Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Metabolic Adaptations of Cyanobacteria to Environmental Stress: Mechanisms and Biotechnological Potentials

Laboratory of Photobiology and Molecular Microbiology, Department of Botany, Institute of Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, 221005, India

* Corresponding Author: Rajeshwar P. Sinha. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Metabolic Mechanisms of Plant Responses to Stress)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3371-3399. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.070712

Received 22 July 2025; Accepted 09 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Cyanobacteria are photosynthetic prokaryotes. They exhibit remarkable metabolic adaptability, enabling them to withstand oxidative stress, high salinity, temperature extremes, and UV radiation (UVR). Their adaptive strategies involve complex regulatory networks that affect gene expression, enzyme activity, and metabolite fluxes to maintain cellular homeostasis. Key stress response systems include the production of antioxidants such as peroxidases (POD), catalase (CAT), and superoxide dismutase (SOD), which detoxify reactive oxygen species (ROS). To withstand environmental stresses, cyanobacteria maintain osmotic balance by accumulating compatible solutes, such as glycine betaine, sucrose, and trehalose. They also adapt to temperature and light fluctuations by modifying membrane properties and regulating photosynthetic activity. Furthermore, secondary metabolites such as mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) and scytonemin act as natural UV protectors. This study highlights current advances in understanding these stress tolerance mechanisms, including exopolysaccharide (EPS) formation, compatible solute accumulation, and ROS detoxification. Recent advancements in proteomics and synthetic biology have shed light on novel defense mechanisms, identifying stress-induced proteins and regulatory networks that enhance resilience. This review thoroughly explores the underlying molecular and biochemical mechanisms of cyanobacterial stress tolerance, which make them promising candidates for various biotechnological applications. Future research on cyanobacterial stress adaptation should bring together synthetic biology, omics tools, and environmental biotechnology. Using these approaches together could help create stress-tolerant cyanobacteria with improved use in farming, pollution control, and biofuel production, supporting solutions to global environmental and energy challenges.Keywords

Cyanobacteria are one of the most important photosynthetic organisms, playing a vital role in ecosystems by contributing to the global carbon and nitrogen cycles. They are cosmopolitan and found in diverse environments such as polar regions, arid conditions, and hot springs [1]. Despite harsh environmental conditions, cyanobacteria exhibit adaptive strategies to survive in extreme environments, including oxidative stress, salinity, temperature, desiccation, and UV radiation. They evolved in an oxygen-free environment, so when oxygen levels increased, they had to adapt their internal systems to defend themselves.

As photosynthetic organisms, cyanobacteria continuously generate oxygen under light conditions. However, this oxygen can give rise to reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are harmful by-products that cause oxidative stress [2]. To minimize this, cyanobacteria have evolved mechanisms to prevent electrons from leaking to oxygen and to mitigate ROS production [3].

Cyanobacteria must deal with oxidative stress if the equilibrium between the oxidant levels and antioxidant synthesis is disrupted. Several cyanobacteria are found in waters of different salt concentrations [4]. High salt concentrations pose osmotic stress for cyanobacteria. To counteract this, they accumulate compatible solutes such as sucrose or glucosylglycerol (GG), which restore cellular water balance and turgor pressure. While this strategy is crucial for survival, the continuous synthesis and maintenance of these solutes impose a metabolic cost because large amounts of carbon, ATP, and reducing power are diverted from growth and photosynthetic processes. As a result, cyanobacteria under prolonged salt stress often show reduced growth rates despite effective osmotic adjustment [5].

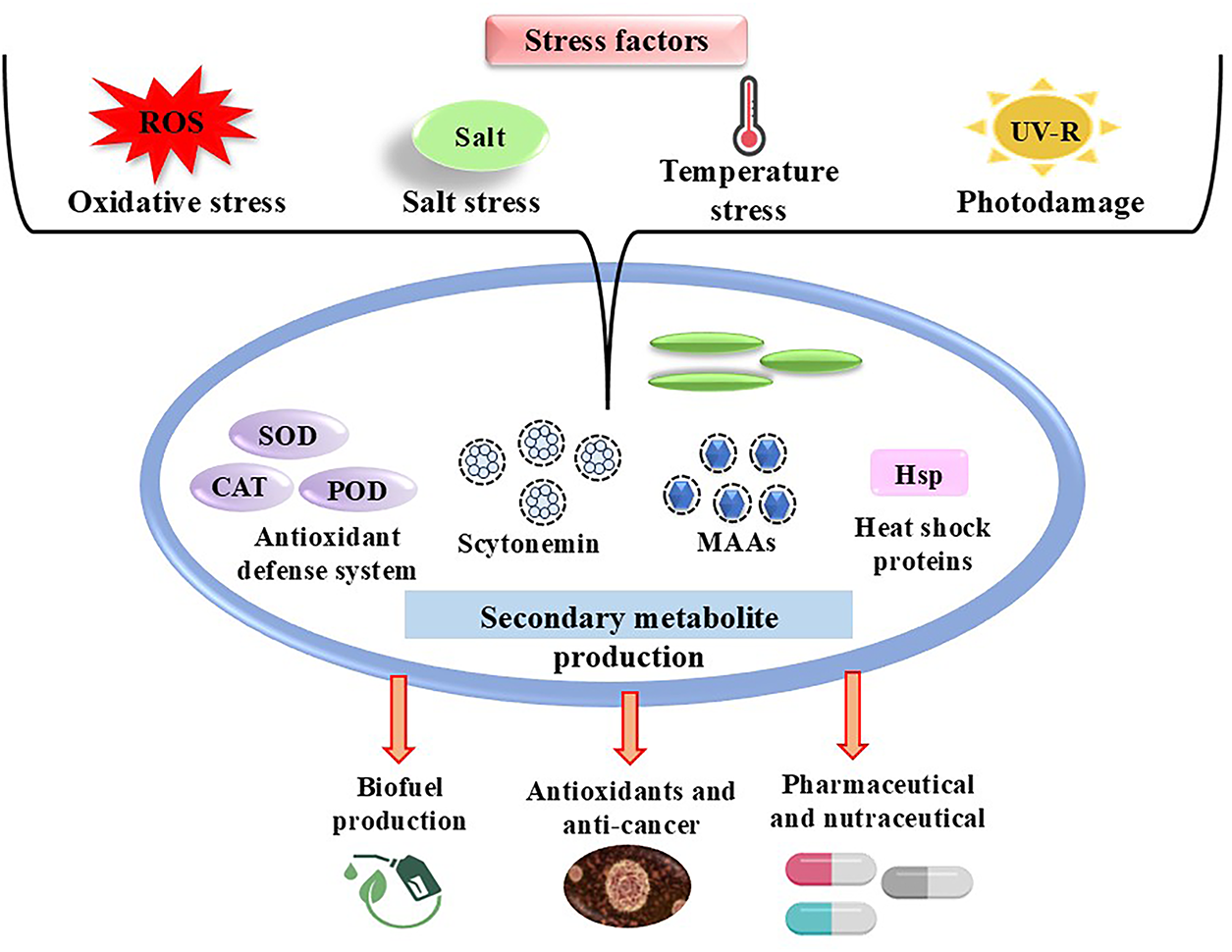

The detrimental effects of UV-B on terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, which impact macroalgae, phytoplankton, and cyanobacteria, have led to significant concerns due to its increasing incidence [5]. Cyanobacteria have devised numerous innovative methods to defend themselves from damaging UV rays. They can move away from excessive light or create protective layers (mats) to block it (Fig. 1) [6].

Figure 1: Stress-induced response in cyanobacteria and their potential applications, including the production of secondary metabolites, antioxidant enzymes, and heat shock proteins

They also repair damaged DNA using mechanisms such as photoreactivation and excision repair. To limit injury, they produce antioxidants and natural sunscreens such as Mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) and scytonemin (Fig. 1). In severe instances, they may allow damaged cells to die (a process known as apoptosis) to safeguard the colony as a whole [7]. Different stresses are sensed, signalled, and regulated by several factors. Small RNAs (sRNAs), heat shock proteins (HSPs), DNA-binding proteins (Dps), and sigma factors are a few of the elements that play a part in this process [8].

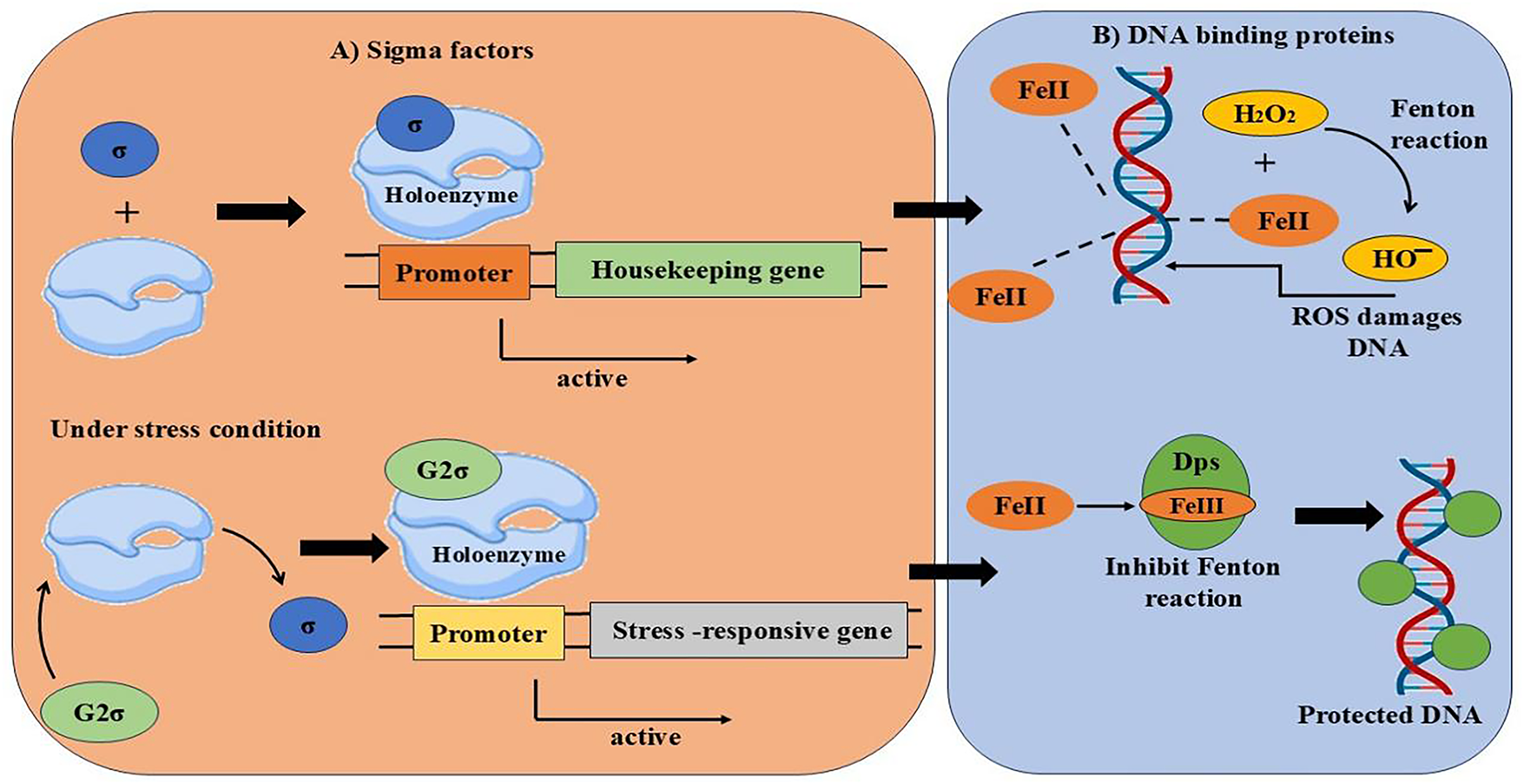

Researchers have studied different types of sigma factors and their role in how cyanobacteria sense and respond to stress. Sigma factors act as regulatory proteins that control which genes are turned on or off, thereby allowing cells to adjust their metabolism and activate defense systems under oxidative stress, high light (HL), or elevated salinity [9]. In this way, they serve as key signalling switches that connect environmental stress sensing to changes in gene expression. Similarly, special stress-related proteins such as Dps not only participate in cellular processes but also protect DNA during adverse conditions. Dps proteins bind to DNA and shield it from ROS or from damage caused by nutrient and iron limitation [10]. Together, sigma factors, Dps, HSPs, and sRNAs form an interconnected signalling and regulatory network: stresses are sensed by the cell, signals are transmitted through these molecules, and protective genes and pathways are then activated to enhance survival [8].

Like other environmental stressors, heat stress can cause denaturation, or the loss of protein structure, which can cause the cells to produce harmful molecules called ROS, which further damage the cell. To counteract these effects, cyanobacteria produce heat shock proteins (HSPs) [11]. Despite having a considerably simpler structure than plants, cyanobacteria share many important characteristics that make them a great model for researching stress responses in photosynthetic organisms.

Because of their small genomes, cyanobacteria are easier to study genetically than plants, which are complicated and challenging to genetically alter [12]. They assist scientists to learn how photosynthetic organisms adapt in severe conditions by triggering stress response mechanisms that allow them to live in extreme situations. Researching cyanobacteria can also result in biotechnology breakthroughs that benefit the environment, biofuel production, and sustainable agriculture [13]. They synthesize a wide array of bioactive secondary metabolites—including mycosporine-like amino acids, pigments, polysaccharides, and enzymes—that are increasingly exploited in medicine, nutrition, pharmaceuticals, and the chemical industry [14]. Their potential extends further into sustainable agriculture, where they enhance soil fertility and act as natural biofertilizers, and into renewable energy through biofuel production and carbon sequestration [15]. Owing to their scalability in cultivation and versatility in metabolic engineering, cyanobacteria represent a promising resource for developing eco-friendly and economically viable technologies. This review, therefore, emphasizes not only their stress adaptation mechanisms but also their diverse biotechnological potentials that can benefit both humans and the environment [16].

2 Environmental Stresses Affecting Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria thrive in diverse aquatic and terrestrial environments but are frequently challenged by abiotic stressors such as temperature fluctuations, high salinity, oxidative stress, desiccation, and ultraviolet radiation (UVR), which can disrupt cellular functions and alter physiological and biochemical processes [17]. These extreme stressors can even lead to cell death, making cyanobacteria valuable model organisms for studying adaptive and defensive mechanisms. Stress-induced damage includes protein denaturation, photosystem degradation, and disruption of cellular ion balance, which collectively impair growth and reduce photosynthetic efficiency [18]. Cyanobacteria thus develop appropriate solutes like GG and glycine betaine and stimulate ion transport systems to fight this [19]. In response to temperature extremes that affect membrane fluidity and enzyme stability, HSPs such as caseinolytic peptidase genes (clpB1 and clpB2) are elevated to preserve protein folding and prevent thermal damage. Cyanobacteria change their molecular, physiological, and biochemical processes to fit various forms of stress. Oxidative stress results from the overproduction of ROS brought on by either HL, salinity, or chemical contact. These molecules attack proteins, lipids, and DNA. UV light especially UV-B causes oxidative stress and DNA damage in cyanobacteria [20].

To protect themselves, they produce UV-absorbing molecules, including amino acids resembling MAAs and scytonemin. MAAs act as natural sunscreens and antioxidants, helping cells cope with UV exposure. Nutrient depletion is a major challenge for cyanobacteria, which, unlike many bacteria, do not form dormant spores but survive during starvation through metabolic adjustments [21]. Under carbon limitation, they enhance carbon fixation via a carbon-concentrating mechanism that elevates CO2 near RubisCO [22]. During nitrogen starvation, cyanobacteria downregulate central metabolism and degrade the photosynthetic apparatus, entering a chlorotic state with reduced autofluorescence [23]. Phosphate deficiency impairs photosynthesis, growth, nucleic acid synthesis, and membrane integrity, forcing activation of phosphate acquisition and conservation pathways. These strategies highlight the remarkable metabolic plasticity of cyanobacteria in nutrient-poor environments. This study gives a general overview of how various stresses affect cyanobacteria and the defense mechanisms that these prokaryotes have evolved to deal with the negative impacts of the stress [24].

Oxidative stress occurs when there is an imbalance between the light energy captured by the cell, the flow of electrons during photosynthesis, and the amount of CO2 the cell can absorb. Because both light and oxidative stress raise the levels of ROS, the reactions to these stimuli are frequently similar [24]. ROS include hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide ions (

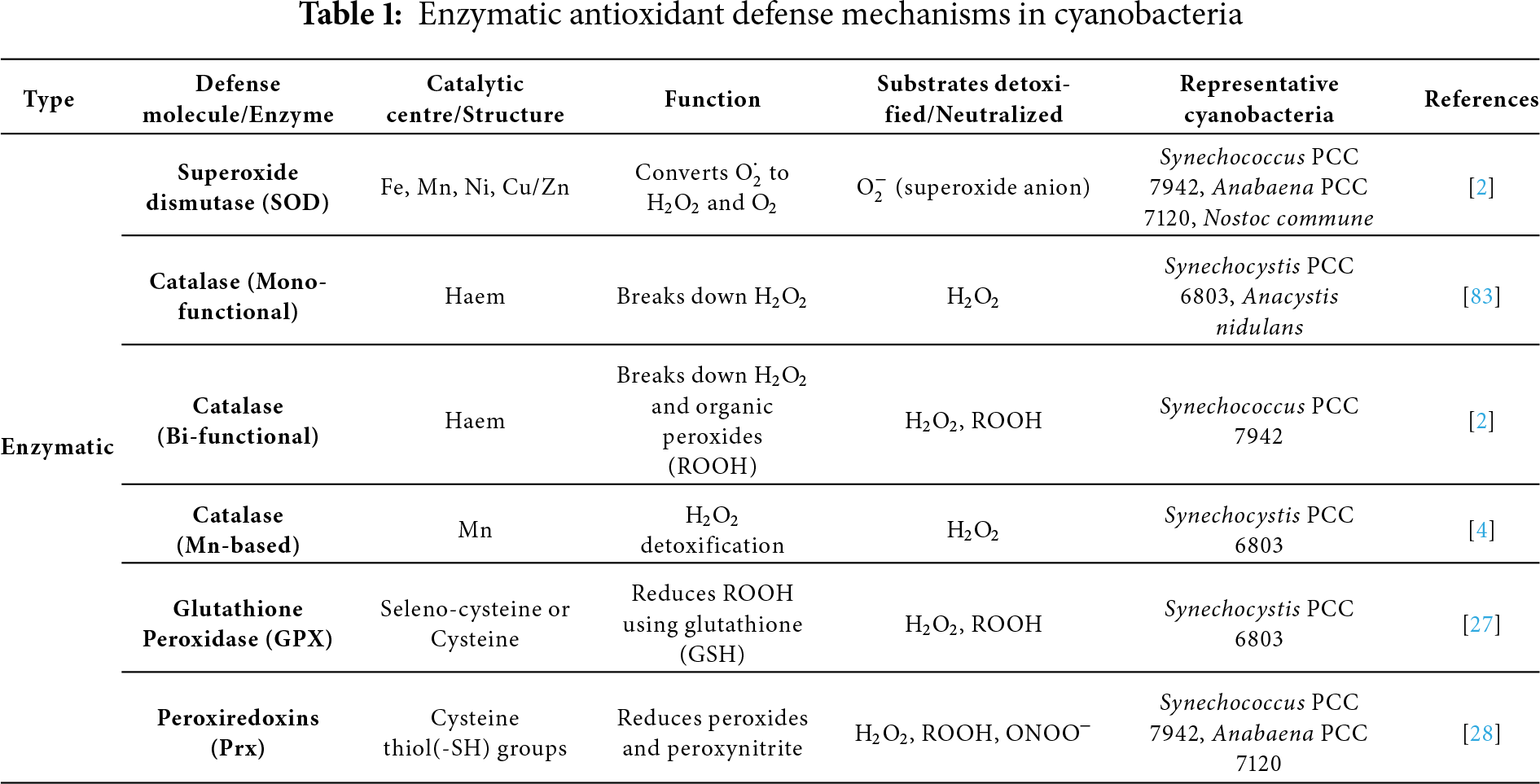

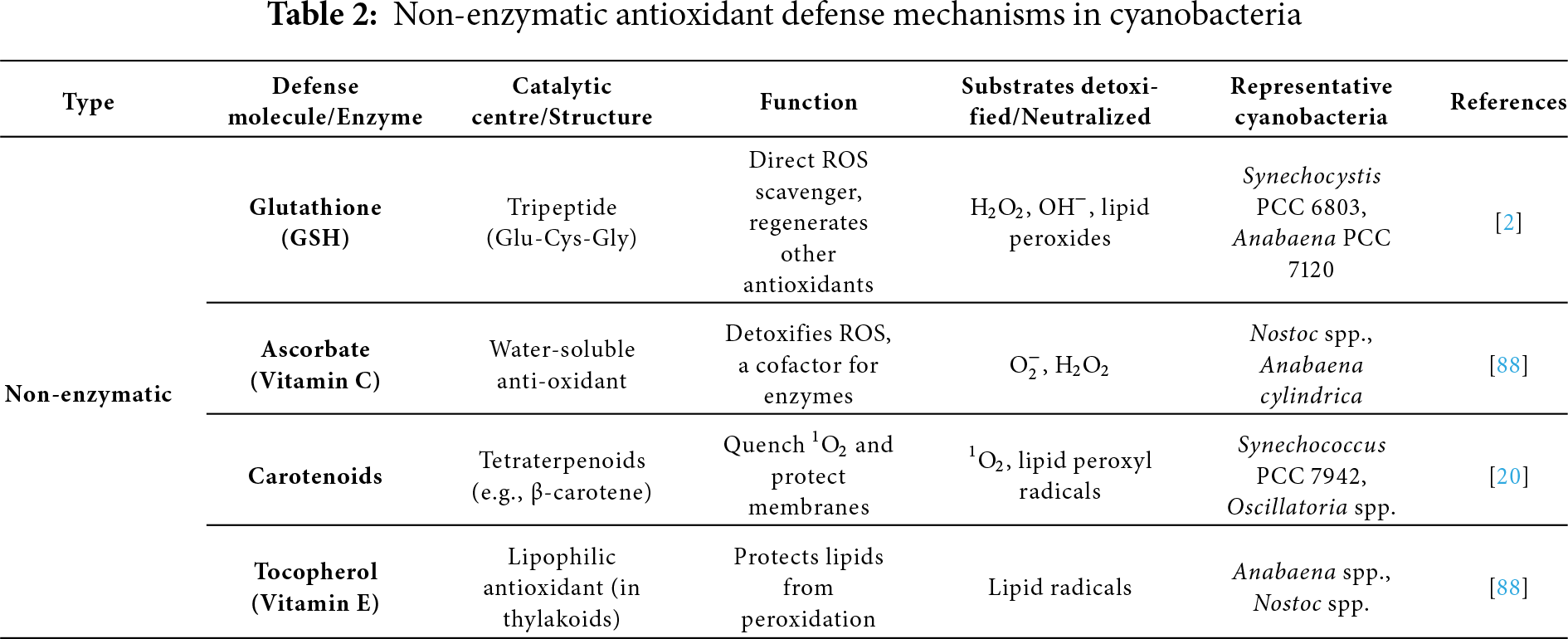

Cyanobacteria employ two different kinds of antioxidant defense mechanisms to keep themselves safe. Proline, ascorbic acid, glutathione, vitamins A, C, and E, and carotenoids are among the chemicals that make up the non-enzymatic system. The enzymes POD, CAT, and SOD are part of the enzymatic system [27]. One of the few ROS that may readily cross cell membranes is H2O2, which can also create the extremely dangerous OH· when iron is present [28]. SOD is the first line of defense because it transforms superoxide anion (

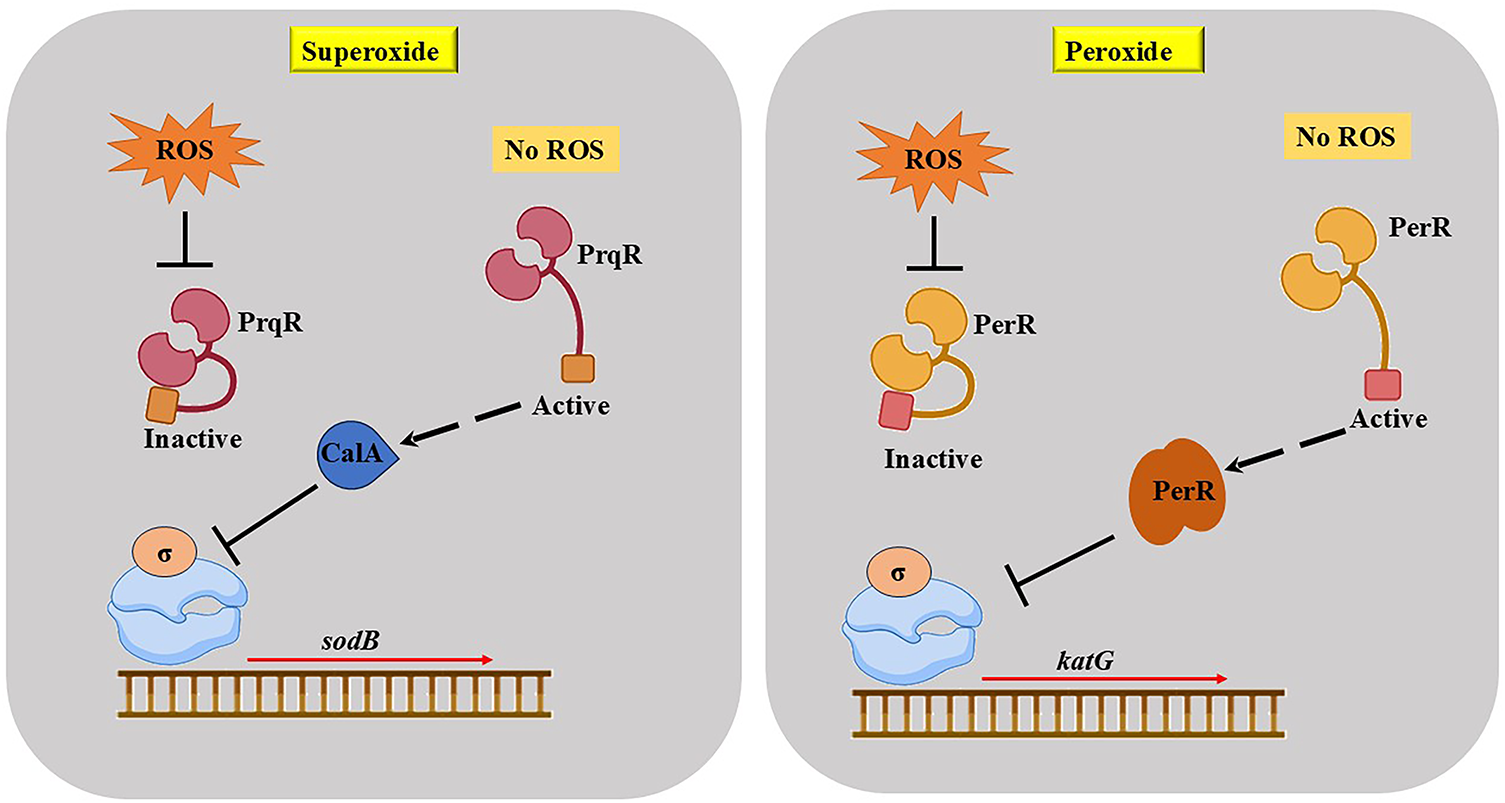

In the cyanobacterium Nostoc (Anabaena PCC 7120), the sodB gene produces the enzyme iron superoxide dismutase (FeSOD), which plays a vital role in protecting the cell by converting harmful superoxide radicals (

Figure 2: Cyanobacteria regulate gene expression in response to two different ROS: superoxide and peroxide

The quantity of dissolved salts (inorganic ions) in soil or water is referred to as salinity. Whether cyanobacteria exist on land or in water, it’s one of the main environmental issues they have to contend with [19]. Though cells respond differently to high or low salinity, the term “salt stress” usually refers to high salinity conditions [18]. Cyanobacteria employ a technique known as the “salt-out strategy” to withstand salt stress; they store tiny organic substances (such as sugars) inside their cells and push out excess inorganic salts. It’s interesting to note that a cyanobacterium’s tolerance for salt is influenced by the kind of solute it produces, which varies depending on the strain [40]. Although many different forms of salts, such as chlorides, carbonates, and sulphates, are found in the environment, the main cause of salinity stress is an excess of NaCl. This stress inhibits plant or cyanobacterial growth, destroys cell membranes, and impairs photosynthesis [41].

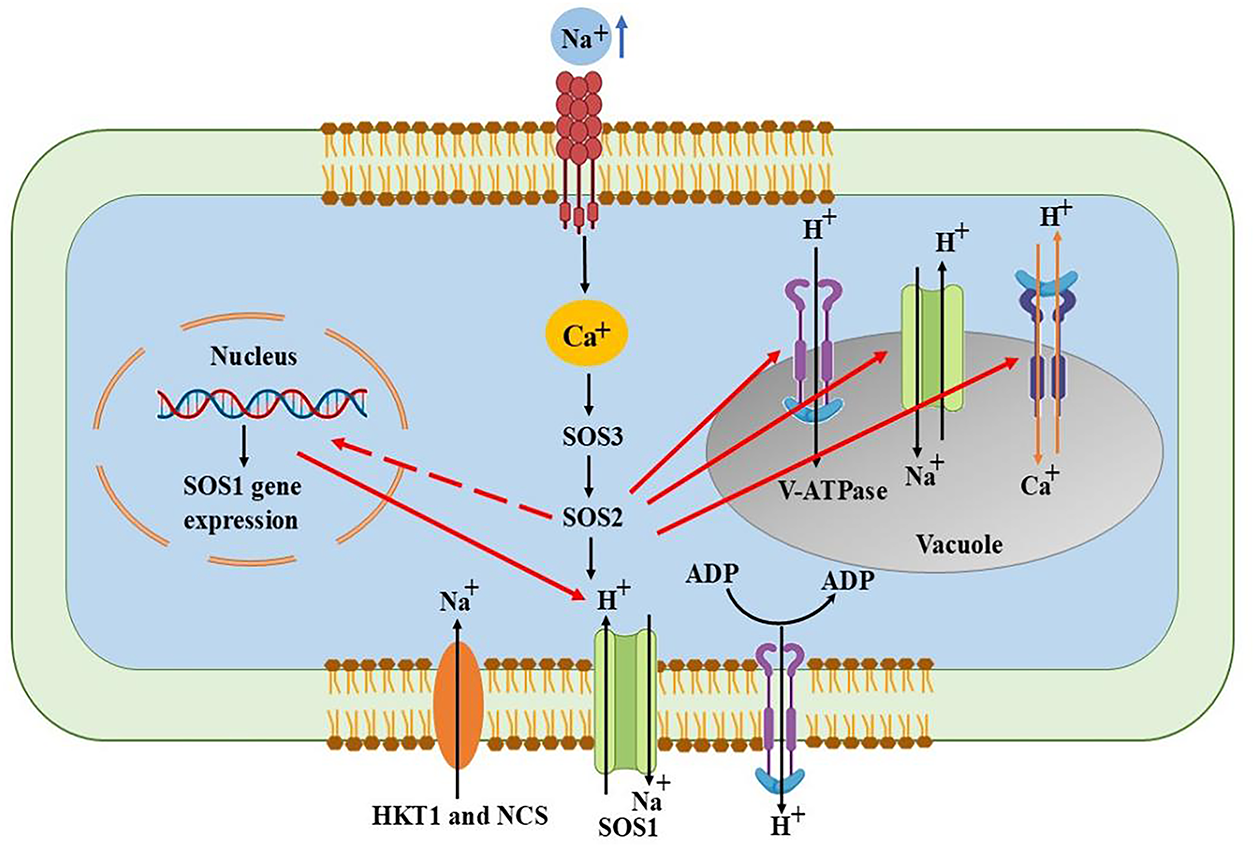

In addition to oxidative damage, salt stress produces an increase in the number of ions in the lumen, the thylakoid space, which results in an imbalance of water within the cells. Consequently, PS I and PS II, the two primary components of photosynthesis, momentarily cease to function. This is caused by the detachment of crucial proteins that promote photosynthesis, such as PsbO, PsbV, and PsbU [18]. The harm could be irreversible if this stress persists over an extended period of time. This is because Na+ ions enter the cell through certain channels and disrupt the functions of proteins and genes involved in Photosystem II, such as psbA. Cyanobacteria such as Synechocystis PCC 6803 produce more of two essential enzymes, GGPP (glucosylglycerol-phosphate phosphatase) and GgpS (glucosylglycerol-phosphate synthase), as the salt content rises. These enzymes aid in the synthesis of GG, a crucial substance that shields cells from the damaging effects of salt. Remarkably, even in the presence of low salt levels, a protein known as LexA aids in the creation of GgpS; yet, in a strain in which the sigF gene is absent, GgpS levels decrease, and the cells become more susceptible to salt [42]. These protective molecules, particularly GG, are essential for maintaining cell division stability and safeguarding the internal environment of the cell in stressful, salty conditions [43]. To survive in saline environments, different cyanobacteria employ various kinds of protective solutes. For instance, Nostoc muscorum uses glycine or glutamate betaine, Spirulina mostly employs GG, and Synechocystis PCC 6803 uses sucrose [44]. Trehalose or sucrose is typically produced by cyanobacteria that are less salt-tolerant (can withstand up to 0.7 M NaCl). GG are produced by those that are moderately tolerant (up to 1.25 M NaCl) [19]. The salt overly sensitive (SOS) pathway is a unique sensing mechanism that cyanobacteria use to defend themselves against elevated salt levels (Fig. 3). This mechanism aids in the cells’ ability to recognize excessive salt in their environment and initiates an internal reaction to lessen harm.

Figure 3: SOS pathway to overcome salt stress by sensing excess sodium and activating ion transporters to restore ionic balance and maintain cell function

Three crucial genes are activated when the plasma membrane detects salt stress: Through a process known as Na+/H+ exchanger, SOS1 aids in the pumping out of excess Na+. Similar to a switching protein (kinase), SOS2 activates other beneficial proteins. SOS3 sends signals inside the cell when it detects variations in Ca2+ levels. These three genes work together to support the cyanobacteria in preserving the proper ion balance both inside and outside the cell [45]. The Ca2+ levels within the cell are disrupted by this stress. After recognizing this calcium shift, the protein SOS3 combines with another protein, SOS2. The complex formed by SOS3 and SOS2 activates antiporter proteins on the cell membrane, primarily the Na+/H+ antiporters. Antiporters promote a healthy ion balance by removing excess Na+ and taking in H+. Additionally, this SOS2-SOS3 complex inhibits the action of AtHKT1, another transporter that could otherwise allow more salt to enter the cell. In order to lessen the negative effects of certain sodium ions, SOS2 also aids in their movement into internal storage compartments, a process known as ion compartmentalization [46].

Rising temperatures brought on by Global environmental change have already had an impact on the majority of Earth’s ecosystems and are a significant cause of stress in natural settings. Because various stressors, such as invasive species spread and nutrient changes, interact with increasing temperatures, it is challenging to forecast how ecosystems will react to environmental changes [47,48]. By altering cellular metabolic methods, cyanobacteria are able to respond flexibly to both short-term and long-term stressors. Changes in the photosynthetic light-harvesting complex, membrane mobility, enzyme modification, gene expression pattern, and structural modifications are among the short- and long-term adaptations [49].

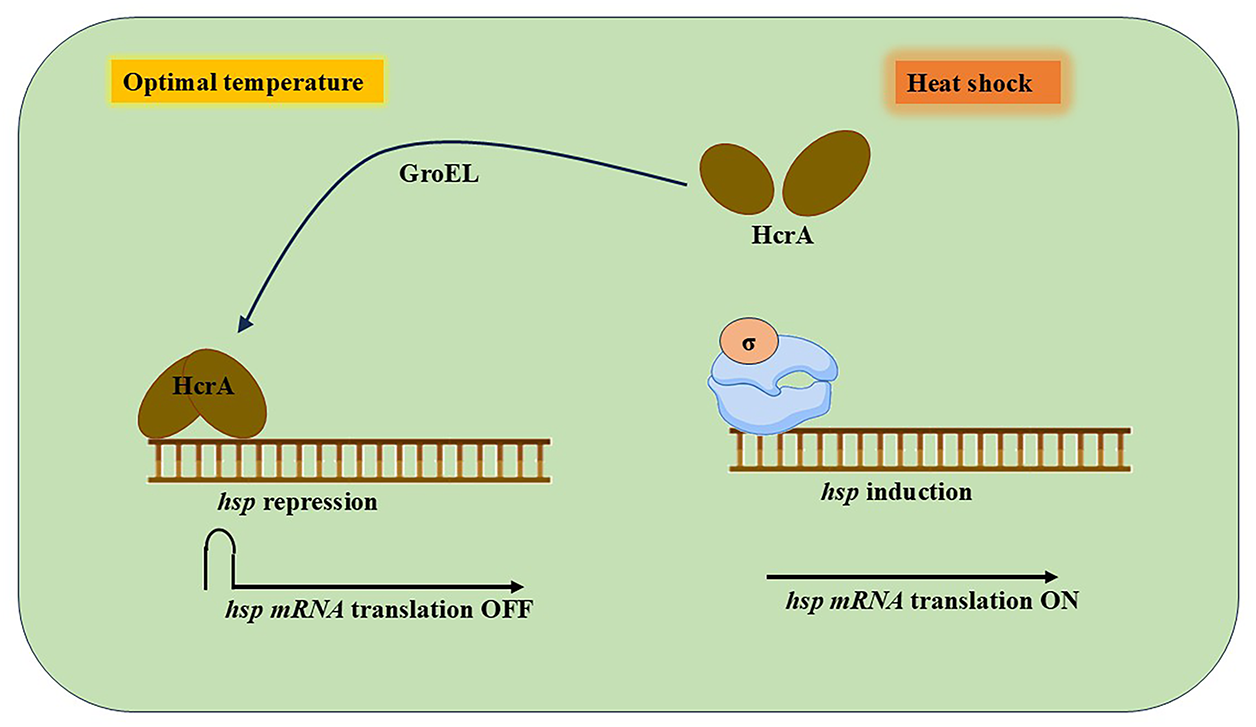

Cyanobacteria activate heat shock genes in response to increasing temperatures, just like other species do. These genes aid in the production of unique proteins known as HSPs by the cells. These HSPs help other proteins maintain their proper structure or eliminate damaged ones by acting as chaperones or proteases. HSP60 proteins, particularly GroEL and GroES, are among the most prevalent HSPs produced during heat stress and are essential for a cell’s survival and recovery following temperature increases [50,51] (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Regulation of HSPs gene expression in cyanobacteria

A transcriptional regulator HrcA keeps the genes that make it in check when cyanobacteria are growing normally. To stop these genes from working, HrcA binds to a particular region of the DNA known as the controlling inverted repeat of chaperone expression (CIRCE) [52]. However, HrcA ceases functioning when cells are subjected to heat stress, and the genes for heat shock proteins are activated to assist the cell in coping with the stress. A helper protein known as GroEL aids in the refolding and reactivation of HrcA so that the genes can be turned off once more after the stress has passed. Additionally, the region where ribosomes would typically attach to form the protein is hidden by a unique folded shape found in some heat shock protein messages (mRNAs). This fold prevents translation at room temperature. However, the fold breaks down when the temperature rises, enabling the ribosome to start producing the HSPs.

As ambient temperatures rise, cyanobacterial species tend to grow more prevalent and dominant, as Carey and his colleagues have clearly documented. This increased dominance is largely due to their physiological adaptations, such as high thermal tolerance of their photosynthetic machinery, efficient nutrient uptake under warm conditions, and the ability to regulate buoyancy and form surface blooms, which together provide a strong competitive advantage over other organisms [53,54]. Therefore, by controlling ecosystem productivity through nitrogen fixation, photosynthesis, and the accumulation of various inorganic materials under high temperatures, cyanobacteria have naturally carried out the most important physiological, metabolic, and genetic algorithms for maintaining life on Earth’s surface. While cyanobacteria clearly exhibit remarkable resilience to both high and low temperatures, and although the underlying mechanisms are still being uncovered, recent studies continue to shed light on the strategies that enable their survival [49].

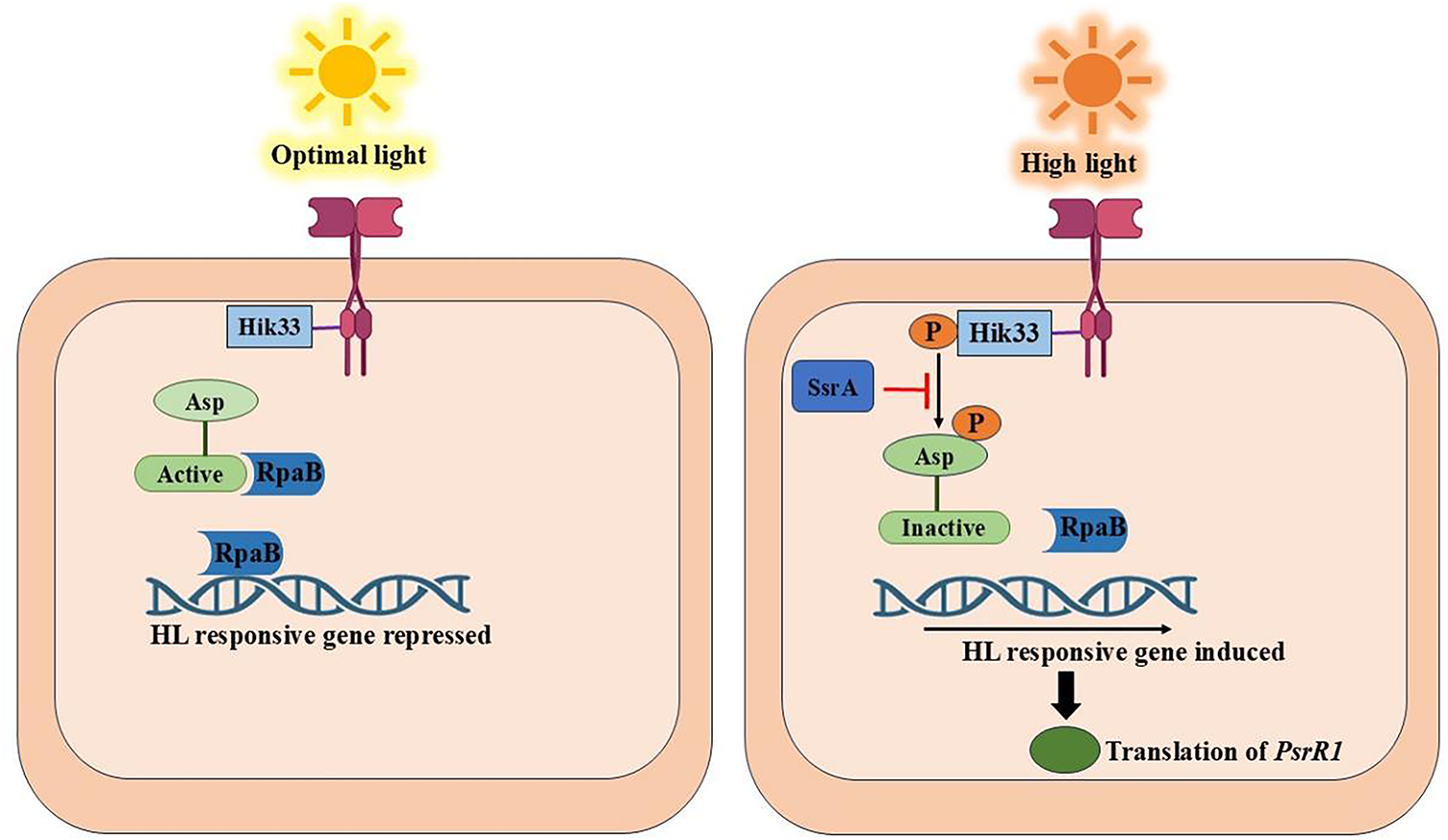

Since cyanobacteria rely on sunlight for growth, they must be able to detect variations in light and modify their internal mechanisms correspondingly. Their unique light-absorbing structures, known as phycobilisomes, enable them to absorb light for photosynthesis. On the other hand, their photosynthetic system may be harmed by excessive light. Their capacity to produce energy from sunlight may be diminished by this damage, which is known as photoinhibition and photodestruction [55]. Therefore, in order to protect themselves and continue to operate correctly, cyanobacteria need to carefully control how they react to fluctuations in light intensity. Cyanobacteria modify their gene expression patterns in response to prolonged light exposure. The high-light regulatory region (HLRR), a common sequence found in the promoter regions of several genes triggered by high-light stress, aids in the detection and investigation of how cells react to light stress [56,57].

A protein known as RpaB was discovered by researchers to be a crucial modulator of (HL) stress in Synechocystis PCC 6803 and Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 using this method. Under normal light conditions, RpaB, which is a component of the two-component regulatory system, functions as a repressor to keep HL-response genes inactive [58,59]. NblS, a histidine kinase sensor protein, recognizes HL stress in Synechococcus and triggers RpaB. Both NblS and Hik33 (DpsA), a related variant found in Synechocystis, are extensively conserved in cyanobacteria. Additionally, during HL stress, NblS activates another regulator, SsrA, which may assist in balancing the signal between NblS and RpaB [60]. The response regulator RpaB can continue to be active and suppress HL-responsive genes under normal light conditions because the sensor protein Hik33 is inactive. Hik33 becomes active and phosphorylates RpaB in response to increased light intensity, inactivating it and enabling the expression of HL-responsive genes. Furthermore, the protein SsrA disrupts the phosphorylation pathway, keeping RpaB dormant for a more robust stress response. The RpaB protein in cyanobacteria regulates a set of genes called the RpaB regulon, which includes the psrR1 gene. A sRNA is produced by psrR1 when it is under HL stress. Instead of producing a protein, this sRNA attaches itself to particular mRNAs of many target genes. By binding to these mRNAs, psrR1 sRNA blocks their translation into proteins, effectively inhibiting the generation of proteins that may be detrimental or not required during HL stress (Fig. 5). By doing this, the cell can conserve energy and prevent harm from harsh light [58,59].

Figure 5: The response of cyanobacteria to optimal and high light conditions

But an increase in HL, especially UVR, can hamper many essential cellular processes. Different biomolecules are directly or indirectly impacted by various UV-induced photochemical processes, thereby acting as the primary cellular targets of UV-B radiation. One of the most UV-sensitive macromolecules is nucleic acid, such as DNA. Different processes involving single-strand breakage, interactions between neighbouring bases (dimerization), and non-adjacent bases (inter- or intra-strand crosslinks), can disperse the absorbed energy [7]. The second main consequence of UVR on cyanobacteria, after DNA photoproducts, is damage to protein molecules. Target proteins typically include those connected to the plasmalemma or engaged in photosynthesis, such as the Calvin cycle enzyme RuBisCO and the D1 protein of photosystem II [61,62]. Furthermore, absorbed UV-B radiation results in cleavage of disulfide bonds between cysteine residues in proteins [63]. UV radiation damages both proteins and DNA; however, protein damage is usually less critical since proteins exist in multiple copies and can be replaced, whereas DNA damage is more severe because it directly threatens the integrity of the genetic blueprint [64]. UV-B radiation may affect the membrane integrity of the thylakoid membrane as it initiates lipid peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) via oxidative damage [65].

3 Metabolic Adaptations to Stress Tolerance

Cyanobacteria exhibit remarkable metabolic plasticity that enables them to survive under diverse environmental stresses. Significant metabolic adjustments that reduce oxidative stress are displayed by cyanobacteria to withstand these difficulties [17]. To tolerate these challenges, cyanobacteria remodel their metabolism by activating antioxidant defense systems, including enzymatic components such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidases, along with non-enzymatic antioxidants like carotenoids, MAAs, and phenolic compounds, redirecting carbon flux toward reductive pathways, synthesizing osmoprotectants, and producing specialized photoprotective compounds [66]. Accumulation of compatible solutes such as sucrose, trehalose, and glycine betaine further maintains osmotic balance and protects macromolecules. Together, these metabolic strategies provide resilience against oxidative stress and enable cyanobacteria to thrive under fluctuating environmental conditions. These adaptations not only prevent oxidative damage but also maintain energy homeostasis and cellular viability under fluctuating conditions [24].

Besides UV, salinity, nutrient, and temperature stress, cyanobacteria are also well known for their remarkable tolerance to drought and desiccation. Many terrestrial forms exhibit poikilohydry, the ability to survive near-complete dehydration and resume photosynthetic activity upon rehydration. This adaptation is ecologically significant, particularly in soil crusts and arid land ecosystems, where cyanobacteria contribute to resilience under water scarcity. Previous studies have documented that both soil algae and cyanobacteria can withstand severe drought conditions and rapidly recover metabolic activity after water availability is restored [67]. Furthermore, drought-tolerant cyanobacteria have been highlighted as promising biotechnological tools to support land degradation neutrality due to their ecological role in stabilizing soils and enhancing fertility [68]. While the phenomenon of desiccation tolerance in cyanobacteria is well established, the underlying metabolic mechanisms are still less understood compared to other stresses, and thus represent an important area for future research.

3.1 Antioxidant Defense Mechanism

Nonenzymatic antioxidants include ascorbate, vitamin E, carotenoids, and reduced glutathione. Ascorbate and the enzyme Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) break down H2O2, a toxic ROS. APX transforms H2O2 to H2O using two ascorbate molecules. Ascorbate neutralizes a variety of ROS, including OH· and H2O2. Ascorbate is a direct scavenger of ROS and a substrate for APX and violaxanthin de-epoxidase [69]. Ascorbate reduces ROS to monodehydroascorbate (MDA), which is then converted back into ascorbate by monodehydroascorbate reductase (MDAR) using NADPH or ferredoxin. If not lowered immediately, MDA can disproportionate into dehydroascorbate (DHA) and ascorbate. Ascorbate is found in all organisms, requires less energy to synthesize, is less toxic, and preserves the enzyme pool for the ascorbate-glutathione cycle [70].

Cyanobacteria produce extremely little ascorbate compared to higher plants. Even in modest concentrations, ascorbate reduces oxidative damage by regulating enzyme activity and influencing gene expression in the AsA-GSH cycle [71]. Top of FormBottom of FormVitamin E is an organic antioxidant that is lipid soluble and found only in oxygenic phototrophs, such as higher plants, all green algae, and certain cyanobacteria (such as Synechocystis PCC 6803). Cells are shielded from oxidative damage by tocopherol. Tocopherol is first oxidized by ROS to form tocopheryl radicals, which are further converted into hydroperoxides by 1O2. By converting tocopherol back to its active form, ascorbate can reverse both processes. In the PSII reaction center, tocopherol mostly scavenges 1O2, preventing the peroxidation of membrane lipids [72]. Another group of hydrophobic pigments that shield photosynthetic organisms from photooxidative damage is carotenoids.

To stop the accumulation of ROS, carotenoids quench 1O2 and absorb the energy from the excited chlorophyll molecules [73]. Thus, they scavenge ROS, protect PSI and PSII, control membrane fluidity and homeostasis during stress, and dissipate excess energy from excited chlorophyll as heat by non-photochemical quenching. β-carotene, zeaxanthin, synechoxanthin, nostoxanthin, echinenone, myxoxanthophyll, and caloxanthin are examples of common carotenoids [74]. In comparison to the wild type, Synechocystis PCC 6803 mutants deficient in zeaxanthin were more vulnerable to elevated PAR and oxidative stress. Zeaxanthin contributes to the photoacclimation of Synechococcus PCC 7942 to UV-B stress [75]. According to Peers and colleagues [76], zeaxanthin is formed in the presence of intense light, but NPQ (the qE component) is dependent on the LHCSR3 protein. According to Ehling-Schulz and his colleagues [77], under UV-B stress, Nostoc commune produces myxoxanthophyll and echinenone, which function as UV-B photoprotectors attached to the outer membrane. The most crucial antioxidant enzyme that serves as cyanobacteria’s initial line of defense against ROS is SOD, which dismutates

SOD produces H2O2 and O2 from extremely harmful O·2. Different types of SOD are encoded by distinct genes and are frequently expressed in different places. For instance, in Synechococcus, sodB encodes FeSOD, which is essential for photoprotection and oxidative stress development [78]. SOD fulfills a number of functional tasks. The first indication that SOD shields photosystems, particularly PSI, against light stress was found in Synechococcus (Anacystis nidulans). FeSOD reverses damage from rehydration-desiccation cycles and builds up in situ in Nostoc commune [80]. In Anabaena PCC 7120, MnSOD shields nitrogenase from ROS in high-light and aerobic environments. Under nitrogen-fixing conditions, FeSOD exhibits a specific function, while MnSOD-deficient mutants exhibited reduced nitrogen fixation and photoinhibition [81].

Catalases are well-known antioxidant enzymes that break the peroxidic link in H2O2 to release oxygen and water, therefore detoxifying the compound. They are distinct because they don’t use up cellular reducing equivalents and offer defense against oxidative damage, particularly when exposed to environmental stressors, including UV, Cu, and dehydration. The most prevalent monofunctional hemocatalases, which exclusively contain catalase activity, are found in bacteria, archaea, and eukarya. Bifunctional Haem Catalase-Peroxidases (KatGs) are phylogenetically linked to cytochrome c peroxidases and ascorbate peroxidases, and they exhibit both catalase and peroxidase activity, as shown in (Table 1) [82]. It is found in around 30% of cyanobacteria, such as Synechococcus PCC 7942 and Synechocystis PCC 6803. Anabaena PCC7120-KatA, KatB are examples of diazotrophic cyanobacteria that have binuclear manganese catalases (Mn-Cats, Non-haem) [83].

Using ascorbate as an electron donor, APX, a crucial antioxidant enzyme, is well recognized for its role in detoxifying H2O2 in higher plants. APX-like activity has been shown in a number of strains of cyanobacteria, despite their normally low ascorbate levels, suggesting a potential conserved antioxidant role across species [84]. In Synechococcus PCC 7942, enzymes such as dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR) and glutathione reductase (GR) aid in the regeneration of ascorbate and glutathione, maintaining the ascorbate–glutathione cycle, which are crucial for sustaining APX activity under oxidative stress (Table 2), APX-like enzymes have been found in Nostoc muscorum PCC 7119 and Synechococcus PCC 6311 [85]. APX helps Synechocystis PCC 6803 reduce H2O2 and quench chlorophyll fluorescence caused by oxidative stress, a function that is not present in organisms like Aspergillus nidulans that lack APX. APX is also the main enzyme used by Synechococcus PCC 9742 to detoxify H2O2 under oxidative stress. Numerous cyanobacteria, such as Nostoc, Phormidium corium, and Nostoc spongiaeforme, show elevated APX activity in response to environmental stressors like UV-B and intense light [86]. Notably, the hot spring isolate Nostoc strain HKAR-2 exhibits more APX induction than its rice-field counterpart HKAR-6, demonstrating strain-specific stress responses. These results imply that APX plays an important and inducible function in cyanobacterial oxidative stress tolerance, while being less well understood than in plants [87].

3.2 Production of Secondary Metabolites: MAAs and Scytonemin

MAAs are small (<400 Da), colorless, water-soluble secondary metabolites widely found in cyanobacteria, algae, fungi, lichens, and some marine animals [20]. The structural composition of MAAs includes a cyclohexanone or cyclohexenimine ring, which conjugates with amino alcohols or amino acids. This conjugation gives them significant stability, chemically and structurally [89]. Consequently, MAAs have a strong UV absorption at 309–362 nm along with significant molar extinction coefficients (ε = 28,100–50,000 M−1 cm−1). Their ability to dissipate the UV energy, simply in the form of heat, makes MAAs suitable as natural photoprotective compounds [90]. This feature also helps in preventing ROS generation and thereby shielding the essential cellular molecules like DNA and proteins, e.g., UV-induced thymine dimer formation in DNA. Scavenging of H2O2,

In certain organisms like Nostoc commune, Lyngbya aestruarii, Klebsormidium, etc., some abiotic factors like salinity or availability of nitrogen may further increase the MAAs biosynthesis. Among the 33 recognised MAAs, the most often that are found in cyanobacteria are shinorine, porphyra-334, and palythine. A substantial UV-induced photoprotective mechanism was observed in HPLC-MS studies in Lyngbya sp. with identification of palythine (λmax: 319 nm, m/z: 245), asterina-330 (λmax: 330 nm, m/z: 289), and an unknown MAA (λmax: 312 nm, m/z: 312) [93]. Sensitive cellular targets are shielded against thermal, desiccation, and osmotic stress by the MAA’s ability to block at least 30% of the UV photons. This potential of photostability makes them suitable as industrial and commercial products in sun-protection skincare regimes, e.g., Helioguard 365 containing MAAs extracted from Porphyra umbilicalis. Due to the absence of the shikimate pathway in animals, the MAAs are acquired through diet. These factors contribute to making MAAs a promising candidate for use in commercial synthetic biology and biotechnology [94].

The yellow-brown, lipid-soluble pigment known as scytonemin is only found in cyanobacteria and sometimes in their symbiotic lichen partners. Found mostly in the extracellular polysaccharide sheath, it functions as a passive sunscreen. As a dimer of indolic and phenolic subunits connected by an olefinic carbon, scytonemin has a molecular mass of 544 Da when oxidized and 546 Da when reduced (fuscorhodin) [20]. With clear peaks at 252, 278, 300, and 386 nm (in vitro) and a UV-A peak shift to 370 nm in vivo, it demonstrates broad-spectrum UV absorption, efficiently filtering UV-A, UV-B, and UV-C rays. With a molar extinction coefficient as high as ε = 250 g−1 cm−1 at 384 nm, scytonemin to reduce the absorption of UV-A by around 90%. Hence, it has a significant role in the survival of cyanobacteria in the environment where UV penetration is high. However, some environmental stress factors like nitrogen deprivation, salinity, desiccation, and photooxidative stress contribute to the induction of scytonemin biosynthesis, with the most important role being that of UV-A.

However, the blue, green, or red wavelengths of light are not known to induce its formation [6]. Known producers include Chroococcidiopsis sp., Scytonema sp., and Nostoc punctiforme (PCC 73102 and ATCC 29133). The latter has an 18-ORF gene cluster (NpR1276–NpR1259) that is involved in its biosynthesis, possibly through an acyloin-type reaction that condenses tryptophan and phenylpropanoid derivatives [95]. Although oxidative stress (e.g., 0.25% H2O2) can cause partial degradation, scytonemin is highly photostable and can withstand abiotic stressors such as high temperatures (60°C), UV-B radiation (0.78 W m−2), and desiccation. Although it is a rather slow radical scavenger, scytonemin has dose-dependent antioxidant activity; at 0.4 and 0.8 mM concentrations, it neutralizes DPPH and ABTS radicals with 22% and 52% activity, respectively, in comparison to 0.5 mM ascorbic acid [96].

3.3 Compatible Solute Accumulation

Compatible solutes are tiny organic compounds that enable cyanobacteria to live in harsh environments, particularly when there is insufficient water or a high concentration of salt. These solutes protect cells from water loss, prevent proteins from unfolding or being damaged, and stabilize key components within the cell [97]. The most prevalent suitable solutes in cyanobacteria are trehalose, GG, sucrose, and glycine betaine. Other solutes, such as proline and glucosylglycerate, are less common and only found in certain cyanobacteria, in contrast to higher plants. Furthermore, cyanobacteria also produce compounds like glycogen and PHB (polyhydroxybutyrate), which are crucial for the general health and survival of cells because they perform a variety of beneficial functions under stress [98]. Several land-dwelling (terrestrial) cyanobacteria have additional genes that help them to survive in harsh or dry environments, according to a recent study that examined the DNA of 650 different cyanobacterial species [99].

The production of sugar molecules like sucrose and trehalose, which shield cells from dehydration, is primarily the function of these additional genes. Land-dwelling cyanobacteria were more likely to have the sucrose synthase gene and a group of genes known as the treZY cluster, which aids in the production of trehalose. This indicates that these organisms frequently use the production of these sugars as a defense against environmental stressors like drying out [100]. According to recent research, trehalose, a kind of sugar, aids in the survival of organisms such as yeast, fungi, and archaea in situations where there is either insufficient water or enough salt. For the first time, researchers discovered that the coastal red algae Porphyra umbilicalis produces trehalose when it is under drying stress [101]. This is unexpected since trehalose was primarily thought to be a protective substance found in terrestrial species. In plants, trehalose serves more functions than just direct cell protection.

Rather, it functions more like a signal molecule, facilitating interactions and communication between plants and beneficial soil bacteria (the rhizosphere). Therefore, trehalose plays a significant function in signaling and control in plants in addition to protection [102]. One crucial phase in cyanobacteria’s ability to adapt and endure stress is the accumulation of suitable solutes. These solutes enable the cells to react to various forms of stress, including heat, thirst, and oxidative conditions, in addition to protecting them against salt stress. These results demonstrate the critical role that suitable solutes and EPS play in cyanobacteria’s survival during desiccation. The rapid production and regulation of protective substances such as scytonemin, MAAs, and suitable solutes by cyanobacteria during dehydration, however, remains a mystery to scientists. The precise biochemical mechanisms underlying these stress reactions require further investigation [103].

4 Molecular and Genetic Regulation of Stress Responses

In order to deal with various environmental stressors like heat, light, or nutrient limitation, cyanobacteria have evolved adaptive and effective internal systems. Together, these systems identify stress, communicate inside the cell, and modify gene activity to safeguard and restore the cell. A well-functioning system that regulates the synthesis and utilization of specific chemicals and proteins within the cell is how cyanobacteria react to stress. To assist the cell in adapting to challenging circumstances, this system consists of sRNAs, sigma factors, and transcriptional regulators. These controls take place at several points in time, including during the processing of genes (transcription), the translation of proteins, and even after the production of proteins (post-translational). To live and function under stress, the cell might alter which genes are activated, how proteins behave, and how its metabolism functions in general [24]. HSPs, which aid in repairing or eliminating damaged proteins under stress, are important participants in this reaction. When cyanobacteria are exposed to high temperatures or heat stress, they produce more HSPs, which are unique kinds of proteins. Some proteins may become deformed and unable to function when cells become overheated. By repairing these broken proteins and returning them to their natural form, HSPs assist. They also aid in the breakdown and removal of proteins from the cell if they are too damaged to be restored. During heat stress, this procedure maintains the cell safe and ensures proper functioning [104].

Sigma factors are unique proteins that direct the cell’s machinery to activate stress-related genes, allowing the cell to prepare its defenses. Particularly during oxidative stress, Dps aid in protecting the cell’s DNA from harmful substances. Numerous recent studies have employed integrated omics techniques, including transcriptomics, proteomics, and genomics, to gain a better understanding of how cyanobacteria regulate their genes and how sRNAs aid in their ability to adapt to changes in their environment. These cutting-edge instruments provide a comprehensive view of the internal workings of the cell under stress. The reaction of cyanobacteria to various forms of stress is the main aim of this review, which also explains the molecular strategies they employ to defend themselves and endure in harsh environments [105]. One of the main processes in living cells’ adaptation to environmental changes is the sensing of stress in the environment and the subsequent transduction of stress signals [106].

In response to mild or moderate stressors, such as variations in temperature, salinity, or light, cyanobacteria or other organisms activate gene sets specifically designed to cope with that stressor. These genes aid in the production of novel proteins by the cell, some of which go on to aid in the production of unique substances (metabolites) linked to stress. These metabolites and the freshly produced proteins are both crucial for the cell’s adaptation to the new surroundings. This process, known as acclimatization, enables the organism to maintain its health and function even in less-than-optimal circumstances [107]. The consequences of various stress situations on cyanobacteria are discussed in the following sections, as well as how their metabolism alters under each form of stress. These alterations are investigated using metabolomics, which is the study of all metabolites-generally low molecular weight intermediates and end products of cellular metabolism, although some secondary metabolites can be structurally complex and of higher molecular weight. By studying these metabolic alterations, scientists can gain a better understanding of how cyanobacteria adapt their internal processes to survive and remain active during stressors such as excessive salt, heat, or nutritional scarcity [8].

4.1 Metabolomics Applied to Different Stresses

Metabolomic investigations in cyanobacteria have provided important insights into how these organisms respond to environmental stress. While only a limited number of studies have specifically addressed the effects of HL on the cyanobacterial metabolome, a relatively larger body of work has examined metabolic responses under high temperature stress. Because light and temperature stresses often occur together in natural habitats, it is logical to consider them jointly when evaluating metabolomic adjustments. Comparative studies reveal that various cyanobacterial species use different metabolomic strategies based on their ecological niches: the planktonic strain Planktothricoides sp. SR001 is more sensitive to light, while the surface-dwelling strain Hapalosiphon sp. MRB220 is more sensitive to temperature [108]. Secondary metabolites, including antitoxins, alkaloids, and flavonoids, modulate temperature and heat stress tolerance. Development, light intensity, and thermal conditions affect the diversity and dynamics of Aliinostoc sp. PMC 882.14’s metabolome. Exposure to HL leads to the synthesis of metabolites such as shinorine, while high temperature causes the development of microviridins. These metabolites aid in abiotic stress adaptation [109]. Under HL circumstances, studies on MBR220, SR001, and Planktothricoides raciborskii PMC 877.14 showed an elevation in the metabolites involved in antioxidant activity and photoprotection. They are the substances that are involved in the manufacture of terpenoid and steroid compounds, ergothioneine, MAAs, folate, and carotenoid compounds, as well as elevated proline and serine levels [108].

Glucose causes oxidative stress in PCC 6803 cells when exposed to light, demonstrating that light intensity that is otherwise physiologically favourable becomes fatal when glucose is present. According to the metabolomics study, cyanobacteria create more antioxidants, like ascorbate (vitamin C) and glutathione, which help shield the cells from harm when they are stressed, particularly by intense light or heat [110]. Additionally, it detected increased amounts of cysteinyl-glycine, a chemical produced when glutathione breaks down, and glutamate and γ-glutamyl-cysteine, which are building blocks required to generate glutathione. Furthermore, higher concentrations of other substances such as galacturonate, gluconate, and gluconolactone were also detected. All of these alterations point to the cells’ attempt to defend themselves by creating more protective molecules against oxidative stress [111].

There are three stages to the cyanobacterial reaction to salt stress. The initial phase lasts only a few seconds and is characterized by the quick entry of Na+ and Cl− ions as well as the cytosolic water’s outflow. In the second phase, K+ ions take the place of Na+, lowering the intracellular concentration of Na+ and its harmful consequences. In the last stage, compatible solutes and low molecular weight, uncharged organic molecules, including glycine betaine, proline, sucrose, trehalose, and GG are synthesized [112]. Through their ability to absorb water, compatible solutes aid in maintaining turgor pressure [113]. According to this metabolomic research, carbon is redistributed in many pathways under stress. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP), sucrose, and glycogen levels significantly increased in 21 UTEX 2973 mutants with antiporters of various sources when exposed to 0.4 M NaCl. This shows that flow from the glycolytic pathway was metabolically redirected toward the production of sucrose and glycogen, improving tolerance. The Mrp (Multiple Resistance and pH) antiporter from Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 was overexpressed in the top-performing mutant, JY13 [114]. It was suggested in numerous investigations to clarify how Synechocystis adjusts to salt stress [115].

Although the precise mechanisms of how these processes function are still unclear, cells adapt to stress by altering the activity of their transporters and enzymes, which are regulated by allosteric regulation, as well as by changing whether genes are activated or inactive. The exception in this case is the control of gene transcription that produces the organic solutes that Synechocystis produces, specifically sucrose and GG. Two enzymes are involved in the manufacture of sucrose: the rate-limiting enzyme, sucrose phosphate synthase (SpsA), and the enzyme sucrose phosphate phosphatase (Spp) [116]. Certain genes are activated by cyanobacteria due to salinity stress to defend themselves. Although the sensor that regulates RpaB is yet unknown, a protein known as RpaB typically inhibits the spsA gene, which produces sucrose. Similarly, two proteins, GgpR and LexA, generally suppress the ggpS gene, which aids in the production of GG, another protective molecule. Although the precise mechanisms remain incompletely understood, metabolomic studies clearly show that cyanobacterial cells adapt to salt stress by accumulating protective organic solutes, most prominently sucrose and GG. These metabolites act as compatible solutes, balancing osmotic pressure and stabilizing cellular structures under high salinity. Sucrose biosynthesis involves two key enzymes, sucrose phosphate synthase (SpsA, the rate-limiting enzyme) and sucrose phosphate phosphatase (Spp), while GG production depends on glucosylglycerol-phosphate synthase (GgpS) [115]. Thus, the metabolomic response to salt stress in Synechocystis is tightly coordinated with transcriptional regulation, ensuring that protective solutes are synthesized in sufficient amounts to maintain cell survival under high-salinity conditions [116].

4.2 Molecular Mediators Involved in Stress Response

Cyanobacteria can detect and react to stress from a variety of circumstances. These elements identify stress and communicate within the cell. They also aid in regulating the cell’s response. Small RNAs, heat shock proteins, DNA-binding proteins, and sigma factors are a few of these crucial elements. We shall describe each of their roles in this section.

Sigma factors are unique proteins that help RNA polymerase (the enzyme that creates RNA) discover the proper position on DNA to start generating a gene’s copy. There are three primary groups of sigma factors. The primary group is known as SigA. By activating “housekeeping” genes, it supports normal cell functioning and is always active. Sigma factors such as SigB, SigC, SigD, and SigE are included in Group 2 [117]. Under normal circumstances, they are not required; nevertheless, when the cell is under stress, such as excessive light or a shortage of nutrients, they become active. Complex interactions and collaborations between these sigma factors are possible. The appearance of Group 3 (SigF to SigJ) differs slightly from that of the other groups. They aid in the production of components like flagella, which are utilized for movement, and aid in the cell’s reaction to stressors like heat. The primary sigma factor is used by the cell in normal circumstances. However, it can switch to employing other sigma factors when stress occurs. This switch helps to activate the appropriate genes necessary for their survival (Fig. 6). For cyanobacteria to withstand many forms of stress, such as excessive light, salt, oxidative damage, and nutritional deficiency, sigma factors are crucial [117].

Figure 6: Sigma factors activating stress-related genes and Dps proteins safeguarding DNA from ROS by blocking iron-driven oxidative damage

Dps, or DNA-binding proteins, are essential for a variety of cellular processes. They also aid in shielding the cell from oxidative stress and other stressors like low iron or inadequate nutrition [10]. Twelve unique locations in Dps proteins, known as ferroxidase centres, are capable of capturing and securely storing iron (Fe2+). They accomplish this by converting Fe2O+ into a harmless state (Fe2O3) using oxygen or H2O2. By doing this, the iron is kept from producing dangerous chemicals known as free radicals, which have the potential to injure cells. Additionally, Dps can generally bind to DNA. By doing this, they prevent DNA damage or breakage without impairing its ability to operate normally. They also aid in the regulation of genes linked to stress reactions [118]. Five Dps (NpDps1, NpDps2, NpDps3, NpDps4, and NpDps5) proteins were found in Nostoc punctiforme ATCC 29133 in one investigation. Regular (vegetative) cells often have larger levels of Dps proteins than do specialized cells known as heterocysts. However, with the exception of NpDps2, four of the five Dps proteins are present in the heterocysts of this specific cyanobacterial strain. Like other Dps proteins, the three Dps proteins (NpDps1, NpDps2, and NpDps3) have a very similar structure and probably transport iron (Fe2+) into the cell [119].

Cyanobacteria activate specific genes in response to heat stress to defend themselves. Making unique proteins known as HSPs is one of the primary ways they accomplish this. These HSPs aid in maintaining the proper shape of other proteins within the cell and preventing their adhesion or degradation. The majority of stressors, such as excessive heat or salt, can cause proteins to deform and produce toxic chemicals known as ROS, which can damage cells. A broad range of temperatures can be tolerated by cyanobacteria. While some thrive in mild climates up to 45°C, some can even survive in extremely hot environments like deserts and hot springs [120]. Caseinolytic peptidase genes (clpBI and clpBII) are two significant genes that belong to the HSP100 family. Cyanobacteria that possess these genes are able to withstand high temperatures. Cells can withstand extreme heat (thermotolerance) because of the clpBI gene, while they can withstand cold temperatures (cold tolerance) due to clpBII gene. Both genes contribute to the protection of the cell during temperature stress in the cyanobacteria strain PCC 7942 [121].

sRNAs play a key role in regulating a number of critical functions, including biofilm formation, stress responses, mobility, and environmental adaptation. Although these sRNAs do not produce proteins, they control the transcription of other genes [8]. Many genes in cyanobacteria, such as PCC 6803 and PCC 7120, are controlled by sRNAs. For instance, NsiR4, csiR1, and psiR1 react to deficiencies in nitrogen, carbon, and phosphorus, PsrR1 aids during severe light stress, and IsaR1 is crucial when iron levels are low. Other sRNAs, such as RblR, regulate genes essential for photosynthesis, including rbcL, which aids in the production of RuBisCO, the primary carbon fixation enzyme. By binding to messenger RNAs (mRNAs), sRNAs can either prevent or facilitate translation by altering the structure of the mRNA [8]. All of the aforementioned environmental stressors often impair cyanobacteria’s capacity to carry out photosynthesis to their maximum potential. This results in an imbalance and slows down the cell’s ability to produce vital chemicals (anabolism) by overloading the system with electrons. This makes it difficult to determine whether the damage is due to the particular stressor or merely to alterations in the redox state, or internal chemical balance, of the cell [24]. Although oxidative, UV, salinity, temperature, and nutrient stresses all disturb redox homeostasis and stimulate the activation of antioxidant defenses, each stress also drives unique molecular responses in cyanobacteria [2]. UV stress induces the synthesis of photoprotective pigments such as scytonemin and MAAs [20]. Salinity stress promotes the accumulation of compatible solutes like sucrose, trehalose, and glycine betaine to maintain osmotic balance [19]. Heat stress enhances the expression of molecular chaperones and heat-shock proteins that stabilize proteins and membranes. In contrast, nutrient deprivation often results in chlorosis and metabolic downregulation, accompanied by degradation of the photosynthetic apparatus to recycle cellular resources. Together, these differences highlight the stress-specific metabolic adaptations of cyanobacteria while underscoring the common role of redox regulation and antioxidant defenses in sustaining survival [24].

5 Biotechnological Applications of Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria are seen as a promising method for purifying distillery waste since they can produce their carbon and nitrogen. However, the dark coloration of untreated effluent must be reduced to allow light to enter because it requires light to thrive [122]. They can also remove heavy metals from contaminated environments utilizing a range of methods, such as biosorption, bioaccumulation, and biotransformation. Their defense strategy includes enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants, metal-binding proteins such as metallothioneins, phytochelatins, and specific enzymes that help neutralize toxic metals [123,124]. Biosorption occurs when contaminants in an aqueous solution stick to the surface of algae or substances they release. This process depends on the type of algae, environmental conditions, and how active the algae are [125]. On the other hand, bioaccumulation is a more complex process that uses energy to take in and store heavy metals inside the cell, often in vacuoles or near membranes. This detoxification happens in two steps: the first is like biosorption, and the second uses energy to move metals into the cell [126]. The potential of microbes to clean up pollution from the environment in an eco-friendly way has increased the demand for resistant organisms that can biotransform harmful substances such as arsenic. Cyanobacteria are interesting due to their dominance in aquatic environments influenced by numerous pollutants. Recent research has shed new light on the special ability of cyanobacteria to change harmful substances into less toxic forms, helping to clean up the environment.

Cyanobacteria such as Anabaena, Nostoc, and Calothrix may convert atmospheric nitrogen (N2) into ammonia. Cyanobacteria can create symbiotic or associative interactions with plants (particularly rice), boosting nitrogen nutrition and crop production. Cyanobacteria secrete EPS, which are sticky, gel-like molecules that help to improve soil structure, retain water, and prevent erosion. Cyanobacteria-based biofertilizers, including species such as Anabaena sp., Nostoc sp., and Scenedesmus sp., improve nutrient cycling while also releasing growth-promoting compounds such as vitamins and hormones [127,128]. Cyanobacteria produce a variety of bioactive substances, including phytohormones (auxins and cytokinins), vitamins, and amino acids, which promote plant growth and development. These chemicals can boost root and shoot growth, increase chlorophyll content, and improve stress tolerance (for example, drought and salinity). Certain cyanobacteria create antimicrobial chemicals that assist plants in resisting infections [129]. Because they don’t require additional nitrogen or carbon sources to grow, cyanobacteria are highly helpful in the production of environmentally acceptable fuels. They can produce a variety of biofuels, including short-chain fuels like butanol and biogas, ethanol, biodiesel, and biohydrogen [130]. Due to their inherent biological processes, these bacteria are very good at absorbing solar energy and turning it into fuel.

For instance, it is simple to convert the fats (lipids) they generate into biodiesel. Through a variety of techniques, including stepwise processing, dark fermentation, or genetic modification for a process known as photofermentation, their sugar content can also be utilized to produce bioethanol [131]. By breaking down water to generate hydrogen and producing just water as waste, a process known as indirect biophotolysis creates biohydrogen. The direct synthesis of butanol in cyanobacteria is also gaining popularity since it might be simpler and less expensive for producing large amounts of fuel [132]. Because they can directly create ethanol by photofermentation using light and CO2, cyanobacteria hold particular promise for the manufacture of ethanol. Certain strains, such as Synechocystis PCC 6803 and Synechococcus PCC 7942, have undergone genetic modification to incorporate particular enzymes (alcohol dehydrogenase II and pyruvate decarboxylase) that aid in the production of ethanol [133]. Cyanobacteria offer several advantages for producing bioethylene: they are inexpensive, have simple genomes that are easy to modify, and don’t require external carbon sources. Ethylene is frequently produced using strains such as Synechocystis PCC 6803 and Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 [134,135]. Finally, another interesting product is isobutanol, a four-carbon alcohol that can be utilized as a chemical feedstock or as fuel. With the help of sunshine and CO2, cyanobacteria can be modified to create isobutanol [136].

One of the most remarkable traits of cyanobacteria, particularly those that thrive in extreme environments, involves producing UV-absorbing or screening compounds like MAAs and scytonemin, which act as natural sunscreens [137]. MAAs are naturally occurring substances that are frequently referred to as “microbial sunscreens” due to their capacity to absorb damaging UV radiation (310–365 nm) and shield cells from injury [138]. They are present in algae like Porphyra umbilicalis and are utilized in commercial sunscreens like Helioguard365, which has anti-aging properties, enhances cell health, and protects skin from UV-A rays [139]. In addition to neutralizing dangerous ROS, including 1O2 and free radicals, which can destroy DNA, they protect by absorbing UV radiation and releasing it as heat. According to studies, substances like mycosporine-glycine and shinorine can lessen inflammation by reducing the expression of genes linked to inflammation; however, porphyra-334 may not always have the same impact [140]. Mycosporine-glycine, shinorine, and porphyra-334 were tested for their anti-inflammatory effects on UV-induced HaCaT cell lines. Only glycine and shinorine significantly reduced the expression of COX-2, a marker gene associated with inflammation, in a concentration-dependent manner [141]. Choi and colleagues explored that shinorine (0.05 mg/mL), porphyra-334 (0.05 mg/mL), and mycosporine-glycine (0.1 mg/mL), isolated from C. hedlyei and P. yezoensis, effectively promoted wound repair in HaCaT cells [142].

With its potent ability to block up to 90% of damaging UV radiation, scytonemin—a naturally occurring UV-absorbing chemical generated by cyanobacteria—protects cells from injury by transforming the absorbed energy into innocuous heat [96,143]. Additionally, it functions as a potent antioxidant by lowering the production of thymine dimers and ROS, which are markers of UV-induced DNA damage [144]. In pharmaceuticals and cosmetics, scytonemin is valued for its non-toxic properties, stability under stress, and capacity to scavenge free radicals [14]. It also has anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory properties. For example, it causes cell cycle arrest in cancer cells such as multiple myeloma and kidney cancer by inhibiting PLK1, an enzyme essential for cell division [145]. Scytonemin caused apoptosis in 24% of cells at 3 μM and inhibited proliferation in Jurkat T-cell leukemia cells (IC50 = 7.8 μM). These characteristics make scytonemin an attractive option for the development of novel medicinal medications in addition to being a natural sunscreen [146].

Cyanobacteria have extraordinary metabolic plasticity, allowing them to flourish in a wide range of sometimes harsh environmental circumstances such as salinity, temperature variations, oxidative stress, desiccation, and UV radiation. A complex web of genetic, biochemical, and physiological processes, such as the synthesis of suitable solutes, antioxidant enzymes, and photoprotective secondary metabolites like scytonemin and MAAs, regulates these stress responses. To maintain cellular homeostasis and survival, regulatory components like transcriptional repressors, sRNAs, and sigma factors are essential for detecting and responding to environmental stressors. In addition to expanding our understanding of the biology of cyanobacterial stress, an understanding of these metabolic responses creates new opportunities for their use in sustainable biotechnology. Applications for stress-resilient cyanobacterial strains in biofertilizers, bioremediation, bioenergy production, and the creation of natural antioxidant and UV-protective compounds are extremely promising.

A promising direction for basic science and applied biotechnology is the metabolic flexibility of cyanobacteria under environmental stress. Uncovering the entire regulatory networks that control stress-responsive pathways should be the main goal of future research, particularly using integrative multi-omics techniques such as transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and genomics. These methods will offer a thorough understanding of the dynamic molecular reactions of cyanobacteria in various abiotic stress situations, including oxidative stress, UV radiation, salinity, and temperature conditions. Advances in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering offer the opportunity to enhance the production of key protective metabolites such as scytonemin, MAAs, and compatible solutes by targeting stress-responsive genes and transcription factors, including sigma factors, sRNAs, and Dps proteins. Another important direction is the development of cost-effective and scalable cultivation strategies that enable the translation of stress-adapted cyanobacterial strains into industrial applications, particularly in biofertilizers, bioenergy, bioremediation, and cosmeceuticals. Finally, a deeper understanding of ecological resilience and symbiotic associations under climate change conditions will provide valuable knowledge for designing sustainable environmental solutions. Together, these approaches can bridge the gap between laboratory findings and real-world applications, maximizing the biotechnological potential of cyanobacteria under stress.

Acknowledgement: Riya Tripathi and Ashish P. Singh are thankful to the University Grants Commission (UGC), New Delhi, India, for financial assistance in the form of JRF and SRF, respectively. Varsha K. Singh and Palak Rana are thankful to the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, India, for Senior Research Fellowship (SRF). Payel Rana is thankful to the CSIR, New Delhi, India, for Junior Research Fellowship (JRF). Sapana Jha is thankful to BHU for providing institutional fellowship.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the University Grants Commission (UGC), New Delhi, India [Ref. Nos. 231620041285, 191620014505]; the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, India [Ref. Nos. 09/0013(12862)/2021-EMR-1, 09/0013(16603)/2023-EMR-I, 09/0013(21806)/2025-EMR-I]; and Banaras Hindu University (BHU), India [No. R/Dev./Sch./UGC Non-NET Fello./2022-23/52561].

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Riya Tripathi and Palak Rana; methodology, Riya Tripathi; validation, Riya Tripathi, Varsha K. Singh and Palak Rana; formal analysis, Rajeshwar P. Sinha; investigation, Sapana Jha, Ashish P. Singh and Payel Rana; writing—original draft preparation, Riya Tripathi and Varsha K. Singh, Palak Rana, Sapana Jha, Ashish P. Singh and Payel Rana; writing—review and editing, Rajeshwar P. Sinha; visualization, Riya Tripathi and Varsha K. Singh; supervision, Rajeshwar P. Sinha. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| UVR | Ultraviolet radiation |

| POD | Peroxidases |

| CAT | Catalases |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| MAAs | Mycosporine-like amino acids |

| EPS | Exopolysaccharide |

| sRNAs | Small RNAs |

| HSPs | Heat Heat shock proteins |

| Dps | DNA binding proteins |

| GG | Glucosylglycerol |

| ClpB | Caseinolytic peptidase B |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| Superoxide ions | |

| OH· | Hydroxyl radicals |

| O2· | singlet oxygen |

| FeSOD | Iron superoxide dismutase |

| Cal A | Cyanobacterial AbrB like |

| GGPP | glucosylglycerol-phosphate phosphatase |

| GgpS | glucosylglycerol-phosphate synthase |

| GG | Glucosylglycerol |

| SOS | Salt overly sensitive pathway |

| HrcA | Heat-inducible transcriptional repressor A |

| CIRCE | Controlling Inverted Repeat of Chaperone Expression |

| HLRR | High Light Regulatory Region |

| HL | High light |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| APX | Ascorbate peroxidases |

| MDA | Monodehydroascorbate |

| MDAR | Monodehydroascorbate reductase |

| DHA | Dehydroascorbate |

| DHAR | Dehydroascorbate reductase |

| GR | Glutathione reductase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| PHB | Polyhydroxybutyrate |

| SpsA | Sucrose phosphate synthase A |

| Spp | Sucrose phosphate phosphatase |

References

1. Yadav P, Singh RP, Rana S, Joshi D, Kumar D, Bhardwaj N, et al. Mechanisms of stress tolerance in cyanobacteria under extreme conditions. Stresses. 2022;2(4):531–49. doi:10.3390/stresses2040036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kumar V, Gupta A, Mondal S, Tiwari S, Singh SP. Methods for estimation of oxidative stress indices in cyanobacteria. In: Singh SP, Sinha RP, Häder DP, editors. Methods in cyanobacterial research. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2024. p. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

3. Shawer EE, Sabae SZ, El-Gamal AD, Elsaied HE. Characterization of bioactive compounds with antioxidant activity and antimicrobial activity from freshwater cyanobacteria. Egyp J Chem. 2022;65(9):723–35. doi:10.21608/ejchem.2022.127880.5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hagemann M. Molecular biology of cyanobacterial salt acclimation. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35(1):87–123. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00234.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Rai S, Sitther V. Oxidative stress in cyanobacteria: sources, mitigation, and defense. In: Singh PK, Fillat MF, Sitther V, Kumar A, editors. Expanding horizon of cyanobacterial biology. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 2022. p. 163–78. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-91202-0.00003-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Rastogi RP, Sinha RP, Moh SH, Lee TK, Kottuparambil S, Kim YJ, et al. Ultraviolet radiation and cyanobacteria. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2014;141(4):154–69. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.09.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Singh VK, Jha S, Rana P, Mishra S, Kumari N, Singh SC, et al. Resilience and mitigation strategies of cyanobacteria under ultraviolet radiation stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(15):12381. doi:10.3390/ijms241512381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Rai P, Pathania R, Bhagat N, Bongirwar R, Shukla P, Srivastava S. Current insights into molecular mechanisms of environmental stress tolerance in cyanobacteria. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2025;41(2):53. doi:10.1007/s11274-025-04260-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Srivastava A, Varshney RK, Shukla P. Sigma factor modulation for cyanobacterial metabolic engineering. Trends Microbiol. 2021;29(3):266–77. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2020.10.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Karas VO, Westerlaken I, Meyer AS. The DNA-binding protein from starved cells (Dps) utilizes dual functions to defend cells against multiple stresses. J Bacteriol. 2015;197(19):3206–15. doi:10.1128/jb.00475-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Adhikary SP. Heat shock proteins in the terrestrial epilithic cyanobacterium Tolypothrix byssoidea. Biol Plant. 2003;47(1):125–8. doi:10.1023/A:1027301503204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Lau SE, Lucas W, Hamdan M, Chan C, Saidi N, Ong-Abdullah J, et al. Enhancing plant resilience to abiotic stress: the power of biostimulants. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2025;94(1):1–31. doi:10.32604/phyton.2025.059930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Garlapati D, Chandrasekaran M, Devanesan A, Mathimani T, Pugazhendhi A. Role of cyanobacteria in agricultural and industrial sectors: an outlook on economically important by products. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;103(12):4709–21. doi:10.1007/s00253-019-09811-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Rastogi RP, Sinha RP. Biotechnological and industrial significance of cyanobacterial secondary metabolites. Biotechnol Adv. 2009;27(4):521–39. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.04.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Nawaz T, Gu L, Fahad S, Saud S, Bleakley B, Zhou R. Exploring sustainable agriculture with nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria and nanotechnology. Molecules. 2024;29(11):2534. doi:10.3390/molecules29112534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Singh JS, Kumar A, Rai AN, Singh DP. Cyanobacteria: a precious bio-resource in agriculture, ecosystem, and environmental sustainability. Front Microbiol. 2016;7(12):529. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00529. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Singh AP, Gupta A, Singh PR, Jaiswal J, Sinha RP. Synergistic effects of salt and ultraviolet radiation on the rice-field cyanobacterium Nostochopsis lobatus HKAR-21. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2024;23(2):285–302. doi:10.1007/s43630-023-00517-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Pandey A, Singh G, Pandey N, Patel A, Tiwari S, Prasad SM. Impacts of environmental stress on physiology and biochemistry of cyanobacteria. In: Rastogi RP, editor. Ecophysiology and biochemistry of cyanobacteria. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 65–89. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-4873-1_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Pade N, Hagemann M. Salt acclimation of cyanobacteria and their application in biotechnology. Life. 2014;5(1):25–49. doi:10.3390/life5010025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Sinha RP, Häder DP. UV-protectants in cyanobacteria. Plant Sci. 2008;174(3):278–89. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2007.12.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Klotz A, Georg J, Bučinská L, Watanabe S, Reimann V, Januszewski W, et al. Awakening of a dormant cyanobacterium from nitrogen chlorosis reveals a genetically determined program. Curr Biol. 2016;26(21):2862–72. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.08.054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Kaplan A, Reinhold L. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in photosynthetic microorganisms. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 1999 Jun;50(1):539–70. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Schwarz R, Forchhammer K. Acclimation of unicellular cyanobacteria to macronutrient deficiency: emergence of a complex network of cellular responses. Microbiology. 2005 Aug;151(8):2503–14. doi:10.1099/mic.0.27883-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Rachedi R, Foglino M, Latifi A. Stress signaling in cyanobacteria: a mechanistic overview. Life. 2020;10(12):312. doi:10.3390/life10120312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Orozco MF, Vázquez-Hernández A, Fenton-Navarro B. Active compounds of medicinal plants, mechanism for antioxidant and beneficial effects. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2019;88(1):1–10. doi:10.32604/phyton.2019.04525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Johnson LA, Hug LA. Distribution of reactive oxygen species defense mechanisms across domain bacteria. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;140(7):93–102. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.03.032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Dash S, Pradhan S, Sahoo B, Rath B. Characterization of selected marine cyanobacteria as a source of compounds with antioxidant activity. Discover Plants. 2024;1(1):1–8. doi:10.1007/s44372-024-00056-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Checa J, Aran JM. Reactive oxygen species: drivers of physiological and pathological processes. J Inflamm Res. 2020;2020: 1057–73. doi:10.2147/JIR.S275595. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Liu XG, Zhao JJ, Wu QY. Oxidative stress and metal ions effects on the cores of phycobilisomes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(21):4571–6. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Menezes I, Maxwell-McQueeney D, Capelo-Neto J, Pestana CJ, Edwards C, Lawton LA. Oxidative stress in the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7813: comparison of different analytical cell stress detection assays. Chemosphere. 2021;269(2):128766. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128766. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. He YY, Häder DP. UV-B-induced formation of reactive oxygen species and oxidative damage of the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp.: protective effects of ascorbic acid and N-acetyl-L-cysteine. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2002;66(2):115–24. doi:10.1016/S1011-1344(02)00231-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Agervald Å, Baebprasert W, Zhang X, Incharoensakdi A, Lindblad P, Stensjö K. The CyAbrB transcription factor CalA regulates the iron superoxide dismutase in Nostoc sp. strain PCC 7120. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12(10):2826–37. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02255.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Larsson J, Nylander JA, Bergman B. Genome fluctuations in cyanobacteria reflect evolutionary, developmental and adaptive traits. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11(1):1–21. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Khan RI, Wang Y, Afrin S, Wang B, Liu Y, Zhang X, et al. Transcriptional regulator PrqR plays a negative role in glucose metabolism and oxidative stress acclimation in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):32507. doi:10.1038/srep32507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Yingping F, Lemeille S, Talla E, Janicki A, Denis Y, Zhang CC, et al. Unravelling the cross-talk between iron starvation and oxidative stress responses highlights the key role of PerR (alr 0957) in peroxide signalling in the cyanobacterium Nostoc PCC 7120. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2014;6(5):468–75. doi:10.1111/1758-2229.12157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Li H, Singh AK, McIntyre LM, Sherman LA. Differential gene expression in response to hydrogen peroxide and the putative PerR regulon of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(11):3331–45. doi:10.1128/jb.186.11.3331-3345.2004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Kobayashi M, Ishizuka T, Katayama M, Kanehisa M, Bhattacharyya-Pakrasi M, Pakrasi HB, et al. Response to oxidative stress involves a novel peroxiredoxin gene in the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45(3):290–9. doi:10.1093/pcp/pch034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Lee JW, Helmann JD. The PerR transcription factor senses H2O2 by metal-catalysed histidine oxidation. Nature. 2006;440(7082):363–7. doi:10.1038/nature04537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Garcin P, Delalande O, Zhang JY, Cassier-Chauvat C, Chauvat F, Boulard Y. A transcriptional-switch model for Slr1738-controlled gene expression in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis. BMC Struc Biol. 2012;12(1):1. doi:10.1186/1472-6807-12-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Kageyama H, Waditee-Sirisattha R. Osmoprotectant molecules in cyanobacteria: their basic features, biosynthetic regulations, and potential applications In: Kageyama H, Waditee-Sirisattha R, editors. Cyanobacterial physiology. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 2022. p. 113–23. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-96106-6.00006-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]