Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Thermal Insulation Performance of Natural Fibre-Reinforced Composites—A Comprehensive Review

Mechanical & Production Engineering Department, University of Mauritius, Réduit, 80837, Mauritius

* Corresponding Author: Raviduth Ramful. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Eco-friendly Wood-Based Composites: Design, Manufacturing, Properties and Applications – Ⅱ)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2026, 14(1), 7 https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0116

Received 25 June 2025; Accepted 09 September 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

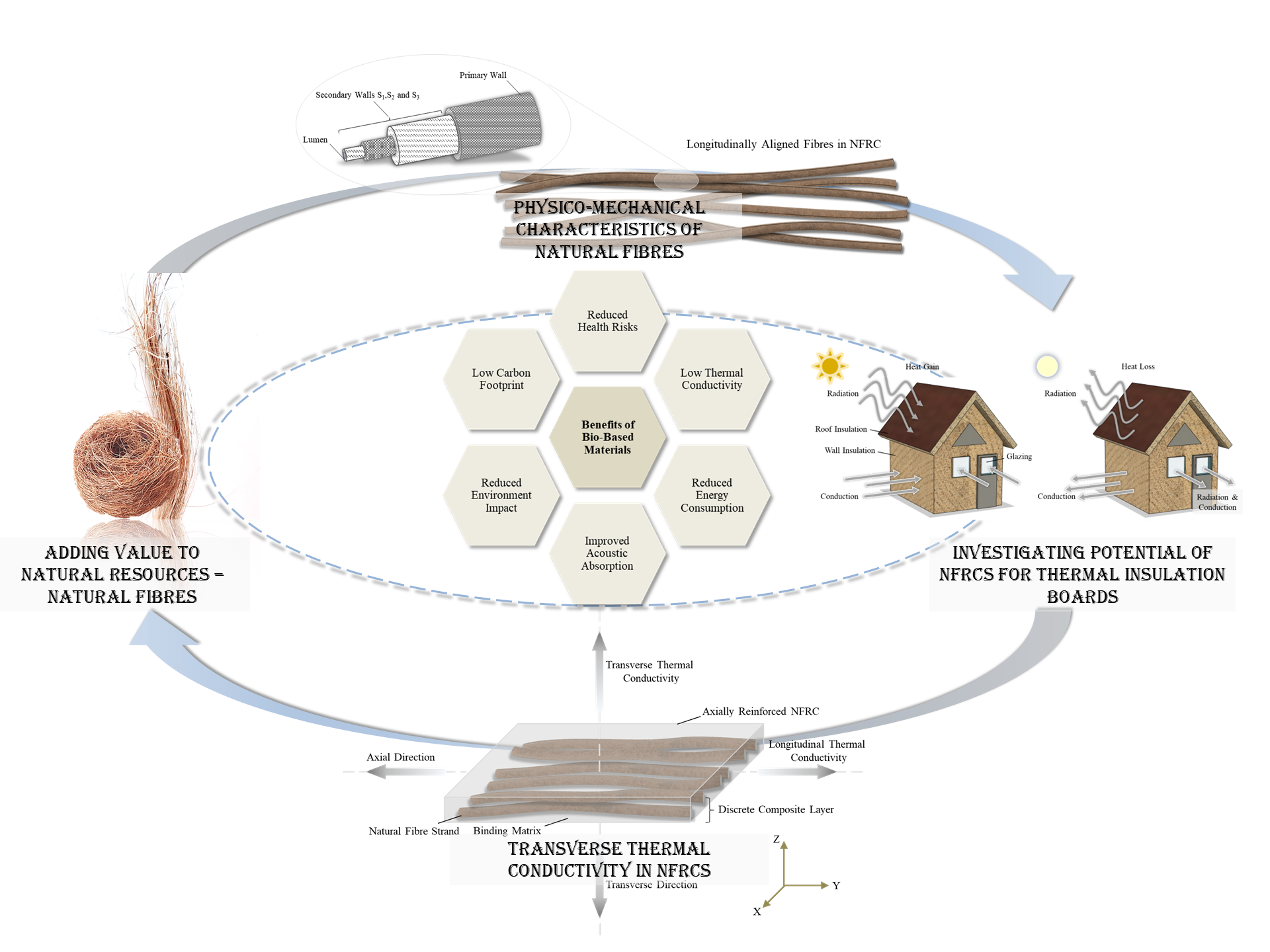

Typically used thermal insulation materials such as foam insulation and fibreglass may pose notable health risks and environmental impacts thereby resulting in respiratory irritation and waste disposal issues, respectively. While these materials are affordable and display good thermal insulation, their unsustainable traits pertaining to an intensive manufacturing process and poor disposability are major concerns. Alternative insulation materials with enhanced sustainable characteristics are therefore being explored, and one type of material which has gained notable attention owing to its low carbon footprint and low thermal conductivity is natural fibre. Among the few review studies conducted on Natural Fibre Reinforced Composite (NFRC) insulation boards, the multitude of factors and underlying mechanisms affecting their thermal conductivity performance have been sparsely covered. This review study aimed to address this gap by providing a holistic overview of some of the key intrinsic and extrinsic factors affecting the thermal conductivity performance of NFRCs. Key intrinsic factors pertaining to the microstructural features and to the physico-mechanical traits of NFRCs, namely the fibre lumen size, α, and the fibre-matrix thermal conductivity ratio, β, respectively, were found to largely affect the Transverse Thermal Conductivity (TTC) in NFRC boards. Extrinsic factors, which were found to indirectly affect NFRCs’ thermal conductivity, such as fibre pre-processing, composite manufacturing and environmental factors, were also covered. Some of the noteworthy NFRC features which were found to affect their thermal conductivity are volume fraction of fibres, bulk density and porosity. The findings of this study highlight the need for additional research investigation to address the foregoing limitations observed in NFRC thermal insulation boards by considering appropriate natural fibres, composition and fabrication techniques. The fabrication of high-grade NFRC boards, which will display an optimum balance between enhanced thermal insulation and long-term durability performance, could further replace conventionally used thermal insulation boards in the modern building and construction industry.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

One booming sector in which greener materials are required to curb its environmental impacts is the building and construction industry. An estimated two-fifths of the carbon footprint is attributed to the building and construction industry which is predominantly associated with the operational emissions and production of key materials requiring carbon-intensive processes such as cement and steel [1]. To reduce environmental impact and promote the concept of circular economy, eco-friendly materials with reduced carbon footprints, such as natural fibre composites, are necessary. Typical components in the building and construction industry which can be manufactured from natural fibre composites include structural elements such as roofing sheets, door frames, multi-purpose panels and other load-bearing elements [2,3].

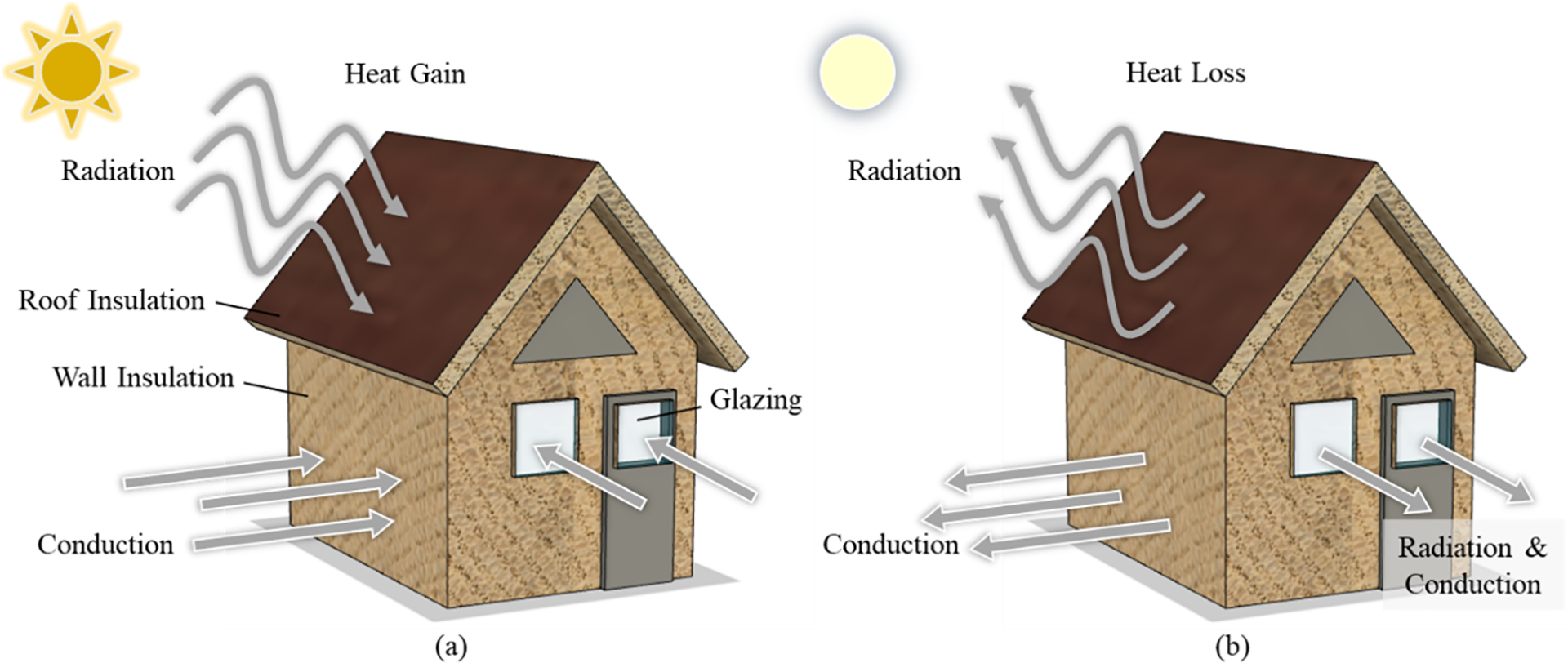

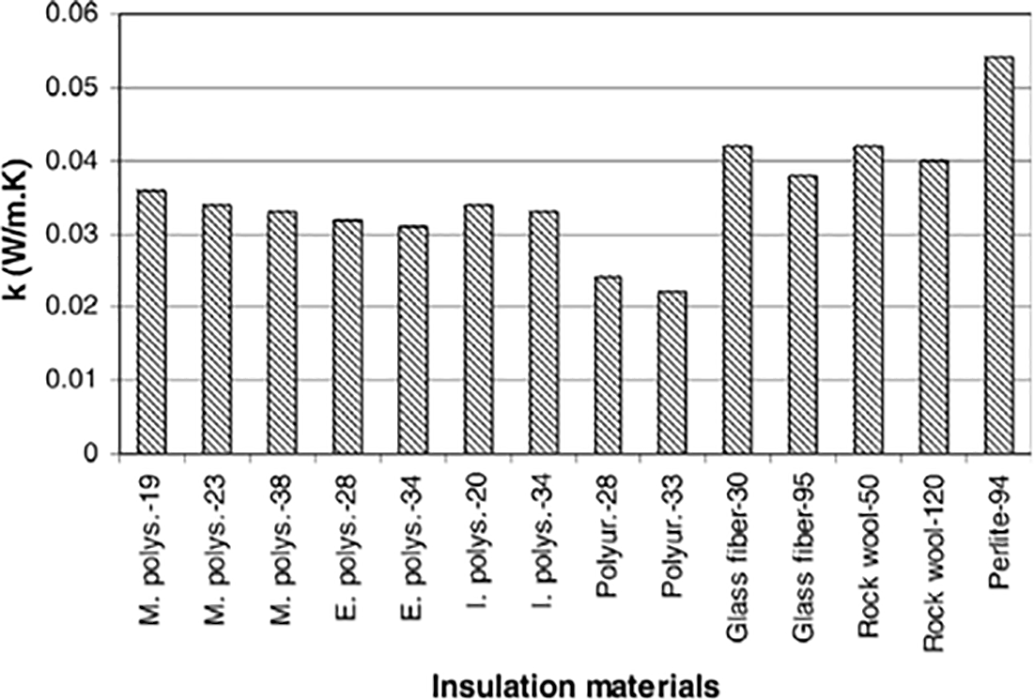

One essential component which is required in modern building design and construction to cope with the harsh weather patterns occurring due to climate change, is thermal insulation board [4]. Thermal insulation boards play an important role in the building envelope and are generally fitted in the roof and wall sections of modern constructions, as displayed in Fig. 1. These boards are utilized to act as a physical barrier between the exterior and interior environments of buildings, and their primary function is to control heat transfer [4]. Besides addressing thermal comfort in buildings, the use of proper thermal insulation minimizes heat transfer, thereby rendering buildings more energy-efficient and reducing the need for additional heating and cooling. Some of the conventionally used thermal insulation boards are made of polystyrene, glass fibre or rock wool owing to their low thermal conductivity performance, as indicated in Fig. 2 [5]. The efficiency of recently developed advanced insulation panels, such as the Vacuum Insulation Panels (VIPs) [6] and wood-based sandwich panel [7], was found to hinge on the thermal conductivity of the core material and of their surrounding layers.

Figure 1: Thermal insulation boards are fitted in the roof and wall sections of modern constructions to minimize heat gains and losses in: (a) warm and (b) cold climates, respectively

Figure 2: Summary bar chart displaying the thermal conductivity of typical insulation materials used in the building and construction industry, namely molded polystyrene, extruded polystyrene, injected polystyrene, polyurethane board, glass fibre, rock wool and perlite. Reprinted/adapted with permission from reference [5]. Copyright 2006, Elsevier

Presently used insulation panels, which are made of conventional materials like fibreglass and foams, have notable drawbacks in terms of health risks and environmental impacts [8]. In the recent past, loose-fill asbestos insulation, which was widely utilized in older residential buildings, was known to lead to serious health complications [9]. Besides, long-term exposure to presently used insulation materials such as mineral wool, fibreglass and foams, has also been reported to result in health issues leading to skin irritation and respiratory complications [10]. Moreover, both fibreglass and foam-based insulation materials have high environmental impacts given their intensive process of production and poor disposability attributes, respectively [11]. Other limitations associated with fibrous-type insulation are their propensity to trap and absorb moisture content in hot-humidity environments thereby leading to an increase in heat transfer and energy inefficiencies [12,13].

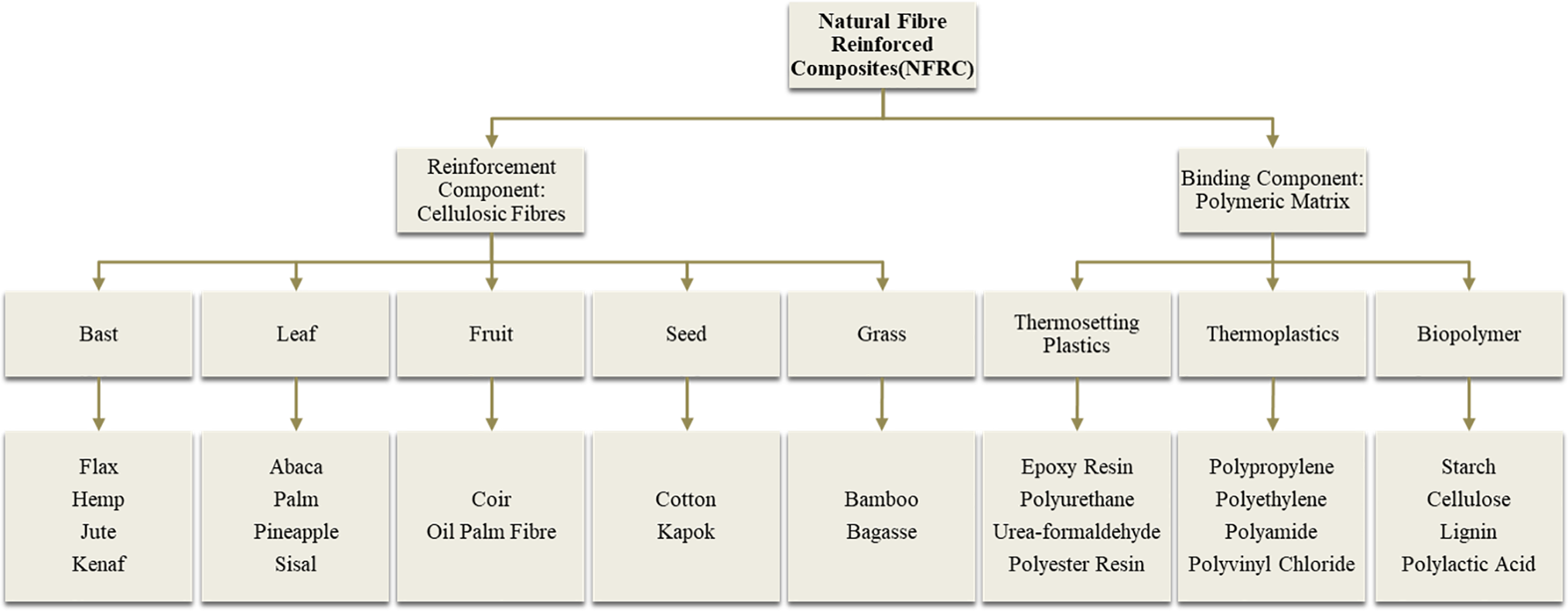

One potential alternative and eco-friendly material which can address the foregoing issues is Natural Fibre-Reinforced Composites (NFRCs) [14,15]. As one of the main reinforcement components in NFRCs, natural fibres offer numerous benefits to manufacturers based on their ubiquitous presence in the environment, affordability, disposability and sustainability traits [16,17]. In terms of sustainability, natural fibres have zero environmental impacts, are renowned for their inherent biodegradability and act as carbon sinks when integrated into products [18,19]. As a result, NFRCs have been increasingly considered in both engineering and non-engineering applications for the automotive industry [20] and for the food packaging industry, respectively [21]. The use of natural fibres and their hybrid composites was also hypothesized to partially reduce the dependency on synthetic fibres as reinforcing components in modern NFRCs [22]. Moreover, the use of natural fibres in insulation boards can also be derived from organic waste materials, thereby addressing environmental concerns pertaining to improper waste management [23,24]. A classification chart of typical fibre reinforcement and polymeric binders used in NFRCs is provided in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Classification chart of typical components used in NFRCs’ fabrication, namely cellulosic fibre reinforcement components and polymeric binding matrix components

Besides their numerous environmental benefits, the consideration of natural fibres in the development of insulation panels for the building and construction industry can address some of the drawbacks posed by conventional insulation panels. For instance, their integration in modern buildings can partly address the high carbon footprint associated with the construction industry [25]. The utilization of such insulation panels will provide better compatibility for humans thereby limiting the risks for health hazards. Besides negligible environmental impact, other determinant factors which can further propel their integration as insulation materials into modern engineering applications include their lightweight nature, porous structure and low thermal conductivity [26–29]. Some of the key benefits provided by bio-based thermal insulation boards are summarized in Fig. 4. Moreover, additional promising traits in NFRCs, which can be further explored and exploited in building insulation panels, are their acoustic performance [30,31] and fire resistance [32]. Fire resistance, which encompasses flame resistance and flame retardancy, is a paramount factor normally considered to ensure the fire safety of modern building design [32,33]. Flame resistance and flame retardancy, which refer to the material’s ability to resist ignition and spread of flames, respectively, have been reported to depend on multitude of factors ranging from the volume fraction of fibres [33,34] to the heat release rate of fibres [32,35]. Moreover, both the flame resistance and flame retardancy of NFRCs can be enhanced by considering specific fire-retardant additives [32,34,36–38].

Figure 4: Schematic illustration outlining some of the key benefits provided by thermal insulation boards manufactured from bio-based materials

From past review studies on NFRCs, emphasis was mainly directed on specific areas pertaining to the recent development in particular application, comprehensive investigation of their fibre-matrix composition and corresponding physico-mechanical performance and durability attributes [3,20,21,28,39–43]. Moreover, even though few review studies have been conducted on NFRC thermal insulation boards, the numerous factors and underlying mechanisms affecting their thermal conductivity performance have only been sparsely covered [24,34,36]. This study was therefore conducted to review the latest advancements made in the development of eco-friendly thermal insulation boards for the building and construction industry by considering NFRCs. The key physical and mechanical characteristics of natural fibres affecting the thermal conductivity performance of NFRC boards were first reviewed and discussed. In the second part of this study, key extrinsic factors which were found to indirectly affect NFRCs’ thermal conductivity performance, namely pre-processing stage of fibres, manufacturing-related factors and environmental factors were further examined. The key findings of this review study will be useful to material scientists and designers as they will shed light on the latest progress made in the utilization of natural fibres for the development of thermal insulation boards while revealing new opportunities for further research and development.

2 Thermal Conductivity of Typical NFRCs

The thermal conductivity, normally measured in Wm−1K−1, is one of the essential parameters to assess the heat flow through a material [44]. Several methods have been considered in past studies to measure the thermal conductivity of NFRCs, namely via the guarded hot plate method [45], specialized sensors such as the Modified Transient Plane Source (MTPS) sensor [46], the thermal conductivity ring probe method [47] and via thermocouples [48]. In other studies, advanced heat flow meter [49] and laser-operated thermal conductivity equipment, such as the Fox-304 LaserComp [50], were utilized to investigate the thermal conductivity characteristics of fibrous insulation materials.

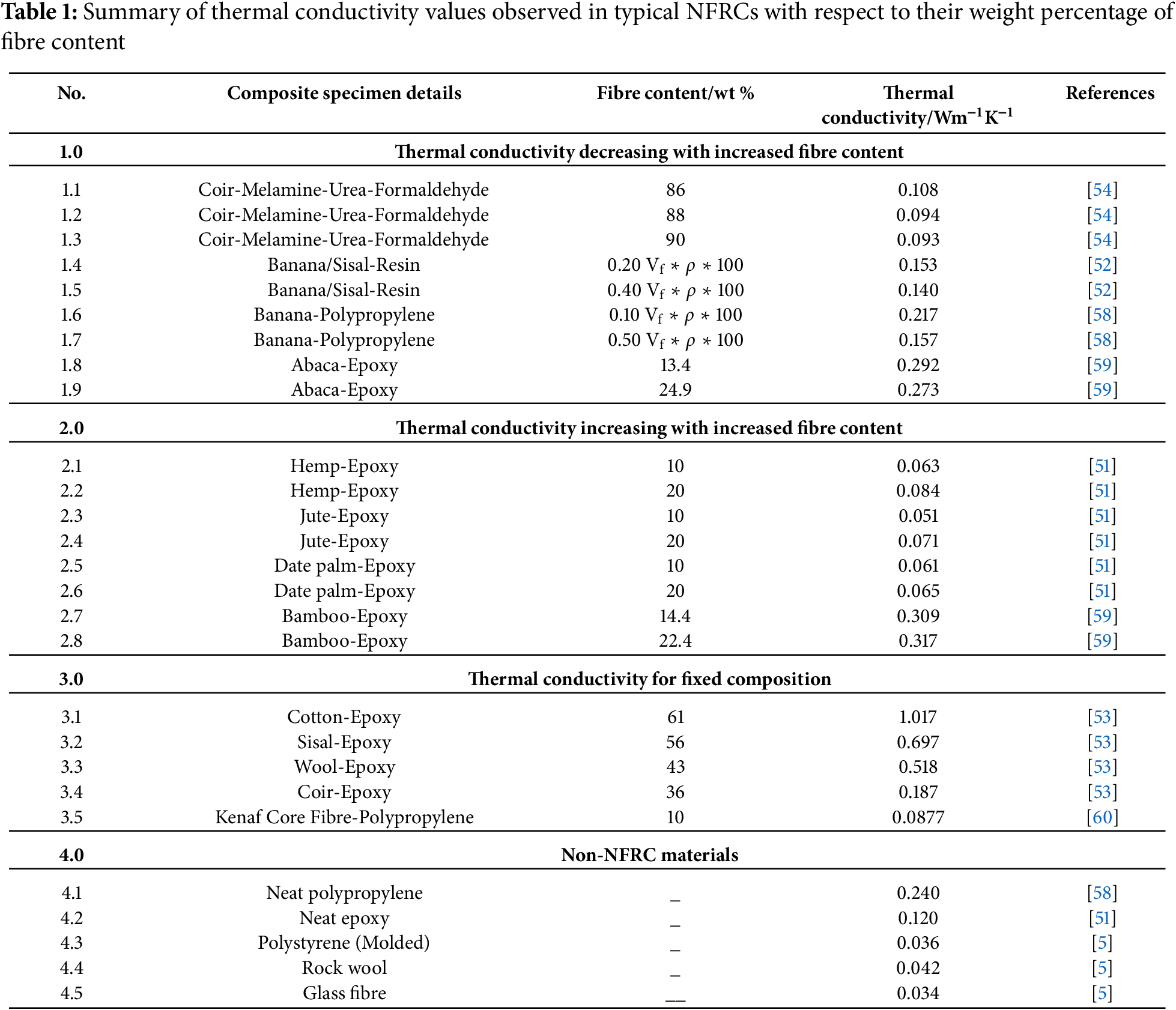

As reviewed from past literature, polymeric resin-based composite materials reinforced with natural fibres have shown satisfactory thermal insulation characteristics even though the thermal conductivity of neat epoxy material was reported to be around 0.120 Wm−1K−1 (Alazzawi et al., 2024). The thermal conductivity for NFRCs was found to range between 0.050 and 0.150 Wm−1K−1 for those having a weight percentage of fibre content not exceeding 20% [51,52]. The thermal conductivity of banana-sisal resin composite was reported to be 0.153 Wm−1K−1 for a volume fraction of fibre content of 0.20 [52]. In another study for instance, a higher thermal conductivity value of 0.187 Wm−1K−1 was observed in coir-epoxy composite having a weight percentage of fibre content of 36% [53]. The thermal conductivity performance observed in typical NFRCs with respect to their weight percentage of fibre content is summarized in Table 1.

In other studies, the thermal conductivities of typical NFRCs such as hemp-, jute- and date palm-epoxy composites with a weight percentage of fibre content of 10% were found to be approximately 0.063, 0.051 and 0.061 Wm−1K−1, respectively [51]. Interestingly, the thermal conductivities of the foregoing composite were found to increase by 5% to 35% with an increase in weight percentage of fibre content from 10% to 20% [51]. A similar trend was observed in other NFRCs whereby the weight percentage of fibre content was greater than 20% [53]. For instance, cotton-, sisal- and wool-epoxy composite having a weight percentage of fibre content of 61%, 56% and 43%, respectively, displayed corresponding thermal conductivity values of 1.017, 0.697 and 0.518 Wm−1K−1, respectively [53].

Moreover, a significantly lower thermal conductivity value of 0.093 Wm−1K−1 was observed with respect to the high weight percentage of fibre content of 90% in coir-melamine-urea-formaldehyde composite [54]. This notable variation was attributed to the nature of both the fibre and matrix components and their interaction. As a general observation, an increase in fibre content in most NFRCs was found to result in a reduction in the thermal conductivity based on the fact that the natural fibre reinforcement component tends to display notably lower thermal conductivity performance than the binding matrix material [50,51,55,56]. Another observation along the same line revealed that the thermal conductivity in one type of NFRC decreased from 0.166 to 0.159 W/mk as the wt % of fibre content increased from 10% to 40% [56].

Being an orthotropic material, the thermal conductivity in NFRCs normally varies with respect to the fibre direction. The thermal conductivity measured in-plane direction was found to be much greater than measurements taken perpendicular to the fibre direction [57]. Moreover, the notable disparity observed in the thermal conductivity of various NFRCs with respect to their increasing weight percentage of fibre content is further discussed in the forthcoming sections by probing further into the inherent microstructural features of the natural fibres.

3 Influence of Physical and Mechanical Characteristics of Natural Fibres on Their Thermal Conductivity Performance

3.1 Microstructure of Natural Fibres

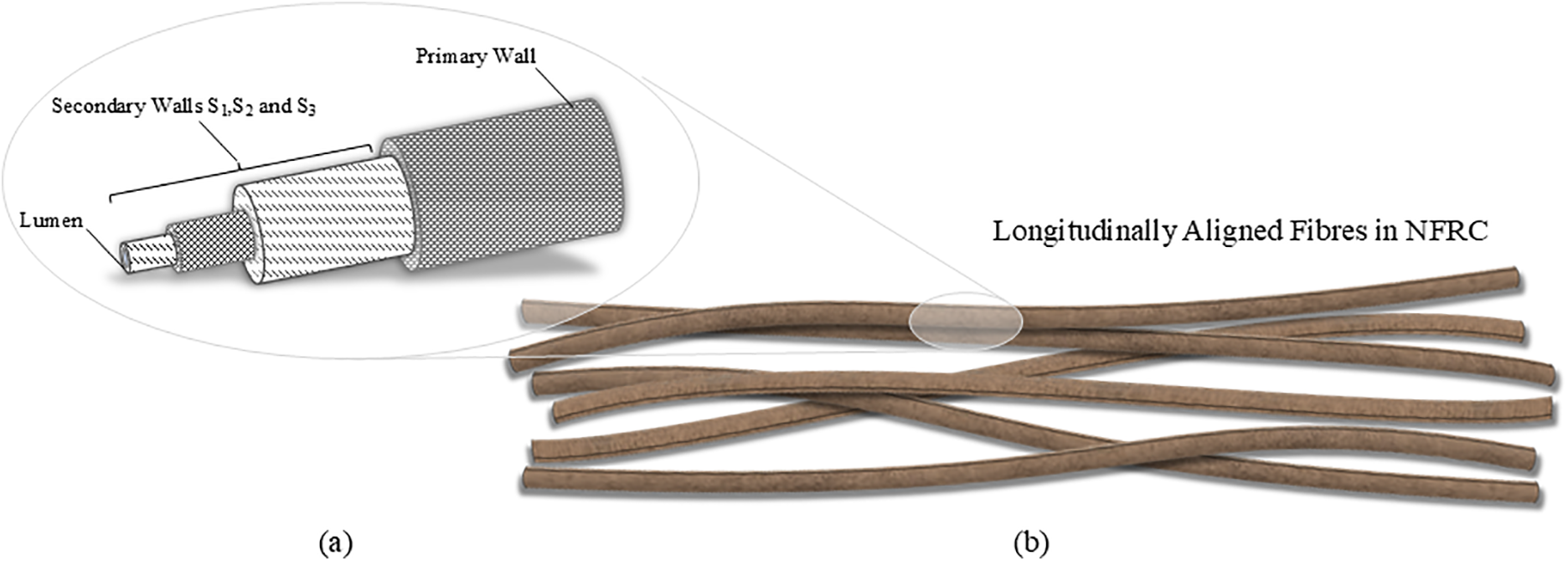

The thermal conductivity characteristic in natural fibres is the result of their unique microstructure arrangement. In general, a densely arranged microstructure free of defects tends to promote heat transfer, hence leading to higher thermal conductivity. The structure of plant cell walls is composed of several key layers, namely a primary cell wall, secondary cell walls and a central lumen section, which determine the cell’s shape while providing strength and support to the plant structure [61]. A schematic illustration of the microstructure of plant cell walls is given in Fig. 5. Both the primary and secondary cell walls are made-up of cellulose microfibrils which are strengthened by hemicellulose and lignin components [39].

Figure 5: (a) Schematic illustration of the microstructure of plant cell wall and (b) longitudinally aligned fibre bundles in NFRCs

The layered arrangements and orientation of microfibrils have a notable influence on the corresponding mechanical characteristics of the fibres [40]. From past studies, the mechanical strength in natural fibres was found to be highest when the microfibrils were primarily aligned in the fibre’s loading direction [62]. Moreover, this distinctive composition of layers’ arrangement in plant cell walls has a marked influence on the thermal conductivity performance of natural fibres which results in a direction-dependent or orthotropic behaviour [29]. As reported in another research investigation, longitudinally aligned cellulose microfibrils in the fibre direction in thick lamellae sections were found to display the highest thermal conductivity along their length [63].

3.2 Physical Characteristics of Natural Fibres

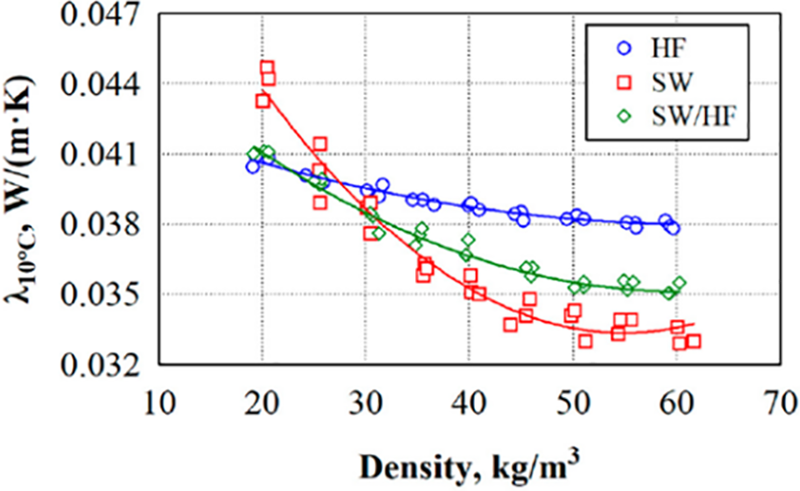

One main challenge when dealing with natural fibres is their inherent physical variability owing to several factors pertaining to their origin, plant species and maturity among other factors. These factors can notably affect some of the key physical characteristics of natural fibres such as their moisture content and density which can in turn influence their thermal conductivity performance [41]. In conditions of high humidity, an increase in moisture content was found to adversely affect the thermal insulation characteristics in bio-based materials as water molecules tend to be a good conductor of heat in comparison to air [64]. Density, on the other hand, was also found to affect the thermal conductivity of natural fibrous composite specimens as shown in Fig. 6 [65]. An increase in bulk density for instance, was found to enhance the thermal insulation characteristics of natural fibres which resulted from their reduction in thermal conductivity performance [50]. From past literature, the heat transfer distance, which is defined as the average distance between particles and related to pore size and shape, was considered to determine the rate of heat transfer in particulate-based materials. In such materials, where porosity tends to largely depend on particles’ shape and size, the heat transfer distance was found to be reduced with increasing bulk density thereby decreasing their thermal conductivity [55].

Figure 6: Variation of thermal conductivity of fibrous composite specimens, namely hemp fibres, sheep wool and equal portion of hemp and sheep wool fibre mix with respect to density. Source: [65], License CC-BY 4.0.

Being an organic material, natural fibres undergo degradation due to thermal exposure at relatively low temperatures of around 200°C thereby limiting their processing temperatures and subsequent utilization in high-temperature applications. The degradation of natural fibres was found to be closely related to the degradation of their main chemical constituents [66]. At 200°C and above, micro-constituents of natural fibres such as lignin start to degrade [67] followed by hemicellulose and cellulose which start to degrade as from 220°C and 300°C, respectively [32,68]. Moreover, when integrated in composites such as in epoxy-based NFRCs, the overall decomposition of the composite material, as evidenced from the Differential thermal analysis (DTA) curves, was found to occur at a higher temperature than the fibre reinforcement component at around 375°C [66,69,70]. Owing to their relatively high curing temperature, care must be taken when using thermoset resins in NFRC fabrication as it has a bearing on the thermal degradation of natural fibres [42]. Moreover, given the notable limitation observed in the thermal stability of natural fibres and their derived composites, their use as insulation materials in high-temperature applications such as in industrial furnaces and in automotive exhaust systems can be highly compromised.

3.3 Mechanical Characteristics of Natural Fibres and NFRCs

Besides affecting their strength-to-weight ratio, the intrinsic physico-mechanical properties of plant fibres, which are influenced by microstructural features, also affect their thermal conductivity performance. For thermal insulation boards, mechanical strength plays an important role in maintaining a high structural integrity, minimize failure and ensure consistent performance in engineering applications. From a material insulation point of view, high mechanical strength and excessive reinforcement have been postulated to enhance the material’s thermal conductivity, hence affecting its thermal insulation performance [71]. The current challenges posed to material scientists and engineers, especially in the fabrication of thermal insulation boards with NFRCs, is to develop a structurally viable material which can exhibit both satisfactory thermal insulation characteristics while having adequate mechanical properties for long-term durability [47]. Moreover, numerical modelling and other simulation techniques, which have been widely utilized in past studies to predict the elastic properties of natural fibre composites, can be considered to determine the optimum mechanical characteristics of NFRC-based insulation boards [72–74].

Some of the key mechanical attributes which are required in thermal insulation boards made from bio-based materials for use in the building and construction industry are high stiffness, tensile strength and compressive strength in order to resist external loadings and self-weight [75,76]. In recent years, advanced NFRCs with satisfactory degradability traits have been developed by considering biodegradable polymer matrices [77]. From reviewed literature, hemp-Polylactic acid (PLA), Flax-PLA, Kenaf-PLA and Ramie-PLA with random fibre orientation were found to display tensile strength and Young’s modulus ranging between 30 and 75 MPa and between 4.0 and 9.0 GPa, respectively [78]. In contrast to randomly arranged fibres, both aligned and carded fibres in NFRCs were found to display improved mechanical characteristics [79,80]. In short, the mechanical characteristics of NFRCs were affected by a multitude of factors, namely by fibre type, fibre orientation, weight percentage composition of fibre, characteristic of binding matrix and fabrication techniques among other factors [40]. Moreover, for long term durability, further mechanical testing is essential to uncover key aspects of the fracture mechanisms in NFRC thermal insulation boards ranging from crack propagation to crack growth [81,82].

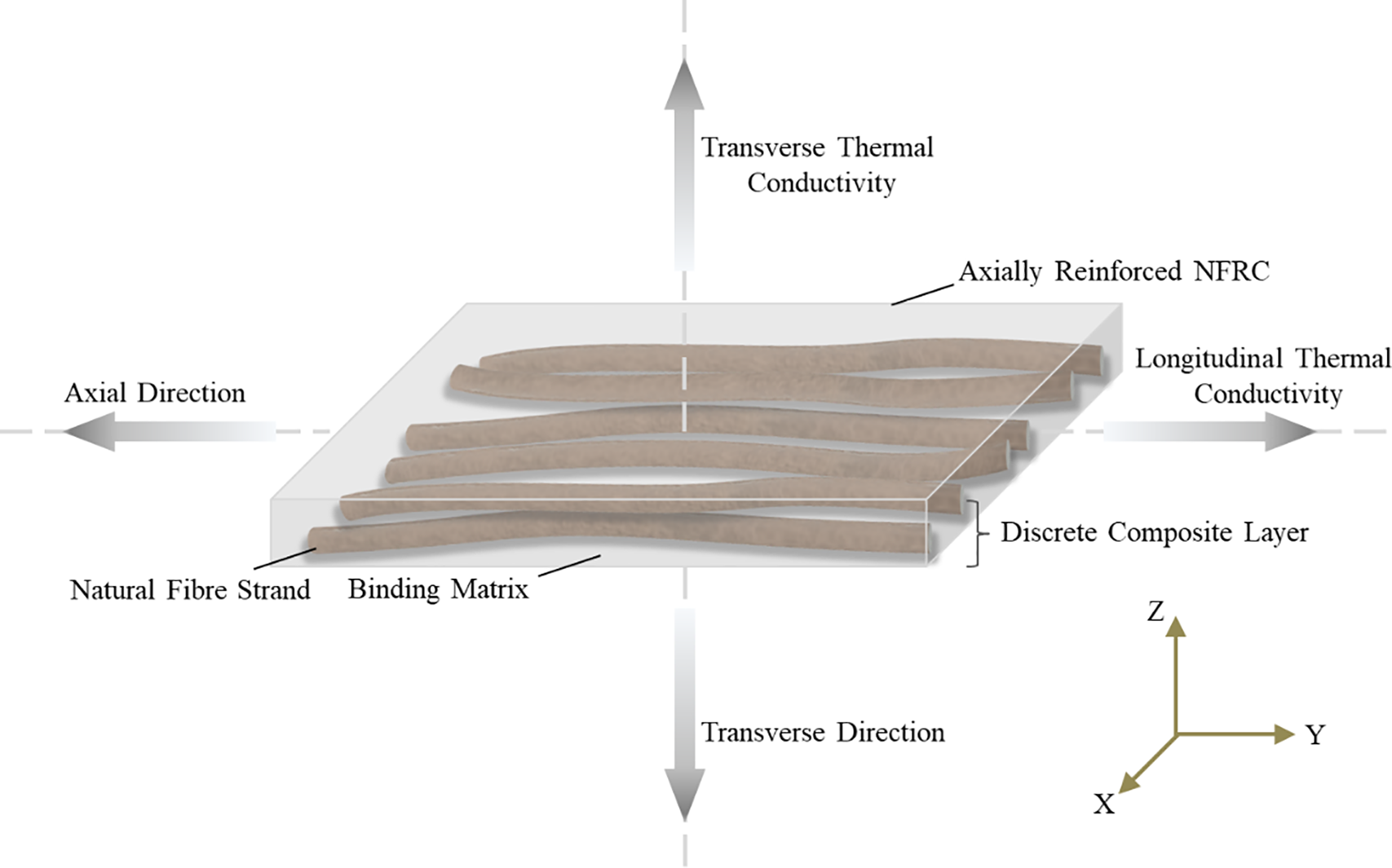

4 Transverse Thermal Conductivity in NFRCs

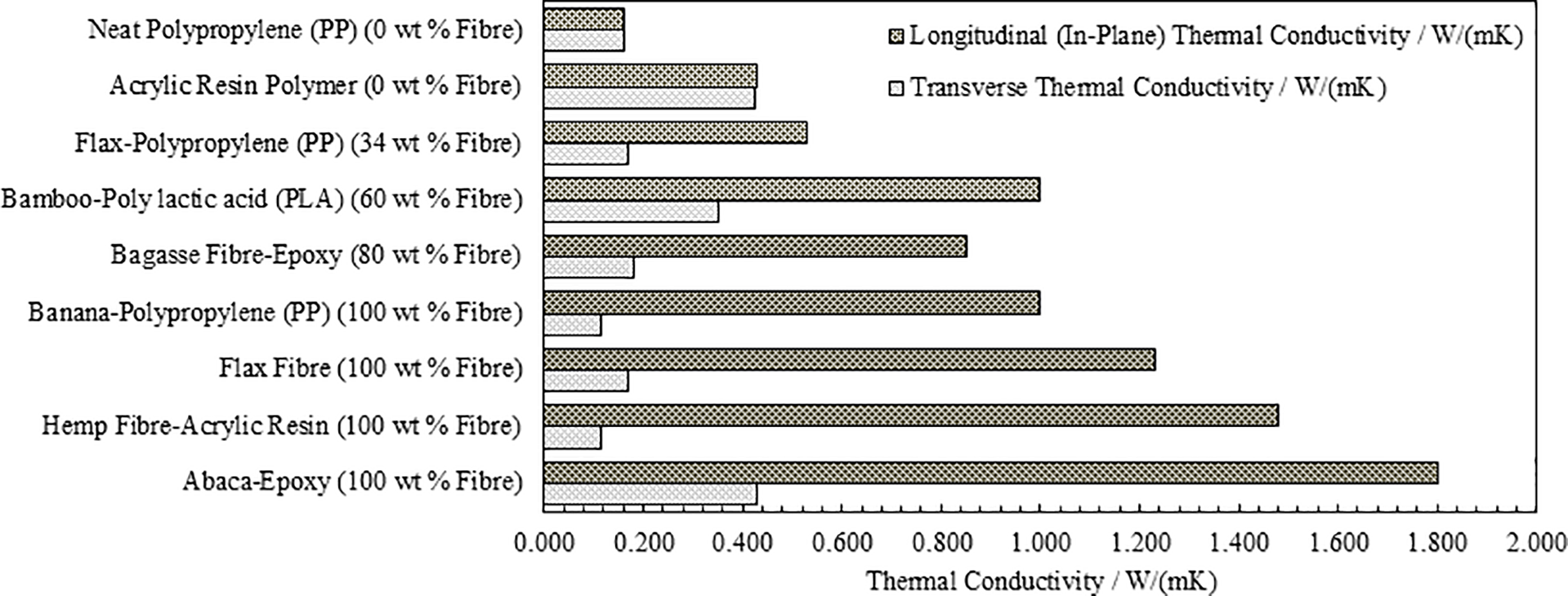

The combination of axially aligned fibre reinforcement in NFRC and the foregoing orthotropic thermal characteristic owing to the plant structure often results in a distinctive thermal behaviour which has been characterized as the transverse thermal conductivity (TTC) [29]. The TTC in NFRCs is generally measured perpendicular to the direction of the fibres as depicted in Fig. 7. The TTC in NFRCs has been reported to be affected by the inherent microstructure of plant fibres and by their arrangement [29]. In contrast to randomly reinforced composites, the TTC in axially reinforced NFRCs was reported to be lower. While this observation was mainly attributed to the unidirectional alignment of the fibres, the underlying microstructural features of the fibres were found to be determinant factors [29]. Besides, the thermal conductivity in composites reinforced with unidirectional natural fibres, such as abaca fibres for instance, was found to be greatest in the longitudinal direction and lowest in the transverse direction (Liu et al., 2012) (Liu et al., 2014). The notable disparity observed between the longitudinal thermal conductivity and the transverse thermal conductivity performance of typical NFRCs is summarized in the horizontal bar chart displayed in Fig. 8.

Figure 7: Schematic illustration depicting the principal directions for longitudinal thermal conductivity and transverse thermal conductivity in the discrete layer of NFRC

Figure 8: Summary bar chart displaying the longitudinal thermal conductivity and transverse thermal conductivity performance of typical NFRCs. Neat Polypropylene (PP) [84], Acrylic Resin Polymer [57], Flax-Polypropylene (PP) [84], Bamboo-PLA [85], Bagasse Fibre-Epoxy [86], Banana-Polypropylene (PP) [58], Flax Fibre [84], Hemp Fibre-Acrylic Resin [57], Abaca-Epoxy [29]

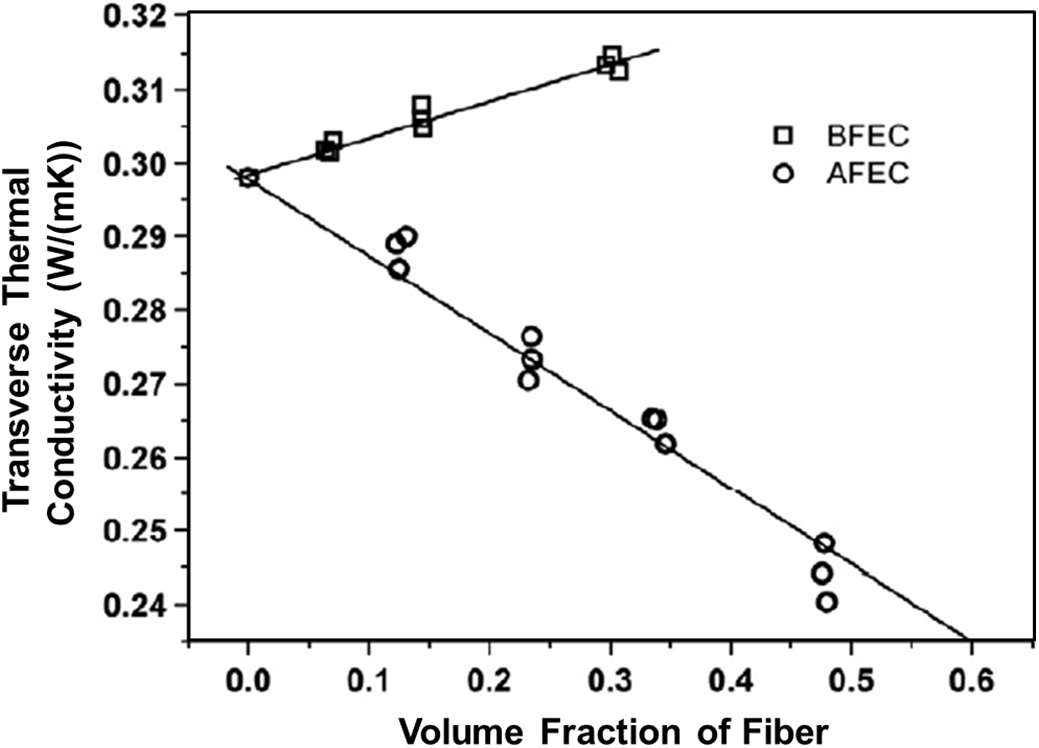

As reported in previous studies, microstructural features such as fibre cell walls and lumen sections were found to reduce the TTC in the transverse direction, an effect which further intensified with increasing fibre content [29,57,83]. Moreover, the TTC was found to further decrease with increasing size of fibres’ lumen section which acted as a natural barrier for heat transmission in NFRCs [29]. This observation could be further observed in Fig. 9, whereby the TTC of bamboo fibre epoxy composites (BFECs) and unidirectional abaca fibre epoxy composites (AFECs) increased and decreased respectively with respect to volume fraction of fibres [29]. The disparity observed in the results of these two composite specimens was attributed to their lumen sections which were found to be very small and large in bamboo fibres and abaca fibres, respectively [29].

Figure 9: Variation of transverse thermal conductivity of bamboo fibre epoxy composites (BFECs) and unidirectional abaca fibre epoxy composites (AFECs) with respect to volume fraction of fibres. Reprinted/adapted with permission from reference [29]. Copyright 2012, Elsevier

Several models have been formulated to investigate the TTC performance in unidirectional NFRCs. For instance, the numerical modelling of the TTC behavior of Manila-hemp fibre in the solid region (Ksf) has shown a large dependency on the fibre’s features such as lumen size in contrast to the lumen’s shape and distribution across the fibre’s cross-section (Liu et al., 2011). In another study, investigation about the TTC in unidirectional NFRCs by considering the two-dimensional Square Arrayed Pipe Filament (SAPF) unit cell model, has shown that the transverse thermal insulation properties tend to originate from the inherent morphological features of natural fibres [59]. The results demonstrated that the key factors affecting the TTC are the lumen size of the natural fibre (α) and the fibre-to-matrix thermal conductivity ratio (β) [59]. The TTC was observed to be inversely proportional with respect to parameter α and somewhat proportional with respect to the parameter β [59].

This observation was evidenced in another study, whereby the TTC of unidirectional natural composites reinforced with Manila-hemp (abaca) fibre bundles were modelled by considering the progressive Locally Exact Homogenization Theory (LEHT) [87]. In contrast to in-plane thermal conductivity, which increased in a monotonic manner with increasing volume fraction of fibres, a linear reduction in the TTC of the composite model was observed with respect to increasing percentage volume composition of hollow fibres [87]. Besides, from the investigation results, the effective TTC of the composite material was also found to decrease with an increase in size of lumen sections (α) and a reduction in thermal conductivity of hollow natural fibres (β) [87].

5 Factors Affecting the Thermal Conductivity in NFRCs

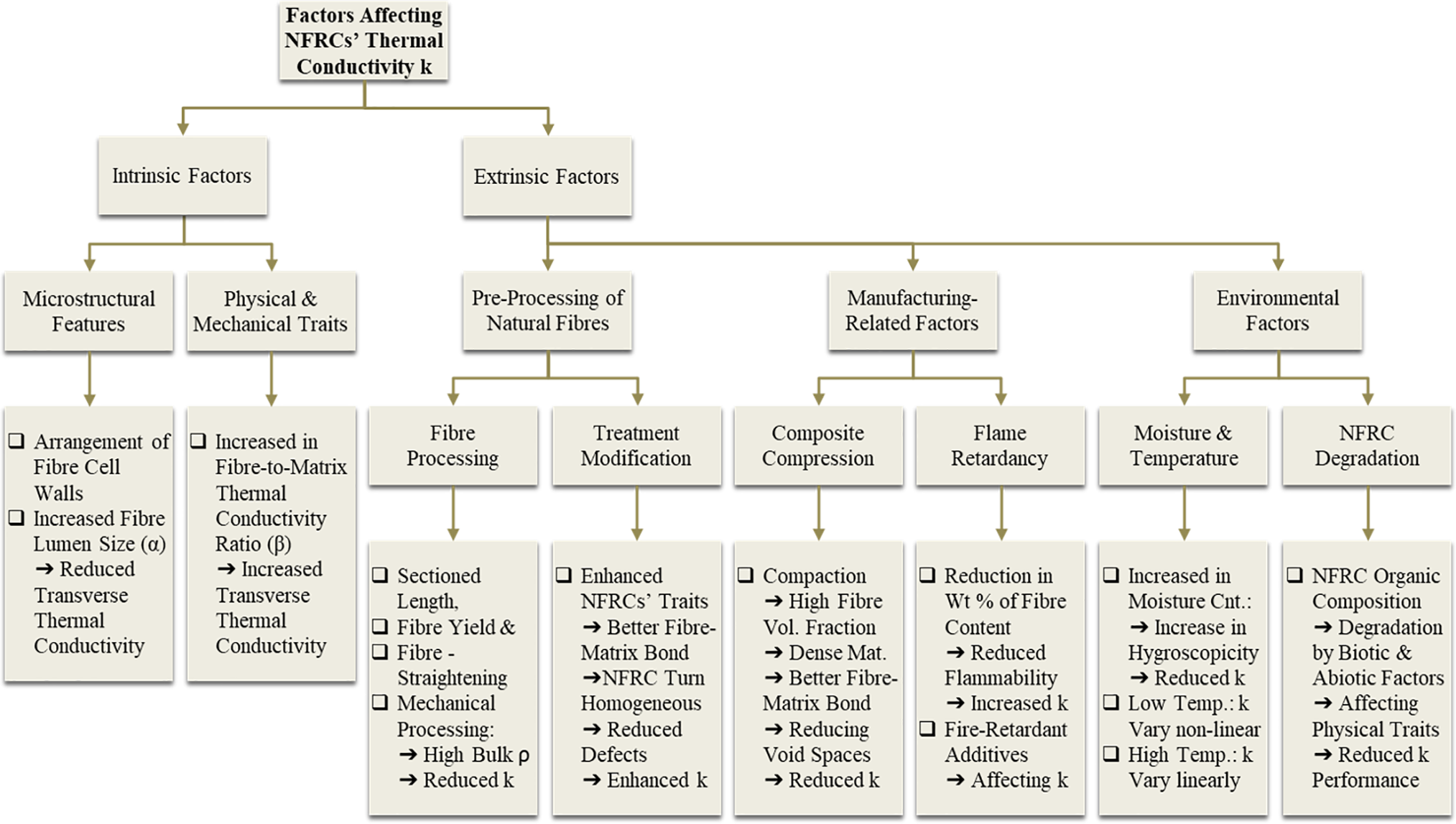

Besides intrinsic factors pertaining to microstructural features and physico-mechanical traits, the thermal conductivity in NFRCs is also largely affected by extrinsic factors such as the fibres’ pre-processing stage, manufacturing-related factors and environmental factors. A classification chart outlining some of the key intrinsic and extrinsic factors affecting the thermal conductivity performance in NFRCs is provided in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Classification chart summarizing key factors ranging from intrinsic to extrinsic factors affecting the thermal conductivity performance in NFRCs

5.1 Pre-Processing of Natural Fibres

The mechanical processing of natural fibres involving thinning, chopping and combing stages, was found to result in fibre damage thereby affecting the fibre microstructure [28,50]. The processing methods of natural fibres in terms of their sectioned length, fibre yield and fibre straightening were consequently found to affect their thermal conductivity [50]. For instance, short fibres processed via grooved rollers were found to display a thermal conductivity ranging between 0.0530 and 0.0390 W/(m · K) while chopped fibres displayed a thermal conductivity ranging between 0.0475 and 0.0420 W/(m · K) [50]. The mechanical processing of natural fibres was also found to largely affect their overall bulk density, hence leading to a decreasing thermal conductivity performance at higher density values [40,50].

Treatment modification remains one of the indispensable stages for the pre-processing of natural fibres in order to promote their usage into a wider range of applications [88]. Considerable research studies have been conducted to develop NFRCs with enhanced physico-mechanical and durability attributes by considering specific treatment modification for the natural fibre component [41,61,89–92]. Accordingly, diverse types of treatment methodologies ranging from thermal to chemical treatment methods have been developed [40,50]. While some of the thermal treatments are considered to address the physical properties by improving their dimensional stability and reducing the moisture content, chemical treatments on the other hand, are considered to enhance their mechanical properties by improving their tensile and flexural strengths [93].

Besides reducing moisture absorption, specific treatment methodologies are also employed to preserve their structural characteristics and enhance their compatibility with the matrix component [41]. Some of the typical treatment methodologies which have been considered to enhance the surface characteristics of fibres and to improve their dimensional stability include the alkaline [90]and the acetylation [89] treatments, respectively. Besides, the improvement in the fibre-matrix adhesion can lead to the formation of composite materials with homogeneous structure and consistent characteristics thereby reducing the manufacturing defects while enhancing the thermal conductivity performance. For instance, the effect of NaOH-based alkaline treatment on epoxy composite reinforced with kenaf fibres was found to enhance the fibre-matrix interfacial contact, hence resulting in improved thermal conductivity and diffusivity performance [60].

5.2 Manufacturing Related Factors

The manufacturing defects associated in the fabrication of thermal insulation boards by considering NFRCs can also result in inconsistent thermal performance. Natural fibres can pose notable challenges when integrated into NFRC boards given their inherent natural variability, geometry and surface roughness among other factors [61]. Being a naturally derived material, natural fibres have a high tendency to absorb moisture, exhibit poor dimensional stability, have limited durability and are susceptible to degrading over time in the absence of adequate treatment [61,94]. Besides, the characteristics of natural fibres can largely vary following the fibre extraction phase and treatment modification stage [93,95]. Other typical defects in NFRC boards may arise due to insufficient fibre-matrix adhesion and due to irregular dispersion and concentration of fibre bundles [41].

5.2.1 Volume Fraction and Density of Compacted Fibres

In NFRC manufacturing, the volume fraction of fibres can affect their heat transfer attributes. Even though the optimum percentage of fibre content for optimum mechanical performance does not exceed 40% in most cases, this amount can be subjected to change in thermal insulation boards [80]. Moreover, one common obstacle faced in the integration of high-volume fractions of fibres in NFRCs is poor fibre-matrix interaction due to poor interfacial strength and adhesion [41]. To overcome this challenge, specifically designed compression moudling machines are utilized under controlled pressure and temperature conditions to promote adequate fibre-matrix adhesion while reducing void spaces [43]. Accordingly, the compaction of natural fibres in a finite volume tends to naturally increase the density of the NFRC material. In densely compacted NFRCs, the thermal conductivity has been reported to be reduced [55]. Similarly, reduced thermal conductivity performance was also observed with respect to increasing density in conventional insulation materials [49].

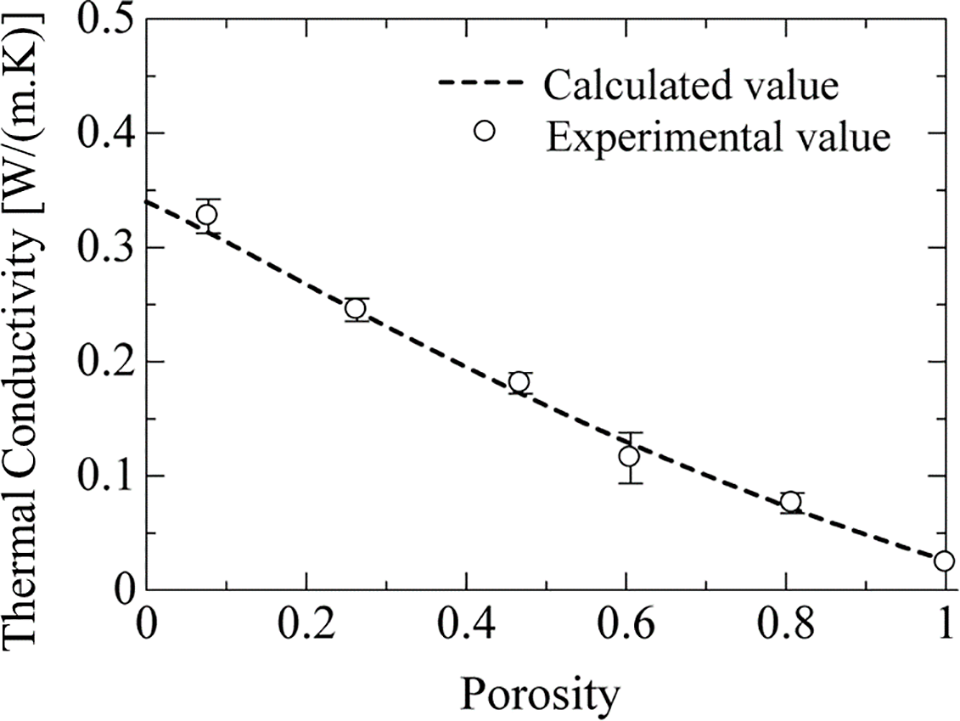

Moreover, less dense insulation materials such as loose-fill insulation were found to exhibit a reduced thermal resistance at larger temperature differences across the insulation [96]. In less dense NFRCs however, the presence of air bubbles could also increase the thermal insulation performance as air molecules are in general a poor conductor of heat. For instance, greater porosity or void content was found to occur in less dense composite specimens such as in bamboo fibre reinforced composites (BFGC) fabricated by using a reduced compaction pressure of 1.6 MPa during the hot pressing stage. The specimens with greater porosity were in turn found to display a reduced thermal conductivity performance as shown in Fig. 11 [85].

Figure 11: Variation of the thermal conductivity in bamboo fibre reinforced composites (BFGC) with respect to increased porosity (void content). Reprinted/adapted with permission from reference [85]. Copyright 2007, Taylor & Francis

Moreover, with increasing fibre content, the overall thermal conductivity of NFRC tends to decrease as the latter component displays lower thermal conductivity than typical matrix materials [51,53]. This trend about the overall decrease in the thermal conductivity of NFRCs, is also in line with the increasing bulk density of natural fibres. An increase in the bulk density, which accounts for the density of the fibre component and includes its void spaces, was found to promote a reduction in heat transfer [55]. Besides bulk density, the thermal conductivity in porous structures such as in natural fibres was found to depend on other key features pertaining to the convection of gas-phase within the fibres and radiance transmitted between the fibre wall sections [50].

5.2.2 Flame Retardancy of NFRCs

In the building and construction industry, low flammability and high fire retardancy are desirable characteristics in modern materials including NFRCs to enhance fire safety [32]. In the recent past, numerous studies have been conducted to investigate the flammability and fire resistance characteristics of natural fibres and NFRCs [32,33]. The heat release rate, which was assessed during the flammability tests, was found to be lower for bast fibres and was attributed to their reduced lignin content [32]. Moreover, the heat release rate observed in NFRC during flammability tests was also found to decrease with increasing wt % of fibre content [34]. In terms of flammability, the propensity of ignition in natural fibre composite material was reported to be greatly reduced at a volume fraction of fibres exceeding 25% [33]. The thermal decomposition of natural fibre composites is generally accompanied by blackening and blistering of the exposed surface originating from polyester residues and charred regions of the fibre laminas [33]. Moreover, the charred layers have also been reported to act as a natural insulation barrier against further thermal degradation of the remaining lignocellulosic fibres [42].

To maximize the flame retardancy and exposure time prior to ignition, specific fire-retardant additives in powder form, such as boric acid, phosphoric acid, zinc borate, and magnesium hydroxide are added to the composite in the manufacturing stage [32,34,36,37]. In another study, the addition of expandable graphite fillers having a weight percentage of 5% into NFRC was reported to significantly improve their fire resistivity characteristics [97]. Moreover, expandable graphite is a good conductor of heat and can adversely affect the insulation characteristics of NFRCs if utilized in high percentage composition [98]. Additionally, during thermal degradation of NFRC, expandable graphite fillers were found to lead to higher char generation thereby reducing both the pyrolysis reactions and thermal conductivity of burning substances [97].

In contrast to synthetic-based composites, the effect of fire-retardant additives on the thermal conductivity of NFRCs has been sparsely investigated in literature. Among the few studies, the thermal conductivity and flammability in terms of burning rate of NFRC, which were found to be 0.159 W/mk and 35 mm/min respectively for a wt % of fibre content of 40%, were found to increase and decrease respectively with a reduction in the wt % of fibre content [56]. In another study based on synthetic composites, optimum flame retardancy and thermal conductivity in epoxy-based alumina composites were achieved by incorporating 5 wt % of magnesium hydroxide and 7 wt % of graphene nanoplatelets in the composite mix, respectively [99].

5.3.1 High Temperature and Moisture Exposure

Detailed studies on the influence of interconnected environmental factors such as humidity and temperature, which can largely affect the thermal conductivity of NFRC-based insulation materials in their operating environment, are sparsely available in literature. In terms of operating temperatures for instance, the thermal conductivity was observed to vary non-linearly at low temperatures and linearly at higher temperatures above 35°C [5]. As discussed in the foregoing section, a high-temperature environment exceeding 200°C could result in thermal degradation of natural fibres thereby affecting their thermal conductivity. Moreover, an increase in temperature, even at room temperature along with high humidity conditions, can adversely affect the dimensional stability of NFRCs and their corresponding thermal conductivity behaviour.

Long term exposure to varying temperature and humidity levels in actual locations in the building envelope can greatly affect the dimensional stability of NFRCs used for thermal insulation. This can in turn affect the effectiveness of thermal insulation boards over their service lifetime, which is dependent on the thermal conductivity (k-value). In one study on fibrous insulation materials, the increase in moisture content due to a surge in the humidity level in the ambient environment, was found to affect the thermal insulation performance of insulation materials [100]. The impact of moisture content on the insulation thermal conductivity has been reported to vary in accordance with the composition, properties and internal structure of the insulation materials [12].

In hot and humid climates for instance, condensation has been reported to occur within conventional fibrous insulation materials. The increase in humidity content in the surrounding environment due to condensation led to an increase in the amount of moisture absorbed in the material thereby exceeding its hygroscopic level [12]. This has a notable impact on its thermal conductivity performance and on its k-value, which tends to increase with increasing moisture content. This trend in the increase of thermal conductivity can be explained by the fact that the presence of water molecules within the porous fibrous material, which have a k-value greater than natural fibres, tend to foster the heat transfer within the material [12].

In contrast to synthetic fibres which display satisfactory durability in various operating environments such as glass fibres, aramid fibres and carbon fibres, natural fibres on the other hand have limited durability owing to their organic composition. This composition tends to attract insects and microorganisms primarily bacteria and fungi during their service lifetime leading to biological degradation [40]. Besides, exposure to environmental conditions such as UV, rain and wind can lead to physical degradation thereby affecting the physical structure and properties of natural materials [40]. From past studies, even fully treated and modified natural fibres were found to degrade over time, though adequate preservative treatment protection can considerably curb the effects arising from both biological and physical degradation [40]. In contrast to the numerous treatment modifications devised to enhance the physico-mechanical traits of NFRCs, few treatments such as thermal modification [101], acetylation [102] and enzymatic treatments [93] have been considered to address their biological and physical degradation.

Thermal modification for instance has been reported to enhance the dimensional stability of natural fibres by lowering their moisture content and rendering them stronger. This modification was found to impart positive thermal insulation attributes in natural fibres as a reduction in moisture content generally tends to reduce the k-value [12]. Besides improving the water repellency, thermal stability and resistance to environmental degradation, the application of acetylation treatment to natural fibres, on the other hand, was also found to result in a low thermal conductivity performance which was below 0.050 W/mK [103]. While enzymatic treatment can be considered to break down the lignin content and improve their resistance to fungal and bacterial degradation [93], a reduction in lignin content can also affect the fibres’ strength while reducing their flammability given its structural contribution as a binding agent [104] and lower heat release rate, respectively [32]. Moreover, in one study the addition of kraft lignin filler particles in polypropylene-based composites was found to lead to an increase in density from 910 to 980 kg/m3 hence slightly increasing their thermal conductivity performance from 0.085 to 0.088 W/mK [60].

6 Future Work to Advance the Development of NFRC Thermal Insulation Boards

In line with the key findings obtained from this review study, some of the priority areas for future study and development on NFRC thermal insulation boards are listed in this section. Firstly, for advanced engineering applications, high-end NFRC thermal insulation boards can be devised by considering specifically modified natural fibres or hybrid mix of fibres which would attain both the high thermal insulation and mechanical performance requirements. Even though there are no specific standards for NFRCs, the ISO 6324:2024 and ISO 24260:2022 standards, which have been developed for composite material consisting of fibres and fibre mats, respectively, can be considered to evaluate their thermal insulation performance.

Advanced research and development could also be conducted on NFRC thermal insulation boards to achieve low flammability and high fire retardancy while maintaining a high thermal insulation performance in order to meet the pressing requirements of modern building design. Moreover, to maintain high and consistent performance in diverse environments with varying temperature and moisture conditions, additional research study to enhance the hydrophobic characteristics of natural fibres and their derived composites could be envisaged. Last but not least, the integration of automated technologies in key stages of NFRC fabrication from fibre processing to composite curing, could enable the close monitoring of key manufacturing-related factors affecting their thermal insulation traits such as porosity and fibre distribution.

This review study was conducted on NFRCs which could be considered as an alternative thermal insulation material to conventionally used ones, such as foam insulation and fibreglass, in the building and construction industry. The review included a holistic summary of thermal conductivity performance of recently developed NFRC boards including their notable variation with respect to the weight percentage of fibre content. To determine the suitability of NFRCs for thermal insulation boards, emphasis was mainly directed on key factors affecting their thermal insulation performance, ranging from intrinsic to extrinsic factors. Among the reviewed intrinsic factors, an increase in microstructural features such as the fibre lumen size, α, and in physico-mechanical features such as the fibre-matrix thermal conductivity ratio, β, was found to result in a decrease and increase in the TTC, respectively. Besides, the extrinsic factors covered in this study, namely fibre pre-processing, composite manufacturing and environmental factors, were also found to have indirect effects on the thermal insulation performance of NFRC boards. While fibre pre-processing factors were found to be related to fibre length, fibre yield and treatment modification, manufacturing-related factors included fibre orientation, volume fraction of fibres, fibre-matrix adhesion, bulk density and porosity among other factors. Moreover, the thermal insulation performance of NFRC boards was also found to be adversely affected by external environmental factors such as high humidity levels and degradation. Despite NFRCs having noteworthy sustainable attributes and high potential, some of the underlying factors affecting their thermal conductivity properties as highlighted through this review study should be addressed to devise high-grade thermal insulation boards with enhanced performance and durability. Besides aligning with the decarbonization policy in modern building and construction industry given their lower embodied carbon, the increasing use of NFRC thermal insulation boards will gradually reduce the heavy reliance on less eco-friendly and synthetic insulation materials.

Acknowledgement: The University of Mauritius is acknowledged for providing the necessary facilities and resources required to accomplish this research work.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hertwich EG. Increased carbon footprint of materials production driven by rise in investments. Nat Geosci. 2021;14(3):151–5. doi:10.1038/s41561-021-00690-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Rocco A, Vicente R, Rodrigues H, Ferreira V. Adobe blocks reinforced with vegetal fibres: mechanical and thermal characterisation. Buildings. 2024;14(8):2582. doi:10.3390/buildings14082582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Al-Azad N, Asril MFM, Shah MKM. A review on development of natural fibre composites for construction applications. J Mater Sci Chem Eng. 2021;9(7):1–9. doi:10.4236/msce.2021.97001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Dong Y, Kong J, Mousavi S, Rismanchi B, Yap PS. Wall insulation materials in different climate zones: a review on challenges and opportunities of available alternatives. Thermo. 2023;3(1):38–65. doi:10.3390/thermo3010003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Al-Ajlan SA. Measurements of thermal properties of insulation materials by using transient plane source technique. Appl Therm Eng. 2006;26(17–18):2184–91. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2006.04.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yue J, Liu J, Song X, Yan C. Research on the design and thermal performance of vacuum insulation panel composite insulation materials. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;64(2):105437. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2024.105437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Vladimirova E, Gong M. Advancements and applications of wood-based sandwich panels in modern construction. Buildings. 2024;14(8):2359. doi:10.3390/buildings14082359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Klemczak B, Kucharczyk-Brus B, Sulimowska A, Radziewicz-Winnicki R. Historical evolution and current developments in building thermal insulation materials—a review. Energies. 2024;17(22):5535. doi:10.3390/en17225535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Moitra S, Tabrizi AF, Machichi KI, Kamravaei S, Miandashti N, Henderson L, et al. Non-malignant respiratory illnesses in association with occupational exposure to asbestos and other insulating materials: findings from the Alberta insulator cohort. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(19):7085. doi:10.3390/ijerph17197085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Kupczewska-Dobecka M, Konieczko K, Czerczak S. Occupational risk resulting from exposure to mineral wool when installing insulation in buildings. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2020;33(6):757–69. doi:10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01637. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Dickson T, Pavía S. Energy performance, environmental impact and cost of a range of insulation materials. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;140(3):110752. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.110752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Abdou A, Budaiwi I. The variation of thermal conductivity of fibrous insulation materials under different levels of moisture content. Constr Build Mater. 2013;43(2):533–44. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.02.058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Guo H, Cai S, Li K, Liu Z, Xia L, Xiong J. Simultaneous test and visual identification of heat and moisture transport in several types of thermal insulation. Energy. 2020;197(4):117137. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.117137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Suriani MJ, Ilyas RA, Zuhri MM, Khalina A, Sultan MH, Sapuan SM, et al. Critical review of natural fiber reinforced hybrid composites: processing, properties, applications and cost. Polymers. 2021;13(20):3514. doi:10.3390/polym13203514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Samal A, Kumar S, Mural PKS, Bhargava M, Das SN, Katiyar JK. A critical review of different properties of natural fibre-reinforced composites. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part E J Process Mech Eng. 2023;19:09544089231202915. doi:10.1177/09544089231202915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. de Queiroz HFM, dos Santos NV, Neto JSS, Banea MD. Mechanical characterization of novel natural fibre-reinforced composites via a three-dimensional fibre architecture. Compos Sci Technol. 2025;261(3):110996. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2024.110996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sivaranjana P, Arumugaprabu V. A brief review on mechanical and thermal properties of banana fiber based hybrid composites. SN Appl Sci. 2021;3(2):176. doi:10.1007/s42452-021-04216-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. de Beus N, Carus M. Carbon footprint and sustainability of different natural fibres for biocomposites and insulation material [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://pantanova.nl/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/pantanova_multihemp_nova_carbon-footprint-of-natural-fibres.pdf. [Google Scholar]

19. Manohar K, Ramlakhan D, Kochhar G, Haldar S. Biodegradable fibrous thermal insulation. J Braz Soc Mech Sci Eng. 2006;28(1):45–7. doi:10.1590/s1678-58782006000100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Tyagi A, Punia U, Dadhich A, Meena SL. Global perspective of natural fibre reinforced composites: properties, and applications. J Inst Eng Ind Ser C. 2024;105(5):1335–50. doi:10.1007/s40032-024-01076-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Arman Alim AA, Mohammad Shirajuddin SS, Anuar FH. A review of nonbiodegradable and biodegradable composites for food packaging application. J Chem. 2022;2022(2):7670819. doi:10.1155/2022/7670819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Shalwan A, Alajmi A, Yousif BF. Theoretical study of the effect of fibre porosity on the heat conductivity of reinforced gypsum composite material. Polymers. 2022;14(19):3973. doi:10.3390/polym14193973. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Savio L, Pennacchio R, Patrucco A, Manni V, Bosia D. Natural fibre insulation materials: use of textile and agri-food waste in a circular economy perspective. Mater Circ Econ. 2022;4(1):6. doi:10.1007/s42824-021-00043-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Shakir MA, Ahmad MI, Ramli NK, Yusup Y, Alosaimi AM, Alorfi HS, et al. Review on the influencing factors towards improving properties of composite insulation panel made of natural waste fibers for building application. J Ind Text. 2023;53(3):1–33. doi:10.1177/15280837231151440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Karthik K, Rajamanikkam RK, Venkatesan EP, Bishwakarma S, Krishnaiah R, Saleel CA, et al. State of the art: natural fibre-reinforced composites in advanced development and their physical/chemical/mechanical properties. Chin J Anal Chem. 2024;52(7):100415. doi:10.1016/j.cjac.2024.100415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ulutaş A, Balo F, Topal A. Identifying the most efficient natural fibre for common commercial building insulation materials with an integrated PSI, MEREC, LOPCOW and MCRAT model. Polymers. 2023;15(6):1500. doi:10.3390/polym15061500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Alshahrani H, Arun Prakash VR. Effect of silane-grafted orange peel biochar and Areca fibre on mechanical, thermal conductivity and dielectric properties of epoxy resin composites. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(6):8081–9. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-02801-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Awais H, Nawab Y, Amjad A, Anjang A, Md Akil H, Zainol Abidin MS. Environmental benign natural fibre reinforced thermoplastic composites: a review. Compos Part C Open Access. 2021;4(05):100082. doi:10.1016/j.jcomc.2020.100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Liu K, Takagi H, Osugi R, Yang Z. Effect of physicochemical structure of natural fiber on transverse thermal conductivity of unidirectional abaca/bamboo fiber composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2012;43(8):1234–41. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2012.02.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Abdellah MY, Sadek MG, Alharthi H, Abdel-Jaber GT. Mechanical, thermal, and acoustic properties of natural fibre-reinforced polyester. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part E J Process Mech Eng. 2024;238(3):1436–48. doi:10.1177/09544089231157638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Das PP, Chaudhary V, Ahmad F, Manral A, Gupta S, Gupta P. Acoustic performance of natural fiber reinforced polymer composites: influencing factors, future scope, challenges, and applications. Polym Compos. 2022;43(3):1221–37. doi:10.1002/pc.26455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kozłowski R, Władyka-Przybylak M. Flammability and fire resistance of composites reinforced by natural fibers. Polym Adv Technol. 2008;19(6):446–53. doi:10.1002/pat.1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Fan M, Naughton A. Mechanisms of thermal decomposition of natural fibre composites. Compos Part B Eng. 2016;88(2):1–10. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.10.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Prabhakar MN, Shah AUR, Song JI. A review on the flammability and flame retardant properties of natural fibers and polymer matrix based composites. Compos Res. 2015;28(2):29–39. doi:10.7234/composres.2015.28.2.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Kandola BK. CHAPTER 5. flame retardant characteristics of natural fibre composites. In: Natural polymers. Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2012. p. 86–117. doi:10.1039/9781849735193-00086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Parkunam N, Ramesh M, Saravanakumar S. A review on thermo-mechanical properties of natural fibre reinforced polymer composites incorporated with fire retardants. Mater Today Proc. 2022;69(1):641–4. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2022.06.534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kozlowski R, Przybylak MW. Natural polymers, wood and lignocellulosic materials. In: Fire retardant materials. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2001. p. 293–317. doi:10.1533/9781855737464.293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Jefferson Andrew J, Sain M, Ramakrishna S, Jawaid M, Dhakal HN. Environmentally friendly fire retardant natural fibre composites: a review. Int Mater Rev. 2024;69(5–6):267–308. doi:10.1177/09506608241266302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Elfaleh I, Abbassi F, Habibi M, Ahmad F, Guedri M, Nasri M, et al. A comprehensive review of natural fibers and their composites: an eco-friendly alternative to conventional materials. Results Eng. 2023;19(3):101271. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Ramful R. Mechanical performance and durability attributes of biodegradable natural fibre-reinforced composites—a review. J Mater Sci Mater Eng. 2024;19(1):50. doi:10.1186/s40712-024-00198-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Pickering KL, Aruan Efendy MG, Le TM. A review of recent developments in natural fibre composites and their mechanical performance. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2016;83(10):98–112. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2015.08.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Saheb DN, Jog JP. Natural fiber polymer composites: a review. Adv Polym Technol. 1999;18(4):351–63. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-2329(199924)18:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ismail NF, Sulong AB, Muhamad N. Review of the compression moulding of natural fiber-reinforced thermoset composites: material processing and characterisations. Pertanika J Trop Agric Sci. 2015;38:533–47. [Google Scholar]

44. Gunawan A, Putra N, Sofia E, Sukarno R. Determining the thermal conductivity of natural fibres with axial flow method. In: AIP Conference Proceedings. Yogyakarta, Indonesia: AIP Publishing; 2024. doi:10.1063/5.0188599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Salmon D. Thermal conductivity of insulations using guarded hot plates, including recent developments and sources of reference materials. Meas Sci Technol. 2001;12(12):R89–98. doi:10.1088/0957-0233/12/12/201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Yeon S, Cahill DG. Analysis of heat flow in modified transient plane source (MTPS) measurements of the thermal effusivity and thermal conductivity of materials. Rev Sci Instrum. 2024;95(3):034903. doi:10.1063/5.0191859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Vidil L, Fiorelli J, Bilba K, Onésippe C, Arsène MA, Savastano H. Thermal insulating particle boards reinforced with coconut leaf sheaths. Green Mater. 2016;4(1):31–40. doi:10.1680/jgrma.15.00029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Chircan E, Gheorghe V, Costiuc I, Costiuc L. The effect of thermal conductivity for buildings’ composite panels including used materials on heat variation and energy consumption. Buildings. 2025;15(10):1599. doi:10.3390/buildings15101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Abdou AA, Budaiwi IM. Comparison of thermal conductivity measurements of building insulation materials under various operating temperatures. J Build Phys. 2005;29(2):171–84. doi:10.1177/1744259105056291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Stapulionienė R, Vaitkus S, Vėjelis S, Sankauskaitė A. Investigation of thermal conductivity of natural fibres processed by different mechanical methods. Int J Precis Eng Manuf. 2016;17(10):1371–81. doi:10.1007/s12541-016-0163-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Alazzawi S, Mahmood WA, Shihab SK. Comparative study of natural fiber-Reinforced composites for sustainable thermal insulation in construction. Int J Thermofluids. 2024;24(12):100839. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2024.100839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Idicula M, Boudenne A, Umadevi L, Ibos L, Candau Y, Thomas S. Thermophysical properties of natural fibre reinforced polyester composites. Compos Sci Technol. 2006;66(15):2719–25. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2006.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Tasgin Y, Demircan G, Kandemir S, Acikgoz A. Mechanical, wear and thermal properties of natural fiber-reinforced epoxy composite: cotton, sisal, coir and wool fibers. J Mater Sci. 2024;59(24):10844–57. doi:10.1007/s10853-024-09810-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Faridul Hasan KM, Horváth PG, Kóczán Z, Alpár T. Thermo-mechanical properties of pretreated coir fiber and fibrous chips reinforced multilayered composites. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):3618. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-83140-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Presley MA, Christensen PR. Thermal conductivity measurements of particulate materials: 4. Effect of bulk density for granular particles. J Geophys Res Planets. 2010;115(E7):1–20. doi:10.1029/2009JE003482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. NagarajaGanesh B, Rekha B, Yoganandam K. Assessment of thermal insulation and flame retardancy of cellulose fibers reinforced polymer composites for automobile interiors. J Nat Fibres. 2022;19(15):11021–9. doi:10.1080/15440478.2021.2009395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Behzad T, Sain M. Measurement and prediction of thermal conductivity for hemp fiber reinforced composites. Polym Eng Sci. 2007;47(7):977–83. doi:10.1002/pen.20632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Annie Paul S, Boudenne A, Ibos L, Candau Y, Joseph K, Thomas S. Effect of fiber loading and chemical treatments on thermophysical properties of banana fiber/polypropylene commingled composite materials. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2008;39(9):1582–8. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2008.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Takagi H, Nakagaito AN, Liu K. Heat transfer analyses of natural fibre composites. In: WIT Transactions on the Built Environment; 2014 Jun 9–11; Ostend, Belgium; 2014. p. 237–43. doi:10.2495/hpsm140211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Ahmad Saffian H, Talib MA, Lee SH, Tahir PM, Lee CH, Ariffin H, et al. Mechanical strength, thermal conductivity and electrical breakdown of kenaf core fiber/lignin/polypropylene biocomposite. Polymers. 2020;12(8):1833. doi:10.3390/polym12081833. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Kabir MM, Wang H, Lau KT, Cardona F. Chemical treatments on plant-based natural fibre reinforced polymer composites: an overview. Compos Part B Eng. 2012;43(7):2883–92. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2012.04.053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Ho MP, Wang H, Lee JH, Ho CK, Lau KT, Leng J, et al. Critical factors on manufacturing processes of natural fibre composites. Compos Part B Eng. 2012;43(8):3549–62. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2011.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Shah DU, Konnerth J, Ramage MH, Gusenbauer C. Mapping thermal conductivity across bamboo cell walls with scanning thermal microscopy. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16667. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53079-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Troppová E, Švehlík M, Tippner J, Wimmer R. Influence of temperature and moisture content on the thermal conductivity of wood-based fibreboards. Mater Struct. 2015;48(12):4077–83. doi:10.1617/s11527-014-0467-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Vėjelis S, Vaitkus S, Skulskis V, Kremensas A, Kairytė A. Performance evaluation of thermal insulation materials from sheep’s wool and hemp fibres. Materials. 2024;17(13):3339. doi:10.3390/ma17133339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Asim M, Paridah MT, Chandrasekar M, Shahroze RM, Jawaid M, Nasir M, et al. Thermal stability of natural fibers and their polymer composites. Iran Polym J. 2020;29(7):625–48. doi:10.1007/s13726-020-00824-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Joseph PV, Joseph K, Thomas S, Pillai CKS, Prasad VS, Groeninckx G, et al. The thermal and crystallisation studies of short sisal fibre reinforced polypropylene composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2003;34(3):253–66. doi:10.1016/s1359-835x(02)00185-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. El-Sayed SA, Khass TM, Mostafa ME. Thermal degradation behaviour and chemical kinetic characteristics of biomass pyrolysis using TG/DTG/DTA techniques. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(15):17779–803. doi:10.1007/s13399-023-03926-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Azwa ZN, Yousif BF. Characteristics of kenaf fibre/epoxy composites subjected to thermal degradation. Polym Degrad Stab. 2013;98(12):2752–9. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2013.10.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Bachtiar EV, Kurkowiak K, Yan L, Kasal B, Kolb T. Thermal stability, fire performance, and mechanical properties of natural fibre fabric-reinforced polymer composites with different fire retardants. Polymers. 2019;11(4):699. doi:10.3390/polym11040699. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Han F, Lv Y, Liang T, Kong X, Mei H, Wang S. Improvement of aerogel-incorporated concrete by incorporating polyvinyl alcohol fiber: mechanical strength and thermal insulation. Constr Build Mater. 2024;449(2):138422. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.138422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Alhijazi M, Safaei B, Zeeshan Q, Asmael M. Modeling and simulation of the elastic properties of natural fiber-reinforced thermosets. Polym Compos. 2021;42(7):3508–17. doi:10.1002/pc.26075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Alhijazi M, Safaei B, Zeeshan Q, Arman S, Asmael M. Prediction of elastic properties of thermoplastic composites with natural fibers. J Text Inst. 2023;114(10):1488–96. doi:10.1080/00405000.2022.2131352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Ramful R, Sakuma A. Investigation of the effect of inhomogeneous material on the fracture mechanisms of bamboo by finite element method. Materials. 2020;13(21):5039. doi:10.3390/ma13215039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Panyakaew S, Fotios S. New thermal insulation boards made from coconut husk and bagasse. Energy Build. 2011;43(7):1732–9. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2011.03.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Alhijazi M, Zeeshan Q, Qin Z, Safaei B, Asmael M. Finite element analysis of natural fibers composites: a review. Nanotechnol Rev. 2020;9(1):853–75. doi:10.1515/ntrev-2020-0069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Munimathan A, Muthu K, Subramani S, Rajendran S. Environmental behaviour of synthetic and natural fibre reinforced composites: a review. Adv Mech Eng. 2024;16(10):16878132241286020. doi:10.1177/16878132241286020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Yu Tao, Li Yan. Handbook of sustainable polymers: processing and applications. In: Thakur VK, Thakur MK, editors. Singapore: Jenny Stanford Publishing; 2016. p. 857–91. [Google Scholar]

79. Prashanth B.H. M, Shivakumar Gouda PS, Manjunatha TS, Banapurmath NR, Edacheriane A. Understanding the impact of fiber orientation on mechanical, interlaminar shear strength, and fracture properties of jute-banana hybrid composite laminates. Polym Compos. 2021;42(10):5475–89. doi:10.1002/pc.26239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Aruan Efendy MG, Pickering KL. Comparison of strength and Young modulus of aligned discontinuous fibre PLA composites obtained experimentally and from theoretical prediction models. Compos Struct. 2019;208(4):566–73. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.10.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Jawaid M, Thariq M, Saba N. editors. Mechanical and physical testing of biocomposites, fibre-reinforced composites and hybrid composites. UK: Woodhead Publishing; 2019. doi:10.1016/C2016-0-04437-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Ramful R. Investigation of the transverse fracture mechanisms of bamboo by the finite element method. J Mater Sci. 2022;57(11):6233–48. doi:10.1007/s10853-022-07041-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Liu K, Yang Z, Takagi H. Anisotropic thermal conductivity of unidirectional natural abaca fiber composites as a function of lumen and cell wall structure. Compos Struct. 2014;108(4):987–91. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2013.10.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Bodaghi M, Delfrari D, Lucas M, Senoussaoui NL, Koutsawa Y, Uğural BK, et al. On the relationship of morphology evolution and thermal conductivity of flax reinforced polypropylene laminates. Front Mater. 2023;10:1150180. doi:10.3389/fmats.2023.1150180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Takagi H, Kako S, Kusano K, Ousaka A. Thermal conductivity of PLA-bamboo fiber composites. Adv Compos Mater. 2007;16(4):377–84. doi:10.1163/156855107782325186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Prasanthi PP, Ramacharyulu DA, Babu KS, Madhav VVV, Chaitanya CS, Saxena KK, et al. Role of fiber orientation and design on thermal and mechanical properties of natural composite. Int J Interact Des Manuf Ijidem. 2025;19(2):1383–93. doi:10.1007/s12008-024-02042-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Zhao X, Tu W, Chen Q, Wang G. Progressive modeling of transverse thermal conductivity of unidirectional natural fiber composites. Int J Therm Sci. 2021;162:106782. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2020.106782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Elaiyarasan U, Ananthi N, Sathiyamurthy S, Vinoth V. Chemical treatments and mechanical characterization of natural fiber reinforced composite materials—a review. Int J Mater Eng Innov. 2022;13(1):1. doi:10.1504/ijmatei.2022.10045602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Zaman HU, Khan RA. Acetylation used for natural fiber/polymer composites. J Thermoplast Compos Mater. 2021;34(1):3–23. doi:10.1177/0892705719838000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Rajendran S, Palani G, Trilaksana H, Marimuthu U, Kannan G, Yang YL, et al. Advancements in natural fibre based polymeric composites: a comprehensive review on mechanical-thermal performance and sustainability aspects. Sustain Mater Technol. 2025;44(1):e01345. doi:10.1016/j.susmat.2025.e01345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Seisa K, Chinnasamy V, Ude AU. Surface treatments of natural fibres in fibre reinforced composites: a review. Fibres Text East Eur. 2022;30(2):82–9. doi:10.2478/ftee-2022-0011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Kumari N, Meena S, Chaparia M, Choudhury SP, Choubey RK, Dwivedi UK. Natural fibre reinforced composites for industrial applications. In: Polymer composites. Singapore: Springer; 2024. p. 301–27. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-2075-0_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Ferreira DP, Cruz J, Fangueiro R. Surface modification of natural fibers in polymer composites. In: Green composites for automotive applications. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2019. p. 3–41. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-102177-4.00001-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Musthaq MA, Dhakal HN, Zhang Z, Barouni A, Zahari R. The effect of various environmental conditions on the impact damage behaviour of natural-fibre-reinforced composites (NFRCs)—a critical review. Polymers. 2023;15(5):1229. doi:10.3390/polym15051229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Amel BA, Paridah MT, Sudin R, Anwar UMK, Hussein AS. Effect of fiber extraction methods on some properties of kenaf bast fiber. Ind Crops Prod. 2013;46(1):117–23. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.12.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Besant RW, Miller E. Thermal resistance of loose-fill fiberglass insulation in spaces heated from below. In: Proceedings of the Thermal Performance of the Exterior Envelope of Building II; 1981 Dec 7–10; Las Vegas, NV, USA. [Google Scholar]

97. Khalili P, Tshai KY, Kong I. Natural fiber reinforced expandable graphite filled composites: evaluation of the flame retardancy, thermal and mechanical performances. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2017;100(8):194–205. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2017.05.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Kmeťová E, Kačíková D, Jurczyková T, Kačík F. The influence of different types of expandable graphite on the thermal resistance of spruce wood. Coatings. 2023;13(7):1181. doi:10.3390/coatings13071181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Guan FL, Gui CX, Zhang HB, Jiang ZG, Jiang Y, Yu ZZ. Enhanced thermal conductivity and satisfactory flame retardancy of epoxy/alumina composites by combination with graphene nanoplatelets and magnesium hydroxide. Compos Part B Eng. 2016;98(11):134–40. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.04.062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Kochhar GS, Manohar K. Effect of moisture on thermal conductivity of fibers biological insulating materials. In: Thermal Performance of the Exterior Envelopes of Building VI; 1995 Dec 4–8; Clearwater Beach, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

101. Ramful R, Sunthar TPM, Zhu W, Pezzotti G. Investigating the underlying effect of thermal modification on shrinkage behavior of bamboo culm by experimental and numerical methods. Materials. 2021;14(4):974. doi:10.3390/ma14040974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Bari E, Morrell JJ, Sistani A. Durability of natural/synthetic/biomass fiber-based polymeric composites. In: Durability and life prediction in biocomposites, fibre-reinforced composites and hybrid composites. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2019. p. 15–26. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-102290-0.00002-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Chen C, Tan J, Wang Z, Zhang W, Wang G, Wang X. Effect of acetylation modification on the structure and properties of windmill palm fiber. Text Res J. 2022;92(19–20):3693–703. doi:10.1177/00405175221091882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. AL-Oqla FM, Alothman OY, Jawaid M, Sapuan SM, Es-Saheb MH. Processing and properties of date palm fibers and its composites. In: biomass and bioenergy. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2014. p. 1–25. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-07641-6_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools