Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Facile Preparation of Robust Peach Gum Polysaccharide with Remarkably Enhanced Antibacterial and Antioxidant Performance

Guangxi Key Laboratory of Optical and Electronic Materials and Devices, Guangxi Colleges and Universities Key Laboratory of Natural and Biomedical Polymer Materials, and College of Materials Science and Engineering, Guilin University of Technology, Guilin, 541004, China

* Corresponding Author: Li Zhou. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Recent Advances on Renewable Materials)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(10), 2077-2090. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0122

Received 26 June 2025; Accepted 02 September 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

Peach gum polysaccharide (PGP), a readily available natural polysaccharide, boasts substantial potential across diverse applications, yet its practical utility is severely limited by its vulnerability to bacterial growth and limited antioxidant activity. Herein, we introduced a simple and effective method to enhance the antibacterial and antioxidant properties of PGP by conjugating it with salicylic acid (SA). Cytotoxicity evaluation results confirmed that the resulting PGP-SA retains the excellent biocompatibility of PGP. Notably, PGP-SA demonstrates outstanding antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive (S. aureus) and Gram-negative (E. coli) bacteria, outperforming non-modified PGP. Its antibacterial mechanism is hypothesized to stem from disrupting bacterial cell membranes and proteins, targeting structures vital to microbial survival. Beyond fighting bacteria, PGP-SA also delivers robust antioxidant activity, efficiently scavenging ABTS radicals. Harnessing these dual enhancements, PGP-SA proves highly effective as a fruit preservation coating. Most impressively, it extends the post-harvest shelf life of mangoes: under identical storage conditions, PGP-SA-coated mangoes stay fresh for seven extra days compared to uncoated fruit. With its simple synthesis process and standout performance, this work not only overcomes PGP’s key limitations but also opens new avenues for its application in food preservation and related industries.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Peach gum polysaccharide (PGP) is a natural heteropolysaccharide predominantly made up of arabinose and galactose. It is extracted from the gelatinous secretion, known as peach gum, which forms on peach trees following physical injury or microbial attack [1–4]. This biopolymer is widely available across the world, and China represents a major source with an annual output reaching over ten million metric tons. Structural and functional studies have recently revealed that PGP exhibits remarkable water solubility, a highly branched architecture, and excellent biocompatibility [5–7]. These characteristics make it a promising candidate for various applications, including the preparation of functional carbon materials [8–11], adsorbent materials [12,13], stabilizers [14], adhesives [15–17], catalysts [18], medical materials [19,20], and as well as food packaging materials [21–23]. Despite its potential, PGP faces critical limitations: it is highly prone to bacterial growth in humid environments or aqueous solutions, leading to mold formation and hindering long-term storage. Additionally, its antioxidant activity is relatively weak. These drawbacks severely restrict its practical application. For example, in the realm of food packaging, current research increasingly focuses on multifunctional materials that integrate antibacterial, antioxidant, and sensing capabilities to preserve food quality and degrade naturally [24]. While existing research has explored functionalization of PGP to endow them with specialized functionalities, such as encapsulation, adsorption, and emulsification capabilities [3], there remains a notable gap: simple, effective chemical modification methods specifically designed to boost their antibacterial and antioxidant activities have been rarely reported. Therefore, developing simple yet effective strategies to enhance PGP’s antibacterial and antioxidant properties—while mitigating its susceptibility to microbial growth—remains key to unlocking its widespread utility.

Salicylic acid (SA) is renowned for its exceptional biocompatibility and robust antibacterial and antioxidant properties [25,26], which have made it a prevalent ingredient in a wide range of daily products and pharmaceutical applications. However, the limited solubility and stability of SA in aqueous solutions pose significant limitations on its potential applications. To address these challenges and expand the utility of SA, researchers have initiated the combination of SA with biocompatible polysaccharides [27,28]. This approach leads to the development of biocompatible materials that possess enhanced comprehensive properties, particularly in terms of improved antibacterial capabilities, making them highly suitable for applications in food preservation. For example, Liu and colleagues developed a chitosan (CTS)-SA composite film, which demonstrated superior antibacterial performance and preservation effects in grape preservation compared to pure chitosan film [29]. Du and colleagues grafted SA onto hemicellulose macromolecules, resulting in a product that exhibited remarkable antibacterial performance in blueberry preservation [30]. Shi and colleagues modified CTS with SA to produce the CTS-g-SA polymer [31], which showed significant antibacterial effects in preventing fruit green mold rot. The synergistic action of CTS and SA greatly enhanced the antibacterial activity of CTS-g-SA compared to using SA or CTS alone. Moreover, compared to pure SA, the SA-polysaccharide complex exhibits better durability and stability [32,33], maintaining effective antibacterial properties over a longer period. This is because the polysaccharide matrix protects SA from environmental factors such as light and temperature. Currently, antibacterial materials based on SA-polysaccharide composites have shown great potential in applications such as antibacterial packaging materials, wound dressings, and antibacterial daily products [34–36]. Hence, it is anticipated that functionalizing PGP with SA could effectively address the issues of PGP’s vulnerability to bacterial growth.

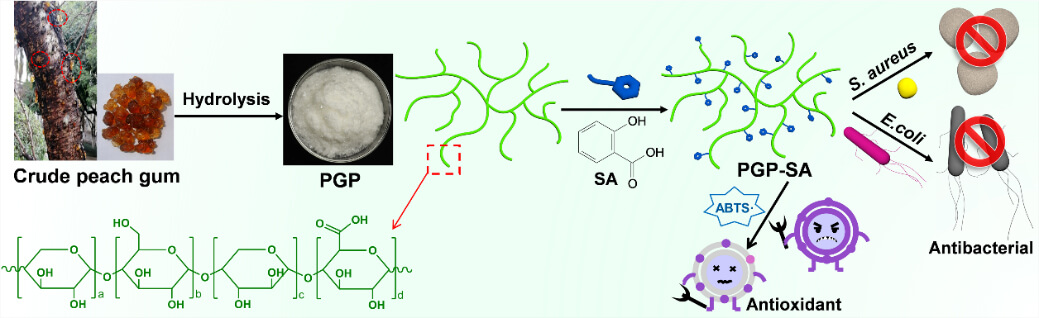

In this study, we demonstrate a simple and effective approach to overcome the limitations of natural PGP by tailoring it with SA to produce PGP-SA (Fig. 1). The selection of SA for modifying PGP is based on its desirable attributes, including excellent biocompatibility, high antibacterial and antioxidant activities, and the presence of a carboxylic group that readily reacts with the hydroxyl groups of PGP. Upon conjugation with SA, the resulting PGP-SA conjugate not only retains excellent biocompatibility but also exhibits significantly enhanced antibacterial and antioxidant properties in comparison to PGP. Furthermore, the potential application of PGP-SA as a fruit preservation coating to enhance the quality preservation of mangoes was explored.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of preparation of PGP-SA with superior antibacterial and antioxidant activities

The natural crude peach gum used in this study was collected from peach trees located on the campus of Guilin University of Technology, situated in Guilin, China. Salicylic acid (SA, 99%), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30 wt%), calcein AM (96%), 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS, 98%), Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, pro-pidium iodide (PI, 99%), agar, N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC, 99%), 4-(N,N-dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP, 99%), thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT), potas-sium persulfate (K2S2O8, 99%), and anhydrous ferric chloride (FeCl3, 98%) were all purchased from Beijing Innochem Technology Co. Ltd. in Beijing, China. All other chemicals used were of analytical grade and were used without further purification.

2.2.1 Preparation of Water-Soluble PGP

A water-soluble polysaccharide from peach gum (PGP) was prepared through alkaline hydrolysis of raw peach gum, following a modified procedure based on a previous report [37]. The product exhibited a number-average molecular weight (Mn) of approximately 18.7 kDa and a polydispersity index (PDI) of 1.64. Briefly, 1 g of dried crude peach gum was ground into a fine powder and immersed in 1 L of water for 12 h to obtain a dispersed suspension. The pH of this suspension was adjusted to 12 using NaOH solution. Subsequently, the mixture was heated to 95–97°C under continuous stirring for 12 h to facilitate hydrolysis. After filtration, hydrogen peroxide (0.5 mL, 30 wt%) was added to the resulting PGP solution, which was then agitated at room temperature for 30 min. The mixture was dialyzed and freeze-dried, yielding a white powdered PGP. Monosaccharide composition analysis revealed that arabinose was the major sugar unit, constituting 53.3% of the total molar composition, followed by galactose (32.6%), xylose (6.9%), and glucuronic acid (3.1%), along with minor amounts of other constituents.

The PGP-SA samples can be synthesized by reacting the carboxylic group of SA with the hydroxyl group of PGP. In this study, three PGP-SA samples, named PGP-SA4/1, PGP-SA2/1, and PGP-SA1/1, were prepared by adjusting the weight ratio of PGP to SA to 4/1, 2/1, and 1/1, respectively. For instance, in the preparation of PGP-SA1/1, 276 mg of SA (2 mmol) and 122 mg of DMAP (1.2 mmol) were dissolved in 10 mL of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) in a flask. Then, 5 mL of DMF solution containing DCC (495 mg, 2.4 mmol) was added under an ice bath, and the mixture was stirred for 1 h. Subsequently, 10 mL of DMF solution containing PGP (276 mg) was added, and the mixture was stirred for 24 h at room temperature under an argon atmosphere. After the reaction, the product was filtered, and the collected solution was precipitated in ethanol. The solid was then washed repeatedly with ethanol, followed by centrifugation, and the resulting product was freeze-dried to afford PGP-SA1/1. To quantify the final SA content in the PGP-SA products, UV-vis absorption spectroscopy was employed, utilizing the distinct absorption peak of the SA moiety at about 301 nm in DMF. A standard calibration curve was pre-established, correlating the absorbance of SA with its concentration in DMF. Using this method, the final SA contents in PGP-SA4/1, PGP-SA2/1, and PGP-SA1/1 were determined to be 158, 226, and 312 mg/g, respectively.

The cytotoxicity of PGP-SA was assessed using the MTT assay and live/dead double staining, according to established methods [1,38,39]. In the MTT assay, B16 melanoma and L929 fibroblast cells were seeded into plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per mL. After 24 h of incubation, the culture medium was replaced with various concentrations of PGP-SA dispersions (0–400 μg/mL) for another 24 h. The wells were then rinsed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by the addition of 100 μL of MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL) to each well. After 2 h of incubation, the MTT-containing medium was carefully removed, and 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide was introduced. The plates were gently agitated for 20 min, and the absorbance at 490 nm was measured using a microplate reader. Cell viability was calculated using the following equation:

where C1 represents the absorbance of the PGP-SA-treated cells at 490 nm, and C0 represents the absorbance of the control at 490 nm.

For the live/dead cell co-staining experiment, B16 and L929 cells were seeded into culture plates. Subsequently, the culture medium containing PGP-SA at a concentration of 400 μg/mL was added, and the cells were further incubated for 24 h. The cells were then washed twice with PBS. Next, they were co-stained with a buffer solution containing PI and calcein-AM in the dark for 30 min. After co-staining, the cells were washed twice with PBS. Finally, the cells were visualized using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (CLSM, Olympus FV3000) to capture images.

2.2.4 Antibacterial Evaluation

The antibacterial activity of PGP-SA was tested against Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Escherichia coli (E. coli), both obtained from the Guangdong Province Microbial Culture Collection Center (Guangzhou, China). The tube broth dilution method was applied to determine antibacterial effects, which involved three main stages. First, test strains were activated by inoculating S. aureus and E. coli into separate test tubes containing 5 mL of LB medium using a sterile loop. The tubes were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Next, the activated cultures were serially diluted with sterile saline to achieve a bacterial suspension concentration of 106 CFU/mL for subsequent antibacterial assays. Finally, antibacterial performance was analyzed by assessing tube turbidity and measuring transmittance. Different concentrations of PGP-SA (2–8 mg/mL) were prepared in 5 mL of LB medium, followed by the addition of 100 µL of bacterial suspension to each tube. A positive control tube containing only bacterial suspension without PGP-SA was also prepared. After thorough mixing, all samples were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Visual inspection of turbidity was conducted, and the optical density (OD) at 600 nm was recorded with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer to calculate antibacterial efficiency according to the following equation [40]:

where OD0 represents the OD value of the test tube containing only the bacterial suspension, OD1 denotes the OD value of the LB medium, and OD2 is the OD value of the test tube containing the bacterial suspension with PGP-SA added.

Additionally, the antibacterial activity of PGP-SA was assessed by constructing bacterial growth curves. The antibacterial efficacy was evaluated against S. aureus and E. coli at a concentration of 105 CFU/mL, using various concentrations of PGP-SA ranging from 0 to 8 mg/mL. The inoculated culture medium was incubated on a shaker at 150 rpm and 37°C. The OD value was recorded hourly to monitor bacterial growth. The growth rate of bacteria incubated with PGP-SA was determined by plotting a curve of the OD values against time.

2.2.5 Antioxidant Activity of PGP-SA against ABTS Radicals

Typically, ABTS radicals were generated by reacting 5 mL of ABTS aqueous solution (7 mM) with 5 mL of potassium persulfate (K2S2O8, 2.4 mM) in the dark for 16 h. This resulting solution was then diluted until its absorbance at 734 nm fell within the range of 0.7 to 0.8. Different concentrations of PGP-SA (50–400 μg/mL) were introduced into 3 mL of the diluted radical solution. The mixtures were left to stand for 30 min, centrifuged, and the absorbance of the supernatant was recorded at 734 nm. The ABTS radicals scavenging rate was calculated according to the given equation:

where A0 represents the absorbance of the ABTS radicals solution at 734 nm before the addition of PGP-SA, and A1 is the absorbance after the mixture has stood for 30 min with PGP-SA.

2.2.6 PGP-SA for Fruit Preservation

To evaluate PGP-SA1/1 as a preservative coating, unblemished mangoes of uniform size and ripeness were selected, and randomly divided into four treatment groups. Each group was fully immersed for 5 min at 25°C in aqueous solutions containing 0 wt% (control), 1.0 wt%, or 2.0 wt% PGP-SA1/1, prepared by dissolving the PGP-SA1/1 in water under constant stirring (500 rpm, 30 min). Following immersion, mangoes were air-dried under controlled environmental conditions (25 ± 1°C, 60 ± 5% relative humidity) until no surface moisture remained and weight stabilized (±0.1 g). The dried mangoes were then stored on sterile trays in ventilated chambers under identical temperature/humidity conditions (25 ± 1°C, 60 ± 5% RH). Periodic photographs were captured to monitor and record the spoilage progression in each group of mangoes.

The cytotoxicity, antibacterial, and antioxidant assays were each conducted with 3 biological replicates, and each biological replicate was analyzed in 3 technical replicates to ensure result reliability. All quantitative data are presented as the mean from three independent replicates, with a p-value < 0.05 deemed statistically significant.

The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) s spectra of PGP and PGP-SA, ranging from 500 to 4000 cm−1, were examined via the KBr pellet technique on a PE Paragon 1000 spectrometer. NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Avance 500 spectrometer, using deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6) as the solvent. The molecular weight of PGP was measured with a Waters 1525-Agilent PL-GPC 50 gel permeation chromatography system, utilizing polystyrene as the standard and DMF as the eluent at a flow rate of 1 mL/min and a testing temperature of 40°C. The monosaccharide composition of PGP was analyzed using an Agilent 1100 HPLC system equipped with a THERMO ULTRA detector. UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy was carried out at room temperature using a Shimadzu UV-3600 spectrophotometer. Field-emission SEM observations were conducted using a Hitachi S4800 SEM. CLSM images of cells were captured with an Olympus FV3000 CLSM, with a 405 nm excitation wavelength.

3.1 Preparation and Characterization of PGP-SA

The synthetic procedure for PGP-SA is illustrated in Fig. 1. Initially, crude peach gum was hydrolyzed to yield water-soluble PGP. The PGP macromolecule features a highly branched structure and numerous hydroxyl groups, providing an ideal platform for reaction with the carboxylic group of SA via a one-step esterification process. In this study, to explore how the content of SA influences the antibacterial and antioxidant performance of PGP-SA, three PGP-SA samples were prepared, designated as PGP-SA4/1, PGP-SA2/1, and PGP-SA1/1. These samples were created by adjusting the weight ratio of SA to PGP to 1:4, 1:2, and 1:1, respectively. It is worth noting that, unless otherwise stated, the PGP-SA mentioned in this paper refers to the PGP-SA1/1 sample.

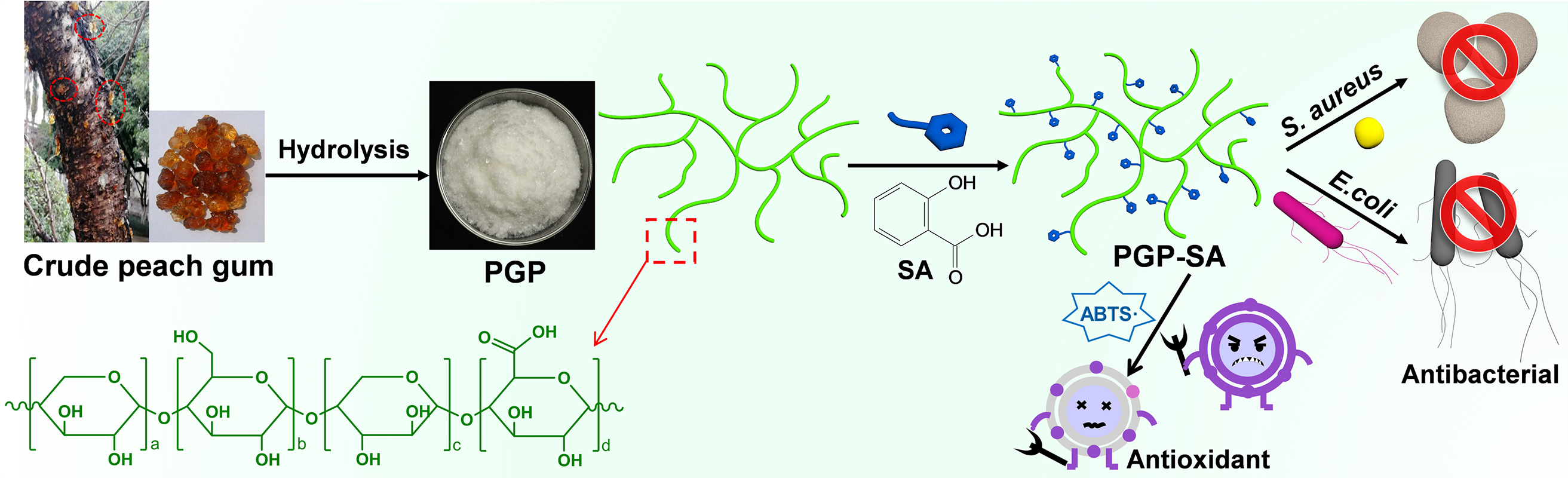

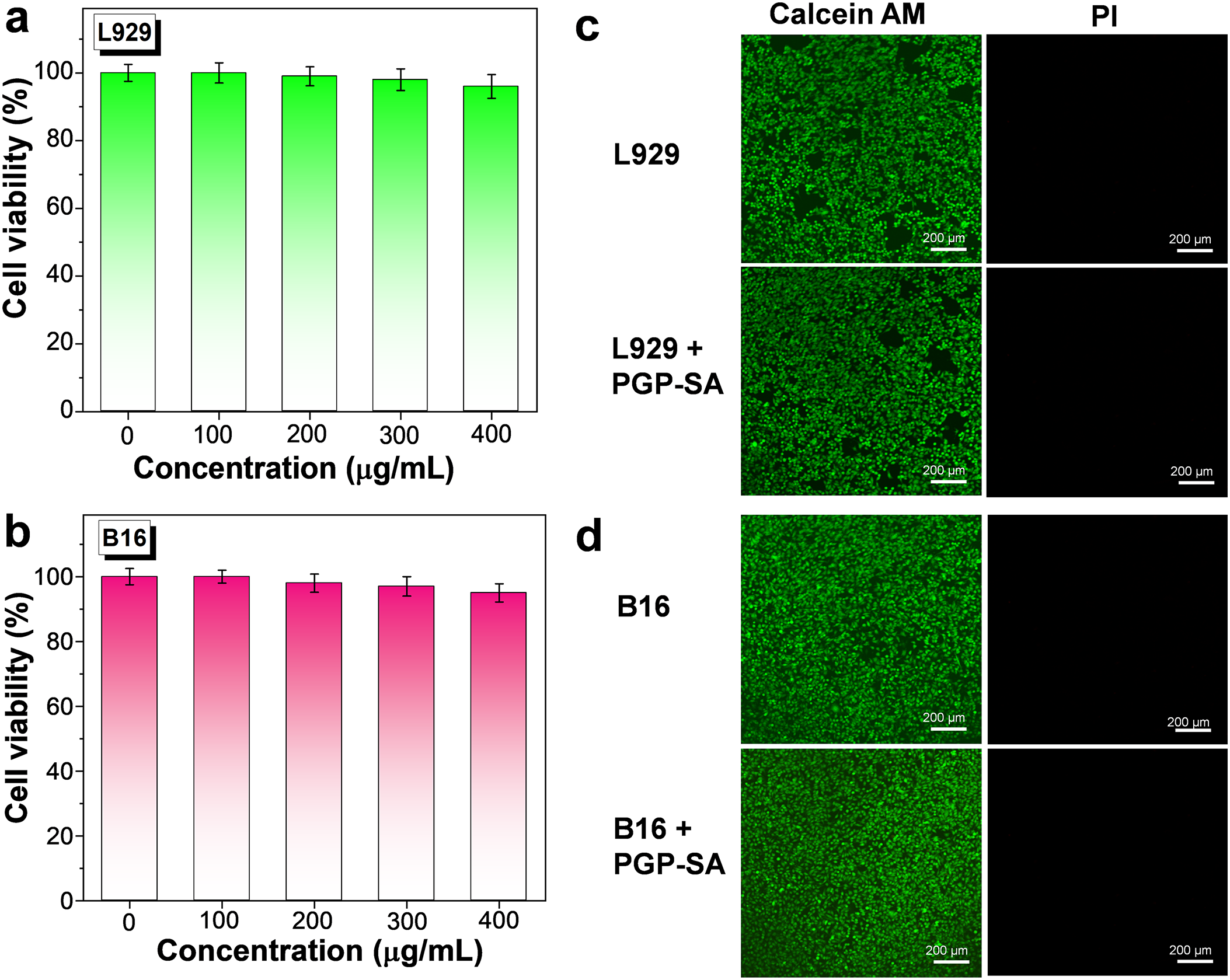

The esterification reaction between SA and PGP was monitored using a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer, with the results presented in Fig. 2a. In the FTIR spectrum of pure PGP, distinct absorption bands centered at approximately 3420 and 1050 cm−1, corresponding to O-H and C-O stretching vibrations, are clearly visible. Following the reaction with SA, a prominent peak at around 1720 cm−1, associated with the O-C=O bonds, emerges. Additionally, two strong peaks at 1603 and 1498 cm−1, corresponding to the benzene ring structure, are observed [34]. These spectral changes confirm that SA has been successfully conjugated to PGP. Additionally, the successful synthesis of PGP-SA was also verified through nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. As depicted in Fig. 2b, the characteristic peaks of the sugar ring protons of pure PGP are predominantly found within the range of 2.5–5.5 ppm. In comparison to PGP, the 1H NMR spectrum of PGP-SA (Fig. 2c) exhibits characteristic peaks of the benzene ring between 7–8 ppm, which is consistent with the expected structure of PGP-SA. In addition to FTIR and NMR characterization, UV-visible absorption spectroscopy was employed to further analyze the reaction process. As illustrated in Fig. 2d, pure PGP shows no significant absorption peaks in the range of 225–400 nm. In contrast, PGP-SA exhibits two distinct absorption peaks at 240 and 301 nm. These peaks are indicative of the incorporation of SA moieties [41] into the PGP structure. This observation provides further evidence supporting the successful synthesis of PGP-SA. Additionally, the amount of SA in PGP-SA samples can be determined using the characteristic peak at 301 nm, based on the established relationship between SA concentration and absorbance at this wavelength. Employing this method, the final SA contents in PGP-SA4/1, PGP-SA2/1, and PGP-SA1/1 were measured to be 158, 226, and 312 mg/g, respectively.

Figure 2: (a) FTIR spectra of PGP and PGP-SA. 1H NMR spectra of PGP (b) and PGP-SA (c). (d) UV-vis absorption spectra of PGP, SA and PGP-SA

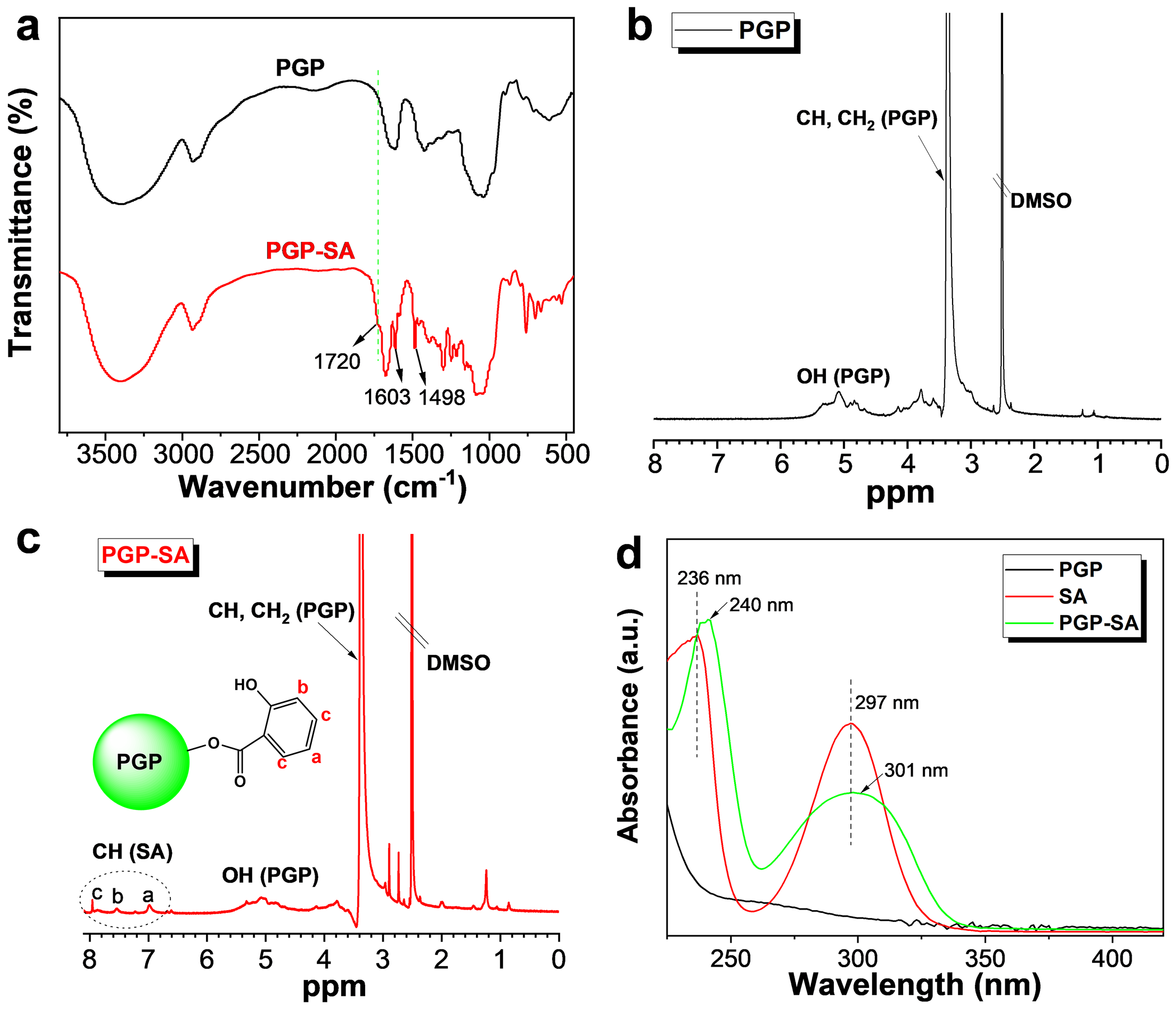

3.2 Cytotoxicity Evaluation of PGP-SA

To ensure practical applicability, it is crucial that PGP-SA exhibits favorable biocompatibility. Therefore, the cytotoxicity of PGP-SA was thoroughly evaluated using the MTT assay, with L929 mouse fibroblast cells and B16 mouse melanoma cells serving as the cellular models. The cells were incubated with varying concentrations of PGP-SA for a period of 24 h. As shown in Fig. 3a,b, both cell lines demonstrated remarkable resilience, maintaining over 95% cell viability even at the high concentration of 400 μg/mL. To further elucidate the in vitro cytotoxic profile of PGP-SA, a co-staining method was employed utilizing calcein AM (which fluoresces green in live cells) and PI (which fluoresces red in dead cells). In line with the MTT assay outcomes, confocal laser-scanning microscopy (CLSM) images reveal that both L929 cells (Fig. 3c) and B16 cells (Fig. 3d) display only green fluorescence following a 24-h exposure to PGP-SA at 400 μg/mL, with no discernible red fluorescence. This indicates the absence of dead cells. Collectively, these findings underscore the low cytotoxicity of PGP-SA, thereby paving the way for its practical applications.

Figure 3: Cell viability of L929 (a) and B16 cells (b) after incubation with PGP-SA for 24 h. CLSM images of L929 (c) and B16 cells (d), both with and without incubation of PGP-SA, were co-stained using calcein AM and PI

3.3 Antibacterial Performance of PGP-SA

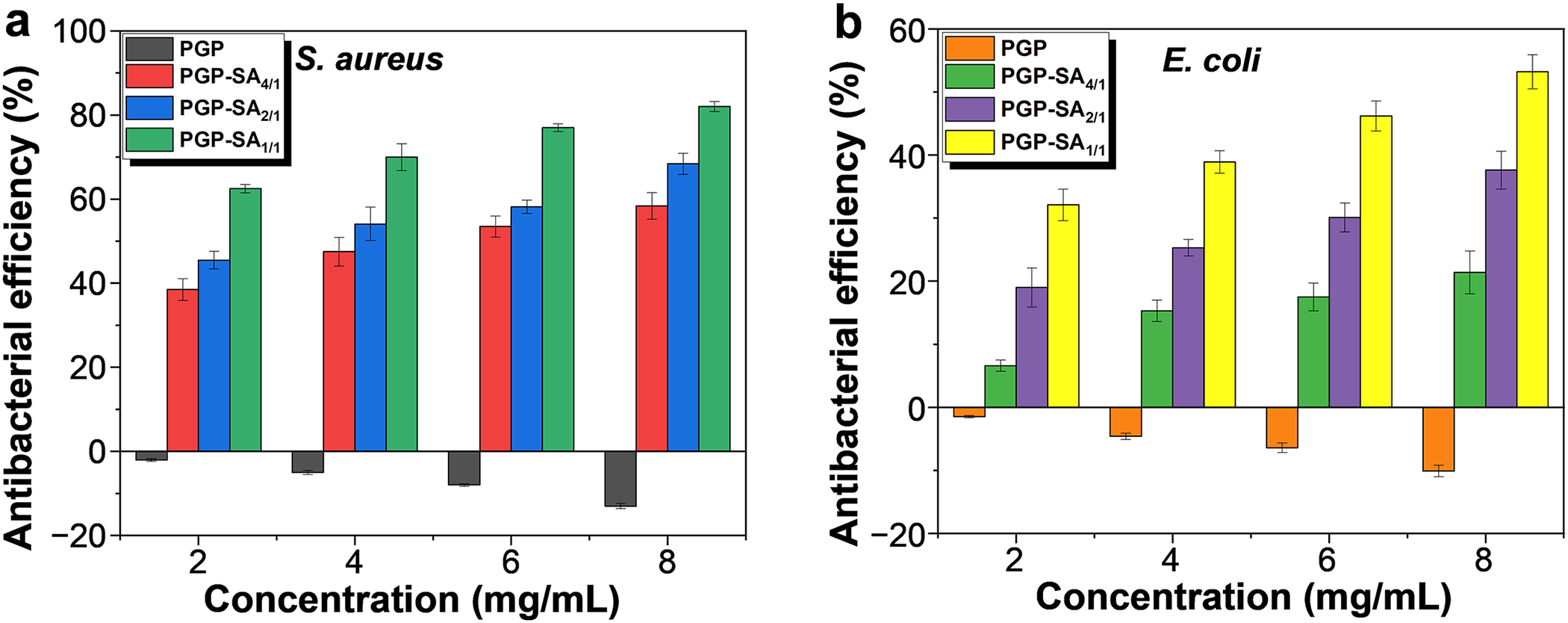

To evaluate the antibacterial activity of PGP-SA, S. aureus (Gram-positive) and E. coli (Gram-negative) were selected as model strains. The effect of various concentrations of PGP-SA on bacterial growth was monitored using UV-Vis spectrophotometry. Higher transmittance values of the bacterial suspension indicated stronger antibacterial activity. For reference, PGP was also tested under identical conditions. As shown in Fig. 4a,b, PGP did not inhibit the growth of either strain; instead, it appeared to promote bacterial proliferation, which aligns with its known susceptibility to microbial contamination in aqueous environments. In comparison, PGP-SA samples demonstrated a concentration-dependent enhancement in antibacterial efficacy against both bacteria. Furthermore, at equivalent concentrations, the inhibitory effect on S. aureus was markedly greater than that on E. coli. For example, the antibacterial efficiency of PGP-SA1/1 at a concentration of 8 mg/mL was 82.4% for S. aureus and 53.4% for E. coli. The differing antibacterial efficacies of PGP-SA against S. aureus and E. coli may be attributed to their distinct outer membrane characteristics. Additionally, PGP-SA samples prepared with a higher weight feed ratio of SA to PGP exhibited higher antibacterial efficiency. For instance, the antibacterial efficiency values of PGP-SA4/1, PGP-SA2/1, and PGP-SA1/1 at a concentration of 8 mg/mL for S. aureus were 58.4%, 68.3%, and 82.4% (Fig. 4a), respectively. This can be explained by the fact that samples prepared with a higher weight feed ratio of SA to PGP contain a greater amount of SA, thereby demonstrating higher antibacterial efficiency.

Figure 4: Antibacterial efficiency values of PGP, PGP-SA4/1, PGP-SA2/1, and PGP-SA2/1 at different concentrations against S. aureus (a) and E. coli (b)

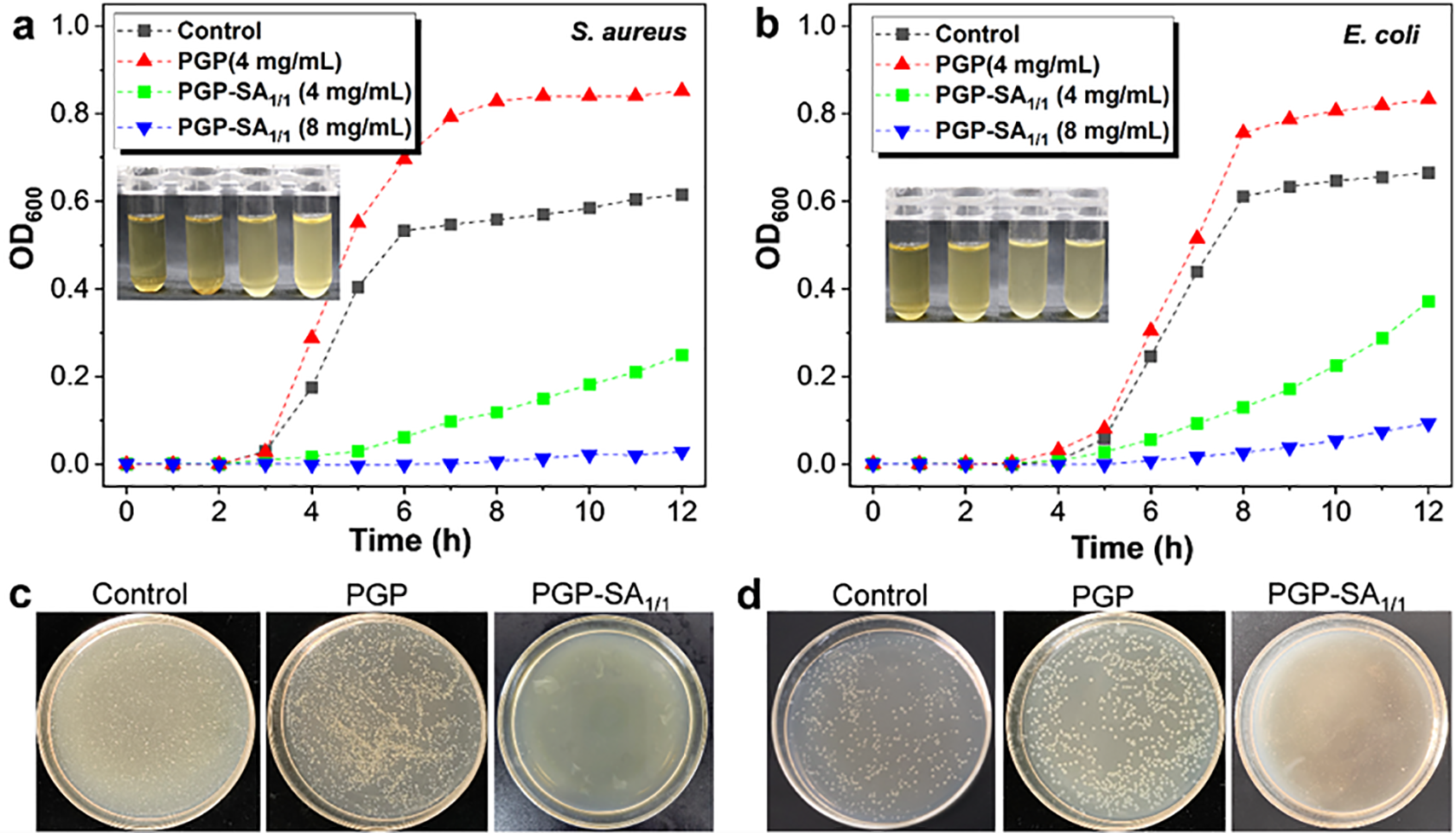

PGP-SA1/1 was chosen as a representative sample to quantitatively analyze its effect on the growth of S. aureus and E. coli by monitoring optical density (OD) at 600 nm, which correlates with bacterial density. For reference, PGP was also included under the same conditions. Bacterial cultures were grown in LB medium, diluted, and then exposed to PGP-SA1/1 or PGP at 37°C. As depicted in Fig. 5a,b, the control and PGP-treated groups exhibited similar growth patterns: both S. aureus and E. coli entered exponential growth around 3 and 4 h, respectively. After 12 h, samples with 4 mg/mL PGP reached OD values of 0.85 (S. aureus) and 0.83 (E. coli), exceeding those of the control (0.62 and 0.67), indicating that PGP supports bacterial proliferation. In contrast, increasing concentrations of PGP-SA1/1 led to reduced OD values for both bacteria, demonstrating effective growth inhibition. At 8 mg/mL PGP-SA1/1, OD values were near zero, indicating nearly complete suppression of growth. These results are supported by visual evidence (Fig. 5a and b insets), where solutions with PGP-SA1/1 remained clear, while control and PGP samples showed visible turbidity. To further confirm the antibacterial activity of PGP-SA1/1, the colonies were counted after incubating PGP and PGP-SA1/1 at 37°C for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 5c,d, PGP (4 mg/mL) exhibited no growth inhibition against either S. aureus or E. coli, and even resulted in more colonies than the control sample. In contrast, PGP-SA1/1 at the same concentration demonstrated significant growth inhibition against both S. aureus and E. coli, with higher antibacterial activity observed against S. aureus. This finding is consistent with the antibacterial efficiency results.

Figure 5: Growth curves of S. aureus (a) and E. coli (b) without and with incubation of different concentrations of PGP and PGP-SA1/1. Insets: The corresponding photographs of bacterial solutions after 12 h of culture (From left to right: 8 mg/mL of PGP-SA1/1, 4 mg/mL of PGP-SA1/1, control, and 4 mg/mL of PGP). Photographs of bacterial colonies of S. aureus (c) and E. coli (d) without and with incubation of PGP and PGP-SA1/1

Thus, the conjugation of SA significantly enhances the antibacterial activities of PGP. To elucidate the antibacterial mechanism of PGP-SA, the morphologies of bacteria before and after incubation with PGP-SA1/1 were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Prior to treatment with PGP-SA1/1, S. aureus and E. coli exhibited typical spherical and rod shapes, respectively (Fig. 6a and 6c). Following incubation with PGP-SA1/1, both S. aureus and E. coli underwent substantial morphological alterations (Fig. 6b and 6d). Notably, the spherical structure of S. aureus was completely disrupted, and severe aggregation was observed among the damaged S. aureus (Fig. 6b). It has been reported that the antibacterial mechanisms of plant-derived antibacterial agents, such as SA, mainly involve causing damage to bacterial cell walls and disrupting cell membranes and membrane proteins [42]. Based on the experimental results and literature reports, we hypothesize that the possible antibacterial mechanism of PGP-SA is the destruction of the bacterial cell membrane and its membrane proteins, ultimately leading to bacterial lysis and death. However, the detailed interactions between the PGP-SA and bacteria remains unclear and will be further investigated in our laboratory in future studies.

Figure 6: SEM images of S. aureus (a, b) and E. coli (c, d) before (a, c) and after (b, d) incubation with PGP-SA1/1

3.4 Antioxidant Activity of PGP-SA

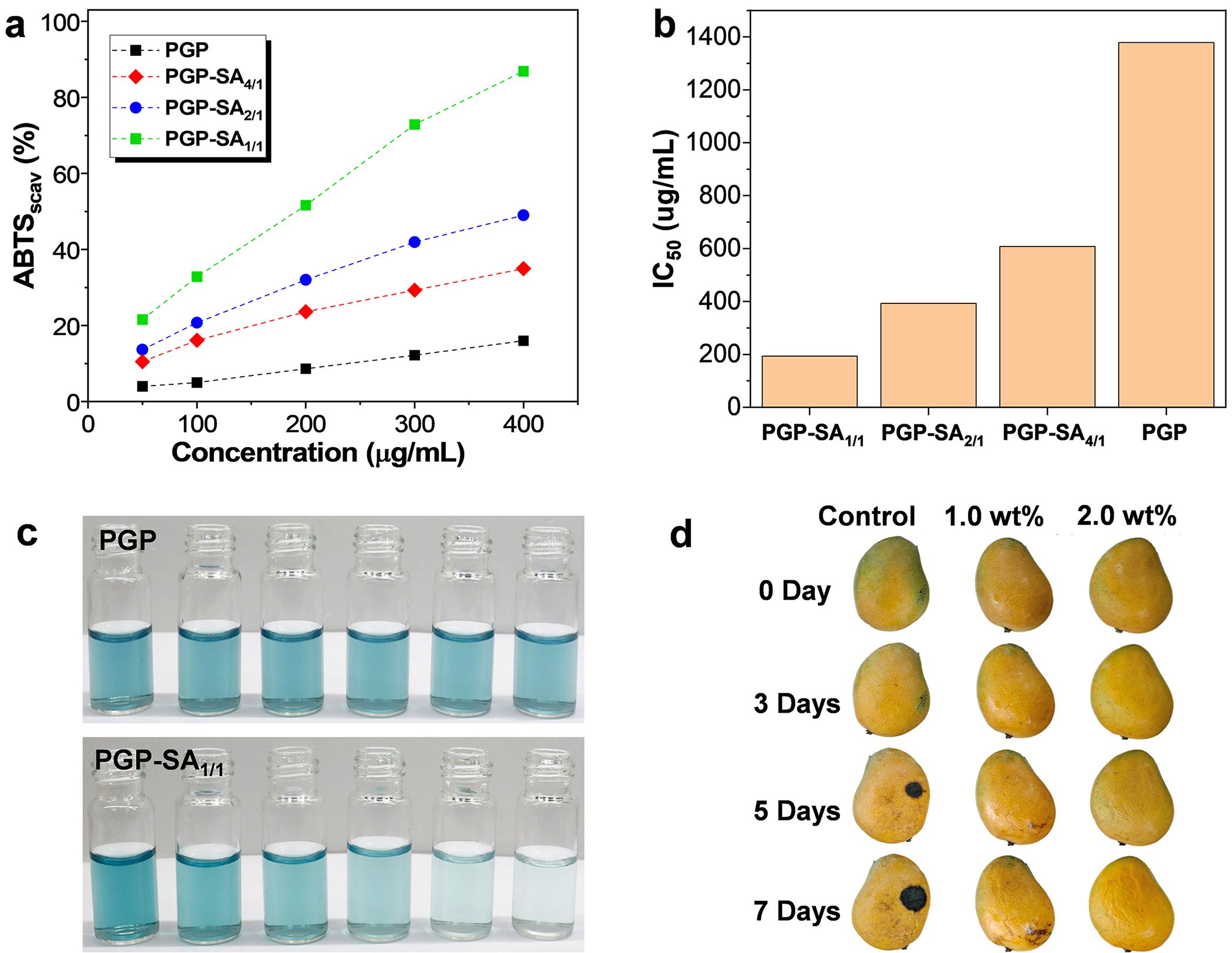

In addition to enhancing the antibacterial activity of PGP, the conjugation of SA also confers favorable antioxidant capability on PGP-SA. The antioxidant activity of PGP-SA was evaluated by its ability to scavenge ABTS radicals. ABTS solution reacts with K2S2O8 to form a blue ABTS radical solution, which has an absorption peak at 734 nm. The antioxidant activity of PGP-SA samples can be assessed by measuring the change in absorbance at 734 nm after adding PGP-SA samples. As shown in Fig. 7a, PGP itself possesses some antioxidant activity. However, after conjugation with SA, the resulting PGP-SA samples exhibit significantly higher antioxidant activity than PGP at the same concentration. Notably, PGP-SA prepared with a higher weight feed ratio of SA to PGP demonstrates greater antioxidant activity due to the increased content of SA moieties. The half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of PGP, PGP-SA4/1, PGP-SA2/1, and PGP-SA1/1 were determined to be 1378.8, 607.6, 393.2 and 193.4 μg/mL, respectively (Fig. 7b). Moreover, the scavenging efficiency of PGP-SA samples for ABTS radicals increases notably with increasing concentrations of the samples. For instance, when the concentration of PGP-SA1/1 is increased from 50 μg/mL to 400 μg/mL, the scavenging efficiency rises from 21.5% to 86.8%. Correspondingly, the color of the ABTS radical solution does not change significantly after the addition of PGP, while the color of the ABTS radical solution gradually fades with increasing concentrations of PGP-SA1/1 (Fig. 7c). All these results demonstrate that the conjugation of SA can significantly enhance the antioxidant activity of PGP.

Figure 7: (a) Scavenging efficiencies of varying concentrations of PGP, PGP-SA4/1, PGP-SA2/1, and PGP-SA1/1 on ABTS radicals. (b) IC50 value of PGP, PGP-SA4/1, PGP-SA2/1, and PGP-SA1/1. (c) Photographs of ABTS radicals solutions in the presence of varying concentrations (from left to right: 0, 50, 100, 200, 300, and 400 μg/mL) of PGP and PGP-SA1/1. (d) Photographs of mangoes with and without treating diverse concentrations of PGP-SA1/1 solution over varying periods

Leveraging the outstanding biocompatibility and robust antibacterial and antioxidant properties of PGP-SA, it presents a highly promising candidate for applications in food preservation. In this study, mangoes were chosen as a model to assess the efficacy of PGP-SA1/1 coatings in prolonging the shelf life of fruits. Notably, the PGP-SA1/1 coating is both hydrophilic and washable, enabling its removal via water washing. The mangoes were initially submerged in aqueous solutions of PGP-SA1/1 at varying concentrations, subsequently air-dried at ambient temperature, and stored, with meticulous documentation of changes in the mango peel over time. As depicted in Fig. 7d, untreated fresh mangoes exhibited conspicuous signs of peel decay by the 5th day. In stark contrast, mangoes coated with a 1 wt% PGP-SA1/1 solution displayed only minor black spots on their peels after a 7-day storage period. Remarkably, mangoes treated with a 2 wt% PGP-SA1/1 solution maintained an appearance nearly indistinguishable from their initial state even after 7 days, underscoring the remarkable capacity of PGP-SA1/1 coatings to enhance the storage longevity of fresh mangoes. In fact, PGP-SA1/1 can extend the post-harvest shelf life of mangoes: under the same storage conditions, mangoes coated with PGP-SA1/1 remain fresh for seven additional days compared to uncoated ones. Consequently, PGP-SA1/1 has the potential to serve as an effective sustainable and non-toxic preservation coating, capable of extending the shelf life of food products.

In summary, we have successfully developed a simple yet highly effective method for preparing robust PGP-SA with significantly enhanced antibacterial and antioxidant properties. This approach effectively overcomes the inherent limitations of traditional PGP, such as its susceptibility to bacterial contamination and its relatively low antioxidant activity. The biocompatibility of PGP-SA has been confirmed through both MTT assays and live/dead cell co-staining techniques, demonstrating its safety for practical applications. PGP-SA exhibits remarkable antibacterial performance against both Gram-positive (S. aureus) and Gram-negative (E. coli) bacteria, with higher efficiency observed against S. aureus. The antibacterial mechanism is hypothesized to involve the destruction of bacterial cell membranes and proteins, leading to bacterial lysis and death. In addition, the conjugation of SA can also significantly enhance the antioxidant activity of PGP, as evidenced by the efficient scavenging of ABTS radicals by the PGP-SA. Furthermore, PGP-SA has been effectively utilized as a fruit preservation coating, significantly extending the shelf life of mangoes. This study not only provides a simple approach to overcome the limitations of PGP, facilitating the utilization of abundant peach gum resources, but also opens up new possibilities for the application of PGP in food preservation, pharmaceuticals, and other related industries.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Guangxi Science and Technology Plan Project (No. Guike AA25069007) and Guilin Scientific Research and Technology Development Plan (No. 20220103-2).

Author Contributions: Mengting Huang: Conceptualization, investigation, validation and writing—original draft preparation. Meiting Lu: Conceptualization, formal analysis, and investigation. Li Yang: Investigation and validation. Jiwen Long: Conceptualization and validation. Li Zhou: writing—review & editing, supervision, project administration and Funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Qian HF, Cui SW, Wang Q, Wang C, Zhou HM. Fractionation and physicochemical characterization of peach gum polysaccharides. Food Hydrocolloid. 2011;25(5):1285–90. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2010.09.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yang HY, Wang DW, Deng J, Yang J, Shi C, Zhou FL, et al. Activity and structural characteristics of peach gum exudates. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;2018(1):4593735. doi:10.1155/2018/4593735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zeng SH, Long JW, Sun JH, Wang G, Zhou L. A review on peach gum polysaccharide: hydrolysis, structure, properties and applications. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;279(5):119015. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.119015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Dai KY, Ding WJ, Ji HY, Liu AJ. Structural characteristics of peach gum arabinogalactan and its mechanism of inhibitory effect on leukemia cells. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;307(9):142131. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.142131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Dai KY, Ding WJ, Li ZT, Liu C, Ji HY, Liu AJ. Comparison of structural characteristics and anti-tumor activity of two alkali extracted peach gum arabinogalactan. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;279(1):135407. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.135407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Song G, Chen F, Chen S, Ye S. Effect of peach gum polysaccharide, a new fat substitute, on sensory properties of skimmed milk. Int Dairy J. 2022;125:105224. doi:10.1016/j.idairyj.2021.105224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhu K, Yu D, Chen XY, Song GL. Preparation, characterization and controlled-release property of Fe3+ cross-linked hydrogels based on peach gum polysaccharide. Food Hydrocolloid. 2019;87(2):260–9. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.08.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lin Y, Chen Z, Yu C, Zhong W. Heteroatom-doped sheet-like and hierarchical porous carbon based on natural biomass small molecule peach gum for high-performance supercapacitors. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2019;7(3):3389–403. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b05593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ma YS, Chen MF, Zheng XZ, Yu D, Dong XP. Synergetic effect of swelling and chemical blowing to develop peach gum derived nitrogen-doped porous carbon nanosheets for symmetric supercapacitors. J Taiwan Inst Chem E. 2019;101:24–30. doi:10.1016/j.jtice.2019.04.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yu D, Zheng XZ, Chen MF, Dong XP. Large-scale synthesis of Ni(OH)2/peach gum derived carbon nanosheet composites with high energy and power density for battery-type supercapacitor. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;557:608–16. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2019.09.061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang RY, Wang L, Ettoumi FE, Javed M, Li L, Lin XY, et al. Ultrasonic-assisted green extraction of peach gum polysaccharide for blue-emitting carbon dots synthesis. Sustain Chem Pharm. 2021;24(3):100555. doi:10.1016/j.scp.2021.100555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li L, Li Y, Yang K, Luan X, Li M, Cui M, et al. Removal of methylene blue from water by peach gum based composite aerogels. J Polym Environ. 2021;29(6):1752–62. doi:10.1007/s10924-020-01987-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yang H, Wu K, Zhu J, Lin Y, Ma X, Cao Z, et al. Highly efficient and selective removal of anionic dyes from aqueous solutions using polyacrylamide/peach gum polysaccharide/attapulgite composite hydrogels with positively charged hybrid network. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;266:131213. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Zeng SH, Tan JS, Wen T, Huang XH, Zhou L. General and facile synthesis of robust composite nanocrystals with natural peach gum polysaccharide. Compos Commun. 2022;31:101105. doi:10.1016/j.coco.2022.101105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Liu ZW, Chen S, Wan Y, Miao X, Zhang QC, Jiang T, et al. Efficient utilization of peach gum to prepare UV-responsive peelable pressure-sensitive adhesives for non-destructive fabrication of ultrathin electronics. Appl Surf Sci. 2023;612(39):155748. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.155748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wan Z, Huang Y, Zeng X, Guo X, Wu Z, Tian M, et al. Peach gum as an efficient binder for high-areal-capacity lithium-sulfur batteries. Sustain Mater Technol. 2021;30:e00334. doi:10.1016/j.susmat.2021.e00334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wu Q, Jiang K, Wang Y, Chen Y, Fan DB. Cross-linked peach gum polysaccharide adhesive by citric acid to produce a fully bio-based wood fiber composite with high strength. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;253:127514. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Huang B, Lu M, Wang D, Song YH, Zhou L. Versatile magnetic gel from peach gum polysaccharide for efficient adsorption of Pb2+ and Cd2+ ions and catalysis. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;181:785–92. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.11.077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Li SG, Li GP, Liu DJ, Li MX, Liu HH, Zhu WX, et al. Peach gum polysaccharide protects intestinal barrier function, reduces inflammation and oxidative stress, and alleviates pulmonary inflammation induced by Enterococcus faecium E745. J Funct Foods. 2024;115(2):106098. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2024.106098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lu TY, Han XK, Chen DM, Li JX, Zhang ZC, Lu SR, et al. Multifunctional bio-films based on silk nanofibres/peach gum polysaccharide for highly sensitive temperature, flame, and water detection. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;231(3):123472. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Chen Y, Ye YY, Zhu Z, Xu B, Meng LH, Yang T, et al. Preparation and characterization of peach gum/chitosan polyelectrolyte composite films with dual cross-linking networks for antibacterial packaging. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;261(2):129754. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.129754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Mahdi AA, Al-Maqtari QA, Al-Ansi W, Hu W, Hashim SBH, Cui HY, et al. Replacement of polyethylene oxide by peach gum to produce an active film using Litsea cubeba essential oil and its application in beef. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;241(2):124592. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124592. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang RY, Li L, Ma CX, Ettoumi FE, Javed M, Lin XY, et al. Shape-controlled fabrication of zein and peach gum polysaccharide based complex nanoparticles by anti-solvent precipitation for curcumin-loaded Pickering emulsion stabilization. Sustain Chem Pharm. 2022;25(1–2):100565. doi:10.1016/j.scp.2021.100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Feng Z, Sun P, Zhao F, Li M, Ju J. Advancements and challenges in biomimetic materials for food preservation: a review. Food Chem. 2025;463(7):141119. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.141119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Ezzat A, Ammar A, Szabó Z, Holb IJ. Salicylic acid treatment saves quality and enhances antioxidant properties of apricot fruit. Hortic Sci. 2017;44(2):73–81. doi:10.17221/177/2015-hortsci. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mikhnavets L, Abashkin V, Khamitsevich H, Shcharbin D, Burko A, Krekoten N, et al. Ultrasonic formation of Fe3O4-reduced graphene oxide-salicylic acid nanoparticles with switchable antioxidant function. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2022;8(3):1181–92. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.1c01603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Díaz-Díaz ED, Haro MLM, Patriarca A, Melaj M, Foresti ML, López-Córdoba A, et al. Assessment of the enhancement potential of salicylic acid on physicochemical, mechanical, barrier, and biodegradability features of potato starch films. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2023;38(3–4):101108. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2023.101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Fang YS, Fu JX, Tao CJ, Liu PF, Cui B. Mechanical properties and antibacterial activities of novel starch-based composite films incorporated with salicylic acid. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;155:1350–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.11.110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Liu J, Wang TH, Hu CM, Lei L, Liang Y, Gao ZD, et al. Hydrophobic chitosan/salicylic acid blends film with excellent tensile properties for degradable food packaging plastic materials. J Appl Polym Sci. 2022;139(43):e53042. doi:10.1002/app.53042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Du RY, Deng J, Huang EB, Chen L, Tang JR, Liu Y, et al. Effects of salicylic acid-grafted bamboo hemicellulose on gray mold control in blueberry fruit: the phenylpropanoid pathway and peel microbial community composition. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;251:126303. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Shi ZJ, Yang HY, Jiao JY, Wang F, Lu YY, Deng J. Effects of graft copolymer of chitosan and salicylic acid on reducing rot of postharvest fruit and retarding cell wall degradation in grapefruit during storage. Food Chem. 2019;283(2):92–100. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.12.078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Ding J, Hao Y, Liu BQ, Chen YX, Li L. Development and application of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/thermoplastic starch film containing salicylic acid for banana preservation. Foods. 2023;12(18):3397. doi:10.3390/foods12183397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Xue C, Wilson LD. Preparation and characterization of salicylic acid grafted chitosan electrospun fibers. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;275(4):118751. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118751. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Hu F, Sun T, Xie J, Xue B, Li X, Gan JH, et al. Functional properties of chitosan films with conjugated or incorporated salicylic acid. J Mol Struct. 2021;1223:129237. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Oh GW, Kim SC, Kim TH, Jung WK. Characterization of an oxidized alginate-gelatin hydrogel incorporating a COS-salicylic acid conjugate for wound healing. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;252(2):117145. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zhang H, Chen Z, Yang G, Yao X, Zhang Y, Shao H. Antibacterial cellulose solution-blown nonwovens modified with salicylic acid microcapsules using NMMO as solvent. Carbohydr Polym. 2024;345(17):122567. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Huang BT, Liao J, Zhou L. Peach gum-derived aminated magnetic gel: an exceptional and recyclable adsorbent for efficient removal of diclofenac sodium. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;222:120044. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.120044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Prakash A, Yadav S, Saxena PS, Srivastava A. Development of folate-conjugated polypyrrole nanoparticles incorporated with nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dots for targeted bioimaging and photothermal therapy. Talanta. 2024;278(1–2):126528. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2024.126528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Chen J, Xing X, Liu D, Gao L, Liu Y, Wang Y, et al. Copper nanoparticles incorporated visible light-curing chitosan-based hydrogel membrane for enhancement of bone repair. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2024;158(3):106674. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2024.106674. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Hejna M, Dell’Anno M, Liu Y, Rossi L, Aksmann A, Pogorzelski G, et al. Assessment of the antibacterial and antioxidant activities of seaweed-derived extracts. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):21044. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-71961-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Matyasovszky N, Tian M, Chen A. Kinetic study of the electrochemical oxidation of salicylic acid and salicylaldehyde using UV/vis spectroscopy and multivariate calibration. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113(33):9348–53. doi:10.1021/jp904602j. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Bae JY, Seo YH, Oh SW. Antibacterial activities of polyphenols against foodborne pathogens and their application as antibacterial agents. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2022;31(8):985–97. doi:10.1007/s10068-022-01058-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools