Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Advances in Expression Regulation, Molecular Targeting Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Applications of the Let-7 MicroRNA Family in Gastric Cancer

The First Affiliated Hospital, Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Hengyang Medical School, University of South China, Hengyang, 421001, China

* Corresponding Author: Qiulin Huang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Signaling Pathway Crosstalk in Malignant Tumors: Molecular Targets and Combinatorial Therapeutics)

Oncology Research 2025, 33(12), 3731-3752. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.067546

Received 06 May 2025; Accepted 21 July 2025; Issue published 27 November 2025

Abstract

Gastric cancer (GC) is a prevalent malignant tumor globally, with high incidence and mortality rates. Advances in understanding molecular mechanisms underlying GC have highlighted the role of microRNAs (miRNAs) in its initiation, progression, and treatment. The Let-7 family, an important class of miRNAs, is closely associated with the biological behaviors of GC. Aberrant expression of various Let-7 family members in GC patients contributes to disease progression, as they target multiple molecular pathways and participate in diverse regulatory mechanisms throughout GC pathogenesis. This article systematically summarizes the expression patterns of Let-7 family members in GC, explores their influence on GC cell behaviors such as proliferation, invasion, and metastasis through key target gene regulation, and reviews current advances in Let-7-based interventions for GC treatment. It aims to provide foundational insights for a deeper understanding of Let-7-related mechanisms in GC and optimize therapeutic strategies.Keywords

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most prevalent cancer globally and ranks as the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths [1]. The majority of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages, which significantly restricts the available treatment options and leads to a poor prognosis [2,3]. GC is characterized by high recurrence, metastasis, and mortality rates, especially in cases with distant spread, where the five-year survival rate is alarmingly low, posing a serious risk to health and life [4]. Conventional treatment strategies for GC mainly consist of surgical removal, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy [4,5]. Although surgical intervention is the primary method for treating GC, its effectiveness diminishes in advanced cases [6,7]. Chemoradiotherapy can serve as an adjuvant to surgery, either enhancing the therapeutic effect before the operation or complementing post-surgical treatment to address potential residual lesions; however, its efficacy is often limited and highly variable, frequently accompanied by a range of adverse events [8,9]. As research into the mechanisms underlying GC progresses, biomolecular therapy has gained attention as a significant area of focus. Although this novel cancer treatment method is gradually becoming a crucial component of GC management, its development continues to encounter numerous challenges [7,10]. Key challenges in the realm of biomolecular therapy for GC include the absence of specific tumor markers, the relative delay in the advancement of molecular targeted therapy compared to other malignancies (such as lung and breast cancer), and the issue of patients developing resistance during biomolecular therapy [11–13]. Overcoming these obstacles is imperative for improving treatment outcomes for GC.

Recent investigations into the molecular processes involved in GC have increasingly highlighted the role of microRNAs (miRNAs), which are small non-coding RNAs that play a crucial regulatory role in tumorigenesis, development, angiogenesis, and metastasis [14,15]. These miRNAs exert their influence by binding to complementary sites in the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of specific mRNAs, leading to the inhibition of gene translation or promoting mRNA degradation, thus affecting the behavior of cancer cells [15,16]. Notably, existing studies have demonstrated that the expression of Let-7, an important member of the miRNA family, is aberrant in GC, and this abnormal expression is closely associated with disease progression and patient prognosis [17,18]. A thorough investigation into the Let-7 family’s role and mechanisms in GC not only deepens our comprehension of the disease’s origins but also has the potential to identify new biomarkers and therapeutic targets for early detection, targeted treatment, and prognosis, ultimately contributing to the improvement of patient survival outcomes and the enhancement of their quality of life.

2 Overview of the Let-7 Family

2.1 Classification and Biosynthesis of the Let-7 Family

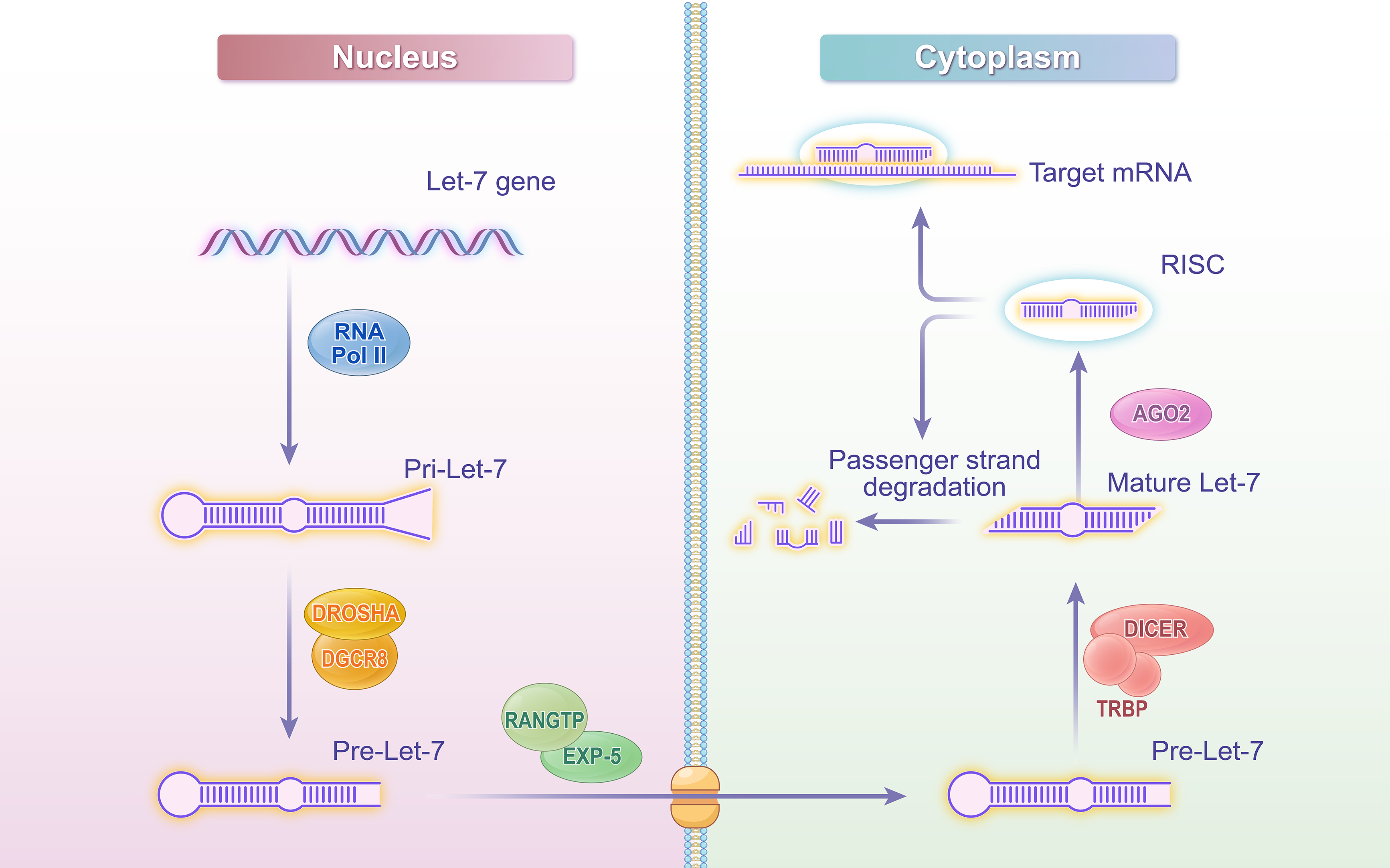

Most miRNAs feature a conserved sequence of 2–8 nucleotides, referred to as the seed “sequence”, which facilitates their categorization into various families. Among these, members with the seed sequence “T G A G G T A” are categorized into the Let-7 family [19,20]. Let-7, recognized as the first miRNA identified in humans, exhibits a high degree of conservation across different species [21,22]. The biosynthesis of Let-7 has been extensively studied within miRNA research. Initially, RNA polymerase II (Pol II) transcribes the primary Let-7 (Pri-Let-7). Subsequently, Pri-Let-7 is cleaved in the nucleus by the microprocessor complex, which comprises the Drosha enzyme and its cofactor DiGeorge Syndrome Critical Region 8 (DGCR8), resulting in the generation of precursor Let-7 (Pre-Let-7). Transport proteins, including Exportin-5 and Ran guanosine triphosphatase (Ran-GTPase), translocate Pre-Let-7 to the cytoplasm through the nuclear pore complex. In the cytoplasm, the enzyme Dicer and its cofactor TAR RNA binding protein (TRBP) further cleave and process Pre-Let-7 to form a double-stranded Let-7 molecule, consisting of a guide strand and a passenger strand. The guide strand is loaded onto the Argonaute protein to form the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). This complex can recognize target sequences and degrade the passenger strand. The mature Let-7-RISC complex binds to the 3′-UTR region of the target mRNA, leading to the degradation of the target mRNA or inhibition of its translation [23–26]. Through this mechanism, Let-7 effectively regulates the expression level of the target mRNA, thereby playing a crucial regulatory role within the cell and influencing cellular biological functions and signaling pathways [23,24,27,28]. The detailed process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Let-7 biogenesis schematic diagram. Created with adobe illustrator

This figure illustrates the biosynthesis process of Let-7 microRNA, depicting key steps from transcription to the formation of the mature functional complex. The process begins with the transcription of the let-7 gene by Pol II in the nucleus, generating pri-let-7. The microprocessor complex, consisting of Drosha and DGCR8, cleaves pri-let-7 to produce pre-let-7. Pre-let-7 is then transported to the cytoplasm via EXP-5 in a Ran-GTP-dependent manner. In the cytoplasm, Dicer and TRBP further process pre-let-7 into a double-stranded molecule, from which the guide strand is loaded onto AGO2 to form the RISC. The mature let-7-RISC complex binds to the 3′-UTR of target mRNAs, leading to mRNA degradation or translational inhibition. Abbreviations: Pol II (RNA polymerase II), DGCR8 (DiGeorge Syndrome Critical Region 8), EXP-5 (Exportin-5), Ran-GTPase (Ras-related nuclear protein GTPase), TRBP (TAR RNA-binding protein), RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex), Ago (Argonaute), 3′-UTR (3′-untranslated region).

2.2 Members and Functions of the Let-7 Family

MiRNAs within the same gene cluster frequently exhibit high sequence homology. To differentiate between the highly similar members of the Let-7 family, letter suffixes are typically appended to their names (e.g., Let-7a, Let-7b). The distinctions represented by these letter suffixes often correspond to subtle variations in nucleotide sequences, suggesting that while they are generally homologous, they may possess differing functional characteristics. In contrast, when pre-miRNAs originating from different chromosomal loci produce the same mature miRNA sequence, they are differentiated by appending Arabic numeral suffixes to their designations. For instance, Let-7a-1 and Let-7a-2 are precursors located on distinct chromosomes, yet both generate the mature sequence Let-7a [29].

In humans, there are a total of 10 mature Let-7 family sequences (Let-7a, Let-7b, Let-7c, Let-7d, Let-7e, Let-7f, Let-7g, Let-7i, miR-98, and miR-202), derived from 13 Pre-Let-7 expressions [29,30]. Pre-Let-7, located at different chromosomal sites, can yield the same mature Let-7 sequence. As an example, three separate pre-Let-7 genes give rise to the identical mature Let-7a sequence. To identify these specific precursor transcripts, they are designated as Let-7a-1, Let-7a-2, and Let-7a-3. Similarly, the mature Let-7f sequence is produced by two distinct pre-Let-7 genes, which are consequently named Let-7f-1 and Let-7f-2 [29–31].

Let-7 plays a pivotal role in various essential physiological and pathological processes within organisms. In embryonic development, Let-7 regulates cell lineage differentiation [32,33]. In metabolic homeostasis, it finely modulates the metabolism of sugars, lipids, and amino acids [34–36]. Within the cardiovascular system, Let-7 is involved in the proliferation and differentiation of cardiomyocytes, as well as the regulation of angiogenesis [37,38]. In the field of neurology, it protects neurons and delays the progression of neurodegenerative diseases [39–42]. Additionally, in immune regulation, Let-7 bidirectionally controls the differentiation and function of immune cells [43–45]. Furthermore, Let-7 holds significant importance in oncology, often classified as a tumor suppressor that reduces tumor invasiveness and is closely associated with tumor resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. It influences cancer development by targeting oncogenes and stem cell factors, as well as regulating related target genes involved in the cell cycle and proliferation, thereby demonstrating its substantial value in cancer prevention and treatment [46–48].

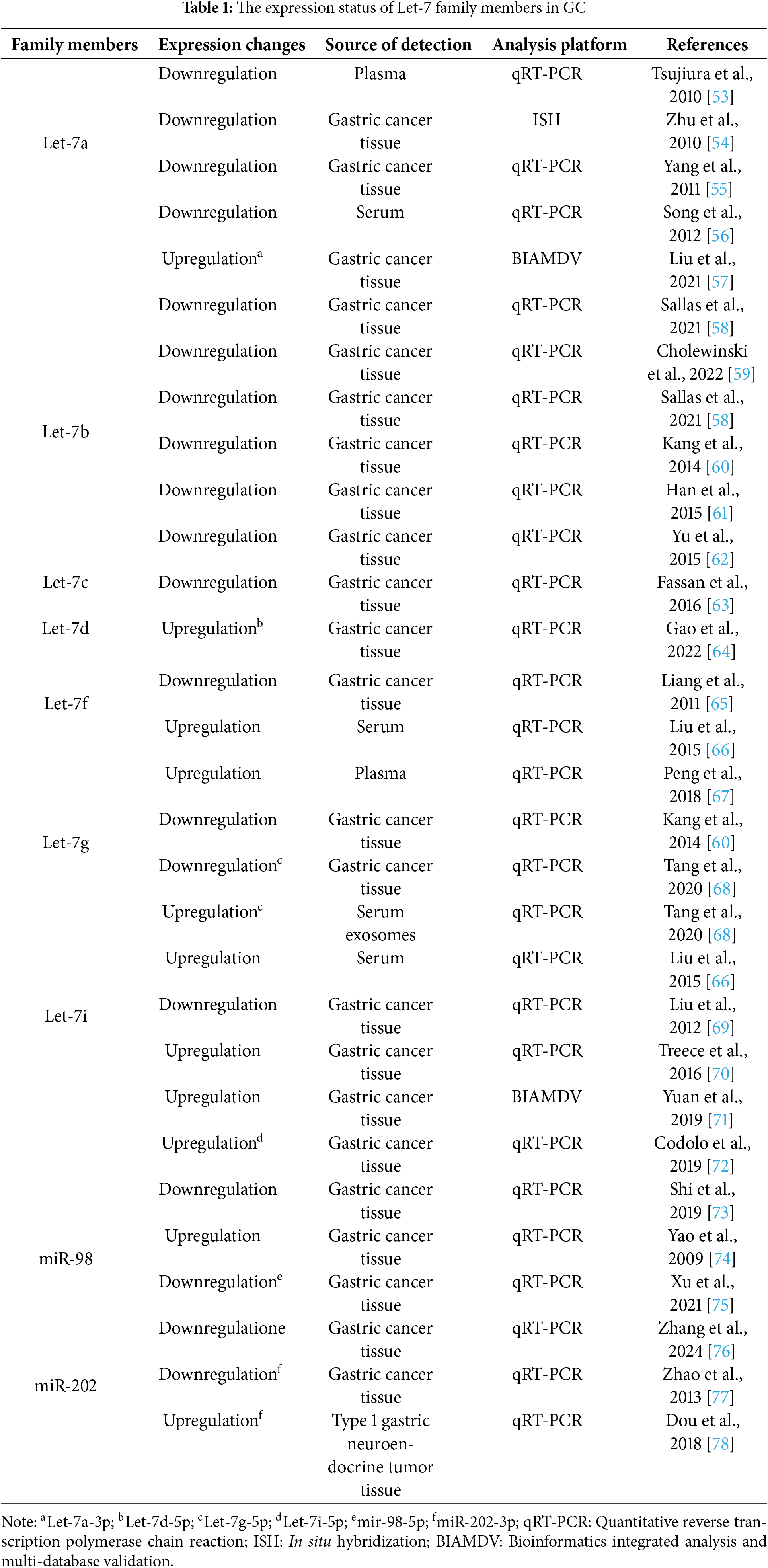

3 Expression of the Let-7 Family in GC

The expression profiles of miRNAs in tumor tissues exhibit significant variability, with miRNA signatures closely linked to specific clinical and biological characteristics [49,50]. While a general downregulation of Let-7 family members has been observed across various malignant tumors, research indicates that, under certain conditions, the expression of specific Let-7 family members can be upregulated in these tumors [51,52]. This variability in expression patterns is also evident in GC, where different Let-7 family members display distinct expression levels, and even the same Let-7 family member may demonstrate varying expression trends under different conditions. To achieve a comprehensive understanding of the expression patterns and variations of the Let-7 family in GC, we systematically summarized the expression profiles of the Let-7 family in GC (Table 1).

3.1 Members of the Let-7 Family Showed Generally Low Expression in GC

Most studies have found that members of the Let-7 family generally exhibit a downregulated expression trend in tumor tissues, plasma, and serum of GC patients. Among them, Let-7a, a typical tumor suppressor, shows significant downregulation in GC patients, with experimental data confirming that its overexpression can induce apoptosis in GC cells [55,79]. Furthermore, the expression level of Let-7a gradually decreases as the gastric mucosa progresses from normal to cancerous, reflecting the tumor differentiation stage in GC patients [55]. Studies have demonstrated a significant association between Let-7a and GC metastasis: its expression level is notably lower in GC tissues with lymph node metastasis compared to those without [54]. Similarly, other members of the Let-7 family, such as Let-7b, Let-7c, Let-7g, and miR-202, are generally downregulated. These molecules, which share similar functions with Let-7a, are closely related to poor prognosis and lymph node metastasis, and they inhibit the growth, invasion, and migration of GC cells while inducing their apoptosis [60–62,76,77].

3.2 Expression Differences of Pre-Let-7 Arm End Splicing Subtypes

Pre-Let-7 can generate mature Let-7 from either its 5′ or 3′ arm. Notably, Let-7 derived from different arms may exhibit distinct expression patterns. Specifically, while Let-7a generally functions as a tumor suppressor and shows an overall downregulation trend in GC, studies have indicated that Let-7a-3p (produced from the 3′ arm cleavage of Pre-Let-7a) is actually upregulated in GC tissues [57]. The expression of miR-98 and its isoforms in GC also demonstrates variability. Although miR-98 is typically upregulated in GC tissues, miR-98-5p (derived from the 5′ arm of Pre-miR-98) exhibits a downregulation trend, with studies showing that miR-98-5p can inhibit the proliferation, migration, and invasion capabilities of GC cells [74–76]. Additionally, the expression of Let-7i and its isoform Let-7i-5p in samples from GC patients also reflects diversity. Multiple studies have reported the upregulation of Let-7i and Let-7i-5p expression in GC tissues or serum [66,70–72]. Significantly, some studies have also noted the downregulation of Let-7i, suggesting that increased expression of Let-7i may inhibit the proliferation, metastasis, and invasion of cancer cells. Conversely, decreased expression levels of Let-7i are closely associated with shorter survival, local invasiveness, and lymph node metastasis [69,73].

3.3 Expression Differences of the Let-7 Family in Distinct Tissue Sources of GC

Let-7 exhibits differential expression in different sample types from GC patients. Specifically, Let-7f expression detected in serum and plasma samples of GC patients generally shows an upregulation trend [66,67], whereas its expression in GC tissue samples demonstrates a downregulation trend and is associated with inhibition of cell invasion and metastasis [65]. This expression discrepancy is also observed in Let-7g-5p: its expression is upregulated in serum exosomes of early-stage GC patients but significantly downregulated in tissue samples from early-stage GC patients [68]. However, some members of the Let-7 family maintain relatively consistent expression patterns across different tissues in GC patients. For example, a study comparing Let-7a expression in malignant tissues of the gastric body versus the gastric antrum found no statistically significant difference in expression levels between the two [59].

3.4 Expression Differences across Tumor Types and Histological Subtypes of GC

The expression profile of Let-7 exhibits significant variations among different tumor tissue types and across various stages of the same tumor type. For instance, miR-202-3p is downregulated in GC tissues and has been demonstrated to inhibit cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in both in vitro and in vivo experiments [77]. In contrast, in type 1 gastric neuroendocrine tumor tissues, the expression of miR-202-3p is upregulated [78]. Studies of GC histological subtypes reveal that miR-202 is upregulated in intestinal-type GC compared to diffuse-type GC [80]. Furthermore, differences in Let-7 expression have been observed between signet ring cell carcinoma and tubular adenocarcinoma, with research indicating that Let-7i expression is higher in signet ring cell carcinoma than in tubular adenocarcinoma [81].

3.5 The Association between Let-7 Family Expression and Molecular Subtypes of GC

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) classified GC into four molecular subtypes: Epstein-Barr virus-positive (EBV), microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H), chromosomal instability (CIN), and genomically stable (GS) [82,83]. Research reveals distinct Let-7 miRNA expression patterns across these subtypes. Some analyses demonstrate reduced Let-7c-5p expression in MSI-H subtype [84]. For EBV-positive tumors, some Let-7 family members (Let-7a and Let-7f) show marked expression downregulation linked to tumor progression [85].

Despite these advances, systematic investigations correlating GC molecular subtypes with Let-7 expression remain limited. Future in-depth and comprehensive studies are necessary to clarify these relationships, to thoroughly explore the expression profiles of the Let-7 family across all molecular subtypes, and their pathological significance.

3.6 Causes of Expression Differences

This article presents several reasons for the observed discrepancies. First, functional differences exist among members of the Let-7 family and across different subtypes, suggesting that Let-7 regulatory mechanisms may be specific to individual members and subtypes. Second, significant variations in miRNA absorption and degradation efficiency across various tissues contribute to differences in Let-7 expression characteristics. Third, the distinct microenvironments of different GC subtypes may influence miRNA biological functions. Fourth, variations in technology and sequencing platforms may also contribute to the differential expression of Let-7 family members in GC.

Given that the dysregulation of Let-7 expression has been linked to the onset and progression of GC, it is reasonable to consider Let-7 family members as potential prognostic, diagnostic, and therapeutic indicators in GC treatment. A more profound understanding of Let-7’s differential expression during GC development and progression may provide new insights for its clinical application.

3.7 Clinical Significance of Expression Differences and Bioinformatics Models

The differential expression of miRNAs serves as a critical indicator for the clinical diagnosis and prognostic assessment of GC [86,87]. The incorporation of bioinformatics and machine learning models has significantly improved the precision of risk stratification and the depth of mechanistic interpretation [88,89]. Numerous studies integrating bioinformatics predictions with experimental validation have systematically demonstrated the potential value of Let-7 family members in the progression and therapy of GC, a finding corroborated in large-scale clinical cohorts, underscoring their translational application potential.

Bioinformatics and machine learning models have emerged as powerful tools for screening biomarkers of the Let-7 family. For instance, Let-7a-3p [57], the circulating miR-106a/Let-7a ratio [53], and serum exosomal Let-7g-5p [68]—identified through algorithmic screening and clinically validated—demonstrate superior diagnostic efficacy. Their area under the curve (AUC) values are significantly higher than those of traditional tumor biomarkers, providing novel strategies for the non-invasive diagnosis of GC. Furthermore, members of the Let-7 family exhibit prognostic relevance. An integrative bioinformatics analysis, combined with functional experiments, revealed that low expression of Let-7i serves as an independent poor prognostic factor, closely associated with the aberrant activation of genes that drive tumor invasion and metastasis [69].

Clinical translational studies have confirmed the application value of several markers from the Let-7 family, including their use in early diagnostic panels, prognostic prediction models, and therapeutic response assessment indicators. However, current research still encounters challenges, such as addressing expression heterogeneity, optimizing population-specific models, and standardizing detection methods. Future studies should prioritize multi-omics integrated analysis and single-cell level mechanistic interpretation to offer more comprehensive theoretical support for the precision diagnosis and treatment of GC.

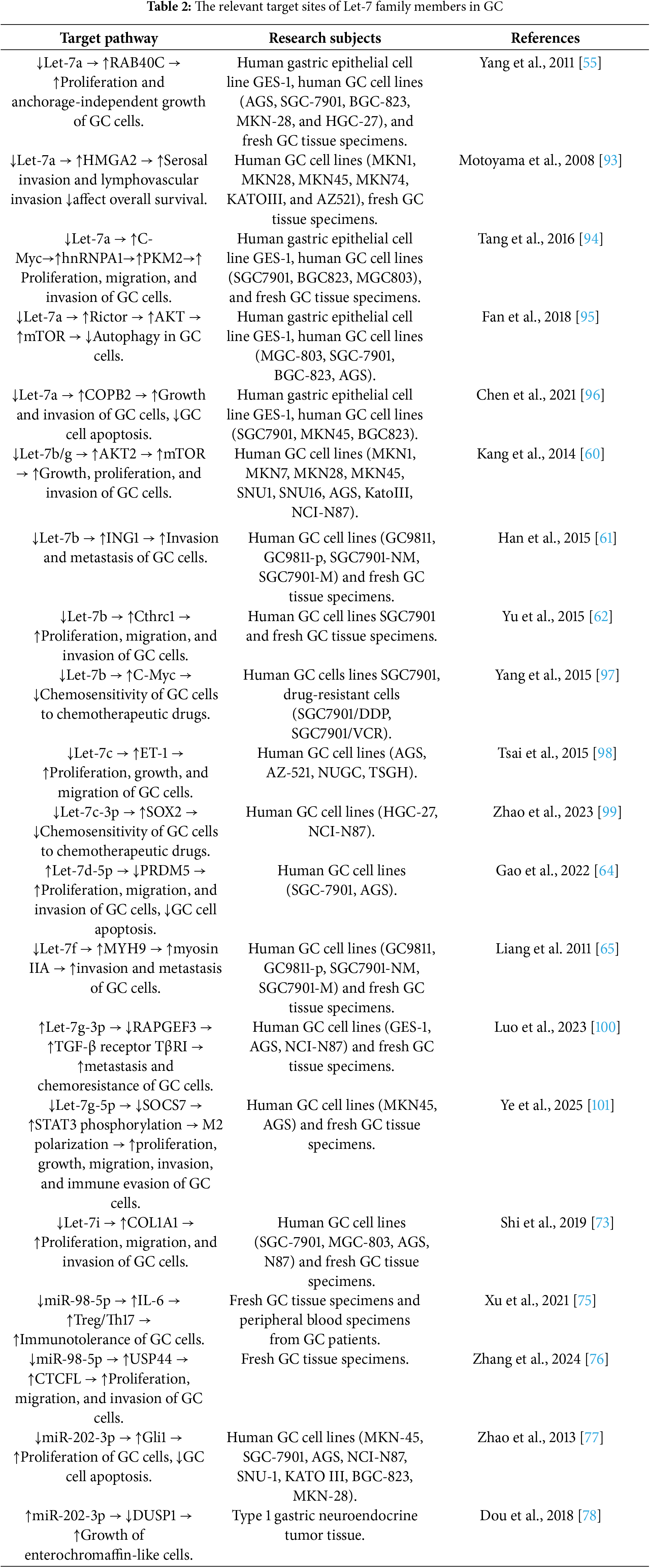

4 Related Targets and Mechanisms of Action of the Let-7 Family in GC

By analyzing the evolutionary sequence conservation between nematodes and humans, researchers have discovered that Let-7 specifically targets RAS in human cancer cells [90–92]. This finding has led to increasing recognition that members of the Let-7 family influence the occurrence and progression of cancer by regulating a series of key targets. In recent years, research on the role of Let-7 in GC has progressed significantly. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the specific associations between Let-7 and its targets in the occurrence and development of GC, we have summarized the target genes and their roles, along with the corresponding regulatory mechanisms, of Let-7 family members in GC (Table 2).

4.1 Related Targets Involved in Let-7 Regulation of Growth, Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion of GC

The Let-7 family members exhibit bidirectional regulatory characteristics in the development and progression of GC. Most members exert tumor-suppressive effects through multiple targets, inhibiting the growth, proliferation, migration, and invasion of GC cells. For instance, Let-7a binds to the 3′-UTR of RAB40C mRNA, negatively regulating this gene and downregulating hnRNPA1 and PKM2 by targeting C-Myc, thereby blocking glycolysis-dependent proliferation and invasion [55,94]. Concurrently, Let-7a downregulates HMGA2, further inhibiting the invasion of GC cells [93]. Let-7b/g targets the AKT/mTOR pathway to obstruct pro-cancer signaling, and their expression is negatively correlated in humans [60]. Additionally, Let-7b/c/f/i and miR-98-5p inhibit the proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastasis of GC cells by negatively regulating genes such as ING1/CTHRC1 [61,62], ET-1 [98], MYH9 [65], COL1A1 [73], and USP44 [76], respectively. In normal tissues, the Let-7 family maintains cellular homeostasis by negatively regulating oncogenes, while its downregulation in GC patients often leads to the dysregulation of oncogenic pathways.

However, certain members can promote the growth, proliferation, migration, and invasion of GC by inhibiting tumor suppressor genes. For instance, Let-7d-5p targets the tumor suppressor gene PRDM5 [64], Let-7g-3p targets RAPGEF3 [100], and miR-202-3p targets DUSP1 [78]. Collectively, these interactions accelerate the malignant transformation of GC cells by attenuating tumor suppressor signaling.

This bidirectional regulatory characteristic underscores the complexity of the Let-7 family within the molecular network of GC. Its function is dependent on specific family members, target genes, and microenvironmental variations, establishing it as both a tumor suppressor and a therapeutic target. A comprehensive analysis of its precise regulatory mechanisms will provide a more robust theoretical foundation for the precision stratification and targeted intervention of GC.

4.2 Related Targets Involved in the Regulation of Apoptosis and Autophagy in GC

Members of the Let-7 family play a significant role in influencing GC cell apoptosis and autophagy through the regulation of downstream targets. Let-7a can activate autophagy by targeting Rictor, which is an upstream molecule in the AKT-mTOR pathway [95]. Additionally, it inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis by silencing the oncogene Coatomer protein complex subunit beta 2 (COPB2), thereby suppressing the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling pathway [96]. Let-7d-5p targets the tumor suppressor gene PRDM5, which not only promotes GC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion but also reduces patient survival by inhibiting autophagy [64]. Furthermore, miR-202-3p directly targets Gli1, a key transcription factor in the Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) pathway, leading to downregulation of its target genes, γ-catenin and Bcl-2. This action inhibits GC cell growth and induces apoptosis both in vitro and in vivo [77].

These regulatory patterns illustrate the dual role of Let-7 family members in determining the fate of GC cells. They can exert tumor-suppressive effects by activating autophagy or inducing apoptosis, while also promoting tumor progression by inhibiting autophagy or interfering with apoptosis pathways. The complex molecular mechanisms provide a multi-dimensional theoretical foundation for elucidating the development of GC and for developing targeted therapeutic strategies.

4.3 Related Targets Involved in the Regulation of the Immune Microenvironment in GC

Some studies have revealed that members of the Let-7 family play a dual regulatory role in the immune microenvironment of GC. Specifically, miR-98-5p promotes anti-tumor immune activation by reshaping the balance between regulatory T cell (Treg) and Th17 cells [75], while Let-7g-5p facilitates immune escape through the induction of M2 macrophage polarization and the upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules [101]. This bidirectional regulatory mechanism underscores the complexity of the Let-7 family in tumor-immune interactions: its members may serve as potential targets to enhance the sensitivity of immunotherapy, while also acting as drivers of immune escape. An in-depth analysis of the precise regulatory nodes of the Let-7 family within the immune microenvironment could provide novel insights for developing a combined “microenvironment remodeling + immunotherapy” strategy. This approach presents a potential direction for intervention, particularly in addressing treatment resistance issues arising from the immunosuppressive microenvironment in GC.

4.4 Signal Network Integration and Functional Collaboration of Let-7 Family Target Genes

The regulatory role of the Let-7 family is not isolated; rather, its target genes often form complex signaling networks that collectively influence the biological processes of GC through cross-regulation [76,101]. These target genes are primarily enriched in core pathways such as cell proliferation and metabolism, invasion and metastasis, therapeutic resistance, and immune evasion, all of which collaboratively shape the progression of GC through intersecting regulatory mechanisms.

In the proliferation-metabolism network, the Let-7 family inhibits key hub molecules such as C-Myc and the AKT/mTOR pathway, thereby blocking the cascade of glycolytic metabolic reprogramming and cell growth signals. This establishes a coordinated inhibitory axis of “transcriptional regulation-metabolism-proliferation” [60,94,95,97]. Invasion and metastasis-related targets converge on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) regulatory network, which synergistically modulates cytoskeletal remodeling, extracellular matrix degradation, and transcription factor networks to suppress tumor cell migration and invasion [60,77]. Within the therapeutic resistance-immune escape network, Let-7 family members construct an intersecting regulatory framework of “drug response-immune microenvironment-metabolic reprogramming” by regulating genes associated with chemotherapy sensitivity, immune checkpoint molecules, and tumor microenvironmental signals [75,101].

C-Myc and AKT/mTOR serve as critical network hubs that integrate the multifaceted regulatory effects of the Let-7 family. Specifically, C-Myc orchestrates downstream pathways, including glycolytic metabolism and cytoskeletal remodeling [94,97], while AKT/mTOR coordinates growth signaling, autophagic inhibition, and the expression of molecules related to immune escape [60,95]

This highly interconnected network architecture underscores that the tumor-suppressive efficacy of the Let-7 family relies on synergistic multi-target regulation; single-target interventions are often compromised by signaling redundancy. Network-based analyses suggest that combined targeting of core nodes, such as C-Myc/AKT or EMT-associated signaling axes, holds promise for overcoming the limitations of single Let-7 analogs, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for developing multi-target combinatorial therapies in GC.

5 Association of the Let-7 Family with Chemotherapy in GC

Chemotherapy is a common treatment modality for various types of cancer; however, most cancers typically exhibit a certain degree of drug resistance [102–104]. Understanding the evolutionary mechanisms of drug resistance in GC is crucial for enhancing the efficacy of chemotherapy and reducing cancer-related mortality. Research indicates that members of the Let-7 family not only predict the response of GC patients to chemotherapy drugs but also directly participate in regulating this response.

5.1 Potential of Members of the Let-7 Family as Biomarkers for Predicting Chemotherapy Efficacy in GC

Let-7a has shown potential in evaluating the efficacy of chemotherapy for GC. A study utilizing qRT-PCR demonstrated a significant decrease in Let-7a expression levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients following neoadjuvant chemotherapy [105]. Additionally, in docetaxel-resistant and sensitive cell lines, Let-7a showed variable expression (both downregulation and upregulation), suggesting its utility as a biomarker for sensitivity to docetaxel treatment [106]. Furthermore, Let-7g-3p expression is associated with the efficacy of neoadjuvant intraperitoneal and systemic chemotherapy, with studies revealing a reduction in its expression post-treatment; low expression levels significantly correlate with negative outcomes in peritoneal metastasis [100]. In hydroxycamptothecin (HCPT)-resistant GC cells, Let-7g and miR-98 display an upregulation trend, and their low expression predicts better efficacy of HCPT chemotherapy, highlighting their predictive value for the effectiveness of the HCPT regimen [107]. Moreover, the overexpression of Let-7f and Let-7g is linked to prolonged time to progression following treatment with cisplatin combined with fluorouracil (CF), suggesting their potential utility in identifying patients who are likely to respond favorably to the CF regimen [108].

Members of the Let-7 family demonstrate considerable potential for application in predicting the efficacy and screening biomarkers for various chemotherapy regimens in GC, as evidenced by their differential expression patterns. The dynamic alterations in Let-7 expression are closely associated with treatment sensitivity, metastasis risk, and disease progression, thereby providing novel molecular targets for the development of individualized chemotherapy regimens.

5.2 Regulation of Chemotherapy Sensitization by the Let-7 Family

Let-7b enhances the chemosensitivity of cisplatin/vincristine-resistant GC cell lines (SGC7901/DDP, SGC7901/VCR) by targeting and downregulating C-Myc, indicating its potential as a chemosensitizer [97]. Mechanistically, Let-7b directly targets and regulates Aurora kinase B (AURKB) and X-inactive specific transcript (Xist), thereby inhibiting the growth of cisplatin-resistant cells [109,110]. Furthermore, low expression levels of Let-7i are significantly associated with poor responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in GC patients, underscoring its dual role as both a predictive marker for therapeutic efficacy and a regulator of chemosensitivity [69].

These findings indicate that specific members of the Let-7 family regulate the chemosensitivity of GC through distinct molecular mechanisms. When most family members, which act as tumor suppressors, are downregulated, they promote tumor cell proliferation and invasion by activating target genes such as RAB40C and C-Myc, thereby significantly reducing chemosensitivity [55,94]. Conversely, the upregulation of specific members like Let-7g and Let-7d-5p contributes to drug resistance by targeting tumor suppressor genes such as PRDM5 [64]. Furthermore, members of the Let-7 family are intricately involved in the molecular network of chemotherapy resistance, regulating key signaling pathways such as AKT/mTOR and Wnt/β-catenin, which affect the balance of cell apoptosis and autophagy [95]. These mechanisms provide multi-dimensional molecular targets and potential therapeutic strategies for overcoming chemotherapy resistance in GC. The consistent results observed in drug-resistant cell lines and clinical samples further underscore the translational application prospects of these findings.

5.3 Mechanisms of Drug Resistance in GC Regulated by Let-7-lncRNA Interaction

Let-7c-3p exhibits a competitive interaction with an lncRNA (NONHSAT160169.1). Elevating the expression of this lncRNA mitigates the inhibitory effect of Let-7c-3p on SRY-box transcription factor 2 (SOX2), leading to increased resistance of GC cells to lapatinib [99]. Additionally, miR-98-5p is negatively correlated with the lncRNA PITPNA-AS1, which is overexpressed in cisplatin-resistant GC cells and tissues. Knockdown of PITPNA-AS1 enhances cisplatin sensitivity in GC cells. Therefore, increasing miR-98-5p levels downregulates PITPNA-AS1, thereby improving cisplatin sensitivity in GC cells [111]. These findings underscore the regulatory role of the “miRNA-lncRNA” axis in drug resistance pathways, offering a novel target for lncRNA-targeted therapies aimed at reversing drug resistance.

Personalized chemotherapy decision-making is of paramount importance in the treatment of GC patients [7]. Research indicates that Let-7 expression not only predicts responses to chemotherapy but also serves as a biomarker for evaluating the sensitivity of GC patients to specific chemotherapy agents. The Let-7 family, as a crucial regulatory factor, facilitates more precise personalized treatment options by modulating mechanisms of chemotherapy sensitization. Moreover, analyzing Let-7 expression profiles enables clinicians to select effective chemotherapy drug combinations more accurately, thereby optimizing treatment regimens. With ongoing research into Let-7’s role in regulating chemotherapy sensitivity in GC, more refined personalized chemotherapy regimens based on Let-7 expression profiles are anticipated in the future.

6 Frontier Advances of Let-7 in GC Treatment

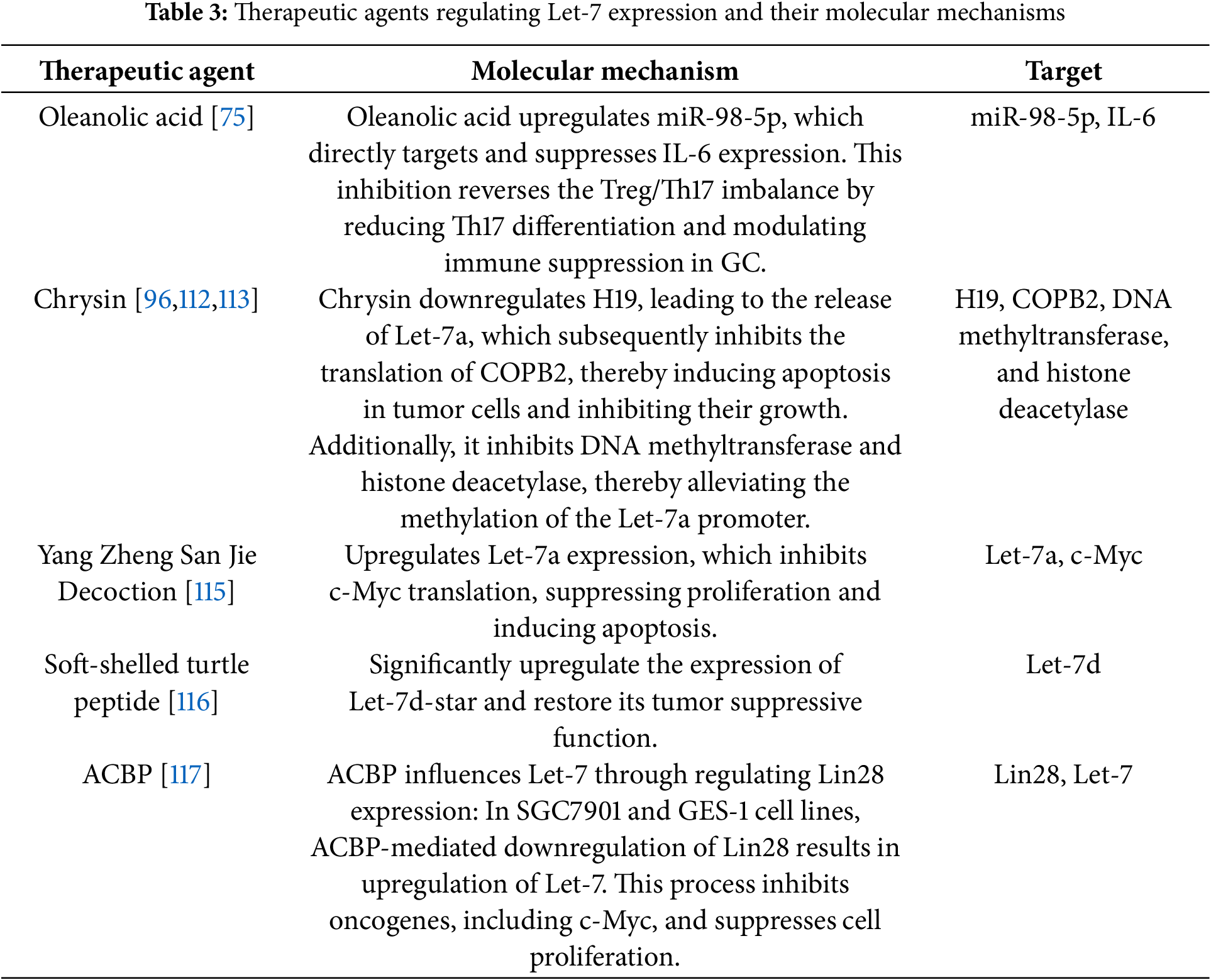

6.1 Exogenous Interventions for the Regulation of Let-7 Expression and Antigastric Cancer Mechanisms

Modulating the expression levels of the Let-7 family in GC tissues has emerged as a critical approach for optimizing existing therapies and exploring novel treatment strategies. Studies have demonstrated that plant-derived chrysin can alleviate the inhibitory effect on Let-7a, thereby promoting its upregulation in GC tissues [112]. However, the poor water solubility of chrysin limits its bioavailability and clinical application. To overcome this challenge, researchers have employed nanoencapsulation technology. Experimental results indicate that nanoencapsulated chrysin significantly enhances the expression level of Let-7a [113]. A detailed investigation of its mechanism revealed that chrysin induces apoptosis in GC cells by upregulating Let-7a expression and downregulating COPB2 levels, effectively inhibiting cell growth and invasive behavior [96].

Moreover, oleanolic acid, a pentacyclic triterpenoid compound widely present in plants, has emerged as a significant agent in the treatment of GC. Studies have confirmed that oleanolic acid can promote the balance of Treg and Th17 cells by upregulating the expression of miR-98-5p, thereby exerting therapeutic effects on GC [75,114]. In the realm of traditional Chinese medicine, the formula Yang Zheng San Jie Decoction has also demonstrated anticancer potential. Early animal experiments indicated that this formula can upregulate the expression of Let-7a and downregulate the expression of C-Myc in transplanted tumors in nude mice. Subsequently, using the serum pharmacological method of traditional Chinese medicine, serum containing the components of Yang Zheng San Jie Decoction was prepared and applied to human GC cell lines AGS and HS-746T. It was found that the levels of Let-7a in both cell lines significantly increased, while the expression of C-Myc decreased. This further confirms that Yang Zheng San Jie Decoction can inhibit cell proliferation by enhancing the expression of Let-7a in GC cells and induce apoptosis by suppressing its target gene, C-Myc [115].

In studies involving various substances, the functional peptide product soft-shelled turtle peptide, developed based on the nutritional and medicinal value of soft-shelled turtles, demonstrates a regulatory relationship with miRNA expression in GC tissues. Treatment of the human GC cell line AGS with soft-shelled turtle peptide resulted in alterations to the miRNA expression profile, notably increasing the expression of 101 miRNAs, including Let-7d [116]. Additionally, the small-molecule compound anticancer bioactive peptide (ACBP) warrants attention, as it influences Let-7 expression both as a standalone agent and in conjunction with oxaliplatin. The combination of ACBP and oxaliplatin not only exhibits a significant anticancer sensitization effect but also substantially enhances the quality of life in tumor-bearing nude mice while reducing the toxic side effects of chemotherapy drugs on these animals [117]. Table 3 summarizes the therapeutic agents that regulate Let-7 expression and their corresponding molecular mechanisms.

6.2 Research Breakthroughs in Let-7 Targeted Delivery Systems

The delivery of Let-7 into tumors represents a promising therapeutic approach. However, the rapid degradation of miRNA in plasma necessitates further research into delivery methods for Let-7. The selection of appropriate carriers may offer a viable solution. Currently, aptamer-mediated delivery systems have demonstrated significant advantages; for instance, a conjugate of the DNA-targeting aptamer nucleolin-specific aptamer (AptNCL) and Let-7d selectively inhibits the proliferation of GC MKN-45 cells while sparing normal gastric mucosal epithelial cells [118]. Furthermore, a chimera constructed with AptNCL and Let-7d enhances the inhibitory effect on GC cells by suppressing the JAK-2 pathway [119]. In the realm of nanocarrier research, a polyethylene glycol (PEG)-modified nanoparticle system has achieved tumor suppression in vivo without significant toxicity through the co-delivery of Let-7 and paclitaxel [120]. This type of carrier not only addresses the stability issues associated with miRNA but also facilitates targeted delivery to tumor cells via surface functionalization modifications, providing an innovative paradigm to overcome the delivery limitations of traditional chemotherapy drugs.

Accumulating evidence demonstrates that members of the Let-7 family exhibit dysregulated expression in GC and play crucial roles in regulating various biological processes in GC cells, including proliferation, cell cycle progression, migration, stemness, and metabolism. A thorough comprehension of the differential expression patterns of Let-7 in GC, coupled with its comprehensive regulatory network of targets, not only elucidates the specific mechanisms driving GC pathogenesis and progression but also provides a robust theoretical basis and potential targets for innovative therapeutic strategies. Notably, recent studies highlight that Let-7 significantly modulates, and may even dictate, the chemosensitivity of GC, as evidenced by certain drugs exerting anti-GC effects through modulation of Let-7 expression. These findings substantially elevate the therapeutic value of Let-7 as a promising target. However, despite these significant advances, the safe and efficacious translation of Let-7-based miRNA therapy into clinical practice faces substantial hurdles, such as delivery challenges and off-target effects. To realize the safe application of Let-7-based therapies for GC patients, enhance their quality of life, and prolong survival, concerted clinical research efforts are imperative to address these obstacles.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was financed by grants from the Hunan Province Foundation of High-Level Health Talent (225 Program, 20231526) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2025JJ81050).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Xinke Chai, Qiulin Huang; Draft manuscript preparation: Xinke Chai, Qian Shen; Review and editing: Xinke Chai, Shifeng Wu; Visualization: Xinke Chai; Supervision: Qiulin Huang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. doi:10.3322/caac.21660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Qiu H, Cao S, Xu R. Cancer incidence, mortality, and burden in China: a time-trend analysis and comparison with the United States and United Kingdom based on the global epidemiological data released in 2020. Cancer Commun. 2021;41(10):1037–48. doi:10.1002/cac2.12197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Huang L, Chen L, Gui ZX, Liu S, Wei ZJ, Xu AM. Preventable lifestyle and eating habits associated with gastric adenocarcinoma: a case-control study. J Cancer. 2020;11(5):1231–9. doi:10.7150/jca.39023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Sundar R, Nakayama I, Markar SR, Shitara K, van Laarhoven HWM, Janjigian YY, et al. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2025;405(10494):2087–102. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(25)00052-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Li GZ, Doherty GM, Wang J. Surgical management of gastric cancer: a review. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(5):446–54. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2022.0182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Guo J, Xu A, Sun X, Zhao X, Xia Y, Rao H, et al. Three-year outcomes of the randomized phase III SEIPLUS trial of extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage for locally advanced gastric cancer. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):6598. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26778-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Joshi SS, Badgwell BD. Current treatment and recent progress in gastric cancer. CA A Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):264–79. doi:10.3322/caac.21657. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Leong T, Smithers BM, Michael M, Haustermans K, Wong R, Gebski V, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for resectable gastric cancer. New Engl J Med. 2024;391(19):1810–21. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2405195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Mafi A, Rezaee M, Hedayati N, Hogan SD, Reiter RJ, Aarabi MH, et al. Melatonin and 5-fluorouracil combination chemotherapy: opportunities and efficacy in cancer therapy. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21(1):33. doi:10.1186/s12964-023-01047-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Alsina M, Arrazubi V, Diez M, Tabernero J. Current developments in gastric cancer: from molecular profiling to treatment strategy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20(3):155–70. doi:10.1038/s41575-022-00703-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Luo D, Liu Y, Lu Z, Huang L. Targeted therapy and immunotherapy for gastric cancer: rational strategies, novel advancements, challenges, and future perspectives. Mol Med. 2025;31(1):52. doi:10.1186/s10020-025-01075-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang X, Xu H, Zhang Y, Sun C, Li Z, Hu C, et al. Immunohistochemistry and bioinformatics identify GPX8 as a potential prognostic biomarker and target in human gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:878546. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.878546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Zhong L, Li Y, Xiong L, Wang W, Wu M, Yuan T, et al. Small molecules in targeted cancer therapy: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):201. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00572-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Rupaimoole R, Slack FJ. MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(3):203–22. doi:10.1038/nrd.2016.246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Smolarz B, Durczyński A, Romanowicz H, Szyłło K, Hogendorf P. miRNAs in cancer (review of literature). Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5):2805. doi:10.3390/ijms23052805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Mulcahy EQX, Zhang Y, Colόn RR, Cain SR, Gibert MKJr, Dube CJ, et al. MicroRNA, 3928 suppresses glioblastoma through downregulation of several oncogenes and upregulation of p53. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(7):3930. doi:10.3390/ijms23073930. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Hayashi Y, Tsujii M, Wang J, Kondo J, Akasaka T, Jin Y, et al. CagA mediates epigenetic regulation to attenuate let-7 expression in Helicobacter pylori-related carcinogenesis. Gut. 2013;62(11):1536–46. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301625. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Jia ZF, Cao DH, Wu YH, Jin MS, Pan YC, Cao XY, et al. Lethal-7-related polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility to and prognosis of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(8):1012–23. doi:10.3748/wjg.v25.i8.1012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Tong KL, Mahmood Zuhdi AS, Wan Ahmad WA, Vanhoutte PM, de Magalhaes JP, Mustafa MR, et al. Circulating MicroRNAs in young patients with acute coronary syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(5):1467. doi:10.3390/ijms19051467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Brancati G, Großhans H. An interplay of miRNA abundance and target site architecture determines miRNA activity and specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(7):3259–69. doi:10.1093/nar/gky201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang J, Yan S, Chang L, Guo W, Wang Y, Wang Y, et al. Direct microRNA sequencing using nanopore-induced phase-shift sequencing. iScience. 2020;23(3):100916. doi:10.1101/747113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ke S, Liu Z, Wan Y. Let-7 family as a mediator of exercise on Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2025;45(1):43. doi:10.1007/s10571-025-01559-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ. Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009;136(4):642–55. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Yıldız A, Hasani A, Hempel T, Köhl N, Beicht A, Becker R, et al. Trans-amplifying RNA expressing functional miRNA mediates target gene suppression and simultaneous transgene expression. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2024;35(2):102162. doi:10.1016/j.omtn.2024.102162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Yazarlou F, Kadkhoda S, Ghafouri-Fard S. Emerging role of let-7 family in the pathogenesis of hematological malignancies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;144(3):112334. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Mizuno R, Kawada K, Sakai Y. The Molecular basis and therapeutic potential of Let-7 MicroRNAs against colorectal cancer. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;2018(31):5769591. doi:10.1155/2018/5769591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Denli AM, Tops BB, Plasterk RH, Ketting RF, Hannon GJ. Processing of primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor complex. Nature. 2004;432(7014):231–5. doi:10.1038/nature03049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Seasock MJ, Shafiquzzaman M, Ruiz-Echartea ME, Kanchi RS, Tran BT, Simon LM, et al. Let-7 restrains an epigenetic circuit in AT2 cells to prevent fibrogenic intermediates in pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):4353. doi:10.1101/2024.05.22.595205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Roush S, Slack FJ. The let-7 family of microRNAs. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18(10):505–16. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Su JL, Chen PS, Johansson G, Kuo ML. Function and regulation of Let-7 family microRNAs. MicroRNA. 2012;1(1):34–9. doi:10.2174/2211536611201010034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Letafati A, Najafi S, Mottahedi M, Karimzadeh M, Shahini A, Garousi S, et al. MicroRNA Let-7 and viral infections: focus on mechanisms of action. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2022;27(1):14. doi:10.1186/s11658-022-00317-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Liu W, Chen J, Yang C, Lee KF, Lee YL, Chiu PC, et al. Expression of microRNA Let-7 in cleavage embryos modulates cell fate determination and formation of mouse blastocysts. Biol Reprod. 2022;107(6):1452–63. doi:10.1093/biolre/ioac181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Liu J, Sauer MA, Hussein SG, Yang J, Tenen DG, Chai L. SALL4 and microRNA: the role of Let-7. Genes. 2021;12(9):1301. doi:10.3390/genes12091301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Li CH, Liao CC. The Metabolism Reprogramming of microRNA Let-7-mediated glycolysis contributes to autophagy and tumor progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;23(1):113. doi:10.3390/ijms23010113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Simino LAP, Panzarin C, Fontana MF, de Fante T, Geraldo MV, Ignácio-Souza LM, et al. MicroRNA Let-7 targets AMPK and impairs hepatic lipid metabolism in offspring of maternal obese pregnancies. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):8980. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-88518-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Xie Y, Li X, Wang M, Chu M, Cao G. Lin28b-let-7 modulates mRNA expression of GnRH1 through multiple signaling pathways related to glycolysis in GT1-7 cells. Animals. 2025;15(2):120. doi:10.3390/ani15020120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Yuko AE, Carvalho Rigaud VO, Kurian J, Lee JH, Kasatkin N, Behanan M, et al. LIN28a induced metabolic and redox regulation promotes cardiac cell survival in the heart after ischemic injury. Redox Biol. 2021;47(7):102162. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2021.102162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Yu X, Huang J, Liu X, Li J, Yu M, Li M, et al. LncRNAH19 acts as a ceRNA of let-7g to facilitate endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension via regulating TGF-β signalling pathway. Respir Res. 2024;25(1):270. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-4367962/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Han JS, Fishman-Williams E, Decker SC, Hino K, Reyes RV, Brown NL, et al. Notch directs telencephalic development and controls neocortical neuron fate determination by regulating microRNA levels. Development. 2023;150(11):dev201408. doi:10.1101/2022.09.16.508220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Dai W, Li Y, Du J, Shen G, Fan M, Su Z, et al. Transplanting neural stem cells overexpressing miRNA-21 can promote neural recovery after cerebral hemorrhage through the SOX2/LIN28-let-7 signaling pathway. Anim Models Exp Med. 2025;11(7):330. doi:10.1002/ame2.70009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Chen O, Jiang C, Berta T, Powell Gray B, Furutani K, Sullenger BA, et al. MicroRNA let-7b enhances spinal cord nociceptive synaptic transmission and induces acute and persistent pain through neuronal and microglial signaling. Pain. 2024;165(8):1824–39. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000003206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Ghosh S, Kumar V, Mukherjee H, Lahiri D, Roy P. Nutraceutical regulation of miRNAs involved in neurodegenerative diseases and brain cancers. Heliyon. 2021;7(6):e07262. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Allela OQB, Al-Hussainy AF, Sanghvi G, Roopashree R, Kashyap A, Anand DA, et al. Tumor immune evasion and the Let-7 family: insights into mechanisms and therapies. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2025;1–8. doi:10.1007/s00210-025-04283-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Wang L, Wu K, Li L, Amuda TO, Wu Y, Pu G, et al. Regulation of host regulatory t cell differentiation by emu-let-7-5p in echinococcus multilocularis infection through targeting NFκB2. FASEB J. 2025;39(9):e70603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

45. Chen SJ, Hashimoto K, Fujio K, Hayashi K, Paul SK, Yuzuriha A, et al. A let-7 microRNA-RALB axis links the immune properties of iPSC-derived megakaryocytes with platelet producibility. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):2588. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-46605-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Chen H, Wang J, Wang H, Liang J, Dong J, Bai H, et al. Advances in the application of Let-7 microRNAs in the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of leukemia. Oncol Lett. 2022;23(1):1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

47. Wang F, Zhou C, Zhu Y, Keshavarzi M. The microRNA Let-7 and its exosomal form: epigenetic regulators of gynecological cancers. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2024;40(1):42. doi:10.1007/s10565-024-09884-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. De Santis C, Götte M. The Role of microRNA Let-7d in female malignancies and diseases of the female reproductive tract. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(14):7359. doi:10.3390/ijms22147359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Xi Y, Shen Y, Wu D, Zhang J, Lin C, Wang L, et al. CircBCAR3 accelerates esophageal cancer tumorigenesis and metastasis via sponging miR-27a-3p. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):145. doi:10.1186/s12943-022-01615-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Xie T, Fu DJ, Li ZM, Lv DJ, Song XL, Yu YZ, et al. CircSMARCC1 facilitates tumor progression by disrupting the crosstalk between prostate cancer cells and tumor-associated macrophages via miR-1322/CCL20/CCR6 signaling. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):173. doi:10.1186/s12943-023-01881-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Boyerinas B, Park SM, Hau A, Murmann AE, Peter ME. The role of let-7 in cell differentiation and cancer. Endocr-Relat Cancer. 2010;17(1):F19–36. doi:10.1677/erc-09-0184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Xie D, Chen F, Zhang Y, Shi B, Song J, Chaudhari K, et al. Let-7 underlies metformin-induced inhibition of hepatic glucose production. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2022;119(14):e2122217119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2122217119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Tsujiura M, Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Shiozaki A, Takeshita H, Kosuga T, et al. Circulating microRNAs in plasma of patients with gastric cancers. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(7):1174–9. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Zhu YM, Zhong ZX, Liu ZM. Relationship between let-7a and gastric mucosa cancerization and its significance. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(26):3325–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

55. Yang Q, Jie Z, Cao H, Greenlee AR, Yang C, Zou F, et al. Low-level expression of let-7a in gastric cancer and its involvement in tumorigenesis by targeting RAB40C. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(5):713–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

56. Song J, Bai Z, Han W, Zhang J, Meng H, Bi J, et al. Identification of suitable reference genes for qPCR analysis of serum microRNA in gastric cancer patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(4):897–904. doi:10.1007/s10620-011-1981-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Liu X, Pu K, Wang Y, Chen Y, Zhou Y. Gastric cancer-associated microRNA expression signatures: integrated bioinformatics analysis, validation, and clinical significance. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(9):797. doi:10.21037/atm-21-1631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Sallas ML, Zapparoli D, Dos Santos MP, Pereira JN, Orcini WA, Peruquetti RL, et al. Dysregulated expression of apoptosis-associated genes and MicroRNAs and their involvement in gastric carcinogenesis. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2021;52(2):625–33. doi:10.1007/s12029-019-00353-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Cholewinski G, Garczorz W, Francuz T, Owczarek AJ, Kimsa-Furdzik M, Blaszczynska M, et al. Expression of let-7a, miR-106b and miR-29b is changed in human gastric cancer. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2022;73(1):30–9. [Google Scholar]

60. Kang W, Tong JH, Lung RW, Dong Y, Yang W, Pan Y, et al. let-7b/g silencing activates AKT signaling to promote gastric carcinogenesis. J Transl Med. 2014;12(1):281. doi:10.1186/s12967-014-0281-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Han X, Chen Y, Yao N, Liu H, Wang Z. MicroRNA let-7b suppresses human gastric cancer malignancy by targeting ING1. Cancer Gene Ther. 2015;22(3):122–9. doi:10.1038/cgt.2014.75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Yu J, Feng J, Zhi X, Tang J, Li Z, Xu Y, et al. Let-7b inhibits cell proliferation, migration, and invasion through targeting Cthrc1 in gastric cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(5):3221–9. doi:10.1007/s13277-014-2950-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Fassan M, Saraggi D, Balsamo L, Cascione L, Castoro C, Coati I, et al. Let-7c down-regulation in Helicobacter pylori-related gastric carcinogenesis. Oncotarget. 2016;7(4):4915–24. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.6642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Gao X, Liu H, Wang R, Huang M, Wu Q, Wang Y, et al. Hsa-let-7d-5p promotes gastric cancer progression by targeting PRDM5. J Oncol. 2022;2022(2):2700651. doi:10.1155/2022/2700651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Liang S, He L, Zhao X, Miao Y, Gu Y, Guo C, et al. MicroRNA let-7f inhibits tumor invasion and metastasis by targeting MYH9 in human gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18409. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Liu WJ, Xu Q, Sun LP, Dong QG, He CY, Yuan Y. Expression of serum let-7c, let-7i, and let-7f microRNA with its target gene, pepsinogen C, in gastric cancer and precancerous disease. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(5):3337–43. doi:10.1007/s13277-014-2967-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Peng W, Liu YN, Zhu SQ, Li WQ, Guo FC. The correlation of circulating pro-angiogenic miRNAs’ expressions with disease risk, clinicopathological features, and survival profiles in gastric cancer. Cancer Med. 2018;7(8):3773–91. doi:10.1002/cam4.1618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Tang S, Cheng J, Yao Y, Lou C, Wang L, Huang X, et al. Combination of four serum exosomal miRNAs as novel diagnostic biomarkers for early-stage gastric cancer. Front Genet. 2020;11:237. doi:10.3389/fgene.2020.00237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Liu K, Qian T, Tang L, Wang J, Yang H, Ren J. Decreased expression of microRNA let-7i and its association with chemotherapeutic response in human gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10(1):225. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-10-225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Treece AL, Duncan DL, Tang W, Elmore S, Morgan DR, Dominguez RL, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma microRNA profiles in fixed tissue and in plasma reveal cancer-associated and Epstein-Barr virus-related expression patterns. Lab Investig. 2016;96(6):661–71. doi:10.1038/labinvest.2016.33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Yuan C, Zhang Y, Tu W, Guo Y. Integrated miRNA profiling and bioinformatics analyses reveal upregulated miRNAs in gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2019;18(2):1979–88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

72. Codolo G, Toffoletto M, Chemello F, Coletta S, Soler Teixidor G, Battaggia G, et al. Helicobacter pylori dampens HLA-II expression on macrophages via the up-regulation of miRNAs targeting CIITA. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2923. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Shi Y, Duan Z, Zhang X, Zhang X, Wang G, Li F. Down-regulation of the let-7i facilitates gastric cancer invasion and metastasis by targeting COL1A1. Protein Cell. 2019;10(2):143–8. doi:10.1007/s13238-018-0550-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Yao Y, Suo AL, Li ZF, Liu LY, Tian T, Ni L, et al. MicroRNA profiling of human gastric cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2009;2(6):963–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

75. Xu QF, Peng HP, Lu XR, Hu Y, Xu ZH, Xu JK. Oleanolic acid regulates the Treg/Th17 imbalance in gastric cancer by targeting IL-6 with miR-98-5p. Cytokine. 2021;148(1):155656. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Zhang K, Zhao J, Bi Z, Feng Y, Zhang H, Zhang J, et al. Mechanism of miR-98-5p in gastric cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion through the USP44/CTCFL axis. Toxicol Res. 2024;13(2):tfae040. doi:10.1093/toxres/tfae040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Zhao Y, Li C, Wang M, Su L, Qu Y, Li J, et al. Decrease of miR-202-3p expression, a novel tumor suppressor, in gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69756. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Dou D, Shi YF, Liu Q, Luo J, Liu JX, Liu M, et al. Hsa-miR-202-3p, up-regulated in type 1 gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms, may target DUSP1. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(5):573–82. doi:10.3748/wjg.v24.i5.573. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Zhu Y, Xu F. Up-regulation of Let-7a expression induces gastric carcinoma cell apoptosis in vitro. Chin Med Sci J. 2017;32(1):44–7. doi:10.24920/j1001-9242.2007.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Ueda T, Volinia S, Okumura H, Shimizu M, Taccioli C, Rossi S, et al. Relation between microRNA expression and progression and prognosis of gastric cancer: a microRNA expression analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):136–46. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70343-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Li FQ, Xu B, Wu YJ, Yang ZL, Qian JJ. Differential microRNA expression in signet-ring cell carcinoma compared with tubular adenocarcinoma of human gastric cancer. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14(1):739–47. doi:10.4238/2015.january.30.17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Shi D, Yang Z, Cai Y, Li H, Lin L, Wu D, et al. Research advances in the molecular classification of gastric cancer. Cell Oncol. 2024;47(5):1523–36. doi:10.1007/s13402-024-00951-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. do Nascimento CN, Mascarenhas-Lemos L, Silva JR, Marques DS, Gouveia CF, Faria A, et al. EBV and MSI status in gastric cancer: does it matter? Cancers. 2022;15(1):74. doi:10.3390/cancers15010074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Qu X, Zhao L, Zhang R, Wei Q, Wang M. Differential microRNA expression profiles associated with microsatellite status reveal possible epigenetic regulation of microsatellite instability in gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(7):484. doi:10.21037/atm.2020.03.54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Wang H, Liu W, Luo B. The roles of miRNAs and lncRNAs in Epstein-Barr virus associated epithelial cell tumors. Virus Res. 2021;291:198217. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Li J, Chen Z, Li Q, Liu R, Zheng J, Gu Q, et al. Study of miRNA and lymphocyte subsets as potential biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of gastric cancer. PeerJ. 2024;12:e16660. doi:10.7717/peerj.16660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. So JBY, Kapoor R, Zhu F, Koh C, Zhou L, Zou R, et al. Development and validation of a serum microRNA biomarker panel for detecting gastric cancer in a high-risk population. Gut. 2021;70(5):829–37. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Kori M, Gov E. Bioinformatics prediction and machine learning on gene expression data identifies novel gene candidates in gastric cancer. Genes. 2022;13(12):2233. doi:10.3390/genes13122233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Li Y, Pan L, Mugaanyi J, Li H, Li G, Huang J, et al. Pathomic and bioinformatics analysis of clinical-pathological and genomic factors for pancreatic cancer prognosis. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):27769. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-81889-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, et al. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120(5):635–47. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Shaik Syed Ali P, Ahmad MP, Parveen KMH. Lin28/let-7 axis in breast cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 2025;52(1):311. doi:10.1007/s11033-025-10413-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Messina S. The RAS oncogene in brain tumors and the involvement of let-7 microRNA. Mol Biol Rep. 2024;51(1):531. doi:10.1007/s11033-024-09439-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Motoyama K, Inoue H, Nakamura Y, Uetake H, Sugihara K, Mori M. Clinical significance of high mobility group A2 in human gastric cancer and its relationship to let-7 microRNA family. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(8):2334–40. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-07-4667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Tang R, Yang C, Ma X, Wang Y, Luo D, Huang C, et al. miR-let-7a inhibits cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by down-regulating PKM2 in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(5):5972–84. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.6821. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Fan H, Jiang M, Li B, He Y, Huang C, Luo D, et al. MicroRNA-let-7a regulates cell autophagy by targeting Rictor in gastric cancer cell lines MGC-803 and SGC-7901. Oncol Rep. 2018;39(3):1207–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

96. Chen L, Li Q, Jiang Z, Li C, Hu H, Wang T, et al. Chrysin induced cell apoptosis through H19/let-7a/COPB2 axis in gastric cancer cells and inhibited tumor growth. Front Oncol. 2021;11:651644. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.651644. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Yang X, Cai H, Liang Y, Chen L, Wang X, Si R, et al. Inhibition of c-Myc by let-7b mimic reverses mutidrug resistance in gastric cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2015;33(4):1723–30. doi:10.3892/or.2015.3757. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Tsai KW, Hu LY, Chen TW, Li SC, Ho MR, Yu SY, et al. Emerging role of microRNAs in modulating endothelin-1 expression in gastric cancer. Oncol Rep. 2015;33(1):485–93. doi:10.3892/or.2014.3598. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Zhao X, Xu Z, Meng B, Ren T, Wang X, Hou R, et al. Long noncoding RNA NONHSAT160169.1 promotes resistance via hsa-let-7c-3p/SOX2 axis in gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):20858. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-47961-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Luo J, Jiang L, He C, Shi M, Yang ZY, Shi M, et al. Exosomal hsa-let-7g-3p and hsa-miR-10395-3p derived from peritoneal lavage predict peritoneal metastasis and the efficacy of neoadjuvant intraperitoneal and systemic chemotherapy in patients with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2023;26(3):364–78. doi:10.1007/s10120-023-01368-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Ye Z, Yi J, Jiang X, Shi W, Xu H, Cao H, et al. Gastric cancer-derived exosomal let-7 g-5p mediated by SERPINE1 promotes macrophage M2 polarization and gastric cancer progression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2025;44(1):2. doi:10.1186/s13046-024-03269-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. To KKW, Huang Z, Zhang H, Ashby CRJr, Fu L. Utilizing non-coding RNA-mediated regulation of ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters to overcome multidrug resistance to cancer chemotherapy. Drug Resist. 2024;73(1):101058. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2024.101058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Dong D, Yu X, Xu J, Yu N, Liu Z, Sun Y. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of gastrointestinal cancer liver metastases and drug resistance. Drug Resist Update. 2024;77(6409):101125. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2024.101125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Liu C, Li S, Tang Y. Mechanism of cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer and associated microRNAs. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2023;92(5):329–40. doi:10.1007/s00280-023-04572-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Hu W, Chen Y, Lv K. The Expression profiles of MicroRNA Let-7a in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients of gastric cancer with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Clin Lab. 2018;64(5):835–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

106. Shekari N, Asghari F, Haghnavaz N, Shanehbandi D, Khaze V, Baradaran B, et al. Let-7a could serve as a biomarker for chemo-responsiveness to docetaxel in gastric cancer. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2019;19(3):304–9. doi:10.2174/1871520619666181213110258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Wu XM, Shao XQ, Meng XX, Zhang XN, Zhu L, Liu SX. Genome-wide analysis of microRNA and mRNA expression signatures in hydroxycamptothecin-resistant gastric cancer cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2011;32(2):259–69. doi:10.1038/aps.2010.204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Kim CH, Kim HK, Rettig RL, Kim J, Lee ET, Aprelikova O, et al. miRNA signature associated with outcome of gastric cancer patients following chemotherapy. BMC Med Genom. 2011;4(1):79. doi:10.1186/1755-8794-4-79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Han X, Zhang JJ, Han ZQ, Zhang HB, Wang ZA. Let-7b attenuates cisplatin resistance and tumor growth in gastric cancer by targeting AURKB. Cancer Gene Ther. 2018;25(11–12):300–8. doi:10.1038/s41417-018-0048-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Han X, Zhang HB, Li XD, Wang ZA. Long non-coding RNA X-inactive-specific transcript contributes to cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer by sponging miR-let-7b. Anticancer Drugs. 2020;31(10):1018–25. doi:10.1097/cad.0000000000000942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Ma Z, Liu G, Hao S, Zhao T, Chang W, Wang J, et al. PITPNA-AS1/miR-98-5p to Mediate the Cisplatin Resistance of Gastric Cancer. J Oncol. 2022;2022(20):7981711–14. doi:10.1155/2022/7981711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Mohammadian F, Pilehvar-Soltanahmadi Y, Alipour S, Dadashpour M, Zarghami N. Chrysin alters microRNAs expression levels in gastric cancer cells: possible molecular mechanism. Drug Res. 2017;67(9):509–14. doi:10.1055/s-0042-119647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Mohammadian F, Pilehvar-Soltanahmadi Y, Zarghami F, Akbarzadeh A, Zarghami N. Upregulation of miR-9 and Let-7a by nanoencapsulated chrysin in gastric cancer cells. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2017;45(6):1–6. doi:10.1080/21691401.2016.1216854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Sarfraz M, Afzal A, Yang T, Gai Y, Raza SM, Khan MW, et al. Development of dual drug loaded nanosized liposomal formulation by a reengineered ethanolic injection method and its pre-clinical pharmacokinetic studies. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(3):151. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics10030151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Deng HX, Yu YY, Zhou AQ, Zhu JL, Luo LN, Chen WQ, et al. Yangzheng Sanjie decoction regulates proliferation and apoptosis of gastric cancer cells by enhancing let-7a expression. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(30):5538–48. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i30.5538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Wu YC, Liu X, Wang JL, Chen XL, Lei L, Han J, et al. Soft-shelled turtle peptide modulates microRNA profile in human gastric cancer AGS cells. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(3):3109–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

117. Li X, Kang L, Han W, Su X. An anticancer bioactive peptide combined with oxaliplatin inhibited gastric cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2025;26(6):493–510. doi:10.2174/0113892037350632241205040150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Ramezanpour M, Daei P, Tabarzad M, Khanaki K, Elmi A, Barati M. Preliminary study on the effect of nucleolin specific aptamer-miRNA let-7d chimera on Janus kinase-2 expression level and activity in gastric cancer (MKN-45) cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2019;46(1):207–15. doi:10.1007/s11033-018-4462-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Daei P, Ramezanpour M, Khanaki K, Tabarzad M, Nikokar I, Ch MH, et al. Aptamer-based targeted delivery of miRNA let-7d to gastric cancer cells as a novel anti-tumor therapeutic agent. Iran J Pharm Res. 2018;17(4):1537–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

120. Dai X, Fan W, Wang Y, Huang L, Jiang Y, Shi L, et al. Combined delivery of Let-7b microrna and paclitaxel via biodegradable nanoassemblies for the treatment of kras mutant cancer. Mol Pharm. 2016;13(2):520–33. doi:10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools