Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Novel Strategies against Hepatocellular Carcinoma through Lipid Metabolism

1 Guangxi Key Laboratory of Molecular Medicine in Liver Injury and Repair, The Affiliated Hospital of Guilin Medical University, Guilin, 541001, China

2 College of Pharmacy, Guilin Medical University, Guilin, 541199, China

3 Guangxi Key Laboratory of Diabetic Systems Medicine, Guilin Medical University, Guilin, 541199, China

4 Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, Guangzhou, 510632, China

5 Department of Anesthesiology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guilin Medical University, Guilin, 541199, China

* Corresponding Authors: Zhigang Zhou. Email: ; Jian Tu. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work and shared the first authorship

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Novel Biomarkers and Treatment Strategies in Solid Tumor Diagnosis, Progression, and Prognosis)

Oncology Research 2025, 33(11), 3247-3268. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.066440

Received 08 April 2025; Accepted 15 August 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is characterized by its highly invasive and metastatic potential, as well as a propensity for recurrence, contributing to treatment failure and increased mortality. Under physiological conditions, the liver maintains a balance in lipid biosynthesis, degradation, storage, and transport. HCC exhibits dysregulated lipid metabolism, driving tumor progression and therapeutic resistance. This review aims to elucidate the roles of fatty acid, sphingolipid, and cholesterol metabolism in HCC pathogenesis and explore emerging therapeutic strategies targeting these pathways. Key findings demonstrate that upregulated enzymes like fatty acid synthase (FASN), acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), enhance de novo lipogenesis and β-oxidation, and promote HCC proliferation, invasion, and apoptosis evasion. Sphingolipids exert dual functions: ceramides suppress tumors, while sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) drives oncogenic signaling. Aberrant cholesterol metabolism, mediated by HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR), liver X receptor α (LXRα), and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1), contributes to immunosuppression and drug resistance. Notably, inducing ferroptosis by disrupting lipid homeostasis represents a promising approach. Pharmacological inhibition of key nodes—such as FASN (Orlistat, TVB-3664), sphingomyelin synthase (D609), or cholesterol synthesis (statins, Genkwadaphnin)—synergizes with sorafenib/lenvatinib and overcomes resistance. We conclude that targeting lipid metabolic reprogramming, alone or combined with conventional therapies, offers significant potential for novel HCC treatment strategies. Future efforts should focus on overcoming metabolic plasticity and optimizing combinatorial regimens.Keywords

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), one of the most common solid malignant tumors, ranks sixth in incidence and third in mortality worldwide [1,2]. The liver is a central organ regulating energy metabolism, mainly depending on the balance of lipid metabolism [3]. Lipids not only serve as the primary energy storage substances, but also play crucial roles in cellular membranes [4]. Once this balance is disrupted, it could result in hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, and even cancer. The energy of lipid metabolism can promote the proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of HCC cells [5]. Additionally, bioactive metabolites and intermediates generated during lipid metabolism can modulate cellular signaling pathways and influence cytoskeletal organization. Recent studies have shown that targeting lipid metabolism is a promising approach for treating HCC [6,7]. The metabolic processes mediated by fatty acids, sphingolipids, and cholesterol are closely related to the pathogenesis of HCC [8].

HCC subtypes demonstrate marked heterogeneity in lipid metabolic functions across distinct molecular classifications and disease stages. These differences not only profoundly influence tumor proliferation, invasion, and metastasis but also are closely linked to therapeutic response and clinical prognosis. HCC cells predominantly rely on de novo lipogenesis (DNL) for energy metabolism, characterized by the synergistic activation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1) and fatty acid synthase (FASN), which drives the synthesis of saturated fatty acids to fuel abnormal cancer cell proliferation. In contrast, intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) adopt an exogenous lipid uptake-dependent mode, where cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36)-mediated influx of long-chain fatty acids predominates. Concurrently, bile acid metabolic reprogramming enhances the conversion of primary bile acids to secondary bile acids, thereby promoting invasion and metastasis [9]. In addition, mixed liver cancer of those two types exhibits a unique “dual-driven” lipid metabolic phenotype, combining DNL and exogenous lipid uptake. This metabolic adaptability allows tumor cells to maintain proliferative advantages under microenvironmental nutrient fluctuations: DNL supplies raw materials for membrane phospholipid synthesis, while CD36-mediated lipid influx is transported via fatty acid binding protein 1(FABP1) to mitochondrial β-oxidation, sustaining ATP production and tumor growth [10].

In the early stages of HCC (I-II), tumor cells undergo lipid metabolic reprogramming, marked by significant activation of the DNL pathway [11], which drives the synthesis of nascent fatty acids to meet the demands of rapid proliferation [12]. During this phase, small, dispersed lipid droplets form in the cytoplasm, sequestering excess free fatty acids (FFA) and scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) to maintain redox homeostasis, thereby delaying the transition to an invasive phenotype. As the tumor progresses to stage III, enhanced mitochondrial β-oxidation activity dominates, fueling energy production and activating EMT-related pathways to promote cancer cell invasion and migration. At stage IV, pathological lipid droplets accumulate, which physically sequester lipophilic targeted agents like sorafenib, thereby reducing their effective intracellular concentration and contributing to drug resistance [13].

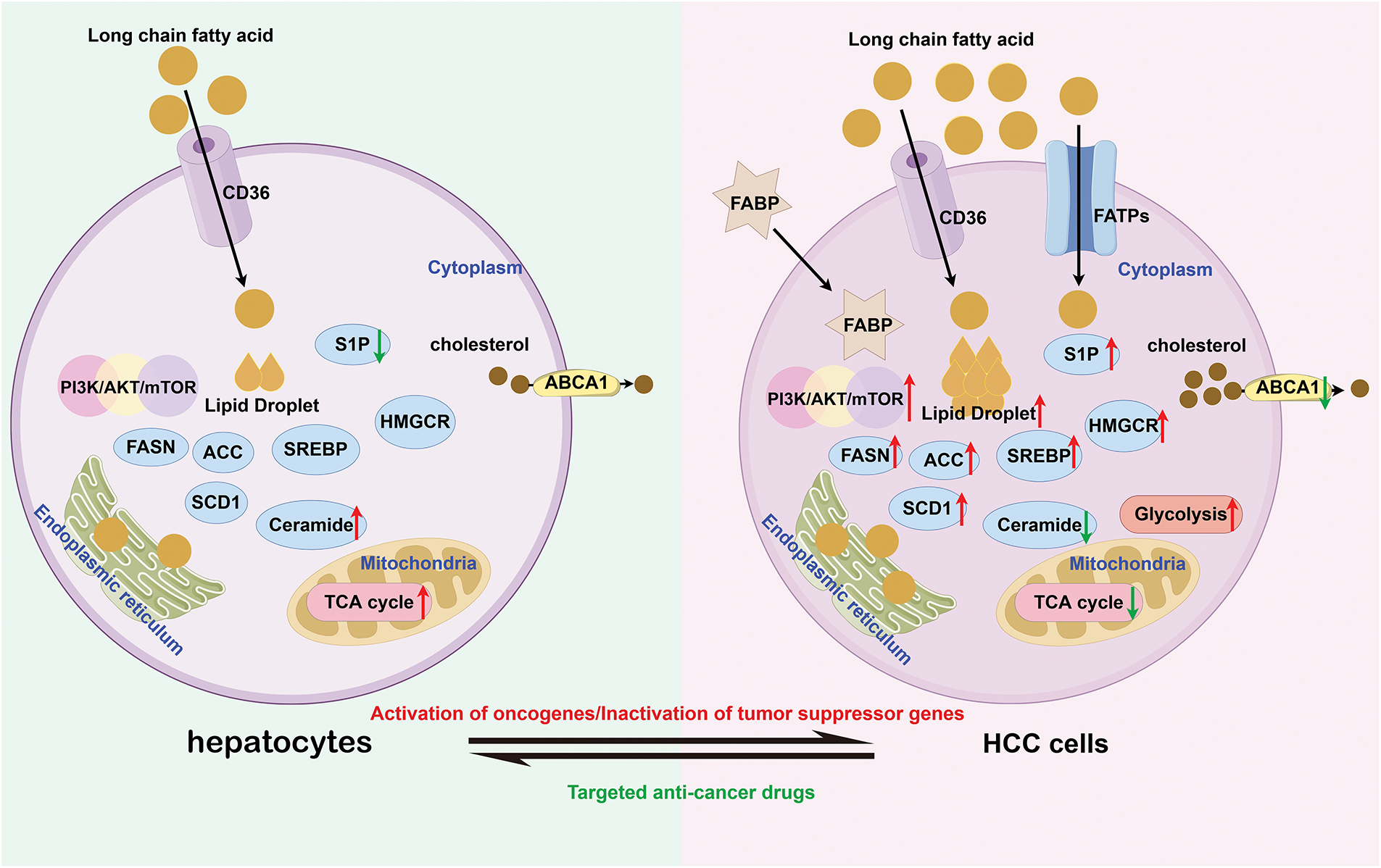

The above suggests that targeting lipid metabolism might be an effective approach for the treatment of HCC. Compared with hepatocytes, HCC cells exhibit significant differences in lipid metabolism (Fig. 1). Therefore, this article reviews novel strategies against HCC through lipid metabolism, aiming to advance future diagnostic and preventive strategies for this malignancy.

Figure 1: The difference of metabolism between hepatocytes and HCC cells (by Figdraw 2.0). Compared to hepatocytes, HCC cells not only enhance endogenous fatty acid synthesis capacity but also markedly increase exogenous fatty acid uptake to meet the metabolic demands of rapid proliferation. Notably, HCC cells exhibit aberrant upregulation in both expression and activity of lipid-synthesizing enzymes (e.g., FASN, ACC) and key signaling pathways, including PI3K/AKT/mTOR. In contrast, the activity of the ABCA1 transporter responsible for lipid efflux is markedly suppressed, leading to intracellular lipid accumulation and characteristic lipid droplet formation. From an energy metabolism perspective, while normal cells primarily rely on the TCA cycle for efficient ATP production, HCC cells demonstrate the Warburg effect by preferentially utilizing enhanced glycolytic pathways for energy supply. CD36, Cluster of Differentiation 36; S1P, Sphingosine-1-phosphate; FASN, Fatty Acid Synthase; ACC, Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase; SCD1, Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1; SREBP, Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein; HMGCR, HMG-CoA reductase; ABCA1, ATP-Binding Cassette Subfamily A Member 1; FABP, Fatty Acid-Binding Protein; FATPs, Fatty Acid Transport Proteins; TCA, Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle; PI3K, Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase; AKT, Protein Kinase B; mTOR, Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin; HCC, Hepatocellular carcinoma

Lipid metabolism is a complex process occurring at different levels in various organs and tissues. It requires the combined action of multiple genes and metabolic enzymes to achieve dynamic equilibrium. In the liver, lipids are mainly divided into eight categories: fatty acyl groups (including fatty acids), sphingolipids, sterols (including cholesterol), and so on [14,15]. Among them, fatty acid metabolism, sphingolipid metabolism, and cholesterol metabolism are closely related to HCC.

2.1 Fatty Acid Metabolism in HCC

Fatty acid metabolism can modulate the expression and activity of lipid metabolism enzymes as a result of the abnormal activation of oncogenic signaling pathways. This process may accelerate the occurrence and progression of HCC. Fatty acids are signal precursors that regulate metabolism during the development of HCC, and are also energy sources in cell proliferation, invasion/migration and apoptosis [16].

2.1.1 Promoting Cell Proliferation

Fatty acids can promote cell cycle progression, thereby increasing the proliferation rate of cells. They could activate certain signaling pathways, such as the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway (PI3K/Akt), which promotes cell survival and proliferation. Furthermore, the most typical feature of HCC is the upregulation of FA synthesis-related genes, and high expression of FASN usually indicates poor prognosis. The study found that knocking out FASN significantly inhibited HCC driven by Akt activation in a mouse model [17]. The study also confirmed that linear free energy (LFE) could upregulate the relative expression levels of genes related to the PI3K/Akt pathway and fatty acid metabolism [18]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor c (PPARc) belongs to the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 (PGC-1) coactivator family and is considered a major regulator of mitochondrial biosynthesis, oxidative metabolism, and antioxidant defense [19]. The coactivators PGC-1α and PGC-1β display comparable expression patterns and are significantly expressed in tissues characterized by heightened mitochondrial energy metabolism [20]. Additionally, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) governs the constitutive transcription of genes that encode enzymes involved in fatty acid transport. Cytochrome P450 consists of a group of ω-hydroxylase enzymes that convert fatty acids into forms suitable for mitochondrial uptake, facilitating their transport to mitochondria for energy production. This process not only eliminates excess FFA but also contributes to the synthesis of bioactive fatty acid molecules [21]. The decrease in cytochrome p450 family 4 (CYP4) expression is associated with liver fat accumulation [22]. CYP4A, CYP4B, and CYP4F, together with CYP4V, metabolize short-chain fatty acids, medium-chain fatty acids, and long-chain fatty acids, respectively. Among them, CYP4F2, CYP4F12, and CYP4V2 are significantly positively correlated with lipid metabolism pathways, and their functional components contribute to HCC progression through diverse metabolic mechanisms [23]. A study that analyzed gene expression profiles in the liver and serum of HCC patients suggests that the lncRNA RP11-466I1 is involved. It may increase FA uptake and promote the occurrence of HCC by upregulating PPAR γ and FA metabolism-related gene LPL [24]. A study found that the inactivation of fatty acid synthase could downregulate the expression level of 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) in HepG2 cells and reduce the content of leukotriene B4 (LTB4) in culture medium and cell lysates. This indicates that hepatitis B virus X protein with deletion at residue 127 (HBx Δ 127) promotes cell growth in liver cancer cells through a positive feedback loop involving fatty acid synthase (FAS) and 5-LOX [25].

2.1.2 Increasing Cell Invasion/Migration

HCC metastasis represents a clinically critical stage associated with dismal patient prognosis [26,27]. Given the tight pathophysiological interplay between fatty acid metabolism and hepatic function, identifying biomarkers and therapeutic targets in this context is imperative [28]. Saturated fatty acids, for instance, can promote cancer cell invasion, possibly mediated by altering membrane fluidity and permeability. The protein arginine methyltransferase 1-9 (PRMT1-9) governs protein arginine methylation, an essential post-translational modification pathway that dynamically regulates cellular signaling. By suppressing cell viability, migration, and invasion, PRMT1 knockout in HCC cells concurrently reduces expression of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism. Furthermore, PRMT1-coexpressed genes are enriched in fatty liver diseases and drug-induced liver injury, with functional links to fatty acid metabolism [29–31]. PRMT1 accelerates hepatocellular carcinogenesis through immune microenvironmental reprogramming and fatty acid metabolic dysregulation. Acyl-coenzyme A thioesterase 9 (ACOT9), a pivotal gatekeeper of intracellular fatty acid flux, cleaves acyl-CoA thioesters to liberate free fatty acids and coenzyme A. ACOT9 drives hepatocellular carcinoma progression by reprogramming lipid metabolism, emerging as a promising therapeutic target in HCC [32]. As a secreted acid-phosphorylated glycoprotein, Tuftelin 1 (TUFT1) is pathologically overexpressed during hepatocarcinogenesis and highly correlated with poor patient survival and aggressive tumor phenotypes [33]. TUFT1 modulates fatty acid metabolism to drive intracellular lipid deposition in HCC cells, while demonstrating physical interaction with the lipid metabolic regulator CREB1. TUFT1 could also regulate the activity of CREB1 and the transcription of key enzymes involved in lipid production. TUFT1 significantly promotes HCC cell proliferation, partially reversed by treatment with CREB1 inhibitor KG-501. In addition, TUFT1 promotes the ability of HCC cells to invade in vitro. Research has shown that CD147 overexpression triggers AKT-mTOR cascade activation, potentiating SREBP1c transcriptional output [34]. SREBP1c transactivation elevates FASN/ACC expression, propelling hepatocellular carcinoma progression and metastasis. In addition, the reduction of krüppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) levels showed the reverse of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) via PI3K/AKT signaling and the decreased expression of MMP2/ MMP9 in HCC cells both in vitro and in vivo [35]. In addition, FA could also influence the progression of HCC by regulating signal prerequisites and serving as an energy source.

Research has identified miR-377-3p as a key regulator of carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1C (CPT1C) expression and lipid metabolism [36]. Through 3’-UTR targeting-mediated CPT1C downregulation, miR-377-3p attenuates fatty acid β-oxidation, thereby curbing HCC oncogenicity (proliferation, migration, invasion, metastasis) across in vitro and in vivo systems. Additionally, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) knockdown triggers de novo lipogenesis by upregulating rate-limiting enzymes FASN and SCD in HCC cells, which could inhibit cell migration [37]. An experiment has confirmed that the silence of solute carrier family 25 member 19 (SLC25A19) and FASN potently curbs oncogenic proliferation and migratory capacity [38]. Recent research found that a DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) inhibitor effectively increases acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 5 (ACSM5) expression and reduces promoter region methylation [39]. ACSM5 overexpression in Huh7 cells attenuated fatty acid accrual and malignant phenotypes (proliferation/migration/invasion) in vitro, while suppressing xenograft tumorigenesis in vivo. Furthermore, ACSM5 overexpression also decreased signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) phosphorylation, subsequently affecting downstream cytokine transforming growth factor-β (TGFB) and fibroblast growth factor 12 (FGF12) messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) levels.

All cellular activities require the provision of energy. Fatty acids are one of the major sources of energy for cells. In rapidly proliferating cells, such as cancer cells, the demand for energy is particularly high. Therefore, the supply of fatty acids is crucial for supporting the growth and survival of cancer cells. Research has shown that the methyltransferase-like 5 (METTL5)- acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 (ACSL4) axis promotes β-oxidation [40]. The ACSL family plays an important role in fatty acid metabolism in cancer [41,42]. The ACSL family of proteins has a dual function of promoting de novo adipogenesis and β-oxidation, thereby promoting cancer growth and progression [43,44]. Beyond β-oxidation facilitation, ACSL isoforms orchestrate lipogenesis and lipid droplet biogenesis via transcriptional reprogramming. ACSL4 potentiates METTL5-driven fatty acid metabolism and HCC progression, while dual targeting synergistically suppresses hepatocarcinogenesis in vivo. METTL5- tRNA methyltransferase 112 (TRMT112)-mediated 18S rRNA N6-methyl adenosine (m6A) modification promotes HCC growth and metastasis in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, 18S rRNA m6A modification promotes the assembly and translation of 80S ribosomes involved in HCC fatty acid metabolism [45,46]. In addition, targeting METTL5 and fatty acid metabolism may synergistically inhibit the occurrence of HCC tumors in vivo. METTL5 promotes de novo fat generation and fatty acid beta oxidation processes. An increasing number of studies indicate that de novo adipogenesis and fatty acid oxidation are simultaneously activated and coordinated to promote cancer progression [47,48].

2.1.3 Resisting Cell Apoptosis

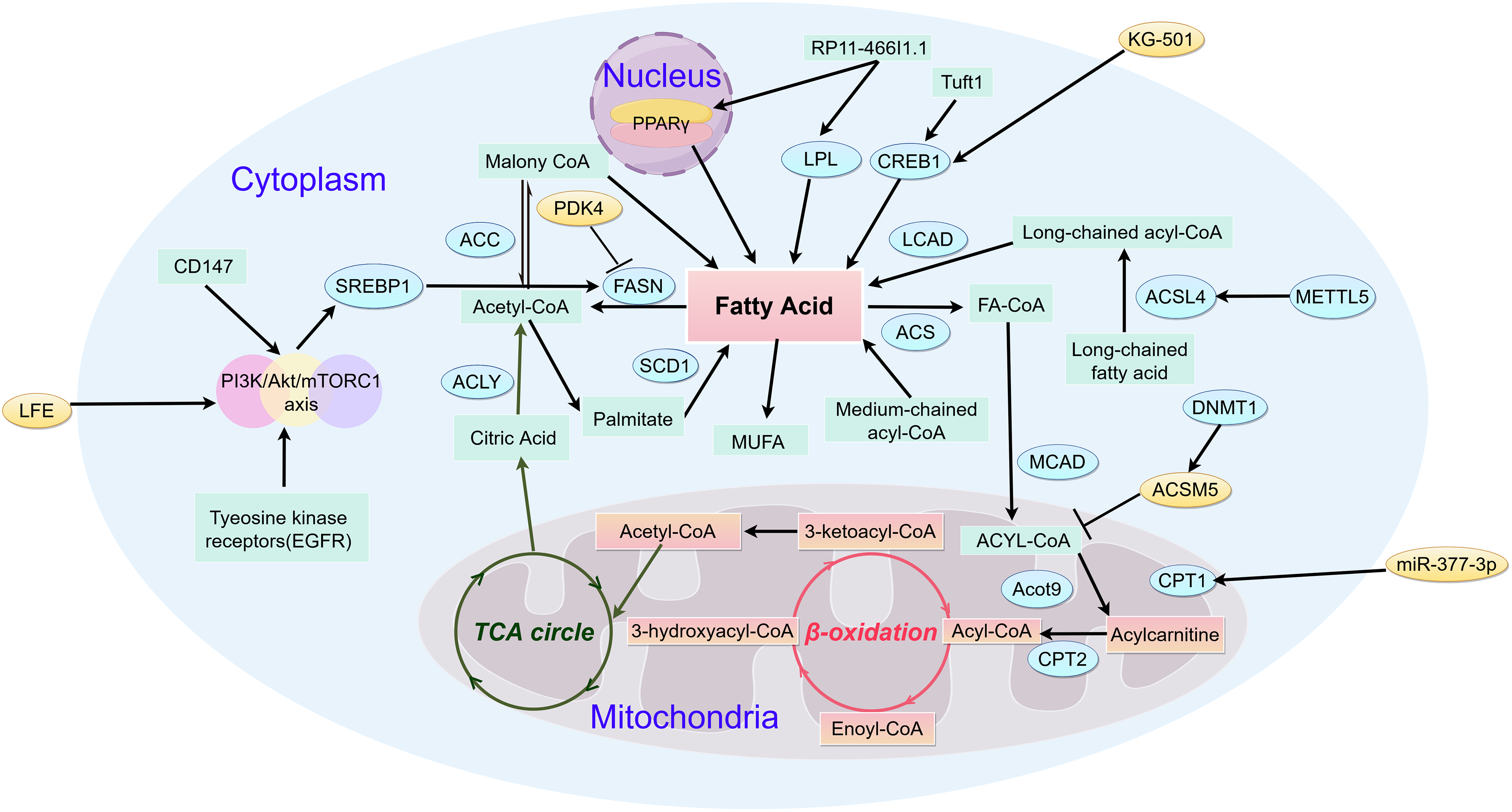

Fatty acids may inhibit cell apoptosis, thereby prolonging the lifespan of cancer cells. Research suggests that the absence of FASN only delays the occurrence of tumors, indicating the existence of other mechanisms that promote HCC cell proliferation and survival [49]. Recent research demonstrates that an increase in monounsaturated fatty acids contributes to the de novo synthesis of fatty acids in liver cancer cells [50]. The role of SCD1 in HCC is related to the regulation of p53 protein (P53), WNT/β-catenin, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and autophagy [51]. CD147 upregulation triggers AKT-mTOR signaling, thereby increasing sterol regulatory element-binding SREBP1c expression [52]. The upregulation of SREBPlc levels increases the expression of FASN and ACC, leading to tumor growth and metastasis. The upregulation of CD147 also reduces PPAR α, and downregulates CPT1A and ACOX1, leading to HCC growth and metastasis [53]. High expression of thyroid hormone receptor interactor protein 13 (TRIP13) in liver cancer affects survival rate and is associated with enrichment of certain molecules in the processes of RNA degradation and fatty acid metabolism. The increased expression of TRIP13 in liver cancer tissues is associated with liver cancer progression. Silencing TRIP13 may inhibit cell viability, migration, and invasion, and induce cell apoptosis. Knocking down TRIP13 could also inhibit tumor formation in vivo [54]. In HCC, the FA metabolic pathway involves the mitochondrial breakdown of long-chain fatty acids, which are oxidized to generate acetyl-CoA and subsequently fuel the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), a critical step in cellular energy production (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Metabolic pathways of fatty acid in HCC (by Figdraw 2.0). Fatty acid catabolism critically regulates metabolic reprogramming throughout hepatocarcinogenesis. The initial flux-controlling step, mediated by mitochondrial outer membrane-bound CPT1, catalyzes acyl-CoA conversion to acylcarnitine—essential for mitochondrial acyl-CoA import. In contrast, medium/short-chain acyl-CoAs diffuse freely across the inner membrane. Subsequent carnitine/acylcarnitine translocase-facilitated transport delivers acylcarnitine to the matrix, where CPT2 regenerates acyl-CoA. Cytosolic ACLY converts TCA cycle-derived citrate to acetyl-CoA, which ACC1 carboxylates into malonyl-CoA—the cytoplasmic rate-limiting precursor. FAS then condenses 7 malonyl-CoA molecules yielding palmitate, fueling ATP/NADH production via mitochondrial β-oxidation and TCA cycling. CD147, Cluster of Differentiation 147; SREBP1, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1; ACC, Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase; ACLY, ATP Citrate Lyase; FASN, Fatty Acid Synthase; SCD1, Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase 1; LPL, Lipoprotein Lipase; CREB1, cAMP Responsive Element Binding Protein 1; LACD, Long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase; ACS, Acyl-CoA Synthetase; MCAD, Medium Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase; Acot9, Acyl-CoA Thioesterase 9; CPT2, Carnitine Palmitoyl Transferase 2; CPT1, Carnitine Palmitoyl Transferase 1; DNMT1, DNA Methyltransferase 1; ACSL4, Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long-Chain Family Member 4; METTL5, Methyltransferase Like 5

2.2 Sphingolipid Metabolism in HCC

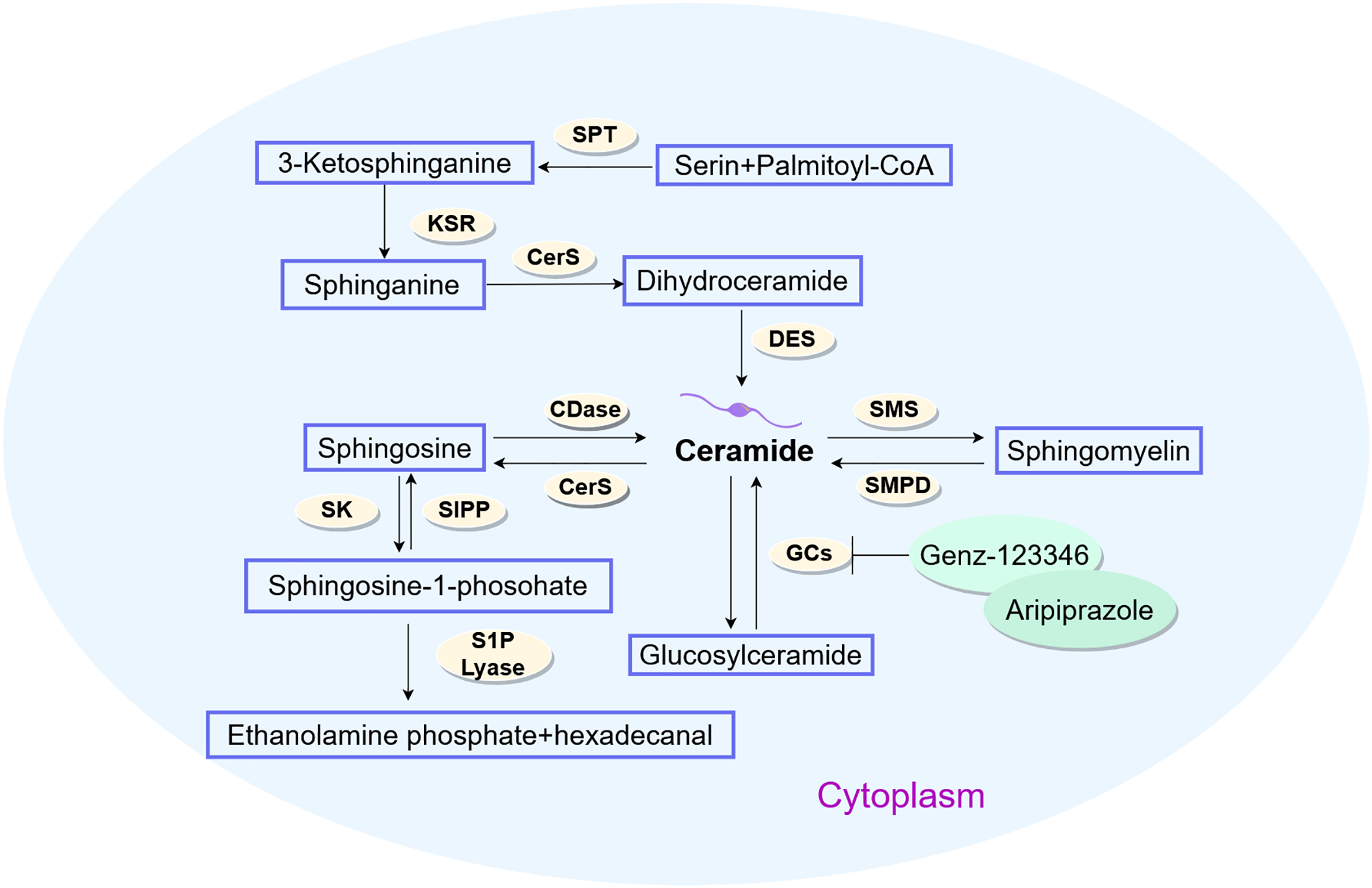

Bioactive sphingolipids—including ceramides, sphingosine, C1P, and S1P—critically modulate hepatocellular carcinoma cell fate decisions, such as proliferation, senescence and apoptosis [55,56]. As the metabolic nexus of sphingolipids, ceramides orchestrate their biotransformation. Endogenous ceramide biosynthesis proceeds via the de novo route through serine palmitoyl transferase (SPT), ceramide synthase (CerS), and dihydroceramide desaturase (DES) [57] sphingomyelinases (SMase) and glucosylceramidase-mediated enzymatic hydrolysis liberates ceramides from membrane sphingomyelins (SMs) or complex sphingolipids [58]. CerS reacylates sphingosine—a sphingolipid catabolic intermediate—recycling it into ceramides. Ceramides may accumulate briefly or serve as precursors for sphingolipids like C1P, S1P, and glucosylceramide (GlcCer). They can also be recycled back into sphingomyelins (SMs) [59]. The enzymatic conversion of phosphorylcholine and ceramide into sphingomyelins (SMs) is mediated by sphingomyelin synthetase [60]. Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis from ceramides occurs in the Golgi apparatus (GA), where specific glycosyltransferases mediate glycosylation [61]. Additionally, glycosylation of sphingolipids occurs within lysosomes. Concurrently, ceramide kinase phosphorylates ceramide in the GA. As central metabolites in sphingolipid pathways, ceramides exert anti-proliferative effects by suppressing tumor cell proliferation/migration while inducing autophagy and apoptosis. Conversely, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) and related sphingolipids demonstrate oncogenic properties, driving malignant progression through tumor cell transformation, motility, proliferation, and chemoresistance induction. Research indicates that in ceramide-refractory malignancies, sphingolipid metabolic reprogramming diverts exogenous ceramides toward pro-survival sphingolipid synthesis, enabling acquired ceramide resistance [62,63]. Clinical evidence indicates upregulated sphingolipid expression in HCC tissues, suggesting metabolic dysregulation linked to hepatocarcinogenesis [64]. Within this pathway, the SPHK1/S1P signaling axis functions as a pivotal oncogenic driver, with SPHK1 overexpression established as a consistent biomarker in hepatic malignancies [65]. SHPK1 knockdown perturbs sphingolipid homeostasis, characterized by depleted sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P), accumulated ceramides, and suppressed cellular viability [66]. A study has shown that Genz-123346 and aripiprazole synergistically suppress Huh7/Hepa1-6 HCC cell proliferation and tumor microsphere expansion [67] (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Metabolic pathways of sphingolipid in HCC (by Figdraw 2.0). Ceramides serve as pivotal metabolic integrators in sphingolipid biotransformation, biosynthesized through de novo pathways via SPT-CerS-DES enzymatic cascades, sphingomyelinase-mediated membrane sphingomyelin hydrolysis, or glucosylceramidase-catalyzed complex sphingolipid catabolism. SPT, Serine Palmitoyl Transferase; KSR, 3-Ketosphinganine Reductase; CerS, Ceramide Synthase; DES, Dihydroceramide Desaturase; CDase, Ceramidase; SMS, Sphingomyelin Synthase; SMPD, Sphingomyelin Phosphodiesterase; GCs, Gangliosides; S1PP, Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Phosphatase; SK, Sphingosine Kinase; S1P Lyase, Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Lyase

2.3 Cholesterol Metabolism in HCC

Emerging evidence implicates cholesterol transport in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) pathogenesis, driving malignant progression through proliferation, metastasis, and chemoresistance [68]. Notably, dysregulated cholesterol metabolism in HCC exhibits aberrant synthetic pathways that constitute critical oncogenic mechanisms for tumor growth [69].

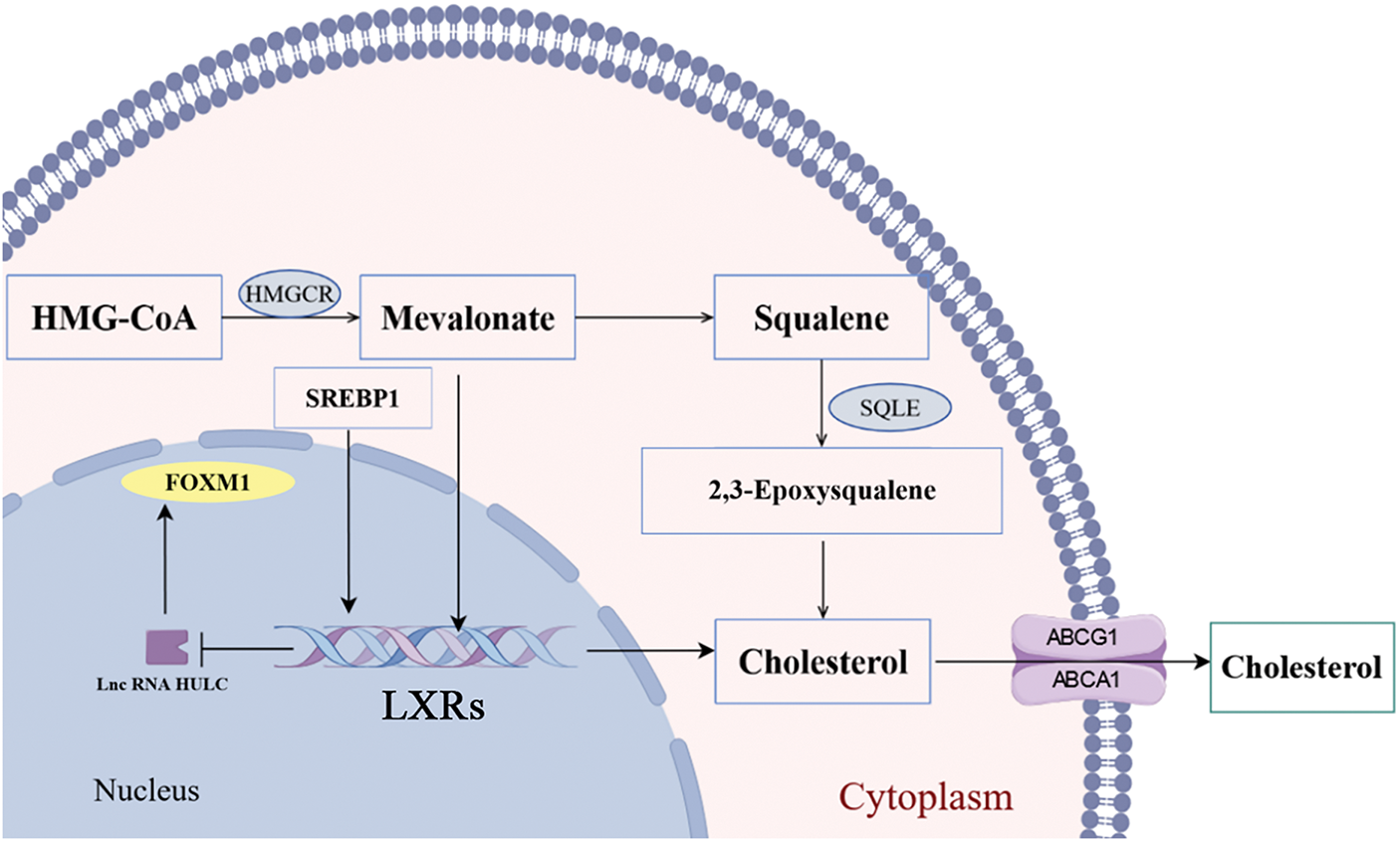

Liver X receptor α (LXRα) mediates transcriptional activation upon binding cholesterol and its oxidized derivatives, promoting cholesterol conversion to bile acids [70]. Current evidence indicates that synthetic LXRs agonists demonstrate anti-proliferative effects and modulate progression phenotypes—including growth, invasion, and metastasis in malignant tumors [71,72]. Collectively, these findings establish LXRα as a pivotal regulatory hub in oncogenesis. Mechanistically, LXRα constrains TGF-β signaling activation to suppress HCC proliferation. Contemporary studies further confirm its potent anti-neoplastic effects, significantly impairing metastatic competence through reduced invasion and migration capacities [73]. Our research group has also conducted studies on LXRs in HCC. We found that LXR alpha and high expression of liver cancer transcript (highly upregulated in liver cancer, HULC) cut the HULC promoter region, combining expression, thereby lowering fork frame M1 (FOXM1) expression [74]. However, FOXM1 could activate c-myc promoter and promote the proliferation of liver cancer cells [75]. Notably, HMGCR silencing downregulates FOXM1 expression, implicating cholesterol biosynthesis in transcriptional control during HCC. Bergamottin (a natural LXRα agonist) upregulates ABCA1 transporter activity, enhancing cholesterol efflux and reducing intracellular lipid droplet accumulation in hepatoma cells [76]. Numerous preclinical studies have demonstrated that liver cholesterol has a tumorigenic effect in promoting the transition from non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) to HCC [77,78]. Cholesterol critically modulates membrane fluidity—thereby regulating protein functionality—through its role as a key membrane rheostat [79]. Metabolic syndrome-induced cholesterol accumulation disrupts plasma and organelle membrane integrity. Mitochondrial cholesterol enrichment reduces membrane fluidity, impairing electron transport chain function. This triggers ROS overproduction, lipid peroxidation, hepatocyte necrosis, and apoptosis—collectively constituting established HCC risk factors [80]. Cholesterol critically regulates invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cell activation—effectors with intrinsic anti-tumor capacity. Membrane cholesterol levels further modulate CD8+ T cell activity and PD-1/PD-L1 axis suppression. In the tumor microenvironment, excessive cholesterol consumes CD8+ T cells by regulating the expression of X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1), which in turn activates a series of endoplasmic reticulum stress related pathways that impair the function and induce apoptosis of CD8+ T cells and promotes the immune escape of tumor cells [81]. DDX39B drives hepatocellular carcinoma progression by activating SREBP1-dependent de novo lipogenesis, establishing its dual utility as a prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target [82]. Overall, the cholesterol load on the membrane system could increase the risk of HCC through multi-level mechanisms (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Metabolic pathways of cholesterol in HCC (by Figdraw 2.0). HMGCR is a rate-limiting enzyme for cholesterol synthesis in the mevalonate pathway, affecting the synthesis of mevalonate and acting on LXRs, which could be blocked by statins. Furthermore, LXRs functions to regulate cholesterol homeostasis by transactivation of metabolic players as SREBP1 and FASN. HMGCR, 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Reductase; SQLE, Squalene Epoxidase; SREBP1, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1; FOXM1, Forkhead Box Protein M1; LXRs, Liver X Receptors; ABCG1, ATP-Binding Cassette Sub-family G Member 1; ABCA1 ATP-Binding Cassette Sub-family A Member 1

2.4 Other Lipid Metabolism in HCC

Glycerophospholipid metabolism also plays an important role in HCC [83]. Studies have shown that in the early stages of HCC development, glycerophospholipid metabolism may have been disrupted, and phospholipid levels are positively correlated with tumor burden [84,85]. Some studies have found that both lysophosphatidyl choline and lysophosphatidyl ethanolamine continue to increase in liver cancer [86,87]. The reason for this phenomenon may be that lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) is a structural unit of cell membrane glycerophospholipids, and the increase of these metabolites may reflect the high metabolic demand of HCC, which is consistent with the increased demand for glycerophospholipids in liver cancer.

Fat-soluble vitamins, including vitamin D, could regulate the process of HCC [88–90]. In vitro experiments have shown that vitamin D plays an anti-tumor role in HCC and could regulate the growth/progression of HCC by regulating the cell cycle and inhibiting mTOR. In vivo, vitamin D could regulate the progression of HCC, thereby activating cell apoptosis, reducing oxidative stress, and inhibiting inflammation [91–93].

3 New Strategies of HCC Treatment

With the increasing incidence rate and mortality of HCC, it is urgent to explore new treatment strategies. Numerous studies have shown that changes in lipids significantly affect the efficacy of drugs [94,95]. Hcc cells exhibit profound metabolic reprogramming distinct from normal hepatocytes, wherein dysregulated lipid metabolism fuels bioenergetic demands for proliferation and metastasis while generating onco-signaling mediators that perturb cellular architecture; consequently, targeting lipid metabolic vulnerabilities represents a promising HCC therapeutic strategy.

Clinically, however, current clinical trials in HCC face multiple challenges. Drug resistance remains a major hurdle, exemplified by platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA)/c-Jun pathway activation or lipid metabolism reprogramming leading to targeted therapy failure, while immunotherapy efficacy is limited by tumor microenvironment suppression such as CD8+ T-cell exhaustion [96]. Patient stratification lacks standardization; although multi-omics studies like proteogenomics have proposed subtypes such as metabolism-driven and microenvironment-dysregulated HCC, clinical translation is hindered by tumor heterogeneity and the absence of reliable biomarkers, including the limited prognostic utility of PD-L1 expression in HCC [97,98]. Combination strategies such as hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) combined with targeted immunotherapy or stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) with sorafenib demonstrate high conversion rates or survival benefits in single-arm trials but lack head-to-head comparisons and large-scale randomized validation [99]. Additionally, novel therapies like T cell receptor-engineered T cells (TCR-T) cell therapy or ultrasound-activated artificial enzyme-gene combinations show promise but require resolution of technical limitations and long-term safety assessments [100].

3.1 New Strategies for Treating HCC from the Perspective of Ferroptosis Pathways for HCC

Ferroptosis refers to iron-dependent, and regulatory necrosis mediated by lipid peroxidation, which is closely related to the occurrence and development of various cancers. Research has shown that the ferroptosis process of HCC cells is regulated by multiple signaling pathways and cytokines [101]. Inducing ferroptosis is of great significance in the treatment of HCC. Ferroptosis could regulate the growth of malignant tumors and has shown significant advantages in the treatment of malignant tumors. In HCC, changes in lipid metabolism are crucial for regulating ferroptosis [102]. Compared with normal cells, cancer cells have higher levels of iron demand and lipid metabolism, and lipid metabolism is widely present during ferroptosis [103]. Next, we will discuss how lipid metabolism affects the process of ferroptosis from three pathways: fatty acid metabolism, sphingolipid metabolism, and cholesterol metabolism.

3.1.1 Ferroptosis of Fatty Acid Metabolism

Ferroptosis is a novel form of programmed cell death that has garnered significant attention in cancer treatment research in recent years [104]. Cellular fatty acid uptake is orchestrated by specialized transporters—including fatty acid translocase (FAT/CD36), fatty acid transport proteins (FATPs), and fatty acid-binding proteins (FABPs). CD36-mediated fatty acid internalization correlates with metastatic progression, where elevated transporter expression enhances oncogenic dissemination. Notably, CD36-overexpressing neoplastic cells preferentially store internalized fatty acids over oxidative utilization, potentially inducing ferroptotic vulnerability [105]. On the other hand, CD36 could inhibit ferroptosis by outputting trihydroxy arachidonic acid (AA) [106]. Beyond CD36, fatty acid transport protein 2 (FATP2) functionally complements fatty acid internalization. Pharmacological FATP2 inhibition delays oncogenic progression, whereas genetic ablation impairs arachidonic acid (AA) uptake, rendering cells ferroptosis-resistant [107]. Ferroptosis progression is pathognomonically driven by lipid peroxide accrual. Convergent contributions from iron dyshomeostasis, polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) biogenesis, and peroxidation chain reactions propagate PUFA-peroxide generation. Critically, arachidonic acid (AA) and adrenic acid (AdA) serve as essential precursors for PUFA synthesis. Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and associated lipid droplets confer ferroptosis resistance by competitively suppressing PUFA biosynthesis [108]. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) has been shown to prevent lipid damage and combat ferroptosis [109]. The cystine/glutamate antiporter/glutathione/glutathione peroxidase 4 (Xc/GSH/GPX4) axis and ferroptosis suppressor protein 1/dihydroorotate dehydrogenase/coenzyme Q10 (FSP1/DHODH/CoQ10) axis of the system could neutralize peroxides via free radical trapping [110].

3.1.2 Ferroptosis of Sphingolipid Metabolism

A study had shown that glutamate-induced decrease in intracellular GSH could lead to activation of acid sphingophospholipase and upregulation of sphingosine levels, thereby inhibiting mitochondrial respiratory chain, promoting ROS generation, opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores, and ferroptosis [111]. As a pleiotropic gene, sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) could regulate various cell death pathways through stimulation and specific substrate targeting, such as the acid sphingophospholipase/sphingosine-mediated ferroptosis pathway, thereby exerting a protective effect. Another research has found the relationship between sphingolipids and ferroptosis, and acid sphingophospholipase mediated redox activation activated autophagic degradation of GPX4, ultimately leading to lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis [112].

3.1.3 Ferroptosis of Cholesterol Metabolism

A recent study [113] found that dysregulation of cholesterol homeostasis could lead to resistance to ferroptosis, thereby increasing the tumorigenicity and metastasis of cancer. Previous studies have shown that the precursor of cholesterol, 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC), has a higher redox activity and could resist ferroptosis by directly inhibiting lipid peroxidation [114,115]. B7 homolog 3 (B7H3) ablation disrupts cholesterol homeostasis through AKT/SREBP2 hyperactivation, depleting membrane polyunsaturated phospholipids and sensitizing HCC cells to ferroptosis [116]. Researchers found that high cholesterol could lead to the resistance of cancer cells to ferroptosis and increase their tumorigenicity and metastasis. During metastatic dissemination, cholesterol accumulation in migratory HCC cells suppresses phospholipid peroxidation by stabilizing membrane PUFAs, thereby conferring ferroptosis resistance absent in static populations. However, in the late stage of liver cancer, when extensive liver damage occurs, higher cholesterol may indicate better preservation of liver function. In this case, the study may conclude that the higher cholesterol could inhibit the occurrence and development of liver cancer. In addition, in diagnosed liver cancer, an increase in intracellular cholesterol may have harmful effects on a cell type (such as tumor cells), but may promote the immune surveillance function of immune cells, thereby exhibits an overall beneficial effect [117].

3.2 New Strategies for Treating HCC from the Perspective of Fatty Acid Metabolism

Research found that the lipid metabolism of HCC cells was downregulated by the ketogenic rate-limiting enzyme 3-hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA (HMGCS2), thereby increasing the synthesis of fatty acids [118]. HMGCS2-knockdown tumors exhibited accelerated growth under ketogenic diet (KD) conditions, concomitant with elevated lipogenic markers and tumor weight-lipid content correlation. This demonstrates that HMGCS2 suppression enhances hepatic de novo lipogenesis via ketogenesis perturbation, compromising KD-mediated oncosuppression. Mechanistically, HMGCS2 governs HCC proliferation/migration through apoptosis modulation, c-Myc/cyclin D1 axis, and EMT pathway regulation—operating in a β-hydroxybutyrate-dependent manner [119]. In HMGCS2-expressing HCC, KD upregulates HMGCS2 expression, amplifying ketogenesis to constrain tumor proliferation. Orlistat, as a FASN inhibitor, could regulate fat metabolism by inhibiting FA synthesis, reduce HCC resistance to sorafenib, and improve drug efficacy [120]. Fatty acid transporter-5 (FATP5/SLC27A5) orchestrates fatty acid trafficking while constraining HCC invasive-metastatic cascades and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Notably, synergistic targeting of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) and thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1) with sorafenib—using bromosulfophthalein and auranofin—potentiates therapeutic vulnerability in FATP5-deficient malignancies [121,122]. After using the fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) inhibitor etomoxir, the resistance of HCC to sorafenib significantly improved. Another FASN inhibitor, TVB3664, has limited efficacy as a single drug, but it significantly improves the efficacy of cabozantinib and sorafenib in the treatment of HCC [123].

3.3 New Strategy for Treating HCC from the Perspective of Sphingolipid Metabolism

Ultrasmall lipid nanoparticles (UsLNPs) engineered with phospholipid matrices and tumor-targeting peptides enable precision sorafenib delivery to murine neoplastic cells, eliciting potent therapeutic efficacy [124]. Sphingophospholipid metabolism critically governs HCC pathogenesis and chemoresistance. Sorafenib treatment potently upregulates sphingomyelin synthase 1 (SMS1) in HCC models, attenuating drug cytotoxicity. Consequently, SMS1 inhibitor D609 synergistically enhances sorafenib efficacy by suppressing rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (RAS) signaling [125]. S1P generation by SK2 promotes oncogenic survival. Synergy between sorafenib and SK2 inhibitor ABC294640 improves anti-tumor activity, whereas bavituximab targeting phosphatidylserine exerts dual anti-angiogenic and immunostimulatory effects [126]. Emerging evidence correlates acquired sorafenib resistance with profound phosphatidylcholine remodeling in tumor tissues. This suggests that phosphatidylcholine has the potential as a biomarker for sorafenib-resistant HCC [127].

3.4 New Strategy for Treating HCC from the Perspective of Cholesterol Metabolism

The norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor maprotiline could significantly reduce the phosphorylation level of SREBP2 through the ERK signaling pathway, reduce cholesterol biosynthesis, and thus inhibit tumor generation [128]. Beyond modulating sorafenib efficacy, cholesterol is functionally repurposed as a drug delivery vehicle. Recent studies demonstrate that polyethylene-cholesterol conjugates self-assemble into polymeric nanocarriers capable of encapsulating sorafenib and other hydrophobic agents [129]. Cholesterol dysregulation further contributes to lenvatinib resistance by remodeling cell surface lipid raft topology, which modulates ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1 (ABCB1) activity. This enhanced efflux machinery potentiates drug resistance through accelerated exocytosis [130]. Caspase-3 could regulate the cleavage of SREBP2, promote cholesterol synthesis, and activate the Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway, thereby increasing the resistance of liver cancer to Lenvatinib [131]. Statins exert anti-HCC effects primarily through cholesterol pathway modulation. By inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, they suppress mevalonate pathway flux—reducing cholesterol and dolichol biosynthesis—which dysregulates cellular processes (growth, differentiation, apoptosis) to constrain oncogenic progression [132]. Statins may block the lifecycle of HBV and HCV by inhibiting cholesterol synthesis and virus replication, which could potentially prevent their transmission and further liver damage [133]. Genkwadaphnin (GD), a diterpenoid from Daphne genkwa (Thymelaeaceae), suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma progression by inhibiting DHCR24. This enzyme blockade disrupts cholesterol biosynthesis and lipid raft integrity, ultimately impeding HCC cell growth and invasion [134]. Concomitant application of lovastatin—a cholesterol biosynthesis inhibitor—to DHCR24-overexpressing HCC cells confirmed cholesterol’s pivotal role in driving oncogenic growth and invasion. These findings substantiate cholesterol reduction as a viable therapeutic strategy for HCC intervention.

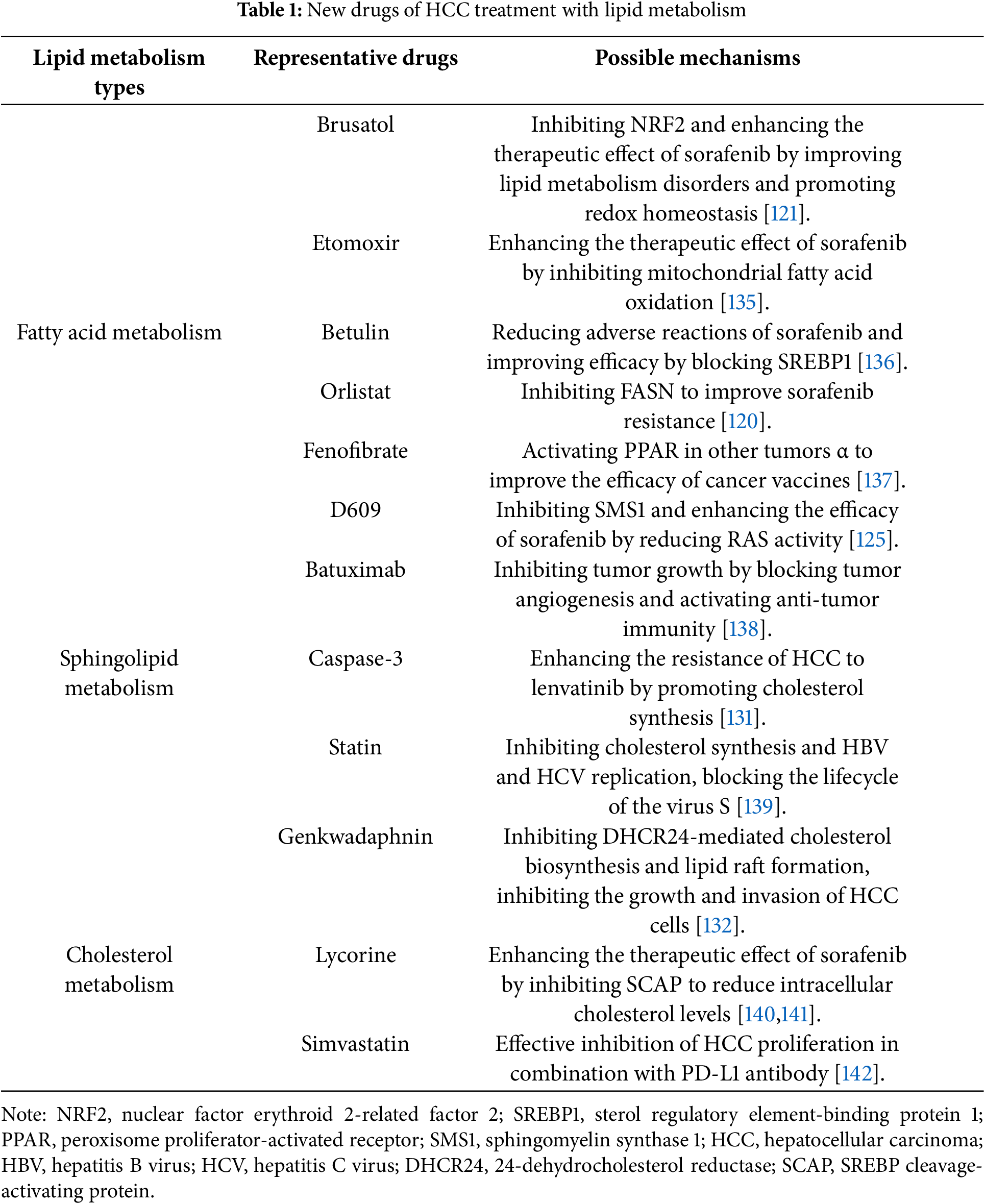

Targeting lipid metabolism in HCC cells is a promising anti-cancer strategy. Many new pathways and drugs have been developed to treat HCC, and clinical research is currently underway (Table 1)

Lipid metabolism critically sustains HCC progression by supplying bioenergetic and biosynthetic substrates for neoplastic proliferation, invasion, and metastatic dissemination. As the central hub of lipid homeostasis, the liver manifests HCC-specific lipidomic signatures that unveil pathogenic mechanisms. Delineating such metabolic reprogramming uncovers actionable therapeutic targets and informs clinical strategies. Notwithstanding therapeutic advances, persistent obstacles include dose-limiting toxicities requiring treatment de-escalation, alongside acquired resistance rooted in tumor heterogeneity and clonal evolution. Confronting these challenges necessitates developing low-toxicity, high-efficacy modalities targeting metabolic vulnerabilities.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This paper was funded by grants from Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (2022JJA140639, 2022JJA140776), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82060662, 82560721) and Guangxi University Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program Project (S202410601137, S202510601106).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows. Study conception and design: Yuanyuan Yang and Jian Tu; image processing: Peipei Zhao, Hepu Chen, Lyly Sreang and Xu Liu; literature search: Zhigang Zhou, Yixuan Tu, Peipei Zhao and Yujia Zhou; draft manuscript preparation: Yuanyuan Yang, Zhigang Zhou and Jian Tu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| ACSL4 | acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 |

| MUFA | monounsaturated fatty acid |

| ACC | acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

| ACLY | ATP citrate lyase |

| CPT1 | Carnitine Palmitoyl Transferase 1 |

| FASN | fatty acid synthase |

| MCAD | Medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase |

| LCAD | long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase |

| CREBP | cAMP-response element binding protein |

| LPL | Lipoprotein Lipase |

| ACSM5 | acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 5 |

| SPT | serine palmitoyl transferase |

| KSR | 3-Ketosphinganine Reductase |

| CerS | ceramide synthase |

| DES | dihydroceramide desaturase |

| SMPD | Sphingomyelin Phosphodiesterase |

| SMS | Sphingomyelin synthase |

| SK | Sphingosine kinase |

| SIPP | Sphingosine phosphatase |

References

1. Lin XT, Luo YD, Mao C, Gong Y, Hou Y, Zhang LD, et al. Integrated ubiquitomics characterization of hepatocellular carcinomas. Hepatology. 2025;82(1):42–58. doi:10.1097/hep.0000000000001096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Jiang Y, Yu Y, Pan Z, Glandorff C, Sun M. Ferroptosis: a new hunter of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Discov. 2024;10(1):136. doi:10.1038/s41420-024-01863-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. van der Meeren PE, de Wilde RF, Sprengers D, IJzermans JNM. Benefit and harm of waiting time in liver transplantation for HCC. Hepatology. 2025;82(1):212–31. doi:10.1097/hep.0000000000000668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Paul B, Lewinska M, Andersen JB. Lipid alterations in chronic liver disease and liver cancer. JHEP Rep. 2022;4(6):100479. doi:10.1016/j.jhepr.2022.100479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Wu K, Lin F. Lipid metabolism as a potential target of liver cancer. J Hepatocell Carcin. 2024;11:327–46. doi:10.2147/jhc.s450423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Liu Z, Hu Q, Luo Q, Zhang G, Yang W, Cao K, et al. NUP37 accumulation mediated by TRIM28 enhances lipid synthesis to accelerate HCC progression. Oncogene. 2024;43(44):3255–67. doi:10.1038/s41388-024-03167-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Pan Y, Li Y, Fan H, Cui H, Chen Z, Wang Y, et al. Roles of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;177(Suppl 19):117089. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2024.117089. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Cao LQ, Xie Y, Fleishman JS, Liu X, Chen ZS. Hepatocellular carcinoma and lipid metabolism: novel targets and therapeutic strategies. Cancer Lett. 2024;597(9):217061. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2024.217061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Liu Q, Zhang X, Qi J, Tian X, Dovjak E, Zhang J, et al. Comprehensive profiling of lipid metabolic reprogramming expands precision medicine for HCC. Hepatology. 2025;81(4):1164–80. doi:10.1097/hep.0000000000000962. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Vasseur S, Guillaumond F. Lipids in cancer: a global view of the contribution of lipid pathways to metastatic formation and treatment resistance. Oncogenesis. 2022;11(1):46. doi:10.1038/s41389-022-00420-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ning Z, Guo X, Liu X, Lu C, Wang A, Wang X, et al. USP22 regulates lipidome accumulation by stabilizing PPARγ in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):2187. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-29846-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Weng L, Tang WS, Wang X, Gong Y, Liu C, Hong NN, et al. Surplus fatty acid synthesis increases oxidative stress in adipocytes and induces lipodystrophy. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):133. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-44393-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Wang XY, Liao Y, Wang RQ, Lu YT, Wang YZ, Xin YQ, et al. Tribbles Pseudokinase 3 converts sorafenib therapy to neutrophil-mediated lung metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv Sci. 2025;12(13):e2413682. [Google Scholar]

14. Musso G, Saba F, Cassader M, Gambino R. Lipidomics in pathogenesis, progression and treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASHrecent advances. Prog Lipid Res. 2023;91(4):101238. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2023.101238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ye J, Wu S, Quan Q, Ye F, Zhang J, Song C, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 promotes triple-negative breast cancer progression via regulating fatty acid metabolism through the AKT/RYR2 signaling. Cancer Med. 2024;13(23):e70439. doi:10.1002/cam4.70439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Guo Y, Shi R, Xu Y, Cho WC, Yang J, Choi YY, et al. Bioinformatics-based analysis of fatty acid metabolic reprogramming in hepatocellular carcinoma: cellular heterogeneity, therapeutic targets, and drug discovery. Acta Materia Medica. 2024;3(4):477–508. doi:10.15212/amm-2024-0057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Qi L, Tan Y, Zhou Y, Dong Y, Yang X, Chang S, et al. Proteogenomic Identification and Analysis of KIF5B as a Prognostic Signature for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Curr Gene Ther. 2024;25(4):532–545. doi:10.2174/0115665232308821240826075513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wang S, Yang XX, Li TJ, Zhao L, Bao YR, Meng XS. Analysis of the absorbed constituents and mechanism of liquidambaris fructus extract on hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:999935. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.999935. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Qian L, Zhu Y, Deng C, Liang Z, Chen J, Chen Y, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 (PGC-1) family in physiological and pathophysiological process and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):50. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01756-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Li J, Lv M, Yuan Z, Ge J, Geng T, Gong D, et al. PGC-1α Promotes mitochondrial biosynthesis and energy metabolism of goose fatty liver. Poult Sci. 2025;104(1):104617. doi:10.1016/j.psj.2024.104617. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Yao W, Fan M, Qian H, Li Y, Wang L. Quinoa polyphenol extract alleviates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease via inhibiting lipid accumulation, inflammation and oxidative stress. Nutrients. 2024;16(14):2276. doi:10.3390/nu16142276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Leahy C, Osborne N, Shirota L, Rote P, Lee YK, Song BJ, et al. The fatty acid omega hydroxylase genes (CYP4 family) in the progression of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLDan RNA sequence database analysis and review. Biochem Pharmacol. 2024;228(11):116241. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2024.116241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Yahoo N, Dudek M, Knolle P, Heikenwälder M. Role of immune responses in the development of NAFLD-associated liver cancer and prospects for therapeutic modulation. J Hepatol. 2023;79(2):538–51. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2023.02.033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Chang W, Wang J, You Y, Wang H, Xu S, Vulcano S, et al. Triptolide reduces neoplastic progression in hepatocellular carcinoma by downregulating the lipid lipase signaling pathway. Cancers. 2024;16(3):550. doi:10.3390/cancers16030550. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Wang Q, Zhang W, Liu Q, Zhang X, Lv N, Ye L, et al. A mutant of hepatitis B virus X protein (HBxDelta127) promotes cell growth through a positive feedback loop involving 5-lipoxygenase and fatty acid synthase. Neoplasia. 2010;12(2):103–15. doi:10.1593/neo.91298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Li Y, Ming R, Zhang T, Gao Z, Wang L, Yang Y, et al. TCTN1 induces fatty acid oxidation to promote melanoma metastasis. Cancer Res. 2025;85(1):84–100. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-24-0158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Yi J, Li B, Yin X, Liu L, Song C, Zhao Y, et al. CircMYBL2 facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma progression by regulating E2F1 expression. Oncol Res 2024;32(6):1129–39. doi:10.32604/or.2024.047524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Jeon YG, Kim YY, Lee G, Kim JB. Physiological and pathological roles of lipogenesis. Nat Metabol. 2023;5(5):735–59. doi:10.1038/s42255-023-00786-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. de Korte D, Hoekstra M. Protein arginine methyltransferase 1: a multi-purpose player in the development of cancer and metabolic disease. Biomolecules. 2025;15(2):185. doi:10.3390/biom15020185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Kim E, Rahmawati L, Aziz N, Kim HG, Kim JH, Kim KH, et al. Protection of c-Fos from autophagic degradation by PRMT1-mediated methylation fosters gastric tumorigenesis. Inte J Bio Sci. 2023;19(12):3640–60. doi:10.7150/ijbs.85126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Yan J, Li KX, Yu L, Yuan HY, Zhao ZM, Lin J, et al. PRMT1 integrates immune microenvironment and fatty acid metabolism response in progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carci. 2024;11:15–27. doi:10.2147/jhc.s443130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wang B, Zhang H, Chen YF, Hu LQ, Tian YY, Tong HW, et al. Acyl-CoA thioesterase 9 promotes tumour growth and metastasis through reprogramming of fatty acid metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int Off J Int Assoc Study Liver. 2022;42(11):2548–61. doi:10.1111/liv.15409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Zhu L, Zhou KX, Ma MZ, Yao LL, Zhang YL, Li H, et al. Tuftelin 1 facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma progression through regulation of lipogenesis and focal adhesion maturation. J Immunol Res. 2022;2022(12):1590717–14. doi:10.1155/2022/1590717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Huang W, Zhong L, Shi Y, Ma Q, Yang X, Zhang H, et al. An anti-CD147 antibody-drug conjugate Mehozumab-DM1 is efficacious against hepatocellular carcinoma in cynomolgus monkey. Adv Sci. 2025;12(15):e2410438. [Google Scholar]

35. Gong Z, Zhu J, Chen J, Feng F, Zhang H, Zhang Z, et al. CircRREB1 mediates lipid metabolism related senescent phenotypes in chondrocytes through FASN post-translational modifications. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):5242. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-40975-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zhang T, Zhang Y, Liu J, Ma Y, Ye Q, Yan X, et al. MicroRNA-377-3p inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma growth and metastasis through negative regulation of CPT1C-mediated fatty acid oxidation. Cancer Metabol. 2022;10(1):2. doi:10.1186/s40170-021-00276-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Wu J, Luo J, He Q, Xia Y, Tian H, Zhu L, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid alters lipid metabolism processes via H3K9ac epigenetic modification in dairy goat. J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71(22):8527–39. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.3c01606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Liu S, Zhang P, Wu Y, Zhou H, Wu H, Jin Y, et al. SLC25A19 is a novel prognostic biomarker related to immune invasion and ferroptosis in HCC. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;136(6):112367. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2024.112367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Yang L, Pham K, Xi Y, Jiang S, Robertson KD, Liu C. Acyl-CoA synthetase medium-chain family member 5-Mediated fatty acid metabolism dysregulation promotes the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2024;194(10):1951–66. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2024.07.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Gao Y, Li J, Ma M, Fu W, Ma L, Sui Y, et al. Prognostic prediction of m6A and ferroptosis-associated lncRNAs in liver hepatocellular carcinoma. J Transl Internal Med. 2024;12(5):526–9. doi:10.1515/jtim-2024-0023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Kazmirczak F, Vogel NT, Prisco SZ, Patterson MT, Annis J, Moon RT, et al. Ferroptosis-mediated inflammation promotes pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2024;135(11):1067–83. doi:10.1161/circresaha.123.324138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Wright T, Turnis ME, Grace CR, Li X, Brakefield LA, Wang YD, et al. Anti-apoptotic MCL-1 promotes long-chain fatty acid oxidation through interaction with ACSL1. Mol Cell. 2024;84(7):1338–53. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2024.02.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Lin Z, Long F, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Yang M, Tang D. The lipid basis of cell death and autophagy. Autophagy. 2024;20(3):469–88. doi:10.1080/15548627.2023.2259732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Tan S, Sun X, Dong H, Wang M, Yao L, Wang M, et al. ACSL3 regulates breast cancer progression via lipid metabolism reprogramming and the YES1/YAP axis. Cancer Biol Med. 2024;21(7):606–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

45. Wang Q, Huang Y, Zhu Y, Zhang W, Wang B, Du X, et al. The m6A methyltransferase METTL5 promotes neutrophil extracellular trap network release to regulate hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Cancer Med. 2024;13(7):e7165. doi:10.1002/cam4.7165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Wang L, Peng JL. METTL5 serves as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma by influencing the immune microenvironment. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):10755. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-37807-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Jian H, Li R, Huang X, Li J, Li Y, Ma J, et al. Branched-chain amino acids alleviate NAFLD via inhibiting de novo lipogenesis and activating fatty acid β-oxidation in laying hens. Redox Biol. 2024;77(11):103385. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2024.103385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Chang BY, Bae JH, Lim CY, Kim YH, Kim TY, Kim SY. Tricin-enriched Zizania latifolia ameliorates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through AMPK-dependent pathways. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2023;32(14):2117–29. doi:10.1007/s10068-023-01311-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Wu D, Yang Y, Hou Y, Zhao Z, Liang N, Yuan P, et al. Increased mitochondrial fission drives the reprogramming of fatty acid metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through suppression of Sirtuin 1. Cancer Commun. 2022;42(1):37–55. doi:10.1002/cac2.12247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Terry AR, Nogueira V, Rho H, Ramakrishnan G, Li J, Kang S, et al. CD36 maintains lipid homeostasis via selective uptake of monounsaturated fatty acids during matrix detachment and tumor progression. Cell Metab. 2023;35(11):2060–76. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2023.09.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Ding Z, Pan Y, Shang T, Jiang T, Lin Y, Yang C, et al. URI alleviates tyrosine kinase inhibitors-induced ferroptosis by reprogramming lipid metabolism in p53 wild-type liver cancers. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):6269. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-41852-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Zhang CL, Zhao CY, Dong JM, Du CP, Wang BS, Wang CY, et al. CD147-high extracellular vesicles promote gastric cancer metastasis via VEGF/AKT/eNOS and AKT/mTOR pathways. Oncogenesis. 2025;14(1):21. doi:10.1038/s41389-025-00564-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Li J, Huang Q, Long X, Zhang J, Huang X, Aa J, et al. CD147 reprograms fatty acid metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through Akt/mTOR/SREBP1c and P38/PPARα pathways. J Hepatol. 2015;63(6):1378–89. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2015.07.039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Zhang G, Yang R, Wang B, Yan Q, Zhao P, Zhang J, et al. TRIP13 regulates progression of gastric cancer through stabilising the expression of DDX21. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(8):622. doi:10.1038/s41419-024-07012-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Zhang X, Zeng B, Zhu H, Ma R, Yuan P, Chen Z, et al. Role of glycosphingolipid biosynthesis coregulators in malignant progression of thymoma. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19(14):4442–56. doi:10.7150/ijbs.83468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Jiang X, Ge X, Huang Y, Xie F, Chen C, Wang Z, et al. Drug resistance in TKI therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: mechanisms and strategies. Cancer Lett. 2025;613:217472. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2025.217472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Zeng J, Zhao D, Y-l Tai, Jiang X, Su L, Wang X, et al. Dysregulated sphingolipid metabolism contributes to NASH-HCC disease progression. Physiology. 2023;38(S1):5734514. [Google Scholar]

58. Nojima H, Shimizu H, Murakami T, Shuto K, Koda K. Critical roles of the sphingolipid metabolic pathway in liver regeneration, hepatocellular carcinoma progression and therapy. Cancers. 2024;16(5):850. doi:10.3390/cancers16050850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Meulewaeter S, Aernout I, Deprez J, Engelen Y, De Velder M, Franceschini L, et al. Alpha-galactosylceramide improves the potency of mRNA LNP vaccines against cancer and intracellular bacteria. J Control Release. 2024;370:379–91. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2024.04.052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Gamal M, Tallima H, Azzazy HME, Abdelnaser A. Impact of HepG2 cells glutathione depletion on neutral sphingomyelinases mRNA levels and activity. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2023;45(6):5005–17. doi:10.3390/cimb45060318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Giussani P, Brioschi L, Gjoni E, Riccitelli E, Viani P. Sphingosine 1-phosphate stimulates ER to golgi ceramide traffic to promote survival in T98G glioma cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(15):8270. doi:10.3390/ijms25158270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Zhakupova A, Zeinolla A, Kokabi K, Sergazy S, Aljofan M. Drug resistance: the role of sphingolipid metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(8):3716. doi:10.3390/ijms26083716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Green CD, Brown RDR, Uranbileg B, Weigel C, Saha S, Kurano M, et al. Sphingosine kinase 2 and p62 regulation are determinants of sexual dimorphism in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Metab. 2024;86(3):101971. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2024.101971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Li L, Lu Y, Du Z, Fang M, Wei Y, Zhang W, et al. Integrated untargeted/targeted metabolomics identifies a putative oxylipin signature in patients with atrial fibrillation and coronary heart disease. J Transl Internal Med. 2024;12(5):495–509. doi:10.1515/jtim-2023-0141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Guan J, Wu F, Wu S, Ren Y, Wang J, Zhu H. FTY720 alleviates D-GalN/LPS-induced acute liver failure by regulating the JNK/MAPK pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;157(10201):114726. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2025.114726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Zhang J, Ge Q, Du T, Kuang Y, Fan Z, Jia X, et al. SPHK1/S1PR1/PPAR-α axis restores TJs between uroepithelium providing new ideas for IC/BPS treatment. Life Sci Alliance. 2024;8(2):e202402957. doi:10.26508/lsa.202402957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Jennemann R, Volz M, Frias-Soler RC, Schulze A, Richter K, Kaden S, et al. Glucosylceramide synthase inhibition in combination with aripiprazole sensitizes hepatocellular cancer cells to sorafenib and doxorubicin. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;26(1):304. doi:10.3390/ijms26010304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Wu Q, He C, Huang W, Song C, Hao X, Zeng Q, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease influences blood pressure components, lipid profile and cardiovascular diseases: evidence from a Mendelian randomization study. J Transl Internal Med. 2024;12(5):510–25. doi:10.1515/jtim-2024-0017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Guo X, Wang F, Li X, Luo Q, Liu B, Yuan J. Mitochondrial cholesterol metabolism related gene model predicts prognosis and treatment response in hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Cancer Res. 2024;13(12):6623–44. doi:10.21037/tcr-24-1153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Endo-Umeda K, Makishima M. Exploring the roles of liver x receptors in lipid metabolism and immunity in atherosclerosis. Biomolecules. 2025;15(4):579. doi:10.3390/biom15040579. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Piccinin E, Arconzo M, Pasculli E, Tricase AF, Cultrera S, Bertrand-Michel J, et al. Pivotal role of intestinal cholesterol and nuclear receptor LXR in metabolic liver steatohepatitis and hepatocarcinoma. Cell Biosci. 2024 Jun 1;14(1):69. doi:10.1186/s13578-024-01248-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Carbó JM, León TE, Font-Díaz J, De la Rosa JV, Castrillo A, Picard FR, et al. Pharmacologic activation of LXR Alters the expression profile of tumor-associated macrophages and the abundance of regulatory T cells in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2021;81(4):968–85. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-19-3360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Wang YX, Liu YQ, Yuan M, Zhou ZG, Tu J. Liver X receptor α: the common platform for cholesterol transport and cance. Acta Medicinae Sinica. 2023;36(3):8–13. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

74. He J, Yang T, He W, Jiang S, Zhong D, Xu Z. Liver X receptor inhibits the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via regulating HULC/miR-134-5p/FOXM1 axis. Cell Sig. 2020;74:109720. doi:10.21203/rs.2.22627/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Ke M, Zhu H, Lin Y, Zhang Y, Tang T, Xie Y, et al. Actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 1B promotes ovarian cancer progression by regulating the AKT/PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway. J Trans Internal Med. 2024;12(4):406–23. doi:10.2478/jtim-2024-0025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Zhou F, Sun X. Cholesterol metabolism: a double-edged sword in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:762828. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.762828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Feng XC, Liu FC, Chen WY, Du J, Liu H. Lipid metabolism of hepatocellular carcinoma impacts targeted therapy and immunotherapy. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2023;15(4):617–31. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v15.i4.617. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Kong Y, Wu M, Wan X, Sun M, Zhang Y, Wu Z, et al. Lipophagy-mediated cholesterol synthesis inhibition is required for the survival of hepatocellular carcinoma under glutamine deprivation. Redox Biol. 2023;63:102732. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2023.102732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Khodadadi E, Khodadadi E, Chaturvedi P, Moradi M. Comprehensive insights into the cholesterol-mediated modulation of membrane function through molecular dynamics simulations. arXiv:2504.05564v1. 2025. [Google Scholar]

80. Zou Y, Zhang H, Liu F, Chen ZS, Tang H. Intratumoral microbiota in orchestrating cancer immunotherapy response. J Transl Internal Med. 2024;12(6):540–42. doi:10.1515/jtim-2024-0038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Feng T, Li S, Zhao G, Li Q, Yuan H, Zhang J, et al. DDX39B facilitates the malignant progression of hepatocellular carcinoma via activation of SREBP1-mediated de novo lipid synthesis. Cell Oncol. 2023;46(5):1235–52. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-2171990/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Rashid MM, Varghese RS, Ding Y, Ressom HW. Biomarker discovery for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis using untargeted metabolomics and lipidomics studies. Metabolites. 2023;13(10):1047. doi:10.3390/metabo13101047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Dong M, Cui Q, Li Y, Li Y, Chang Q, Bai R, et al. Ursolic acid suppresses fatty liver-associated hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating lipid metabolism. Food Biosci. 2024;60(7):104460. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2024.104460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Wang YY, Yang WX, Cai JY, Wang FF, You CG. Comprehensive molecular characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma based on multi-omics analysis. BMC Cancer. 2025;25(1):573. doi:10.1186/s12885-025-13952-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Bi Y, Ying X, Chen W, Wu J, Kong C, Hu W, et al. Glycerophospholipid-driven lipid metabolic reprogramming as a common key mechanism in the progression of human primary hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Lipids Health Dis. 2024;23(1):326. doi:10.1186/s12944-024-02298-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Zhang F, Wu J, Zhang L, Zhang J, Yang R. Alterations in serum metabolic profiles of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients after radiofrequency ablation therapy. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2024;243:116073. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2024.116073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Wen Y, Li Y, Liu T, Huang L, Yao L, Deng D, et al. Chaiqin chengqi decoction treatment mitigates hypertriglyceridemia-associated acute pancreatitis by modulating liver-mediated glycerophospholipid metabolism. Phytomedicine. 2024;134:155968. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2024.155968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Qin LN, Zhang H, Li QQ, Wu T, Cheng SB, Wang KW, et al. Vitamin D binding protein (VDBP) hijacks twist1 to inhibit vasculogenic mimicry in hepatocellular carcinoma. Theranostics. 2024;14(1):436–50. doi:10.7150/thno.90322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. El-Masry AS, Medhat AM, El-Bendary M, Mohamed RH. Vitamin D receptor rs3782905 and vitamin D binding protein rs7041 polymorphisms are associated with hepatocellular carcinoma susceptibility in cirrhotic HCV patients. BMC Med Genomics. 2023;16(1):319. doi:10.1186/s12920-023-01749-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Tourkochristou E, Mouzaki A, Triantos C. Gene polymorphisms and Biological Effects of Vitamin D Receptor on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Development and Progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(9):8288. doi:10.3390/ijms24098288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Ravaioli F, Pivetti A, Di Marco L, Chrysanthi C, Frassanito G, Pambianco M, et al. Role of Vitamin D in liver disease and complications of advanced chronic liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(16):9016. doi:10.3390/ijms23169016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Ferrín G, Guerrero M, Amado V, Rodríguez-Perálvarez M, De la Mata M. Activation of mTOR signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4):1266. doi:10.3390/ijms21041266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Adelani IB, Rotimi OA, Maduagwu EN, Rotimi SO. Vitamin D: possible therapeutic roles in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:642653. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.642653. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Inoue FSR, Concato-Lopes VM, Bortoleti BTDS, Cruz EMS, Detoni MB, Tomiotto-Pellissier F, et al. 3,3’,5,5’-Tetramethoxybiphenyl-4,4’-diol exerts a cytotoxic effect on hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines by inducing morphological and ultrastructural alterations, G2/M cell cycle arrest and death by apoptosis via CDK1 interaction. Biomed Pharmacother. 2025;187:118082. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2025.118177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Pezzoli A, Abenavoli L, Scarcella M, Rasetti C, Svegliati Baroni G, Tack J, et al. The management of cardiometabolic Risk in MAFLD: therapeutic strategies to modulate deranged metabolism and cholesterol levels. Medicina. 2025;61(3):387. doi:10.3390/medicina61030387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Yang X, Yang C, Zhang S, Geng H, Zhu AX, Bernards R, et al. Precision treatment in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2024;42(2):180–97. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2024.01.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Cioli E, Gervaso L, Fazio N. Systemic therapies for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: which gaps should we try to fill? JCO Oncol Pract. 2025;20:OP2500253. doi:10.1200/op-25-00253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Xie E, Yeo YH, Scheiner B, Zhang Y, Hiraoka A, Tantai X, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for child-pugh class B advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(10):1423–31. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.3284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Yalikun K, Li Z, Zhang J, Chang Z, Li M, Sun Z, et al. Hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy combined with camrelizumab and apatinib as conversion therapy for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a single-arm exploratory trial. BMC Cancer. 2025;25(1):838–2395. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.am2024-2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Lyu Y, Li Q, Xie S, Zhao Z, Ma L, Wu Z, et al. Synergistic ultrasound-activable artificial enzyme and precision gene therapy to suppress redox homeostasis and malignant phenotypes for controllably combating hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Chem Soc. 2025;147(3):2350–68. doi:10.1021/jacs.4c10997. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Jin X, Huang CX, Tian Y. The multifaceted perspectives on the regulation of lncRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma ferroptosis: from bench-to-bedside. Clin Exp Med. 2024;24(1):146. doi:10.1007/s10238-024-01418-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Lv X, Lan G, Zhu L, Guo Q. Breaking the barriers of therapy resistance: harnessing ferroptosis for effective hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. J Hepatocell Carci. 2024;11:1265–78. doi:10.2147/jhc.s469449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Li D, Li Y. The interaction between ferroptosis and lipid metabolism in cancer. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):108. [Google Scholar]

104. Li JY, Feng YH, Li YX, He PY, Zhou QY, Tian YP, et al. Ferritinophagy: a novel insight into the double-edged sword in ferritinophagy-ferroptosis axis and human diseases. Cell Prolif. 2024;57(7):e13621. doi:10.1111/cpr.13621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Sadagopan NS, Gomez M, Tripathi S, Billingham LK, DeLay SL, Cady MA, et al. NOTCH3 drives fatty acid oxidation and ferroptosis resistance in aggressive meningiomas. Res Square. 2025;rs.3:6779386. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-6779386/v1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Ma X, Sun Z, Chen H, Cao L, Zhao S, Fan L, et al. 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid suppresses Lewis lung cancer growth through protecting immune cells from ferroptosis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2024;93(6):575–85. doi:10.1007/s00280-024-04639-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Kudo K, Yanagiya R, Hasegawa M, Carreras J, Miki Y, Nakayama S, et al. Unique lipid composition maintained by extracellular blockade leads to prooncogenicity. Cell Death Discov. 2024;10(1):221. doi:10.1038/s41420-024-01971-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Mortensen MS, Ruiz J, Watts JL. Polyunsaturated fatty acids drive lipid peroxidation during ferroptosis. Cells. 2023;12(5):804. doi:10.3390/cells12050804. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Yang J, Lee Y, Hwang CS. The ubiquitin-proteasome system links NADPH metabolism to ferroptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2023;33(12):1088–103. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2023.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Bai C, Hua J, Meng D, Xu Y, Zhong B, Liu M, et al. Glutaminase-1 mediated glutaminolysis to glutathione synthesis maintains redox homeostasis and modulates ferroptosis sensitivity in cancer cells. Cell Prolif. 2025;144:e70036. doi:10.1111/cpr.70036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Xu T, Ma Q, Zhang C, He X, Wang Q, Wu Y, et al. A novel nanomedicine for osteosarcoma treatment: triggering ferroptosis through GSH depletion and inhibition for enhanced synergistic PDT/PTT therapy. J Nanobiotechnol. 2025;23(1):323. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-5440173/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

112. Valentini N, Requejo Cier CJ, Lamarche C. Highlights of 2024: tregs immunometabolism and how to counter inflammatory niches. Immunol Cell Biol. 2025;103(6):504–8. doi:10.1111/imcb.70027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Maniscalchi A, Benzi Juncos ON, Conde MA, Funk MI, Fermento ME, Facchinetti MM, et al. New insights on neurodegeneration triggered by iron accumulation: intersections with neutral lipid metabolism, ferroptosis, and motor impairment. Redox Biol. 2024;71:103074. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2024.103074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Sun Q, Liu D, Cui W, Cheng H, Huang L, Zhang R, et al. Cholesterol mediated ferroptosis suppression reveals essential roles of Coenzyme Q and squalene. Communications Biology. 2023;6(1):1108. doi:10.1038/s42003-023-05477-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Zheng J, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: when metabolism meets cell death. Physiol Rev. 2025;105(2):651–706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

116. Jin H, Zhu M, Zhang D, Liu X, Guo Y, Xia L, et al. B7H3 increases ferroptosis resistance by inhibiting cholesterol metabolism in colorectal cancer. Canc Sci. 2023;114(11):4225–36. doi:10.1111/cas.15944. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Peng L, Yan Q, Chen Z, Hu Y, Sun Y, Miao Y, et al. Research progress on the role of cholesterol in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Pharmacol. 2023;938(38):175410. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2022.175410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Li SL, Zhou H, Liu J, Yang J, Jiang L, Yuan HM, et al. Restoration of HMGCS2-mediated ketogenesis alleviates tacrolimus-induced hepatic lipid metabolism disorder. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2024;45(9):1898–911. doi:10.1038/s41401-024-01300-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Suresh VV, Sivaprakasam S, Bhutia YD, Prasad PD, Thangaraju M, Ganapathy V. Not just an alternative energy source: diverse biological functions of ketone bodies and relevance of HMGCS2 to health and disease. Biomolecules. 2025;15(4):580. doi:10.3390/biom15040580. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Huang J, Tsang WY, Fang XN, Zhang Y, Luo J, Gong LQ, et al. FASN inhibition decreases MHC-I degradation and synergizes with PD-L1 checkpoint blockade in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2024;84(6):855–71. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-23-0966. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Xu FL, Wu XH, Chen C, Wang K, Huang LY, Xia J, et al. SLC27A5 promotes sorafenib-induced ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma by downregulating glutathione reductase. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(1):22. doi:10.1038/s41419-023-05558-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Hsieh MS, Ling HH, Setiawan SA, Hardianti MS, Fong IH, Yeh CT, et al. Therapeutic targeting of thioredoxin reductase 1 causes ferroptosis while potentiating anti-PD-1 efficacy in head and neck cancer. Chem Biol Interact. 2024;395(8):111004. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2024.111004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Wang H, Zhou Y, Xu H, Wang X, Zhang Y, Shang R, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of FASN inhibition in preclinical models of HCC. Hepatology. 2022;76(4):951–66. doi:10.1002/hep.32359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Younis MA, Khalil IA, Elewa YHA, Kon Y, Harashima H. Ultra-small lipid nanoparticles encapsulating sorafenib and midkine-siRNA selectively-eradicate sorafenib-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma in vivo. J Control Release. 2021;331:335–49. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.01.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Lu H, Zhou L, Zuo H, Le W, Hu J, Zhang T, et al. Overriding sorafenib resistance via blocking lipid metabolism and Ras by sphingomyelin synthase 1 inhibition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Canc Chemother Pharmacol. 2021;87(2):217–28. doi:10.1007/s00280-020-04199-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. Cieniewicz B, Bhatta A, Torabi D, Baichoo P, Saxton M, Arballo A, et al. Chimeric TIM-4 receptor-modified T cells targeting phosphatidylserine mediates both cytotoxic anti-tumor responses and phagocytic uptake of tumor-associated antigen for T cell cross-presentation. Mol Ther. 2023;31(7):2132–53. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.05.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Li Z, Liao X, Hu Y, Li M, Tang M, Zhang S, et al. SLC27A4-mediated selective uptake of mono-unsaturated fatty acids promotes ferroptosis defense in hepatocellular carcinoma. Free Radic Biol Med. 2023;201:41–54. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2023.03.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Benatzy Y, Palmer MA, Lütjohann D, et al. ALOX15B controls macrophage cholesterol homeostasis via lipid peroxidation, ERK1/2 and SREBP2. Redox Biol. 2024;72:103149. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2024.103149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]