Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Field Supplements of Ultraviolet-B Radiation in Veraison and Pre-Harvest Differentially Modify the Phenolic Composition of Grape Skins and Wines

Faculty of Science and Technology, University of La Rioja, Madre de Dios 53, Logroño, 26006, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Javier Martínez-Abaigar. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Adaptation Mechanisms of Grapevines to Growing Environments and Agricultural Strategies)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3453-3470. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.070087

Received 08 July 2025; Accepted 06 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) is one of the main crops worldwide, and ultraviolet-B (UV-B, 280–315 nm) radiation is emerging as a promising technical tool to enhance secondary metabolites that can contribute to the quality and health-promoting properties of both grapes and the resulting wines. However, few studies have assessed the effectiveness of UV-B supplements under field conditions. Here, we compared the effects of two different field UV-B treatments (a single supplement applied at pre-harvest, and a double supplement applied at both veraison and pre-harvest) on the phenolic composition of Tempranillo grape skins and the resulting wines. The double supplement induced stronger changes than the single supplement, with responses being more pronounced in grape skins than in wines. In skins, UV-B supplements significantly increased flavonols, phenolic acids, and flavanols, consistent with previous reports highlighting flavonols as the most reliable UV-B-responsive compounds in grape skins. In wines, the clearest responses were increases in anthocyanins and color intensity. Overall, UV-B supplements improved grape and wine quality, although skin responses were only partially transmitted to the wines. Moreover, wine responses were more unpredictable than skin responses, likely reflecting not only the UV-B–induced changes in grape skins but also the complex chemical interactions among phenolic compounds (and also with other metabolites) during vinification. Further experimentation, particularly in the long term, is required to optimize the application of UV-B supplements as a viticultural and enological practice.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileGrapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) is cultivated on approximately 7.4 million hectares worldwide, producing over 73 million metric tons of fruit with an estimated market value of 70 billion USD [1]. Consequently, grapevine probably remains the world’s most economically important fruit crop, primarily due to the added value generated through winemaking. However, climate change poses significant challenges for viticulture and enology, including shifts in the geographical distribution of wine regions, the need for varietal adaptation, alterations in berry metabolites and quality, and uncertainties regarding the future typicity of wines [2,3]. In addition to global warming, water scarcity, and increased solar radiation and atmospheric CO2, climate change also influences ultraviolet-B (UV-B: 280–315 nm wavelength) radiation. Although future UV-B levels at the Earth’s surface are difficult to predict, and may vary geographically, most projections indicate an overall increase, primarily due to interactions with climate (reductions in cloud cover and aerosols) rather than changes in stratospheric ozone [4]. UV-B radiation is a minor component of the solar spectrum, constituting about 0.30% of the photosynthetically active radiation [5]. Beyond its well-known damaging effects when received in excess, UV-B radiation is now recognized as a key environmental signal regulating plant growth and development, mainly through specific photoreceptors, such as UVR8, and downstream signaling networks [6–8]. Moreover, UV-B manipulation has emerged as an innovative technique opening new opportunities for crop improvement, particularly by enriching fruits, vegetables, and herbs with health-promoting secondary metabolites [5,9,10].

The effects of UV-B on grapevines have been extensively investigated. Effects on leaves are mostly coincident with those reported in other crops, although leaf UV-B tolerance may vary among cultivars [11]. Effects on berries are of greater commercial interest because artificial UV-B manipulations offer potential to improve the quality of grapes and, eventually, the resulting wines made from them. In this regard, three different experimental approaches have been employed: exploiting natural UV-B gradients, excluding ambient solar UV-B with cut-off filters, and applying artificial UV-B supplements. Natural gradient studies can identify the environmental factors best associated with the chemical composition of grapes [12] and even wines [13], but their interpretability is often limited because multiple variables may change in the same direction, masking the specific effects of UV-B [12]. Exclusion experiments allow for the exploration of the specific responses of grapes (and the resulting wines) to ambient UV-B levels [14–16], but their commercial relevance is restricted to mitigating excess UV-B in regions with intense solar radiation. Artificial UV-B supplementation, by contrast, enables the targeted modification of specific grape metabolites, making it the most promising approach for commercial application. However, it also presents technical challenges because UV-B lamps are required to provide the supplements. Hence, this approach has been only rarely used under field conditions, and most studies have been carried out by cultivating plants or cuttings in pots within growth chambers or greenhouses [15,17–19], or applying the supplements to postharvest grapes [20]. While informative, these studies cannot fully replicate the field commercial viticultural conditions. Only a few studies to our knowledge have applied UV-B supplements to grapes directly in vineyards, analyzing the effects in both grape skins and the resulting wines [21–23]. Comprehensive variables, such as total phenolics and total anthocyanins, were mostly analyzed [21,22], with only one study extending the scope to individual phenolic and volatile organic compounds [23]. In that study, a single pre-harvest supplement was applied, and clear increases in flavonols, phenolic acids, flavanols, and antioxidant capacity were found in UV-B-supplemented grape skins and the resulting wines, thereby enhancing the quality and potential health benefits of both grapes and wines. These promising results highlight the need for further research to evaluate the effects of UV-B supplements under field commercial conditions.

In the present study, we investigated the effects of field-applied UV-B supplements on grapes and the resulting wines, building on the logistics and methods established in a previous study [23]. A key novelty of our approach was the application of two distinct UV-B supplements—at veraison and at pre-harvest–two periods of berry development that had previously been identified as critical for phenolic compounds biosynthesis [12]. This design allowed us to test whether an additional supplement at veraison would alter the responses observed with a single pre-harvest supplement. The treatments were applied in a commercial vineyard to evaluate the feasibility of UV-B supplementation as a new complementary practical viticultural technique at a crop scale. Such a practice could improve grape and wine quality, particularly by increasing phenolic compounds linked to human health (e.g., reduced risk of certain cancers and cardiovascular diseases) [24,25] and with potential applications in the cosmetic industry [26]. We selected Tempranillo, a major international wine grape cultivar, currently the third most widely planted worldwide and the fastest expanding in recent years [27]. Importantly, Tempranillo is also the dominant cultivar in the Rioja Qualified Denomination of Origin (Spain), where this study was performed.

2.1 Plant Material and Cultivation Conditions

Plants of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Tempranillo (clone 261), grafted onto 110R rootstocks and planted in 2010, was used in the present study. Plants were cultivated in a private commercial vineyard located in Baños de Río Tobía (La Rioja, northern Spain, 42°20′ N, 2°45′ W; 574 m elevation). The soil was loamy, and vines were spaced 2.7 m between rows and 1.0 m within rows, with a N–S row orientation. All vines were spur-pruned (12 buds per vine) in a bilateral cordon and trained on a vertically shoot-positioned trellis system. This field experiment was carried out in 2016. Annual precipitation in the year of study was 430.8 mm, with a corresponding mean annual temperature of 12.2°C (data from the observatory of Arenzana de Abajo, 5 km from the experimental site). Plants were not irrigated during cultivation. The total annual doses of photosynthetic, UV-A, and UV-B radiations were 2.08 GJ m−2, 0.21 GJ m−2, and 6.52 MJ m−2, respectively. UV data come from the observatory of Logroño, which is the closest observatory to the experimental site that provides this kind of data. This observatory is located at 384 m elevation and 30 km from the experimental site.

2.2 Experimental Design: UV-B Supplements and Grape Collection

Grapes were exposed to UV-B radiation under field conditions, either during a single period (pre-harvest) or two periods (veraison and pre-harvest) (Fig. S1). A completely randomized block design was set up, with nine blocks of ten vines each, divided into three experimental conditions (three biological replicates per experimental condition):

• Control plants (C), which only received ambient solar UV-B radiation.

• Plants artificially supplemented with UV-B radiation only at pre-harvest (H).

• Plants artificially supplemented with UV-B radiation at both veraison and pre-harvest (VH).

At veraison (August), approximately 10 leaves per plant were removed in both Control and UV-B-supplemented plants (H and VH), to leave the bunches exposed. On the same day of leaf removal, and for five consecutive days, VH plants were irradiated at the height of the bunches using a manufactured lamp mounted on the front part of a tractor [23] (Fig. S1). The position of the lamp was finely controlled to homogeneously apply the UV-B supplement at a distance of 20 cm from the lamp to the bunches. The lamp held four fluorescent tubes (Philips UV-B Narrowband TL 20W/01, Philips Lighting, Madrid, Spain) covered by a metal case. These tubes emitted only UV-B wavelengths between 305 and 315 nm, with a peak at 311 nm. Bunches were irradiated in the evening before sunset. The spectral irradiance of the lamp was daily checked using a spectroradiometer (Macam SR9910, Macam Photometrics Ltd., Livingstone, Scotland, UK) to confirm the lamp stability.

In September, close to grape commercial maturity (harvest), H and VH plants were irradiated over five consecutive days as previously described. The total supplemental UV-B doses received by H and VH plants were 1.25 and 2.5 kJ m−2, respectively, representing approximately 1.4%–2.8% increase over the ambient values recorded during the study period. The UV-B irradiance used in the supplements was 8.5 W m−2, around 5-fold and 8-fold higher than the natural monthly means of peak daily UV-B irradiances in Logroño for clear skies around veraison (July) and harvest (September), respectively [28]. These mean values were confirmed by using UV data from the same observatory (see above), which were recorded during the experimental season. These UV-B supplements were roughly similar to those applied in previous studies [23]. Given that the supplemental UV-B dose applied would represent a much lower increase in relation to ambient levels than that represented by the supplemental irradiance used, it could be assumed that the changes found in the UV-B-supplemented grape skins would mainly be caused by the irradiance peaks rather than by the UV-B dose received. Overall, bunch exposure to UV-B supplements was considered homogeneous because: (1) leaves were removed before exposure; (2) irradiation was performed in the evening before sunset, minimizing ambient UV-B; and (3) the spectral irradiance emitted by the lamp was daily checked with a spectroradiometer. The day after pre-harvest irradiation, grapes from Control, H, and VH plants were collected around noon. These grapes had total soluble solid contents close to commercial maturity (around 22 °Bx). For each experimental condition and replicate, 30 grapes from 10 different plants were sampled from sun-exposed portions of the bunches (bottom, middle, and top parts). Grapes were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, transported to the laboratory, and stored at −80°C until analysis. The remaining grapes were used for vinification.

The use of a commercial vineyard for experimentation was essential to derive real agronomic applications at a crop scale, but its private nature limited both the UV-B treatments imposed (i.e., the absence of a UV-B supplement applied only at veraison) and the number of years of experimentation. This was exclusively due to the logistical necessities of the company. Nevertheless, this setback did not affect our main aim, which was to compare a single vs. a double field UV-B supplement (H and VH treatments, respectively).

2.3 Analysis of Phenolic Compounds in Grapes

Frozen grapes were allowed to partially thaw, and skins were carefully separated from the flesh using a scalpel. Skins were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, lyophilized, and ground (UltraTurrax® T25 Basic homogenizer, IKA Labortechnik, Staufen, Germany). For each analytical sample, 50 mg of powder was further homogenized using a TissueLyser (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and mixed with 4 mL of methanol: water:7 M HCl (70:29:1 v:v:v) for the extraction process (24 h at 4°C in the dark). Extracts were centrifuged at 6000× g for 15 min, and the supernatant was used for phenolic compounds.

The analysis of phenolic compounds was described in a previous paper [12]. The bulk level of UV-absorbing compounds (UVAC) was measured as the area under the absorbance curve in the interval 280–400 nm (AUC280–400) per unit of dry mass (DM), using a PerkinElmer λ35 spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, Wilton, CT, USA). Individual phenolic compounds were analyzed by UPLC (Waters Acquity Ultra Performance LC system, Waters Corporation, Milford, CT, USA). This UPLC system was coupled to a micrOTOF II high-resolution mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) equipped with an Apollo II ESI/APCI multimode source and controlled with Bruker Daltonics Data Analysis software. A UV detector module was set at 520 and 324 nm for anthocyanins and other compounds, respectively. The electrospray source was operated in the negative mode, except for the anthocyanins for which the positive mode was used. The capillary potential was set to 4 kV; the drying gas temperature was 200°C, and its flow rate was 9 L min−1; the nebulizer gas was set to 3.5 bar and 25°C. Spectra were acquired between m/z 120 and 1505, in both modes. The following different phenolic compounds were identified and quantified using specific commercial pure compounds or, in their absence, compounds with the same chromophore: caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, t-resveratrol, isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside, kaempferol-glucoside, myricetin, quercetin, quercetin-3-O-galactoside, quercetin-3-O-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-glucuronide, quercetin-3-O-rutinoside, syringetin-3-O-glucoside, catechin, epigallocatechin, procyanidin B2, and malvidin-3-O-glucoside (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; Fluka, Buchs, Germany; Extrasynthese, Genay, France). Total contents of each phenolic family (i.e., phenolic acids, stilbenes, flavonols, flavanols, and monomeric anthocyanins) were obtained as the sum of their respective individual compounds. Total phenols were determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, expressing data as gallic acid equivalents. Total flavonoids were determined [29] and contents were expressed as mg quercetin equivalents per DM unit. The antioxidant capacity of grape skins (Trolox equivalents per DM unit) was measured by generating the radical cation 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS•+) [12] by using a PerkinElmer λ35 spectrophotometer. All grape analyses (spectrophotometric, UPLC, total phenols, total flavonoids, and antioxidant capacity) were performed in triplicate using three biological replicates.

2.4 Vinification and Wine Analysis

For each treatment and replicate (three biological replicates per treatment, and also for the controls), grapes were destemmed, crushed, and subjected to alcoholic fermentation [23]. All microvinifications were performed under identical conditions, ensuring consistency across treatments and replicates. Specifically, ca. 3 kg of pomace (must, seed, and skin) was introduced into 2.5-L glass bottles equipped with fermentation locks to minimize oxygen ingress while allowing CO2 release. Potassium metabisulfite (0.09 g kg−1) was added to each sample to yield a final total SO2 concentration of 50 mg L−1. Afterwards, musts were inoculated in all cases with the same commercial active dry yeast at the same dose (Saccharomyces cerevisiae r.f. bayanus at 0.2 g kg−1) (Enartis, Trecate, Italy). Musts fermentations were carried out in a temperature-controlled chamber at 25°C, and alcoholic fermentation ended when the reducing sugars had fallen below 2.5 g L−1 (ca. two weeks after the yeast inoculation). Then, wines were separated from solids by pressing, and analyses of UVAC, total phenols, total flavonoids, individual phenolic compounds, and total antioxidant capacity were performed as described for grape skins. Color intensity was determined according to official methods [30].

The overall effect of the treatment (C, H, and VH samples) on the response variables measured was tested using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), after confirming the data met the assumptions of normality (Shapiro–Wilks’s test) and homoscedasticity (Levene’s test). In the case of a significant effect, post hoc mean comparisons were performed by using Tukey’s test. Non-parametric tests (Kruskal–Wallis) were used if the data did not meet those assumptions. In this case, and when significant effects occurred, means were compared by the Mann–Whitney’s test. All statistical procedures were performed with SPSS 24.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3.1 Phenolic Composition of Grape Skins and the Resulting Wines

A total of 38 phenolic compounds were identified in both grape skins and the resulting wines (Table S1), belonging to five different families: phenolic acids, stilbenes, flavonols, flavanols, and anthocyanins. Anthocyanins were the most abundant family in both grape skins and wines, followed by flavonols in skins and phenolic acids in wines. The anthocyanin profiles were identical in skins and wines, with malvidin-3-O-glucoside as the predominant compound.

Differences were observed between skins and wines in the remaining phenolic families. Two phenolic acids were detected in both matrices, with an additional caffeic acid ethyl ester present in wines. Caffeoyl tartaric acid and coumaroyl tartaric acid were the most abundant phenolic acids in skins and wines, respectively. Only small amounts of one stilbene (resveratrol) were detected in skins, while the derivative resveratrol-3-O-glucoside was also observed in wines. The most notable differences were found in flavonols. Among the 16 identified compounds, 14 were detected in skins and only 11 in wines. Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-glucuronide, myricetin, myricetin-3-O-galactoside, and quercetin-3-O-rutinoside were exclusive to skins, whereas isorhamnetin and laricitrin-3-O-glucoside were detected only in wines. Quercetin-3-O-glucoside and myricetin-3-O-glucoside were the major flavonols in skins and wines, respectively. Regarding flavanols, the only difference between matrices was the presence of procyanidin B3 in wines. Catechins and procyanidin B1 were the major flavanols in skins and wines, respectively.

3.2 Effects of UV-B Supplements on Individual Phenolic Compounds in Skins and Wines

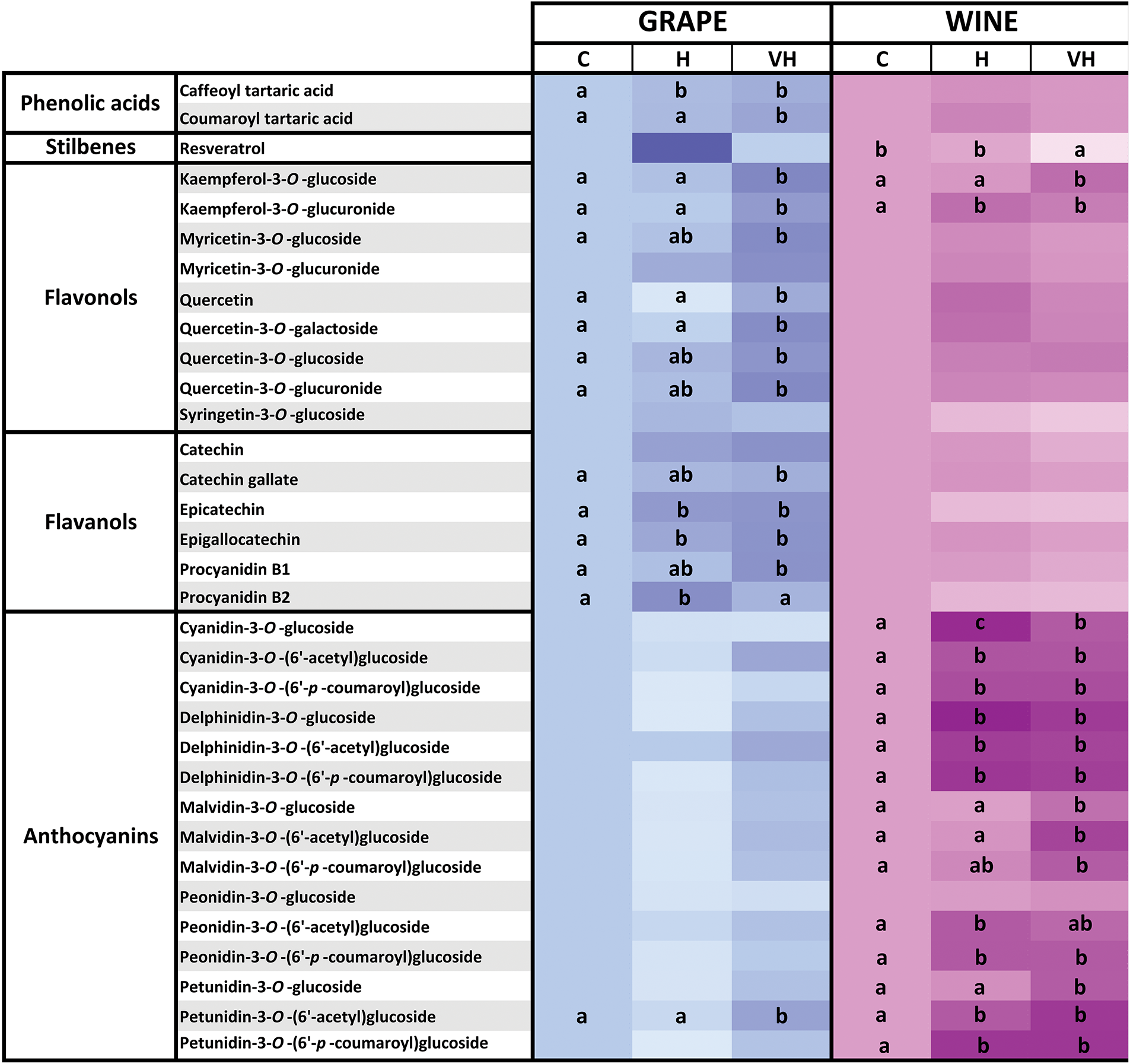

In grape skins, phenolic compound levels were generally higher in UV-B supplemented samples (H and/or VH) than in Control samples. UV-B supplements significantly affected 16 of the 38 individual phenolic compounds: two phenolic acids, nine flavonols (including isorhamnetins, kaempferols, quercetins, and one myricetin), four flavanols, and one anthocyanin (Table S1; Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Individual phenolic compounds found in both grapes and the resulting wines, as influenced by the radiation received by grapes. Grapes received only ambient solar UV-B radiation (C, controls) or were artificially supplemented with UV-B radiation before harvest (H) or both in veraison and before harvest (VH). The higher the color intensity, the higher the values of the compounds (see Table S1). Different letters ‘a–c’ mean significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 for either grapes or wines.

In wines, concentrations of all anthocyanins and two kaempferols were significantly higher in the wines obtained from UV-B-supplemented grapes (H and VH samples) than in Control wines. Specifically, UV-B supplements significantly affected 20 of the 38 compounds (14 anthocyanins, four flavonols, and two stilbenes), with no effects observed on phenolic acids or flavanols. The overall effects of the UV-B supplements on the individual phenolic compounds are more easily compared when only the 33 compounds present in both grape skins and wines are shown (Fig. 1). In skins, the VH treatment induced stronger changes in the individual phenolics than the H treatment. Specifically, 14 compounds were significantly higher in VH skins than in Controls: the two phenolic acids, seven of nine flavonols (including kaempferols, quercetins, and one myricetin), four of six flavanols (including catechin gallate, epicatechin, epigallocatechin, and procyanidin B1), and only one of 15 anthocyanins (a minor petunidin). In contrast, only four compounds were significantly higher in H skin than in Controls: caffeoyl tartaric acid and three flavanols (epicatechin, epigallocatechin, and procyanidin B2). No flavonol or anthocyanin changed significantly with H treatment. Moreover, three of the four affected compounds in H samples showed similar contents to those found in VH samples, while only one (procyanidin B2) was higher in H than VH. Five additional compounds in H samples (three flavonols and two flavanols) were intermediate between Control and VH.

In wines, UV-B effects differed from those in skins. The most striking changes were found in anthocyanins, which mostly increased in H and VH samples in comparison to the Control samples. Indeed, although the total number of compounds significantly affected by the UV-B supplements was similar to that of skins (17 compounds out of 33), 14 were anthocyanins, with 13 showing higher concentrations in H and/or VH wines than in Control wines, including the most abundant ones (malvidin-3-O-glucoside, petunidin-3-O-glucoside, and malvidin-3-O-(6′-p-coumaroyl) glucoside). Apart from anthocyanins, only two flavonols (both kaempferols) showed higher concentrations in VH and/or H samples than in Control samples. Resveratrol, the only stilbene significantly affected by the UV-B supplement, showed higher concentrations in Control and H wines than VH wines. Flavanols were not affected. Overall, UV-B effects were stronger in VH than in H wines but less pronounced than in skins.

3.3 Effects of UV-B Supplements on the Phenolic Families and the Remaining Variables Measured

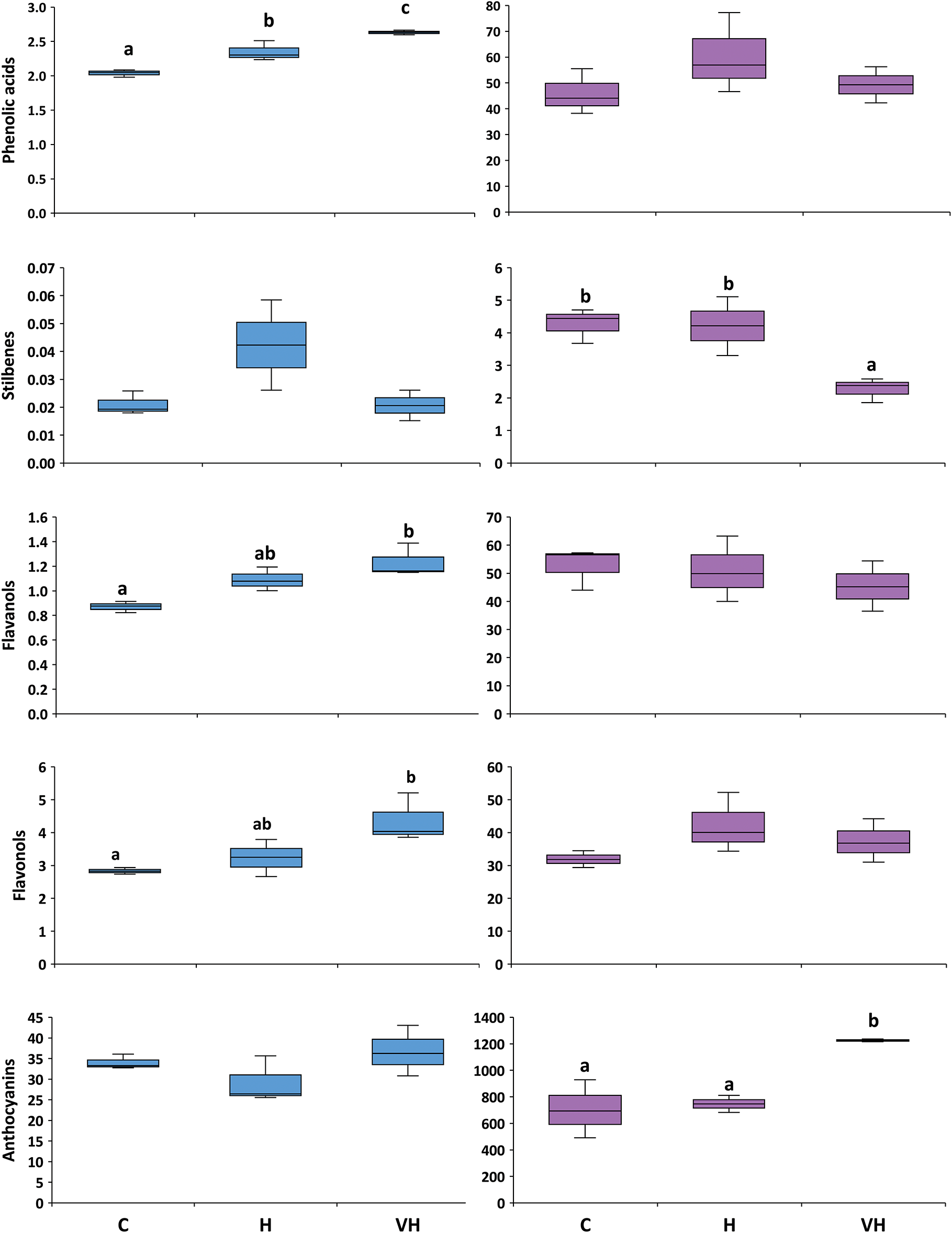

The overall effects of the UV-B supplements on the phenolic composition of both grape skins and wines were more evident when compounds were summed by family (Fig. 2). In grape skins, phenolic acids, flavonols, and flavanols differed between treatments. Phenolic acids were significantly higher in VH than in H (12% increase), and in H than in Controls (15% increase). Flavonols and flavanols were significantly higher in VH than in Controls (54% and 41% increases, respectively), with H samples showing intermediate values. Stilbenes and anthocyanins were not affected by any UV-B supplement. In wines, UV-B supplements significantly affected only anthocyanins and stilbenes (Fig. 2). Anthocyanin levels increased in VH wines relative to H and Control wines (64%–74% increase). Stilbenes were significantly higher in Control and H than in VH wines. Phenolic acids, flavonols, and flavanols were unaffected.

Figure 2: Boxplots showing the phenolic families measured in grapes (blue) and the resulting wines (purple). Grapes received only ambient solar UV-B radiation (C, controls) or were artificially supplemented with UV-B radiation before harvest (H) or both in veraison and before harvest (VH). In each boxplot, the horizontal line indicates the median, the colored area indicates the upper and lower quartiles, and the whiskers indicate the 0% and 90% percentiles. Different letters ‘a–c’ mean significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 for either grapes or wines. Grape compounds are expressed in mg per g dry mass, and wine compounds are expressed in mg per liter.

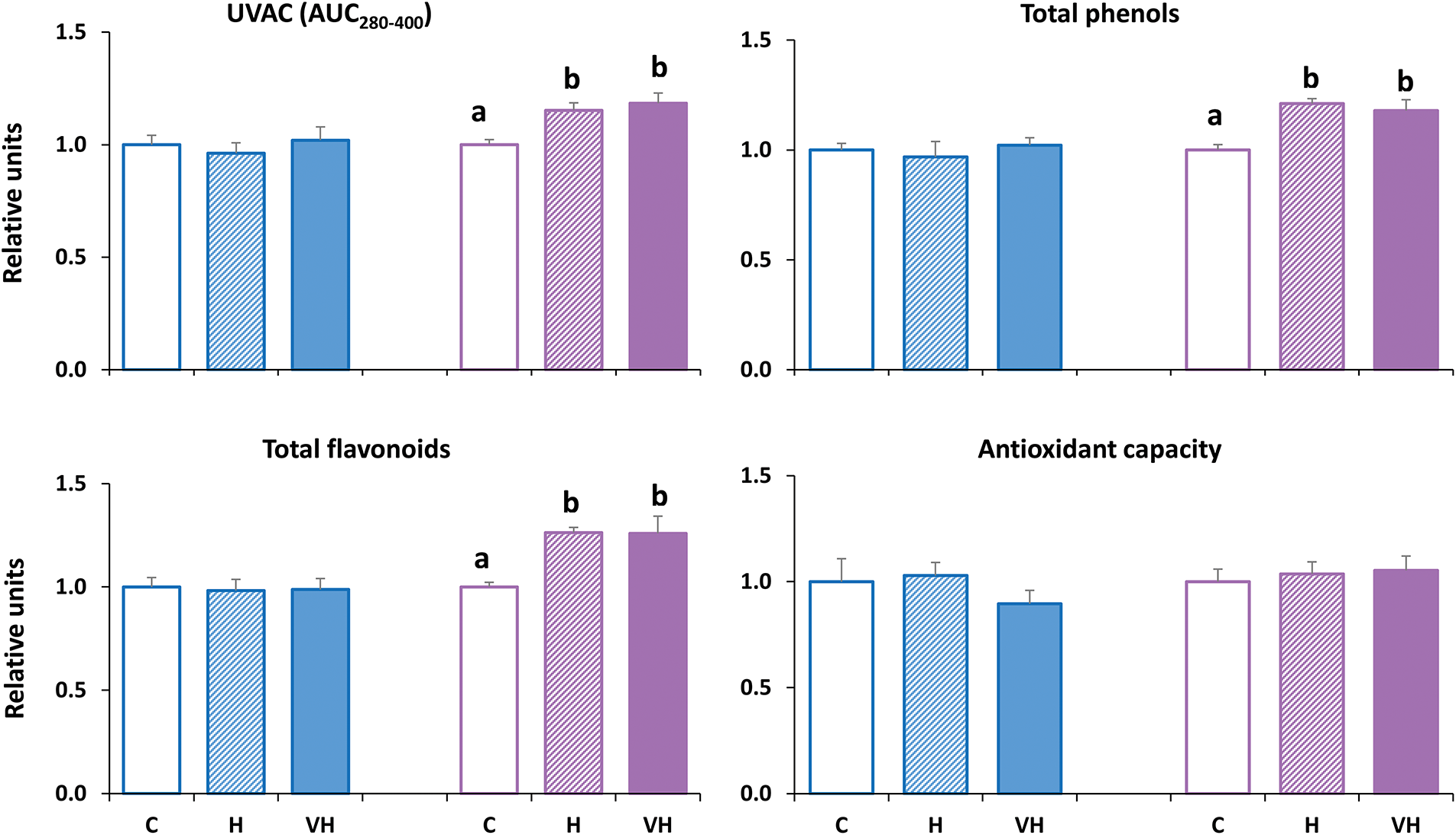

For a better comparison of the comprehensive variables analyzed (total phenols, total flavonoids, UVAC, and antioxidant capacity), they were normalized using Control samples as the unit (Fig. 3). In skins, no variable showed any significant difference between the three groups (Control, H, and VH). In wines, total phenols, total flavonoids, and UVAC were significantly higher in H and VH samples than in Controls, whereas antioxidant capacity remained unchanged.

Figure 3: Comprehensive variables measured in grapes (blue) and the resulting wines (purple). Grapes received only ambient solar UV-B radiation (C, controls) or were artificially supplemented with UV-B radiation before harvest (H) or both in veraison and before harvest (VH). Results are shown in relative units, taking the control samples as the reference unit value, while the remaining values are the respective quotients H/C and VH/C. Values are expressed as means + standard errors. Different letters ‘a–b’ mean significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 for either grapes or wines. UVAC, the bulk level of UV-absorbing compounds, expressed as the area under the absorbance curve in the interval 280–400 nm (AUC280–400).

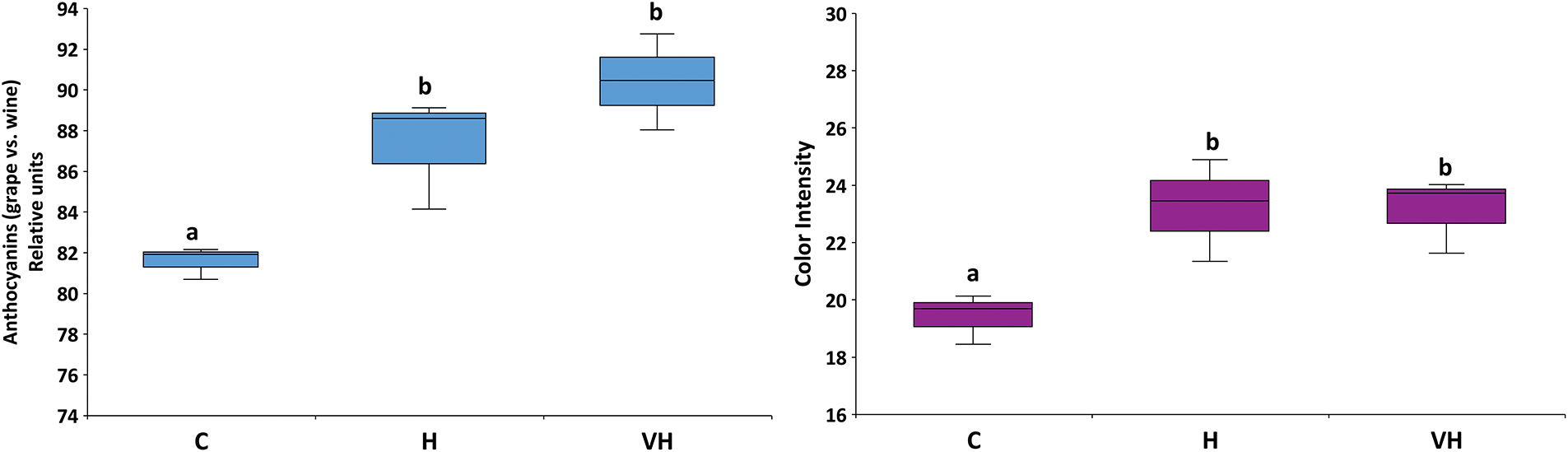

A second attempt at data normalization was performed to compare the proportion of skin anthocyanins further retained in the resulting wines (Fig. 4). This proportion was calculated using log-normalization (A = anthocyanin content):

Figure 4: Boxplots showing the relative anthocyanin contents in grapes and the resulting wines (left, calculated after log-normalization, see Results), and their reflection on wine color intensity (right). Grapes received only ambient solar UV-B radiation (C, controls) or were artificially supplemented with UV-B radiation before harvest (H) or both in veraison and before harvest (VH). In each boxplot, the horizontal line indicates the median, the colored area indicates the upper and lower quartiles, and the whiskers indicate the 0% and 90% percentiles. Different letters ‘a–b’ mean significant differences at p ≤ 0.05.

In Controls, around 82% of skin anthocyanins were preserved in wine, whereas the percentages in H and VH wines were significantly higher (88–90%). These differences were concurrently reflected in wine color intensity (Fig. 4), which was higher in H and VH wines than in Controls.

4.1 Phenolic Composition of Grape Skins and the Resulting Wines

The total number of compounds identified in grape skins and wines in our study (38), as well as the major (anthocyanins) and minor (stilbenes) compounds, were similar to those reported in previous studies on Tempranillo, which identified 45–47 compounds [16,23]. The high abundance of anthocyanins was expected in a red variety such as Tempranillo. Moreover, the phenolic profiles in grape skins and wines were largely consistent across studies, with only two wine compounds (isorhamnetin and procyanidin B3) detected for the first time in our study [16,23].

4.2 Effects of UV-B Supplements on Grape Skins and the Resulting Wines: General Considerations

Among the 33 phenolic compounds detected in both grape skins and wines, UV-B supplements significantly affected 15 compounds in skins (45% of the total) and 17 in wines (52%), mostly increasing their concentrations relative to non-supplemented controls (Fig. 1, Table S1). These proportions are similar to those reported in the only previous study examining the effects of supplemental UV-B on both skins and wines (39% and 53%, respectively) [23], confirming that artificial UV-B supplements can substantially alter the phenolic composition of both skins and wines.

However, in contrast to that study, where the same compounds (mainly flavonols, phenolic acids, and flavanols) were affected in both skins and wines, our results showed clear differences: skins were primarily affected in phenolic acids, flavonols, and flavanols, while wines were mainly affected in anthocyanins and, to a lesser extent, flavonols (specifically kaempferols). The reasons for these discrepancies are likely multifactorial:

1. Interannual variation in meteorological conditions, such as temperature, rainfall, sunshine hours, ambient UV-B levels, etc., can affect grape phenolic composition [23,31,32]. In particular, a higher ambient UV-B, especially during critical periods (veraison and 5–10 days before harvest) [12], may attenuate the effect of UV-B supplements. Given that previous studies had already demonstrated the influence of interannual meteorological changes on the phenolic composition of grapes and wines, here we focused on the influence of one vs. two UV-B supplements (see Section 4.6). Nevertheless, long-term studies are required to understand how the interactions between meteorological factors and UV-B supplements determine the phenolic composition of grapes and wines.

2. Different vineyards and locations, despite using the same variety (Tempranillo), which may affect the ambient UV-B received by plants due to, for example, elevation differences (373–574 m) [33].

3. Experimental design differences, as we applied two UV-B supplements (veraison and pre-harvest) vs. a single pre-harvest UV-B supplement (similar to our H treatment) in the previous study.

4. Vinification differences, including maceration and fermentation protocols, which influence the extraction of skin compounds and their incorporation into wines [34,35].

5. Complex interactions among the wide variety of compounds present in wines, which can lead to dynamic chemical changes during vinification [35], independently of the UV-B effect on grape skins (see Section 4.5).

Other studies are less comparable because (1) plants were not cultivated under field commercial conditions but in pots, cabinets, or greenhouses; (2) only grape skins and not wines were analyzed; and/or (3) only comprehensive variables, such as total phenolics and total anthocyanins, were measured [15,17–19].

4.3 Effects of UV-B Supplements on the Variables Measured in Grape Skins

In grape skins, UV-B supplements affected individual phenolic compounds (mainly phenolic acids, flavonols, and flavanols), which increased in VH samples relative to Controls (Fig. 1). Differences among treatments were most evident in families already showing significant changes in individual compounds (Fig. 2). The increase in skin phenolic acids and flavonols is a well-established response to UV-B-supplements under field conditions [23]. In particular, the increase in flavonols is the most usual response of grape skin to UV-B radiation across varieties and experimental conditions [16,17,36,37]. Glycosilated quercetins, kaempferols, isorhamnetins, and myricetins have been found to be particularly UV-B-responsive. The increase in flavonols would improve grape quality because they are bioactive, healthy compounds due to their antioxidant capacity [38,39].

In contrast, UV-B-induced increases in flavanols are less frequently reported [11,23,37]. Yet, catechin gallate and epicatechin consistently responded to UV-B. This can be important to grapes due to the recognized antioxidant and anticarcinogenic properties of flavanols [40]. Skin anthocyanins were largely unaffected, except for a minor petunidin. This outcome was expected, as anthocyanin responses depend on interactions among variety, berry development, and environmental factors, leading to variable outcomes, including increases, decreases, or no effect [16,17,36,41]. In addition, anthocyanins compete with other phenolic compounds for the same precursors in their biosynthesis pathways [42], limiting their accumulation. Like anthocyanins, stilbenes showed no clear response, consistent with most UV-B studies using ambient [11,16] or supplemented UV-B [23], given that, in general, stilbenes are phytoalexins primarily induced by wounding or pathogens rather than UV-B [43]. Nevertheless, stilbenes increased when grapes were exposed to high-altitude UV-B levels [21].

The action mechanisms leading to the biosynthesis of phenolic compounds (and other secondary metabolites) in grapes are complex, especially under field conditions [18]. As derived from a field study performed on Arabidopsis thaliana, both UVR8-dependent and -independent pathways may regulate these mechanisms [8]. Their elucidation is crucial to fully understand the UV-B-induced phenolic changes occurring in UV-B-supplemented grapes and to further implement the associated applications.

Comprehensive variables, such as total phenols or UVAC, did not show higher values in VH and H samples than in Controls (Fig. 3). This is consistent with studies using ambient UV-B [11,16,21], although increases have been reported under a single pre-harvest UV-B supplement [23]. Thus, higher-than-ambient UV-B levels would be needed to induce a response in these comprehensive variables in grape skins, as occurs in some individual compounds. However, these relatively high UV-B levels would not guarantee a positive response, probably because comprehensive variables integrate many different compounds whose individual responses to UV-B could also be different and even opposite. Antioxidant capacity also remained unchanged, which contrasts with the results obtained in similar studies [23]. Although the UV-B supplement applied in our study led to an increase in numerous compounds with antioxidant properties (i.e., flavonols and phenolic acids), non-responsive compounds (notably anthocyanins) may have masked the overall response of the antioxidant capacity.

4.4 Effects of UV-B Supplements on the Variables Measured in the Resulting Wines

In wines, we measured the same variables as in grape skins (individual phenolic compounds, the total contents of the different phenolic families, total phenols, total flavonoids, UVAC, and antioxidant capacity), together with color intensity (Figs. 1–4). Anthocyanins and, to a much lesser extent, flavonols, showed positive responses to UV-B, with higher concentrations in VH and H samples than in Controls. As occurred in grape skins, when the individual compounds were grouped in phenolic families, the differences between VH and H were mainly concentrated in those families that had already shown differences in individual compounds (i.e., anthocyanins in wines). The positive response of wine anthocyanins was surprising because these compounds usually show limited responsiveness to the UV-B levels received by the grapes used for vinification [23]. This lack of response could be attributed not only to the similar lack of response usually found in the grapes themselves (see Section 4.3), but also to chemical changes during vinification [35,44] (see Section 4.5). For example, anthocyanin polymerization and degradation could reduce the content of monomeric anthocyanins, which are the compounds usually analyzed. However, in line with our results, anthocyanins increased in the wines elaborated with grapes exposed to ambient UV-B or the full solar spectrum in comparison with wines made with non-UV-B-exposed or shaded grapes [16,22,45]. Given the crucial importance of anthocyanins for the red coloring of wine, further research is needed to fully understand the effects of ambient and supplemented UV-B radiation on grape and wine anthocyanins. The important increase in flavonols in UV-B-supplemented grapes was only partially transmitted to the wines, where only a couple of minor kaempferols showed higher concentrations in VH and/or H samples in comparison to Controls. This contrasts with previous studies where multiple flavonols increasing in UV-B-exposed grapes (mainly quercetins but also kaempferols) were retained in wines [16,23]. As pointed out above, these discrepancies could be due to differences occurring during vinification. Thus, the UV-B-induced changes occurring in skin flavonols may not guarantee similar changes in the resulting wines. In principle, this would be adverse because flavonols are important for wine co-pigmentation by stabilizing anthocyanins [46]. As occurred with flavonols, positive UV-B responses of phenolic acids and flavanols in skins did not persist in the resulting wines. Regarding phenolic acids, our results contrasted with those found in previous studies using UV-B supplements, where the positive response found in skins largely persisted in the resulting wines [23]. Again, chemical interactions during vinification could be responsible for this discrepancy. Regarding flavanols, previous studies confirm our results in wines [16,23]. Hence, it may be difficult to increase wine flavanols by only using UV-B radiation. This could be negative, because flavanols contribute to wine color and mouthfeel properties, such as astringency and bitterness, and they also have antioxidant activity [35,40,46]. Stilbenes did not show any clear response to UV-B supplements in wines, as occurred in grape skins. This was expected on the basis of previous studies [23]. However, a surprising increase in stilbenes was found in wines made with Tempranillo grapes exposed to ambient UV-B [16], but this increase would probably occur during vinification [47]. Given that stilbenes are considered health-promoting compounds [43], more research is needed to elucidate the role of UV-B on their content in grapes and wines.

In contrast to grape skins, total phenols and UVAC were higher in VH and H wines than in Controls. These results were partially opposite to those obtained in previous studies using ambient or supplemented UV-B. In general, these studies showed significant increases in skins but only a non-significant increasing trend [16,22,23] or no increase at all [21] in wines. The reasons underlying these differences can be multifactorial, as summarized above (Section 4.2). Other influencing factors could be the different grapevine varieties used in the different studies, and (as pointed out in Section 4.3) the fact that comprehensive variables integrate the responses of many different individual compounds to UV-B radiation. Thus, the analysis of individual compounds is highly recommended to have a more complete picture of how UV-B radiation can influence grapes and wines. In line with the results found in grape skins, the antioxidant capacity remains unchanged in wines. This contrasted with the increase found in previous studies using Tempranillo [16,23]. Once again, changes in the wide variety of antioxidant metabolites occurring during vinification could explain this discrepancy.

As occurred in total phenols and UVAC, wine color intensity showed higher values in VH and H samples than in Controls, reflecting the strong response of anthocyanins. Similar [22] and opposite [16,21,23] results were found in previous studies, and discrepancies could be due to a combination of the factors mentioned above (Section 4.2).

Artificial UV-B supplements greatly modify the phenolic composition of grape skins and the resulting wines, and it is clear from the present study that UV-B supplements can be combined in two grapevine phenological periods (veraison and pre-harvest) that are critical for the synthesis of different phenolic compounds [1,12]. However, the magnitude and specificity of the UV-B-induced changes in both grape skins and wines can vary as a function of different factors (see Section 4.2), not only related to the UV-B treatments imposed, the meteorological conditions experienced by the plants under field conditions, or the vinification methods used, but also to the chemical transformations and interactions that phenolic compounds can undergo in wines [35]. This latter aspect might have been disregarded in the past, but it should be considered to explain the fact that the phenolic compounds increasing in UV-B-treated grape skins can be different from those increasing in the resulting wines, as occurs in our study. Notably, a higher proportion of skin anthocyanins was retained in wine in UV-B-supplemented samples (H and VH treatments) than in Controls, which was reflected in a higher color intensity (Fig. 4). It could be speculated that UV-B-induced changes in skins may shift metabolite interactions during vinification, amplifying effects in wines, particularly for anthocyanins.

Many different processes can lead to changes in phenolic compounds during vinification [34,35,44,46]. Anthocyanins have been particularly studied in this regard, due to their crucial importance in wine color. Anthocyanins can suffer condensation and polymerisation reactions, as well as degradation, hydrolysis, oxidation, adsorption to the yeast cell walls, and reactions with sugars, primary acids, or phenolic acids. These processes can lead to increases or decreases of specific anthocyanins in the wine. In addition, the rate and velocity of extraction of each compound can vary depending on the time and temperature, causing additional variability in their concentrations in wine. Several of these processes can also affect other phenolic compounds, such as flavonols, flavanols, and phenolic acids, while stilbenes seem to be more stable [34,35,46].

4.6 One vs. Two UV-B Supplements

This is the first study to our knowledge in which the effects of one vs. two UV-B supplements applied to grapes were compared and analyzed in both grape skins and the resulting wines. The two supplements were applied in veraison and pre-harvest, critical periods for phenolic biosynthesis [12]. The double supplement (VH treatment) induced stronger effects than the single pre-harvest supplement (H treatment) in both grape skins and the resulting wines. The variables affected were mostly individual phenolic compounds, whose levels were higher in VH than in H samples. In skins, this effect occurred in some kaempferols and quercetins, together with one phenolic acid and one anthocyanin, while in wines, only one kaempferol and a few anthocyanins were affected. Although apparently, there were few differences between VH and H treatments, there were many more differences between VH samples and Controls than between H samples and Controls. Regarding the comprehensive variables analyzed (levels of phenolic compounds grouped in families, total phenols, total flavonoids, UVAC, antioxidant capacity, and wine color intensity), they showed few differences between VH and H treatments. Only total phenolic acids in skins and total anthocyanins in wines showed higher values in VH than in H samples. This limited number of differences was probably due to the fact that comprehensive variables integrate the effects of UV-B radiation on many different compounds with divergent responses (see Sections 4.3 and 4.4). Overall, a double UV-B supplement appears more effective than a single supplement in increasing phenolic content of grape skins and wines. Comparison with the most similar previous study, in which a single pre-harvest supplement was applied (similarly to our H treatment) [23], reveals similarities and differences. In grape skins, both studies reported increases in many flavonols (and to a lesser extent in flavanols and phenolic acids) in response to the UV-B supplement, and weaker or no effect on stilbenes and anthocyanins. However, UVAC, total phenols, and antioxidant capacity also increased in the previous study, but not in the current one. Regarding wines, most variables showed opposite results between the two studies. Discrepancies could be due to differences in vineyard elevation, meteorological conditions, and vinification (see Section 4.2). The absence of a veraison-only treatment was due to the requirements of the private company where our study was performed. Such a treatment would likely have smaller effects than H or VH due to the longer period between veraison and harvest, which could attenuate immediate UV-B responses.

In conclusion, a double UV-B supplementation at veraison and pre-harvest stages (VH treatment) significantly enhanced flavonols, flavanols, and phenolic acids accumulation in grape skins, although these changes were only partially transmitted to the resulting wines, where only anthocyanins and color intensity increased. In addition, a single supplement at pre-harvest (H treatment) was less efficient than the double supplement. Hence, our study confirms that field UV-B supplements modify the phenolic composition of grape skins and the resulting wines. It also demonstrates that the timing of UV-B application strongly determines the effects, and that wine responses are less predictable than grape skin responses, because they would be the result of a three-step process: (1) the initial changes induced by UV-B in grape skins; (2) how these changes are transmitted to the resulting wines; and (3) the further chemical changes that phenolic compounds can experience in wines. The last two steps could (at least partially) be independent of the specific UV-B treatments applied to the grapes. Further experimentation, particularly in the long-term, is needed to optimize UV-B supplementation strategies for desired phenolic profiles in both grapes and wines, in order to implement them in viticulture and enology. This implementation should also consider the associated costs of lamps, the work hours of workers, and mechanization.

Acknowledgement: The collaboration of Bodegas Juan Carlos Sancha (Baños de Río Tobía, La Rioja) is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding Statement: This paper is a result of the project PID2023-150695NB-I00, funded by MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER, UE. Additional funding from the Agencia de Desarrollo Económico de La Rioja (ADER, Government of La Rioja) through the Project S-UV-STAINABLE Rioja (2022-I-IDI-00064) is also acknowledged.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Encarnación Núñez-Olivera and Javier Martínez-Abaigar; formal analysis, Raquel Hidalgo-Sanz, María-Ángeles Del-Castillo-Alonso, Rafael Tomás-Las-Heras, Laura Monforte and Encarnación Núñez-Olivera; funding acquisition, Encarnación Núñez-Olivera and Javier Martínez-Abaigar; investigation, Raquel Hidalgo-Sanz, María-Ángeles Del-Castillo-Alonso, Laura Monforte, Rafael Tomás-Las-Heras and Encarnación Núñez-Olivera; methodology, María-Ángeles Del-Castillo-Alonso, Laura Monforte and Rafael Tomás-Las-Heras; project administration, Encarnación Núñez-Olivera and Javier Martínez-Abaigar; resources, Raquel Hidalgo-Sanz, María-Ángeles Del-Castillo-Alonso, Laura Monforte, Rafael Tomás-Las-Heras and Encarnación Núñez-Olivera; supervision, Encarnación Núñez-Olivera and Javier Martínez-Abaigar; validation, Encarnación Núñez-Olivera; visualization, Encarnación Núñez-Olivera, María-Ángeles Del-Castillo-Alonso, Raquel Hidalgo-Sanz and Javier Martínez-Abaigar; writing—original draft preparation, Raquel Hidalgo-Sanz, Javier Martínez-Abaigar and Encarnación Núñez-Olivera; writing—review and editing, Javier Martínez-Abaigar and Encarnación Núñez-Olivera. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Materials.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: Figure S1: Irradiation of Tempranillo bunches with UV-B radiation under field conditions, using a manufactured lamp mounted on the front part of a tractor. Table S1: Individual phenolic compounds identified in grape skins and the resulting wines as influenced by the radiation received by grapes. The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.070087/s1.

References

1. Keller M. The science of grapevines: anatomy and physiology. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

2. Santos JA, Fraga H, Malheiro AC, Moutinho-Pereira J, Dinis LT, Correia C, et al. A review of the potential climate change impacts and adaptation options for European viticulture. Appl Sci. 2020;10(9):3092. doi:10.3390/app10093092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Rienth M, Vigneron N, Darriet P, Sweetman C, Burbidge C, Bonghi C, et al. Grape berry secondary metabolites and their modulation by abiotic factors in a climate change scenario—a review. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:643258. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.643258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Bais AF, Bernhard G, McKenzie RL, Aucamp PJ, Young PJ, Ilyas M, et al. Ozone—climate interactions and effects on solar ultraviolet radiation. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2019;18(3):602–40. doi:10.1039/c8pp90059k. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Robson TM, Aphalo PJ, Banaś AK, Barnes PW, Brelsford CC, Jenkins GI, et al. A perspective on ecologically relevant plant-UV research and its practical application. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2019;18(5):970–88. doi:10.1039/c8pp00526e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Pescheck F, Bilger W. Uv-B resistance of plants grown in natural conditions. Annu Plant Rev Online. 2020;3(3):337–98. doi:10.1002/9781119312994.apr0733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Podolec R, Demarsy E, Ulm R. Perception and signaling of ultraviolet-B radiation in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2021;72(1):793–822. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-095946. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Neugart S, Steininger V, Fernandes C, Martínez-Abaigar J, Núñez-Olivera E, Schreiner M, et al. A synchronized, large-scale field experiment using Arabidopsis thaliana reveals the significance of the UV-B photoreceptor UVR8 under natural conditions. Plant Cell Environ. 2024;47(10):4031–47. doi:10.1111/pce.15008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Schreiner M, Mewis I, Huyskens-Keil S, Jansen MAK, Zrenner R, Winkler JB, et al. UV-B-induced secondary plant metabolites—potential benefits for plant and human health. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2012;31(3):229–40. doi:10.1080/07352689.2012.664979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mmbando GS. Harnessing UV radiation for enhanced agricultural production: benefits on nutrition, quality, and sustainability. Life. 2024;17(1):2381141. doi:10.1080/26895293.2024.2381141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Del-Castillo-Alonso MÁ, Diago MP, Tomás-Las-Heras R, Monforte L, Soriano G, Martínez-Abaigar J, et al. Effects of ambient solar UV radiation on grapevine leaf physiology and berry phenolic composition along one entire season under Mediterranean field conditions. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2016;109(12):374–86. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.10.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Del-Castillo-Alonso MÁ, Castagna A, Csepregi K, Hideg É, Jakab G, Jansen MAK, et al. Environmental factors correlated with the metabolite profile of Vitis vinifera cv. Pinot Noir berry skins along a European latitudinal gradient. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64(46):8722–34. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.6b03272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Muñoz F, Urvieta R, Buscema F, Rasse M, Fontana A, Berli F. Phenolic characterization of Cabernet Sauvignon wines from different geographical indications of Mendoza, Argentina: effects of plant material and environment. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2021;5:700642. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2021.700642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Alonso R, Berli FJ, Fontana A, Piccoli P, Bottini R. Malbec grape (Vitis vinifera L.) responses to the environment: berry phenolics as influenced by solar UV-B, water deficit and sprayed abscisic acid. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2016;109(12):84–90. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.09.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Liu L, Gregan SM, Winefield C, Jordan B. Comparisons of controlled environment and vineyard experiments in Sauvignon Blanc grapes reveal similar UV-B signal transduction pathways for flavonol biosynthesis. Plant Sci. 2018;276:44–53. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.08.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Del-Castillo-Alonso MÁ, Monforte L, Tomás-Las-Heras R, Martínez-Abaigar J, Núñez-Olivera E. Phenolic characteristics acquired by berry skins of Vitis vinifera cv. Tempranillo in response to close-to-ambient solar ultraviolet radiation are mostly reflected in the resulting wines. J Sci Food Agric. 2020;100(1):401–9. doi:10.1002/jsfa.10068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Martínez-Lüscher J, Sánchez-Díaz M, Delrot S, Aguirreolea J, Pascual I, Gomès E. Ultraviolet-B alleviates the uncoupling effect of elevated CO2 and increased temperature on grape berry (Vitis vinifera cv. Tempranillo) anthocyanin and sugar accumulation: effect of UV-B, elevated CO2 and increased temperature. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2016;22(1):87–95. doi:10.1111/ajgw.12213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Del-Castillo-Alonso MÁ, Monforte L, Tomás-Las-Heras R, Ranieri A, Castagna A, Martínez-Abaigar J, et al. Secondary metabolites and related genes in Vitis vinifera L. cv. Tempranillo grapes as influenced by ultraviolet radiation and berry development. Physiol Plant. 2021;173(3):709–24. doi:10.1111/ppl.13483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Del-Castillo-Alonso MÁ, Monforte L, Tomás-Las-Heras R, Martínez-Abaigar J, Núñez-Olivera E. To what extent are the effects of UV radiation on grapes conserved in the resulting wines? Plants. 2021;10(8):1678. doi:10.3390/plants10081678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Narra F, Castagna A, Palai G, Havlík J, Bergo AM, D’Onofrio C, et al. Postharvest UV-B exposure drives changes in primary metabolism, phenolic concentration, and volatilome profile in berries of different grape (Vitis vinifera L.) varieties. J Sci Food Agric. 2023;103(13):6340–51. doi:10.1002/jsfa.12708. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Berli F, D’Angelo J, Cavagnaro B, Bottini R, Wuilloud R, Silva MF. Phenolic composition in grape (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Malbec) ripened with different solar UV-B radiation levels by capillary zone electrophoresis. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56(9):2892–8. doi:10.1021/jf073421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Song J, Smart R, Wang H, Dambergs B, Sparrow A, Qian MC. Effect of grape bunch sunlight exposure and UV radiation on phenolics and volatile composition of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Pinot noir wine. Food Chem. 2015;173(6):424–31. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.09.150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Del-Castillo-Alonso MÁ, Monforte L, Tomás-Las-Heras R, Núñez-Olivera E, Martínez-Abaigar J. A supplement of ultraviolet-B radiation under field conditions increases phenolic and volatile compounds of Tempranillo grape skins and the resulting wines. Eur J Agron. 2020;121:126150. doi:10.1016/j.eja.2020.126150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yang J, Xiao YY. Grape phytochemicals and associated health benefits. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2013;53(11):1202–25. doi:10.1080/10408398.2012.692408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Mintie CA, Musarra AK, Singh CK, Ndiaye MA, Sullivan R, Eickhoff JC, et al. Protective effects of dietary grape on UVB-mediated cutaneous damages and skin tumorigenesis in SKH-1 mice. Cancers. 2020;12(7):1751. doi:10.3390/cancers12071751. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Tsiapali OI, Ayfantopoulou E, Tzourouni A, Ofrydopoulou A, Letsiou S, Tsoupras A. Unveiling the utilization of grape and winery by-products in cosmetics with health promoting properties. Appl Sci. 2025;15(3):1007. doi:10.3390/app15031007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Anderson K, Aryal NR. Which winegrape varieties are grown where? A global empirical picture. Adelaide, Australia: University of Adelaide Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

28. Häder DP, Lebert M, Schuster M, del Ciampo L, Helbling EW, McKenzie R. ELDONET—a decade of monitoring solar radiation on five continents. Photochem Photobiol. 2007;83(6):1348–57. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00168.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Farhadi K, Esmaeilzadeh F, Hatami M, Forough M, Molaie R. Determination of phenolic compounds content and antioxidant activity in skin, pulp, seed, cane and leaf of five native grape cultivars in West Azerbaijan province, Iran. Food Chem. 2016;199(2):847–55. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.12.083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. EEC (European Economic Community). Commission regulation (EEC) No. 2676/90 of 17 september 1990 determining community methods for the analysis of wines. Official J. 1990;272:1–192. [Google Scholar]

31. Kemp BS, Harrison R, Creasy GL. Effect of mechanical leaf removal and its timing on flavan-3-ol composition and concentrations in Vitis vinifera L. cv. Pinot Noir wine: leaf removal effects on tannin in wine. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2011;17(2):270–9. doi:10.1111/j.1755-0238.2011.00150.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Rouxinol MI, Martins MR, Salgueiro V, Costa MJ, Barroso JM, Rato AE. Climate effect on morphological traits and polyphenolic composition of red wine grapes of Vitis vinifera. Beverages. 2023;9(1):8. doi:10.3390/beverages9010008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. McKenzie RL, Björn LO, Bais A, Ilyasd M. Changes in biologically active ultraviolet radiation reaching the Earth’s surface. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2003;2(1):5–15. doi:10.1039/b211155c. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Morata A, González C, Tesfaye W, Loira I, Suárez-Lepe JA. Maceration and fermentation: new technologies to increase extraction. In: Morata A, editor. Red wine technology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2019. p. 35–49. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-814399-5.00003-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Jackson RS. Wine science: principles and applications. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

36. Spayd SE, Tarara JM, Mee DL, Ferguson JC. Separation of sunlight and temperature effects on the composition Vitis vinifera cv. Merlot berries. Am J Enol Vitic. 2002;53(3):171–82. doi:10.5344/ajev.2002.53.3.171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Jordan BR. The effects of ultraviolet-B on Vitis vinifera—how important is UV-B for grape biochemical composition?. In: Jordan BR, editor. UV-B radiation and plant life: molecular biology to ecology. Wallingford, UK: CABI; 2017. p. 144–60. [Google Scholar]

38. Blancquaert EH, Oberholster A, Ricardo-da-Silva JM, Deloire AJ. Effects of abiotic factors on phenolic compounds in the grape berry—a review. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 2019;40(1). doi:10.21548/40-1-3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Agati G, Brunetti C, dos Santos Nascimento LB, Gori A, Lo Piccolo E, Tattini M. Antioxidants by nature: an ancient feature at the heart of flavonoids’ multifunctionality. New Phytol. 2025;245(1):11–26. doi:10.1111/nph.20195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Arseni A, Crudu S. The role of procyanidins in grapes and wines: effects on quality and composition. J Eng Sci. 2025;31(4):175–92. doi:10.52326/jes.utm.2024.31(4).13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Li X, Ren Q, Zhao W, Liao C, Wang Q, Ding T, et al. Interaction between UV-B and plant anthocyanins. Funct Plant Biol. 2023;50(8):599–611. doi:10.1071/fp22244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Kolb CA, Käser MA, Kopecký J, Zotz G, Riederer M, Pfündel EE. Effects of natural intensities of visible and ultraviolet radiation on epidermal ultraviolet screening and photosynthesis in grape leaves. Plant Physiol. 2001;127(3):863–75. doi:10.1104/pp.010373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Bejenaru LE, Biţă A, Belu I, Segneanu AE, Radu A, Dumitru A, et al. Resveratrol: a review on the biological activity and applications. Appl Sci. 2024;14(11):4534. doi:10.3390/app14114534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Dimitrovska M, Bocevska M, Dimitrovski D, Doneva-Sapceska D. Evolution of anthocyanins during vinification of Merlot and Pinot Noir grapes to wines. Acta Aliment. 2015;44(2):259–67. doi:10.1556/066.2015.44.0003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ristic R, Downey MO, Iland PG, Bindon K, Francis IL, Herderich M, et al. Exclusion of sunlight from Shiraz grapes alters wine colour, tannin and sensory properties. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2007;13(2):53–65. doi:10.1111/j.1755-0238.2007.tb00235.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Escribano-Bailón MT, Rivas-Gonzalo JC, García-Estévez I. Wine color evolution and stability. In: Morata A, editor. Red wine technology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2019. p. 195–205. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-814399-5.00013-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Sun B, Ribes AM, Leandro MC, Belchior AP, Spranger MI. Stilbenes: quantitative extraction from grape skins, contribution of grape solids to wine and variation during wine maturation. Anal Chim Acta. 2006;563(1–2):382–90. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2005.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools