Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Combination of Appropriate Drip Irrigation and Straw Mulching Increased the Yield of Maize

1 Institute of Agricultural Resources and Environment, Jilin Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Changchun, 130033, China

2 Agronomy College, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun, 130118, China

3 College of Life Science and Resources and Environment, Yichun University, Yichun, 336000, China

4 Jilin Agriculture Science and Technology College, Jilin, 132101, China

5 Jilin Engineering Vocational College, Siping, 136001, China

* Corresponding Authors: Lihua Zhang. Email: ; Hongxiang Zhao. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Abiotic Stress in Agricultural Crops)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3703-3719. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.071324

Received 05 August 2025; Accepted 07 November 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Optimizing drip irrigation with straw mulch return represents a promising sustainable intensification strategy for revolutionizing regional water management. This 2-year controlled field experiment examined straw incorporation effects (removal and return) and drip irrigation levels (200, 350, 500 mm) on maize carbon-nitrogen metabolism, root bleeding sap characteristics, dry matter accumulation, and yield. Dry matter and yield increased with irrigation amount. Under 200–350 mm irrigation, straw return enhanced root bleeding intensity; elevated nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium concentrations in bleeding sap; and promoted soluble sugar and hydrolyzed amino acid contents, establishing material foundations for yield formation. Straw mulching increased cytokinin while reducing abscisic acid content, delaying senescence. Leaf activities of nitrate reductase, glutamine synthetase, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase significantly increased under straw return, enhancing photosynthesis and improving 100-grain weight, ear length, ear diameter, and yield while decreasing bald tip length. Low irrigation amplified straw return benefits on maize growth and metabolism, whereas high irrigation negated these effects. Therefore, combining drip irrigation with straw return provides scientific foundations for water resource management in Jilin Province and theoretical bases for sustainable agricultural development in water-limited regions.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileMaize (Zea mays L.) serves as a crucial global cereal crop, providing direct food sources and indirect applications as feed and raw material [1]. As China’s most widely cultivated crop with highest grain output, it plays a vital role in food security [2]. Northeast China, particularly Jilin Province—one of three global maize golden belts alongside Ukraine and the Americas—significantly impacts China’s food security and crop trade [3,4]. However, climate change has caused uneven precipitation distribution in central and western Jilin, with alternating precipitation patterns and increasing reproductive-stage drought occurrence. Water scarcity severely affects maize growth and development. While irrigation is key to yield improvement, China’s irrigation efficiency (52%) lags behind developed countries (70%–80%) [5]. Drip irrigation offers superior water and fertilizer utilization efficiency with increased yields compared to other water-saving methods [6,7], making it the most widely adopted strategy in Northeast China [8].

Water conservation strategies maximize soil moisture and efficient rainwater use, reduce irrigation requirements, and enhance irrigation water use efficiency [9]. Mulching is a widely adopted agricultural production technique used globally to conserve soil moisture and enhance agricultural productivity. Particularly in rain-fed dryland farming regions, the application of effective mulching techniques and methods reduces water loss from both soil and crops, improves water use efficiency, thereby meeting the crucial research objectives of water conservation and yield increase [10,11]. Straw mulch return is an effective strategy for sustainable agriculture due to soil organic matter accumulation, which can be readily decomposed. Straw mulching is a dual-purpose technique that provides both conservation and productivity benefits [12,13]. Straw mulching plays a prominent role in increasing yield and efficiency, as well as conserving water and reducing erosion [14,15]. When combined with technologies such as no-till farming and water-saving irrigation, it can produce synergistic effects. Franco et al. [16] confirmed that this model effectively improved the sustainability of corn production in the semi-arid Mediterranean region.

The development of crop root systems is closely related to the growth of aboveground parts, with root activity determining nutrient and water absorption efficiency as well as yield levels [17–19]. Root bleeding sap can serve as physiological indicators for evaluating root activity intensity, and their nutrient concentrations reflect crop nutritional status and root function [20,21]. Studies have shown that straw mulch return improves soil fertility and soil productivity [22,23]. Straw carbon (C) inputs provide additional organic matter, supplementing soil nutrients and increasing crop yields [24]. Research by Mubarak et al. indicated that the combined effect of straw mulching and irrigation regimes enhanced variation in the nutrient utilization and productivity of maize [25]. The study by Niknam et al. [26] demonstrated that the interaction between straw mulching and pre-sowing irrigation successfully enhanced maize physiological indicators, yield, and water productivity. In summary, the combination of straw mulching and drip irrigation has a certain positive impact on maize production.

Straw mulch return has been widely implemented in the central and western parts of Jilin Province. However, natural precipitation in this area has been consistently insufficient over the years. Shifts in annual precipitation patterns cause intermittent drought during the maize reproductive period, making supplemental irrigation crucial for stable production. Drip irrigation has emerged as a water-saving technology that allows precise control of water supply, but its optimal management under local conditions requires further research. Despite extensive research on drip irrigation and straw mulching, some aspects remain insufficient. (1) Research on the effects of straw mulching and drip irrigation levels on carbon and nitrogen metabolism in maize is limited. (2) The physiological responses of maize roots (characteristics of root bleeding sap) to straw mulching and drip irrigation levels remain unclear. (3) There is limited research on the effects of straw mulching and drip irrigation levels on maize growth and yield formation. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the effects of straw mulch return to the field under different irrigation conditions on maize growth and development to increase the yield in this region. This study adopted a controlled field experiment approach to evaluate the changes in root bleeding sap characteristics, leaf C and nitrogen (N) metabolism, and yield components in maize under different drip irrigation amounts and straw management methods. The mechanisms by which root bleeding sap regulates aboveground biomass accumulation were determined under different interaction modes, providing a theoretical basis for combining straw mulching with drip irrigation in the central and western regions of Jilin Province.

2.1 Overview of the Experimental Site

Experiments were conducted at Crop Water Nursery Farm, Gongzhuling, Jilin Province (124.81°42′ E, 43.52°06′ N) during 2023–2024. Initial soil properties are shown in Table S1.

Maize variety ‘Xiangyu 218’, which is commonly planted in Jilin Province, was used in the experiments. This variety is a mid- to late-maturing variety with a growth period of 132 days. The experiment was carried out in a fully open, removable rain shelter (the shelter could be completely closed within 15 min to avoid precipitation) in the nursery. Each plot had an area of 24 m2. Two factors were evaluated in the experiment: straw return (straw removal and straw mulch return) and drip irrigation amount (500, 350, and 200 mm). The 500 mm treatment approximated regional decade-average rainfall (470 mm) during the growing season, establishing it as the maximum irrigation level. Drip irrigation tape was positioned 5 cm laterally from planting strips, with water meters installed at each plot inlet to monitor irrigation volumes. The irrigation system was consistent across both years (Table 1). Straw removal from the field refers to the manual removal of all straw after harvest; straw mulch return to the field refers to crushed straw (≤10 cm) being used to cover the entire plot after harvest. The irrigation regime was consistent for 2 years (Table S2), with the first irrigation coinciding with the sowing dates, which were 10 May 2023 and 08 May 2024. Two straw management practices were utilized: straw removal and straw mulching return. Straw removal involved the complete removal of all straw from the plots after maize harvest. Straw mulching return involved chopping the straw to ≤10 cm in length and then spreading it over the plots after maize harvest. The experiment included a total of six treatments: A1 (straw removal, 200 mm irrigation), S1 (straw mulching return, 200 mm), A2 (straw removal, 350 mm), S2 (straw mulching return, 350 mm), A3 (straw removal, 500 mm), and S3 (straw mulching return, mm). Each treatment consisted of 3 pools, amounting to 18 pools in total. The spacing for maize planting is 60 cm, with a density of 65,000 plants/ha. The maize harvest dates were 29 September 2023 and 08 October 2024. The compound fertilizer (28N-10P-14K) utilized was produced by Gongzhuling Difu Fertilizer Technology Co., Ltd., with a basal fertilizer application rate of 750 kg/hm2. Field management strictly adhered to the local farmers’ management practices. The flowchart of this experiment is presented in Fig. S1.

2.3.1 Determination of Root Bleeding Intensity and Component Content

During 2023–2024, three maize plants per plot were collected at V8, R1, and R3 stages for root bleeding analysis. Plants were cut 5 cm above roots, sealed in bags with defatted cotton, and weighed before (W0) and after 4–6 h collection (W1). Bleeding strength was calculated as (W1-W0)/T. Root sap was analyzed via ELISA for soluble sugar, ABA, cytokinin, and free amino acids, while mineral elements (K, Ca, Mg, P, N) in V8 samples were determined using ICP-MS.

2.3.2 Enzyme Activity Related to Leaf Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism

Three plants per plot were sampled at R1 stage (2023–2024) from leaf positions identical to photosynthesis measurements. ELISA determined activities of RuBP, PEP, NR, and GS enzymes.

Net photosynthetic rate (Pn) was measured using Li-6400XT system on three maize plants per plot at V8, R1, and R3 stages. Upper leaves (V8) and ear leaves (R1, R3) were measured under 400 ± 5 μmol∙mol−1 CO2 and 1800 μmol∙m−2·s−1 light intensity.

During 2023–2024, three representative plants per treatment were sampled at V8, R1, R3, and R6 stages. Samples were segmented, bagged, and oven-dried (105°C for 30 min, then 80°C to constant weight) for biomass determination using precision balance.

2.3.5 Yield and Yield Components

At R6 stage (2023–2024), three 5 m2 areas per treatment were harvested for yield assessment. Ear fresh weight, number, and kernel moisture content were recorded. Yield was calculated at 14% moisture using 10 representative cobs, which were also analyzed for 100-grain weight, bald tip length, spike length, and diameter.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 23.0 following Excel organization. Two-way ANOVA examined straw treatment and irrigation effects with their interactions. Duncan’s test and t-tests compared treatment differences at p < 0.05. Graphs were created using Origin 2021.

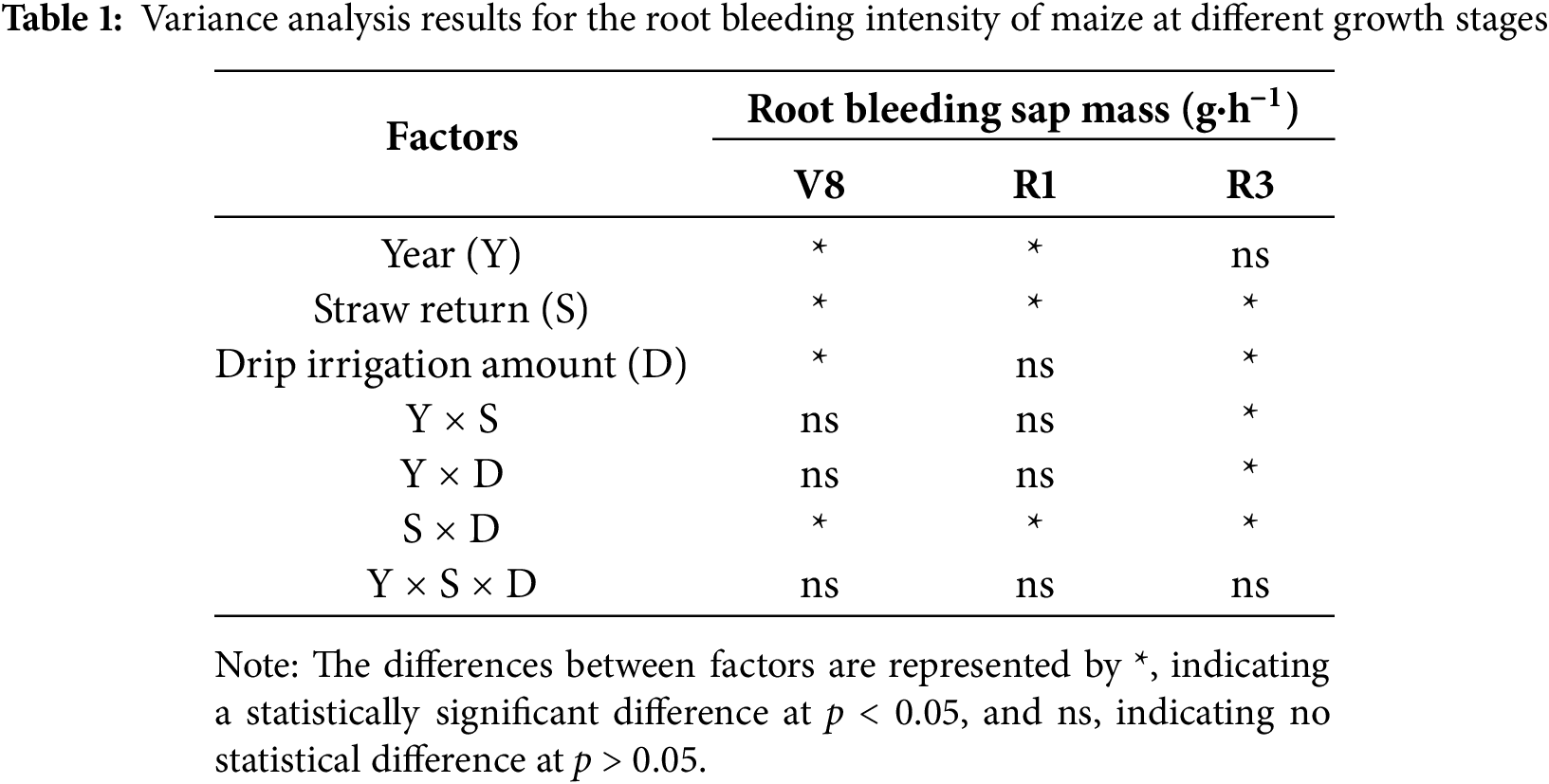

Root bleeding intensity showed an increasing trend at each reproductive period. Straw mulch return had a certain effect on the root bleeding intensity of maize, and a higher drip irrigation amount increased the root bleeding intensity of maize (Fig. 1). In 2023 and 2024, the root bleeding intensity of the A3 and S3 treatments was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than that under the A1 and S1 treatments. During the 2-year period, at stages R1 and R3, compared with straw removal, straw mulch return significantly (p < 0.05) promoted the root bleeding intensity, with increases of 11.59%–17.36% in 2023 and 15.42%–23.53% in 2024.

Figure 1: Effects of the drip irrigation amount and straw return on root bleeding intensity in maize. Note: Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among straw treatments within irrigation levels; lowercase letters show differences between irrigation treatments within straw methods

Straw return significantly affected root bleeding intensity at V8, R1, and R3 stages, while year effects were significant at V8 and R1 (Table 1). Irrigation significantly influenced bleeding intensity at V8 and R3. Irrigation straw interactions were significant across all growth stages, but three-way interactions were not.

3.2 Hormone Content in the Root Bleeding Sap

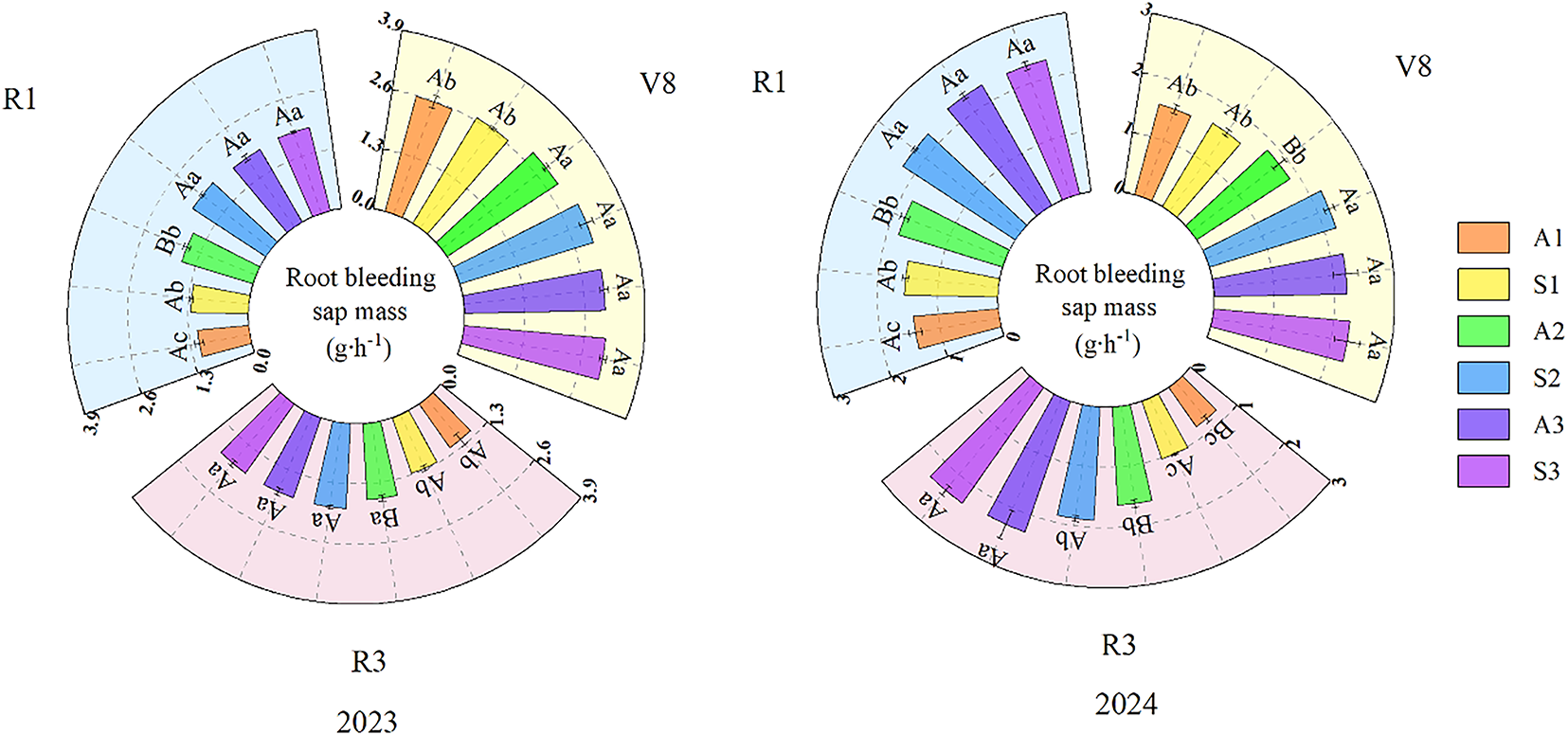

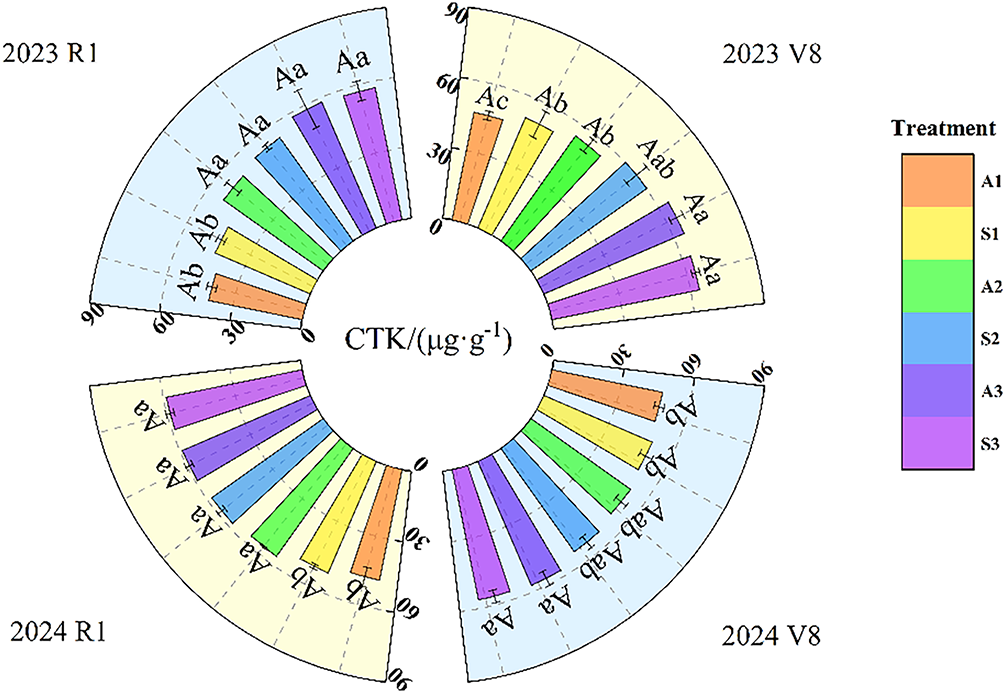

CTK content increased with irrigation amount over both years (Fig. 2). A3 and S3 treatments showed significantly higher CTK levels (p < 0.05) than A1 and S1. Straw mulching had no significant effect versus straw removal.

Figure 2: Effects of the drip irrigation amount and straw return on the cytokinin (CTK) content in maize root bleeding sap. Note: Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among straw treatments within irrigation levels; lowercase letters show differences between irrigation treatments within straw methods

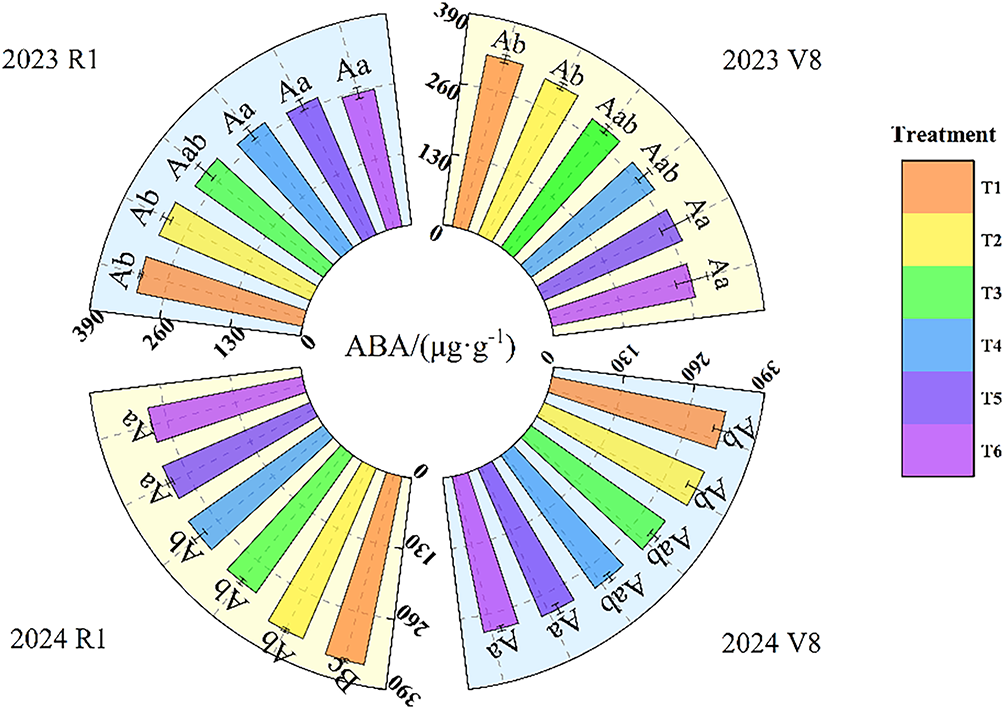

In 2023 and 2024, the ABA content in the root bleeding sap showed a decreasing trend with the increase in the drip irrigation amount (Fig. 3). In 2023 and 2024, the ABA content in the root bleeding sap of the A3 and S3 treatments was significantly lower (p < 0.05) than that under the A1 and S1 treatments. The two-year results showed that compared with straw removal, straw mulching did not significantly affect ABA content.

Figure 3: Effects of the drip irrigation amount and straw return on the abscisic acid (ABA) content in maize root bleeding sap. Note: Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among straw treatments within irrigation levels; lowercase letters show differences between irrigation treatments within straw methods

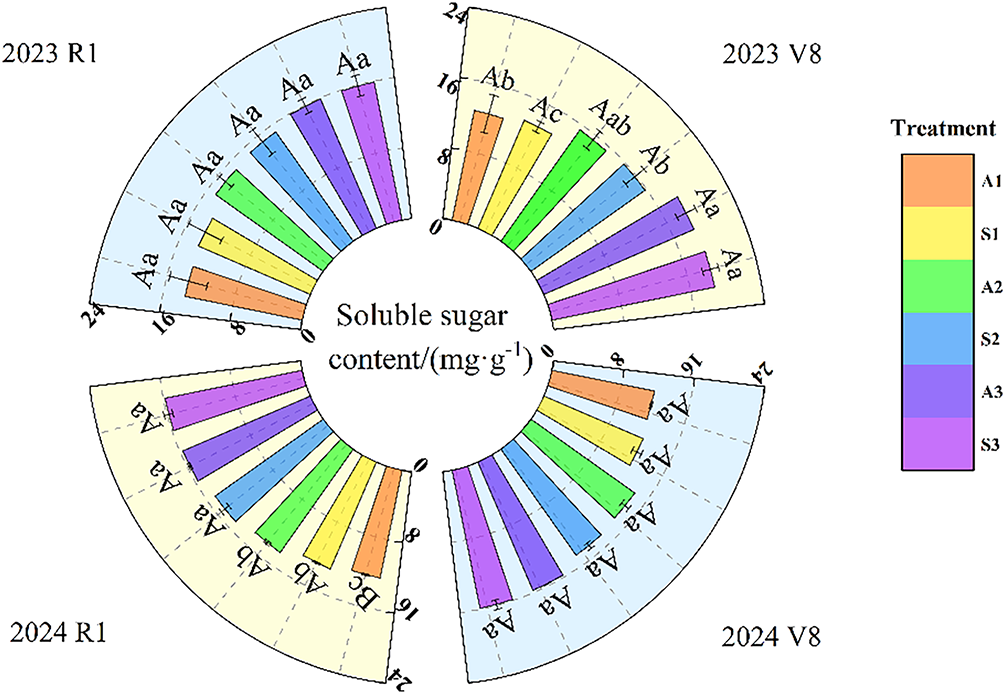

3.3 Soluble Sugar and Amino Acid Contents in Root Bleeding Sap

Soluble sugar content increased with irrigation amount (Fig. 4). A3 and S3 treatments significantly exceeded A1 and S1 (p < 0.05) during V8 2023 and R1 2024. Straw management effects were non-significant across both years.

Figure 4: Effects of the drip irrigation amount and straw return on the soluble sugar content in maize root bleeding sap. Note: Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among straw treatments within irrigation levels; lowercase letters show differences between irrigation treatments within straw methods

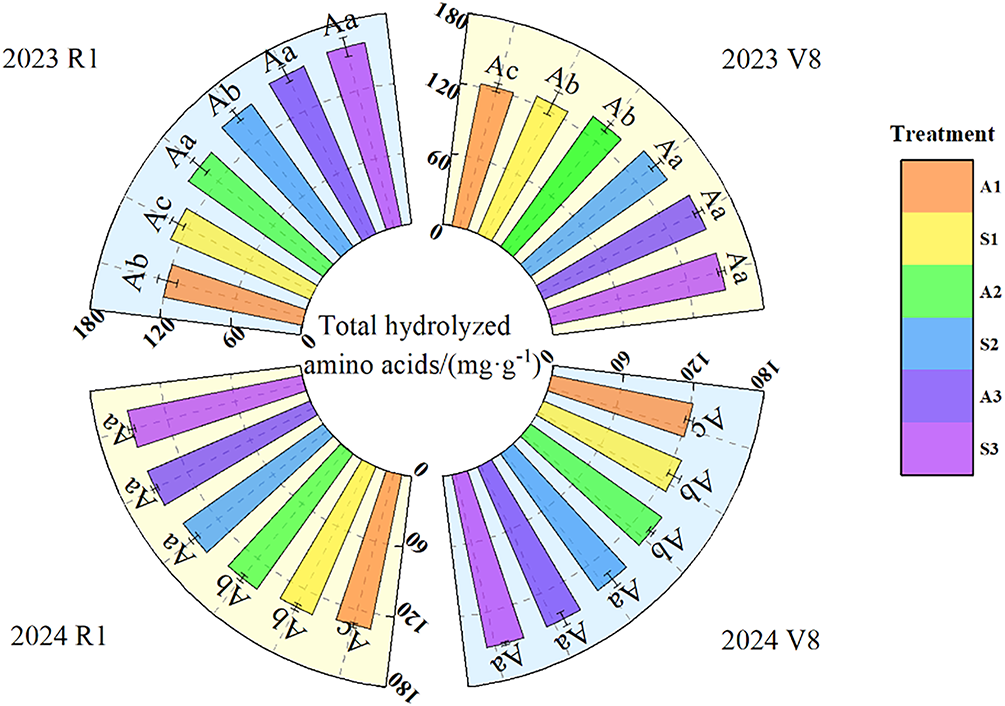

The hydrolyzed amino acid content in the root bleeding sap increased with the increase in the drip irrigation amount (Fig. 5). In 2023 and 2024, the hydrolyzed amino acid content in the root bleeding sap under the A3 and S3 treatments was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than that of the A1 and S1 treatments. The two-year results showed that compared with straw removal, straw mulching did not significantly affect the hydrolyzed amino acid content of root bleeding sap.

Figure 5: Effects of the drip irrigation amount and straw return on the hydrolyzed amino acid content in maize root bleeding sap. Note: Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among straw treatments within irrigation levels; lowercase letters show differences between irrigation treatments within straw methods

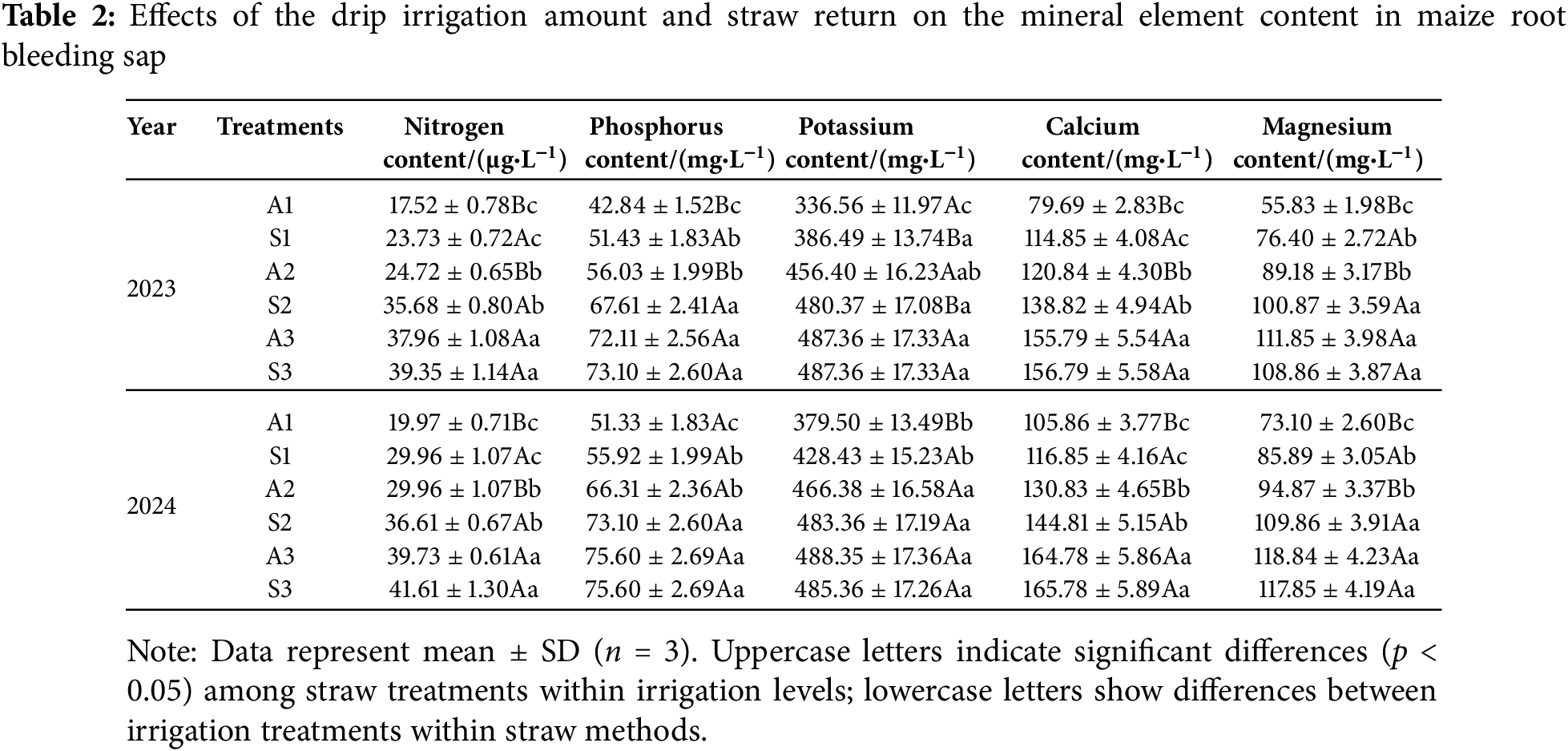

3.4 Mineral Element Contents in Root Bleeding Sap

N and P contents were significantly higher in A3 and S3 versus A1 and S1 treatments across both years (Table 2). Straw mulching significantly increased N content at 200 and 350 mm irrigation. K content in A3 exceeded A1, while Ca and Mg in A3 surpassed A1 and A2. Under straw treatments, S3 Ca and Mg contents were higher than S1 and S2, with S treatments generally exceeding corresponding A treatments (p < 0.05).

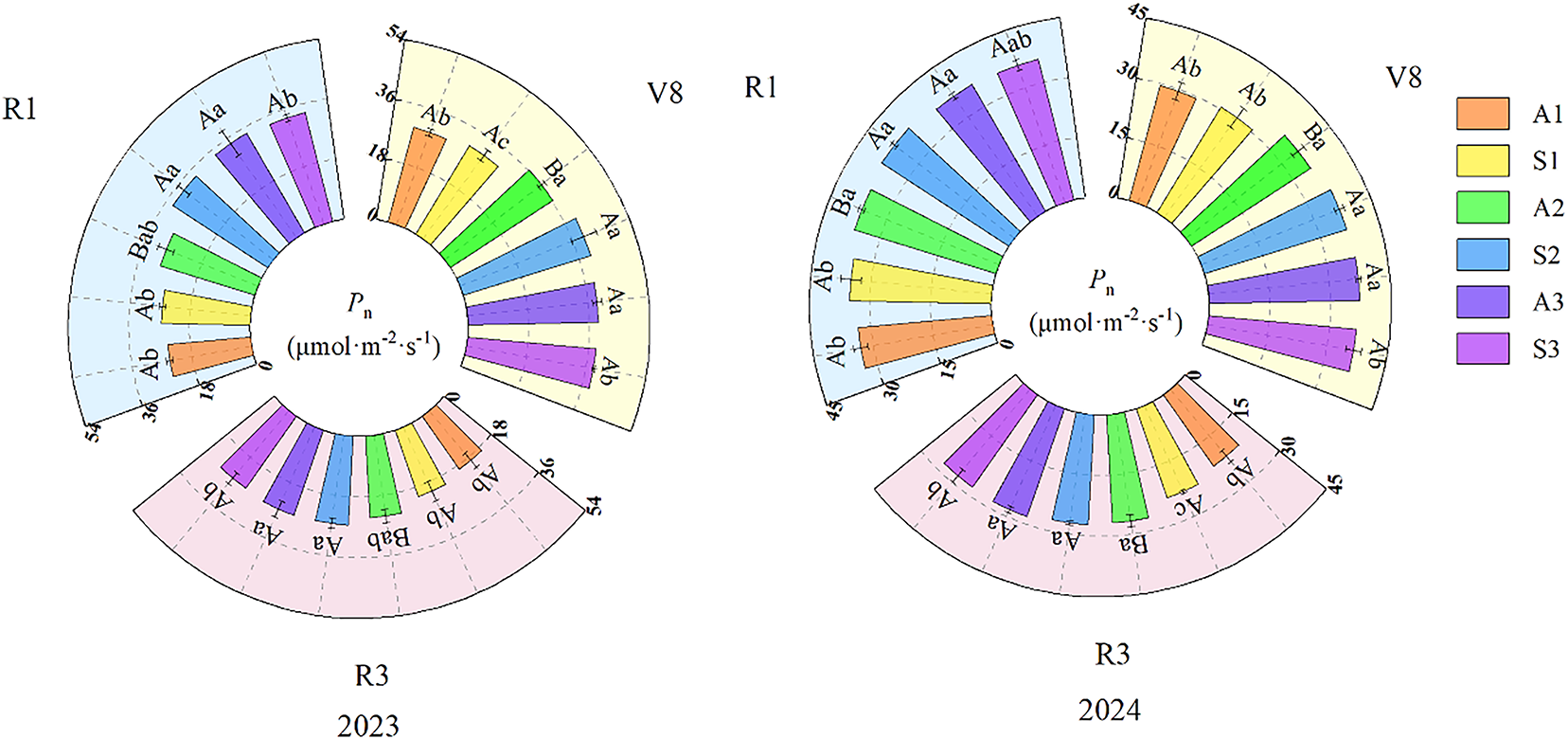

3.5 Net Photosynthetic Rate of Leaves

Photosynthetic rates were relatively stable until R3 when decline occurred (Fig. 6). Increasing irrigation and straw mulching both improved leaf Pn. A3 and S3 significantly outperformed A1 and S1 at V8 and R3, while S2 exceeded A2 during V8-R1 stages (p < 0.05).

Figure 6: Effects of the drip irrigation amount and straw return on the net photosynthetic rate of maize leaves. Note: Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among straw treatments within irrigation levels; lowercase letters show differences between irrigation treatments within straw methods

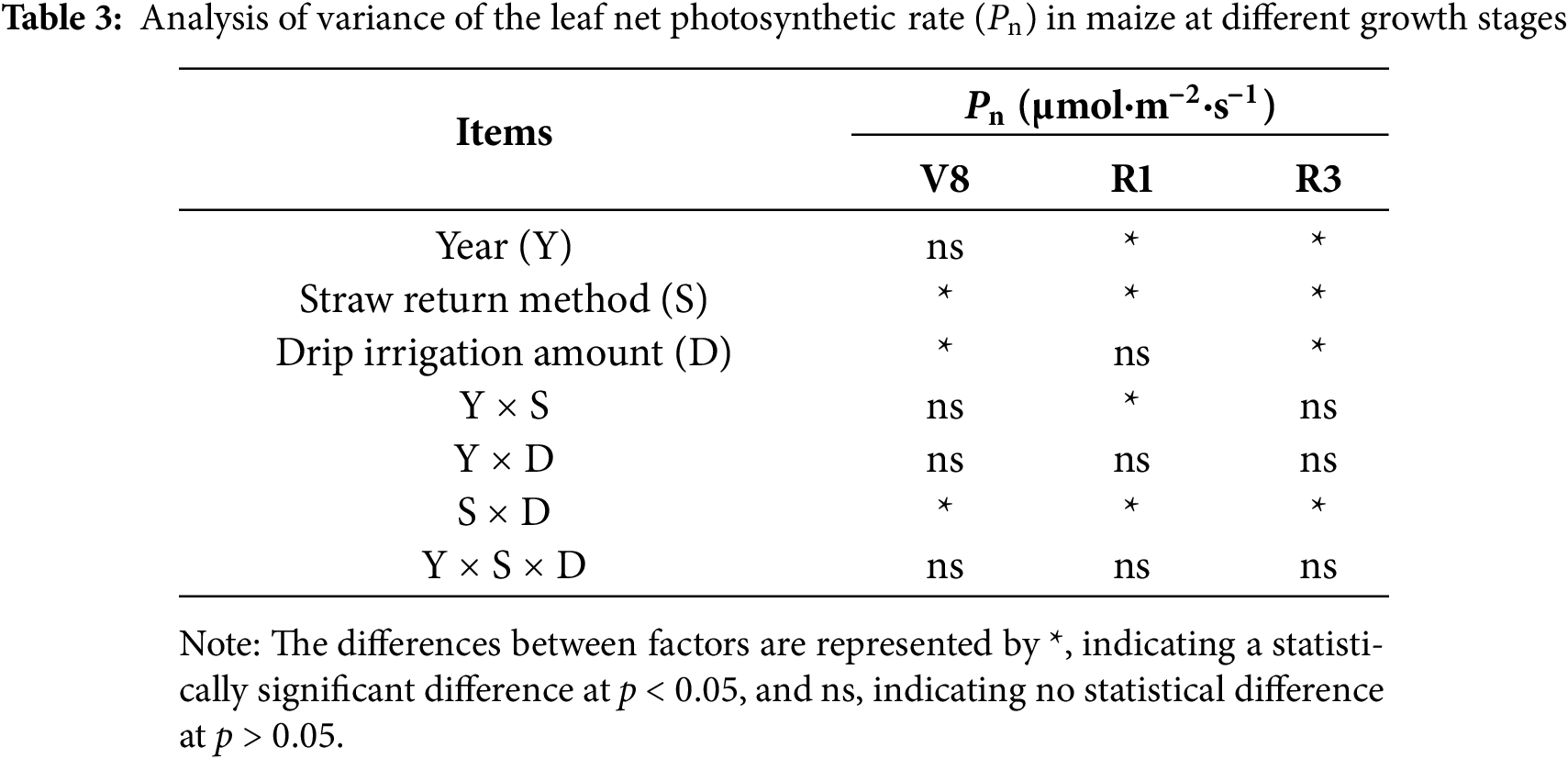

Both straw return and irrigation amount significantly influenced leaf Pn throughout V8, R1, and R3 stages, whereas year showed significance only during R1 and R3 (Table 3). Two-way interactions between irrigation and straw return were significant across all stages, while three-way interactions proved non-significant.

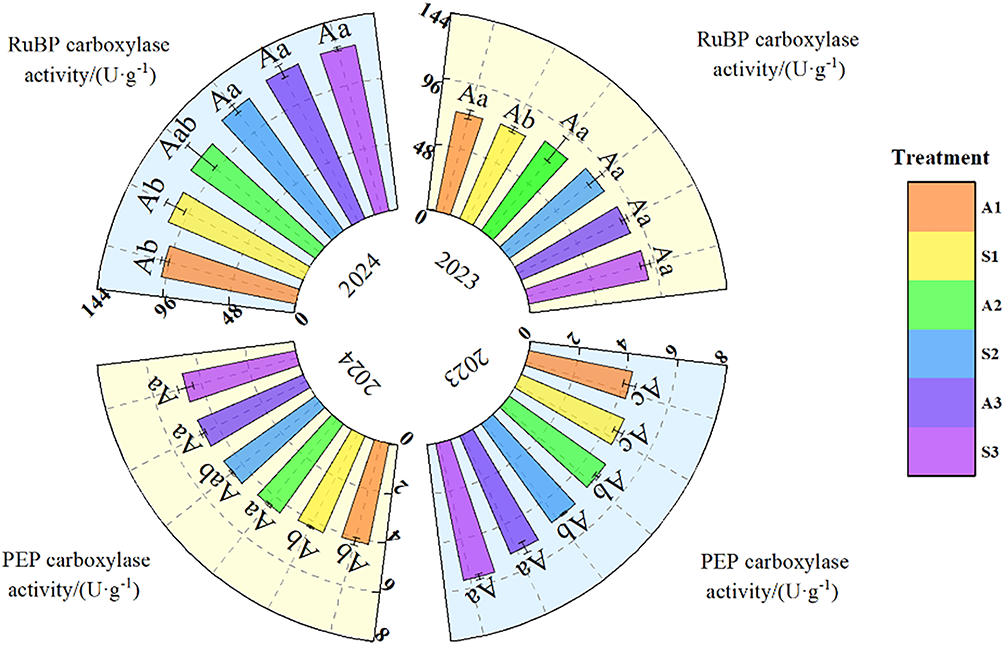

3.6 Enzyme Activity Related to Leaf Carbon Metabolism

The RuBP carboxylase and PEP carboxylase activities in maize leaves showed an increasing trend with the increase in the drip irrigation amount (Fig. 7). Under the same drip irrigation amount, the RuBP carboxylase and PEP carboxylase activities increased after straw mulch return. Compared to A1, S1 resulted in an average increase of 4.40% in RuBP carboxylase activity and 4.07% in PEP carboxylase activity over 2 years. Similarly, compared to A2, S2 led to an average increase of 6.03% in RuBP carboxylase activity and 2.75% in PEP carboxylase activity over 2 years. The RuBP carboxylase and PEP carboxylase activities were significantly higher (p < 0.05) under A3 and S3 than under A1 and S1.

Figure 7: Effects of the drip irrigation amount and straw return on the activities of carbon metabolism-related enzymes in maize leaves. Note: Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among straw treatments within irrigation levels; lowercase letters show differences between irrigation treatments within straw methods

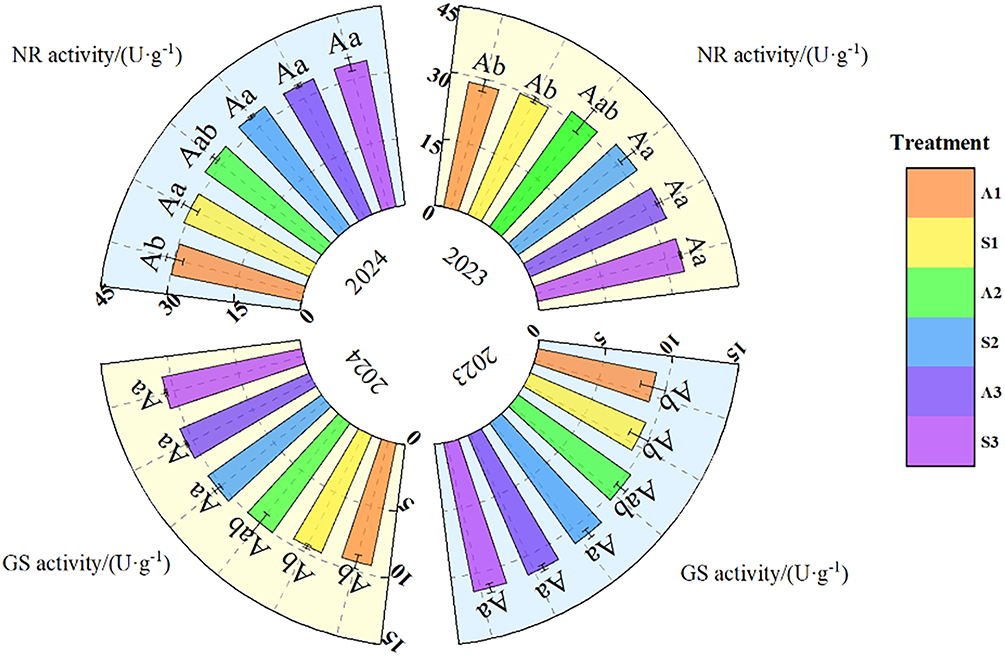

3.7 Enzyme Activity Related to Leaf Nitrogen Metabolism

The NR and GS activities in maize leaves showed an increasing trend with the increase in the drip irrigation amount (Fig. 8). Under the same drip irrigation amount, the NR and GS activities increased after straw mulch return, mainly under S1 and S2. Compared to A1, S1 showed an average increase of 3.03% in NR activity and 3.17% in GS activity over 2 years. Similarly, compared to A2, S2 demonstrated an average increase of 3.07% in NR activity and 5.81% in GS activity over the same period. The NR and GS activities were significantly higher (p < 0.05) under A3 and S3 than under A1 and S1.

Figure 8: Effects of the drip irrigation amount and straw return on nitrogen metabolism-related enzyme activities in maize leaves. Note: Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among straw treatments within irrigation levels; lowercase letters show differences between irrigation treatments within straw methods

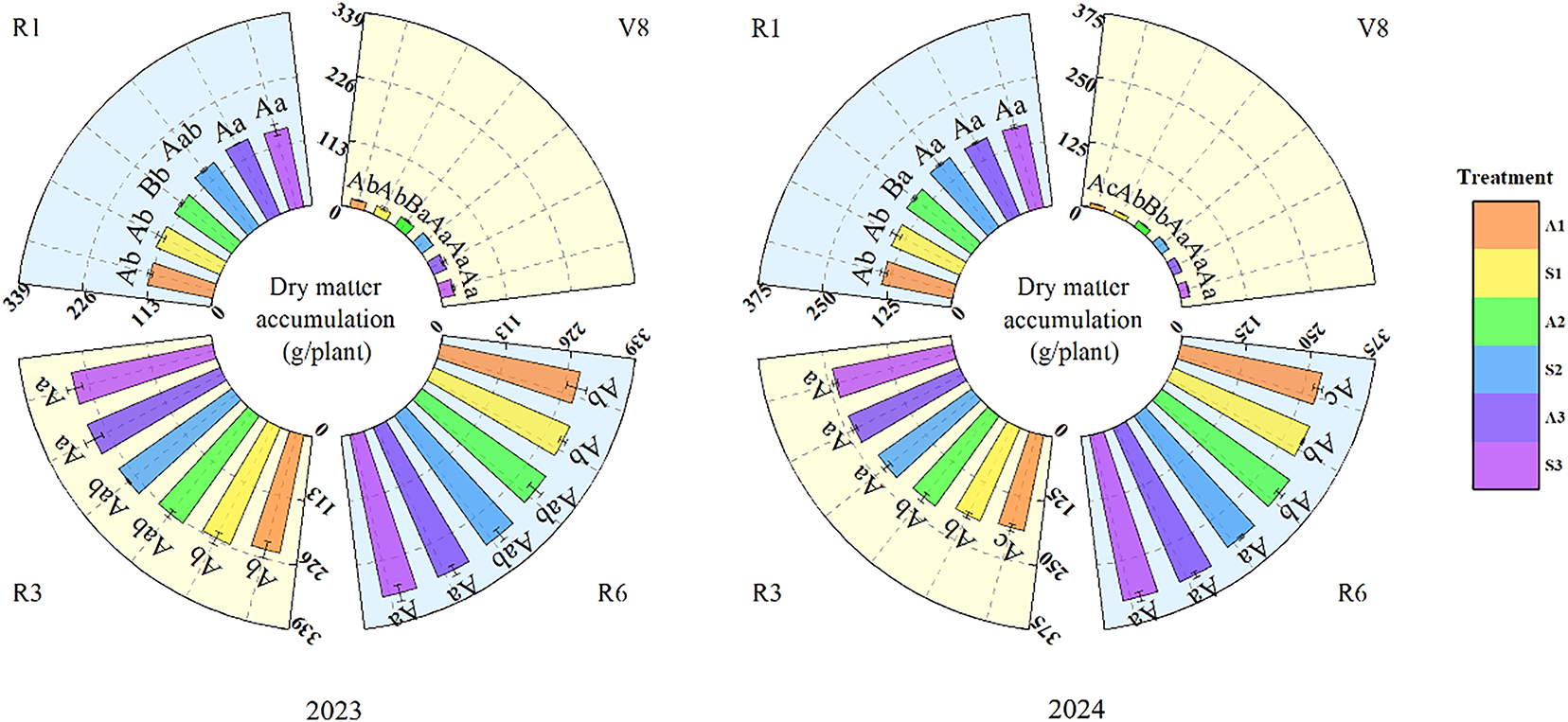

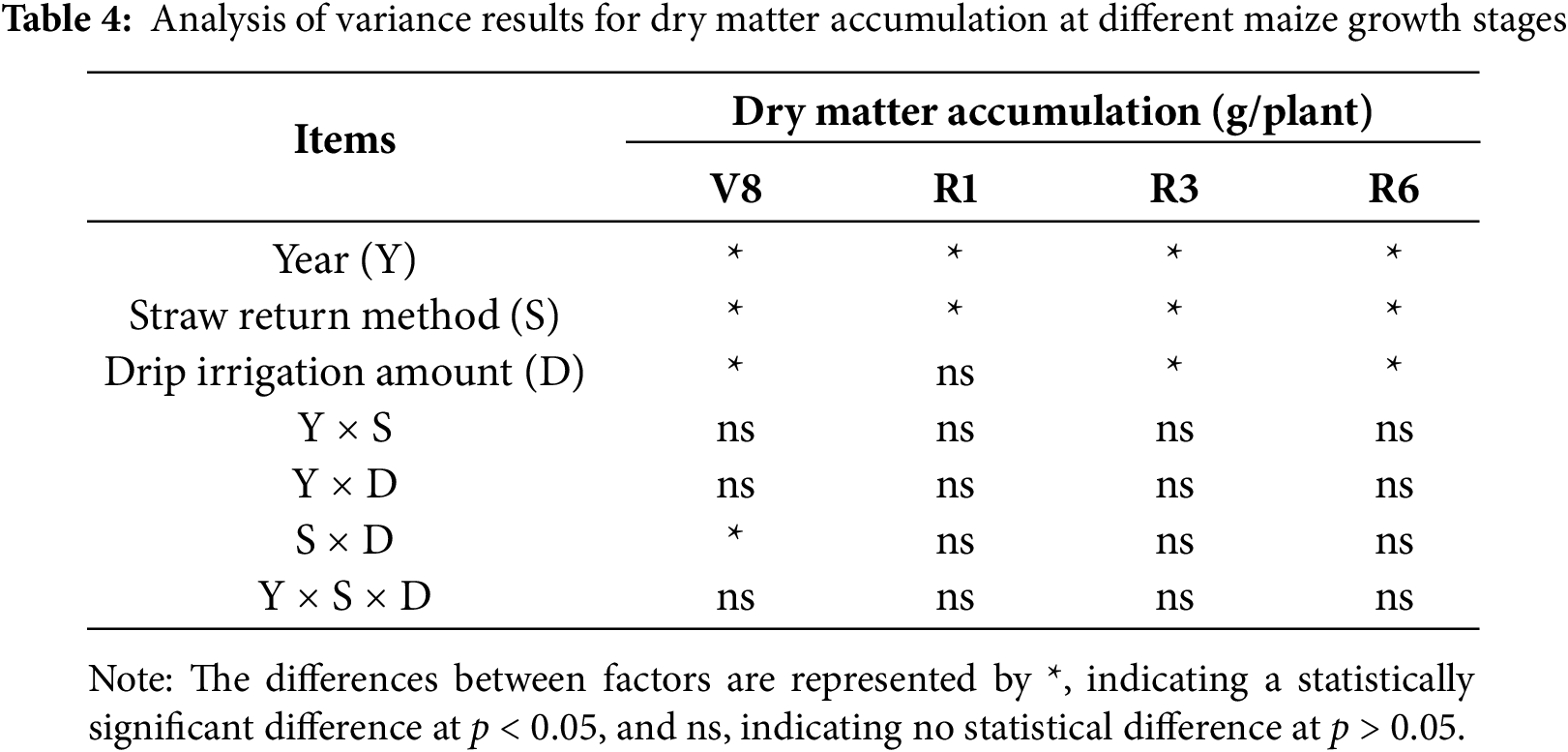

Irrigation amount and straw mulching significantly enhanced dry matter accumulation throughout maize development (Fig. 9). Treatment differences ranged from 12%–99%, with early stages showing greatest responses. Straw benefits were evident even at moderate irrigation levels (p < 0.05).

Figure 9: Effects of the drip irrigation amount and straw return on the dry matter accumulation in maize. Note: Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among straw treatments within irrigation levels; lowercase letters show differences between irrigation treatments within straw methods

The effects of year and straw return on maize dry matter accumulation reached a significant level at the V8, R1, R3, and R6 stages, but the effect of the drip irrigation amount was only significant at the V8, R3, and R6 stages (Table 4).

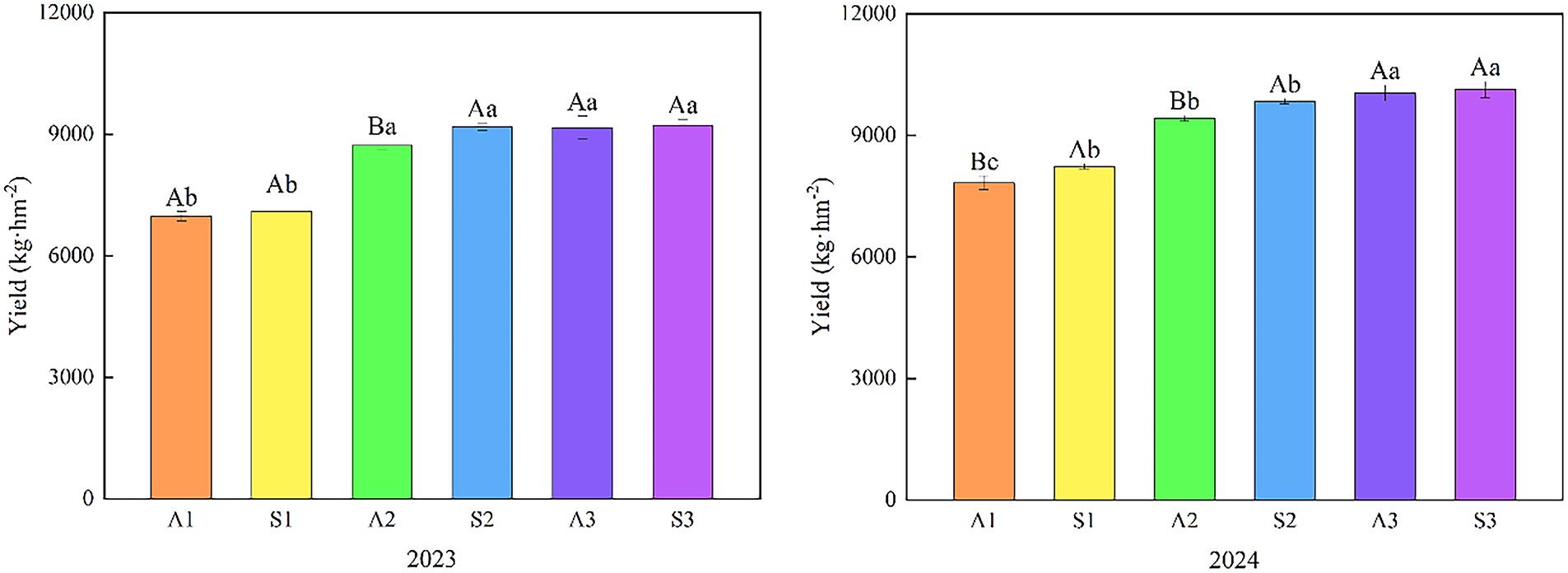

Maize yield increased with irrigation amount, while straw mulching effects varied (Fig. 10). A2 and A3 significantly exceeded A1 by 20%–32% across both years. S2 and S3 surpassed S1 by 23%–30%, though S2 benefits were inconsistent between years. S2 consistently exceeded A2 by 4%–5% (p < 0.05).

Figure 10: Effects of the drip irrigation amount and straw return on maize yield. Note: Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) among straw treatments within irrigation levels; lowercase letters show differences between irrigation treatments within straw methods

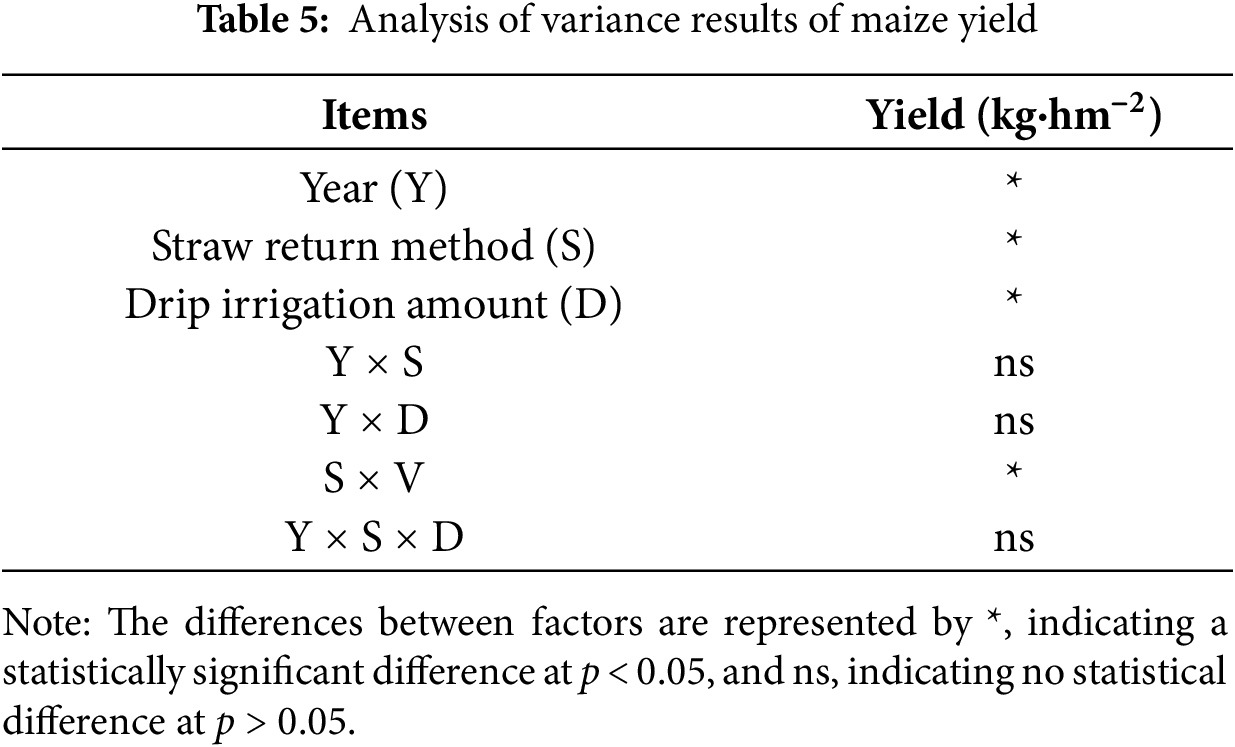

The results showed that the year, irrigation amount, and straw return method all affected the yield of maize at a significant level (p < 0.05) (Table 5). The combined influence of irrigation amount and straw return method on the maize yield also reached significance (p < 0.05).

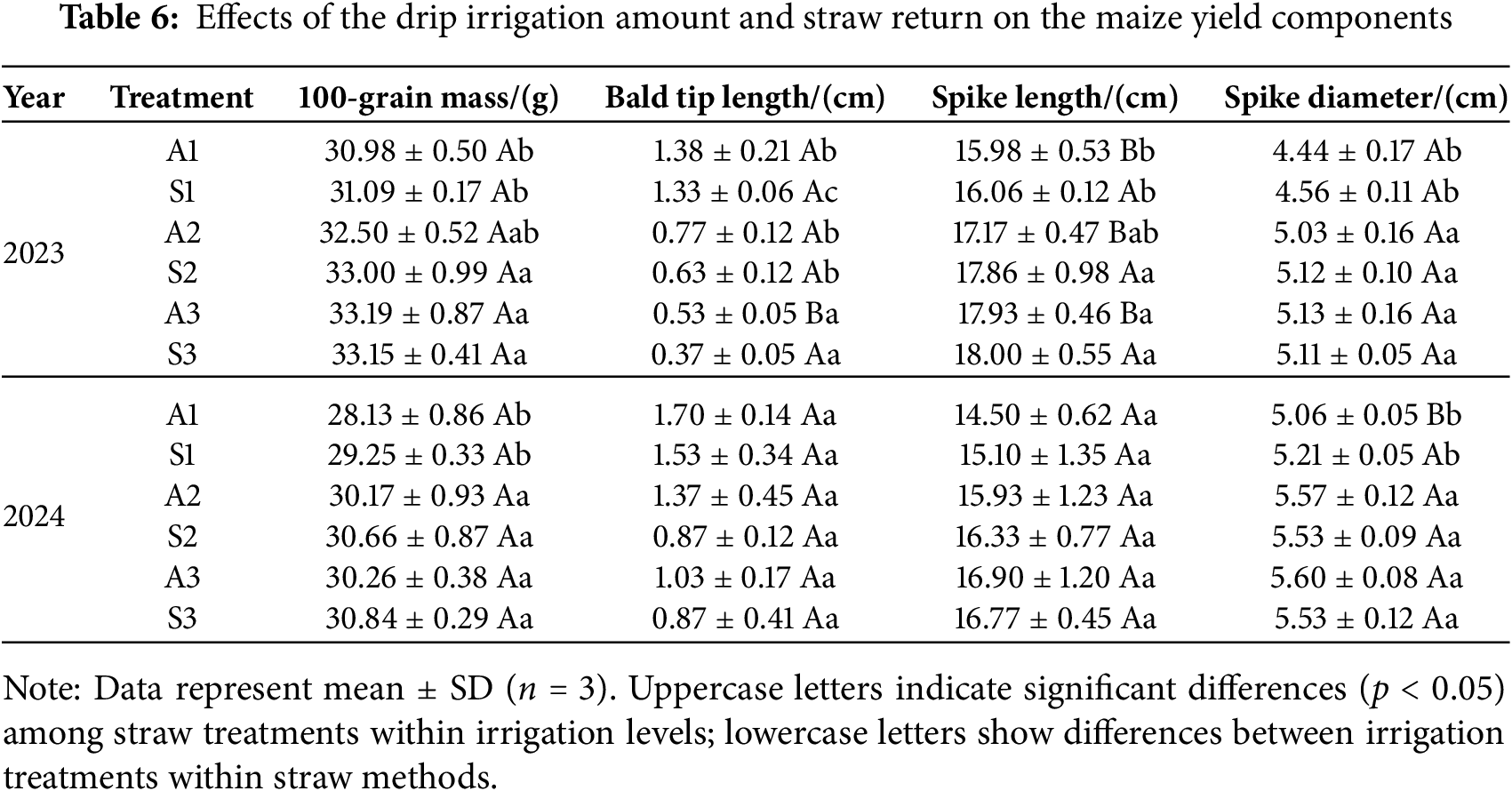

Irrigation and straw mulching interactions significantly affected yield components (Table 6). High irrigation treatments A3 and S3 consistently improved 100-grain weight and spike diameter compared to low irrigation, while A1 and S1 showed greater bald tip length in 2023. Medium irrigation treatments also enhanced these components in 2024 (p < 0.05).

Straw mulching influences soil temperature and crop physiological processes including nutrient absorption and hormone metabolism [27]. Root bleeding intensity indicates root activity [28] and increased with irrigation levels across growth stages. Straw mulching provided 3.49%–26.99% greater bleeding intensity than removal under 200–350 mm irrigation, but minimal benefits (0.37%–2.87%) under high irrigation (500 mm). Bleeding sap nutrients reflect plant nutritional status [29], with straw return enhancing soil fertility and nutrient utilization [30]. All measured elements (N, P, K, Ca, Mg) increased with irrigation, enhanced by straw mulching under moderate water supply. Mechanisms involve straw decomposition releasing nutrients, improved soil organic matter promoting microbial activity, and enhanced soil structure facilitating mineral absorption. Root bleeding sap amino acids promote development [31], while soluble sugars indicate metabolic activity linked to nitrogen enzyme systems [32]. Both parameters increased with irrigation at V8 and R1 stages. Straw return enhanced these contents under moderate irrigation (200–350 mm), demonstrating improved synthesis under water limitation. Hormones enable environmental perception and stress adaptation through regulated synthesis and transport [33]. Low water typically elevates ABA and reduces CTK [34]. Results showed inverse CTK and ABA responses to irrigation, confirming hormonal antagonism in growth regulation. Straw mulching consistently promoted cell activities and delayed senescence relative to removal treatments. Previous studies have shown that water deficit decreases the activities of key N metabolism enzymes, thereby reducing N uptake and assimilation [35]. However, these activities in wheat grain increase under high temperature, drought, and combined stressors [36]. As the rate-limiting enzyme for NO3− assimilation, the decreased activity of NR under water stress helps maintain cellular osmotic balance [37]. GS catalyzes the conversion of NH4+ to amides and amino acids, and its high activity under water-limited conditions promotes nitrogen use efficiency. In this study, the NR and GS activities in maize leaves increased when the drip irrigation amount was increased from 200 to 500 mm. Under 200 mm of irrigation, straw mulch return increased the NR and GS activities to a greater extent (2.47%–3.80%) than straw removal. The increase in the NR and GS activities due to straw mulch return to the field was smaller with 500 mm irrigation (0.14%–0.96%). Under a low irrigation amount, straw mulch return enhanced the activities of N metabolism enzymes in maize, exhibiting strong capabilities in NO3− assimilation and amide and amino acid synthesis, providing a foundation for N absorption and utilization. N metabolism is closely related to C metabolism. The photosynthetic carbon assimilation process relies on RuBP carboxylase and PEP carboxylase, with changes in their activities directly regulating photosynthetic efficiency [27]. In this study, the RuBP carboxylase and PEP carboxylase activities in maize leaves increased as the drip irrigation amount increased, reaching their highest levels at a drip irrigation amount of 500 mm. At drip irrigation amounts of 200 and 350 mm, the increase in RuBP carboxylase and PEP carboxylase activities was greater under straw mulch return than under straw removal (1.73%–7.10%). The effect of straw mulch return on RuBP carboxylase and PEP carboxylase activities was lower with a drip irrigation amount of 500 mm. When the drip irrigation amount increases, the activities of N metabolism enzymes promote N absorption and utilization and increase the C metabolism enzyme activity. When the drip irrigation amount was lower, straw mulch return and incorporation into the soil can further enhance the activities of C and N metabolism enzymes.

Dry matter accumulation is the fundamental condition for crop yield formation. Maize grain yield is determined by the aboveground dry matter, and photosynthesis is the process by which plants accumulate dry matter. Maize growth is highly sensitive to changes in soil moisture, and drought slows the growth rate and reduces its biomass and the number or weight of grains, decreasing maize yield [38]. During the early stages of corn (V8, R1), irrigation at 350 and 500 mm did not significantly increase dry matter accumulation. At the R3 and R6 stages, there was a significant difference between 200 and 350 mm irrigation levels. Straw mulch return treatment enhanced dry matter accumulation compared to removal treatment, with more pronounced effects under lower irrigation levels. Under 350 mm irrigation, straw mulch significantly improved the Pn value. The changes in dry matter and Pn indicate that the water requirement is low in the early stages of maize growth and increases as maize grows, but straw mulch return increases soil moisture. Straw mulch return has a greater effect on dry matter accumulation in maize when irrigation is low.

Water stress severely affects maize growth and reduces its yield potential. However, over-irrigation can also lead to a yield reduction, water wastage, soil salinization, and reduced soil fertility [38,39]. The results of this study indicate that the yield increased with the increase in the drip irrigation amount, with the highest yield achieved at a volume of 500 mm. Straw mulch return significantly increased the maize yield under drip irrigation amounts of 200 and 350 mm. The irrigation amount not only influenced yield but also affected yield components, depending on straw return. Increased drip irrigation enhanced 100-grain weight, spike length, and diameter while reducing bald tip length. Significant differences in 100-grain weight and spike diameter occurred between 200 and 500 mm irrigation levels. Straw mulch improved these parameters compared to straw removal under 200 and 350 mm irrigation. These results indicate that an increase in drip irrigation amount is beneficial for maize yield formation, while straw return has a positive effect on maize kernel formation. Based on our results, we recommend that farmers in the semi-arid regions of Jilin Province adopt a combination of straw mulching and 350 mm drip irrigation. Compared to the traditional 500 mm drip irrigation, this approach can reduce irrigation water usage by approximately 30% while maintaining comparable yields. Our research findings suggest that policymakers should consider: (1) providing subsidies for drip irrigation infrastructure and straw management equipment to reduce initial investment barriers; (2) incorporating water-saving technologies into regional agricultural development plans and water resource management strategies; and (3) establishing technical standards and extension services to ensure proper implementation.

Drip irrigation combined with straw mulch return influenced the characteristics of root bleeding sap, key enzymes of leaf C and N metabolism, dry matter accumulation, and yield formation in maize. Drip irrigation and straw mulch return differentially affected maize growth and development. Compared to straw removal, straw mulch return increased the root bleeding intensity, the mineral element (N, P, K, Ca, and Mg) contents in the exudate, and the soluble sugar and hydrolyzed amino acid contents under drip irrigation amounts of 200 and 350 mm, providing a material basis for the growth and development of aboveground maize. Moreover, straw mulch return increased the CTK content and decreased the ABA content in the root bleeding sap, which delayed senescence to a certain extent. Straw mulch return also promoted the activities of NR, GS, RuBP carboxylase, and PEP carboxylase in maize leaves and maintained N and sugar metabolism. Leaf Pn increased, which increased the dry matter accumulation and maize yield. There was no significant difference between straw removal and straw mulch return under a drip irrigation amount of 500 mm. Therefore, the cultivation method combining moderate deficit irrigation with straw mulch return provides a solution for water resource management and maize yield improvement in semi-arid regions. These results offer a theoretical basis for maize production and the application of straw mulch return in semi-arid regions. Future research should explore the optimal combinations of drip irrigation amount and straw mulch return under different drought intensities in semi-arid regions, and assess the sustainability of this integrated system in terms of crop production. This combined approach of drip irrigation and straw mulching, can be adopted to improve maize yields in water-scarce agricultural regions and the rational utilization of water resources.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Key R&D Plan Project of China (2024YFD2300101); the Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Development Plan Project (20240303026NC); and the Jilin Provincial Department of Education’s “Black Soil Granary” Science and Technology Battle “Unveiling the List and Leading the Way” Scientific Research Project (JJKH20241118HT).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Chen Xu and Lihua Zhang; methodology, Lihua Zhang and Hongxiang Zhao; software, Zexin Qi and Yaliang Liu; validation, Tianhao Luan and Hongxiang Zhao; formal analysis, Zexin Qi, Xiaolong Liu and Shaofeng Bian; investigation, Chen Xu, Tianhao Luan, Zexin Qi, Xiaolong Liu, Yueqiao Li, Hui Sun, Ning Sun, Qian Li and Hongxiang Zhao; resources, Chen Xu, Tianhao Luan, Lihua Zhang and Hongxiang Zhao; writing—original draft preparation, Chen Xu and Tianhao Luan; writing—review and editing, Hongxiang Zhao and Lihua Zhang; supervision, Hongxiang Zhao; project administration, Lihua Zhang and Hongxiang Zhao; funding acquisition, Chen Xu, Shaofeng Bian, Lihua Zhang and Hongxiang Zhao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors declare that all relevant data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.071324/s1.

References

1. Chen Q, Qu Z, Ma G, Wang W, Dai J, Zhang M, et al. Humic acid modulates growth, photosynthesis, hormone and osmolytes system of maize under drought conditions. Agric Water Manag. 2022;263:107447. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2021.107447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Guo Q, Huang G, Guo Y, Zhang M, Zhou Y, Duan L. Optimizing irrigation and planting density of spring maize under mulch drip irrigation system in the arid region of Northwest China. Field Crops Res. 2021;266(4):108141. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2021.108141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wu D, Xu X, Chen Y, Shao H, Sokolowski E, Mi G. Effect of different drip fertigation methods on maize yield, nutrient and water productivity in two-soils in Northeast China. Agric Water Manag. 2019;213:200–11. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2018.10.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Lu S, Bai X, Zhang J, Li J, Li W, Lin J. Impact of virtual water export on water resource security associated with the energy and food bases in Northeast China. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2022;180(1):121635. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kang S, Hao X, Du T, Tong L, Su X, Lu H, et al. Improving agricultural water productivity to ensure food security in China under changing environment: from research to practice. Agric Water Manag. 2017;179:5–17. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2016.05.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Cao Y, Zhang W, Ren J. Efficiency analysis of the input for water-saving agriculture in China. Water. 2020;12(1):207. doi:10.3390/w12010207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Yunyun S, Fangming L, Yushan G, Zhonghua H, Jingang D, Huitao L. Regulating water and fertilizer application in film-mulched drip irrigation to improve growth and water—fertilizer utilization of maize in Western Jilin. Irrig Drain. 2020;39(11):76. doi:10.13522/j.cnki.ggps.2019384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Sui J, Wang J, Gong S, Xu D, Zhang Y, Qin Q. Assessment of maize yield-increasing potential and optimum N level under mulched drip irrigation in the Northeast of China. Field Crops Res. 2018;215:132–9. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2017.10.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jia Q, Xu Y, Ali S, Sun L, Ding R, Ren X, et al. Strategies of supplemental irrigation and modified planting densities to improve the root growth and lodging resistance of maize (Zea mays L.) under the ridge-furrow rainfall harvesting system. Field Crops Res. 2018;224:48–59. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2018.04.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Fan J, Zheng J, Wu L, Zhang F. Estimation of daily maize transpiration using support vector machines, extreme gradient boosting, artificial and deep neural networks models. Agric Water Manag. 2021;245:106547. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2020.106547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zheng J, Fan J, Zou Y, Chau HW, Zhang F. Ridge-furrow plastic mulching with a suitable planting density enhances rainwater productivity, grain yield and economic benefit of rainfed maize. J Arid Land. 2020;12:181–98. doi:10.1007/s40333-020-0001-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Bakht J, Shafi M, Jan MT, Shah Z. Influence of crop residue management, cropping system and N fertilizer on soil N and C dynamics and sustainable wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) production. Soil Till Res. 2009;104(2):233–40. doi:10.1016/j.still.2009.02.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Hu Y, Ma P, Zhang B, Hill RL, Wu S, Dong QG, et al. Exploring optimal soil mulching for the wheat-maize cropping system in sub-humid drought-prone regions in China. Agric Water Manag. 2019;219(1):59–71. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2019.04.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Chen S, Zhang X, Pei D, Sun H. Effects of corn straw mulching on soil temperature and soil evaporation of winter wheat field. Trans Chin Soc Agric Eng. 2005;21(10):171–3. (In Chinese). doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.2007.00144.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Jayakumar M, Bosu SS, Kantamaneni K, Rathnayake U, Surendran U. Drip irrigation on productivity, water use efficiency and profitability of turmeric (Curcuma longa) grown under mulched and non-mulched conditions. Results Eng. 2024;22(3):102018. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2024.102018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Franco-Luesma S, Cavero J, Álvaro-Fuentes J. Relevance of the irrigation and soil management system to optimize maize crop production under semiarid Mediterranean conditions. Agric Water Manag. 2025;307(2):109272. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2024.109272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Fan Y, Gao J, Sun J, Liu J, Su Z, Wang Z, et al. Effects of straw returning and potassium fertilizer application on root characteristics and yield of spring maize in China inner Mongolia. Agron J. 2021;113(5):4369–85. doi:10.1002/agj2.20742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Chen P, Gu X, Li Y, Qiao L, Li Y, Fang H, et al. Effects of residual film on maize root distribution, yield and water use efficiency in Northwest China. Agric Water Manag. 2022;260:107289. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2021.107289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Li G, Zhao B, Dong S, Zhang J, Liu P, Ren B, et al. Morphological and physiological characteristics of maize roots in response to controlled-release urea under different soil moisture conditions. Agron J. 2019;111(4):1849–64. doi:10.2134/agronj2018.08.0508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hou D, Liu K, Liu S, Li J, Tan J, Bi Q, et al. Enhancing root physiology for increased yield in water-saving and drought-resistance rice with optimal irrigation and nitrogen. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1370297. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1370297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Nishanth D, Biswas DR. Kinetics of phosphorus and potassium release from rock phosphate and waste mica enriched compost and their effect on yield and nutrient uptake by wheat (Triticum aestivum). Bioresour Technol. 2008;99(9):3342–53. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2007.08.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Akhtar K, Đalović I, Prasad PV, Wang W, Ren G, Yang G. Wheat straw mulching with fertilizer nitrogen: an approach for improving soil water storage and maize crop productivity. Book Abstr. 2005:162–2. doi:10.17221/96/2018-pse. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Sheidai KE, Sepehry A, Barani H, Motamedi J, Shahbazi F. Establishing a suitable soil quality index for semi-arid rangeland ecosystems in northwest of Iran. J Soil Sci Plant Nut. 2019;19:648–58. doi:10.1007/s42729-019-00065-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang X, Xing Y. Effects of mulching and nitrogen on soil nitrate-N distribution, leaching and nitrogen use efficiency of maize (Zea mays L.). PLoS One. 2016;1(8):e0161612. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Mubarak M, Salem EM, Kenawey MK, Saudy HS. Changes in calcareous soil activity, nutrient availability, and corn productivity due to the integrated effect of straw mulch and irrigation regimes. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2021;21(3):2020–31. doi:10.1007/s42729-021-00498-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Niknam N, Farajee H, Movahhedi Dehnavi M, Yadavi A. Improvement of physiological indices and sweet corn performance by sowing methods and wheat residue mulching under two irrigation regimes. Gesunde Pflanz. 2023;75(6):2853–63. doi:10.1007/s10343-023-00922-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhao R, Li Y, Xu C, Zhang Z, Zhou Z, Zhou Y, et al. Expression of heterosis in photosynthetic traits in F1 generation of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) hybrids and relationship with yield traits. Funct Plant Bio. 2024;51(9):FP24135. doi:10.1071/FP24135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Wang P, Wang Z, Pan Q, Sun X, Chen H, Chen F, et al. Increased biomass accumulation in maize grown in mixed nitrogen supply is mediated by auxin synthesis. J Exp Bot. 2019;70(6):1859–73. doi:10.1093/jxb/erz047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Liang XY, Feng G, Ye F, Zhang JL, Sha Y, Meng JJ, et al. Single-seed sowing increased pod yield at a reduced seeding rate by improving root physiological state of Arachis hypogaea. J Integr Agr. 2020;19(4):1019–32. doi:10.1016/S2095-3119(19)62712-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Biswal P, Faisal A, Tripathy S, Swain DK, Jha MK, Mohan G. Influence of drip irrigation and straw mulching on economic feasibility and soil fertility of rice-potato system in subtropical India. Irrigation Sci. 2025;43(3):363–76. doi:10.1007/s00271-024-00951-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zheng T, Haider MS, Zhang K, Jia H, Fang J. Biological and functional properties of xylem sap extracted from grapevine (cv. Rosario Bianco). Sci Hortic. 2020;272:109563. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kaur M, Sharma S, Singh D. Influence of selenium on carbohydrate accumulation in developing wheat grains. Commun Soil Sci Plan. 2018;49(13):1650–9. doi:10.1080/00103624.2018.1474903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Suzuki N, Rivero RM, Shulaev V, Blumwald E, Mittler R. Abiotic and biotic stress combinations. New Phytol. 2014;203(1):32–43. doi:10.1111/nph.12797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Guo PR, Wu LL, Wang Y, Liu D, Li JA. Effects of drought stress on the morphological structure and flower organ physiological characteristics of Camellia oleifera flower buds. Plants. 2023;12(13):2585. doi:10.3390/plants12132585. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Ahanger MA, Tittal M, Mir RA, Agarwal RM. Alleviation of water and osmotic stress-induced changes in nitrogen metabolizing enzymes in Triticum aestivum L. cultivars by potassium. Protoplasma. 2017;254(5):1953–63. doi:10.1007/s00709-017-1086-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Ru C, Hu X, Chen D, Song T, Wang W, Lv M, et al. Effects of nitrogen on nitrogen accumulation and distribution, nitrogen metabolizing enzymes, protein content, and water and nitrogen use efficiency in winter wheat under heat and drought stress after anthesis. Sci Agri Sin. 2022;55(17):3303–20. (In Chinese). doi:10.3390/w14091407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Singh M, Singh VP, Prasad SM. Responses of photosynthesis, nitrogen and proline metabolism to salinity stress in Solanum lycopersicum under different levels of nitrogen supplementation. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2016;109:72–83. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.08.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Guo J, Fan J, Xiang Y, Zhang F, Yan S, Zhang X, et al. Coupling effects of irrigation amount and nitrogen fertilizer type on grain yield, water productivity and nitrogen use efficiency of drip-irrigated maize. Agric Water Manag. 2022;261:107389. doi:10.1007/s11099-007-0012-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Cai F, Mi N, Ming H, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Zhang S, et al. Responses of dry matter accumulation and partitioning to drought and subsequent rewatering at different growth stages of maize in Northeast China. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1110727. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1110727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools