Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Vivipary in Festuca glauca: Analysis of Inflorescence Anatomy and Endogenous Hormones

1 Guizhou Horticulture Institute, Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Guizhou Horticultural Engineering Technology Research Center, Guiyang, 550006, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Vegetable Biobreeding, Institute of Vegetables and Flowers, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, 100081, China

3 Key Laboratory of Biology and Genetic Improvement of Flower Crops (North China), Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Beijing, 100081, China

* Corresponding Authors: Panpan Yang. Email: ; Zhilin Chen. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 3157-3173. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.071147

Received 01 August 2025; Accepted 24 September 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

Vivipary in plants evolved under long-term adaptation to harsh environments and is an important reproduction pathway. However, the mechanisms driving vegetative vivipary are still unclear. In this study, we investigated the anatomy of viviparous inflorescences of Festuca glauca ‘Elijah Blue’ using stereomicroscopy and paraffin section anatomical observation. We also determined the contents of endogenous hormones in normal and viviparous inflorescences using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. In viviparous inflorescences, typical upper and lower epidermal tissues, spongy tissue, and palisade tissue of leaves appeared in developmental stages 2 and 3 (20 and 45 days after emergence), indicating vegetative vivipary, which was consistent with the stereomicroscope results. The contents of auxin, gibberellin, and abscisic acid in viviparous inflorescences increased from stage 1 to stage 4, with the content of abscisic acid showing a particularly large increase. At stage 2, the difference in abscisic acid content between viviparous and normal inflorescences was 95.2410 ng/g fresh weight (FW) (81.49% increase in content). These results indicate that high levels of abscisic acid promote vivipary. There were also significant differences (p < 0.05) in zeatin riboside and brassinosteroid between normal and viviparous inflorescences at each developmental stage. Our results lay a foundation for the preliminary exploration of the mechanisms driving vivipary in F. glauca. Further research on the genes and transcription factors involved in vivipary is still needed.Keywords

Festuca glauca (Poaceae), commonly known as blue fescue, is a plant native to the southern part of France. It is a perennial cool-season herb whose ornamental value and versatility is due primarily to its blue leaves. It has a cool blue color and can be combined with white plants to increase this sense of coolness, and with red, yellow, or brown plants to add a sense of warmth. It can be planted in gardens in clusters or used as an edging plant, thereby playing a uniquely versatile role in flower beds or borders. Furthermore, high-quality potted ornamental plants can be planted alone or in combination with other plants [1]. In some regions, such as Linyi,and Nanjing, studies on the introduction and growth adaptability of ornamental grasses have indicated that ornamental grasses like F. glauca have a high ornamental value relative to other ornamental grass species due to their cool-toned blue color [2–4].

Generally, plants of the genus Festuca are used as forage; there has been relatively little research on F. glauca as an ornamental grass. In China and abroad, research on F. glauca and other Festuca species has primarily focused on their introduction and landscape applications [5–7]. In other countries and regions, research on Festuca species has primarily focused on molecular dwarfing mechanisms, molecular and physiological aspects, ecological adaptability, stress tolerance, sclerenchyma distribution, and genetic diversity [8–17]. Studies have also analyzed transcriptomes and genomic mapping markers [18–23]. However, there has been little research on vegetative vivipary in F. glauca.

Vivipary in plants is a reproductive strategy in which seeds or embryos begin to develop while they are still attached to the parent plant. This strategy provides self-protection and emerged through long-term adaptation and evolution. Vivipary can improve the reproductive pathway, is conducive to the growth and spread of populations, and can enhance plant adaptability to their environment. Generally, plant vivipary is divided into seed vivipary and vegetative vivipary. Plants with seed vivipary are mostly distributed in mangrove populations along the coast [24]. Vegetative viviparous plants are more widely distributed in China, and most of them are terrestrial or marshy vascular plants. Yang et al. [25] conducted morphological and anatomical observations and found that the bulbil formation of Lilium lancifolium is typical of vegetative viviparity. He et al. [26] studied the interaction between genes and cytokinins in the formation of vegetative viviparous bulbils in lilies.

Plant hormones regulate all processes of plant life and coordinate the signal transmission between the internal and external environments of plants. The phenomenon of vegetative viviparous seedlings occurs in F. glauca plants. Understanding the effects of hormones throughout the development process of viviparous seedlings could reveal the mechanisms driving plant somatic cell totipotency and cell differentiation. In China, there have been numerous studies on the regulatory role of plant hormones and the molecular mechanisms during seed vivipary development in mangrove plants along the coast. The research has particularly focused on the regulatory role of the metabolism of plant hormones ABA/GA and the gene expression in the response pathways during the obvious vivipary process of the mangrove plant Kandelia obovata [27]. Other studies have shown that ABA plays an important regulatory role in the initial stage of vivipary. It can promote the dormancy of artificial “seeds” (viviparous seedling capsules) of Bryophyllum tubiflorum, and prevent premature germination during storage [28], which is consistent with the function of ABA in promoting embryo maturation and inhibiting germination [29]. Research has also indicated that the loss of function of the KdDLEC1 protein in Bryophyllum daigremontianum blocks the accumulation of ABA, which is a prerequisite for the viviparous seedlings to bypass dormancy and for the normal development of somatic embryos. Moreover, after introducing the intact KdLEC1 gene with functional integrity, the number of serrated depressions on the leaf margins of the plants decreased, the development of viviparous seedling primordia was hindered, and traits similar to the accumulation of oil bodies during the seed dormancy period appeared [30]. The level of ABA transduces internal and external environmental signals into instructions for controlling the dormant state of viviparous seedling primordia and serves as a gating function for the initiation of viviparous seedling development.

Understanding the anatomical structure of plant organs is the basis for exploring plant adaptations to environmental changes and has important theoretical and practical significance. For example, numerous studies have investigated the structural anatomy and transcriptomics of the leaves of various plants [31–40], mainly focusing on stress resistance. Therefore, investigating the anatomical structure of inflorescences could provide insights into vivipary.

Plant hormones regulate all plant processes and coordinate signal transmission between the internal and external environments of plants. Plant hormones play an important role in plant growth and development and thus are likely involved in vivipary. Currently, most studies on vivipary have investigated plant anatomical structures after vivipary has occurred; few studies have investigated the causes of vivipary and the endogenous hormones involved.

We observed vegetative vivipary in the inflorescences of the introduced ornamental grass F. glauca ‘Elijah Blue’ [41], which is a rare case of vegetative vivipary in an introduced cultivated species. In this study, we further investigated the vivipary in F. glauca ‘Elijah Blue’. First, we investigated the anatomical structure of viviparous and normal inflorescences. Then, we determined the contents of endogenous hormones in the inflorescences. Our results provide theoretical and practical support for further research on vivipary in inflorescences of cultivated varieties.

Festuca glauca ‘Elijah Blue’ was supplied by Yunnan Huajing Horticulture Company. Individuals with normal inflorescences and those with viviparous inflorescences were derived from the same batch of seedlings and planted in the field at the Ornamental Grass Germplasm Resource Nursery of the Institute of Horticulture, Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Jinxin Community, Huaxi District, Guiyang City. This site has a subtropical humid and mild climate, with an altitude of approximately 1100 m, a longitude ranging from 106° 27′ E to 106° 52′ E, and a latitude ranging from 26° 11′ N to 26° 55′ N. The annual average temperature is 15.3°C, with an average frost-free period of 246 days. The coldest period with snow and temperatures below freezing (known as the “Snow-freezing period” locally, with a minimum temperature of around −5°C) occurs from December to January. The annual rainfall is 1129.5 mm, the number of days with good air quality reaches 341 per year, and the annual number of snowy days is low, averaging only 11.3 days.

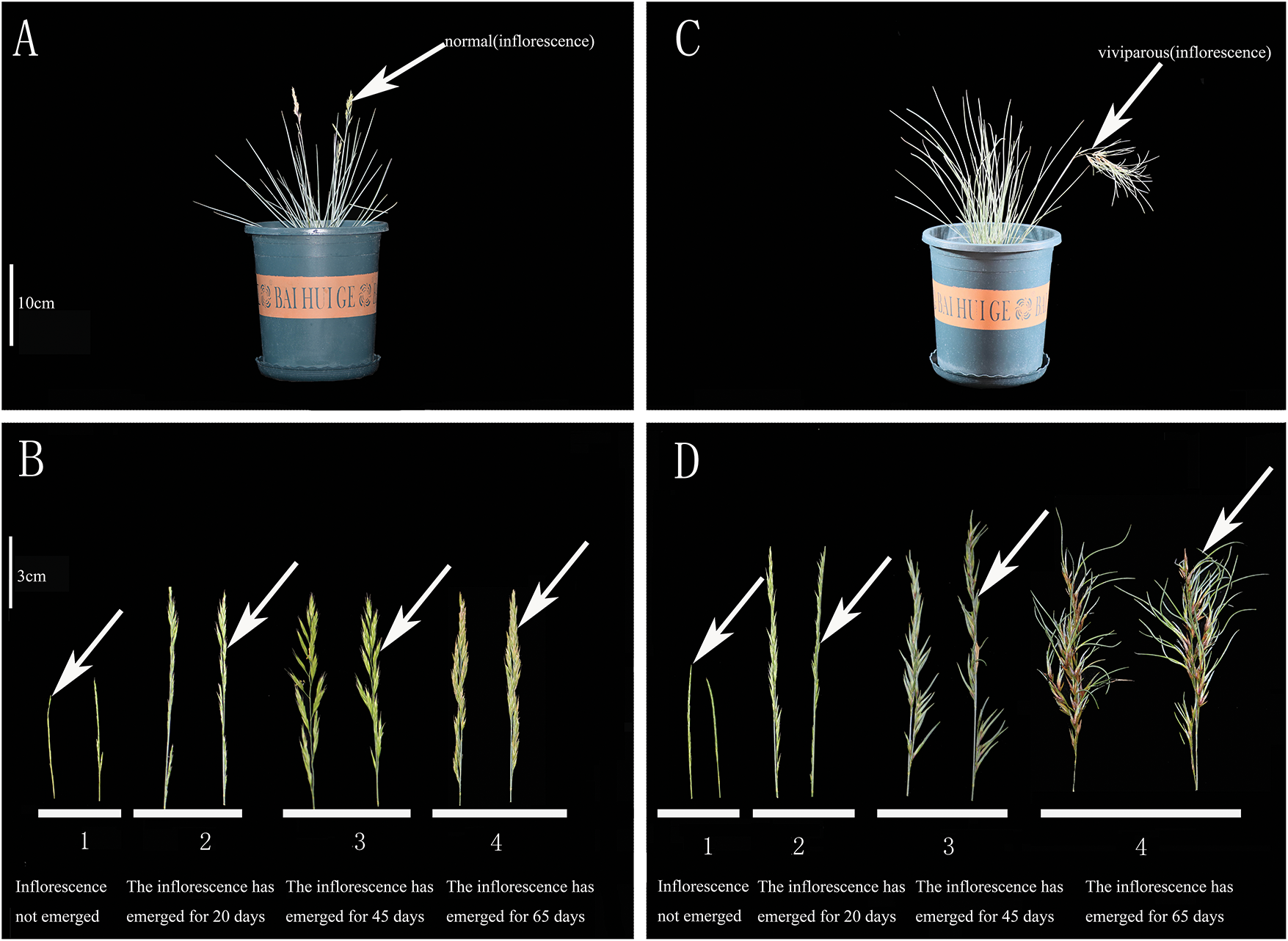

Inflorescences were also sampled from April to August 2024, under the same cultivation environment in the field (normal water and fertilizer management), using the method of random sampling. Plants with normal inflorescences and plants with viviparous inflorescences at four developmental stages (stages 1–4; Fig. 1) were collected at 8:00 a.m. each time. After sampling, the samples were quickly put into pre-prepared liquid nitrogen for rapid freezing and then stored at −80°C. The endogenous hormones of the normal inflorescences and the viviparous inflorescences were measured three times, and the average value was calculated.

Figure 1: Inflorescences of Festuca glauca ‘Elijah Blue’ in normal and viviparous plants at four different developmental stages. (A,B) Normal plants at four different developmental stages; (C,D) Viviparous plants at four different developmental stages

2.2 Stereomicroscopic Determination of Festuca glauca Inflorescences

Dynamic shooting and observation of samples at different developmental stages were carried out using a stereomicroscope (M165C/Leica, Singapore) and a computer (E2211HB/DELL) at the Comprehensive Experiment Center of Guizhou Institute of Horticulture. Eight viviparous inflorescences and eight normal inflorescences (as the control group) were analyzed.

2.3 Determination of Anatomical Structure of Festuca glauca Inflorescences

Sixteen inflorescence samples (eight viviparous inflorescences and eight normal inflorescences) were cut into 1-cm pieces and fixed in 70% FAA fixative solution. The paraffin section method was used to observe anatomical structures based on the method of Zhang et al. [42] with some modifications. Dehydration boxes were placed in a dehydrator for gradient alcohol dehydration, counterstained with safranin and fast green, made transparent with xylene, and sealed with neutral balsam to prepare permanent sections. The sections were cut with a Lecia RM2016 pathological microtome, with a section thickness of 4 μm. The sections were observed and photographed using a NIKON ECLIPSE E100 upright optical microscope, and the anatomical structures were viewed using the image measurement software (Case Vewer Users Guides).

2.4 Determination of Endogenous Hormones in Festuca glauca Inflorescences

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which is characterized by high sensitivity, high specificity, convenience, rapidity, safety and low cost, was used to determine the levels of five endogenous hormones (indoleacetic acid [IAA], gibberellic acid [GA3], abscisic acid [ABA], zeatin riboside [ZR], and brassinosteroids [BR]) in the samples. For hormone extraction, a mixed sample of 0.3 g of fresh tissue was collected for each inflorescence type at each of the four developmental stages. Then, 0.2 g material and 2 mL sample extraction solution were ground into a homogenate in an ice-bath. The homogenate was transferred into a 10 mL test tube. Then, the mortar was rinsed with 2 mL of the extraction solution, and the rinsing liquid was transferred into the test tube as well. After shaking well, the test tube was kept at 4°C for 4 h. Then, the sample was centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 8 min and the supernatant was collected. Extraction solution (1 mL) was added to the precipitate, stirred well, and extracted again at 4°C for 1 h. After centrifugation, the supernatants were combined, the volume was recorded, and the residue was discarded. The combined supernatant was passed through a C-18 solid-phase extraction column. The column was equilibrated with 1 mL of 80% methanol before loading each sample. After removing each sample, the column was washed with 5 mL of 100% methanol, then with 5 mL of 100% diethyl ether, and then with 5 mL of 100% methanol again. After passing through the column, the sample was transferred into a 10 mL plastic centrifuge tube. Samples were concentrated and dried under vacuum or nitrogen gas to remove the methanol from the extract. Then, the volume was made up with the sample dilution solution. When measuring different hormones, the sample was diluted by an appropriate multiple before loading. During the measurement, a 96-well plate was used to hold the standard substances, test samples, and antibodies. For the addition of standard samples and test samples, an appropriate amount of the provided standard samples was diluted with the sample dilution solution (the dilution factor was indicated on the label). For IAA and ABA, the maximum concentration of the standard curve was 50 ng/mL; for ZR, iPA, and DHZR, it was 10 ng/mL; for GA and Br, the maximum concentration was 10 ng/mL; and for JA-ME, the maximum concentration was 10 ng/mL. Then, a 2-fold serial dilution was performed to obtain eight concentrations (including 0 ng/mL). The standard samples were added to the first two rows of the 96-well microplate, with 2 i.e.n and 50 μL per well. The test samples were added to the remaining wells, with 2 replicate wells for each sample and 50 μL per well. Antibodies were added to 5 mL of sample dilution solution (the appropriate dilution factor was indicated on the kit label). For a dilution factor of 1:2000, 2.5 μL of antibodies was added. Antibodies were mixed well and then 50 μL was added to each well. Then, the microplate was placed in a humid chamber to start the competition reaction, which was carried out at 37°C for 0.5 h. To wash the plates, the reaction solution was flicked off and the plate was tapped dry on absorbent paper (e.g., newspaper). The washing buffer was immediately discarded after the first addition, then the washing process was repeated for a total of four times. To add the enzyme-labeled secondary antibody, the appropriate enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody was diluted in 10 mL of sample dilution buffer (e.g., 10 μL was added for a 1:1000 dilution ratio). After thorough mixing, 100 μL of the solution was dispensed into each well of the microplate. The plate was incubated in a humid chamber at 37°C for 0.5 h. Post-incubation, plates were washed using the same procedure as after the competitive binding step (i.e., liquid was flicked off, plate was tapped dry, and washing was repeated four times). Next, substrate was added for color development. o-Phenylenediamine (OPD; 10–20 mg) was dissolved in 10 mL of substrate. Once fully dissolved, 4 μL of 30% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was added and mixed immediately (the chromogenic solution was prepared fresh before use). Then, 100 μL of the solution was added to each well and incubated in a humid chamber. The reaction was terminated by adding 50 μL of 2 M sulfuric acid (H2SO4) to each well when a visible color gradient appeared in the standard curve (with the highest-concentration standard well still showing a relatively light color). The optical density (OD) values of all standard concentrations and samples were measured at 490 nm using an ELISA microplate reader in sequential order. The most convenient curve for calculating ELISA results is the logit curve. The x-axis of the curve represents the natural logarithm of each concentration (ng/mL) of the hormone standard samples, while the y-axis represents the logit value of the color-development value at each concentration. The calculation method for the logit value was as follows: Logit(B/B0) = ln((B/B0)/(1 − B/B0)) = ln(B/(B0 − B)), where B0 is the color development value of the 0 ng/mL standard well, and B represents the color development values of other concentrations. For test samples, the natural logarithm of the hormone concentration (ng/mL) can be determined from the logit curve based on the logit value of their color development value. The actual hormone concentration (ng/mL) is then obtained by calculating the antilogarithm of this natural logarithm. After determining the hormone concentration in the sample, the hormone content (ng/g·fw, nanograms per gram of fresh weight) was calculated accordingly.

The images were processed using Adobe Photoshop 2020. Statistical analyses of endogenous hormone content data were conducted with WPS Office 2019 and SPSS Statistics 17.0. For the multiple comparison procedures, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was integrated with Duncan’s new multiple range test, with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05.

3.1 Stereomicroscopic Observations of Inflorescences

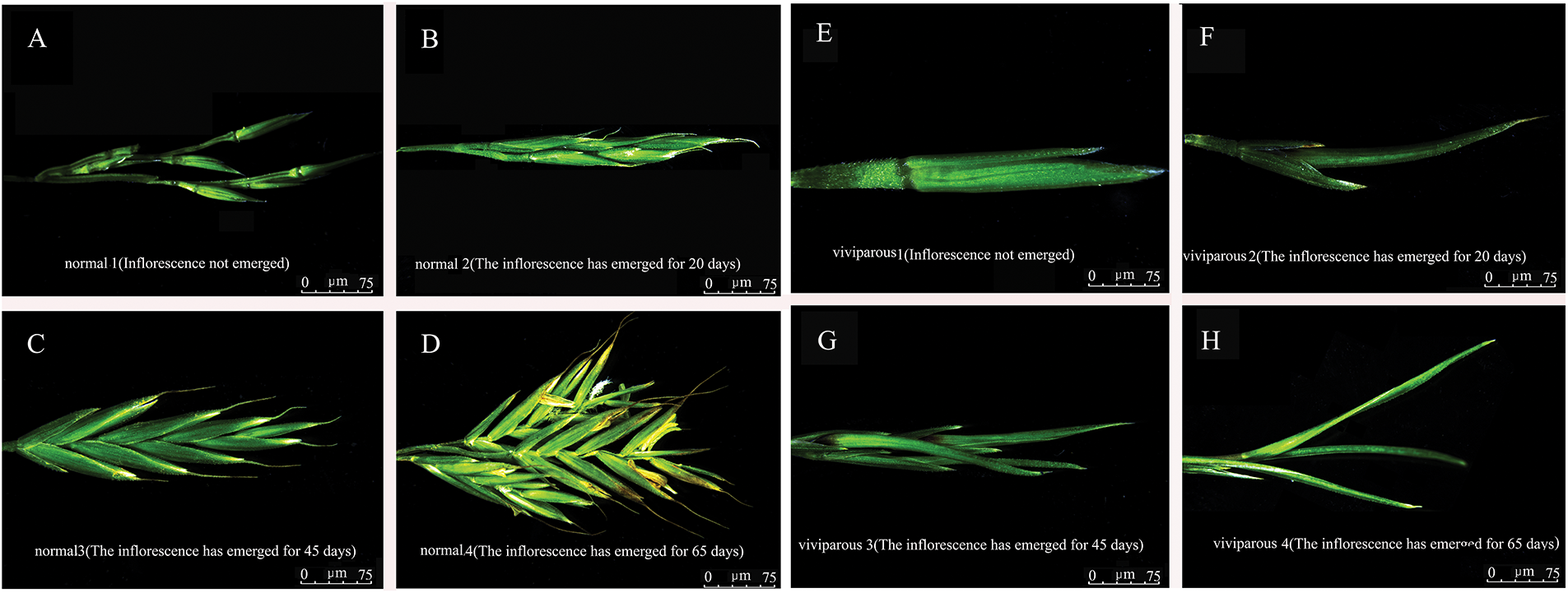

Stereomicroscopic observations (Fig. 2) showed that normal inflorescences formed a spike at stage 1 (Fig. 2A). At stage 2 (Fig. 2B) and stage 3 (Fig. 2C), clear spike inflorescences were observed. At stage 4 (Fig. 2D), flowering and pollen were clearly seen under the stereomicroscope.

Figure 2: Morphology of normal inflorescences (A–D) and viviparous inflorescences (E–H) of Festuca glauca ‘Elijah Blue’ at four developmental stages under a stereomicroscope

In viviparous plants, leaves could be vaguely seen wrapped by the lemma in stage 1 (Fig. 2E), a complete leaf had already developed in stage 2 (Fig. 2F), and multiple complete leaves were observed under the stereomicroscope at stage 3 (Fig. 2G). At stage 4, a complete new plant had developed (Fig. 2H).

3.2 Anatomical Structure of Inflorescences

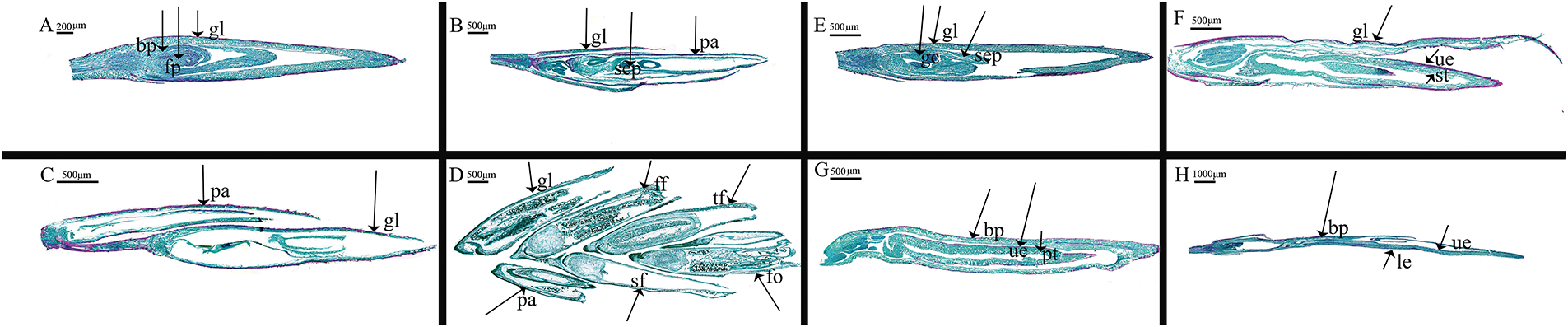

Understanding the anatomical structure of plant tissues is the foundation for exploring plant responses and adaptations to environmental changes. We found clear anatomical differences between normal and viviparous inflorescences of F. glauca (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Anatomical structure of normal and viviparous inflorescences of Festuca glauca ‘Elijah Blue’ at four developmental stages. (A–D) Cross-sections of normal Festuca glauca inflorescences at four developmental stages; (E–H) cross-sections of viviparous Festuca glauca inflorescences at four developmental stages. Magnification: A and C, 4.0 × 4.0 times; B and D, 2.0 × 2.0 times; E and F, 3.0 × 3.0 times; G, 2.0 × 2.0 times; H, 1.2 × 1.2 times. Abbreviations: gl, glume; bp, bract primordia; fp, floret primordium; pa, palea; sep, sepal primordia; ff, the first floret; sf, the second floret; tf, the third floret; ff, the fourth floret; gc, growing cone; ue, upper epidermis; st, spongy tissue; bp, bract primordia; pt, palisade tissue; le, lower epidermis

In normal plants, differentiation of bract primordia and floret primordia was observed at stage 1 (Fig. 3A). At stage 2, differentiation of lemma, palea, and sepal primordia occurred (Fig. 3B). Lemma and palea were present at both stage 3 and 4 (Fig. 3C,D). At stage 4, the spike was typical of inflorescences of the Gramineae family with the first floret, second floret, third floret, and fourth floret clearly differentiated (Fig. 3D). These results are consistent with the stereomicroscope observations (Fig. 2D).

For the viviparous inflorescences, in addition to the lemma and sepal primordia, the growth of cone primordia was also observed at stage 1 (Fig. 3E). At stage 2, in addition to the lemma, the upper epidermis and spongy tissue of the leaf epidermal tissue were differentiated (Fig. 3F). At stage 3, in addition to the bract primordia, obvious palisade tissue was differentiated (Fig. 3G). At stage 4, in addition to the bract primordia, the upper and lower epidermal tissues of the leaf were already evident (Fig. 3H).

3.3 Endogenous Hormones in Inflorescences

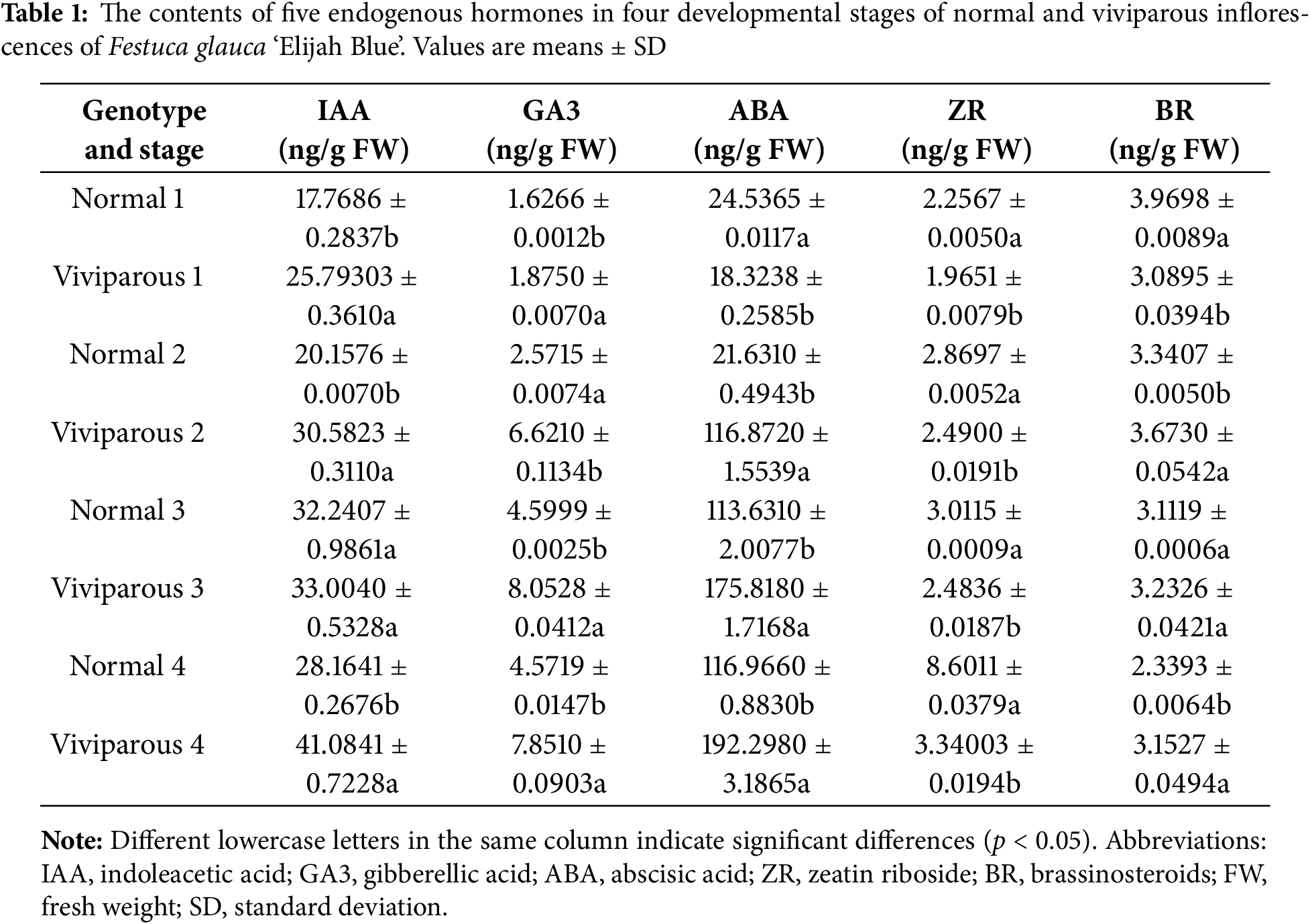

The growth and development of higher plants are ubiquitously modulated by plant hormones. The endogenous hormone levels within plants orchestrate the signal transduction between the internal and external environments. We quantified the levels of five endogenous hormones, namely IAA, GA3, ABA, ZR, and BR, in the normal and viviparous inflorescences of F. glauca (Table 1). In normal inflorescences, the concentrations of IAA and GA3 increased from stage 1 to 3 and then decreased in stage 4. The ABA content decreased from stage 1 to 2 and then increased until stage 4. In viviparous inflorescences, the contents of IAA, GA3, and ABA increased from stage 1 to stage 4, with the increase being particularly great for ABA content.

The IAA content differed significantly between normal and viviparous inflorescences in each stage except stage 3 (p < 0.05). At stage 2, the ABA content in viviparous inflorescences exceeded that in normal inflorescences by 95.2410 ng/g FW, corresponding to an 81.49% increase. There were significant differences in GA3 and ABA between normal and viviparous inflorescences at all four stages (p < 0.05).

In normal inflorescences, the ZR content increased from stage 1 to stage 4, whereas the BR content decreased from stage 1 to stage 4. In the viviparous inflorescences, the ZR and BR contents fluctuated between stages. There were significant differences (p < 0.05) in the contents of ZR and BR between normal and viviparous inflorescences across the four developmental stages. The content of ABA was relatively high compared with the other four hormones in normal and viviparous inflorescences. In particular, the ABA content rapidly increased from stage 2 to stage 4 of viviparous inflorescence development, indicating that ABA is important for the formation of viviparous inflorescences in F. glauca.

4.1 Anatomy of Viviparous Inflorescences

Both leaves and flowers are sensitive and can evolve in response to changes in environmental conditions. Leaves capture light energy for photosynthesis to provide energy for plants. Leaf anatomy can directly reflect the stress responses brought about by various adverse conditions. Therefore, many scholars study leaf anatomy to analyze plant responses to adverse conditions and ecological adaptability [43–46]. Vieira-Goncalves and Roddy [47] characterized how epidermal pavement cell size and shape, cell wall thickness, and hydraulic traits change during leaf expansion in the tropical understory fern Microsorum grossum (Polypodiaceae). As fronds expanded by approximately two orders of magnitude in size, epidermal pavement cells became increasingly lobed as cell walls thickened. Furthermore, the timing of these developmental changes varied across the lamina, beginning near the frond base and midrib, followed by more apical and lateral regions. During expansion, fronds also underwent substantial physiological changes: as cells expanded and cell walls thickened, intracellular turgor pressure and the bulk cell wall modulus of elasticity both increased while the water potential at turgor loss and the minimum epidermal conductance to water vapor both decreased. These results highlight the dynamic coordination between anatomical and physiological traits throughout leaf development, provide valuable data for biophysical modeling of leaf development, and highlight the vulnerability of developing leaves to drought conditions. In a study of olive trees under water deficit, the cultivar ‘Maurino’ exhibited more conservative water use, supported by increased leaf cuticle thickness [48]. Yang et al. [49] investigated 36 different cultivars (lines) of goji germplasm resources and found significant variations in leaf structural indices and stoma. Firouzeh et al. [50] studied the leaf anatomy of the genus Acantholimon (Plumbaginaceae). Pshennikova [51] found that the leaf anatomy of Syringa oblata is particularly useful in determining the degree of kinship between different species and genera as well as in breeding.

The differentiation of flower buds is a key step in the differentiation of vegetative leaves and developing inflorescences. In bud differentiation in the blue sheep plant, changes in endogenous hormones likely control normal inflorescence reproductive differentiation and whether the plant is vegetative. Plant flowering begins with flower induction. After a certain period of vegetative growth, external and internal factors induce the transition from vegetative growth to reproductive growth. The inflorescence meristem differentiates to produce flower organ primordia and finally develops into mature flower organs with a complete structure. At present, there is no clear standard defining the different developmental stages of flowering, but most studies identify stages based on morphological structures and physiological changes [52], including the growing tip and the differentiation of different flower structures.

In this study, we observed substantial anatomical differences between the normal and viviparous inflorescences of F. glauca (Fig. 3). Normal inflorescence development followed the typical Gramineae spikelet differentiation, with the first, second, third, and forth florets being differentiated by the fourth developmental stage (Figs. 2 and 3D). In developmental stage 1, differentiation of floret primordia occurred in normal inflorescences (Fig. 3A) and there was also differentiation of the growing tip primordia in viviparous inflorescences. Therefore, normal and viviparous inflorescences could not be distinguished at this stage. In the second and third stages, viviparous inflorescences developed typical upper and lower epidermal tissues, spongy tissue, and palisade tissue of leaves, indicating vegetative growth (Figs. 2 and 3F,G). In viviparous inflorescences, it took 75 days to produce a new vegetative plant from the first stage (before inflorescence emergence). In summary, microscopic analyses showed that the vivipary observed in F. glauca ‘Elijah Blue’ is vegetative vivipary, not seed vivipary.

The vegetative vivipary in F. glauca ‘Elijah Blue’ may have arisen as an adaptation to the arid or rainy climate environment in Guizhou. Festuca glauca enters its flowering period in March. In Guizhou during this month, due to exposed rocks, shallow soil layers, and occasional precipitation that is prone to infiltration, the soil remains in a prolonged arid state. However, the mother plant can temporarily provide a water buffer: on the inflorescence, bracts directly utilize water from the mother plant and continuously absorb water and nutrients from the mother plant through vascular tissue. Meanwhile, the aerial roots of differentiated axillary buds come into contact with the air and can retain water when precipitation occurs (the season is characterized by intermittent drought with occasional rainfall). By the time the rainy season in Guizhou arrives (from April to August), seedlings have already developed a root system. Therefore, when the seedlings detach, they can quickly take root and absorb water, significantly improving the survival rate of offspring. The bulbils of vegetative viviparous F. glauca plants skip the process of seed formation on inflorescences and seedling germination. Instead, they rely on the indirect water supply from the mother plant for survival and exist in the form of axillary buds that directly germinate from the inflorescence and develop into seedlings—this adaptation to the environment reduces the risk of death during the seed stage. Therefore, vegetative vivipary in F. glauca is an adaptation to the arid or rainy climate in Guizhou, protecting the early development of seedlings and enhancing the survival rate of offspring. Plants sharing a similar developmental mechanism include Poa vivipara and Setaria viridis var. vivipara, which are viviparous species belonging to the same family (Poaceae) as F. glauca. In these grasses, the spikelets on the spike-like inflorescences do not develop into normal seeds; instead, all or part of them are specialized into fleshy bulbils, which resemble miniature seedlings in appearance. Other plants, such as Lilium lancifolium of the Liliaceae family and Kalanchoe daigremontiana of the Crassulaceae family, have evolved alternative strategies: they form vegetative propagules (e.g., bulbils, adventitious buds) at different attachment sites of propagules, including inflorescences, leaf axils, and leaf margins. Regardless of the specific site, these propagules rely on nutrients supplied by the mother plant to complete their early development. The core adaptation across all these species is the combination of maternal protection and vegetative propagation, which ultimately enhances the survival rate of their off spring.

4.2 Endogenous Hormones in Viviparous Inflorescences

Endogenous hormones are small organic compounds produced in trace amounts that regulate (promote or inhibit) plant physiological processes, including reproduction [53]. Current research on plant endogenous hormones has mainly focused on responses to biotic and abiotic stresses, seed germination, and the stimulation of in vitro plant regeneration by endogenous hormones [54–56]. Few studies have investigated endogenous hormones in viviparous inflorescences. Yang Shengchang investigated changes in the contents of ABA, GA3, soluble sugar and starch in the flower buds, seeds and hypocotyls of the viviparous mangrove plant Aegiceras corniculatum. The results showed that the comprehensive regulatory effect of ABA and GA3 on sugar metabolism may be an important mechanism for the vivipary of mangrove plants [57]. At the gene level, studies found that mangroves with seed vivipary have a preference for using certain amino acids in their genomes, that is, the substitution of amino acids may be of great significance for the evolution of vivipary and other adaptive traits as well as for the adaptability to the coastal wetland environment [58]. In Kandelia obovata, vivipary was associated with down-regulation of ABA synthesis genes and up-regulation of ABA-responsive genes, indicating that the viviparous propagules have a mechanism to reduce the ABA level and alleviate the inhibition of development to ensure vivipary. Moreover, during K. obovata embryonic development, differentially expressed genes were significantly enriched in metabolic pathways such as organ morphogenesis and photosynthesis, suggesting that the viviparous reproductive organs are carrying out nutrient synthesis during embryo development, which may be related to the nutrient supply during the seed germination process [59,60]. However, the role of endogenous hormones in vegetative vivipary, including the role of ABA, is still unclear.

In this study, we measured the contents of five endogenous hormones in the normal and viviparous inflorescences of F. glauca ‘Elijah Blue’ at four developmental stages. The content of ABA was high compared with the other four hormones. Moreover, ABA content rapidly increased from the 2nd to the 4th stage of the development of viviparous inflorescences, indicating that ABA is important for the formation of viviparous inflorescences in F. glauca. Research on A. corniculatum, which exhibits seed vivipary, found that the endogenous ABA content in reproductive organs significantly decreases and then increases during the viviparous development process. The comprehensive regulatory effect of ABA and GA3 on sugar metabolism may be an important mechanism for the vivipary of mangrove plants [61]. This is inconsistent with the increase in ABA content from the 2nd to 4th developmental stages of the viviparous inflorescences of F. glauca in this study. This discrepancy may be due to the different developmental mechanisms of vegetative vivipary in F. glauca and seed vivipary in A. corniculatum. Ismial et al. posited that, during the viviparous development process of Rhizophora mucronata, ABA can regulate the specific expression of dehydrins, and the 50 kD dehydrin is related to the initiation of vivipary [62].

During the plant development process, there is generally an antagonistic relationship between the endogenous hormone ABA and gibberellin. ABA can induce seed dormancy and inhibit premature germination, while gibberellin can break seed dormancy [63]. Plants can regulate germination and dormancy by controlling the relative balance of these two hormones. Yang et al. [64] found that multiple endogenous hormones differentially regulated flower bud differentiation in three Sophora japonica ‘Jinhuai’ varieties in northern Guangxi, providing a foundation for further research on flowering regulation mechanisms and flower quality improvement. Many studies have shown that ABA in plants can inhibit premature germination during the in vitro culture of isolated embryos, promote the accumulation of storage proteins and embryo development, and cause seed dormancy [65]. Regarding seed vivipary, Yang et al. [66] identified the VIVIpary protein in rice. VIVIpary is specifically expressed in embryos and is associated with shortened seed dormancy. VIVIpary exhibits elevated expression level in the PHS sensitive variety, and its overexpression induces PHS, whereas its knockdown delays germination. Mechanically, VIVIpary promotes the release of seed dormancy by regulating ABA signaling. VIVIpary serves as a spatial organizer shaping chromatin architecture by directly binding to the chromatin adaptor protein OsMSI1 and enhancing its interaction with the histone deacetylase OsHDAC1, thereby decreasing chromatin accessibility and fine-tuning ABA signaling. VIVIpary is differentially expressed between wild and cultivated rice, indicating its appropriateness as a target of selection during domestication. In this study, the viviparous inflorescences of F. glauca had relatively high ABA contents, which may be due to the different viviparous mode of this plant. For example, during the flower bud differentiation process of Phalaenopsis pulcherrima, the GA3 and IAA content first decreased and then increased. The changes in soluble sugar and soluble protein content during flower bud differentiation were consistent, while the changes in GA3 and IAA were consistent [67]. In this study, the content of IAA increased throughout viviparous inflorescence development. However, in normal inflorescences, IAA content increased from stage 1 to stage 3 but then decreased at stage 4. This suggests that a high level of IAA can promote vivipary in F. glauca. The changes in IAA content during the development of viviparous inflorescences in F. glauca were inconsistent with those during flower bud differentiation in P. pulcherrima reported in [67]. This result indicates that the effect of IAA level on flower bud differentiation differs among species.

GA3 is one of the most extensively studied members of the gibberellin family and has a relatively high physiological activity. Its role in plant flower bud differentiation is not simply promotive or inhibitory; instead, it is highly dependent on the plant species, cultivar, growth stage, and environmental conditions. The core mechanism of GA3 involves regulating the hormonal balance, nutrient allocation, and gene expression within plants, thereby indirectly or directly influencing flower bud differentiation. Research conducted by Zhu et al. has revealed that during the flower bud differentiation period of Hibiscus mutabilis (Confederate Rose), the contents of GA3, cytokinins (CTK), and ABA are relatively high in the leaves. A lower GA3/CTK ratio in the leaves is conducive to promoting flower bud differentiation in H. mutabilis. Additionally, a relatively high level of ABA inhibits the vegetative growth of the shoot apex through interactions with IAA, GA3, and CTK; this inhibition enables the shoot apex to transition from vegetative growth to reproductive growth, ultimately facilitating flower bud differentiation. In this study, the content of GA3 in viviparous inflorescences increased from stage 1 to stage 3 and slightly decreased at stage 4. This is consistent with the finding that a high level of GA3 is beneficial to flower bud differentiation in H. mutabilis [68]. Low GA3/ABA and IAA/CTK ratios are advantageous to inflorescence formation. Increases in ABA/CTK and ABA/IAA ratios promoted the differentiation of floret and sepal primordium. Petal primordium and stamen primordium differentiation needed higher GA3/CTK, GA3/ABA, and GA3/IAA ratios [69]. In this study, the content of ABA in viviparous inflorescences increased substantially from stage 1 to stage 4, which is consistent with the research by Zhu et al. [68]. It is possible that a high level of ABA is favorable for vivipary in F. glauca. At stage 2, the difference in ABA content between viviparous and normal inflorescences was 95.2410 ng/g FW, with an 81.49% increase in content. This indicates that a high ABA content in stage 2 is critical for vivipary in F. glauca.

ZR promotes plant cell division and flower bud differentiation. For example, a high level of ZR is beneficial to flower bud differentiation in Olea europaea [70]. In this study, the content of ZR in normal inflorescences increased from stage 1 to stage 4, indicating that ZR also promotes flower bud differentiation in F. glauca. In viviparous inflorescences, the ZR content increased from stage 1 to stage 3, but decreased at stage 4. This is different from the hormonal changes in other viviparous plants. This may be related to different plant species or differences caused by mixed sampling of viviparous inflorescences, and further research is needed.

Dai et al. [71] found that cold could induce early flowering of tobacco by activating BR signaling. Sheng et al. [72] found that endogenous GA, ETH, and BR signaling can promote vegetative and reproductive development of lotus, with BR signaling acting as a growth promoter. The highest BR levels were detected in the vegetative shoot tips. Moreover, external application of 28-epihomobrassinolide resulted in growth-promoting phenotypes including longer scapes, thicker leaves, and prolonged flowering. In this study, the content of BR in normal inflorescences gradually decreased from stage 1 to stage 4, and the content of BR in the viviparous inflorescences gradually decreased from stage 2 to stage 4. There were significant differences in BR content between the normal and viviparous inflorescences at each stage. These results indicate that the gradual decrease in BR content promotes normal inflorescences and impacts viviparous inflorescences of F. glauca.

Vivipary is a reproductive strategy that can lead to population expansion and evolved in plants in response to environmental changes. In this study, we compared normal and viviparous inflorescences of F. glauca. We analyzed the anatomical structure, microstructure and endogenous hormone content of inflorescences. We found that the content of endogenous abscisic acid (ABA) was relatively high in the viviparous inflorescences, indicating that ABA promotes the differentiation of viviparous flower buds—this is a distinct mechanism from that observed in seed vivipary. ABA likely regulates the transition from the reproductive pathway to the vegetative viviparous germination pathway in F. glauca. Our results highlight the key mechanisms involved in vivipary of F. glauca and could be used to improve the breeding speed of F. glauca seedlings and therefore meet the market demand. In the present study, abscisic acid (ABA) was found to accelerate the differentiation rate of viviparous seedlings in F. glauca. Based on this finding, two strategies can be implemented in breeding practice to enhance breeding efficiency. First, targeted application of ABA directly capitalizes on the regulatory activity of this hormone to expedite seedling differentiation. Second, modulation of the endogenous ABA biosynthesis pathway in F. glauca—for instance, via gene editing, environmental induction, or other approaches to boost endogenous ABA production—enables optimization of the differentiation rhythm from the standpoint of the plant’s intrinsic physiological processes. Both of these strategies can shorten the period required for seedlings to progress from germination to the transplantable stage, ultimately leading to an improvement in breeding efficiency.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by funding from the Guizhou Provincial Department of Science and Technology Project (Guizhou Science and Service Enterprises [2022] 005) and Guizhou Agricultural Science Youth Foundation ([2023] 35).

Author Contributions: Hongjuan Xu: Writing—original draft, Validation, Methodology. Lan Yang: Supervision, Funding acquisition. Lejuan Shi: Methodology, Data curation. Weize Wang: Resources. Yiwen Guan: Formal analysis. Ye Liu: Laboratory auxiliary personnel. Panpan Yang, Zhilin Chen: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization, Dissertation supervisor. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yuan X. Appreciating grass and landscape. Beijing, China: China Forestry Publishing House; 2015. p. 89–125. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

2. Zhang Y, Wang L, Song H. Evaluation on growth and ornamental value of 16 species of ornamental grass in Linyi. Shandong Agric Sci. 2018;50(05):67–71. (In Chinese). doi:10.14083/j.issn.1001-4942.2018.05.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhao B, Yang X. Application survey of ornamental grass in Shandong University. J Anhui Agric Sci. 2018;46(31):104–6,10. (In Chinese). doi:10.13989/j.cnki.0517-6611.2018.31.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li X, Yin Z, Yang J, Wu H, Wang D. Study on adaptability of twenty-three ornamental grasses in Nanjing. Acta Agric Jiangxi. 2022;34(04):192–8. (In Chinese). doi:10.19386/j.cnki.jxnyxb.2022.04.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Oakes AJ. Ornamental grasses and grasslike plants. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2012. p. 1–331. [Google Scholar]

6. Hamar-Farkas D, Kisvarga S, Ördögh M, Orlóci L, Honfi P, Kohut I. Comparison of Festuca glauca ‘Uchte’ and Festuca amethystina ‘Walberla’ varieties in a simulated extensive roof garden environment. Plants. 2024;13(16):2216. doi:10.3390/plants13162216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Zhao HS, Zhao ZY. Application and adaptability of ornamental grasses in road flower borders in Hefei, Anhui Province. J Landsc Res. 2024;16(4):70–2,9. doi:10.16785/j.issn1943-989x.2024.4.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang Y, Han P, Zhao R, Yu S, Liu H, Wu H, et al. RNA-seq transcriptomics and iTRAQ proteomics analysis reveal the dwarfing mechanism of blue fescue (Festuca glauca). Plants. 2024;13(23):3357. doi:10.3390/plants13233357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Geng J, Zhang M, Hu J, Bilal M, Yang J, Hu T. Genome-wide expression analysis of Festuca sinensis symbiotic with endophyte of reveals key candidate genes in response to nitrogen starvation. BMC Plant Biol. 2025;25(1):819. doi:10.1186/S12870-025-06817-Y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Jabbari AR, Amini F, Mortazavian SMM, Tanha SS. Genetic diversity and morphological characterization of Festuca ovina using expressed sequence tag simple sequence repeats (EST-SSR) markers. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2025;72(7):7963–75. doi:10.1007/S10722-025-02426-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yang L, Gao M, Tian P. Effect of the fungal endophyte Epichloë sinensis on the physiology of different Festuca sinensis ecotypes under salt-alkaline treatment. Plant Soil. 2025;2025:1–24. doi:10.1007/S11104-025-07683-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Katarzyna J, Jacek S. The effect of a growth stimulant based on iodine nanoparticles on Festuca glauca. J Ecol Eng. 2021;22(11):72–8. doi:10.12911/22998993/142948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Bostan C. Allelopathic effect of Festuca rubra on perennial grasses. Rom Biotech Lett. 2013;18(2):8190–96. [Google Scholar]

14. Bettany AJ, Dalton SJ, Timms E, Manderyck B, Dhanoa MS, Morris P. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Festuca arundinacea (Schreb.) and Lolium multiflorum (Lam.). Plant Cell Rep. 2002;21(5):437–44. doi:10.1007/s00299-002-0531-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Deng X, Wang Z, Qin Y, Cao L, Cao P, Xie Y, et al. Experimental study on the reinforcement of calcareous sand using combined microbial-induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) and Festuca arundinacea techniques. J Mar Sci Eng. 2025;13(5):883. doi:10.3390/JMSE13050883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Goremykina EV, Ryabysheva AA. Spatial distribution of sclerenchyma in leaf blades of some fescues (Festuca L., Gramineae Juss.). Mosc Univ Biol Sci Bull. 2019;74(3):127–32. doi:10.3103/S0096392519030040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Alsaleh A, Doğrusoz MC, Basaran U, Tamkoc A, Avci MA. Genetic diversity and molecular taxonomy study of genus festuca. J Anim Plant Sci. 2020;30(4):931–43. doi:10.36899/JAPS.2020.4.0109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Alam MN, Yang L, Yi X, Wang QF, Robin AHK. Role of melatonin in inducing the physiological and biochemical processes associated with heat stress tolerance in Tall Fescue (Festuca arundinaceous). J Plant Growth Regul. 2021;41(7):1–10. doi:10.1007/S00344-021-10472-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hahn D, Leinauer B, Bastiaans L, VanLeeuwen D. Festuca sp. interfere with germination and early growth of three weeds. Agron J. 2023;115(5):2579–89. doi:10.1002/agj2.21389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yang C, Zhong L, Ou E, Tian F, Yao M, Chen M, et al. Using isoform sequencing for de novo transcriptome sequencing and the identification of genes related to drought tolerance and agronomic traits in Tall Fescue (Festuca arundinacea Schreb.). Agronomy. 2023;13(6):1484. doi:10.3390/agronomy13061484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Batog J, Wawro A, Bujnowicz K, Gieparda W, Bilińska E, Pietrowiak A, et al. Utilization of Festuca arundinacea schreb. biomass with different salt contents for bioethanol and biocomposite production. App Sci. 2023;13(15):8738. doi:10.3390/app13158738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Li XQ, Wu FM, Xiang YH, Fan JB. Transcriptomic analysis of antimony response in Tall Fescue (Festuca arundinacea). Agriculture. 2024;14(9):1504. doi:10.3390/agriculture14091504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Bushman B, Robbins M, Qiu Y, Watkins E, Hollman A, Mihelich N, et al. Association of hard fescue (Festuca brevipila) stress tolerances with genome mapped markers. Crop Sci. 2024;64(2):1002–14. doi:10.1002/CSC2.21155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang XC, Ren LC, Chen JX, Chen FL. The kinds and geographical distribution of viviparous plants in China. J Northeast For Univ. 2024;32(4):90–1. (In Chinese). doi:10.13759/j.cnki.dlxb.2004.04.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Yang PP, Xu LF, Xu H, He GR, Feng YY, Cao YW, et al. Morphological and anatomical observation during the formation of bulbils in Lilium lancifolium. Caryologia. 2018;71(2):146–9. doi:10.1080/00087114.2018.1449489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. He GR, Cao YW, Wang J, Song M, Bi MM, Tang YC, et al. WUSCHEL-related homeobox genes cooperate with cytokinin to promote bulbil formation in Lilium lancifolium. Plant Physiol. 2022;190(1):387–402. doi:10.1080/00087114.2018.1449489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Fu MP. Gene expression analysis of ABA/GA pathway and their impact on vivipary process in Kandelia obovata [master’s thesis]. Xiamen, China: Xiamen University. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

28. Palmer JP, Jasrai YT. Precocious growth and effect of ABA: encapsulated buds of Kalanchoe tubiflora. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol. 1996;5(2):103–4. doi:10.1007/BF03262991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Roberts K. Handbook of plant science. Vol. 2. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

30. Garcês HM, Koenig D, Townsley BT, Kim M, Sinha NR. Truncation of LEAFY COTYLEDON1 protein is required for asexual reproduction in Kalanchoë daigremontiana. Plant Physiol. 2014;165(1):196–206. doi:10.1104/pp.114.237222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Zhou A, Ge B, Chen S, Kang D, Wu J, Zheng Y, et al. Leaf ecological stoichiometry and anatomical structural adaptation mechanisms of Quercus sect Heterobalanus in southeastern Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):325. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-05010-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Fleurial KG, Sebastián AJ, Hamann A, Zwiazek JJ. White spruce (Picea glauca) population differences in needle anatomy, foliar water uptake, and aquaporin expression indicate trade-offs between hydraulic safety and productivity. Tree Physiol. 2025;45(9):tpaf096. doi:10.1093/TREEPHYS/TPAF096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. de Oliveira JPV, Duarte VP, Dos Reis CHG, da Silva PN, de Castro EM, Magalhães PC, et al. Anatomical variations along the leaf axis modulate photosynthetic responses of sorghum and maize under different water availabilities. Plant Biol. 2025;37:554. doi:10.1111/PLB.70084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang H, Liu Y, Huangfu S, Zhang B, Ma H, Ma H, et al. Elevational variation in leaf anatomical and stomatal traits and their allometric relationships of Quercus variabilis from a warm-temperateforest. Photosynth Res. 2025;163(4):39. doi:10.1007/S11120-025-01161-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Boor Z, Taheri Abkenar K, Mohammadi Galangash M, Ghanbary E, Sadeghi SMM. Physiological, biochemical and leaf anatomical responses of tree species to air pollution in forests surrounding Chamestan Industrial Zone, Iran: a case study. Environ Dev Sustain. 2025;137(1):1–23. doi:10.1007/S10668-025-06521-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Amitrano C, Kacira M, Arena C, De Pascale S, De Micco V. Leaf anatomical traits shape lettuce physiological response to vapor pressure deficit and light intensity. Planta. 2025;262(2):48. doi:10.1007/S00425-025-04774-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Pan TH, Zhang WY, Du WT, Fu BY, Zhou XT, Cao K, et al. Synergistic effects of elevated CO2 and enhanced light intensity on growth dynamics, stomatal phenomics, leaf anatomy, and photosynthetic performance in tomato seedlings. Horticulturae. 2025;11(7):760. doi:10.3390/HORTICULTURAE11070760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Anatov DM, Asadulaev ZM, Ramazanova ZR, Osmanov RM. Features of the anatomical structure of leaves depending on the high-altitude growth of apricot in Dagestan. Proc Appl Bot Genet Breed. 2023;184(2):176–89. doi:10.30901/2227-8834-2023-2-176-189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Castillo-Figueroa D, Posada JM. Are leaf anatomical traits strong predictors of litter decomposability? Evidence from upper Andean tropical species along a forest successional gradient. Oecologia. 2025;207(7):110. doi:10.1007/S00442-025-05739-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Castillo-Figueroa D. Variation in leaf anatomical traits of trees and shrubs in upper Andean tropical forests. Folia Geobot. 2025;60(1):1–16. doi:10.1007/S12224-025-09467-Y110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Xu HJ, Zhang BH, Yang L, Jin YX, Wang WZ, Ao N, et al. Transcriptome analysis of inflorescence embryogenesis in Festuca glauca. Plant Gene. 2024;40(14):100468. doi:10.1016/j.plgene.2024.100468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zhang YM, Bai XM, Tian YF, Gong LJ. Anatomical observation of leaf structure and adaptability analysis to environment in 4 ornamental grasses. Acta Agrestia Sinica. 2019;27(5):1377–83. (In Chinese). doi:10.11733/j.issn.1007-0435.2019.05.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Amanda PPD, Enes FJ, Liliane SDC, Ricardo AFR, Thalissa CP, Mariana MDLHF, et al. Nitrogen modifies the leaf anatomy and the antioxidant system of cotton in irrigated and rainfed cultivation. J Plant Growth Regul. 2024;44(5):2485–503. doi:10.1007/S00344-024-11562-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Ashish KM, Shivani G, Shashi BA, Supriya T. Role of stomatal and leaf anatomical features in defining plant performance under elevated carbon dioxide and ozone, in the changing climate scenario. Environ Sci Pollut R. 2025;32(5):2536–50. doi:10.1007/S11356-024-35877-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang H, Ge Y, Hu J, Wang Y, Ni D, Wang P, et al. Integrated analyses of metabolome, leaf anatomy, epigenome, and transcriptome under different light intensities reveal dynamic regulation of histone modifications on the high light adaptation in Camellia sinensis. Plant J. 2025;121(5):e70040. doi:10.1111/TPJ.70040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Hu W, Zhang S, Huang W, Chang H, Li Y, Gu C, et al. Nitrogen-driven changes in leaf anatomy affect the coupling between leaf mass per area and photosynthesis. J Exp Bot. 2025;76(12):3444–56. doi:10.1093/jxb/eraf108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Vieira-Goncalves D, Roddy AB. Developmental changes in epidermal anatomy, drought tolerance, and biomechanics in the leaves of a tropical fern. Ann Bot. 2025:mcaf204. doi:10.1093/AOB/MCAF204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Alderotti F, Lo Piccolo E, Brunetti C, Stefano G, Ugolini T, Cecchi L, et al. Cultivar-specific responses of young olive trees to water deficit: impacts on physiology, leaf anatomy, and fruit quality in ‘Arbequina’, ‘Leccio del Corno’ and ‘Maurino’. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2025;229(6):110331. doi:10.1016/J.PLAPHY.2025.110331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Yang Z, Dai G, Qin K, Wu J, Wang Z, Wang C. Comprehensive evaluation of germplasm resources in various goji cultivars based on leaf anatomical traits. Forests. 2025;16(1):187. doi:10.3390/F16010187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Firouzeh B, Azar SA, Najmeh A, Farkhondeh R, Mansour M. Leaf anatomical investigations in Acantholimon (Plumbaginaceae). Braz J Bot. 2022;45(2):729–41. doi:10.1007/S40415-022-00807-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Pshennikova LM. The implication of leaf anatomical structure for the selective breeding of lilacs. Vavilovskii Zhurnal Genet Sel. 2021;25(5):534–42. doi:10.18699/VJ21.060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Lan H, Liu L, Li W, Hao D, Lin S, Ye B, et al. Morphological analysis, bud differentiation, and regulation of Bud Jumping phenomenon in Oncidium using plant growth regulators. Horticulturae. 2025;11(7):852. doi:10.3390/HORTICULTURAE11070852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Irshad A, Tatiana M, Saglara M, Vishnu DR, Svetlana S, Khushnuma I. Effect of novel plant growth regulator and nitrogen fertilization on endogenous hormones content and its relation with grain filling in winter wheat. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2025;25(2):1–18. doi:10.1007/S42729-025-02697-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Waadt R, Seller CA, Hsu PK, Takahashi Y, Munemasa S, Schroeder JI. Plant hormone regulation of abiotic stress responses. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23(10):680–94. doi:10.1038/S41580-022-00479-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Wang DY, Li YY, Gao J, Zhang G, Song ZX, Tang ZS, et al. Differences in seed germination, endogenous hormones, and non-structural carbohydrates in seedlings of rhubarb species under temperature fluctuations. J Plant Growth Regul. 2025;44(7):1–19. doi:10.1007/S00344-025-11661-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Liu D, Cheng L, Tang L, Yang L, Jiang Z, Song X, et al. Transcriptome and endogenous hormone analysis reveals the molecular mechanism of callus hyperhydricity in flax (Linum usitatissimum L.). Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(11):5360. doi:10.3390/IJMS26115360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Yang SC, Lu L, Zhu H, Li WQ. Changes in the contents of endogenous ABA, GA3 and carbohydrates during the vivipary of Aegiceras corniculatum. J Appl Oceanogr. 2021;4(40):608–13. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/J.ISSN.2095-4972.2021.04.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Pan LH, Mo ZY, Shi XF. Study on the relationship between propagule characteristics and reproductive dispersal of viviparous mangrove plants. J Guangxi Acad Sci. 2024;40(3):223–22. (In Chinese). doi:10.13657/j.cnki.gxkxyxb.20241108.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Guo JM, Yang S, Liu X, Wang JW. Transcriptome analysis and gene discovery of abscisic acid signaling pathway in Kandelia obovata under low temperature stress. For Res. 2023;36(2):39–49. (In Chinese). doi:10.12403/j.1001-1498.20220417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Li QS, Qiao HM, Zhou XX. Advancement of omics level studies on mangrove vivipary. J Xiamen Univ (Nat Sci). 2021;60(2):339–47. (In Chinese). doi:10.6043/j.issn.0438-0479.202010006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Wang J, Li M, Zhang YH, Yang SC. HPLC analysis of ABA and GA3 in reproductive organs of Bruguiera gymnorrhiza. J Xiamen Univ Nat Sci. 2008;47(5):752–6. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

62. Ismail FA, Nitsch LM, Wolters-Arts MM, Mariani C, Derksen JW. Semi-viviparous embryo development and dehydrin expression in mangrove Rhizophora mucronata Lam. Sex Plant Reprod. 2010;23(2):95–103. doi:10.1007/s00497-009-0127-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Wu WH. Plant physiology. Beijing, China: Science Press; 2003. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

64. Yang YS, Zou R, Chen ZY, Jiang HL, Yang XR, Jian MT, et al. Changes of endogenous hormone content in flower bud differentiation period of different Sophora japonica cv. “Jinhuai” in northern Guangxi. J Biotech Res. 2021;17:289–97. [Google Scholar]

65. Gallardo K, Job C, Groot SP, Puype M, Demol H, Vandekerckhove J, et al. Protemics of arabidopsis seed germination. A comparative study of wild-type and gibberellin-deficient seeds. Plant Physiol. 2002;129(2):823–37. doi:10.1104/pp.002816. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Yang L, Cheng Y, Yuan C, Zhou YF, Huang QJ, Zhao WL, et al. The long non-coding RNA VIVIpary promotes seed dormancy release and pre-harvest sprouting through chromatin remodeling in rice. Mol Plant. 2025;18(6):978–94. doi:10.1016/J.MOLP.2025.04.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Dong F, Qi Y, Wang YN, Wang CZ, Zhu J, Wang CP, et al. Screening of flower bud differentiation conditions and changes in metabolite content of Phalaenopsis pulcherrima. S Afr J Bot. 2024;171(3):529–35. doi:10.1016/J.SAJB.2024.06.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Zhu ZS, Wang QF, Li Q, Ma J, Xia ZM, Hou Y, et al. Changes of endogenous hormone content in main organs of Hibiscus mutabilis Linn during the flowering period. J West China For Sci. 2021;50(6):16–23. (In Chinese). doi:10.16473/j.cnki.xblykx1972.2021.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Yi RZ, Qin J, Huang QJ. Study on the changes of morphological and physiological indexes during flower bud differentiation of Vitex agnus-castus. Acta Bot Boreal-Occident Sin. 2023;43(10):1760–9. (In Chinese). doi:10.7606/j.issn.1000-4025.2023.10.1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Zhu ZJ, Jiang CY, Shi YH, Chen WQ, Chen NL, Zhao MT, et al. Variations of endogenous hormones in lateral buds of olive trees (Olea europaea) during floral induction and flower-bud differentiation. For Sci. 2015;51(11):32–9. (In Chinese). doi:10.11707/j.1001-7488.20151105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Dai X, Zhang Y, Xu X, Ran M, Zhang J, Deng K, et al. Transcriptome and functional analysis revealed the intervention of brassinosteroid in regulation of cold induced early flowering in tobacco. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1136884. doi:10.3389/FPLS.2023.1136884. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Sheng JY, Li X, Zhang D. Gibberellins, brassinolide, and ethylene signaling were involved in flower differentiation and development in Nelumbo nucifera. Hortic Plant J. 2022;8(2):243–50. doi:10.1016/J.HPJ.2021.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools