Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Catalytic Cracking of Crude Palm Oil-Based Biorefinery to Biogasoline over γ-Al2O3: Study of Physico-Chemical Properties and Life Cycle Assessment

1 Department of Materials and Metallurgical Engineering, Faculty of Industrial Technology and Systems Engineering, Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember, Jl. Arif Rahman Hakim, Kampus ITS Keputih-Sukolilo, Surabaya, 60111, Indonesia

2 Department of Industrial Engineering, Faculty of Industrial Technology and Systems Engineering, Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember, Jl. Arif Rahman Hakim, Kampus ITS Keputih-Sukolilo, Surabaya, 60111, Indonesia

3 Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science and Data Analytics, Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember, Jl. Arif Rahman Hakim, Kampus ITS Keputih-Sukolilo, Surabaya, 60111, Indonesia

* Corresponding Author: Hosta Ardhyananta. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(10), 1913-1934. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0018

Received 22 February 2025; Accepted 14 May 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

The total replacement of old fossil fuels poses obstacles, making the production of efficient biogasoline vital. Despite its potential as an environmentally friendly fossil fuel substitute, the life cycle assessment (LCA) of palm oil-derived biogasoline remains underexplored. This study investigated the production of biogasoline from crude palm oil (CPO) based biorefinery using catalytic cracking over mesoporous γ-Al2O3 catalyst and LCA analysis. High selectivity of converting CPO into biogasoline was achieved by optimizing catalytic cracking parameters, including catalyst dose, temperature, and contact time. γ-Al2O3 and CPO were characterized by several methods to study the physical and chemical properties. The physical properties of biogasoline, such as density, calorific value, viscosity, and flash point, were investigated. An overall yield of 60.11% was achieved after catalytic cracking produced several C5-C11 short-chain hydrocarbons. Additionally, this research proposes innovative emission reduction strategies, including waste-to-biogasoline conversion and the use of biodegradable feedstocks that enhance the sustainability of biogasoline production. LCA of γ-Al2O3’s energy and environmental implications reveals minor effects on global warming (0.0068%) and freshwater ecotoxicity (0.187%). LCAs show a 0.085% impact in the energy sector. This focus on both ecological impacts and practical mitigation strategies deepens the understanding of biogasoline production.Keywords

The depletion of fossil fuel reserves, coupled with rising global energy demands driven by industrialization and population growth, has spurred significant research efforts aimed at developing renewable and sustainable energy sources. Increased energy consumption has predominantly occurred in specific sectors, notably in industry, residential areas, and transportation. The transportation sector emerged as the largest consumer of energy, with oil and gas serving as the primary sources, collectively representing 60% of total fuel consumption in 2020 [1]. An investigation was conducted into natural oils derived from agricultural plants, such as rubber seed [2], olive [3], palm [4], and coconut [5], as a potential biogasoline source. Indonesia possessed petroleum reserves of 2.5 billion gallons in 2020 [6,7]. Due to increasing consumption and a lack of renewable sources of fossil fuels, they are predicted to be eliminated around 2050–2060 [8,9]. As a result of this phenomenon, researchers have begun to develop alternative fuels to supplant the exciting fossil fuel sources.

Biogasoline represents a promising alternative energy source that can be chemically produced from various natural oils [10]. The production process involves the conversion of hydrocarbons from a heavy molecular structure of feedstock oil derived from plants through a range of chemical reactions, including transesterification [11], cracking [12], and hydro-dexygenation [13]. The process of transesterification involves a lot of oxygen, which can make it incompatible with engines, unstable, and less effective at cold flow. Moreover, this method requires the separation of a mixture comprising vegetable oil, alcohol, catalyst, and saponified impurities from the final biogasoline product [14]. In addition, hydro-deoxygenation has limitations due to the complexity of its process [15]. Consequently, cracking emerges as a more efficient method for biogasoline production. There are three main cracking techniques: thermal cracking, catalytic cracking, and hydrocracking. The use of a catalyst in catalytic cracking offers significant advantages, as it operates at lower temperatures compared to thermal cracking or hydrocracking [16]. The thermal cracking process requires a high operating temperature, namely up to 850°C, resulting in significant costs and reduced efficiency [17]. Mota et al. conducted an investigation on the thermal catalytic cracking of CPO to produce green diesel. The cracking process was carried out within the temperature range of 235–450°C. The green diesel has a yield of approximately 24.9%. It has an acid value of 1.68 mg KOH/g and a kinematic viscosity of 1.48 mm2/s. The analysis revealed that green diesel consists of 91.38% (w/w) hydrocarbons, with 31.27% being normal paraffins, 54.44% olefins, and 5.67% naphthenics. Additionally, 8.62% (w/w) of the compound consists of oxygenates [18]. Hydrocracking necessitates the inclusion of hydrogen gas during its operation, rendering it less cost-effective compared to catalytic cracking [19].

γ-Al2O3 is an ideal active component for catalytic cracking catalysts for biogasoline, attributed to its advantageous acidic properties within porous materials [20,21]. γ-Al2O3 has been generally used as a catalyst for catalytic cracking due to its low cost, high surface area and high thermal stability, which possesses Brönsted and Lewis acidity [22]. The presence of Brönsted acid and Lewis acid in γ-Al2O3 is important for the catalytic cracking process of CPO. Specifically, the Brönsted acidity facilitates the cleavage of double bonds in hydrocarbons, such as oleic acid, present in triglyceride structures derived from palm oil. Additionally, the Brönsted acid acts as a proton donor, thereby enhancing hydrogenation reactions. Besides, Lewis acid sites contribute by breaking single bonds, exemplified by palmitic acid [23]. Ratchahat et al. reported the effectiveness of γ-Al2O3 in producing cellulose via pyrolysis was evaluated, revealing that γ-Al2O3 provides a beneficial anti-coking effect. Furthermore, γ-Al2O3 particles enhance thermal conductivity in molten salt, ultimately improving conversion rates and selectivity [24].

Several factors contribute to uncertainties in catalytic cracking, which complicates the reliable prediction of its yield due to the variability in parameters. Consequently, advanced analytical approaches are required to accurately assess these uncertainties. In a recent study by [25], researchers conducted a comparative analysis on the uncertainty of fluid catalytic cracking. The study employed a two-level data-driven uncertainty analysis to investigate the topic. The study revealed that the characteristics of the feed oil, operational expenses, and energy costs had an impact on fluid catalytic cracking. Despite significant advancements in the discovery of novel fuel sources via catalytic cracking of CPO, unresolved challenges remain, including the long-term environmental and energy consequences. The environmental impacts of biogasoline production, particularly from catalytic cracking, are not fully understood. Several factors such as feedstock choice, energy input, and byproduct generation significantly influence the overall sustainability of biogasoline [26]. By applying LCA to catalytic cracking processes, researchers can evaluate the trade-offs and synergies between environmental impact categories, such as greenhouse gas emissions, resource depletion, and ecological toxicity [27]. Several studies have combined it with LCA to determine how friendly a process and product are and what the impact is on the environment [28–30]. Bouter et al. [31] showed in their research the significance of LCA in evaluating the environmental implications associated with the production processes of biofuels for the both road and aviation sectors. Their conclusion indicated that climate change during the fuel replacement process was the primary factor influencing the results. Consequently, using LCA analysis, researchers may identify the appropriate process and fuel to attain optimal outcomes. This study aims to overcome the limits of gasoline. The limitation will be finished using produced biogasoline from CPO using the catalytic cracking method with γ-Al2O3 as a catalyst. This study will evaluate the ability of γ-Al2O3 to crack CPO and explore the LCA of biogasoline catalytic cracking.

The tools used in this research include: Digital balance sheet analysis (thermo fisher), condensor (pyrex), distillation flask (pyrex), heating mantle (thermo fisher), water pump, and hose. Mesoporous γ-Al2O3 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Crude Palm oil (CPO) were obtained from palm industry in Indonesia. All chemicals were utilised as received, without any additional purification.

Mesoporous γ-Al2O3 is initially purified to obtain optimal performance. Firstly, γ-Al2O3 was washed several times with aquaDM and ethanol, and the pH of γ-Al2O3 was estimated to be 7. Then, it was dried at a temperature of 100°C for a duration of 12 h.

2.3 Catalytic Cracking Process

The catalytic cracking process is shown in Fig. 1. Prior to cracking, γ-Al2O3 were first activated to remove water vapour physically bound using furnaces at 60°C for 24 h. The cracking process was conducted for a contact time variation of 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 h at a temperature variation of 380, 400, and 420°C.

Figure 1: Catalytic cracking pyrolysis scheme

Specifically, the catalyst variation of 0.5, 0.75, 1, and 1.25 g in 100 g CPO for each respective cracking. In this study yield of biogasoline are obtained based on calculations on the Eq. (1).

The response variables in this study were biogasoline yield, density, calor, viscosity, flash point, and molecular weight.

The γ-Al2O3 crystal structure is determined using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD). The measurement uses CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) as the light source, with a sequential voltage and current acceleration of 40 kV and 30 mA, respectively. The analysis is conducted at a 2θ angle ranging from 5 to 50 degrees, with a scan interval of 0.017 degrees. The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) study was conducted to ascertain the existence of a functional group on the catalyst. The γ-Al2O3 exhibits distinct characteristics related to its crystal’s morphological structure, particle size, and elemental distribution, which may be analysed using Scanning electron microscope-energy dispersive X-Ray (SEM-EDX). The coated samples are then placed in the chamber to be detected by the SEM-EDX detector. The surface area and pore structure characteristics were calculated using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) and Barret–Joyner–Halender (BJH) models. Before analysis, the samples were degassed at 250°C for 24 h. The biogasoline density is conducted in accordance with ASTM D1217. The calorific value was determined by employing a bomb calorimeter instrument manufactured by IKA and belonging to the C200 series. This test determines the calorific value of the biogasoline after catalytic cracking in accordance with the ASTM D 240-021 standard. The ASTM D-445 standard is employed to determine the viscosity of biogasoline products after undergoing the catalytic cracking process. The flash point test, as described in ASTM D-92, is used to determine the point at which a particular sample ignites. This test ascertains the temperature at which the sample undergoes a phase change from a liquid state to a vapor state under particular conditions. In addition to determining the molecular weight of biogasoline generated via catalytic cracking, GC-MS characterization is utilized to ascertain the compositions of the associated compounds found in biogasoline. Temperature-programmed desorption and reduction (TPD/TPR) characterization were conducted using Quantachrome ChemBET Pulsar with nitrogen as carrier gas.

This research investigated the techno-economic aspects by studying heat and mass balances. Several assumptions are incorporated into a rigorous calculation of the heat and mass balance in the initial phase. The experimental data and assumptions utilized in the calculation of heat and mass balances. The calculations for heat and mass balance are presented in equation:

3.1 Characterization of γ-Al2O3

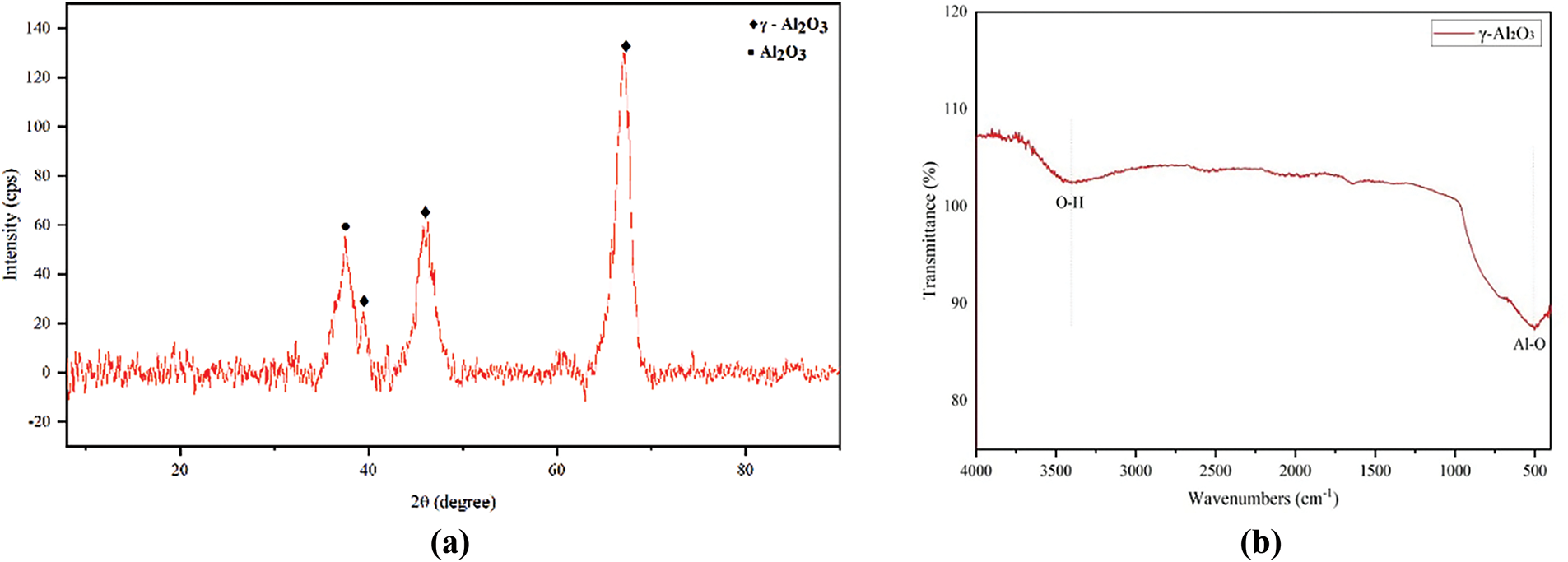

The γ-Al2O3 diffractogram (Fig. 2a) revealed its characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ = 19.2, 31.0, 36.6, 39.3, 46, 61.5, and 67°, which can be indexed as (1 1 1), (2 2 0), (3 1 1), (2 2 2), (4 0 0), (5 1 1), and (4 4 0) [32]. Furthermore, the Scherrer equation indicated that the crystal size is 25.15 nm. The solubility of γ-Al2O3 in CPO is facilitated by the crystal’s comparatively small size, which renders it functional as a catalyst. The FTIR spectra γ-Al2O3 is illustrated in Fig. 2b. The γ-Al2O3 elucidated a wide band at around 3372 cm−1, assigned to the stretching vibration of the O–H group of water molecules. In addition, the characteristic peaks of metal oxide bonds (Al-O) was observed at 501 cm−1 [33]. The surface morphologies of γ-Al2O3 were disclosed using SEM.

Figure 2: (a) Diffractogram and (b) FTIR spectra of γ-Al2O3

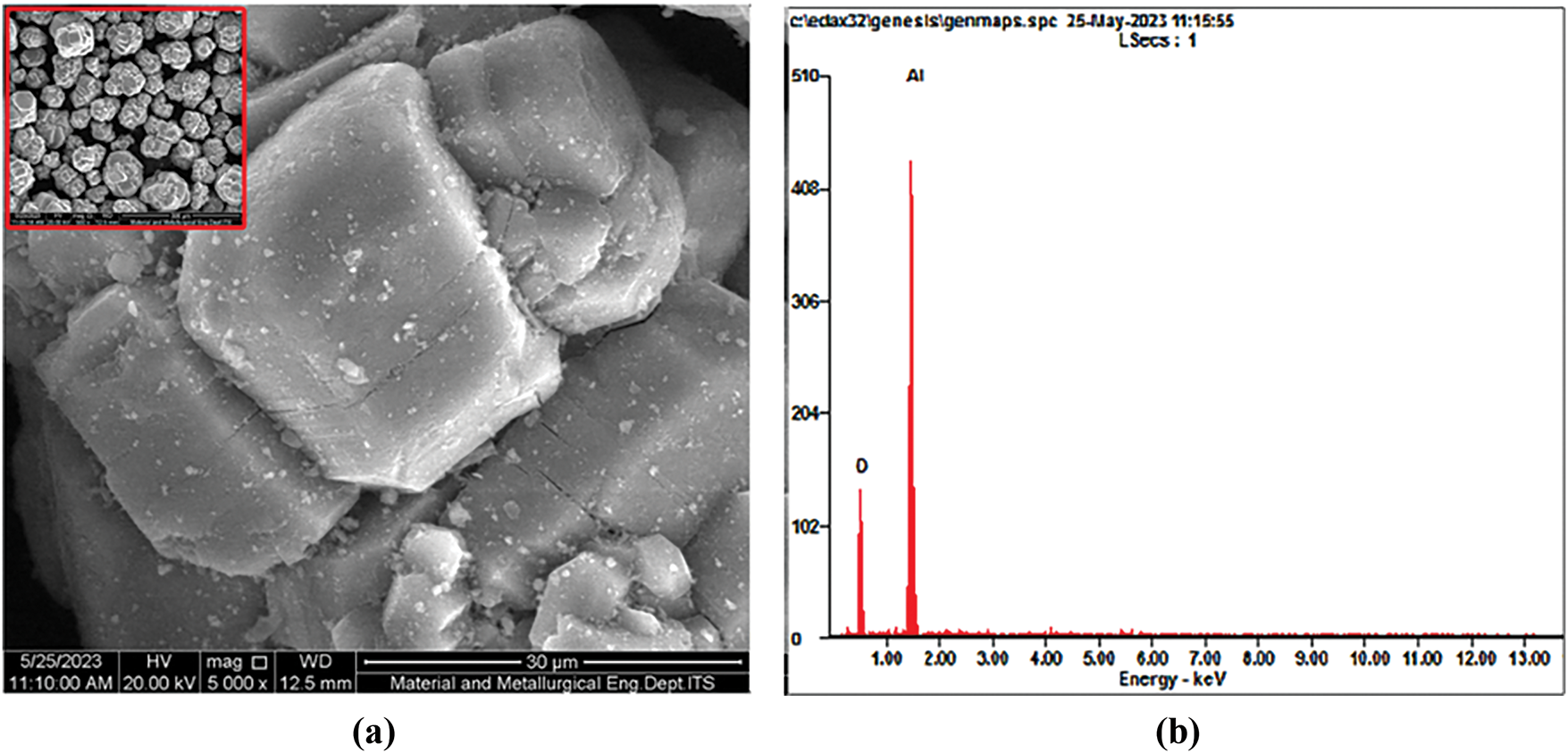

The SEM image (Fig. 3a) showed that γ-Al2O3 exhibits the presence of a bigger, non-uniformly structured cluster consisting of particles ranging in size up to several microns (10–30 μm), resulting from the process of smaller powder particles coming together and forming aggregates with a spheric-rectangular shape [34]. The EDX mapping showed that γ-Al2O3 contains Al and O elements without any impurities (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3: (a) SEM image (b) EDX distribution of γ-Al2O3

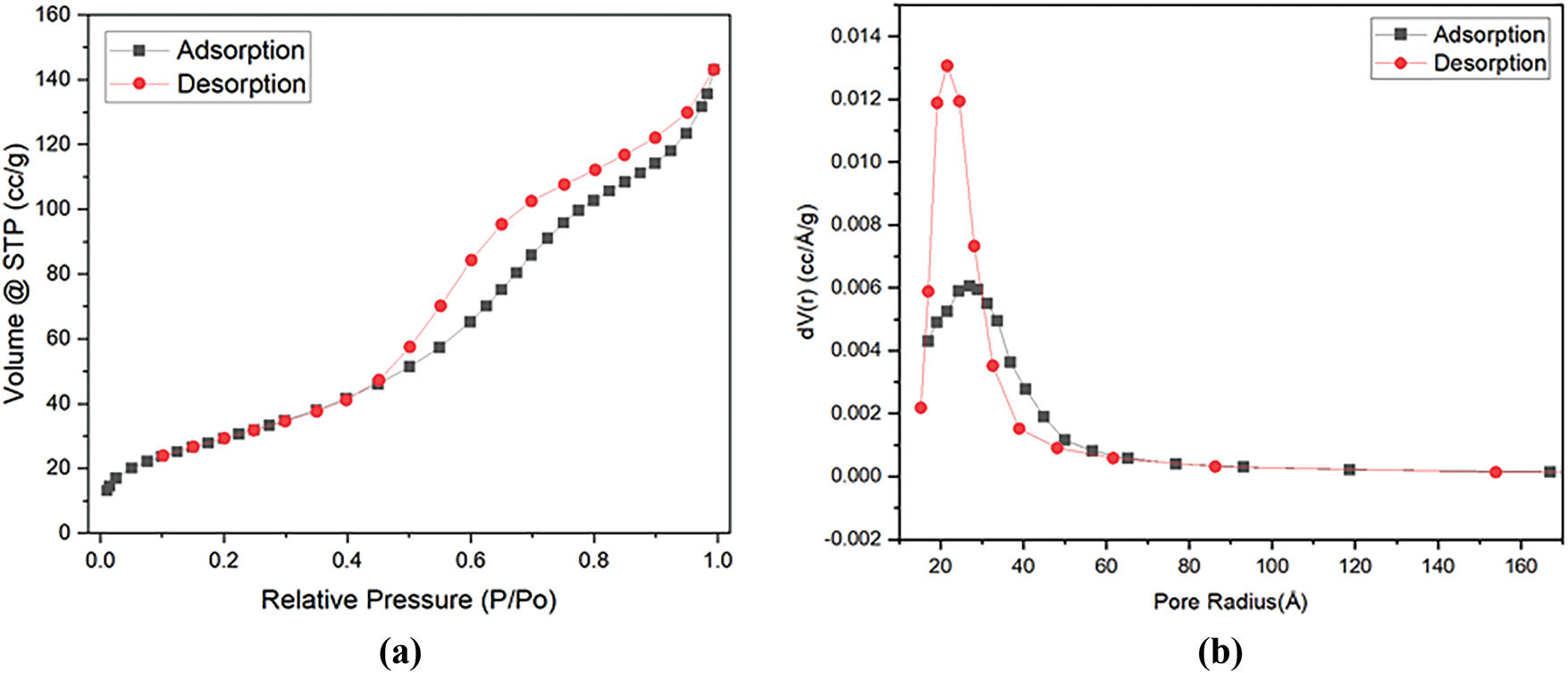

This is evidenced that γ-Al2O3 has high impurity. The γ-Al2O3 catalyst exhibits characteristic type-IV curves with the H3 hysteresis loop (Fig. 4a) following IUPAC classification, which is caused by the presence of adjacent small aggregates leading to the formation of a larger cavity, which is identified as plate-like pores [35,36]. The hysteresis loops seen at a greater relative pressure range of 0.45 to 0.9 show the presence of homogenous mesoporosity in the γ-Al2O3.

Figure 4: (a) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm (b) BJH pore distribution of γ-Al2O3

The specific surface area of γ-Al2O3 is 110.66 m2/g. The pore diameter distribution analysis (Fig. 4b) of γ-Al2O3 indicates that the predominant pore diameter of γ-Al2O3 is 4 nm, providing confirmation that γ-Al2O3 is mesoporous. This is in accordance with isotherm type IV, which is characteristic of mesoporous materials.

The NH3-TPD characterization is utilized to study the acidic properties of γ-Al2O3. Typically, the specific surface area of a desorption peak indicates the number of acid sites, while the peak position reflects the strength of the associated acid centers. The NH3-TPD profile for γ-Al2O3 was shown in Fig. 5. Fig. 5 shows that γ-Al2O3 contains two types of acid sites, as indicated by the presence of two peaks with varying intensities across different temperature ranges due to ammonia desorption. The presence of moderate acidity is identified by a peak in the temperature range of 320–350°C with low intensity, while strong acidity is denoted by a peak appearing in the range of 360–560°C [37]. The peak in the 320–350°C range is attributed to Brönsted acid sites, whereas the peak in the 360–560°C range originates from Lewis acids [38]. This analysis suggests that a significant number of acid sites in γ-Al2O3 exhibit strong acidity derived from Lewis acid sites, with only a small proportion of Brönsted acid sites classified as moderate acidity.

Figure 5: NH3-TPD analysis of γ-Al2O3

3.2 Characterization of Biogasoline

The FTIR spectra of CPO and biogasoline under several temperature and contact time variations are shown in (Fig. 6a–d). FTIR spectra of CPO are depicted in Fig. 6a. Peaks at 721.38, 1159.26, and 1464.57 cm−1 assigned to C-H double bond distortion, C=C, and C-O-C double bond, respectively. The stretching vibration of C-H is located at 2920.83 and 2851.85 cm−1. The peak at 3005.89 cm−1 shows the stretching of the aliphatic C=C double bond [39]. The characteristic peaks of all biogasoline (Fig. 6b–d) can be observed at 2955.2, 2921.15, and 2852.32 cm−1 corresponding to the asymmetric CH stretching vibrations from the methylene group and symmetric CH stretching vibrations from the methyl group in alkane compounds. The weak peak at 1708.82 cm−1 is attributed to the carbonyl stretching frequency of the carboxyl group. The peaks at 1646.6, 938.13, and 721.28 cm−1 represent the C=C from the olefin compound, the CH group, and the long chain of the hydrocarbon compound [40]. No absorption was detected at 1600 cm−1, indicating the absence of a C=C group in the initial cracking proces. This suggests that the contact time was insufficient to reduce the oxygen concentration and convert it into C=C bonds [41]. In addition, none of the spectra exhibited OH absorption, suggesting the absence of alcohol groups in the biogasoline.

Figure 6: Spectra FTIR of (a) CPO. Biogasoline at variation temperature (b) 380°C (c) 400°C (d) 420°C

When comparing the CPO FTIR spectrum (Fig. 6a) with the FTIR spectrum of biogasoline obtained from catalytic cracking (Fig. 6b–d), a noticeable decrease in intensity is observed, indicating a reduction in the presence of C=O and C-O-C groups that are characteristic of CPO [42]. These results also suggest that the conversion of CPO into biogasoline has been successfully achieved.

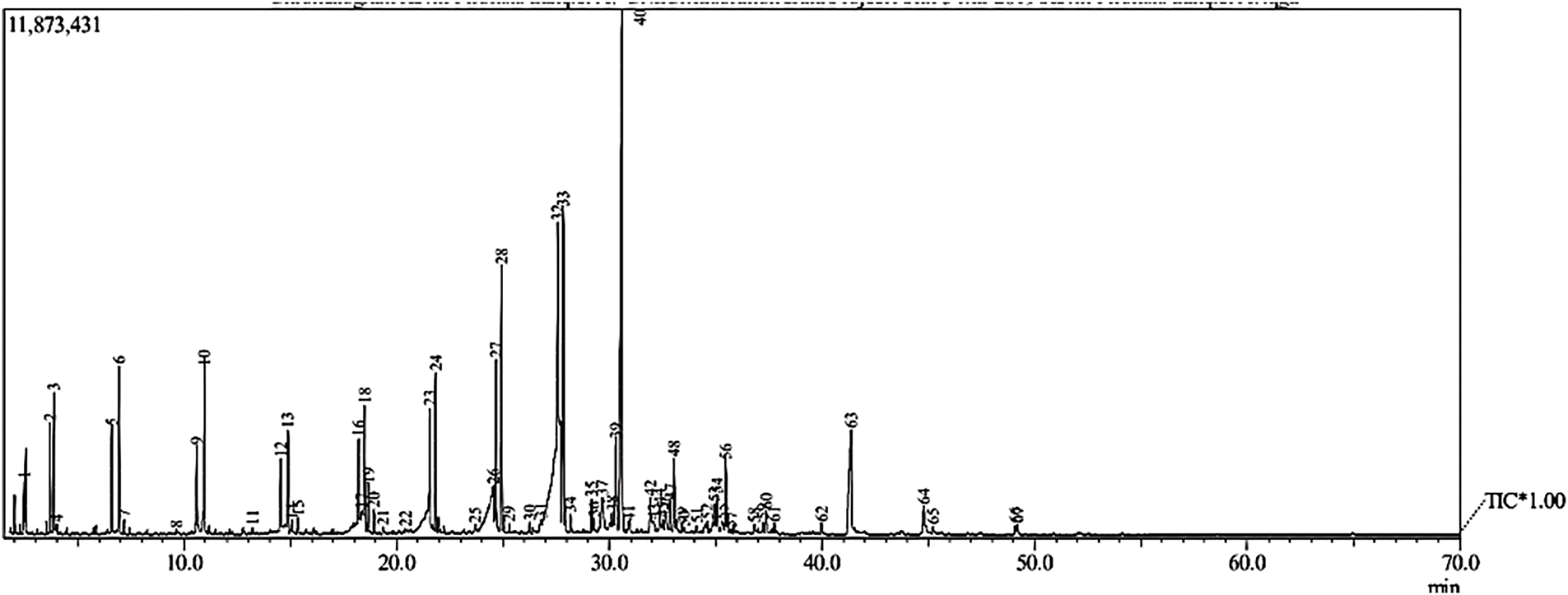

The liquid yield composition was examined using GC-MS characterization (Fig. 7) and classified into several categories, including hydrocarbons, cyclic compounds, ketones, alcohols, and ethers [43]. Alkane hydrocarbons are the primary compounds in biogasoline, followed by alkene hydrocarbons and cyclic compounds. Ketones and alcohols are present in small quantities within the produced biogasoline. The processes of decarboxylation and decarbonylation can reduce the presence of oxygen atoms in fatty acids, thereby facilitating the formation of hydrocarbons within the biogasoline range [44,45]. Furthermore, the GC-MS chromatogram of the biogasoline obtained in this study indicate that hydrocarbons serve as the main products. Biogasoline fuel typically consists of hydrocarbons with carbon chains ranging from C5-C11 [46]. Based on GC-MS spectra (Fig. 7), Fig. 8a shows the distribution of the carbon chains in biogasoline. The C5-C11 chain is a biogasoline fraction with an amount of 57.69%, the C12-C14 chain is a biodiesel and kerosene fraction up to 36.53%, then the >C14 chain is a heavy oil fraction with a content of 5.76%. Based on these results, it can be concluded that biogasoline is the dominant product in this process. This demonstrated that the combination of γ-Al2O3 with temperature during the catalytic cracking produces a synergistic effect to break the higher molecular weight (CPO) into a lower molecular weight (biogasoline) [47,48].

Figure 7: GC chromatogram of the biogasoline

Figure 8: (a) Hydrocarbon chain distriution (b) Effect of catalyst dosage of biogasoline yield. Error bars reveal the standard deviations of repeated in six times (c) Effect of temperature and contact time of biogasoline yield. Error bars reveal the standard deviations of repeated in six times

A possible mechanism (Fig. 9) for catalytic cracking to produce biogasoline was proposed below: (1) The initial step is the thermal decomposition of complex oxygen-containing hydrocarbons, such as fatty acids in CPO, into oxygenated hydrocarbons and large hydrocarbons. Furthermore, the pore of γ-Al2O3 has been believed to adsorb the CPO, thus producing the cracking in the CPO structure [45]. The presence of pores in γ-Al2O3 affects the interaction with CPO molecules (Fig. 7). The existence of mesopores (4 nm) facilitates the adsorption of the CPO into the γ-Al2O3 pores, thereby enhancing the efficiency of the catalytic cracking process [49]. (2) Light molecules (CO, CO2, H2O, and CH4) are released during decarboxylation, decarbonylation, and dehydrogenation processes in order to generate shorter chain hydrocarbons (olefins, paraffins, and dienes). At this step, more C1-C14 hydrocarbons are produced. (3) In the third stage, biogasoline-range hydrocarbons, aromatics, and isoparaffins are made through isomerization, cyclization, and aromatization [50]. Therefore, the presence of mesopores combined with the catalytic cracking process provides a synergistic effect to facilitate the absorption of CPO followed by its decomposition into hydrocarbons according to the biogasoline range.

Figure 9: The proposed catalytic mechanism for CPO cracking utilizing γ-Al2O3

In this study, the γ-Al2O3 catalyst was studied for its performance on biogasoline production via catalytic cracking. Characterization of the biogasoline produced was carried out using GC-MS to determine its components. The physical properties of biogasoline, such as density, calorific value, viscosity, and flash point, were determined for its commercial gasoline prospect.

Based on Fig. 8b, the biogasoline yield has an increasing trend at 0.5 and 0.75 but then declines at a catalyst amount of 1.25 g. The highest biogasoline yield achieved was 60.11% at 1 g catalyst weight, while the lowest yield was 20% when 0.5 g of catalyst was used. The observed rise in biogasoline production for catalyst weights ranging from 0.5 to 1 g can be attributed to the greater abundance of active sites, which facilitate the efficient conversion of CPO into biogasoline as the catalyst weight increases. However, exceeding a catalyst quantity of 1 g might result in interaction issues between the reactants and the catalyst’s active sites, leading to reduced biogasoline production due to mass transfer resistance. In addition, excessive catalyst addition causes clouding in the system, which can decrease biogasoline yield [51,52]. Furthermore, the presence of Lewis acid in γ-Al2O3 is an active center that can interact with the CPO target molecule, facilitating the cracking process [53].

3.3.2 Effect of Cracking Temperature and Time

Based on the Fig. 8c, it indicated that the temperature and contact time of cracking catalytically have a significant effect on the biogasoline product. The optimum biogasoline yield of 60.11% was achieved at the operating temperature and time are 420°C and 2 h. Catalytic cracking is an endothermic reaction that takes place at high temperatures; hence, an increase in temperature would facilitate the reversible reaction forward [54]. Furthermore, increasing temperature led to an increase in the kinetic energy of the molecules, thus promoting higher collision rates between γ-Al2O3 and CPO [55]. As a result, the biogasoline yield increased due to the cracking of long hydrocarbons into short hydrocarbons. Fig. 6c also showed that with constant temperature (420°C), the biogasoline yield under contact time variation did not show a significant increase in yield. This is because a higher cracking temperature possesses a greater energy content, resulting in a faster cracking response time compared to a lower cracking temperature [56]. In addition, the lower yield was a result of secondary cracking in the gaseous phase, which led to a decrease in the liquid yield.

3.3.3 Characteristics of Biogasoline Product

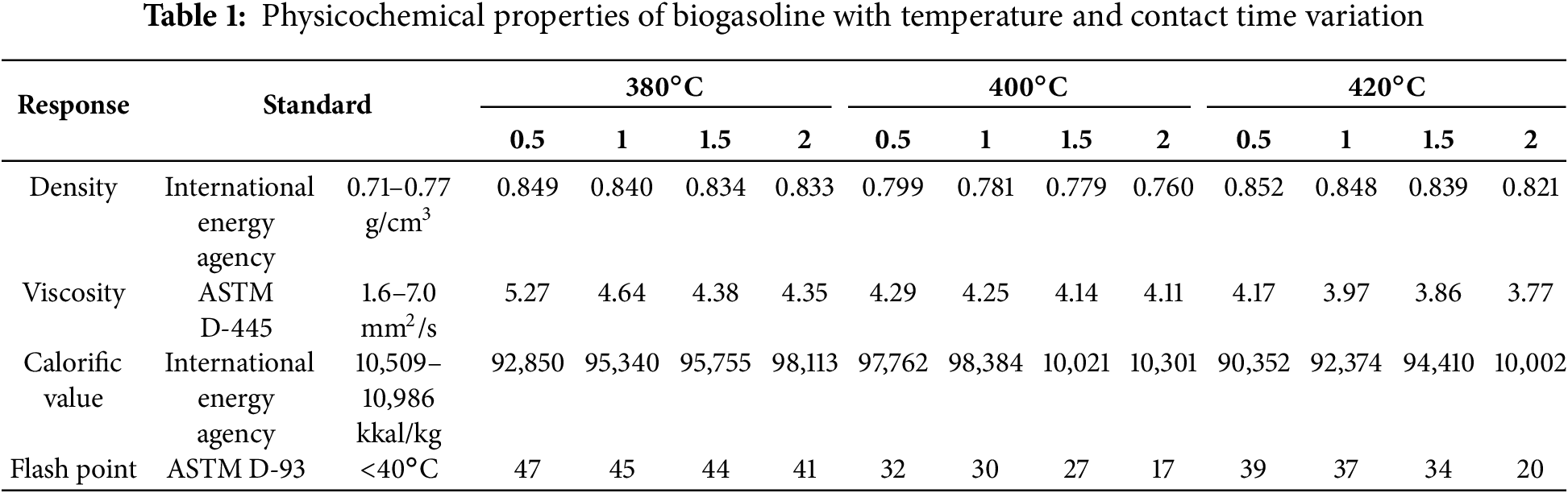

The physico-chemical properties, such as density, viscosity, entalphy, flash point, and molecular weight, were investigated and compared to the Indonesian and International Standard.

Interaction of Process Variables with Respect to Biogasoline Density

The density normally decreases as the operating temperature increases. Increasing the temperature variation provided additional active sites and increased kinetic energy for the reactants, resulting in a greater density of biogasoline [57]. The standard density of gasoline (0.71–0.77 g/cm3), as reported by the International Energy Agency (IEA) (Table 1), indicates that 400°C is the optimal temperature for biogasoline production according to IEA. These results indicate that temperature plays an important role in influencing product density. The density values of biogasoline show fluctuations due to several factors. At higher temperatures, molecules move more rapidly, leading to bond breakage, which results in a decrease in the density of biogasoline [58]. In addition, the higher temperature is directly proportional to the rise in energy, leading to an increase in the frequency of collisions between the CPO and the γ-Al2O3 catalyst surface [59]. Consequently, at elevated temperatures, the process of hydrocarbon chain cracking occurs more rapidly, resulting in the production of short-chain hydrocarbons with low density. At a temperature of 420°C, the density increased as a result of the catalytic cracking process achieving saturation, leading to the formation of charcoal and other by-products. This condition ultimately contributed to the rise in biogasoline density. Furthermore, Table 1 also illustrated that the contact time can also have an impact on the density of biogasoline. Increasing the contact time of cracking leads to an ideal interaction between CPO and γ-Al2O3, resulting in a more optimum hydrocarbon chain breaking compared to a short contact time [60]. It can be seen that for all temperature variations, the lowest density value can be achieved at a contact time of 2 h and a temperature of 400°C.

Interaction of Process Variables with Respect to Biogasoline Calorific Value

The combustion of a defined amount of fuel in the presence of air or oxygen produces thermal energy, quantified by its calorific value. Notably, the heating value exhibits an inverse relationship with density; specifically, it is inversely related to the density of the oil. The calorific value is utilized to determine the amount of fuel oil that an engine will consume over a specified period [61]. Table 1 showed the impact of catalytic cracking temperature and contact time on the calorific value. The comparison with Table 1 shows that the calorific value obtained in this study does not yet meet the standard specifications based on the IEA. This situation may be due to the presence of impurities [62,63]. However, the calorific value obtained is 1224–685 kcal/kg lower than the standard gasoline (10,509–10,986 kkal/kg). The calorific value initially increased untill reaching a temperature of 400°C, but then declined after further increasing to 420°C. The condition is positively associated with the density value, which exhibits an increase at a temperature of 420°C. The highest calorific value was obtained at a temperature of 400°C of 10,301 kcal/kg. The calorific value is affected by the quantity of oxygen present during the combustion process [64,65]. The FTIR spectra of CPO, biogasoline, and pertalite are shown in Fig. 5a–c. Biogasoline showed the presence of the C-O-C and C=O functional groups, while pertalite did not show this functional group. This functional group arises from the deoxygenation process during catalytic cracking [66]. The increased oxygen content in biogasoline, as opposed to gasoline, fulfills the air requirement during combustion, thereby leading to a reduction in calorific value [67,68]. Table 1 also shows the correlation between the contact time and the calorific value. It is evident that a longer contact time leads to a rise in the heating value.

Interaction of Process Variables with Respect to Biogasoline Viscosity

Fuel viscosity is one of several factors to consider. It serves as an indicator of the frictional resistance encountered by molecules during fluid flow. The viscosity value provides insight into the fuel’s fluidity within the engine cylinder and its circulation system [69]. Fuel with a high viscosity necessitates vigorous compression or ignition chamber pouring. Furthermore, an excessively high viscosity leads to inadequate atomization, thereby causing incomplete combustion [70,71]. The increase in temperature and contact time led to a decrease in viscosity (Table 1). Based on Table 1, the viscosity of biogasoline was in accordance with the standard over a range of temperature and time variations. Extending the contact time allows intensive condensation of heavy hydrocarbon fractions into lighter fractions. A reduced viscosity signifies enhanced atomization efficiency and a greater concentration of oxygen, both of which contribute to a high level of combustion efficiency [72].

Interaction of Process Variables with Respect to Biogasoline Flash Point

The flash point of biogasoline decreased over time, whereas the cracking temperature increased (Table 1). The data presented in Table 1 indicates that temperature significantly influences the production of biogasoline in accordance with established specifications (ASTM D-93). At a temperature of 380°C, the flash point value of biogasoline exceeds the standard (>40°C). As the temperature rises, the flash point of biogasoline attains the standard (<40°C). A reduction in flash point signifies the efficacy of catalytic cracking in generating hydrocarbons with shorter molecular chains. Short-chain hydrocarbons exhibit greater flame propagation rates in comparison to long-chain hydrocarbons [30]. A closer inspection reveals that the flash point increases at 420°C; this is the result of the saturation condition that the cracking process has reached. Moreover, the increase in flash point could potentially be attributed to the dissipation of energy required to sustain the hydrocarbon cracking [73]. Conversely, the impact of contact time on the flash point is attributable to the distribution-influencing hydrocarbon conversion rate. The high flash point is evident when the contact time is short, as illustrated in Table 1. A high flash point signifies that the rate of hydrocarbon conversion remains low [74]. It can be deduced that the catalytic cracking process, conducted at a temperature of 400°C for a variable period of 2 h, produces the most favorable conditions for attaining the lowest flash point.

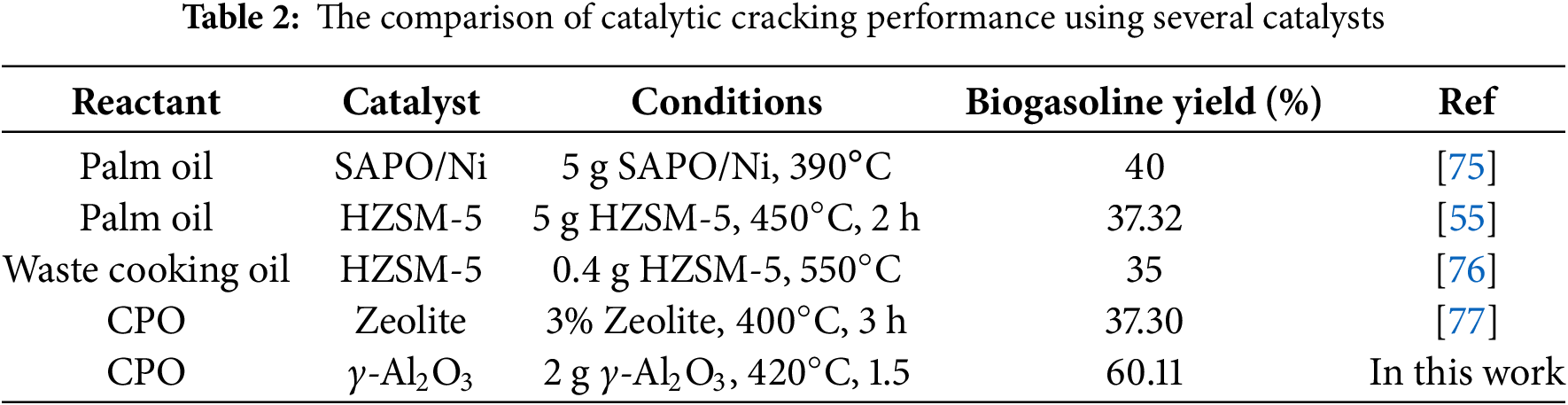

3.3.4 Comparison Catalytic Cracking Performance

A study has been conducted on biogasoline production with CPO as a raw material. As shown in Table 2, we conducted a comparison of the effectiveness of our experiment with that of recent literature. We conducted a thorough analysis of various factors that influenced their performance, including operating conditions and biogasoline yield.

Previous studies have been conducted using HZSM-5 catalysts at 390°C using palm oil as a raw material [55]. However, these processes required a large amount of catalyst, up to 5 g, but produced a low yield of biogasoline, as listed in Table 2. The γ-Al2O3 purification process before catalytic cracking leads to a significantly improved yield, which is better than previous studies. Eliminating impurities in catalysts can enhance their performance. In comparison to previous studies, this study yielded a higher percentage of biogasoline (60.11%). The aforementioned results demonstrate the feasibility of implementing our system on a pilot scale to produce biogasoline.

Heat and mass balancing is a method employed to verify that the quantity of heat and mass entering and exiting a system remains constant [78]. According to Eq. (2), the mass balance of this process is as follows:

It is found that in the process that has been carried out, the input mass is not equal to the output. The output mass is reduced by 15.015 g from the input mass. This can be possible due to mass loss during the reaction process.

From Eq. (3)–(5), the heat loss is quantified as 5.92 kJ. The breakdown of this value is as follows:

Calculation of catalytic cracking at a temperature of 420°C and a time of 2 h:

Heat input CPO = 135 g × 0.27 J/g/°C × (420°C − 25°C) = 14,397.75 J = 14.397 kJ

Heat input of catalyts = 1.35 × 0.27 J/g/°C × (420°C − 25°C) = 143.97 J = 0.143 kJ

Heat input of average = 14.54 kJ

Heat output = 95.198 g × 80.2 J/g + 3.4 g × 22.4 J/g + 22,737 g × 40 J/g = 8.62 kJ

Heat input = Heat output + Heat loss

14.54 kJ = 8.62 kJ + Heat loss

Heat loss = 5.92 kJ

The heat loss can be attributed to several sources, including incomplete combustion, heat transmission from the process to the surroundings, or equipment inefficiencies [79]. Aside from the heat loss of 5.92 kJ, there exists a disparity between the anticipated output of biogasoline and the factual output of biogasoline. Theoretical biogasoline yield exceeds 60%, but the practical yield is approximately 60.11%. This difference may arise from the reaction conditions and the impurities in CPO. The weight percentage of residue and gas in the product is calculated as follows:

It is found that the percentage of product in the form of biogasoline, residue, and gas is 78.46%, 2.80%, and 18.74%, respectively.

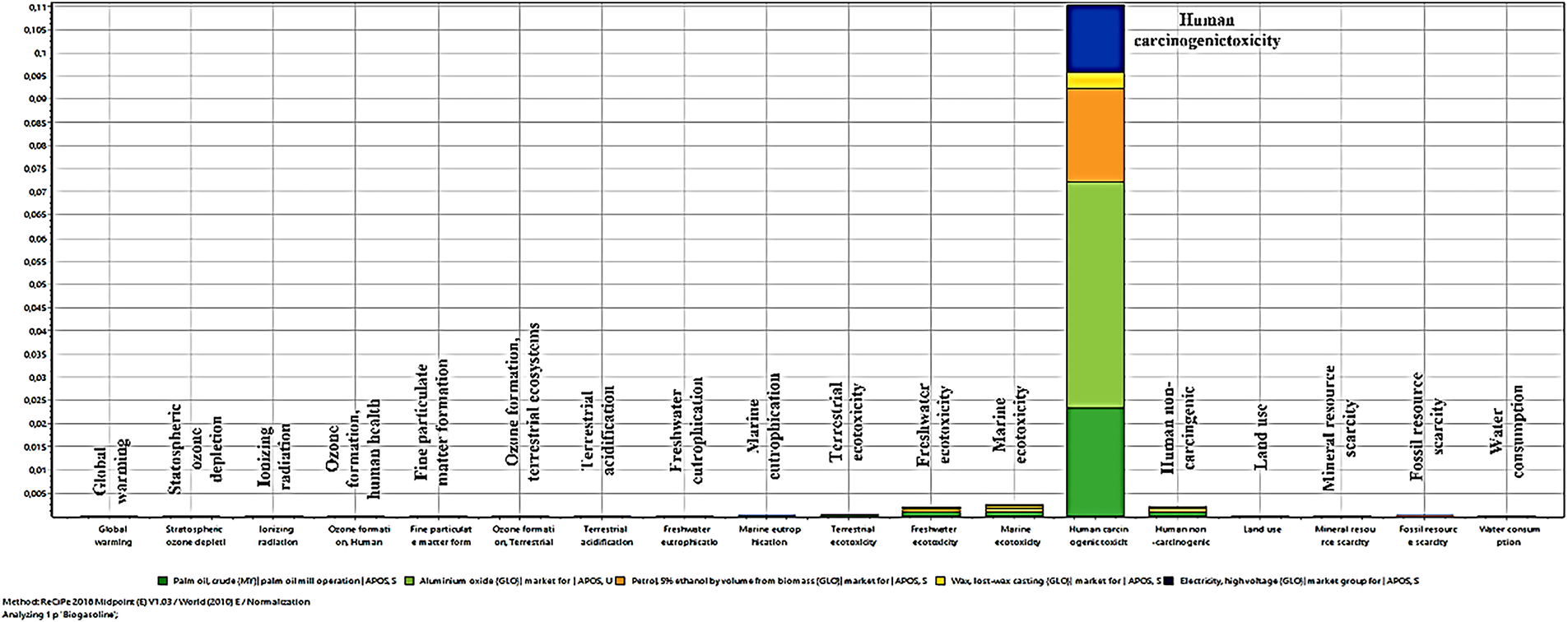

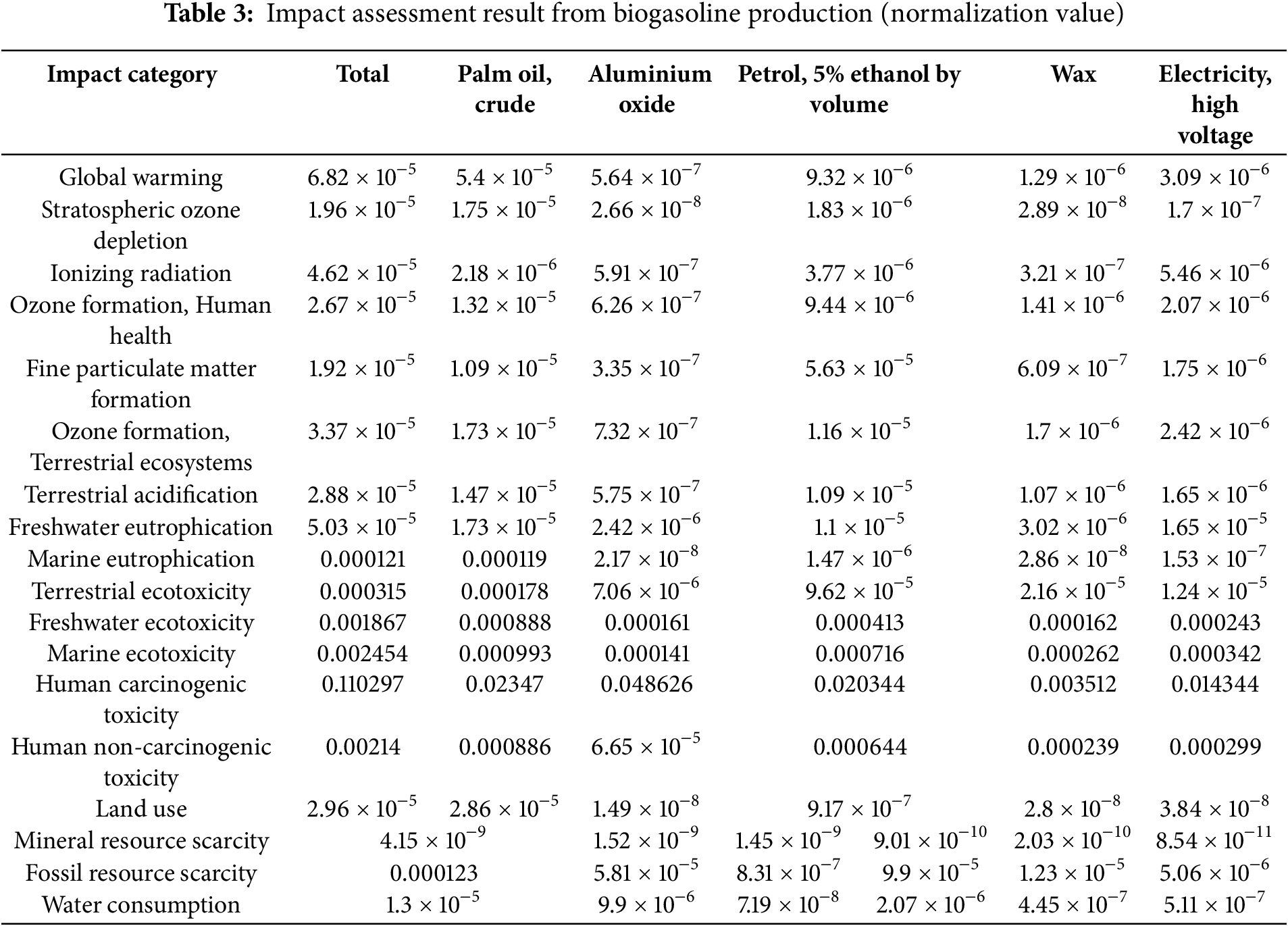

LCA is an essential phase in enhancing the synthetic design of a product from laboratory scale to industrial scale. Elementary laboratory processes should be examined, commencing with the production process, which can avert product failure and integrate environmental and energy advantages for ecological equilibrium. Fig. 10 showed the comparison of results from the three executed scenarios for environmental impact assessment. The “ReCiPe 2016 Midpoint (E) V1.03/World (2010)” technique, viewed via an egalitarian lens, is notably comprehensive, encompassing all potential short- and long-term consequences.

Figure 10: The synthetic design of a product from laboratory scale to industrial scale

Fig. 10 shows the results of the environmental impact assessment drawn from Table 3 visually. Table 3 offers the normalized figures of biogasoline production from CPO related environmental consequences. Table 3 clearly shows that global warming, stratospheric ozone depletion, ionizing radiation, ozone formation (human health), and fine particulate matter formation have the greatest value among the effect categories, therefore suggesting the most severe environmental repercussions. Particularly in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, atmospheric damage, and air pollution, which seriously compromise human health and ecosystem stability, these categories draw attention to important environmental issues. The high impact values in these categories highlight the necessity of mitigating techniques to reduce the biogasoline manufacturing environmental effect.

Fig. 11 shows the five impact categories with the highest values from Table 3 in the biogasoline production from CPO. With a total value of 6.82 × 10−5, mostly driven by crude palm oil (5.4 × 10−5), followed by contributions from fuel (5% ethanol by volume) and electricity (high voltage), the global warming category has the most significant influence according to the table among the others. The main elements causing these effects are shown in the bar chart in different colors, according to different materials or techniques used in the biogasoline manufacturing. Mostly in global warming, stratospheric ozone depletion, and ozone formation (human health), CPO is the main contributor to most effect categories. Variations also result from various elements including gasoline (5% ethanol by volume), aluminum oxide, wax, and high voltage electricity. Though at less levels than global warming, categories including stratospheric ozone depletion, ionizing radiation, ozone formation (human health), and fine particulate matter formation also show somewhat high values. Particularly in ionizing radiation (3.77 × 10−5), gasoline (5% ethanol by volume) is rather important; nevertheless, electricity (high voltage) has a clear influence in several spheres. These results imply that especially in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, atmospheric deterioration, and air pollution-related health hazards, biogasoline production from CPO calls for particular attention to its environmental and health consequences. To reduce environmental and public health hazards, mitigating solutions should concentrate on maximizing feedstock choices, enhancing manufacturing processes, and lowering of hazardous emissions.

Figure 11: The impact categories regarding the toxicity of carcinogens for humans

The use of γ-Al2O3 may be responsible for the significant difference in gasoline production compared to other materials [80]. It is believed that the impact occurs as a result of the catalysis process, especially if the alumina material is affected, possibly leading to the release of heavy metals or fine particles. On the other hand, it is also claimed that the use of gasoline products causes ecotoxicity, especially in aquatic areas (fresh water and oceans), both through a series of production processes and by combustion on the use side, releasing quite significant amounts of emissions into the environment.

Reducing hazardous emissions in biogasoline manufacture calls for a mix of techniques aiming at fuel composition, feedstock choice, waste use, and emission control. Reducing amine-based additives is one smart strategy since, as Manzetti and Andersen (2015) advised, these molecules fuel harmful emissions when burned [81]. Furthermore, as Shearian Sattari et al. (2022) investigate, the acceptance of biodegradable feedstocks such jatropha and palm oil presents a sustainable substitute for fossil fuels, so minimizing greenhouse gas emissions and environmental toxicity [82]. Another interesting approach, emphasized by Gaur et al. (2020), is waste-to- fuel conversion, in which industrial waste is converted into biofuels, therefore lowering reliance on hazardous raw materials and hence increasing emission control [83]. Furthermore, as suggested by Emmanuel et al. (2019), benzene emissions—which carry major carcinogenic hazards—need close monitoring and control to guarantee safer combustion methods [84]. Moreover, Ahmed (2001) supported replacing the carcinogenous oxygenator MTBE with safer substitutes to lower health risks [85]. By reducing negative emissions, enhancing fuel safety, and promoting environmental preservation, these techniques used together increase the sustainability of biogasoline manufacturing. Emphasizing the requirement of ongoing research and regulatory control in the development of biofuel, such actions are essential for balancing energy needs with public health and ecological preservation.

In conclusion, biogasoline has been successfully produced with CPO as the raw material using the catalytic cracking method at different temperatures and contact times, and its LCA was studied. The synergistic effect between γ-Al2O3, temperature, and contact time during catalytic cracking enhanced the biogasoline fraction through the proposed thermal decomposition, decarboxylation, decarbonylation, and dehydrogenation mechanisms. The biogasoline that is produced exhibits the following characteristics: density: 0.76 g/cm3, viscosity: 4.14 mm2/s, heating value: 10.301 kcal/kg, and flash point: 17°C. The γ-Al2O3 compound was identified as the active species in the reaction by the XRD, FTIR, SEM-EDX, and BET studies. The LCA study delineates the effects of catalytic cracking of CPO to biogasoline on both the environmental and energy balance. The impact on global warming for a single cracking process is quantified at 0.0068%, while the associated electricity consumption is measured at 0.085%. The low produced value suggests that the catalytic cracking process of CPO is effective. This study offers a simple strategy for the ongoing generation of biogasoline as a substitute for fossil fuels. Future research will explore the development of innovative mesoporous materials and explore the reuse of catalysts for biogasoline production through catalytic cracking processes. This approach could enhance both economic and environmental benefits. For instance, catalyst doping, composites, and surface modification techniques can enhance the reliability of catalytic cracking.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Palm Oil Plantation Fund Management Agency (BPDPKS), Indonesia, for this work, under Grant Riset Sawit (GRS) Program.

Funding Statement: The contract No. PRJ-395/DPKS/2022 or 2383/PKS/ITS/2022 on 14 November 2022.

Author Contributions: Hosta Ardhyananta: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Widyastuti Widyastuti: Supervision, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Maria Anityasari: Methodology, Formal analysis. Sigit Tri Wicaksono: Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. Vania Mitha Pratiwi: Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. Rindang Fajarin: Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. Liyana Labiba Zulfa: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Komang Nickita Sari: Methodology, Visualization, Formal analysis. Ninik Safrida: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Haris Al Hamdi: Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviation

| CPO | Crude palm oil |

| LCA | Life cycle assessment |

| XRD | X-ray diffractometer |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared |

| SEM-EDX | Scanning electron microscope-energy dispersive X-ray |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller |

| BJH | Barret–Joyner–Halender |

| ASTM | American standard testing and material |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

References

1. IEA. Global Energy Review 2021. IEA, Paris; 2021 [cited 2025 May 13]. Available from: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2021/oil. [Google Scholar]

2. Singh HKAG, Yusup S, Wai CK. Physicochemical properties of crude rubber seed oil for biogasoline production. Procedia Eng. 2016;148(1):426–31. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2016.06.441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Vilas Bôas TF, Barros RM, Pinto JA, dos Santos IFS, Lora EES, Andrade RV, et al. Energy potential from the generation of biogas from anaerobic digestion of olive oil extraction wastes in Brazil. Clean Waste Syst. 2023;4:100083. doi:10.1016/j.clwas.2023.100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Santoso A, Mulyaningsih A, Sumari S, Retnosari R, Aliyatulmuna A, Pramesti IN, et al. Catalytic cracking of off grade crude palm oil to biogasoline using Co-Mo/α-Fe2O3 catalyst. Energy Sour Part A Recover Util Environ Eff. 2023;45(1):1886–99. doi:10.1080/15567036.2023.2183998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Cloin J. Coconut oil as a biofuel in Pacific Islands—challenges and opportunities. SOPAC Miscellaneous Report 592; 2005. [Google Scholar]

6. US Energy Information Adminsitration (EIA). Country analysis executive summary: Canada. Washington, DC, USA: US Energy Inf. Adminsitration; 2022. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

7. KESDM. Team handbook energy & economic statistics Indonesia. The Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources [Internet]; 2021. p. 23–26. [cited 2025 May 13]. Available from: https://www.esdm.go.id/en/publication/handbook-of-energy-economic-statistics-of-indonesia-heesi. [Google Scholar]

8. Holechek JL, Geli HME, Sawalhah MN, Valdez R. A global assessment: can renewable energy replace fossil fuels by 2050? Sustainability. 2022;14(8):4792. doi:10.3390/su14084792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kober T, Schiffer H-W, Densing M, Panos E. Global energy perspectives to 2060—WEC’s World Energy Scenarios 2019. Energy Strateg Rev. 2020;31:100523. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2020.100523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Herawaty N, Rifdah R, Pratama MA. Pembuatan biogasoline dari limbah ampas tebu dan eceng gondok dengan proses thermal catalytic. J Distilasi. 2017;2(2):15–22. doi:10.32502/jd.v2i2.1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Xu W, Mou K, Zhou H, Xu J, Wu Q. Transformation of triolein to biogasoline by photo-chemo-biocatalysis††Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. Green Chem. 2022;24:6589–98. doi:10.1039/d2gc01992b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ge S, Ganesan R, Sekar M, Xia C, Shanmugam S, Alsehli M, et al. Blending and emission characteristics of biogasoline produced using CaO/SBA-15 catalyst by cracking used cooking oil. Fuel. 2022;307(4):121861. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2021.121861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Bharath G, Rambabu K, Hai A, Banat F, Taher H, Schmidt JE, et al. Catalytic hydrodeoxygenation of biomass-derived pyrolysis oil over alloyed bimetallic Ni3Fe nanocatalyst for high-grade biofuel production. Energy Convers Manag. 2020;213(12):112859. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2020.112859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ooi XY, Gao W, Ong HC, Lee HV, Juan JC, Chen WH, et al. Overview on catalytic deoxygenation for biofuel synthesis using metal oxide supported catalysts. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2019;112(2):834–852. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2019.06.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gollakota ARK, Shu C-M. Chapter 23—hydro-deoxygenation of biofuel. In: Shadangi KP, Sarangi PK, Mohanty K, Deniz I, Kiran Gollakota ARBT-BE, editors. Bioenergy engineering: fundamentals, methods, modelling, and applications. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing; 2023. p. 487–506. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-98363-1.00017-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Alam PP, Nugraha IWA, Ghozali M, Suminar DR. Pengaruh perbandingan katalis ZSM-5 dengan katalis alumina terhadap pembentukan biofuel dengan bahan baku minyak jelantah. Fluida. 2021;14(2):50–56. doi:10.35313/fluida.v14i2.2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hassan SN, Sani YM, Abdul Aziz AR, Sulaiman NMN, Daud WMAW. Biogasoline: an out-of-the-box solution to the food-for-fuel and land-use competitions. Energy Convers Manag. 2015;89(3):349–67. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2014.09.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mancio AA, da Costa KMB, Ferreira CC, Santos MC, Lhamas DEL, da Mota SAP, et al. Thermal catalytic cracking of crude palm oil at pilot scale: effect of the percentage of Na2CO3 on the quality of biofuels. Ind Crops Prod. 2016;91(1):32–43. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.06.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Han-U-Domlarpyos V, Kuchonthara P, Reubroycharoen P, Hinchiranan N. Quality improvement of oil palm shell-derived pyrolysis oil via catalytic deoxygenation over NiMoS/γ-Al2O3. Fuel. 2015;143:512–18. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2014.11.068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kirgizov A, Valieva G, Laskin A, Il’yasov I, Lamberov A. Development of (γ-Al2O3-Zeolite Y)/α-Al2O3-HPCM catalyst based on highly porous α-Al2O3-HPCM support for decreasing oil viscosity. Catalysts. 2020;10(2):250. doi:10.3390/catal10020250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Miao C, Zhou G, Chen S, Xie H, Zhang X. Synergistic effects between Cu and Ni species in NiCu/γ-Al2O3 catalysts for hydrodeoxygenation of methyl laurate. Renew Energy. 2020;153:1439–54. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2020.02.099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Henpraserttae S, Buarod E, Goodwin V, Saisirirat P, Yoosuk B, Chollacoop N. Enhancement of hydrodearomatization catalyst by brönsted acid site of Al2O3Support for clean diesel production. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2023;1199(1):012037. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/1199/1/012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wijanarko A, Mawardi DA, Nasikin M. Produksi biogasoline dari minyak sawit melalui reaksi perengkahan katalitik dengan katalis Γ-alumina. MAKARA Technol Ser. 2010;10(2):51–60. doi:10.7454/mst.v10i2.423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ratchahat S, Srifa A, Koo-amornpattana W, Sakdaronnarong C, Charinpanitkul T, Wu KC-W, et al. Syngas production with low tar content from cellulose pyrolysis in molten salt combined with Ni/Al2O3 catalyst. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2021;158(4):105243. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2021.105243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Li T, Long J, Zhao L, Du W, Qian F. A bilevel data-driven framework for robust optimization under uncertainty—applied to fluid catalytic cracking unit. Comput Chem Eng. 2022;166:107989. doi:10.1016/j.compchemeng.2022.107989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ibitoye SE, Mahamood RM, Jen T-C, Loha C, Akinlabi ET. An overview of biomass solid fuels: biomass sources, processing methods, and morphological and microstructural properties. J Bioresour Bioprod. 2023;8(4):333–60. doi:10.1016/j.jobab.2023.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Elfallah S, Benzaouak A, Bayssi O, Hirt A, Mouaky A, Fadili HEl, et al. Life cycle assessment of biomass conversion through fast pyrolysis: a systematic review on technical potential and drawbacks. Bioresour Technol Rep. 2024;26(6):101832. doi:10.1016/j.biteb.2024.101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Gan Yupanqui KR, Zeug W, Thrän D, Bezama A. A regionalized social life cycle assessment of a prospective value chain of second-generation biofuel production. J Clean Prod. 2024;472(8):143370. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Jozami E, Mele FD, Piastrellini R, Civit BM, Feldman SR. Life cycle assessment of bioenergy from lignocellulosic herbaceous biomass: the case study of Spartina argentinensis. Energy. 2022;254(2):124215. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.124215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Widyastuti, Zulfa LL, Safrida N, Ardhyananta H, Triwicaksono S, Kurniawansyah F, et al. Catalytic cracking of crude palm oil into biogasoline over HZSM-5 and USY-Zeolite catalysts: a comparative study. South African J Chem Eng. 2024;50(1):27–38. doi:10.1016/j.sajce.2024.07.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Bouter A, Duval-Dachary S, Besseau R. Life cycle assessment of liquid biofuels: what does the scientific literature tell us? A statistical environmental review on climate change. Biomass Bioenergy. 2024;190(311):107418. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2024.107418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Romero Toledo R, Ruiz Santoyo V, Anaya Esparza LM, Pérez Larios A, Martínez Rosales M. Study of arsenic (V) removal of water by using agglomerated alumina. Nov Sci. 2019;11(23):1–25. doi:10.21640/ns.v11i23.1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ahmed zeki NS, Hussein SJ, Aoyed KK, Ibrahim SK, Mehawee IK. Synthesis and characterization of Co-Mo/γ-Alumina catalyst from local kaolin clay for hydrodesulfurization of Iraqi Naphtha. J Pet Res Stud. 2021;11(1):84–106. doi:10.52716/jprs.v11i1.431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Urbonavicius M, Varnagiris S, Pranevicius L, Milcius D. Production of gamma alumina using plasma-treated aluminum and water reaction byproducts. Materials. 2020;13(6):1300. doi:10.3390/ma13061300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Meng F, Wang L, Li X, Perdjon M, Li Z. Mesoporous nano Ni-Al2O3 catalyst for CO2 methanation in a continuously stirred tank reactor. Catal Commun. 2022;164:106437. doi:10.1016/j.catcom.2022.106437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zulfa LL, Ediati R, Hidayat ARP, Subagyo R, Faaizatunnisa N, Kusumawati Y, et al. Synergistic effect of modified pore and heterojunction of MOF-derived α-Fe2O3/ZnO for superior photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. RSC Adv. 2023;13(6):3818–34. doi:10.1039/d2ra07946a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Liu Y, Hou Y, Han X, Wang J, Guo Y, Xiang N, et al. Effect of ordered mesoporous alumina support on the structural and catalytic properties of Mn−Ni/OMA Catalyst for NH3−SCR performance at low-temperature. ChemCatChem. 2020;12(3):953–62. doi:10.1002/cctc.201901466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Mostafa MS, El Naga AOA, Galhoum AA, Guibal E, Morshedy AS. A new route for the synthesis of self-acidified and granulated mesoporous alumina catalyst with superior Lewis acidity and its application in cumene conversion. J Mater Sci. 2019;54(7):5424–44. doi:10.1007/s10853-018-03270-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Japir AAW, Salimon J, Derawi D, Bahadi M, Al-Shuja’A S, Yusop MR. Physicochemical characteristics of high free fatty acid crude palm oil. OCL—Oilseeds Fats, Crop Lipids. 2017;24(5):D506. doi:10.1051/ocl/2017033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Silalahi D, Supeno M, Taufik M. Conversion of palm oil (CPO) into fuel biogasoline through thermal cracking using a catalyst based na-bentonite and limestone of soil limestone NTT. Int J Biol Phys Chem Stud. 2021;3(2):1–15. doi:10.32996/ijbpcs.2021.3.2.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wako FM, Reshad AS, Bhalerao MS, Goud VV. Catalytic cracking of waste cooking oil for biofuel production using zirconium oxide catalyst. Ind Crops Prod. 2018;118:282–9. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.03.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Muangsuwan C, Kriprasertkul W, Ratchahat S, Liu C-G, Posoknistakul P, Laosiripojana N, et al. Upgrading of light bio-oil from solvothermolysis liquefaction of an oil palm empty fruit bunch in glycerol by catalytic hydrodeoxygenation using NiMo/Al2O3 or CoMo/Al2O3 catalysts. ACS Omega. 2021;6(4):2999–3016. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c05387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Buyang Y, Suprapto S, Nugraha RE, Holilah H, Bahruji H, Hantoro R, et al. Catalytic pyrolysis of Reutealis trisperma oil using raw dolomite for bio-oil production. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2023;169(11):105852. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2022.105852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Muanruksa P, Winterburn J, Kaewkannetra P. Biojet fuel production from waste of palm oil mill effluent through enzymatic hydrolysis and decarboxylation. Catalysts. 2021;11(1):78. doi:10.3390/catal11010078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Gurdeep Singh HK, Yusup S, Quitain AT, Abdullah B, Ameen M, Sasaki M, et al. Biogasoline production from linoleic acid via catalytic cracking over nickel and copper-doped ZSM-5 catalysts. Environ Res. 2020;186:109616. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2020.109616. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Molefe M, Nkazi D, Mukaya HE. Method selection for biojet and biogasoline fuel production from castor oil: a review. Energy and Fuels. 2019;33(7):5918–32. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.9b00384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Kasetsupsin P, Vitidsant T, Permpoonwiwat A, Phowan N, Charusiri W. Combined activated carbon with spent fluid catalytic cracking catalyst and MgO for the catalytic conversion of waste polyethylene wax into diesel-like hydrocarbon fuels. ACS Omega. 2022;7(23):20306–20. doi:10.1021/acsomega.2c02301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Hasanudin H, Asri WR, Mara A, Muttaqii MAl, Maryana R, Rinaldi N, et al. Enhancement of catalytic activity on crude palm oil hydrocracking over SiO2/Zr assisted with potassium hydrogen phthalate. ACS Omega. 2023;8:20858–68. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c01569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Nugraha RE, Prasetyoko D, Nareswari NA, Aziz A, Holilah H, Bahruji H, et al. Jet-fuel range hydrocarbon production from Reutealis trisperma oil over Al-MCM-41 derived from Indonesian Kaolin with different Si/Al ratio. Case Stud Chem Environ Eng. 2024;10:100877. doi:10.1016/j.cscee.2024.100877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Wang J, Ding Z, Shi F, Chen Y, Hou D, Yang F, et al. Novel porous CaO-MgO-promoting γ-Al2O3-catalyzed selective hydrogenation of oleic acid to green hydrocarbon fuels in biogasoline range with methanol as an internal hydrogen source. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2023;173:106103. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2023.106103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Al-Muhtaseb AH, Jamil F, Myint MTZ, Baawain M, Al-Abri M, Dung TNB, et al. Cleaner fuel production from waste Phoenix dactylifera L. kernel oil in the presence of a bimetallic catalyst: optimization and kinetics study. Energy Convers Manage. 2017;146:195–204. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2017.05.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Al-Muhtaseb AH, Jamil F, Al-Haj L, Zar Myint MT, Mahmoud E, Ahmad MNM, et al. Biodiesel production over a catalyst prepared from biomass-derived waste date pits. Biotechnol Rep. 2018;20(1):e00284. doi:10.1016/j.btre.2018.e00284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Kim KD, Wang Z, Tao Y, Ling H, Yuan Y, Zhou C, et al. The comparative effect of particle size and support acidity on hydrogenation of aromatic ketones. ChemCatChem. 2019;11(19):4810–7. doi:10.1002/cctc.201900993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Hagelberg P, Alopaeus V, Lipiäinen K, Aittamaa J, Krause AOI. Mass and heat transfer effects in the kinetic modelling of catalytic cracking. In: Studies in surface science and catalysis. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2001. p. 165–71. doi:10.1016/S0167-2991(01)81959-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Istadi I, Riyanto T, Buchori L, Anggoro DD, Pakpahan AWS, Pakpahan AJ. Biofuels production from catalytic cracking of palm oil using modified HY zeolite catalysts over a continuous fixed bed catalytic reactor. Int J Renew Energy Dev. 2021;10(1):149–56. doi:10.14710/ijred.2021.33281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Akin O, Varghese RJ, Eschenbacher A, Oenema J, Abbas-Abadi MS, Stefanidis GD, et al. Van Geem, Chemical recycling of plastic waste to monomers: effect of catalyst contact time, acidity and pore size on olefin recovery in ex-situ catalytic pyrolysis of polyolefin waste. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2023;172(6223):106036. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2023.106036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Gerber M, Schneider N. Density of biogas digestate depending on temperature and composition. Bioresour Technol. 2015;192(3):172–176. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2015.05.061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Jahirul MI, Rasul MG, Chowdhury AA, Ashwath N. Biofuels production through biomass pyrolysis—a technological review. Energies. 2012;5(12):4952–5001. doi:10.3390/en5124952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Kovarik L, Bowden M, Szanyi J. High temperature transition aluminas in δ-Al2O3/θ-Al2O3 stability range: review. J Catal. 2021;393:357–68. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2020.10.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Ahmed HA, Altalhi AA, Elbanna SA, El-Saied HA, Farag AA, Negm NA, et al. Effect of reaction parameters on catalytic pyrolysis of waste cooking oil for production of sustainable biodiesel and biojet by functionalized montmorillonite/chitosan nanocomposites. ACS Omega. 2022;7(5):4585–94. doi:10.1021/acsomega.1c06518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Adoe DGH, Tarigan BV, Selan RN, Bistolen B. The effect of addtion bioethanol from palm fruit to calorific value gasoline and exhaust emissions of vehicle 4 stroke 125 cc. In: Prosiding SNTTM XVII; 2018 Oct 4–5; Nusa Tenggara Timur, Indonesia. p. 224–9. [Google Scholar]

62. Werkneh AA. Biogas impurities: environmental and health implications, removal technologies and future perspectives. Heliyon. 2022;8(10):e10929. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10929. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Bragança I, Sánchez-Soberón F, Pantuzza GF, Alves A, Ratola N. Impurities in biogas: analytical strategies, occurrence, effects and removal technologies. Biomass and Bioenergy. 2020;143(2605):105878. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2020.105878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Mujtaba MA, Kalam A, Masjuki HH, Gul M, Ahmed W, Soudagar MEM, et al. Chapter 2—comparative investigation of the suitability of fuel properties of oxygenated biofuels in internal combustion engines. In: Kumar N, Mathiyazhagan K, Sreedharan VR, Kalam MA.Advancement in oxygenated fuels for sustainable development: feedstocks and precursors for catalysts synthesis. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2023. p. 7–25. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-90875-7.00010-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Song H, Quinton KS, Peng Z, Zhao H, Ladommatos N. Effects of oxygen content of fuels on combustion and emissions of diesel engines. Energies. 2016;9(1):28. doi:10.3390/en9010028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Vogt ETC, Weckhuysen BM. Fluid catalytic cracking: recent developments on the grand old lady of zeolite catalysis. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44(20):7342–70. doi:10.1039/c5cs00376h. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Sendzikiene E, Makareviciene V, Janulis P. Influence of fuel oxygen content on diesel engine exhaust emissions. Renew Energy. 2006;31(15):2505–12. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2005.11.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Chen W-H, Lin B-J, Lin Y-Y, Chu Y-S, Ubando AT, Show PL, et al. Progress in biomass torrefaction: principles, applications and challenges. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2021;82(Part 2):100887. doi:10.1016/j.pecs.2020.100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Zhu L, Chen J, Liu Y, Geng R, Yu J. Experimental analysis of the evaporation process for gasoline. J Loss Prev Process Ind. 2012;25(6):916–22. doi:10.1016/j.jlp.2012.05.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Sidheshware RK, Ganesan S, Bhojwani V. Experimental investigation on the viscosity and specific volume of gasoline fuel under the magnetisation process. Int J Ambient Energy. 2022;43(1):486–91. doi:10.1080/01430750.2019.1653987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Rabie AM, Mohammed EA, Negm NA. Feasibility of modified bentonite as acidic heterogeneous catalyst in low temperature catalytic cracking process of biofuel production from nonedible vegetable oils. J Mol Liq. 2018;254(1):260–66. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2018.01.110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Imtenan S, Masjuki HH, Varman M, Kalam MA, Arbab MI, Sajjad H, et al. Impact of oxygenated additives to palm and jatropha biodiesel blends in the context of performance and emissions characteristics of a light-duty diesel engine. Energy Convers Manag. 2014;83:149–58. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2014.03.052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Jing Q, Wang D, Liu Q, Liu C, Wang Z, He Z, et al. Deflagration evolution characteristic and chemical reaction kinetic mechanism of JP-10/DEE mixed fuel in a large-scale tube. Fuel. 2022;322:124238. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2022.124238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Speight JG. Gas condensate. In: Natural gas. 2nd ed. Boston, MA, USA: Gulf Professional Publishing; 2019. p. 325–58. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-809570-6.00009-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Panarmasar N, Hinchiranan N, Kuchonthara P. Catalytic hydrotreating of palm oil for bio-jet fuel production over Ni supported on mesoporous zeolite. Mater Today Proc. 2022;57(2016):1082–87. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2021.09.385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Vu XH, Armbruster U. Catalytic cracking of triglycerides over micro/mesoporous zeolitic composites prepared from ZSM-5 precursors with varying aluminum contents. React Kinet Mech Catal. 2018;125(1):381–94. doi:10.1007/s11144-018-1415-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Zikri A, Puspita I, Erlinawati MS, Agus PL, Zalita PBE, Andre K. In: Production of Green Diesel From Crude Palm Oil (CPO) Through Hydrotreating Process by Using Zeolite Catalyst BT—Proceedings of the 4th Forum in Research, Science, and Technology (FIRST-T1-T2-2020). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Atlantis Press; 2021. p. 67–74. doi:10.2991/ahe.k.210205.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Dincer I, Zamfirescu C. Chapter 1—fundamentals of thermodynamics. In: Dincer I, Zamfirescu CBT-APGS, editors. Boston, MA, USA: Elsevier; 2014. p. 1–53. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-383860-5.00001-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Kohse-Höinghaus K. Combustion in the future: the importance of chemistry. Proc Combust Inst. 2021;38(1):1–56. doi:10.1016/j.proci.2020.06.375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Ziva AZ, Suryana YK, Kurniadianti YS, Ragadhita R, Nandiyanto ABD, Kurniawan T. Recent progress on the production of aluminum oxide (Al2O3) nanoparticles: a review. Mech Eng Soc Ind. 2021;1(2):54–77. doi:10.31603/mesi.5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Manzetti S, Andersen O. A review of emission products from bioethanol and its blends with gasoline. Background for new guidelines for emission control. Fuel. 2015;140(11):293–301. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2014.09.101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Shearian Sattari M, Ghobadian B, Gorjian S. A critical review on life-cycle assessment and exergy analysis of Enomoto bio-gasoline production. J Clean Prod. 2022;379(4):134387. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Gaur VK, Sharma P, Sirohi R, Awasthi MK, Dussap C-G, Pandey A. Assessing the impact of industrial waste on environment and mitigation strategies: a comprehensive review. J Hazard Mater. 2020;398(2):123019. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Emmanuel O, Rozina, Ezeji TC. Utilization of biomass-based resources for biofuel production: a mitigating approach towards zero emission. Sustain Chem One World. 2024;2(6):100007. doi:10.1016/j.scowo.2024.100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Ahmed FE. Toxicology and human health effects following exposure to oxygenated or reformulated gasoline. Toxicol Lett. 2001;123(2–3):89–113. doi:10.1016/S0378-4274(01)00375-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools