Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Review: Functionalized Renewable Natural Fibers as Substrates for Photo-Driven Desalination, Photocatalysis, and Photothermal Biomedical Applications in Sustainable Photothermal Materials

1 Jiangsu Province Key Laboratory of Fine Petrochemical Engineering, Changzhou University, Changzhou, 213164, China

2 School of Materials Science and Engineering, Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Nanjing, 210023, China

3 Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Advanced Catalytic Materials and Technology, School of Petrochemical Engineering, Changzhou University, Changzhou, 213164, China

* Corresponding Authors: Man Zhou. Email: ; Zhongyu Li. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(10), 1993-2041. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0065

Received 18 March 2025; Accepted 25 June 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

Natural fibers, as a typical renewable and biodegradable material, have shown great potential for many applications (e.g., catalysis, hydrogel, biomedicine) in recent years. Recently, the growing importance of natural fibers in these photo-driven applications is reflected by the increasing number of publications. The utilization of renewable materials in photo-driven applications not only contributes to mitigating the energy crisis but also facilitates the transition of society toward a low-carbon economy, thus enabling harmonious coexistence between humans and the environment within the context of sustainable development. This paper provides an overview of the recent advances of natural fibers which acted as substrates or precursors to construct an efficient system of light utilization. The different chemical properties and pretreatment methods of cellulose affect its performance in final photo-driven applications, including solar-driven water purification, photocatalysis, and photothermal biomedical applications. Nevertheless, current research rarely conducts a comprehensive comparison of them from a broad perspective. As a whole, this review first reveals the different structural advantages as well as the matching degree between natural fibers (bacterial cellulose, plant cellulose, and animal fiber) and three typical photo-driven applications. Besides, new strategies for optimizing the utilization of natural fibers are an important subject under the background of low-carbon and circular economy. Finally, some suggestions and prospects are put forward for the limitations and research prospects of natural fibers in photo-driven applications, which provides a new idea for the synthesis of renewable functional materials.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Over the course of billions of years of Earth’s natural history, the growth and reproduction of natural animals and plants have relied on solar energy, a key driver in maintaining their life cycles. This evolutionary optimization has enabled highly efficient light-to-chemical energy conversion in natural systems. However, yet human-engineered solar technologies (solar thermal, photovoltaic, photoelectric) currently lag in mimicking such efficiency at both macro and micro scales. While global integration of solar energy technologies has increased steadily over recent decades [1], challenges persist in scaling sustainable, cost-effective photo-driven applications for real-world demands like water desalination, medical therapy, and controlled drug release [1–3]. Obviously, solar light-dependent technologies play a critically important role in aligning modern human activities with low-carbon principles. Generally, photo-driven applications have attracted substantial development and marketing efforts in view of the low-carbon characteristics. Photo-driven applications are those that harness the power of light to perform specific functions such as generating changes in surface properties, detecting sub-bandgap rays, or enabling the movement of robotic components. These technologies utilize light energy to drive chemical and physical processes, with advantages such as high efficiency, low environmental impact, and potential for renewable energy integration. Therefore, in the context of current environmental challenges, photo-driven technologies are becoming increasingly important.

To fully unleash the potential of photo-driven technologies, the selection and optimization of substrates cannot be ignored. Different types of substrate materials have emerged in the last couple of decades, which can be broadly categorized into organic [4–6] (e.g., sponge, organic resin, polymer), inorganic [7,8] (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), metal oxides), and biomass [9]. Compared with natural biomass, most of these artificial materials have limited applicability due to their high cost, non-biodegradability, complex synthesis conditions, insufficient scalability, etc. [10]. More importantly, almost all the artificial materials are non-renewable due to the lack of natural recycling processes.

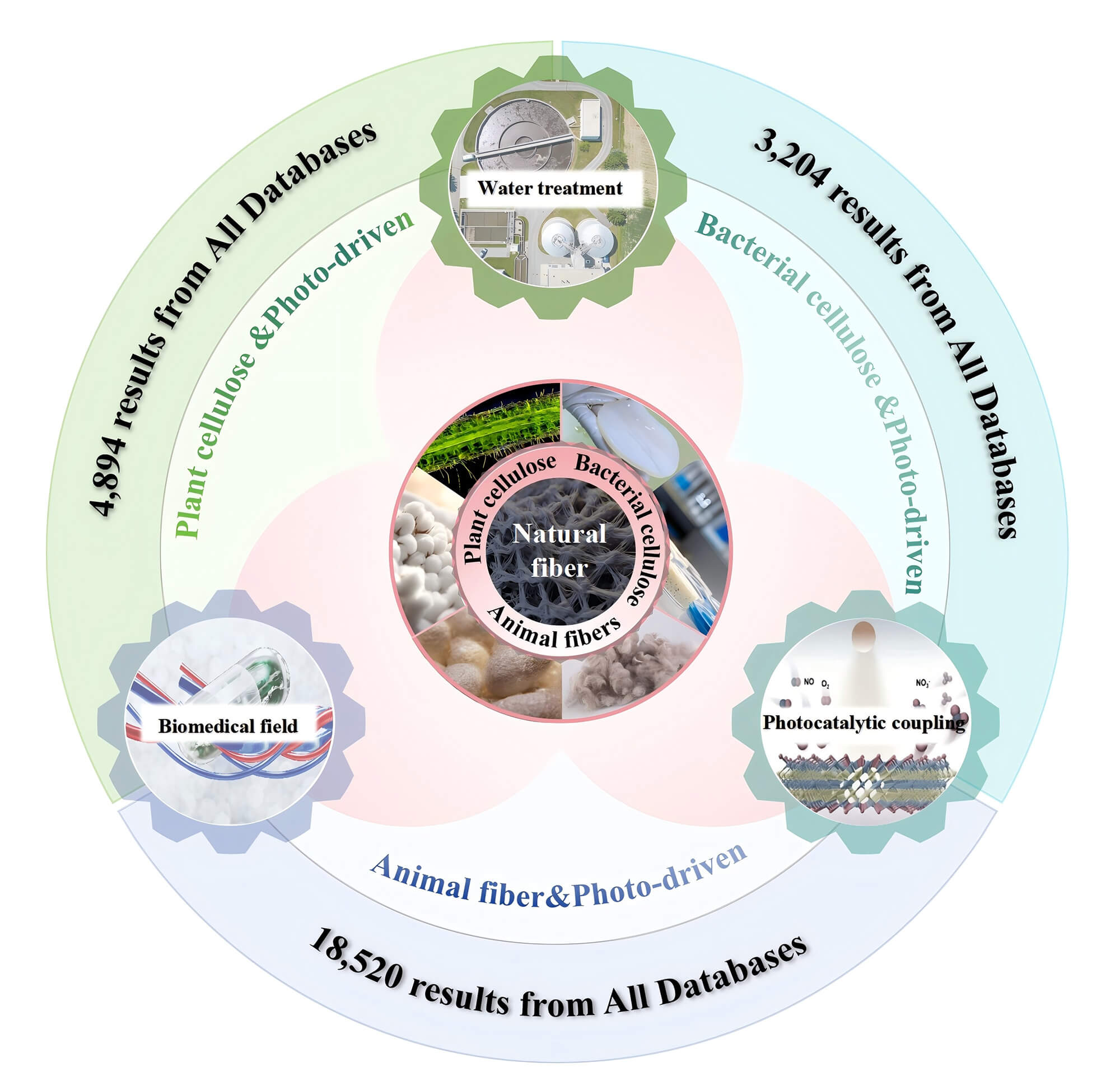

As detailed in Table 1, natural fibers exhibit significant advantages over synthetic fibers, particularly in terms of material cost (USD/kg), when quantitatively evaluated for optical drive applications. As a typical one-dimensional structure, natural fibers have gradually emerged as a superior substrate material for many technologies (e.g., energy conversion, catalysis, and biomedical applications). Natural fibers can be extracted from three different sources: plants, animals, and minerals [11]. Plant fibers are derived from bast, leaf, seed, fruit, wood, stalk, grass, and reed. They contain cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [12–14]. Plant cellulose (PC) is the most common and is widely present in plants such as cotton, wood, and hemp, serving as the main component of plant cell walls [15]. For example, PC in cotton fibers has a high degree of polymerization and regularity, as well as a high degree of crystallinity (about 70%–80%), which determines its wide application in the textile field [16]. In addition, bacterial cellulose (BC), produced by specific microorganisms, belongs to natural fibers and has unique nanofiber structures and high-purity characteristics [17,18]. BC exhibits high surface areas, strong adsorption capacities, and outstanding morphological characteristics, with Specific surface areas up to 220 m2/g have been reached [19]. This characteristic makes BC have great potential in the field of adsorption. Animal fibers are relatively rare, as found in the exoskeletons of certain marine organisms. The cellulose obtained from the tunic of sea squirts has been used as a material for membranes, in particular, membranes for regenerative medicine [20]. In terms of structural characteristics, natural cellulose exhibits a linear polymer morphology composed of glucose units connected by β-1,4-glycosidic bonds [21]. These molecular chains intertwine and aggregate with each other, forming highly ordered microfibril structures that bestow cellulose with excellent mechanical properties [22]. Meanwhile, the abundant hydroxyl groups on the cellulose molecular chain not only endow it with hydrophilicity, but also provide numerous active sites for subsequent chemical modifications [23]. Based on the above characteristics, natural cellulose is gradually playing a key role in hot research areas such as water treatment, photocatalysis, and biomedical field (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Schematic of nature fibers classification and photo-driven applications

As is well known, natural cellulose is not only an irreplaceable structure in plants, but also a fascinating biopolymer with special importance in both industry and daily life. In the past decades, the design and development of renewable resources and innovative products have led to a global revival of interdisciplinary research and utilization in material science, biomedicine, energy storage materials, etc. As a famous natural polymer, cellulose is low-cost [25,26] and sustainable [27,28] material with good physicochemical properties [29,30]. For instance, cellulose exhibits outstanding hydrophilicity [31], which bestows it with excellent biocompatibility for applications in biomedical fields and photo-driven technologies [32,33]. Furthermore, the biodegradability of cellulose is a significant advantage [34]. Unlike synthetic polymers, which may pose long-term environmental risks due to their non-biodegradable nature, cellulose can naturally decompose, thereby reducing the final pollution and waste [35]. This eco-friendly characteristic aligns with the current global trend of promoting green chemistry and sustainable production. Moreover, various modified cellulose-based materials using diverse chemical and physical approaches open up a broad spectrum of opportunities for many specific application requirements. This adaptability in design and functionality further amplifies the versatility of cellulose as an ideal substrate for photo-driven technologies.

This review focuses on sustainable natural cellulose, revealing its complex structural characteristics and properties, while exploring effective pretreatment and purification methods that can better utilize the unique advantages of natural cellulose in photo-driven fields such as desalination, photocatalysis, and photothermal biomedical applications. The aim is to provide a comprehensive analysis of how cellulose can be harnessed in the burgeoning field of photo-driven technologies (such as processing techniques, material modifications, and real-world applications), examining cellulose’s unique application modes and the distinct advantages. This review aims to explore the structural features, modifications, and applications of natural cellulose in photo-driven technologies, offering insights into its role in sustainable material innovation.

2 Structural Characteristics and Pretreatments of Natural Fibers

Natural fibers or cellulose are primarily derived from natural plants or animals [11]. Their environmental friendliness and biodegradability have attracted great interest from numerous academics worldwide in utilizing natural fibers in composites. The structure and chemical properties of natural fibers, such as crystallinity, purity, and porosity, directly affect their applicability in photo-driven applications. In solar desalination, fibers with high porosity and surface area can promote water transport and improve the efficiency of solar energy conversion. For photothermal biomedical applications, the stiffness and strength of natural fibers can ensure the stability of composite materials under high temperature conditions. However, natural fibers often contain various impurities during their formation and acquisition. For example, natural BC may contain culture medium components as well as residual bacterial cells. Natural PC contains impurities such as lignin, hemicellulose, pectin, and so on. The presence of impurities may interfere with the interactions between natural fiber molecules, affecting their physical properties and reducing their performance in photo-driven applications.

The pretreatment of natural fibers can significantly improve their performance in photo-driven applications. For instance, removing lignin from natural fibers can increase their surface area and porosity, thereby enhancing their photocatalytic activity. High-purity fibers allow for uniform and controllable chemical modifications, such as esterification, etherification, and grafting. These modifications can also improve the interfacial compatibility between natural fibers and other components in composite materials, further enhancing their performance in solar desalination and photothermal biomedical applications. Therefore, it is essential to analyze the structural characteristics and pretreatments of natural fibers to optimize their performance in photo-driven applications.

Brown announced the first report of cellulose production from bacteria, specifically from Acetobacter xylinum, in 1886. Recent studies have revealed that various bacteria, including both Gram-negative species such as Acetobacter, Azotobacter, Rhizobium, Agrobacterium, Pseudomonas, Salmonella, and Alcaligenes, as well as Gram-positive species like Sarcina, and ventriculi, are capable of producing bacterial cellulose (BC) [36]. BC fibers produced by different bacteria exhibit distinct morphologies, structures, properties, and applications. Usually, BC fibers can be synthesized by the bacteria cultivated in static and dynamic state in the laboratory. The static state results in the accumulation of a gelatinous membrane of cellulose at the surface of the nutrient solution [37], whereas the agitated/shaking state results in irregular products such as asterisk-like, sphere-like, pellet-like, etc. The specific morphological differences are shown in Table 2. The choice of method depends on the final applications of BC as well as the physical, morphological, and mechanical characteristics required.

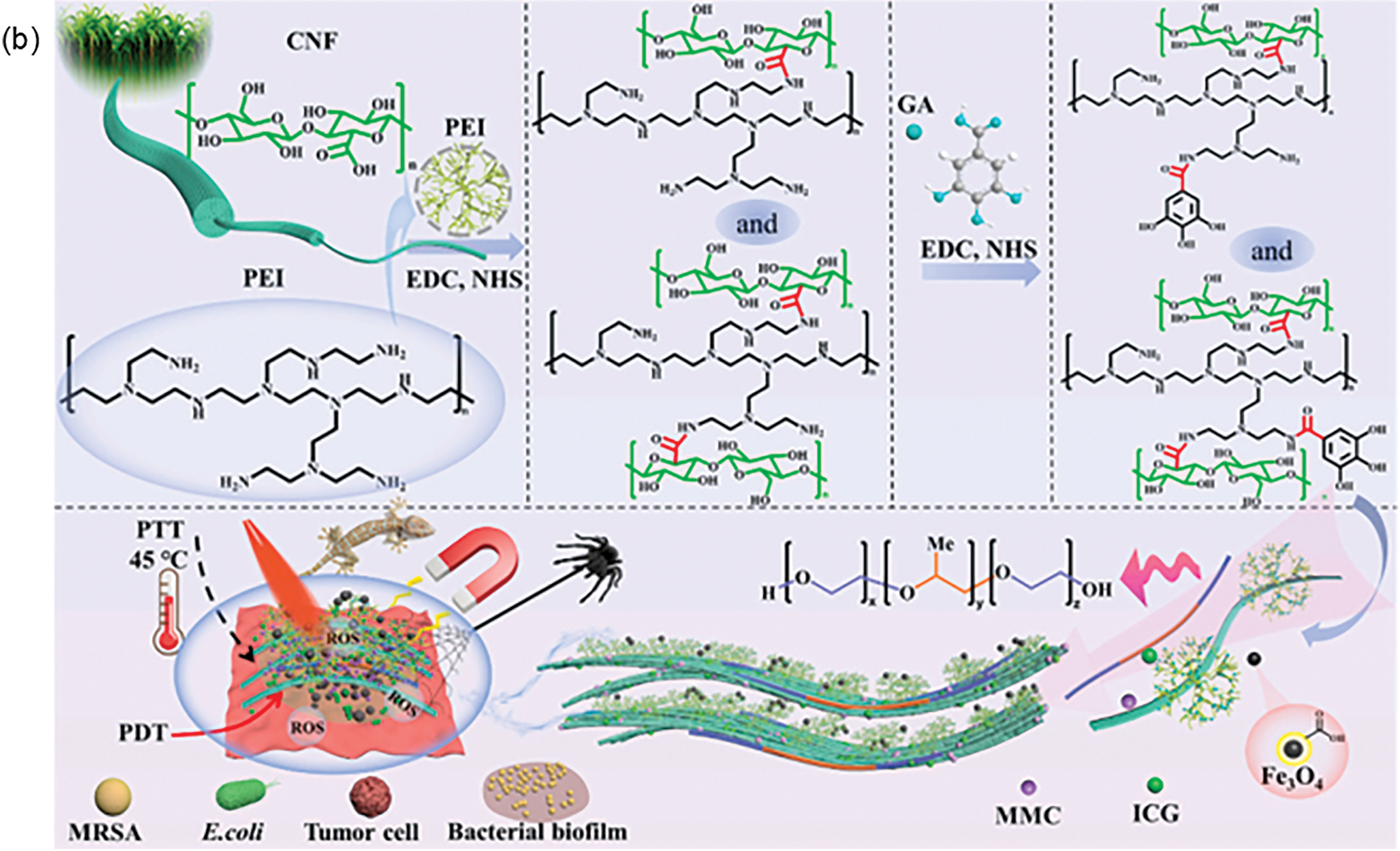

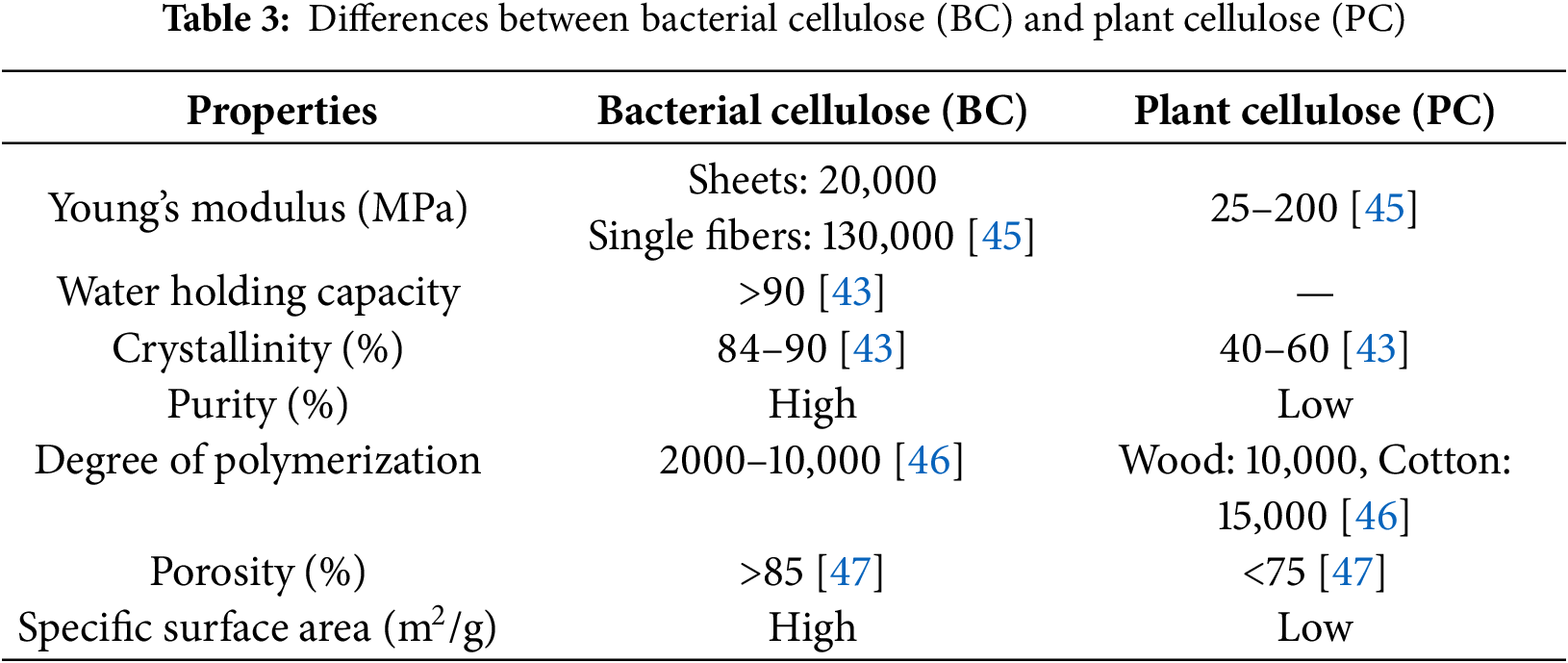

The degree of BC typically ranges from 2000 to 6000, whereas plant cellulose has a higher degree of polymerization, ranging from 13,000 to 14,000 [40]. As illustrated in Table 3, despite both BC and plant cellulose having the same molecular formula, of (C6H10O5)n, they display significant differences in their physicochemical properties [41]. BC has a chemical structure similar to that of PC but lacks organic impurities such as lignin and hemicellulose, making it easy to purify and modify [42]. Due to its unique synthesis mechanism, BC exhibits a series of special structural features and properties, including high purity, high crystallinity (84%–90%) [43], high water holding capacity (90%–99%) [43], and high mechanical stability [44]. These remarkable physicochemical properties have garnered considerable interest from both research scientists and industrialists. To date, BC has found extensive applications in various fields, including medicine, food, and advanced acoustic diaphragms, among others.

From production to purification, the methodology of BC preparation significantly influences various parameters and properties, such as crystallinity index, porosity, cellulose concentration, thermal resistance, and mechanical resistance. Cultivating specific bacterial strains (e.g., Komagataeibacter xylinus, Gluconacetobacter hansenii, and Gluconacetobacter xylinus) in an appropriate culture medium under controlled conditions is essential for achieving high yields of BC. Factors such as temperature, pH level, dissolved oxygen, stirring condition, and the choice of containers or bioreactors can also significantly impact the production of BC. It is known that unpurified BC contains some impurities, which are primarily derived from bacterial cell fragments. Typical impurities include proteins, by-products (e.g., acetic acid) and other cellular remnants such as lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) [41]. These impurities exert numerous detrimental effects on the performance of bacterial cellulose. Residual components from the culture medium and bacterial cells can disrupt the uniformity of its cellulose network structure, thereby diminishing the tensile strength and elastic modulus. Proteins and lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) have the potential to heighten cytotoxicity, elicit immune responses, and diminish their application value within the biomedical domain. Moreover, impurities can also occupy active sites, thereby curtailing their application efficacy across various fields. Presently, several technologies including washing, bleaching, and chemical treatment are employed to remove impurities before obtaining high-purity BC. According to the rich density of hydroxyl groups on the surface, BC fibers can be easily modified to achieve alternative functional groups and functionalization modes [44].

BC serves as an optimal substrate for integrating photoactive materials [39] due to its abundant surface hydroxyl groups, which enable uniform dispersion and stable loading of metal nanoparticles (e.g., gold, silver, zinc, etc.) [48,49] and dye molecules [50,51] via chemical bonding or physical adsorption. This enhances the photoresponsive properties of the composite materials, making them suitable for photo-driven applications. It is worth noting that the high porosity of BC facilitates the controlled release of substances [38], making it highly significant in the fields of photothermal biomedical applications and drug delivery. BC exhibits excellent biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity, rendering it highly suitable for biomedical applications [41]. Its three-dimensional porous network structure and nanofiber properties enable it to support cell adhesion and proliferation while promoting tissue regeneration. Moreover, this structure allows BC to be readily combined with various photothermal or photodynamic conversion materials [52], thereby demonstrating enormous potential for applications in biomedical photo-driven fields. The architecture and pretreatment methodologies of bacterial cellulose provide a fundamental framework for comprehending the properties of natural fibers. Subsequently, we will delve into plant cellulose, which similarly holds a significant position in the realm of natural fibers.

The primary component of plant fiber is cellulose, along with a small number of hemicellulose and lignin. Take cotton fibers for example, the content of extracted lignin and hemicellulose is negligible. Actually, the amount of cellulose varies depending on the source of extraction. For instance, the cellulose content derived from various hardwood species ranges from 33% to 42%, whereas that from different coniferous tree species ranges from 38% to 51%. In contrast, the cellulose content in herbaceous plants varies significantly, ranging from 25% to 95%. The content of cellulose has been found to be comparatively higher in pineapple, ramie, flax, jute, curaua, and kenaf fibers than in other types of natural fibers [53].

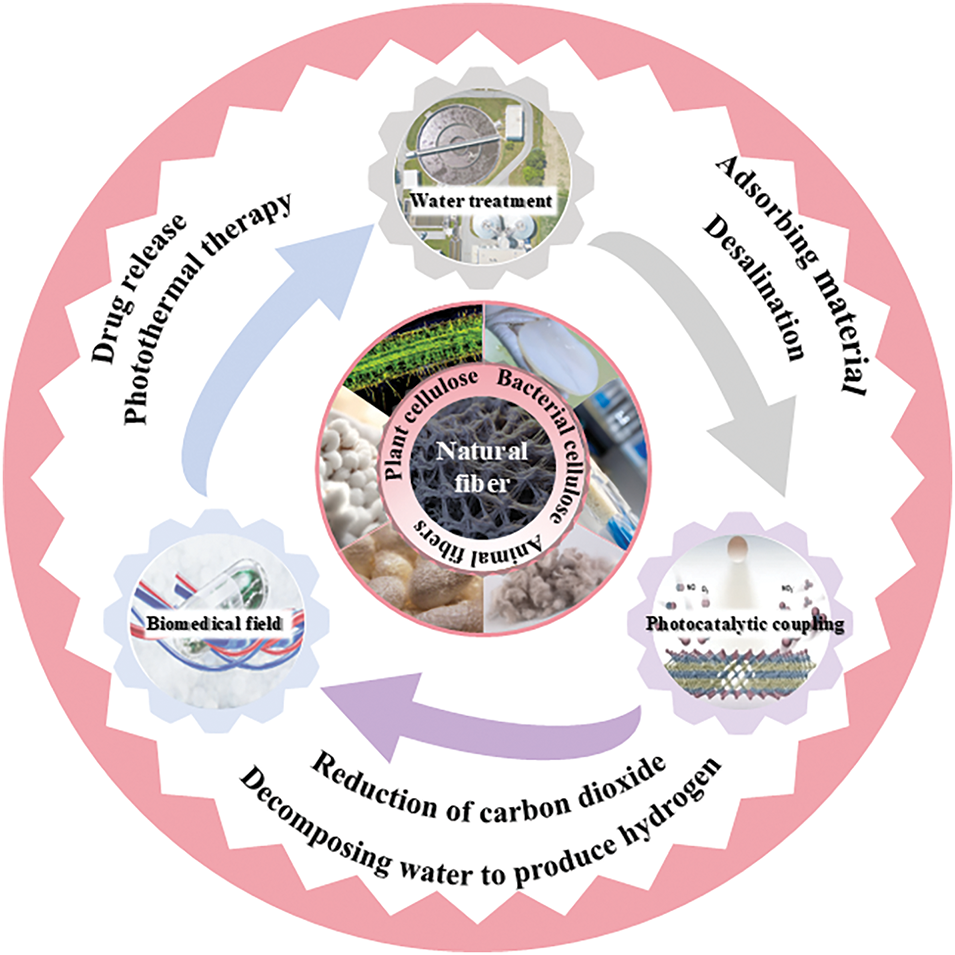

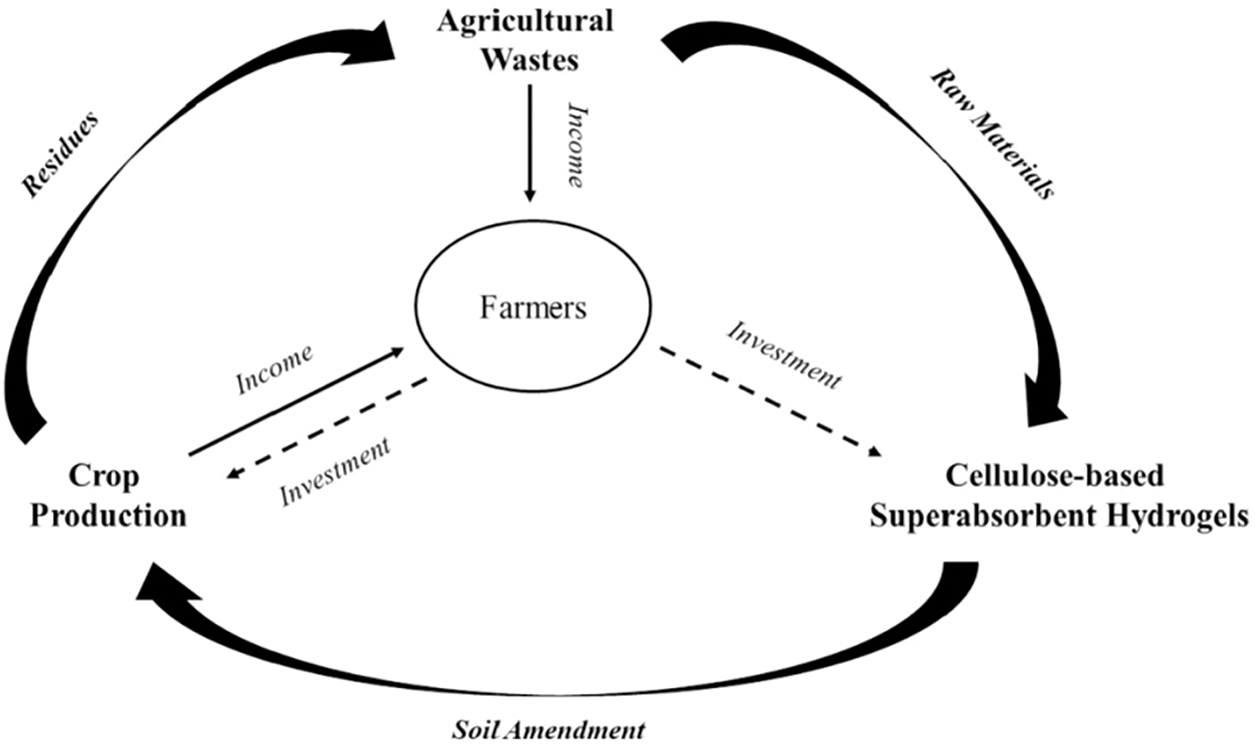

Cellulose is an unbranched linear polymer composed of cellobiose repeating units (C6H10O5)n linked by β-1,4-glycosidic bonds (Fig. 2) [54,55]. The hydroxyl groups on C-1 and C-4 of adjacent glucose molecules are joined by ether bonds following dehydration, resulting in cellobiose, which measures approximately 1.03 nm in length. Subsequently, numerous cellobiose molecules are linked together in a head-to-tail fashion to create a cellulose macromolecular chain. Through both inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonds between cellulose molecular chains, the cellulose macromolecular chains in plants are organized into elementary fibrils with cross-sectional widths ranging from 3–5 nm and lengths extending over several hundred nanometers [55].

Figure 2: (a) Structure of cellulose molecule, indicating the repeating cellulose unit, the non-reducing and reducing ends of the chain [54]; (b) Molecular model of cellobiose [55] Copyright © 2023, Elsevier Ltd.

Through top-down pretreatment techniques [56], such as dilute acid prehydrolysis, recoverable organic acid treatment, or deep eutectic solvent cracking, lignin and hemicellulose are depolymerized or dissolved, thereby extracting cellulose from plants in the form of visible microfibers of about tens of microns. Lignin and hemicellulose can interfere with light absorption, and their structural characteristics lead to light scattering and energy loss. In addition, their presence causes uneven fiber surfaces, thereby weakening the adhesion of functional coatings. After removing lignin and hemicellulose through pretreatment, the crystallinity of the material increases and the specific surface area increases [57,58]. This not only improves the light absorption performance, but also provides more active sites for functional coatings, which is of great significance for the development of high-performance light driven application materials.

The pretreatment methods for extracting cellulose from plants include extraction by alkaline treatment, extraction by ultrasound, extraction by microwave irradiation, and extraction using enzymes, among others (Table 4). While traditional alkali and acid treatment processes are well-established, they produce substantial chemical wastewater that can harm the environment and necessitate elevated temperature and pressure conditions [59], leading to significant energy consumption. In contrast, eutectic solvent extraction and enzymatic treatment [60] offer more environmentally-friendly alternatives. However, they are confronted with challenges regarding solvent recovery and relatively long reaction times. Although ultrasound and microwave irradiation [60] technologies typically operate under mild conditions with lower energy consumption, they are associated with relatively high equipment costs. The effects of different pretreatment on cellulose are shown in Table 5. Combining two or more of these preprocessing methods can fully leverage their respective advantages and improve the preprocessing effect. Choosing the appropriate pretreatment method is crucial for the effective utilization of PC, which requires comprehensive consideration of various factors such as raw material characteristics, treatment costs, environmental impact, and subsequent applications.

In our further exploration of the diversity of natural fibers, animal fibers stand out with their distinctive protein-based structures. Animal fibers derived from animal hair or secretions, primarily consisting of hair fibers and glandular secretion fibers (Fig. 3). Common examples include wool, silk, and spider silk. As shown in Fig. 3, the source of animal fibers covers both mammalians (e.g., rabbit, sheep, goat, etc.) and insects (e.g., silkworm, spider, etc.).

Figure 3: Sources of different types of animal fibers

The length of wool can range from 38 to 380 mm, but its specific length depends on the breed, for instance the significant difference in wool length between sheep and goats. The unique properties of wool include low moisture content, fire resistance, and excellent insulation. Additionally, its recyclability and cost-effectiveness further enhance its potential for diversified applications in modern composite materials. The significant elongation and durability of sheep wool fibers can be attributed to their keratin content [79]. Keratin has a special helical structure and tight molecular arrangement, which endows wool fibers with good mechanical properties and chemical stability. In functional composite materials, the compatibility and adhesion between keratin and the polymer matrix can be significantly enhanced through chemical modifications, such as grafting and cross-linking [80], as well as through physical blending [81]. These approaches effectively improve the overall performance of the composite materials. However, it is important to note that keratin-based biocomposites often exhibit poor optical properties [82]. Further research is required to enhance the overall performance of the final product.

Besides wool fibers, silk is a naturally occurring biomaterial composed of fibroin and sericin, exhibiting excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, blood compatibility, and good mechanical properties [83]. Silk fiber is mainly composed of silk fibroin and silk protein. As the main component of silk, silk fibroin is composed of a large number of amino acid residues connected by peptide bonds, forming a β-folded layered structure and a random coiled structure. This β-folding layer structure gives silk high-strength and wear-resistance, while the random curling structure endows silk with certain flexibility and elasticity. Silk fibroin is wrapped around the outer layer of silk fibroin to achieve protecting effect. It has a relatively loose molecular structure, which is consisted of hydrophilic amino acid residues. Silk fibroin can interact with the polymer matrix in functional composite materials through physical mixing and chemical cross-linking [84]. Meanwhile, the functional groups of silk fibroin can form covalent bonds with inorganic phases, enabling the design of scaffolds with specific patterns and fine-tunable porosity [85]. These characteristics make silk fibroin have broad application prospects in biomedical, environmental remediation, and energy conversion fields, especially in tissue engineering and drug delivery systems.

Similarly, spider silk as another type of natural biological fiber, has garnered extensive research interest due to its exceptional properties, including high tensile strength, excellent thermal conductivity, supercontraction, and unique rotational actuatio [86]. Moreover, spider silk exhibits remarkable thermal conductivity, excellent light transmission, and outstanding biocompatibility. Its thermal conductivity can reach up to 416 W/(m·K) and increases as the strain increases [87]. These excellent properties make spider silk an attractive biomaterial. Spidroins are high-molecular-weight proteins, typically ranging from 250 to 400 kDa, with variable sequences. They usually consist of a highly repetitive sequence segment, flanked by amino- and carboxyl-terminal domains. The sequence and secondary structure of spider silk, such as the β-sheet and α-helix, are highly correlated with their specific mechanical properties [87]. The high thermal conductivity of spider silk facilitates efficient heat transfer within solar photothermal conversion systems, thereby enhancing energy conversion efficiency. Its excellent biocompatibility ensures seamless integration with biological tissues, enabling stable performance in bio-optoelectronic applications such as biosensors. These unique properties render spider silk a promising candidate for advancing both efficient, sustainable energy technologies and innovative biomedical solutions. However, the utilization of spider silk proteins remains limited, partly due to the low silk yield from spiders. Moreover, the intricate relationship between the structure of spider silk proteins and their properties is not yet fully understood. This gap in knowledge means that most bioinspired and biomimetic approaches struggle to replicate the nanoscale properties of spider silk proteins in macroscopic materials as effectively as nature does [88].

The molecular structures and mechanical properties of key proteins in the above three different animal fibers were summarized, as shown in Table 6.

The usability of plant cellulose has been significantly enhanced through alkali treatment and enzymatic hydrolysis technology. In contrast, in the realm of animal fibers, the core challenge of pretreatment has shifted to how to gently remove impurities while preserving the natural properties of protein fibers. During the growth and collection of wool, oils, dust, and plant-based impurities may be introduced. These impurities can greatly affect the biocompatibility of wool. Similarly, silk contains impurities such as pigments and waxy substances, which are generated during the cocoon formation process and can reduce the comfort and biocompatibility of silk. Additionally, impurities in spider silk, like host cell proteins and endotoxins, mainly originate from the biosynthesis process. Their presence can interfere with the formation of spider silk fibers and diminish their application value in the biomedical field. To address these challenges, pretreatment methods for animal fibers, especially wool fibers, have been developed. These methods encompass physical processes such as cutting, grading, sorting, washing, carding, and spinning, as well as technical means like chemical modification pretreatment and biological enzyme pretreatment. However, the pretreatment of animal fibers is a complex and crucial process. Different animal fibers and application fields often require a combination of various methods and processes to precisely ensure the quality and performance of the final product and maximize the value of the fibers.

3 Photo-Driven Applications and Recovery of Natural Cellulose-Based Materials

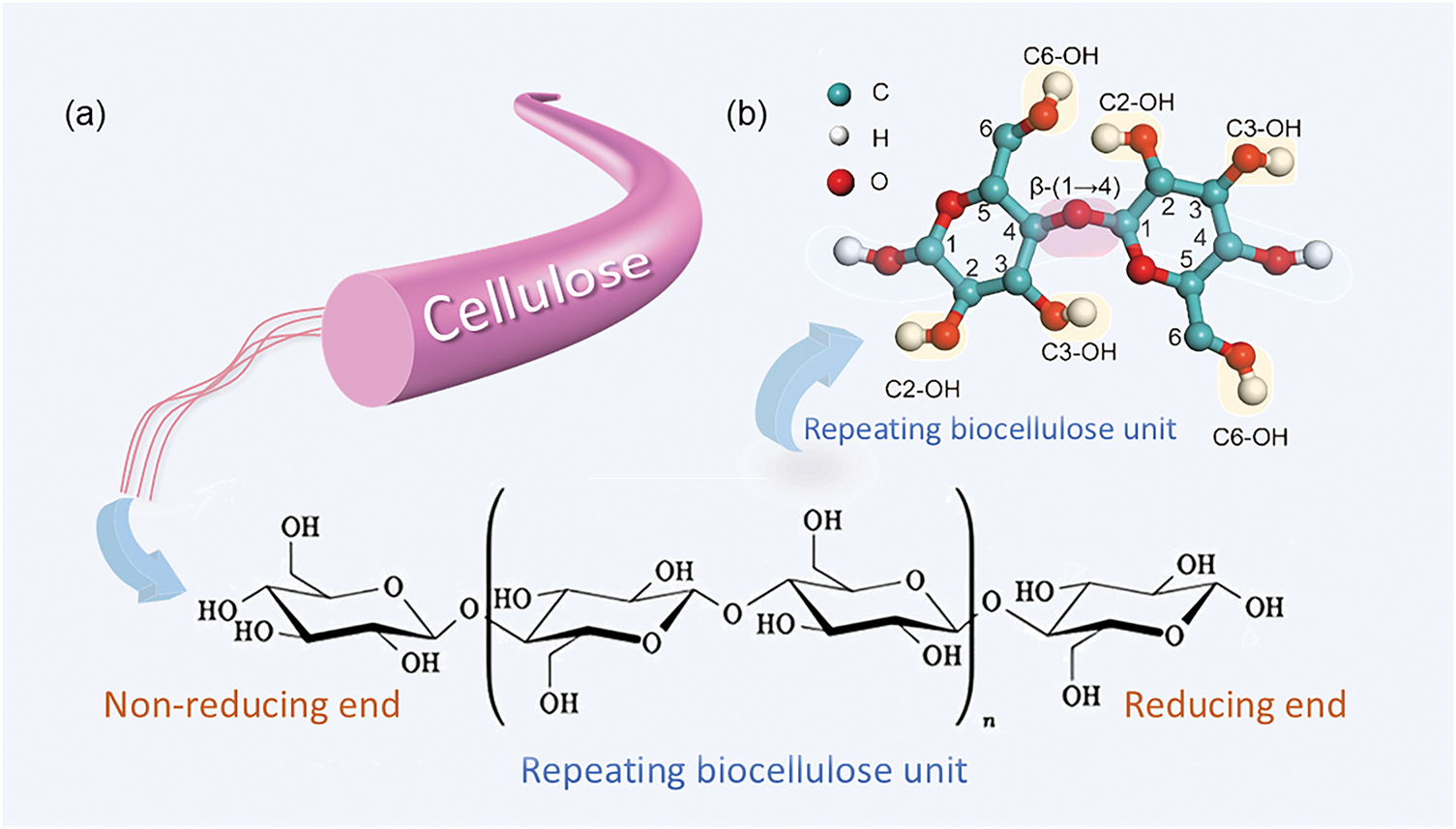

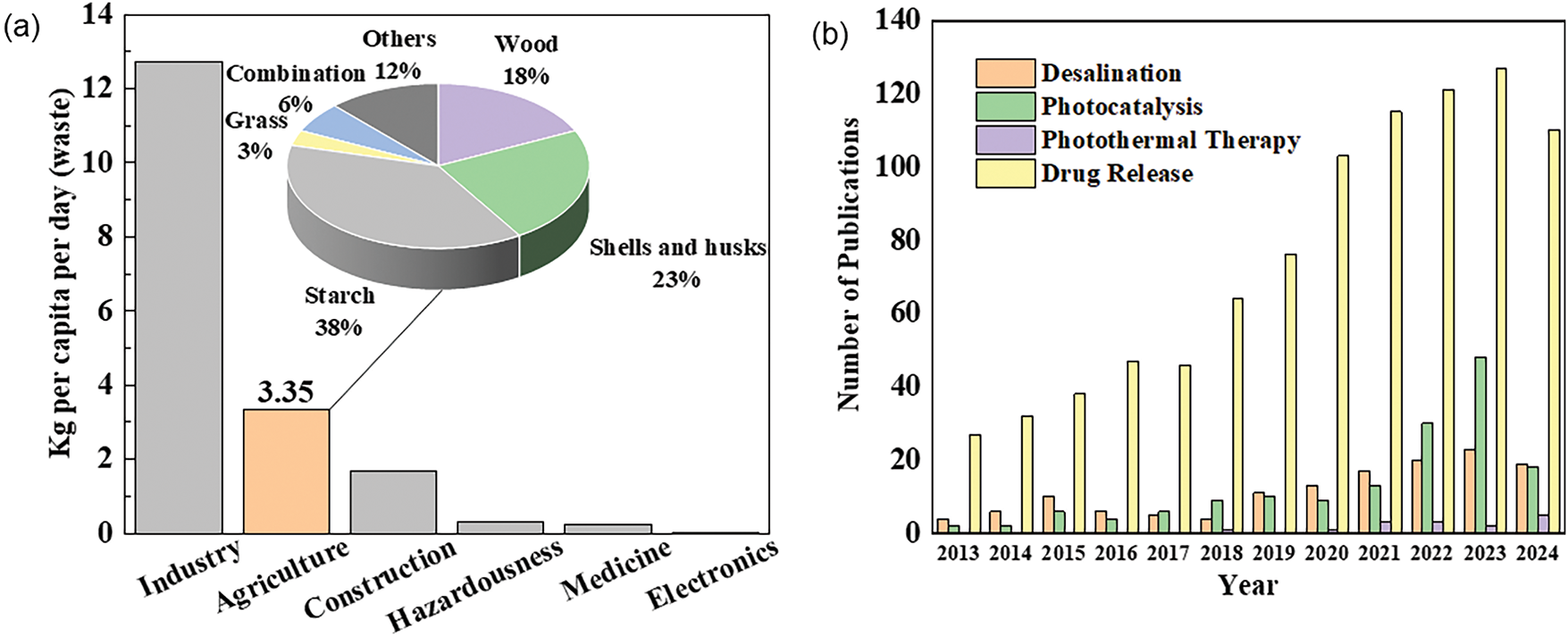

It is worth mentioning that one of the most significant advantages of natural cellulose as a substrate material lies in its sustainability and ease of recovery [92,93]. Unlike synthetic polymers, cellulose can be easily regenerated or recycled through simple chemical or physical processes, minimizing environmental impact. For example, deep eutectic solvent (DES) extraction preserves cellulose integrity while minimizing chemical waste. A large amount of agricultural and forestry wastes is produced every year on the earth, such as rice straw, corncob, wheat straw, wheat bran, ginkgo leaf, orange peel, grapefruit peel, coffee husk, etc. [94]. Li and Chen [95] believed that the use of agricultural waste derived superabsorbent hydrogel as a soil conditioner to promote agricultural production is a “farmer centered” cycle process (as shown in Fig. 4), which can maximize the net income of farms and minimize the ecological footprint. Fig. 5a provides a comparative analysis of the daily per capita waste generation across different sectors, with agricultural waste leading at 3.35 kg per capita per day. In China, a giant in the agro scenario, the annual agricultural waste reaches around 0.9 billion tons [96], the average annual production of crop straw is 865 million tons [97]. These insights are crucial for developing effective agricultural waste management policies and for identifying opportunities for the sustainable processing of agricultural waste into valuable products. Alexandra Lanot et al. [98] present a biobased alternative that proposes to use enzymes and bacteria to convert cellulosic wastes into BC for textile application. This method will not affect its mechanical properties. It copes with inaccurately labelled dyed fabrics and synthetic materials such as elastane and could be implemented alongside existing recycling technologies. By transforming agricultural waste into valuable cellulose, this approach not only reduces environmental pollution but also aligns with the principles of sustainable development.

Figure 4: Farmer-centered circular process of producing agricultural waste-derived superabsorbent hydrogels as soil amendments [95]. Copyright © 2020, Elsevier Ltd.

Figure 5: (a) Worldwide average production of industrial waste, agricultural waste, construction waste, hazardous waste, electronic waste and classifications of agricultural waste represented as a percentage of total worldwide agricultural waste content [99]; Copyright © 2023, Elsevier B.V. (b) Publications in the last 12 years on photo-driven applications of natural cellulose based materials

Regarding waste textiles and fibers, traditional methods for the regeneration of natural fibers usually employ concentrated acidic or alkaline solutions, which destroy the polymer structures of fibers, rendering them unusable as fibers in textiles and fashion. Hence, Sun et al. [100] chose ionic liquids (ILs) as solvents for textile waste separation. ILs are closely related to green chemistry movements due to their low volatility, non-volatility, and renewability. ILs are capable of dissolving recalcitrant natural biopolymers with massive inter- and intra-molecular hydrogen bonds which cannot be recycled via melt spinning, without producing hazardous byproducts or gas discharge in the reaction. Such regenerated composite fibers showed excellent water vapor adsorption capability and suitable mechanical properties for textile manufacture, supporting their wearability.

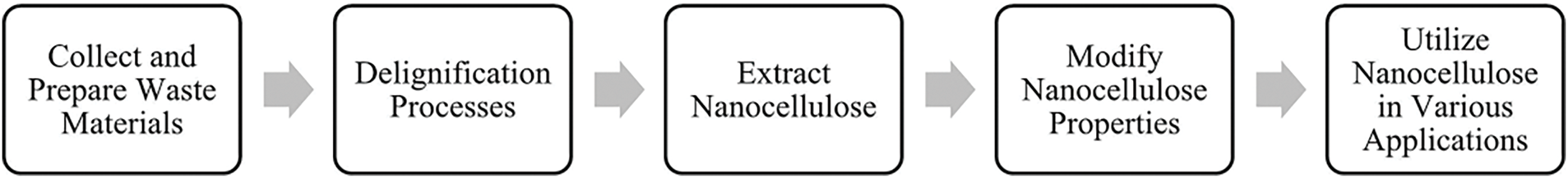

The transformation of waste streams into valuable outputs, especially nanocellulose, entails several critical stages that garner significant academic attention, as shown in Fig. 6 [101]. In addition to cellulose, agricultural waste also contains a certain proportion of hemicellulose and lignin. Lignin, hemicellulose, and other impurities must be removed to obtain pure cellulose [102].

Figure 6: Process flowchart: converting waste materials to nanocellulose and its utilization [101]

Biopolymers like cellulose are inherently biodegradable in natural environments although the rate can vary largely depending on the type of environment and biopolymer. Erdal and Hakkarainen [103] have studied the degradation of commercial cellulose derivatives under different laboratory conditions and in real natural, agricultural, and man-made environments. It has been confirmed that waste derived cellulose should be designed for material recycling in specific predetermined environments based on specific applications. It is evident that the type and degree of modification, combined with the actual degradation environment, are important factors affecting degradation susceptibility and degradation rate.

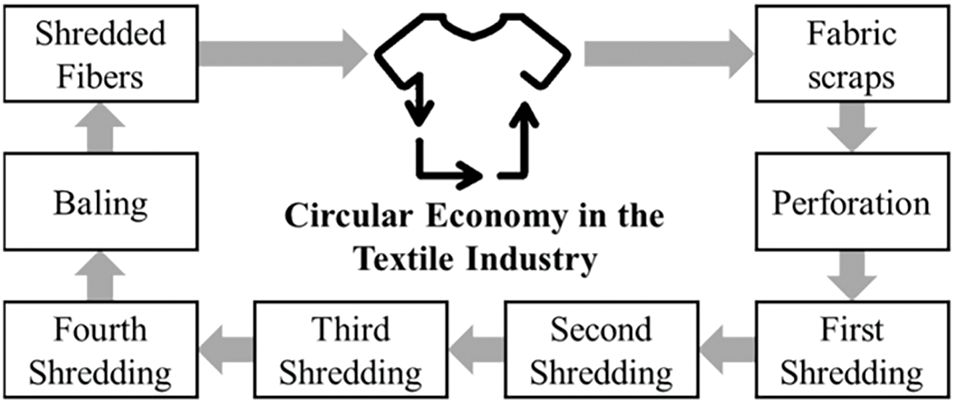

There are many definitions of circular economy, and its central idea is to strive to restore and regenerate the environment, contributing to sustainable development from a systemic perspective of optimizing the social, environmental, technological, and economic value of social materials and products [104]. In recent years, new industrial machinery within the textile sector has gained greater production capacity and requires fibers with higher intrinsic quality. This situation exacerbates the difficulties associated with attaining the objectives of circular manufacturing processes. Fig. 7 presents the flowchart for the stages involved in the process of mechanic recovery of cellulose by splitting textile material.

Figure 7: Process for the mechanical recovery of cotton fiber [105]

The hierarchical structure of natural cellulose consists of highly ordered crystalline regions and amorphous domains. This unique high-purity structure, especially the surface rich hydroxyl, forms an ideal renewable carrier, which can be well modified by plasma and sol-gel coating. Pretreated natural fibers provide a multifunctional platform that enables effective integration of photoactive components such as nanoparticles, organic dyes, clusters, carbonized cellulose, and metal oxide cellulose hybrids, all of which can improve thermal conversion efficiency [106–108]. It enhances light absorption via Mie scattering, providing excellent mechanical strength, flexibility, and biocompatibility, making it an ideal candidate material for advanced photo-driven technology.

For instance, TiO2 nanoparticles incorporated into cellulose matrices enhance light absorption via their broad-spectrum photocatalytic activity [109], while gold nanorods improve photothermal conversion efficiency through localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) [110]. The controlled nanostructuring of cellulose further optimizes surface interactions in photo-driven processes. Porous cellulose nanofibril networks increase specific surface area for photocatalyst loading, while aligned crystalline domains facilitate charge carrier separation in photoelectrochemical systems [111,112]. These structural advantages have been translated into practical applications. Huang et al. [113] were inspired by the superhydrophobic surface of lotus leaves, is the first to show the potential of constructing molecular-level hydrophilic domains on a superhydrophobic surface with excellent droplet nucleation and water-repellent functions. A new prototype for an advanced biomimicking fog harvesting approach is also provided. Its ability to modulate light scattering and absorption through controlled nanostructuring, offers exceptional mechanical strength, flexibility, and biocompatibility, making it an ideal candidate for photo-driven advanced technologies [111,112]. A search using the keywords “natural cellulose” suggests that at least 26,450 results were published. As shown in Fig. 5b, the increasing research output of natural cellulose in fields such as solar-driven water purification, photocatalysis, photothermal biomedical applications, and drug release is showing an increasing trend since 2013.

However, there are still key challenges in expanding the scale of cellulose-based photo-driven materials, such as cost, stability, and industrial applicability. Obviously, since 2013, due to various factors that intersect technology and environmental awareness, research on photo-driven cellulose has experienced a significant boom. Technically speaking, new methods for extracting and modifying nanocellulose have emerged, which can create materials with customized optical properties. At the same time, the growing environmental issues have become the main driving force. Photo-driven cellulose-based systems provide potential solutions for energy conversion and environmental remediation. For example, in photocatalytic water splitting, cellulose based materials may contribute to the production of clean hydrogen and reduce dependence on fossil fuels [114].

3.1 Solar-Driven Water Purification

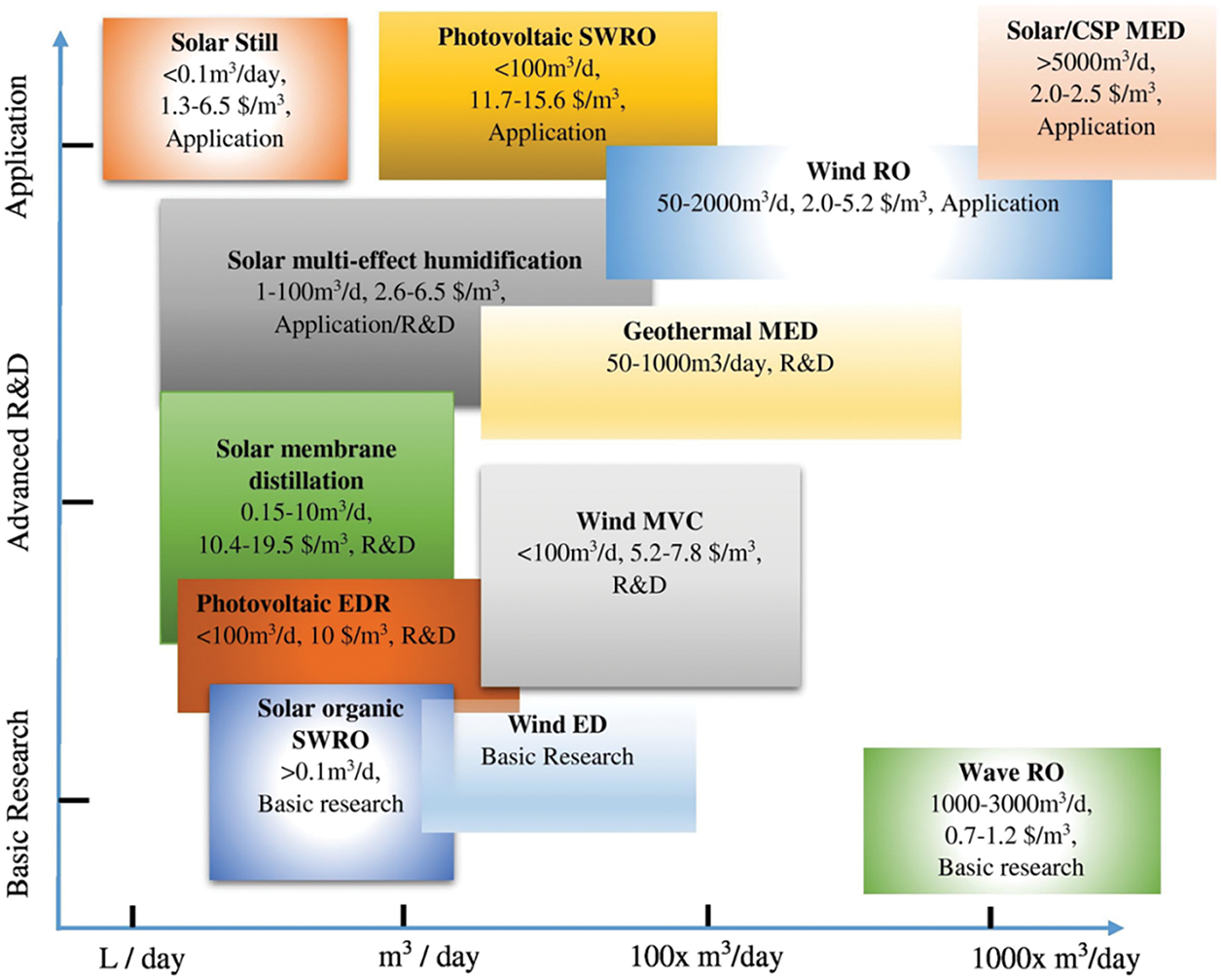

With the continuous growth of the global population and rapid economic development, the shortage of freshwater resources is becoming increasingly severe. About 1.5 billion people in over 80 countries around the world are facing a shortage of freshwater. Among them, 300 million people in 26 countries face daily water shortages [115]. Consequently, choosing the appropriate desalination technology is gradually becoming more significant in the field of water resource management. Conventionally, through various methods, including reverse osmosis, electrodialysis, and membrane distillation [116–118], etc., salt and other impurities can be effectively removed from seawater, producing fresh water that meets both drinking and industrial water standards. As shown in Fig. 8, the energy efficiency of light driven desalination is compared with traditional methods. It is evident that although other forms of renewable energy are also used in seawater desalination processes, solar energy holds special significance as it is the most abundant permanent energy source on Earth.

Figure 8: Technological status of renewable energy desalination technologies [123]. Copyright © 2018, Elsevier B.V.

Although reverse osmosis has been regarded as one of the most energy-efficient processes for seawater desalination, it still involves a larger amount of fossil fuel and other energy sources for water production, which imposes a negative impact on the environment such as greenhouse gas emission [119]. In addition, one of the environmental challenges associated with desalination technologies is the production of a hyper-salty charged water as a byproduct, which also called briefly “the brine” [120]. This high salinity substance poses a threat to the environment and must be managed effectively in order to reduce pollution. Aside from brine, other difficulties include marine species entrainment and trapping, as well as high chemical use [121]. In contrast, natural fiber solutions offer several advantages. Natural fibers are renewable resources that can be obtained from plants or other natural sources. They are biodegradable and have a lower environmental impact compared to synthetic materials. In the context of desalination, natural fibers can be used in various ways.

Currently, to reduce our carbon footprint and enhance cost-effectiveness, desalination technologies like solar or nuclear desalination, when paired with renewable energy, can achieve a win-win situation for energy, freshwater, and food security [122]. Therefore, the research and development of photo-driven technologies is extremely important in the field of desalination.

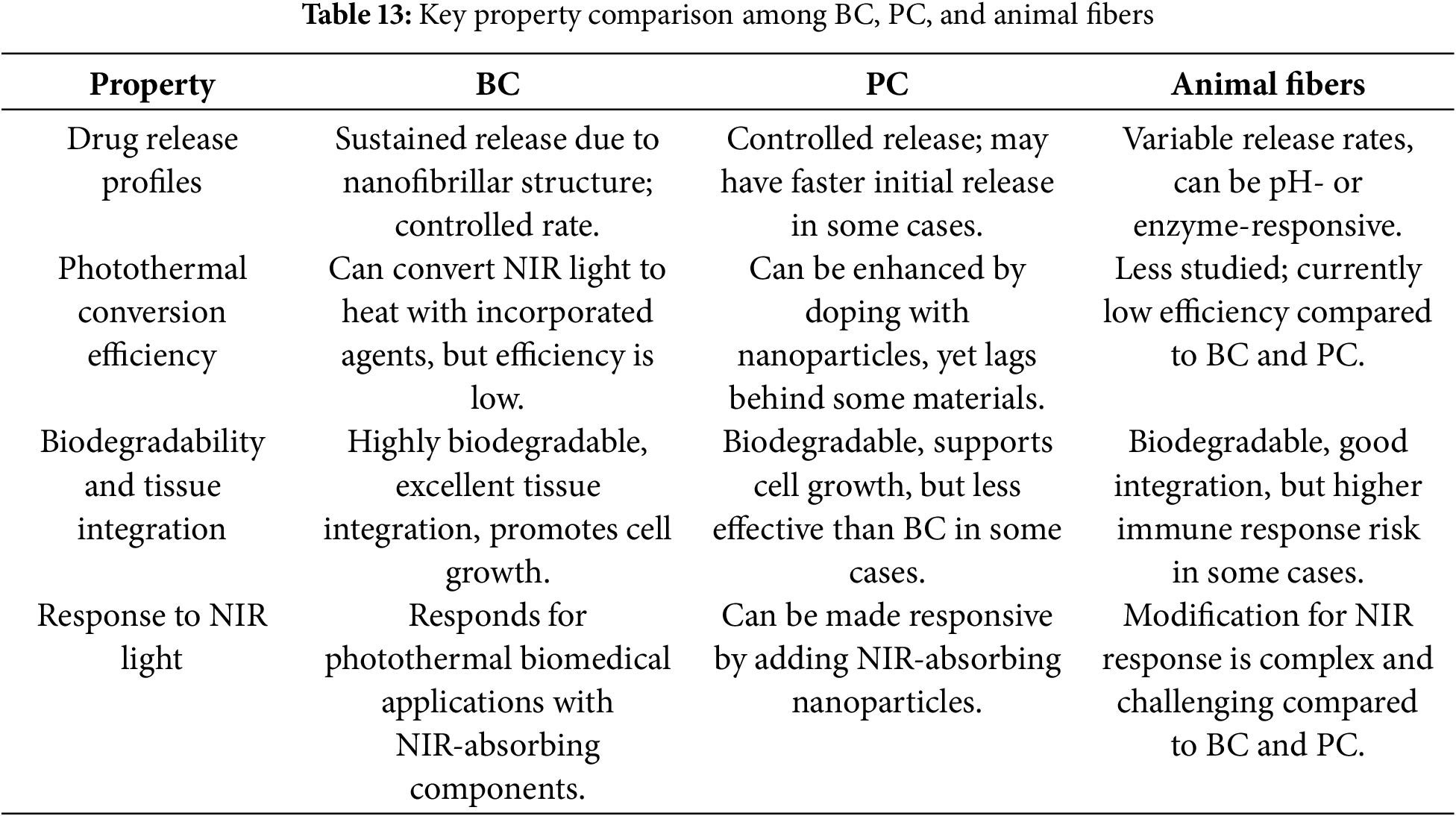

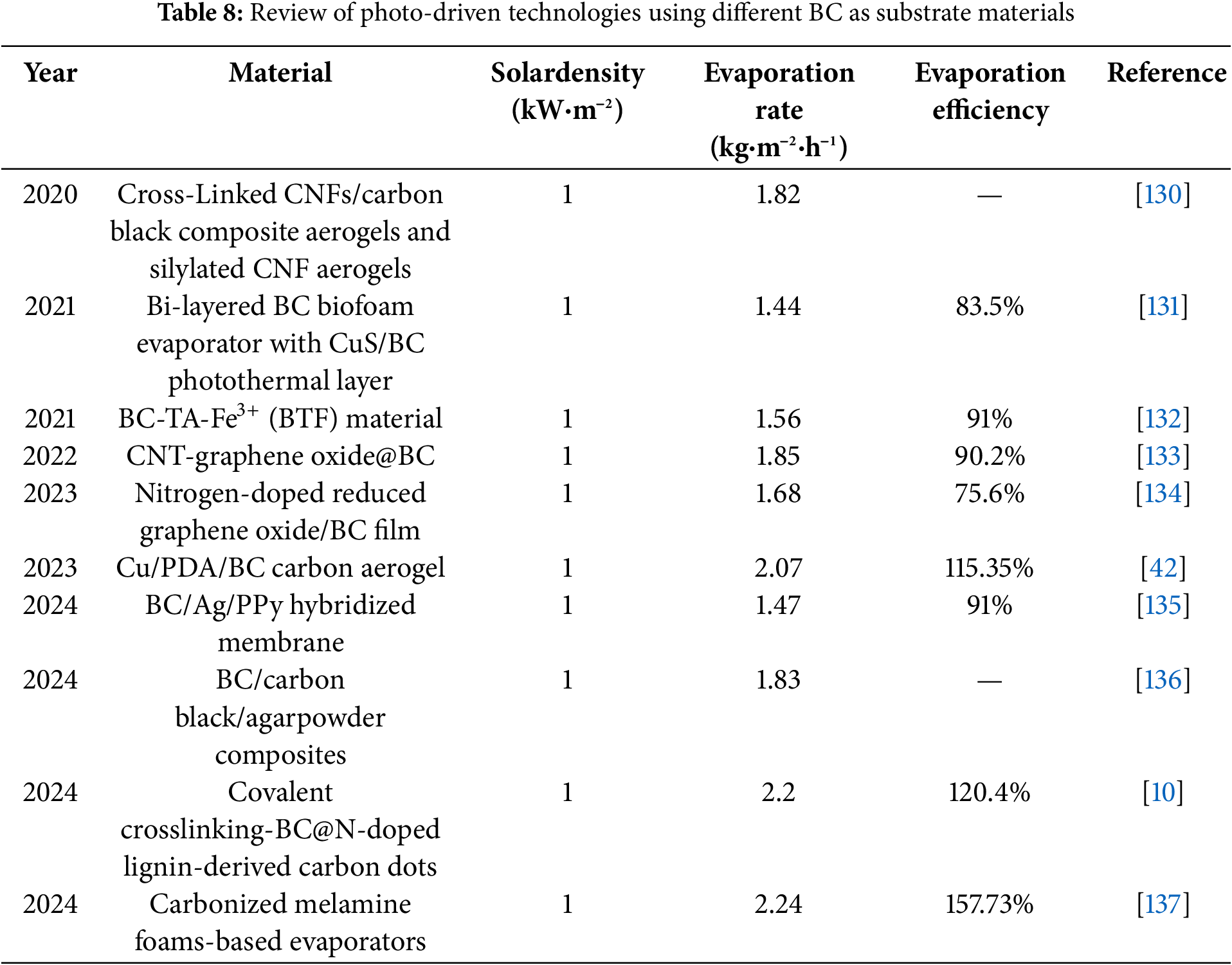

Key performance parameters play a crucial role in evaluating BC, PC, and animal fiber-based materials. Among them, parameters such as evaporation rate and photothermal conversion efficiency have become important evaluation benchmarks.

The evaporation rate was obtained by Eq. (1), the photothermal conversion efficiency was obtained by Eq. (2) [124].

where is the weight variation (kg), A is the irradiation area (m2), and t is the irradiation time (h).

where

BC, which is synthesized by microorganisms such as Komagataeibacter xylinus, has become a focal point in the field of biomaterials due to its exceptional purity and structural integrity [125]. Compared to synthetic membranes, BC is a deliberate choice for researchers and engineers. Table 7 confirms the excellent performance of BC membrane compared to synthetic polymer membrane in terms of permeability, anti biofouling, durability, and sustainability. It is a deliberate choice for researchers and engineers, based on its multitude of advantageous properties, such as its biocompatibility, high crystallinity, and mechanical strength. The desalination properties of materials enhanced by several natural BC sources, have been extensively studied in the literature. The advantages of different BC-based solar-absorbing photothermal composites in the field of seawater desalination have been summarized in Table 8. The table highlights the evaporation rate and the evaporation efficiency of these materials, which are both crucial factors in the development of next-generation desalination technologies. The data presented in the table is a testament to the potential of BC to revolutionize the way we approach water scarcity.

BC membranes exhibit remarkable salt rejection capabilities through several mechanisms. Size exclusion is a primary mechanism, as the nanofibrous structure of BC creates a highly porous network with pore sizes typically ranging from 20 to 100 nm, which can effectively exclude larger salt ions while allowing water molecules to pass through [138]. Additionally, the abundant hydroxyl groups on BC membranes enhance the membrane’s hydrophilicity, leading to reduced fouling and improved salt rejection. The hydrophilic-hydrophobic interactions between the membrane surface and salt ions also play a significant role. The hydrophilic nature of BC membranes promotes the formation of a hydration layer, which can hinder the approach of salt ions to the membrane surface [139]. Furthermore, ion selectivity is another key factor. The negatively charged surface of BC membranes can induce electrostatic repulsion against anions, thereby enhancing salt rejection efficiency [140]. For instance, a study demonstrated that BC membranes with a contact angle of less than 30° exhibited excellent anti-fouling properties and salt rejection rates exceeding 90% [141]. These mechanisms collectively contribute to the high performance of BC membranes in water desalination applications.

Besides, by harnessing the power of light, these innovative materials can be activated to remove salt and impurities from seawater, providing a clean and renewable source of drinking water [142]. Yin et al. [143] reported a directed continuous two-dimensional metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) coating on BC as a filter material with high flux and selectivity for removing nitrobenzene from water. The supported MOF film could improve permeance while maintaining selectivity because its pores are able to selectively let molecules smaller than the pores to pass through while rejecting ones larger than pore size. MOFs enhance the performance of BC in several significant ways. Firstly, MOFs possess high porosity and a large specific surface area, which can significantly improve the water flux of BC membranes by providing more channels for water permeation. Secondly, MOFs have abundant functional groups and adjustable pore sizes, enabling them to adsorb a wide range of contaminants effectively. This adsorption capacity is further enhanced when MOFs are combined with BC. Thirdly, MOFs can enhance the structural stability of BC by forming a robust composite structure. The 20 nm thick coating reported shows high water permeance (10.85 L/(h·m2·psi)) and high rejection of nitrobenzene (68.6%), which are higher than state-of-the-art polymeric membranes. Kallayi Nabeela et al. [144] designed a sustainable bacterial nanocellulose based self-floating bilayer photothermal (PTFb) foam that could be used in applications such as solar desalination, contaminated water purification, extraction of water from moisture, etc. The fabricated PTFb is found to yield a water evaporation efficiency of 84.3% (under 1054 W·m−2) with 4 wt% BT loading. PTFb shows a solar conversion efficiency of 84.3%. Furthermore, scalable PTFb realized a water production rate of 1.26 L·m−2·h−1 under real-time conditions. To summarize, desalination products not only provide additional freshwater resources for humans but also aid in treating impurities in wastewater through desalination processes, further optimizing the utilization efficiency of water resources. It not only addresses a critical global issue but also opens up new avenues for the application of bacterial cellulose in environmental remediation and resource sustainability.

PC, as the main component of natural cellulose, can be roughly divided into several types based on its source and structural properties, including wood-derived cellulose, cotton cellulose, and agricultural waste-derived cellulose (e.g., from sugarcane bagasse, rice straw, or corn husks) [15,145]. Each type of PC exhibits unique characteristics that influence its performance in photo-driven desalination applications. Wood-derived cellulose membranes typically possess a highly porous structure, which facilitates efficient water transport and enhances evaporation rates. Their interconnected pore network allows for rapid water permeation while maintaining reasonable salt rejection efficiency. Cotton cellulose membranes, are known for their high degree of crystallinity and excellent hydrophilicity, which promote efficient water absorption and transport. This hydrophilic nature reduces the energy required for evaporation and improves overall desalination efficiency. Agricultural waste-derived cellulose, offers a sustainable and cost-effective option. These membranes often exhibit good mechanical stability, which is crucial for maintaining structural integrity during prolonged desalination operations. The combination of these properties makes PC membranes promising candidates for energy-efficient and environmentally friendly desalination technologies. In recent years, researchers have explored the potential of these cellulose types as sustainable and efficient substrates for desalination technologies, leveraging their inherent advantages while addressing their limitations through innovative material engineering.

Despite its promising potential, the application of PC in photo-driven desalination faces several challenges. The major issue is the inherent limitations in light absorption and conversion efficiency, as cellulose is not inherently photoactive. To address this, researchers have explored the integration of photoactive nanomaterials, such as graphene oxide, MOFs, or plasmonic nanoparticles, into cellulose matrices. Simultaneously, appropriate crosslinking agents must be chosen to ensure uniform dispersion and robust interfacial bonding among these components. Table 9 presents a comparison of the performance of materials or evaporators made with various types of PC as matrix materials and incorporating different photoactive nanomaterials. Given these advantages, recent advancements in material engineering have shown the potential for PC to surmount these challenges.

Furthermore, studies have shown that PC membranes can undergo structural degradation or fouling over time, which reduces their desalination performance. Weng et al. [146] prepared an antimicrobial cellulose-based membrane (Ag/UiO-66-NH2@BCM), which exhibited significant improvements, including a 31% increase in pure water flux, a water flux recovery of 97.4%, and broad-spectrum and highly effective antimicrobial properties, along with efficient removel of heavy metal ions. This emphasizes the necessity of strengthening material design and optimization. As research continues to address existing limitations, PC is poised to play a pivotal role in advancing sustainable and efficient photo-driven desalination technologies.

In recent years, animal fiber (derived from sources such as silk, spider silk and wool), though less commonly discussed than PC, has emerged as a unique and promising material for photo-driven desalination applications. While animal fibers are not traditional sources of cellulose, their protein-based structures can be functionalized or combined with cellulose to enhance desalination performance. Silk-based materials have excellent light absorption and salt resistance properties, high evaporation rate, and are suitable for desalination of high salt concentration seawater [160]. BC has a high evaporation rate, good light absorption efficiency, and is stable under acidic conditions, making it suitable for complex wastewater treatment [161]. PC has a high water flux, but its light absorption efficiency and salt resistance are relatively weak, making it suitable for low salt concentration treatment [162]. Below, we will concentrate on examining the innovations, benefits, challenges, and data associated with silk in the realm of seawater desalination.

Silk and spider silk have several advantageous characteristics that make them particularly suitable for seawater desalination applications. Especially spider silk, known for its high tensile strength and toughness, which allows it to withstand immense stress without breaking. This characteristic is crucial for desalination membranes that need to maintain structural integrity under pressure and water flow [87]. In addition, these materials can adhere well to various substrates, preventing scaling and ensuring long-term functionality. This is particularly important in environments where the membrane is exposed to saltwater and potential pollutants. The hydrophilicity of silk and spider silk is another key factor. This helps with water transportation and reduces energy consumption during seawater desalination processes. In addition, their low surface energy helps prevent salt and other pollutants from adhering to the membrane surface, thereby improving desalination efficiency [163]. Most importantly, silk and spider silk are sustainable and biodegradable, making them environmentally friendly alternatives to traditional seawater desalination materials.

Silk, produced by silkworms, is renowned for its exceptional mechanical strength, flexibility, and biocompatibility. These attributes make it an appealing material for desalination membranes, especially in photo-driven systems. Compared to other bio-based membranes like BC and PC, silk-derived materials offer superior photothermal stability and efficiency, making them promising candidates for sustainable and high-performance desalination systems. In terms of desalination efficiency, they can exhibit high levels. In terms of mechanical stability, silk fibroin, a main component of silk-derived materials, provides good mechanical properties. It can maintain structural integrity under various conditions, offering better mechanical stability than some fragile bio-based membranes. However, the overall performance also depends on factors such as the specific structure of the silk-derived material, the presence of additives, and the operating conditions of the desalination system.

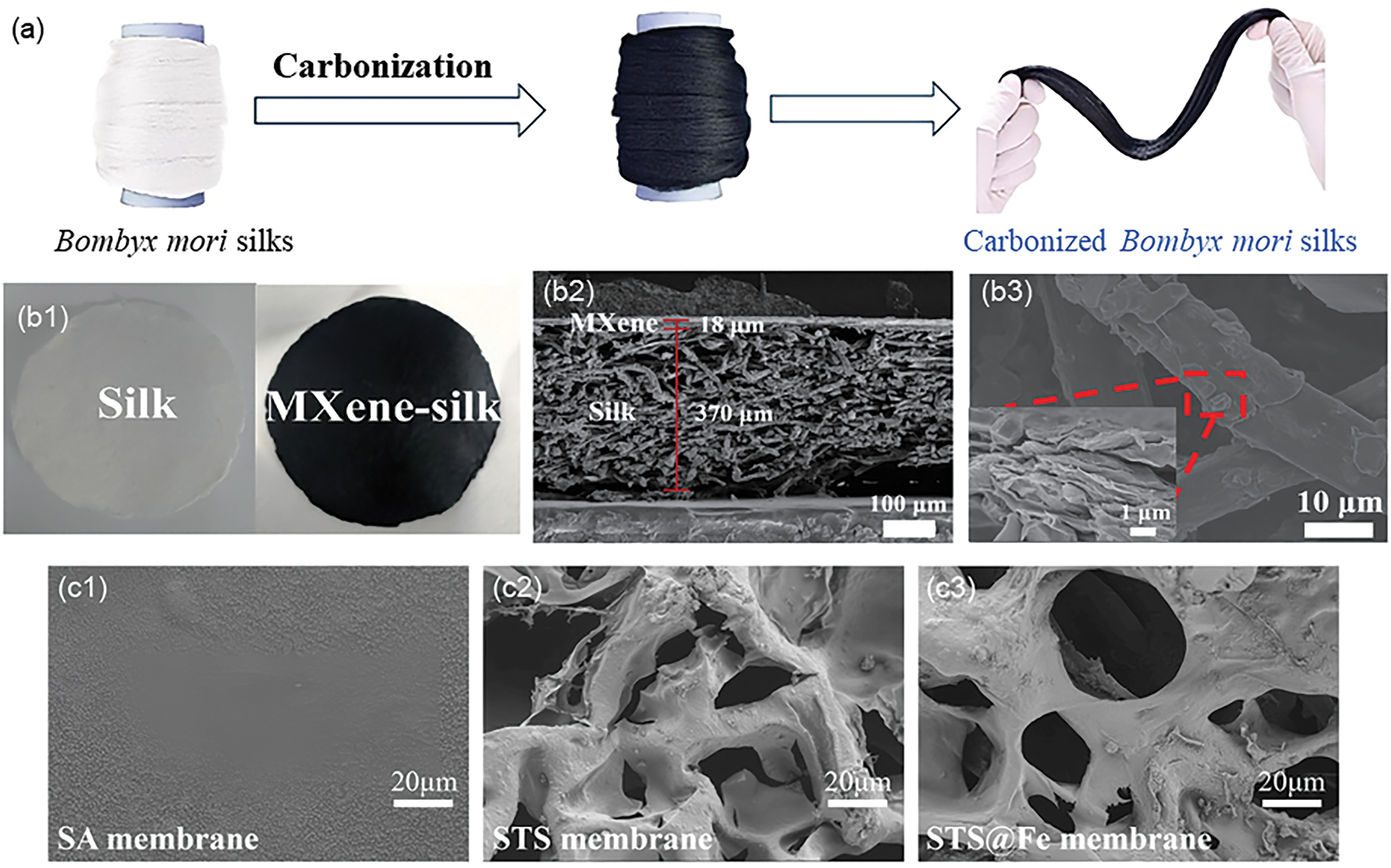

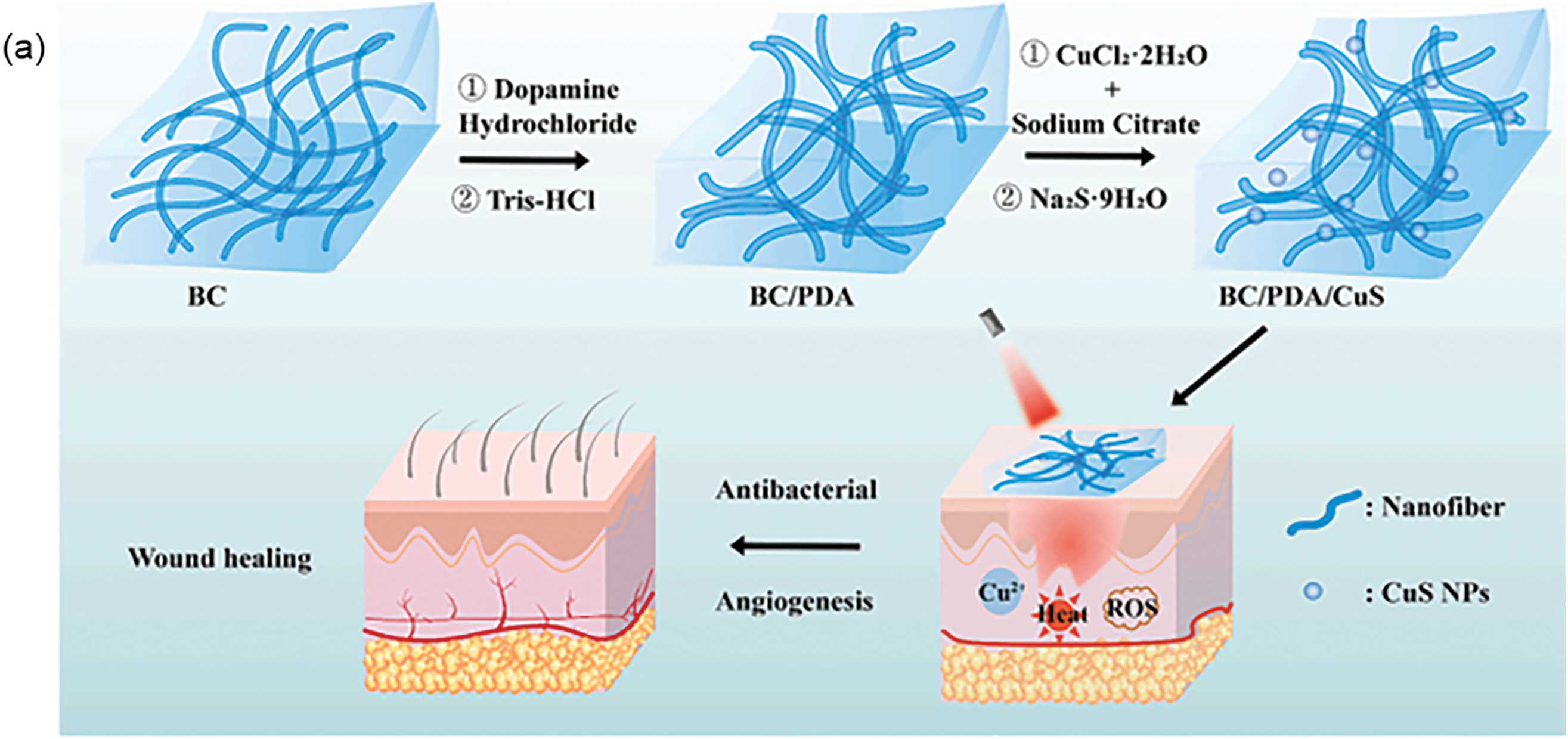

Qi et al. [164] demonstrated the use of carbonized silk fibers derived from Bombyx mori and Antheraea pernyi silks for solar steam generation, achieving a water flux of 28 L/m2·h and a salt rejection rate of 94% under solar irradiation. The study emphasized the mechanical robustness and electrical conductivity of carbonized silk, which allowed for its integration into functional fabrics for desalination. Similarly, Qian et al. [165] developed a MXene-silk composite inspired by plant leaves, achieving an evaporation rate of 1.51 kg·m−2·h−1 and a conversion efficiency of 86.9% under 1 kW·m−2 solar intensity. The composite also exhibited mechanical actuation properties, with a bending curvature of 0.91 cm−1 under higher solar intensity. Fang et al. [166] synthesized the metal-phenolic networks (MPN) utilizing the natural plant polyphenol tannic acid (TA) and Fe3O4 nanoparticles. This research incorporated MPN into dissolved and regenerated silk fibroin and sodium alginate (SA) solution, enhanced mechanical properties through cryogenic salt precipitation, and prepared STS@Fe hydrogel, which enhanced mechanical strength (31 times higher than traditional fibroin hydrogel) and photothermal antibacterial properties. The hydrogel achieved an evaporation rate of 2.0 kg·m−2·h−1 and demonstrated excellent stability in real seawater conditions. The three studies collectively explore the potential of animal-derived fibers, particularly silk, in photo-driven desalination applications, highlighting their unique properties.

Despite these similarities, the studies differ in their approaches and material designs. As shown in Fig. 9a, Qi et al. [164] focused on the carbonization of silk to enhance its mechanical and photothermal properties. The carbonized silk fibers retained their fiber morphology while turning black in color and exhibiting conductivity. Whereas the MXene-silk composite in Qian et al. [165]. (Fig. 9b) showed a smooth surface with high light absorption. In contrast, Fang et al. [166] prepared using a bidirectional crosslinking strategy STS@Fe Hydrogel (Fig. 9c), showing a porous structure with enhanced hydrophilicity and photothermal efficiency. These differences highlight the versatility of silk-based materials in desalination, with each study offering unique insights into optimizing their performance for sustainable water purification.

Figure 9: (a) The morpholoy of Bombyx mori silks before and after the carbonization [164]; (b1) Optical photographs of silk and MS composite film (diameter: 5 cm); (b2) Cross-secional SEM image of MS composite film (b3) High-magnifiation SEM image of MS composite film [165]. Copyright © 2023, Tsinghua University Press; (c) SEM images of (c1) SA, (c2) STS, (c3) STS@Fe [166]. Copyright © 2024, Elsevier B.V.

The use of animal fibers such as silk and spider silk in desalination applications faces several challenges. Firstly, the production of these materials is often associated with higher costs due to the complexity of extraction and processing procedures [167]. Secondly, the mechanical properties of silk and spider silk exhibit significant variability. This variability arises from factors such as differences in fiber structure, spinning behavior, and environmental conditions during production [168]. Additionally, ethical concerns related to the sourcing of animal-derived materials may limit their widespread adoption in industrial applications [169]. Despite these challenges, ongoing advancements in genetic engineering and recombinant silk production offer promising solutions to improve yield and reduce costs.

Although laboratory scale research on natural fibers in seawater desalination has achieved phased results, laying the foundation for future development, in order to successfully translate these research findings into practical commercial applications, efforts must be focused on addressing a series of commercialization challenges such as expanding production, improving cost-effectiveness, and conducting sufficient practical testing. Guo et al. [170] studied the combination of FeOOH and 3D carbon nanofiber aerogel derived from bacterial cellulose for capacitive deionization (CDI) system. Research has shown that this material exhibits excellent cycling stability in desalination performance, with no significant decrease after 100 cycles and only a 17.85% decrease after 200 cycles. El Bestawy et al. [162] studied the application of agricultural waste such as corn stover and sugarcane bagasse in seawater desalination. Research has found that these materials exhibit good performance in water treatment, especially in desalination processes with high water flux and salt removal rates. In addition, the production technology of these materials is relatively mature and can be produced on a large scale. Abdel-Fatah et al. [171] studied the application of silk fibroin based photothermal materials in solar driven seawater desalination. Research shows that the photothermal conversion efficiency of these materials exceeds 90%, with an evaporation rate of 2.31 kg·m−2·h−1. These materials also have good salt resistance and mechanical stability, making them suitable for high salt concentration environments.

These case studies indicate that BC, PC and silk fibers have their own advantages in seawater desalination, but also face commercialization challenges. Future research needs to focus on reducing costs, improving yield, and achieving consistent performance to promote the widespread application of these materials in desalination.

Photocatalysis is an advanced oxidation process that has gained significant attention in the field of environmental science and materials engineering due to its potential in solving energy and environmental challenges [172]. This process involves the use of light energy to drive chemical reactions on the surface of a catalyst, leading to the degradation of pollutants and the production of renewable energy. The research in photocatalysis has been expanding rapidly, with a focus on developing efficient and sustainable photocatalytic materials that can harness a wider spectrum of light and exhibit high stability and reactivity [2].

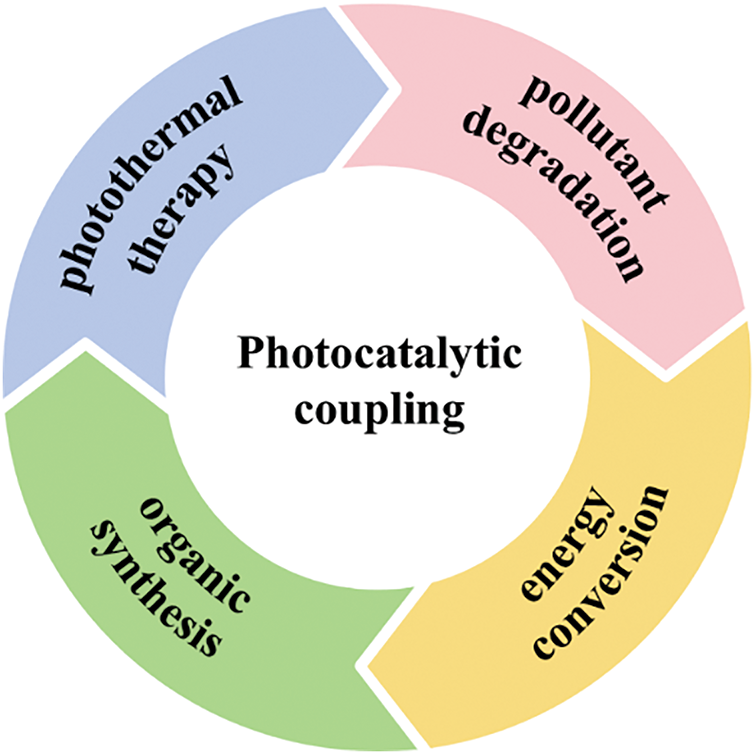

The imperative for researching in the field of photocatalysis stems from the increasing demand for clean energy and the need to address environmental issues such as water pollution and air quality deterioration [173]. Photocatalytic materials offer a promising solution by converting solar energy into chemical energy and by degrading harmful substances in the environment. As shown in Fig. 10, photocatalysis can produce synergistic effects with various fields. The development of novel photocatalytic materials is crucial for enhancing the efficiency of these processes and for making them more viable for large-scale applications.

Figure 10: Collaborative field coupled with photocatalysis

Conventional photocatalysts often suffer from limited light absorption and rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs, which restrict their photocatalytic efficiency [174]. In contrast, cellulose-based materials, such as cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) functionalized with TiO2 nanorods and gold nanocrystals, exhibit enhanced light absorption and charge separation [175]. These hybrid materials demonstrate superior photocatalytic performance in degrading pollutants like methylene blue, showing higher degradation efficiency and stability under UV irradiation. Support materials (cellulose-based materials) address these issues by providing a stable platform that increases the surface area, enhances light absorption, and improves charge separation.

Additionally, cellulose-based photocatalysts are more sustainable due to their abundance, renewability, and low environmental impact. For instance, cellulose nanofibers derived from agricultural waste can be used as substrates for growing nanocrystals, minimizing aggregation and enhancing reusability [176]. This combination of high efficiency, stability, and sustainability makes cellulose-based photocatalytic materials promising candidates for real-world applications in environmental remediation and water treatment.

The utilization of natural cellulose as a material in photocatalysis marks a significant advancement in the field. As the most abundant renewable biopolymer, cellulose offers several advantages over traditional photocatalytic materials. For example, ZnO nanoparticles supported on zeolite Na-A exhibit better dispersion, increased surface area, and higher photocatalytic activity compared to unsupported ZnO. This enhanced performance is attributed to the combined effects of ZnO and the zeolite aluminosilicate network, which minimizes charge recombination and increases active sites for photodegradation [177]. Its high abundance and renewability make it a sustainable choice, while its biocompatibility and non-toxic properties are environmentally friendly [178,179]. Additionally, cellulose can be easily modified to enhance its photocatalytic properties, such as by doping with other elements or by creating composite materials [108]. The integration of cellulose into photocatalytic systems not only contributes to the development of green chemistry but also opens up new possibilities for the design of efficient and eco-friendly photocatalytic materials.

In the field of sustainable materials, the utilization of natural cellulose based materials has attracted widespread attention due to their environmental characteristics. To establish a benchmark for evaluating BC, PC, and animal fibers in photocatalytic applications, key performance metrics such as photocatalytic degradation rate, charge carrier separation efficiency, and recyclability are critical. The photocatalytic degradation rate refers to the efficiency of a photocatalyst in degrading target pollutants within a specific time period. It is usually expressed as a percentage, reflecting the ability of photocatalysts to degrade pollutants under specific conditions [180]. The charge carrier separation efficiency refers to the proportion of photo generated electrons and holes that can reach the semiconductor electrolyte interface and participate in oxidation reactions. It reflects the effective separation and transport ability of photogenerated charges in photocatalysts [181]. Recyclability refers to the ability of a photocatalyst to maintain its structure and physicochemical properties over multiple cycles. It evaluates the stability and efficiency of the catalyst in repeated use [182]. Below, we have cited two literature to explore in depth the application of BC in the field of photocatalysis. Both studies showcase the efficacy of utilizing BC as a scaffold for various photocatalytic applications. Li et al. [183] focuses on the synergistic enhancement of TiO2 nanoparticles within a BC matrix, leading to improved photocatalytic degradation efficiency. Tao et al. [184] explores the incorporation of Bi2MoO6 nanoparticles onto a bacterial cellulose/polydopamine (BC/PDA) composite nanofiber membrane, demonstrating efficient removal of organic pollutants from wastewater.

While both studies highlight the advantageous properties of BC in photocatalysis, they differ in their approaches and materials. Li et al. [183] emphasizes the use of TiO2 nanoparticles for stabilizing Pickering emulsions, resulting in enhanced photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B. In contrast, Tao et al. [184] utilizes Bi2MoO6 nanoparticles loaded onto BC/PDA membranes, show excellent stability and efficient removal of organic pollutants.

In addition, visual comparisons between the two studies reveal distinct structural differences in the nanofiber membranes. The SEM images show the uniform distribution of TiO2 nanoparticles in the first study, while the second study demonstrates a well-dispersed arrangement of Bi2MoO6 nanoparticles on BC/PDA membranes. These contrasting structures highlight the versatility of BC in accommodating different photocatalytic materials, emphasizing its potential in diverse environmental remediation applications. To sum up, these studies underscore the potential of BC in photocatalysis, as its unique properties make it an ideal substrate for integrating photocatalytic nanoparticles.

BC-based composites exhibit higher photocatalytic degradation rates compared to traditional photocatalysts. For example, BC combined with nano-TiO2 achieved degradation rates of 89.30%–94.51% for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) under UV irradiation, outperforming pure TiO2. This is attributed to BC’s ability to enhance light absorption and reduce electron-hole recombination [185]. BC provides an efficient electron transport channel, reducing the recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes. This is evident in studies where BC was used as a substrate for dispersing photocatalytic nanoparticles, such as BiPO4 and AgI, leading to improved charge separation and photocatalytic activity [186]. In summary, BC’s high specific surface area, porous structure, and excellent light absorption make it superior to traditional base materials in enhancing photocatalytic performance. Its environmental sustainability and renewability further solidify its position as an ideal scaffold for photocatalysts. As shown in Table 10, the performance of BC based photocatalysts and traditional carriers (such as graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes, polymer matrices) in the field of photocatalysis was compared.

In the current landscape, there is a limited amount of literature focusing on the application of BC in the field of photocatalysis. Through the analysis provided in the preceding paragraphs, it is evident that the advantages of using bacterial cellulose in photocatalytic applications include its high surface area, excellent mechanical properties, and biocompatibility. Studies have shown that BC can enhance the stability and efficiency of photocatalytic materials such as TiO2 and Bi2MoO6, leading to improved degradation of organic pollutants. Additionally, the unique structure of BC allows for the uniform dispersion of nanoparticles, promoting enhanced catalytic performance.

However, some limitations exist in the utilization of BC in photocatalysis. Challenges may arise in achieving optimal loading of nanoparticles, ensuring consistent dispersion, and enhancing the overall catalytic efficiency. Further research and development are needed to address these limitations and optimize the performance of BC-based photocatalytic systems [190]. In addition, the aggregation of nanoparticles and the loss of mechanical integrity under long-term ultraviolet irradiation. Continued research efforts can focus on exploring novel methods for nanoparticle loading, enhancing the stability of composite materials, and optimizing the photocatalytic efficiency of BC-based systems. By addressing the current limitations and building on the existing advantages, BC has the potential to play a key role in photocatalysis processes. For example, BC-carbon mixed photocatalyst is used to improve conductivity and charge mobility.

Recent studies have highlighted the potential of PC as a sustainable substrate for photocatalysis systems. In the realm of photo-driven applications and the recovery of natural cellulose-based materials, the exploration of photocatalysis, particularly focusing on PC, has garnered significant attention in recent research studies. Plant fiber types can be differentiated in terms of their photocatalytic properties based on their source and structural characteristics. Wood-derived plant fibers, with their high cellulose content and natural pigments, offer good mechanical strength and light absorption, making them suitable for robust photocatalytic applications. Agricultural waste-derived plant fibers, such as rice straw and sugarcane bagasse, are cost-effective and environmentally friendly, with high surface areas that enhance pollutant adsorption and light absorption. Microcrystalline cellulose, known for its high purity and crystallinity, provides excellent light absorption and efficient electron-hole separation, making it ideal for high-efficiency photocatalytic systems. Each type of plant fiber offers unique advantages, and the choice depends on specific application requirements such as cost, stability, and efficiency. Delving into the literature, several prominent articles shed light on this intriguing subject matter.

Additionally, Natural PC, such as cellulose extracted from banana stems, is modified with plant tannins and chitosan polymers to enhance the absorption of UV protective natural chromophores (UVPNCs). The presence of plant tannins and chitosan in this bio crosslinked cellulose template improved the absorption of UVPNCs by nearly 2-fold and 1.8-fold, respectively. Although the main focus here is on the absorption of ultraviolet radiation, it can also be inferred that the hierarchical pore structure plays a certain role in it [191]. For synthetic PC materials, such as cellulose triacetate fabrics, the effect of hierarchical pore structure on light absorption is mainly reflected in the absorption of dye molecules. By analyzing the attenuation of light on dyed fabric under different conditions, the relationship between the light absorption values of dye molecules added to the fabric and the absorbance values measured under total transparency conditions can be understood. This indicates that the hierarchical pore structure can affect the distribution and absorption of dye molecules in fabrics, thereby altering the light absorption properties of fabrics [192].

Xiong et al. [193] delve into the intricate interplay between photocatalysis and biodegradation using bagasse cellulose as a primary medium. This study underscores the efficacy of harnessing natural cellulose materials for the degradation of methylene blue, showcasing a sustainable approach towards pollutant removal. In contrast, Zhang et al. [194] explore the synthesis of a novel straw cellulose-cerium oxide nanocomposite through a hydrothermal method. By enhancing visible light-induced photocatalytic activity for Cr(VI) reduction, this research highlights the potential of coupling PC with cerium oxide in pollutant remediation applications. Examining these studies collectively, a key similarity lies in the emphasis on harnessing natural cellulose materials for enhanced photocatalytic activity. Each article underscores the synergistic effects of coupling PC with various photocatalysts to achieve efficient pollutant degradation. However, notable differences surface in the cellulose sources utilized, the types of photocatalysts employed, and the experimental methodologies employed in each research endeavor.

On a different trajectory, Yan et al. [195] pretreated bamboo with NaOH to expose hydroxyl groups for anchoring ZnO/WO3 nanoparticles. This innovative approach showcases the effectiveness of utilizing bamboo as a substrate for anchoring ZnO/WO3 nanoparticles, reporting >89% formaldehyde degradation after 10 cycles. Zhou et al. [196] engineered sugarcane cellulose-TiO2 carriers with hierarchical pore structures, which maintained >93% methylene blue removal over 20 cycles. These porous frameworks enhance light scattering and provide active sites for pollutant adsorption. Both papers utilize plant-derived cellulose as a porous matrix. These porous frameworks enhance light scattering and provide active sites for pollutant adsorption. Moreover, their high stability facilitates reusability. As shown in Table 11, we provided a detailed comparison of the performance of cellulose-TiO2, cellulose-ZnO, and cellulose-MOF composites in terms of degradation efficiency, reusability, and recyclability.

The surface functionalization of cellulose-based materials, such as hydroxyl modification, carboxylation, and amination, significantly enhances their photocatalytic activity. These modifications increase the specific surface area and the number of active sites, thereby enhancing the adsorption capacity for pollutants. For example, the introduction of carboxyl groups enhances the adsorption performance of cellulose, making it more effective in removing metal cations and organic pollutants. Introducing amino groups to improve the solubility of materials and their adsorption of heavy metal ions. Hydroxyl modification alters the structure and surface charge, reduces the recombination of electron hole pairs, and improves the efficiency of charge separation. Overall, surface functionalization not only improves photocatalytic activity, but also enhances the stability and reusability of cellulose-based materials, making them more efficient and practical in environmental remediation applications.

Therefore, in the realm of photocatalysis, PC emerges as a highly attractive material due to its unique combination of sustainability, biodegradability, and remarkable efficacy in pollutant removal [199]. These attributes collectively position PC as a cornerstone for the development of innovative photocatalytic systems. Future investigations in this domain are expected to focus on the development of novel plant-based nanocomposites, which can be tailored to optimize the photocatalytic properties of cellulose [200]. Advancements in synthesis techniques will be crucial for scaling up the production of these materials, ensuring their commercial viability and widespread adoption [199]. Ultimately, the integration of PC into photocatalysis systems holds the promise of revolutionizing environmental remediation strategies, fostering a more sustainable and efficient approach to addressing global environmental challenges [201]. However, cellulose-based photocatalysts face several challenges that limit their practical applications. One major issue is photo corrosion, where photocatalysts undergo degradation or structural changes under light irradiation, resulting in loss of catalytic activity. This is particularly problematic for materials such as TiO2, as they undergo photo corrosion when exposed to ultraviolet light for extended periods of time. Another challenge is the degradation under prolonged ultraviolet irradiation, which may lead to the decomposition or loss of structural integrity of the cellulose matrix, affecting the overall stability and performance of the photocatalyst. In addition, limited stability under acidic/alkaline conditions is a problem, as cellulose-based materials may hydrolyze or degrade in extreme pH environments, thereby reducing their effectiveness in various chemical environments.

For example, argon plasma treatment of bacterial nanocellulose films resulted in a significant increase in surface-to-mass ratio and improved adhesion of nanoparticles, which is beneficial for photocatalytic applications [202]. Additionally, carbonized cellulose nanocrystals have been utilized to create photothermal films that exhibit superior thermal stability and mechanical strength. These films demonstrate enhanced photothermal effects, with temperature increases significantly higher than those of pure materials, making them promising for applications in food preservation and other areas requiring efficient photothermal conversion [203]. Ultimately, the integration of PC into photocatalysis systems holds the promise of revolutionizing environmental remediation strategies, fostering a more sustainable and efficient approach to addressing global environmental challenges [201].

Photocatalysis is an emerging field that leverages the unique properties of various materials to drive chemical reactions using light energy. Among these materials, animal fibers have garnered significant attention due to their inherent structural and functional characteristics. While PC dominates current research, animal fibers offer distinct advantages, including hierarchical protein-based architectures, biocompatibility, and tunable surface functionalities [204]. These properties have led to their emergence as innovative substrates for photocatalysis systems, particularly in the context of environmental remediation and sustainable energy production. Although animal fibers demonstrate excellent mechanical strength and biocompatibility, other cellulose based materials have advantages in sustainability and cost-effectiveness. The choice between the two depends on the specific requirements of the application, such as durability and environmental impact. This section critically evaluates recent advances in animal fiber-based photocatalytic systems, focusing on their structural adaptability, catalytic performance, and environmental compatibility.

Animal fibers share several common features that contribute to their suitability in photocatalysis. For instance, their fibrous structure provides a high surface area-to-volume ratio, facilitating efficient light absorption and catalytic activity. Additionally, the natural biopolymer composition of these fibers ensures biodegradability and environmental sustainability, aligning with the principles of green chemistry [205]. However, significant differences exist among these fibers, which can influence their performance in photocatalytic applications.

Protein-based fibers, such as keratin and fibroin, influence photocatalytic reactions in several ways. Their hydrophilicity enhances pollutant adsorption by providing numerous active sites for pollutants to adhere to, which is crucial for improving the efficiency of photocatalytic processes. For example, the hydrophilic nature of rice bran protein (RBP) fibers, when combined with carboxymethyl cellulose and ZrO2 nanoparticles, has been shown to reduce surface hydrophobicity and improve the adsorption of pollutants, leading to excellent antibacterial effects and the ability to scavenge ethylene [206]. Additionally, the surface charge of these fibers affects the distribution and adhesion of photocatalytic nanoparticles. Positively charged surfaces can attract and stabilize negatively charged nanoparticles, preventing their aggregation and enhancing their photocatalytic activity. Furthermore, protein-based fibers can mediate the stabilization of catalysts under harsh environmental conditions. The complex structure and high moisture absorption of wool fibers, for instance, can protect catalysts from degradation in extreme pH environments, ensuring their long-term effectiveness. Overall, the unique properties of protein-based fibers make them valuable in enhancing the performance of photocatalytic systems.

Wool, primarily composed of keratin, exhibits moderate mechanical strength and light absorption efficiency. Its lower surface area compared to silk and spider silk limits its photocatalytic performance. However, wool’s inherent elasticity and flexibility make it suitable for applications requiring mechanical robustness [207]. Silk and spider silk, both composed of fibroin, demonstrate superior mechanical strength and light absorption efficiency. Spider silk, in particular, has the highest surface area and light absorption efficiency among the three, making it a promising candidate for high-performance photocatalytic applications. However, its limited availability and high production cost pose challenges for large-scale applications.

Animal fibers offer several advantages in photocatalysis. Their biodegradability and renewable nature make them environmentally sustainable alternatives to synthetic materials. Additionally, their tunable surface chemistry allows for functionalization with photocatalytic agents, enhancing their catalytic activity [208]. As shown in Table 12, while Butman et al. [209] focused on the intrinsic properties of wool fibers and their ability to self-dope TiO2, Grčić et al. [210] explored the practical application of wool in a textile blend for greywater treatment. The former study utilized hydrothermal synthesis and calcination to create highly active photocatalysts, whereas the latter employed solar photocatalysis with chitosan as a co-flocculant to enhance pollutant removal.