Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

ARPC1B Promotes Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Progression via the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway

1 Department of Urology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, Guangzhou, 510620, China

2 Department of Urology, Central People’s Hospital of Zhanjiang, Guangdong Medical University, Zhanjiang, 524000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yutong Li. Email: ; Yumin Zhuo. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Discover Biomarkers for Personalized Oncology)

Oncology Research 2025, 33(10), 3127-3154. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.067340

Received 30 April 2025; Accepted 15 August 2025; Issue published 26 September 2025

Abstract

Background: Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is an aggressive malignancy associated with limited treatment options and poor prognosis. Emerging studies suggest that the actin-regulating protein actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 1B (ARPC1B), a key regulatory protein within the actin cytoskeleton, could play a pivotal role in ccRCC progression. The current study aimed to uncover the biological functions of ARPC1B and the molecular mechanisms driving its effects in ccRCC. Methods: ARPC1B expression and prognostic implications were analyzed using data sourced from the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) platform, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining on 150 tumor samples along with 30 corresponding normal tissues, and Western blotting (WB) analyses across multiple ccRCC-derived cell lines. Functional assays assessing cell proliferation, colony formation capability, migration, invasion, and in vivo tumorigenicity were conducted following either ARPC1B suppression or upregulation. Additionally, WB analysis was utilized to evaluate proteins linked to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Results: The findings revealed a substantial elevation of ARPC1B in ccRCC tissues and cell lines, significantly associated with advanced TNM stages, higher Fuhrman grades, and reduced overall survival (OS) (p < 0.001). Multivariate statistical analysis identified ARPC1B as a standalone prognostic factor. Silencing ARPC1B notably impaired ccRCC cellular activities, and tumorigenesis in animal models, whereas augmented ARPC1B expression enhanced these malignant phenotypes. Mechanistically, downregulation of ARPC1B suppressed Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disrupted EMT, indicated by reduced β-catenin, c-Myc, cyclin D1, and ZEB-1 levels, and concurrently increased E-cadherin expression. Additionally, reactivation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway partly reversed the inhibitory effects of ARPC1B depletion on tumor growth and invasiveness. Conclusions: ARPC1B emerges as an essential oncogenic factor in ccRCC by stimulating EMT and activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, ultimately enhancing tumor aggressiveness and metastatic potential. Thus, targeting ARPC1B represents a promising therapeutic strategy, warranting further exploration in ccRCC management.Keywords

RCC is among the most prevalent and aggressive cancers involving the urinary system [1–3]. ccRCC constitutes about 80% of RCC diagnoses [4–7]. At initial diagnosis, nearly 30% of ccRCC patients already present with distant metastases [8,9], leading to a dismal 5-year survival rate of approximately 28% [10,11]. Surgical removal remains the most effective therapeutic approach for localized RCC, achieving survival outcomes as high as 97.4% for patients treated with partial nephrectomy at an early stage [12–14]. Thus, early diagnosis is essential for preventing metastasis and associated complications. However, ccRCC typically presents asymptomatically during early stages, and effective biomarkers for early detection remain unavailable. Although previous studies have identified various molecular markers, including DNA methylation [15–17], microRNAs [18–20], and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) [21–23], their clinical application remains challenging due to the complexity of the molecular regulatory networks involved. Consequently, identifying reliable predictive biomarkers and clarifying their biological roles are critical steps toward early diagnosis and personalized treatment.

ARPC1B is an integral component of the ARP2/3 complex [24], characterized by structural similarities at its amino-terminal and carboxy-terminal ends [24]. ARPC1B significantly modulates actin cytoskeleton rearrangements and engages extensively with numerous proteins [25,26]. ARPC1B plays significant roles in various cellular processes, particularly in regulating cytoskeletal remodeling, cell motility, and invasion [27]. Additionally, ARPC1B participates in cell division processes and modulates multiple signaling pathways [26,28]. Elevated ARPC1B expression has been reported in various cancers, correlating with increased malignancy, invasiveness, and poorer clinical outcomes in prostate cancer [29], ovarian cancer [30,31], and glioblastoma [32,33]. However, its specific biological function and mechanism in ccRCC have not been thoroughly explored.

This study aims to investigate the clinical significance of ARPC1B expression in ccRCC and elucidate its functional contributions to tumor progression. We hypothesize that ARPC1B promotes ccRCC aggressiveness through activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Utilizing comprehensive in vitro and in vivo approaches, this research seeks to establish ARPC1B as both a prognostic biomarker and a potential therapeutic target for ccRCC management.

2.1 Database and Data Analysis

Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (accessed on 14 August 2025) provided the transcriptome datasets GSE53757 and GSE68418 that were utilized in this study. This data was preprocessed in R/Bioconductor with the limma package. Precision weighting was accomplished using the voom method, normalization was based on quantiles, and background correction was accomplished using the Robust Multiarray Average (RMA) method. To find differentially expressed genes (DEGs), an empirical Bayes method was employed, using stringent criteria like a |log2 fold-change (log2 FC)| > 1 and an adjusted p-value False Discovery Rate (FDR) < 0.05. We accomplished functional enrichment for Gene Ontology (GO) keywords and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways using the package clusterProfiler (v4.0.5; Guangchuang Yu Lab, Guangzhou, China). The clinical validation of ARPC1B expression was investigated using GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/) (accessed on 14 August 2025).

2.2 Tissue Specimens and IHC Analysis

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition TNM staging system was employed for all cases. This tissue microarray (TMA; XT15-050) includes 150 ccRCC tissues from patients who underwent radical nephrectomy with regional lymph node dissection and 30 matched neighboring non-tumor controls; it was acquired from Shanghai Outdo Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) (SOBC). Critically, all surgical specimens had confirmed pathological nodal status (pN0/pN1) with no pNX cases, enabling precise pathological TNM staging (pT/pN). In the years 2008–2010, the pathological validity of surgical specimens was determined. Approval No. SHYJS-C1510001 from the SOBC Ethics Committee meant that the research could go forward in compliance with the 1975, revised 2000 Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. For in-house histological detection of ARPC1B, Proteintech of Wuhan, China, utilized rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Cat# 13835-1-AP; dilution 1:2000). Sections were preheated at 60°C for 1 h before being rehydrated with graded ethanol (100%, 90%, and 70%, 5 min each concentration). The next step was deparaffinization twice in pure xylene, with a 15-min interval between each cycle. The sections were subjected to 3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min to eliminate any intrinsic peroxidase activity. Once that was done, they were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.01 M, pH 7.4; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA, Cat# P3813) that included 0.5% Tween 20. For 5 min at room temperature, DAKO/Agilent’s (Glostrup, Denmark) Cat# S2023, which is for protein blocking without serum, was used. To observe the results of the immunoreactivity test, antibodies were diluted with DAKO antibody diluent and then placed into the EnVision Plus Anti-Rabbit Labeled Polymer Kit (DAKO/Agilent, Cat# S0809). To ascertain the outcomes of the immunostaining procedure, the staining intensity and percentage of cells that tested positive were quantified. For no staining at all, a score of 0, moderate staining at 2, strong staining at 3, and a value of 4, indicating that more than 25% of cells stained positively, were all possible. To get the overall IHC score (ranging from 0 to 12), we multiplied the staining intensity by the percentage. With a score of 6 or more, ARPC1B expression was considered high, while with a score of 6 or lower, it was considered low. Three highly experienced uropathologists evaluated the materials separately, without any background in clinical practice.

2.3 Plasmids and Short Hairpin RNA (shRNA)

Lentiviral constructs for ARPC1B overexpression and gene silencing were obtained commercially (GeneChem Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). To achieve overexpression (OE-ARPC1B), the complete human ARPC1B open reading frame (ORF, NM_005720.4) was cloned into a GV492 lentiviral vector (GeneChem, Cat# GV492). For ARPC1B silencing, three different shRNA sequences targeting ARPC1B were inserted into GV493 lentiviral vectors (GeneChem, Cat# GV493). These constructs included shRNA1 (#118761: 5′-GCTGACCTTCATCACAGACAA-3′), shRNA2 (#118762: 5′-GCTGGGTACATGGCGTCTGTT-3′), and shRNA3 (#118763: 5′-CCCAACGAGAACAAGTTTGCT-3′). A scrambled control shRNA (con#1: 5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′) was also synthesized. For knockdown experiments, GV493 vectors expressing scrambled shRNA sequences were transduced as negative controls (-NC), while empty GV492 vectors lacking ARPC1B cDNA sequences served as control vectors (-Vec) in overexpression experiments.

The human ccRCC cell lines 786-O (ATCC CRL-1932; short tandem repeat (STR)-authenticated Dec/2022; Mycoplasma-free) and Caki-1 (ATCC HTB-46; STR-authenticated Nov/2022; Mycoplasma-free) were procured from Pricella Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Additionally, ccRCC cell line A-498 (ATCC HTB-44; STR-authenticated Jan/2023; Mycoplasma-free), papillary renal carcinoma cell line Caki-2 (ATCC HTB-47; STR-authenticated Jan/2023; Mycoplasma-free), and normal renal tubular epithelial cell line HK-2 (ATCC CRL-2190; STR-authenticated Aug/2022; Mycoplasma-free) were generously provided by Professor Jian Wang (Guangdong Medical University, Zhanjiang, China). Standard conditions at 37°C and 5% CO2 were used for cell culture in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA, C11875500BT) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin solution (PS; Solarbio Technology, Beijing, China, P1400). Utilizing lentiviral-mediated gene delivery, stable ARPC1B overexpression and knockdown cell lines were established. These cell lines were engineered utilizing GV492 vectors encoding ARPC1B or GV493 vectors expressing particular shRNAs. The cells were treated with polybrene (8 μg/mL; Sigma, MO, USA, Cat# TR-1003-G) throughout the lentiviral infection. After that, they were cultured in RPMI-1640 media with 2 μg/mL puromycin (Thermo Fisher, MA, USA, Cat# A1113803) for 72 h.

2.5 Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

Isolating total RNA from different isogenic cell groups (786-O and Caki-1 parental, ARPC1B-overexpressing, ARPC1B-knockdown, and corresponding vector/scrambled control cells) was done using the TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 15596026). The ToloScript All-in-one RT kit (Tolobio, Shanghai, China, Cat# 22107)’s instructions were followed for the synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA). The 2× SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA, Cat# A46109) was used to conduct the real-time PCR. The ARPC1B amplification primers were 5′-CAAGGACCGCACCCAGATT-3′ and 5′-TGCCGCAGGTCACAATACG-3′. The internal control β-actin primers were 5′-TGGAACGGTGAAGGTGACAG-3′ and 5′-TTAGAGAGAAGTGGGGTGGC-3′. Using threshold cycle (Ct) values, the relative quantification of ARPC1B mRNA expression was computed using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo, Tokyo, Japan, Cat# CK04) was used to evaluate the cells’ performance. So that rescue studies could be carried out, cells that did not have ARPC1B were treated for 24 h before plating with 30 μM of Wnt/β-catenin agonist 3 (Proteintech, Wuhan, China, Cat# CM20349). Proliferation was then assessed at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after cell seeding at 5,000 cells/well in 96-well plates using 786-O and Caki-1 isogenic panels. Each well was incubated for an additional two hours at 37°C with 5% CO2 after ten microliters of CCK-8 solution were added at each time interval. The data was acquired from an optical density (OD) of 450 nm using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA).

After being seeded onto 6-well plates from the isogenic 786-O and Caki-1 panels in triplicate at around 500 cells per well, cells were cultured continuously for 12 days. The colonies were successfully stained with a 0.5% crystal violet solution and then fixed in 100% methanol. If a colony lacked at least 50 cells, it was not counted using the ImageJ software (v1.53; NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) program. The colony formation rate was calculated using the formula: (Number of colonies/500 seeded cells) × 100%.

During the whole experiment period, the ARPC1B-knockdown cells were consistently treated with 30 μM of Wnt/β-catenin agonist 3 to create relief circumstances. In 6-well plates, cells from the 786-O and Caki-1 groups were grown for 24 h after being seeded at 1 × 105 cells/well in order to assess migratory capacity. We then used a sterile 1 mL pipette tip to make a linear scratch in the cell monolayer. After that, we gently washed the cells to remove any detached cells. A Nikon Eclipse Ts2 inverted fluorescent microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan) was used to take photographs of the wound closure at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. At each specified time point, the migrated area was quantified using the ImageJ program.

The rescue tests involved supplementing both chambers of the transwell device with 30 μM of Wnt/β-catenin agonist 3. The migration assays were conducted by adding 5 × 104 cells from the 786-O and Caki-1 isogenic groups to the upper chamber of a 24-well transwell insert (manufactured by Jet Biotherapy, Guangzhou, China) with an 8.0 μm pore. The cells were then suspended in 200 μL of serum-free RPMI-1640 culture. The 500 μL lower chambers were supplemented with 10% FBS. In order to investigate invasion, matrix gel (MCE, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA, Cat# HY-K0301) was utilized before 5 × 104 cells were seeded into the upper chambers. The cells that managed to pass the membrane throughout the 16-h incubation period were carefully preserved in 100% methanol and stained with 0.5 percent crystal violet. Five randomly chosen microscopic fields per chamber were captured at a 200× magnification, and then the number of cells that moved or invaded was automatically tallied using ImageJ software.

The proteins from ccRCC tissues or cells from the isogenic 786-O and Caki-1 panels were extracted using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Solarbio, Beijing, China, Cat# R0020) that contained protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, Basel, Switzerland, Cat# 04693159001). Protein levels were quantified using the BCA assay (Cat# 23225; Pierce, Waltham, MA, USA). Electrophoretic conditions of 80 V for 30 min and 120 V for 45 min were used to separate samples with 30 μg of protein per lane. The samples were denatured in 4× Laemmli loading buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA, Cat# 1610747). For complete protein transfer, intact gels containing pre-stained molecular weight markers (10–250 kDa) were electrophoretically transferred to PVDF membranes (0.45 μm; Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA, Cat# IPVH00010) using a wet transfer system at constant 200 mA current. Transfer durations were optimized according to protein molecular weight: high-molecular-weight proteins (e.g., ZEB-1 at 210 kDa) required extended transfer times of 120 min to ensure efficient membrane immobilization, while standard-duration transfers of 45 min were employed for mid-range molecular weights, including β-actin (42 kDa) and ARPC1B (41 kDa). The blocking process was carried out for 1 h using 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 (TBST, pH 7.6). Following an overnight primary antibody incubation period at 4°C, the membranes were subjected to three five-minute washes with TBST. After that, primary antibodies (1:10,000; goat anti-rabbit/mouse; Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat# ab6721/ab6789) that were conjugated with HRP were left to incubate at 4°C for 1.5 h. In order to identify protein signals, researchers utilized enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA, Cat# 1705060). Each experiment was repeated three times independently.

Antibodies utilized in this research included: β-actin (Cat# 66009-1-Ig; WB 1:10,000), ARPC1B (Cat# 13835-1-AP; WB 1:5,000, IHC 1:1000), c-Myc (Cat# 10828-1-AP; WB 1:5,000, IHC 1:2000), Cyclin D1 (Cat# 60186-1-Ig; WB 1:10,000, IHC 1:3000), GSK3β (Cat# 22104-1-AP; WB 1:5,000, IHC 1:400), Phospho-GSK3β (Ser9) (Cat# 14850-1-AP; WB 1:5,000, IHC 1:600), β-catenin (Cat# 51067-2-AP; WB 1:10,000, IHC 1:200), Vimentin (Cat# 60330-1-Ig; WB 1:10,000, IHC 1:3000), N-cadherin (Cat# 22018-1-AP; WB 1:6000, IHC 1:1000), E-cadherin (Cat# 20874-1-AP; WB 1:6000, IHC 1:100), ZEB1 (Cat# 21544-1-AP; WB 1:2000, IHC 1:100), and Ki-67 (Cat# 27309-1-AP; IHC 1:2000) can from Proteintech. The Wnt/β-catenin agonist 3 (Cat# CM20349, 30 µmol/mL) was obtained from Proteintech (Wuhan, China, Cat# CM20349).

Hunan Slaike Jingda Experimental Animal Co., Ltd. of Changsha, China, was the source of the 24 male BALB/c-nu mice. License No. SCXK 2021-0002 certifies that these 4-week-old, 18–22 g specimens are of SPF grade. The mice were acclimated to their new environment for one week before being employed in the research. No infections were present in this environment. Stratified randomization was used to divide the mice into four groups, with six mice in each, after they had acclimated. To inject subcutaneously into the axillary region, cells (5 × 106 cells per animal), particularly 786-O/shARPC1B#1 or Caki-1/shARPC1B#1, were mixed with 100 μL of PBS and Matrigel (Corning, Bedford, MA, USA, Cat# 356234; 1:1 ratio v/v). Tumor dimensions were measured every 48 h by two separate investigators who were blinded to the therapy groups, starting seven days after injection. (L × W2)/2 was used to determine the tumor volume. Ethical endpoints, such as tumor size > 1500 mm3 or body weight loss > 20%, or day 14 post-inoculation, were used to euthanize the animals. Isoflurane 5% (RWD Life Science, Shenzhen, China), administered in 100% oxygen and maintained at a dosage of 2.5% was used to induce anesthesia during the cervical dislocation procedure. Upon tumor collection, they were assessed for size, mass, and fixation in 4% neutral buffered formalin (Cat# HT50128) from Sigma-Aldrich in St. Louis, MO, USA for 24 h. After that, paraffin was used to embed them. Deparaffinization was performed on the 4 µm thick sections using xylene and graded ethanol. Prior to conducting the subsequent immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies, the samples were stained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, Cat# MHS16; 0.1% w/v) and eosin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, Cat# HT110116; 1% w/v) according to standard procedures [34]. Zhanjiang Central People’s Hospital’s Animal Research Committee gave their stamp of approval to all animal procedures (Approval No. DW-2024016-01, Zhanjiang, China) and ensured that they adhered completely to the 3R principles: replacement, reduction, and refinement.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA, version 27.0). Comparisons of categorical variables were conducted utilizing Fisher’s exact tests or chi-square tests, especially in instances where the expected frequency in any cell fell below five. Based on the distribution characteristics of continuous variables, we employed either Mann–Whitney U tests, Student’s t-tests, or Kruskal–Wallis tests. The analysis of cell proliferation under different conditions was conducted using two-way repeated-measures ANOVA. Survival outcomes were assessed through the creation of Kaplan–Meier survival tests. The application of Cox proportional hazards regression was utilized for both univariate and multivariate evaluations. The threshold for statistical significance was established at p < 0.05.

3.1 ARPC1B Overexpression in Tumor Tissues Correlates with Poor Prognosis of ccRCC

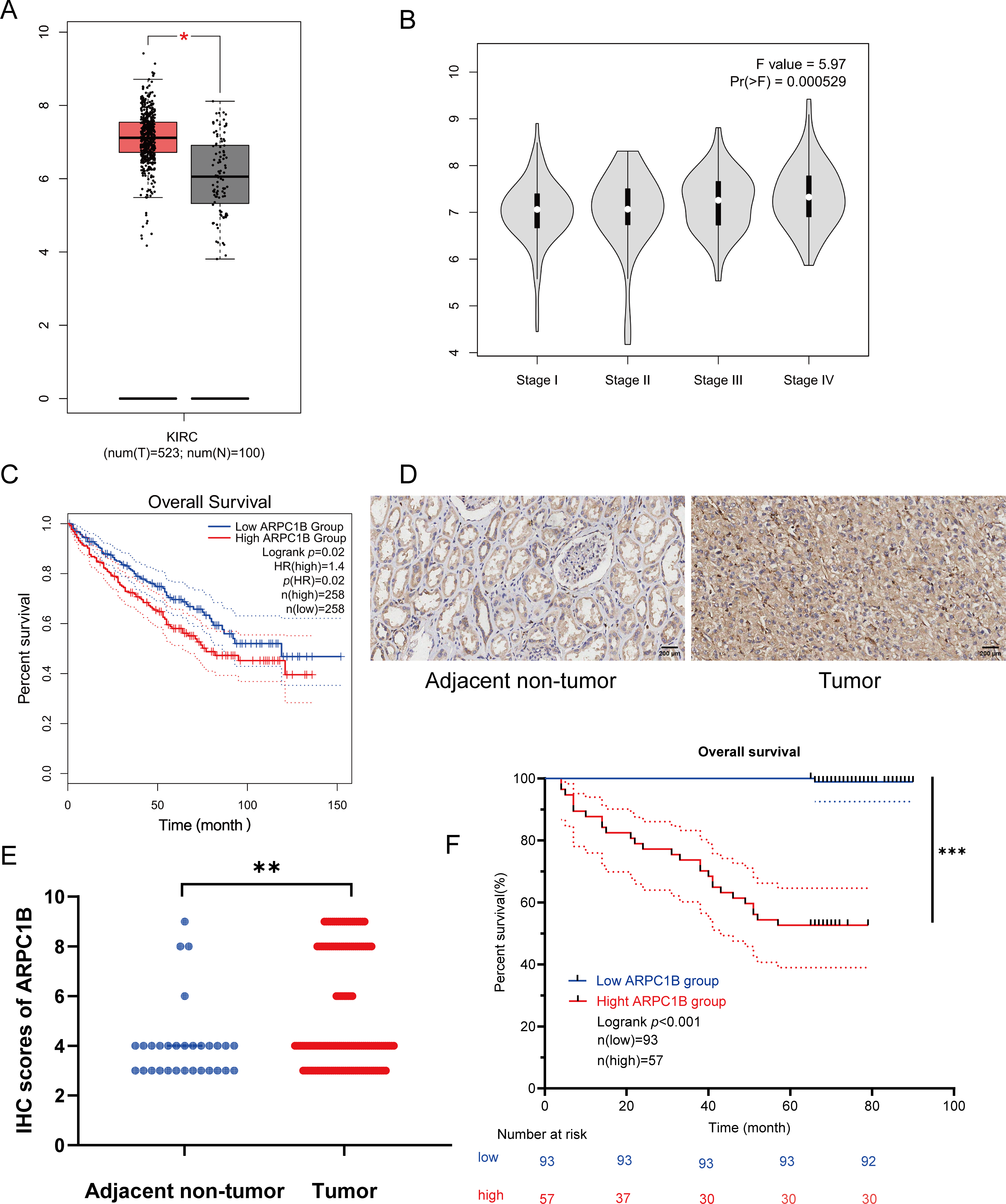

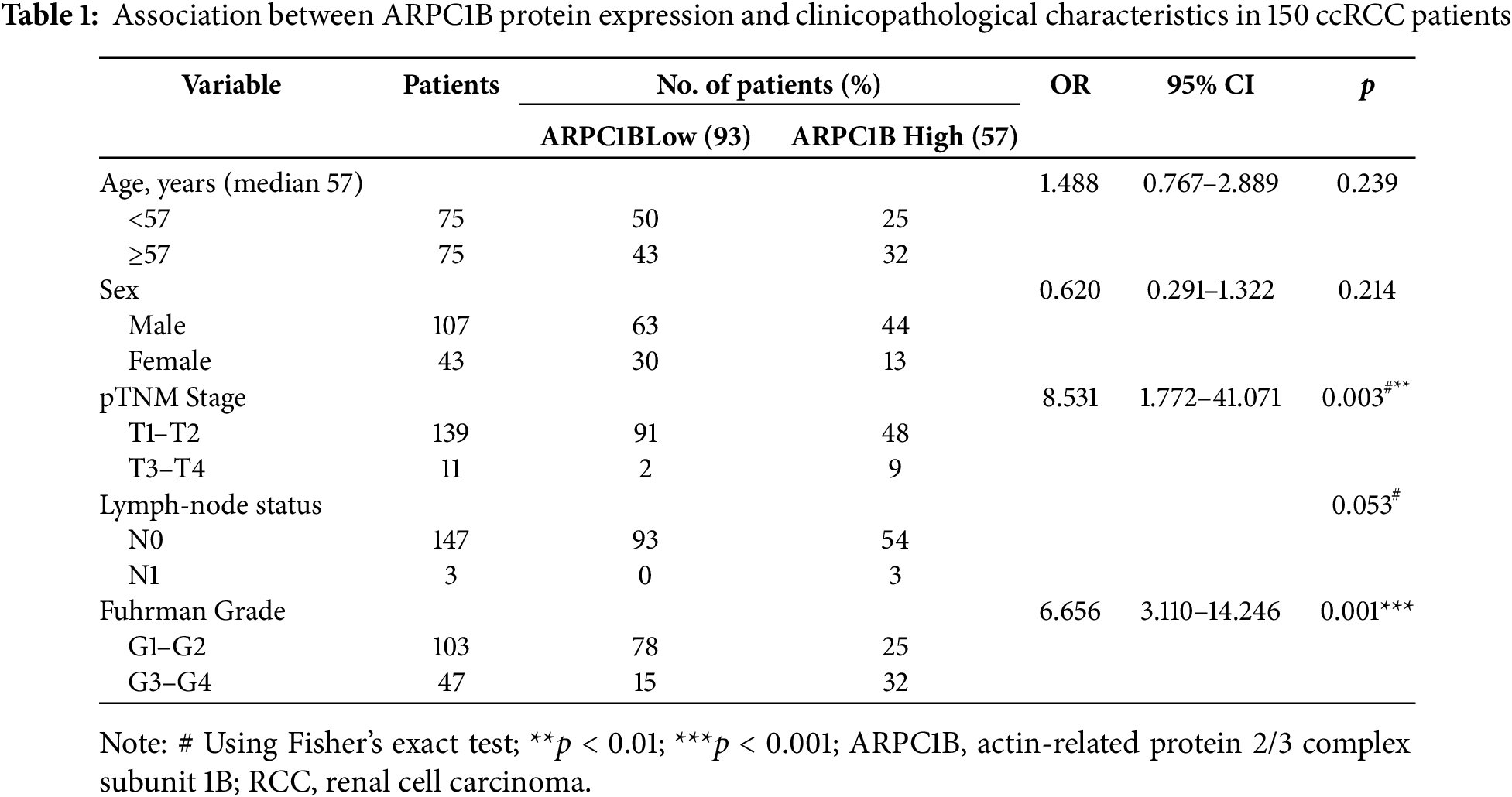

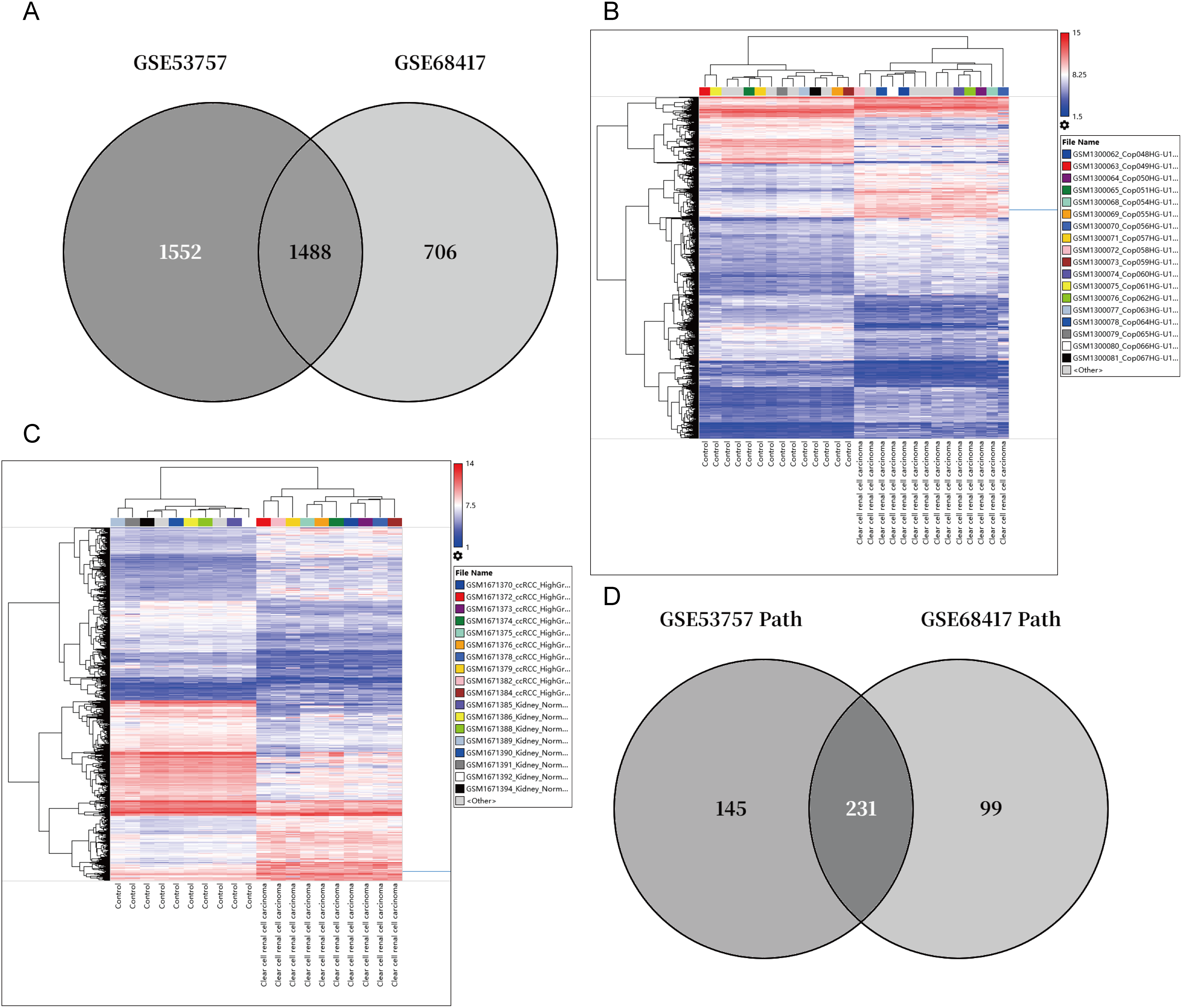

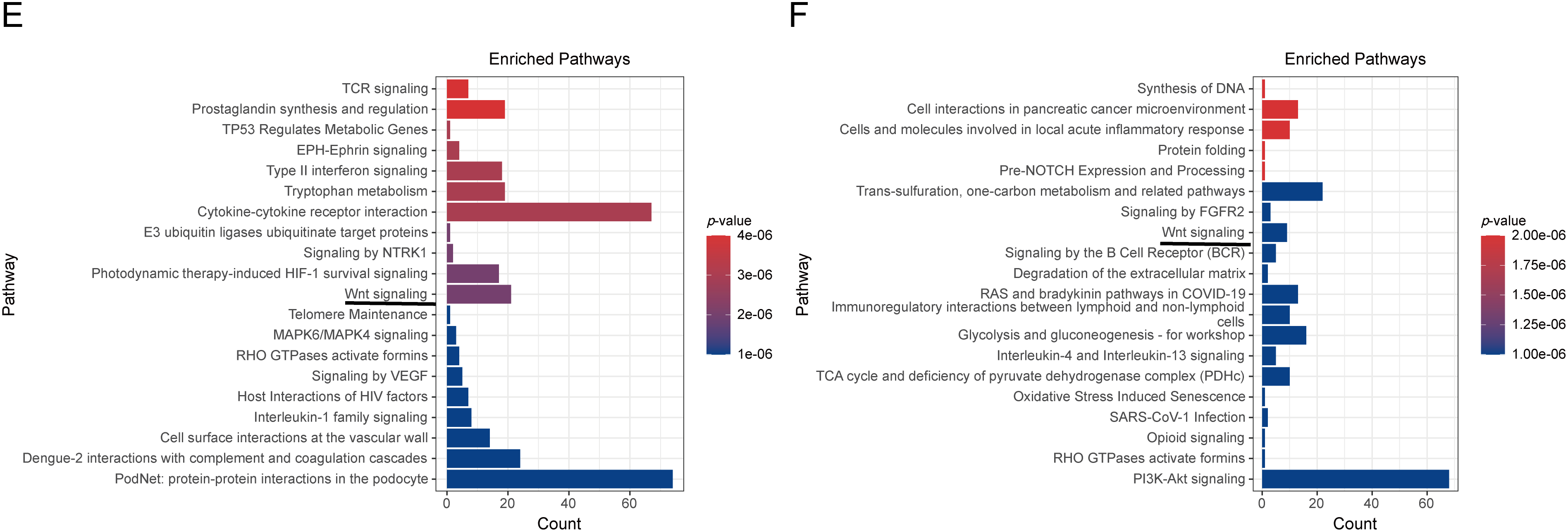

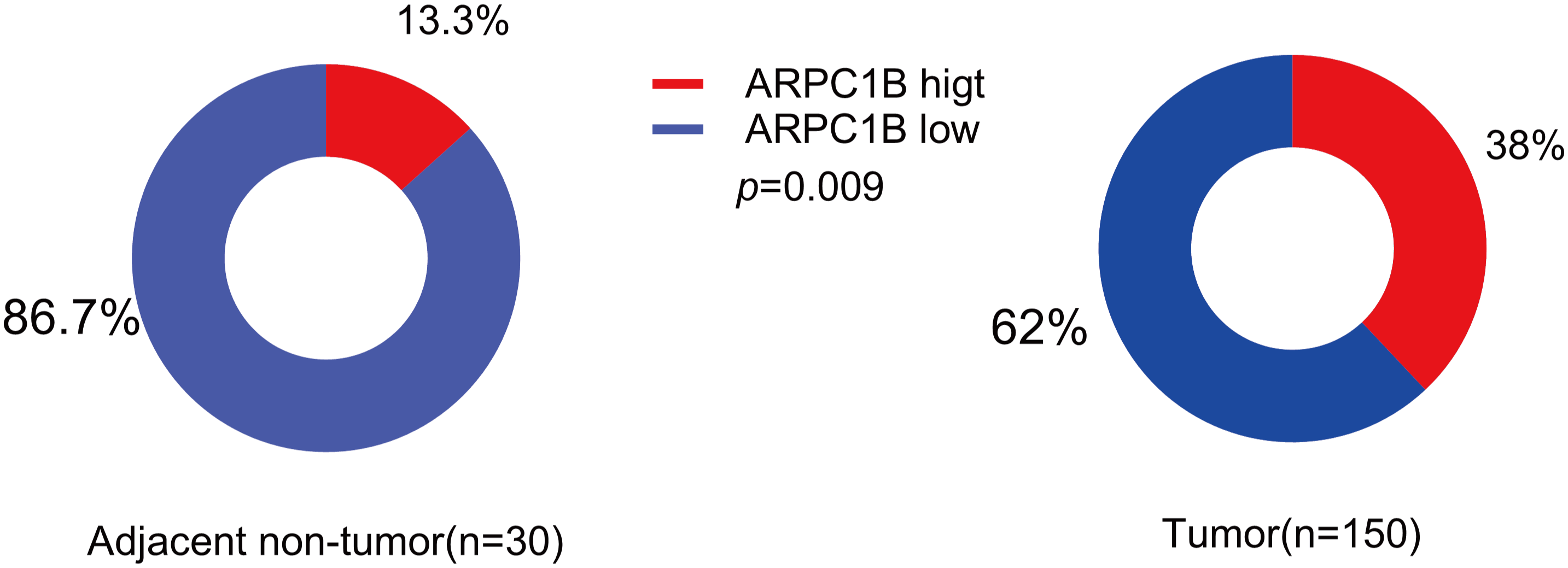

Transcriptomic analysis identified 1,488 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) common to both GEO datasets GSE53757 and GSE68417 (|log2FC| > 1, FDR < 0.05), including ARPC1B (Fig. A1A–C). Pathway enrichment via clusterProfiler revealed 231 conserved pathways (FDR < 0.05), with Wnt/β-catenin signaling demonstrating the most significant dysregulation (Fig. A1D–F). Complementing these findings, GEPIA analysis demonstrated significant overexpression of ARPC1B in ccRCC vs. normal kidney tissues (Fig. 1A). In addition, ARPC1B expression significantly increased with advancing clinical disease stage (p = 0.000529, Fig. 1B). Higher levels were related to worse OS (Fig. 1C). Expression of ARPC1B protein in 150 ccRCC specimens, including 30 matched non-cancerous samples, was analyzed by IHC staining. ARPC1B is predominantly localized to the cytoplasmic regions (Fig. 1D). Elevated ARPC1B was identified in 57 (38%) of the tumor samples, significantly higher compared to only 4 cases (13%) in matched non-tumorous tissues (OR = 0.2510; 95% CI: 0.09093–0.7292; p = 0.009; Fig. A2). Furthermore, quantitative scoring revealed notably increased ARPC1B protein levels within tumor tissues (mean ± SD: 5.3 ± 2.3) relative to the paired adjacent normal samples (4.1 ± 1.6; 95% CI: 0.3442–2.096; p < 0.01; Fig. 1E). ARPC1B expression exhibited significant relationships with clinical parameters, particularly tumor stage (T stage; p = 0.003) and Fuhrman grading (p < 0.001). However, no clear relationship was found between ARPC1B levels and patient demographics such as age, sex, or lymphatic metastasis (all p < 0.05), as illustrated in Table 1. Survival curves generated by Kaplan–Meier analysis indicated that patients expressing higher ARPC1B had notably worse OS (p < 0.001; Fig. 1F). Similarly, univariate Cox regression confirmed high ARPC1B as predictive of diminished survival (HR = 59.6; 95% CI: 8.1–439.1; p < 0.001; Table 2). Multivariate Cox regression further reinforced the independent prognostic significance of elevated ARPC1B (HR = 44.0; 95% CI: 5.8–334.5; p < 0.001; Table 2). Taken together, these observations robustly support the notion that ARPC1B elevation characterizes ccRCC and is associated with unfavorable clinical prognosis.

Figure 1: Enhanced ARPC1B expression in ccRCC tissues predicts poor patient prognosis. (A) ARPC1B expression across ccRCC samples from GEPIA (Y-axis: log2 [TPM + 1], TPM: transcripts per million). (B) ARPC1B expression stratified by tumor stage from GEPIA (Y-axis: log2 [TPM + 1]). (C) OS analysis based on median ARPC1B expression level; HR: hazard ratio. (D) Representative IHC images showing ARPC1B expression in ccRCC vs. normal adjacent tissues. (E) Quantitative comparison of IHC scores between ccRCC and non-tumor tissues. (F) Kaplan–Meier curves stratified by ARPC1B expression. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

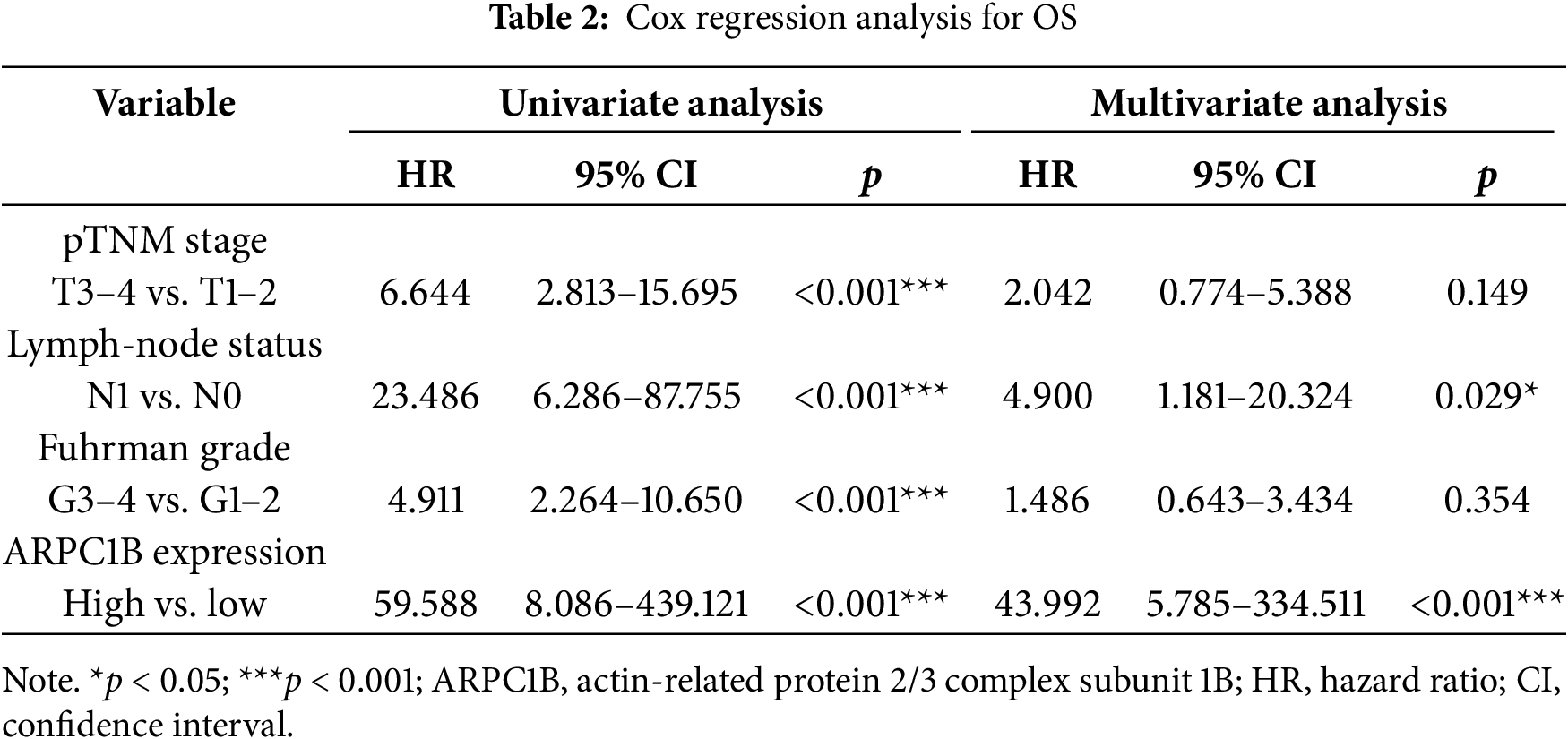

3.2 Establishment of Stable Cell Lines and RT-qPCR Validation

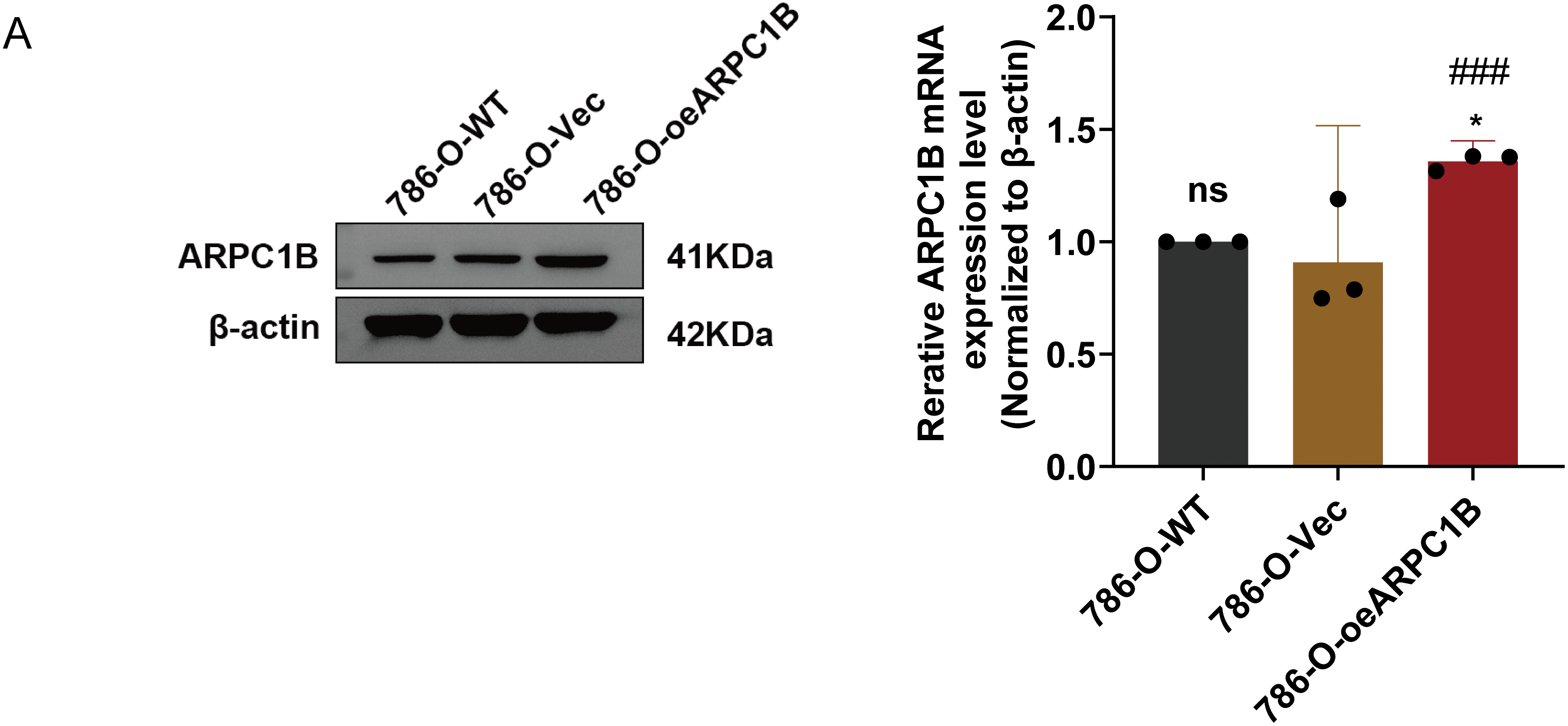

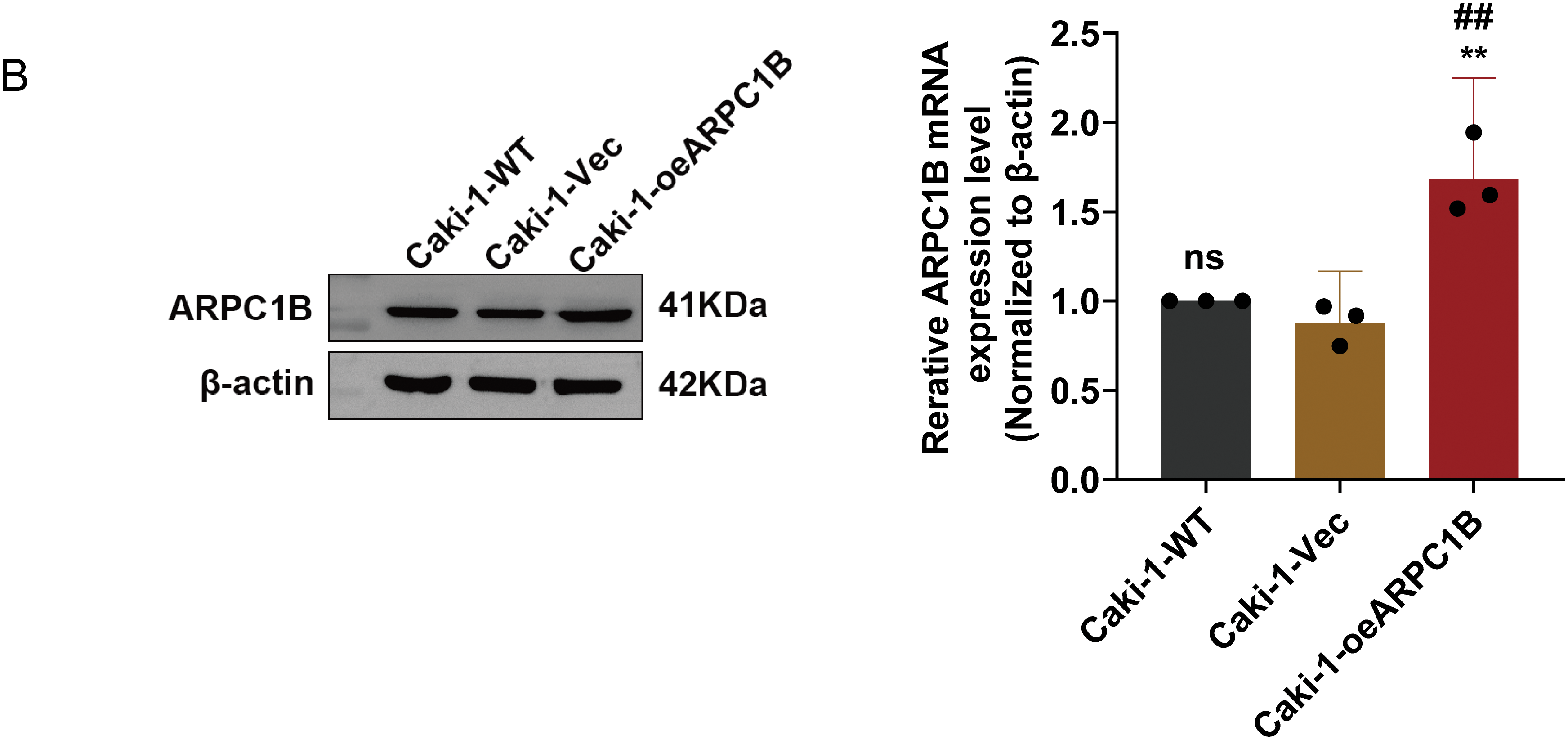

There was a notable increase in the expression of the ARPC1B protein in all ccRCC-derived cell lines (786-O, A-498, and Caki-1) and papillary renal carcinoma cell line Caki-2 (p < 0.05; Fig. 2A). Among these, the cell lines 786-O and Caki-1 exhibited the most elevated levels of ARPC1B, leading to their selection for subsequent functional studies. Subsequently, stable cell lines with ARPC1B overexpression and knockdown were created from these ccRCC cell models. Successful ARPC1B knockdown was confirmed by RT-qPCR and WB, showing significant reduction of ARPC1B protein in knockdown groups compared with both negative control (NC) and wild-type (WT) cells (p < 0.001; Fig. 2B for 786-O; Fig. 2C for Caki-1). Conversely, ARPC1B overexpression was validated by increased ARPC1B levels relative to the corresponding WT and empty vector (Vec) controls (p < 0.05 for both cell lines; Fig. A3A,B). Quantitative analysis showed that ARPC1B protein abundance in overexpressed cells was approximately twofold greater than endogenous levels. Collectively, these results confirm the generation of robust ARPC1B-knockdown and -overexpression cell models, reinforcing the elevated expression of ARPC1B in ccRCC and its potential oncogenic role.

Figure 2: Validation of ARPC1B protein and mRNA levels in RCC cell lines. (A) WB analysis of ARPC1B expression in normal renal tubular epithelial HK-2 cells vs. RCC-derived cells. All samples were analyzed simultaneously under consistent conditions, and were normalized to β-actin. (B,C) Quantification of ARPC1B protein and mRNA in ARPC1B-knockdown cells (786-O and Caki-1) compared with WT and negative controls (-NC; GV493-scrambled). Compared to the sh-NC group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, p >0.05; Compared to the WT group; #p < 0.05, ###p < 0.001

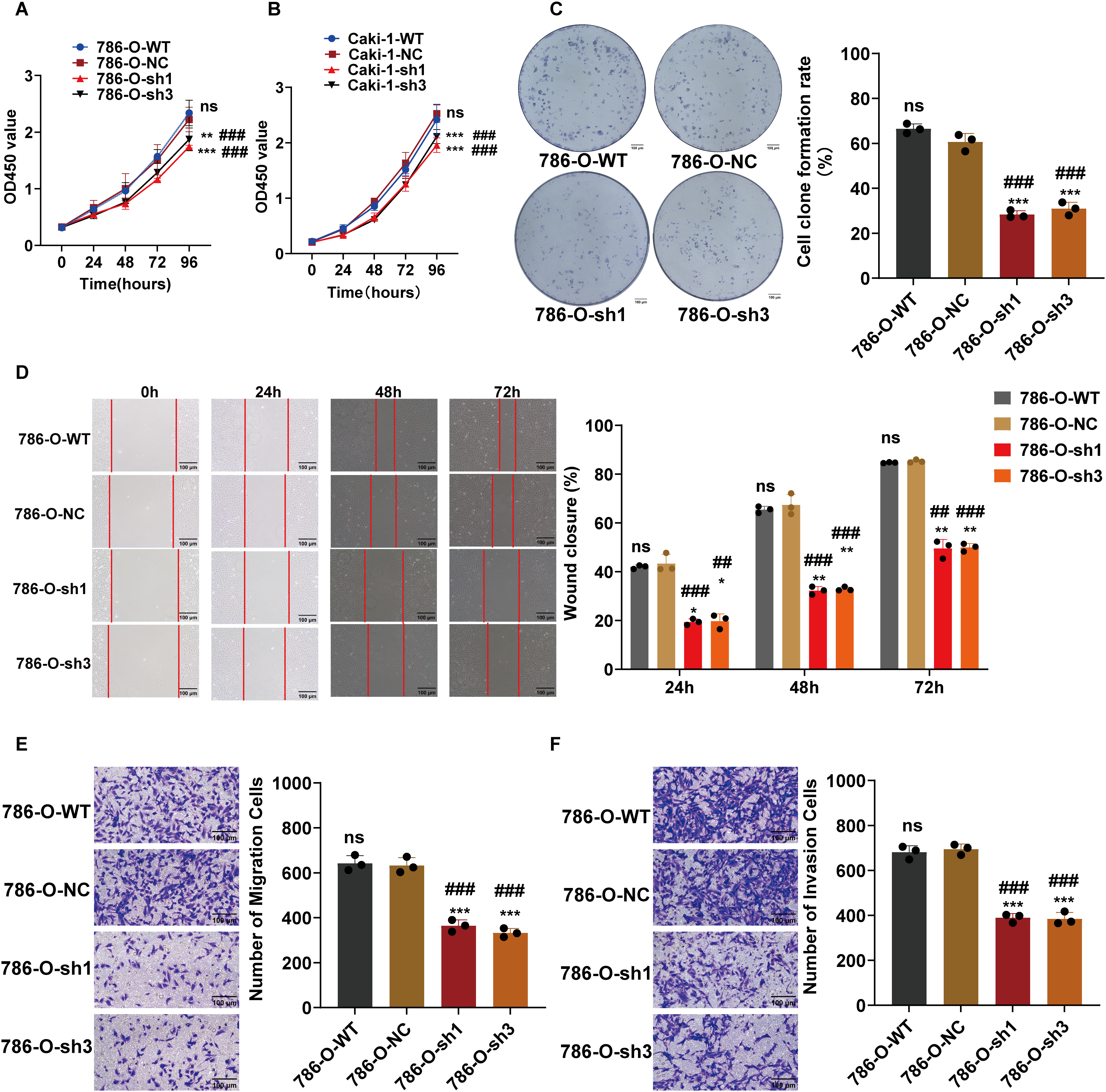

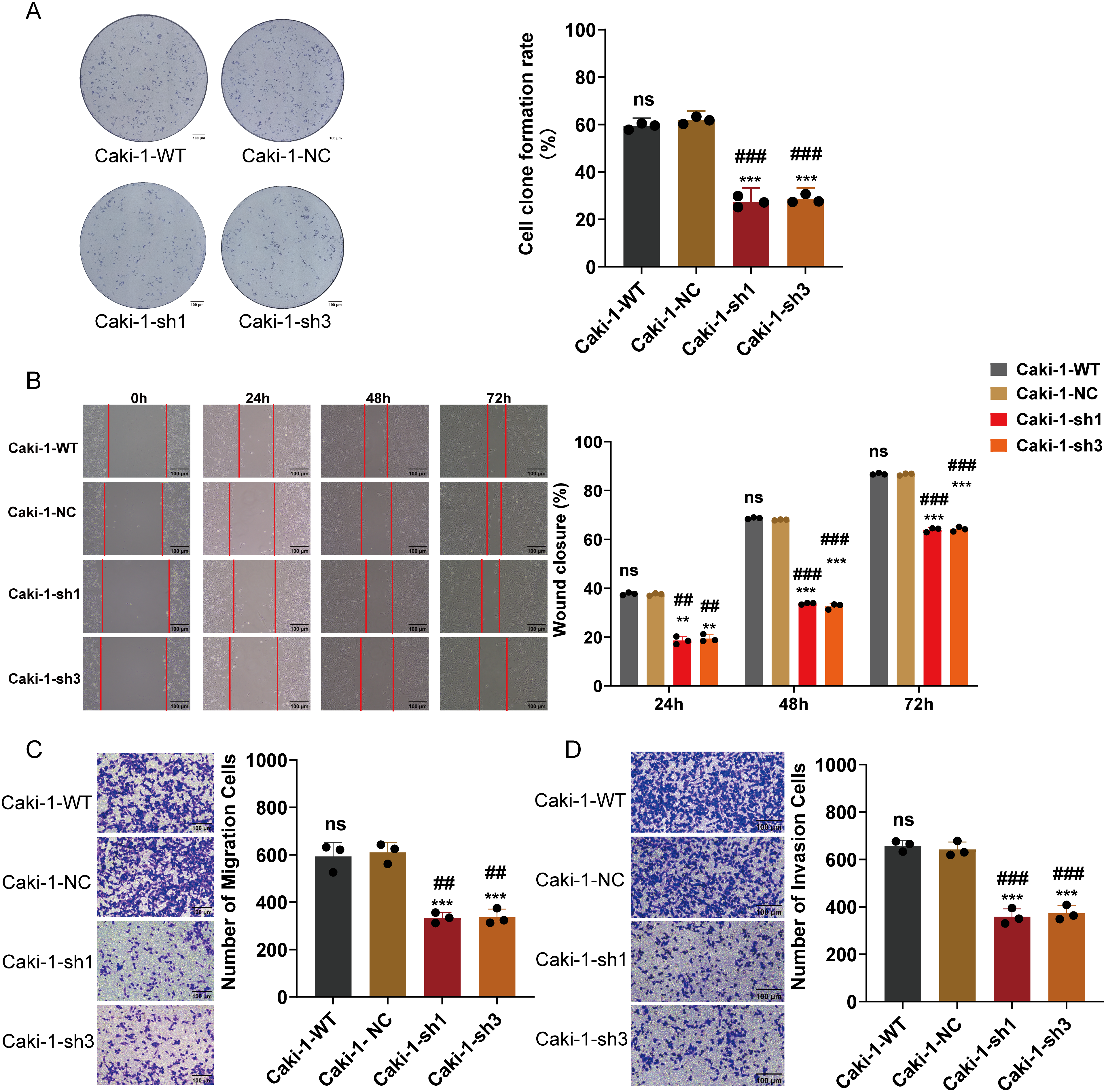

3.3 ARPC1B Knockdown Inhibits ccRCC Cellular Functions In Vitro

To elucidate the biological impact of reduced ARPC1B expression, various cellular functional assays were conducted, focusing on ccRCC cellular behaviors. Cell proliferation assays using the CCK-8 method revealed a significant suppression of growth rate in ARPC1B-silenced 786-O and Caki-1 cells (p < 0.001; Fig. 3A,B), confirming ARPC1B’s supportive role in cellular proliferation. Colony formation assays further illustrated significantly impaired clonogenic capacity in cells lacking ARPC1B expression relative to controls (p < 0.001; Figs. 3C, A4A), underscoring ARPC1B’s relevance to cellular survival and colony-forming abilities. Additionally, wound-healing assays demonstrated significantly reduced migratory abilities in ARPC1B-depleted cells over 72 h in comparison with WT and NC groups (p < 0.05; Figs. 3D, A4B). Correspondingly, Transwell-based migration and invasion assays showed notably diminished invasive and migratory capacities in ARPC1B-knockdown groups compared to controls (p < 0.001; Figs. 3E,F, A4C,D). Collectively, these results substantiate that ARPC1B depletion prominently diminishes proliferation, clonogenicity, migratory potential, and invasiveness in ccRCC cell lines.

Figure 3: Functional effects of ARPC1B silencing on ccRCC cells. (A,B) CCK-8 showing decreased growth rates in ARPC1B-knockdown 786-O and Caki-1 cells. (C) Reduced clonogenic potential of 786-O cells after ARPC1B knockdown. (D) Inhibition of migration observed in 786-O cells upon ARPC1B silencing (WHA). (E,F) Reduced migration and invasion capabilities demonstrated by Transwell assays following ARPC1B knockdown. Compared to the sh-NC group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, p >0.05. Compared to the WT group; ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001

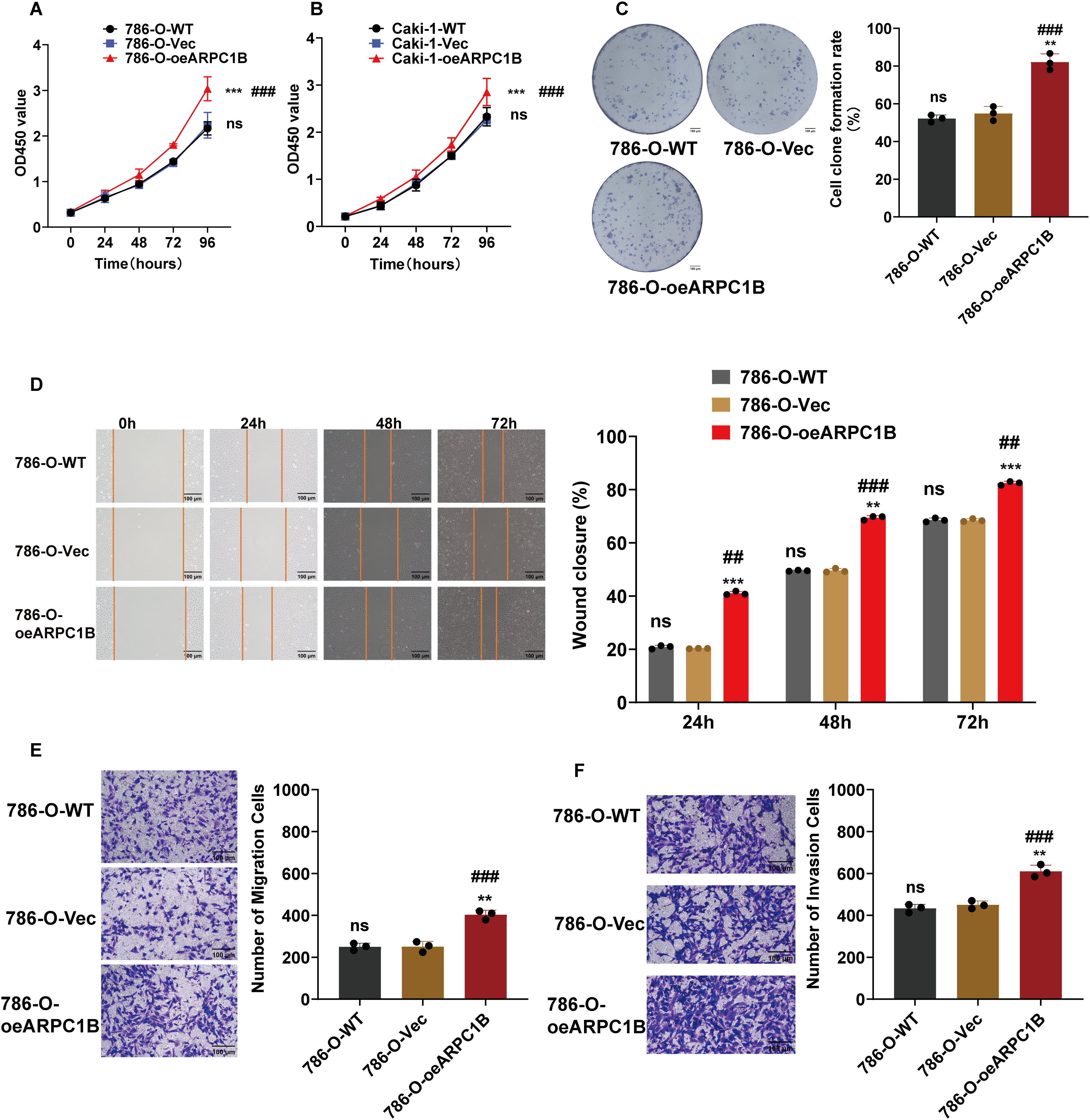

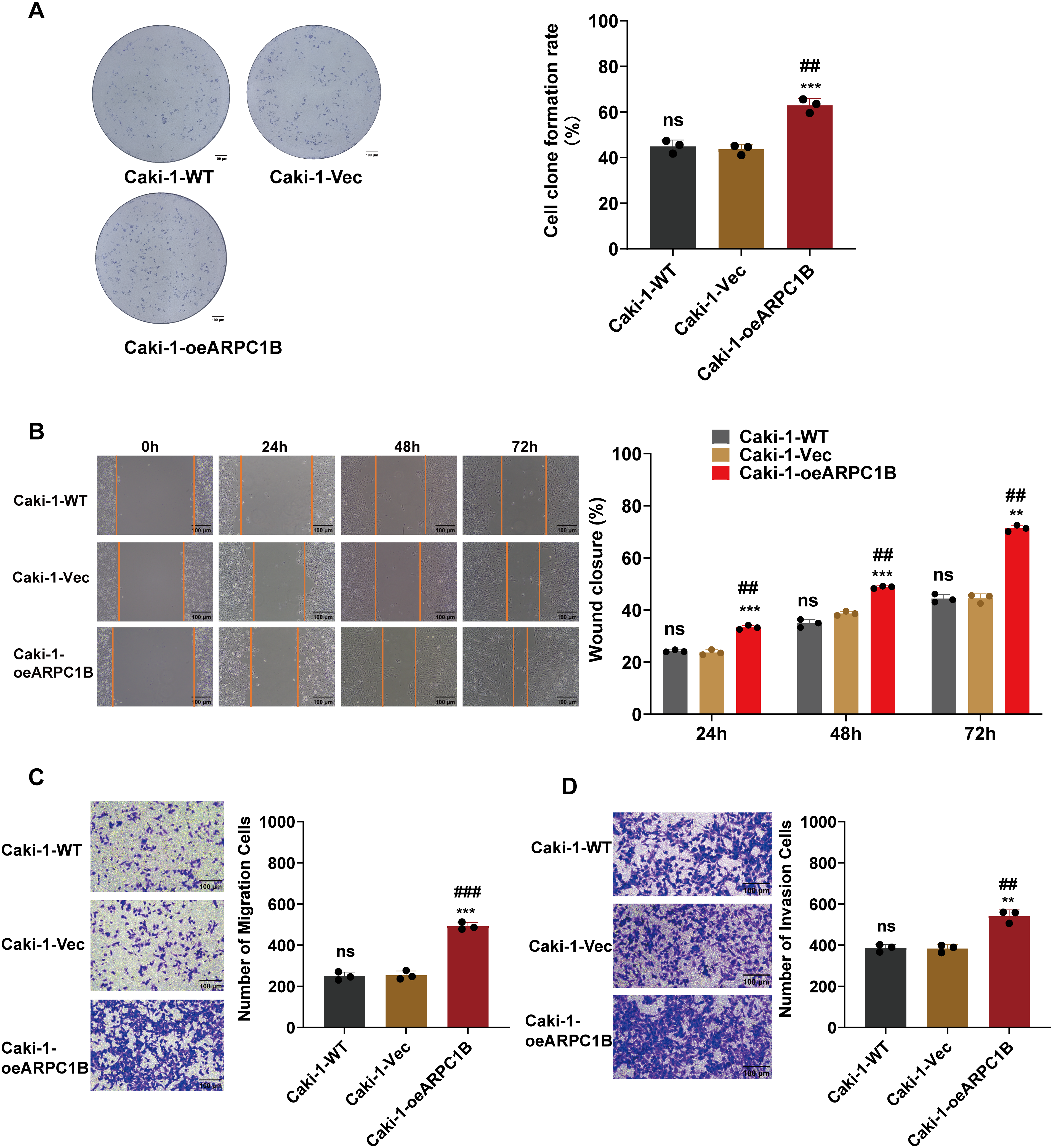

3.4 ARPC1B Overexpression Promotes Proliferation, Colony Formation, Migration, and Invasion of ccRCC Cells In Vitro

To further confirm ARPC1B’s oncogenic activity, functional assays were conducted on 786-O and Caki-1 cells stably overexpressing ARPC1B. CCK-8 proliferation assays showed significantly increased proliferation rates in ARPC1B-overexpressing cells compared to WT and empty vector control groups (p < 0.001; Fig. 4A,B). Colony formation assays similarly revealed an elevated number and size of colonies in ARPC1B-overexpressing cells vs. control cells (p < 0.01; Figs. 4C, A5A), reflecting the enhanced long-term growth potential conferred by ARPC1B. WHAs indicated significantly accelerated wound closure rates in ARPC1B-overexpressing 786-O and Caki-1 cells relative to controls (p < 0.01; Figs. 4D, A5B). Moreover, Transwell assays demonstrated that ARPC1B-overexpressing cells displayed significantly enhanced migration and invasion activities compared with WT and vector controls (p < 0.001; Figs. 4E,F, A5C,D), further validating ARPC1B’s role in promoting ccRCC metastatic properties. Collectively, these results underscore that ARPC1B upregulation enhances proliferation, colony formation, migration, and invasion capacities of ccRCC cells.

Figure 4: Effect of ARPC1B overexpression on ccRCC cell behavior. (A,B) Increased cell proliferation rates in ARPC1B-overexpressing 786-O and Caki-1 cells measured by CCK-8 assays. (C) Enhanced colony formation ability of 786-O cells following ARPC1B overexpression. (D) Accelerated migration observed in ARPC1B-overexpressing cells by WHA. (E,F) Transwell assays demonstrating increased migration and invasion capabilities in ARPC1B-overexpressing 786-O cells. Control group: Vec (GV492-empty). Compared to the Vec group; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, p >0.05. Compared to the WT group; ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001

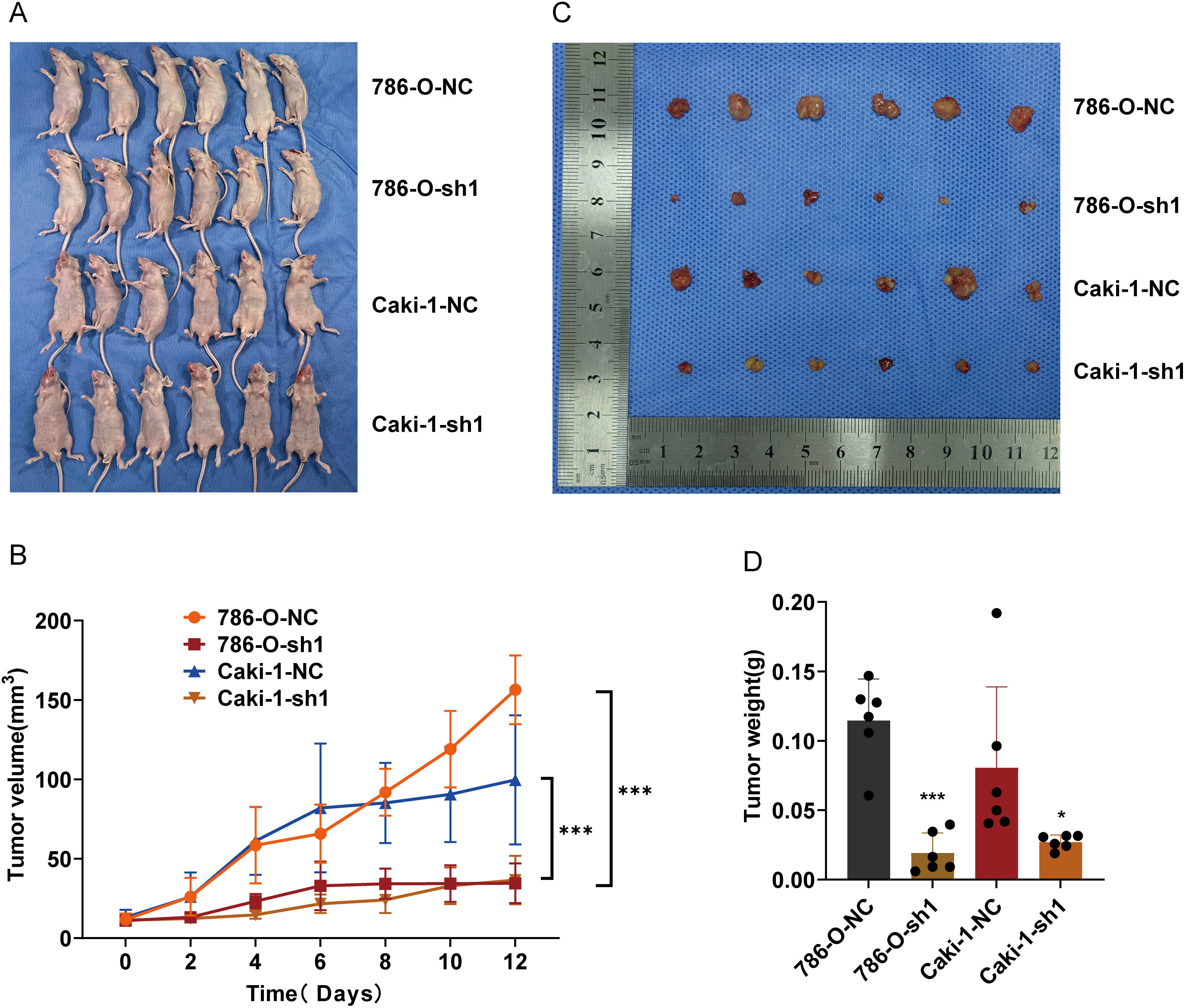

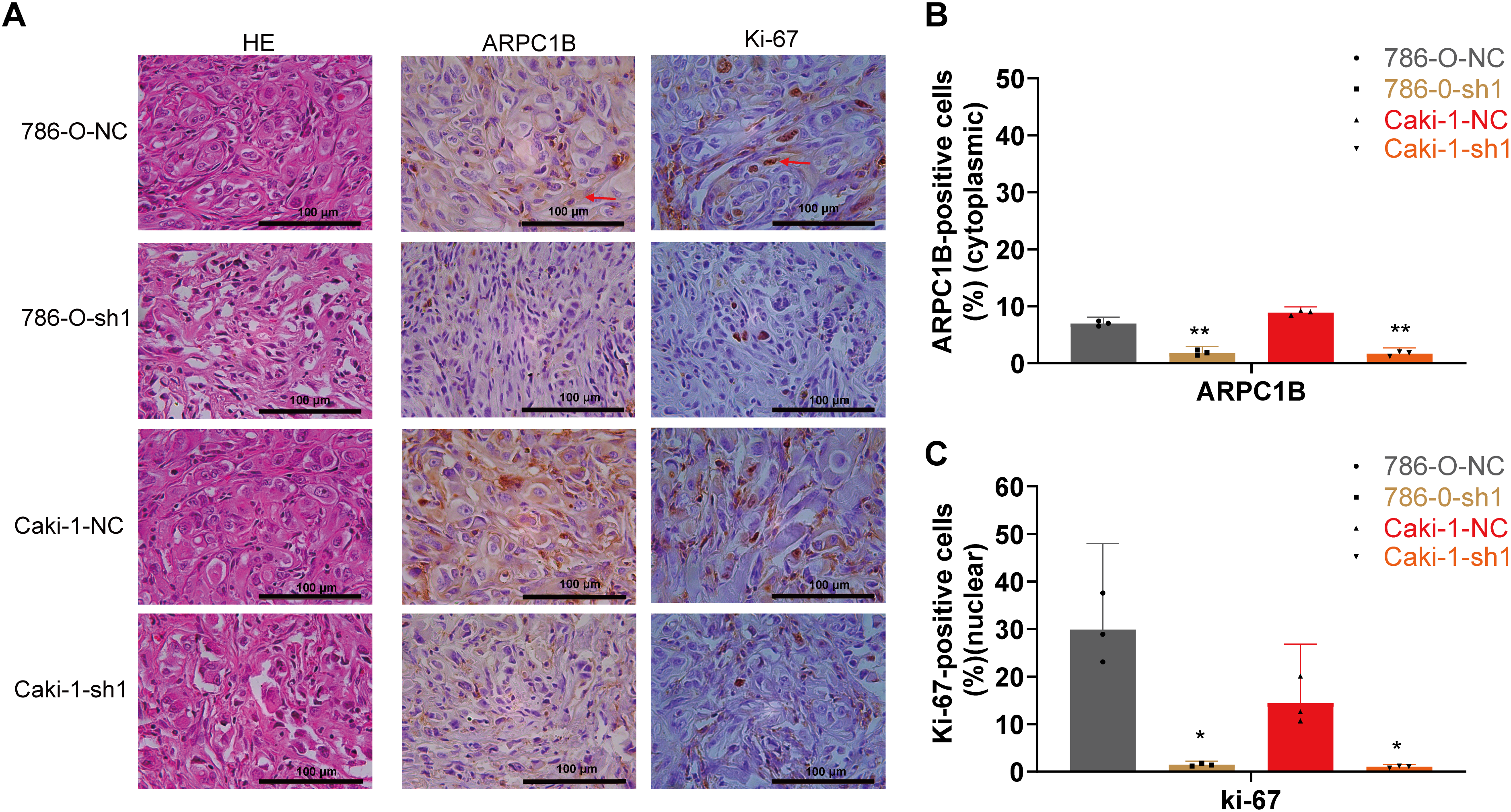

3.5 ARPC1B Knockdown Inhibits Tumor Growth In Vivo

To assess ARPC1B’s functional role in vivo, tumor xenografts were established in nude mice via subcutaneous injection of ARPC1B-knockdown or NC cells (786-O and Caki-1). Tumor volume monitoring over 12 days revealed significantly suppressed tumor growth in ARPC1B-knockdown groups (p < 0.001, Fig. 5A,B). Representative images confirmed smaller tumor sizes upon ARPC1B silencing (Fig. 5C). At the conclusion of experiments, tumor weights were significantly lower in ARPC1B-knockdown groups relative to NC groups (p < 0.001 for 786-O; p < 0.05 for Caki-1; Fig. 5D). Histological evaluation using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining indicated lower cellular density and less aggressive tumor morphology in ARPC1B-knockdown xenografts (Fig. A6). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) further demonstrated reduced ARPC1B expression and diminished Ki-67 staining in ARPC1B-silenced tumors, indicating decreased tumor cell proliferation (Fig. A6). Taken together, these findings strongly support that ARPC1B knockdown significantly reduces tumor growth, tumor mass, and proliferation in vivo, highlighting its critical contribution to ccRCC progression.

Figure 5: Influence of ARPC1B knockdown on ccRCC tumor growth in vivo. (A) Representative images of nude mice bearing xenografts. (B) Images of excised ccRCC xenografts. (C) Tumor volume curves over time. (D) Comparison of tumor weights. Compared to the sh-NC group; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001

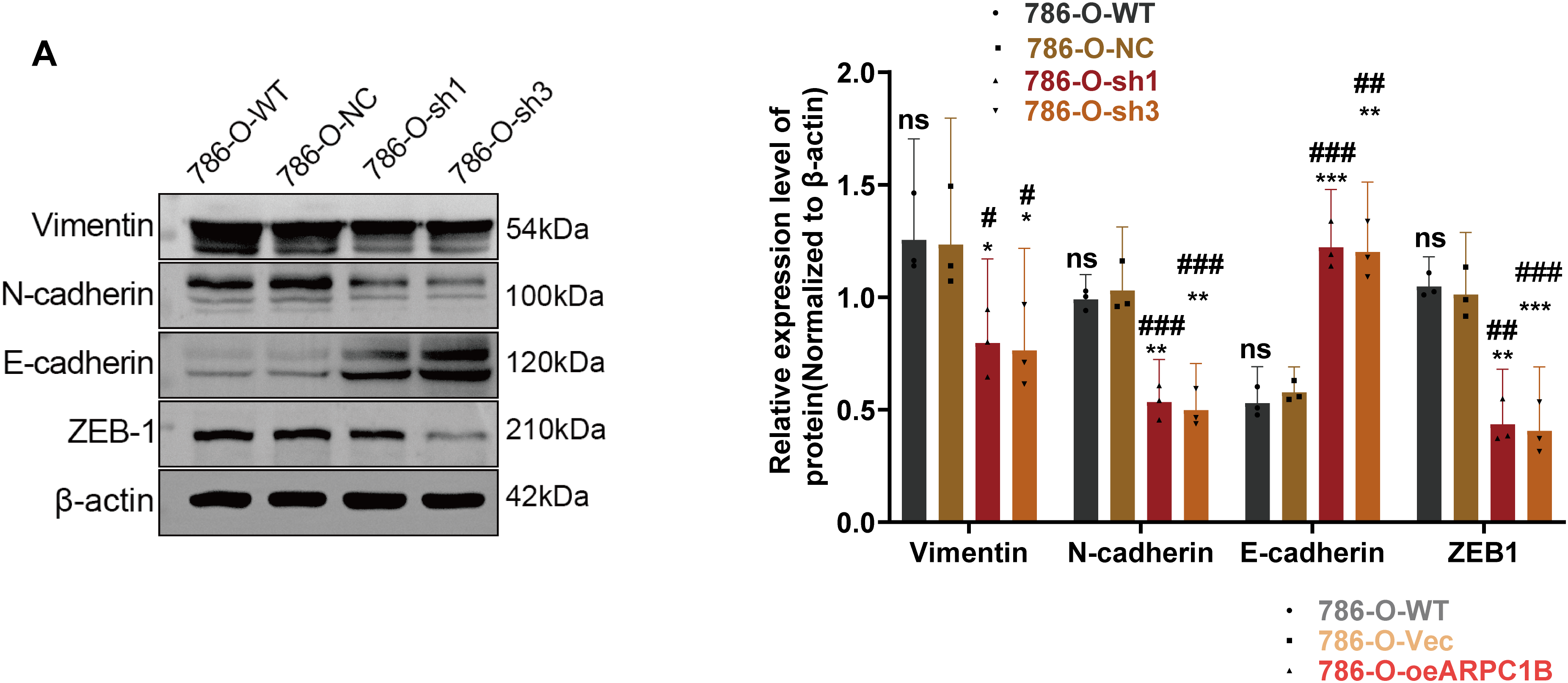

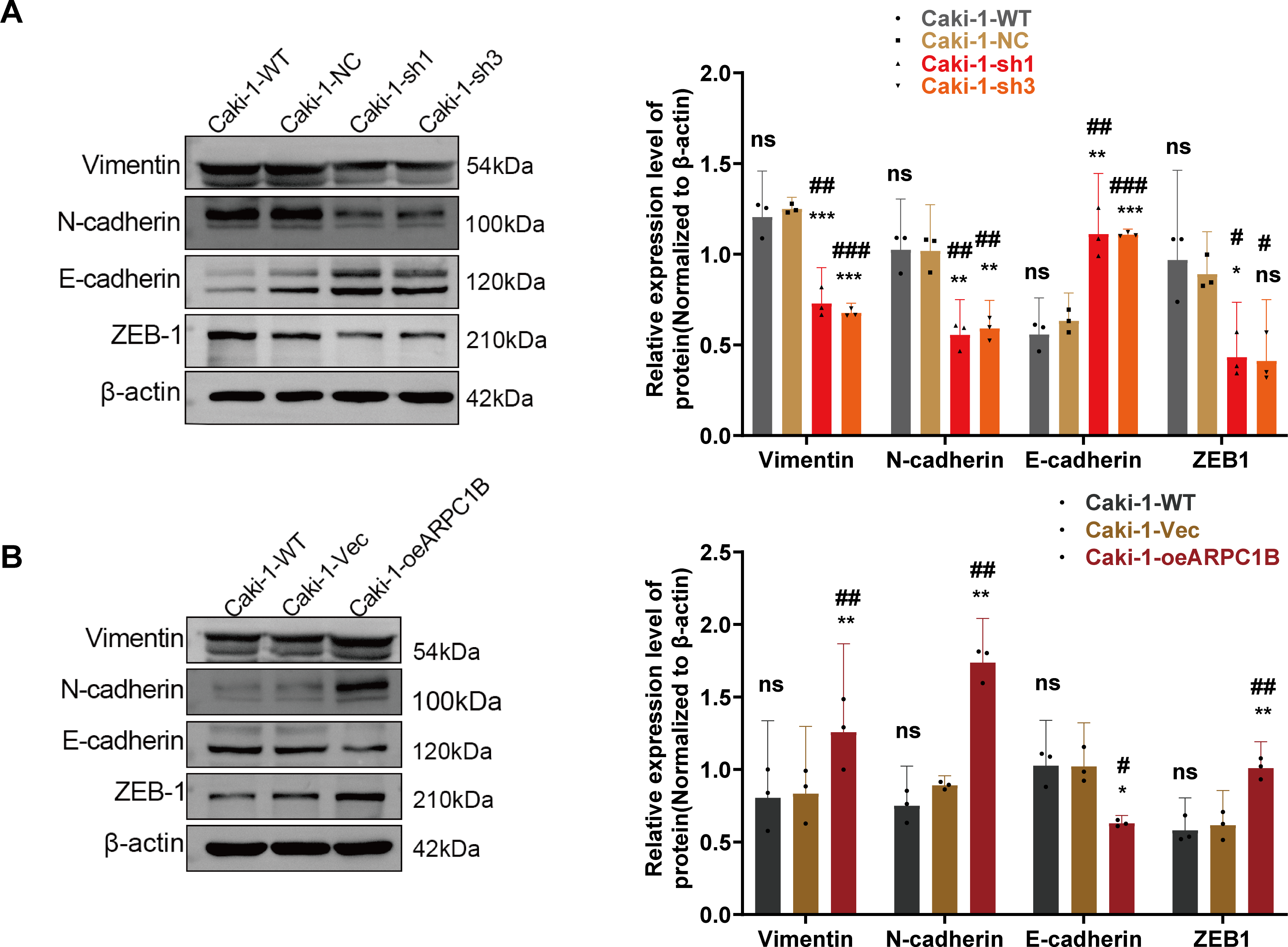

3.6 ARPC1B Promotes ccRCC Progression via EMT In Vitro and In Vivo

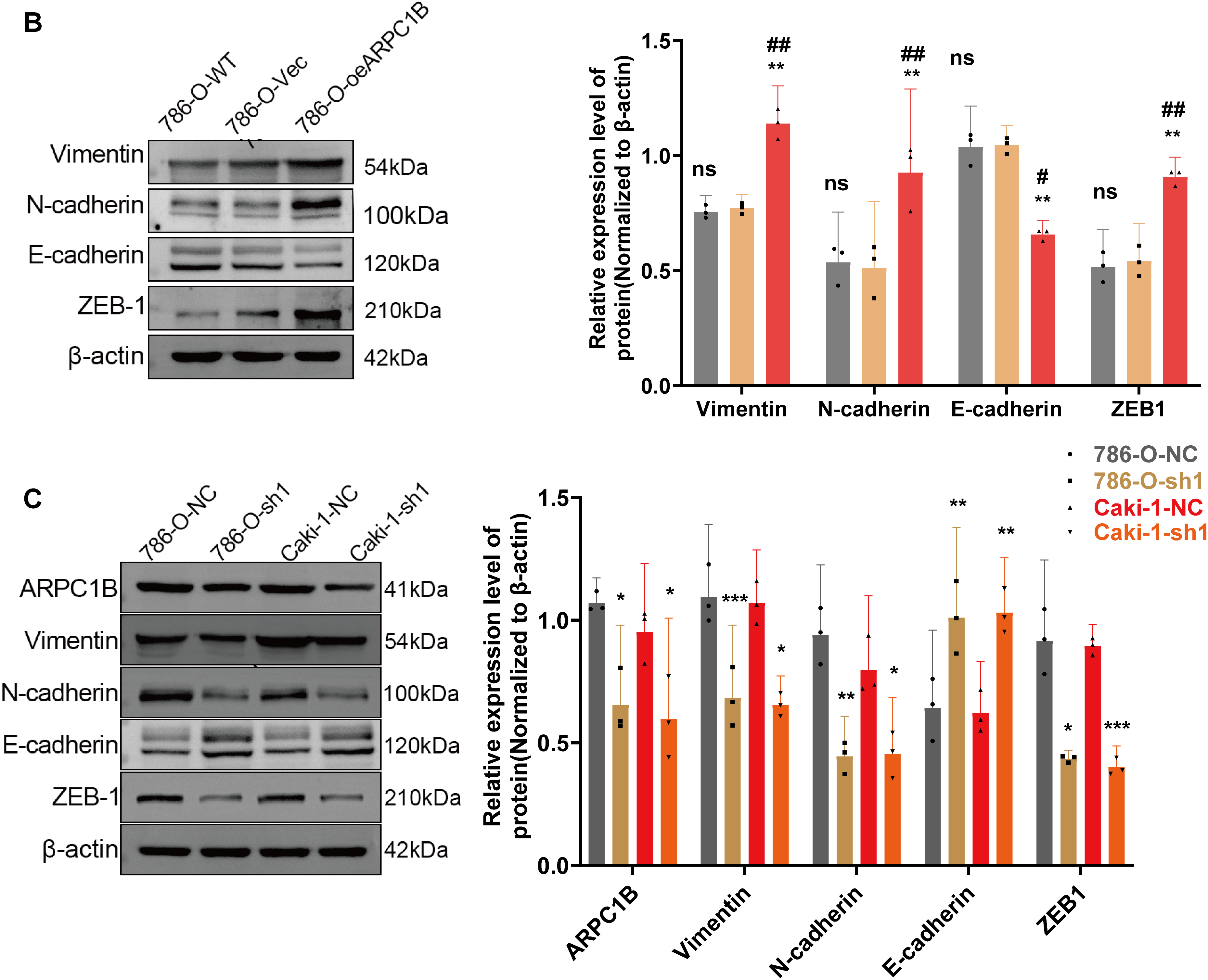

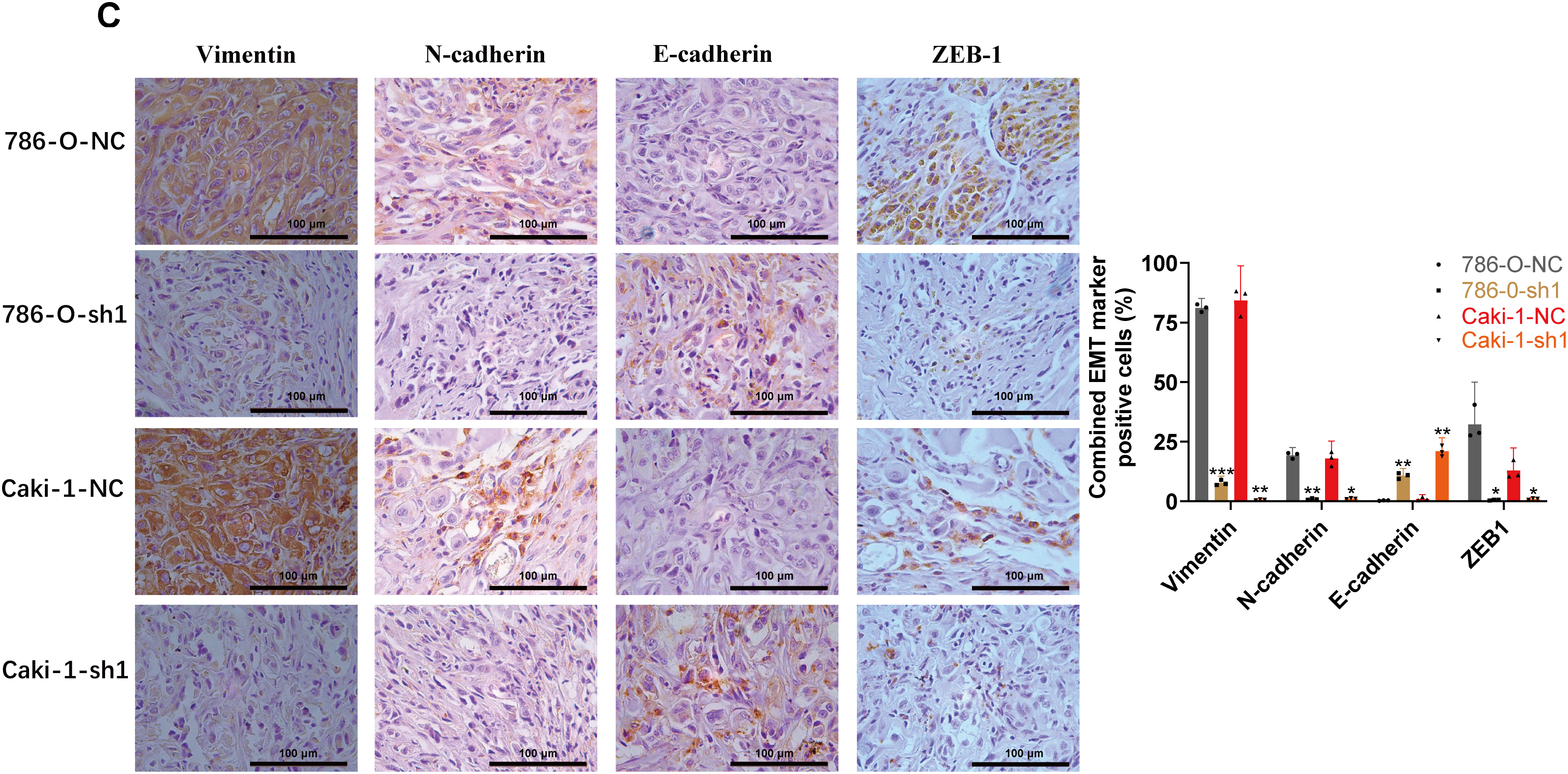

EMT is essential for facilitating tumor cell invasion and metastasis [35–37]. To determine whether ARPC1B affects ccRCC invasiveness by modulating EMT processes, EMT-related markers were analyzed via WB. In 786-O and Caki-1 cells, suppression of ARPC1B significantly diminished mesenchymal marker proteins, including Vimentin, N-cadherin, and ZEB-1, while concurrently increasing the epithelial marker E-cadherin (p < 0.05; Figs. 6A, A7A). These data suggest that loss of ARPC1B expression inhibits EMT. Conversely, cells with enhanced ARPC1B expression showed marked increases in the levels of Vimentin, N-cadherin, and ZEB-1 proteins, alongside a decline in E-cadherin expression (p < 0.05; Figs. 6B, A7B), indicating that ARPC1B overexpression promotes EMT, thereby facilitating cell invasion. To substantiate these findings in vivo, xenograft tumors established from 786-O and Caki-1 cells with ARPC1B knockdown were examined. WB assays demonstrated decreased expression of mesenchymal proteins coupled with elevated E-cadherin levels in ARPC1B-deficient tumors compared with negative control (NC) tumors (Fig. 6C). IHC analysis corroborated these findings, with reduced staining intensity for mesenchymal markers (Vimentin, N-cadherin, ZEB-1) and increased intensity for E-cadherin observed in ARPC1B-knockdown tumor tissues (Fig. A7C). Collectively, these observations imply that ARPC1B enhances ccRCC migration and invasion through EMT induction.

Figure 6: Relationship between ARPC1B expression and EMT markers in vitro and in vivo. (A) WB analysis of EMT markers (Vimentin, N-cadherin, ZEB-1, and E-cadherin) in ARPC1B-silenced 786-O cells. (B) Protein expression of EMT markers in 786-O cells with ARPC1B overexpression. (C) WB assessment of EMT marker expression in xenograft tumors from ARPC1B-knockdown groups. All samples were analyzed simultaneously under consistent conditions, and were normalized to β-actin. Compared to the sh-NC group, Vec group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, p > 0.05. Compared to the WT group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001

3.7 ARPC1B Promotes ccRCC Progression via Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling In Vitro and In Vivo

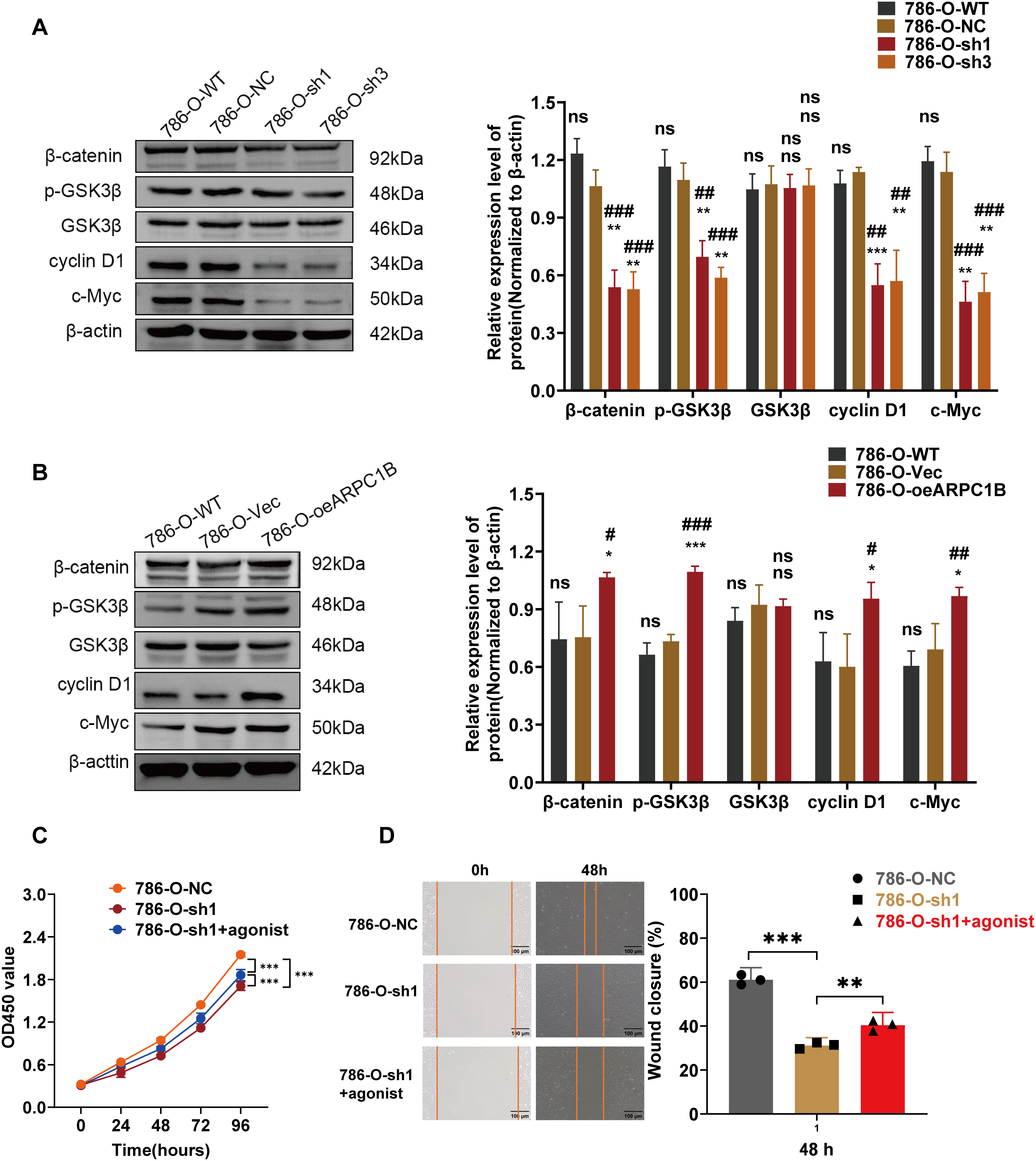

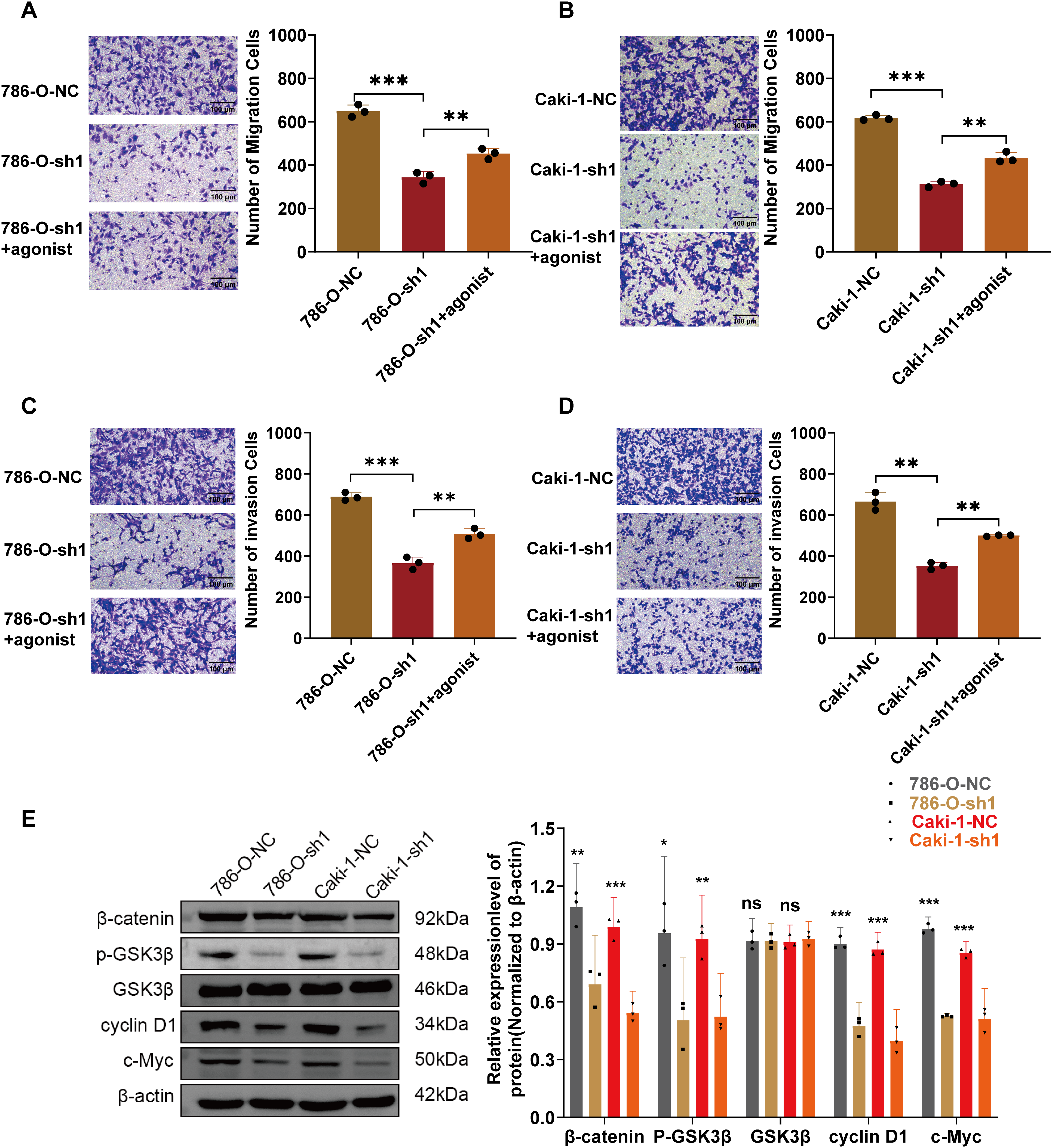

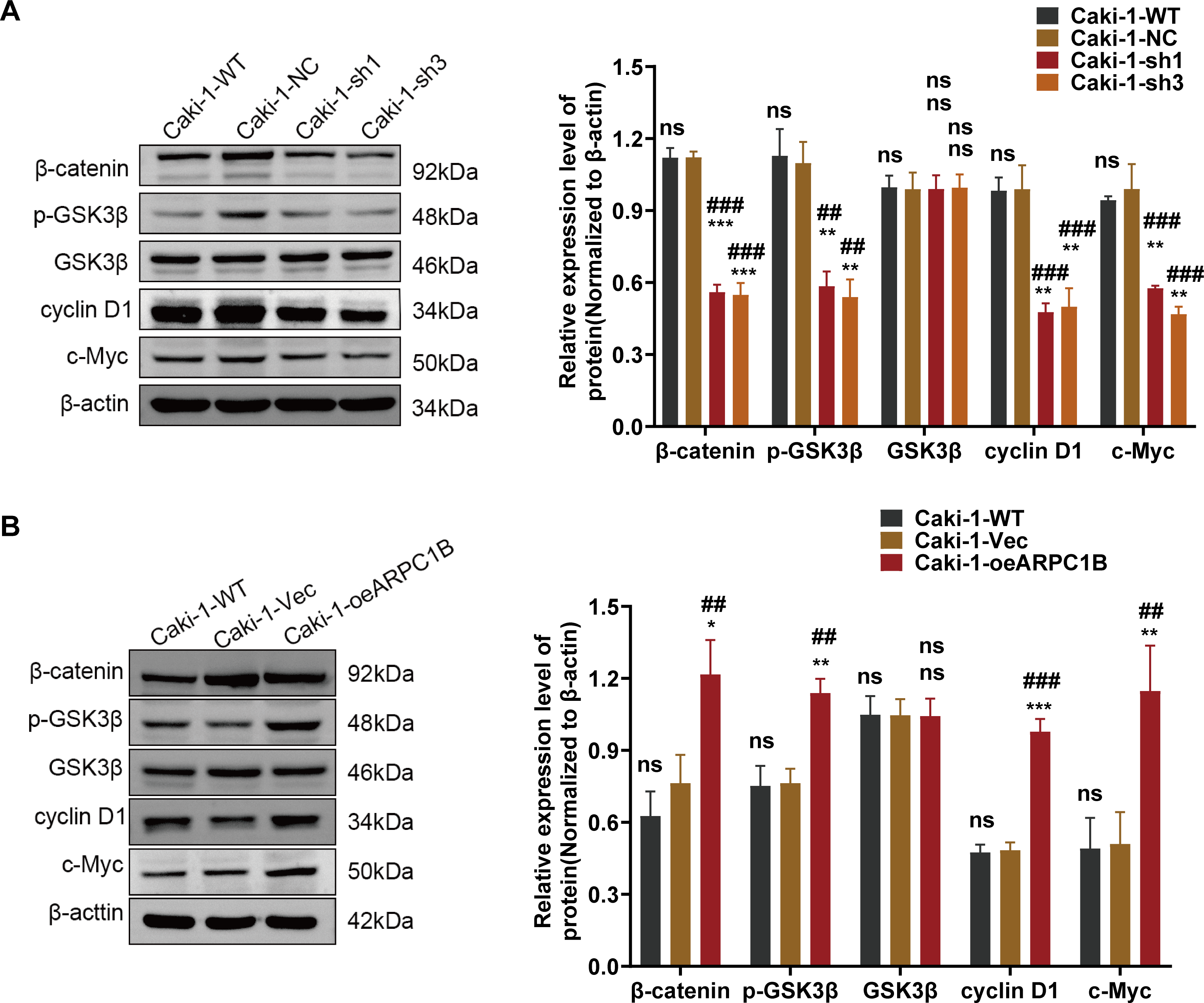

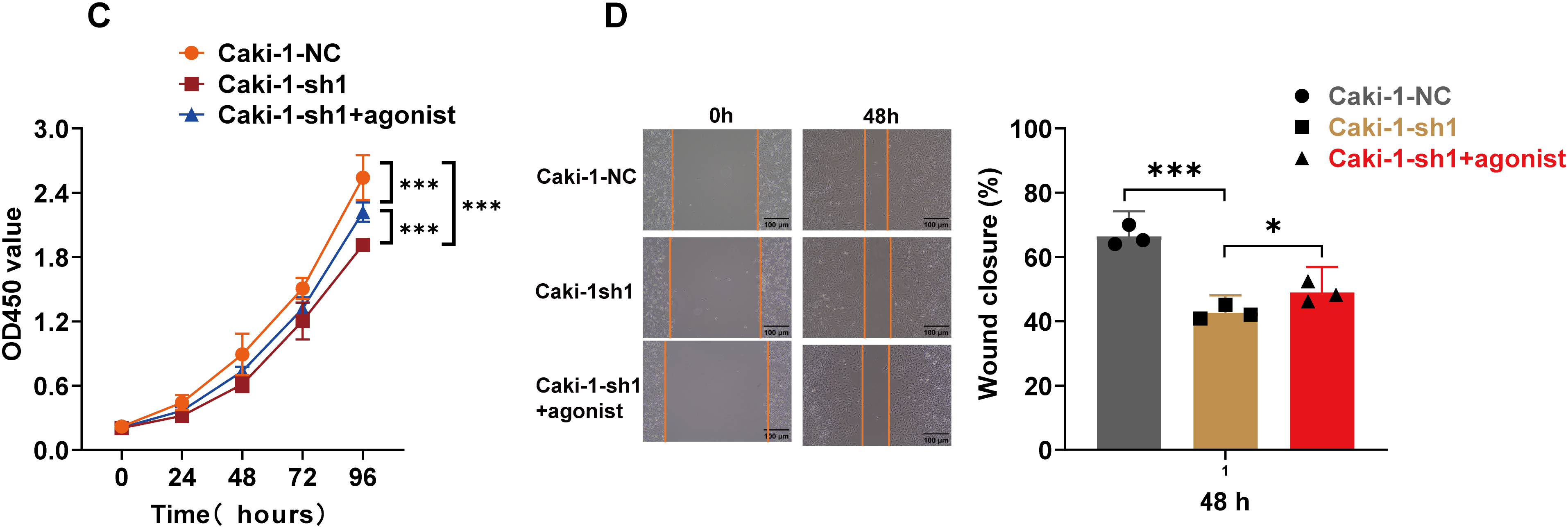

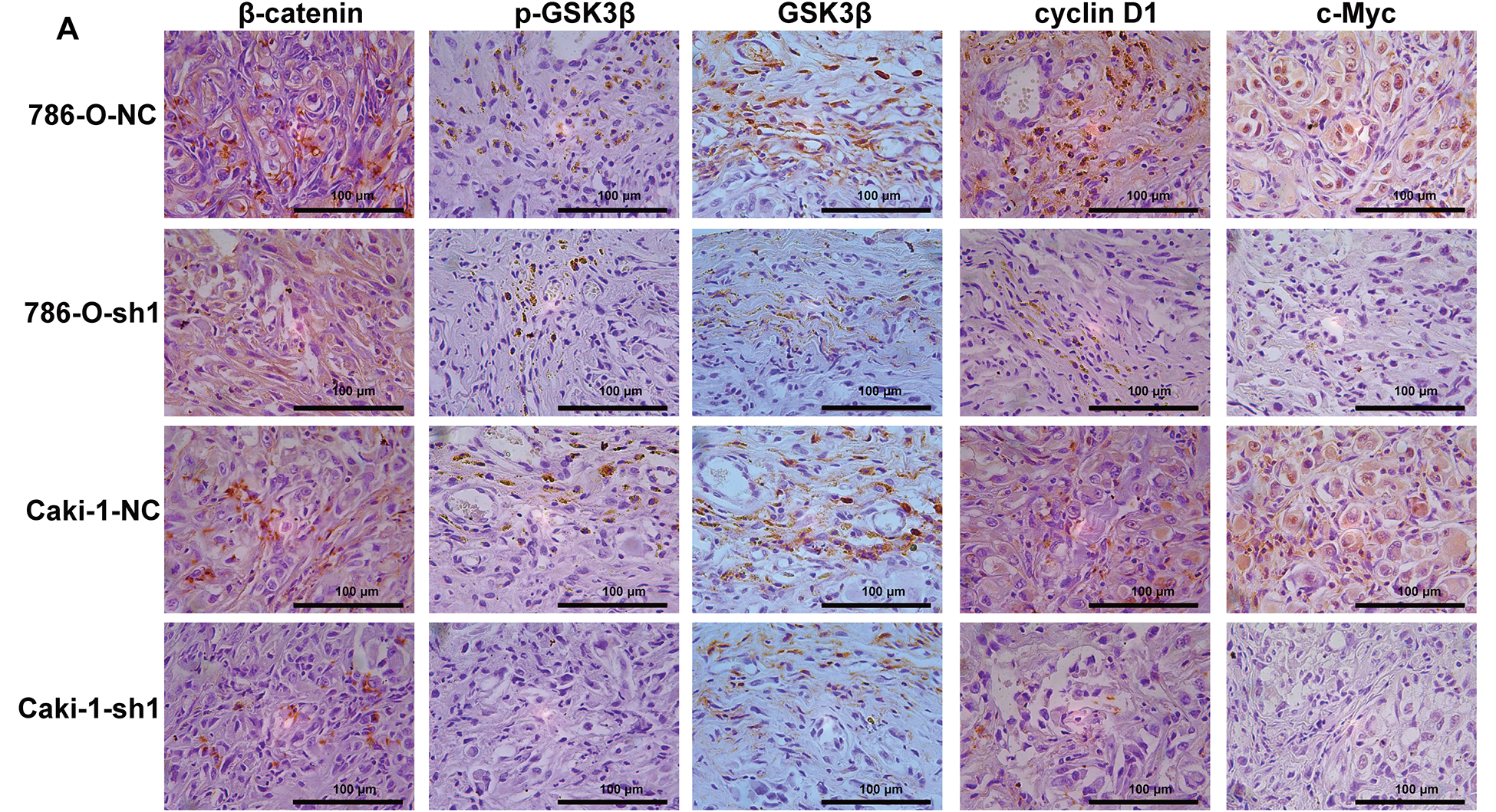

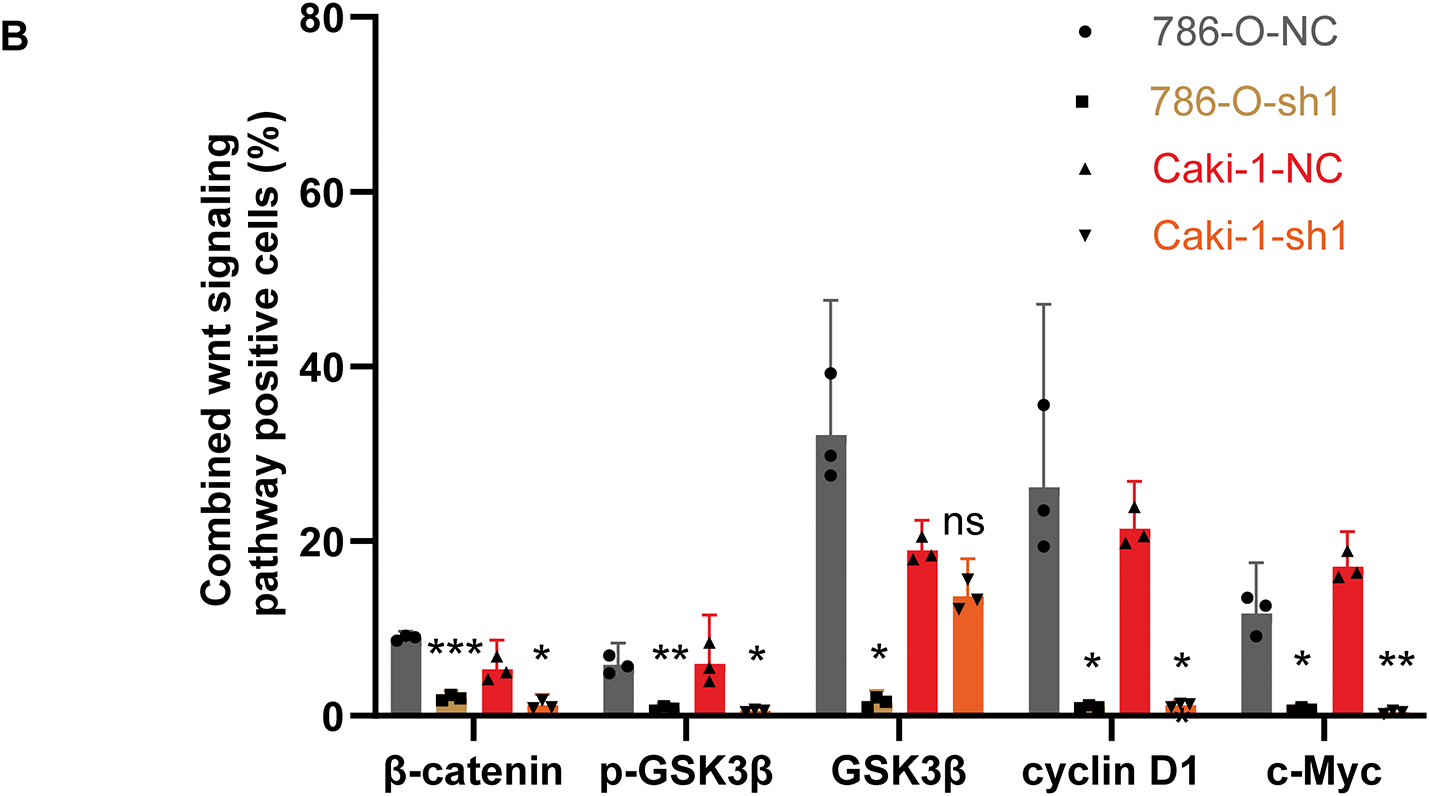

Prior research has demonstrated that ARPC1B facilitates ovarian cancer progression via activation of the Wnt/β-catenin cascade [30]. Consequently, this study hypothesized a parallel regulatory role of ARPC1B in ccRCC progression. WB analyses revealed significant decreases in protein levels of β-catenin, phosphorylated GSK3β (p-GSK3β), c-Myc, and cyclin D1 in 786-O and Caki-1 cells following ARPC1B silencing (p < 0.01, Figs. 7A, A8A). Conversely, ARPC1B overexpression notably increased these signaling molecules (p < 0.05, Figs. 7B, A8B), confirming ARPC1B’s regulatory role in Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation. Rescue experiments using Wnt/β-catenin agonist 3 further validated this mechanistic link. Treatment with agonist 3 restored β-catenin, p-GSK3β, c-Myc, and cyclin D1 expression levels and reversed the inhibitory effects of ARPC1B knockdown on cell proliferation (p < 0.001, Figs. 7C, A8C), wound healing (p < 0.05, Figs. 7D, A8D), Transwell migration (Fig. 8A,B), and invasion (Fig. 8C,D) assays in both cell lines. These findings demonstrate ARPC1B-mediated tumor aggressiveness via Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Consistent with in vitro findings, xenograft tumor tissues from ARPC1B-knockdown groups exhibited significantly reduced protein levels of β-catenin, p-GSK3β, c-Myc, and cyclin D1 (p < 0.05, Fig. 8E). IHC analysis confirmed reduced staining of these proteins in ARPC1B-knockdown tumor tissues relative to NC controls (Fig. A9). Altogether, these results highlight ARPC1B as a critical regulator of ccRCC progression, exerting oncogenic effects through activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

Figure 7: Correlation between ARPC1B expression and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. (A) WB analysis of β-catenin, p-GSK3β, GSK3β, c-Myc, and cyclin D1 expression in 786-O cells following ARPC1B knockdown. (B) WB assessment of β-catenin, p-GSK3β, GSK3β, c-Myc, and cyclin D1 protein levels in ARPC1B-overexpressing 786-O cells. All samples were analyzed simultaneously under consistent conditions, and were normalized to β-actin. (C, D) Rescue experiments examining proliferation (CCK-8 assay) and migration (WHA) in ARPC1B-silenced cells treated with Wnt/β-catenin agonist 3. Compared to the sh-NC group, Vec group, sh1 group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, p >0.05. Compared to the WT group; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ns, p >0.05

Figure 8: Validation of ARPC1B involvement in Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation. (A–D) Rescue experiments evaluating migration and invasion capabilities in ARPC1B-knockdown cells treated with Wnt/β-catenin agonist 3. (E) WB analysis of β-catenin, p-GSK3β, GSK3β, c-Myc, and cyclin D1 protein expression in xenograft tumor tissues derived from ARPC1B-silenced cells. All samples were analyzed simultaneously under consistent conditions, and were normalized to β-actin. Compared to the sh1 group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, p >0.05

ccRCC ranks among the most frequent malignancies of the urinary system. Despite recent progress in targeted treatment strategies, patients with advanced or metastatic ccRCC continue to exhibit poor clinical outcomes [38,39]. Thus, clarifying the molecular mechanisms driving ccRCC progression remains crucial for identifying novel therapeutic targets. Recent investigations have underscored ARPC1B as a significant contributor to tumor progression, particularly in promoting invasion and metastasis, and associated its elevated expression with unfavorable prognoses in multiple cancer types [29,30,40]. Nevertheless, the precise functional significance of ARPC1B in ccRCC progression remains inadequately characterized.

ARPC1B emerges as a multi-dimensional regulator orchestrating ccRCC progression through synergistic control of metastatic dissemination and pathway activation. IHC profiling validated its clinical relevance, demonstrating strong correlations with advanced TNM stages (p = 0.003) and high Fuhrman grades (p < 0.001), alongside 2.9-fold tumor-specific overexpression (38% vs. 13% in paracancerous tissues, p = 0.009). Critically, multivariate analysis revealed ARPC1B’s independent prognostic value (Cox p = 0.009), surpassing conventional staging systems, establishing its utility as a stratification biomarker.

Clinically, the association between ARPC1B overexpression and lymph node metastasis (p = 0.029) underscores its relevance to advanced disease management. However, limited statistical power due to sample imbalance in lymph node-positive subgroups (3 vs. 147 cases) necessitates cautious interpretation. Future multicenter studies with enriched metastatic cohorts are required to validate ARPC1B’s role. Nevertheless, concordance between IHC profiles and the GEPIA database validation strengthens clinical data reliability. Independent functional coherence across 786-O and Caki-1 models further supports biological plausibility despite cohort constraints.

Through comprehensive functional analyses, this study established ARPC1B’s critical role in ccRCC progression. In vitro experiments indicated that ARPC1B significantly facilitates proliferation, migration, and invasion, while knockdown effectively suppresses these oncogenic processes. Corroborating these in vitro results, xenograft models demonstrated that ARPC1B depletion markedly decreased tumor growth, reinforcing its importance in tumor development. These findings align with prior research in ovarian cancer and glioblastoma, which similarly reported ARPC1B’s capacity to enhance tumor cell proliferation and invasive behavior [30,40].

At a mechanistic level, our data underscore that ARPC1B promotes ccRCC advancement through stimulation of EMT, an essential mechanism underlying tumor invasion and metastatic capability [35–37]. Specifically, depletion of ARPC1B led to decreased mesenchymal markers (N-cadherin, Vimentin, and ZEB-1) alongside elevated epithelial marker E-cadherin, indicative of EMT inhibition. Conversely, elevated ARPC1B expression strongly upregulated EMT markers, affirming ARPC1B’s crucial role in facilitating tumor cell invasiveness. Additionally, our investigation identified the Wnt/β-catenin pathway as a key downstream effector regulated by ARPC1B in ccRCC. Suppression of ARPC1B resulted in reduced expression of pivotal signaling proteins, including β-catenin, p-GSK3β, c-Myc, and cyclin D1, whereas ARPC1B overexpression enhanced their levels. Rescue experiments with Wnt/β-catenin agonist 3 reversed the inhibitory effects caused by ARPC1B knockdown, thus establishing a clear functional linkage between ARPC1B and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. These observations align with earlier reports suggesting that ARPC1B stabilizes β-catenin, enhancing its oncogenic signaling activities [41–43].

Nevertheless, the present study has several limitations. In particular, the relatively small clinical cohort and lack of genetically engineered animal models may restrict the generalizability of these conclusions. Furthermore, although we have demonstrated the activation of EMT and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by ARPC1B, the precise molecular interactions through which ARPC1B modulates key proteins such as β-catenin and N-cadherin still require further detailed investigation. Subsequent research will employ techniques such as proximity-dependent biotin identification (BioID) and co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) to systematically identify ARPC1B-binding proteins and further elucidate their precise functional roles in these signaling networks.

Collectively, our findings provide compelling evidence highlighting ARPC1B as a vital regulator of ccRCC tumor progression. Elevated ARPC1B expression correlates significantly with aggressive tumor phenotypes, poor clinical outcomes, and activation of key oncogenic signaling pathways, specifically EMT and Wnt/β-catenin. Therapeutic targeting of ARPC1B in ccRCC is mechanistically supported by preclinical evidence from glioblastoma, where its modulation enhances radiotherapy sensitivity and synergizes with immune checkpoint inhibitors to augment antitumor immunity [40,44]. Given ARPC1B’s role in cytoskeletal dynamics and metastasis suppression, combining its inhibition with immune checkpoint blockade represents a promising strategy for metastatic ccRCC that may improve survival outcomes. This approach, however, presents dual therapeutic challenges: ARPC1B deficiency compromises cytotoxic T lymphocyte effector functions as demonstrated by impaired tumor cell killing and attenuated IFN-γ secretion in standardized systems [25], while close structural homology with ARPC1A raises toxicity and specificity concerns [45]. Further research remains essential to delineate ARPC1B’s role in ccRCC and advance its application in precision oncology.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Cell Biology Laboratory and the Animal Experimentation Center at Zhanjiang Central People’s Hospital for their invaluable assistance and outstanding technical support.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Jiayin Peng, Yijun Xue; methodology, Jiayin Peng, Yijun Xue; software, Yijun Xue; validation, Jiayin Peng, Yijun Xue; formal analysis, Jiayin Peng; investigation, Zhiren Cai, Zhaoguan Li; resources, Jiayin Peng; data curation, Kangyan Han, Xiaoqi Lin; writing—original draft preparation, Jiayin Peng, Yijun Xue; writing—review and editing, Yutong Li; visualization, Jiayin Peng; supervision, Yumin Zhuo; project administration, Yutong Li, Yumin Zhuo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Authors, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study adhered to the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000, and received approval from the Ethics Committee of SOBC (Approval No. SHYJS-C1510001), Informed consent was obtained from all participants; furthermore, all procedures related to animal research were approved by the Animal Research Committee of Zhanjiang Central People’s Hospital (Approval No. DW-2024016-01, Zhanjiang, China).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| ARPC1B | Actin-Related Protein 2/3 Complex Subunit 1B |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| ccRCC | Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| CT | Threshold Cycle |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| EMT | Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition |

| ECL | Enhanced Chemiluminescence |

| GEPIA | Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis |

| HRP | Horseradish Peroxidase |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| lncRNAs | Long non-coding RNAs |

| NC | Negative Control |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| ORF | Open Reading Frame |

| OD | Optical Density |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered Saline |

| p-GSK3β | Phosphorylated GSK3β |

| RIPA | Radioimmunoprecipitation Assay |

| shRNA | Short Hairpin RNA |

| TMA | Tissue Microarray |

| TBST | Tris-buffered Saline with Tween®-20 |

| RT-qPCR | Tissue Microarray Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| WB | Western blotting |

| WT | Wild-Type |

Appendix A

Figure A1: Cross-Cohort Transcriptomic Analysis of ccRCC. (A) Venn diagram showing 1488 overlapping differentially expressed genes (DEGs, |log2FC| > 1, FDR < 0.05) between GSE53757 (n = 3040 DEGs) and GSE68417 (n = 2194 DEGs). (B,C) Heatmap of GSE53757, GSE68417. The blue line indicates ARPC1B. (D) Pathway overlap analysis identifies 231 shared enriched pathways (FDR < 0.05) from 376 (GSE53757) and 330 (GSE68417) total pathways. (E,F) Top 10 enriched pathways in GSE53757 and GSE68417, including Wnt/β-catenin

Figure A2: Levels of ARPC1B-positive (IHC score ≥ 6) in ccRCC tissues (n = 150) were much greater than in adjacent non-tumor tissues (n = 30) (38% vs. 13%, p = 0.009)

Figure A3: Validation of ARPC1B protein and mRNA levels in ccRCC cell lines. (A,B) Quantification of ARPC1B protein and mRNA in ARPC1B-overexpressing cells (786-O and Caki-1) compared with WT and negative controls (-Vec; GV492-empty). All samples were analyzed simultaneously under consistent conditions, and were normalized to β-actin. Compared to the Vec group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ns, p > 0.05. Compared to the WT group, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001

Figure A4: Functional effects of ARPC1B silencing on Caki-1 cells. (A) Reduced clonogenic potential of Caki-1 cells after ARPC1B knockdown. (B) Inhibition of migration observed in Caki-1 cells upon ARPC1B silencing (WHA). (C,D) Reduced migration and invasion capabilities demonstrated by Transwell assays following ARPC1B knockdown. Compared to the sh-NC group, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, p >0.05. Compared to the WT group, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001

Figure A5: Effect of ARPC1B overexpression on Caki-1 cell behavior. (A) Enhanced colony formation ability of Caki-1 cells following ARPC1B overexpression. (B) Accelerated migration observed in ARPC1B-overexpressing cells by WHA. (C,D) Transwell assays demonstrating increased migration and invasion capabilities in ARPC1B-overexpressing Caki-1 cells. Control group: Vec (GV492-empty). Compared to the Vec group, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, p >0.05. Compared to the WT group; ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001

Figure A6: Effects of ARPC1B knockdown on tumor growth in vivo. (A) Representative images of HE stained and IHC stained xenografts. Red arrows were used to highlight the positive area. (B) Quantification of cytoplasmic ARPC1B-positive cells. (C) Quantification of nuclear Ki-67-positive cells. Compared to the sh-NC group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Figure A7: Relationship between ARPC1B expression and EMT markers in vitro and in vivo. (A) WB analysis of EMT markers (Vimentin, N-cadherin, ZEB-1, and E-cadherin) in ARPC1B-silenced Caki-1 cells. (B) Protein expression of EMT markers in Caki-1 cells with ARPC1B overexpression. (C) IHC examination of EMT marker expression in xenograft tumors from ARPC1B-knockdown groups. All samples were analyzed simultaneously under consistent conditions, and were normalized to β-actin. Compared to the sh-NC group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, p >0.05. Compared to the WT group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001

Figure A8: Correlation between ARPC1B expression and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. (A) WB analysis of β-catenin, p-GSK3β, GSK3β, c-Myc, and cyclin D1 expression in Caki-1 cells following ARPC1B knockdown. (B) WB assessment of β-catenin, p-GSK3β, GSK3β, c-Myc, and cyclin D1 protein levels in ARPC1B-overexpressing Caki-1 cells. All samples were analyzed simultaneously under consistent conditions, and were normalized to β-actin. (C,D) Rescue experiments examining proliferation (CCK-8 assay) and migration (WHA) in ARPC1B-silenced cells treated with Wnt/β-catenin agonist 3. Compared to the sh-NC group, Vec group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, p >0.05. Compared to the WT group, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ns, p >0.05

Figure A9: IHC examination of Wnt/β-catenin signaling marker expression in xenograft tumors from ARPC1B-knockdown groups. (A) Representative images of IHC stained xenografts. (B) Quantification of Wnt/β-catenin signaling marker positive cells (%). Compared to the sh-NC group; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns, p >0.05

References

1. Bukavina L, Bensalah K, Bray F, Carlo M, Challacombe B, Karam JA, et al. Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma: 2022 update. Eur Urol. 2022 Nov;82(5):529–42. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2022.08.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Mohanty SK, Lobo A, Cheng L. The 2022 revision of the World Health Organization classification of tumors of the urinary system and male genital organs: advances and challenges. Hum Pathol. 2023 Jun;136:123–43. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2022.08.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Garje R, Elhag D, Yasin HA, Acharya L, Vaena D, Dahmoush L. Comprehensive review of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021 Apr;160:103287. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Young M, Jackson-Spence F, Beltran L, Day E, Suarez C, Bex A, et al. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet. 2024 Aug 3;404(10451):476–91. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00917-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Rizzo M, Caliò A, Brunelli M, Pezzicoli G, Ganini C, Martignoni G, et al. Clinico-pathological implications of the 2022 WHO Renal Cell Carcinoma classification. Cancer Treat Rev. 2023 May;116:102558. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2023.102558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Moch H, Amin MB, Berney DM, Compérat EM, Gill AJ, Hartmann A, et al. The 2022 World Health organization classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs—Part A: renal, penile, and testicular tumours. Eur Urol. 2022 Nov;82(5):458–68. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2022.06.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Ljungberg B, Albiges L, Abu-Ghanem Y, Bedke J, Capitanio U, Dabestani S, et al. European association of urology guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: the 2022 update. Eur Urol. 2022 Oct;82(4):399–410. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2022.03.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Xu L, Hu H, Zheng LS, Wang MY, Mei Y, Peng LX, et al. ETV4 is a theranostic target in clear cell renal cell carcinoma that promotes metastasis by activating the pro-metastatic gene FOSL1 in a PI3K-AKT dependent manner. Cancer Lett. 2020 Jul 10;482:74–89. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2020.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Mohamed AH, Abdullahi IM, Eraslan A, Mohamud HA, Gur M. Epidemiological and histopathological characteristics of renal cell carcinoma in somalia. Cancer Manage Res. 2022 May 30;14:1837–44. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S361765. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Rose TL, Kim WY. Renal cell carcinoma: a review. JAMA. 2024 Sep 24;332(12):1001–10. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.12848. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Bafadni MM, Osman YM, Ahmed MEIM, Taha MM, Idris DA, Kheiralla KEK, et al. Clinical pathological characteristics and treatment outcomes of renal cell carcinoma (RCCa retrospective study from Sudan. Ecancermedicalscience. 2023 Mar 23;17:1524. doi:10.3332/ecancer.2023.1524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Cheaib JG, Patel HD, Johnson MH, Gorin MA, Haut ER, Canner JK, et al. Stage-specific conditional survival in renal cell carcinoma after nephrectomy. Urol Oncol. 2020 Jan;38(1):6.e1–7. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2019.08.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Motzer RJ, Jonasch E, Agarwal N, Alva A, Baine M, Beckermann K, et al. Kidney Cancer, Version 3.2022, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022 Jan;20(1):71–90. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2022.0001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Carbonara U, Simone G, Capitanio U, Minervini A, Fiori C, Larcher A, et al. Robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: 7-year outcomes. Minerva Urol Nephrol. 2021 Aug;73(4):540–3. doi:10.23736/S2724-6051.20.04151-X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Joosten SC, Deckers IA, Aarts MJ, Hoeben A, Van Roermund JG, Smits KM, et al. Prognostic DNA methylation markers for renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Epigenomics. 2017 Sep;9(9):1243–57. doi:10.2217/epi-2017-0040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. de Martino M, Klatte T, Haitel A, Marberger M. Serum cell-free DNA in renal cell carcinoma: a diagnostic and prognostic marker. Cancer. 2012 Jan 1;118(1):82–90. doi:10.1002/cncr.26254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Kubiliūtė R, Žukauskaitė K, Žalimas A, Ulys A, Sabaliauskaitė R, Bakavičius A, et al. Clinical significance of novel DNA methylation biomarkers for renal clear cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2022 Feb;148(2):361–75. doi:10.1007/s00432-021-03837-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Heinemann FG, Tolkach Y, Deng M, Schmidt D, Perner S, Kristiansen G, et al. Serum miR-122-5p and miR-206 expression: non-invasive prognostic biomarkers for renal cell carcinoma. Clin Epigenetics. 2018 Jan 23;10:11. doi:10.1186/s13148-018-0444-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Zheng Z, Zeng X, Zhu Y, Leng M, Zhang Z, Wang Q, et al. CircPPAP2B controls metastasis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma via HNRNPC-dependent alternative splicing and targeting the miR-182-5p/CYP1B1 axis. Mol Cancer. 2024 Jan 6;23(1):4. doi:10.1186/s12943-023-01912-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Outeiro-Pinho G, Barros-Silva D, Moreira-Silva F, Lobo J, Carneiro I, Morais A, et al. Epigenetically-regulated miR-30a/c-5p directly target TWF1 and hamper ccRCC cell aggressiveness. Transl Res. 2022 Nov;249:110–27. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2022.06.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Rysz J, Konecki T, Franczyk B, Ławiński J, Gluba-Brzózka A. The role of long noncoding RNA (lncRNAs) biomarkers in renal cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Dec 30;24(1):643. doi:10.3390/ijms24010643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Chen Z, Zhang M, Lu Y, Ding T, Liu Z, Liu Y, et al. Overexpressed lncRNA FTX promotes the cell viability, proliferation, migration and invasion of renal cell carcinoma via FTX/miR-4429/UBE2C axis. Oncol Rep. 2022 Sep;48(3):163. doi:10.3892/or.2022.8378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Liu H, Ye T, Yang X, Lv P, Wu X, Zhou H, et al. A panel of four-lncRNA signature as a potential biomarker for predicting survival in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Cancer. 2020 Apr 27;11(14):4274–83. doi:10.7150/jca.40421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Gournier H, Goley ED, Niederstrasser H, Trinh T, Welch MD. Reconstitution of human Arp2/3 complex reveals critical roles of individual subunits in complex structure and activity. Mol Cell. 2001 Nov;8(5):1041–52. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00393-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Randzavola LO, Strege K, Juzans M, Asano Y, Stinchcombe JC, Gawden-Bone CM, et al. Loss of ARPC1B impairs cytotoxic T lymphocyte maintenance and cytolytic activity. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(12):5600–14. doi:10.1172/JCI129388. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Welch MD, DePace AH, Verma S, Iwamatsu A, Mitchison TJ. The human Arp2/3 complex is composed of evolutionarily conserved subunits and is localized to cellular regions of dynamic actin filament assembly. J Cell Biol. 1997 Jul 28;138(2):375–84. doi:10.1083/jcb.138.2.375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Kempers L, Sprenkeler EGG, Van Steen ACI, Van Buul JD, Kuijpers TW. Defective neutrophil transendothelial migration and lateral motility in ARPC1B deficiency under flow conditions. Front Immunol. 2021 May 31;12:678030. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.678030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Kumar A, Dumasia K, Deshpande S, Gaonkar R, Balasinor NH. Actin related protein complex subunit 1b controls sperm release, barrier integrity and cell division during adult rat spermatogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016 Aug;1863(8):1996–2005. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.04.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Gamallat Y, Zaaluk H, Kish EK, Abdelsalam R, Liosis K, Ghosh S, et al. ARPC1B is associated with lethal prostate cancer and its inhibition decreases cell invasion and migration in vitro. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jan 27;23(3):1476. doi:10.3390/ijms23031476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Huang J, Zhou H, Tan C, Mo S, Liu T, Kuang Y. The overexpression of actin related protein 2/3 complex subunit 1B(ARPC1B) promotes the ovarian cancer progression via activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Front Immunol. 2023 May 25;14:1182677. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1182677. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Ke M, Zhu H, Lin Y, Zhang Y, Tang T, Xie Y, et al. Actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 1B promotes ovarian cancer progression by regulating the AKT/PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway. J Transl Int Med. 2024 Oct 1;12(4):406–23. doi:10.2478/jtim-2024-0025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Lin H, Wang K, Xiong Y, Zhou L, Yang Y, Chen S, et al. Identification of tumor antigens and immune subtypes of glioblastoma for mRNA vaccine development. Front Immunol. 2022 Feb 2;13:773264. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.773264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Liao C, Chen W, Xu G, Wang J, Dong W. High expression of ARPC1B correlates with immune infiltration and poor outcomes in glioblastoma. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2023 Dec 19;37:101619. doi:10.1016/j.bbrep.2023.101619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Paul ED, Huraiová B, Valková N, Matyasovska N, Gábrišová D, Gubová S, et al. The spatially informed mFISHseq assay resolves biomarker discordance and predicts treatment response in breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2025 Jan 2;16(1):226. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-55583-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Polyak K, Weinberg RA. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009 Apr;9(4):265–73. doi:10.1038/nrc2620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Wu Y, Terekhanova NV, Caravan W, Naser Al Deen N, Lal P, Chen S, et al. Epigenetic and transcriptomic characterization reveals progression markers and essential pathways in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2023 Mar 27;14(1):1681. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-37211-7. Erratum in: Nat Commun. 2023 May 17;14(1):2817. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-38561-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Meng L, Gao J, Mo W, Wang B, Shen H, Cao W, et al. MIOX inhibits autophagy to regulate the ROS -driven inhibition of STAT3/c-Myc-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Redox Biol. 2023 Dec;68:102956. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2023.102956. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Reustle A, Di Marco M, Meyerhoff C, Nelde A, Walz JS, Winter S, et al. Integrative -omics and HLA-ligandomics analysis to identify novel drug targets for ccRCC immunotherapy. Genome Med. 2020 Mar 30;12(1):32. doi:10.1186/s13073-020-00731-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Rathmell WK, Rumble RB, Van Veldhuizen PJ, Al-Ahmadie H, Emamekhoo H, Hauke RJ, et al. Management of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2022 Sep 1;40(25):2957–95. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.00868. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Gao Z, Xu J, Fan Y, Zhang Z, Wang H, Qian M, et al. ARPC1B promotes mesenchymal phenotype maintenance and radiotherapy resistance by blocking TRIM21-mediated degradation of IFI16 and HuR in glioma stem cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022 Nov 16;41(1):323. doi:10.1186/s13046-022-02526-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Wang W, Li M, Wang Y, Li Q, Deng G, Wan J, et al. GSK-3β inhibitor TWS119 attenuates rtPA-induced hemorrhagic transformation and activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway after acute ischemic stroke in rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2016 Dec;53(10):7028–36. doi:10.1007/s12035-015-9607-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Wang X, Jung YS, Jun S, Lee S, Wang W, Schneider A, et al. PAF-Wnt signaling-induced cell plasticity is required for maintenance of breast cancer cell stemness. Nat Commun. 2016 Feb 4;7:10633. doi:10.1038/ncomms10633. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Wang H, Liu Z, Du Y, Cheng X, Gao S, Liang W, et al. High expression of ARPC1B promotes the proliferation and apoptosis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma cells, leading to a poor prognosis. Mol Cell Probes. 2025 Feb;79:102011. doi:10.1016/j.mcp.2025.102011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Liu T, Sun T, Chen X, Wu J, Sun X, Liu X, et al. Targeting ARPC1B overcomes immune checkpoint inhibitor resistance in glioblastoma by reversing protumorigenic macrophage polarization. Cancer Res. 2025;85(7):1236–52. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-24-2286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Cao L, Huang S, Basant A, Mladenov M, Way M. CK-666 and CK-869 differentially inhibit Arp2/3 iso-complexes. EMBO Rep. 2024;25(8):3221–39. doi:10.1038/s44319-024-00201-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools