Open Access

Open Access

COMMENTARY

CD47-Targeted Therapy in Cancer Immunotherapy: At a Crossroads of Promise and Challenge

1 Department of Hematology, Puyang Oilfield General Hospital Affiliated to Henan Medical University, Puyang, 457001, China

2 Puyang Cell Therapy Engineering Technology Research Center, Puyang, 457001, China

3 China Medical University-the Queen’s University of Belfast Joint College, Shenyang, 110112, China

4 Department of Hematology and Central Hematology Laboratory, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, Bern, 3012, Switzerland

5 Department of Internal Medicine, Sanford School of Medicine, University of South Dakota, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Sioux Falls, SD 57104, USA

6 Department of Medicine, Sanford Stem Cell Institute, Moores Cancer Center, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, San Diego, CA 92093, USA

* Corresponding Author: Wenxue Ma. Email:

Oncology Research 2025, 33(11), 3375-3385. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.071708

Received 11 August 2025; Accepted 22 September 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

Cluster of differentiation 47 (CD47), an immune checkpoint commonly referred to as the “don’t eat me” signal, plays a pivotal role in tumor immune evasion by inhibiting phagocytosis through interaction with signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) on macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs). Although early enthusiasm drove broad clinical development, recent discontinuations of major CD47-targeted programs have prompted re-evaluation of its therapeutic potential. The purpose of this commentary is to contextualize the setbacks observed with first-generation CD47 inhibitors and to highlight strategies aimed at overcoming their limitations. Clinical challenges, including anemia, thrombocytopenia, suboptimal pharmacokinetics, and limited single-agent efficacy, underscore the need to develop safer, more selective approaches. Emerging next-generation strategies, such as SIRPα-directed agents, bispecific antibodies, and conditionally active therapeutics, are designed to enhance safety and tumor selectivity and reduce systemic toxicity. In addition, spatial profiling and biomarker-driven patient selection are advancing toward guiding rational therapeutic combinations, including with “eat-me” signals (e.g., calreticulin [CALR]) or DNA damage response therapies (e.g., poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase [PARP] inhibitors). Rather than signaling failure, these developments underscore the need for precision, context-specific applications, and adaptive trial designs to realize the durable therapeutic promise of CD47 blockade in cancer immunotherapy.Keywords

The immune checkpoint molecule cluster of differentiation 47 (CD47), often described as the “don’t eat me” signal, has gained increasing attention for its role in promoting tumor immune evasion [1,2]. CD47 is broadly expressed on normal cells but is frequently upregulated in cancer, including hematologic malignancies and solid tumors, where it engages signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) on macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) [3,4]. This interaction transmits a potent anti-phagocytic signal that inhibits the clearance of tumor cells, allowing them to persist despite immunologic recognition [5].

Given its upstream role in immune regulation, CD47 has emerged as a promising therapeutic target with the potential to bridge innate and adaptive immunity [6]. This is especially relevant for immunologically “cold” tumors that lack sufficient T-cell infiltration and respond poorly to programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) blockade [7].

Despite this strong rationale, clinical translation has been more complex than anticipated. However, clinical translation has been hampered by on-target/off-tumor toxicities (notably anemia and thrombocytopenia), suboptimal pharmacokinetics, and modest single-agent efficacy, which together have tempered initial enthusiasm [8]. To address these barriers, several next-generation strategies are under active investigation. SIRPα-targeted agents seek to bypass direct CD47 engagement and may reduce hematologic toxicity [9]. Bispecific antibodies pair CD47 blockade with tumor-restricted antigens (e.g., CD20, EpCAM) to improve selectivity, while conditionally active therapeutics are engineered to activate preferentially within the tumor microenvironment, thereby widening the therapeutic index and minimizing systemic exposure [10]. Together, these innovations represent a shift toward more clinically translatable approaches that address the limitations of first-generation CD47 inhibitors [11].

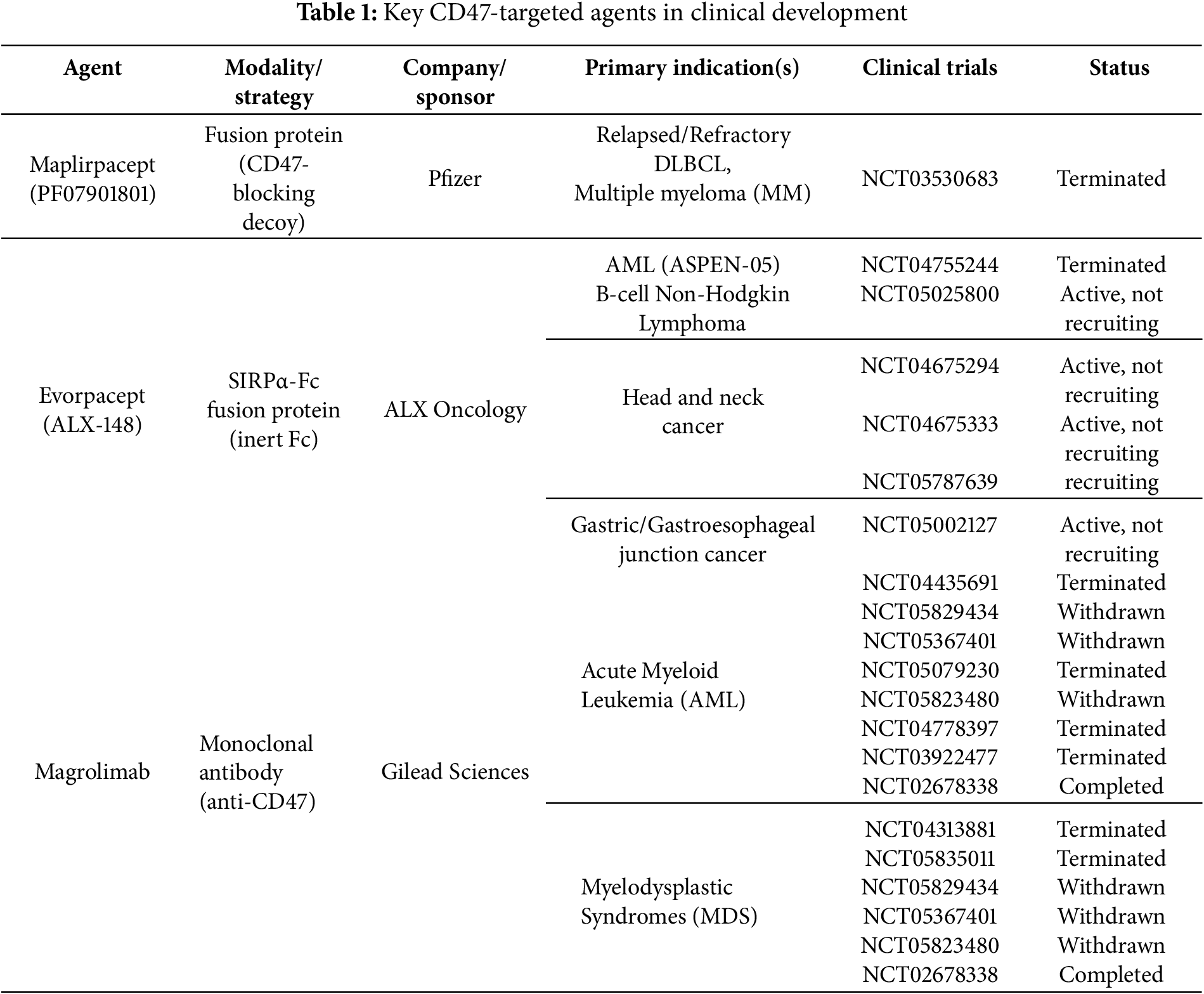

Over the past decade, this rationale has driven the development of multiple anti-CD47 therapeutics, including CD47 monoclonal antibodies (e.g., magrolimab, letaplimab, lemzoparlimab, ligufalimab (AK117), maplirpacept, and AUR103), SIRPα-Fc function protein (e.g., evorpacept (ALX148), IMM01, BYON4228), and bispecific antibodies (e.g., IBI322, TG1801, IMM0306), among others [12].

However, clinical experience with CD47 inhibition has been more complex than anticipated [13–15]. In July 2025, Pfizer terminated a Phase II trial of its investigational CD47-targeting fusion protein maplirpacept (PF-07901801) in combination with tafasitamab and lenalidomide for relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), citing an inability to recruit the planned number of subjects after enrolling only six patients since August 2023. The decision was explicitly stated to be unrelated to safety or efficacy concerns (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05626322; last updated 29 June 2025). This follows a series of high-profile disappointments in the CD47 space, most notably Gilead’s complete discontinuation of magrolimab after multiple trial holds, including the termination of a Phase 3 study in higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) for futility (Gilead press release, 2023) and the termination of other ongoing MDS trials following cessation of magrolimab development (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05835011; last updated 02 October 2024).

Together with other setbacks, these events highlight not only the biological and clinical complexities of CD47 blockade, including anemia from red blood cell clearance but also strategic and operational challenges in trial design, patient selection, and combination approaches. Collectively, these developments underscore the urgent need to re-evaluate CD47-targeted strategies. This commentary aims to contextualize recent clinical outcomes, dissect mechanistic insights, refine their clinical translation, and outline future directions for advancing CD47 blockade into durable, safe, and effective cancer immunotherapies.

2 Mechanistic Insights: Beyond the “Don’t Eat Me” Signal

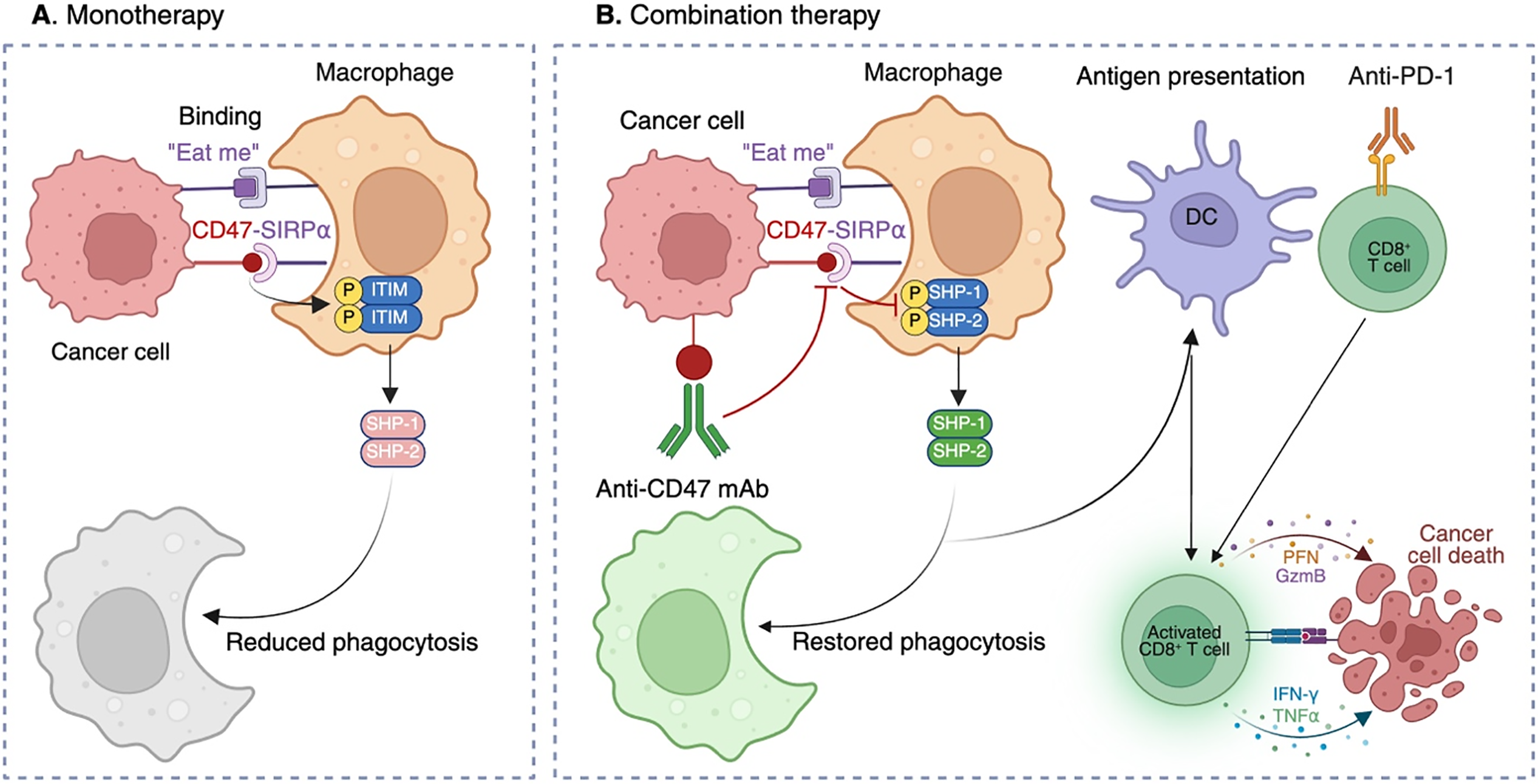

The CD47-SIRPα interaction constitutes a multifaceted checkpoint at the interface of innate immunity [16]. CD47 is a transmembrane protein that binds the extracellular immunoglobulin variable (IgV) domain of SIRPα, an inhibitory receptor expressed predominantly on myeloid cells [17]. Upon ligand engagement, SIRPα’s intracellular immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) become phosphorylated, recruiting the SH2-domain containing phosphatases Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-1 (SHP-1) and Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-2 (SHP-2) [18]. These phosphatases dephosphorylate key effectors required for actin remodeling, effectively halting phagocytic-cup formation and target engulfment [19].

Importantly, this pathway not only suppresses macrophage phagocytosis but also limits antigen uptake and presentation by DCs [4,20]. Because antigen presentation is essential for initiating T-cell responses, CD47 functions as a pan-immune checkpoint, impairing both innate and adaptive immunity [2,6]. This provides strong rationale for therapeutic inhibition, particularly in tumors with poor T-cell infiltration or loss of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) expression.

3 Clinical Setbacks: Lessons from Anemia, Selectivity, and Limited Efficacy

Despite compelling biological rationale, CD47-targeted therapies have encountered significant clinical hurdles. A primary concern is on-target, off-tumor toxicity resulting from CD47 expression on red blood cells (RBCs) [21,22]. Antibodies with unmodified Fc domains can opsonize RBCs, causing anemia and dose-limiting toxicities that complicate safe and sustained treatment [23]. Beyond RBCs, additional on-target/off-tumor effects warrant consideration. These include thrombocytopenia due to platelet targeting, potential involvement of hematopoietic stem cells, and risks of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) or other immune-related adverse events in certain contexts, particularly in combination regimens [24,25].

In addition, monotherapy trials, particularly in solid tumors, have generally shown modest efficacy [26,27]. This limited activity likely reflects redundancy within the tumor microenvironment (TME), where alternative immune-evasion pathways compensate for CD47 blockade [1]. The absence of robust predictive biomarkers further obscures whether poor responses stem from intrinsic resistance or suboptimal patient selection [8].

These challenges do not negate CD47 as a therapeutic target; rather, they highlight the need for more refined approaches that integrate tumor context, rational combinations, and biomarker-driven precision [28]. To visualize these concepts, Fig. 1 depicts the dual roles of the CD47-SIRPα axis in tumor immune evasion and the restoration of antitumor immunity through combination strategies.

Figure 1: Mechanisms of CD47-mediated immune evasion and restoration of antitumor immunity through combination therapy. (A) Monotherapy: Tumor cells overexpress CD47, which binds SIRPα on macrophages. This interaction triggers phosphorylation of ITIMs in SIRPα, leading to recruitment of SHP-1 and SHP-2 and inhibition of cytoskeletal rearrangement, thereby suppressing phagocytosis despite “eat me” signals. (B) Combination therapy: Anti-CD47 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) block the CD47-SIRPα interaction, preventing ITIM phosphorylation and SHP-1/SHP-2 recruitment. Macrophage phagocytosis is restored, enabling tumor cell engulfment and subsequent antigen presentation by DCs. Antigen-loaded DCs prime CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, which mediate tumor killing through perforin (PFN), granzyme B (GzmB), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Concomitant PD-1 blockade further enhances T-cell effector function. In parallel, myeloid reactivation supports recruitment of natural killer (NK) cells, contributing to direct tumor cell lysis and reshaping of the TME toward a pro-inflammatory, antitumor state. This figure originally conceived and created by the authors using BioRender (BioRender, Toronto, ON, Canada; https://app.biorender.com).

To complement this discussion, Table 1 summarizes key CD47-targeted agents, their modalities, sponsors, indications, and trial outcomes, highlighting the patterns of both progress and discontinuation across the clinical landscape. This structured overview underscores the translational challenges of CD47 blockade and sets the stage for mechanistic considerations illustrated in Fig. 1.

4 Strategic Innovations in CD47-Based Therapy

Several approaches are being developed to overcome the limitations of first-generation CD47 inhibitors. Combination immunotherapy is among the most promising: co-blockade of CD47 with immune checkpoints such as PD-1, v-domain immunoglobulin suppressor of T cell activation (VISTA), or CD24 can synergistically restore phagocytosis, enhance antigen presentation, and reinvigorate exhausted T cells [29–31]. Such dual-targeting strategies are particularly appealing in tumors employing multiple, redundant layers of immune suppression [32].

Bispecific antibodies represent another strategy. By pairing CD47 blockade with tumor-specific targets (e.g., CD20 or EpCAM), these agents achieve selective activity on malignant cells while sparing RBCs and other healthy tissues. Early data suggest improved safety and specificity with this approach [33,34]. Likewise, nanoparticle-based delivery systems can localize CD47 inhibitors to the TME, enhancing the therapeutic index by reducing systemic exposure [35,36].

Targeting the receptor side of the axis is also gaining traction. SIRPα-directed agents including decoy receptors and fusion proteins, bypass the “red-cell sink” and directly activate myeloid cells, offering a potentially broader therapeutic window [37–39]. Several candidates are now advancing through early-phase clinical trials [40,41].

Rational integration with chemotherapy provides additional opportunities. Cytotoxic agents can upregulate CD47 in response to stress, sensitizing tumors to blockade [42]. Sequence-dependent combinations may be particularly relevant in diseases like ovarian cancer, where chemotherapy remains the frontline therapy [41,43].

Other innovative antibody formats are also being engineered. Fc-silencing and Fc-tuning reduce off-tumor effector functions; extended half-life variants and intratumoral delivery strategies provide spatial control of immune activation and may mitigate hematologic toxicity [44,45]. Novel constructs such as diphtheria toxin-based bivalently immunotoxins, expressed through yeast-based systems, have also demonstrated high specificity and potent efficacy against CD47+ cancers with minimized off-target binding [46].

Finally, dual-targeting strategies are emerging as a particularly promising avenue. Combining CD47 inhibition with pro-phagocytic “eat-me” signals, such as calreticulin (CALR), can amplify macrophage-mediated clearance of tumor cells. Similarly, pairing CD47 blockade with DNA damage response therapies, including poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, has shown synergistic potential by promoting immunogenic stress responses and facilitating tumor cell recognition [47,48]. These approaches may be especially valuable in immunologically “cold” tumors lacking endogenous “eat-me” signals, thereby providing a rationale for rational dual-targeting combinations in future clinical development.

5 Future Perspectives: Contextual Precision in CD47 Blockade

The next generation of CD47-targeted and other precision immunotherapies will hinge on optimized drug design, rigorous patient selection, and context-specific application. A central challenge is identifying which morphologically, genetically, and metabolically heterogeneous tumors are functionally dependent on CD47-mediated immune evasion [3,49]. Advanced technologies such as single-cell profiling, spatial-transcriptomics, and special proteomics can delineate immune phenotypes and uncover predictive biomarkers [50].

Spatially resolved technologies, including multiplex immunohistochemistry (mIHC) and co-detection by indexing (CODEX), add crucial context by assessing not only macrophage abundance but also their polarization state (M1 vs. M2), proximity to tumor cells, and co-localization with T cells [51]. Tumors enriched with M2-like, SIRPα+ macrophages at the invasive margin are more likely to benefit from CD47 blockade than those with sparse or M1-polarized macrophages [52]. Integrating these spatial metrics into biomarker development will refine patient stratification and guide rational therapeutic combinations [53].

Companion diagnostics incorporating CD47 expression levels, SIRPα isoforms, and myeloid signatures may further refine patient selection [54,55]. Such approaches could follow a stepwise process: baseline clinical evaluation to confirm diagnosis and associated symptoms, genetic risk stratification with mutation testing and identification of driver mutations, as well as immune transcriptomic profiling with comprehensive gene activity analysis, culminating in clustering by immune activity state (hyperactive, moderate, no active) [56,57].

The TME must also guide therapeutic choices. Macrophage-rich but T-cell-excluded tumors may benefit more from CD47 modulation than highly inflamed lesions dominated by lymphocytes [58]. Understanding each tumor’s immunologic “terrain” will be key to selecting effective combinations, whether with PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies, CD40 agonists, stimulator of interferon gene (STING) agonists, radiotherapy, or molecularly targeted drugs [59,60].

Clinical trial design should evolve accordingly. Adaptive frameworks incorporating real-time immune monitoring, pharmacodynamic biomarkers, and built-in combination arms can generate clearer efficacy signals and accelerate optimization [61,62]. Endpoints should extend beyond response rates to capture immune reprogramming within the TME [63,64]. In chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), MDS, and multiple myeloma (MM), patient-oriented endpoints, including quality of life and patient-reported outcomes, will be essential to define the long-term value of CD47 blockade [65].

The CD47-SIRPα axis remains a compelling and versatile target in cancer immunotherapy. Recent clinical disappointments reflect the complexity of immune modulation rather than invalidation of the target itself. Moving forward, success will depend on strategic refinements of antibody engineering to minimize hematologic toxicity, biomarker-driven patient selection, and rational combinatorial regimens that exploit tumor context. The promise of CD47-targeted therapy lies not in questioning its relevance, but in applying it with precision: the right combinations, in the right patients, at the right time.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Xuejun Guo, Yilin Fu and Natalia Baran: Investigation, writing—original draft, review & editing. Wenxue Ma: Conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft, visualization, review, editing, finalizing, and supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| CALR | Calreticulin |

| CD47 | Cluster of differentiation 47 |

| CLL | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| CODEX | Co-detection by indexing |

| CRS | Cytokine release syndrome |

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| DLBCL | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| EpCAM | Epithelial cell adhesion molecule |

| GzmB | Granzyme B |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| ITIM | Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif |

| mAb | Monoclonal antibody |

| MDS | Myelodysplastic syndrome |

| mIHC | Multiplex immunohistochemistry |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| MM | Multiple myeloma |

| NK | Natural killer |

| PARP | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PFN | perforin |

| RBC | Red blood cell |

| SHP-1 | Src Homology region 2 domain-containing Phosphatase-1 |

| SHP-2 | Src Homology region 2 domain-containing Phosphatase-2 |

| SIRPα | Signal regulatory protein alpha |

| STING | Stimulator of interferon genes |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| VISTA | v-domain immunoglobulin suppressor of T cell activation |

References

1. Chen Q, Guo X, Ma W. Opportunities and challenges of CD47-targeted therapy in cancer immunotherapy. Oncol Res. 2023;32(1):49–60. doi:10.32604/or.2023.042383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Liu Y, Weng L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Wu Q, Zhao P, et al. Deciphering the role of CD47 in cancer immunotherapy. J Adv Res. 2024;63:129–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Ahvati H, Roudi R, Sobhani N, Safari F. CD47 as a potent target in cancer immunotherapy: a review. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2025;1880(2):189294. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2025.189294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zimarino C, Moody W, Davidson SE, Munir H, Shields JD. Disruption of CD47-SIRPalpha signaling restores inflammatory function in tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells. iScience. 2024;27(4):109546. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2024.109546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Zhou Y, Tang X, Du W, Shu C, Yan X, Ma N, et al. Deciphering the role of signal regulatory protein alpha in immunotherapy for solid tumors. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1612234. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2025.1612234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Hu A, Sun L, Lin H, Liao Y, Yang H, Mao Y. Harnessing innate immune pathways for therapeutic advancement in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):68. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01765-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Wu B, Zhang B, Li B, Wu H, Jiang M. Cold and hot tumors: from molecular mechanisms to targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):274. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01979-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Maute R, Xu J, Weissman IL. CD47-SIRPalpha-targeted therapeutics: status and prospects. Immunooncol Technol. 2022;13:100070. doi:10.1016/j.iotech.2022.100070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Haddad F, Daver N. Targeting CD47/SIRPalpha in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome: preclinical and clinical developments of magrolimab. J Immunother Precis Oncol. 2021;4(2):67–71. doi:10.36401/jipo-21-x2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang B, Li W, Fan D, Tian W, Zhou J, Ji Z, et al. Advances in the study of CD47-based bispecific antibody in cancer immunotherapy. Immunology. 2022;167(1):15–27. doi:10.1111/imm.13498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Chen Y, Shi W, Shi J, Lu J. Progress of CD47 immune checkpoint blockade agents in anticancer therapy: a hematotoxic perspective. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2022;148(1):1–14. doi:10.1007/s00432-021-03815-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Xu Y, Jiang P, Xu Z, Ye H. Opportunities and challenges for anti-CD47 antibodies in hematological malignancies. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1348852. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1348852. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Yang H, Xun Y, You H. The landscape overview of CD47-based immunotherapy for hematological malignancies. Biomark Res. 2023;11(1):15. doi:10.1186/s40364-023-00456-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Sun T, Nguyen B, Chen S, Natkunam Y, Padda S, van de Rijn M, et al. Brief report: high levels of CD47 expression in thymic epithelial tumors. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2023;4(4):100498. doi:10.1016/j.jtocrr.2023.100498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Al-Sudani H, Ni Y, Jones P, Karakilic H, Cui L, Johnson LDS, et al. Targeting CD47-SIRPa axis shows potent preclinical anti-tumor activity as monotherapy and synergizes with PARP inhibition. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2023;7(1):69. doi:10.1038/s41698-023-00418-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Fenalti G, Villanueva N, Griffith M, Pagarigan B, Lakkaraju SK, Huang RY, et al. Structure of the human marker of self 5-transmembrane receptor CD47. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5218. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-25475-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Xu L, Wang X, Zhang T, Meng X, Zhao W, Pi C, et al. Expression of a mutant CD47 protects against phagocytosis without inducing cell death or inhibiting angiogenesis. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5(3):101450. doi:10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101450. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang B, Zou Y, Tang Q, Yuan Z, Jiang K, Zhang Z, et al. SIRPalpha modulates microglial efferocytosis and neuroinflammation following experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage via the SHP1/STAT6 axis. J Neuroinflammation. 2025;22(1):88. doi:10.1186/s12974-025-03414-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Le T, Ferling I, Qiu L, Nabaile C, Assuncao L, Roskelley CD, et al. Redistribution of the glycocalyx exposes phagocytic determinants on apoptotic cells. Dev Cell. 2024;59(7):853–68.e7. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2024.01.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Zhao H, Song S, Ma J, Yan Z, Xie H, Feng Y, et al. CD47 as a promising therapeutic target in oncology. Front Immunol. 2022;13:757480. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.757480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Osorio JC, Smith P, Knorr DA, Ravetch JV. The antitumor activities of anti-CD47 antibodies require Fc-FcgammaR interactions. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(12):2051–65. e6. doi:10.1101/2023.06.29.547082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Reischer A, Leutbecher A, Hiller B, Perini E, White K, Hernandez-Caceres A, et al. Targeted CD47 checkpoint blockade using a mesothelin-directed antibody construct for enhanced solid tumor-specific immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2025;74(7):214. doi:10.1007/s00262-025-04032-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Bauer-Smith H, Sudol ASL, Beers SA, Crispin M. Serum immunoglobulin and the threshold of Fc receptor-mediated immune activation. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2023;1867(11):130448. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2023.130448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Ansell S, Maris M, Lesokhin A, Chen R, Flinn IW, Sawas A, et al. Phase I study of the CD47 blocker TTI-621 in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(8):2190–9. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-20-3706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Sun J, Chen Y, Lubben B, Adebayo O, Muz B, Azab AK. CD47-targeting antibodies as a novel therapeutic strategy in hematologic malignancies. Leuk Res Rep. 2021;16(6230):100268. doi:10.1016/j.lrr.2021.100268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Chen C, Lu F, Huang H, Pan Y. Translating CD47-targeted therapy in gastrointestinal cancers: insights from preclinical to clinical studies. iScience. 2024;27(12):111478. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2024.111478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Yamada-Hunter SA, Theruvath J, McIntosh BJ, Freitas KA, Lin F, Radosevich MT, et al. Engineered CD47 protects T cells for enhanced antitumour immunity. Nature. 2024;630(8016):457–65. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07443-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Morchon-Araujo D, Catani G, Mirallas O, Pretelli G, Sanchez-Perez V, Vieito M, et al. Emerging immunotherapy targets in early drug development. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(11):5394. doi:10.3390/ijms26115394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Li Y, Jia W, Zhu M, Hu X, Ya Z, Liu Y, et al. Focused acoustic vortex-activated dual-stimuli nanoplatform synergizes with checkpoint blockade to enhance macrophage phagocytosis and antitumor immunity. ACS Nano. 2025;19(30):27957–76. doi:10.1021/acsnano.5c10591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Christo S, McDonald K, Burn T, Kurd N, Stanfield J, Kaneda M, et al. Dual CD47 and PD-L1 blockade elicits anti-tumor immunity by intratumoral CD8(+) T cells. Clin Transl Immunol. 2024;13(11):e70014. doi:10.1002/cti2.70014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Martins T, Kaymak D, Tatari N, Gerster F, Hogan S, Ritz MF, et al. Enhancing anti-EGFRvIII CAR T cell therapy against glioblastoma with a paracrine SIRPgamma-derived CD47 blocker. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):9718. doi:10.1101/2023.08.31.555122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhuang T, Zhang C, Strati P. SOHO state of the art updates and next questions | novel immunotherapy combinations for the treatment of indolent B-cell lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2025;25(7):455–64. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2025.01.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Shan K, Musleh Ud Din S, Dalal S, Gonzalez T, Dalal M, Ferraro P, et al. Bispecific antibodies in solid tumors: advances and challenges. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(12):5838. doi:10.3390/ijms26125838. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Ma L, Zhu M, Gai J, Li G, Chang Q, Qiao P, et al. Preclinical development of a novel CD47 nanobody with less toxicity and enhanced anti-cancer therapeutic potential. J Nanobiotechnol. 2020;18(1):12. doi:10.1186/s12951-020-0571-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Sabir S, Thani A, Abbas Q. Nanotechnology in cancer treatment: revolutionizing strategies against drug resistance. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2025;13:1548588. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2025.1548588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Papp T, Zeng J, Shahnawaz H, Akyianu A, Breda L, Yadegari A, et al. CD47 peptide-cloaked lipid nanoparticles promote cell-specific mRNA delivery. Mol Ther. 2025;33(7):3195–208. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2025.03.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Andrejeva G, Capoccia B, Hiebsch R, Donio MJ, Darwech I, Puro RJ, et al. Novel SIRPalpha antibodies that induce single-agent phagocytosis of tumor cells while preserving T cells. J Immunol. 2021;206(4):712–21. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.2001019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Qu T, Li B, Wang Y. Targeting CD47/SIRPalpha as a therapeutic strategy, where we are and where we are headed. Biomark Res. 2022;10(1):20. doi:10.1186/s40364-022-00373-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Isenberg J, Montero E. Tolerating CD47. Clin Transl Med. 2024;14(2):e1584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

40. van Helden MJ, Zwarthoff SA, Arends RJ, Reinieren-Beeren IMJ, Parade M, Driessen-Engels L, et al. BYON4228 is a pan-allelic antagonistic SIRPalpha antibody that potentiates destruction of antibody-opsonized tumor cells and lacks binding to SIRPgamma on T cells. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11(4):e006567. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.am2022-5589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lakhani N, Stewart D, Richardson D, Dockery L, Van Le L, Call J, et al. First-in-human phase I trial of the bispecific CD47 inhibitor and CD40 agonist Fc-fusion protein, SL-172154 in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13(1):e010565. doi:10.1136/jitc-2024-010565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Lau A, Khavkine Binstock S, Thu K. CD47: the next frontier in immune checkpoint blockade for non-small cell lung cancer. Cancers. 2023;15(21):5229. doi:10.3390/cancers15215229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Zhao L, Wang X, Liu H, Lang J. Chemotherapy-induced increase in CD47 expression in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gland Surg. 2024;13(10):1770–84. doi:10.21037/gs-24-400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Yin N, Li X, Zhang X, Xue S, Cao Y, Niedermann G, et al. Development of pharmacological immunoregulatory anti-cancer therapeutics: current mechanistic studies and clinical opportunities. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):126. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01826-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Li H, Zhou Q, Cao N, Hu C, Wang J, He Y, et al. Nanobodies and their derivatives: pioneering the future of cancer immunotherapy. Cell Commun Signal. 2025;23(1):271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

46. Ma J, Wang Z, Mintzlaff D, Zhang H, Ramakrishna R, Davila E, et al. Bivalent CD47 immunotoxin for targeted therapy of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2025;145(5):508–19. doi:10.1182/blood.2024025277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Zhang Y, Luo J, Zhang J, Miao W, Wu J, Huang H, et al. Nanoparticle-enabled dual modulation of phagocytic signals to improve macrophage-mediated cancer immunotherapy. Small. 2020;16(46):e2004240. doi:10.1002/smll.202004240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Liu Y, Xue R, Duan X, Shang X, Wang M, Wang F, et al. PARP inhibition synergizes with CD47 blockade to promote phagocytosis by tumor-associated macrophages in homologous recombination-proficient tumors. Life Sci. 2023;326(4):121790. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121790. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Bian H, Shen Y, Zhou Y, Nagle D, Guan Y, Zhang W, et al. CD47: beyond an immune checkpoint in cancer treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2022;1877(5):188771. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2022.188771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Jin Y, Wu Y, Reuben A, Zhu L, Gay CM, Wu Q, et al. Single-cell and spatial proteo-transcriptomic profiling reveals immune infiltration heterogeneity associated with neuroendocrine features in small cell lung cancer. Cell Discov. 2024;10(1):93. doi:10.1038/s41421-024-00755-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Matusiak M, Hickey J, van ID, Lu G, Kidzinski L, Zhu S, et al. Spatially segregated macrophage populations predict distinct outcomes in colon cancer. Cancer Discov. 2024;14(8):1418–39. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.cd-23-1300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Liu M, Bertolazzi G, Sridhar S, Lee R, Jaynes P, Mulder K, et al. Spatially-resolved transcriptomics reveal macrophage heterogeneity and prognostic significance in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):2113. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-46220-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Khanduri I, Maki H, Verma A, Katkhuda R, Anandappa G, Pandurengan R, et al. New insights into macrophage polarization and its prognostic role in patients with colorectal cancer liver metastasis. BJC Rep. 2024;2(1):37. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3439308/v1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Li Q, Geng S, Luo H, Wang W, Mo YQ, Luo Q, et al. Signaling pathways involved in colorectal cancer: pathogenesis and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):266. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01953-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Singh S, Dey D, Barik D, Mohapatra I, Kim S, Sharma M, et al. Glioblastoma at the crossroads: current understanding and future therapeutic horizons. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10(1):213. doi:10.1038/s41392-025-02299-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Che Z, Wang W, Zhang L, Lin Z. Therapeutic strategies targeting CD47-SIRPalpha signaling pathway in gastrointestinal cancers treatment. J Pharm Anal. 2025;15(1):101099. doi:10.1016/j.jpha.2024.101099. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Yu W, Ye Z, Shi J, Deng W, Chen J, Lu JJ. Dual blockade of GSTK1 and CD47 improves macrophage-mediated phagocytosis on cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2025;236(10400):116898. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2025.116898. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Saeed A. Tumor-associated macrophages: polarization, immunoregulation, and immunotherapy. Cells. 2025;14(10):741. doi:10.3390/cells14100741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Yang S, Ta YN, Chen Y. Nanotechnology-enhanced immunotherapies for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: challenges and opportunities. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2025;379(25):2395. doi:10.1007/s13346-025-01908-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Li T, Zhang W, Niu M, Wu Y, Deng X, Zhou J. STING agonist inflames the cervical cancer immune microenvironment and overcomes anti-PD-1 therapy resistance. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1342647. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1342647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Marron T, Luke J, Hoffner B, Perlmutter J, Szczepanek C, Anagnostou V, et al. A SITC vision: adapting clinical trials to accelerate drug development in cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13(3):e010760. doi:10.1136/jitc-2024-010760. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Luke J, Bever K, Hodi F, Taube J, Massey A, Yao D, et al. Rationale and feasibility of a rapid integral biomarker program that informs immune-oncology clinical trials: the ADVISE trial. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13(5):e011170. doi:10.1136/jitc-2024-011170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Imani S, Farghadani R, Roozitalab G, Maghsoudloo M, Emadi M, Moradi A, et al. Reprogramming the breast tumor immune microenvironment: cold-to-hot transition for enhanced immunotherapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2025;44(1):131. doi:10.1186/s13046-025-03394-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Wang Q, Ma W. Revisiting TAM polarization: beyond M1- and M2-type TAM toward clinical precision in macrophage-targeted therapy. Exp Mol Pathol. 2025;143:104982. doi:10.1016/j.yexmp.2025.104982. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Patel K, Ivanov A, Jocelyn T, Hantel A, Garcia J, Abel G. Patient-reported outcomes in phase 3 clinical trials for blood cancers: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(6):e2414425. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.14425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools