Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Experimental Investigation into a Superheated Water Jet in Visible and InfraRed Ranges

1 Institute of Thermal Physics, Ural Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, Yekaterinburg, 620085, Russia

2 Turbines and Engines Department, Ural Federal University, Yekaterinburg, 620085, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Konstantin Busov. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Issues of Hydro and Gas Dynamics, Heat and Mass Transfer in Mechanical Engineering and Energy)

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(4), 1203-1214. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.067598

Received 07 May 2025; Accepted 10 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Experimental research into the boiling-up of a free jet of superheated water discharging through a short cylindrical nozzle with sharp inlet and outlet edges into the atmosphere has been carried out. The change in the shape of a liquid jet has been traced through changes in thermodynamic parameters (temperature, pressure) along the saturation line in both the visible range and the infrared spectrum. The flow shapes corresponding to various modes of boiling-up have been identified. With thermal-imaging diagnostics, heterogeneities in the spray plume of a superheated liquid jet have been recorded and temperature distributions have been obtained in various sections of a boiling-up flow. The maximum temperature in the flare of a boiling-up jet has been determined at different distances from the short nozzle’s exit edge.Keywords

Cold liquid jets are used in various fields, such as engineering machinery, agriculture, medicine, power engineering, etc. Many issues concerning fluid flowing inside or outside various nozzles have been addressed [1–4]. Research into cold liquid jets has been carried out in a typical temperature range, from the crystallization temperature to the boiling point. Important features and distinctive properties of a liquid appear in the range from the boiling point to the thermodynamic critical point temperature (superheated liquid), which makes it possible to apply the liquid much more efficiently.

During the discharge of a metastable (superheated) liquid [5–7] through short nozzles, several features completely uncharacteristic of cold jets are manifested. One of the main features is a finely dispersed structure [8–11]. In addition, in experimental research, various phenomena that manifest themselves in superheated liquid jets, such as a significant change in the shape of the boiling medium [12,13], the minimum reaction thrust [14], and extreme pulsations with a diverging power spectrum according to the 1/f law, were recorded [15]. The listed features normally arise during a transition from one state to another with a sharp change in internal or external conditions and can lead to both positive and negative consequences. Despite the considerable research and use of boiling liquid jets in various devices, several questions related to the nature of their discharge remain open. In particular, problems concerning the kinetics of the creation of vapor nuclei within the flow (various models are discussed in the article [16]), the temperature distribution in the spray plume, the stability of the jet shape, and the methods of regulating flow remain unexplored.

The study has the following objectives:

– to study changes in the shape of a liquid jet at various points of superheating;

– to apply a non-contact thermal imaging method to study the temperature distribution in various sections of the spray plume;

– to determine the maximum value of the liquid temperature in a two-phase jet;

– to analyze the structure of a boiling liquid flow based on the thermograms obtained.

2 Vapour Generation Mechanisms in Boiling Liquid Jets

Much experimental research into the metastable state of matter [5,6,17,18] has shown that an important and, in some cases, decisive role in arranging the structure and behavior of a system is played by the formation, development, and interaction of the typical nuclei formed in it (crystals in a supercooled liquid and vapor bubbles in a superheated liquid). In the case of a superheated liquid, with an increase in superheat, an increase in the number of vapor bubbles in a unit of volume per time unit occurs, which is of a complex (stepwise) nature [19]. Due to the probabilistic nature of boiling up, it is impossible to be clear about the number of bubbles at a certain superheat. The complexity of the issue is primarily related to assessing the system’s purity. Even in a medium that is as close as possible to a free jet of liquid devoid of contact with a solid (rough) surface, there remain factors (dissolved gases, minerals, and other possible inclusions) whose influence is very difficult to take into account. The conducted research into vapor generation kinetics intensities in superheated liquids made it possible to conditionally distinguish several modes of boiling-up and the corresponding superheats, i.e., low, moderate, high, and limited. A transition from one boiling-up mode to another is directly related to the number of emerging bubbles per unit of liquid volume per unit of time.

For low superheats (Тs < 0.6Тc, Тs is the initial temperature of the liquid at the saturation line; Тc is the temperature at the critical thermodynamic point), separate few and non-interacting bubbles are generated, the number (J) of which per second in a cubic centimeter varies from several units to several dozens. At moderate superheats (0.6Тc < Тs < 0.7Тc), the number of generated bubbles significantly increases and varies over a wider range, J = 102–104 CM–3C–1. With an increase in superheat, so-called ready-made boiling centres begin to activate, which contributes to an increase in the intensity of the generated bubbles. At high superheats Тs/Тc ≈ 0.7, the number of nuclei generated in a unit of liquid volume per second sharply increases to values J ≈ 108 CM–3C–1. It is noted in [6,7] that a jump of J by four orders of magnitude occurs within a very narrow temperature range (ΔT = 1–2 K). In this case, boiling up occurs mainly on external inclusions in the liquid and is accompanied by a chain initiation of boiling centers. This avalanche-like bubble growth is known as intense heterogeneous nucleation. It manifests itself and develops within the range from 0.7 Тc to 0.9 Тc. At Тs > 0.9 Тc, the homogeneous fluctuation nucleation mechanism comes into play. The number of nuclei in one cubic centimeter generated per second exceeds J > 1020 cm−3s−1. The generation of a large number of bubbles per time unit, for both the intense heterogeneous mode and the homogeneous fluctuation mode, occurs explosively. In the case of extremely high rates of vapor bubble formation shock waves can be generated that can initiate explosive boiling-up in adjacent regions of a superheated liquid [12,20,21]. Therefore, boiling up is often called explosive boiling-up.

The experimental and theoretical investigations conducted have made it possible to obtain a criterion E for the implementation of the explosive boiling up mode of a superheated liquid discharging through a short nozzle [6]:

where

This condition was obtained for homogeneous approximation without taking into account the mutual slip of the phases. The bubble volume is calculated at the pressure of the medium where the discharge takes place.

The research into boiling water jets was conducted in a laboratory setup, the main part of which was a high-pressure working chamber made of stainless steel (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Cross-section of a high-pressure chamber: 1—the body of the working chamber, 2—the casing for the thermocouple, 3—an electric heater, 4—a locking rod, 5—water, 6—heat insulation, 7—a short cylindrical nozzle

The vessel had a cylindrical shape with a volume of 0.65 L. The superheated water was discharged into the atmosphere through a short cylindrical nozzle with a diameter of d = 0.5 mm with sharp inlet and outlet edges. The initial parameters (temperature, pressure) of the liquid inside the vessel corresponded to the conditions on the liquid-vapor phase equilibrium line and varied within the appropriate limits, Тs = 380–570 K, p = 0.1–8.6 MPa. The error in measuring the temperature was ±0.3%. The error in measuring the pressure was ±0.2%.

In our experiments, a short nozzle was used to transfer the liquid to the region of metastable states. On the phase diagram of water in р–V coordinates (Fig. 2), the ab arrow shows how the liquid enters from the stable region into the region of superheated states through abrupt pressure suppression. The depth of penetration and the delay in boiling in the region with the relative stability of the liquid phase are determined by the degree of superheat.

Figure 2: Phase diagram of water: ACB is the phase equilibrium line or binodal, DCE is the boundary of thermodynamic stability or spinodal and C is the thermodynamic critical point (adapted from [6,22])

The jets were photographed using a Nikon 7200 digital camera. The boiling-up flow was illuminated by two external flashes installed between the jet and the camera. Photography and thermal imaging diagnostics were carried out independently of each other.

4 Boiled-Up Liquid Jet Breakup

This study has shown that a jet of boiling-up liquid is quite sensitive to changes in the kinetics of vaporization, which is reflected in a change in its shape. With an increased degree of supersaturation of the system, several different shapes of the discharged jet can be recorded (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Superheated water jet shape at different temperatures: (a) Тs < 413 K (ps < 0.36 MPa), (b) Тs = 433 K (ps = 0.62 MPa), (c) Тs = 453 K (ps = 1.0 MPa), (d) Тs = 493 K (ps = 2.32 MPa), (e) Тs = 533 K (ps = 4.69 MPa), (f) Тs = 583 K (ps = 9.87 MPa)

At low superheats, the jet has the shape of a cylinder or rod, typical of a cold liquid (Fig. 3a). The cylindrical shape of the jet is carried on for 650 mm, and then begins to break up into drops. Individual vapor bubbles cannot yet be seen in the flow. This boiling mode is characterized by low-intensity evaporation from the jet surface. The destruction of the jet occurs due to capillary instability or Kelvin-Helmholtz instability.

At moderate superheats, the jet takes the shape of a cone with different apex angles (Fig. 3b,c). An increase in the opening angle occurs due to the increasing growth rate of bubbles generated in the flow. In the boiling-up mode, the destruction of the boiling-up jet occurs due to barocapillary instability [23].

At high superheats, when intense heterogeneous nucleation occurs in the flow, jet discharge in the shape of a hollow cone with a large opening angle (~110°) at the apex can be seen (Fig. 3d,e). In this case, boiling-up intensity becomes the dominant factor in the destruction of the liquid jet.

When the thermodynamic parameters approach intense fluctuation nucleation (homogeneous nucleation) conditions, the jet shape changes again and takes the shape of an elliptical paraboloid (Fig. 3f).

Fig. 4 shows how the jet expansion angle (the angle between the visible jet boundaries) changed with increased temperature.

Figure 4: Changes in the expansion angle of a superheated water jet

As can be seen from the diagram, the change in the jet expansion angle has a complex nature, which is directly related to the transitions from one boiling-up mode to another. The onset of growth corresponds to the transition from weak to intense evaporation on the mirror of the jet surface. The solid liquid core is destroyed and a conical jet is formed. A gradual increase in the jet expansion angle is associated with an increase in the liquid-vapor phase transition intensity. The solid cone of the jet is replaced by a hollow cone and the expansion angle reaches its maximum. A subsequent decrease in the jet expansion angle is due to the increased boiling-up intensity, which leads to the following change in the jet shape: the hollow cone is replaced by a shape close to an elliptical paraboloid.

5 Thermal Imaging Diagnostics of a Boiling-Up Water Jet

With advances in technical devices, strict requirements for the reliability and safety of operation have been introduced. Miniaturization, tightness, and extreme conditions of use present significant difficulties for correct diagnosing equipment. Non-contact research methods are quite effective here. One of these methods is the thermal imaging analysis used in various fields, such as medicine [24], agriculture and food science [25], engine manufacturing [16,26,27], power equipment and heat transfer devices [28–31]. In research into dispersion processes, the non-contact diagnostic method is more appropriate than the contact method, since it does not have any effect on the discharging medium. In addition to the lack of influence on the flow of liquid or gas, another significant addition is the possibility not only to record the temperature in a local area but also to conduct research into the temperature field of an extended region.

In this experimental investigation, the temperature change in a jet of boiling-up water was analyzed. An infrared survey was carried out with a Testo 890-2 thermal imager. This thermal imager, which measures infrared radiation in the long-wave spectrum (7.5–14 μm), was configured to record temperatures in the range from T = 273 K to T = 623 K. The error in measuring the temperature was ±2%. The emissivity for water was taken to be ε = 0.95.

The thermograms in Fig. 5, as well as the photographs in Fig. 3, reflect fairly well the change in the shape of the superheated water jet with changing vaporization modes (Fig. 5a is low, Fig. 5b–d is moderate, Fig. 5e–i is high and Fig. 5j is extreme).

Figure 5: Boiling-up water jet thermograms: (a) Тs < 413 K (ps < 0.36 MPa), (b) Тs = 433 K (ps = 0.62 MPa), (c) Тs = 453 K (ps = 1.0 MPa), (d) Тs = 473 K (ps = 1.55 MPa), (e) Тs = 493 K (ps = 2.32 MPa), (f) Тs = 513 K (ps = 3.35 MPa), (g) Тs = 533 K (ps = 4.69 MPa), (h) Тs = 553 K (ps = 6.42 MPa), (i) Тs = 573 K (ps = 8.95 MPa), (j) Тs = 578 K (ps = 9.21 MPa)

In particular, it can be seen that when boiling-up (heterogeneous nucleation) is intense, the discharged liquid mass is redistributed to the periphery of the spray plume (Fig. 5e–h), which cannot always be seen in photographs. Statistical analysis of thermograms made it possible to establish a change in the maximum temperature of the liquid behind the outlet section of the nozzle and obtain the temperature distributions in different sections of the boiling jet (Figs. 6–8).

Figure 6: Local dependence of the maximum temperature of a jet behind the outlet of the short nozzle for the corresponding temperature in the high-pressure vessel

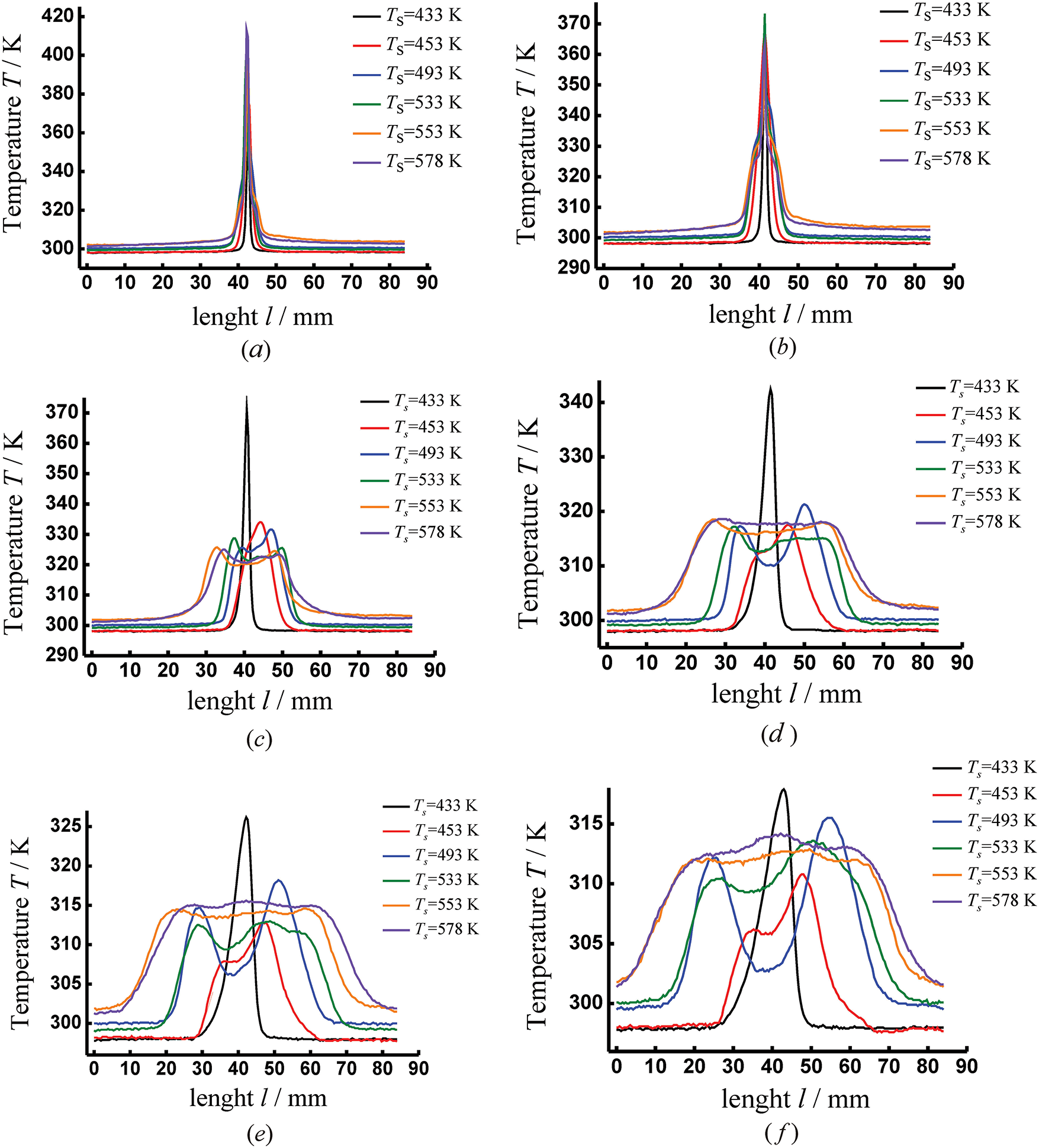

Figure 7: Temperature distribution in the longitudinal section of a superheated water jet at various superheats

Figure 8: Temperature distribution in the jet’s cross-section for various superheats. The distance from the outlet cross section of the nozzle: (a) l = 1 mm, (b) l = 2 mm, (c) l = 5 mm, (d) l = 10 mm, (e) l = 15 mm, (f) l = 20 mm

The liquid transfer from a metastable (superheated) state to a stable one is accompanied by vapor nucleus generation, which requires some work [5,6,32]. The energy expended is the reason the liquid jet cools. As can be seen from Fig. 6, the heat outflow is rapid. In other words, the time the flow is in the liquid state behind the nozzle before boiling up is rather short. This is reflected in a change in the maximum flow temperature (Fig. 6). The maximum temperature of the liquid jet exceeds its boiling point within a millimeter (l < 1 mm) from the nozzle’s exit edge. The difference between the liquid temperature at the nozzle inlet (the temperature in the high-pressure vessel) and the outlet becomes greater, and the higher the intensity of the appearance of vapor nuclei. At a distance of about l = 2 mm from the cylindrical nozzle’s exit section, there is a tendency for the maximum temperature in the jet to decrease, despite an increase in the temperature in the high-pressure vessel. This also indicates significant energy consumption during the liquid-vapor phase transition. At l > 2 mm, a slight change in the jet’s maximum temperature can be recorded. In this case, the liquid-vapor phase transition has time to come to an end, so only the condensation, coalescence, and evaporation of droplets take place.

Fig. 7 shows how the temperature decreases in the longitudinal section of the flow when moving away from the cylindrical nozzle’s outlet section.

The figure shows that there are two segments where the temperature decreases. The first segment has a characteristic stepwise decrease temperature (except for low superheats), and the second is a very slow decline. The shape of the line related to low superheats (Тs < 433 K), when the jet is cooled due to low-intensity evaporation, is different. In this case, the first half of the curve has a fairly flat portion of temperature decrease, while the second has a steeper dependence. For medium and high superheats, the more intensive the liquid-vapor phase transition in the jet, the steeper the first section of the temperature decrease curve.

The change in the jet temperature at its cross-section is shown in Fig. 8.

The integral temperature distributions obtained during an analysis of thermograms correlate well with the change in the jet shape. Before the manifestation of a liquid-vapor phase transition, a non-boiled part of a jet can be seen near the outlet cross-section of the nozzle. That is, the liquid ‘lives’ for some time before boiling up. The higher the temperature (pressure) in the working chamber, the shorter the length of the unboiled section. In this region, at the cross-section of the jet, the integral temperature distribution had the shape shown in Fig. 8a. The top of the peak corresponds to the maximum temperature in the flow. As can be seen from this figure, all distributions have almost the same shape. Only the peaks corresponding to high temperatures (Тs > 493 K) have a slight broadening in the base region.

With distance from the outlet cross-section of the cylindrical nozzle, the temperature distribution at the cross-section of the boiling-up jet changes significantly. The shape of a single sharp peak is retained only for low superheats (Fig. 8c). At moderate superheats, a single but more extended peak can also be observed. For high superheats the temperature distributions take a trapezoidal shape, which can be explained by an increase in the jet expansion angle.

At a distance of l = 10 mm (Fig. 8d), each temperature distribution takes on its special shape, according to the shape of the superheated liquid jet with the corresponding superheat. So, for low superheats, the peak remains but with a lower maximum temperature and a wider area at the base. In the temperature distribution for moderate and high superheats, both a significant broadening of the region in which the maximum temperature rises and falls and the beginning of the creation of the second peak are visible. The presence of two zones (Fig. 5d–h) in the spray torch of the boiling liquid is associated with a change in the shape of the jet (Fig. 4, the jet takes the shape of a hollow cone). In this case, when the liquid boils, a two-phase flow is formed, consisting of small drops and vapor. The redistribution of the mass (density) of the discharging volumetric medium begins to play an important role. Taking into account that near the axis the density of the boiling-up liquid becomes less relative to its density at the edges this leads to the registration of radiation in the form of two peaks. This two-peak distribution is typical of the temperature range from Тs = 493 K to Тs = 553 K. When approaching extreme superheats, the plume of the boiling-up jet again takes on a homogeneous structure without distinguished directions of the discharge, which is reflected in the temperature distributions of the trapezoidal curve.

With a further increase in the distance from the outlet cross-section of the cylindrical nozzle (Fig. 8e,f), the above characteristic features for each curve are even more pronounced in the temperature distributions, which reflect boiling-up processes that manifest themselves in a jet of superheated water.

It is worth emphasizing that the data obtained in Figs. 6–8 correspond to the temperature values with the emissivity of water equal to ε = 0.95. However, it should be taken into account that with intense boiling-up of the liquid (Тs > 473 K) the amount of the vapor phase increases, the emissivity of which is less than the emissivity of water. Water vapor is a semitransparent medium and the characteristics of its radiation strongly depend on the density and thickness of the gas layer [33] as well as on the velocity in the flow and the nature of the jet movement as a whole. With an increase in the vapor phase and a decrease in the droplet size (liquid phase), the emissivity of the two-phase flow decreases which of course affects the accuracy of the spray temperature measurement. Thus, because it is objectively impossible to speak with sufficient accuracy about the emissivity of a two-phase jet, the obtained results for the spray torch temperature should be considered approximate. Despite this, the curves on the graphs correctly display the nature of the thermal distribution in the boiling-up jet which provides valuable information for further studies of metastable liquids.

Experimental research carried out to study the dynamics of boiling up a water jet when it discharges through a short cylindrical nozzle has shown that the changes in the shape and the jet expansion angle are directly related to the intensity of the interacting vapor nuclei generated. For various degrees of superheat, typical shapes of a boiling jet have been distinguished.

Temperature distributions have been obtained at a qualitative level and the maximum temperature in different flow sections has been determined.

The obtained distributions and dependences of the change in the maximum temperature for different distances from the cylindrical nozzle’s outlet section made it possible to evaluate the length of the unboiled part of the jet or the beginning of the liquid-vapor phase transformation. Analysis of the experimental data has shown that the change in the length of the unboiled section of the liquid correlates with the degree of superheat.

Experiments have shown that the more the liquid in the high-pressure vessel is superheated, the more intensively the liquid-vapor phase transition proceeds and, therefore, the more abruptly the temperature drops.

Thus, this research into jets of boiling water made it possible to obtain with thermal imaging new data on the maximum temperature in the flow beyond the nozzle’s outlet section and the distribution of the temperature field in a spray of a superheated liquid during intense boiling up. The data obtained have shown good agreement with the experimental results and theoretical concepts obtained previously. The infrared photography method is an effective scientific tool that made it possible to study processes in boiling up superheated liquid much more broadly and to obtain reliable information about the temperature change in the jet.

The experimental investigation results can be used in various technical applications where it is necessary to obtain a finely dispersed spraying of a working liquid. Thermal imaging analysis data can be useful for the advancement of the ideas of the physics of boiling-up in general, as well as for the construction of particular problems and theoretical models.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Konstantin Busov, Nikolay Mazheiko, Leonid Plotnikov, Boris Zhilkin; methodology, Konstantin Busov, Leonid Plotnikov; software, Konstantin Busov, Leonid Plotnikov; validation, Nikolay Mazheiko, Boris Zhilkin; formal analysis, Nikolay Mazheiko, Boris Zhilkin; investigation, Konstantin Busov, Nikolay Mazheiko, Leonid Plotnikov, Boris Zhilkin; resources, Konstantin Busov, Leonid Plotnikov; data curation, Nikolay Mazheiko, Leonid Plotnikov; writing—original draft preparation, Konstantin Busov; writing—review and editing, Nikolay Mazheiko, Leonid Plotnikov; visualization, Leonid Plotnikov, Boris Zhilkin; supervision, Nikolay Mazheiko, Boris Zhilkin; project administration, Konstantin Busov, Leonid Plotnikov. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature:

| Symbol | |

| d | Nozzle diameter [mm] |

| E | Explosive boiling-up criterion |

| f | Frequency [Hz] |

| J | Rate of nucleation [cm−3s−1] |

| l | Distance [mm] |

| p | Pressure [MPa] |

| t | Time [s] |

| T | Temperature [K] |

| V | Volume [m3] |

| Greek Symbol | |

| α | Spray angle [°] |

| ω | Velocity [m/s] |

| Number of heterogeneous centres | |

| ρ | Density [kg/m3] |

| Subscripts | |

| a | Atmospheric |

| c | Critical |

| s | Saturation |

| * | Homogeneous nucleation |

References

1. Rayleigh L. On the instability of jets. Proc Lond Math Soc. 1878;1(1):4–13. doi:10.1112/plms/s1-10.1.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Lefebvre AH, McDonell VG. Atomization and sprays. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2017. doi:10.1201/9781315120911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Xi W, Yang D, Skripov P, Chen L. Quantitative experiment and numerical simulation on sub-critical and supercritical CO2-N2 multiphase jet flows. Int J Heat Fluid Flow. 2025;114(2):109830. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2025.109830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ashgriz N. Handbook of atomization and sprays: theory and applications. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2011. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-7264-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Skripov VP. Metastable liquids. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1974. 272 p. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

6. Skripov VP, Sinitsyn EN, Pavlov PA. Thermophysical properties of liquids in the metastable (superheated) state. London, UK: Atomizdat; 1988. [Google Scholar]

7. Varaksin AY. Hydrogasdynamics and thermal physics of two-phase flows with solid particles, droplets, and bubbles. High Temp. 2023;61(6):852–70. doi:10.1134/s0018151x23060159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhong W, Xin Z, Wang L, Liu H. Investigations on high-speed flash boiling atomization of fuel based on numerical simulations. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;139(2):1427–53. doi:10.32604/cmes.2023.031271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Bachanek J, Rogóż R, Pachler K, Tatschl R, Teodorczyk A, Kapusta Ł.J. Experimental study and empirical modelling of direct-injection n-heptane sprays formed under flash-boiling conditions. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2025;236:126282. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2024.126282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kim WH, Yoon WS. Spray characteristics of a flash swirl spray ejected into an atmospheric pressure zone. Int J Multiph Flow. 2012;39(3):1–12. doi:10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2011.10.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Busov KA. The effect of boiling-up on the shape and droplet size of a jet of superheated water discharged through a semi-cylindrical nozzle. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2022;136(1):106199. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2022.106199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Simoes-Moreira JR, Vieira MM, Angelo E. Highly expanded flashing liquid jets. J Thermophys Heat Transf. 2002;16(3):415–24. doi:10.2514/2.6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhu Y, Zhu X, Song Z, Pan X, Wang X, Mei Y, et al. Droplets behaviors of flashing jet in accidental release of superheated liquid. J Loss Prev Process Ind. 2020;68:104275. doi:10.1016/j.jlp.2020.104275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Pavlenko AN, Koverda VP, Reshetnikov AV, Surtaev AS, Tsoi AN, Mazheiko NA, et al. Disintegration of flows of superheated liquid films and jets. J Eng Thermophys. 2013;22(3):174–93. doi:10.1134/S1810232813030028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Skokov VN, Koverda VP, Reshetnikov AV, Skripov VP, Mazheiko NA, Vinogradov AV. 1/f noise and self-organized criticality in crisis regimes of heat and mass transfer. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2003;46(10):1879–83. doi:10.1016/S0017-9310(02)00475-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Li X, Wang S, Yang S, Qiu S, Sun Z, Hung DLS, et al. A review on the recent advances of flash boiling atomization and combustion applications. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2024;100(4):101119. doi:10.1016/j.pecs.2023.101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Pavlenko AN. Boiling in high temperature publications: from basic mechanisms to development of flow control methods for enhancement of heat transfer. High Temp. 2023;61(6):742–58. doi:10.1134/s0018151x23060184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Faizullin MZ, Vinogradov AV, Tomin AS, Koverda VP. Nonstationary nucleation (explosive crystallization) in layers of amorphous ice prepared by low-temperature condensation of supersonic molecular beams. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2017;108(3):1292–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2016.12.109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Reshetnikov AV, Busov KA, Mazheiko NA, Skokov VN, Koverda VP. Transient behavior of superheated water jets boiling. Thermophys Aeromech. 2012;19(2):329–36. doi:10.1134/S0869864312020151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Mansour A, Müller N. A review of flash evaporation phenomena and resulting shock waves. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2019;107(16):146–68. doi:10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2019.05.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yusupov VI, Konovalov AN. Features of heat/mass transfer and explosive water boiling at the laser fiber tip. Int J Therm Sci. 2024;203(1):109131. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2024.109131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Bar-Kohany T, Levy M. State of the art review of flash-boiling atomization. Atomiz Spr. 2016;26(12):1259–305. doi:10.1615/atomizspr.2016015626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Pavlov PA, Isaev OA. Barocapillary instability of the surface of a jet of a superheated liquid. High Temp. 1984;22(4):603–9. [Google Scholar]

24. Vainer BG. A novel high-resolution method for the respiration rate and breathing waveforms remote monitoring. Ann Biomed Eng. 2018;46(7):960–71. doi:10.1007/s10439-018-2018-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. ElMasry G, ElGamal R, Mandour N, Gou P, Al-Rejaie S, Belin E, et al. Emerging thermal imaging techniques for seed quality evaluation: principles and applications. Food Res Int. 2020;131(7):109025. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Choi J, Moon S, Kim H, Choi S. Effectiveness of water spray in infrared signature suppression of engine plumes. Infrared Phys Technol. 2023;135(1):104959. doi:10.1016/j.infrared.2023.104959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Kopyev EP, Anufriev IS, Shadrin EY, Loboda EL, Agafontsev MV, Mukhina MA. Studying the diesel flame structure in superheated water vapor jets by using IR thermography. Infrared Phys Technol. 2019;102(1):103028. doi:10.1016/j.infrared.2019.103028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Boukhanouf R, Haddad A, North MT, Buffone C. Experimental investigation of a flat plate heat pipe performance using IR thermal imaging camera. Appl Therm Eng. 2006;26(17–18):2148–56. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2006.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Nasiri A, Taheri-Garavand A, Omid M, Carlomagno GM. Intelligent fault diagnosis of cooling radiator based on deep learning analysis of infrared thermal images. Appl Therm Eng. 2019;163:114410. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.114410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Li H, Hrnjak P. Quantification of liquid refrigerant distribution in parallel flow microchannel heat exchanger using infrared thermography. Appl Therm Eng. 2015;78(1):410–8. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2015.01.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Jeon BG, Choi MH, Kam DH, Youn YJ, Moon SK. Observation of departure from nucleate boiling under flow using optical visualization and IR thermometry. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2022;185(10):122417. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.122417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Skripov VP. Metastable states. J Non-Equilib Thermodyn. 1992;17(3):193–236. doi:10.1515/jnet.1992.17.3.193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Isachenko VP, Osipova VA, Sukomel AS. Heat transfer. Pune, India: Nirali Prakashan; 1980. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools