Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effect of D-Lactide Content and Molecular Weight of PLA on Interfacial Compatibilization with PBAT and the Resultant Morphological, Thermal, and Mechanical Properties

1 Metallurgical & Materials Engineering Department, Faculty of Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering, Yildiz Technical University, Esenler, Istanbul, 34220, Turkey

2 Sustainable & Green Plastics Laboratory, Metallurgical & Materials Engineering Department, Faculty of Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, 34469, Turkey

* Corresponding Author: Mohammadreza Nofar. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(8), 1605-1621. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0048

Received 25 February 2025; Accepted 28 May 2025; Issue published 22 August 2025

Abstract

Interfacial compatibilization is essential to generate compatible blend structures with synergistically enhanced properties. However, the effect of molecular structure on the reactivity of compatibilizers is not properly known. This study investigates the compatibilization effect of multifunctional, epoxy-based Joncryl chain extender in blends of polylactide (PLA) and polybutylene adipate-co-terephthalate (PBAT) using PLA with varying D-lactide contents and molecular weights. These PLAs were high molecular weight amorphous PLA (aPLA) with D-content of 12 mol% and semi-crystalline PLA (scPLA) grades with D-contents below 1.5 mol% at both high (h) and low (l) molecular weights. The reactivity of Joncryl was assessed with each individual neat polymer, and its compatibilization effect was examined in blends at a weight ratio of 75 wt/25 wt using small amplitude oscillatory shear (SAOS) rheological analysis. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA), tensile and impact tests, as well as scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations, were conducted to characterize the blends. The addition of Joncryl resulted in remarkable improvements rheological behavior of all neat polymers and noticeably refined PBAT droplets in all blends, particularly in aPLA/PBAT and scPLA(l)/PBAT. The ductility, toughness and impact strength of these blends were significantly enhanced, while their tensile strength and modulus also showed slight improvements. Although the addition of Joncryl retarded the crystallization of the scPLA samples, the scPLA(h)/PBAT blend with Joncryl exhibited the highest thermomechanical performance over a wide temperature range. This was attributed to the higher crystallinity of scPLA(h), which, even in the presence of Joncryl, provided high thermal stability.Keywords

The global production and consumption of petrochemical plastics have surged in recent decades, resulting in a sharp increase in their accumulation in landfills [1]. Efforts to manage these plastics through disposal or recycling often demand complex and labor-intensive physical or chemical treatment processes [2,3]. These inefficiencies contribute to persistent plastic waste, positioning petroleum-derived polymers as a major environmental challenge [4,5]. In response, the plastics industry has increasingly turned to bioplastics—whether derived from renewable resources, biodegradable, or both—as a sustainable alternative [6–8]. Among these, polylactic acid (PLA) has emerged as a leading material, valued for being both bio-based and biodegradable [9,10]. Due to its compatibility with biological systems, semi-crystalline structure, and advantageous thermal and mechanical behavior, PLA is widely used in food packaging and medical applications [11,12]. Recognizing its safety, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized PLA for direct contact with biological fluids as early as the 1970s [13–16].

Commercially available PLAs are typically synthesized as copolymers comprising poly(L-lactide) (PLLA) and poly(DL-lactide) (PDLLA), which originate from the ring-opening polymerization of L-lactide and DL-lactide dimers—a method known for its cost efficiency [17–19]. These polymers are predominantly built from L-lactic acid units, with varying proportions of D-isomers incorporated as co-monomers [20]. The crystallization behavior of PLA is closely linked to its D-lactide content: higher concentrations of D-units diminish the polymer’s ability to crystallize and lower its melting temperature (Tm), leading to increased amorphousness at elevated D-content levels [21]. Specifically, PLAs with more than 8 mol% D-lactide are entirely amorphous, while those containing between 4 and 8 mol% display sluggish crystallization kinetics [17,22,23]. Beyond stereochemical composition, other structural parameters—such as molecular weight and architecture (linear vs. branched)—also play a crucial role in determining the polymer’s crystallization behavior, melt characteristics, and overall mechanical performance [19,22]. Despite the potential for enhancing PLA’s crystallinity, rheological profile, and mechanical properties through molecular engineering, it still exhibits drawbacks including low impact resistance and inherent brittleness [23–25].

Researchers are exploring practical solutions to address PLA’s limitations by blending it with flexible biopolymers in a more environmentally friendly manner. Polycaprolactone (PCL) [26–28], poly (propylene carbonate) (PPC) [29–31], poly(3hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBH) [32,33], poly (butylene succinate) (PBS) [34,35], poly [(butylene succinate)-co-adipate] (PBSA) [34,35] and polybutylene adipate-co-terephthalate (PBAT) [36–39] are among the most extensively used sustainable commercial biopolymers for blending PLA. Among these, PBAT stands out as a highly ductile polymer with excellent toughness, making it one of the most promising options for blending with PLA. Numerous studies have investigated the performance of PLA/PBAT blends, both with and without the use of compatibilizers [36–39]. Recent findings suggest that the specific PLA grade used in these blends significantly influences the resulting mechanical and morphological properties. Higher viscosity PLA, often associated with increased crystallinity, can contribute to improved dispersion of PBAT domains, thereby enhancing the composite’s mechanical attributes [39]. However, due to differences in molecular chain segments and lack of strong compatibility between PLA and PBAT, phase separation tends to occur as the PBAT content increases, which limits the ductility and toughness [40–43]. To address this challenge, incorporating a compatibilizer has been shown to improve the interfacial adhesion and overall miscibility between PLA and PBAT components [41–43]. For instance, Yang et al. [41] demonstrated that using an isosorbide-derived diisocyanate for reactive compatibilization enhanced the toughness of PLA/PBAT blends. Among available additives, Joncryl® ADR chain extenders—epoxy-functionalized, multifunctional acrylic oligomers—are widely recognized for their effectiveness in modifying the morphology and improving the performance of polyester-based polymer blends via reactive compatibilization mechanisms [44–48]. The epoxy functionalities in Joncryl are capable of reacting with carboxyl and hydroxyl groups present in both PLA and PBAT. This interaction may lead to molecular chain extension and the formation of copolymers that enhance the interfacial linkage between the two polymers [47–51]. Al-Itry et al. utilized Joncryl® ADR4368 in a blend of PLA and PBAT containing scPLA with 2% D-content [47]. They observed an increase in complex viscosity and storage modulus, along with an improvement in in elongation at break; however, no enhancement was noted in stress values. Similarly, Arruda et al. found that this additive led to finer dispersion and more homogeneous blend morphology, significantly enhancing the system’s ductility [48]. This was attributed to reduced interfacial tension and greater stability of the dispersed PBAT phase due to in-situ copolymer generation. Wu et al. further explored different Joncryl grades with varying epoxy content in PLA/PBAT blends and concluded that higher epoxy content led to superior compatibility and improved mechanical and rheological properties [52]. Recently, our group demonstrated how Joncryl reactivity can vary in PLA [53] and in its blends with PBAT [54]. The slower reactivity of Joncryl with PBAT compared to PLA has been reported [54], and this phenomenon has even been leveraged to explore Joncryl’s potential in improving the redressability of PLA-based systems [55].

Previous studies on PLA/PBAT blends incorporating Joncryl have largely centered around a single PLA grade [56–58]. However, since Joncryl’s reactivity is affected by factors like the D-lactide content and molecular weight of the neat PLA, it is crucial to investigate how different PLA grades influence the overall performance and interaction within the blends. The present study aims to examine the impact of incorporating 0.5 wt% Joncryl® ADR 4468 into PLA/PBAT blends using multiple PLA variants: a high-molecular-weight amorphous PLA (aPLA) containing 12 mol% D-lactide, and two semi-crystalline PLA (scPLA) grades with D-lactide contents below 1.5 mol%, available in both high (h) and low (l) molecular weights. The reactivity with PBAT, as well as with the corresponding PLA/PBAT blends, is also examined. Joncryl’s reactivity was evaluated using small amplitude oscillatory shear rheological measurements. To evaluate the overall performance of the blends, their morphological, mechanical, and thermomechanical properties were analyzed, focusing on the effects of PLA’s D-lactide content and molecular weight, along with the compatibilization role of Joncryl.

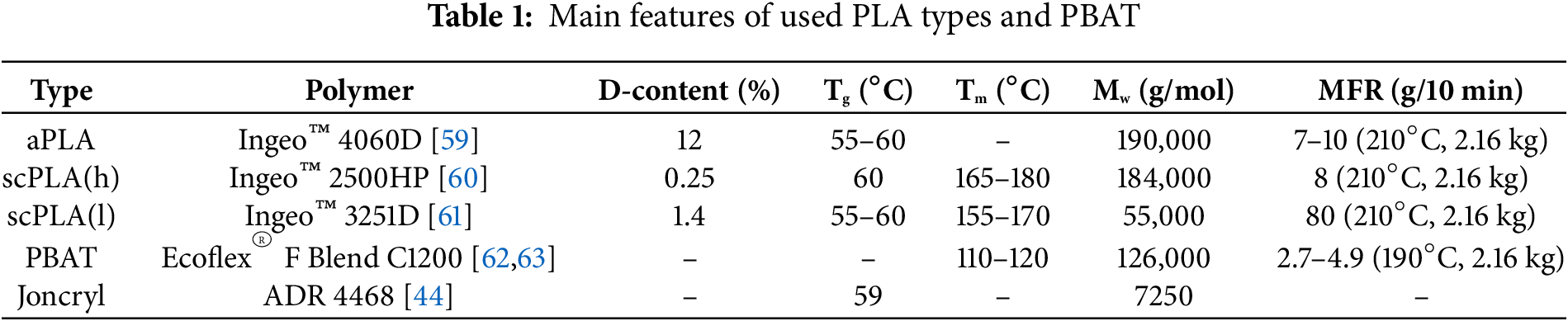

Three commercial grades of high molecular weight aPLA (Ingeo™ 4060D), scPLA(h) (Ingeo™ 2500HP), and scPLA(l) (Ingeo™ 3251D) were supplied by NatureWorks LLC. The PBAT (Ecoflex® F Blend C1200) was provided by BASF; it’s a grade intended for blown or cast film processing. The chain extender employed in this study was Joncryl® ADR4468, a multifunctional, epoxy-functionalized oligomeric acrylic resin developed by BASF, featuring an epoxy equivalent weight of 310 g/mol. Detailed information on the PLA types—including their D-lactide content, glass transition temperature (Tg), melting temperature (Tm), molecular weight (Mw), and melt flow rate (MFR)—is summarized in Table 1. Both aPLA and scPLA(h) exhibit comparable molecular weights and similar melt flow characteristics. In contrast, scPLA(l) is distinguished by a lower Mw and an elevated MFR, reflecting a more fluid melt profile. The chemical structures of PLA, PBAT, and Joncryl could also be found available elsewhere [44].

Prior to processing, overnight drying was applied to all polymers in a vacuum at 50°C. Blending was carried out using an internal melt mixer (Kökbir RTX-M40, Turkey), where different PLA types, PBAT, and PLA/PBAT blends (at a 75:25 weight ratio) were processed both with and without the incorporation of 0.5 wt% Joncryl. Although Joncryl has FDA approval for use [64], employing it in minimal amounts can help mitigate environmental concerns related to chemical additives during production and disposal. All melt blending operations were performed at 190°C for 5 min with a rotor speed of 100 rpm. The resulting blends were then formed into test specimens using a compression molding press (MSE Technology LP_M4SH10, Turkey) under 2 bar pressure at 190°C for 5 min.

The rheological analysis of polymers and their blends was conducted using a rotational rheometer (Anton Paar MCR-301, Austria) equipped with a parallel-plate geometry, featuring a plate diameter of 25 mm and a gap of 1 mm. SAOS analysis was performed at 190°C in a nitrogen atmosphere, progressing from high to low frequencies with a strain of 5%, which was maintained within the linear viscoelastic range.

Cryofractured specimens were sputter-coated with a thin layer of platinum using a Polaron SC7640 coater (Quorum Technologies, Lewes, UK) to enhance conductivity. The morphological features of the PLA/PBAT blends were then characterized using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JSM 6510LV, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) operated at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. To quantify the size distribution of the dispersed droplets observed in the SEM images, ImageJ software was employed for image analysis.

2.5 Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Analysis

The thermal transitions of the blends, including melting and crystallization behavior, were assessed using differential scanning calorimetry (Perkin Elmer DSC 4000, USA) in a nitrogen environment. Samples were initially heated from ambient temperature to 200°C at a rate of 10 °C/min and held isothermally for 5 min. This was followed by cooling to 30°C at a rate of 2 °C/min, and then a second heating cycle to 200°C, again at 10 °C/min. The crystallinity degree (X) was determined based on the enthalpies of melting (ΔHm), cold crystallization (ΔHcc) during the heating phases, and melt crystallization (ΔHc) during cooling, following Eqs. (1) and (2):

where wPLA is the weight fraction of PLA and

2.6 Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

The thermomechanical properties of the blends were assessed using a dynamic mechanical analyzer (Perkin Elmer DMA 8000, Springfield, IL, USA). Rectangular specimens with dimensions of 35 mm3 × 10 mm3 × 2 mm³ were tested in single cantilever mode. The analysis was performed with a constant deformation amplitude of 30 µm and a frequency of 1 Hz, while the temperature was increased from 25°C to 120°C at a rate of 3 °C/min. Throughout the test, both storage modulus (E′) and loss modulus (E″) were recorded as functions of temperature. The damping behavior was quantified by calculating the loss factor (tan δ), defined as the ratio of E″ to E′.

Tensile performance of the PLA/PBAT blends was evaluated using a universal testing device (Instron 3369, Norwood, MA, USA). Specimens were shaped into dog-bone profiles with dimensions of 20 mm (length), 4 mm (width), and 2 mm (thickness), following the ISO EN 527-2 standard. Testing was carried out at ambient conditions with a crosshead speed of 5 mm/min. The stress-strain curves were obtained to determine the tensile modulus, tensile strength, elongation at break, and toughness of the samples. For each blend, the tests were repeated five times, and the average values were reported.

To evaluate the impact strength, impact test was performed on unnotched specimens using an Izod impact tester (Zwick Roell, Ulm, Germany) equipped with a 5.5 J pendulum. Rectangular shaped samples with 80 mm3 × 10 mm3 × 4 mm3 were tested at room temperature, following ISO EN 180 standards. Each blend underwent a minimum of five testing repetitions.

3.1 Rheological Characterization of Neat Polymers

Fig. 1 represents the complex viscosity (η*) and storage modulus (G′) as a function of angular frequency (ω) for various PLA types and PBAT, both processed with and without the addition of Joncryl. The introduction of Joncryl noticeably altered the rheological responses of the polymers compared to their unmodified counterparts. Among the unmodified neat PLAs, both aPLA and scPLA(h) exhibited nearly identical rheological behavior. Conversely, scPLA(l) exhibited the lowest values for both η* and G′, which is consistent with its reduced molecular weight. Neat PBAT displayed the highest viscosity compared to all PLAs. The addition of 0.5 wt% of Joncryl increased η* and G′ values for all polymers, likely due to induced chain extensions and branching. This suggests that, while Joncryl can extend the molecular structure of PLAs and PBAT, it may also act as a reactive compatibilizer at the interface between PLA matrix and PBAT, enhancing interfacial interaction between the phases.

Figure 1: (a) Complex viscosity and (b) storage modulus of PLA grades and PBAT with/without Joncryl

3.2 Characterization of Blends

3.2.1 Rheological and Morphological Analysis

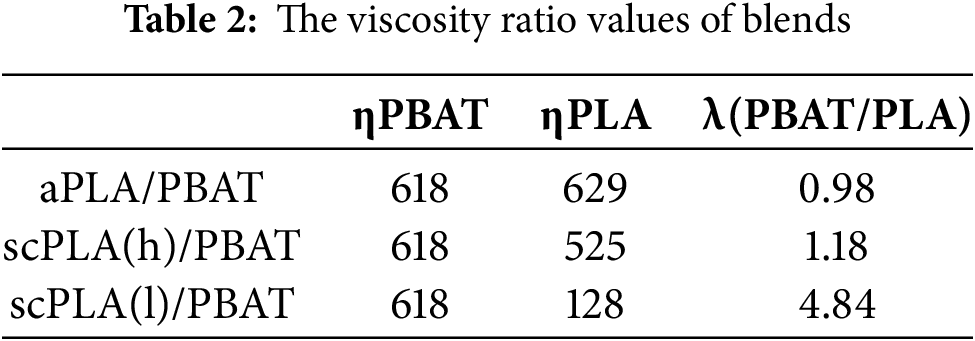

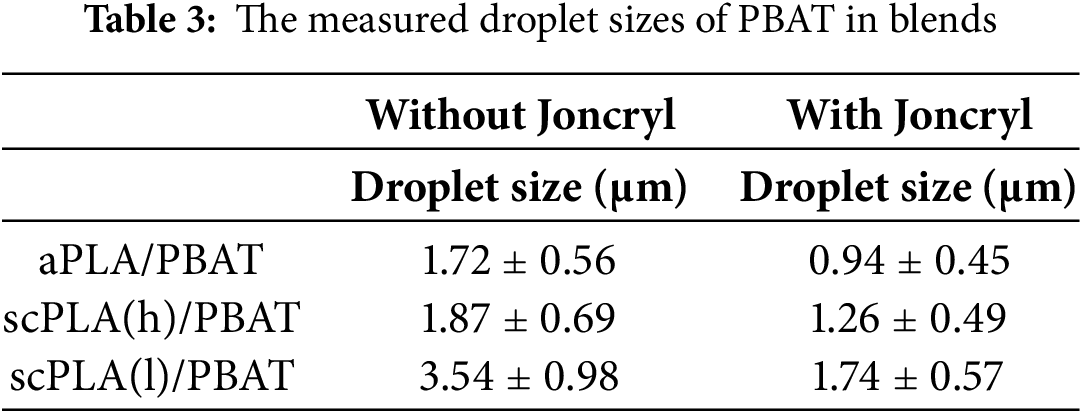

Fig. 2 shows the SAOS rheological properties of various PLA/PBAT blends processed with and without the addition of Joncryl. Table 2 presents the viscosity ratio (λ: ηdroplet/ηmatrix) values of the blends, calculated using the η* values of each neat phase obtained from the SAOS tests at a frequency of 50 rad/s. This frequency is roughly equivalent to the shear conditions experienced during melt processing in the internal mixer operating at 100 rpm [66]. Fig. 3 illustrates the SEM morphological characteristics of these unmodified and modified blends. Table 3 reports the mean droplet sizes of PBAT in blends.

Figure 2: (a) Complex viscosity and (b) storage modulus of various PLA/PBAT blends with/without Joncryl

Figure 3: SEM images: (a) aPLA/PBAT, (a’) aPLA/PBAT/J; (b) scPLA(h)/PBAT, (b’) scPLA(h)/PBAT/J; and (c) scPLA(l)/PBAT, (c’) scPLA(l)/PBAT/J

All blends exhibited an upward trend in complex viscosity at lower frequencies, likely linked to the relaxation dynamics of PBAT droplet deformation. In blends with Joncryl, the overall complex viscosity of blends was enhanced, and the low-frequency upturn behavior was even more pronounced due to the refined PBAT droplet morphology (Fig. 3). This refinement resulted from the increased PLA matrix viscosity, which caused further droplet breakup and enhanced the Joncryl compatibilization effect. In unmodified blends, the aPLA/PBAT blend exhibited the highest complex viscosity, followed by scPLA(h)/PBAT and scPLA(l)/PBAT, respectively. The higher complex viscosity behavior of aPLA/PBAT blend, compared to that in scPLA(h)/PBAT blend (despite both matrices having similar rheological characteristics), was due to the finer PBAT droplet structure obtained in the aPLA/PBAT blend (Fig. 3).

The rise in storage modulus at lower frequencies in PLA/PBAT blends suggests that some level of interfacial interaction exists, even without the use of compatibilizers. At low frequencies, the storage modulus values of PLA/PBAT blends without Joncryl increased as the molecular weight increased. This effect was further enhanced in the presence of Joncryl almost in all blends. The presence of Joncryl resulted in a more significant rise in modulus, likely due to its stronger interaction with the constituent polymers and its improved effectiveness in promoting interfacial compatibility.

As shown in Fig. 3 and Table 3, the aPLA/PBAT and scPLA(h)/PBAT blends displayed similar droplet sizes. However, the scPLA(l)/PBAT blend had significantly larger droplets, consistent with the results in Table 2. A viscosity ratio close to or less than unity indicates that a higher viscosity polymer matrix is more effective at immobilizing and breaking up droplets. In contrast, a viscosity ratio considerably greater than unity indicates that the higher viscosity of the droplets may hinder their breakup, potentially leading to coalescence [67,68]. Therefore, the viscosity ratio (λ) between droplet viscosity (ηPBAT) and matrix viscosities (ηPLA), which is closer to unity in the aPLA/PBAT and scPLA(h)/PBAT blends, could explain the finer PBAT droplets. When Joncryl was incorporated, a significant reduction in the droplet sizes was observed, resulting from the increased PLA matrix viscosity and, more importantly, the Joncryl compatibilization effect.

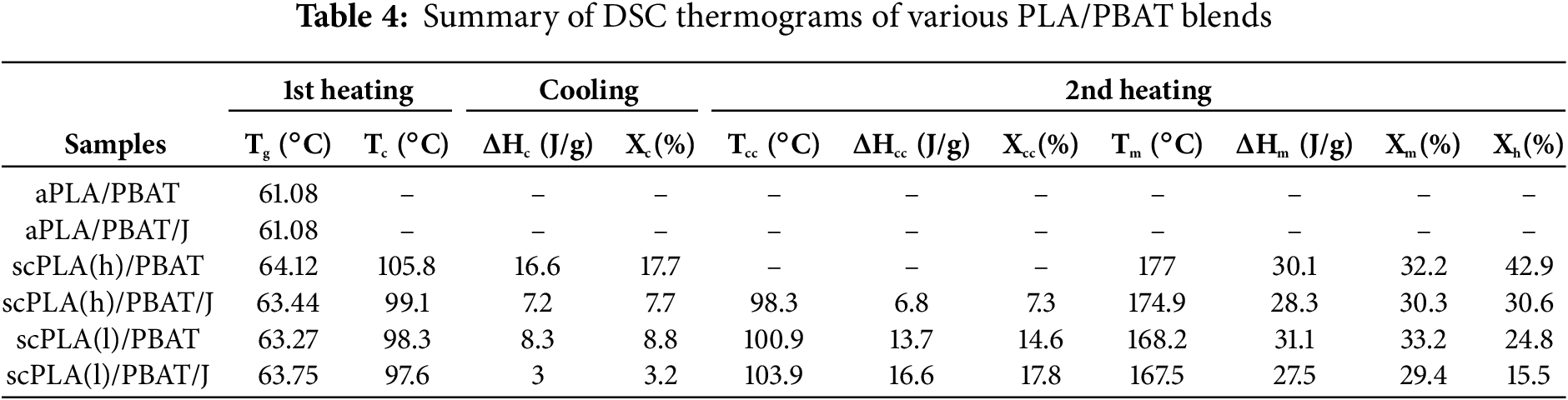

Fig. 4 shows the DSC heat/cool/heat curves of blends with and without Joncryl. The thermal properties of the blends, as determined from DSC analysis, are presented in Table 4. The Tg in aPLA/PBAT blends was lower than the blends with scPLAs, while the addition of 0.5 wt% Joncryl did not significantly affect the Tg values. In the scPLA(h)/PBAT blends, cold crystallization (Tcc) occurred earlier, and the PLA melting temperature (Tm) was higher than that in the scPLA(l)/PBAT blends. This was due to the lower D-content and, consequently, the higher crystallizability of scPLA(h) compared to scPLA(l). As a result, the scPLA(h)/PBAT blend exhibited higher crystallization temperature (Tc) values than the scPLA(l)/PBAT blend. The addition of Joncryl, however, significantly reduced the crystallizability of PLA and postponed Tc. Additionally, the Tcc during heating cycles was delayed in blends with Joncryl. These changes were due to the hindered molecular mobility in chain-extended structures. In the second heating cycle, the scPLA(h)/PBAT blend did not exhibit a cold crystallization peak, whereas this peak appeared in the Joncryl-modified scPLA(h)/PBAT/J blend, suggesting that crystallization did not occur during the prior cooling stage. Overall, the inclusion of Joncryl led to a reduction in total crystallinity, likely due to its restricting effect on the molecular mobility of the PLA matrix.

Figure 4: DSC curves of various PLA/PBAT blends: (a) 1st heating, (b) cooling, (c) 2nd heating

Fig. 5 illustrates the thermomechanical behavior of the blends, displaying the temperature-dependent trends of both storage and loss moduli. Table 5 presents the Tg values of the blends derived from the tan δ and loss modulus peaks. Among the unmodified blends, scPLA(h)/PBAT exhibited highest the storages modulus, while scPLA(l)/PBAT showed the lowest values at lower temperatures. This result is likely due to the lower molecular weight of the scPLA(l). However, aPLA showed lower values at higher temperatures (approximately above 55°C) due to its amorphous structure and even lower Tg. The loss modulus, which indicates the viscous behavior of the blends, was highest in the aPLA/PBAT blend and lowest in scPLA(h)/PBAT. The high crystallinity of scPLA(h)/PBAT increased the stiffness of this blend over a wider temperature range, leading to its higher thermal resistivity.

Figure 5: (a) Storage modulus and (b) Loss factor curves of various PLA/PBAT blends with/without Joncryl

The incorporation of Joncryl notably enhanced the E′ of the blends, with the most significant improvement observed in scPLA(l)/PBAT. This enhancement was likely due to finer PBAT droplets resulting from improved interfacial compatibilization and higher viscosity of the PLA matrix. A significant improvement in scPLA(l) with Joncryl modification was also observed in the loss modulus results, indicating an enhancement in rigidity.

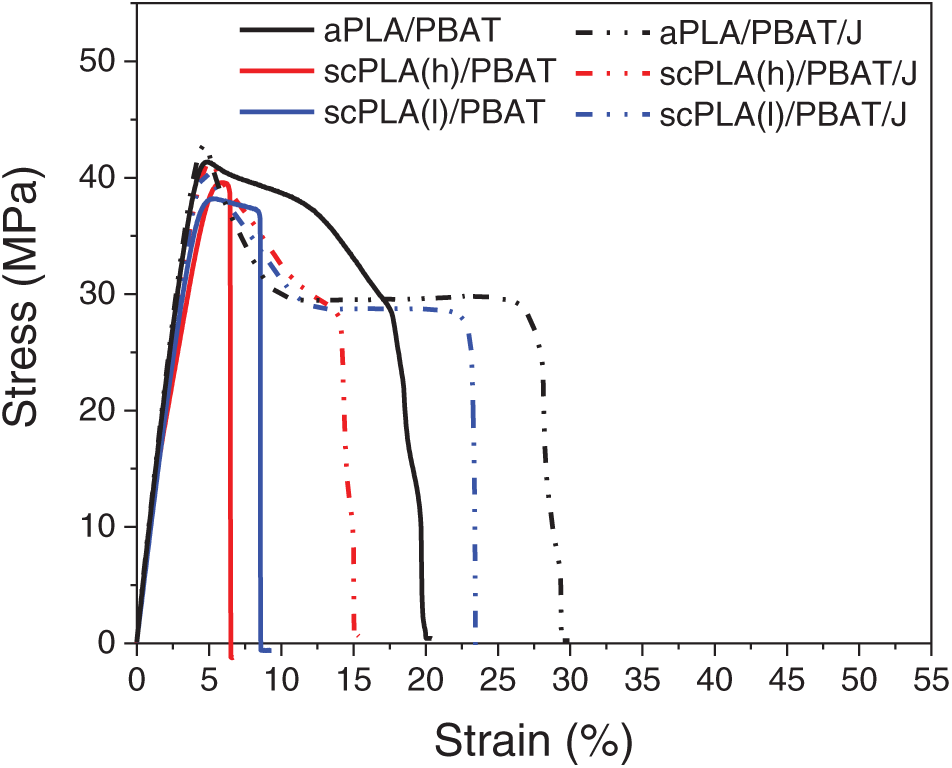

The stress-strain curves obtained from the tensile test are shown in Figs. 6 and 7, which also compare the modulus, strength, elongation at break and toughness values of the blends based on their stress-strain curves. The highest strength, toughness and elongation at break values were observed in aPLA/PBAT among the unmodified blends, with the elongation at break value being significantly higher. Elongation at break plays a crucial role in PLA-based blends, as it is directly related to ductility, an area in which PLA is typically lacking. These results were most likely due to the finer PBAT droplets in these blends. In blends containing semi-crystalline PLA, the ultimate stress was marginally higher in scPLA(h)/PBAT, which can be attributed to the greater crystallizability of scPLA(h) relative to scPLA(l). Meanwhile, the smaller droplet size in aPLA/PBAT blends likely contributed to the enhanced elongation at break and toughness observed in these blends compared to the blends containing semi-crystalline PLA.

Figure 6: Tensile curves of various PLA/PBAT blends

Figure 7: Tensile behaviors of PLA/PBAT blends: (a) modulus, (b) strength, (c) elongation at break, and (d) toughness

The addition of Joncryl resulted in modest increases in tensile modulus and strength for all blends, while more substantial enhancements were seen in elongation at break and toughness. These improvements in ductility and toughness are attributed to the finer PBAT droplets and potentially stronger interfacial adhesion in the presence of 0.5 wt% Joncryl. For example, the tensile strength of aPLA/PBAT increased from 38 MPa to approximately 42 MPa with the addition of Joncryl, while its elongation at break increased from 22% to 35%. These enhancements were confirmed to be statistically significant based on ANOVA results (p < 0.05). scPLA(l)/PBAT also exhibited nearly a three-fold improvement in ductility and toughness with Joncryl. This is consistent with the results observed in DMA.

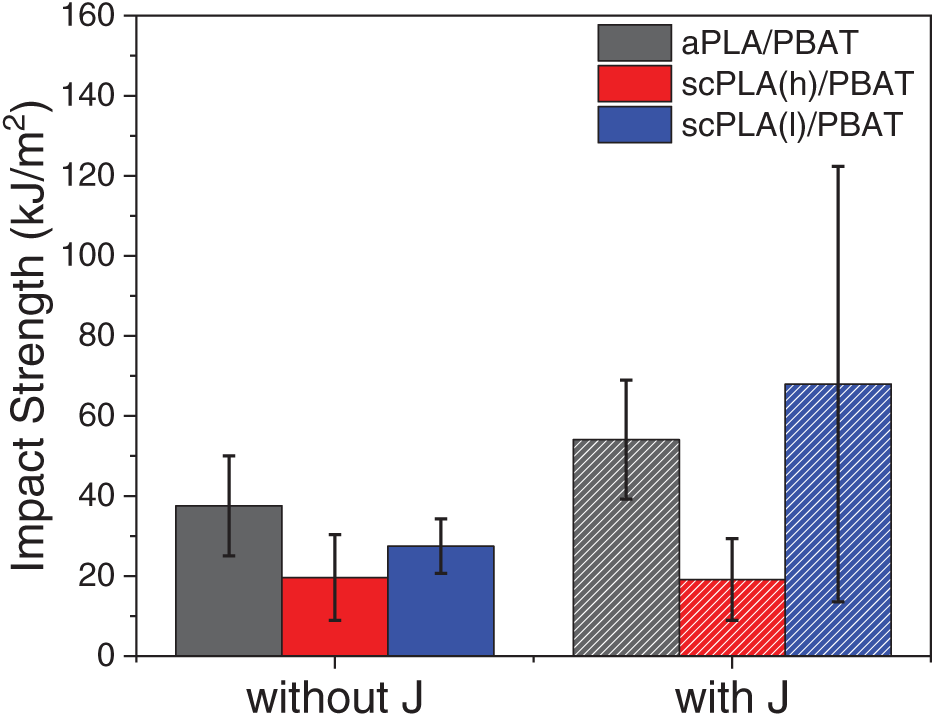

Fig. 8 illustrates the impact strength of the blends, both with and without Joncryl modification. Consistent with the results for elongation at break and toughness, the aPLA/PBAT blend demonstrated the greatest impact strength. The scPLA(l)/PBAT blend followed, showing a statistically significant reduction (p < 0.05) based on ANOVA analysis. The scPLA(h)/PBAT blend, however, demonstrated the lowest impact toughness, indicating its more brittle behavior, which is dominated by higher crystallizability of scPLA(h) matrix. The incorporation of Joncryl significantly increased the impact strength of the blends. This improvement is primarily due to enhanced interfacial compatibility and better dispersion of PBAT, especially in the aPLA/PBAT and scPLA(l)/PBAT systems. In contrast, the scPLA(h)/PBAT blend exhibited minimal response to Joncryl modification, with no statistically significant change observed (p > 0.05). This lack of response is likely attributed to the high crystallization capability of PLA HP2500, which contains less than 0.5 mol% D-lactide. Although the crystallinity of scPLA(h)/PBAT decreased with Joncryl, it still maintained nearly twice the crystallinity of scPLA(l)/PBAT/J, which could significantly contribute to the brittleness of its corresponding blend.

Figure 8: Impact strength of PLA/PBAT blends with and without Joncryl

This study investigated PLA/PBAT blends using various PLA grades with varying D-content and molecular weight, modified with the multifunctional epoxy-based Joncryl chain extender. The role of molecular weight and D-content of the PLA on the reactivity of Joncryl was examined in amorphous PLA and semi-crystalline PLAs with high and low molecular weights. The rheological behavior of all PLA types and PBAT improved with the addition of Joncryl, suggesting that Joncryl is an effective interfacial compatibilizer. Similar rheological improvements were observed in the corresponding blends. The viscosity ratio values in neat blends were highly determinant in the PBAT droplet sizes; however, the addition of Joncryl dramatically refined the PBAT droplets due to the increased viscosity of PLA and enhanced interfacial compatibilization. DSC results indicated that Joncryl suppressed PLA crystallization. DMA results showed that the Tg of the blends was enhanced with Joncryl modification, and scPLA(h)/PBAT blends exhibited high thermal stability due to the very high crystallizability of the scPLA used. Mechanical testing demonstrated significant improvements in ductility and toughness with the incorporation of Joncryl, particularly in scPLA(l)/PBAT blends, where elongation at break and toughness increased nearly threefold. The aPLA/PBAT blend exhibited the highest impact strength, whereas the scPLA(h)/PBAT blend displayed more brittle behavior due to its higher crystallinity. Joncryl modification further enhanced impact resistance by promoting finer dispersion of PBAT droplets and improving interfacial adhesion.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the Istanbul Technical University-Scientific Research Projects (ITU-BAP) with project number of 45964. Additional financial support was granted by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK) under the 2218 Domestic Post-Doctoral Research Fellowship Program (Project No. 118C574).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Aylin Altınbay, Ceren Özsaltık, and Mohammadreza Nofar; data collection: Aylin Altınbay and Ceren Özsaltık; analysis and interpretation of results: Aylin Altınbay, Ceren Özsaltık, and Mohammadreza Nofar; validation: Aylin Altınbay and Ceren Özsaltık; draft manuscript preparation: Aylin Altınbay and Mohammadreza Nofar; review and editing of the manuscript: Aylin Altınbay and Mohammadreza Nofar; supervision and project administration: Mohammadreza Nofar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jiao H, Ali SS, Alsharbaty MHM, Elsamahy T, Abdelkarim E, Schagerl M, et al. A critical review on plastic waste life cycle assessment and management: challenges, research gaps, and future perspectives. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2024;271(1):115942. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.115942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Li H, Aguirre-Villegas HA, Allen RD, Bai X, Benson CH, Beckham GT, et al. Expanding plastics recycling technologies: chemical aspects, technology status and challenges. Green Chem. 2022;24(23):8899–9002. doi:10.1039/D2GC02588D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Alaghemandi M. Sustainable solutions through innovative plastic waste recycling technologies. Sustainability. 2024;16(23):10401. doi:10.3390/su162310401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Dogu O, Pelucchi M, Van de Vijver R, Van Steenberge PHM, D’hooge DR, Cuoci A, et al. The chemistry of chemical recycling of solid plastic waste via pyrolysis and gasification: state-of-the-art, challenges, and future directions. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2021;84:100901. doi:10.1016/j.pecs.2020.100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Caudle B, Nguyen TTH, Kataoka S. Evaluation of three solvent-based recycling pathways for circular polypropylene. Green Chem. 2025;27(6):1667–78. doi:10.1039/D4GC02646B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. European Bioplastics. Bioplastic materials [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://www.european-bioplastics.org/bioplastics/materials/. [Google Scholar]

7. Moshood TD, Nawanir G, Mahmud F, Mohamad F, Ahmad MH, AbdulGhani A. Sustainability of biodegradable plastics: new problem or solution to solve the global plastic pollution? Current Res Green Sustain Chem. 2022;5:100273. doi:10.1016/j.crgsc.2022.100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhao X, Wang Y, Chen X, Yu X, Li W, Zhang S, et al. Sustainable bioplastics derived from renewable natural resources for food packaging. Matter. 2023;6(1):97–127. doi:10.1016/j.matt.2022.11.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Nizamuddin S, Baloch AJ, Chen C, Arif M, Mubarak NM. Bio-based plastics, biodegradable plastics, and compostable plastics: biodegradation mechanism, biodegradability standards and environmental stratagem. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. 2024;195(5):105887. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2024.105887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Rezvani Ghomi ER, Khosravi F, Saedi Ardahaei AS, Dai Y, Neisiany RE, Foroughi F, et al. The life cycle assessment for polylactic acid (PLA) to make it a low-carbon material. Polymers. 2021;13(11):1854. doi:10.3390/polym13111854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ahmad A, Banat F, Taher H. A review on the lactic acid fermentation from low-cost renewable materials: recent developments and challenges. Environ Technol Innov. 2020;20(4):101138. doi:10.1016/j.eti.2020.101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Lim L-T, Auras R, Rubino M. Processing technologies for poly(lactic acid). Prog Polym Sci. 2008;33(8):820–52. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2008.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ahmad A, Banat F, Alsafar H, Hasan SW. An overview of biodegradable poly (lactic acid) production from fermentative lactic acid for biomedical and bioplastic applications. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(3):3057–76. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-02581-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. DeStefano V, Khan S, Tabada A. Applications of PLA in modern medicine. Eng Regenerat. 2020;1(5):76–87. doi:10.1016/j.engreg.2020.08.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Singhvi MS, Zinjarde SS, Gokhale DV. Polylactic acid: synthesis and biomedical applications. J Appl Microbiol. 2019;127(6):1612–26. doi:10.1111/jam.14290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Alonso-Fernández I, Haugen HJ, López-Peña M, González-Cantalapiedra A, Muñoz F. Use of 3D-printed polylactic acid/bioceramic composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering in preclinical in vivo studies: a systematic review. Acta Biomater. 2023;168:1–21. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2023.07.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Auras R, Harte B, Selke S. An overview of polylactides as packaging materials. Macromol Biosci. 2004;4(9):835–64. doi:10.1002/mabi.200400043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Gruber PR, Hall ES, Kolstad JH, Iwen ML, Benson RD, Borchardt RL, et al. Continuous process for manufacture of lactide polymers with controlled optical purity. United States patent US5142023A; 1992 Aug 25. [Google Scholar]

19. Palade L-I, Lehermeier HJ, Dorgan JR. Melt rheology of high l-content poly(lactic acid). Macromol. 2001;34(5):1384–90. doi:10.1021/ma001173b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. NatureWorks LLC. New Ingeo products offer structure and property capabilities that enhance performance in fiber/nonwovens, injection molding and durables markets. 2012 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://www.natureworksllc.com/~/media/files/natureworks/resources/high-performance-grades/natureworks_new-high-performance-ingeo-gradesitr2012randall_pdf.pdf?la=en. [Google Scholar]

21. Södergård A, Stolt M. Properties of lactic acid based polymers and their correlation with composition. Prog Polym Sci. 2002;27(6):1123–63. doi:10.1016/S0079-6700(02)00012-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Saeidlou S, Huneault MA, Li H, Park CB. Poly(lactic acid) crystallization. Prog Polym Sci. 2012;37(12):1657–77. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2012.07.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Dorgan JR, Janzen J, Clayton MP, Hait SB, Knauss DM. Melt rheology of variable L-content poly(lactic acid). J Rheol. 2005;49(3):607–19. doi:10.1122/1.1896957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Qu Y, Chen Y, Ling X, Wu J, Hong J, Wang H, et al. Reactive micro-crosslinked elastomer for supertoughened polylactide. Macromolecules. 2022;55:7711–23. doi:10.1021/acs.macromol.2c00824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wachirahuttapong S, Thongpin C, Sombatsompop N. Effect of PCL and compatibility contents on the morphology, crystallization and mechanical properties of PLA/PCL blends. Energy Proc. 2016;89:198–206. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2016.05.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Takayama T, Todo M, Tsuji H. Effect of annealing on the mechanical properties of PLA/PCL and PLA/PCL/LTI polymer blends. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2011;4(3):255–60. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2010.10.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Fortelny I, Ujcic A, Fambri L, Slouf M. Phase structure, compatibility, and toughness of PLA/PCL blends: a review. Front Mater. 2019;6:206. doi:10.3389/fmats.2019.00206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Haneef INHM, Buys YF, Shaffiar NM, Shaharuddin SIS, Nor Khairusshima MK. Miscibility, mechanical, and thermal properties of polylactic acid/polypropylene carbonate (PLA/PPC) blends prepared by melt-mixing method. Mater Today Proc. 2019;17(5):534–42. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2019.06.332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Qin S-X, Yu C-X, Chen X-Y, Zhou H-P, Zhao L-F. Fully Biodegradable poly(lactic acid)/poly(propylene carbonate) shape memory materials with low recovery temperature based on in situ compatibilization by dicumyl peroxide. Chin J Polym Sci. 2018;36(6):783–90. doi:10.1007/s10118-018-2065-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Cvek M, Paul UC, Zia J, Mancini G, Sedlarik V, Athanassiou A. Biodegradable films of PLA/PPC and curcumin as packaging materials and smart indicators of food spoilage. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(12):14654–67. doi:10.1021/acsami.2c02181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Ivorra-Martinez J, Manuel-Mañogil J, Boronat T, Sanchez-Nacher L, Balart R, Quiles-Carrillo L. Development and characterization of sustainable composites from bacterial polyester poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) and almond shell flour by reactive extrusion with oligomers of lactic acid. Polymers. 2020;12(5):1097. doi:10.3390/polym12051097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Jin Y, Guo J, Cheng H, Li Y, Han C. Supertoughened biodegradable poly(L-lactic acid) by multiphase blends system: crystallization, rheological and mechanical properties. Thermochim Acta. 2024;739(10):179810. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2024.179810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Su S, Kopitzky R, Tolga S, Kabasci S. Polylactide (PLA) and its blends with poly(butylene succinate) (PBSa brief review. Polymers. 2019;11(7):1193. doi:10.3390/polym11071193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Supthanyakul R, Kaabbuathong N, Chirachanchai S. Random poly(butylene succinate-co-lactic acid) as a multi-functional additive for miscibility, toughness, and clarity of PLA/PBS blends. Polymer. 2016;105:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2016.10.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Xie L, Xu H, Chen J-B, Zhang Z-J, Hsiao BS, Zhong G-J, et al. From nanofibrillar to nanolaminar poly(butylene succinatepaving the way to robust barrier and mechanical properties for full-biodegradable poly(lactic acid) films. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:8023–32. doi:10.1021/acsami.5b00294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Letwaba J, Muniyasamy S, Lekalakala R, Mavhungu L, Mbaya R. Design of compostable toughened PLA/PBAT blend with algae via reactive compatibilization: the effect of algae content on mechanical and thermal properties of bio-composites. J Appl Polym Sci. 2024;141(14):e55204. doi:10.1002/app.55204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Cai K, Liu X, Ma X, Zhang J, Tu S, Feng J. Preparation of biodegradable PLA/PBAT blends with balanced toughness and strength by dynamic vulcanization process. Polymer. 2024;291(10):126587. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2023.126587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zhou S, Yu H, Li Y, Qi C, Li J. Preparation and characterization of PLA/PBAT blends toughened by poly(lactic acid-r-malic acid) copolymer. Colloid Polym Sci. 2024;302(8):1201–7. doi:10.1007/s00396-024-05252-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Eraslan K, Altınbay A, Nofar M. In-situ self-reinforcement of amorphous polylactide (PLA) through induced crystallites network and its highly ductile and toughened PLA/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) blends. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;272(2):32936. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Deng Y, Yu C, Wongwiwattana P, Thomas NL. Optimising ductility of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) blends through co-continuous phase morphology. J Polym Environ. 2018;26(9):3802–16. doi:10.1007/s10924-018-1256-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Yang H-R, Jia G, Wu H, Ye C, Yuan K, Liu S, et al. Design of fully biodegradable super-toughened PLA/PBAT blends with asymmetric composition via reactive compatibilization and controlling morphology. Mater Lett. 2022;329:133067. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2022.133067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Wang X, Peng S, Chen H, Yu X, Zhao X. Mechanical properties, rheological behaviors, and phase morphologies of high-toughness PLA/PBAT blends by in-situ reactive compatibilization. Compos B Eng. 2019;173:107028. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Aversa C, Barletta M, Cappiello G, Gisario A. Compatibilization strategies and analysis of morphological features of poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT)/poly(lactic acid) PLA blends: a state-of-art review. Eur Polym J. 2022;173:111304. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2022.111304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Standau T, Nofar M, Dörr D, Ruckdäschel H, Altstädt V. A review on multifunctional epoxy-based Joncryl® ADR chain extended thermoplastics. Polym Rev. 2022;62(2):296–350. doi:10.1080/15583724.2021.1918710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Al-Itry R, Lamnawar K, Maazouz A. Reactive extrusion of PLA, PBAT with a multi-functional epoxide: physico-chemical and rheological properties. Eur Polym J. 2014;58:90–102. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2014.06.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Al-Itry R, Lamnawar K, Maazouz A, Billon N, Combeaud C. Effect of the simultaneous biaxial stretching on the structural and mechanical properties of PLA, PBAT and their blends at rubbery state. Eur Polym J. 2015;68(7):288–301. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2015.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Al-Itry R, Lamnawar K, Maazouz A. Improvement of thermal stability, rheological and mechanical properties of PLA, PBAT and their blends by reactive extrusion with functionalized epoxy. Polym Degrad Stab. 2012;97:1898–914. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2012.06.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Arruda LC, Magaton M, Bretas RES, Ueki MM. Influence of chain extender on mechanical, thermal and morphological properties of blown films of PLA/PBAT blends. Polym Test. 2015;43:27–37. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2015.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Dong W, Zou B, Yan Y, Ma P, Chen M. Effect of Chain-Extenders on the properties and hydrolytic degradation behavior of the poly(lactide)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) blends. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:20189–203. doi:10.3390/ijms141020189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Al-Itry R, Lamnawar K, Maazouz A. Rheological, morphological, and interfacial properties of compatibilized PLA/PBAT blends. Rheol Acta. 2014;53:501–17. doi:10.1007/s00397-014-0774-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Li X, Yan X, Yang J, Pan H, Gao G, Zhang H, et al. Improvement of compatibility and mechanical properties of the poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) blends and films by reactive extrusion with chain extender. Polym Eng Sci. 2018;58:1868–78. doi:10.1002/pen.24795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Wu DD, Guo Y, Huang AP, Xu RW, Liu P. Effect of the multi-functional epoxides on the thermal, mechanical and rheological properties of poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/polylactide blends. Polym Bull. 2021;78:5567–91. doi:10.1007/s00289-020-03379-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Akdevelioğlu Y, Alanalp MB, Siyahcan F, Randall J, Gehrung M, Durmus A, et al. Joncryl chain extender reactivity with polylactide: effect of d-lactide content, Joncryl type, and processing temperature. J Rheol. 2024;68(2):247–62. doi:10.1122/8.0000718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Altınbay A, Özsaltık C, Jahani D, Nofar M. Reactivity of Joncryl chain extender in PLA/PBAT blends: effects of processing temperature and PBAT aging on blend performance. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;303:140703. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.140703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Salehiyan R, Kim MC, Xia T, Jin S, Nofar M, Chalmers L, et al. Enhanced re-processability of poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) via chain extension toward a more sustainable end-of-life. Polym Eng Sci. 2024;65(3):1187–99. doi:10.1002/pen.27067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Farias da Silva JM, Soares BG. Epoxidized cardanol-based prepolymer as promising biobased compatibilizing agent for PLA/PBAT blends. Polym Test. 2021;93:106889. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2020.106889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Li X, Ai X, Pan H, Yang J, Gao G, Zhang H, et al. The morphological, mechanical, rheological, and thermal properties of PLA/PBAT blown films with chain extender. Polym Adv Technol. 2018;29(6):1706–17. doi:10.1002/pat.4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Zhang N, Zeng C, Wang L, Ren J. Preparation and properties of biodegradable poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) blend with epoxy-functional styrene acrylic copolymer as reactive agent. J Polym Environ. 2013;21(1):286–92. doi:10.1007/s10924-012-0448-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. NatureWorks LLC. Ingeo™ Biopolymer 4060D Technical data sheet. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://www.natureworksllc.com/~/media/Files/NatureWorks/Technical-Documents/Technical-Data-Sheets/TechnicalDataSheet_4060D_films_pdf. [Google Scholar]

60. NatureWorks LLC. Ingeo™ Biopolymer 2500HP technical data sheet. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://www.natureworksllc.com/~/media/Files/NatureWorks/Technical-Documents/Technical-Data-Sheets/TechnicalDataSheet_2500HP_extrusion_pdf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

61. NatureWorks LLC. Ingeo™ Biopolymer 3251D technical data sheet. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://www.natureworksllc.com/~/media/Files/NatureWorks/Technical-Documents/Technical-Data-Sheets/TechnicalDataSheet_3251D_injection-molding_pdf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

62. BASF. Product Information ecoflex® F Blend C1200. [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 3]. Available from: https://download.basf.com/p1/8a8082587fd4b608017fd63230bf39c4/en/ecoflex%3Csup%3E%C2%AE%3Csup%3E_F_Blend_C1200_Product_Data_Sheet_English.pdf?view. [Google Scholar]

63. Dil JE, Carreau PJ, Favis BD. Morphology, miscibility and continuity development in poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) blends. Polymer. 2015;68(6):202e212. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2015.05.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Oosterbeek RN, Kwon K-A, Duffy P, McMahon S, Zhang XC, Best SM, et al. Tuning structural relaxations, mechanical properties, and degradation timescale of PLLA during hydrolytic degradation by blending with PLCL-PEG. Polym Degrad Stab. 2019;170(21):109015. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2019.109015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Fischer EW, Sterzel HJ, Wegner G. Investigation of the structure of solution grown crystals of lactide copolymers by means of chemical reactions. Kolloid Z Z Polym. 1973;251(11):980–90. doi:10.1007/BF01498927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Ludwiczak J, Frąckowiak S, Leluk K. Study of thermal, mechanical and barrier properties of biodegradable PLA/PBAT films with highly oriented MMT. Materials. 2021;14(23):7189. doi:10.3390/ma14237189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Favis BD, Chalifoux JP. The effect of viscosity ratio on the morphology of polypropylene/polycarbonate blends during processing. Polym Eng Sci. 1987;27(21):1591–600. doi:10.1002/pen.760272105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Favis BD. Polymer alloys and blends: recent advances. Can J Chem Eng. 1991;69(3):619–25. doi:10.1002/cjce.5450690303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools