Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Intrathecal Pemetrexed Administration and Myelosuppression in Patients with Leptomeningeal Metastases from Lung Adenocarcinoma: A Retrospective Study

1 Department of Oncology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang, 330006, China

2 School of Public Health, Nanchang University, Nanchang, 330006, China

3 Department of Radiotherapy, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Zhejiang Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Hangzhou, 310000, China

4 Radiation Induced Heart Damage Institute of Nanchang University, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Jiangxi Medical College, Nanchang University, Nanchang, 330006, China

5 Department of Nosocomial Infection Control, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang, 330006, China

6 Jiangxi Province Key Laboratory of Immunology and Inflammation, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Jiangxi Medical College, Nanchang University, Nanchang, 330006, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yanqing He. Email: ; Zhimin Zeng. Email:

# These two authors contributed equally to this work

Oncology Research 2025, 33(8), 2107-2121. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.064237

Received 09 February 2025; Accepted 29 April 2025; Issue published 18 July 2025

Abstract

Background: Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) have a very poor prognosis. Intrathecal pemetrexed (IP) has shown moderate efficacy in treating patients with NSCLC-LM. Myelosuppression is the most common adverse effect following IP administration. Despite this trend, the specific risk factors contributing to IP-related myelosuppression remain unclear. Methods: This study conducted a retrospective analysis of lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) patients with LM who received IP treatment at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University from April 2017 to April 2024. Risk factors for myelosuppression were identified through univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. Non-linear relationships and determined the inflection points were subsequently determined using smooth curve fitting and threshold effect analysis Results: A total of 95 patients were identified, among whom 64 (68.42%) experienced myelosuppression, with 43 (45.26%) cases classified as severe myelosuppression. Leukopenia emerged as the most prevalent form of myelosuppression. Age was established as an independent risk factor for both myelosuppression and its severe form. A nonlinear relationship between age and severe myelosuppression was observed. The risk of developing severe myelosuppression increased significantly with age, beyond the turning point of 58 years old (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.08–1.52; p = 0.0042) Conclusions: Advanced age is associated with the occurrence of myelosuppression and severe myelosuppression. The probability of developing severe myelosuppression increases significantly in individuals aged 58 years or olderKeywords

Leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) is a severe complication of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), characterized by the dissemination of tumor cells to the leptomeninges, including the pia mater, arachnoid membrane, subarachnoid space, and other cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) compartments [1,2]. LM occurs in approximately 3%–5% of patients with NSCLC, and its incidence has been increasing in recent years because of the extended survival period of cancer patients [3,4]. Otherwise, LM typically demonstrates poor response to conventional chemotherapy (CT) and radiotherapy, with a median overall survival (OS) of only 1 to 3 months [3]. However, for lung cancer patients with driver gene-positive LM who receive targeted therapy, the median OS extends to 3 to 11 months [3,5–7].

Previous studies have indicated a higher incidence of LM in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) patients with driver gene mutations, including 9.4% of patients with EGFR mutations and 10.3% of patients with ALK rearrangement [8,9]. Some studies have suggested that intrathecal pemetrexed (IP) exerts certain curative effects on these patients [10]. Prospective trials involving NSCLC patients with LM (NSCLC-LM) have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of IP, with response rates of 30%–70% and disease control rates of 50%–80% [11–13]; Notably, myelosuppression emerged as the most frequent adverse event in these studies [11–13]. Recently, Fan et al. reported an 84.6% response rate and a median OS of 9 months in 30 NSCLC-LM patients with EGFR mutations who did not respond to tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment with IP; moreover, myelosuppression was identified as the predominant side effect in these patients [14]. Subsequently, the authors expanded their phase II study to include 132 NSCLC-LM patients. The results of this trial indicated an 80% response rate and a median OS of 12 months, with 31.8% of patients experiencing myelosuppression; this finding further emphasized the prevalence of myelosuppression as a side effect [15]. Our group reported an IP response rate of 68.3% and a median OS of 10.1 months; additionally, consistent with other studies, myelosuppression was also identified as the most common adverse effect [16]. Collectively, these findings suggest that myelosuppression is the primary adverse event associated with IP treatment.

Myelosuppression resulting from intravenous CT is typically associated with several factors such as advanced age, poor performance status, comorbidities, female sex, impaired hepato-renal functions, low baseline white blood cell counts (WBC), low body mass index (BMI) or body surface area, and advanced disease stage [17–20]. However, the risk factors for myelosuppression, particularly severe cases, related to IP remain unclear. The present study aimed to investigate the association between IP and myelosuppression in patients with LM from LUAD (LUAD-LM).

This retrospective cohort study collected data from LUAD-LM patients treated at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University between April 2017 and April 2024. The study adhered to the STROBE guidelines, by following the 22-item checklist for transparent and rigorous reporting, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. The ethics committee waived off the requirement for informed consent because of the retrospective nature of the study. LM was diagnosed based on clinical suspicion according to the European Association of Neuro-Oncology and European Society for Medical Oncology criteria and confirmed through positive imaging and/or CSF findings [21]. IP was defined as the administration of pemetrexed through lumbar puncture or an Ommaya reservoir. Myelosuppression was evaluated according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0. The specific criteria are as follows: (1) leukopenia is graded by WBC count as follows: Grade I (≥3.0 but <4.0 × 109/L), Grade II (≥2.0 but <3.0 × 109/L), Grade III (≥1.0 but <2.0 × 109/L), and Grade IV (<1.0 × 109/L); (2) neutropenia is graded by absolute neutrophil count: Grade I (≥1.5 but <2.0 × 109/L), Grade II (≥1.0 but <1.5 × 109/L), Grade III (≥0.5 but <1.0 × 109/L), and Grade IV (<0.5 × 109/L); and (3) thrombocytopenia is graded by platelet count: Grade I (≥75 but <100 × 109/L), Grade II (≥50 but <75 × 109/L), Grade III (≥25 but <50 × 109/L), and Grade IV (<25 × 109/L). Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) pathologically confirmed LUAD; (2) LM confirmed by radiographical and/or CSF pathological examination; (3) at least one intrathecal CT session; and (4) baseline WBC count >3.5 × 109/L, neutrophil count >2 × 109/L, and platelet count >100 × 109/L. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with concurrent malignancies other than LUAD and (2) use of intrathecal CT drugs other than pemetrexed.

Clinical data, including demographic information, clinical characteristics, tumor-related features, treatment modalities, and clinical outcomes, were extracted from the electronic medical record database. The study analyzed variables potentially associated with myelosuppression, including sex, age, smoking history, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) score at LM diagnosis, timing of LM diagnosis, presence of bone metastasis (BM) and brain metastasis (BMs) at LM diagnosis, and hematological parameters (WBC count, neutrophil count, and platelet count) at myelosuppression occurrence. Treatment information and clinical outcomes included the timing and cycle of intrathecal injections, time to myelosuppression occurrence, systemic treatment pre- and post-LM diagnosis, and date of death or last follow-up.

IP was primarily administered through lumbar puncture or an Ommaya reservoir. Prior to IP administration, patients received an intramuscular injection of 1000 μg of vitamin B12, followed by vitamin B12 injections every 3 weeks, and daily oral administration of 400 μg of folic acid. The IP procedure involved pretreatment with 5 mg of dexamethasone, followed by the administration of pemetrexed. Based on our previous research and other studies [12,13,15,16], the dosing schedule and treatment cycle were as follows: (1) induction therapy: 10 mg of pemetrexed administered twice weekly for 2 weeks, (2) consolidation therapy: 10–30 mg, with some doses at 50 mg, administered weekly for 4 weeks, and (3) maintenance therapy: 10–30 mg administered every 3–4 weeks.

Continuous variables were analyzed using the t-test for normally distributed data or the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed data, while categorical variables were assessed using the chi-square test. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize myelosuppression occurrence, with rates reported for various levels and types of myelosuppression. Additionally, medians with interquartile ranges were provided to indicate the number of IP cycles at the onset of myelosuppression.

Univariate analyses were conducted to identify potential variables associated with myelosuppression. Variables with a p-value of <0.5 in univariate analysis were incorporated into multivariate regression analysis, which identified age as a risk factor for both myelosuppression and severe myelosuppression. Subsequently, the relationship between age and severe myelosuppression was examined using a smoothing plot, following adjustment for potential confounders. A two-piecewise linear regression model was employed to investigate the threshold effect of age on severe myelosuppression based on the smoothing plot. The threshold age at which the relationship between age and severe myelosuppression attained significance was determined using an iterative method, where the inflection point was adjusted within a predefined interval to maximize model likelihood. A two-tailed p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using R program (http://www.R-project.org).

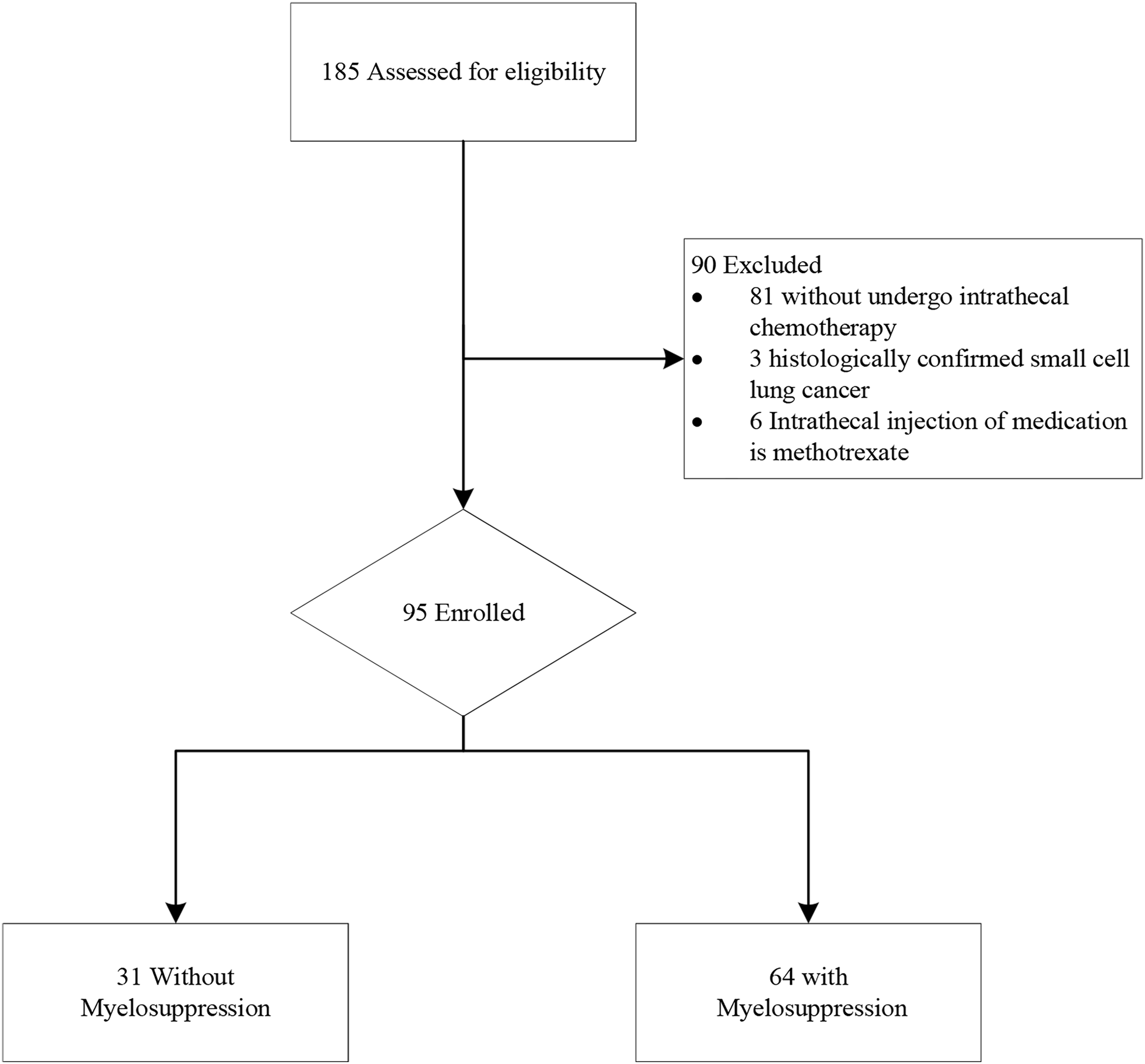

The study included the data of 185 patients diagnosed to have lung cancer and LM from the electronic medical record system between April 2017 and April 2024. A flowchart of the patient screening process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Study flow chart of patient selection

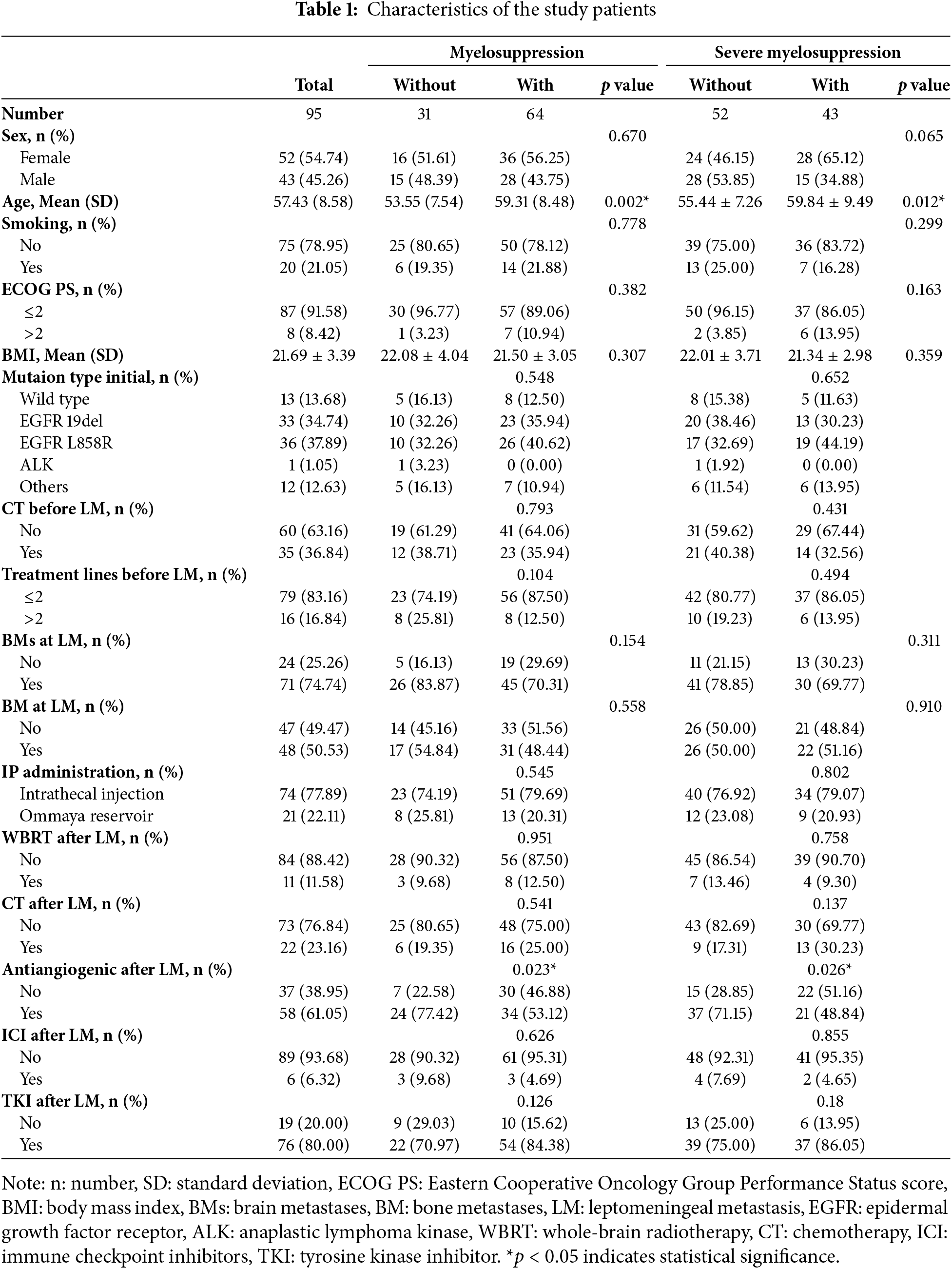

Of the 95 patients enrolled in this study, the median follow-up time was 7.43 months. Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Fifty-two patients were women (54.74%) and 43 patients were men (45.26%). The mean (SD) age of the patients was 57.43 (8.58) years. The mean (SD) BMI of the patients at LM diagnosis was 21.69 (3.39) kg/m². The majority of patients were positive for driver gene mutations at the initial diagnosis. Prior to the diagnosis of LM, 35 (36.84%) patients received intravenous CT, with only 16 (16.84%) patients receiving beyond second-line treatment. At LM diagnosis, 71 patients (74.74%) had BMs, 48 patients (50.53%) had BM, and 8 patients (8.42%) had an ECOG PS > 2. Seventy-six patients (80.00%) received TKI therapy, 22 patients (23.16%) underwent intravenous CT, 11 patients (11.58%) received whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT), and 58 patients (61.05%) received antiangiogenic therapy. Regarding the IP administration route, 74 (77.89%) patients received medication through lumbar puncture.

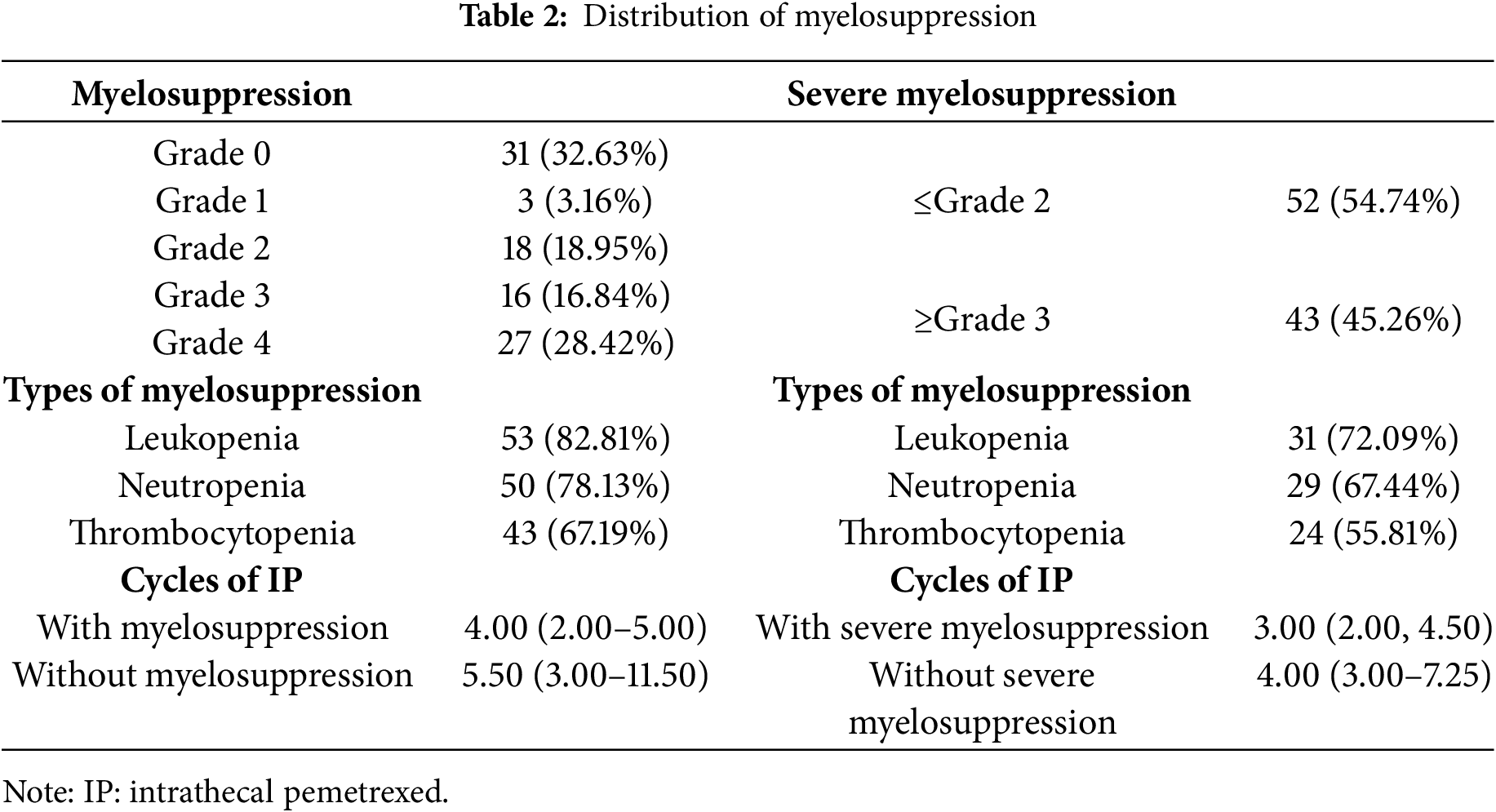

3.2 Profile of Myelosuppression after Intrathecal Pemetrexed

A major proportion of the patients (64/95, 67.37%) experienced myelosuppression during IP treatment, with 43 patients (45.26%) developing severe myelosuppression (Table 2). The distribution of myelosuppression grades 0 to 4 is detailed in Table 2. Leukopenia, observed in 82.81% of the patients, was the most prevalent cytopenia associated with myelosuppression, followed by neutropenia (78.13%) and thrombocytopenia (67.19%). These findings are consistent with the hematological profile observed in severe myelosuppression. The median number of IP cycles required to induce myelosuppression was 4 (range: 2–5), while the median number of IP cycles for severe myelosuppression development was 3 (range: 2–4.5).

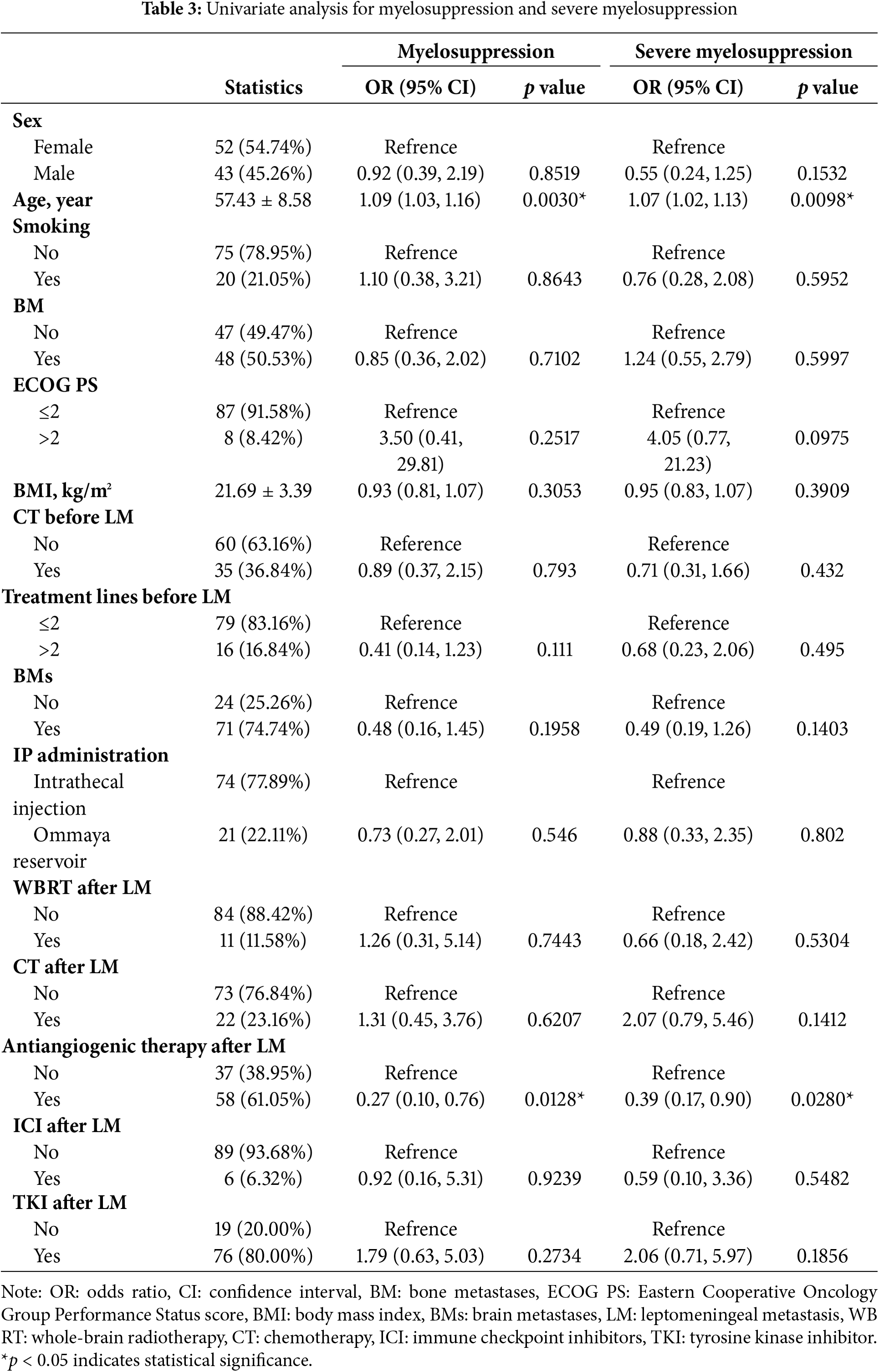

3.3 Univariate and Multivariate Analyses of Myelosuppression and Severe Myelosuppression

To evaluate the factors associated with myelosuppression and severe myelosuppression in our cohort, we conducted univariate and multivariate analyses. In the univariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3), age was independently associated with an increased risk of myelosuppression (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 1.03–1.16; p = 0.003) and severe myelosuppression (OR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.02–1.13; p = 0.0098). In contrast, antiangiogenic therapy after LM was associated with a decreased risk of myelosuppression (OR: 0.27; 95% CI: 0.10–0.76; p = 0.0128) and severe myelosuppression (OR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.17–0.90; p = 0.028).

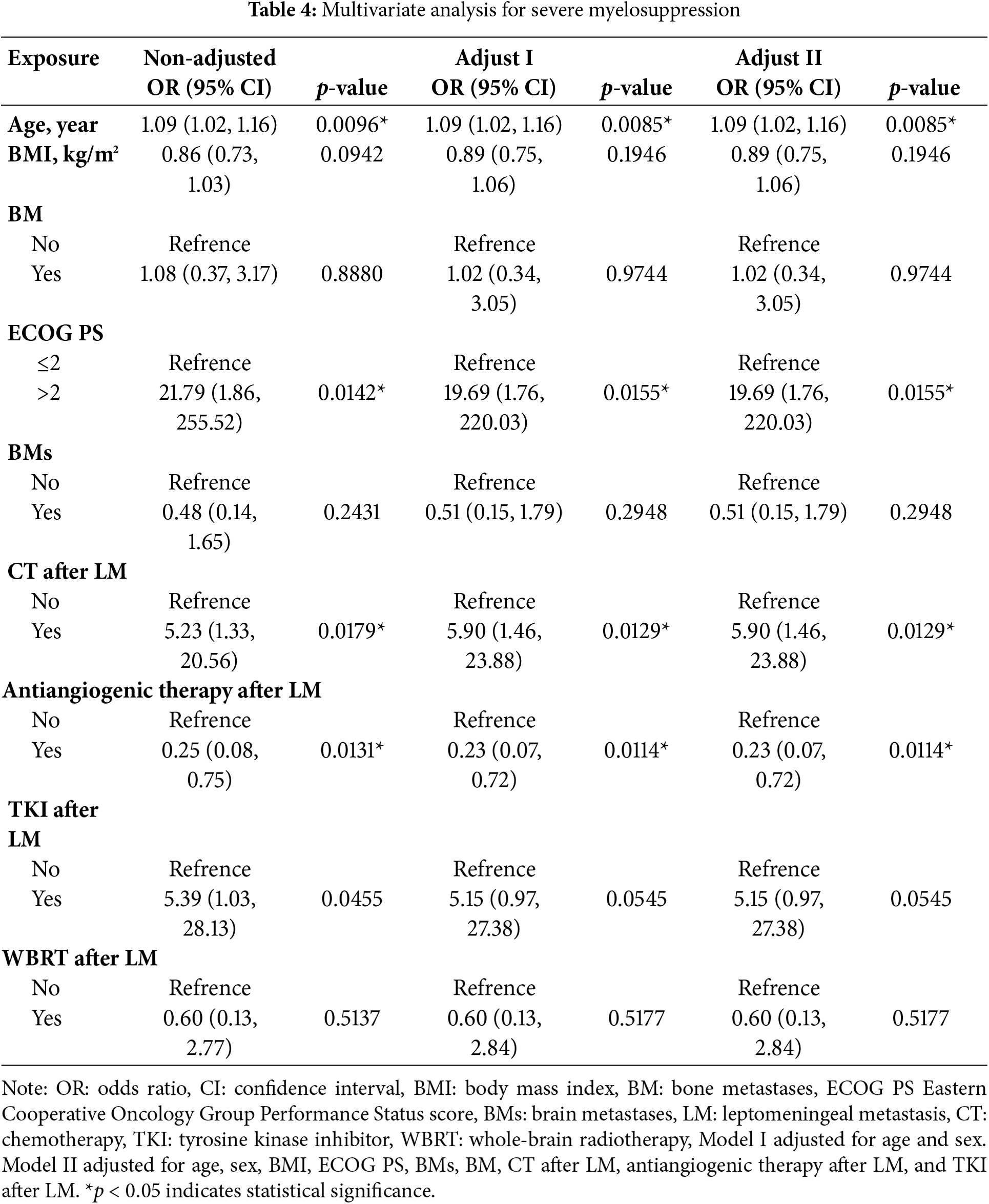

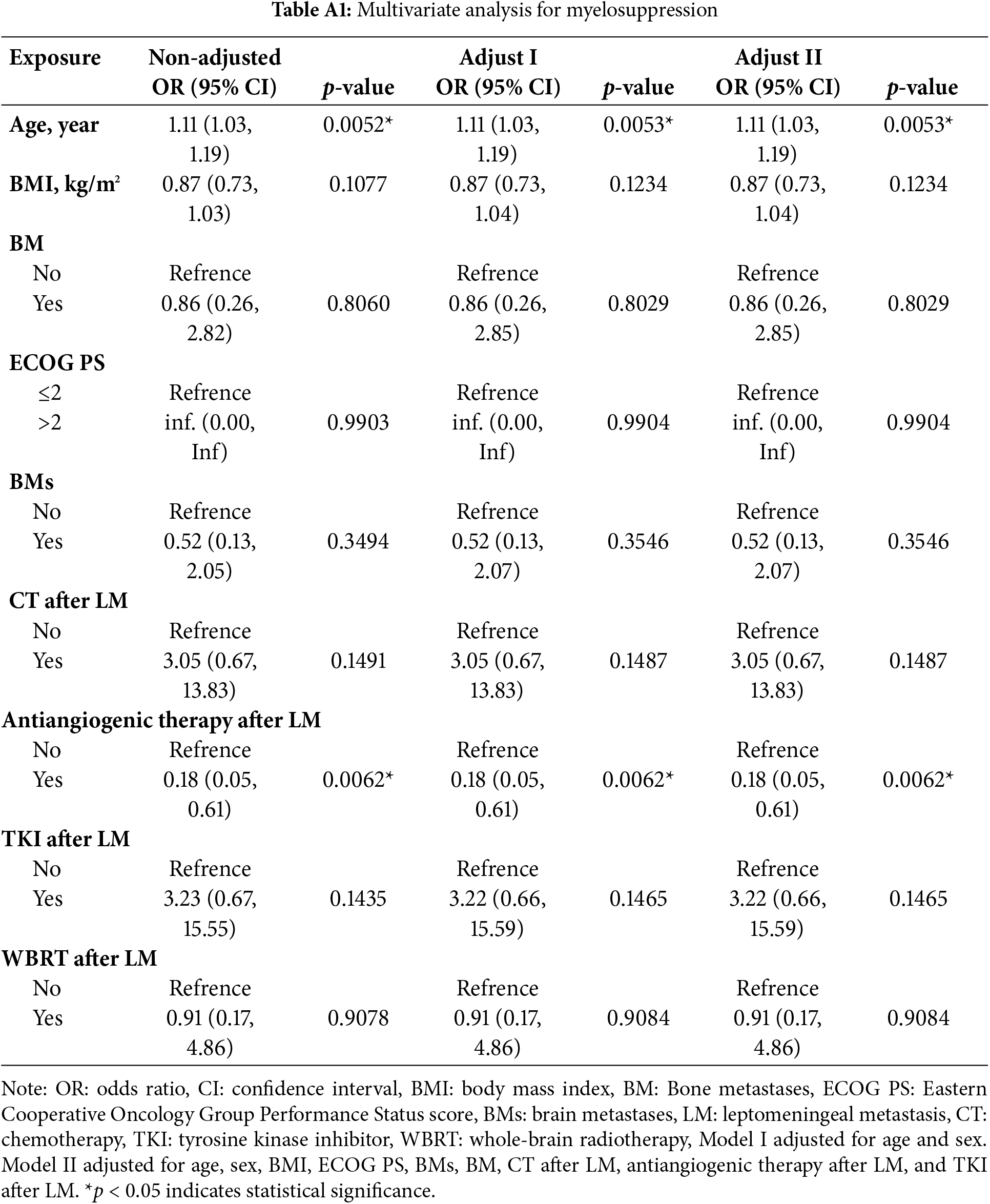

Subsequently, variables with a p value of <0.5 in the univariate analysis were incorporated into a multivariate logistic regression model. Stepwise adjustments were applied for age, sex, ECOG PS, BMs, BMI, BM, CT after LM, antiangiogenic therapy after LM, and TKI after LM. The multivariate analysis identified age as a significant risk factor for myelosuppression (OR: 1.11; 95% CI: 1.03–1.19; p = 0.0053) (Table A1). Additionally, age (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 1.02–1.16; p = 0.0085), CT after LM (OR: 5.90; 95% CI: 1.46–23.88; p = 0.0129), and ECOG PS > 2 (OR: 19.69; 95% CI: 1.76–220.03; p = 0.0155) were identified as risk factors for severe myelosuppression (Table 4).

3.4 Smooth Curve Fitting and Threshold Effect Analysis

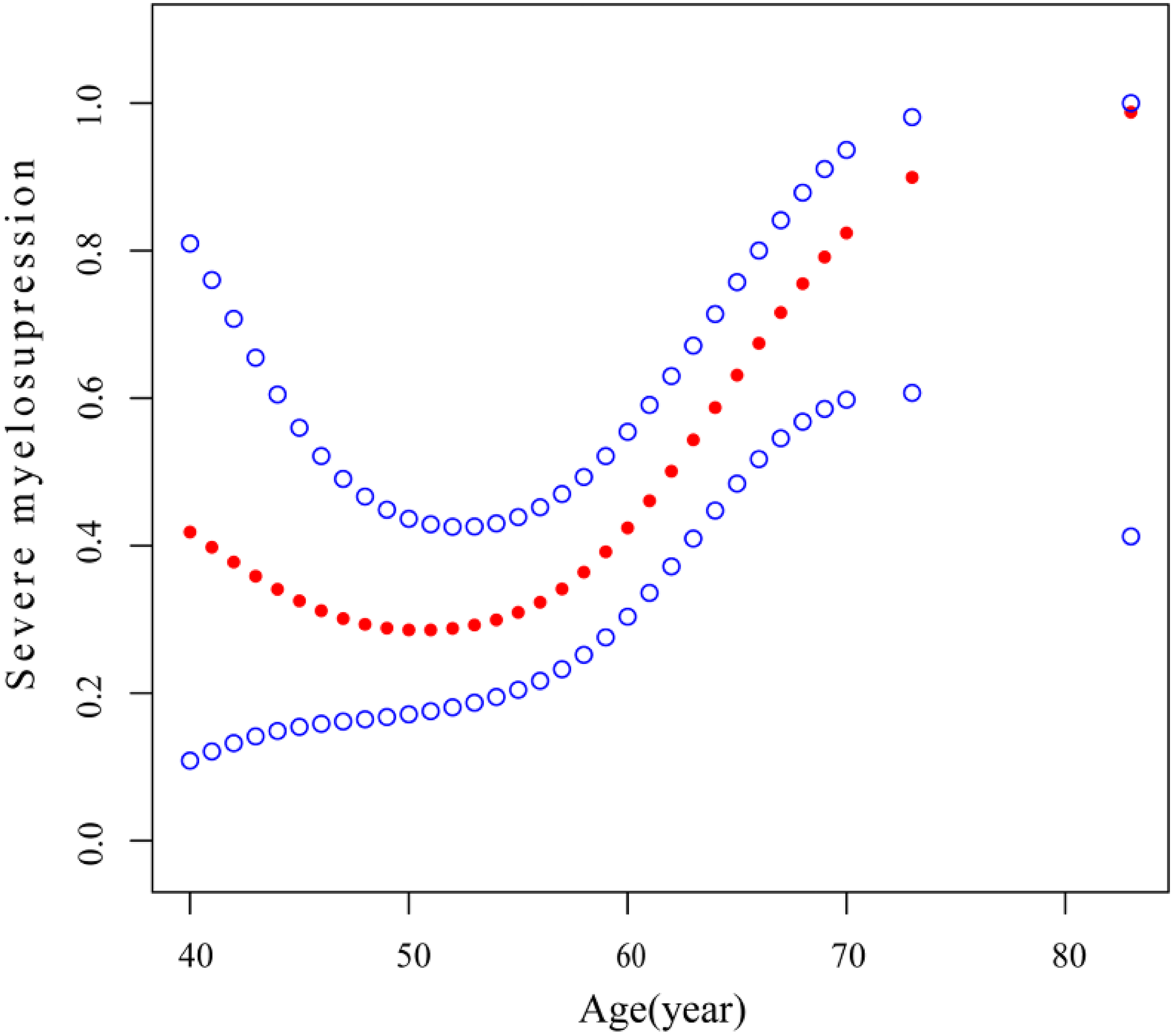

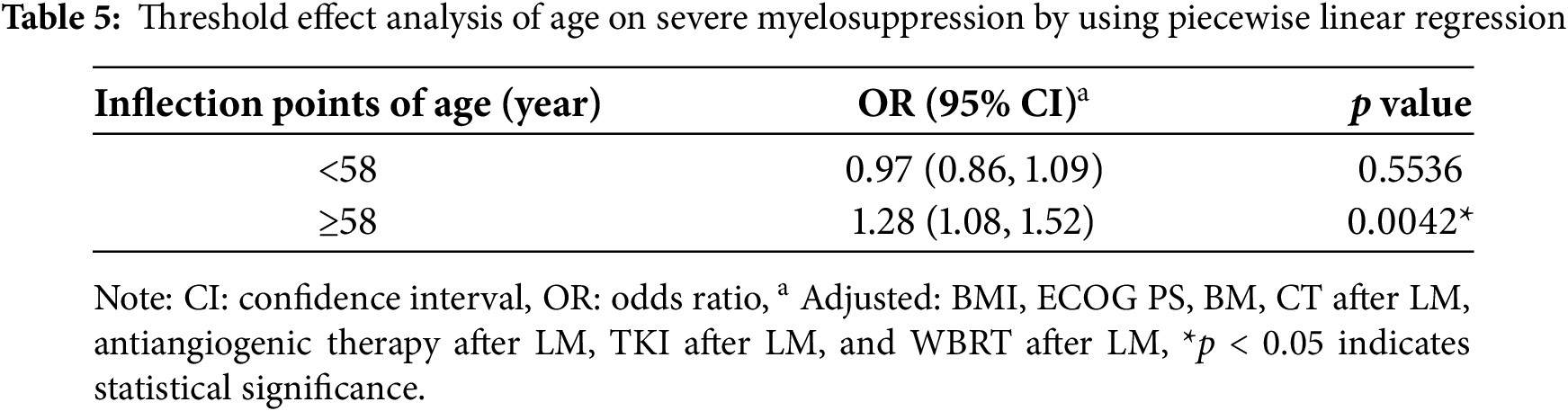

Our analysis revealed that age is associated with both myelosuppression and severe myelosuppression, which can significantly impact treatment outcomes and potentially pose a life-threatening risk [22–25]. To further investigate this relationship, we conducted curve fitting and threshold effect analysis to examine the association between age and severe myelosuppression. After adjusting for potential confounding factors—including smoking status, sex, BM, ECOG PS, BMI, BMs, WBRT, CT after LM, antiangiogenic therapy after LM, and TKI after LM— a smoothing curve fitting demonstrated a nonlinear relationship between age and severe myelosuppression following IP (Fig. 2). Beyond the turning point age of 58 years (OR: 1.28; 95% CI: 1.08–1.52; p = 0.0042), the risk of developing severe myelosuppression increased with age (Table 5). This finding suggests that severe myelosuppression is associated with age, with an elevated risk observed in patients aged 58 years or older.

Figure 2: Association between age and severe myelosuppression. A threshold, nonlinear association between age and severe myelosuppression was identified (p = 0.023) using a generalized additive model. The solid red line represents the smooth curve fit between variables, and the blue bands indicate the 95% confidence interval of the fit. All results were adjusted for smoking status, sex, BM, ECOG PS, BMI, BMs, WBRT after LM, antiangiogenic therapy after LM, and TKI after LM. Abbreviations: BM: bone metastases, ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status score, BMI: body mass index, BMs: brain metastases, WBRT: whole-brain radiotherapy, LM: leptomeningeal metastasis, TKI: tyrosine kinase inhibitor

This study investigates the incidence and characteristics of myelosuppression in LUAD-LM patients treated with IP and the risk factors associated with the development of myelosuppression and severe myelosuppression. The findings revealed that a major proportion of patients (67.37%) experienced myelosuppression following IP treatment, with a considerable number of patients (45.26%) developing severe myelosuppression. Notably, the study found that age ≥58 years is a risk factor for severe myelosuppression. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first comprehensive examination of risk factors for myelosuppression in LUAD-LM patients undergoing IP treatment.

Previous prospective and retrospective studies have demonstrated that myelosuppression after IP is a common adverse effect [12–14,26,27]. However, the incidence of myelosuppression in previous studies typically ranged from 30% to 40% [12–15], whereas this study reported an incidence as high as 68.42%. Notably, apart from the study of Pan et al., which incorporated involved-field radiotherapy alongside IP treatment, the other three studies only evaluated IP treatment and/or its combination with TKI therapy. In contrast, our study included a major proportion of patients who, following LM diagnosis, received additional systemic therapies—including TKI therapy, CT, and radiotherapy—alongside IP treatment. Our study concluded that CT after LM (OR: 5.90; 95% CI: 1.46–23.88; p = 0.0129) and ECOG PS >2 (OR: 19.69; 95% CI: 1.76–220.03; p = 0.0155) are significant risk factors for severe myelosuppression. Although TKI after LM (OR: 5.15; 95% CI: 0.97–27.38; p = 0.0545) did not reach statistical significance, there was a trend toward increased risk. Consequently, undergoing additional systemic anti-tumor therapies—including TKI therapy and CT—alongside IP treatment may elevate the risk of myelosuppression, potentially explaining the higher incidence of myelosuppression observed in our study as compared to that in other studies.

In this study, BMI was not identified as a risk factor for myelosuppression following IP. This observation can be attributed to the characteristic behavior of most intrathecal chemotherapeutic agents, which do not rapidly transfer from the CSF to the bloodstream. The metabolic inactivation of these drugs in the CSF is negligible; instead, they are primarily eliminated directly from the CSF [28]. Considering the relatively constant volume of the subarachnoid space [29], the dose of intrathecal CT should be calibrated based on the CSF volume and drug concentration rather than on BMI.

The precise mechanism underlying myelosuppression induced by low-dose pemetrexed in IP treatment remains elusive. The pemetrexed dose utilized in IP typically ranges from 10 to 30 mg, which is substantially lower than the standard 500 mg/m² administered in intravenous CT. Nevertheless, myelosuppression persists as the primary adverse effect of IP. A plausible explanation involves the blood-brain barrier: the protein concentration in the CSF is significantly lower than that in the blood. This reduced protein-binding capacity of pemetrexed in the CSF may result in higher free-drug concentrations, potentially compromising bone marrow function.

Moreover, this study demonstrated that antiangiogenic therapy administered after LM significantly reduced the risk of severe myelosuppression following IP (HR: 0.23, 95% CI: 0.07–0.72; p = 0.0114). However, the precise mechanism through which antiangiogenic therapy mitigates the risk of severe myelosuppression post-IP remains elusive. Our previous research indicated that patients with LUAD-LM might benefit from a combination of osimertinib and bevacizumab. Specifically, bevacizumab significantly enhanced the intracranial concentration of osimertinib, suggesting that it may alleviate IP-induced myelosuppression by improving drug penetration through the blood-brain barrier and reducing pemetrexed accumulation in the CSF [30].

This study presents several limitations. First, as a retrospective analysis, the completeness and accuracy of the data relied on electronic medical records, which potentially introduced certain biases. Second, the study included patients treated at a single center, which may have resulted in selection bias. Third, the analysis did not include the dose and cycles of IP. This omission is due to the consistency of the IP regimen and dose in this study with current literature reports, where pemetrexed is typically administered at relatively low doses of 10–30 mg. Furthermore, the median cycles of IP prior to the development of myelosuppression and severe myelosuppression were 3 and 4, respectively, indicative of the induction phase of IP treatment. This study investigates myelosuppression development due to IP administration at a low dose, potentially offering insights into the prevention and management of IP-induced myelosuppression.

The present study identified age as a crucial risk factor for myelosuppression following IP, with a significantly elevated risk of severe myelosuppression in patients aged 58 years or older. These findings have substantial implications for IP administration guidelines, suggesting that IP should be administered cautiously in patients over 58 years of age, accompanied by the consideration of preventive strategies.

Subsequent research and more extensive prospective trials should prioritize the optimization of IP administration, frequency, and its integration with systemic therapies. Furthermore, investigating the underlying mechanisms of myelosuppression induced by low-dose IP treatment will be crucial for advancing this therapeutic approach.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 82360629, awarded to ZZM) and the Jiangxi Provincial Health Department Project (grant number 202410026, awarded to ZZM, 202510363, awarded to HYQ).

Author Contributions: Zhimin Zeng and Yanqing He: Conceptualization, project administration, and statistical analysis. Junxing Chen, Luping Pan, and Yunzhi Liu: Data acquisition, methodology, and writing of the original draft. Yan Fang, Zhiqin Lu, and Ruoxuan Li: Data acquisition. Zhimin Zeng, Anwen Liu, and Yanqing He: Data collection, writing assistance, and manuscript revision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The dataset supporting the study’s conclusions is available from the corresponding author upon request, as its dissemination is limited by privacy and ethical considerations.

Ethics Approval: This study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. Because of the retrospective nature of this research, the aforementioned Institutional Ethics Committee waived the requirement for informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

List of Abbreviations

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| LM | Leptomeningeal metastasis |

| LUAD | Lung adenocarcinoma |

| IP | Intrathecal pemetrexed |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| OS | Overall survival |

| TKI | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| ECOG PS | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status |

| BM | Bone metastasis |

| BMs | Brain metastasis |

| CT | Chemotherapy |

| WBRT | Whole-brain radiotherapy |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

Appendix A

References

1. Grossman SA, Krabak MJ. Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Cancer Treat Rev. 1999 Apr;25(2):103–19. [Google Scholar]

2. Gleissner B, Chamberlain MC. Neoplastic meningitis. Lancet Neurol. 2006 May;5(5):443–52. [Google Scholar]

3. Wang Y, Yang X, Li NJ, Xue JX. Leptomeningeal metastases in non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis and treatment. Lung Cancer. 2022 Dec;174:1–13. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2022.09.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Ozcan G, Singh M, Vredenburgh JJ. Leptomeningeal metastasis from non-small cell lung cancer and current landscape of treatments. Clin Cancer Res. 2023 Jan 4;29(1):11–29. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-22-1585. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Wu H, Zhang Q, Zhai W, Chen Y, Yang Y, Xie M, et al. Effectiveness of high-dose third-generation EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in treating EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer patients with leptomeningeal metastasis. Lung Cancer. 2024 Feb;188(1):107475. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2024.107475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Felip E, Shaw AT, Bearz A, Camidge DR, Solomon BJ, Bauman JR, et al. Intracranial and extracranial efficacy of lorlatinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with second-generation ALK TKIs. Ann Oncol. 2021 May;32(5):620–30. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2021.02.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Yang JCH, Kim SW, Kim DW, Lee JS, Cho BC, Ahn JS, et al. Osimertinib in patients with epidermal growth factor receptor mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer and leptomeningeal metastases: the BLOOM study. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Feb 20;38(6):538–47. doi:10.1200/jco.19.00457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Zheng MM, Li YS, Jiang BY, Tu HY, Tang WF, Yang JJ, et al. Clinical utility of cerebrospinal fluid cell-free DNA as liquid biopsy for leptomeningeal metastases in ALK-rearranged NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2019 May;14(5):924–32. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2018.08.455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li YS, Jiang BY, Yang JJ, Tu HY, Zhou Q, Guo WB, et al. Leptomeningeal metastases in patients with NSCLC with EGFR mutations. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(11):1962–9. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2016.06.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Wu YL, Zhou L, Lu Y. Intrathecal chemotherapy as a treatment for leptomeningeal metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis. Oncol Lett. 2016 Aug;12(2):1301–14. doi:10.3892/ol.2016.4783. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Pan Z, Yang G, Cui J, Li W, Li Y, Gao P, et al. A pilot phase 1 study of intrathecal pemetrexed for refractory leptomeningeal metastases from non-small-cell lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2019 Aug 30;9:838–49. doi:10.3389/fonc.2019.00838. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Pan Z, Yang G, He H, Cui J, Li W, Yuan T, et al. Intrathecal pemetrexed combined with involved-field radiotherapy as a first-line intra-CSF therapy for leptomeningeal metastases from solid tumors: a phase I/II study. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020 Jan;12:175883592093795–809. doi:10.1177/1758835920937953. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Li H, Zheng S, Lin Y, Yu T, Xie Y, Jiang C, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetic and clinical activity of intrathecal chemotherapy with pemetrexed via the ommaya reservoir for leptomeningeal metastases from lung adenocarcinoma: a prospective phase I study. Clin Lung Cancer. 2023 Mar;24(2):e94–104. doi:10.1016/j.cllc.2022.11.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Fan C, Zhao Q, Li L, Shen W, Du Y, Teng C, et al. Efficacy and safety of intrathecal pemetrexed combined with dexamethasone for treating tyrosine kinase inhibitor-failed leptomeningeal metastases from EGFR-mutant NSCLC—a prospective, open-label, single-arm phase 1/2 clinical trial (unique identifier: ChiCTR1800016615). J Thorac Oncol. 2021 Aug;16(8):1359–68. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2021.04.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Fan C, Jiang Z, Teng C, Song X, Li L, Shen W, et al. Efficacy and safety of intrathecal pemetrexed for TKI-failed leptomeningeal metastases from EGFR+ NSCLC: an expanded, single-arm, phase II clinical trial. ESMO Open. 2024 Apr;9(4):102384–91. doi:10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhou T, Zhu S, Xiong Q, Gan J, Wei J, Cai J, et al. Intrathecal chemotherapy combined with systemic therapy in patients with refractory leptomeningeal metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2023 Apr 11;23(1):333–44. doi:10.1186/s12885-023-10806-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Park K, Kim Y, Son M, Chae D, Park K. A pharmacometric model to predict chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression and associated risk factors in non-small cell lung cancer. Pharmaceutics. 2022 Apr 22;14(5):914. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics14050914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Han CJ, Ning X, Burd CE, Spakowicz DJ, Tounkara F, Kalady MF, et al. Chemotoxicity and associated risk factors in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers. 2024 Jul 20;16(14):2597. doi:10.3390/cancers16142597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Lyman GH, Abella E, Pettengell R. Risk factors for febrile neutropenia among patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2014 Jun;90(3):190–9. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.12.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Laskey RA, Poniewierski MS, Lopez MA, Hanna RK, Secord AA, Gehrig PA, et al. Predictors of severe and febrile neutropenia during primary chemotherapy for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012 Jun;125(3):625–30. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.03.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Le Rhun E, Weller M, Van Den Bent M, Brandsma D, Furtner J, Rudà R, et al. Leptomeningeal metastasis from solid tumours: EANO-ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. ESMO Open. 2023 Oct;8(5):101624. doi:10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Crawford J, Dale DC, Lyman GH. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia: risks, consequences, and new directions for its management. Cancer. 2004 Jan 15;100(2):228–37. doi:10.1002/cncr.20218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kuderer NM, Dale DC, Crawford J, Cosler LE, Lyman GH. Mortality, morbidity, and cost associated with febrile neutropenia in adult cancer patients. Cancer. 2006 May 15;106(10):2258–66. doi:10.1002/cncr.21847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lyman GH, Michels SL, Reynolds MW, Barron R, Tomic KS, Yu J. Risk of mortality in patients with cancer who experience febrile neutropenia. Cancer. 2010 Dec;116(23):5555–63. doi:10.1002/cncr.25332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zeiner PS, Filipski K, Filmann N, Forster MT, Voss M, Fokas E, et al. Sex-dependent analysis of temozolomide-induced myelosuppression and effects on survival in a large real-life cohort of patients with glioma. Neurology. 2022 May 17;98(20):e2073–83. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000200254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Hong Y, Miao Q, Zheng X, Xu Y, Huang Y, Chen S, et al. Effects of intrathecal pemetrexed on the survival of patients with leptomeningeal metastasis from lung adenocarcinoma: a propensity score matching analysis. J Neuro-Oncol. 2023 Nov;165(2):301–12. doi:10.1200/jco.2023.41.16_suppl.e21048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Geng D, Guo Q, Huang S, Zhang H, Guo S, Li X. A retrospective study of intrathecal pemetrexed combined with systemic therapy for leptomeningeal metastasis of lung cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2022 Jan;21:153303382210784–93. doi:10.1177/15330338221078429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Fleischhack G, Jaehde U, Bode U. Pharmacokinetics following intraventricular administration of chemotherapy in patients with neoplastic meningitis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44(1):1–31. doi:10.2165/00003088-200544010-00001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Courchesne E, Chisum HJ, Townsend J, Cowles A, Covington J, Egaas B, et al. Normal brain development and aging: quantitative analysis at in vivo MR imaging in healthy volunteers. Radiology. 2000 Sep;216(3):672–82. doi:10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00au37672. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Yi Y, Cai J, Xu P, Xiong L, Lu Z, Zeng Z, et al. Potential benefit of osimertinib plus bevacizumab in leptomeningeal metastasis with EGFR mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. J Transl Med. 2022 Dec;20(1):122. doi:10.1186/s12967-022-03453-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools