Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Biomass-Derived Hard Carbon Anodes from Setaria Viridis for Na-Ion Batteries

1 College of Materials and Energy, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangdong, 510006, China

2 Guangzhou Liangyue Materials Technology Co., Ltd., Guangdong, 510006, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yonggang Min. Email: ; Jintao Huang. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(12), 2297-2308. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0098

Received 02 May 2025; Accepted 18 September 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

Biomass-derived hard carbon has gradually become an important component of sodium-ion batteries’ anodes. In this work, Setaria viridis, a widely distributed plant, was employed as a precursor to synthesize hard carbon anodes for sodium-ion batteries. However, the hard carbon derived from raw precursors contains substantial impurities, which limit the performance of the obtained hard carbon. With different chemical etching processes, the content of impurities in the resultants was reduced to varying degrees. The optimized hard carbon anode delivered a reversible capacity of 198 mAh g−1 at a current density of 0.04 A g−1. This work shows the effects of impurities, especially the Si-based matter, on the formation of microstructure and electrochemical performance of the regulated hard carbon, which broadens the application of the biomass-derived materials. This work also provides a strategy for processing impurity-rich biomass precursors to develop hard carbon anodes for sodium-ion batteries (SIBs).Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileRecently, the development of new energy vehicles has intensified the shortage of lithium resources [1]. Additionally, the application of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) is inherently limited by uneven lithium resource distribution, poor low-temperature performance, and high cost [2]. Under these circumstances, sodium-ion batteries (SIBs) are considered one of the most promising candidates for extensive energy storage systems because of the abundance of sodium, lower cost, and similar electrochemical characteristics to LIBs [3]. However, the sodium-ion (0.102 nm) is much larger than the lithium-ion (0.072 nm), making it unsuitable for intercalation into graphite anode [4–7]. Therefore, the development of alternative anode materials specifically suited for SIBs is urgently needed.

Biomass is a renewable material that has found widespread applications in many fields [8–12]. After pyrolysis, it can be carbonized into the hard carbon (HC), which is regarded as one of the most promising anodes for SIBs [13–16]. Among various types of HC, biomass-derived HC has attracted considerable attention due to its sustainability and low cost [17–19]. Generally, HC derived from biomass via high-temperature pyrolysis retains many structural features of the original precursor, resulting in diverse morphologies and heteroatom doping. However, the incomplete graphitization structure of hard carbon also leads to poor initial Coulombic efficiency (ICE) and cycling stability, prompting extensive research into its optimization [12,20,21]. Compared to precursors like polymers and small molecules, which consist of purified components, biomass is composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, starch, and other impurities such as inorganic minerals [22]. Therefore, precise control over the composition and structure of biomass-derived HC is essential for developing high-performance anodes.

The effects of different compositions on structure and performance have been extensively investigated in numerous works. Most biomass-derived hard carbons are primarily derived from lignin, hemicellulose, cellulose, and starch [21,23–26]. To enhance the plateau capacity, which is strongly correlated with the volume of closed pores in hard carbon [27], the component ratio in biomass precursors should be properly controlled. High-crystallinity cellulose tends to promote an overly ordered graphitic structure, whereas the partial retention of more amorphous components such as lignin and hemicellulose can suppress excessive graphitization during high-temperature carbonization [28,29]. These carbonized components (cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin) form a porous structure consisting of short-range graphitic domains that surround pores. However, the effects of inorganic matter on the performance of hard carbon anodes have received limited attention. The inorganic matter that remains in precursors after pyrolysis not only clogs the pores [22,30], but also influences the formation of the material’s structure during pyrolysis, thereby affecting the electrochemical performance through interactions with the electrolyte [31,32].

In this work, we used seeds of Setaria viridis (SV) to fabricate a hard carbon anode for SIBs. SV is a widespread cereal plant whose stems are valued in traditional Chinese medicine and whose cilia have been explored as anode materials [33–35]. However, the seeds of this grain plant remain underutilized. Thanks to their low cost and natural abundance, SV seeds are a promising feedstock for large-scale anode production. However, direct pyrolysis in air yielded a high ash content (Table S1), indicating substantial inorganic impurities. This high impurity content necessitates an investigation into how these non-carbonaceous species influence electrochemical performance. Meanwhile, due to the low carbon yield, a low-temperature pre-oxidation process was adopted before carbonization to optimize the sample [36,37]. Subsequently, chemical etching was employed to tune the inorganic content and to elucidate its impact on anode performance. Finally, the resultant material with appropriate chemical etching showed an optimized performance of 198 mAh g−1 reversible capacity at a current density of 0.04 A g−1.

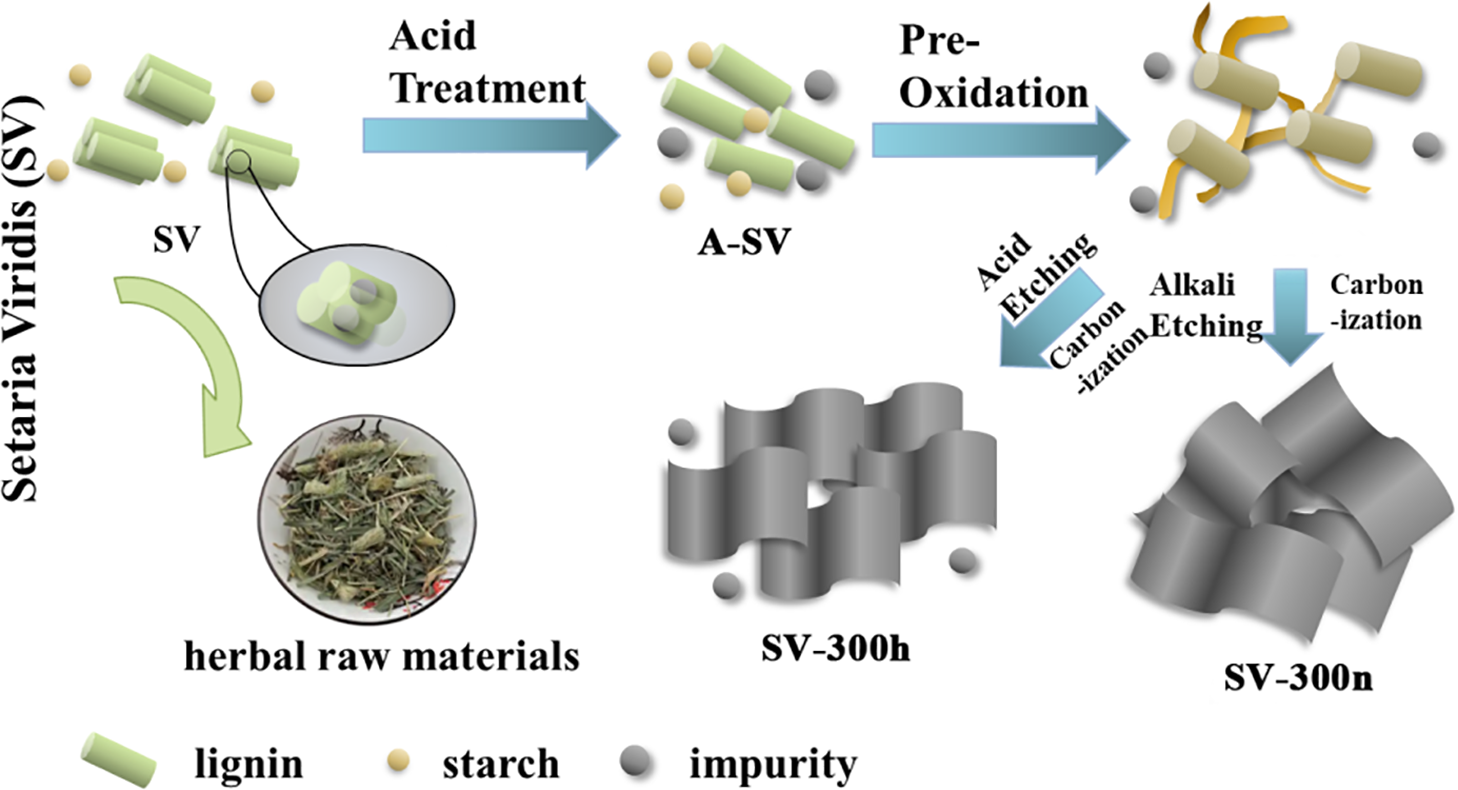

The seeds of Setaria viridis (SV, purchased and collected from Suqian, China) were washed by ultrasonic cleaning in deionized water for 1 h, and the cleaned sample was dried in a vacuum oven at 80°C for 12 h. After being ground into powder, the sample was acid-washed with 1 M HCl at 40°C for 1 h. Subsequently, the acid-treated SV (A-SV) was pre-oxidized in a muffle furnace at 300°C for 2 h to stabilize the structure. The pre-oxidation was carried out in air to enhance cross-linking. Following the chemical etching process, the samples were carbonized at 1300°C for 2 h under an Ar atmosphere. To achieve different component ratios, the pre-oxidized A-SV was separately treated with chemical etching using acidic and alkaline agents. The sample treated in 1 M HCl solution for 2 h was denoted as SV-300h, while the sample treated in 1 M NaOH solution for 2 h at 70°C was denoted as SV-300n, where ‘h’ means HCl treatment and ‘n’ means NaOH treatment.

2.2 Materials Characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, ZEISS, GEMINI 1, Oberkochen, Germany) was used to obtain the microstructure and elemental distribution images of SV-derived hard carbon. The phase assemblages of derived hard carbons were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku, Smart Lab, Tokyo, Japan). The biomass precursors and acid-treated intermediate materials were tested by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Nicolet 6700, Waltham, MA, USA) to identify the functional groups of biomass precursors and acid-treated intermediates. Thermalgravimetric analyzer (TGA, METTLER, Thermogravimetric Analysis/Differential Scanning Calorimetry, Columbus, OH, USA) was used to evaluate the thermal stability of the biomass materials. The surface chemistry and specific surface areas of the carbonized samples were quantified using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Scientific, K-Alpha) and aperture analyzer (ASAP2460, Micromeritics Co., Ltd., Hexton, UK), respectively. The molecular structure of the resulting hard carbons was characterised by LabRAM HR Evolution micro-Raman spectrometer (HORIBA Jobin Yvon, Palaiseau, France) using a Coherent laser (532 nm) with a 1% filter.

2.3 Electrochemical Measurements

The SV-derived hard carbons were used to fabricate working electrodes for half-cell tests. The samples were mixed with conductive carbon black (Timcal super P LI, KJ Group, Tokyo, Japan) and polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF, AkemaHSV900) at a weight ratio of 8:1:1 using N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP, MACKLIN, Shanghai, China) as solvent. After coating it onto Cu foil and drying at 80°C for 12 h, the obtained electrodes were cut into 12 mm diameter pieces, and subsequently assembled with electrolyte (1.0 M NaClO4 in ethylene carbonate/polycarbonate = 1:1 vol% with 5% fluoroethylene carbonate, Canrd, Guangdong, China), sodium metal as cathode.

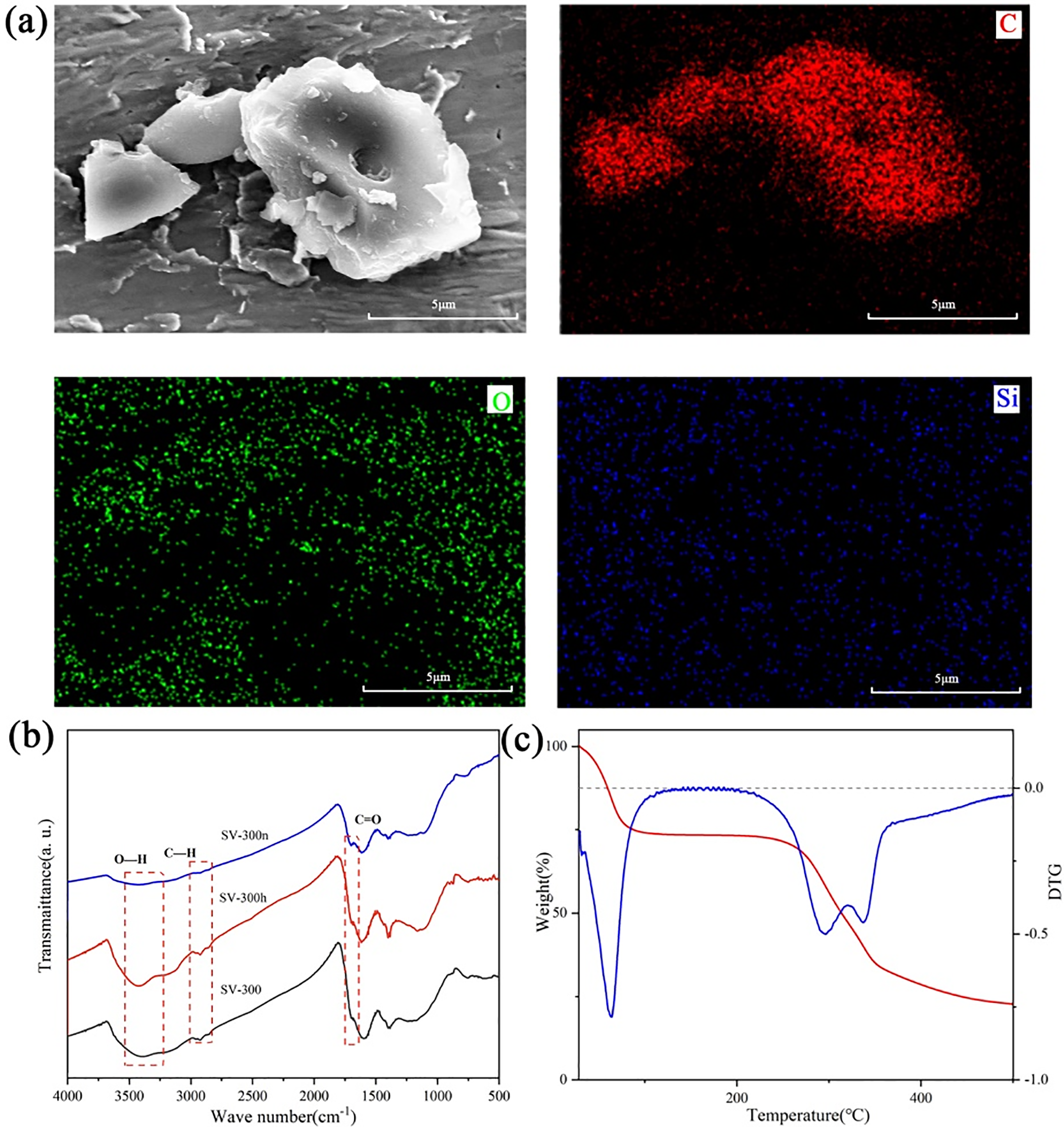

The synthesis of SV-derived hard carbon is illustrated in Fig. 1. To explore the components of the raw materials, the seeds of SV were ground into powder and tested by FTIR, shown in Fig. S1. It is clear that the absorption peaks at 1607, 1520, and 1430 cm−1, which correspond to the aromatic ring stretching vibrations in lignin molecules, and 1248, 1225 cm−1 correspond to the C–C and C–O stretching peaks of lignin. There were additional absorption peaks at 1430, 910, 851, and 771 cm−1, which belong to starch in the seeds. To further study the effect of chemical etching process on the molecular structure, the samples with different pre-treatments were tested by FTIR before carbonization (Fig. 2b). The results show SV-300 and SV-300h have the similar molecular structure, whereas SV-300n shows weaker O–H (~3400 cm−1) and aliphatic C–H (~2930 cm−1) bands, consistent with a more condensed or aromatic structure.

Figure 1: The preparation processes of the SV-derived hard carbon anode materials

Figure 2: (a) SEM and elemental mapping images of the carbonized samples with alkali etching treatment. (b) The FTIR spectra of pre-oxidized samples with different etching processes. (c) TG/DTG curves under nitrogen of the pristine SV

The thermal stability of SV was characterized by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) as shown in Fig. 2c. There were apparent stepwise mass-loss steps in the testing interval: (1) The water in the sample evaporated below 100°C; (2) Subsequently, the breaking of glycosidic bonds and a series of condensation reactions of the starch molecules occurred between 220 and 350°C; (3) Finally the residual carbonaceous intermediate gradually decomposed its oxygen-containing functional groups and formed carbon material between 350 and 500°C. Simultaneously, it is common to use thermogravimetric and derivative thermogravimetric analysis (TG/DTG) to optimize the temperature of the pre-oxidation process [38]. In this work, the pre-treatment temperature was set at 300°C in an air atmosphere to achieve an adequate degree of cross-linking and introduce surface oxygen functional groups. As seen in Fig. 2a, the carbonized samples generally presented as stable bulk and retained a large number of surface oxygen functional groups, which could be attributed to the pre-oxidation process.

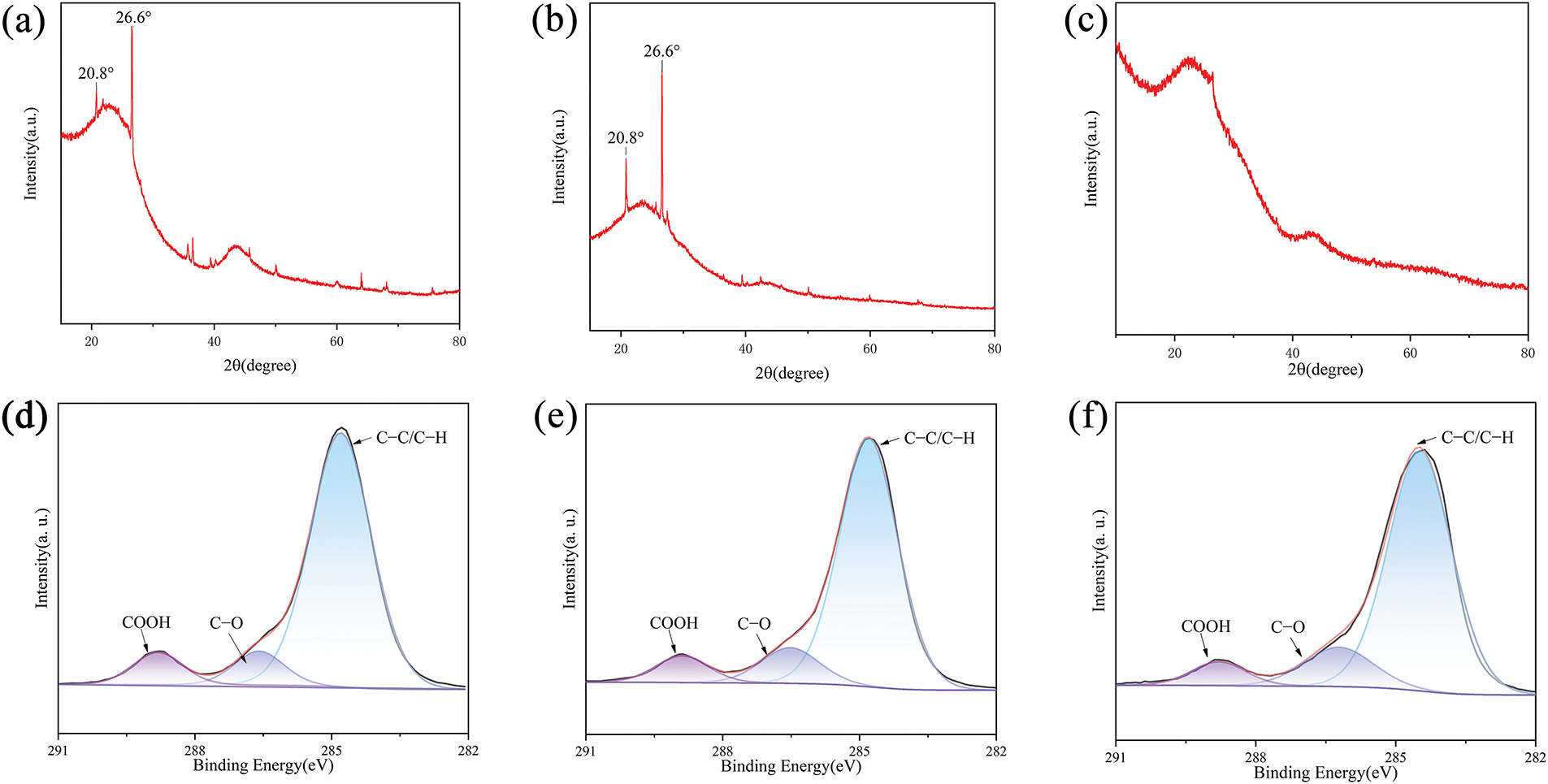

The high impurity content in the intermediate samples could not be ignored, as it could substantially compromise the performance of the resultant anodes. After the chemical etching processes prior to carbonization, the impurities were significantly reduced while the primary structural features were retained. As shown in Fig. 3a–c, there are distinct peaks at 20.8° and 26.6° that belong to quartz phase SiO2, the predominant impurity retained post-carbonization. Meanwhile, the alkali etching proved more effective than the acid or no etching in eliminating impurities and preserving the original structure. However, considering the absence of an evident Si-based phase in the pre-carbonization XRD spectrum (seen in Fig. S2), it is possible that certain Si-containing constituents transformed into SiO2 during the pyrolysis process. Moreover, all samples displayed distinct diffraction peaks at ~23° and 43°, corresponding to the (002) and (100) crystal planes of graphite microcrystals, respectively. The interlayer spacings of samples were determined to be 0.362, 0.372, and 0.374 nm for SV-300, SV-300h, and SV-300n. Notably, SV-300 exhibited particles with partial melting and foaming, which could be attributed to the catalytic effect of SiO2 during carbonization, as seen in Fig. S3.

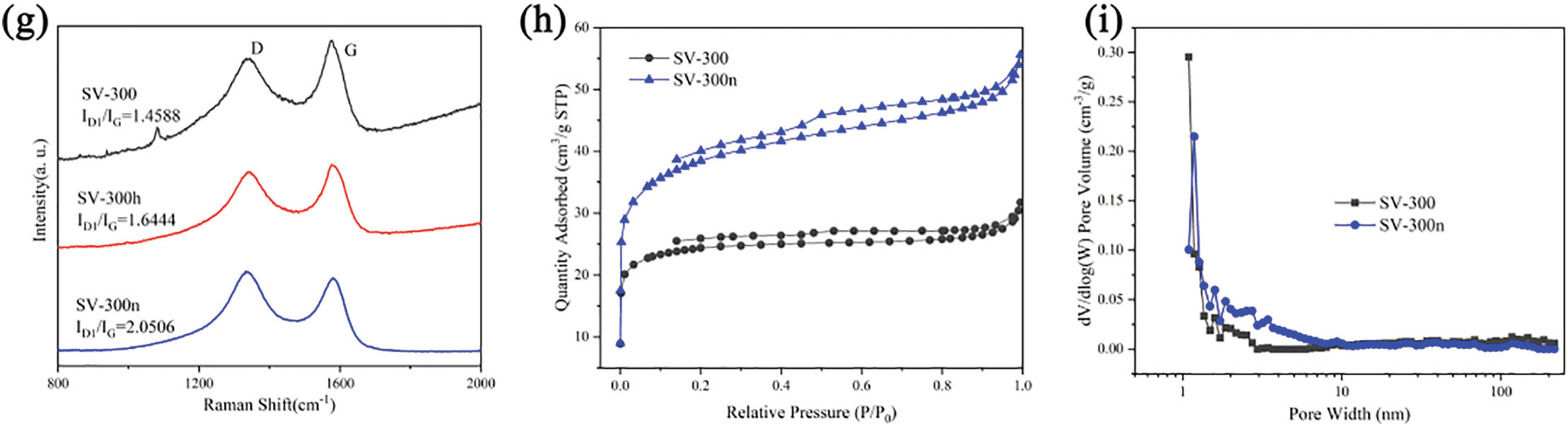

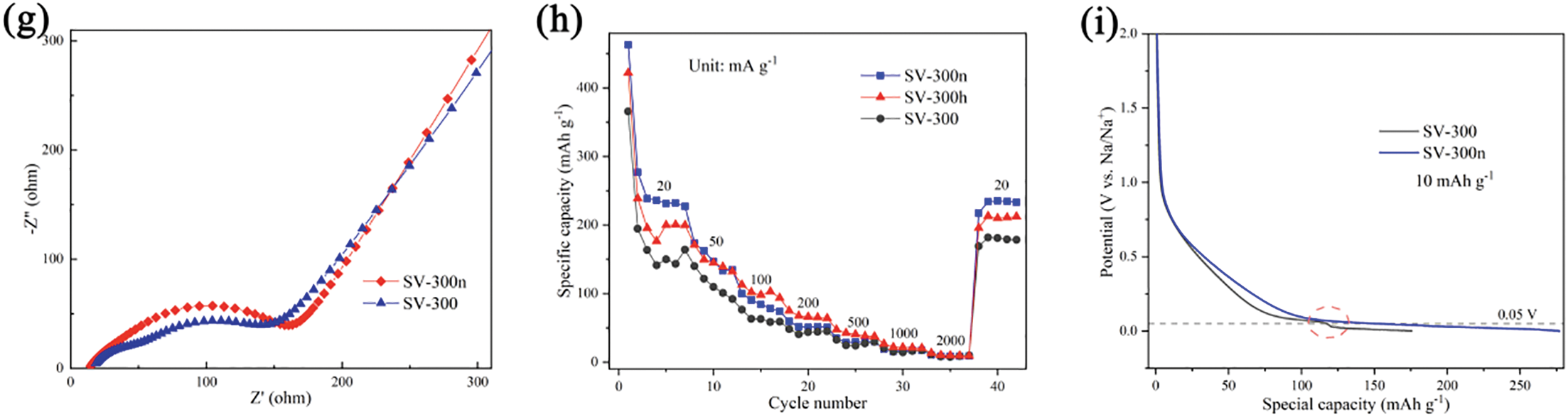

Figure 3: The effects of chemical etching on the derived hard carbon in XRD (a) pristine sample, (b) acid etching samples, (c) alkali etching samples. And (d–f) the C1s fitting results of SV-300, SV-300h, and SV-300n, respectively. (g) Raman spectra and ID/IG of samples. (h,i) The specific surface area and pore volume of SV-300 and SV-300n tested by BET

As shown in Fig. 3d–f, the surface functional groups of SV-300 and SV-300n were characterized by XPS. In the C 1s peaks, binding energies of C–C/C=C, C–O, and COOH bonds were observed at 284.8, 286.4, and 288.9 eV, respectively. Analysis from the C 1s peaks showed that all samples exhibited a certain degree of oxidation due to pre-oxidation. Additionally, the effects of chemical etching on the surface oxygen functional groups were very mild, as revealed by O1s peaks, which also yielded similar results, seen in Fig. S4. Thus, the chemical etching did not affect the surface properties of the samples.

The effects of chemical etching on the degree of graphitization were further characterized by Raman spectroscopy. Two characteristic carbon bands were observed at approximately 1349 and 1598 cm−1, corresponding to the disordered sp3 carbon (D band) and the ordered sp2 carbon (G band), respectively. As shown in Fig. 3g, the peak area intensity ratio of the D-band to the G-band (ID1/IG) decreased from 2.0506 for SV-300n to 1.644 for SV-300h and 1.4588 for SV-300. Additionally, SV-300 exhibited a few serrated peaks, likely due to impurities in the sample. These findings could indicate that the chemical etching efficiently decreases the ratio of inorganic matter that catalyzes graphitization of the carbonaceous matrix, thereby decreasing the degree of graphitization in SV-300n and SV-300h.

The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms and pore structures of SV-300 and SV-300n were presented in Fig. 3h,i. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) specific surface areas of SV-300 and SV-300n based on N2 adsorption were 78.9 and 127.9 m2 g−1, respectively. The type of isotherm was changed with the alkali etching process from I type to IV type, as seen in the expansion of the hysteresis loop and the increase of slope in the middle P/P0 (Fig. 3h). These changes were associated with capillary condensation taking place in mesopores and adsorption on the surface. The pore size distributions were estimated using the N2-density function theory model. The alkali etching process notably increased the pore volume in the 2–10 nm range (Fig. 3i). Although the process enlarged the specific surface area, it promoted the formation of mesopores, thereby boosting the hard carbon anode’s capacity.

3.2 Electrochemical Properties

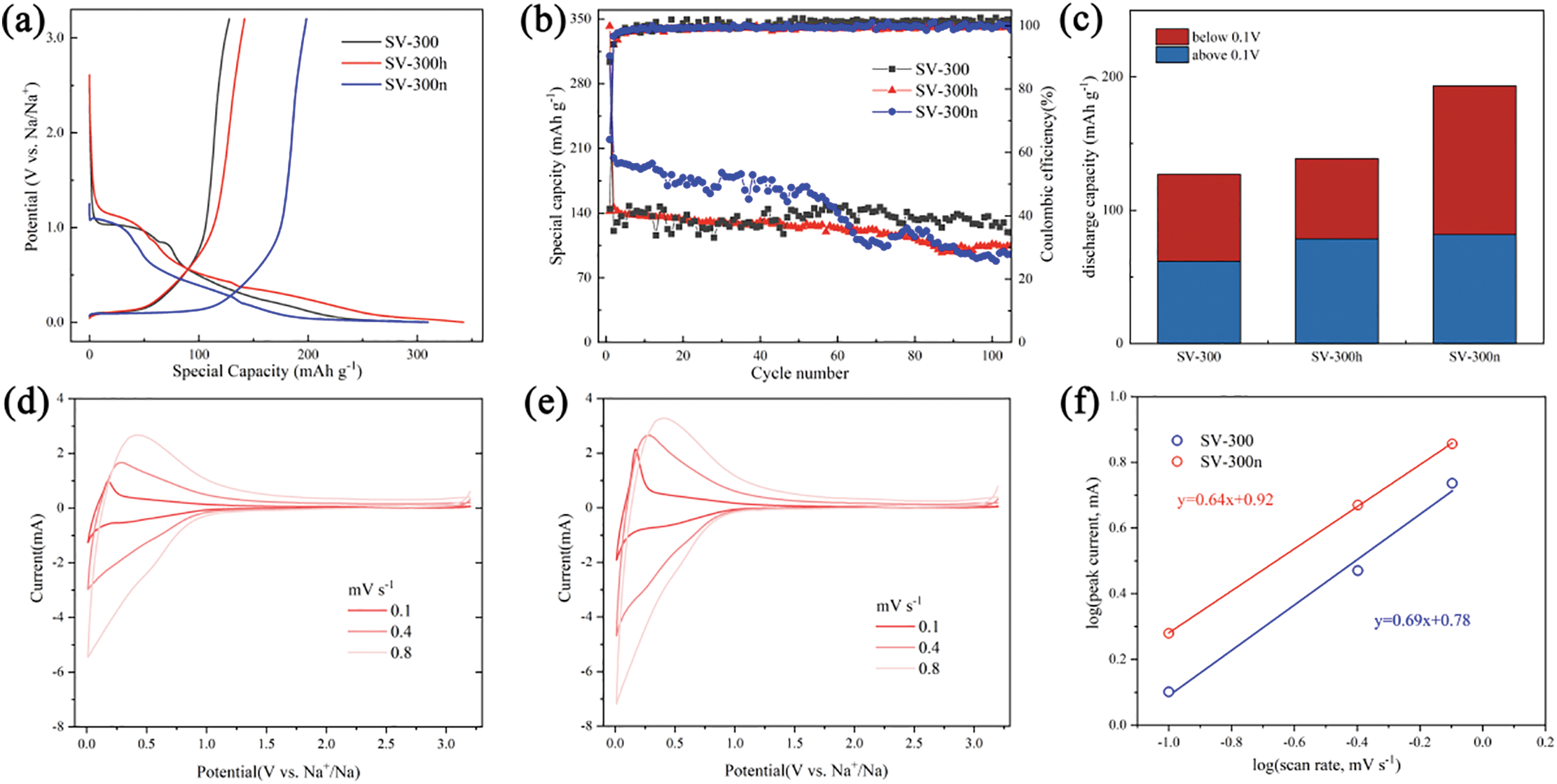

The electrochemical measurements concretely demonstrated the effects of chemical etching and the impact of impurities removal on performance. Fig. 4a,c showed the results of charge-discharge tests at a current density of 0.04 A g−1 within a potential window of 0.01–3.2 V, as well as the capacity distribution between plateau and slope regions during the 5th cycle. Notably, an additional discharge plateau around 0.8 V was observed only occurring in the non-etched sample (SV-300), which may be caused by some undetected inorganic impurities also presented in another SV-300 sample (Fig. S5). The sample without chemical etching treatment (SV-300) exhibited the lowest reversible capacity of 127 mAh g−1, with a plateau capacity of 65 mAh g−1. While the acid-etched sample (SV-300h) exhibited the most initial discharging capacity of 342 mAh g−1 due to the more sodium-ion active sites exposed by acid etching, it also had the lowest plateau capacity of 60 mAh g−1. Compared to the samples above, the alkali-etched sample (SV-300n) possessed the most reversible capacity of 193 mAh g−1 and the highest ratio of plateau capacity of 111 mAh g−1. Additionally, the SV-300n showed the best ICE of 64% compared to 42% for SV-300 and 41% for SV-300h. This indicated that alkali etching could increase the reversible capacity by removing Si-based matter, which creates more pores. Fig. 4b showed cycling performance of the non-etched sample (SV-300), the acid-etched sample (SV-300h), and the alkali-etched sample (SV-300n) at a current density of 0.04 A g−1. The alkali-etched sample (SV-300n) displayed the best capacity during the first 60 cycles but the worst stability, with only 45% capacity retained after 100 cycles. The non-etched and acid-etched samples (SV-300 and SV-300h) both showed relatively better cycle performance. This might be due to the excessive etching process destabilizing the pore structure. Notably, an obvious capacity decay around 0.05 V was observed in the discharging curve after 60 cycles (Fig. S6), which is discussed in detail below.

Figure 4: (a) The charge-discharge curves of derived hard carbon at the first cycle. (b) The cycle test of SV-300, SV-300h, and SV-300n at 0.04 A g−1. (c) The potential contribution of slope capacity (>0.1 V) and plateau capacity (<0.1 V) after 5 cycles. (d,e) CV curves at different scan rates of 0.1, 0.4, 0.8 mV s−1 correspond to SV-300 and SV-300n, respectively. (f) The anodic linear relationship between log (peak current) and log (scan rate) of SV-300 and SV-300n for calculating the exponent (b values) in half cells. (g) EIS spectra of SV-300 and SV-300n in the 1st cycle. (h) The rate performances of SV-300, SV-300h, and SV-300n, respectively. (i) The discharging capacity hiatus around 0.05 V at low current density

The rate performance was evaluated over 5 cycles at current densities of 20, 50, 100, 200, 500, 1000, 2000 mA g−1, as shown in Fig. 4h. The results indicated that all three samples exhibited similar trends in the test, yet the SV-300n achieved the best specific capacities with 233, 149, 79, 52, 30, 17, 9 mAh g−1 at the respective current densities. Notably, SV-300n maintained a specific capacity of 230 mAh g−1 after returning to 20 mA g−1, highlighting its good electrochemical reversibility. Remarkably, at a relatively lower discharge current density (10 mA g−1), SV-300 would exhibit a slight capacity drop around 0.05 V (Fig. 4i), which was similar to the discharging curve of SV-300n after 50 cycles. Following the “Absorption-intercalation-filling” model [3], the capacity below 0.1 V was owed to both the pore filling and sodium-ion intercalation. Compared to SV-300n (1st), the capacity decrease could be mainly attributed to the reduced pore volume in the 2–10 nm range. This is because the filling of closed pores with Na+ below 0.1 V enhances its diffusion coefficient, which makes the discharge behavior near 0.01 V predominantly controlled by pore filling [39].

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was employed to investigate the electrochemical performance of the hard carbon derived from SV. As shown in Fig. S7, the first cycle exhibited a cathodic peak at 0.3 V, corresponding to the formation of a solid electrolyte interphase (SEI). The narrow peak at 0.1 V for SV-300n was attributed to the intercalation and de-intercalation of sodium-ions. The electrochemical kinetics of half-cell batteries with SV-300 and SV-300n anodes were further examined by CV tests at different scan rates (Fig. 4d,e). The SV-300n exhibited a higher intensity and more symmetrical redox peaks at ≈0.1 V compared to SV-300, endowing it with greater plateau capacity below 0.1 V. To explore the sodiation/desodiation process of the samples, the equations between peak current (i) and scan rate (ν) were led out:

here, a and b are adjustable parameters. The b value, calculated from the slope of the log(i) vs. log(v) plot, indicates the charging/discharging process of the anode. When a b value is close to 1, it indicates a capacitive-controlled process, while 0.5 suggests a semi-infinite diffusion. The anodic fitting results, presented in Fig. 4f, showed the b values of 0.69 and 0.64 for SV-300 and SV-300n, respectively. These were attributed to the greater contribution of the increased pore volume compared to the increase in specific surface area in SV-300n.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was further conducted on these samples. The fitting results of SV-300 and SV-300n were shown in Fig. 4g. The SV-300 showed two distinct semicircles that may be attributed to residual mineral impurities. These non-conductive impurities hindered charge transfer in the high-frequency region, leading to charge transfer (Rct) values of 113 Ω and 85 Ω for SV-300n and SV-300, respectively. The alkali etching process removed the impurities blocked in pores that gradually close during the carbonization process. The resulting closed pores create additional sodium-ion storage sites but also increase resistance during sodium-ion intercalation and de-intercalation, thereby raising the Rct of alkali-etched samples. Further investigation of the impedance variation over cycles (Fig. S8) revealed that the Rct of SV-300 decreased from 85 Ω to 62 Ω after 50 cycles, likely due to the stabilization of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer.

In summary, the seeds of Setaria viridis were developed into a kind of biomass-derived hard carbon anode for SIBs. Through various chemical etching processes, this starch-rich biomass precursor was converted into hard carbon with distinct microstructures. This work revealed the compositional changes of etching processes and their effects on the carbonization structure, and the structure-performance relationship was also studied.

With the optimized process, the derived hard carbon anode exhibited an enhanced reversible capacity of 198 mAh g−1 in a half cell. However, the chemical etching processes weakened the stability of the microstructure in graphitic domains, resulting in poor cycle performance compared with the non-etched ones. This indicated that to obtain the hard carbon possessing both high capacity and stability, it is important to decrease the content of impurities in a milder manner.

Furthermore, given the high ratio of impurity in the precursor, these findings have significant implications for the application of biomass, particularly regarding the removal of impurities from Si-containing materials.

Acknowledgement: This research was conducted at the Key Laboratory of Graphene and Emerging Materials at Guangdong University of Technology (Guangzhou, China). The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Foshan Introducing Innovative and Entrepreneurial Teams (No. 1920001000108), and Guangzhou Hongmian Project (No. HMJH-2020-0012).

Funding Statement: This research was financially supported by Foshan Introducing Innovative and Entrepreneurial Teams (No. 1920001000108), and Guangzhou Hongmian Project (No. HMJH-2020-0012).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jingxiang Meng, Xin Liu, Songyi Liao; data collection: Jingxiang Meng, Wenping Zeng; analysis and interpretation of results: Jingxiang Meng, Songyi Liao, Jintao Huang; draft manuscript preparation: Jianjun Song, Yonggang Min. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Materials.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0098/s1.

References

1. Li Z, Wang C, Chen J. Supply and demand of lithium in China based on dynamic material flow analysis. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2024;203:114786. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2024.114786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yang J, Wang M, Ruan J, Li Q, Ding J, Fang F, et al. Research progress in non-aqueous low-temperature electrolytes for sodium-based batteries. Sci China Chem. 2024;67(12):4063–84. doi:10.1007/s11426-024-1964-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chu Y, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Li Q, Jia Y, Dong X, et al. Reconfiguring hard carbons with emerging sodium-ion batteries: a perspective. Adv Mater. 2023;35(31):2212186. doi:10.1002/adma.202212186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Chen X, Tian J, Li P, Fang Y, Fang Y, Liang X, et al. An overall understanding of sodium storage behaviors in hard carbons by an adsorption-intercalation/filling hybrid mechanism. Adv Energy Mater. 2022;12(24):2200886. doi:10.1002/aenm.202200886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kim H, Hyun JC, Kim DH, Kwak JH, Lee JB, Moon JH, et al. Revisiting lithium-and sodium-ion storage in hard carbon anodes. Adv Mater. 2023;35(12):2209128. doi:10.1002/adma.202209128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Alvin S, Cahyadi HS, Hwang J, Chang W, Kwak SK, Kim J, et al. Revealing the intercalation mechanisms of lithium, sodium, and potassium in hard carbon. Adv Energy Mater. 2020;10(20):2000283. doi:10.1002/aenm.202000283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Bartoli M, Piovano A, Elia GA, Meligrana G, Pedraza R, Pianta N, et al. Pristine and engineered biochar as Na-ion batteries anode material: a comprehensive overview. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2024;194:114304. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2024.114304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. He Q, Chen H, Chen X, Zheng J, Que L, Yu F, et al. Tea-derived sustainable materials. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(11):2310226. doi:10.1002/adfm.202310226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Saule Z, Shynggyskhan S, Suleimenova M, Azat S, Sailaukhanuly Y, Tulepov M. Enhanced adsorption of mercury and methylene blue using silver and surface modified zeolite-NaX derived from rice husk. Eng Sci. 2024;31:1241. doi:10.30919/es1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Das S, Goswami T, Ghosh A, Bhat M, Hait M, Jalgham RT, et al. Biodiesel from algal biomass: renewable, and environment-friendly solutions to global energy needs and its current status. ES Gen. 2024;4(2):1133. doi:10.30919/esg1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sivasankarapillai VS, Sundararajan A, Eswaran M, Dhanusuraman R. Hierarchical porous activated carbon derived from callistemon viminalis leaf biochar for supercapacitor and methylene blue removal applications. ES Energy Environ. 2024;24:1124. doi:10.30919/esee1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liu Y, Chen Y, Liu H, Chen W, Lei Z, Ma C, et al. Controlled-release of plant volatiles: new composite materials of porous carbon-citral and their fungicidal activity against exobasidium vexans. J Renew Mater. 2023;11(2):811–23. doi:10.32604/jrm.2022.022594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Qiu Y, Su Y, Jing X, Xiong H, Weng D, Wang JG, et al. Rapid closed pore regulation of biomass-derived hard carbons based on flash joule heating for enhanced sodium ion storage. Adv Funct Mater. 2025;35(29):2423559. doi:10.1002/adfm.202423559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Li X, Zhang S, Tang J, Yang J, Wen K, Wang J, et al. Structural design of biomass-derived hard carbon anode materials for superior sodium storage via increasing crystalline cellulose and closing the open pores. J Mater Chem A. 2024;12(32):21176–89. doi:10.1039/d4ta03284e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wu C, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Xu H, He X, Wu X, et al. Hard carbon for sodium-ion batteries: progress, strategies and future perspective. Chem Sci. 2024;15(17):6244–68. doi:10.1039/D4SC00734D. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Wang J, Xi L, Peng C, Song X, Wan X, Sun L, et al. Recent progress in hard carbon anodes for sodium-ion batteries. Adv Energy Mater. 2024;26(8):2302063. doi:10.1002/adem.202302063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Alvira D, Antorán D, Manyà JJ. Plant-derived hard carbon as anode for sodium-ion batteries: a comprehensive review to guide interdisciplinary research. Chem Eng J. 2022;447(6058):137468. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2022.137468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhen Y, Chen Y, Li F, Guo Z, Hong Z, Titirici MM. Ultrafast synthesis of hard carbon anodes for sodium-ion batteries. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2021;118(42):e2111119118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2111119118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Zhou L, Cui Y, Niu P, Ge L, Zheng R, Liang S, et al. Biomass-derived hard carbon material for high-capacity sodium-ion battery anode through structure regulation. Carbon. 2025;231(8):119733. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2024.119733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li F, Mei R, Wang N, Lin X, Mo F, Chen Y, et al. Regulating the closed pore structure of biomass-derived hard carbons towards enhanced sodium storage. Carbon. 2024;230(5):119556. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2024.119556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wu XS, Dong XL, Wang BY, Xia JL, Li WC. Revealing the sodium storage behavior of biomass-derived hard carbon by using pure lignin and cellulose as model precursors. Renew Energy. 2022;189:630–8. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2022.03.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Beda A, Le Meins JM, Taberna PL, Simon P, Ghimbeu CM. Impact of biomass inorganic impurities on hard carbon properties and performance in Na-ion batteries. Sustain Mater Technol. 2020;26(18):e00227. doi:10.1016/j.susmat.2020.e00227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhong B, Liu C, Xiong D, Cai J, Li J, Li D, et al. Biomass-derived hard carbon for sodium-ion batteries: basic research and industrial application. ACS Nano. 2024;18(26):16468–88. doi:10.1021/acsnano.4c03484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lu B, Lin C, Xiong H, Zhang C, Fang L, Sun J, et al. Hard-carbon negative electrodes from biomasses for sodium-ion batteries. Molecules. 2023;28(10):4027. doi:10.3390/molecules28104027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Xie LJ, Tang C, Song MX, Guo XQ, Li XM, Li JX, et al. Molecular-scale controllable conversion of biopolymers into hard carbons towards lithium and sodium ion batteries: a review. J Energy Chem. 2022;72:554–69. doi:10.1016/j.jechem.2022.05.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kumar A, Arora N, Rawat S, Mishra RK, Deshpande A, Hotha S, et al. Biomass-based carbon material for next-generation sodium-ion batteries: insights and SWOT evaluation. Environ Res. 2025;279(2):121854. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2025.121854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Liu Y, Yin J, Wu R, Zhang H, Zhang R, Huo R, et al. Molecular engineering of pore structure/interfacial functional groups toward hard carbon anode in sodium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2025;75(1):104008. doi:10.1016/j.ensm.2025.104008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Shang L, Yuan R, Liu H, Li X, Zhao B, Liu X, et al. Precursor screening of fruit shell derived hard carbons for low-potential sodium storage: a low lignin content supports the formation of closed pores. Carbon. 2024;223(41):119038. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2024.119038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Tang Z, Zhang R, Wang H, Zhou S, Pan Z, Huang Y, et al. Revealing the closed pore formation of waste wood-derived hard carbon for advanced sodium-ion battery. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):6024. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39637-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Xia P, Chen F, Lei W, Pan Y, Ma Z. Long cycle performance folium cycas biochar/S composite material for lithium-sulfur batteries. Ionics. 2020;26(1):183–9. doi:10.1007/s11581-019-03169-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Dong G, Cheng Y, Zhang H, Hu X, Xu H, Abdelmaoula AE, et al. Molecular-scale interaction between sub-1 nm cluster chains and polymer for high-performance solid electrolyte. Energy Storage Mater. 2024;69:103381. doi:10.1016/j.ensm.2024.103381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Gao Y, Chen R, Jiang C, Bai Y, Qiu X, Zou Z. Tuning the microstructure of biomass-derived hard carbons by controlling the impurity removal process for enhanced Na ion storage performance. Diam Relat Mater. 2024;148:111388. doi:10.1016/j.diamond.2024.111388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Lv J, Wang W, Dai T, Liu B, Liu G. Experimental study on the effect of soil reinforcement and slip resistance on shallow slopes by herbaceous plant root system. Sustainability. 2024;16(8):3475. doi:10.3390/su16083475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kwon EY, Kim JW, Choi JY, Hwang K, Han Y. Setaria viridis ethanol extract attenuates muscle loss and body fat reduction in sarcopenic obesity by regulating AMPK in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Food Scince Nutr. 2025;13(7):e70655. doi:10.1002/fsn3.70655. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Chen C, Huang Y, Meng Z, Zhang J, Lu M, Liu P, et al. Insight into the rapid sodium storage mechanism of the fiber-like oxygen-doped hierarchical porous biomass derived hard carbon. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;588(22):657–69. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2020.11.058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Nieto N, Porte J, Saurel D, Djuandhi L, Sharma N, Lopez-Urionabarrenechea A, et al. Use of hydrothermal carbonization to improve the performance of biowaste-derived hard carbons in sodium ion-batteries. ChemSusChem. 2023;16(23):e202301053. doi:10.1002/cssc.202301053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Kydyrbayeva U, Baltash Y, Mukhan O, Nurpeissova A, Kim SS, Bakenov Z, et al. The buckwheat-derived hard carbon as an anode material for sodium-ion energy storage system. J Energy Storage. 2024;96(1):112629. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.112629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Gao Y, Xing Y, Jiao Y, Jiang C, Zou Z. High performance spherical hard carbon anodes for Na-ion batteries derived from starch-rich longan kernel. J Energy Storage. 2024;98:113167. doi:10.1016/j.est.2024.113167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Chen Y, Peng G, Zhao M, Zhou Y, Zeng Y, He H, et al. Dual-element synergy driven breakthrough in sodium storage performance of phenolic resin-based hard carbon. Carbon. 2025;238(5):120269. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2025.120269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools