Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancing Corn Starch-Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) and Glycerol Composite Films with Citric Acid Cross-Linking Mechanism: A Green Approach to High-Performance Packaging Materials

1 Department of Food Technology, Faculty of Agro-Industrial Technology, Universitas Padjadjaran, Sumedang, 45363, Indonesia

2 Research Center for Process Technology, National Research and Innovation Agency, South Tangerang, 15314, Indonesia

3 Food Engineering, Agricultural Technology Department, Politeknik Negeri Jember, Mastrip, P.O. Box 164, Jember, 68121, Indonesia

4 Research Center for Molecular Chemistry, National Research and Innovation Agency, South Tangerang, 15314, Indonesia

5 Research Center for Food Technology and Processing, National Research and Innovation Agency, Cibinong, 16911, Indonesia

* Corresponding Author: Novita Indrianti. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2026, 14(1), 8 https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0145

Received 22 July 2025; Accepted 20 October 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

Corn starch (CS) is a renewable, biodegradable polysaccharide valued for its film-forming ability, yet native CS films exhibit low mechanical strength, high water sensitivity, and limited thermal stability. This study improves CS-based films by blending with poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) or glycerol (GLY) and using citric acid (CA) as a green, non-toxic cross-linker. Composite films were prepared by casting CS–PVA or CS–GLY with CA at 0%–0.20% (w/w of starch). The influence of CA on physicochemical, mechanical, optical, thermal, and water barrier properties was evaluated. CA crosslinking markedly enhanced the tensile strength, water resistance, and thermal stability of CS–PVA films while increasing transparency in CS–GLY films. At 0.20% CA, the composite achieved 34.99 MPa tensile strength, reduced water vapor permeability, and minimized water uptake. FTIR confirmed ester bond formation between CA and hydroxyl groups of CS, PVA, and GLY, whereas thermal analysis showed higher decomposition temperatures and lower weight loss in crosslinked films. Increasing CA levels also decreased opacity and improved light transmittance, indicating greater homogeneity and reduced crystallinity. This dual-polymer matrix combined with a natural crosslinking strategy provides a sustainable route to high-performance, biodegradable CS-based packaging materials.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe increasing environmental concerns over pollution caused by petroleum-based synthetic plastics have led to a growing interest in biodegradable packaging materials derived from renewable resources [1,2]. Among these, starch-based films have received considerable attention due to their biodegradability, low cost, and wide availability [2]. Corn starch (CS), a natural, biodegradable, and renewable polysaccharide, is frequently utilized in the packaging industry because of its great film-forming capacity, low price, and availability [3,4]. CS contains approximately 75% amylopectin and 25% amylose, which contribute to its film-forming potential [5]. However, it also exhibits limitations, including poor mechanical properties and high hydrophilicity, limiting its application in food packaging [6,7]. To address this, enhancing the performance of corn starch films has become a major focus of research.

Combining starch polymers with other polymers like PVA, which have excellent mechanical and physical properties, can improve the properties of corn starch film [8]. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), a water-soluble synthetic polymer, is often used in combination with starch to enhance the performance of starch-based films [9]. PVA is a popular choice due to its hydrophilic, nontoxic, degradable, and easily film-forming qualities [10]. PVA and starch are compatible because they have enough hydroxyl groups in their molecular chains to produce strong intermolecular hydrogen bonds [11]. Previous study demonstrated that films containing mixed PVA and starch perform better than films containing only starch, such as increased tensile strength by 1.24–1.93 times and elongation by 1.93–3.74 times compared to pure starch films [12]. Furthermore, the use of plasticizer such as glycerol reduces the brittleness of starch films, enhancing their flexibility [13]. For example, Nordin et al. [14] demonstrated that combining corn starch film with glycerol significantly increased the elongation to 52% (8-fold). Tarique et al. [15] reported that increasing the glycerol concentration (15%–45%) resulted in a significant rise in arrowroot starch film elongation from 2.41% to 57.33%.

In this study, two distinct modification ways were purposefully compared: blending starch with PVA, which serves as a co-polymeric component to reinforce the matrix, and adding glycerol, which acts as a small-molecule plasticizer. The rationale for this comparison stems from the fundamentally distinct ways by which these chemicals affect film characteristics. PVA introduces extra polymer chains that can form strong hydrogen bonds with starch, improving strength, barrier efficiency, and thermal stability. In contrast, glycerol inserts itself between starch chains, lowering intermolecular interactions and increasing chain mobility, which improves flexibility and optical clarity while reducing mechanical strength and barrier capacity. Despite these advancements, corn starch-PVA and glycerol composite films still have challenges, particularly in terms of water sensitivity, which limits their use for application in humid environments.

To address these limitations, cross-linking agents are widely used to improve the mechanical and barrier properties of starch films. Glutaraldehyde (GLU), a commonly used crosslinking agent, can react with -OH in starch/PVA to create hemiacetals and acetals. However, the toxicity of glutaraldehyde limits their use in biopolymer films [16]. Furthermore, Wei et al. [17] discovered that GLU cross-linking has not been proven to enhance the mechanical characteristics of corn starch/PVA composite films. Therefore, investigating effective and environmentally friendly natural cross-linking agents like citric acid is a way to overcome these limitations and improve the performance of starch-PVA composite films.

Citric acid (CA), a naturally occurring tricarboxylic acid, is a cost-effective and environmentally friendly cross-linker for biopolymeric materials [18]. Citric acid was chosen for its excellent performance as a low-level a crosslinker agent, as well as its lower hazard level compared to glutaraldehyde, epichlorohydrin, and sodium hypophosphite [19]. Citric acid can react with at least two of the hydroxyl molecules present in starch. CA molecules have three carboxylic groups that can be esterified with hydroxyl groups in different chains of glycerol, starch, or PVA, thereby forming cross-links [20]. This cross-linking mechanism has the potential to enhance the mechanical properties, water resistance, and thermal stability of the composite films [21]. For instance, Yao et al. [9] found that adding 3% CA to mung bean starch films decreased water vapor permeability by more than 7% compared to films without CA. de Paula Farias et al. [22] reported that wolf’s fruit starch (Solanum lycocarpum) can partially or fully replace corn starch in thermopressed biodegradable films, exhibiting comparable physical, mechanical, and biodegradation properties.

This study aims to enhance the functional properties of corn starch-based films by incorporating PVA and glycerol as blending agents and citric acid as a natural cross-linking agent. Composite films were prepared using varying concentrations of citric acid to evaluate its effects on the mechanical, thermal, optical, and barrier properties of the films. This study clarifies how polymer blending and plasticization affects its starch-based films by contrasting these two techniques under the same citric acid crosslinking conditions. The novelty of this work lies in the use of a dual-polymer matrix approach combined with a green cross-linking strategy to develop high-performance, biodegradable packaging materials derived from renewable resources.

Commercial corn starch (Maizenaku) was purchased from a local market located in Subang, Indonesia. Analytical grade chemicals, including citric acid monohydrate (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), sodium hydroxide (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), glycerol (98%, Himedia, Mumbai, India), and fully hydrolyzed poly(vinyl alcohol) with a molecular weight of 70,000–100,000 g/mol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were employed to make the composite film.

2.2 Preparation of Corn Starch Films

The casting technique was utilized to prepare the starch films. Corn starch films were prepared following the previously procedure with some modifications [23]. Corn starch solution was prepared by dissolving 2% (w/v) corn starch (CS) in distilled water. The mixture was agitated using a magnetic stirrer at a temperature of 85°C, approximately 30 min. Subsequently, the alkaline pH (pH = 8) was achieved with the addition of a diluted solution of sodium hydroxide (0.1 M). The mixture was then blended with glycerol (GLY) or poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) at 25% (w/w) based on the dry weight of corn starch. Afterwards, the film solutions were mixed by stirring and heating until they reached a temperature of 80°C. Following this, different concentrations of citric acid (0%, 0.10%, 0.15%, and 0.20% (w/w) of corn starch) were added and stirred for a period of 10 min. A vacuum oven operating at a temperature of 60°C and a pressure of 300 hPa was employed for a duration of 1 min to eliminate air bubbles. A volume of 90 mL of mixture was put into an acrylic plat (20 cm × 20 cm). The acrylic plate was then placed in an oven and dried at a temperature of 40°C for approximately one night.

2.3 Moisture Content, Thickness, Water Uptake

Moisture content was determined using the gravimetric method according to Ratnawati and Afifah [24], with minor modifications. One gram (1 g) of film samples was oven-dried at 105°C until they reached a consistent weight. The sample was examined in duplicate, and the results were represented in grams of evaporated water per 100 g of dry film. The film thickness was measured by a manual micrometer (Mitutoyo, Japan) with an accuracy of 0.001 mm. The film thickness was estimated by average six random positions on the corner and center of films [25]. The film’s water absorption was determined using the procedure outlined by Sholichah et al. [23]. The 2 cm × 2 cm films were dried in an oven at 100–105°C for 1 h. Subsequently, they were stored in a desiccator for 30 min and weighed to obtain their original weight. The subsequent procedure involved immersing the film in water for a duration of 10 s, removing any residual water from the film surface using a brush, and subsequently measuring the weight of the films. This technique was done again until a constant weight (final weight) was achieved. The calculation of water uptake was determined using Eq. (1).

2.4 Water Vapor Permeability (WVP)

Water vapor permeability is determined using the gravimetric method described in ASTM E96-00 [26]. A film is sealed onto a weighing container (diameter ±2.5 cm) loaded with silica gel (±5 g) and placed in a desiccator under controlled RH conditions of ±78% with a saturated NaCl solution. The bottle’s weight is recorded every hour for seven hours. The weight change per time interval (slope) is calculated to obtain the WVTR value in Eq. (2), which is then utilized to calculate the WVP value using Eq. (3).

where L is the film thickness (mm) and ΔP is the difference in partial pressure of water vapor between inside and outside the film. All film samples are measured with three replicates.

The mechanical properties of the films, specifically the tensile strength (TS) and elongation at break (EB), were measured using the Universal Testing Machine, following the standard ASTM method D 882-88 as reported by Indrianti et al. [27]. The testing parameters (load cell capacity 400 N; crosshead speed is 10 mm/min, with the distance between the clamps being 50 mm) were employed in this measurement. The tensile strength and the percentage of elongation at break were determined using Eqs. (4) and (5). Where TS is the tensile strength (MPa); Fmax is the maximum force (N); A is the area of film cross-section (mm2); dr is the distance of rupture (mm) and do is the distance onset of separation (mm).

2.6 Opacity and Light Transmittance Measurement

The opacity and light transmittance of films was measured using procedure as stated by Jiang et al. [28]. The films were divided into rectangular strips of 1 cm × 5 cm. A spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1900, Kyoto, Japan) was used to scan the spectra within the wavelength range of 200 nm to 800 nm in order to acquire a pattern of light transmittance. The films were cut into 1 cm × 5 cm rectangular strips, and their average thickness (H) was properly measured with a spiral micrometer. The film’s absorbance A600 was measured using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1900, Japan) at a wavelength of 600 nm. The opacity was computed using the formula in Eq. (6).

2.7 Thermal Properties Measurement

Thermal properties of films were analyzed by using a derivative thermogravimetry (DTG-60, Shimadzu, Japan). An empty aluminum pan served as a reference. Approximately 5 mg of the material was sealed in an aluminum pan. The measurement was performed using nitrogen gas at a flow rate of 100 mL/min and a heat rate of 10°C/min within temperature range of 25 to 450°C [27].

2.8 Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Analysis

FTIR analysis were carried out using a FTIR Spectrometer ALPHA II (Bruker instrument, Billerica, MA, USA) with operation conditions were scanning wavenumber 500–4000 cm−1 [23]. In this study, the FTIR analysis also focused on the O–H stretching region (3000–3600 cm−1), where changes in peak intensity and integrated area were monitored. This region is sensitive to hydrogen bonding and thus provides a reliable indicator of hydroxyl group involvement during film formation. A decrease in intensity suggests that hydroxyl groups participated in intermolecular interactions, such as starch–glycerol or starch–PVA hydrogen bonding, or in esterification reactions with citric acid. The calculation of peak area and intensity in the 3000–3600 cm−1 region was performed using software Origin 9.7 (Origin 2020).

2.9 Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

This work employed a factorial experiment in a completely randomised design (CRD) to evaluate the effect of polymer blending method and citric acid (CA) content on the characteristics of corn starch films. The two fixed factors were: (i) polymer blending method: corn starch mixed with PVA (25% w/w) or glycerol (25% w/w) based on the dry weight of corn starch; and (ii) CA level: 0%, 0.10%, 0.15%, and 0.20% (w/w of starch). This resulted in eight treatments in all (CS/PVA-CA0, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20; and CS/GLY-CA0, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20). Each treatment was carried out in triple. The results were compared in two ways: (i) within each polymer system (CS/PVA and CS/glycerol) across the four citric acid concentrations (0.0%–0.20%), and (ii) between the two polymer systems at the same citric acid concentration. This approach allowed for the assessment of both the major effects and the interaction between the polymer system and the CA level. All data were handles using the SPSS software version 26 and analyzed for variance using Multivariate Analysis of Variance (Mannova) with additional testing using Duncan’s test. The difference in results was considered significant at p < 0.05.

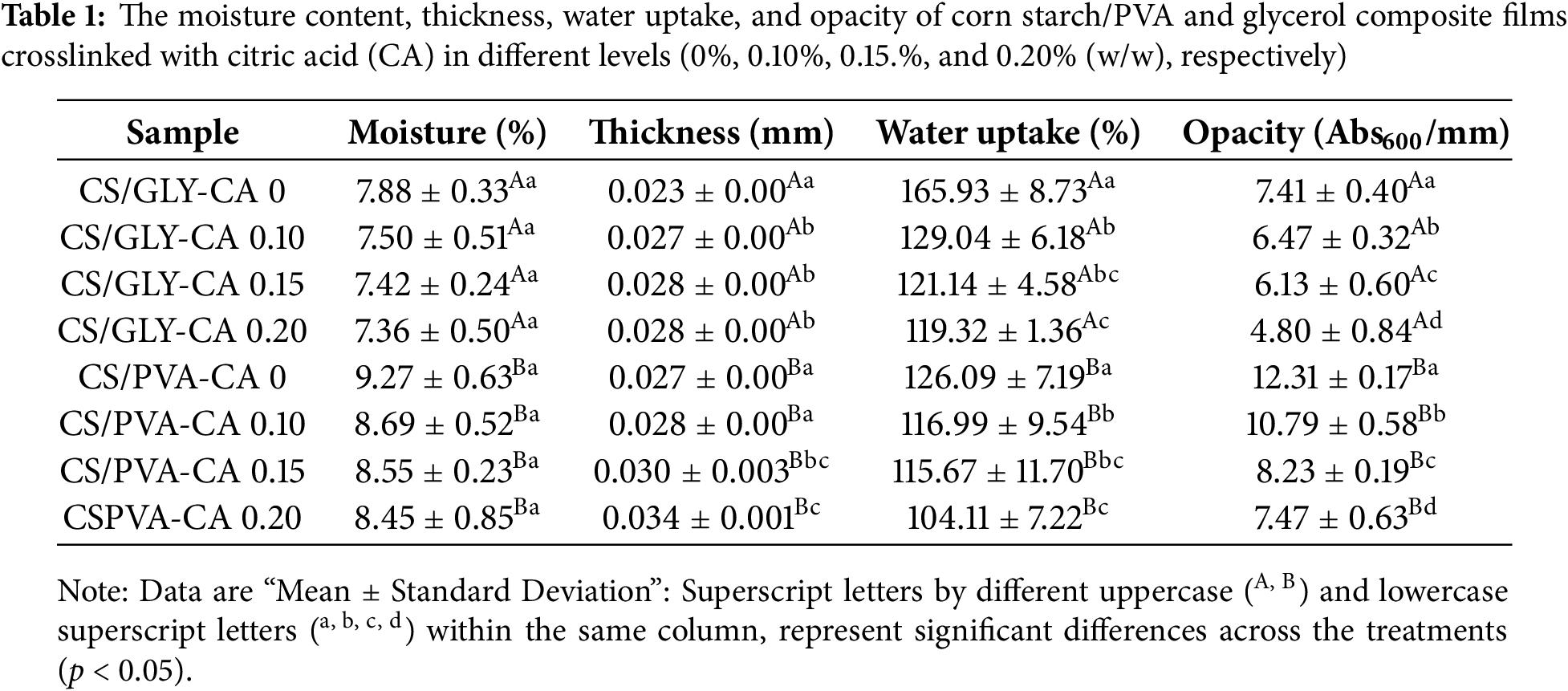

3.1 Moisture Content, Thickness, Water Uptake of CS Films

Table 1 displayed the composite film’s thickness, moisture content, and water uptake. Statistical analysis revealed that the corn starch-PVA (CS-PVA) composite films exhibited higher moisture content (8.45%–9.27%) and greater thickness (0.027–0.034 mm) compared to CS-glycerol films (moisture content 7.36%–7.88%; thickness 0.023–0.028 mm). This dual effect stems from PVA’s molecular structure: its high density of hydroxyl groups not only increases water affinity via hydrogen bonding (explaining the elevated moisture content [29]) but also enhances polymer-polymer interactions. The stronger hydrogen bonding between PVA and starch chains improves miscibility and reduces chain mobility, leading to more cohesive matrix with increased thickness and structural homogeneity. Consequently, this reinforced network directly impacts functional properties critical for packaging applications, including barrier efficiency and mechanical stability [30,31]. PVA (less polar than glycerol) is a polymer, and then, much more viscous and rigid than glycerol, which is a liquid. Corn starch-glycerol composite films are thinner because some glycerol could have been evaporated when casting the film overnight [32,33]. The findings in Table 1 also show an increasing trend in film thickness as the concentration of citric acid increased. The corn starch-PVA composite films with 0.20% of citric acid as cross-linker exhibited the highest thickness (0.034 mm). Citric acid acts as a cross-linker by forming ester bonds between the hydroxyl groups of starch and PVA. This cross-linking improves the density of the polymers network and thus resulting in a more tight structure [23]. The presence of citric acid would have increased the quantity of solid content in the film-forming fluid, resulting in a thicker film [34]. In this study, the same volume of casting solution was used for all film samples. Therefore, the final film thickness is primarily governed by the density of the dried composition (including residual moisture content) rather than being directly determined by the degree of crosslinking. Any differences observed in thickness among films are better explained as a secondary effect of compositional and structural changes induced by citric acid crosslinking, which may alter molecular packing, water retention, and network rigidity, thereby indirectly influencing the density of the dried films.

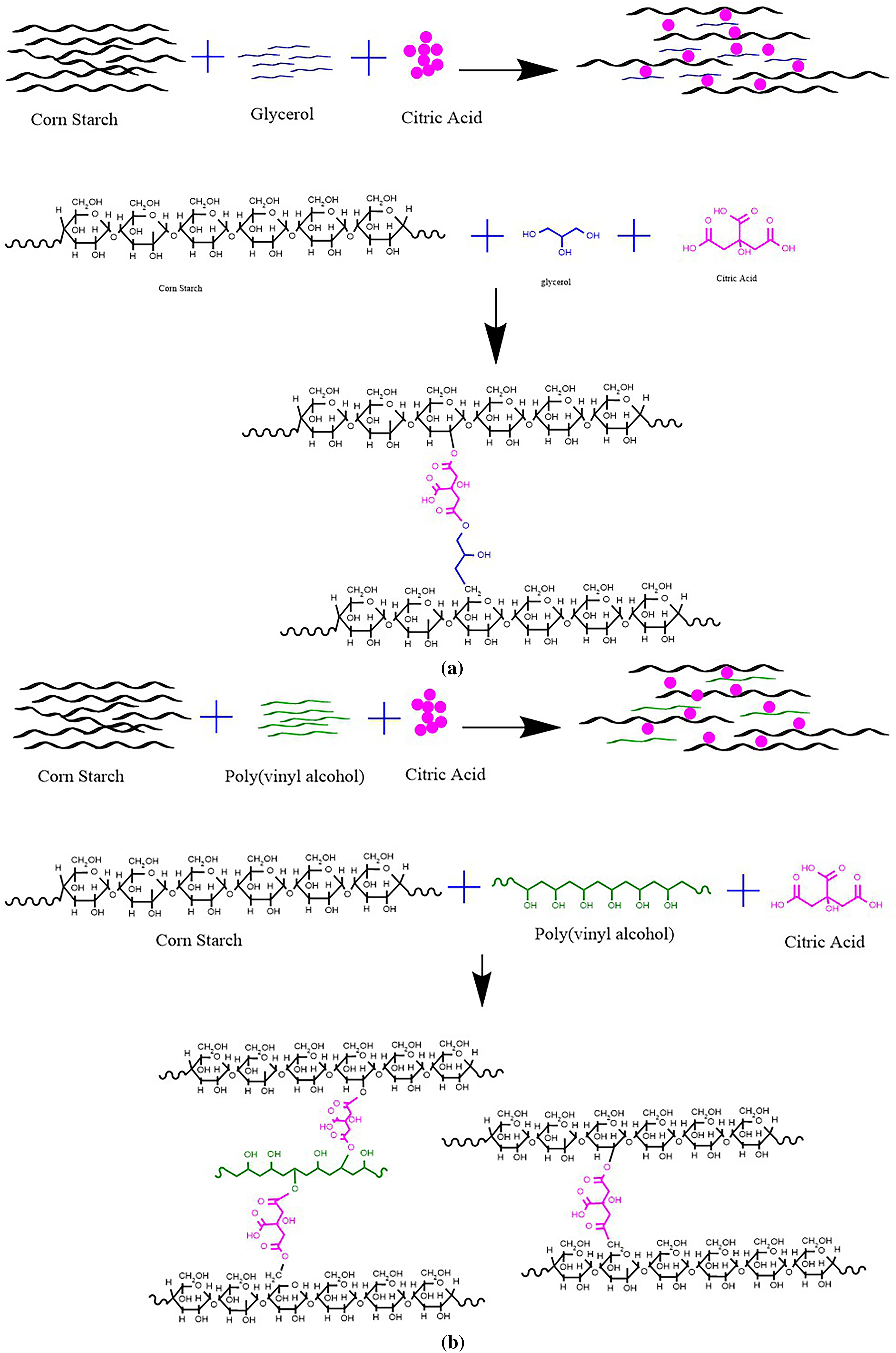

Water uptake is a characteristic of a film’s resistance to water. A lower water uptake value indicates a higher resistance of the film to water [35]. Table 1 demonstrates that corn starch-glycerol composite films exhibited considerably higher water uptake (119.32%–165.93%) compared to corn starch-PVA composite films (104.11%–126.09%) (p < 0.05). Glycerol is a highly hydrophilic plasticizer with numerous hydroxyl chains that can create strong hydrogen bonds with water molecules [15]. This increases the water absorption capacity of starch-glycerol films. Poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA), while also hydrophilic, forms stronger intermolecular hydrogen bonds with starch, which can reduce the availability of free hydroxyl groups to interact with water, thus lowering water uptake [36]. Table 1 also show a gradual decrease in water uptake of the composite films with the increasing concentration of citric acid. The corn starch-PVA composite film with 0.20% of citric acid exhibited the lowest level of water uptake. The cross-linking process involves the formation of ester bonds between the hydroxyl groups of starch and PVA with citric acid. This reaction limits the accessibility of free groups of hydroxyl, as seen in possible approach of crosslink reaction (Fig. 7), which are responsible for water absorption. The ester bonds create a more hydrophobic network, thereby decreasing the film’s affinity for water [20]. Similar findings were also documented for arrowroot starch-PVA composite edible films when citric acid was included [23].

3.2 Mechanical Properties of CS Films

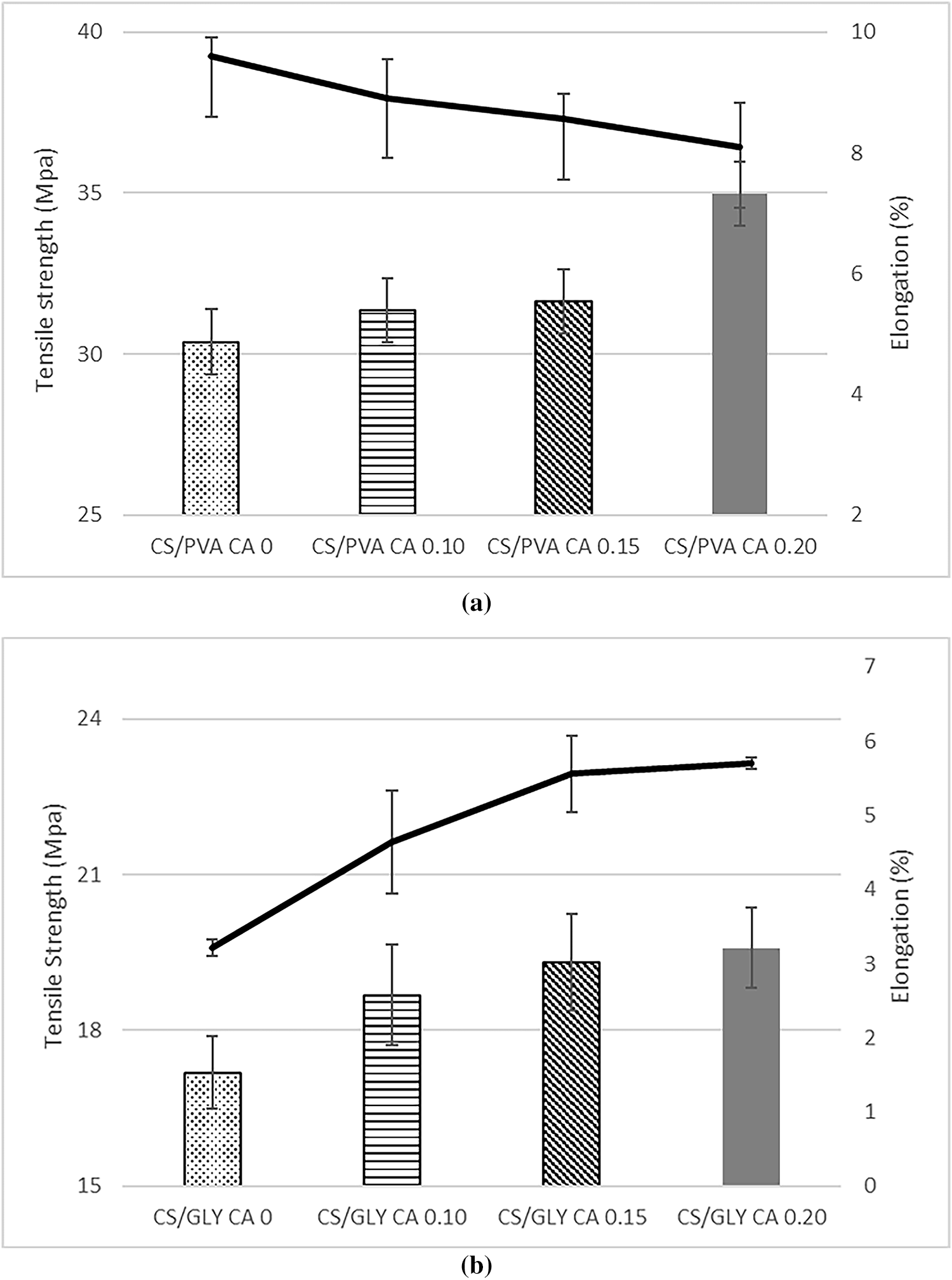

The mechanical characteristics of films determine their strength and capacity to improve the strength and durability of food items. Tensile load and extension at break quantify the amount of force per unit area needed to break the film and the film’s capacity to stretch [37]. Tensile strength and elongation at break of corn starch-PVA and corn starch-glycerol composite films are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Tensile strength and elongation of corn starch/PVA composite films (a) and corn starch/glycerol composite film (b) with varied levels of citric acid (CA) (0%, 0.10%, 0.15%, and 0.20% v/w, respectively)

The tensile strength of corn starch-PVA and glycerol composite films with adding different levels of citric acid ranged from 30.38 to 34.99 MPa and 17.19 to 19.59 MPa, respectively. This study found that corn starch-PVA composite films have a higher tensile strength than corn starch-glycerol composite films. PVA contains hydroxyl groups that can form hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl groups in starch. This interaction enhances the compatibility and intermolecular bonding between the two polymers, leading to improved mechanical properties, including tensile strength [23]. In contrast, glycerol works as a plasticizer, improving flexibility and decreasing tensile strength by breaking the intermolecular interactions within the starch matrix. This is consistent with previously published findings, which reveal that the PVA film has higher mechanical properties and is more resistant to breaking than starch films plasticized using glycerol [38]. These findings highlight the distinct mechanisms that underlying the two modification approaches. Blending with PVA is a polymer-polymer blending strategy in which the inclusion of extra polymer chains promotes strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding with starch. This dense and cohesive network accounts for the increased tensile strength and decreased elongation, found in CS-PVA films. In contrast, adding glycerol is a plasticization technique because glycerol molecules intercalate between starch chains, weakening intermolecular interactions and increasing chain mobility. This results in lower tensile strength but increased flexibility.

Fig. 1 also showed that adding more citric acid to corn starch/PVA composite film increased its tensile strength 1.15 times (from 30.38 MPa to 34.99 MPa), however reduced its elongation by 1.19 times (from 9.60% to 8.09%). Citric acid, a cross-linked chemical, generates ester connections with the hydroxyl groups of starch and PVA as shown in Fig. 7. This crosslinking enhances the density and rigidity of the polymer network, therefore increasing the tensile strength of the films. Yao et al. [39] stated that the addition of citric acid would enhance the intermolecular stability through the formation of covalent bonds, thereby strengthening the films and consequently improving their tensile strength values. The incorporation of citric acid to corn starch/PVA films reduces elongation principally by forming a more stiff and less flexible network via cross-linking and hydrogen bonding. This increased rigidity restricts the film’s capacity to stretch, resulting in decreased elongation at break [40].

The incorporation of 0.20% of citric acid to the corn starch/glycerol film composite increases the tensile strength by 1.13 time (from 17.19 MPa to 19.59 MPa) and elongation by 1.77 times (from 3.22% to 5.70%). Citric acid is an agent of crosslinking that creates ester bonds with the hydroxyl groups of starch and glycerol. This crosslinking produces a more flexible network structure, which can increase the film’s elongation [20]. Citric acid produces stronger hydrogen bonds with starch than glycerol, which improves the bonding of citric acid, glycerol, water, and starch [41]. This strong hydrogen-bond interaction is essential for increasing the film’s characteristics, particularly elongation. Excess CA not only tightened the film structure but also reduced the tension between macromolecules, resulting in greater elongation at break [42]. Yao et al. [39] found similar outcomes for the effect of citric acid on the tensile strength and elongation of mung bean starch films.

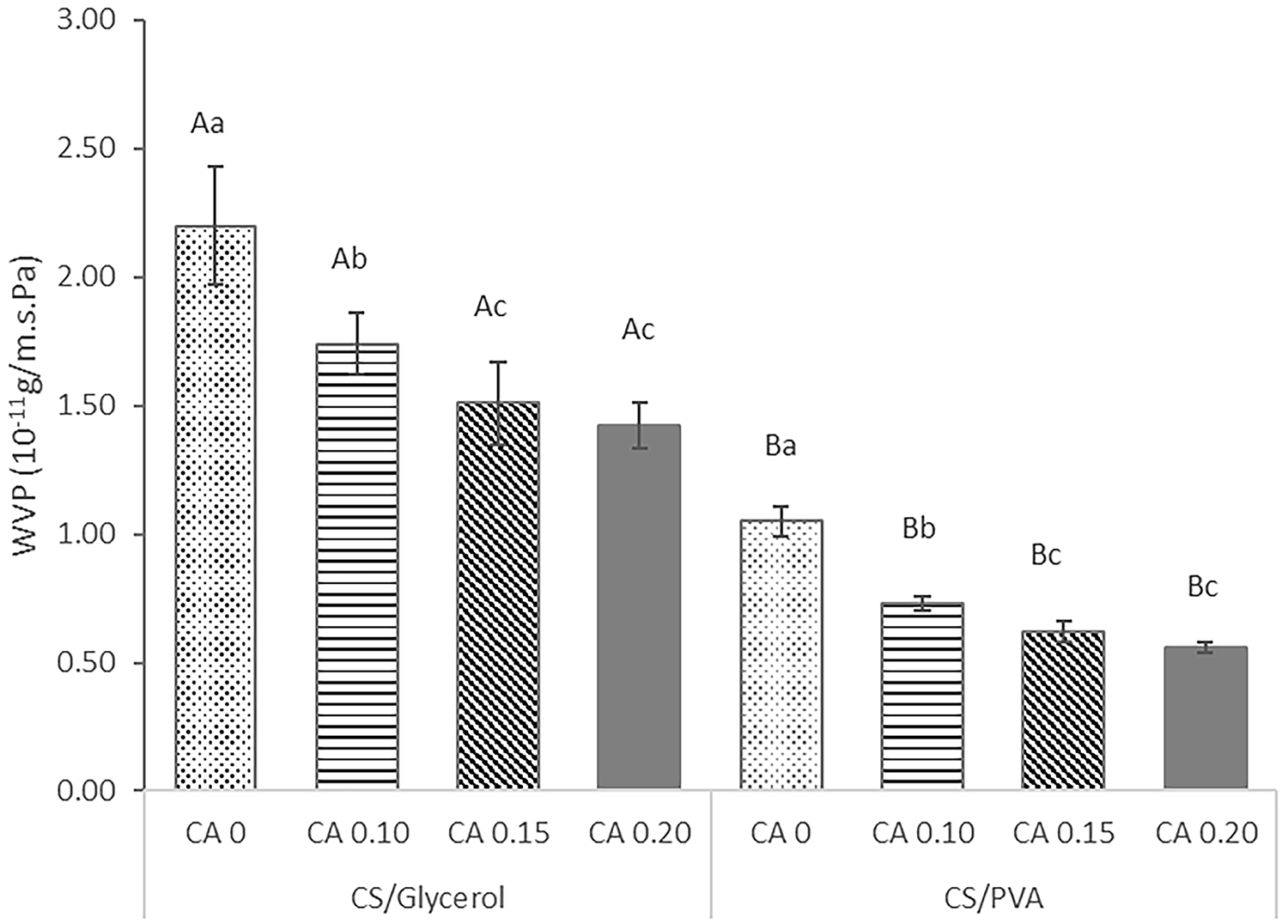

3.3 Water Vapor Permeability of CS Films

Water vapor permeability (WVP) is a crucial property that significantly impacts the performance of film as a packaging material, which is in extending the shelf life of food products [23]. The water vapor permeability (WVP) in food packaging films should be minimized. Due the regular need to restrict the movement of moisture between food and the surrounding surroundings [35]. Among the corn starch/PVA and glycerol composite films in Fig. 2, corn starch/PVA films (0.56 × 10−11 to 1.05 × 10−11 gm−1·s−1·Pa−1) exhibited lower WVP than that of the corn starch/glycerol films (1.42 × 10−11 to 2.20 × 10−11 gm−1·s−1·Pa−1). Corn starch/PVA films have a lower WVP compared to corn starch/glycerol films because PVA is less hydrophilic, generates a denser and more homogenous film structure, and is more compatible and interacts with starch. Collectively, these characteristics produce a tighter film matrix that is less permeable to water vapour [43,44]. The compatibility of starch with PVA produces films with improved mechanical characteristics and decreased WVP. The combination of starch and PVA results in a tighter network that is less permeable to water vapour [37].

Figure 2: Water vapor permeability of corn starch/PVA composite films and corn starch/glycerol composite film with varied levels of citric acid (CA) (0%, 0.10%, 0.15%, and 0.20% v/w, respectively). Different uppercase (A, B) and lowercase (a, b, c) superscript letters indicate indicate statistical significance between sample groups (p < 0.05)

Fig. 2 also demonstrated a significant reduction in the water vapor permeability (WVP) of the both of composite film with increasing levels of citric acid (CA). The addition of 0.20% citric acid decreased the WVP of the corn starch/glycerol film composite by 155% and that of the corn starch/PVA film composite by 188%. The occurrence can be attributed to the replacement of hydrophilic OH groups with hydrophobic ester groups within the film structure [16] and the possible approach of cross-linking reaction of starch and other ingredients of the films in our work is depicted in Fig. 7. Cross-linking of starch results in the development of a more compact structure, which inhibits swelling and restricts molecular movement. As a consequence, the permeability of water vapor decreases [35]. A similar trend was observed by several authors [27,42,45].

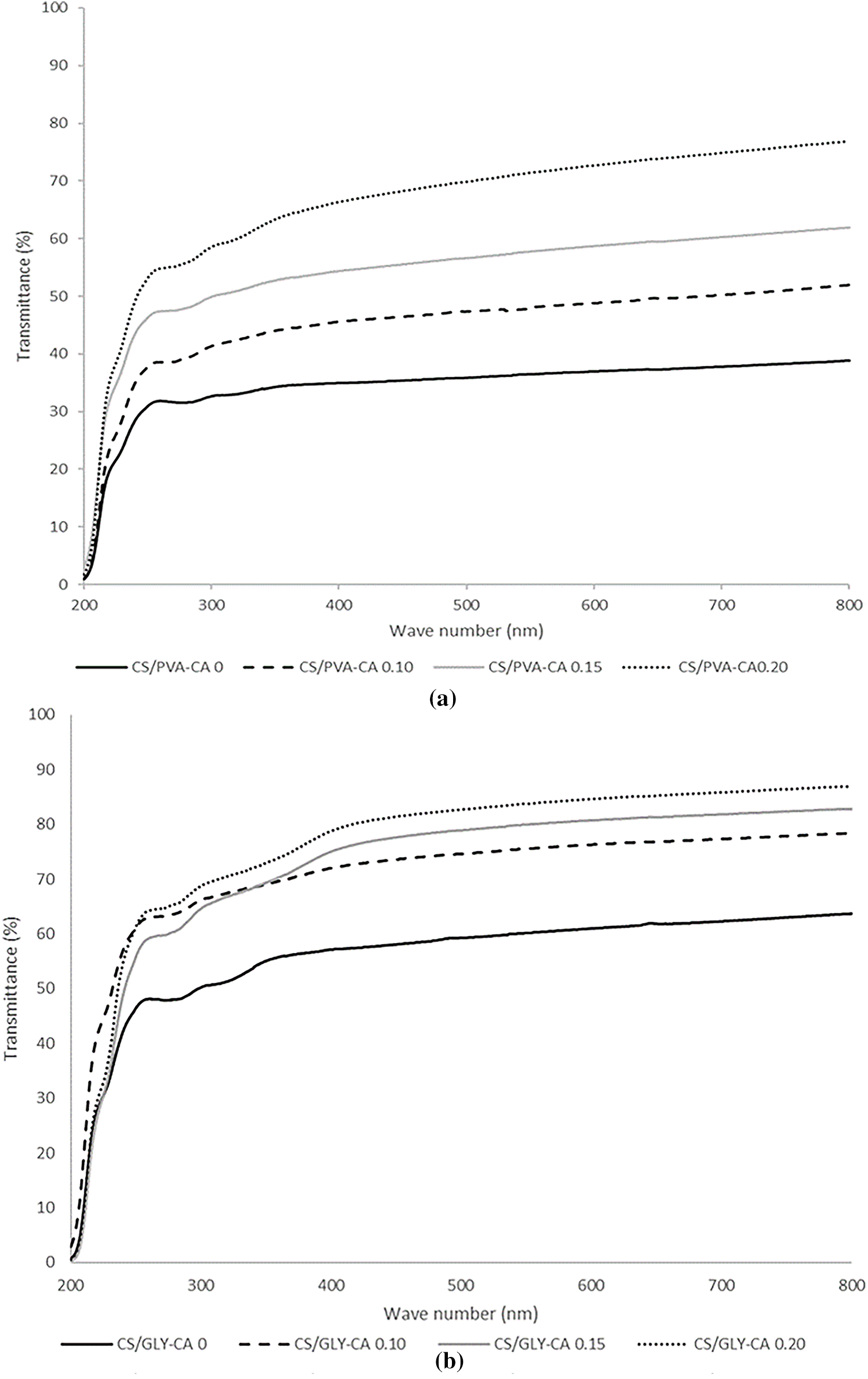

3.4 Opacity and Light Transmittance of CS Films

Opacity is a measurement used to quantify the level of transparency exhibited by a film. A high level of opacity suggests that the sample has a low level of transparency [40]. The light transmittance and opacity of the corn starch films are illustrated in Fig. 3 and Table 1.

Figure 3: The Light Transmittance of corn starch/PVA composite films (a) and corn starch/glycerol composite film (b) with varied levels of citric acid (CA) (0%, 0.10%, 0.15%, and 0.20% v/w, respectively).

The results in Table 1 showed that the opacity of corn starch/glycerol composite films (ranging from 4.80 to 7.41) are comparatively lower than those observed for the corn starch/PVA composite films (ranging from 7.47 to 12.31). It means that corn starch/glycerol composite films are more transparent compared to corn starch/PVA composite films. Corn starch/glycerol composite films have a lower opacity than corn starch/PVA composite films due to their homogenous matrix and reduced crystallinity, resulting in less light scattering [41]. Table 1 also demonstrated a decreasing relationship between citric acid levels and film opacity. Citric acid is an agent for crosslinking that produces ester bonds with the hydroxyl groups of starch and PVA and the possible approach of cross-linking reaction is illustrated in Fig. 7. This crosslinking decreases free hydroxyl groups, resulting in a more compact and homogenous film structure [20]. The reduction of free hydroxyl groups and the development of a more homogenous matrix might reduce light scattering, resulting in less opacity. In contrast, the greater refractive index and more heterogeneous structure of PVA-starch films cause enhanced opacity [42]. In order to assess the light transmission characteristics of the films, spectral scanning was conducted across wavelengths spanning from 200 to 800 nm, and the corresponding percentage of light transmittance was meticulously recorded, as depicted in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 demonstrated that the corn starch/glycerol composite films have a higher optical clarity than corn starch/PVA composite films. In wave number 800 nm exhibited the percentage transmittance of CS/GLY ranged from 50 to >80%. While the percentage transmittance of CS/PVA ranged from 30 to <70%. Fig. 3 illustrated that the transparency of corn starch/PVA and glycerol composite films is greater when citric acid is added, compared to when it is absent in both composite films. The highest light transmittance was resulted in both corn starch composite film with addition citric acid 0.20%. Starch undergoes cross-linking, which reduces its crystallinity and enhances the dispersion of light through the film matrix. Consequently, the transparency of the film increases [28].

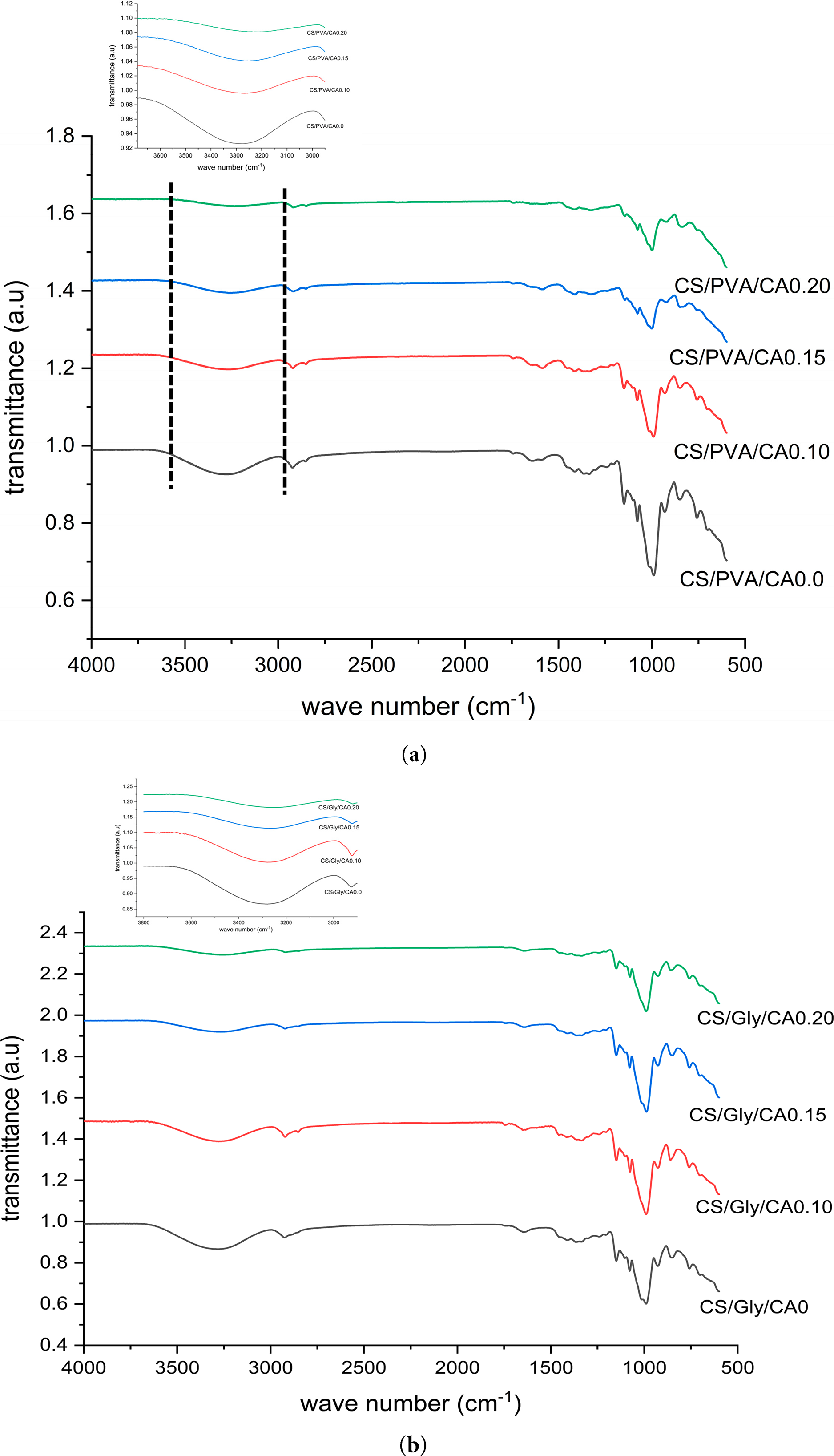

FTIR analysis was conducted to identify the potential functional chemical groups and molecular interactions present in the cross-linked biopolymer films [16]. The FTIR spectra of composite films are depicted in Fig. 4. The FTIR spectra of both of composite films exhibited similar patterns. The peak spectra observed in this study show closeness to the previous research on mung bean starch edible films, as documented by Yao et al. [9]. Fig. 4 displayed that the three typical bands at 990, 1015, and 1077 cm−1 correlate to the C-O bond stretching band attributed to primary alcohols [43]. As the citric acid level increased the bands broadened and the peak intensity decreased. This alteration indicates that the carboxyl chains of citric acid formed through covalent connections to the C-O groups found in starch [44]. Analysis of the O–H stretching region (3000–3600 cm−1) showed a decrease in both peak area and intensity with increasing citric acid concentration. Peak area and intensity decreased with higher citric acid levels, from 18.44 to 3.94 and 0.05 to 0.01 in CS/PVA-CA and from 37.76 to 11.04 and 0.11 to 0.03 in CS/GLY-CA, respectively, indicating consumption of free –OH groups during esterification and cross-linking. These reductions in peak area and height suggest that a portion of the free hydroxyl groups in starch, glycerol, and PVA were consumed during esterification and cross-linking reactions with citric acid. Consequently, fewer free –OH groups were available to participate in hydrogen bonding, leading to weakening of the original hydrogen-bonded network. This phenomenon is consistent with the possible approach of citric acid cross-linking, in which citric acid forms ester linkages with hydroxyl groups of starch, glycerol, and/or PVA (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the observed shift in the peak center values (from ~3298 cm−1 to ~3254 cm−1 in CS/PVA-CA and from ~3306 cm−1 to ~3269 cm−1 in CS/GLY-CA) reflects alterations in the hydrogen bond strength and distribution. A shift toward lower wavenumbers typically indicates stronger hydrogen bonding interactions due to newly formed intermolecular linkages. Taken together, the FTIR results confirm that citric acid introduction significantly altered the hydroxyl environment and promoted cross-linking in the starch-based films. According to Marvdashti et al. [26], the formation of intermolecular and intramolecular hydrogen bonds results in a shift of the absorption band towards a lower frequency as a consequence of stretching vibration. As the strength of hydrogen bonding increases, the occurrence of O–H stretches is observed at progressively lower frequency. Wu et al. [38] reported similar finding in potato starch/chitosan films that were cross-linked with citric acid.

Figure 4: FTIR spectra of corn starch/PVA composite films (a) and corn starch/glycerol composite film (b) with varied levels of citric acid (CA) (0%, 0.10%, 0.15%, and 0.20% v/w, respectively)

3.6 Thermal Properties of CS Films

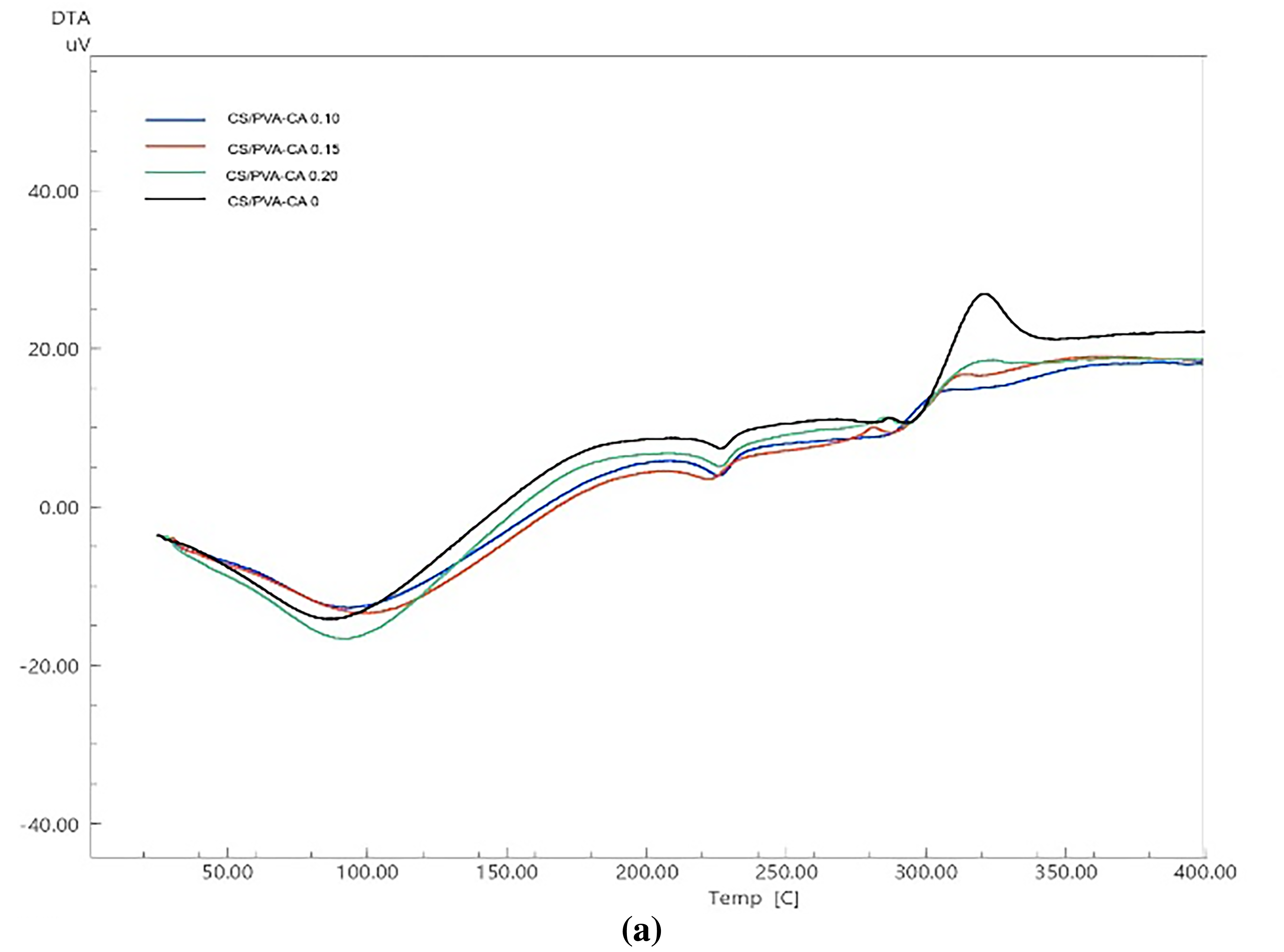

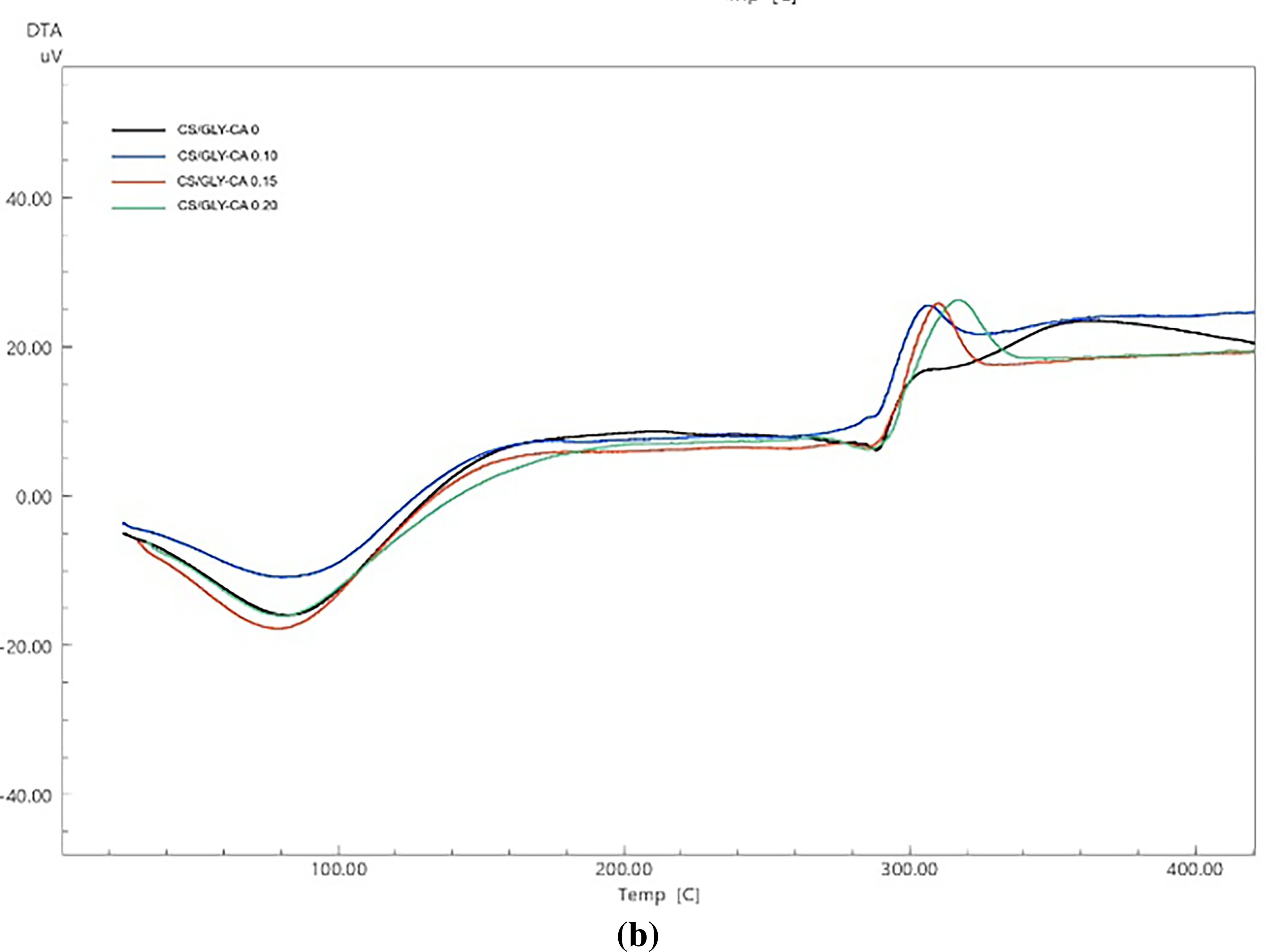

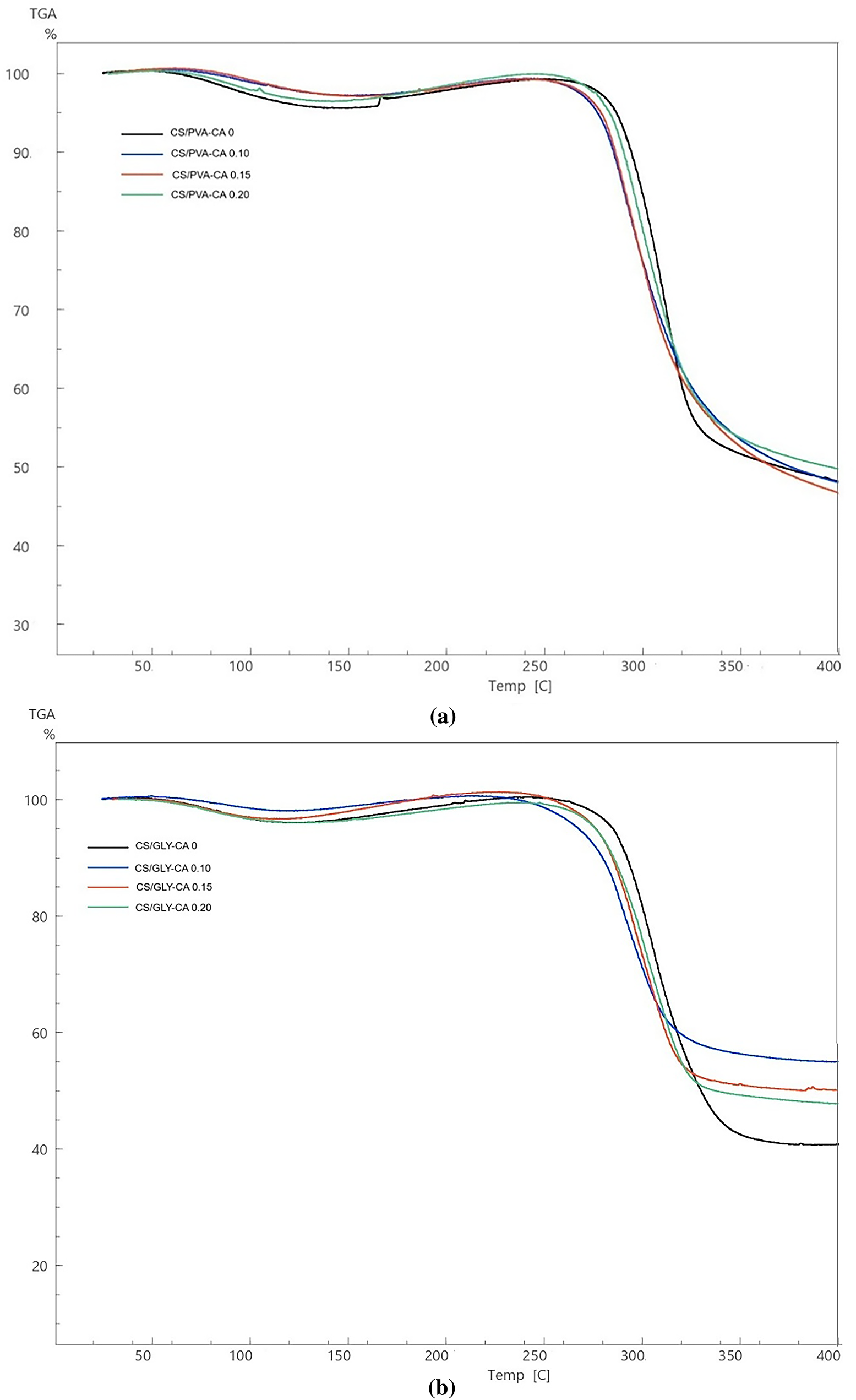

The graphs of DTA (differential thermal analysis) and TGA (thermal gravimetry analysis) of corn starch/PVA (CS/PVA) and corn starch/glycerol (CS/GLY) composite films with different levels of citric acid (CA) are shown in Figs. 5 and 6. The endothermic peak in Fig. 5 indicates that the first mass loss was driven by thermal action at temperatures below 100°C. This was mostly due to evaporation of moisture and water fragments [45]. The PVA glass transition (Tg ~70–85°C) does not have a clear baseline shift, possibly due to water loss, plasticization, and citric-acid crosslinking. The curve DTA of corn starch/PVA (CS/PVA) composite films showed the second endothermic peak at temperatures between 200 and 250°C. Normally, PVA exhibits a melting endotherm (a peak indicating melting) around 220°C. However, in this CS-PVA composite film, that peak is not observed. The lack of the endotherm suggests that the PVA within the composite is not as crystalline as it would be in its pure form. This is because the solution casting process and the strong interactions between starch and PVA disrupt the PVA’s ability to form its typical crystalline structure. The interactions between the components, such as the hydrogen bonding of starch and PVA, improve the thermal stability of the composite films. At higher temperatures, this stability can produce different thermal events, such as the second endothermic peak [46]. The exothermic peak in both of composite films within the temperature range 306.39–324.04°C. The occurrence of this peak can be ascribed to the complete breakdown of starch that occurs at temperatures above 300°C [47]. Results observed that corn starch/PVA (CS/PVA) demonstrated a greater peak temperature (314.84 to 324.04°C) in comparison to corn starch/glycerol (CS/GLY) (306.39 to 316.86°C). The interactions between PVA and starch, notably hydrogen bonding, assist to create a stronger network within the composite film. This network needs more energy to break down, which leads to greater peak temperatures [46].

Figure 5: The curves of differential thermal analysis (DTA) of (a) corn starch-PVA (CS/PVA) and (b) corn starch-glycerol (CS/GLY) with varied level of citric acid (CA) (0%, 0.10%, 0.15%, and 0.20% v/w, respectively)

Figure 6: The curves of thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of (a) corn starch-PVA (CS/PVA) composite films and (b) corn starch-glycerol (CS/GLY) composite films with varied level of citric acid (CA) (0%, 0.10%, 0.15%, and 0.20% v/w, respectively)

The thermogravimetric curves as presented in Fig. 6 also exhibited two weight loss events that agreed with their DTA curves. The first weight loss at the endothermic peak of all the films occurred at approximately 50°C–100°C ranged from 1% to 4%. The weight loss below 100°C was mainly ascribed to water loss [48]. And then, the second weight loss occurring between 270°C and 360°C was attributed to the fragmentation of side chains in the starch. The findings of this study align with the outcomes given by Nordin et al. [14], which indicate that the degradation process occurred within the temperature range of 286–328°C, indicating significant starch decomposition. The weight loss of the corn starch/PVA composite film with the addition of 0.20% citric acid (39.63%) was lower compared to the corn starch/PVA composite film without citric acid (46.77%). This is owing to the creation of strong hydrogen bonds and ester linkages, which provide the film greater resistance to thermal degradation. Improved thermal stability relates to decreased weight loss after thermal analysis [20].

Thermal characteristics associated with film degradation (exothermic peak) included onset temperature (to), endset temperature (tc), and peak temperature (tp) of CS/GLY composite films ranged from 291.79 to 299.36°C, 319.27 to 330.75°C, and 306.39 to 316.86°C, respectively. While the onset temperature (to), endset temperature (tc), and peak temperature (tp) of CS/PVA composite films ranged from 293.01 to 312.40°C, 319.76 to 333.08°C, and 314.84 to 324.04°C, respectively. Results showed that thermal properties of the both of composite films increased with the addition of citric acid (Supplementary Data Table S1). The trend revealed that the CS/PVA-CA 0.20 onset temperature (312.40°C) and peak temperature (324.04°C) were greater than the CS/PVA-CA 0 onset temperature (303.64°C) and peak temperature (320.79°C). This data suggests that CA (citric acid) improves thermal stability in CS-PVA films. The same results were obtained with the addition of citric acid to the CS/GLY composite film. This confirmed that the citric acid had successfully improved the thermal stability of the starch film by developing the crosslinked structure in the system [49]. Citric acid’s cross-linking and strong hydrogen bonds improved the bonding between molecules, increasing the film’s thermal stability [50]. Similarly, the addition of citric acid improved the thermal stability of the films, indicating that a more consistent, strong, and stable structure was produced through intermolecular interactions [21]. Other findings have been observed in composite films consisting of potato starch and chitosan, which were crosslinked with citric acid, as well as in films composed of konjac glucomannan/surface deacetylated chitin and citric acid, which exhibited increased hydrophobicity [20,28].

3.7 Citric Acid Cross-Linking Possible Approach

The possible approach of crosslink reaction between citric acid and the ingredients of the film was shown in Fig. 7. The citric acid is bound between the starch molecules and polyvinyl alcohol or glycerol. The corn starch was gelatinized to swell the chains and form an amorphous structure [51]. Then, the sodium hydroxide was added to gelatinized starch and affected the reduction of crystallinity due to the breakage of hydrogen bonds of starch molecules [52]. Besides that, the reactivity of citric acid was generated by a heating process. The citric acid released a hydrate molecule, which became an anhydrate and then reacted with starch and polyvinyl alcohol or glycerol [53]. Based on the insert FTIR spectra (Fig. 5), in both of composite film (CS/PVA and CS/glycerol) the band ranged from 3000 cm−1 to 3600 cm−1 became broader and the intensity of peak less intense as the citric acid level increased, suggesting a reduction in free O-H groups due to the formation of ester bonds by citric acid. The structural alterations influenced the composite films’ properties, including water barrier, water vapor permeability, optical clarity and thermal properties. Citric acid (CA) considerably enhanced the tensile strength, water resistance, and thermal stability of CS-PVA films, while also improving optical clarity in CS-GLY films. The addtion of 0.20% CA resulted in a tensile strength of 34.99 MPa, reduced water vapour permeability, and minimal water uptake. The addition of citric acid increased the thermal properties of both composite films (see Supplementary Data Table S1). The trend showed that the CS/PVA-CA 0.20 onset temperature (312.40°C) and peak temperature (324.04°C) were higher than the CS/PVA-CA 0 onset temperature (303.64°C) and peak temperature (320.79°C). This study demonstrates that CA (citric acid) enhances thermal stability in CS-PVA films. The same results were obtained by adding citric acid to the CS/GLY composite film.

Figure 7: Possible approach of crosslink reaction (a) corn starch and glycerol with citric acid; (b) corn starch and polyvinyl alcohol with citric acid

This study demonstrates that employing citric acid as a green cross-linker in dual-polymer corn starch matrices is a sustainable approach to enhance the performance of biodegradable packaging films. The novelty of this work consists in the combination of a renewable polysaccharide (corn starch) with poly(vinyl alcohol) or glycerol, as well as the use of a non-toxic, naturally generated crosslinker to improve specified functional properties. The comparison research indicated distinct roles for the two blending agents. PVA incorporation resulted in films with higher tensile strength, water vapour barrier efficiency, and thermal stability due to its rich hydroxyl functionality and strong hydrogen bonding interactions with starch. Glycerol, on the other hand, performed primarily as a plasticizer, lowering brittleness and enhancing the optical clarity through increased homogeneity and lower crystallinity. These complementary effects highlight the potential of tailoring film properties according to application requirements. Among the tested formulations, 0.20% citric acid was identified as the optimal concentration, delivering significant improvements in structural cohesion and functional performance. Overall, the findings confirm that citric acid crosslinking in CS–PVA and CS–GLY systems offers a green, effective, and versatile strategy for developing high-performance, biodegradable, and renewable packaging materials.

Acknowledgement: We thanks to the Research Center for Appropriate Technology, Department of Food Technology, Faculty of Agro-Industrial Technology, Universitas Padjadjaran, and Studi Program of Food Engineering Technology, Majoring of Agricultural Technology, State Polytechnic of Jember for supporting this research activities.

Funding Statement: This research activity is supported through RIIM Competition funding from the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education Agency, Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia and National Research and Innovation Agency of Indonesia according to the contract number: 61/IV/KS/5/2023 and 2131/UN6.3.1/PT.00/2023.

Author Contributions: Herlina Marta: Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review & editing; Novita Indrianti: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization; Allifiyah Josi Nur Aziza: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft; Enny Sholichah: Supervision, Methodology, Validation; Writing—original draft; Titik Budiati: Supervision, Validation; Writing—original draft; Achmat Sarifudin: Visualization; Writing—original draft; Yana Cahyana: Writing—original draft, Supervision, Investigation; Nandi Sukri: Writing—original draft, Supervision, Investigation; Aldila Din Pangawikan: Writing—original draft, Supervision, Investigation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0145/s1.

References

1. Onyeaka H, Obileke K, Makaka G, Nwokolo N. Current research and applications of starch-based biodegradable films for food packaging. Polymers. 2022;14(6):1–16. doi:10.3390/polym14061126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. García-Guzmán L, Cabrera-Barjas G, Soria-Hernández CG, Castaño J, Guadarrama-Lezama AY, Llamazares SR. Progress in starch-based materials for food packaging applications. Polysaccharides. 2022;3(1):136–77. doi:10.3390/polysaccharides3010007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cheng H, Chen L, McClements DJ, Yang T, Zhang Z, Ren F, et al. Starch-based biodegradable packaging materials: a review of their preparation, characterization and diverse applications in the food industry. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2021;114:70–82. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2021.05.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Cheng M, Kong R, Zhang R, Wang X, Wang J, Chen M. Effect of glyoxal concentration on the properties of corn starch/poly(vinyl alcohol)/carvacrol nanoemulsion active films. Ind Crop Prod. 2021;171:113864. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Putri TR, Adhitasari A, Paramita V, Yulianto ME, Ariyanto HD. Materials today: proceedings effect of different starch on the characteristics of edible film as functional packaging in fresh meat or meat products: a review. Mater Today Proc. 2023;87:192–9. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2023.02.396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Huang X, Chen L, Liu Y. Effects of ultrasonic and ozone modification on the morphology mechanical thermal and barrier properties of corn starch films. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;147(8):109376. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.109376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Huang Y, Yao Q, Wang R, Wang L, Li J, Chen B, et al. Development of starch-based films with enhanced hydrophobicity and antimicrobial activity by incorporating alkyl ketene dimers and chitosan for mango preservation. Food Chem. 2025;467(3):142314. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.142314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Abedi-firoozjah R, Chabook N, Rostami O, Heydari M, Kolahdouz-Nasiri A, Javanmardi F, et al. PVA/starch films: an updated review of their preparation characterization and diverse applications in the food industry. Polym Test. 2023;118:107903. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2022.107903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yao Y, Hsu Y, Uyama H. Enhanced physical properties and water resistance of films using modified starch blend with poly(vinyl alcohol). Ind Crop Prod. 2024;222:119870. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.119870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chen J, Zheng M, Bing K, Lin J, Chen M, Zhu Y. Polyvinyl alcohol/xanthan gum composite film with excellent food packaging storage and biodegradation capability as potential environmentally-friendly alternative to commercial plastic bag. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;212:402–11. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.05.119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Wu F, Zhou Z, Li N, Chen Y, Zhong L, Law WC, et al. Development of poly(vinyl alcohol) starch/ethyl lauroyl arginate blend films with enhanced antimicrobial and physical properties for active packaging. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;192:389–97. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.09.208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Patil S, Bharimalla AK, Mahapatra A, Dhakane-lad J, Arputharaj A, Kumar M, et al. Effect of polymer blending on mechanical and barrier properties of starch-polyvinyl alcohol based biodegradable composite films. Food Biosci. 2021;44(12):101352. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2021.101352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ben Z, Samsudin H, Yhaya MF. Glycerol: its properties polymer synthesis and applications in starch based films. Eur Polym J. 2022;175:11377. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2022.111377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Nordin N, Hajar S, Abdul S, Kadir R. Effects of glycerol and thymol on physical mechanical and thermal properties of corn starch films. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;106(1):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Tarique J, Sapuan SM, Khalina A. Effect of glycerol plasticizer loading on the physical, mechanical, thermal and barrier properties of arrowroot (Maranta arundinacea) starch biopolymers. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–17. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-93094-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Garavand F, Rouhi M, Razavi SH, Cacciotti I, Mohammadi R. Improving the integrity of natural biopolymer films used in food packaging by crosslinking approach: a review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;104(11):687–707. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.06.093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wei H, Liu X, Wang C, Feng R, Zhang B. Characteristics of corn starch/polyvinyl alcohol composite film with improved flexibility and UV shielding ability by novel approach combining chemical cross-linking and physical blending. Food Chem. 2024;456(1):140051. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.140051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Dudeja I, Mankoo RK, Singh A, Kaur J. Citric acid: an ecofriendly cross-linker for the production of functional biopolymeric materials. Sustain Chem Pharm. 2023;36:101307. doi:10.1016/j.scp.2023.101307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kim JY, Lee Y, Chang YH. Structure and digestibility properties of resistant rice starch cross-linked with citric acid. Int J Food Prop. 2017;20:2166–77. doi:10.1080/10942912.2017.1368551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Gerezgiher A, Szabó T. Crosslinking of starch using citric acid crosslinking of starch using citric acid. J Phys Conf Ser. 2022;2315(1):12036. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2315/1/012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wang B, Zhang G, Yan S, Xu X, Wang D, Cui B, et al. Correlation between chain structures of corn starch and properties of its film prepared at different degrees of disorganization. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;226:580–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.12.084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. de Paula Farias V, Ascheri DPR, Ascheri JLR. Substituting corn starch with wolf’s fruit and butterfly lily starches in thermopressed films: physicochemical, mechanical, and biodegradation properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;281:136378. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.136378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Sholichah E, Purwono B, Nugroho P. Improving properties of arrowroot starch (Maranta arundinacea)/PVA blend films by using citric acid as cross-linking agent. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2017;101:012018. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ratnawati L, Afifah N. Effect of antimicrobials addition on the characteristic of arrowroot starch-based films. AIP Conf Proc. 2019;2175:1–8. doi:10.1063/1.5134575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Luchese CL, Frick JM, Patzer VL, Spada JC, Tessaro IC. Synthesis and characterization of bio films using native and modified pinhão starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2015;45(6):203–10. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.11.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Marvdashti LM, Koocheki A, Yavarmanesh M. Alyssum homolocarpum seed gum-polyvinyl alcohol biodegradable composite film: physicochemical, mechanical, thermal and barrier properties. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;155(5):280–93. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.07.123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Indrianti N, Pranoto Y, Abbas A. Preparation and characterization of edible films made from modified sweet potato starch through heat moisture treatment. Indones J Chem. 2018;18(4):679–87. doi:10.22146/ijc.26740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Jiang H, Sun J, Li Y, Ma J, Lu Y, Pang J, et al. Preparation and characterization of citric acid crosslinked konjac glucomannan/surface deacetylated chitin nano fibers bionanocomposite film. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;164(2):2612–21. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Ma N, Dong W, Qin D, Dang C, Xie S, Wang Y, et al. Green and renewable thermoplastic polyvinyl alcohol/starch blend film fabricated by melt processing. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;279(1):134866. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134866. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Kocira A, Kozłowicz K, Panasiewicz K, Staniak M, Szpunar-Krok E, Hortyńska P. Polysaccharides as edible films and coatings: characteristics and influence on fruit and vegetable quality—a review. 2021;11(5):813. doi:10.3390/agronomy11050813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wang W, Zhang H, Jia R, Dai Y, Dong H. High performance extrusion blown starch/polyvinyl alcohol/clay nanocomposite films. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;79:534–43. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.12.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Tijani AT, Ayodele T, Liadi M, Sarker NC, Hammed A. Mechanical and thermal characteristics of films from glycerol mixed emulsified carnauba wax/polyvinyl alcohol. Polymers. 2024;16(21):1–12. doi:10.3390/polym16213024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Chousidis N. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-based films: insights from crosslinking and plasticizer incorporation. Eng Res. 2024;6(2):025010. doi:10.1088/2631-8695/ad4cb4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wu Z, Wu J, Peng T, Li Y, Lin D, Xing B, et al. Preparation and application of starch/polyvinyl alcohol/citric acid ternary blend antimicrobial functional food packaging films. Polymers. 2017;9(3):1–19. doi:10.3390/polym9030102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Seligra PG, Jaramillo CM, Famá L, Goyanes S. Biodegradable and non-retrogradable eco-films based on starch-glycerol with citric acid as crosslinking agent. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;138(2):66–74. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.11.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Isotton FS, Bernardo GL, Baldasso C, Rosa LM, Zeni M. The plasticizer effect on preparation and properties of etherified corn starchs films. Ind Crops Prod. 2015;76(1):717–24. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kryuk TV, Zavyazkina TI, Tyurina TG, Goncharuk GP, Buyanovskaya MV, Senenko VA. Preparation, physicochemical properties, and antibacterial activity of hydrogel films based on starch and poly(vinyl alcohol) with added ethonium. Pharm Chem J. 2024;58(5):839–45. doi:10.1007/s11094-024-03213-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wu H, Lei Y, Lu J, Zhu R, Xiao D, Jiao C, et al. Food hydrocolloids effect of citric acid induced crosslinking on the structure and properties of potato starch/chitosan composite films. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;97(3):1–10. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.105208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Yao S, Wang BJ, Weng YM. Preparation and characterization of mung bean starch edible films using citric acid as cross-linking agent. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2022;32:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2022.100845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Guzman-Puyol S, Benítez JJ, Heredia-Guerrero JA. Transparency of polymeric food packaging materials. Food Res Int. 2022;161(3):111792. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Jamali AR, Shaikh AA, Chandio AD. Preparation and characterisation of polyvinyl alcohol/glycerol blend thin films for sustainable flexibility. Mater Res. 2024;11(4):045102. doi:10.1088/2053-1591/ad4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zanela J, Olivato JB, Dias AP, Grossmann MVE, Yamashita F. Mixture design applied for the development of films based on starch, polyvinyl alcohol, and glycerol. J Appl Polym Sci. 2015;132(43):42697. doi:10.1002/app.42697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Owi WT, Ong HL, Sam ST, Villagracia AR, Tsai CK, Akil HM. Unveiling the physicochemical properties of natural Citrus aurantifolia crosslinked tapioca starch/nanocellulose bionanocomposites. Ind Crop Prod. 2019;139(1):111548. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Ye J, Luo S, Huang A, Chen J, Liu C, Julian D. Synthesis and characterization of citric acid esterified rice starch by reactive extrusion: a new method of producing resistant starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;92(2):135–42. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.01.064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ibrahim MIJ, Sapuan SM, Zainudin ES, Zuhri MYM. Physical, thermal, morphological, and tensile properties of cornstarch-based films as affected by different plasticizers. Int J Food Prop. 2019;22(1):925–41. doi:10.1080/10942912.2019.1618324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Yurong G, Dapeng L. Preparation and characterization of corn starch/PVA/glycerol composite films incorporated with ε-polylysine as a novel antimicrobial packaging material. e-Polymers. 2020;20(1):154–61. doi:10.1515/epoly-2020-0019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Colussi R, Pinto ZV, Halal SLME, Biduski B, Prietto L, Castilhos DD, et al. Acetylated rice starches films with different levels of amylose: mechanical water vapor barrier thermal and biodegradability properties. Food Chem. 2017;221(4):1614–20. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.10.129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Yu J, Wang N, Ma X. The effects of citric acid on the properties of thermoplastic starch plasticized by glycerol. Starch-Stärke. 2005;57(10):494–504. doi:10.1002/star.200500423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Chen WC, Judah SNMSM, Ghazali SK, Munthoub DI, Alias H, Mohamad Z, et al. The effects of citric acid on thermal and mechanical properties of crosslinked starch film. Chem Eng Trans. 2021;83:199–204. doi:10.3303/CET2183034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Shi R, Bi J, Zhang Z, Zhu A, Chen D, Zhou X, et al. The effect of citric acid on the structural properties and cytotoxicity of the polyvinyl alcohol/starch films when molding at high temperature. Carbohydr Polym. 2008;74(4):763–70. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2008.04.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Nor Nadiha MZ, Fazilah A, Bhat R, Karim AA. Comparative susceptibilities of sago, potato and corn starches to alkali treatment. Food Chem. 2010;121(4):1053–9. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.01.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Qiao D, Yu L, Liu H, Zou W, Xie F, Simon G, et al. Insights into the hierarchical structure and digestion rate of alkali-modulated starches with different amylose contents. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;144(3):271–81. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.02.064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Utomo P, Nizardo NM, Saepudin E. Crosslink modification of tapioca starch with citric acid as a functional food. AIP Conf Proc. 2020;2242(1):40055. doi:10.1063/5.0010364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools