Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Bamboo Parenchymal Cells: An Untapped Bio-Based Resource for Sustainable Material

1 Research Institute of Wood Industry, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing, 100091, China

2 College of Materials Science and Technology, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, 100091, China

* Corresponding Author: Yuxiang Huang. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(10), 1881-1898. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0068

Received 20 March 2025; Accepted 05 June 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

Bamboo parenchymal cells (PCs) represent an underutilized resource with significant potential as a sustainable and versatile bio-based material. Despite the extensive research on bamboo fibers, PCs, comprising a considerable portion of bamboo, have been largely overlooked. This review examines the multi-scale structure of bamboo PCs, including their microcapsules, multi-wall layers, and pits, which provide the structural foundation for diverse applications. Various physical and chemical isolation methods, impacting the properties of extracted PCs, are also discussed. Notably, the review explores the promising applications of bamboo PCs, highlighting their use as filler materials in formaldehyde-free composites, as components in phase-change materials and supercapacitors, as sources for biodegradable microcapsules and antimicrobial hydrogels, as precursors for activated carbon in environmental remediation, and as a valuable feedstock for biomass refining processes. This comprehensive analysis underscores the importance of bamboo PCs in the development of renewable materials, encouraging further research to fully harness their capabilities.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Bamboo is a fast-growing and renewable herbaceous plant [1]. There is a massive demand for bamboo in the market. Currently, bamboo is mainly used as a raw material for papermaking, artificial bamboo, and furniture handicrafts. China is the primary source of bamboo materials, yet the utilization rate of bamboo resources is generally less than 55% [2]. With the proposal of bamboo instead of plastic and the need for bamboo industry development, it is urgent to realize the high-value utilization of bamboo resources [3].

Bamboo has been one of the common materials used by people since ancient times [4]. In ancient times, individual workers processed bamboo into baskets, stretchers, bamboo mats, various agricultural tools, etc. In the 1960s and 1970s, with mechanical processing and the joining of state-run bamboo processing factories, bamboo flooring, and furniture began to appear in the market. Nowadays, bamboo is mainly processed into bamboo curtains, mats, bamboo plywood, bamboo flooring, daily necessities, and bamboo processing semi-finished products, which are widely used [5–7]. However, at present, the bamboo processing industry is dominated by rejuvenated small and medium-sized enterprises, which are relatively weak in research. They are dominated by brash overall utilization of bamboo materials, resulting in significant homogenization of bamboo products and low value-added products. The primary profit strategy of these enterprises is to adopt micro-profit operations and win by volume, which is not conducive to the development of the bamboo material industry and does not give full play to the potential of bamboo material [8]. Liangbing Hu et al. [9] found that by simply partially removing the lignin and hemicellulose and then hot pressing, the specific strength of bamboo material was as high as 777 MPa cm3/g, surpassing the specific strength of most natural polymers, plastics, steels, and alloys. This indicates that bamboo has a vast untapped potential, so considering whether bamboo can be utilized on a smaller and finer scale to develop new utilization values for bamboo is worth considering.

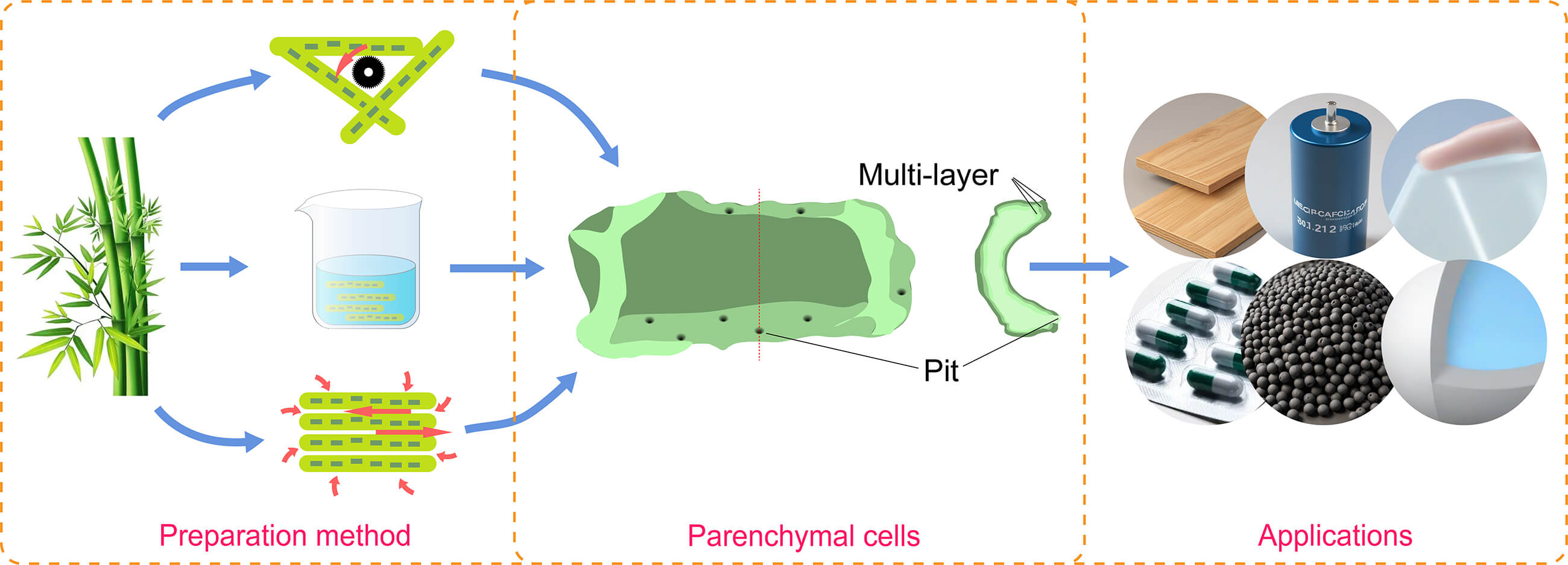

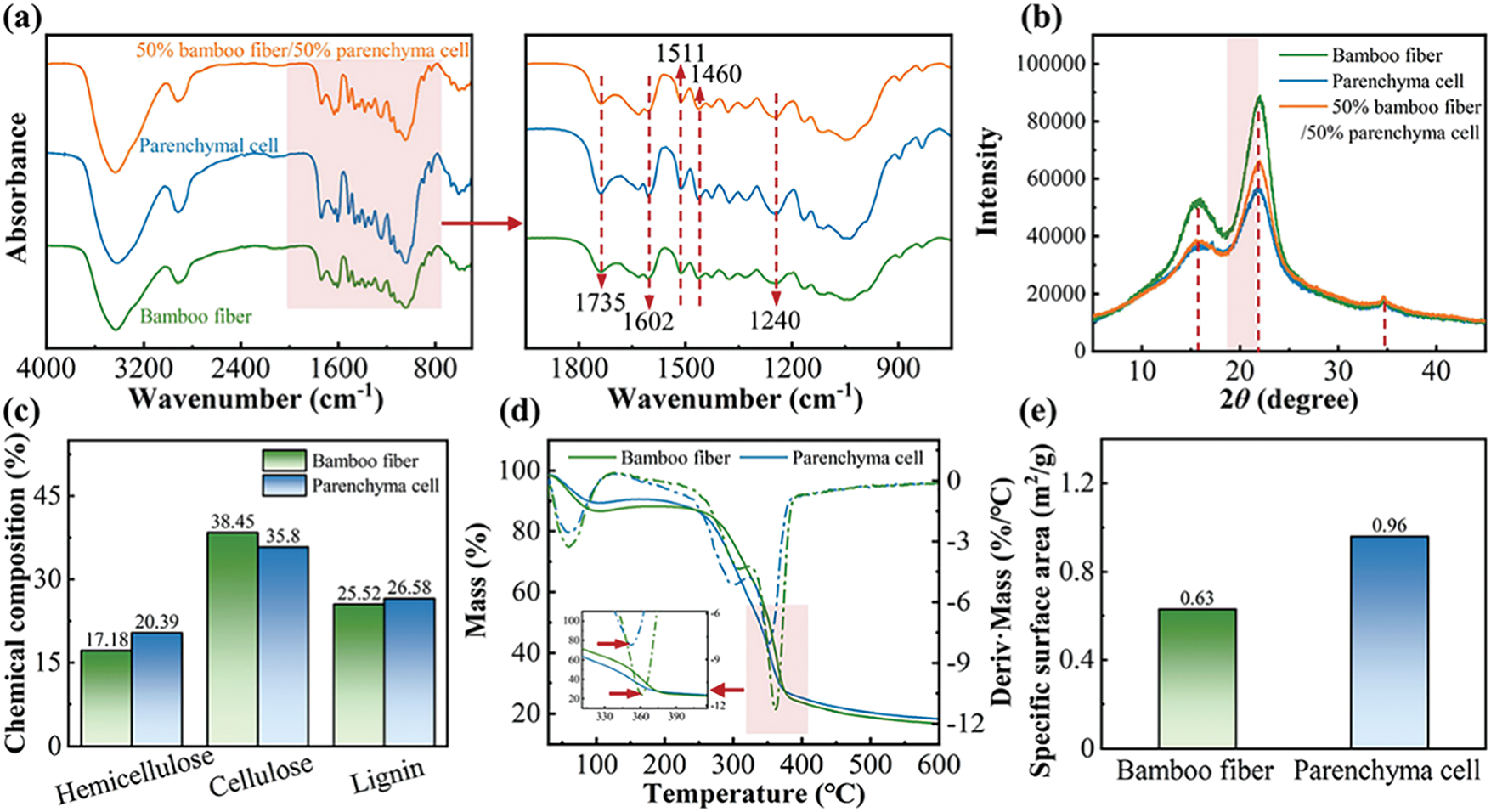

With an in-depth study of bamboo structure, researchers have found that bamboo mainly consists of bamboo fibers and bamboo parenchymal cells [10]. Bamboo fibers have high tensile strength and a large aspect ratio, which are currently applied as the reinforcing phase of composite materials, such as cement and textile fabrics [11,12]. However, bamboo PCs, which account for 52% of the total, have yet to be studied, mainly due to two reasons: (1) It is difficult to separate and extract bamboo PCs. Today’s bamboo separation technology is mainly based on bamboo fiber extraction, and bamboo PCs are often torn and discarded in the process of bamboo fiber extraction [13]; (2) bamboo PCs are mechanically weaker compared to bamboo fibers and macroscopically powdered, so their application value is not as high as that of bamboo fibers [14]. But recent studies have found that the cell walls of bamboo PCs have excellent toughness and elasticity [15,16]. The particular microcapsule structure of bamboo PCs can be applied in filler materials, electrode materials, phase change materials, drug release materials, and so on (Fig. 1) [17–19]. This indicates that the development value of bamboo PCs has yet to be significantly underestimated. Therefore, this paper reflects the research value of bamboo PCs by reviewing the structure, the isolation method, and the application.

Figure 1: Schematic of the application of PCs

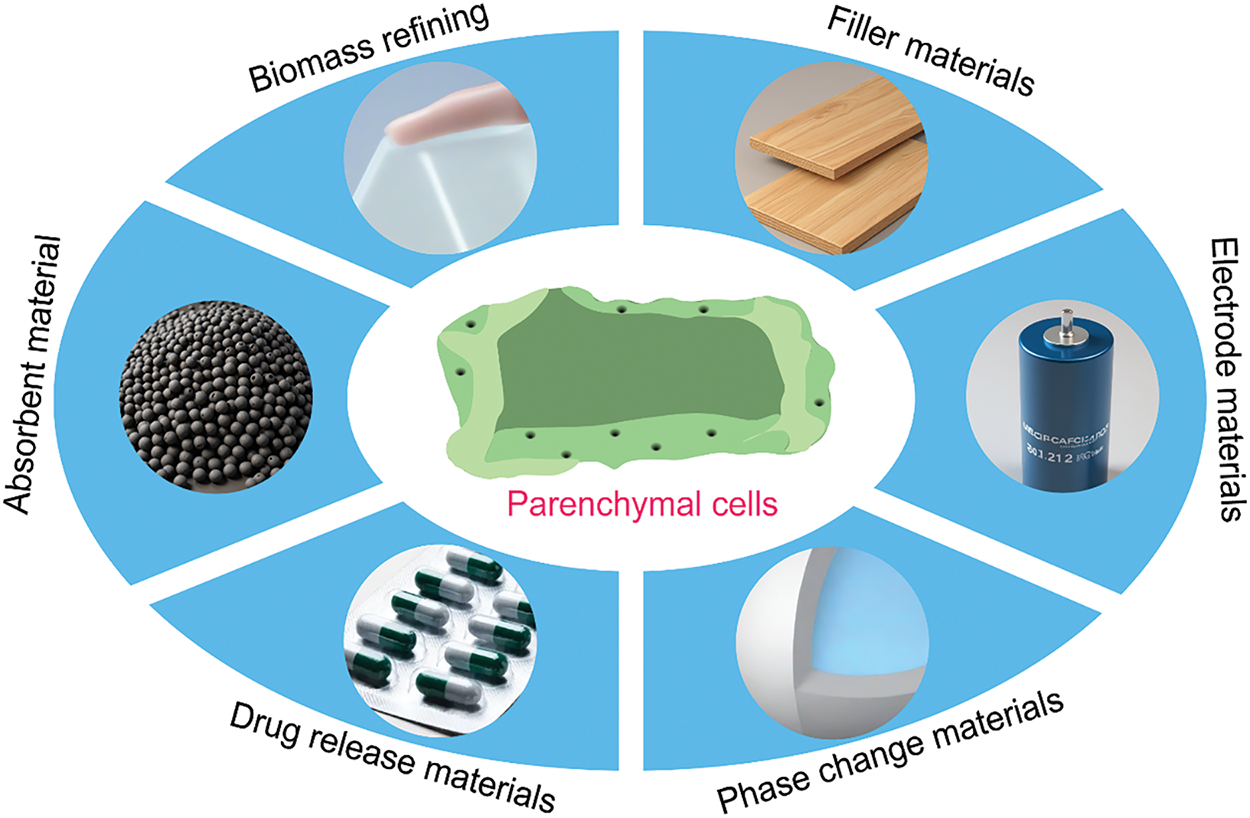

There are two main types of bamboo cells: bamboo fibers, which are extremely strong in tensile strength, and bamboo PCs, which have excellent bending toughness. Bamboo PCs, which account for 52% of the total, can considerably realize the bending process by bending the cell wall. This is due to the cell wall’s multilayer and microfilament mesh structure, which provides bamboo PCs with specific mechanical properties and stability [20]. At the cellular scale, bamboo PCs are ellipsoid or rounded, mainly because they store nutrients in bamboo growth. At the macroscopic scale, bamboo parenchymal cellular tissues surround the bamboo fibers in a form of foamy, providing the bamboo material with extreme toughness. The multi-scale delicate structure of bamboo PCs provides an essential structural basis for the growth of bamboo (Fig. 2) [21].

Figure 2: Multi-scale structural sketch of bamboo PCs

2.1 Morphological Characteristics of Bamboo PCs

According to the location of bamboo PCs in the culm diameter of bamboo, bamboo PCs are classified as essential tissue PCs and vascular bundle PCs [22]. The essential tissue PCs are mainly distributed between the vascular system, play the role of starch and water storage, and provide mechanical properties. Additionally, the vascular bundle PCs are distributed in the vascular bundle system and play an essential role in the transportation of the xylem and phloem. Using dissecting sections, it was found that the geometry of essential tissue PCs mainly contains subcircular, square, rectangular, ellipsoid-like, and irregular shapes and that the vascular bundle PCs are mainly of elongated and thin type. Bamboo PCs have a variety of morphologies because the final shape of the plant is controlled by cell division and expansion. This process is influenced by various endogenous and exogenous factors, such as cell differentiation and expansion, mechanical stimuli, etc. [23].

2.2 Ultrastructure of Bamboo PCs Wall Layers

The Bamboo PCs wall has a complex, multilayered structure containing an intercellular layer, primary wall, and secondary wall, and the main components are cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, pectin, and a small amount of protein. For the multilayered structure of bamboo PCs walls, most of the cell walls are tight-loosely arranged, the number of wall layers of the primary tissue PCs is between 1–11 layers, most of them are seven layers, and the average thickness of each layer is between 0.32–0.41 μm, and the number of wall layers of the PCs of the vascular bundles is between 1–9 layers. Most of them are 5 or 7 layers, and the average thickness of each layer is between 0.26 and 0.32 μm [24]. Bamboo fibers also have a multi-wall layer structure and the number of bamboo fiber cell wall layers can be up to 18 layers, compared to the bamboo PCs layer number is lower [25]. In addition, fiber cell walls are denser, with hardness and modulus of elasticity of 0.44 ± 0.09 GPa and 10.4 ± 1.8 GPa, respectively. In contrast, PCs walls are more lax, with relatively lower hardness and modulus of elasticity, with hardness and modulus of elasticity of 0.43 ± 0.22 GPa and 3.4 ± 1.3 GPa, respectively [26]. Microfibrils are an ultrastructure of fibers arranged in the cell wall. Microfibrils on the primary cell wall show a chaotic structure, while microfibrils on the secondary wall show a particular regular arrangement, usually described by microfilament angle. The microfibril angle is between the direction of microfibrils and the axial direction of the cell. The microfibril angle of the secondary walls of the essential tissues PCs is mainly in the range of 50°–70°. In contrast, the microfibril angle of the secondary walls of the vascular bundles PCs is in the range of 45°–60°. The above indicates that the PCs wall is a multilayered fine micro- and nanostructure.

2.3 Pits Structure of Bamboo PCs

Pits are indentations formed by the unthickened secondary wall of plant cells. These are essential constituent structures of the cell wall and critical pathways for the lateral transportation of water, nutrients, and other substances between plant cells [27]. The main structural parameters describing the pit include the inner mouth of the pit, the outer mouth of the pit, the striatal channel, the striatal membrane, and the number of striae. The inner orifice of bamboo PCs is mainly round or oval, while the outer orifice of the pit has various forms and is more complex. The diameter of the pit is generally 0.6–1.7 μm. The pit channel is generally columnar or dumbbell-shaped and most of pits are single-pit channels. Futhermore, some of them have multiple branching “branching pit cavities,” and the length of the pit channel is generally 2.5–4.5 μm. 2.5–4.5 μm [28]. The striatal membrane has no striatal plugs or lignin-like shell-like substances attached. Also, it has an intercellular connective filament structure and overall unevenness, the thickness of which is generally 0.3–0.5 μm. Due to the bamboo material’s poor transverse mass transfer efficiency, which is usually one-thousandth of the efficiency of longitudinal mass transfer, and bamboo fiber tissue is relatively dense and sparsely porous relative to the bamboo PCs [29]. Therefore, studying the striated pore structure of bamboo PCs plays a vital role in improving the efficiency of the interaction between bamboo material and external substances.

2.4 Cellulose Crystal Structure and Composition of Bamboo PCs

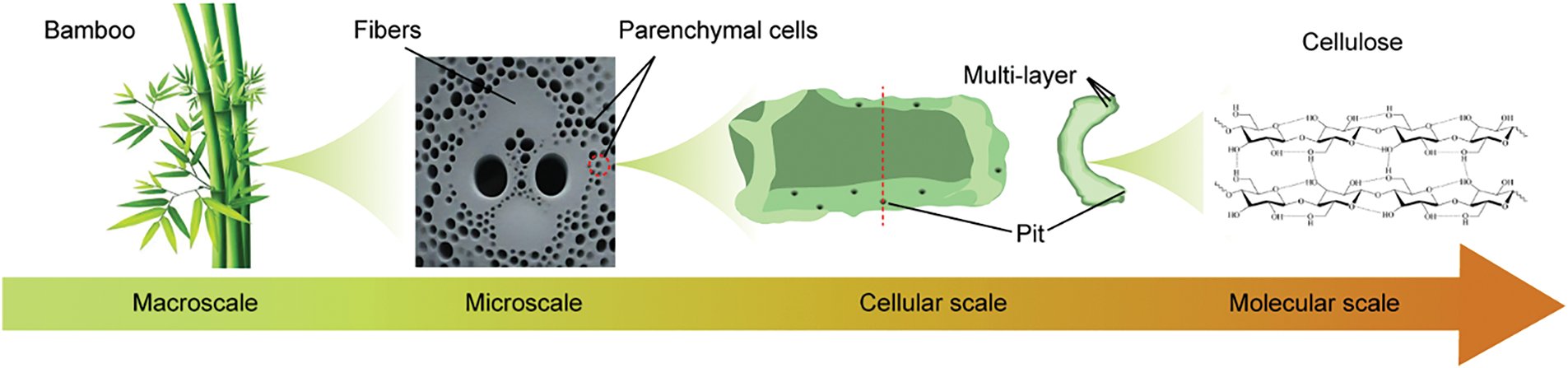

As shown in Fig. 3, bamboo PCs and bamboo fiber are similar in composition, consisting of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin (Fig. 3a). However, the cellulose content of bamboo PCs is lower (38.45% for bamboo fiber and 35.8% for bamboo PCs), and the crystallinity of cellulose is also lower (55.1% for bamboo fiber and 41.6% for bamboo PCs) (Fig. 3b and c), with more amorphous cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. Correspondingly, bamboo PCs are less thermally stable (maximum decomposition temperature of 361°C for bamboo fibers and 352°C for bamboo PCs) (Fig. 3d) and have a more significant void fraction (specific surface area of 0.63 m2/g for bamboo fibers and 0.96 m2/g for bamboo PCs) (Fig. 3e) [30,31]. In addition, the pebble-shaped polygonal cellulose nanocrystals in the cell walls of most bamboo fibers were found to have diameters ranging from 21–198 nm.

Figure 3: Composition and characterization of PCs after isolation. (a) infrared spectrum, (b) XRD, (c) crystallinity, (d) thermogravimetric, (e) specific surface area [30]. With permission from ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, Copyright 2023

3 Methods of Isolation of Bamboo PCs

3.1 Physical and Chemical Methods

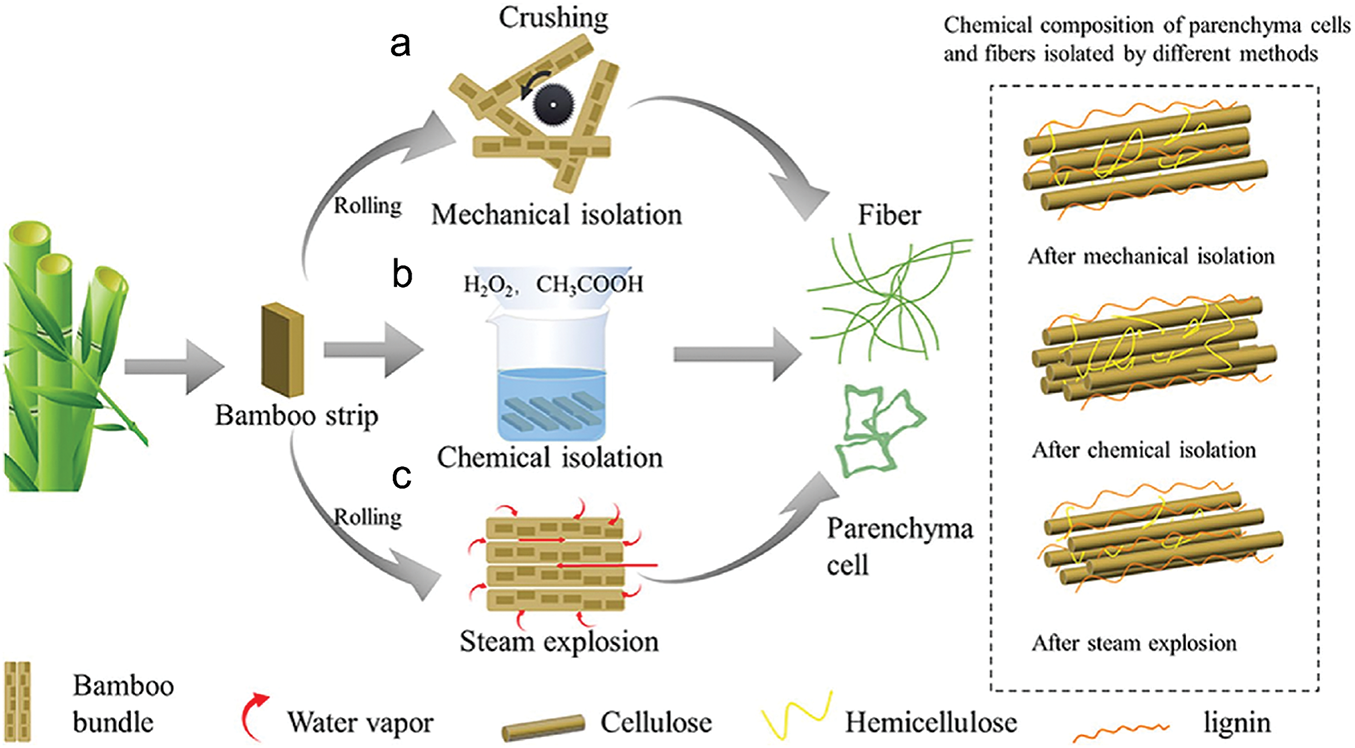

Separation of bamboo PCs refers to extracting PCs from bamboo by physical or chemical methods. Currently, the main methods of bamboo PCs separation are physical and chemical, and some new methods have emerged in recent years, such as steam blasting (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Flowchart of part of the experiment. (a) Mechanical isolation, (b) chemical isolation, (c) steam explosion [41]. With permission from Cellulose, Copyright 2023

The principle of separating PCs by physical method is to directly use mechanical force to tear bamboo fibers and PCs tissues, thus realizing the separation of bamboo PCs (Fig. 4a). Depending on the type of mechanical force, the following methods are currently available:

Crushing and pounding processing methods. The basic concept is like the water composting, killing, and pounding steps in traditional bamboo paper manufacturing. In this process, the cut bamboo is first cooked to soften the fibers and to reduce the bonding between the fiber bundles and the PCs. Mechanical forces such as crushing and hammering are used to further weaken the bonding strength between the fibers and ultimately achieve the effective separation of the fiber bundles from the PCs [32].

Mechanical combing method. The bamboo strips are flattened and finely shredded through the synergistic action of the feed chute and the spreading device. Subsequently, the bamboo strips enter the drum equipped with combing needles and are finely combed into a coarser filamentous form by the drum’s action, which helps to promote the natural shedding of PCs. Finally, precise separation of PCs and vascular tissues was achieved with the help of an efficient wind-screening system [33].

Screw press crushing method. This is a method of processing materials using a screw press. The material enters the screw chute through the inlet of the screw press and is then pushed by the rotating screw shaft into the compression or fiber-crushing zone of the press. In this compression or crushing zone, the material is subjected to pressing, crushing, or kneading to form bundles or masses of fiber structure. The steam-softened bamboo slices are subjected to multiple actions, such as pressing and crushing during the spiral pressing process, resulting in the separation of the PCs-tissue portion from the slices, which achieves an effective separation of the PCs from the vascular bundle tissues [34].

Density gradient method. First, the whole piece of bamboo is carefully pulverized and precisely stolen to ensure that the particles are of uniform size. These bamboo powder particles are then carefully added to the water and stirred continuously to ensure that the particles are evenly distributed. With the cessation of stirring, the mixture will gradually come to a resting state. Due to the difference in density, the PCs in the bamboo material will float up to the surface of the liquid due to buoyancy, making it easy to collect. At the same time, the denser fibers will settle in the lower layer of the liquid, which can also be collected and separated systematically [35].

Physical separation of PCs has the advantages of simplicity and high efficiency, low water consumption, green environmental protection, and high lignin content, but the bamboo fibers obtained are mostly short fibers, bamboo PCs are clusters, and the structural properties of the fibers and PCs are not fully preserved. The fibers and the PCs have a certain degree of damage.

The main principle of the chemical method is to weaken the connection between bamboo fibers and bamboo PCs by removing lignin and then using the difference in the physical properties of bamboo fibers and PCs to separate these two types of cells (Fig. 4b). In 1946, Wise et al. separated individual cells by preparing plant sections and removing the lignin in the middle layer. This was done by collecting individual dispersed cells every three hours from plant sections after lignin removal and rinsing them with distilled water until their pH was neutral. This process was repeated for residual sections until the sections were excised and almost completely disintegrated into individual cells. Finally, the single-cell aqueous suspension was repeatedly screened with a sieve, thus separating the PCs from the fibers [36]. Consequently, the solvent for lignin removal in the chemical method is the key.

In the paper industry, sodium chlorite (NaClO2), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sodium sulfite (Na2CO3), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are all commonly used chemicals to remove lignin and hemicellulose. However, since achieving the desired removal effect with a single solution is often tricky, multiple solutions are usually combined. Yu Yanglun’s team pioneered the chemical separation of PCs using multiple solutions (NaClO2 and NaOH) and realized its application. It removes lignin by NaClO2, hemicellulose by NaOH, and drying, weakens the connection between bamboo fibers and bamboo PCs, and achieves the separation of single bamboo fibers from bamboo PCs by further mechanical external force [37]. Separate bamboo PCs can be made into bamboo capsules, which are used to encapsulate magnetic and pharmaceutical substances [38].

Chemical separation of PCs ensures both the fibrous nature of bamboo fibers and the separation of individually dispersed bamboo PCs. Moreover, the surface of PCs and fibers is smooth and clean, forming a dense and orderly structure with low requirements for equipment [39,40]. However, the many steps of experimental operation, long experimental period, large water consumption, and the inability to prepare bamboo PCs in large quantities became a new problem.

Steam blasting method. This method utilizes the blasting force to separate the different components of bamboo material and comprehensively utilize each component, a new type of physical method in nature (Fig. 4c). In the steam explosion process, the water vapor generated by high temperature and pressure can penetrate the fiber bundles, making them wet and swollen. When the pressure is released, the vast impact generated will prompt the rupture or oscillation of the swollen cell wall, thus separating PCs and fibers [41].

3.2 Effect of Isolation Methods on Bamboo PCs

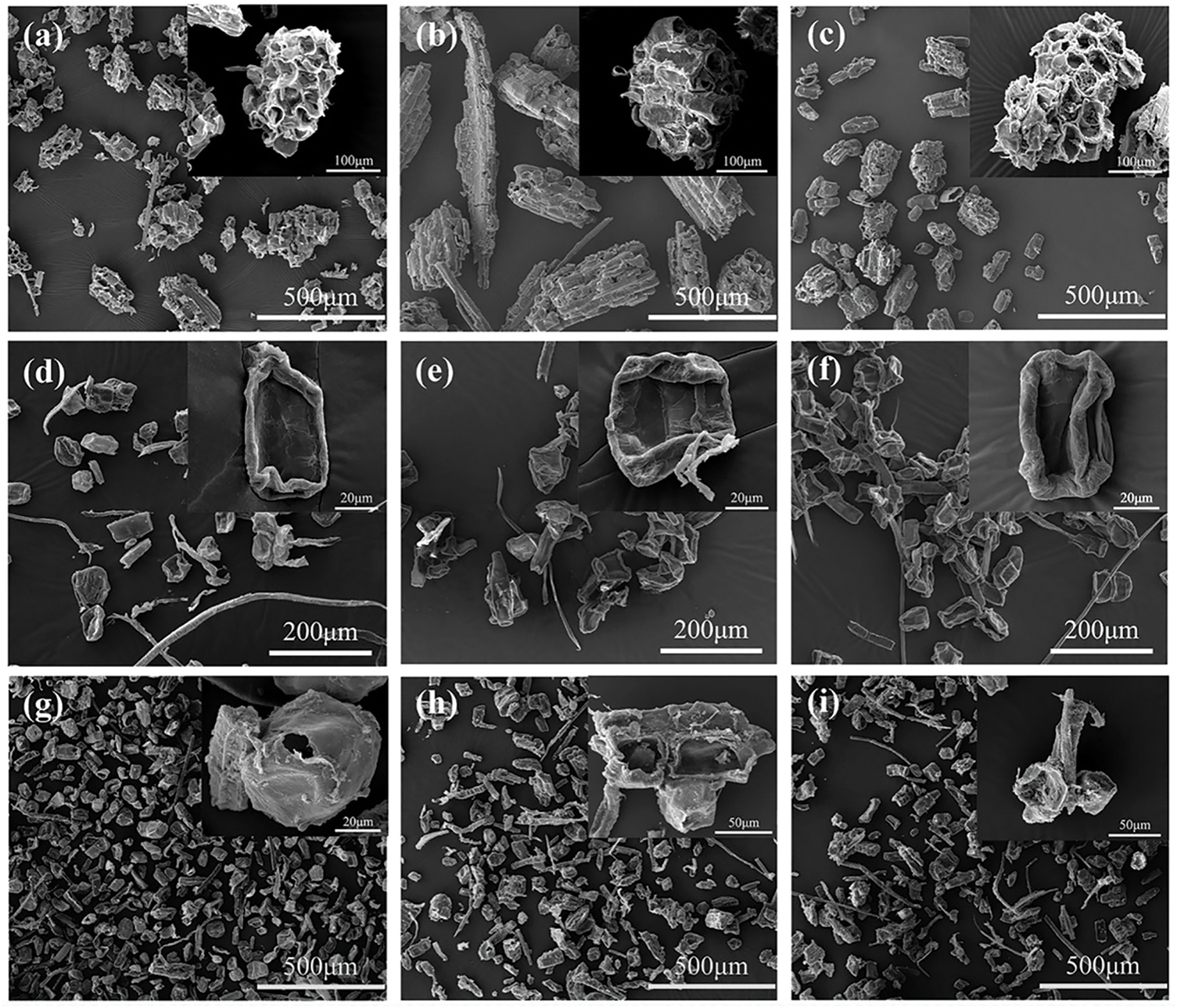

From the morphological point of view (Fig. 5), the physical method of separation of bamboo PCs is mostly clusters (Fig. 5a–c). However, chemical separation of PCs is mostly morphologically structurally intact single cells, and the PCs are collapsed and wrinkled (Fig. 5d–f). The steam explosion method is mainly for single cells, most of which are morphologically intact, but a small portion will be destroyed into fragments (Fig. 5g–i). This suggests that the physical method of separating PCs is more rugged, the chemical method is gentler, and the steam blasting method is somewhere in between.

Figure 5: Morphology of PCs after isolation: (a–c) physical method, (d–f) chemical method, (g–i) steam blasting method [41]. With permission from Cellulose, Copyright 2023

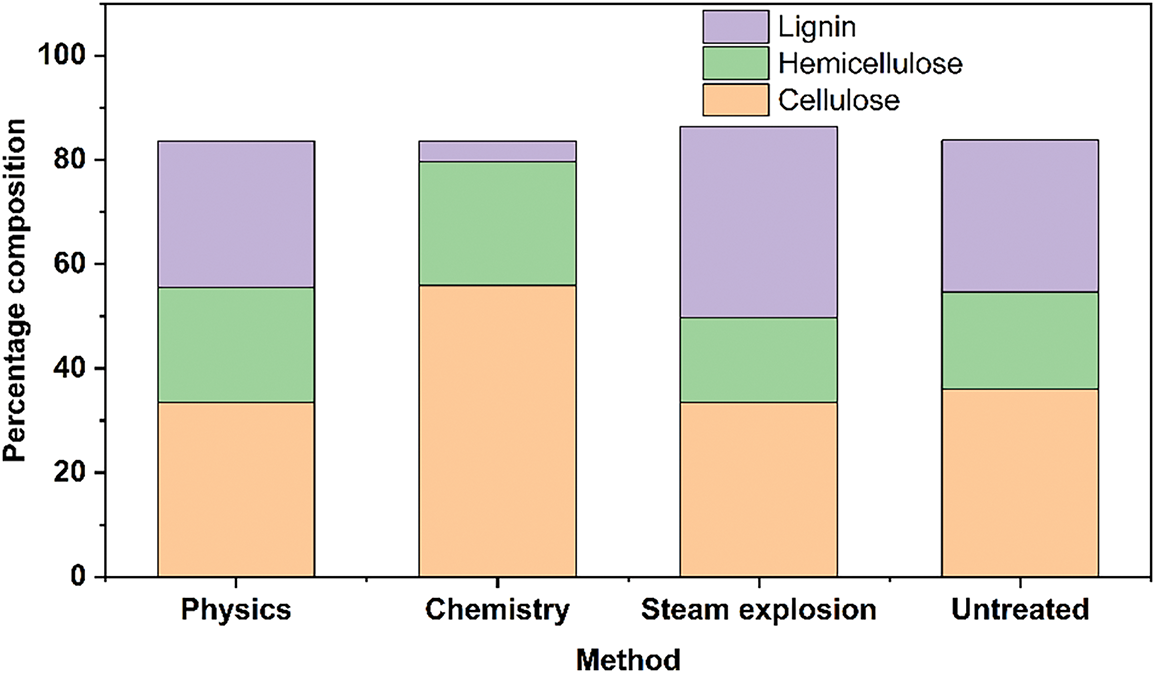

Compositionally (Fig. 6). The bamboo PCs separated by different methods still maintained the three major components but in different proportions [42]. The physical method showed the most significant decrease in cellulose content from 36.01% to 33.37% compared to untreated bamboo, which was caused by removing bamboo fibers with high cellulose content. The chemical method significantly increased the cellulose content from 36.01% to 55.87% due to removing a large amount of lignin from 29.06% to 4.04%. Steam blasting method decreases the cellulose and hemicellulose content, possibly due to the loss of tissue composition due to crack expansion during blasting.

Figure 6: Percentages of the three major elements for the three methods [41]. With permission from Cellulose, Copyright 2023

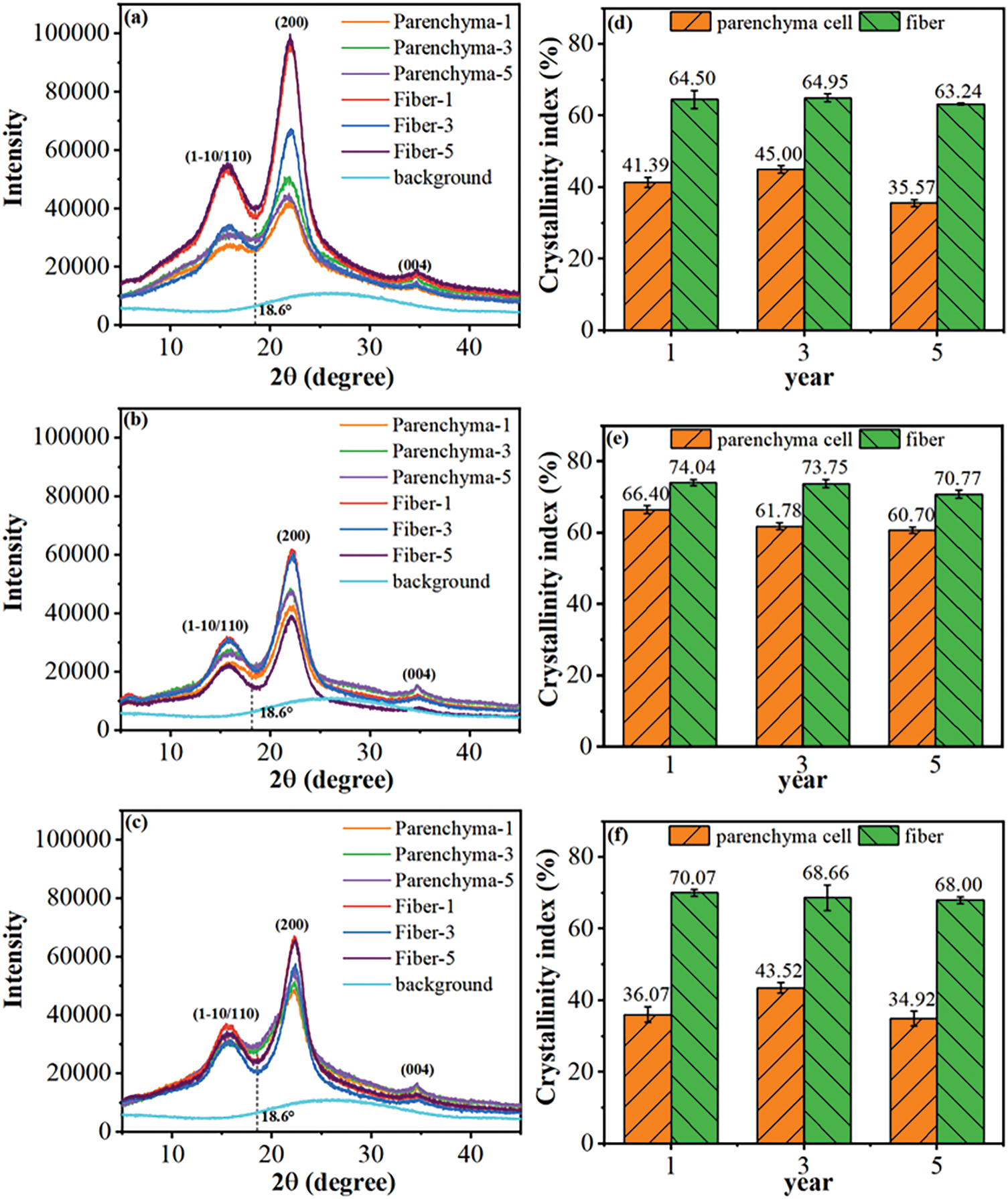

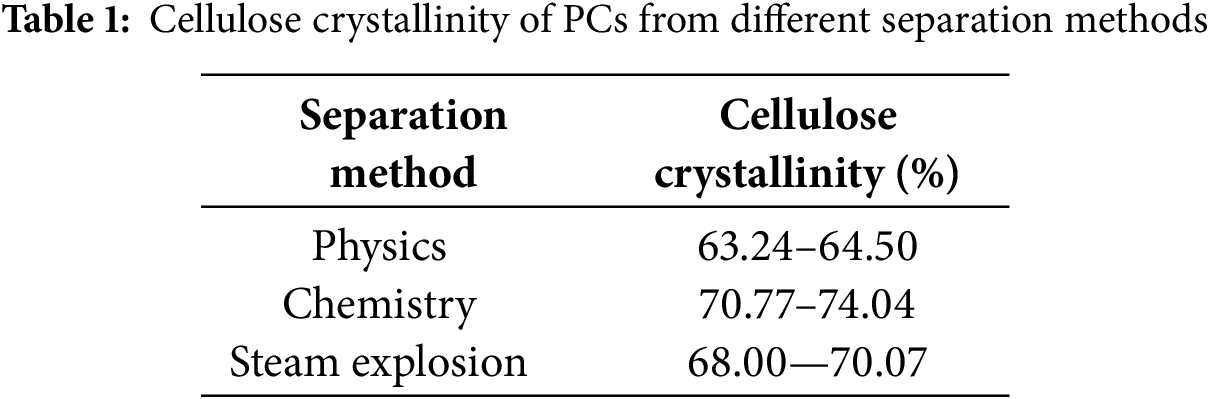

From the point of view of cellulose crystal shape (Fig. 7), the characteristic peaks of the PCs and fibers obtained through the three methods were located at 16°, 22°, and 34.7° for the (110), (200) and (004) characteristic peaks, which are the typical characteristic peaks of cellulose, type I [43]. This indicates that the different treatments did not change the crystal structure. The lower cellulose crystallinity of bamboo PCs suggests that the molecular structure of bamboo PCs is laxer than bamboo fibers (Table 1). In addition, Lin et al. used a chemical method to separate bamboo fibers and bamboo PCs by stepwise treatment of bamboo powder with NaClO2 and NaOH. The cellulose was analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy as the crystalline form of cellulose class I. The low concentration of sodium hydroxide alkaline solution did not change the aggregation structure of the cellulose. However, cellulose’s amorphous and partially crystalline regions were altered with its intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonding and glycosidic bonding [44].

Figure 7: XRD patterns and the corresponding crystalline index of PCs and fibers (a,d) isolated mechanically, (b,e) isolated chemically, and (c,f) isolated by steam explosion [40]. With permission from Cellulose, Copyright 2023

Bamboo PCs have unique multi-wall microcapsules and porous structures, so PCs have a wide range of applications in many fields, such as drug release, adsorption, electrochemistry, biomass refining, etc. The morphology of PCs isolated by physical and chemical methods is not the same. The physical method is mainly in the form of clusters, and the chemical method is mainly in the form of single dispersed cells, so the PCs are isolated by the two methods that do not have the same application areas.

Physical separation is rough, so PCs are mainly clustered. Clustered PCs are rich in internal space and have high deformation capacity. They can be used as a phase change of energy storage materials, filler materials, etc.

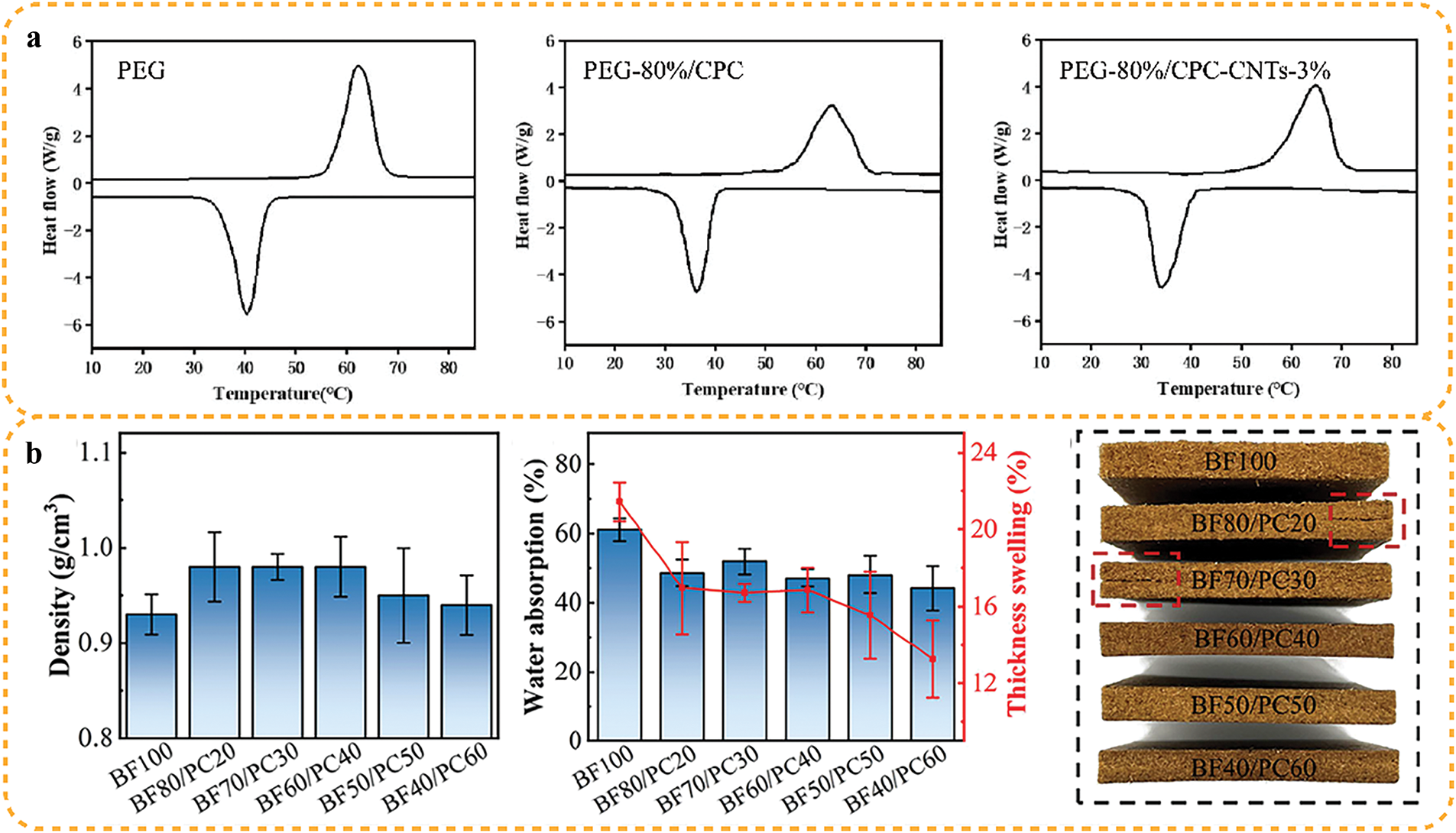

Phase change materials are a class capable of undergoing phase changes under specific conditions. They store energy by absorbing or releasing latent heat and have a large energy storage capacity. However, organic phase change materials are prone to leakage, low thermal conductivity, and low photothermal conversion performance, significantly hindering their practical applications. To address these shortcomings, Chaowei Zheng [45] innovatively utilized and prepared a novel shape-stabilized composite phase change material by adding polyethylene glycol (PEG) to porous carbonized bamboo PCs (CPCs) containing carbon nanotubes (CNTs) (Fig. 8a). The support material containing carbon nanotubes has a unique three-dimensional porous structure and a continuous heat transfer network structure. Compared with pure PEG, the thermal conductivity of PEG/CPC-CNTs at 0.494 W/m⋅K was increased by 128%. The prepared composite phase change materials had latent heat of fusion and crystallization of 149.4 J/g and 144.1 J/g, respectively. Regarding shape stability, the PEG encapsulation of CPC reached 80%, which was superior to that of untreated PEG. Therefore, the composite phase change materials of PEG/CPC-CNTs with a simple preparation method have great potential for use in bamboo and wood construction materials such as wood-plastic composites, particle boards, flooring or roofing panels, etc. field, with great potential for application.

Figure 8: Application of physical method for separation of bamboo PCs: (a) phase change energy storage material [44] With permission from Journal of Building Engineering, Copyright 2022, (b) filler material [45]. With permission from ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, Copyright 2023

Filler materials are substances added to the primary material to increase volume, improve performance, or reduce costs. Chen et al. [30] recombined reasonably proportioned bamboo fibers with bamboo PCs filler materials to generate formaldehyde-free and bamboo self-bonding composites, which utilized the characteristics of high deformation of bamboo PCs (Fig. 8b). Bamboo PCs lock the bamboo fibers together to form a dense structure so that the recombined fiberboards have excellent mechanical properties.

Chemical separation of PCs is relatively mild, so most of PCs are single-dispersed. Single-dispersed PCs have a larger specific surface area and a unique capsule-like structure, so they can be used in energy, medicine, and adsorption fields.

The energy field covers all aspects of energy production, conversion, storage, transportation, distribution, consumption, energy efficiency and environmental impact, such as supercapacitors for storing electricity and textiles with sensors, electronic components, communication systems, and other technologies [46].

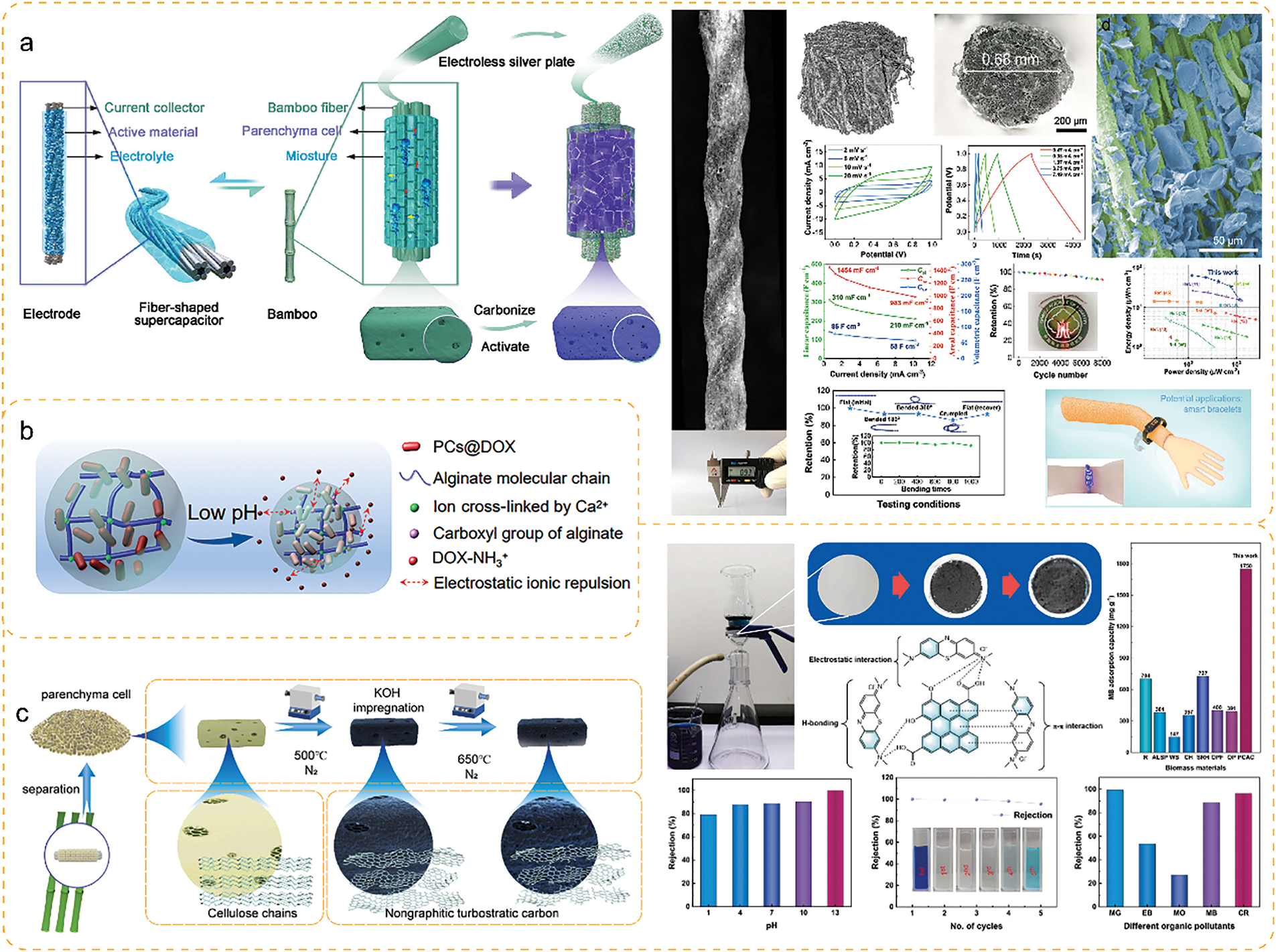

Xia et al. [47] prepared supercapacitors utilizing activated carbon from bamboo PCs, which had a high specific capacitance of 276 F/g at 0.1 A/g and exhibited good capacity retention (89.48%) even after 15,000 cycles at 10 A/g. KOH activated the bamboo PCs to form an ultra-high specific surface area (3973 m2/g) and pore volume (2.076 cm3/g), which provided the structural basis for their superior electrical properties. This indicates that the activated bamboo PCs have excellent electrical energy storage capacity.

Intelligent textiles are functional with integrated electronics, sensors, communications, and other advanced technologies. They can sense, respond, and adapt to different conditions and needs through interaction with the human body, environment, or other devices. Intelligent textiles are moving towards being lightweight, low cost, and having high energy density. Lin et al. [48] prepared a low-cost, high energy/power density fibrous supercapacitor by wrapping bamboo PCs around bamboo fibers after activation (Fig. 9a). Its mechanical flexibility enabled the weaving of wearable wristbands to drive ultra-small voltmeter indicators.

Figure 9: Application of chemical methods for separation of bamboo PCs: (a) energy sector [48]. With permission from NPJ Flexible Electronics, Copyright 2022, (b) pharmaceutical sector [49]. With permission from ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, Copyright 2022, (c) adsorption sector [47]. With permission from Journal of Cleaner Production, Copyright 2023

Microcapsules have attracted much attention due to their fundamental value in storing and releasing various drugs. However, most of the microcapsules prepared from synthetic polymers are non-biodegradable and have the risk of causing microplastic contamination. So, it is essential to develop sustainable and green microcapsules. Li et al. [49] prepared biodegradable, low-cost, and environmentally friendly hollow lignocellulosic microcapsules from delignified bamboo PCs (Fig. 9b). Adriamycin hydrochloride was well encapsulated with 92.2% encapsulation efficiency. Moreover, the slow-release behavior of adriamycin hydrochloride was achieved by embedding alginate beads.

Adsorption is an essential method for water pollution treatment. Activated carbon, mainly used for physical adsorption, is one of the most used materials for water pollution treatment. Ma et al. [50] prepared a thin-walled hollow ellipsoid-based activated carbon from PCs rich in oxygen groups and pore structure, with a specific surface area of up to 730.87 m2/g. The CPCs-900 in water adsorption Pb2+ was 37.26 mg/g, and the efficiency of removing Pb2+ from water was 98.13%, three times higher than that of ordinary activated carbon. In addition, bamboo PCs-activated carbon has excellent cationic dye removal capacity with maximum adsorption of 1750 mg/g for methylene blue, which is 2–5 times higher than that of ordinary biomass-activated carbon (Fig. 9c) [47]. This suggests that activated carbon prepared from bamboo PCs is essential to meet the great demand for removing pollutants from water.

Biomass refining mainly refers to converting the main components of plant resources, including cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose, into high-value-added materials, energy, chemical products, etc., after specific treatments [51]. Since the main component of PCs is cellulose and is more chemically active compared to bamboo fibers, PCs can be prepared into biomass-refined products such as cellulose hydrogel, biorefined glucose, nanocellulose fibril aerogels and cellulose membranes [52,53].

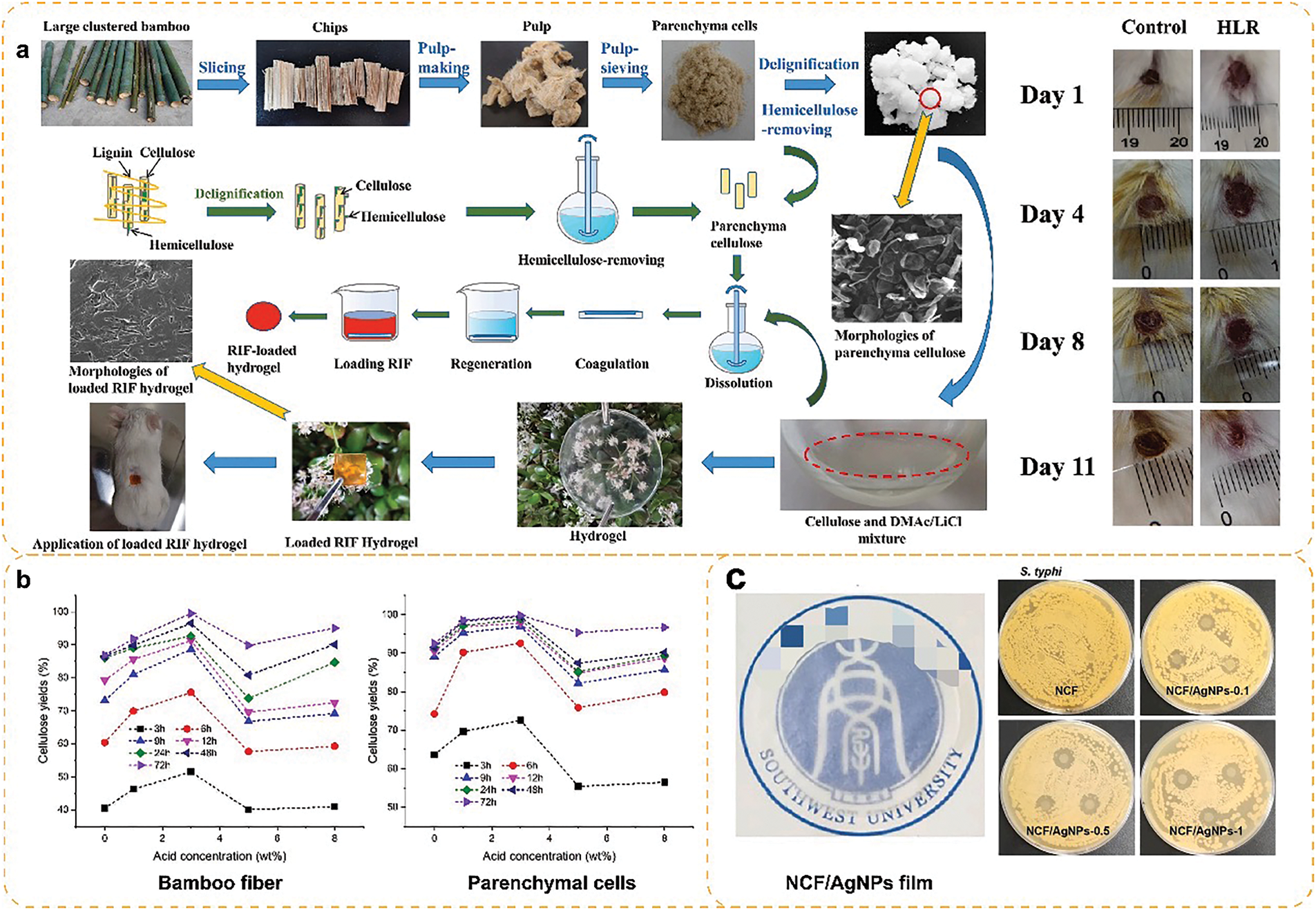

Cellulose hydrogel is a polymer material made of cellulose with good biocompatibility, hydrophilicity and mechanical properties, and is widely used in hygiene products, food additives, soil conditioners and biomedical applications [54]. Zhang et al. developed cellulose hydrogels (HLRs) by utilizing the high specific surface area of bamboo PCs and the accessibility of chemical reagents (Fig. 10a). HLRs are drug-encapsulated and biocompatible against a variety of external bacterial influences, and therefore, the healing time of hydrogel-treated wounds was shortened in mice [55].

Figure 10: Bamboo PCs biorefinery applications: (a) cellulose hydrogel [55]. With permission from International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, Copyright 2022, (b) biorefinery glucose [56]. With permission from ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, Copyright 2019, (c) cellulose membrane [60]. With permission from International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, Copyright 2022

Bamboo is rich in cellulose and hemicellulose, which can be converted to glucose by biorefinery. However, the hierarchical and heterogeneous structure of plant cell walls greatly influences the conversion process. It was found that after the same deep eutectic solvent treatment, the degree of delignification of PCs was significantly higher than that of bamboo fiber tissues. Consequently, the PCs had higher enzymatic efficiency. The sugar conversion ratio of PCs was also higher than that of bamboo fibers [56]. It was also found that the cellulose chains in bamboo PCs were more loosely arranged, and their crystalline spacing was more significant. Hence, chemical degradation of PCs is easier [57]. In conclusion, industrial bamboo processing residues (mainly PCs) are a promising feedstock for current biorefinery programs [58].

Cellulose membranes are films made of cellulose materials. Such films usually have the properties of cellulose, such as high strength, high air permeability, and biodegradability, and thus have essential roles in packaging, separation, etc. Gao et al. [59] prepared cellulose membranes based on bamboo PCs isolated from sulfate pulp, which provided a way to utilize bamboo PCs in a high value-added way. In addition, Ren et al. [60] prepared a composite film (NCF/AgNPs film) based on nanocellulose extracted from bamboo PCs as a matrix and silver nanoparticles as embedding material (Fig. 10b). The composite film showed good tensile strength, modulus, elongation at break, high antimicrobial activity, and thermal stability. This suggests that bamboo PCs have great potential for application in packaging.

Based on the above analysis, it is suggested that future research on bamboo PCs focus on the following aspects:

(1) Bamboo PCs obtained by different isolation methods have different cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin content, microfilament network structure, supramolecular structure, crystalline structure, etc., but the relationship between the two is not clear, so a systematic study is necessary.

(2) There is no efficient method to separate bamboo PCs with minor damage, so their industrial application is hindered. Therefore, the exploration of solvents for PCs separation and physical methods for weakening the bonding force between PCs and bamboo fibers is crucial. Chemical approaches should prioritize the development of greener and more efficient solvents for delignification. For example, deep eutectic solvent [61]. Meanwhile, advanced physical techniques (e.g., steam explosion) require optimized experimental parameters to mitigate the structural degradation of PCs. In addition the development of new techniques for the isolation of bamboo PCs is also noteworthy. For example, Reductive catalytic fractionation [62], Lignin-degrading enzymes [63], etc.

(3) Bamboo PCs have a unique structure, but at present, the application of its structural advantages is still in the preliminary stage of research; the need to be developed through further PCs application potential, such as slow release, thermal management, adsorption, and other areas. One separation method may significantly influence the application potential of PCs. When isolated via physical techniques, parenchyma cells form granular aggregates with robust mechanical properties, making them promising candidates for filling applications, especially after surface modification or functional material encapsulation. In contrast, chemically isolated PCs exhibit capsular morphology with fine particle size and high cellulose purity, rendering them ideal for eco-friendly controlled-release materials or highly reactive carbon-based green precursors.

(4) Compared with bamboo fiber, which exhibits high mechanical strength, capsule-like PCs are expected to diverge significantly in their future applications, focusing instead on high-performance adsorption, controlled/smart release systems, and advanced anode materials. Nevertheless, since both PCs and bamboo fibers originate from the same bamboo matrix, their separation methods are inherently interdependent. Consequently, advancements in PCs isolation techniques will likely parallel those in bamboo fiber extraction.

Bamboo PCs possess delicate multi-scale structures, including microcapsules, multiwall layers, and pits. These structures provide the structural basis for their application design.

Bamboo PCs separation methods mainly include physical and chemical methods, which have advantages and disadvantages. The physical method is simple and efficient, but the bamboo PCs and fibers are damaged to a certain extent. The PCs prepared by the chemical method were individually dispersed and morphologically complete, but the separation process was cumbersome and time-consuming.

Bamboo PCs have great potential for application in fiberboard, extended release, heavy metal ion removal, cellulose membrane, antimicrobial cellulose hydrogel, intelligent textiles and biorefinery glucose. This indicates that bamboo PCs have the ability for multifunctional applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was financially supported by the Fundamental Research Funds of CAF (CAFYBB2022QA004).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Yao Xia and Yuxiang Huang; methodology, Yao Xia; software, Yao Xia; validation, Yao Xia and Yuxiang Huang; formal analysis, Yao Xia; investigation, Yao Xia; resources, Yuxiang Huang; data curation, Yao Xia; writing—original draft preparation, Yao Xia; writing—review and editing, Yuxiang Huang, Shifeng Zhang and Yanglun Yu; visualization, Yao Xia; supervision, Yuxiang Huang; project administration, Yuxiang Huang; funding acquisition, Yuxiang Huang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

List of Aabbreviations

| Abbreviations | Explanation |

| PCs | Parenchyma cells |

| NaClO2 | Sodium chlorite |

| NaOH | Sodium hydroxide |

| Na2CO3 | Sodium sulfite |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| CPCs | Porous carbonized bamboo pcs |

| CNTs | Carbon nanotubes |

| PEG/CPC-CNTs | Porous Carbonized Bamboo PCs Embedded with Polyethylene Glycol and Attached to Carbon Nanotubes |

| CPCs-900 | PCs carbonized at 900 degrees |

| HLRs | Cellulose hydrogels |

| NCF/AgNPs film | Nanocellulose fibril-based composite film with embedded silver nanoparticles from bamboo parenchyma cell |

References

1. Chen M, Guo L, Ramakrishnan M, Fei Z, Vinod KK, Ding Y, et al. Rapid growth of moso bamboo (Phyllostachys eduliscellular roadmaps, transcriptome dynamics, and environmental factors. Plant Cell. 2022;34(10):3577–610. doi:10.1093/plcell/koac193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Cheng L, Li LJ, Huang KY, Lan X, Dai J, Huang DY. Research progress on the processing application of Dendrocalamus latiflorus. J Anhui Agric Sci. 2023;51(19):1–4,11. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.0517-6611.2023.19.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhao X, Ye H, Chen F, Wang G. Bamboo as a substitute for plastic: research on the application performance and influencing mechanism of bamboo buttons. J Clean Prod. 2024;446(19):141297. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Nkeuwa WN, Zhang J, Semple KE, Chen M, Xia Y, Dai C. Bamboo-based composites: a review on fundamentals and processes of bamboo bonding. Compos Part B Eng. 2022;235:109776. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.109776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sharma B, Gatóo A, Bock M, Ramage M. Engineered bamboo for structural applications. Constr Build Mater. 2015;81(2):66–73. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.01.077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Huang Y, Ji Y, Yu W. Development of bamboo scrimber: a literature review. J Wood Sci. 2019;65(1):25. doi:10.1186/s10086-019-1806-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Yuan T, Han X, Wu Y, Hu S, Wang X, Li Y. A new approach for fabricating crack-free, flattened bamboo board and the study of its macro-/micro-properties. Eur J Wood Wood Prod. 2021;79(6):1531–40. doi:10.1007/s00107-021-01734-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Sun PC, Wang D. Historical changes and current status of bamboo resource utilization in Yixing City, Jiangsu Province. World Bamboo Rattan. 2023;21(1):46–54. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

9. Li Z, Chen C, Mi R, Gan W, Dai J, Jiao M, et al. A strong, tough, and scalable structural material from fast-growing bamboo. Adv Mater. 2020;32(10):e1906308. doi:10.1002/adma.201906308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Wei X, Wang G, Chen X, Jiang H, Smith LM. Natural bamboo coil springs with high cyclic-compression durability fabricated via a hydrothermal-molding-fixing method. Ind Crops Prod. 2022;184(5):115055. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gao X, Zhu D, Fan S, Rahman MZ, Guo S, Chen F. Structural and mechanical properties of bamboo fiber bundle and fiber/bundle reinforced composites: a review. J Mater Res Technol. 2022;19(1):1162–90. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.05.077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li Z, Chen C, Xie H, Yao Y, Zhang X, Brozena A, et al. Sustainable high-strength macrofibres extracted from natural bamboo. Nat Sustain. 2021;5(3):235–44. doi:10.1038/s41893-021-00831-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chen C, Li H, Dauletbek A, Shen F, Hui D, Gaff M, et al. Properties and applications of bamboo fiber-a current-state-of-the art. J Renew Mater. 2022;10(3):605–24. doi:10.32604/jrm.2022.018685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang D, Lin L, Fu F. Fracture mechanisms of moso bamboo (Phyllostachys pubescens) under longitudinal tensile loading. Ind Crops Prod. 2020;153:112574. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Dixon PG, Muth JT, Xiao X, Skylar-Scott MA, Lewis JA, Gibson LJ. 3D printed structures for modeling the Young’s modulus of bamboo parenchyma. Acta Biomater. 2018;68:90–8. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2017.12.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Chen M, Ye L, Wang G, Ma X, Chen Q, Fang C, et al. In-situ investigation of deformation behaviors of moso bamboo cells pertaining to flexural ductility. Cellulose. 2020;27(16):9623–35. doi:10.1007/s10570-020-03414-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chaturvedi K, Singhwane A, Dhangar M, Mili M, Gorhae N, Naik A, et al. Bamboo for producing charcoal and biochar for versatile applications. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(14):15159–85. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-03715-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Chaudhary P, Bansal S, Sharma BB, Saini S, Joshi A. Waste biomass-derived activated carbons for various energy storage device applications: a review. J Energy Storage. 2024;78:109996. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.109996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Okasha MM, Abbas M, Formanova S, Faiz Z, Ali AH, Akgül A, et al. Scrutinization of local thermal non-equilibrium effects on stagnation point flow of hybrid nanofluid containing gyrotactic microorganisms: a bio-fuel cells and bio-microsystem technology application. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2025;150(1):797–811. doi:10.1007/s10973-024-13828-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Chen Q, Razi H, Schlepütz CM, Fang C, Ma X, Fei B, et al. Bamboo’s tissue structure facilitates large bending deflections. Bioinspiration Biomim. 2021;16(6):065005. doi:10.1088/1748-3190/ac253b. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Nishida M, Tanaka T, Miki T, Shigematsu I, Kanayama K, Kanematsu W. Study of nanoscale structural changes in isolated bamboo constituents using multiscale instrumental analyses. J Appl Polym Sci. 2014;131(9):153. doi:10.1002/app.40243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. He XQ, Suzuki K, Kitamura S, Lin JX, Cui KM, Itoh T. Toward understanding the different function of two types of parenchyma cells in bamboo culms. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43(2):186–95. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcf027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Cosgrove DJ. Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 2005;6(11):850–61. doi:10.1038/nrm1746. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lian C, Liu R, Cheng X, Zhang S, Luo J, Yang S, et al. Characterization of the pits in parenchyma cells of the moso bamboo [Phyllostachys edulis (Carr.) J Houz] Culm. Holzforschung. 2019;73(7):629–36. doi:10.1515/hf-2018-0236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chen H. Research on the structural characterization of bamboo fiber cell wall [dissertation]. Beijing, China: China Academy of Forestry Sciences; 2014. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

26. Zou L, Jin H, Lu WY, Li X. Nanoscale structural and mechanical characterization of the cell wall of bamboo fibers. Mater Sci Eng C. 2009;29(4):1375–9. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2008.11.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Christman MA, Sperry JS, Adler FR. Testing the ‘rare pit’ hypothesis for xylem cavitation resistance in three species of Acer. New Phytol. 2009;182(3):664–74. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02776.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Lian CP. Ultrastructure of thin-walled cells of moso bamboo timber [dissertation]. Beijing, China: China Academy of Forestry; 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

29. Lei W, Huang Y, Yu W, Wang X, Wu J, Yang Y, et al. Evolution of structural characteristics of bamboo scrimber under extreme weather. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;203(1952):117195. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chen H, Shi J, Zhong T, Fei B, Xu X, Wu J, et al. Tunable physical-mechanical properties of eco-friendly and sustainable processing bamboo self-bonding composites by adjusting parenchyma cell content. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2023;11(28):10333–43. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c01149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chen H, Wu J, Shi J, Zhang W, Wang H. Effect of alkali treatment on microstructure and thermal stability of parenchyma cell compared with bamboo fiber. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;164(1):113380. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ye LP, Fang GG, Shen KZ, Deng YJ, Li P. Research and development of mechanical progress to separate bamboo parenchyma cells from bamboo. China Pulp Pap Ind. 2013;34(8):26–9. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

33. Zhang W, Yao WB, Li WB. Research and development of technology for processing bamboo fiber. Trans Chin Soc Agric Eng. 2008;24(10):308–12. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

34. Xie DY, Xu GH, Liu XH, He XX. Research on pretreatment of wood chips for high yield chemical machine pulp and key equipment-screw extrusion ripper. Light Indus Mach. 2010;28:20–2. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

35. Yu Y, Jiang ZH, Wang HK, Li WJ, Ren D. A method for separation of thin-walled cells and fibers in bamboo wood. China Patent CN105150328B. 2017 Jul;14:1–8. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

36. Abe K, Yano H. Comparison of the characteristics of cellulose microfibril aggregates isolated from fiber and parenchyma cells of Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys pubescens). Cellulose. 2010;17(2):271–7. doi:10.1007/s10570-009-9382-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yu YL, Huang YX, Li SN, Yu WJ, Gao RQ. A method for separating fibers and thin-walled cells of bamboo wood. China Patent CN105150328B. 2017 Jul;14:1–8. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

38. Yu YL, Lu Y, Huang YX, Yu WJ, Gao RQ. A bamboo capsule and its preparation method and application. China Patent CN114307890A. 2022 Apr;12:1–8. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

39. Lin Q, Huang Y, Yu W. Effects of extraction methods on morphology, structure and properties of bamboo cellulose. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;169(10):113640. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Li X, Peng H, Niu S, Liu X, Li Y. Effect of high-temperature hydrothermal treatment on chemical, mechanical, physical, and surface properties of moso bamboo. Forests. 2022;13(5):712. doi:10.3390/f13050712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Li J, Lian C, Wu J, Zhong T, Zou Y, Chen H. Morphology, chemical composition and thermal stability of bamboo parenchyma cells and fibers isolated by different methods. Cellulose. 2023;30(4):2007–21. doi:10.1007/s10570-022-05030-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Guo F, Zhang X, Yang R, Salmén L, Yu Y. Hygroscopicity, degradation and thermal stability of isolated bamboo fibers and parenchyma cells upon moderate heat treatment. Cellulose. 2021;28(13):8867–76. doi:10.1007/s10570-021-04050-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Toba K, Nakai T, Shirai T, Yamamoto H. Changes in the cellulose crystallinity of moso bamboo cell walls during the growth process by X-ray diffraction techniques. J Wood Sci. 2015;61(5):517–24. doi:10.1007/s10086-015-1490-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Lin Q, Huang Y, Yu W. An in-depth study of molecular and supramolecular structures of bamboo cellulose upon heat treatment. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;241(4633):116412. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zheng C, Zhang H, Xu L, Xu F. Carbonized bamboo parenchyma cells loaded with functional carbon nanotubes for preparation composite phase change materials with superior thermal conductivity and photo-thermal conversion efficiency. J Build Eng. 2022;56:104749. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Li Y, Zhang J, Chen Q, Xia X, Chen M. Emerging of heterostructure materials in energy storage: a review. Adv Mater. 2021;33(27):e2100855. doi:10.1002/adma.202100855. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Xia Y, Zuo H, Lv J, Wei S, Yao Y, Liu Z, et al. Preparation of multi-layered microcapsule-shaped activated biomass carbon with ultrahigh surface area from bamboo parenchyma cells for energy storage and cationic dyes removal. J Clean Prod. 2023;396:136517. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Lin Q, Gao R, Li D, Lu Y, Liu S, Yu Y, et al. Bamboo-inspired cell-scale assembly for energy device applications. npj Flex Electron. 2022;6(1):13. doi:10.1038/s41528-022-00148-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Li X, Liao Q, Yang Y, Guo X, Xu D, Li M, et al. Facile, high-yield, and freeze-and-thaw-assisted approach to fabricate bamboo-derived hollow lignocellulose microcapsules for controlled drug release. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2022;10(47):15520–9. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c04796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Ma H, Zhao Y, Li X, Liao Q, Li Y, Xu D, et al. Efficient removal of Pb2+ from water by bamboo-derived thin-walled hollow ellipsoidal carbon-based adsorbent. Langmuir. 2022;38(40):12179–88. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.2c01706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Deng Y, Zhang Z, Cheng X, Zhou H, He L, Guan Q, et al. Alkali-oxygen cooking coupled with ultrasonic etching for directly defibrillation of bagasse parenchyma cells into cellulose nanofibrils. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;237(3):124121. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Zhang S, Wang C. A new type of nanocomposite based on bamboo parenchymal cells. For Prod J. 2017;67(3–4):283–7. doi:10.13073/fpj-d-16-00043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Wang H, Zhang X, Jiang Z, Yu Z, Yu Y. Isolating nanocellulose fibrills from bamboo parenchymal cells with high intensity ultrasonication. Holzforschung. 2016;70(5):401–9. doi:10.1515/hf-2015-0114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Du H, Liu W, Zhang M, Si C, Zhang X, Li B. Cellulose nanocrystals and cellulose nanofibrils based hydrogels for biomedical applications. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;209(6):130–44. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.01.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Zhang S, Shan S, Zhang H, Gao X, Tang X, Chen K. Antimicrobial cellulose hydrogels preparation with RIF loading from bamboo parenchyma cells: a green approach towards wound healing. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;203:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.01.046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Jin K, Kong L, Liu X, Jiang Z, Tian G, Yang S, et al. Understanding the xylan content for enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis of individual bamboo fiber and parenchyma cells. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2019;7(22):18603–11. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b04934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Ren W, Guo F, Zhu J, Cao M, Wang H, Yu Y. A comparative study on the crystalline structure of cellulose isolated from bamboo fibers and parenchyma cells. Cellulose. 2021;28(10):5993–6005. doi:10.1007/s10570-021-03892-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Zhang C, Guo KN, Ma CY, Bian J, Wen JL, Yuan TQ. Assessing the availability of bamboo (Phyllostachys pubescens) fibers and parenchyma cells for producing lignin nanoparticles and fermentable sugars by rapid carboxylic acid-based deep eutectic solvents pretreatment. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;193(1):116204. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.116204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Gao X, Li M, Zhang H, Tang X, Chen K. Fabrication of regenerated cellulose films by DMAc dissolution using parenchyma cells via low-temperature pulping from Yunnan-endemic bamboos. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;160:113116. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.113116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Ren D, Wang Y, Wang H, Xu D, Wu X. Fabrication of nanocellulose fibril-based composite film from bamboo parenchyma cell for antimicrobial food packaging. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;210(7):152–60. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.04.171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Shen XJ, Wen JL, Mei QQ, Chen X, Sun D, Yuan TQ, et al. Facile fractionation of lignocelluloses by biomass-derived deep eutectic solvent (DES) pretreatment for cellulose enzymatic hydrolysis and lignin valorization. Green Chem. 2019;21(2):275–83. doi:10.1039/C8GC03064B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Van den Bosch S, Renders T, Kennis S, Koelewijn SF, Van den Bossche G, Vangeel T, et al. Integrating lignin valorization and bio-ethanol production: on the role of Ni-Al2O3 catalyst pellets during lignin-first fractionation. Green Chem. 2017;19(14):3313–26. doi:10.1039/C7GC01324H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Pollegioni L, Tonin F, Rosini E. Lignin-degrading enzymes. FEBS J. 2015;282(7):1190–213. doi:10.1111/febs.13224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools