Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancing Energy Efficiency in Vapor Compression Refrigeration Systems Using Phase Change Materials

1 Unité de Recherche Appliquée en Energies Renouvelables (URAER), Centre de Développement des Energies Renouvelables (CDER), Ghardaia, 47133, Algeria

2 Laboratory of Biomaterials and Transport Phenomena, University of Medea, Medea, 26000, Algeria

3 Biotechnology, Water, Environment and Health Laboratory, Abbes Laghrour University, Khenchela, 40000, Algeria

4 CIP Team, Institute of Chemical Sciences of Rennes, ISCR—UMR6226, CNRS, Ecole Nationale Supérieure de Chimie de Rennes, University Rennes, Rennes, 35000, France

5 School of Engineering, Merz Court, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 7RU, UK

* Corresponding Author: Abdeltif Amrane. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative Cooling Systems: Design, Optimization, and Applications)

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(4), 1129-1149. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.067734

Received 11 May 2025; Accepted 25 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Refrigeration systems are essential across various sectors, including food preservation, medical storage, and climate control. However, their high energy consumption and environmental impact necessitate innovative solutions to enhance efficiency while minimizing energy usage. This paper investigates the integration of Phase Change Materials (PCMs) into a vapor compression refrigeration system to enhance energy efficiency and temperature regulation for food preservation. A multifunctional prototype was tested under two configurations: (1) a standard thermally insulated room, and (2) the same room augmented with eutectic plates filled with either Glaceol (−10°C melting point) or distilled water (0°C melting point). Thermocouples were calibrated and deployed to record air and PCM temperatures during freeze–thaw cycles at thermostat setpoints of −30°C and −35°C. Additionally, a defrosting resistor and timer were added to mitigate frost buildup, a known cause of efficiency loss. The experimental results show that PCM-enhanced rooms achieved up to 10.98°C greater temperature stability during defrost cycles and reduced energy consumption by as much as 7.76% (from 0.4584 to 0.4231 kWh/h). Moreover, the effectiveness of PCMs depended strongly on thermostat settings and PCM type, with distilled water demonstrating broader solidification across plates under higher ambient loads. These findings highlight the potential of PCM integration to improve cold-chain performance, offering rapid cooling, moisture retention, and extended product conservation during power interruptions.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

A phase change material (PCM) is a type of material that can absorb or release energy in the form of heat when it changes its physical state, for instance, transitioning from solid to liquid or vice versa. This phenomenon is primarily used for the storage and management of thermal energy. It operates by exploiting thermal properties that can change state at specific temperatures. When heated and reaching its melting point, it begins to melt. During this process, it absorbs a significant amount of heat without an increase in temperature. This heat is used to break the bonds between the molecules, allowing the material to transition to a liquid state. When the temperature decreases and the material solidifies, it releases the heat it has absorbed. This occurs when the material transitions from a liquid state to a solid state, and this heat is often referred to as latent heat of fusion. However, the selection of a PCM depends on several factors, including the desired phase change temperature, thermal storage capacity, thermal stability, the latent heat which is precisely the amount of heat required to change one unit of mass of a substance or a phase change material from solid to liquid (melting) or vice versa (solidification) without altering its temperature, and compatibility with other materials [1].

Given these characteristics, PCMs have garnered significant attention for their potential to enhance energy efficiency in various thermal systems. One such application is in refrigeration, where the integration of PCMs can help reduce energy consumption and improve thermal regulation. Refrigeration systems play a pivotal role in modern society, supporting essential functions such as food preservation, medical storage, and climate control. However, these systems are among the largest consumers of energy globally, accounting for approximately 17% of global electricity consumption [2]. The environmental impact of refrigeration systems is further exacerbated by their reliance on high Global Warming Potential (GWP) refrigerants and inefficient energy usage. As global energy demands continue to rise, compounded by the urgent need to mitigate climate change, there is an increasing necessity for innovative solutions to enhance the efficiency of refrigeration systems while reducing their energy consumption.

The book published by the American Society of Heating discusses the latest advancements in the field of refrigeration, including new refrigerants, absorption refrigeration systems, and heat recovery technologies [3]. Some authors [4] examine various strategies to improve energy efficiency in refrigeration and air conditioning systems, including the use of variable speed compressors and advanced control systems. An overview of innovative technologies in the field of refrigeration, including adsorption systems, Peltier effect refrigerators, and systems using phase change materials (PCMs), has been presented [5]. Another work [6] explores the use of thermal energy storage to improve the efficiency of refrigeration systems by enabling optimal energy use during periods of low demand. Some studies conducted [7,8] have sufficiently discussed natural refrigerants and their potential to reduce the environmental impact of refrigeration systems while improving their efficiency. In 2024, an overview of technologies and strategies to improve the energy efficiency of refrigeration systems, including component enhancements and energy management systems, was conducted by Harun Or Rashid et al. [9].

One promising approach involves the integration of PCMs as thermal storage media. PCMs can store and release large amounts of latent heat during phase transitions, making them ideal for stabilizing temperature fluctuations and extending cooling durations during power outages or periods of low energy availability [10]. Despite their potential, the adoption of PCMs in refrigeration systems remains limited due to challenges such as material selection, cost-effectiveness, and performance optimization under varying operating conditions. The adoption of PCMs in refrigeration systems is an active area of research, with studies focusing specifically on the use of PCMs in refrigeration systems, addressing both the benefits and the challenges [11].

The concept of using PCMs for thermal energy storage has been extensively studied over the past few decades. Early research focused on understanding the fundamental properties of PCMs, including their melting points, latent heat capacities, and thermal conductivity. Zalba et al. [12] provided a comprehensive overview of PCMs, categorizing them into organic, inorganic, and eutectic materials based on their chemical composition. Organic PCMs, such as paraffin waxes and fatty acids, are widely used due to their stability, non-corrosiveness, and high latent heat capacities. However, their relatively low thermal conductivity remains a significant limitation, often requiring enhancements through additives or encapsulation techniques.

A series of experimental trials were conducted under various conditions to assess the effectiveness of a household refrigerator. The performance of the system was tested using two eutectic PCMs arranged in a cascade configuration. The off-time of the compressor in the new system was significantly reduced. The energy consumption of the refrigerator using a single PCM decreased by 8%, while a further reduction of up to 13% was achieved with the cascade configuration [13]. However, a comprehensive review offers insights into the present status and future possibilities of PCM technology in cold thermal energy storage, emphasizing the established advantages of traditional PCMs in improving refrigeration system efficiency, as well as the potential sustainability of bio-based PCMs [14]. On the other hand, an investigation was conducted on a direct current refrigerator system combining phase change cooling storage and micro-electric storage. The experimental device provided insights into the energy-saving potential of direct current refrigeration systems [15].

The application of PCMs in refrigeration systems has gained significant attention due to their ability to extend cooling durations during power outages and stabilize internal temperatures. Djeffal et al. [16] conducted an experimental study on the effect of PCM eutectic plates on the electric consumption of a designed refrigeration system. Their findings revealed a notable reduction in energy usage, underscoring the potential of PCMs to enhance the efficiency of refrigeration systems. This aligns closely with the objectives of the present study, which seeks to evaluate the thermal performance and energy-saving potential of PCMs in refrigeration applications.

PCMs are substances that absorb or release heat when they change state, but their selection primarily depends on their transition temperature, or more precisely, their phase change temperature, which must correspond to the desired application. For example, for thermal comfort applications, a PCM that changes state around 20–26°C would be appropriate [17]. The second condition for PCM selection relates to its thermal capacity to ensure that the material can store enough heat for the application. The effectiveness of these materials also requires a strategic placement within the thermal system, integrating them into areas where they can effectively regulate temperature, utilizing appropriate environments to protect the PCM and enable efficient heat transfer. For example, films or membranes that facilitate thermal conduction while protecting the material. Physical mechanisms require strict control of the environment by ensuring that ambient conditions allow the PCM to operate efficiently. For example, good air circulation can help maximize the efficiency of the material. Additionally, proper insulation around the PMC helps prevent heat loss and maximizes its efficiency.

Aggoune et al. [18] investigated the impact of PCMs on reducing electricity consumption in building roofs, demonstrating their effectiveness in stabilizing temperatures and lowering energy demands. While their study focused on buildings, the principles of PCM integration for temperature regulation and energy savings are directly applicable to refrigeration systems. These findings collectively suggest that PCMs can serve as a sustainable solution for improving the thermal performance and reliability of refrigeration systems, particularly during periods of low energy availability or power interruptions.

Recent advancements in PCM technology have emphasized their role in enhancing thermal storage systems. Djeffal et al. [19] developed and tested a PCM-enhanced domestic hot water system, demonstrating its potential to improve energy efficiency and reduce operational costs. Their findings highlight the versatility of PCMs in various thermal applications, including refrigeration, where they can be used to stabilize temperatures and extend cooling durations during power outages. In addition to their role in refrigeration and thermal storage, PCMs have been explored for their ability to enhance hygrothermal performance in multi-zone constructions. Abboud et al. [20] investigated the integration of PCMs to regulate temperature and humidity levels in multi-zone buildings. Their findings demonstrated that PCMs could effectively reduce energy consumption while maintaining comfortable indoor conditions. This highlights the broader potential of PCMs in thermal management systems, reinforcing their relevance to the present study on refrigeration systems. Emerging trends in PCM research include the development of nano-enhanced PCMs and composite materials to address challenges such as low thermal conductivity.

Zhang et al. [21] demonstrated a 40% increase in heat transfer rates using nano-enhanced PCMs, paving the way for more efficient thermal storage systems. Similarly, Wang et al. [22] explored composite PCMs combining paraffin with metallic foams, achieving enhanced thermal performance and structural stability. Another promising direction is the integration of PCMs with renewable energy sources, such as solar photovoltaic systems and geothermal heat pumps. Zhou et al. [23] demonstrated the feasibility of a solar-powered refrigeration system incorporating PCMs, achieving a 30% reduction in grid electricity consumption while maintaining consistent cooling performance. Similarly, Li et al. [24] explored the use of PCMs in conjunction with cold thermal energy storage systems, highlighting their potential to balance energy demand and supply in smart grids. Bio-based PCMs derived from renewable sources, such as coconut oil and soybean wax, have also gained attention due to their sustainability and biodegradability. Kumar et al. [25] reviewed the potential of bio-based PCMs in refrigeration applications, noting their alignment with global efforts to reduce carbon footprints and promote circular economies. However, challenges related to scalability, cost-effectiveness, and performance optimization remain areas of ongoing research. Adaptive PCM systems represent another promising direction, leveraging sensors and machine learning algorithms to optimize energy usage in real-time.

Chen et al. [26] introduced a novel PCM-based thermal management system capable of dynamically adjusting its properties based on operational conditions, achieving a 20% improvement in energy efficiency compared to static configurations. Finally, hybrid refrigeration systems integrating PCMs with thermoelectric cooling modules have shown significant potential. Liu et al. [27] evaluated the performance of such systems, reporting a 25% reduction in energy consumption and improved temperature uniformity within the refrigerated space. In conclusion, the effective use of PCMs requires a thorough understanding of their thermal properties, as well as careful integration into the desired system or application. By following these steps, it will be possible to maximize the benefits of PCM for thermal management.

Regarding refrigeration systems, the integration of PCMs still requires a methodical approach to ensure their efficiency and sustainability. This necessitates careful planning, proper design, and continuous monitoring to ensure optimal results:

– The chemical compatibility of the PCMs with other materials in the refrigeration system must be verified to avoid any undesirable reactions [28].

– The integration of PCMs in strategic areas of the system, such as heat exchangers or storage tanks, to maximize their efficiency [29].

– Its correct design in the system involves determining the volume and quantity of PCMs needed based on the thermal requirements of the system and the required heat storage capacity [30].

– Use of suitable insulating materials to prevent unwanted thermal losses and exchanges [29,31].

– Integration of heat transfer fluids that can circulate efficiently around the PCMs to transfer heat while ensuring that the circulation system is designed to avoid stagnation points [32].

– Control and regulation by implementing monitoring systems to oversee the temperature and phase of the PCMs. This may include sensors and controllers to optimize the system’s operation [33].

– Implementing a maintenance program to manage and monitor the entire system [34].

The main objective of this study is to develop and improve a vapor compression refrigeration system, already tested in previous experiments, to provide greater flexibility and performance in food preservation. This includes more efficient freezing and cooling of products within a shorter time frame. The study compares two configurations: the first is a standard thermally insulated room without any enhancements; the second is a thermally insulated room equipped with cold eutectic plates containing PCMs, designed to extend temperature retention and improve the preservation of fresh or frozen goods within isothermal containers. In addition, special attention is paid to the energy consumption of the refrigeration system to assess the impact of PCMs on improving the system’s energy efficiency.

This paper proposes a novel approach to enhancing the performance of vapor compression refrigeration systems through the integration of PCMs. Unlike traditional setups, the study explores a dual-configuration experimental platform and investigates the effects of different PCM types and thermostat settings on thermal regulation and energy behavior. The system design includes a defrosting mechanism and a precise temperature monitoring setup, allowing for a detailed analysis of PCM behavior during freeze–thaw cycles. This research advances current knowledge by demonstrating the practical feasibility and added value of PCM-enhanced refrigeration for food preservation and cold-chain reliability under variable operating conditions.

2.1 Testing Bench Conditioning

The test bench consisted of an isothermal enclosure designed to simulate the internal volume of a cold storage room as shown in Fig. 1. The cell was built using rigid polyurethane insulation panels with a thickness of 5 cm, providing an internal volume of approximately 0.3 m3. The internal surfaces were lined with reflective foil to reduce thermal radiation losses.

Figure 1: Photograph of the experimental setup. (a) Interior view; (b) Exterior view

The developed prototype (Fig. 2) is designed around a conventional vapor-compression refrigeration cycle using R134a as the working fluid. The system comprises four primary components: a compressor, condenser, expansion valve, and evaporator (Fig. 2b). It delivers a cooling capacity of approximately 500 W and is regulated by a programmable digital thermostat, enabling precise temperature control within the range of −40°C to +10°C. The experimental setup is configured as a compact refrigerating/freezing chamber integrated with PCM eutectic plates (Fig. 2c). These plates act as thermal batteries, capable of absorbing, storing, and releasing energy through latent heat transfer during phase transitions. The PCM used is Glaceol, a coolant with anti-corrosive and refrigerant properties and a freezing point of −10°C. To characterize the volumetric behavior of Glaceol during freezing, measurements were conducted using a graduated container (Fig. 3). The results show a volumetric expansion of 2.5% at −20°C (equivalent to 100 mL per 4 L) and 7.5% at −30°C (300 mL per 4 L).

Figure 2: Descriptive diagram of the refrigeration prototype. (a) Main setup; (b) Refrigeration/control unit; (c) Refrigeration/freezing cell

Figure 3: Experimental measurement of Glaceol volumetric expansion during freezing. (a) Initial liquid state; (b) Partial freezing phase; (c) Fully frozen state

To ensure consistency in thermal behavior, the entire setup is placed in a thermally stable environment to minimize external fluctuations. The refrigeration cycle operates by extracting heat from the low-temperature chamber and rejecting it to the surrounding high-temperature environment, thus maintaining controlled cold conditions while enhancing efficiency through PCM integration.

Table 1 outlines the safe fill volume of Glaceol in parallelepiped cavities under different thermal expansion scenarios. For example, cavity 1 with a nominal volume of 1320 mL should only be filled with 1221 mL or 1190 mL depending on expected expansion. The same process applies when using distilled water instead of Glaceol.

It was stated in a previous study [16] that ice layers’ form on part of the refrigeration circuit. This common problem is likely caused by condensation, which can lead to ice buildup. Condensation droplets then freeze, especially on the coldest rear walls. In fact, according to the literature, just 2–3 mm of frost can increase the energy consumption of refrigerator or freezer by up to 30%, resulting in higher electricity bills. For this case, ice layers formed in the pipes, which restricted the flow of refrigerant and affected the entire system. This issue caused the compressor to work harder to compensate for the loss of efficiency. To prevent and resolve these technical issues encountered over the past two years, a defrost heating element and a timer were installed to melt the frost that forms on the circuit and evaporator as shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Components and integration of the automatic defrosting system. (a) Defrost heater; (b) Mechanical timer; (c) Timing control; (d) Thermostat assembly; (e) Assembly of the defrost resistance and timer

2.3 Thermocouple Calibration Procedure

To ensure precise temperature measurements, a calibration process was implemented using multiple Type-K thermocouples. They were cross-checked with two reference thermocouples in the same environment. The process contains two steps: (1) Calibration in air inside the refrigeration unit, (2) Calibration during the slow cooling and solidification of Glaceol.

This double-check confirmed the accuracy of readings across different temperature ranges (Fig. 5). The accuracy of type K thermocouples used depends on the quality of manufacturing, calibration, and operating conditions. The accuracy can vary depending on the measured temperature. For instance, at very high or very low temperatures, the error may be minimal. In such cases, the maximum measurement error is approximately ±0.5%.

Figure 5: Different stages of thermocouple calibration: (a) Calibration of thermocouples by measuring the air temperature inside the refrigeration cell; (b) Calibration of thermocouples by measuring the temperature of the PCM

The initial tests involved evaluating the prototype by recording the air temperature inside the refrigeration room, the ambient air temperature around the unit, and the temperature of the PCM contained within the eutectic plates. To measure the internal air temperature of the refrigeration room, two type-K thermocouples were placed vertically along the central axis of the room. All experiments were conducted with the activation of a defrosting heater and a timer every 3 h and 45 min to melt the ice accumulated during operation. For a liquid, a food item, or in our case, a PCM, to reach the solidification temperature inside a freezer, the condenser temperature (the source) of this refrigeration system must be significantly lower than the desired solidification temperature to compensate for heat losses and ensure proper system operation. For this experiment, the temperature of the condenser can vary depending on the efficiency of the refrigeration system, which is influenced by external conditions. However, it can be significantly lower than the solidification temperature of over −20°C to ensure that the material reaches its solidification temperature within the refrigeration system’s enclosure, especially if the surrounding temperatures are generally above 30°C. For all these reasons, it is practically necessary to set the thermostat to a very low temperature to compensate for the losses that appear to be significant, especially when the outdoor temperatures are high.

3.1 Experiment (1): Thermostat Set to −35°C

In the first experiment, the thermostat was set to −35°C and Glaceol was used as the PCM. Figs. 6–8 show external air temperature, average internal air temperature, and Glaceol temperature inside the eutectic plates respectively. The obtained results showed that only three of the ten eutectic plates (plates 1, 2, and 6) underwent a complete phase change, while the others remained in a liquid state as indicated in Fig. 8. The temperatures corresponding to the other eutectic plates are not depicted in the figures, but this aspect has been clearly noted from our observations.

Figure 6: Ambient air temperature surrounding the refrigeration unit

Figure 7: Average air temperature inside the refrigeration unit

Figure 8: Temperature of the PCM (Glaceol) inside the plates

This partial activation of the PCM suggests that the temperature distribution within the room was not uniform, possibly due to airflow limitations or suboptimal placement of the eutectic plates. Consequently, the system failed to fully capitalize on the latent heat storage capability of the PCM, and the energy consumption remained at 0.45 kWh per hour, comparable to the control configuration without PCMs. This indicated that without full PCM activation, the energy-saving potential remains largely untapped.

In theory, the PCM absorbs or releases a thermal flux when it changes state, in this case transitioning from a liquid state to a solid state. Except for the PCM contained in eutectic plate number 10, which undergoes state changes characterized by the appearance of several alternating cycles (storage and release) and its temperature fluctuating around the solidification/melting temperature of the Glaceol (−10°C), no state changes have been observed in the other plates. This leads to the conclusion that the surrounding and test temperatures are not favorable for the efficient operation of the refrigeration machine and for properly exploiting the advantages of this PCM. In this case, the Glaceol functions properly by utilizing its latent heat, which is the amount of heat required to change the state without changing its temperature. The synchronization of temperatures is not an issue, as the timer counts 3 h and 45 min from the previous defrosting. This means that if the refrigeration system was turned off, for example, after 1 h from the last defrosting, the next defrosting will occur after 2 h and 45 min from the system’s restart.

For all these reasons, there will not be a synchronization of temperatures, which does not pose a problem for our experimental protocol anyway. The air temperature does not drop below −8°C, despite the thermostat being set to −35°C, primarily due to the testing conditions conducted in a non-ventilated environment and unfavorable average temperatures, as the external environment is above 33°C. When outdoor temperatures are high, several factors can limit the compressor’s effectiveness in lowering the indoor air temperature. In hot weather, the amount of heat that the machine needs to extract from the inside is greater. If the thermal load exceeds the cooling capacity of the device, it will not be able to maintain the desired indoor temperature. Secondly, the condenser, which dissipates the heat extracted from the inside to the outside, may be less efficient in hot weather. If the outdoor air temperature is high, it becomes more difficult for the condenser to release heat, which can lead to an increase in pressure within the system and reduce overall efficiency. Thirdly, due to the high ambient temperature, the compressor may overheat, which can lead to a reduction in its efficiency or even a temporary shutdown to prevent damage. Additionally, if the airflow around the outdoor unit is obstructed or insufficient, this can also hinder the condenser’s ability to dissipate heat, affecting the system’s optimal operation.

During the phase transitions of PCM, latent heat is involved, meaning that energy is exchanged without a temperature change. In other words, when latent heat exchanges occur, the temperature of the system does not necessarily remain constant, but it may stay constant during the state change phase. In this case, the state change happens rapidly. However, in the presence of combined sensible and latent heat exchanges within the same process, the temperature of the PCM can vary and does not remain constant. The impact of these exchanges will depend on the amount of heat exchanged as sensible heat compared to the latent heat exchanges and the specific conditions of the system.

Heat is transferred by convection from the indoor air of the cell to the surface of the eutectic plate, and then the heat flow is conducted to the other surface of the eutectic plate facing the PCM, which subsequently exchanges heat by convection with the PCM. In a turbulent flow regime, an emitting fluid (the indoor air of the cell in this case) can be used to cool another receiving fluid (PCM in its liquid state in this case). If the emitting fluid, which is a cooling fluid, has a lower initial temperature before coming into contact with the receiving fluid, heat will transfer from the receiving fluid (hotter) to the emitting fluid (colder) through conduction and convection. In turbulent flow, heat transfer is generally more efficient due to turbulent mixing that promotes better temperature distribution. The mixing of the two fluids occurs rapidly.

The fluctuations in speed and pressure within the turbulent fluid allow for a more intense interaction between the layers of fluid, which increases the rate of heat transfer. As the emitting fluid absorbs heat, its temperature rises, while that of the receiving fluid decreases. This process continues until thermal equilibrium is reached or the fluids move apart. The physical properties of the fluids, such as viscosity and density, can also change depending on the temperature. This can influence the flow behavior, particularly turbulence and flow regime. In summary, just after contact, there is a rapid heat transfer from the receiving fluid to the emitting fluid, accompanied by turbulent mixing that promotes temperature homogenization. However, in the opposite case, several factors can explain why the temperature of the receiving fluid sometimes becomes lower than that of the emitting fluid, even if the emitting fluid has a lower initial temperature. The dynamics of fluids, the thermal properties of the fluids involved, as well as the flow conditions and heat exchange, are all factors that can explain why the temperature of the receiving fluid may become lower than that of the emitting fluid in a turbulent flow regime. The specific heat capacity of the fluids and their respective flow rates, for example, play a crucial role. If the receiving fluid has a higher heat capacity or a lower flow rate (a situation that corresponds to our case), it may not be able to retain its heat in the face of the input from the emitting fluid, which can lead to a more noticeable decrease in its temperature.

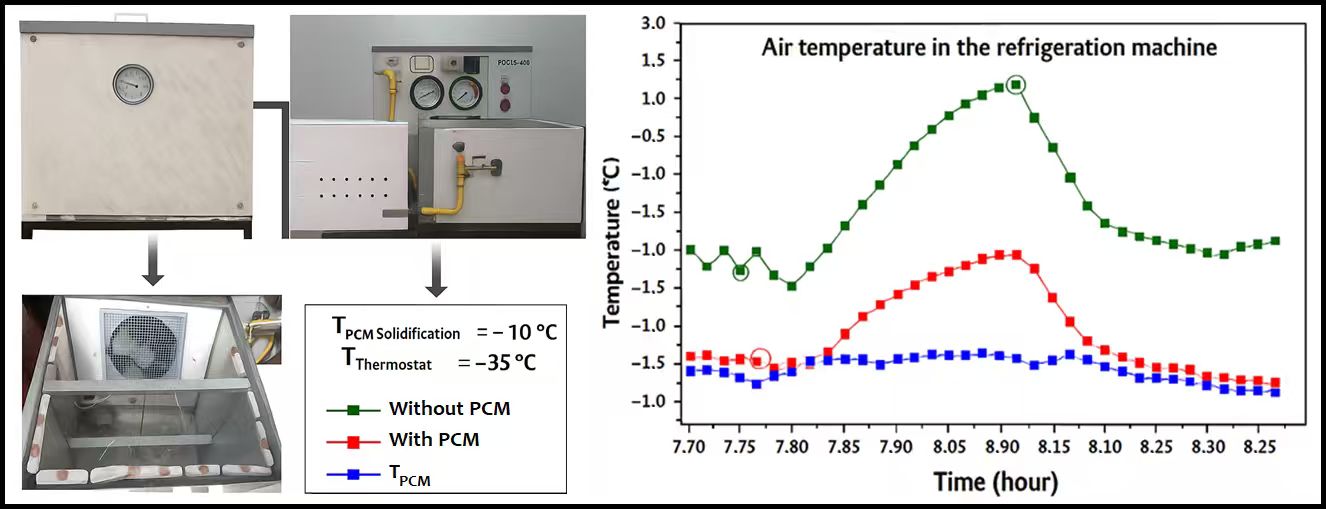

3.2 Experiment (2): Thermostat Still at –35°C but with Defrosting

The second experiment was conducted under the same thermostat setting of −35°C, but with the addition of a defrosting resistor and a timer to melt ice buildup during operation (Figs. 9 and 10). During defrost cycles, temperature measurements revealed a significant difference between the PCM-enhanced and standard configurations. The phenomena that emerge and are characterized by temperature peaks can be explained in the same way as in the previous example.

Figure 9: Ambient air temperature surrounding the refrigeration unit

Figure 10: Average air temperature inside the refrigeration unit

Table 2 compares internal air temperatures with and without PCMs. For instance, a temperature gain of up to 10.98°C was observed in favor of the PCM-integrated setup. This demonstrated the effectiveness of PCMs as thermal buffers, capable of absorbing heat during defrost events and maintaining lower, more stable internal temperatures. Such thermal stabilization is particularly beneficial in preserving the quality of stored food and reducing thermal stress on the system. Unlike the previous example, the temperature range for the phase change of the material is suitable for the application in this case. The PCM changes state at −10°C, a temperature that is conducive to the operating conditions. The temperature behavior inside the plates was similar to that of plate 10 in the previous example. We therefore observe that the regulation of the thermostat temperatures and the phase change of the PCM is maintained, but the laboratory test conditions, that is to say, the air temperature near the machine, are radically different. The first experiment corresponds to a temperature close to 34°C, while in the second, it is around 17°C.

Fig. 11 shows the thermal response of the cold cell when the electric defrost element is activated. Without PCM, the cell temperature increases suddenly and, upon activating the defrosting resistance, its value was precisely −8.9°C. After 15 min of operation, this temperature becomes exactly 0.7°C. This means that the increase in the cell temperature related to the activation of the electric defrost resistance amounts to 9.6°C. Conversely, when the PCM plates are integrated, the temperature increase has been significantly moderated, reaching values ranging from −13.5 to only −8.25°C. This demonstrates the PCM’s ability to absorb defrosting heat and dampen thermal fluctuations. The blue curve, representing the PCM temperature, remains stable below its phase transition threshold, confirming the latent heat absorption process during this critical period. Overall, the PCM contributes to improved thermal stability and protects stored products from abrupt warming, thereby enhancing preservation quality and supporting greater energy efficiency during defrost cycles. Generally, the same analyses and interpretations will remain valid concerning the increases in indoor air temperatures of the machine and the decreases in PCM temperatures.

Figure 11: Temperature profiles during electric defrost activation

3.3 Experiment (3): Thermostat at −30°C

In the third experiment, the thermostat was adjusted to −30°C while continuing to use Glaceol as the PCM. Despite the slightly higher setpoint, the PCM-integrated system still demonstrated notable performance advantages during defrosting. Table 3 and the corresponding figures (Figs. 12–14) confirm notable temperature gains ranging from 7.71°C to 8.83°C in the PCM-enhanced configuration compared to the control setup. These results emphasize the critical role of properly configured defrost cycles and lower thermostat setpoints in maximizing the effectiveness of PCMs.

Figure 12: Ambient air temperature surrounding the refrigeration unit

Figure 13: Average air temperature inside the refrigeration unit

Figure 14: Temperature profiles during electric defrost activation

Notably, Glaceol demonstrated reliable thermal buffering performance even at slightly elevated operating temperatures, suggesting its adaptability under varying thermal conditions. Although energy savings were not explicitly quantified in this experiment, the observed thermal stability indicates meaningful potential for reduced energy consumption. Moreover, the findings underscore the importance of aligning the PCM’s phase transition with the refrigeration system’s thermal cycles, as this synchronization is essential for fully harnessing the material’s latent heat storage and release capabilities.

The temperature range for the PCM is appropriate for this application, as it transitions at −10°C, which aligns well with the operating conditions. The temperature profile within the plates resembled that of plate 10 from the earlier example. The PCMs in this refrigeration system can help smooth out variations in thermal load, allowing the compressor to operate more steadily and efficiently. In these systems, where the aim is to minimize the use of electrical energy, PCMs can be used to create passive refrigeration systems that exploit phase changes to maintain low temperatures without requiring active compressors.

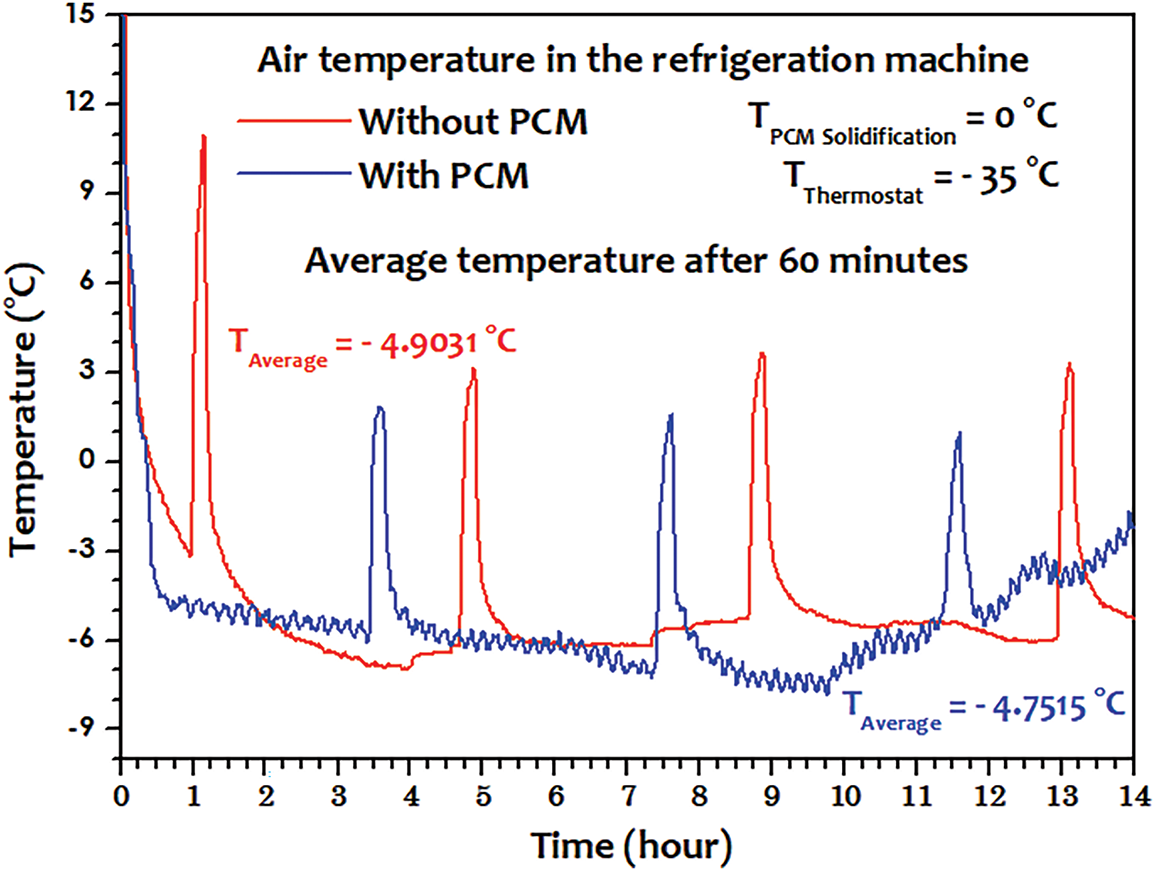

3.4 Experiment (4): Thermostat at −35°C and Using Distilled Water as the PCM

The testing conditions, as shown in Fig. 15, indicate that the temperatures surrounding the test bench are very high. The fourth and final experiment introduced distilled water as the PCM, again under a thermostat setting of −35°C (Fig. 16). Unlike Glaceol, distilled water achieved a more widespread phase change across most eutectic plates (plates 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10), despite the internal and ambient temperatures being higher than in previous tests (up to 36°C). Only plates 1 and 3 showed incomplete phase transitions, possibly due to localized thermal or airflow irregularities (Fig. 17).

Figure 15: Ambient air temperature surrounding the refrigeration unit

Figure 16: Internal chamber temperature profile using distilled water as PCM

Figure 17: Temperature of the PCM (Water) inside the plates

Most importantly, this configuration led to a clear reduction in energy consumption, from 0.4584 to 0.4231 kWh per hour, representing a 7.76% improvement. This result underscores the potential of distilled water, a cost-effective and environmentally friendly PCM, to significantly enhance the energy efficiency of refrigeration systems when properly integrated. This confirms water as a viable PCM under the right conditions.

In this experiment, when distilled water changes state from liquid to solid during freezing, it can indeed absorb or release a flow of heat. However, its thermal storage capacity and phase change temperature are conducive to the operating conditions of the refrigeration system. Distilled water may have better thermal conductivity, which can enhance heat transfer efficiency. It is free of minerals, contaminants, and impurities, which reduces the risk of corrosion.

However, there are some plates where the water has not reached the freezing temperature of 0°C. This is due to several factors that can influence a freezer’s ability to freeze water, ranging from environmental conditions to internal technical issues. Regarding technical problems, the machine’s operation was very satisfactory. We did not detect any failures in the cooling system, such as a faulty compressor or a lack of refrigerant. The reasons mainly concern environmental conditions:

– First, the high ambient temperature: if the ambient temperature around the freezer is too high, as shown in Fig. 16, it can affect cooling efficiency and prevent the water from reaching freezing temperature.

– The overloading of the freezer and the uneven distribution of items inside (water bottles and loaves of bread): if this distribution is random and the freezer is too full, cold air cannot circulate properly. Poor air circulation inside the freezer can lead to warm spots where water does not freeze. This can be caused by obstructions or a poor arrangement of items inside, thus preventing uniform freezing of food and the water contained in the eutectic plates.

Furthermore, regardless of the experimental conditions, when the defrosting resistance is activated in this refrigeration machine, several things happen. The defrosting heater generates heat that is transferred to the evaporator. This allows for the melting of ice or frost that has accumulated on the circuit and the surfaces of the evaporator. The compressor will stop, knowing that we have adopted it to avoid operating even at a reduced capacity, so that we can speed up the defrosting process. According to several tests, we have experimentally observed that 15 min is the optimal duration to completely melt ice or frost while also preventing overheating or excessive defrosting. During this phase, the normal cooling cycle will be interrupted, leading to several subsequent consequences. The temperature in the space to be cooled will start to rise, as the system will no longer be able to extract heat from that space.

This explains the temperature increases observed in the temperature curves inside the refrigeration cell (Figs. 7, 10, 11, 13, 14 and 16), and at the same time, there are sometimes less significant temperature increases in the PCMs containing the eutectic plates (Figs. 8 and 13). This can lead to the deterioration of food or other temperature-sensitive products if this duration is long or excessive. The heat that was normally dissipated by the condenser will no longer be removed, which may lead to a buildup of heat in the system. The machine no longer generates heat into the external environment, which in our case is the ambient air represented by its temperature in Fig. 6, which automatically explains the drop in temperatures during the defrosting phase. Once the defrosting is complete, the system returns to its normal operating mode.

This study explored the integration of two PCMs: Glaceol (with a melting point of −10°C) and distilled water (melting point of 0°C) into a vapor compression refrigeration system, with the aim of enhancing energy efficiency and improving temperature regulation. The PCMs were incorporated into eutectic plates positioned within the refrigeration room, and their performance was evaluated under various thermostat settings, both with and without defrosting mechanisms.

The experimental findings of this study highlight several important outcomes, summarized as follows:

– Energy savings of up to 7.76% were achieved when using distilled water as PCM (from 0.4584 to 0.4231 kWh per hour).

– Temperature stabilization gains between 7.71°C and 10.98°C were recorded during deforest cycles when PCMs were integrated, compared to the control setup.

– Distilled water outperformed Glaceol in terms of consistent solidification across eutectic plates under high ambient conditions (~36°C).

– Glaceol showed partial activation, with only 3 out of 10 plates undergoing phase change at −35°C, limiting its effectiveness.

– The addition of a defrosting resistor and timer improved system performance by preventing frost buildup, which can otherwise increase energy consumption by up to 30%.

– The PCM performance was highly dependent on thermostat settings, placement of plates, and airflow uniformity inside the refrigeration room.

– The system demonstrated potential for thermal buffering during power outages, extending the preservation time of stored products.

However, the performance of PCMs was found to be highly sensitive to thermostat calibration, placement of eutectic plates, and the distribution of airflow within the room. Inconsistent solidification in some plates, especially with Glaceol, suggests the need for improved thermal design. Additionally, long-term operational durability, repeated phase change cycling, and performance under varying load conditions were not explored in depth and warrant further investigation.

Future studies could explore alternative PCMs with tailored melting points that better match the thermal profile of specific refrigeration applications. The integration of smart controls, such as dynamic thermostats or sensors, may enhance the synchronization between phase transition cycles and refrigeration demand. Moreover, field testing under real-world commercial or transport conditions, including prolonged power outages and fluctuating ambient temperatures, could provide valuable insights into practical deployment and scalability.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge and gratefully thank the financial support provided by DG-RSDT of Algeria.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in entire part by the Biomaterials and Transport Phenomena Laboratory Agreement No. 303 03-12-2003, at the University of Medea.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Rachid Djeffal, Sidi Mohammed El Amine Bekkouche, Zakaria Triki, Abir Abboud, Sabrina Lekmine, Hichem Tahraoui, Jie Zhang, Abdeltif Amrane; Methodology: Rachid Djeffal, Sidi Mohammed El Amine Bekkouche, Zakaria Triki, Abir Abboud, Sabrina Lekmine, Hichem Tahraoui, Jie Zhang, Abdeltif Amrane; Software: Rachid Djeffal, Sidi Mohammed El Amine Bekkouche, Zakaria Triki, Abir Abboud; Validation: Rachid Djeffal, Sidi Mohammed El Amine Bekkouche, Zakaria Triki, Abir Abboud; Formal analysis: Rachid Djeffal, Sidi Mohammed El Amine Bekkouche, Zakaria Triki; Investigation: Rachid Djeffal, Sidi Mohammed El Amine Bekkouche, Zakaria Triki, Abir Abboud; Resources: Rachid Djeffal, Sidi Mohammed El Amine Bekkouche, Zakaria Triki, Abir Abboud; Data curation: Rachid Djeffal, Sidi Mohammed El Amine Bekkouche, Zakaria Triki, Abir Abboud; Writing—original draft: Rachid Djeffal, Sidi Mohammed El Amine Bekkouche, Zakaria Triki, Abir Abboud; Writing—review & editing: Sabrina Lekmine, Hichem Tahraoui, Jie Zhang, Abdeltif Amrane; Visualization: Rachid Djeffal, Sidi Mohammed El Amine Bekkouche, Zakaria Triki, Abir Abboud, Sabrina Lekmine, Hichem Tahraoui, Jie Zhang, Abdeltif Amrane; Supervision: Zakaria Triki, Sabrina Lekmine, Hichem Tahraoui, Abdeltif Amrane, Jie Zhang; Project administration: Zakaria Triki, Hichem Tahraoui, Abdeltif Amrane, Jie Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Aftab W, Usman A, Shi J, Yuan K, Qin M, Zou R. Phase change material-integrated latent heat storage systems for sustainable energy solutions. Energy Environ Sci. 2021;14(8):4268–91. doi:10.1039/D1EE00523F. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Tassou SA, Ge Y, Hadawey A, Marriott D. Energy consumption and conservation in food retailing. Appl Therm Eng. 2011;31(2):147–56. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2010.08.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. ASHRAE. Transactions—American society of heating, refrigerating and air conditioning engineers. Vol. 28. Peachtree Corners, GA, USA: ASHRAE; 2023. [Google Scholar]

4. Lima de Aguiar M, Gaspar PD, Dinho da Silva P. Additive manufacturing of a frost detection resistive sensor for optimizing demand defrost in refrigeration systems. Sensors. 2024;24(24):8193. doi:10.3390/s24248193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Centro Studi Galileo, & European Energy Centre. The road to competence in future green technologies: refrigeration and air conditioning international—special issue 2016–17 refrigeration and air conditioning. In: XVII European Conference on Technological Innovations in Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Industry, Polytechnic University of Milan; 2017 Jun 9–10; Milan, Italy. [Google Scholar]

6. Liang J, Du W, Wang D, Yuan X, Liu M, Niu K. Analysis of the refrigeration performance of the refrigerated warehouse with ice thermal energy storage driven directly by variable photovoltaic capacity. Int J Photoenergy. 2022;2022:3441926. doi:10.1155/2022/3441926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Gupta A, Sankhla VS, Sharma D. A comprehensive review on the sustainable refrigeration systems. Mater Today Proc. 2021;44(6):4850–4. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2020.11.700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Emani MS, Manda BK. International conference on mechanical, materials and renewable energy. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2018;377:012064. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/377/1/012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Harun Or Rashid M, Hasan MT, Alam TB, Hossain S. Energy efficient refrigeration system using latent heat storage, PCM. Int J Thermofluids. 2024;100717. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2024.100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Qin Y, Ghalambaz M, Sheremet M, Fteiti M, Alresheedi F. A bibliometrics study of phase change materials (PCMs). J Energy Storage. 2023;73(19):108987. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.108987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Nguyen VN, Le TL, Duong XQ, Le VV, Nguyen DT, Nguyen PQP, et al. Application of phase change materials in improving the performance of refrigeration systems. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2023;56(353):103097. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2023.103097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zalba B, Marín JM, Cabeza LF, Mehling H. Review on thermal energy storage with phase change: materials, heat transfer analysis and applications. Appl Therm Eng. 2003;23(3):251–83. doi:10.1016/S1359-4311(02)00192-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Pirvaram A, Sadrameli SM, Abdolmaleki L. Energy management of a household refrigerator using eutectic environmental friendly PCMs in a cascaded condition. Energy. 2019;181(12):321–30. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2019.05.129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ouaouja Z, Ousegui A, Toublanc C, Rouaud O, Havet M. Phase change materials for cold thermal energy storage applications: a critical review of conventional materials and the potential of bio based alternatives. J Energy Storage. 2025;110:115339. doi:10.1016/j.est.2025.115339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gao L, Xu S, Yu G, Ma G, Chang Y, Li S. Application study of direct current refrigerator combining phase change cold storage and mini electrical storage. Energy. 2025;320(9):135308. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.135308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Djeffal R, Bekkouche SMA, Samai M, Younsi Z, Mihoub R, Benkhelifa A. Effect of phase change material eutectic plates on the electric consumption of a designed refrigeration system. Instrum Mes Métrologie. 2020;19(1):1–8. doi:10.18280/i2m.190101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang H, Lu W, Wu Z, Zhang G. Parametric analysis of applying PCM wallboards for energy saving in high-rise lightweight buildings in Shanghai. Renew Energy. 2020;145(1):52–64. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2019.05.124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Aggoune A, Hamdani M, Marif Y, Bekkouche SMA, Cherier MK, Djeffal R. The effect of a phase change material on a building’s roof on reducing the electricity consumption. J Compos Adv Mater ICETME. 2021 Dec 18–20. [Google Scholar]

19. Djeffal R, Cherier MK, Bekkouche SMA, Younsi Z, Hamdani M, Al-Saadi S. Concept development and experimentation of a Phase Change Material (PCM) enhanced domestic hot water. J Energy Storage. 2022;51(Part 1):104400. doi:10.1016/j.est.2022.104400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Abboud A, Triki Z, Djeffal R, Bekkouche SMA. Enhancing hygrothermal performance in multi zone constructions through phase change material integration. Front Heat Mass Transf. 2024;22(3):769–89. doi:10.32604/fhmt.2024.050330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang H, Li C, Wang X. Nano enhanced phase change materials for thermal energy storage: recent advances and prospects. Nano Energy. 2022;95:107002. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2022.107002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wang X, An B, Lin Z, Huang R. Advanced composite phase change materials for enhanced thermal performance in refrigeration applications. Mater Today Energy. 2021;20:100716. doi:10.1016/j.mtener.2021.100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhou T, Zhang J, Liu Z. Solar powered refrigeration systems with integrated phase change materials: design, performance, and economic analysis. Sol Energy. 2023;240(4):111–22. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2022.12.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li H, Zhang Q, Liu J. Integration of phase change materials with cold thermal energy storage systems for smart grid applications. Energy Convers Manag. 2022;268(10):116048. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2022.116048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kumar R, Sharma S, Singh AK. Bio based phase change materials for sustainable refrigeration: a review. J Clean Prod. 2022;376(11):134489. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chen X, Zhang Y, Wang L. Adaptive phase change materials for dynamic thermal management in refrigeration systems. Appl Energy. 2023;330(23):120345. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.120345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu Y, Chen Z, Wu W. Hybrid refrigeration systems using phase change materials and thermoelectric modules: performance evaluation and optimization. Renew Energy. 2023;202(9):278–89. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2022.12.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Arora RC. Refrigeration and air conditioning. Delhi, India: PHI Learning Pvt Ltd.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

29. Dinçer I, Rosen MA. Thermal energy storage: systems and applications. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

30. Martínez FR, Borri E, Kala SM, Ushak S, Cabeza LF. Phase change materials for thermal energy storage in industrial applications. Heliyon. 2025;11(1):e41025. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e41025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Pielichowska K, Pielichowski K. Phase change materials for thermal energy storage. Prog Mater Sci. 2014;65:67–123. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2014.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Trigui A, Abdelmouleh M. Improving the heat transfer of phase change composites for thermal energy storage by adding copper: preparation and thermal properties. Sustainability. 2023;15(3):1957. doi:10.3390/su15031957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Abhinay S, Alparslan O. Thermal performance of phase change material based heat exchangers. In: Proceedings of the ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition IMECE2022 (Paper No. 94810); 2022 Oct 30–Nov 3; Columbus, OH, USA. doi:10.1115/IMECE2022-94810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kuta M, Matuszewska D, Wójcik TM. The role of phase change materials for sustainable energy. E3S Web Conf. 2016;10:00068. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/20161000068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools