Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Comparative Study on the Phenolic Compound Extraction in the Biorefinery Upgrading Process of Multi-Feedstock Biomass Waste Based Bio-Oil

1 Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Negeri Semarang, Gd. E1 Lt. 2 UNNES Kampus Sekaran, Gunungpati, Semarang, 50229, Indonesia

2 Chemical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang, 50275, Indonesia

3 Research Center for Biomass and Bioproducts, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Jl Raya Bogor KM 46, Cibinong, 16911, Indonesia

* Corresponding Author: Haniif Prasetiawan. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(7), 1347-1366. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0070

Received 22 December 2024; Accepted 12 May 2025; Issue published 22 July 2025

Abstract

Bio-oil is a renewable fuel that can be obtained from biomass waste, such as empty palm fruit bunches, sugarcane bagasse, and rice husks. Within a biorefinery framework, bio-oil had not met the standards as a fuel due to the presence of impurities like corrosive phenol. Therefore, the separation of phenol from bio-oil is essential and can be achieved using the extraction method. In this study, biomass wastes (empty fruit bunches of oil palm, sugarcane bagasse, and rice husk) were pyrolyzed in a biorefinery framework to produce bio-oil, which was then refined through liquid-liquid extraction with a methanol-chloroform and ethyl acetate solvents to remove its phenolic compound. The extraction with methanol-chloroform solvent was carried out for 1 h at 50°C. Meanwhile, extraction with ethyl acetate solvent was carried out for 3 h at 70°C. Both extractions used the same variations, i.e., bio-oil: solvent ratio at 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, and 1:4, and stirring speeds of 150 rpm, 200 rpm, 250 rpm, and 300 rpm. The bio-oil obtained from this study contained complex chemical compounds and had characteristics such as a pH of 5, a density of 1.116 g/mL, and a viscosity of 29.57 cSt. The optimization results using response surface methodology (RSM) showed that the best yield for methanol-chloroform was 72.98% at a stirring speed of 250 rpm and a ratio of 1:3. As for ethyl acetate solvent, the highest yield obtained was 71.78% at a stirring speed of 237.145 rpm and a ratio of 1:2.Keywords

As the world’s population increases, the availability of energy is gradually diminishing. Alternative energy sources that are environmentally friendly and renewable, such as bio-oil, are needed. Bio-oil is a dark-colored liquid fuel obtained from the thermal conversion of biomass without the presence of oxygen (pyrolysis) [1]. Compared to other fossil fuels such as crude oil, heavy fuel oil, diesel and gasoline, bio-oil has the characteristics of high oxygen concentration, high moisture content, high viscosity, high acidity, low calorific value and poor stability. However, it is high in energy density, low in sulfur and nitrogen content, and is easy to store, transport, and utilize [2].

Bio-oil can be processed from biomass waste, such as empty palm fruit bunches (EFB), sugarcane bagasse, and rice husks. These three types of biomasses are the most dominant waste from plantations in Indonesia [3], and they generally have a high lignocellulosic content. Lignocellulosic content in biomass plays a vital role in the characteristics of pyrolysis products. High lignin content can decrease the pyrolysis reaction rate, while higher cellulose in biomass can increase the reaction rate of the pyrolysis process. The lignocellulosic content of each biomass is shown in Table 1.

Biomass is processed using fast pyrolysis techniques to produce bio-oil. This pyrolysis occurs at temperatures of 400–650°C, heat transfer rates of 10–1000°C/s, and residence times of less than 2 s [7]. Based on its operating conditions (temperature, residence time, heating rate, and particle size), pyrolysis is divided into three categories, namely slow, fast, and flash pyrolysis [8]. Products produced in the pyrolysis process include biochar, bio-oil, and non-condensed gases such as hydrogen, methane, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and other hydrocarbon gases. In the bio-oil production process, key indicators of bio-oil quality include yield, calorific value, and application-specific parameters such as viscosity and chemical composition. After undergoing the pyrolysis process, bio-oil still contains impurities, including phenols and carboxylic acids, which contribute to its corrosive nature and instability. Additionally, bio-oil has a low heating value, primarily due to its high water and oxygen content, and exhibits high viscosity, making it challenging to use directly as a fuel [9]. Therefore, it is necessary to perform an upgrading process to improve the bio-oil quality.

There are three methods to upgrade bio-oil: catalytic, chemical, and physical upgrading. Physical upgrading can be accomplished with additional solvents, liquid-liquid extraction, and emulsification. Bio-oil upgrading using the catalytic approach is accomplished by steam reform, hydrocracking, and hydro-oxygenation (HDO). On the other hand, chemical upgrading uses an esterification reaction [10]. Liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) offers distinct advantages compared to other bio-oil upgrading processes, such as fractional condensation, catalytic upgrading, and distillation. Fractional condensation, which separates pyrolysis vapors by cooling at different temperatures, is effective at removing water and increasing energy density but lacks the specificity to target and remove certain oxygenated compounds, such as phenols and carboxylic acids, that contribute to bio-oils instability and corrosiveness. While fractional condensation enhances overall bio-oil quality, it does not selectively eliminate these problematic compounds [11]. In comparison, LLE is a relatively simple and low-energy process that allows for selective separation based on chemical properties such as polarity. It effectively isolates oxygenated compounds, particularly phenols, which are responsible for bio-oil’s corrosiveness and instability. Additionally, LLE can be performed under mild conditions and does not require complex temperature controls or expensive catalysts. These factors make LLE more advantageous when the goal is to selectively remove phenols and other undesirable compounds from bio-oil, improving its overall quality and suitability for fuel applications [12].

Previous studies focused on the utilization of a liquid-liquid extraction process to remove the phenolic compounds from single feedstock-based bio-oil such as rice husk [9], coconut shells [13], and sugarcane bagasse [14]. Nevertheless, not all biomass waste is constantly accessible. Each region possesses distinct biomass waste. For instance, oil palm empty fruit bunch waste is more prevalent in one area than sugar cane waste, and vice versa. The application of multi-feedstock biomass waste is to complements one another without lowering the quality of the bio-oil that is produced. Bio-oil produced from a variety of feedstocks. Compared to bio-oil made from a single feedstock, biomass waste has more complex components. The multi-feedstock approach improves the scalability of bio-oil production and offers a more complete solution for a range of biomass resources. Multi-feedstock approaches provide a more comprehensive solution for diverse biomass resources and enhance the scalability of bio-oil production.

According to Yang et al. [15], solvents such as methanol and ethyl acetate have relatively high polarity and good solubility of phenol compared to several commonly used solvents for extracting phenol from bio-oil. Meanwhile, chloroform is a semi-polar solvent that can effectively extract the organic phase from bio-oil [16]. Methanol-chloroform solvent had been used to collect phenolic compounds from bio-oil derived from single feedstock such as rice husk pyrolysis [9], coconut shells [13], and sugarcane bagasse [14]. The use of ethyl acetate solvent has previously been conducted to extract phenol from bio-oil obtained from the pyrolysis of Jatropha curcas seed cake [1]. Currently, extraction of phenolic compounds from multi-feedstocks biomass-based bio-oil has never been done.

Aim of this study is to extraction of phenolic compounds from multi feedstocks biomass-based bio-oil using various solvents. The composition of the biomass waste mixture was based on previous studies [17]. The operating condition of the extraction process was then optimized by using response surface methodology (RSM). The optimized operating condition can be used to produce bio-oil with a better physical and chemical characteristic close to fossil fuel.

The bagasse was obtained from sugarcane ice traders in Semarang, Central Java, and EFB was obtained from Samarinda, East Kalimantan. Rice husk obtained from a rice mill in Gunungpati, Semarang. Other materials used in this study were Nitrogen (Surya Industri Gas, Central Java, Semarang, Indonesia), ethyl acetate, chloroform-methanol 80% v/v, Na2CO3, Folin-Ciocalteu, gallic acid and aquadest. All chemicals were purchased from Merck (Kenilworth, NJ, USA). Furthermore, all reagents used in here are analytical reagent grade and used as received without further purification. Distilled water and deionized water are available in the laboratory.

The biomass materials were cleaned and dried under the sun for three days. The materials were then ground and sieved using a 60-mesh screen. The materials were further dried using an oven to reduce their water content to 100°C. Furthermore, the materials were weighed to produce biomass with a weight composition of rice husk at 30.54%, EFB at 36.64% and sugarcane bagasse at 32.82%. Next, the biomass mixture undergone fast pyrolysis process at a temperature of 500°C with a reaction time of 60 min, and a nitrogen gas flow of 3 L/min. The results of the fast pyrolysis reaction were divided into three main categories, which are bio-oil, biochar and non-condensable gas. The gas from the pyrolysis process quickly flowed into the condenser tube, while the cooling water flowed at the condenser’s shell. The gas that had been condensed into liquid or bio-oil was then transferred to a vessel whose volume could be known. The bio-oil obtained was then analyzed for its physical and chemical characteristics. The schematic diagram for the pyrolysis process is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the pyrolysis process

2.2.2 Bio-Oil Characterization

GC-MS analysis was carried out to determine the chemical components present in the bio-oil. The operating condition of GC-MS was set according to the previous study [17] by using gas chromatography-mass spectrophotometry (GC–MS), GC Clarus 680, and MS Clarus SQ 8 T from Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA, USA). Physical properties characterization in this study included the bio-oil, density, pH, and viscosity. The test results were later compared with the applicable fuel standards. The bio-oil density was measured by using a pycnometer. The weight of bio-oil was obtained from the difference between the pycnometer which is fully filled with the bio-oil sample and the empty pycnometer. The obtained bio-oil weight was then divided by the pycnometer volume to obtain its density. The pH of the bio-oil was measured by using a pH meter. The viscosity of the bio-oil was measured by using a viscometer Ostwald.

2.2.3 Bio-Oil Extraction Process

Two solvent systems were utilized in this study, i.e., 80% chloroform-methanol and ethyl acetate. Chloroform-methanol and ethyl acetate are considered a green alternative since it has a lower toxicity profile and is less harmful to the environment, making them preferable in laboratory settings where safety and environmental impact are concerns. Ethyl acetate was also chosen since it is a moderately polar solvent, making it effective for extracting a wide range of organic compounds, including phenols. Its polarity allows for efficient extraction of phenolic compounds without excessively extracting non-polar impurities. Previous studies also showed that ethyl acetate is able to extract the highest phenolic content compared to other solvents such as methanol, ethanol, acetone, dichloromethane and chloroform [18]. In this study, the ratio of bio-oil: solvent and stirring speed were varied. A higher amount of solvent would increase the extracted solute. However, the more solvents used, the less effective the extraction process would be. In liquid-liquid extraction, optimum liquid distribution or homogenization can also be obtained by adjusting the appropriate stirring speed. First, 6.5 mL of alkaline solution was added to the three-neck flask. Then, solvent was added with variations ratio of bio-oil: solvent (v/v) of 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, and 1:4. The extraction process was carried out for 3 h at 70°C for ethyl acetate. Meanwhile, the extraction process for 80% chloroform-methanol was done for 50 min at 50°C. The specific temperature and extraction time were chosen based on the best operating conditions from previous studies to obtain the highest phenolic compounds [19,20]. In this stage, stirring speed variations (150, 200, 250, and 300 rpm) were also employed. After the extraction process was completed, the mixture of bio-oil and solvent was separated using a series of separatory funnels and allowed to stand for 120 and min for ethyl acetate and 80% methanol-chloroform extraction processes, respectively. The schematic diagram of the experimental setup for the extraction process is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Experimental setup for the extraction process

2.2.4 Phenolic Compound Analysis

Phenolic compound analysis was determined by using the Folin-Ciocalteu (FC) method. This method was commonly used for phenol determination. This method also has a limitation where it may be influenced by other reducing agents in bio-oil. However, the total phenolic content in bio-oil detected by the FC method was comparable to the number of total phenolics obtained by liquid-liquid extraction. The FC method uncertainty of measurement was ±1.1% at the 95% confidence level [21,22]. First, 0.1 mL of extract or raffinate was added to the sample bottle, followed by the addition of 0.5 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu. Then, the mixture was mixed until homogeneous and was allowed to stand for 3 min. Next, 1.5 mL of Na2CO3 solution was added, and the mixture was homogenized and left for 2 h at room temperature [13]. The absorbance was measured at a maximum wavelength of 751 nm with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu 1800, Kyoto, Japan). The phenol concentrations were calculated using the standard linear regression curve method with a standard solution of gallic acid and the reagent of Folin-Ciocalteu. Total phenol concentration was then calculated by using Eq. (1).

2.2.5 Response Surface Methodology (RSM) Optimization

In this study, the extraction parameters were optimized using RSM with central composite design (CCD) in the Design Expert 13. CCD was performed for a total of 13 trials, with five repetitions at the central point. The ANOVA method was used to analyze the F-test, lack of fitness, predicted R2, and plot the 3D model. From the ANOVA test, an equation for phenol yield as a function of bio-oil: solvent ratio and stirring speed was obtained for each solvent. The experimental data were then compared with the predicted results from the model equation by using the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) as shown in Eq. (2).

An optimization process was then performed to obtain the best operating conditions for phenol extraction from bio-oil. The best operating conditions were then validated by comparing them with the experimental data.

3.1 Chemical Characterization of Bio-Oil

Production of bio-oil from multi-feedstock of biomass waste had been performed in an earlier study [17]. Prasetiawan et al. reported that the best biomass waste mixture was composed of rice husk, EFB, and sugarcane bagasse with percentages of 30.54%, 36.64%, and 32.82%, respectively [17]. Similarly, the operating parameters were selected based on previous pyrolysis studies of various biomass wastes [20], which used 500°C temperature and 3 L/min of nitrogen flowrate. The best mixture and operating parameters for pyrolysis of biomass waste were utilized in this study.

Fig. 3 shows the results of the GC-MS analysis. There were 20 peaks indicating the types of compounds contained in the bio-oil. The bio-oil content produced in this study was dominated by 27.15% fatty acid compounds, fatty acid esters 20.99%, aldehyde 17.53%, and phenol 16.55%. The concentration of each component represents the area percentage from GC-MS analysis. Previously, these compounds were also produced in several studies of bio-oil from EFB [23], bagasse [24] and rice husks [25].

Figure 3: GC-MS bio-oil chromatogram

The detailed bio-oil content is presented in Table 2. The fatty acid compounds in bio-oil were produced from the hydrolysis reaction of carbohydrate compounds consisting of lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose. The fatty acids that are formed can eventually undergo esterification and substitution reactions to form fatty acid esters [26]. Aldehydes and phenols in bio-oil are also derived from lignocellulose through hemolysis reactions [27]. The presence of aldehydes can cause bio-oil to become unstable [28]. It easily reacts with the remaining components. Meanwhile, the high phenol content has a negative impact on engine performance since it will cause corrosion when the phenol is oxidized [13].

In terms of bio-oil potential as a fuel, the presence of fatty acid derivatives like hexadecanoic acid (C16) and octadecenoic acid (C18) is advantageous due to their higher energy content and potential to enhance the calorific value of bio-oil after the removal of impurities like phenols and other oxygenated compounds. However, the presence of these acids also introduces challenges, such as increasing viscosity and contributing to instability, which must be addressed during the upgrading process. The presence of oxygenated compounds like furfurals and ketones (peaks 2, 4, 6) can also contribute to instability, as they are prone to polymerization and degradation over time, which affects the storage stability of the bio-oil.

3.2 Physical Characterization of Bio-Oil

The bio-oil produced was tested for its physical characteristics, including pH, density, and viscosity. The physical characteristics of the bio-oil from this study were compared to the Indonesian National Standard [43], as shown in Table 3.

The pH value represents the corrosiveness level of bio-oil on metal materials. The lower the pH of the bio-oil, the more acidic and corrosive it is, which can damage storage facilities, piping systems, and engine combustion chambers. The acidity of bio-oil is caused by the presence of acidic compounds formed during the pyrolysis process of cellulose, lignin, and extractive compounds [44]. However, in this study, the bio-oil had a pH of 5, which is in accordance with the minimum pH requirement for diesel fuel [45].

The bio-oil resulting from this research has a density of 1.116 g/mL, which is higher than the standard density of diesel fuel (0.85–0.89 g/mL). The high density of the bio-oil is influenced by the molecular weight of its components [46]. The presence of impurities, such as water, can increase the fuel density [47]. The higher the fuel density, the larger the molecular weight of the impurities. This causes the fuel to be difficult to evaporate and ignite [48].

According to SNI, the standard viscosity ranges from 2.3 to 6 cSt. However, the bio-oil from the research has a higher viscosity of 29.57 cSt. Fuel with high viscosity can hinder the fuel flow to the engine, resulting in a decrease in efficiency during the combustion process and damaging the engine components [49]. The high viscosity of bio-oil is partly attributed to the presence of phenol content [13]. Therefore, it is necessary to perform an extraction to separate the phenol content from bio-oil.

3.3 Effects of Stirring Speed and Solvent Ratioon Phenol Extraction Yield

3.3.1 Phenol Extraction by Using 80% Methanol-Chloroform

The effects of stirring speed and bio-oil and solvent ratio on the yield of phenol extraction were investigated using variable stirring speed in the range of 150–300 rpm and bio-oil and solvent ratios of 1:1–1:4 with an extraction time of 50 min and temperature of 50°C. The results are shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Effect of stirring speed on yield extraction in the extraction using 80% chloroform-methanol

The phenol yield at a ratio of 1:2 increased as the stirring rate increased, although the increase was only slightly visible. This phenomenon can be explained because increasing the speed of stirring can increase the interfacial area so that the mass transfer rate of phenol from bio-oil to solvent also increases [50]. As for the 1:3 and 1:4 ratios, they had a slightly fluctuating trend. However, in general, the yield also increased with increasing agitation rate. This is reflected in the highest yield obtained at the peak stirring speed, which was 300 rpm. This result can also be explained by the same phenomenon as before. Meanwhile, for the 1:1 ratio, the yield trend experienced slight fluctuations from the stirring speed of 150–250 rpm. Extraction yield peaked at a stirring speed of 250 rpm, then decreased at a stirring speed of 300 rpm. According to Zhou et al. [51], this is thought to occur due to the back-mixing phenomenon, where the final product formed is mixed back into the unreacted substances.

As for the ratio of bio-oil:solvent, the yield decreases as the ratio of bio-oil:solvent increases. The results showed that the highest yield was obtained at a ratio of 1:1, while the lowest was 1:4. This is not in accordance with the theory described earlier, where more solvents produce higher yields [52]. According to Yulianti et al. this phenomenon is possible because of the limited components to be extracted from the sample and the limited ability of each solvent to dissolve these components [53]. In other words, increasing the volume of methanol-chloroform solvent to a certain amount can no longer dissolve phenol effectively. In addition, the extraction using methanol-chloroform focuses on separating the organic and aqueous phases from the bio-oil so that the extracted components are not only phenol but also other components with similar polarity. This causes phenolic compounds to compete with other compounds to bind to methanol, decreasing phenol’s extraction yield [54]. The lowest phenol extraction yield was 52.9% at a bio-oil:solvent ratio of 1:4 and a stirring speed of 150 rpm. Meanwhile, the highest yield was 88.2% at a 1:1 ratio using a stirring speed of 250 rpm.

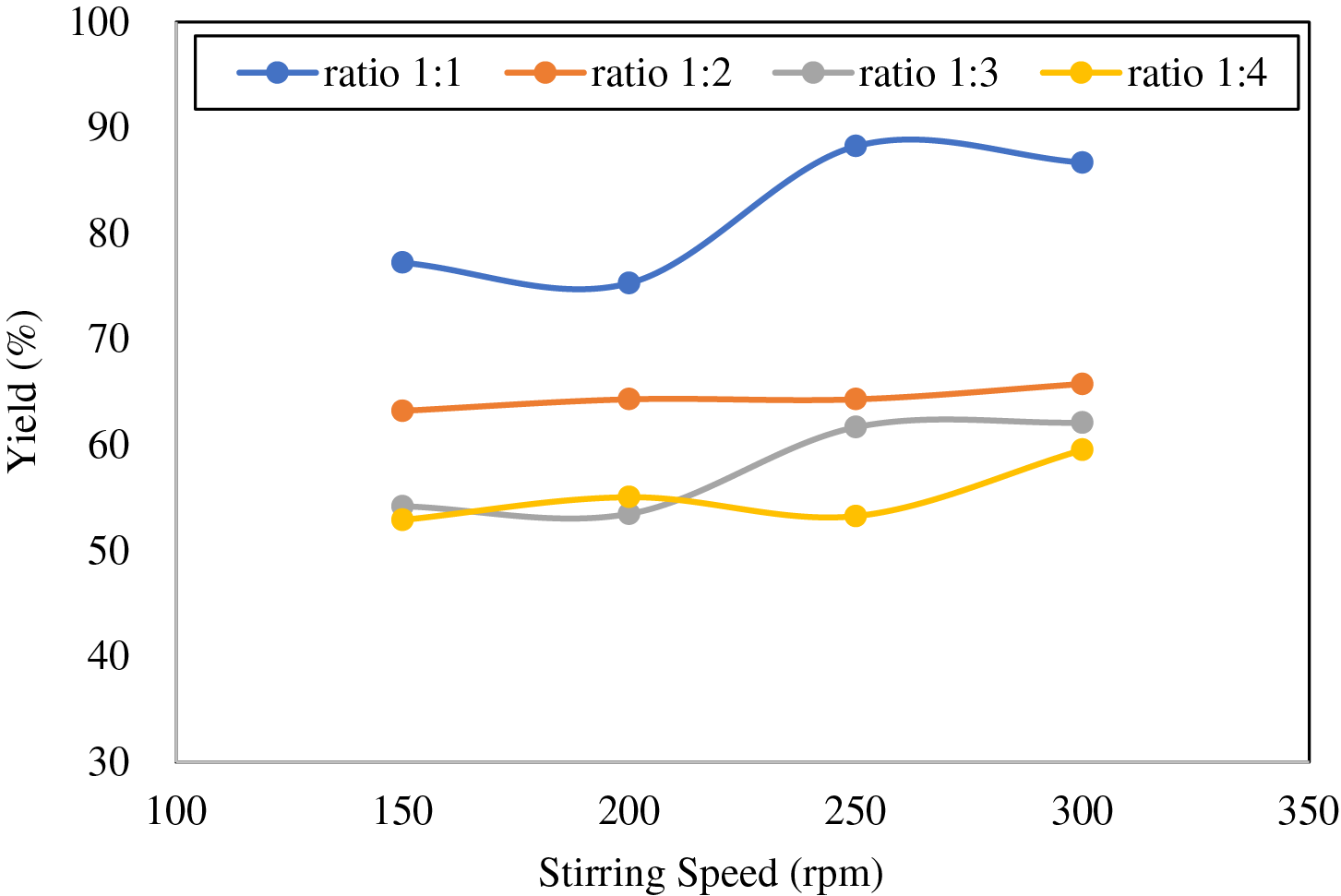

3.3.2 Phenol Extraction by Using Ethyl Acetate

In this study, the effects of stirring speed and the ratio of solvent to phenol yield are shown in Fig. 5. Based on the figure, the highest value was obtained at a stirring speed of 250 rpm and a solvent ratio of 1:3 with a yield of 79.11%. Meanwhile, the smallest value was found at a stirring speed of 150 rpm and a ratio of 1:1 with a yield of 40.79%. There was an increase in the yield of each sample with increasing stirring speed and solvent ratio. This happens because the distance between the particles decreases at a fast-mixing speed so that the attractive force between the particles increases. In this case, the contact between phenol and solvent becomes increasingly frequent [55]. Meanwhile, when the solvent ratio used increases, the contact between the solvent and the material becomes larger. Thus, the compounds in the material can be more dissolved in the solvent [56].

Figure 5: Effect of stirring speed on extraction of phenol using Ethyl Acetate

Fig. 5 shows that the phenol yield decreases at a stirring speed of 250 rpm and a solvent ratio of 1:4. This result may occur due to the formation of vortices that produce turbulence in the solution. As a result, the solid particles in the solvent will move in circles with the solvent without colliding [57]. At a stirring speed of 250 rpm, the 1:4 ratio produced less yield than the 1:2 and 1:3 ratios. This occurs because the components to be extracted have reached the saturation point in the solution, so the addition of solvent will not increase the extraction results [58]. The same phenomenon happened at the stirring speed of 300 rpm, where the 1:4 ratio had a smaller yield compared to the 1:2 ratio.

As seen in Figs. 4 and 5, increasing the stirring speed initially leads to a rise in phenol yield for both the 80% methanol-chloroform and ethyl acetate extractions. This trend can be attributed to enhanced mass transfer rates, where faster stirring speeds help in better mixing and more efficient contact between the solvent and biomass, thus increasing the extraction efficiency [51]. However, at higher solvent ratios, the phenol yield decreases, especially beyond certain stirring speeds. This could be due to the dilution effect, where an excessive number of solvents leads to lower concentrations of phenolic compounds in the solvent phase, reducing extraction efficiency [59,60]. Furthermore, at higher solvent volumes, the interaction between phenols and the solvent could become less favorable due to thermodynamic limitations or changes in solubility parameters.

The choice of solvent and the solvent recovery process play crucial roles in scaling up the extraction process. Solvent recovery techniques like distillation or membrane separation should be considered to minimize losses and improve the sustainability of the process. Furthermore, the solvent cost, toxicity, and recyclability should be taken into account when evaluating the overall economic viability of the process. The scalability of these methods depends on optimizing solvent-to-feed ratios that balance yield with operational costs and energy requirements. Future studies should investigate solvent recovery efficiency, which can significantly influence the economic feasibility of this process.

3.4 Response Surface Methodology Optimization

The RSM optimization was performed using the CCD experimental design. RSM is a robust model for optimizing phenolic extraction. However, it also has limitations such as it is only able to find the optimum condition inside the determined operating parameters. In this study, the RSM also did not include the variation of biomass waste composition since it acquired the optimum biomass waste composition from the previous studies. The variable used in this study was based on the range of operating parameters that gave the highest phenol yield, as shown in the previous section. The range used for the methanol-chloroform was stirring speeds of 200–300 rpm and bio-oil:solvent ratios of 1:1–1:3. Meanwhile, for the ethyl acetate, the variable ranges included stirring speed of 200–300 rpm and bio-oil to solvent ratio of 1:2–1:4.

Based on optimization, the fit summary results for each solvent are shown in Table 4. The suggested model for each solvent is quadratic, which has an R2 value close to 1, but is not aliased. This result shows that the predicted results obtained from the generated mathematical model are in accordance with the experimental data. As depicted in Fig. 6, the data spread forms a diagonal line, which is the line of y = x.

Figure 6: Predicted results vs. experimental data of phenol yield from an extraction process using (a) methanol-chloroform and (b) ethyl acetate

The suitability of the quadratic model used can be determined by comparing the results of the experiments with the predicted data. Fig. 6 shows the distribution of the research data, where it can be observed that the experimental points are still close to the predictions of the model. These results can also be verified using the percentage error and MAPE in Tables 5 and 6.

A MAPE of less than 10% indicates very high accuracy, 10%–20% indicates good accuracy, 20%–50% indicates reasonable accuracy, and more than 50% indicates inaccuracy [61]. The MAPE values in the experimental and predictive results of this study were 3.155% and 1.269%, respectively, demonstrating very high accuracy.

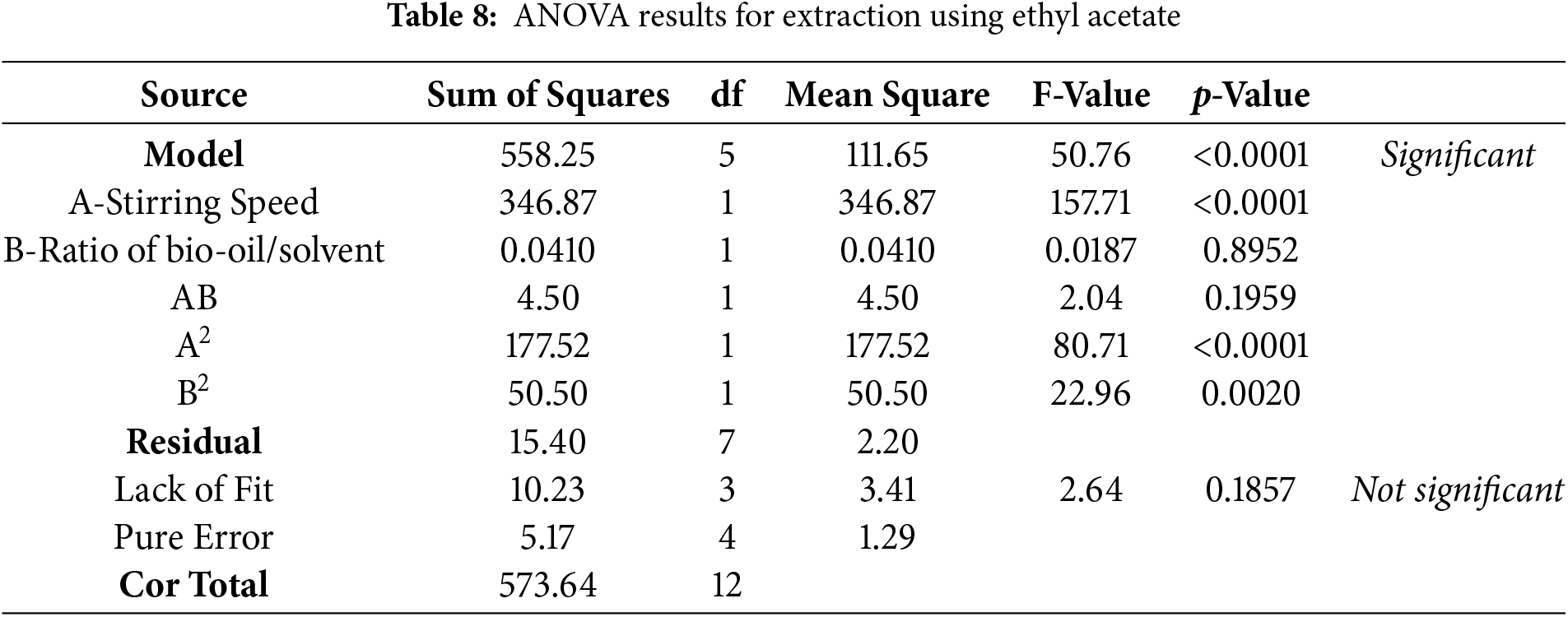

Tables 7 and 8 show that the models used in this optimization are significant (p-value = 0.0004 for methanol-chloroform and p-value < 0.0001 for ethyl acetate). The optimization results indicate that the significant models for the methanol-chloroform solvent are A, B, and B2, while AB and A2 are considered less significant. As for the ethyl acetate solvent, the significant models are A, A2, and B2, while B and AB are considered less significant. Additionally, each solvent shows indications of lack of fit that are not significant, suggesting that the optimization models for both solvents are suitable for use.

Based on the optimization model, the optimal yield can be obtained using Eqs. (3) and (4) for methanol-chloroform and ethyl acetate.

where A is the stirring speed (rpm) and B is for the ratio of bio-oil: solvent (v/v).

Figs. 7 and 8 show that the extraction with methanol-chloroform does not increase phenol yield as the bio-oil:solvent ratio increases. This is because the solvent has reached its solubility limit for phenolic components, and phenol also competes with other compounds to bind with methanol [53,54]. Meanwhile, extraction with ethyl acetate showed an increase in the phenol yield as the ratio of bio-oil:solvent increased. However, the increase was not significant, making it economically unfavorable.

Figure 7: Optimization contours of bio-oil:solvent ratio and stirring speed for extraction using (a) Methanol-Chloroform and (b) Ethyl Acetate

Figure 8: 3D graph optimizations of stirring speed and bio-oil:solvent for extraction using (a) Methanol-Chloroform and (b) Ethyl Acetate

As the stirring speed increases, both solvents show higher yield results. This can occur due to the mass transfer of solvents and phenol improves at high stirring speeds (Shakib et al., 2019).

The most optimal result is obtained by minimizing the operating conditions and maximizing the phenol yield. The optimization parameters used are shown in Table 9. Based on the optimization in Table 10, methanol-chloroform produces five solutions, while ethyl acetate produces three solutions. The best condition for methanol-chloroform is at an agitation speed of 200 rpm and a bio-oil:solvent ratio of 1:1. Meanwhile, the best condition for ethyl acetate is at an agitation speed of 237.145 rpm and a bio-oil:solvent ratio of 1:2. The selection of the best condition is based on desirability, which is better when approaching one. Desirability was chosen as a metric for optimization because it allows the integration of multiple response variables, such as phenol yield and solvent consumption into a single output. This helps in selecting conditions that balance all factors and provide the most efficient extraction process overall.

After obtaining the optimization results, validation was performed by comparing actual and predicted outcomes. The results of this validation are shown in Table 11.

In Table 11, the methanol-chloroform solvent has an actual yield of 72.98 and a predicted yield of 76.8, with an error of 4.29%. Meanwhile, the ethyl acetate solvent has an actual yield of 71.781 and a predicted yield of 17.950, with an error of 4.41%. An error of less than 5% indicates good agreement [62]. Therefore, both validation results are acceptable.

The produced bio-oil had a pH of 5, a density of 1.116 g/mL, and a viscosity of 29.57 cSt. Based on the GC-MS result, the chemical components of the bio-oil consisted of 27.16% fatty acids, 20.99% fatty acid esters, 17.53% aldehydes, and 16.55% phenols. Increased stirring speeds led to improved yields in phenol extraction. Conversely, a rise in the solvent ratio decreased the extraction yield for 80% chloroform-methanol, whereas the extraction yield increased for ethyl acetate. The maximum phenol yield achieved was 88.26%, attained at a stirring speed of 250 rpm with a bio-oil:solvent ratio of 1:1 using 80% chloroform-methanol, and 79.10% under the same stirring speed with a bio-oil:solvent ratio of 1:3 using ethyl acetate. When 80% chloroform-methanol was used in the extraction process, optimization resulted in an optimal yield of 76.8% at a stirring speed of 200 rpm and a bio-oil/solvent ratio of 1:1. The validation results showed that the actual experimental yield was 72.98%, resulting in an error of 4.29%. Meanwhile, for the utilization of ethyl acetate as the extraction solvent, the optimization showed an optimal yield of 74.95% at a stirring speed of 237.145 rpm and a bio-oil: solvent ratio of 1:2. The validation of the optimization results revealed that the actual experimental yield was 71.781%, with an error of 4.41%. Future work will focus on exploring alternative solvents with lower environmental impact and optimizing the process for industrial integration. Additionally, scaling up the extraction process and investigating its applicability to diverse biomass feedstocks will be key areas of further study.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank the Universitas Negeri Semarang and the Faculty of Engineering for equipment and laboratory support.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Universitas Negeri Semarang through DPA UNNES 2024. The grant number is No. 271.26.2/UN37/PPK.10/2024.

Author Contributions: Haniif Prasetiawan prepared methodology, formal analysis, investigation, original draft. Dewi Selvia Fardhyanti supervised and acquired funding, prepared methodology and conceptualization, validated data, reviewed and edited original article. Widya Fatriasari reviewed and edited original article. Hadiyanto prepared methodology and conceptualization. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated during the current study will be made available upon request by the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kanaujia PK, Naik DV, Tripathi D, Singh R, Poddar MK, Siva Kumar Konathala LN, et al. Pyrolysis of Jatropha Curcas seed cake followed by optimization of liquid-liquid extraction procedure for the obtained bio-oil. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2016;118:202–24. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2016.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chen D, Zhou J, Zhang Q, Zhu X. Evaluation methods and research progresses in bio-oil storage stability. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2014;40:69–79. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. FAO. Top 10 commodities production in Indonesia 2021. Rome, Italy: FAO; 2021. [Google Scholar]

4. Nguyen NT, Tran NT, Phan TP, Nguyen AT, Nguyen MXT, Nguyen NN, et al. The extraction of lignocelluloses and silica from rice husk using a single biorefinery process and their characteristics. J Ind Eng Chem. 2022;108:150–8. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2021.12.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Bittencourt GA, da Barreto ES, Brandão RL, Baêta BEL, Gurgel LVA. Fractionation of sugarcane bagasse using hydrothermal and advanced oxidative pretreatments for bioethanol and biogas production in lignocellulose biorefineries. Bioresour Technol. 2019;292:1–12. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2019.121963. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Dewanti DP. Potensi selulosa dari limbah tandan kosong kelapa sawit untuk bahan baku bioplastik ramah lingkungan. J Teknol Lingkung. 2018;19(1):81–8. doi:10.29122/jtl.v19i1.2644. (In Indonesia). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Dickerson T, Soria J. Catalytic fast pyrolysis: a review. Energies. 2013;6(1):514–38. doi:10.3390/en6010514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Campuzano F, Brown RC, Martínez JD. Auger reactors for pyrolysis of biomass and wastes. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2019;102:372–409. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2018.12.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Fardhyanti DS, Triwibowo B, Prasetiawan H, Chafidz A, Triwibowo B, Prasetiawan H, et al. Improving the quality of bio-oil produced from rice husk pyrolysis by extraction of its phenolic compounds. J Bahan Alam Terbarukan. 2020;8(2):90–100. doi:10.15294/jbat.v8i2.22530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mandal SC, Mandal V, Das AK. Essentials of botanical extraction: principles and applications. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

11. Mati A, Buffi M, Dell’orco S, Lombardi G, Ruiz Ramiro PM, Kersten SRA, et al. Fractional condensation of fast pyrolysis bio-oil to improve biocrude quality towards alternative fuels production. Appl Sci. 2022;12(10):4822. doi:10.3390/app12104822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Bokhary A, Leitch M, Liao BQ. Liquid-liquid extraction technology for resource recovery: applications, potential, and perspectives. J Water Process Eng. 2021;40:101762. doi:10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Fardhyanti DS, Pradana SH, Setyani L, Triwibowo B, Kurniawan C, Lestari RAS. Pemungutan senyawa fenol dari bio-oil hasil pirolisis tempurung kelapa dengan metode ekstraksi cair-cair. Pros Semin Nas Tek Kim UNNES 2018. 2018;2018:1–8. (In Indonesia). [Google Scholar]

14. Megawati, Fardhyanti DS, Prasetiawan H, Habibah U, Raharjo PT. Peningkatan yield fenol dari bio-oil hasil pirolisis bagasse tebu melalui proses ekstraksi pada suhu dan kecepatan pengadukan. Pros Semin Nas Tek Kim UNNES 2018. 2018;2018:9–17. (In Indonesia). [Google Scholar]

15. Yang X, Lyu H, Chen K, Zhu X, Zhang S, Chen J. Selective extraction of bio-oil from hydrothermal liquefaction of salix psammophila by organic solvents with different polarities through multistep extraction separation. BioResources. 2014;9:5219–33. [Google Scholar]

16. Mariana E, Cahyono E, Rahayu EF, Nurcahyo B. Validasi metode penetapan kuantitatif metanol dalam urin menggunakan gas chromatography-flame ionization detector. Indones J Chem Sci. 2018;7:277–84. [Google Scholar]

17. Prasetiawan H, Fardhyanti DS, Fatrisari W, Hadiyanto H. Preliminary study on the bio-oil production from multi feedstocks biomass waste via fast pyrolysis process. J Adv Res Fluid Mech Therm Sci. 2023;103:216–27. [Google Scholar]

18. Thi Thuong B, Xuan Sinh P, Thanh Hai N, Thi Thanh Binh N, Xuan Tung N. Effect of extraction solvent on total phenol content, total flavonoid content, and antioxidant activity of avicennia officinalis. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2022;12(4):2678–90. doi:10.25073/2588-1132/vnumps.4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Maulina S, Nurtahara. Extraction of phenol compounds in the liquid smoke by pyrolysis of oil palm fronds. J Innov Technol. 2020;1(1):1–5. doi:10.31629/jit.v1i1.2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Fardhyanti DS, Megawati, Chafidz A, Prasetiawan H, Raharjo PT, Habibah U, et al. Production of bio-oil from sugarcane bagasse by fast pyrolysis and removal of phenolic compounds. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2024;14(1):217–27. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-02527-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Rover MR, Brown RC. Quantification of total phenols in bio-oil using the Folin-Ciocalteu method. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2013;104:366–71. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2013.06.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Pérez M, Dominguez-López I, Lamuela-Raventós RM. The chemistry behind the Folin-Ciocalteu method for the estimation of (poly)phenol content in food: total phenolic intake in a mediterranean dietary pattern. J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71(46):17543–53. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.3c04022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Solikhah MD, Pratiwi FT, Heryana Y, Wimada AR, Karuana F, Raksodewanto AA, et al. Characterization of bio-oil from fast pyrolysis of palm frond and empty fruit bunch. In: Proceedings of the 12th Joint Conference on Chemistry; 2017 Sep 19–20; Central Java, Indonesia. Bristol, UK: IOP Publishing; 2018. p. 8–13. [Google Scholar]

24. Ahmed Baloch H, Nizamuddin S, Siddiqui MTH, Mubarak NM, Dumbre DK, Srinivasan MP, et al. Sub-supercritical liquefaction of sugarcane bagasse for production of bio-oil and char: effect of two solvents. J Environ Chem Eng. 2018;6(5):6589–601. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2018.10.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Alvarez J, Lopez G, Amutio M, Bilbao J, Olazar M. Bio-oil production from rice husk fast pyrolysis in a conical spouted bed reactor. Fuel. 2014;128(Suppl. 1):162–9. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2014.02.074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chen WH, Lin YY, Liu HC, Chen TC, Hung CH, Chen CH, et al. A comprehensive analysis of food waste derived liquefaction bio-oil properties for industrial application. Appl Energy. 2019;237:283–91. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.12.084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Cheng S, Shu J, Xia H, Wang S, Zhang L, Peng J, et al. Pyrolysis of crofton weed for the production of aldehyde rich bio-oil and combustible matter rich bio-gas. Appl Therm Eng. 2019;148(6):1164–70. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.12.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Chen WH, Wang CW, Kumar G, Rousset P, Hsieh TH. Effect of torrefaction pretreatment on the pyrolysis of rubber wood sawdust analyzed by Py-GC/MS. Bioresour Technol. 2018;259(1):469–73. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2018.03.033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Majid ZANM, Rahmawati L, Riyani C. Identification of bio-oil chemical compounds from pyrolysis process of oil palm empty fruit bunches. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Innovation in Technology and Management for Sustainable Agroindustry; 2021 Oct 25–26; Bogor, Indonesia. Bristol, UK: IOP Publishing; 2022. [Google Scholar]

30. Gunawan R, Li X, Lievens C, Gholizadeh M, Chaiwat W, Hu X, et al. Upgrading of bio-oil into advanced biofuels chemicals. Part I. Transformation of GC-detectable light species during the hydrotreatment of bio-oil using Pd/C catalyst. Fuel. 2013;111:709–17. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2013.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chen W, Luo Z, Yang Y, Li G, Zhang J, Dang Q. Upgrading of bio-oil in supercritical ethanol: using furfural and acetic acid as model compounds. BioResources. 2013;8:3934–52. doi:10.1109/icecc.2011.6067982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wibowo S. Karakteristik bio-oil serbuk gergaji sengon (Paraserianthes falcataria L. Nielsen) menggunakan proses pirolisis lambat. J Penelit Has Hutan. 2013;31(4):258–70. doi:10.20886/jphh.2013.31.4.258-270. (In Indonesia). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang Y. Study on hydrogen production oyf bio-oil catalytic reforming by charcoal catalyst. Appl Ecol Environ Res. 2019;17(4):8541–53. doi:10.15666/aeer/1704_85418553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Rizal WA, Suryani R, Wahono SK, Anwar M, Prasetyo DJ, Amdani RZ, et al. Pirolisis Limbah biomassa serbuk gergaji kayu campuran: parameter proses dan analisis produk asap cair. J Ris Teknol Ind. 2020;14(2):353. doi:10.26578/jrti.v14i2.6606. (In Indonesia). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lachos-Perez D, Martins-Vieira JC, Missau J, Anshu K, Siakpebru OK, Thengane SK, et al. Review on biomass pyrolysis with a focus on bio-oil upgrading techniques. Analytica. 2023;4(2):182–205. doi:10.3390/analytica4020015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Fardhyanti DS, Prasetiawan H, Hermawan, Sari LS. Ternary liquid-liquid equilibria for the phenolic compounds extraction from artificial textile industrial waste. In: Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Education, Concept, and Application of Green Technology; 2016 Oct 5–6; Melville, NY, USA: AIP Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

37. Hadiyane A, Navila A, Karliati T, Pari G, Darmawan S, Rumidatul A. Utilization of liquid smoke from pine wood in inhibiting the attacks of coffe fruit press (Hypothenemus hampei Ferr.). J Penelit Has Hutan. 2024;42:17–30. [Google Scholar]

38. Fardhyanti DS, Megawati M, Istanto H, Anajib MK, Prayogo P, Habibah U. Extraction of phenol from bio-oil produced by pyrolysis of coconut shell. J Phys Sci. 2018;29(2):195–202. doi:10.1016/j.cjche.2018.08.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Hagr TE, Ali KS, Satti AAE, Omer SA. GC-MS analysis, phytochemical, and antimicrobial activity of Sudanese Nigella sativa (L) oil. Eur J Biomed Pharm Sci. 2018;5:23–9. [Google Scholar]

40. Xu K, Li J, Zeng K, Zhong D, Peng J, Qiu Y, et al. The characteristics and evolution of nitrogen in bio-oil from microalgae pyrolysis in molten salt. Fuel. 2023;331:125903. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Nava Bravo I, Velásquez-Orta SB, Cuevas-García R, Monje-Ramírez I, Harvey A, Orta Ledesma MT. Bio-crude oil production using catalytic hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) from native microalgae harvested by ozone-flotation. Fuel. 2019;241(1):255–63. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2018.12.071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Oyebanji JA, Okekunle PO, Lasode OA, Oyedepo SO. Chemical composition of bio-oils produced by fast pyrolysis of two energy biomass. Biofuels. 2018;9(4):479–87. doi:10.1080/17597269.2017.1284473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. SNI. Karakteristik kualitas Biodiesel (parameter, nilai mutu, dan metode uji). Biodiesel. 2023;7182:2015. (In Indonesia). [Google Scholar]

44. Wijayanti W, Musyaroh, Sasongko MN, Kusumastuti R, Sasmoko. Modelling analysis of pyrolysis process with thermal effects by using Comsol Multiphysics. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2021;28(19):101625. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2021.101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Sunarno S, Randi A, Utama PS, Yenti SR, Wisrayetti W, Wicakso DR. Improving bio-oil quality via co-pyrolysis empty fruit bunches and polypropilen plastic waste. Konversi. 2021;10(2):109–14. doi:10.20527/k.v10i2.11384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Jahiding M, Arsyad WOS, Rif’ah SM, Rizki RS, Mashuni. Effect of pyrolysis temperature on bio-fuel quality produced from pine bark (pinus merkusii) by pyro-catalytics method. In: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Physics and Its Applications (ICOPIA 2020); 2020 Aug 26; Surakarta, Indonesia. Bristol, UK: IOP Publishing; 2021. [Google Scholar]

47. Jamilatun S, Pitoyo J, Puspitasari A, Sarah D. Pirolisis tandan kelapa sawit untuk menghasilkan bahan bakar cair, gas, water fase. In: Prosiding Seminar Nasional Penelitian LPPM UMJ; 2022; Jakarta, Indonesia: LPPM UMJ. (In Indonesia). [Google Scholar]

48. Wijayanti H, Ratnasari D, Hakim R. Studi kinetika pirolisis sekam padi untuk menghasilkan bio-oil sebagai energi alternatif. Bul Profesi Ins. 2020;3(2):83–8. doi:10.20527/bpi.v3i2.67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Kim J, Lee J, Kim K. Numerical study on the effects of fuel viscosity and density on the injection rate performance of a solenoid diesel injector based on AMESim. Fuel. 2019;256(4):115912. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2019.115912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Shakib B, Torab-Mostaedi M, Outokesh M, Asadollahzadeh M. Mass transfer coefficients of extracting Mo (VI) and W (VI) in a stirred tank by solvent extraction using mixture of Cyanex272 and D2EHPA. Sep Sci Technol. 2019;55(17):3140–50. doi:10.1080/01496395.2019.1672741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Zhou Y, Gao F, Zhao Y, Lu J. Study on the extraction kinetics of phenolic compounds from petroleum refinery waste lye. J Saudi Chem Soc. 2014;18(5):589–92. doi:10.1016/j.jscs.2011.11.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Mantilla SV, Manrique AM, Gauthier-Maradei P. Methodology for extraction of phenolic compounds of bio-oil from agricultural biomass wastes. Waste Biomass Valorization. 2015;6(3):371–83. doi:10.1007/s12649-015-9361-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Yulianti D, Susilo B, Yulianingsih R, Korespondensi P. Pengaruh lama ekstraksi dan konsentrasi pelarut etanol terhadap sifat fisika-kimia ekstrak daun stevia (Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni M.) dengan metode microwave assisted extraction (MAE). J Bioproses Komod Trop. 2014;2:35–41. doi:10.24843/itepa.2021.v10.i04.p14. (In Indonesia). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Kartika IA, Fataya I, Yunus M, Yuliana ND. Optimasi proses ekstraksi minyak dan resin nyampung dengan pelarut biner menggunakan sesponse surface method. J Teknol Ind Pertan. 2022;32:21–31. (In Indonesia). [Google Scholar]

55. Nababan F, Zultiniar, Herman S. Pengaruh variasi kecepatan pengadukan terhadap hasil pada pembuatan asam oksalat dari bahan dasar ampas tebu [master’s thesis]. Riau, Indonesia: Riau University; 2014. (In Indonesia). [Google Scholar]

56. Putra IKW, Ganda Putra G, Wrasiati LP. Pengaruh perbandingan bahan dengan pelarut dan waktu maserasi terhadap ekstrak kulit biji kakao (Theobroma cacao L.) sebagai sumber antioksidan. J Rekayasa Dan Manaj Agroindustri. 2020;8(2):167. doi:10.24843/jrma.2020.v08.i02.p02.(In Indonesia). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Yuniwati M, Tanadi K, Andaka G, Kusmartono B. Pengaruh waktu, suhu, dan kecepatan pengadukan terhadap proses pengambilan tannin dari pinang. J Teknol. 2019;12:109–15. (In Indonesia). [Google Scholar]

58. Noviyanty A, Salingkat CA. Pengaruh rasio pelarut terhadap ekstraksi dari kulit buah naga merah (Hylocereus polyrhizus). KOVALEN J Ris Kim. 2019;5(3):280–9. doi:10.22487/kovalen.2019.v5.i3.14029. (In Indonesia). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Rubashvili I, Tsitsagi M, Zautashvili M, Chkhaidze M, Ebralidze K, Tsitsishvili V. Extraction and analysis of oleanolic acid and ursolic acid from apple processing waste materials using ultrasound-assisted extraction technique combined with high performance liquid chromatography. Rev Roum Chim. 2020;65(2):919–28. doi:10.29333/ejac/82931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Jiménez-Moreno N, Volpe F, Moler JA, Esparza I, Ancín-Azpilicueta C. Impact of extraction conditions on the phenolic composition and antioxidant capacity of grape stem extracts. Antioxidants. 2019;8(12):597. doi:10.3390/antiox8120597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Moreno JJM, Pol AP, Abad AS, Blasco BC. Using the R-MAPE index as a resistant measure of forecast accuracy. Psicothema. 2013;25:500–6. [Google Scholar]

62. Mariana W, Widjarnako SB, Widyastuti E. Optimasi formulasi dan karakterisasi fisikokimia dalam pembuatan daging restrukturisasi menggunakan response surface methodology (konsentrasi jamur tiram serta gel porang dan karagenan). J Pangan Dan Agroindustri. 2017;5:83–91. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools