Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) Hybrids: Strategic Crossbreeding Techniques to Efficiently Enhance Yield and Oil Quality

1 Wheat Research Institute, Ayub Agricultural Research Institute, Faisalabad, 38850, Pakistan

2 Department of Plant Breeding and Genetics, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, 38040, Pakistan

3 Mid-Florida Research & Education Center, Department of Horticultural Sciences, University of Florida, Apopka, FL 32703, USA

4 Center of Agricultural Biochemistry and Biotechnology, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, 38040, Pakistan

5 Oilseeds Research Institute (ORI), Ayub Agricultural Research Institute (AARI), Faisalabad, 38850, Pakistan

* Corresponding Authors: Fida Hussain. Email: ; Muhammad Umer Farooq. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Enhancing Grain Yield: From Molecular Mechanisms to Sustainable Agriculture)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 3231-3249. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.069654

Received 27 June 2025; Accepted 28 September 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

The analysis of combining ability and heterosis is very important in enhancing the yield and oil quality of sunflowers under adverse conditions, and it reveals the potential of the parents and the mechanism of gene action. In this study, twenty-one hybrids were developed by crossing seven cytoplasmic male sterile (CMS) lines with three restorer lines and evaluated for agronomic and quality traits. Highly significant general combining ability (GCA) and specific combining ability (SCA) effects were observed, confirming the role of both additive and non-additive gene actions. Among the tested crosses, A-42 × R-86, A-92 × R-86, and A-92 × R-114 exhibited the greatest heterotic advantage, with seed yields exceeding 340 kg ha−1 over the better parent, oil contents above 19%, and 100-seed weights greater than 27 g. The hybrid A-92 × R-114 was particularly notable for its elevated oleic acid level and balanced fatty acid profile, making it a strong candidate for premium oilseed production. In contrast, hybrids like A-20 × R-39 exhibited moderate heterosis and less quality superiority. The oleic-to-linoleic acid ratio, a key determinant of oil stability, was strongly controlled by genetic factors. Oil content was largely influenced by additive effects, whereas yield heterosis was predominantly governed by non-additive effects. Overall, A-42 × R-86 and A-92 × R-114 emerged as the most promising hybrids, combining yield benefits with improved oil quality, and offering practical guidance for parental selection in sunflower breeding programs.Keywords

Supplementary Material

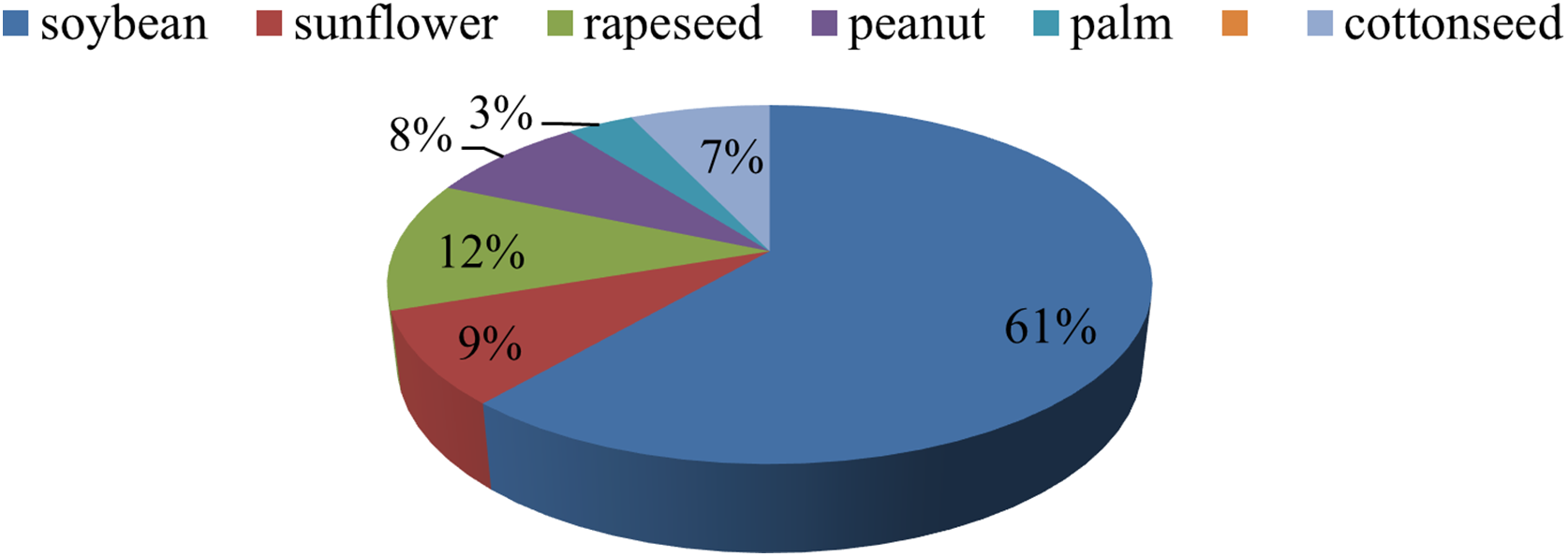

Supplementary Material FileThe global demand for food and energy is rising rapidly, driven by population growth and increasing consumption. To meet these needs, agricultural productivity must increase by an estimated 70%–100% by 2050 [1,2]. Edible oils serve a vital role in our diet because they provide us with energy, essential fatty acids, and valuable nutrients. They are also popular in cookery and have a variety of health benefits. Fats are a high-energy food, having over two times the amount of energy per gram than either protein or carbohydrates [3]. Four major crops, soybean, palm, brassica, and sunflower, together account for over 90% of global edible oil production (Fig. 1) [4]. Palm oil leads with nearly 40% of the market, followed by soybean (29%), brassica (13%), and sunflower (9%) [5]. This reliance on a few crops underscores the need to enhance their productivity, quality, and sustainability.

Figure 1: Global production shares of important oilseed crops

1.1 Global Importance of Sunflower

Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) is being cultivated successfully in all crop-growing continents of the world. It is the 2nd largest hybrid seed crop after corn [1,2] and the 3rd major oilseed crop in the world next to soybean and rape [3]. It is an oil as well as protein-rich crop, so it competes in both the oil market, led by palm oil, and the protein meal market led by soybean. Its seed contains about 35%–50% premium-quality edible oil [4] and a high-quality protein meal for animals after oil extraction [5]. It is also encouraged as a successful practice for earning a livelihood and the eradication of poverty in some parts of the world [6]. The area and production of sunflowers is 56 million tons from 27 million ha around the globe. Out of the 83 sunflower-growing countries in the world, 82% of the area and 87% of production is contributed by the top 10 countries. The Russian Federation, Ukraine, Argentina, China, and Turkey are the top 5 producers of sunflower seeds globally [7].

High yield with better quality is the most essential breeding objective throughout the world to eliminate hunger and malnutrition [8,9]. The oil quality is determined by the oleic: linoleic acid ratio: higher ratios enhance oxidative stability and shelf life (preferred for frying/industrial use), while lower ratios supply essential polyunsaturated fatty acids (nutritional value). Consistent use of saturated fats obtained either from animal or plant sources leads to serious health implications. Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the number one cause of death worldwide, and poor diet is the leading risk factor [10,11]. Diabetes mellitus, various types of cancers, and inflammations are some other malignant diseases of the present time. Sunflower seed oil is considered an excellent choice to curb these high-risk global diseases [12,13]. Furthermore, many other industries like pharmaceuticals, chemicals, cosmetics, honey, dairy, bird feed, and biodiesel production are also being promoted from sunflowers [14]. Nutritionists in recent times have recommended vegetable oil as a healthier form of dietary fats [15].

It is challenging to improve the yield because of its quantitatively controlled nature and dependence on many other contributing traits. For the successful transmission of genetic traits to enhance the yield potential of any crop, a plant breeder must have sound knowledge of all the involved genetic mechanisms [16].

Plant breeders hunt for improving yield and quality by harnessing genetic diversity, with heterosis and combining ability guiding the selection of superior parents and hybrids [17,18]. Sunflower breeding was revolutionized by the discovery of cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) by Leclercq (1969) and fertility restorer genes by Kinman (1970), which enabled large-scale hybrid seed production; since then, hybrids have replaced open-pollinated varieties worldwide, achieving 20%–40% yield gains, higher oil quality, and improved stress resistance, making sunflower the second most important hybrid seed crop after maize [19–22].

Previous combining ability studies in sunflower have mainly focused on yield and basic morphological traits, often overlooking oil quality parameters and fatty acid composition [23–25]. Developing inbred lines with superior combining abilities is essential for producing high-yielding hybrids. Combining ability reflects how different parental lines contribute genetically to hybrid performance. General combining ability (GCA), controlled largely by additive gene effects, measures the average performance of a line across many crosses and is valuable for identifying stable, high-potential parents for line development and recurrent selection. In contrast, specific combining ability (SCA), arising from non-additive effects such as dominance and epistasis, highlights unique cross combinations that outperform expectations, guiding the development of superior hybrids. Together, GCA and SCA offer a genetic outline that permits breeders to improve parent selection, forecast hybrid performance, and hasten genetic gains in sunflower breeding [23,24]. Heterosis and combining ability studies in sunflower breeding offer significant opportunities for creating hybrids with enhanced seed yield, improved oil quality, and greater resilience to environmental stresses [16]. These advancements will ultimately benefit both sunflower farmers and consumers by increasing productivity and crop reliability. The objectives of this study were to: (1) assess the heterosis levels in the hybrids developed, (2) Evaluate the General Combining Ability (GCA) of the restorer lines and CMS testers under study, (3) Estimate the Specific Combining Ability (SCA) of the hybrid crosses, (4) Analyze the nature and extent of gene actions and heritability, and (5) Examine the correlation between genetic distance, performance, heterosis, and combining ability for grain yield and related traits. The study could be helpful and serve as an impetus to uplift the deteriorating edible oil situation in the country by designing future breeding programs to attain high seed yield with better oil quality in sunflowers [26].

Pakistan faces a widening edible oil shortfall, importing more than 70% of its requirement, making sunflower improvement a state priority. Hybrid breeding exploiting heterosis for yield and oil content, combined with combining ability studies to recognize superior parents and cross combinations, proposes a sustainable pathway. This study appraises newly established sunflower hybrids for heterosis, combining ability, and yield–quality traits to guide the development of productive, climate-resilient hybrids for local conditions.

Unlike previous heterosis studies in sunflower that mostly stressed on yield or a limited set of morphological traits, this study advances the field by simultaneously evaluating yield mechanisms and oil quality (including fatty acid profile) traits, while integrating combining ability analysis to divide both additive and non-additive gene actions, thus providing a more inclusive understanding of heterosis for guiding hybrid development.

Sunflower has the potential to serve as the prime oilseed crop of Pakistan because of its proven yield potential and premium oil quality [21,27]. The crop is best suited in the many climatic zones as well as in different cropping systems in the country. It is obvious from the fact that it is maintaining its worldwide production share even as it is being shifted towards marginal areas in many parts of the world. One of its key advantages is that it can be harvested twice a year, making it adaptable to diverse regions of Pakistan [28]. Availability of hybrid seeds is another advantage as it offers higher seed yield due to hybrid vigor, disease resistance, fertilizer responsiveness, and increased seed setting and productivity. Shorter duration, lodging resistance, photo insensitivity, drought tolerance, high oil contents, and better adaptability are the other key characteristics [29,30]. All these features are making it the best potential oilseed crop, giving a new hope to the sinking oilseed industry of Pakistan.

2.1 Experimental Location, Climate, and Soil Properties

The study was executed in the fields of Oilseeds Research Institute (ORI) and University of Agriculture, Faisalabad (UAF) during 2020–2022 (latitude 31°4′ N, longitude 73°1′ E, altitude 610 ft). All the inbred lines were received from the Oilseeds Research Institute. The experimental site received a total of 210 mm of rainfall, supplemented with two irrigations at critical growth stages. With temperatures ranging from 10°C in January to 40°C in May during the crop-growing months, the Relative humidity averaged 60%. The experimental soil was found to be alkaline, having a pH of around 8.15, with deficient nitrogen and phosphorus macro nutrients and organic matter. Alkaline soil (pH 8.15) restricted micronutrient uptake, while heat stress during flowering and grain filling reduced seed set and altered fatty acid composition. These stresses amplified genotype × environment interactions and strengthened the role of non-additive effects. Despite this, certain genotypes confirmed resilience and adaptability under harsh environments.

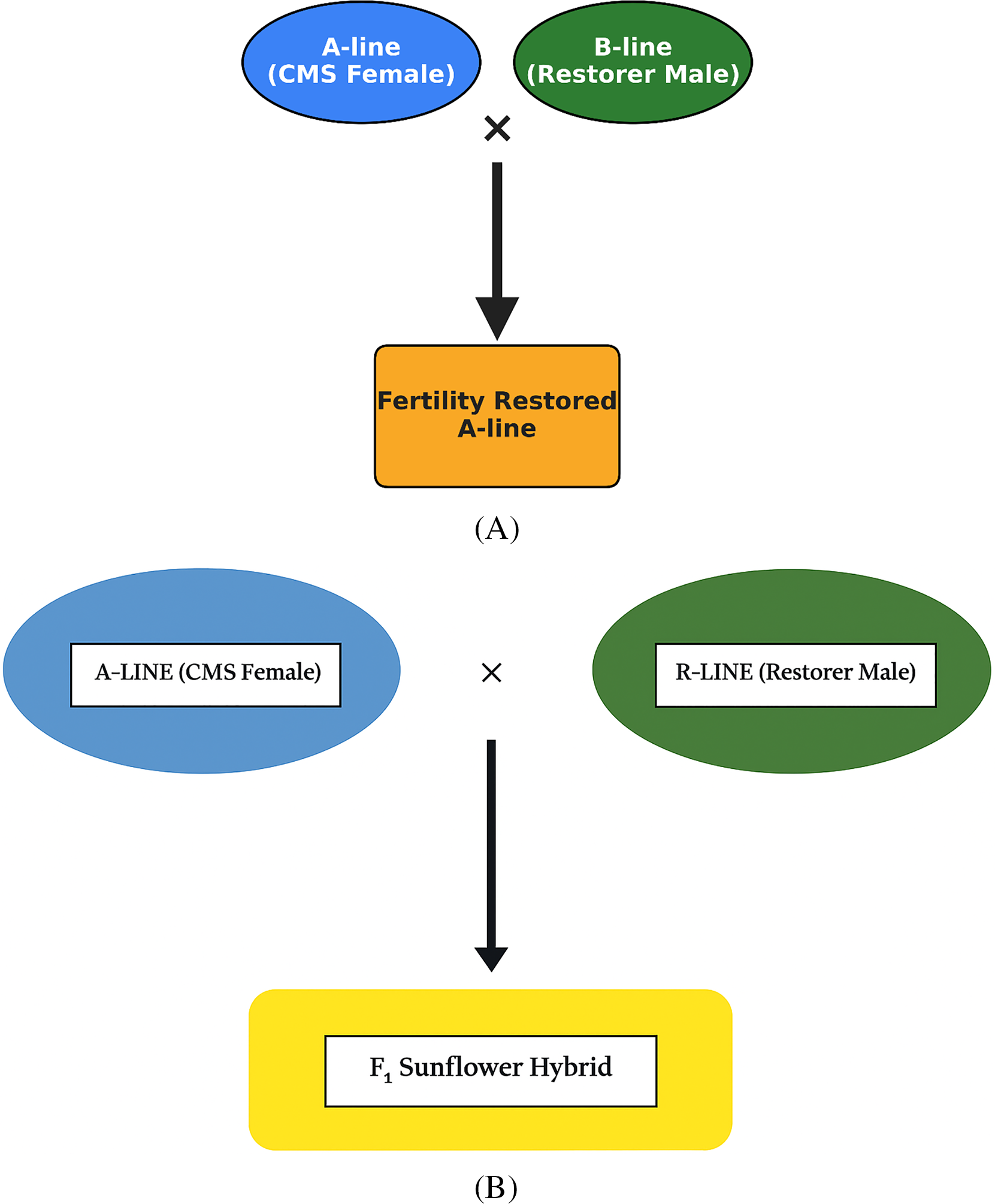

The scheme of seed production of inbred lines and sunflower hybrids is given in Fig. 2A,B.

Figure 2: (A) Process of seed production for A-line in sunflower. (B) Process of seed production for F1 sunflower hybrid

2.2 Agronomic Practices and Data Recording

Twenty-one (21) crosses were performed by using Seven (7) female inbred (A-lines) and three (3) male restorer lines (R-lines), followed by the method described by [18]. A detailed list of parents and their respective cross combinations is given in Table 1. The experimental plot for each genotype measured 4 m × 1.5 m. Fertilizers (NPK) were applied at a ratio of 148:99:62 kg/ha throughout the crop duration. All the Phosphorus and Potash were applied at the land preparation stage, but nitrogen was applied in three (3) installments. The genotypes were sown with the help of a dibbler; three seeds in one-inch depth were sown in each hole by maintaining plant-to-plant distance at 23 cm and row to row at 75 cm. Each genotype was thinned to one plant per hole at the leaf stage of the experiment, resulting in 16 plants per row, and five competitive plants were randomly selected from the central portion of each plot, avoiding border plants to minimize border effects. All the agronomic practices were kept constant during the entire experiment. Data was recorded for germination percentage (%; GP) plant height (cm; PH), stem thickness (cm; ST), days to flower initiation (DFI), days to 50% flowering (DFP), head diameter (cm; HD), achene yield per plant (gm; AYP), days to maturity (DTM), hundred seed weight (gm; HSW), number of leaves per plant (NLP), oil contents (%; OC), protein contents (%; PC), linoleic acid (%; LA) and oleic acid (%; OA). Trait measurements were recorded using standardized tools to ensure accuracy. Plant height was measured with a graduated meter rod (±0.5 cm), and stem thickness with a digital Vernier caliper (±0.01 mm). Head diameter and seed weight were measured using precision digital calipers and electronic balances (±0.001 g), respectively. Oil content was analyzed using a Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectrometer (Oxford MQA-7005, accuracy ±0.1%), while protein content was determined through the Kjeldahl method (Velp Scientifica analyzer). Fatty acid composition (oleic and linoleic acid) was assessed with Near-Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy (NIR; Perten DA 7250, Stockholm Sweden, accuracy ±0.01%). Most of the traits were measured at the R9 stage, while head diameter at the R6 stage.

Harvested sunflower heads were threshed, and seeds were cleaned, stable at 8%–10% moisture, and ground to ≤0.5 mm using a mill. For oil estimation, seed meal samples were analyzed by NMR spectrometer (Oxford MQA-7005); calibration was performed with certified oil standards, and three replicate readings per sample were averaged. Oleic and linoleic acid contents were determined by a non-destructive NIR spectrometer (Perten DA 7250) using whole seeds scanned in reflectance mode (850–2500 nm). Protein content was determined by the Kjeldahl method (digestion, distillation, titration), and moisture by oven-drying at 105°C for 24 h.

The experiment followed a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three replications. The data obtained was subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the formula provided by [31]. The ANOVA for combining ability was performed using the line × tester method. Correlation analysis was conducted based on Pearson’s method (1920). Heterosis and heterobeltiosis were calculated using the method outlined by [17]. Analysis was performed with the Software programs Statistica 14.0.0, Minitab 21, and R software 4.2.0.

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA):

To partition variability among genotypes, replications, and error:

Yij = μ + Gi + Rj + εij

where Yij = observation of the ith genotype in the jth replication, μ = overall mean, Gi = effect of the ith genotype, Rj = effect of the jth replication, εij = experimental error.

Estimation of Combining Abilities and Genetic Effects

GCA effects estimation

Testers effects: gt = {(x.j./lr) − (x…/006Ctr)}

Here,

l = Numbers of lines. t = Numbers of Ts. r = Numbers of reps. i = Number of inbred lines in inbred range. j = Number of testers from tester range. xi.. = Total F1 testers crossed ith line.

x.j. = All the crosses of jth tester with all the lines. x… = Total of all the crosses.

SCA effects estimation

Sij = {(xij./r) − (xi.../tr) − (x.j./lr) + (x…/ltr)

Here,

xij. = Total of F1 by crossing ith line with jth tester.

Assessment of additive variance (D) and dominance variance (H)

D = ∂ GCA/[(1 + F)/4]

H = ∂ SCA/[{(1 + F)/2}2]

Here,

Additive variance (D) and Dominance variance (H) were considered by taking inbreeding coefficient F = 1, as parents used were inbred.

Relative contribution of lines, testers, and their interaction to total variance

Contribution of lines = {SS (l)/SS (Crosses)} × 100

Contribution of testers = {SS (t)/SS (Crosses)} × 100

Contribution of (lxt) = {SS (lxt)/SS (Crosses)} × 100

Heterosis

Mid Parent Heterosis (MPH) = 100 × (F1 − MP)/MP

Better Parent Heterosis (BPH) = 100 × (F1 − BP)/BP

MP = [Female parent + Male parent]/2

MP heterosis = (F1 − MP)/(3/8 σ2e)½

BP heterosis = (F1 − BP)/(1/2 σ2e)½

Heritability

h2 = δ2 g/δ2 p

δ2 p = δ2g + δ2e, δ2g = (VMS − EMS)/r, δ2 e = EMS, δ2 g = genotypic variance,

δ2 p = Phenotypic variance, VMS = Variety mean square from ANOVA

EMS = Error mean square from ANOVA

An arbitrary scale for convenience was made, as follows, for the estimates of heritability.

High heritability = >0.5

Medium heritability = 0.2−0.5

Low heritability = <0.2

This study provides critical insights into the genetic architecture of key agronomic and quality traits in sunflower hybrids through combining ability analysis, heterosis estimation, and gene action studies. The findings have significant implications for hybrid breeding programs, guiding parental selection and cross-combination strategies to maximize yield and oil quality. This study used the PET1 cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) system, indispensable for commercial hybrid sunflower production because it offers a natural, stable, and cost-effective method of preventing self-pollination, eliminating the need for manual emasculation, and fertility in F1 hybrids is restored by dominant Rf genes from restorer lines, resulting in normal seed set.

CMS lines (A-lines) were resultant from the PET1 cytoplasm of Helianthus petiolaris [19] through backcrossing, inbreeding, and selection, with corresponding B-lines maintained for cytoplasmic stability. They signify diverse genetic backgrounds, carrying traits like earliness (A-106), high oil content (A-51), large head size (A-42), and short stature with lodging resistance (A-92). Restorer lines (R-lines), developed by recurrent selection and carrying dominant Rf genes [20], restore fertility and contribute to hybrid performance, with R-39 noted for adaptability and oil quality, R-86 for early maturity and yield, and R-114 for head size and disease resistance.

By using sterile female (A-lines) and fertile restorer (R-lines), breeders certify controlled cross-pollination, maintain genetic purity, and fully exploit heterosis, while restorer genes (Rf) restore fertility in the hybrids for normal seed production in farmers’ fields [19–21].

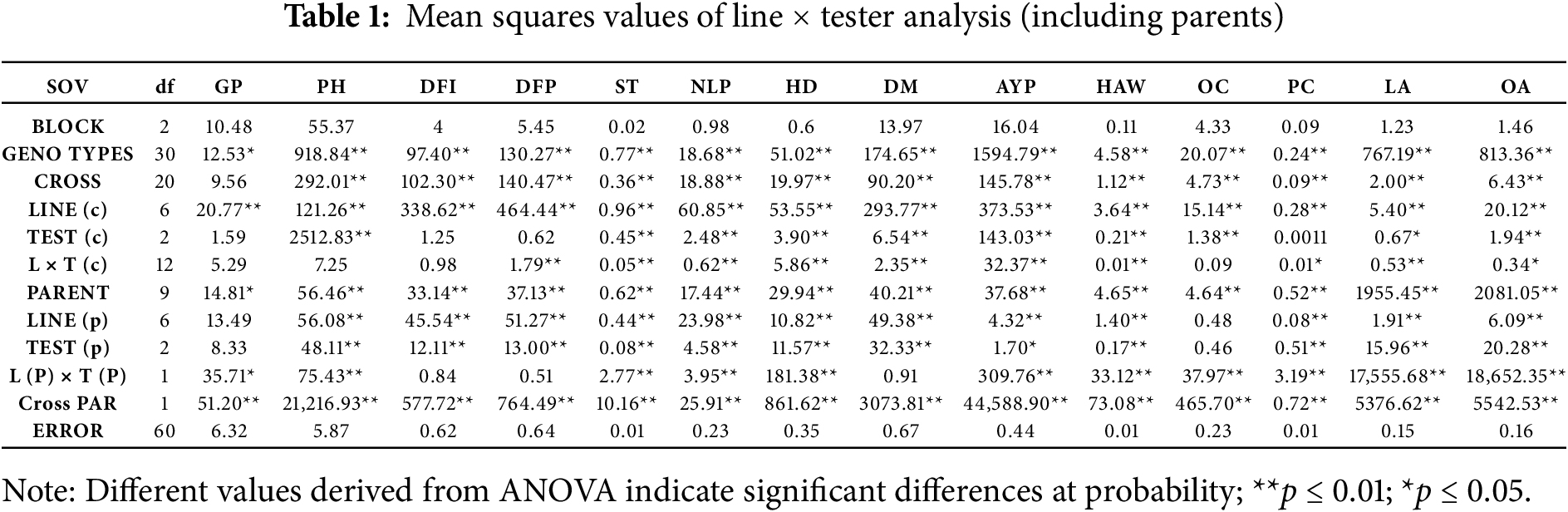

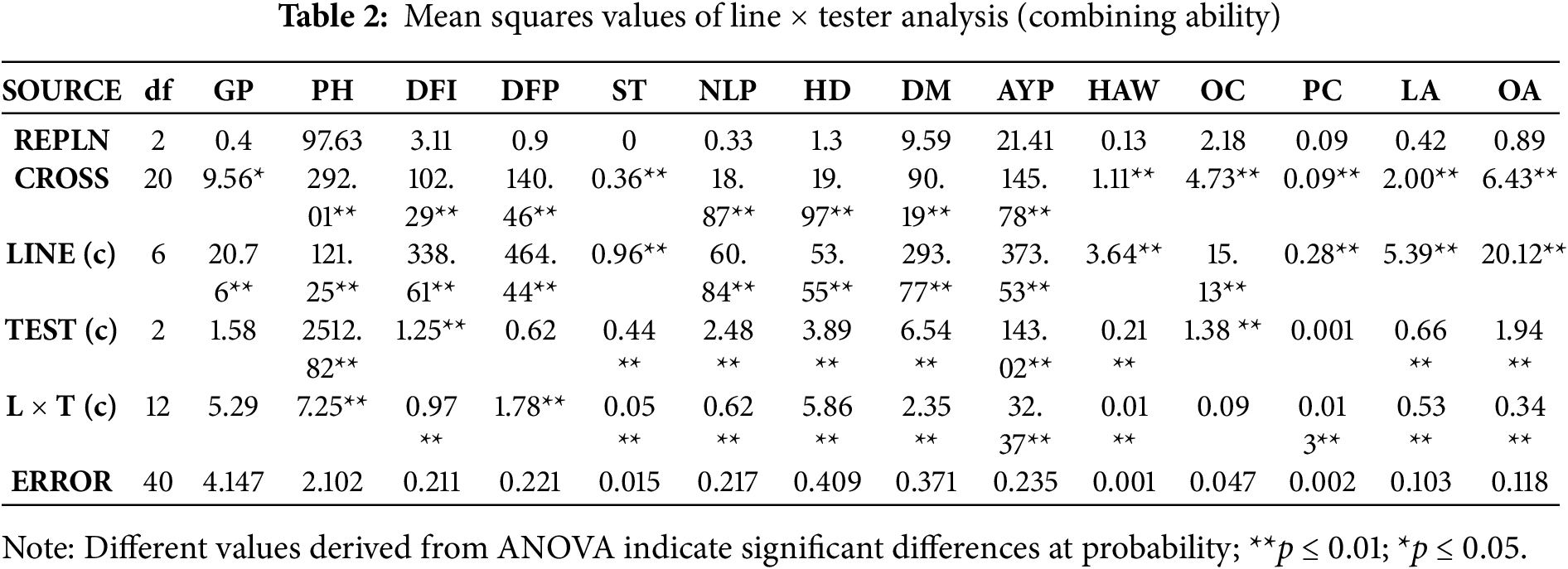

Highly significant differences were observed for all the traits under study except GP. Further breaking down of the ANOVA showed a similar pattern for parents and crosses, while the means of crosses and parents differed highly significantly for all the traits. In the case of crosses, lines showed significant differences for all traits, while testers were non-significant for GP, days to flower initiation (DFI), days to 50% flowering (DFP), and protein content (PC). However, L × T interaction was found to be non-significant for GP, PH, DFI, and OC, while highly significant for all the remaining traits (Table 1). It depicts the potential of significant yield improvement through non-additive gene action in this crop. This study also helps breeders develop smarter and higher-yielding hybrids by knowing the underlying genetic mechanisms. Similar results were observed for the combining ability ANOVA (Table 2) [16].

So, high variation was present for all the traits under study. The mean performance of all the traits can be observed in Table S1. The range for the parameters under study with mean value were: GP-88.3 to 95 (92.7), PH-124.3 to 176.3 (150.5), ST-2.3 to 4.3 (3.4), DFI-65 to 86.3 (73.4), DFP 68.7 to 91.3 (78.6), HD-9.3 to 29.1 (21.2), AYP-9.6 to 77.1 (48.5), DTM-96 to 23 (108.2), HSW-2.3 to 6.5 (5.1), NL-22 to 34.7 (28.2), OC-31 to 38.4 (35.6), PC-15 to 18.2 (16.8), MP-4.6 to 6.3 (5.7), LA-11.9 to 67.9 (25.3) and OA-16.4 to 74.6 (60.4). All by knowing the underlying genetic mechanism, the top yielders were hybrids with a maximum value of 77.1 by A-92 × R-86.

The average value of hybrids for all the traits was higher than both the A-lines and R-lines, with the exception of PC, LA, and OA. For PC, the highest mean value was found for R-lines, and the least for the hybrids. Similarly, R-lines also showed the highest mean value for LA but the lowest for A-lines. However, A-lines performed best for OA, followed by hybrids and testers. Furthermore, A-lines outbid R-lines for all the traits except for NL, PC, and LA. The hybrid A-106 × R-86 was identified as the shortest-duration sunflower hybrid, while A-42 × R-114 emerged as the longest-duration hybrid (Fig. 3). These short-duration and climate-resilient sunflower hybrids are the best fit in our prevailing climatic conditions as well as in our cropping pattern [32].

Figure 3: Comparison of short-duration sunflower hybrid (L = left) vs long-duration (R = right)

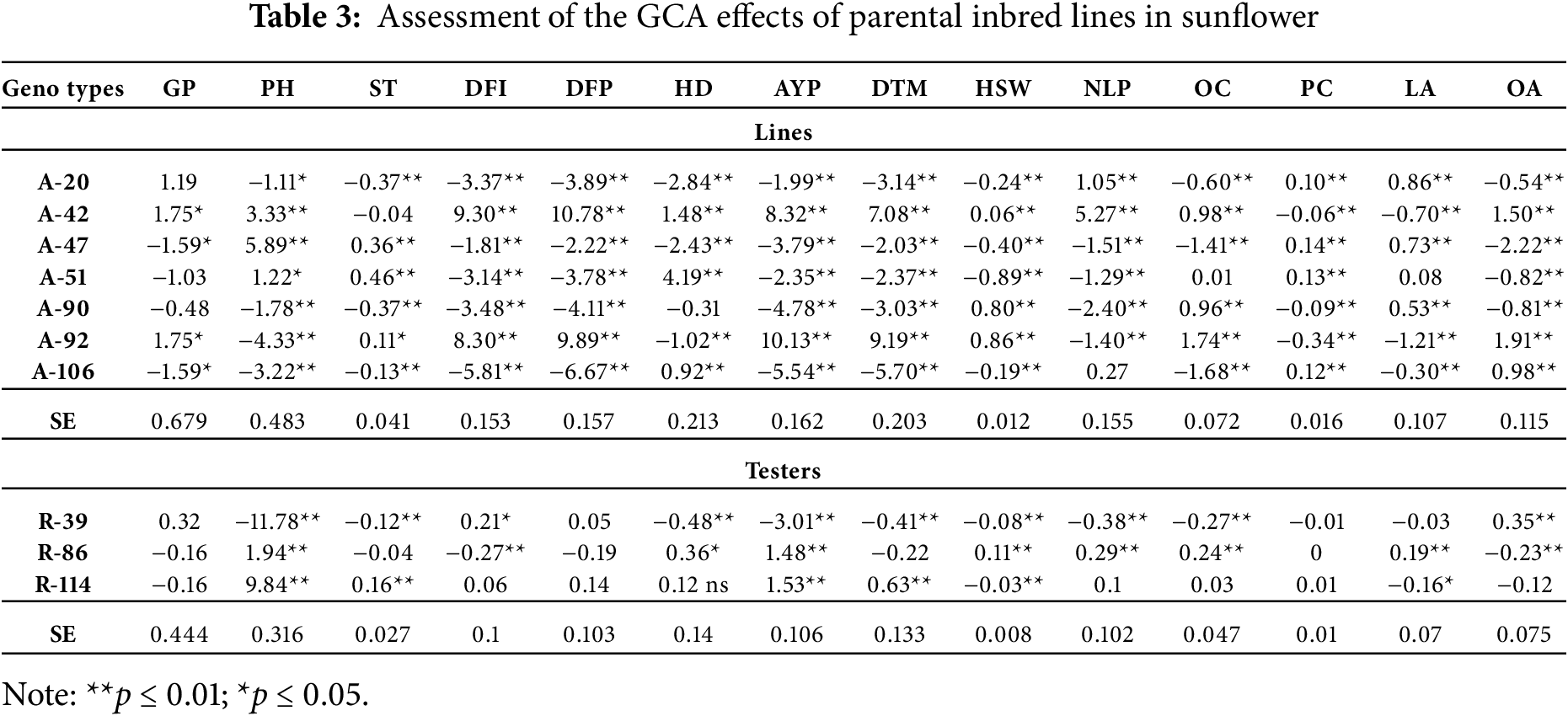

3.2 Combining Ability Analysis

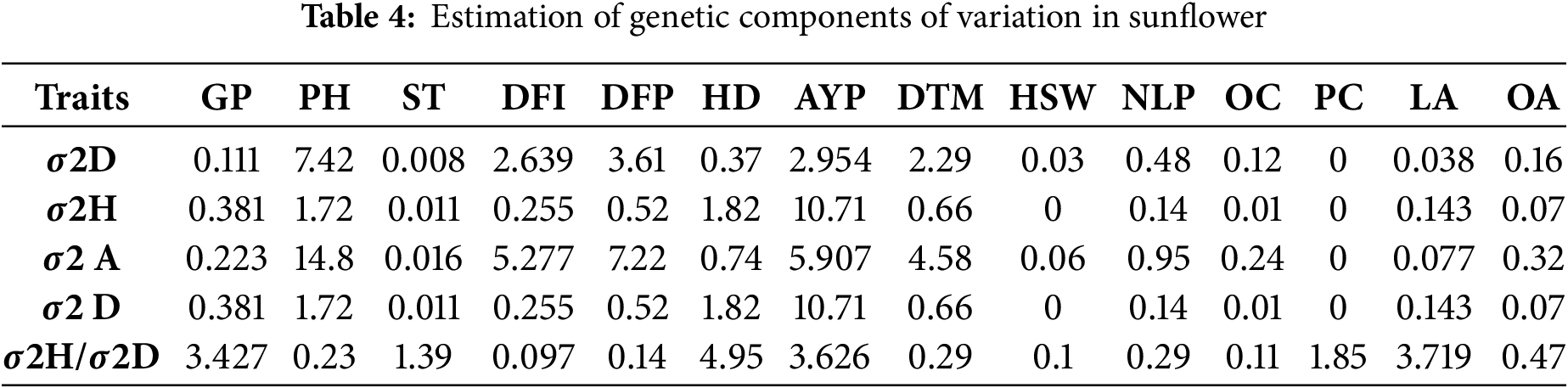

The significant interactions of lines × tester in important morphological traits indicate the importance of analyzing each hybrid combination rather than lines and testers alone [13,29]. Among lines, A-92 was found to be best general combiner for most of the traits viz., AYP, DTM, OC, PC and LA followed by A-42, A-51 and A-47 while among testers R-39 was the best general combiner for most of the traits viz., GP, PH, HD, NLP, OC and OA followed by R-114 and R-86 (Table 3). Among crosses, A-20 × R-86 was the best specific combiner for 3 traits viz., DFI, DFP, and OC, followed by A-47 × R-114, which was the best specific combiner for both HD and NLP. Also, A-51 × R-39 for GP, A-42 × R-39 for PH, A-90 × R-114 for ST, A-106 × R-86 for AYP, A-47 × R-39 for DTM, A-92 × R-86 for HSW, A-51 × R-86 for PC, A-90 × R-86 for LA and A-51 × R-114 for OA were found to be best specific combiners [23,33] (Table S2). The genetic components (Table 4) showed that traits like PH, DFI, DFP, DTM, HSW, NLP, OC, and OA were controlled by additive genes, as the dominance to additive variance ratio was found to be lower than 1 for these traits. Similarly, all the remaining traits viz., GP, ST, HD, AYP, PC, and LA were found to be controlled by non-additive genes.

3.3 Genetic Relationships among Material

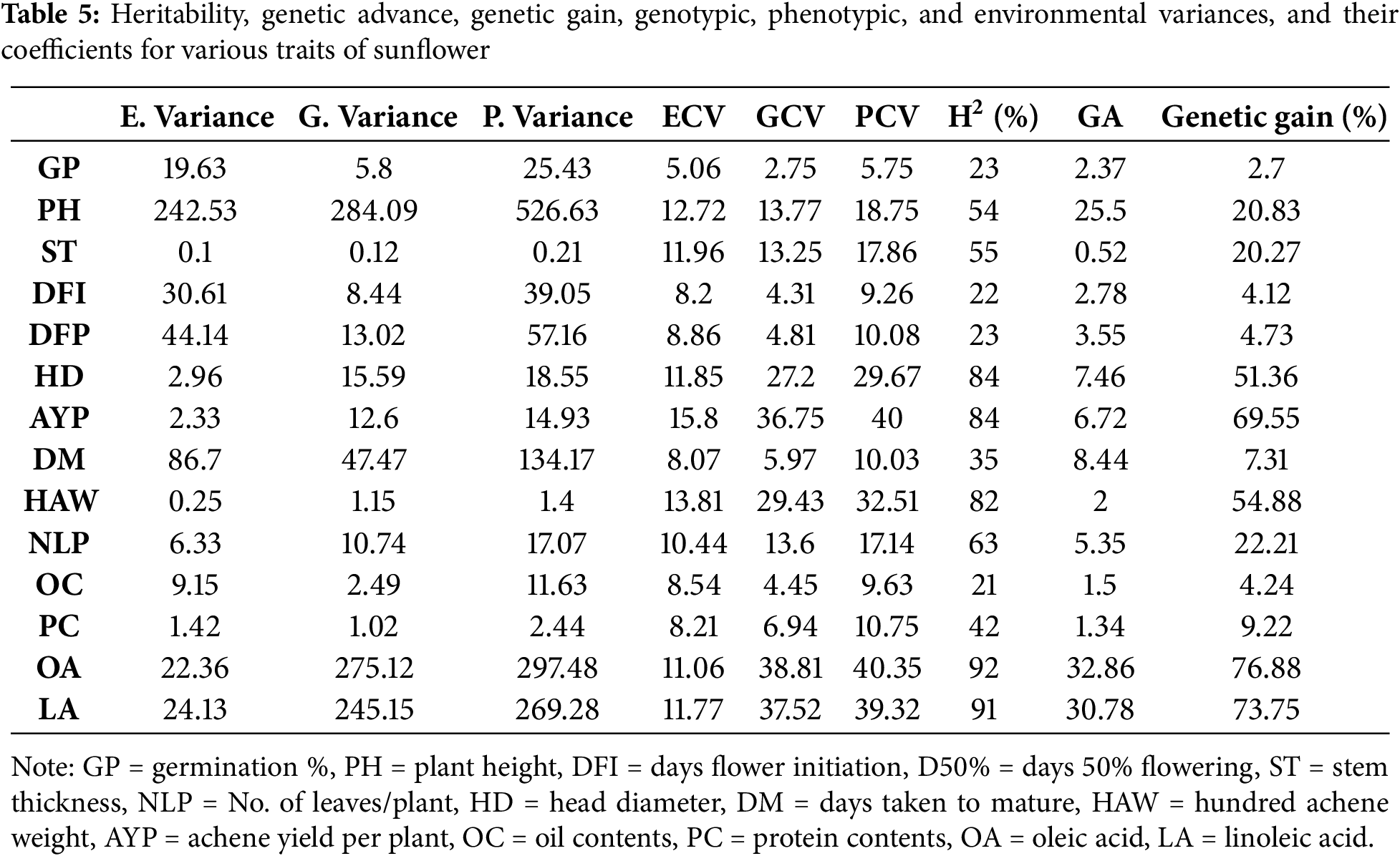

The parents were selected based on high yield and better quality (High Oleic Acid %). The crosses were made, and their different genetic aspects were studied. A vast range of genetic analysis was performed, i.e., mean performance, combining ability analysis, GCA effects, and genetic components for parents (lines, testers) and their cross combinations. High GCA effects show strong additive gene action, meaning such parents reliably transmit favorable alleles to their offspring. These parents are most valued for recurrent selection, pedigree breeding, and developing broad-based populations. Broad-sense heritability (H2) was usually high (>80%) for most traits, demonstrating strong genetic control, while narrow-sense heritability (h2) was mostly low (<10%), showing the predominance of non-additive effects. Developmental and morphological traits are often additive, while complex fitness and metabolic traits depend on gene interactions. Thus, selection is effective for additive traits, whereas hybrid breeding is vital for non-additive traits.

Genetic variability study exhibited that OA, LA, AYP, HD, and HAW had high heritability with high genetic gain, signifying strong additive effects and appropriateness for direct selection (Table 5). Traits like PH, ST, and NLP displayed moderate heritability, suggesting both additive and non-additive control and worth in hybrid breeding. Low heritability for GP, flowering traits, and OC echoed a strong environmental impact and limited genetic gain. Overall, yield- and quality-related traits offer the utmost potential for genetic improvement in sunflower.

The biological meaning of σ2GCA/σ2SCA ratios indicates the relative importance of additive and non-additive genetic effects. A ratio >1 shows predominance of additive effects, favoring selection-based breeding; a ratio <1 reflects dominance of non-additive effects, favoring heterosis breeding; while values 1 endorse that both types of gene action contribute significantly.

Heterosis results from genetic complementation (dominance, overdominance, epistasis), enhanced physiological efficiency (photosynthesis, assimilate partitioning, stress resilience), and molecular regulation (non-additive gene expression, proteomic adjustments, epigenetics) in sunflower, collectively leading to higher yield and adaptability of hybrids over their parents [34].

Mid-parent heterosis shows hybrid superiority over the parental mean, indicating dominance effects and usefulness for population improvement. Better-parent heterosis (heterobeltiosis) shows superiority over the best parent, reflecting over-dominance or strong non-additive effects, and is critical for commercial hybrid development. Thus, mid-parent heterosis helps broaden the genetic base, while better-parent heterosis identifies hybrids with direct market potential.

Mid-Parent Heterosis

A-92 × R-39 was found to have the best mid-parent heterosis for 3 traits viz., DFI, DFP, and DTM. Also, A-92 × R-86 had the best mid-parent heterosis for both HSW and OC. All the hybrids under study showed negative heterosis for LA. Moreover, A-42 × R-86 for GP, A-47 × R-114 for PH, A-47 × R-86 for ST, A-51 × R-86 for HD, A-106 × R-86 for AYP, A-42 × R-39 for NLP, A-20 × R-86 for PC and A-92 × R-114 for OA showed highest mid-parent heterosis. A-106 × R-114 showed the least negative mid-parent heterosis for both DFI and DFP. All the hybrids under study showed positive heterosis for PH, ST, HD, DTM, HSW, OC, and OA [24,35]. Furthermore, A-106 × R-86 for GP, A-51 × R-86 for AYP, A-51 × R-114 for NLP, A-92 × R-39 for PC, and A-92 × R-114 for LA [22,25,35] showed the lowest negative mid-parent heterosis (Table S3).

The level of heterosis required for commercial adoption varies by trait. For yield, at least 15%–20% better-parent heterosis is needed to justify hybrid costs. For earliness, even a 5%–10% reduction in days to maturity is valuable for stress escape. Seed size and test weight benefit from ~10%–15% heterosis, improving grain quality. For oil content and fatty acid composition, 5%–10% heterosis is commercially important due to direct effects on nutritional and industrial value. The hybrid A-92 × R-86 (Fig. 4) exhibited the highest better-parent heterosis for three traits: average yield per plant (AYP), days to maturity (DTM), and oil content (OC) [22,25]. A-92 × R-114 also showed better parent heterosis for both DFI and DFP. All the hybrids under study showed negative better parent heterosis for LA, just like for mid-parent heterosis. Moreover, A-42 × R-86 for GP, A-47 × R-114 for PH, A-20 × R-114 for ST, A-90 × R-86 for HD, A-51 × R-86 for HSW, A-42 × R-114 for NLP, A-92 × R-39 for PC and A-106 × R-39 for OA showed highest better parent heterosis [25,36,37].

Figure 4: High-yielding, with better quality sunflower hybrid

A-106 × R-114 showed the least negative better parent heterosis for both DFI and DFP, just like for mid-parent heterosis (Table S4). A-51 × R-114 showed the least negative better parent heterosis for both GP and NLP. A-51 × R-114 value for NLP overlapped with A-90 × R-114, and both A-42 × R-39 and A-90 × R-39 showed the lowest negative better parent heterosis for PC. All the hybrids under study showed positive heterosis for PH, ST, HD, AYP, DTM, HSW, and OC [24,38]. Furthermore, A-92 × R-114 for LA and A-20 × R-114 for OA showed the lowest negative better-parent heterosis [25,37].

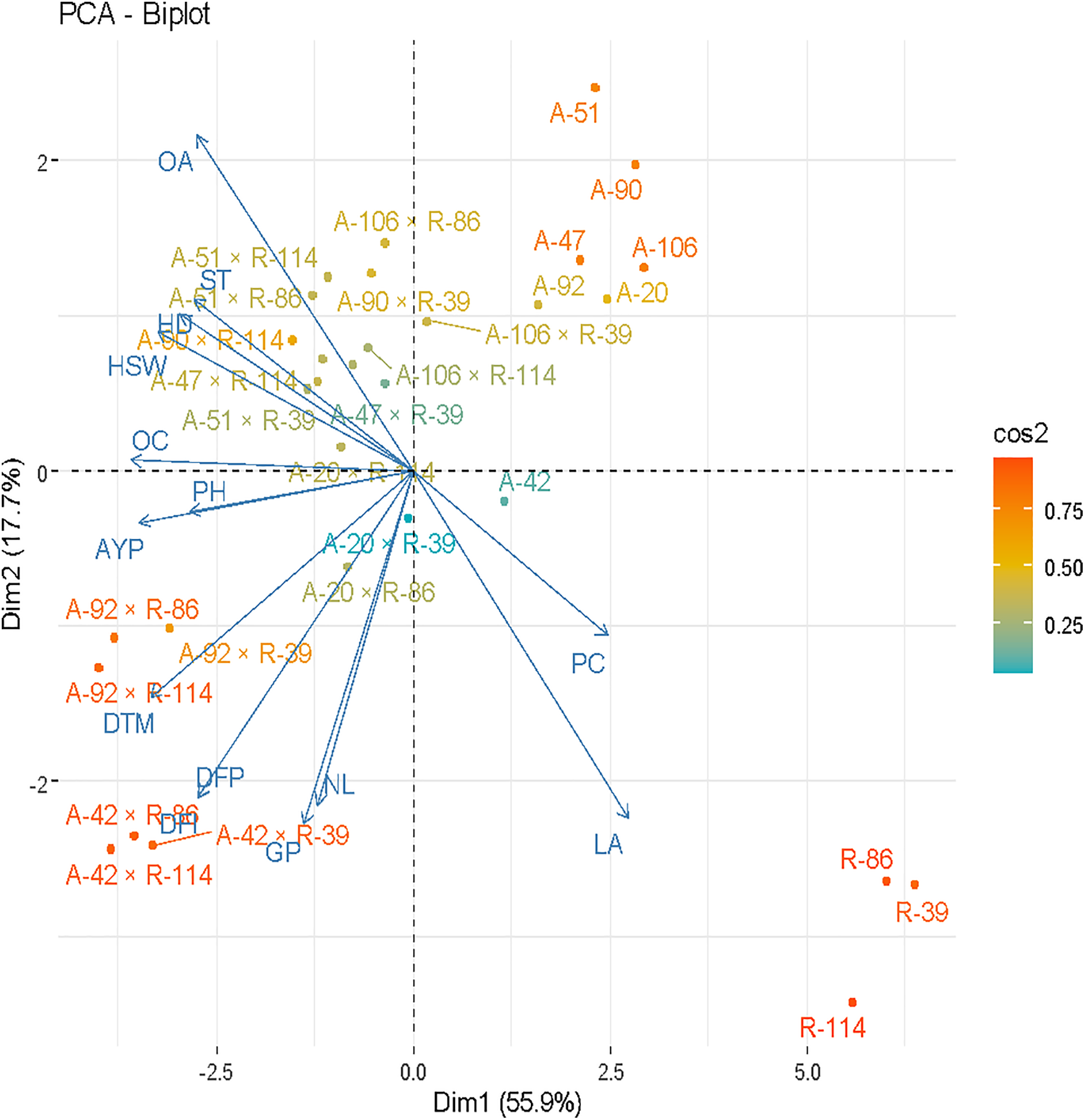

The biplot graph showed the longer vector length of the trait oleic acid, DTM 50% and germination percentage in these studies; hence, these traits comparatively contributed more to variability than other traits (Fig. 5). High-performing traits and genotypes were the best identified through OP (origin and position) vector measurement. Another variability performance indicator was expressed by its change in color from the origin towards the outer boundaries. Highly stable genotypes but with average performance were seen near the origin whereas genotypes far away from the origin performed better with compromised stability. Higher stability was also expressed by genotypes closer to the vector line for that trait and vice versa. The hybrid combinations of A-42 × R-114, A-92 × R-114, A-42 × R-86, and A-92 × R-114 were found to be the best for achene yield per plant, plant height, and days taken to maturity. The high-performance crosses observed for the oleic acid, stem thickness, HD, HAW, and OC were A-51 × R-114, A-51 × R-86, A-106 × R-86, A-90 × R-114, A-47 × R-114, and A-51 × R-39. Similar findings were reported by [39,40] in their studies.

Figure 5: Biplot analysis of various traits on sunflowers, cross combinations, and their parents

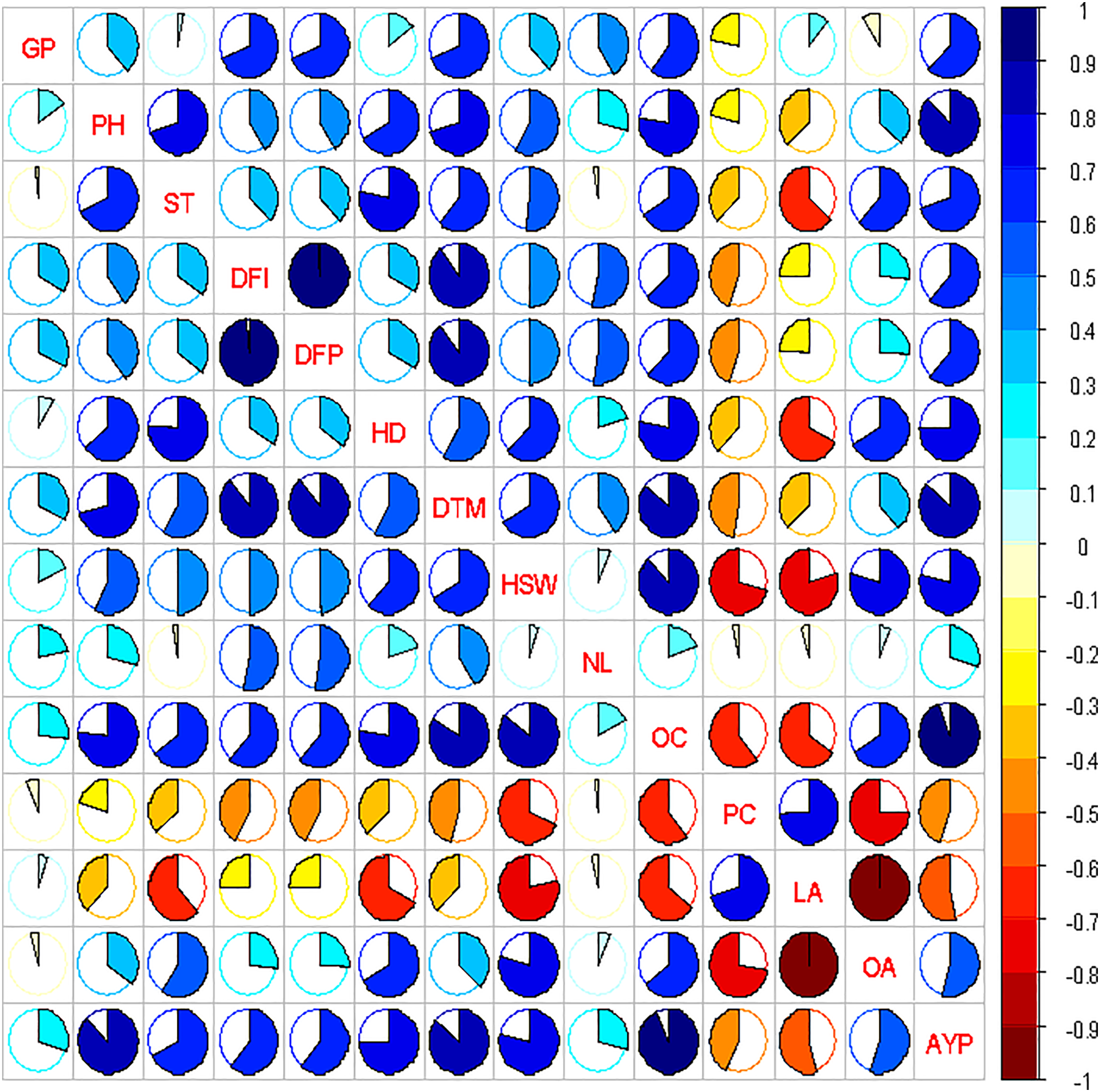

The strength of association between any two characters was explained by the correlation analysis. The strength of association between various traits in yield and contributing traits could be strong, medium, or weak [41]. Genotypic and phenotypic correlations among yield and its different components (Fig. 6). Medium genotypic and phenotypic correlations were expressed by most of the traits with oleic acid, except germination percentage, which has a negligible negative correlation [42,43]. Oleic acid and 100 seed weight showed a highly strong negative genotypic and phenotypic correlation, and protein content showed a strong positive in accordance with [42,43].

Figure 6: Correlation studies among various traits of sunflower hybrids

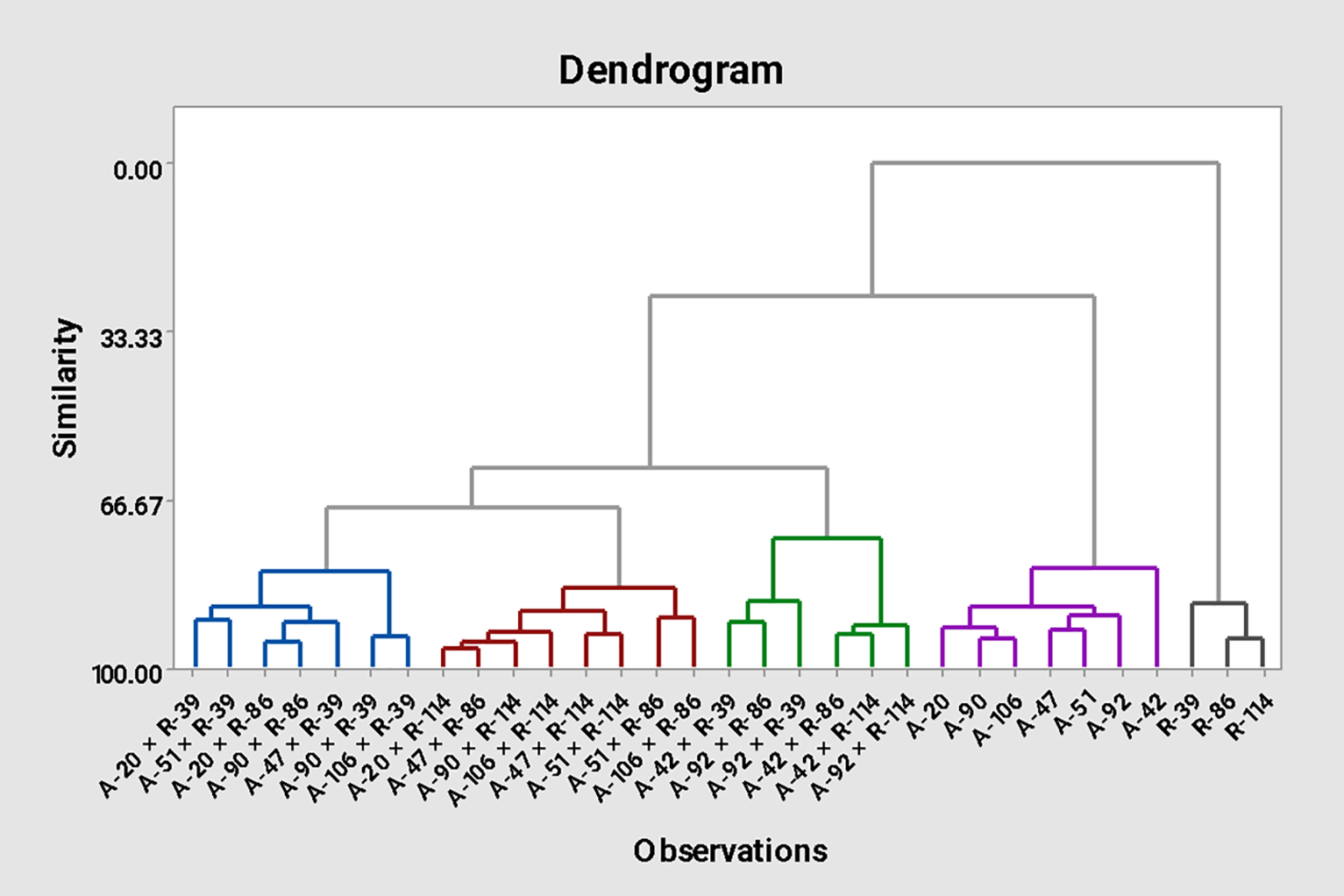

Path coefficient analysis partitioned genotypic correlations of sunflower traits into direct and indirect effects (Fig. 6). Cluster analysis of 7 CMS lines, 3 restorers, and 21 hybrids produced a dendrogram grouping 31 genotypes into five clusters (Fig. 7), revealing genetic diversity and potential heterotic relationships valuable for hybrid development.

Figure 7: Dendrogram constructed for 31 sunflower genotypes based on yield and quality traits

Cluster 5 consisted of all the male parents (R-lines), cluster 4 consisted of all the female parents (A-lines). 21 cross combinations were grouped into three clusters. Cluster 3 contained six hybrids namely A-92 × R-114, A-42 × R-114, A-42 × R-86, A-92 × R-39, A-92 × R-86 and A-22 × R-39. Cluster 2 is comprised of eight sunflower hybrids, A-106 × R-86, A-51 × R-86, A-51 × R-114, A-47 × R-114, A-106 × R-114, A-90 × R-114, A-47 × R-86 and A-20 × R-114. Cluster 1 included seven hybrids namely A-106 × R-39, A-90 × R-39, A-47 × R-39, A-90 × R-86, A-20 × R-86, A-51 × R-39 and A-20 × R-39.

Hybrids in Cluster 3 have maximum germination percentage, days taken to 50% flowering, 100 achene weight, days taken to maturity, oil contents, achene yield, and oleic acid percentage. Stem thickness and plant height were better in cluster 2, whereas cluster 5, which includes all male parents (R-lines), was best for protein contents and linoleic acid percentage. Clusters 2 and 3 included the hybrids that have better achene yield per plant. All the female parents (A-lines) lie in cluster 4, which is better for oleic acid contents, which is in accordance with [44,45].

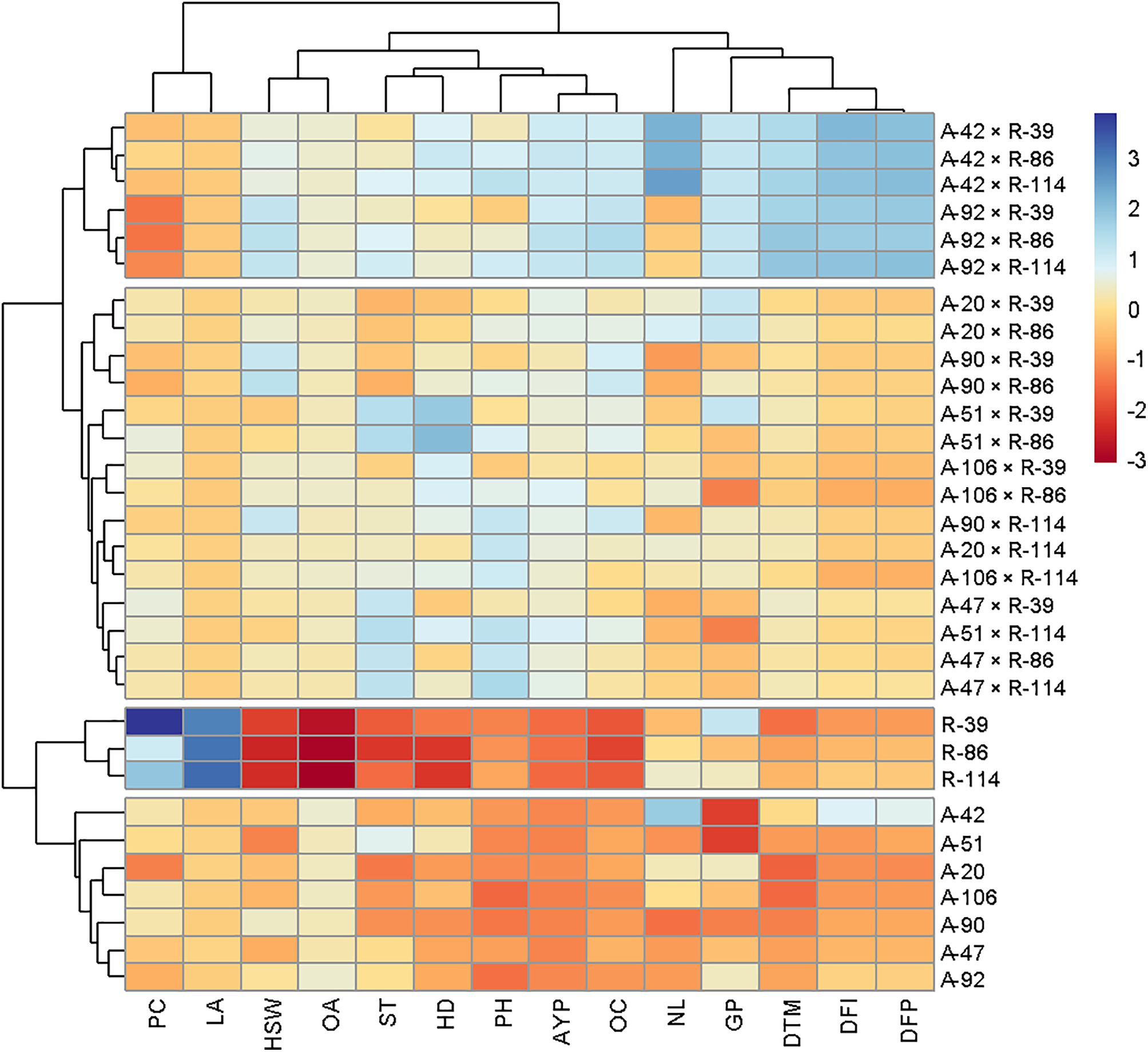

According to heat map analysis, the 31 genotypes were grouped into 4 clusters (Fig. 8). The 21 cross combinations have been grouped into 2 clusters. The 1st and top-most cluster was the best cluster, which includes 6 cross combinations, i.e., A-42 × R-39, A-42 × R-86, A-42 × R-114, A-92 × R-39, A-92 × R-86, and A-92 × R-114. There were 15 cross combinations which included in 2nd cluster, i.e., A-20 × R-30, A-20 × R-86, A-90 × R-39, A-90 × R-86, A-51 × R-39, A-51 × R-86, A-106 × R-39, A-106 × R-86, A-90 × R-114, A-20 × R-114, A-106 × R-114, A-47 × R-39, A-51 × R-114, A-47 × R-86 and A-47 × R-114. The 3rd cluster has all the male parents (R-lines) in it, and the 4th and final cluster has all the female parents (A-lines) in it. Similar findings of the heat map approach were also found earlier in sunflowers by [46,47].

Figure 8: A hybrid presentation of dendrogram and heatmap to explain the diversity among 31 sunflower genotypes

For line improvement (additive traits): Focus on high-GCA parents (A-92, R-39) in recurrent selection. For hybrid development (non-additive traits): Exploit high-SCA crosses (A-106 × R-86, A-51 × R-114) for maximum heterosis. Based on results, A-51 × R-114 as a high-yielding, high-oleic hybrid is recommended for release to farmers. While A-92 and R-39 could be used as core parents in future breeding cycles. The sunflower germplasm was screened both for seed yield and oil quality. High heritability combined with high genetic advance showed the majority of additive gene action, whereas high heritability coupled with low genetic advance designated a key role of non-additive genetic components. The best genotypes found for achene yield per plant, oleic acid, stem thickness, and number of leaves per plant were A-42, A-92, A-20, A-47, A-51, A-90, and R-214. Most of the parameter values contributing to achene yield in sunflower were higher in cluster 8, including achene yield itself. The genotypes included in cluster 8 are A-20, A-38, A-42, A-47, and A-92. Red and blue colors in heatmaps corresponded to low and high diversity for expressed traits simultaneously. The best performing parents were A-42, A-92, and R-214.

The genetic variability, mean performance of genotypes, heterosis estimation, gene actions, heat map, correlation, and path coefficient analysis of diverse sunflower germplasm were conducted for yield and quality traits. Among the selected parents, female parents or A-lines were A-20, A-42, A-47, A-51, A-90, A-92 and A-106 whereas male parents or R-lines were R-39, R-86, R-114. The sunflower cross combinations so produced were studied for agronomic traits like PH, D 50%, ST, HD, DTM, HAW, AYP, OC, PC, OA, and LA. The genotypes, lines, testers, and line × tester expressed highly significant values for all the characters studied. The contribution of lines was higher for most of the traits in this study. Higher SCA values were found for germination percentage, stem thickness, head diameter, achene yield per plant, protein contents, and linoleic acid. These traits have a ratio of σ2 SCA/σ2 GCA greater than 1; hence, non-additive gene action was found to be more important in the inheritance of these traits. This type of gene action could be used for heterosis breeding and improvement of achene yield in sunflower. Parent lines A-42, A-92, A-20, A-106, R-86, and R-114 proved themselves good combiners for achene yield as well as oil quality. Heterotic potential of these sunflower hybrids was assessed for achene yield, oil quality, and other yield contributing traits. Positive and significant heterosis was observed in the traits’ germination percentage, plant height, stem thickness, NLP, HD, days to maturity, achene yield per plant, HAW, oil and protein contents, and oleic acid. A-42, A-92, A-20, A-47, A-51, A-90, and R-214 were the best genotypes identified through PCA biplot. The best cross combinations recognized through the study were A-42 × R-114, A-92 × R-114, and A-42 × R-86. Most of the traits studied correlated positively with yield and oleic acid, with few exceptions. The positive direct effects were found on the achene yield and oleic acid by most of the traits studied, both for sunflower accessions and subsequently for the cross combinations developed from the selected parental genotypes. The yield contributing traits are predominantly controlled by a non-additive type of gene action. For the production of a high-yielding as well as better oleic acid hybrid, A-51 × R-114 was found to be the best in this study.

This study displayed that sunflower hybrids can significantly outperform their parents for yield and oil quality, with heterosis playing a fundamental role. Crosses such as A-92 × R-86 (high yield) and A-106 × R-86 (early maturity) emerged as especially promising under climate stress. Non-additive gene action was predominant for key traits, confirming the efficacy of hybrid breeding, while the variation experimentally observed among parents and hybrids highlights opportunities for targeted improvement. Overall, these conclusions emphasize heterosis breeding, supported by modern genomic tools, as an applied approach for developing resilient, high-yielding sunflower hybrids to meet future food and industrial demands.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge the Ayub Agricultural Research Institute and the University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, for their continuous support.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Fida Hussain, Farooq Khan; Data collection: Fida Hussain; Analysis and interpretation of results: Javed Ahmad, Iqrar Rana, Muhammad Umer Farooq; Draft manuscript preparation: Fida Hussain, Heqiang Huo, Tao Jiang, Sajida Habib. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data associated with this study were not deposited into a publicly available repository before. All data are included in the manuscript and in the supplementary file.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: Table S1. Mean values of sunflower accessions for all the traits under study. Table S2. Assessment of SCA for yield and related traits. Table S3. Heterosis manifestation (mid parent). Table S4. Heterosis manifestation (better parent). The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.069654/s1.

Abbreviations

| GP | Germination % |

| PH | Plant Height (cm) |

| ST | Stem thickness |

| DFI | Days flower initiation |

| DFP | Days 50% flowering |

| HD | Head diameter |

| AYP | Achene yield per plant |

| DTM | Days taken to mature |

| HAW | Hundred achene weight |

| NLP | No. of leaves/plant |

| OC | Oil contents |

| PC | Protein contents |

| LA | Linoleic acid |

| OA | Oleic acid |

| GCA | General Combining Ability |

| SCA | Specific Combining Ability |

| df | Degree of freedom |

| σ2GCA | Variance of GCA |

| σ2D | Additive genetic variance |

| σ2SCA | Variance of SCA |

| σ2H | Dominant genetic variance |

| σ2GCA/σ2SCA | Variance ratio of GCA to SCA |

| sqrt(σ2D/σ2H) | Degree of dominance |

| ORI | Oilseeds Research Institute |

| AARI | Ayub Agricultural Research Institute |

References

1. Culpan E, Arslan B. Heterosis and combining ability via line × tester analysis for quality and some agronomic characters in safflower. Turk J Field Crops. 2022;27(1):103–11. [Google Scholar]

2. Meena H, Sujatha M. Sunflower breeding. In: Fundamentals of field crop breeding. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2022. p. 971–1008. [Google Scholar]

3. Ramya K, Reddy AV, Sujatha M. Agro-morphological and molecular analysis discloses wide genetic variability in sunflower breeding lines from USDA, USA. Indian J Genet Plant Breed. 2019;79(02):444–52. doi:10.31742/ijgpb.79.2.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Naeem MA, Zahran HA, Hassanein MM. Evaluation of green extraction methods on the chemical and nutritional aspects of roselle seed (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) oil. Oilseeds Fats Crops Lipids. 2019;26:33. doi:10.1051/ocl/2019030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Peyronnet C, Lacampagne JP, Le Cadre P, Pressenda F. Les sources de protéines dans l’alimentation du bétail en France: la place des oléoprotéagineux. Oilseeds Fats Crops Lipids. 2014;21(4):D402. doi:10.1051/ocl/2014012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mgeni CP, Müller K, Sieber S. Sunflower value chain enhancements for the rural economy in Tanzania: a village computable general equilibrium-CGE approach. Sustainability. 2018;11(1):75. doi:10.3390/su11010075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. FAO. World food and agriculture. Italy, Roma: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2013. p. 22–35. [Google Scholar]

8. Dudhe M, Sasikala R, Ramteke R, Sakthivel K, Kumaraswamy H. Breeding climate-resilient sunflowers in the climate change era: current breeding strategies and prospects. In: Breeding climate resilient and future ready oilseed crops. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2025. p. 349–405. [Google Scholar]

9. Lagiso TM, Singh BCS, Weyessa B. Evaluation of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) genotypes for quantitative traits and character association of seed yield and yield components at Oromia region. Ethiopia Euphytica. 2021;217(2):27. doi:10.1007/s10681-020-02743-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Dong C, Bu X, Liu J, Wei L, Ma A, Wang T. Cardiovascular disease burden attributable to dietary risk factors from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2022;32(4):897–907. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2021.11.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Forouzanfar MH, Sepanlou SG, Shahraz S, Dicker D, Naghavi P, Pourmalek F, et al. Evaluating causes of death and morbidity in Iran, global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors study 2010. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(5). doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61349-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Rehman A, Saeed A, Kanwal R, Ahmad S, Changazi SH. Therapeutic effect of sunflower seeds and flax seeds on diabetes. Cureus. 2021;13(8):e17256. doi:10.7759/cureus.17256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Mylne JS, Colgrave ML, Daly NL, Chanson AH, Elliott AG, McCallum EJ, et al. Albumins and their processing machinery are hijacked for cyclic peptides in sunflower. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(5):257–9. doi:10.1038/nchembio.542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Castro C, Leite RM. Main aspects of sunflower production in Brazil. Oilseeds Fats Crops Lipids. 2018;25(1):D104. doi:10.1051/ocl/2017056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sharma K, Kumar M, Lorenzo JM, Guleria S, Saxena S. Manoeuvring the physicochemical and nutritional properties of vegetable oils through blending. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2023;100(1):5–24. doi:10.1002/aocs.12661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Delen Y, Palali-Delen S, Xu G, Neji M, Yang J, Dweikat I. Dissecting the genetic architecture of morphological traits in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Genes. 2024;15(7):950. doi:10.3390/genes15070950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Jinks J. Biometrical genetics of heterosis. In: Heterosis: reappraisal of theory and practice. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1983. p. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

18. Kempthorne O. An introduction to genetic statistics. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1957. 545 p. [Google Scholar]

19. Leclercq P. Une sterilite male cytoplasmique chez le tournesol. Ann De L’amélioration Des Plantes. 1969;2:99–106. [Google Scholar]

20. Kinman M. New developments in the USDA and state experiment station sunflower breeding programs. In: Proceedings of the 4th International Sunflower Conference; 1970 Jun 23–25; Memphis, TN, USA. p. 181–3. [Google Scholar]

21. Hu J, Seiler G, Kole C. Genetics, genomics and breeding of sunflower. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

22. Virupakshappa K, Ranganatha A. Heterosis and hybrid seed production in sunflower. In: Heterosis and hybrid seed production in agronomic crops. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2024. p. 185–215. [Google Scholar]

23. Imran M, Saif-ul-Malook S, Nawaz MA, Ahabaz M, Asif M, Ali Q. Combining ability analysis for yield related traits in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Am Eurasian J Agric Env Sci. 2015;15(3):424–36. doi:10.56739/jor.v36i3.126973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Bhoite K, Dubey R, Vyas M, Mundra S, Ameta K. Evaluation of combining ability and heterosis for seed yield in breeding lines of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) using line × tester analysis. J Pharm Phyt. 2018;7(5):1457–64. doi:10.56739/jor.v37ispecialissue.139106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ahmed MA, Hassan TH, Zahran HA. Heterosis for seed, oil yield and quality of some different hybrids sunflower. Oilseeds Fats Crops Lipids. 2021;28(25):1–15. doi:10.1051/ocl/2021010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Rehman H, Khan FA, Iqbal A, Saeed A, Naeem A, Mehmood MA. Combining ability studies for yield and others quality traits of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) by using line × tester analysis. J Agri Res. 2021;59(1):7–12. doi:10.21608/jesj.2020.204902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Mariam T, Bibi S, Nawaz S, Khan NH, Naheed S, Aman Z, et al. Genetic innovation in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) exploring combining ability and heterosis revealed by line × tester analysis. Int J Agric Innov Cut Edge Res. 2025;3(1):86–94. doi:10.56739/jor.v37ispecialissue.139106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Manzoor M, Sadaqat HA, Tahir MHN, Sadia B. Genetic analysis of achene yield in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) through pyramiding of associated genetic factors. Pak J Agric Sci. 2016;53(1):113–20. [Google Scholar]

29. Anastasi U, Santonoceto C, Giuffrè A, Sortino O, Gresta F, Abbate V. Yield performance and grain lipid composition of standard and oleic sunflower as affected by water supply. Field Crops Res. 2010;119(1):145–53. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2010.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Sharma M, Shadakshari Y. Comparative performance of elite inbred lines with alien cytosterile sources and their corresponding hybrids in sunfower (Helianthus annuus L.). Electron J Plant Breed. 2021;12(4):1281–91. [Google Scholar]

31. Steel RGD, Torrie JH. Principles and procedures of statistics. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill; 1960. 481 p. [Google Scholar]

32. Sheunda P. Heterosis, combining ability and yield performance of sorghum hybrids for the semi-arid lands of Kenya [master’s thesis]. Nairobi, Kenya: University of Nairobi; 2019. [Google Scholar]

33. Pandya M, Patel P, Narwade A. A study on correlation and path analysis for seed yield and yield components in Sun flower [Helianthus annuus (L.)]. Electron J Plant Breed. 2016;7(1):177–83. doi:10.5958/0975-928x.2016.00027.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Fiévet JB, Nidelet T, Dillmann C, De Vienne D. Heterosis is a systemic property emerging from non-linear genotype-phenotype relationships: evidence from in vitro genetics and computer simulations. Front Genet. 2018;9(1):159. doi:10.3389/fgene.2018.00159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Ghaffari M, Shariati F, Fard NS. Heterosis expression for agronomic features of sunflower. J Agric Food. 2020;1(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

36. Harun M. Fatty acid composition of sunflower in 31 inbreed and 28 hybrid. Biomed J Sci Technol Res. 2019;16(3):12032–8. [Google Scholar]

37. Tyagi V, Dhillon SK, Kaur G, Kaushik P. Heterotic effect of different cytoplasmic combinations in sunflower hybrids cultivated under diverse irrigation regimes. Plants. 2020;9(4):465. doi:10.3390/plants9040465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Arshad A, Iqbal M, Farooq S, Abbas A. Genetic evaluation for seed yield and its component traits in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) using line × tester approach. Bull Biol Allied Sci Res. 2024;2024(1):63–3. doi:10.54112/bbasr.v2024i1.63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Leite RM, Oliveira MC. Grouping sunflower genotypes for yield, oil content, and reaction to Alternaria leaf spot using GGE biplot. Pesqui Agropec Bras. 2015;50(08):649–57. doi:10.1590/s0100-204x2015000800003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Riaz A, Iqbal MS, Fiaz S, Chachar S, Amir RM, Riaz B. Multivariate analysis of superior Helianthus annuus L. genotypes related to metric traits. Sains Malays. 2020;49(3):461–70. [Google Scholar]

41. Akoglu H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk J Emerg Med. 2018;18(3):91–3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

42. Baraiya VK, Patel P. Genetic variability, heritability and genetic advance for seed yield in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Indian J Crop Sci. 2018;6(5):2141–3. doi:10.56739/jor.v38i1.137005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Çetin N, Karaman K, Beyzi E, Sağlam C, Demirel B. Comparative evaluation of some quality characteristics of sunflower oilseeds (Helianthus annuus L.) through machine learning classifiers. Food Anal Method. 2021;14(1):1666–81. doi:10.1007/s12161-021-02002-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Ruzdik NM, Karov I, Mitrev S, Gjorgjieva B, Kovacevik B, Kostadinovska E. Evaluation of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) hybrids using multivariate statistical analysis. Helia. 2015;38(63):175–87. doi:10.1515/helia-2015-0007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Hussain F, Rafiq M, Ghias M, Qamar R, Razzaq MK, Hameed A, et al. Genetic diversity for seed yield and its components using principal component and cluster analysis in. Life Sci J. 2017;14(5):71–8. [Google Scholar]

46. Babec B, Šeremešić S, Hladni N, Ćuk N, Stanisavljević D, Rajković M. Potential of sunflower-legume intercropping: a way forward in sustainable production of sunflower in temperate climatic conditions. Agronomy. 2021;11(12):2381. doi:10.3390/agronomy11122381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Dudhe M, Meena H, Sujatha M, Sakhre S, Ghodke M, Misal A, et al. Genetic analysis in sunflower germplasm across the four states falling under the semi-arid environments of India. Electron J Plant Breed. 2021;12(4):1075–84. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools