Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Tumor Vaccines for Malignant Melanoma: Progress, Challenges, and Future Directions

1 Department of Dermatology, Jinzhou Medical University, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou Medical University, Jinzhou, 121001, China

2 Department of Urology, Jinzhou Medical University, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou Medical University, Jinzhou, 121001, China

3 Department of Clinical Lab, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University (Zhejiang Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine), Hangzhou, 310060, China

4 Department of Pharmacy, The First People’s Hospital of Lin’an District, Hangzhou, Lin’an People’s Hospital Affiliated to Hangzhou Medical College, Hangzhou, 311399, China

5 Department of Postpartum Rehabilitation, The First People’s Hospital of Lin’an District, Hangzhou, Lin’an People’s Hospital Affiliated to Hangzhou Medical College, Hangzhou, 311399, China

* Corresponding Authors: Judong Song. Email: ; Yunzhen Ding. Email:

# These two authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: New Insights in Drug Resistance of Cancer Therapy: A New Wine in an Old Bottle)

Oncology Research 2025, 33(8), 1875-1893. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.063843

Received 25 January 2025; Accepted 16 April 2025; Issue published 18 July 2025

Abstract

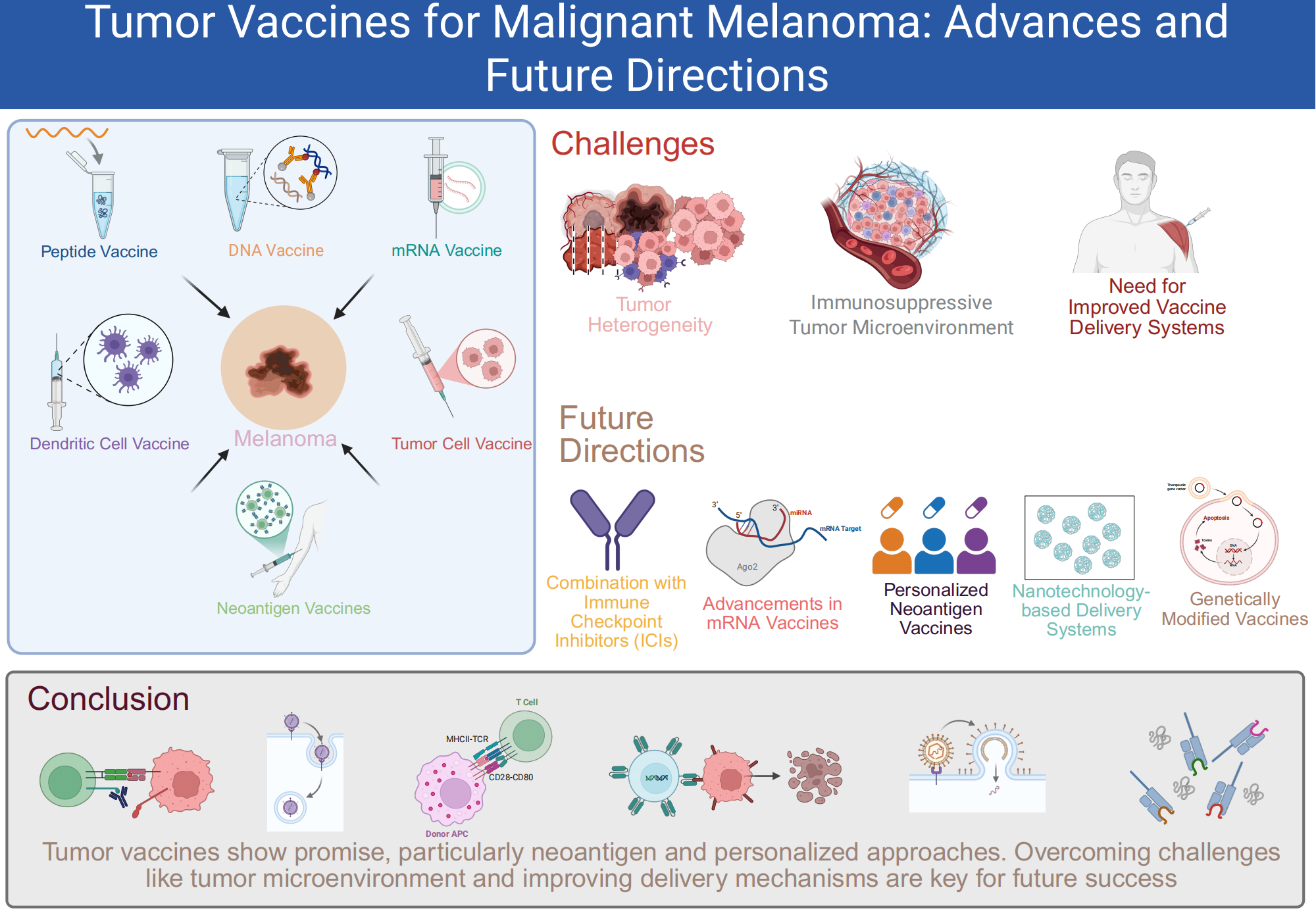

Malignant melanoma, characterized by its high metastatic potential and resistance to conventional therapies, presents a major challenge in oncology. This review explores the current status and advancements in tumor vaccines for melanoma, focusing on peptide, DNA/RNA, dendritic cell, tumor cell, and neoantigen-based vaccines. Despite promising results, significant challenges remain, including the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, patient heterogeneity, and the need for more effective antigen presentation. Recent strategies, such as combining vaccines with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), aim to counteract immune evasion and enhance T cell responses. Emerging approaches, including personalized neoantigen vaccines and the use of self-amplifying RNA platforms, hold promise for overcoming tumor heterogeneity and improving vaccine efficacy. Additionally, optimizing vaccine delivery systems through nanotechnology and genetic modifications is essential for increasing stability and scalability. This review highlights the potential of these innovative strategies to address current limitations, with a focus on how future research can refine and combine these approaches to improve melanoma treatment outcomes.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Malignant melanoma, the most aggressive form of skin cancer, is responsible for 65% of skin cancer deaths, with rising global incidence and a poor prognosis in advanced stages [1,2]. Despite advances in early detection, the five-year survival rate for metastatic melanoma remains low [3]. Characterized by irregular skin lesions, melanoma is strongly linked to UV exposure [4]. Although targeted therapies like vemurafenib show initial success for BRAF V600E mutations, relapse is common, highlighting the limitations of current treatments [5]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) further hinders immune responses, complicating treatment effectiveness [6]. These challenges underscore the need for innovative therapeutic strategies, such as tumor vaccines, to enhance immune recognition of cancer cells [7]. Combining vaccines with other therapies may offer promising new solutions [6].

2 Immunotherapy, a Historical Background

Immunotherapy has emerged as a promising treatment strategy for various cancers, including malignant melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), renal cell carcinoma, bladder carcinoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma [8,9]. Unlike traditional therapies that directly target cancer cells, immunotherapy leverages the body’s immune system to recognize and attack tumor cells [7,10]. Tumor vaccines represent a novel and potentially transformative approach in cancer immunotherapy. These vaccines aim to stimulate the immune system to recognize and eliminate cancer cells by targeting tumor-specific antigens (TSAs), a strategy that has shown promise in clinical trials [11,12].

The historical roots of cancer immunotherapy trace back to the late 19th century when German physicians Fehleisen and Busch first noted significant tumor regression following erysipelas infections [13]. This observation laid the foundation for William Bradley Coley’s pioneering use of bacterial toxins in the 1890s to stimulate the immune system against cancer [13]. Interleukin-2 (IL-2) and interferon-alpha were among the first immunotherapeutic agents approved for treating metastatic melanoma, marking an early phase in the evolution of immunotherapy for this cancer [10,14].

Recent advancements have focused on personalized neoantigen-based vaccines and mRNA vaccines. Personalized neoantigen vaccines, tailored to the unique mutations in a patient’s tumor, have shown promise in early clinical trials by inducing robust tumor-specific immune responses [15,16]. Similarly, mRNA vaccines, which gained prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic, are being explored for their potential in cancer immunotherapy due to their ability to rapidly deliver TSAs [17].

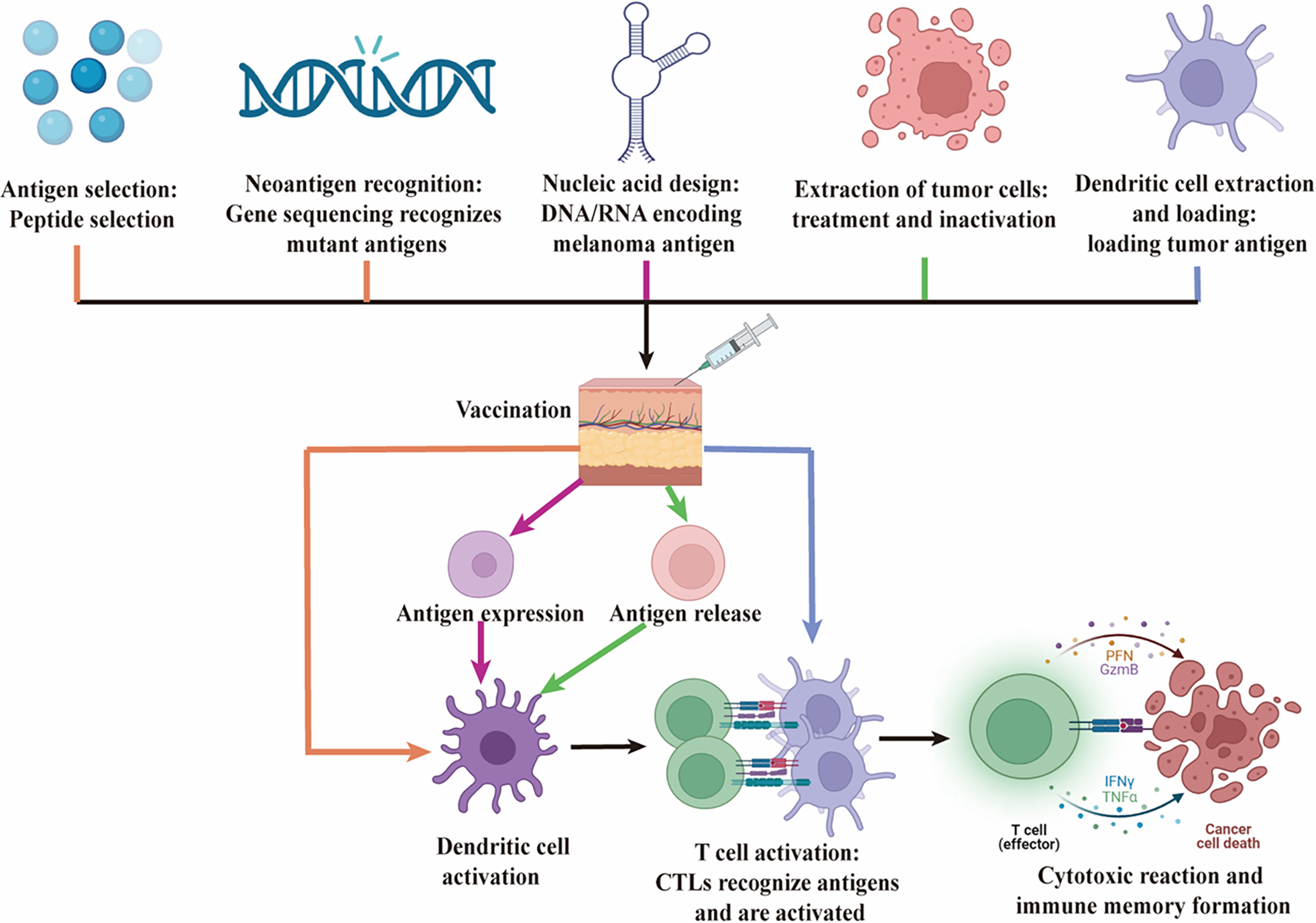

Recent advancements in cancer immunotherapy have introduced a range of vaccine strategies aimed at targeting malignant melanoma by leveraging the immune system. These include peptide vaccines derived from melanoma-associated antigens [18], DNA or RNA vaccines encoding these antigens [19,20], dendritic cell-based vaccines primed with melanoma-specific antigens [21], and whole melanoma cell vaccines that present a broad spectrum of tumor antigens [22]. Neoantigen vaccines, which are tailored to target the unique mutations in a patient’s melanoma, have emerged as a particularly promising approach in personalized medicine [15,23]. Each vaccine type engages the immune system through distinct pathways to effectively combat melanoma [24]. The various vaccine formulations and their mechanisms of action are depicted in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Mechanisms of action of various vaccines in melanoma immunotherapy. This figure illustrates the mechanisms of action of five different types of vaccines—Peptide Vaccines, DNA/RNA Vaccines, Dendritic Cell Vaccines, Tumor Cell Vaccines, and Neoantigen Vaccines—in the immunotherapy of melanoma. Black represents common steps. 1. Peptide Vaccines (orange): Specific melanoma antigen peptides are selected and administered, after which they are taken up and processed by DC. This leads to the activation of CTLs, which recognize and destroy melanoma cells. 2. Neoantigen Vaccines (orange): Neoantigens, which are unique to the patient’s tumor, are identified through genomic sequencing. A personalized vaccine is then designed and administered to induce a strong, specific T cell response aimed at targeting and eliminating melanoma cells. 3. DNA/RNA Vaccines (pink): DNA or RNA encoding melanoma antigens is injected into the body, where host cells express the antigen. This antigen is then presented by DC, leading to the proliferation and functional activation of CTLs, ultimately resulting in a cytotoxic response against melanoma cells. 4. Tumor Cell Vaccines (green): Inactivated whole tumor cells are used as the antigen source, stimulating the patient’s immune system. DC mediate this response, eliciting a broad T cell response targeting multiple tumor antigens. 5. Dendritic Cell Vaccines (blue): Autologous DC are loaded with tumor antigens ex vivo and then reintroduced into the patient. These DC directly activate CTLs, driving a specific immune response against melanoma cells. This figure emphasizes the distinct immunological pathways and final goal of each vaccine type, which is to activate the body’s immune system, particularly CTLs, to recognize and eradicate melanoma cells. Created by BioRender

Peptide vaccines are a promising melanoma immunotherapy strategy that use short peptides derived from tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) or TSA [25]. These vaccines aim to stimulate immune responses by presenting peptides to antigen-presenting cells (APCs), leading to the activation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) which target tumor cells [26]. Peptide vaccines can be divided into B cell epitope-based and T cell epitope-based vaccines, with melanoma vaccines typically focusing on T cell epitopes to activate CD8+ CTLs [18,27].

The mechanism involves processing peptides by dendritic cells (DC), which then present them on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. Peptides presented on MHC class I activate CD8+ CTLs to kill tumor cells, while MHC class II activates CD4+ helper T cells to enhance CTL and B cell activation [26]. The inclusion of AS02B, a combination of an oil-in-water emulsion containing monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) and Quillaja saponaria fraction 21 (QS-21), is essential for improving the immunogenicity of the vaccine and ensuring long-term immune responses [28]. AS02B has been used in clinical trials to enhance the effectiveness of vaccines like MAGE-A3 [28].

In melanoma, several peptide vaccine candidates have been explored, including MAGE-A3, a cancer-testis antigen that is highly expressed in melanoma but not in normal tissues [29]. Clinical trials have shown that MAGE-A3 vaccines with adjuvants stimulate strong humoral and cellular immune responses, which can be further enhanced with booster doses [28]. Similarly, gp100 refers to a melanoma-associated peptide derived from the gp100 protein, a component of melanocyte differentiation antigens [30]. The gp100: 209–217(210M) peptide has been tested as a vaccine in combination with IL-2 to improve clinical outcomes in patients with advanced melanoma [30,31].

To improve peptide vaccine effectiveness, strategies such as incorporating cell-penetrating domains (CPDs) and using advanced delivery systems like water-in-oil-in-water (W/O/W) emulsions have been explored to enhance antigen presentation and CTL activation [26]. Additionally, combining peptide vaccines with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and cytokines like IL-2 has shown promise in enhancing immune responses and improving clinical survival [18,31].

DNA and RNA vaccines are innovative genetic vaccines being developed for melanoma treatment. These vaccines use the body’s own cells to produce TAAs, triggering immune responses that target and destroy cancer cells. DNA vaccines involve plasmid DNA encoding tumor antigens, while RNA vaccines utilize mRNA or circular RNA (circRNA) to deliver the same goal. RNA vaccines offer the added advantage of transient expression, reducing long-term risks [32].

The action of DNA vaccines starts with the introduction of plasmid DNA into host cells, where it is transcribed into mRNA and translated into a tumor antigen. This stimulates an immune response, activating CTLs and helper T cells to attack cancer cells [19]. RNA vaccines, on the other hand, bypass transcription by directly delivering mRNA, which is quickly translated into the antigen, offering flexibility and rapid adaptation to evolving tumor targets. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) improve the stability and bioavailability of mRNA vaccines [20,33].

For melanoma, the MAGE-A3 DNA vaccine targets a cancer-testis antigen found in melanoma but not normal tissues, showing promise in preclinical studies [19]. RNA vaccines like mRNA-4157 and BNT111, which target multiple tumor antigens, have shown enhanced T cell responses, especially when combined with ICIs like pembrolizumab [34,35]. Additionally, circRNA vaccines have shown superior stability and prolonged antigen expression, improving anti-tumor immunity in mouse models [36].

In summary, while DNA vaccines like MAGE-A3 face challenges in immunogenicity and delivery efficiency, RNA vaccines, including mRNA and circRNA, hold significant potential, especially when combined with ICIs. Continued research and optimization of delivery systems, such as LNPs, are crucial for enhancing the efficacy of these vaccines [37,38].

DC vaccines are a promising cancer immunotherapy, particularly for their ability to present TAAs to T cells, inducing strong anti-tumor immune responses. DC, as professional APCs, initiate immune responses by processing and presenting antigens to CTLs. The standard method for creating DC vaccines involves isolating DC from the patient, loading them with TAAs, and then reintroducing these primed DC to trigger a targeted immune response [39]. However, clinical response rates remain modest, particularly in melanoma, highlighting the need for further optimization to improve efficacy [40].

The mechanism of action for DC vaccines depends on the ability of DC to process and present tumor antigens. After loading with TAAs, DC mature and migrate to lymph nodes, where they activate CD8+ T cells to recognize and eliminate tumor cells [40]. Strategies like silencing programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) ligands using siRNA-lipid nanoparticles have been shown to enhance the immunogenicity of DC and improve antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses [40]. Additionally, metabolic reprogramming of DC has emerged as a key strategy to enhance vaccine efficacy, with changes in glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) pathways improving DC function and overcoming the immunosuppressive TME [41,42].

In melanoma, innovative strategies such as pulsing DC with iPSC-derived exosomes have shown promise in enhancing the anti-tumor immune response. This approach increases the diversity of TAAs presented to the immune system, improving the overall efficacy of melanoma immunotherapy [43]. Combining DC vaccines with ICIs like PD-1 inhibitors has also demonstrated synergistic effects, addressing the challenges posed by the immunosuppressive TME and supporting long-term anti-tumor immunity [44].

In conclusion, while DC vaccines hold significant potential for melanoma treatment, challenges such as modest clinical response rates and the need to overcome the immunosuppressive TME remain. Ongoing research focusing on genetic modulation, metabolic reprogramming, and advanced delivery systems is essential for improving DC vaccines efficacy and clinical outcomes [39,41].

Tumor cell vaccines (TCV) are a promising cancer immunotherapy approach, utilizing whole tumor cells to elicit a broad and robust immune response [45]. These vaccines present a wide array of TAAs, stimulating both innate and adaptive immunity. By activating APCs like DC, TCV also engage T cells to target and destroy cancer cells. Compared to single-antigen vaccines, TCV offer greater specificity and stronger immune responses, making them valuable for treating various cancers, including melanoma [46].

TCV work by using whole tumor cells, either in their native form or genetically modified for improved immunogenicity. These tumor cells are processed by APCs, which present the antigens to T cells, initiating an immune response. For instance, incorporating immunostimulatory molecules like CpG oligodeoxynucleotides into tumor cells can enhance their ability to activate T cells and promote tumor-specific immunity [47]. In melanoma, modified B16-F10 cells expressing toll-like receptors (TLRs) and TLR7 agonists have shown promising results by inhibiting tumor growth and prolonging survival in animal models [22]. Additionally, adding molecules like VEGF164 to tumor vaccines can enhance immune responses by promoting macrophage infiltration and cancer cell death [48].

Several TCV strategies have shown potential in melanoma, including whole TCV modified with genetic alterations or irradiated to preserve antigenic properties. For example, irradiated melanoma cells combined with IL-12 have demonstrated enhanced antitumor immunity [45]. Another approach involves combining TCV with photothermal therapy and nanoparticle-loaded tumor cells, boosting immune responses at the vaccination site in melanoma models [49]. Additionally, bacteria-based autologous cancer vaccines have improved therapeutic efficacy by inducing immunogenic cell death and enhancing antigen presentation [50].

In conclusion, TCV represent a versatile and potent strategy for cancer immunotherapy, particularly in melanoma. By utilizing whole tumor cells, TCV present a comprehensive array of antigens, triggering strong and specific immune responses. Ongoing development of genetic modifications, immunostimulatory molecules, and advanced delivery techniques holds great promise for improving the clinical efficacy of TCV [49,51].

Neoantigen vaccines are a highly promising approach in cancer immunotherapy, leveraging tumor-specific mutations unique to each patient’s cancer. These neoantigens arise from non-synonymous mutations in tumor DNA, producing novel protein sequences absent in normal tissues, making them ideal targets for personalized cancer vaccines [15]. Advances in high-throughput sequencing and bioinformatics tools have significantly accelerated the identification of these neoantigens, allowing for vaccines tailored to the individual mutational landscape of a patient’s tumor [52].

The creation of a personalized neoantigen vaccine involves several key steps [15]. Tumor and normal tissue samples are sequenced to identify somatic mutations, and bioinformatics algorithms predict which mutations will produce peptides that can be presented on MHC molecules and recognized by T cells [53]. These predicted neoantigens are synthesized and incorporated into vaccine formulations, including synthetic long peptides (SLPs), RNA, or DC. Preclinical and early clinical studies have demonstrated that neoantigen vaccines can induce strong tumor-specific T cell responses and show preliminary evidence of antitumor activity, especially in melanoma and other cancers [23].

A key advantage of neoantigen vaccines is their high specificity, as the targeted antigens are exclusive to tumor cells, reducing the risk of autoimmunity, a concern with other cancer vaccines [54]. However, challenges remain, particularly in efficiently and safely delivering the vaccine components to elicit potent, durable immune responses [52]. Recent advances focus on improving vaccine delivery strategies, such as LNPs or viral vectors, to enhance the immunogenicity of neoantigens [52]. Despite these advancements, further research is needed to address tumor heterogeneity and the immunosuppressive TME, which can limit the effectiveness of neoantigen-based therapies [55].

In melanoma, neoantigen vaccines have shown significant promise. Clinical trials have demonstrated that these vaccines can induce strong T cell responses and improve survival rates in patients [56]. Personalized neoantigen vaccines, utilizing mRNA and dendritic cell-based platforms, are being tested to target melanoma-specific neoantigens, with promising early results [15,57,58]. Although the clinical application is still evolving, neoantigen vaccines are expected to play a critical role in transforming the treatment landscape for melanoma and other cancers [59].

In conclusion, neoantigen vaccines represent a cutting-edge, personalized approach to cancer immunotherapy, with the potential to greatly improve the precision and efficacy of cancer treatments. Ongoing research and clinical trials are refining these vaccines to enhance their efficacy and expand their application across various cancer types [60,61].

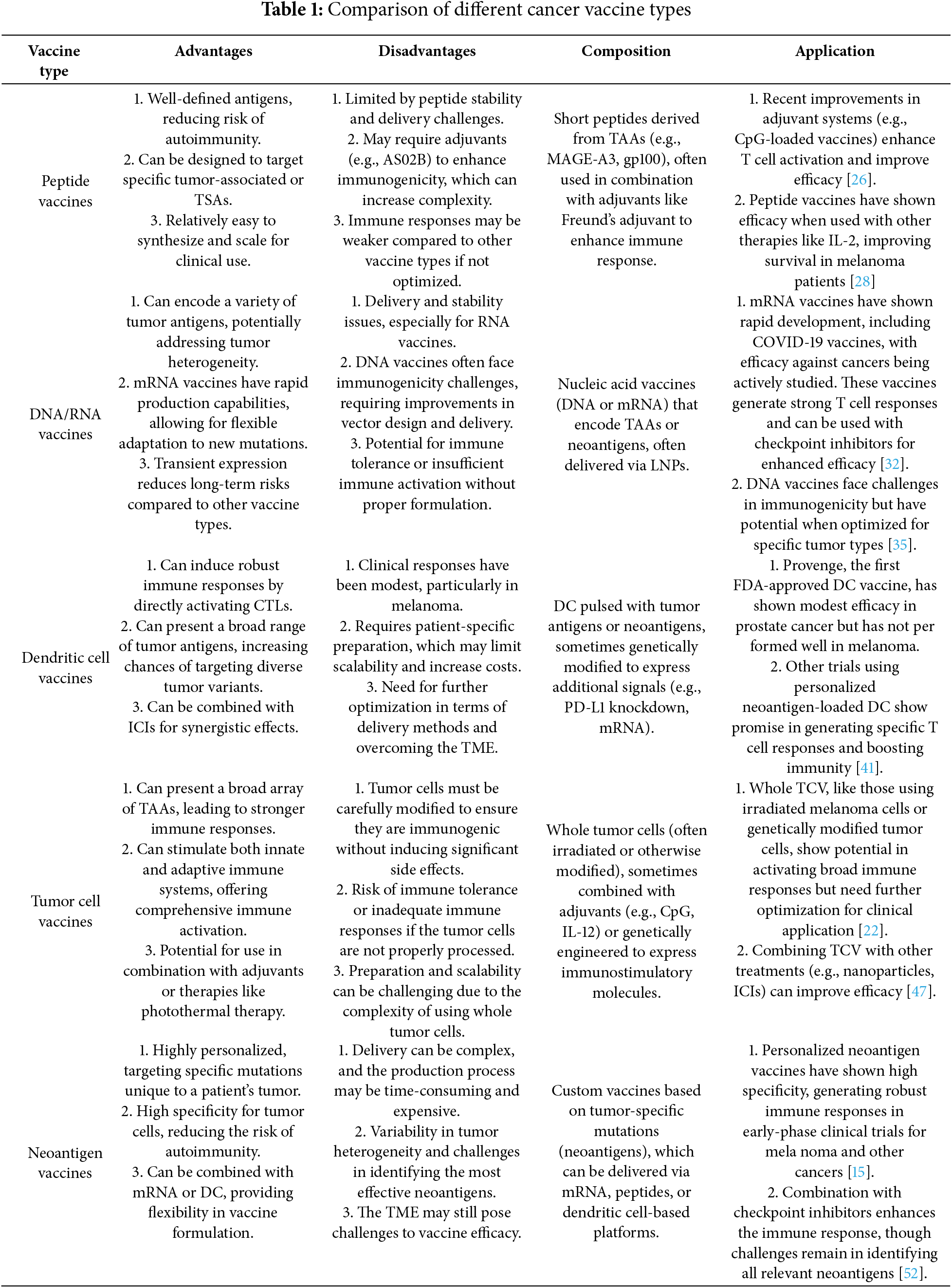

As summarized in Table 1, each type of cancer vaccine is characterized by its unique composition, advantages, and disadvantages, which collectively influence its effectiveness and clinical application in melanoma treatment.

The exploration of various vaccine types in the treatment of melanoma has led to significant advancements in immunotherapy, particularly in targeting the unique challenges presented by this aggressive form of cancer. Vaccine-based therapies are designed to elicit and amplify the body’s immune response against melanoma cells, aiming to improve patient outcomes by enhancing tumor-specific immunity. The following sections provide an overview of the different vaccine types tested in clinical trials, including their mechanisms of action, clinical trial results, and potential impact on melanoma treatment.

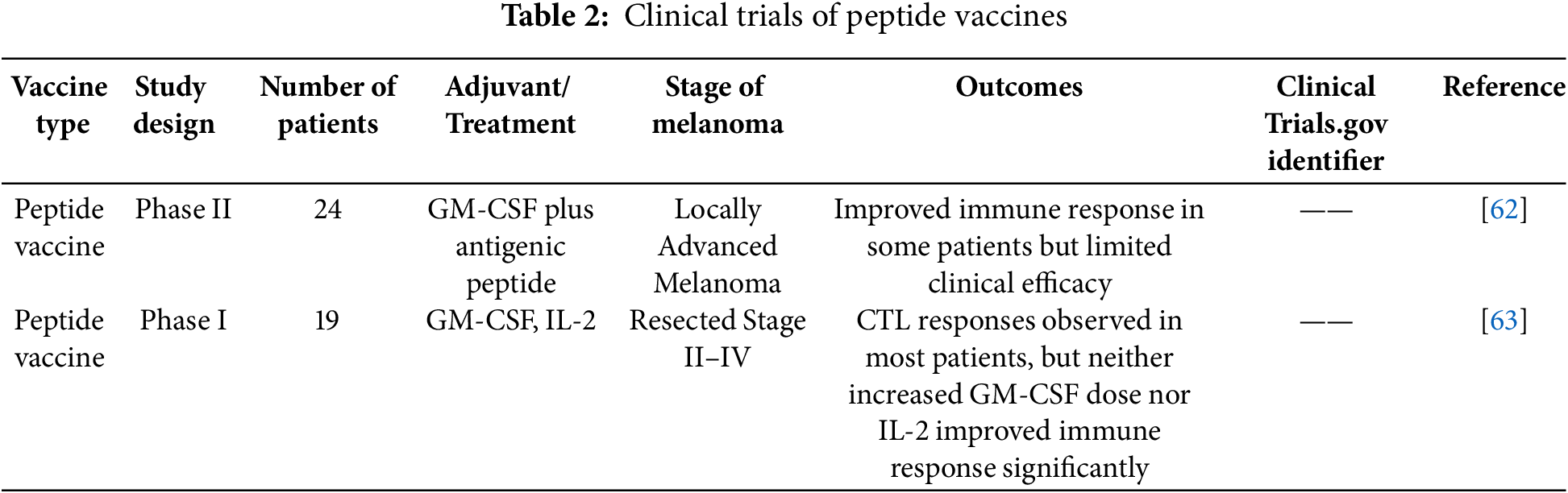

Peptide vaccines for melanoma have been studied in several clinical trials, with varying degrees of success. These studies typically combine specific peptides with immune modulators to evaluate their therapeutic potential.

In one such trial, 24 patients with relapsed, high-risk melanoma were administered a peptide vaccine composed of melanosomal antigens such as Melan-A/MART-1, MAGE-1, gp100, and tyrosinase, along with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). The results revealed that 20 patients showed local delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reactions, indicating a strong immune response. Seven patients were able to remain relapse-free for extended periods, although 17 patients did experience disease progression, with metastases occurring in 13 during the vaccination process. Despite the challenges, the study confirmed the safety and possible clinical advantages of peptide vaccines in treating high-risk melanoma patients who have relapsed [62].

In another study, researchers tested a combination of peptide vaccines, GM-CSF, and low-dose IL-2 in patients with melanoma at stages II, III, or IV who had undergone resection. The peptides used were MART-1a, gp100(207–217), and survivin. While the combination stimulated immune responses, it was found that adding IL-2 did not improve the results. Furthermore, IL-2 administration increased the levels of T regulatory cells (Tregs), which are known to suppress immune activity, thus potentially reducing the effectiveness of the vaccine [63].

A comprehensive review of multiple clinical trials examining peptide vaccines for melanoma demonstrated that the addition of IL-2 to peptide vaccines could enhance disease control in patients, as compared to IL-2 alone. Moreover, patients who exhibited a tumor-specific immune response showed improved survival rates. However, the review emphasized that further studies are necessary to conclusively determine whether peptide vaccines offer greater clinical benefits than other treatment modalities [64].

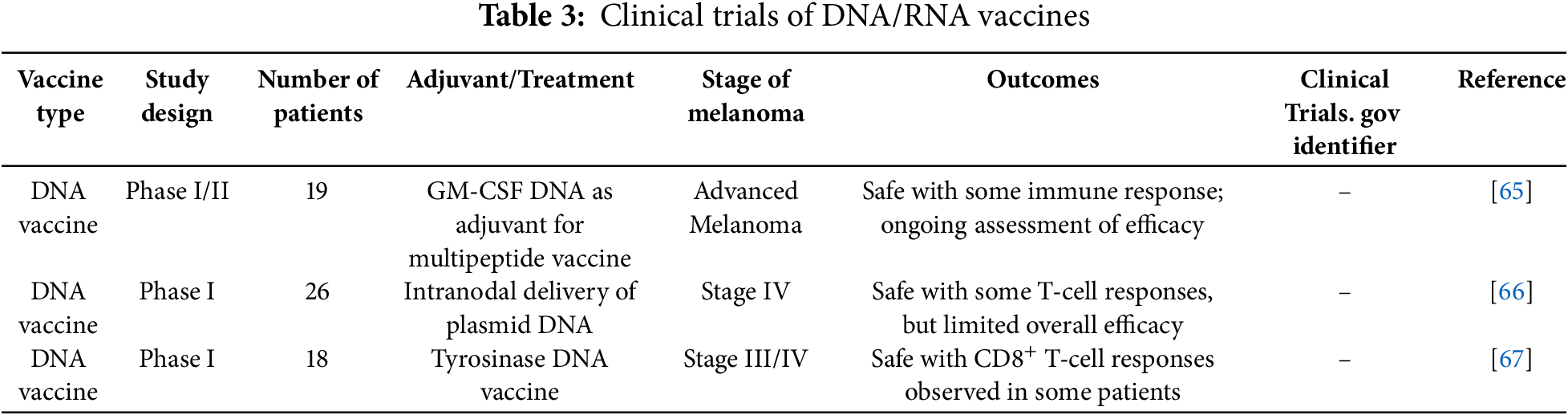

Recent clinical trials evaluating DNA and RNA vaccines for melanoma have shown promising results, demonstrating their potential to provoke strong immune responses in patients.

In one Phase I/II study, a GM-CSF DNA vaccine was used as an adjuvant in a multi-peptide cancer vaccine for patients with advanced melanoma. The trial included 19 patients and focused on assessing the safety and immune-stimulating effects of the vaccine. The findings indicated that the vaccine was generally well tolerated, with only mild injection-site reactions being reported. Notably, 42% of the patients developed CD8+ T-cell responses, suggesting that the vaccine was effective in enhancing anti-tumor immunity [65].

Another study explored the use of a DNA vaccine encoding tyrosinase epitopes delivered intranodally in Stage IV melanoma patients. The vaccine was injected directly into a groin lymph node, targeting local APCs. The treatment showed minimal toxicity, and immune responses to tyrosinase were detected in 11 out of 26 patients. Despite the lack of clinical responses, the survival rate was surprisingly high, with 16 of the 26 patients alive after a median follow-up of 12 months [66].

RNA vaccines have also demonstrated significant potential. One study involving an mRNA vaccine encoding TAAs induced both humoral and cellular immune responses. The use of LNPs as a delivery system was shown to improve the stability and effectiveness of the mRNA vaccine, reinforcing the versatility of RNA-based platforms for cancer immunotherapy [67]. These promising results underline the growing interest and ongoing development of DNA and RNA vaccines as effective melanoma treatments.

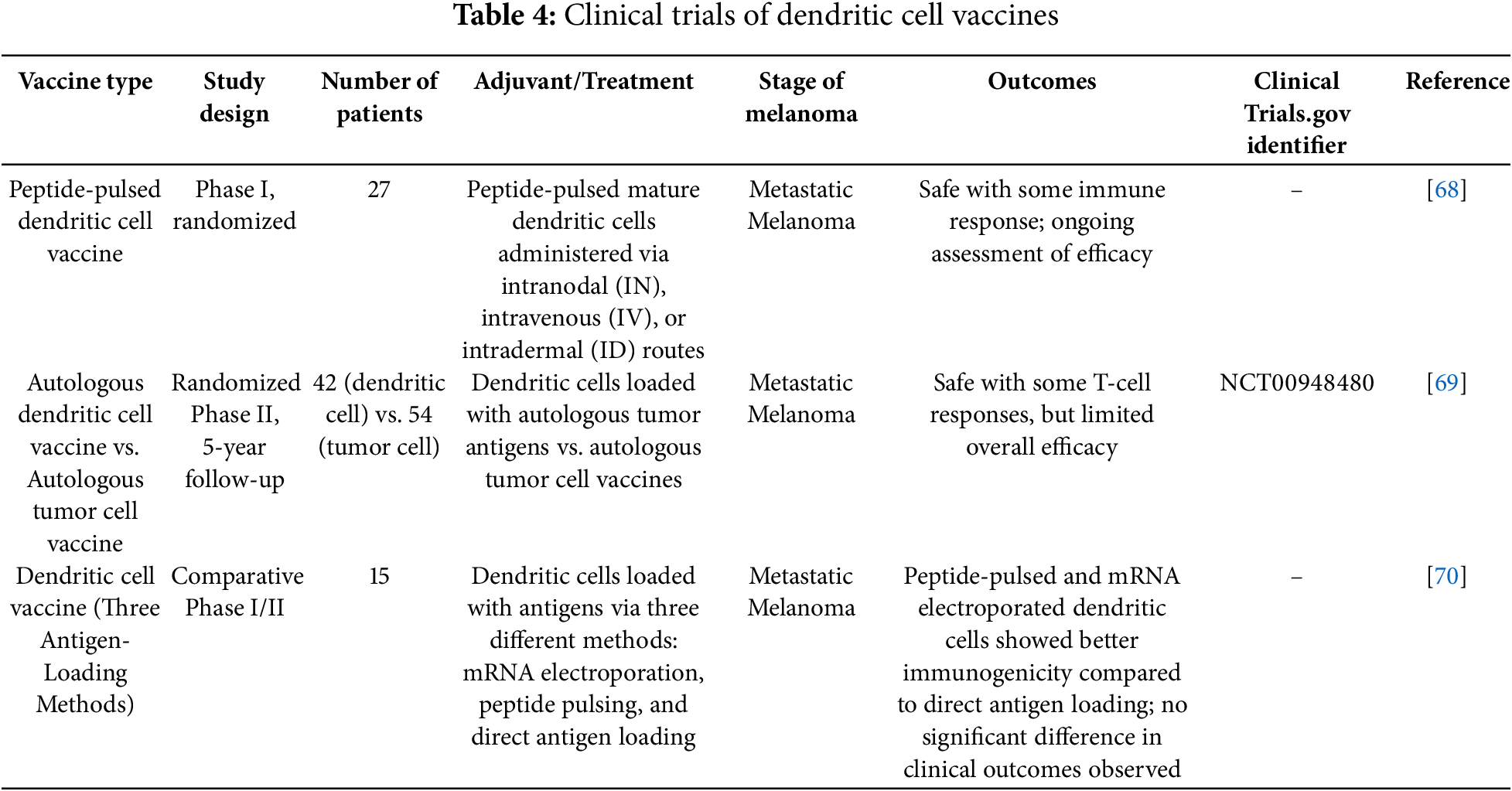

Clinical trials have shown that DC vaccines have the potential to induce strong immune responses and improve clinical outcomes in melanoma treatment.

In a study by Bedrosian, the feasibility, safety, and immunogenicity of peptide-pulsed mature DC vaccines were evaluated in 27 patients with metastatic melanoma. The study found that intranodal (IN) injection significantly enhanced CD8+ T-cell responses and DTH reactions compared to intravenous (IV) and intradermal (ID) injections. Therefore, IN injection was recommended as the preferred route for DC vaccine administration [68].

A randomized phase II clinical trial by Dillman compared autologous DC vaccines with autologous TCV in 42 patients with metastatic melanoma. The results showed that the median survival of patients receiving DC vaccines was 43.4 months, compared to 20.5 months for those receiving TCV. DC vaccines significantly prolonged patient survival with relatively mild side effects [69].

In addition, a phase II trial by Geskin investigated three different antigen-loading methods in DC vaccines for 15 patients with metastatic melanoma. Although the effectiveness of DC vaccines alone was limited, the study suggested that combining DC vaccines with other immunotherapies, such as checkpoint inhibitors, might enhance their therapeutic potential [70].

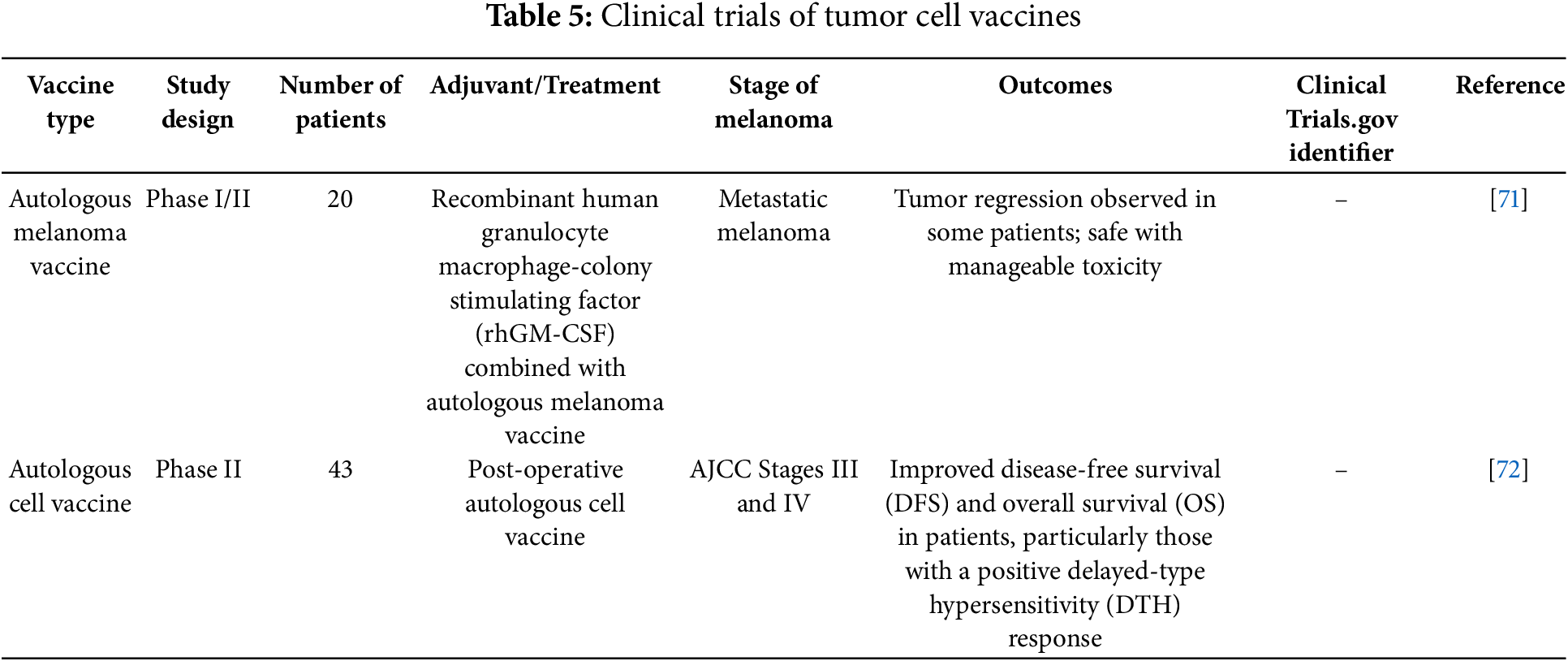

TCV, which use whole tumor cells to stimulate an immune response, have demonstrated varying success levels in clinical trials.

In a randomized phase II trial by Dillman, autologous TCV were compared with dendritic cell vaccines (DCV) in metastatic melanoma patients. The study showed that DCV was associated with significantly longer survival, with a median survival of 43.4 months compared to 20.5 months for TCV. The results suggested that DCV might offer superior clinical outcomes due to its more efficient presentation of TAAs [69].

Leong’s study evaluated the combination of recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (rhGM-CSF) with autologous melanoma vaccines in stage IV melanoma patients. In this trial of 20 patients, 10% achieved a complete response, and another 10% had partial responses. The addition of rhGM-CSF appeared to enhance the immune response, leading to tumor regression in some patients, suggesting its potential as an adjuvant in TCV [71].

In a study by Lotem, the use of an autologous melanoma cell vaccine as adjuvant therapy was explored in high-risk melanoma patients. The trial included 43 patients, and the results showed that patients who developed a strong DTH response to the vaccine had significantly better disease-free and overall survival (OS) rates. These findings suggest that the intensity of the immune response correlates with improved clinical outcomes, supporting the use of TCV in adjuvant melanoma therapy [72].

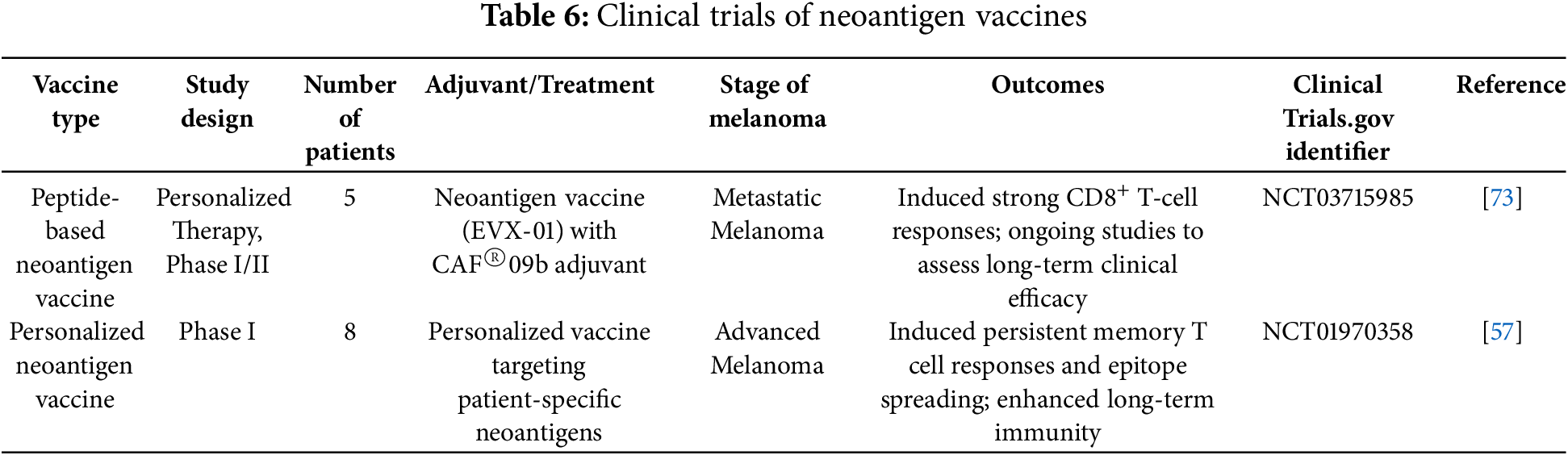

Neoantigen vaccines have shown significant promise in melanoma treatment by targeting tumor-specific mutations unique to each patient. Personalized neoantigen vaccines, developed through advances in sequencing and bioinformatics, have demonstrated strong tumor-specific immunogenicity and preliminary antitumor activity.

A notable clinical trial tested the personalized peptide-based neoantigen vaccine EVX-01, combined with the novel CAF®09b adjuvant, in patients with metastatic melanoma. This study showed that the vaccine induced long-lasting T-cell responses specific to neoantigens, with all patients demonstrating immune responses. Importantly, the vaccine was well-tolerated with no severe adverse events, supporting its safety and promising efficacy in melanoma treatment [73].

Additionally, a significant study by Hu investigated the long-term effects of the NeoVax vaccine, which targets multiple personalized neoantigens. The results revealed persistent neoantigen-specific T-cell responses and epitope spreading, suggesting durable immune memory and effective tumor cell killing. Six out of eight patients remained disease-free at a median follow-up of nearly four years, underscoring the vaccine’s potential for long-term cancer control [57].

Combination therapies in melanoma have gained significant attention due to their potential to enhance immune responses and improve patient outcomes. Tumor vaccines, when combined with ICIs, have demonstrated synergistic effects that bolster the body’s ability to combat cancer. One study emphasized the potential of combining vaccines and oncolytic viral therapies with ICIs, noting that such combinations can convert ‘cold’ tumors into ‘hot’ tumors, enhancing their vulnerability to immune attacks and improving survival rates in metastatic melanoma [74].

Other research has examined the pairing of vaccines with ICIs, such as sipuleucel-T and talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), which have shown promise in eliciting robust antitumor responses. These vaccines help prime the immune system, expand immune responses, and enhance immune function within the TME [75]. Moreover, the combination of BRAF inhibitors and MEK inhibitors with ICIs for BRAF-mutant melanomas has proven effective. Anti-PD-1 agents, like nivolumab and pembrolizumab, are central to these combination strategies, offering high efficacy and low toxicity [76].

In another study, a novel injectable polypeptide hydrogel was developed to co-deliver a tumor vaccine alongside dual ICIs. This method not only increased the number of activated effector CD8+ T cells but also reduced the ratio of Tregs, thereby strengthening overall antitumor immunity [77].

Recent advancements in melanoma treatment, particularly in neoadjuvant therapy, are crucial for melanoma vaccine development. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy with nivolumab and ipilimumab has shown significant promise, improving event-free survival compared to adjuvant therapy. For example, a study by Georgina Long et al. demonstrated that neoadjuvant therapy for resectable stage III melanoma resulted in an estimated 12-month event-free survival of 83.7%, compared to 57.2% with adjuvant therapy. Additionally, 59% of patients had a major pathological response, emphasizing the potential of neoadjuvant approaches to improve outcomes [78].

Integrating melanoma vaccines with neoadjuvant immunotherapies could further enhance immune responses prior to surgery, increasing tumor vulnerability to immune attacks. This combination could significantly improve treatment efficacy, survival rates, and reduce recurrence in high-risk melanoma patients.

Tables 2–6 summarizes the clinical trials of various vaccines against melanoma, highlighting the vaccine types, study designs, patient cohorts, adjuvants used, stages of melanoma targeted, and the observed outcomes. This table serves as a comprehensive reference to understand the effectiveness and safety profiles of these vaccines, supporting the ongoing development and optimization of melanoma immunotherapy strategies.

Future cancer vaccine research should focus on enhancing tumor antigen immunogenicity, particularly in melanoma. Combining vaccines with ICIs, such as anti-PD-1/PD-L1(Programmed death-ligand 1) and anti-CTLA-4, can counteract immune evasion and boost T cell responses in melanoma patients [79,80]. Targeting the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) pathway in the TME holds promise for reducing immunosuppression and improving vaccine effectiveness in melanoma [81].

Advances in personalized melanoma vaccines, particularly neoantigen-based approaches, are key to addressing tumor heterogeneity in melanoma. Enhanced sequencing and bioinformatics can speed up antigen identification, lowering the cost and time required for personalized vaccine development [82]. Multi-antigen strategies, such as targeting multiple melanoma-specific antigens, also show potential in ensuring broader, longer-lasting immune responses [83].

For vaccine delivery, optimizing nanotechnology-based systems like LNPs and hydrogels is critical for stability and scalability in melanoma vaccines [84]. Innovations such as self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) and circRNA vaccines can improve antigen expression and immune activation, while minimizing safety concerns [85]. Combining these platforms with ICIs or other adjuvants could enhance therapeutic outcomes in melanoma patients [86].

Genetically modified vaccines, which enhance antigen presentation or include immune-boosting components, have significant potential in melanoma treatment [82]. Research into modulating the TME, overcoming immunosuppressive factors like Tregs and MDSCs, and enhancing effector T cell recruitment is crucial for further improvement [87].

Collaboration between researchers, clinicians, and regulatory bodies will be essential for translating these advances into clinical practice, making melanoma vaccines safer, more effective, and accessible [88].

In conclusion, tumor vaccines hold immense potential as a therapeutic strategy for melanoma, leveraging the body’s immune system to target and destroy cancer cells. The advances in personalized medicine, particularly with neoantigen vaccines, offer a promising avenue for individualized treatment plans that could improve patient outcomes. However, despite these advancements, several challenges and limitations must be addressed to optimize the efficacy of tumor vaccines.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wenfei Luo, Dingming Song; material and data preparation: Yibo He, Dingming Song; draft manuscript preparation: Wenfei Luo; review and editing: Wenfei Luo, Yunzhen Ding, Judong Song; supervision: Yunzhen Ding, Judong Song. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| APCs | Antigen-presenting cells |

| AS02B | Adjuvant System 02B |

| BRAF | B-Raf proto-oncogene |

| CAR-T | Chimeric antigen receptor T cells |

| circRNA | Circular RNA |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 |

| CTLs | Cytotoxic T lymphocytes |

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| DCV | Dendritic cell vaccines |

| DFS | Disease-free survival |

| DTH | Delayed-type hypersensitivity |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| gp100 | Glycoprotein 100 |

| HLA | Human leukocyte antigen |

| ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| ID | Intradermal |

| IL-2 | Interleukin-2 |

| IL-12 | Interleukin-12 |

| IN | Intranodal |

| iPSC | Induced pluripotent stem cell |

| IV | Intravenous |

| LNPs | Lipid nanoparticles |

| MAGE-A3 | Melanoma-associated antigen 3 |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MEK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| MPL | Monophosphoryl lipid A |

| NeoVax | Personalized neoantigen vaccine |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| OS | Overall survival |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| QS-21 | Quillaja saponaria fraction 21 |

| rhGM-CSF | Recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| saRNA | Self-amplifying RNA |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| SLPs | Synthetic long peptides |

| TAA | Tumor-associated antigen |

| TCV | Tumor cell vaccines |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| Tregs | Regulatory T cells |

| TSA | Tumor-specific antigen |

| T-VEC | Talimogene laherparepvec |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

1. Long GV, Swetter SM, Menzies AM, Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA. Cutaneous melanoma. Lancet. 2023;402(10400):485–502. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00821-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Waseh S, Lee JB. Advances in melanoma: epidemiology, diagnosis, and prognosis. Front Med. 2023;10:1268479. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1268479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Chen XY, Li YD, Xie Y, Cao LQ, Ashby CRJ, Zhao H, et al. Nivolumab and relatlimab for the treatment of melanoma. Drugs Today. 2023;59(2):91–104. doi:10.1358/dot.2023.59.2.3509756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Ahmed B, Qadir MI, Ghafoor S. Malignant melanoma: skin cancer-diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2020;30(4):291–7. doi:10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.2020028454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Sabit H, Kaliyadan F, Menezes RG. Malignant melanoma: underlying epigenetic mechanisms. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86(5):475–81. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_791_19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Saxena M, van der Burg SH, Melief CJM, Bhardwaj N. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21(6):360–78. doi:10.1038/s41568-021-00346-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Igarashi Y, Sasada T. Cancer vaccines: toward the next breakthrough in cancer immunotherapy. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020(2):5825401. doi:10.1155/2020/5825401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Bender C, Hassel JC, Enk A. Immunotherapy of melanoma. Oncol Res Treat. 2016;39(6):369–76. doi:10.1159/000446716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Abbott M, Ustoyev Y. Cancer and the immune system: the history and background of immunotherapy. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2019;35(5):150923. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2019.08.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Snyder A, Zamarin D, Wolchok JD. Immunotherapy of melanoma. Prog Tumor Res. 2015;42:22–9. doi:10.1159/000436998. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Kaczmarek M, Poznańska J, Fechner F, Michalska N, Paszkowska S, Napierała A, et al. Cancer vaccine therapeutics: limitations and effectiveness—a literature review. Cells. 2023;12(17):2159. doi:10.3390/cells12172159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Leonardi GC, Candido S, Falzone L, Spandidos DA, Libra M. Cutaneous melanoma and the immunotherapy revolution (review). Int J Oncol. 2020;57(3):609–18. doi:10.3892/ijo.2020.5088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Dobosz P, Dzieciątkowski T. The intriguing history of cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2965. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02965. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Leonardi GC, Falzone L, Salemi R, Zanghì A, Spandidos DA, Mccubrey JA, et al. Cutaneous melanoma: from pathogenesis to therapy (review). Int J Oncol. 2018;52(4):1071–80. doi:10.3892/ijo.2018.4287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Blass E, Ott PA. Advances in the development of personalized neoantigen-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(4):215–29. doi:10.1038/s41571-020-00460-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Li Y, Ma X, Yue Y, Zhang K, Cheng K, Feng Q, et al. Rapid surface display of mRNA antigens by bacteria-derived outer membrane vesicles for a personalized tumor vaccine. Adv Mater. 2022;34(20):e2109984. doi:10.1002/adma.202109984. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Lorentzen CL, Haanen JB, Met Ö, Svane IM. Clinical advances and ongoing trials on mRNA vaccines for cancer treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(10):e450–8. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00372-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Kalariya M, Ganta S, Amiji M. Multi-compartmental vaccine delivery system for enhanced immune response to gp100 peptide antigen in melanoma immunotherapy. Pharm Res. 2012;29(12):3393–403. doi:10.1007/s11095-012-0834-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Cui Z. DNA vaccine. Adv Genet. 2005;54(Pt. 6):257–89. doi:10.1016/S0065-2660(05)54011-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Al Fayez N, Nassar MS, Alshehri AA, Alnefaie MK, Almughem FA, Alshehri BY, et al. Recent advancement in mRNA vaccine development and applications. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(7):1972. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics15071972. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Lee KW, Yam JWP, Mao X. Dendritic cell vaccines: a shift from conventional approach to new generations. Cells. 2023;12(17):2147. doi:10.3390/cells12172147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Chi H, Hao Y, Wang X, Tang L, Deng Y, Chen X, et al. A therapeutic whole-tumor-cell vaccine covalently conjugated with a TLR7 agonist. Cells. 2022;11(13):1986. doi:10.3390/cells11131986. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Peng M, Mo Y, Wang Y, Wu P, Zhang Y, Xiong F, et al. Neoantigen vaccine: an emerging tumor immunotherapy. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):128. doi:10.1186/s12943-019-1055-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Maurer DM, Butterfield LH, Vujanovic L. Melanoma vaccines: clinical status and immune endpoints. Melanoma Res. 2019;29(2):109–18. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Liu W, Tang H, Li L, Wang X, Yu Z, Li J. Peptide-based therapeutic cancer vaccine: current trends in clinical application. Cell Prolif. 2021;54(5):e13025. doi:10.1111/cpr.13025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Batchu RB, Gruzdyn O, Potti RB, Weaver DW, Gruber SA. MAGE-A3 with cell-penetrating domain as an efficient therapeutic cancer vaccine. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(5):451–7. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Li WH, Su JY, Li YM. Rational design of T-cell- and B-cell-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Acc Chem Res. 2022;55(18):2660–71. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Atanackovic D, Altorki NK, Cao Y, Ritter E, Ferrara CA, Ritter G, et al. Booster vaccination of cancer patients with MAGE-A3 protein reveals long-term immunological memory or tolerance depending on priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(5):1650–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707140104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Esfandiary A, Ghafouri-Fard S. MAGE-A3: an immunogenic target used in clinical practice. Immunotherapy. 2015;7(6):683–704. doi:10.2217/imt.15.29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Schwartzentruber DJ, Lawson DH, Richards JM, Conry RM, Miller DM, Treisman J, et al. gp100 peptide vaccine and interleukin-2 in patients with advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(22):2119–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1012863. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–23. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Schlake T, Thess A, Fotin-Mleczek M, Kallen KJ. Developing mRNA-vaccine technologies. RNA Biol. 2012;9(11):1319–30. doi:10.4161/rna.22269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Chen Z, Meng C, Mai J, Liu Y, Li H, Shen H. An mRNA vaccine elicits STING-dependent antitumor immune responses. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13(3):1274–86. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2022.11.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Schmidt C, Schnierle BS. Self-amplifying RNA vaccine candidates: alternative platforms for mRNA vaccine development. Pathogens. 2023;12(1):138. doi:10.3390/pathogens12010138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Zhou W, Jiang L, Liao S, Wu F, Yang G, Hou L, et al. Vaccines’ new era-RNA vaccine. Viruses. 2023;15(8):1760. doi:10.3390/v15081760. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Li H, Peng K, Yang K, Ma W, Qi S, Yu X, et al. Circular RNA cancer vaccines drive immunity in hard-to-treat malignancies. Theranostics. 2022;12(14):6422–36. doi:10.7150/thno.77350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Mbatha LS, Akinyelu J, Maiyo F, Kudanga T. Future prospects in mRNA vaccine development. Biomed Mater. 2023;18(5):510. doi:10.1088/1748-605X/aceceb. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Niu D, Wu Y, Lian J. Circular RNA vaccine in disease prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):341. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01561-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Elwakeel A, Bridgewater HE, Bennett J. Unlocking dendritic cell-based vaccine efficacy through genetic modulation-how soon is now? Genes. 2023;14(12):2118. doi:10.3390/genes14122118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Hobo W, Novobrantseva TI, Fredrix H, Wong J, Milstein S, Epstein-Barash H, et al. Improving dendritic cell vaccine immunogenicity by silencing PD-1 ligands using siRNA-lipid nanoparticles combined with antigen mRNA electroporation. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(2):285–97. doi:10.1007/s00262-012-1334-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Adamik J, Munson PV, Maurer DM, Hartmann FJ, Bendall SC, Argüello RJ, et al. Immuno-metabolic dendritic cell vaccine signatures associate with overall survival in vaccinated melanoma patients. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):7211. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-42881-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Farhood B, Najafi M, Mortezaee K. CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: a review. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(6):8509–21. doi:10.1002/jcp.27782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Wang R, Zhu T, Hou B, Huang X. An iPSC-derived exosome-pulsed dendritic cell vaccine boosts antitumor immunity in melanoma. Mol Ther. 2023;31(8):2376–90. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.06.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Xue L, Zhang H, Zheng X, Sun W, Lei J. Treatment of melanoma with dendritic cell vaccines and immune checkpoint inhibitors: a mathematical modeling study. J Theor Biol. 2023;568(19):111489. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2023.111489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Sheikhi A, Jafarzadeh A, Kokhaei P, Hojjat-Farsangi M. Whole tumor cell vaccine adjuvants: comparing IL-12 to IL-2 and IL-15. Iran J Immunol. 2016;13(3):148–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

46. Yannelli JR, Wroblewski JM. On the road to a tumor cell vaccine: 20 years of cellular immunotherapy. Vaccine. 2004;23(1):97–113. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.12.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Goldstein MJ, Varghese B, Brody JD, Rajapaksa R, Kohrt H, Czerwinski DK, et al. A CpG-loaded tumor cell vaccine induces antitumor CD4+ T cells that are effective in adoptive therapy for large and established tumors. Blood. 2011;117(1):118–27. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-06-288456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Kan B, Yang L, Wen YJ, Yang JR, Niu T, Li J, et al. Irradiated VEGF164-modified tumor cell vaccine protected mice from the parental tumor challenge. Anticancer Drugs. 2017;28(2):197–205. doi:10.1097/CAD.0000000000000447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Meng J, Lv Y, Bao W, Meng Z, Wang S, Wu Y, et al. Generation of whole tumor cell vaccine for on-demand manipulation of immune responses against cancer under near-infrared laser irradiation. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):4505. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-40207-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Guo L, Ding J, Zhou W. Converting bacteria into autologous tumor vaccine via surface biomineralization of calcium carbonate for enhanced immunotherapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13(12):5074–90. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2023.08.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Zhao L, Mei Y, Sun Q, Guo L, Wu Y, Yu X, et al. Autologous tumor vaccine modified with recombinant new castle disease virus expressing IL-7 promotes antitumor immune response. J Immunol. 2014;193(2):735–45. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1400004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Guo Y, Lei K, Tang L. Neoantigen vaccine delivery for personalized anticancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1499. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01499. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Ho SY, Chang CM, Liao HN, Chou WH, Guo CL, Yen Y, et al. Current trends in neoantigen-based cancer vaccines. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16(3):392. doi:10.3390/ph16030392. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Zhang Z, Lu M, Qin Y, Gao W, Tao L, Su W, et al. Neoantigen: a new breakthrough in tumor immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2021;12:672356. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.672356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Minati R, Perreault C, Thibault P. A roadmap toward the definition of actionable tumor-specific antigens. Front Immunol. 2020;11:583287. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.583287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Palmer CD, Rappaport AR, Davis MJ, Hart MG, Scallan CD, Hong SJ, et al. Individualized, heterologous chimpanzee adenovirus and self-amplifying mRNA neoantigen vaccine for advanced metastatic solid tumors: phase 1 trial interim results. Nat Med. 2022;28(8):1619–29. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01937-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Hu Z, Leet DE, Allesøe RL, Oliveira G, Li S, Luoma AM, et al. Personal neoantigen vaccines induce persistent memory T cell responses and epitope spreading in patients with melanoma. Nat Med. 2021;27(3):515–25. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-01206-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. D’Alise AM, Leoni G, Cotugno G, Siani L, Vitale R, Ruzza V, et al. Phase I trial of viral vector-based personalized vaccination elicits robust neoantigen-specific antitumor T-cell responses. Clin Cancer Res. 2024;30(11):2412–23. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-23-3940. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Pavelić K. Personalized neoantigen vaccine against cancer. Psychiatr Danub. 2021;33(Suppl 3):S331–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

60. Supabphol S, Li L, Goedegebuure SP, Gillanders WE. Neoantigen vaccine platforms in clinical development: understanding the future of personalized immunotherapy. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2021;30(5):529–41. doi:10.1080/13543784.2021.1896702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Shen Y, Yu L, Xu X, Yu S, Yu Z. Neoantigen vaccine and neoantigen-specific cell adoptive transfer therapy in solid tumors: challenges and future directions. Cancer Innov. 2022;1(2):168–82. doi:10.1002/cai2.26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Atzpodien J, Reitz M. GM-CSF plus antigenic peptide vaccination in locally advanced melanoma patients. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2007;22(4):551–5. doi:10.1089/cbr.2007.376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Block MS, Suman VJ, Nevala WK, Kottschade LA, Creagan ET, Kaur JS, et al. Pilot study of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-2 as immune adjuvants for a melanoma peptide vaccine. Melanoma Res. 2011;21(5):438–45. doi:10.1097/CMR.0b013e32834640c0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Chi M, Dudek AZ. Vaccine therapy for metastatic melanoma: systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Melanoma Res. 2011;21(3):165–74. doi:10.1097/CMR.0b013e328346554d. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Perales MA, Yuan J, Powel S, Gallardo HF, Rasalan TS, Gonzalez C, et al. Phase I/II study of GM-CSF DNA as an adjuvant for a multipeptide cancer vaccine in patients with advanced melanoma. Mol Ther. 2008;16(12):2022–9. doi:10.1038/mt.2008.196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Tagawa ST, Lee P, Snively J, Boswell W, Ounpraseuth S, Lee S, et al. Phase I study of intranodal delivery of a plasmid DNA vaccine for patients with Stage IV melanoma. Cancer. 2003;98(1):144–54. doi:10.1002/cncr.11462. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Wolchok JD, Yuan J, Houghton AN, Gallardo HF, Rasalan TS, Wang J, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of tyrosinase DNA vaccines in patients with melanoma. Mol Ther. 2007;15(11):2044–50. doi:10.1038/sj.mt.6300290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Bedrosian I, Mick R, Xu S, Nisenbaum H, Faries M, Zhang P, et al. Intranodal administration of peptide-pulsed mature dendritic cell vaccines results in superior CD8+ T-cell function in melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(20):3826–35. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.04.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Dillman RO, Cornforth AN, Nistor GI, McClay EF, Amatruda TT, Depriest C. Randomized phase II trial of autologous dendritic cell vaccines versus autologous tumor cell vaccines in metastatic melanoma: 5-year follow up and additional analyses. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):19. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0330-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Geskin LJ, Damiano JJ, Patrone CC, Butterfield LH, Kirkwood JM, Falo LD. Three antigen-loading methods in dendritic cell vaccines for metastatic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2018;28(3):211–21. doi:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Leong SP, Enders-Zohr P, Zhou YM, Stuntebeck S, Habib FA, Allen REJr, et al. Recombinant human granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (rhGM-CSF) and autologous melanoma vaccine mediate tumor regression in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 1999;22(2):166–74. doi:10.1097/00002371-199903000-00008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Lotem M, Peretz T, Drize O, Gimmon Z, Ad El D, Weitzen R, et al. Autologous cell vaccine as a post operative adjuvant treatment for high-risk melanoma patients (AJCC stages III and IV). The new American Joint Committee on Cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(10):1534–9. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Mørk SK, Kadivar M, Bol KF, Draghi A, Westergaard MCW, Skadborg SK, et al. Personalized therapy with peptide-based neoantigen vaccine (EVX-01) including a novel adjuvant, CAF®09b, in patients with metastatic melanoma. Oncoimmunology. 2022;11(1):2023255. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2021.2023255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Cavalcante L, Chowdhary A, Sosman JA, Chandra S. Combining tumor vaccination and oncolytic viral approaches with checkpoint inhibitors: rationale, pre-clinical experience, and current clinical trials in malignant melanoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19(5):657–70. doi:10.1007/s40257-018-0359-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Collins JM, Redman JM, Gulley JL. Combining vaccines and immune checkpoint inhibitors to prime, expand, and facilitate effective tumor immunotherapy. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17(8):697–705. doi:10.1080/14760584.2018.1506332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Eggermont AMM, Crittenden M, Wargo J. Combination immunotherapy development in melanoma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:197–207. doi:10.1200/EDBK_201131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Song H, Yang P, Huang P, Zhang C, Kong D, Wang W. Injectable polypeptide hydrogel-based co-delivery of vaccine and immune checkpoint inhibitors improves tumor immunotherapy. Theranostics. 2019;9(8):2299–314. doi:10.7150/thno.30577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Long GV, Menzies AM, Scolyer RA. Neoadjuvant checkpoint immunotherapy and melanoma: the time is now. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(17):3236–48. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.02575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Gjerstorff MF, Burns J, Ditzel HJ. Cancer-germline antigen vaccines and epigenetic enhancers: future strategies for cancer treatment. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10(7):1061–75. doi:10.1517/14712598.2010.485188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Guo C, Manjili MH, Subjeck JR, Sarkar D, Fisher PB, Wang XY. Therapeutic cancer vaccines: past, present, and future. Adv Cancer Res. 2013;119(Suppl. 1):421–75. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-407190-2.00007-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Bang J, Zippin JH. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) signaling in melanocyte pigmentation and melanomagenesis. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2021;34(1):28–43. doi:10.1111/pcmr.12920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Hu X, Zhou W, Pi R, Zhao X, Wang W. Genetically modified cancer vaccines: current status and future prospects. Med Res Rev. 2022;42(4):1492–517. doi:10.1002/med.21882. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Kwak M, Leick KM, Melssen MM, Slingluff CL. Vaccine strategy in melanoma. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2019;28(3):337–51. doi:10.1016/j.soc.2019.02.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Tan Y, Chen H, Gou X, Fan Q, Chen J. Tumor vaccines: toward multidimensional anti-tumor therapies. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19(3):2271334. doi:10.1080/21645515.2023.2271334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Li Y, Wang M, Peng X, Yang Y, Chen Q, Liu J, et al. mRNA vaccine in cancer therapy: current advance and future outlook. Clin Transl Med. 2023;13(8):e1384. doi:10.1002/ctm2.1384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Sorieul C, Papi F, Carboni F, Pecetta S, Phogat S, Adamo R. Recent advances and future perspectives on carbohydrate-based cancer vaccines and therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 2022;235(5):108158. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2022.108158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Hirayama M, Nishimura Y. The present status and future prospects of peptide-based cancer vaccines. Int Immunol. 2016;28(7):319–28. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxw027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Zahedipour F, Zamani P, Jamialahmadi K, Jaafari MR, Sahebkar A. Vaccines targeting angiogenesis in melanoma. Eur J Pharmacol. 2021;912(1):174565. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools