Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Highly Pure Water-Soluble Aspen Wood Hemicelluloses Derived by Catalytic Peracetic Treatment and Their Antioxidant and Flocculation Activity

1 Institute of Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Krasnoyarsk Science Center, Siberian Branch Russian Academy of Sciences, Akademgorodok 50/24, Krasnoyarsk, 660036, Russia

2 School of Non-Ferrous Metals and Material Science, Siberian Federal University, pr. Svobodny 79, Krasnoyarsk, 660041, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Valentina Sergeevna Borovkova. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(12), 2281-2296. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0067

Received 28 March 2025; Accepted 28 May 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

The valorization of plant biomass towards high-value chemicals is a global trend aimed at solving the problem of the huge accumulation of lignocellulosic waste. Plant polysaccharides are natural polymers that make up about 20% by weight of biomass, with a unique variety of structures and properties that depend on the type of raw materials and the method of their extraction. In this study, the effect of variability of the oxidative delignification process conditions in the «acetic acid-hydrogen peroxide-water-(NH4)6Mo7O24» on the extraction and properties of aspen (Populus tremula) wood hemicelluloses was investigated for the first time. The developed method for the extraction of hemicelluloses provided the production of water-soluble polysaccharides with a high yield (to 62.55 wt.% in relation to total content in wood), high purity, with a branched structure and active centers on the side chains in the form of uronic acids. In the course of the work, it was found that the obtained hemicelluloses are mainly represented by partially acetylated galactoxylan and glucuronoxylan. Promising results of biological studies of the antioxidant and flocculation activity of xylans are promising for the use of plant polysaccharides in health care and food industry.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Due to the rapid depletion of the Earth’s resources and fossil fuels, there is an active transformation of the linear economy into a more cyclical and carbon-negative form [1–3]. Regarding to existing context, a trend of the bioeconomy development arises, approaching in order to handle industries with limited resources consumption and large-scale biological waste utilization [4,5]. Transition towards bioeconomy involves the application of natural renewable resources potential [5] and theirs valorization into high-valued products, such as transport fuels, chemicals and functional materials [6,7], which could provide competitive alter for fossil fuel-based assortment on the global market [8].

Lignocellulosic biomass (LCB) is a virtually inexhaustible renewable resource, most widely represented by wood [6,9,10]. At the point of easy processing and natural biodegradability [11], wood biomass is a promising raw material for new materials production with various purposes [8]. A modern approach of wood lignocellulosic fractionation allows to process biomass materials into their main organic valuable components [6]. At the same time, non-cellulosic polysaccharides (NCP), hemicelluloses, being the second most common natural carbohydrates after cellulose [12], still drag particular attention as a potential source for practical application as hydrogels [13], films [14] and composites [13,15]. Notably, the functionality of hemicelluloses is directly related to their molecular structure and configuration depending on their origin and isolation method [16,17]. The key points in choosing a method for isolating NCP are the breaking of hydrogen bonds between cellulose and hemicelluloses, complex, hard-to-reach chemical bonds between carbohydrates and lignin [9,18], as well as the preservation of the polymer structure of polysaccharides. However, due to their non-crystalline structure, hemicelluloses are usually depolymerized during traditional biomass pretreatment processes. Since existing methods of lignocellulosic raw material processing, in addition to breaking complex chemical bonds, are accompanied by side reactions of hydrolysis, this introduces corresponding limitations in their practical application [17,18]. Thus, one of the most promising methods for processing LCB is oxidative organosolvent pretreatment, which involves not only the use of environmentally friendly reaction systems, but also promotes the effective rupture of lignin-carbohydrate bonds without decomposition of polymers under optimized conditions [6,19]. Moreover, treatment of wood using organic solvents to conduct oxidative processing at atmospheric pressure and temperatures equal or below 100°C. Organic peracids, formed as a rule by hydrogen peroxide and acetic acid interaction, are capable of depolymerizing lignin into water-soluble monomeric phenolic fragments, which significantly promotes their extraction from LCB [19,20]. In addition, peracetic acid activation is accompanied by active formation of RO• organic radicals, including HO•, CH3CO2•, CH3CO3•, possessing a prolonged half-decay period and higher selectivity than during traditional oxidation processing [21]. Various compounds, including transition metals-based catalysts were successfully used as peracetic acid activators [22–24]. Notably, that molybdenum-based compounds in particular used traditionally for catalytic oxidative cleavage of lignin C–C bonds [6,24]. However, in such studies, the target product is still cellulose, and hemicelluloses remain a by-product in the form of monosaccharide residues. In turn, the use of oxidative delignification using a catalytic system can facilitate the production of purified water-soluble hemicelluloses while maintaining their native polymer form, opening up new opportunities and potential for non-cellulosic polysaccharides in sought-after areas, including the food, pharmaceutical and chemical industries.

Thus, this work concerned with the study of the impact of oxidative delignification conditions using a water-soluble catalyst (NH4)6Mo7O24 with different concentrations on the isolation and properties of aspen (Populus tremula) wood hemicelluloses. To achieve this aim, the obtained products were characterized by a set of physicochemical and biological methods to assess changes in the structural features of hemicelluloses.

In course of present study, the air-dried aspen wood (Populus tremula) was milled to a fraction size of 2.5 mm and then dried at 100°C–150°C in an oven to a constant weight. The up mentioned species was chosen due its wide distribution all over the world.

2.2 Isolation of the Hemicelluloses

To obtain polysaccharides 10 g of wood sawdust was treated with delignifying mixture acetic acid-hydrogen peroxide-water in a 250 mL three-necked glass batch equipped with a reflux condenser under a constant stirring (300 rpm). Reagents ratio of the delignifying mixture was selected basing on the previously conducted studies [6,25], and specifically with an acetic acid (Reagent, Samara, Russia) content of 30 wt.%, hydrogen peroxide (Lego, Dzerzhinsk, Russia) of 6 wt.% and a liquid/sawdust ratio of 15. In addition, the impact of an addition water-soluble catalyst (NH4)6Mo7O24 (Sigma Tech., Moscow, Russia) by varying its concentration in the range of 0.5–1.5 wt.% (relative to an absolutely dry sample) and delignification conditions, such as temperature (90°C or 100°C) and duration (3–4 h) of treatment on the isolation and properties of the hemicelluloses, were explored. The subsequent procedure for the isolation of hemicelluloses is similar to the studies [7,24].

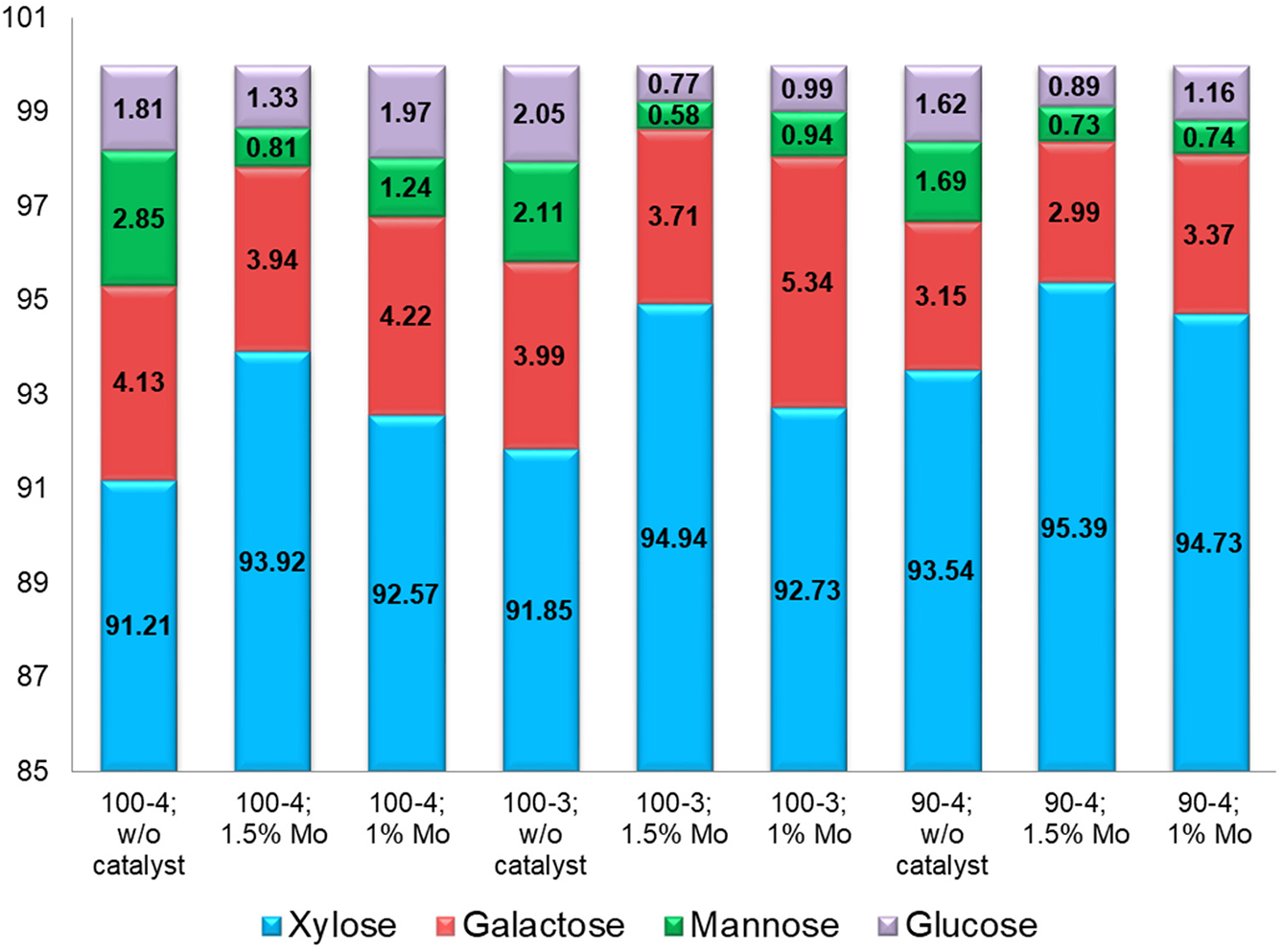

As a result, the composition and structure of the obtained hemicelluloses samples (Table 1) were characterized by a set of modern physicochemical methods of analysis. In addition, various model compounds were used to reveal the impact of the hemicellulos’s composition and structure on their antioxidant and flocculation activities.

2.3 Hydrolysis of the Hemicelluloses and Determination of Uronic Acids Content

Uronic acids were determined using modified carbazole and tetraborate methods [26]. The calibration curve was performed using the stock solution of the analytical standard of D-galacturonic acid (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The samples with specified concentration were diluted in distilled water and further treated with 0.025 M sodium tetraborate (SCRS, Krasnoyarsk, Russia) in sulfuric acid (Reagent, Samara, Russia) and carbazole solution.

In typical procedure, 6 mL of sodium tetraborate dissolved in sulfuric acid was slowly added to 1 mL of the investigated sample. These operations allows to decompose the hemicellulose’s samples into monomeric compounds.

To proceed the reaction with galacturonic acid the 0.5 mL of 0.015% carbazole-ethanol solution reagent was added and reaction mixture was shaken gently at first and then thoroughly vortexed for 30 s followed by incubation at 80°C for 10 min. Finally, the cooled sample solutions optical absorbance were spectrophotometrically measured at 530 nm with distilled water used as a reference solution.

2.4 Monosaccharide Composition of the Isolated Hemicelluloses

The monosaccharide units composition of the hemicellulose was determined by the hydrolysis of initial samples in a 10% solution of H2SO4 [27] followed by derivatization according to method [28]. Analysis of derivated hydrolysates was conducted using gas chromatograph VARIAN-450 GC (Varian, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA), equipped with a VF-624ms capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm). As an analytical standards xylose, mannose, arabinose, galactose, glucose, sorbitol (Panreac, Darmstadt, Germany) were used.

2.5 Gel Permeation Chromatography Studies of the Isolated Samples

To evaluate the molecular weight properties of the isolated hemicelluloses, gel permeation chromatography analysis was performed using an Agilent 1260 Infinity II GPC/SEC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with the refractometer detector and three Agilent PL Aquagel-OH columns. The sample eluent solutions (5 mg/mL in 0.1 M aqueous NaNO3 (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany) with 250 ppm of NaN3 (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany)) were filtered through a membrane (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). The calibration was performed using polyethylene glycol (PEG) Agilent standard (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with Mp 106–500,000 g/mol. The eluent flow rate during the analysis was 1 mL/min. The molecular weight distribution characteristics were depicted basing on the data registered and processed by Agilent GPC/SEC MDS software version 2.2.

2.6 Infra-Red Spectral Characteristics of the Isolated Hemicelluloses

The absorbance units in the Infra-Red spectra of hemicellulose samples were registered by Shimadzu IRTracer-100 (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and characterized in 2000–800 cm−1 region, witnessing the structural changes of hemicelluloses depended on specific isolation conditions. In a typical procedure, the 3 mg of sample were pressed with 1 g of potassium bromide into tablets.

2.7.1 Antioxidant Activity Assays

Hemicellulose ability to scavenge 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) (Tokyo Chemical Ind. Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used to estimate a connection between the obtaining conditions of polysaccharides and their antioxidant activity. According to the methods developed and described earlier [25], DPPH was dissolved in ethanol directly before UV measurements on a spectrophotometer Ecoview UV 6900 spectrophotometer (Shanghai Mapada Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at 517 nm. Hemicellulose samples were dissolved in distilled water resulting in their concentration in solution of 0.5, 2 and 5 mg/mL. Then, 2 mL of DPPH solution and 2 mL of ethanol were added to the 1 mL polysaccharide solution and thoroughly mixed. The assays were conducted in triplicates and the obtained values were averaged.

The DPPH radicals scavenging ability of hemicelluloses was evaluated according to the Eq. (1):

where AC is the absorbance of the DPPH solution without the hemicellulose, AS is the absorbance of the test sample mixed with the DPPH solution, and AB is the absorbance of the sample without DPPH solution.

In addition, the ability of hemicelluloses to scavenge hydroxyl radicals was assessed similarly to the work [25].

The hydroxyl radical scavenging capacity was calculated using Eq. (2):

where AC is the absorbance of the mixture without the sample of hemicellulose, AS is the absorbance of the test sample mixed with a reaction solution, and AB is the absorbance of the sample without a salicylic acid solution.

2.7.2 Flocculation Activity Assays

To study the effect of the flocculating activity of hemicelluloses, experiments were conducted based on the interaction of the polysaccharide with suspension bentonite supplemented with metal ions, including aqueous solutions of NaCl (Reagent, Samara, Russia), CaCl2 (Reagent, Samara, Russia) and FeCl3 (Reagent, Samara, Russia), using modified techniques as follows [21,29].

The flocculating mixture (10 g/L) was obtained using 5 mL of an aqueous suspension of bentonite clay, processed using an ultrasonic homogenizer (Volna-M, Moscow, Russia) and brought to pH 7.0. Then 0.04 M aqueous solution of metal salts and 3 mL of 0.1 g/L hemicellulose solution were added. The resulting mixture was stirred for 5 min. The absorbance of the samples was measured using Ecoview UV 6900 spectrophotometer at 550 nm. The analyses were carried out three times and the obtained values were averaged. The flocculating activity of was calculated using Eq. (3):

where OD550—absorbance of the supernatant, OD550, blank—the metal ion-free blank control absorbance.

3.1 Impact of Delignifying Conditions on Hemicelluloses Yields

Water-soluble (NH4)6Mo7O24 catalyst has been previously demonstrated efficiency in intensifying of biomass delignification, as indicated by low values of lignin content in cellulosic residue (~1 wt.%) [6], as well as promising results with high spruce wood galactoglucomannan yield up to 48.2 wt.% [3]. However, this study reveals the effect of molybdenum catalyst concentration with varying process temperature and duration, which were investigated for the first time not only for hemicelluloses yields, but also on their composition, structure and physicochemical properties.

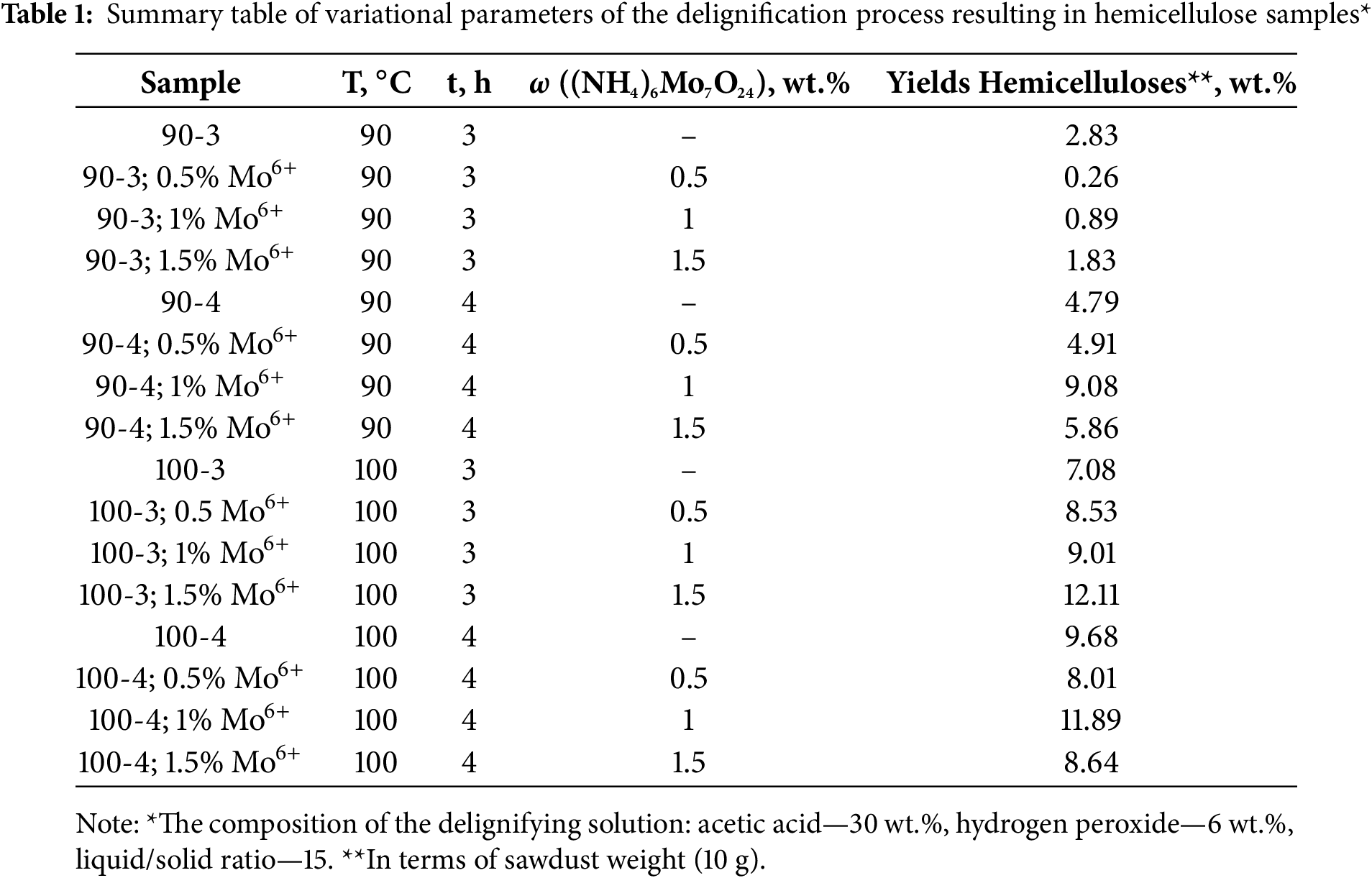

The target products yields were estimated by gravimetric method in relation to the total aspen wood hemicelluloses content, the results of which are presented in the Fig. 1. The total hemicelluloses in aspen wood contains up to ~20 wt.% [25].

Figure 1: Impacts of the delignifying conditions on the hemicelluloses yields

Thus, based on the obtained data in terms of the total content of hemicelluloses in wood (Fig. 1), peculiar tendency is observed: in general, catalyst presence results in a significant increase of polysaccharides yield due to effect of the ammonium paramolybdate active catalytic complex with peracetic acid on lignocarbohydrate matrix and, consequently, hemicelluloses release. The samples of hemicelluloses isolated at 90°C and 3 h of processing, being the exception and distinguish by the lowest yield values not only in non-catalytic process conditions, but also in entire range of catalyst concentrations. Apparently, the given conditions lignocarbohydrate bonds oxidation occurs at a low intensity due to their chemical strength and insufficient duration of oxidizer exposure resulting in minor yields of purified hydrolysate hemicelluloses.

However, increasing the duration of the process to 4 h at 90°C leads to oxidation process activation, accompanied by a significant growth in target product yield to 45.6 wt.%, which is comparable with the data obtained at a 100°C process temperature (Fig. 1). Notably, in an earlier work [30] under similar synthesis conditions (90°C and 3 h), yields of pine wood hemicelluloses contains up to 58.1 wt.%, which undoubtedly indicates the importance of choosing the conditions for carrying out the delignification process from the raw materials used.

From the point of view of product yield the most preferred conditions for aspen wood delignification process are: 100°C process temperature, 3 and 4 h duration with 1.5 and 1 wt.% ammonium paramolybdate presence, accordingly. The above mentioned conditions allows obtain maximum yields of hemicelluloses reaching up to 62.55 wt.% in relation to total content in wood. However, isolation of polysaccharides not only with a high yield, but also with their native polymer structure preservation is still being crucial.

3.2 Monosaccharide Composition of Isolated Hemicelluloses

It is important to mention that xylan is the most common polysaccharide presented in deciduous biomass [31], depending on raw material nature and the extraction method xylose links contain additional side chains, for example, in the form of glucuronic acid residues [32]. In addition, according to various plant sources, the xylan hydroxyls could be easily substituted by acetyl groups [33].

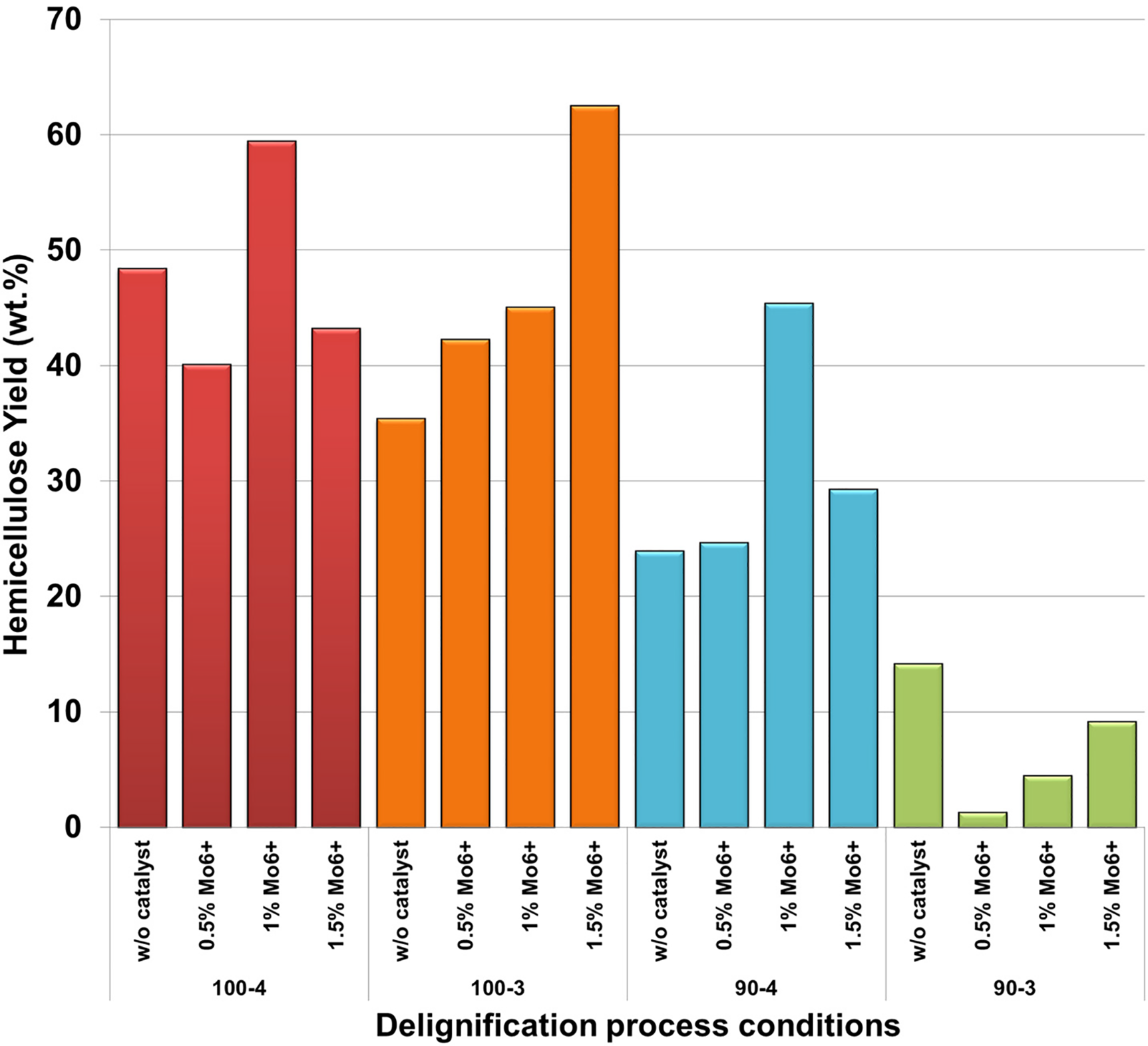

The monosaccharide units composition of isolated hemicelluloses represented mainly by xylose, galactose, mannose and glucose (Fig. 2), varies depending on the oxidative delignification conditions used.

Figure 2: Hemicelluloses monosaccharide composition (in relation to the total monosaccharide content)

The predominant monosaccharide in the hydrolysates of all samples are xylose with some galactose and glucose, indicating that obtained polysaccharides represented mainly by galactoxylan and glucuronoxylan. However, mannose trace amounts and increased amount of galactose indicates the presence of easily hydrolysable polysaccharides residues in side chains of the xylan backbone, subjective to destruction regardless of oxidative delignification conditions. At the same time, initial presence of mannose and galactose in xylan structure provides complicated branched conformation and, as a consequence, greater solubility in aqueous medium.

Activation of peracetic acid by ammonium paramolybdate catalyst also intensifies the hydrolysis process, which accompanied with side chains cleavage, expressed by monosaccharide ratio rearrangement (Fig. 2). As a result, the purified xylan off accompanying polysaccharides was obtained at the output, however, with reduced solubility.

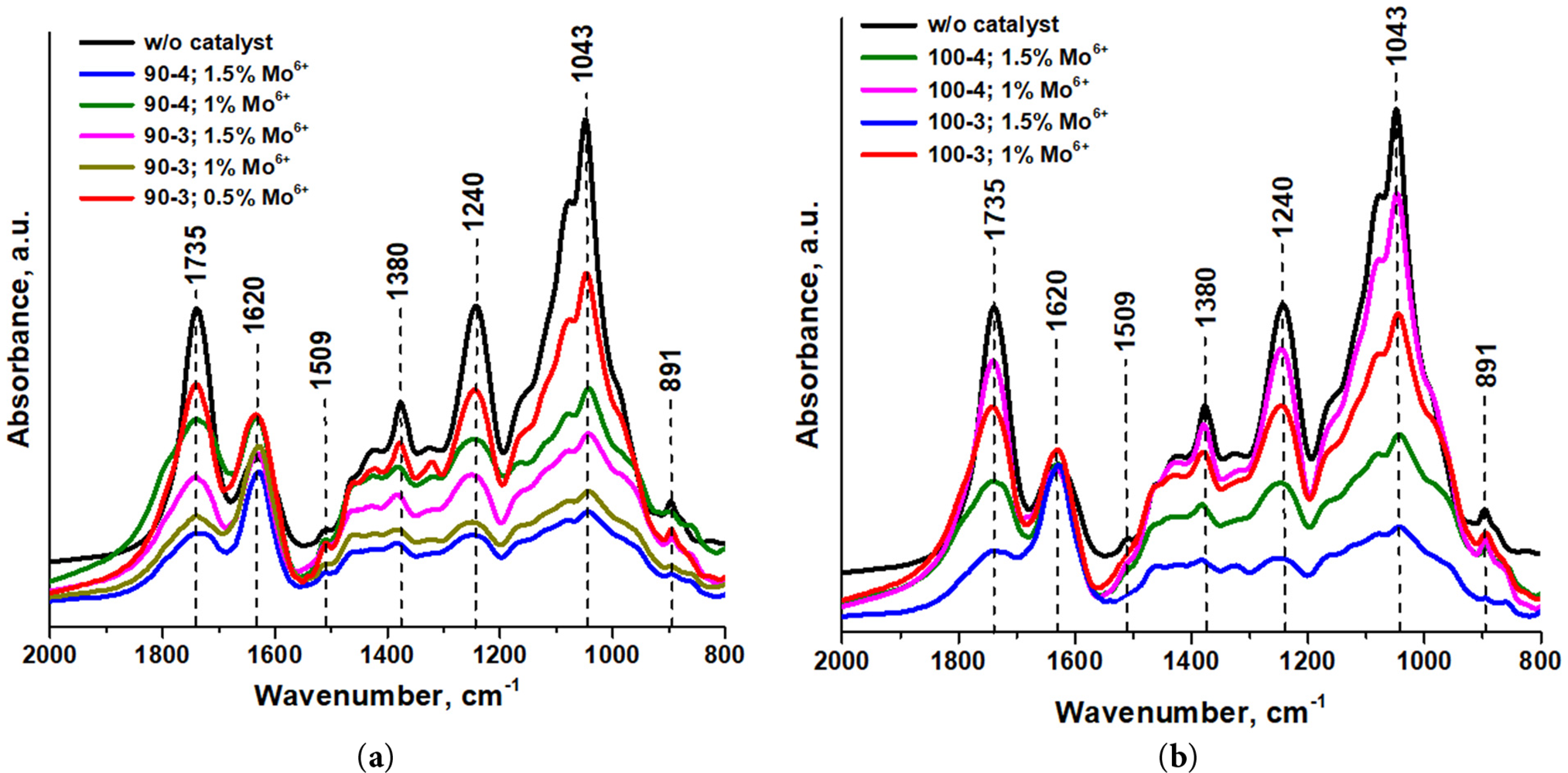

3.3 Spectral Characteristics of the Isolated Hemicelluloses

The structure of xylan samples depending on isolation conditions were studied by FTIR spectroscopy. As a result, most notable absorption units (a.u.) were identified, which are characteristic for polysaccharides (Fig. 3a,b). In general, the IR spectra of the samples are partially similar, but there are some differences.

Figure 3: The registered spectra of the isolated hemicelluloses at: (a) 90°C and (b) 100°C without/with catalyst (NH4)6Mo7O24

The pronounced absorption units in regions of ~1735, 1380 and 1240 cm−1, characterizing vibrations of carbonyl, –C–CH3 and –C–O– groups accordingly, witnesses that all of the obtained hemicellulose samples are acetylated [34]. Intensive signal of a.u. at 1620 cm−1 commonly associated with water adsorbed by sample. Notably, a.u. at 1509 cm−1 corresponding to skeletal vibrations of the lignin’s phenolic fragments is not observed for only spectrum of hemicelluloses isolated at 100°C in presence of the peracetic acid activator. This phenomenon is caused by oxidative complex interaction on lignocarbohydrate matrix at elevated temperatures, undoubtedly significant for polysaccharides release and purification. The outstanding a.u. at 1043 cm−1 region refers to the C–O–C bonds stretching vibrations in xylan pyranose ring [35]. Finally, a.u. 891 cm−1 characterizes C–O–C of glycosides β-configuration between first and fourth carbon atoms [36].

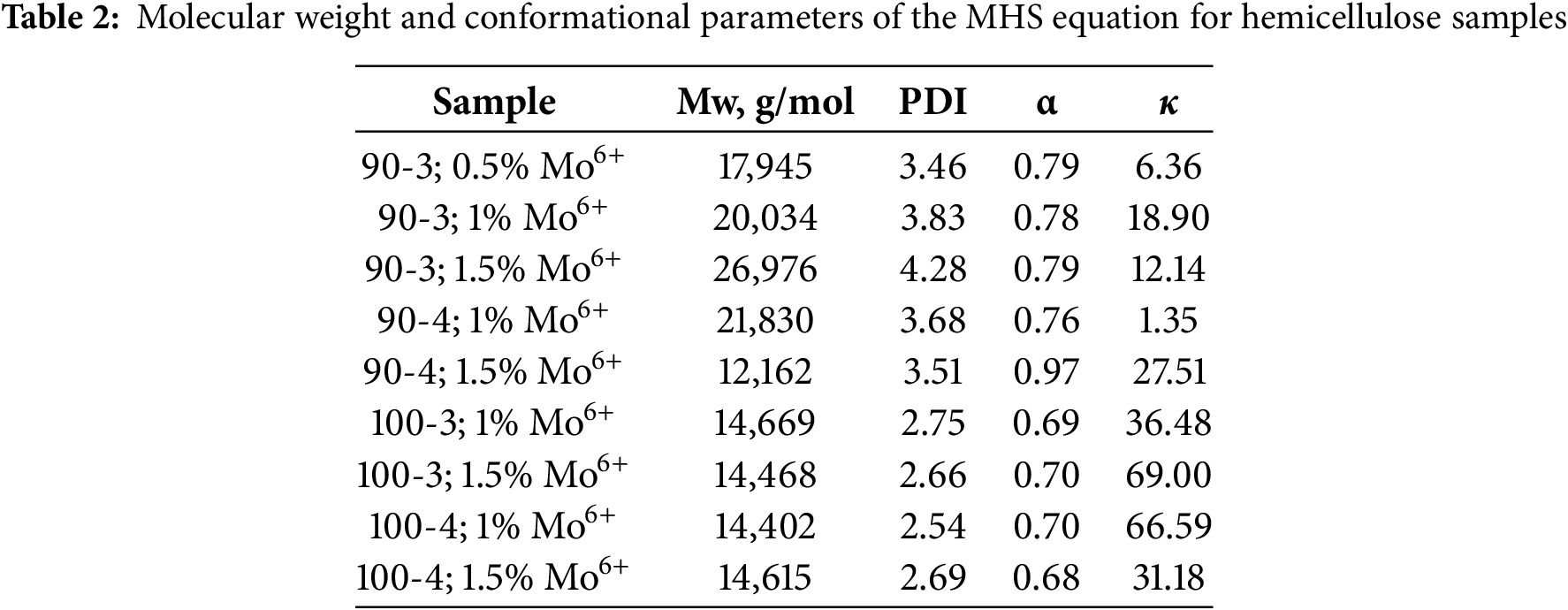

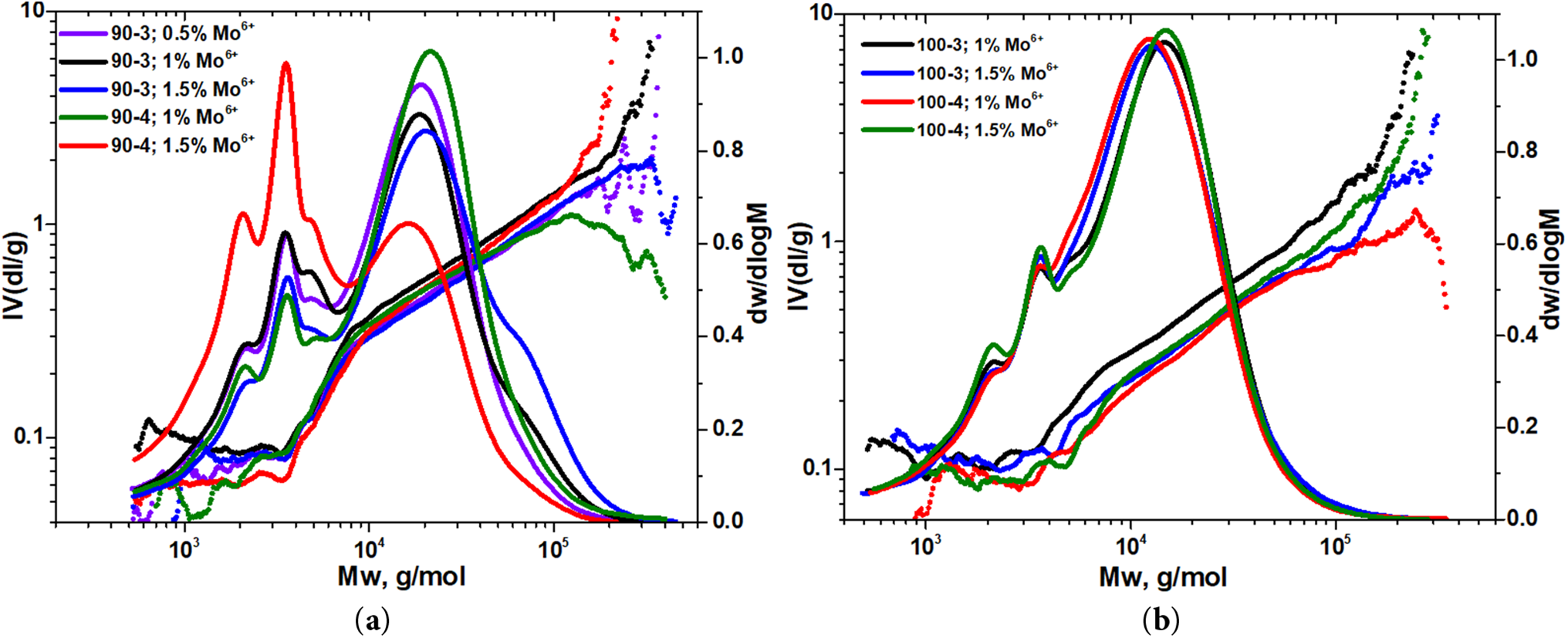

3.4 Molecular Weight Distribution Properties of Isolated Hemicelluloses

Such characteristics as molecular weight and conformation are being high desirable to adjust structural properties of polysaccharides, tuning of which impacts on their further application, as well as on their biological activity [37,38].

The parameters of Mark-Houwink-Sakurada equation (MHS) were obtained using the multidetector gel permeation method (Eq. (4)).

where [η]—intrinsic viscosity, М—molecular weight (g/mol), K and α—constants characterizing molecules branching and conformation in a solvent, data of which is represented in Table 2.

Molecular mass distribution curves and graphs based on calculated MHS equation parameters are depicted on Fig. 4a,b.

Figure 4: Molecular weight distribution curves and MHS graphs of hemicelluloses isolated by oxidative delignification of aspen wood at: (a) 90°C and (b) 100°C in presence of (NH4)6Mo7O24

The obtained data analysis revealed that in the presence of ammonium paramolybdate, polysaccharides were mainly isolated of the conformation of a «random coil» (α ranging from 0.68 to 0.81). As it could be seen, temperature, duration and (NH4)6Mo7O24 catalyst concentration do not take part in transformation of polysaccharide molecules, while in a greater extent affecting on their branching.

Nevertheless, a more branched molecular structure inherent for aspen hemicelluloses obtained at 90°C as indicated by molecular weight data (ranging from 17,945 to 26,976 g/mol), polydispersity (ranging from 3.68 to 4.28), as well as lower values of constant K (ranging from 1.35 to 1.90) (Table 2) and the curved MHS graph shape (Fig. 4a).

Generally, this allows us to conclude that obtained hemicellulose samples are represented by a mixture of high-molecular xylan fraction with certain amount of oligomers, which is consistent with the monosaccharide composition data due to an increased percentage of xylose, as well as the product yields values with a maximum of ~46 wt.%. At the same time, a simultaneous prolongation of oxidative delignification to 4 h and activator concentration to 1.5 wt.% at 90°C are accompanied by high-molecular fraction degradation. It could be detected both based on a main peak shift to the low-molecular region with a noticeable decrease in the polysaccharide molecular weight to 12,162 g/mol so as the sample yield, in particular. To sum up, due to polysaccharide molecules redistribution, its conformation undergoes “random coil—semi-flexible coil” transformation (α = 0.97).

On the other hand, performance of oxidative delignification at 100°C leads to the medium molecular weight polysaccharides formation (~14 × 103 g/mol) (Table 2). At the same time, a prolonged processing and higher ammonium paramolybdate concentration in the reaction medium do not entail significant changes in polysaccharides structure, as indicated by identical molecular weight distribution profiles and MHS curves with their slight shifts (Fig. 4b), witnessing side chains cleavage with possible partial oxidation of polysaccharide terminal groups. While the maximum of parameters varying reached, the low-molecular fraction is completely released out from obtained mixture, but although it does not affect on main polymer chain structural changes, the yield of the target product decreases from 59 to 42 wt.%.

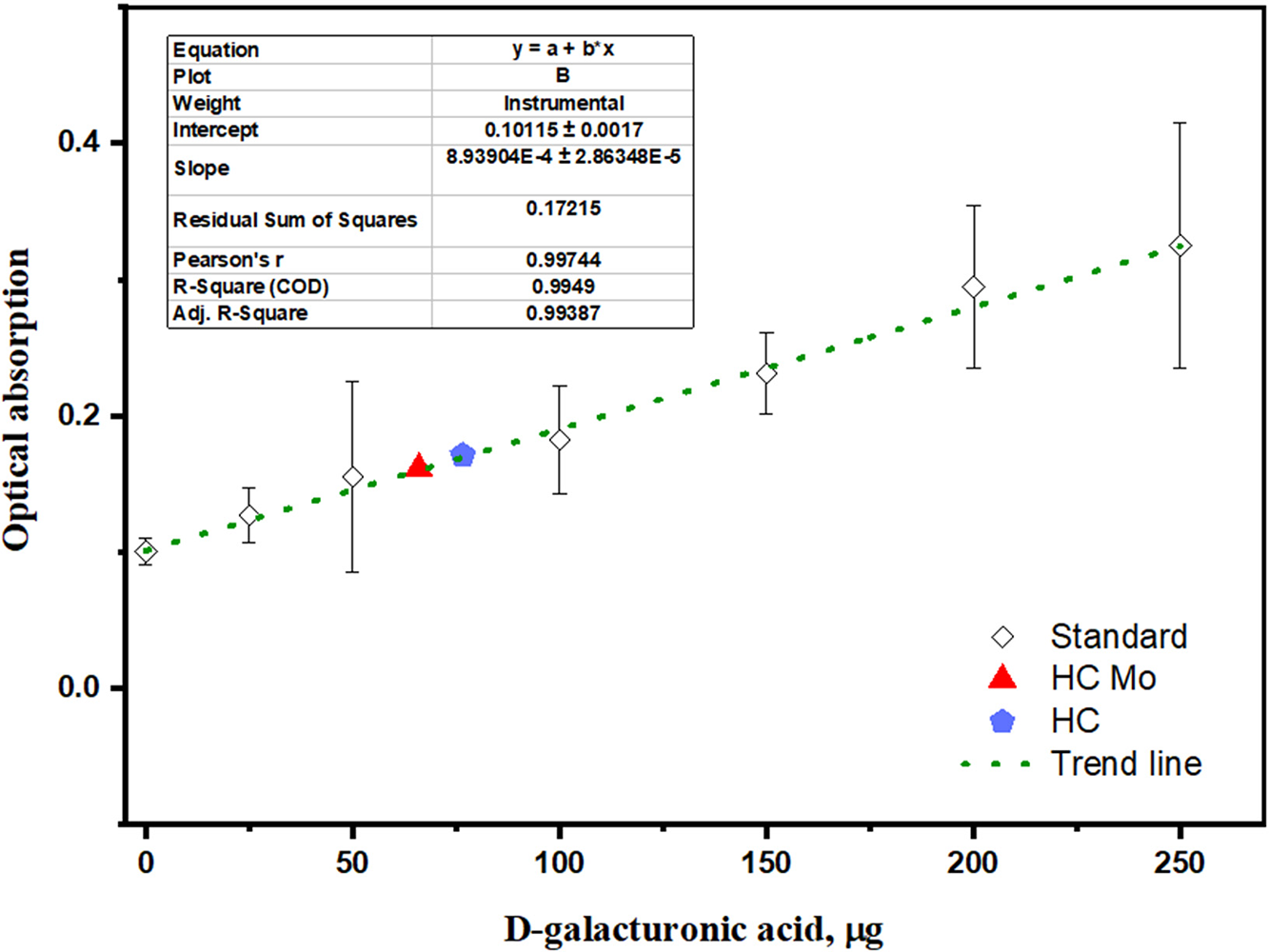

3.5 Hemicellulose Hydrolysis and Determination of the Formed Uroniс Acids

The physicochemical properties of hemicelluloses depend on the amount of charged groups caused by carboxylic acids, which are commonly represented by carbohydrates with a carboxylic acid groups (uronic acids) [39]. They could present as both base unit or as side chains of hemicellulose, affecting its biological and antioxidant activity. Therefore, its evaluation is desirable and could indirectly point at obtained hemicelluloses application potential for drug production.

The calibration curve was depicted after spectrophotometric determination of D-galacturonic acid analytical standard (Fig. 5), and the uronic content in hemicellulose’s samples were determined basing on plotted calibration curve and trend line Eq. (5):

where Y = is the measured optical adsorbance and x is the concentration of D-galacturonic acid (μg/mL), formed by hemicellulose’s hydrolysis.

Figure 5: Results of D-galacturonic acid quantification by carbazole-ethanol-tetraborate method

Nevertheless, uronic acid content in hydrolysate sample of hemicellulose obtained with presence of Mo6+ is slightly lower than in sample of hemicellulose obtained without the catalyst (66.0 μg/mL compared to 76.6 μg/mL). The ratio of uronic acids, based on the mass of the sample used for analysis are 7.76 wt.% and 9.01 wt.%, respectively.

3.6 Antioxidant Activity Analysis

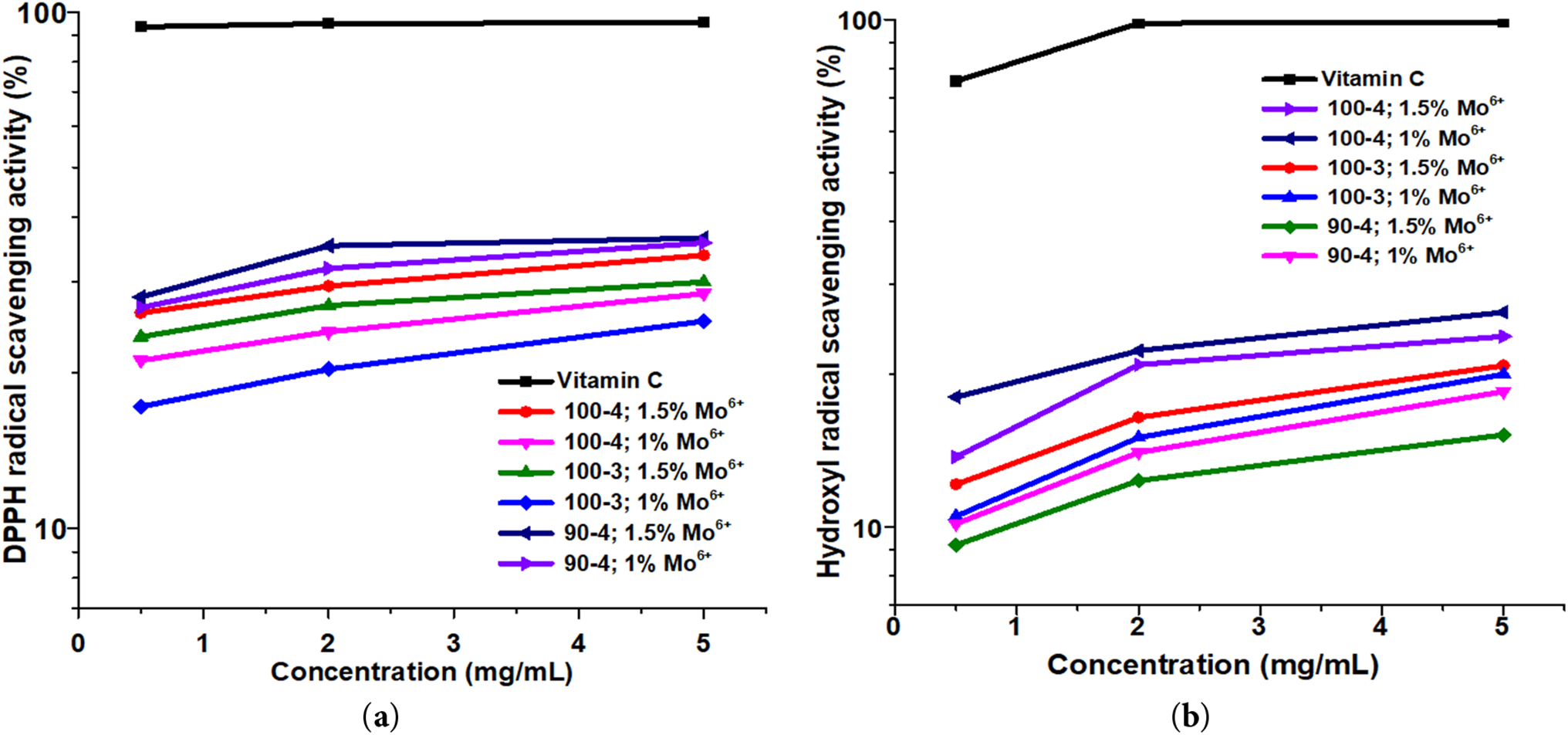

The potential application of various polysaccharides and their derivatives as antioxidant agents has been previously reported [4,40,41]. Due to the fact that unique diverse composition and structure of polysaccharides depends on the source, method of extraction and purification degree, their biological activity could vary to some extent. Possibility of regulation polysaccharides isolation parameters contributes to expand their application areas, such as food, medical and pharmaceutical industries [42,43]. The traditional methods for evaluating of polysaccharides scavenging activity nowadays are based on the hemicellulose absorption ability of 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radicals so as hydroxyl radicals. Thus, the performed DPPH scavenging tests to observe a decrease in light absorption at 517 nm with an increase in the concentration of hemicelluloses in the solution, which indicates a dose-dependent nature of reagents interacted (Fig. 6а).

Figure 6: Scavenging activity of free DPPH (а) and hydroxyl radicals (b) by aspen-derived hemicelluloses at different concentrations in solution

However, differences in the conditions of polysaccharide synthesis entail significant differences in their absorption of free radicals. The sample of hemicellulose obtained at 90°C after 4 h oxidative delignification in presence of 1.5 wt.% ammonium paramolybdate has the maximum DPPH scavenging activity (Fig. 6а). Obviously, this phenomenon is directly related to the structural composition and conformation of the molecule of this polysaccharide. Possessing the lower molecular weight and, probably, a significant amount of sterically available reactive hydroxyl end groups, due to conformational features of the molecule, these hemicelluloses actively bind with DPPH free radicals. Nevertheless, phenolic fragments in residual structure of polysaccharides obtained at 90°C also significantly contributes to its activity [44]. Such limitation does not allow to estimate objectively the antioxidant activity of unpurified polysaccharides performed by DPPH method [44,45]. At the same time, the lowest values (~12.7%) of hydroxyl radicals scavenging activity (Fig. 6b), combined with physicochemical research of samples confirms the hypothesis of accompanying structural fragments main contribution to isolated polysaccharides biological activity.

At the same time, polysaccharides without lignin phenolic fragments exhibit a lower ability to bind DPPH free radicals, which is also consistent with similar studies [37] and this study. However, these same samples, obtained precisely at a process temperature of 100°C, most actively capture hydroxyl radicals, reaching a maximum of ~26.4%. Such results of polysaccharide scavenging activity, although inferior to vitamin C control sample in both cases, anyway represent a possibility to tune properties of obtained hemicelluloses by varying the oxidative delignification parameters which modification could improve their potential as biologically active agents.

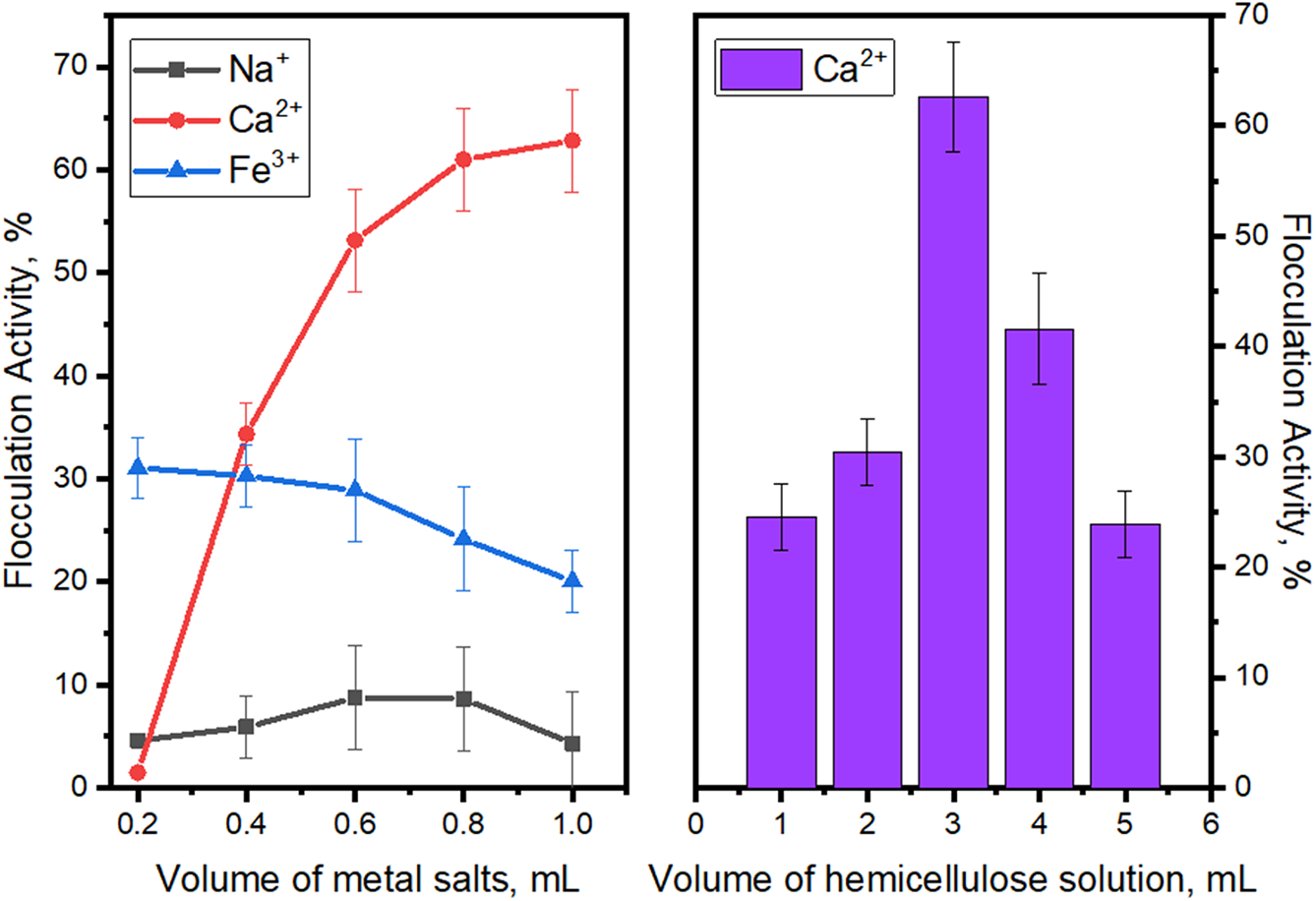

3.7 Flocculating Ability Study of the Hemicelluloses

It is widely accepted that polysaccharides are capable of binding with metal ion by exchange and/or complexation since the structure of polysaccharide is relatively open and has low steric effect for that kind of interaction [46]. Most researchers are interested in the cleansing activity of polysaccharides and the mechanisms of their interaction with inorganic salts [29,47,48]. The coagulation and flocculation processes are the inexpensive, non-toxic methods for acceleration of the suspended pollutant particles in water separation. This is why such processes are commonly used for the surface water treatment. In particular, the bivalent and trivalent salts of an aluminium and iron are predominantly applied as coagulating agents in water treatment technologies among the world [49].

Therefore, the flocculating activity of obtained hemicelluloses with the same amounts of the Na+, Ca2+ and Fe3+ (Fig. 7) salts was studied. To simulate wastewater conditions, the 10 g/L bentonite clay water dispersion with known composition [50] was used.

Figure 7: Impact of metal salts ions volume on flocculation activity in presence of hemicellulose

As it indicated above the presence of hemicellulose in bentonite dispersion supplied by rising quantities of metal salts promotes the flocculating activity. The maxima at 62.8% has been achieved using the salt containing bivalent Ca2+ salt, which is slightly even without the hemicellulose sample. Still, the absence of hemicellulose in reaction media affects aggregation of pollutant’s particles insignificantly, which results in absence of the flocculation. This fact was accepted as sedimentation processes of the bentonite particles and further used for comparison of flocculation capabilities [50].

On the contrary to Ca2+, the impact of Na+ or Fe3+ ions on hemicellulose flocculation activity is lower—their binding activity could not reach higher than 30% at their best. Such results could be connected with nature of polysaccharide-metal ion complexation—calcium ions added to the hemicellulose solution, more likely provokes the dimerization of polymer followed by an aggregation step of chain [46,51], than monovalent Na+, able to form salts without connection, or trivalent Fe3+ sterically hindering the complexation.

In this study, the effect of different contents of the catalyst (NH4)6Mo7O24 on the extraction and properties of hemicelluloses from aspen wood sawdust by oxidative delignification in the «acetic acid-hydrogen peroxide-water» medium was investigated for the first time. The maximum yield of hemicelluloses, which amounted to 62.55 wt.% (based on the total hemicelluloses content in wood), was achieved precisely at 100°C after 3 h of treatment, as well as the concentration of ammonium paramolybdate of 1.5 wt.%. The composition, structure and properties of the obtained products were identified using modern physicochemical research methods. Gas chromatography and FTIR spectroscopy methods established that the dominant polysaccharides in aspen wood are acetylated hemicelluloses of the xylan type, namely galactoxylan and glucuronoxylan. Moreover, we assume that the presence of the ammonium paramolybdate catalyst in the delignification medium allows to obtain highly purified hemicelluloses, which is crucial for their future individual application.

In addition, the parameters of the Mark-Houwink-Sakurada equation (α and K) were obtained using multidetector gel permeation chromatography, according to which it was established that the molecules of these heteropolysaccharides are sufficiently branched and have a “random coil” conformation. At the same time, higher temperature and duration of the delignification allow to obtain more homogeneous polymer structures. The developed method for extracting xylans ensures the production of water-soluble polysaccharides with active centers on the side chains of uronic acids. It is important to note that the data on the biological activity (antioxidant and flocculating) of xylans are promising and indicate the prospects for application of the plant polysaccharides in such fields as medicine and food industry in the form of biological activity additive.

Acknowledgement: This study was carried out using the equipment of the Krasnoyarsk Regional Centre for Collective Use, Krasnoyarsk Scientific Center, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation, project no. 22-73-10212, https://rscf.ru/en/project/22-73-10212/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Valentina Sergeevna Borovkova and Yuriy Nikolaevich Malyar; methodology, Valentina Sergeevna Borovkova, Vladislav Alexandrovich Ionin and Alexander Sergeevich Kazachenko; validation, Valentina Sergeevna Borovkova and Yuriy Nikolaevich Malyar; formal analysis, Alexander Sergeevich Kazachenko; investigation, Valentina Sergeevna Borovkova and Vladislav Alexandrovich Ionin; resources, Yuriy Nikolaevich Malyar; data curation, Yuriy Nikolaevich Malyar; writing—original draft preparation, Valentina Sergeevna Borovkova; writing—review and editing, Valentina Sergeevna Borovkova; visualization, Valentina Sergeevna Borovkova and Vladislav Alexandrovich Ionin; supervision, Yuriy Nikolaevich Malyar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data openly available in a public repository.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Biswal AK, Hengge NN, Black IM, Atmodjo MA, Mohanty SS, Ryno D, et al. Composition and yield of non-cellulosic and cellulosic sugars in soluble and particulate fractions during consolidated bioprocessing of poplar biomass by Clostridium thermocellum. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod. 2022;15(1):23. doi:10.1186/s13068-022-02119-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Corona B, Shen L, Reike D, Carreón JR, Worrell E. Towards sustainable development through the circular economy—A review and critical assessment on current circularity metrics. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2019;151:104498. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Uranga J, Nguyen BT, Si TT, Guerrero P, de la Caba K. The effect of cross-linking with citric acid on the properties of agar/fish gelatin films. Polymers. 2020;12(2):291. doi:10.3390/polym12020291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Krotenko TY, Kanunikova MI, Lesnikova OV, Malkova YV. Vectors of development of bioeconomics. Econ Syst. 2021;14(3):45–53. doi:10.29030/2309-2076-2021-14-3-45-53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Nesterenko MA, Komlatsky GV. Bioeconomics as a new paradigm of development. Russ J Manage. 2022;9:4. doi:10.29039/2409-6024-2021-9-4-96-100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kuznetsov BN, Sharypov VI, Grishechko LI, Celzard A. Integrated catalytic process for obtaining liquid fuels from renewable lignocellulosic biomass. Kinet Catal. 2013;54:344–52. doi:10.1134/S0023158413030105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kuznetsov BN, Sudakova IG, Garyntseva NV, Tarabanko VE, Yatsenkova OV, Djakovitch L, et al. Processes of catalytic oxidation for the production of chemicals from softwood biomass. Catal Today. 2021;375:132–44. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2020.05.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kemppainen K, Inkinen J, Uusitalo J, Nakari-Setälä T, Siika-aho M. Hot water extraction and steam explosion as pretreatments for ethanol production from spruce bark. Bioresour Technol. 2012;117:131–9. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.04.080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Sun X, Zhou Z, Tian D, Zhao J, Zhang J, Deng P, et al. Acidic deep eutectic solvent assisted mechanochemical delignification of lignocellulosic biomass at room temperature. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;234:123593. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123593. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Yelle DJ, Broda M. Characterizing the chemistry of artificially degraded Scots pine wood serving as a model of naturally degraded waterlogged wood using 1H–13C HSQC NMR. Wood Sci Technol. 2024;59(1):8. doi:10.1007/s00226-024-01618-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Donev E, Gandla ML, Jönsson LJ, Mellerowicz EJ. Engineering non-cellulosic polysaccharides of wood for the biorefinery. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1537. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.01537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Gallina G, Alfageme ER, Biasi P, García-Serna J. Hydrothermal extraction of hemicellulose: from lab to pilot scale. Bioresour Technol. 2018;247:980–91. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2017.09.155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Guo Z, Fang Y, Wang Z. High-strength hemicellulose-based conductive composite hydrogels reinforced by hofmeister effect. BioResources. 2024;19(4):7708–22. doi:10.15376/biores.19.4.7708-7722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Liu G, Shi K, Sun H. Research progress in hemicellulose-based nanocomposite film as food packaging. Polymers. 2023;15(4):979. doi:10.3390/polym15040979. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ma M, Ji X. Extraction, purification, and applications of hemicellulose. Pap Biomater. 2021;6(3):47–60. doi:10.1213/j.issn.2096-2355.2021.03.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Liu T, Ren Q, Wang S, Gao J, Shen C, Zhang S, et al. Chemical modification of polysaccharides: a review of synthetic approaches, biological activity and the structure–activity relationship. Molecules. 2023;28(16):6073. doi:10.3390/molecules28166073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Borovkova VS, Maliar YUN. Methods of isolation of wood hemicelluloses (Review). Chem Plant Raw Mater. 2024;(4):46–63. doi:10.14258/jcprm.20240415090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lu Y, He Q, Fan G, Cheng Q, Song G. Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: a review. Green Process Synth. 2021;10(1):779–804. doi:10.1515/gps-2021-0065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Başar İA, Perendeci NA. Optimization of zero-waste hydrogen peroxide—Acetic acid pretreatment for sequential ethanol and methane production. Energy. 2021;225:120324. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2021.120324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Teixeira LC, Linden JC, Schroeder HA. Simultaneous saccharification and cofermentation of peracetic acid-pretreated biomass. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2000;86:111–27. doi:10.1385/abab:84-86:1-9:111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Yuan D, Yang K, Pan S, Xiang Y, Tang S, Huang L, et al. Peracetic acid enhanced electrochemical advanced oxidation for organic pollutant elimination. Sep Purif Technol. 2021;276:119317. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2021.119317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Oh W-D, Chang VWC, Hu Z-T, Goei R, Lim T-T. Enhancing the catalytic activity of g-C3N4 through Me doping (Me=Cu, Co and Fe) for selective sulfathiazole degradation via redox-based advanced oxidation process. Chem Eng J. 2017;323:260–9. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2017.04.107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Xing D, Shao S, Yang Y, Zhou Z, Jing G, Zhao X. Mechanistic insights into the efficient activation of peracetic acid by pyrite for the tetracycline abatement. Water Res. 2022;222:118930. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2022.118930. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Ma Y, Ma J, Xia F, Lu F, Du Z, Xu J. Molybdenum-catalyzed oxidative cleavage of raw poplar sawdust into mono-aromatics and organic acid esters. Asian J Org Chem. 2019;8(8):1348–53. doi:10.1002/ajoc.201900310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Borovkova VS, Malyar YN, Sudakova IG, Chudina AI, Zimonin DV, Skripnikov AM, et al. Composition and structure of Aspen (Pópulus trémula) hemicelluloses obtained by oxidative delignification. Polymers. 2022;14(21):4521. doi:10.3390/polym14214521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Plätzer M, Ozegowski JH, Neubert RH. Quantification of hyaluronan in pharmaceutical formulations using high performance capillary electrophoresis and the modified uronic acid carbazole reaction. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1999;21(3):491–6. doi:10.1016/s0731-7085(99)00120-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Sun SL, Wen JL, Ma MG, Sun RC. Successive alkali extraction and structural characterization of hemicelluloses from sweet sorghum stem. Carbohydr Polym. 2013;92(2):2224–31. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.11.098. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ruiz-Matute AI, Hernández-Hernández O, Rodríguez-Sánchez S, Sanz ML, Martínez-Castro I. Derivatization of carbohydrates for GC and GC-MS analyses. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2011;879(17–18):1226–40. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.11.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Salehizadeh H, Yan N, Farnood R. Recent advances in polysaccharide bio-based flocculants. Biotechnol Adv. 2018;36(1):92–119. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2017.10.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Garyntseva NV, Levdansky VA, Kondrasenko AA, Skripnikov AM, Kuznetsov BN. Isolation and characterization of the hemicelluloses polysaccharides of scots pine (Pinus Sylvestris) wood. Russ J Bioorganic Chem. 2023;49(7):1596–606. doi:10.1134/S1068162023070683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Gröndahl M, Teleman A, Gatenholm P. Effect of acetylation on the material properties of glucuronoxylan from aspen wood. Carbohydr Polym. 2003;52(4):359–66. doi:10.1016/S0144-8617(03)00014-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ebringerová A, Heinze T. Xylan and xylan derivatives-biopolymers with valuable properties, 1. Naturally occurring xylans structures, isolation procedures and properties. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2000;21(9):542–56. doi:10.1002/1521-3927(20000601)21:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang M, Li Q, Qi H, Xiang Z. Significantly improve film formability of acetylated xylans by structure optimization and solvent screening. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;256:128523. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. de Paula Castanheira J, Llanos JHR, Martins JR, Costa ML, Brienzo M. Acetylated xylan from sugarcane bagasse: advancing bioplastic formation with enhanced water resistance. Polym Bull. 2024;82:1705–22. doi:10.1007/s00289-024-05597-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Liu D, Tang W, Xin Y, Wang Z-X, Huang X-J, Hu J-L, et al. Isolation and structure characterization of glucuronoxylans from Dolichos lablab L. hull. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;182:1026–36. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.04.033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Kotlyarova IA. IR spectroscopy of pine, birch and oak wood modified with monoethanolamine (N→B) trihy-droxyborate. Chem Plant Raw Mater. 2019;(2):43–49. doi:10.14258/jcprm.2019024609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Boris VN, Diganta K, Alexander Y, Nifantiev N, Yakov IY. In vitro Antioxidant activities of natural polysaccharides: an overview. J Food Res. 2024;8:78. doi:10.5539/jfr.v8n6p78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wang Z, Zhou X, Shu Z, Zheng Y, Hu X, Zhang P, et al. Regulation strategy, bioactivity, and physical property of plant and microbial polysaccharides based on molecular weight. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;244:125360. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Batsoulis AN, Nacos MK, Pappas CS, Tarantilis PA, Mavromoustakos T, Polissiou MG. Determination of uronic acids in isolated hemicelluloses from kenaf using diffuse reflectance infrared fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) and the curve-fitting deconvolution method. Appl Spectrosc. 2004;58(2):199–202. doi:10.1366/000370204322842931. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Cao S, He X, Qin L, He M, Yang Y, Liu Z, et al. Anticoagulant and antithrombotic properties in vitro and in vivo of a novel sulfated polysaccharide from marine green alga Monostroma nitidum. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(4):247. doi:10.3390/md17040247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Wang J, Wang J, Hao J, Jiang M, Zhao C, Fan Z. Antioxidant activity and structural characterization of anthocyanin-polysaccharide complexes from aronia melanocarpa. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(24):13347. doi:10.3390/ijms252413347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Dong S, Wu Y, Luo Y, Lv W, Chen S, Wang N, et al. Study on the extraction technology and antioxidant capacity of Rhodymenia intricata Polysaccharides. Foods. 2024;13(23):3964. doi:10.3390/foods13233964. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Homayouni-Tabrizi M, Asoodeh A, Soltani M. Cytotoxic and antioxidant capacity of camel milk peptides: effects of isolated peptide on superoxide dismutase and catalase gene expression. J Food Drug Anal. 2017;25(3):567–75. doi:10.1016/j.jfda.2016.10.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Fernandes PAR, Coimbra MA. The antioxidant activity of polysaccharides: a structure-function relationship overview. Carbohydr Polym. 2023;314:120965. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.120965. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Hu S, Yin J, Nie S, Wang J, Phillips GO, Xie M, et al. In vitro evaluation of the antioxidant activities of carbohydrates. Bioact Carbohydr DIET Fibre. 2016;7(2):19–27. doi:10.1016/j.bcdf.2016.04.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Joly N, Ghemati D, Aliouche D, Martin P. Interaction of metal ions with mono-and polysaccharides for wastewater treatment: a review. Nat Prod Chem Res. 2020;8(3):373. doi:10.35248/2329-6836.20.8.373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Ho YC, Norli I, Alkarkhi AFM, Morad N. Analysis and optimization of flocculation activity and turbidity reduction in kaolin suspension using pectin as a biopolymer flocculant. Water Sci Technol. 2009;60(3):771–81. doi:10.2166/wst.2009.303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Wu J-Y, Ye H-F. Characterization and flocculating properties of an extracellular biopolymer produced from a Bacillus subtilis DYU1 isolate. Process Biochem. 2007;42(7):1114–23. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2007.05.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Asharuddin SM, Othman N, Al-Maqtari QA, Al-towayti WAH, Arifin SNH. The assessment of coagulation and flocculation performance and interpretation of mechanistic behavior of suspended particles aggregation by alum assisted by tapioca peel starch. Environ Technol Innov. 2023;32:103414. doi:10.1016/j.eti.2023.103414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Ionin VA, Malyar YN, Borovkova VS, Zimonin DV, Gulieva RM, Fetisova OY. Inherited structure properties of larch arabinogalactan affected via the TEMPO/NaBr/NaOCl oxidative system. Polymers. 2024;16(11):1458. doi:10.3390/polym16111458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Manunza B, Deiana S, Gessa C. Molecular dynamics study of Ca-polygalacturonate clusters. J Mol Struct: THEOCHEM. 1996;368:27–9. doi:10.1016/S0166-1280(96)90529-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools