelly, and human blood. Several industrial and engineering sectors, such as the pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and textile industries, as well as food processing facilities, utilize Casson fluid, which can either be shear-thinning or shear-thickening depending on the shear stress [13–15].

Non-Newtonian fluids are integrated with nanoparticles to create nanofluids, which possess exceptional thermal, electrical, and magnetic properties, hence enhancing reliability. These qualities serve a variety of industries, including energy, engineering, and technology, by producing enhanced heat transfer efficiency, improved fluid behavior, and superior control [16,17]. The numerical study, namely, the Runge-Kutta-Fehlberg method, was utilized to analyze the boundary layer flow of Casson nanofluid across a stretching sheet by Nadeem et al. [18] shows that the Casson parameter raises the fluid’s temperature and decreases the fluid’s velocity. Sulochana et al. [19] investigated the heat and flow of the fluid over a stretching sheet of Casson nanofluid using the Runge-Kutta based shooting numerical method and showed that the magnetic field parameter governs the flow, reducing friction; hence, the heat and mass transfer rate are comparatively high in non-Newtonian fluids. Vajravelu et al. [20] analyzed the impacts of thermal conductivity on Casson nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet, which shows that the thermal transmission and thickness of the thermal boundary layer enhance for the rise in thermal radiation parameter.

In addition to this, the interesting components that can be added to study the heat transmission or control of the nanofluid boundary layer are the MHD, ohmic, and viscous dissipation effects. Ohm’s law regulates kinetic dissipation in electrical flows by turning electrical energy into heat through resistance and exploring the effects of electrical currents on other substances. Viscous dissipation occurs when the kinetic energy in a fluid is transformed into heat energy due to the viscous effect of the fluid. This phenomenon is used in various industrial processes, including electronic cooling systems, gas and oil transportation, and polymer processing [21–25]. Pal et al. [26] observed the impacts of ohmic heating and heat radiation in Casson nanofluid along a sheet stretched vertically, noting that suction reduces thermal boundary layer thickness and fluid temperature with increasing Eckert number. Ghadikolaei et al. [27] studied the impacts of viscous and joule’s heating on Casson nanofluid across an inclined stretching sheet and observed that the radiation effect reduces the buoyancy and thermal boundary layer thickness. Khader et al. [28] revealed the effects of joule’s and viscous dissipations on the Casson fluid flow. Wang et al. [29] investigated the magnetohydrodynamic flow of a Casson-type sodium alginate nanofluid across a radiatively heated stretching sheet, revealing that thermal radiation enhances heat energy within the fluid, thereby increasing both temperature and thermal boundary layer thickness. Additionally, the Casson parameter and nanoparticle volume fraction also improve entropy generation.

Magnetic field-dependent (MFD) viscosity refers to changes in a fluid’s viscosity due to interactions between the magnetic field and charged particles or magnetic domains, affecting its flow behavior. This peculiar characteristic allows for dynamic changes in fluid viscosity in response to magnetic field changes, enhancing its worth across multiple industries, including automotive, aeronautical engineering, and medical applications [30]. Vaidyanathan et al. [31] noted that MFD viscosity increases resistance, delaying the onset of convection in ferrofluids and making it more difficult for thermal gradients to induce convection using the Brickman analytical method. An analytical study by Ramanathan et al. [32] looked into the effects of MFD viscosity in porous medium for ferro convection via the Darcy model. They found that MFD viscosity helps keep things stable by changing its thickness in response to the magnetic field. Sheikholeslami et al. [33,34] used the finite element method to analyze the impacts of MFD viscosity on the velocity of the flow and temperature within the boundary layer of MHD nanofluids and found that MFD viscosity dominated significantly. Molana et al. [35] revealed the hydrothermal characteristics of a water-based nanofluid-filled cavity under the effect of MFD viscosity using the finite element method and discovered that increasing the Hartmann number, which is controlled by a magnetic field, slows down the heat transfer.

It is clear from the existing literature remains limited in exploring the impacts of MFD viscosity, and no study has examined the combined dynamics of mixed convection and MFD viscosity. In this work, we conduct a SQLM analysis to investigate the mixed convection and MFD viscosity impact on a sodium alginate-based Casson nanofluid containing Fe3O4 nanoparticles as it flows across a sheet stretched vertically under the impacts of both ohmic and viscous dissipations. It focused on the variations in the temperature characteristics of sodium alginate-based Fe3O4 nanofluid across a sheet stretched vertically. To approach the problem, lie group transformations were applied to non-dimensionalize the governing equations, and the non-linear coupled equations were solved using the implicit method, specifically the SQLM. Numerical results are obtained for specific parameters, and graphical representations were generated to facilitate deeper understanding of the outcomes.

The physical model involves a 2-D incompressible and steady flow of sodium alginate-based Fe3O4 nanofluid occurring across a sheet stretched vertically in an impermeable surface with the velocity

Figure 1: Physical configuration of the model

The Lorentz force governs the fluid flow under the influence of a uniform transverse magnetic field (

where σnf and

The Lorentz force is defined under E = 0 as:

Nanofluid velocity, influenced by the magnetic field, is defined as [35]:

where

The problem governing the equations of mass, momentum and energy of a Casson based Fe3O4 nanofluid can be derived, with respect to the influence of MFD viscosity, thermal radiation, viscous and ohmic dissipations given as [19]:

where the velocities U* along x* direction, and V* in y* directions, respectively, and T* is the fluid’s local temperature. Here,

The radiative heat flux

where

Applying the expressions in (8) and (9), Eq. (6) becomes:

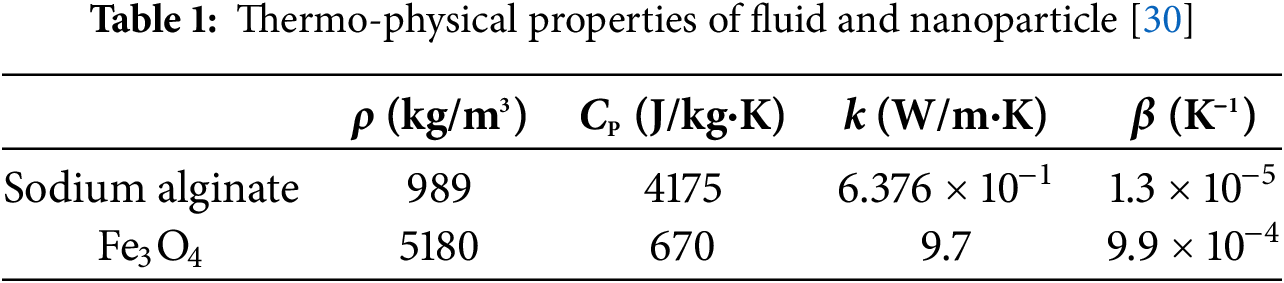

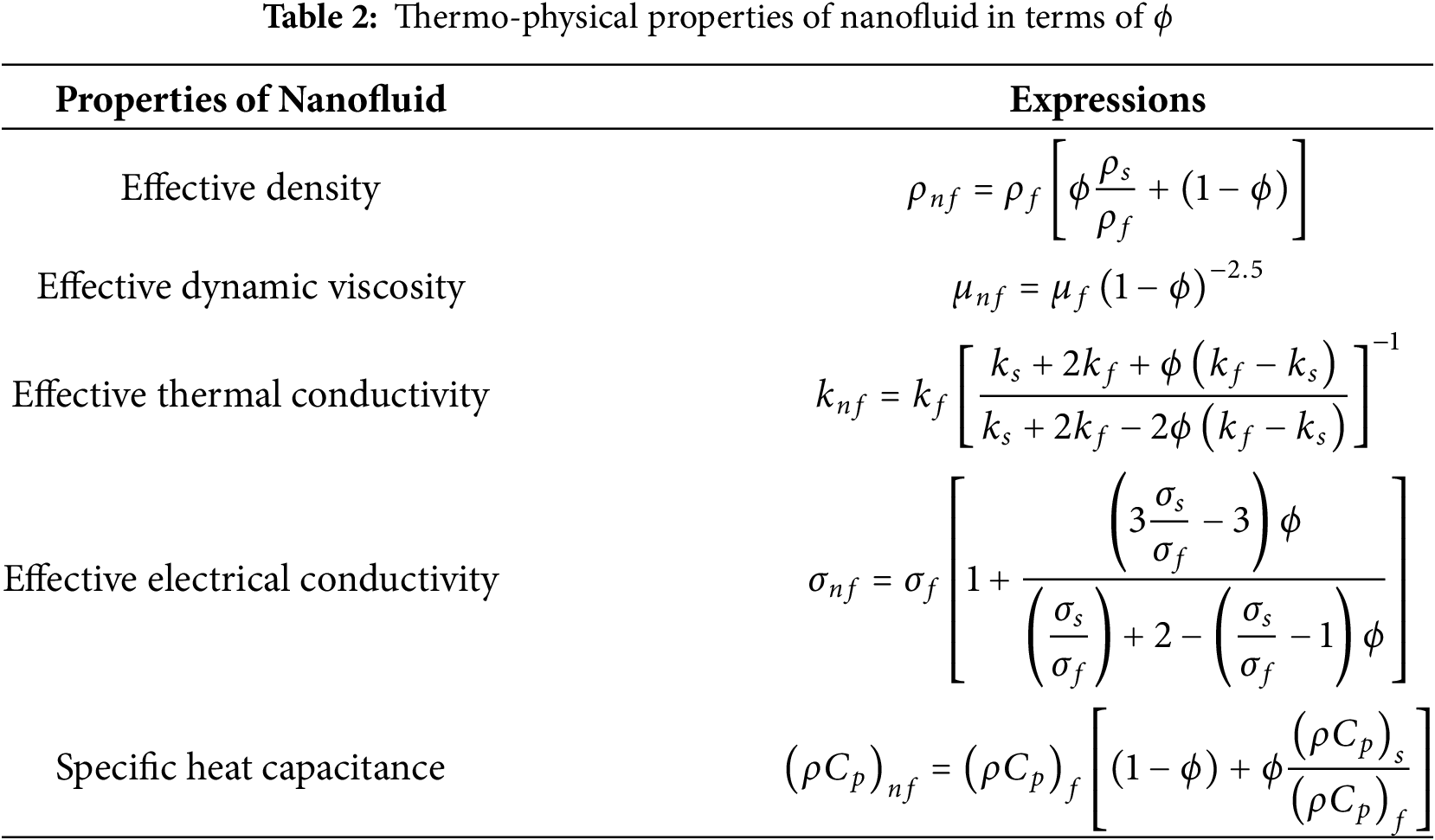

the physical and thermal quantities in Eqs. (4) and (10) are expressed in Tables 1 and 2.

3 Non Dimensionalization and Lie Group Transformation

The non-dimensional variables utilized in the study are:

Using the foremost equations, Eqs. (4), (5), and (10) transform into the following:

along the boundary constraints,

Eq. (12) is verified using

Using the Eq. (16), the Eqs. (13) and (14) are expressed as follows:

Eq. (15) is derived as follows:

Employing the following Lie-group transforms [37]:

Here, the dimensionless constants Pr, M, λ, R and Ec denote the Prandtl number, magnetic parameter, mixed convection parameter, radiation parameter and Eckert number which are all expressed as:

The pertinent boundary conditions are listed below:

4 Essential Quantities in the Physical Study

The LSF coefficient

4.1 Local Skin Friction Coefficient

The LSF coefficient is expressed as:

The wall shear stress

The following relation is obtained from the Eqs. (23) and (24), and Table 2.

The RNN is expressed as:

where the surface heat transfer rate is represented as:

Thus, the dimensionless relation between wall heat transfer rates is obtained as follows, by using the Eqs. (26) and (27),

where

5 Computational Solution Using SQLM

System of non-linear differential Eqs. (20) and (21) with pertaining conditions in Eq. (22) is computed using SQLM [38,39]. We linearize the nonlinear components using the Taylor series expansion. Thus, the method converges rapidly if the differences between the consecutive iterations are minimal. For simplification, let us denote F and θ for the following expressions:

An iterative procedure for the error function is constructed below:

with the relevant conditions,

Expansions of the abbreviation used in Eq. (31) are as follows:

The initial guesses taken for the numerical procedure is:

The spectral collocation method is used in Eqs. (20) and (21) to obtain the approximate solutions, change the flow domain

The matrix D is expressed as:

where

Using the fore-mentioned results from Eqs. (29), (30), (33) and (34), the following system of simultaneous equations are,

Therefore, the matrix transformation of simultaneous equations in Eq. (35) are as follows:

where

where the diag[ ] is the diagonal matrix, and I is the identity matrix, respectively. To derive the solution, the matrix system provided in Eq. (36) is solved in conjunction with the boundary conditions specified in Eq. (32).

The practical challenges in fluid dynamics often involve complex, multi-order nonlinear differential equations due to their association with various physical processes. Solving these equations can be time-consuming, with traditional methods sometimes showing slow convergence or failure to yield results. The Spectral Quasi Linearization Method (SQLM) offers a notable improvement, providing faster convergence and simpler iterative steps. Its ability to break down complex systems into smaller, more manageable subsystems makes it a widely accepted and efficient numerical technique.

The following relation gives the residue errors as follows:

where

Figure 2: The residues of velocity profile and temperature profile

6 Validation of Numerical Solution

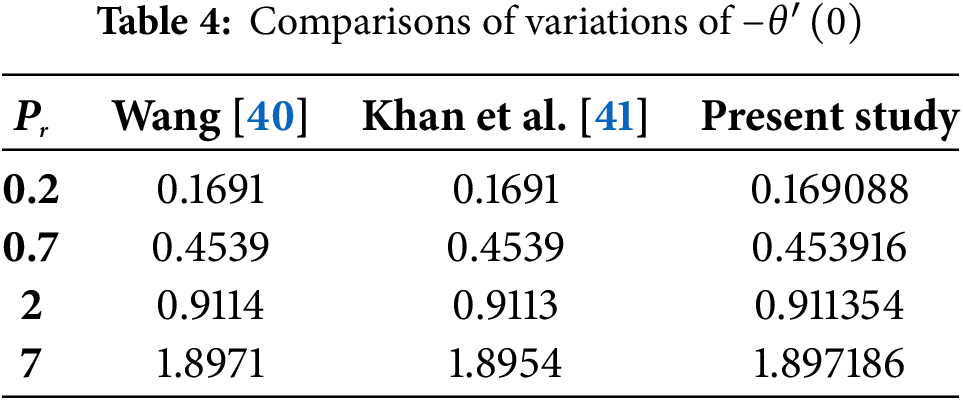

The governing equations of a non-Newtonian (Casson)-based Fe3O4 nanofluid was solved using the SQLM. The results showed excellent consistency with benchmark results from Wang [40] and Khan et al. [41], without the existence of MFD viscosity, Eckert number, and Hartmann number, which are listed in Table 4. Numerical outcomes for LSF and RNN are tabulated in Table 3. In this observation, the tolerance error was set to 10−7, and the residuals used to access accuracy had errors value for momentum and energy are 1/1010 and 1/1012, as shown in Fig. 2. Due to the limited availability of experimental data on magnetic field-dependent viscosity in nanofluids, direct validation remains a challenge. However, the present results offer a theoretical basis for future experimental investigations to enhance practical relevance.

Computational outcomes obtained from the system of equations for momentum and energy using the SQLM are interpreted through graphical representation. These graphs are analysed to know the relevance of key parameters on the buoyancy-driven boundary layer flow of sodium alginate-based Fe3O4 nanofluid over an impermeable moving surface. The parameters considered include the nanoparticle volume fraction (ϕ), magnetic parameter (M), isotropic MFD viscosity (δ*) parameter, Casson parameter (β), Eckert number (Ec), mixed convection parameter (λ), and thermal radiation parameter (R). Individual effects of each parameter are examined by holding certain parameters constant throughout the study. Initially, the collocation points are fixed at N = 80, and the constant values are fixed for the other parameters: Pr = 6.45, M = 0.5, ϕ = 0.1, Ec = 0.1, β = 0.1, λ = 1, and δ* = 0.1. The thermophysical properties of the nanoparticles are assumed to be constant for numerical simplicity, as is commonly done in nanofluid modeling. However, it is acknowledged that these properties may vary with temperature and magnetic field strength, which could slightly affect the quantitative accuracy of the results under extreme conditions.

The combined impacts of δ* and ϕ on the velocity

Figure 3: Impacts of MFD viscosity and volume fraction of nanoparticle with Pr = 6.45, M = 0.5, Ec = 0.1, R = 1, β = 0.1, and λ = 1, (δ* variation with ϕ = 0.1, & ϕ variation with δ* = 0.1) on (a) velocity profile (b) temperature profile

Fig. 4 displays the combined impacts of M and β on the

Figure 4: Impacts of Magnetic parameter and Casson parameter with Pr = 6.45, ϕ = 0.1, Ec = 0.1, R = 1, δ* = 0.1, and λ = 1, (β variation with M = 0.5, & M variation with β = 0.1) on (a) velocity profile (b) temperature profile

The variations in λ and Ec are observed in Fig. 5 for the

Figure 5: Impacts of Eckert number and mixed convection parameter with Pr = 6.45, ϕ = 0.1, M = 0.5, R = 1, δ* = 0.1, and β = 0.1, (λ variation with Ec = 0.1, & Ec variation with λ = 1) on (a) velocity profile (b) temperature profile

The R and Ec variations are observed in Fig. 6 for the

Figure 6: Impacts of Eckert number and Radiation parameter with Pr = 6.45, ϕ = 0.1, M = 0.5, δ* = 0.1, λ = 1 and β = 0.1, (R variation with Ec = 0.1, & Ec variation with R = 1) on (a) velocity profile (b) temperature profile

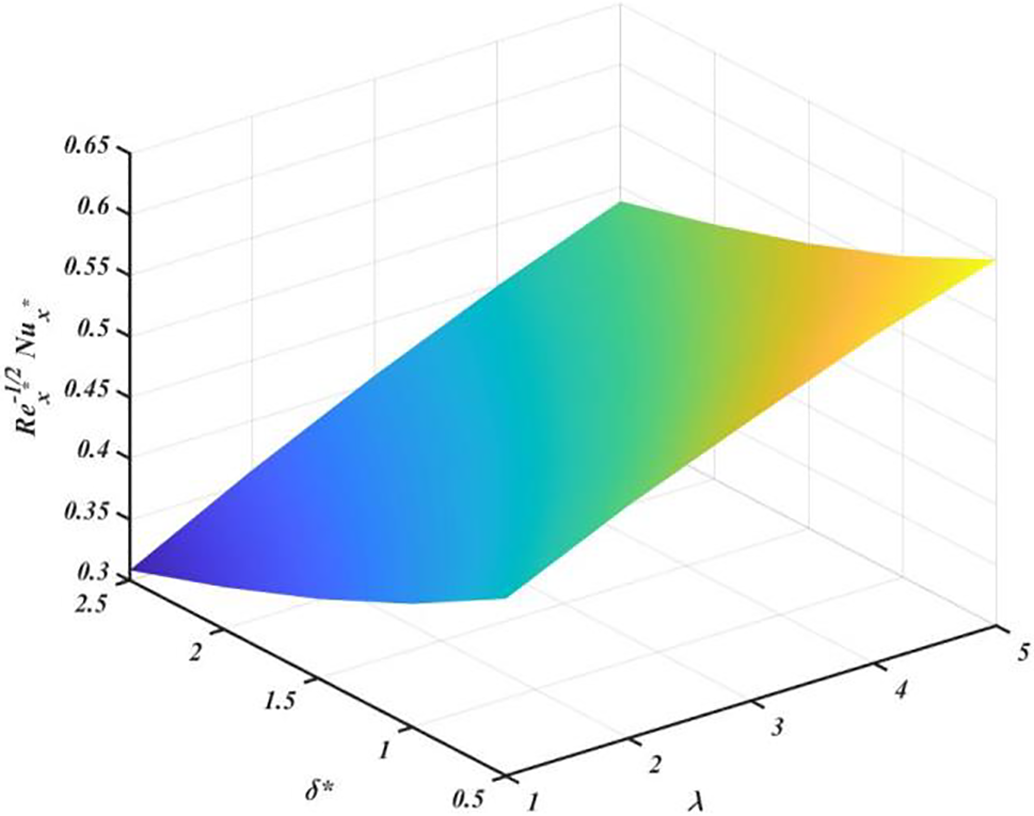

Figs. 7 and 8 show the impacts of δ* and λ on important physical quantities like RNN and LSF. For further reference, Table 4 displays the numerical results of the LSF and the RNN. As the δ* increases, the surface drag or LSF decreases due to reduced shear stress caused by δ*. A similar argument is observed with increasing λ, where stronger buoyancy forces reduce the wall shear stress, leading to a decrease in LSF, as shown in Fig. 7. The RNN decreases with increasing δ*, indicating a decline in convective heat transfer efficiency and increased thermal resistance. In contrast, the RNN increases with higher λ, reflecting enhanced heat transfer due to intensified buoyancy-driven convection. Based on the above findings, it is clear that both the δ* and λ are inversely proportional for local skin friction. Additionally, the δ* is inversely proportional to RNN, while the λ is directly proportional to RNN.

Figure 7: Impacts of MFD viscosity parameter and mixed convection parameter with Pr = 6.45, M = 0.5, Ec = 0.1, R = 1, β = 0.1, and ϕ = 0.1, (δ* variation with λ = 1, & λ variation with δ* = 0.1) on skin friction

Figure 8: Impacts of MFD viscosity parameter and mixed convection parameter with Pr = 6.45, M = 0.5, Ec = 0.1, R = 1, β = 0.1, and ϕ = 0.1, (δ* variation with λ = 1, & λ variation with δ* = 0.1) on Nusselt number

Impacts of MFD viscosity, mixed convection, and radiation effects on nanofluid flow across a sheet which is stretched in the existence of viscous and ohmic dissipation, utilizing Casson-based sodium alginate and Fe3O4 nanoparticles to stimulate the flow and heat transfer rate. Governing dimensionless system of equations is solved using a SQLM scheme, and relevant graphs and computational results are explored to elucidate the parametric impacts on the flow and heat transfer. Key outcomes include:

• MFD viscosity parameter rises the

• As the mixed convection parameter and the Eckert number increases, the velocity and momentum boundary layer expand, with a slight temperature variation for the former and a significant one for the latter.

• The temperature of the fluid rises due to more efficient heat distribution within the fluid if the radiation parameter enhances.

• MFD viscosity parameter decreases both the LSF and the RNN as it increases, whereas a rise in the mixed convection parameter reduces the LSF but raises the RNN.

• This work can be extended to three-dimensional flow problems and to different sheet orientations, providing engineers and researchers with insights to optimize industrial processes for improved control and efficiency.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, draft manuscript preparation: B. Rajesh, Fateh Mebarek-Oudina, N. Vishnu Ganesh, Qasem M. Al-Mdallal, Sami Ullah Khan, Murali Gundagnai, Hillary Muzara. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data is available on request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sakiadis BC. Boundary-layer behavior on continuous solid surfaces: II. the boundary layer on a continuous flat surface. AlChE J. 1961;7(2):221–5. doi:10.1002/aic.690070211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sakiadis BC. Equilibrium flow of a general fluid through a cylindrical tube. AlChE J. 1962;8(3):317–21. doi:10.1002/aic.690080311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Raza J, Mebarek-Oudina F, Ali H, Sarris IE. Slip effects on Casson nanofluid over a stretching sheet with activation energy: RSM analysis. Front Heat Mass Transf. 2024;22(4):1017–41. doi:10.32604/fhmt.2024.052749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Crane LJ. Flow past a stretching plate. J Appl Math Phys. 1970;21(4):645–7. doi:10.1007/bf01587695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang CY. The three-dimensional flow due to a stretching flat surface. Phys Fluids. 1984;27(8):1915–7. doi:10.1063/1.864868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lakshmisha KN, Venkateswaran S, Nath G. Three-dimensional unsteady flow with heat and mass transfer over a continuous stretching surface. J Heat Transf. 1988;110(3):590–5. doi:10.1115/1.3250533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Mahanta G, Shaw S. 3D Casson fluid flow past a porous linearly stretching sheet with convective boundary condition. Alex Eng J. 2015;54(3):653–9. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2015.04.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Arruna Nandhini C, Jothimani S, Chamkha AJ. Combined effect of radiation absorption and exponential parameter on chemically reactive Casson fluid over an exponentially stretching sheet. Partial Differ Equ Appl Math. 2023;8(5):100534. doi:10.1016/j.padiff.2023.100534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Mustafa M, Hayat T, Ioan P, Hendi A. Stagnation-point flow and heat transfer of a Casson fluid towards a stretching sheet. Z Für Naturforschung A. 2012;67(1–2):70–6. doi:10.5560/zna.2011-0057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sobamowo MG. Combined effects of thermal radiation and nanoparticles on free convection flow and heat transfer of Casson fluid over a vertical plate. Int J Chem Eng. 2018;2018(339):7305973–25. doi:10.1155/2018/7305973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kumar MA, Mebarek-Oudina F, Mangathai P, Shah NA, Vijayabhaskar C, Venkatesh N, et al. The impact of Soret Dufour and radiation on the laminar flow of a rotating liquid past a porous plate via chemical reaction. Mod Phys Lett B. 2025;39(10):2450458. doi:10.1142/s021798492450458x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mebarek-Oudina F, Dharmaiah G, Rama Prasad JL, Vaidya H, Kumari MA. Thermal and flow dynamics of magnetohydrodynamic Burgers’ fluid induced by a stretching cylinder with internal heat generation and absorption. Int J Thermofluids. 2025;25(3):100986. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2024.100986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Narsimha Reddy B, Maddileti P. Casson nanofluid and Joule parameter effects on variable radiative flow of MHD stretching sheet. Partial Differ Equ Appl Math. 2023;7(2):100487. doi:10.1016/j.padiff.2022.100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ali MY, Reza-E-Rabbi S, Ahmmed SF, Nabi MN, Azad AK, Muyeen SM. Hydromagnetic flow of Casson nano-fluid across a stretched sheet in the presence of thermoelectric and radiation. Int J Thermofluids. 2024;21(4):100484. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2023.100484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ramesh K, Mebarek-Oudina F, Souayeh B. Mathematical modelling of fluid dynamics and nanofluids. 1st ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2023. 556 p. doi:10.1201/9781003299608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sahoo B. Flow and heat transfer of a non-Newtonian fluid past a stretching sheet with partial slip. Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul. 2010;15(3):602–15. doi:10.1016/j.cnsns.2009.04.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Gopal D, Kishan N, Raju CSK. Viscous and Joule’s dissipation on Casson fluid over a chemically reacting stretching sheet with inclined magnetic field and multiple slips. Inform Med Unlocked. 2017;9(4):154–60. doi:10.1016/j.imu.2017.08.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Nadeem S, Haq RU, Akbar NS. MHD three-dimensional boundary layer flow of Casson nanofluid past a linearly stretching sheet with convective boundary condition. IEEE Trans Nanotechnol. 2014;13(1):109–15. doi:10.1109/TNANO.2013.2293735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Sulochana C, Ashwinkumar GP, Sandeep N. Similarity solution of 3D Casson nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with convective boundary conditions. J Niger Math Soc. 2016;35(1):128–41. doi:10.1016/j.jnnms.2016.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Vajravelu K, Prasad KV, Vaidya H, Basha NZ, Ng CO. Mixed convective flow of a Casson fluid over a vertical stretching sheet. Int J Appl Comput Math. 2017;3(3):1619–38. doi:10.1007/s40819-016-0203-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ibrahim SM, Lorenzini G, Vijaya Kumar P, Raju CSK. Influence of chemical reaction and heat source on dissipative MHD mixed convection flow of a Casson nanofluid over a nonlinear permeable stretching sheet. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2017;111:346–55. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2017.03.097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Baithalu R, Mishra SR, Pattnaik PK, Panda S. Analysis of heat and mass transfer rates in conducting Casson fluid flow over an expanding surface considering Ohmic heating and Darcy dissipation effects. Partial Differ Equ Appl Math. 2024;12(2):100972. doi:10.1016/j.padiff.2024.100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hussain M, Fatima S, Qayyum M. Radiative mixed convection flow of Casson nanofluid through exponentially permeable stretching sheet with internal heat generation. J Math. 2024;2024(4):9038635–12. doi:10.1155/2024/9038635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mebarek-Oudina F, Bouselsal M, Biswas N, Vaidya H, Ramesh K. Thermal performance of MgO-SWCNT/water hybrid nanofluids in a zigzag walled cavity with differently shaped obstacles. Mod Phys Lett B. 2025;39(29):2550163. doi:10.1142/S0217984925501635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Alomari MA, Hassan AM, Alajmi A, Salho AK, Sadeq AM, Alqurashi F, et al. Analysis of double-diffusive transport and entropy generation in a wavy cylindrical enclosure with inner heated core: effects of MHD and radiation on Casson Cu-H2O nanofluid. Energy Sci Eng. 2025;13(6):2810–41. doi:10.1002/ese3.70069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Pal D, Roy N, Vajravelu K. Effects of thermal radiation and Ohmic dissipation on MHD Casson nanofluid flow over a vertical non-linear stretching surface using scaling group transformation. Int J Mech Sci. 2016;114(2):257–67. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2016.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ghadikolaei SS, Hosseinzadeh K, Ganji DD, Jafari B. Nonlinear thermal radiation effect on magneto Casson nanofluid flow with Joule heating effect over an inclined porous stretching sheet. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2018;12(12):176–87. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2018.04.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Khader MM, Babatin MM, Megahed AM. On the numerical evaluation for studying Ohmic dissipation and thermal conductivity impacts on the flow of Casson fluid. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2023;49(335):103192. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.103192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wang J, Farooq U, Waqas H, Muhammad T, Khan SA, Hendy AS, et al. Numerical solution of entropy generation in nanofluid flow through a surface with thermal radiation applications. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;54(1):103967. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.103967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Said BO, Mebarek-Oudina F, Medebber MA. Magneto-hydro-convective nanofluid flow in porous square enclosure. Front Heat Mass Transf. 2024;22(5):1343–60. doi:10.32604/fhmt.2024.054164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Vaidyanathan G, Sekar R, Vasanthakumari R, Ramanathan A. The effect of magnetic field dependent viscosity on ferroconvection in a rotating sparsely distributed porous medium. J Magn Magn Mater. 2002;250(2):65–76. doi:10.1016/S0304-8853(02)00355-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ramanathan A, Suresh G. Effect of magnetic field dependent viscosity and anisotropy of porous medium on ferroconvection. Int J Eng Sci. 2004;42(3–4):411–25. doi:10.1016/S0020-7225(02)00273-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Sheikholeslami M, Rashidi MM, Hayat T, Ganji DD. Free convection of magnetic nanofluid considering MFD viscosity effect. J Mol Liq. 2016;218(8):393–9. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2016.02.093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Sheikholeslami M, Sadoughi MK. Numerical modeling for Fe3O4-water nanofluid flow in porous medium considering MFD viscosity. J Mol Liq. 2017;242(9):255–64. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2017.07.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Molana M, Dogonchi AS, Armaghani T, Chamkha AJ, Ganji DD, Tlili I. Investigation of hydrothermal behavior of Fe3O4-H2O nanofluid natural convection in a novel shape of porous cavity subjected to magnetic field dependent (MFD) viscosity. J Energy Storage. 2020;30(3):101395. doi:10.1016/j.est.2020.101395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Hamid M, Usman M, Khan ZH, Ahmad R, Wang W. Dual solutions and stability analysis of flow and heat transfer of Casson fluid over a stretching sheet. Phys Lett A. 2019;383(20):2400–8. doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2019.04.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Metri PG, Guariglia E, Silvestrov S. Lie group analysis for MHD boundary layer flow and heat transfer over stretching sheet in presence of viscous dissipation and uniform heat source/sink. AIP Conf Proc. 2017;1798(1):020096. doi:10.1063/1.4972688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Muzara H. Recent numerical techniques for differential equations arising in fluid flow problems [dissertation]. Thohoyandou, South Africa: University of Venda; 2019. [Google Scholar]

39. Akolade MT, Tijani YO. A comparative study of three dimensional flow of Casson-Williamson nanofluids past a Riga plate: spectral quasi-linearization approach. Partial Differ Equ Appl Math. 2021;4(3):100108. doi:10.1016/j.padiff.2021.100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wang CY. Free convection on a vertical stretching surface. J Appl Math Mech. 1989;69(11):418–20. [Google Scholar]

41. Khan WA, Pop I. Boundary-layer flow of a nanofluid past a stretching sheet. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2010;53(11–12):2477–83. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2010.01.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools