Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

HCAR1 Modulates Ferroptosis in Gastric Cancer via Lactate-Mediated AMPK-SCD1 Signaling and Lipid Metabolism

1 Fengxian District Center Hospital Graduate Student Training Base, Jinzhou Medical University, Shanghai, 201499, China

2 Endoscopy Center, Minhang Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, 201100, China

3 Department of Gastroenterology, Shanghai Jiaotong University Affiliated Sixth People’s Hospital South Campus, Shanghai, 201499, China

* Corresponding Authors: Xiaohong Zhang. Email: ; Li Feng. Email:

; Xingxing Zhang. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Novel Biomarkers and Treatment Strategies in Solid Tumor Diagnosis, Progression, and Prognosis)

Oncology Research 2025, 33(10), 3101-3125. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.067247

Received 28 April 2025; Accepted 30 July 2025; Issue published 26 September 2025

Abstract

Background: Ferroptosis is a type of regulated cell death characterized by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, which has been linked to tumor progression and therapeutic resistance. However, the contribution of lactate metabolism and its receptor, hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 1 (HCAR1), in ferroptosis regulation in gastric cancer (GC) remains poorly understood. Focusing specifically on its effects on cell proliferation, ferroptosis regulation, and the disruption of lactate-mediated metabolic pathways, the study aimed to clarify the role of HCAR1 in GC progression. Methods: Bioinformatics analysis identified prognostic genes associated with ferroptosis in GC. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated to assess the diagnostic potential of the predictive genes. The biological role of HCAR1 was investigated through gain and loss-of-function experiments in GC cell lines, followed by assessments of cell viability, oxidative stress indicators, gene/protein expression, and ferroptosis sensitivity under lactate stimulation or HCAR1 modulation. Results: HCAR1 was significantly upregulated in GC tissues and linked to poor patient outcomes. Silencing HCAR1 inhibited GC cell growth and induced ferroptosis, as shown by increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and malondialdehyde (MDA), along with decreased expression of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4). Conversely, HCAR1 overexpression or exposure to extracellular lactate inhibited ferroptosis and activated antioxidant defenses. Mechanistically, lactate activation of HCAR1 increases ATP levels, which in turn inactivates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). It also upregulates stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) through the sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 (SREBP1) signaling pathway. Blocking HCAR1 reversed these effects and restored ferroptosis sensitivity. Conclusion: HCAR1 mediates lactate-driven ferroptosis resistance in GC through the AMPK-SCD1 signaling pathway. Targeting the HCAR1-lactate axis may offer a promising strategy for overcoming metabolic adaptation and improving GC treatment outcomes.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileGastric cancer (GC), also referred to as stomach cancer, ranks as the fifth most prevalent malignancy and the fourth leading cause of cancer mortality globally [1]. About 95% of cases of GC are stomach adenocarcinoma [2], which is the most common kind [3]. Research has demonstrated that the highest incidence of GC occurs in East Asia, with relatively high rates also observed in Eastern and Central Europe [4]. GC development has been associated with Helicobacter pylori infection, diet-related influences, and genetic vulnerability [5]. Diagnosis is typically confirmed through upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsy. Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent cell death mechanism characterized by lipid peroxidation, has gained increasing attention in recent research [6]. Research has demonstrated that Ophiopogonin B inhibits GC cell growth by inducing ferroptosis by downregulating solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11, also known as xCT) and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) expression [7]. Emerging evidence suggests that ferroptosis is critically involved in the development of GC and may serve as a promising therapeutic target. Furthermore, numerous studies are exploring the impact of various signaling pathways on ferroptosis in GC cells. Thus, it is essential to comprehend the processes and regulatory functions of ferroptosis in GC to create novel treatment approaches.

As a newly identified form of regulated cell death, ferroptosis has garnered growing interest in the field of oncology. For instance, high doses of artesunate (ART) induce reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated DNA damage and cell death in ovarian cancer (OV) cells. This process is closely related to ferroptosis [8]. According to melanoma research, ferroptosis is negatively regulated by miR-137, which targets the glutamine transporter SLC1A5, and ferroptosis is promoted by decreased miR-137 expression [9]. GPX4 inhibitors (1s, 3R)-RSL3, ML-162, as well as ART cause ferroptosis in head and neck cancer (HNC) cells, which is followed by the buildup of ROS and the depletion of glutathione (GSH) [10]. In addition, growing evidence indicates that biomarkers associated with ferroptosis contribute to both prognosis evaluation and therapeutic targeting in GC. For instance, ferroptosis induces GC cell death by promoting ROS accumulation, while ACTL6A inhibits ferroptosis by upregulating GCLC, thereby promoting the development of GC [11]. SOX13 stimulates the formation of mitochondrial supercomplexes, enhances GC cell resistance to ferroptosis, and renders them therapeutically resistant [12]. ATF2 promotes the malignant progression of GC cells by inhibiting sorafenib-induced ferroptosis and is associated with poor prognosis [13]. BAP31 inhibits ferroptosis of GC cells by regulating VDAC1 function. Its high expression not only promotes GC progression but may also become a potential therapeutic target [14]. Therefore, in-depth exploration of the key regulatory factors of ferroptosis is of great significance for exploring new therapeutic strategies.

HCAR1 is primarily activated by lactate, a metabolic byproduct of glycolysis [15]. According to recent research, HCAR1 may be involved in cancer metabolism. Enhanced glycolysis driven by the Warburg effect accounts for the elevated lactate concentrations frequently seen in cancer cells [16]. HCAR1 may contribute to tumor development and progression through its regulation of lactate-mediated signaling pathways. For instance, Shi et al. reported that the curcumin analog NL01 suppressed the expression of HCAR1 and monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1), while activating the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway, ultimately triggering ferroptosis in OV cells via the sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1) axis [17]. According to Zhao et al., lactate promotes ATP production via MCT1 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells, suppressing AMPK and upregulating SREBP1 and SCD1, which in turn increases their resistance to ferroptosis [18]. Inhibition of lactate absorption activated AMPK, decreased SCD1, and enhanced ferroptosis. Additionally, Xie et al. demonstrated that lactate upregulates HCAR1 expression through the Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling pathway [19]. Lactate induces the formation of the Snail Family Transcription Factor 1 (SNAI1)/Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 (EZH2)/STAT3 complex, which activates STAT3 and subsequently promotes HCAR1 transcription. Thus, exploring the regulatory mechanisms of HCAR1 and related pathways in GC ferroptosis is of significant interest.

Based on the above background, we hypothesized that HCAR1 regulates lipid metabolism by activating the AMP-activated protein kinase-stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (AMPK-SCD1) signaling pathway, which affects the ferroptosis process. Clarifying the role of HCAR1 in GC development was the primary objective of this investigation, with particular attention paid to its effects on cell proliferation, ferroptosis control, and dysregulation of lactate-mediated metabolic pathways. Through bioinformatics analysis, we identified key prognostic genes and pathways associated with GC. Our findings demonstrate that HCAR1 influences ferroptosis via the lactate-mediated AMPK-SCD1 axis, highlighting its value in therapeutic intervention. This research provides fresh perspectives on the metabolic regulation of ferroptosis in GC and presents new opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://www.cancer.gov/tcga (accessed on 10 July 2025)) provided the genomic data for 375 STAD samples and 32 adjacent standard samples and 375 STAD samples was obtained from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://www.cancer.gov/tcga (accessed on 10 July 2025)). Gene expression profiles were retrieved from the GSE19826 dataset inside the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) collection (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/ (accessed on 10 July 2025)) for 12 GC tissue samples with 15 nearby standard tissue samples. Furthermore, the FerrDB database (http://www.zhounan.org/ferrdb/current/ (accessed on 10 July 2025)) yielded 395 ferroptosis-associated genes (Table S1).

2.1.1 Differential Expression and Ferroptosis-Related Gene Analysis

Using the R software’s “Limma” package (version 4.1.0), differential gene expression analysis was performed on the TCGA-STAD dataset. Genes were filtered based on fold change (FC), with FC > 1.5 considered upregulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and FC < 0.67 considered downregulated DEGs, establishing statistical significance at p < 0.05. The Venn online graph tool (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/) is accustomed to analyzing the overlap between ferroptosis-related genes and between TCGA-upregulated and downregulated DEGs, and the intersection genes were filtered out for follow-up examination.

2.1.2 Analysis of Functional Enrichment Analysis

The intersecting genes were subjected to enrichment analysis using the DAVID database (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/tools.jsp (accessed on 10 July 2025)), which integrates Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway information. GO classification categorizes gene and protein functions into three categories: Biological Process (BP), Cell Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF) [20].

2.1.3 Analysis of the Prognostic Signature Model in GC

Using the R package “glmnet” (version 4.1.1), we applied the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) Cox regression to analyze the overlapping genes obtained in this study. With ten-fold cross-validation, the ideal regularization parameter (λ) was identified, with λ.min = 0.0534 ensuring model robustness and predictive performance. The coefficients were utilized to determine the risk ratings for every patient that came from the Cox regression model with LASSO: Riskscore = (0.1041) ∗ PHKG2 + (−0.0958) ∗ MYB + (0.0187) ∗ NADPH Oxidase 4 (NOX4) + (−0.0019) ∗ Solute Carrier Family 11 Member 2 (SLC11A2) + (−0.004) ∗ SAT1 + (0.0069) ∗ KRAS + (0.0268) ∗ PARP15 + (0.1221) ∗ HCAR1 + (0.005) ∗ CP + (0.087) ∗ Aldo-Keto Reductase Family 1 Member C2 (AKR1C2) + (0.0272) ∗ LIFR. Patients were divided into high-risk and low-risk groups according to their median risk ratings. The distribution of survival status and risk ratings among these categories was investigated. To assess the progression-free survival (PFS) probabilities across the groups, Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival curves were produced using R’s “survival” package (version 4.1.2). The risk model’s forecast precision was evaluated using ROC curves. The area under the curve (AUC) values for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival were determined, confirming the model’s ability to forecast over different time points.

2.1.4 Mutation Analysis of Prognostic Genes in GC

Mutation analysis of the 11 prognostic genes identified in our study was conducted using the Gene Set Cancer Analysis (GSCA) database, accessible at http://guolab.wchscu.cn/GSCA/#/ (accessed on 09 July 2025). This database provides comprehensive genomic data, comprising single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) as well as copy number variations (CNVs), relevant to various cancer types, including GC. First, we retrieved SNV data for the prognostic genes from the GSCA database. SNVs were analyzed to identify the frequency and types of mutations present in these genes across GC samples. Next, using the “maftools” package in R (version 4.1.0), a Spearman correlation analysis was carried out between the CNV data and the mRNA expression levels of the 11 prognostic genes. This analysis assessed the relationship between copy number alterations and gene expression, providing insights into how genomic variations might influence gene expression patterns in GC.

2.1.5 Survival Analysis and Nomogram Construction for Prognostic Genes in GC Patients

Survival analysis of the overlapping prognostic genes was conducted using both univariate Cox regression (uni-Cox) and multivariate Cox regression (multi-Cox) methods. These analyses were performed using the R software, specifically utilizing the “survival” (version 4.1.2) and “forestplot” (version 4.1.2) packages for statistical computation and visualization. For the multivariate Cox regression analysis, clinical variables, along with predictive gene expression levels, were included as covariates. The “rms” tool in R (version 4.1.0) was used to create a nomogram based on the results of the multi-Cox regression. Each prognostic gene and clinical variable’s contribution to predicting the likelihood of survival for GC patients at 1, 3, and 5 years was graphically represented by the nomogram.

2.1.6 Expression Analysis and Survival Evaluation of Candidate Genes in Patients with GC

The Sangerbox website (http://vip.sangerbox.com/home.html (accessed on 09 July 2025)) was utilized to examine the TCGA-STAD and GSE19826 datasets to evaluate possible gene expression levels. In order to evaluate the prognostic importance of the discovered hub genes, survival curve analysis was carried out using the GSCA database. The statistical significance of two groups is ascertained using the log-rank test. The median gene expression distribution was used to define “high expression” and “low expression” in these studies.

2.2 Cell Culture and Treatments

GC cell lines (AGS, HGC-27, MKN-45) and GES-1 (non-malignant gastric epithelial cell line) were provided by the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Cell Bank in Shanghai, China. Every cell line was grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Cat. No. 11965, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), which was enhanced with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; cat. no. 16000044; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (cat. no. 15140122; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). GES-1, AGS, HGC-27, and MKN-45 cells were maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere with humidity containing 5% CO2. The chemical reagents used in this study, including lactate, Erastin (cat. no. S7242), and Liproxstatin-1 (Lip-1, cat. no. S7699), were purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Shanghai, China). For lactate treatment, cells were incubated in DMEM with varied lactate concentrations (0, 10, 20, and 30 mM) for 24 h. Erastin and Lip-1 were diluted in Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) to 5 µM and administered to cultured cells, which were subsequently treated for 24 h. All cell lines had undergone Short Tandem Repeat (STR) identification prior to purchase and tested negative for mycoplasma contamination upon receipt.

Cells were cultivated at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates. Incubation was continued until the cells attained 70%–80% confluence. 10 µL of LipofectamineTM 2000 (cat. no. 11668; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) was used for transfection, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Specifically, AGS and HGC-27 cells were transfected with small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting HCAR1 (si-HCAR1) and a siRNA negative control (si-NC). In overexpression experiments, AGS and HGC-27 cells were transfected using the pcDNA3.1 expression vector (cat. no. V79020; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) that overexpresses the HCAR1 gene, while NC cells were transfected using an empty vector. During transfection, a final siRNA concentration of 50 nM and a plasmid DNA concentration of 2 μg/mL were used. siRNA sequence (sense: 5′-UCAUCAUGGUGGUGGCAAUTT-3′, antisense: 5′-AUUGCCACCACCAUGAUGATT-3′) targeting HCAR1 was used. The transfection effect was verified by Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) with Western blotting (WB).

2.3.1 Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

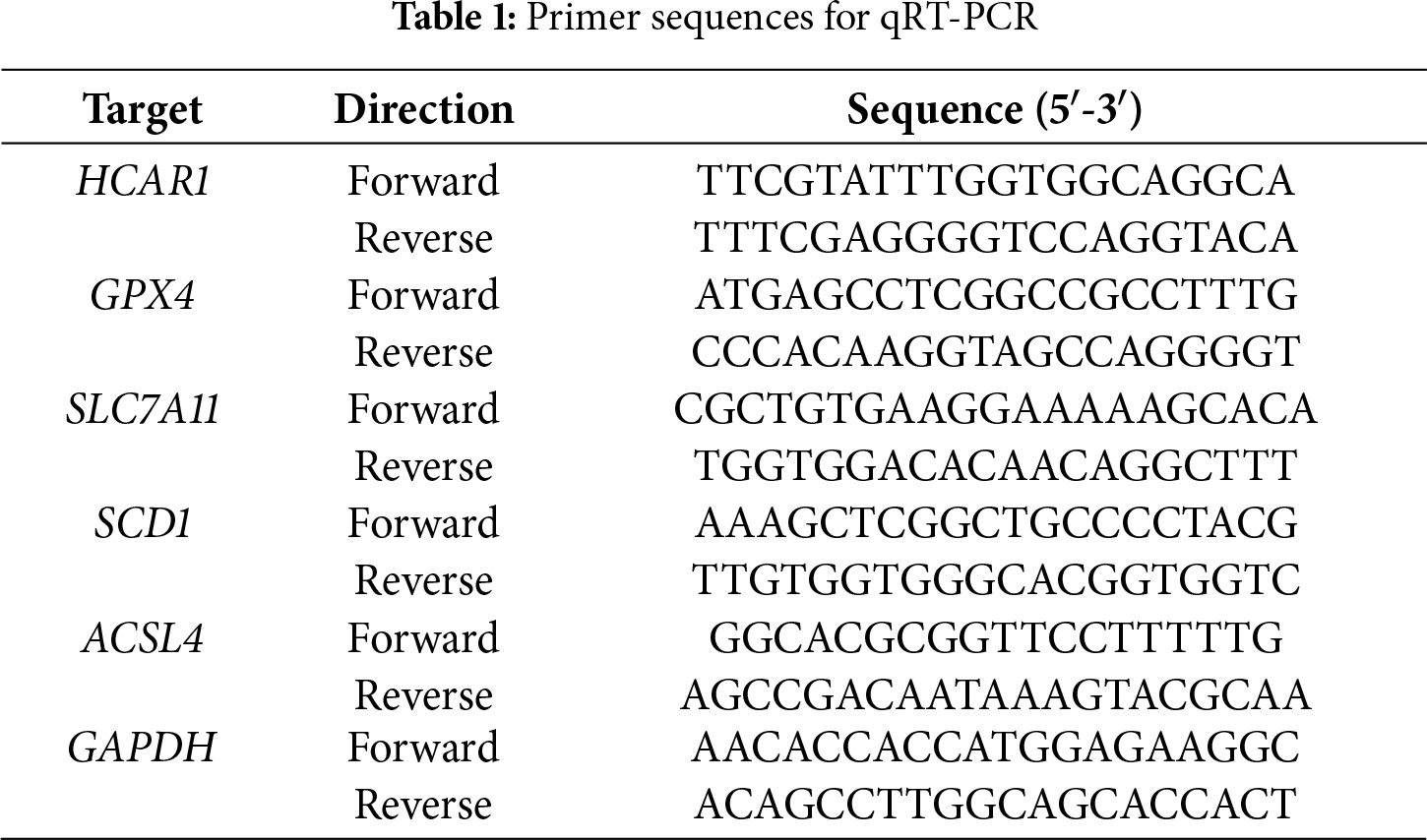

Following the manufacturer’s instructions, total RNA was extracted from GES-1, AGS, HGC-27, and MKN-45 cells using the TRIzol reagent (cat. no. DP424; Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (cat. no. RR037A; Takara, Nojihigashi, Japan) was used to create complementary DNA (cDNA). Quantitative PCR was conducted with SYBR Green Master Mix (cat. no. Q121-02; Vazyme, Nanjing, China) on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min comprised the amplification technique. The internal control was GAPDH. The 2−ΔΔCt technique was used to calculate relative gene expression. Table 1 contains the primer sequences.

2.3.2 Western Blotting (WB) Assay

For total protein extraction, GES-1, AGS, HGC-27, and MKN-45 cells were treated with RIPA lysis buffer enriched with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Beyotime, cat. no. P1046, Shanghai, China). To determine the protein content, the BCA Protein Assay Kit (cat. no. P0011; Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was utilized. Using SDS-PAGE, the protein was divided into equal portions and then applied to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF; cat. no. FFP39; Beyotime, Shanghai, China) membranes. To probe the membranes, primary antibodies against HCAR1 (cat. no. ab106942, 1:1000), GPX4 (cat. no. ab125066, 1:3000), SLC7A11 (cat. no. ab307601, 1:1000), SCD1(cat. no. ab19862, 1:1000), ACSL4 (cat. no. ab155282, 1:5000), AMPK (cat. no. ab222491, 1:1000), phosphorylated (p)-AMPK (cat. no. ab23875, 1:1000), SREBP1 (cat. no. ab28481, 1:5000), were used, all of which were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). The loading control for cytoplasmic proteins was GAPDH (cat. no. ab8245, 1:5000). After being incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), the protein bands were detected using an ECL detection system (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and captured on camera using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0). The expression of these proteins in cells was evaluated by WB analysis.

2.3.3 Assay for Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

The CCK-8 kit (cat. no. CK04, Dojindo Laboratories, Inc., Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan) was used to assess the viability of AGS and HGC-27 cells. Cells were seeded onto 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well. A CCK-8 reagent was applied to each well following cell siRNA transfection or treatment with erastin (5 μM), lactate (20 mM), or Lip-1 (5 μM). After 24 h, the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

2.3.4 Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Malondialdehyde (MDA)

In 96-well plates, AGS and HGC-27 cells were grown at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well. Following cell apposition, the medium and unidentified cell debris were removed from the cell monolayer by twice washing it with PBS buffer (pH 7.4, 10 mM). Subsequently, lysate was added to each well, and the well plates containing the cell lysate were placed in an ultrasonic crusher for sonication to fragment the cells further. The resulting lysates were centrifuged at 10,000× g for 5 min to extract the supernatant. These supernatants experienced sonication and were subsequently used to assess the levels of ROS and MDA. As instructed by the manufacturer, measurements were performed using commercial assay kits. The assay kits for ROS and MDA were obtained from the Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Cat. No. E004-1-1, Cat. No. A003-2-2, Nanjing, China).

The ATP test was performed using an ATP detection kit (cat. no. S0026; Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and following the manufacturer’s instructions. AGS and HGC-27 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 4 × 105 cells per well. After incubation, each well received 200 µL of cell lysate, which was then centrifuged at 12,000× g for 10 min at 4°C to remove the supernatant. The supernatant (10 µL) was added for detection after the background ATP was depleted using 100 µL of ATP detection buffer. The Infinite M200 PRO microplate reader (Tecan Group, Ltd., Zurich, Switzerland) was used to record the optical density data.

Statistical analysis was conducted using R (version 4.3.3). Data are presented as mean ± SD from triplicate experiments. For comparisons among groups, one-way or two-way ANOVA was performed based on the experimental design. Post hoc analysis using Tukey’s or Bonferroni tests was conducted for multiple comparisons when ANOVA results showed significance, and differences were regarded as significant at p < 0.05.

3.1 Ferroptosis-Related Gene Differential Expression and Functional Enrichment Study in GC

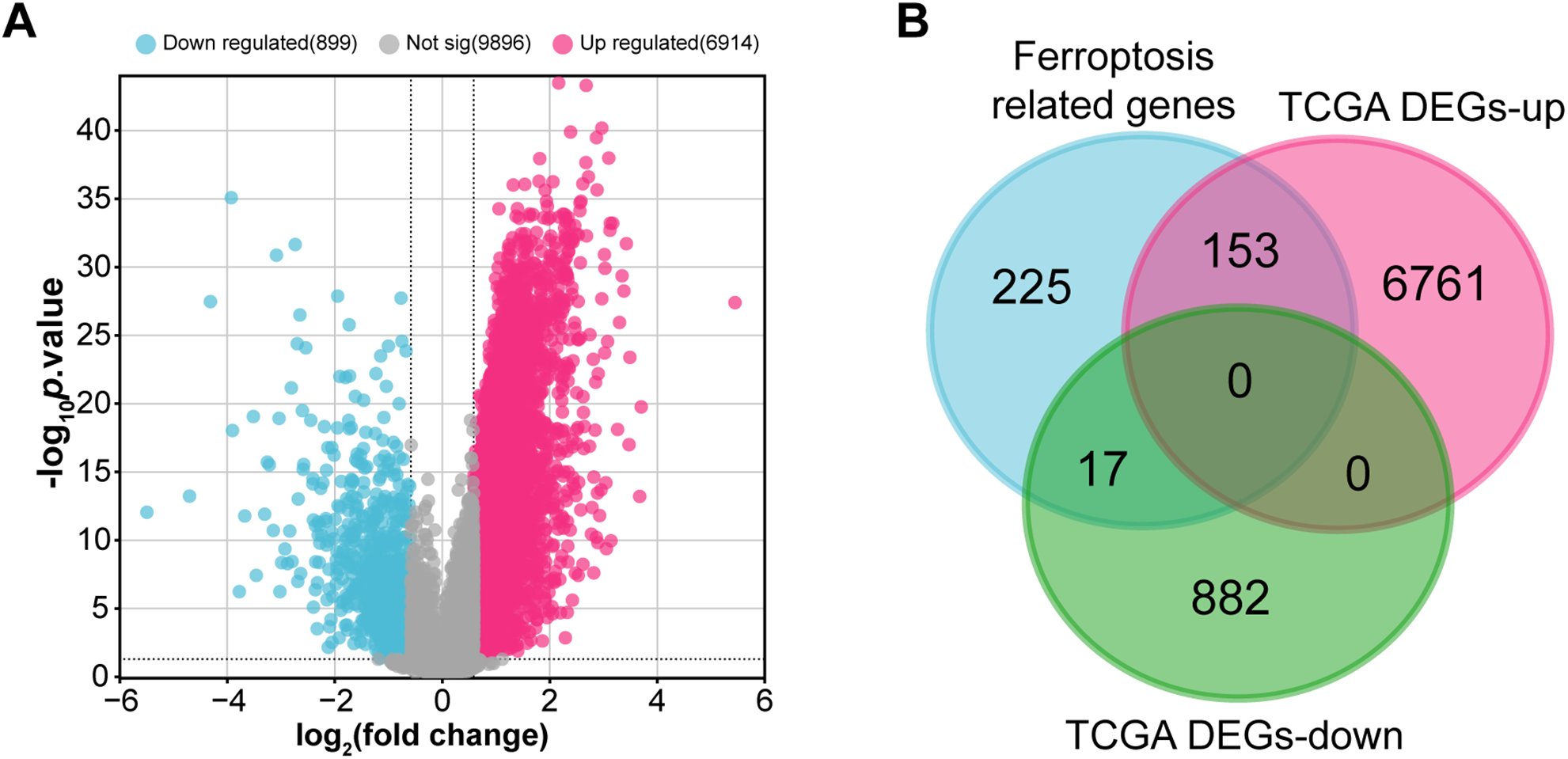

Within the TCGA-STAD cohort, 3914 upregulated and 899 downregulated DEGs were observed (Fig. 1A). Further analysis of 395 ferroptosis-related genes alongside the DEGs that are downregulated and upregulated revealed 170 intersection genes (Fig. 1B). Functional examination of the enrichment of these intersecting genes indicated significant enrichment in several BP terms, including “Cellular Response to Starvation”, “Regulation of Gene Expression”, and “Cellular Response to Chemical Stress”. Within the CC division, intersecting genes were notably enriched in terms such as “Nucleus”, “Intracellular Non-Membrane-Bounded Organelle”, and “Intracellular Membrane-Bounded Organelle”. For MF terms, significant enrichment was observed in “NAD+ ADP-ribosyltransferase Activity”, “Pentosyltransferase Activity”, and “Kinase Binding” (Fig. 1C). Moreover, pathway analysis using KEGG highlighted that most intersecting genes were enriched in pathways like “Ferroptosis”, “FoxO signaling pathway”, and “Insulin signaling pathway” (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1: Identification and functional annotation of ferroptosis-related genes in GC. (A) Volcano plot of DEGs in the TCGA-STAD dataset. The x-axis shows the log2 fold change in gene expression between tumor and normal samples, while the y-axis represents statistical significance (−log10 p-value). Upregulated and downregulated DEGs are indicated in pink and blue, respectively. (B) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap among 395 ferroptosis-related genes and the DEGs. (C, D) Bubble plots summarizing GO and KEGG enrichment results for ferroptosis-associated genes. The x-axis indicates gene ratio; the y-axis shows enriched GO terms or KEGG pathways. GC, Gastric Cancer; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; STAD, Stomach Adenocarcinoma; DEGs, Differentially Expressed Genes; GO, Gene Ontology; BP, Biological Process; CC, Cell Component; MF, Molecular Function; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

3.2 Prognostic Significance of Potential Target Genes in GC

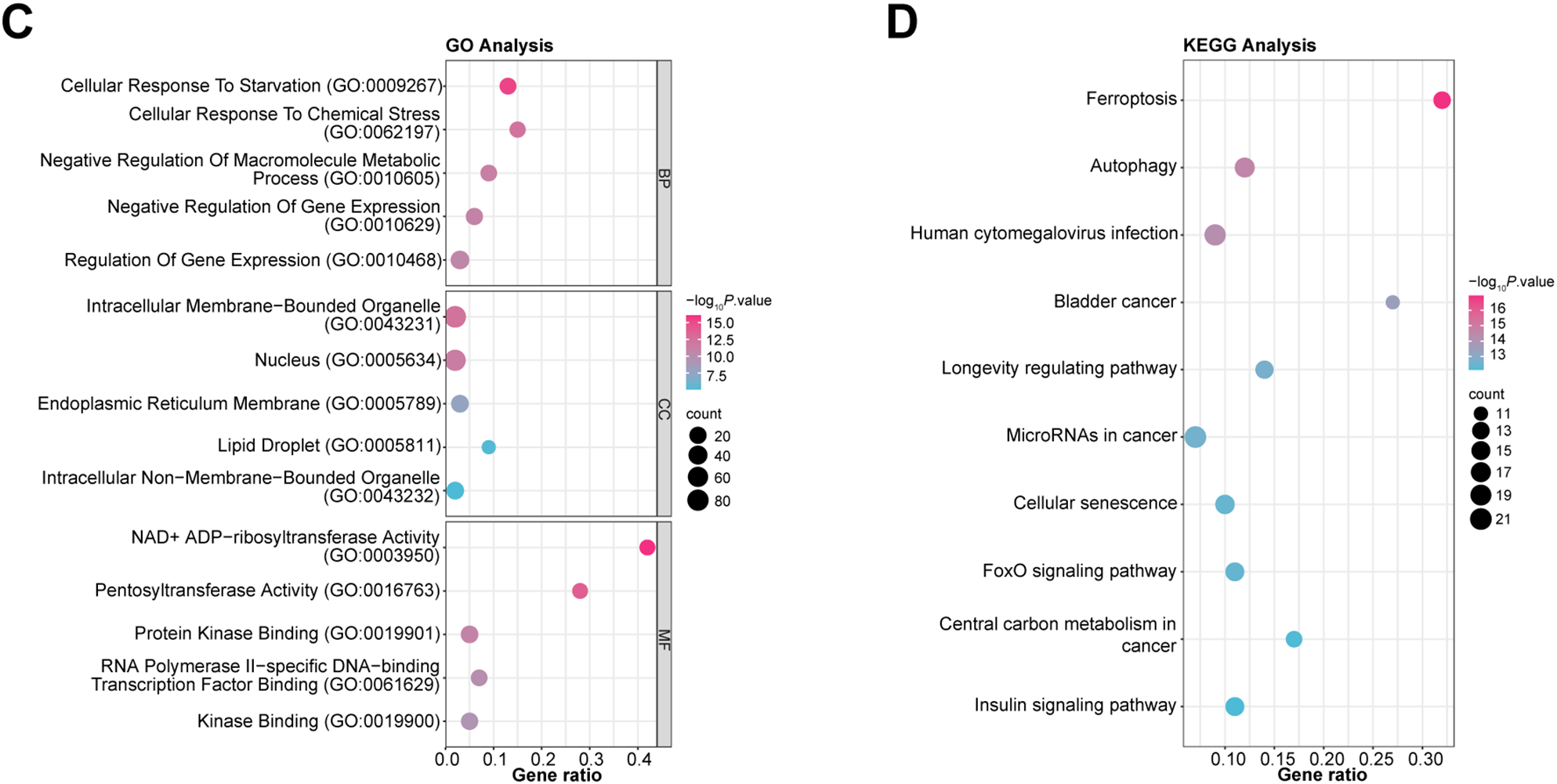

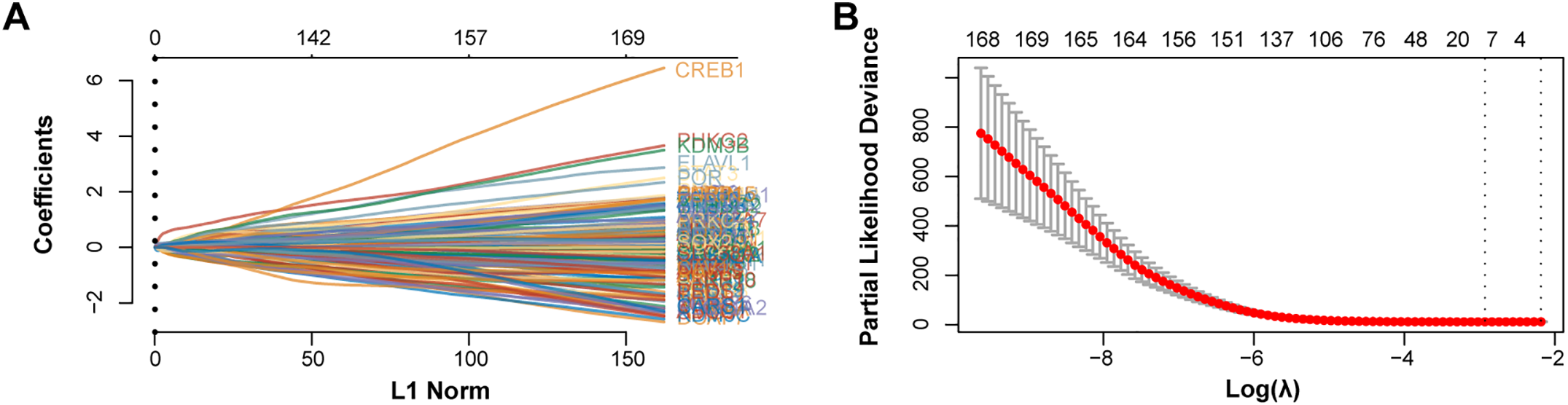

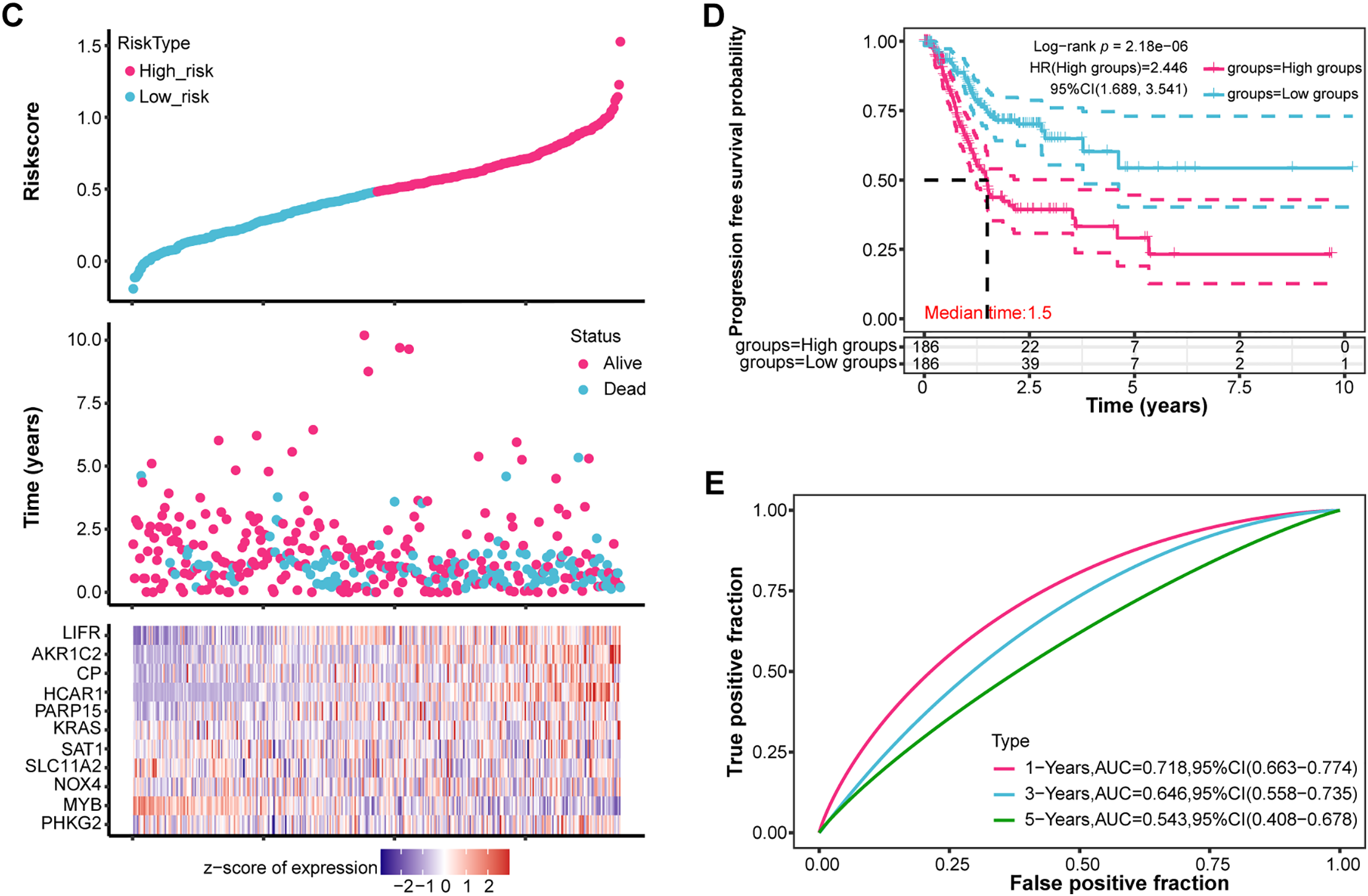

Employing the LASSO Cox regression model, the study analyzed the trajectories of 170 intersecting genes as independent variables. With 10-fold cross-validation, we identified 11 potential prognostic genes [Phosphorylase Kinase Gamma 2 (PHKG2), MYB, NOX4, SLC11A2, SAT1, KRAS, PARP15, HCAR1, CP, AKR1C2, LIFR] according to the optimal lambda value (lambda.min = 0.0534) as prognostic markers (Fig. 2A,B). The high-risk group had a lower survival rate and a greater death rate than the low-risk group, as seen in Fig. 2C. The high-risk group’s prognosis was further shown to be considerably worse using KM survival curves, with both groups showing a median survival time of 1.5 years (Fig. 2D). Additionally, ROC curve research revealed that the 1-year prognostic prediction accuracy was good (AUC = 0.718) (Fig. 2E). In conclusion, our study highlights the significant prognostic potential of these 11 potential prognostic genes.

Figure 2: Prognostic significance of candidate genes in GC. (A) The coefficient spectrum was derived from LASSO regression analysis of 11 putative prognostic genes. (B) Tenfold cross-validated LASSO regression was utilized to optimize lambda selection. (C) Risk scores (top), patient survival outcomes (middle), and gene expression heatmaps (bottom) are visualized for the two risk groups and the four prognostic genes. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the four prognostic genes are shown, with time (years) on the x-axis and PFS probability on the y-axis. (E) Time-dependent ROC curves were generated for the risk model at 1, 3, and 5 years, and AUCs are shown using distinct colors. ROC curves of the risk model in 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years. The curves in different colors represent the AUC values in different periods. GC, Gastric Cancer; LASSO, Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator; ROC, Receiver Operating Characteristic; AUC, Area Under the Curve

3.3 Mutation Analysis of Potential Target Genes in GC

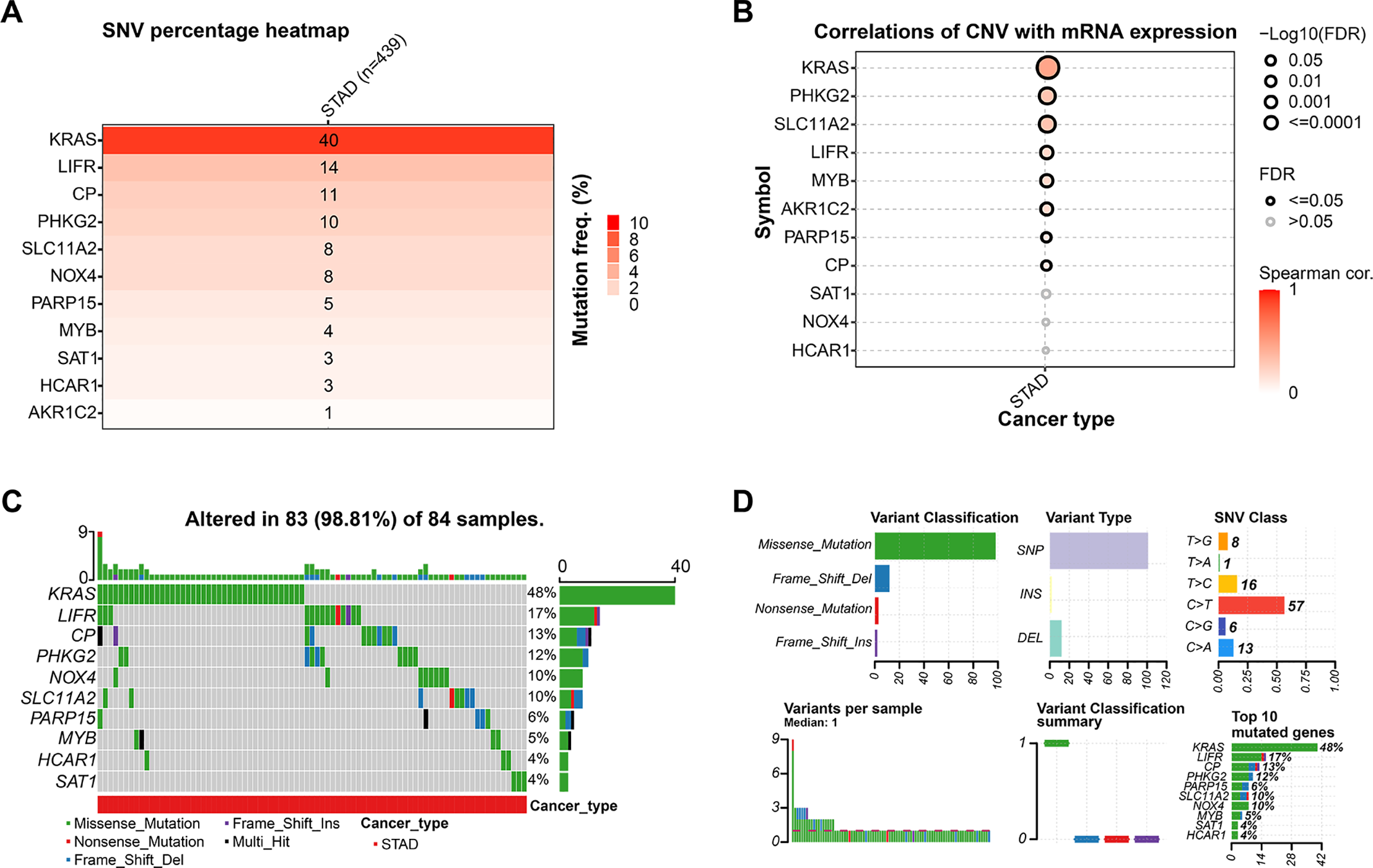

The mutation analysis of 11 prognostic genes in STAD, conducted through the GSCA database, revealed that KRAS had the most significant percentage of mutations, at 40%, followed by LIFR (14%) and CP (11%) (Fig. 3A). Using the Spearman method, CNVs were significantly positively correlated with the mRNA expression of KRAS along with PHKG2 (Fig. 3B), further underscoring the relationship between genomic variation and gene expression regulation (p < 0.05). In 84 STAD samples, 83 (98.81%) exhibited alterations in at least one prognostic gene, with KRAS mutations present in 48% of the samples (Fig. 3C). Missense mutations were the predominant variant classification, and the most prevalent kind of mutation was SNP, with C > T being the most frequent SNV category. The top 10 mutated genes included KRAS, LIFR, CP, PHKG2, NOX4, SLC11A2, PARP15, MYB, SAT1, and HCAR1 (Fig. 3D). Their high mutation rate in STAD may be closely associated with tumor progression and prognosis.

Figure 3: Mutation landscape of candidate genes in GC. (A) This heatmap shows the distribution of gene mutations in STAD, with deeper color tones representing higher mutation percentages. (B) Correlation analysis between CNVs and gene expression for the 11 prognostic markers in STAD, with significant correlations (p < 0.05) indicated. (C) This bar plot shows the distribution of gene mutations across 84 STAD samples. Different colors represent various types of mutations. (D) Variant classification summary displaying mutation types, variant types, SNV classes, and the top 10 mutated genes in the analyzed STAD samples. x-axis: number of mutations (upper left, upper center), Proportion of SNVs (upper right), Sample ID (lower left), Mutations of different functional classifications (middle and lower), Percentage of samples with mutations (lower right). GC, Gastric Cancer; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; STAD, Stomach Adenocarcinoma; FDR, False Discovery Rate; SNV, Single Nucleotide Variant

3.4 Identification of Significant Prognostic Variables in GC Using Cox Regression Models

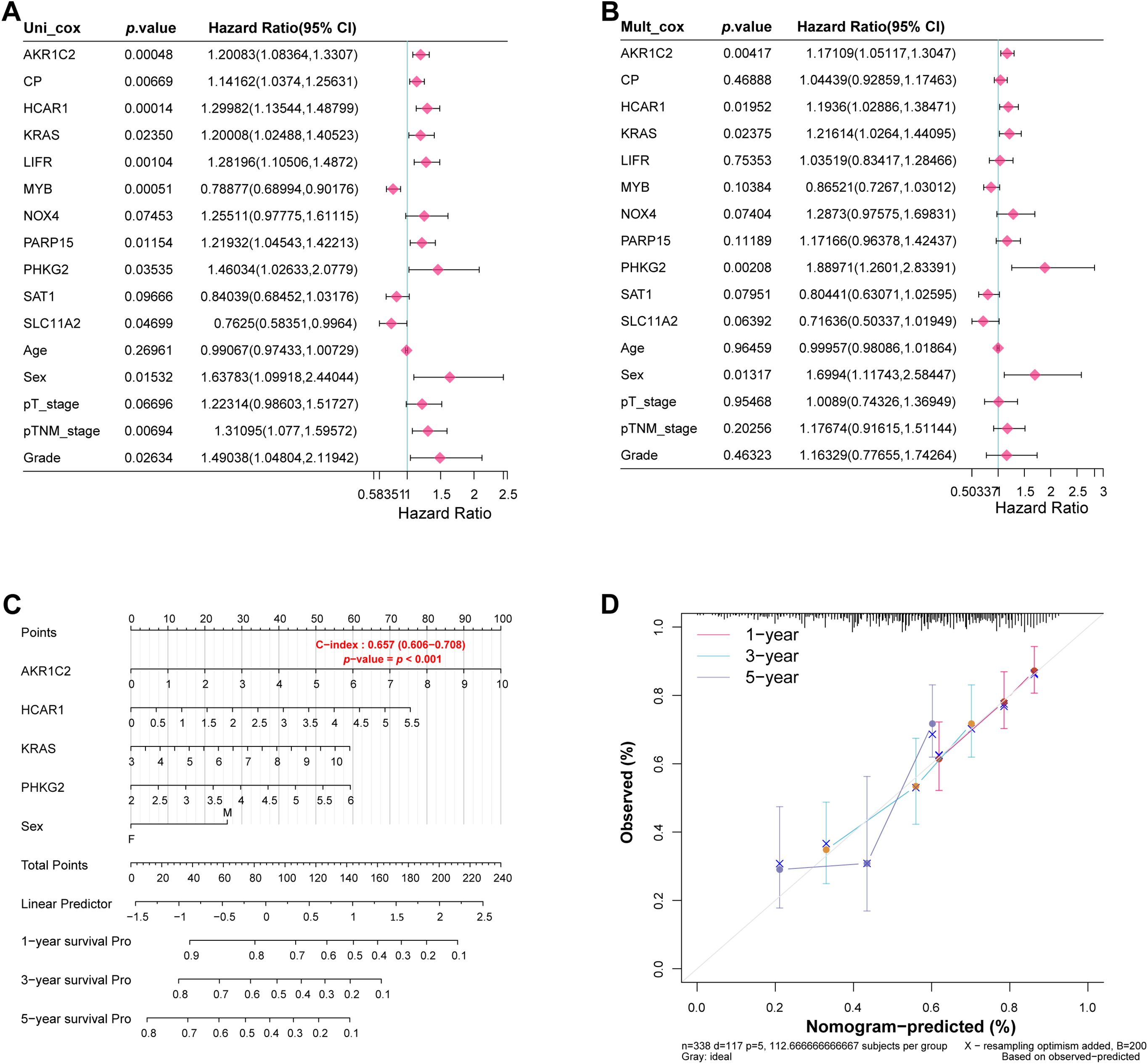

Through multivariate and univariate Cox regression evaluations of the 11 potential target genes and five clinical variables, we identified five statistically significant variables (p < 0.05): AKR1C2, HCAR1, KRAS, PHKG2, and sex (Fig. 4A,B). Nomogram analysis showed the highest prediction accuracy for 1-year survival. Calibration curves further confirmed the reliability of these predictions (Fig. 4C,D).

Figure 4: Identification of significant prognostic variables in GC. (A) Forest plot presenting hazard ratios (HRs) from univariate Cox regression analysis of candidate genes and clinical variables. (B) Forest plots show the HRs after multivariate Cox regression analysis to identify significant prognostic variables. (C) Based on significant prognostic factors, nomograms forecast survival rates for 1, 3, and 5 years. (D) Calibration curves evaluate the predictive accuracy of the nomogram for 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival probabilities. GC, Gastric Cancer

3.5 Evaluation of Gene Expression Patterns and Survival Associations in GC

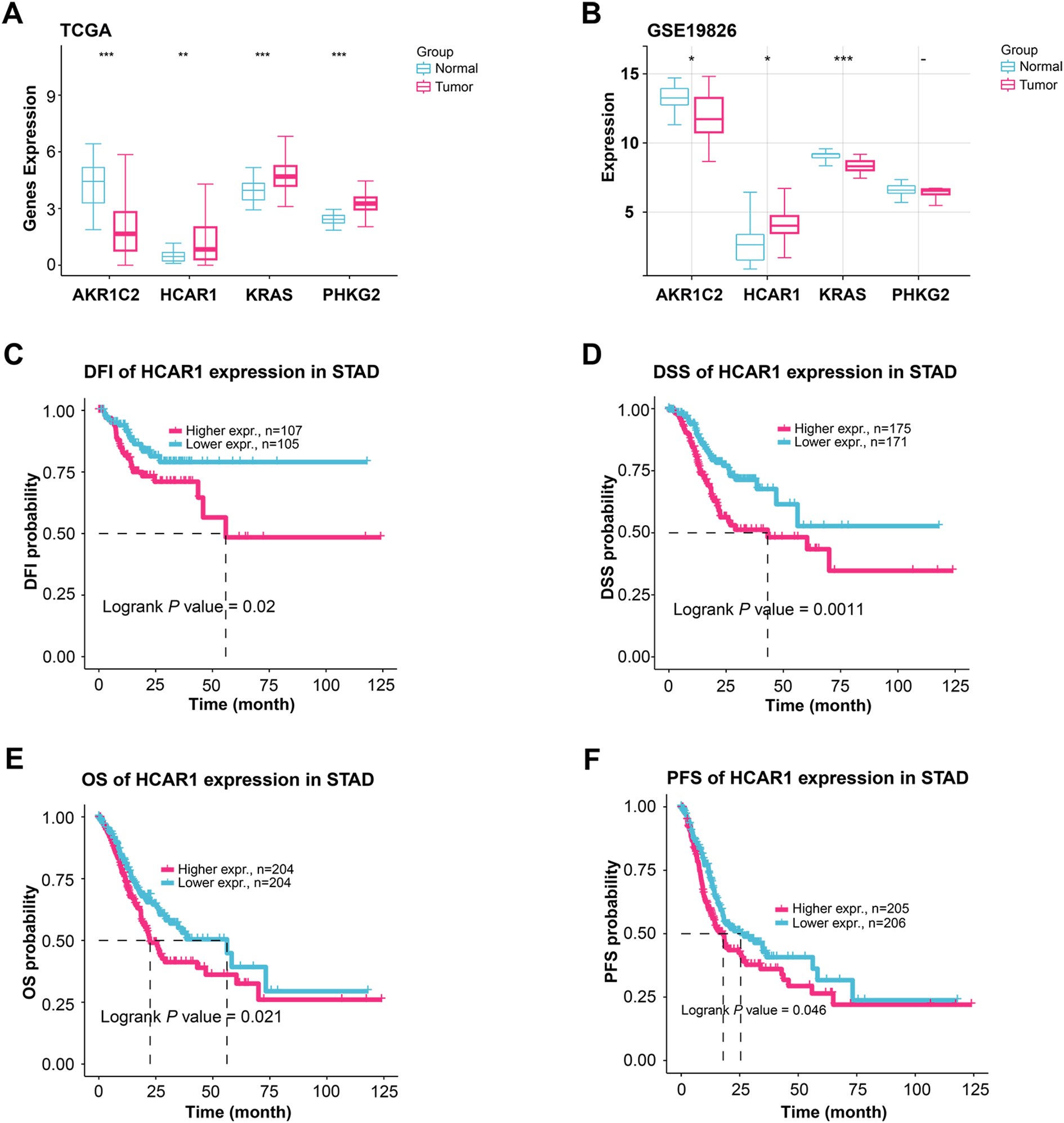

The study examined how four highly predictive genes in the TCGA-STAD and GSE19826 datasets (Fig. 5A,B). In the TCGA-STAD dataset, AKR1C2 exhibited reduced expression in the tumor group; conversely, HCAR1, KRAS, and PHKG2 showed increased expression in the tumor group. In the GSE19826 dataset, the tumor group’s expression levels of AKR1C2 and KRAS declined compared to the normal group; however, HCAR1 expression levels increased. The expression levels of KRAS and PHKG2 exhibited different trends across different datasets. Conversely, elevated HCAR1 expression correlated with unfavorable outcomes across both datasets, making HCAR1 a more consistent and significant marker. Therefore, HCAR1 was selected as the pivotal gene. HCAR1 expression was associated with significantly poorer disease-free interval (DFI), disease-specific survival (DSS), overall survival (OS), and progression-free survival (PFS) than the low-expression group (Fig. 5C–F). These findings imply that a poor prognosis in GC patients may be directly associated with high HCAR1 expression.

Figure 5: Expression patterns of key genes and their prognostic relevance in GC. (A, B) Comparing the expression levels of AKR1C2, HCAR1, KRAS, and PHKG2 in tumor and normal samples from the TCGA-STAD as well as the GSE19826 dataset, comparing tumor and normal samples. (C–F) KM curves illustrate the differences in DFI (C), DSS (D), OS (E), and progression-free survival (PFS) (F) based on HCAR1 expression levels. GC: Gastric Cancer; TCGA-STAD: The Cancer Genome Atlas-Stomach Adenocarcinoma; DFI: Disease-Free Interval; DSS: Disease-Specific Survival; OS: Overall Survival. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

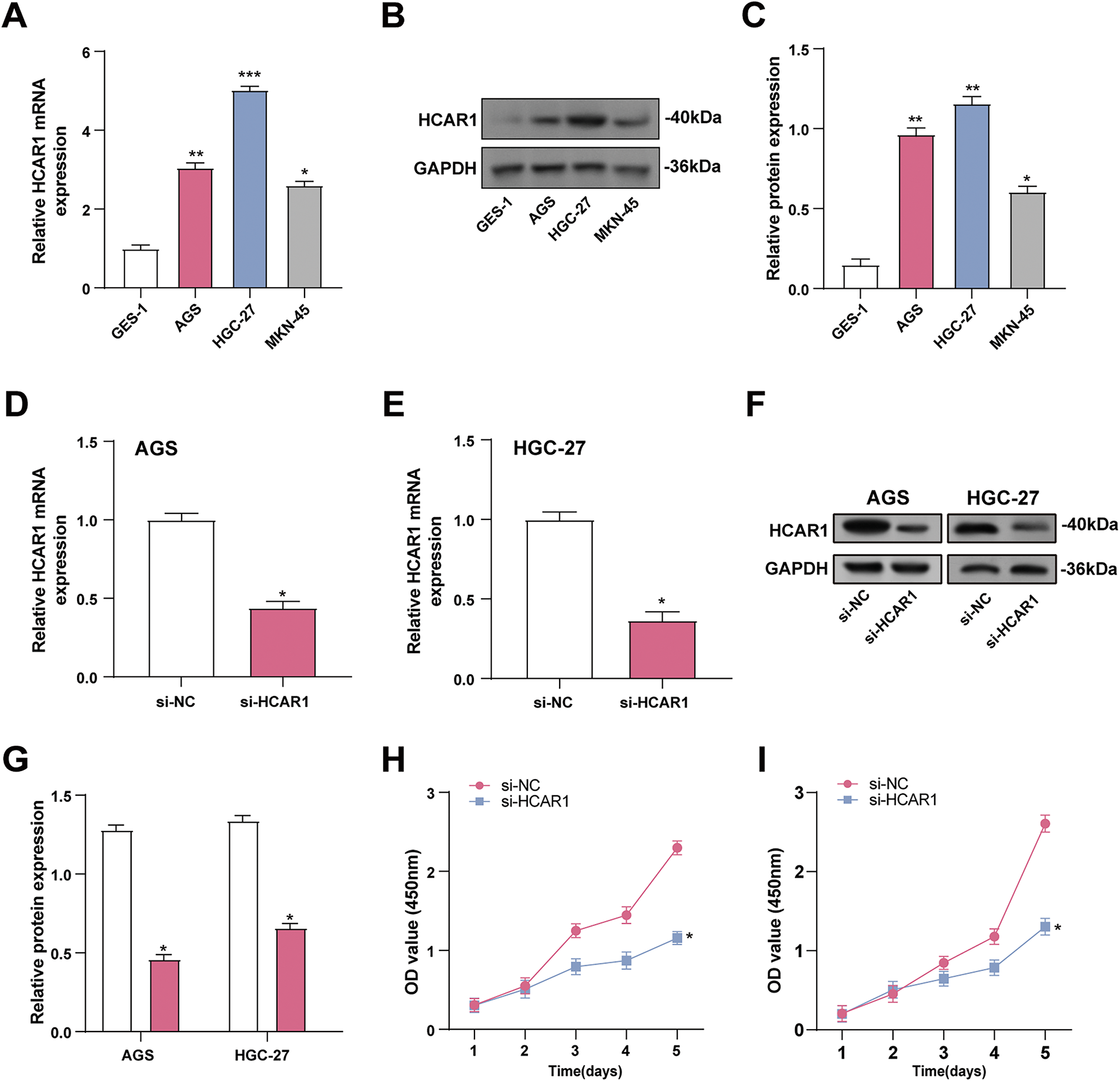

3.6 Silencing HCAR1 Inhibits GC Cell Proliferation

HCAR1 mRNA and protein levels were measured in GC cells and normal gastric cells (GES-1). The data indicated HCAR1 overexpression in GC cells, with AGS and HGC-27 exhibiting the most prominent levels (Fig. 6A–C). The effectiveness of HCAR1 knockdown was then assessed using qRT-PCR with WB techniques (Fig. 6D–G). Silencing HCAR1 reduced AGS and HGC-27 cell viability, implying its role in promoting GC cell proliferation (Fig. 6H,I).

Figure 6: Silencing HCAR1 inhibits GC cell proliferation. (A–C) HCAR1 mRNA and protein levels were examined by qRT-PCR and WB in GES-1, AGS, SGC-7901, and HGC-27 cells. (D, E) The effectiveness of HCAR1 knockdown in AGS and HGC-27 cells was tested by qRT-PCR. (F, G) WB analysis demonstrating HCAR1 protein levels in AGS and HGC-27 cells following HCAR1 knockdown. (H, I) Quantitative analysis of CCK-8 assay results indicating cell viability following HCAR1 knockdown. GC, Gastric Cancer; qRT-PCR, Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; mRNA, messenger RNA; WB, Western blotting; CCK-8, cell counting kit-8. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

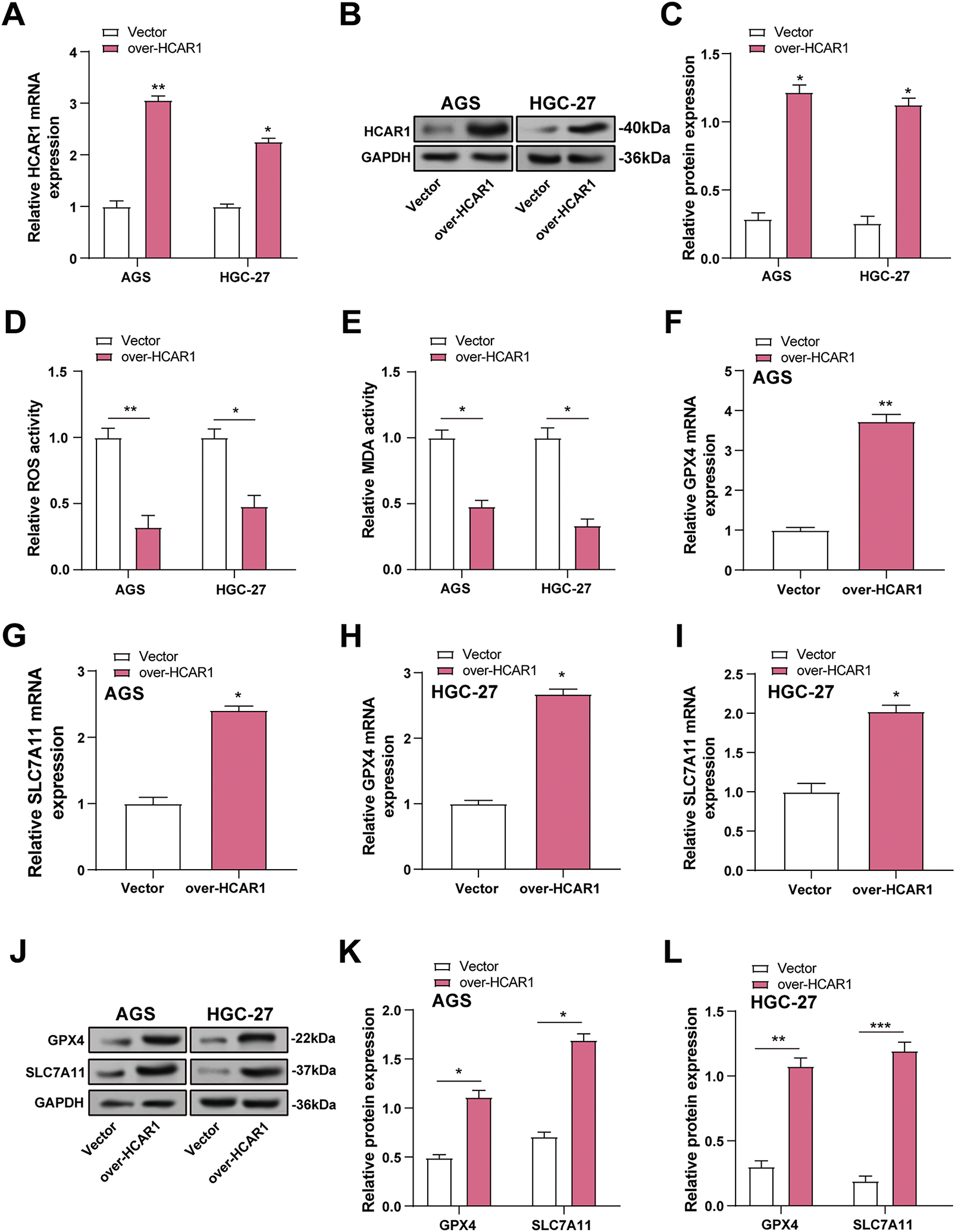

3.7 HCAR1 Upregulation Inhibits Ferroptosis in GC

The efficiency of HCAR1 overexpression in GC cells was verified by qRT-PCR and WB (Fig. 7A–C). Although ROS is essential for redox signaling, too much of it can cause oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, which are signs of ferroptosis. MDA, a lipid peroxidation product, reflects oxidative damage. GPX4 reduces lipid peroxides, while SLC7A11 maintains cysteine for glutathione synthesis. To explore the role of HCAR1 overexpression in regulating ferroptosis, ROS, MDA, and GPX4/SLC7A11 expression were quantified in GC cells. HCAR1 overexpression decreased ROS levels and MDA concentrations, according to assays conducted using ROS and MDA kits (Fig. 7D,E). In the results of qRT-PCR and WB analysis, GPX4 and SLC7A11 expressions were also upregulated after HCAR1 overexpression compared with the control group (Fig. 7F–L). These findings imply that HCAR1 has a function in controlling ferroptosis in GC cells.

Figure 7: Overexpression of HCAR1 inhibits ferroptosis in GC cells. (A–C) QRT-PCR and WB assessed expression levels of HCAR1 in AGS and HGC-27 cells overexpressing HCAR1. (D, E) In AGS and HGC-27 cells with HCAR1 overexpression, ROS and MDA levels were quantified. (F–I) qRT-PCR was used to evaluate GPX4 and SLC7A11 mRNA expression in AGS and HGC-27 cells overexpressing HCAR1. (J–L) Upregulation of GPX4 and SLC7A11 was detected by WB in response to HCAR1 overexpression. GC, Gastric Cancer; qRT-PCR, Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; mRNA, messenger RNA; WB, Western blotting; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species; MDA, Malondialdehyde. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

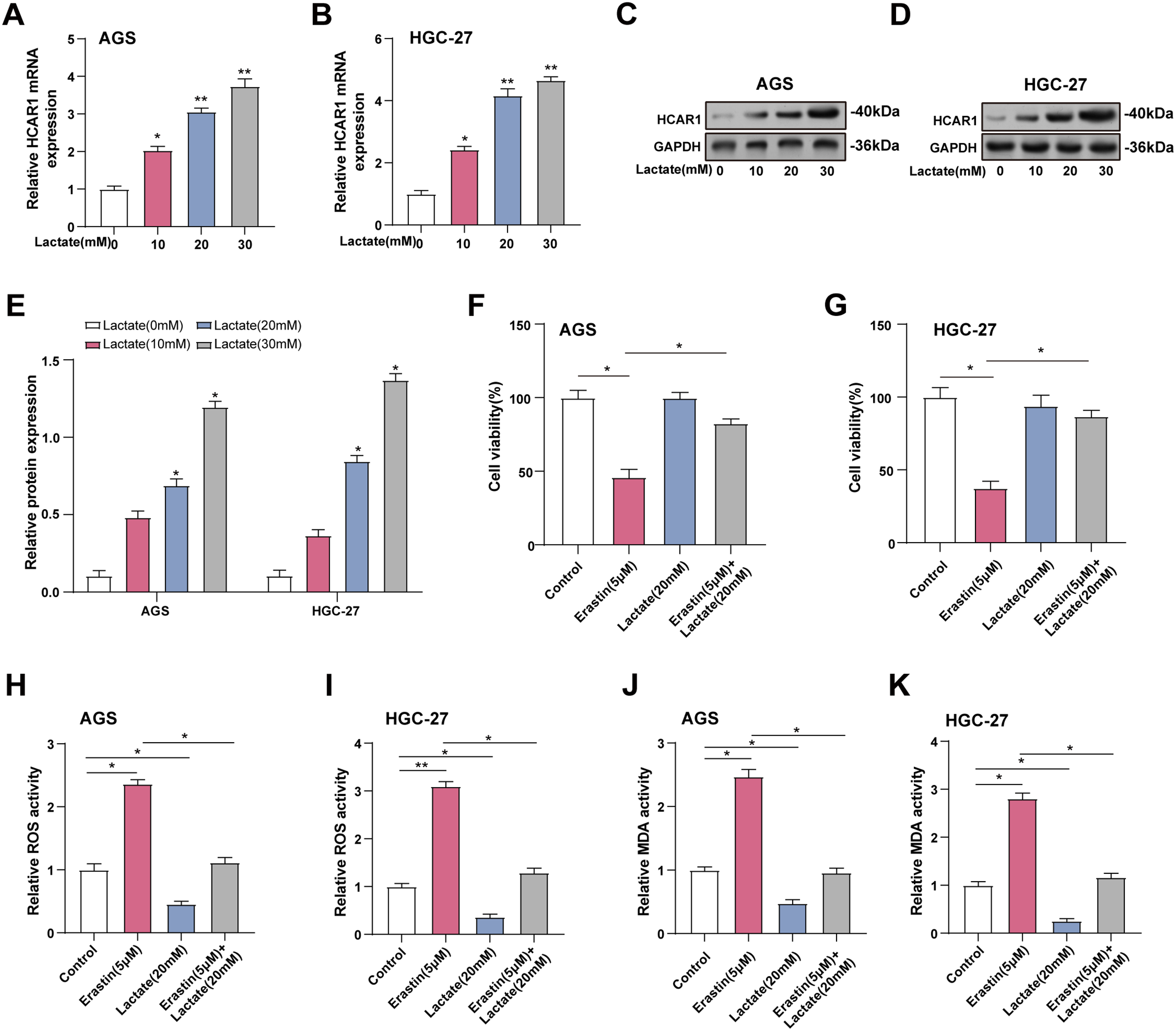

3.8 Elevated Extracellular Lactate Levels Inhibit Ferroptosis in GC Cells

To mimic the increase in extracellular lactate, we assessed HCAR1 expression in GC cells given different lactate concentrations (0, 10, 20, 30 mM) using qRT-PCR and WB. According to earlier research, lactate levels in tumor tissues are considerably higher, ranging from 10 to 40 mM, while they are modest in normal tissues, at about 1.3 mM [18,21,22]. HCAR1 expression was elevated with increasing lactate concentration and was significantly upregulated at 20 and 30 mM (Fig. 8A–E). However, to avoid potential cytotoxicity associated with excessive lactate levels, we referenced the settings of previous studies and maintained a lactate concentration of 20 mM in subsequent experiments. We employed 5 μM Erastin, a dose adjusted in a prior investigation, to trigger iron-mediated cell death in cells to examine the impact of lactate on this process [14]. CCK-8 demonstrated that treatment with erastin reduced viability in AGS and HGC-27 cells, whereas lactate mitigated this reduction (Fig. 8F,G). In cells exposed to lactate and/or erastin, lactate was found to reduce ROS and MDA levels, while erastin therapy raised them (Fig. 8H–K). Additionally, qRT-PCR and WB were utilized to measure GPX4 as well as SLC7A11 expression in GC cells treated with lactate and/or erastin. GPX4 and SLC7A11 expression was downregulated by erastin and upregulated by lactate relative to the control group. Combined lactate and erastin treatment mitigated the erastin-induced reduction in GPX4 and SLC7A11 expression (Fig. 8L–Q). These data show that increased extracellular lactate reduces ferroptosis in GC cells by modulating antioxidant enzyme expression.

Figure 8: Elevated extracellular lactate inhibits ferroptosis in GC cells. (A, B) Cells treated with increasing doses of lactate (0–30 mM) were analyzed for HCAR1 mRNA expression via qRT-PCR. (C–E) WB analysis showing HCAR1 protein expression in AGS and HGC-27 cells treated with lactate. (F, G) CCK-8 assay was used to detect cell viability after treatment with erastin and/or lactate (H, I) Changes in ROS levels after treatment with erastin and/or lactate. (J, K) Changes in MDA levels after treatment with erastin and/or lactate. (L, M) qRT-PCR analysis of GPX4 and SLC7A11 mRNA expression in AGS and HGC-27 cells treated with erastin and/or lactate. (N–Q) WB analysis showing GPX4 and SLC7A11 protein expression in AGS and HGC-27 cells treated with erastin and/or lactate. GC, Gastric Cancer; qRT-PCR, Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; mRNA, messenger RNA; WB, Western blotting; CCK-8, cell counting kit-8; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species; MDA, Malondialdehyde. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

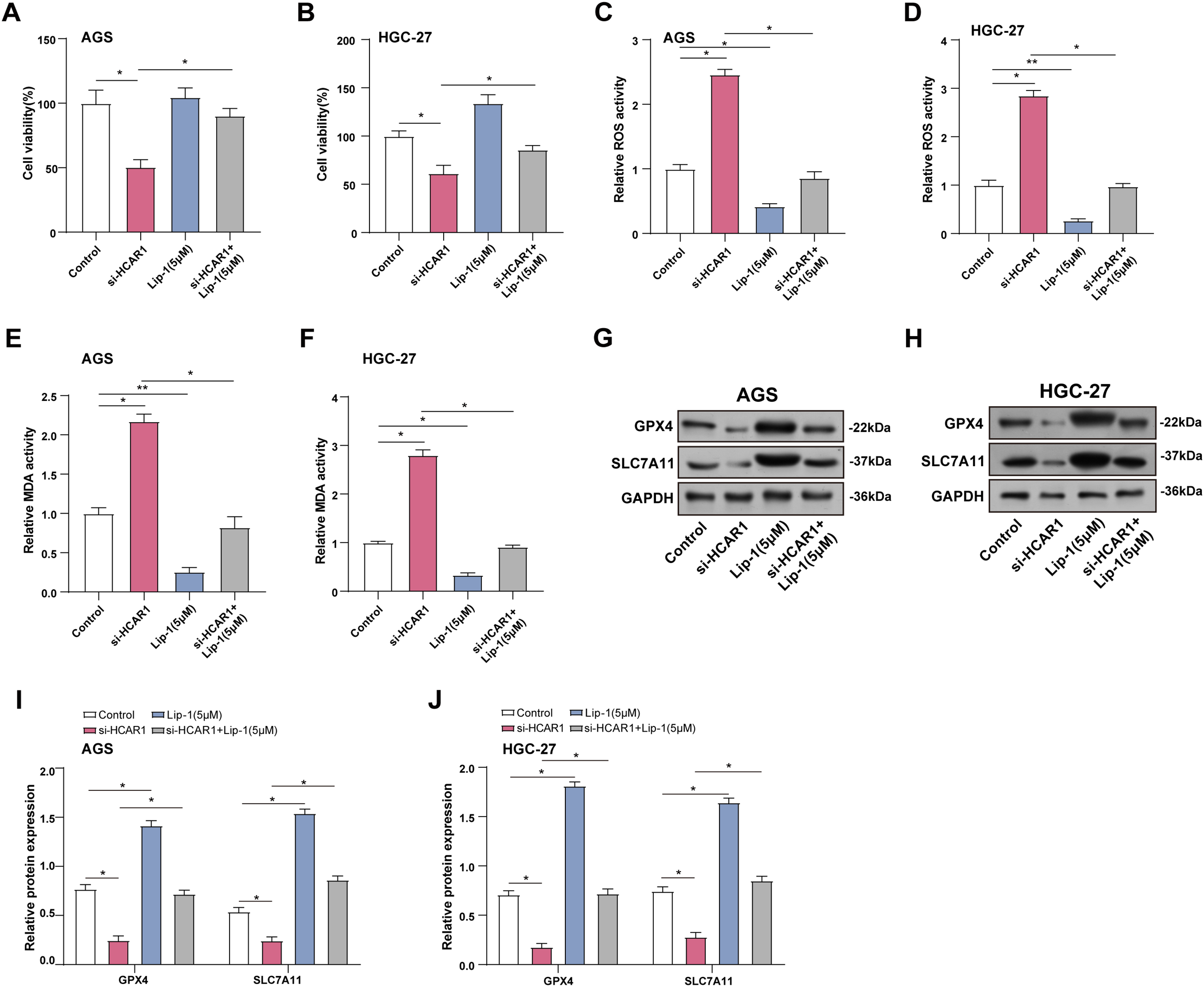

3.9 Inhibition of HCAR1-Promoted Lactate Transport Enhances Ferroptosis in GC Cells

Cell viability in GC cells was assessed using the CCK-8 assay after HCAR1 knockdown and/or Lip-1 treatment. The outcomes demonstrated that the cell viability was severely decreased by HCAR1 knockdown. However, the addition of Lip-1 attenuated this inhibitory effect on GC cells (Fig. 9A,B). ROS and MDA levels were measured in GC cells following HCAR1 knockdown and/or Lip-1 treatment using specific detection kits. Compared to the control group, HCAR1 knockdown increased ROS and MDA expression, whereas Lip-1 treatment reduced their levels. The combination of HCAR1 knockdown and Lip-1 treatment reversed the upregulation of ROS and MDA expression after HCAR1 knockdown (Fig. 9C–F). In addition, WB technology detected that after HCAR1 knockdown, GPX4 and SLC7A11 expression were downregulated, while Lip-1 treatment enhanced their expression. Combined treatment could reverse the effect of HCAR1 silencing (Fig. 9G–J). Lactate can also enter tumor cells via monocarboxylate transporter proteins (MCTs) [23]. To further clarify the dual role of lactate as both a signaling molecule activating HCAR1 and a metabolic substrate transported by MCTs. WB was performed to assess MCT1 expression after HCAR1 knockdown in GC cells, revealing a marked reduction in MCT1 protein levels (Fig. S1A–C). Treatment with the MCT1-specific inhibitor AZD3965 markedly reduced GC cell viability (Fig. S1D–E), and significantly elevated ROS (Fig. S1F–G) and MDA (Fig. S1H–I), whereas the ferroptosis inhibitor addition partially reversed the above changes. The above results suggest that lactate may enhance its ability to enter cells through the HCAR1-MCT1 axis, thus regulating metabolism and iron-death-related processes in GC cells.

Figure 9: Inhibition of HCAR1-promoted lactate transport enhances ferroptosis in GC cells. (A, B) Viability of GC cells after HCAR1 knockdown and Lip-1 administration was measured via CCK-8. (C, D) ROS levels were assessed in GC cells after HCAR1 silencing and/or Lip-1 administration. (E, F) MDA concentrations were assessed in AGS and HGC-27 cells following HCAR1 silencing and/or Lip-1 treatment. (G–J) WB analysis showing GPX4 and SLC7A11 levels in AGS and HGC-27 cells following HCAR1 silencing and/or Lip-1 treatment. GC, Gastric Cancer; Lip-1, Liproxstatin-1; CCK-8, cell counting kit-8; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species; MDA, Malondialdehyde; WB, Western blotting. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

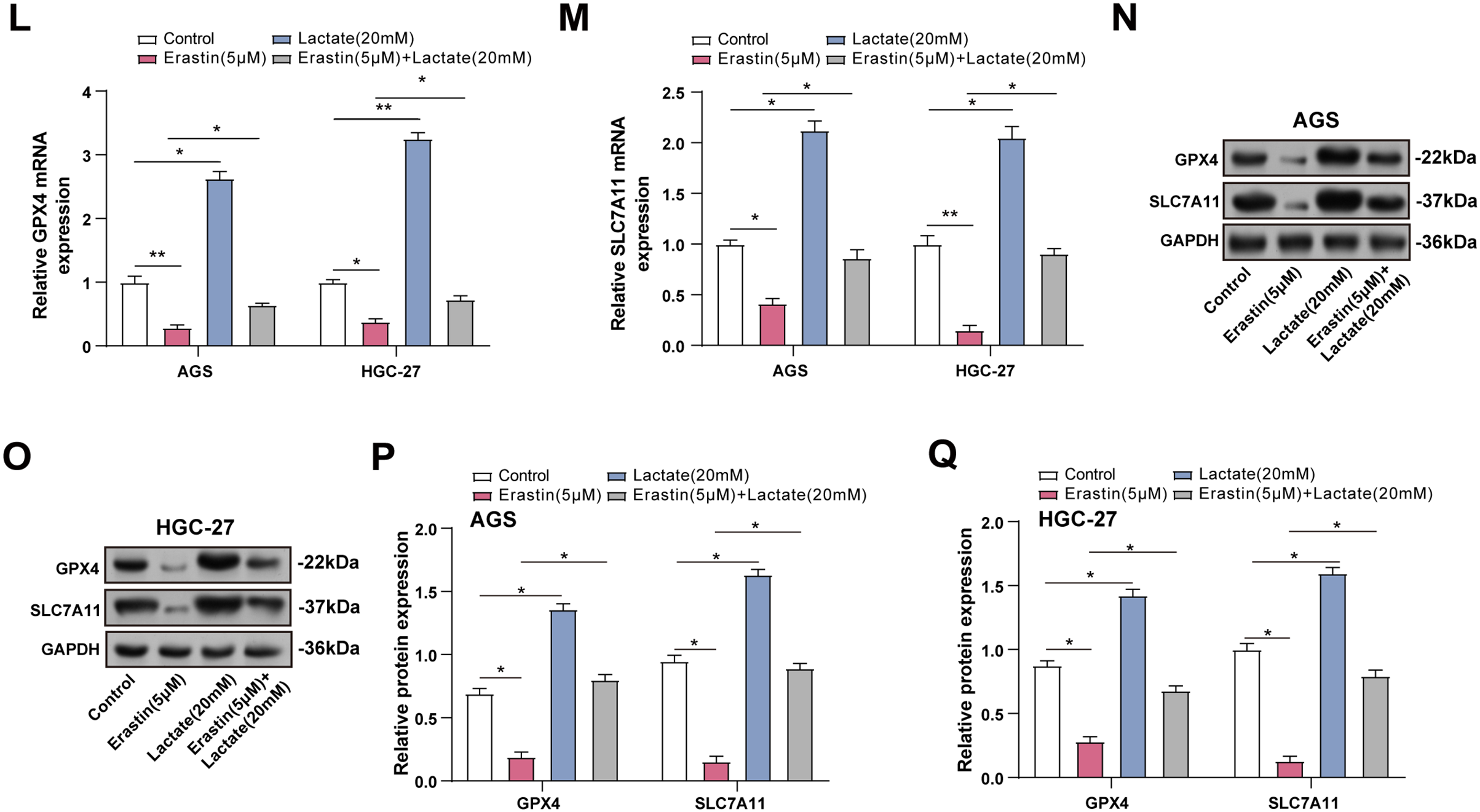

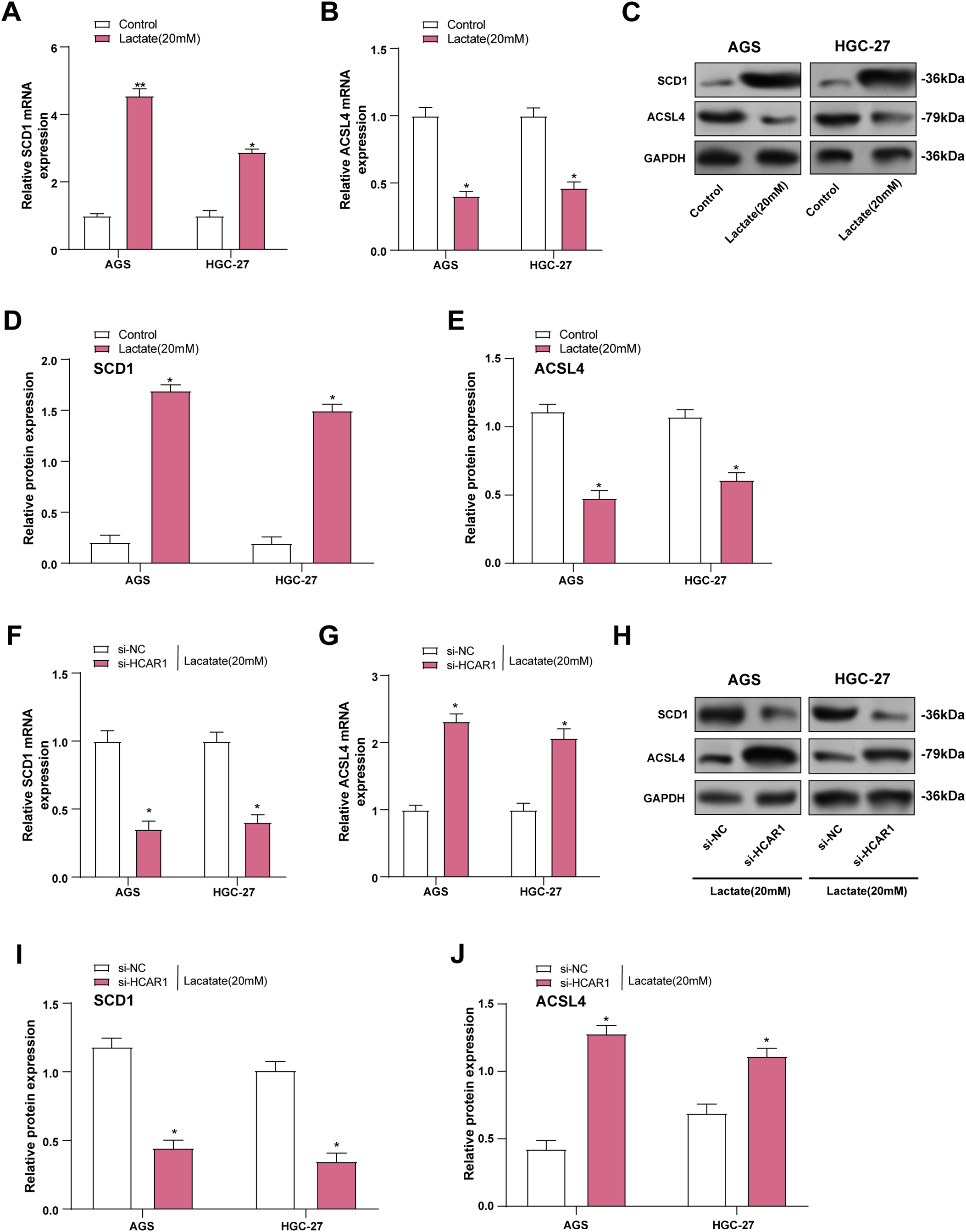

3.10 Lactate Induces Dysregulation of Lipid Metabolism in GC Cells

SCD1 plays a key role in lipid metabolism by converting saturated fatty acids into monounsaturated forms [24]. Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) participates in polyunsaturated fatty acid processing, which is critical for lipid signaling and the induction of ferroptosis [25]. In our study, SCD1 expression was upregulated as well, and ACSL4 expression was downregulated in GC cells after lactate treatment than the control group (Fig. 10A–E). Subsequently, we further examined the expression changes of both proteins after HCAR1 knockdown, and the results showed that HCAR1 knockdown significantly downregulated SCD1 expression, while upregulating ACSL4 expression (Fig. 10F–J). To further validate the role of lactate transmembrane uptake in this process, we performed experiments with AZD3965 treatment. Western blot results showed that SCD1 expression was downregulated and ACSL4 expression was upregulated in GC cells after AZD3965 treatment (Fig. S2A–C), which was in line with the trend after HCAR1 knockdown. These results further support that lactate enters cells through the HCAR1-MCT1 axis.

Figure 10: Lactate induces dysregulation of lipid metabolism in GC cells. (A, B) SCD1 and ACSL4 levels were assessed by qRT-PCR in lactate-treated GC cells. (C–E) WB analysis showing SCD1 and ACSL4 levels in GC cells after lactate treatment. (F, G) In GC cells, HCAR1 knockdown-induced changes in SCD1 and ACSL4 mRNA were quantified using qRT-PCR. (H–J) WB analysis showing SCD1 and ACSL4 protein expression in AGS and HGC-27 cells following HCAR1 knockdown. GC, Gastric Cancer; qRT-PCR, Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; mRNA, messenger RNA; WB, Western blotting. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

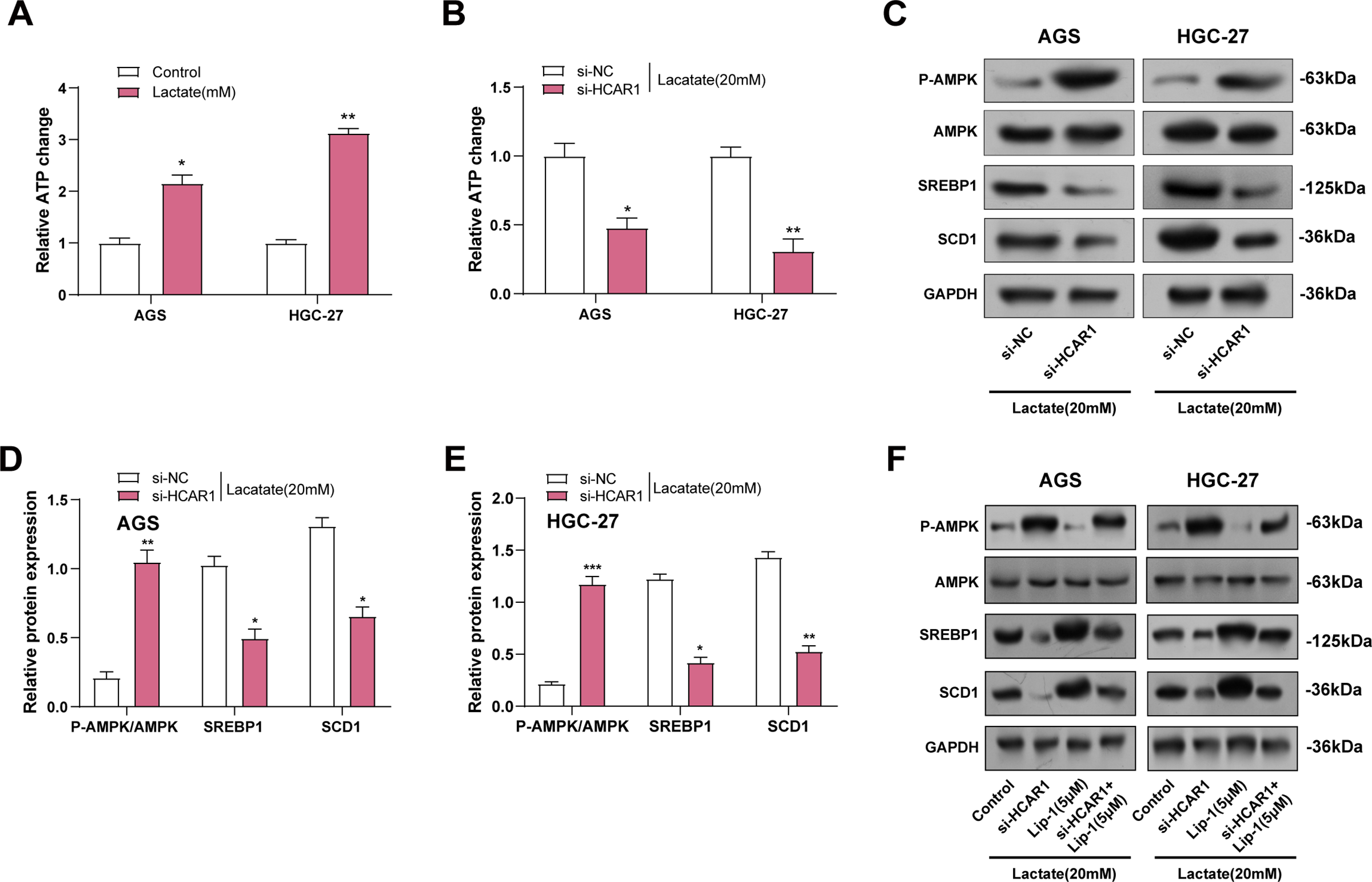

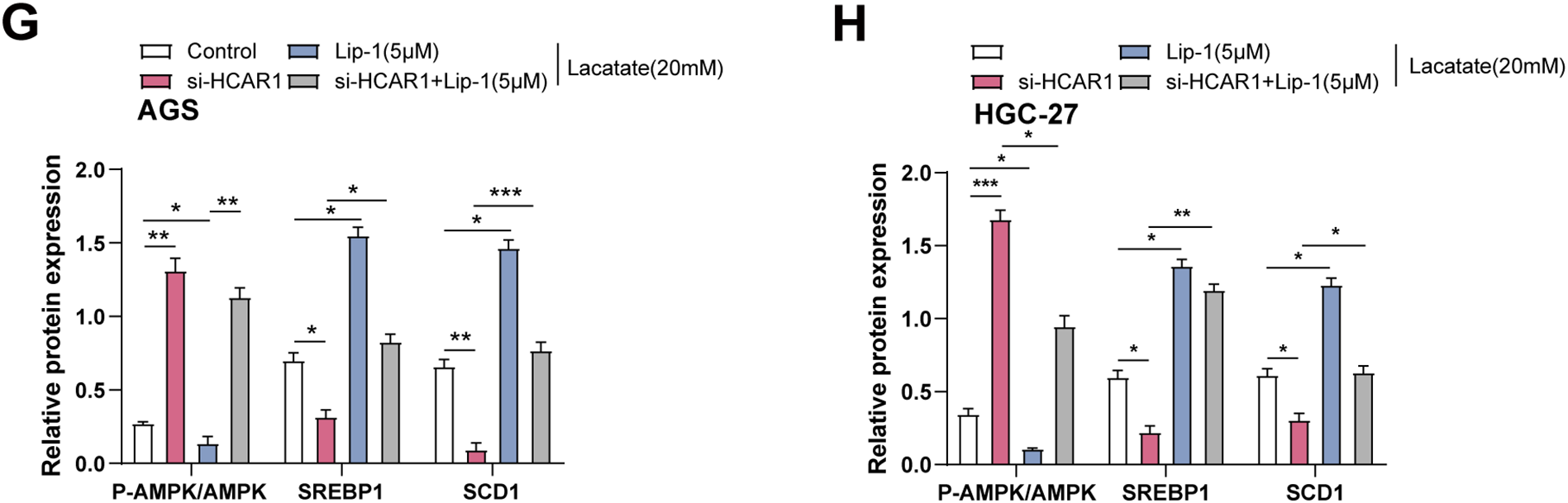

3.11 HCAR1 Regulates Ferroptosis in GC Cells via Lactate-Mediated AMPK-SCD1 Activity

ATP assay kits were utilized to measure changes in ATP levels in GC cells treated with lactate. It was noted that ATP levels increased with the addition of Lactate (Fig. 11A). As depicted in Fig. 11B, ATP levels were reduced in GC cells following HCAR1 knockdown. AMPK, a key regulator of cellular metabolism and an energy sensor, has been shown to regulate ferroptosis via altering lipid metabolism as well as oxidative stress responses [26]. To this end, we further analyzed the effects of HCAR1 knockdown on p-AMPK, AMPK, SREBP1, and SCD1 levels by WB. HCAR1 knockdown led to a marked increase in p-AMPK expression and a reduction in SREBP1 and SCD1 protein levels (Fig. 11C–E). Furthermore, we analyzed the effects of HCAR1 knockdown and/or Lip-1 treatment, a ferroptosis inhibitor, on the above pathway proteins. The results showed that Lip-1 treatment alone decreased p-AMPK expression and up-regulated SREBP1 and SCD1 expression. In contrast, the combined treatment of HCAR1 knockdown and Lip-1 partially reversed the changes induced by HCAR1 knockdown (Fig. 11F–H). Following treatment with the MCT1 inhibitor AZD3965 and/or Lip-1, we conducted pertinent protein expression experiments to confirm the regulatory role of lactate transport on the aforementioned pathways. WB revealed that p-AMPK expression was increased, and SREBP1 and SCD1 expression were decreased after treatment with AZD3965, and after treatment with Lip-1, p-AMPK expression decreased, and SREBP1 and SCD1 expression were upregulated after Lip-1 treatment. And after AZD3965 combined with Lip-1 treatment, p-AMPK expression was again elevated, while SREBP1 and SCD1 expression were decreased (Fig. S2D–F). These results further support the involvement of lactate in regulating the AMPK-SCD1 signaling axis and affecting the ferroptosis sensitivity of GC cells after lactate transport mediated by HCAR1.

Figure 11: HCAR1 regulates ferroptosis in GC cells via lactate-mediated AMPK-SCD1 activity. (A) Changes in ATP levels in AGS and HGC-27 cells treated with lactate were measured using ATP assay kits. (B) Effects of HCAR1 knockdown on changes in ATP levels in AGS and HGC-27 cells. (C–E) WB analysis showing p-AMPK, AMPK, SREBP1, and SCD1 protein expression levels in AGS and HGC-27 cells following HCAR1 knockdown. (F–H) Effects of HCAR1 knockdown and Lip-1 treatment on p-AMPK, SREBP1, and SCD1 levels. GC, Gastric Cancer; ATP, Adenosine Triphosphate; WB, Western Blotting; Lip-1, Liproxstatin-1. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

GC is still characterized by substantial morbidity and a high death rate [27]. Current research focuses on identifying novel biomarkers, elucidating their molecular mechanisms, and developing new therapeutic strategies. In our study, differential expression analysis of GC-related datasets identified 170 intersecting genes that were markedly enhanced in pathways like “Ferroptosis”, “FoxO signaling pathway”, and “Insulin signaling pathway”. Subsequent analysis identified four highly predictive genes (AKR1C2, HCAR1, KRAS, PHKG2) with prognostic potential. Liu et al. discovered that AKR1C2 (a ferroptosis-related gene) is deregulated in GC tissues and is connected to various tumor characteristics and favorable prognosis [28]. AKR1C2 also participates in immune-related features, underscoring its importance in GC tumorigenesis and biological function. Additionally, Yuan et al. reported that the long non-coding RNA LINC00514 is upregulated in GC, promoting cell growth and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by inhibiting miR-204-3p and enhancing KRAS expression [29]. According to Geng and Wu [30], KRAS promotes GC cell growth and metabolism through ARF6, influencing the Warburg effect and oxidative stress. These effects may contribute to ferroptosis inhibition and drug resistance, highlighting KRAS as a key factor in GC development. In a study by Zhu et al. [31], PHKG2 was found to enhance RSL3-induced ferroptosis sensitivity by regulating ALOX5 expression in H. pylori-infected GC cells. Lactate acts as a paracrine and autocrine signaling molecule in the tumor microenvironment [32] through the HCAR1 receptor. Longhitano et al. demonstrated that lactate, via its transporter MCT1 and receptor HCAR1, promotes the proliferation and migration of glioblastoma (GBM) cells, regulates EMT and mitochondrial function, suggesting lactate and its related pathways as potential therapeutic targets against tumor progression and recurrence [33]. Given the limited research on HCAR1 in GC, this research aims to investigate the processes of HCAR1 in GC.

A unique type of cell death caused by lipid peroxidation that is dependent on iron is called ferroptosis [34]. Increased intracellular free iron catalyzes the Fenton reaction, generating ROS that degrade the lipids in membranes [35]. Endale et al. highlighted the role of ROS in lipid oxidation, producing compounds such as 4-hydroxynonenal, which promote lipid peroxidation of the phospholipid bilayer and potentially trigger ferroptosis [36]. MDA is produced when polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) on cell membranes oxidize due to lipid peroxidation [37]. GPX4 is a critical enzyme in inhibiting ferroptosis by reducing lipid peroxides to lipid alcohols, thereby protecting cell membranes from oxidative damage [38]. Research by Cui et al. revealed the essential role of GPX4 in regulating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis in regulatory T cells (Tregs), maintaining immune homeostasis and anti-tumor immune function [39]. Specific depletion of GPX4 in Tregs leads to elevated lipid peroxide buildup and ferroptosis, enhancing superoxide generation and IL-1β secretion upon antigen stimulation, thereby promoting TH17 cell responses. SLC7A11, additionally referred to as xCT, encodes a membrane transporter protein that regulates the balance of intracellular and extracellular cystine [40]. Lee and Roh. summarized SLC7A11 as the light chain component of the system xc- (xCT), which transports extracellular cystine into cells to promote glutathione synthesis, maintain redox balance, and inhibit ferroptosis [41]. This study examines the effect of HCAR1 on GC cells and ferroptosis-related markers. The findings demonstrate that destruction of HCAR1 inhibits the proliferation of GC cells, while overexpression of HCAR1 upregulates GPX4 and SLC7A11, thereby suppressing ferroptosis. These findings underscore the interplay between ferroptosis, HCAR1, and GC.

Tumor cells utilize aerobic glycolysis to generate energy, resulting in the rapid accumulation of lactate [42]. This accumulation alters the tumor microenvironment, contributing to acidosis, nutrient deprivation, and immune suppression, promoting cancer cell growth, infiltration, and metastasis. Elevated lactate levels in GC patients are associated with poor prognosis, indicating that lactate detection may aid in assessing disease progression and prognosis. Wang et al. demonstrated that lactate enhances DBF4 expression by inhibiting miR-30a, playing a crucial role in tumor progression and chemotherapy sensitivity [43]. Moreover, Yang et al. found that the hypoxic tumor microenvironment enhances solid tumor resistance to ferroptosis through HIF-1α-dependent mechanisms, with HIF-1α and HIF-2α acting as major drivers of tumor resistance under hypoxic conditions [44]. Erastin primarily inhibits xCT by targeting SLC7A11, resulting in a decreased intracellular cystine concentration and inhibited glutathione synthesis, which sensitizes cells to oxidative stress and induces ferroptosis [45]. Li-1 prevents ferroptosis by inhibiting lipid peroxidation and reducing free oxygen radical production, thereby protecting cell membranes from lipid peroxidation damage and blocking the execution of ferroptosis [46]. This study investigated the impact of extracellular lactate levels and ferroptosis inducers on GC cells, revealing that elevated extracellular lactate levels inhibit ferroptosis in GC cells. Additionally, by examining the effects of HCAR1 knockdown and ferroptosis inhibitors on GC cells, it was found that blocking HCAR1-mediated lactate influx exacerbates ferroptosis. These findings underscore the intricate relationship between lactate metabolism, ferroptosis, and HCAR1 in GC cells, offering new insights into potential therapeutic strategies.

SCD1 and ACSL4 are critical regulators of lipid metabolism, playing essential roles in maintaining cellular membrane structure and function, as well as in signal transduction and energy metabolism. Wang et al. revealed that SCD1 promotes tumor growth, migration, and resistance to ferroptosis in GC, potentially through the modulation of cancer stem-like properties and regulation of cell cycle-related proteins [47]. ACSL4 specifically binds to polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) like arachidonic acid (AA) and docosahexaenoic acid [48,49]. Lee et al. indicated that high ACSL4 expression sensitizes intestinal-type GC cells to ferroptosis by synthesizing AA and adrenic acid (AdA). In contrast, DNA methylation-induced inhibition confers resistance to ferroptosis in stromal-type GC cells [50]. In this study, we observed that lactate treatment increases SCD1 expression and decreases ACSL4 expression in GC cells. Interestingly, knocking down HCAR1 had the opposite effects regarding the expression of ACSL4 and SCD1 in GC cells. Considering the role of SCD1 as the central enzyme in monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) biosynthesis in humans, these findings imply that SCD1 and similar upstream pathways may be connected to lactate-mediated resistance to ferroptosis [51].

SREBP1 is a transcription factor primarily involved in regulating genes related to cholesterol and lipid biosynthesis [52]. Changes in the ratio of ATP to AMP activate the AMP-activated protein kinase; SREBP1 is a transcription factor primarily involved in regulating genes related to cholesterol and lipid biosynthetic pathways [53]. Changes in the ATP/AMP ratio activate the AMPK pathway within cells. AMPK activation promotes various energy-producing pathways, such as glucose uptake, glucose oxidation, and the oxidation of fatty acids, to enhance ATP synthesis, even though it inhibits energy-consuming pathways, including protein and lipid synthesis [54]. Sun et al. observed the activation of SREBP-1c in human GC tissues, promoting the expression of genes linked to fatty acid production, such as SCD1 and FASN [55]. Silencing SREBP-1c restored defects in migration and invasion abilities in AGS and SGC-7901 GC cells. Zou et al. demonstrated that AMPK inhibits TGF-β1 induction by suppressing Smad3 phosphorylation and activation in GC cells [56]. Liu et al. found that in lactate-enriched hepatocellular carcinoma cells, lactate uptake via MCT1 enhances ATP production and suppresses AMPK, thereby upregulating SREBP1 and its downstream targets, including SCD1, promoting MUFA production and resistance to ferroptosis [57]. Our study suggests that lactate acts as an agonist of HCAR1 extracellularly, and activation of HCAR1 may affect intracellular ATP production and AMPK activity. This activation may influence tumor growth and progression by regulating lactate signaling. In addition, lactate enters GC cells through the HCAR1-MCT1 axis and is involved in regulating metabolism and iron-related processes. Our study demonstrates that blocking HCAR1-mediated lactate uptake exacerbates iron-induced cell death in GC cells, whereas HCAR1 activation inhibits iron-induced cell death and activates antioxidant defense mechanisms. Thus, the different mechanisms of lactate action within and outside GC cells provide new insights into understanding its complex role in GC progression and therapy.

The present study provides new insights into the role of HCAR1 in regulating iron mutation in GC cells through the lactate-HCAR1-APK-SCD1 axis. However, we should also recognize some limitations of the study. First, due to resource constraints, we were unable to perform in vivo validation experiments to assess the functional relevance of HCAR1 in tumor progression and iron mutation sensitivity. Animal studies, such as xenografts or orthotopic models, are needed to confirm the therapeutic potential of targeting this axis in vivo. Second, although we identified HCAR1 as a potential therapeutic target, we did not experimentally evaluate the effects of known pharmacological agonists or antagonists of HCAR1 (e.g., 3-hydroxybutyrate or 3-chloro-5-hydroxybenzoic acid), nor did we test small-molecule inhibitors of SCD1 (e.g., A939572 or CAY10566) on the iron mutant phenotype. These remain important avenues for future translational exploration. Finally, these results were primarily obtained from AGS and HGC-27 cell lines. Therefore, further validation in additional GC subtypes or cells derived from patients is required to confirm their broader applicability.

This study set out to elucidate the role of HCAR1 in GC progression, with a particular focus on its influence on ferroptosis and lipid metabolism. Our findings underscore the critical role of HCAR1 in modulating ferroptosis in GC cells through lactate-mediated AMPK-SCD1 signaling. By identifying HCAR1 as a significant prognostic marker, our research highlights its potential as a therapeutic target for overcoming metabolic adaptations in GC. Modulating the HCAR1-lactate pathway could serve as a potential approach to boost ferroptosis responsiveness and optimize therapeutic efficacy in GC. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the underlying role of HCAR1 in lipid metabolism and its wider relevance to cancer treatment.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Songhua Bei, Qianqian Guo, Xinglei Wu, and Fan Li conceived and designed the research. Songhua Bei, Yaya Xie, Xiaohong Zhang, and Xingxing Zhang, acquisition of data. Songhua Bei, Qianqian Guo, and Li Feng, analysis and interpretation of data. Xinglei Wu, Fan Li, and Xiaohong Zhang are drafting the manuscript. Li Feng, Yaya Xie, and Xingxing Zhang, revision of manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/or.2025.067247/s1.

References

1. Yang L, Ying X, Liu S, Lyu G, Xu Z, Zhang X, et al. Gastric cancer: epidemiology, risk factors and prevention strategies. Chin J Cancer Res. 2020;32:695. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

2. Piazuelo MB, Correa P. Gastric cancer: overview. Colomb Medica. 2013;44(3):192–201. doi:10.25100/cm.v44i3.1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Luo W-Z, Li X, Wu X-X, Shang Y-W, Meng D-H, Chen Y-L, et al. MAGED4B is a poor prognostic marker of stomach adenocarcinoma and a potential therapeutic target for stomach adenocarcinoma tumorigenesis. Int J Gen Med. 2023;16:1681–93. doi:10.2147/ijgm.s401507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Shin WS, Xie F, Chen B, Yu P, Yu J, To KF, et al. Updated epidemiology of gastric cancer in Asia: decreased incidence but still a big challenge. Cancers. 2023;15(9):2639. doi:10.3390/cancers15092639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Kumar S, Patel GK, Ghoshal UC. Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation: possible factors modulating the risk of gastric cancer. Pathogens. 2021;10(9):1099. doi:10.3390/pathogens10091099. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Su L-J, Zhang J-H, Gomez H, Murugan R, Hong X, Xu D, et al. Reactive oxygen species-induced lipid peroxidation in apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019(30):5080843–13. doi:10.1155/2019/5080843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang L, Li C, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Yang X. Ophiopogonin B induces gastric cancer cell death by blocking the GPX4/xCT-dependent ferroptosis pathway. Oncol Lett. 2022;23:1–9. [Google Scholar]

8. Zhang C, Liu N. Ferroptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis in the occurrence and development of ovarian cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13:920059. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.920059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Talty R, Bosenberg M. The role of ferroptosis in melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2022;35(1):18–25. doi:10.1111/pcmr.13009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Li J, Cao F, Yin H-L, Huang Z-J, Lin Z-T, Mao N, et al. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

11. Yang Z, Zou S, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Zhang P, Xiao L, et al. ACTL6A protects gastric cancer cells against ferroptosis through induction of glutathione synthesis. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):4193. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39901-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Yang H, Li Q, Chen X, Weng M, Huang Y, Chen Q, et al. Targeting SOX13 inhibits assembly of respiratory chain supercomplexes to overcome ferroptosis resistance in gastric cancer. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):4296. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-48307-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Xu X, Li Y, Wu Y, Wang M, Lu Y, Fang Z, et al. Increased ATF2 expression predicts poor prognosis and inhibits sorafenib-induced ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Redox Biol. 2023;59:102564. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2022.102564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Zhou Q, Liu T, Qian W, Ji J, Cai Q, Jin Y, et al. HNF4A-BAP31-VDAC1 axis synchronously regulates cell proliferation and ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(6):356. doi:10.1038/s41419-023-05868-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Briquet M, Rocher A-B, Alessandri M, Rosenberg N, de Castro Abrantes H, Wellbourne-Wood J, et al. Activation of lactate receptor HCAR1 down-modulates neuronal activity in rodent and human brain tissue. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2022;42(9):1650–65. doi:10.1177/0271678x221080324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Spencer NY, Stanton RC. The Warburg effect, lactate, and nearly a century of trying to cure cancer. Semin Nephrol. 2019;39(4):380–93. doi:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2019.04.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Shi M, Zhang M-J, Yu Y, Ou R, Wang Y, Li H, et al. Curcumin derivative NL01 induces ferroptosis in ovarian cancer cells via HCAR1/MCT1 signaling. Cell Signal. 2023;109(6):110791. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2023.110791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zhao Y, Li M, Yao X, Fei Y, Lin Z, Li Z, et al. HCAR1/MCT1 regulates tumor ferroptosis through the lactate-mediated AMPK-SCD1 activity and its therapeutic implications. Cell Rep. 2020;33(10):108487. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108487. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Xie Q, Zhu Z, He Y, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Wang Y, et al. A lactate-induced Snail/STAT3 pathway drives GPR81 expression in lung cancer cells. Biochim et Biophys Acta (BBA)—Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866:165576. [Google Scholar]

20. Saxena R, Bishnoi R, Singla D. Gene ontology: application and importance in functional annotation of the genomic data. In: Bioinformatics. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. p. 145–57. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-89775-4.00015-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Harmon C, Robinson MW, Hand F, Almuaili D, Mentor K, Houlihan DD, et al. Lactate-mediated acidification of tumor microenvironment induces apoptosis of liver-resident NK cells in colorectal liver metastasis. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7(2):335–46. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.Cir-18-0481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Roland CL, Arumugam T, Deng D, Liu SH, Philip B, Gomez S, et al. Cell surface lactate receptor GPR81 is crucial for cancer cell survival. Cancer Res. 2014;74(18):5301–10. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.Can-14-0319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Chen J, Huang Z, Chen Y, Tian H, Chai P, Shen Y, et al. Lactate and lactylation in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10(1):38. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-02082-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Ravaut G, Légiot A, Bergeron K-F, Mounier C. Monounsaturated fatty acids in obesity-related inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;22(1):330. doi:10.3390/ijms22010330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Yang Y, Zhu T, Wang X, Xiong F, Hu Z, Qiao X, et al. ACSL3 and ACSL4, distinct roles in ferroptosis and cancers. Cancers. 2022;14(23):5896. doi:10.3390/cancers14235896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Wang X, Tan X, Zhang J, Wu J, Shi H. The emerging roles of MAPK-AMPK in ferroptosis regulatory network. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21:200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

27. Lu L, Mullins CS, Schafmayer C, Zeißig S, Linnebacher M. A global assessment of recent trends in gastrointestinal cancer and lifestyle-associated risk factors. Cancer Commun. 2021;41(11):1137–51. doi:10.1002/cac2.12220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Liu W, Zhang F, Yang K, Yan Y. Comprehensive analysis regarding the prognostic significance of downregulated ferroptosis-related gene AKR1C2 in gastric cancer and its underlying roles in immune response. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0280989. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0280989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Yuan L, Yang Y, Li X, Zhou X, Du Y-H, Liu W-J, et al. 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid regulates mitochondrial ribosomal protein L35-associated apoptosis signaling pathways to inhibit proliferation of gastric carcinoma cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28(22):2437–456. doi:10.3748/wjg.v28.i22.2437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Geng D, Wu H. Abrogation of ARF6 in promoting erastin-induced ferroptosis and mitigating capecitabine resistance in gastric cancer cells. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;13(3):958–67. doi:10.21037/jgo-22-341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Zhu W, Liu D, Lu Y, Sun J, Zhu J, Xing Y, et al. PHKG2 regulates RSL3-induced ferroptosis in Helicobacter pylori related gastric cancer. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2023;740(8):109560. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2023.109560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Jin L, Guo Y, Chen J, Wen Z, Jiang Y, Qian J. Lactate receptor HCAR1 regulates cell growth, metastasis and maintenance of cancer-specific energy metabolism in breast cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2022;26(2):268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

33. Longhitano L, Vicario N, Tibullo D, Giallongo C, Broggi G, Caltabiano R, et al. Lactate induces the expressions of MCT1 and HCAR1 to promote tumor growth and progression in glioblastoma. Front Oncol. 2022;12:871798. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.871798. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Li S, Huang Y. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent cell death form linking metabolism, diseases, immune cell and targeted therapy. Clin Transl Oncol. 2022;24(1):1–12. doi:10.1007/s12094-021-02669-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Rochette L, Dogon G, Rigal E, Zeller M, Cottin Y, Vergely C. Lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism: two corner stones in the homeostasis control of ferroptosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24(1):449. doi:10.3390/ijms24010449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Endale HT, Tesfaye W, Mengstie TA. ROS induced lipid peroxidation and their role in ferroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1226044. doi:10.3389/fcell.2023.1226044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Mas-Bargues C, Escriva C, Dromant M, Borras C, Vina J. Lipid peroxidation as measured by chromatographic determination of malondialdehyde. Human plasma reference values in health and disease. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2021;709(18):108941. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2021.108941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Wei Y, Lv H, Shaikh AB, Han W, Hou H, Zhang Z, et al. Directly targeting glutathione peroxidase 4 may be more effective than disrupting glutathione on ferroptosis-based cancer therapy. Biochim et Biophys Acta (BBA)—Gen Subj. 2020;1864(4):129539. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2020.129539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Cui C, Yang F, Li Q. Post-translational modification of GPX4 is a promising target for treating ferroptosis-related diseases. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;9:901565. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2022.901565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Lim JK, Delaidelli A, Minaker SW, Zhang H-F, Colovic M, Yang H, et al. Cystine/glutamate antiporter xCT (SLC7A11) facilitates oncogenic RAS transformation by preserving intracellular redox balance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(19):9433–42. doi:10.1073/pnas.1821323116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Lee J, Roh J-L. SLC7A11 as a gateway of metabolic perturbation and ferroptosis vulnerability in cancer. Antioxidants. 2022;11(12):2444. doi:10.3390/antiox11122444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Rabinowitz JD, Enerbäck S. Lactate: the ugly duckling of energy metabolism. Nat Metab. 2020;2(7):566–71. doi:10.1038/s42255-020-0243-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Wang T, Ji R, Liu G, Ma B, Wang Z, Wang Q. Lactate induces aberration in the miR-30a-DBF4 axis to promote the development of gastric cancer and weakens the sensitivity to 5-Fu. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:1–12. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-577190/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Yang Z, Su W, Wei X, Qu S, Zhao D, Zhou J, et al. HIF-1α drives resistance to ferroptosis in solid tumors by promoting lactate production and activating SLC1A1. Cell Rep. 2023;42(8):112945. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Tu H, Tang L-J, Luo X-J, Ai K-L, Peng J. Insights into the novel function of system Xc-in regulated cell death. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25:1650–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

46. Li Y, Sun M, Cao F, Chen Y, Zhang L, Li H, et al. The ferroptosis inhibitor liproxstatin-1 ameliorates LPS-induced cognitive impairment in mice. Nutrients. 2022;14:4599. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1722038/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Wang L-M, Zhang W-W, Qiu Y-Y, Wang F. Ferroptosis regulating lipid peroxidation metabolism in the occurrence and development of gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2024;16(6):2781–92. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v16.i6.2781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Kuthiala G, Chaudhary G. Ropivacaine: a review of its pharmacology and clinical use. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55(2):104–10. doi:10.4103/0019-5049.79875. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Quan J, Bode AM, Luo X. ACSL family: the regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic implications in cancer. Eur J Pharmacol. 2021;909(Pt 2):174397. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Lee J-Y, Nam M, Son HY, Hyun K, Jang SY, Kim JW, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis pathway determines ferroptosis sensitivity in gastric cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(51):32433–42. doi:10.1073/pnas.2006828117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Weiss-Hersh K, Garcia AL, Marosvölgyi T, Szklenár M, Decsi T, Rühl R. Saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids in membranes are determined by the gene expression of their metabolizing enzymes SCD1 and ELOVL6 regulated by the intake of dietary fat. Eur J Nutr. 2020;59(6):2759–69. doi:10.1007/s00394-019-02121-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Ferré P, Phan F, Foufelle F. SREBP-1c and lipogenesis in the liver: an update. Biochem J. 2021;478(20):3723–39. doi:10.1042/bcj20210071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Fang C, Pan J, Qu N, Lei Y, Han J, Zhang J, et al. The AMPK pathway in fatty liver disease. Front Physiol. 2022;13:970292. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.970292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Szewczuk M, Boguszewska K, Kaźmierczak-Barańska J, Karwowski BT. The role of AMPK in metabolism and its influence on DNA damage repair. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47(11):9075–86. doi:10.1007/s11033-020-05900-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Sun Q, Yu X, Peng C, Liu N, Chen W, Xu H, et al. Activation of SREBP-1c alters lipogenesis and promotes tumor growth and metastasis in gastric cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;128(2):110274. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Zou J, Li C, Jiang S, Luo L, Yan X, Huang D, et al. AMPK inhibits Smad3-mediated autoinduction of TGF-β1 in gastric cancer cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25(6):2806–15. doi:10.1111/jcmm.16308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Liu Y’, Lu S, Wu L-L, Yang L, Yang L, Wang J. The diversified role of mitochondria in ferroptosis in cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(8):519. doi:10.1038/s41419-023-06045-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools