Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Sustainable Particleboards Based on Sugarcane Bagasse and Bonded with a Waste-Grown Black Soldier Fly Larvae Commercial Flour-Based Adhesive: Rheological, Physical, and Mechanical Properties

1 Dirección Técnica de Materiales Avanzados, Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Industrial (INTI), Buenos Aires, 1650, Argentina

2 Instituto de Calidad e Innovación Industrial (INCALIN), Universidad Nacional de San Martín (UNSAM), Buenos Aires, 1650, Argentina

3 Laboratorio de Investigaciones en Madera (LIMAD), Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias y Forestales, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Diag. 113 N° 469, La Plata, B1904, Argentina

4 Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Buenos Aires, 1425, Argentina

* Corresponding Author: Alejandro Bacigalupe. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Renewable and Biosourced Adhesives-2023)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2026, 14(1), 2 https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0181

Received 16 September 2025; Accepted 27 October 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

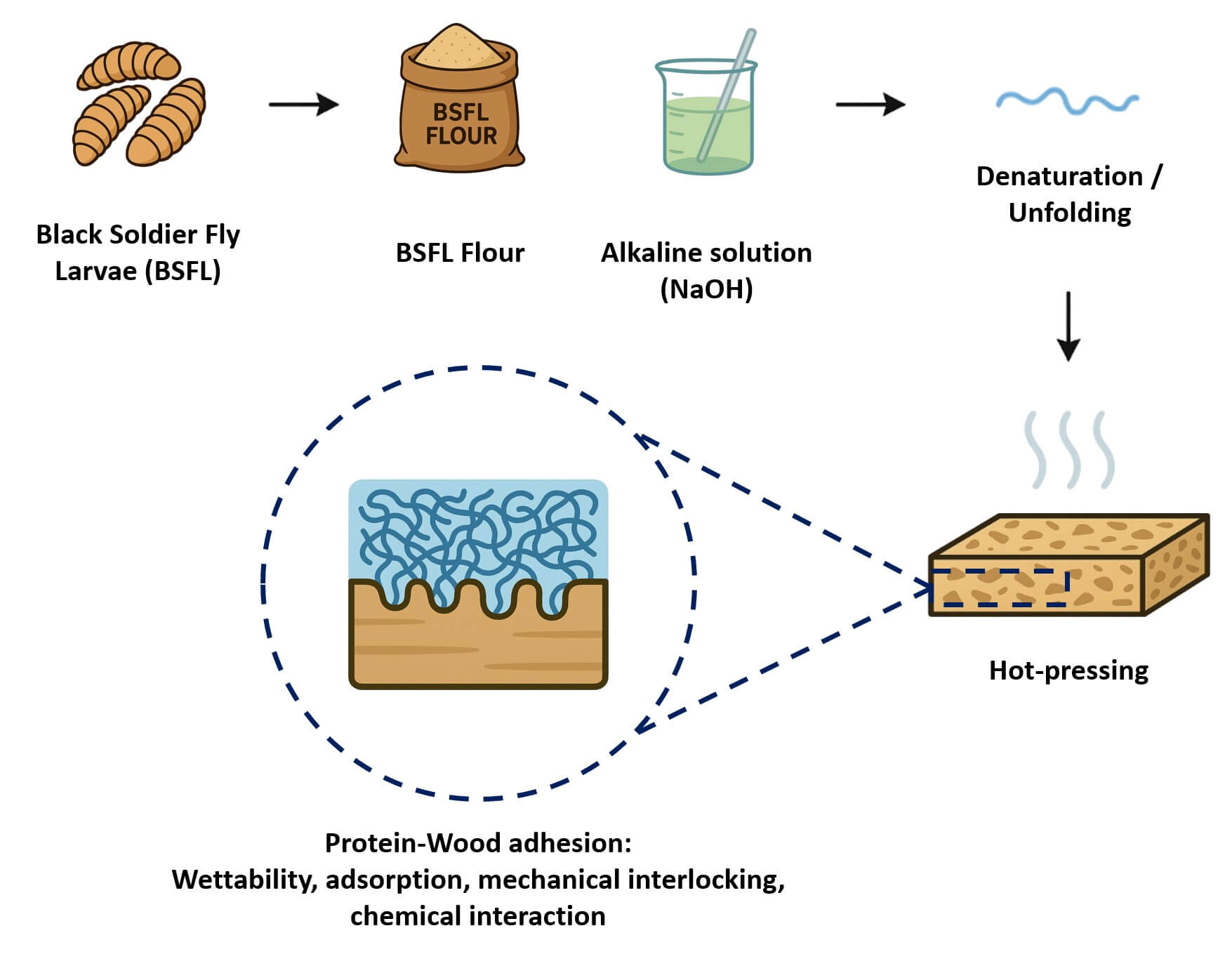

This study explores the use of black soldier fly larvae protein as a bio-based adhesive to produce particleboards from sugarcane bagasse. A comprehensive evaluation was conducted, including rheological characterization of the adhesive and physical–mechanical testing of the panels according to European standards. The black soldier fly larvae-based adhesive exhibited gel-like viscoelastic behavior, rapid partial structural recovery after shear, and favorable application properties. Particleboards manufactured with this adhesive and sugarcane bagasse achieved promising mechanical performance, with modulus of rupture and modulus of elasticity values of 30.2 and 3500 MPa, respectively. Internal bond strength exceeded 0.4 MPa, complying with European standard 312-3 specifications. For comparative purposes, a panel made with Eucalyptus grandis particles was also produced under the same conditions to demonstrate the versatility of the adhesive system. Compared to other bio-based and synthetic adhesives, this bio-based system showed competitive performance and derives from the bioconversion of organic residues. Protein adhesives were synthesized from Hermetia illucens larvae grown commercially on agricultural waste from potato chip production, emphasizing the renewable origin of both the biomass and the final adhesive. These results highlight the potential of insect proteins as sustainable and circular alternatives for the wood panel industry.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) established a set of global goals under a new sustainable development agenda, which includes the creation of sustainable cities and communities, as well as the promotion of responsible production and consumption. A principal aspect of this agenda is the reduction of the carbon footprint of urban areas and human settlements. To this end, a key strategy for mitigating the environmental impact of mass production involves the rational use of raw materials from renewable sources and the valorization of waste, thereby advancing the principles of a circular economy [1].

In the context of the 2030 Agenda, the timber industry is looking for more sustainable alternatives [2,3]. Particleboards are one of the main timber industry products. They are versatile and low-cost materials that are uniform in terms of density, texture, and performance [4]. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), in the last decade, global production of boards increased by around 25%, reaching 375 million m3 by 2022 (last year of data available), of which Asia produces 47.4%, Europe 26.5% and America 24.3%, while the remaining 1.8% corresponds to Africa and Oceania [5].

Regarding the manufacture of particleboards, one promising alternative is the increased utilization of waste from the forestry and agricultural sectors as raw materials. It is important to note that, in South America, the particleboard industry currently relies on raw materials sourced from cultivated forests, including logs of various species such as pine, eucalyptus, willow, and poplar, as well as by-products from the industrial wood sector, primarily from sawmills [6]. Numerous authors have worked on non-conventional sources of particles such as rice husk [7], wheat [8], corn [9], peanut shell [10], walnut shell [11], coconut [12], barley [13], and pruning residues [14,15]. Another residue that could constitute an alternative for this use is sugarcane bagasse, a residue from sugar mills [16], which consists of a fibrous portion of the cane composed mainly of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [17].

A critical factor in the manufacturing of particleboards is the choice of adhesive, which constitutes between 9% and 15% of the final board’s composition. Given the production volumes, the industry requires between 33 and 56 million cubic meters of adhesive to meet current demand. The adhesives commonly used in the production of these boards are based on amino resins (urea formaldehyde, UF, and melamine formaldehyde, MF), phenol-based (phenol formaldehyde, PF) or isocyanate-based (methylene diphenyl diisocyanate, MDI) [18]. However, all these commercial resins are petroleum-based products and, as their names indicate, most of them contain formaldehyde [19]. Therefore, their use is often limited or reduced because they do not meet the conditions of sustainability and harmlessness to the environment and/or human health [20].

Building on the drawbacks associated with formaldehyde-based synthetic resins derived from fossil resources, recent research has increasingly focused on bio-based adhesives obtained from renewable feedstocks for particleboard production. Anggini et al. [21] investigated tannin–glyoxal formulations for particleboard made of Areca catechu leaf sheath, reporting good cohesion and adhesion performance. Zhang et al. [22] developed lightweight particleboards, with a density of 550 kg/m3, using epoxidized soybean oil foams, achieving modulus of rupture (MOR) ≈ 11 MPa, modulus of elasticity (MOE) ≈ 1.9 GPa, internal bonding (IB) ≈ 0.56 MPa and thickness swelling ≈ 6.6%. Tene Tayo et al. [23] optimized canola protein adhesives, where nitrite-crosslinked formulations reached IB ≈ 0.8 MPa and MOR ≈ 20 MPa, outperforming commercial UF under selected conditions. Fagbemi and Sithole [24] used keratin hydrolysates from poultry feather waste, obtaining MOR in the range 6–9 MPa and MOE around 1.1–1.3 GPa. Islam et al. [25] tested natural rubber latex blended with starch as a binder for sugarcane bagasse particleboard, producing panels of density around 830 kg/m3 with MOR ≈ 15–20 MPa and MOE ≈ 2.4 GPa, though with limited water resistance. Finally, Grossi et al. [26] screened protein flours and concentrates from soybean, cotton, hemp, carob, grape, maize and jatropha, demonstrating that crosslinking with polyamide-amine epichlorohydrin can raise wet shear strength above 2 MPa, exceeding minimum requirements for interior plywood.

Recent studies on bio-based binders show promising results but also reveal significant limitations. Protein-based adhesives offer competitive dry strength, yet often require costly chemical crosslinkers and still exhibit reduced durability under humid conditions. Polyurethane resins from castor oil achieve excellent properties but rely on relatively expensive feedstocks. Even with novel formulations, challenges such as poor dimensional stability and high production costs continue to limit industry-scale applications. Against this background, black soldier fly larvae (BSFL) proteins emerge as a promising alternative: larvae can be mass-reared on agricultural or food-processing wastes, ensuring a sustainable raw material supply, while their intrinsic viscoelasticity contributes to improved adhesion and water resistance compared with conventional plant proteins.

Building on this context, our research group has synthesized protein adhesives using BSFL (Hermetia illucens) reared under commercial conditions on potato chip industry residues [27]. BSFL can efficiently convert such organic residues into proteins and fatty acids [28]. In this regard, insect proteins are increasingly recognized as renewable raw materials due to their high protein content, functional versatility, and the possibility of obtaining them through circular economic processes. Recent reviews have highlighted the potential of BSFL proteins not only for food and feed, but also as sustainable alternatives for the development of bioplastics and other renewable materials [29]. For example, Falgayrac et al. [30] highlighted insect proteins as renewable feedstocks for bioplastics and sustainable composites. González-Lara et al. [31] reported that BSFL biomass can serve as an alternative source of chitin and chitosan, proposing their use as functional additives in concrete to enhance strength and sustainability. Similarly, D’Amora et al. [32] extracted eumelanin from BSFL cuticles and incorporated it into tissue-engineered scaffolds, confirming its biocompatibility and functional benefits. More recently, Le et al. [33] developed a green extraction method to obtain chitin and nanochitin from BSFL and demonstrated their potential in biodegradable packaging films with antioxidant properties. Additionally, Lomonaco et al. [34] reviewed the use of BSFL frass as an organic fertilizer, showing its nutrient content and beneficial effects on crops, further expanding the spectrum of applications for insect-derived products in circular bioeconomy frameworks.

In our previous study, we concluded that proteins produced by BSFL are promising alternatives for bio-based adhesives, since they show good mechanical properties (tested on pine), do not contain formaldehyde in their composition, and add value to agricultural and forestry waste, promoting the circular economy [27]. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to develop fully bio-based particleboards using sugarcane bagasse and a protein adhesive derived from black soldier fly larvae reared on agricultural waste, and to evaluate their rheological and mechanical behavior in compliance with international standards, highlighting the potential of insect-derived proteins as renewable and circular materials for the wood panel industry. In addition, a comparative board using Eucalyptus grandis particles (a commonly used raw material in commercial particleboard production) was included to assess the versatility of the adhesive system and to benchmark the performance of bagasse-based panels. This research aimed to explore an ecological alternative that integrates waste valorization with the use of renewable components in the wood panel industry.

2.1 Manufacturing of BSFL-Based Adhesive

For the synthesis of the bio-based adhesive, BSFL flour (kindly donated by Procens, from Balcarce, Argentina) was used, with a composition of 58% protein, 14% lipids, 8% moisture, 8% ash, 6% fibers, 5% Ca and 0.3% Mg (data provided by the supplier). The chemical reagents (pure for analysis—p.a. quality) used for the manufacture of the adhesive were sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and n-hexane, purchased from Biopack (Buenos Aires, Argentina). Eucalyptus grandis lumber was purchased from Aserradero Vagol (San Martín, Argentina), which was subsequently chipped and milled in the laboratory to produce the particles used for board manufacturing. Sugarcane bagasse particles were sourced from a core business unit located in Jesús Menéndez, Las Tunas, Cuba, and were used as received, without additional pretreatment, except for oven-drying to adjust the moisture content prior to board manufacture.

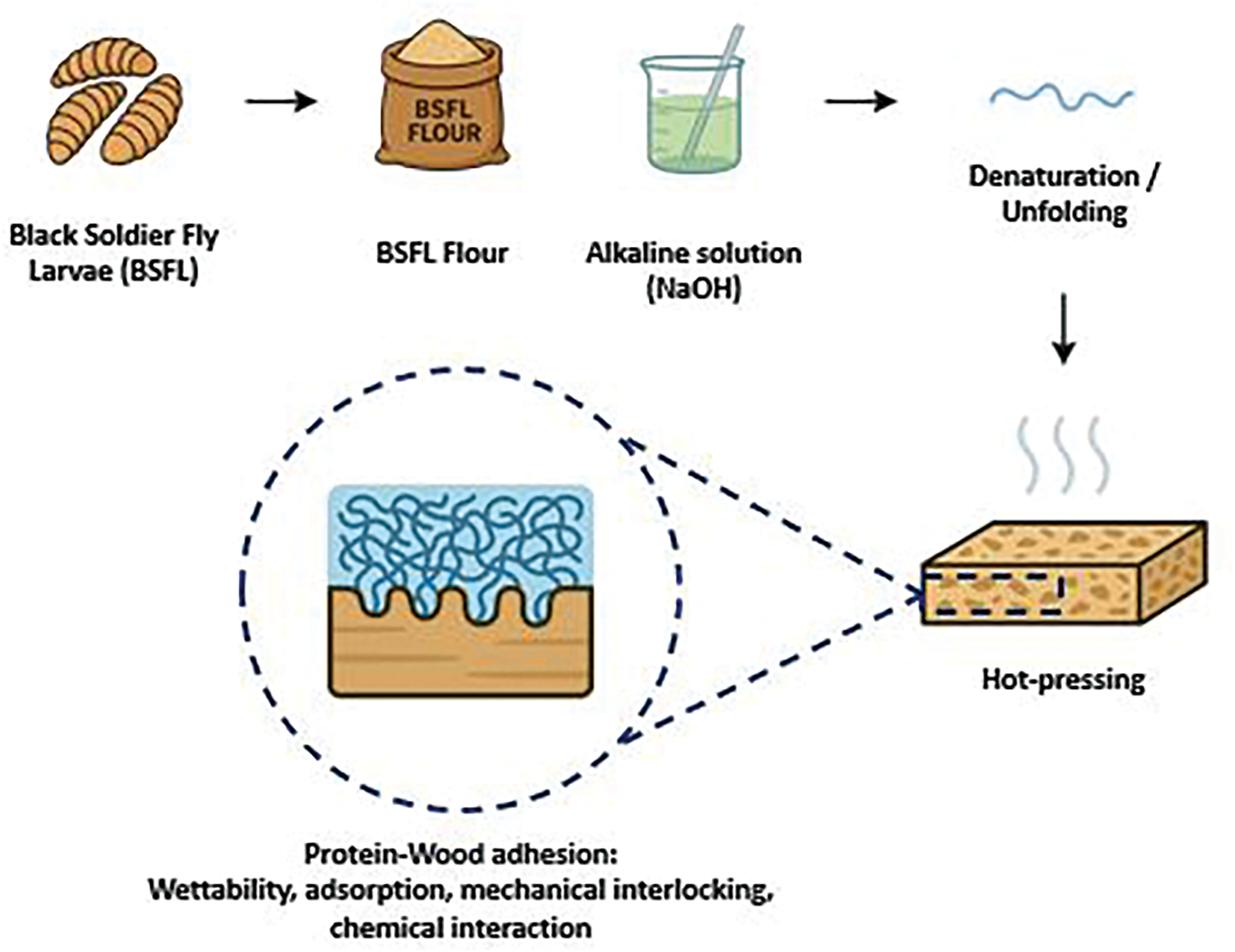

The BSFL flour was defatted by Soxhlet extraction with n-hexane at 70°C for 6 h [35]. Then, the sample was ground to reduce the particle size. The adhesive formulation followed the procedure described by García et al. [27], which consisted of preparing an alkaline solution of 6 g of NaOH in 150 g of H2O and subsequently incorporating 37.5 g of degreased BSFL. The mixture was homogenized in an industrial stirrer at 300 rpm for 1 h at room temperature. At the end of the process, a homogeneous suspension with pseudoplastic behavior and suitable for spray application was obtained.

2.2 Rheology of BSFL-Based Adhesive

Rheological characterization of the BSFL-based adhesive was carried out using an Anton Paar MCR301 rheometer (Graz, Austria) equipped with a parallel plate geometry (diameter 50 mm, PP50). Viscosity (η) profiles were obtained in rotational mode, applying a shear rate (

where

2.3 Characterization of Lignocellulosic Raw Material

Sugarcane bagasse fibers were used; they were crushed and dried to produce the particle board. A hammer mill with a mesh diameter of 11 mm was used for this purpose. The sugarcane bagasse used in this study had a moisture content of 9% and the following chemical composition (dry basis), as provided by the supplier: 1.2% ash, 1.9% extractives (ethanol/benzene), 46.0% cellulose, 23.3% lignin, and 26.3% pentosans. The Eucalyptus grandis particles were obtained from 50 mm × 50 mm × 3000 mm wooden slats purchased from a local supplier and immersed in water for 24 h to increase plasticity and facilitate processing in a chipper. The resulting chips were then processed using a hammer mill to achieve the final particle size.

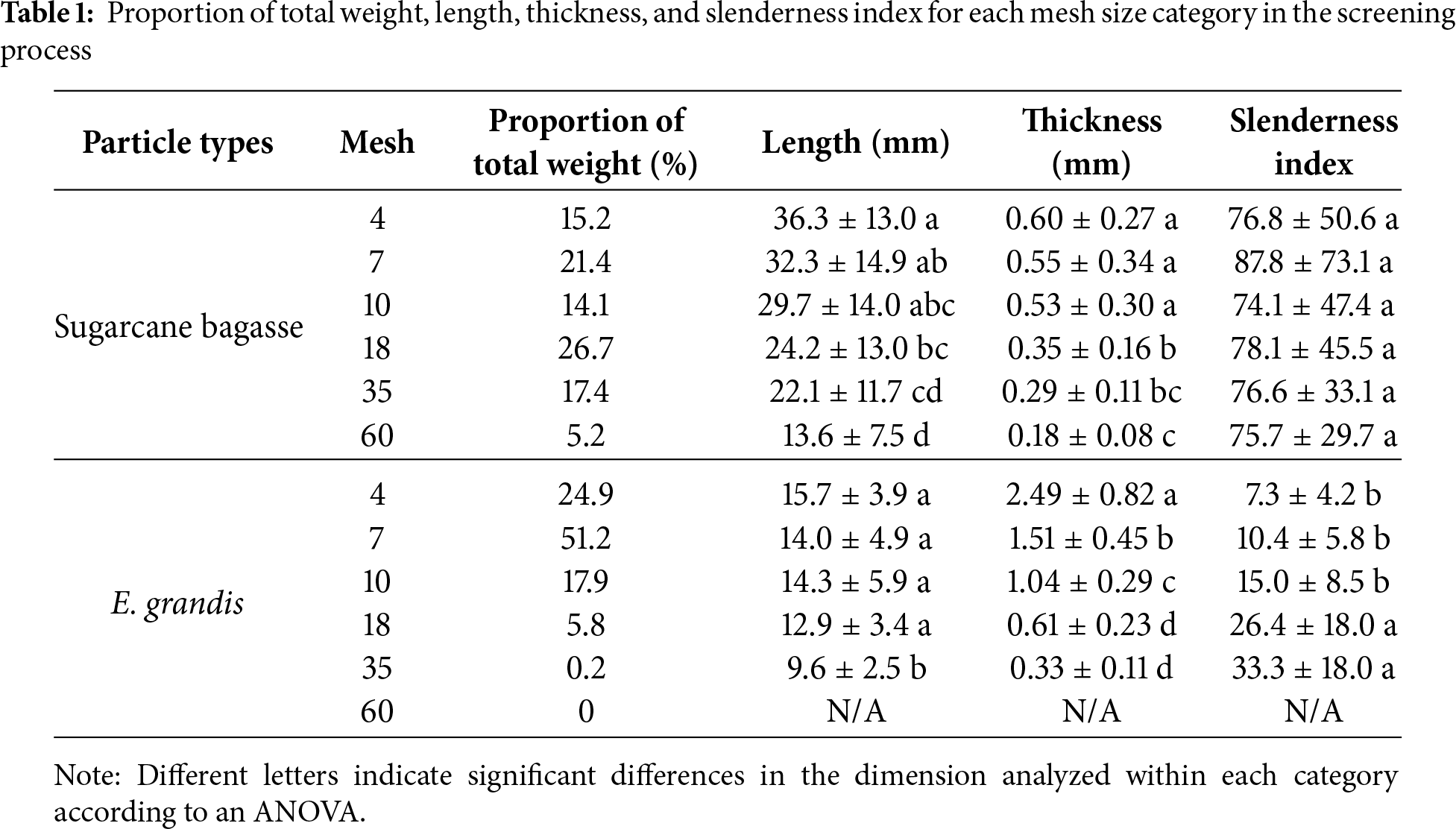

At this stage, the particle size distribution of both sugarcane bagasse fibers and Eucalyptus grandis wood particles was characterized by recording the proportion of material retained on a series of ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials) sieves: 4760 μm (mesh 4), 2830 μm (mesh 7), 2000 μm (mesh 10), 1000 μm (mesh 18), 500 μm (mesh 35), and 250 μm (mesh 60). The proportion retained in each size category for both materials was analyzed using contingency table methodology. The individual dimensions of fibers and particles retained on each sieve were measured (length and thickness) using a digital caliper (n = 15, for each size category and material), and the slenderness ratio (length/thickness) was calculated. These results were analyzed through analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by a post hoc comparison using Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test.

2.4 Production and Characterization of Wood Particleboards

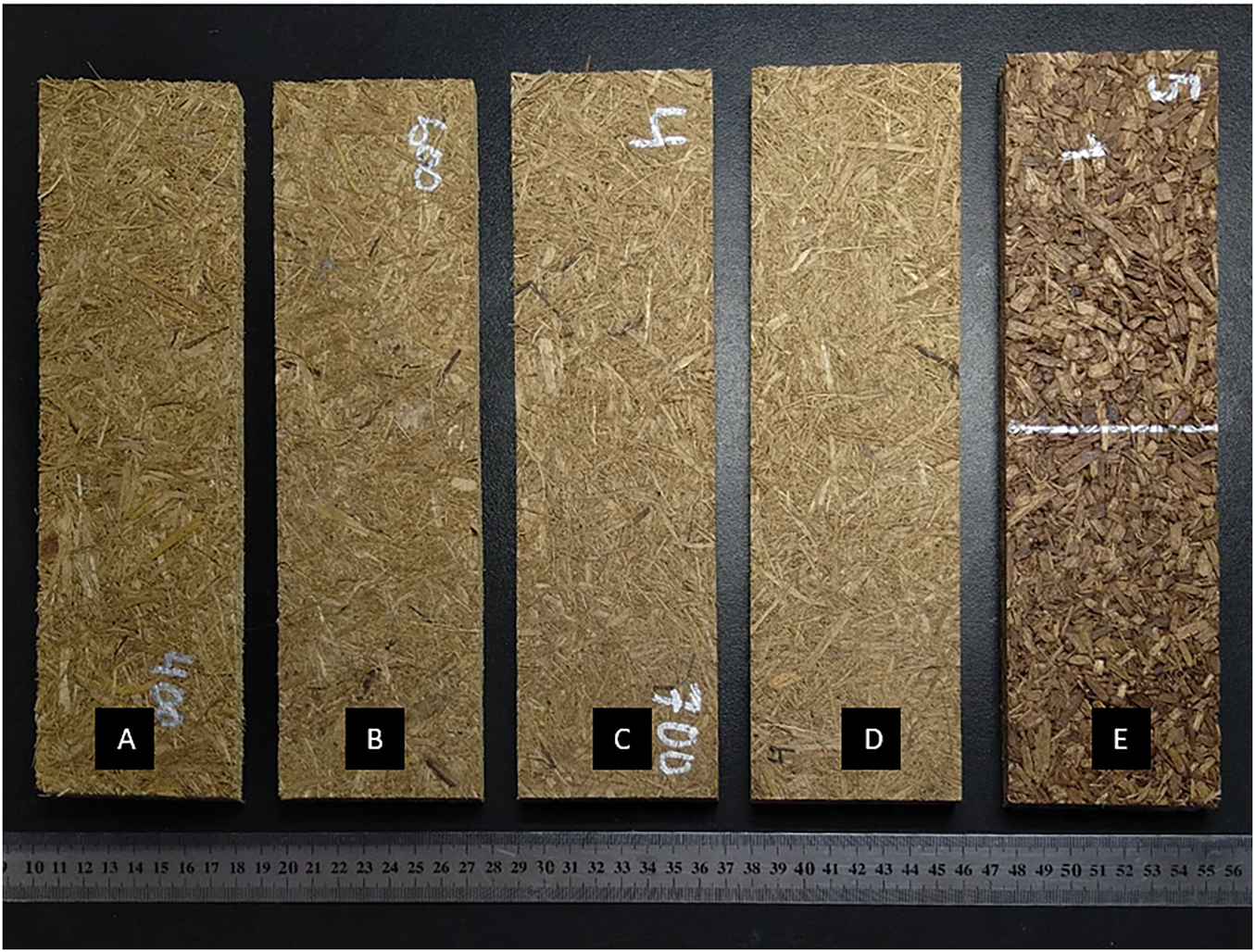

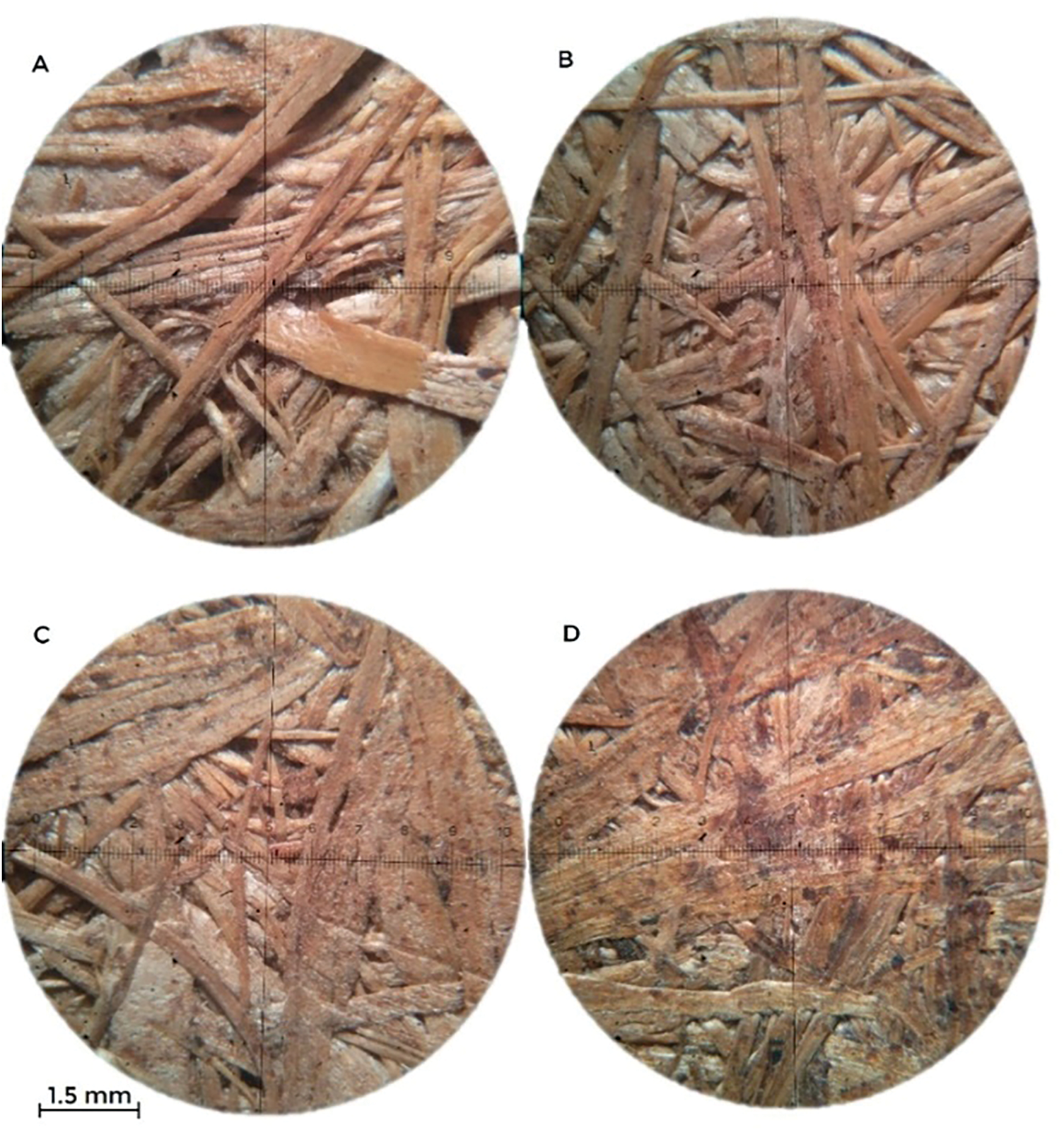

Particleboards were manufactured from sugarcane bagasse, with a density around 400, 600, 700, and 800 kg/m3. The samples were identified as D400, D600, D700, and D800, respectively (Fig. 1). The dry adhesive content was 12 wt.% in the final board and was applied by spraying.

Figure 1: Flexural test specimens on particleboards made with of black soldier fly larvae flour-based adhesive and sugarcane bagasse particles ((A): D400, (B): D600, (C): D700, (D): D800) and eucalyptus particles (E)

For the manufacture, the impregnated particles were dried in a forced convection oven at 70 ± 1°C until their moisture content was reduced to 8%. Subsequently, pre-pressing was carried out at 10 MPa for 5 min at room temperature. Finally, curing was carried out in a press at 160°C using three successive compression intervals: 7.5 MPa for 3 min, 5 MPa for 6 min, and finally 2.5 MPa for 3 min. This stepped pressure schedule was selected based on our previous work on protein/UF adhesives [36], as it allows gradual removal of water, reduces vapor blistering and cracks compared with constant pressure pressing, and ensures more efficient curing and reproducibility of the panels. Once cured, panels were cut 415 mm long, 415 mm wide and 9 mm thick.

To investigate the influence of particle size on board properties, a panel with a target density of 700 kg/m3 was produced using Eucalyptus grandis particles (Fig. 1E), employing the same processing variables as those used for sugarcane bagasse panels. It is worth noting that Eucalyptus is one of the materials commonly used in large-scale commercial particleboard production [37]. The Eucalyptus grandis board was manufactured following the same methodology applied for the sugarcane bagasse-based panels.

The surface texture of the particleboard was evaluated with an electronic contact roughness tester according to the Deutsches Institut für Normung—DIN 4768 [38]. Three measurements were taken on each sample using a SURTRONIC 3+ roughness tester, with the following parameters: measurement modulus (Rz, cut off) of 2.5 mm and measurement length (Lm) of 12.5 mm. To qualitatively evaluate the surface porosity, a Lancet optical microscope with 20× optical magnification and a 12-megapixel resolution camera was used.

Regarding mechanical properties, two tests were carried out: the tensile perpendicular to the plane and the static bending test, both performed on a universal testing machine (INSTRON 5982, Norwood, MA, USA). The tensile perpendicular to the plane test was carried out following the guidelines of the European Standard EN 319 [39] standard on specimens of 50 mm × 50 mm × 9 mm. A crosshead speed of 7.2 mm/min was used. The internal bonding (IB) was calculated as the ratio between the maximum load and the cross-section of the test piece. A total of seven specimens were tested, and results are reported as mean ± standard deviation. The three-point bending test was performed following the guidelines of the EN 310 [40] standard with the aim of determining the MOR and the MOE. Nine specimens were tested for each condition, and the results are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

The swelling test was carried out following the guidelines of the EN 317 [41] standard with the aim of determining the water absorption (WA) and the thickness swelling (TS). For this test, specimens of 50 mm × 50 mm × 9 mm were immersed in water at room temperature. The thickness and weight of the swelled samples were measured at 2 and 24 h.

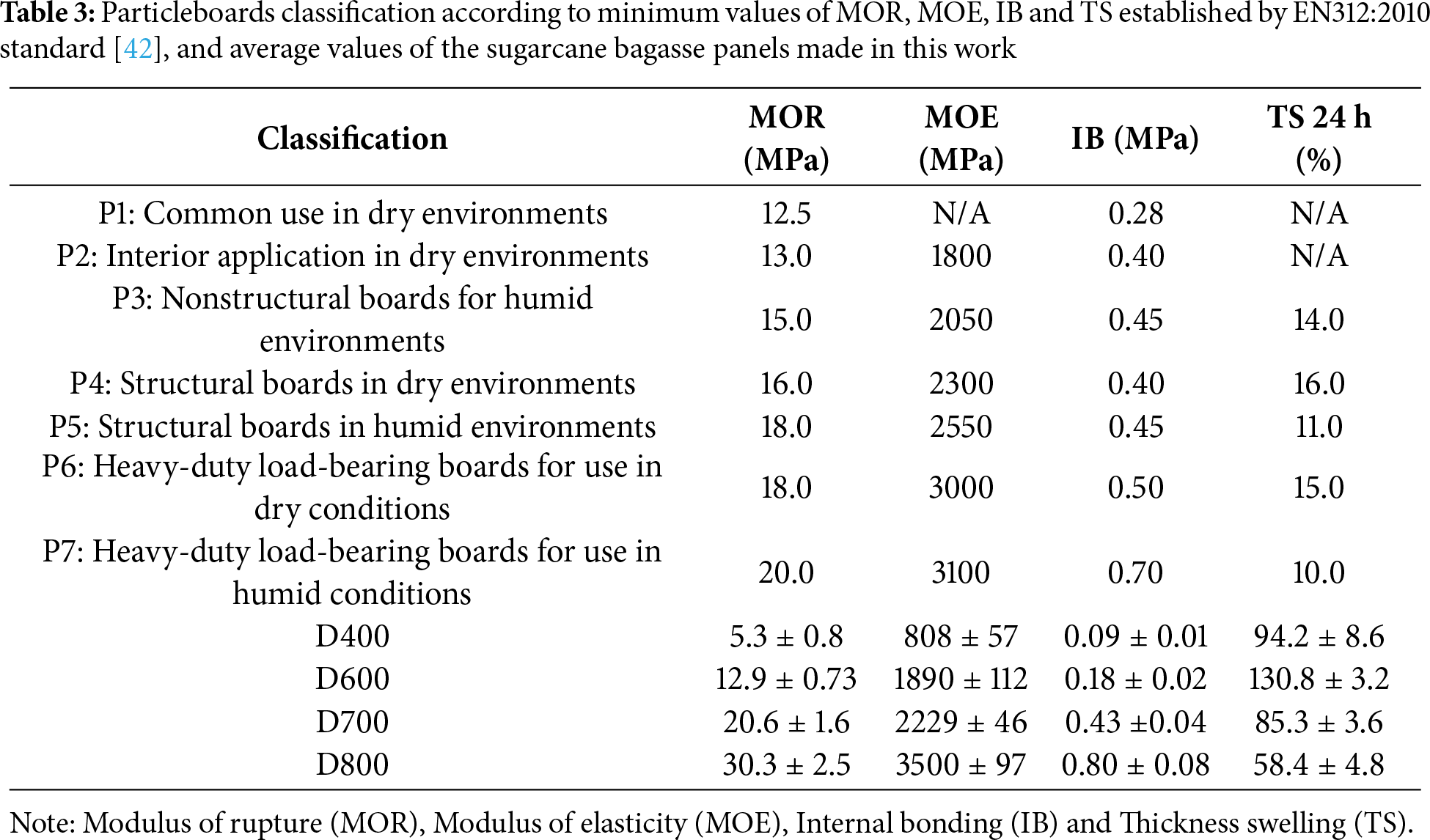

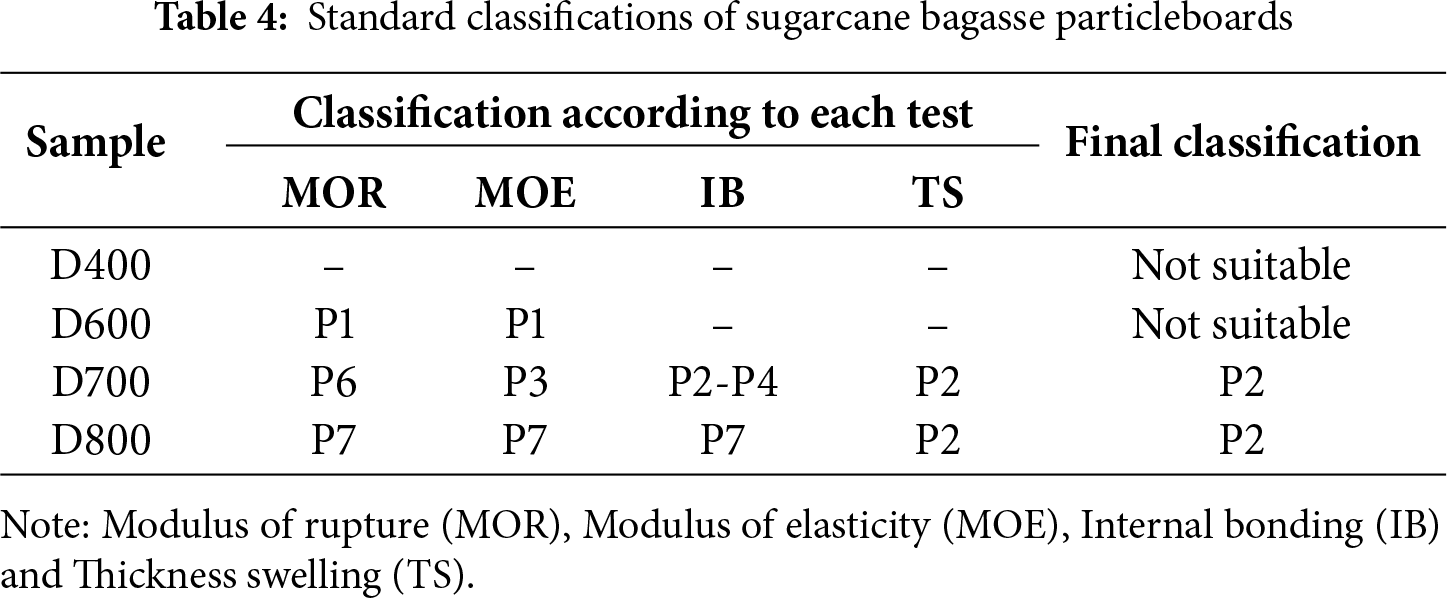

The measured MOR, MOE, IB, and TS values of the particleboards bonded with the BSFL-based adhesive were assessed according to the classification criteria defined in the European standard EN 312 for wood particleboards [42].

The MOR, MOE, IB, TS and WA values were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Mean values were analyzed with the Tukey-Test for paired comparisons at a significance level P 0.05 using the Origin Pro 8 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

3.1 Characterization of BSFL-Based Adhesive

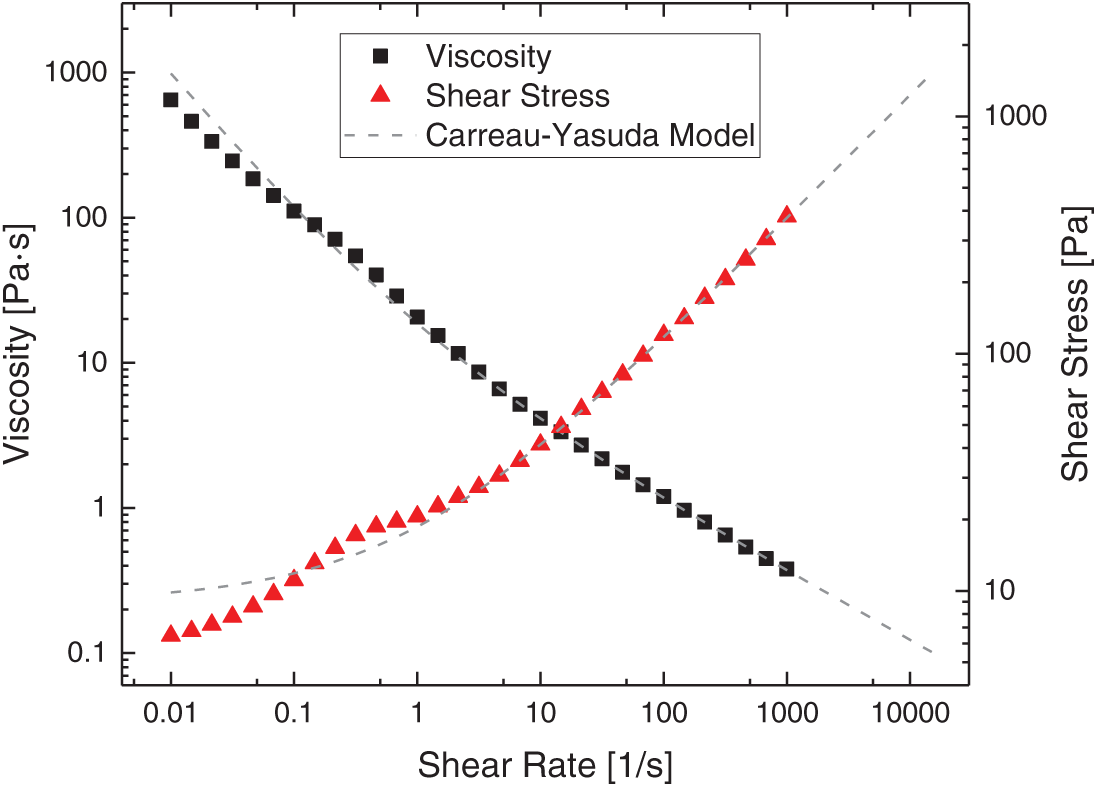

Fig. 2 presents the viscosity curves of BSFL-based adhesive. Given that particleboard adhesives are typically applied by spraying under high shear conditions (above 1000 1/s), the Carreau–Yasuda model (Eq. (2)) was employed to fit the experimental data and extrapolate viscosity values at shear rates beyond the measurement limits of the rheometer:

where

Figure 2: Viscosity and shear stress curves of BSFL-based adhesive. Experimental data were fitted by Carreau-Yasuda model (R2 = 0.99934)

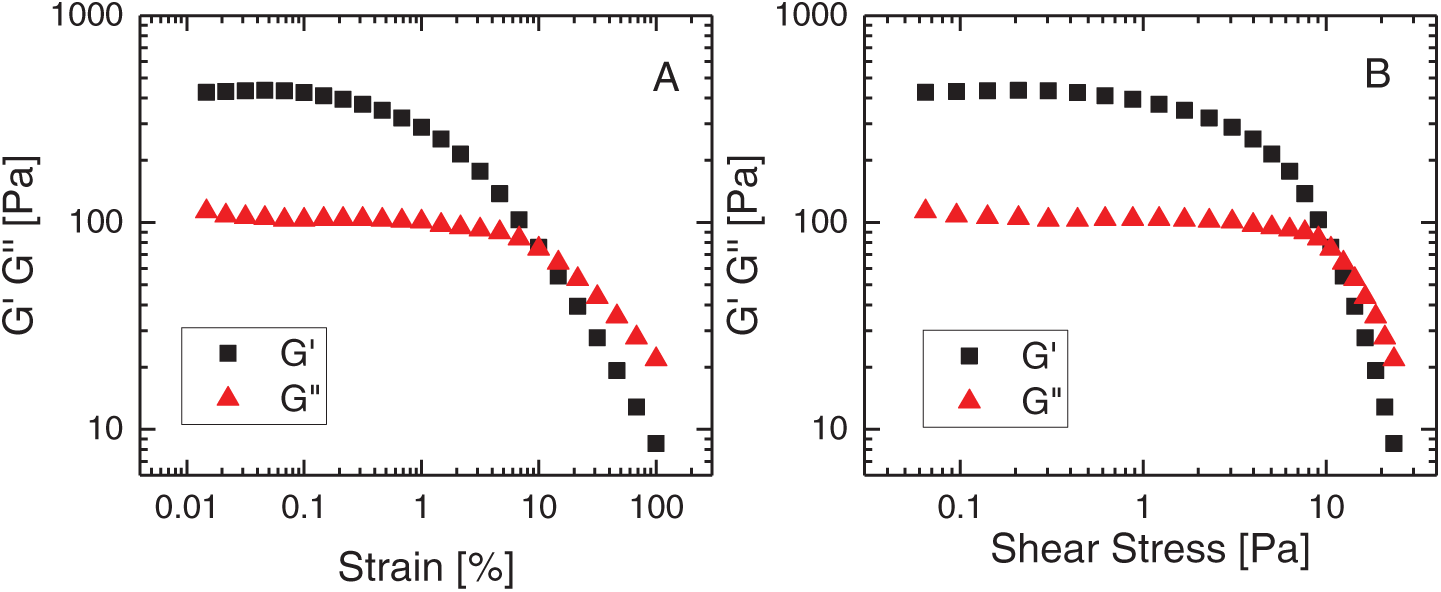

Amplitude sweep tests were conducted to identify the linear viscoelastic region (LVR). For the BSFL-based adhesive, the LVR was found to extend up to 0.1% strain (Fig. 3A), where both the storage modulus (

Figure 3: Amplitude sweeps results of BSFL-based adhesive. (A): as a dependence of shear strain, and (B): as a dependence of shear stress

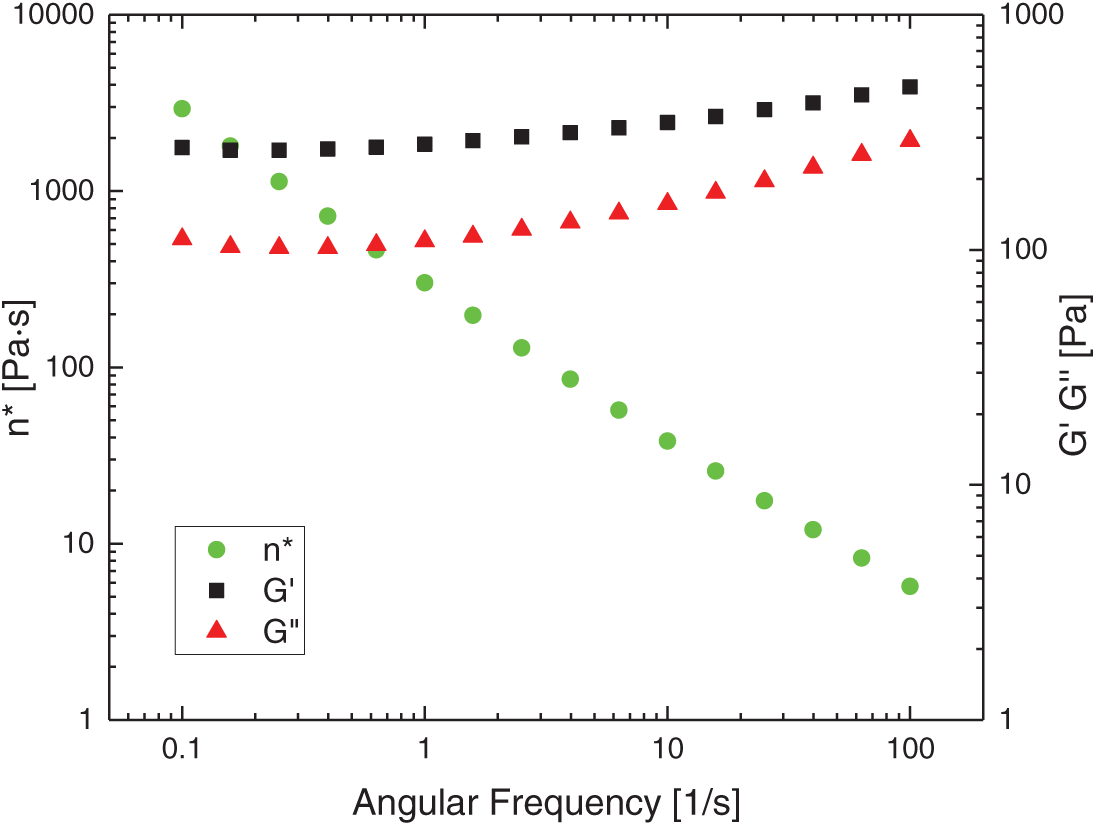

The frequency sweep test was carried out within the previously determined LVR to evaluate the viscoelastic behavior of the BSFL-based adhesive. As shown in Fig. 4,

Figure 4: Complex viscosity, storage and loss modulus as a function of angular frequency of BSFL-based adhesive

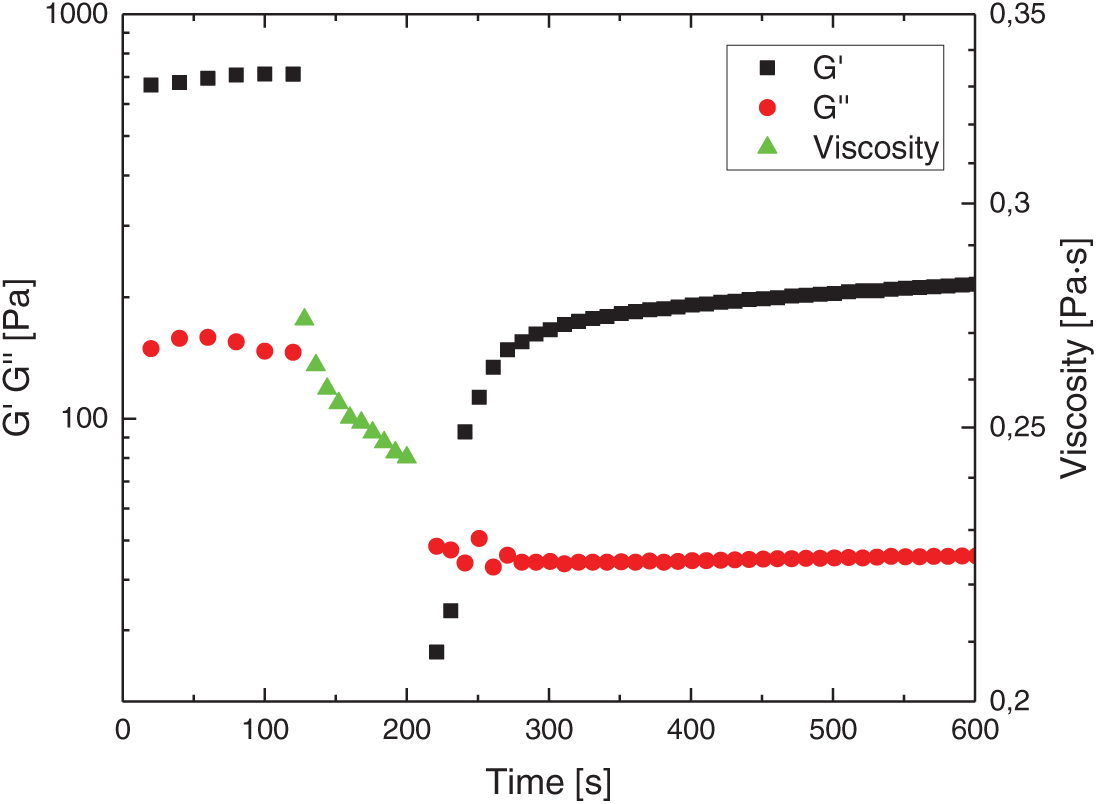

The 3ITT was performed to evaluate the structural recovery behavior of the BSFL-based adhesive under shear. As shown in Fig. 5, the crossover between

Figure 5: Three-interval thixotropy test (3ITT) of BSFL-based adhesive

3.2 Morphological Characterization of Sugarcane Bagasse Particles

The morphological characterization of the bagasse particles is shown in Table 1. Analyzing the proportion of material retained in each mesh, a bimodal distribution was observed, with two peaks corresponding to mesh sizes 7 and 18. When comparing the morphometry of the retained fractions, differences were found in all three measured variables (length, thickness, and slenderness), although similar trends were observed for both length and thickness, with particle dimensions decreasing as the mesh number increased. However, the slenderness ratio remained statistically unchanged across mesh sizes for bagasse particles, ranging from 74.1 (mesh 10) to 87.8 (mesh 7), with a mean value of 78.2 for all sieves.

When comparing Eucalyptus grandis and bagasse particles, significant differences were observed in the distribution of particle sizes across mesh fractions, as confirmed by a highly significant Pearson Chi-square statistic (χ2 = 54.15; p < 0.0001). Mainly, eucalyptus particles were shorter and thicker than bagasse particles. Both materials followed similar overall trends, with length and thickness decreasing as mesh number increased. However, the rate and magnitude of these changes differed by material: length reduction was more pronounced in bagasse, while thickness decreased more sharply in eucalyptus particles. For slenderness ratio, bagasse particles exhibited no significant variation across mesh sizes, while eucalyptus particles showed an increasing slenderness ratio as mesh size decreased. Moreover, the slenderness ratio was consistently and significantly higher in bagasse particles across all mesh fractions.

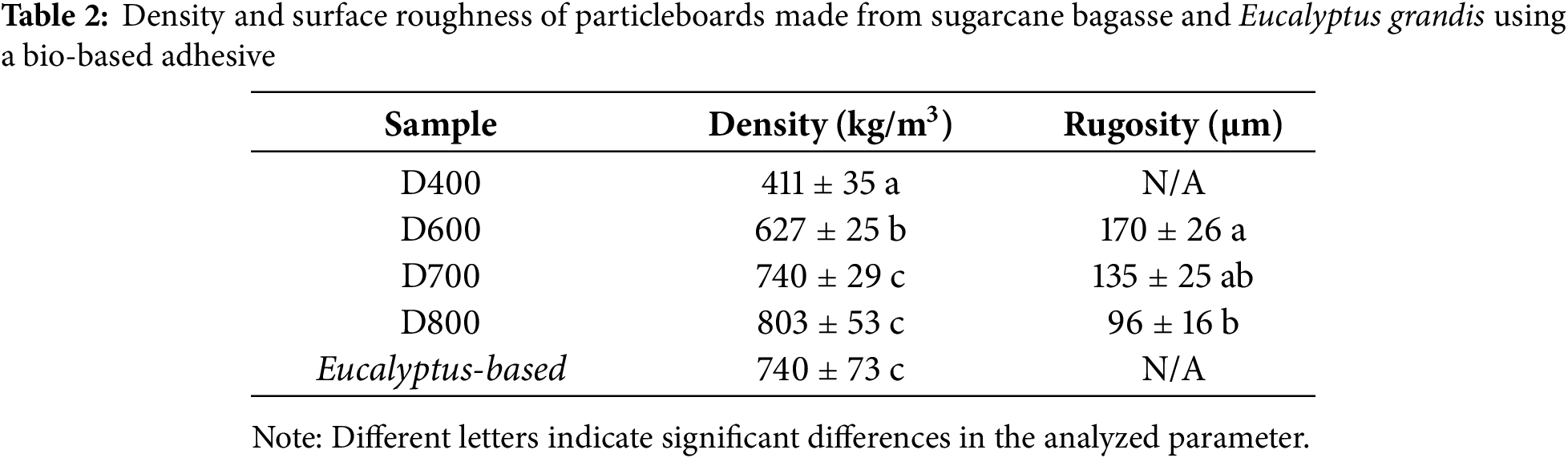

3.3 Density and Roughness of Sugarcane Bagasse Particleboards

The measured density values of the manufactured boards, along with surface roughness, are presented in Table 2. Significant differences were found between the densities of the bagasse particleboards, except for D700 and D800. The density of the Eucalyptus grandis panel was 740 ± 73 kg/m3, comparable to the D700 and D800 panels. As shown in Table 2 and Fig. 6, the surfaces of the finished boards exhibited a good overall appearance: at higher densities (Fig. 6C,D), the surface was notably smoother, with fewer and smaller voids. The roughness of the D400 board could not be determined because it exceeded the maximum measuring range of the device. This parameter decreased as the density of the board increased. Surface roughness was not measured for the eucalyptus-based panel, as the particles were predominantly cubic and in the centimeter range, resulting in voids that prevented reliable measurement with the available equipment.

Figure 6: Optical microscopy images of particleboards made from sugarcane bagasse at different densities: D400 (A), D600 (B), D700 (C), and D800 (D)

3.4 Mechanical Testing of Boards

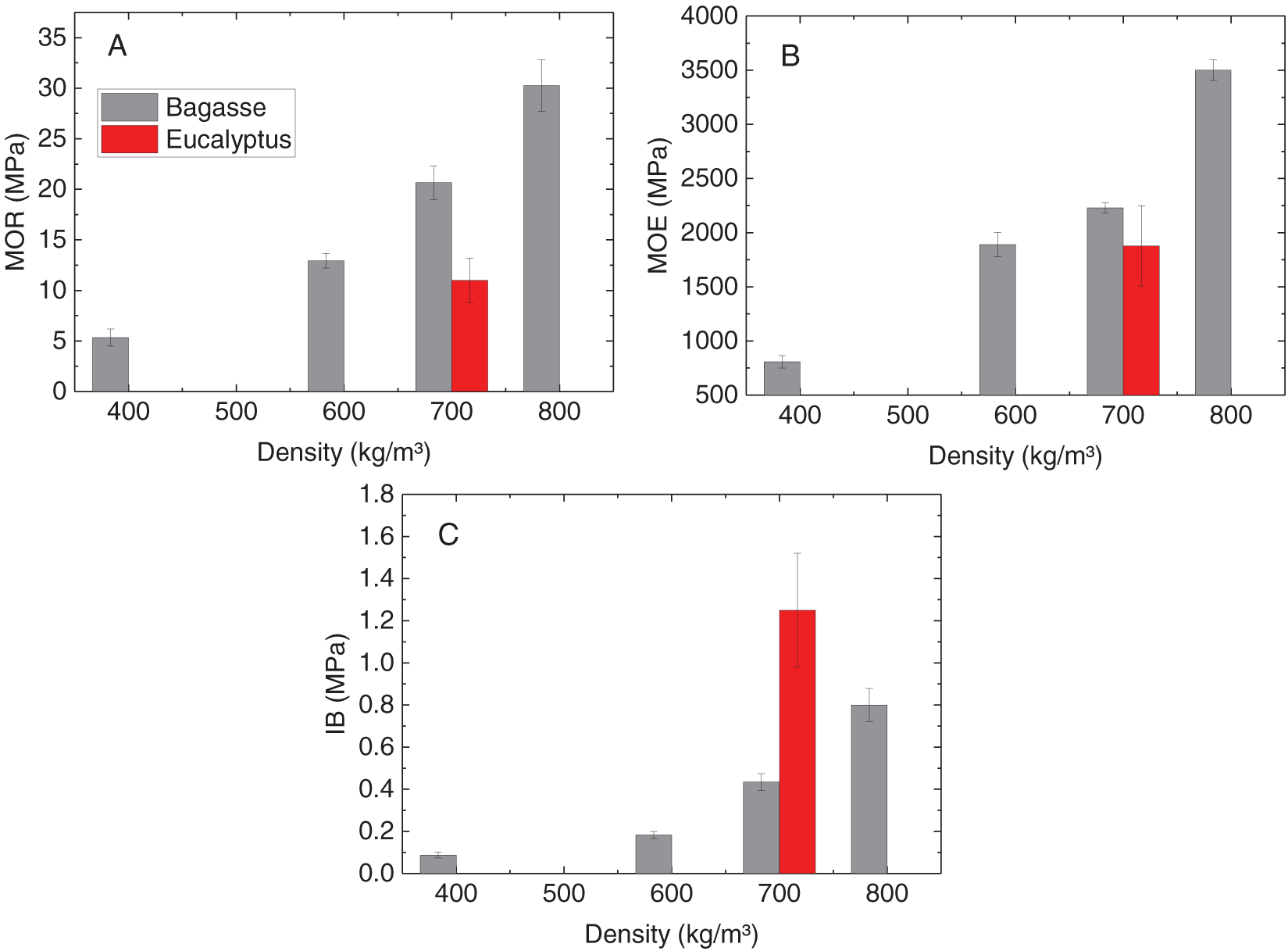

The results of MOR, MOE, and IB as a function of panel density are shown in Fig. 7. A significant increase in these properties was observed with increasing panel density. For instance, MOR for the D400 board was 5.34 MPa, whereas for the D800 board it reached 30.26 MPa, marking an increase of 466%. Similarly, MOE increased 333%, from 808 MPa for the D400 board to 3500 MPa for the D800 board. The IB values also showed a gradual increase with density: 0.09 MPa (D400), 0.18 MPa (D600), 0.43 MPa (D700), and 0.80 MPa (D800). Notably, the IB value of the D800 sample was 900% higher than that of the D400 sample. These results demonstrated a strong positive correlation between the mechanical properties and the density of the particleboard, indicating that higher compaction significantly enhanced mechanical strength. The Eucalyptus grandis-based panel exhibited lower MOR (11.0 ± 2.2 MPa) and MOE (1878 ± 370 MPa) values compared to the sugarcane bagasse particleboard. In contrast, IB was higher in the eucalyptus panel (1.25 ± 0.27 MPa).

Figure 7: Modulus of rupture (A), Modulus of elasticity (B) and internal bonding (C) as a function of density for particleboards made from sugarcane bagasse and Eucalyptus grandis

3.5 Dimensional Stability of Boards

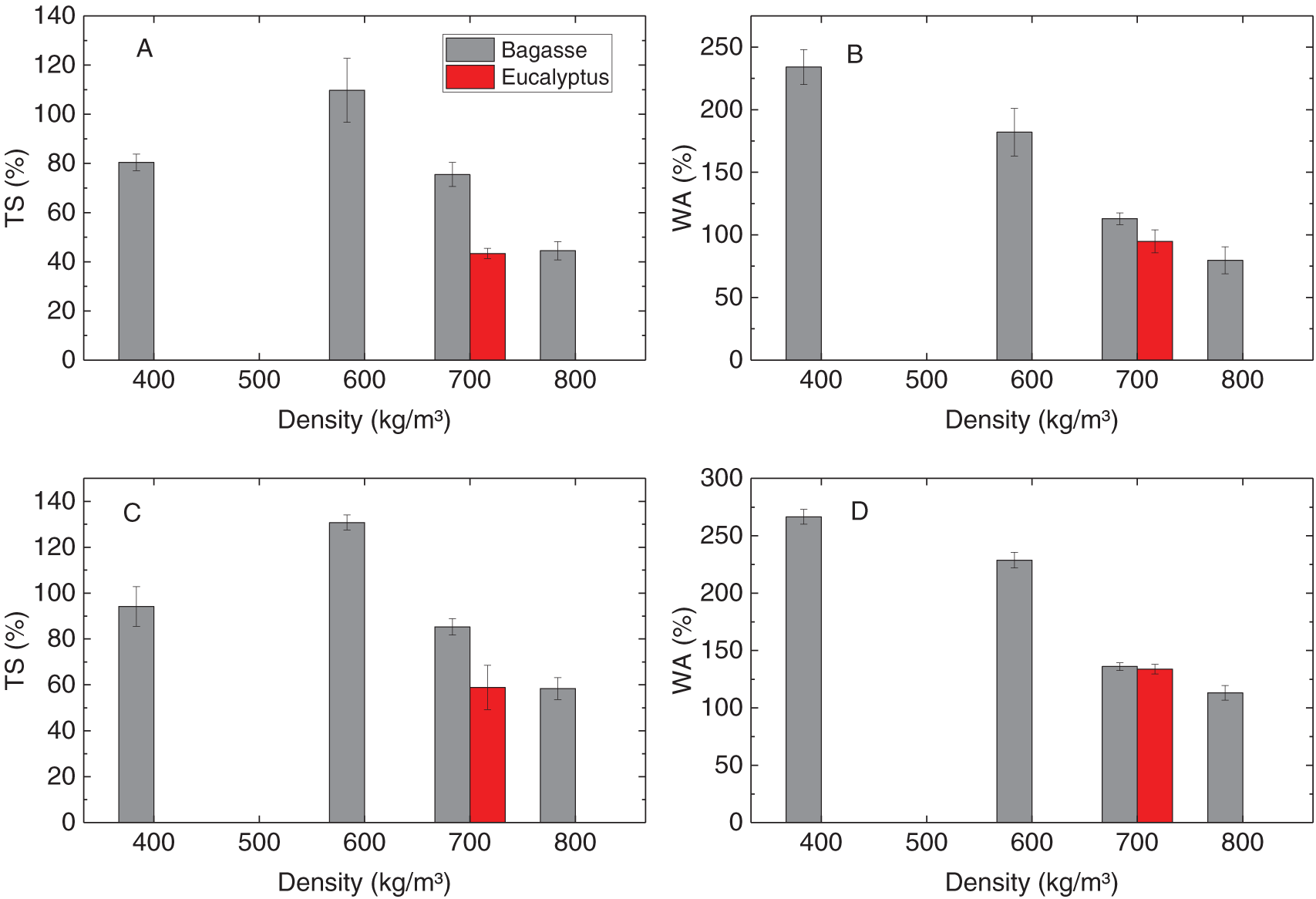

The results of thickness swelling (TS) and water absorption (WA) at 2 and 24 h are shown in Fig. 8. WA decreased with increasing board density, regardless of exposure time. According to TS data (Fig. 8A,C), TS after 24 h increased from 94.2 ± 8.6% in the D400 panel to 130.8 ± 3.2% in the D600 panel, followed by a reduction to 85.3 ± 3.6% and 58.4 ± 4.8% in the D700 and D800 panels, respectively. To contextualize these results, the Eucalyptus grandis-based panel, with a density similar to the D700 bagasse board (≈740 kg/m3), exhibited lower WA and TS values at both time points. Specifically, WA after 24 h was 133.7% for eucalyptus compared to 136.0% for bagasse, while TS after 24 h was 58.9% vs. 85.3%, respectively.

Figure 8: Variation of thickness swelling (TS) and water absorption (WA) at 2 h (A,B) and at 24 h (C,D) as a function of density for particleboards made from sugarcane bagasse and Eucalyptus grandis

3.6 Standard Classification of Sugarcane Bagasse Particleboards

The experimental values of MOR, MOE, IB, and TS for the particleboards made from sugarcane bagasse and a BSFL-based adhesive were compared with the requirements of the European standard EN 312 for wood particleboards [42]. This comparison was conducted to assess potential applications of the boards (Table 3). According to this standard (Table 4), the D400 sample did not meet the minimum requirements for particleboards. The D600 sample reached the P1 rating for MOR and MOE but failed the IB requirement, thus not meeting the minimum classification either. The D700 sample showed good bending properties and an IB value of 0.43 ± 0.04 MPa, which would place it in P3; however, due to insufficient water resistance, its classification dropped to P2 (indoor dry environments). Finally, the D800 sample exhibited a TS of 58.4 ± 4.8% at 24 h, exceeding the 10% limit for P7 classification. Despite surpassing the mechanical requirements for P7, its classification was also P2 due to excessive swelling.

4.1 Rheology of BSFL-Based Adhesives

Rheological behavior is a critical parameter for non-Newtonian systems such as protein-based adhesives [43]. Viscosity curves are commonly employed to anticipate adhesive performance during industrial operations such as mixing, pumping, or spraying. Moreover, although the use of the Carreau–Yasuda model for protein-based wood adhesives is still limited, it has been widely adopted for describing the flow behavior of protein systems [44]. The pseudoplastic behavior observed for the BSFL-based adhesive in Fig. 2 is consistent with our previous findings [27]. Importantly, the extrapolated viscosity values (0.157–0.101 Pa·s at high shear rates) fall within the recommended range for particleboard production (0.1–0.15 Pa·s) [45], confirming that BSFL adhesives are suitable for spraying applications under typical processing conditions.

Oscillatory rheological tests are essential for characterizing protein-based adhesives because they provide insights into viscoelastic structure without inducing structural breakdown [46]. Determining the LVR ensures that subsequent frequency sweeps or time-dependent measurements are performed under conditions that reflect intrinsic material properties rather than structural damage. The flow point, observed in Fig. 3B at ≈10 Pa for the BSFL-based adhesive, is a particularly relevant parameter, as it defines the transition from solid-like to liquid-like behavior. This benchmark can be used to evaluate the mechanical stability of protein adhesives under external stress and to guide formulation adjustments for improving processing and performance during panel manufacture.

Frequency sweeps provide key insights into the molecular organization of protein-based adhesives, as they reflect the balance between elastic and viscous contributions [46]. The predominance of

The 3ITT test is a valuable tool for assessing the structural recovery behavior of viscoelastic materials, particularly relevant for bio-based adhesives subjected to high shear during processing or application. In the context of protein-based adhesives, where the formation and recovery of a physical network governs performance, thixotropic analysis provides insight into both formulation robustness and industrial applicability [43]. The rapid but partial structural recovery observed in Fig. 5 for the BSFL adhesive is advantageous, as it ensures that mechanical strength is regained shortly after application. This behavior is especially beneficial in spraying or spreading processes, where fast recovery minimizes sagging, enhances substrate wetting, and promotes uniform adhesive distribution, ultimately contributing to strong and reliable bonding in particleboard or plywood production.

To better illustrate how the rheological properties of the BSFL adhesive relate to its bonding performance, Fig. 9 presents a simplified scheme of the proposed adhesion mechanism between protein chains and bagasse particles during hot-pressing. In this conceptual model, protein unfolding and partial denaturation under alkaline conditions expose functional groups capable of establishing hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with the wood surface, while the liquid medium ensures adequate wettability and penetration into pores. Short chains can penetrate into the surface porosity, favoring adsorption and mechanical interlocking, whereas longer chains remain at the interface, contributing to cohesion across particles. These interactions, combined with the consolidation effect of pressing and drying, explain the ability of the BSFL adhesive to form continuous networks and generate adequate internal bond strength in the manufactured panels.

Figure 9: Simplified scheme of BSFL protein adhesive preparation and proposed adhesion mechanisms with lignocellulosic particles during hot-pressing

4.2 Effect of Bagasse and Eucalyptus Particle Morphology on Board Performance

The dimensions of the bagasse particles used in this study (Table 1) were slightly higher than those reported by Brito et al. [47], who observed lengths between 9.2 and 18.78 mm, thicknesses between 0.22 and 0.27 mm, and slenderness ratios ranging from 42 to 69. Also, the morphological distinctions between Eucalyptus grandis and sugarcane bagasse particles are critical, as they are expected to influence the mechanical behavior of the resulting panels. Bagasse particles, with their higher slenderness ratio, provide greater contact area and potential for mechanical interlocking, while eucalyptus particles, being shorter and thicker, tend to adopt a more cuboidal shape, leading to increased void content and reduced surface area available for adhesive bonding. These differences in particle morphology are therefore expected to influence the mechanical properties of the panels.

4.3 Performance of Particleboards Bonded with BSFL Adhesives

Surface roughness is a quantifiable measure of surface irregularities, which can significantly influence the interaction between panels and melamine-impregnated paper commonly used as the external face in veneers [48,49]. This coating not only improves the finishing of the panels but also enhances the water resistance of the boards [50]. The decrease in surface roughness with increasing density observed in Table 2 is consistent with previous reports for particleboards [51]. Furthermore, surface roughness has been shown to depend on multiple factors, including particle type and morphology, panel density, and pressing conditions [52,53]. In agreement with these findings, our results suggest that particle morphology plays a key role in surface quality, with particles of higher slenderness ratio leading to more homogeneous and smoother surfaces.

The contrasting mechanical behavior observed in Fig. 7 between bagasse and eucalyptus panels can be attributed to particle morphology. According to the literature, both MOE and MOR are positively influenced by particle length and negatively by particle thickness [54], with slenderness being the most critical factor, exerting a direct positive effect on these properties [55]. In this context, the higher slenderness ratio of bagasse particles (Table 1) is consistent with the superior MOR and MOE values obtained in this study (Fig. 7A,B). Regarding IB, previous reports indicate that this property is influenced by particle geometry at fixed density, with higher values occurring when particles are shorter and thicker, i.e., with a lower slenderness ratio [56]. This trend was also observed in our results, where the eucalyptus panel, composed of shorter and thicker particles, achieved higher internal bonding compared to bagasse panels. These findings reinforce the key role of particle morphology in determining the mechanical performance of particleboards manufactured from alternative lignocellulosic raw materials.

The decrease in WA with increasing density observed in Fig. 8 is consistent with previous findings that denser panels exhibit reduced water diffusion [57]. This trend may also be influenced by the adhesive content, since at fixed resin loading (12 wt.%), denser boards concentrate a higher adhesive amount per unit volume, contributing to reduced WA [58]. The marked increase in TS from D400 to D600 can be attributed to the greater amount of lignocellulosic material present in the D600 panel, which increased water uptake capacity, combined with a porous internal structure that facilitated moisture penetration. In contrast, the reduction in TS from D600 to D800 correlates with enhanced compaction of the board, leading to reduced void content and limited water intrusion. This structural effect was supported by optical microscopy (Fig. 6), which showed fewer interparticle gaps in higher-density panels [59,60]. The comparison with Eucalyptus grandis highlights the dual role of particle morphology and board compaction in determining dimensional stability. Despite a coarser and more porous panel structure, the eucalyptus particles were thicker and less slender than bagasse particles, which may have limited water absorption at the particle level. This explains why eucalyptus boards showed lower WA and TS values than bagasse panels of similar density.

As is evident from these results, the weakest point of the studied particleboards is water resistance, since all samples presented TS values at 24 h considerably higher than those required for use in humid environments (Table 3). This limitation is consistent with other studies on protein-based adhesives, which typically show lower water resistance compared with synthetic resins [61]. Nevertheless, strategies such as incorporating cross-linking agents have been reported to improve the hydrophobicity of protein-based adhesives [62–64]. In addition, surface roughness analysis (Table 2) showed that higher-density boards presented smoother and more homogeneous surfaces, which could favor the adhesion of melamine-impregnated papers with excellent water resistance, often surpassing UF resins [65]. Therefore, by combining protein-based adhesives with hydrophobic modifications or overlay techniques, the D700 and D800 panels could potentially achieve the more demanding EN 312 classifications for use in humid environments. These findings reinforce the potential of bagasse-based boards bonded with natural resins to reach high-performance applications under appropriate modifications.

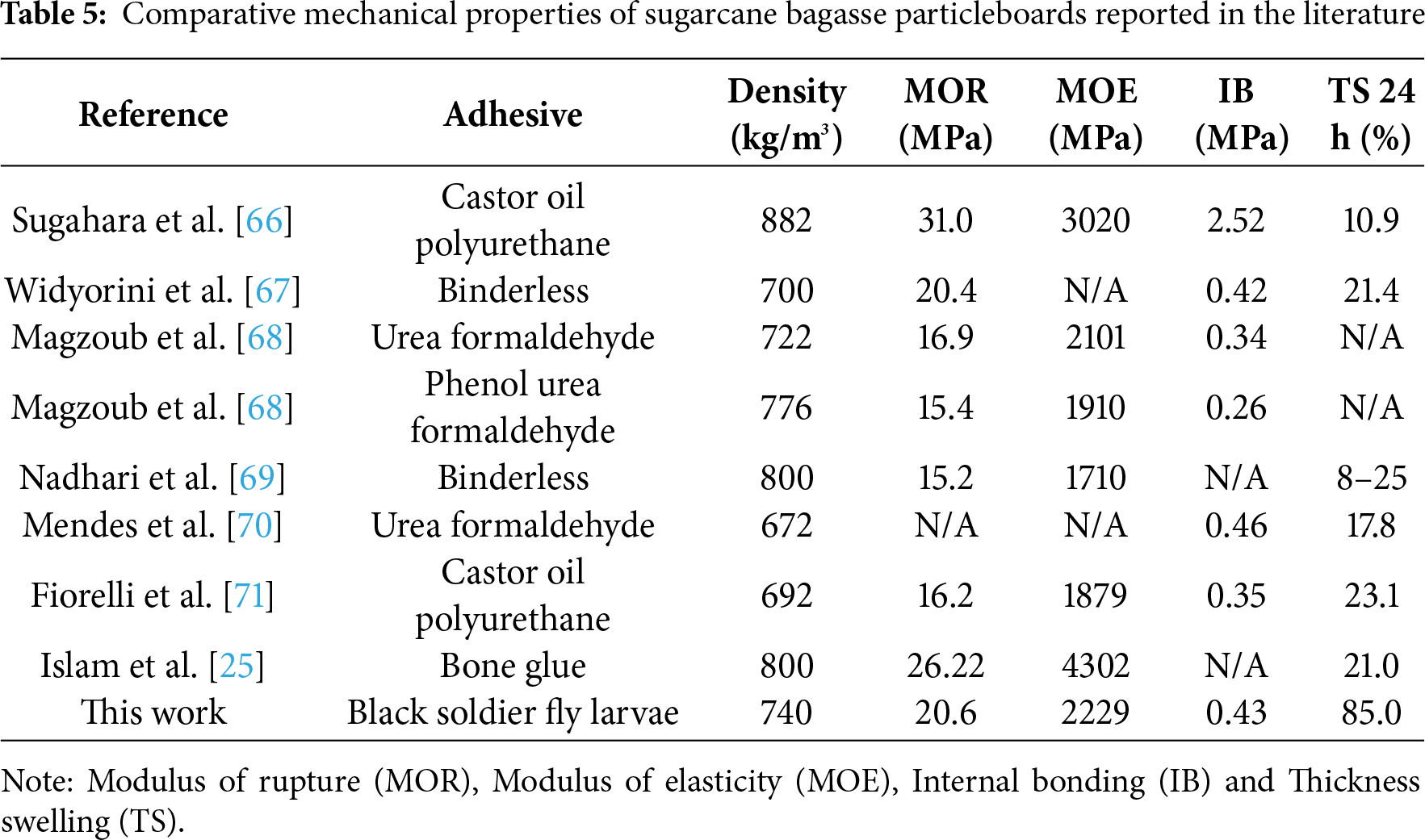

4.4 Comparative Discussion of Sugarcane Bagasse Particleboards

The mechanical and physical performance of the particleboards produced in this work was compared with several previous studies that employed sugarcane bagasse as the main lignocellulosic raw material (Table 5). Although some formulations reported higher absolute values in flexural or bonding strength, such as the castor oil polyurethane (PU) system by Sugahara et al. [66] or the bone glue-based panel from Islam et al. [25] those panels have a higher density than those studied in this work; also, the results must be contextualized by the adhesive type, board composition, and sustainability profile.

The binderless boards reported by Widyorini et al. [67] achieved IB values close to 0.42 MPa, comparable to our bagasse-based formulation (0.43 MPa), but those boards yet required high pressure and long pressing times. In contrast, our adhesive system based on BSFL protein achieved these results with milder processing conditions and without the need for synthetic additives or chemical pretreatments. Nadhari et al. [69] also researched binderless systems with lower MOR and MOE values.

When benchmarked against UF and phenol urea formaldehyde (PUF) systems, our formulation displayed superior MOR, MOE and IB values. For instance, Magzoub et al. [68] reported 16.9, 2101 and 0.34 MPa for MOR, MOE and IB, respectively, with PUF adhesives, while our bagasse board reached 20.6, 2229 and 0.43 MPa. Similarly, Mendes et al. [70] achieved an internal bond of 0.46 MPa using UF at 8 wt%, although the panel exhibited lower density (672 kg/m3) and no data were provided for flexural strength. Compared to these conventional formulations, the BSFL protein adhesive offers competitive bonding strength while being derived from renewable and circular sources.

The castor oil-based polyurethane PU adhesives presented by Fiorelli et al. [71] and Sugahara et al. [66] yielded similar and strong mechanical properties, with Sugahara’s panel achieving 31 MPa in MOR and an exceptionally high IB of 2.52 MPa. However, the density of this panel was 882 kg/m3, significantly higher than our system (740–745 kg/m3), and the formulation included 60% wood particles. Additionally, these resins still require petrochemical-derived components (e.g., isocyanates), raising concerns regarding volatile organic compounds (VOC) emissions and toxicity during production and use.

The system by Islam et al. [25], based on bone glue, reported very high MOE (4302 MPa) and good MOR (26.22 MPa), though its internal bond was not reported. Although technically effective, animal-based adhesives such as bone glue may face limitations regarding consumer acceptance and traceability under circular bioeconomy frameworks.

In this context, the BSFL protein adhesive used in our study offers a balanced combination of mechanical performance and environmental benefit. It is derived from upcycled organic waste via insect bioconversion, aligned with circular bioeconomy principles and offering an innovative alternative to conventional protein-based adhesives (soy, casein, blood). While water resistance (TS 24 h = 85% for bagasse boards) remains a challenge, our approach presents a viable bio-based route to particleboard production without synthetic resins.

In this work, we successfully produced particleboards from sugarcane bagasse bonded with a BSFL protein-based adhesive, and their rheology and performance were thoroughly evaluated. The BSFL adhesive showed desirable rheological features for wood bonding, including non-Newtonian gel-like behavior and thixotropy with rapid recovery after shear, which favor wetting and homogeneous distribution. Bagasse particles, characterized by high slenderness ratios, contributed to improved inter-particle contact and stress transfer. Panel density emerged as the key variable controlling performance: increasing density from 400 to 800 kg/m3 led to nearly 900% higher IB values and substantial gains in MOR and MOE. Although higher density reduced WA and TS, dimensional stability did not meet the thresholds of conventional standards. Panels at 700 kg/m3 or above achieved P2 classification, suitable for interior dry use. The comparison with Eucalyptus grandis panels confirmed that the BSFL adhesive is also applicable to conventional lignocellulosic feedstocks, while sugarcane bagasse offers advantages due to its morphology and agro-industrial availability.

Overall, the findings demonstrate the feasibility of using insect-derived protein adhesives for wood-based panel production, combining competitive mechanical performance with renewable sourcing. While water resistance remains a limitation, this work establishes a promising foundation for the development of fully bio-based, non-toxic, and circular-economy-compatible particleboards. Future research should focus on formulation strategies to improve dimensional stability in humid conditions and explore upscaling pathways for industrial application.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of their respective institutions and collaborators who contributed to the development of this work.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) via grant Proyectos de Investigación Plurianuales (PIP 2021:2894), and Agencia I+D+i via grant Proyectos de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (PICT-2021-I-A-00294).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Alejandro Bacigalupe, Marcela Angela Mansilla; Methodology: Mariano Martín Escobar; Investigation: Francisco Daniel García, Solange Nicole Aigner, Natalia Raffaeli, Antonio José Barotto, Eleana Spavento; Writing—Original Draft: Alejandro Bacigalupe; Writing—Review & Editing: Marcela Angela Mansilla; Supervision: Mariano Martín Escobar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yang M, Chen L, Wang J, Msigwa G, Osman AI, Fawzy S, et al. Circular economy strategies for combating climate change and other environmental issues. Environ Chem Lett. 2023;21(1):55–80. doi:10.1007/s10311-022-01499-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Koutika LS, Matondo R, Mabiala-Ngoma A, Tchichelle VS, Toto M, Madzoumbou JC, et al. Sustaining forest plantations for the united nations’ 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Sustainability. 2022;14(21):14624. doi:10.3390/su142114624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Fritz C, Garay R. Advancing sustainable timber protection: a comparative study of international wood preservation regulations and Chile’s framework under environmental, social, and governance and sustainable development goal perspectives. Buildings. 2025;15(9):1564. doi:10.3390/buildings15091564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Lee SH, Lum WC, Boon JG, Kristak L, Antov P, Pędzik M, et al. Particleboard from agricultural biomass and recycled wood waste: a review. J Mater Res Technol. 2022;20(2):4630–58. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.08.166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT database 2024. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home. [Google Scholar]

6. González-García S, Ferro FS, Lopes Silva DA, Feijoo G, Lahr FAR, Moreira MT. Cross-country comparison on environmental impacts of particleboard production in Brazil and Spain. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2019;150(89):104434. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Olupot PW, Menya E, Lubwama F, Ssekaluvu L, Nabuuma B, Wakatuntu J. Effects of sawdust and adhesive type on the properties of rice husk particleboards. Results Eng. 2022;16:100775. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2022.100775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Abobakr H, Raji M, Essabir H, Bensalah MO, Bouhfid R, el kacem Qaiss A. Enhancing oriented strand board performance using wheat straw for eco-friendly construction. Constr Build Mater. 2024;417:135135. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ramos A, Briga-Sá A, Pereira S, Correia M, Pinto J, Bentes I, et al. Thermal performance and life cycle assessment of corn cob particleboards. J Build Eng. 2021;44(1):102998. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Cheng X, He X, Xie J, Quan P, Xu K, Li X, et al. The effects of particle geometry on adhesive properties in wood composites. BioResources. 2016;11(3):7271–81. doi:10.15376/biores.11.3.7271-7281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Pędzik M, Auriga R, Kristak L, Antov P, Rogoziński T. Physical and mechanical properties of particleboard produced with addition of walnut (Juglans regia L.) wood residues. Materials. 2022;15(4):1280. doi:10.3390/ma15041280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Narciso CRP, Reis AHS, Mendes JF, Nogueira ND, Mendes RF. Potential for the use of coconut husk in the production of medium density particleboard. Waste Biomass Valorization. 2021;12(3):1647–58. doi:10.1007/s12649-020-01099-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Neitzel N, Eder M, Hosseinpourpia R, Walther T, Adamopoulos S. Chemical composition, particle geometry, and micro-mechanical strength of barley husks, oat husks, and wheat bran as alternative raw materials for particleboards. Mater Today Commun. 2023;36:106602. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.106602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ferrandez-Villena M, Ferrandez-Garcia A, Garcia-Ortuño T, Ferrandez-Garcia MT. Acoustic and thermal properties of particleboards made from mulberry wood (Morus alba L.) pruning residues. Agronomy. 2022;12(8):1803. doi:10.3390/agronomy12081803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kougioumtzis MA, Tsiantzi S, Athanassiadou E, Karampinis E, Grammelis P, Kakaras E. Valorisation of olive tree prunings for the production of particleboards. Evaluation of the particleboard properties at different substitution levels. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;204:117383. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Singh SP, Jawaid M, Chandrasekar M, Senthilkumar K, Yadav B, Saba N, et al. Sugarcane wastes into commercial products: processing methods, production optimization and challenges. J Clean Prod. 2021;328(1):129453. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. de Moraes Rocha GJ, Nascimento VM, Gonçalves AR, Silva VFN, Martín C. Influence of mixed sugarcane bagasse samples evaluated by elemental and physical-chemical composition. Ind Crops Prod. 2015;64(5):52–8. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mantanis GI, Athanassiadou ET, Barbu MC, Wijnendaele K. Adhesive systems used in the European particleboard, MDF and OSB industries. Wood Mater Sci Eng. 2018;13(2):104–16. doi:10.1080/17480272.2017.1396622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Liang J, Wu J, Xu J. Low-formaldehyde emission composite particleboard manufactured from waste chestnut bur. J Wood Sci. 2021;67(1):21. doi:10.1186/s10086-021-01955-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Arias A, González-Rodríguez S, Vetroni Barros M, Salvador R, de Francisco AC, Moro Piekarski C, et al. Recent developments in bio-based adhesives from renewable natural resources. J Clean Prod. 2021;314(1–2):127892. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Anggini AW, Lubis MAR, Sari RK, Papadopoulos AN, Antov P, Iswanto AH, et al. Cohesion and adhesion performance of tannin-glyoxal adhesives at different formulations and hardener types for bonding particleboard made of Areca (Areca catechu) leaf sheath. Polymers. 2023;15(16):3425. doi:10.3390/polym15163425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang J, Luo S, Gao L, Zhang F, Tang Q, Guo W. Development of lightweight particleboards using epoxidized soybean oil foamable adhesive. Polym Compos. 2025;46(S2):S819–34. doi:10.1002/pc.29874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Tene Tayo L, Shivappa Nayaka D, Cárdenas-Oscanoa AJ, Euring M. Enhancing physical and mechanical properties of single-layer particleboards bonded with canola protein adhesives: impact of production parameters. Eur J Wood Wood Prod. 2024;83(1):6. doi:10.1007/s00107-024-02163-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Fagbemi OD, Sithole B. Evaluation of waste chicken feather protein hydrolysate as a bio-based binder for particleboard production. Curr Res Green Sustain Chem. 2021;4:100168. doi:10.1016/j.crgsc.2021.100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Islam MN, Liza AA, Dey M, Das AK, Faruk MO, Khatun ML, et al. Bio-based composites from bagasse using carbohydrate enriched cross-bonding mechanism: a formaldehyde-free approach. Carbohydr Polym Technol Appl. 2024;7(1):100467. doi:10.1016/j.carpta.2024.100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Grossi B, Pizzo B, Siano F, Varriale A, Mabilia R. Formaldehyde-free wood adhesives based on protein materials from various plant species. Results Eng. 2025;25:104033. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2025.104033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. García FD, Aigner SN, Cedres JP, Luna A, Escobar MM, Mansilla MA, et al. Novel adhesive based on black soldier fly larvae flour for particleboard production. Constr Build Mater. 2024;411(1):134758. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Siddiqui SA, Ristow B, Rahayu T, Putra NS, Widya Yuwono N, Nisa K, et al. Black soldier fly larvae (BSFL) and their affinity for organic waste processing. Waste Manag. 2022;140(3):1–13. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2021.12.044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Khayrova A, Lopatin S, Varlamov V. A review on characteristics, extraction methods and applications of renewable insect protein. J Renew Mater. 2024;12(5):923–50. doi:10.32604/jrm.2024.050033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Falgayrac A, Pellerin V, Terrol C, Fernandes SCM. Turning black soldier fly rearing by-products into valuable materials: valorisation through chitin and chitin nanocrystals production. Carbohydr Polym. 2024;344(3):122545. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. González-Lara H, Parra-Pacheco B, Rico-García E, Aguirre-Becerra H, Feregrino-Pérez AA, García-Trejo JF. Black soldier fly culture as a source of chitin and chitosan for its potential use in concrete: an overview. Polymers. 2025;17(6):717. doi:10.3390/polym17060717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. D’Amora U, Soriente A, Ronca A, Scialla S, Perrella M, Manini P, et al. Eumelanin from the black soldier fly as sustainable biomaterial: characterisation and functional benefits in tissue-engineered composite scaffolds. Biomedicines. 2022;10(11):2945. doi:10.3390/biomedicines10112945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Le TM, Tran CL, Nguyen TX, Duong YHP, Le PK, Tran VT. Green preparation of chitin and nanochitin from black soldier fly for production of biodegradable packaging material. J Polym Environ. 2023;31(7):3094–105. doi:10.1007/s10924-023-02793-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Lomonaco G, Franco A, De Smet J, Scieuzo C, Salvia R, Falabella P. Larval frass of Hermetia illucens as organic fertilizer: composition and beneficial effects on different crops. Insects. 2024;15(4):293. doi:10.3390/insects15040293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Firmansyah M, Abduh MY. Production of protein hydrolysate containing antioxidant activity from Hermetia illucens. Heliyon. 2019;5(6):e02005. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Bacigalupe A, Fernández M, Eisenberg P, Escobar MM. Greener adhesives based on UF/soy protein reinforced with montmorillonite clay for wood particleboard. J Appl Polym Sci. 2020;137(37):49086. doi:10.1002/app.49086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Seng Hua L, Wei Chen L, Antov P, Kristak L, Md Tahir P. Engineering wood products from Eucalyptus spp. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2022;2022(1):8000780–14. doi:10.1155/2022/8000780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. DIN 4768. Determination of values of surface roughness parameters—using electrical contact (stylus) instruments; concepts and measuring conditions. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Deutsches Institut für Normung; 1990. [Google Scholar]

39. UNE-EN 319. Particleboards and fibreboards-determination of tensile strength perpendicular to the plane of the board. Brussels, Belgium: European Committee for Standardization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

40. UNE-EN 310. Wood-based panels-determination of modulus of elasticity in bending and of bending strength. Brussels, Belgium: European Committee for Standardization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

41. UNE-EN 317. Particleboards and fibreboards-determination of swelling in thickness after immersion in water. Brussels, Belgium: European Committee for Standardization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

42. UNE-EN 312. Particleboards-specifications. Brussels, Belgium: European Committee for Standardization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

43. Bacigalupe A, He Z, Escobar MM. Effects of rheology and viscosity of bio-based adhesives on bonding performance. In: Pizzi A, Mittal KL, editors. Bio-based wood adhesives: preparation, characterization, and testing. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2017. p. 17–36. doi:10.1201/9781315369242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Olivares ML, Shahrivar K, de Vicente J. Soft lubrication characteristics of microparticulated whey proteins used as fat replacers in dairy systems. J Food Eng. 2019;245(2):157–65. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.10.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Gama N, Ferreira A, Barros-Timmons A. Cure and performance of castor oil polyurethane adhesive. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2019;95:102413. doi:10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2019.102413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Bacigalupe A, Cova M, Cedrés JP, Cancela GE, Escobar M. Rheological characterization of a wood adhesive based on a hydrolyzed soy protein suspension. J Polym Environ. 2020;28(9):2490–7. doi:10.1007/s10924-020-01784-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Brito FMS, Júnior GB, Paes JB, Belini UL, Tomazello-Filho M. Technological characterization of particleboards made with sugarcane bagasse and bamboo culm particles. Constr Build Mater. 2020;262:120501. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Hiziroglu S, Graham M. Effect of press closing time and target thickness on surface roughness of particleboard. For Prod J. 1998;48(3):50–4. [Google Scholar]

49. Tabarsa T, Ashori A, Gholamzadeh M. Evaluation of surface roughness and mechanical properties of particleboard panels made from bagasse. Compos Part B Eng. 2011;42(5):1330–5. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2010.12.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Nemli G, Ozturk I, Aydin I. Some of the parameters influencing surface roughness of particleboard. Build Environ. 2005;40(10):1337–40. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2004.12.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Nemli G, Demirel S. Relationship between the density profile and the technological properties of the particleboard composite. J Compos Mater. 2007;41(15):1793–802. doi:10.1177/0021998307069892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Hiziroglu S, Jarusombuti S, Fueangvivat V. Surface characteristics of wood composites manufactured in Thailand. Build Environ. 2004;39(11):1359–64. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2004.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Xiong XQ, Yuan YY, Niu YT, Zhang LT. Effect of surface roughness on bonding strength of wood-based composites: a review. Sci Adv Mater. 2020;12(6):795–801. doi:10.1166/sam.2020.3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Arabi M, Faezipour M, Layeghi M, Enayati AA. Interaction analysis between slenderness ratio and resin content on mechanical properties of particleboard. J For Res. 2011;22(3):461–4. doi:10.1007/s11676-011-0188-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Arabi M, Haftkhani AR, Pourbaba R. Investigating the effect of particle slenderness ratio on optimizing the mechanical properties of particleboard using the response surface method. BioResources. 2023;18(2):2800–14. doi:10.15376/biores.18.2.2800-2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Sackey EK, Semple KE, Oh SW, Smith GD. Improving core bond strength of particleboard through particle size redistribution. Wood Fiber Sci. 2008;40(2):214–24. [Google Scholar]

57. Vital BR, Wilson JB, Kanarek PH. Parameters affecting dimensional stability of flakeboard and particleboard. For Prod J. 1981;30(12):23–9. Available from: https://cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/19810668693. [Google Scholar]

58. Sarı B, Nemli G, Baharoğlu M, Bardak S, Zekoviç E. The role of solid content of adhesive and panel density on the dimensional stability and mechanical properties of particleboard. J Compos Mater. 2013;47(10):1247–55. doi:10.1177/0021998312446503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Xu J, Sugawara R, Widyorini R, Han G, Kawai S. Manufacture and properties of low-density binderless particleboard from kenaf core. J Wood Sci. 2004;50(1):62–7. doi:10.1007/s10086-003-0522-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Choupani Chaydarreh K, Lin X, Guan L, Hu C. Interaction between particle size and mixing ratio on porosity and properties of tea oil camellia (Camellia oleifera Abel.) shells-based particleboard. J Wood Sci. 2022;68(1):43. doi:10.1186/s10086-022-02052-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Bacigalupe A, Escobar MM. Soy protein adhesives for particleboard production—a review. J Polym Environ. 2021;29(7):2033–45. doi:10.1007/s10924-020-02036-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Jin S, Li K, Gao Q, Zhang W, Chen H, Li J, et al. Multiple crosslinking strategy to achieve high bonding strength and antibacterial properties of double-network soy adhesive. J Clean Prod. 2020;254(4):120143. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Zhao S, Pang H, Li Z, Wang Z, Kang H, Zhang W, et al. Polyurethane as high-functionality crosslinker for constructing thermally driven dual-crosslinking plant protein adhesion system with integrated strength and ductility. Chem Eng J. 2021;422(18):130152. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.130152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Cui Z, Xu Y, Sun G, Peng L, Li J, Luo J, et al. Improving bond performance and reducing cross-linker dosage of soy protein adhesive via hyper-branched and organic-inorganic hybrid structures. Nanomater. 2023;13(1):203. doi:10.3390/nano13010203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Wang B, Zhang Y, Tan H, Gu J. Melamine-urea-formaldehyde resins with low formaldehyde emission and resistance to boiling water. Pigment Resin Technol. 2019;48(3):229–36. doi:10.1108/prt-01-2018-0009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Sugahara ES, da Silva SA, Buzo ALS, de Campos CI, Morales EA, Ferreira BS, et al. High-density particleboard made from agro-industrial waste and different adhesives. BioResources. 2019;14(3):5162–70. doi:10.15376/biores.14.3.5162-5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Widyorini R, Xu J, Umemura K, Kawai S. Manufacture and properties of binderless particleboard from bagasse I: effects of raw material type, storage methods, and manufacturing process. J Wood Sci. 2005;51(6):648–54. doi:10.1007/s10086-005-0713-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Magzoub R, Osman Z, Tahir P, Nasroon TH, Kantner W. Comparative evaluation of mechanical and physical properties of particleboard made from bagasse fibers and improved by using different methods. Cellul Chem Technol. 2015;49(5–6):537–42. [Google Scholar]

69. Nadhari WNAW, Karim NA, Boon JG, Salleh KM, Mustapha A, Hashim R, et al. Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarium L.) bagasse binderless particleboard: effect of hot pressing time study. Mater Today Proc. 2020;31(13):313–7. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2020.06.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Mendes RF, Mendes LM, Oliveira SL, Freire TP. Use of sugarcane bagasse for particleboard production. Key Eng Mater. 2014;634:163–71. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/kem.634.163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Fiorelli J, de Lucca Sartori D, Cravo JCM, Savastano HJr, Rossignolo JA, do Nascimento MF, et al. Sugarcane bagasse and castor oil polyurethane adhesive-based particulate composite. Mat Res. 2013;16(2):439–46. doi:10.1590/s1516-14392013005000004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools