Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Design of Nanostructured Surfaces and Hydrogel Coatings for Anti-Bacterial Adhesion

1 Wuliangye Yibin Co., Ltd., Yibin, 644000, China

2 School of Mechanical Engineering, Sichuan University of Science and Engineering, Zigong, 643000, China

* Corresponding Author: Fa Zhang. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(3), 661-675. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.067313

Received 29 April 2025; Accepted 18 July 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

This review systematically summarizes recent advancements in the design of antibacterial hydrogels and the surface-related factors influencing microbial adhesion to polymeric materials. Hydrogels, characterized by their three-dimensional porous architecture and ultra-high water content, serve as ideal platforms for incorporating antibacterial agents (e.g., metal ions, natural polymers) through physical/chemical interactions, enabling sustained release and enhanced antibacterial efficacy. For traditional polymers, surface properties (e.g., roughness, charge, superhydrophobicity, free energy, nanoforce gradients) play critical roles in microbial adhesion. Modifying the surface properties of polymers through surface treatment can regulate antibacterial performance. In particular, by referencing the micro/nanostructures found on natural surfaces such as lotus leaves and cicada wings, antibacterial surfaces with multiple superior functions can be fabricated. Collectively, these findings provide a theoretical basis for the rational design of multifunctional antibacterial materials, offering material-based solutions to address complex infection scenarios and advance infection management strategies.Keywords

Bacterial contamination not only directly threatens human health and ecological safety but also triggers cascading economic losses by degrading the performance of industrial materials [1]. In manufacturing and medical applications, bacterial adhesion and proliferation on material surfaces can significantly compromise stability and functional longevity [2–4]. Polymeric materials, as a diverse and functionally unique class of materials, are widely utilized in medical fields. These materials, when in contact with external environments, allow bacteria to adhere to their surfaces through electrostatic interactions and van der Waals forces. The bacteria then secrete extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) such as polysaccharides and proteins while proliferating. Over time, as EPS secretion increases, a biofilm forms and covers the material surface. This leads to alterations in the surface properties of the materials and further promotes bacterial proliferation. Ultimately, this process causes material corrosion, degradation, performance deterioration, and surface contamination. To mitigate bacterial-induced polymer degradation and environmental contamination, the development of antibacterial polymeric materials is imperative.

Hydrogels, as quintessential elastomeric materials [5–7], have become indispensable biomimetic materials in medical applications due to their bioinspired structures, stimuli-responsive properties, and biofunctional characteristics. Their ultrahigh water content and fluidity enable rapid exchange with the external environment [8–10]. However, bacteria can degrade hydrogel networks by secreting alginate, lipases, proteases, or reacting with metal ions within hydrogels via metabolic byproducts, leading to network deterioration [11–13].

However, unlike hydrogels, conventional polymers (e.g., polyethylene, polypropylene, rubber matrices, or engineering plastics) generally exhibit limited capacity for integrating antibacterial agents into their bulk material and often lack intrinsic antimicrobial properties. Therefore, distinct antibacterial strategies must be employed. In natural environments, medical implants, or industrial fluid systems, their surface hydrophobicity, roughness, or electrostatic charge distribution often renders them preferential substrates for bacterial colonization. Bacteria exploit hydrophobic proteins, polysaccharide adhesins, and other biomolecules on their cell walls to irreversibly anchor onto surfaces via van der Waals forces, electrostatic attraction, or hydrogen bonding, rapidly proliferating into dense biofilms within hours to days [14–17]. These biofilms form self-sustaining ecosystems where concentrated organic acids, proteases, and sulfide metabolites persistently alter interfacial chemistry through osmosis, inducing oxidative degradation, chain depolymerization, or plasticizer leaching. This results in microscopic phase separation, increased porosity, or mechanical deterioration [18,19]. Surface modification represents an effective antibacterial strategy by inhibiting bacterial adhesion [20–23].

This review summarizes advances in antibacterial material design, juxtaposing the advantages of hydrogel-based systems with surface engineering strategies for conventional polymers. For hydrogels, integrating multifunctional antibacterial components into their networks establishes active antimicrobial mechanisms, steering medical devices toward proactive antibacterial pathways. For traditional polymers, elucidating microbial adhesion mechanisms and the role of material surfaces in modulating these interactions provides a comprehensive framework for next-generation antimicrobial materials. This comparative analysis highlights the unique strengths of hydrogels in dynamic antibacterial responses while underscoring the irreplaceability of surface engineering in regulating microbe-material interactions, charting a course for interdisciplinary innovation in antimicrobial material development.

Hydrogels are elastic materials characterized by a three-dimensional network structure that maintains stability even at water contents exceeding 90%. This material is highly suitable for surface functional group modification and multifunctional composite design, owing to its inclusion capacity for ionic and molecular species. These properties render hydrogels an ideal platform for the development of antibacterial materials. The three-dimensional porous architecture of hydrogels enables efficient loading of antibacterial agents (e.g., silver nanoparticles, antibiotics), while their ultra-high water content facilitates sustained release through physical/chemical interactions. For instance, Li et al. introduced AgNO3 into a chitosan/ammonia hydrogel system, yielding a chitosan-Ag+/NH3 physical hydrogel with excellent comprehensive properties [24]. The incorporation of Ag+ imparts outstanding antibacterial performance to this material due to its ion-mediated bactericidal effects. In contrast to the research methods of Li et al., Dai et al. designed cationic dendritic macromolecule-coated silver ion nanoparticles as antibacterial components, which were then integrated into a hydrogel network to form a pH-responsive hydrogel [25]. In this system, antibacterial agents are released in response to acidic conditions generated by bacterial metabolism. This smart-release strategy exhibits superior antibacterial efficacy compared to hydrogels loaded with antibacterial agents via direct incorporation. Similarly, other metal ions, such as magnesium (Mg2+), can be incorporated into hydrogels to enhance their antibacterial properties. However, these materials rely on sustained metal ion release. Studies show their antibacterial efficacy typically lasts only 7 days under fluid contact conditions after multiple washing cycles [26,27]. Through modifying hyperbranched polylysine to load silver nanoparticles, Ho et al. successfully extended the active period to 6 weeks [28], achieving a significant enhancement in antimicrobial performance.

In addition to metal ions, natural polymers such as chitosan, quaternary ammonium salts, and antimicrobial peptides inherently possess antibacterial properties, making them ideal candidates for incorporation into hydrogels as antibacterial components. For instance, Hoque et al. developed a hydrogel using the antimicrobial polymer N-(2-hydroxypropyl)-3-trimethylammonium chloride chitosan. High-molecular-weight chitosan derivative hydrogels alter cell membrane permeability through electrostatic interactions, leading to cytoplasmic leakage or the formation of a polymeric membrane around cells that blocks material exchange. Low-molecular-weight chitosan derivatives can penetrate bacterial cell walls, bind to DNA, and inhibit mRNA synthesis and DNA transcription, thereby achieving antimicrobial effects [29]. Other cationic polymers, such as guanidine-based polymers and peptide salts, also form hydrogels with notable antibacterial efficacy [30]. Strassburg et al. synthesized antimicrobial 3,4-enionene (PBI) via the polyaddition of trans-1,4-Dibromo-2-butene and N,N,N ′,N ′-Tetramethyl-1,3-propandiamine, subsequently fabricating an interpenetrating network hydrogel, which exhibits prolonged antimicrobial activity and hemocompatibility [31]. Baral et al. developed a hydrogel from long-chain amino acid-containing dipeptides in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 6.0–8.8), these dipeptide-based hydrogels not only exhibit superior antibacterial performance but also display thixotropic behavior under specific pH conditions, conferring high practical utility in biomedical applications [32]. The findings indicate a diversified trend in the design of antibacterial hydrogels. Through innovations in material architecture and functional modifications, researchers have achieved broad-spectrum inhibition against common pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, while simultaneously endowing hydrogels with advanced functionalities—including bacterial growth-sensing capabilities and pH-responsive properties. These advancements provide material-based solutions to address complex infection scenarios, offering a paradigm shift in infection management strategies.

Since the antimicrobial activity of agent-loaded hydrogels is typically short-lived, environmentally responsive antimicrobial materials have emerged to prevent functional loss before deployment. Guo et al. developed a polyacrylamide (PAM) hydrogel incorporating photothermal polydopamine and Mg2+, which rapidly heats up (>20°C) under laser irradiation. This temperature increase causes bacterial membrane rupture and protein denaturation, achieving effective bactericidal effects [33]. The hydrogel also exhibits excellent tissue adhesion, enhanced wound healing stimulation, and collagen deposition properties. Mao et al. integrated black phosphorus nanosheets as photosensitizers into hydrogels, enabling light-triggered reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation for antibacterial effects [34], with additional benefits including reusability, biocompatibility, and wound healing promotion. As human/animal tissues are opaque, light-responsive hydrogels only work on surfaces, requiring alternative stimuli for deeper applications. This led to ultrasound-responsive hydrogels, such as Tao et al.’s design combining stanene nanosheets with thermosensitive poly(d,l-lactide)-poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(d,l-lactide) (PLEL) [35]. This hydrogel generates ROS under ultrasound for antibacterial action (Fig. 1). Moreover, the hydrogel exhibits favorable rheological properties that facilitate its ease of injection, while concurrently promoting cell migration and accelerating wound healing—a feature that constitutes a key advantage of this biomaterial. All three hydrogels combine antimicrobial properties, biocompatibility, and wound healing stimulation, making them highly valuable for medical material development.

Figure 1: The antibacterial effects of the materials for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli. (a) Images on spread plates. Spread plate; (b) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images. (I): Control group (hydrogel without nanosheets); (II): Hydrogel without nanosheets with acoustic stimulation; (III): Hydrogel with nanosheets without acoustic stimulation; (IV): Hydrogel with nanosheets with acoustic stimulation (Reprinted with permission from Reference [35]. Copyright (2023) Elsevier)

3 Effect of Polymer Surface Properties on Microbial Adhesion

Traditional polymeric materials commonly rely on surface modification strategies to enhance their antibacterial properties. Thus, elucidating the influence of surface/interface properties of polymeric materials on microbial adhesion behavior is critical for advancing the development of antibacterial functionalities in conventional polymers. Current research has revealed that microbial adhesion on surfaces and interfaces is influenced by various factors, including microbial species, environmental media, and substrates [36,37].

Numerous studies have thoroughly demonstrated that even extremely subtle changes in polymer material surface properties (such as roughness, micro/nanostructures, and charge characteristics) can exert significant and direct regulatory effects on microbial adhesion behavior [38,39]. Mu et al. systematically and profoundly investigated bacterial adhesion patterns on hydrophobic surfaces by constructing surfaces with roughness gradients ranging from 2 to 390 nm. The study results were remarkable, revealing that bacterial contamination levels could vary by up to 75-fold depending on surface roughness (see Fig. 2). This finding provides highly valuable empirical evidence for understanding the relationship between roughness and bacterial adhesion [40]. Surface roughness, as a critical factor involving structural changes at the micro- and nanoscale, influences microbial adhesion, further indicating that the micro/nanostructures, of substrate surfaces significantly affect microorganism adhesion. This conclusion is more intuitively demonstrated in the study of Kuo et al., which investigated the intrinsic correlation between microorganism adhesion strength and nanopillar diameter. The study clearly showed that microorganism adhesion strength is inversely correlated with nanopillar diameter [41], strongly confirming the synergistic role of polymer material surface stiffness and micro- and nano-structures in regulating microbial adhesion behavior. These results effectively elucidate the significant impact of the characteristics of micro- and nano-structures on the surface of materials on microbial adhesion behavior. The studies conducted by Mu et al. and Kuo et al. have revealed the associations between surface roughness, nanostructures, etc., and microbial adhesion from different perspectives, providing abundant empirical evidence for research in this field. This helps to gain a deeper understanding of the interaction mechanism between microorganisms and material surfaces as well as offers theoretical support for the development of materials with anti-microbial adhesion properties.

Figure 2: SEM images of bacterial adsorption on surfaces with different roughness. (A) Root-mean-square (RMS) roughness of the surface is 1.7 ± 0.1 nm; (B) RMS roughness is 3.0 ± 1.6 nm; (C) RMS roughness is 5.8 ± 1.2 nm; (D) RMS roughness is 9.1 ± 1.7 nm; (E) RMS roughness is 11.3 ± 2.3 nm; (F) RMS roughness is 16.8 ± 1.1 nm (Reprinted with permission from Reference [40]. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society)

In the realm of microbial adhesion research, while much attention has been paid to surface roughness and micro- and nano-structures, the role of surface charge is also a crucial aspect worthy of in-depth exploration. On the other hand, the impact of surface charge on microorganism adhesion has been meticulously studied by Oh et al., who found that Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli exhibited the strongest adhesion capabilities on positively charged hydrophilic substrates; on negatively charged hydrophilic substrates, their adhesion forces significantly weakened to the lowest level; and on hydrophobic substrates, the adhesion forces were intermediate. This series of findings clearly reveals the complex influence mechanism of surface charge properties on microbial adhesion behavior [42]. The study of Oh et al. provides a comprehensive understanding of how surface charge affects the adhesion of different bacteria to various substrates, highlighting the need to consider multiple surface properties when studying microbial adhesion. These findings open up new avenues for the development of antibacterial materials by allowing for targeted manipulation of surface charge to control microbial attachment.

3.3 Surface Superhydrophobicity

The micro- and nano-structures inherent in superhydrophobic surfaces exert varying influences on the attachment sites and quantities of adhering microorganisms. Compared to surfaces with microstructures or smooth substrates, surfaces featuring nanostructures often demonstrate superior uniformity and efficacy in inhibiting microbial adhesion [43,44]. This finding provides a significant basis for a deeper understanding of the application potential of superhydrophobic surfaces in the field of microbial prevention and control. In fact, surface morphologies with greater roughness and more irregular topography tend to promote cell adhesion, whereas engineered surfaces with regular micro-patterned structures demonstrate the opposite effect, exhibiting superior anti-adhesive properties. Chung et al. discovered that the surface of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) elastomer with a regular a biomimetic microtopography exhibited remarkable anti-adhesion and anti-biofilm formation properties against Staphylococcus aureus (see Fig. 3) [44], when compared to its smooth counterpart. It was observed that the smooth surface displayed early-stage bacterial colonization at 7 days and mature biofilms at 14 days, whereas bacterial cells on the Sharklet-featured surfaces were effectively isolated and only witnessed a minor increase in the number of microorganism clusters. Notably, the area coverage of bacterial attachment was 54% on the smooth surface, in contrast to only 7% on the Sharklet AFTM surface at 14 days.

Figure 3: SEM images of microbial adhesion on smooth surface (left) and a biomimetic microtopography surface (right). (A) Microbial adhesion on a smooth surface at day 0; (B) On microtopography surfaces at day 0; (C) On smooth surfaces at day 2; (D) On microtopography surfaces at day 2; (E) On smooth surfaces at day 7; (F) On microtopography surfaces at day 7; (G) On smooth surfaces at day 14; (H) On microtopography surfaces at day 14 (Reprinted with permission from Reference [44]. Copyright 2007 AIP Publishing)

Superhydrophobic surfaces typically exhibit hierarchical structures formed by the interaction of micro- and nano-structures. Due to the ability of hierarchical structures to achieve a more effective and stable Cassie-Baxter wetting state, microbial adhesion and biofilm formation are most significantly inhibited compared to superhydrophobic substrates with single microstructures or nanostructures [45,46].

One of the widely accepted anti-adhesion mechanisms is the obstruction effect [47–49]. Once water droplets or trapped air bubbles are in a wetted state, a robust air-liquid interface is formed. Due to the high surface tension of water, microbial cells are unable to penetrate this interface. Consequently, microbial cells find it difficult to locate anchor points for attachment to these highly adhesive air bubbles. When constructing appropriate anti-biofouling topologies on superhydrophobic surfaces, the microbial adhesion effect can be effectively further enhanced. Multiscale air bubbles also influence the adhesion sites of microorganisms. On the surface of natural superhydrophobic banana leaves with hierarchical structures, Ma et al. observed circular patterns of bacterial adhesion, as cells primarily adhered to the concave boundaries between epidermal microorganism units [50]. Therefore, microbial cells are unable to directly contact the top nanobubbles of the hierarchical structures and preferentially adhere to the grooves where microscale air rapidly dissipates, providing sufficient shelter from water flow.

In summary, the antifouling capabilities of superhydrophobic surfaces primarily stem from their trapped air layers. Surface topography and low surface energy are not only requirements for developing superhydrophobic surfaces but also play decisive roles in conferring improved anti-adhesion properties to the surfaces.

Interfacial free energy, as a key physicochemical property of material surfaces, exerts a non-negligible influence on microbial adhesion behavior, with this effect being closely related to microbial species [51–53]. Pereni and their team conducted a study centered on Pseudomonas aeruginosa, aiming to explore how the surface energy of five distinct coatings (namely, silicone, polished stainless steel, and unpolished stainless steel) affects bacterial adhesion, see Fig. 4. Their study revealed a strong correlation between Pseudomonas aeruginosa attachment and total surface free energy (SFE), particularly its polar and dispersive components. Notably, when the total SFE fell within the 20–27 mN/m range, bacterial adhesion decreased significantly [54]. This finding provides critical insights into the adhesion mechanisms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa across different surfaces.

Figure 4: The mean values of viable counts of Pseudomonas aeruginosa per cm2 at different surfaces. The surfaces exhibit varying surface free energy characteristics (Reprinted with permission from Reference [54]. Copyright (2006) Elsevier)

At the microscopic level, free energy can be regarded as the surface tension of solids, arising from excess energy due to unsaturated bonds in surface atoms. The magnitude of this excess energy depends on the type and number of intermolecular forces. Consequently, it is widely acknowledged that these intermolecular forces constitute the primary mechanistic basis by which SME affect microorganism adhesion to material surfaces. Yongabi et al. further validated this by studying Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli adhesion on gold and silica surfaces. Their results demonstrated that SFE regulates adhesion for both microorganism types: high SFE surfaces promoted yeast adhesion but inhibited Escherichia coli adhesion. The adhesion level and the state of long-term microbial retention are determined by the equilibrium between polar and non-polar components of surface free energy [55]. Key factors included dispersive van der Waals forces and polar interactions (e.g., Ulva hydrogen bonding and dipole-dipole forces) [49,56,57].

These studies underscore the dual nature of surface free energy in microbial adhesion acting as either a promoter or inhibitor depending on the microorganism and surface chemistry. The opposing effects on yeast and Escherichia coli highlight the need for species-tailored surface modifications in industrial or biomedical contexts.

3.5 Surface Nanoforce Gradients

As research on microbial surface adhesion advances, the innovative concept of nanoforce gradients has emerged. Schumacher et al. engineered patterned PDMS surfaces with 3 μm feature height generating 0–374 nN nanoscale pressure gradients. Their experiments revealed that Ulva zoospore density peaked on gradient-free surfaces (the SM and GR5 in Fig. 5), while the maximum gradient surface (GR3 in Fig. 5) reduced adhesion by 72% [58,59]. This effect stems from the disruption of the microorganism membrane’s mechanical equilibrium by microtopography during the initial adhesion process, enabling physical destabilization without chemical modification or biocides. Feng et al. demonstrated a paradigm for such topography engineering: two-step anodization created 15–50 nm nanopores on aluminum. These nanoscale features altered surface charge distribution, lowered free energy, and amplified localized force gradients via edge stress concentration, effectively inhibiting Escherichia coli and Listeria adhesion [60,61]. These studies underscore a transformative shift in anti-fouling strategies, emphasizing the utilization of physical nanomechanical signals as opposed to conventional chemical methodologies. The 72% reduction in spore adhesion via pure topographical intervention suggests immense potential for eco-friendly marine coatings. Meanwhile, Feng’s nanopore system reveals how multiscale effects (charge modulation and stress concentration) can synergistically block pathogens, offering a blueprint for dual-function antimicrobial surfaces in biomedical devices.

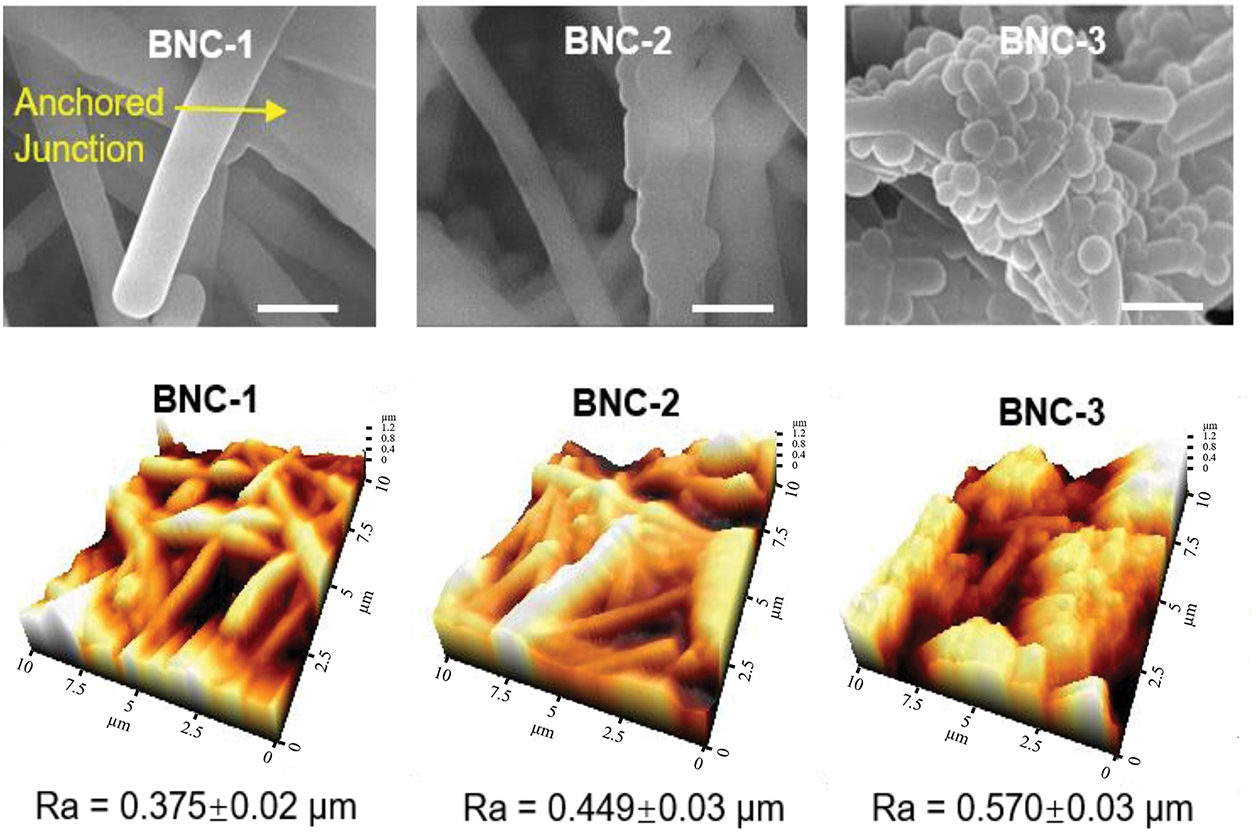

Figure 5: Comparison of roughness, water contact angle and water slide angle of surfaces with different microstructures (Reprinted with permission from Reference [63]. Copyright (2023) Elsevier)

Surface properties exhibit intricate correlations, as exemplified by the fabrication of micro/nanostructures on smooth substrates. The introduction of such hierarchical architectures significantly alters surface roughness, which in turn modulates hydrophobicity. For instance, the lotus leaf surface demonstrates a dual-scale micro/nanostructure (papillae with secondary nanoscale wax tubules), establishing a direct correlation between surface roughness and superhydrophobicity. Similarly, surfaces with low surface energy inherently exhibit enhanced hydrophobicity. These interdependent factors synergistically regulate surface antibacterial performance. Cao et al. developed an antibacterial material by replicating the rose petal’s hierarchical structure, featuring hemispherical protrusions (~23 μm diameter) with secondary nanoscale wrinkles (~700 nm width), which conferred exceptional hydrophobicity [62]. As illustrated in Fig. 5 [63], the engineered micro/nanostructures exert dual effects on surface roughness and hydrophobicity. The observed antibacterial efficacy of Cao’s modified surface arises from the synergistic interaction between surface roughness and hydrophobicity. Strategic exploitation of such synergistic effects offers significant advantages for enhancing antibacterial performance. Jiang et al. demonstrated this principle by creating low-surface-energy, superhydrophobic coatings capable of releasing silver nanoparticles [64]. This multifaceted synergistic approach substantially improved antibacterial efficacy through combined mechanisms [65].

4 Design of Antibacterial Polymer Surface

Gaining a profound understanding of bacterial adhesion behavior holds significant implications for the rational design of polymeric materials with surface-antibacterial properties. Notably, the aqueous environment stands as an essential niche for most bacteria to thrive. Under this special background, the strategy of regulating the interfacial hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity of polymeric materials has emerged as a highly promising and practically significant avenue. It offers a precise means to fine-tune the antibacterial behavior of these materials, paving the way for the development of more effective antibacterial solutions. Xie and his colleagues embarked on an innovative endeavor to fabricate antibacterial polymeric materials through surface modification of polyurethane. The experimental outcomes were striking. The modified surfaces demonstrated a remarkable enhancement in antibacterial activity against three notorious bacterial strains: Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Specifically, the bacterial survival rates on these surfaces were drastically reduced, ranging from 24% to 57%. Moreover, there was a substantial decrease in the adsorption of human serum albumin (HSA) onto the modified surfaces, with reductions between 64% and 70%. This study ingeniously leveraged the alterations in the hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity of the polymer surface as a key mechanism to modulate the polymer’s antibacterial attributes [66]. The study results of Sellenet et al. further enrich our understanding in this field. Their investigations reveal that by carefully engineering and constructing the surface structure of antibacterial materials with distinct hydrophilic features, the repulsive force exerted by these materials against bacteria can be significantly amplified. As a direct consequence, the overall efficacy of the antibacterial materials is markedly improved [67]. This discovery is consistent with the research findings of others, which emphasize the crucial and indispensable role of hydrophilic/hydrophobic regulation in the design and optimization of antibacterial polymer materials.

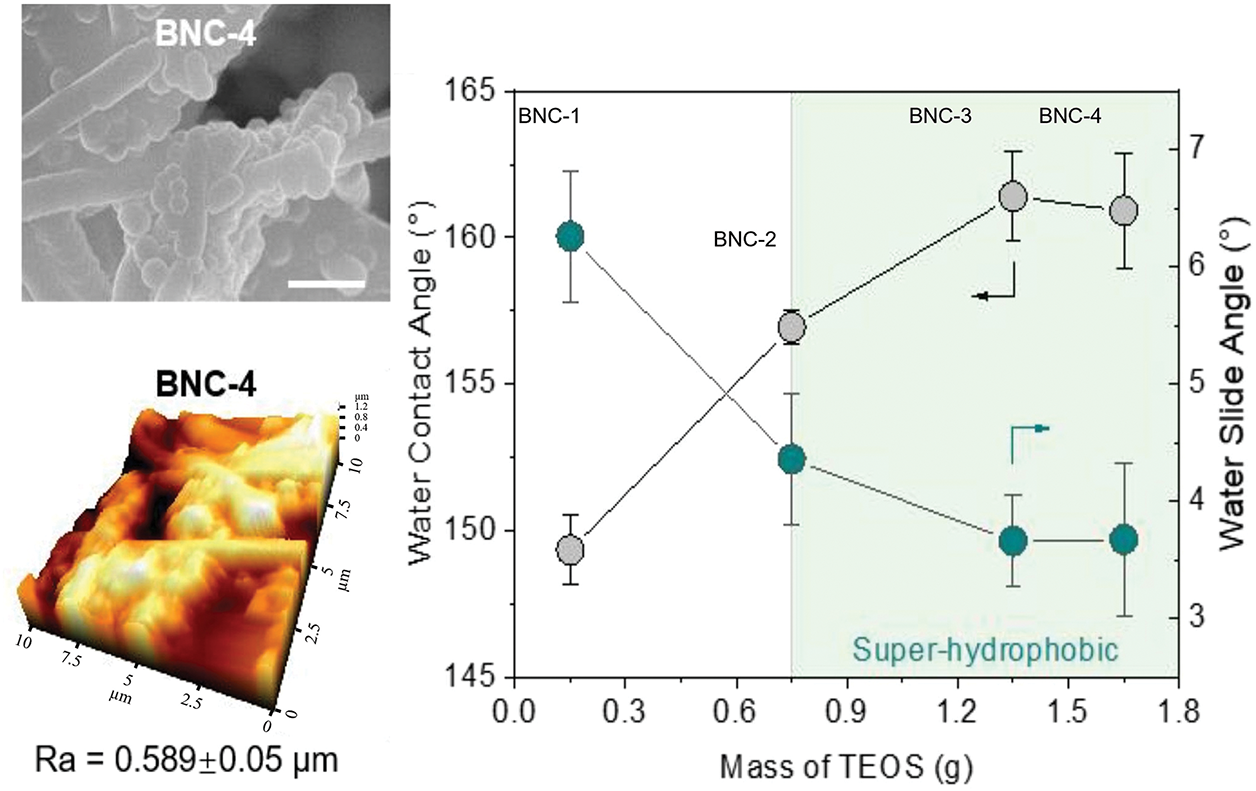

On the other hand, the micro-nanostructures on the material surface play a pivotal regulatory role in the adhesion behavior of cells. Leveraging this characteristic, it is possible to significantly modulate the antibacterial efficacy of the material against bacteria, thereby providing a novel strategy for the development of highly efficient antibacterial materials. Based on this property, Gillett et al. employed laser treatment on poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET). The treated surface exhibited a substantial reduction in bacterial adhesion [68]. However, a certain proportion of bacteria still adhered to the surface. In stark contrast to the design concept of primary micro-nanostructures adopted by Gillett et al., Francone et al. designed and constructed secondary micro-nanostructures on the surface of polypropylene (PP) [69]. Herein, the primary structure consists of pillars with a diameter of 10 μm, a height of 10 μm, and a pitch (spacing) of 23 μm, while the secondary structure comprises spikes with a height of 2.2 μm and a base diameter of 300 nm. Consequently, spaces of 13 μm containing spikes exist between these pillars, where bacterial adhesion is inhibited. Taking into account the additional influences of hydrophobicity and surface roughness, the surface with secondary nanostructures demonstrated remarkably superior antibacterial performance (see Fig. 6). Specifically, the bacterial attachment of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus on this surface was reduced by 82% and 86%, respectively. By comparing the antibacterial performances of primary and secondary micro-nanostructures, we found that due to their richer morphological features, secondary micro-nanostructures are more effective in interfering with bacterial adhesion and growth.

Figure 6: The effect of changes in the primary structure and secondary structure of materials on the adhesion of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus to polypropylene (Reprinted with permission from Reference [69]. Copyright (2021) Elsevier)

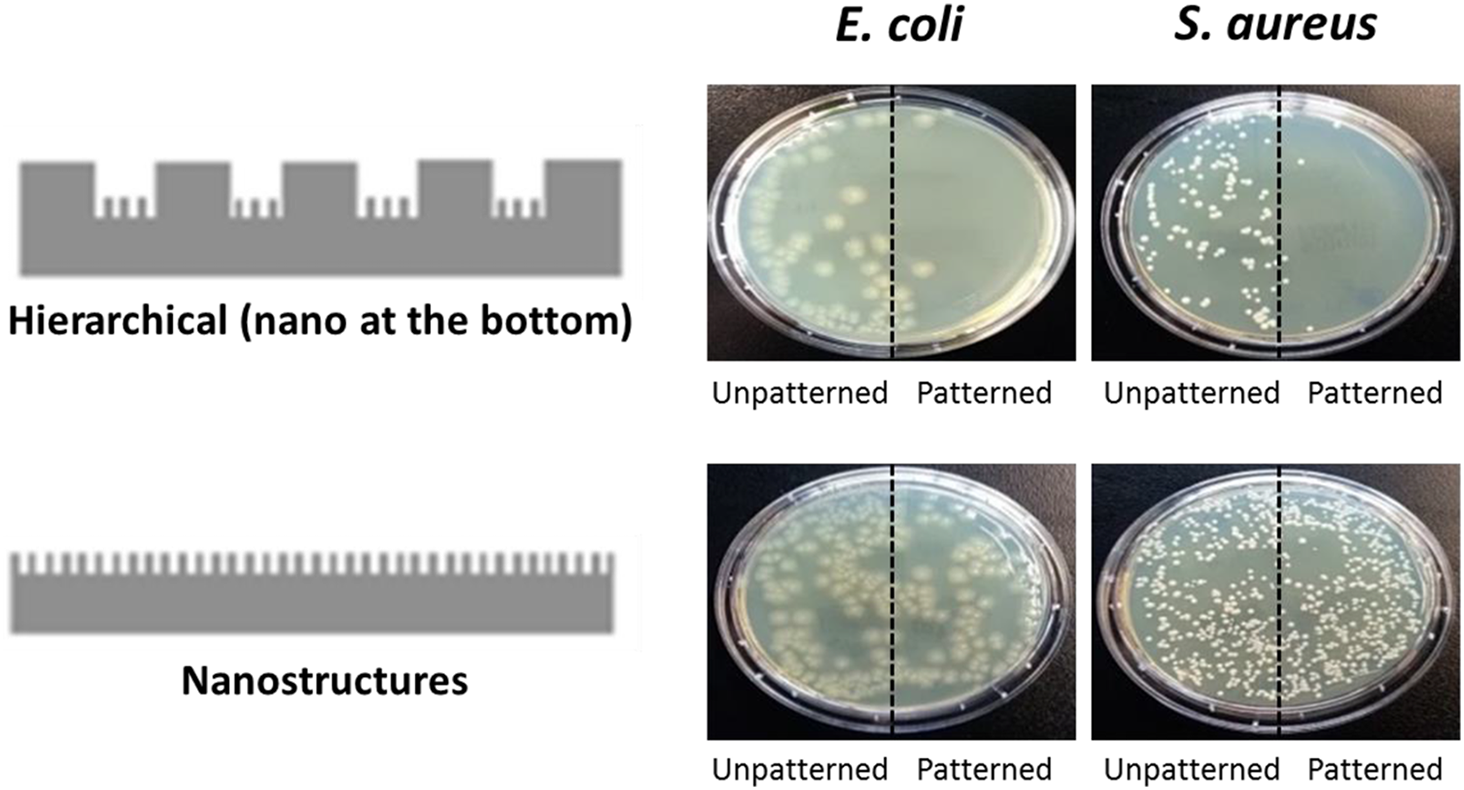

It is known that antimicrobial approaches utilizing functional groups with antibacterial properties (such as quinoline or ammonium groups) or loaded with antibacterial agents (including ammonium salts, silver nanoparticles, etc.) often exhibit toxic effects on human cells, tissues, or organs [70]. Moreover, the use of such functional groups and agents can lead to the development of bacterial resistance. In contrast, surface microstructures employ physical mechanisms for antibacterial action, and there is currently no evidence demonstrating that bacteria can develop resistance mechanisms against these physically antibacterial nanomaterials [71]. Consequently, despite the manufacturing challenges associated with surface microstructures, this approach has garnered significant attention as an antimicrobial strategy. Researchers have attempted to fabricate various surface micro/nanostructures, which indeed reduce bacterial adhesion. However, the antibacterial efficacy of many surfaces is not long-lasting, as they are accompanied by effects such as protein adsorption, local destruction of nano/microstructures during the antibacterial process, leading to diminished effectiveness of the surface micro/nanostructures in reducing cell adhesion. Particularly in complex biological environments, nanostructured surfaces are rapidly covered, resulting in their failure. Surface self-cleaning properties can mitigate this phenomenon. In nature, there exist surfaces that maintain long-term antibacterial activity and self-cleaning functions, such as lotus leaves, cicada wings, and the skin of sharks, dolphins, and geckos. These surfaces have been confirmed to possess special micro/nanostructures (Fig. 7 shows the nanostructure of a cicada wing), which confer superhydrophobicity, antibacterial properties, and self-cleaning functions [71–73]. Mimicking these structures holds promise for the development of self-cleaning surfaces capable of sustaining long-term antibacterial performance.

Figure 7: The effect of changes in the primary structure of materials on the adhesion of Escherichia coli. (A) Scanning electron microscopy of nanopillar features on cicada wing epicuticles from a top-view; (B) Nanopillar features on cicada wing epicuticles from a top-view side-view; (C) Neotibicen pruinosus cicadae; (D) Magicicada septendecim cicadae (Adapted with permission from Reference [73]. Copyright (2020) Elsevier)

The development of antimicrobial materials has achieved significant progress. Hydrogels, as a novel material with excellent compatibility for antimicrobial components and highly tunable functionality, have become a key focus in current antimicrobial material research. Through the incorporation of metal ions (e.g., Ag+, Mg2+) and natural polymers (such as chitosan derivatives), various antimicrobial hydrogels can be fabricated. Environmentally responsive antibacterial hydrogels are capable of recognizing bacterial growth and enabling targeted release of antibacterial agents, offering innovative strategies for the design of medical antibacterial materials and demonstrating significant potential for clinical translation.

For traditional materials, since bacteria can only adhere to the material surface, research has primarily focused on analyzing the impact of surface properties on bacterial adhesion. These findings have guided the design of antibacterial materials, particularly through cross-scale structural design of secondary micro/nano surface architectures inspired by natural surfaces such as lotus leaves. The remarkable antimicrobial performance of these materials undoubtedly validates the rationality of current conventional antimicrobial strategies.

In the future, the following research directions will be key priorities: (1) Development of biocompatible and non-toxic antibacterial materials; (2) Creation of multifunctional antibacterial materials (e.g., combining antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties, antibacterial self-repairing materials, etc.); (3) Utilization of artificial intelligence or machine learning to optimize surface structural design; (4) Development of environmentally responsive antibacterial materials that function within biological systems; (5) Regardless of whether antibacterial materials are prepared by loading antibacterial agents or modifying surface microstructures, the duration of their antibacterial activity is a critical parameter that cannot be overlooked. Therefore, the future design of antibacterial materials capable of maintaining long-term activity within biological systems is of particular importance.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by Science and Technology Plan of Luzhou under Grant No. 2024JYJ039.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Nanpu Cao, Fa Zhang, Song Yue; draft manuscript preparation: Nanpu Cao, Huan Luo, Yong Chen, Mao Xu, Pu Cao, Tao Xin, Hongying Luo; supervision and verification of manuscript: Fa Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. DeFlorio W, Liu S, White AR, Taylor TM, Cisneros-Zevallos L, Min Y, et al. Recent developments in antimicrobial and antifouling coatings to reduce or prevent contamination and cross-contamination of food contact surfaces by bacteria. Compr Rev Food Sci F. 2021;20(3):3093–134. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12750. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Caldara M, Belgiovine C, Secchi E, Rusconi R. Environmental, microbiological, and immunological features of bacterial biofilms associated with implanted medical devices. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2022;35(2):e00221–20. doi:10.1128/cmr.00221-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Debroy A, George N, Mukherjee G. Role of biofilms in the degradation of microplastics in aquatic environments. J Chem Technol Biot. 2022;97(12):3271–82. doi:10.1002/jctb.6978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Qiu H, Feng K, Gapeeva A, Meurisch K, Kaps S, Li X, et al. Functional polymer materials for modern marine biofouling control. Prog Polym Sci. 2022;127:101516. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2022.101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang F, Cui S. A two-component statistical model for natural rubber. Polymer. 2022;242:124462. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2021.124462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang F, Gong Z, Cai W, Qian HJ, Lu ZY, Cui S. Single-chain mechanics of cis-1,4-polyisoprene and polysulfide. Polymer. 2022;240:124473. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2021.124473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang F, Cao N. Revealing the effect of the length of chains on rubber mechanical properties by the two-component quantum mechanical Gaussian model. Macromol Chem Phys. 2024;225(7):2300414. doi:10.1002/macp.202300414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lei K, Chen M, Guo P, Fang J, Zhang J, Liu X, et al. Environmentally adaptive polymer hydrogels: maintaining wet-soft features in extreme conditions. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33(41):2303511. doi:10.1002/adfm.202303511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhao B, Bai Z, Lv H, Yan Z, Du Y, Guo X, et al. Self-healing liquid metal magnetic hydrogels for smart feedback sensors and high-performance electromagnetic shielding. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023;15(1):79. doi:10.1007/s40820-023-01043-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Bai M, Chen Y, Zhu L, Li Y, Ma T, Li Y, et al. Bioinspired adaptive lipid-integrated bilayer coating for enhancing dynamic water retention in hydrogel-based flexible sensors. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):10569. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-54879-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Jiang M, Zheng J, Tang Y, Liu H, Yao Y, Zhou J, et al. Retrievable hydrogel networks with confined microalgae for efficient antibiotic degradation and enhanced stress tolerance. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):3160. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-58415-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Alkekhia D, LaRose C, Shukla A. β-lactamase-responsive hydrogel drug delivery platform for bacteria-triggered cargo release. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(24):27538–50. doi:10.1021/acsami.2c02614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Jeong Y, Irudayaraj J. Hierarchical encapsulation of bacteria in functional hydrogel beads for inter- and intra-species communication. Acta Bio. 2023;158:203–15. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2023.01.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Flemming HC, Van Hullebusch ED, Neu TR, Nielsen PH, Seviour T, Stoodley P, et al. The biofilm matrix: multitasking in a shared space. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21(2):70–86. doi:10.1038/s41579-022-00791-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Sauer K, Stoodley P, Goeres DM, Hall-Stoodley L, Burmølle M, Stewart PS, et al. The biofilm life cycle: expanding the conceptual model of biofilm formation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;20(10):608–20. doi:10.1038/s41579-022-00767-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ashok D, Cheeseman S, Wang Y, Funnell B, Leung SF, Tricoli A, et al. Superhydrophobic surfaces to combat bacterial surface colonization. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2023;10(24):2300324. doi:10.1002/admi.202300324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Subbiahdoss G, Reimhult E. Biofilm formation at oil-water interfaces is not a simple function of bacterial hydrophobicity. Colloid Surface B. 2020;194:111163. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Jakubovics NS, Goodman SD, Mashburn-Warren L, Stafford GP, Cieplik F. The dental plaque biofilm matrix. Periodontol. 2000;2021:86(1):32–56. doi:10.1111/prd.12361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Vandana DS. Genetic regulation, biosynthesis and applications of extracellular polysaccharides of the biofilm matrix of bacteria. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;291:119536. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284(5418):1318–22. doi:10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Geisel S, Secchi E, Vermant J. The role of surface adhesion on the macroscopic wrinkling of biofilms. eLife. 2022;11:e76027. doi:10.1101/2021.12.09.471895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. El Othmany R, Zahir H, Ellouali M, Latrache H. Current understanding on adhesion and biofilm development in actinobacteria. Int J Microbiol. 2021;2021(1):6637438. doi:10.1155/2021/6637438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Gomes LC, Mergulhão FJM. A selection of platforms to evaluate surface adhesion and biofilm formation in controlled hydrodynamic conditions. Microorganisms. 2021;9(9):1993. doi:10.3390/microorganisms9091993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Li P, Zhao J, Chen Y, Cheng B, Yu Z, Zhao Y, et al. Preparation and characterization of chitosan physical hydrogels with enhanced mechanical and antibacterial properties. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;157:1383–92. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.11.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Dai T, Wang C, Wang Y, Xu W, Hu J, Cheng Y. A nanocomposite hydrogel with potent and broad-spectrum antibacterial activity. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(17):15163–73. doi:10.1021/acsami.8b02527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Sileika TS, Kim HD, Maniak P, Messersmith PB. Antibacterial performance of polydopamine-modified polymer surfaces containing passive and active components. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2011;3(12):4602–10. doi:10.1021/am200978h. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Slistan-Grijalva A, Herrera-Urbina R, Rivas-Silva JF, Ávalos-Borja M, Castillón-Barraza FF, Posada-Amarillas A. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles in a polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) paste, and their optical properties in a film and in ethylene glycol. Mater Res Bull. 2008;43(1):90–6. doi:10.1016/j.materresbull.2007.02.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ho CH, Odermatt EK, Ingo B, Tiller JC. Long-term active antimicrobial coatings for surgical sutures based on silver nanoparticles and hyperbranched polylysine. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2013;24(13):1589–600. doi:10.1080/09205063.2013.782803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Hoque J, Prakash RG, Paramanandham K, Shome BR, Haldar J. Biocompatible injectable hydrogel with potent wound healing and antibacterial properties. Mol Pharm. 2017;14(4):1218–30. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b01104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Yuan J, Zhang D, He X, Ni Y, Che L, Wu J, et al. Cationic peptide-based salt-responsive antibacterial hydrogel dressings for wound healing. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;190:754–62. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.09.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Strassburg A, Petranowitsch J, Paetzold F, Krumm C, Peter E, Meuris M, et al. Cross-linking of a hydrophilic, antimicrobial polycation toward a fast-swelling, antimicrobial superabsorber and interpenetrating hydrogel networks with long lasting antimicrobial properties. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(42):36573–82. doi:10.1021/acsami.7b10049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Baral A, Roy S, Ghosh S, Hermida-Merino D, Hamley IW, Banerjee A. A peptide-based mechano-sensitive, proteolytically stable hydrogel with remarkable antibacterial properties. Langmuir. 2016;32(7):1836–45. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b03789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Guo Z, Zhang Z, Zhang N, Gao W, Li J, Pu Y, et al. A Mg2+/polydopamine composite hydrogel for the acceleration of infected wound healing. Bioact Mater. 2022;15:203–13. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.11.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Mao C, Xiang Y, Liu X, Cui Z, Yang X, Li Z, et al. Repeatable photodynamic therapy with triggered signaling pathways of fibroblast cell proliferation and differentiation to promote bacteria-accompanied wound healing. ACS Nano. 2018;12(2):1747–59. doi:10.1021/acsnano.7b08500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Tao N, Zeng Z, Deng Y, Chen L, Li J, Deng L, et al. Stanene nanosheets-based hydrogel for sonodynamic treatment of drug-resistant bacterial infection. Chem Eng J. 2023;456:141109. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2022.141109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Fan H, Guo Z. Bioinspired surfaces with wettability: biomolecule adhesion behaviors. Biomater Sci. 2020;8(6):1502–35. doi:10.1039/c9bm01729a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Sterzenbach T, Helbig R, Hannig C, Hannig M. Bioadhesion in the oral cavity and approaches for biofilm management by surface modifications. Clin Oral Invest. 2020;24(12):4237–60. doi:10.1007/s00784-020-03646-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Chinnaraj SB, Jayathilake PG, Dawson J, Ammar Y, Portoles J, Jakubovics N, et al. Modelling the combined effect of surface roughness and topography on bacterial attachment. J Mater Sci Technol. 2021;81:151–61. doi:10.1016/j.jmst.2021.01.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Teutle-Coyotecatl B, Contreras-Bulnes R, Rodríguez-Vilchis LE, Scougall-Vilchis RJ, Velazquez-Enriquez U, Almaguer-Flores A, et al. Effect of surface roughness of deciduous and permanent tooth enamel on bacterial adhesion. Microorganisms. 2022;10(9):1701. doi:10.3390/microorganisms10091701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Mu M, Liu S, DeFlorio W, Hao L, Wang X, Salazar KS, et al. Influence of surface roughness, nanostructure, and wetting on bacterial adhesion. Langmuir. 2023;39(15):5426–39. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.3c00091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Kuo CW, Chueh DY, Chen P. Investigation of size-dependent cell adhesion on nanostructured interfaces. J Nanobiotechnol. 2014;12(1):54. doi:10.1186/s12951-014-0054-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Oh JK, Yegin Y, Yang F, Zhang M, Li J, Huang S, et al. The influence of surface chemistry on the kinetics and thermodynamics of bacterial adhesion. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):17247. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-35343-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Helbig R, Günther D, Friedrichs J, Rößler F, Lasagni A, Werner C. The impact of structure dimensions on initial bacterial adhesion. Biomater Sci. 2016;4(7):1074–8. doi:10.1039/c6bm00078a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Chung KK, Schumacher JF, Sampson EM, Burne RA, Antonelli PJ, Brennan AB. Impact of engineered surface microtopography on biofilm formation of Staphylococcus aureus. Biointerphases. 2007;2(2):89–94. doi:10.1116/1.2751405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Wang T, Wang Z. Liquid-repellent surfaces. Langmuir. 2022;38(30):9073–84. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.2c01533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Rasitha TP, Vanithakumari SC, Nanda Gopala Krishna D, George RP, Srinivasan R, Philip J. Facile fabrication of robust superhydrophobic aluminum surfaces with enhanced corrosion protection and antifouling properties. Prog Org Coat. 2022;162:106560. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2021.106560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Souza JGS, Bertolini M, Costa RC, Cordeiro JM, Nagay BE, de Almeida AB, et al. Targeting pathogenic biofilms: newly developed superhydrophobic coating favors a host-compatible microbial profile on the titanium surface. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(9):10118–29. doi:10.1021/acsami.9b22741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Bartlet K, Movafaghi S, Dasi LP, Kota AK, Popat KC. Antibacterial activity on superhydrophobic titania nanotube arrays. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2018;166:179–86. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.03.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Owens DK, Wendt RC. Estimation of the surface free energy of polymers. J Appl Polym Sci. 1969;13(8):1741–7. [Google Scholar]

50. Ma J, Sun Y, Gleichauf K, Lou J, Li Q. Nanostructure on taro leaves resists fouling by colloids and bacteria under submerged conditions. Langmuir. 2011;27(16):10035–40. doi:10.1021/la2010024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Ratheesh A, Elias L, Aboobakar Shibli SM. Tuning of electrode surface for enhanced bacterial adhesion and reactions: a review on recent approaches. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2021;4(8):5809–38. doi:10.1021/acsabm.1c00362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Li W, Thian ES, Wang M, Wang Z, Ren L. Surface design for antibacterial materials: from fundamentals to advanced strategies. Adv Sci. 2021;8(19):2100368. doi:10.1002/advs.202100368. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Yan H, Wu Q, Yu C, Zhao T, Liu M. Recent progress of biomimetic antifouling surfaces in marine. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2020;7(20):2000966. doi:10.1002/admi.202000966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Pereni CI, Zhao Q, Liu Y, Abel E. Surface free energy effect on bacterial retention. Colloid Surface B. 2006;48(2):143–7. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.02.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Yongabi D, Khorshid M, Gennaro A, Jooken S, Duwé S, Deschaume O, et al. QCM-D study of time-resolved cell adhesion and detachment: effect of surface free energy on eukaryotes and prokaryotes. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(16):18258–72. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c00353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Gentleman MM, Gentleman E. The role of surface free energy in osteoblast-biomaterial interactions. Int Mater Rev. 2014;59(8):417–29. doi:10.1179/1743280414y.0000000038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Nakamura M, Hori N, Ando H, Namba S, Toyama T, Nishimiya N, et al. Surface free energy predominates in cell adhesion to hydroxyapatite through wettability. Mat Sci Eng C. 2016;62:283–92. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2016.01.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Meng YF, Yu CX, Zhou LC, Shang LM, Yang B, Wang QY, et al. Nanograded artificial nacre with efficient energy dissipation. Innovation. 2023;4(6):100505. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2023.100505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Schumacher JF, Long CJ, Callow ME, Finlay JA, Callow JA, Brennan AB. Engineered nanoforce gradients for inhibition of settlement (attachment) of swimming algal spores. Langmuir. 2008;24(9):4931–7. doi:10.1021/la703421v. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Feng G, Cheng Y, Wang SY, Hsu LC, Feliz Y, Borca-Tasciuc DA, et al. Alumina surfaces with nanoscale topography reduce attachment and biofilm formation by Escherichia coli and Listeria spp. Biofouling. 2014;30(10):1253–68. doi:10.1080/08927014.2014.976561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Huang X, Kaissner R, Renz B, Börner J, Ou X, Neubrech F, et al. Organic metasurfaces with contrasting conducting polymers. Nano Lett. 2025;25(2):890–7. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.4c05856. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Cao Y, Jana S, Bowen L, Tan X, Liu H, Rostami N, et al. Hierarchical rose petal surfaces delay the early-stage bacterial biofilm growth. Langmuir. 2019;35(45):14670–80. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b02367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Liang Y, Yang E, Kim M, Kim S, Kim H, Byun J, et al. Lotus leaf-like SiO2 nanofiber coating on polyvinylidene fluoride nanofiber membrane for water-in-oil emulsion separation and antifouling enhancement. Chem Eng J. 2023;452:139710. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2022.139710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Jiang Y, Geng H, Peng J, Ni X, Pei L, Ye P, et al. A multifunctional superhydrophobic coating with efficient anti-adhesion and synergistic antibacterial properties. Prog Org Coat. 2024;186:108028. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2023.108028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Lv J, Jin J, Chen J, Cai B, Jiang W. Antifouling and antibacterial properties constructed by quaternary ammonium and benzyl ester derived from Lysine methacrylamide. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11(28):25556–68. doi:10.1021/acsami.9b06281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Xie D, Howard L, Almousa R. Surface modification of polyurethane with a hydrophilic, antibacterial polymer for improved antifouling and antibacterial function. J Biomater Appl. 2018;33(3):340–51. doi:10.1177/0885328218792687. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Sellenet PH, Allison B, Applegate BM, Youngblood JP. Synergistic activity of hydrophilic modification in antibiotic polymers. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(1):19–23. doi:10.1021/bm0605513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Gillett A, Waugh D, Lawrence J, Swainson M, Dixon R. Laser surface modification for the prevention of biofouling by infection causing Escherichia coli. J Laser Appl. 2016;28:022503. doi:10.2351/1.4944442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Francone A, Merino S, Retolaza A, Ramiro J, Alves SA, de Castro JV, et al. Impact of surface topography on the bacterial attachment to micro- and nano-patterned polymer films. Surf Interfaces. 2021;27:101494. doi:10.1016/j.surfin.2021.101494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Jaggessar A, Shahali H, Mathew A, Yarlagadda PKDV. Bio-mimicking nano and micro-structured surface fabrication for antibacterial properties in medical implants. J Nanobiotechnol. 2017;15(1):64. doi:10.1186/s12951-017-0306-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Linklater DP, Ivanova EP. Nanostructured antibacterial surfaces—what can be achieved? Nano Today. 2022;43:101404. doi:10.1016/j.nantod.2022.101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Luan Y, Liu S, Pihl M, Van der Mei HC, Liu J, Hizal F, et al. Bacterial interactions with nanostructured surfaces. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2018;38:170–89. doi:10.1016/j.cocis.2018.10.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Román-Kustas J, Hoffman JB, Alonso D, Reed JH, Gonsalves AE, Oh J, et al. Analysis of cicada wing surface constituents by comprehensive multidimensional gas chromatography for species differentiation. Microchem J. 2020;158:105089. doi:10.1016/j.microc.2020.105089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools