Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Is miR-10a a tumor suppressor that modulates proliferation and invasion in high-grade bladder cancer?

1 Laboratory of Medical Investigation (LIM55), Urology Department, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (FMUSP), São Paulo, 01246-903, Brazil

2 Department of Biology, Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de São Paulo (IFSP), Campus São Paulo, São Paulo, 01109-010, Brazil

3 Moriah Institute of Science and Education (MISE), Hospital Moriah, São Paulo, 04084-002, Brazil

4 Department of Biomedical Science, Centro Universitário São Camilo, São Paulo, 04263-200, Brazil

5Uro-Oncology Group, Urology Department, University of São Paulo Medical School and Institute of Cancer Estate of São Paulo (ICESP), São Paulo, 01246-000, Brazil

6 Urology Department, D’Or Institute for Research and Education (ID’Or), São Paulo, 01401-002, Brazil

7 Department of Bioscience, Universidade do Estado de Minas Gerais-UEMG, Passos, 37900-106, Brazil

* Corresponding Author: NAYARA IZABEL VIANA. Email:

Oncology Research 2025, 33(6), 1377-1382. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.055306

Received 23 June 2024; Accepted 14 March 2025; Issue published 29 May 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Bladder Cancer (BC) is one of the most commonly diagnosed malignancies worldwide, with high rates of mortality and morbidity. It can be classified as non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) or muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC), with radical cystectomy being the treatment for MIBC, which significantly reduces quality of life. MicroRNAs (miRs) act as critical genetic regulators, with both oncogenic and tumor-suppressive roles. MiR-10a is described as a tumor suppressor in various neoplasms, but its role in BC is controversial. This study aims to assess the activity of miR-10a in cellular invasion and proliferation in two distinct BC cell lines. Methods: The study used high-grade T24 and low-grade RT4 bladder cell lines. Cells were transfected with miR-10a mimic or a non-targeting control. Transfection efficiency was validated by qPCR. Cell proliferation was cultured for 10–14 days. Cell migration and invasion were evaluated using Matrigel. All assays were conducted in triplicate. Results: The T24 cells transfected with miR-10a presented decreased cellular proliferation and invasion compared to the Scramble (p = 0.0481 and p < 0.0001, respectively). In the RT4 cell line, there was only a significant reduction in cellular proliferation after miR-10a transfection (p = 0.0029). Conclusions: Our findings suggest that miR-10a has a tumoral suppressor role in BC, demonstrating higher efficacy in high-grade cells.Keywords

Bladder cancer (BC) is one of the most common carcinomas, associated with high rates of mortality and morbidity [1,2]. The most prevalent type, urothelial cancer (UC), is classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) into papillary urothelial neoplasia of low malignant potential (PUNLMP) [3,4], low-grade, and high-grade cancer [5,6]. Risk factors for BC include environmental and genetic elements that can lead to mutations affecting cellular proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation [1,4].

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) is typically managed with transurethral resection of the bladder (TURB), followed by intravesical chemotherapy [4,5]. However, a significant portion of in situ tumors are high-risk, with increased rates of progression and metastasis [6,7]. Muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC), is primarily treated with radical cystectomy and systemic chemotherapy, which carries substantial morbidity over the medium and long term [7,8].

Given these challenges, there is a growing interest in less invasive yet effective therapies for BC [9,10]. Advances in understanding epigenetics, DNA methylation, and microRNA (miRNA) have been pivotal. MiRNAs, small non-coding RNAs with post-transcriptional regulatory functions, are classified as oncogenic miRNAs or tumor-suppressor miRNAs, depending on their role in tumorigenesis [11–13].

MiR-10a has been identified as a tumor-suppressor miRNA in prostate cancer and as an oncomiRNA in cervical cancer [14,15]. However, its role in BC is more complex. Two studies by Dai et al. [16] and Li et al. [17] present conflicting results: the first found miR-10 underexpressed in BC samples and UC cell lines, while the second showed overexpression in stage I and II BC tissues, complicating our understanding of its function in BC [16,17]. These discrepancies may reflect phenotype-dependent expression of miR-10a, though the literature remains inconsistent, with studies reporting both under- and over-expression in different grades of BC [18,19].

This study aims to clarify miR-10a’s role by evaluating its activity in two distinct BC cell line phenotypes and determining whether its expression is stage-dependent in bladder tumorigenesis.

The in vitro models for BC were the T24 (high-grade BC) and RT4 (low-grade BC) cell lines, cultured according to the manufacturer’s guidelines (ATCC Culture Guides), before the experiments, the cells were tested for the presence of mycoplasma. Both T24 and RT4 cells were cultured in appropriate growth media (Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 Medium-RPMI-1640, 11875085, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco™, A5670701, MA, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (15140122, Gibco). Cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ humidified incubator.

The lipofectamine transfection method was used to induce miR-10a expression. The procedure was conducted in triplicate with three conditions: the transfection complex alone, with the miR-10a mimic (MH10787), and with a scramble/negative control microRNA precursor (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). The transfection complex was prepared by diluting the mimics in OPTI-MEM I medium (A4124801, Gibco). After dilution, the solution was mixed with the transfection reagent Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Invitrogen, 13778100, Carlsbad, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The final concentration of the transfection complex was 20 nM. The procedure was validated by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). The primer sequence used for the validation of miR-10a transfection was: UACCCUGUAGAUCCGAAUUUGUG.

Genetic expression analysis—miRNA extraction and qPCR

miRNA was extracted from the cell lines using the mirVana kit (Ambion, AM1560, Austin, TX, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity (260/280 nM ratio) and concentration of the genetic material were assessed using a Nanodrop® spectrophotometer (ND-1000, Wilmington, EUA), and the samples were stored at −80°C. Complementary DNA (cDNA) from miR-10a was synthesized using the TaqMan miRNA Reverse Transcription kit (Thermo Fisher, 4366596, MA, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The primer sequence used for the cDNA of miR-10a was: ACAAAUUCGGAUCUACAGGGUA. Target sequences were amplified using qPCR on the ABI 7500 Fast RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems, 4351105, Waltham, MA, USA) with a reaction volume of 10 µL, containing 2 µL of HOT FIREPol Probe Universal qPCR mix (Solis BioDyne, 08-88-0000S, Tartu, Estonia) and 0,5 µL of a specific probe. All reactions were performed in duplicate, using RNU48 as an endogenous control (Sequence: AGTGATGATG ACCCCAGGTA ACTCTGAGTG TGTCGCTGAT GCCATCACCG CAGCGCTCTGACC).

Expression levels were calculated using the relative quantification method. Data analysis was conducted with DataAssist software version: 3.01 (Applied Biosystems, USA).

Cells were seeded at low density (3 × 102 cells/well) in 12-well plates and transfected after 48 h. They were then incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 10 days. Colonies were fixed (using 4% paraformaldehyde), stained using 1 mL of 3% methylene blue (Millipore Sigma, M4159, Maryland) for 30 min (2×), washed with PBS, and counted. Colonies smaller than 1 mm were excluded. Images were captured and analyzed with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA, Version 1.54j).

Following transfection, T24, and RT4 cells were seeded at an inoculation density of 1 × 105 cells per well into separate Corning BioCoat Matrigel Invasion chambers (Becton Dickinson, Bedford, MA, USA), containing 24 wells with 8 µm pores coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, 356255, San Jose, CA, EUA). Matrigel was diluted in 450 µL of serum-free medium, seeded with 1 × 104 cells/mL in 250 µL of serum-free medium, and 750 µL of medium supplemented with 10% FBS was added to the lower chambers. The cells were incubated for 48 h at 37°C with CO2 at 5%, then fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS, stained with 0.2% crystal violet in methanol, and counted under an optical microscope (Nikon Model Eclipse E200, Tokyo, Japan) at 200× magnification.

Descriptive analysis was presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) Student’s t-test (for parametric variables) or Mann-Whitney test (for nonparametric variables) was used for group comparisons. All assays were repeated three times (n = 3) to ensure the reliability of the results. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, with a 5% significance level applied for all tests.

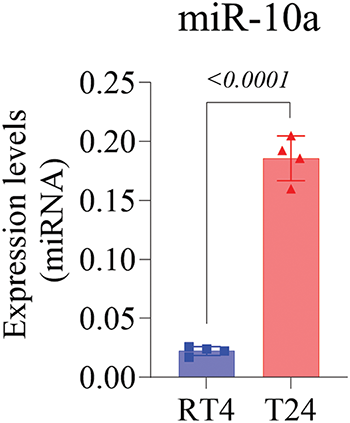

Overexpression of miR-10a in the T24 cell lines

Genetic expression analysis showed that the T24 cell line had significantly higher miR-10a expression than the RT4 cell line (p < 0.0001; Fig. 1).

Figure 1: MiR-10a expression levels in non-manipulated T24 and RT4 cell lines, showing higher expression in T24 (p < 0.0001). Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3).

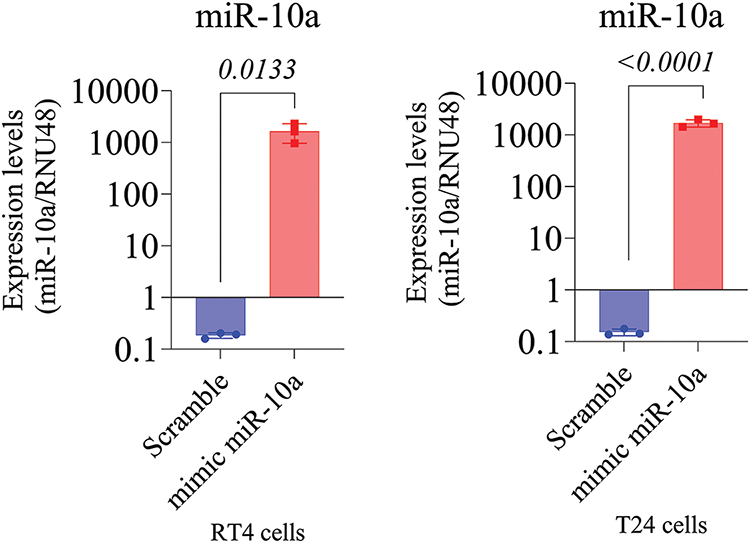

Validation of MiR-10a transfection in BC cell lines

miR-10a transfection was validated in the T24 and RT4 cell lines via q-PCR, demonstrating a 1000-fold increase in miR-10a concentration in transfected groups compared to scramble controls (p = 0.0133 for T24, p < 0.0001 for RT4; Fig. 2A and B).

Figure 2: MiR-10a expression in transfected T24 and RT4 cells. A) MiR-10a expression in transfected T24 cells showing a 1000-fold compared to control (p = 0.0133). B) MiR-10a expression level in transfected RT4 cells, showing a 1000-fold increase compared to control (p < 0.0001). Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3).

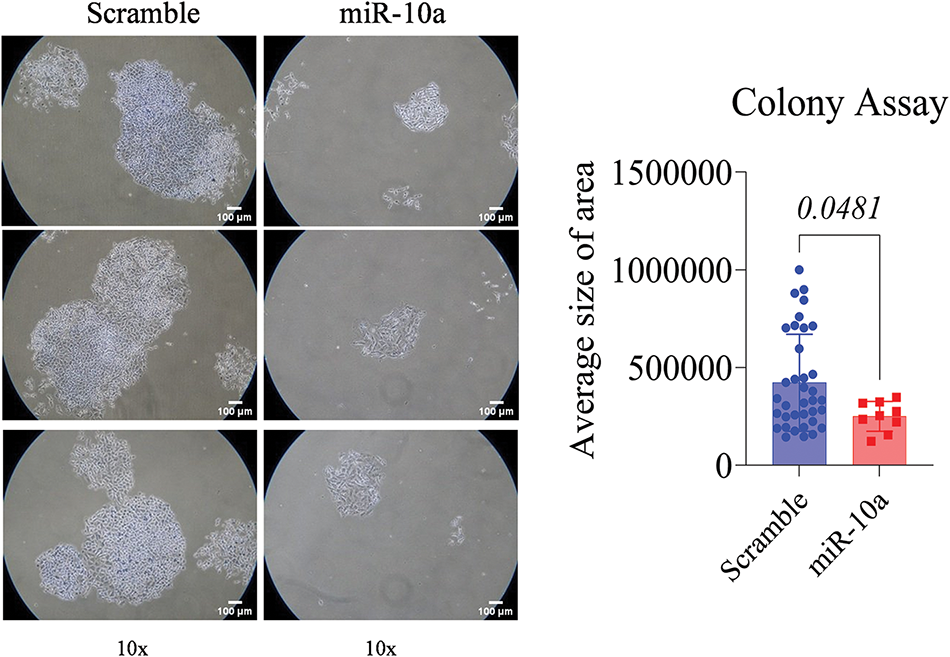

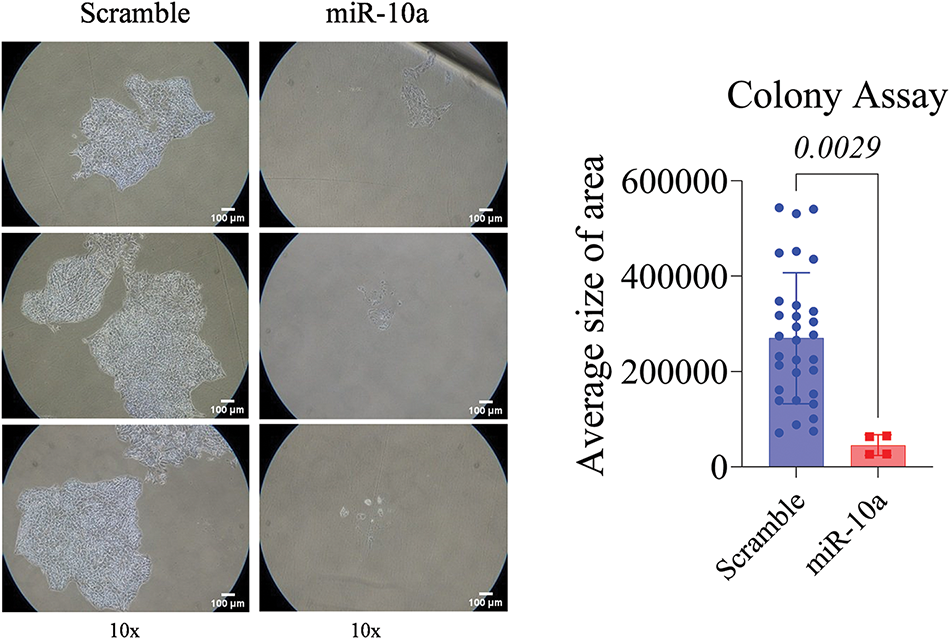

Inhibitory effect of miR-10a on cell proliferation in BC cell lines

A significant reduction in proliferation was observed in the miR-10a transfected groups compared to the scramble controls, with p = 0.0481 for T24 and p = 0.0029 for RT4 (Figs. 3 and 4).

Figure 3: Colony formation assay in transfected T24 cells, showing s reduced colony area compared to control (p = 0.0481). Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3).

Figure 4: Colony formation assay in transfected RT4 cells, showing reduced colony area compared to control (p = 0.0029). Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3).

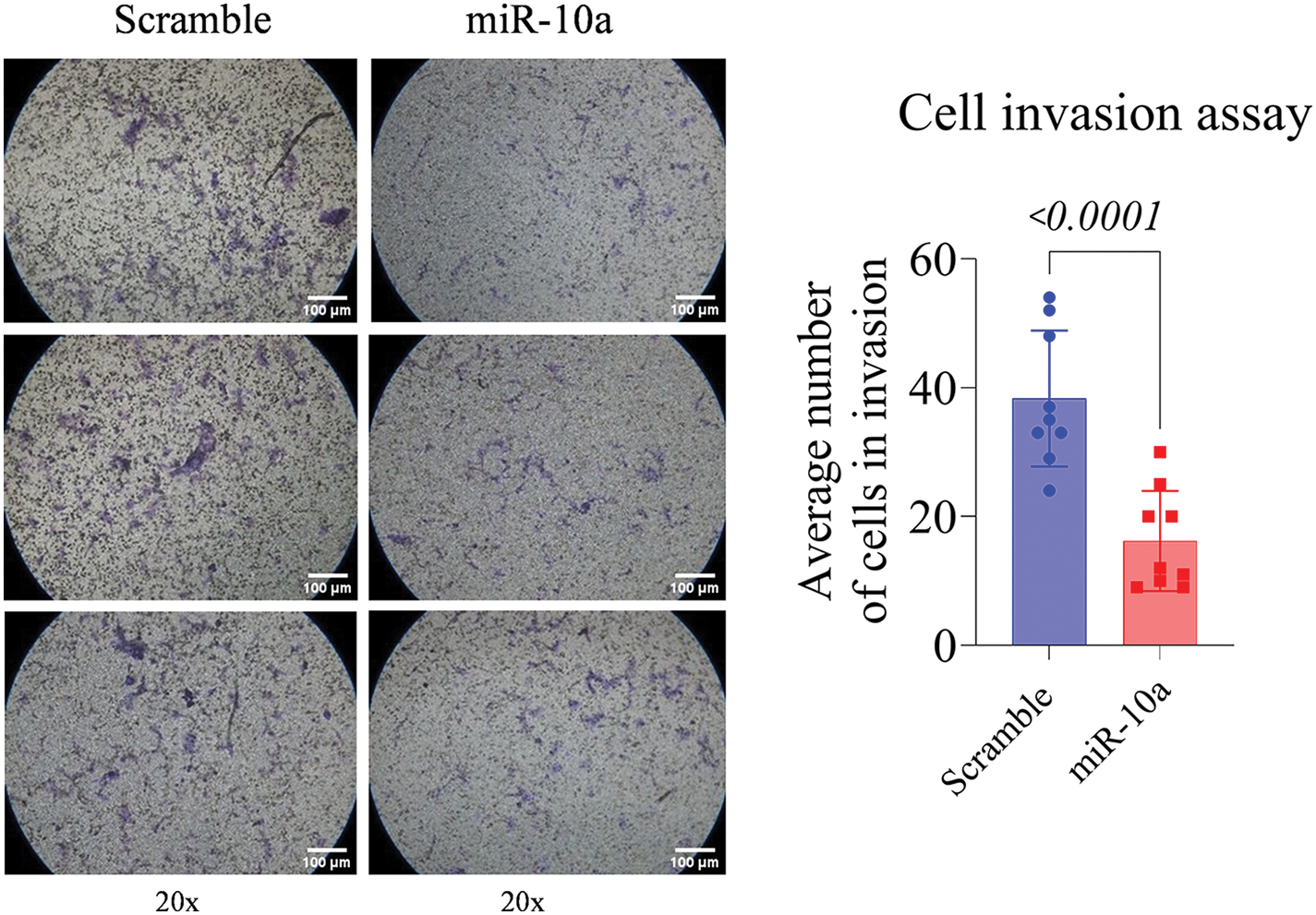

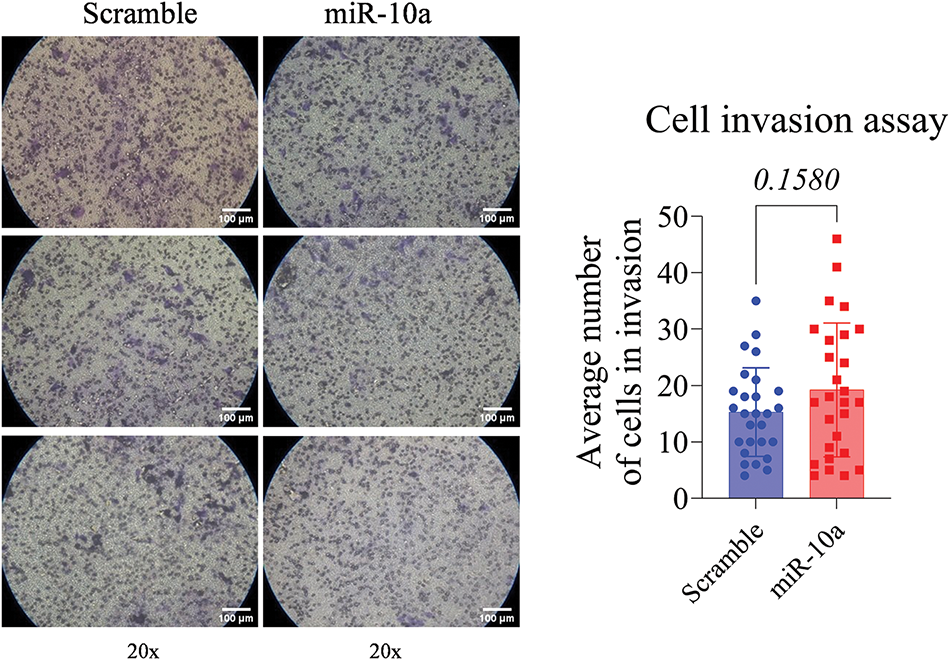

Invasion assay: inhibitory effect of miR-10a in T24 cells

The T24 cells showed a reduced invasion rate compared to the control (p < 0.0001). No significant difference was detected between e groups in the RT4 cell line (p = 0.158, Figs. 5 and 6).

Figure 5: Invasion assay in transfected T24 cells, showing reduced invasion rate compared to control (p < 0.0001). Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3).

Figure 6: Invasion assay in transfected RT4 cells, showing no significant difference between groups (p = 0.1580). Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n = 3).

In recent years, miRNAs have been recognized as significant regulators of cell development and tumorigenesis, with applications in diagnosing and differentiating disease stages [20]. Moreover, many studies have demonstrated their potential in treating malignancies, particularly challenging ones like high-grade BC [21,22]. Our data contribute to understanding the inhibitory role of miR-10a in BC, regardless of disease stage.

Initial analysis of miR-10a concentration in non-transfected cell lines revealed increased expression in high-grade disease, while low-grade BC was associated with decreased expression, consistent with findings by Yang et al. [23]. Their study showed under-expression of miR-10a in grade I BC cells compared to normal urothelial cells. For high-grade diseases, Köhler and colleagues categorized them into grades II and III, as per the 1973 WHO classification. MiR-10a was upregulated in grade II but downregulated in grade III BC cells. Similarly, Dip et al. [18] found miR-10a under-expression in high-grade pT2-T3 samples compared to benign ones, with overexpression in high-grade samples linked to poorer prognosis [18]. These findings suggest stage-dependent expression, possibly due to DNA methylation differences affecting transcription [19]. Epigenetic modifications, including promoter hypermethylation, have been reported as key regulators of miRNA expression in BCa [24]. Our data reinforce this phenotype-dependent expression of miR-10a, despite the lack of consensus in the literature.

In the colony formation assay, miR-10a transfection showed a negative effect on cellular proliferation in both cell lines. This tumor-suppressor role in BC has been described by Dai et al. [16], where miR-10a upregulation reduced proliferation in two urothelial cancer cell lines (EJ and 253J), consistent with our findings. However, Li et al. [17] did not associate miR-10 with proliferation in two other cell lines (HT-1197 and HT-1376) using a CCK-8 assay. Notably, both studies assessed miR-10a expression secondary to another regulator, rather than as a primary intervention. Our findings support the inhibitory effect of miR-10a on BC cell proliferation.

Regarding the invasion assay, miR-10a’s suppressor effect was observed only in the high-grade cell line. In contrast, Dip et al. [18] found a positive association between miR-10 induction and cell invasion in other high-grade cell lines (HT-1197 and HT-1376). Xiao et al. [25] using a miR-10b mimic in BC cell lines and nude mice, reported an increase in miR-10a expression in BC cell lines, especially high-grade J82 cells, aligning with our findings. However, their transfection experiments indicated that miR-10b enhances metastatic potential by targeting tumor-suppressor genes KLF4 and HOXD10 [25].

Our results differ from those of Yang et al. [23], who found that miR-10a-5p mimics upregulation in high-grade BC cell lines in increased invasion, proliferation, and migration of cells. Two factors may explain these discrepancies: genomic variability between the cell lines, even among those classified as high-grade UC, and the use of different miR-10 family members across studies [23]. Although similar, the miR-10a and miR-10b may have distinct functions, leading to divergent results [23,26,27].

miR-10a did not significantly affect the invasion potential in the RT4 cell line but did in the T24 cell line. We hypothesize that the heterogeneity in proliferation rates, among low-grade suggests that miR-10a is more effective in cells with higher division rates. Differences in cellular metabolism could also explain the variation between cell lines [26]. Zhao et al. [27] found that T24 cells, which had a faster metabolism and higher division rate than RT4 cells, might be more influenced by miR-10a.

One limitation of our study is the difficulty in comparing findings across the literature due to the use of different BC cell lines and miR-10 family members. A recent systematic review identified 157 human BC cell lines, each with unique gene mutations, locations, and clinicopathological characteristics [28]. Previous studies have also emphasized the importance of selecting appropriate BC cell models to ensure translational relevance of in vitro findings [29]. Future studies should aim to define the most appropriate BC cell line and miR-10 member for investigation.

Our results suggest that miR-10a may act as an inhibitor of BC tumorigenesis, particularly in malignancy proliferation and cellular invasion, which are critical to metastasis and tumor progression. However, further studies are necessary to clarify the role of miR-10a across different stages of BC and its potential as a molecular-targeted therapy, as suggested by Singh et al., who explored the dual roles of miR-10a as a tumor suppressor and its therapeutic potential in various cancers [30].

This study revealed promising evidence regarding the regulation of miR-10a in BC, highlighting its inhibitory capacity in cellular invasion and progression. The molecule was found to be more effective in high-grade cells, indicating its increasing importance in the advanced stages of BC. These findings suggest the therapeutic potential of miR-10a in the treatment of BC. However, further research is needed to better understand the underlying mechanisms of miR-10 activity and its clinical applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by grants from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) to Thainá Rodrigues (2021/04603-8).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Nayara Izabel Viana, Ruan Pimenta, Sabrina T. Reis, Katia Ramos Moreira Leite, William C. Nahas; data collection: Thainá Rodrigues, Patrícia Candido, Caroline Mie Mioshi, Karina Serafim da Silva; analysis and interpretation of results: Nayara Izabel Viana, Ruan Pimenta, Thainá Rodrigues, Feres Camargo Maluf, Vanessa Ribeiro Guimarães, Gabriel Arantes dos Santos; draft manuscript preparation: Nayara Izabel Viana, Ruan Pimenta, Thainá Rodrigues, Feres Camargo Maluf, Poliana Romão, Juliana Alves de Camargo, Iran Amorim Silva. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sanli O, Dobruch J, Knowles MA, Burger M, Alemozaffar M, Nielsen ME, et al. Bladder cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17022. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Raspollini MR, Comperat EM, Lopez-Beltran A, Montironi R, Cimadamore A, Tsuzuki T, et al. News in the classification of WHO 2022 bladder tumors. Pathologica. 2022;115(1):32–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Guo CC, Shen SS, Czerniak B. Recent advances in the classification of bladder cancer—updates from the 5th edition of the world health organization classification of the urinary and male genital tumors. Bladder Cancer. 2023;9(1):1–14. doi:10.3233/BLC-220106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Korkes F, Spiess PE, Garcia-Perdomo HA, Necchi A. Challenging dilemmas of low grade, non-invasive bladder cancer: a narrative review. Int Braz J Urol. 2022;48(3):397–405. doi:10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2021.0259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Pfail JL, Katims AB, Alerasool P, Sfakianos JP. Immunotherapy in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: current status and future directions. World J Urol. 2021;39(5):1319–29. doi:10.1007/s00345-020-03474-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Sylvester RJ, Rodríguez O, Hernández V, Turturica D, Bauerová L, Bruins HM, et al. European association of urology (EAU) prognostic factor risk groups for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) incorporating the WHO 2004/2016 and WHO, 1973 classification systems for grade: an update from the EAU NMIBC guidelines panel. Eur Urol. 2021;79(4):480–8. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2020.12.033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Lenis AT, Lec PM, Chamie K, Mshs MD. Bladder cancer: a review. JAMA. 2020;324(19):1980–91. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.17598. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Grossman HB, Natale RB, Tangen CM, Speights VO, Vogelzang NJ, Trump DL, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(9):859–66. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Li R, Sundi D, Zhang J, Kim Y, Sylvester RJ, Spiess PE, et al. Systematic review of the therapeutic efficacy of bladder-preserving treatments for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer following intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin. Eur Urol. 2020;78(3):387–99. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2020.02.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Winnicka A, Brzeszczyńska J, Saluk J, Wigner-Jeziorska P. Nanomedicine in bladder cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(19):10388. doi:10.3390/ijms251910388. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Leitão AL, Enguita FJ. A structural view of miRNA biogenesis and function. Non-Coding RNA. 2022;8(1):10. [Google Scholar]

12. Otmani K, Lewalle P. Tumor suppressor miRNA in cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment: mechanism of deregulation and clinical implications. Front Oncol. 2021;11:708765. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.708765. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Otmani K, Rouas R, Lewalle P. OncomiRs as noncoding RNAs having functions in cancer: their role in immune suppression and clinical implications. Front Immunol. 2022;13:913951. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.913951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang XL, Wei YW, Liu LN, Li HFL, Zhang H, et al. Screening of target genes and regulatory function of miRNAs as prognostic indicators for prostate cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:3748–59. doi:10.12659/MSM.894670. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Gu Y, Feng X, Jin Y, Liu Y, Zeng L, Zhou D, et al. Upregulation of miRNA-10a-5p promotes tumor progression in cervical cancer by suppressing UBE2I signaling. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2023;43(1):2171283. doi:10.1080/01443615.2023.2171283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Dai L, Chai CM, Shen TY, Tian Y, Shang ZQ, Niu YJ. LncRNA ITGB1 promotes the development of bladder cancer through regulating microRNA-10a expression. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23(16):6858–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

17. Li G, Zhang Y, Mao J, Hu P, Chen Q, Ding W, et al. lncRNA TUC338 is a potential diagnostic biomarker for bladder cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(10):18014–9. doi:10.1002/jcb.29104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Dip N, Reis ST, Timoszczuk LS, Viana NI, Piantino CB, Morais DR, et al. Stage, grade and behavior of bladder urothelial carcinoma defined by the microRNA expression profile. J Urol. 2012;188(5):1951–6. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.07.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Tehler D, Høyland-Kroghsbo NM, Lund AH. The miR-10 microRNA precursor family. RNA Biol. 2011;8(5):728–34. doi:10.4161/rna.8.5.16324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Conti I, Varano G, Simioni C, Laface I, Milani D, Rimondi E, et al. miRNAs as influencers of cell-cell communication in tumor microenvironment. Cells. 2020;9(1):220. doi:10.3390/cells9010220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Smolarz B, Durczyński A, Romanowicz H, Szyłło K, Hogendorf P. miRNAs in cancer (review of literature). Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5):2805. doi:10.3390/ijms23052805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Mu H, Zhang W, Qiu Y, Tao T, Wu H, Chen Z, et al. miRNAs as potential markers for breast cancer and regulators of tumorigenesis and progression (review). Int J Oncol. 2021;58(5):16. doi:10.3892/ijo.2021.5196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Yang L, Sun HF, Guo LQ, Cao HB. MiR-10a-5p: a promising biomarker for early diagnosis and prognosis evaluation of bladder cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:7841–50. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S326732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Saviana M, Le P, Micalo L, Del Valle-Morales D, Romano G, Acunzo M, et al. Crosstalk between miRNAs and DNA methylation in cancer. Genes. 2023;14(5):1075. doi:10.3390/genes14051075. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Xiao H, Li H, Yu G, Xiao W, Hu J, Tang K, et al. MicroRNA-10b promotes migration and invasion through KLF4 and HOXD10 in human bladder cancer. Oncol Rep. 2014;31(4):1832–8. doi:10.3892/or.2014.3048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Czyrnik ED, Wiesehöfer M, Dankert JT, Wennemuth G. The regulation of HAS3 by miR-10b and miR-29a in neuroendocrine transdifferentiated LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;523(3):713–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.01.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Zhao ZF, Wang K, Guo FF, Lu H. Inhibition of T24 and RT4 human bladder cancer cell lines by heterocyclic molecules. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:1156–64. doi:10.12659/MSM.898265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zuiverloon TCM, de Jong FC, Costello JC, Theodorescu D. Systematic review: characteristics and preclinical uses of bladder cancer cell lines. Bladder Cancer. 2018;4(2):169–83. doi:10.3233/BLC-180167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Singh SP, Pathuri G, Asch AS, Rao CV, Madka V. Stat3 inhibitors TTI-101 and SH5-07 suppress bladder cancer cell survival in 3D tumor models. Cells. 2024;13(17):1463. doi:10.3390/cells13171463. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Singh R, Ha SE, Yu TY, Ro S. Dual roles of miR-10a-5p and miR-10b-5p as tumor suppressors and oncogenes in diverse cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(1):415. doi:10.3390/ijms26010415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools