Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Experimental Method for Studying the Effect of Dissolved Substances on the Evaporation Rate of Watwer Droplets Suspended in Air

1 X-BIO Institute, University of Tyumen, 6 Volodarskogo St, Tyumen, 625003, Russia

2 Institute of Mechanics, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, 119991, Russia

3 Heat Transfer Department, Joint Institute for High Temperatures, 17A Krasnokazarmennaya St, Moscow, 111116, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Leonid A. Dombrovsky. Email:

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(4), 1091-1102. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.068244

Received 23 May 2025; Accepted 23 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

A new experimental method is developed to investigate the effect of dissolved substances on the evaporation rate of small water droplets suspended in the atmosphere. The laboratory setup is based on converting a generated droplet jet of complex structure into a directed flow of evaporating droplets falling in a vertical tube. Images of falling droplets captured by a high-speed camera through a window in the vertical channel wall are used to determine the sizes and velocities of individual droplets. The computational modeling of droplet motion and evaporation proved useful at all stages of the experimental work: from selecting the position of the vertical channel to processing the experimental data. It was found that even a 0.1% mass concentration of the dissolved ionic salt KCl has a considerable effect on decreasing the evaporation rate of the droplets. In contrast, a typical fungicide with a mass concentration of 2.5% has only a slight impact on the evaporation rate. The laboratory results enabled the authors to refine the evaporation model of water droplets to account for the presence of dissolved substances. Modified models of this type are expected to be useful in controling crop spraying and also in other potential applications.Keywords

The effect of dissolved substances on the evaporation rate of small airborne droplets of aqueous solutions is of interest for studying some natural phenomena in nature and solving various industrial problems in quite different applications. Among others, we should mention the drying of droplets in the pharmaceutical industry to obtain solid drugs in the form of powders or tablets [1–3] and some processes in food production [4]. The application in agriculture, which was the main motivation for this work, is to control the spraying of crop protection products [5–10]. The transfer of aqueous solution droplets and watered aerosols in the atmosphere, which is important for meteorology and possible pathogen transfer, should also be mentioned [11–13].

The research efforts have been focused mainly on pharmaceutical applications where water evaporation causes a non-volatile dissolved substance to form a solid crust on the droplet surface. Subsequent water evaporation from the droplet center usually results in the breakdown of the solid shell. As for the droplets of a salt solution, this often leads to the appearance of hollow particles with orifices through which the vapor and concentrated solution escape to the outside, forming small solid particles. This interesting phenomenon and related effects are discussed in papers [14–20].

The present work is oriented mainly towards agricultural problems related to the drip irrigation of plants. Therefore, only low-concentration solutions of dissolved substances are considered, and the main issue concerns the reduction of the droplet evaporation rate due to the dissolved substances. The influence of the same additives to water droplets on the balance between evaporation and condensation in the conditions of an equilibrium cluster of levitating small droplets was studied by the authors in papers [21–23]. The experiments showed a significant effect of even small concentrations of some non-volatile substances dissolved in water on the increase of the equilibrium droplet size, which is associated with the hindered evaporation of water at increasing concentrations of these substances near the surface of the evaporating droplet.

To the above-mentioned applied problem, one has to deal not with equilibrium droplets, as in the droplet cluster, when evaporation is compensated by condensation from the surrounding humid air. Therefore, one should consider a physically simpler process when the condensation of water vapor is negligible. We can focus on the motion and evaporation of the droplets suspended in atmospheric air. Unfortunately, the physical simplicity of the process (in comparison with the equilibrium droplet cluster) is combined with new difficulties of measurements, since one has to track the droplets travelling in the gas. As a result, it was necessary to create a fundamentally new laboratory setup and to develop a special measurement technique.

2 Laboratory Setup and Experimental Procedure

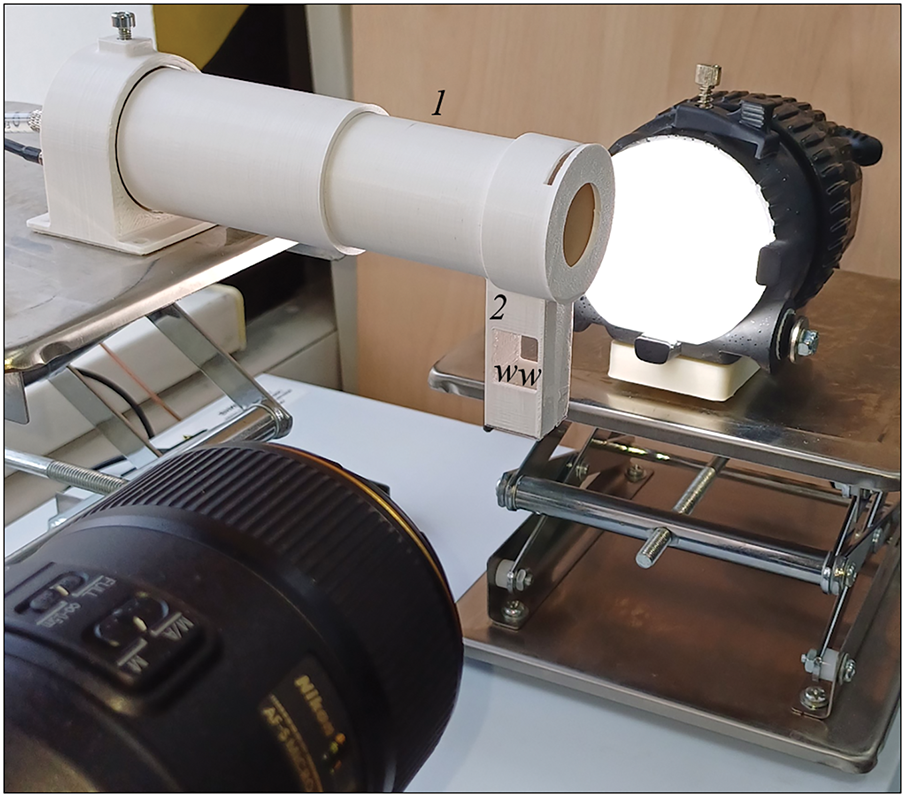

It is impossible to measure the size and velocity of individual evaporating droplets in the original droplet jet of a complex structure. The experimental technique used in this work eliminates the need to study the sprayed droplet stream. The basic idea of the present paper was to convert the complex droplet stream generated by the dispenser into a directed flow of evaporating droplets falling in an air-filled vertical tube. This can be done using a design shown in Fig. 1, where “1” is the plastic protective casing, inside which there is an ultrasonic dispenser (Altrasonic, China), the horizontal axis of which coincides with the axis of the protective casing. The cylindrical part of the casing (inner diameter of 38 mm) ends with a vertical channel “2” of square cross section of 17 × 17 mm. Only those droplets whose horizontal motion has completely ceased due to the viscosity of the gas remain in the vertical channel. These droplets fall vertically downward under the action of gravity. Of course, the viscosity of the gas leads to a stabilization of the droplets’ falling velocity, which changes only as a result of the gradual evaporation of the droplets. The distance of the vertical channel from the dispenser was chosen to observe a sufficient number of droplets falling in the channel. The corresponding calculations will be considered below. Two opposite rectangular windows “ww” (17 mm width and 19 mm height) were closed with a transparent film. The falling droplets are illuminated and observed through these windows. The vertical position of the windows was chosen to exclude the effects of the flow disturbances at the lower and upper ends of the channel. The LED light source BM-50 V 3200/5600 (Logocam, Israel) and a high-speed camera FASTCAM Nova (Photron, Japan) with a lens AF-S VR Micro-Nikkor 105 mm f/2.8 G (Nikon, Japan) are used.

Figure 1: The image of the experimental setup

Distilled water and solutions of fungicide “Therapist Pro” and KCl with a mass concentration of

The natural uncertainty of the initial velocity of droplets generated by the dispenser and the complex interaction of evaporating polydisperse droplets at the initial part of the droplet jet [24–32] does not require theoretical analysis for the problem being solved. To clarify the droplets’ motion from the dispenser to the top of the vertical channel, it is sufficient to consider a single-droplet model, neglecting the droplets’ evaporation in this part of their trajectories. The velocity components of a droplet of radius

where

and rewrite Eqs. (1) and (2) as follows:

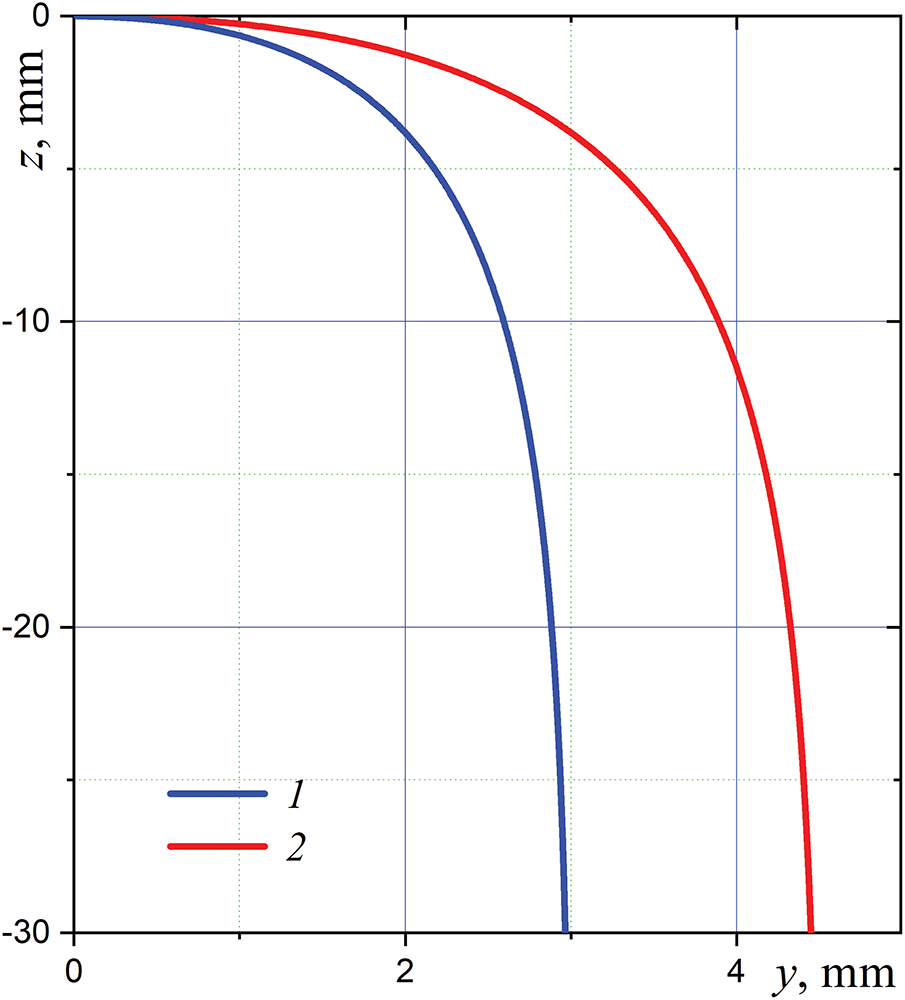

The trajectories of water droplets obtained by solving these equations for typical values of the droplet radius and its initial velocity are shown in Fig. 2, where

Figure 2: Calculated initial parts of trajectories for a droplet of radius

Note that the dynamic relaxation time of a water droplet in immovable air does not depend on the droplet velocity, and it is equal to

For convenience of calculations, this equation can be written as follows:

It should be noted that Eq. (7) is based on the Stokes approximation, which is applicable at a small Reynolds number. We will check below if this approach is sufficiently accurate for our laboratory experiments.

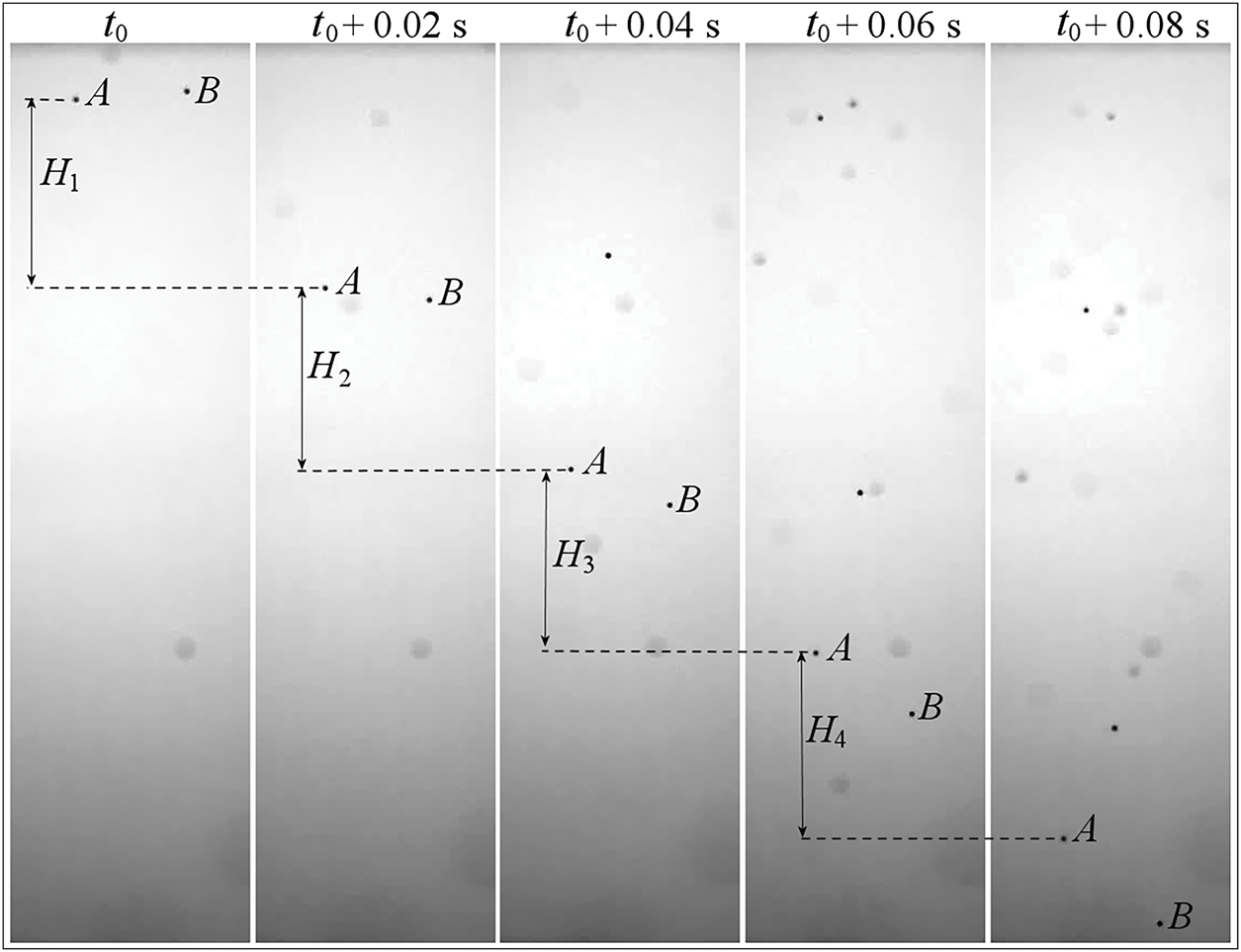

Fig. 3 shows an example of a series of frames with an interval of

Figure 3: Typical images depicting falling droplets of pure water

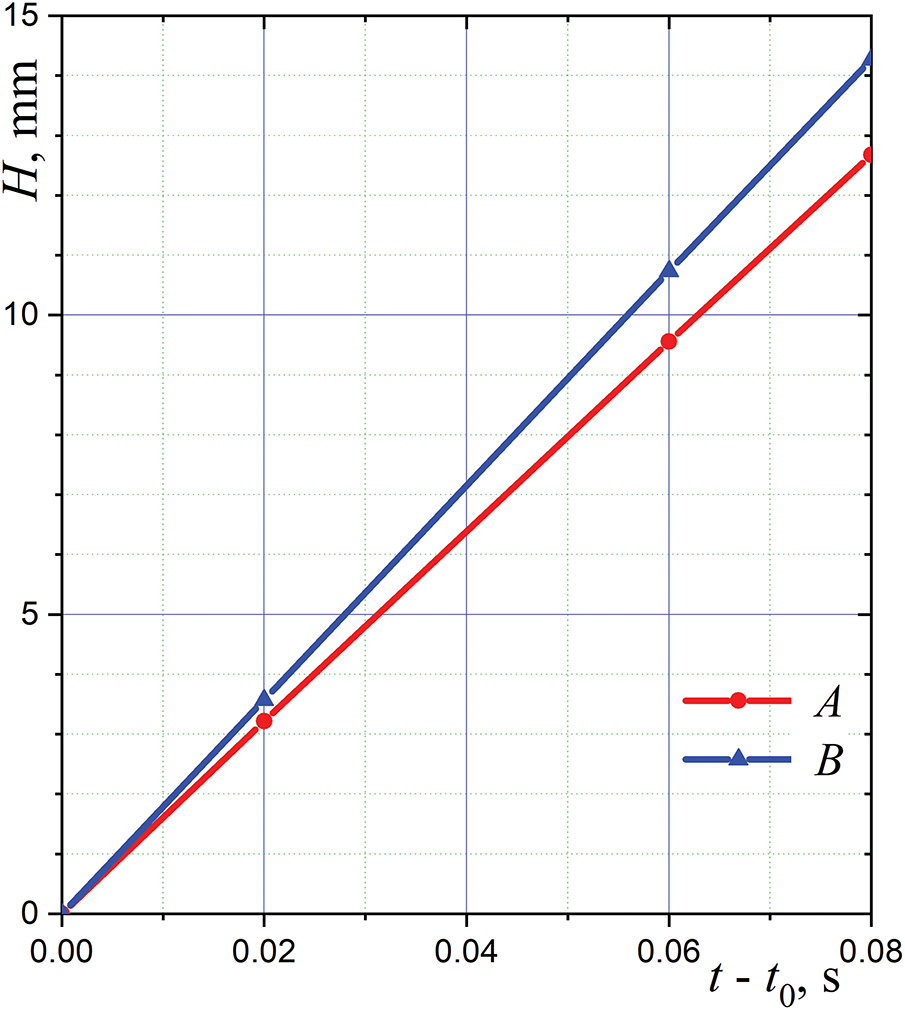

The results for two initial and two final time intervals shown in Fig. 3 are presented in Fig. 4. The four points on each of the colored lines in Fig. 4 do not lie on straight lines. In other words, the line segments connecting the first two points and the last two points are not parallel. The tangent of the angle of inclination of these lines is the average droplet falling velocity at the considered part of the trajectory. For example, the velocity of droplet A decreases from about

Figure 4: The distance travelled by the droplets of pure water

In addition to the unavoidable measurement error, there is a systematic error due to the Stokes approximation. To estimate this physical error, it is necessary to determine the Reynolds number of the observed droplets. Using the above-specified values of

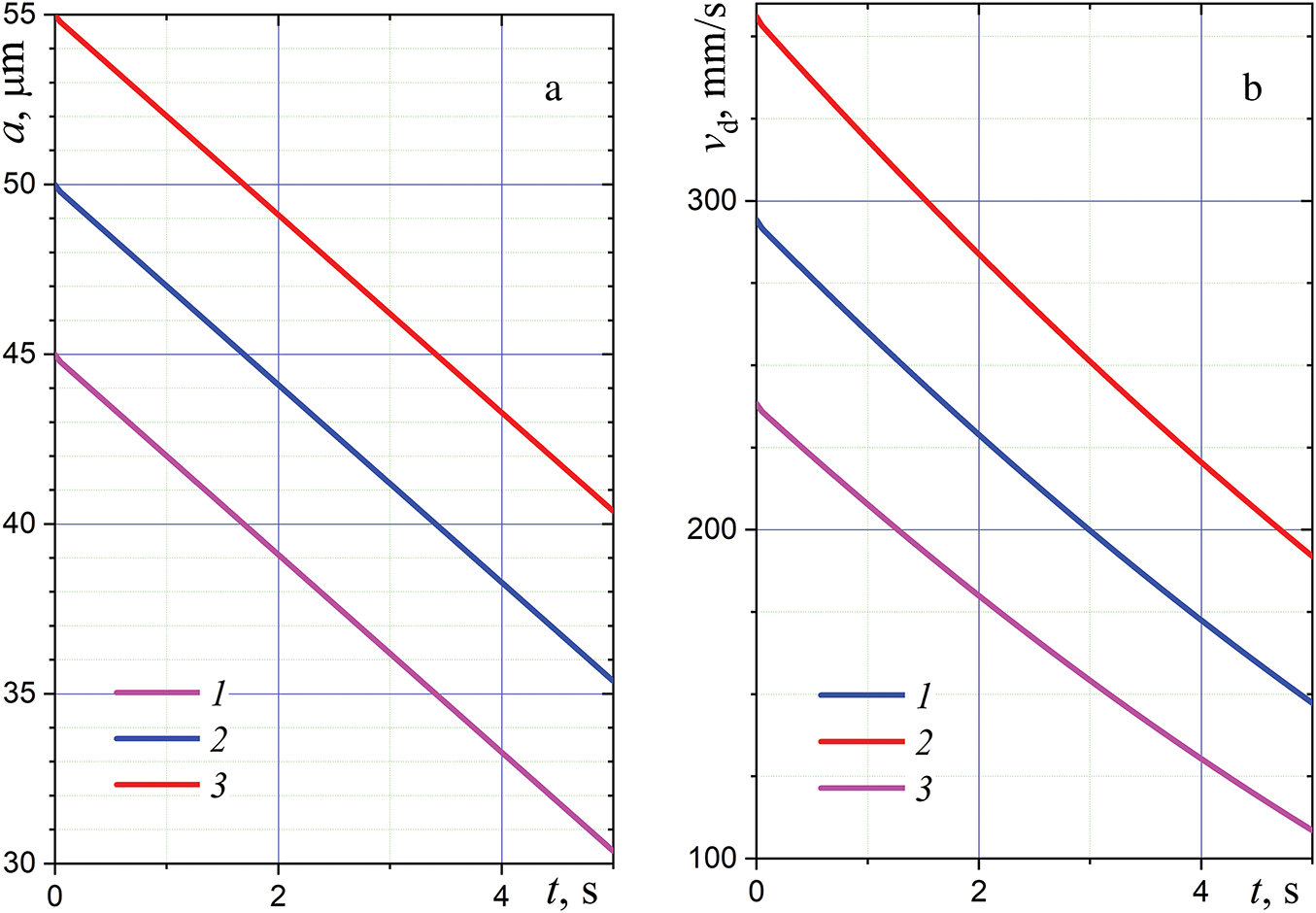

To obtain more accurate results, measurements were taken of the fall velocity of 90 droplets (thirty droplets of pure water and thirty droplets of fungicide and KCl solutions). The average values of the rate of decrease in the radius of the drops were found to be 2.7 μm/s for water, 2.4 μm/s for the selected fungicide solution at

4 Computational Model for Falling Droplets of Water Solutions

The problem statement for an isothermal droplet falling in immovable air is as follows:

where

It is assumed that the values of

In the case of pure water, the mass flow rate of water vapor is determined as follows [42,43]:

where

The molecular mass and gas constant of humid air are:

where

Calculations for the conditions of the laboratory experiment show that the mass rate of evaporation of pure water droplets is equal to

Figure 5: (a) decrease in the radius of evaporating water droplets over time, (b) decreasing the equilibrium droplet fall velocity: 1—

The theoretically predicted value of

This means that laboratory methodology is sufficiently accurate and applicable for comparative experiments with aqueous solutions of various substances at their small concentrations. Of course, the mass rate of evaporation,

where

According to the authors, the same laboratory setup and similar procedure (with possible additional infrared heating) can be used to study specific effects (up to the formation of hollow solid particles) observed in droplets of aqueous solutions with a high concentration of non-volatile substances.

A new experimental method and laboratory setup were developed to investigate the effect of low-concentration dissolved substances on the evaporation rate of small water droplets suspended in the atmosphere. The main idea of this method is based on converting a complex droplet jet produced by an ultrasound dispenser into a directed flow of evaporating droplets falling in a vertical tube. The computational modeling of droplet motion was used to choose the setup geometrical parameters. Images of droplets with radii from 30 to 40 μm captured by a high-speed camera of 5000 fps were used to determine the velocities and sizes of individual falling droplets. The calculations using the previously developed evaporation model for pure water droplets agree well with the measurements. The new experimental data for low-concentration aqueous solutions of various substances were used to modify this evaporation model for these solutions. It was confirmed that the correction factor for droplets of aqueous solution of a typical fungicide is insignificant for agricultural applications. At the same time, the modified evaporation model for the sea salt components gives a realistically lower evaporation rate. The suggested approximate exponential variation of the correction factor is convenient for estimations at not small concentrations of dissolved substances. The latter is expected to be important for some industrial and geophysical applications.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to the financial support for the work by the Russian Science Foundation.

Funding Statement: This study was financially supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project No. 24-29-00303: https://rscf.ru/project/24-29-00303/, accessed on 01 July 2025). The grant was received by the first author.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception, Alexander A. Fedorets, Leonid A. Dombrovsky; Experimental design and procedure, Alexander A. Fedorets, Anna V. Nasyrova, Vyacheslav O. Mayorov; Computer processing of the experimental data, Eduard E. Kolmakov, Dmitry N. Medvedev, Anna V. Nasyrova; Physical analysis of experimental data, Alexander A. Fedorets, Vladimir Yu. Levashov, Leonid A. Dombrovsky; Computational model and calculations, Leonid A. Dombrovsky, Vladimir Yu. Levashov; Draft manuscript preparation, Alexander A. Fedorets, Leonid A. Dombrovsky. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| Droplet radius | |

| Drag coefficient | |

| Mass concentration | |

| Specific heat capacity | |

| Diffusion coefficient | |

| Coefficient in Eq. (11) | |

| Acceleration of gravity | |

| Vertical distance | |

| Thermal conductivity | |

| Latent heat of evaporation | |

| Molecular mass | |

| Mass flow rate | |

| Nu | Nusselt number |

| Pressure | |

| Gas constant | |

| Reynolds number | |

| Temperature | |

| Current time | |

| Horizontal velocity | |

| Vertical velocity | |

| Horizontal coordinate | |

| Vertical coordinate | |

| Greek Symbols | |

| Dynamic viscosity | |

| Density | |

| 𝜏 | Characteristic time |

| Relative humidity | |

| Subscripts and Superscripts | |

| air | Air |

| av | Average |

| D | Drag |

| d | Droplet |

| ev | Evaporation |

| exp | Experimental |

| fu | Fungicide |

| K | Knudsen |

| max | Maximum |

| rel | Relaxation |

| sat | Saturation |

| sol | Solute |

| vap | Vapor |

| w | Water |

| 0 | Initial |

References

1. Ziaee A, Albadarin AB, Padrela L, Femmer T, O’Reilly E, Walker G. Spray drying of pharmaceuticals and biopharmaceuticals: critical parameters and experimental process optimization approaches. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2019;127:300–18. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2018.10.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Baumann JM, Adam MS, Wood JD. Engineering advances in spray drying for pharmaceuticals. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2021;12(1):217–40. doi:10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-091720-034106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Partheniadis I, Al-Zoubi N, Nikolakakis I. Pharmaceutical spray drying. In: Lamprou D, editor. Nano- and microfabrication techniques in drug delivery. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2023. p. 71–97. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-26908-0_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. O’Sullivan JJ, Norwood EA, O’Mahony JA, Kelly AL. Atomisation technologies used in spray drying in the dairy industry: a review. J Food Eng. 2019;243(B):57–69. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.08.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li H, Cryer S, Raymond J, Acharya L. Interpreting atomization of agricultural spray image patterns using latent Dirichlet allocation techniques. Artif Intell Agric. 2020;4(8):253–61. doi:10.1016/j.aiia.2020.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Jiang Y, Yang Z, Xu X, Shen D, Jiang T, Xie B, et al. Wetting and deposition characteristics of air-assisted spray droplet on large broad-leaved crop canopy. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1079703. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1079703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Wang B, Wang J, Yu C, Luo S, Peng J, Li N, et al. Sustained agricultural spraying: from leaf wettability to dynamic droplet impact behavior. Glob Chall. 2023;7(9):2300007. doi:10.1002/gch2.202300007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Aminpour Y, Dehghan D, Playán E, Maroufpoor E. Estimation of wind drift and evaporation losses of sprinkler irrigation systems using dimensional analysis. Agric Water Manag. 2023;289:108518. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2023.108518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Spaska OA, Daszykowski M, Bushuev YG. Evaluation of evaporation fluxes for pesticides and low volatile hazardous materials based on evaporation kinetics of net liquids. ACS Omega. 2024;9(16):18617–23. doi:10.1021/acsomega.4c01405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Lankinen Å, Witzell J, Aleklett K, Furenhed S, Karlsson Green K, Latz M, et al. Challenges and opportunities for increasing the use of low-risk plant protection products in sustainable production. A review. Agron Sustain Dev. 2024;44(2):21. doi:10.1007/s13593-024-00957-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Karset IHH, Gettelman A, Storelvmo T, Alterskjær K, Berntsen TK. Exploring impacts of size-dependent evaporation and entrainment in a global model. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2020;125(4):e2019JD031817. doi:10.1029/2019JD031817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Huynh E, Olinger A, Woolley D, Kohli RK, Choczynski JM, Davies JF, et al. Evidence for a semisolid phase state of aerosols and droplets relevant to the airborne and surface survival of pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(4):e2109750119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2109750119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Leung GR, Saleeby SM, Sokolowsky GA, Freeman SW, van den Heever SC. Aerosol-cloud impacts on aerosol detrainment and rainout in shallow maritime tropical clouds. Atmos Chem Phys. 2023;23(9):5263–78. doi:10.5194/acp-23-5263-2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Charlesworth DH, Marshall Jr WRJr. Evaporation from drops containing dissolved solids. AIChE J. 1960;6(1):9–23. doi:10.1002/aic.690060104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Cheng RJ, Blanchard DC, Cipriano RJ. The formation of hollow sea-salt particles from the evaporation of drops of seawater. Atmos Res. 1988;22(1):15–25. doi:10.1016/0169-8095(88)90009-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Vehring R, Foss WR, Lechuga-Ballesteros D. Particle formation in spray drying. J Aerosol Sci. 2007;38(7):728–46. doi:10.1016/j.jaerosci.2007.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Vehring R. Pharmaceutical particle engineering via spray drying. Pharm Res. 2008;25(5):999–1022. doi:10.1007/s11095-007-9475-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Fairhurst D. Droplets of ionic solutions. In: Brutin D, editor. Droplet wetting and evaporation. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 2015. p. 295–313. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800722-8.00020-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Dombrovsky LA, Levashov VY, Kryukov AP, Dembele S, Wen JX. A comparative analysis of shielding of thermal radiation of fires using mist curtains containing droplets of pure water or sea water. Int J Therm Sci. 2020;152(1–3):106299. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2020.106299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Miles BEA, Winter E, Mirembe S, Hardy D, Mahato LK, Miles REH, et al. Evaporation kinetics and final particle morphology of multicomponent salt solution droplets. J Phys Chem A. 2025;129(3):762–73. doi:10.1021/acs.jpca.4c07439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Dombrovsky LA, Fedorets AA, Levashov VY, Kryukov AP, Bormashenko E, Nosonovsky M. Stable cluster of identical water droplets formed under the infrared irradiation: experimental study and theoretical modeling. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2020;161(8):120255. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2020.120255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Fedorets AA, Shcherbakov DV, Levashov VY, Dombrovsky LA. Self-stabilization of droplet clusters levitating over heated salt water. Int J Therm Sci. 2022;182(5):107822. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2022.107822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Fedorets AA, Kolmakov EE, Dombrovsky LA. Experimental study of the effect of water salinity on the parameters of an equilibrium droplet cluster levitating over a water layer. Front Heat Mass Transf. 2024;22(1):1–14. doi:10.32604/fhmt.2024.049335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Bellan J, Cuffel R. A theory of nondilute spray evaporation based upon multiple drop interactions. Combust Flame. 1983;51(37):55–67. doi:10.1016/0010-2180(83)90083-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Castanet G, Perrin L, Caballina O, Lemoine F. Evaporation of closely-spaced interacting droplets arranged in a single row. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2016;93(5–6):788–802. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2015.09.064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. de Rivas A, Villermaux E. Dense spray evaporation as a mixing process. Phys Rev Fluids. 2016;1(1):014201. doi:10.1103/physrevfluids.1.014201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Markadeh RS, Arabkhalaj A, Ghassemi H, Azimi A. Droplet evaporation under spray-like conditions. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2020;148(17–18):119049. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2019.119049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Lupo G, Gruber A, Brandt L, Duwig C. Direct numerical simulation of spray droplet evaporation in hot turbulent channel flow. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2020;160(1):120184. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2020.120184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zamani S, Morris A. Effect of droplet collisions on evaporation in spray-drying. Dry Technol. 2022;40(7):1292–306. doi:10.1080/07373937.2020.1866006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Liu Q, Lu R, Qiao Y, Zhao F, Tan S. Analysis of the correction factors and coupling characteristics of multi-droplet evaporation. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2022;195(4):123138. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2022.123138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Najafian M, Mortazavi S. Simulation of group of droplets evaporation. Eur J Mech B/Fluids. 2024;107(5):95–111. doi:10.1016/j.euromechflu.2024.06.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Pandurangan N, Sahu S. Analysis of group evaporation characteristics of droplet clusters in an evaporating spray. J Fluid Mech. 2024;998:A26. doi:10.1017/jfm.2024.669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Johnson TA, Patel VC. Flow past a sphere up to a Reynolds number of 300. J Fluid Mech. 1999;378:19–70. doi:10.1017/s0022112098003206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Duan Z, He B, Duan Y. Sphere drag and heat transfer. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):12304. doi:10.1038/srep12304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Goossens WRA. Review of the empirical correlations for the drag coefficient of rigid spheres. Powder Technol. 2019;352(5):350–9. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2019.04.075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Singh N, Kroells M, Li C, Ching E, Ihme M, Hogan CJ, et al. General drag coefficient for flow over spherical particles. AIAA J. 2022;60(2):587–97. doi:10.2514/1.j060648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Michaelides EE, Sommerfeld M, van Wachem B. Multiphase flows with droplets and particles. 3rd ed. New York, NY, USA: CRC Press; 2022. 478 p. [Google Scholar]

38. Fuchs NA. Evaporation and droplet growth in gaseous media. London, UK: Pergamon Press; 1959. 72 p. [Google Scholar]

39. Labuntsov DA, Kryukov AP. Analysis of intensive evaporation and condensation. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 1979;22(7):989–1002. doi:10.1016/0017-9310(79)90172-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Chambre PA, Schaaf SA. Flow of rarefied gases. New York NY, USA: Princeton University Press; 2017. 66 p. [Google Scholar]

41. Wu L. Rarefied gas dynamics: kinetic modeling and multi-scale simulation. New York NY USA: Springer; 2022. 460 p. [Google Scholar]

42. Levashov VY, Kryukov AP. Numerical simulation of water droplet evaporation into vapor-gas medium. Colloid J. 2017;79(5):647–53. doi:10.1134/s1061933x1705009x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Levashov VY, Kryukov AP, Shishkova IN. Influence of the noncondensable component on the characteristics of temperature change and the intensity of water droplet evaporation. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2018;127(5):115–22. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.07.069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Stull DR. Vapor pressure of pure substances. Organic and inorganic compounds. Ind Eng Chem. 1947;39(4):517–50. doi:10.1021/ie50448a022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Kryukov AP, Levashov VY, Shishkova IN. Evaporation in mixture of vapor and gas mixture. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2009;52(23–24):5585–90. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2009.06.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Borodulin VY, Letushko VN, Nizovtsev MI, Sterlyagov AN. Determination of parameters of heat and mass transfer in evaporating drops. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2017;109(4):609–18. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2017.02.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools