Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Nanocellulose: A Comprehensive Review of Sustainable Applications and Innovations

1 Department of Chemistry, People’s Education Society University, Electronic City Campus, Hosur Road, Bangalore, Karnataka, 560 100, India

2 Department of Physics, People’s Education Society University, Electronic City Campus, Hosur Road, Bangalore, Karnataka, 560 100, India

3 Faculty of Health Sciences, Durban University of Technology, Durban, 4000, South Africa

4 School of Life Sciences, Westville Campus, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, 4000, South Africa

* Corresponding Author: Suresh Babu Naidu Krishna. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(7), 1315-1346. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0050

Received 03 December 2024; Accepted 22 May 2025; Issue published 22 July 2025

Abstract

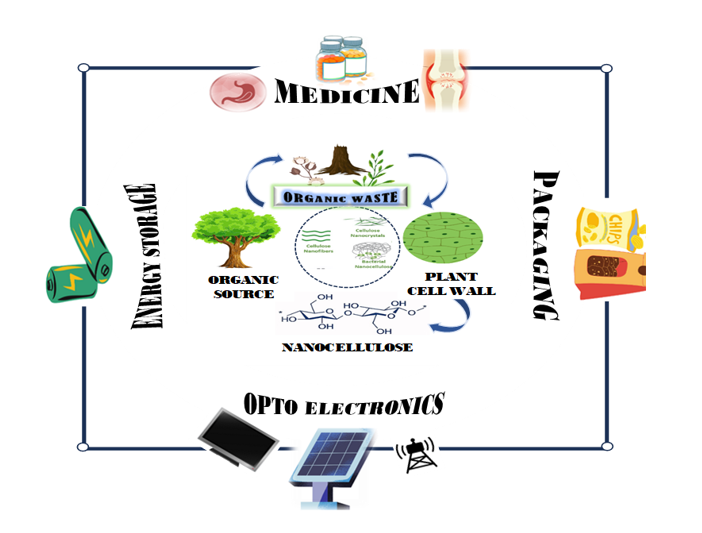

In the past two decades, nanocellulose has become an innovative material with unique properties. This substance has exceptional mechanical strength, an extensive surface area, and biodegradability. Collaborative integration of nanocellulose offers a more environmentally friendly solution to the current limitations by substituting carbon. Due to its versatility, nanocellulose is commonly employed in various industrial sectors, including paints, adhesives, paper production, and biodegradable polymers. Such versatility enables the creation of customized structures for potential use in emulsion and dispersion applications. Given its biocompatibility and nontoxicity, nanocellulose is particularly well-suited for biomedical purposes such as tissue engineering, drug delivery systems, and medical implants. Future advancements in nanotechnology are likely to heavily depend on nanocellulose as it continues to garner attention. Current research has focused on improving synthetic methods, investigating their properties, and expanding their potential applications across various fields. Consequently, enhancing this material presents a promising avenue for eco-friendly technologies and cutting-edge innovations in contemporary studies.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

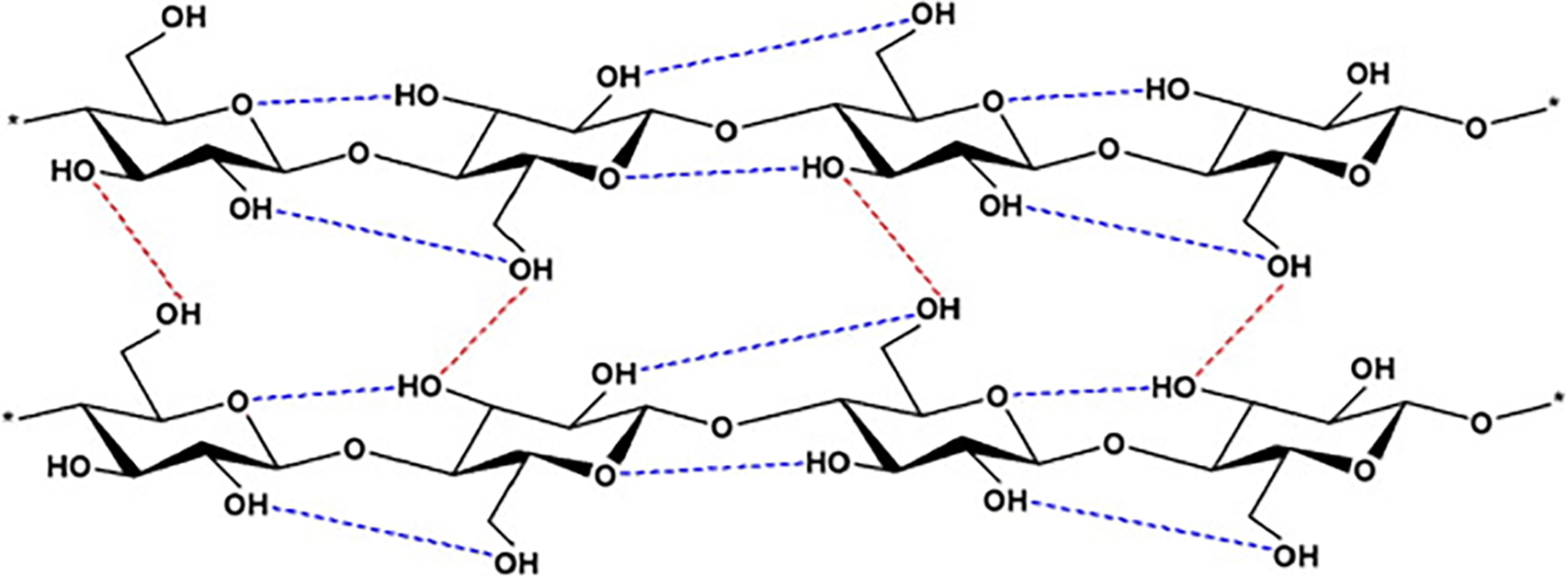

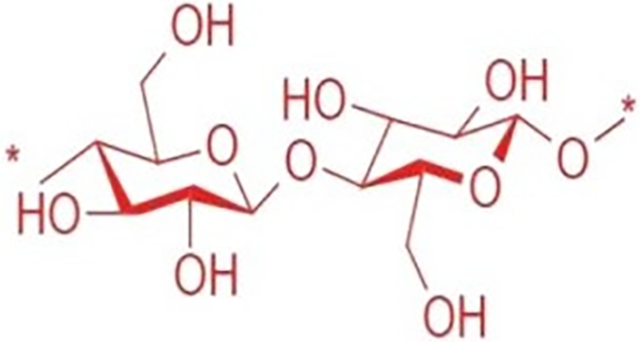

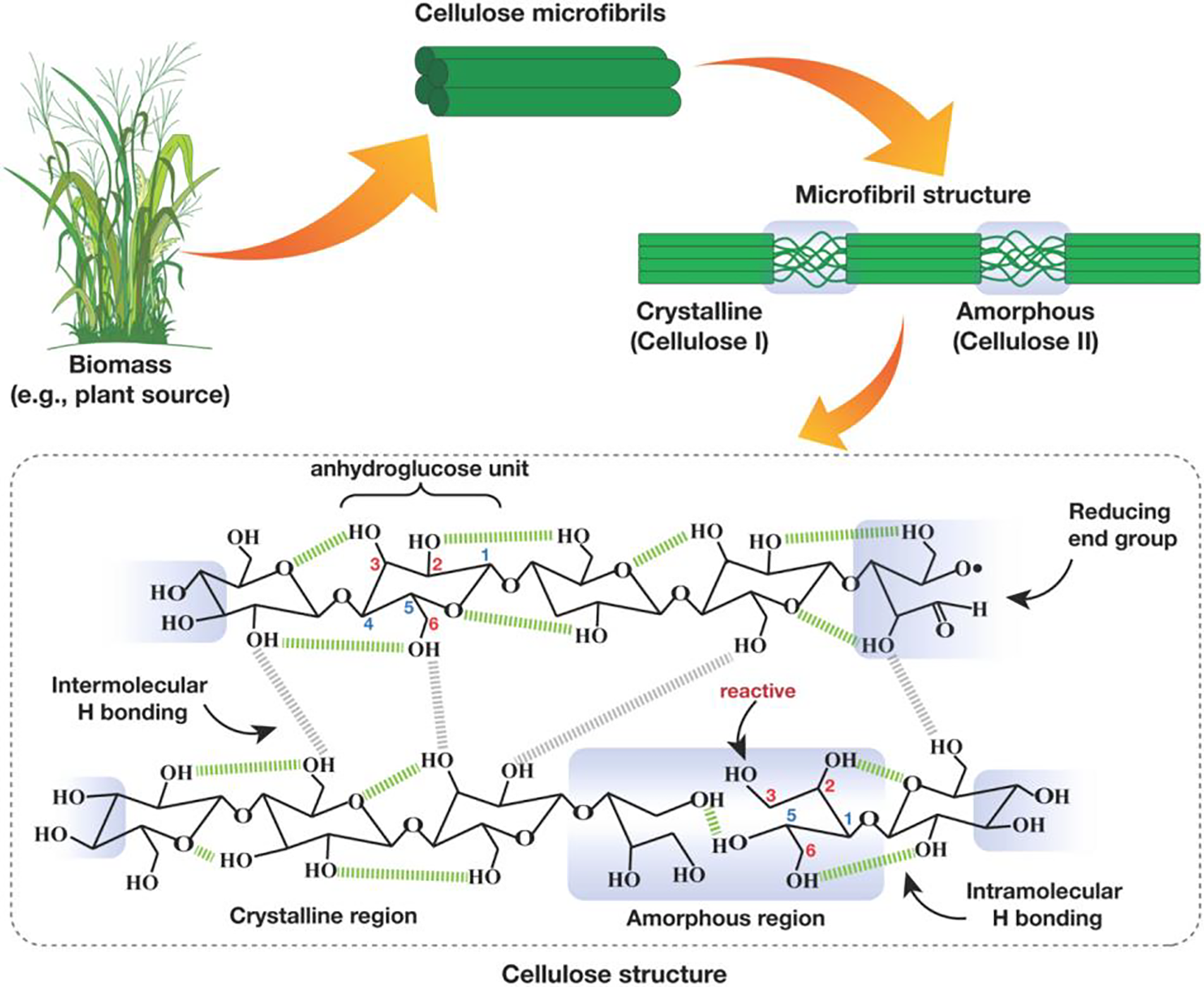

Nanocellulose molecules are derived from the naturally occurring polysaccharide cellulose (C6H10O5)n, a polysaccharide composed of thousands of glucose molecules linked by glycosidic linkages (Fig. 1). Cellulose is the most vital structural component of plant cell walls [1]. Nanocellulose is bland, odorless, and hydrophilic in the natural environment. It is insoluble in most organic solvents and water. Cellulose has a linear polymer chain with no branching [2]. In the polymer, the oxygen atoms on the same chain or an adjacent chain form hydrogen bonds with multiple hydroxyl clusters on glucose from one chain, holding the chains rigidly connected adjacent to each other and yielding microfibrils with enormous tensile strength [3]. Various types of cellulose are also outlined in our survey. Various types of cellulose can be distinguished by examining the specific positions of hydrogen bonds, both inside and between individual molecular strands. Naturally, cellulose exhibits two configurations,

Figure 1: Structure of cellulose networks with intramolecular ( ) and intermolecular (

) and intermolecular ( ) hydrogen bonds [6]

) hydrogen bonds [6]

Several domains have demonstrated the adaptability of nanocellulose, highlighting the background studies. The ability to form an intricate framework at the nanoscale has led to its utilization as a nanoadditive in multiple fields, including its ability to alter the viscosity and rheological properties of emulsions and dispersions, making it a perfect additive for formulations in which texture, stability, and consistency are key factors. The safe and compatible nature of nanocellulose has opened up new possibilities for various innovations, like regenerative medicine, cellular scaffolds, drug delivery, wound healing, and biological implants [7].

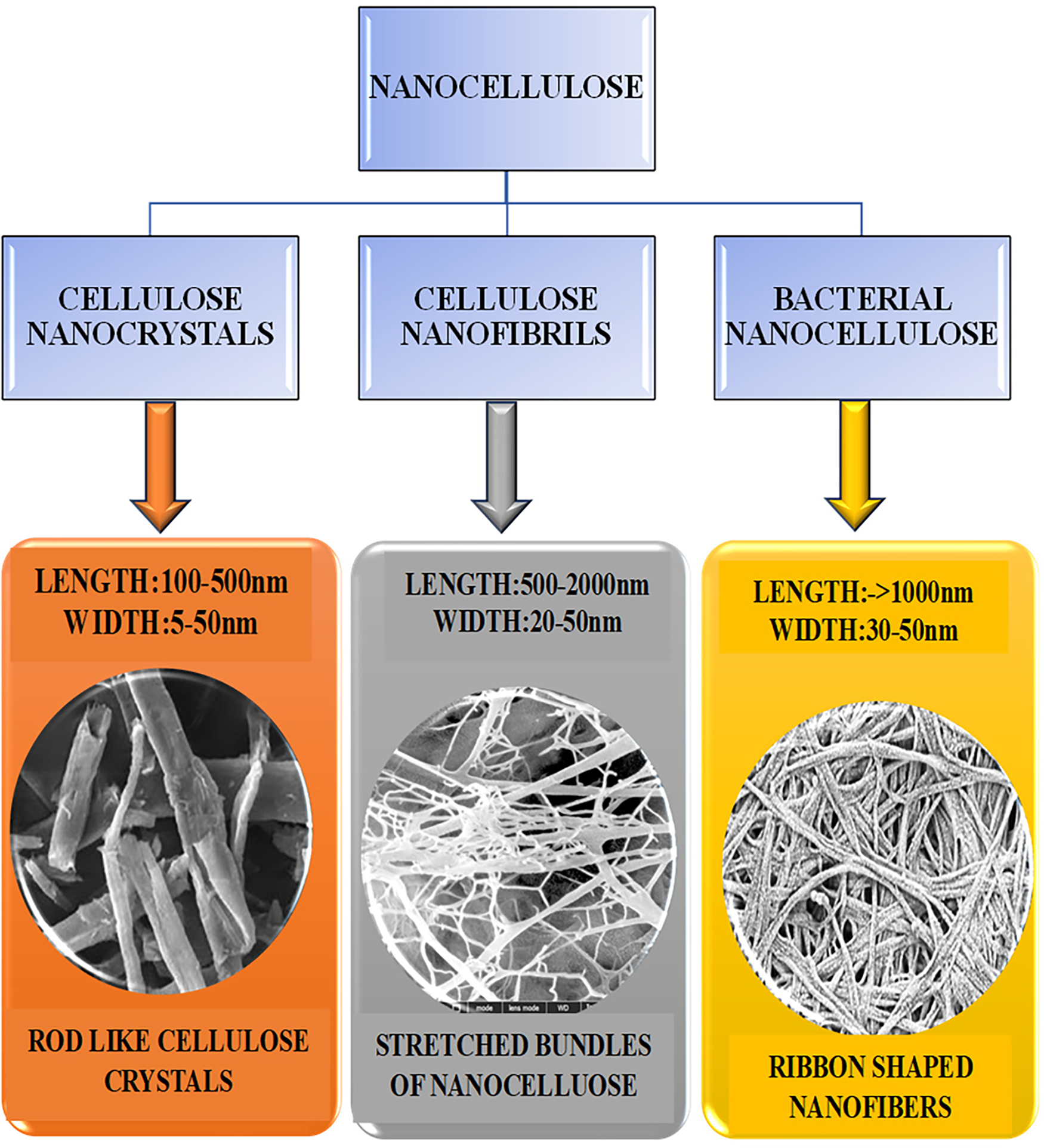

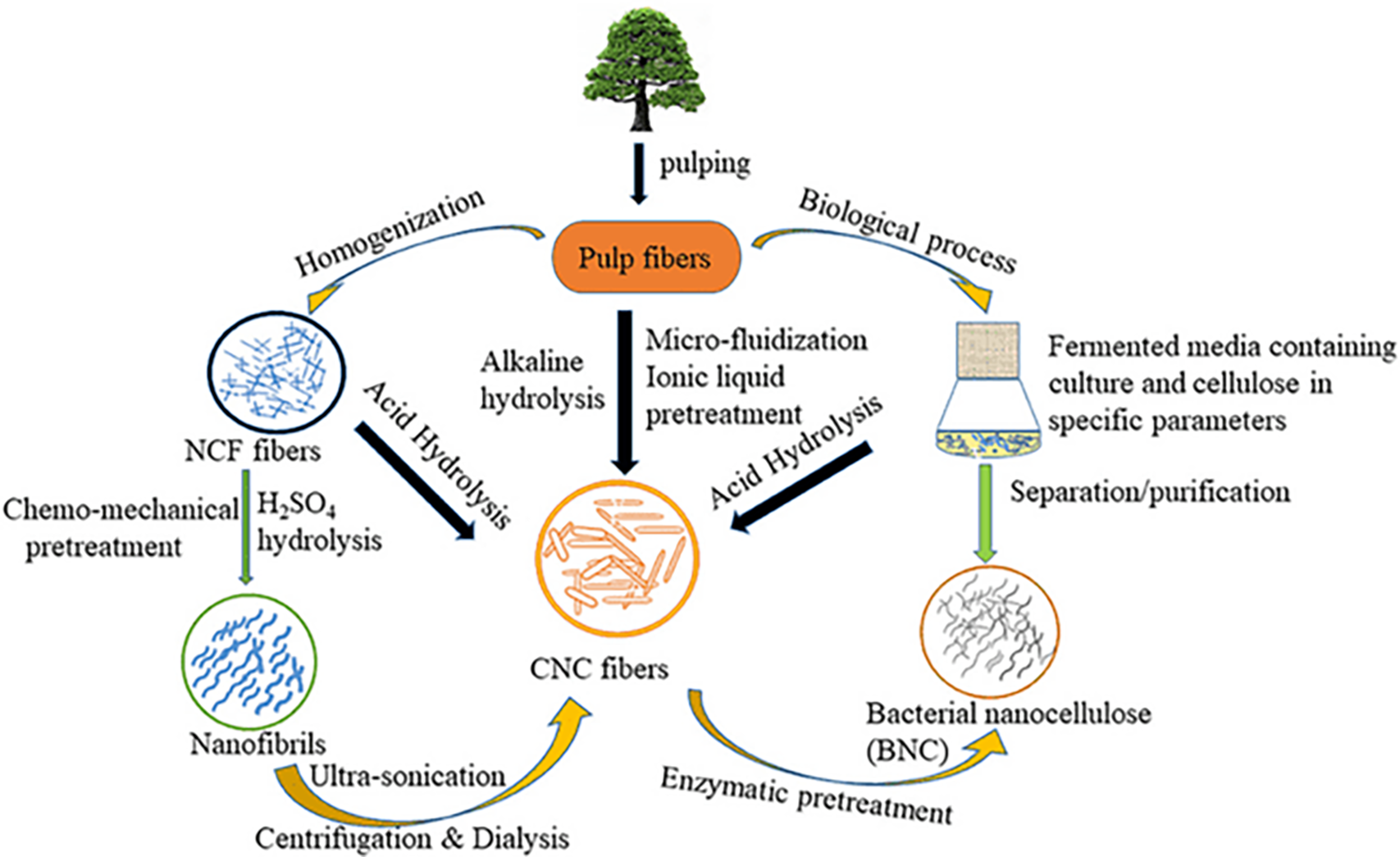

In addition, nanocellulose has significant environmental benefits for medical and industrial applications. Its biodegradability and renewable origin make it an attractive alternative to carbon-based materials, which are often derived from non-renewable fossil fuels. The fabrication and utilization of nanocellulose contribute to reducing the carbon footprint of manufacturing processes and mapping with global sustainability goals. However, using nanocellulose in biodegradable polymers helps solve problems with plastic waste, like how long it takes to break down, because nanocellulose-based bioplastics break down faster and are less harmful to the environment than regular plastics. As the field of nanotechnology is diversifying, the role of nanocellulose in modeling the future of sustainable materials has become clear. Ongoing research is focused on improving the synthesis and performance of nanocellulose to make the material more available for wide commercial use. Researchers are also looking into new ways to change the surface of nanocellulose to better suit different uses. These modifications can enhance the interaction of nanocellulose with other materials, enhance its ability to disperse in different media, and increase its functionality in specific applications. All plant cells contain cellulose in the form of fibers in their walls. Nanocellulose can be categorized into three types: (1) Cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs); (2) Cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs); (3) Bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) [8], as shown in Fig. 2. Each has a distinctive framework and mechanical properties that amplify the adaptability of nanocellulose to different fields. CNCs are highly rigid and are often used to improve the mechanical properties of various composites, whereas CNFs are highly flexible and are used as supporting materials in biodegradable polymers produced by certain bacterial species, such as Pseudomonas sp., Agrobacterium sp., Rhizobium sp., Salmonella sp., and E. coli. They are ideal for biomedical applications and wound healing because they are extremely pure and have structured nanostructures [9]. Cellulose is the predominant polymeric material present on Earth and is produced by the photosynthesis of living organisms, namely algae and certain bacteria, via carbon dioxide fixation [10]. Plant tissues, algae, and bacteria are the major producers of cellulose, and some marine organisms have the potential to produce large quantities of cellulose. This review discusses recent developments in nanocellulose, briefly introduces its types, and surveys the advancements in potential applications in recently.

Figure 2: Classification of nanocellulose

2 Overview of Classification of Nanocellulose and Its Characteristics

In recent decades, significant attention has been paid to the applications of nanocellulose in various sectors. Cellulose-based nanomaterials are arranged according to their size, form, and preparation method (Fig. 2). The following is a general taxonomy of nanocellulosic materials.

1. Cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs)

2. Cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs)

3. Bacterial nanocellulose (BNCs)

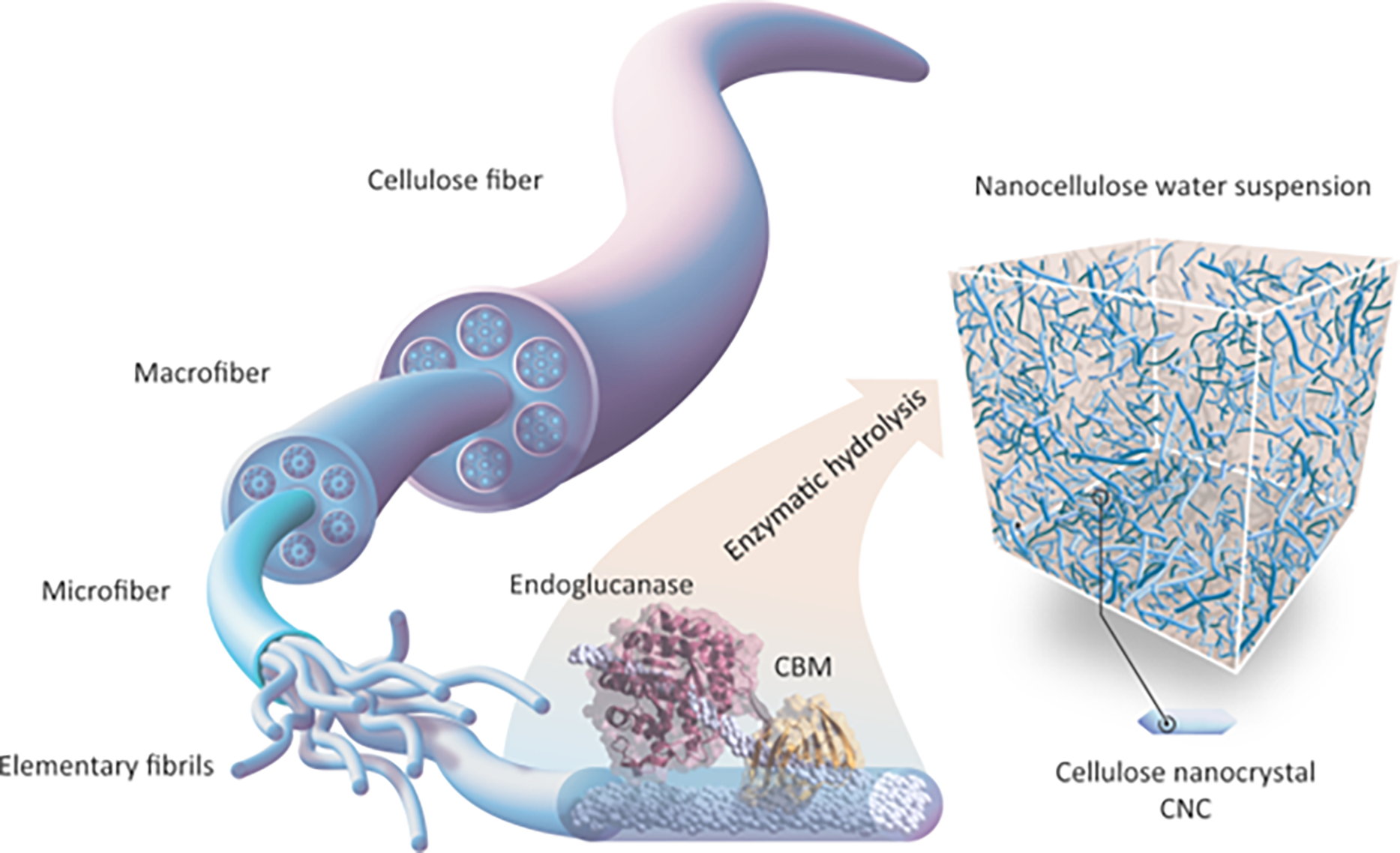

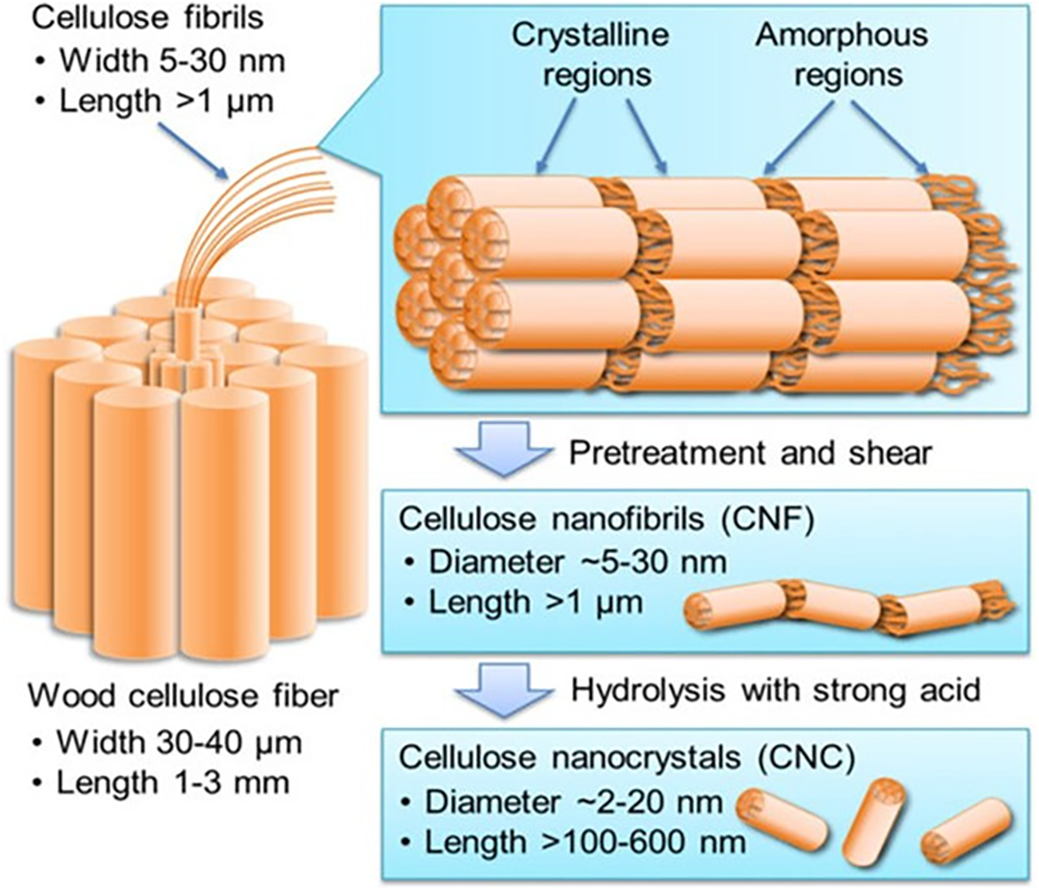

Nickerson and Habrle first reported cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) in 1947. Cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) are rigid, rod-shaped nanoparticles composed of cellulosic chain fragments with nearly pure crystalline structures (Fig. 3). Other acronyms for nanocrystals include whiskers, nanoparticles, nanofibers, and microcrystallites, as shown in Fig. 4 [11]. Depending on the source and level of preparation, CNCs can range in width from 3 to 50 nm and length from 100 to 2000 nm [12,13]. However, they also act as insulators. The enhanced performance of coatings makes them promising candidates for fragile structures or device fabrication, owing to the nonlinear geometry of cellulose nanocrystals (CNC). Capsular polysaccharides of bacteria and plant fibers contain cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs), which are organic crystallization macromolecular compounds. Their attributes include robust biocompatibility, low density, excellent physical properties, high strength, and enhanced crystallization [14].

Figure 3: Chemical structure of nanocellulose

Figure 4: Enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose. Adapted with permission from Ref. [15]. Copyright © 2020, Springer Nature

Unlike regular cellulase, most of these enzymes improve how cellulase interacts with cellulose pulp fibers or the properties of fibrils without changing the cellulose itself, which helps break down cellulose [16]. Turbak and Herrick developed CNF as an innovative cellulosic substance [17]. They did this by continuously passing a watery mixture of softwood pulp through a homogenizer at high pressure, which produced cellulose with tiny sizes in the nanometer range (Fig. 5). During treatment, a high shearing pressure resulted in tightly entangled networks with amorphous crystalline domains. They have high aspect ratios and display shear-thinning and thixotropic features when gelled in water. Under certain processing conditions, cellulose fibers can turn into flexible CNF with widths from tens of nanometers, which are single microfibrils and their bundles, to over 5 nm, which are basic fibrils, and their bundles, to over 5 nm, which represent elementary fibrils. CNFs typically lenghten to a few micrometers and have a diameter of 5–50 nm. Wood bark and plants consist of cellulose, a combination of hemicellulose and lignin. Typically, the papermaking sector employs bleaching and boiling treatments to remove the latter before CNF synthesis. This section reviews all activities, most of which have been experimented on cellulose pulp that has already been refined. TEMPO-mediated oxidation, followed by either blending [18] or homogenization, carboxymethylation, or quaternization, then performed, followed by homogenization [19]. Successive refining, enzymatic hydrolysis, further refinement, and finally homogenization are examples of CNF production methods that typically involve several steps. Consequently, the production process involves numerous activities that change to produce various types of CNF [20].

Figure 5: Schematic illustration of CNF and CNC production from wood adapted with permission from Ref. [21]. Copyright © 2016, American Chemical Society

In 1886, Brown conducted a study on the production of bacterial cellulose (BC). After culturing the bacterium xylinum in a static state, Brown discovered a thin layer resembling a white gel formed on the surface of the culture medium. According to chemical examination, the primary constituents of white gel are cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Subsequent investigations have revealed that the diameter of cellulose is on the nanoscale [22]. Ribbon-shaped and intertwine in a 3-D network, to form the BNC, rendering it ultra-fine and pure. It is regarded as an environmentally friendly, economically viable, and promising type of nanocellulose [23]. This ribbon-shaped structure provides a distinct nanofiber system 20–100 nm in length [24]. Various types of bacteria can biosynthesize bacterial nanocellulose (Fig. 6) using a liquid culture medium composed of carbon (such as glucose), nitrogen (such as tea), vitamins, and minerals (such as yeast) [25] (Table 1).

Figure 6: Synthesis and structure of bacterial cellulose. Adapted with permission from Ref. [26]. Copyright © 2022, Springer Nature

3 Production Methods of Nanocellulose

The preparation of nanocellulose involves a wide range of unique techniques such as pretreatment, mechanical processes, and chemical hydrolysis (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Chemical synthesis of nanocellulose. Adapted with permission from Ref. [44]. Copyright © 2020, Frontiers in Chemistry

Pretreatments are one of the key factors that determine the ingredients that give a material color. The chemicals and excess components were removed during bleaching. The extracted cellulose was light in color and white. Sodium dithionate, hydrogen peroxide, and chlorine dioxide are used in this process [45]. There are several pretreatment methods for the conversion of nanocellulose, such as alkaline-acid pretreatment, organosolv, ionic liquids, and enzyme hydrolysis.

Different hydrolysis and pretreatment procedures are used to help dissolve and recover lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose from lignocellulosic biomass. The alkaline method of hydrolysis is greatly aided by high proportions of lignin, since it breaks down both lignin and hemicellulose with the help of oxidizing agents to enhance efficiency. On the other hand, the spread of acid hydrolysis, whether concentrated or diluted, depends on the kind of acid, its pH, temperature, and reaction time. Although effective, this mechanism requires stronger acids, such as corrosive materials, which can break down parts of the structure of lignocellulosic materials. Unlike previous methods, organosolv treatment does not use acids; instead, organic solvents are used to dissolve two constituents, making this method easier to perform on a wider scale, yet it still requires a bit more research before being commercially available. Low toxicity, and higher dissolving ability do aid in reducing the degree of crystallinity of cellulose and disrupting intramolecular hydrogen bonds, which helps ionic liquids. The last method is removing cellulose; specialized exoglucanases are used, which act on the amorphous areas of the structure, while cellobiohydrolases, which act on highly crystalline regions, are known to remove lignin and hemicellulose.

Mechanical processes, such as high-pressure homogenization, microfluidization, grinding, cryo-crushing, high-intensity ultrasonication, and ball milling, are used to convert nanocellulose.

• High-pressure homogenization, which is normally free of organic solvents, is an efficient method. However, preventing such concerns is a key challenge because it is a pressure-based defibrillation procedure.

• Although this approach is simple to use and does not considerably change the kappa number of cellulose nanofibrils compared to the original pulps, it is not always suitable at the industrial level. The result is comparable to high-pressure homogenization.

• Micro-grinding: This process is quicker and relies heavily on refining the pre-treatment. It employs shear stresses on the hydrogen bond and cell wall structure. However, this technique modifies the crystal structure of the CNFs.

• High-intensity ultrasonication is an effective method typically used to achieve a high rate of defibrillation; however, it has certain limitations. For instance, this procedure is useful at the laboratory scale but also produces a high level of noise, and pretreatments are offered for releasing cellulose nanofibrils.

• Cryo crushing: This mechanical process, which involves the use of liquid nitrogen followed by crushing, is used to fibrillate cellulose [46].

Chemical hydrolysis, which includes acid hydrolysis and TEMPO oxidation, is the easiest and most effective way to make a lot of nanocellulose, helping it mix better in different materials [47].

3.3.1 TEMP O-Mediated Surface Oxidation

Using chemical pretreatment in gentle and watery conditions helps stop nanoparticles from clumping together when they dry and keeps nanofibrils from separating because of the repelling forces from the charged carboxylate groups. In contrast to acid hydrolysis and mechanical treatment, the oxidization method can be employed to create CNCs. After natural cellulose is oxidized with 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO) radicals, it is mechanically homogenized. The cellulose fiber initiates a reaction both on its surface and in its amorphous regions. The carboxylic group was used in a TEMPO–NaBr–NaClO system with direct ultrasonication to transform the CNC surface. Better dispersibility in an aqueous solution is exhibited by carboxylated CNCs because of anionic-charged electrostatic repulsion. This oxidation technique produces a stable and uniformly distributed aqueous solution by gradually hydrolyzing the amorphous portion. With high crystallinity and high surface area, this approach produces an 80% yield of CNCs; however, it has significant disadvantages, notably the use of hazardous chemicals (TEMPO reagents) [48].

Biological processing is a method for cellulose production that primarily involves the fermentation of microbes, known as bacterial nanocellulose. Biological processing is a method for cellulose production that primarily involves the fermentation of microbes known as bacterial nanocellulose [49]. Bacterial nanocellulose is synthesized using different techniques such as static, agitated, and bioreactor cultures. A static culture is a type of cultivation in which the medium is not moved or stirred. After a defined culture period, this approach yielded a BNC pellicle at the liquid-air interface, illustrating the efficiency of static circumstances in creating BNC [50]. Agitated culture is a fermentation technique that involves cultivating bacteria via stirring or mixing, which boosts the yield of BNC [51]. After a predetermined culture period, this approach produced a BNC pellicle at the liquid-air interface, displaying the efficiency of static circumstances in the production of BNC [52].

BNC can be generated through a variety of methods, such as bioreactors, agitatation/shaking, and static. These three techniques aim to enhance BNC production while reducing expenses and cultivation time, although each technique has a unique impact on the structure and morphology of BNC [53].

Static culture is a popular technique used for BC production. Hydrogel sheets with exceptional qualities are produced by incubating containers with nutrient solutions for one–14 days at temperatures between 28°C and 30°C and 4 < pH < 7. BNCs develop at the gas-liquid interface, and the air-liquid surface area is crucial. Additionally, the metabolism of bacteria produces stored carbon dioxide, which greatly inhibits the delivery of oxygen [54]. This technique creates cellulose in the shape of a sheet, film, or membrane. Compact texture, strength, water permeability, and biocompatibility are some of the advantages of static cultures. Nevertheless, it has certain disadvantages, such as low production and time-consuming cultivation [55]. The use of an agitated culture method has been recommended as a solution for the low yield rates and high production costs associated with static culture systems. A significant drawback of the static culture approach is the agitated culture’s attempt to improve oxygen delivery to the bacteria during culture. Studies have revealed comparable BNC yields to static cultures, despite their promise. BNC can be generated in various forms under agitated culture conditions, including pellets, spheres, ellipsoids, stellates, fibers, or irregular masses. The configuration of the agitator, oxygen supply, rotational speed, length of the culture period, continuous shear force, and types of additives in the culture medium affects the shape and size of BNC. For producing large amounts of BNC for different commercial purposes, cultures that are stirred often have weaker mechanical strength, lower crystallinity, and less polymerization compared to those grown without movement. Furthermore, a disadvantage of the agitation method is the occurrence of non-cellulose mutants due to shear stress [56,57].

4 Applications of Nanocellulose

4.1 Innovations in Cellulose Nanocrystals

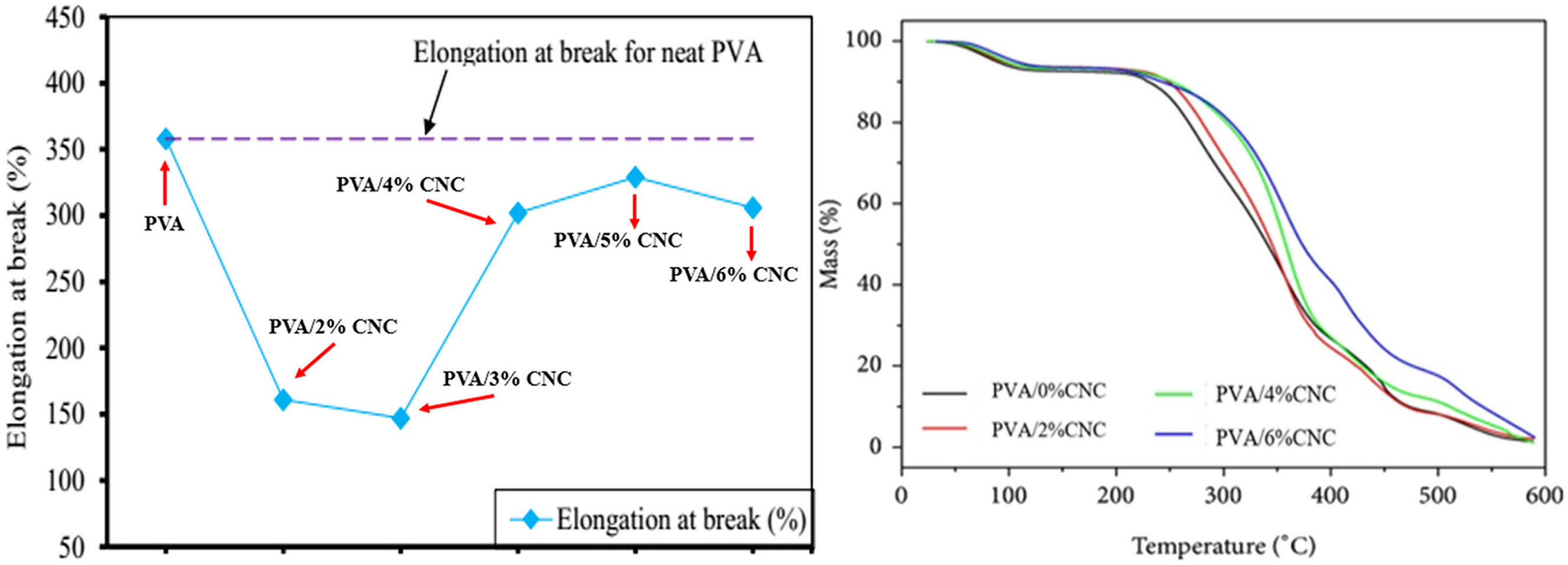

Prior research [46] investigated cellulose nanocrystals from organic waste, such as corncob-influenced reinforcing cellulose nanowhiskers in a polyvinyl alcohol/PVA matrix, to boost their mechanical attributes (Fig. 8). Therefore, sulfuric acid hydrolysis extracted the cellulose. The equation represents the yield of cellulose whiskers, as follows: yield percentage = actual yield/theoretical yield × 100%.

Figure 8: A comparative study on the elongation at break of reinforced PVA composite films and that of pristine PVA films and TGA profiles for PVA/0%CNC, PVA/2%CNC, PVA/4%CNC, and PVA/6% CNC composite films. Adapted with permission from Ref. [58]. Copyright © 2024, Springer Nature

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) demonstrated the thermal stability of the nanocomposite reinforced with 6% mass CNC, which tolerates temperatures as high as 500°C (Fig. 8). Pristine PVA films exhibit a higher percentage of elongation at break than PVA films dispersed with nanocellulose dispersants [58].

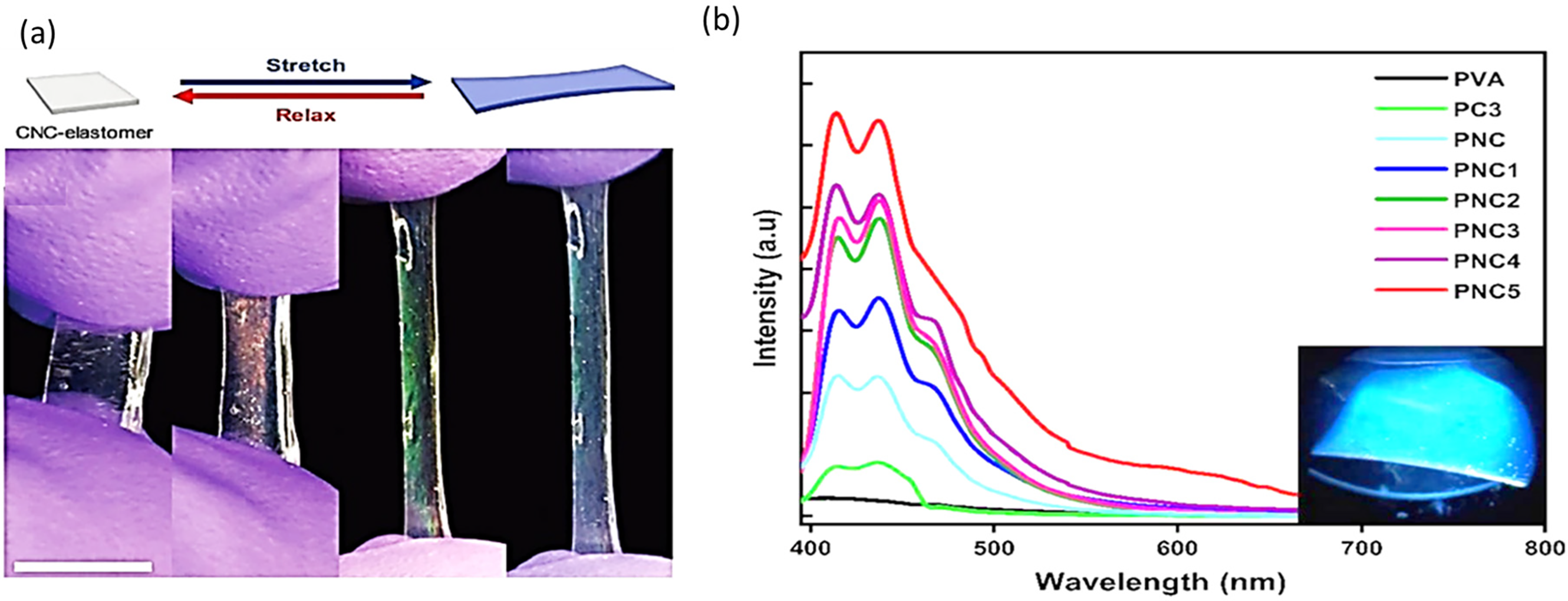

4.1.2 Impacts of Ozone Depletion

In recent decades, ozone depletion has become a major concern. Therefore, there is a high demand for UV-blocking materials. This film was used to convert ultraviolet (UV) light into blue light. This successfully shielded 99.7% of ultraviolet C, 98.5% of ultraviolet, and 92.1% of ultraviolet A, transmitting 80.1% of visible light (Fig. 9). This fabrication method is cost-effective and eco-friendly for use in large-scale UV-blocking films [59].

Figure 9: (a) Mechanical sensors from CNC. Adapted with permission (a, b) from Ref. [60]. Copyright © 2022, Springer Nature. (b) Excitation at 365 nm of photoluminescence emission spectra for PVA, PC3, PNC1 to PNC5, and PNC. Adapted with permission from Ref. [59]. Copyright © 2023, Springer Nature

4.1.3 Transformative Adoptions of Mechanical Sensors

There are numerous possibilities for producing responsive photonic crystals, including mechanical sensors. To address this issue, we fabricated stretchable chiral nematic cellulose nanocrystal (CNC) elastomer composites that display a reversible visible color when subjected to mechanical stress. The CNC-elastomer composite becomes colored when the helical pitch is decreased to the visible area, whereas colorless materials retain their chiral nematic structure when stretched (or compressed) [60].

4.1.4 Pioneering Applications of Catalysis and Medicine

To establish poverty eradication and zero hunger, this study focuses on the biological applications of nanorods and natural resources by employing a sub-wear-out fiber from a semiarid region of Brazil. Nucleation and nanorod growth rely on thermodynamic kinetics. The CNC used in this study explains how various chemical processes lead to modifications in the chemical groups and surface morphologies. Its biocompatibility is 90% [61]. Cellulose nanowhiskers have a wide range of applications in the sectors of catalysis and medicine [62]. The process involves the fabrication of low-cost catalytic substances in aqueous solutions for the purpose of CO2 electroreduction. Through pyrolysis, we retrieved conductive CNC as a microstructure carbon framework and then implemented an environmentally friendly and efficient method to deposit SnS nanocrystals on carbon at the nanoscale [63].

4.1.5 Potential Uses on Optoelectronic Applications

In a recent study, a comprehensive investigation of CdSe nanocrystals was conducted by examining the optoelectronic properties of size-dependent spectral features and radiation duration in cubic zincblende CdSe nanorods with diameters ranging from 3.4 to 5.5 nm. Owing to their quantum confinement and discrete energy states, CdSe nanorods are attractive options for a broad range of optoelectronic applications [64].

4.1.6 Material Packaging and Electrical Appliances

The mechanical features and exceptionally high crystallinity index of nanocellulose may influence thermal variables such as expansion and heat capacity. Consequently, nanocellulose whiskers are increasingly being used in material packaging and electrical appliances. Nanocomposite production at high temperatures can constrain its application if the nanocellulose crystals are thermally stable [14].

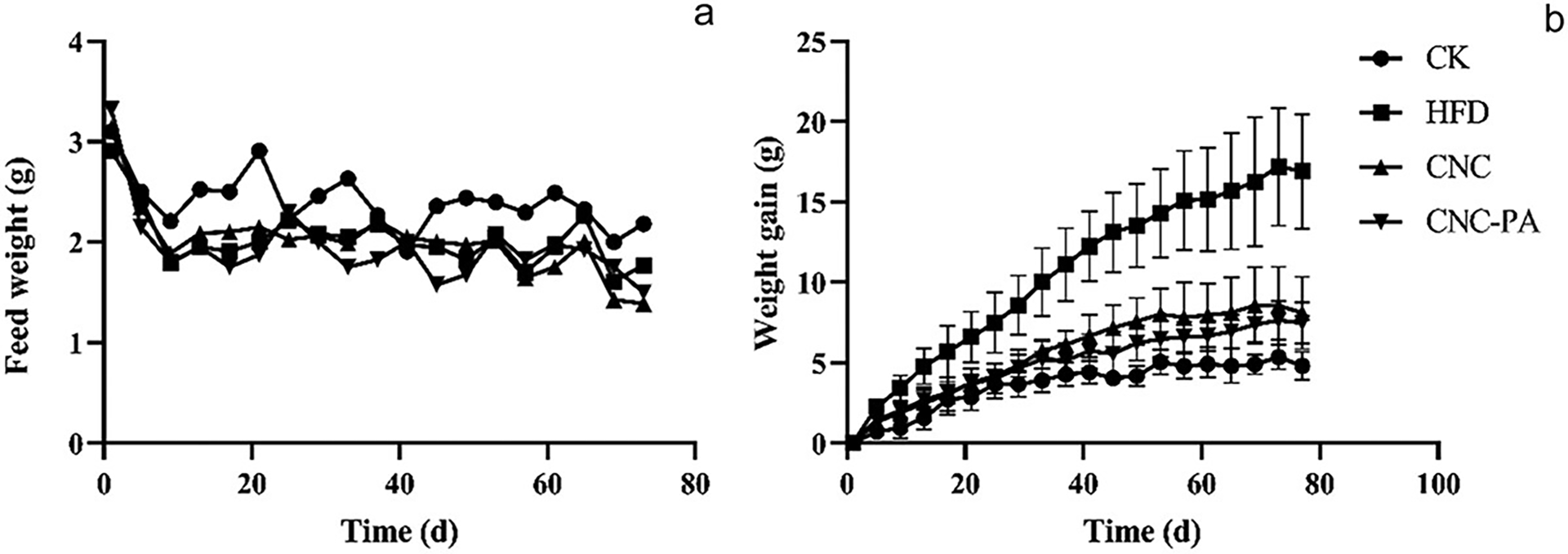

This study focuses on high-sugar and fat-based foods, which have drawn considerable attention. The grafting of ester groups of palmitic acid onto CNC was used to investigate the effectiveness of the adsorption process using a greener technique. The raw source was bran cellulose. Both CNC and CNC-PA are capable of adsorbing fats in the intestine, preventing fats from encountering lipase and bile acids, diminishing the hydrolysis and digestion of fats, and hindering the passage of triglycerides through intestinal cells and the body. Collectively, these actions reduce the amount of fat absorbed by the body. Despite this, CNC-PA had a greater lipid-lowering effect than CNC, according to the analysis of its capacity to adsorb lipids, in vitro hydrolysis, transport and absorption of triglycerides, and long-term feeding studies in mice (Fig. 10). Nanocellulose has a broad variety of applications as a naturally occurring emulsifier and stable component in salad dressings, sauces, foam, soup, pudding, dipping sauce, and other meals. Foods containing nanocellulose have a reduced energy density [5].

Figure 10: Effects CNC-PA on weight gain (a) and food intake (b) in mice. Adapted with permission from Ref. [5]. Copyright © 2024, Taylor and Francis

4.1.8 Sustainability Initiatives in Biopackaging

Carbonized cellulose nanocrystals (GCNCs) are potent nucleating agents owing to their barrier properties, thermal stability, crystallization capacity, and kinetics. Structurally strong GCNC with a range of shapes were successfully fabricated and used as nanofillers for PLA. For example, the research validated the two theories that GCNCs uses the distinct properties of carbonized carbon and cellulose nanocrystals, successfully lowering CNC agglomeration and increasing the tensile strength and crystalline nature of PLA. There are several useful methods for creating environmentally friendly food packaging (Table 2) [65].

4.2 Applications of Nanofibrils

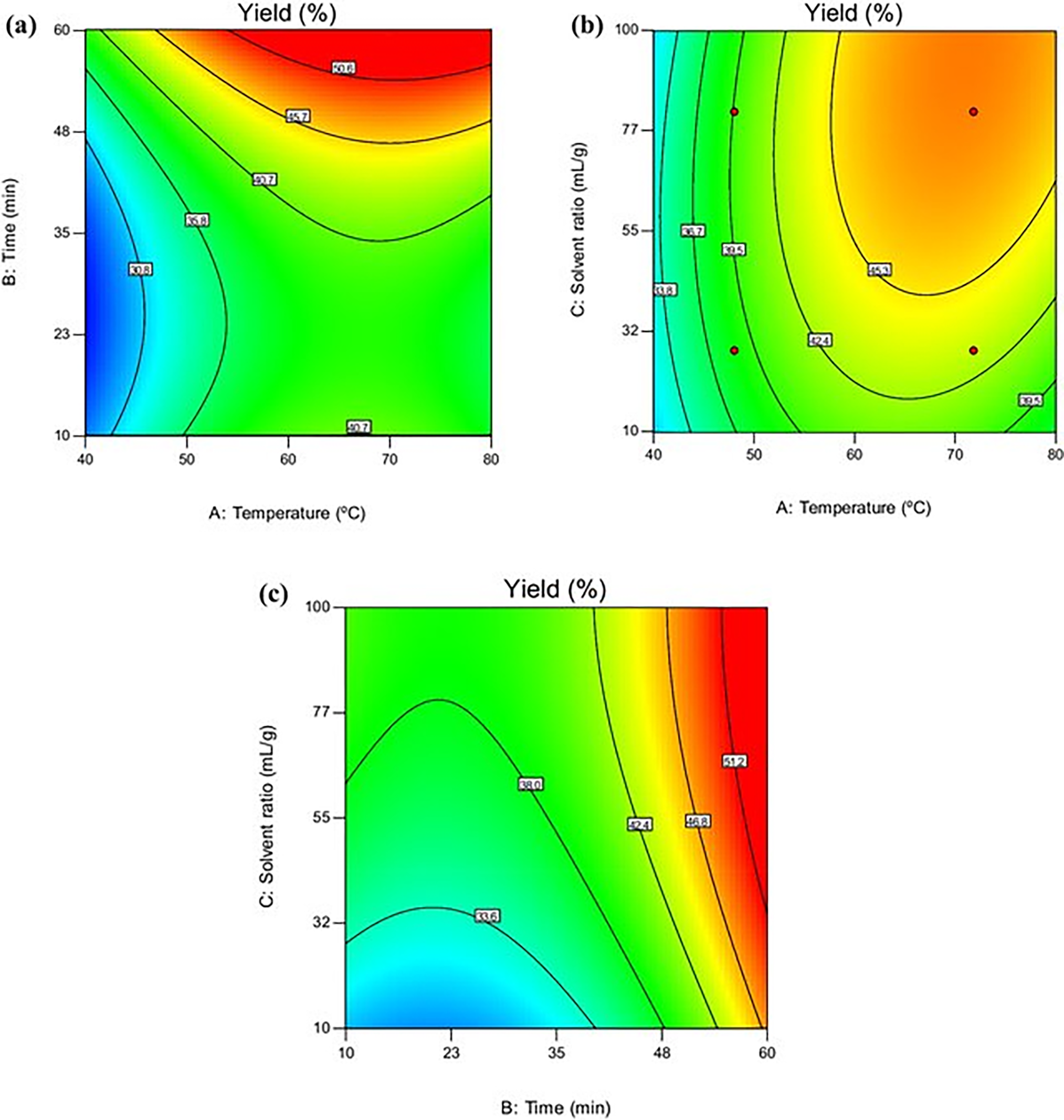

Prior research on nanofibrils demonstrated that this is a green extraction technique. Hence, it uses organic waste pistachio hull synthesis through hydrotropic and deep-eutectic solvent extraction techniques via extraction with sulfuric acid, which can be used in the synthesis of cellulose nanocrystals. The genetic algorithm led to an increased yield of nanocellulose through numerical optimization (Fig. 11). This investigation was conducted in various disciplines using agro-industrial wastes [70].

Figure 11: Traditional acid hydrolysis during nanocellulose extraction, temperature, duration, and solvent ratio affect the yield of nanocellulose (a–c). Adapted with permission from Ref. [70]. Copyright © 2024, Springer Nature

4.2.2 Self-Cleaning Properties

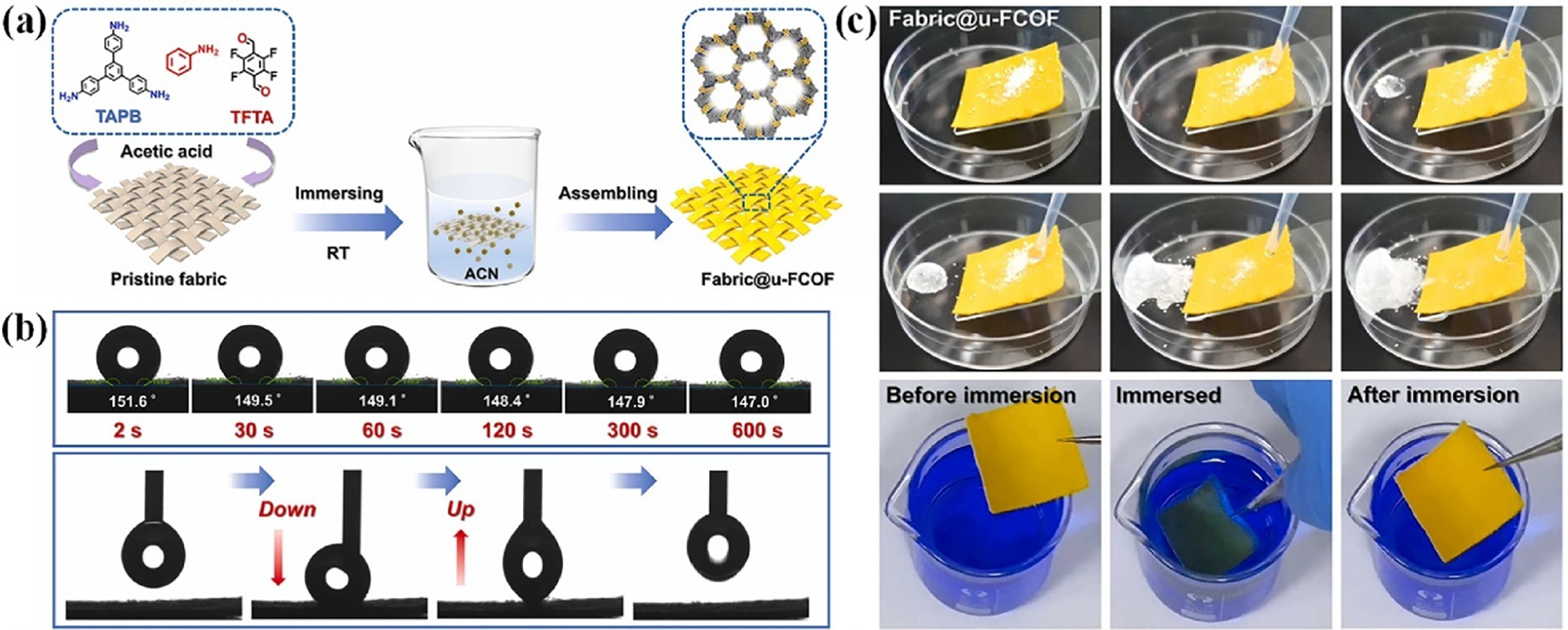

Previous studies have demonstrated extensive applications of biomass. Extracted cellulose nanofibrils can be used as superhydrophobic aerogels in peanut shells. Cellulose was extracted using chemical-mechanical methods. The resultant fabric exhibited excellent antifouling performance, leading to self-cleaning ability and 82.2% oil-water separation effectiveness. Superhydrophobic aerogels were synthesized using a freeze-drying technique. The contact angle is 151.4°. After oil-water separation, the superhydrophobic characteristics of the fabric were retained [71]. Orange-coated nano-sea urchins and their fluorinated structures, believed to be formed in a one-step immersion process, were demonstrated in the membrane fabric@u-FCOF device (Fig. 12a). Depicts the superhydrophobicity of the membrane with a 152° water contact angle, where water droplets maintain their spherical shape for over 10 min, which demonstrates minimum adhesion (Fig. 12b) illustrates the antifouling and self-cleaning activities as the water droplets roll off the surface with the adhered dust and leave no deposits when colored water is poured on the surface (Fig. 12c).

Figure 12: (a) Schematic of the preparation of fabric@u-FCOF. (b) Photographs depicting the state of the water droplets on the modified fabric at different time intervals, as well as the water adhesion force test of the fabric. (c) The self-cleaning performance of the modified fabric; immersion of the fabric in dyed water and subsequent retrieval. Adapted with permission from Ref. [72]. Copyright © 2024, KeAI Publishing Group

4.2.3 Nanoarchitectural Structural Studies

Investigating the surface chemistry of functionalized cellulose nanofibrils at the atomic level is an extremely challenging endeavor in this emerging field. This paper discusses studies on surface properties. Center Technique du Papier synthesized suspensions of oxidized cellulose nanofibrils (CNF-t). This indicates that the adsorption of the initial reactant depends on structural factors including the hydrogen-bonding potential, hydrophobicity, and protonation state. This study is limited to the functionalization of carbon nanofibrils. DNP-enhanced ssNMR should undoubtedly be used for future endeavors to enhance the coupling and washing processes. Hence, this study offers distinctive insights into surface chemistry [73].

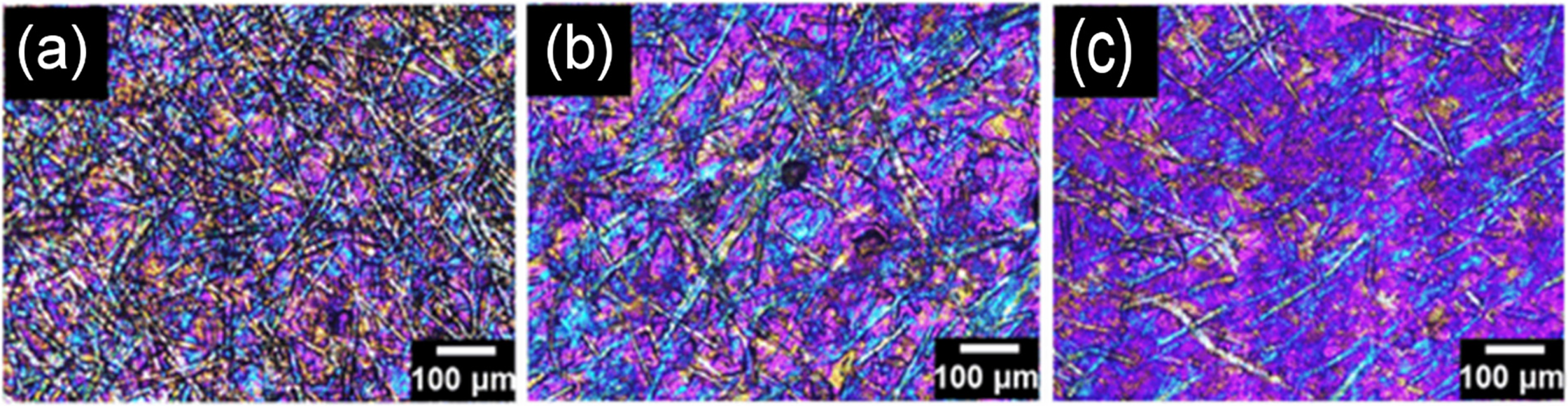

Researchers and co-researchers have studied a novel self-cleaning function of a nanofiltration membrane to efficiently eradicate the cationic dye methylene blue (MB) from industrial effluents. Vinyl resin (VR), cellulose nanofibrils (CNF), and titanium alpha aluminate (TAAL) nanoparticles are the components of the membrane. The dead-end filtration system used on the (VR/CNF@TAAL) membrane with a concentration of 5 wt% TAAL at pH 10 displayed outstanding results. It offers an excellent removal efficiency of 98.6% for 30 ppm of the MB dye and has an optimum adsorption capability of 125.8 mg/g. This study demonstrated its economic viability and environmental friendliness. Water permeability and filtration efficiency are the two characteristics of a membrane that are significantly affected by its porosity (Fig. 13). However, few studies have been conducted on this new raw material. These results illustrate that holocellulose fibers (HCFs) can be extracted from natural sources. During sulfation, bamboo, pine, and eucalyptus fibers showed remarkable reactivity compared to cellulose fibers for the preparation of nanofibrils. The bamboo HCFs obtained via chemical pretreatment reacted faster than the other two HCFs. The resultant films exhibited promising mechanical performance with a tensile stress of approximately 201 MPa. This high dispersibility provides a novel perspective for producing composite materials based on functional nanocellulose [74].

Figure 13: Comparative analysis of sulfated holocellulose nanofibrils derived from various plant sources (a–c). Adapted from Ref. [74]. Copyright © 2024, Springer Nature

Recently, micronanofibrillated cellulose has attracted considerable attention for its preparation via dry dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) using oxygen plasma in a treated powder precursor assisted by ultrasonics. Materials containing nanofibrillar cellulose are among the most promising lignocellulose derivatives. Consequently, sustainability has emerged as a key concern in recent studies. Paper pulp was used as the raw source to enable controlled refinement before implementing the innovative plasma pretreatment step. The novel process of utilizing cellulose fibrils via water-free (dry/ambient) DBD oxygen plasma treatment of cellulose fibrils provides an opportunity for the addition of radicals on the surface of cellulose to extend the treatment to other gases via a cost-effective approach [75].

4.2.6 Stability and Durability

The researchers worked on the durability of water through the cellulose nanofibril-based foam so that it could be extended further. Oven-dried CMCNF foams use two straightforward crosslinking methods that have been found to improve water durability. Crosslinked oven-dried foams exhibit potent adsorption properties for chemicals that require slow adsorption or eliminate a large proportion of chemicals and are reusable [76].

4.2.7 Carbon Replacement with Nanofibrils

This study addresses the major concern related to environmental sustainability, which indicates the green tire applications of organic waste, such as rice husks derived from type 1 cellulosic nanofibrils, which are utilized in the production of natural rubber compounds. Carbon black is exchanged with rice-husk-derived nanofibrillated cellulose in natural rubber, which exhibits excellent improvisation in green tiers. A decreased rolling resistance can be imparted by rice-husk-derived nanocellulose fibrils [77].

4.2.8 Groundbreaking Advancements in Sensing and Biopackaging

To express the breadth of our current knowledge of nanocellulose as a coated paper sensor to measure glucose concentration in the blood, blood glucose measurement is one of the most significant studies from prior investigations, as high blood glucose levels are related to adverse health consequences in patients with health conditions, such as diabetes mellitus. The sensor was not intended to monitor glucose levels with decimal place accuracy; rather, its purpose was to identify when diabetes first appeared. It is simple to identify patients with high blood glucose levels using this method. This study emphasizes the growing use of nanocellulose superabsorbent diagnostic devices that use a variety of enzymes to detect a wide range of illnesses and outlines the possibilities of paper-based enzyme colorimetry glucose sensors. The designed sensor is stable at standard test temperatures, typically between 20°C and 30°C [78].

The application of anthocyanins in smart packaging has several weaknesses, and anthocyanins are sensitive to high temperatures; therefore, monitoring the freshness of refrigerated or frozen food products is recommended [79]. The synergistic combination of PVA/CNF films from pineapple leaves of CNFs improved the tensile strength of the PVA/CNF films. This bio-nano composite PVA/CNF film was found to have outstanding tensile strength and flexibility, achieving the specifications for bio-packaging applications with a certain degree of rigidity. The morphology of the bio-nanocomposite surfaces became rougher and clustered together as the CNF concentration of the film increased. In addition, the use of CNFs enhanced the CI and thermal stability of the PVA films. This bio-nanocomposite may therefore be especially beneficial in applications involving short-term storage of food, such as innovative takeaway containers [80]. In contrast, laccase was immobilized on dialdehyde films for active packaging. After storage at 4°C for a month, the films with immobilized laccase maintained all their activity, while those that were reused over 11 or 12 cycles lost less than 25% of their activity and were very effective at breaking down the Methylene Blue dye [81]. The multilevel reinforcement structure of (polylactic acid, 3 wt% CNFene (cellulose nanofiber) PLA-C3 demonstrated a broader melt-processing window (197.6°C), a higher thermal decomposition onset temperature (T0), and remarkably low overall migration levels in ethanol (68.6 μg/kg) and isooctane (16.3 μg/kg). This enhanced interaction between CNFene and PLA influences PLA’s crystallization ability and kinetics/mechanism of PLA to meet the demands of industrial and environmentally friendly bio-packaging applications [82] (Table 3).

4.3.1 Cultural Methods and Process Optimization to Produce Bacterial Nanocellulose

Bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) can be synthesized through an array of processes, including, but not limited to, static, agitated/shaking, and bioreactor systems, which provide BNC with a diverse morphology/microstructure to improve production efficiency, cost, and duration of cultivation as an overarching priority. Among these, the static culture method is preferred. and BNC was produced at the gas-liquid interface, with a temperature range of 28–30°C and a pH of 4–7 for periods of 1 to 14 days. This method produces BNC in the form of membranes or films, and its characteristics include compact texture, durability, good water permeability, and biocompatibility. However, it still has disadvantages in that the productivity rates are extremely low and the periods required for cultivation are far too long. Further modification of the existing technology or new technology development is required to enhance the scalability of this approach [85]. The opposite is the agitated culture method, in which the oxygen deficiency of the static culture is fixed by supplying sufficient oxygen through agitation of the static culture medium, which in turn accelerates BNC production, the yield of which is not very different from that of the static culture. Instead, it is faster to produce BNC in a number of varieties, including pellets and fibers. Although there is great potential for large-scale production, BNC produced under agitation has lower mechanical strength, crystallinity, and polymerization degree. It is also possible that non-cellulose mutants were formed because of the application of shear force. This is not something that has been expanded in detail above, but bioreactors are another option to consider for the mass production of BNC, as they are more efficient with better environmental control; hence, they can also be used in large-scale applications.

DYPD medium was complemented with polyglutamic acid at concentrations of 0.06, 0.15, 1, 2, and 5 g/L, while glutamic acid at concentration of 0.06 and 0.15 g/L was used as a control. After sterilization, pH of the medium was brought to 5.0. To study the influence of pH on nanocellulose production, a pH of 5.0 was selected and adjusted to 4.0, 5.0, or 6.0 using 20% H2SO4 or 8 mol/L NaOH solutions. The main bacterial strains isolated in a previous study, LDU-K, LDU-LC, and LDU-LY, were patched during the fermentation process carried out internally [86].

4.3.2 Biomedical Application: Tissue Engineering and Kombucha-Derived Production

The versatility of nanocellulose allows its use in diverse types, including one-dimensional, two-dimensional, and three-dimensional structures. It enables a wide range of applications from biosensing and drug delivery to wound dressing and tissue engineering [87]. The standard operating protocol for the removal of pulp tissue was as follows: 39 cell culture suspensions were seeded into a culture medium on culture plates consisting of 12 cells, which were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% carbon dioxide. The medium was inoculated again 24 h after the first inoculation and then once every three days. These standard conditions were maintained until a 90% yield was attained during the first inoculation. The cells were collected using 0.5% trypsin-EDTA solution and were later sub-cultured. The cell cultures remained as monolayers until subsequent development. Upon reaching 90% confluence, the cells were passaged until the fifth generation. A Trypan Blue A Neubauer chamber was used to examine cell viability at 4%, and additional testing was performed to examine the interaction between the cells and scaffolds, which is crucial for understanding biological processes and tissue engineering. Although fermentation of kombucha tea produces bacterial nanocellulose, the manufacturing of this material, which includes several metabolic pathways, is complicated. Under aerobic conditions, a community of competing and cooperative multispecies bacteria and yeasts forms a kombucha. This clarifies that the cellulose disk that is produced because of this process is known as SCOBY, which represents the “symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast”. Because of its osmophilic nature (adaptation to high pressure), Saccharomyces cerevisiae is usually the predominant yeast species found in kombucha) [88].

4.3.3 Therapeutic Applications of Wound Dressings

Nanocellulose-based dressings are changing the way wounds are managed, as they combine features of great importance in the healing process. They are non-toxic and antimicrobial and allow gas and fluid exchange, moisture retention, and exudate control while enhancing tissue development. In particular, bacterial nanocellulose has been found to possess unique wearing characteristics, enhancing the treatment of burn wounds by cooling the surface via evaporation and facilitating healing without frequent dressing changes or pain during removal. From the clinical reviews performed, BNC has shown remarkable success in rubbing off rapid re-epithelialization with the most complete wound closure in partial and full-thickness burns in weeks, and we obtained some crucial details regarding burn treatment. With the use of BNC, experimental studies have demonstrated the boon BNC has against severe burn cases. Complete healing was witnessed within a span of two months, whilst 70% wound closure was achieved within three weeks [89]. Focusing on antibacterial properties, hydrogels infused with thymol were able to kill burn-specific pathogens. According to in vitro tests performed using mouse 3T3 fibroblasts and in vivo trials, the hydrogels were able to promote fibroblast cell growth and achieve nearly 100% wound closure within 25 days. However, the nanocellulose-based composite sponges retained a micromechanically robust structure with a porosity of 75%. Building upon their use, the sponges also demonstrated antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus and showed no sign of hemolytic effects during blood compatibility tests. With the integration of cCNCs and aerogels with medicinal extracts, advanced wound care solutions have been obtained that strengthen compressive strength, durability, and even pathogen resistance. Owing to their exceptional biocompatibility, ease of mimicking biological tissues, and mechanical sturdiness, nanocellulose-incorporated dressings have proven helpful in healing and safeguarding wounds from infections [90].

4.3.4 Clinical Implementation of Biomedical Implants: Orthopedic, Cardiovascular, Dental, and Neurological Implants

Devices for biomedical implants are cautiously designed and constructed from biocompatible materials such as metals, ceramics, polymers, and biological tissues. These implants are the consequence of interdisciplinary cooperation between biomedical engineers, materials scientists, physicians, and regulatory bodies and have various therapeutic applications in the human body. They are vital in modern healthcare because they may regulate physiological processes, such as heart rhythm, with pacemakers to restore structural integrity and function, as evidenced by orthopedic implants for joint replacements. Orthopedic implants provide significant solutions for the treatment of joint and bone ailments. A hip implant uses artificial components, such as the femoral stem, acetabular cup, and ball-and-socket framework, to address hip joint abnormalities. Knee replacements are composed of femoral and tibial components separated by a plastic spacer that replicates the normal knee motion to restore functionality. Spinal implants such as rods, screws, and plates support the spine and treat problems such as fractures or spinal abnormalities [91].

Several heart and blood artery disorders can be treated with cardiovascular implants using medical devices. To heal damaged valves, control heart rhythm, or repair or enhance blood flow, they are surgically inserted into the body. Stents, pacemakers, and prosthetic heart valves are examples of common cardiovascular implants. Nanocellulose (especially BC) can be developed as a material for artificial tubes that can replace small (4 mm) or large (>6 mm) vascular grafts. Compared with common synthetic vascular graft materials, such as polyester (Dacron) and ePTFE, biosynthetic BC tubes can be employed in vascular conduits with a modest diameter (4 mm) and can avoid stenosis and thrombus development. Dental implants are critical interventions for wisdom teeth and offer both practical and aesthetic advantages. These implants are comprised of elements such as crowns, bridges, and implant-supported dentures. Crowns and custom-fabricated caps substitute damaged or absent teeth, reinstating their form and functionality. Bridges bridge the void left by absent teeth, supported by adjacent natural teeth or implants, enhancing both aesthetics and masticatory function. Implant-supported dentures provide stable and secure prosthetic devices affixed to dental implants, thereby improving comfort and functionality compared to conventional removable dentures. These implants resolve tooth-related issues, enhance oral health, and markedly increase the quality of life of patients with edentulism. They are advanced devices intended to engage the neurological system, encompassing the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves. These implants are frequently employed to regulate or reinforce neuronal function through the administration of electrical impulses or the observation of cerebral activity. They include various technologies, such as deep brain stimulators for Parkinson’s disease, periprosthetic devices for recovering limb function in paralysis, and devices for managing epilepsy, chronic pain, and other neurological disorders. Neurological implants seek to mitigate symptoms, restore impaired function, and enhance the overall quality of life of patients with neurological disorders. Millions of individuals worldwide now enjoy a far better quality of life because of these implants [92].

4.3.5 Building Materials and Agitation’s Impact on Bacterial Nanocellulose

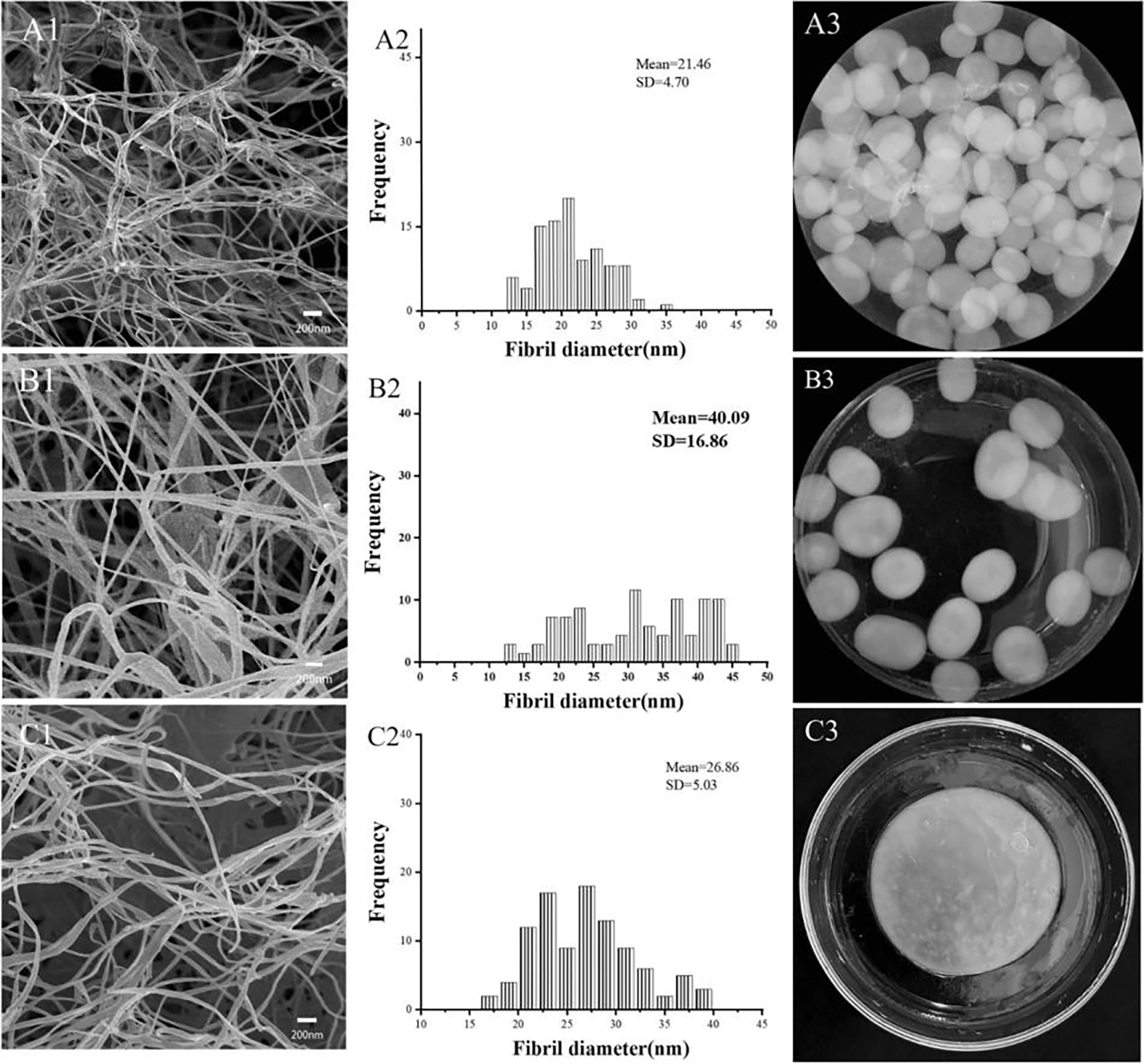

The effect of agitation on BNC morphology was also studied using FESEM, as shown in Fig. 14. In the presence of γ-PGA and DYPD, even so, it can be noted that the BNC was produced from the agitated culture medium. Similar and distinctive features were observed, such as gel-like spheres floating above the surface of the culture medium, whereas the fibrils developed a consistent three-dimensional net structure. The diameter of the BNC fibers harvested from the DYPD agitated culture was 12.5 to 35.0 nm (Fig. 14(A2)), while in variety 3 of the static culture, they were 16.5 to 40.0 nm (Fig. 14(C3)). In contrast, the fibers observed in the γ-PGA-supplemented medium had thicknesses of 12.5 to 45.0 nm (Fig. 14(B2)). Dark Cathodic BNC fibers grown in static DYPD culture patterns were generally thicker than those grown in agitated culture B (Fig. 14(A1,A2,C1,C2)). In contrast, the BNC fibers derived from the γ-PGA medium were approximately 2 times as thick as the DYPD medium fibers (Fig. 14(A1,A2)). The hydrogel pellets containing BNC from the DYPD medium appeared to be clearer than those from the γ-PGA medium (Fig. 14(A3,B3)). The difference indicates the presence of thicker and denser fibers in the γ-PGA medium. This hypothesis is plausible because γ-PGA may minimize mechanical tension caused by shaking. BNC with larger and denser fiber components can be used in the production of building materials, such as cement, asbestos boards, and fiberglass-reinforced plastics.

Figure 14: Illustration of FE-SEM and BNC fibers diameter (A1–C3). Adapted with permission from Ref. [94]. Copyright © 2024, Springer Nature

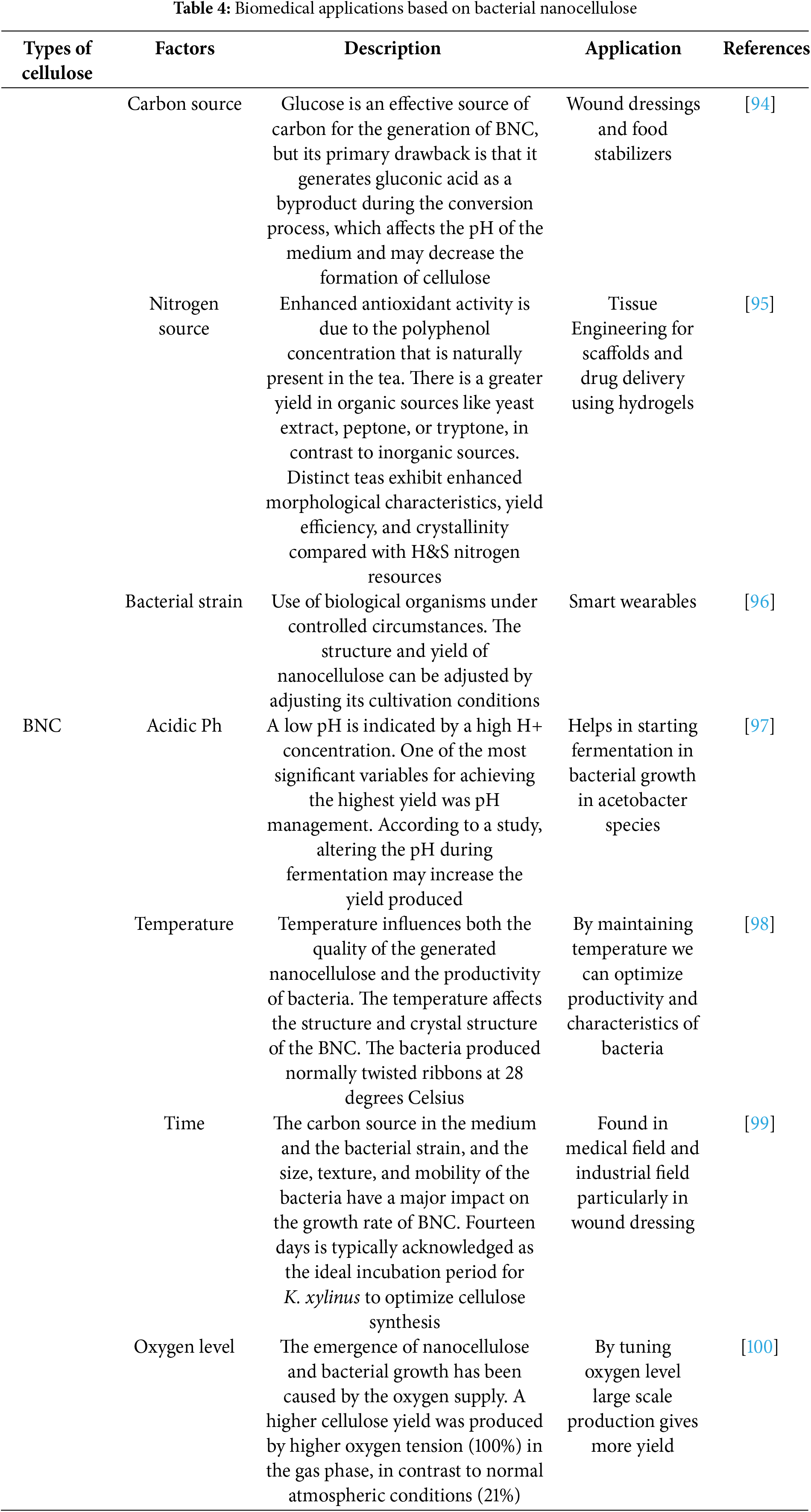

In conclusion, static culture produces poor yields of BNC but produces high yields of BNC, and agitated culture improves yield as well, but productivity increases at the cost of some material properties. Bioreactors may provide an ideal compromise for the production of BNC in controlled, efficient, and large volumes [93]. The opposite is the agitated culture method, in which the oxygen deficiency of the static culture is fixed by supplying sufficient oxygen through agitation of the static culture medium, which in turn speeds up BNC production, the yield of which is not very different from that of the static culture. Alternatively, BNC production is more efficient in various forms, including pellets and fibers. Although there is enoromous potential for large-scale production, BNC produced under agitation has lower mechanical strength, crystallinity, and polymerization degree. It is also possible that non-cellulose mutants were formed because of the application of shear forces. This is not something that has been expanded in detail above, but bioreactors are another option to consider for the mass production of BNC, as they are more efficient with better environmental control; hence, they can also be used in large-scale applications (Table 4).

5 Conclusion and Future Prospects

As per a report for 2023, it is $419.1 million. The opposite growth rate indicates that there may be a chance of 20.1% in the next seven years. Nanocellulose has created a broad platform for nanoscience and green technology. Today’s generations demand nanocellulose for every step of life, as the application of the material is vast. Bacterial nanocellulose has excellent drug stability; hence, it is used in the field of medicine for drug coating because it is soluble in a controlled manner and plays a vital role in tissue engineering. This is an emerging trend in nanocellulose with unique surface modifications and functionalizations. Its cost-effectiveness scales the market and property rules with applications in all fields, including wound dressings, material packaging, wastewater treatment, storage devices, and self-cleaning properties. CNC is a sustainable source with excellent biocompatibility and a nontoxic environment. CNFs are renewable materials with good barrier and shielding properties.

The versatility of nanocellulose has challenged recent hybrid contact technology. This study focuses on the biodegradability of the material and its consequences on the environment. This has immense potential for innovation in various industries. Nanocellulose is a facile approach that uses plants through the comparative assessment of cellulose nanocrystals, cellulose nanofibrils, and bacterial nanocellulose. Further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis. Synergistic combinations of nanocellulose have multipurpose applications in various fields. Owing to its remarkable properties, nanocellulose is an emerging area in nanotechnology with an ever-increasing demand for cost-effective and environmentally friendly materials. Promising advancements in nanocellulose have resulted in its applications in yield, UV blocking, optoelectronics, strain resistance, wastewater treatment, paper production, cosmetics, and some carbon-replacing materials.

Biodegradability, sustainability, and renewability were considered in the early phases of scientific studies during this period of growing environmental concerns. Therefore, nanocellulose reduces the carbon footprint. Therefore, traditional packaging resource catalysts, ray blockers, adsorbents, self-cleaning, fat reduction, and mechanically dispersed substances can be replaced by cellulosic substances. The primary reason for this is that it can be extracted from a variety of natural sources, such as biomass. As plant waste is frequently burned, processing assists in the prevention of air pollution.

Acknowledgement: KSBN would like to thank Durban University of Technology for the research fellowship. The authors would like to express their gratitude to the management of PES University, Electronic City Campus, Bangalore.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Data curation, formal analysis, writing of original draft and review: Arun Kumar and Thulasi Rajendran. Conceptualization, formal analysis, data curation, resources, visualization, review and editing: Revanasiddappa Moolemane and Suresh Babu Naidu Krishna. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper. If any raw data files are required in another format, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Streimikyte P, Viskelis P, Viskelis J. Enzymes-assisted extraction of plants for sustainable and functional applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(4):2359. doi:10.3390/ijms23042359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Garcia KR, Beck RCR, Brandalise RN, Dos Santos V, Koester LS. Nanocellulose, the green biopolymer trending in pharmaceuticals: a patent review. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16(1):145. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16010145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Abd El-Fattah M, Hasan AMA, Keshawy M, El Saeed AM, Aboelenien OM. Nanocrystalline cellulose as an eco-friendly reinforcing additive to polyurethane coating for augmented anticorrosive behavior. Carbohydrate Polym. 2018;183(2):311–8. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.12.084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Carlsson DO, Lindh J, Strømme M, Mihranyan A. Susceptibility of Iα- and Iβ-dominated cellulose to TEMPO-mediated oxidation. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16(5):1643–9. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Yang J, Liu J, Zhang X. Study on surface esterification of cellulose nanocrystals their and lipid-lowering effect. J Nat Fibers. 2024;21(1):2410937. doi:10.1080/15440478.2024.2410937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Phanthong P, Reubroycharoen P, Hao X, Xu G, Abudula A, Guan G. Nanocellulose: extraction and application. Carbon Resour Convers. 2018;1(1):32–43. doi:10.1016/j.crcon.2018.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Dugan JM, Gough JE, Eichhorn SJ. Bacterial cellulose scaffolds and cellulose nanowhiskers for tissue engineering. Nanomedicine. 2013;8(2):287–98. doi:10.2217/nnm.12.211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Qi YG, Guo Y, Liza AA, Yang GH, Sipponen MH, Guo JQ, et al. Nanocellulose: a review on preparation routes and applications in functional materials. Cellulose. 2023;30(7):4115–47. doi:10.1007/s10570-023-05169-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hu M, Lv X, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Dai H. Guideline for the extraction of nanocellulose from lignocellulosic feedstocks. Food Biomacromol. 2024;1(1):9–17. doi:10.1002/fob2.12011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Lengowski EC, Franco TS, Viana LC, Bonfatti Júnior EA, de Muñiz GIB. Micro and nanoengineered structures and compounds: nanocellulose. Cellulose. 2023;30(17):10595–632. doi:10.1007/s10570-023-05532-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. George J, Sabapathi SN. Cellulose nanocrystals: synthesis, functional properties, and applications. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2015;8:45. doi:10.2147/nsa.s64386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Channab BE, El Idrissi A, Essamlali Y, Zahouily M. Nanocellulose: structure, modification, biodegradation and applications in agriculture as slow/controlled release fertilizer, superabsorbent, and crop protection: a review. J Environ Manag. 2024;352:119928. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Dardari O, Amadine O, Sair S, Ousaleh HA, Essamlali Y, El Idrissi A, et al. Cellulose nanocrystal stabilized copper nanoparticles for grafting phase change materials with high thermal conductivity. J Energy Storage. 2024;79:110182. doi:10.1016/j.est.2023.110182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Rashid AB, Hoque ME, Kabir N, Rifat FF, Ishrak H, Alqahtani A, et al. Synthesis, properties, applications, and future prospective of cellulose nanocrystals. Polymers. 2023;15(20):4070. doi:10.3390/polym15204070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Alonso-Lerma B, Barandiaran L, Ugarte L, Larraza I, Reifs A, Olmos-Juste R, et al. High performance crystalline nanocellulose using an ancestral endoglucanase. Commun Mater. 2020;1(1):1–10. doi:10.1038/s43246-020-00055-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yi T, Zhao H, Mo Q, Pan D, Liu Y, Huang L, et al. From cellulose to cellulose nanofibrils—a comprehensive review of the preparation and modification of cellulose nanofibrils. Materials. 2020;13(22):5062. doi:10.3390/ma13225062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Chinga Carrasco G. Cellulose fibres, nanofibrils and microfibrils: the morphological sequence of MFC components from a plant physiology and fibre technology point of view. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6(1):417. doi:10.1186/1556-276x-6-417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Saito T, Nishiyama Y, Putaux JL, Vignon M, Isogai A. Homogeneous suspensions of individualized microfibrils from TEMPO-catalyzed oxidation of native cellulose. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(6):1687–91. doi:10.1021/bm060154s. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Aulin C, Johansson E, Wågberg L, Lindström T. Self-organized films from cellulose I nanofibrils using the layer-by-layer technique. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11(4):872–82. doi:10.1021/bm100075e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Nechyporchuk O, Belgacem MN, Bras J. Production of cellulose nanofibrils: a review of recent advances. Ind Crops Prod. 2016;93(6):2–25. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.02.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Rajala S, Siponkoski T, Sarlin E, Mettänen M, Vuoriluoto M, Pammo A, et al. Cellulose nanofibril film as a piezoelectric sensor material. ACS App Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(24):15607–14. doi:10.1021/acsami.6b03597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Ao H, Xun X, Ao H, Xun X. Bacterial nanocellulose: methods, properties, and biomedical applications. In: Kazi MSN, Huang J, editors. Nanocellulose—sources, preparations, and applications. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2024. doi:10.5772/intechopen.114223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Trache D, Tarchoun AF, Derradji M, Hamidon TS, Masruchin N, Brosse N, et al. Nanocellulose: from fundamentals to advanced applications. Front Chem. 2020;8:392. doi:10.3389/fchem.2020.00392. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Pääkkö M, Ankerfors M, Kosonen H, Nykänen A, Ahola S, Österberg M, et al. Enzymatic hydrolysis combined with mechanical shearing and high-pressure homogenization for nanoscale cellulose fibrils and strong gels. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(6):1934–41. doi:10.1021/bm061215p. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Moon RJ, Martini A, Nairn J, Simonsen J, Youngblood J. Cellulose nanomaterials review: structure, properties and nanocomposites. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40(7):3941. doi:10.1039/c0cs00108b. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Rana MM, De la Hoz Siegler H. Influence of ionic liquid (IL) treatment conditions in the regeneration of cellulose with different crystallinity. J Mater Res. 2023;38(2):328–36. doi:10.1557/s43578-022-00797-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Nyakuma BB, Oladokun O, Ogunbode EB, Akinyemi SA, Wong S, Ali JB, et al. Extraction and characterisation of natural fibres from Imperata cylindrica: morphological, microstructural, thermal, and kinetic properties. J Nat Fibers. 2022;19(15):12325–38. doi:10.1080/15440478.2022.2057384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Dankovich TA, Gray DG. Contact angle measurements on smooth nanocrystalline cellulose (I) thin films. J Adhes Sci Technol. 2011;25(6–7):699–708. doi:10.1163/016942410x525885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Stanislas TT, Tendo JF, Ojo EB, Ngasoh OF, Onwualu PA, Njeugna E, et al. Production and characterization of pulp and nanofibrillated cellulose from selected tropical plants. J Nat Fibers. 2022;19(5):1592–608. doi:10.1080/15440478.2020.1787915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Costa LR, Silva LE, Matos LC, Tonoli GHD, Hein PRG. Cellulose nanofibrils as reinforcement in the process manufacture of paper handsheets. J Nat Fibers. 2022;19(14):7818–33. doi:10.1080/15440478.2021.1958415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chu B, Cui X, Dong X, Li Y, Liu X, Guo Z, et al. SLA printing of shape memory bio-based composites consisting of soybean oil and cellulose nanocrystals. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2024;19(1):e2401933. doi:10.1080/17452759.2024.2401933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Lan X, Fu S, Kong Y. A new recognition of the binding of cellulose fibrils in papermaking by probing interaction between nanocellulose and cationic hemicellulose. Cellulose. 2024;31(9):5823–42. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3785502/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Agbakoba VC, Mokhena TC, Ferg EE, Hlangothi SP, John MJ. PLA bio-nanocomposites reinforced with cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs) for 3D printing applications. Cellulose. 2023;30(18):11537–59. doi:10.1007/s10570-023-05549-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Long K, Liu J, Zhang S, Luo H, Zhang P, Yu L, et al. Production of highly substituted cationic cellulose nanofibrils through disk milling/high-pressure homogenization. Cellulose. 2024;31(7):4217–30. doi:10.1007/s10570-024-05861-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Costa GR, Nascimento MV, de Souza Marotti B, Arantes V. Reducing hydrophilicity of cellulose nanofibrils through lipase-catalyzed surface engineering with renewable grafting agents. J Polym Environ. 2024;32(10):5254–71. doi:10.1007/s10924-024-03316-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Varghese RT, Cherian RM, Antony T, Chirayil CJ, Kargarzadeh H, Malhotra A, et al. Thermally stable, highly crystalline cellulose nanofibrils isolated from the lignocellulosic biomass of G. Tiliifolia plant barks by a facile mild organic acid hydrolysis. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(24):31591–605. doi:10.1007/s13399-023-05049-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Machfidho A, Ismayati M, Sholikhah KW, Kusumawati AN, Salsabila DI, Fatriasari W, et al. Characteristics of bacterial nanocellulose composite and its application as self-cooling material. Carbohydr Polym Technol Appl. 2023;6(2):100371. doi:10.1016/j.carpta.2023.100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Suleimenova A, Frasco MF, Soares da Silva FAG, Gama M, Fortunato E, Sales MGF. Bacterial nanocellulose membrane as novel substrate for biomimetic structural color materials: application to lysozyme sensing. Biosens Bioelectron X. 2023;13:100310. doi:10.1016/j.biosx.2023.100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Liu D, Labas A, Long B, McKnight S, Xu C, Tian J, et al. Bacterial nanocellulose production using cost-effective, environmentally friendly, acid whey based approach. Bioresour Technol Rep. 2023;24:101629. doi:10.1016/j.biteb.2023.101629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. de Souza GB, Müller D, Cesca K, Bernardes JC, Hotza D, Rambo CR. Porous biomorphic silicon carbide nanofibers from bacterial nanocellulose. Open Ceram. 2023;14:100338. doi:10.1016/j.oceram.2023.100338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Soares Silva FAG, Carvalho M, Bento de Carvalho T, Gama M, Poças F, Teixeira P. Antimicrobial activity of in situ bacterial nanocellulose-zinc oxide composites for food packaging. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2023;40(19):101201. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2023.101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Almeida T, Karamysheva A, Valente BFA, Silva JM, Braz M, Almeida A, et al. Biobased ternary films of thermoplastic starch, bacterial nanocellulose and gallic acid for active food packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;144(1):108934. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Heidarian P, Kouzani AZ. A self-healing nanocomposite double network bacterial nanocellulose/gelatin hydrogel for three dimensional printing. Carbohydr Polym. 2023;313(6):120879. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.120879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Gupta GK, Shukla P. Lignocellulosic biomass for the synthesis of nanocellulose and its eco-friendly advanced applications. Front Chem. 2020;8:601256. doi:10.3389/fchem.2020.601256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zinge C, Kandasubramanian B. Nanocellulose based biodegradable polymers. Eur Polym J. 2020;133:109758. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2020.109758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Mishra RK, Sabu A, Tiwari SK. Materials chemistry and the futurist eco-friendly applications of nanocellulose: status and prospect. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2018;22(8):949–78. doi:10.1016/j.jscs.2018.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Nasir M, Hashim R, Sulaiman O, Asim M. Nanocellulose: preparation methods and applications. In: Jawaid M, Boufi S, Abdul Khalil HPS, editors. Cellulose-reinforced nanofibre composites: production, properties and applications. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2017. p. 261–76. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-100957-4.00011-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Singh S, Bhardwaj S, Tiwari P, Dev K, Ghosh K, Maji PK. Recent advances in cellulose nanocrystals-based sensors: a review. Mater Adv. 2024;5(7):2622–54. doi:10.1039/d3ma00601h. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhou Z, Li Y, Zhou W. The progress of nanocellulose in types and preparation methods. J Phys Conf Ser. 2021;2021(1):012042. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2021/1/012042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Corujo VF, Arroyo S, Cerrutti P, Foresti L. Production of bacterial nanocellulose in alternative culture media under static and dynamic conditions. Lat Am Appl Res Int J. 2023;53(2):137–44. doi:10.52292/j.laar.2023.973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Páez MA, Casa-Villegas M, Aldas M, Luna M, Cabrera-Valle D, López O, et al. Insights into agitated bacterial cellulose production with microbial consortia and agro-industrial wastes. Fermentation. 2024;10(8):425. doi:10.3390/fermentation10080425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Murugarren N, Roig-Sanchez S, Antón-Sales I, Malandain N, Xu K, Solano E, et al. Highly aligned bacterial nanocellulose films obtained during static biosynthesis in a reproducible and straightforward approach. Adv Sci. 2022;9(26):e2201947. doi:10.1002/advs.202201947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Revin VV, Pestov NA, Shchankin MV, Mishkin VP, Platonov VI, Uglanov DA. A study of the physical and mechanical properties of aerogels obtained from bacterial cellulose. Biomacromolecules. 2019;20(3):1401–11. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.8b01816. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Öz YE, Kalender M. A novel static cultivation of bacterial cellulose production from sugar beet molasses: series static culture (SSC) system. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;225(24):1306–14. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.11.190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Andriani D, Apriyana AY, Karina M. The optimization of bacterial cellulose production and its applications: a review. Cellulose. 2020;27(12):6747–66. doi:10.1007/s10570-020-03273-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Diaz-Ramirez J, Urbina L, Eceiza A, Retegi A, Gabilondo N. Superabsorbent bacterial cellulose spheres biosynthesized from winery by-products as natural carriers for fertilizers. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;191:1212–20. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.09.203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. de Andrade Arruda Fernandes I, Pedro AC, Ribeiro VR, Bortolini DG, Ozaki MSC, Maciel GM, et al. Bacterial cellulose: from production optimization to new applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;164:2598–611. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Demewoz GE, Tiruneh AH, Wilson VH, Jose S, Sundramurthy VP. Enhancing mechanical properties of polyvinyl alcohol films through cellulose nanocrystals derived from corncob. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;5(2):1–15. doi:10.1007/s13399-024-06128-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Jose J, Mathew RM, Zachariah ES, Thomas V. Blue emissive PVA blended cellulose nanocrystals/carbon dots film for UV shielding applications. Cellulose. 2023;30(9):5623–39. doi:10.1007/s10570-023-05232-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Boott CE, Tran A, Hamad WY, MacLachlan MJ. Cellulose nanocrystal elastomers with reversible visible color. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2020;132(1):232–7. doi:10.1002/anie.201911468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. da Cunha Silva N, Rodrigues JS, de Souza Bernardes M, Gonçalves MP, Borsagli FGLM. Cellulose nanocrystals and nanofiber from sub-wear out Brazilian semiarid source for biological applications. J Clust Sci. 2024;35(6):1903–13. doi:10.1007/s10876-024-02622-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Aziz T, Ullah A, Fan H, Ullah R, Haq F, Khan FU, et al. Cellulose nanocrystals applications in health, medicine and catalysis. J Polym Environ. 2021;29(7):2062–71. doi:10.1007/s10924-021-02045-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Garino N, Monti N, Bartoli M, Pirri CF, Zeng J. Tin sulfide supported on cellulose nanocrystals-derived carbon as a green and effective catalyst for CO2 electroreduction to formate. J Mater Sci. 2023;58(37):14673–85. doi:10.1007/s10853-023-08925-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Hoa NM, Toan LD, Van Duong P, Minh PH, Tuyen NT, Thi LA. Fine-tuning bandgap, lifetime, and phonon characteristics in CdSe nanocrystals for enhanced optoelectronic device applications. J Mater Sci Mater Electron. 2024;35(26):1756. doi:10.1007/s10854-024-13478-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Wu B, Abdalkarim SYH, Li Z, Lu W, Yu HY. Synergistic enhancement of high-barrier polylactic acid packaging materials by various morphological carbonized cellulose nanocrystals. Carbohydr Polym. 2025;351(6):123118. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.123118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Xu Y, Atrens A, Stokes JR. A review of nanocrystalline cellulose suspensions: rheology, liquid crystal ordering and colloidal phase behaviour. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;275:102076. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2019.102076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Rana AK, Frollini E, Thakur VK. Cellulose nanocrystals: pretreatments, preparation strategies, and surface functionalization. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;182:1554–81. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Pradhan D, Jaiswal AK, Jaiswal S. Emerging technologies for the production of nanocellulose from lignocellulosic biomass. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;285(1):119258. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Martínez-Luévanos A, Perez Berumen C, Lara Ceniceros A, Owoyokun T, Sifuentes L. Cellulose nanocrystals: obtaining and sources of a promising bionanomaterial for advanced applications. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2021;11(4):11797–816. doi:10.33263/briac114.1179711816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Görgüç A, Bayraktar B, Gençdağ E, Demirci K, Yılmaz S, Zungur-Bastıoğlu A, et al. Cellulose nanofibrils and nanocrystals valorized from pistachio hull possess unique chemo-structural and rheological properties depending upon solvent system: potencies of green techniques and genetic algorithm. Waste Biomass Valorization. 2024;15(12):7077–96. doi:10.1007/s12649-024-02645-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Chen K, Wang L, Xu L, Pan H, Hao H, Guo F. Preparation of peanut shell cellulose nanofibrils and their superhydrophobic aerogels and their application on cotton fabrics. J Porous Mater. 2023;30(2):471–83. doi:10.1007/s10934-022-01354-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Lu X, Shen L, Chen C, Yu W, Wang B, Kong N, et al. Advance of self-cleaning separation membranes for oil-containing wastewater treatment. Environ Funct Mater. 2024;3(1):72–93. doi:10.1016/j.efmat.2024.06.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Ragab AH, Gumaah NF, El Aziz Elfiky AA, Mubarak MF. Exploring the sustainable elimination of dye using cellulose nanofibrils-vinyl resin based nanofiltration membranes. BMC Chem. 2024;18(1):121. doi:10.1186/s13065-024-01211-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Tao S, Li Y, Chen Y, Li Q, Peng F, Meng L, et al. Comparative characterization of sulfated holocellulose nanofibrils from different plant materials. Cellulose. 2024;31(5):2849–63. doi:10.1007/s10570-024-05781-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Dimic-Misic K, Obradovic B, Kuraica M, Kostic M, Lê HQ, Korica M, et al. Production of micro nanofibrillated cellulose from prerefined fiber via a dry dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) oxygen plasma-treated powder precursor. J Nat Fibers. 2024;21(1):2394146. doi:10.1080/15440478.2024.2394146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Park SY, Shin H, Youn HJ. Facile crosslinking methods for water-durable oven-dried cellulose nanofibril foams and their application as dye adsorbents. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;267(Pt 1):131432. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Dominic M, Joseph R, Sabura Begum PM, Kanoth BP, Chandra J, Thomas S. Green tire technology: effect of rice husk derived nanocellulose (RHNC) in replacing carbon black (CB) in natural rubber (NR) compounding. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;230(41):115620. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Hossain L, De Francesco M, Tedja P, Tanner J, Garnier G. Nanocellulose coated paper diagnostic to measure glucose concentration in human blood. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:1052242. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2022.1052242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Perdani CG, Gunawan S. A short review: nanocellulose for smart biodegradable packaging in the food industry. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2021;924(1):012032. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/924/1/012032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Mahardika M, Masruchin N, Amelia D, Ilyas RA, Septevani AA, Syafri E, et al. Nanocellulose reinforced polyvinyl alcohol-based bio-nanocomposite films: improved mechanical, UV-light barrier, and thermal properties. RSC Adv. 2024;14(32):23232–9. doi:10.1039/d4ra04205k. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Fernández-Santos J, Valls C, Cusola O, Roncero MB. Periodate oxidation of nanofibrillated cellulose films for active packaging applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;267(Pt 2):131553. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Yan L, Abdalkarim SYH, Chen X, Chen Z, Lu W, Zhu J, et al. Nucleation and property enhancement mechanism of robust and high-barrier PLA/CNFene composites with multi-level reinforcement structure. Compos Sci Technol. 2024;245(6):110364. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2023.110364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Alvarado MC, Ignacio MCCD, Acabal MCG, Lapuz ARP, Yaptenco KF. Review on nanocellulose production from agricultural residue through response surface methodology and its applications. Nano Trends. 2024;8(2):100054. doi:10.1016/j.nwnano.2024.100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Kępa K, Amiralian N, Martin DJ, Grøndahl L. Grafting from cellulose nanofibres with naturally-derived oil to reduce water absorption. Polymer. 2021;222:123659. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2021.123659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Faria M, Mohammadkazemi F, Aguiar R, Cordeiro N. Agro-industrial byproducts as modification enhancers of the bacterial cellulose biofilm surface properties: an inverse chromatography approach. Ind Crops Prod. 2022;177(1):114447. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.114447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Bai Y, Tan R, Yan Y, Chen T, Feng Y, Sun Q, et al. Effect of addition of γ-poly glutamic acid on bacterial nanocellulose production under agitated culture conditions. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod. 2024;17(1):68. doi:10.1186/s13068-024-02515-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Awasthi S, Pandey SK. Recent advances in smart hydrogels and carbonaceous nanoallotropes composites. Appl Mater Today. 2024;36:102058. doi:10.1016/j.apmt.2024.102058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Villarreal-Soto SA, Beaufort S, Bouajila J, Souchard JP, Taillandier P. Understanding kombucha tea fermentation: a review. J Food Sci. 2018;83(3):580–8. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.14068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Subhedar A, Bhadauria S, Ahankari S, Kargarzadeh H. Nanocellulose in biomedical and biosensing applications: a review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;166:587–600. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.10.217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Khorsandi D, Jenson S, Zarepour A, Khosravi A, Rabiee N, Iravani S, et al. Catalytic and biomedical applications of nanocelluloses: a review of recent developments. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;268(3):131829. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131829. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Raymond D, Weerarathna I, Jallah JK, Kumar P. Nanoparticles in biomedical implants: pioneering progress in healthcare. AIMS Bioeng. 2024;11(3):391–438. doi:10.3934/bioeng.2024019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Das S, Ghosh B, Sarkar K. Nanocellulose as sustainable biomaterials for drug delivery. Sens Int. 2021;3(5):100135. doi:10.1016/j.sintl.2021.100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Li Z, Chen SQ, Cao X, Li L, Zhu J, Yu H. Effect of pH buffer and carbon metabolism on the yield and mechanical properties of bacterial cellulose produced by Komagataeibacter hansenii ATCC 53582. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;31(3):429–38. doi:10.4014/jmb.2010.10054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Aswini K, Gopal NO, Uthandi S. Optimized culture conditions for bacterial cellulose production by Acetobacter senegalensis MA1. BMC Biotechnol. 2020;20(1):46. doi:10.1186/s12896-020-00639-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Ramírez Tapias YA, Di Monte MV, Peltzer MA, Salvay AG. Bacterial cellulose films production by Kombucha symbiotic community cultured on different herbal infusions. Food Chem. 2022;372(2):131346. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Horta-Velázquez A, Morales-Narváez E. Nanocellulose in wearable sensors. Green Anal Chem. 2022;1:100009. doi:10.1016/j.greeac.2022.100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

97. Zahan KA, Pa’e N, Muhamad II. Monitoring the effect of pH on bacterial cellulose production and acetobacter xylinum 0416 growth in a rotary discs reactor. Arab J Sci Eng. 2015;40(7):1881–5. doi:10.1007/s13369-015-1712-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Hirai A, Tsuji M, Horii F. Culture conditions producing structure entities composed of Cellulose I and II in bacterial cellulose. Cellulose. 1997;4(3):239–45. [Google Scholar]

99. Zendehbad SM. Controllable fabrication of BC based on time growth. Int J Mater Sci Appl. 2015;4(5):299–302. doi:10.11648/j.ijmsa.20150405.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Hestrin S, Schramm M. Synthesis of cellulose by Acetobacter xylinum. 2. Preparation of freeze-dried cells capable of polymerizing glucose to cellulose. Biochem J. 1954;58(2):345–52. doi:10.1042/bj0580345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools