Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Study on the Improvement of Foaming Properties of PBAT/PLA Composites by the Collaboration of Nano-Fe3O4 Carbon Nanotubes

1 Key Laboratory of Bio-Based Material Science & Technology, Northeast Forestry University, Ministry of Education, Harbin, 150040, China

2 Northeast Forestry University Engineering Consulting and Design Research Institute Co., Ltd., Harbin, 150040, China

* Corresponding Authors: Ce Sun. Email: ; Yanhua Zhang. Email:

# These two authors contributed equally and should be considered as co-first authors

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(4), 669-685. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0042

Received 20 February 2025; Accepted 26 March 2025; Issue published 21 April 2025

Abstract

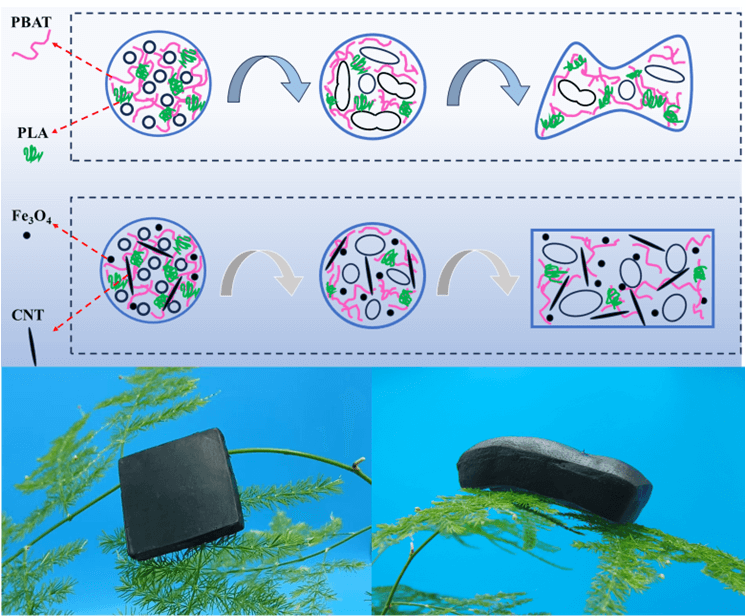

In recent years, degradable materials to replace petroleum-based materials in preparing high-performance foams have received much research attention. Degradable polymer foaming mostly uses supercritical fluids, especially carbon dioxide (Sc-CO2). The main reason is that the foams obtained by Sc-CO2 foaming have excellent performance, and the foaming agent is green and pollution-free. In current research, Poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT), poly (lactic acid) (PLA), and other degradable polymers are generally used as the main foaming materials, but the foaming performance of these degradable polyesters is poor and requires modification. In this work, 10% PLA was added to PBAT to enhance the melt strength and improve the foaming performance. To improve the foaming properties of the PBAT/PLA composites, two kinds of nano-filler (nano-Fe3O4 and carbon nanotubes (CNTs)) were innovatively introduced for foaming modification. There was a synergistic effect between the two nano-fillers to enhance the foaming properties significantly. When 6 wt% CNTs and 4 wt% nano-Fe3O4 were added, the 4Fe3O4/6CNT foam had the best comprehensive performance. Its foaming rate reached 14.8 times, which was 2.8 and 2.1 times that after adding 10 wt% CNTs or 10 wt% nano-Fe3O4 alone. The combined action could adjust the melt elasticity of different PBAT/PLA composites to the optimum. The nanofillers also served as skeleton structures to support the foam cells, significantly improving the foaming performance. The density and foaming ratio did not change significantly at 14 days after foaming. The compressive strength of the composite foam reached up to 0.27 MPa and the water contact angle reached 120.1°. The synergistic foaming effect of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs could significantly improve the Sc-CO2 foaming performances of the composites, providing a new method for degradable materials to replace petroleum-based materials.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The porous architecture of foams endows them with excellent thermal insulation, sound absorption, shock resistance, and other functional properties, rendering them indispensable in packaging, automotive interiors, construction, and various industrial applications [1]. Current foaming materials primarily rely on non-degradable polymer matrices such as polyethylene (PE) and polystyrene (PS) [2]. However, the non-biodegradable nature of these polymers has triggered severe environmental challenges, most notably persistent white pollution. The accumulation of microplastic residues poses long-term risks to human health and ecological systems [3]. To mitigate these issues, biodegradable polymers are increasingly being explored as sustainable alternatives. Among them, poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) stands out as a flexible biodegradable polymer [4] with substantial potential to replace conventional non-degradable foams across multiple sectors. Its degradability, combined with favorable mechanical properties, positions PBAT-based foams as a promising solution for addressing environmental concerns while maintaining functional performance.

The foaming of polymers can be roughly divided into physical foaming and chemical foaming methods, but the foaming agents used are usually chemicals, which pose a certain pollution to the environment. In recent years, supercritical fluid foaming has been studied because of its use of green foaming agents such as nitrogen (N2) and carbon dioxide (CO2), and supercritical fluid foaming can form excellent cell structures [5,6]. At present, the foaming technology of PBAT mainly uses supercritical fluid CO2 foaming (Sc-CO2). However, the strength of PBAT melt is low, and it is difficult for Sc-CO2 to form good cell structures under high pressure, and even a large number of vacuoles will appear [7]. In addition, the dimensional stability of PBAT after Sc-CO2 foaming is poor, and the volume shrinkage can reach more than 50%, which seriously limits the use of PBAT foams [8].

The methods to improve the Sc-CO2 foaming performance of PBAT have been studied a lot, including chemical modification. However, chemical modification will destroy the complete degradability of PBAT, which goes against the purpose of use. There are also some studies by adding some rigid degradable polymer chains such as poly (butylene succinate) (PBS) or poly (lactic acid) (PLA) to improve the melt strength of the blend [9] and to obtain better foaming properties [10]. Due to the compatibility problem between these biodegradable polymers, additional interface modifiers need to be added to obtain a good foaming effect [11]. Although the addition of compatibilizers may improve the compatibility of the composites, the effective compatibilizers are non-degradable materials, which will destroy the complete degradability of the composite foam. Another way to improve the melt strength of PBAT is to add some inorganic fillers [12]. Rigid inorganic fillers will inhibit the movement of PBAT molecular chains, thereby improving the strength of the melt [13]. The study on the foaming properties of PBAT enhanced by inorganic fillers has not obtained much research. Since inorganic fillers do not affect the degradability of PBAT and can also effectively improve the melt strength of PBAT, their effects on the foaming properties of PBAT still need to be further studied. Nanofillers such as nano-Fe3O4 and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are common nano-inorganic fillers [14,15]. The morphologies of the two fillers are different, and the influence of blending of the two on PBAT molecular chains is not clear, which needs further exploration.

In this work, only 10% PLA was added to improve the melt strength of PBAT, and then the effect of the addition ratios of two kinds of nano-fillers with different morphologies on the foaming properties of PBAT/PLA composite was studied. The purpose of this study was to study the effect of two kinds of nano-fillers on the foaming properties of PBAT/PLA composites. Under the premise of ensuring the complete degradation of the composite foams, the most suitable method to promote PBAT to improve the Sc-CO2 foaming performance was found, to broaden the scope of application of PBAT composite foam.

PBAT TH801T was purchased from Lanshan Tunhe Chemical Co. Ltd. (Xinjiang, China), with a density of 1.25 g/cm3. PLA 4032D was purchased from NatureWorks (USA), with a density of 1.24 g/cm3. The nano-Fe3O4 with an average particle size of 80 nm was purchased from Yuande New Materials Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China), and CNTs with a purity of 95% were purchased from Suiheng Graphene Technology Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China), with an outer diameter of 8–15 nm. All the raw materials were dried at 80°C for 12 h to remove the water.

The raw materials were weighed 50 g according to the proportions shown in Table 1. Then raw materials were put into the torque rheometer (Polylab OS, Thermo Fisher Co., Ltd., Waltham, MA, USA), and mixed at 180°C and 50 r/min for 5 min to obtain the composite pellets. The composite pellets were placed in a hot press at a temperature of 175°C and 3 MPa for 5 min to prepare composite plates.

The composite plates were cut to the size of 20 mm × 20 mm × 3.6 mm, and the Sc-CO2 foaming process was carried out. The composite plate was placed in a reaction kettle at 180°C for 25 min to ensure that the plate completely melted. CO2 was then added to the reactor and the pressure in the reactor was raised to 15 MPa to ensure that the gas CO2 was transformed into a supercritical fluid state and filled with the melted plate, resulting in volume expansion. After holding the pressure for 20 min, the temperature was reduced the temperature to 100°C for 60 min to ensure that the foam could be obtained after the pressure relief. Finally, PBAT/PLA foams with different nano-filler ratios were obtained. The CO2 with 99.9% purity was purchased from Qinghua Industrial Gases Co., Ltd. (Harbin, China)

2.3 Composite Foam Appearance Characterization

The mass, volume, density, and foaming rate of the composite before and after foaming was measured using a high-precision solid density meter (JHY-120Y, Yuemang Intelligent Equipment Co., Ltd., Shenzhen China). Three experiments were conducted for each foam to ensure the accuracy of the data, and the tests were conducted at 48, 72, 168, and 336 h intervals to compare the shrinkage properties of different composite foams.

2.4 Rotational Rheometer Analysis

The AR 2000ex rotational rheometer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) was used to evaluate the rheometer properties of different composite foams. The test temperature was 180°C, and the test frequency was 0.1 to 628.3 rad/s.

2.5 Structure Analysis of Composite Foam

The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Tensor II, Bruker, Hong Kong, China) analysis: The scanning range of different composite foam samples was 500–4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 using the Tensor II FTIR spectrometer.

X-ray diffraction (XRD, D/max 220, Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan): X-ray diffraction analysis of the foams was performed in the range of 2θ = 5°–80° and the scanning rate was 8°/min. The measured voltage and current were 40 kV and 30 mA, respectively. The characteristic diffraction peaks of PLA, PBAT, nano-Fe3O4, and CNTs were characterized and analyzed.

2.6 Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Analysis

SEM (JSM-7500 F, JEOL) was used to observe the cell diameter of different composite foams under 5 kV acceleration voltage, and the cell diameter distribution was analyzed.

2.7 Compression Property and Resilience Analysis

The composite foam was cut into a cube with a size of 8 mm × 8 mm × 8 mm, and then the compressive strength of the foam was tested with a universal mechanical testing machine (TestPilot X10A, Wance Technologies Ltd., Shenzhen, China) at a rate of 1 mm/min. The compressive strain of the test was 50%. Ten tests were performed and the relevant stress-strain curves were collected. Three samples of each foam were selected for testing, and the compressive strength obtained was averaged and the variance calculated.

A contact angle tester (Theta, Biolin Scientific, Göteborg, Sweden) was used to test the water contact of different PBAT/PLA composite boards and foams. The test was performed at room temperature using distilled water, the volume of which was about 1.5 μL per drop, and the size was recorded by the instrument camera. Each sample was tested three times and averaged the data.

2.9 Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Analysis

A differential calorimetric scanner (DSC204, Netzsch, Selb, Germany) was used to analyze the thermal properties of different PBAT/PLA composite foams. The foam was heated to 210°C at 10°C/min and held for 5 min to eliminate the thermal history. Then the temperature was rapidly lowered to 25°C at 10°C/min and then heated to 210°C at 10°C/min. The curve of the second heating was recorded and the crystallinity of the sample was calculated according to the following formula:

2.10 Thermogravimetric (TG) Analysis

The thermal decomposition stability of the foams was tested by a TG analyzer (TG209, Netzsch, Germany) at a temperature range of 30°C–700°C with a heating rate of 10°C/min. Nitrogen was used as the purging atmosphere.

2.11 Thermal Conductivity Test

The thermal conductivity of different foams was using the TPS method (TPS 2500S, SETARAM, Caluire-et-Cuire, France).

3.1 Foaming Properties of Composite Foams

The foaming properties of different PBAT/PLA composites are shown in Fig. 1. The main problem of PBAT Sc-CO2 foaming was that the molecular chain strength was low, and it was easy to form a large void under high pressure, resulting in foaming failure. Adding some rigid molecular chains into PBAT was helpful in improving the Sc-CO2 foaming performance, and adding PLA was a good method. The content of PLA should not be too high, because the compatibility of PLA and PBAT was poor [16]. The general addition amount was between 5 wt%–20 wt%, and 10 wt% PLA was chosen in this work [17]. However, the foaming performance of PBAT/PLA composite foam after adding 10 wt% PLA was still poor (Fig. 1a No. 7). This phenomenon was also confirmed by other studies, so additional enhancement phases needed to be added.

Figure 1: (a) The appearances of different proportions of Fe3O4 and CNT modified PBAT/PLA foam after Sc-CO2 foaming, (b) the weight display of 4Fe3O4/6CNT composite foam, (c) the weight display of the unframed 4Fe3O4/6CNT composite

To improve the foaming properties of PABT/PLA composites, nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs were added with different proportions. From samples Nos. 1–6 (Fig. 1a), the Sc-CO2 foaming performances of the composite foams were significantly improved after the nanofillers were added. Every sample could form a good foaming structure. The foaming properties of 6Fe3O4/4CNT composite and 4Fe3O4/6CNT composite was significantly improved. The modification ability of mixed Fe3O4 and CNT fillers on foaming properties was significantly stronger than that of the single fillers, which indicated that there was a synergistic effect between nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs. Compared with Fig. 1b and Fig. 1c, the density of the 6Fe3O4/4CNT composite foam was significantly reduced under the combined action of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs [18].

Another major disadvantage of PBAT Sc-CO2 foaming was that the shrinkage rate of the foam was very high. Due to the high molecular chain flexibility, PBAT foam was difficult to maintain the shape. The shrinkage rate even exceeded 50%, which seriously hindered the promotion and use of PBAT foam. After the addition of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs, the foaming performance of PBAT/PLA composites were significantly improved. The 6Fe3O4/4CNT foam showed the highest foaming ratio, reaching about 20 times. And with the increasing storage time, the stability of the PBAT/PLA composite foams after the addition of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs was greatly improved (Fig. 2a). Taking 4Fe3O4/6CNT foam as an example, the shrinkage rate was only 2% after 14 storage days, indicating that the addition of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs could effectively inhibit the contraction of the foams. The slight foaming ratio increase of 6Fe3O4/4CNT foam was mainly caused by the instrument measurement error [19]. The density of the 6Fe3O4/4CNT foam decreased from 0.066 to 0.059 g/cm3 after 14 storage days (Fig. 2b), indicating that the 6Fe3O4/4CNT foam remained stable. The 8Fe3O4/2CNT and 2Fe3O4/8CNT foam showed better Sc-CO2 foaming performances, and the foaming properties did increase linearly, which indicated that nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs had the advantage of synergistically enhancing foaming. Further research was needed [20].

Figure 2: (a) The expansion ratio and (b) the density of different PBAT/PLA composite foams

3.2 The Rheological Properties of PBAT/PLA Composites

The rheological properties of PBAT/PLA composites with different proportions of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs were shown in Fig. 3. The relationship between the storage modulus (G’), loss modulus (G”) and melt viscosity (η*) of PBAT/PLA composites with frequency changes after the addition of different ratios of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs were studied, respectively [21]. After the addition of nano-Fe3O4, the G’ and G” of the PBAT/PLA composite did not change much, which was mainly due to the small size of rare surface groups of nano-Fe3O4, resulting in a limited effect on the obstruction of molecular chain movements [22].

Figure 3: (a) The storage modulus (G’), (b) the loss modulus (G”), and (c) the melt viscosity (η*) of PBAT/PLA composites

With the increase of the content of CNTs, the value of G ‘gradually increased, thus improving the melt elasticity of PBAT/PLA composites. It was obvious that the value changes of G’ and G” were not linear changes, which might be that nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs worked together to ensure that the molecular chains of PBAT/PLA composites presented the best melting elasticity. This was the main reason why the best foaming performance of the 4Fe3O4/6CNT foam reached 19.6 times. Moreover, with the good supporting effect of nanofillers, the foam shrinkage was little after Sc-CO2 foaming (Fig. 2a).

When the CNTs content was less than 2%, the composites exhibited typical Newtonian fluid behavior. As the content of CNTs continued to increase, the η* of the composites gradually increased due to the enhanced blocking effect of CNTs on the molecular chain movement of PBAT/PLA. The advantage of this change was that CNTs significantly increased the melt strength of PBAT/PLA composites, thus significantly improving the foaming properties of 4Fe3O4/6CNT and 6Fe3O4/4CNT composites. High melt strength ensured that the foam cells did not collapse and thus formed a good cell foaming structure, which was also the main reason for the best foaming properties of these two composites. However, as the content of CNTs continued to increase, the melt strength of the composites was too high to foam, so the foaming properties of the composites with higher CNTs contents gradually declined.

3.3 The Chemical and Crystal Structure of PBAT/PLA Foams

The types of functional groups in different PBAT/PLA foams were studied by FTIR analysis. PBAT and PLA were both degradable polyesters, so two typical ester bond stretching vibration peaks appeared in the FTIR spectrum (Fig. 4a). Due to the different addition ratios of PBAT and PLA in the composite foams, the corresponding ester bonds were easily distinguished. The peak at 1710 cm−1 belonged to the easter bonds of PBAT, and that of PLA was at 1758 cm−1. This indicated that the molecular chains of PBAT and PLA were entangled to some extent after processing, thus forming a blend structure.

Figure 4: (a) The FTIR spectrum, (b) the DSC curve, (c) and (d) the crystal structures of PBAT/PLA foams

The crystal structures of different PBAT/PLA composite foams were shown in Fig. 4c, and the crystal structures of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs were shown in Fig. 4d as reference. The crystal structure of PBAT in the foams did not change significantly after the addition of nanofillers with different contents. There were five diffraction peaks corresponding to five crystal surfaces of PBAT successively (16.8°-011, 17.6°-010, 20.1°-101, 23.1°-100 and 24.6°-111) [23]. For PLA, a wider diffraction peak appeared between 17° and 25°. When different proportions of nano-fillers were added, the characteristic peak strength of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs changed obviously with the proportion of fillers. The crystal characteristic peaks corresponding to PBAT and PLA decreased to a certain extent with the addition of nano fillers [24]. This might be due to the restriction of PBAT/PLA molecular chain movement after the addition of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs, thus inhibiting the crystallization of the composite foams [25]. In order to better explore the effect of nano-fillers on the crystallization properties of molecular chains, it was necessary to use DSC to analyze the molecular crystallinity of different PBAT/PLA foam.

The DSC curve of different PBAT/PLA foam was shown in Fig. 4b. The results were consistent with those of XRD analysis that the crystallization of the composite foams was decreased after the addition of nanofillers. The addition of nanofillers would restrict the movement of molecular chains of PBAT/PLA composites, so that the crystallinity would decrease to a certain extent (Table 2). For the 10Fe3O4/0CNT composite foam, even though the viscosity did not increase significantly after nano-Fe3O4 was added, it hindered the movement of molecular chain to a certain extent [26], resulting in a decrease in the crystallinity of the 10Fe3O4/0CNT composite foam, which also explained the foaming performance increased than pure PBAT/PLA foam.

3.4 The SEM Analysis of Different PBAT/PLA Foams

The cell structure of different PBAT/PLA composite foams was analyzed by SEM analysis (Fig. 5). As shown in Fig. 6, after Sc-CO2 foaming of PBAT/PLA, huge vacuoles formed inside the foam, which resulted in extremely irregular internal shape of the PBAT/PLA foam. With the addition of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs, the composite foam showed a regular structure. Because the melt strength of the PBAT/PLA composite was too low, it was difficult to form a complete cell structure after Sc-CO2 foaming (Fig. 5b1), and the inside of the PBAT/PLA foam was fractured PBAT/PLA fibers.

Figure 5: (a) The interior structure of the PBAT/PLA and 4Fe3O4/6CNT foam, (b1) the SEM image of the PBAT/PLA foam, (b2) the cell diameter of the PBAT/PLA foam, (c1) the SEM image of the 10Fe3O4/0CNT foam, (c2) the cell diameter of the 10Fe3O4/0CNT foam, (d1) the SEM image of the 8Fe3O4/2CNT foam, (d2) the cell diameter of the 8Fe3O4/2CNT foam, (e1) the SEM image of the 2Fe3O4/8CNT foam, (e2) the cell diameter of the 2Fe3O4/8CNT foam, (f1) the SEM image of the 0Fe3O4/10CNT foam, and (f2) the cell diameter of the 0Fe3O4/10CNT foam

Figure 6: (a1) the SEM image of the 6Fe3O4/4CNT foam, (a2) the cell diameter of the 6Fe3O4/4CNT foam, (b1) the SEM image of the 4Fe3O4/6CNT foam, (b2) the cell diameter of the 4Fe3O4/6CNT foam

With the addition of nanofillers, the foaming performance began to improve, and the foam diameter of the 10Fe3O4/0CNT foam remained basically the same as that of PBAT (Fig. 5c1), reaching 80.0 ± 13.4 μm (Fig. 5c2). Due to the strengthening effect of nano-Fe3O4 on the molecular chains, the cells of the 10Fe3O4/0CNT foam did not burst. The irregular shape of the cells indicated that the use of nano-Fe3O4 alone was limited in enhancing the foaming ability of PBAT/PLA foam [27].

With the synergistic effect of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs (Fig. 5d1–f2), the Sc-CO2 foaming performance of different PBAT/PLA composites was gradually enhanced. When the content of CNTs was different from that of nano-Fe3O4, the cell diameters of the PBAT/PLA composite foam were stable at about 110 μm. The size of the 0Fe3O4/10CNT foam was only 116. 9 ± 23.6 μm, which indicated that nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs showed synergistic effects to ensure the good foaming effect of the PBAT/PLA foams.

When the contents of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs in the foams were similar (Fig. 6a1–b2), the foaming properties of the composite foams were obviously improved. The cell diameter of the 10Fe3O4/0CNT foam was increased to 187.2 ± 23.6 μm. When the CNT content was increased to 6%, the cell shape of the 4Fe3O4/6CNT foam was the most regular, and the cell diameter was between 80 and 240 μm. This once again proved that the good foaming performance of the PBAT/PLA composite under Sc-CO2 was guaranteed due to the synergistic promotion of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs during Sc-CO2 foaming.

3.5 Cyclic Compressive Strength

The compressive strength and resilience of different PBAT/PLA foams were very important. For this reason, the compressive strength and resilience were tested by ten times compression, and the compression strain was 50% each time. The stress-strain curves of each type of foams were shown in Fig. 7a–f. The melt strength of the PBAT/PLA composite was too low, so the PBAT/PLA foam produced a large number of vacuums, which was difficult to test the compression strength. The foaming properties of the composites were improved after the addition of nano-fillers, and all of them had certain compressive resilience [24].

Figure 7: The stress-strain curves of different PBAT/PLA foams: (a) 10Fe3O4/0CNT foam, (b) 8Fe3O4/2CNT foam, (c) 6Fe3O4/4CNT foam, (d) 4Fe3O4/6CNT foam, (e) 2Fe3O4/8CNT foam, (f) 0Fe3O4/10CNT foam

The compressive strength of the foam was directly related to the strength of the foam cells. The PBAT/PLA foams with different proportions and types of nano-fillers had different compressive strength, which was mainly related to their foaming rates and cell structures [28]. The compressive strength of all foams was 0.05–0.27 MPa. The 6Fe3O4/4CNT foam had the best foaming properties, but the compressive strength was only 0.05 MPa. According to SEM analysis, the 6Fe3O4/4CNT foam had the largest cell diameter (120–260 μm) and the highest foaming ratio, which lead to low cell strength and low compression strength. Because the size of different PBAT/PLA composites for foaming was the same, the foaming ratio was negatively correlated with the compression performance.

The 4Fe3O4/6CNT foam showed the best overall performance. The compressive strength of the 4Fe3O4/6CNT foam reached 0.17 MPa, and it had good dimensional recovery. After 10 cycles of compression, the compressive strength of the 4Fe3O4/6CNT foam was only reduced by 13.2%. The compression recovery performance was lower than that of the 0Fe3O4/10CNT foam, but its foaming rate was 2.10 times that of the 0Fe3O4/10CNT foam. This was mainly due to the fact that the 4Fe3O4/6CNT foam had a better cell structure, as shown by SEM analysis, the foam had very regular cell diameters mainly distributed 145.1 ± 26.9 μm.

3.6 The TG and DTG Analysis of Composite Foams

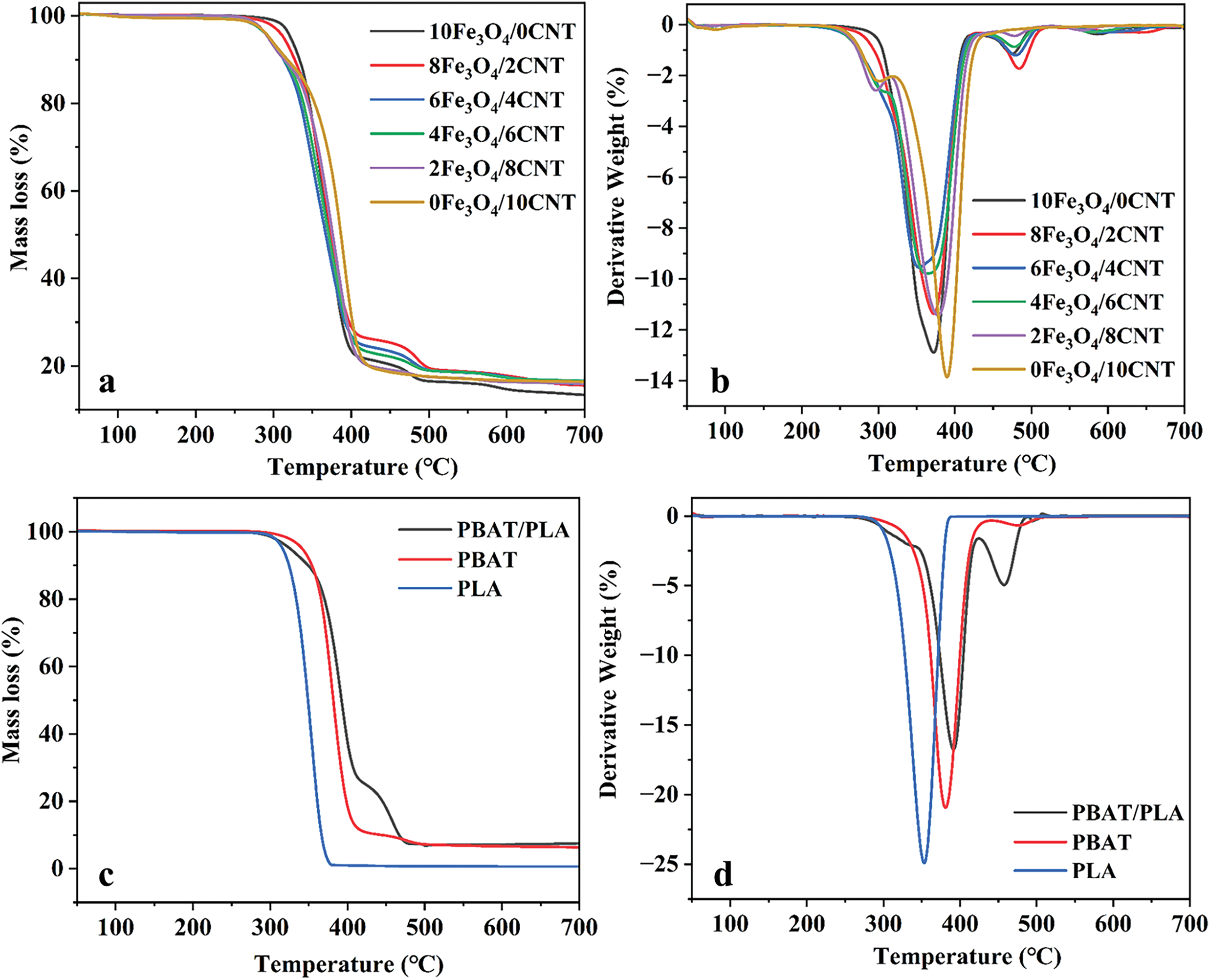

The thermal decomposition performances of different PBAT/PLA foams were shown in Fig. 8. The main decomposition interval of the PBAT/PLA foam was between 260°C–500°C, which was divided into three main stages. The first stage was 260°C–343°C. because the thermal decomposition temperature of PLA was lower than that of PBAT, so the decomposition of PLA mainly occurred in this stage. The second stage was 343°C–420°C, where the decomposition of PBAT in this stage. And the final stage was the decomposition of remaining carbon materials.

Figure 8: (a) The TG curve and (b) DTG curve of different PBAT/PLA composites, and (c) the TG curve and (d) DTG curve of different before and after Sc-CO2 foaming

When the nano-filler was added, the decomposition temperature of different PBAT/PLA foams was advanced to a certain extent. This was mainly due to the high thermal conductivity of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs [29], which promoted the decomposition of the composite foams after absorbing a lot of heat. For example, the main highest decomposition rate temperature of 4Fe3O4/6CNT foam was advanced to 366°C. However, the main decomposition interval of foams did not change significantly, and the main decomposition interval remained between 343°C–420°C. The higher decomposition temperature would not show significant impacts on the use of foams.

3.7 The Comprehensive Analysis of Composite Foams Properties

The contact angle changes of different PBAT/PLA composites before and after foaming were shown in Fig. 9. Even if nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs were added, the contact angle of unfoamed composites was still around 70°, showing hydrophilicity. The contact angle of different PBAT/PLA foam increased to about 120.1° with the addition of nano-Fe3O4 between 2% and 6%. Taking the 4Fe3O4/6CNT foam with the best foaming performance as an example, its water contact angle reached 117.9°, which was 70.4% higher than that of the unfoamed PBAT/PLA composite. The main reason for the increase of the contact angle was that the bubble provided an uneven surface after foaming, which effectively broaden the application of composite foams in packaging, automotive interior and other fields.

Figure 9: The contact angle of different PBAT/PLA composites before and after Sc-CO2 foaming

The comprehensive properties of different PBAT/PLA foams were shown in Fig. 10. The PBAT showed flexible molecular chains, so it was a soft foam after Sc-CO2 foaming, which could be mainly used in packaging, building insulation and other fields. The foaming ratio, cell structure and thermal conductivity of the foams had important effects on the performance The compressive properties and the retention efficiency of the foam could be used as reference for the performance parameters.

Figure 10: (a) The thermal conductivity of different PBAT/PLA foams, (b) the average contact angle of composite foams, (c) the average compressive strength of foams, (d) the comprehensive properties of different PBAT/PLA foams, and (e) mechanism of enhancing foaming properties by two nano-fillers

All combined parameters indicated that the 6Fe3O4/4CNT composite foam and 4Fe3O4/6CNT composite foam had the most outstanding performance. The 6Fe3O4/4CNT had excellent thermal insulation performance, with a thermal conductivity of only 41.3 mW/mK, which was similar to that of other modified PBAT-based composite foams [30]. This was mainly due to the excellent synergistic effects between nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs in the 6Fe3O4/4CNT composite foam, which ensured that the composite foam had good melt elasticity. Because the 6Fe3O4/4CNT foam had the largest foaming ratio and cell size, and it contained the highest air content which was a thermal poor conductor, this made the 6Fe3O4/4CNT foam had the lowest thermal conductivity [31]. In addition, the nanofillers played a certain supporting role to ensure that the PBAT/PLA composite material after adding 6% nano-Fe3O4 and 4% CNTs had excellent Sc-CO2 foaming performance. In the radar chart (Fig. 10d), the 6Fe3O4/4CNT composite foam had the largest area, indicating that its comprehensive performance was the most outstanding [32]. The foaming properties of PBAT/PLA composites enhanced by nanometer fillers were as follows: Although rigid PLA molecular chains were incorporated into PBAT, the poor compatibility between these two components still resulted in relatively low melt strength of the composites, making PBAT/PLA composites remain unfoamable [33]. Rheological analysis indicated that spherical nano-Fe3O4 nanoparticles dispersed within the PBAT/PLA molecular chains. Therefore, the viscosity of the PBAT/PLA composite segments did not significantly increase but partially improved the melt strength. CNTs were served as skeletal structures to support the cell walls of foams, thereby inhibiting cell collapsed and ruptured. The combined effects of these two components can significantly enhance the foaming effectiveness of the foams [34].

Nanofillers nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs had synergistic effects, effectively enhancing the foaming properties of PBAT/PLA composites. The synergistic effects could significantly regulate the melt elasticity of PBAT/PLA molecular chains, achieving the highest expansion ratio. Additionally, nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs could serve as a framework structure to support foam cells. The 6Fe3O4/4CNT composite foam had the best foaming performance, with an expansion ratio of 21.8 times due to its moderate melt strength. The 6Fe3O4/4CNT composite foam showed no significant shrinkage after 366 h of placement, demonstrating excellent anti-shrinkage performance. The 6Fe3O4/4CNT composite foam had the largest cell diameter, reaching 187.2 ± 35.2 μm. The good foaming structure ensured that the 6Fe3O4/4CNT composite foam had the lowest thermal conductivity, only 41.26 mW/mK, which was similar to that of PBAT foams in other modification studies. The cell size of the foam was positively correlated with compressive strength. The 4Fe3O4/6CNT composite foam was outstanding in compressive strength and compressive retention, with a foaming ratio of 14.5 times. After 10 times of 50% strain compressions, the compressive strength was still maintained at 77.6%. This indicated that when the contents of nano-Fe3O4 and CNTs in the foam were similar, their synergistic effects enhanced the Sc-CO2 foaming ability. After Sc-CO2 foaming, the hydrophobicity of all composite foams was significantly improved, from a maximum of 69.0° to 120.1°. This work provided a reference for preparing PBAT/PLA composite foams with good foaming performance, thereby broadening the related applications of degradable polyesters in packaging, building insulation, and heat insulation fields.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Northeast Forestry University Engineering Consulting and Design Research Institute Co., Ltd. for funding support.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by National Undergraduate Training Programs for Innovations (Northeast Forestry University, grant number 202410225023). This work was funded by Young Elite Scientist Sponsorship Program by Heilongjiang Province (2024QNTG006), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2572024DP05). This work was funded by The Collaborative Innovation Project of First-Class Disciplines in Heilongjiang Province (LJGXCG2024-F11). We thank Northeast Forestry University Engineering Consulting and Design Research Institute Co., Ltd. for experimental help and funding.

Author Contributions: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Investigation: Jiahao Liu; Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing: Xinyu Zhang; Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation: Huiwei Wang; Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis: Yupeng Li; Methodology, Conceptualization: Shan Jin; Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis: Guanxian Qiu; Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Funding acquisition: Ce Sun; Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis: Haiyan Tan; Writing—review & editing, Resources, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization: Yanhua Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data are available in the paper.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Pawłowska A, Stepczyńska M, Walczak M. Flax fibres modified with a natural plant agent used as a reinforcement for the polylactide-based biocomposites. Ind Crops Prod. 2022;184:115061. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Li Y, Zhang Z, Wang W, Gong P, Yang Q, Park CB, et al. Ultra-fast degradable PBAT/PBS foams of high performance in compression and thermal insulation made from environment-friendly supercritical foaming. J Supercrit Fluids. 2022;181:105512. doi:10.1016/j.supflu.2021.105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Sun C, Wei S, Tan H, Huang Y, Zhang Y. Progress in upcycling polylactic acid waste as an alternative carbon source: a review. Chem Eng J. 2022;446:136881. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2022.136881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wang Z, Wang G, Wang X, Xu Z, Li S, Zhao G. Ultrafast-degradable and super-elastic PBAT/polybutylene succinate foam with stable cellular structure and enhanced thermal insulation. Eur Polym J. 2024;211:112996. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2024.112996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Bai Y, Hou J, Yu K, Liang J, Zhang X, Chen J. Three-layered PBAT/CNTs composite foams prepared by supercritical CO2 foaming for electromagnetic interference shielding. Mater Today Sustain. 2024;26:100763. doi:10.1016/j.mtsust.2024.100763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Xue K, Chen P, Yang C, Xu Z, Zhao L, Hu D. Low-shrinkage biodegradable PBST/PBS foams fabricated by microcellular foaming using CO2 & N2 as co-blowing agents. Polym Degrad Stab. 2022;206:110182. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2022.110182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Eraslan K, Altınbay A, Nofar M. In-situ self-reinforcement of amorphous polylactide (PLA) through induced crystallites network and its highly ductile and toughened PLA/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) blends. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;272:132936. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Chang YP, Rwei SP, Liao SJ, Chen CM, Liu LC. Preparation of waste paper fiber-reinforced biodegradable polybutylene adipate terephthalates (PBATs) and their feasible evaluation for food package films with high oxygen barrier and antistatic performances. J Ind Eng Chem. 2024;133:394–400. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2023.12.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhou H, Hu D, Zhu M, Xue K, Wei X, Park CB, et al. Review on poly (butylene succinate) foams: modifications, foaming behaviors and applications. Sustain Mater Technol. 2023;38:e00720. doi:10.1016/j.susmat.2023.e00720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu S, Zhong M, Wang X, Wang Y. Preparation of antishrinkage and high strength poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) microcellular foam via in situ fibrillation of polylactide. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;282:136782. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.136782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Rahmatabadi D, Khajepour M, Bayati A, Mirasadi K, Amin Yousefi M, Shegeft A, et al. Advancing sustainable shape memory polymers through 4D printing of polylactic acid-polybutylene adipate terephthalate blends. Eur Polym J. 2024;216:113289. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2024.113289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang R, Han W, Jiang H, Wang X, Wang B, Liu C, et al. PBAT/MXene monolithic solar vapor generator with high efficiency on seawater evaporation and swage purification. Desalination. 2022;541:116015. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2022.116015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Nofar M, Salehiyan R, Ciftci U, Jalali A, Durmuş A. Ductility improvements of PLA-based binary and ternary blends with controlled morphology using PBAT, PBSA, and nanoclay. Compos Part B Eng. 2020;182:107661. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang P, Liu J, Yang L, Zhou Y, Gao S, Hu X, et al. Poly(lactide)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/carbon nanotubes composites with robust mechanical properties, fatigue-resistance and dielectric properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;295:139464. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.139464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Yang J, Chen Y, Yan X, Liao X, Wang H, Liu C, et al. Construction of in-situ grid conductor skeleton and magnet core in biodegradable poly (butyleneadipate-co-terephthalate) for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding and low reflection. Compos Sci Technol. 2023;240:110093. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2023.110093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Li W, Sun C, Li C, Xu Y, Tan H, Zhang Y. Preparation of effective ultraviolet shielding poly (lactic acid)/poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) degradable composite film using co-precipitation and hot-pressing method. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;191:540–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.09.097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wang YY, Wang Y, Zhu W, Lan D, Song YM. Flexible poly(butylene adipate-co-butylene terephthalate) enabled high-performance polylactide/wood fiber biocomposite foam. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;204:117381. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhou H, Meng R, Wang L, Zhu M, Wei X, Wang X, et al. Preparation of open-cell chain-extend poly (lactic acid)/poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) foams and their selective oil absorption characteristics. J Supercrit Fluids. 2024;204:106114. doi:10.1016/j.supflu.2023.106114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang Z, Wang G, Xu Z, Zhang A, Li S. A novel reinforcing-foaming-recovering strategy for achieving thermally insulating green foams with ultrafast degradation. J Clean Prod. 2024;481:144161. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.144161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Gao H, Li J, Li Z, Li Y, Wang X, Jiang J, et al. Enhancing interfacial interaction of immiscible PCL/PLA blends by in-situ crosslinking to improve the foamability. Polym Test. 2023;124:108063. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2023.108063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sun C, Yu Z, Jia L, Zhang X, Zhao Y, Zhang Z. Lightweight and insulation polylactide/poly(butyleneadipate-co-terephthalate) foam with good cushioning performance prepared by supercritical CO2. Ind Crops Prod. 2025;223:120067. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.120067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Guo F, Liao X, Li S, Yan Z, Tang W, Li G. Heat insulating PLA/HNTs foams with enhanced compression performance fabricated by supercritical carbon dioxide. J Supercrit Fluids. 2021;177:105344. doi:10.1016/j.supflu.2021.105344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Arruda LC, Magaton M, Bretas RES, Ueki MM. Influence of chain extender on mechanical, thermal and morphological properties of blown films of PLA/PBAT blends. Polym Test. 2015;43:27–37. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2015.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Huang J, Jin B, Zhang X, Wang S, Wu B, Gong P, et al. High energy absorption efficiency and biodegradable polymer based microcellular materials via environmental-friendly CO2 foaming for disposable cushioning packaging. Polymer. 2024;292:126612. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2023.126612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Cui W, Wei X, Luo J, Xu B, Zhou H, Wang X. CO2-assisted fabrication of PLA foams with exceptional compressive property and heat resistance via introducing well-dispersed stereocomplex crystallites. J CO2 Util. 2022;64:102184. doi:10.1016/j.jcou.2022.102184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Liu H, Wang F, Wu W, Dong X, Sang L. 4D printing of mechanically robust PLA/TPU/Fe3O4 magneto-responsive shape memory polymers for smart structures. Compos Part B Eng. 2023;248:110382. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.110382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Du J, Yang H, Zhao X. Preparation of tomato peel pomace powder/polylactic acid foams under supercritical CO2 conditions: improvements in cell structure and foaming behavior. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;270:132480. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Al-Itry R, Lamnawar K, Maazouz A, Billon N, Combeaud C. Effect of the simultaneous biaxial stretching on the structural and mechanical properties of PLA, PBAT and their blends at rubbery state. Eur Polym J. 2015;68:288–301. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2015.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Behera K, Veluri S, Chang YH, Yadav M, Chiu FC. Nanofillers-induced modifications in microstructure and properties of PBAT/PP blend: enhanced rigidity, heat resistance, and electrical conductivity. Polymer. 2020;203:122758. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2020.122758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wang Z, Wang G, Xu Z, Zhang A, Zhao G. A novel in-situ fibrillation enhancement strategy to achieve super-elastic green foam with enhanced biodegradation. J Environ Chem Eng. 2024;12:114642. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2024.114642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chen P, Gao X, Zhao L, Xu Z, Li N, Pan X, et al. Preparation of biodegradable PBST/PLA microcellular foams under supercritical CO2: heterogeneous nucleation and anti-shrinkage effect of PLA. Polym Degrad Stab . 2022;197:109844. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2022.109844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Palaniappan SK, Singh MK, Rangappa SM, Siengchin S. Eco-friendly biocomposites: a step towards achieving sustainable development goals. Appl Sci Eng Prog. 2024;17(4):7373. doi:10.14416/j.asep.2024.02.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ramanadha reddy S, Venkatachalapathi DN. A review on characteristic variation in PLA material with a combination of various nano composites. Mater Today Proc. 202310.1016/j.matpr.2023.04.616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Liu T, Feng H, Jin C, Pawlak M, Saeb MR, Kuang T. Green segregated honeycomb biopolymer composites for electromagnetic interference shielding biomedical devices. Chem Eng J. 2024;493:152438. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.152438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools