Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Molasses Adhesive Boosts Bio-Pellet Potential: A Study on Oyster Mushroom Baglog Waste

1 Research Center for Biomass and Bioproducts, National Research and Innovation Agency, Cibinong, 16911, Indonesia

2 Faculty of Biology, Universitas Jenderal Soedirman, Purwokerto, 53122, Indonesia

3 Research Center for Advance Material, National Research and Innovation Agency, Serpong, 15314, Indonesia

4 Research Center for Nanotechnology System, National Research and Innovation Agency, Serpong, 15314, Indonesia

* Corresponding Author: Sukma Surya Kusumah. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Renewable and Biosourced Adhesives-2023)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(9), 1765-1781. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0014

Received 16 January 2025; Accepted 11 April 2025; Issue published 22 September 2025

Abstract

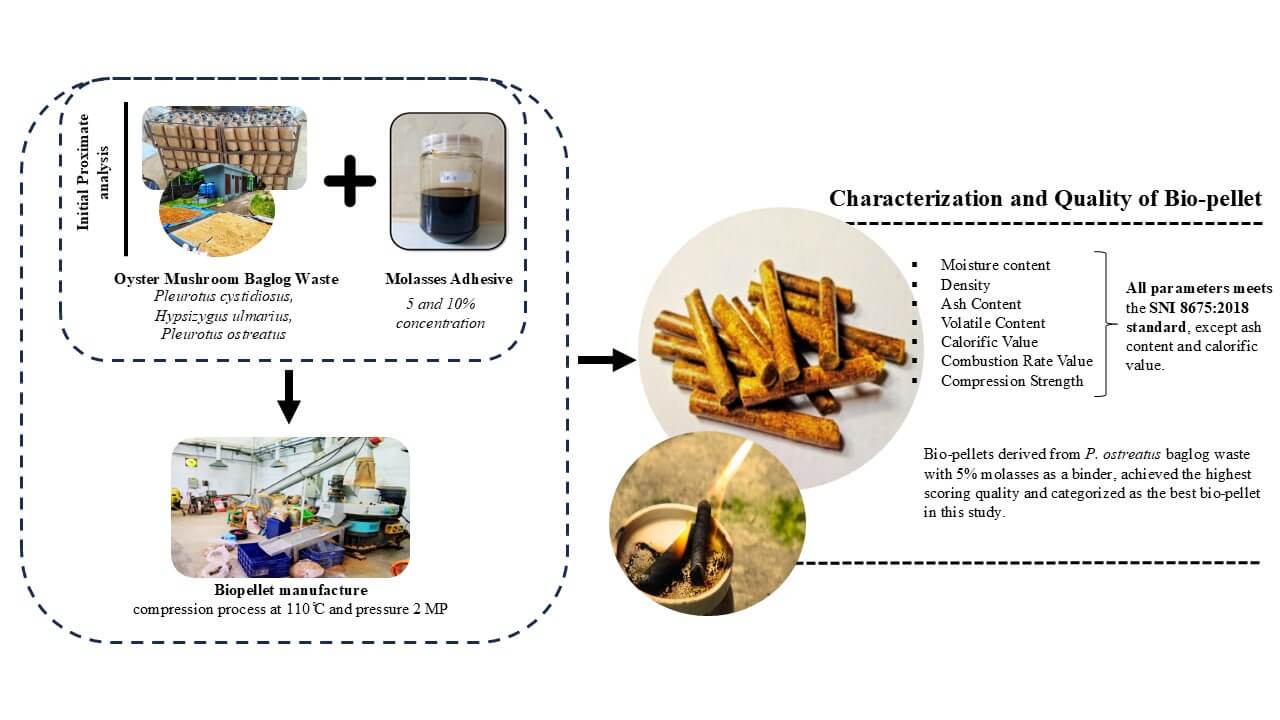

The increasing demand for renewable energy sources has driven the exploration of innovative materials for biofuel production. This study investigates bio-pellet characteristics derived from several oyster mushroom baglog wastes with varying concentrations of molasses as an adhesive. The process began with sun-drying the baglog waste for three days, followed by oven drying at 80°C for 24 h. Bio-pellets were produced by blending baglog waste with molasses at concentrations of 5% and 10% (w/v), then subsequently fed into a pellet mill. The bio-pellets were left to rest for one hour before analysis. The quality of bio-pellets was determined by evaluating moisture content, ash content, volatile matter, calorific value, combustion rate, density, and compressive strength following SNI 8675:2018 standards. Results indicate that adding molasses as a binder significantly affected the bio-pellet quality. The optimal molasses concentration for balanced performance was found at 5%, providing a lower moisture content (6.8%), volatile matter (68.42%), and density (1.55 g·cm−3). In addition, the bio-pellet has a slightly higher calorific value (approximately 3614 cal·g−1), compressive strength (40.68 N·mm−2), and ash content (18.59%). All of the parameters for the bio-pellet containing 5% molasses satisfied the standard except for ash content and calorific value.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Mushrooms are categorized as higher fungi or macro-fungi within the phylum Basidiomycetes. They have a broad range of applications in the pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, and cosmeceuticals sectors due to their rich chemical composition, nutritional value, and therapeutic properties [1,2]. Worldwide, over 15,000 mushroom species have been identified, with approximately 2000 considered edible species, and about 100 species cultivated for commercial purposes [3]. Among the various mushroom species, oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus spp.) are the most widely recognized and extensively cultivated on the industrial scale. In Indonesia, oyster mushroom production reached approximately 537,866 quintals in 2023, surpassing straw mushrooms and other varieties, which were produced at 46,410 and 23,986 quintals, respectively [4]. According to Mahari et al. [5], cultivating oyster mushrooms offers several advantages, including a short cultivation cycle (28–35 days), lower financial costs, and a simple sterilization process, leading to higher yield and profitability.

During cultivation, oyster mushrooms require specific substrates that support their inoculation and growth process. A widely used method utilizes cylindrical baglogs, which are plastic bags filled with lignocellulose-rich substrates, primarily sawdust [6,7]. The cultivation process using the latter method generates faster spawning time and higher mushroom yield [5]. In addition, the utilization of sawdust as a substrate has been widely recognized as a suitable substrate for growing media of oyster mushrooms [8]. However, after several harvesting cycles, the effectiveness of the baglog substrate filled with sawdust depletes significantly, necessitating replacement with a new/fresh substrate. This activity generates mushroom baglog waste known as waste mushroom substrate (WMS)—a byproduct containing residual lignocellulose, mushroom mycelia, organic matter, nutrients, heavy metals, and hydrocarbons [5]. According to Attalah et al. [9], the production of 1 kg of mushrooms generates approximately 5 kg of WMS. The large amount of WMS is often disposed of through open burning, incineration, burying, and landfilling, posing significant environmental risks and potentially spreading mushroom diseases, which can negatively affect production rates and the cultivation process [5,10]. To mitigate these issues, proper waste handling should be done by applying various valorization techniques and turning it into more valuable products for agriculture and energy conversion applications, mainly as bio-compost [11], biofertilizers [12], animal feed supplements [5], bio-briquettes [13], and biochar [14].

Apart from these applications, this kind of waste can also be converted into solid biofuel through a compressing process, known as bio-pellet. The fabrication of bio-pellets from WMS has been explored by several researchers using various methods, both without and with the application of adhesives. Alves et al. [15] successfully converted diverse types of WMS from Pleurotus ostreatus, Lentinula edodes, and Agaricus subrufescens directly through compaction process without the use of adhesives. Their study found that bio-pellet fabricated from WMS of P. ostreatus has a unique characteristic, exhibited high density, greater durability, and stability in terms of thermal degradation. Additionally, the VOC emission was measured at 21.60 mg·m−3, meeting the ISO 17225 standard, making it superior to bio-pellet from Lentinula edodes and Agaricus subrufescens [15]. Similarly, Baharin et al. [16] fabricated WMS bio-coke sourced from Pleurotus sp. cultivation, demonstrating excellent characteristics, including high density (1.435 g·cm−3), high mechanical compression strength (MCS) value (105.2 MPa), and an extended combustion period (1890 s). These values were better than those of empty fruit bunch (EFB) pellets studied by Ruksathamcharoen et al. [17]. Despite their promising characteristics for bioenergy applications, WMS bio-pellets face challenges due to their lack of mechanical strength, making them prone to breaking during transportation and storage. Ju et al. [18] supported this finding, stating that bio-pellet derived from sawdust (particle size approx. 0.6 mm) are prone to moisture absorption, cracking, or even shattering after densification. Puspitawati et al. [13] studied solid biofuel made from WMS binding with starch as an adhesive with characteristics as follows: combustion rate 0.0019 gr·sec−1 and ash content 0.16%. Their study suggested to incorporate additional adhesive materials in the manufacturing process to improve the quality of end-products.

Combining such compounds with sucrose-based adhesives at a mixture ratio of 25%–75% has been shown to deliver excellent bonding performance, particularly in composite products [19,20]. Molasses, a sucrose-based adhesive derived from sugar factory waste, contains a high sucrose concentration of approximately 47%–48% [21]. Studies have demonstrated that composites bonded with molasses exhibit enhanced physical and mechanical properties as molasses content increases [22]. Wang et al. [23], studied the pelletization of food waste hydrochar using molasses as an adhesives. Their findings revealed that increasing molasses content from 10% to 20% resulted in a decrease in the Higher Heating Value (HHV) of pellets, while mass density and energy density significantly increased to a range of 947.1–1301.9 kg·m−3 and 23.55–33.40 GJ·m−3, respectively. Additionally, molasses concentrations between 10% and 15% significantly increased the equilibrium moisture content (EMC) of bio-pellet made from food waste by approximately 6%–10% [23]. However, the utilization of WMS as a raw material for bio-pellet production remains limited, despite the abundance and widespread availability of various types of oyster mushroom baglog waste. Moreover, the potential of molasses as a binding agent in bio-pellet fabrication remains an interesting aspect worth exploring. Therefore, this research focuses to evaluate the characterization of bio-pellets derived from several oyster mushroom baglog waste/WMS using different molasses concentrations (0%, 5%, and 10%) as a binding agent. The selected molasses concentration were based on the previous study by Wang et al. [23].

The WMS used in this study was sourced from various oyster mushroom baglog wastes, including Pleurotus cystidiosus, Hypsizygus ulmarius, and Pleurotus ostreatus, obtained from CV Asa Agro Corporation in Cianjur, West Java, Indonesia. This waste primarily consists of wood sawdust, wheat bran, and water in an approximate ratio of 70:20:10, respectively. Prior further processing, the baglog waste was sun-dried for 3 days, then crushed, and screened using a sieving machine to obtain a uniform particle size, which passed through a 20 mesh sieving grit. The uniform dried baglog waste particles were oven-dried at 80°C for 24 h until the moisture content was reduced to less than 12%. In addition, the main bio-adhesive used in this study was molasses (MO) which was obtained from PTPN XII, East Java, Indonesia. The preparation process for oyster mushroom baglog waste and MO adhesive used in this study is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Preparation of baglog waste and molasses adhesive

2.2 Characterization of Oyster Mushroom Baglog Waste

The characteristics of oyster mushroom baglog waste were observed by analyzing its initial chemical component, which can influence bio-pellets quality. The sample used was baglog waste particles with a size range of 40–60 mesh (Fig. 1). The moisture content of the wood powder was measured, followed by chemical component analysis. The holocellulose, alpha-cellulose, and hemicellulose contents were determined based on TAPPI T-203 [24], acid insoluble and soluble lignin following TAPPI 222 om-88 [25], while solubility in ethanol-benzene was assessed using ASTM D-1107-96 [26].

2.3 Manufacturing of Bio-Pellets from Oyster Mushroom Baglog Waste

The bio-pellet manufacturing process began with the mixing of dried baglog waste particles, sourced from various mushroom cultivation, with molasses at different mixture ratios, specifically 5% and 10% (w/v). The mixed particles were placed in the pellet mill and subjected to a compression process at a temperature of 110°C and pressure of 2 MPa to produce bio-pellets derived from oyster mushroom baglog waste. After production, the bio-pellets were conditioned at room temperature for 1 h before testing. A schematic diagram illustrating the bio-pellet manufacture derived from oyster mushroom baglog waste in different mixture ratios of molasses is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: The schematic diagram of the bio-pellet manufacture derived from oyster mushroom baglog waste in different mixture ratios of molasses

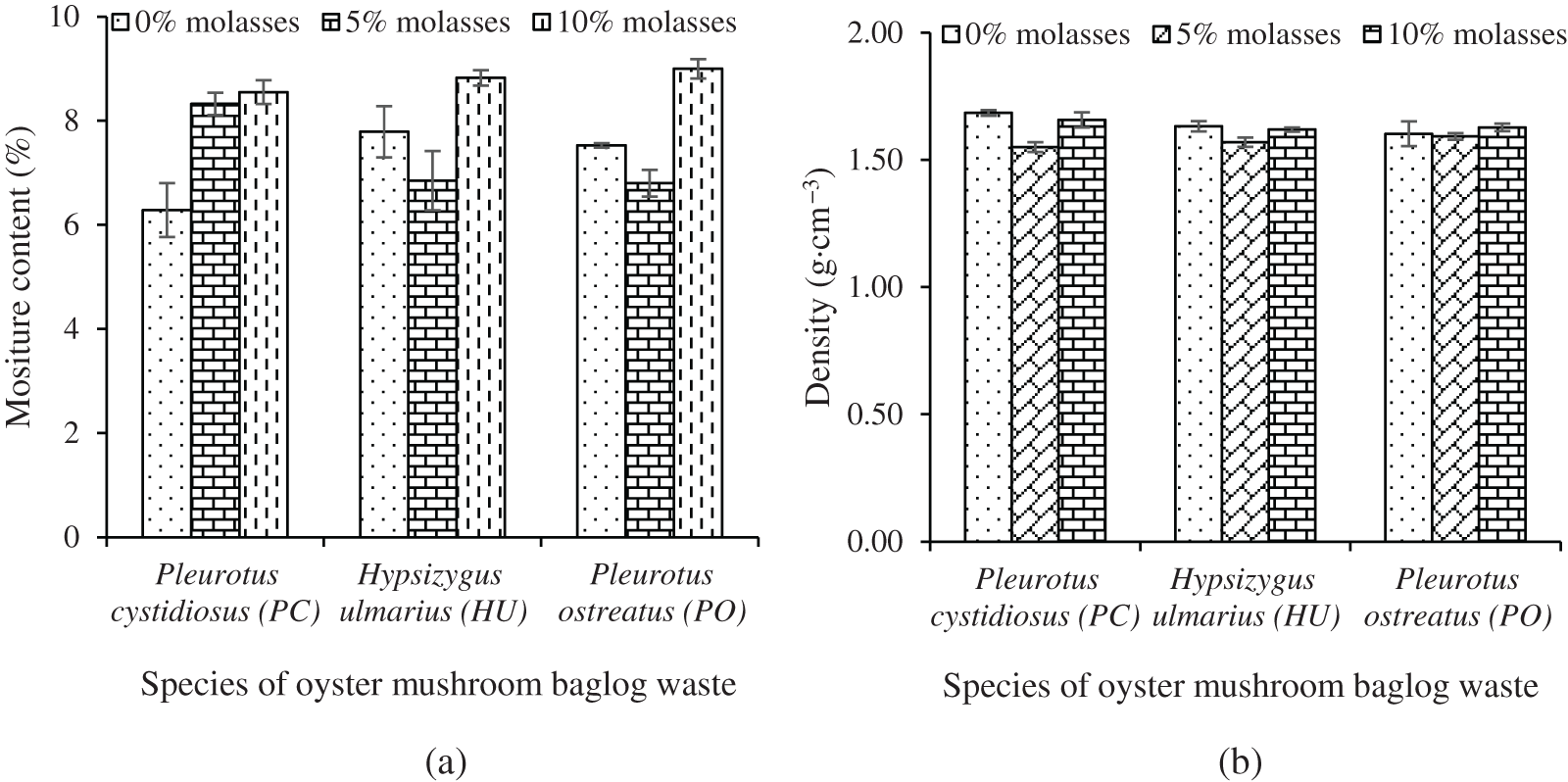

Several characteristics of bio-pellet derived from oyster mushroom baglog waste in different mixture ratios of molasses were assessed as outlined in Table 1. These characteristics observed included moisture content, density, ash content, volatile content, calorific value, combustion rate value, as well as compression strength. A total of 36 replications were used for all of the treatments applied (3 types of oyster mushroom baglog waste × 4 replications × 3 molasses concentrations).

2.4 Characterization of Bio-Pellets from Oyster Mushroom Baglog Waste

2.4.1 Moisture Content and Density

Several physical properties of bio-pellets (Fig. 3), including moisture content (MC) and density, were conducted by weighing and measuring the bio-pellet sample to obtain their initial weight and volume using an analytical balance and a caliper, respectively. The samples were oven-dried at 105°C for 24 h and subsequently cooled in a desiccator until a constant weight was reached. The MC and density values were calculated using the following Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively:

where, MC = moisture content (%); ρ = density (g·cm−3); p = initial weight of bio-pellet (g); q = constant weight of bio-pellet (gr); v = initial volume of bio-pellet (cm3).

Figure 3: Bio-pellet products derived from oyster mushroom baglog waste

2.4.2 Ash and Volatile Content

Ash content was analyzed by weighing a 3-g bio-pellet in an uncovered porcelain crucible and heating it in a furnace at 800°C for 4 h. Similarly, volatile content was determined by weighing a 2-g bio-pellet sample in a porcelain crucible with a lid, with its dry weight previously recorded beforehand. The sample was heated in a furnace at 950°C for 15 min. Both samples were then cooled in a desiccator and weighed until a constant weight was reached. The ash and volatile content were calculated using the following Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively:

2.4.3 Calorific and Combustion Rate Value

The calorific value test was conducted using a bomb calorimeter. The bio-pellet sample was cut and adjusted to the appropriate size, with a maximum weight capacity of 1.1 g. The parameters observed included temperature increase inside the bomb calorimeter, the length of the burned wire, and any remaining sample, if present, which together indicated the calorific value. Temperature data was recorded at one-minute intervals.

where, LP = combustion rate (g · sec−1); ma = weight of bio-pellet before burning process (g); mb = weight of bio-pellet after burning process (g); Tburned = burning period (sec).

The compression strength test was conducted following the method described by Liku et al. [27]. Bio-pellet samples were prepared with an approximate size of ±1 cm and placed on the test platform of the Universal Testing Machine. The load device was then adjusted vertically and lowered at a controlled speed, set by the operator via the monitor until the bio-pellet was fractured under the applied pressure. Subsequently, the compression force and compression strength values were appeared on the monitor. The pressing device was then raised back to its original position, and the test platform was cleaned before the next test.

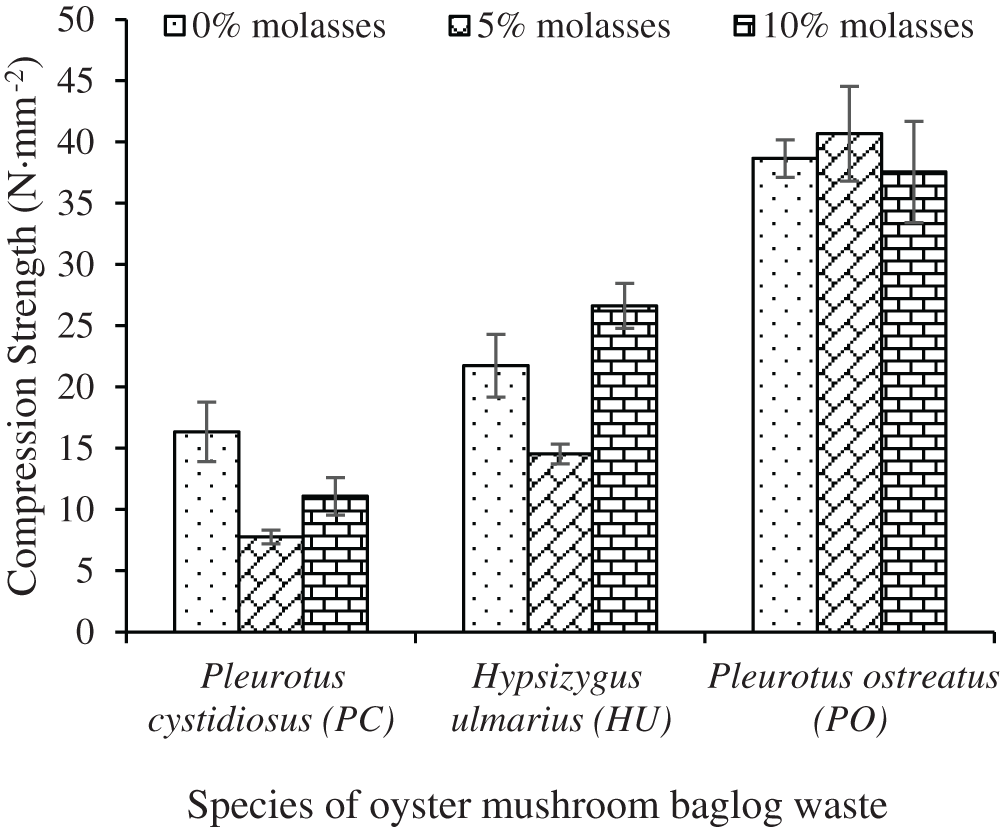

The data for several characteristics of bio-pellet derived from oyster mushroom baglog waste were presented as mean values with standard deviation. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was undertaken to determine the effect of the treatments applied in bio-pellet products, specifically on their moisture content, density, ash content, volatile compound, calorific value, combustion value, as well as compression strength. Duncan’s multiple distance test using IBM SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) follows if each factor and their interaction differ significantly.

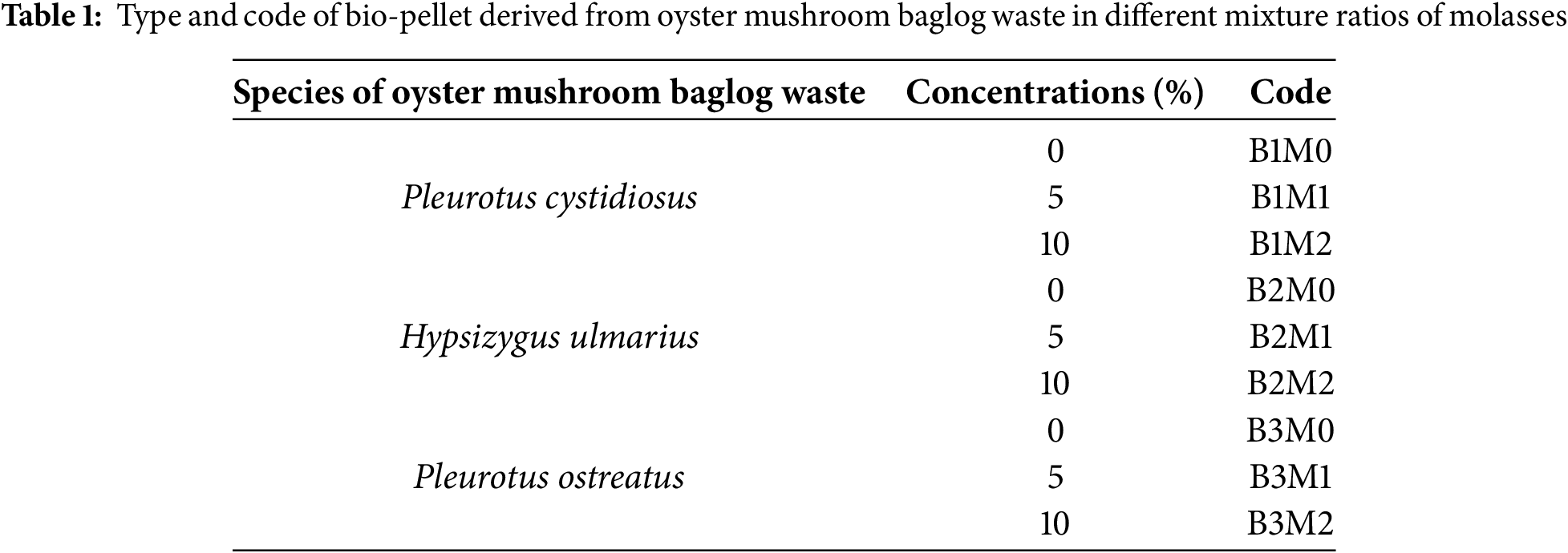

3.1 Characterization of Oyster Mushroom Baglog Waste

Oyster mushroom baglog waste exhibits varied properties depending on the substrate composition, treatments applied, and the mushroom species used for inoculation during cultivation. As previously mentioned, the oyster mushroom baglog waste used in this study primarily consists of sawdust, which is rich in lignocellulosic materials. The fundamental chemical composition of each type of oyster mushroom baglog waste is presented in Table 2. It was observed that H. ulmarius baglog waste has a lower moisture content, extractive, and lignin content, with a higher ash content, cellulose, and hemicellulose content than that of P. cystidiosus and P. ostreatus. Among Pleurotus baglog waste, the chemical compositions were quite similar, with P. ostreatus having slightly lower moisture content, lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose content, as well as slightly higher ash and extractive content than that of P. cystidiosus.

Compared to previous studies on the basic properties of raw materials for bio-pellet production, the moisture content observed in this study was lower than that of other woody and non-woody biomass, which typically ranges from 12%–13% and 13%–14%, respectively [28]. According to Frodeson et al. [29], the suitable moisture content for bio-pellet production ranges from 5%–8%. This statement shows a good sign, suggesting that these three types of oyster mushroom baglog waste are potentially well-suited for the pelletization process. The amount of moisture content in raw materials plays a critical role in bio-pellet production and quality, influencing not only production capacity and specific energy consumption but also the final bio-pellet properties, particularly their physical and bonding strength properties, as well as storage life duration [29–31].

As shown in Table 2, the ash content of the three oyster mushroom baglog wastes ranged from 14.13%–29.10%. These values were higher than other studies reported by Putra et al. [28], which found that the ash content of woody and nonwoody biomass ranged from 0.92%–11.52%. However, Alves et al. [15] reported higher ash content in raw materials for bio-pellets derived from various spent mushroom wastes, with values ranging from 28.30% to 32.30%. Alves et al. [15] found that spent mushroom waste with higher ash content tends to generate lower volatile content. Ash content is generally attributed to the accumulation of inorganic elements in the substrate, including Cu, Fe, K, MN, Ca, P, K, and Mg [28]. A higher ash content can significantly affect the calorific value and combustion process during pelletization, leading to issues such as slagging, fouling, agglomeration, and deposition. These phenomenon can reduce heat transfer efficiency during the process, causing broad issues related to corrosion and erosion, as well as potential equipment damage [32].

Extractive content also plays a significant role in the pelletization process, particularly in terms of specific energy consumption. As shown in Table 2, the extractive content of the three-oyster mushroom baglog wastes ranged from 2.03%–13.26%. Similar results were also reported by Nielsen et al. [33], who studied the pelletizing process using several types of sawdust and their correlation with extractive content. It was found that the extractive content of sawdust derived from hardwood and softwood species ranged from 0.7%–11.4%. A high extractive content can significantly affect the compression and friction coefficient during pelletization process, as well as the bonding strength of the final products [33]. The presence of extractives in the pelletizing raw materials act as lubricant and plasticizer agents, which minimize the compression and friction during the process. However, an excessive extractive content can also hinder optimal bonding between the substrate and adhesive [33,34].

According to Table 2, the lignin content of the three-oyster mushroom baglog wastes ranged from 19.38%–25.54%. These values were lower than other studies reported by Yunianti et al. [35], who found that lignin content in pelletized sawdust ranged from 15.63%–42.36%. Another study reported that lignin content from woody and nonwoody biomass ranged from 25%–31%. According to Yang et al. [36], higher lignin content within the pelletizing sawdust material produced slightly better bio-pellet durability, as evidenced by a positive correlation between pellet durability and Klason lignin content. Lignin plays a role as a natural binding agent within the substrate during pelletization process, which can significantly increase the durability of the final bio-pellet products [28,36]. Furthermore, cellulose and hemicellulose obtained in this study ranged from 33.02%–64.02% and 19.07%–22.75%, respectively. A higher cellulose and hemicellulose contents within the substrate influences the absorption and removal of water during pelletization process since these matters contain a lot of hydrophilic functional group (hydrogen bonds), as well as affect its calorific value of bio-pellet [37]. Variations in the cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin compositions influence the carbon content of biomass materials, which in turn impacts their calorific values on a dry basis.

3.2 Characterization of Bio-Pellets from Oyster Mushroom Baglog Waste

3.2.1 Moisture Content and Density

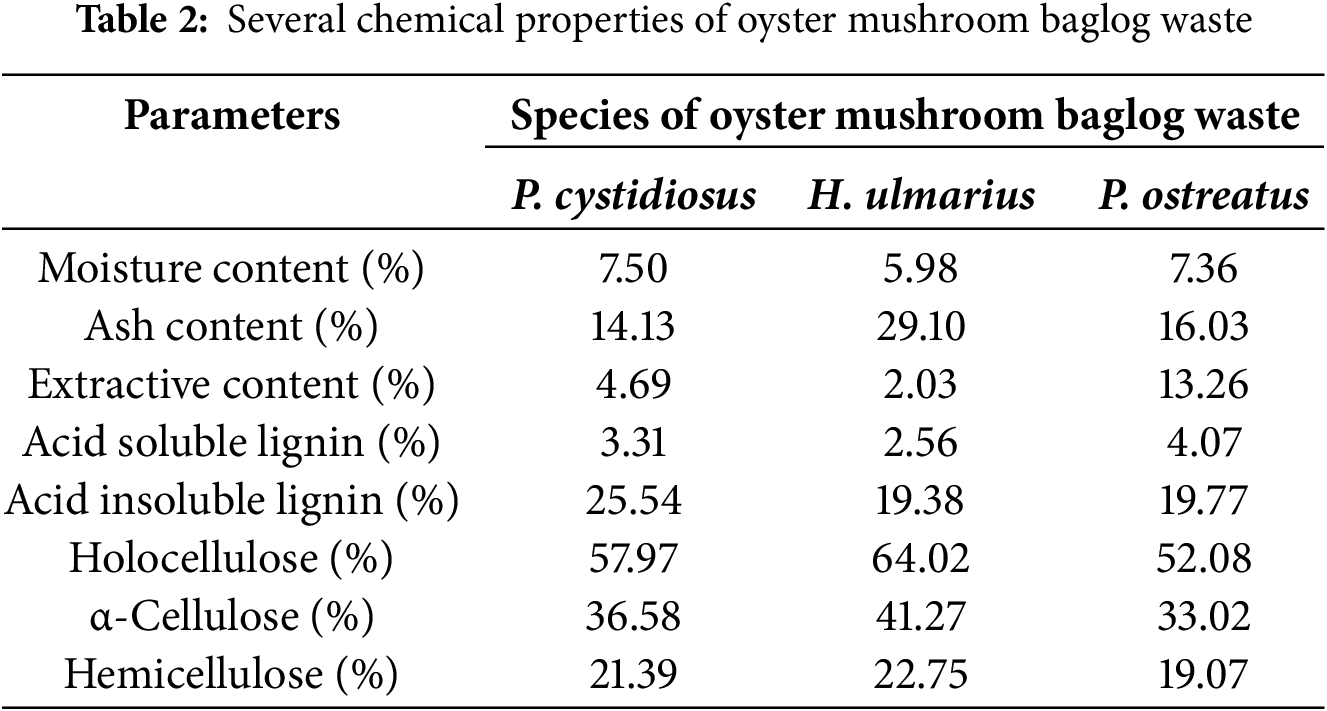

A bio-pellet derived from several types of oyster mushroom baglog waste was successfully synthesized at different mixture ratios of molasses adhesive. The physical properties of the bio-pellets, including moisture content (MC) and density, are shown in Fig. 4a,b, respectively. It can be observed that the MC and density of the bio-pellet at different molasses adhesive mixture ratios ranged from 6.80% to 9.00% and 1.55 to 1.66 g·cm−3, respectively. Previous research reported that bio-pellets made from sawdust particles of woody and non-woody biomass exhibit moisture content and density values ranging from 1.4% to 7.5% and 0.7 to 1.1 g·cm−3, respectively [28]. Munawar and Subiyanto [31] reported that bio-pellets derived from oil palm solid waste have moisture content and density values ranging from 1.5% to 5.8% and 0.44 to 0.97 g·cm−3, respectively. Compared to these previous studies, the bio-pellets in the current research show slightly higher moisture content but significantly superior density values, indicating improved structural integrity and potential for enhanced durability.

Figure 4: Physical properties of bio-pellet derived from oyster mushroom baglog waste in different mixture ratios of molasses, (a) moisture content, (b) density

In addition, the moisture content (MC) and density values slightly increased as the ratio of molasses adhesive increased. This trend aligns with ANOVA results, which shows that molasses concentration significantly affected the MC and density values of the bio-pellet (Table 3). As seen in Fig. 4a, the application of molasses during pelletization slightly increased the moisture content of bio-pellet products ranging from 7.33% and 8.79% at 5% and 10% concentrations, respectively. Those values were slightly higher than that of bio-pellet made without molasses (7.20%). These findings are consistent with studies by Wang et al. [23] and Rhén et al. [38], who reported that adding molasses at 10%–15% significantly increased MC by approximately 6%–10%. This could be due to the sugar compounds in molasses, which may enhance the hygroscopic behavior of the bio-pellets. In addition, the density values tended to decrease at 5% molasses treatment (1.57 g·cm−3) and slightly increased at 10% molasses treatment (1.63 g·cm−3). Although there was a slight increase (Fig. 4b), the density remained slightly lower than that of bio-pellets made without molasses (1.64 g·cm−3). This contrast with other researchers’ findings, who stated that molasses can act as a binding and reinforcement agent during the pelletization process by forming solid bridges between particles to improve the bonding performance and significantly enhance the density values [23,39]. A minor increase in density value could be due to insufficient temperature applied during pelletization. Mišljenović et al. [39] reported that high-quality bio-pellets made with molasses require processing temperatures above the transition glass (Tg) of lignin, specifically within the range of 120°C–180°C. The application of temperatures below Tg resulted in lower bio-pellet density because the binding process primarily relied on Van der Waals forces and fiber interlocking, without forming solid bridges that could strongly bind the bio-pellet [39]. Based on these results, the bio-pellets derived from several oyster mushroom baglog wastes met the standard values of SNI 8675:2018, which require MC to be less than 12% and density to be greater than 0.8 g·cm−3 [40].

Aside from the different mixture ratios of molasses adhesive, the moisture content (MC) and density values of the bio-pellets varied among the types of oyster mushroom baglog waste used in this study. However, these differences were not statistically significant based on ANOVA results (Table 3). The average values for MC and density were 8.44%, 7.84%, and 7.90%, and 1.60, 1.59, and 1.61 g·cm−3 for bio-pellets derived from P. cystidiosus, H. ulmarius, and P. ostreatus, respectively. Pelletizing using baglog waste from H. ulmarius resulted in lower MC and density compared to P. cystidiosus and P. ostreatus. Among the Pleurotus baglog wastes, bio-pellets derived from P. ostreatus had slightly lower MC but higher density than those from P. cystidiosus. Despite these variations, the ANOVA results confirmed that differences in MC and density values among the types of oyster mushroom baglog waste were not statistically significant.

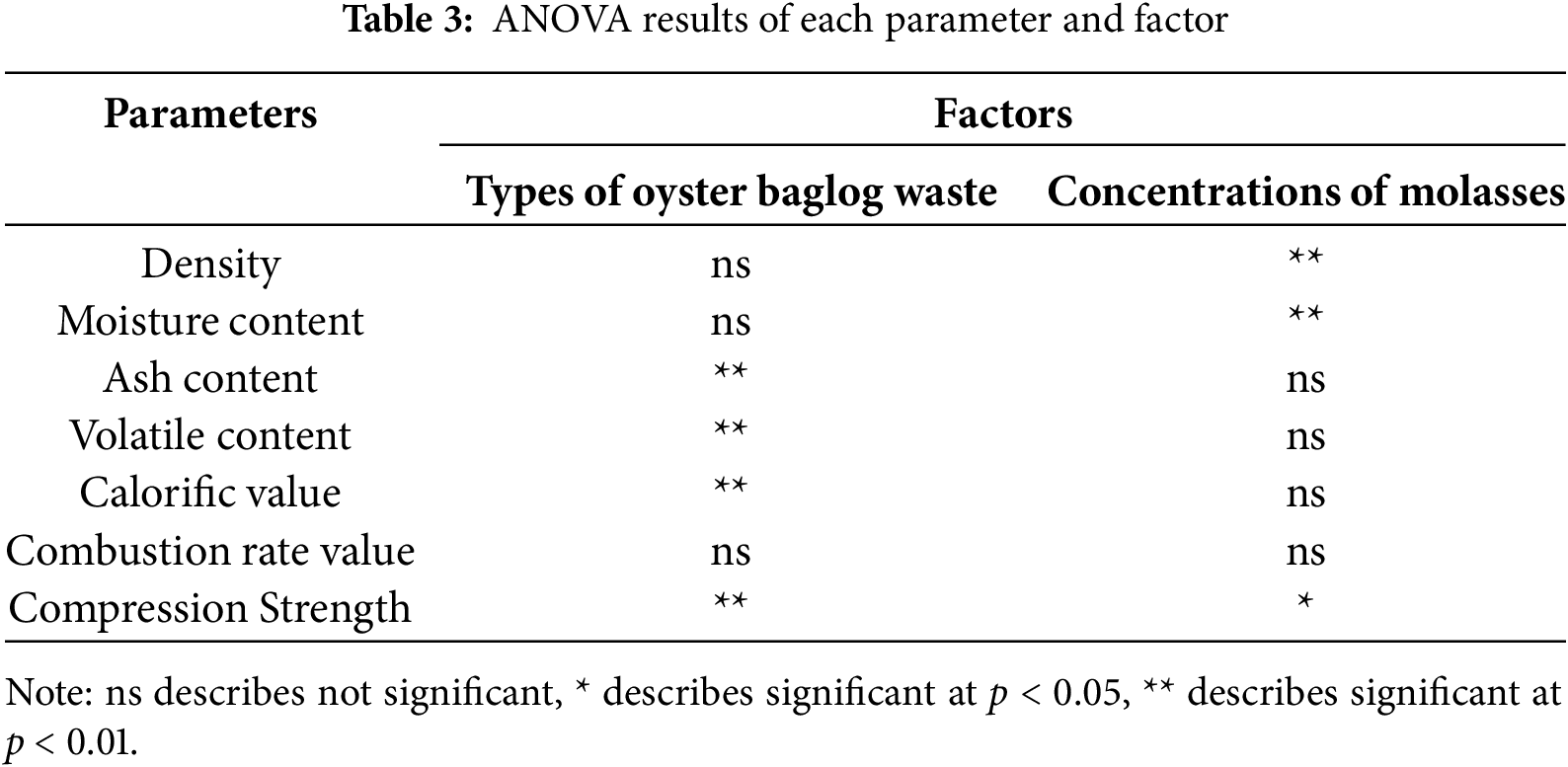

3.2.2 Ash and Volatile Compound

The chemical properties of the bio-pellets, including ash and volatile content, are shown in Fig. 5a,b, respectively. The ash content of the bio-pellets, across different mixture ratios of molasses adhesive, ranged from 11.92% to 18.59%, while the volatile content ranged from 68.42% to 72.75%. Previous research reported that bio-pellets made from sawdust particles of woody and non-woody biomass had moisture content values ranging from 1.31% to 10.75% and volatile content values ranging from 71% to 82% [28]. Munawar and Subiyanto [31] reported that bio-pellets derived from oil palm solid waste had ash content values ranging from 4.15% to 18.03%. Similarly, Mawardi et al. [41] studied bio-pellets derived from oil palm waste and found ash and volatile content values of approximately 1.64% and 69.83%, respectively.

Figure 5: Chemical properties of bio-pellet derived from oyster mushroom baglog waste in different mixture ratios of molasses, (a) ash content, (b) volatile content

In addition, slightly higher ash content and relatively lower volatile content were obtained in bio-pellet mixed with molasses adhesive, particularly in H. ulmarius and P. ostreatus. However, these differences were not statistically significant based on ANOVA results (Table 3). Compared to previous research, the current study showed higher ash content and slightly lower volatile content than the findings of Putra et al. [28], but relatively similar results to those reported by Mawardi et al. [41]. Wang et al. [23] and Tanui et al. [42]. They were found that adding molasses during the pelletization process generally leads to higher ash content, which is attributed to the high amount of non-combustible material that remains in ash form after combustion. Tanui et al. [42] also reported a positive correlation (R2 = 0.93) between the amount of molasses added during pelletization and the ash content of bio-pellet products. Similarly, Wang et al. [23] and Wibowo et al. [43] observed a slight increase in volatile content as the molasses ratio increased for bio-pellets derived from food waste and cow dung. Volatile content is closely related to combustion properties. Wang et al. [23] highlighted that the addition of molasses in bio-pellet production results in a lower ignition temperature and a longer combustion range. Based on these results, bio-pellets derived from various oyster mushroom baglog waste met the standard values of SNI 8675:2018 for volatile content (<80%). However, the ash content (>5%) did not meet the standard requirements [40]. In the industrialization aspect, lower ash and volatile content are preferable as they result in higher energy output and a slower combustion rate [44,45]. Kamga et al. [45] state that industrial-grade agricultural pellets should have an ash content below 7%, while wood pellets should not exceed 3%. Additionally, the volatile matter content typically ranges from 65–85 wt% for general biomass and 76–86 wt% for woody biomass.

Apart from the different mixture ratios of molasses adhesive, the ash and volatile content of the bio-pellets varied among the types of oyster mushroom baglog waste used in this study. The average ash and volatile content values were 12.25%, 18.10%, and 13.03%, and 72.69%, 68.87%, and 72.65% for bio-pellets derived from P. cystidiosus, H. ulmarius, and P. ostreatus, respectively. Bio-pellets produced using baglog waste from H. ulmarius had higher ash content and lower volatile content compared to those from P. cystidiosus and P. ostreatus. Among the Pleurotus baglog waste types, bio-pellets derived from P. cystidiosus exhibited slightly lower ash content but approximately similar volatile content compared to P. ostreatus. This phenomenon is closely related to the initial characteristics of the raw materials, as shown in Table 1. Higher ash content is generally undesirable due to various issues it can cause during combustion and pelletization processes. Therefore, bio-pellets derived from Pleurotus sp. baglog waste are more suitable for pelletization in terms of ash and volatile compound values than those derived from H. ulmarius baglog waste.

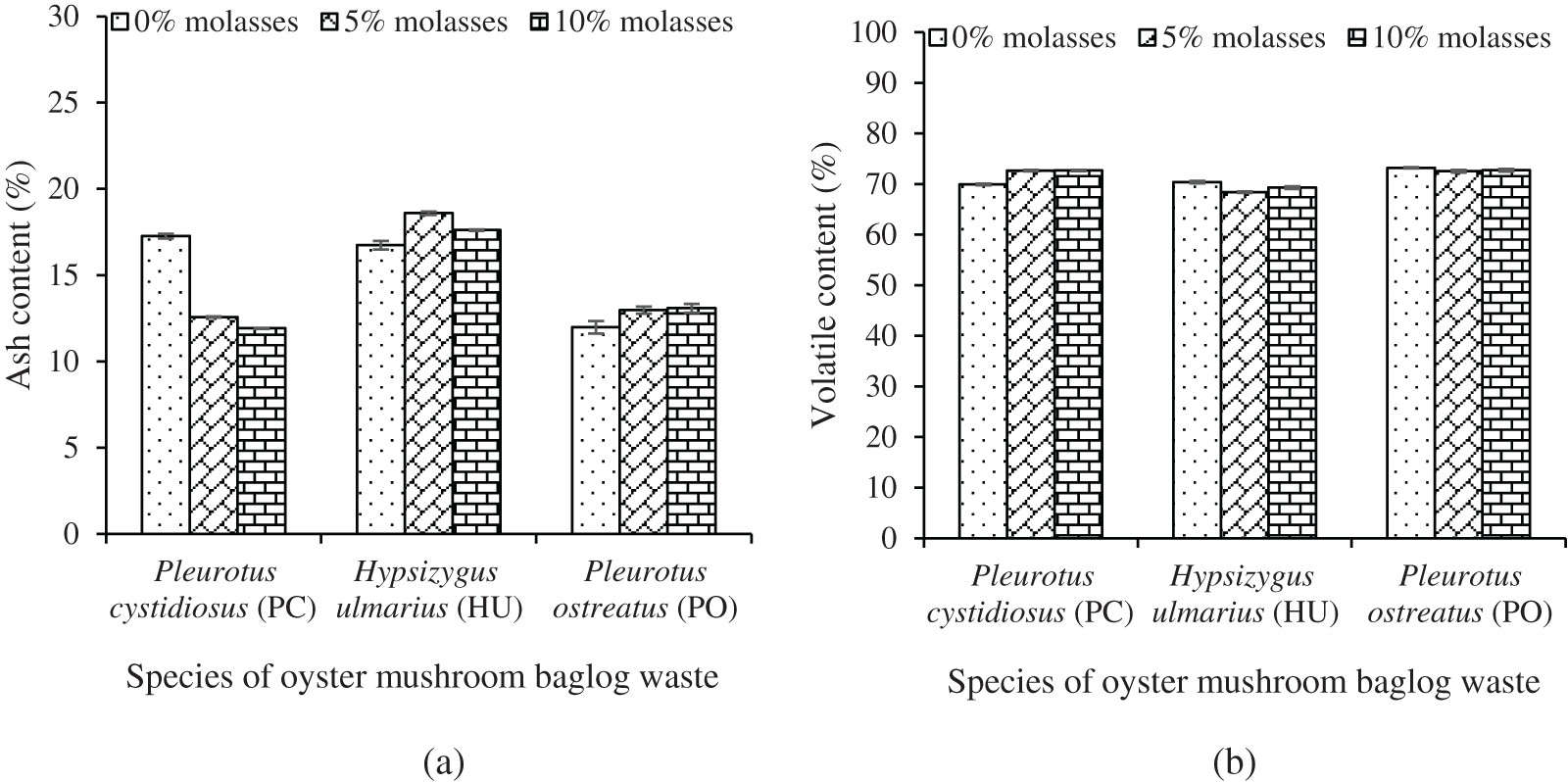

3.2.3 Calorific and Combustion Rate Value

The thermal properties of the bio-pellets, including calorific values and combustion rates, are shown in Fig. 6a,b, respectively. The calorific values and combustion rates of the bio-pellets, with varying molasses adhesive ratios, ranged from 3273 to 3667 cal·g−1 and 0.0267 to 0.0393 g·sec−1, respectively. Previous research reported that bio-pellets made from sawdust particles of woody and non-woody biomass have calorific values ranging from 3578 to 4393 cal·g−1 [28]. Similarly, Munawar and Subiyanto [31] found that bio-pellets derived from oil palm solid waste had calorific values ranging from 3096 to 4724 cal·g−1. Suhasman et al. [46] studied bio-pellets made from shrub and woody biomass and reported calorific values of 3627 to 3845 cal·g−1 and combustion rates of 0.37 to 0.42 g·sec−1. In comparison with previous studies, bio-pellets derived from oyster mushroom baglog waste exhibit moderate thermal properties, making them suitable for applications in moderate combustion processes.

Figure 6: Thermal properties of bio-pellet derived from oyster mushroom baglog wastes in different mixture ratios of molasses, (a) calorific value, (b) combustion rate

In addition, the calorific values and combustion rates slightly increased as the ratio of MO adhesive increased, except for all B3 treatments. However, these differences were not statistically significant based on ANOVA results (Table 3). The calorific values are closely related to the fixed carbon content of the bio-pellet products. Putra et al. [28] reported a positive relationship between calorific values and fixed carbon content, while an inverse relationship was observed between volatile content and fixed carbon content. According to Wang et al. [23], the addition of molasses during the pelletization process produces bio-pellets with easy-to-burn characteristics, including a lower ignition temperature and a longer combustion period. Mišljenović et al. [39] stated that pelletizing with molasses is more effective at lower temperatures, which significantly affects pellet quality and reduces energy consumption. They also noted that molasses acts as a ‘natural lubricant,’ reducing friction in the die holes, thereby lowering energy consumption and improving the physical properties of the bio-pellets. Furthermore, Baharin et al. [16] reported that bio-pellets derived from spent mushroom waste exhibited longer combustion periods due to their higher density, which made them more resistant to breakdown during combustion. Based on these findings, bio-pellets derived from oyster mushroom baglog waste did not meet the standard calorific value requirements of SNI 8675:2018, which specifies a minimum calorific value of 4000 cal·g−1 [40]. In terms of industrial application, higher calorific values are preferred since they can produce higher energy output from the same amount of product, thus lowering the cost for the customer. This value can be affected by the concentrations of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, sulfur, nitrogen, and ash, as well as the composition of lignin present in the raw material for bio-pellet production [47].

Apart from the different mixture ratios of molasses adhesive, the calorific value and combustion rate of the bio-pellets varied among the types of oyster mushroom baglog waste used in this study. The average calorific values and combustion rates were 3660, 3301, and 3527 cal·g−1, and 0.022, 0.031, and 0.028 g·sec−1 for bio-pellets derived from P. cystidiosus, H. ulmarius, and P. ostreatus, respectively. Bio-pellets produced using baglog waste from H. ulmarius had lower calorific values but slightly higher combustion rates compared to those from P. cystidiosus and P. ostreatus. Among the Pleurotus baglog wastes, bio-pellets derived from P. cystidiosus exhibited slightly higher calorific values with lower combustion rates than those derived from P. ostreatus. This phenomenon is closely related to the lignin and extractive content of the raw materials, as mentioned in Table 1. Lower lignin and extractive content in H. ulmarius resulted in bio-pellet products with reduced calorific values. A similar phenomenon was reported by Suhasman et al. [46], who studied bio-pellets derived from shrub and woody biomass. Therefore, bio-pellets derived from Pleurotus sp. baglog waste, which have higher lignin and extractive content, are more suitable for pelletization applications in terms of calorific value and combustion rate compared to those derived from H. ulmarius baglog waste.

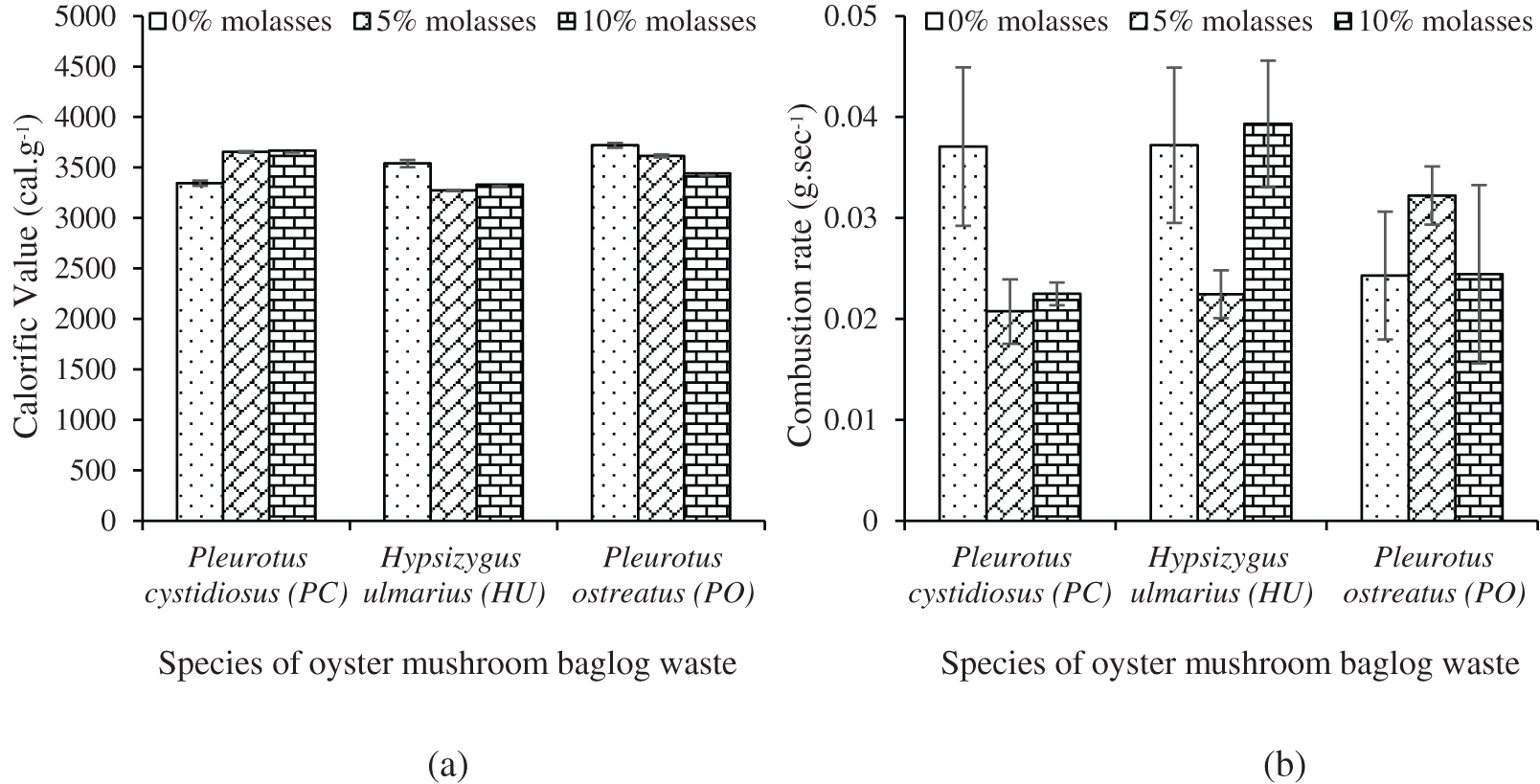

The compression strength of the bio-pellets is shown in Fig. 7. The compression strength of the bio-pellets with different molasses adhesive ratios ranged from 7.75 to 40.68 N·mm−2. Previous research reported that bio-pellets made from sawdust particles of woody biomass had compression strengths ranging from 0.542 to 0.835 kN [48]. Baharin et al. [16] reported that bio-pellets derived from spent mushroom waste exhibited compression strengths of 87.744 to 105.20 MPa at room temperature, with values reducing to around 3.73 to 5.5 MPa at 700°C. Wang et al. [23] found that bio-pellets produced with molasses had compression strengths ranging from 9.57 to 19.86 kN.

Figure 7: Compression strength of bio-pellet derived from oyster mushroom baglog wastes in different mixture ratios of molasses

The compression strength is related to the durability of the bio-pellet when subjected to external forces during transportation and storage [16]. This value significantly increased as the ratio of MO adhesive increased and varied among types of oyster mushroom baglog waste. This phenomenon aligns with the ANOVA results, which shows that both factors significantly affect the compression strength values of the bio-pellet (Table 3). As seen in Fig. 7, the average compression strength values of bio-pellet products were increased as the addition of molasses ranged from 20.99 and 25.09 N·mm−2 at 5% and 10% concentration, respectively. Those values are slightly lower than those of bio-pellets made without molasses (25.58 N·mm−2). A similar phenomenon was reported by Wang et al. [23], who stated that the addition of molasses can increase the maximum force during compression tests, although it may also reduce the maximum load distance. This suggests that while the bio-pellet becomes more durable, with higher tensile and compressive strength, it may also become more brittle. In comparison to the previous studies, bio-pellets derived from oyster mushroom baglog waste exhibited lower compression strength than bio-pellets derived from other biomass, both with and without adhesive. This could be due to smaller particle sizes, the composition of the adhesive, and the characteristics of the raw materials used in this study, all of which affect the compression strength of the bio-pellet products. In addition, insufficient temperature applied during pelletization (below Tg) could produce a lower density of bio-pellet, which can also significantly affect the compression strength value.

Apart from the different mixture ratios of molasses adhesive, the compression strength of the bio-pellets varied among the types of oyster mushroom baglog waste used in this study. The average compression strength values were 9.41, 20.58, and 39.12 N·mm−2 for bio-pellets derived from P. cystidiosus, H. ulmarius, and P. ostreatus, respectively. Bio-pellets produced from P. cystidiosus baglog waste exhibited lower compression strength than those from H. ulmarius and P. ostreatus. Among the Pleurotus baglog wastes, bio-pellets derived from P. ostreatus had the highest compression strength. This phenomenon is closely related to the lignin and extractive content of the raw materials, as mentioned in Table 1. Lignin acts as a natural bonding agent within the substrate during the pelletization process, significantly increasing the durability of the final bio-pellet products [28,36]. Yang et al. [36] reported a positive correlation between pellet durability and Klason lignin content. Additionally, the presence of extractives in the raw materials can serve as lubricants and plasticizers, reducing compression and friction during the pelletization process [33,34]. Therefore, bio-pellets derived from P. ostreatus baglog, which has higher lignin and extractive content, are more suitable for pelletization applications in terms of compression strength, as well as ash and volatile compound values, compared to bio-pellets derived from H. ulmarius baglog waste.

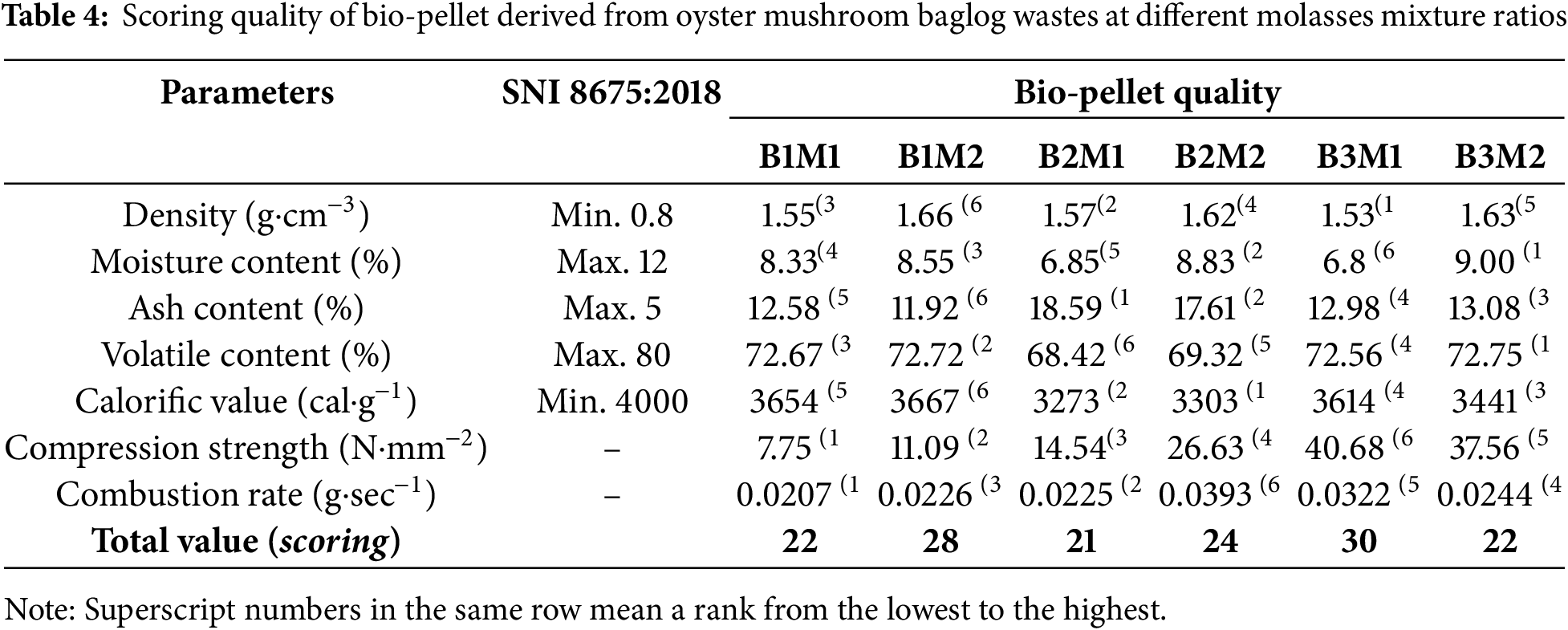

3.2.5 Scoring of Bio-Pellet Quality

The quality of bio-pellets can be assessed using a scoring method based on various testing results, including density, moisture content, ash content, volatile content, calorific value, combustion rate, and compression strength.

The scoring method involved assigning ratings to the analysis results from the lowest to the best, with scores ranging from 1 to 6. The results were then summarized, and the total highest score was selected as the best bio-pellet quality among each types of oyster mushroom baglog waste and within different mixture ratios of molasses applied. The scoring method results (Table 4) indicated that the B3M1 treatment, which consisted of bio-pellets derived from P. ostreatus baglog waste with 5% molasses as a binder, achieved the highest score and categorized as the best bio-pellet in this study. From these results, it was determined that the B3M1 bio-pellet had high density, low moisture content, good volatile matter content, a higher calorific value, high compressive strength, and a faster combustion rate than the others.

A bio-pellet derived from several types of oyster mushroom baglog waste was successfully synthesized at different molasses adhesive mixture ratios. The quality of the bio-pellets was directly influenced by the composition of the raw materials used during the pelletization process. Oyster mushroom baglog waste exhibits varying properties depending on the substrate composition, the treatments applied, and the mushroom species used for inoculation during cultivation. In this study, H. ulmarius baglog waste had lower moisture content, extractive and lignin content, but higher ash content, cellulose, and hemicellulose compared to P. cystidiosus and P. ostreatus baglog waste. Among the Pleurotus species, the chemical composition of P. ostreatus was quite similar to that of P. cystidiosus, with P. ostreatus having slightly lower moisture content, lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose content, as well as slightly higher ash and extractive content. The characterization of the bio-pellets was carried out by evaluating moisture content, ash content, volatile matter, calorific value, combustion rate, density, and compressive strength in accordance with SNI 8675:2018 standards. The results indicated that the addition of molasses as a binder significantly affected the bio-pellet quality. The optimal molasses concentration for balanced performance was found to be 5%, which resulted in a lower moisture content (6.8%), volatile matter (68.42%), and density (1.55 g·cm−3). Additionally, the bio-pellet exhibited a slightly higher calorific value (approximately 3614 cal·g−1), compressive strength (40.68 N·mm−2), and ash content (18.59%). All parameters for the bio-pellet containing 5% molasses met the standard, except for the ash content and calorific value.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Universitas Jenderal Soedirman especially the Faculty of Biology for their invaluable guidance and support. Special appreciation to BRIN for financial and facilities support.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by RIIM LPDP Grant and BRIN (B-3838/II.7.5/FR.06.00/11/2023), and the Research Organization for Nanotechnology and Materials-National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) research grand 2025, the postdoctoral program of the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), the Republic of Indonesia Decree Number 140/II/HK/2024.

Author Contributions: Sarah Augustina: Methodology; Visualization; Writing—Review & Editing Original Draft. Ananda Suci Bazhafah: Investigation; Methodology; Visualization. Jajang Sutiawan: Investigation. Sudarmanto: Investigation. Eko Setio Wibowo: Investigation. Nissa Nurfajrin Solihat: Writing—Review & Editing. Alvin Muhammad Savero: Investigation. Ismadi Ismadi: Investigation. Jayadi Jayadi: Investigation. Agus Sukarto Wismogroho: Investigation. Nuniek Ina Ratnaningtyas: Resources; Investigation; Methodology; Visualization; Writing—Review & Editing. Sukma Surya Kusumah: Writing—Review & Editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lu H, Luo H, Hu J, Liu Z, Chen Q. Macrofungi: a review of cultivation strategies, bioactivity, and application of mushrooms. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2020;19(5):2333–56. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Zhang Y, Wang D, Chen Y, Liu T, Zhang S, Fan H, et al. Healthy function and high valued utilization of edible fungi. Food Sci Hum Wellness. 2021;10(4):408–20. doi:10.1016/j.fshw.2021.04.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Aditya, Neeraj Jarial RS, Jarial K, Bhatia JN. Comprehensive review on oyster mushroom species (Agaricomycetesmorphology, nutrition, cultivation and future aspects. Heliyon. 2024;10(5):e265392. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Badan Pusat Statistik. Statistic of horticulture 2023. Indonesia: BPS; 2023. [Google Scholar]

5. Mahari WAW, Peng W, Nam WL, Yang H, Lee XY, Lee YK, et al. A review on valorization of oyster mushroom and waste generated in the mushroom cultivation industry. J Hazard Mater. 2020;400:123156. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Boadu KB, Nsiah-Asante R, Antwi RT, Obirikorang KA, Anokye R, Ansong M. Influence of the chemical content of sawdust on the levels of important macronutrients and ash composition in Pearl oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). PLoS One. 2023;18(6):e0287532. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0287532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Hultberg M, Asp H, Bergstrand KH, Golovko O. Production of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) on sawdust supplemented with anaerobic digestate. Waste Manag. 2023;155:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2022.10.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Islam MH, Rahman H, Hafiz F. Cultivation of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus flabellatus) on different substrates. Int J Sustain Crop Prod. 2009;4(1):45–8. [Google Scholar]

9. Atallah E, Zeaiter J, Ahmad MN, Leahy JJ, Kwapinski W. Hydrothermal carbonization of spent mushroom compost waste compared against torrefaction and pyrolysis. Fuel Process Technol. 2021;216:106795. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2021.106795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Martín C, Zervakis GI, Xiong S, Koutrotsios G, Strætkvern KO. Spent substrate from mushroom cultivation: exploitation potential toward various applications and value-added products. Bioengineered. 2023;14(1):2252138. doi:10.1080/21655979.2023.2252138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Rastono A, Muzadi M, Siswara HN. The potential of mushroom baglog waste compost by adding FMA on ground water spinach (Ipomoea reptans Poir) growth. Jurnal Agronomi Tanaman Tropika. 2023;5(1):20–9. doi:10.36378/juatika.v%vi%i.2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Rajavat AS, Megashwaran V, Bharadwaj A, Tripathi S, Pandiyan K. Spent mushroom waste: an emerging bio-fertilizer for improving soil health and plant productivity. In: New and future developments in microbial biotechnology and bioengineering. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. p. 345–54. ISBN 978-0-323-85579-2. [Google Scholar]

13. Puspitawati IN, Wahyusi KN, Santi SS, Suprihatin, Saputro EA, Karaman N. Characteristics biobriquettes from mushroom baglog waste carbonization production. Int J Eco-Innovation Sci Eng. 2023;4(1):18–23. doi:10.33005/ijeise.v4i1.112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jin Y, Zhang M, Jin Z, Wang G, Li R, Zhang X, et al. Characterization of biochars derived from various spent mushroom substrates and evaluation of their adsorption performance of Cu(II) ions from aqueous solution. Environ Res. 2021;196:110323. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2020.110323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Alves LDS, Moreira BRDA, Viana RDS, Pardo-Gimenez A, Dias ES, Noble R, et al. Recycling spent mushroom substrate into fuel pellets for low-emission bioenergy producing systems. J Clean Prod. 2021;313:127875. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Baharin NSK, Koesoemadinata VC, Nakamura S, Azman NF, Yuzir MAM, Akhir FNM, et al. Production of Bio-Coke from spent mushroom substrate for a sustainable solid fuel. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2020;12:4095–104. doi:10.1007/s13399-020-00844-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ruksathamcharoen S, Chuenyam T, Stratong-on P, Hosoda H, Ding L, Yoshikawa K. Effects of hydrothermal treatment and pelletizing temperature on the mechanical properties of empty fruit bunch pellets. Appl Energy. 2019;251(11):113385. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.113385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ju X, Zhang K, Chen Z, Zhou J. A method of adding binder by high-pressure spraying to improve the biomass densification. Polymers. 2020;12(10):2374. doi:10.3390/polym12102374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Umemura K, Sugihara O, Kawai S. Investigation of a new natural adhesive composed of citric acid and sucrose for particleboard. J Wood Sci. 2013;59(3):203–8. doi:10.1007/s10086-013-1326-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Umemura K, Sugihara O, Kawai S. Investigation of a new natural adhesive composed of citric acid and sucrose for particleboard II: effects of board density and pressing temperature. J Wood Sci. 2015;61(1):40–4. doi:10.1007/s10086-014-1437-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Mustafa G, Arshad M, Bano I, Abbas M. Biotechnological applications of sugarcane bagasse and sugar beet molasses. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2023;13(2):1489–501. doi:10.1007/s13399-020-01141-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Syahfitri A, Hermawan D, Kusumah SS, Ismadi Lubis, Widyaningrum MAR, Ismayati BA, et al. Conversion of agro-industrial wastes of sorghum bagasse and molasses into lightweight roof tile composite. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2022;14(331):1001–15. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-02435-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wang T, Wang Z, Zhai Y, Li S, Liu X, Wang B, et al. Effect of molasses binder on the pelletization of food waste hydrochar for enhanced biofuel pellets production. Sustain Chem Pharm. 2019;14:100183. doi:10.1016/j.scp.2019.100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. TAPPI. T-203 Alpha-, Beta-, Gamma-cellulose in pulp. Atlanta (USTechnical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry (TAPPI) Press; 1999a. [Google Scholar]

25. TAPPI. T-222 acid insoluble lignin in wood and pulp. Atlanta (USTechnical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry (TAPPI) Press; 2002b. [Google Scholar]

26. ASTM. Standard test method for ethanol-toluene solubility of wood. ASTM D 1107–96. West Conshohocken (USAAmerican Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) International; 2007. [Google Scholar]

27. Liku EH, Iskandar, Sulardjaka. Pengaruh Kompisisi Binder Tanah Liat Terhadap Kekuatan Pelet Katalis Zeolit Alam. Jurnal Teknik Mesin. 2021;9(2):255–60. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

28. Putra AR, Iswanto AH, Nuryawan A, Darmawan S, Madyaratri EW, Fatriasari W, et al. Characteristics of biopellets manufactured from various lignocellulosic feedstocks as alternative renewable energy sources. J Renew Mater. 2024;12(6):1103–23. doi:10.32604/jrm.2024.051077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Frodeson S, Henriksson G, Berghel J. Effects of moisture content during densification of biomass pellets, focusing on polysaccharide substances. Biomass Bioenergy. 2024;122:322–30. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2019.01.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yilmaz H, Çanakcı M, Topakcı M, Karayel D. The effect of raw material moisture and particle size on agri-pellet production parameters and physical properties: a case study for greenhouse melon residues. Biomass Bioenergy. 2021;150:106125. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2021.106125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Munawar SS, Subiyanto B. Characterization of biomass pellet made from solid waste oil palm industry. Procedia Environ Sci. 2014;20:336–41. doi:10.1016/j.proenv.2014.03.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Fang X, Jia L. Experimental study on ash fusion characteristics of biomass. Bioresour Technol. 2012;104:769–74. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2011.11.055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Nielsen NPK, Gardner DJ, Felby C. Effect of extractives and storage on the pelletizing process of sawdust. Fuel. 2010;89:94–8. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2009.06.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Liu J, Cheng W, Jiang X, Khan M, Zhang Q, Cai H. Effect of extractives on the physicochemical properties of biomass pellets: comparison of pellets from extracted and non-extracted sycamore leaves. BioResources. 2020;15(1):544–56. doi:10.15376/biores.15.1.544-556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Yunianti AD, Pangestu KTP, Syahidah, Bastian F, Pari G, Darmawan S. Dataset of biopellet characteristics from various lignocellulosic agricultural waste and shrubs produced using different method. Data Brief. 2024;57:110879. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2024.110879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Yang I, Jeong H, Lee JJ, Lee SM. Relationship between lignin content and the durability of wood pellets fabricated using larix kaempferi C. Sawdust. J Korean Wood Sci Technol. 2019;47(1):110–23. doi:10.5658/WOOD.2019.47.1.110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Asia-Pasific Economic Cooperation. Heating applications of bio-pellet to enhance utilization of renewable energy in the APEC region. Singapura: APEC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

38. Rhén C, Gref R, Sjöström M, Wästerlund I. Effects of raw material moisture content, densification pressure and temperature on some properties of Norway spruce pellets. Fuel Process Technol. 2005;87(1):11–6. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2005.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Mišljenović N, Čolović R, Vukmirović Đ., Brlek T, Bringas CS. The effects of sugar beet molasses on wheat straw pelleting and pellet quality. A comparative study of pelleting by using a single pellet press and a pilot-scale pellet press. Fuel Process Technol. 2019;144:220–9. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2016.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Standard National Indonesia. Pellet biomassa for energy. Jakarta (IDNSNI; 2018. [Google Scholar]

41. Mawardi I, Razali M, Zuhaimi Z, Ibrahim A, Akadir Z, Razak H, et al. Characteristics of hybrid biopellet based on oil palm wood and natural activated charcoal as a renewable alternative energy source. J Ecol Eng. 2023;24(9):80–91. doi:10.12911/22998993/168412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Tanui JK, Kioni PNK, Kariuki PN, Ngugi JM. Influence of processing conditions on the quality of briquettes produced by recycling charcoal dust. Int J Energy Environ Eng. 2018;9:341–50. doi:10.1007/s40095-018-0275-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wibowo WA, Susanti AD, Paryanto. Characterization and combustion kinetics of binderless and bindered dry cow dung bio-pellets. Equilib J Chem Eng. 2018;8(1):19–27. doi:10.20961/equilibrium.v8i1.83645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Sutapa JPG, Hidyatullah AH. Torrefaction for improving quality of pellets derived from calliandra wood. J Korean Wood Sci Technol. 2023;51(5):381–91. doi:10.5658/WOOD.2023.51.5.381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Kamga PLW, Vitoussia T, Bissoue AN, Nguimbous EN, Dieudjio DN, Bot BV, et al. Physical and energetic characteristics of pellets produced from Movingui sawdust, corn spathes, and coconut shells. Energy Rep. 2024;11:1291–301. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2024.01.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Suhasman S, Yunianti AD, Pangestu KTP, Agussalim, Kitta I, Arisandi H, et al. Biopellets from four shrub species for co-firing in East Indonesia. J Korean Wood Sci Technol. 2024;52(6):539–54. doi:10.5658/WOOD.2024.52.6.539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Tarasov D, Shahi C, Leitch M. Effect of additives on wood pellet physical and thermal characteristics: a review. Int Sch Res Notices. 2013. doi:10.1155/2013/876939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Scott C, Desamsetty TM, Rahmanian N. Unlocking power: impact of physical and mechanical properties of biomass wood pellets on energy release and carbon emissions in power sector. Waste Biomass Valori. 2024. doi:10.1007/s12649-024-02669-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools