Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Physical, Mechanical and Chemical Properties as a Decision-Support Tool to Promote Alternative Woods: Case of Dabema (Piptadeniastrum africanum) in Cameroon

1 Laboratory of Forest Resources and Wood Valorization, University of Douala, Douala, P.O. Box 2701, Cameroon

2 LERMAB-ENSTIB, University of Lorraine, 27 rue Philippe Seguin, Epinal, 88051, France

3 Applied Biotechnology and Engineering Laboratory, University of Ebolowa, Ebolowa, P.O. Box 886, Cameroon

* Corresponding Author: Jean Jalin Eyinga Biwôlé. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(5), 901-914. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0005

Received 02 October 2024; Accepted 31 December 2024; Issue published 20 May 2025

Abstract

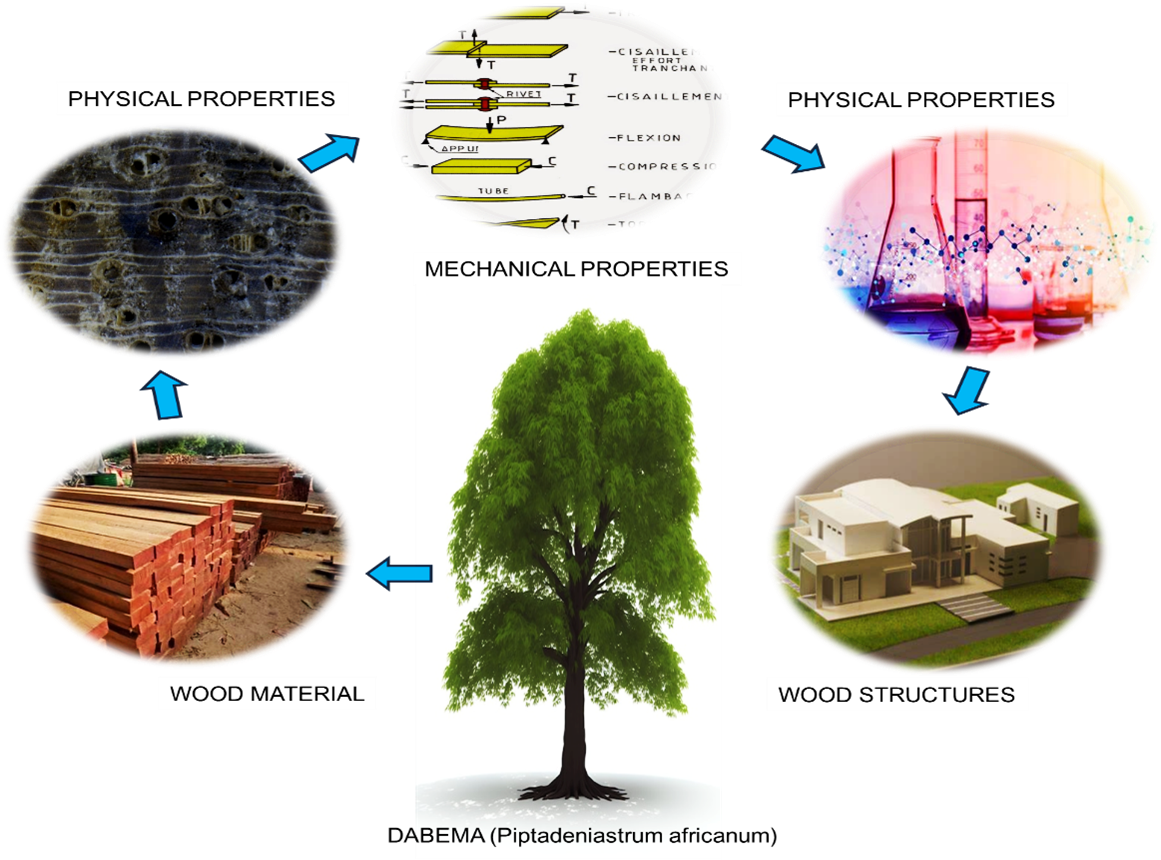

This review aims to identify the assets and limitations of Dabema (Piptadeniastrum africanum) as a sustainable alternative to traditional timber species for furniture and construction applications. Dabema is characterized by its high density and dimensional stability, meeting ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials) standards for mechanical strength, which is essential for promoting its use. However, its limited availability in trade and ingrained habits of use are obstacles to its widespread commercialization. In addition, thermal and oleothermal treatments have shown great potential for improving the characteristics of this wood, although they require ongoing optimization and rigorous environmental assessment. Consequently, increased awareness of the benefits of Dabema is decisive to encourage its sustainable adoption in modern economies. This could help to diversify forest resources and encourage more sustainable building practices, taking advantage of Dabema’s unique properties while mitigating environmental sustainability concerns.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Traditionally, wood plays a prominent role in furniture-making and building, thanks to its diverse properties [1]. Indeed, its physical, mechanical and chemical attributes enable it to meet the specific requirements of structural applications [2]. These characteristics make it possible to meet specific structural requirements while offering sustainable functional and aesthetic solutions, in keeping with the responsible management of natural resources [1,3]. However, in Cameroon, despite a forest rich in nearly 600 tree species, only 80 main species are exploited for industrial purposes, leading to excessive exploitation of prized species to the detriment of biodiversity [4]. This imbalance highlights the need for policies aimed at diversifying the species harvested and documenting their technological characteristics. Such measures would help limit deforestation while maximizing the added value of forest resources [5]. Furthermore, the forestry sector is an essential component of the Cameroonian economy, accounting for around 5% of GDP and generating annual revenues of $17 million from artisanal logging [6]. However, this industry remains largely oriented towards primary products and relies on rudimentary technologies [7]. By integrating sustainable practices and technological innovations, it becomes possible to increase economic benefits while preserving forest resources for future generations. In this context, the study and promotion of little-known species as alternatives to overexploited species is paramount [8–10].

Previous research has shown that little-known woods can offer properties comparable to those of prized species, while still being available in sufficient quantities in forests [2]. However, a lack of knowledge about their technical characteristics leads to their unregulated exploitation and scarcity on the market [11]. Diversifying the types of wood harvested and actively promoting lesser-known species would help to remedy the excessive concentration of specific species [12]. By encouraging users to opt for abundantly available species with similar structural performance, it would be possible to preserve valuable resources while ensuring a more equitable and sustainable exploitation of Cameroon’s forest heritage [13]. Among these species, Dabema (Piptadeniastrum africanum) appears to be a promising candidate. Although it is widely present in tropical Africa and Cameroon, its market integration remains limited, despite an average harvestable volume of 1.6 m3/ha [10]. In 2008, the ALPICAM-GRUMCAM forestry company reported a harvestable volume of 33,067.3 m3 in its forest concession 10–053 (82,308 ha) in eastern Cameroon, representing 4.01 m3/ha and 16.57% of the total standing volume [14]. This finding illustrates the considerable potential of tropical woods from the Congo Basin, and particularly those from Cameroon, for a variety of applications in line with the dynamics of sustainability and innovation. Dabema (Piptadeniastrum africanum) stands out for its remarkable mechanical properties, notably a static bending strength of 98 MPa, a compressive strength of 57 MPa and a longitudinal modulus of elasticity of 15.170 MPa, making it a species of choice for industrial and construction applications [15]. A shear strength study of 12 wood species from the Congo Basin revealed a strong correlation between shear strength and density, enabling improved predictions using probabilistic models such as the three-parameter Weibull distribution [16]. These findings open up new prospects for the design of wood products that meet structural requirements while promoting the use of lesser-known tropical species. In terms of industrial applications, the feasibility of manufacturing glulam beams in tropical climates, using species such as Abura (Mitragyna ciliata), Dabema, Difou (Morus mesozygia) and Tali (Erythrophleum ivorense), highlights the high potential for the production of high mechanical performance materials. Glulam products boast satisfactory bonding qualities and mechanical performances comparable to those of solid wood [17]. Enhancing the value of little-used species in this way contributes not only to the preservation of forest diversity, but also to the sustainable development of the timber industry in Cameroon. Furthermore, the pharmacological properties of Dabema have been demonstrated through its bark extract, which showed no adverse effects on serum electrolyte balance in albino rats, even at high doses [18]. This has opened up prospects for safe and effective medical applications, reinforcing the potential of local essences in the health sector. This review aims to identify the assets and limitations of Dabema (Piptadeniastrum africanum) as a sustainable alternative to traditional timber species for furniture and construction applications. It also explores innovative strategies for integrating Dabema into sustainable forest management, thereby helping to strengthen the economic development of the forestry sector while meeting current ecological and industrial requirements [19–22].

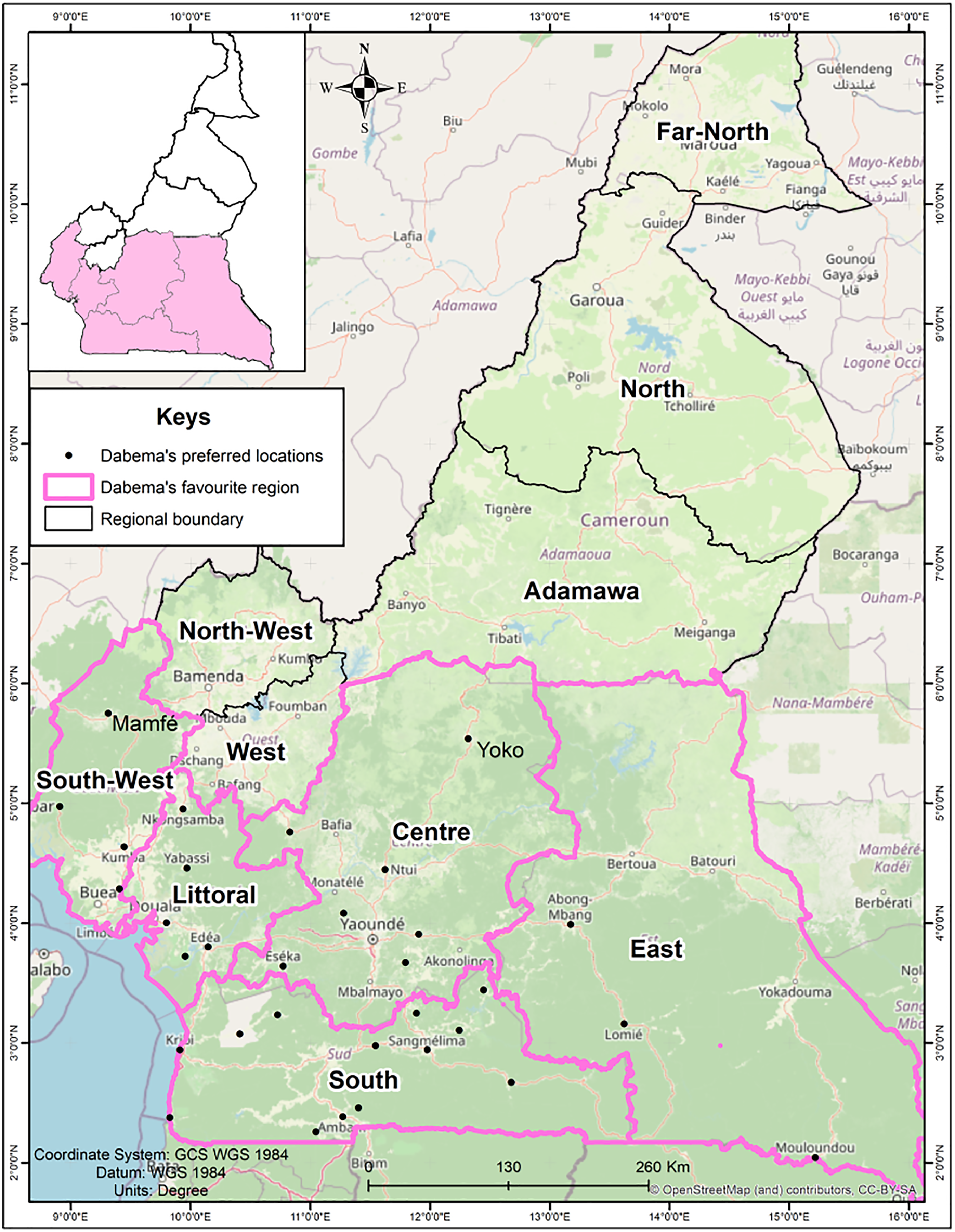

2.1 Mapping of Dabema Distribution in Cameroon

A geolocation map (Fig. 1) of Dabema (Piptadeniastrum africanum) was produced using ArcGIS software, following a precise method. First, we collected reliable data, including vector layers (GPS points, administrative boundaries), which we imported into ArcMap. To ensure consistency, we aligned all layers to a common geographic projection, essential to avoid overlay errors. Using GIS tools, notably geoprocessing (Clip) and attribute queries, we identified and extracted the five Cameroonian regions where Dabema is present. Overlaying GPS points enabled us to analyze spatial relationships and gain a better understanding of the species’ distribution. Finally, we customized the symbology to make the information legible, while integrating elements such as legends, titles and scales, to produce a map that is both clear and attractive.

Figure 1: Distribution of Dabema species in Cameroon

2.2 Selection of Published Research Articles

Research articles were searched in the electronic databases of Google Scholar, Web of Science, Science Direct, ResearchGate, JSTOR, Academia.edu and Wiley Online Library. The keywords and phrases used to find relevant publications were Dabema, physical properties of Dabema, mechanical properties of Dabema, chemical properties of Dabema, social and economic importance of forest products, wood processing, forest management. Published research articles have been selected on the basis of their interest in the physical, mechanical and chemical properties of Dabema. Technical reports from relevant organizations such as the Center for International Forestry Research, TRAFFIC, were also considered. A data mining approach was used to extract all relevant information on the physical, mechanical or chemical parameters measured in the selected studies. A total of sixty-one (61) publications dealing with the different themes were examined.

Authors used standardized methods to evaluate density, water content, tangential and radial shrinkage to study the physical properties of Dabema [23]. Density was determined gravimetrically on 20 × 20 × 20 mm3 samples taken from sapwood-free Dabema (Piptadeniastrum africanum) quarters. They were then conditioned in the laboratory at an ambient temperature of 21 ± 1°C, then at a relative humidity of between 25% and 28% until equilibrium humidity with the environment was reached [2]. Density was determined in accordance with the calculation standards described in [24,25]. To assess the moisture content of Dabema, the authors followed the kiln-drying method prescribed by BS 373:1957 [26] and [27], which guarantees consistent and reliable results with regard to the moisture content of the wood material. Shrinkage measurements were carried out according to established methodologies described in the specialist literature [28]. In addition to these fundamental physical properties, the authors also examined macroscopic characteristics such as color and texture, in line with the recommendations of [29].

To evaluate the mechanical properties of Dabema, the authors of the reviewed articles carried out a series of tests to assess its performance under different types of mechanical stress [16,17,23]. Firstly, they carried out compression, tensile, flexural and shear strength tests [30]. To understand the material’s behavior under various loading conditions, these strength tests proved essential in determining its suitability for structural applications. The authors followed the relevant ASTM methods throughout the testing process to ensure that the results would be comparable to those of other wood species and materials commonly used in the timber industry [31]. In addition, the authors used Weibull analysis to predict failure modes under load. This statistical method enabled a detailed assessment of the material’s reliability and structural strength, giving an insight into its performance in real-life applications [2,32].

Research on Dabema (Piptadeniastrum africanum) has focused mainly on the phytochemical analysis of its leaves and bark, utilizing several advanced techniques to characterize the compounds present in these plant extracts [18]. HPLC (High-performance liquid chromatography) and 13C NMR (Nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry) was employed to accurately identify and analyze flavonoids and other active constituents [33]. In addition, MALDI-TOF/MS (Time-of-flight analysis by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry) enabled a detailed examination of the monomers and oligomers found in the extracted tannins [34]. Finally, ATR-FT-MIR (Attenuated Total Reflectance–Fourier Transform Mid-Infrared spectrometry) was used to analyze the functional groups associated with condensed and hydrolyzable tannins [35–37].

Recent research into the mechanical properties of wood, such as modulus of elasticity (MOE) and modulus of rupture (MOR), indicates that these properties vary according to density, moisture content, geographical origin and wood age, with notable differences between juvenile and mature wood [23,25]. Dabema (Piptadeniastrum africanum) has a relatively high density, which gives it good mechanical strength, making it suitable for applications requiring strength and dimensional stability, such as construction and joinery [38–41]. Indeed, this characteristic is a major asset in environments where material strength and durability are essential [26,27,40,42]. In addition, Dabema’s moisture content, studied mainly by the kiln-drying method, is relatively low, which contributes to its stability under fluctuating humidity conditions [37,38]. In comparison, Amouk (Detarium macrocarpum), analyzed, has a higher desorbed moisture content than Dabema, which may influence the choice of material according to specific conditions of use. However, Dabema exhibits higher shrinkage rates, particularly volumetric shrinkage (14.71 ± 0.83%), compared with Amouk (10.09 ± 2.19%), indicating lower dimensional stability under fluctuating environmental conditions. Nevertheless, although the radial (Rr) and tangential (Rt) shrinkage coefficients are slightly higher for Dabema, the tangential shrinkage coefficient (0.29 ± 0.01) is significantly lower than that of Amouk (0.63 ± 0.08), suggesting that Dabema is less prone to deformation in practical applications. However, its high volumetric shrinkage coefficient (0.61 ± 0.03) highlights the difficulties associated with drying and processing. Consequently, although Amouk, with its generally lower values, is more stable, Dabema can be optimized by targeted treatments or used in applications where aesthetic or mechanical properties take precedence over dimensional changes [2]. In terms of stability, wood shrinkage is a key factor in dimensional stability, particularly under the effect of moisture [5]. In this context, studies have evaluated the tangential and radial shrinkage rates of Dabema, concluding that this wood has relatively low shrinkage rates compared with other species, making it a favorable candidate for applications requiring increased resistance to deformation [41,43–46]. Heat treatments are also being explored to reduce the hygroscopicity of wood, but these treatments result in a loss of mechanical strength at elevated temperatures [24]. Density is a key indicator of mechanical performance, making it possible to assess the strength of little-used species, particularly as lightweight alternatives to woods such as ayous and balsa [26]. Moisture, for its part, has a significant impact on the mechanical properties of wood, reducing MOE and MOR, and modifying its behavior from brittle to semi-ductile [27,28]. Recent research has made it possible to improve light transmission while reducing the anisotropy of wood, thus broadening the application possibilities of wood in various fields [26,29]. In terms of its aesthetic properties, Dabema is distinguished by its light brown color, fine texture and moderate sheen, characteristics that enhance its appeal for craft uses, particularly in joinery and furniture manufacture, where aesthetics are paramount [41,29]. However, although these properties have been evaluated, research into these aspects remains limited. Further studies are needed to better understand the impact of surface treatments on these properties and their influence on material durability and performance under different conditions. Such research would make it possible to broaden Dabema’s fields of application in sectors where aesthetics and durability are essential criteria.

Studies on the mechanical properties of wood show that shear strength is strongly correlated with density and can be reliably predicted with specific statistical distributions [16,40]. For instance, results obtained by [40] highlighted that, although often less valued than traditional woods such as Bilinga and Padauk, Dabema offers remarkable performance under mechanical stress. Energy recovery rate (Gic), in particular, although decreasing with increasing initial crack size, remains significant. It reached 581.11 ± 226.91 J/m2 for an 8 mm crack, reflecting a residual capacity to absorb energy even under unfavorable conditions. Furthermore, the stress intensity factor (Kic) testifies to its resistance to crack propagation, with values of 1.29 ± 0.38 MPa*m1/2 at 4 mm and 0.98 ± 0.44 MPa*m1/2 at 8 mm. These findings underline the consistency of Dabema’s mechanical performance in the face of increasing stress. Its bending stress (δn) reaches 66.94 ± 17.82 MPa in the absence of cracks and retains a significant value of 16.78 ± 7.56 MPa in the presence of an 8 mm crack. This resilience highlights its potential for structural applications, confirming that Dabema, despite its low economic value, offers opportunities thanks to its mechanical reliability and ability to maintain acceptable performance under stress [47–51]. Studies of glulam in tropical climates indicate that it is possible to achieve good mechanical performance while valorizing fewer common species [17,52]. These findings are in line with previous research on glulam development, which has established values for other tropical species. For example, Tali has a flexural strength of 18.30 ± 1.70 MPa, Bilinga (Nauclea diderrichii) 15.84 ± 1.53 MPa, Azobe (Lophira alata) 15.40 ± 1.60 MPa, Doussie (Afzelia bipindensis) 14.84 ± 1.45 MPa, Padouk (Pterocarpus soyauxii) 13.02 ± 1.38 MPa, Movingui (Distemonanthus benthamianus) 10.52 ± 1.21 MPa, Frake (Terminalia superba) 9.86 ± 1.12 MPa and Ayous (Triplochiton scleroxylon) 8.75 ± 1.05 MPa. However, although Bilinga offers good performance, it is classified in the same cluster 3 as Dabema and Sapelli, due to similarities in durability and mechanical behavior [52]. These similarities can be explained by specific characteristics of the species, which reflect similar mechanical properties and durability. In addition, geographical differences influence the mechanical properties of wood, which can have an impact on the performance of species depending on their origin and environmental conditions [23]. Furthermore, regression models enable mechanical strengths to be estimated with good accuracy, making it easier to select the most suitable species for specific applications in the glulam sector [30]. Nevertheless, studies such as those in [2] have noted that Dabema has a lower compressive strength than species such as Amouk (Detarium macrocarpum), which limits its structural capacity under high axial loads. The results call for further evaluation of Dabema’s performance in various structural applications. Although Dabema may be suitable for certain applications under load, it may not be ideal for applications requiring high compressive strength. However, work carried out in accordance with ASTM standards, such as that reported in [31], indicates that Dabema has adequate tensile strength. Essential for applications subject to tensile forces, this property makes it a competitive material for uses such as construction and furniture manufacture [16]. Further research is needed, however, to assess its behavior under dynamic and cyclic loads, frequently encountered in real-life scenarios. In parallel, the flexural strength of Dabema has been assessed by three-point bending tests, as documented in [53]. Such tests revealed a tendency to abrupt failure after elastic deformation, indicating brittle behavior. Precise structural design is therefore essential to avoid premature failure, especially for applications requiring a certain degree of flexibility [44]. Likewise, its shear strength, another key mechanical property, was assessed on prismatic specimens according to established standards [40]. Results show that Dabema can withstand the typical shear forces encountered in joinery and assembly applications. While the exact shear modulus has not yet been determined, preliminary results suggest promising performance in structural applications requiring shear strength. Furthermore, Weibull analysis comparing Dabema with other hardwoods such as Amouk (Detarium macrocarpum) revealed a relatively low Weibull modulus (m < 20), as reported in [2,32]. This suggests that sample failures are mainly due to compressive stresses rather than crack propagation. This characteristic therefore makes Dabema a potential candidate for structural applications, although certain limitations must be taken into account, notably its compressive strength and brittle behavior under certain loads. Further research into its dynamic and cyclic behavior will better define its performance in real-life scenarios, offering a more complete perspective on its potential applications.

Dabema (Piptadeniastrum africanum) has great potential due to its flavonoid content and its medicinal and industrial applications [34]. Key compounds such as chalcones, flavonols and anthocyanins are renowned for their antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, as documented in the literature [54–56]. However, their poor oral bioavailability linked to structural features such as hydroxyl, methoxyl, prenyl or glycosidic substitutions presents a challenge to their effective use. These attributes make Dabema a promising candidate for pharmacological applications, including the development of therapeutics and dietary supplements. However, industrial-scale exploitation would require optimizing extraction protocols to ensure high yields while preserving extract quality [18]. HPLC analyses have also revealed that the chemical diversity of these extracts depends on the solvents used, underlining the need to fine-tune extraction conditions in order to target specific compounds for various applications [33,57]. Furthermore, the presence of tannin monomers and oligomers, such as catechin and quercetin, reinforces the interest of this species for the development of sustainable materials. These results, in line with previous research [54,57,58], underline the need for further studies to refine extraction methods and fully explore the bioactive potential of Dabema. These compounds, known for their antioxidant properties, could also be incorporated into cosmetic formulations or UV protection products [18,54,57]. Additionally, the development of unidirectional biocomposites based on tannins extracted from Dabema and reinforced with natural fibers, particularly Urena lobata, illustrates significant potential for industries seeking to reduce their ecological footprint [59]. However, further research into the mechanical properties and durability of these bio-composites under real-life conditions is necessary to ensure their competitiveness with conventional materials. ATR-FT-MIR analysis in the 4000 to 600 cm−1 range enables specific functional groups to be identified on the basis of their characteristic vibration bands. In this context, the results obtained showed bands at 1606 cm−1, typical of C=C vibrations in aromatic rings, confirming the presence of condensed and hydrolysable tannins [59,60]. Works by [35–37] also observed similar bands in their analyses, thus corroborating these results. The similarity of the findings between these studies reinforces the reliability of the current observations and suggests a consistency in the spectroscopic characteristics of tannins. It may also indicate a common chemical composition or similar structures among the samples studied. Thus, the precise identification of functional groups at 1606 cm−1 and the concordance with previous studies provide a solid basis for asserting the presence of these specific compounds, validating the methodology and conclusions of the analysis. This approach can also be extended to assess how these tannins interact with other polymers or fibers, opening the door to solutions in the construction and furniture sectors. However, despite these promising results, significant gaps remain in the comprehensive chemical characterization of the wood itself [18,61]. While the bark and leaves have been extensively studied, Dabema wood, which represents a valuable resource in joinery and construction, warrants further investigation to explore its chemical potential, natural durability, and interactions with protective treatments. Moreover, targeted studies on the wood’s resistance to biological agents (fungi, insects) or its behavior after thermal or chemical treatments could enhance its appeal in the field of sustainable materials [61]. Finally, it is important to emphasize that, to fully exploit the potential of this species in medical and industrial applications, interdisciplinary collaborations will be essential, involving chemists, biologists, pharmacists and engineers. Therefore, studies on the toxicity, bioavailability, and stability of extracts in various formulations will also be necessary to ensure their safety and efficacy.

4 Strategies and Innovations for Sustainable Management of Alternative Woods

Integrating Dabema (Piptadeniastrum africanum) and other alternative species into Cameroon’s timber industry is a strategic lever for diversifying forest resources while reducing pressure on traditional, often overexploited species. Renowned for its mechanical properties similar to European woods such as oak, Dabema is a potentially competitive material in sectors such as construction and furniture. At the same time, alternative species such as Bilinga (Nauclea diderrichii), Moabi (Baillonella toxisperma) and Ayous (Triplochiton scleroxylon) offer remarkable properties that can meet the technical requirements of the industry while considering sustainable development concerns. On the other hand, successful integration will require a rigorous approach to sustainable forest management. Without regeneration and conservation mechanisms, uncontrolled harvesting of these species could lead to irreversible loss of biodiversity and habitat and a rapid decline in resource availability. It is therefore essential to implement a forest management model based on the principles of sustainable yield, combining the preservation of biodiversity, targeted reforestation and the reduction of environmental impacts associated with exploitation. Within this framework, the optimization of harvesting practices for local species must be based on methods that respect the integrity of forest ecosystems. The use of selective harvesting technologies, such as rational area-based harvesting and the introduction of assisted natural regeneration techniques, will limit deforestation while maximizing timber production. In addition, improved processing methods for Dabema and other alternative woods, including innovative ecological treatments (such as thermal or oleothermal treatments), could enhance their durability and resistance to biotic and abiotic factors, while preserving the mechanical properties required for construction applications. From an industrial perspective, the competitiveness of these local woods in relation to imported species will depend on their ability to meet regulatory requirements and quality standards. To this end, certification and standardization processes are essential to ensure that Dabema and other alternative woods meet the expected durability and performance criteria. Mechanical testing, accelerated aging under extreme climatic conditions and characterization of resistance to biological attack are essential steps in demonstrating the viability of these species for long-term applications. The perception and acceptance of these alternative woods by local stakeholders, including producers, consumers and craftsmen, will also play a key role in their adoption. Awareness-raising and education, accompanied by concrete demonstrations of their ecological, economic and technical benefits, will help convince stakeholders of the relevance of these materials for a more self-sufficient circular economy. Emphasis should be placed on the environmental co-benefits, notably the reduction of the carbon footprint and the fight against deforestation, which make these materials particularly well suited to a transition towards energy and ecological sustainability. Closer cooperation with research institutes, local businesses, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and international organizations will facilitate the development of innovative solutions for the conservation and processing of local woods. Combining advanced technologies, such as nanotechnologies or biotechnologies, to improve seeds and plants and preservation treatments for local woods could provide long-term sustainable solutions. The result is not only an improvement in the durability of Dabema and other alternative species, but also the positioning of these materials as preferred alternatives in an increasingly global market focused on sustainable construction and the responsible management of natural resources.

5 Challenges and Prospects for the Adoption of Alternative Woods in Cameroon

Cameroon’s potential for the industrialization of alternative woods, while high due to the diversity and availability of local species, faces a number of challenges that hinder their large-scale adoption. This problem can be analyzed along several technical, economic, environmental and socio-cultural axes, each requiring targeted interventions to maximize the impact of this valorization. Firstly, substitute woods in general, and Dabema (Piptadeniastrum africanum) in particular, have interesting physical, mechanical and chemical properties. However, these properties vary according to environmental factors, the growing area, the age of the species and the section of the log from which they are harvested. Density, flexural strength and modulus of elasticity are heterogeneous, representing a major challenge for standardization and integration into international markets. Further research is therefore needed to better understand the properties of these woods and develop appropriate processing methods. This includes optimizing their natural durability, particularly against pathogens such as insect attacks, termites and fungi. Thermal and chemical treatment protocols, such as treatments with oils or natural products, are therefore essential to improve resistance to moisture and biological attack. In addition, the processing of local woods requires specialized equipment and technological adjustments to maximize their profitability and performance in specific applications. The development of more efficient drying technologies and more precise cutting equipment, for example, would improve the quality of finished products and thus meet the requirements of local and international markets. Nevertheless, the lack of appropriate infrastructure for these treatments is a major obstacle to the adoption of these woods. As a result, the competitiveness of substitute woods compared to exotic woods such as pine or oak is affected by higher production costs, due to factors such as inadequate processing infrastructure, inefficiencies in supply chains and a low level of industrial valorization of local forest resources. In addition, the lack of appropriate standards and certification for these local woods hinders their entry into international markets, where quality and sustainability requirements are stringent. At the same time, uncertainty over the quality and availability of substitute species adds an element of economic instability, discouraging both investors and producers. Under these conditions, the exploitation of substitute woods must be carried out within a framework of sustainability, considering the management of forest resources to avoid over-exploitation. Although Cameroon has a wealth of forest resources, sustainable forest management remains a major challenge. The growing cultivation of certain alternative species could have an impact on the environment if unsustainable forestry practices are adopted, leading to the degradation of local ecosystems. The use of sustainable forest management mechanisms, including the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the Program for the Endorsement of Forest Certification schemes (PEFC), forest management plans and simple management plans in community forests, would be fundamental to ensuring that the development of alternative woods has no long-term negative impact on biodiversity, habitats, soil quality and forest inhabitants. Socially, the adoption of alternative woods is also limited by a lack of awareness among stakeholders in the sector, in particular wood industry professionals, wood consumers and forest dwellers. Perceptions of the quality, provenance and aesthetics of these woods are often an obstacle to their adoption, particularly in the construction and furniture sectors. Programs to raise awareness and train local players in the technical and environmental benefits of alternative woods could therefore help overcome these obstacles. In addition, the recognition of alternative woods as viable alternatives by public policies and building standards would promote their integration into local value chains and their acceptance by local communities. Strategies are needed to overcome these obstacles. Firstly, more scientific research is needed to refine the characteristics of local woods and standardize processing methods. Research should also focus more on comparing the strength and durability of alternative woods with other local and exotic species used in construction, in order to identify niches where these woods could be particularly competitive, such as in low-cost construction or industrial applications. In addition, it should also study the favorable conditions for harvesting seeds, processing, storing and propagating plants of these species. Increased support from public authorities through incentive policies such as subsidies for processing technologies and tree planting, tax credits for local businesses and encouragement for the certification of these local woods could also boost their competitiveness. At the same time, certification of sustainable forest management practices would enhance the credibility of local woods on international markets. The strengthening of processing infrastructures and innovation in protective treatments represent an important lever for reducing production costs and facilitating the integration of alternative woods into industrial processes. This would offer long-term competitive advantages, enabling local woods, including Dabema (Piptadeniastrum africanum), to position themselves as competitive and sustainable materials on national and international markets.

6 Regional and International Collaboration for Alternative Wood Value Chains

Development of alternative woods in Central Africa and Cameroon requires a multi-level collaborative approach, including regional and international partnerships. Adding value to these woods, such as Dabema, relies on effective cooperation between countries producing wood, forest dwellers, NGOs, researchers, international institutions and private companies. Working at regional level, cooperative initiatives between Central African countries can help pool resources and knowledge to ensure sustainable forest management and enhance the value of local species. Shared research, designing and implementing convergent forest policies and development programs can be set up to improve processing techniques, while promoting product standardization to facilitate marketing in the region. Furthermore, this cooperation could encourage the exchange of best practices in forest certification and the fight against deforestation and forest degradation, thereby contributing to the alignment of regional forestry policies. Internationally, collaboration with organizations and companies specializing in the sustainable management of natural resources, as well as with technical and financial partners, is essential. This includes trade agreements for the export of alternative woods to European and Asian markets, where demand for sustainable, environmentally-friendly materials is growing. In addition, cooperation with international institutions, such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) or World Wildlife Fund (WWF), ITTO (International Tropical Timber Organization), International Tropical Timber Technical Association (ITTTA) could reinforce FSC’s ecological certification efforts and raise the profile of alternative woods on world markets. Partnerships with international researchers, particularly in the field of ecological treatments or biotechnologies for disease resistance, are also essential. The use of these cutting-edge technologies would enhance the durability of alternative woods, while strengthening their competitiveness in relation to traditional woods. These collaborations could also pave the way for new solutions for the preservation and sustainable use of tropical forests.

This study aims to assess the assets and limitations of Dabema (Piptadeniastrum africanum) as a sustainable alternative to traditional woods in the furniture and construction sectors. Thanks to its high density and low propensity to warp, Dabema offers outstanding dimensional stability and mechanical strength, in line with ASTM standards, making it particularly suitable for structural applications requiring high durability. However, its adoption remains limited, due to the scarcity of research into its chemical properties and its potential in pharmacology, thus hindering its use in certain fields. In addition, the limited availability of this species and the difficulties associated with its cultivation outside tropical zones slow down its large-scale commercialization. Although thermal and oleothermal treatments can improve its properties, their optimization and environmental impact deserve particular attention. Raising awareness and educating people about the benefits of Dabema is therefore essential to stimulate demand and promote its sustainable development in today’s economy.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their deep gratitude to Mr. Pierre Marie Tefack for his formal analysis and to Dr. Philippes Mbevo Fedoung for his invaluable contribution to the production of the detailed map illustrating the distribution of Dabema wood in Cameroon, an essential element which considerably enhances the scope and accuracy of this study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the article as follows: conception and design of the study: John Nwoanjia. Data collection: John Nwoanjia. Analysis and interpretation of results: John Nwoanjia. Jean Jalin Eyinga Biwôlé. Evariste Fedoung Fongnzossie. Preparation of the draft manuscript: Joseph Zobo Mfomo. Jalin Eyinga Biwôlé. Salomé Ndjakomo Essiane. Antonio Pizzi. Achille Bernard Biwolé. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data and materials in the paper are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mirzaakbarovna MS, Sultanbayevich TN. Wood processing for construction. Am J Appl Sci. 2021;3(5):186–9. [Google Scholar]

2. Kana SK, Biwolé AB, Mejouyo HPW, Ganou KBM, Ngono MRR, Tounkam MN, et al. Physical and mechanical properties of two tropical wood (Detarium macrocarpum and Piptadeniastrum africanum) and their potential as substitutes to traditionally used wood in Cameroon. Int Wood Prod J. 2024;15(1):5–19. doi:10.1177/20426445241233343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Eba’a AR, Lescuyer G, Ngouhouo PJ, Moulendè FT, Abdon A, Betti JL, et al. Étude de l’importance économique et sociale du secteur forestier et faunique au Cameroun: Rapport final. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR; 2013 (In French). Available from: https://agritrop.cirad.fr/573085/. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

4. Nga L, Ndiwe B, Biwolé AB, Pizzi A, Biwole JJE, Mfomo JZ. Matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF)-mass spectrometry and 13C-NMR-identified new compounds in Paraberlinia bifoliolata (Ekop-Beli) bark tannins. J Renew Mater. 2024;12(3):553–68. doi:10.32604/jrm.2023.046568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ndongmo ZA, Biwolé AB, Zobo Mfomo J, Fongnzossie FE, Tchomi NP, Fokwa D. Physical and mechanical properties of Brachystegia cynometroides wood from Cameroon, a potential substitute for timbers used for engineering applications. J Indian Acad Wood S. 2023;20(2):157–64. doi:10.1007/s13196-023-00321-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Cerutti PO, Tacconi L. Forests, illegality, and livelihoods: the case of Cameroon. Soc Natur Resour. 2008;21(9):845–53. doi:10.1080/08941920801922042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Biwôlé JJE, Biwolé AB, Pizzi A, Mfomo JZ, Segovia C, Ateba A, et al. A review of the advances made in improving the durability of welded wood against water in light of the results of African tropical woods welding. J Renew Mater. 2023;11(3):1077–99. doi:10.32604/jrm.2023.024079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Sousa V, Miranda I, Quilhó T, Pereira H. The diversity of wood and non-wood forest products: anatomical, physical, and chemical properties, and potential applications. Forests. 2023;14(10):1988. doi:10.3390/f14101988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Cerutti PO, Guillaume L. The domestic market for small-scale chainsaw milling in Cameroon: present situation, opportunities and challenges. Indonesia: CIFOR; 2011. doi:10.17528/cifor/003421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mahonghol D, Ringuet S, Nkoulou J, Amougou OG, Chen HK. Les flux et les circuits de commercialisation du bois: Le cas du Cameroun. Yaoundé, Cameroun et Cambridge, Royaume-Uni: TRAFFIC; 2016 Aug (In French). [Google Scholar]

11. Rahamanou A, Mahamat H, Frédéric V, Gérard J, Valorisation et promotion des essences forestières camerounaises peu ou non utilisées. Bordeaux: INRA; 2016 (In French). [Google Scholar]

12. Tchatchou B, Sonwa DJ, Ifo S, Tiani AM. Déforestation et dégradation des forêts dans le Bassin du Congo: État des lieux, causes actuelles et perspectives. Indonesia: CIFOR; 2015 (In French). [Google Scholar]

13. Cerutti PO, Mbongo M, Vandenhaute M. État du secteur forêts-bois du Cameroun. Publié par Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture et Centre de recherche forestière internationale (CIFOR); 2016 (In French). [Google Scholar]

14. Lescuyer G, Tal M. Intra-African trade of timber: the Cameroon-Chad case in 2015; 2016. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.2940.5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gérard J, Kouassi AE, Daigremont C. Synthèse sur les caractéristiques technologiques de référence des principaux bois commerciaux africains. CIRAD-forêt; 1998 (In French). Available from:https://agritrop.cirad.fr/515643/. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

16. Ndiapi O, Njankouo JM, Ayina OLM, Gerard J. Characterisation and statistical modelling of shear strength in 12 hardwood timber species from the Congo Basin. Bois et Forêts des Tropiques. 2024;360:27–40. doi:10.19182/bft2024.360.a37284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sout F, Oum LR, Ngono MRR, Pommier R, Ntédé NH, Ayina OLM. Mechanical qualification of green glued laminated timbers from the Congo Basin towards preservation of forest species diversity. J Trop For Sc. 2022 Jan 1;34(3):359–70. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48678136. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

18. Chinonye OK, Ugboaja CI, Chinedu ED, Chinedu IB. Effect of ethanol stem bark extract of Piptadeniastrum africanum (Hook. f.) on serum electrolytes balance of albino rats. GSC Biol Pharm Sci. 2023;22(3):193–6. doi:10.30574/gscbps.2023.22.3.0049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Onana JM. The world flora online 2020 project: will cameroon come up to the expectation? Rodriguésia. 2015;66(4):961–72. doi:10.1590/2175-7860201566403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Vogt P, Riitters KH, Caudullo G, Eckhardt B. FAO-State of the World’s forests: forest fragmentation. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2019. [Google Scholar]

21. Asia E, Region P. Review on sustainable forest management and financing in China. USA: The World Bank; 2019. [Google Scholar]

22. Arce JJ. Forests, inclusive and sustainable economic growth and employment. In: Background study prepared for the fourteenth session of the United Nations Forum on Forest (UNFFForests and SDG8. New York, NY, USA: United Nations; 2019. [Google Scholar]

23. Tumenjargal B, Ishiguri F, Aiso H, Takahashi Y, Nezu I, Takashima Y, et al. Physical and mechanical properties of wood and their geographic variations in Larix sibirica trees naturally grown in Mongolia. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12936. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69781-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Rasdianah D, Zaidon A, Hidayah A, Lee SH. Effects of superheated steam treatment on the physical and mechanical properties of light red meranti and kedondong wood. J Trop For Sci. 2018;30(3):384–92. doi:10.26525/jtfs2018.30.3.384-392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Roslan SN, Salim S, Muhammad RAS, Najiha ZAWN. Physico-mechanical properties of Paraserianthes falcataria (Batai) in relation to age and position variation. Pertanika J Sci Tech. 2024;32:39–61. doi:10.47836/pjst.32.S4.03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ohemeng E. Functional relationship between density and mechanical properties of Ricinidendron heudelotii. Global J Med Plant Res. 2022;9(1):9–17. [Google Scholar]

27. Kherais M, Csébfalvi A, Len A, Fülöp A, Pál SJ. The effect of moisture content on the mechanical properties of wood structure. Pollack Periodica. 2024;19(1):41–6. doi:10.1556/606.2023.00917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zauer M, Porath J, Krüger R, Wagenführ A. Investigations into the swelling pressure of wood as a function of the anatomical direction. Open Phys. 2024;23:100244. doi:10.1016/j.physo.2024.100244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wu Y, Zhou J, Yang F, Wang Y, Wang J, Zhang J. A strong multilayered transparent wood with natural wood color and texture. J Mater Sci. 2021;56:8000–13. doi:10.1007/s10853-021-05833-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Arroyo FN, Borges JF, Junior WM, Santos HF, Oliveira IA, Panzera TH, et al. Estimation of flexural tensile strength as a function of shear of timber structures. Forests. 2023;14(8):1552. doi:10.3390/f14081552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. ASTM E399-09e1. Standard test method for linear-elastic plane strain fracture toughness (KIC) of metallic materials. USA: ASTM International Philadelphia; 2009. [Google Scholar]

32. O’Connor P, Kleyner A. Practical reliability engineering. USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2011 Nov 22. [Google Scholar]

33. Ortega VJ, Cobo A, Ortega ME, Gálvez A, Alejo AA, Salido S, et al. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of flavonoids isolated from wood of sweet cherry tree (Prunus avium L.). J Wood Chem Technol. 2021;41(2–3):104–17. doi:10.1080/02773813.2021.1910712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Eyinga BJJ, Biwolé AB, Zobo MJ, Segovia C, Pizzi A, Chen X, et al. Causes of differential behavior of extractives on the natural cold-water durability of the welded joints of three tropical woods. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2022;36(12):1314–31. doi:10.1080/01694243.2021.1970318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Njom AE, Voufo J, Segovia C, Konai N, Mewoli A, Tapsia LK, et al. Characterization of a composite based on Cissus dinklagei tannin resin. Heliyon. 2024;10(4):e25582. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25582. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Mewoli AE, Segovia C, Njom AE, Ebanda FB, Biwôlé JJ, Xinyi C, et al. Characterization of tannin extracted from Aningeria altissima bark and formulation of bioresins for the manufacture of Triumfetta cordifolia needle-punched nonwovens fiberboards: novel green composite panels for sustainability. Ind Crop Prod. 2023;206:117734. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. da Silva BAR, de Oliveira VM, Fernandez AS, Sakai OA, Março PH, Valderrama P. Attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy and chemometrics for organic cinnamon evaluation. Food Chem. 2021;365:130466. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Kuai B, Xu Q, Zhan T, Lv J, Cai L, Gong M, et al. Development of super dimensional stable poplar structure with fire and mildew resistance by delignification/densification of wood with highly aligned cellulose molecules. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;257:128572. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128572. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. De Almeida TH, de Almeida DH, De Araujo VA, da Silva SA, Christoforo AL, Lahr FA. Density as estimator of dimensional stability quantities of Brazilian tropical woods. BioResources. 2017;12(3):6579–90. doi:10.15376/biores.12.3.6579-6590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Biyo’o R, Biwole AB, Moutou Pitti R, Nyobe CJ, Ndiwe B, Onana EJ, et al. Mode I cracking of three tropical species from Cameroon: the case of bilinga, Dabema, and padouk wood. Wood Mater Sci Eng. 2024;19(6):1234–43. doi:10.1080/17480272.2024.2314750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Dong Y, Yan Y, Wang K, Li J, Zhang S, Xia C, et al. Improvement of water resistance, dimensional stability, and mechanical properties of poplar wood by rosin impregnation. Eur J Wood Wood Prod. 2016;74:177–84. doi:10.1007/s00107-015-0998-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Engonga EAC, Pambou NCF, Ekomy AS, Ikogou S, Moutou PR. Comparative studies of three tropical wood species under compressive cyclic loading and moisture content changes. Wood Mater Sci Eng. 2021;16(3):196–203. doi:10.1080/17480272.2020.1712739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. De Melo JE, Pellicane PJ, De Souza MR. Goodness-of-fit analysis on wood properties data from six Brazilian tropical hardwoods. Wood Sci Technol. 2000;34(2):83–97. doi:10.1007/s002260000033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Susanti CM, Nakao T, Yoshihara H. Examination of the failure behaviour of wood with a short crack in the tangential-radial system by single-edge-notched bending test. Eng Fract Mech. 2010;77(13):2527–36. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2010.05.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Glass S, Zelinka S. Moisture relations and physical properties of wood. In: Wood handbook—wood as an engineering material; FPL-GTR-282. Madison, WI, USA: Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory; 2021. [Google Scholar]

46. Mvondo RR, Damfeu JC, Meukam P, Jannot Y. Influence of moisture content on the thermophysical properties of tropical wood species. Heat Mass Transfer. 2020;56:1365–78. doi:10.1007/s00231-019-02795-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Asdrubali F, Ferracuti B, Lombardi L, Guattari C, Evangelisti L, Grazieschi G. A review of structural, thermo-physical, acoustical, and environmental properties of wooden materials for building applications. Build Environ. 2017;114:307–32. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2016.12.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Ofori J, Brentuo B, Mensah M, Mohammed AI, Boamah TR. Properties of 10 Ghanaian high density lesser-used-species of importance to bridge construction—part 1: green moisture content, basic density and shrinkage characteristics. Ghana J Forestry. 2009;25:67–77. [Google Scholar]

49. NF B51-008. Bois-Essai de Flexion Statique-Détermination de La Résistance à La Flexion Statique de Petites Éprouvettes sans Défaut. Afnor; 2017. [Google Scholar]

50. Nganko JM, Koffi EP, Kane M, Gbaha P, Yao KB. Application of principal component analysis (PCA) to the study of the influence of the thermochemical treatment process of tropical wood sawdust on the calorific, mechanical, physicochemical and combustion properties of the resulting fuel briquettes. Biofuels. 2024;15(10):1281–94. doi:10.1080/17597269.2024.2361981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Ofori J, Brentuo B, Mohammed AI, Mensah M, Boamah TR. Properties of 10 Ghanaian high density lesser-used-species of importance to bridge construction—part 2: mechanical strength properties. Ghana J For. 2009;25(1):77–91. doi:10.4314/gjf.v25i1.60701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Lissouck RO, Ngono MRR, Ateba FR, Pommier R. Investigation of green-glued laminated timber from the Congo Basin: durability, mechanical strength and variability trends of the bondlines. South Forests. 2022;84(3):225–41. doi:10.2989/20702620.2022.2045881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Mvondo RRN, Meukam P, Jeong J, Meneses DD, Nkeng EG. Influence of water content on the mechanical and chemical properties of tropical wood species. Results Phys. 2017;7:2096–103. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2017.06.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Fang Y, Cao W, Xia M, Pan S, Xu X. Study of structure and permeability relationship of flavonoids in Caco-2 cells. Nutrients. 2017;9(12):1301. doi:10.3390/nu9121301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Bangar SP, Chaudhary V, Sharma N, Bansal V, Ozogul F, Lorenzo JM. Kaempferol: a flavonoid with wider biological activities and its applications. Crit Rev Food Sci. 2023;63(28):9580–604. doi:10.1080/10408398.2022.2067121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Mbiantcha M, Almas J, Shabana SU, Nida D, Aisha F. Anti-arthritic property of crude extracts of Piptadeniastrum africanum (Mimosaceae) in complete Freund’s adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. BMC Complement Med. 2017;17:1–6. doi:10.1186/s12906-017-1623-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Sinan KI, Chiavaroli A, Orlando G, Bene K, Zengin G, Cziáky Z, et al. Evaluation of pharmacological and phytochemical profiles of Piptadeniastrum africanum (Hook. f.) brenan stem bark extracts. Biomolecules. 2020;10(4):516. doi:10.3390/biom10040516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Luo M, Zhou DD, Shang A, Gan RY, Li HB. Influences of microwave-assisted extraction parameters on antioxidant activity of the extract from Akebia trifoliata peels. Foods. 2021;10(6):1432. doi:10.3390/foods10061432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Wedaïna AG, Pizzi A, Nzie W, Danwe R, Konaï N, Amirou S, et al. Performance of unidirectional biocomposite developed with piptadeniastrum africanum tannin resin and urena lobata fibers as reinforcement. J Renew Mater. 2021;9(3):477–93. doi:10.32604/jrm.2021.012782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Brusotti G, Tosi S, Tava A, Picco AM, Grisoli P, Cesari I, et al. Antimicrobial and phytochemical properties of stem bark extracts from Piptadeniastrum africanum (Hook f.) Brenan. Ind Crop Prod. 2013;43:612–6. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.07.068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Rowell RM, Pettersen R, Han JS, Rowell JS, Tshabalala MA. Cell wall chemistry, handbook of wood chemistry and wood composites. In: Rowell RM, Ed. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis Group; 2005. p. 9–40. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools