Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Polymeric Nanofiber Scaffolds for Diabetic Wound Healing: A Review

1 Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

2 Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya Research Centre for Biopharmaceuticals and Advanced Therapeutics (UBAT), Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

3 Centre of Advanced Materials (CAM), Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

4 Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chulalongkorn University, Pathum Wan, Bangkok, 10330, Thailand

* Corresponding Authors: Shaik Nyamathulla. Email: ; Syed Mahmood. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Polymer Materials in Controlled Drug Delivery)

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(4), 959-992. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.072005

Received 17 August 2025; Accepted 10 October 2025; Issue published 26 December 2025

Abstract

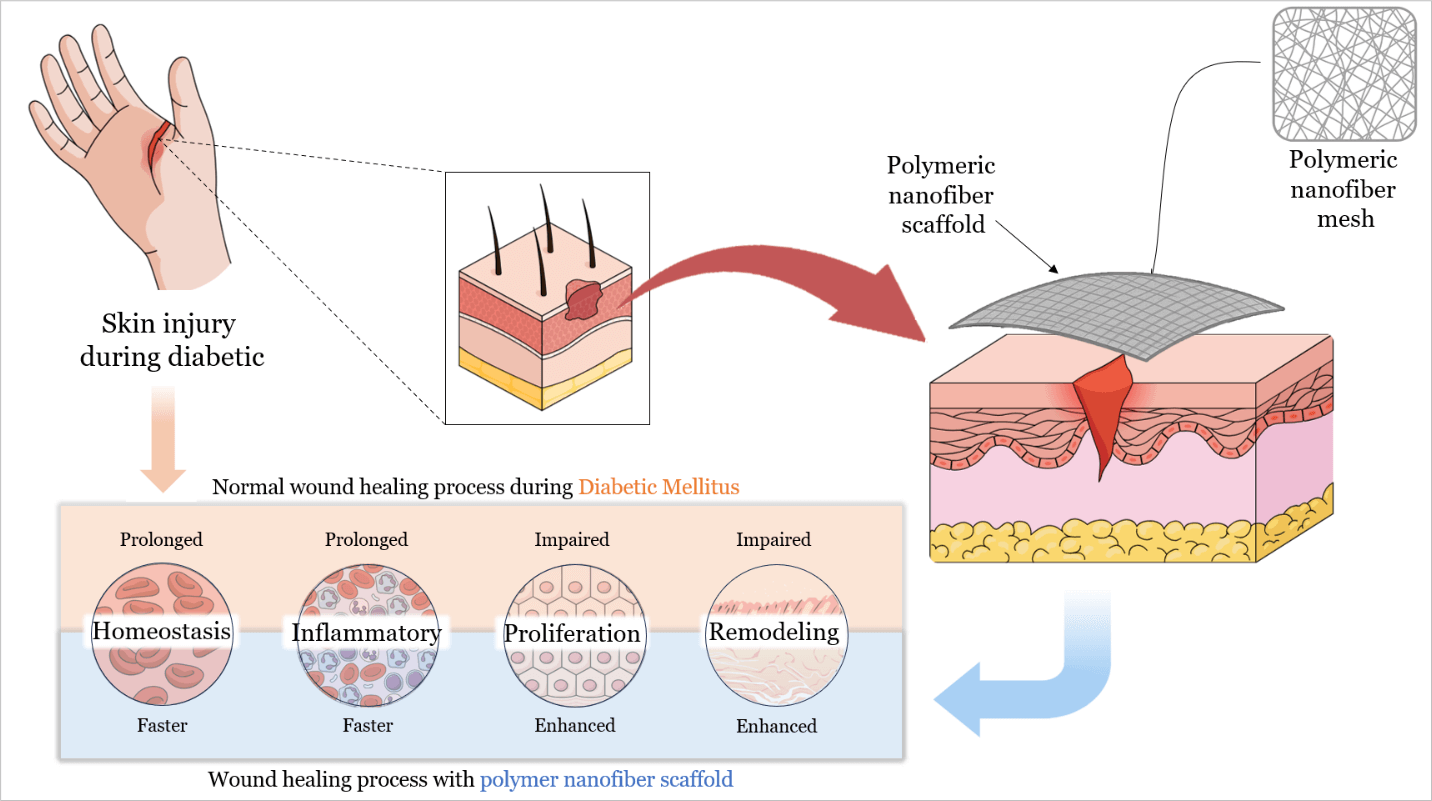

With the global diabetes epidemic, diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) have become a major health burden, affecting approximately 18 million people worldwide each year, and account for about 80% of diabetes-related amputations. Five-year mortality among DFU patients approaches 30%, which is comparable to that of many malignancies. Yet despite standard wound care, only about 30%–40% of chronic DFUs achieve complete healing within 12 weeks. This persistent failure shows that conventional dressings remain passive supports. They do not counteract underlying pathologies such as ischemia, prolonged inflammation, and infection. Recent advances in polymeric nanofiber scaffolds, particularly electrospun matrices, provide bioactive wound dressings designed to overcome these limitations. By mimicking extracellular matrix architecture (ECM) and delivering therapeutic biomolecules, polymeric nanofiber scaffolds can promote tissue regeneration and angiogenesis. They also modulate the wound immune response and combat infection through embedded antimicrobial agents. Innovative scaffold architectures further enhance healing outcomes. Core–shell and multilayer nanofibers enable sequential or sustained release of multiple factors. Biomimetic “basketweave” fiber layouts improve cell alignment, neovascularization, and wound closure, and stimuli-responsive scaffolds release therapeutics in response to wound pH or oxidative stress. Preclinical diabetic wound models and early clinical trials show that these engineered scaffolds accelerate wound closure, increase re-epithelialization, and reduce chronic inflammation relative to standard care. Notably, a recent clinical trial in patients with DFU reported 74% wound closure by 12 weeks with an electrospun scaffold vs. 33% with conventional therapy. However, translational challenges persist, including stability, sterilization compatibility, and scalable manufacturing of nanofiber scaffolds. This review discusses these hurdles and highlights future directions, including the development of smart biosensor-integrated scaffolds for responsive drug delivery, personalized patient-specific dressings, and AI-assisted design of polymer nanofibers to further optimize DFU healing outcomes.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Diabetes mellitus (DM) has reached epidemic proportions globally, currently affecting more than 550 million people, with projections exceeding 1.3 billion by 2050 [1]. As this global burden worsens, there has been a parallel rise in diabetes-related complications, most notably chronic foot ulcers, which have been observed [2]. Diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) affects approximately 18.6 million individuals worldwide each year, and up to one-third of individuals with diabetes will develop a foot ulcer during their lifetime [3]. DFUs precede about 80% of non-traumatic lower-extremity amputations in people with diabetes [4]. Approximately 20% of patients with a DFU eventually require a lower-extremity amputation, and the five-year mortality among DFU patients approaches 30%, comparable to or worse than many cancers [5,6].

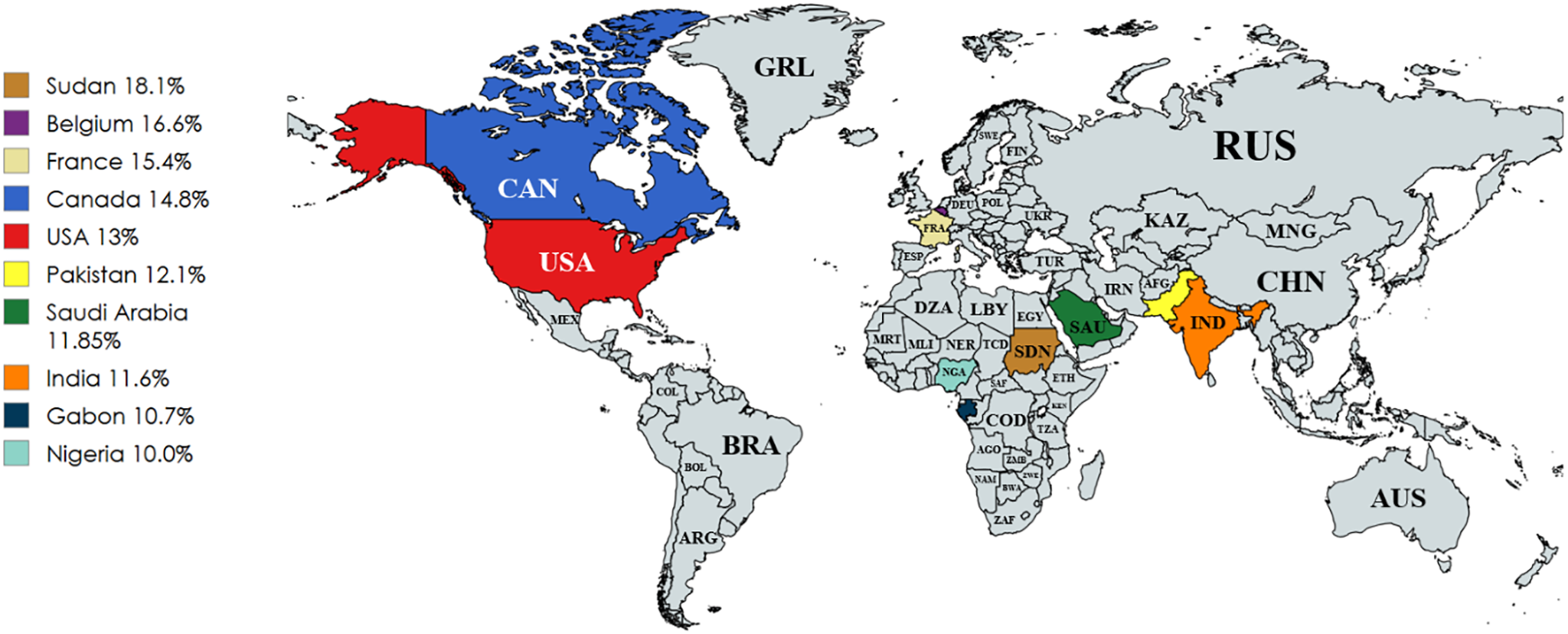

Beyond the human toll, chronic diabetic wounds impose an enormous socioeconomic burden. Prevalence rates vary markedly across regions: North America reports the highest DFU prevalence at about 13% of patients with diabetes. Asia and Europe average around 5%–6%, and Oceania has the lowest, at about 3%. In Africa, hospital-based studies have documented DFU prevalence ranging from about 10% to 30%. The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region similarly shows wide variation, with reported DFU prevalence ranging from 5% to 20% [7–13]. Fig. 1 provides a global perspective, illustrating the distribution of DFU prevalence across the world and highlighting the ten most affected countries.

Figure 1: Global distribution of DFU prevalence. Countries with the highest reported prevalence are highlighted and all countries are labeled using ISO 3166-1 alpha-3 codes [7–13]

Despite advances in wound care, outcomes for chronic DFUs remain suboptimal. Standard interventions, including pressure off-loading, debridement, infection control, and basic wound dressings, often fail to achieve complete or timely healing. Only 30%–40% of DFUs achieve full healing within 12 weeks of standard care, while the remainder persist for months, increasing the risk of infection and hospitalization. Once a DFU becomes chronic, the chance of recurrence exceeds 40% within one year [14,15].

Conventional therapies are largely passive and fail to adequately address key biological deficiencies in diabetic wounds such as ischemia, prolonged inflammation, and impaired tissue remodeling [16]. These limitations have prompted exploration of advanced wound-healing approaches, including bioengineered scaffolds and polymeric nanofiber scaffolds designed to address underlying molecular barriers. Recent advances in polymer chemistry and nanofiber fabrication (e.g., electrospinning) now enable fine-tuning of scaffold properties, establishing structure–function relationships whereby fiber composition, diameter, alignment, and porosity are engineered to influence cell behavior and tissue regeneration [17]. Moreover, polymeric nanofibers can be biofunctionalized with therapeutic cargo (such as growth factors or antimicrobials), thereby transforming passive dressings into interactive biomaterial platforms that actively promote healing [18].

This review systematically evaluates recent advances in the roles, design, and functionalization of polymeric nanofiber scaffolds for diabetic wound healing, with a focus on their material composition, structural biomimicry of the ECM, incorporation of bioactive agents, and observed healing outcomes across in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies. Furthermore, it discusses key materials engineering and regulatory challenges and explores future directions toward personalized, smart, and AI-assisted polymer-based wound care systems. Unlike earlier reviews that mainly catalog polymer types or fabrication methods, this work integrates material chemistry, nanofiber architectures, therapeutic functionalization, and translational challenges into a unified framework. The novelty of this review lies in its central hypothesis that polymeric nanofiber scaffolds should be considered as a multifunctional therapeutic system, rather than passive scaffolds. Also, we discuss emerging scaffold designs such as basketweave, core-shell, and multilayer nanofibers, highlight underexplored translational barriers including sterilization and large-scale manufacturing, and propose a forward-looking roadmap toward smart, biosensor-integrated, and AI-assisted scaffolds. Together, these elements establish the originality and novel contributions of this review.

2 Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Diabetic Wounds

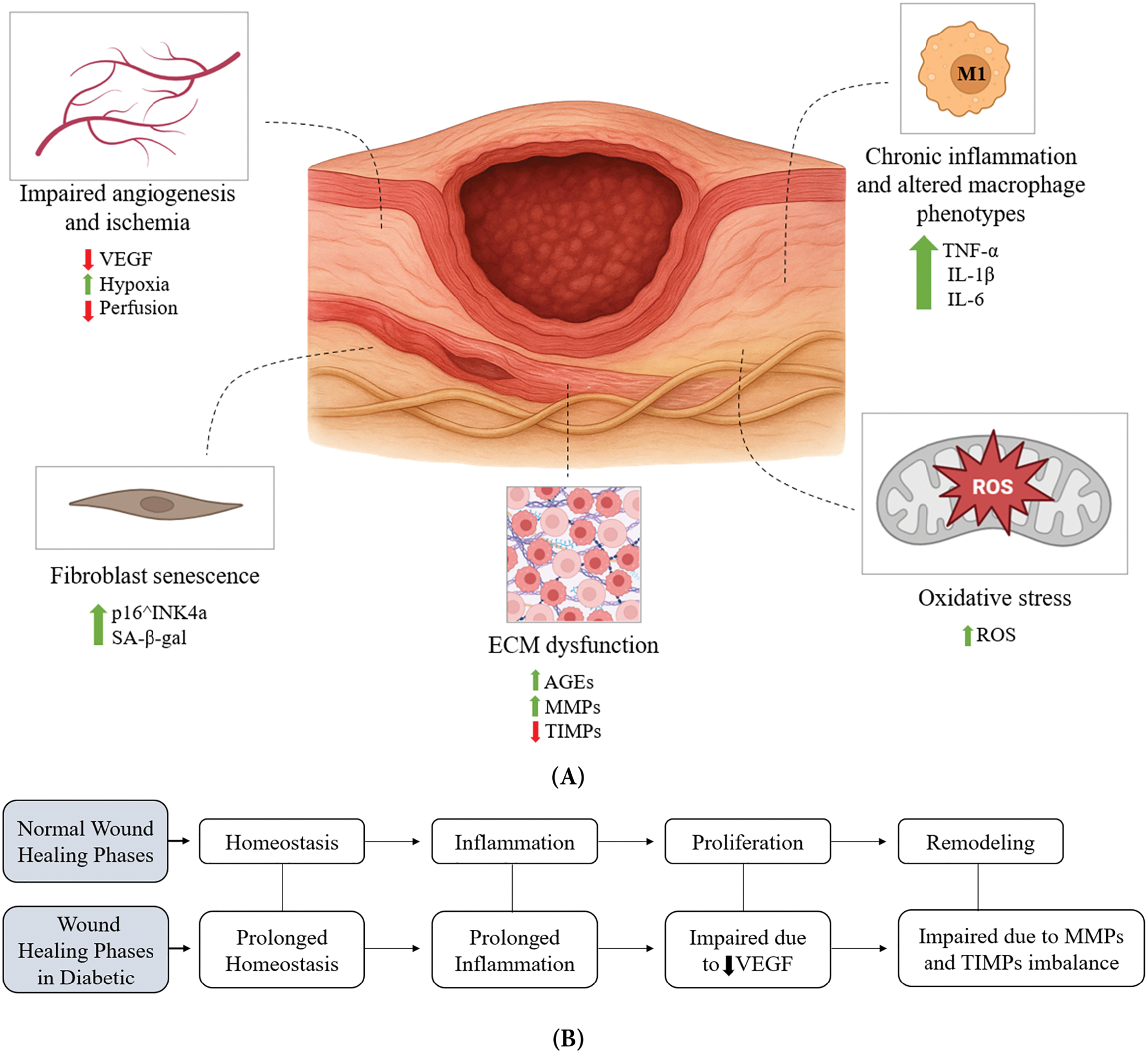

Chronic diabetic wounds result from a convergence of molecular and cellular derangements that impede the normal wound healing process [19]. In healthy individuals, wound healing is a well-orchestrated sequence of hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [20]. Diabetes disrupts each of these phases by several pathophysiological mechanisms, including impaired angiogenesis and ischemia, chronic inflammation, altered macrophage phenotypes, and oxidative stress [21], and more as shown in Fig. 2A,B along with the solutions that can be addressed by nanofiber scaffolds as displayed in Fig. 2C.

Figure 2: The pathophysiological mechanisms of diabetic wounds and the therapeutic role of nanofiber scaffolds. Chronic diabetic wounds arise from multiple molecular and cellular impairments as in (A), including ischemia with reduced VEGF signaling, chronic inflammation driven by persistent M1 macrophages, fibroblast senescence, oxidative stress, and ECM dysfunction characterized by advanced glycation end products and protease imbalance. These defects disrupt the normal sequential phases of wound healing as in (B), leading to prolonged hemostasis and inflammation, impaired angiogenesis during proliferation, and defective ECM remodeling. Electrospun nanofiber scaffolds as shown in (C) provide a multifunctional strategy to counteract these barriers by supporting keratinocyte and fibroblast migration, promoting angiogenesis and granulation tissue formation, facilitating oxygen diffusion, modulating immune responses, reducing inflammation, and sequestering excess proteases, thereby accelerating regeneration in diabetic wounds

Impaired angiogenesis and ischemia are hallmarks of diabetic wounds, where the formation of new blood vessels leads to inadequate perfusion of the healing tissue [22]. Chronic hyperglycemia damages endothelial cells and small blood vessels, resulting in peripheral ischemia and reduced delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the wound bed [23]. Diabetic wounds exhibit reduced production of pro-angiogenic factors, for instance, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and an inability to effectively recruit endothelial progenitor cells and pericytes for neovascularization [24].

Another mechanism is chronic inflammation and altered macrophage phenotypes, which are characterized by a prolonged inflammatory phase that fails to properly resolve [25]. In an acute wound, inflammatory cells such as neutrophils and classically activated M1 macrophages initially dominate to clear bacteria and debris, but then subsequently transition to alternatively activated M2 macrophages that promote tissue repair [26]. In diabetes, this phenotypic switch is impaired: macrophages persist in an M1 pro-inflammatory state with excessive secretion of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) and proteolytic enzymes, but insufficient conversion to the pro-healing M2 phenotype [27]. This imbalance leads to a smoldering inflammatory milieu that damages tissue and inhibits the progression to the proliferative phase of healing.

Additionally, oxidative stress, where an overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and a deficiency in antioxidant defenses are commonly observed in chronic diabetic wounds [28]. Hyperglycemia, ischemia, and sustained inflammation all contribute to ROS generation in the wound environment [29]. Excessive oxidative stress causes cellular damage, including DNA, protein, and lipid oxidation in local tissues, and it perpetuates inflammation by activating redox-sensitive inflammatory pathways such as the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway [30]. Moreover, high ROS levels further impair wound healing by inhibiting fibroblast and keratinocyte proliferation, inducing premature cellular senescence, and promoting apoptosis of key reparative cells [31].

ECM dysfunction is another proposed mechanism, where proper wound healing requires a provisional ECM scaffold that supports cell migration and new tissue formation [32]. In diabetic wounds, the quality and turnover of ECM are profoundly disturbed. Hyperglycemia induces non-enzymatic glycation of matrix proteins, resulting in advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) that cross-link collagen and elastin. These AGEs stiffen tissue and alter matrix signaling, ultimately impairing wound contraction and matrix remodeling [33]. In addition, chronic wounds exhibit an imbalance between proteases and their inhibitors. Diabetic wound fluid often contains excessively high levels of matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) (e.g., MMP-2, MMP-9) and neutrophil elastase, with concurrently low levels of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) [34]. This protease-rich environment leads to degradation of newly deposited ECM components and essential growth factors, effectively sabotaging the formation of stable granulation tissue.

Another mechanism is cellular dysfunction and senescence. At the cellular level, diabetes impairs the key players of wound repair. Fibroblasts in diabetic wounds often exhibit a senescent phenotype, with reduced proliferative capacity, diminished motility, and lower amounts of collagen and growth factors compared to normal fibroblasts [19,35]. Hyperglycemia-induced senescence is marked by increased senescence markers such as cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (p16^INK4a) and senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) in wound fibroblasts and endothelial cells from diabetic patients [36]. These senescent cells develop a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) that paradoxically secretes pro-inflammatory factors and proteases, exacerbating local inflammation and tissue breakdown [37]. Endothelial cells exposed to high glucose also undergo premature senescence and dysfunction, losing their angiogenic potential. Keratinocytes, which are responsible for re-epithelialization, show impaired migration and proliferative responses in the diabetic milieu. Hyperglycemia and persistent inflammation reduce keratinocyte capacity to cover the wound, in part by downregulating growth factors such as epidermal growth factor (EGF) and by the presence of barrier defects in the surrounding skin. Additionally, diabetic peripheral neuropathy and ischemia lead to diminished growth factor signaling and reduced cell recruitment to the wound site [38,39].

It should be noted that DFUs are frequently complicated by bacterial colonization and infection, with common pathogens including Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. These infections exacerbate inflammation, delay re-epithelialization, and increase the risk of sepsis and amputation [40]. Conventional approaches to combat this problem involve systemic and topical antibiotic therapy, debridement, and infection control measures such as moist wound dressings [41]. More recently, advanced biomaterial-based strategies have emerged to enhance antimicrobial protection. Polymeric nanofiber scaffolds can be engineered to incorporate silver nanoparticles, zinc oxide nanoparticles, antimicrobial peptides such as LL-37, or controlled-release antibiotic formulations [42–44]. These multifunctional scaffolds provide a physical barrier against bacterial invasion while delivering sustained antimicrobial activity directly to the wound site, thereby reducing infection risk and supporting tissue regeneration.

Subsequently, each of the pathological pathways mentioned above can be enhanced by nanofiber scaffolds. For instance, nanofibers provide a highly porous and oxygen-permeable structure, that enhances oxygen exchange at the wound site and can be further functionalized with oxygen-releasing nanoparticles to counter local hypoxia [45]. The high surface area-to-volume ratio and tunable release profiles of electrospun fibers allow sustained delivery of antimicrobial agents (e.g., silver nanoparticles, antibiotics, antimicrobial peptides), thereby mitigating recurrent infections common in DFU [42,46]. To combat oxidative stress, scaffolds can be loaded with antioxidant molecules or enzyme-mimetic nanoparticles (e.g., cerium oxide), which scavenges excess ROS and restores redox balance [47]. Impaired angiogenesis can be addressed by incorporating pro-angiogenic cues such as VEGF, stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), or mesenchymal stem cells, which are released in a controlled manner to stimulate neovascularization [48]. Finally, nanofiber scaffolds structurally mimic the native ECM through their fibrous architecture, providing mechanical support for fibroblast migration, keratinocyte proliferation, and collagen deposition, thus promoting organized tissue regeneration [49].

3 Conventional Therapies: Limitations in Chronic Wound Resolution

The current standard of care for DFU focuses on wound management and symptomatic control, but it provides only limited bioactive stimulation for tissue regeneration. The conventional therapeutic toolkit includes regular wound debridement, infection control with antibiotics, off-loading of pressure (especially for plantar foot ulcers), and application of appropriate wound dressings to maintain a moist, clean environment [50]. Adjuvant measures such as glycemic control and optimization of nutrition and perfusion (including revascularization procedures when peripheral arterial disease is present) are also crucial components of care [51]. Although these measures are the foundation of good wound care practice, chronic diabetic wounds often fail to respond fully to such treatment due to the complex pathophysiology described above.

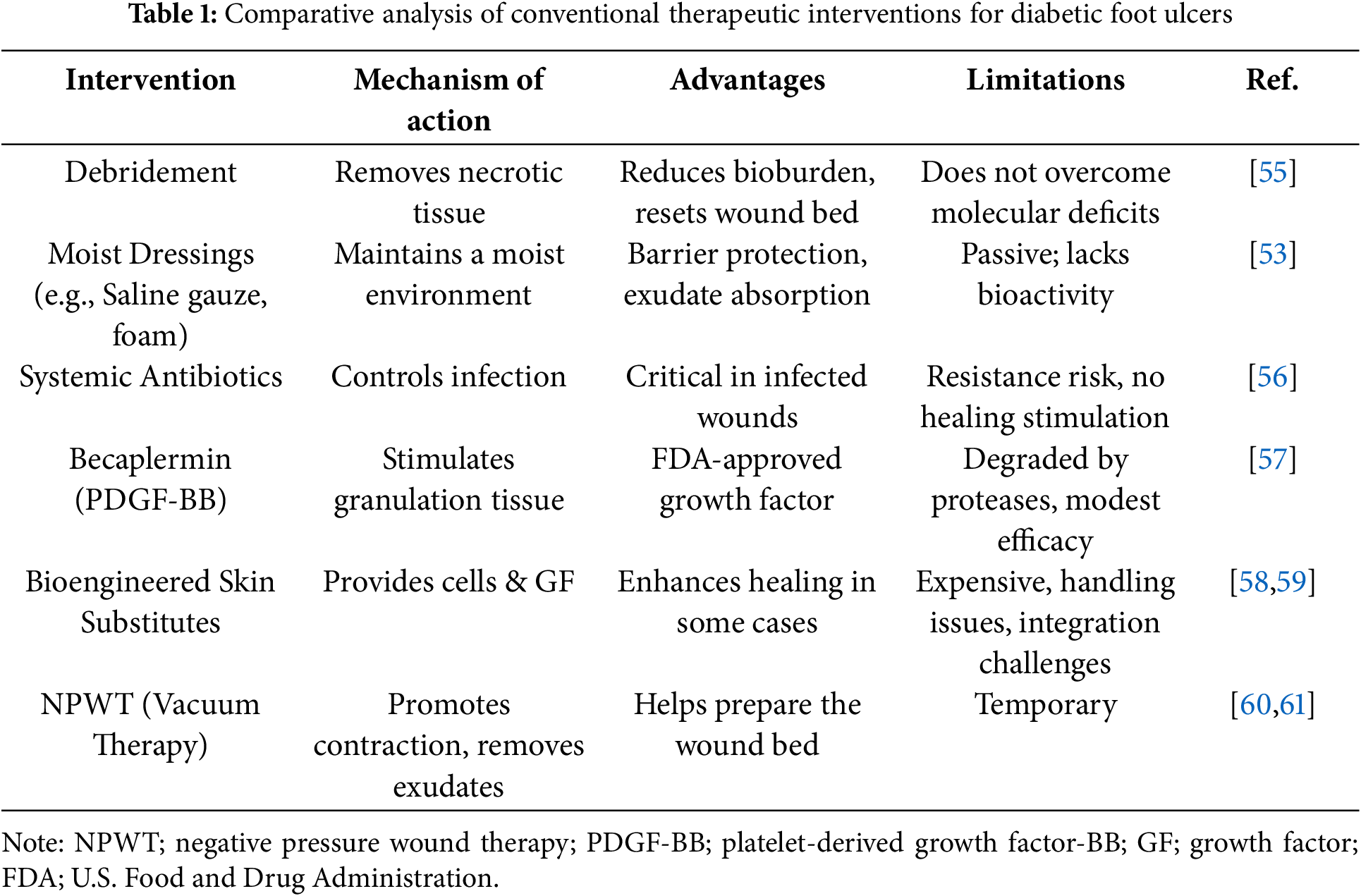

One major limitation is that standard wound dressings and debridement are principally passive or supportive in nature. Dressings (e.g., saline gauze, foams, hydrocolloids) assist by covering the ulcer, absorbing exudate, and preventing external contamination, but traditional dressings do not actively engage with the wound biology to accelerate healing [52]. They lack bioactive components, and they do not supply growth factors, cells, or gene therapies that chronic wounds critically require. Even advanced moist dressings primarily optimize the wound environment (temperature, moisture) rather than trigger regeneration [53]. Frequent debridement is beneficial for removing devitalized tissue and reducing bacterial bioburden, temporarily resetting the wound to a “fresh” state. However, debridement alone cannot overcome intrinsic deficits like poor angiogenesis or cellular senescence; thus, the wound often returns to an inflammatory, non-healing state [35,54]. These limitations are inherent to most conventional interventions for DFUs, which primarily serve supportive roles without addressing the underlying biological dysfunctions. Table 1 systematically summarizes the mechanisms, benefits, and constraints of current standard-of-care therapies.

Likewise, systemic antibiotics or topical antimicrobials are critical for controlling infection, but they do not inherently promote new tissue growth or address the impaired healing mechanisms. Also, over-reliance on antibiotics can lead to resistance and does not substitute for the biological stimulation required for wound closure [56]. Therefore, conventional pharmacological therapies for wound healing have shown only modest success in chronic DFUs. The only FDA-approved growth factor therapy for DFUs is becaplermin (recombinant PDGF-BB gel), which has shown modest improvements in healing rates in clinical trials by stimulating granulation tissue formation [62]. In practice, however, the impact of becaplermin has been limited due to the fact that chronic wounds often contain high protease levels that degrade applied growth factors, and the single-factor approach does not fully address the complex healing deficits [57]. Other growth factors (e.g., EGF, FGF, VEGF) and cytokines have been tested topically or via injection, but none have become standard care due to inconsistent efficacy or safety concerns [63].

On the other hand, bioengineered skin substitutes (e.g., living bi-layered skin analogues) can provide cells and growth factors to the wound and have demonstrated improved healing in some cases; however, these products are expensive, require specialized handling, and may not integrate well in an environment of uncontrolled diabetes and infection. Moreover, such grafts do not address deeper issues such as angiogenesis unless combined with revascularization efforts [58,59]. Negative pressure wound therapy (vacuum-assisted closure) is another adjunct used to stimulate wound contraction and remove exudates; it can help prepare wound beds for closure, but its benefits cease once the device is removed, and it does not inherently correct molecular impairments [64].

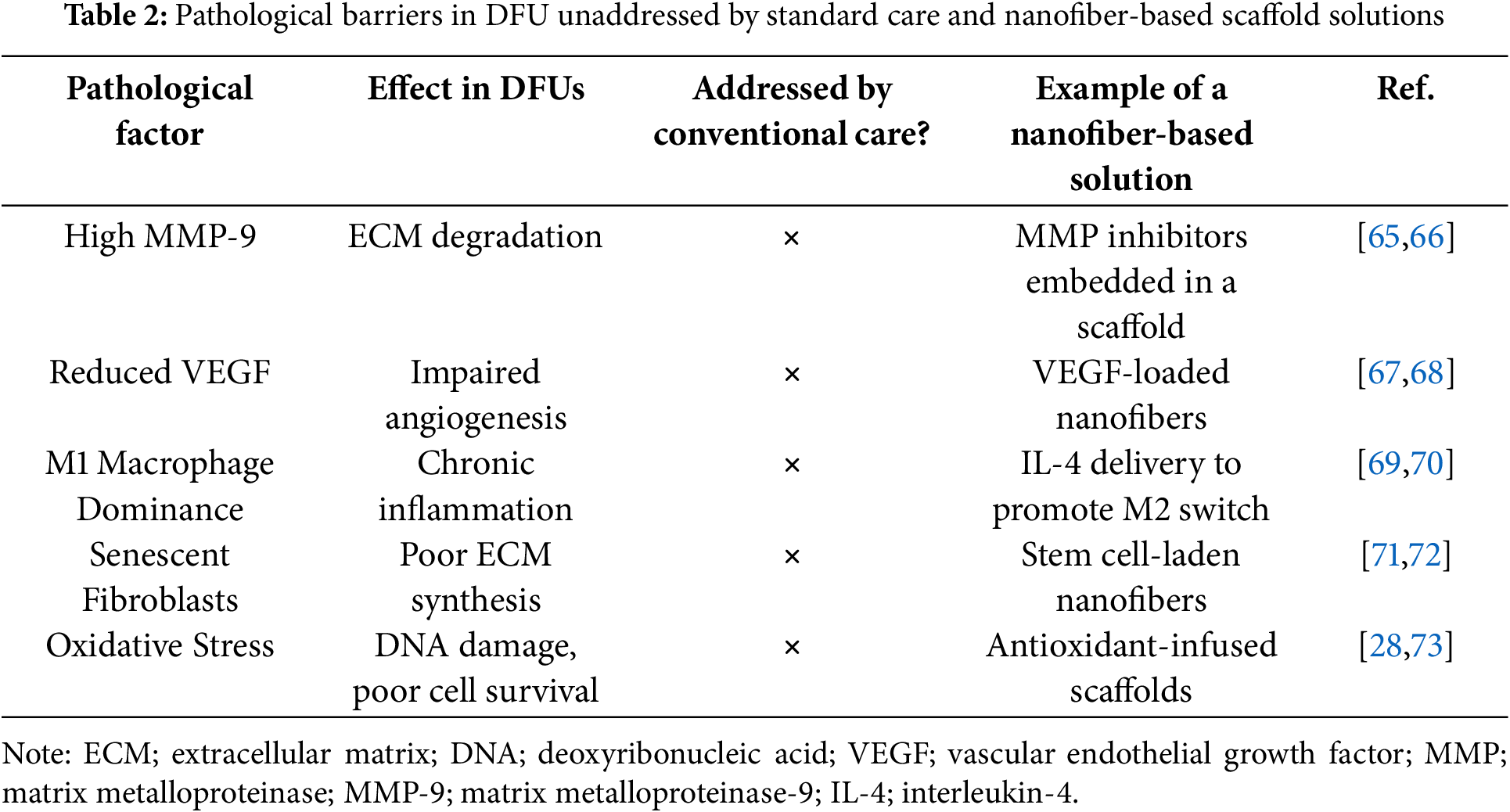

These drawbacks are reflected across current clinical interventions, as outlined in Table 1. Although these measures provide critical wound support, they do not stimulate regeneration at the molecular level. Consequently, chronic wounds persist due to pathophysiological factors such as high MMP activity, oxidative stress, and impaired angiogenesis. Additionally, Table 2 highlights these unresolved biological deficits and presents nanofiber-based scaffold innovations capable of addressing them through targeted therapeutic delivery.

As noted in recent reviews, the outcomes of standard care for chronic diabetic wounds remain unsatisfactory, prompting the search for novel approaches. This is where advanced biomaterials such as nanofiber-integrated scaffolds offer exciting potential. Electrospun nanofiber scaffolds can be engineered to mimic the skin’s ECM and serve as a delivery platform for therapeutic agents. These scaffolds can fill wound defects, maintain a favorable moisture balance, deliver angiogenic factors, anti-inflammatory drugs, matrix stabilizers, and even living cells, thus directly addressing the deficits in diabetic wound healing [74]. Early studies have shown that nanofiber scaffolds can promote tissue and vascular regeneration and accelerate wound closure in diabetic models [75].

4 Structure–Function Engineering of Polymeric Nanofiber Scaffolds

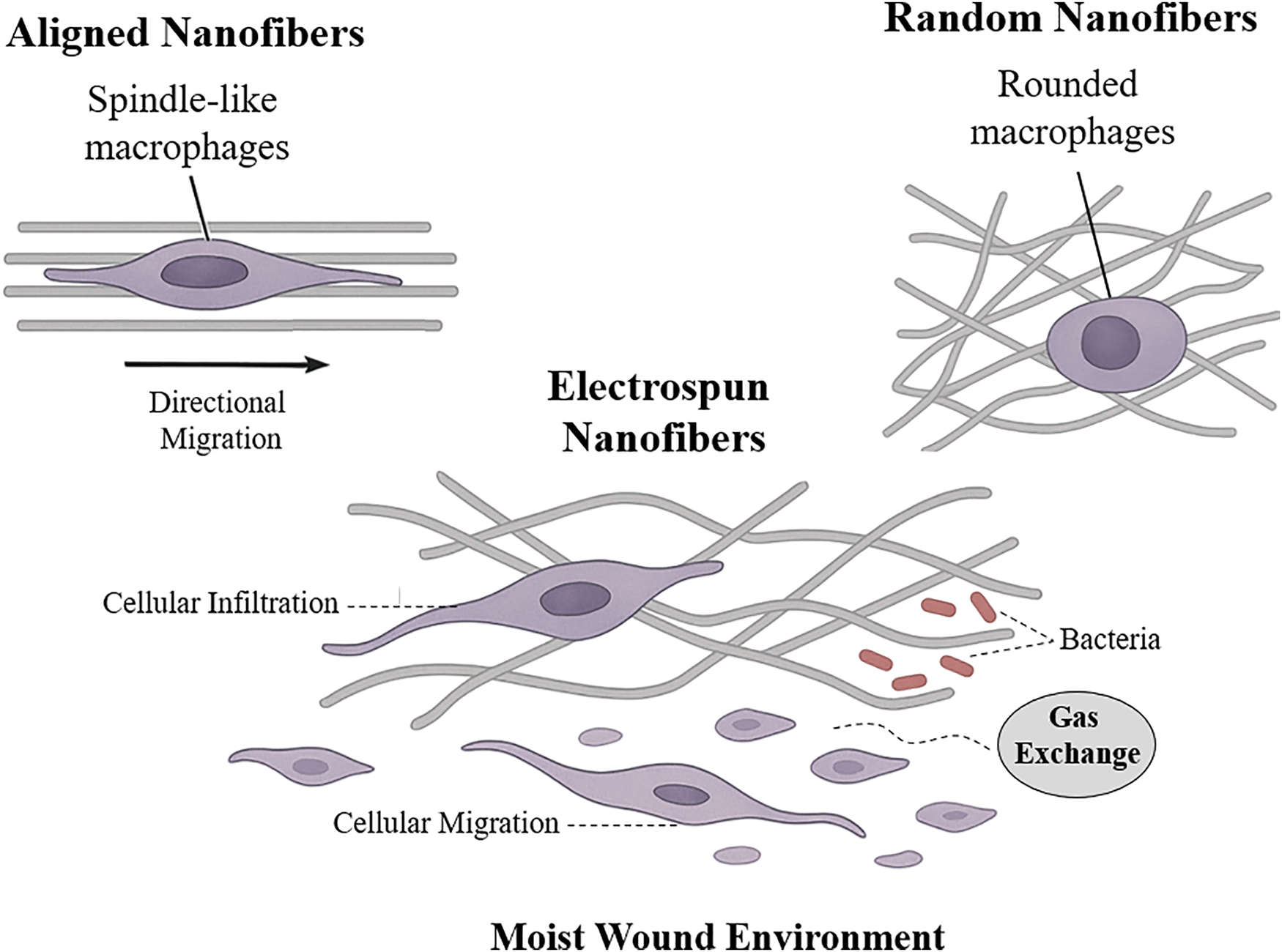

Electrospun polymeric nanofiber scaffolds have rapidly emerged as biomimetic wound scaffolds that mimic the skin’s ECM architecture [76]. These fibers form a nonwoven polymer scaffold with high porosity and surface area, providing a fibrillar framework similar to dermal collagen [77]. Material selection and molecular design are key: hydrophobic polyesters like polycaprolactone (PCL), polylactic acid (PLA), or poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) impart mechanical integrity and controlled biodegradation, whereas natural hydrophilic polymers (e.g., gelatin, chitosan) offer high wettability, biocompatibility, and support cell adhesion [78]. By adjusting polymer composition and fiber morphology, these scaffolds fill wound defects and serve as delivery platforms for therapeutic agents [79]. Nanofibrous ECM-mimetic architecture provides a provisional scaffold for the wound bed, with a highly porous structure that permits cell infiltration and gas exchange. The nanoscale pores also act as a barrier to microbial penetration, thereby reducing infection risk [80]. Moreover, appropriate fiber hydrophilicity helps regulate the wound’s moisture, creating a hydrated yet breathable interface conducive to healing. Cells readily adhere to these fibrous matrices and proliferate within them, resembling natural granulation tissue [81].

An essential design parameter in electrospun scaffolds is fiber morphology, particularly fiber orientation, which strongly influences cellular responses. Aligned and random fiber architectures impart different topographical cues that influence cell behavior and tissue organization [82]. Aligned nanofibers provide anisotropic contact guidance, causing cells to elongate and migrate along the fiber axis; for example, macrophages on aligned fibers assume spindle-like shapes characteristic of an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [83]. In contrast, random fibers form an isotropic mesh akin to native dermis, allowing multidirectional cell ingrowth with less directional guidance [84] as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: The illustration of how electrospun nanofiber scaffolds support wound healing by promoting cell infiltration, migration, and maintaining a moist, protective environment. Aligned nanofibers guide directional cell movement and induce spindle-like macrophage shapes, while random fibers result in less organized cell behavior and rounded macrophages

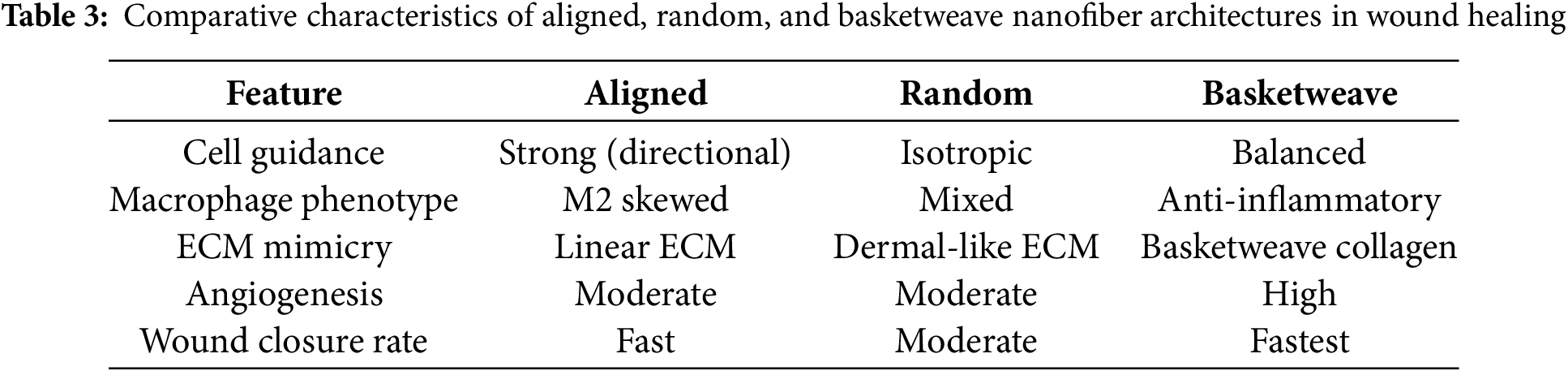

Notably, a biomimetic “basketweave” nanofiber layout that mimics the crisscrossed collagen fibrils of skin can further enhance repair [85]. In vivo diabetic wound studies found that crossed fiber (basketweave) scaffolds outperformed aligned or random mats, achieving faster wound closure, greater angiogenesis, and reduced inflammation [86]. Table 3 presents a comparative overview of how fiber alignment patterns affect cell guidance, macrophage polarization, ECM mimicry, angiogenesis, and overall healing outcomes.

Beyond structural guidance, polymeric nanofiber scaffolds serve as bioactive matrices that modulate the wound microenvironment. The fibrous architecture of the scaffold recapitulates critical ECM cues, triggering integrin-mediated polymer–cell interactions [74]. For instance, nanofibers promote keratinocyte and fibroblast proliferation, guide endothelial cells to form new capillaries, facilitate oxygen and nutrients diffusion, and sequester excess proteases from chronic wound exudate [87]. By modulating immune responses (e.g., promoting an M2 macrophage phenotype), these scaffolds accelerate re-epithelialization and granulation tissue formation, overall accelerating wound repair.

4.1 Types of Polymeric Nanofiber Architectures for Diabetic Wound Healing

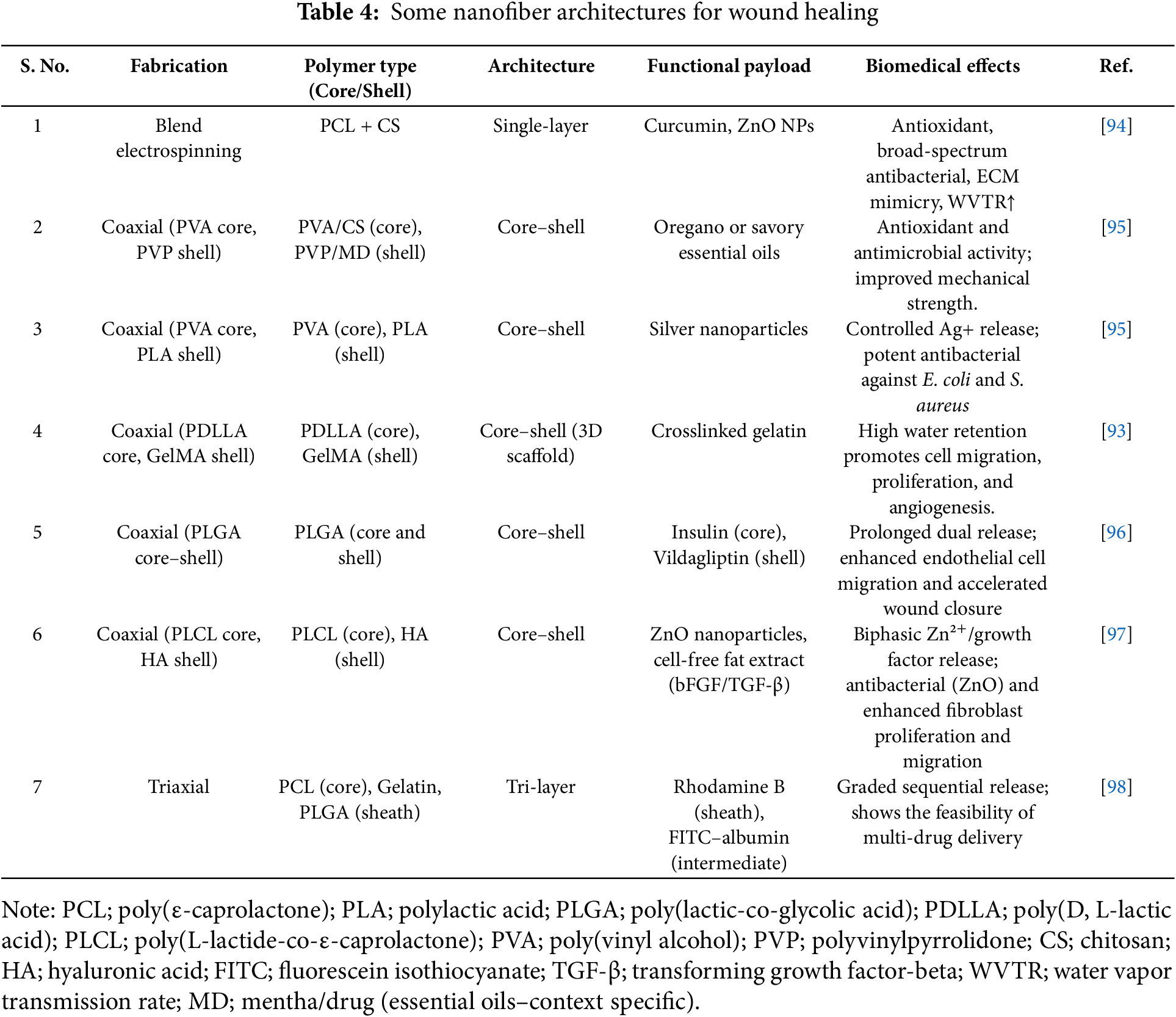

Diabetic wounds require dressings that combine structural support with targeted delivery of antimicrobials and growth factors. Electrospun nanofibers can mimic the ECM and be engineered with core–shell or multilayer structures to independently tune each function. For example, Li et al. fabricated a 3D micropatterned scaffold of poly(dl-lactic acid) (PDLLA) core and a gelatin-methacryloyl (GelMA) hydrogel shell. The hydrophilic GelMA shell greatly enhanced water uptake and vapor permeability (up to ~21× water retention vs. a plain 2D PDLLA mat), while the PDLLA core provided mechanical integrity. This core–shell scaffold markedly improved fibroblast adhesion, migration, and neovascularization: in diabetic wound models, it accelerated closure by stimulating the formation of a 3D capillary network and collagen deposition [88].

Core–shell fibers are produced by coaxial electrospinning, which generates fibers with two distinct layers. The core layer typically consists of a biodegradable polyester (PCL, PLA, PLGA) that degrades slowly and can encapsulate hydrophobic drugs or nanoparticles. The shell layer is typically a hydrophilic polymer (e.g., gelatin, chitosan, PVA, PVP, hyaluronic acid) that interfaces with tissue and allows rapid initial drug release or cell signaling [89]. For instance, Rajabifar et al. created PLA–PVA core–shell fibers by injecting a PVA solution containing silver nitrate (AgNO3) into the core and a PLA solution in the shell. Following electrospinning and in situ reduction, silver nanoparticles formed in the PVA core and on the fiber surface. The high-water solubility of the PVA core enabled a burst release of Ag+ (powerful antibacterial), while the PLA shell slowed overall fiber degradation. These PVA/Ag–PLA fibers showed strong antibacterial zones against E. coli and S. aureus [90].

Intermediate (tri-layer) fibers are produced by triaxial electrospinning, which adds a third concentric layer. This intermediate layer can serve as a barrier or secondary reservoir to create multi-stage release profiles [88]. Liu et al. first showed that a tri-layer spinneret can produce fibers with a gradient structure capable of controlling the release of three distinct components [75]. In diabetic wounds, such tri-layer fibers could segregate antibiotics into one layer and growth factors into another, thus addressing infection and angiogenesis in one patch.

As illustrated in Table 4, the specific polymer combination used in core–shell nanofiber fabrication directly dictates the physicochemical behavior, release kinetics, and therapeutic outcomes [91]. Meanwhile, natural and hydrophilic polymers like chitosan, gelatin, and GelMA, used predominantly in the shell or coating layers, support cell adhesion, moisture retention, and facilitate the incorporation of labile bio-actives such as essential oils, peptides, and proteins [92,93].

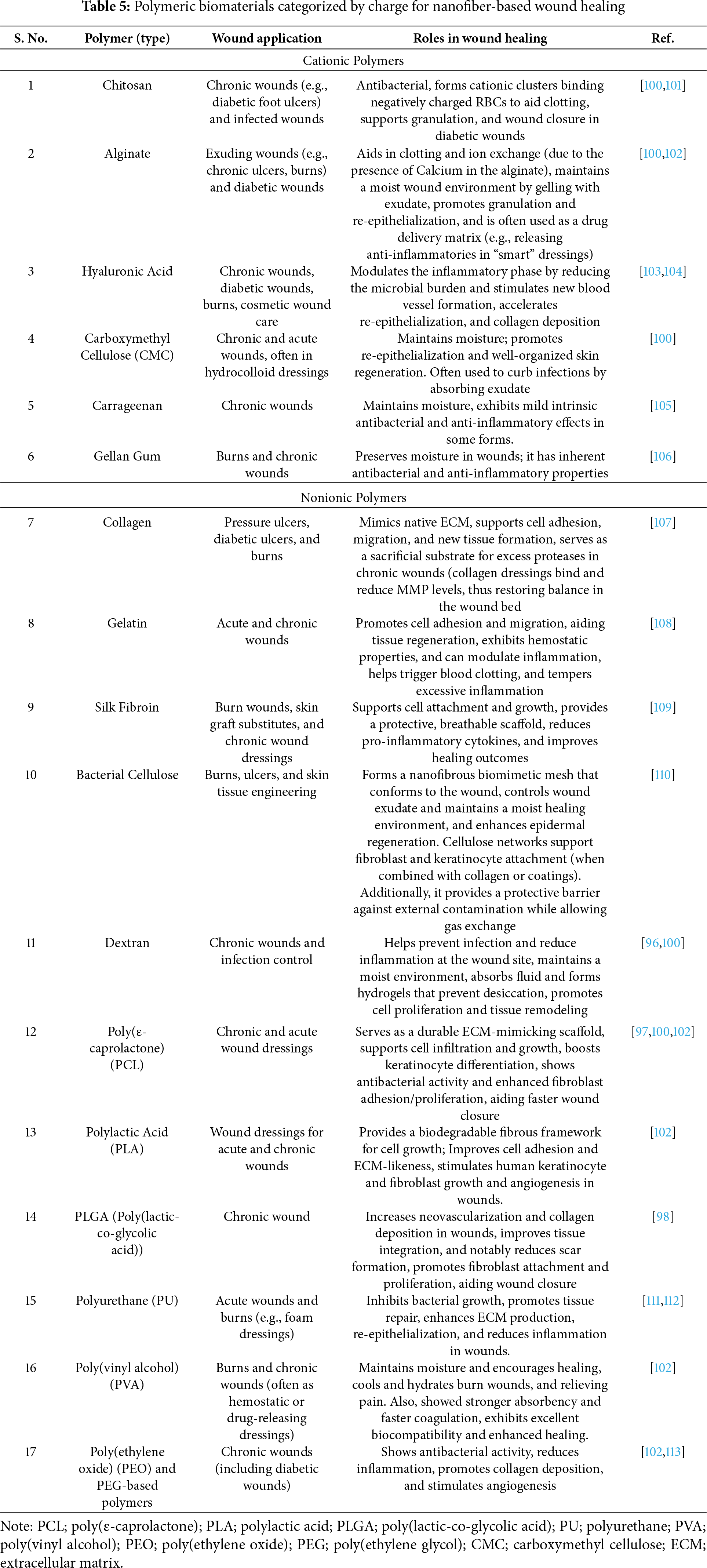

Moreover, recent designs have explored hybrid nanomaterials that combine natural and synthetic polymers to balance mechanical strength, biocompatibility, and degradation [99]. Therefore, Table 5 presents a comprehensive classification of natural and synthetic polymers employed in nanofiber-based wound healing applications, categorized by their ionic nature: cationic, anionic, and nonionic.

4.2 Functional Enhancements: Bioactive Payloads, Cell Integration and Release Profile

The versatility of electrospinning allows functional enhancement of nanofiber scaffolds with biochemical and cellular cues, transforming passive dressings into active therapeutic systems. A wide range of bioactive agents, from pro-healing growth factors to antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory molecules can be incorporated into nanofibers to directly counteract the hostile diabetic wound environment [114]. For example, growth factors such VEGF, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) have been loaded into nanofibrous scaffolds to stimulate angiogenesis and granulation tissue formation in chronic wounds [115]. However, the integration of these proteins into a scaffold is not sufficient; controlled delivery strategies are essential due to the short half-life and potential off-target effects of growth factors.

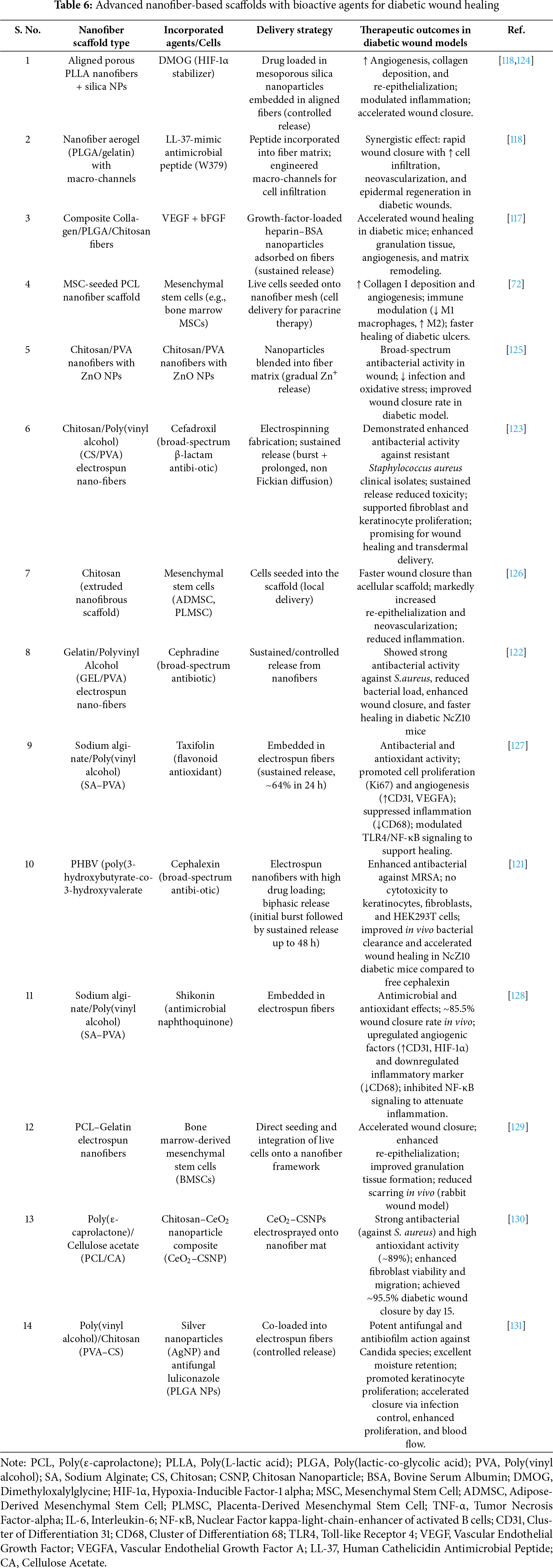

Core–shell electrospinning is one technique that enables sustained release, in which a core fiber reservoir of growth factor or drug is encased by a protective shell polymer, yielding a prolonged release over days to weeks rather than a rapid burst [116]. Similarly, nanoparticle integration has been used to improve bio-factor stability and bioavailability; for instance, heparin-functionalized nanoparticles can bind growth factors and gradually release them when embedded in nanofiber mats. In one study, a collagen/PLGA nanofiber scaffold was enriched with heparinized albumin nanoparticles carrying VEGF and bFGF achieved controlled release of these factors and significantly accelerating diabetic wound closure in vivo [117]. Another approach used mesoporous silica nanoparticles loaded with dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG, a HIF-1α stabilizer) within aligned PLLA fibers; this system provided sustained DMOG delivery that enhanced angiogenesis and collagen deposition in diabetic wounds and modulated the inflammatory response [118].

Recent studies have demonstrated that polysaccharide-based nanofibers can serve as multifunctional scaffolds by carrying diverse bioactive payloads. For example, chitosan/PVA fibers loaded with the herbal compound ursolic acid showed sustained release and strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects; these mats reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines and ROS, shifted macrophages toward the pro-regenerative phenotype, and significantly accelerated diabetic wound closure with enhanced angiogenesis and collagen remodeling [118]. Similarly, alginate/PVA fibers loaded with natural polyphenols (e.g., taxifolin or shikonin) provided controlled release of therapeutics and exhibited antibacterial/antioxidant activity. In vivo this flavonoid-loaded scaffolds promoted cell proliferation and angiogenesis while suppressing chronic inflammation in diabetic ulcers [119].

Antimicrobial-loaded nanofibers have also shown a potential efficacy in the treatment of DFU, for instance a one study have showed the potential of antibiotic loaded nanofibers to address infection related complications in DFUs [120]. For example, cephalexin-loaded PHBV nanofibers, fabricated via electrospinning, exhibited high entrapment efficiency (~75%) and a biphasic drug release profile, with an initial burst followed by sustained release for up to 48 h. These scaffolds significantly inhibited MRSA growth in vitro and enhanced bacterial clearance in a diabetic mouse model while maintaining biocompatibility with keratinocytes and fibroblasts [121]. Additionally, Razzaq et al. (2025) developed gelatin/polyvinyl alcohol electrospun nanofibers loaded with Cephradine, a broad-spectrum first-generation cephalosporin. These nanofibers exhibited sustained release, enhanced antibacterial activity against S. aureus clinical isolates, and significantly accelerated wound closure in diabetic NcZ10 mice compared to free cephradine [122]. Additionally, some studies stated the efficacy of the incorporation of nanomaterials with dual functionality (e.g., antibacterial and pro-angiogenic) into nanofiber scaffolds significantly improves both infection control and vascularization in chronic wound models [99].

Moreover, hybrid nanosystems, particularly nanoparticle-in-nanofiber (NP-in-NF) constructs, have recently emerged for the treatment of DFU. Whereby embedding nanoparticles within electrospun fibers offers synergistic advantages such as stabilization of labile nanoparticles, protection from burst release, and improved therapeutic localization at the wound site. These systems can be engineered to deliver antimicrobial agents, antioxidants, or growth factors in a sustained and controlled manner, thereby overcoming the limitations of free nanoparticles. For instance, Iqbal et al. fabricated electrospun polymeric nanofibers embedded with nanoparticles as drug-delivery platforms, demonstrating enhanced antibacterial activity, controlled release kinetics, and favorable cytocompatibility in vitro [123]. These nanosystems are quite unique due to their dual-function scaffolds that simultaneously address infection, inflammation, and impaired angiogenesis in diabetic wounds. Additional examples of these advanced nanofiber scaffolds are included in Table 6 along with the details of their design and therapeutic outcomes.

Importantly, in diabetic ulcers, sustained and localized release is crucial to counteract proteolysis and impaired healing. Electrospinning techniques enable the incorporation of therapeutics into fibers and precise control over release kinetics [132]. In monolithic (single-fluid) electrospun fibers, drugs are directly blended into the polymer, often resulting in an initial burst release [133]. In contrast, coaxial electrospinning creates a protected core for the bioactive agent surrounded by an outer polymer sheath, which regulates diffusion and protects the payload [134].

The choice of scaffold composition also plays a pivotal role in determining the therapeutic performance of nanofiber-based wound dressings. Synthetic polymers such as PLGA, PCL, and PLA are commonly used due to their mechanical robustness and slow degradation rates. These hydrophobic materials enable sustained drug release by tightly encapsulating bioactives and gradually releasing them through hydrolysis [135]. For instance, PLGA-based nanofibers loaded with insulin or PDGF have demonstrated controlled in vivo release profiles lasting several weeks [95]. In contrast, natural biopolymers such as collagen, gelatin, chitosan, and alginate offer superior biocompatibility and biological activity. Their hydrophilic nature allows them to absorb wound exudates and facilitate faster drug diffusion, which is particularly beneficial during the early healing phases [136].

Moreover, the structural attributes of nanofiber scaffolds, particularly fiber diameter, porosity, alignment, and morphology, also play crucial roles in modulating drug release kinetics and therapeutic performance. Smaller-diameter nanofibers offer a significantly higher surface-area-to-volume ratio, which facilitates faster drug diffusion and accelerates release. This parameter can be precisely controlled by electrospinning conditions such as polymer concentration, flow rate, and applied voltage, enabling fiber diameters to range from tens of nanometers to several microns [137]. Also, highly porous, loosely packed nanofiber mats facilitate rapid wound fluid uptake and enhance drug mobility, whereas densely packed or coated fibers restrict penetration and prolong release [138].

Additionally, sustained release and “smart” release are critical for diabetic wounds, which often exhibit chronic inflammation and altered local conditions. Generally, researchers aim to minimize the initial burst and extend delivery of the payload over days to weeks, aligning with the typical chronic wound timeframe. Core–shell designs, hydrophobic polymers, and drug–polymer interactions all contribute to steady, long-term drug release. For instance, the PDGF/antibiotic PLGA fibers described above steadily released growth factor and antibiotics for approximately three weeks in vitro, far exceeding the 1–2 day bursts seen with many single-fluid fibers [139].

Another mechanism is the stimuli-responsive drug release, where one prominent approach is pH-responsive release, which takes advantage of the fact that wound pH shifts during healing, healthy skin is slightly acidic (pH ~4.5–6.5), whereas chronic or infected wounds often become alkaline (pH ~7.5–8.9) [140]. Smart nanofibers can exploit this pH variation to modulate drug release. For instance, Miranda-Calderón et al. developed electrospun mats with antibiotic-loaded fibers that remained stable under normal skin pH but swelled and degraded more rapidly in alkaline conditions, leading to accelerated drug release in infected environments. This is typically achieved using pH-sensitive polymers such as poly(β-amino esters) or poly(acrylic acid), which respond to pH changes by altering their swelling behavior or chemical integrity. As a result, drug delivery can be synchronized with the wound’s pathological state, releasing more therapeutics when the wound is less acidic and more likely to be infected [141].

Another critical strategy is enzyme-responsive release, which targets the elevated levels of MMPs, particularly MMP-9, found in chronic diabetic ulcers. These enzymes degrade ECM components and impair healing. Nanofiber scaffolds can be engineered with MMP-cleavable peptide linkers or coatings that degrade in response to protease activity, thereby triggering targeted drug release [142]. Other stimuli, such as temperature, ROS, glucose, or external triggers like near-infrared light and ultrasound, have also been explored. For example, fibers embedded with up-conversion nanoparticles can release drugs upon near-infrared NIR irradiation, while ROS- or glucose-responsive fibers containing scavengers or boronic acid moieties are being investigated for diabetic wound applications [143,144]. Among all these approaches, pH- and enzyme-responsive systems remain the most directly relevant to the biochemical environment of diabetic wounds, offering promising avenues for smart, stage-specific therapeutic interventions.

4.3 Preclinical, Clinical Trials, and Commercially Available Nanofiber Scaffolds for Diabetic Wound Healing

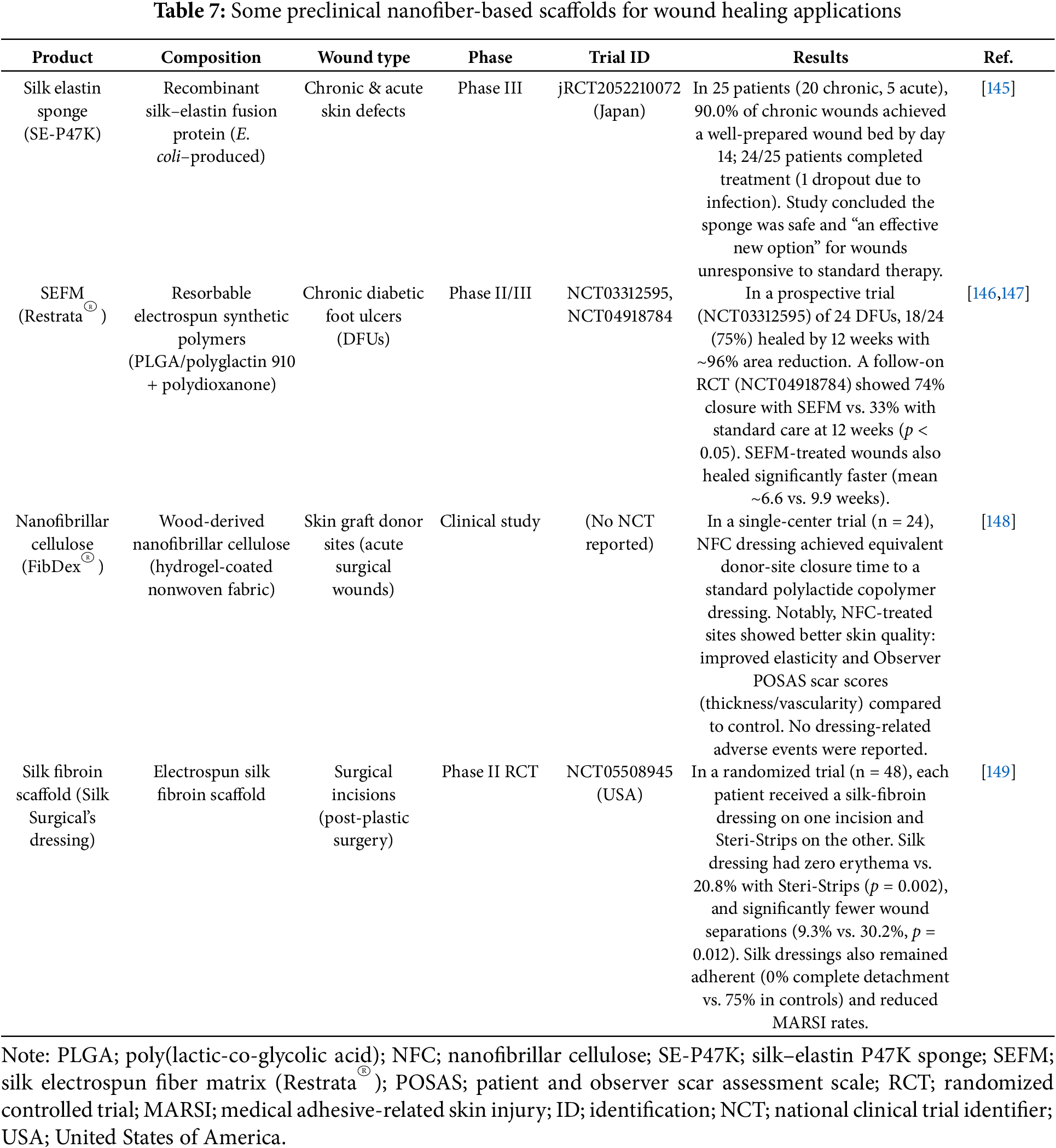

Nanofiber scaffolds are often formulated to deliver antibiotics, growth factors, or anti-inflammatory agents, and some designs even incorporate sensors or electronic elements for advanced wound monitoring. Across trials to date, many dressings have shown efficacy signals such as high closure rates, reduced inflammation, or scarring that compare favorably to standard care. Table 7 shows some examples of nanofibers that are currently under clinical trials and intended to be used for wound healing applications.

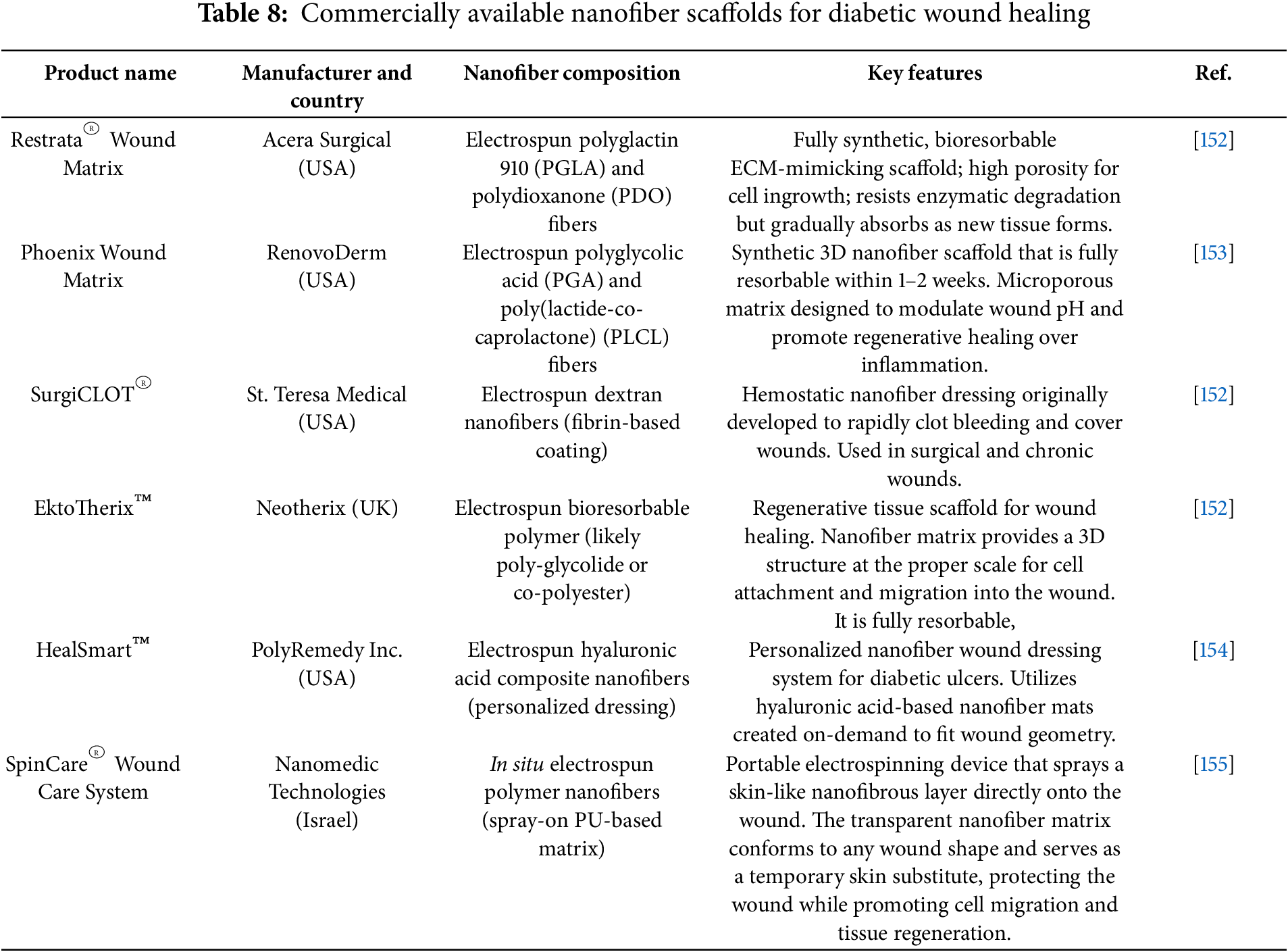

While preclinical studies dominate the literature on nanofiber scaffolds, several systems have advanced to clinical evaluation. In an early-phase randomized trial evaluated gelatin-based electrospun nanofiber scaffolds loaded with human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells combined with platelet-rich plasma in chronic wound patients, reporting high biocompatibility, excellent moisture balance, and accelerated healing rates [150]. Additionally, chitosan/PVA nanofiber mats functionalized with silver nanoparticles have entered early clinical testing in Asia, showing promising outcomes in infection control and wound closure in DFU cohorts [151]. Furthermore, several nanofiber scaffolds have already been commercialized, as shown in Table 8, which summarizes their nanofiber composition and key features in human use.

4.4 AI-Driven Design and Smart Biosensor Integrated Nanofiber Scaffolds for Diabetic Wounds

Machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) tools are increasingly used to optimize nanofiber scaffold designs for diabetic wound healing. AI models can predict which configurations will yield the best healing outcomes, thereby reducing trial-and-error experimentation. For example, Virijević et al. trained a neural network on data from 125 electrospun formulations of PCL blended with PEG to identify an optimal nanofiber composition. Guided by the model’s predictions, they fabricated a PCL/PEG scaffold loaded with antibiotics that significantly improved angiogenesis and wound closure in vivo [156].

Recent developments include dual-layer nanofiber scaffolds that visually indicate pH changes while simultaneously releasing bioactives to suppress bacterial growth. Such designs allow early infection detection without removing the scaffold. Multiplexed sensing systems have also been reported, in which nanofiber-based patches detect multiple factors such as pH, temperature, moisture, inflammatory metabolites and communicate data via smartphone applications powered by AI image recognition. These systems achieve near-clinical accuracy and hold strong potential for integration into diabetic wound monitoring platforms [157].

Furthermore, one of the most prominent examples is the PETAL sensor patch, developed by Zheng and colleagues in 2023. This battery-free device integrates five sensing regions that detect pH, temperature, moisture, trimethylamine, and uric acid. The results are displayed as colorimetric changes, and a smartphone application powered by a convolutional neural network interprets the images with nearly 97% accuracy to classify wounds as healing or non-healing. This example demonstrates how AI-based image recognition can transform raw biomarker signals into actionable diagnostic information without removing the dressing [158]. On the other hand, Palani et al. reviewed and experimentally demonstrated an AI-assisted nanofiber scaffold incorporating sensing modules for pH, temperature, moisture, oxygen levels, and inflammatory biomarkers. These scaffolds exemplify the potential to combine the regenerative properties of nanofibers with real-time monitoring, enabling AI algorithms to predict wound trajectories and support personalized treatment strategies [159].

Another noteworthy development was introduced by Levin et al. who engineered bioelectronic smart bandages that integrate multiple biosensors into a single platform. These dressings monitored pH, temperature, moisture, and selected inflammatory metabolites, transmitting data wirelessly to provide continuous feedback. Although not yet fully optimized for diabetic wound care, they represent a clear step toward clinical translation of multiplexed bioelectronic systems [160].

Finally, Noushin et al. described an IoT-enabled wound sensor capable of monitoring inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-10 directly at the wound site. The device incorporated nanostructured electrodes and communicated data wirelessly, allowing remote tracking of inflammatory status. Although primarily demonstrated as a flexible electronic platform, this approach can be adapted into nanofiber scaffolds to combine structural support with real-time biomarker detection [161].

Despite the rapid progress, several challenges remain before these systems reach clinical translation. Biosensor stability in the fluctuating wound environment, biocompatibility of integrated electronic components, and secure real-time data transmission remain key obstacles. On the AI side, robust model training requires large, standardized datasets of wound parameters and outcomes, which are not yet widely available. Regulatory approval will also require thorough validation to prove safety, reliability, and cost-effectiveness.

Translating nanofiber-based wound therapies from bench to bedside requires overcoming several engineering and manufacturing challenges, as well as navigating complex regulatory pathways. One major hurdle is the scale-up of nanofiber fabrication. Electrospinning, the most common technique to produce nanofiber scaffolds, is relatively easy at the laboratory scale but notoriously difficult to translate to industrial-scale throughput. Typical single-needle electrospinning produces only about 0.1–1 g of nanofiber per hour, far below the quantities required for mass production [162].

Efforts to increase output, such as using multi-needle spinnerets or needleless electrospinning (e.g., rotating drum or free-surface systems methods), introduce new variability and quality control challenges. For instance, multi-needle setups suffer from electric field interference between jets and frequent needle clogging, which can lead to inconsistent fiber diameters and scaffold morphology. Needleless electrospinning can produce higher fiber yields, but rapid solvent evaporation in these open systems may change the polymer solution concentration over time, making the process harder to control and reducing reproducibility [163,164].

Batch-to-batch consistency is a critical concern: studies have noted that using natural polymers such as silk or collagen can result in variable fiber properties between batches due to inherent source variability, and even synthetic polymers can behave differently at scale if processing parameters are not perfectly optimized. Additionally, residual solvents used during electrospinning pose safety and quality challenges; any solvent not fully removed could be toxic, and scaling up often involves larger volumes of flammable organic solvents that require robust ventilation and safety measures [165].

All implantable or wound-contacting medical products must be sterilized; however, nanofibrous materials can be highly sensitive to common sterilization methods. Techniques such as autoclave sterilization are often incompatible with polymer fibers, which may melt or deform, while ethylene oxide (EtO) gas and γ-irradiation, commonly used for medical devices, can induce chemical or structural changes in polymer nanofibers. Studies have shown that γ-irradiation or prolonged UV exposure can degrade polymer chains in nanofibers, altering their mechanical strength and morphology. Research indicates that the choice of sterilization method can affect both the scaffold’s physical properties and the stability and release profile of incorporated biomolecules. For example, a growth factor-loaded nanofiber scaffold may lose bioactivity if exposed to certain sterilants or stored at room temperature for extended periods [165,166].

Beyond the technical challenges of fabrication, sterilization, and stability, several additional hurdles must be addressed for successful translation of nanofiber scaffolds. One key barrier is regulatory classification: many nanofiber-based products incorporate both biomaterials and therapeutic agents, leading to uncertainties whether they are regulated as medical devices, combination products, or biologics [167]. This complicates approval pathways and often prolongs the time to market. Cost-effectiveness is another critical factor. Although electrospinning can produce highly functional scaffolds, the incorporation of growth factors, nanoparticles, or living cells markedly increases manufacturing costs [168], raising concerns about affordability for widespread clinical use, especially in low- and middle-income settings.

Additionally, patient compliance also plays a role in therapeutic success. Advanced nanofiber scafolds may require specialized application, controlled storage conditions, or frequent monitoring, which could limit patient acceptance compared to conventional dressings [169]. Designing user-friendly, stable, and easy-to-apply scaffolds will be important for real-world adoption. Finally, clinical validation remains a pressing challenge. Despite encouraging preclinical data, relatively few nanofiber scaffolds have been evaluated in well-designed randomized clinical trials. Without robust clinical evidence, adoption by regulatory agencies and clinicians will remain limited.

As research and development progress, several exciting future directions are expected to further enhance nanofiber scaffold therapy for diabetic wounds. One major trend is the incorporation of “smart” technologies, biosensors, and responsive electronics into wound scaffolds, creating interactive dressings that not only treat the wound but also monitor and adapt to its state in real time. For example, next-generation smart bandages are being developed with built-in sensors that continuously track wound conditions such as pH, temperature, moisture levels, and biochemical markers of infection [170]. Since chronic diabetic wounds often precede visible infection with subtle changes such as a rise in wound pH or temperature, before visible infection occurs, these sensor-integrated dressings can provide early warning of complications.

A recent advanced device combined a one-way microfluidic drainage system with an ultrathin pH sensor that actively wicked excess exudate from the wound while simultaneously measuring wound pH, successfully detecting shifts between normal (~pH 5–7) and infected (~pH 8–9) wound states in a diabetic wound model. Data from such dressings can be transmitted wirelessly to caregivers’ smartphones or hospital systems, enabling remote monitoring of wound healing progress. However, the durability of these sensors in a moist, enzyme-rich wound environment remains a significant challenge, and power supply for continuous monitoring is also problematic. Researchers are exploring flexible biodegradable electronic materials and energy harvesting approaches (e.g., from body heat or motion) to overcome these barriers [159,170,171].

Building on this progress, researchers are also integrating active therapeutic components into smart scaffolds, achieving a closed-loop “sense and respond” capability. For instance, flexible electronics can be embedded in a nanofiber scaffold to deliver electrical stimulation to the wound bed. One bioresorbable electronic bandage developed in 2023 delivers controlled electrotherapy to a diabetic wound and was shown to accelerate healing by approximately 30% in preclinical trials, then harmlessly dissolves away once the wound is healed [172]. Likewise, sensor feedback can be used to trigger on-board drug release, for example, releasing antibiotics when an infection is detected, or growth factors when a certain healing phase is delayed. The main challenge here lies in synchronizing drug release with the dynamic wound environment; smart release systems such as pH-sensitive or enzyme-cleavable linkers are being investigated as practical solutions [173].

A recent design demonstrated a wireless closed-loop bandage that continuously monitored wound states and automatically administered electrical stimulation to the tissue when sensing poor healing dynamics, thereby significantly improving healing outcomes in a diabetic wound model [174]. These smart, biosensing, and stimuli-delivering nanofiber systems represent a convergence of wound care and wearable technology, promising more individualized and timely therapy for chronic wounds. In the near future, a patient with a diabetic foot ulcer might wear a smart nanofiber scaffold that not only accelerates healing with embedded therapeutic agents, but also actively tracks the wound’s condition and adjusts the treatment or alerts the patient and the clinician as needed in real time.

Another key future direction is the shift toward patient-specific, personalized wound therapy using nanofiber scaffolds. Because every chronic wound is different in size, shape, depth, and microenvironment, a one-size-fits-all dressing may not be optimal. Advanced fabrication methods such as 3D printing and tailored electrospinning now allow the creation of custom-shaped scaffolds that conform exactly to an individual patient’s wound geometry [175]. For example, 3D printers can use patient wound scans to print a wound dressing that has the precise contours of a deep foot ulcer, ensuring intimate contact with the wound bed [176]. The main challenge here is scalability and cost: custom devices are more expensive and time-consuming to manufacture. A possible solution is on-demand, point-of-care fabrication platforms integrated within hospitals, which could reduce costs and improve accessibility.

In addition, companies are exploring personalization platforms where clinicians can input wound characteristics and receive a bespoke nanofiber dressing manufactured on demand. One existing system (HealSmart™) creates patient-specific dressings by varying the ratio of two fiber types: a hydrophilic, absorbent fiber vs. a hydrophobic, moisture-barrier fiber to suit the wound’s moisture level. This personalized approach has been shown to eliminate a lot of trial and error in dressing selection and was associated with improved healing outcomes in chronic wounds [162]. However, regulatory pathways for personalized devices remain poorly defined, which may delay clinical adoption. Collaborative regulatory frameworks and adaptive approval models could help accelerate translation into real-world use.

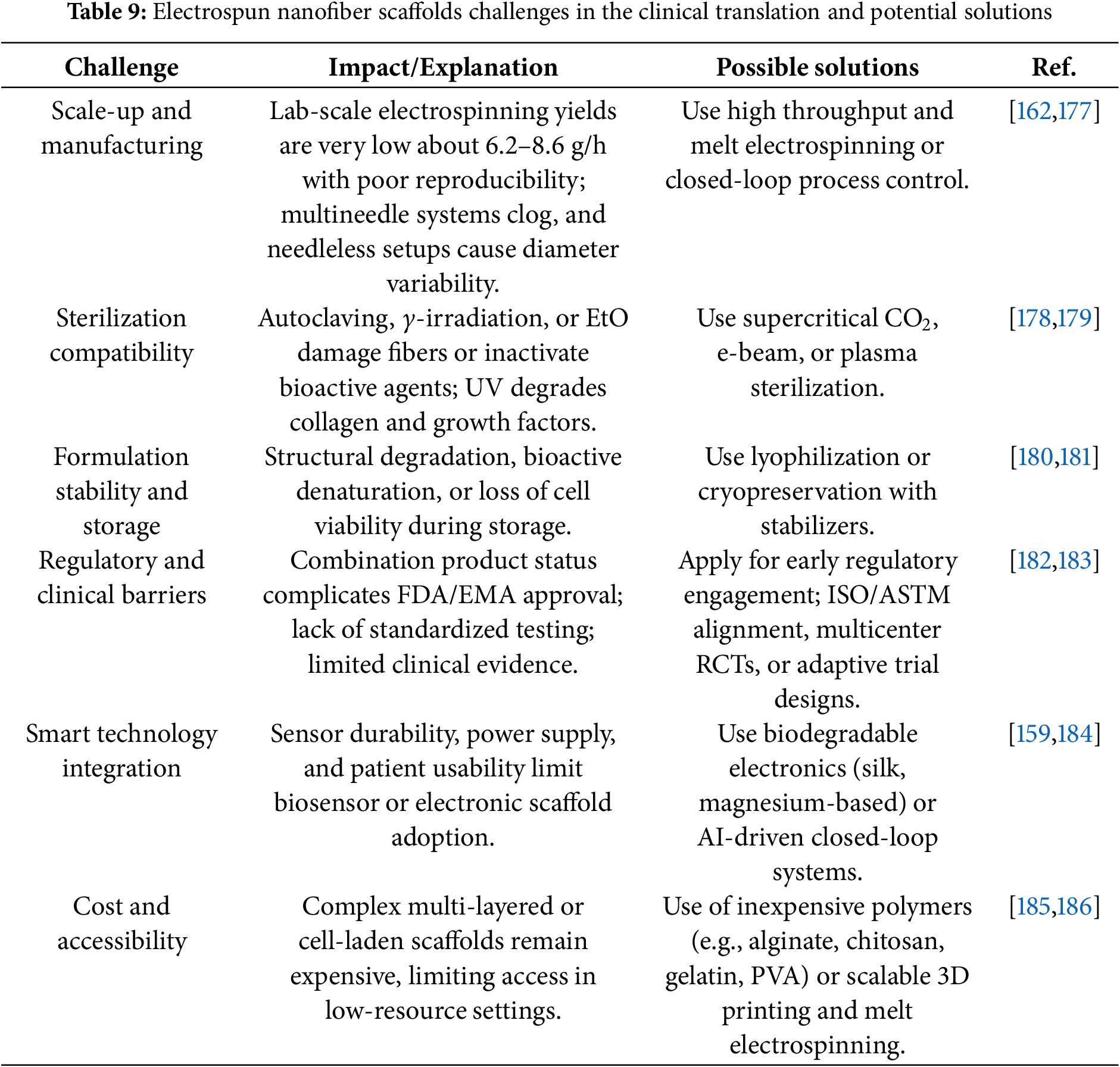

Therefore, several barriers still hinder the clinical translation of nanofiber scaffolds, as discussed above. These include difficulties in scaling up production, challenges with sterilization methods, limited formulation stability during storage, complex regulatory and clinical pathways, hurdles in integrating smart technologies, and concerns about cost and accessibility. Addressing these challenges requires strategies such as advanced electrospinning techniques, alternative sterilization approaches, stabilizers and optimized packaging, early regulatory engagement with multicenter trials, development of biodegradable electronics with wireless powering, and adoption of low-cost polymers with scalable fabrication. Table 9 presents the current challenges facing nanofiber scaffolds for diabetic wound healing and outlines potential solutions under active investigation.

Polymeric nanofiber scaffolds have shown significant promise in addressing the multifaceted pathophysiological impairments of chronic diabetic wounds, including impaired angiogenesis, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and aberrant ECM remodeling. By providing a biomimetic ECM-like architecture and serving as platforms for therapeutic delivery, such as growth factors and antimicrobial agents, these scaffolds act as multifunctional dressings that promote neovascularization, modulate immune responses, mitigate oxidative damage, combat infection, and accelerate granulation and re-epithelialization. Extensive preclinical and initial clinical evidence indicate that nanofiber scaffolds achieve faster wound closure, improved granulation, and reduced inflammation compared to conventional dressings.

Despite this progress, translating nanofiber scaffolds into routine clinical practice remains challenging, with hurdles including scaffold stability, sterilization compatibility, scalable manufacturing, and regulatory approval. Future scaffold designs are expected to integrate smart technologies such as built-in biosensors for real-time wound monitoring and stimuli-responsive drug release, while leveraging AI-assisted design to optimize fiber architectures and enable patient-personalized wound care. Moving forward, continued interdisciplinary collaboration among polymer scientists, bioengineers, clinicians, and regulatory stakeholders will be essential to overcome these challenges and accelerate the clinical translation of multifunctional nanofiber scaffolds, thereby improving outcomes for patients with diabetic wounds.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their utmost gratitude and appreciation to Universiti Malaya for supporting research activities related to biomaterials and wound healing.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Universiti Malaya Research Excellence Grant (UMREG071-2024) awarded to Shaik Nyamathulla (SN) [https://umresearch.um.edu.my], and by the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) grant (FP-048-2020) from the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia, awarded to Shaik Nyamathulla (SN) [https://www.mohe.gov.my].

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Rafl M. Kamil, Syed Mahmood and Shaik Nyamathulla; methodology, Rafl M. Kamil; formal analysis, Rafl M. Kamil; resources, Syed Mahmood and Shaik Nyamathulla; writing—original draft preparation, Rafl M. Kamil; writing—review and editing, Syed Mahmood and Shaik Nyamathulla; supervision, Syed Mahmood and Shaik Nyamathulla; funding acquisition, Shaik Nyamathulla. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Albai O, Timar B, Braha A, Timar R. Predictive factors of anxiety and depression in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Med. 2024;13(10):3006. doi:10.3390/jcm13103006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Edmonds M, Manu C, Vas P. The current burden of diabetic foot disease. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2021;17:88–93. doi:10.1016/j.jcot.2021.01.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Armstrong DG, Orgill DP, Galiano RD, Glat PM, Carter MJ, Hanft J, et al. A multicentre clinical trial evaluating the outcomes of two application regimens of a unique keratin-based graft in the treatment of Wagner grade one non-healing diabetic foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2024;21(9):e70029. doi:10.1111/iwj.70029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Ortiz-Zúñiga Á., Samaniego J, Biagetti B, Allegue N, Gené A, Sallent A, et al. Impact of diabetic foot multidisciplinary unit on incidence of lower-extremity amputations by diabetic foot. J Clin Med. 2023;12(17):5608. doi:10.3390/jcm12175608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Lin C, Liu J, Sun H. Risk factors for lower extremity amputation in patients with diabetic foot ulcers: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0239236. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0239236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Armstrong DG, Swerdlow MA, Armstrong AA, Conte MS, Padula WV, Bus SA. Five year mortality and direct costs of care for people with diabetic foot complications are comparable to cancer. J Foot Ankle Res. 2020;13(1):16. doi:10.1186/s13047-020-00383-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. McDermott K, Fang M, Boulton AJM, Selvin E, Hicks CW. Etiology, epidemiology, and disparities in the burden of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(1):209–21. doi:10.2337/dci22-0043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Chaves CRS, Salamandane C, da Sorte Maurício B, Machamba AAL, Salamandane A, Brito L. Multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in diabetic foot infections (DFI) from Beira, Mozambique: prevalence and virulence profile. Infect Drug Resist. 2025;18:2779–96. doi:10.2147/IDR.S521876. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Jeyaraman K. Diabetic-foot complications in American and Australian continents. In: Diabetic foot ulcer. Singapore: Springer; 2020. p. 41–59. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-7639-3_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ong KL, Stafford LK, McLaughlin SA, Boyko EJ, Vollset SE, Smith AE, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2023;402(10397):203–34. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01301-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Bandarian F, Qorbani M, Nasli-Esfahani E, Sanjari M, Rambod C, Larijani B. Epidemiology of diabetes foot amputation and its risk factors in the middle east region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2025;24(1):31–40. doi:10.1177/15347346221109057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Ponirakis G, Elhadd T, Al Ozairi E, Brema I, Chinnaiyan S, Taghadom E, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic peripheral neuropathy, neuropathic pain and foot ulceration in the Arabian Gulf region. J Diabetes Investig. 2022;13(9):1551–9. doi:10.1111/jdi.13815. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Haile KE, Asgedom YS, Azeze GA, Amsalu AA, Gebrekidan AY, Kassie GA. Diabetic foot: a systematic review and meta-analysis on its prevalence and associated factors among patients with diabetes mellitus in a sub-Saharan Africa. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2025;220(1):111975. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2024.111975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Cortes-Penfield NW, Armstrong DG, Brennan MB, Fayfman M, Ryder JH, Tan TW, et al. Evaluation and management of diabetes-related foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;77(3):e1–e13. doi:10.1093/cid/ciad255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Huang ZH, Li SQ, Kou Y, Huang L, Yu T, Hu A. Risk factors for the recurrence of diabetic foot ulcers among diabetic patients: a meta-analysis. Int Wound J. 2019;16(6):1373–82. doi:10.1111/iwj.13200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Yadav JP, Singh AK, Grishina M, Pathak P, Verma A, Kumar V, et al. Insights into the mechanisms of diabetic wounds: pathophysiology, molecular targets, and treatment strategies through conventional and alternative therapies. Inflammopharmacology. 2024;32(1):149–228. doi:10.1007/s10787-023-01407-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Chen Y, Dong X, Shafiq M, Myles G, Radacsi N, Mo X. Recent advancements on three-dimensional electrospun nanofiber scaffolds for tissue engineering. Adv Fiber Mater. 2022;4(5):959–86. doi:10.1007/s42765-022-00170-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Phutane P, Telange D, Agrawal S, Gunde M, Kotkar K, Pethe A. Biofunctionalization and applications of polymeric nanofibers in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Polymers. 2023;15(5):1202. doi:10.3390/polym15051202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Berlanga-Acosta JA, Guillén-Nieto GE, Rodríguez-Rodríguez N, Mendoza-Mari Y, Bringas-Vega ML, Berlanga-Saez JO, et al. Cellular senescence as the pathogenic hub of diabetes-related wound chronicity. Front Endocrinol. 2020;11:573032. doi:10.3389/fendo.2020.573032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Yu H, Wang Y, Wang D, Yi Y, Liu Z, Wu M, et al. Landscape of the epigenetic regulation in wound healing. Front Physiol. 2022;13:949498. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.949498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Roy B. Pathophysiological mechanisms of diabetes-induced macrovascular and microvascular complications: the role of oxidative stress. Med Sci. 2025;13(3):87. doi:10.3390/medsci13030087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Shi Z, Yao C, Shui Y, Li S, Yan H. Research progress on the mechanism of angiogenesis in wound repair and regeneration. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1284981. doi:10.3389/fphys.2023.1284981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Manisha, Niharika, Gaur P, Goel R, Lata K, Mishra R. Understanding diabetic wounds: a review of mechanisms, pathophysiology, and multimodal management strategies. Curr Rev Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2025;20(3):207–28. doi:10.2174/0127724328326480240927065600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Okonkwo UA, Chen L, Ma D, Haywood VA, Barakat M, Urao N, et al. Compromised angiogenesis and vascular Integrity in impaired diabetic wound healing. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231962. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0231962. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Li M, Hou Q, Zhong L, Zhao Y, Fu X. Macrophage related chronic inflammation in non-healing wounds. Front Immunol. 2021;12:681710. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.681710. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Aitcheson SM, Frentiu FD, Hurn SE, Edwards K, Murray RZ. Skin wound healing: normal macrophage function and macrophage dysfunction in diabetic wounds. Molecules. 2021;26(16):4917. doi:10.3390/molecules26164917. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Sharifiaghdam M, Shaabani E, Faridi-Majidi R, De Smedt SC, Braeckmans K, Fraire JC. Macrophages as a therapeutic target to promote diabetic wound healing. Mol Ther. 2022;30(9):2891–908. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.07.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Deng L, Du C, Song P, Chen T, Rui S, Armstrong DG, et al. The role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in diabetic wound healing. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:8852759. doi:10.1155/2021/8852759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. González P, Lozano P, Ros G, Solano F. Hyperglycemia and oxidative stress: an integral, updated and critical overview of their metabolic interconnections. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(11):9352. doi:10.3390/ijms24119352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Bellanti F, Coda ARD, Trecca MI, Lo Buglio A, Serviddio G, Vendemiale G. Redox imbalance in inflammation: the interplay of oxidative and reductive stress. Antioxidants. 2025;14(6):656. doi:10.3390/antiox14060656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Khorsandi K, Hosseinzadeh R, Esfahani H, Zandsalimi K, Shahidi FK, Abrahamse H. Accelerating skin regeneration and wound healing by controlled ROS from photodynamic treatment. Inflamm Regen. 2022;42(1):40. doi:10.1186/s41232-022-00226-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Diller RB, Tabor AJ. The role of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in wound healing: a review. Biomimetics. 2022;7(3):87. doi:10.3390/biomimetics7030087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Xiao P, Zhang Y, Zeng Y, Yang D, Mo J, Zheng Z, et al. Impaired angiogenesis in ageing: the central role of the extracellular matrix. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):457. doi:10.1186/s12967-023-04315-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Kaur K, Singh A, Attri S, Malhotra D, Verma A, Bedi N, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and diabetic foot: pathophysiological findings and recent developments in their inhibitors of natural as well as synthetic origin. In: The eye and foot in diabetes. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2020. doi:10.5772/intechopen.92982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wilkinson HN, Hardman MJ. Senescence in wound repair: emerging strategies to target chronic healing wounds. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:773. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.00773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Narasimhan A, Flores RR, Robbins PD, Niedernhofer LJ. Role of cellular senescence in type II diabetes. Endocrinology. 2021;162(10):bqab136. doi:10.1210/endocr/bqab136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Wang B, Han J, Elisseeff JH, Demaria M. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its physiological and pathological implications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25(12):958–78. doi:10.1038/s41580-024-00727-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Fang WC, Lan CE. The epidermal keratinocyte as a therapeutic target for management of diabetic wounds. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(5):4290. doi:10.3390/ijms24054290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Li R, Li DH, Zhang HY, Wang J, Li XK, Xiao J. Growth factors-based therapeutic strategies and their underlying signaling mechanisms for peripheral nerve regeneration. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020;41(10):1289–300. doi:10.1038/s41401-019-0338-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Baker CL. Metabolic adaptation of staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis and therapeutic approach in diabetic foot ulcers [dissertation]. Starkville, MS, USA: Mississippi State University; 2023. [Google Scholar]

41. Husain M, Agrawal YO. Antimicrobial remedies and emerging strategies for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2023;19(5):e280222201513. doi:10.2174/1573399818666220228161608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Khan HM, Liao X, Sheikh BA, Wang Y, Su Z, Guo C, et al. Smart biomaterials and their potential applications in tissue engineering. J Mater Chem B. 2022;10(36):6859–95. doi:10.1039/d2tb01106a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Lewandowski RB. Biomaterial-based scaffolds as carriers of topical antimicrobials for bone infection prophylaxis. Pol J Microbiol. 2025;74(2):232–43. doi:10.33073/pjm-2025-019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Firdous SO, Sagor MMH, Arafat MT. Advances in transdermal delivery of antimicrobial peptides for wound management: biomaterial-based approaches and future perspectives. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2024;7(8):4923–43. doi:10.1021/acsabm.3c00731. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Bayraktar S, Üstün C, Kehr NS. Oxygen delivery biomaterials in wound healing applications. Macromol Biosci. 2024;24(3):e2300363. doi:10.1002/mabi.202300363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Bakhshi A, Naghib SM, Rabiee N. Antibacterial and antiviral nanofibrous membranes. In: Antibacterial and antiviral functional materials. Vol. 2. Washington, DC, USA: American Chemical Society; 2024. p. 47–88. doi:10.1021/bk-2024-1472.ch002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Allu I, Kumar Sahi A, Kumari P, Sakhile K, Sionkowska A, Gundu S. A brief review on cerium oxide (CeO2NPs)-based scaffolds: recent advances in wound healing applications. Micromachines. 2023;14(4):865. doi:10.3390/mi14040865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Rautiainen S, Laaksonen T, Koivuniemi R. Angiogenic effects and crosstalk of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cells and their extracellular vesicles with endothelial cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(19):10890. doi:10.3390/ijms221910890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Wang Z, Gao C, Yang R, Xiong F. The interface effect of electrospun fiber promotes wound healing. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2025;46(15):e2500038. doi:10.1002/marc.202500038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Patton D, Avsar P, Wilson P, Mairghani M, O’Connor T, Nugent L, et al. Treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: review of the literature with regard to the TIME clinical decision support tool. J Wound Care. 2022;31(9):771–9. doi:10.12968/jowc.2022.31.9.771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Hinchliffe RJ, Forsythe RO, Apelqvist J, Boyko EJ, Fitridge R, Hong JP, et al. Guidelines on diagnosis, prognosis, and management of peripheral artery disease in patients with foot ulcers and diabetes (IWGDF, 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36(Suppl 1):e3276. doi:10.1002/dmrr.3276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Kus KJB, Ruiz ES. Wound dressings—a practical review. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2020;9(4):298–308. doi:10.1007/s13671-020-00319-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Nuutila K, Eriksson E. Moist wound healing with commonly available dressings. Adv Wound Care. 2021;10(12):685–98. doi:10.1089/wound.2020.1232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Holloway S. Principles of wound interventions. In: Wound care nursing e-book: wound care nursing e-book. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2020. 37 p. [Google Scholar]

55. Mayer DO, Tettelbach WH, Ciprandi G, Downie F, Hampton J, Hodgson H, et al. Best practice for wound debridement. J Wound Care. 2024;33(Sup6b):S1–32. doi:10.12968/jowc.2024.33.Sup6b.S1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Caldwell MD. Bacteria and antibiotics in wound healing. Surg Clin North Am. 2020;100(4):757–76. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2020.05.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Chen M, Chang C, Levian B, Woodley DT, Li W. Why are there so few FDA-approved therapeutics for wound healing? Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(20):15109. doi:10.3390/ijms242015109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Kondej K, Zawrzykraj M, Czerwiec K, Deptuła M, Tymińska A, Pikuła M. Bioengineering skin substitutes for wound management-perspectives and challenges. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(7):3702. doi:10.3390/ijms25073702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Kelangi SS, Theocharidis G, Veves A, Austen WG, Sheridan R, Goverman J, et al. On skin substitutes for wound healing: current products, limitations, and future perspectives. Technology. 2020;8(01n02):8–14. doi:10.1142/s2339547820300024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Normandin S, Safran T, Winocour S, Chu CK, Vorstenbosch J, Murphy AM, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy: mechanism of action and clinical applications. Semin Plast Surg. 2021;35(3):164–70. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1731792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Niederstätter IM, Schiefer JL, Fuchs PC. Surgical strategies to promote cutaneous healing. Med Sci. 2021;9(2):45. doi:10.3390/medsci9020045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Barakat M, DiPietro LA, Chen L. Limited treatment options for diabetic wounds: barriers to clinical translation despite therapeutic success in murine models. Adv Wound Care. 2021;10(8):436–60. doi:10.1089/wound.2020.1254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Berry-Kilgour C, Cabral J, Wise L. Advancements in the delivery of growth factors and cytokines for the treatment of cutaneous wound indications. Adv Wound Care. 2021;10(11):596–622. doi:10.1089/wound.2020.1183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Keenan C, Obaidi N, Neelon J, Yau I, Carlsson AH, Nuutila K. Negative pressure wound therapy: challenges, novel techniques, and future perspectives. Adv Wound Care. 2025;14(1):33–47. doi:10.1089/wound.2023.0157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Luchian I, Goriuc A, Sandu D, Covasa M. The role of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-13) in periodontal and peri-implant pathological processes. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1806. doi:10.3390/ijms23031806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Kasravi M, Yaghoobi A, Tayebi T, Hojabri M, Taheri AT, Shirzad F, et al. MMP inhibition as a novel strategy for extracellular matrix preservation during whole liver decellularization. Biomater Adv. 2024;156(1):213710. doi:10.1016/j.bioadv.2023.213710. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Ahmad A, Nawaz MI. Molecular mechanism of VEGF and its role in pathological angiogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2022;123(12):1938–65. doi:10.1002/jcb.30344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Pajooh AMD, Tavakoli M, Al-Musawi MH, Karimi A, Salehi E, Nasiri-Harchegani S, et al. Biomimetic VEGF-loaded bilayer scaffold fabricated by 3D printing and electrospinning techniques for skin regeneration. Mater Des. 2024;238:112714. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2024.112714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Hassanshahi A, Moradzad M, Ghalamkari S, Fadaei M, Cowin AJ, Hassanshahi M. Macrophage-mediated inflammation in skin wound healing. Cells. 2022;11(19):2953. doi:10.3390/cells11192953. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Almeida AF, Miranda MS, Vinhas A, Gonçalves AI, Gomes ME, Rodrigues MT. Controlling macrophage polarization to modulate inflammatory cues using immune-switch nanoparticles. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(23):15125. doi:10.3390/ijms232315125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Blokland KEC, Pouwels SD, Schuliga M, Knight DA, Burgess JK. Regulation of cellular senescence by extracellular matrix during chronic fibrotic diseases. Clin Sci. 2020;134(20):2681–706. doi:10.1042/CS20190893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Chen S, Wang H, Su Y, John JV, McCarthy A, Wong SL, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-laden, personalized 3D scaffolds with controlled structure and fiber alignment promote diabetic wound healing. Acta Biomater. 2020;108:153–67. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2020.03.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Astaneh ME, Fereydouni N. Electrospun-based nanofibers as ROS-scavenging scaffolds for accelerated wound healing: a narrative review. Int J Polym Mater Polym Biomater. 2025;74(15):1349–81. doi:10.1080/00914037.2024.2429576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Zheng Z, Zhang H, Yang J, Liu X, Chen L, Li W, et al. Recent advances in structural and functional design of electrospun nanofibers for wound healing. J Mater Chem B. 2025;13(18):5226–63. doi:10.1039/d4tb02718c. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Liu Y, Li C, Feng Z, Han B, Yu DG, Wang K. Advances in the preparation of nanofiber dressings by electrospinning for promoting diabetic wound healing. Biomolecules. 2022;12(12):1727. doi:10.3390/biom12121727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Keirouz A, Chung M, Kwon J, Fortunato G, Radacsi N. 2D and 3D electrospinning technologies for the fabrication of nanofibrous scaffolds for skin tissue engineering: a review. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2020;12(4):e1626. doi:10.1002/wnan.1626. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Aghazadeh MR, Delfanian S, Aghakhani P, Homaeigohar S, Alipour A, Shahsavarani H. Recent advances in development of natural cellulosic non-woven scaffolds for tissue engineering. Polymers. 2022;14(8):1531. doi:10.3390/polym14081531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Bazgir M. Fabrication, characterization and optimization of biodegradable scaffolds for vascular tissue engineering: application of PCL and PLGA electrospun polymers for vascular tissue engineering [dissertation]. Bradford, UK: University of Bradford; 2021 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk/entities/publication/df58ca30-c285-4664-8eb8-fac3bd4853a4. [Google Scholar]

79. Jiang Z, Zheng Z, Yu S, Gao Y, Ma J, Huang L, et al. Nanofiber scaffolds as drug delivery systems promoting wound healing. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(7):1829. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics15071829. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Yeh YC, Huang TH, Yang SC, Chen CC, Fang JY. Nano-based drug delivery or targeting to eradicate bacteria for infection mitigation: a review of recent advances. Front Chem. 2020;8:286. doi:10.3389/fchem.2020.00286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Anand K, Sharma R, Sharma N. Recent advancements in natural polymers-based self-healing nano-materials for wound dressing. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater. 2024;112(6):e35435. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.35435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Dolgin J, Hanumantharao SN, Farias S, Simon CG, Rao S. Mechanical properties and morphological alterations in fiber-based scaffolds affecting tissue engineering outcomes. Fibers. 2023;11(5):39. doi:10.3390/fib11050039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Martinier I, Trichet L, Fernandes FM. Biomimetic materials to replace tubular tissues. hal-04788753. 2024. doi: 10.26434/chemrxiv-2024-r99zr. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Omidinia Anarkoli A. Fiber spinning for tissue engineering applications [dissertation]. Aachen, Germany: RWTH Aachen University; 2020. [Google Scholar]