Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Ultrasonic Modification of Wood Surface: Study of Macro and Micro Properties after Long-Term Storage

1 Department of Electroacoustics and Ultrasonic Engineering, Saint Petersburg Electrotechnical University “LETI”, 5 Professora Popova Street, St. Petersburg, 197376, Russia

2 Department of Wood Science and Forest Protection, Saint Petersburg State Forest Technical University, 5 Institute per., St. Petersburg, 194021, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Alena Vjuginova. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(9), 1819-1828. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0061

Received 17 March 2025; Accepted 23 June 2025; Issue published 22 September 2025

Abstract

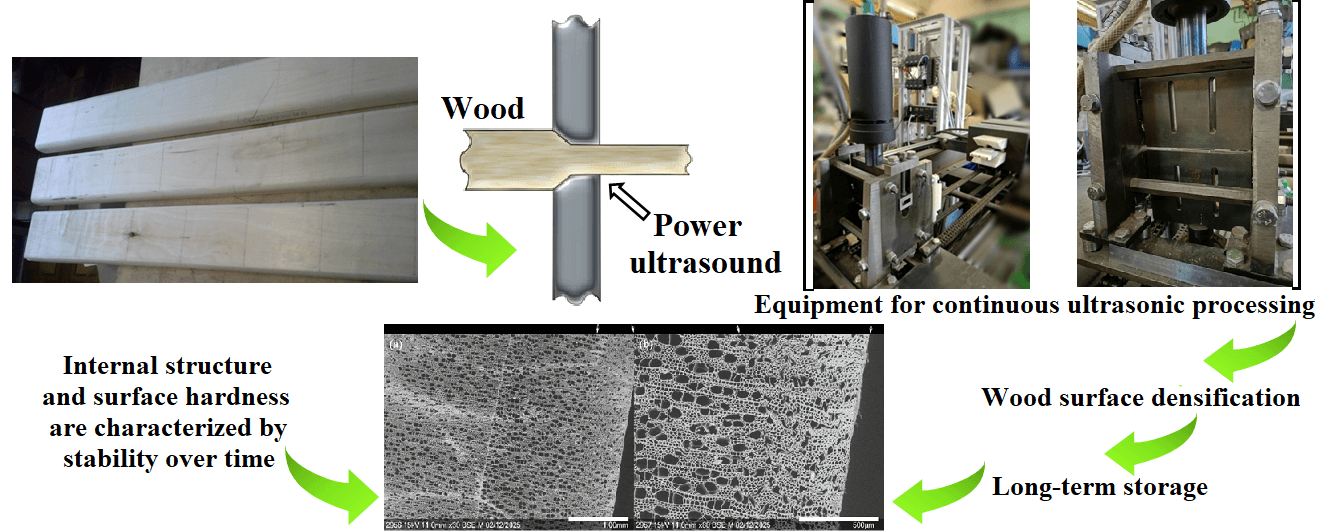

In this paper, the stability of the results of ultrasonic wood surface modification after long-term storage, including macroscopic properties and microstructure of specimens, was investigated. Specimens of aspen wood (Populus tremula) were processed by the developed ultrasonic method of wood surface modification in three different treatment modes and the surface hardness of the specimens was evaluated after processing and after storing the specimens for more than 5 years since long-term stability is an important factor for the use of ultrasonically modified sawn timber as construction and finishing materials. The obtained results of surface hardness measurements by the Leeb method showed that the decrease in hardness after long-term storage is approximately 6.6% for the lowest degree of treatment and approximately 3.4% and 2.4% for medium and high degrees of treatment, taking into account the fact of the average increase in surface hardness approximately 2–4 times, this decrease is insignificant. The internal structure of the specimens after storage was studied by scanning electron microscope (SEM), and deformations of the wood surface layer without damage or rupture were analyzed. The derived stable results confirm the potential of the ultrasonic method for wood surface modification.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Wood is a widely available natural renewable resource. Since ancient times, mankind has used wood in various spheres of life, for home improvement, and for making household items. The rapid development of materials science and the creation of a wide range of synthetic materials, on the one hand, has become one of the foundations of human development for almost a century; on the other hand, materials science has become a source of increasing difficulties, such as a lack of energy and resources, waste accumulation, environmental pollution and negative impacts on the environment. Under these conditions, interest in environmentally friendly materials obtained from wood, which are renewable and biodegradable, is understandable, and many studies have focused on the possibility of using wood-based materials. Increasing the use of renewable natural resources and the introduction of more environmentally friendly methods for processing them are highly important for the sustainable development of society [1,2].

Wood, as a natural resource and a building and finishing material, has several well-known advantages, such as renewability, relative ease of processing and use, reasonable cost, and an excellent strength-density ratio. At the same time, in several cases, increasing the absolute values of density, strength, hardness, resistance to air moisture changes, biological durability, etc., is necessary, which can be obtained via various methods of additional processing or modification; a detailed analysis of such targeted changes in the properties of wood is presented in [3,4], and several commercialized technologies are analyzed in [5].

Various modification, processing, and impregnation technologies make it possible to change the structure of the material and improve the physical and mechanical properties of wood—to increase the density, hardness, strength, wear resistance, and abrasion resistance [6,7]; reduce water absorption; increase the fire resistance and biological durability of the material; and improve its decorative properties [8–10]. Of particular interest are technologies for modifying softwood [11], which can be an effective way to overcome the shortage of high-quality, less accessible, and more expensive wood and reduce the problem of a shortage of wood with specified properties.

One of the possible tasks of wood modification is to increase the density and hardness of the surface layer (densification) [12]. While a wide range of wood species are used in construction and furniture, some lack the desired density and surface hardness values. Improving the surface quality of low-density wood can significantly improve its performance. The task of improving the quality of wood surfaces has been studied worldwide [13–15]; many studies have been conducted to develop appropriate technological processes [16–18]. The authors noted that surface densification technology should be high-speed, economical, and energy-efficient [3], and such properties can be possessed by devices realizing the principle of continuous processing. In this case, the cost of the final product will not be out of the category of affordable materials. The technology of continuous ultrasonic processing of wood surfaces is discussed in this paper.

The first work describing the development of wood surface densification technology was that of [19], whose authors proposed the use of heating and pressure. Various methods of densification of the wood surface in a continuous mode were studied by the author of [20], who investigated roller pressing for a continuous densification process using chemical agents to stabilize the results. In [21], a continuous press was proposed, which allows the processing of full-size products with a length of 6 m. In [22], a variant of continuous processing of the wood surface via a belt press was presented.

In this work, a technology for ultrasonic modification of wood surfaces without the use of heating or impregnating agents is studied. Previously, the possibility of using power ultrasonic fields in combination with pressure to affect wood structure was described in several patents, i.e., for round solid wood [23,24]. However, in all the previously described methods, ultrasonic oscillations were applied to the matrix or die rather than directly to the wood surface, so ultrasonic treatment of wood with a high amplitude of oscillations and without energy loss could not be realized. On the other hand, the possibility of using low-frequency mechanical vibrations to increase the hardness of a wood surface was described in [25]. Technology and equipment for the ultrasonic treatment of wood surfaces, the peculiarity of which is the direct contact of ultrasonic sonotrodes and treated lumber, was proposed by the authors in two patents [26,27]. This technology was subsequently studied in more detail for several wood species, such as aspen (Populus tremula), pine (Pinus sylvestris), linden (Tilia europaea), alder (Alnus glutinosa), and oak (Quercus robur) [28]. This work has been continued by the development of equipment for a combined technology for increasing density and impregnation [29], the study of the possibilities of the described ultrasonic modification method to increase the surface hardness of Thermo-modified wood [30], and the study of the acoustic properties of ultrasonically modified wood [31].

The density and strength of wood, as well as many other physical and mechanical properties of wood, vary over a very wide range both within a single species and between different species. Wood is a material with a uniquely wide range of uses. Therefore, different uses of wood may require wood with diametrically opposite properties: in one case, it is light and therefore has low strength; in the other case, it is dense wood with high strength properties. Most of the fast-growing wood species that allow large volumes of large-sized wood to be obtained are characterized by a low density of the resulting wood. The proposed method of wood surface treatment allows for an increase in wood mechanical properties and expands the possibilities of using less dense and strong wood from fast-growing species.

The effect of high-intensity ultrasonic oscillations combined with mechanical pressure on the surface of wood results in the formation of a surface layer with improved properties, such as increased density and hardness. In this work, the stability of the results of ultrasonic modification of wood after long-term storage was investigated. For samples of aspen (Populus tremula), the surface of which was subjected to ultrasonic treatment under three different modes, the surface hardness was repeatedly measured after storage for more than 5 years, and the internal structure was studied. The results of this study are important for determining the potential uses of ultrasonically modified wood as construction and finishing materials.

2 Method of Ultrasonic Wood Modification

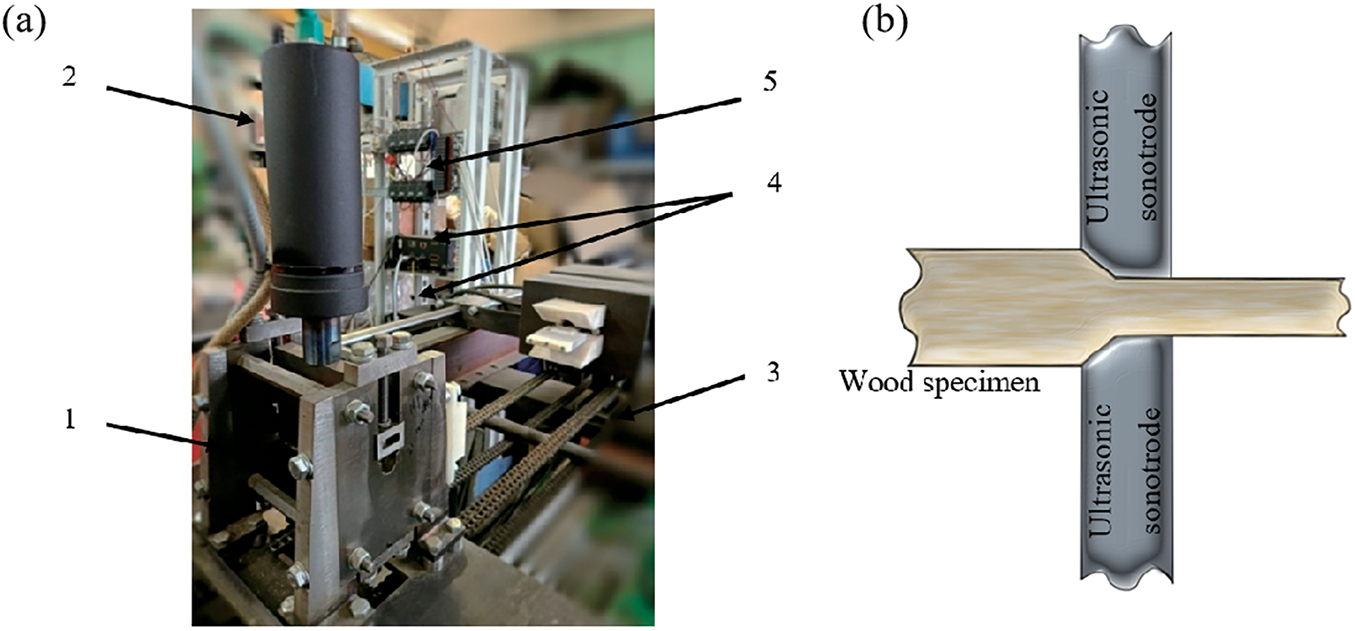

The considered ultrasonic technology realizing densification, modification, and improvement of the quality of a surface layer of wood, is implemented by ultrasonic equipment of a continuous type. Wood products with plane-parallel surfaces are fed by a hydraulic transportation system into an ultrasonic processing module, where the upper and lower surfaces are exposed to the power ultrasonic vibrations of ultrasonic sonotrodes located opposite each other and mechanical pressure (Fig. 1). The technology does not require heating or the use of chemical agents; importantly, the technology is realized in a single pass through the device at a processing speed of a few meters per minute. The processing speed depends on the initial density and hardness of the wood; it can vary from 1–2 m per minute for wood species with high hardness to 4–6 m per minute for wood species with low hardness.

Figure 1: Ultrasonic equipment for wood surface modification: (a) design: 1—ultrasonic module, 2—magnetostrictive ultrasonic transducer, 3—infeed system, 4—ultrasonic generators, 5—control unit; (b) ultrasonic processing scheme

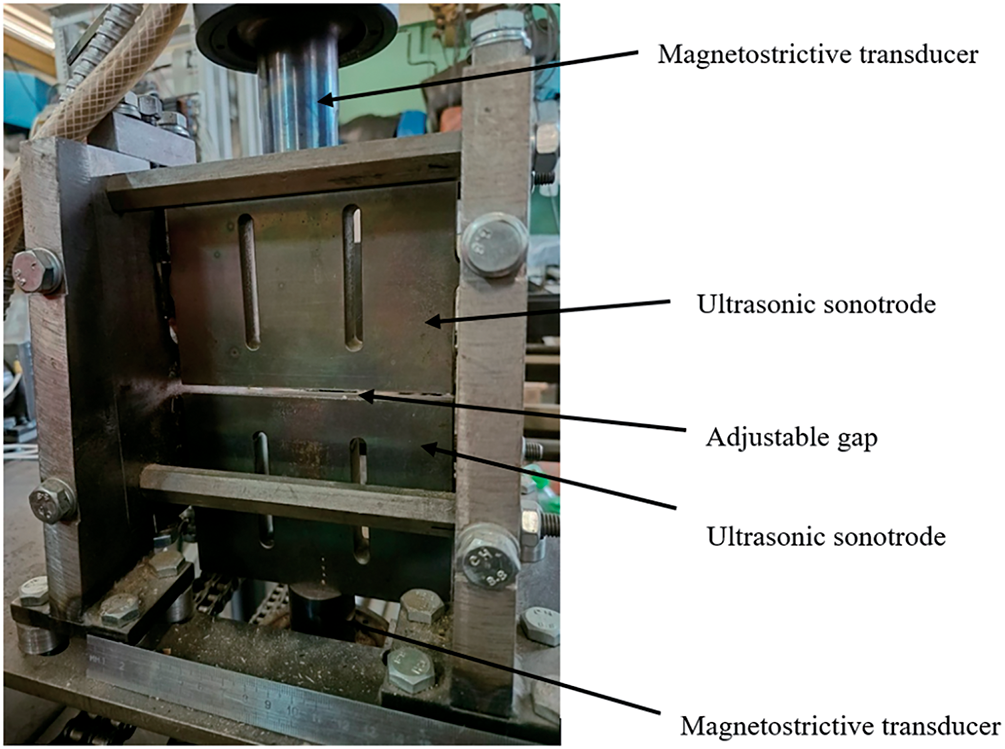

The ultrasonic module of the ultrasonic device has an adjustable gap (Fig. 2). During processing, the gap is thinner than the thickness of the sample. The difference between these values is the processing parameter Δ, characterizing its degree.

Figure 2: Ultrasonic module of ultrasonic equipment with an adjustable gap

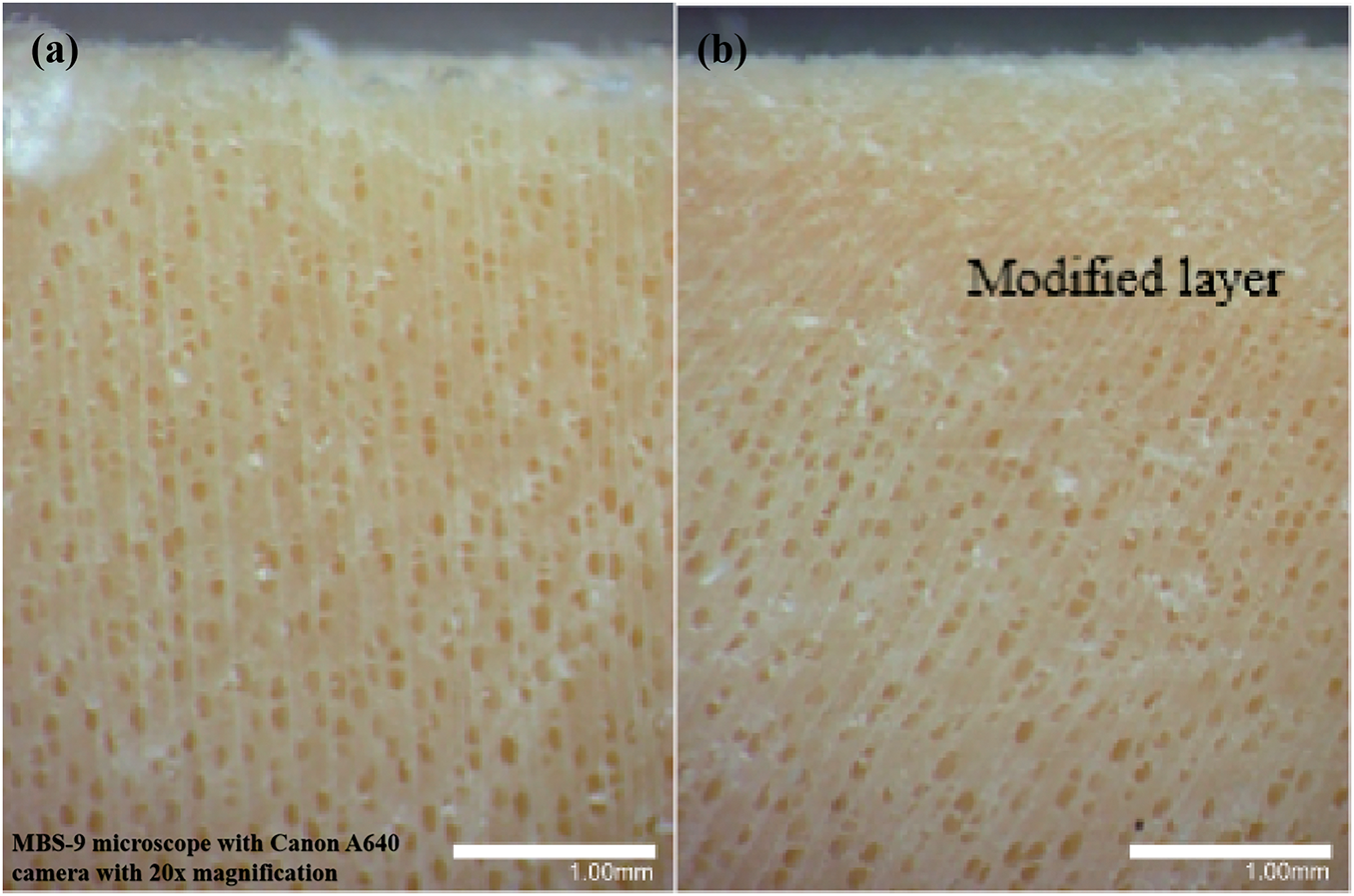

After processing, modified layers are formed on both surfaces of the sample, which have increased density, hardness, and reduced porosity; micrographs by optical microscopy of the internal structure of aspen wood (Populus tremula) before and after ultrasonic treatment are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Micrographs of aspen (Populus tremula): (a) before ultrasonic modification; (b) and after ultrasonic modification

The larger the processing parameter Δ is, the more the workpiece is modified, and the smaller its final thickness. The power of each ultrasonic generator and the corresponding magnetostrictive transducer is 2 kW, and the operating frequency of the ultrasonic system is 22 kHz.

3 Specimens and Estimation Methods

When modified wood is used in any way, the stability of the changes that occur in the wood as a result of surface modification is an important indicator of the quality of such treatment. Aspen was chosen for the experiments; in particular, it was noted in [32] that aspen is one of the most suitable species for densification.

Initially, three samples of aspen (Populus tremula) with a moisture content of 12%, length of 2.5 m, thickness of 27.8 mm, and width of 90 mm, wood of flat-grain type, were prepared (Fig. 4). The samples were treated via the described ultrasonic method and equipment with processing parameters of Δ = 1.8, 2.8, and 3.8 mm and a processing speed of 4 m/min. The surface hardness was estimated along the length of the samples before and after ultrasonic treatment for the longitudinal coordinate L (mm) with a step of 100 mm between the coordinates by the Leeb method (HL); for each coordinate, the measurements were carried out at three points, and the results were subsequently averaged for each coordinate.

Figure 4: Specimens of aspen boards

For surface hardness measurements, a MET-UD hardness testing instrument based on the Leeb method (ASTM A956-02) was used, which is appropriate for hardness measurements of a 1–2 mm densified surface layer without damage. The instrument is based on the Leeb method, which determines the ratio of the impact body velocity before (V0) and after impact (V1) with the surface, and HL = 1000 ∗ V1/V0. Thus, this method allows estimation of the relative change in hardness of the wood surface.

To confirm the stability of the surface hardness increase after ultrasonic treatment, the surface hardness of the aspen samples was remeasured after more than 5 years of storage in heated room conditions at a relative humidity of 55 ± 15%, at a temperature of 20 ± 5°C, under conditions that correspond to several standards (for example, GOST 862.1-2020). As in the previous case, the measurements were carried out at three points for each coordinate and then averaged. To study the internal structure of the samples after storage, a Hitachi TM4000Plus scanning electron microscope (SEM) was used. For microscopic examination of changes in the cell structure of the wood modified by ultrasound, a sample was cut from the middle part of the board in the form of a full cross-cut. The end surfaces of individual sections of this cut were cleaned with a microtome knife for examination under a microscope.

These studies aimed to determine whether any relaxation processes are present in the wood after ultrasonic treatment and whether air humidity affects the results of the treatment during storage.

Since the study used flat-grain sawn timber, during modification, the wood was compacted in the radial direction and cell deformation occurred in the radial direction; moreover, at the lateral sides of the board, cell deformation occurred in the tangential-radial direction.

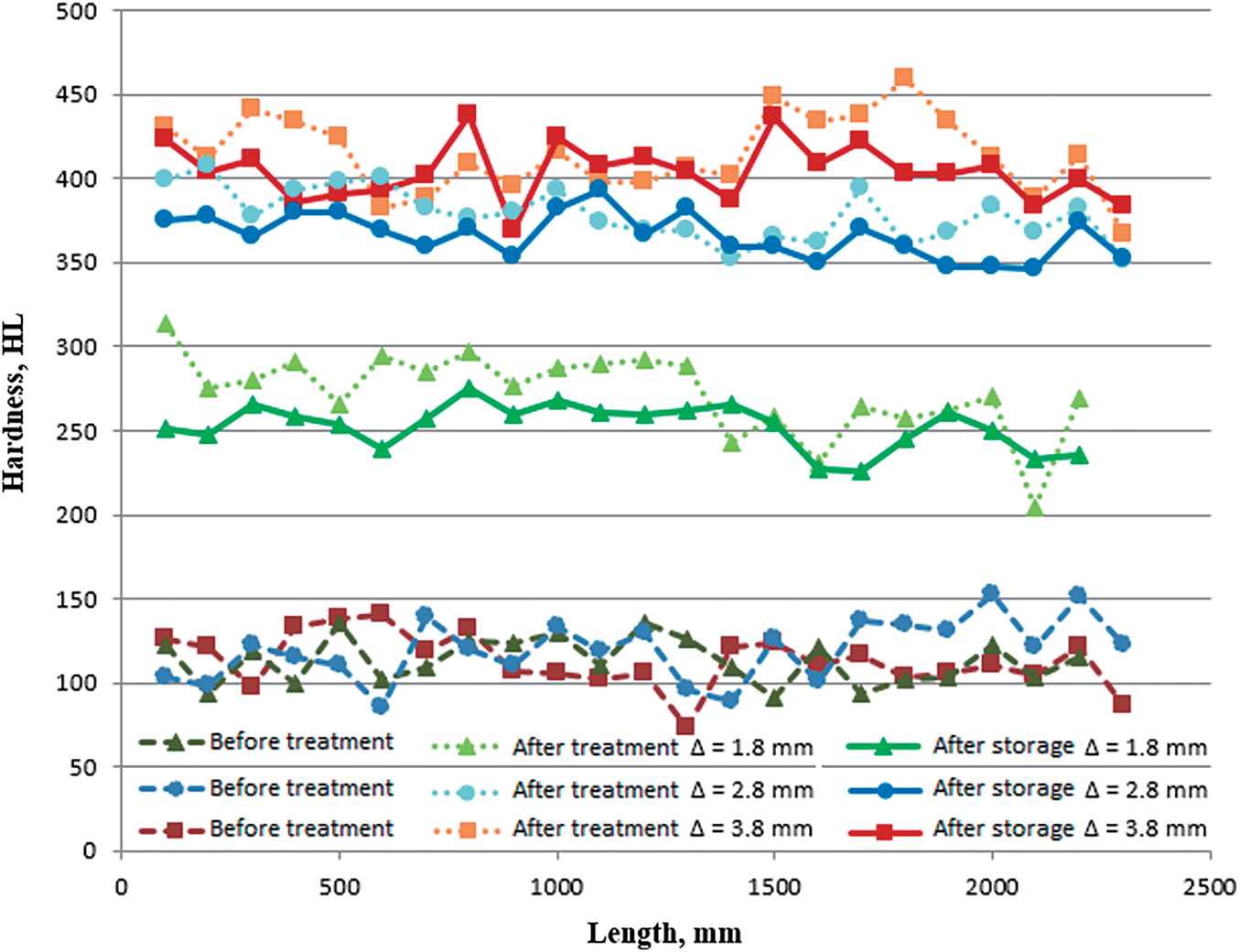

The results of hardness measurements of the three investigated aspen (Populus tremula) samples (with processing parameters of Δ = 1.8, 2.8, and 3.8 mm) along the length before ultrasonic treatment, after ultrasonic treatment, and after storage are shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Results of surface hardness measurements for the investigated aspen samples before and after ultrasonic treatment and after storage for different values of the processing parameter Δ

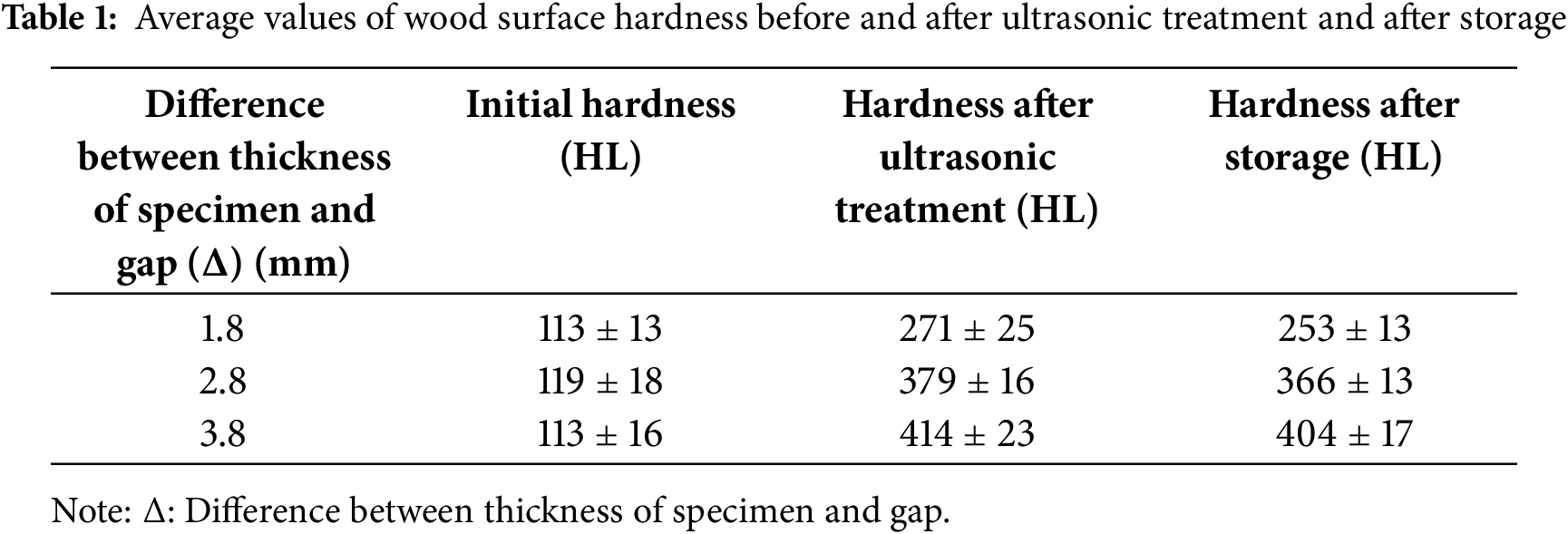

The results shown in the graphs in Fig. 5 are summarized in Table 1, which presents the average values for all the samples before and after ultrasonic treatment and after storage.

As seen from the measurement results presented above for the sample with the smallest processing parameter equal to 1.8 mm, the average increase in hardness after ultrasonic treatment is 2.4 times, and the decrease in surface hardness after storage is 6.6%. For the sample with a medium processing parameter equal to 2.8 mm, the averaged increase in hardness after ultrasonic treatment is 3.2 times, and the decrease in surface hardness after storage is 3.4%. For the sample with the highest processing parameter equal to 3.8 mm, the averaged increase in hardness after ultrasonic treatment is 3.7 times, and the decrease in surface hardness after storage is 2.4%. Thus, an insignificant decrease in the hardness of the wood surface after long-term storage can be observed. This decrease is lower for samples with a higher degree of ultrasonic treatment. The obtained results confirm the stability of the derived wood surface hardness and the potential of the ultrasonic method for wood surface modification.

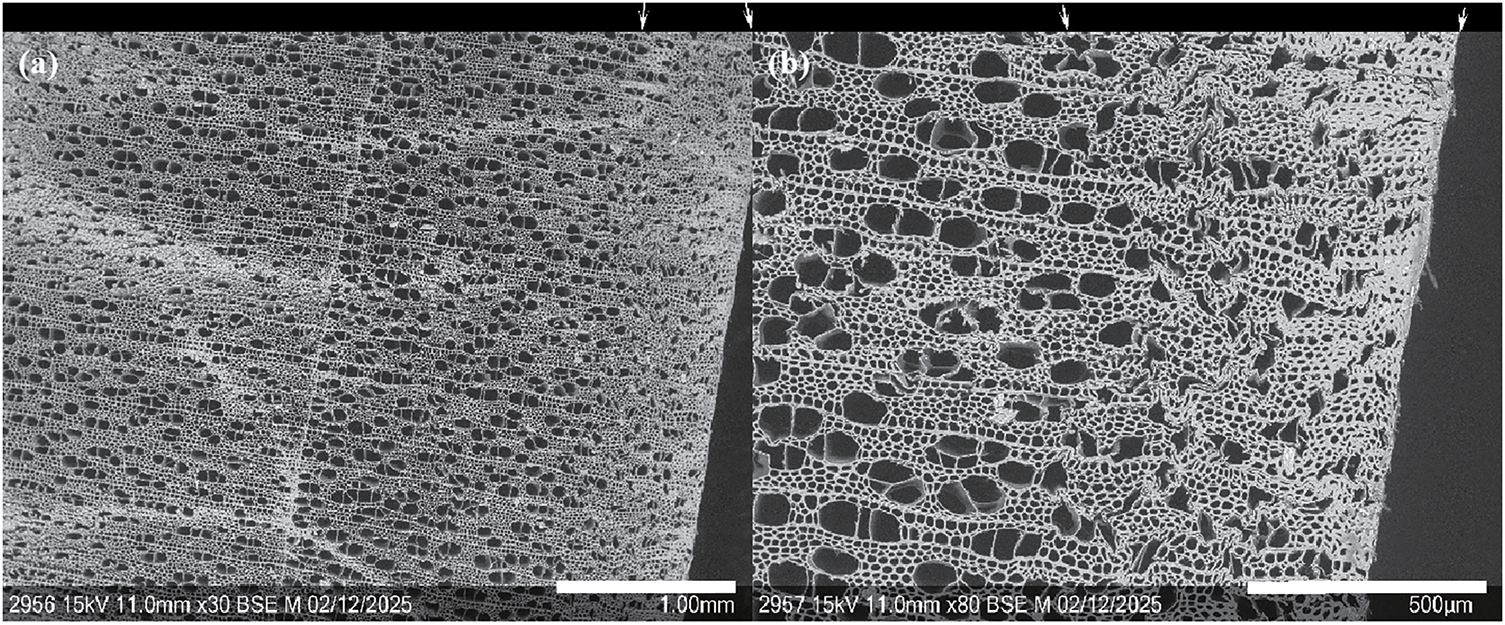

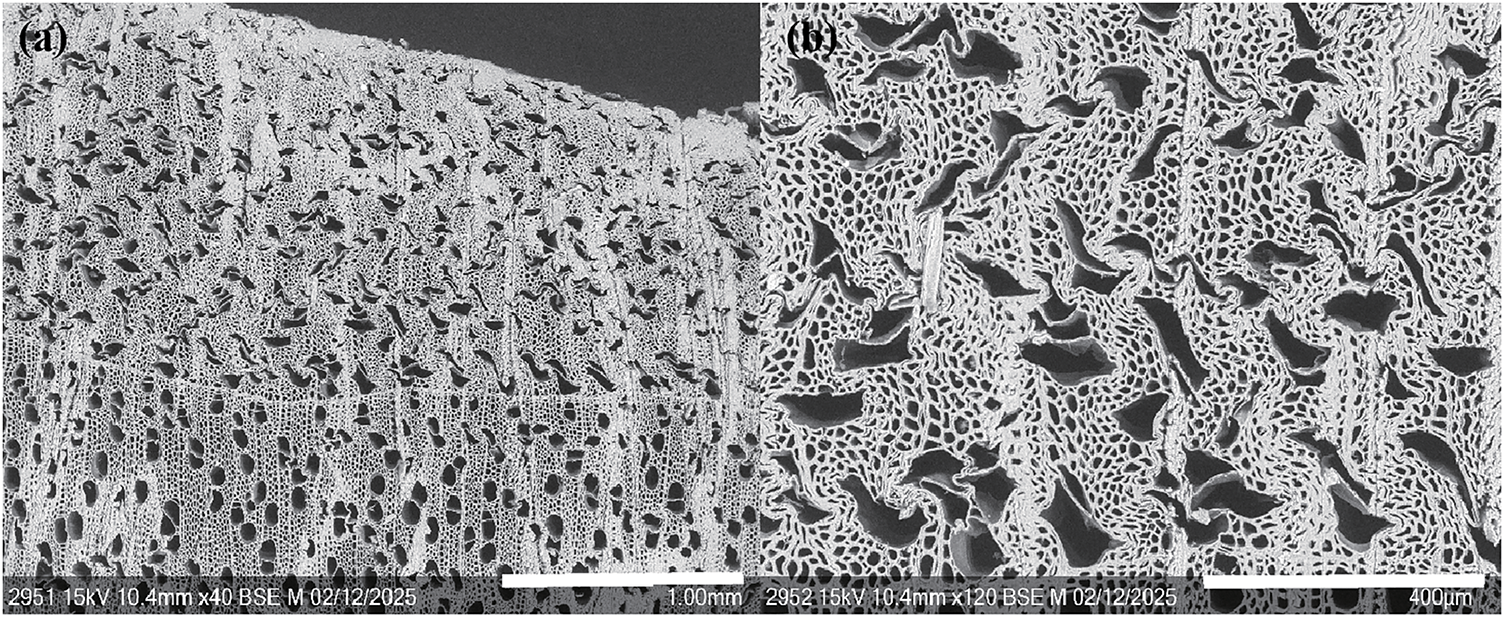

The results of internal structure investigations by SEM for samples after storage are presented below. The study was realized for two variants of processing parameters: the minimum (Δ = 1.8) – images are presented in Fig. 6 for different magnifications, and the maximum (Δ = 3.8) – images are presented in Fig. 7.

Figure 6: SEM images of the sample with the minimum processing parameter: (a) ×30; (b) ×80

Figure 7: SEM images of sample with the maximum processing parameter: (a) ×40; (b) ×120

As shown in Fig. 6, all deformations in the wood sample approximately 5 years after the treatment are well observed (the modification zone is indicated with arrows). Significant transverse deformation of the cells to a depth of up to 0.7 mm with a shift towards the edge of the board (in the direction of the inclination of the medullary rays) and partial deformation at a depth of 1.0 mm under the layer of undeformed cells are observed. In this case, cavities of vessels and fibers, regardless of the transverse size of the cell in the surface zone of the sample, almost disappear or take a slit-shaped form without rupture of cell membranes, and the medullary rays are curved and bent.

Fig. 7 also shows that all deformations in the wood sample after storage are well observed. In this case, significant transverse deformation of the cells to a depth of up to 3–3.5 mm with displacement towards the inclination of the core rays is present, with zigzag wrinkling when the rays are perpendicular to the surface. In addition, in this case, the cavities of vessels and fibers, regardless of the transverse size of the cell in the surface zone of the sample, almost disappear or take a slit-shaped form without rupture of the cell membranes, and the core rays are curved and bent. Thus for the maximum processing parameter, the surface structure changes are stronger and occur at greater depths, but are of the same nature.

Lignin provides the cell sheaths of wood with rigidity. The distribution of lignin in the cell sheath is non-uniform: in formed wood, the middle lamella (ML) and the primary wall (P) are most strongly lignified; the secondary wall layers S1, S2, and S3 are characterized by lower lignin content and a predominance of cellulose and hemicelluloses, with a greater total thickness of this layer [33,34]. The high-power ultrasonic treatment softens lignin [35], reducing the rigidity of cellular shells and allowing wood compression, but does not affect cellulose-hemicellulose structures, which allows the cells to be compacted without destroying the integrity of the cell walls.

The results of SEM studies confirm that the structure of the cell walls of wood is not damaged during ultrasonic treatment. If damage to the wood cell wall structure occurs, it can potentially lead to a decrease in wood strength. In our case, all the deformations are plastic in nature and remain during storage. This fact confirms that the mechanism of ultrasonic modification includes a lignin plasticization regime that allows fixation of the compressed wood surface layer. In addition, the porosity of the surface layer of wood after treatment with the proposed ultrasonic method is reduced because of a decrease in the proportion of cell cavities, which leads to a change in the influence of external factors on the treated wood as a whole.

The stability of ultrasonic modification of the wood surface after long-term storage was investigated. Specimens of aspen (Populus tremula) were processed with different degrees of treatment by the ultrasonic method. The surface hardness was measured after processing and repeatedly after storage for more than 5 years in heated room conditions at a relative humidity of 55 ± 15%. The results of this study are important for determining the potential uses of ultrasonically modified wood as construction and finishing materials. Ultrasonic modification significantly increased the surface hardness, and the improvement was in the range of 2.4 to 3.7 times, depending upon the processing parameters. Long-term storage did not cause any significant decrease in surface hardness.

The results of SEM studies allow us to draw an important conclusion that the structure of the cell walls of wood is not damaged during ultrasonic treatment and that there is no visible damage to the structure after storage. This fact confirms that the mechanism of ultrasonic modification includes a lignin plasticization regime that allows fixation of the compressed wood surface layer. All the deformations observed in the wood surface layer were plastic in nature and remained during storage.

The results obtained confirm the potential of the ultrasonic method for wood surface modification, as the internal structure and surface hardness are characterized by stability over time.

Acknowledgement: The authors are thankful to LLC «INLAB–Ultrasonic» for their technical assistance.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Alena Vjuginova; data collection: Alena Vjuginova, Leonid Leontyev; analysis and interpretation of results: Alena Vjuginova, Leonid Leontyev; draft manuscript preparation: Alena Vjuginova, Leonid Leontyev. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Olivetti EA, Cullen JM. Toward a sustainable materials system. Science. 2018;360(6396):1396–8. doi:10.1126/science.aat6821. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Fu A, Lu Y, Wu G, Bai L, Barker-Rothschild D, Lyu J, et al. Wood elasticity and compressible wood-based materials: functional design and applications. Prog Mater Sci. 2025;147(7):101354. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2024.101354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Sandberg D, Kutnar A, Karlsson O, Jones D. Wood modification technologies: principles, sustainability, and the need for innovation. 1st ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2021. doi:10.1201/9781351028226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hill CAS. Wood modification: chemical, thermal and other processes. Chichester, UK: Wiley and Sons; 2006. doi:10.1002/0470021748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zelinka SL, Altgen M, Emmerich L, Guigo N, Keplinger T, Kymäläinen M, et al. Review of wood modification and wood functionalization technologies. Forests. 2022;13(7):1004. doi:10.3390/f13071004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mubarok M, Gérardin-Charbonnier C, Azadeh E, Akong FO, Dumarçay S, Pizzi A, et al. Modification of wood by tannin-furfuryl alcohol resins-effect on dimensional stability, mechanical properties and decay durability. J Renew Mater. 2023;11(2):505–21. doi:10.32604/jrm.2022.024872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang B, Pizzi A, Petrissans M, Petrissans A, Colin B. A melamine-dialdehyde starch wood particleboard surface finish without formaldehyde. J Renew Mater. 2023;11(11):3867–89. doi:10.32604/jrm.2023.028888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ni M, Li L, Wu Y, Qiao J, Qing Y, Li P, Zuo Y. Biobased furfurylated poplar wood for flame-retardant modification with boric acid and ammonium dihydrogen phosphate. J Renew Mater. 2024;12(8):1355–68. doi:10.32604/jrm.2024.054050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Grosse C, Noël M, Thévenon M, Rautkari L, Gérardin P. Influence of water and humidity on wood modification with lactic acid. J Renew Mater. 2018;6(3):259–69. doi:10.7569/JRM.2017.634176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Hill CAS, Altgen M, Rautkari L. Thermal modification of wood—a review: chemical changes and hygroscopicity. J Mater Sci. 2021;56(11):6581–614. doi:10.1007/s10853-020-05722-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sandberg D, Kutnar A, Mantanis G. Wood modification technologies—a review. iForest. 2017;10(6):895–908. doi:10.3832/ifor2380-010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Petrič M. Surface modification of wood. Rev Adhes Adhes. 2013;2(2):216–47. doi:10.7569/raa.2013.097308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Gong M, Lamason C, Li L. Interactive effect of surface densification and post-heat-treatment on aspen wood. J Mater Process Technol. 2010;210(2):293–6. doi:10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2009.09.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Rautkari L, Laine K, Kutnar A, Medved S, Hughes M. Hardness and density profile of surface densified and thermally modified Scots pine in relation to degree of densification. J Mater Sci. 2013;48(6):2370–5. doi:10.1007/s10853-012-7019-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Teacă CA, Tanasă F. Wood surface modification—classic and modern approaches in wood chemical treatment by esterification reactions. Coatings. 2020;10(7):629. doi:10.3390/coatings10070629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Inoue M, Norimoto M, Otsuka Y, Yamada T. Surface compression of coniferous wood lumber I. A new technique to compress the surface layer. Mokuzai Gakkaishi. 1990;36(11):969–75. [Google Scholar]

17. Rautkari L, Properzi M, Pichelin F, Hughes M. Surface modification of wood using friction. Wood Sci Technol. 2009;43(3-4):291–9. doi:10.1007/s00226-008-0227-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ma Z, Wu Y, Wang H, Yuan S, Zhang J. Research on the hydrophobic performance of bamboo surface treated via coordinated plasma and PDMS solution treatments. J Renew Mater. 2025;13(5):931–55. doi:10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Tarkow H, Seborg R. Surface densification of wood. For Prod J. 1968;18(9):104–7. doi:10.5555/19680604746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Neyses B. Surface densification of solid wood: paving the way towards industrial implementation [dissertation]. Luleå, Sweden: Lulea University of Technology; 2019 [cited 2025 Jun 22]. Available from: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1347640&dswid=6736. [Google Scholar]

21. Sadatnezhad SH, Khazaeian A, Sandberg D, Tabarsa T. Continuous surface densification of wood: a new concept for large-scale industrial processing. BioResources. 2017;12(2):3122–32. doi:10.15376/biores.12.2.3122-3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Scharf A, Neyses B, Sandberg D. Continuous densification of wood with a belt press: the process and properties of the surface-densified wood. Wood Mater Sci Eng. 2023;18(4):1573–86. doi:10.1080/17480272.2023.2216660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Bazarov S, Guryanov A, Legusha F, Pugachev S, Inventors. Method of compression and molding of raw wood articles and a device to implement. Russia Patent RU2089385C1; 1997 Sep 10 [cited 2025 Jun 22]. (In Russian). Available from: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2089385C1/ru?oq=RU2089385C1+. [Google Scholar]

24. Sun-Tae An, Inventors. Method and apparatus for increasing the hardness and intensity of wood. Russia Patent WO2000013865A3; 2000 Oct 26 [cited 2025 Jun 22]. (In Russian). Available from: https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2000013865A3/en?oq=WO2000013865A3. [Google Scholar]

25. Pizzi A, Leban JM, Zanetti M, Pichelin F, Wieland S, Properzi M. Surface finishes by mechanically induced wood surface fusion. Holz Als Roh-Und Werkst. 2005;63(4):251–5. doi:10.1007/s00107-004-0569-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ivanov V, Novik A, Novik A, Novik A, Inventors. Apparatus for ultrasonic treatment of wood. Russia Patent RU2419537C1; 2011 May 27 [cited 2025 Jun 22]. (In Russian). Available from: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2419537C1/en?oq=RU2419537. [Google Scholar]

27. Vjuginova A, Vjuginov S, Inventors. pparatus for ultrasonic treatment of lumber. Russia Patent RU130909U1; 2013 Aug 10 [cited 2025 Jun 22]. (In Russian). Available from: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU130909U1/en?oq=RU130909. [Google Scholar]

28. Vjuginova AA, Novik AA, Vjuginov SN, Ivanov VA. Ultrasonic modification for improvement of wood-Surface properties. Wood Mater Sci Eng. 2021;18(1):193–200. doi:10.1080/17480272.2021.2006778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Vjuginova A, Vjuginov S, Novik A, Inventors. Apparatus for ultrasonic modification of sawn timber. Russia Patent RU213732U1; 2022 Sep 27 [cited 2025 Jun 22]. (In Russian). Available from: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU213732U1/en?oq=RU213732U1. [Google Scholar]

30. Vjuginova AA, Baranov AD, Vjuginov SN. Improvement of thermally modified oak wood surface hardness by ultrasonic treatment. In: Proceedings of the 2023 Seminar on Fields, Waves, Photonics and Electro-optics: Theory and Practical Applications (FWPE); 2023 Nov 21; Saint Petersburg, Russia. doi:10.1109/FWPE60445.2023.10368484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Vjuginova AA, Teplyakova AV, Popkova ES. Acoustic properties of aspen wood (Populus tremulamodified by ultrasonic method. Russ J Nondestruct Test. 2023;59(1):33–9. doi:10.1134/S1061830923700195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Neyses B, Sandberg D. Application of a new method to select the most suitable wood species for surface densification. In: Proceedings of the New Horizons for the Forest Products Industry: 70th Forest Products Society International Convention; 2016 Jun 26–29; Portland, OR, USA. [Google Scholar]

33. Kollmann F, Cote W. Principles of wood science and technology: Ⅰ solid wood. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1984 [cited 2025 Jun 22]. Available from: https://www.google.ru/books/edition/_/EUuOzgEACAAJ?hl=ru&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjGjc6a99yNAxV3GxAIHfLPH3oQre8FegQIDxAL. [Google Scholar]

34. Hon D, Shiraishi N. Wood and cellulosic chemistry. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL USA: CRC Press; 2000. doi:10.1201/9781482269741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Bucur V. Acoustics of wood. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2025. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-70209-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools