Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Association among Noncoding-RNAs, APRO Family Proteins, and Gut Microbiota in the Development of Breast Cancer

Department of Food Science and Nutrition, Nara Women’s University, Kita-Uoya Nishimachi, Nara, 630-8506, Japan

* Corresponding Author: Satoru Matsuda. Email:

Oncology Research 2025, 33(9), 2205-2219. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.062810

Received 28 December 2024; Accepted 12 June 2025; Issue published 28 August 2025

Abstract

The non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are a family of single-stranded RNAs that have become recognized as crucial gene expression regulators in normal and cancer cell biology. The gut microbiota, which consists of several different bacteria, can actively contribute to the regulation of host metabolism, immunity, and inflammation. Roles of ncRNAs and gut microbiota could significantly interact with each other to regulate the growth of various types of cancer. In particular, a causal relationship among ncRNAs, gut microbiota, and immune cells has been shown for their potential importance in the development of breast cancer. Alteration of ncRNA expression and/or gut microbiota profiles could also influence several intracellular signaling pathways with the function of anti-proliferative (APRO) family proteins associated with the malignancy. Targeting ncRNAs and/or APRO family proteins for the treatment of various cancers has been revealed with novel immune therapies. Here, the most recent studies to underline the key role of ncRNAs, APRO family proteins, and gut microbiota in breast cancer progression have been discussed. For more effective breast cancer therapy, it would be imperative to figure out the collective mechanism of ncRNAs, APRO family proteins, and gut microbiota.Keywords

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer afflicting women globally. The incidence rate ascends with age, and more than 80% of breast cancer cases are identified in women above 50 years old worldwide [1]. Breast cancer may be a complicated and heterogeneous disorder, which exhibits the highest morbidity among female cancers [2,3]. Although there are distinct genetic risk factors such as tumor suppressor BRCA1/2 gene mutations and various environmental risk factors, there might be other unidentified risk factors for the majority of sporadic cases [4]. In recent years, the gut microbiota has been garnering significant attention from researchers [5]. An epidemiological study had demonstrated that the gut microbiota may increase to about 20% of malignant tumors [6]. In addition, the connection between the composition of the gut microbiota and the aggressiveness of cancers has been underlined [7]. These relationships have been reported during the function of Helicobacter pylori in gastric cancer and that of Fusobacterium in colon cancer for the promotion of carcinogenesis [8,9]. Interestingly, it has been shown that chronic bacterial infection in the bladder could change the bladder epithelial cells to cancerous cells [10]. Bladder bacterial infection may increase the risk of gene mutation and malignant transformation of cells [11].

Gut microbiota may crucially affect many aspects of individual biology from nutrient gaining to immunological function in the host. The gut microbiota is a community of trillions of microorganisms that utilize dietary components to produce several available metabolites that may influence the host’s health. Some metabolites could underlie the relationship between the gut and distal organs [12]. The gut microbiota also plays crucial roles in immune modulation and the maintenance of body homeostasis [13]. The composition of gut microbiota is closely related to the gut environment, which might include the redox state, pH, nutrients, and temperature of the host [14]. Bacterial infection can activate cancer-promoting signaling pathways including nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling, promoting the growth, survival, and metastasis of cancer cells [15]. The link between gut microbiota and breast cancer has firstly restricted from epidemiological studies [16]. Afterward, the interaction between the host and gut microbiota can form a complex and intricate regulatory network. Notably, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as important mediators in this communication.

The role of ncRNAs in the interaction between host and gut microbiota as well as their influence on the host homeostasis and the host carcinogenesis is attracting increasing attention, suggesting a further interaction between ncRNAs and gut microbiota with carcinogenesis. By underlying host response mechanism to metabolic signals of gut microbial metabolites, therefore, several ncRNA expressions could be modulated. Interestingly, developmental patterns of mammary gland ncRNAs may provide clues to their dysregulated role in breast cancer [17]. ncRNAs are functional RNA molecules that are not translated into proteins, which may include transfer RNAs, ribosomal RNAs, circular RNAs (circRNAs), micro RNAs (miRNAs), and long non-coding (lncRNAs) based on their length and structure. Among them, miRNAs and lncRNAs are currently the most intensively studied [18]. Around 90% of the human genome is transcribed into ncRNA [19,20]. The discovery of these ncRNAs is regarded as an important breakthrough in life sciences [19,20]. Several ncRNAs play crucial roles in cellular development, physiological functions, and disease progression [21,22]. Therefore, ncRNAs have been rigorously explored for their roles in regulating human diseases including cancer development [23]. Now, ncRNAs have been providing them with encouraged candidates for the tool of cancer therapeutics [24]. Also, the gut microbiota can be altered for the prevention of various diseases including cancer by dietary interventions via the modification of ncRNAs. Here, we discuss the key role of ncRNAs, APRO family proteins, and gut microbiota mainly in the development of breast cancer, which would facilitate the study of pathogenesis for accelerating the process of therapeutic discovery against breast cancer.

2 Gut Microbiota and ncRNAs in the Development of Various Types of Cancer

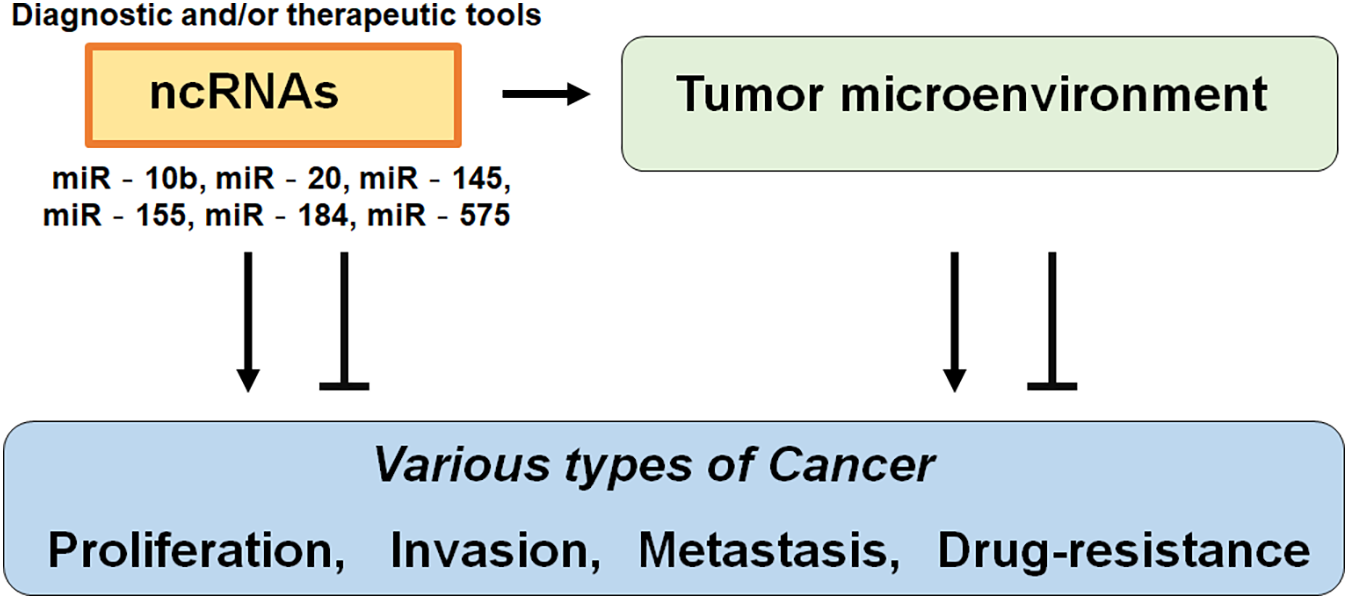

Again, ncRNAs are RNA transcripts that are not translated, which may regulate biological processes such as cell proliferation, cell death, tumorigenesis, and immunity [25]. The miRNAs are short non-coding RNA sequences about 22 nucleotides long, which can bind to the 3′UTR of the specific mRNAs affecting the expression of mRNAs [26,27]. It has been suggested that serum miRNAs may serve as predictive prognostic biomarkers in various malignancies including breast cancer [28,29]. Numerous miRNAs including miR-10b, miR-20, miR-145, miR-155, and/or miR-575 have been identified as important in the progression of breast cancer [30]. In addition, several miRNAs have been found in the host serum [26–29] (Fig. 1) For instance, miR-184 may control the metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer by targeting the AKT/mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway to cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and migration [31]. It has been suggested that abnormal expression levels of miRNAs could also influence the development of breast cancer [32]. In addition, increased expression of miR-25 may predict the better survival of breast cancer patients [33]. Moreover, some ncRNAs can be therapeutically targeted for targeting protein-coding mRNAs [34]. Therefore, understanding the specific signature of ncRNAs could help to understand the carcinogenic mechanisms of breast cancer for the development of the diagnosis and/or treatment. One of the challenges in the cancer therapy field is to clear the action of various ncRNAs, which is critical for developing its potential use as a biomarker and/or medical treatment target [23,35]. Fortunately, it has been demonstrated that some ncRNAs including the miR-25-3p can be used as a prognosis biomarker and a cell proliferation regulator in various types of cancer such as ovarian cancer, hepatoma, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [36–39].

Figure 1: Illustration of the general action of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) to various types of cancer. Functions of ncRNAs have been proposed to relate to the proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and/or drug resistance of cancers. Consequently, certain ncRNAs could be diagnostic and/or therapeutic tools for cancers. The arrowhead means stimulation and/or augmentation, whereas the hammerhead represents inhibition.

Gut microbiota and ncRNAs can interact in the gut epithelial cells, leading to the activation of key signaling pathways and modulation of gene expression for the host cells [40]. The gut epithelial cells could secrete various types of major ncRNAs in the gut [41]. Host ncRNAs can be incorporated into several bacteria and specifically modify the bacterial transcripts, which possibly alleviate the symptoms of host colitis [41]. At the same time, the gut microbiota can control the expression of ncRNAs of gut epithelial cells, thereby modifying the homeostasis of gut microbiota [41]. The probiotics could therefore improve the damage to the gut by regulating the ncRNA expression [42]. For example, the Lactobacillus fermentum can increase the expression of miR-159 and/or miR-143, thereby maintaining the function of the intestinal barrier via their anti-inflammatory effects [42]. In addition, A. muciniphila can also increase the expression of miR-143 and/or miR-145, which may promote the gut barrier integrity [43]. After the inoculation with S. enterica to the gut, the expression of miR-214 may reduce, whereas that of miR-331-3p may increase, which can induce several immune responses against S. enterica [44]. Other pathogenic bacteria including H. pylori can also affect the expression of ncRNAs in the gut [45,46]. Interestingly, commensal bacteria can downregulate the expression of miR-10a in dendritic cells [47]. Gut microbiota and commensal bacteria might alter the mucosal immune response by regulating the mucosal innate response [47]. Therefore, the gut microbiota has a significant impact on the host immune homeostasis. Alterations in the composition of gut microbiota may also be associated with metabolic disorders including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and/or cardiovascular disease [48,49]. The gut microbiota homeostasis can be affected by inflammatory stressors such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and/or dietary ingredients [50]. An imbalanced population of gut microbiota may contribute to the compromised gut barrier integrity [51], which may allow bacteria to start systemic immune responses [52]. In addition, some bacteria such as F. prausnitzii can reduce the proliferation of colorectal cancer cells by producing butyrate. Then, the butyrate can inhibit miR-92a transcription, thus increasing the tumor suppressor p57 level to suppress the cancer activity [53]. The P. bivia may also be involved in the fermentation of dietary fibers to synthesize butyrate, serving a key role in intestinal homeostasis [54]. The butyrate could play a significant role in the development of human cancers via epigenetic action by inhibiting histone deacetylase 3 [55]. Therefore, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is a possible strategy to modulate the gut microbiota for the production of butyrate to regulate the cancer-immune system [56]. In addition, the FMT could also alternate the gut microbiota for the production of some ncRNAs that can directly alter the expression of cancer-related genes to interfere with the development of several malignant tumors [57,58]. In line with this, dysbiosis can eventually lead to the dysregulation of gene expression in the mammary glands for the increased risk of breast cancer development [59]. These findings suggest that certain gut microbiota could alter the expression of cancer-related genes for the inhibition of various types of cancer.

3 APRO Family Proteins Involved in Breast Cancer

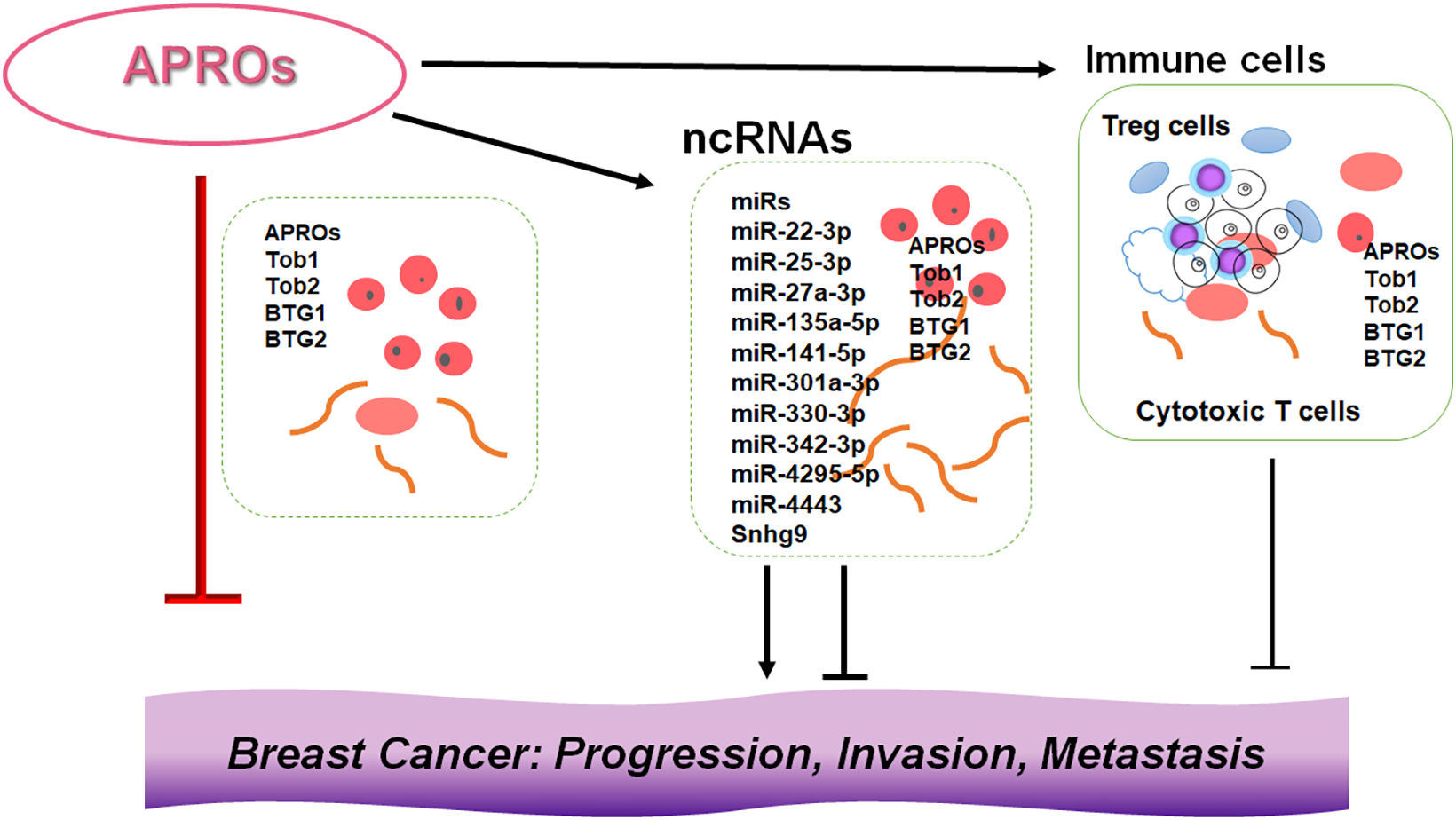

Breast cancer is a common malignancy in women worldwide [60]. The incidence of breast cancer has increased over the past few decades [61]. Although multidisciplinary therapies have been used for the treatment of breast cancer, the morbidity and mortality rates remain high and the prognosis of breast cancer remains poor [62]. Early diagnosis may result in a significant improvement in the disease prognosis and quality of life (QOL) of patients [63]. Previous findings have indicated that the transducer of ERBB2, 1 (Tob1) gene expression is downregulated in various cancers including breast cancer [64]. In addition, Tob1, which is ubiquitously expressed in human adult tissues, could work as a tumor suppressor in certain types of cancers [65]. The Tob1 gene is located on chromosome 17q21 and encodes for a 45 kDa Tob1 protein [66]. Tob1 is a member of the APRO protein family. Tob1 is associated with the regulation of tumor cell proliferation and invasion, which may also contribute to the inhibition of cancer migration and metastasis [67]. It has been shown that Tob1 knockdown can promote tumor cell migration and invasion in gastric and lung cancer cells [68,69]. In breast cancer cells, Tob1 overexpression could induce the apoptosis of cancer cells [70]. In general, the Tob1 is downregulated in breast cancer cells compared with normal cells, and the miR-25-3p knockdown can repress the proliferation of breast cancer cells by upregulating Tob1 expression [70,71]. It has been shown that the Tob1 gene may be a key determinant of survival in estrogen-dependent estrogen receptor-positive breast cells [71]. A previous study demonstrated that miR-25-3p functions as an oncogene and promotes proliferation via the induction of B-cell translocation gene 2 (BTG2), another member of the APRO protein family, in breast cancer [72]. Analysis of ncRNAs shows that the miR-25-3p is overexpressed in the serum of patients with breast cancer [73]. The B-cell translocation gene 1 (BTG1) could reverse the miR-22 for the inhibition of autophagy, while the miR-4295 could significantly promote the proliferation and migration of cancer cells via directing the BTG1 [74,75]. By inhibiting BTG1, miR-511 can strengthen the proliferation of human hepatoma cells, while miR-301 can promote the development of colitis-associated cancer [76,77]. In addition, the BTG1 may function as a direct target of miR-330-3p in hepatocellular carcinoma, which could reduce the cell viability, migration, and/or invasion, whereas promoting cancer cell apoptosis [78]. On the contrary, the miR-141-5p can enhance the proliferation and inhibit apoptosis in cervical cancer cells by targeting the BTG1 gene [79]. In addition, the miR-301a-3p can promote the proliferation and invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma squamous cells also by targeting the BTG1 gene [80]. In these ways, APRO family proteins including Tob1, BTG2, and BTG1 have been reported to control/regulate/promote cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, and/or cell differentiation in various types of cancer [81] (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Illustration of the relationship among APRO family proteins, ncRNAs, and immune cells in the breast cancer development. Although APRO family proteins (APROs) could individually inhibit the progression, invasion, and/or metastasis of cancer cells, the other conditions such as expression levels of ncRNAs and/or the function of immune cells in the microenvironment of tumors may also contribute to the development of breast cancer. Indicated proteins and/or RNAs are examples. Arrowhead means stimulation, whereas hammerhead represents inhibition. Note that some critical pathways have been omitted for clarity. Abbreviation: APROs, APRO family proteins; miRs: microRNAs.

4 Roles of APRO Family Proteins in the Regulation of Cancer and Immune Cells

The APRO family may be associated with the initiation and progression of cancers. The APRO family includes 6 members: Tob1, Tob2, BTG1, BTG2, Abundant in Neuroepithelium Area (ANA), and BTG4, which some members are of significance for the prognosis of cancers [82–85]. Consequently, the expression of APRO family members is linked with patient prognosis. In addition, APRO family genes show significant association with immune infiltration, cancer cell stemness, and tumor microenvironment [82,84]. Several lines of evidence suggest that the quiescence of naïve T cells is tightly regulated by the activity of nuclear factors including Tob1 [86]. The Tob1 is also a transcriptional repressor, which has been shown to play a crucial role in keeping naïve T cells from excess proliferating [87]. Remarkably, the decreased Tob1 expression at the mRNA and protein levels in immune cells has been confirmed in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and/or multiple sclerosis [88]. Interestingly, it has been also reported that Tob1 participates in tumor occurrence as well as T-cell activation [89,90]. In addition, high expression of Tob1 could inhibit the proliferation of malignant pancreatic cells [91]. Therefore, some researchers suppose that Tob1 can be used as an independent indicator to evaluate the prognosis of patients with various types of cancer [92]. In the study of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, down-regulated Tob1 expression may be correlated with the unfavorable prognosis of the patients [93]. Additionally, Tob1 has been uncovered to trigger autophagy to suppress cancer progression by activating the AKT/mTOR pathway [94]. BTG1 mutations may also disrupt a critical immune porter mechanism that can limit the B cell suitability during the antibody maturation in diffuse B cell lymphoma [95,96]. The overexpressed BTG2 could reduce the proliferation and migration of various types of cancer cells, which may also act as an effective target for the treatment of breast cancer [97,98]. Both BTG1 and BTG2 are closely correlated with the prognosis of cancer patients [99]. Consistently, the ANA overexpression could also inhibit the proliferation and invasion of various types of cancers including epithelial ovarian cancer [100].

Follicular B cells can induce the production of regulatory T (Treg) cells, further enhancing the immunosuppressive microenvironment. Tumor cells may favor the immunosuppressive microenvironment to evade immune surveillance, thereby aggravating the development of the cancer disease [101]. In general, during the immune response, the activation of T cells may be a crucial step that qualifies them to respond to various alien antigens. However, to keep the balance of the immune system for avoid excessive immune responses, some T cells are required to be in a dormant state, known as quiescent T cells [102]. Under specific conditions, activated T cells may also be suppressed to avoid autoimmune reactions. Tob1 could play a significant role in the development of these quiescent T cells as a negative regulator for T cell activation [103]. In addition, other APRO family proteins could also play a role in adaptive immunity by inhibiting immune cell proliferation/differentiation, thereby keeping immune cells in a quiescent state [87,104]. Therefore, it would be possible that several ncRNAs could activate immune cells against cancers via the inhibition of APRO family proteins (Fig. 2).

5 Gut Microbiota Could Modify the Development of Breast Cancer via the Alteration of ncRNAs and APRO Family Proteins

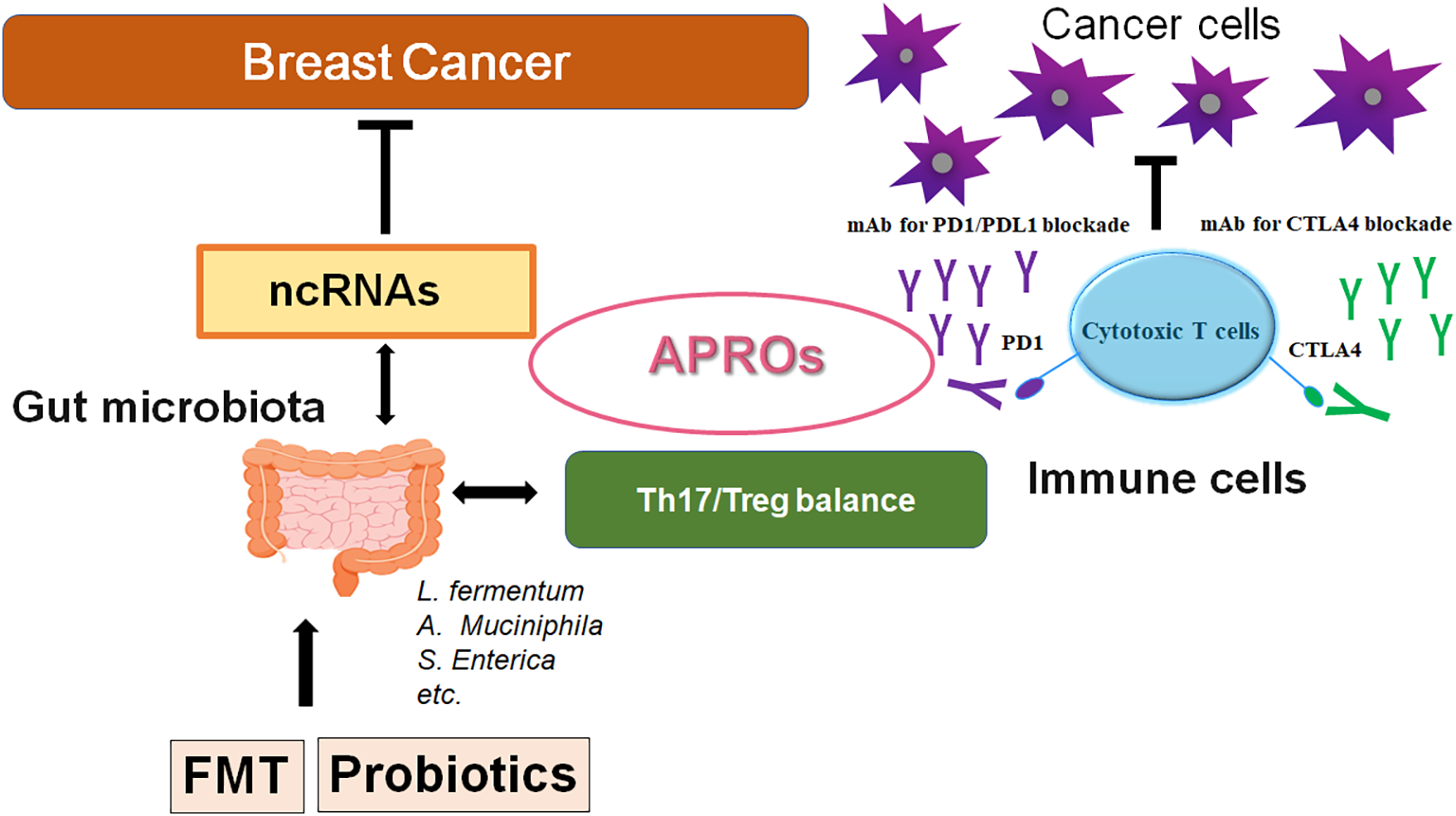

The gut microbiome has been demonstrated to be associated with various types of cancer [105,106]. In particular, previous studies have provided evidence suggesting that immune cells possess fundamental links with both the gut microbiota and breast cancer [107,108]. Remarkably, gut microbiota could modulate the response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in breast cancer and melanoma patients [107,108]. Studies have demonstrated that dysbiosis could facilitate the development of malignant tumors by stimulating unregulated inflammatory responses, which may also suggest to play a crucial role in cancer prevention [109,110]. Given the function of gut microbiota in the process of inflammation-mediated carcinogenesis, it is predictable that specific gut microbiota or the relevant dieting might be correlated with the development of specific cancers [111,112]. Interestingly, flaxseed oil is among the highest plant-based sources of alpha-linolenic acid, which might reduce mammary tumor growth and tumor proliferation via the alteration of gut microbiota composition [113]. The flaxseed oil can also increase the serum levels of eicosapentaenoic acid and/or docosahexaenoic acid, which may improve the inflammation intensity [113]. For the occurrence and the development of breast cancer, the mechanism of the interaction between gut microbiota and immune cells might be complex, and the gut microbiota could affect carcinogenesis through immune cells in a variety of ways including inflammatory signaling with intestinal epithelium [114,115]. A causal relationship between gut microbiota, immune cells, and breast cancer, underlining the critical role of the gut microbiota in regulating immune responses and its potential importance in breast cancer has also been shown [116]. The gut microbiota is capable of generating several metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and lactic acid. These metabolites can regulate the immune response by activating immune cells, thus maintaining the immune homeostasis of the gut mucosa [117]. The SCFAs have been suggested to regulate the development of breast cancer. The microbiota could also reprogram the gut lipid metabolism by inhibiting the expression of lncRNA such as Snhg9 in gut epithelial cells, which could promote cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [118]. Patterns of mammary gland miRNA expression may also provide some clues to their dysregulated role in the development of breast cancer [17,119] (Fig. 2). Inflammation mediators can alter the gene and ncRNA expression in mammary cells, leading to the development of a cancer stem cell (CSC) phenotype, which can contribute to the onset of breast cancer [120]. By epigenetic regulation, the gut microbiota could also modify the host physiological process via the alteration of ncRNAs [121]. An intricate regulatory network exists between the host and the microbiota, and elucidating this complicated network may be required for future cancer research. Interactions of various ncRNAs with the gut microbiota would influence tumor development and therapy, as the gut microbiota with ncRNAs has been identified to possess a close association with the immune system [122]. For example, colonization of the gut microbiota can assist the neonatal immune system in establishing immune tolerance [122]. Gut microbiota could also influence the development of several immune organs such as the spleen and thymus [123], which can enhance the intrinsic immune defense system by stimulating Toll-like receptors and/or the complement system [124]. Again, gut microbiota could control adaptive immune responses by affecting the function of dendritic cells (DCs) as well as adjusting the antibody production of immune B cells [125]. These effects may be essential for the regulation of the host’s inflammatory responses. Interestingly, it has been shown that Tob1 can exhibit close associations with infiltrating Treg cells in pancreatic cancer, suggesting its involvement in the control of Treg cell function [126], which may reduce the number of Treg cells [127]. Treg cells can construct an immunosuppressive microenvironment through the secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines, thereby facilitating the escape of cancer cells from immune systemic cancer surveillance shown in urologic malignancies [128]. Although these findings have been obtained from non-breast cancers, we believe that further elucidation of the interaction between the host microbiota and ncRNAs involved in the regulation of immune surveillance might also clarify the phenotypic roles of breast cancer (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: A schematic representation and hypothetical overview of the gut microbiota and ncRNAs therapy against breast cancers. Certain gut microbiota could contribute to the potentiation of the immune checkpoint immunotherapy with the improvement of Th17/Treg immune cell balance. Some kinds of probiotics and/or FMT could contribute to the alteration of the gut microbial community for playing valuable roles in cancer therapy with the alteration of ncRNAs and APRO family proteins. APRO family proteins could further stimulate the cytotoxic T cells. Examples of certain microbial species with several effects on immune responses have been shown. The arrowhead indicates stimulation (or bidirectional stimulation), whereas the hammerhead shows inhibition. Note that several important activities such as cytokine induction have been omitted for clarity. Abbreviation: APROs, APRO family proteins; miRNAs: microRNAs; PD1, programmed cell death protein 1; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4.

6 Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

Traditional treatments for breast cancer mainly include radiotherapy, chemotherapy, surgical excision, and/or novel immunotherapies. Among the available treatments for breast cancer, the combination of cancer therapies is the first-line treatment [129]. High-risk patients of breast cancer may take simultaneous chemotherapy, which may include the PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors [130]. Although these cancer therapies may play an imperative role in the treatment of breast cancers, which has several limitations with adverse effects. In contrast, the ncRNAs-related therapy has potential advantages over the conventional treatment. For example, ncRNA therapies may be specific reducing the impact on normal/noncancerous cells, which can interfere with the biological behavior of cancer cells from a specific perspective (Fig. 1). Therefore, ncRNA therapies may have superior safety with fewer adverse effects [131]. Interestingly, it has been found that many ncRNAs involved in metformin anticancer therapy have been identified [132]. The interaction between the host and the gut microbiota forms a complex and intricate regulatory network. Importantly, several ncRNAs have emerged as important mediators and/or outputs of this communication. The role of ncRNAs in host-microbiome interactions as well as their influence on breast cancers has been increasing attention. Clarifying these relationships with APRO family proteins would provide valuable insights into the prevention/treatment of breast cancers (Fig. 3).

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Akari Fukumoto and Satoru Matsuda; draft manuscript preparation: Akari Fukumoto and Satoru Matsuda; review and editing: Akari Fukumoto and Satoru Matsuda; visualization: Akari Fukumoto and Satoru Matsuda; supervision: Satoru Matsuda. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| ANA | Abundant in Neuroepithelium Area |

| BTG1 | B-cell translocation gene 1 |

| BTG2 | B-cell translocation gene 2 |

| circRNAs | Circular RNAs |

| CSC | Cancer stem cell |

| CTLA4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| FMT | Fecal microbiota transplantation |

| lncRNAs | Long non-coding |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| miRNAs | Micro RNAs |

| mTOR | Mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| ncRNAs | Non-coding RNAs |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor-kappa B |

| PD1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| QOL | Quality of life |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| Th17 | T helper 17 cell |

| Tob1 | Transducer of ERBB2, 1 |

| Tob2 | Transducer of ERBB2, 2 |

| Treg | Regulatory T cell |

References

1. Kawiak A. Molecular research and treatment of breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(17):9617. doi:10.3390/ijms23179617. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Arnold M, Morgan E, Rumgay H, Mafra A, Singh D, Laversanne M, et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast. 2022;66(8):15–23. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2022.08.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Huang L, Jiang C, Yan M, Wan W, Li S, Xiang Z, et al. The oral-gut microbiome axis in breast cancer: from basic research to therapeutic applications. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1413266. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2024.1413266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Chen J, Douglass J, Prasath V, Neace M, Atrchian S, Manjili MH, et al. The microbiome and breast cancer: a review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;178(3):493–6. doi:10.1007/s10549-019-05407-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Schluter J, Peled JU, Taylor BP, Markey KA, Smith M, Taur Y, et al. The gut microbiota is associated with immune cell dynamics in humans. Nature. 2020;588(7837):303–7. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2971-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(6):607–15. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Fernández MF, Reina-Pérez I, Astorga JM, Rodríguez-Carrillo A, Plaza-Díaz J, Fontana L. Breast cancer and its relationship with the microbiota. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(8):1747. doi:10.3390/ijerph15081747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Parida S, Sharma D. The power of small changes: comprehensive analyses of microbial dysbiosis in breast cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2019;1871(2):392–405. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2019.04.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Walker MM, Talley NJ. Review article: bacteria and pathogenesis of disease in the upper gastrointestinal tract—beyond the era of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(8):767–79. doi:10.1111/apt.12666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Davis CP, Cohen MS, Gruber MB, Anderson MD, Warren MM. Urothelial hyperplasia and neoplasia: a response to chronic urinary tract infections in rats. J Urol. 1984;132(5):1025–31. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49992-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Whiteside SA, Razvi H, Dave S, Reid G, Burton JP. The microbiome of the urinary tract—a role beyond infection. Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12(2):81–90. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2014.361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Schroeder BO, Bäckhed F. Signals from the gut microbiota to distant organs in physiology and disease. Nat Med. 2016;22(10):1079–89. doi:10.1038/nm.4185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Luo P, Zheng L, Zou J, Chen T, Zou J, Li W, et al. Insights into vitamin A in bladder cancer, lack of attention to gut microbiota? Front Immunol. 2023;14:1252616. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1252616. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Molinero N, Ruiz L, Sánchez B, Margolles A, Delgado S. Intestinal bacteria interplay with bile and cholesterol metabolism: implications on host physiology. Front Physiol. 2019;10:185. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.00185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Walter CEJ, Durairajan S, Periyandavan K, George Priya Doss C, Dicky John Davis G, Hannah Rachel Vasanthi A, et al. Bladder neoplasms and NF-κB: an unfathomed association. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2020;20(5):497–508. doi:10.1080/14737159.2020.1743688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Parida S, Sharma D. Microbial alterations and risk factors of breast cancer: connections and mechanistic insights. Cells. 2020;9(5):1091. doi:10.3390/cells9051091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wu D, Thompson LU, Comelli EM. microRNAs: a link between mammary gland development and breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(24):15978. doi:10.3390/ijms232415978. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Ratti M, Lampis A, Ghidini M, Salati M, Mirchev MB, Valeri N, et al. microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) as new tools for cancer therapy: first steps from bench to bedside. Target Oncol. 2020;15(3):261–78. doi:10.1007/s11523-020-00717-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Saw PE, Xu X, Chen J, Song EW. Non-coding RNAs: the new central dogma of cancer biology. Sci China Life Sci. 2021;64(1):22–50. doi:10.1007/s11427-020-1700-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Palazzo AF, Koonin EV. Functional long non-coding RNAs evolve from junk transcripts. Cell. 2020;183(5):1151–61. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Cai Z, Cao C, Ji L, Ye R, Wang D, Xia C, et al. RIC-seq for global in situ profiling of RNA-RNA spatial interactions. Nature. 2020;582(7812):432–7. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2249-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zong Y, Wang X, Cui B, Xiong X, Wu A, Lin C, et al. Decoding the regulatory roles of non-coding RNAs in cellular metabolism and disease. Mol Ther. 2023;31(6):1562–76. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.04.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Nemeth K, Bayraktar R, Ferracin M, Calin GA. Non-coding RNAs in disease: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Nat Rev Genet. 2024;25(3):211–32. doi:10.1038/s41576-023-00662-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Li Y, Li G, Guo X, Yao H, Wang G, Li C. Non-coding RNA in bladder cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020;485:38–44. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2020.04.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Huang D, Chen J, Yang L, Ouyang Q, Li J, Lao L, et al. NKILA lncRNA promotes tumor immune evasion by sensitizing T cells to activation-induced cell death. Nat Immunol. 2018;19(10):1112–25. doi:10.1038/s41590-018-0207-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(30):10513–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Li Q, Liu M, Ma F, Luo Y, Cai R, Wang L, et al. Circulating miR-19a and miR-205 in serum may predict the sensitivity of luminal A subtype of breast cancer patients to neoadjuvant chemotherapy with epirubicin plus paclitaxel. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104870. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104870. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Shen L, Wan Z, Ma Y, Wu L, Liu F, Zang H, et al. The clinical utility of microRNA-21 as novel biomarker for diagnosing human cancers. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(3):1993–2005. doi:10.1007/s13277-014-2806-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Winter J, Jung S, Keller S, Gregory RI, Diederichs S. Many roads to maturity: microrna biogenesis pathways and their regulation. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(3):228–34. doi:10.1038/ncb0309-228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Singh R, Pochampally R, Watabe K, Lu Z, Mo YY. Exosome-mediated transfer of miR-10b promotes cell invasion in breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2014;13(1):256. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-13-256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Fattahi M, Rezaee D, Fakhari F, Najafi S, Aghaei-Zarch SM, Beyranvand P, et al. microRNA-184 in the landscape of human malignancies: a review to roles and clinical significance. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9(1):423. doi:10.1038/s41420-023-01718-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wang WT, Han C, Sun YM, Chen TQ, Chen YQ. Noncoding RNAs in cancer therapy resistance and targeted drug development. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):55. doi:10.1186/s13045-019-0748-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Chang JT, Wang F, Chapin W, Huang RS. Identification of microRNAs as breast cancer prognosis markers through the cancer genome atlas. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0168284. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Levin AA. Treating disease at the RNA level with oligonucleotides. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):57–70. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1705346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Weiten R, Engler T, Schorle H, Ellinger J, Saponaro M, Alajati A, et al. The new tumour biomarker miRNA-371-3p influences cisplatin sensitivity of testicular germ cell tumour cell lines. J Cell Mol Med. 2024;28(24):e70314. doi:10.1111/jcmm.70314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Sárközy M, Kahán Z, Csont T. A myriad of roles of miR-25 in health and disease. Oncotarget. 2018;9(30):21580–612. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.24662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Wang X, Meng X, Li H, Liu W, Shen S, Gao Z. microRNA-25 expression level is an independent prognostic factor in epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2014;16(11):954–8. doi:10.1007/s12094-014-1178-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Wen Y, Han J, Chen J, Dong J, Xia Y, Liu J, et al. Plasma miRNAs as early biomarkers for detecting hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(7):1679–90. doi:10.1002/ijc.29544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Jia Y, Lu H, Wang C, Wang J, Zhang C, Wang F, et al. miR-25 is upregulated before the occurrence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Transl Res. 2017;9(10):4458–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

40. Dong J, Tai JW, Lu LF. miRNA-microbiota interaction in gut homeostasis and colorectal cancer. Trends Cancer. 2019;5(11):666–9. doi:10.1016/j.trecan.2019.08.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Liu S, da Cunha AP, Rezende RM, Cialic R, Wei Z, Bry L, et al. The host shapes the gut microbiota via fecal microRNA. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(1):32–43. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2015.12.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Rodríguez-Nogales A, Algieri F, Garrido-Mesa J, Vezza T, Utrilla MP, Chueca N, et al. Differential intestinal anti-inflammatory effects of Lactobacillus fermentum and Lactobacillus salivarius in DSS mouse colitis: impact on microRNAs expression and microbiota composition. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61(11):5185. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201700144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Wade H, Pan K, Duan Q, Kaluzny S, Pandey E, Fatumoju L, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila and its membrane protein ameliorates intestinal inflammatory stress and promotes epithelial wound healing via CREBH and miR-143/145. J Biomed Sci. 2023;30(1):38. doi:10.1186/s12929-023-00935-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Bao H, Kommadath A, Liang G, Sun X, Arantes AS, Tuggle CK, et al. Genome-wide whole blood microRNAome and transcriptome analyses reveal miRNA-mRNA regulated host response to foodborne pathogen Salmonella infection in swine. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):12620. doi:10.1038/srep12620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Wang F, Liu J, Zou Y, Jiao Y, Huang Y, Fan L, et al. microRNA-143-3p, up-regulated in H. pylori-positive gastric cancer, suppresses tumor growth, migration and invasion by directly targeting AKT2. Oncotarget. 2017;8(17):28711–24. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.15646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Roy BC, Subramaniam D, Ahmed I, Jala VR, Hester CM, Greiner KA, et al. Role of bacterial infection in the epigenetic regulation of Wnt antagonist WIF1 by PRC2 protein EZH2. Oncogene. 2015;34(34):4519–30. doi:10.1038/onc.2014.386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Xue X, Feng T, Yao S, Wolf KJ, Liu CG, Liu X, et al. Microbiota downregulates dendritic cell expression of miR-10a, which targets IL-12/IL-23p40. J Immunol. 2011;187(11):5879–86. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1100535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Cheng J, Duncan AE, Kau AL, et al. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science. 2013;341(6150):1241214. doi:10.1126/science.1241214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Pascale A, Marchesi N, Marelli C, Coppola A, Luzi L, Govoni S, et al. Microbiota and metabolic diseases. Endocrine. 2018;61(3):357–71. doi:10.1007/s12020-018-1605-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Dahl WJ, Rivero Mendoza D, Lambert JM. Diet, nutrients and the microbiome. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2020;171(8):237–63. doi:10.1016/bs.pmbts.2020.04.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Camilleri M. Leaky gut: mechanisms, measurement and clinical implications in humans. Gut. 2019;68(8):1516–26. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Régnier M, Van Hul M, Knauf C, Cani PD. Gut microbiome, endocrine control of gut barrier function and metabolic diseases. J Endocrinol. 2021;248(2):R67–82. doi:10.1530/JOE-20-0473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Hu S, Liu L, Chang EB, Wang JY, Raufman JP. Butyrate inhibits pro-proliferative miR-92a by diminishing c-Myc-induced miR-17-92a cluster transcription in human colon cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2015;14(1):180. doi:10.1186/s12943-015-0450-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Yoo J, Groer M, Dutra S, Sarkar A, McSkimming D. Gut microbiota and immune system interactions. Microorganisms. 2020;8(10):1587. doi:10.3390/microorganisms8101587. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Schulthess J, Pandey S, Capitani M, Rue-Albrecht KC, Arnold I, Franchini F, et al. The short chain fatty acid butyrate imprints an antimicrobial program in macrophages. Immunity. 2019;50(2):432–45.e7. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2018.12.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Brusnic O, Onisor D, Boicean A, Hasegan A, Ichim C, Guzun A, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation: insights into colon carcinogenesis and immune regulation. J Clin Med. 2024;13(21):6578. doi:10.3390/jcm13216578. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Yang Y, Weng W, Peng J, Hong L, Yang L, Toiyama Y, et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum increases proliferation of colorectal cancer cells and tumor development in mice by activating toll-like receptor 4 signaling to nuclear factor-κB, and up-regulating expression of microRNA-21. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):851–66.e24. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Cougnoux A, Dalmasso G, Martinez R, Buc E, Delmas J, Gibold L, et al. Bacterial genotoxin colibactin promotes colon tumour growth by inducing a senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Gut. 2014;63(12):1932–42. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Ruo SW, Alkayyali T, Win M, Tara A, Joseph C, Kannan A, et al. Role of gut microbiota dysbiosis in breast cancer and novel approaches in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Cureus. 2021;13(8):e17472. doi:10.7759/cureus.17472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Yan W, Xiang S, Feng J, Zu X. Role of ubiquitin-specific proteases in programmed cell death of breast cancer cells. Genes Dis. 2024;12(3):101341. doi:10.1016/j.gendis.2024.101341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Wang H, Wang Z, Zhang Z, Liu J, Hong L. β-sitosterol as a promising anticancer agent for chemoprevention and chemotherapy: mechanisms of action and future prospects. Adv Nutr. 2023;14(5):1085–110. doi:10.1016/j.advnut.2023.05.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Barbour AB, Kotecha R, Lazarev S, Palmer JD, Robinson T, Yerramilli D, et al. Radiation therapy in the management of leptomeningeal disease from solid tumors. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2023;9(2):101377. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2023.101377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Liang F, Liang H, Li Z, Huang P. JAK3 is a potential biomarker and associated with immune infiltration in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;86:106706. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Lee HS, Kundu J, Kim RN, Shin YK. Transducer of ERBB2.1 (TOB1) as a tumor suppressor: a mechanistic perspective. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(12):29815–28. doi:10.3390/ijms161226203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Lin S, Zhu Q, Xu Y, Liu H, Zhang J, Xu J, et al. The role of the TOB1 gene in growth suppression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2012;4(5):981–7. doi:10.3892/ol.2012.864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. O’Malley S, Su H, Zhang T, Ng C, Ge H, Tang CK. TOB suppresses breast cancer tumorigenesis. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(8):1805–13. doi:10.1002/ijc.24490. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Guo H, Ji F, Zhao X, Yang X, He J, Huang L, et al. MicroRNA-371a-3p promotes progression of gastric cancer by targeting TOB1. Cancer Lett. 2019;443:179–88. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2018.11.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Kundu J, Wahab SM, Kundu JK, Choi YL, Erkin OC, Lee HS, et al. Tob1 induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells by activating Smad4 and inhibiting β-catenin signaling. Int J Oncol. 2012;41(3):839–48. doi:10.3892/ijo.2012.1517. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Jiao Y, Sun KK, Zhao L, Xu JY, Wang LL, Fan SJ. Suppression of human lung cancer cell proliferation and metastasis in vitro by the transducer of ErbB-2.1 (TOB1). Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012;33(2):250–60. doi:10.1038/aps.2011.163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Wu D, Zhou W, Wang S, Zhou Z, Wang S, Chen L. Tob1 enhances radiosensitivity of breast cancer cells involving the JNK and p38 pathways. Cell Biol Int. 2015;39(12):1425–30. doi:10.1002/cbin.10545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Zhang YW, Nasto RE, Varghese R, Jablonski SA, Serebriiskii IG, Surana R, et al. Acquisition of estrogen independence induces TOB1-related mechanisms supporting breast cancer cell proliferation. Oncogene. 2016;35(13):1643–56. doi:10.1038/onc.2015.226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Chen H, Pan H, Qian Y, Zhou W, Liu X. miR-25-3p promotes the proliferation of triple negative breast cancer by targeting BTG2. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):4. doi:10.1186/s12943-017-0754-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Zou X, Xia T, Li M, Wang T, Liu P, Zhou X, et al. microRNA profiling in serum: potential signatures for breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer Biomark. 2021;30(1):41–53. doi:10.3233/CBM-201547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Zhang H, Tang J, Li C, Kong J, Wang J, Wu Y, et al. miR-22 regulates 5-FU sensitivity by inhibiting autophagy and promoting apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2015;356(2 Pt B):781–90. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2014.10.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Nan YH, Wang J, Wang Y, Sun PH, Han YP, Fan L, et al. MiR-4295 promotes cell growth in bladder cancer by targeting BTG1. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8(11):4892–901. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

76. He C, Yu T, Shi Y, Ma C, Yang W, Fang L, et al. microRNA 301A promotes intestinal inflammation and colitis-associated cancer development by inhibiting BTG1. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(6):1434–48.e15. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Zhang SQ, Yang Z, Cai XL, Zhao M, Sun MM, Li J, et al. miR-511 promotes the proliferation of human hepatoma cells by targeting the 3'UTR of B cell translocation gene 1 (BTG1) mRNA. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38(8):1161–70. doi:10.1038/aps.2017.62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Zhao X, Chen GQ, Cao GM. Abnormal expression and mechanism of miR-330-3p/BTG1 axis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23(16):6888–98. doi:10.26355/eurrev_201908_18728. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Ni Z, Shen Y, Wang W, Cheng X, Fu Y. miR-141-5p affects the cell proliferation and apoptosis by targeting BTG1 in cervical cancer. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2024;39(6):395–405. doi:10.1089/cbr.2021.0227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Cheng Q, Li Q, Xu L, Jiang H. Exosomal microRNA-301a-3p promotes the proliferation and invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by targeting BTG1 mRNA. Mol Med Rep. 2021;23(5):328. doi:10.3892/mmr.2021.11967. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Busson M, Carazo A, Seyer P, Grandemange S, Casas F, Pessemesse L, et al. Coactivation of nuclear receptors and myogenic factors induces the major BTG1 influence on muscle differentiation. Oncogene. 2005;24(10):1698–710. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1208373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Zhang S, Gu J, Shi LL, Qian B, Diao X, Jiang X, et al. A pan-cancer analysis of anti-proliferative protein family genes for therapeutic targets in cancer. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):21607. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-48961-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Winkler GS. The mammalian anti-proliferative BTG/Tob protein family. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222(1):66–72. doi:10.1002/jcp.21919. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Ikeda Y, Taniguchi K, Sawamura H, Yoshikawa S, Tsuji A, Matsuda S. Presumed roles of APRO family proteins in cancer invasiveness. Cancers. 2022;14(19):4931. doi:10.3390/cancers14194931. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Ikeda Y, Morikawa S, Nakashima M, Yoshikawa S, Taniguchi K, Sawamura H, et al. CircRNAs and RNA-binding proteins involved in the pathogenesis of cancers or central nervous system disorders. Noncoding RNA. 2023;9(2):23. doi:10.3390/ncrna9020023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Tzachanis D, Lafuente EM, Li L, Boussiotis VA. Intrinsic and extrinsic regulation of T lymphocyte quiescence. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45(10):1959–67. doi:10.1080/1042819042000219494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Tzachanis D, Freeman GJ, Hirano N, van Puijenbroek AA, Delfs MW, Berezovskaya A, et al. Tob is a negative regulator of activation that is expressed in anergic and quiescent T cells. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(12):1174–82. doi:10.1038/ni730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Corvol JC, Pelletier D, Henry RG, Caillier SJ, Wang J, Pappas D, et al. Abrogation of T cell quiescence characterizes patients at high risk for multiple sclerosis after the initial neurological event. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(33):11839–44. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805065105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Lin R, Ma C, Fang L, Xu C, Zhang C, Wu X, et al. TOB1 blocks intestinal mucosal inflammation through inducing ID2-mediated suppression of Th1/Th17 cell immune responses in IBD. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;13(4):1201–21. doi:10.1016/j.jcmgh.2021.12.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Fonseca-Camarillo G, Furuzawa-Carballeda J, Priego-Ranero ÁA, Martínez-Benítez B, Barreto-Zúñiga R, Yamamoto-Furusho JK. Expression of TOB/BTG family members in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Immunol. 2021;93(4):e13004. doi:10.1111/sji.13004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Bai Y, Qiao L, Xie N, Li Y, Nie Y, Pan Y, et al. TOB1 suppresses proliferation in K-Ras wild-type pancreatic cancer. Cancer Med. 2020;9(4):1503–14. doi:10.1002/cam4.2756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Guo H, Zhang R, Afrifa J, Wang Y, Yu J. Decreased expression levels of DAL-1 and TOB1 are associated with clinicopathological features and poor prognosis in gastric cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 2019;215(6):152403. doi:10.1016/j.prp.2019.03.031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Dong Z, Zhang G, Lu J, Guo Y, Liang J, Shen S, et al. Methylation mediated downregulation of TOB1-AS1 and TOB1 correlates with malignant progression and poor prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68(4):1316–31. doi:10.1007/s10620-022-07664-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Wang D, Li Y, Sui S, Cai M, Dong K, Wang P, et al. Involvement of TOB1 on autophagy in gastric cancer AGS cells via decreasing the activation of AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. PeerJ. 2022;10(8):e12904. doi:10.7717/peerj.12904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Delage L, Lambert M, Bardel É, Kundlacz C, Chartoire D, Conchon A, et al. BTG1 inactivation drives lymphomagenesis and promotes lymphoma dissemination through activation of BCAR1. Blood. 2023;141(10):1209–20. doi:10.1182/blood.2022016943. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Mlynarczyk C, Teater M, Pae J, Chin CR, Wang L, Arulraj T, et al. BTG1 mutation yields supercompetitive B cells primed for malignant transformation. Science. 2023;379(6629):eabj7412. doi:10.1126/science.abj7412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Tong H, Zhao K, Wang J, Xu H, Xiao J. CircZNF609/miR-134-5p/BTG-2 axis regulates proliferation and migration of glioma cell. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2020;72(1):68–75. doi:10.1111/jphp.13188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Wang R, Wang R, Tian J, Wang J, Tang H, Wu T, et al. BTG2 as a tumor target for the treatment of luminal A breast cancer. Exp Ther Med. 2022;23(5):339. doi:10.3892/etm.2022.11269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Yuniati L, Scheijen B, van der Meer LT, van Leeuwen FN. Tumor suppressors BTG1 and BTG2: beyond growth control. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(5):5379–89. doi:10.1002/jcp.27407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. An Q, Zhou Y, Han C, Zhou Y, Li F, Li D. BTG3 overexpression suppresses the proliferation and invasion in epithelial ovarian cancer cell by regulating AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin signaling. Reprod Sci. 2017;24(10):1462–8. doi:10.1177/1933719117691143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Germain C, Gnjatic S, Tamzalit F, Knockaert S, Remark R, Goc J, et al. Presence of B cells in tertiary lymphoid structures is associated with a protective immunity in patients with lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(7):832–44. doi:10.1164/rccm.201309-1611OC. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Valdor R, MacIan F. Induction and stability of the anergic phenotype in T cells. Semin Immunol. 2013;25(4):313–20. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2013.10.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Bista P, Mele DA, Baez DV, Huber BT. Lymphocyte quiescence factor Dpp2 is transcriptionally activated by KLF2 and TOB1. Mol Immunol. 2008;45(13):3618–23. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2008.05.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Heczey A, Xu X, Courtney AN, Tian G, Barragan GA, Guo L, et al. Anti-GD2 CAR-NKT cells in relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma: updated phase 1 trial interim results. Nat Med. 2023;29(6):1379–88. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02363-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Mima K, Nakagawa S, Sawayama H, Ishimoto T, Imai K, Iwatsuki M, et al. The microbiome and hepatobiliary-pancreatic cancers. Cancer Lett. 2017;402:9–15. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2017.05.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Vogtmann E, Goedert JJ. Epidemiologic studies of the human microbiome and cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(3):237–42. doi:10.1038/bjc.2015.465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer CN, Nezi L, Reuben A, Andrews MC, Karpinets TV, et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2018;359(6371):97–103. doi:10.1126/science.aan4236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Monnot GC, Romero P. Rationale for immunological approaches to breast cancer therapy. Breast. 2018;37:187–95. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2017.06.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Corthay A. Does the immune system naturally protect against cancer? Front Immunol. 2014;5:197. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Alspach E, Lussier DM, Schreiber RD. Interferon γ and its important roles in promoting and inhibiting spontaneous and therapeutic cancer immunity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2019;11(3):a028480. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a028480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Alizadehmohajer N, Shojaeifar S, Nedaeinia R, Esparvarinha M, Mohammadi F, Ferns GA, et al. Association between the microbiota and women’s cancers—cause or consequences? Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;127(4):110203. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Hwang SW, Kim MK, Kweon MN. Gut microbiome on immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy and consequent immune-related colitis: a review. Intest Res. 2023;21(4):433–42. doi:10.5217/ir.2023.00019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Truan JS, Chen JM, Thompson LU. Flaxseed oil reduces the growth of human breast tumors (MCF-7) at high levels of circulating estrogen. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54(10):1414–21. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200900521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Yu LX, Schwabe RF. The gut microbiome and liver cancer: mechanisms and clinical translation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(9):527–39. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2017.72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Orberg ET, Fan H, Tam AJ, Dejea CM, Destefano Shields CE, Wu S, et al. The myeloid immune signature of enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis-induced murine colon tumorigenesis. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10(2):421–33. doi:10.1038/mi.2016.53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Lv R, Wang D, Wang T, Li R, Zhuang A. Causality between gut microbiota, immune cells, and breast cancer: mendelian randomization analysis. Medicine. 2024;103(49):e40815. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000040815. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Zhang L, Liu X, Liu Y, Cheng X, Xu M, Qu H, et al. Prebiotics enhance the immunomodulatory effect of Limosilactobacillus fermentum DALI02 by regulating intestinal homeostasis. Food Sci Nutr. 2024;12(10):7521–32. doi:10.1002/fsn3.4361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Wang Y, Wang M, Chen J, Li Y, Kuang Z, Dende C, et al. The gut microbiota reprograms intestinal lipid metabolism through long noncoding RNA Snhg9. Science. 2023;381(6660):851–7. doi:10.1126/science.ade0522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Yasavoli-Sharahi H, Shahbazi R, Alsadi N, Robichaud S, Kambli DB, Izadpanah A, et al. Edodes cultured extract regulates immune stress during puberty and modulates microRNAs involved in mammary gland development and breast cancer suppression. Cancer Med. 2024;13(19):e70277. doi:10.1002/cam4.70277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Ma Y, Zhu Y, Shang L, Qiu Y, Shen N, Wang J, et al. LncRNA XIST regulates breast cancer stem cells by activating proinflammatory IL-6/STAT3 signaling. Oncogene. 2023;42(18):1419–37. doi:10.1038/s41388-023-02652-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Malmuthuge N, Guan LL. Noncoding RNAs: regulatory molecules of host-microbiome crosstalk. Trends Microbiol. 2021;29(8):713–24. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2020.12.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Méndez CS, Bueno SM, Kalergis AM. Contribution of gut microbiota to immune tolerance in infants. J Immunol Res. 2021;2021(11):7823316. doi:10.1155/2021/7823316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Kayisoglu Ö, Schlegel N, Bartfeld S. Gastrointestinal epithelial innate immunity-regionalization and organoids as new model. J Mol Med. 2021;99(4):517–30. doi:10.1007/s00109-021-02043-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Cristofori F, Dargenio VN, Dargenio C, Miniello VL, Barone M, Francavilla R. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of probiotics in gut inflammation: a door to the body. Front Immunol. 2021;12:578386. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.578386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Kim M, Qie Y, Park J, Kim CH. Gut microbial metabolites fuel host antibody responses. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20(2):202–14. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. Xu W, Zhang W, Zhao D, Wang Q, Zhang M, Li Q, et al. Unveiling the role of regulatory T cells in the tumor microenvironment of pancreatic cancer through single-cell transcriptomics and in vitro experiments. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1242909. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1242909. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. May SL, Zhou Q, Lewellen M, Carter CM, Coffey D, Highfill SL, et al. Nfatc2 and Tob1 have non-overlapping function in T cell negative regulation and tumorigenesis. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100629. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Kübler H, Gschwend JE. Active immunotherapy of urologic malignancies and tumor-mediated immunosuppression. Urologe A. 2008;47(9):1122–7. doi:10.1007/s00120-008-1822-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

129. Nader-Marta G, Martins-Branco D, de Azambuja E. How we treat patients with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer. ESMO Open. 2022;7(1):100343. doi:10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

130. Fan W, Chen Y, Zhou Z, Duan W, Yang C, Sheng S, et al. An innovative antibody fusion protein targeting PD-L1, VEGF and TGF-β with enhanced antitumor efficacies. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;130:111698. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2024.111698. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

131. Wirges A, Bunse M, Joedicke JJ, Blanc E, Gudipati V, Moles MW, et al. EBAG9 silencing exerts an immune checkpoint function without aggravating adverse effects. Mol Ther. 2022;30(11):3358–78. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.07.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

132. Conceição IMCAD, Luscher-Dias T, Queiroz LR, de Melo AGB, Machado CR, Gomes KB, et al. Metformin treatment modulates long non-coding RNA isoforms expression in human cells. Noncoding RNA. 2022;8(5):68. doi:10.3390/ncrna8050068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools