Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Ultrasound-Assisted Hydrothermal Treatment in Combination with Chitosan for Fungal Control of Botrytis cinerea

1 Laboratorio Integral de Investigación en Alimentos, Tecnológico Nacional de México/Instituto Tecnológico de Tepic, Avenida Tecnológico #2595, Col. Lagos del Country, Tepic, 63175, Nayarit, México

2 Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias, Campo Experimental Uruapan, Av. Latinoamericana 1101, Col. Revolución, Uruapan, 60150, Michoacán, Mexico

* Corresponding Author: Porfirio Gutiérrez–Martínez. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in the Physiological, Biochemical and Molecular Mechanisms Regulating Fruit Ripening in Tropical Fruits)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 3145-3156. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.071543

Received 07 August 2025; Accepted 10 September 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

A significant portion of losses in the fruit and vegetable sector are caused by the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea, due to its high prevalence in over 1000 crop species. Identifying a technology capable of exclusively inhibiting its growth and development remains challenging; therefore, various treatments have been proposed to act synergistically in preventing the spread of this pathogen. The objective of this study was to evaluate an ultrasound-assisted treatment combined with chitosan to control the development of B. cinerea. In vitro analyses showed that combining temperature, ultrasound, and chitosan inhibited the fungal radial growth by 80%, reduced sporulation, and decreased germination. Electrolyte leak analysis indicated damage to the B. cinerea cell wall, causing intracellular material to escape into the environment. Scanning and transmission electron microscopy images also revealed severe structural damage, including loss of the cytoplasmic membrane and cell lysis.Keywords

In line with the 2030 Agenda objectives for sustainable development and fight against hunger, environmental degradation, and poverty, considerable research has focused on food preservation and the elimination of harmful microorganisms through clean technologies. According to Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) [1], the fruit and vegetable sector is among the most significant contributors to food waste, making up about 14% of global losses. Many of these losses are caused by phytopathogenic fungi that attack crops during growth, development, and post-harvest storage.

Botrytis cinerea is a highly prevalent fungal pathogen in the food industry, causing gray mold in more than 1000 species of fruits and vegetables [2]. This pathogen causes significant economic losses due to its necrotrophic attack on plants and the costs incurred from the application of synthetic fungicides to prevent spoilage [3].

A conventional method, hydrothermal treatment, is used to reduce the proliferation of pathogenic microorganisms during post-harvest fruit storage [4]. During this process, the fruit is immersed in hot water (40–60°C) for short periods of time [5]. Additionally, ultrasound is a promising clean technology for controlling pathogenic microorganisms, mainly through the cavitation effect [6]. This phenomenon causes alteration and sublethal damage to the pathogen’s membranes due to the formation of vapor bubbles in the environment [6,7]. Furthermore, the use of chitosan has been evaluated as an alternative method to preserve fruit quality. This non-toxic polymer is derived from the deacetylation of chitin, which is extracted from the exoskeletons of certain crustaceans, fungi, and insects [8]. Its chemical structure, characterized by amino and hydroxyl groups, confers a polycationic nature, allowing interactions with the negatively charged components of phytopathogenic fungal cell walls and membranes [9].

These technologies alone are insufficient to effectively reduce pathogenic microorganisms; therefore, the combining of multiple control strategies are recommended [7]. This was demonstrated by Wang and Wu [10] who employed a chlorine and peracetic acid wash combined with ultrasound to inhibit the growth of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Similarly, the combination of ultrasound and hydrothermal treatment significantly inhibited the mycelial growth of Rhizopus stolonifer, leading to both morphological and cellular damage [7].

To advance the search for sustainable, efficient and environmentally friendly treatments to control phytopathogenic fungi, the main objective of this study was to evaluate the in vitro effect of chitosan and ultrasound-assisted hydrothermal treatment as alternative to inhibit the development of Botrytis cinerea. To achieve this objective, it was essential to assess the impact of these treatment on mycelial growth, sporulation, germination, structural damage, cell viability of B. cinerea, among other parameters.

In vitro experiments were conducted using a combined hydrothermal treatment with commercial-grade chitosan (47.5 kDa, 99% deacetylation) at 0.1%. Treatments were applied using an FTVOGUE ultrasonic bath (Los Angeles, CA, USA) with a 6.5 L capacity. The equipment operated at a fixed frequency of 45 kHz and power of 180 W. The treatments were performed at 45°C for 2 and 5 min. The fungus Botrytis cinerea, isolated from blueberry fruits, was provided by the Comprehensive Food Research Laboratory of the Technological Institute of Tepic, Nayarit, Mexico.

2.1 Evaluation of Radial Growth of B. cinerea

To determine the radial growth of B. cinerea, two methodologies were used depending on the treatment. An 8 mm diameter disc of the fungus was placed in Petri dishes containing potato dextrose agar (PDA) culture medium added with chitosan. On the other hand, 1 mL of a suspension of fungal spores (1 × 106 spores/mL) was subjected to an ultrasonic bath at 45°C for 2 min. Subsequently, 5 μL of this solution was inoculated at the center of a Petri dish with PDA medium, following the method described by Li et al. [7]. In both cases, the control consisted of PDA plates inoculated with untreated B. cinerea fungus. All plates were incubated for 8 days at 25°C. Mycelial diameter was measured using the ImageJ® software, and the percentage of inhibition was calculated using Eq. (1) [11].

2.2 Sporulation Process of B. cinerea

To quantify B. cinerea spores after 8 days of growth, 10 mL of sterile distilled water was added to the Petri dishes (with individual treatments, combined treatments, and untreated control). The surface of the mycelium was carefully scraped, and the resulting suspensions were filtered and collected in test tubes. Spore counts of B. cinerea for each treatment were performed using a Neubauer chamber and an optical microscope (Motic BA 300, Langley, BC, Canada) with a 40× objective, allowing determination of the number of spores/mL in each suspension.

2.3 Evaluation of the Germinal Development of B. cinerea

The evaluation of B. cinerea germinal development was performed following the methodology described by Moreno-Hernández et al. [12]. Aliquots of B. cinerea spore suspensions (treated and untreated) were prepared in Eppendorf tubes with potato dextrose broth, adjusting the final concentration to 1 × 106 spores/mL. The Eppendorf tubes were kept at 25°C under constant shaking for 10 h, corresponding to the germination period of untreated B. cinerea. The germinated spore count was performed using an optical microscope (Motic BA 300, Canada) with 10× and 40× objectives. The germination percentage was calculated using Eq. (2).

2.4 Leakage of Intracellular Material of B. cinerea

Electrolyte leakage was evaluated following the methodology described by Martos et al. [13]. Aliquots of 20 mL of B. cinerea suspension (1 × 105 spores/mL) in sterile distilled water were exposed to various chitosan and ultrasound treatments, along with a control (water). The conductivity was measured continuously at 25°C and 100 rpm using a Metrohm E 527 conductivity meter. Results were expressed in μS/cm.

The viability of both treated and untreated B. cinerea spores was evaluated using an automatic cell counter (Olympus Model R1 Cell Counter) following the procedures described in the operating manual and using trypan blue dye. For the experiment, B. cinerea spore suspensions at a concentration of 8 × 106 spores/mL were subjected to various treatments. After 2 h of continuous shaking at 25°C, 10 µL aliquots from each suspension were placed on a cell counting slide (Olympus R1-SLI) for analysis. The percentage of cell viability, spore size, and the ratio of live to dead spores was measured for each treatment.

2.6 Scanning Electron Microscopy

Scanning microscopic analysis was performed on a control sample and a sample of the pathogen treated with 0.1% chitosan. To do this, 8 mm diameter samples were taken from the control and treated plates. The pathogen fragments were prepared by immersing them in a vial containing a 3% glutaraldehyde solution in 0.1 M Sorensen’s phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, for 24 h. Gradual washes were performed with ethanol at increasing concentrations (30%–100% v/v) for 1 h. The samples were dried in a critical point dryer (Samdri–780A, Arlington, VA, USA) and coated with gold-palladium using an ionizer (Ion Sputter JFC–1100, Jeol, Peabody, MA, USA). Sample analysis was carried out using a scanning electron microscope (Jeol JSM-6390, USA) at 5 kV.

2.7 Transmission Electron Microscopy

Samples of B. cinerea, both treated with 0.1% chitosan and untreated (control), were prepared for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) following this protocol. First, the samples were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, followed by rinsing the phosphate buffer for 30 min. Post-fixation was performed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h. The samples were washed four times with PBS, each wash lasting 5 min. Gradual dehydration was carried out using ethanol at increasing concentrations (70%, 80%, 90%, and 96%) for 10 min each, followed by three changes of 100% ethanol, 5 min per change. Next, the samples were treated with three 5-min changes of propylene oxide and infiltrated with epoxy resin for 16 h at 60°C. Finally, ultrathin sections of 70-µm were then cut and mounted on copper grids. Sections were stained with uranyl acetate for 20 min and lead citrate for 10 min. The samples were observed using a transmission electron microscope (Joel model 1010, USA).

In this study, a full factorial design was used, with different treatments acting as independent variables. The results were analyzed statistically using an analysis of variance (ANOVA). Means were compared with Fisher’s LSD test (p < 0.05). All analyses were conducted with Statistica v12.0 (StatSoft Inc., Aliso Viejo, CA, USA, 2013). Five replicates were performed for each treatment, and the tests were run in duplicate.

3.1 Evaluation of Radial Growth of B. cinerea

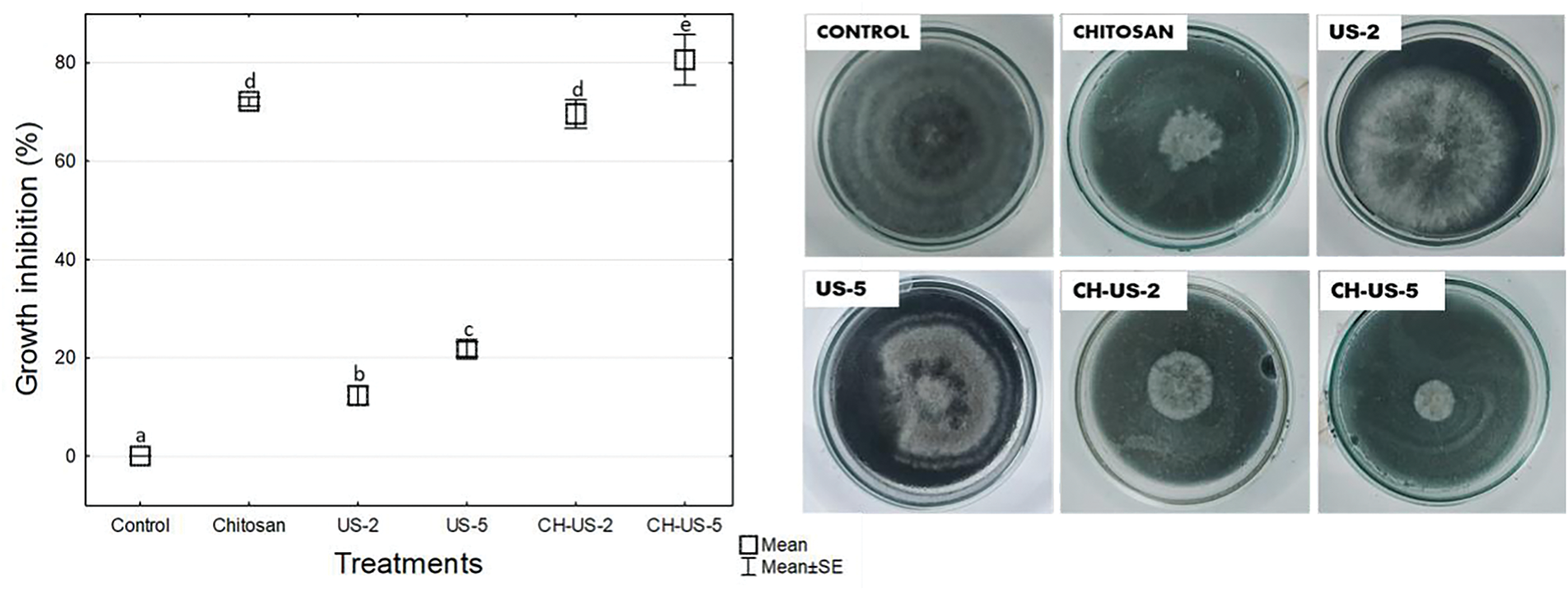

In vitro radial growth of B. cinerea showed significant differences between the treatments and control (Fig. 1). The combination of chitosan and ultrasound-assisted hydrothermal treatment (45°C for 5 min) demonstrated the highest inhibitory effect (80% inhibition) on the growth of B. cinerea. Although ultrasound hydrothermal treatment alone did not show significant inhibition, it reduced the growth of the phytopathogen by 21% compared to the control.

Figure 1: In vitro radial growth of B. cinerea under ultrasound-assisted hydrothermal treatment at 45°C for 2 min (US-2), 45°C for 5 min (US-5), chitosan (CH), and their combination (CH-US-2, CH-US-5). Values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments. Fisher’s LSD test (p < 0.05)

The combination of chitosan with ultrasound-assisted hydrothermal treatment (45°C for 5 min) effectively inhibited the mycelial growth of B. cinerea, surpassing the effects of individual treatments. This finding aligns with previous reports, which suggest that enhancing the inhibitory effects of thermal and ultrasound applications on pathogens requires combining them with another type of physical treatment or coating [10]. Similar results were reported by Li et al. [7], who used ultrasound at a power of 200 W and a temperature of 55°C, achieving approximately 30% inhibition of Rizhopus stolonifer colonies. Being polycationic, chitosan can bind to the external structure of fungi, causing severe damage to the plasma membranes of mycelia and spores [14]. Similarly, ultrasonic technology alters fungal membranes, leading to irreversible cellular damage [7]. The antimicrobial activity of ultrasound primarily results from the physical and mechanical forces generated by acoustic cavitation [15].

3.2 Sporulation Process of B. cinerea

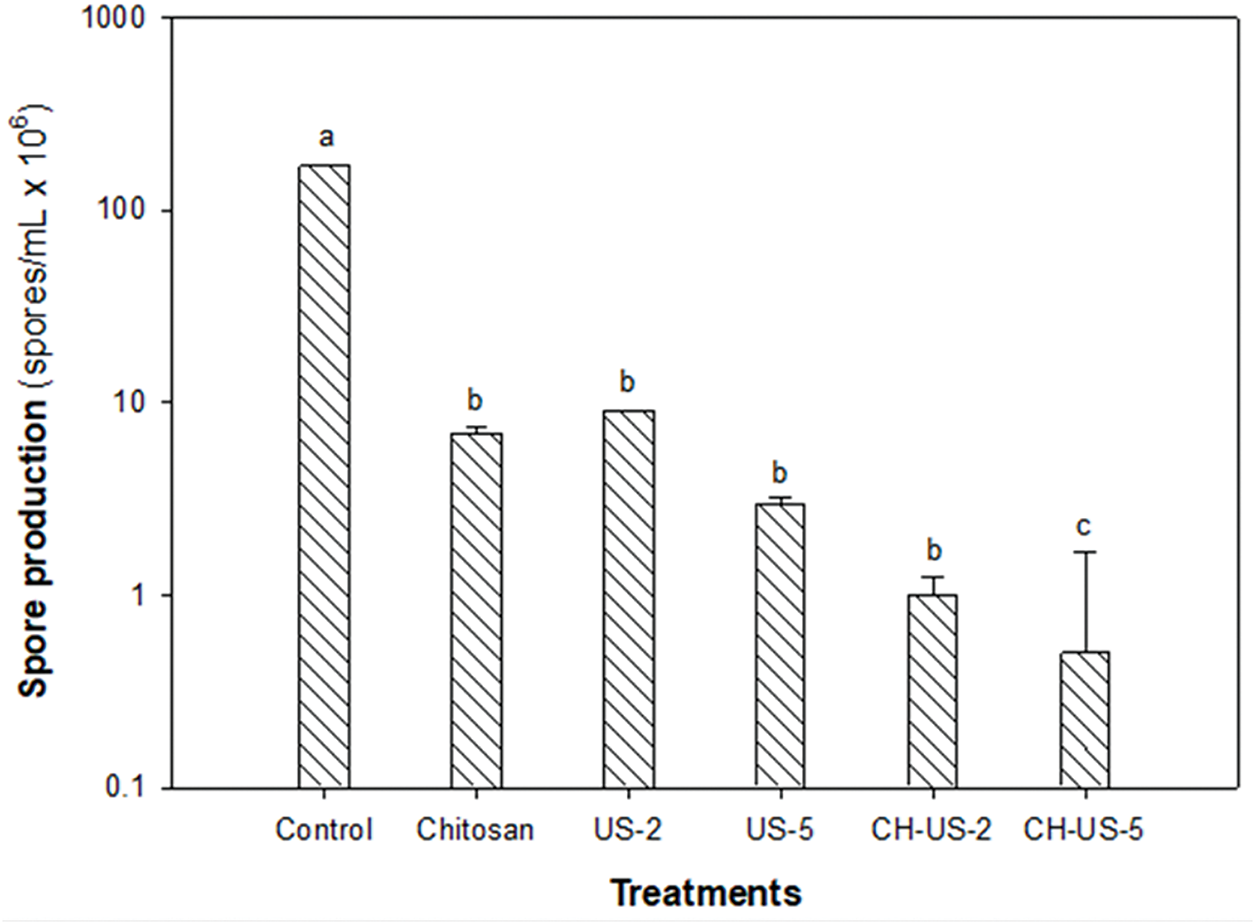

The treatments had a significant impact on the sporulation process of B. cinerea, exhibiting marked differences compared to the control (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Spore production of B. cinerea due to ultrasound-assisted treatment at 45°C for 2 min (US-2), 45°C for 5 min (US-5), chitosan (CH), and a combination of these. Values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments. Fisher’s LSD test (p < 0.05)

Overall, B. cinerea sporulation was effectively reduced by applying chitosan and ultrasound at 45°C for 2 and 5 min. However, the most effective approach was combining chitosan with ultrasound-assisted hydrothermal treatment at 45°C for 5 min. This method reduced spore production from a control level of 1.7 × 108 spores/mL to 0.5 × 106 spores/mL. The observed decrease in sporulation with the combined treatments can be attributed to the additive effects of chitosan and ultrasound.

Zupanc et al. [6] note that ultrasonic waves generated during cavitation, along with heat, produce highly reactive free radicals that kill pathogens. Therefore, the combined action of hot water and ultrasonic waves likely damages the outer layer of B. cinerea, allowing chitosan to penetrate more effectively. The highly reactive amino and hydroxyl groups of chitosan may be responsible for reducing B. cinerea sporulation by damaging fungal structures [11].

3.3 Evaluation of the Germinal Development of B. cinerea

B. cinerea did not germinate when treated with ultrasound (45°C-2 and 5 min), chitosan, or the combination of both treatments. In contrast, untreated spores exhibited 100% germination when untreated. A similar result was found when treating Rhizopus stolonifer spores with ultrasound [7]; germination was completely inhibited, with spores showing thickening, possibly caused by mechanical damage that reduced the pathogen’s resistance to the heat generated by ultrasonic treatment. Regarding the use of chitosan, the results presented by El-araby et al. and Triunfo et al. [15,16] indicate that the low molecular weight of this compound, extracted from crustaceans, is advantageous, as it achieves an inhibitory effect on the germination of B. cinerea spores isolated from strawberries. Another pathogen that was 100% inhibited by different concentrations of low molecular weight chitosan was Colletotrichum asianum [17]. A reduction in phosphate ions and essential elements for the pathogen, such as Ca or K, occurs due to chitosan’s interaction with the phospholipids in the fungal membrane [18]. When lower molecular weight chitosan (3.4 to 51.5 kDa) was used, the effect on B. cinerea germination was inversely proportional; resulting in irreversible inhibition of germination, and pronounced structural damage to the hyphae.

3.4 Leakage of Intracellular Material of B. cinerea

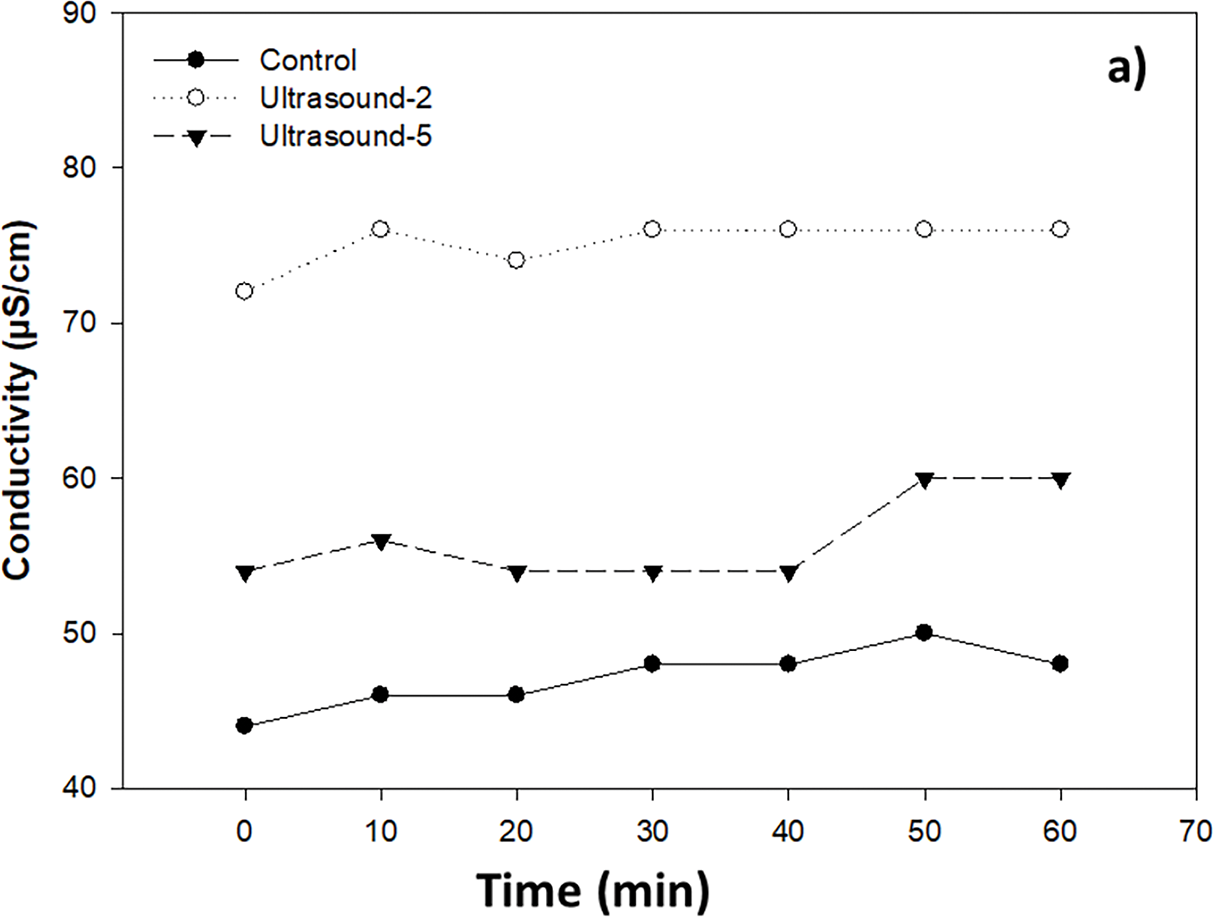

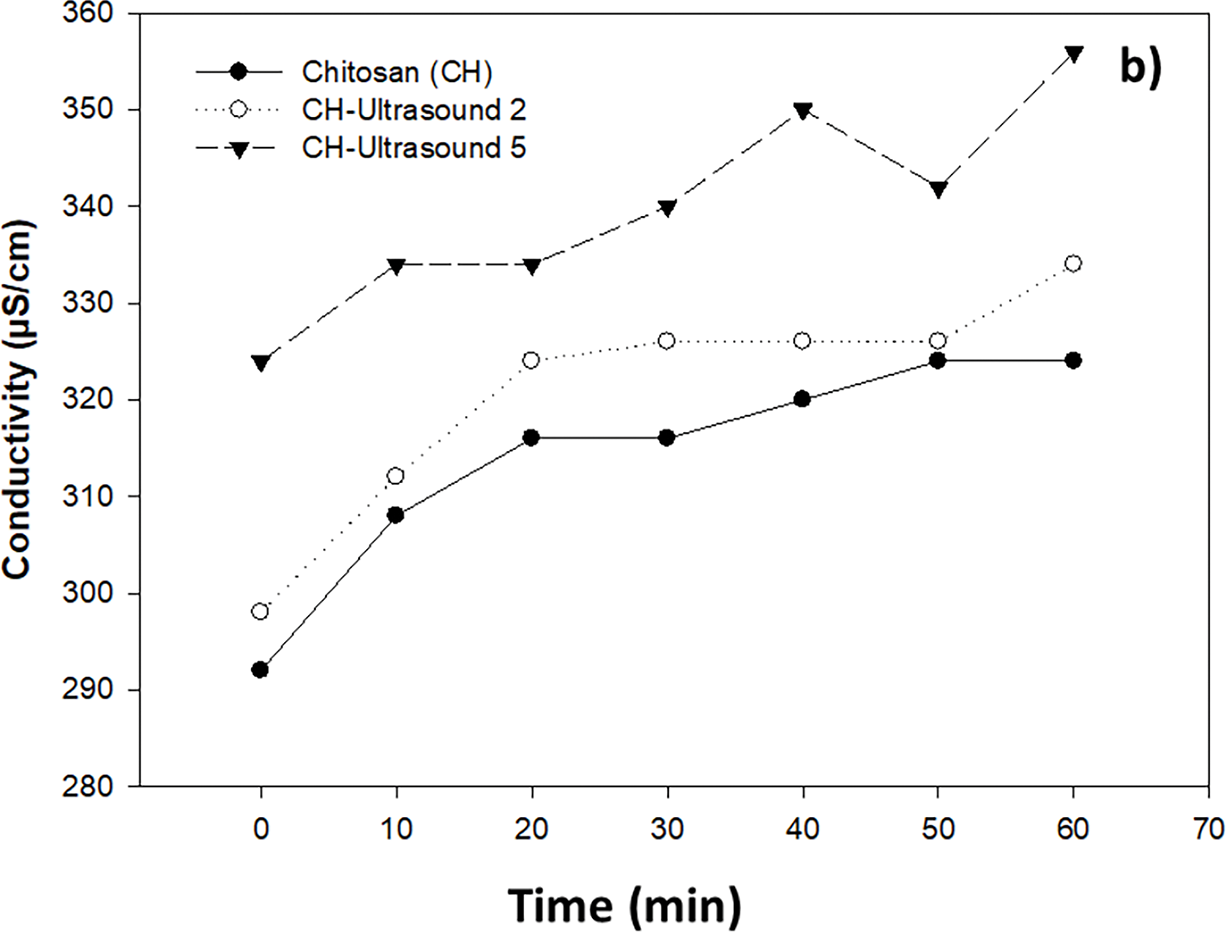

Electrical conductivity, resulting from the combined effect of ultrasound and chitosan, increased over time (Fig. 3a,b). When subjected to ultrasound-assisted hydrothermal treatment for 2 and 5 min, the conductivity was higher than that of the control (untreated B. cinerea solution) (Fig. 3a). Similarly, the spore solution exposed to chitosan, heat, and ultrasound showed higher conductivity values, which increased over time (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3: Effect of ultrasound-assisted hydrothermal treatment at 45°C for 2 and 5 min (a), and chitosan alone and combined with ultrasound-assisted hydrothermal treatment (b), on the conductivity of Botrytis cinerea spore solution (105 spores/mL)

The value measured when assessing electrical conductivity in the solution containing B. cinerea with different treatments indicates the presence of electrolytes in the medium due to an electrolytic leak [13].

The interaction of chitosan with the plasma membrane and the subsequent leakage of material into the extracellular medium was demonstrated by Shi et al. [18]. The authors observed that the cell membrane of Alternaria alternata was altered, resulting in the leakage of nucleic acids and proteins into the medium. Similarly, it has been reported that bubbles produced by ultrasound weaken the external structure of microorganisms, causing the release of cellular components such as proteins and polysaccharides [6].

In this study, combination of chitosan with ultrasound-assisted hydrothermal treatment significantly increased the leakage of intracellular material and caused cellular damage in B. cinerea.

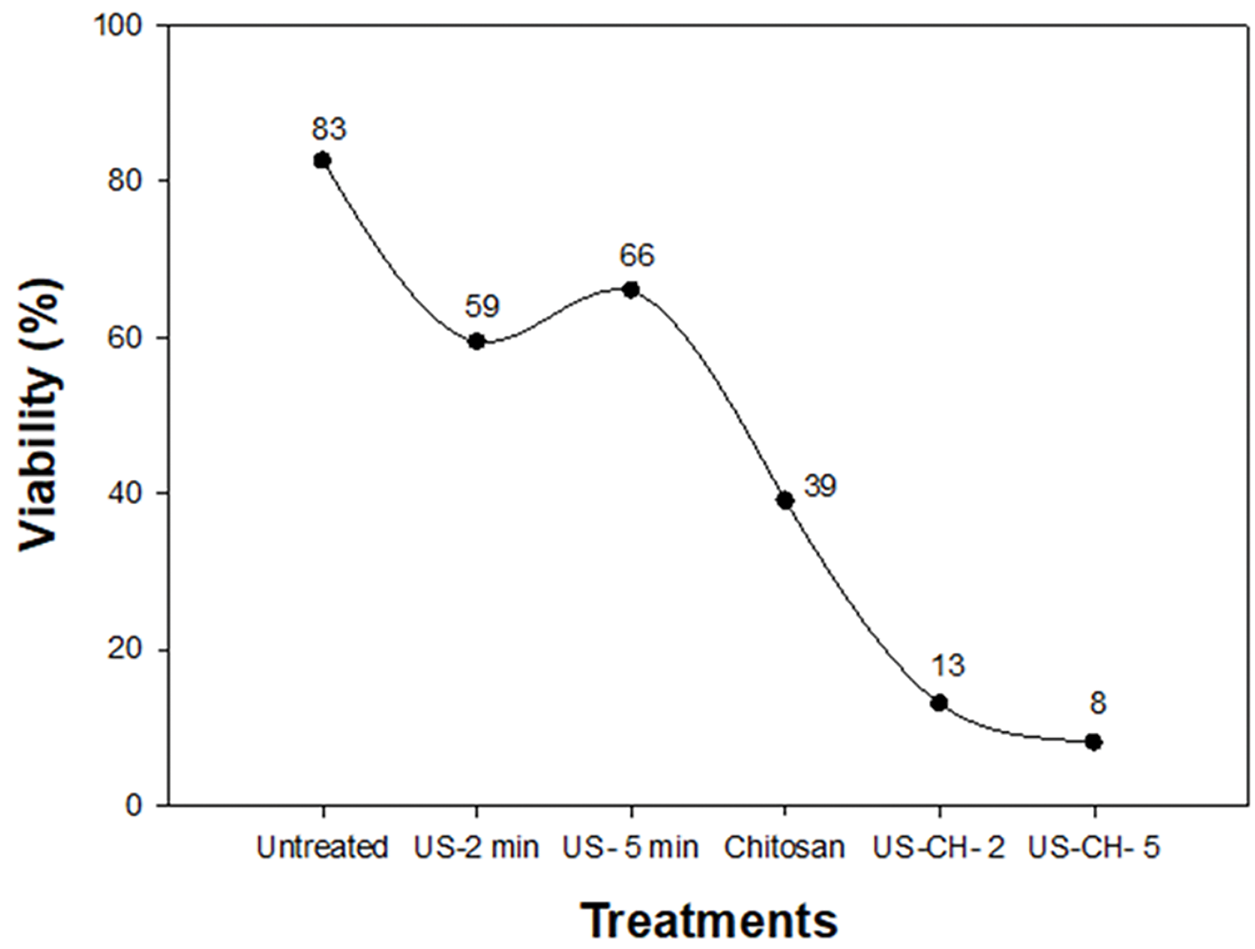

B. cinerea spores treated with heat, ultrasound, and chitosan showed a decrease in viability compared to untreated spores (Fig. 4). The combined treatments of chitosan-ultrasound for 2 and 5 min were the most effective at reducing viability, resulting in 13% and 8% viable cells, respectively.

Figure 4: Percentage of Botrytis cinerea viability influenced by different treatments: US (ultrasound), CH (chitosan)

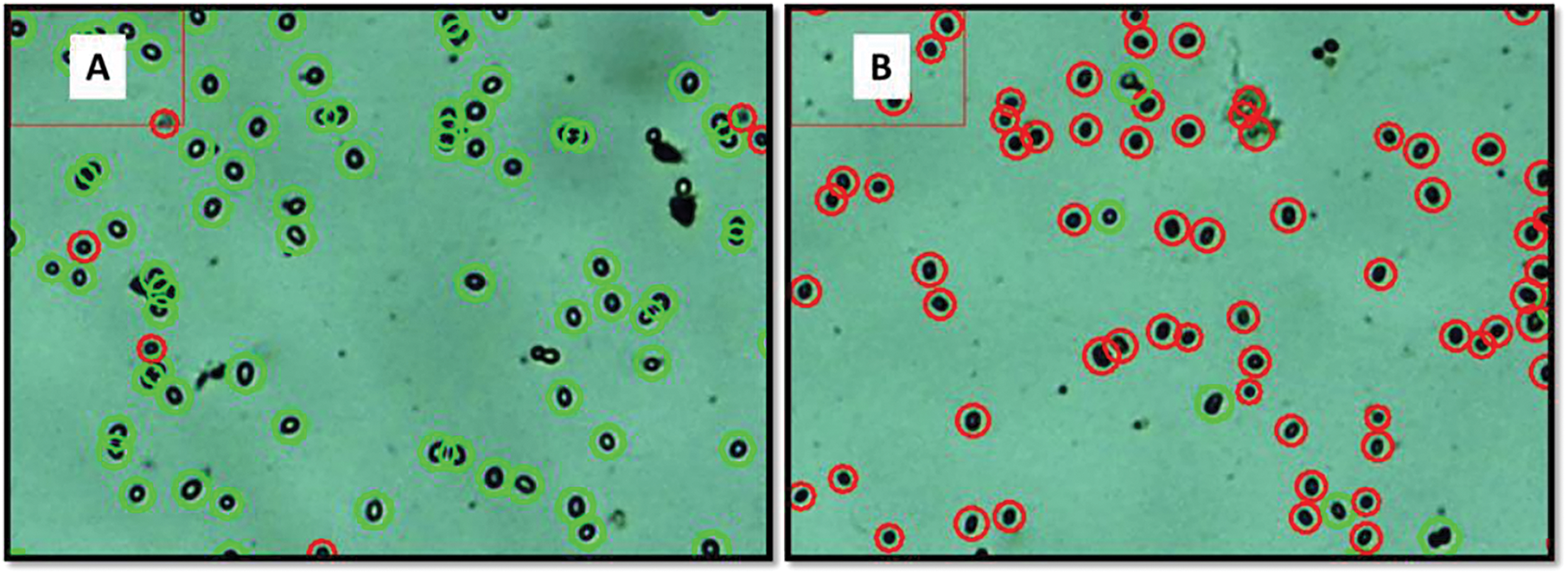

Quantification of live and dead spores revealed the impact of the chitosan-ultrasound treatment (5 min), as shown in Fig. 5. The identification of this viability percentage is established according to the effect that the trypan blue reagent has on the spores of B. cinerea. Those spores that were stained with trypan blue are considered dead while those that were not penetrated by the reagent are considered healthy [19]. The live spore count of untreated B. cinerea was 8.00 × 106 spores/mL. After treatment, the total number of live spores dropped significantly to 6.43 × 105 spores/mL. This indicates that out of 1742 spores, only 140 remained alive. Furthermore, spore morphology was adversely affected by the treatment, as their size decreased from 9.5 to 8.2 µm.

Figure 5: Concentrations of live (green circles) and dead (red circles) spores of B. cinerea without treatment (A) and with hydrothermal treatment and ultrasound for 5 min combined with chitosan (B)

The lowest viability percentage was achieved when the different treatments were combined, suggesting a possible action derived from the multiple mechanisms exerted by each treatment on B. cinerea.

When the pathogen Colletotrichum asianum was treated with commercial chitosan, its reproductive structures underwent modifications [12]. These authors concluded that chitosan is fungistatic in nature, because the treated pathogen grew again when placed in a new nutrient medium. According to the Vitti et al. [20] the activity of B. cinerea was compromised when this fungus was brought into contact with low weight chitosan (75 kDa). The hot water immersion technique coupled with ultrasound waves produces species of oxidizing origin (H2O2 and OH) that attack lipids, proteins and polysaccharides present in pathogenic microorganisms, destabilizing their membrane and irreversibly damaging their DNA [6].

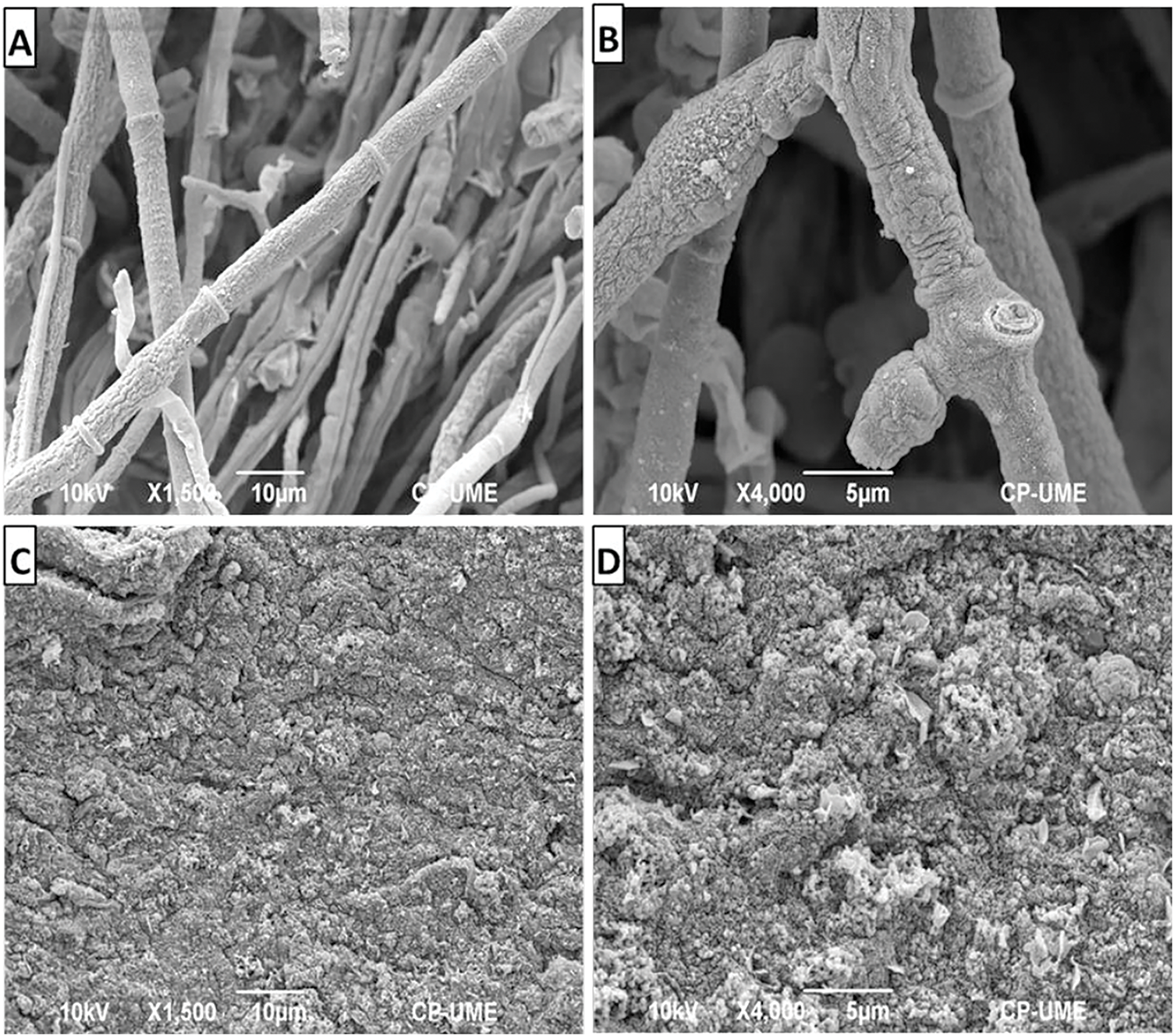

3.6 Scanning Electron Microscopy

The fungal mycelium of B. cinerea, both treated and untreated, was analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Fig. 6). Images of untreated B. cinerea (Fig. 6A,B) revealed complete, septate, and undamaged mycelia. In contrast, the mycelium treated with chitosan (0.1%) appeared clumped, compacted, and irregular, losing its defined shape (Fig. 6C,D).

Figure 6: Scanning electron microscopy images of untreated Botrytis cinerea (A,B) and samples treated with 0.1% chitosan (C,D)

SEM images confirmed that the untreated B. cinerea hyphae were septate and smooth, with a well-formed morphology and normal development, consistent with previous reports [11]. In contrast, the chitosan-treated mycelium showed clear structural damage, appearing completely compromised, deformed, and irregular. These findings align with other SEM analyses where chitosan caused damage to the structures of Fusarium solani, resulting in reduced growth and viability, and possibly cell lysis of the pathogen [21]. Similarly, several studies have suggested that chitosan can cause structural damage in fungi such as, C. asianum, and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum [12,22]. This can be attributed to its multiple modes of action, including lipid peroxidation, the production of reactive oxygen species, and cell membrane disruption, ultimately leading to cell death in these fungi.

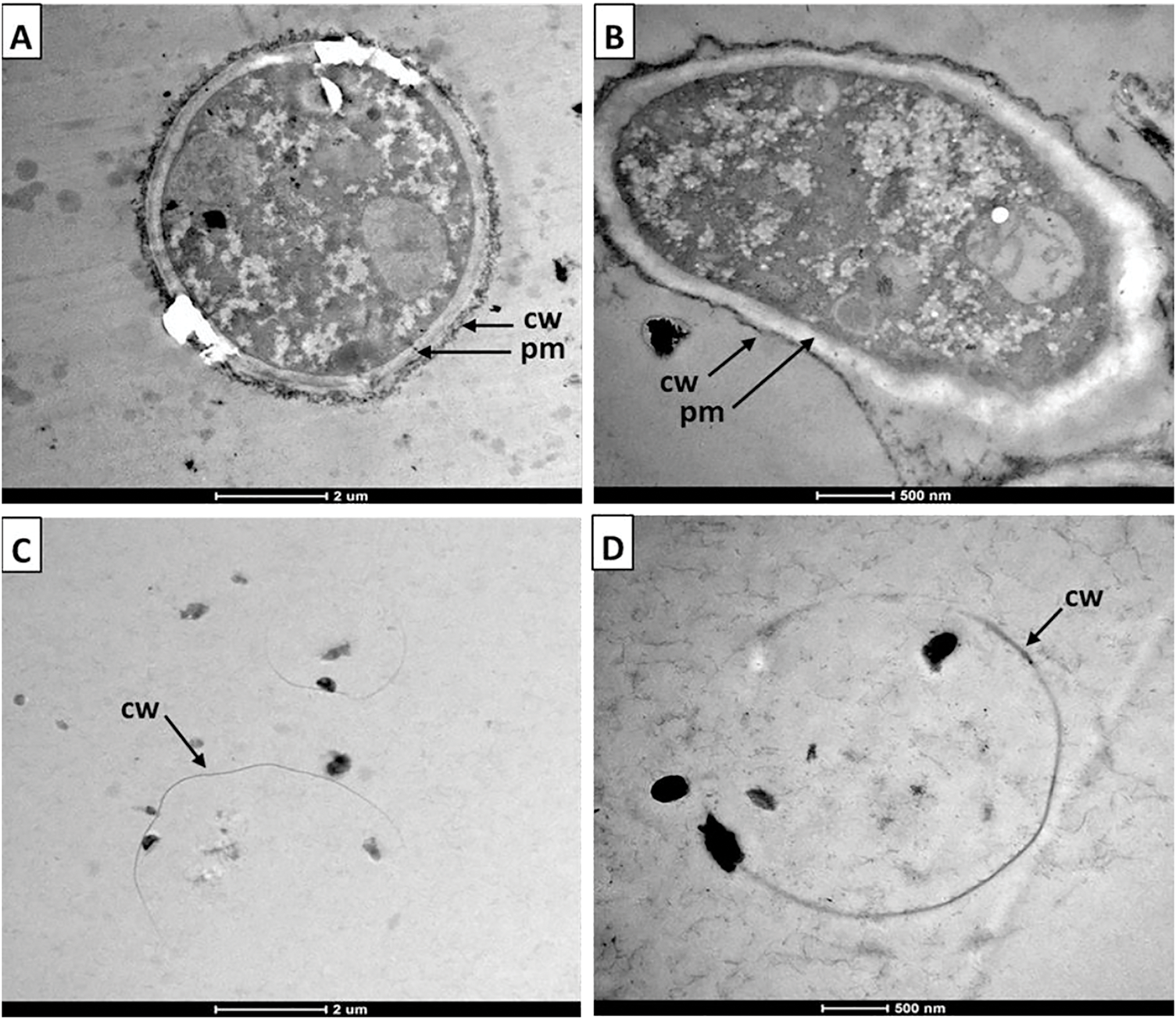

3.7 Transmission Electron Microscopy

The antifungal effect of chitosan on both treated and untreated B. cinerea spores was observed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 7). TEM images of untreated B. cinerea spores (Fig. 7A,B) revealed a well-defined cell wall and membrane, along with the presence of intact cytoplasmic material. These observations are consistent with those of Youssef et al. [23]. In contrast, chitosan caused cell wall permeabilization, resulting in the release of intracellular material from the fungus. In the images (Fig. 7C,D), thin fibrillar strands can be seen that could correspond to cytoplasm released from the cell.

Figure 7: Internal structure of untreated (A,B) and 0.1% chitosan-treated (C,D) Botrytis cinerea spores as observed by transmission electron microscopy. cw: cell wall; pm: plasma membrane

The TEM images reported by López-Mora et al. [24] demonstrated that chitosan induced vacuolation and disruption of the cell membrane, resulting in the loss of cytoplasmic material in spores and hyphae of the pathogen Alternaria alternata. This cell lysis effect induced by chitosan in B. cinerea conidia was also previously reported by Vitti et al. [20]. The authors observed with TEM images that the cytoplasm had dispersed and mixed with the vacuoles and that the internal cell material had dissipated into the medium.

Structurally, fungal spores consist of an outer cell wall (rich in mannoproteins, glucan, and chitin) and an inner cytoplasmic membrane embedded with phospholipids [6]. Chitosan has been shown to interact directly with the phospholipids of the cell membrane, and by damaging it, the fungal cells suffer irreversible damage [25].

Although scanning transmission electron microscopy was not used in this study for the hydrothermal ultrasound treatment of B. cinerea, it has been reported that this treatment, similar to chitosan, causes significant alterations in fungal structures. For example, in a study on R. stolonifer subjected to ultrasound treatment, wrinkled hyphae, damaged cell walls, and massive vacuolation of the cell cytoplasm were observed [7].

Overall, scanning and transmission electron microscopy analyses demonstrated that the loss of cytoplasmic material from B. cinerea structures and the destruction of its membrane, resulting from the treatments, were the primary causes of the decrease in cell viability, as well as the complete inhibition of spore germination.

Ultrasound-assisted hydrothermal treatment combined with chitosan reduced the in vitro growth of B. cinerea. Radial inhibition was inhibited by 80%, sporulation was reduced, and germination was completely suppressed. B. cinerea suffered irreversible damage, with intracellular material detected in the medium, and only 8% of spores remained viable after exposure to the treatment. Hyphae observed by scanning and transmission electron microscopy analysis were compact and shapeless. Spores showed apparent vacuolization, cytoplasmic destruction, and cell lysis. According to these findings, hydrothermal treatment at 45°C, assisted by high-power ultrasound in combination with 0.1% commercial-grade chitosan, can be implemented as an alternative method for controlling the phytopathogen B. cinerea. This treatment is proposed to be implemented post-harvest, during the washing and disinfection process, ensuring that the quality and shelf life of the fruit are maintained throughout storage until it reaches the consumer.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank postdoc Surelys Ramos Bell for her support from SECIHTI.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization and validation: Porfirio Gutiérrez-Martínez, Surelys Ramos-Bell; data curation: Surelys Ramos-Bell; writing—original draft preparation: Surelys Ramos-Bell; writing—review and editing: Surelys Ramos-Bell, Edson Rayón-Díaz, Juan A. Herrera-González, Estefanía Martínez-Batista, Rita M. Velázquez-Estrada, Porfirio Gutiérrez-Martínez. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Tracking progress on food and agriculture-related SDG indicators 2023 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/36f4414a-25cc-4dad-a747-10002e20a573/content. [Google Scholar]

2. Rabasco-Vílchez L, Porras-Pérez E, Possas A, Morcillo-Martín R, Pérez-Rodríguez F. A predictive approach to reducing strawberry post-harvest waste: impact of storage conditions and water activity on Botrytis cinerea germination. Food Res Int. 2025;210(3):116401. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2025.116401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Foster BJ, Wilson I, Jacobs K. First report of Botrytis cinerea in South African blueberry orchards. J Plant Dis Prot. 2024;131(5):1731–8. doi:10.1007/s41348-024-00963-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Di Francesco A, Mari M, Roberti R. Defense response against postharvest pathogens in hot water treated apples. Sci Hortic. 2018;227:181–6. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2017.09.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gomes BAF, Alexandre ACS, de Andrade GAV, Zanzini AP, de Barros HEA, dos Santos Ferraz, et al. Recent advances in processing and preservation of minimally processed fruits and vegetables: a review—part 2: physical methods and global market outlook. Food Chem Adv. 2023;2(1–2):100304. doi:10.1016/j.focha.2023.100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zupanc M, Pandur Ž, Perdih TS, Stopar D, Petkovšek M, Dular M. Effects of cavitation on different microorganisms: the current understanding of the mechanisms taking place behind the phenomenon. A review and proposals for further research. Ultrason Sonochem. 2019;57(5):147–65. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.05.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Li L, Zhang M, Sun HN, Mu TH. Contribution of ultrasound and conventional hot water to the inactivation of Rhizopus stolonifer in sweet potato. LWT. 2021;148:111797. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Debnath D, Samal I, Mohapatra C, Routray S, Kesawat MS, Labanya R. Chitosan: an autocidal molecule of plant pathogenic fungus. Life. 2022;12(11):1908. doi:10.3390/life12111908. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Gong W, Sun Y, Tu T, Huang J, Zhu C, Zhang J, et al. Chitosan inhibits Penicillium expansum possibly by binding to DNA and triggering apoptosis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;259(Pt 1):129113. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.129113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Wang J, Wu Z. Combined use of ultrasound-assisted washing with in-package atmospheric cold plasma processing as a novel non-thermal hurdle technology for ready-to-eat blueberry disinfection. Ultrason Sonochem. 2022;84(1):105960. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.105960. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ramos-Bell S, de México TN, Hernández-Montiel LG, Velázquez-Estrada RM, Sánchez-Burgos JA, Bautista-Rosales PU, et al. Additive effect of alternative treatment to chemical control of Botrytis cinerea in blueberries. Rev Mex De Ingeniería Química. 2022;21(3):1–14. doi:10.24275/rmiq/bio2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Moreno-Hernández CL, de Tepic IT, Zambrano-Zaragoza ML, Velázquez-Estrada RM, Sánchez-Burgos JA, Gutiérrez-Martinez P. Identification of a Collletotrichum species from mango fruit and its in vitro control by GRAS compounds. Rev Mex De Ingeniería Química. 2022;21(3):1–18. doi:10.24275/rmiq/bio2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Martos GG, Mamaní A, Filippone MP, Castagnaro AP, Ricci JCD. The ellagitannin HeT induces electrolyte leakage, calcium influx and the accumulation of nitric oxide and hydrogen peroxide in strawberry. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2018;123(1411):400–5. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.12.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Coutinho TC, Ferreira MC, Rosa LH, de Oliveira AM, de Oliveira Júnior EN. Penicillium citrinum and Penicillium mallochii: new phytopathogens of orange fruit and their control using chitosan. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;234(6):115918. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.115918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. El-Araby A, Janati W, Ullah R, Uddin N, Bari A. Antifungal efficacy of chitosan extracted from shrimp shell on strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) postharvest spoilage fungi. Heliyon. 2024;10(7):e29286. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Triunfo M, Guarnieri A, Ianniciello D, Coviello L, Vitti A, Nuzzaci M, et al. Hermetia illucens, an innovative and sustainable source of chitosan-based coating for postharvest preservation of strawberries. iScience. 2023;26(12):108576. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2023.108576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Rayón-Díaz E, Hernández-Montiel LG, Zamora-Gasga VM, Sánchez-Burgos JA, Ramos-Bell S, Velázquez-Estrada RM, et al. Antifungal and toxicological evaluation of natural compounds such as chitosan, citral, and hexanal against Colletotrichum asianum. Horticulturae. 2025;11(5):474. doi:10.3390/horticulturae11050474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Shi JY, Guo SF, Li TT, Yan ZC, Wang L, Wu C, et al. The molecular mechanism of chitosan-based OEO nanoemulsion edible film in controlling Alternaria alternata and in application for apricot preservation. Food Control. 2025;176(23):111354. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2025.111354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Crowley LC, Marfell BJ, Christensen ME, Waterhouse NJ. Measuring cell death by trypan blue uptake and light microscopy. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2016;2016(7):pdb.prot087155. doi:10.1101/pdb.prot087155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Vitti A, Coviello L, Triunfo M, Guarnieri A, Scieuzo C, Salvia R, et al. In vitro antifungal activity and in vivo edible coating efficacy of insect-derived chitosan against Botrytis cinerea in strawberry. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;279(Pt 2):135158. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.135158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Torres-Rodriguez JA, Reyes-Pérez JJ, Carranza-Patiño MS, Herrera-Feijoo RJ, Preciado-Rangel P, Hernandez-Montiel LG. Biocontrol of Fusarium solani: antifungal activity of chitosan and induction of defence enzymes. Plants. 2025;14(3):431. doi:10.3390/plants14030431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Wang Q, Zuo JH, Wang Q, Na Y, Gao LP. Inhibitory effect of chitosan on growth of the fungal phytopathogen, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, and sclerotinia rot of carrot. J Integr Agric. 2015;14(4):691–7. doi:10.1016/s2095-3119(14)60800-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Youssef K, Roberto SR, de Oliveira AG. Ultra-structural alterations in Botrytis cinerea—the causal agent of gray mold—treated with salt solutions. Biomolecules. 2019;9(10):582. doi:10.3390/biom9100582. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. López-Mora LI, Gutiérrez-Martínez P, Bautista-Baños S, Jiménez-García LF, Zavaleta-Mancera HA. Evaluación de la actividad antifúngica del quitosano en Alternaria alternata y en la calidad del mango tommy atkins durante el almacenamiento. Rev Chapingo Ser Hortic. 2013;19(3):315–31. [Google Scholar]

25. Palma-Guerrero J, Lopez-Jimenez JA, Pérez-Berná AJ, Huang IC, Jansson HB, Salinas J, et al. Membrane fluidity determines sensitivity of filamentous fungi to chitosan. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75(4):1021–32. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07039.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools