Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Lynch syndrome and colorectal cancer: A review of current perspectives in molecular genetics and clinical strategies

1 Department of Laboratory Medicine, Virgen de la Luz Hospital, Cuenca, 16002, Spain

2 Gastroenterology Department, Virgen de la Luz Hospital, Cuenca, 16002, Spain

3 Medical Analysis Expert Group, Institute of Technology, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Cuenca, 16071, Spain

4 Medical Analysis Expert Group, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Castilla-La Mancha (IDISCAM), Toledo, 45071, Spain

* Corresponding Authors: RAQUEL GÓMEZ-MOLINA. Email: ; MIGUEL SUÁREZ. Email:

Oncology Research 2025, 33(7), 1531-1545. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.063951

Received 30 January 2025; Accepted 21 April 2025; Issue published 26 June 2025

Abstract

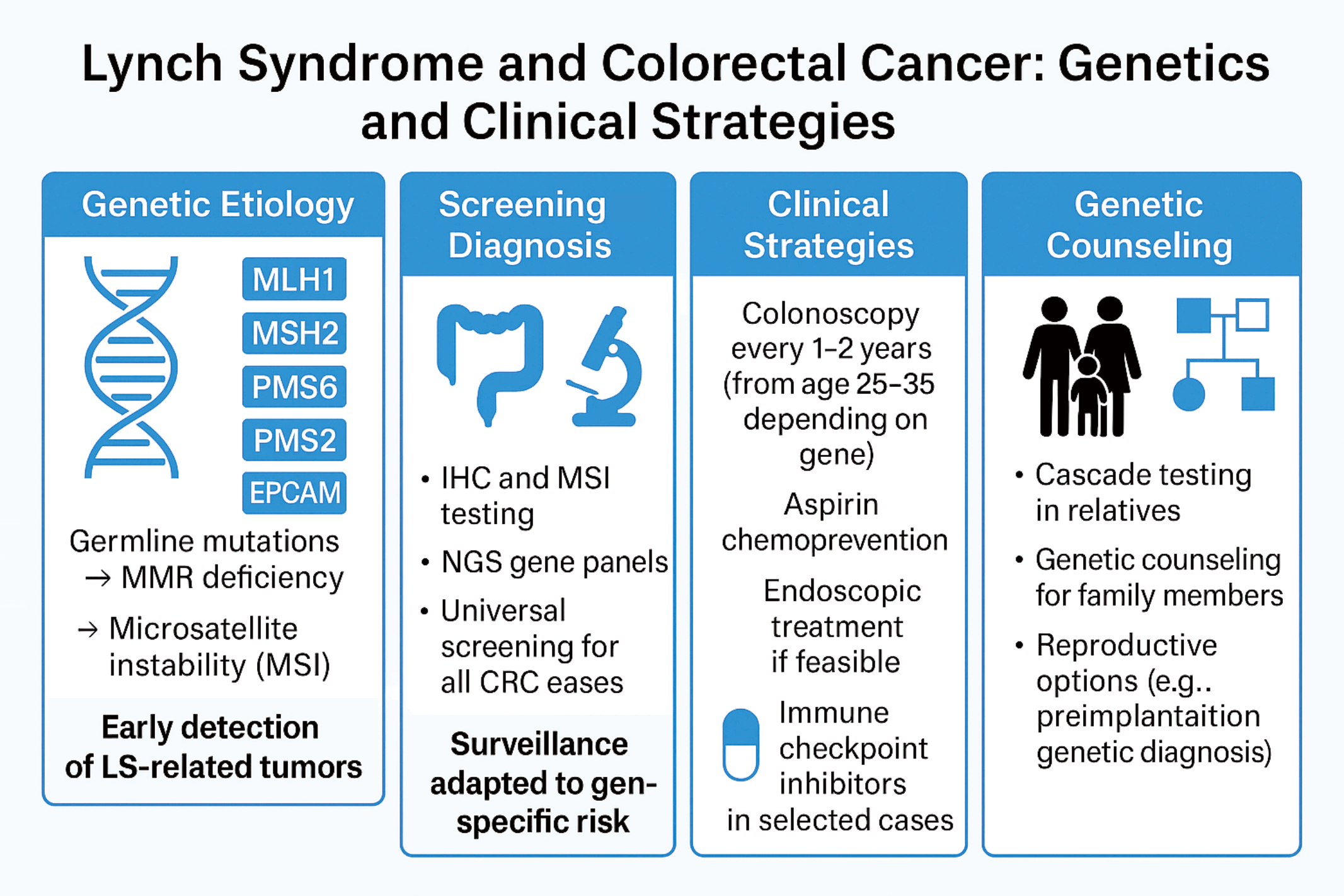

Lynch syndrome (LS), also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), is an inherited condition associated with a higher risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) and other cancers. It is caused by germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes, including MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2. These mutations lead to microsatellite instability (MSI) and defective DNA repair mechanisms, resulting in increased cancer risk. Early detection of LS is crucial for effective management and cancer prevention. Endoscopic surveillance, particularly regular colonoscopy, is recommended for individuals with LS to detect CRC at early stages. Additionally, universal screening of CRC for MMR deficiency can help identify at-risk individuals. Genetic counseling plays a valuable role in LS by guiding patients and their families in understanding the genetic basis, making informed decisions regarding surveillance and prevention, and offering reproductive options to reduce the transmission of pathogenic variants of the offspring. The aim of this review is to outline current strategies for the diagnosis, surveillance, and management of LS, with a focus on the role of genetic counseling, endoscopic screening, and emerging therapeutic approaches to mitigate cancer risk in affected individuals.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Lynch Syndrome (LS) is associated with a significantly increased lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer (CRC), with estimates ranging from 30% to 74% depending on germline pathogenic variant [1–3]. LS is the most common heritable CRC syndrome, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 440 in the general population [4,5]. The syndrome also increases the risk of several other malignancies, such as those of the cancer of stomach, small intestine, pancreas, biliary tract, urinary tract, brain and skin [2,4,6]. Women with LS have a particularly high risk of endometrial and ovarian cancers [7]. Approximately 20% of CRC patients have at least one first-degree relative with a history of this cancer [8,9].

It is recommended that individuals with LS undergo regular surveillance, including colonoscopy every 1–2 years starting in their twenties, to detect and manage CRC early [10,11]. Genetic testing and family history are essential for diagnosing LS and universal genetic testing of colorectal cancers is increasingly used to identify high-risk individuals [12]. Genetic counseling offers additional benefits by helping patients and their families make informed decisions, providing tailored recommendations for personalized management, surveillance and prevention strategies, and presenting reproductive options to reduce the transmission of pathogenic variants to future generations [13].

LS or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) is the most common hereditary CRC, accounting for 2%–4% of cases [9]. It is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by germline variants in DNA MMR genes [14]. MMR dysfunction leads to replication errors, particularly in microsatellites, resulting in microsatellite instability (MSI) or loss of MMR protein expression, the hallmark of LS [15]. Advances in epidemiology and molecular insights, aided by multigene panel testing, have enhanced strategies for cancer prevention, risk reduction and immunotherapy [16].

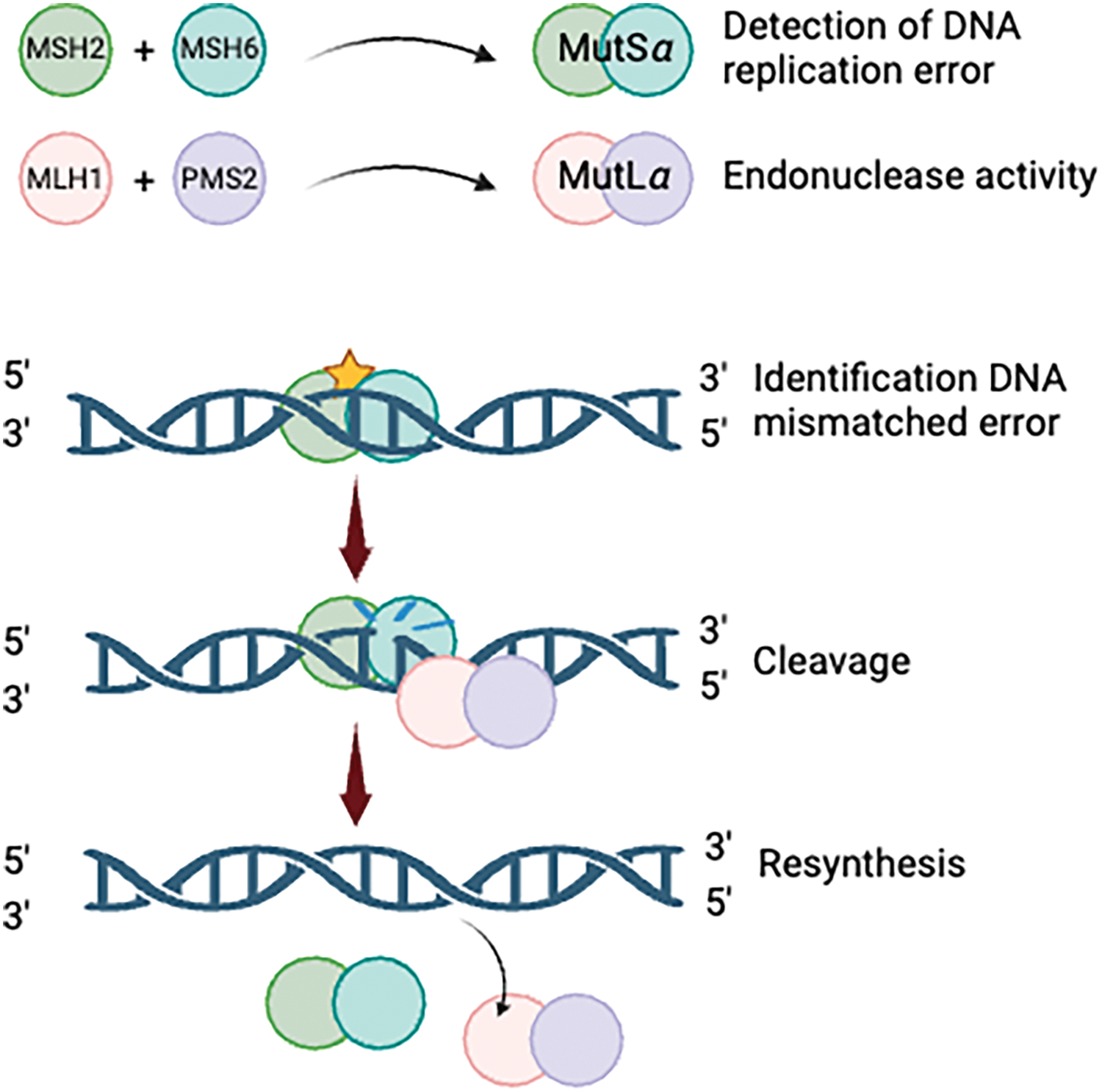

The DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system is crucial for maintaining genomic stability by correcting base substitution errors and small insertion-deletion mismatches that arise during DNA replication [17]. This highly regulated process relies on the coordinated activity of specialized protein complexes. Mismatch recognition is performed by two heterodimeric protein complexes: MutSα (MSH2 and MSH6), which efficiently detects single base-pair mismatches and small insertion-deletion loops, and MutSβ (MSH2 and MSH3), which targets larger insertion-deletion loops. Once mismatches are identified, downstream repair is facilitated by MutL complexes, including MutLα (MLH1 and PMS2), which functions as a key endonuclease in the repair process. MutLβ (MLH1 and PMS1) and MutLγ (MLH1 and MLH3) further assist in excision and resynthesis, ensuring accurate DNA replication [18,19]. These interactions collectively uphold genomic fidelity and prevent mutational accumulation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: The process of DNA mismatch repair. Created with BioRender.com.

Germline variants in MMR genes follow an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, where a single mutated allele is inherited. However, defective MMR function requires biallelic inactivation, typically seen in LS, where a germline variant in one MMR allele is accompanied by somatic inactivation of the second allele [20]. This somatic inactivation may occur through various mechanisms, including mutation, loss of heterozygosity, or epigenetic silencing via promoter hypermethylation. The resulting biallelic inactivation of MMR genes causes a deficient MMR system, leading to an elevated mutation rate and genomic instability due to the inability to repair DNA mismatches during replication [21].

These mismatches often occur in microsatellites, regions of repetitive nucleotide sequences. Tumors with defective MMR frequently show MSI, a defining feature of Lynch-like syndrome (LLS). MSI can affect genes regulating key cellular processes, such as cell growth (e.g., TGF-beta, insulin-like growth factor receptors), apoptosis (e.g., Caspase 5, Bax) and even MMR genes themselves (e.g., hMSH3, hMSH6) [22]. Accumulation of variants in these critical genes is thought to drive tumorigenesis, underscoring the crucial role of MMR deficiency in LLS [23].

Deletions in the terminal codon of the EPCAM gene, located upstream of MSH2, can result in epigenetic silencing of MSH2, particularly in tissues where EPCAM is expressed [24]. When the deletion is confined to the EPCAM stop codon, the phenotype is typically restricted to CRC. However, deletions that extend into the MSH2 promoter region lead to a more comprehensive LS phenotype, which encompasses a broader spectrum of cancers [25]. Although EPCAM is not classified as an MMR gene, its deletion can contribute to LS by silencing the adjacent MSH2 gene.

Phenotypic correlations of molecular alterations

Pathogenic variants in MMR genes result in impaired DNA repair, leading to an increased mutation rate and, consequently, heightened cancer risk. The cancer risk and spectrum of associated malignancies in LS are known to vary based on the specific MMR gene involved. Increasing evidence suggests that the MMR gene affected may influence the molecular pathogenesis of CRC within the context of LS [22,24]. The role of specific MMR gene variants (path_MMR) in cancer penetrance is still debated [25]. In this regard, no significant differences in penetrance have been observed between missense and truncating variants in individuals carrying pathogenic MLH1 (path_MLH1) or MSH2 (path_MSH2) variants [26].

Mutations in MMR genes are primarily missense or truncating, with missense and truncating variants constituting the majority of pathogenic variants in MLH1 (40% each), MSH2 (31% and 49%, respectively) and MSH6 (49% and 43%, respectively). In contrast, PMS2 mutations are predominantly missense (62%), with truncating variants occurring less frequently (24%) [27]. These findings underscore the need for further investigation into the relationship between specific mutation types and cancer penetrance. Data from the International Mismatch Repair Consortium (IMRC) show significant variability in CRC risk among carriers of different MMR gene variants [28]. The risk is influenced by factors such as gene, sex, and geographic region. The penetrance of CRC in LS carriers ranges widely: some individuals have a relatively low risk, with less than 20% developing CRC, while others may have a much higher risk, with over 80% developing the disease. A significant proportion, between 10%–19%, have a moderate risk, with a 40%–60% chance of developing CRC. This highlights the variability in cancer risk, which can depend on factors such as the specific MMR gene mutation and other genetic or environmental factors.

The variable penetrance and expressivity of LS suggest the existence of four distinct inherited syndromes, each associated with a specific MMR gene. According to the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database, these four syndromes correspond to pathogenic variants in MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2, while 3′ EPCAM deletions are recognized as an alternative mechanism leading to MSH2 silencing [29]. The International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumours (InSiGHT) uses its international database to classify MMR gene variants as pathogenic or non-pathogenic, while the Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database (PLSD) provides data on penetrance and expressivity of pathogenic variants to guide patient counseling [30,31].

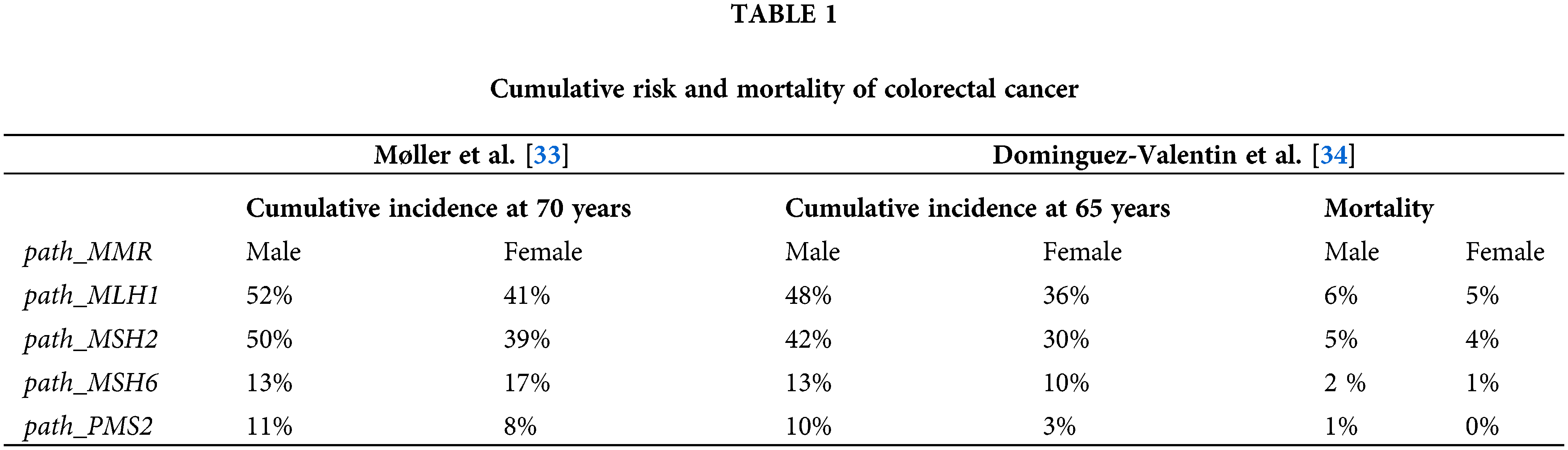

Recent analyses highlight distinct cancer risk profiles among path_MMR carriers (Table 1). Møller et al. compared CRC incidences in path_MMR either in the PLSD and IMRC. In the PLSD, 8.153 carriers were followed under colonoscopic surveillance, identifying 578 CRC cases. By age 70, cumulative CRC incidences were 52% for males and 41% for females with path_MLH1, 50% and 39% for path_MSH2, 13% and 17% for path_MSH6, and 11% and 8% for path_PMS2. In contrast, the IMRC cohort reported lower incidences: 40% and 27% for path_MLH1, 34% and 23% for path_MSH2, 16% and 8% for path_MSH6, and 7% and 6% for path_PMS2 [32]. These findings underscore the heterogeneity in CRC risk, particularly between MLH1/MSH2 and MSH6/PMS2 carriers.

Additionally, age and sex significantly influence CRC risk among path_MMR carriers, with particularly wide confidence intervals for MSH6 and PMS2 [33,34]. For CRC, cumulative lifetime risks by age 75 are estimated at 46% for path_MLH1, 43% for path_MSH2, and 15% for path_MSH6 carriers, with MLH1 and MSH2 carriers showing significantly higher risks (40%–70%) compared to MSH6 and PMS2 heterozygotes (10%–20%) [35]. Comparing just the European carriers in the two series gave similar findings [36]. It is essential to highlight that these incidences are derived from patients undergoing regular colonoscopy surveillance. As reported by Dominguez-Valentin et al., LS-associated cancers outside the colorectum, particularly in women and among path_MSH2 carriers, substantially contribute to the overall cancer burden [37]. Furthermore, familial risk factors contribute to substantial within-gene variation in CRC risk with and without colonoscopy surveillance, underscoring the importance of personalized risk assessment for precision prevention and early detection of CRC in path_MMR carriers [28,35,38].

Genetic diagnosis of LYNCH syndrome

The diagnosis of LS involves a combination of tumor screening and genetic testing. Multiple clinical guidelines recommend universal screening for MMR deficiency, particularly in new CRC cases, to identify potential LS cases for subsequent constitutional testing [39–41]. Universal screening is a cost-effective approach for LS detection and has significant implications for cancer management, particularly with the advent of checkpoint inhibition therapies [42].

Tumor screening methods typically include immunohistochemical analysis (IHC) for MMR protein expression and MSI testing. Both methods exhibit similar sensitivity and specificity, although neither is entirely accurate [43]. Some LS-related variants, such as certain missense or truncating variants, may result in stable but nonfunctional proteins, which can lead to false-negative results. Moreover, clonal heterogeneity or low tumor purity may cause MSI-positive tumors to show normal MMR protein expression. IHC offers the additional benefit of identifying specific MMR proteins with abnormal expression, allowing for the identification of the gene likely altered constitutionally. For example, the loss of both MSH2 and MSH6 proteins points to an MSH2 alteration, while the loss of MLH1 and PMS2 indicates an MLH1 variant. However, exceptions to this pattern exist, so constitutional testing should not be limited to the gene identified by IHC [44].

Regarding IHC testing, the absence of antibodies for either four or two MMR proteins has been investigated to optimize the detection of MMR deficiencies. The four-stain MMR IHC method evaluates the expression of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 proteins, allowing for comprehensive detection of MMR deficiencies. This approach identifies variants in any of the four key MMR genes, ensuring accurate LS screening. In contrast, the two-stain method assesses only MSH6 and PMS2, relying on the fact that MLH1 and MSH2 deficiencies typically lead to secondary loss of PMS2 and MSH6, respectively. However, this method may fail to detect certain MSH2 variants, as some tumors with MSH2 loss can retain MSH6 expression, increasing the risk of false-negative results. While the two-stain approach offers potential cost and time savings, the four-stain method remains the most reliable for minimizing diagnostic errors [45–47].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has emerged as a valuable tool for detecting variants associated with LS. Unlike traditional methods, NGS allows for comprehensive analysis of multiple genes involved in MMR, improving sensitivity and accuracy in identifying pathogenic variants [48,49]. By sequencing tumor DNA, NGS can detect both germline and somatic variants, including double somatic mutations, which are characteristic of LLS [50,51]. This approach not only enhances the detection of LS-related variants but also provides valuable information for treatment planning, such as identifying actionable variants in other genes like KRAS, NRAS or BRAF [52]. By enabling more detailed and efficient genetic testing, NGS plays a crucial role in refining LS diagnosis and guiding clinical management.

In addition, NGS can also provide valuable information on tumor mutation burden (TMB), a key biomarker for predicting response to immunotherapy. TMB, assessed through NGS panels, is associated with better outcomes in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) and can help identify patients likely to benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Antoniotti et al. [53] demonstrated that TMB can stratify mCRC patients for ICI response, while Xiao et al. [54] emphasized combining TMB with MSI status for more accurate predictions. Additionally, Schrock et al. [55] and Manca et al. [56] highlighted TMB’s predictive value in MSI-high mCRC, with higher TMB correlating with improved progression-free survival. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recognizes TMB as a potential biomarker for ICI response, particularly for pembrolizumab in TMB-high tumors [57]. Overall, NGS-based TMB testing aids in personalized treatment strategies for CRC.

The use of tumor mutational signatures for enhanced LS detection through NGS is increasingly common, even in diagnostic settings, and is becoming more cost-effective. Recent advancements in NGS technology have allowed for the comprehensive analysis of tumor mutational signatures, which improves LS detection by identifying both germline and somatic variants in MMR genes. For instance, the TumorNext-Lynch-MMR [58] panel provides a detailed genetic profile, including MSI status and loss of heterozygosity. Furthermore, the clinical utility of NGS has been demonstrated in molecular subtyping and LS screening, especially in endometrial cancer, highlighting NGS’s ability to reduce missed diagnoses [59]. With the decreasing cost of NGS, it is becoming more accessible for broader clinical use [60].

However, despite these advances, NGS-based tumor mutational signature analysis remains outside of routine diagnostic procedures and recommended guidelines. Although the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and other expert consensus groups recognize the potential of NGS for determining MSI/MMR status and TMB, they recommend its application primarily in specialized centers or through validated central laboratory methods [61,62].

Clinical Management and Surveillance Strategies in Lynch Syndrome

Colonoscopy and its follow-up have proven to be a cost-effective measure for reducing incidence, mortality, and improving quality of life [63]. Adherence to the surveillance program is crucial to achieving these objectives, as well as the early identification of patients to begin colonoscopies as soon as possible.

As previously mentioned, not all pathological variables present the same cancer risk over a lifetime. It is estimated that patients with a MLH1 pathogenic variant have a risk close to 46%, and those with MSH2, a 35% risk. Moreover, patients carrying MSH6 and PMS2 pathogenic variants have a 20% and 10% risk, respectively [33]. These data suggest that the initiation and follow-up of colonoscopies should vary based on the patient’s genetic pathogenic variant. Patients with MLH1 and MSH2 pathogenic variants should start surveillance at age 25, while those with MSH6 and PMS2 pathogenic variants should start at age 35 [37,64,65].

Surveillance of these patients is not uniform and varies according to different clinical guidelines. However, there is consensus across almost all guidelines that surveillance should occur every 1 to 3 years [66,67]. The differences between guidelines stem from the fact that most studies used to determine these surveillance intervals are retrospective, and prospective data are lacking. Thus, each guideline adapts the available evidence to its respective population. The scientific evidence clearly shows that intervals longer than 3 years increase the risk of CRC development, and intervals shorter than 1 year do not show any benefit in detecting advanced lesions or CRC [66–69].

Surveillance in patients with the PMS2 pathogenic variants may deviate from this 1–3 years interval. Due to its low penetrance, the risk of developing CRC in these patients is lower compared to other MMR variants [34,63]. Consequently, the latest European guidelines recommend extending screening colonoscopies to every 5 years [37]. This suggests that further studies are needed in LS patients to establish more personalized surveillance, thus avoiding unnecessary invasive testing.

A frequently aspect overlooked when reviewing clinical guidelines for LS patient surveillance is that these recommendations are intended for asymptomatic patients. Patients with a diagnosis of LS and symptoms suggestive of malignancy, such as new-onset abdominal pain, constitutional syndrome, anemia, or rectal bleeding, require proper evaluation and colonoscopy before the established surveillance interval. In fact, although based on low-level evidence, European guidelines recommend performing a colonoscopy as soon as possible [51].

Colonoscopy quality and technique in lynch syndrome management

Colonoscopy quality is crucial for lesion detection in the general population and is even more critical in LS patients. Adenomas in LS tend to be located proximally, have a flat morphology, and often show high-grade dysplasia, even when smaller than 10 mm, making them more challenging to detect [70,71]. The key indicators of colonoscopy quality include:

– Adequate preparation: defined as a Boston Bowel Preparation Scale score ≥ 6, with no segment scoring ≤ 1.

– Complete colonoscopy or cecal pole intubation.

– Adenoma detection rate (ADR): should exceed 30% for expert endoscopists [72].

– Complete resection of adenomas/polyp removal, primarily through en-bloc resection with negative margins and favorable histology [73].

When these quality criteria are met, adenoma miss rate (AMR), and post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer (PCCRC) rates decrease. In LS patients, the AMR is higher than in the general population (over 48% vs. 25%), and the PCCRC rate approaches 8% after 10 years [74,75]. Even with strict adherence to these conditions, CRC may still occur due to new lesion development or rapid adenoma-carcinoma progression between screenings [76].

The use of chromoendoscopy has been debated for improving lesion detection, with earlier studies suggesting better detection of polyps in LS patients [77–79]. However, advances in high-definition (HD) endoscopes and white light endoscopy (WLE) have improved detection rates, and studies now demonstrate the non-inferiority of WLE over dye-based chromoendoscopy [80,81]. Clinical guidelines recommend HD endoscopy routinely, while chromoendoscopy is suggested only for endoscopists with lower adenoma detection rates or less experience [37,51].

Artificial intelligence (AI)-based systems such as computer-aided polyp detection (CADe) and diagnosis (CADx) have been explored. While AI has shown an increase in ADR in the general population, it has not demonstrated improvements in LS patients when using high-quality colonoscopies [82–84]. AI may be beneficial for endoscopists with lower ADR or less experience.

Perhaps the most important aspect, often overlooked, is patient awareness of their condition and cancer risk. Explaining the significance of LS, the necessity of surveillance, and the importance of high-quality colonoscopies is essential for reducing the risk of CRC. Non-adherence to screening is a major risk factor for CRC, especially in MLH1 and MSH2 variant carriers [67]. Adherence to the recommended screening intervals of 1–3 years, along with optimal bowel preparation, reduces this risk. In cases of suboptimal preparation, European guidelines recommend repeating the colonoscopy within three months [51].

In conclusion, high-quality colonoscopy, adherence to established standards, the use of the best available technology, and patient compliance with surveillance are the best strategies to minimize CRC risk. However, the possibility of CRC development between colonoscopies remains a concern, requiring continued research to better understand the underlying mechanisms [74].

Aspirin has shown benefits as a chemopreventive agent for reducing the risk of CRC in LS patients. The randomized CAPP2 trial demonstrated that a daily dose of 600 mg of aspirin for 2–4 years significantly reduced CRC incidence after 5 years of treatment initiation and was well tolerated. Furthermore, more recent studies suggest this protective effect extends up to 20 years post-treatment [85]. The exact mechanism by which aspirin reduces CRC risk remains unknown.

The optimal aspirin dose is under investigation in the ongoing CAPP3 trial. However, based on observational studies in the general population, a minimum dose of 75 mg is recommended, with adjustments based on body weight [37,86,87].

Lifestyle factors have not been clearly linked to an increased cancer risk in LS patients. Nevertheless, general health recommendations include regular physical activity to prevent sedentary behavior, maintaining a healthy body mass index, abstaining from smoking, and minimizing alcohol consumption [37,88–90].

Surgery, chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors

Due to the high efficacy of quality colonoscopies, prophylactic surgery as primary prevention in the absence of lesions is not recommended for any genetic variants of LS [37]. For large lesions or early-stage tumors, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is the preferred first-line treatment. Although technically complex, ESD is a safe procedure that enables en-bloc resections, minimizes recurrence, and preserves the colonic surface, avoiding extensive resections in these patients [91]. Another endoscopic option is endoscopic full-thickness resection (eFTR), although it is limited to lesions measuring 2–3 cm [92].

In cases of invasive cancer, surgical intervention becomes necessary. For invasive CRC, extended surgeries may be considered based on individual patient factors rather than solely on MMR mutation status. Clinical guidelines recommend subtotal colectomy for MLH1 and MSH2 variant carriers due to a higher risk of metachronous CRC, whereas segmental resection is typically sufficient for MSH6 and PMS2 carriers [37]. However, recent studies suggest that MLH1/MSH2 carriers may also be treated with traditional segmental surgeries, provided they undergo close post-surgical monitoring. This approach acknowledges a higher metachronous CRC risk but avoids the morbidity of extensive resections, as expanded surgeries have not demonstrated survival benefits [93,94]. All surgical options, including risks and benefits, should be thoroughly discussed with the patient, considering their comorbidities and preferences.

For rectal cancer in LS patients, standard surgical procedures such as anterior resection or abdominoperineal amputation, depending on tumor location, are recommended [37]. Extended surgeries should be reserved primarily for synchronous tumors. Creating an ileoanal pouch is particularly complex and should be performed in high-volume specialized centers [95].

In early-stage CRC, adjuvant chemotherapy with capecitabine or 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) does not improve overall survival and is associated with increased toxicity. These tumors typically exhibit mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) and high microsatellite instability (MSI-H). This results in limited cytotoxicity of 5-FU, primarily due to alterations in the anabolic pathway mediated by thymidylate synthase (TS). Tumors associated with LS show high expression of this enzyme, the primary target of this chemotherapeutic agent, thereby reducing the sensitivity to 5-FU. Moreover, base excision repair and dMMR systems more effectively remove 5-FU from cellular DNA, further decreasing its cytotoxicity in these cases. Additionally, overexpression of resistance genes such as ABCC1 and ABCC5 may reduce intracellular accumulation of 5-FU [96–98]. These mechanisms collectively explain why these patients do not benefit from treatments typically used in CRC. Consequently, these patients have favorable prognoses with surgical management alone [99].

However, tumors that are proficient in mismatch repair (pMMR) or lack high microsatellite instability (MSS) should be considered for standard chemotherapeutic treatments due to their lower response to ICI, attributed to reduced immunogenicity. Additionally, LS-associated CRC with mucinous differentiation or signet-ring cells also exhibit resistance to ICI, suggesting a potentially greater benefit from chemotherapy [100]. For this reason, combinations of ICI and chemotherapy are being investigated in multiple clinical trials. These combinations have demonstrated improvements in response rates, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared to standard chemotherapy.

Although resistance to chemotherapy accounts for up to 80%–90% of therapeutic failures, some cytotoxic agents have shown the ability to enhance the efficacy of ICIs. These combinations have yielded higher response rates and better survival outcomes compared to chemotherapy monotherapy. It has been established that a resistance probability threshold of 5% is appropriate to define resistance to ICI-chemotherapy combinations, recognizing that the incidence of pseudoprogression may be lower when immunotherapy is administered alongside cytotoxic agents [101].

The advent of immunotherapy has revolutionized the treatment of CRC in the context of LS. While it is already considered the first-line treatment for metastatic cancer, its use in early-stage disease remains under investigation, with promising results [57,102]. The high immunogenicity of these tumors makes ICIs an excellent therapeutic option. In this setting, PD-1 inhibitors are employed, as these tumors exhibit a high density of T lymphocytes and a significant number of neoantigens. These agents block the interaction between the PD-1 receptor on T cells and its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 on tumor cells, thereby enabling cytotoxic T cells to recognize and destroy tumor cells [103].

Immunotherapy with ICIs has demonstrated high efficacy in the treatment of mCRC with dMMR or MSI-H. In advanced stages, trials such as CHECKMATE-142 have shown that the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab achieves objective response rates (ORR) of up to 69%, with PFS in patients with dMMR mCRC and complete responses in 13% of cases. The combination of PD-1 inhibitors (nivolumab and pembrolizumab) with CTLA-4 inhibitors (ipilimumab) has demonstrated superior efficacy compared to PD-1 inhibitors alone [104]. Ongoing trials, such as COMMIT and CHECKMATE-8HW, aim to optimize combination therapies of ICIs and chemotherapy in treatment-naive patients with dMMR mCRC. However, a significant proportion of patients experience primary or secondary resistance to ICIs, highlighting the need for a deeper understanding of the molecular pathways underlying this resistance [105].

At early stages of CRC, immunotherapy has shown limited benefit, although several clinical trials are currently assessing its efficacy. The KEYNOTE-177 trial demonstrated that first-line pembrolizumab improves PFS in patients with dMMR CRC compared to conventional chemotherapy, despite its effectiveness in first stages remains uncertain [106]. Moreover, neoadjuvant research is gaining attention. Several clinical trials, such as the IMPOWER010 (NCT02486718) study, are exploring the use of ICIs in combination with surgery in patients with dMMR, based on the hypothesis that early activation of the immune system could reduce the risk of recurrence [107]. Preliminary results have shown significant tumor reductions and enhanced activation of immune responses in patients with CRC treated with this approach.

Neoadjuvant immunotherapy is being evaluated as a promising strategy for early-stage CRC. In this context, studies such as NICHE (NCT03026140) and VOLTAGE-A (NCT02948348) are investigating the impact of ICIs in combination, such as nivolumab and ipilimumab or pembrolizumab, in dMMR tumors. These studies aim to improve surgical outcomes and reduce recurrence rates, with preliminary results showing pathological complete response (pCR) rates of 60%. Additionally, ongoing trials such as ATOMIC (NCT02912559) and POLEM (NCT03827044) are evaluating ICIs combined with chemotherapy or as standalone therapy in resected stage III dMMR tumors, with the goal of improving disease-free survival. While initial results are promising, further controlled studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in CRC and to establish its potential compared to conventional therapies [108].

Promising results have also been observed following endoscopic resection of CRC in these patients, particularly those with high MSI-H or dMMR. In a retrospective study conducted by Fox et al., which analyzed localized dMMR CRC in 38 patients, 45% achieved a complete endoscopic response, and 23% achieved a radiological response after four cycles of treatment. Additionally, 61% of patients who underwent surgical resection following neoadjuvant therapy achieved a pCR [109]. In another study evaluating the utility of PD-1 inhibitors in these patients, the response of polyps was also assessed. Among 26 patients with polyps, seven adenomas disappeared following treatment, all of which were >7 mm in size [110]. This phenomenon may be explained by a specific immunogenic profile of these polyps, characterized by higher levels of pathogenic variants and neoantigens [111]. While these findings are promising, further studies are needed to validate these results and to identify which patients may benefit most from these treatments.

The safety profile of PD-1 inhibitors is also superior to that of chemotherapy. The KEYNOTE-177 trial demonstrated that grade 3 or higher adverse events related to pembrolizumab occurred in 22% of patients, compared to 66% in the chemotherapy group [106] Similarly, the CHECKMATE-142 trial, which analyzed grade 3 or higher adverse events related to nivolumab treatment, showed a 22% incidence compared to 48% in patients treated with chemotherapy [104]. These findings not only highlight the superior efficacy of ICIs compared to conventional chemotherapy but also demonstrate a more favorable safety profile.

Patients with LS have an estimated cumulative risk of developing gastric cancer by age 80 ranging from 0.7% to 13% [112]. This risk is higher in individuals with MLH1 and MSH2 pathogenic variants. Up to one-third of these patients have a family history of gastric cancer, which is an important consideration for their clinical follow-up [113]. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to recommend universal gastric cancer screening for all LS patients [114]. However, in certain countries such as the United States and the Netherlands, screening is recommended starting at 30–35 years of age, with periodic surveillance every 2–3 years [3,51,115]. A retrospective study by Kim et al. analyzed over 51,000 patients, including nearly 4000 with LS, and identified key risk factors for gastric cancer: male sex, MLH1 and MSH2 pathogenic variants, and the presence of first-degree relatives with the disease [116]. A recent study by Caspers et al. involving a Dutch cohort further identified EPCAM mutations, in addition to MLH1 and MSH2, as significant risk factors. The study also highlighted that the highest risk occurs between the ages of 70 and 75, whereas the risk of gastric cancer before age 50 is minimal [117]. These factors may guide tailored surveillance strategies for LS patients.

Although clear evidence is lacking, clinical guidelines suggest screening for Helicobacter pylori in LS patients, considering it a cost-effective preventive measure [51].

The cumulative lifetime risk of developing small bowel cancer in LS patients varies significantly, reaching up to 12% [63]. The risk is particularly elevated in individuals with MLH1 and MSH2 pathogenic variants, with the duodenum and jejunum being the most affected sites [118–120]. Due to the limited evidence from available studies, routine screening for small bowel cancer is not currently recommended for LS patients [37,51,63].

Genetic counseling is a critical process that provides patients and their families with information regarding the risk of inheriting or transmitting a genetic predisposition to cancer. It includes guidance on molecular diagnostic options and strategies for prevention and early detection. In cases of suspected LS, referral to hereditary cancer units or specialized genetic counseling services is essential. These evaluations involve a detailed personal and family history, a cornerstone for accurately estimating hereditary cancer risk and informing personalized clinical management. Additionally, effective communication between the clinician and the molecular genetic diagnostic laboratory is crucial. Given the emotional burden often experienced by patients and families, psychological support is integral to the counseling process, which typically requires 60–90 min for thorough assessment [121].

Genetic testing for LS serves three main purposes: confirming the diagnosis in patients, determining the risk status of family members and guiding the management of affected and unaffected individuals [63,121]. Despite being the most common cause of HNPCC, LS remains underdiagnosed. Classical clinical criteria, such as those from Amsterdam and Bethesda, have limited specificity and sensitivity, particularly in detecting pathogenic variants in MSH6 and PMS2 [122,123]. Genetic counseling is recommended for individuals with a ≥5% risk of LS based on these models, and universal screening strategies are increasingly adopted to reduce diagnostic gaps [121].

The loss of expression of any of the MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 or PMS2 proteins serves as a referral criterion to a Cancer Genetic Counseling Unit and facilitates the targeted genetic diagnostic evaluation for LS [122,123]. Available diagnostic tests, including immunohistochemistry, MSI testing and multigene NGS enable the detection of LS and other CRC-related variants. Tumor tissue analysis is preferred for confirming LS, and genetic counseling should be offered to at-risk family members, starting with first-degree relatives. However, low rates of genetic counseling and testing have been reported among individuals with risk factors for LS [124].

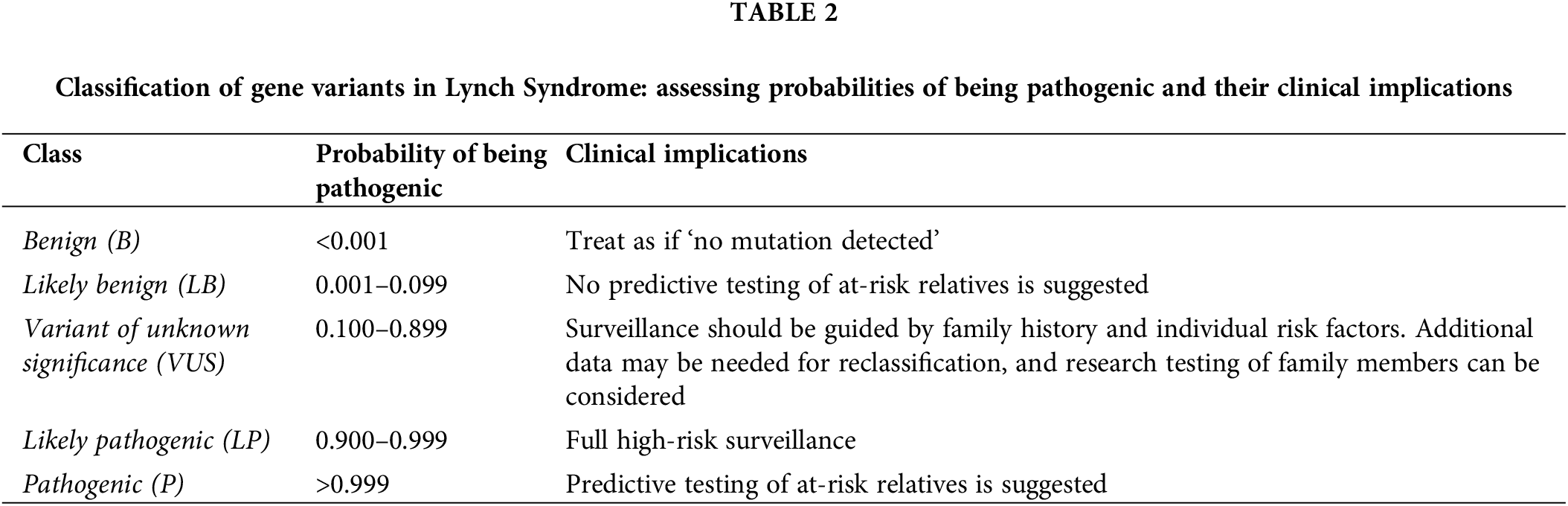

Genetic counseling is a comprehensive process that begins with the evaluation of the index case, following a clear sequence of pre-test counseling, genetic testing and post-test counseling [125,126]. The first step involves pre-test counseling, where the patient’s family history is reviewed to assess the potential hereditary or familial cancer risk. A detailed pedigree is constructed, and the counselor provides information about the suspected hereditary syndrome, including its clinical, molecular and management aspects. This counseling also includes an explanation of the genetic testing process and informed consent as well as the potential outcomes, risks and benefits of testing. Once the pre-test phase is completed, genetic testing is performed. After the test results are available, post-test counseling is conducted to discuss the findings, their implications for the patient and the next steps in management (Table 2). However, no testing method is perfect, and sometimes genetic variants may go undetected even when present [3,127].

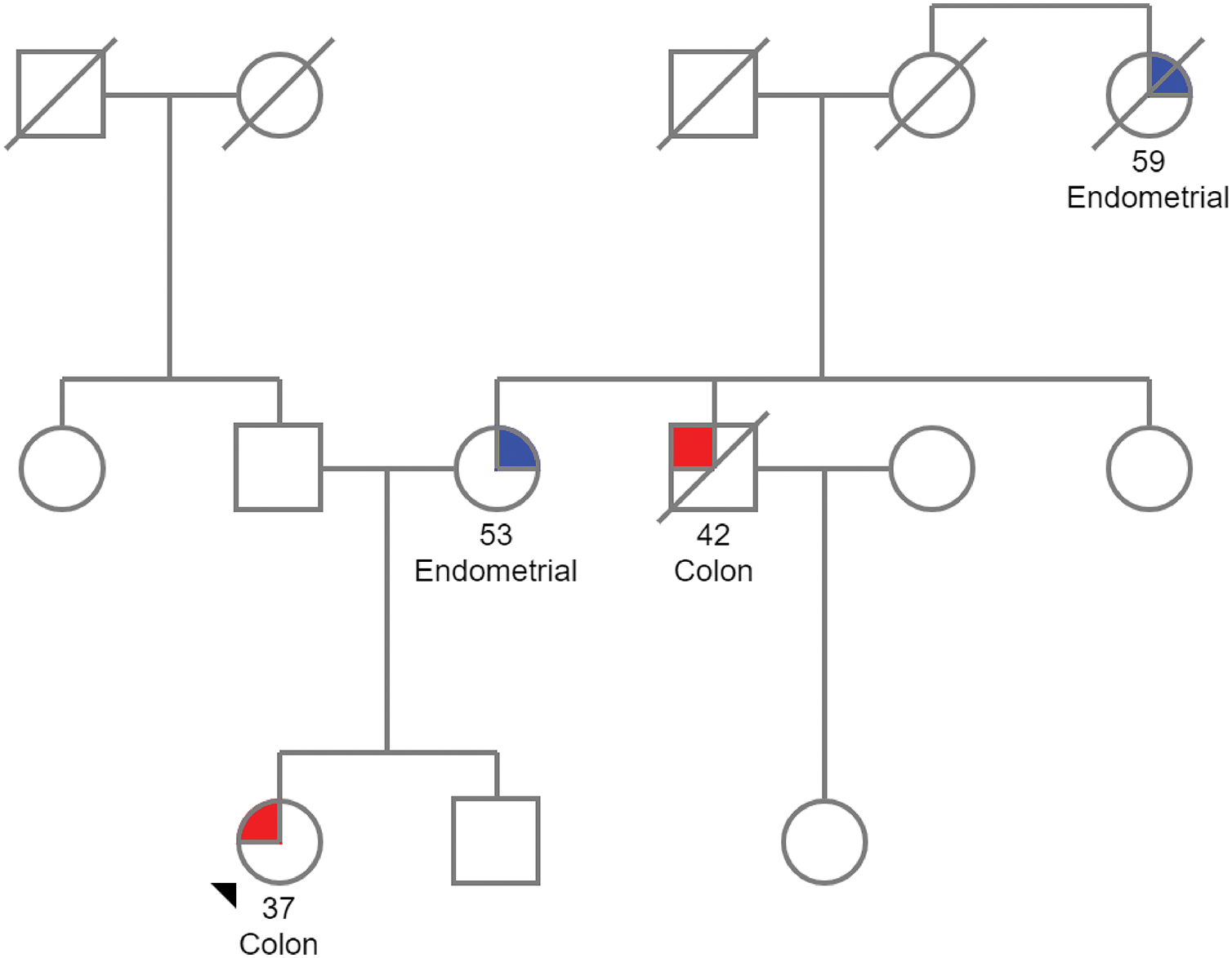

Identifying the carrier of a germline pathogenic variant is critical for managing both the proband and their family (Fig. 2). Once LS is confirmed in the index case, genetic counseling should be offered to first-degree relatives. In this regard, while genetic testing is typically not recommended for individuals under 18, predictive testing may be considered in cases with a family history of early-onset cancers [121,122]. The same process of pre-test counseling, testing and post-test counseling is then extended to at-risk family members identified through the family pedigree. Pre-test counseling for relatives involves providing them with information about the inherited condition and the potential risks of carrying the pathogenic variant. This is followed by genetic testing, which aims to identify individuals who may benefit from early surveillance or preventive measures. Finally, post-test counseling is offered to discuss the results, the implications for the relative’s health and the need for ongoing monitoring and intervention. Several challenges can arise when taking a family history and can obscure the potential presence of a hereditary cancer syndrome, such as incomplete family structure due to unknown or adopted family members, small family size or the loss of relatives at a young age from non-cancer-related causes [127]. These limitations should be carefully considered during the assessment and counseling process. Furthermore, information must be presented clearly, considering the patient’s educational level and prior understanding of genetics.

Figure 2: Pedigree of a family with Lynch syndrome. The proband, located at the lower left of the pedigree, is a woman diagnosed with CRC at the age of 37. Her mother was diagnosed with endometrial cancer at 53, her uncle passed away from CRC diagnosed at 42, and a maternal great-aunt died from endometrial cancer. Given this family history of LS-associated tumors, genetic counseling is recommended. The pedigree was created using the Pedigree software from Progeny Genetics.

Once the pathogenic variant responsible for the disease is identified in the index case, this enables accurate identification of true positive and true negative results in family members. A true positive occurs when the same known pathogenic variant is detected in a family member, confirming their increased risk for associated cancers and guiding the implementation of preventive measures. Conversely, a true negative arises when a family member is found to lack the pathogenic variant, confirming their cancer risk is similar to that of the general population, and no special follow-up is required. At this stage, Variants of Unknown Significance (VUS) no longer applies, as the pathogenic variant has already been conclusively identified [128]. Therefore, ensuring that affected individuals and their families understand the implications of the results and receive appropriate guidance for decision-making and management strategies is fundamental.

LS follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, with a 50% chance of passing the pathogenic variant to offspring [125]. When a germline heterozygous LS-related pathogenic variant is identified in a family member, options for prenatal and preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) become available. While natural conception remains an option for individuals willing to accept this risk, these alternative reproductive strategies are available for those seeking to prevent transmission. However, the use of such testing is a subject of ongoing debate within the medical community and among affected families, as perspectives often reflect differing ethical, cultural and personal values [129,130].

Prenatal genetic testing for LS aims to determine during an ongoing pregnancy whether the fetus has inherited the pathogenic variant. Traditionally, this testing involved invasive procedures, such as chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis, to collect fetal genetic material. However, advancements in non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) now allow analysis using a maternal blood sample, reducing the physical risk to the fetus [131,132]. These molecular diagnostic approaches, supported by technologies like NGS, have made testing more accessible and precise. Nevertheless, selecting the appropriate method for each case is critical, requiring an understanding of the available techniques and their limitations to ensure accurate results.

Otherwise, in recent years PGT offers an alternative during in vitro fertilization cycles, allowing screening of embryos at the blastocyst stage to identify those free of the LS pathogenic variants [133–135]. Selected embryos are implanted, minimizing the risk of transmission. Although PGT has increased in priority due to its ability to provide greater reproductive control, it is still constrained. This is due to the substantial medical, financial and emotional investment required, as well as the need for specialized facilities [129,135]. Additionally, the use of donor gametes represents another viable option for at-risk families.

Due to the high risk of infertility associated with LS, either as a result of the disease itself or the medical or surgical treatments that may affect germ cells, it is recommended to inform patients about fertility preservation options at the time of diagnosis [129]. For women with reduced ovarian reserve or those who have not pursued fertility preservation procedures, egg donation presents a viable reproductive option. Additionally, discussions with women with LS should include the option of risk-reducing surgeries, such as hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, which are typically recommended after childbearing or by age 40 to mitigate the elevated risk of gynecological cancers [136].

It is worth noting that prenatal diagnosis for LS presents unique challenges, as it involves a condition with adult onset, incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity. Unlike conditions traditionally considered for prenatal testing—typically severe, early-onset and highly penetrant—LS poses a complex and ethically sensitive scenario due to the significant variability in cancer risk based on the specific gene pathogenic variant and other modifying factors [137–140]. Moreover, these current approaches highlight the need for advanced molecular technologies and informed counseling to guide decision-making in LS management.

In cases of mosaic LS, genetic counseling is essential for discussing its implications on offspring. Although rare, the risk of passing on the variant may be lower in mosaic cases, but careful evaluation and reproductive planning with a genetic counselor are still necessary. PGT-M can be considered to prevent the transmission of LS to offspring [134]. Additionally, it presents unique challenges in patient management. It results from a post-zygotic mutation, meaning that the pathogenic MMR gene variant is present only in a subset of cells. This leads to variable expression of the syndrome, complicating both genetic testing and cancer risk assessment. Surveillance strategies may need to be tailored to each patient, as the frequency and intensity of monitoring, such as colonoscopies, may differ depending on the extent of mosaicism [57,141]. Furthermore, the cancer risk in mosaic LS cases may be lower or more unpredictable compared to germline genetic variants, requiring a personalized approach to risk management.

LS is characterized by pathogenic variants in MMR genes, with MLH1 and MSH2 variants presenting a higher lifetime risk of CRC compared to MSH6 and PMS2. The variability in cancer risk associated with MMR genes has significant clinical implications. Surveillance strategies should be tailored to reflect gene-specific risks, prioritizing intensive monitoring for MLH1 and MSH2 carriers while considering less frequent screening for MSH6 and PMS2 carriers. Moreover, the observed differences in penetrance between PLSD and IMRC cohorts suggest regional or methodological variations that merit further investigation. Further studies are needed to refine risk stratification and improve management protocols, particularly for underrepresented groups such as PMS2 carriers.

Colonoscopy remain the primary method for CRC prevention in LS patients, with screening beginning at age 25 for MLH1 and MSH2 carriers, and at age 35 for MSH6 and PMS2 carriers. Adherence to screening protocols is critical to reduce CRC incidence, emphasizing patient compliance and high-quality colonoscopies. Despite advancements in genetic testing, LS remains underdiagnosed, as current clinical criteria like the Amsterdam and Bethesda guidelines show reduced sensitivity in detecting MSH6 and PMS2 pathogenic variants. This highlights the need for more inclusive testing approaches. Universal screening strategies are recommended to address these gaps and enable earlier detection of LS. Furthermore, an improved understanding of gene-specific risk differences has led to more personalized clinical management recommendations.

Genetic counseling is crucial for managing LS, offering patients and families essential information on genetic risk, inheritance and personalized care. However, its practice remains controversial and is influenced by factors such as institutions, geographic region and healthcare policies, leading to inconsistencies in accessibility and quality. To improve LS management, further research is needed to refine risk stratification, enhance genetic testing (e.g., NGS) and enhance surveillance protocols. Additionally, the integration of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy and gene-specific interventions could optimize care. Raising awareness and education among healthcare providers are essential to promoting genetic evaluation and testing uptake, ensuring that patients receive timely and informed guidance to improve outcomes and management of LS.

Acknowledgement: This research was sponsored by of Virgen de la Luz Hospital (Spain), Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Castilla-La Mancha (IDISCAM) (Spain), the University of Castilla-La Mancha (Spain) and Chair of Artificial Intelligence, sponsored by Bayer, Barcelona (Spain).

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Raquel Gómez-Molina and Miguel Suárez; draft manuscript preparation: Raquel Gómez-Molina, Miguel Suárez, Raquel Martínez, Ana Peña-Cabia, María Concepción Calderón and Jorge Mateo; review and editing: Raquel Gómez-Molina and Miguel Suárez; visualization: Raquel Gómez-Molina, Miguel Suárez, Raquel Martínez, Ana Peña-Cabia, María Concepción Calderón and Jorge Mateo; supervision: Jorge Mateo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Abildgaard AB, Nielsen SV, Bernstein I, Stein A, Lindorff-Larsen K, Hartmann-Petersen R. Lynch Syndrome, molecular mechanisms and variant classification. Br J Cancer. 2023;128(5):726–34. doi:10.1038/s41416-022-02059-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Boland CR, Goel A. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(6):2073–87. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Giardiello FM, Allen JI, Axilbund JE, Boland CR, Burke CA, Burt RW, et al. Guidelines on genetic evaluation and management of Lynch syndrome: a consensus statement by the U.S. multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80(2):197–220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

4. Heald B, Hampel H, Church J, Dudley B, Hall MJ, Mork ME, et al. Collaborative group of the americas on inherited gastrointestinal cancer position statement on multigene panel testing for patients with colorectal cancer and/or polyposis. Fam Cancer. 2020;19(3):223–39. doi:10.1007/s10689-020-00170-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. American Cancer Society: cancer facts and figs. 2024. Atlanta, GA, USA: American Cancer Socierty; 2024. [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 30]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2024/2024-cancer-facts-and-figures-acs.pdf. [Google Scholar]

6. Abu-Ghazaleh N, Kaushik V, Gorelik A, Jenkins M, Macrae F. Worldwide prevalence of Lynch Syndrome in patients with colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Genet Med. 2022;24(5):971–85. doi:10.1016/j.gim.2022.01.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Underkofler KA, Ring KL. Updates in gynecologic care for individuals with Lynch Syndrome. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1127683. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1127683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Lynch HT, de la Chapelle A. Hereditary colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(10):919–32. doi:10.1056/NEJMra012242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Seppälä TT, Burkhart RA, Katona BW. Hereditary colorectal, gastric, and pancreatic cancer: comprehensive review. BJS Open. 2023;7(3):zrad023. doi:10.1093/bjsopen/zrad023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. American Gastroenterological Association. Lynch Syndrome: AGA patient guideline summary. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(3):814–5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Stoffel EM, Mangu PB, Gruber SB, Hamilton SR, Kalady MF, Lau MW, et al. Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement of the familial risk-colorectal cancer: european society for medical oncology clinical practice guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(2):209–17. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.58.1322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. PDQ® cancer genetics editorial board. PDQ genetics of colorectal cancer. Bethesda, MD, USA: National Cancer Institute; 2025. [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 25]. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal/hp/colorectal-genetics-pdq. [Google Scholar]

13. Kim JY, Byeon JS. Genetic counseling and surveillance focused on Lynch Syndrome. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2019;3(2):60–8. doi:10.23922/jarc.2019-002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Moreira L, Balaguer F, Lindor N, de la Chapelle A, Hampel H, Aaltonen LA, et al. Identification of Lynch Syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2012;308(15):1555–65. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.13088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. De’ Angelis GL, Bottarelli L, Azzoni C, De’ Angelis N, Leandro G, Di Mario F, et al. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Acta Biomed. 2018;89(9–s):97–101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

16. Koessler T, Oestergaard MZ, Song H, Tyrer J, Perkins B, Dunning AM, et al. Common variants in mismatch repair genes and risk of colorectal cancer. Gut. 2008;57(8):1097–101. doi:10.1136/gut.2007.137265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Baretti M, Le DT. DNA mismatch repair in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;189:45–62. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.04.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Rahman MM, Mohiuddin M, Shamima Keka I, Yamada K, Tsuda M, Sasanuma H, et al. Genetic evidence for the involvement of mismatch repair proteins, PMS2 and MLH3, in a late step of homologous recombination. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(51):17460–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA120.013521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Pannafino G, Alani E. Coordinated and independent roles for MLH Subunits in DNA repair. Cells. 2021;10(4). doi:10.3390/cells10040948. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Tamura K, Kaneda M, Futagawa M, Takeshita M, Kim S, Nakama M, et al. Genetic and genomic basis of the mismatch repair system involved in Lynch syndrome. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019;24:999–1011. doi:10.1007/s10147-019-01494-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Keshinro A, Ganesh K, Vanderbilt C, Firat C, Kim JK, Chen CT, et al. Characteristics of mismatch repair-deficient colon cancer in relation to mismatch repair protein loss, hypermethylation silencing, and constitutional and biallelic somatic mismatch repair gene pathogenic variants. Dis Colon Rectum. 2023;66(4):549–58. doi:10.1097/DCR.0000000000002452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Narayan S, Roy D. Role of APC and DNA mismatch repair genes in the development of colorectal cancers. Mol Cancer. 2003;2(1):41. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-2-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Gallon R, Brekelmans C, Martin M, Bours V, Schamschula E, Amberger A, et al. Constitutional mismatch repair deficiency mimicking Lynch syndrome is associated with hypomorphic mismatch repair gene variants. npj Precis Oncol. 2024;8(1):119. doi:10.1038/s41698-024-00603-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Incorvaia L, Bazan Russo TD, Gristina V, Perez A, Brando C, Mujacic C, et al. The intersection of homologous recombination (HR) and mismatch repair (MMR) pathways in DNA repair-defective tumors. npj Precis Oncol. 2024;8(1):190. doi:10.1038/s41698-024-00672-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Møller P, Seppälä TT, Ahadova A, Crosbie EJ, Holinski-Feder E, Scott R, et al. Dominantly inherited micro-satellite instable cancer—the four Lynch syndromes—an EHTG, PLSD position statement. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2023;21(1):19. doi:10.1186/s13053-023-00263-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Dominguez-Valentin M, Plazzer JP, Sampson JR, Engel C, Aretz S, Jenkins MA, et al. No difference in penetrance between truncating and Missense/Aberrant splicing pathogenic variants in MLH1 and MSH2: a prospective lynch syndrome database study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(13):2856. doi:10.3390/jcm10132856. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Andini KD, Nielsen M, Suerink M, Helderman NC, Koornstra JJ, Ahadova A, et al. PMS2-associated Lynch syndrome: past, present and future. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1127329. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1127329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Win AK, Dowty JG, Reece JC, Lee G, Templeton AS, Plazzer J-P, et al. Variation in the risk of colorectal cancer in families with Lynch syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(7):1014–22. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00189-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Entry-#120435—LYNCH SYNDROME 1; LYNCH1—OMIM. Omim.org; 2025. [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/?. [Google Scholar]

30. The Prospective Lynch Syndromes Database (PLSD). Edinburgh, UK: European Hereditary Tumor Group (EHTG); 2025. [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 23]. Available from: https://plsd.eu/. [Google Scholar]

31. Lynch syndrome: InSight London: International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumours (InSiGHT); 2025. [Internet]. [updated 2024 Feb 23, cited 2024 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.insight-group.org/syndromes/lynch-syndrome/. [Google Scholar]

32. Møller P, Seppälä T, Dowty JG, Haupt S, Dominguez-Valentin M, Sunde L, et al. Colorectal cancer incidences in Lynch syndrome: a comparison of results from the prospective lynch syndrome database and the international mismatch repair consortium. Heredit Cancer Clin Pract. 2022;20(1):36. [Google Scholar]

33. Møller P, Seppälä T, Bernstein I, Holinski-Feder E, Sala P, Evans DG, et al. Cancer incidence and survival in Lynch syndrome patients receiving colonoscopic and gynaecological surveillance: first report from the prospective Lynch syndrome database. Gut. 2017;66(3):464–72. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309675. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Dominguez-Valentin M, Sampson JR, Seppälä TT, Ten Broeke SW, Plazzer JP, Nakken S, et al. Cancer risks by gene, age, and gender in 6350 carriers of pathogenic mismatch repair variants: findings from the Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database. Genet Med. 2020;22(1):15–25. doi:10.1038/s41436-019-0596-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Møller P, Seppälä TT, Bernstein I, Holinski-Feder E, Sala P, Gareth Evans D, et al. Cancer risk and survival in path_MMR carriers by gene and gender up to 75 years of age: a report from the Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database. Gut. 2018;67(7):1306–16. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Seppälä TT, Latchford A, Negoi I, Sampaio Soares A, Jimenez-Rodriguez R, Sánchez-Guillén L, et al. European guidelines from the EHTG and ESCP for Lynch syndrome: an updated third edition of the Mallorca guidelines based on gene and gender. Br J Surg. 2021;108(5):484–98. doi:10.1002/bjs.11902. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Dominguez-Valentin M, Haupt S, Seppälä TT, Sampson JR, Sunde L, Bernstein I, et al. Mortality by age, gene and gender in carriers of pathogenic mismatch repair gene variants receiving surveillance for early cancer diagnosis and treatment: a report from the prospective Lynch syndrome database. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;58:101909. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101909. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Helderman NC, van Leerdam ME, Kloor M, Ahadova A, Nielsen M. Emerge of colorectal cancer in Lynch syndrome despite colonoscopy surveillance: a challenge of hide and seek. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2024;197:104331. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2024.104331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Rubenstein JH, Enns R, Heidelbaugh J, Barkun A, Adams MA, Dorn SD, et al. American gastroenterological association institute guideline on the diagnosis and management of Lynch Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(3):777–82. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Cubiella J, Marzo-Castillejo M, Mascort-Roca JJ, Amador-Romero FJ, Bellas-Beceiro B, Clofent-Vilaplana J, et al. Clinical practice guideline. Diagnosis and prevention of colorectal cancer. 2018 Update. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41(9):585–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

41. Stjepanovic N, Moreira L, Carneiro F, Balaguer F, Cervantes A, Balmaña J, et al. Hereditary gastrointestinal cancers: eSMO Clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(10):1558–71. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdz233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Di Marco M, E. DA, Panic N, Baccolini V, Migliara G, Marzuillo C, et al. Which Lynch syndrome screening programs could be implemented in the real world? A systematic review of economic evaluations. Genet Med. 2018;20(10):1131–44. doi:10.1038/gim.2017.244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Snowsill T, Coelho H, Huxley N, Jones-Hughes T, Briscoe S, Frayling IM, et al. Molecular testing for Lynch syndrome in people with colorectal cancer: systematic reviews and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2017;21(51):1–238. doi:10.3310/hta21510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Peltomäki P, Nyström M, Mecklin J-P, Seppälä TT. Lynch Syndrome genetics and clinical implications. Gastroenterology. 2023;164(5):783–99. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.08.058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Eikenboom EL, van der Werf-’t Lam A-S, Rodríguez-Girondo M, Van Asperen CJ, Dinjens WNM, Hofstra RMW, et al. Universal immunohistochemistry for Lynch syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 58,580 colorectal carcinomas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;20(3):e496–507. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Sarode VR, Robinson L. Screening for Lynch syndrome by immunohistochemistry of mismatch repair proteins: significance of indeterminate result and correlation with mutational studies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143(10):1225–33. doi:10.5858/arpa.2018-0201-OA. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Pearlman R, Markow M, Knight D, Chen W, Arnold CA, Pritchard CC, et al. Two-stain immunohistochemical screening for Lynch syndrome in colorectal cancer may fail to detect mismatch repair deficiency. Mod Pathol. 2018;31(12):1891–900. doi:10.1038/s41379-018-0058-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Yurgelun MB, Hampel H. Recent advances in Lynch Syndrome: diagnosis, treatment, and cancer prevention. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:101–9. doi:10.1200/EDBK_208341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Evrard C, Cortes U, Ndiaye B, Bonnemort J, Martel M, Aguillon R, et al. An innovative and accurate Next-generation sequencing-based microsatellite instability detection method for colorectal and endometrial tumors. Lab Invest. 2024;104(2):100297. doi:10.1016/j.labinv.2023.100297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Hampel H, Pearlman R, de la Chapelle A, Pritchard CC, Zhao W, Jones D, et al. Double somatic mismatch repair gene pathogenic variants as common as Lynch syndrome among endometrial cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;160(1):161–8. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.10.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. van Leerdam ME, Roos VH, van Hooft JE, Balaguer F, Dekker E, Kaminski MF, et al. Endoscopic management of Lynch syndrome and of familial risk of colorectal cancer: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2019;51(11):1082–93. doi:10.1055/a-1016-4977. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. García-Alfonso P, García-Carbonero R, García-Foncillas J, Pérez-Segura P, Salazar R, Vera R, et al. Update of the recommendations for the determination of biomarkers in colorectal carcinoma: national consensus of the spanish society of medical oncology and the spanish society of pathology. Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22(11):1976–91. doi:10.1007/s12094-020-02357-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Antoniotti C, Korn WM, Marmorino F, Rossini D, Lonardi S, Masi G, et al. Tumour mutational burden, microsatellite instability, and actionable alterations in metastatic colorectal cancer: next-generation sequencing results of TRIBE2 study. Eur J Cancer. 2021;155:73–84. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2021.06.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Xiao J, Li W, Huang Y, Huang M, Li S, Zhai X, et al. A next-generation sequencing-based strategy combining microsatellite instability and tumor mutation burden for comprehensive molecular diagnosis of advanced colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):282. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-07942-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Schrock AB, Ouyang C, Sandhu J, Sokol E, Jin D, Ross JS, et al. Tumor mutational burden is predictive of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in MSI-high metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(7):1096–103. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdz134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Manca P, Corti F, Intini R, Mazzoli G, Miceli R, Germani MM, et al. Tumour mutational burden as a biomarker in patients with mismatch repair deficient/microsatellite instability-high metastatic colorectal cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2023;187:15–24. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2023.03.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Benson AB, Venook AP, Adam M, Chang G, Chen Y-J, Ciombor KK, et al. Colon Cancer, version 3.2024, NCCN clinical practice Guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024;22(2D):e240029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

58. Gray PN, Tsai P, Chen D, Wu S, Hoo J, Mu W, et al. TumorNext-Lynch-MMR: a comprehensive next generation sequencing assay for the detection of germline and somatic mutations in genes associated with mismatch repair deficiency and Lynch syndrome. Oncotarget. 2018;9(29):20304–22. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.24854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Guo Y, Yan G, Zhang P, Liu Y, Zhao C, Zeng X. The clinical utility of next generation sequencing in endometrial cancer: focusing on molecular subtyping and lynch syndrome. Front Genet. 2024;15:1440971. doi:10.3389/fgene.2024.1440971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Ryan NAJ, Davison NJ, Payne K, Cole A, Evans DG, Crosbie EJ. A micro-costing study of screening for Lynch syndrome-associated pathogenic variants in an unselected endometrial cancer population: cheap as NGS chips? Front Oncol. 2019;9:61. doi:10.3389/fonc.2019.00061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Yoshino T, Pentheroudakis G, Mishima S, Overman MJ, Yeh K-H, Baba E, et al. JSCO-ESMO-ASCO-JSMO-TOS: international expert consensus recommendations for tumour-agnostic treatments in patients with solid tumours with microsatellite instability or NTRK fusions. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(7):861–72. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Chakravarty D, Johnson A, Sklar J, Lindeman NI, Moore K, Ganesan S, et al. Somatic genomic testing in patients with metastatic or advanced cancer: aSCO provisional clinical opinion. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(11):1231–58. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.02767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Syngal S, Brand RE, Church JM, Giardiello FM, Hampel HL, Burt RW. ACG clinical guideline: genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(2):223–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

64. Monahan KJ, Bradshaw N, Dolwani S, Desouza B, Dunlop MG, East JE, et al. Guidelines for the management of hereditary colorectal cancer from the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)/Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI)/United Kingdom Cancer Genetics Group (UKCGG). Gut. 2020;69(3):411–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

65. Anyla M, Lefevre JH, Creavin B, Colas C, Svrcek M, Lascols O, et al. Metachronous colorectal cancer risk in Lynch syndrome patients-should the endoscopic surveillance be more intensive? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33(6):703–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

66. Engel C, Vasen HF, Seppälä T, Aretz S, Bigirwamungu-Bargeman M, de Boer SY, et al. No difference in colorectal cancer incidence or stage at detection by colonoscopy among 3 countries with different Lynch Syndrome surveillance policies. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1400–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

67. Lindberg LJ, Rasmussen M, Andersen KK, Nilbert M, Therkildsen C. Benefit from extended surveillance interval on colorectal cancer risk in Lynch syndrome. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(5):529–36. doi:10.1111/codi.14926. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Aronson M, Gryfe R, Choi YH, Semotiuk K, Holter S, Ward T, et al. Evaluating colonoscopy screening intervals in patients with Lynch syndrome from a large Canadian registry. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2023;115(7):778–87. doi:10.1093/jnci/djad058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Ten Broeke SW, van der Klift HM, Tops CMJ, Aretz S, Bernstein I, Buchanan DD, et al. Cancer Risks for PMS2-Associated Lynch Syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(29):2961–8. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.78.4777. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Rondagh EJ, Gulikers S, Gómez-García EB, Vanlingen Y, Detisch Y, Winkens B, et al. Nonpolypoid colorectal neoplasms: a challenge in endoscopic surveillance of patients with Lynch syndrome. Endoscopy. 2013;45(4):257–64. doi:10.1055/s-00000012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Argillander TE, Koornstra JJ, van Kouwen M, Langers AM, Nagengast FM, Vecht J, et al. Features of incident colorectal cancer in Lynch syndrome. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(8):1215–22. doi:10.1177/2050640618783554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Perrod G, Rahmi G, Cellier C. Colorectal cancer screening in Lynch syndrome: indication, techniques and future perspectives. Dig Endosc. 2021;33(4):520–8. doi:10.1111/den.13702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Kaltenbach T, Anderson JC, Burke CA, Dominitz JA, Gupta S, Lieberman D, et al. Endoscopic removal of colorectal lesions: recommendations by the US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(3):435–64. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000000555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Sánchez A, Roos VH, Navarro M, Pineda M, Caballol B, Moreno L, et al. Quality of colonoscopy is associated with adenoma detection and postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer prevention in Lynch Syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(3):611–21. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.11.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Castillo-Iturra J, Sánchez A, Balaguer F. Colonoscopic surveillance in Lynch syndrome: guidelines in perspective. Fam Cancer. 2024;23(4):459–68. doi:10.1007/s10689-024-00414-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Ahadova A, Seppälä TT, Engel C, Gallon R, Burn J, Holinski-Feder E, et al. The unnatural history of colorectal cancer in Lynch syndrome: lessons from colonoscopy surveillance. Int J Cancer. 2021;148(4):800–11. doi:10.1002/ijc.33224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Hüneburg R, Lammert F, Rabe C, Rahner N, Kahl P, Büttner R, et al. Chromocolonoscopy detects more adenomas than white light colonoscopy or narrow band imaging colonoscopy in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer screening. Endoscopy. 2009;41(4):316–22. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1119628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Buchner AM. The role of chromoendoscopy in evaluating colorectal dysplasia. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;13(6):336–47. [Google Scholar]

79. Houwen B, Hazewinkel Y, Pellisé M, Rivero-Sánchez L, Balaguer F, Bisschops R, et al. Linked Colour imaging for the detection of polyps in patients with Lynch syndrome: a multicentre, parallel randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2022;71(3):553–60. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Haanstra JF, Dekker E, Cats A, Nagengast FM, Hardwick JC, Vanhoutvin SA, et al. Effect of chromoendoscopy in the proximal colon on colorectal neoplasia detection in Lynch syndrome: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(4):624–32. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2019.04.227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Rivero-Sánchez L, Arnau-Collell C, Herrero J, Remedios D, Cubiella J, García-Cougil M, et al. White-Light endoscopy is adequate for lynch syndrome surveillance in a randomized and noninferiority study. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(4):895–904. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Drogan C, Kupfer SS. Colorectal cancer screening recommendations and outcomes in Lynch Syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2022;32(1):59–74. doi:10.1016/j.giec.2021.08.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Hüneburg R, Bucksch K, Schmeißer F, Heling D, Marwitz T, Aretz S, et al. Real-time use of artificial intelligence (CADEYE) in colorectal cancer surveillance of patients with Lynch syndrome-A randomized controlled pilot trial (CADLY). United European Gastroenterol J. 2023;11(1):60–8. doi:10.1002/ueg2.12354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Maida M, Marasco G, Maas MHJ, Ramai D, Spadaccini M, Sinagra E, et al. Effectiveness of artificial intelligence assisted colonoscopy on adenoma and polyp miss rate: a meta-analysis of tandem RCTs. Dig Liver Dis. 2025;57(1):169–75. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2024.09.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Burn J, Sheth H, Elliott F, Reed L, Macrae F, Mecklin JP, et al. Cancer prevention with aspirin in hereditary colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome10-year follow-up and registry-based 20-year data in the CAPP2 study: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10240):1855–63. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30366-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Algra AM, Rothwell PM. Effects of regular aspirin on long-term cancer incidence and metastasis: a systematic comparison of evidence from observational studies vs. randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(5):518–27. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70112-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Rothwell PM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, Price JF, Belch JFF, Roncaglioni MC, et al. Effects of aspirin on risks of vascular events and cancer according to bodyweight and dose: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10145):387–99. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31133-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Campbell PT, Jacobs ET, Ulrich CM, Figueiredo JC, Poynter JN, McLaughlin JR, et al. Case-control study of overweight, obesity, and colorectal cancer risk, overall and by tumor microsatellite instability status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(6):391–400. doi:10.1093/jnci/djq011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Winkels RM, Botma A, Van Duijnhoven FJ, Nagengast FM, Kleibeuker JH, Vasen HF, et al. Smoking increases the risk for colorectal adenomas in patients with Lynch syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(2):241–7. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Dashti SG, Buchanan DD, Jayasekara H, Ait Ouakrim D, Clendenning M, Rosty C, et al. Alcohol consumption and the risk of colorectal cancer for mismatch repair gene mutation carriers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(3):366–75. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Kobayashi N, Takeuchi Y, Ohata K, Igarashi M, Yamada M, Kodashima S, et al. Outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasms: prospective, multicenter, cohort trial. Dig Endosc. 2022;34(5):1042–51. doi:10.1111/den.14223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Langers AMJ, Boonstra JJ, Hardwick JCH, van der Kraan J, Farina Sarasqueta A, Vasen HFA. Endoscopic full thickness resection for early colon cancer in Lynch syndrome. Fam Cancer. 2019;18(3):349–52. doi:10.1007/s10689-019-00132-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Chikatani K, Ishida H, Mori Y, Nakajima T, Ueki A, Akagi K, et al. Risk of metachronous colorectal cancer after colectomy for first colon cancer in Lynch syndrome: multicenter retrospective study in Japan. Int J Clin Oncol. 2023;28(12):1633–40. doi:10.1007/s10147-023-02412-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Eikenboom EL, Moen S, van Leerdam ME, Papageorgiou G, Doukas M, Tanis PJ, et al. Metachronous colorectal cancer risk according to Lynch syndrome pathogenic variant after extensive versus partial colectomy in the Netherlands: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(12):1106–17. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00228-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Leinicke JA. Ileal pouch complications. Surg Clin North Am. 2019;99(6):1185–96. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2019.08.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Kurasaka C, Ogino Y, Sato A. Molecular mechanisms and tumor biological aspects of 5-Fluorouracil resistance in HCT116 human colorectal cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(6):2916. doi:10.3390/ijms22062916. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Miyashita K, Shioi S, Kajitani T, Koi Y, Shimokawa M, Makiyama A, et al. More subtle microsatellite instability better predicts fluorouracil insensitivity in colorectal cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):27257. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-77770-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Radenković N, Nikodijević D, Jovankić J, Blagojević S, Milutinović M. Resistance to 5-fluorouracil: the molecular mechanisms of development in colon cancer cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2024;983:176979. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2024.176979. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Oneda E, Zaniboni A. Adjuvant treatment of colon cancer with microsatellite instability—the state of the art. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2022;169:103537. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Kamal Y, Schmit SL, Frost HR, Amos CI. The tumor microenvironment of colorectal cancer metastases: opportunities in cancer immunotherapy. Immunotherapy. 2020;12(14):1083–1100. doi:10.2217/imt-2020-0026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Rizvi N, Ademuyiwa FO, Cao ZA, Chen HX, Ferris RL, Goldberg SB, et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) consensus definitions for resistance to combinations of immune checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11(3):e005920. doi:10.1136/jitc-2022-005920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Morris VK, Kennedy EB, Baxter NN, Benson AB, Cercek A, Cho M, et al. Treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: aSCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2022;41(3):678–700. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.01690. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Jin Z, Sinicrope FA. Mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer: building on checkpoint blockade. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(24):2735–50. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.02691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Lenz H-J, Van Cutsem E, Luisa Limon M, Wong KYM, Hendlisz A, Aglietta M, et al. First-Line nivolumab plus low-dose ipilimumab for microsatellite instability-High/Mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer: the phase II checkMate 142 study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;40(2):161–70. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.01015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Sahin IH, Akce M, Alese O, Shaib W, Lesinski GB, El-Rayes B, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of MSI-H/MMR-D colorectal cancer and a perspective on resistance mechanisms. Br J Cancer. 2019;121(10):809–18. doi:10.1038/s41416-019-0599-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]