Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Valorisation of Northern Moroccan Centaurium erythraea: Targeted Phytochemistry, Antioxidant, Antimicrobial Efficacy and Drug Likeness Benchmarking

1 Laboratory for the Improvement of Agricultural Production, Biotechnology and Environment (LAPABE), Faculty of Sciences, Mohammed First University, Oujda, 60000, Morocco

2 BIOPI–BioEcoAgro Joint Research Unit 1158, INRAE, University of Picardie Jules Verne, Amiens, 80000, France

3 Laboratory of Applied Chemistry and Environment (LCAE), Faculty of Science, University Mohammed Premier, Oujda, 60000, Morocco

4 Euromed Research Center, Euromed Polytechnic School, Euromed University of Fes (UEMF), Fes, 30000, Morocco

5 Laboratory of Bioresources, Biotechnology, Ethnopharmacology and Health, Faculty of Sciences, Mohammed First University, Boulevard Mohamed VI, BP 717, Oujda, 60000, Morocco

* Corresponding Authors: Yousra Hammouti. Email: ; Mohamed Addi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Medicinal Plants and Natural Bioactives: From Pharmacology to Cosmeceutical Innovation)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3563-3583. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.071139

Received 01 August 2025; Accepted 03 November 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Centaurium erythraea Rafn (“Gosset El Haya”) has long been prized in North African folk medicine, yet Moroccan chemobiological data remain scarce. Ethanol extracts of northern Moroccan aerial parts were profiled by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and found rich in phenolics, dominated by 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (57.8%) and naringin (10.3%). The extract exhibited strong antioxidant power in the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical-scavenging assay, with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of ≈74 µg mL−1, and a total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of ≈201 µg mL−1 and selective antimicrobial activity, sharply inhibiting Aspergillus niger, Penicillium digitatum, and Rhodotorula glutinis while sparing Staphylococcus aureus. In-silico absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiling predicted good oral bioavailability for low-molecular-weight acids and aglycones, low toxicity across all metabolites, but absorption liabilities for bulky glycosides. Molecular docking against A. niger esterase (1UKC), C. glabrata lanosterol 14-α-demethylase CYP51 (5JLC), and P. digitatum ethylene-forming oxidoreductase (9EIR) corroborated bioassays: rutin and naringin bound more tightly than fluconazole (ΔG ≈ −9.1 to −10.0 kcal mol−1), whereas quercetin and catechin offered balanced affinity pharmacokinetic profiles. Robust radical scavenging, targeted antifungal potency, and favorable in-silico pharmacokinetics thus position Moroccan C. erythraea as a promising, though standardization-dependent, source of nutraceutical, medicinal, and food-preservation agents. These results support the valorisation of Centaurium erythraea as a promising source for health promotion and green technology applications through its antioxidant, antimicrobial, and drug-like properties.Keywords

Despite the astounding advances in therapies over the past several decades, the usefulness of synthetic and semi-synthetic antimicrobials is rapidly diminishing, as microbial resistance has emerged as a significant health concern of the 21st century [1,2]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) says that bacterial and fungal infections are already among the most common causes of death and illness in the world. The most current estimates say that by 2050, resistance might kill up to 10 million people every year [3,4].

The worsening of this phenomenon is primarily due to the inappropriate or excessive use of antibiotics, as well as the growing increase in immunocompromised populations [5]. Resistance can be intrinsic, linked to the biological characteristics of the strain, or acquired through chromosomal mutations or horizontal gene transfer between pathogens [6,7]. In this context, the discovery of molecules capable of circumventing these resistances is a matter of urgency.

At the same time, research is focusing on effective natural antioxidants designed to neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) involved in multiple degenerative, cardiovascular, and cancerous diseases [8]. Medicinal and aromatic plants are a vibrant source in this regard [9]. For centuries, plants have provided antimicrobial compounds that are widely used in the empirical treatment of infections [10]. The WHO estimates that 65% to 80% of people in developing countries use medicinal plants for their primary healthcare [11].

The enormous range of biological activities of plant metabolites, particularly essential oils and extracts, can be attributed to their remarkable structural diversity. These activities include antioxidant and antibacterial activity [12]. The substances above comprise a complex combination of terpenoids, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, esters, and organic acids [13]. They can affect many biological targets, such as breaking down membranes, stopping enzymes from functioning, and causing oxidative stress that is lethal to microorganisms.

In this context, Centaurium erythraea Rafn, commonly known as small centaury, is a suitable option in this situation. This biennial plant is widespread in Western Asia, North Africa, and Europe [14]. It has traditionally been used as a cleanser, fever reducer, and digestive tonic [15,16]. Listed by the Council of Europe in category N2 of aromatic agents, it is authorized in small doses in food and certain beverages [17]. According to preliminary findings, the phytocomposition contains a high concentration of flavonoids, phenolic acids, methoxylated xanthones, and secoiridoids, which may account for its potent antioxidant, antifungal, and antibacterial qualities [18]. There are not many studies that thoroughly link its chemical composition to its pharmacological effects, however.

In Morocco, the Gentianaceae family holds significant ecological and economic importance, as it comprises numerous medicinal and aromatic species [19]. Centaurium erythraea (Rafin), known in Morocco by its vernacular name Gosset El Haya, is used in traditional medicine, as described in specific ethnopharmacological research, for the treatment of digestive disorders and kidney illness, as well as an antipyretic and antidiabetic drug [20,21]. Extracts of C. erythraea exhibit diverse biological actions, including antihyperglycemic [22], diuretic [23], antibacterial [20], antioxidant [21], and hepatoprotective activity [24].

Therefore, this study seeks to bridge this gap by first carrying out targeted profiling of the ethanol extract from the aerial parts of Centaurium erythraea using high-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection (HPLC-DAD); next, evaluating its antioxidant capacity through DPPH, TAC and reducing-power assays; then assessing its antimicrobial effectiveness against a representative panel of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria as well as pathogenic yeasts, and finally conducting an in silico analysis that includes ADMET profiling and molecular docking of the principal constituents to predict their pharmacokinetic behavior and establish their safety margin.

This research investigated Centaurium erythraea, a plant endemic to northern Morocco. The plant material was obtained from a local Moroccan market in Chefchaouen, northern Morocco (35.1688° N, 5.2684° W; WGS84), and taxonomically authenticated by a specialist botanist in the Biology Department, Faculty of Science, Mohammed Premier University (UMP), Oujda. C. erythraea is not listed as a protected species under national or international conservation frameworks, and its collection is not subject to specific legal restrictions, although general environmental regulations apply in protected areas.

The procedure commenced with grinding the aerial segments into a uniform powder. Exactly 100 g of this material was extracted with absolute ethanol (99%). Filtration under vacuum was followed by solvent removal via rotary evaporation at 60°C, 250 mbar, and 150 rpm. The concentrated extract was subsequently preserved at 4°C for downstream testing [25].

2.3 Analysis of Phenolic Compounds (HPLC-DAD)

Phenolic compounds were analyzed using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system equipped with a Diode Array Detector (HPLC-DAD, Agilent 1200, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) connected to a diode array UV detector (Bruker, Germany). Data acquisition and processing were carried out using the Agilent ChemStation software (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Ten microlitres of sample were injected onto a Zorbax XDB-C18 column (5 µm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm) preceded by an Agilent C18 guard cartridge. Separation followed a binary gradient of solvent A (water: methanol, 9: 1, 0.1% H3PO4) and solvent B (methanol, 0.1% H3PO4): 80%A/20%B (0–20 min), 74%A/26%B (20–56 min), 24%A/76%B (56–86 min), 0%A/100%B (86–93 min), and 100%A (93–99 min). The mobile phase flowed at a rate of 1 mL min−1, and the column temperature was maintained at 40°C. Chromatograms were recorded at 280 nm, and compounds were assigned by matching retention times and UV spectra with authentic standards [26].

2.4.1 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Radical Capture Assay

The antioxidant performance of the extract was assessed against a recognized standard, ascorbic acid. Triplicate measurements at each concentration ensured data robustness. A 0.1 mM methanolic DPPH solution was prepared, and extract dilutions ranging from 0.2 to 1 mg mL−1 were obtained. For each assay, 2.5 mL of the DPPH solution was mixed with 0.5 mL of a given extract concentration. After 30 min of incubation under subdued light, absorbance at 517 nm was recorded relative to an appropriate blank [27],

Radical scavenging activity (RSA%) was calculated using the Formula (1):

where in A0 is the absorbance of the control, and A1 represents the absorbance obtained from the extract at varying concentrations, accompanied by the sample [28]. The determination of the IC50 value was achieved through the construction of a graph correlating the percentage inhibition with the concentrations of the extract.

2.4.2 Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC)

Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) measures the extract’s inherent ability to counteract reactive species and inhibit oxidative stress, calibrated against an ascorbic acid standard. This investigation employed the phosphomolybdenum method described by Elbouzidi et al. [29]. Results are expressed as ascorbic acid equivalents (AAE), reported as µg AAE per mL.

2.5.1 Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

This study was primarily undertaken to thoroughly scrutinise the natural antibacterial properties attributed to the extract being tested. Using an analogous strategy, we quantified the efficiency of its derivatives against four specific bacterial strains preserved at the Microbial Biotechnology Laboratory, Faculty of Sciences, University of Oujda, Morocco. The selected strains consisted of two Gram-positive bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 and Micrococcus luteus LB 14110, and two Gram-negative bacteria, Escherichia coli ATCC 10536 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 15442. Following standard operating protocols, the strains were cultivated on LB agar and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Before antibacterial testing, each suspension was adjusted to 106 cells mL−1 by monitoring absorbance at 620 nm with a UV–visible spectrophotometer, a measure essential for analytical consistency and dependable outcomes [30].

2.5.2 Agar Well Diffusion Method

The initial evaluation of antimicrobial activity against the aforementioned bacterial strains was systematically performed using the agar-well diffusion method, as described initially by Perez [31]. Mueller–Hinton agar was evenly inoculated with the prepared bacterial suspension, and 8 mm diameter wells were punched into the medium. Fifty microliters of the extract was dissolved in 50% anhydrous DMSO to a concentration of 1 mg/mL [32,33]. They were dispensed into each cavity. Plates were kept at 4°C for two hours to enhance diffusion, then incubated at 37°C for 18–24 h. The diameters of clear inhibition zones were recorded as a measure of efficacy. Experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure reliability and reproducibility.

2.5.3 Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

Evaluating antimicrobial activity begins with determining the MIC in this study, MICs for each extract were measured with the resazurin microtiter assay. Mueller–Hinton broth containing 0.15% agar served as the medium, and stock solutions of the extracts were prepared at a concentration of 1 mg/mL in DMSO. Two-fold serial dilutions from 80 to 0.015 μg/mL were prepared in 96-well plates according to reference [34]. A standardized inoculum of 106 cells/mL and a gentamicin control were added to every well. After 24 h at 37°C, 15 µL of 0.015% resazurin was introduced, followed by a further 2 h at the same temperature to monitor the blue-to-pink change [35]. All tests were performed in triplicate. For MBC assessment, 3 µL from wells without visible growth were streaked on Mueller–Hinton agar [36,37]. Moreover, after incubation for 24 h at 37°C, the lowest concentration yielding no colonies was recorded as the MBC. This experiment was meticulously repeated across three iterations.

2.6.1 Selection and Origin of Strains

To determine antifungal efficacy, four pure fungal cultures, Penicillium digitatum, Aspergillus niger, Rhodotorula glutinis (ON 209167), and Candida glabrata were selected from the laboratory previously cited.

2.6.2 Inoculum Cultivation and Well Diffusion Method

C. glabrata and R. glutinis (ON 209167) were cultured on YPD (yeast-extract peptone dextrose) agar at 25°C for 48 h, after which each suspension was standardised to 106 cells/mL (≈0.5 McFarland). In parallel, P. digitatum and A. niger were incubated on BIOKAR potato-dextrose agar (PDA) at 25°C for 7 days, then adjusted to 2 × 106 spores/mL using a Thoma hematometer, as outlined in Section 2.5.2. Preliminary antifungal activity was screened using the well-diffusion technique, as described in the Manual on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing [38].

2.6.3 Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and the Minimum Fungicidal Concentration (MFC)

To quantify MICs for the quartet of microorganisms, we adopted a 96-well microplate approach. Serial dilutions ranged from 80 to 0.015 μg/mL. Methods followed the refinements described in Section 2.5.3. Fungal inocula containing about 2 × 108 spores mL−1 were incubated for 48 h at 25°C for yeasts and 72 h for molds. After incubation, 15 μL of resazurin was added to each well, and the plates were then incubated for an additional 2 h at 25°C. The MIC corresponded to the lowest concentration that produced a transition from blue to pink. Extract dilutions were prepared in Potato Carrot Broth (PCB) containing 0.15% agar, with cycloheximide serving as the positive control. For MFC determination, 3 µL from growth-free wells were transferred to Yeast Extract Glucose agar (YEG) agar and incubated (48 h, yeasts; 72 h, molds). The MFC was the lowest concentration that abolished visible growth, confirming its fungicidal action.

2.7 Pharmacokinetic Analysis Using Computational Tools

Each compound was drafted in ChemDraw, converted to canonical SMILES, and evaluated with two complementary web platforms. SwissADME [39] generated core physicochemical descriptors and Rule-of-Five compliance metrics, whereas pkCSM [40] supplied computational predictions of cytochrome P450 interactions and renal clearance. Merging the outputs from both tools produced a multidimensional ADME fingerprint for every molecule, offering an early, physiology-oriented preview of its expected in vivo behaviour.

2.8 Prediction of the Toxicity Analysis (Pro Tox III)

Validated SMILES structures generated in ChemDraw were analysed with ProTox-III [41], a web server that integrates large toxicology datasets with Bayesian ensemble models to flag structural alerts at high confidence. In addition to estimating the acute oral LD50 and assigning the corresponding GHS hazard class, ProTox-III provides a quantitative toxicity fingerprint that includes hepatotoxicity, carcinogenicity, immunotoxicity, mutagenicity, and cytotoxicity, each expressed as a probability (%). Consolidating these organ- and mechanism-based probabilities into a single high-resolution screen streamlines candidate prioritisation before wet-lab testing and speeds data-driven decision-making in the drug-discovery pipeline.

2.9 PyRx: Preparation, Configuration, and Validation of the Docking Protocol

Molecular docking was executed in PyRx 0.9.9 running AutoDock Vina 1.2.5 against three fungal targets. The Aspergillus niger esterase EstA (PDB 1UKC) and the Penicillium digitatum ethylene-forming oxidoreductase (PDB 9EIR) were treated with a blind-docking strategy in which the search box encompassed the entire protein surface; exhaustiveness was fixed at eight, and all other Vina parameters were left at their defaults. For the Candida glabrata lanosterol 14-α-demethylase CYP51 (PDB 5JLC), the protocol was first validated by redocking its co-crystallised ligand: crystallographic waters were removed, polar hydrogens added, and Gasteiger charges assigned in AutoDock Tools 1.5.7, after which the grid was centred at −42.93, 77.71, −23.57 Å with dimensions 17.46 × 26.97 × 9.39 Å3 and an exhaustiveness value of 8. The redocked pose reproduced the experimental orientation with an RMSD of 1.596 Å, confirming the protocol’s reliability before screening the eleven phenolic candidates.

Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). Data are reported as mean ± SD for IZ/MIC/MBC/MFC and mean ± SEM for DPPH IC50 and TAC, as specified in each table. Normality and homoscedasticity were checked (Shapiro–Wilk, Levene). One way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD (α = 0.05) was applied.

3.1 Phytochemical Analysis Using HPLC-DAD

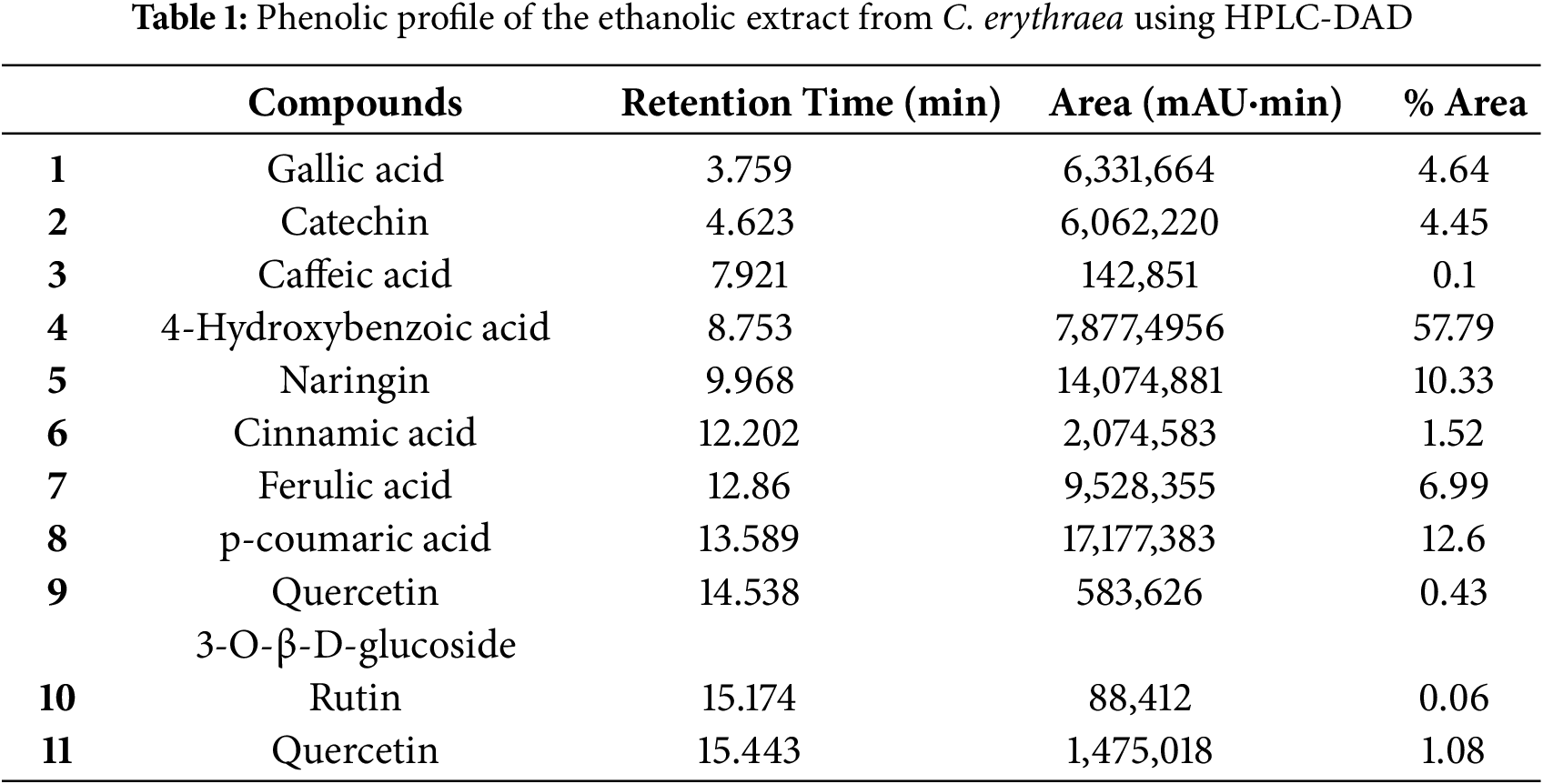

The study found eleven distinct components that combined represent the extract’s whole chemical profile (100%). Compound identities are provided in Table 1 and represented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: HPLC-DAD chromatograms of the phenolic composition of C. erythraea detected at 280 nm. Gallic acid (1); Catechin (2); Caffeic acid (3) 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid (4); Naringin (5); Cinnamic acid (6); Ferulic acid (7); p-coumaric acid (8); Quercetin 3-O-β-D-glucoside (9); Rutin (10); Quercetin (11). Note: the corresponding molecules are in Table 1

In the aerial part of the ethanolic extract, we discovered gallic acid, catechin, caffeic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, naringin, cinnamic acid, ferulic acid, p-coumaric acid, quercetin 3-O-β-D-glucoside, rutin, and quercetin. At 280 nm, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid gave the largest peak area, followed by p-coumaric acid and naringin.

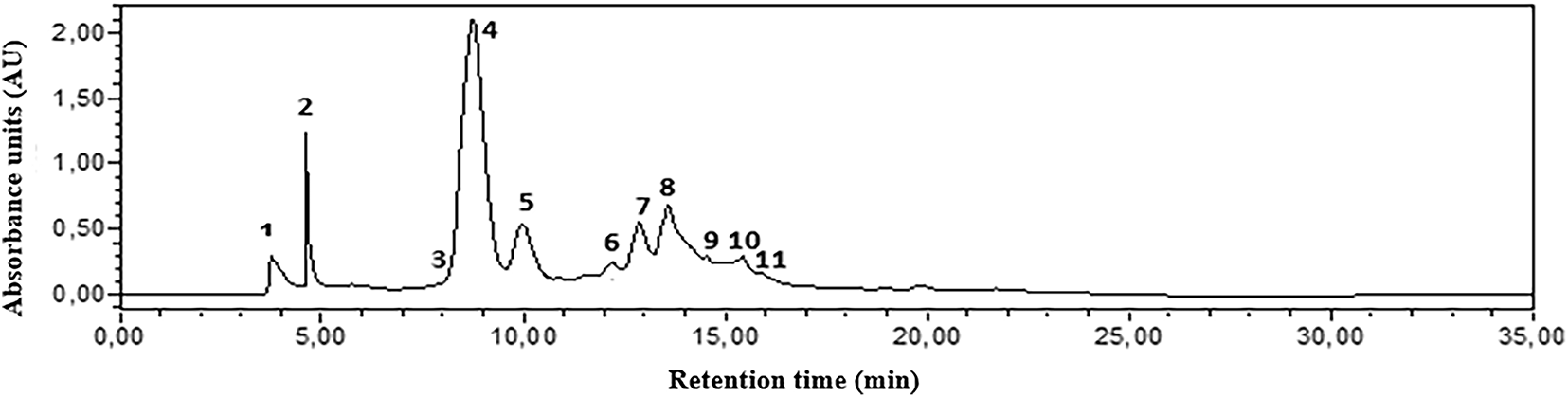

To validate the antioxidant potential of Centaurium erythraea, we employed both the DPPH assay and the phosphomolybdenum TAC assay. The extract exhibited substantial radical quenching power in the DPPH test, with an IC50 of 73.87 ± 5.00 µg/mL (n = 3), while ascorbic acid showed an IC50 of 20.82 ± 0.001 µg/mL. In the TAC assay, the extract reached 201.23 ± 0.06 µg AAE/mL (n = 3), as listed in Table 2.

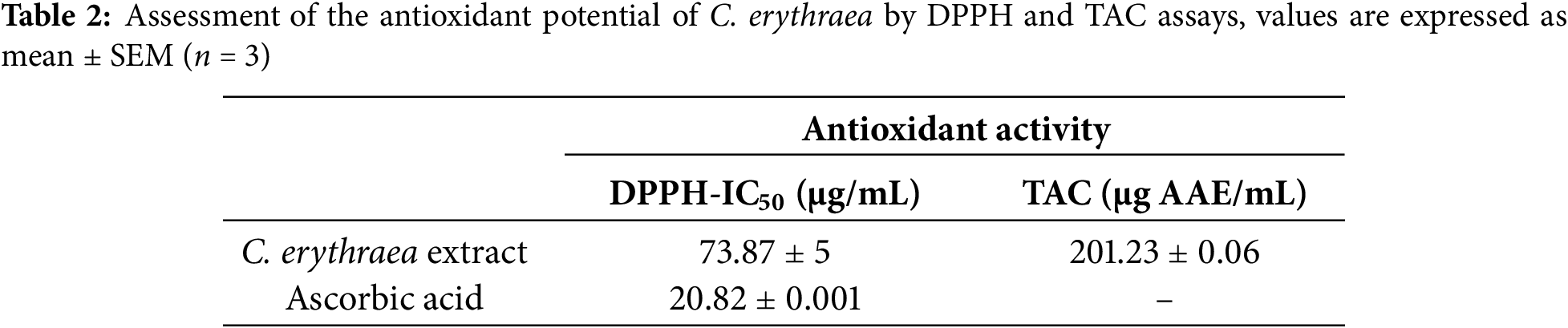

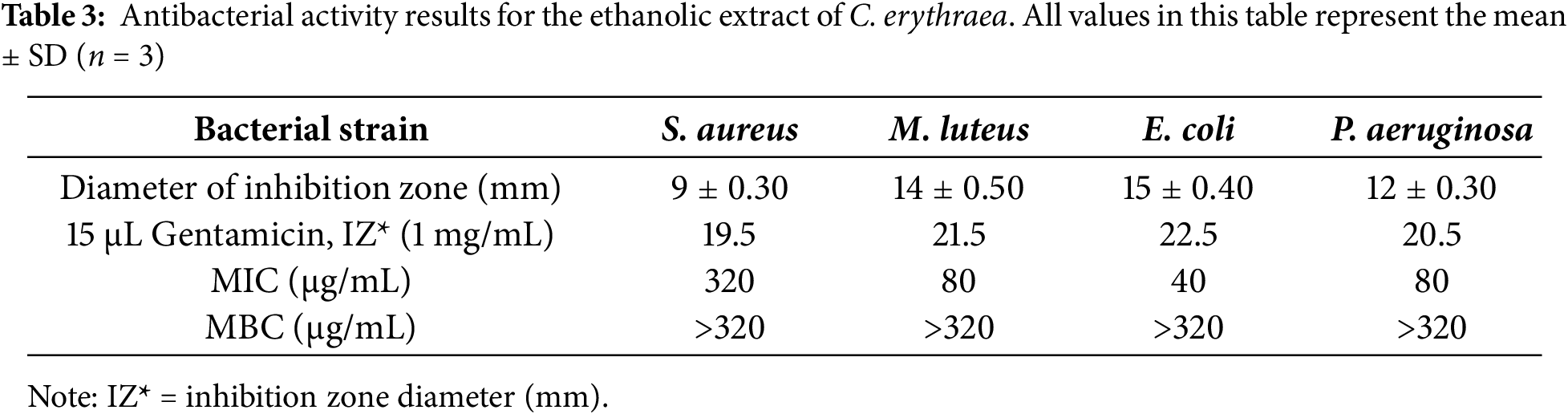

The research aimed to examine whether the botanical extract could inhibit the growth of four bacteria: Staphylococcus aureus, Micrococcus luteus, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, during standardized antimicrobial screening performed in triplicate assays. Agar well diffusion was used to detect inhibition halos, whereas serial microdilutions determined the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) thresholds. According to diffusion readings, activity was moderate, with halo sizes ranging between 9 mm for S. aureus and 15 mm for E. coli (refer to (Fig. 2); Table 3). The evaluation of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) revealed variable sensitivity among the bacterial strains tested. The extract showed an MIC of 40 μg/mL against E. coli, indicating high sensitivity of this strain. In contrast, the MICs were 80 μg/mL for M. luteus and P. aeruginosa, reflecting intermediate inhibition, while S. aureus was the most resistant, with an MIC of 320 μg/mL.

Figure 2: Antibacterial activity results for the ethanolic extract of C. erythraea. (A): S. aureus, (B): M. luteus, (C): E. coli, (D): P. aeruginosa

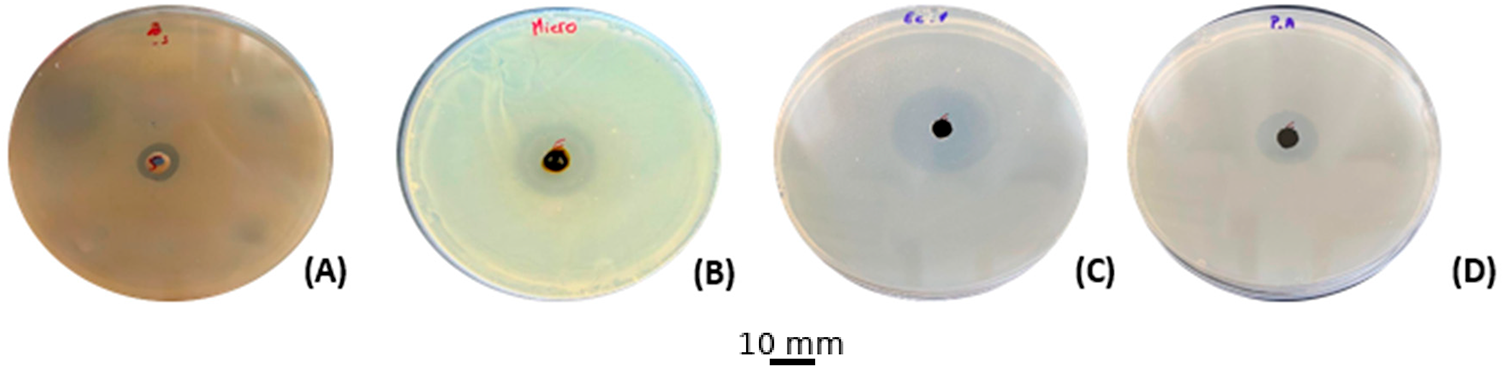

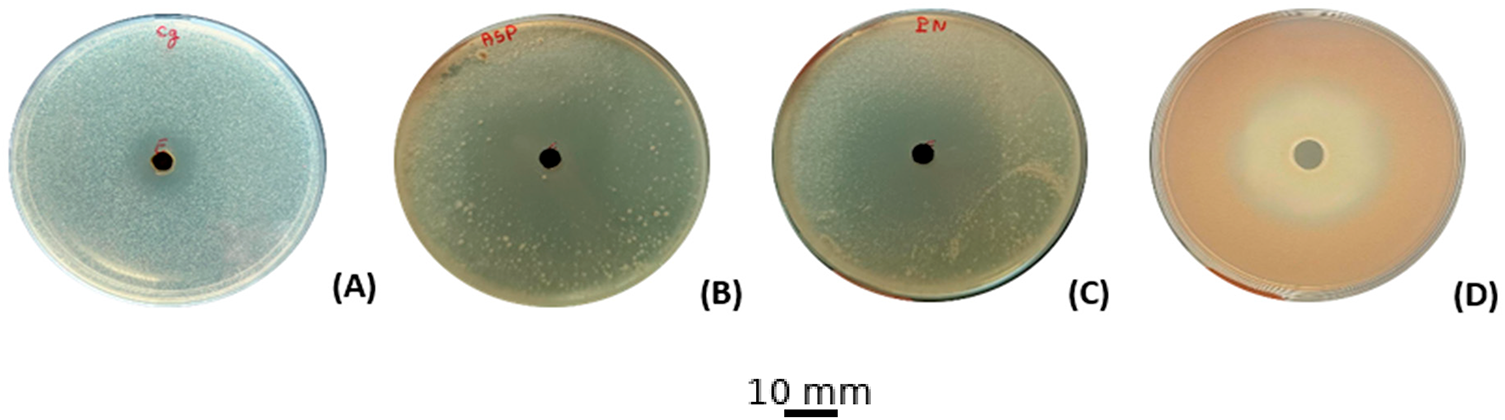

Using 15 µL per test, the ethanol-based extract of C. erythraea displays measurable antifungal power: inhibition halos span 19 mm with A. niger, 18 mm with P. digitatum and R. glutinis, and 12 mm with C. glabrata (Fig. 3) The minimum inhibitory concentration pattern mirrors these data, with 80 μg/mL for both molds and R. glutinis, and 160 μg/mL for the yeast C. glabrata. In contrast, MFCs plateau at 320 μg/mL for susceptible isolates and exceed that threshold for C. glabrata, indicating fungistasis rather than actual killing (Table 4).

Figure 3: Antifungal activities of the ethanolic extract of C. erythraea. (A): C. glabrata, (B): A. niger, (C): P. digitatum, (D): R. glutinis

3.5 Physicochemical and Pharmacokinetic Properties (ADME)

Ethanolic extracts from Centaurium erythraea harbour eleven distinct phenolic metabolites that collectively underpin their antifungal potential. Early-stage in-silico evaluation of ADME parameters, including absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, is therefore essential: it gauges each compound’s ability to cross biological membranes and reach therapeutic concentrations, while flagging liabilities such as poor permeability or rapid clearance that could undermine in vivo efficacy. By applying these ADME filters upfront, we channel experimental effort toward candidates with the most promising pharmacokinetic profiles, reduce late-stage failures, and accelerate the discovery of more effective antifungal agents.

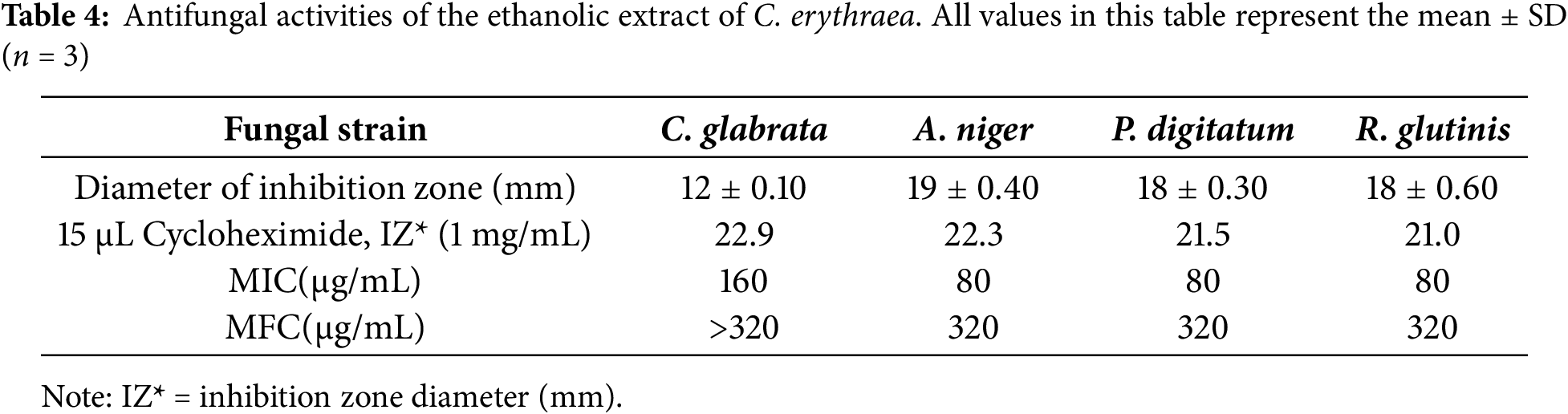

Table 5 summarises the SwissADME-derived physicochemical and rule-based filters for the eleven phenolic metabolites (M1–M11) and immediately delineates two distinct pharmacokinetic profiles. The low-molecular-weight mono- and di-hydroxybenzoates (M1–M4) together with cinnamic (M6), ferulic (M7), p-coumaric (M8), and aglycone quercetin (M11) all remain below the 500 g mol−1 Lipinski threshold, carry ≤10 H-bond acceptors, ≤5 donors, and ≤10 rotatable bonds, and display moderate polarity (TPSA ≤ 110 Å2) coupled to restrained lipophilicity (CLogP ≈ 0.5–1.98). As a consequence, they exhibit zero Lipinski and Veber violations, high predicted gastrointestinal (GI) absorption, and bioavailability scores of 0.55–0.85, indicating an overall favorable oral drug-likeness.

By contrast, the flavonoid glycosides naringin (M5), quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucoside (M9) and rutin (M10) cluster in a “polysaccharidic” space characterised by excessive size (580–611 g mol−1), extreme polarity (TPSA 210–269 Å2) and a dense hydrogen-bonding network (12–16 acceptors, 8–10 donors). These features translate into multiple Lipinski breaches (2–3) and a single Veber violation (TPSA > 140 Å2), driving SwissADME to flag poor passive permeation and to downgrade their GI absorption and bioavailability score to 0.17. Although their negative or near-neutral CLogP values (−1.60 to −0.53) mitigate solubility concerns, the data suggest that any pharmacological efficacy would likely depend on active transport or formulation strategies rather than spontaneous uptake.

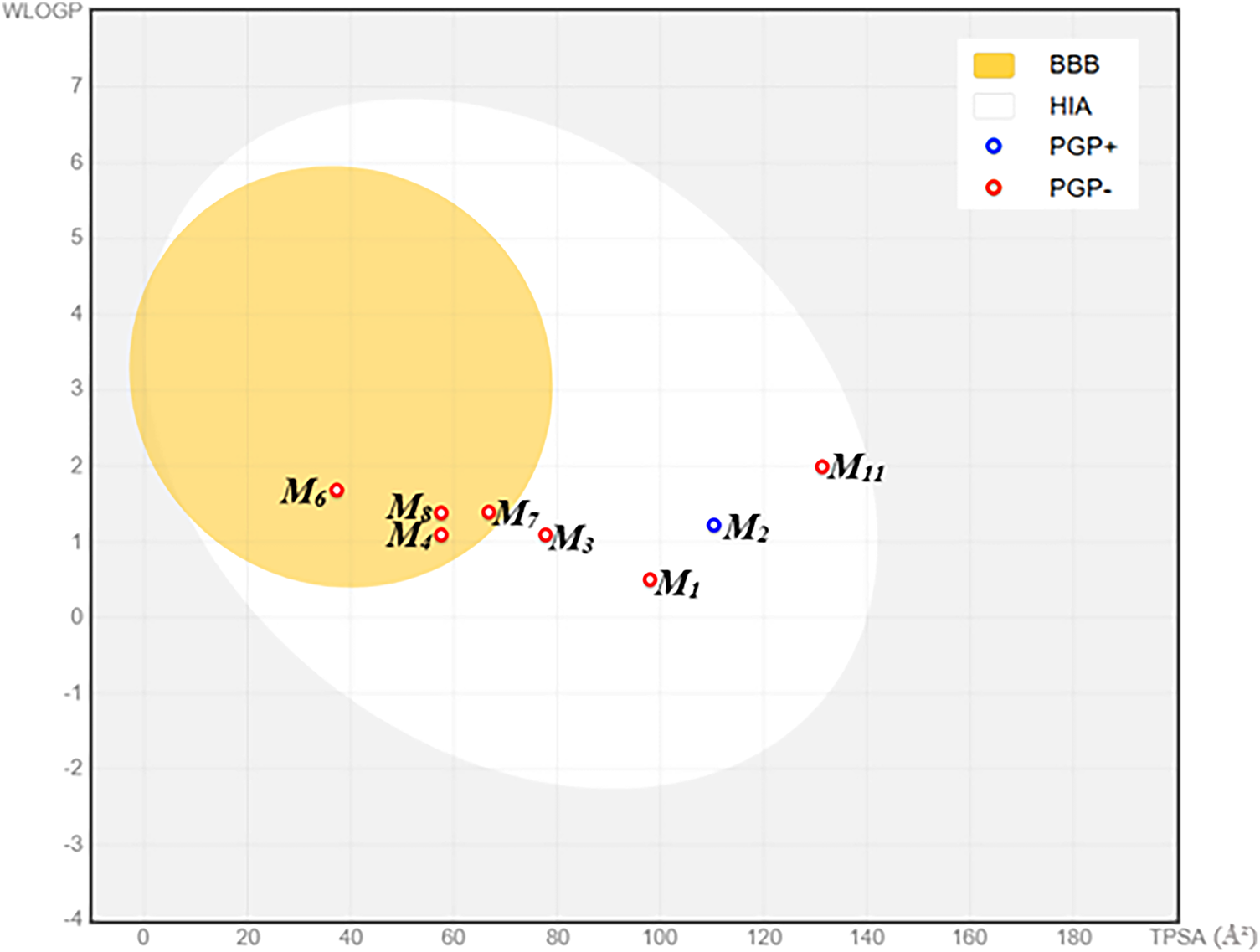

The SwissADME BOILED-Egg projection, which plots W log P against TPSA to define the permeability envelopes for passive human-intestinal absorption (white) and blood-brain-barrier penetration (yellow), reveals a clear physicochemical stratification among the eleven phenolics (Fig. 1). Cinnamic acid (M6) alone resides entirely within both envelopes, marrying low polarity (TPSA ≈ 40 Å2) to moderate lipophilicity (W log P ≈ 1.8) and thus satisfying the dual HIA/BBB criteria. M8, M4, M7, and M3 lie on the BBB boundary consistent with efficient oral uptake but only marginal neuropenetration, whereas gallic acid (M1) and catechin (M2) remain confined to the HIA zone; the latter is additionally flagged as a P-gp substrate, suggesting efflux-limited systemic exposure. Quercetin (M11) breaches the HIA polarity ceiling (TPSA ≈ 140 Å2) and the glycosylated flavonoids (M5, M9, M10) fall far outside the plotted envelopes (TPSA > 210 Å2), underscoring their intrinsic permeability liabilities (Fig. 4). Collectively, the diagram singles out cinnamic acid as the only candidate with genuine CNS delivery potential, positions the mid-sized aglycones for peripheral action, and highlights the need for formulation or transporter-based strategies for the bulky glycosides.

Figure 4: BOILED-egg representation of the pharmacokinetic properties of the studied molecules. Abbreviations: BBB = Blood–Brain Barrier permeation; HIA = Human Intestinal Absorption; PGP+ = P-glycoprotein substrate (positive interaction); PGP− = P-glycoprotein non-substrate (negative interaction); WLOGP = Wildman-Crippen Log P (lipophilicity parameter); TPSA = Topological Polar Surface Area (Å2)

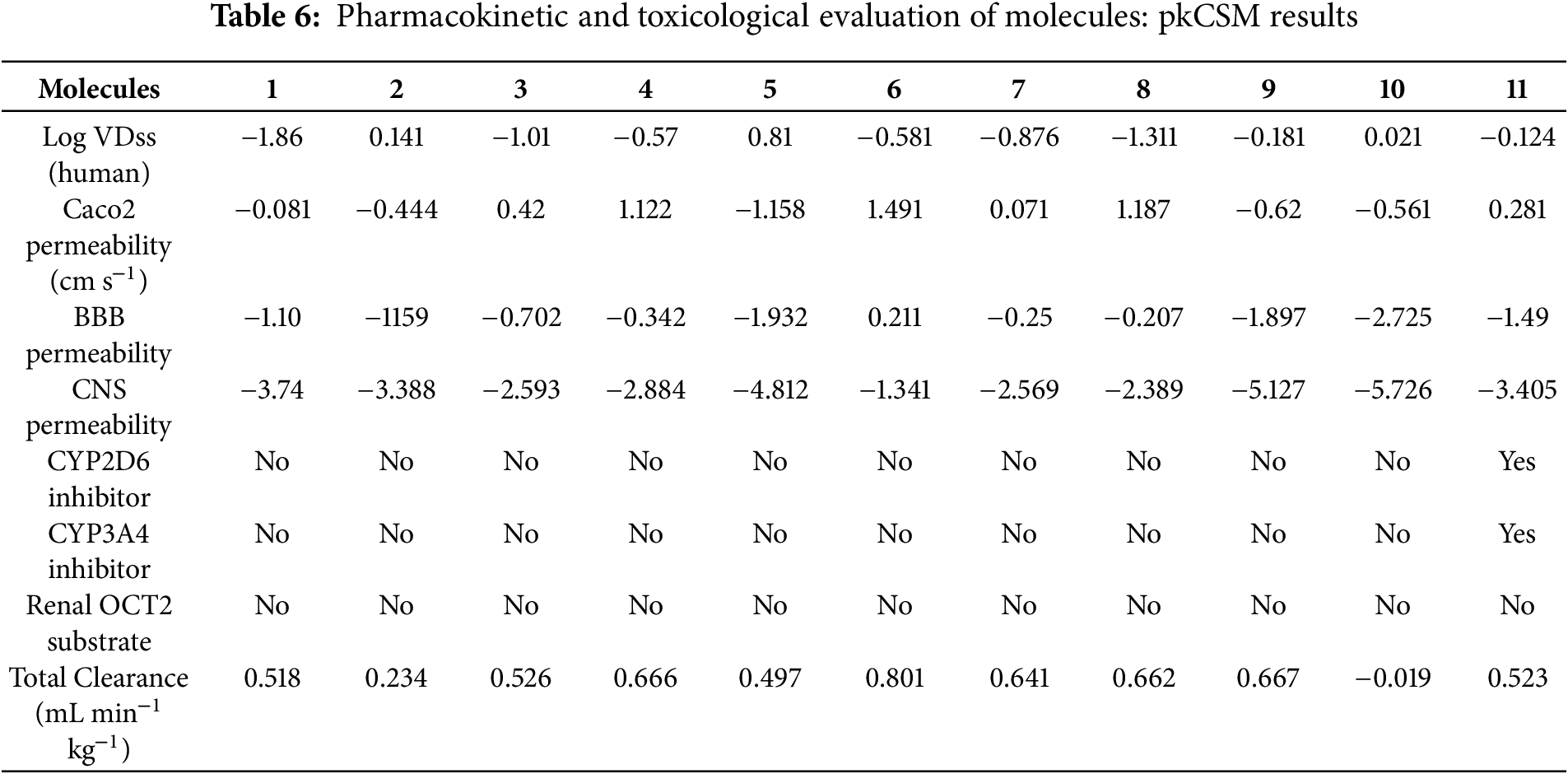

The pkCSM dataset (Table 6) reveals a four-log range in steady-state volume of distribution, with log VDss spanning from −1.86 L kg−1 for gallic acid (M1), indicating vascular confinement, to 0.81 L kg−1 for naringin (M5), signifying deep tissue partitioning. Intestinal permeability Caco2 permeability, reflected by log Papp (10−6 cm s−1), highlights 4-hydroxybenzoic, cinnamic, and p-coumaric acids (M4, M6, M8; 1.12–1.49) as highly permeant, whereas the glycosylated flavonoids (M5, M9, M10; −1.16 to −0.62) are markedly limited. Blood-brain-barrier metrics show cinnamic acid (M6; log BB = 0.21, log PS = −1.34) as the only molecule exceeding CNS-entry thresholds, while all other aglycones fall short and the glycosides are effectively excluded (log BB ≤ −1.90; log PS ≤ −5.13). Metabolic-interaction risk is minimal, except for quercetin (M11), which is predicted to inhibit CYP2D6 and CYP3A4. None of the compounds are OCT2 substrates, suggesting limited renal tubular secretion. Total systemic clearance, expressed as log CLTot (mL min−1 kg−1), ranks cinnamic acid highest (0.80) and rutin (M10; −0.02) slowest, linking rapid elimination to molecular simplicity and sluggish clearance to large, polar scaffolds. Overall, the pkCSM descriptors nominate cinnamic acid as the most pharmacokinetically balanced lead, restrict mid-sized aglycones to peripheral action, expose bulky glycosides to dual absorption-brain-penetration liabilities, and flag quercetin for potential CYP-mediated drug-drug interactions.

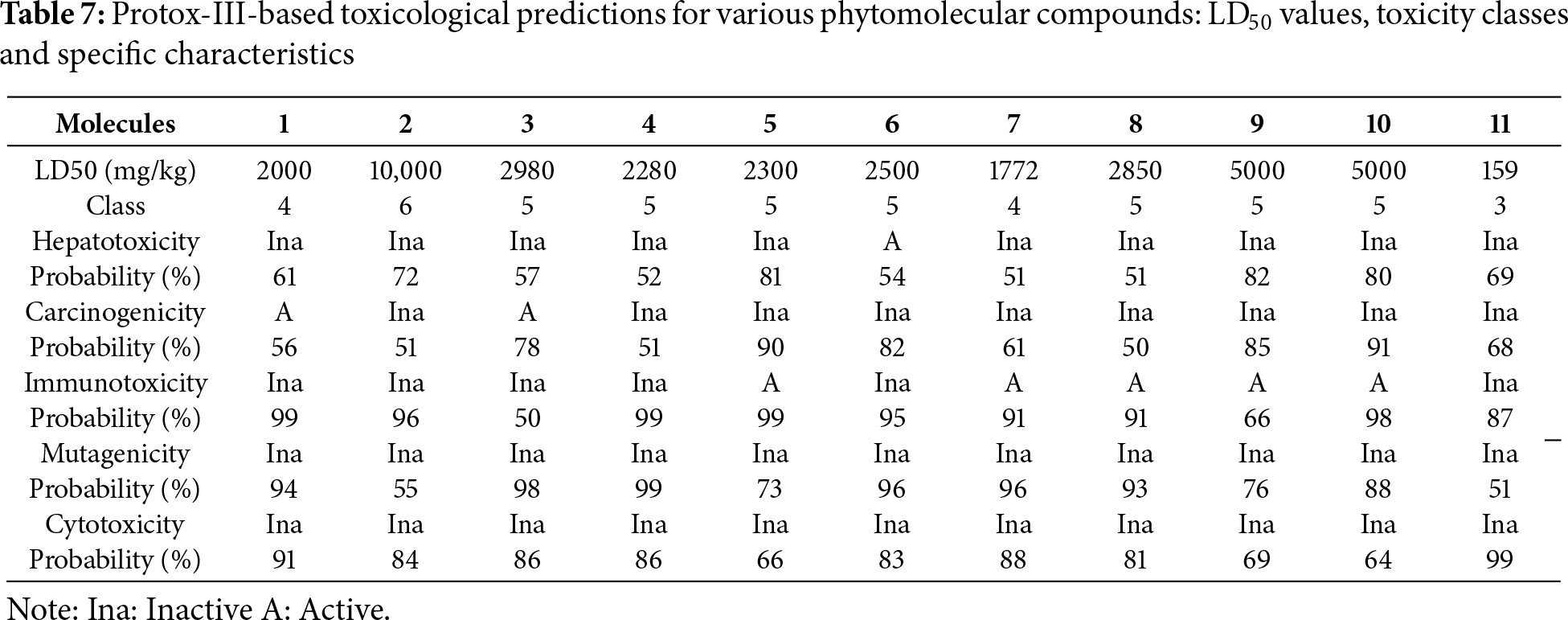

3.6 In Silico Toxicity Prediction (Using Pro-Tox III)

The toxicity assessment, conducted in conjunction with the ADME analysis, refines compound selection by modeling acute oral hazards and organ-specific risks. Table 7 shows that LD50 values (mouse, mg kg−1) range from 159 for M11, rendering it the most acutely toxic, OECD class 3, to 10,000 for M2 (least toxic, class 6), while most aglycones fall into classes 4–5, indicating broadly acceptable dose margins. Only cinnamic acid (M6) triggers a hepatotoxic alert (“Active”, 54% probability), warranting hepatocyte follow-up. Carcinogenicity flags are limited to gallic (M1) and caffeic (M3) acids, with moderate-to-high confidence (56%–78%), consistent with the pro-oxidant nature of their catechol groups. Immunotoxicity signals cluster in the bulky glycosides (M5, M7–M10), with probabilities ranging from 66% to 99%, suggesting possible cytokine modulation, whereas other compounds are inactive in this endpoint. All eleven molecules are predicted to be non-mutagenic, mitigating concerns about DNA damage or baseline cell viability. Overall, catechin (M2) and the two glycosides, M9 and M10, appear to be the safest leads. At the same time, quercetin (M11) requires cautious dosing, cinnamic acid (M6) necessitates liver-specific assays, and the glycoside cluster warrants immunological profiling before advancing to efficacy studies.

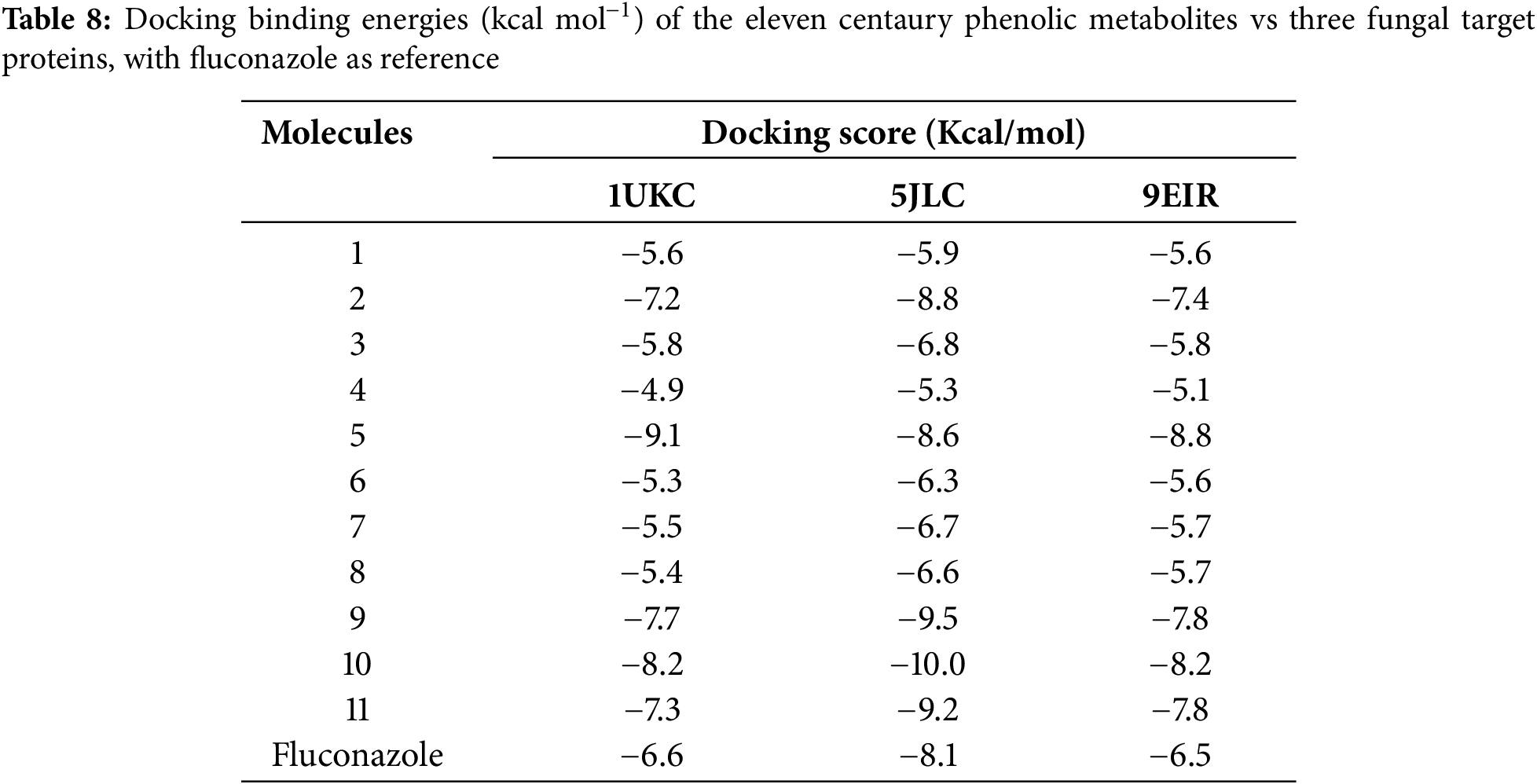

Table 8 summarises the docking results for the eleven metabolites in comparison with the reference drug fluconazole, which served as the universal positive control for the three fungal targets. Fluconazole produced binding energies of −6.6 kcal mol−1 with the A. niger esterase (1UKC), −8.1 kcal mol−1 with C. glabrata CYP51 (5JLC), and −6.5 kcal mol−1 with the ethylene-forming oxidoreductase of P. digitatum (9EIR), providing a pharmacological baseline for affinity comparison.

Against this benchmark, the glycosylated flavonoids stand out: naringin (M5), rutin (M10), and quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucoside (M9) achieve binding energies between −9.1 and −8.2 kcal mol−1 on 1UKC and 9EIR, while rutin reaches −10.0 kcal mol−1 on 5JLC, exceeding fluconazole by 1 to 2.5 kcal mol−1. Catechin (M2, −8.8), quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucoside (M9, −9.5), and quercetin (M11, −9.2) also surpass the fluconazole energy on CYP51, marking them as potential inhibitors of the ergosterol-biosynthesis pathway. By contrast, the low-molecular-weight phenolic acids (M1, M3, M4, M6–M8) cluster between −4.9 and −6.8 kcal mol−1, matching or falling below the fluconazole baseline and thus displaying limited predicted affinity.

Overall, the sugar-rich flavonoids, especially rutin and the quercetin glucoside, emerge as the strongest binders across all targets relative to fluconazole. In contrast, catechin and quercetin appear as promising CYP51-focused leads with a potentially more favourable pharmacokinetic balance.

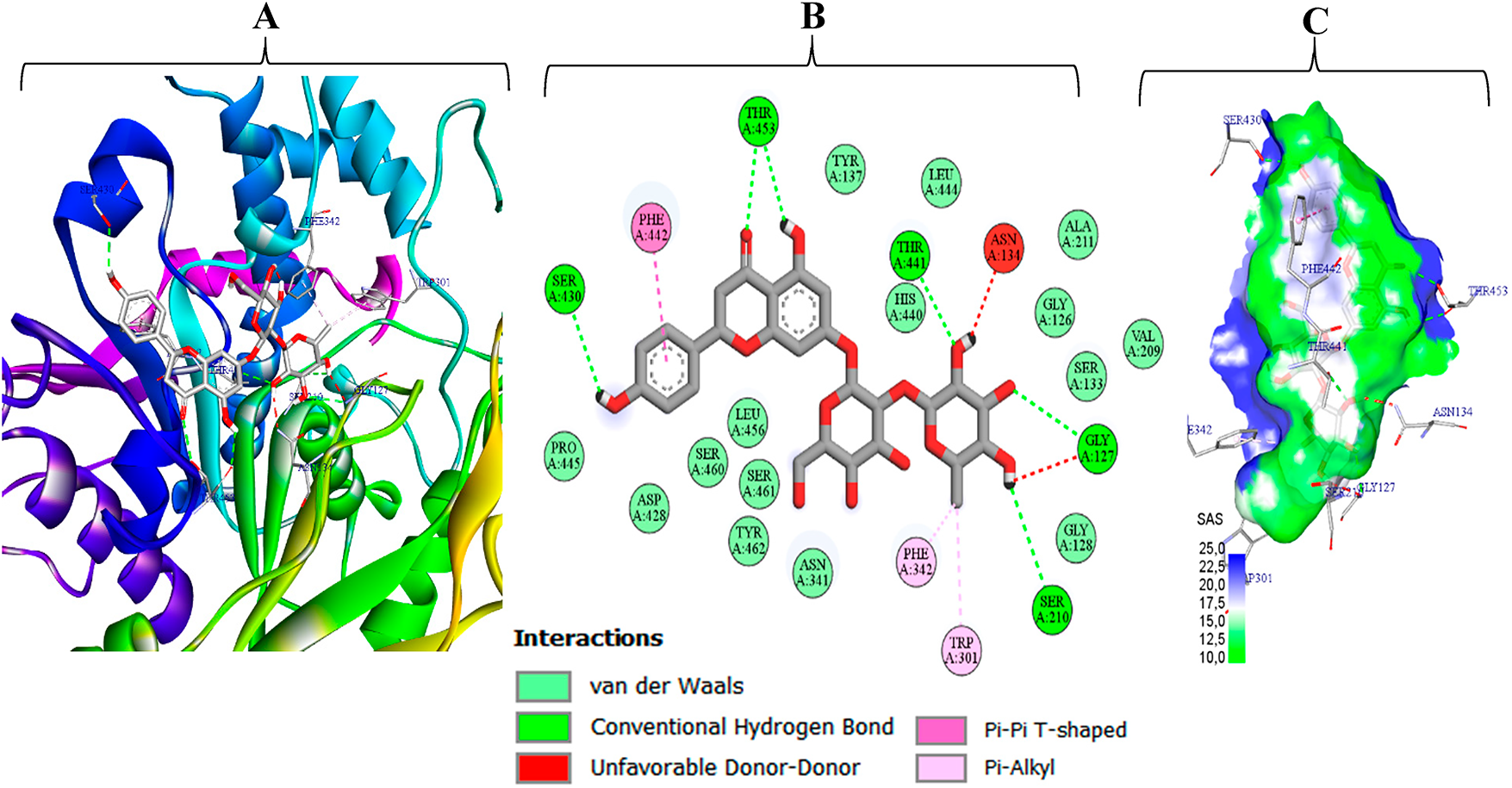

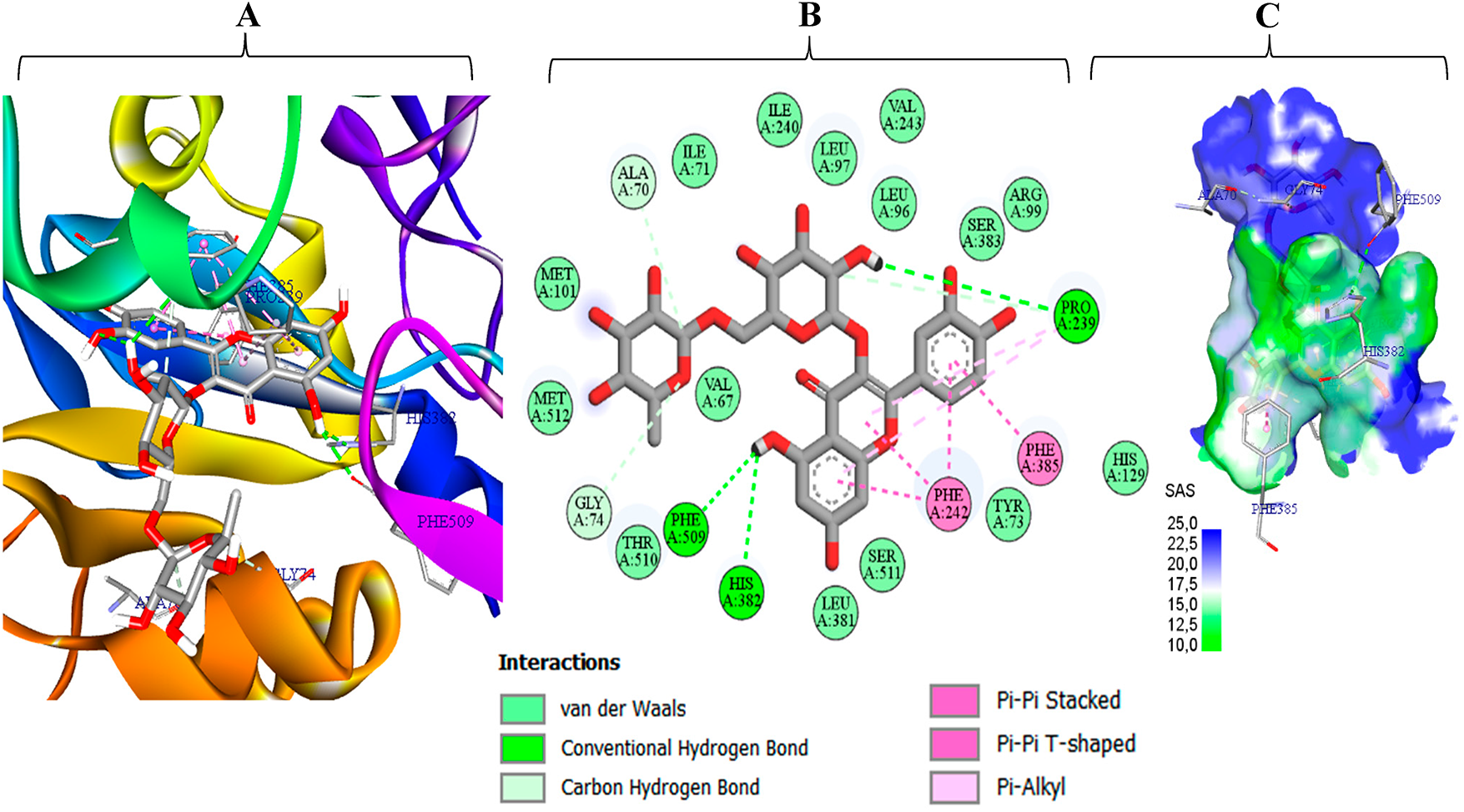

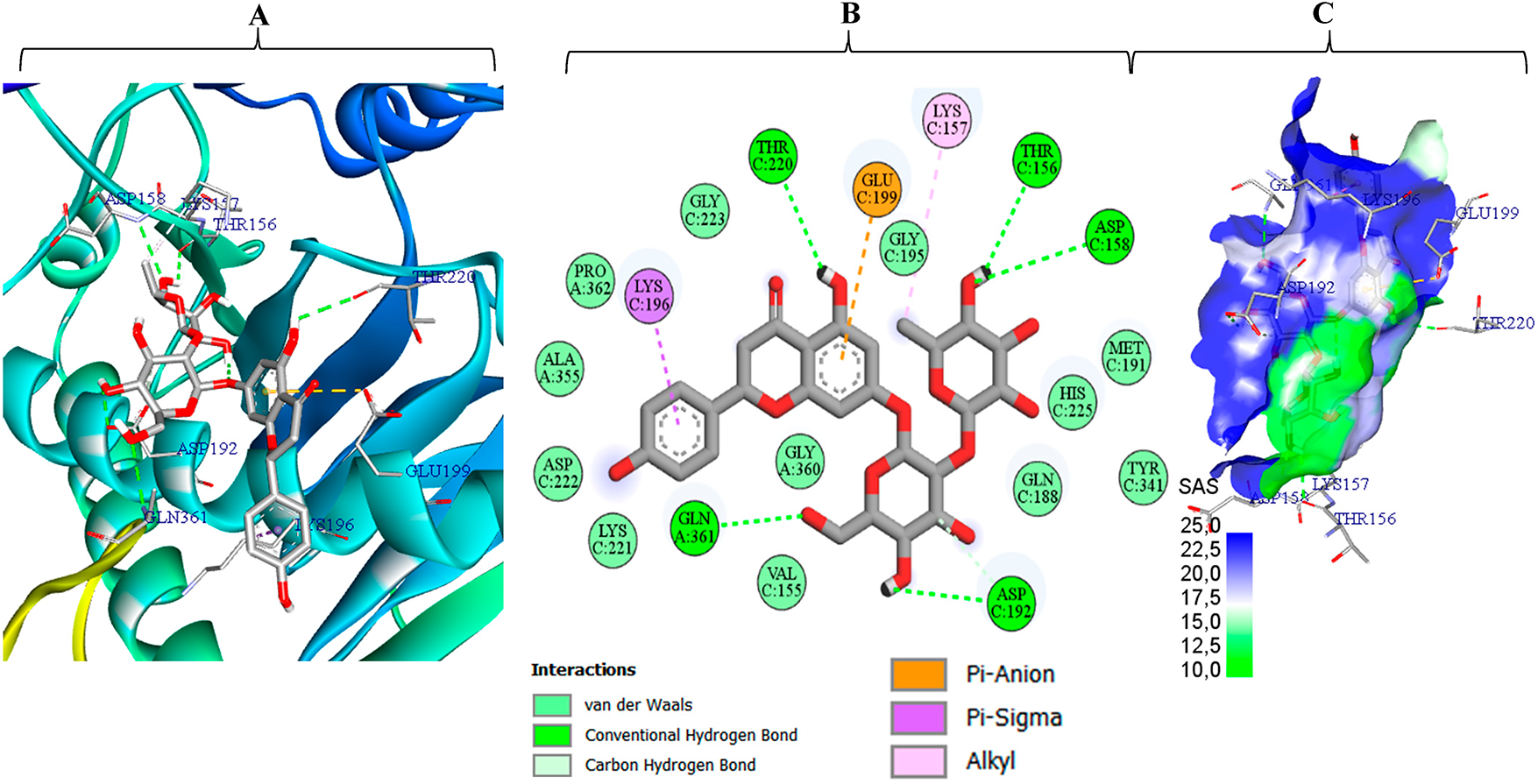

Given their top docking energies naringin (M5, −9.1 kcal mol−1) with 1UKC, rutin (M10, −10.0 kcal mol−1) with 5JLC and naringin (M5, −8.8 kcal mol−1) with 9EIR we retained these complexes as lead hits despite sub-optimal ADME scores. The forthcoming Figs. 5–7 will dissect their binding interactions in detail, clarifying how specific hydrogen bonds, π-π contacts and pocket complementarity rationalise the superior affinities.

Figure 5: Naringin (M5) bound to A. niger EstA (PDB 1UKC): (A) three-dimensional interaction view, (B) two-dimensional interactin map, and (C) solvent-accessible-surface (SAS) rendering

Figure 6: Interaction profile of rutin (M10) with C. glabrata CYP51 (PDB 5JLC), combining 3-D/2-D views (A–C) solvent-accessible-surface SAS rendering

Figure 7: Interaction profile of naringin (M5) with P. digitatum ethylene-forming oxidoreductase (PDB 9EIR), shown with inte-grated 3-D/2-D illustrations (A–C) solvent accessible surface SAS rendering

The extract’s phytochemical profile provides the organizing framework for the observed bioactivities. Among the identified constituents (Table 1), 4-hydroxybenzoic acid stands out as a relevant synthetic intermediate for the manufacture of high value-added bioproducts. As a product example synthesized from 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, methylparaben (methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate) is industrially obtained by esterification of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and is widely used downstream as a cosmetic and pharmaceutical preservative [42]. Beyond 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, p-coumaric acid occurs substantially in the extract’s composition. Belonging to the hy-droxycinnamate family, it stands out for its varied bioactivity profile. Notably, it exhibits excellent antioxidant and antibacterial properties, making it a natural alternative to artificial chemicals in var-ious fields, including medicine, food technology, personal care, and biomedicine. These traits reflect just a portion of its entire worth. P-coumaric acid is also involved in neutralizing carcinogenic nitrosating chemicals, thereby providing it with a chemoprotective function in numerous bodily fluids, including saliva and gastric juice [43]. In addition, it shows anti-inflammatory, antiviral, anticancer, and antimetabolic properties, indicating potential utility in the management of diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidemia [44]. From a biological perspective, p-coumaric acid is crucial as the precursor of resveratrol, a polyphenol renowned for its cardio- and neuroprotective properties [45]. This trait reinforces its standing as a prominent target for medicinal innovation and for techniques that conserve natural foods.

Within this matrix, naringin stands out owing to its various pharmacological characteris-tics. Known for boosting immunity, facilitating DNA repair, and neutralizing free radicals, this flavo-noid possesses antioxidant and anti-inflammatory characteristics that provide it with great thera-peutic utility, especially against chronic inflammatory illnesses. In addition, its considerable hypo-glycemic effects seen in patients with diabetes emphasise its potential in the therapy of metabolic illnesses [46]. Overall, the data indicate that the extracts biological activity arises from the action of multiple constituents, consistent with combined effects, potential synergistic interactions may also contrib-ute, but this remains a hypothesis. Our findings differ from those reported by Kachmar et al. [47], who discovered substantial amounts of glycosylated and acylated flavonols, notably quercetin and kaempferol derivatives, in the aqueous extract. This mismatch demonstrates the important effect of the choice of extraction solvent on the final composition of the extract. Thus, the optimization of extraction methods seems to be a crucial lever for increasing the valorization of bioactive chemicals according to specified applications.

In line with this composition, the antioxidant findings can be rationalized by the dominant phenolics. The antioxidant activity is primarily attributed to the elevated levels of 4-hydroxybenzoic and p-coumaric acids detected by HPLC, compounds that detoxify reactive oxygen species via electron- and hydrogen-transfer mechanisms [48,49]. Reports in the literature vary widely, for example, ultrasound extraction with 80% methanol of aerial parts yielded 79.29 ± 1.22 µmol TE g−1 DW in the study by Tusevski et al. [50], illustrating how methodological differences affect bioactive compound solubilization and retention.

With respect to antimicrobial activity, the in-vitro assays demonstrate measurable inhibition of the tested strains. The profile reflects both constraints imposed by the bacterial envelope and the extract’s chemical richness. The activity data indicate that cell-wall architecture strongly influences susceptibility to the extract’s bioactive constituents. Gram-positive bacteria, characterized by a thick layer of peptidoglycan, may limit the diffusion of active molecules, resulting in the lowest inhibition associated with S. aureus. As for the MBCs, these were greater than 320 μg/mL for all strains, indicating a predominantly bacteriostatic effect of the extract. Such an observation implies that the extract inhibits bacterial growth without necessarily inducing complete cell lysis.

Our results contrast with those reported by Bouyahya et al. [51], notably concerning S. aureus, for which a substantially greater inhibitory zone (34 ± 0.5 mm) was seen. This disagreement might be characterized by discrepancies in the chemical composition of the extracts, the concentration of bioactive chemicals, or the experimental methods utilised, notably the extraction process. However, our findings for P. aeruginosa are comparable to those of others who likewise obtained relatively modest inhibition (11 ± 0.5 mm). This resemblance supports the idea of resistance induced by P. aeruginosa, which is frequently associated with its efflux pump systems and the limited permeability of its outer membrane.

The observed antibacterial activity may be related to the abundance of secondary metabolites identified by HPLC-DAD. The extract contains a high concentration of phenolic acids and flavonoids two classes recognized for antibacterial activity. Among the phenolic acids identified, 4-hydroxybenzoic, gallic, caffeic, p-coumaric, ferulic, and cinnamic acids have not all been fully established for their potential to mitigate diverse bacterial conditions. For example, p-coumaric and 4-hydroxybenzoic acids the principal components of our extract are known to reduce membrane permeability and interfere with bacterial enzymatic processes [52,53]. In a further development, the presence of flavonoids such as catechin, naringin, quercetin, and rutin may play a crucial role in antibacterial activity. These compounds cause synergistic effects, primarily by reducing cell wall production, modulating efflux pumps, interfering with DNA replication, and disrupting the integrity of bacterial membranes [54].

The antifungal profiles observed indicate differential susceptibility among the strains evaluated. The values contrast sharply with those reported for methanolic extracts of the same species by Šiler et al. [17] against eight filamentous fungi (A. flavus, A. niger, A. fumigatus, A. versicolor, Penicillium funiculosum, P. ochrochloron, Trichoderma viride) and Candida albicans, with MICs of 100–400 µg/mL and MFCs of 200–600 µg/mL concentrations 100–200-fold lower whereas Afzal et al. [55] achieved 93% inhibition of Fusarium oxysporum at only 200,000 µg/mL. The lower antifungal activity of our extract is likely explained by (i) ethanol, which is less effective than methanol at extracting bioactive secoiridoids and xanthones, (ii) the plant part used and intraspecific chemical variability, and (iii) the intrinsic tolerance of the strains, C. glabrata, which has efflux pumps and a wall enriched in β-glucans. Nevertheless, the abundant presence of phenolic acids (gallic, caffeic, ferulic, p-coumaric, cinnamic) and flavonoids (catechin, naringin, quercetin, quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucoside, rutin) explains why the extract remains more active on fungi than on bacteria: these metabolites target β-1,3-glucan synthase and ergosterol, generate oxidative stress, inhibit efflux pumps, and chelate fungal metal ions, creating an intra-extract synergy that confers a relatively marked fungistatic/fungicidal effect [56].

From a developability standpoint, in-silico profiling provides a prioritization framework aligned with the bioassay trends. Among the eleven phenolics profiled from C. erythraea, in-silico ADME/toxicity results consistently separate drug-like, mid-weight aglycones from bulky, sugar-rich flavonoids, with clear implications for development [57]. SwissADME indicates that the simple acids and aglycones (e.g., 4-hydroxybenzoic, p-coumaric, and ferulic acids, and quercetin) comply with Lipinski/Veber filters and exhibit high predicted gastrointestinal absorption, whereas the glycosides (naringin, quercetin-3-O-glucoside, rutin) violate multiple rules, lie outside the BOILED-Egg HIA envelope, and are therefore unlikely to achieve oral exposure without transporter-aware formulation or prodrug strategies [58]. Only cinnamic acid is predicted to cross the blood brain barrier, positioning most candidates for peripheral indications. pkCSM further supports this split: the small acids display higher Caco-2 permeability and faster clearance, whereas quercetin uniquely raises a drug–drug interaction risk as a predicted CYP2D6/3A4 inhibitor [59]. ProTox-III forecasts broadly acceptable acute hazards for most aglycones (GHS classes 4–5) and universal non-mutagenicity, but flags a hepatotoxicity alert for cinnamic acid, a low LD50 for quercetin (suggesting cautious dosing), and immunotoxicity alerts concentrated among the glycosides signals that warrant targeted liver and immune safety follow-up [60,61].

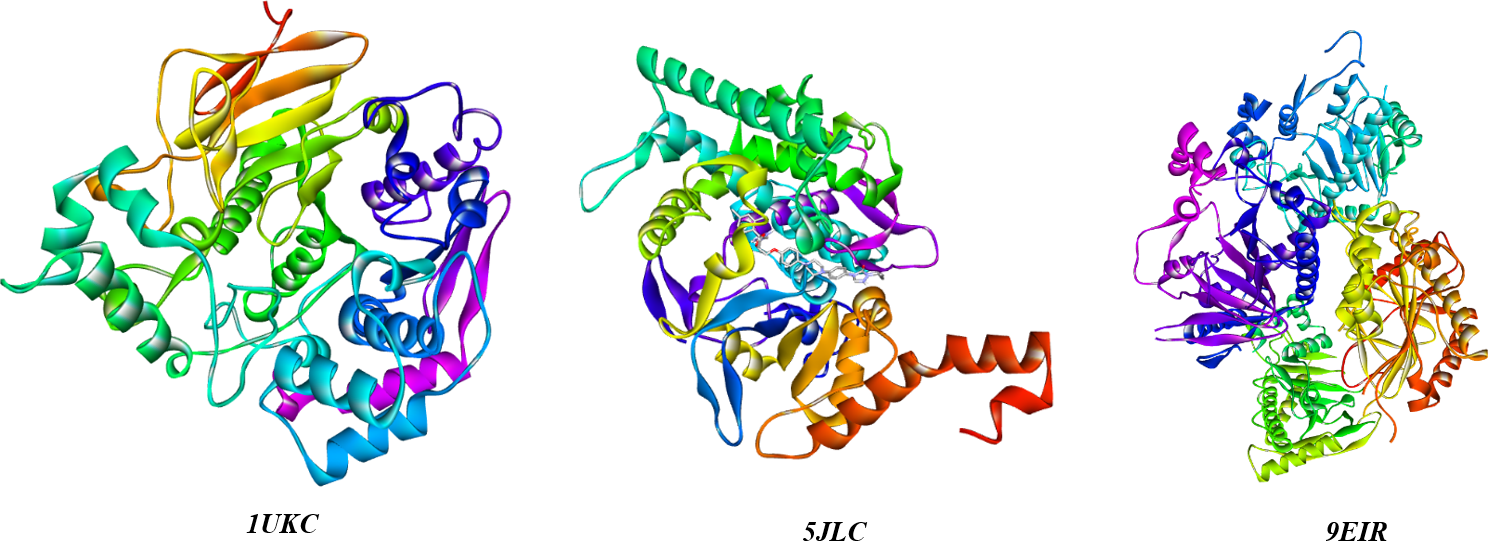

To explain the in-vitro antifungal activity quantified by inhibition zone diameters against Aspergillus niger, Candida glabrata, and Penicillium digitatum a molecular docking study was conducted on three well-characterized targets for each species: the secreted esterase EstA of A. niger (PDB 1UKC, 2.10 Å), lanosterol 14-α-demethylase CYP51 of C. glabrata (PDB 5JLC, 2.40 Å), and the ethylene forming oxidoreductase of P. digitatum (PDB 9EIR, 3.50 Å) (Fig. 8) [60]. These enzymes are essential for fungal viability or membrane biogenesis; their inhibition therefore directly suppresses growth. Docking the eleven centaury-derived phenolic metabolites into the active sites of 1UKC, 5JLC, and 9EIR enables identification of the ligands with the highest binding affinity and correlation of computed scores with measured inhibition zones, thereby pinpointing the compound(s) most responsible for the observed antifungal effect. This structure-guided strategy directs subsequent optimization toward selective potency rather than relying solely on empirical screening. This is especially important because the bioassay was conducted on the crude extract without isolating its constituents, making docking indispensable for recognizing the active component prior to undertaking costly isolation and purification steps [62].

Figure 8: 3D ribbon views of the three target fungal proteins (1UKC, 5JLC, 9EIR)

Consequently, the detailed interaction analyses are consistent with the affinity trends. Fig. 5 shows that naringin (M5) fits tightly into the EstA pocket, burying ≈70% of its solvent-accessible surface. The complex is stabilized by six conventional hydrogen bonds (Gly127, Ser210, Ser430, Thr441, Thr453), a T-shaped π–π contact with Phe442, two π-alkyl contacts with Phe342 and Trp301, and ~15 van der Waals contacts that create a hydrophobic cushion [62–64]. Two minor donor–donor clashes with Asn134 and Gly127 are geometrically marginal and outweighed by the favorable interaction network, accounting for the high binding energy (–9.1 kcal mol−1) that ranks M5 as the strongest predicted binder to 1UKC. Fig. 6 shows rutin (M10) firmly lodged in the catalytic tunnel of C. glabrata CYP51 (5JLC), with its solvent-accessible surface evenly split between polar (blue) and apolar (green) regions evidence of optimal hydrophilic–hydrophobic complementarity. Three conventional hydrogen bonds (His382, Pro239, Phe509) anchor the ligand, while four π–π interactions (stacked and T-shaped) with Phe385 and Phe342, plus two π-alkyl contacts to Pro239, cement the aromatic scaffold. Roughly fifteen van der Waals contacts further stabilize the complex, and two ancillary C–H···O bonds (Gly74, Ala70) help orient the sugar tail. This rich, multi-faceted network explains the very favorable binding energy (–10.0 kcal mol−1), positioning rutin as a stronger CYP51 binder than the fluconazole reference.

Fig. 7 depicts naringin (M5) bound deep within the catalytic tunnel of the ethylene-forming oxidoreductase from P. digitatum (PDB 9EIR). Approximately 70% of the ligand’s solvent accessible surface appears blue, indicating a highly polar microenvironment that matches M5’s dense hydroxyl pattern and minimizes desolvation penalties. A “polar ladder” of five conventional hydrogen bonds to Asp C158, Thr C156, Thr C220, Gln A361, and Asp C192 locks both sugar moieties and the aglycone 5-OH in place. Hydrophobic reinforcement arises from a π–σ contact with Lys C196 and an alkyl interaction with Lys C157, while an additional contact with Glu C199 orients the rhamnose tail. About twelve van der Waals contacts further damp residual motion, providing entropic stabilization [60,65]. The combination of this extensive hydrogen-bond network, targeted cation–π/alkyl anchoring, and broad polar-surface burial rationalizes the favorable binding energy (–8.8 kcal mol−1), identifying M5 as the top predicted binder for 9EIR despite its bulk and high polarity.

5 Conclusions and Future Perspectives

This study, through integrated chemical, biological, and computational analyses, highlights red centaury (Centaurium erythraea) from northern Morocco as a promising source of antifungal agents. chromatographic profiling (HPLC-DAD) revealed the presence of abundant 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, p-coumaric acid, and naringin compounds, whose antioxidant capacity and membrane-disrupting properties explain the extract’s pronounced fungistatic effect. Structure-based simulations revealed that naringin and rutin bind key pathogenic targets with affinities surpassing those of fluconazole. Meanwhile, ADMET and ProTox-III modeling identified cinnamic acid and quercetin derivatives as orally bioavailable, low-toxicity candidates. Accordingly, the study recommends isolating mid-weight aglycones for direct development as oral drugs and leveraging nanocarriers or pro-drug strategies to enhance the potency of high-affinity glycosides. Rigorous extract standardization, mechanism-centric animal studies, and resistance mapping of clinical isolates now represent decisive steps toward translating C. erythraea phytochemistry into safe, broad-spectrum antifungal therapies and multifunctional functional food products.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Center for Scientific and Technical Research (CNRST) under the PhD-Associate Scholarship PASS program.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Yousra Hammouti, Mohamed Addi and François Mesnard; data acquisition: Oussama Khibech; methodology: Yousra Hammouti, Oussama Khibech and Abdeslam Asehraou; software: Yousra Belbachir and El Hassania Loukili; analysis and interpretation of data: Yousra Hammouti and Reda Bellaouchi; drafting of the manuscript: Yousra Hammouti and Mohamed Taibi; critical revision of the manuscript: Mohamed Addi, Abdeslam Asehraou and François Mesnard; supervision: Mohamed Addi and François Mesnard. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Dhingra S, Rahman NAA, Peile E, Rahman M, Sartelli M, Hassali MA, et al. Microbial resistance movements: an overview of global public health threats posed by antimicrobial resistance, and how best to counter. Front Public Health. 2020;8:535668. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.535668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Safari M, Ahmady-Asbchin S. Evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial activities of methanolic extract of medlar (Mespilus germanica L.) leaves. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2019;33(1):372–8. doi:10.1080/13102818.2019.1577701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Banu GS, Kumar G. In vitro antibacterial activity of flower extracts of Woodfordia fruticosa Kurz. Int J Curr Res Chem Pharm Sci. 2014;1:127–30. [Google Scholar]

4. Mickymaray S, Alturaiki W. Antifungal efficacy of marine macroalgae against fungal isolates from bronchial asthmatic cases. Molecules. 2018;23(11):3032. doi:10.3390/molecules23113032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Portillo A, Vila R, Freixa B, Adzet T, Cañigueral S. Antifungal activity of Paraguayan plants used in traditional medicine. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;76(1):93–8. doi:10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00214-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Farhadi F, Khameneh B, Iranshahi M, Iranshahy M. Antibacterial activity of flavonoids and their structure-activity relationship: an update review. Phytother Res. 2019;33(1):13–40. doi:10.1002/ptr.6208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Frieri M, Kumar K, Boutin A. Antibiotic resistance. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10(4):369–78. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2016.08.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Raunsai M, Wulansari D, Fathoni A, Agusta A. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of endophytic fungi extracts of medicinal plants from Central Sulawesi. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2018;8(8):69–74. doi:10.7324/japs.2018.8811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chandra H, Kumari P, Yadav S. Evaluation of aflatoxin contamination in crude medicinal plants used for the preparation of herbal medicine. Orient Pharm Exp Med. 2019;19(2):137–43. doi:10.1007/s13596-018-0356-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chandra H, Kumari P, Prasad R, Gupta SC, Yadav S. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity displayed by a fungal endophyte Alternaria alternata isolated from Picrorhiza kurroa from Garhwal Himalayas, India. Bio-Catal Agric Biotechnol. 2021;33(5):101955. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2021.101955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Johnson OO, Ayoola GA. Antioxidant activity among selected medicinal plants combinations (mul-ti component herbal preparation). Int J Res Health Sci. 2015;3(1):526–32. [Google Scholar]

12. Bereksi MS, Hassaïne H, Bekhechi C, Abdelouahid DE. Evaluation of antibacterial activity of some medici-nal plants extracts commonly used in Algerian traditional medicine against some pathogenic bacteria. Phar-Macogn J. 2018;10(3):507–12. doi:10.1080/0972060x.2010.10643836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Angane M, Swift S, Huang K, Butts CA, Quek SY. Essential oils and their major components: an updated re-view on antimicrobial activities, mechanism of action and their potential application in the food industry. Foods. 2022;11(3):464. doi:10.3390/foods11030464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Brudzińska Kosior A, Kosior G, Sporek M, Ziembik Z, Zinicovscaia I, Frontasyeva M, et al. Nuclear analyti-cal techniques used to study the trace element content of Centaurium erythraea Rafn, a medicinal plant spe-cies from sites with different pollution loads in Lower Silesia (SW Poland). PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0285306. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0285306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Monari S, Ferri M, Salinitro M, Tassoni A. Ethnobotanical review and dataset compiling on wild and culti-vated plants traditionally used as medicinal remedies in Italy. Plants. 2022;11(15):11–5. doi:10.3390/plants11152041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Guedes L, Reis PB, Machuqueiro M, Ressaissi A, Pacheco R, Serralheiro ML. Bioactivities of Centaurium er-ythraea (Gentianaceae) decoctions: antioxidant activity, enzyme inhibition and docking studies. Molecules. 2019;24(20):3795. doi:10.3390/molecules24203795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Šiler B, Živković S, Banjanac T, Cvetković J, Živković JN, Ćirić A, et al. Centauries as underestimated food additives: antioxidant and antimicrobial potential. Food Chem. 2014;147:367–76. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.10.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Valentão P, Fernandes E, Carvalho F, Andrade PB, Seabra RM, Bastos ML. Hydroxyl radical and hypo-chlorous acid scavenging activity of small centaury (Centaurium erythraea) infusion: comparative study with green tea (Camellia sinensis). Phyto Med. 2003;10(6–7):517–22. doi:10.1078/094471103322331485. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Newall CA, Anderson LA, Phillipson JD. Herbal medicines: a guide for health care professionals. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press; 1996. 296 p. [Google Scholar]

20. Laranjinha J, Vieira O, Madeira V, Almeida L. Two related phenolic antioxidants with opposite effects on vit-amin E content in low density lipoproteins oxidized by ferrylmyoglobin: consumption vs regeneration. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;323(2):373–81. doi:10.1006/abbi.1995.0057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Valentão P, Andrade PB, Silva AM, Moreira MM, Seabra RM. Isolation and structural elucidation of 5 formyl 2,3 dihydroisocoumarin from Centaurium erythraea aerial parts. Nat Prod Res. 2003;17(5):361–4. doi:10.1080/1057563031000081938. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Mansar Benhamza L, Djerrou Z, Hamdi Pacha Y. Evaluation of anti hyperglycemic activity and side effects of Erythraea centaurium (L.) Pers. in rats. Afr J Biotechnol. 2013;12(50):6980. [Google Scholar]

23. Haloui M, Louedec L, Michel JB, Lyoussi B. Experimental diuretic effects of Rosmarinus officinalis and Centaurium erythraea. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;71(3):465–72. doi:10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00184-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mroueh M, Saab Y, Rizkallah R. Hepatoprotective activity of Centaurium erythraea on acetamino-phen induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Phytother Res. 2004;18(5):431–3. doi:10.1002/ptr.1498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Hammouti Y, Elbouzidi A, Taibi M, Bellaouchi R, Loukili EH, Bouhrim M, et al. Screening of phytochemi-cal, antimicrobial, and antioxidant properties of Juncus acutus from Northeastern Morocco. Life. 2023;13(11):2135. doi:10.3390/life13112135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Loukili EH, Bouchal B, Bouhrim M, Abrigach F, Genva M, Zidi K, et al. Chemical composition, antibacteri-al, antifungal and antidiabetic activities of ethanolic extracts of Opuntia dillenii fruits collected from Mo-rocco. J Food Qual. 2022;2022:9471239. doi:10.1155/2022/9471239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zrouri H, Elbouzidi A, Bouhrim M, Bencheikh N, Kharchoufa L, Ouahhoud S, et al. Phytochemical analysis, antioxidant activity, and nephroprotective effect of the Raphanus sativus aqueous extract. Mediterr J Chem. 2021;11(84):10–13171. doi:10.13171/mjc02101211565lk. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Taibi M, Elbouzidi A, Ou Yahia D, Dalli M, Bellaouchi R, Tikent A, et al. Assessment of the antioxidant and antimicrobial potential of Ptychotis verticillata Duby essential oil from eastern Morocco: an in vitro and in silico analysis. Antibiotics. 2023;12(4):655. doi:10.3390/antibiotics12040655. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Elbouzidi A, Taibi M, Ouassou H, Ouahhoud S, Ou Yahia D, Loukili EH, et al. Exploring the multi faceted potential of carob (Ceratonia siliqua var. Rahma) leaves from Morocco: a comprehensive analysis of poly-phenols profile, antimicrobial activity, cytotoxicity against breast cancer cell lines, and genotoxicity. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16(6):840. doi:10.3390/ph16060840. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Ferreres F, Grosso C, Gil Izquierdo A, Fernandes A, Valentão P, Andrade PB. Comparing the phenolic profile of Pilocarpus pennatifolius Lem. by HPLC-DAD–ESI/MSn with respect to authentication and enzyme inhi-bition potential. Ind Crops Prod. 2015;77:391–401. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.09.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Perez C. Antibiotic assay by agar well diffusion method. Acta Biol Med Exp. 1990;15:113–5. [Google Scholar]

32. Alqahtani FY, Aleanizy FS, Mahmoud AZ, Farshori NN, Alfaraj R, Al Sheddi ES, et al. Chemical composition and antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti inflammatory activities of Lepidium sativum seed oil. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2019;26(5):1089–92. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.05.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Zarai Z, Boujelbene E, Ben Salem N, Gargouri Y, Sayari A. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of vari-ous solvent extracts, piperine and piperic acid from Piper nigrum. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2013;50(2):634–41. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2012.07.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Remmal A, Bouchikhi T, Rhayour K, Ettayebi M, Tantaoui Elaraki A. Improved method for the determina-tion of antimicrobial activity of essential oils in agar medium. J Essent Oil Res. 1993;5(2):179–84. doi:10.1080/10412905.1993.9698197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lekbach Y, Xu D, El Abed S, Dong Y, Liu D, Khan MS, et al. Mitigation of microbiologically influenced cor-rosion of 304 L stainless steel in the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by Cistus ladanifer leaves extract. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2018;133:159–69. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2018.07.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock REW. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(2):163–75. doi:10.1038/nprot.2007.521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Prastiyanto ME, Tama PD, Ananda N, Wilson W, Mukaromah AH. Antibacterial potential of Jatropha sp. latex against multidrug resistant bacteria. Int J Microbiol. 2020;2020(8):8509650. doi:10.1155/2020/8509650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Lalitha MK. Manual on antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Vellore, India: Department of Microbiology, Christian Medical College; 2004. [Google Scholar]

39. Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):42717. doi:10.1038/srep42717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Pires DE, Blundell TL, Ascher DB. pkCSM: predicting small molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity proper-ties using graph based signatures. J Med Chem. 2015;58(9):4066–72. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Banerjee P, Kemmler E, Dunkel M, Preissner R. ProTox 3.0: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(W1):W513–20. doi:10.1093/nar/gkae303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Soni MG, Carabin IG, Burdock GA. Safety assessment of esters of p hydroxybenzoic acid (parabens). Food Chem Toxicol. 2005;43(7):985–1012. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2005.01.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Wang S, Bilal M, Hu H, Wang W, Zhang X. 4-hydroxybenzoic acid a versatile platform intermediate for value added compounds. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102(8):3561–71. doi:10.1007/s00253-018-8815-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Rémésy C, Jiménez L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(5):727–47. doi:10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Jung DH, Kim EJ, Jung E, Kazlauskas RJ, Choi KY, Kim BG. Production of p hydroxybenzoic acid from p coumaric acid by Burkholderia glumae BGR1. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016;113(7):1493–503. doi:10.1002/bit.25908. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Chen R, Qi QL, Wang MT, Li QY. Therapeutic potential of naringin: an overview. Pharm Biol. 2016;54(12):3203–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

47. Kachmar MR, Oliveira AP, Valentão P, Gil Izquierdo A, Dominguez Perles R, Ouahbi A, et al. HPLC DAD ESI/MSn phenolic profile and in vitro biological potential of the aqueous extract of Centaurium erythraea Rafn. Food Chem. 2019;278:424–33. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Kou Y, Jing Q, Yan X, Chen J, Shen Y, Ma Y, et al. 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid restrains priming and activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome by disrupting PU.1 DNA binding activity and by direct antioxidation. Chem Biol Interact. 2024;404(8):111262. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2024.111262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Kiliç I, Yeşiloğlu Y. Spectroscopic studies on the antioxidant activity of p-coumaric acid. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2013;115:719–24. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2013.06.110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Tusevski O, Kostovska A, Iloska A, Trajkovska L, Simic SG. Phenolic production and antioxidant properties of some Macedonian medicinal plants. Cent Eur J Biol. 2014;9(9):888–900. doi:10.2478/s11535-014-0322-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Bouyahya A, Belmehdi O, El Jemli M, Marmouzi I, Bourais I, Abrini J, et al. Chemical variability of Centau-rium erythraea essential oils at three developmental stages and their in vitro antioxidant, antidiabetic, der-matoprotective and antibacterial activities. Ind Crops Prod. 2019;132:111–7. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.01.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Kosová M, Hrádková I, Mátlová V, Kadlec D, Šmidrkal J, Filip V. Antimicrobial effect of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid ester with glycerol. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2015;40(4):436–40. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Pisoschi AM, Pop A. The role of antioxidants in the chemistry of oxidative stress: a review. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;97(Suppl. 1):55–74. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.04.040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Lonkar P, Dedon PC. Reactive species and DNA damage in chronic inflammation: reconciling chemical mechanisms and biological fates. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(9):1999–2009. doi:10.1002/ijc.25815. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Afzal M, Ahmed E, Sharif A, Khan IH, Javaid A. Evaluation of antifungal potential and phytochemical analysis of a medicinal herb, Centaurium erythraea. Pak J Weed Sci Res. 2022;28(3):295–303. doi:10.28941/pjwsr.v28i3.1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Hetta HF, Melhem T, Aljohani HM, Salama A, Ahmed R, Elfadil H, et al. Beyond conventional antifungals: combating resistance through novel therapeutic pathways. Pharmaceuticals. 2025;18(3):364. doi:10.3390/ph18030364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Chandran K, Shane DI, Zochedh A, Sultan AB, Kathiresan T. Docking simulation and ADMET prediction-based investigation on the phytochemical constituents of Noni (Morinda citrifolia) fruit as a potential anti-cancer drug. Silico Pharmacol. 2022;10(1):14. doi:10.1007/s40203-022-00130-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Daina A, Zoete V. A BOILED Egg to predict gastrointestinal absorption and brain penetration of small mole-cules. ChemMedChem. 2016;11(11):1117–21. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201600182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Merimi C, Benabbou A, Fraj E, Khibech O, Yahyaoui MI, Asehraou A, et al. Valorization of imidazolium-based salts as next-generation antimicrobials: integrated biological evaluation, ADMET, molecular docking, and dynamics studies. ASEAN J Sci Eng. 2026;6(1):11–34. doi:10.17509/ajse.v6i1.89789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Merzouki M, Khibech O, Fraj E, Bouammali H, Bourhou C, Hammouti B, et al. Computational engineering of malonate and tetrazole derivatives targeting SARS CoV 2 main protease: pharmacokinetics, docking, and molecular dynamics insights to support the sustainable development goals (SDGswith a bibliometric analysis. Indones J Sci Technol. 2025;10(2):399–418. doi:10.17509/ijost.v10i2.85146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Suwardi S, Salim A, Mahendra JA, Wijayanto DB, Rochiman NA, Anam SK, et al. Virtual screening, pharma-cokinetic prediction, molecular docking and dynamics approaches in the search for selective and potent nat-ural molecular inhibitors of MAO B for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Indo J Chem Environ. 2023;6(2):95–110. doi:10.21831/ijoce.v6i2.68338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Merzouki M, Khibech O, Bouammali H, El Farh L, Challioui A, Bouammali B. Chromone-thiophene hybrids as non peptidic inhibitors of SARS CoV 2 Mpro: integrated ADME, docking, and molecular dynamics approach. J Biochem Technol. 2025;16(2):1–10. [Google Scholar]

63. Chatterjee S, Rankin JA, Farrugia MA, Rifayee SJB, Christov CZ, Hu J, et al. Biochemical, structural, and conformational characterization of a fungal ethylene forming enzyme. Biochemistry. 2025;64(9):2054–67. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.5c00038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Et Tazy L, Fedeli R, Khibech O, Lamiri A, Challioui A, Loppi S. Effects of monoterpene based biostimulants on chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) plants: functional and molecular insights. Biology. 2025;14(6):657. doi:10.3390/biology14060657. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Touam S, Nacer H, Ziani N, Lebrazi N, Kertiou N, Khibech O, et al. Prediction of surface tension of propane derivatives using QSPR approach and artificial neural networks. Mor J Chem. 2025;13(2):653–66. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools