Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

High Lignin Content Polymer Filaments as Carbon Fibre Precursors

1 Department of Polymer Engineering, Institute for Polymers and Composites (IPC), University of Minho, Campus of Azurem, Guimarães, 4800-058, Portugal

2 Centre for Innovation in Polymer Engineering (PIEP), University of Minho, Campus of Azurem, Guimarães, 4800-058, Portugal

3 Centre of Biological Engineering (CEB), University of Minho, Campus of Gualtar, Braga, 4710-057, Portugal

4 LABBELS—Associate Laboratory, Braga, 4710-057, Portugal

* Corresponding Authors: Rui Ribeiro. Email: ; Maria C. Paiva. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(10), 1859-1880. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0071

Received 24 March 2025; Accepted 03 June 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

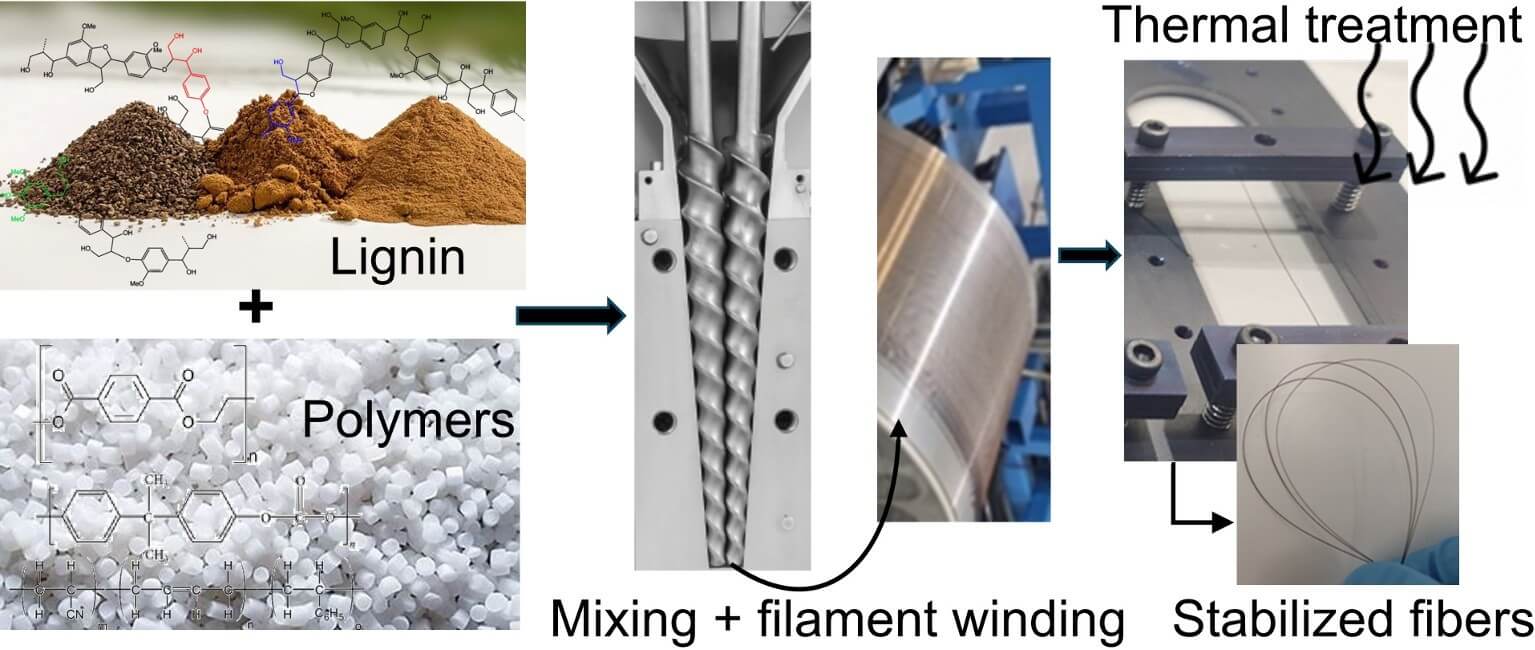

The growing environmental awareness, the search for alternatives to fossil resources, and the goal of achieving a circular economy have all contributed to the increasing valorization of biowaste to produce bio-based polymers and other high-value products. Among the various biowaste materials, lignin has gained significant attention due to its high aromatic carbon content, low cost, and abundance. Lignin is predominantly sourced as a byproduct from the paper industry, available in large quantities from hardwood and softwood, with variations in chemical structure and susceptibility to hydrolysis. This study focuses on softwood lignin obtained through the LignoForce™ technology, comparing the thermal and chemical characteristics, and stability, of a recently produced batch with that of a batch that has been stored for four years. Additionally, the development of lignin-based thermoplastic polymer mixtures using Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol (PET-G) and a blend of Polycarbonate and Acrylonitrile-Butadiene-Styrene (PC/ABS) with high lignin content (50–60 wt%) is explored, as well as the production of filaments for carbon fiber production. For this purpose, following melt mixing, the lignin-based mixtures were spun into filaments, which were subsequently subjected to thermal stabilization in an oxidative atmosphere. The lignin phase was well distributed in the PET-G matrix and the two materials presented a good interface, which further improved after thermal treatment under an oxidative atmosphere. After thermal treatment an increase in tensile modulus, tensile strength, and elongation at break of approximately 160%, 200%, and 100%, respectively, was observed, confirming the good interface established, and consistent with structural changes such as cross-linking. Conversely, the PC/ABS blend did not form a good interface with the lignin domains after melt mixing. Although the interactions improved after thermal treatment, the tensile strength and elongation at break decreased by approximately 30%, while the modulus increased by approximately 20%. Overall, the good processability of the lignin/polymer mixtures into filaments, and their physical, chemical, and mechanical characterization before and after thermal oxidation are good indicators of the potential as precursors for carbon fiber production.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Synthetic fibers such as carbon fibers (CF) play a fundamental role as reinforcement in polymer matrices due to their high strength and modulus, lightweightness, high chemical resistance, and excellent electrical and thermal properties [1,2]. However, the main CF precursor, polyacrylonitrile (PAN), is expensive and its manufacturing process has a negative environmental impact [2–5]. Therefore, more sustainable precursors are actively being sought [1,6].

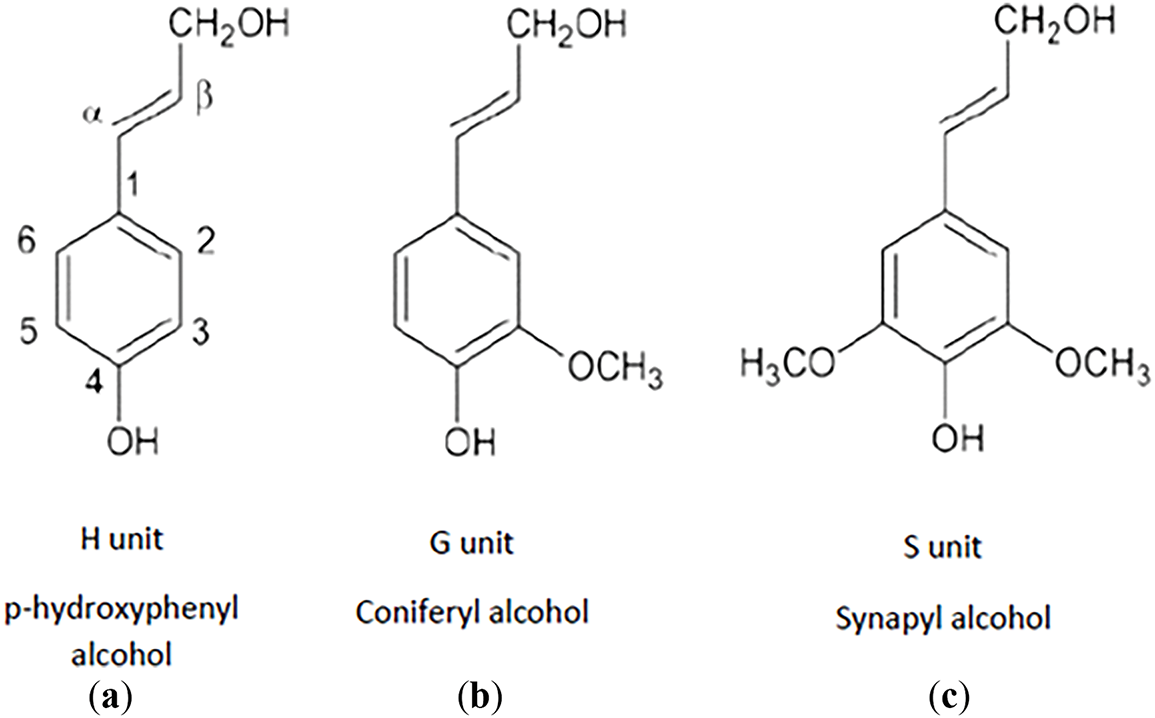

The highly aromatic nature of lignin favors its use as a precursor for graphite-based materials such as CF. Lignin is the second most abundant carbon-based material in nature and is widely available as a residue from the pulp and paper industry [1,4,5,7]. However, lignin may exhibit variations in its physical/chemical properties, depending on its source and extraction method, which includes enzymatic techniques, Klason, Kraft, organosolv processes, or ionic liquid pre-treatments [4,8–10]. Lignin is generally classified as hardwood or softwood based on its susceptibility to hydrolysis and prevailing chemical composition. Its chemical structure is based on three aromatic monolignols: coniferyl, syringyl, and coumarin alcohol [1,11]. Softwood lignin is rich in coniferyl alcohol monolignol, while hardwood lignin contains both coniferyl and sinapyl alcohol monolignols [9,12–14]. The monolignols originate from three phenyl propane derivatives, represented in Fig. 1, namely, guaiacyl (G), syringyl (S), and p-hydroxyphenyl (H). These units are primarily linked through carbon-carbon and ether bonds, forming the complex lignin structure [1,5,13]. Lignin is an amorphous polymer with a characteristic glass transition temperature (Tg) ranging from 95°C to 165°C, depending on its origin and extraction method [15].

Figure 1: Molecular structure of the three lignin monomers: (a) p-hydroxyphenyl (H), (b) guaiacyl (G), and (c) syringyl (S), derived from the monolignols coumaryl, coniferyl and sinapyl alcohol, respectively [5]

Manufacturing CF typically involves wet or melt spinning of the carbon precursor to form filaments, followed by stabilization at 200°C–300°C, normally under an oxidative atmosphere, and carbonization at 1000°C–1600°C under an inert atmosphere [1,7,12,16]. Melt spinning is an eco-friendly and cost-effective technique that avoids the use of solvents, where the precursor is processed at temperatures above its Tg and below the onset of thermal degradation [17–19]. Both spinning routes allow for stretching the fiber upon cooling, increasing molecular orientation and, consequently, improving mechanical properties [20–22]. Then, fibers must be thermostabilized to prevent melting during the subsequent carbonization step. This is achieved through crosslinking, oxidation, cyclization, and condensation under an oxidative atmosphere [10,23,24] which also increases the glass transition temperature [12,17,24]. Finally, carbonization is achieved through dehydration, crosslinking, decarboxylation, and aromatization, converting the fibers into CF, enhancing their graphite-like structure and thus their mechanical properties [10,17].

The melt processing of lignin with thermoplastics as a precursor for producing CF offers improved energy efficiency, environmental benefits, and significant cost reductions. Compounding lignin with polyethylene oxide (PEO) [25,26], thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) [4], polyethylene terephthalate (PET) [27,28], polylactic acid (PLA) [15,29], and polypropylene (PP) [30,31] have been reported in the literature. The compatibility between lignin and polymer is a critical factor in producing stable CF precursor fibers [15,32–34]. Polyolefins and lignin are typically challenging to combine due to their inherent chemical differences, resulting in a mixture of poor quality, which is primarily based on dispersion forces [33,35]. Thermoplastics with polar groups or aromatic moieties such as PLA, polycaprolactone (PCL), polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), polystyrene (PS), polycarbonate (PC), thermoplastic polyurethanes (TPU), and PET, may develop stronger interactions, and thus present improved properties [22,33,35].

This study investigates the combination of softwood lignin with glycol-modified PET (PET-G), and PC/acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene blend (PC/ABS). PET-G finds multiple applications due to its melt processability; it is adequate for food contact and resistant to sterilization and has a relatively low melting point compared to standard PET, and it may be obtained as a recycled material. Its low melting point allows processing at a temperature near 200°C, which is an advantage for melt mixing with lignin without inducing its thermal degradation. PET-G is expected to establish a good interface with lignin as it contains aromatic rings (allowing π-π stacking) and ester bonds (contributing to polarity). PC/ABS is a widely used blend formed by PC, with aromatic rings in its polymer backbone, and ABS, a terpolymer containing styrene, with aromatic rings, and a fraction of acrylonitrile, a key precursor for carbon fiber production. PC/ABS is a widely used blend with excellent impact, mechanical, and thermal properties, finding applications in the automotive industry, electronics housings, toys, filaments for 3D printing, and more. It is expected to be widely available as a recycled material. Thus, PET-G and PC/ABS are promising candidates for mixing with lignin at the end of their life cycle to facilitate filament production. To the authors’ knowledge, these materials have not been previously explored to mix with lignin. The use of two lignin samples derived from the Kraft process, both sourced from the same provider but with a four-year interval between production, enabled an assessment of potential aging and shelf-life effects. Lignin-polymer mixtures were prepared by melt processing, spun into filaments, and thermally stabilized. The filaments were characterized in terms of chemical composition, morphology, and both thermal and mechanical properties. The filaments successfully survived the stabilization process, with the mechanical properties of the lignin/PET-G-based filaments showing a significant increase after stabilization, which is a good indicator that a crosslinked structure was formed.

A Kraft low pH grade lignin produced by the LignoForceTM process was supplied by West Fraser Co., Ltd., in Vancouver, BC, Canada. Two different batches were studied, designated as “LPH18” (received in 2018) and “LPH22” (received in 2022). Their physical-chemical characteristics according to the manufacturer are summarized in Table 1. Two polymers were selected for this study: PET-G “Venuz BD 320” with a melt flow index (MFI) of 4.2 g/10 min (2.16 kg/225°C), supplied by Selenis, Portalegre, Portugal, and PC/ABS “GE Cycoloy FXC810SK” with an MFI of 12.7 g/10 min (10 kg/220°C), obtained from Sabic.

2.2 Polymer-Lignin Mixtures and Filaments Processing

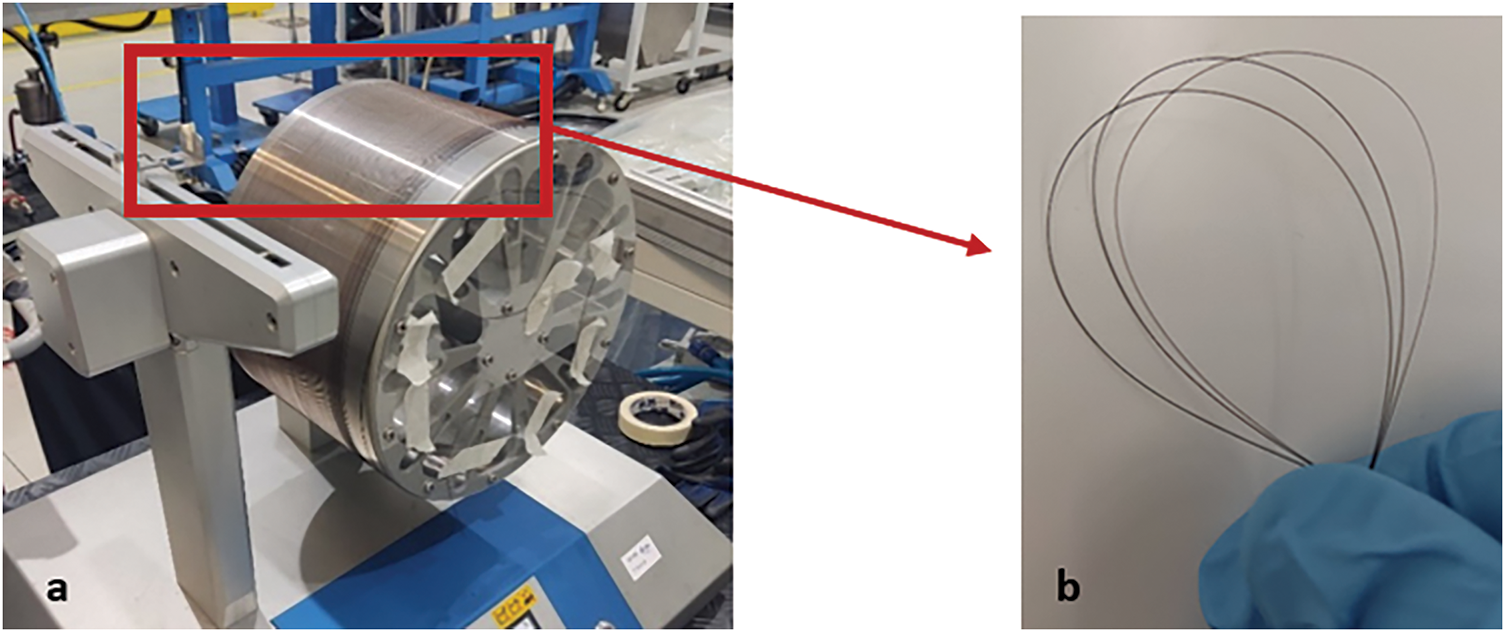

Before processing, PET-G was dried for 8 h at 60°C, and PC/ABS blend was dried for 2 h at 80°C. Filaments were extruded by mixing 50 and 60 wt% of LPH18 or LPH22 with PET-G, and 50 wt% of LPH22 with PC/ABS (Table 2) for 10 min in a micro-extruder Xplore MC15 coupled to a circular die (diameter of 250 μm), with a screw speed of 50 rpm and the set temperature profiles presented in Table 2. The filaments were pulled by a controlled speed Xplore Double Winder Line at a rate of 30 m·min−1, which corresponded to a draw ratio of approximately 5 (the collection of fibers with the take-up roll and the as-produced fibers are depicted in Figs. A1 and A2).

The compositions of the lignin/thermoplastic polymer mixtures were selected considering that a minimum of 50 wt% of lignin is necessary for the development of fibers that, after heat treatment, form stable crosslinked fibers that do not melt further. However, the melt processability of the mixtures depends on the thermoplastic matrix, and only in the case of PET-G higher lignin weight contents (40% PETG/60% Lignin) could be melt-processed into fibers. At this low polymer concentration, PC/ABS did not form a homogeneous and melt-processable mixture with lignin. PCABS-60LPH22, with 40% PC/ABS and 60% LPH22 content, could not be produced due to the heterogeneity and brittleness of the mixture that did not allow filament winding.

2.3 Thermostabilization of Filaments

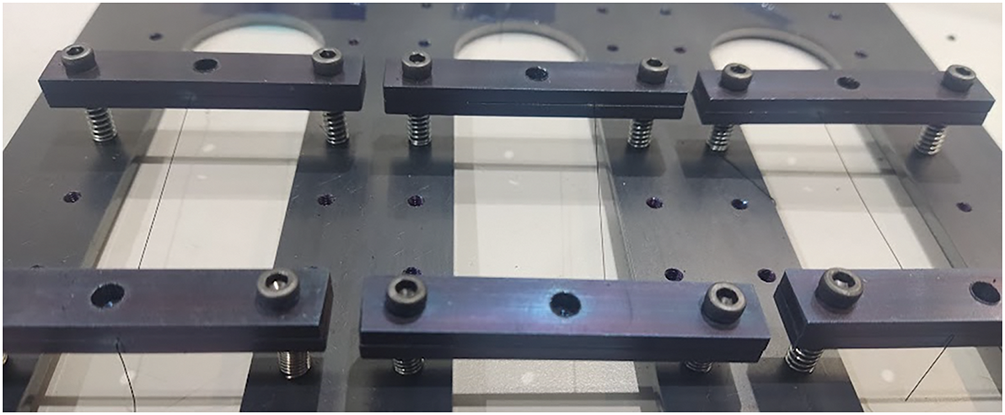

The filaments were thermostabilized in a Memmert UFP 800 convection oven (Schwabach, Germany) in the air using a homemade metal frame holder, capable of accommodating several filaments with lengths in the range of 18–180 mm (see Fig. A3). Heating was carried out from 25°C to 250°C at 0.16, 0.08, and 0.05°C·min−1 and then temperature was held at 250°C for 1 h, followed by cooling to room temperature. The filament contraction observed during heating kept the filaments under stress.

2.4 Characterization of Lignin and Filaments

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted on a TA Instruments Q500® (New Castle, DE, USA) with a weighting precision of ± 0.01%, 0.1 μg sensitivity. Lignin was heated under nitrogen (N2) and oxygen (O2) atmospheres, at a heating rate of 10°C·min−1 from 40°C to 800°C. PET-G, PC/ABS, their filaments with lignin, and the corresponding stabilized filaments, were tested at a heating rate of 5°C·min−1, from 40°C to 800°C, under an N2 atmosphere. To ensure reproducibility, three measurements were conducted for each sample.

2.4.2 Differential Scanning Calorimetry

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed on a Netzsch DSC 200 F3 Maia. Lignin powder was heated from 25°C to 180°C at a rate of 10°C·min−1, cooled to 25°C at 30°C·min−1, and then heated again to 250°C at 10°C·min−1. The first heating step was applied to remove any humidity and thermal history remaining from the purification process. An ultra-microbalance PERKIN-ELMER AD-4 Autobalance was used to weigh the samples in Al crucibles (Ø 6 mm, Netzsch-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany).

2.4.3 Scanning Electron Microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed on a Nano SEM–FEI Nova 200 (FEG/SEM) (FEI Europe Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA) operating under high vacuum conditions, with a resolution of 1.0 nm at 15 kV. The samples were cryo-fractured in liquid nitrogen, and the exposed surfaces were sputter-coated with a gold-palladium (Au/Pd) layer for the morphological analysis of the filament cross-sections and surfaces.

2.4.4 Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) was performed using a Jasco FT/IR-4000 spectrometer (Hachioji, Tokyo, Japan) using ATR Pro One to generate attenuated total reflectance (ATR) spectra in the 4000–600·cm−1 range.

2.4.5 Specific Weight and Diameter

The specific weight of the filaments was measured before and after thermal stabilization. Five filaments were cut with approximately 100 mm length, weighed separately, and then imaged on a Digital Microscope Leica DMS1000 (Wetzlar, Germany). LAS X V4.13 software was used to measure the average diameter and effective length of each filament. For each sample, the diameter of the five filaments prepared was measured in five places along the length of each filament.

Tensile testing was carried out using a texture analyzer (TA.XT Plus Texture Analyzer, Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, UK) equipped with a load cell of 5 kg, with a 0.1 g force resolution. Approximately 30 mm long filament samples were held between tensile grips initially set 10 mm apart, testing being performed at 1 mm·s−1. Tensile strength, elongation at break, and Young’s modulus were evaluated from the stress-strain curves obtained. Six measurements were made for each filament at 21°C. Exponent software v.6.1.1.0 (Stable Microsystems, Surrey, UK) was used for data analysis.

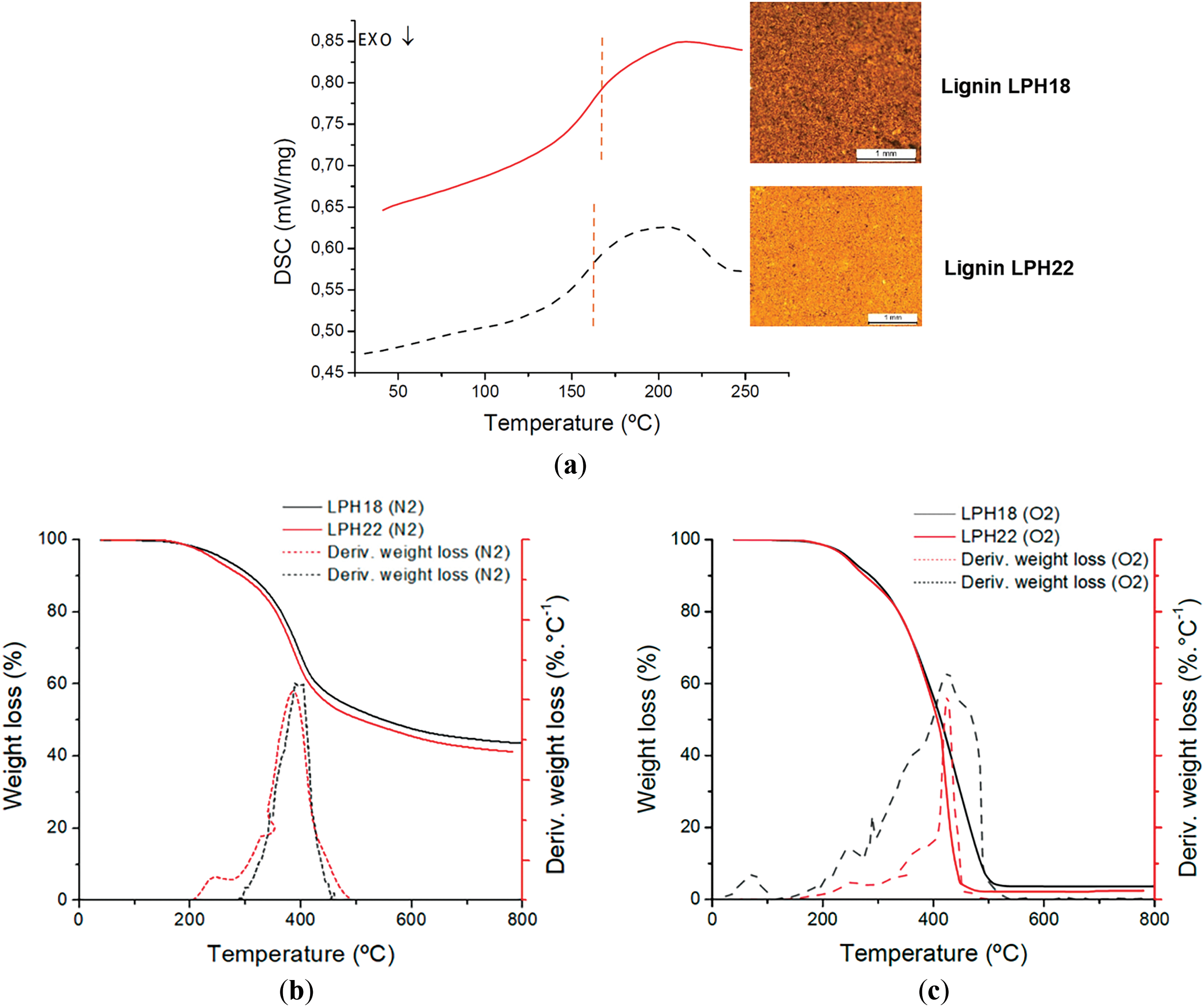

3.1.1 Thermal Characterization

Fig. 2a presents the DSC thermograms for the two lignin materials analyzed, revealing a similar amorphous structure with a Tg above 150°C (155.0 ± 0.9°C and 163.7 ± 3.7°C for LPH18 and LPH22, respectively), the end of the thermal transition occurring above 200°C for both materials.

Figure 2: (a) Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) curves of lignin and images of the lignin powders; thermogravimetric (TGA) curves of lignin under (b) N2 atmosphere and (c) O2 atmosphere

TGA curves obtained under inert and oxidative atmospheres are depicted in Fig. 2b and 2c, respectively. Table 3 compares relevant thermal decomposition parameters obtained from the TGA curves, expressed as thermal decomposition temperatures and residual weight of lignin at specific temperatures. The temperature at the maximum of the TGA curve derivative corresponds to the temperature at which the thermal decomposition occurred at the highest rate, the onset of thermal decomposition is the temperature at which the beginning of the decrease in sample weight is observed. The latter value provides the temperature limit for melt mixing of the polymer/lignin mixtures. While under an inert atmosphere, this value is approximately 220°C, under an oxidative atmosphere it reaches approximately 225°C for the two lignin grades. In general, it was observed that the thermal stability and thermal decomposition characteristics of the two lignin batches, in terms of Tg, decomposition temperatures, and weight loss, are quite similar. This is indicative of the good stability of Kraft softwood lignin that, albeit originating from different batches and one of them having a shelf-life of four years, maintains reproducible properties and is adequate for further applications.

Since melt mixing of polymer/lignin should be carried out above the Tg of lignin and below its decomposition temperature, the selected polymer should be melt processable in the range 165°C–220°C.

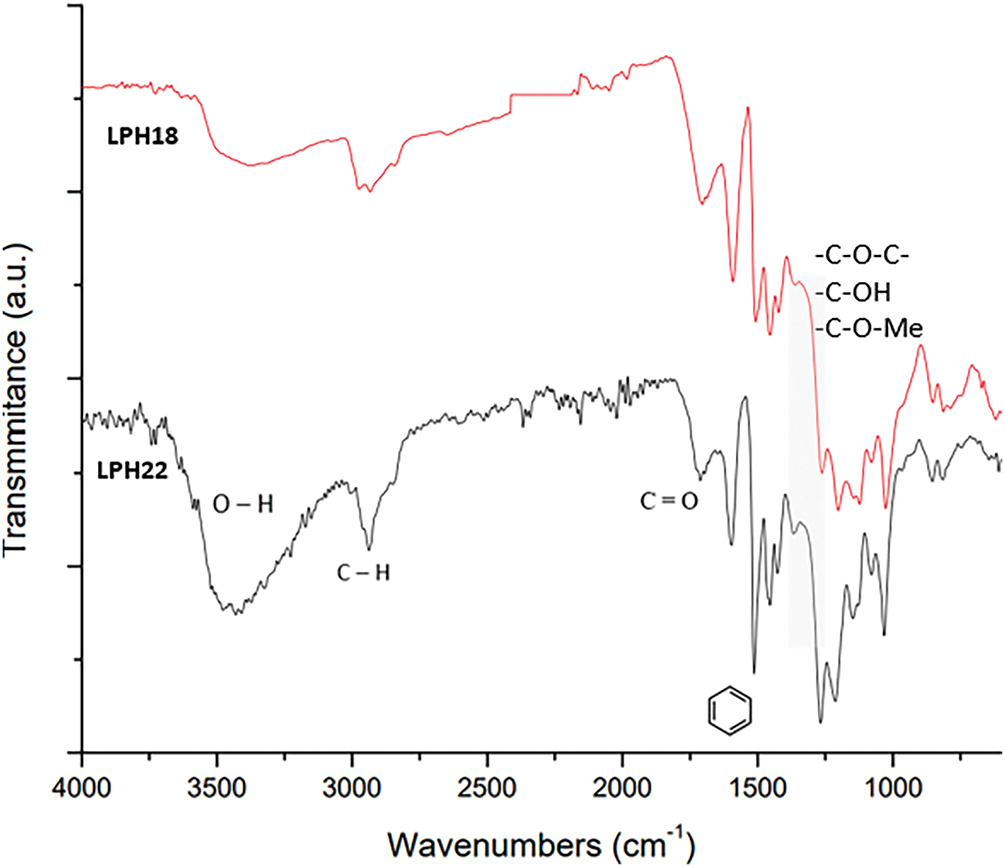

3.1.2 Chemical Characterization

The FTIR spectra of LPH18 and LPH22 lignin are presented in Fig. 3. Table 4 lists the wavenumbers of the relevant FTIR peaks observed and the associated vibration modes. The spectra of the two lignin grades are similar, the major difference between the two materials is observed in the OH stretching region (3600–3300 cm−1), where LPH22 exhibits a higher intensity. An inversion of the relative intensity of peaks at 1260 and 1200 cm−1, with greater intensity for the peak at 1260 cm−1 for LPH22, may relate to a larger concentration of guaiacyl units. Additionally, peaks in the range of 1270–1260 cm−1 and 890–750 cm−1, corresponding to vibrations of the guaiacyl unit, confirm that both lignin grades are derived from softwood. The large aromatic content of the two materials evidences a good potential as precursors for CF manufacturing.

Figure 3: FTIR spectra of LPH18 and LPH22 powders

3.2.1 Production and Stabilization

Mixtures of lignin and polymers with the compositions presented in Table 2 were prepared by melt mixing in a micro-extruder. PET-G was chosen to compare the filament preparation process using both lignin batches, as well as the properties of the filaments obtained. Subsequent stabilization was carried out for the filaments based on LPH22, holding them on the metal frame designed for that purpose. The stabilization step is of major importance for the development of a homogeneous chemical structure through the fibers thickness. During this step oxygen diffuses through the fiber and, at increasing temperature, oxidation, and crosslinking reactions take place, forming an infusible structure. The oxygen concentration and temperature should be as homogeneous as possible throughout the fiber thickness for the development of a continuous chemical structure with minimum defects or voids. Thus, the heating rate and the overall stabilization time are quite relevant for the quality and homogeneity of the structure formed, which in turn is of major importance for the mechanical properties of the fibers. The stabilization conditions may vary for fibers with different diameters, the smaller the diameter the faster is expected to achieve stabilization.

Filaments subjected to a heating rate of approximately 0.16°C·min−1 melted during the process. At 0.08°C·min−1, PETG-50LPH22 (Table A1), and PETG-60LPH22 (Table A2) filaments melted, while PCABS-50LPH22 (Table A3) filaments retained their shape but exhibited bending. A heating rate of 0.05°C·min−1, in line with a previous observation [13], retained the filament’s regular shape, without melting or bending, for both polymers.

3.2.2 Morphology and Specific Weight

The stabilization phase is recognized as an important step for the production of carbon fibers with good mechanical properties, for most precursor materials. It has been studied for homogeneous materials such as polyacrylonitrile (PAN) and PAN copolymers [40–42], as well as for heterogeneous materials such as pitch (isotropic and mesophase) [43,44] and lignin [45]. For each precursor chemistry, it is a challenge to identify the optimum process conditions for precursor stabilization (molecular weight, composition, temperature, heating rate, etc.). For lignin-based precursors, during oxidative stabilization the macromolecules undergo condensation, cross-linking and other reactions, forming an infusible polymer from the initially thermoplastic lignin, allowing for further high-temperature treatment without deformation. A mass loss is observed along the oxidative stabilization process, associated with the release of H2O and CO2. During the slow heating process, the structure of the lignin macromolecules undergo several stages of chemical changes. At an initial stage, the oxidation of the aliphatic side chains of lignin takes place forming ketone, carbonyl, and carboxyl groups; as temperature increases there is a condensation of aromatic rings and a carboxylic acid, leading to the formation of thermostable aromatic C–C, ester and anhydride groups; at the higher temperature the degradation of lignin dominates, eliminating thermolabile oxygenated or hydrogenated groups [32]. Along this process the chemistry and macromolecular morphology changes, leading to an increase in density and a decrease in fiber diameter.

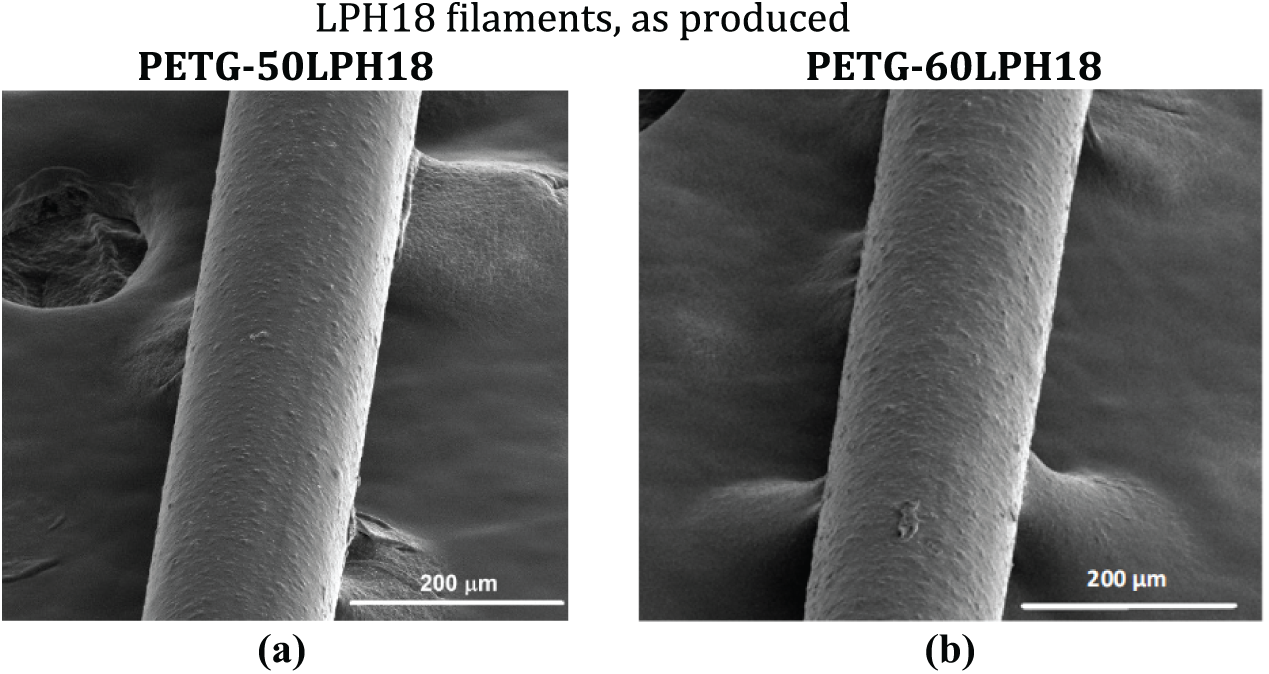

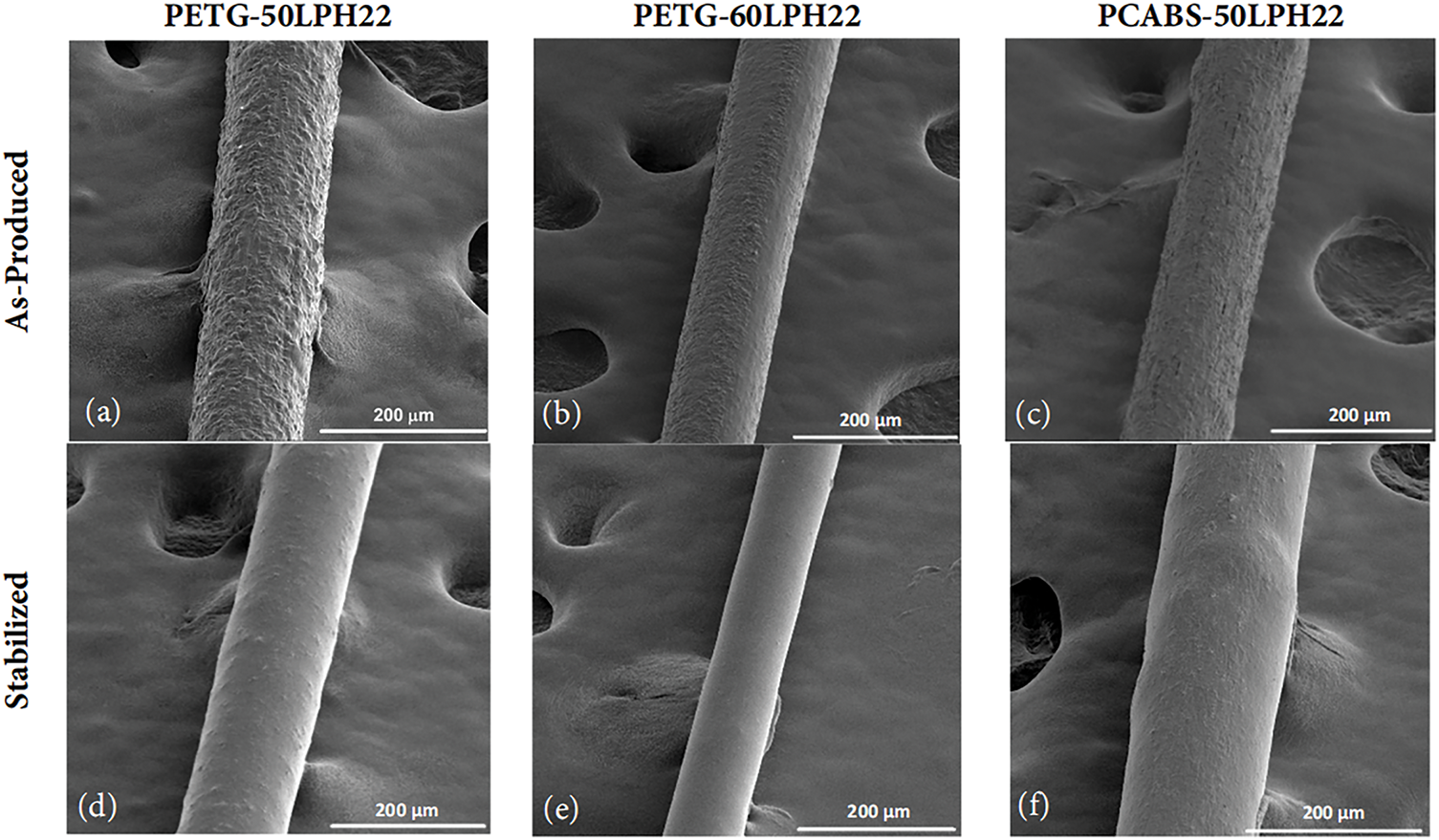

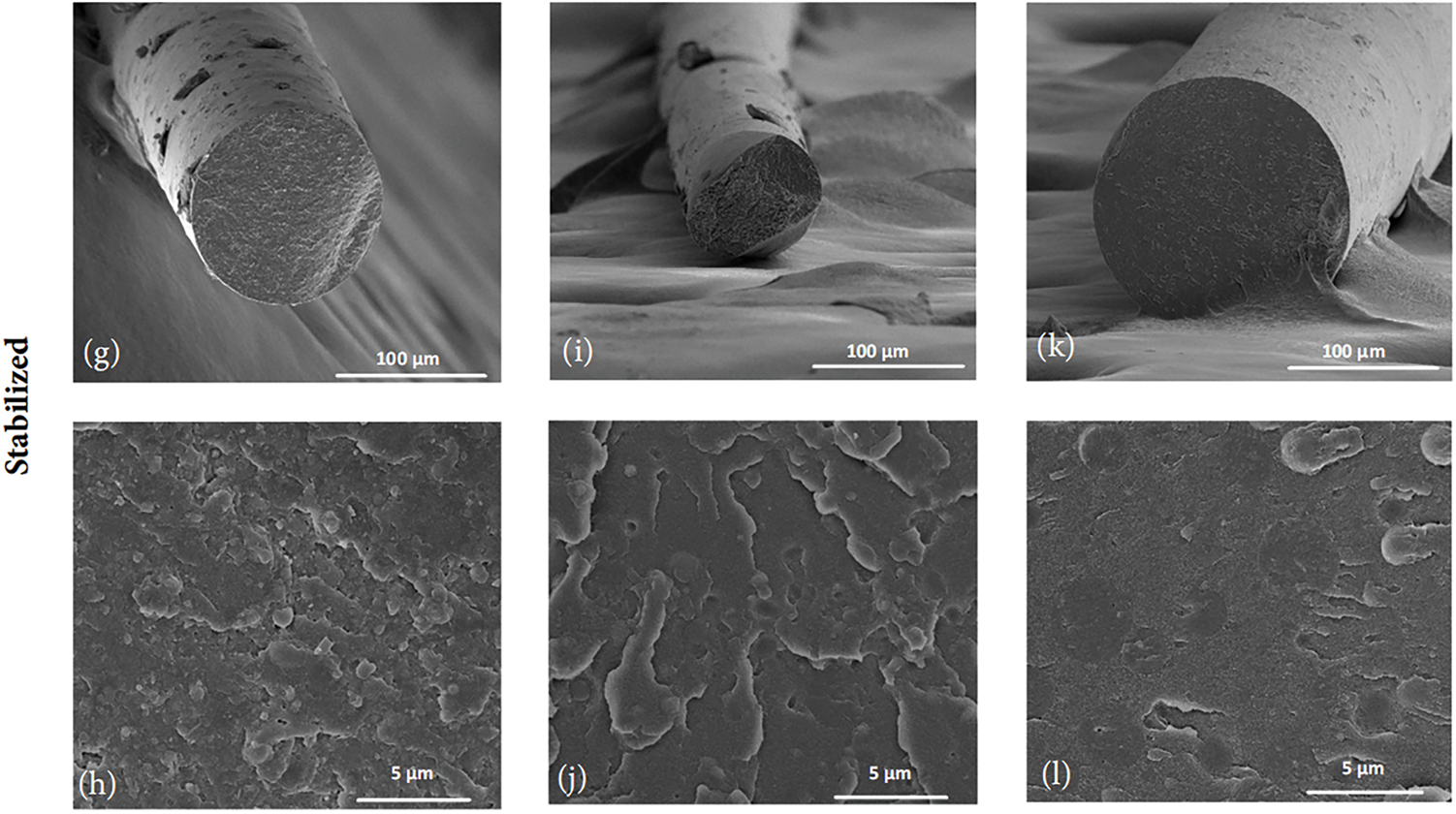

Figs. 4 and 5 show SEM images of the surfaces of extruded and thermally stabilized filaments. Thermal stabilization significantly reduces surface roughness and decreases filament diameter, by approximately 10% for filaments containing 50 wt% lignin (as can be seen in Table 5), without affecting its shape.

Figure 4: SEM micrographs of the surface of extruded filaments produced with LPH18 lignin and PETG: (a) with 50 wt% of lignin; (b) with 60 wt% of lignin

Figure 5: SEM micrographs of the surface of as produced (images a–c) and stabilized (images d–f) filaments with LPH22 lignin. (a,d) are PETG filaments with 50 wt% of lignin, before and after stabilization, respectively; (b,e) are PETG filaments with 60 wt% of lignin, before and after stabilization, respectively; (c,f) are PC/ABS filaments with 50 wt% of lignin, before and after stabilization, respectively

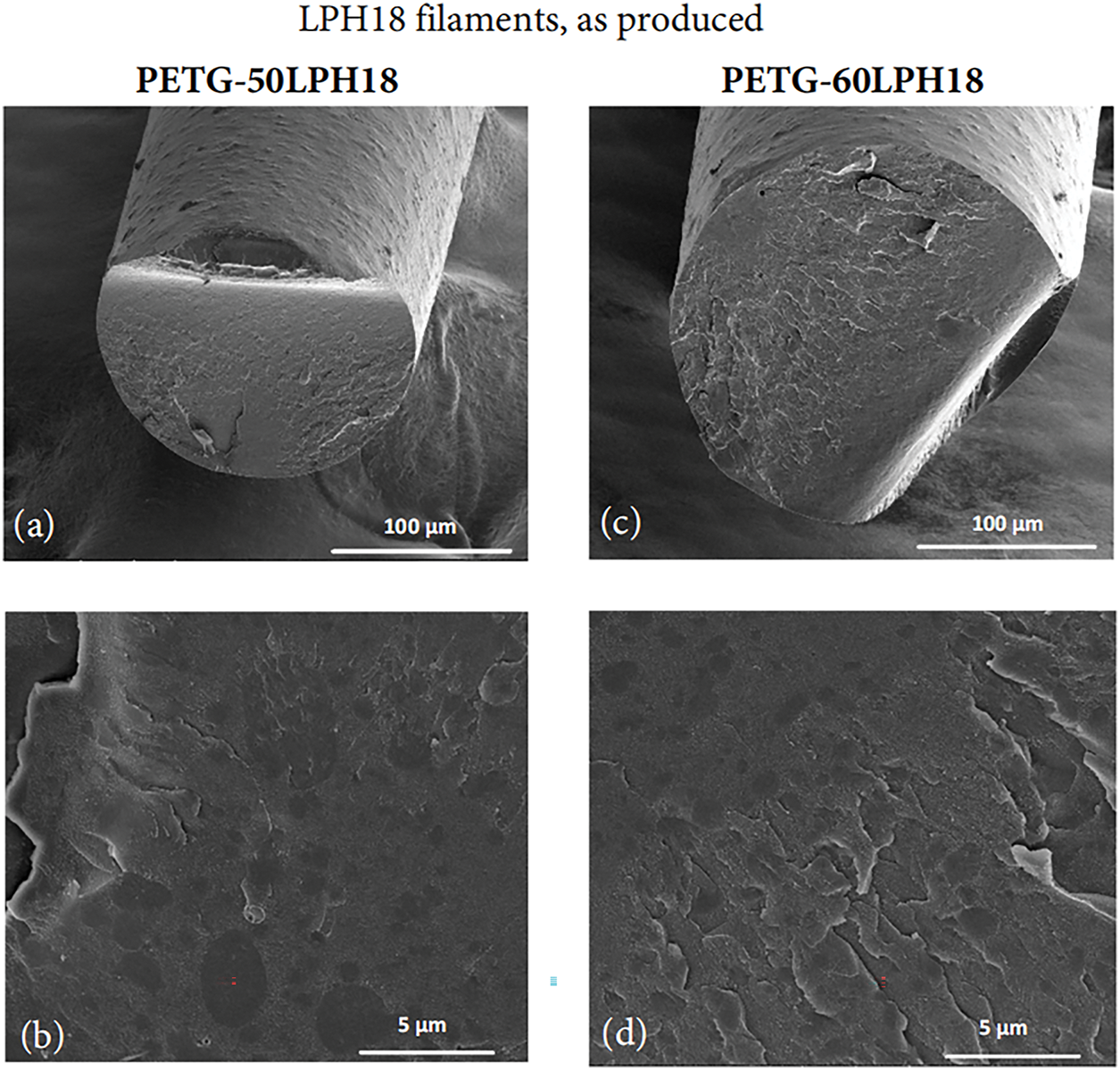

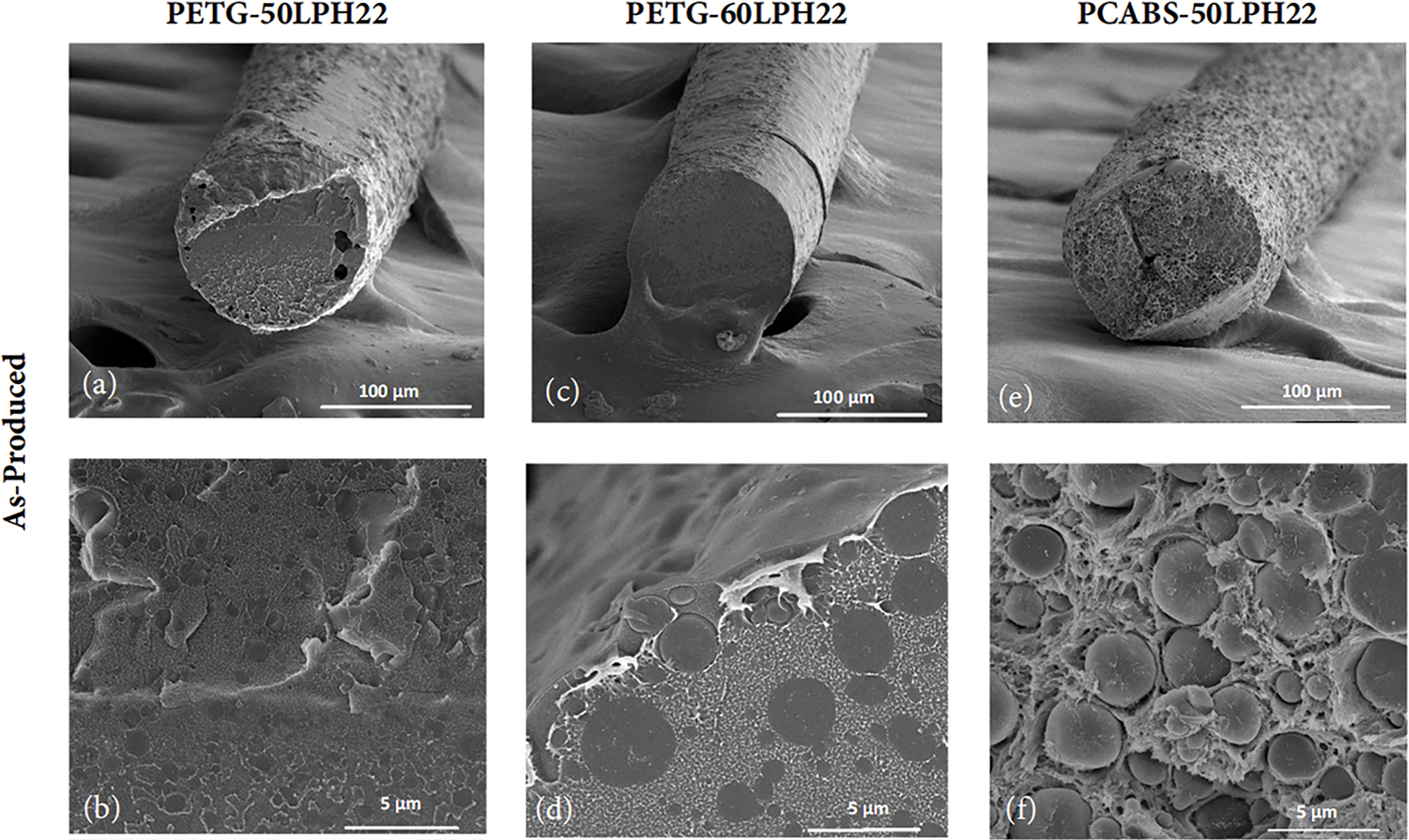

Surface roughness could result from extrusion instabilities [46], or the presence of lignin agglomerates. Figs. 6 and 7 present SEM images of the cross-section of the extruded LPH18 filaments, and extruded and thermally stabilized LPH22 filaments, respectively. Fig. 6 reveals that surface roughness is mostly associated with the existence of lignin domains with a maximum diameter of approximately 5 μm, well distributed within the matrix. Therefore, the possibility of using more intensive mixing conditions should be considered in future studies.

Figure 6: SEM micrographs of the cross-section of extruded filaments produced with LPH18 lignin and PETG: (a) and (b) with 50 wt% of lignin at two magnifications; (c,d) with 60 wt% of lignin at two magnifications

Figure 7: SEM micrographs of the cross-section of extruded and stabilized filaments produced with LPH22 lignin and the two polymer systems, PETG and PC/ABS. From (a–f), all filaments are as-produced and images are presented at two magnifications; (a,b) are PETG with 50 wt% of lignin, (c,d) are PETG with 60 wt% of lignin, (e,f) are PC/ABS with 50 wt% of lignin. From (g–l), all filaments are stabilized and images are presented at two magnifications; (g,h) are PETG with 50 wt% of lignin, (i,j) are PETG with 60 wt% of lignin, (k,l) are PC/ABS with 50 wt% of lignin

The lignin domains present in PET-G filaments show a good polymer-lignin interface. Good compatibility and miscibility of melt-mixed softwood lignin and PET were described in the literature [47], and a similar result was expected for PET-G. With an approximately circular cross-section, the lignin phase may align along the filament axis due to drawing after extrusion. After thermal stabilization, the filaments exhibit a homogeneous cross-section, with smaller lignin domains, almost indistinguishable. PC/ABS is a complex system, a stable polymer blend, however, its compatibility with lignin was not described in the literature. It was observed that softwood lignin formed domains in the PC/ABS phase with similar morphology compared with PET-G mixtures, however with a poor polymer-lignin interface, and higher surface roughness. After thermal stabilization, the polymer/lignin interface improved, which may influence positively the thermal and mechanical properties.

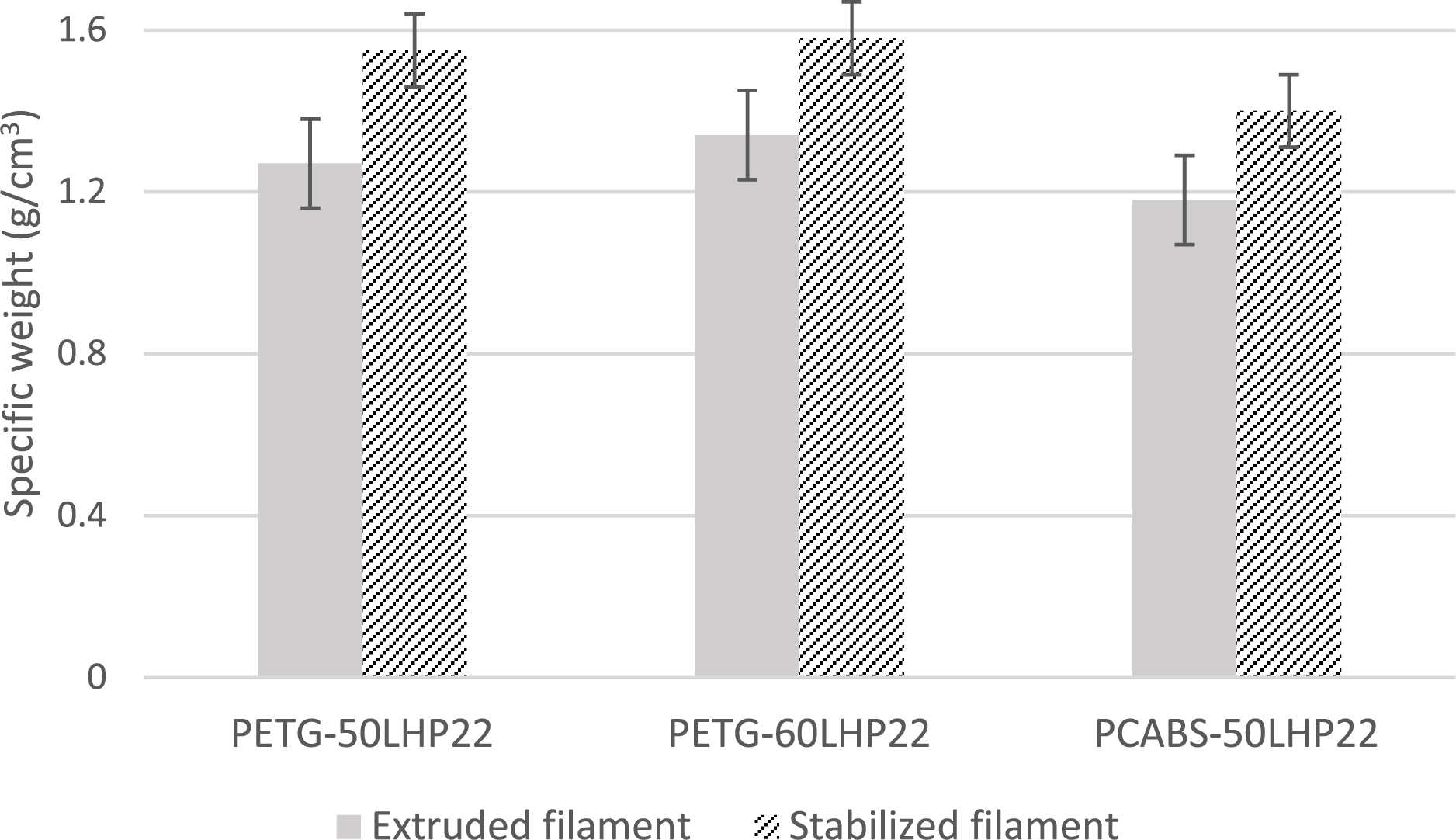

The filaments specific weight is expected to increase upon thermostabilization, due to the effects of oxidation and changes in polymer/lignin molecular interactions. Fig. 8 demonstrates an increase in specific weight of approximately 11% for PETG-60LPH22, 24% for PETG-50LPH22, and 19% for PCABS-50LPH22 as-produced and stabilized filaments.

Figure 8: Lignin-based filaments specific weight before and after thermal stabilization

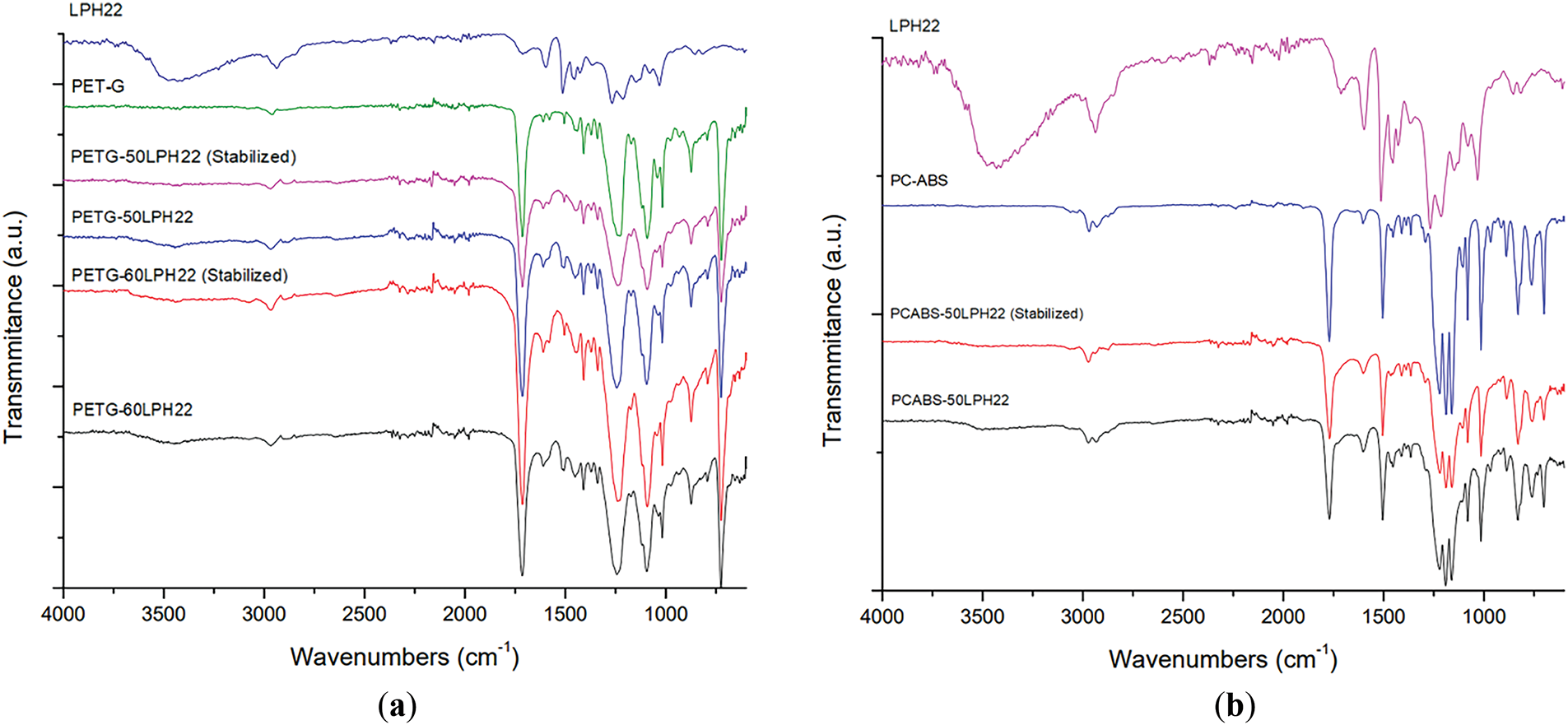

3.2.3 Chemical Characterization

The filaments prepared with LPH22 were characterized by FTIR spectroscopy. Fig. 9 illustrates the spectra obtained for each filament composition before and after thermal stabilization. The spectra are comparable, as they mainly reflect the polymer composition, i.e., the similar chemical functions in lignin and the polymers (aliphatic C-H, aromatic carbon, carbonyl, and ether bonds). PC/ABS blends show a weak (almost negligible) nitrile peak, near 2250 cm−1, possibly indicating a low ABS content. The considerable decrease of the -OH peak (associated with lignin) in the mixtures is observed before and after thermal stabilization.

Figure 9: FTIR spectra of (a) PETG-60LPH22, PETG-50LPH22, and (b) PCABS-50LPH22 (before and after thermal stabilization)

3.2.4 Thermal Characterization

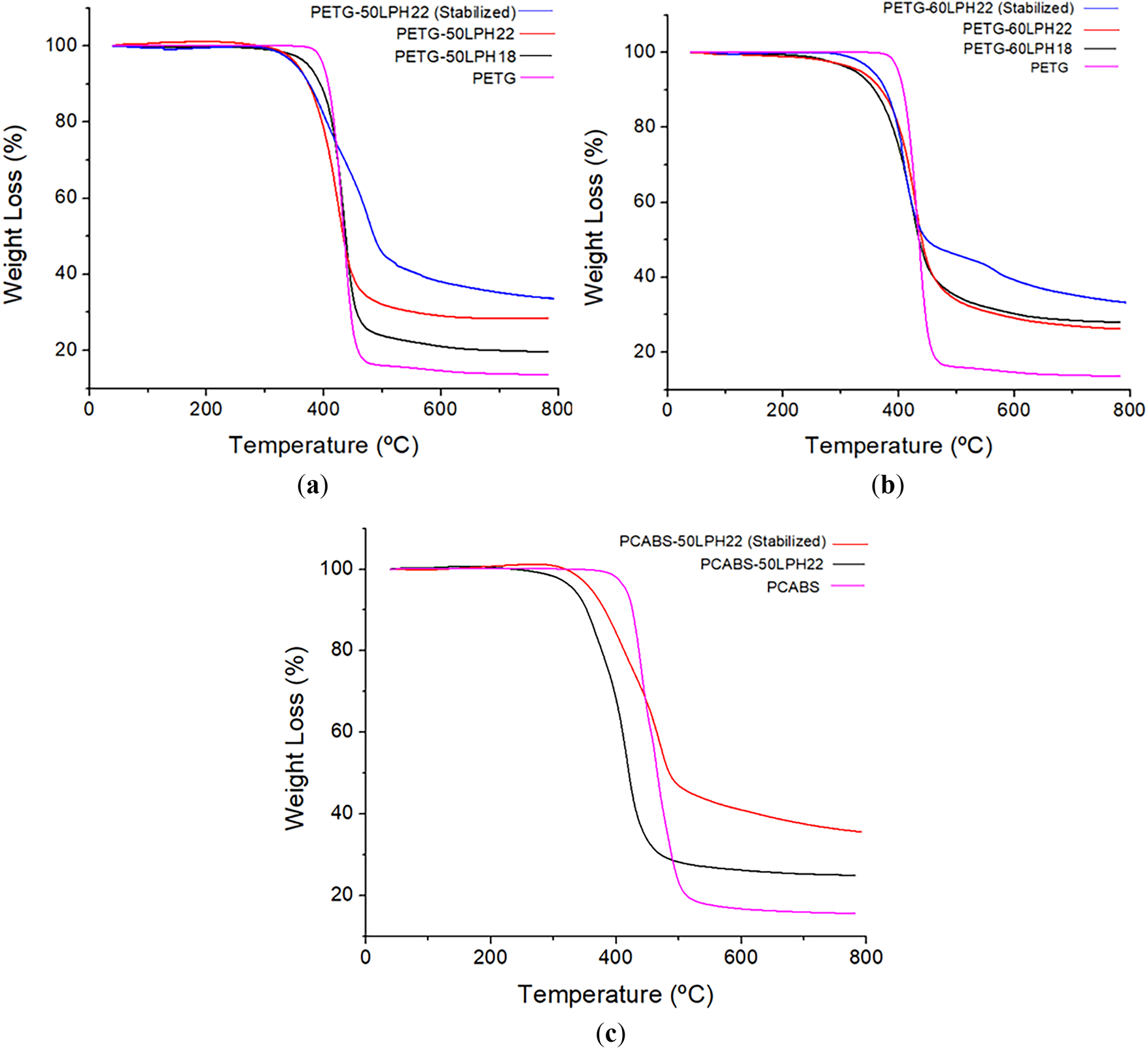

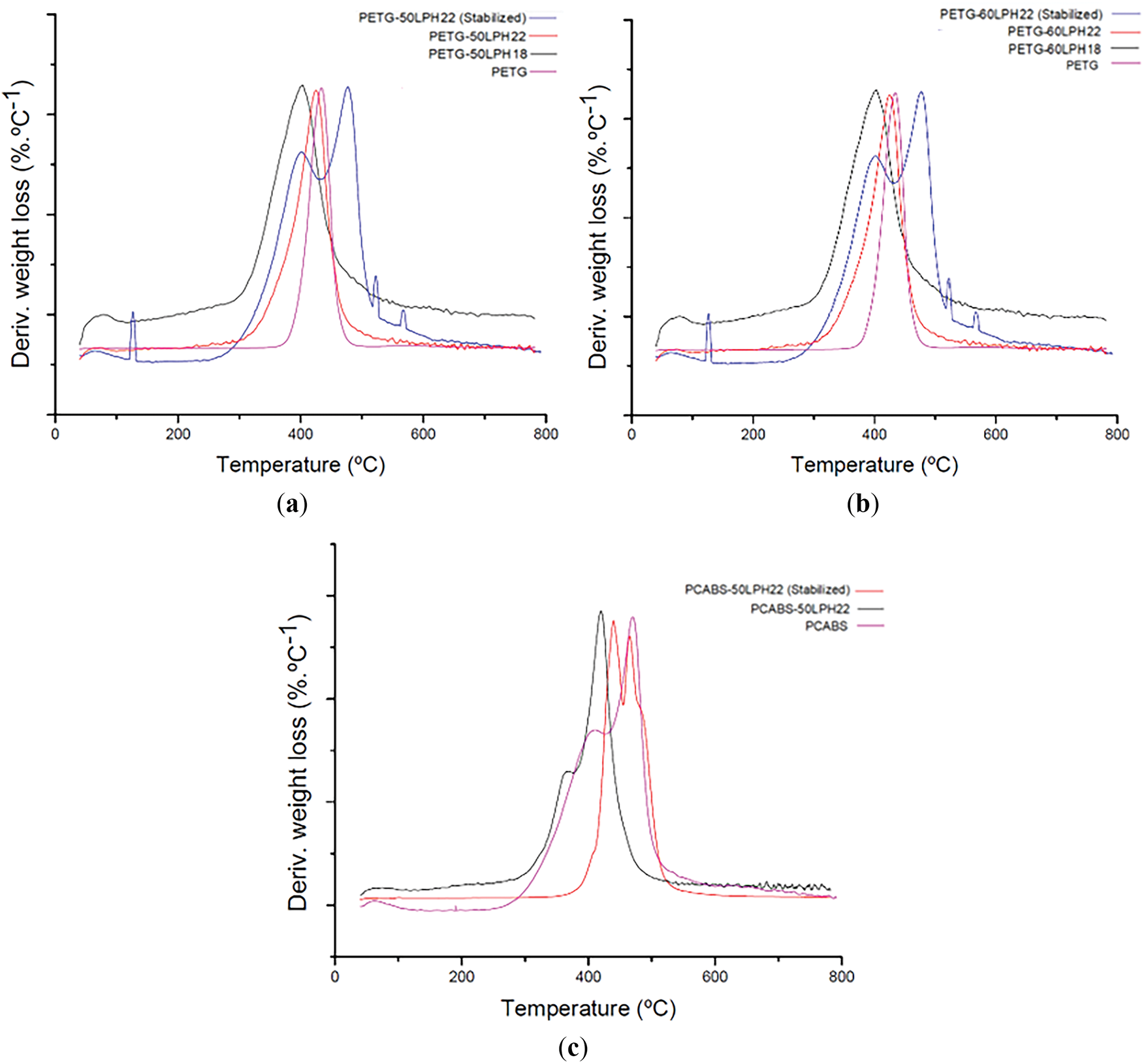

The polymers (PET-G and PC-ABS) and the melt-extruded filaments with high lignin content, before and after thermal stabilization, were characterized by TGA, under N2 atmosphere. Fig. 10 shows the TGA curves of the as-extruded and stabilized filaments, and Table 6 presents the residual weight at 750°C, obtained for all filaments and neat polymers.

Figure 10: Thermal decomposition of (a) filaments of PET-G with 50 wt% of lignin; (b) filaments of PET-G with 60 wt% of lignin; (c) filaments of PC/ABS with 50 wt% of lignin under N2 atmosphere

All extruded filaments show minimal weight loss (approximately 1%) from 25°C to 250°C, indicating stability in this temperature range. Decomposition occurs abruptly above 300°C, presenting a maximum thermal decomposition rate at approximately 400°C. Filaments with 50 wt% lignin showed residual masses near or above 25% at 750°C. After oxidative thermal stabilization, the filaments exhibit two well-defined processes with weight loss in the thermal decomposition region. After oxidative thermal stabilization, the PETG-50LPH22 filaments present TGA derivative peaks near 400°C and 470°C–480°C, PCABS-50LPH22 filaments showed similar peaks around 450°C and 480°C, while for PETG-60 stabilized filaments the second peak shifts to 565°C (Fig. A4). Residual weight at 750°C increases with oxidative thermal stabilization, as summarized in Table 6.

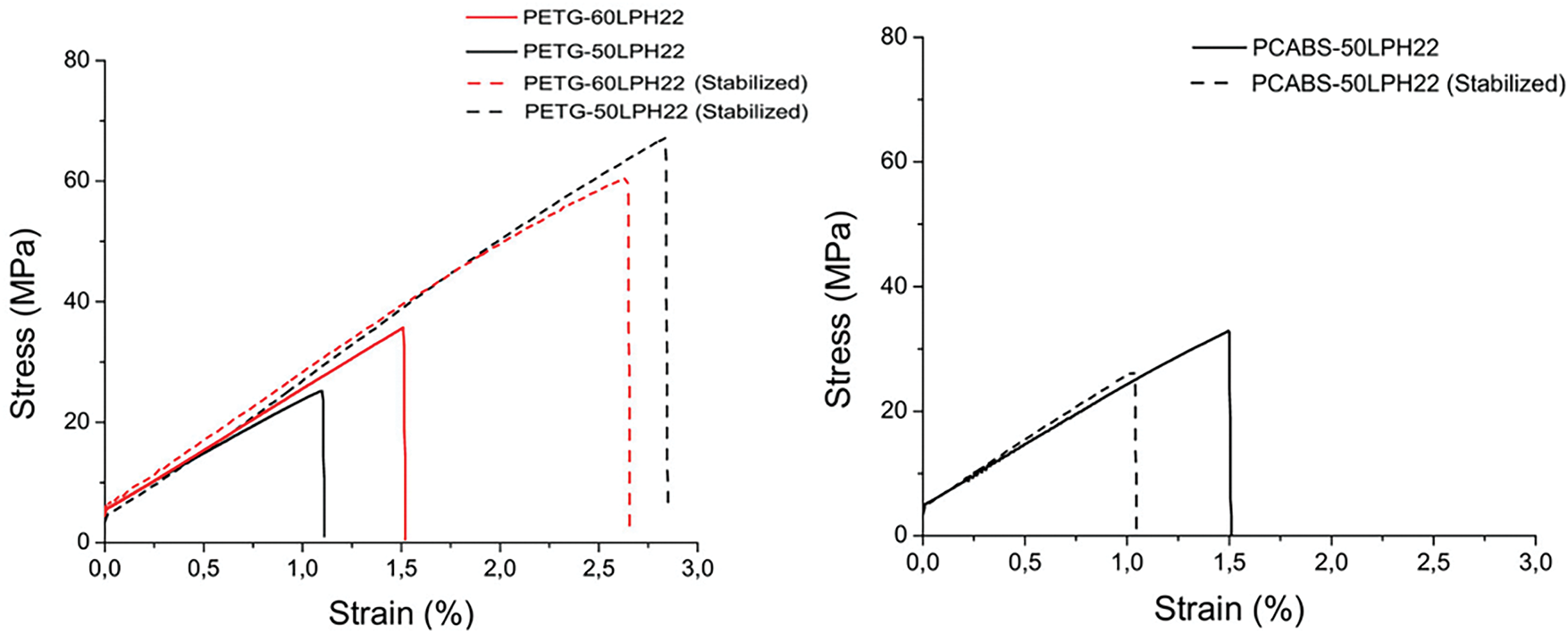

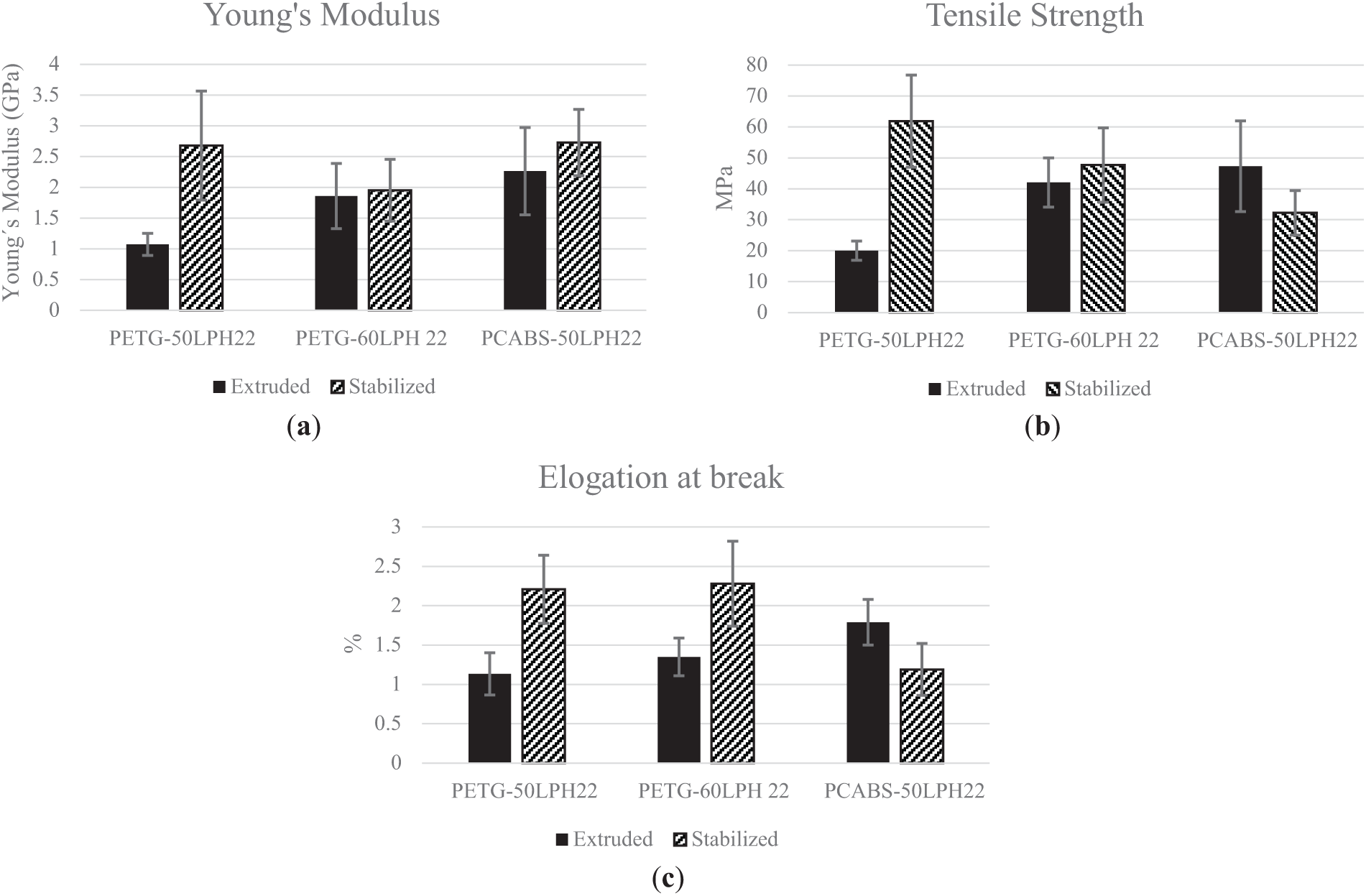

Single filament tensile tests were carried out before and after thermal stabilization, to assess possible structural changes resulting from the thermal stabilization process that may influence the filaments mechanical properties. Fig. 11 illustrates representative stress-strain curves, while the overall results are summarized in Fig. 12.

Figure 11: Stress-strain curves of (a) PETG-50LPH22 and PETG-60LPH22 and (b) PCABS-50LPH22 before and after thermal stabilization

Figure 12: Mechanical properties: (a) Young’s Modulus, (b) Tensile Strength and (c) Elongation at break. of each filament before and after thermal stabilization

A general trend for increase in Young’s modulus after thermal stabilization is observed for the filaments produced with lignin and both polymers, which is consistent with changes in the materials structure or molecular interactions induced by the stabilization process [24,35]. PETG-50LPH22 shows a considerable increase in modulus and strength after thermal stabilization, which is also observed for PETG-60LPH22 at a lower extent. The enhancement in elongation at break is particularly noteworthy for these filaments. Additionally, Fig. 11a shows a significant increase in toughness for PETG filaments, which is a strong indicator of structural strengthening during thermal treatment. Conversely, the decrease in tensile strength and elongation at break observed for the PC/ABS-based filaments may be a consequence of the remanence of the lignin domains after thermal stabilization. These lignin domains within the PC/ABS, possibly with a poor interface and originating voids or other types of flaws, may affect mostly the filaments strength and strain.

An ANOVA analysis (Appendix A (Tables A1–A3)) confirms that these results are statistically significant, with acceptable variation among the data. For PETG-60LPH22 and PCABS-50LPH22 filaments, no significant differences were detected between the post-extrusion and post-thermal stabilization conditions. The ANOVA analysis (Supporting Information) further supports this finding, showing no significant differences between the populations. Conversely, PCABS-50LPH22 filaments exhibit reduced tensile strength and strain after thermal treatment, resulting in a decrease in toughness (Figs. 11 and 12). Despite these outcomes, the filaments retain acceptable mechanical properties, showing interest for future studies of heat treatment under inert atmosphere, to explore the potential for carbon fiber production.

The present work compared the thermal properties and chemical composition of two lignin grades obtained from the same supplier and purified by the same method in different years (2018 and 2022), with 6 and 2 years of shelf life, respectively. Both lignin grades presented similar thermal characteristics under inert and oxidative atmospheres, and similar chemical composition, consistent with a good shelf-life stability.

PET-G and PC/ABS were selected for this work based on their availability as recycled feedstock. Filaments containing 50 and 60 wt% of the two lignin grades and PET-G with diameters ranging from 100 to 130 μm were successfully prepared by melt extrusion. Filaments of LPH22 produced with PET-G or with PC/ABS subjected to thermal stabilization in air and heated from room temperature to 250°C at a heating rate of 0.05°C·min−1 remained consistent and could be handled for further treatment. Thermogravimetric analysis showed thermal stability up to approximately 250°C, with a residual weight at 750°C under an inert atmosphere of approximately 35%. Infrared spectroscopy identified the aromatic structure that may assist further development of a graphitic morphology. PETG filaments retained good tensile properties after thermal stabilization, showing higher Young’s modulus, tensile strength, and an increase in elongation at break.

Future work will focus on the preparation of lignin-based filaments using recycled polymers, the optimization of the lignin-polymer melt-mixing process using twin screw extrusion, as well as the production of smaller diameter fibers by melt spinning and drawing, that may be thermally stabilized at higher heating rates. The application of strain and the heating rate will be optimized, to enhance molecular alignment while maintaining the level of crosslinking [48]. Finally, the fibers stabilized under optimal conditions will be subject to carbonization studies, controlling applied stress and heating rate [49–51].

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the support of the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) under the Scope of the Strategic Funding of UIDB/04469/2020 Unit (DOI 10.54499/UIDB/04469/2020) and LABBELS—Associate Laboratory in Biotechnology, Bioengineering and Microelectromechanical Systems, LA/P/0029/2020.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Project Better Plastics—Plastics in a Circular Economy—PPS4 (Circularity by Alternative Feedstocks) Grant agreement ID: POCI-01-0247-FEDER-046091. RR was funded by FCT through the PhD grant with reference UI/BD/154446/2022.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Maria C. Paiva, José A. Covas; methodology, Maria C. Paiva, José A. Covas, Rui Ribeiro; validation, Rui Ribeiro; formal analysis, Rui Ribeiro, Maria C. Paiva; investigation, Rui Ribeiro, Miguel Guerreiro, Mariana Martins da Silva, Jorge M. Vieira, Joana T. Martins; data curation, Rui Ribeiro, Jorge M. Vieira, Joana T. Martins; writing—original draft preparation, Rui Ribeiro; writing—review and editing, Maria C. Paiva, José A. Covas; visualization, Rui Ribeiro; supervision, Maria C. Paiva, José A. Covas, Renato Reis; project administration, Maria C. Paiva, José A. Covas, Renato Reis; resources, Maria C. Paiva, José A. Covas, Renato Reis. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors, Rui Ribeiro and Maria C. Paiva, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A

The metal frame used for the thermal stabilization of the filaments is shown in Fig. A1, along with the produced filaments illustrated in Figs. A2 and A3.

Figure A1: (a) Drawing of the extruded filament on the Xplore Lignin Fiber Winder; (b) PETG-50LPH filaments produced

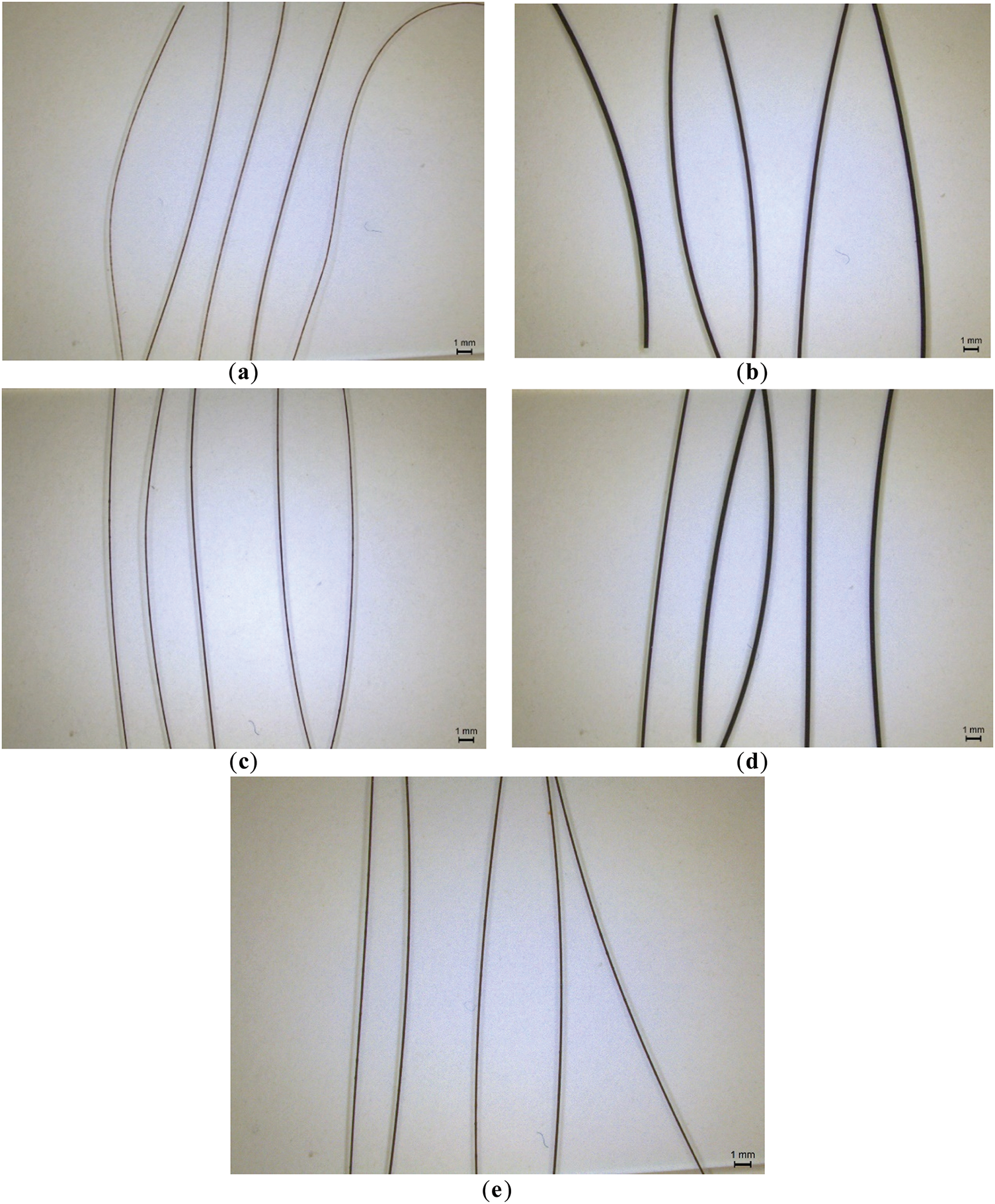

Figure A2: Filaments after extrusion and drawing: (a) PETG-50LPH22; (b) PETG-50LPH18; (c) PETG-60LPH22; (d) PETG-60LPH18; (e) PCABS-50LPH22

Figure A3: Metal frame holding filaments for the thermostabilization process

The first derivatives of the TGA curves for the filaments produced with PET-G and PC/ABS under a nitrogen atmosphere are presented in Fig. A4.

Figure A4: First derivatives of the TGA curves of (a) filaments of PET-G with 50 wt% of lignin; (b) filaments of PET-G with 60 wt% of lignin; (c) filaments of PC/ABS with 50 wt% of lignin, under N2 atmosphere

References

1. Xu Y, Liu Y, Chen S, Ni Y. Current overview of carbon fiber: toward green sustainable raw materials. BioResources. 2020;15(3):7234–59. doi:10.15376/biores.15.3.xu. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Luo Y, Qu W, Cochran E, Bai X. Enabling high-quality carbon fiber through transforming lignin into an orientable and melt-spinnable polymer. J Clean Prod. 2021;307:127252. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Qin W, Kadla JF. Effect of organoclay reinforcement on lignin-based carbon fibers. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2011;50(22):12548–55. doi:10.1021/ie201319p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Culebras M, Beaucamp A, Wang Y, Clauss MM, Frank E, Collins MN. Biobased structurally compatible polymer blends based on lignin and thermoplastic elastomer polyurethane as carbon fiber precursors. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2018;6(7):8816–25. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b01170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yang J, Ching YC, Chuah CH. Applications of lignocellulosic fibers and lignin in bioplastics: a review. Polymers. 2019;11(5):751. doi:10.3390/polym11050751. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Frank E, Steudle LM, Ingildeev D, Spörl JM, Buchmeiser MR. Carbon fibers: precursor systems, processing, structure, and properties. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53(21):5262–98. doi:10.1002/anie.201306129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Bengtsson A, Bengtsson J, Sedin M, Sjöholm E. Carbon fibers from lignin-cellulose precursors: effect of stabilization conditions. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2019;7(9):8440–8. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b00108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Souto F, Calado V, Pereira N. Fibras de carbono a partir de lignina: uma revisão da literatura. Matéria Rio J. 2015;20(1):100–14. (In Portuguese). doi:10.1590/s1517-707620150001.0012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Mu L, Wu J, Matsakas L, Chen M, Vahidi A, Grahn M, et al. Lignin from hardwood and softwood biomass as a lubricating additive to ethylene glycol. Molecules. 2018;23(3):537. doi:10.3390/molecules23030537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Kleinhans H, Salmén L. Development of lignin carbon fibers: evaluation of the carbonization process. J Appl Polym Sci. 2016;133(38):43965. doi:10.1002/app.43965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chatterjee S, Saito T. Lignin-derived advanced carbon materials. ChemSusChem. 2015;8(23):3941–58. doi:10.1002/cssc.201500692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Norberg I, Nordström Y, Drougge R, Gellerstedt G, Sjöholm E. A new method for stabilizing softwood kraft lignin fibers for carbon fiber production. J Appl Polym Sci. 2013;128(6):3824–30. doi:10.1002/app.38588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Nordström Y, Norberg I, Sjöholm E, Drougge R. A new softening agent for melt spinning of softwood kraft lignin. J Appl Polym Sci. 2013;129(3):1274–9. doi:10.1002/app.38795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Thunga M, Chen K, Grewell D, Kessler MR. Bio-renewable precursor fibers from lignin/polylactide blends for conversion to carbon fibers. Carbon N Y. 2014;68(15):159–66. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2013.10.075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kun D, Pukánszky B. Polymer/lignin blends: interactions, properties, applications. Eur Polym J. 2017;93:618–41. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2017.04.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Qin W, Kadla JF. Carbon fibers based on pyrolytic lignin. J Appl Polym Sci. 2012;126(S1):E204–13. doi:10.1002/app.36554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Enengl C, Lumetzberger A, Duchoslav J, Mardare CC, Ploszczanski L, Rennhofer H, et al. Influence of the carbonization temperature on the properties of carbon fibers based on technical softwood kraft lignin blends. Carbon Trends. 2021;5(3):100094. doi:10.1016/j.cartre.2021.100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Hosseinaei O, Harper DP, Bozell JJ, Rials TG. Improving processing and performance of pure lignin carbon fibers through hardwood and herbaceous lignin blends. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(7):1410. doi:10.3390/ijms18071410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Akpan EI. Melt-processing of lignin. In: Akpan EI, Adeosun SO, editors. Sustainable lignin for carbon fibers: principles, techniques, and applications. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2019. p. 281–324. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-18792-7_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Byrne N, De Silva R, Ma Y, Sixta H, Hummel M. Enhanced stabilization of cellulose-lignin hybrid filaments for carbon fiber production. Cellulose. 2018;25(1):723–33. doi:10.1007/s10570-017-1579-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Wang S, Bai J, Innocent MT, Wang Q, Xiang H, Tang J, et al. Lignin-based carbon fibers: formation, modification and potential applications. Green Energy Env. 2022;7(4):578–605. doi:10.1016/j.gee.2021.04.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Dallmeyer I, Ko F, Kadla JF. Electrospinning of technical lignins for the production of fibrous networks. J Wood Chem Technol. 2010;30(4):315–29. doi:10.1080/02773813.2010.527782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Braun JL, Holtman KM, Kadla JF. Lignin-based carbon fibers: oxidative thermostabilization of kraft lignin. Carbon N Y. 2005;43(2):385–94. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2004.09.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Lin J, Koda K, Kubo S, Yamada T, Enoki M, Uraki Y. Improvement of mechanical properties of softwood lignin-based carbon fibers. J Wood Chem Technol. 2014;34(2):111–21. doi:10.1080/02773813.2013.839707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kadla JF, Kubo S, Venditti RA, Gilbert RD, Compere AL, Griffith W. Lignin-based carbon fibers for composite fiber applications. Carbon N Y. 2002;40(15):2913–20. doi:10.1016/S0008-6223(02)00248-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kubo S, Kadla JF. Poly(ethylene oxide)/organosolv lignin blends: relationship between thermal properties, chemical structure, and blend behavior. Macromolecules. 2004;37(18):6904–11. doi:10.1021/ma0490552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Qu W, Bai X. Thermal treatment of pyrolytic lignin and polyethylene terephthalate toward carbon fiber production. J Appl Polym Sci. 2020;137(26):48843. doi:10.1002/app.48843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kubo S, Kadla JF. Lignin-based carbon fibers: effect of synthetic polymer blending on fiber properties. J Polym Environ. 2005;13(2):97–105. doi:10.1007/s10924-005-2941-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wang S, Li Y, Xiang H, Zhou Z, Chang T, Zhu M. Low cost carbon fibers from bio-renewable Lignin/Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) blends. Compos Sci Technol. 2015;119(21):20–5. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2015.09.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Maldhure AV, Ekhe JD, Deenadayalan E. Mechanical properties of polypropylene blended with esterified and alkylated lignin. J Appl Polym Sci. 2012;125(3):1701–12. doi:10.1002/app.35633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kubo S, Yoshida T, Kadla JF. Surface porosity of lignin/PP blend carbon fibers. J Wood Chem Technol. 2007;27(3–4):257–71. doi:10.1080/02773810701702238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sun SC, Xu Y, Wen JL, Yuan TQ, Sun RC. Recent advances in lignin-based carbon fibers (LCFsprecursors, fabrications, properties, and applications. Green Chem. 2022;24(15):5709–38. doi:10.1039/d2gc01503j. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang C, Kelley SS, Venditti RA. Lignin-based thermoplastic materials. ChemSusChem. 2016;9(8):770–83. doi:10.1002/cssc.201501531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Lahtinen MH, Ojala A, Wikström L, Nättinen K, Hietala S, Fiskari J, et al. The impact of thermomechanical pulp fiber modifications on thermoplastic lignin composites. Compos Part C Open Access. 2021;6(2):100170. doi:10.1016/j.jcomc.2021.100170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Parit M, Jiang Z. Towards lignin derived thermoplastic polymers. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;165(pt b):3180–97. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.09.173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Larkin P. Infrared and Raman spectroscopy: principles and spectral interpretation. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2011. 230 p. [Google Scholar]

37. Infrared spectroscopy absorption table [Internet]. [cited 2022 Mar 30]. Available from: https://chem.libretexts.org/Ancillary_Materials/Reference/Reference_Tables/Spectroscopic_Reference_Tables/Infrared_Spectroscopy_Absorption_Table. [Google Scholar]

38. Mainka H, Täger O, Körner E, Hilfert L, Busse S, Edelmann FT, et al. Lignin-an alternative precursor for sustainable and cost-effective automotive carbon fiber. J Mater Res Technol. 2015;4(3):283–96. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2015.03.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Boeriu CG, Bravo D, Gosselink RJA, van Dam JEG. Characterisation of structure-dependent functional properties of lignin with infrared spectroscopy. Ind Crops Prod. 2004;20(2):205–18. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2004.04.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Fitzer E, Frohs W, Heine M. Optimization of stabilization and carbonization treatment of PAN fibres and structural characterization of the resulting carbon fibres. Carbon N Y. 1986;24(4):387–95. doi:10.1016/0008-6223(86)90257-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Khayyam H, Jazar RN, Nunna S, Golkarnarenji G, Badii K, Fakhrhoseini SM, et al. PAN precursor fabrication, applications and thermal stabilization process in carbon fiber production: experimental and mathematical modelling. Prog Mater Sci. 2020;107:100575. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2019.100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Gupta A, Harrison IR. New aspects in the oxidative stabilization of PAN-based carbon fibers. Carbon N Y. 1996;34(11):1427–45. doi:10.1016/S0008-6223(96)00094-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kil HS, Jang SY, Ko S, Jeon YP, Kim HC, Joh HI, et al. Effects of stabilization variables on mechanical properties of isotropic pitch based carbon fibers. J Ind Eng Chem. 2018;58:349–56. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2017.09.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Sieira P, Guimarães C, Braga A, dos Santos CEL, Pereira MH, Borges LEP. Stabilization time and temperature influence on the evolution of the properties of mesophase pitch stabilized fibers and carbon fibers. J Ind Eng Chem. 2024;136(5):465–74. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2024.02.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Vaughan M, Beaucamp A, Collins MN. Development of high stiffness carbon fibres from lignin. Compos Part B Eng. 2025;292(2):112024. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2024.112024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Hatzikiriakos SG, Migler KB. Polymer processing instabilities: control and understanding. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2004. 488 p. doi:10.1201/9781420030686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Canetti M, Bertini F. Supermolecular structure and thermal properties of poly(ethylene terephthalate)/lignin composites. Compos Sci Technol. 2007;67(15–16):3151–7. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2007.04.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Luo Y, Razzaq MEA, Qu W, Mohammed AABA, Aui A, Zobeiri H, et al. Introducing thermo-mechanochemistry of lignin enabled the production of high-quality low-cost carbon fiber. Green Chem. 2024;26(6):3281–300. doi:10.1039/d3gc04288j. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Bengtsson A, Bengtsson J, Jedvert K, Kakkonen M, Tanhuanpää O, Brännvall E, et al. Continuous stabilization and carbonization of a lignin-cellulose precursor to carbon fiber. ACS Omega. 2022;7(19):16793–802. doi:10.1021/acsomega.2c01806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Yan L, Liu H, Yang Y, Dai L, Si C. Lignin-derived carbon fibers: a green path from biomass to advanced materials. Carbon Energy. 2025;7(3):e662. doi:10.1002/cey2.662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Jia G, Innocent MT, Yu Y, Hu Z, Wang X, Xiang H, et al. Lignin-based carbon fibers: insight into structural evolution from lignin pretreatment, fiber forming, to pre-oxidation and carbonization. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;226(6185):646–59. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.12.053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools