Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Characteristics of Food Packaging Bioplastics with Nanocrystalline Cellulose (NCC) from Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunches (OPEFB) as Reinforcement

1 Agro-Industrial Engineering, Politeknik ATI Padang, Padang, 25171, Indonesia

2 Petrochemical Industry Process Technology, Politeknik Industri Petrokimia Banten, Serang, 42166, Indonesia

3 Research Center for Environmental and Clean Technology, National Research and Innovation Agency, Serpong, 15314, Indonesia

4 Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Chemical and Energy Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor Bahru, 1310, Johor, Malaysia

5 Department of Agricultural and Computer Engineering, Politeknik Pertanian Negeri Payakumbuh, Payakumbuh, 26271, Indonesia

* Corresponding Author: Maryam. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Special issue from 1st International Conference of Natural Fiber and Biocomposite (1st ICONFIB) 2024 )

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(12), 2431-2451. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0063

Received 17 December 2024; Accepted 07 May 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

The development of the bioplastics industry addresses critical issues such as environmental pollution and food safety concerns. However, the industrialization of bioplastics remains underdeveloped due to challenges such as high production costs and suboptimal material characteristics. To enhance these characteristics, this study investigates bioplastics reinforced with Nanocrystalline Cellulose (NCC) derived from Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunches (OPEFB), incorporating dispersing agents. The research employs a Central Composite Design from the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with two factors: the type of dispersing agent (KCl and NaCl) and the NCC concentration from OPEFB (1%–5%), along with the dispersing agent concentration (0.5%–3%). The objective of this study is to analyze the characteristics of food packaging bioplastics composed of a sago starch matrix, NCC from OPEFB, and dispersing agents. The novelty of this research lies in the development of food packaging bioplastics using sago starch reinforced with NCC from OPEFB and the addition of dispersing agents (KCl and NaCl). The results indicate that incorporating NCC from OPEFB and dispersing agents significantly enhances the bioplastic’s properties, meeting the JIS 2-1707 standards for food packaging plastic films. The bioplastic was tested as packaging for gelamai (a traditional food from West Sumatra) through an organoleptic evaluation. Consumer acceptance in terms of taste, smell, and color remained satisfactory up to the 14th day. Further research is required to scale up production using the optimal formulation identified in this study. Additionally, this bioplastic is recommended for use as packaging for various food products.Keywords

Synthetic plastics contribute significantly to environmental pollution. This is due to the fact that synthetic plastic materials are difficult to decompose in the soil. The production of synthetic plastics is estimated to increase by approximately 320 million tons each year [1]. More than 40% of the produced plastics are used for packaging [2], with less than 14% being suitable for recycling [3], leading to adverse environmental impacts. Food safety issues are also a concern, particularly regarding toxicity due to the presence of microplastics in food products. Widianarko & Hantoro state that the presence of microplastics can be classified as contaminants that pose health risks to humans, thus failing to meet food safety standards. There is a need for solutions to reduce synthetic plastic waste, one of which is the development of bioplastics [4].

The development of the bioplastics industry addresses several challenges, such as environmental pollution and food safety issues. The commercial application of bioplastics is still not widely developed. Current challenges in the bioplastics industry include the fact that bioplastic production technology is still more expensive than synthetic plastic production costs. Additionally, bioplastics tend to have lower physical and mechanical properties compared to synthetic plastics. However, bioplastics remain a highly potential material as an environmentally friendly alternative to synthetic plastics. Therefore, the development of bioplastics with the addition of fillers as reinforcing agents is one alternative solution to address these challenges. Research and development of bioplastics are still open as we move toward the industrialization of bioplastics in the future.

In recent years, researchers have explored agricultural products, such as from sago starch, for bioplastic development. However, bioplastics derived from sago starch exhibit limitations in physical properties, thermal stability, and hygroscopicity compared to conventional plastics. Despite these challenges, renewable natural materials, including starch, remain a promising alternative for developing bioplastics with improved characteristics.

Nanotechnology provides innovative solutions and opportunities for developing advanced products, including bioplastics. Its application in food packaging has shown great potential to enhance packaging material properties. One approach to improving bioplastic characteristics is by incorporating polysaccharide-based reinforcing fillers, such as cellulose. Nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) is a nano-sized biomaterial derived from cellulose, possessing mechanical characteristics such as good tensile strength and modulus, and is biodegradable. NCC can be applied as a reinforcing material, filler, and carrier in various medical and pharmaceutical products, packaging, composites, wood and paper products, as well as food applications. Previous research has been conducted on bioplastic composites made from starch with various cellulose fiber fillers, such as Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunches (OPEFB) [5,6], sugar palm fiber [7], bamboo [8], and water hyacinth fiber [9]. Nanotechnology in food packaging has shown great potential to improve the properties of packaging materials.

NCC possesses natural properties that are biocompatible and biodegradable, making it an ideal material for research and development. NCC has great potential for various applications due to its superior characteristics, such as high tensile strength, large surface area, low density, non-toxicity, and electromagnetic response [10]. According to [11], nanocellulose is a new type of cellulose characterized by increased crystallinity, aspect ratio, surface area, and improved dispersion and biodegradability. These capabilities enable nanocellulose particles to be used as reinforcing fillers for polymers and additives for biodegradable products. Various cellulose sources from biomass are promising alternatives to be developed as fillers, including Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunches (OPEFB).

Approximately 25%–26% of the total palm oil production consists of empty fruit bunches, which are by-products, with only about 10% currently utilized, while the remainder remains unprocessed waste [12]. OPEFB contains 38.70% cellulose [13]. This makes oil palm empty fruit bunch waste a potential candidate for bioplastic research reinforced with NCC from OPEFB. Some of the advantages of NCC from OPEFB are its renewable nature, biodegradability, and abundant availability.

Maryam et al. [13] developed bioprocessing technology to produce NCC from OPEFB and its application as a composite bioplastic material with Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA). The results showed that NCC from OPEFB is highly promising as a reinforcing filler. Some challenges encountered in this research include the storage of NCC liquid preparations, which experienced agglomeration, and the lengthy process time for making NCC slurry. Additionally, the resulting bioplastics were not fully uniform, as some areas showed blank spots due to non-homogeneous mixing of the solution. According to [14], the method for making cellulose slurry with the addition of a dispersing agent can help homogenize the mixture and smooth the surface of the bioplastic.

The addition of dispersing agents affects the preparation of cellulose, such as Micro fibrillated Cellulose (MFC) and Nanocrystalline Cellulose (NCC). The preparation of MFC and NCC suspensions is influenced by several factors, one of which is ion concentration in forming the cellulose structure as a filler in bioplastics. Several studies have used dispersing agents (such as KCl) in the preparation of MFC from bamboo cellulose, bioplastic made from sago starch and MFC from bamboo [15], and bioplastics from avocado starch with NCC OPEFB filler [16]. The addition of KCl as a dispersing agent can stabilize the bioplastic solution [17] and effectively disperse the NCC suspension [16]. The use of dispersing agents like NaCl in the preparation of cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) and nano fibrillated cellulose (NFC) [18] has also been documented.

Previous research by Chilingar stated that dispersing agents such as KCl and NaCl, which contain salt elements, also function as bioplastic coatings. This results in bioplastics with a smooth, shiny surface while protecting the matrix layer used [19,20]. Similarly, research by Al Fath et al. [21], found that dispersing agents improve the distribution of materials, enhancing the mechanical and thermal properties of the resulting bioplastics. Since these agents are derived from biomass, a similar effect is expected. Rahayu et al. [17] also investigated the use of KCl in sago starch bioplastics, reporting that KCl softens the bioplastic surface without altering the bond structure and increases tensile strength by 89.75% compared to bioplastics without MFC reinforcement and KCl addition.

Most previous research on bioplastics has focused on enhancing the physical properties of the produced bioplastics, with limited studies addressing specific applications such as food packaging. The novelty of this research lies in the development of bioplastics using a sago starch matrix with the addition of NCC OPEFB filler and dispersing agents applied as food packaging. Bioplastics used for food packaging must not only have good quality but also meet food safety standards. It is hoped that this research will improve the quality of bioplastics and provide insight into their application as food packaging. This study aims to make a significant contribution to the advancement of the bioplastics industry in the future.

The serious issues related to synthetic plastic use, along with consumer demand for safe and high-quality food products, serve as the foundation for this research. The appropriate use of packaging is considered one of the ways to enhance quality, prevent food spoilage, and reduce environmental pollution. The objectives of this research are: first, to determine the characteristics of bioplastics as food packaging with the addition of NCC from OPEFB and dispersing agents. The novelty of this research lies in the development of bioplastics from sago starch, incorporating NCC from OPEFB and dispersing agents (KCl and NaCl) for food packaging applications.

The materials used include NCC derived from Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunches (OPEFB). The NCC derived from OPEFB in this research was produced using previously developed bioprocessing technology, involving bio-pulping and bio-bleaching of OPEFB fibers, followed by enzymatic hydrolysis [13]. It has a crystallinity value of 68% as determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD), with a particle size of 79.19 nm. Sago starch was sourced from PT. Pati Sagu Metro—Bogor, Indonesia, while potassium chloride (KCl), sodium chloride (NaCl), and glycerol (all Emsure Merck) were used along with distilled water from PT. Novalindo (Padang, Indonesia). The equipment used included bioplastic molds, a hotplate stirrer, glassware, an analytical balance, a 200-mesh sieve, a hand mixer, a sonicator, and a thermometer.

2.2 Preparation of Bioplastics (Modified Method from López et al., 2012 [22])

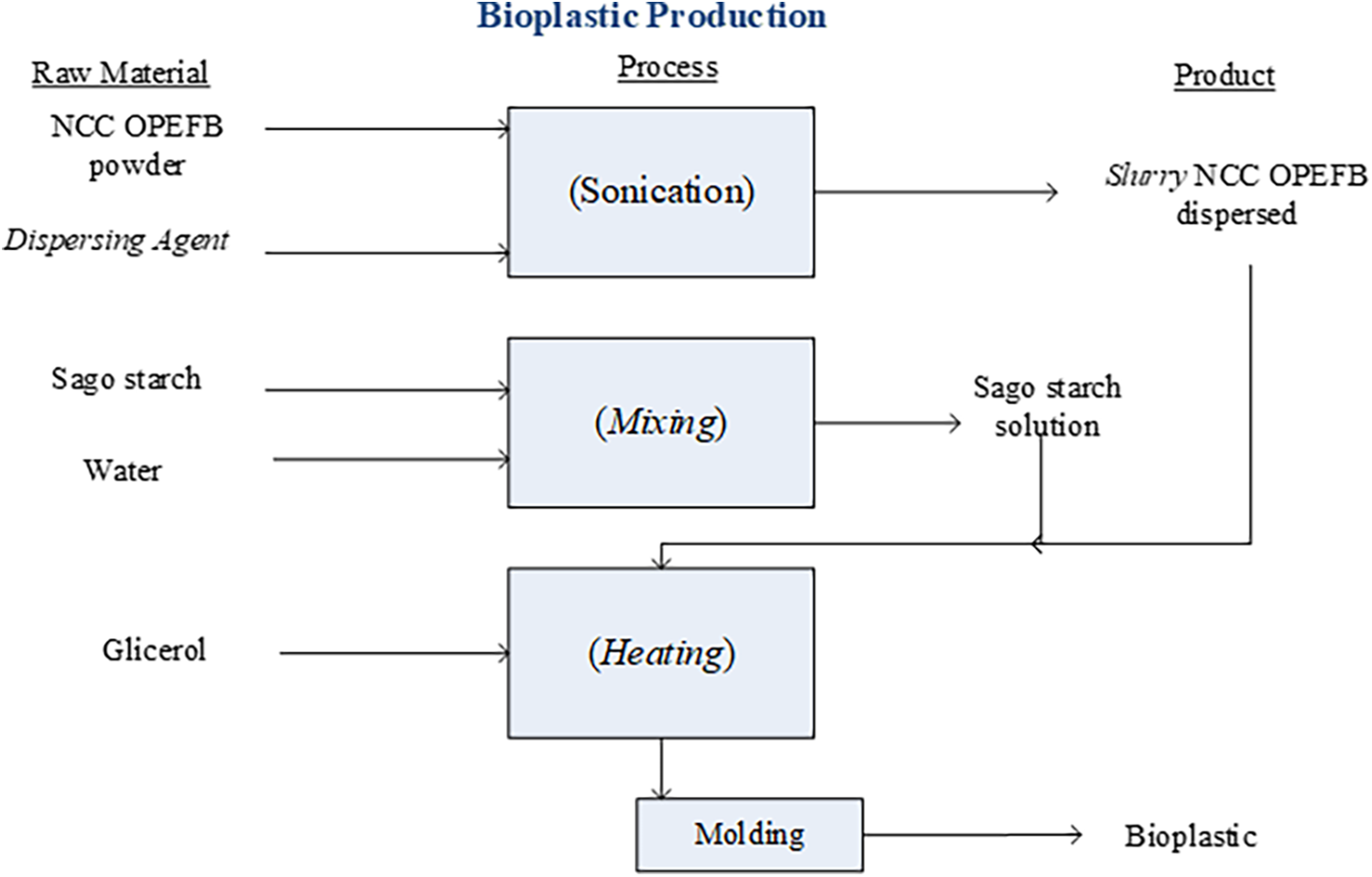

The bioplastic in this study was produced using the casting method, where the specimen is molded under open-space conditions at atmospheric pressure. The materials were mixed in glassware using a mixer, and their even distribution in the mold was ensured by slowly stirring with a stirring rod before the polymerization process. Sago starch is sifted using a 200-mesh sieve. The bioplastics are created through several stages. The first stage involves the preparation of NCC slurry from OPEFB. The NCC slurry is made by mixing NCC powder at concentrations of 1–5 wt.% [23] with a dispersing agent solvent at concentrations of 0.5%–3.0% b/b. In this study, two types of dispersing agents are used as treatments: KCl and NaCl. The Design Expert 13.0 software with Response Surface Methodology (RSM) Mixture Optimal was used to optimize the bioplastic formulation. The research design followed the Central Composite Design (CCD) within the RSM framework, consisting of two blocks: types of dispersing agents (KCl and NaCl), and two factors: NCC TKSS concentration (1%–5%) and dispersing agent concentration (0.5%–3%). The mixture is then processed using sonication for 1 h. The second stage is the preparation of the starch solution, which involves dissolving 4 g of starch in 100 mL of water [14], followed by taking 30 mL of this solution. In the third stage, the bioplastic is made by mixing the NCC slurry and starch solution in specific ratios. This mixture is then heated to 90°C while stirring. After 15 min of heating, 0.3% b/b glycerol is added to the mixture [23]. The final stage involves casting the bioplastic in acrylic molds and allowing it to dry at room temperature for 48 h (casting method). The stages of the bioplastic production process can be seen in the Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Stage of bioplastic production

2.3 Mechanical Testing (ASTM D 882-02)

Mechanical testing of bioplastics includes tensile strength and percentage elongation, tested using a Universal Testing Machine (UTM). Elongation refers to the maximum change in length of the film before it breaks. The elongation test is conducted by comparing the increase in length that occurs with the original length of the material before the tensile test. The measurement results are then calculated using the following formula:

Tensile strength is the test of a bioplastic’s resistance to stress before it breaks (tears), conducted using a Universal Testing Machine in accordance with ASTM D 882-02 standards. The measurement results are calculated using the following formula:

2.4 Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR Spectroscopy) Testing

Structural or functional group analysis is conducted to determine the presence of additional groups in bioplastics with the incorporation of a dispersing agent, using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR spectroscopy). FTIR spectroscopy is a characterization technique based on the vibrations of atoms or molecules by passing infrared radiation through the material or sample and measuring the absorbed energy, which corresponds to the vibrational frequencies of the atoms in the material. The differences in absorption are utilized to identify functional groups.

2.5 Biodegradability Testing [24]

Biodegradability testing is conducted by preparing the sample to be tested. First, the dry weight of the sample is measured. The weighed sample is then buried in a container filled with soil for seven days. After this period, the sample is removed and cleaned of any soil residue. Once cleaned, the sample is dried in a desiccator for 30 min and then further dried in an oven at 105°C for 2 h before measuring its final weight. The calculation for the biodegradability of the bioplastic can be expressed using the following formula:

where M0 and Ma are the weights of the bioplastic before burial and after burial, respectively.

2.6 Water Vapor Transmission Rate (WVTR) Testing

Water Vapor Transmission Rate testing is conducted based on ASTM E96/E96M-16, 2016. The water vapor transmission rate is measured using a water vapor transmission rate tester with the cup method. The film is conditioned in a chamber at 25°C and 75% relative humidity for 24 h. A 10 g moisture-absorbing material is placed in the cup and sealed with wax to ensure that the film has no gaps at the edges. The cup is then weighed with an accuracy of 0.001 g and placed in a jar containing 40 g of NaCl in 100 mL of distilled water (equivalent to 70% relative humidity). The jar is tightly sealed, and the cup is weighed daily at the same time to determine the weight gain of the cup. The water vapor transmission rate is calculated using the following formula:

where:

WVTR = Water Vapor Transmission Rate (g/m2/day)

m = Mass of water vapor that passes through the material (g)

A = Area of the material through which the vapor passes (m2)

t = Time (h).

Thermal analysis measures a material’s response to temperature changes and is used to evaluate the heat resistance and stability of polymers. This analysis is performed using Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA), which determines endothermic and exothermic reactions, as well as weight loss during heating or cooling. Additionally, TGA provides insights into thermal stability (material strength at specific temperatures), oxidative stability (rate of oxygen absorption), and compositional properties (filler reinforcement from NCC) of the bioplastics. For TGA characterization, a Mettler Toledo TGA instrument was used. The test involved heating the sample to 400°C at a rate of 5°C/min, following the methodology of Grega and Liu et al. [25,26].

2.8 Morphological Testing (Scanning Electron Microscopy/SEM)

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) testing was conducted following the ASTM E986 standard using a Zeiss SEM model EVO MA 10 (Baden-Württemberg, Germany) at a voltage of 20 kV with a magnification of 10,000×. This analysis examined the surface morphology of the bioplastic, including its structure, cracks, and smoothness. The test aimed to observe the effects of adding NCC and dispersing agents on the overall quality of the bioplastic.

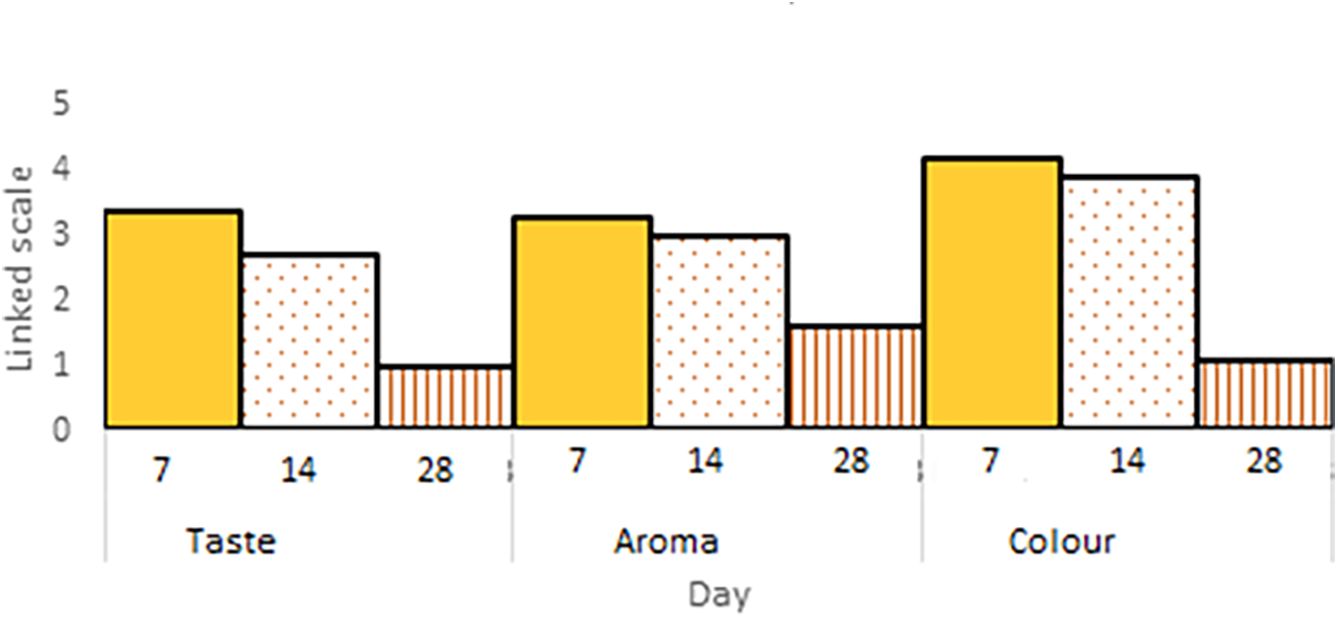

2.9 Product Testing as Food Packaging

The best-performing bioplastic sample will be tested for its application as food packaging, specifically for gelamai (a traditional food from West Sumatra), which is typically packaged using synthetic plastic. The observation parameters include organoleptic tests, assessing taste, aroma, and color [27]. The food products will be stored in bioplastic packaging for 7, 14, and 28 days, after which evaluations will be conducted by a group of respondents using a Likert scale (scores ranging from 1 to 5) for taste, aroma, and color. The organoleptic test results will then be analyzed.

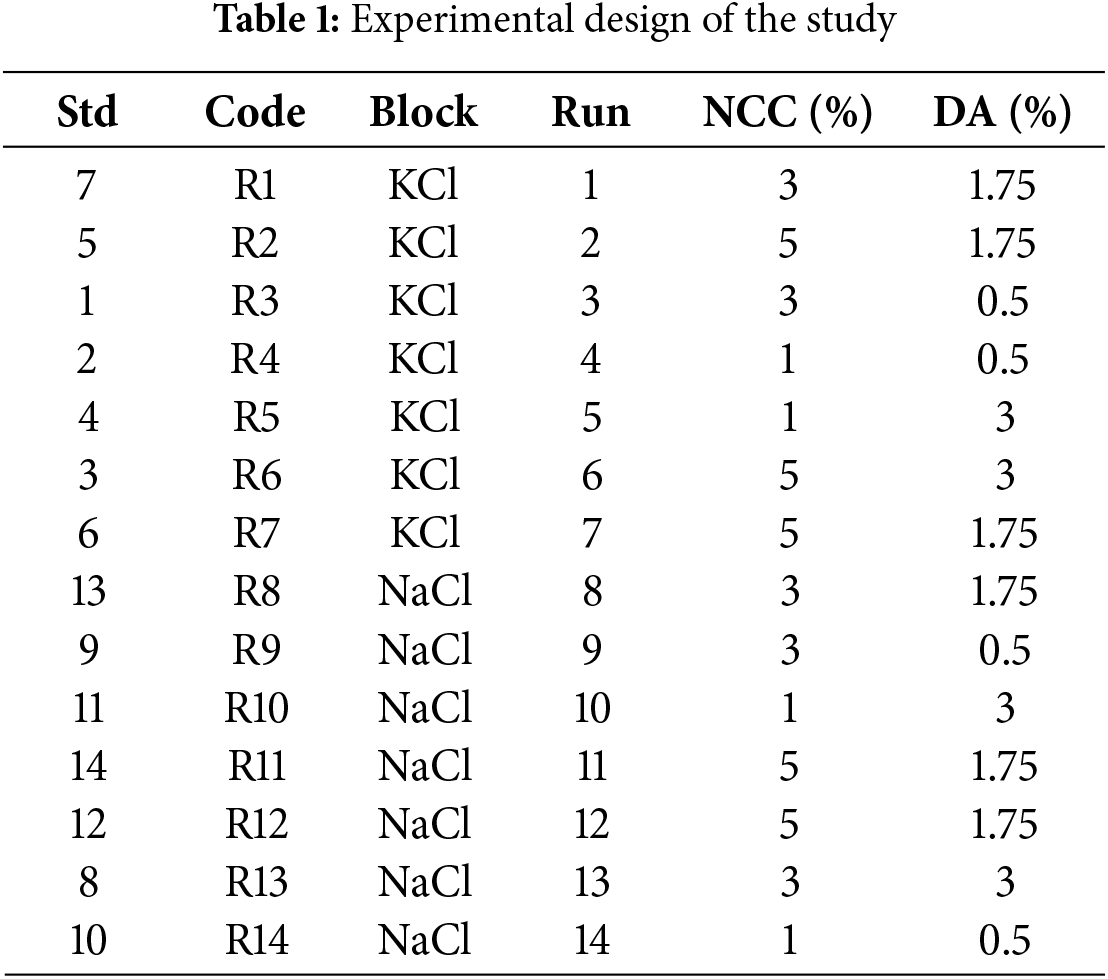

The research design used is Central Composite Design (CCD) with Response Surface Methodology (RSM), comprising 2 blocks: types of dispersing agents (KCl and NaCl) and 2 factors: concentrations of NCC TKSS (1%–5%) and concentrations of the dispersing agent (0.5%–3%). This results in 14 experimental designs labeled R1 to R14. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) is conducted using Design Expert (DX) version 13 to assess the significance of differences in response variables. The experimental design of the study is shown in Table 1 below.

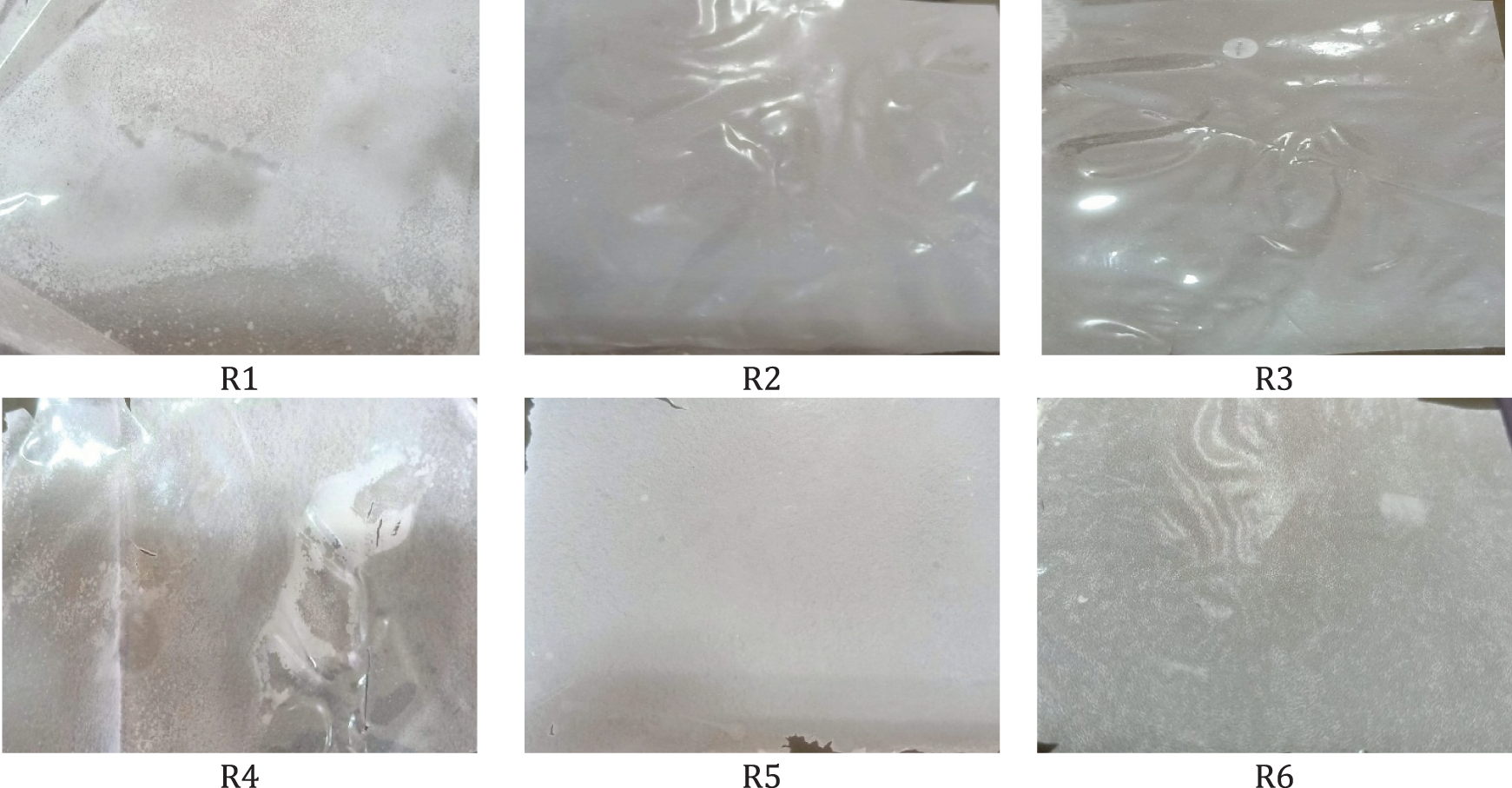

3.1 Food Packaging Bioplastics

The production of bioplastics for food packaging using Nano Crystalline Cellulose (NCC) from Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunches (OPEFB) with a sago starch matrix was conducted following the method outlined in this study. The results from 14 experimental designs (R1–R14) are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Bioplastic products

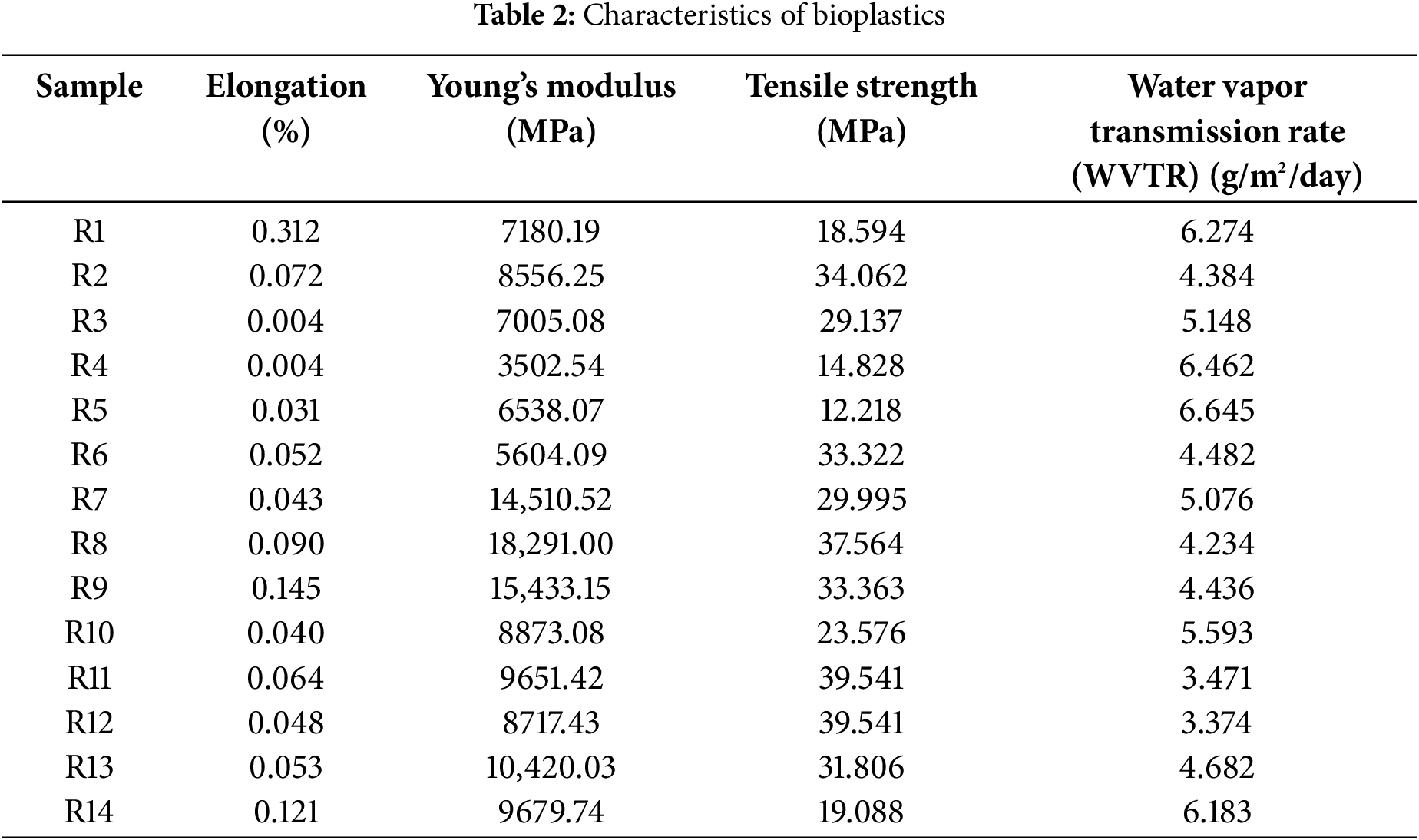

The purpose of mechanical testing of bioplastics is to determine the mechanical properties, specifically the optimal tensile strength and elongation of the bioplastic with varying treatments of NCC and dispersing agents. The values of tensile strength and elongation results for the bioplastic can be found in Table 2.

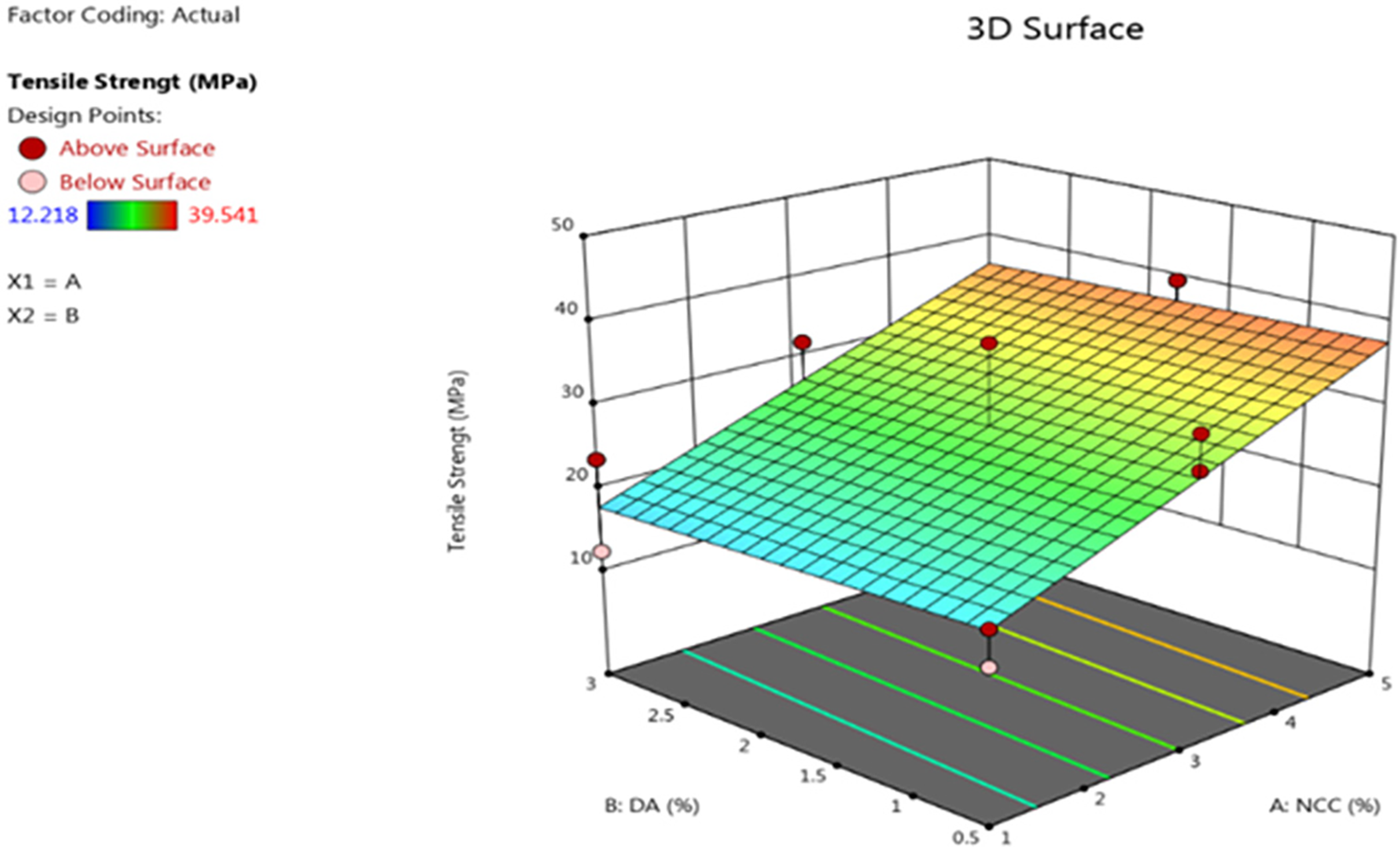

The smallest tensile strength was observed in sample R5, with a value of 12.218 MPa, while the highest values were recorded in samples R11 and R12 at 39.541 MPa. The addition of NCC positively affects the tensile strength of the bioplastic. This change in mechanical properties indicates an interaction between NCC, the sago starch matrix, and glycerol. NCC acts as a reinforcement agent, enhancing the tensile strength of the bioplastic. The tensile strength is influenced by the concentration of NCC added; as the concentration increases, the tensile strength of the bioplastic also improves. Ref. [13] confirm that nanocomposite materials play a significant role in enhancing and limiting material properties. The nano-sized particles have a high surface area for interaction, meaning that a greater number of interacting particles lead to stronger material. This results in stronger bonding between particles, thereby enhancing the mechanical properties. The effect of adding NCC as a reinforcement for bioplastics and a dispersing agent (DA) on the tensile strength (TS) can be observed in Fig. 3 and can be described using an equation or model, as shown in Eq. (5). NCC exhibits a positive correlation with tensile strength, meaning that a higher NCC concentration leads to an increase in tensile strength (maximization). In contrast, DA concentration has an antagonistic effect—reducing DA concentration results in higher tensile strength. Statistical analysis indicates that the type of DA does not have a significant effect on tensile strength.

Figure 3: Graph of tensile strength

Y1 is Tensile strength (MPa)

X1 is NCC (%)

X2 is DA (%)

Other research related to the development of plastic bio composites with cellulose fiber/nanofiber fillers includes a study by [28], which achieved a tensile strength of 20.84 MPa using tapioca starch as a matrix with bagasse nanofiber filler. Mahardika et al. [29] also developed a bio composite plastic with PVA matrix and durian peel cellulose fiber filler, achieving a tensile strength of 24 MPa. Similarly, Maryam et al. [30] developed bioplastic with a PVA matrix and bacterial micro cellulose filler, which had a tensile strength of 15.72 MPa with a 2% addition. According to Suyadi [31], the tensile strength of synthetic plastics like polypropylene (PP) is 13.89 MPa and low-density polyethylene (LDPE) is 10.05 MPa.

High tensile strength value indicates the plastic’s ability to withstand applied forces. Plastic with high tensile strength can protect products from mechanical factors such as physical pressure (drops and friction), vibrations, and impacts [32]. High tensile strength is crucial for food packaging applications, as it ensures protection during handling, transportation, and marketing.

Referring to the JIS 2-1707 standard, which states that the minimum percentage elongation for bioplastics should be 70%, none of the experimental designs met this requirement. Further studies are needed to explore factors affecting elongation. According to Indriani et al. [33], the type and concentration of the base materials used to create edible films (the matrix) influence elongation. Other factors include the concentration of plasticizers. In this study, variations in matrix concentration or plasticizer concentration were not explored, resulting in similar elongation values. Elongation is related to the tensile strength of the bioplastic. The findings indicate higher tensile strength but lower elongation compared to the research by Rusli et al. [34], where elongation ranged from 10.61% to 18.67%. This aligns with Nurindra et al. [35], who noted that elongation is inversely related to tensile strength; lower tensile strength corresponds to higher elongation.

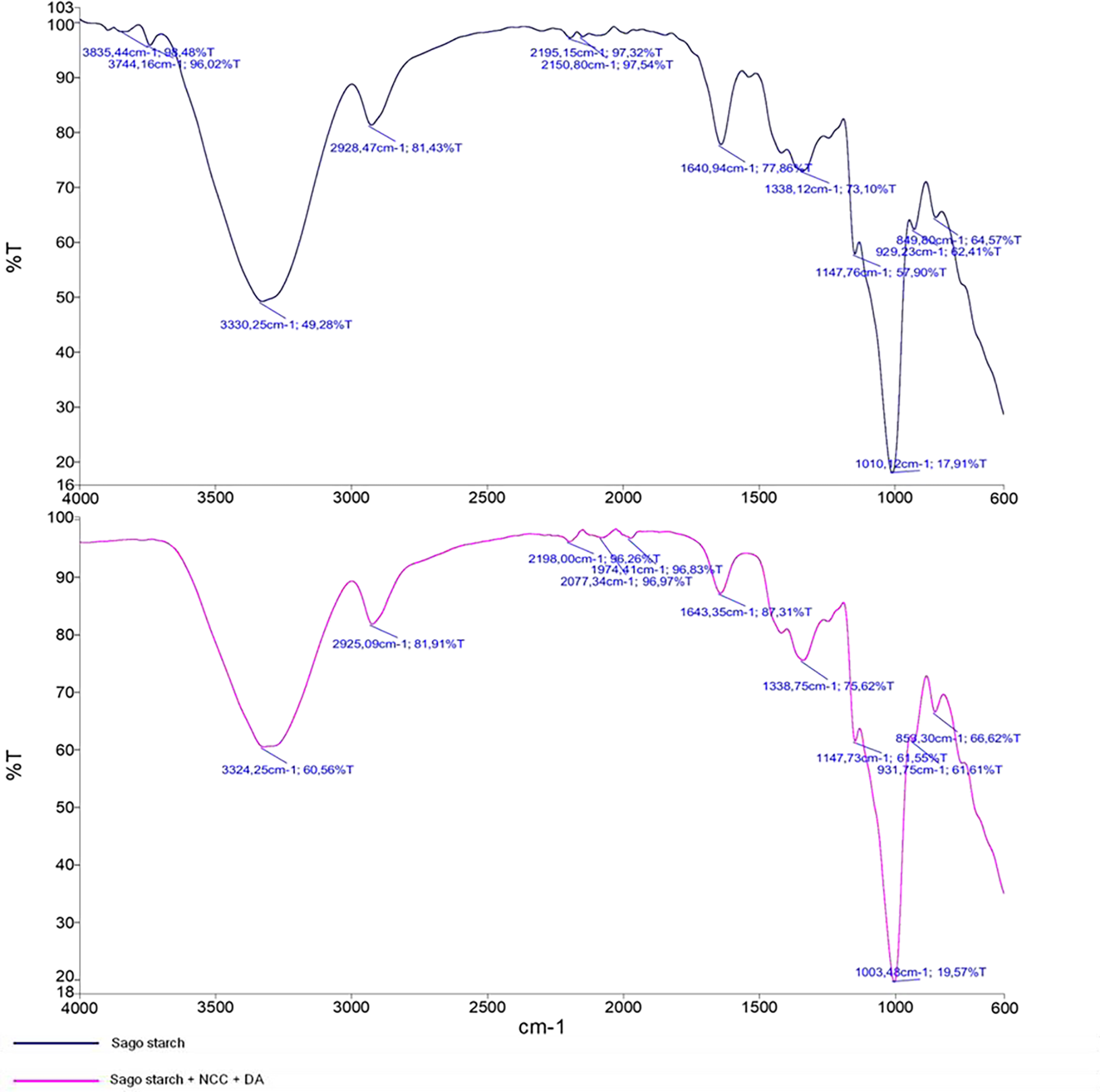

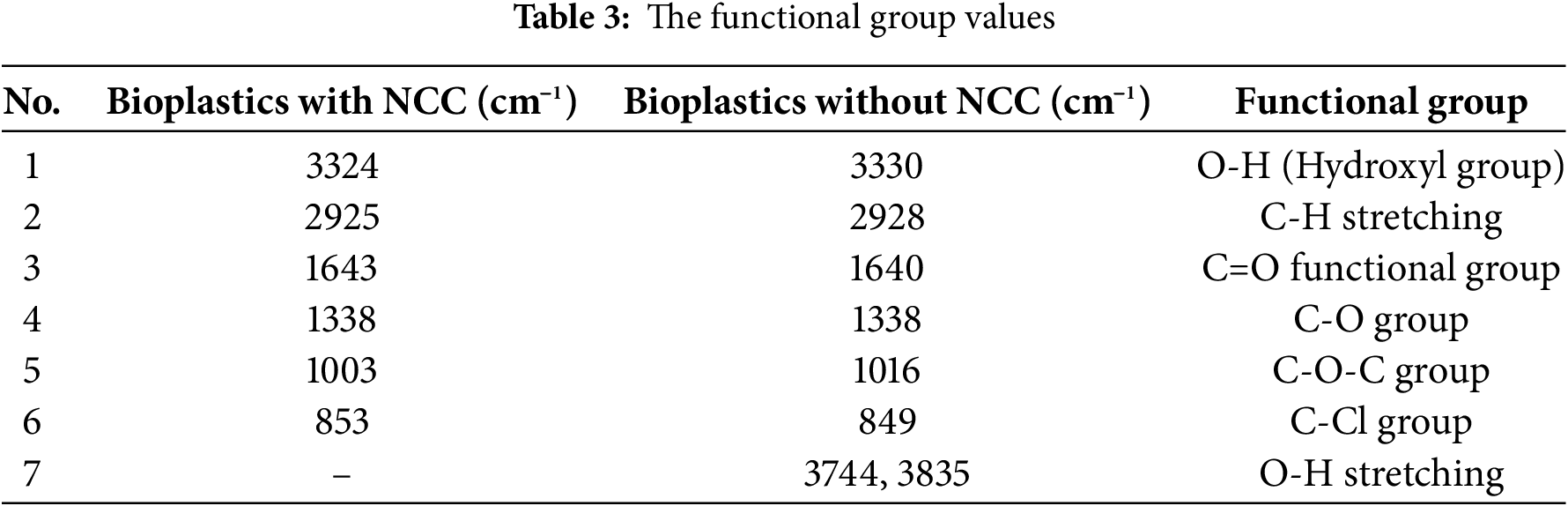

3.3 Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

FTIR spectroscopy analysis (Fig. 4) reveals several absorption peaks. Sago starch bioplastics, both with and without NCC reinforcement, exhibit similar absorption patterns. Bioplastics with NCC show hydroxyl (O-H) groups at 3324 cm−1, while those without NCC appear at 3330 cm−1. The C-H stretching band is observed at 2925 cm−1 in bioplastics with NCC and at 2928 cm−1 in those without NCC, similar to nanocellulose, which has a C-H absorption peak at 2899 cm−1. The C=O functional group appears at 1643 cm−1 in bioplastics with NCC and at 1640 cm−1 in those without NCC. The C-O group is present at 1338 cm−1 in both samples. The C-O-C group appears at 1003 cm−1 in bioplastics with NCC and at 1016 cm−1 in those without NCC. The C-Cl absorption peak is at 853 cm−1 for bioplastics with NCC and 849 cm−1 for those without NCC. Additionally, bioplastics without NCC exhibit O-H stretching at 3744 cm−1 and 3835 cm−1. A summary of the functional groups is presented in Table 3.

Figure 4: FTIR spectroscopy of bioplastic

These results are similar to those of FTIR spectroscopy analysis of sago starch, which exhibits an absorption peak at 1333 cm−1 corresponding to the symmetric CH2 group. The broad absorption band in the range of 1100–990 cm−1 is characteristic of C-O stretching in C-O-C and C-O-H within the glycosidic ring of sago starch [36]. The absorption peak at 853 cm−1 indicates the presence of the C-Cl group, which results from the addition of salt compounds such as KCl and NaCl. Additionally, the broad and weak bands observed in the range of 930–600 cm−1 may arise from out-of-plane bending of bound O-H and C-H deformation frequencies [37].

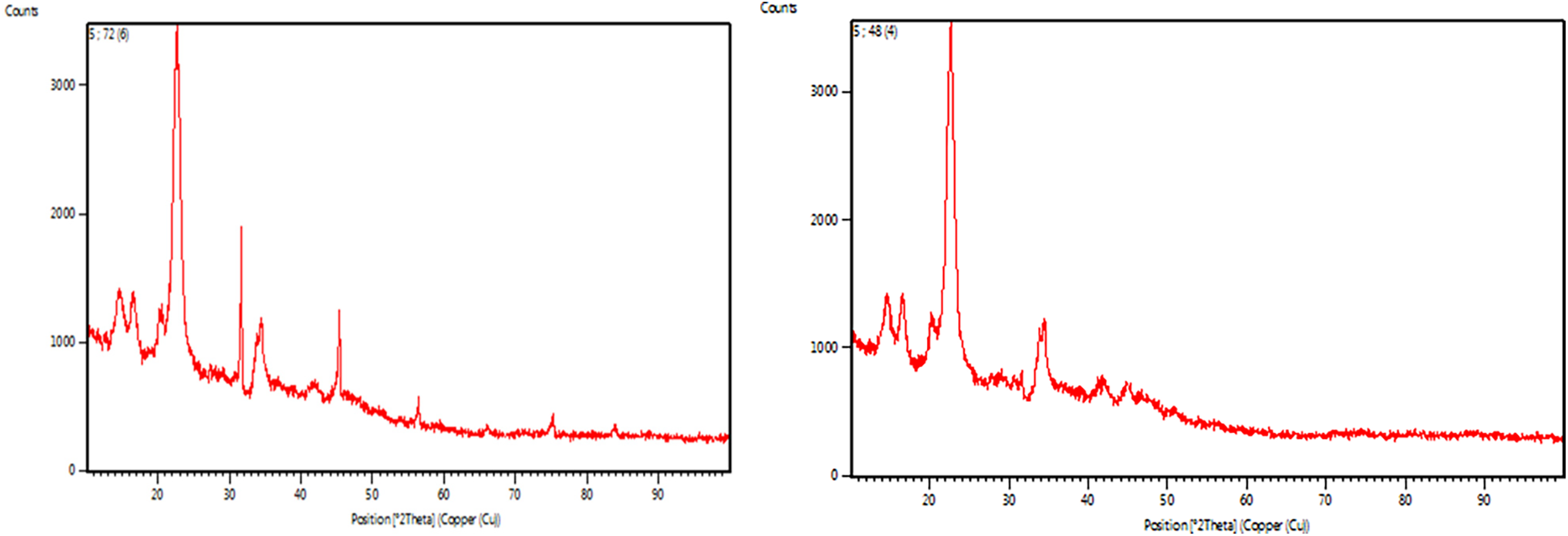

The NCC used in this study was derived from the research of Maryam et al. [13], and has a crystallinity value of 68%, as determined by XRD, with a particle size of 79.19 nm. The XRD images of NCC and the bioplastic are shown in Fig. 5. The diffractogram results indicate that the CI precursor is in a crystalline form, as evidenced by sharp peaks, with a crystallinity degree of 68%. The synthesized bioplastic sample exhibits a crystallinity degree of 68.22%, showing no significant difference from the precursor. The CI value is a crucial physical parameter, as it correlates with the thermal and mechanical properties of the material. According to Tang et al. [38], the XRD pattern of cellulose typically exhibits a major crystalline peak at 2θ = 22.6°, with weaker peaks at 2θ = 14.9° and 16.4°, corresponding to cellulose’s crystalline regions. Yu et al. [39] reported that cellulose diffraction patterns show peak intensities around 2θ = 15° (110), the highest intensity at 2θ = 22°–23° (200), and a weak peak at 2θ = 35° (004). The amorphous regions exhibit minimum diffraction patterns at approximately 2θ = 18° and 19°. Rosli et al. [40] also identified distinctive crystalline peaks of cellulose between 22° and 23°.

Figure 5: XRD NCC and bioplastic

Given its nanoscale dimensions, NCC has a high surface area ranging from 150 to 250 m2/g [41]. The abundant hydroxyl groups on its surface enable various chemical modifications, such as etherification, oxidation, silylation, esterification, and polymer grafting. This versatility allows NCC to be incorporated into both hydrophilic and hydrophobic matrices, provided appropriate surface chemistry is applied before its inclusion in the polymer matrix. By incorporating NCC into a polymer matrix, the properties of the resulting nanocomposite can be modified. NCC is known to influence the thermal, structural, and morphological properties of polymer nanocomposites, with mechanical properties being particularly sensitive to its addition [42].

Biodegradability testing aims to determine the degradation rate of bioplastics, allowing for an estimation of the time required for the bioplastics to decompose, as illustrated in Fig. 6. The concentration of NCC and the type of dispersing agent did not significantly affect the biodegradability of the bioplastics. This is attributed to the fact that all components of the bioplastic are organic materials, namely sago starch, NCC, dispersing agents (KCl and NaCl), and glycerol. Generally, the samples were fully decomposed by the seventh day (100%). Biodegradability standards refer to ASTM 5338 and ASTM D-6002. International standards for biodegradation testing of PLA from Japan and PCL from the UK require 60 days for complete decomposition, indicating that the results of this study align with these standards.

Figure 6: Biodegradability testing of bioplastic

Other research on the development of bioplastics with starch matrices includes a study by Zoungranan et al. [43], which developed bioplastic composites from corn starch, compared to similar research by Fitri et al. [44], which reported degradation times ranging from 7 to 8 days. Arifin et al. [45] noted that bioplastics with varying concentrations of chitosan exhibited biodegradability of 1.63% over 8 days.

The ability of bioplastics to degrade can be influenced by several factors, including soil type, microbial species, and water content [46]. The duration of degradation is also affected by the types of components present in the bioplastics (sago starch, glycerol, NCC, and DA). Increasing the concentration of NCC tends to reduce the degradation time of bioplastics. When the polymer constituent particles are in the nanoparticle size range, the degradation rate significantly increases. Surface erosion in nanocomposite polymers is greater than in synthetic composites, suggesting that the time and process of biodegradation in nanocomposite polymers are more efficient. This implies that nanoparticles provide a larger surface area for erosion.

This study focuses on the development of bioplastics for food packaging applications. Bioplastics used in food packaging must meet high-quality standards and ensure food safety. Biodegradation testing is crucial, as it assesses the material’s performance in high-moisture food packaging and its degradation behavior in soil or water environments. This bioplastic is particularly recommended for packaging edible food products with low moisture content.

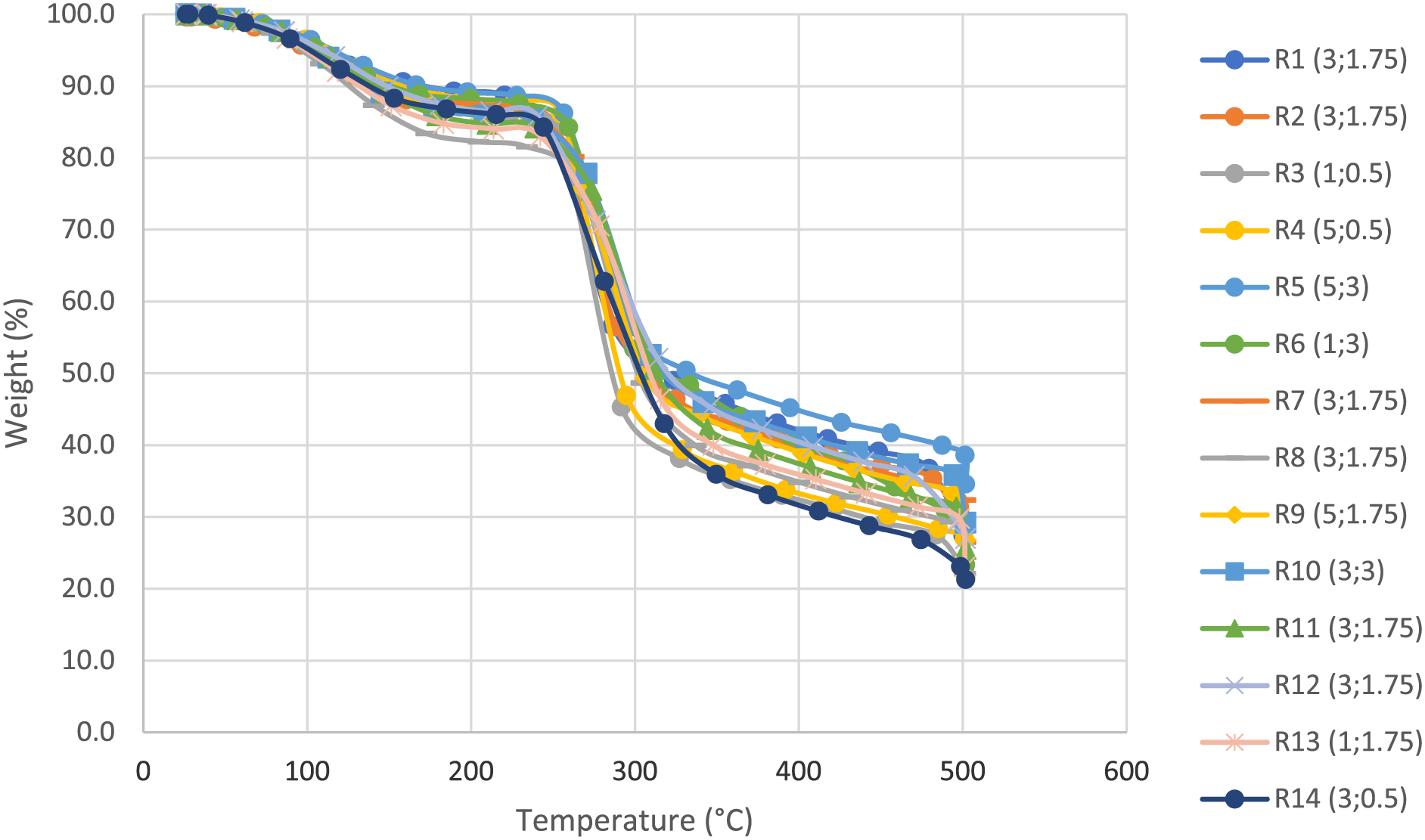

3.5 Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA analysis indicates that there are three phases in the decomposition mechanism, as shown in Fig. 7. In the initial stage, the moisture content in the bioplastic evaporates at temperatures between 50°C and 220°C. Between 220°C and 380°C, sago starch and NCC begin to decompose. Glycerol starts decomposing at temperatures ranging from 290°C to 380°C [47]. The remaining components, such as the dispersing agents KCl and NaCl, will be completely eliminated once the temperature exceeds 500°C.

Figure 7: TGA curve of bioplastic

3.6 Water Vapor Transmission Rate (WVTR)

The water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) is a critical parameter indicating the quality of bioplastics in preserving the integrity of packaged products. A high WVTR value suggests that the bioplastic has large pores, allowing water vapor to pass easily through its matrix. Increased water vapor activity through the bioplastic matrix correlates with lower quality, as it provides insufficient protection against bacteria and environmental moisture, ultimately degrading the product quality. The results of the water vapor transmission rate tests for the bioplastics are shown in Table 1.

The concentration of NCC significantly affects the WVTR, while the type and concentration of the dispersing agent do not have a significant impact. This indicates that NCC binds with the sago starch matrix, effectively closing the pores in the bioplastic and impeding water vapor transmission. As the concentration of NCC increases, the number of cross-links formed also increases, further sealing the pores in the bioplastic.

The addition of NCC reduces the WVTR (Water Vapor Transmission Rate) of the bioplastic by preventing water vapor from passing through and instead being absorbed by the reinforcing material. This effect is attributed to the hydrophobic nature of NCC, which acts as a barrier against water vapor migration. Additionally, NCC has greater water resistance compared to the starch matrix, further decreasing WVTR. By forming a protective barrier, NCC limits water vapor migration, enhancing the bioplastic’s ability to extend the shelf life of packaged food products.

The lowest WVTR value was found in sample R12, with a value of 3.374 g/m2/day. This result is lower than the water vapor transmission rate of pure LLDPE, which is 8.31 g/m2/day, and bioplastic Poly Lactic Acid (PLA), which has a WVTR of 172 g/m2/day [48]. It is also lower than the results reported by Santoso et al. [49], which was 4.18 g/m2/day, but higher than the WVTR of corn starch and glucomannan bioplastic composites, which ranged from 0.76 to 1.24 g/m2/h [44]. A lower WVTR indicates better moisture resistance of the bioplastic. The addition of NCC effectively reduces the WVTR. Pulikkalparambil et al. [50] and Saidi et al. [51] noted that nanoparticles integrated into the macromolecular or polymer structure can reduce water vapor permeability. According to the JIS 2-1707 standard, which specifies a maximum WVTR of 7 g/m2/day for bioplastics, all samples in this study met the required standards.

Bioplastics used for food packaging play a crucial role in minimizing light-induced damage by controlling oxygen-induced degradation reactions, reducing moisture loss, preventing the growth of aerobic microorganisms, and regulating water vapor transmission to preserve food quality. To maintain food quality, bioplastics must have the lowest possible water vapor permeability. An increase in NCC content enhances the water vapor and oxygen barrier properties of the packaging, as NCC is more resistant to gas permeation than conventional polymers. Due to their superior gas barrier properties, nanoparticles in bio/polymer matrices have been extensively explored [52,53] suggested that increasing nanoparticle content leads to reduced film transmission. Experts argue that the strong interactions between nanoparticles and biopolymers, along with a higher degree of crystallinity, contribute to decreased water vapor permeability. This occurs because the addition of nanoparticles reduces the intermolecular space between polymer chains, significantly hindering the passage of water molecules through the bioplastic. Moreover, the incorporation of NCC in bioplastics reduces the water vapor transmission rate (WVTR). Additionally, while the oxygen permeability of the bio nanocomposite film increases, the oxygen transmission rate decreases with the addition of nanoparticles [54].

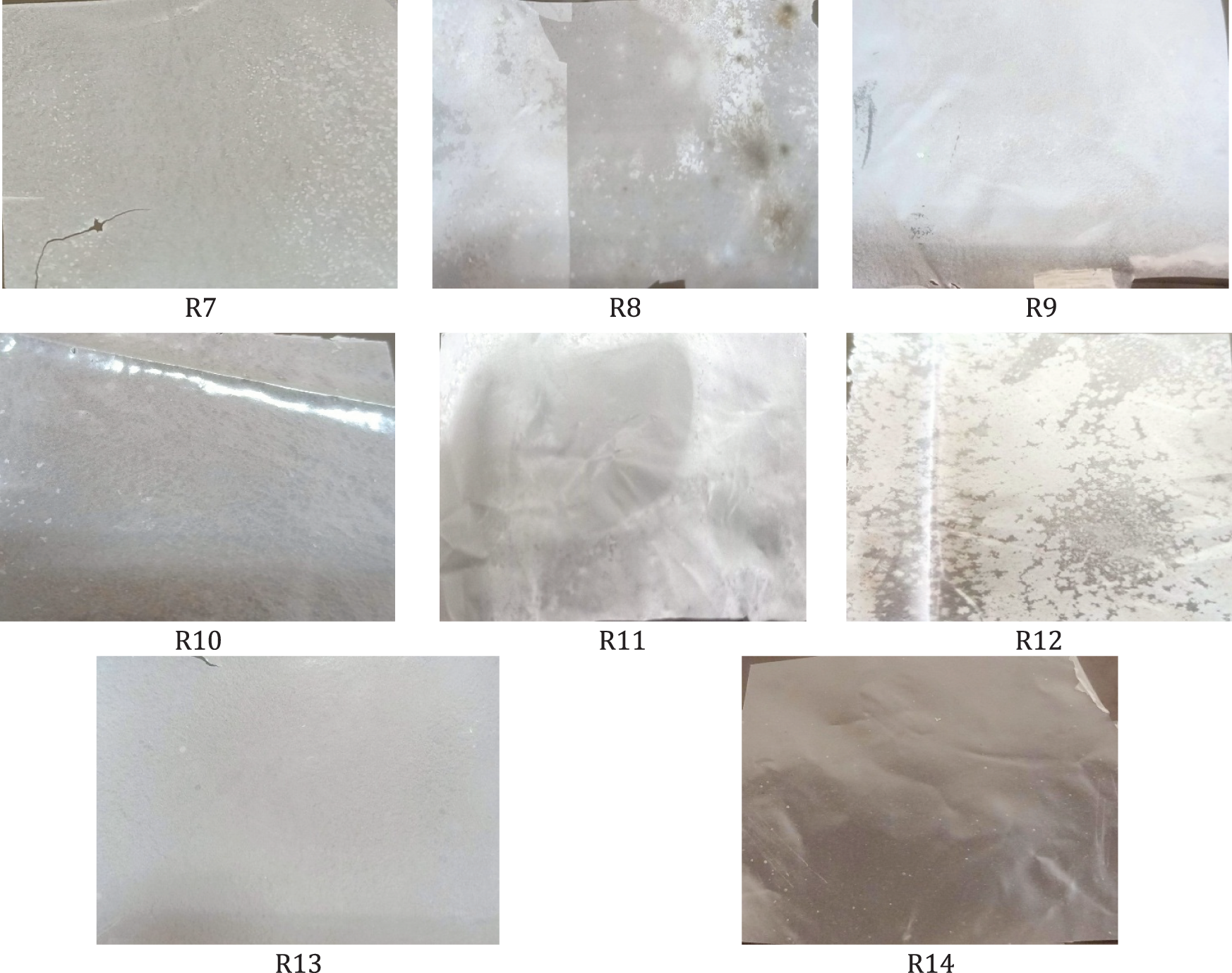

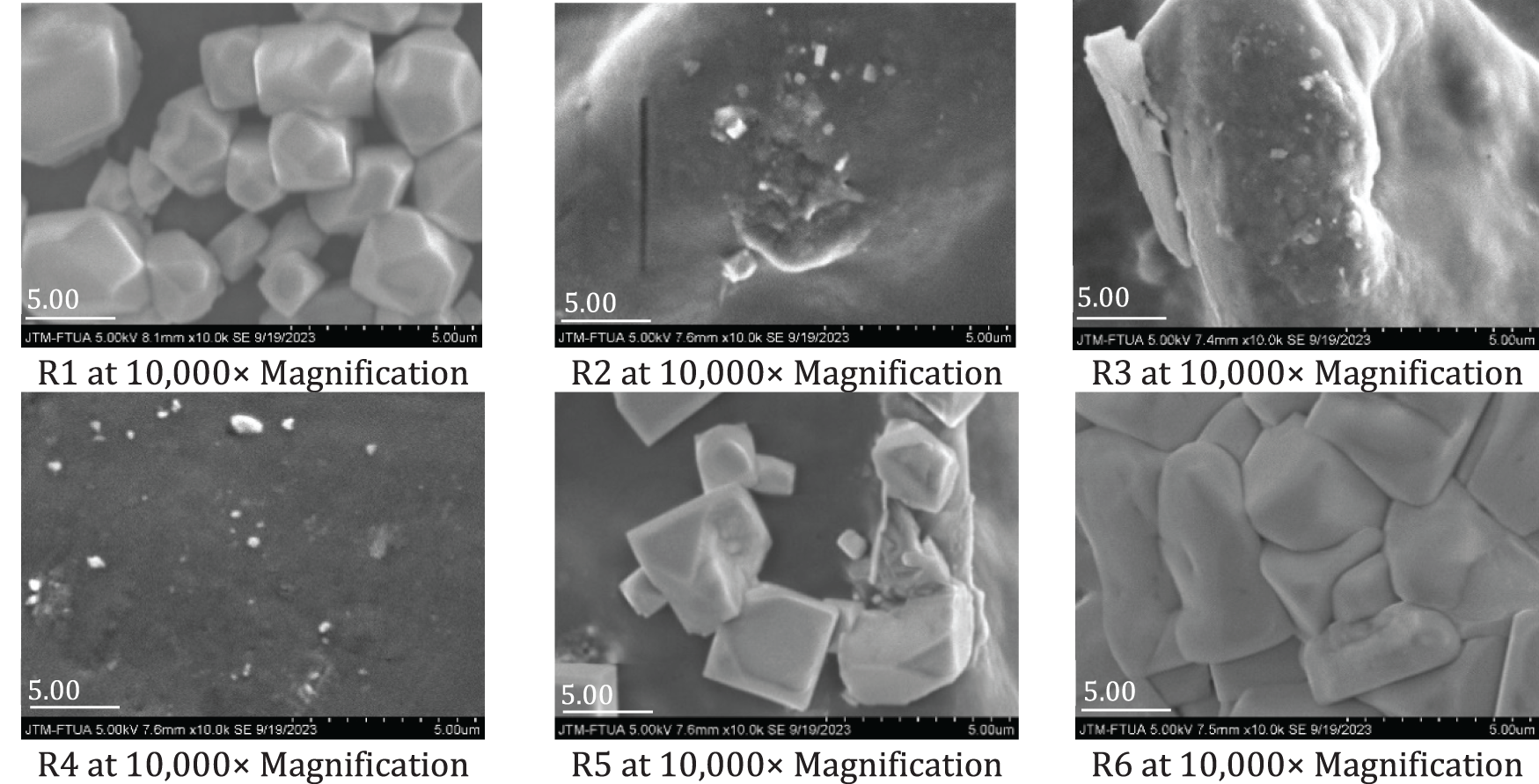

3.7 Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The SEM images of the produced bioplastics are shown in Fig. 8. The distribution and dispersion of NCC within the bioplastic indicate a smoother and more cohesive surface matrix, suggesting uniform incorporation of NCC into the sago starch matrix [55]. As a co-plasticizer, glycerol forms strong interfacial bonds with both the filler and the matrix. In bioplastics with higher salt additions, such as in samples R5 and R9, the presence of irregular aggregates is observed, which may lead to interconnections between these aggregates. The images also reveal white spots, indicating the presence of saturated KCl or NaCl [13,14,16]. In addition to functioning as a dispersing agent, the salts act as a coating, producing bioplastics with a smooth, shiny surface that protects the matrix layer [19,20]. This effect is particularly evident in samples R6, R8, R11, and R12, where salt grains tightly cover the sago starch matrix, enhancing the bioplastic’s reflective appearance. Furthermore, the uniform distribution of NCC and dispersing agents contributes to improved mechanical and thermal properties of the bioplastic [21].

Figure 8: SEM morphology of bioplastic

3.8 Results of Product Testing as Food Packaging

The bioplastic produced in this study was tested for its application in food packaging, specifically for gelamai, a traditional snack from West Sumatra, as shown in Fig. 9. Gelamai is categorized as a semi-moist food with a moisture content of 20%–40% and water activity (Aw) of 0.7–0.8. Research by Septiati et al. [56] indicates that due to its relatively high moisture content, the shelf life of gelamai is short, approximately 4–5 days, depending on the preservation method. The quality of gelamai can be assessed through several indicators: hardening of texture, development of a rancid odor, formation of a cotton-like layer on the surface, and deterioration in taste [57]. Organoleptic testing results revealed a decline in taste, odor, and color of gelamai over time when stored in bioplastic packaging, as illustrated in Fig. 10. Consumer acceptance of gelamai packaged in bioplastic remained favorable only up to day 14 when stored at room temperature.

Figure 9: Testing for food packaging bioplastic

Figure 10: Organoleptic test

In the field of food science, Zhang et al. [58] conducted a study replacing NaCl with KCl to reduce water retention in salted pork, yielding highly correlated results. The presence of K+ ions in KCl was found to induce changes in the physicochemical properties of meat. Similarly, Chen [59] used KCl as a coating for dry sausages, which resulted in a decrease in microbial diversity during fermentation across all sausage samples. Given that KCl is a biomass-derived compound, similar effects may be observed in bioplastics. Rahayu et al. [17] investigated the use of KCl in sago starch bioplastics and found that this dispersing agent softened the bioplastic surface without altering its bond structure. Additionally, the tensile strength of bioplastics with KCl increased by 89.75% compared to bioplastics without MFC reinforcement and KCl addition.

3.9 Optimization of Bioplastic Formulation

The DX 13.0 program generated 17 predicted solution points for optimizing the bioplastic formulation. This substantial number of predicted optimum points highlights the effectiveness of Response Surface Methodology (RSM) as a predictive tool, reducing the need for extensive and costly experimental trials. The optimization process identified a specific formulation as the most optimal, with an NCC concentration of 5% and a dispersing agent concentration of 0.5%. This formulation is projected to achieve a tensile strength of 37.612 MPa, a water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) of 3.990 g/m2/day, and 100% biodegradability. It was recommended due to its highest desirability value of 0.905. According to Patidar et al. [60], the desirability index is used to evaluate the accuracy of an optimal solution, with values approaching one indicating a higher degree of precision in optimization.

The characteristics of the produced bioplastic, including tensile strength, WVTR, and biodegradability, generally meet the requirements for food packaging (JIS 2-1707). The addition of NCC from OPEFB and dispersing agents significantly affects the characteristics of the bioplastic during production. For future research, further studies on oxygen, moisture, and gas permeability, as well as light barrier properties, are recommended to better understand the bioplastic’s performance.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to the Polytechnic ATI Padang for providing laboratory facilities for this research. We would like to express our gratitude to the Industrial Human Resource Development Agency for funding this research, and to the Polytechnic ATI Padang for providing the laboratory facilities that supported its implementation.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Industrial Human Resource Development Agency, Ministry of Industry in 2023. The funding was provided by Industrial Human Resource Development Agency, Ministry of Industry, under Surat Keputusan (Decree) number 23 Tahun (Year) 2023.

Author Contributions: Maryam: paper conceptor; Rahayu Puji: data analyst; Luthfi Muhammad Zulfikar: draft and layout; Ikhsandy Ferry: data analyst; Nadiyah Khairun: translate and proofreading; Hidayat: data analyst; Ilyas Rushdan Ahmad: supervisor; Syafri Edi: supervisor. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Upon request, the corresponding author will make the datasets created during the current study available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Roy S, Rhim JW. Preparation of antimicrobial and antioxidant gelatin/curcumin composite films for active food packaging application. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2020;188:110761. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.110761. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Nor Adilah A, Gun Hean C, Nur Hanani ZA. Incorporation of graphene oxide to enhance fish gelatin as bio-packaging material. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2021;28(48):100679. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2021.100679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Nurul Syahida S, Ismail-Fitry MR, Ainun ZMA, Nur Hanani ZA. Effects of palm wax on the physical, mechanical and water barrier properties of fish gelatin films for food packaging application. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2020;23(1):100437. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2019.100437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Widianarko YB, Hantoro I. Mikroplastik dalam Seafood dari Pantai Utara Jawa [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 10]. Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:127261324. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

5. Hanifah A, Mardawati E, Rosalinda S, Nurliasari D, Kastaman R. Analysis of cellulose and cellulose acetate production stages from oil palm empty fruit bunch (OPEFB) and its application to bioplastics. J Chem Process Eng. 2022;7(1):17–26. doi:10.33536/jcpe.v7i1.1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yang J, Ching YC, Chuah CH, Hai ND, Singh R, Nor ARM. Preparation and characterization of starch-based bioplastic composites with treated oil palm empty fruit bunch fibers and citric acid. Cellulose. 2021;28(7):4191–210. doi:10.1007/s10570-021-03816-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Fahma F, Hori N, Iwamoto S, Iwata T, Takemura A. Cellulose nanowhiskers from sugar palm fibers. Emir J Food Agric. 2016;28(8):566. doi:10.9755/ejfa.2016-02-188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Manamoongmongkol K, Sriprom P, Phumjan L, Permana L, Assawasaengrat P. Production of antimicrobial film-reinforced purified cellulose derived from bamboo shoot shell. Bioresour Technol Rep. 2023;22(4):101429. doi:10.1016/j.biteb.2023.101429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Syamsuri MMF, Marzuki H, Setiawan DWA, Rusmaniar R, Astika T. Synthesis of water hyacinth/cassava starch composite as an environmentally friendly plastic solution. Equilibrium. 2023;7(2):137. doi:10.20961/equilibrium.v7i2.76508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Shen P, Tang Q, Chen X, Li Z. Nanocrystalline cellulose extracted from bast fibers: preparation, characterization, and application. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;290(4):119462. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119462. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Faradilla RHF, Risaldi, Tamrin TAM, Salfia, Rejeki S, Rahmi A, et al. Low energy and solvent free technique for the development of nanocellulose based bioplastic from banana pseudostem juice. Carbohydr Polym Technol Appl. 2022;4(1):100261. doi:10.1016/j.carpta.2022.100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ngadi N, Lani NS. Extraction and characterization of cellulose from empty fruit bunch (EFB) fiber. J Teknologi. 2014;68(5):35–9. doi:10.11113/jt.v68.3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Akli K, Maryam M, Senjawati MI, Ahmad Ilyas R. Eco-friendly bioprocessing oil palm empty fruit bunch (OPEFB) fibers into nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) using white-rot fungi (Tremetes versicolor) and cellulase enzyme (Trichoderma reesei). J Fibres Polym Compos. 2022;1(2):148–63. doi:10.55043/jfpc.v1i2.55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Silviana S, Rahayu P. Production of bioplastics from sago starch with KCl-dispersed bamboo cellulose microfibril reinforcement through sonication process. Reaktor. 2017;17(3):151–6. doi:10.14710/reaktor.17.3.151-156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Silviana S, Rahayu P. Central composite design for optimization of starch-based bioplastic with bamboo microfibrillated cellulose as reinforcement assisted by potassium chloride. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference of Chemical and Materials Engineering; 2018 Sep 19–20; Semarang, Indonesia. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1295/1/012073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Al Fath MT, Lubis M, Ayu GE, Dalimunthe NF. Pengaruh selulosa nanokristal Dari serat buah kelapa sawit sebagai pengisi Dan kalium klorida sebagai agen pendispersi terhadap sifat fisik bioplastik berbasis Pati biji alpukat (Persea americana). J Teknik Kimia. 2022;11(2):89–94. (In Indonesian). doi:10.32734/jtk.v11i2.9239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Rahayu P, Luthfi MZ, Ikhsandy F, Yahya KA. The addition of dispersing agent on the bioplastic morphology, mechanical properties, and biodegradability of sago starch bioplastic with microfiber reinforcement of Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunches. J Ris Ind Has Hutan. 2023;15(1):21–30. doi:10.24111/jrihh.v15i1.7951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Missoum K, Belgacem MN, Barnes JP, Brochier-Salon MC, Bras J. Nanofibrillated cellulose surface grafting in ionic liquid. Soft Matter. 2012;8(32):8338. doi:10.1039/c2sm25691f. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chilingar GV. Study of the dispersing agents. J Sediment Res. 1952;22(4):229–33. doi:10.2110/jsr.22.229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Schmitz J, Frommelius H, Pegelow U, Schulte HG, Höfer R. A new concept for dispersing agents in aqueous coatings. Prog Org Coat. 1999;35(1–4):191–6. doi:10.1016/S0300-9440(99)00028-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Al Fath MT, Ayu GE, Lubis M, Hasibuan GCR, Dalimunthe NF. Mechanical and thermal properties of starch avocado seed bioplastic filled with cellulose nanocrystal (CNC) as filler and potassium chloride (KCl) as dispersion agent. Rasayan J Chem. 2023;16(3):1630–6. doi:10.31788/rjc.2023.1638464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. López OV, García MA. Starch films from a novel (Pachyrhizus ahipa) and conventional sources: development and characterization. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2012;32(7):1931–40. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2012.05.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Maryam, Akli K, MIS. Bioprocess for the production of nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) from empty palm oil fruit bunches (OPEFB) and its application as bioplastic composite material. Jakarta, Indonesia; 2021. [Google Scholar]

24. Ikhwanuddin. Production and characterization of bioplastics based on banana leaf powder and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) reinforced with gum Arabic. Medan, Indonesia: Universitas Sumatera Utara; 2018. [Google Scholar]

25. Klančnik G, Medved J, Mrvar P. Differential thermal analysis (DTA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) as a method of material investigation. RMZ-Mater Geoenviron. 2010;57(1):127–42. doi:10.1007/0-306-48404-8_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Liu M, Huang ZB, Yang YJ. Analysis of biodegradability of three biodegradable mulching films. J Polym Environ. 2010;18(2):148–54. doi:10.1007/s10924-010-0162-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ardi A, Hutomo GS, Noviyanty A. Pengaruh penambahan plasticizer gliserol terhadap karakteristik edible film Dari modifikasi Pati Kentang (Solannum tuberosum) asetat anhidrida. Agrotekbis J Ilmu Pertan. 2023;11(5):1199–209. doi:10.22487/agrotekbis.v11i5.1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Asrofi M, Sujito S, Syafri E, Sapuan SM, Ilyas RA. Improvement of biocomposite properties based tapioca starch and sugarcane bagasse cellulose nanofibers. Key Eng Mater. 2020;849:96–101. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/kem.849.96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Mahardika M, Asrofi M, Junus M, Sujito S. Application of Muntingia calabura natural fiber as filler in polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) matrix biocomposites: characteristics of tensile strength and fracture surface. Agroteknika. 2021;4(1):43–52. doi:10.32530/agroteknika.v4i1.103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Maryam M, Rahmad D, Yunizurwan Y. Sintesis mikro selulosa bakteri sebagai penguat (reinforcement) pada komposit bioplastik dengan matriks PVA (Poli Vinil Alcohol). J Kim Dan Kemasan. 2019;41(2):110. doi:10.24817/jkk.v41i2.4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Suyadi. Experimental study of the tensile strength of products made from recycled plastic. In: Proceedings of the National Seminar on Science and Technology; 2010. [Google Scholar]

32. Nur RA, Nazir N, Taib G. Karakteristik bioplastik dari pati biji durian dan pati singkong yang menggunakan bahan pengisi MCC (Microcrystalline Cellulose) dari kulit kakao. Gema Agro. 2020;25(1):1–10. doi:10.22225/GA.25.1.1713.01-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Indriani DR, Asikin AN, Zuraida I. Characteristics of edible film from kappa carrageenan Kappaphycus alvarezii with different plasticizers. Saintek Perikan Indones J Fish Sci Technol. 2021;17(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

34. Rusli A, Metusalach M, Tahir MM. Characteristics of edible films made from carrageenan with glycerol as a plasticizer. J Pengolah Has Perikan Indones. 2017;20(2):219–29. doi:10.17844/jphpi.v20i2.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Nurindra AP, Alamsjah MA, Sudarno S. Characterization of edible films from mangrove propagule starch (Bruguiera gymnorrhiza) with the addition of carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) as a plasticizer. J Ilm Perikan Dan Kelaut. 2015;7(2):125–32. doi:10.20473/jipk.v7i2.11195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Muljana H, Hasjem I, Sinatra M, Joshua Pesireron D, Wilbert Puradisastra M, Hartono R, et al. Cross-linking of sago starch with furan and bismaleimide via the Diels-alder reaction. J Renew Mater. 2023;11(12):4039. doi:10.32604/jrm.2023.031261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ahmad FB, Williams PA, Doublier JL, Durand S, Buleon A. Physico-chemical characterisation of sago starch. Carbohydr Polym. 1999;38(4):361–70. doi:10.1016/s0144-8617(98)00123-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Tang Y, Shen X, Zhang J, Guo D, Kong F, Zhang N. Extraction of cellulose nano-crystals from old corrugated container fiber using phosphoric acid and enzymatic hydrolysis followed by sonication. Carbohydr Polym. 2015;125(2):360–6. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.02.063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Yu H, Qin Z, Liang B, Liu N, Zhou Z, Chen L. Facile extraction of thermally stable cellulose nanocrystals with a high yield of 93% through hydrochloric acid hydrolysis under hydrothermal conditions. J Mater Chem A. 2013;1(12):3938. doi:10.1039/c3ta01150j. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Rosli NA, Ahmad I, Abdullah I. Isolation and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals from Agave angustifolia fibre. BioResources. 2013;8(2):1893–908. doi:10.15376/biores.8.2.1893-1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Shaheen TI, Emam HE. Sono-chemical synthesis of cellulose nanocrystals from wood sawdust using acid hydrolysis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;107(Pt B):1599–606. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Gan PG, Sam ST, bin Abdullah MF, Omar MF. Thermal properties of nanocellulose-reinforced composites: a review. J Appl Polym Sci. 2020;137(11):48544. doi:10.1002/app.48544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Zoungranan Y, Lynda E, Dobi-Brice KK, Tchirioua E, Bakary C, Yannick DD. Influence of natural factors on the biodegradation of simple and composite bioplastics based on cassava starch and corn starch. J Environ Chem Eng. 2020;8(5):104396. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2020.104396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Fitri A, Na BH, Admadi, Luthfi S. Characteristics of bioplastic composites from corn starch and glucomannan under different types and concentrations of filler treatment. J Rekayasa Dan Manaj Agroindustri. 2021;9(4):456–68. [Google Scholar]

45. Arifin A, Karlina A, Khair A. The effect of chitosan dosage on the color level of liquid waste from the sasirangan home industry ‘oriens handicraft’ landasan ulin. J Health Sci Preven. 2017;1(2):58–67. doi:10.29080/jhsp.v1i2.91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Shakina J, Sathiya LK, Allen GRG. Microbial degradation of synthetic polyesters from renewable resources. Indian J Sci. 2012;1(1):21–8. [Google Scholar]

47. Amin MR, Chowdhury MA, Kowser MA. Characterization and performance analysis of composite bioplastics synthesized using titanium dioxide nanoparticles with corn starch. Heliyon. 2019;5(8):e02009. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Avérous L. Polylactic acid: synthesis, properties and applications. In: Belgacem MN, Gandini A, editors. Monomers, polymers and composites from renewable resources. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2008. p. 433–50. [Google Scholar]

49. Santoso B, Marsega A, Priyanto G, Pambayun R. Improvement of physical, chemical, and antibacterial properties of ganyong starch-based edible films. J Teknol Has Pertan. 2016;36(4):379–86. [Google Scholar]

50. Pulikkalparambil H, Phothisarattana D, Promhuad K, Harnkarnsujarit N. Effect of silicon dioxide nanoparticle on microstructure, mechanical and barrier properties of biodegradable PBAT/PBS food packaging. Food Biosci. 2023;55(9):103023. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2023.103023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Saidi L, Wang Y, Wich PR, Selomulya C. Polysaccharide-based edible films—strategies to minimize water vapor permeability. Curr Opin Food Sci. 2025;61:101258. doi:10.1016/j.cofs.2024.101258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Prasad Panthi K, Panda C, Mohan Pandey L, Lal Sharma M, Kumar Joshi M. Bio-interfacial insights of nanoparticles integrated plant protein-based films for sustainable food packaging applications. Food Rev Int. 2025;2025:1–33. doi:10.1080/87559129.2025.2458563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Jafarzadeh S, Jafari SM. Impact of metal nanoparticles on the mechanical, barrier, optical and thermal properties of biodegradable food packaging materials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021;61(16):2640–58. doi:10.1080/10408398.2020.1783200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. El-Sayed SM, El-Sayed HS, Ibrahim OA, Youssef AM. Rational design of chitosan/guar gum/zinc oxide bionanocomposites based on Roselle calyx extract for Ras cheese coating. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;239(1):116234. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Nasution H, Harahap H, Al Fath MT, Afandy Y. Physical properties of sago starch biocomposite filled with Nanocrystalline Cellulose (NCC) from rattan biomass: the effect of filler loading and co-plasticizer addition. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2018;309:012033. doi:10.1088/1757-899x/309/1/012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Septiati YA, Karmini M, Kamaludin A, Fatimah F. Analisis luas bukaan udara penyimpanan makanan terhadap Kadar air Dan total jamur makanan terkemas bioplastik. J Kesehat Lingkung Indones. 2024;23(2):226–33. (In Indonesian). doi:10.14710/jkli.23.2.226-233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Zhang K, Zhang W, Ruan P, Zhou Y, Yao B, Wang Y, et al. Fabrication and characterization of truxillic alginate bioplastic with decent antibacterial, antioxidant and degradability properties in food packaging. Mater Today Commun. 2024;41(1):111022. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.111022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Zhang D, Li H, Emara AM, Wang Z, Chen X, He Z. Study on the mechanism of KCl replacement of NaCl on the water retention of salted pork. Food Chem. 2020;332(22):127414. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Chen J, Hu Y, Wen R, Liu Q, Chen Q, Kong B. Effect of NaCl substitutes on the physical, microbial and sensory characteristics of Harbin dry sausage. Meat Sci. 2019;156(4):205–13. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2019.05.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Patidar MK, Ranawat K, Jindal T, Das AK. Degradation of cellulose-based bioplastic by Stenotrophomonas acidaminiphila TMF using response surface methodology. Bioresour Technol Rep. 2025;29(48):102084. doi:10.1016/j.biteb.2025.102084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools