Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Tailored Phosphate Glass Powders for Augmented Flame Retardancy and Ceramicization in Silicone Rubber

1 State Key Laboratory of Fire Science, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, 230026, China

2 Suzhou Key Laboratory for Urban Public Safety, Suzhou Institute for Advanced Research, University of Science and Technology of China, Suzhou, 215123, China

3 Yankuang Energy Group Co., Ltd., Zoucheng, 273500, China

* Corresponding Author: Weizhao Hu. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(2), 531-548. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.065040

Received 01 March 2025; Accepted 04 June 2025; Issue published 14 July 2025

Abstract

Silicone rubber (SR) exhibits superior breathability and high-temperature resistance. However, SR is prone to degradation under extreme heat or combustion, limiting its effectiveness in mitigating secondary hazards. In this study, phosphate glass powder was used to calcinate zinc borate, lanthanum oxide, and cerium oxide. Methylphenyl polysiloxane was then grafted onto the surface of the glass powder, resulting in the modified powders designated as Methylphenyl polysiloxane-grafted zinc borate-modified phosphate glass powder (GF-ZnBM), Methylphenyl polysiloxane-grafted lanthanum oxide-modified phosphate glass powder (GF-LaM), and Methylphenyl polysiloxane-grafted cerium oxide-modified phosphate glass powder (GF-CeM). The modified powders were subsequently incorporated into silicone rubber composites to enhance the ceramicization capability of silicone rubber at high temperatures. Specifically, GF-CeM and GF-LaM significantly increased the limiting oxygen index (LOI) to 33% and reduced the tendency for combustion propagation. Additionally, GF-CeM notably contributed to enhancing ceramicization strength. The presence of cerium oxide helps in the melting of the glass powder and enhances its adhesion to the silicone rubber matrix. SR/ZnB-GF exhibited the lowest activation energy among the tested composites, along with the best protective capability. The inclusion of modified glass powder has a minor impact on the rheological properties, indicating that the composite retains its ability to flow and deform under stress. This confirms that the material remains flexible under normal conditions and forms a ceramic structure when heated, thereby exhibiting self-supporting properties. This study provides a practical methodology for the targeted modification of glass powders, thereby further enhancing the fire safety of silicone-based composites.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileSilicone rubber (SR) is extensively utilized in various applications such as medical materials, tires, seals, wires, and cables, owing to its superior breathability and high-temperature resistance [1]. Compared to organic polymers such as polyethylene and polyurethane, polydimethylsiloxane, which features a main chain composed of Si-O-Si inorganic groups and organic side chains such as methyl and ethylene, exhibits superior flame retardancy [2]. Furthermore, during high-temperature exposure or combustion, the polydimethylsiloxane chains tend to depolymerize, forming silica particles that facilitate ceramic formation [3]. This characteristic makes silicone rubber commonly used as a matrix for ceramicizable polymer composites. However, SR is prone to degradation under high temperatures or combustion, often resulting in the loss of mechanical properties or transformation into brittle carbonaceous layers and ashes [4]. Consequently, SR fails to effectively mitigate secondary hazards such as explosions or radiation leaks that may occur following incidents like power outages or fires. Incorporating ceramic fillers and aids into SR can produce ceramicizable SR materials that remain flexible under normal conditions but form ceramic structures and exhibit self-supporting properties upon heating [5]. This enhances their suitability for fire safety applications in specialized fields such as high-speed rail transportation and nuclear power plants [6]. The enhancement of silicone’s ceramicization capability is particularly crucial in industries such as automotive, aerospace, industrial equipment, energy, chemical, and metallurgy [7]. This involves enhancing the wear resistance, high-temperature resistance, and chemical stability of silicone by selecting high-purity raw materials, optimizing formulation ratios, controlling reaction conditions, and refining ceramicization processes [8−10].

However, merely adding common ceramic fillers and aids may not suffice to endow silicone rubber composite materials with adequate flame retardancy and low-temperature ceramicization capabilities, thereby impeding their effectiveness in fire protection scenarios. Therefore, researching and developing silicone rubber composite materials with enhanced flame retardancy and ceramicization capabilities is of paramount importance for the safety protection of critical facilities [11]. The urgency to enhance the flame retardancy of silicone is evident, as it directly impacts fire safety across various sectors, including construction, electronics, transportation, aerospace, furniture, and household goods [12]. In these areas, fires could result in severe casualties and substantial property losses. Various methods are available to enhance the flame retardancy of silicone, including the addition of flame retardants, modification of molecular structures, and synthesis of novel silicone compounds [13,14]. While adding flame retardants is a common method to enhance flame retardancy, this approach may adversely affect other properties of silicone and pose environmental and health risks [15]. Conversely, modifying the molecular structure can effectively improve flame retardancy; however, the synthesis process may be complex and costly [16]. Additionally, synthesizing novel silicone compounds offers the potential to tailor materials with excellent flame retardancy [17]. However, this approach requires extensive research and development efforts and may incur higher costs. Hence, in practical applications, it is necessary to comprehensively consider the advantages and disadvantages of different methods. The selection of appropriate methods to enhance silicone’s flame retardancy should be based on specific requirements and conditions.

Boric acid zinc, a typical boron-based synergistic flame retardant, is capable of forming glassy ceramic layers at high temperatures, thereby delaying heat transfer [18]. Mixing boron oxide, zinc oxide, and phosphorus pentoxide and calcining them at high temperatures yields a hard, low-melting glass, ideal for facilitating ceramicization in composite materials [19]. However, studies have shown that directly adding this low-melting glass into high-temperature sulfur-cured silicone rubber without further modification may disrupt the rubber’s curing process due to the glass’s high acidity [20]. Incorporating borate-zinc into phosphate glasses could potentially mitigate the issue of excessively high acidity in the formed glass, thereby improving both the flame retardancy and ceramicization properties of the glass [21]. Moreover, the addition of lanthanum and cerium, which are rare earth oxides, generally raises the softening point of the glass while increasing its hardness [22]. Incorporating lanthanum oxide and cerium oxide into glass powder could potentially enhance the strength and durability of the resulting glass ceramics [23]. Furthermore, rare earth metal oxides can serve as synergistic flame retardants when used in conjunction with phosphate-based flame retardants, effectively reducing the fire hazards of flame-retardant composite materials.

The value of this study lies in the development of silicone rubber composites that not only exhibit excellent fire resistance but also possess ceramicization properties, which are crucial for safety-critical applications. This research focuses on the synthesis of modified glass powders and their impact on the fire resistance, ceramicization properties, and hydrophobicity of silicone rubber composites, presenting an innovative approach that bridges the gap between material performance and practical safety requirements [24,25]. In this study, modified glass powders will be used to replace the original commercial glass powders in the preparation of flame-retardant and ceramicizable silicone rubber. The research will primarily investigate the composition, morphology, and their effects on the fire resistance, ceramicization, and hydrophobicity of the silicone rubber composite material.

High-temperature vulcanized silicone rubber and the curing agent 2,5-dimethyl-2,5-di(tert-butylperoxy) hexane (DBPH) were purchased from Guangdong Yinxixi Technology Co., Ltd. (Guangdong, China). Calcined kaolin (3000 mesh, 5 μm) was purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Co., Ltd. Glass powder was purchased from Anmi Weina New Materials Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Anhydrous zinc borate, cerium oxide, lanthanum oxide, and methylphenyl polysiloxane were purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2 Preparation of Modified Glass Powder and Its Composites

Initially, the chemical composition of the glass powder was analyzed semi-quantitatively using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) to determine its elemental composition in Table S1. Phosphate glass powder was combined with anhydrous borate-zinc, cerium oxide, and lanthanum oxide at a mass ratio of 19:1. The mixture was then placed into alumina crucibles and compacted. The crucibles were placed in a muffle furnace and heated to 1000°C at a rate of 10°C per minute. They were maintained at this temperature for 30 min and then allowed to cool naturally to room temperature to obtain bulk glass. The fired bulk glass was crushed and sieved through a 10-mesh sieve. Subsequently, the sieved powder was subjected to ball milling in a planetary ball mill at 420 rpm for 5 h. Afterward, methylphenyl polysiloxane, constituting 3 wt% of the total mass of the powder, was added to the ball milling jar. Ball milling was then continued at 420 rpm for an additional 5 h. Upon completion of ball milling, the powder was washed with ethanol to remove excess cyclic polysiloxane, then dried and sieved through a 200-mesh sieve to obtain the final glass powder. The glass powder formulations containing anhydrous borate-zinc, cerium oxide, and lanthanum oxide were designated as methylphenyl polysiloxane-grafted zinc borate-modified phosphate glass powder (GF-ZnBM), methylphenyl polysiloxane-grafted cerium oxide-modified phosphate glass powder (GF-CeM), methylphenyl polysiloxane-grafted lanthanum oxide-modified phosphate glass powder (GF-LaM), respectively.

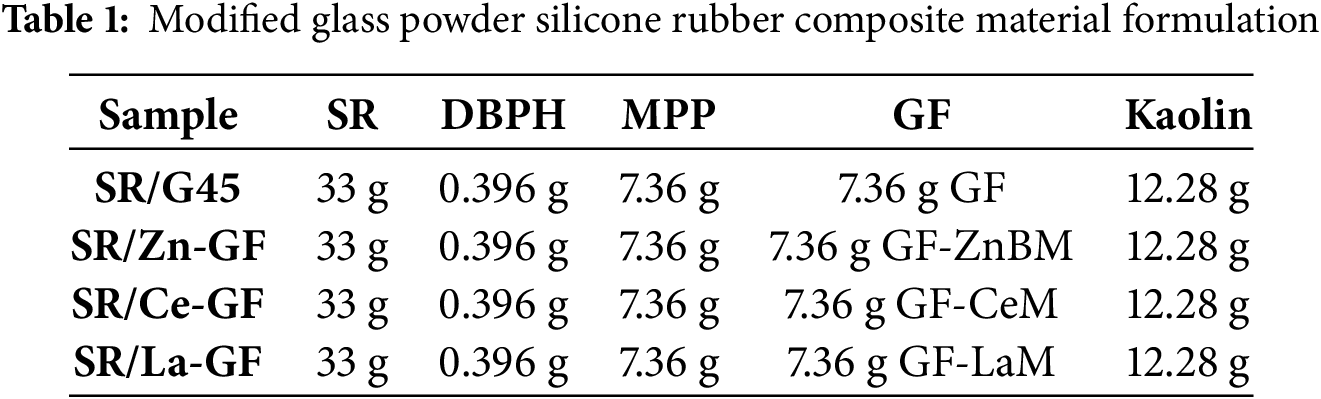

The glass powder silicone rubber composite material was prepared following the formulation specified in Table 1. For instance, in the preparation of SR/G45, the components were added in succession to an internal mixer: 33 g of silicone rubber, 7.36 g of glass powder, 7.36 g of MPP, 0.396 g of DBPH, and 12.28 g of calcined kaolin. The mixture was stirred for 15 min and then processed through an open mill to form the samples. Using suitable iron molds, the pre-vulcanization of each sample was conducted under specific conditions: a temperature of 175°C, a pressure of 15 MPa, and a sulfurization time of 10 min. The samples were then subjected to post-vulcanization in an oven, maintained at a temperature of 200°C, for a duration of 2 h. Ultimately, the samples were trimmed into appropriate shapes to facilitate subsequent testing. Rectangular samples (80 × 10 × 3 mm3) were positioned in a high-temperature muffle furnace and subjected to heating at temperatures of 600°C, 800°C, and 1000°C, with a heating rate of 10°C·min−1. After being maintained at each specified temperature for 30 min, the samples were allowed to cool naturally to room temperature. This process resulted in the formation of ceramic-like bodies from the calcined silicone rubber composite material.

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were acquired using KBr pellets with a Thermo Fisher Nicolet 6700 infrared spectrometer (USA). The measurements were conducted over a spectral range of 400–4000 cm−1.

The thermal stability of the silicone rubber composite materials in a nitrogen atmosphere was analyzed using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) with a Q5000 thermal analyzer. The temperature was increased from ambient to 800°C at a linear heating rate of 20°C·cm−1.

X-ray diffraction analysis was performed using a Japanese Rigaku D Max-Ra rotating anode X-ray diffractometer, equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.1542 nm). The scanning speed was set at 4°·cm−1.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted utilizing a VG ESCALAB MK-II electron spectrometer (V.G. Scientific Ltd., UK), employing Al Kα radiation at 1486.6 eV.

The thermal decomposition products of the silicone rubber composite materials were characterized using a combined approach of TGA and Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometry (TGA-FTIR).

Three-point bending strength was measured using a universal testing machine (MST System Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) at a testing speed of 1 mm·min−1 on the residual materials of the silicone rubber composite materials post-calcination. The mass residue rate was determined by comparing the mass of the silicone rubber composite material samples before and after calcination. Similarly, the volume shrinkage rate was calculated by comparing the average dimensions (length, width, and thickness) of the samples before and after calcination.

The tensile strength and elongation at break of the materials were determined using a universal testing machine (MST System Co., Ltd., China) with a testing speed of 200 mm·min−1. Combustion properties were evaluated in accordance with ISO 5660-1:2015 using a cone calorimeter (TESTech, Beijing, China). The tests utilized specimens measuring 100 × 100 × 3 mm3 and were exposed to a heat flux of 35 kW·m−2. Additionally, vertical burning tests (UL-94) were conducted following the ASTM D3801-20a standard, employing samples with dimensions of 100.0 × 10.0 × 3.0 mm3 (CFZ-II, Jiangning Analytical Instrument Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China).

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images were captured to examine the surface morphology of the samples using an SU8220 cold field emission scanning electron microscope, operated at an experimental voltage of 3 kV.

Limiting oxygen index measurements were conducted in accordance with ASTM D2863-20a using a limiting oxygen index tester (HC-II, Jiangning Analytical Instrument Co., Ltd., China). The specimens measured 100.0 × 6.5 × 3.0 mm3. Additionally, the dynamic mechanical behavior of the materials in tensile mode at 1.00 Hz was analyzed using a TA DMA 242C dynamic mechanical analyzer. Rectangular specimens measuring 25 × 6 × 1 mm3 were heated from −50°C to 0°C at a heating rate of 5°C·min−1. Backboard burning tests were conducted by positioning silicone rubber composite material boards, measuring 100 × 50 × 3 mm3, horizontally on an iron frame table and applying heat using an alcohol lamp. Surface temperatures were recorded using a YET-610/610L digital K-type thermocouple probe thermometer, with flame temperatures reaching approximately 600°C.

3.1 Composition and Structural Characterization of Modified Glass Powder

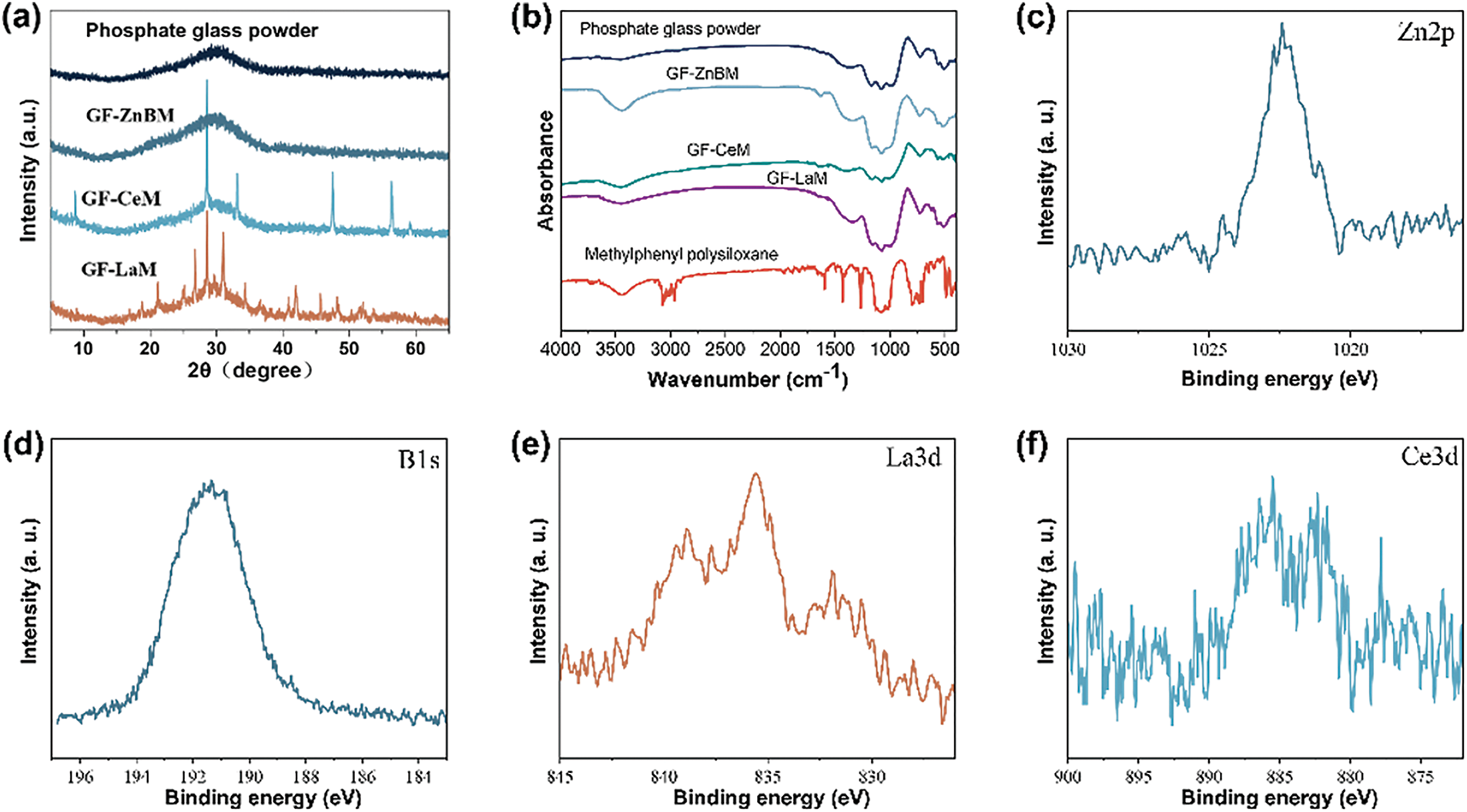

As depicted in Fig. 1a, X-ray diffraction (XRD) was utilized to examine the crystal structure of the modified glass powder. The pure phosphate glass powder displayed a broad peak at 2θ = 30.1°, indicative of the non-crystalline SiO2 diffraction peak. In contrast, despite the introduction of zinc borate in the GF-ZnBM sample, only the SiO2 diffraction peak was evident at the same angle, 2θ = 30.1°. The absence of characteristic diffraction peaks for zinc borate, which are theoretically expected around 15°, is attributed to the complete decomposition of zinc borate and its subsequent integration with the glass powder during high-temperature calcination. In the XRD diffraction pattern of GF-CeM, only the characteristic diffraction peaks of cerium oxide, specifically (002), (111), (200), (220), and (311), were observed [26]. This indicates that no chemical reaction occurred between cerium oxide and the phosphate glass powder during the calcination process. Conversely, the XRD pattern of GF-LaM revealed not only the characteristic diffraction peaks of lanthanum oxide, such as (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (200), and (112), but also characteristic diffraction peaks of lanthanum phosphate [27]. This suggests that a partial chemical reaction occurred between lanthanum oxide and the phosphate glass powder during the calcination process [28].

Figure 1: (a) X-ray diffraction spectra of phosphate glass powder, GF-ZnBM, GF-CeM, and GF-LaM; (b) Infrared spectra of phosphate glass powder, GF-ZnBM, GF-CeM, and GF-LaM; (c,d) High-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectra of Zn 2p and B 1s for GF-ZnBM; (e) High-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectra of Ce 3d for GF-CeM, and (f) High-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectra of La 3d for GF-LaM

As depicted in the infrared spectra shown in Fig. 1b, the prepared GF-ZnBM, GF-CeM, and GF-LaM samples exhibited peaks corresponding to their respective metal oxides, along with peaks associated with the benzene ring [29,30]. This indicates the successful grafting of methylphenyl polysiloxane onto the surface of the modified glass powder. Furthermore, the Zn 2p and B 1s spectra of GF-ZnBM, presented in Fig. 1c,d, displayed characteristic peaks corresponding to Zn2+ 2p5/2 and 2p3/2, as well as to the B-O bond. These observations confirm that the valence states of Zn and B remained unchanged during the calcination process [31]. From Fig. 1e,f, it is evident that La in GF-LaM was present in the trivalent state, while Ce in GF-CeM exhibited a coexistence of trivalent and tetravalent states. This indicates the presence of La as La2O3 and Ce as coexisting CeO2 and Ce2O3, suggesting differential oxidation states of these elements in the respective samples.

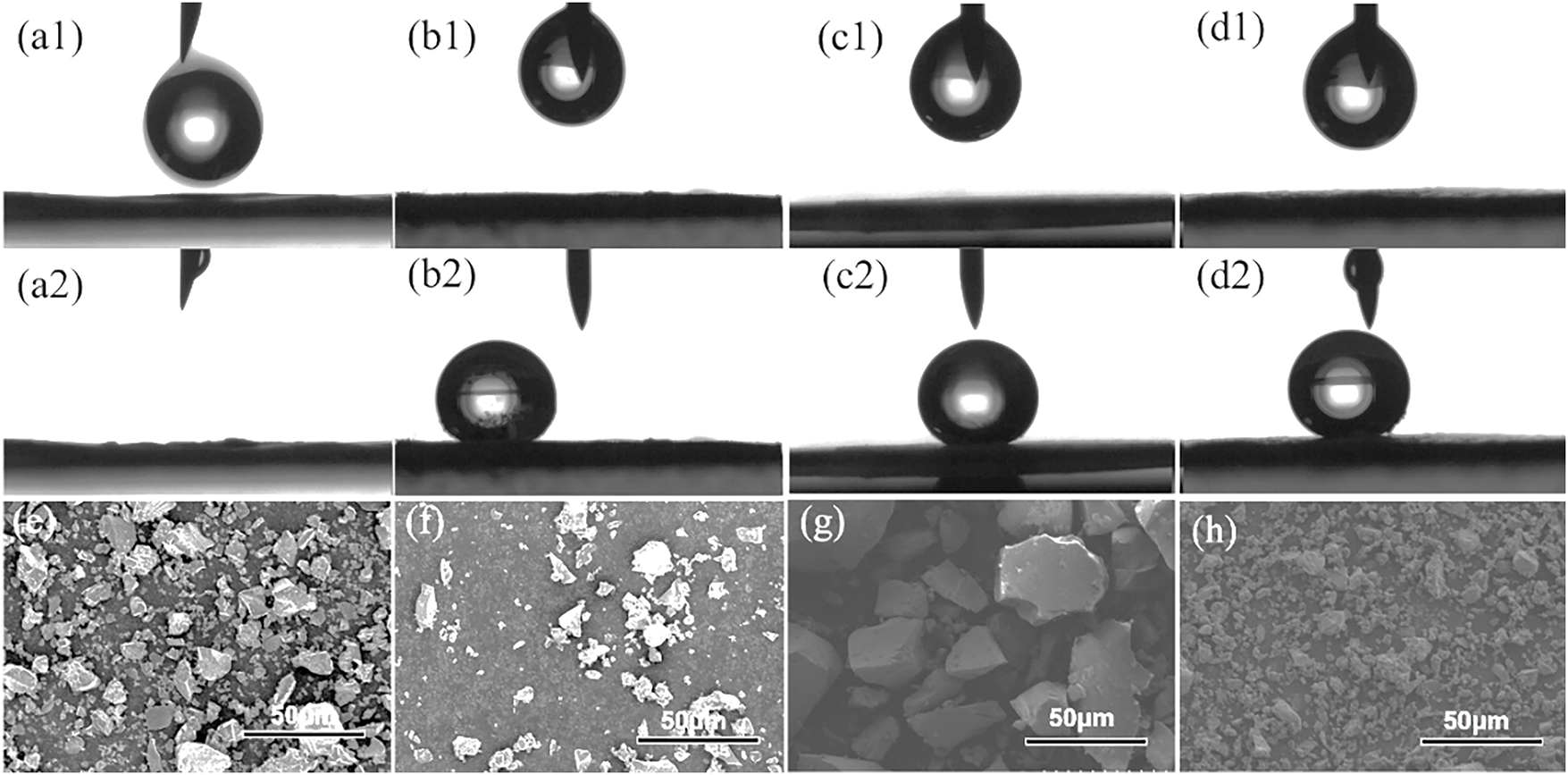

Fig. 2a–d displays the results of the water contact angle tests for phosphate glass powder and modified phosphate glass powder pressed tablets, utilized to assess the hydrophobicity of the glass materials. The findings reveal that the water contact angle of unmodified phosphate glass powder is 0°, indicating pronounced hydrophilicity. In contrast, the water contact angles for GF-LaM, GF-CeM, and GF-ZnBM glass powders modified with silane were recorded at 156°, 159°, and 151°, respectively, demonstrating successful silane grafting onto the surface of the glass powder and effectively rendering it highly hydrophobic [32]. Additionally, as shown in the SEM images in Fig. 2e–h, the modified glass powders continue to display irregular particle shapes of similar sizes, indicating that the modification process did not significantly alter the microscopic scale of the glass powder. Furthermore, Fig. 2f–h reveals that despite undergoing calcination and silane modification, the glass powders did not exhibit any agglomeration.

Figure 2: (a1,a2) Images before and after water droplet contact angle tests for phosphate glass powder; (b1,b2) GF-LaM; (c1,c2) GF-CeM, and (d1,d2) GF-ZnBM; (e) Scanning electron microscope images of phosphate glass powder; (f) GF-ZnBM; (g) GF-CeM, and (h) GF-LaM

Concerning the content of methylphenyl polysiloxane in GF-LaM, GF-CeM, and GF-ZnBM, it is assumed that the mass of the unmodified doped glass powder remains unchanged after being calcined at 1000°C. To quantify the methylphenyl polysiloxane content, the modified glass powders were spread on a corundum dish and heated to 800°C in an air atmosphere [33]. The mass change of the modified glass powder before and after this subsequent high-temperature calcination was then calculated to determine the effective content of the methylphenyl polysiloxane. Theoretically, the observed mass change in the modified glass powders provides an approximation of the effective content of methylphenyl polysiloxane. Experimental results revealed that the mass change rates for GF-LaM, GF-CeM, and GF-ZnBM were 2.7%, 2.7%, and 1.8%, respectively. These values suggest that the effective contents of methylphenyl polysiloxane in GF-LaM, GF-CeM, and GF-ZnBM are approximately 2.7%, 2.7%, and 1.8%, respectively. Furthermore, these findings are consistent with the water contact angle test results, indicating that a higher effective content of methylphenyl polysiloxane correlates with larger hydrophobic angles.

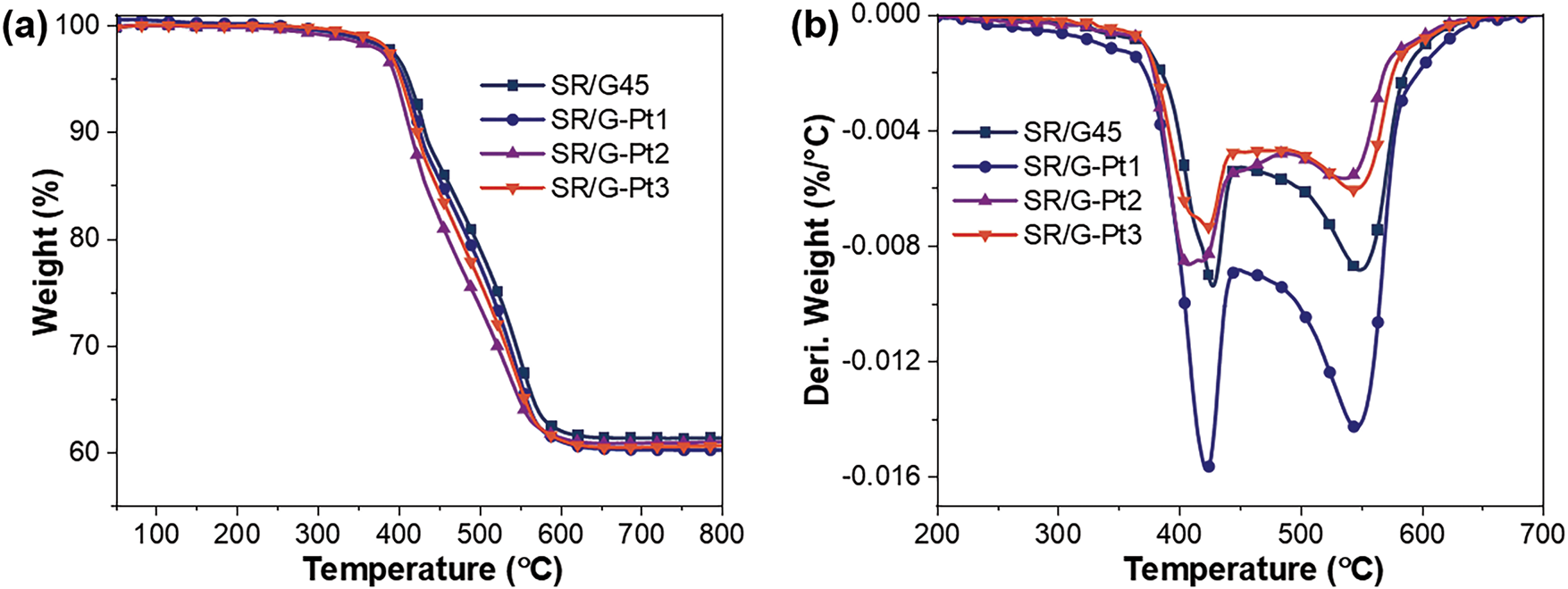

3.2 Thermal Stability of Modified Glass Powder Silicone Rubber

Fig. 3 presents the thermogravimetric curves of SR/G45, SR/Ce-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, and SR/La-GF under a nitrogen atmosphere, with corresponding data detailed in Table 2. Analysis of these curves reveals that SR/G45 and SR/ZnB-GF exhibit a two-step decomposition process, while SR/Ce-GF and SR/La-GF undergo three degradation steps. The two-step decomposition is primarily attributed to differing activation energies required for the degradation of side chains and main chains in polydimethylsiloxane [34]. The emergence of three peaks in the DTG curves for additions of lanthanum and cerium may be related to their anti-aging properties [35]. Furthermore, the introduction of modified phosphate glass powder has altered the thermal stability of the silicone rubber composites, resulting in a slight reduction. Notably, the most significant decrease was observed in SR/Ce-GF at the T5% temperature, while the final mass residual rates for SR/Ce-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, and SR/La-GF were marginally lower than that of SR/G45.

Figure 3: (a) TG curves and (b) Derivative Thermogravimetry (DTG) curves of samples under nitrogen atmosphere

3.3 Flame Retardant Properties of Modified Glass Powder Silicone Rubber

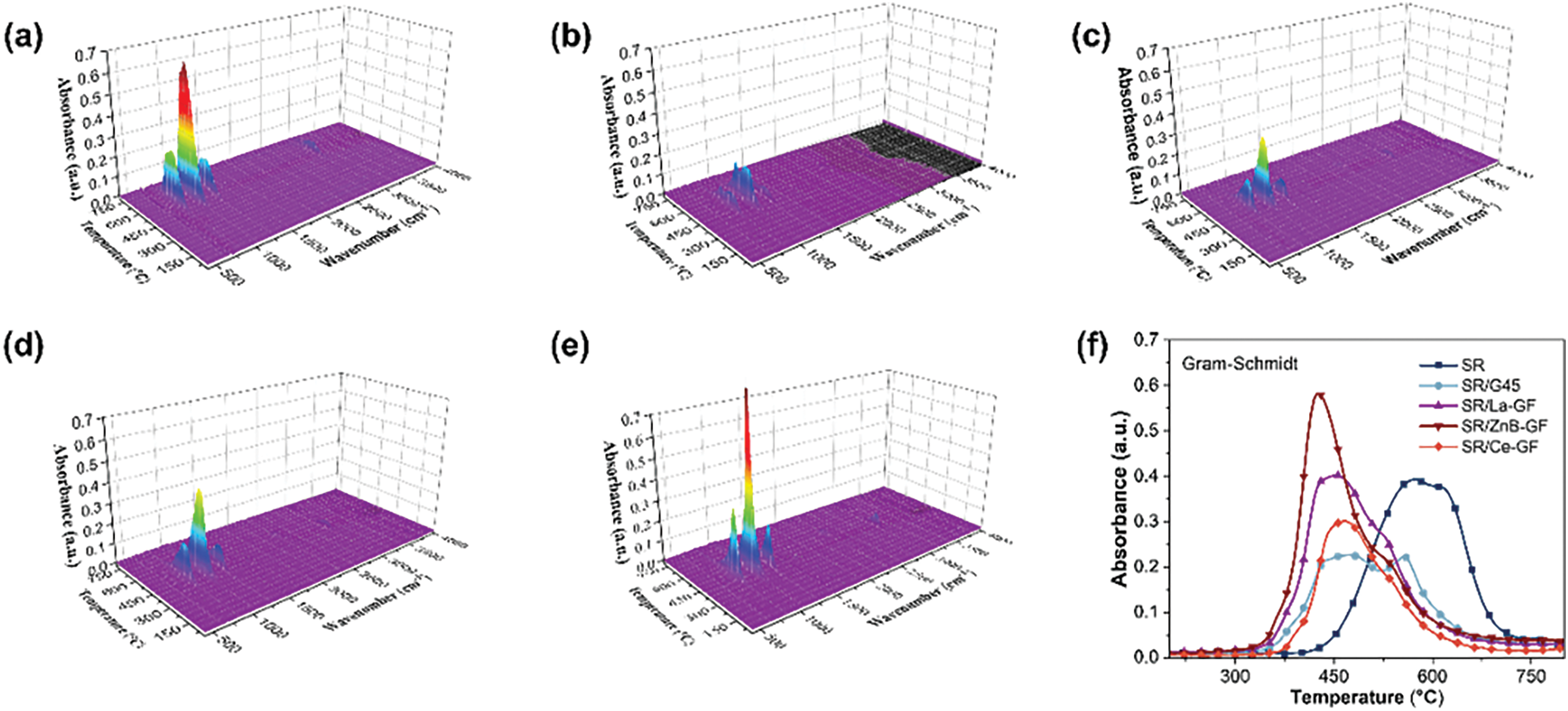

Fig. 4a–e displays the gas-phase infrared spectra generated during the pyrolysis of SR, SR/G45, SR/La-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, and SR/Ce-GF under a nitrogen atmosphere. Fig. 4f illustrates the total thermal decomposition product curve of infrared absorption intensity as a function of temperature. Analysis of the three-dimensional TG-IR spectra of the pyrolysis gas products, coupled with the Gram-Schmidt plot, reveals that the incorporation of kaolin, phosphate glass powder, and MPP leads to a reduction in both the temperature at which absorption peaks appear and the intensity of these peaks. This observation suggests that these additives impact the thermal degradation behavior of the silicone rubber composites, thereby enhancing their thermal stability. Compared to SR/G45, the composites SR/Ce-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, and SR/La-GF display stronger infrared absorption peaks. However, the peak intensity of SR/Ce-GF is still lower than that of pure silicone rubber. Fig. 4h illustrates the curve of peak temperature variation for the most intense absorption peak of cyclic oligomers with temperature, which corresponds to the trends observed in the Gram-Schmidt plot. The addition of fillers reduces the peak temperature of the infrared absorption peaks in silicone rubber materials. Notably, SR/ZnB-GF exhibits the highest absorption peak intensity, whereas SR/G45 shows the weakest. This indicates that the inclusion of GF-ZnBM enhances the release of cyclic oligomers gases from the material, potentially enabling it to achieve a V-1 grade in vertical burning tests. Fig. 4g displays the curve of peak temperature variation for most intense absorption peak of methane with temperature. Notably, SR/Ce-GF exhibits the highest absorption peak intensity, whereas SR shows the weakest. This indicates that the inclusion of GF-CeM enhances the release of methane gases from the material. Fig. 4i displays the infrared spectra at the maximum absorbance of the pyrolysis gases. All samples demonstrate characteristic absorption peaks at 2967, 1263, 1078, 1026, and 820 cm−1, corresponding to the C-C, Si-O-Si, and C-Si bonds of cyclic oligomers. Additionally, it is observed that the absorption peaks for CO2, -N=C=O, and -CN in the SR/G45 curve are less intense in the curves for SR/Ce-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, and SR/La-GF.

Figure 4: (a–e) The three-dimensional TG-IR spectra of the thermal decomposition gas products of SR, SR/G45, SR/La-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, and SR/Ce-GF; (f) the total thermal decomposition product curve of infrared absorption intensity as a function of temperature; the (g) CH4 and (h) cyclic oligomers curve of infrared absorption intensity as a function of temperature; (i) The infrared spectrum at the maximum absorbance of the thermal decomposition gas

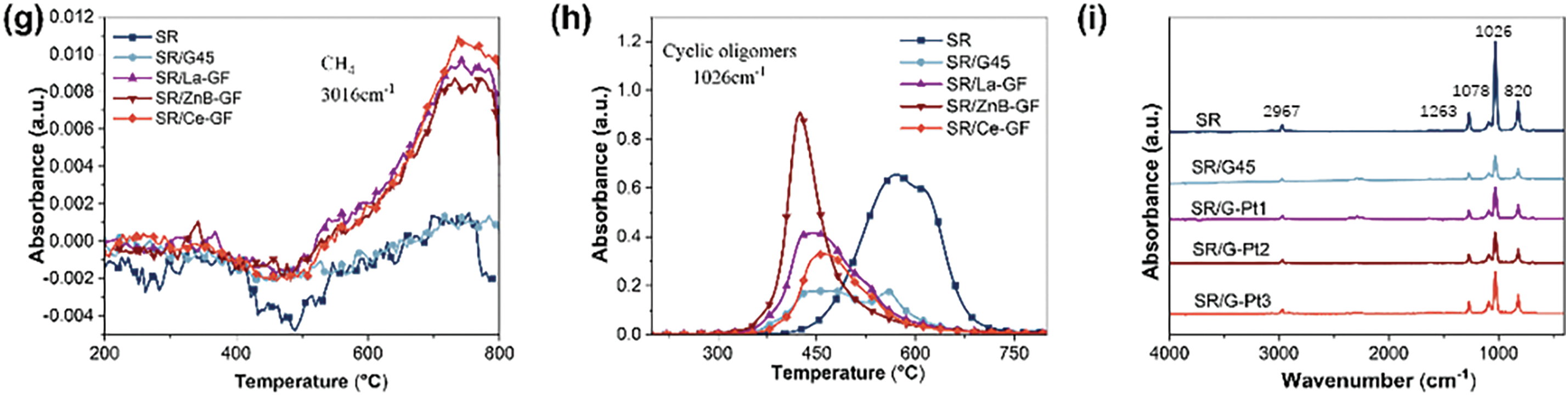

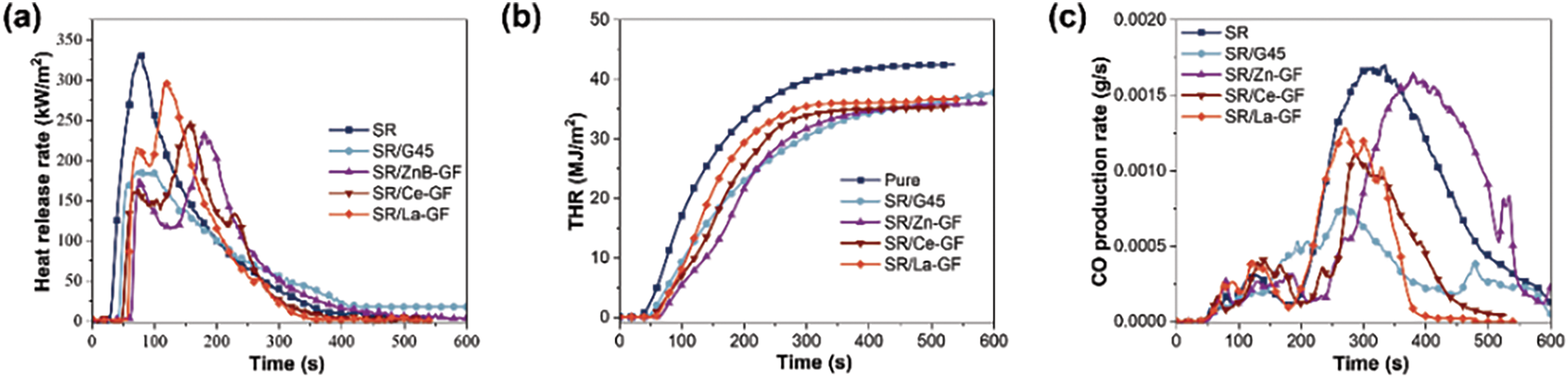

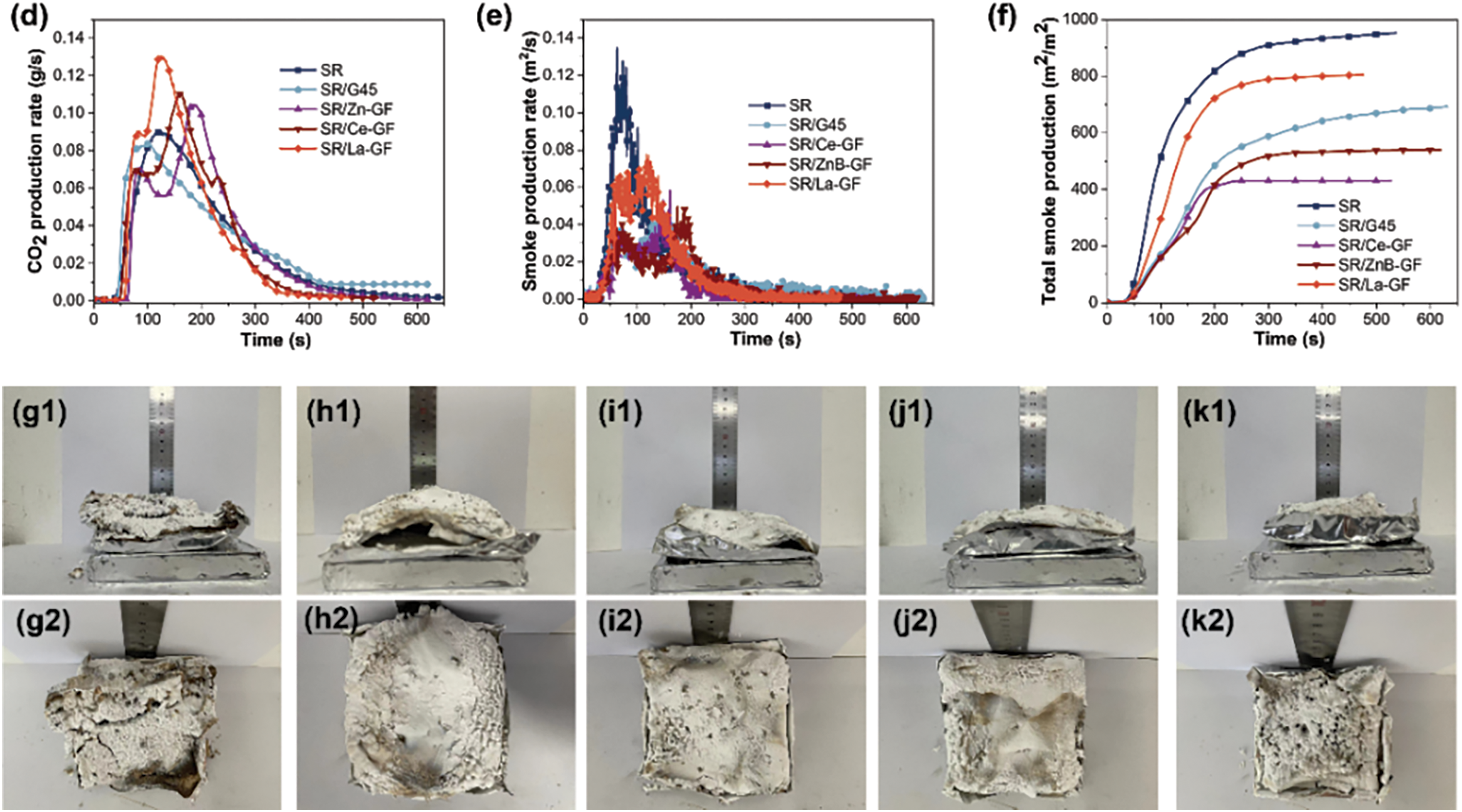

Fig. 5a–f illustrates the characteristic data curves from cone calorimetry analyses of thermal release, CO/CO2 evolution, and smoke release over time for silicone rubber composite materials, with more detailed results documented in Table 3. These results demonstrate that the incorporation of ceramic fillers and flame retardants significantly reduces both the peak heat release rate (PHRR) and total heat release (THR) of the composites. Specifically, the PHRR of the SR/G45 composite material is reduced to 183.5 from 333.4 kW·m−2 observed in pure SR, marking a reduction of 44.9%. Similarly, the THR of SR/Ce-GF is reduced to 35.3 from 42.5 MJ·m−2 in pure SR, a reduction of 16.9%. The addition of GF-ZnBM, GF-CeM, and GF-LaM to pure glass powder results in an increased PHRR but a decreased THR, likely due to the catalytic degradation of the matrix resin by the metal oxides in the modified glass powder during the initial stages of combustion [36]. Moreover, the introduction of modified glass powder significantly delays the time to reach the peak heat release rate (tPHRR). Notably, GF-ZnBM shows the most pronounced effect, increasing the maximum tPHRR to 179 s, a delay of 103 s, and reducing the fire growth index (FGI) from 2.41 to 1.30 kW·(m·s−1)−1, substantially reducing the propensity for fire spread. Additionally, GF-ZnBM and GF-CeM further reduce the total visible smoke release during combustion. The UL-94 and LOI values for SR/G45, SR/Ce-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, and SR/La-GF are listed in Table 4, showing that the addition of modified glass powder has increased the LOI and that the flame retardancy rating for SR/La-GF has reached V-1. This indicates that the metal oxides and boron compounds in the glass powder synergistically enhance flame retardancy when combined with MPP [37].

Figure 5: Cone calorimetry test results of each sample: (a) heat release rate curve; (b) total heat release curve; (c) CO production rate curve; (d) CO2 production rate curve; (e) smoke release rate curve; (f) total smoke release curve; (g1,g2) images of residue after cone calorimeter testing for SR/G45; (h1,h2) SR/Ce-GF; (i1,i2) SR/ZnB-GF; (j1,j2) SR/La-GF, and (k1,k2) SR

Fig. 5g–k displays the residue images of SR/G45, SR/Ce-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, SR/La-GF, and pure silicone rubber following cone calorimetry testing. The residue of the pure silicone rubber shows noticeable cracks at the conclusion of the test, indicating structural weaknesses under high-temperature conditions. Conversely, the residue of SR/G45 exhibits uniformly distributed voids and a significant expansion in height, suggesting that the composition and structure of this composite material allow for better thermal insulation and structural integrity during combustion [38]. Fig. S1 shows the time-temperature curve of the backboard burning test, deviating from one end of the flame. This indicates that the choice of filler plays a crucial role in determining the thermal behavior and protective capabilities of silicone rubber composites. Additionally, all samples containing modified glass powder display varying degrees of fracturing in their final residues, reflecting the material’s response to thermal stress during combustion. While the addition of modified glass powder contributes to certain desirable properties, such as increased flame retardancy, it does not significantly reduce the THR of the silicone rubber composite materials. This observation is evidenced by the appearance and morphology of the final residues, which indicate that the modifications impact the structural integrity under fire conditions but do not drastically alter the overall combustibility of the material.

3.4 The Ceramicization Characteristics of Modified Glass Powder Silicone Rubber

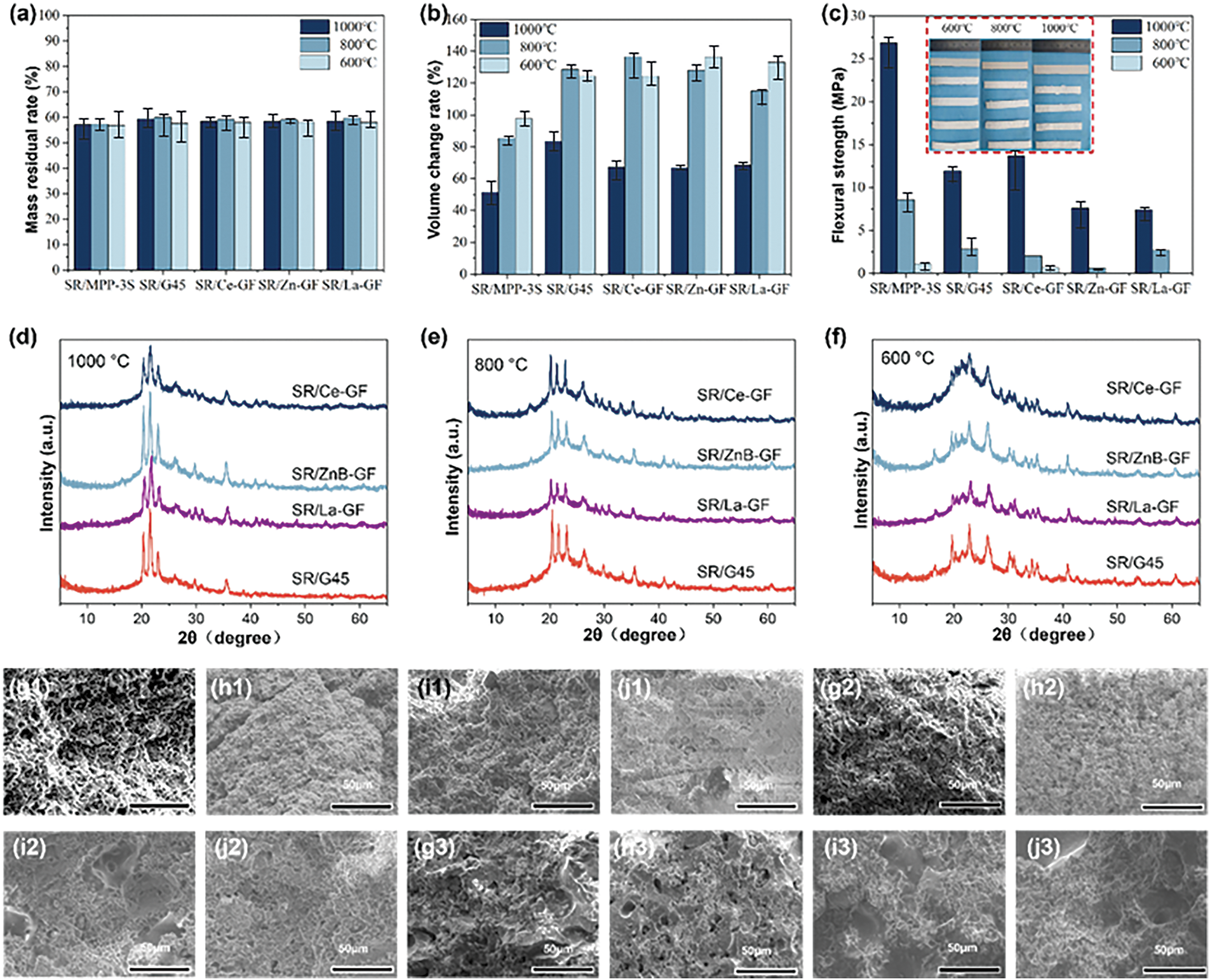

Fig. 6a–c presents the outcomes of tests for mass residual rate, volume change rate, and flexural strength conducted on various samples following calcination at different temperatures in air. The data reveals that SR/G45, SR/Ce-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, and SR/La-GF exhibits marginally higher mass residual rates compared to SR/MPP-3S. This increase may be attributed to a higher proportion of silicone rubber content in these samples. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and infrared analysis of the ceramic residues after calcination were conducted, as shown in Fig. S2, highlighting the structural integrity and compositional traits of the ceramic materials post-calcination. However, regarding the volume change rate, SR/MPP-3S exhibits a lower rate compared to the other samples, demonstrating superior ceramicization performance. This advantage is primarily due to the higher content of kaolin in SR/MPP-3S compared to the other variants. Additionally, when compared to SR/G45, samples such as SR/Ce-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, and SR/La-GF, which contain modified glass powder, show reduced volume change rates following calcination at 1000°C. This suggests that the inclusion of Zinc borate, cerium oxide, and lanthanum oxide positively contributes to enhancing the density of ceramicization in silicone rubber composites. Furthermore, compared to SR/G45, SR/Ce-GF demonstrates a higher flexural strength. This enhancement suggests that the presence of cerium oxide aids in the melting of glass powder and enhances its adhesion to the silicone rubber matrix, thereby improving the structural integrity of the composite.

Figure 6: The (a) mass residual rate; (b) volume change rate, and (c) flexural strength. From left to right, the samples are the uncured SR/MPP-3S, SR/G45, SR/Ce-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, and SR/La-GF after calcination; (d–f) X-ray diffraction spectra of ceramic-like residues from samples calcined at different temperatures in air. The scanning electron micrograph of the cross-section of ceramic-like residue after calcination at different temperatures: (g1–g3) SR/G45, (h1–h3) SR/Ce-GF, (i1–i3) SR/ZnB-GF, and (j1–j3) SR/La-GF under (f) 600°C, (e) 800°C, and (d) 1000°C, respectively

Fig. 6d–f presents the X-ray diffraction spectra of the ceramic residues from SR/Ce-GF, SR/Zn-GF, SR/La-GF, and SR/G45 following calcination at temperatures of 1000°C, 800°C, and 600°C. The broad diffraction peaks observed between 20°–25° are attributed to the amorphous regions consisting of SiO2 and glass powder formed during the pyrolysis process. This characteristic indicates the non-crystalline nature of the materials under the conditions applied. At 600°C, the predominant peak positions correspond to AlPO4 and mullite. As the calcination temperature increases, there is a notable increase in the relative intensity of the AlPO4 phase diffraction peak, while the relative intensity of the mullite phase diffraction peak decreases [39]. Upon further elevation of the temperature, a significant reduction in the diffraction intensity of the amorphous phase peak is observed, which is accompanied by an increase in the intensity of the SiO2 crystalline diffraction peak. This trend highlights the thermal transformation and crystallization behavior of the materials under elevated temperatures.

Fig. 6g–j displays scanning electron microscope images of the cross-sections of SR/G45, SR/Ce-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, and SR/La-GF ceramic residues after sintering at temperatures of 600°C, 800°C, and 1000°C. The images reveal that at 600°C, the cross-sectional morphology of each sample is characterized by a porous and loose structure, with no evident phase regions of melted eutectics. This observation indicates the initial stages of sintering, where densification and phase transformations are not yet prominent. As the sintering temperature rises to 800°C, the morphology of the samples predominantly displays continuous porous regions, accompanied by a slight improvement in bending strength. Upon further increase in the sintering temperature to 1000°C, continuous phase regions of melted eutectics are observed in the cross-sections of samples SR/G45 and SR/Ce-GF. In contrast, SR/ZnB-GF and SR/La-GF continue to exhibit continuous porous regions in their cross-sections, a finding that aligns with the results from three-point bending tests. This differentiation in structure underlines the impact of specific additives on the sintering behavior and mechanical properties of the materials.

3.5 Mechanical Properties of Modified Glass Powder Silicone Rubber

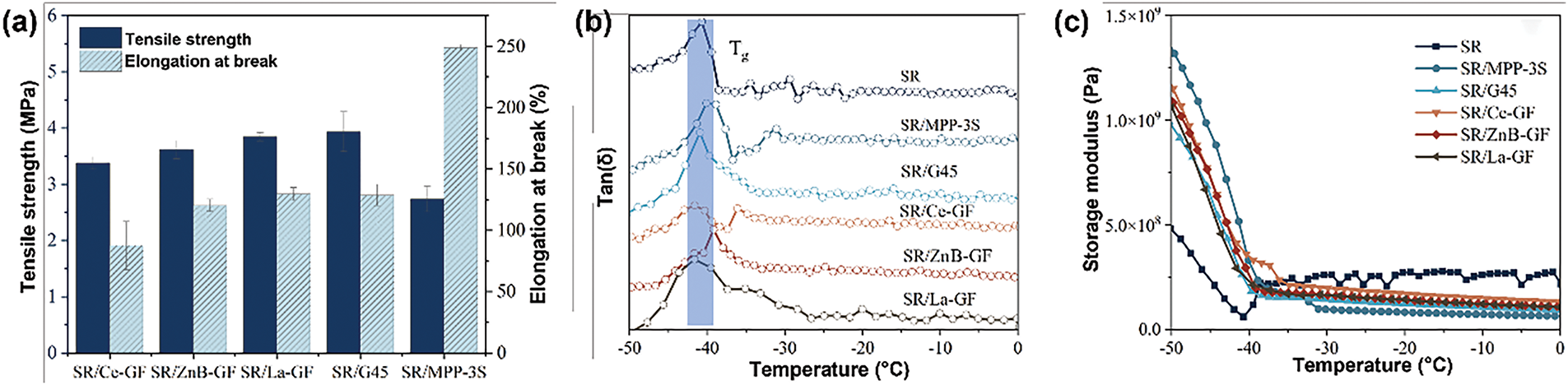

Fig. 7 depicts the tensile and dynamic mechanical properties of silicone rubber composite materials, respectively. The results indicate that the addition of modified glass powder (GF-ZnBM, GF-CeM, GF-LaM) leads to a reduction in both tensile strength and elongation at break of the silicone rubber composites. This suggests that the hydrophobicity imparted by the silane treatment adversely affects the compatibility between the glass powder and the matrix resin, potentially hindering the effective transfer of stress and strain within the composite during mechanical testing [40]. Additionally, compared to silicone rubber composites prepared with commercial glass powder, the storage modulus and the peak representing the glass transition temperature in the tan(δ) curve of the modified glass powders are very similar. This observation suggests that the modification methods employed in this study have minimal impact on the rheological properties of the materials, indicating that the modifications preserve the intrinsic mechanical behavior of the base polymer matrix.

Figure 7: (a) Tensile strength and elongation at break of silicone rubber composite materials; (b) Tan(δ) and (c) storage modulus curves of silicone rubber composite materials

3.6 Activation Energy Calculation of Modified Glass Powder Silicone Rubber

During the program-controlled temperature process, if a sample with an initial mass of w0 undergoes a decomposition reaction and at a certain time t its mass becomes wt, then the decomposition rate is given by:

where,

is the conversion rate, wf is the final mass of the thermal decomposition reaction, k(T) is the rate constant given by the Arrhenius equation:

where Eα is the activation energy of the reaction in J·mol−1; A is the pre-exponential factor in s−1; R is the ideal gas constant, 8.314 J·mol−1; T is the absolute temperature in K. The form of f(α) depends on the reaction mechanism. Different reaction mechanisms correspond to different mechanism functions f(α). Generally, it can be assumed that f(α) is not affected by temperature and time, but only depends on the conversion rate α. For simple reactions, f(α) can be chosen as

Substituting the heating rate β = dT/dt and f(α) into Eq. (4) gives:

Eq. (5) is the basic equation for calculating the kinetic parameters of thermal oxidation decomposition reactions. The Distributed Activation Energy Model (DAEM) can reflect the continuous change and distribution of apparent activation energy with the progress of the reaction, and is more suitable for the kinetic analysis of multi-component reactants, obtaining reaction kinetic parameters with more reference value. It can be derived from Eq. (5) by integral transformation to obtain expression (6):

where mt is the sample mass at time t, m0 is the initial mass of the sample, m∞ is the sample mass when the reaction terminates, β is the heating rate (K/min), and k0 is the frequency factor.

From Eq. (6), it can be observed that at a certain conversion rate α, ln(β·T−2) exhibits a linear relationship with 1·T−1, where the slope corresponds to −Eα·R−1, enabling the determination of the corresponding activation energy.

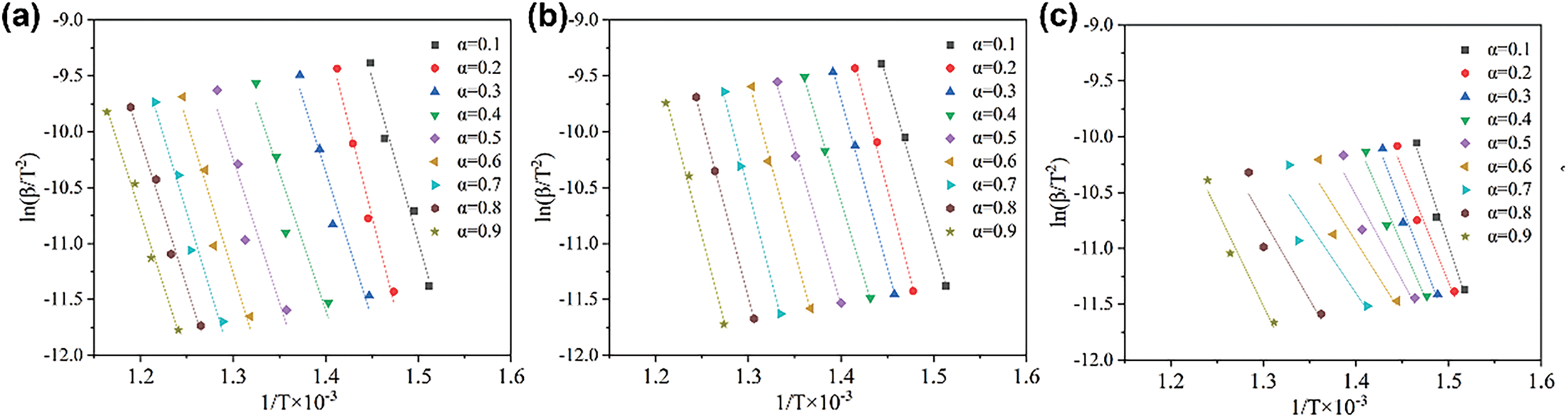

The fitted curves for samples SR/G45, SR/Ce-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, and SR/La-GF, corresponding to conversion rates ranging from 0.1 to 0.9 using the Differential Evolution Algorithm Method (DEAM), are depicted in Fig. 8a–d. The activation energies and correlation coefficients calculated for these conversion rates are detailed in Table S2. The high correlation coefficients suggest that the DEAM effectively models the kinetic behavior of these materials, indicating robust fitting of the experimental data across various stages of conversion. Fig. 8e illustrates the variation in activation energies with conversion rates for SR/G45, SR/Ce-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, and SR/La-GF. Notably, SR/ZnB-GF exhibits the lowest overall activation energy, characterized by an initial decrease followed by an increase as conversion rates rise. In contrast, SR/G45, SR/Ce-GF, and SR/La-GF demonstrate a distinct pattern of variation. Their activation energies initially increase, then decrease, and subsequently rise again. This distinct trend highlights differences in the thermal stability and decomposition kinetics among the various silicone rubber composites. Additionally, SR/G45 exhibits the highest activation energy among the samples during the initial decomposition stage, subsequently followed by a decrease in activation energy similar to that observed in SR/La-GF. Meanwhile, SR/Ce-GF maintains a relatively high activation energy throughout the latter half of the decomposition process. This behavior indicates varying thermal stability and reaction kinetics across the different silicone rubber composites, reflecting their distinct compositional influences on the degradation mechanisms.

Figure 8: (a) Linear fitting curves of 1·T−1 vs. ln(β·T−2) for SR/G45; (b) SR/Ce-GF; (c) SR/ZnB-GF, and (d) SR/La-GF (DAEM method); (e) The activation energy vs. conversion rate curves for SR/G45, SR/Ce-GF, SR/ZnB-GF, and SR/La-GF

This study details the process of calcining zinc borate, lanthanum oxide, cerium oxide, and phosphate glass powder. Subsequently, these materials are modified through ball milling with methylphenyl polysiloxane, leading to the creation of hydrophobic glass powders designated as GF-ZnBM, GF-CeM, and GF-LaM. These modified powders are then utilized in the fabrication of silicone rubber composite materials, illustrating the comprehensive steps taken to enhance the properties of the final composites through chemical modification and material engineering. Experimental results indicate that the modified glass powders significantly enhance the flame retardancy of the composite materials. Specifically, GF-CeM and GF-LaM demonstrate pronounced effects in increasing the LOI and reducing the tendency for combustion propagation. However, the inclusion of GF-ZnBM and GF-LaM appears to diminish the ceramicization performance of the composites. In contrast, GF-CeM notably contributes to enhancing the ceramicization strength, highlighting its beneficial impact on improving the structural integrity of the composites under high temperature conditions. The inclusion of modified glass powders affects the mechanical properties of the composite materials to some extent, although their impact on the rheological properties is relatively minor. Notably, SR/ZnB-GF demonstrates the lowest activation energy among the tested composites, coupled with the best protective capability. This suggests that while the modifications influence the mechanical strength and elasticity, they preserve the material’s ability to flow and deform under stress. The significance of this research lies in its contribution to enhancing the flame retardancy and optimizing the ceramicization performance of silicone rubber composite materials by incorporating modified glass powders. The findings from this study offer valuable insights into how specific modifications to glass powders can significantly improve the safety features of silicone-based composites, potentially leading to broader applications in industries where high thermal resistance and fire safety are crucial.

Acknowledgement: The work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (51991352 and 51874266).

Funding Statement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC).

Author Contributions: Conceptualisation, methodology, investigation (polymerisation, fabrication and characterizations), visualisation and original draft preparation: Yanbei Hou and Xu Chang. Methodology and validation: Yanbei Hou, Shuming Liu and Huimin Zhang. Reviewing and editing: Jianwei Fu, Jianbin Wu, Zhiyong Li and Guoqiang Tang. Supervision, reviewing, editing, funding acquisition: Weizhao Hu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/jpm.2025.065040/s1.

References

1. Zhu Q, Wang Z, Zeng H, Yang T, Wang X. Effects of graphene on various properties and applications of silicone rubber and silicone resin. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2021;142(6):106240. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2020.106240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. González Calderón JA, Contreras López D, Pérez E, Vallejo Montesinos J. Polysiloxanes as polymer matrices in biomedical engineering: their interesting properties as the reason for the use in medical sciences. Polym Bull. 2020;77(5):2749–817. doi:10.1007/s00289-019-02869-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Fu S, Sun Z, Huang P, Li Y, Hu N. Some basic aspects of polymer nanocomposites: a critical review. Nano Mater Sci. 2019;1(1):2–30. doi:10.1016/j.nanoms.2019.02.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Akbar M, Ullah R, Alam S. Aging of silicone rubber-based composite insulators under multi-stressed conditions: an overview. Mater Res Express. 2019;6(10):102003. doi:10.1088/2053-1591/ab3f0d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Han Y, Yang L, Yu Z, Zhao Y, Zhang ZX. Lightweight and flame retardant silicone rubber foam prepared by supercritical nitrogen: the influence of flame retardants combined with ceramicizable fillers. Constr Build Mater. 2023;370(1):130735. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li YM, Hu SL, Wang DY. Polymer-based ceramifiable composites for flame retardant applications: a review. Compos Commun. 2020;21:100405. doi:10.1016/j.coco.2020.100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li M, Li Y, Hong T, Zhao Y, Wang S, Jing X. High ablation-resistant silicone rubber composites via nanoscale phenolic resin dispersion. Chem Eng J. 2023;472(3):145132. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.145132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Han R, Li Y, Zhu Q, Niu K. Research on the preparation and thermal stability of silicone rubber composites: a review. Compos Part C Open Access. 2022;8(1):100249. doi:10.1016/j.jcomc.2022.100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Qi M, Jia X, Wang G, Xu Z, Zhang Y, He Q. Research on high temperature friction properties of PTFE/Fluorosilicone rubber/silicone rubber. Polym Test. 2020;91(5):106817. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2020.106817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang D, Wang C, Wang Q, Wang T. High thermal stability and wear resistance of porous thermosetting heterocyclic polyimide impregnated with silicone oil. Tribol Int. 2019;140(6):105728. doi:10.1016/j.triboint.2019.04.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chen F, Chen Z, Chen Y, Liang M, Heng Z, Zou H. Improving ablation resistant properties of epoxy-silicone rubber composites via boron catalyzed graphitization and ceramization. J Polym Res. 2022;29(8):359. doi:10.1007/s10965-022-03209-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li C, Yang Y, Xu G, Zhou Y, Jia M, Zhong S, et al. Insulating materials for realising carbon neutrality: opportunities, remaining issues and challenges. High Volt. 2022;7(4):610–32. doi:10.1049/hve2.12232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zielecka M, Rabajczyk A, Pastuszka Ł., Jurecki L. Flame resistant silicone-containing coating materials. Coatings. 2020;10(5):479. doi:10.3390/coatings10050479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Przybylak M, Maciejewski H, Dutkiewicz A, Wesołek D, Władyka-Przybylak M. Multifunctional, strongly hydrophobic and flame-retarded cotton fabrics modified with flame retardant agents and silicon compounds. Polym Degrad Stab. 2016;128:55–64. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2016.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Morgan AB. The future of flame retardant polymers-unmet needs and likely new approaches. Polym Rev. 2019;59(1):25–54. doi:10.1080/15583724.2018.1454948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Liu BW, Zhao HB, Wang YZ. Advanced flame-retardant methods for polymeric materials. Adv Mater. 2022;34(46):2107905. doi:10.1002/adma.202107905. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Li N, Ming J, Yuan R, Fan S, Liu L, Li F, et al. Novel eco-friendly flame retardants based on nitrogen-silicone schiff base and application in cellulose. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2019;8(1):290–301. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b05338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ilyas R, Sapuan S, Asyraf M, Dayana D, Amelia J, Rani M, et al. Polymer composites filled with metal derivatives: a review of flame retardants. Polymers. 2021;13(11):1701. doi:10.3390/polym13111701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang H, Yan L, Zhou S, Zou H, Chen Y, Liang M, et al. A comparison of ablative resistance properties of liquid silicone rubber composites filled with different fibers. Polym Eng Sci. 2021;61(2):442–52. doi:10.1002/pen.25587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Mostoni S, Milana P, Di Credico B, D’Arienzo M, Scotti R. Zinc-based curing activators: new trends for reducing zinc content in rubber vulcanization process. Catalysts. 2019;9(8):664. doi:10.3390/catal9080664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Shen KK. Boron-based flame retardants in non-halogen based polymers. Non-Halogenated Flame Retard Handb. 2021;9(2):309–36. doi:10.1002/9781119752240.ch7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Salman S, Salama S, Mahdy EA. Crystallization characteristics and properties of lithium germanosilicate glass-ceramics doped with some rare earth oxides. Boletín De La Soc Española De Cerámica Y Vidr. 2019;58(3):94–102. doi:10.1016/j.bsecv.2018.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhu H, Wang F, Liao Q, Wang Y, Zhu Y. Effect of CeO2 and Nd2O3 on phases, microstructure and aqueous chemical durability of borosilicate glass-ceramics for nuclear waste immobilization. Mater Chem Phys. 2020;249:122936. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2020.122936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Salazar-Hernández C, Salazar-Hernández M, Carrera-Cerritos R, Mendoza-Miranda JM, Elorza-Rodríguez E, Miranda-Avilés R, et al. Anticorrosive properties of PDMS-Silica coatings: effect of methyl, phenyl and amino groups. Prog Org Coat. 2019;136(2):105220. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.105220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Xiong G, Kang P, Zhang J, Li B, Yang J, Chen G, et al. Improved adhesion, heat resistance, anticorrosion properties of epoxy resins/POSS/methyl phenyl silicone coatings. Prog Org Coat. 2019;135:454–64. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.06.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Pujar MS, Hunagund SM, Barretto DA, Desai VR, Patil S, Vootla SK, et al. Synthesis of cerium-oxide NPs and their surface morphology effect on biological activities. Bull Mater Sci. 2020;43(1):24. doi:10.1007/s12034-019-1962-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Kabir H, Nandyala SH, Rahman MM, Kabir MA, Pikramenou Z, Laver M, et al. Polyethylene glycol assisted facile sol-gel synthesis of lanthanum oxide nanoparticles: structural characterizations and photoluminescence studies. Ceram Int. 2019;45(1):424–31. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.09.183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Deepa A, Murugasen P, Muralimanohar P, Kumar SP. Optical studies of lanthanum oxide doped phosphate glasses. Optik. 2018;160(6):348–52. doi:10.1016/j.ijleo.2018.01.108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Jayakumar G, Albert Irudayaraj A, Dhayal Raj A. A comprehensive investigation on the properties of nanostructured cerium oxide. Opt Quantum Electron. 2019;51(9):312. doi:10.1007/s11082-019-2029-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kabir H, Nandyala SH, Rahman MM, Kabir MA, Stamboulis A. Influence of calcination on the sol-gel synthesis of lanthanum oxide nanoparticles. Appl Phys A. 2018;124(12):1–11. doi:10.1007/s00339-018-2246-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Song J, Huang Z, Qin Y, Li X. Thermal decomposition and ceramifying process of ceramifiable silicone rubber composite with hydrated zinc borate. Materials. 2019;12(10):1591. doi:10.3390/ma12101591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Nguyen HH, Wan S, Tieu KA, Zhu H, Pham ST. Rendering hydrophilic glass-ceramic enamel surfaces hydrophobic by acid etching and surface silanization for heat transfer applications. Surf Coat Technol. 2019;370:82–96. doi:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2019.04.062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Xu X, Wu C, Zhang B, Dong H. Preparation, structure characterization, and thermal performance of phenyl-modified MQ silicone resins. J Appl Polym Sci. 2013;128(6):4189–200. doi:10.1002/app.38638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Liu J, Yao Y, Li X, Zhang Z. Fabrication of advanced polydimethylsiloxane-based functional materials: bulk modifications and surface functionalizations. Chem Eng J. 2021;408:127262. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.127262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Patil AS, Patil AV, Dighavkar CG, Adole VA, Tupe UJ. Synthesis techniques and applications of rare earth metal oxides semiconductors: a review. Chem Phys Lett. 2022;796(4):139555. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2022.139555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Lou F, Yan W, Guo W, Wei T, Li Q. Preparation and properties of ceramifiable flame-retarded silicone rubber composites. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2017;130(2):813–21. doi:10.1007/s10973-017-6448-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ullah S, Ahmad F, Shariff AM, Bustam MA, Gonfa G, Gillani QF. Effects of ammonium polyphosphate and boric acid on the thermal degradation of an intumescent fire retardant coating. Prog Org Coat. 2017;109:70–82. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2017.04.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zhong F, Chen C, Zheng J, Li L, Wen X. Zinc ion cross-linked sodium alginate modified hexagonal boron nitride to enhance the flame retardant properties of composite coatings. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2022;647:129200. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.129200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Jouin J, Celerier H, Ouamara L, Tessier-Doyen N, Rossignol S. Study of the formation of acid-based geopolymer networks and their resistance to water by time/temperature treatments. J Am Ceram Soc. 2021;104(10):5445–56. doi:10.1111/jace.17929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Mohammed M, Rahman R, Mohammed AM, Adam T, Betar BO, Osman AF, et al. Surface treatment to improve water repellence and compatibility of natural fiber with polymer matrix: recent advancement. Polym Test. 2022;115(8):107707. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2022.107707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools