Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Genetic Mapping of Grain Length-and Width-Related Genes in the Local Wheat Variety Guizi 1×Zhongyan 96-3 Hybrid Population Using Genome Sequencing

1 College of Agriculture, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

2 Guizhou Sub-Center of National Wheat Improvement Center, College of Agriculture, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

* Corresponding Authors: Ruhong Xu. Email: ; Luhua Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Plant Breeding and Genetic Improvement: Leveraging Molecular Markers and Novel Genetic Strategies)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 3913-3924. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.072229

Received 22 August 2025; Accepted 11 November 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

Wheat grain morphology, particularly grain length (GL) and width (GW), is a key determinant of yield. To improve the suboptimal grain dimensions of the local anthocyanin-rich variety Guizi 1 (GZ1), we crossed it with Zhongyan 96-3 (ZY96-3), an elite germplasm known for faster grain filling and superior grain size. A genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach was applied to an F2 population of 110 individuals derived from GZ1 × ZY96-3, resulting in the identification of 23,134 high-quality SNPs. Most of the SNPs associated with GL and GW were clustered on chromosomes 2B, 3A, and 3B. QTL mapping for GL revealed two major loci, GL1 on chromosome 2B and GL2 on chromosome 3B, and eight candidate genes were identified within their corresponding intervals (2B: 63.6–70.4 Mb; 3B: 631.5–633.3 Mb). These genes encode proteins potentially involved in grain size regulation, including a TOR2 regulation-associated protein, erect spike 2 (EP2), fibroblast growth factor 6 (FGF6), cellulose synthase-like (CSLD), RelA/pot homologue three family protein, and three GDSL esterase/lipase (GLIP) proteins. Additionally, we detected a QTL associated with GW on chromosome 3A and identified two candidate genes, TOR2 regulation and starch synthase within the 61.4–68.5 Mb interval. Overall, this study provides a strong theoretical and technical basis for wheat genetic improvement and offers valuable resources for precise QTL mapping and candidate gene discovery.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileWheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the most important staple crops worldwide and provides a major share of the caloric intake in the human diet. Projections from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) indicate that the global demand for wheat and wheat-derived products will rise by at least 50% by 2050 due to rapid population growth and shifting dietary habits [1,2]. Improving yield potential remains a key objective in modern wheat breeding. Yield is a complex quantitative trait shaped by multiple QTLs, epistatic interactions, and environment–genotype effects. It is largely determined by grain number per spike, spikes per unit area, and thousand-grain weight (TGW) [3]. Among these components, grain morphological traits particularly grain length and width play a critical role in determining final grain weight and overall productivity.

Grain size is influenced by cell division and expansion in the spikelet glume, while grain thickness depends on assimilate accumulation during grain filling [4]. From a developmental perspective, wheat grain formation proceeds through three main stages: cell division and proliferation, grain filling, and physiological maturation. The rate of endosperm cell proliferation shows a strong positive correlation with final grain weight, making genes that regulate mitosis and cell cycle progression key determinants of grain morphology [5,6]. Genetic mapping and QTL studies further demonstrate that grain length and width are generally associated with yield improvement, although these relationships vary depending on genetic background and environmental conditions [7]. Therefore, precise regulation of grain size is essential for enhancing yield, improving grain quality, and strengthening global food security initiatives.

Significant progress has been made in deciphering the genetic and molecular pathways that control grain development in wheat [8]. Well-characterized regulatory mechanisms include G-protein signaling [9,10], the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway [11], and mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades [12,13]. The rice gene GW2, which encodes an E3 ubiquitin ligase, enhances cell proliferation when mutated, resulting in increased grain width, grain weight, and overall yield [14]. Its wheat homolog, TaGW2, similarly acts as a negative regulator of grain width and weight by modulating cell division [15]. Other key genetic regulators have also been identified in wheat. TaGW6 encodes a putative indole-3-acetic acid glucose hydrolase and positively influences TGW [16], while TaGW8-B1a significantly increases grain width, grain length, grain number per spike, and TGW [17]. Variants of TaCWI-5D that enhance cell wall integrity are strongly associated with heavier grains [18]. Glutamine synthetase genes such as TaGS2-2Ab improve spike number, grains per spike, and TGW [19], and TaGS5-3A serves as a positive regulator of grain size with favorable alleles consistently linked to larger grains [20]. Members of the Snakin/GASA family, including TaGASR7-A1, also influence grain length in wheat and rice [21]. MADS-box transcription factors promote grain size by regulating awn development and lateral membrane growth [22], while SLG2, a WD40-domain protein, controls grain width by stimulating cell amplification in spikelet hulls [23]. Conversely, GR5 acts as a transcriptional activator interacting with the Gγ subunit to coordinate cell proliferation and expansion, thereby defining final grain dimensions [24].

Phytohormone signaling is also deeply integrated into the regulation of grain size. Auxin-associated TaIAA21 negatively affects grain length and weight, and loss-of-function mutants show reduced grain dimensions [25]. Jasmonic acid is linked to enhanced grain development through the TaGL1-B1–TaPAP6 module, which improves carotenoid content and photosynthetic efficiency [26]. Abscisic acid signaling modulates grain filling through TaTPP-7A, which regulates sucrose utilization and T6P–SnRK1 feedback in the endosperm [27]. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that grain size is controlled by a complex interplay of genetic and hormonal pathways, providing valuable targets for improving crop yield.

Guizi 1 (GZ1) is a specialty wheat cultivar with high anthocyanin content and strong nutritional value, but it exhibits significantly smaller grain length and width than conventional varieties [28]. In contrast, Zhongyan 96-3 (ZY96-3) is an elite germplasm resource with a faster grain-filling rate and markedly larger grains [29]. To improve grain morphology in Guizi 1, a hybrid segregating population was developed using GZ1 and ZY96-3 as parents. Genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) was used to construct a high-density genetic linkage map, and QTL analysis was performed to identify the loci controlling grain length and width. This study aims to pinpoint key genes associated with grain morphology and provide essential genomic resources for marker-assisted selection in wheat breeding programs.

2.1 Plant Materials and Preparation

GZ1 wheat (Certificate No. Qian2015003) was developed from a complex wide-cross hybrid involving Triticum dicoccoides, Triticum durum, Aegilops ventricosa Tausch., and Aegilops tauschii Coss. Both Guizi 1 (GZ1) and Zhongyan 96-3 (ZY96-3) were cultivated at the Guizhou Sub-Center of the National Wheat Improvement Center at the College of Agriculture in Guizhou University. A randomized block design was employed, with each plot measuring 5 m in length and 2 m in width, and the sowing furrow width set at 20 cm. Consistent field management practices were adhered to, including regular watering, weeding, and fertilization. Single-plant harvesting was conducted, and seed traits were assessed using a seed examiner.

Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) involves the enzymatic cleavage of genomic DNA using restriction endonucleases, followed by the addition of sequencing junctions with barcodes, mixing of samples, construction of small fragment libraries (250–550 bp), and sequencing of paired-end 125 (PE125) reads [30]. A GBS library was constructed using DNA from 110 F2 individuals and two parental lines according to previous report [31]. The DNA was subjected to GBS processing via the Illumina HiSeqTM platform and data filtering was performed to remove adapter-containing reads; reads with an N proportion exceeding 10%; and low-quality reads (where bases with a quality score ≤10 constituted over 50% of the entire read). Sequence reads were aligned to the Chinese Spring reference genome (IWGSC RefSeq v1.0) using BWA-MEM, and subsequent single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calling was performed with the SAMtools mpileup module [32]. Furthermore, genotyping was corrected using the SMOOTH statistical method [33]. Filtered reads were aligned against the reference genome using BWA-MEM (v0.7.12). Subsequently, MarkDuplicates within Picard Tools (v1.129) was employed to flag duplicate reads that had not been filtered out in subsequent steps.

2.3 Linkage Mapping Construction and Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) Analysis

ASMap is an R language package designed for constructing genetic maps, utilizing the Kosambi mapping function via the built-in quickEst function. This allows for the estimation of genetic distances for high-throughput SNP marker data according to Taylor et al. [34]. QTL scans were performed using the R/qtl software, following the selected mode; and specifying a defined step size along with a predetermined number of permutations for each trait. Interval mapping was executed with the scanone ( ) function, while composite interval mapping was performed using the cim ( ) function, as described by Broman et al. [35]. Employ QTL Network v2.1 for composite interval mapping (CIM) to assess epistatic effects among identified QTLs. Model parameters were determined using multiple linear regression analysis (p = 0.05) with a window size of 10 cm, as demonstrated by Xu et al. [36]. Following the identification of QTL intervals, candidate genes located in these intervals were extracted based on reference genome information. Functional annotation and analysis of genes associated with each trait to enrich the Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG).

3.1 Phenotyping of Wheat Grain Length (GL) and Grain Width (GW)

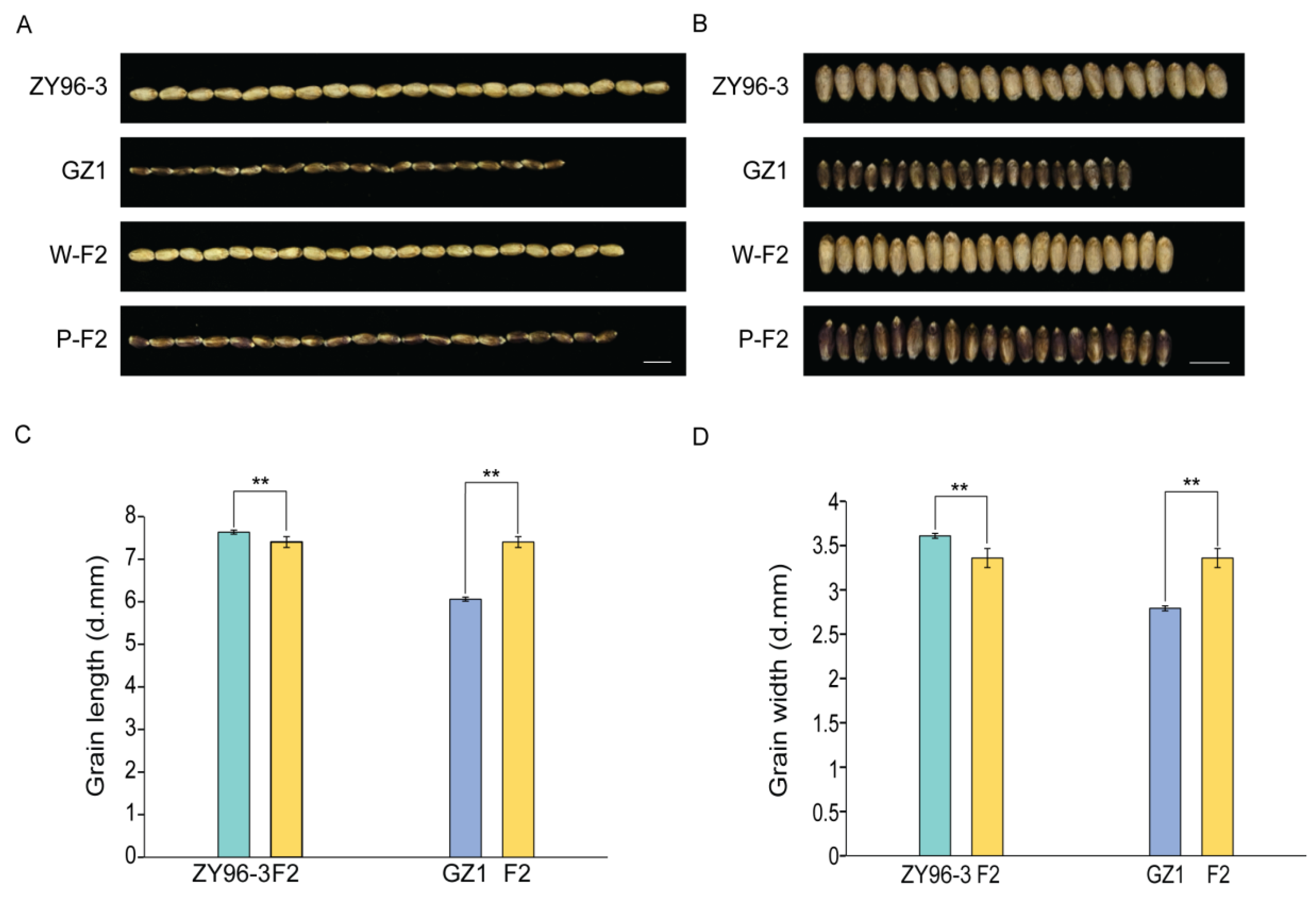

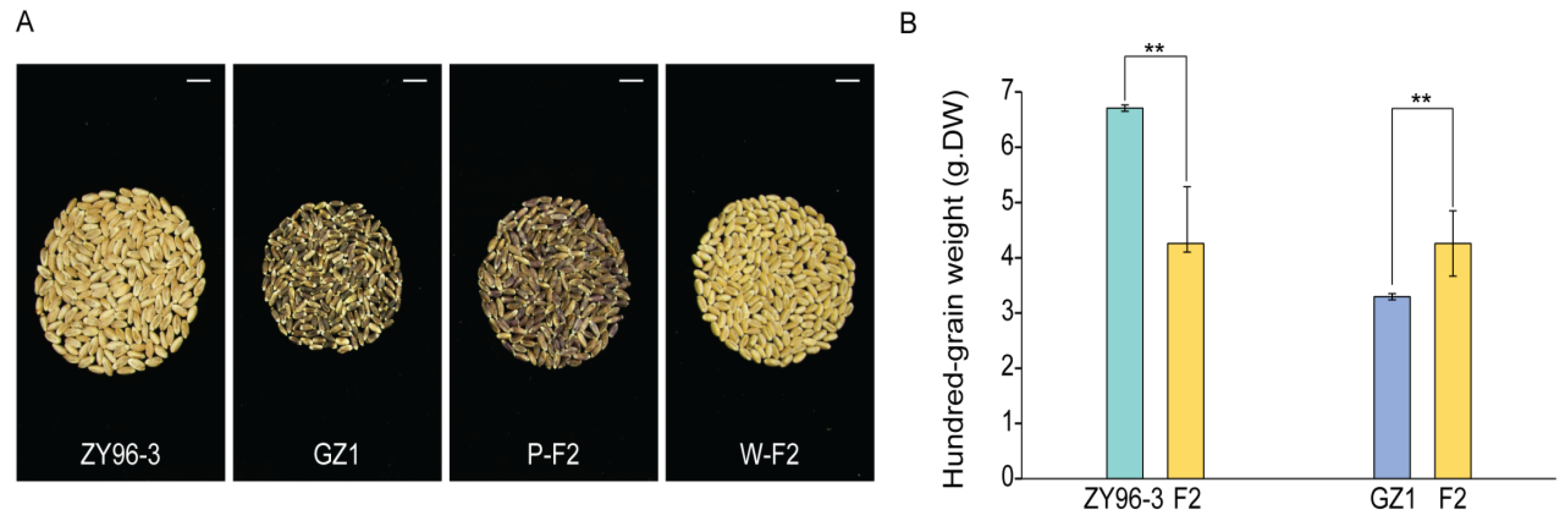

Grain length and width are critical factors influencing crop yield. In this study, we conducted a statistical analysis of 110 samples from GZ1, ZY96-3, and their hybrid progeny, the F2 generation. The results indicated that the average grain length and width were 6.08 ± 0.04 mm and 2.79 ± 0.03 mm for the parent GZ1, 7.67 ± 0.05 mm and 3.61 ± 0.01 mm for the parent ZY96-3, and 7.40 ± 0.31 mm and 3.35 ± 0.19 mm for the F2 generation of the cross (Fig. 1A–D, Tables S1 and S2). The mean hundred-grain was 3.30 ± 0.06 g for GZ1, 6.78 ± 0.07 g for ZY96-3, and 4.27 ± 0.65 g for the F2 generation (Fig. 2A,B, Tables S1 and S2). Statistical analysis revealed significant differences in the length and width of seeds of the F2 generation compared to both parents, GZ1 and ZY96-3 (Fig. 1C,D, Tables S1 and S2). Additionally, the 100-seed weight of the F2 generation exhibited similar significant differences when compared with the parents (Fig. 2B, Tables S1 and S2). Furthermore, color segregation was observed in the grains of the F2 generation, with 39.1% being purple and 60.9% white (Table S1).

Figure 1: (A) Comparison of grain length between parents ZY96-3, GZ1, and their hybrid offspring (20 grains). (B) Comparison of grain width between parents ZY96-3, GZ1, and their hybrid offspring (20 grains). (C) Statistical data on grain length of parental ZY96-3, GZ1, and their hybrid offspring. (D) Statistical data on the grain width of ZY96-3 and GZ1 parents and their hybrid offspring. The ‘W’ in W-F2 refers to the white F2 generation wheat, the ‘P’ in P-F2 refers to the purple F2 generation of wheat; values were mean ± SD, p-values were generated using a two-tailed t-test; **p < 0.01, indicates highest significant difference; scale: 1 cm (A,B).

Figure 2: (A) Comparison of Grain Surface Area between Parent ZY96-3 and GZ1 Hybrid Offspring (200 grains). (B) Statistical data on the hundred-grain weight of parents ZY96-3, GZ1, and their hybrid offspring. The ‘W’ in W-F2 refers to the white F2 generation wheat, the ‘P’ in P-F2 refers to the purple F2 generation of wheat; values were mean ± SD, p-values were generated using a two-tailed t-test; **p < 0.01, indicates highest significant difference; scale: 1 cm (A).

3.2 GBS Analysis of Grain Length and Width

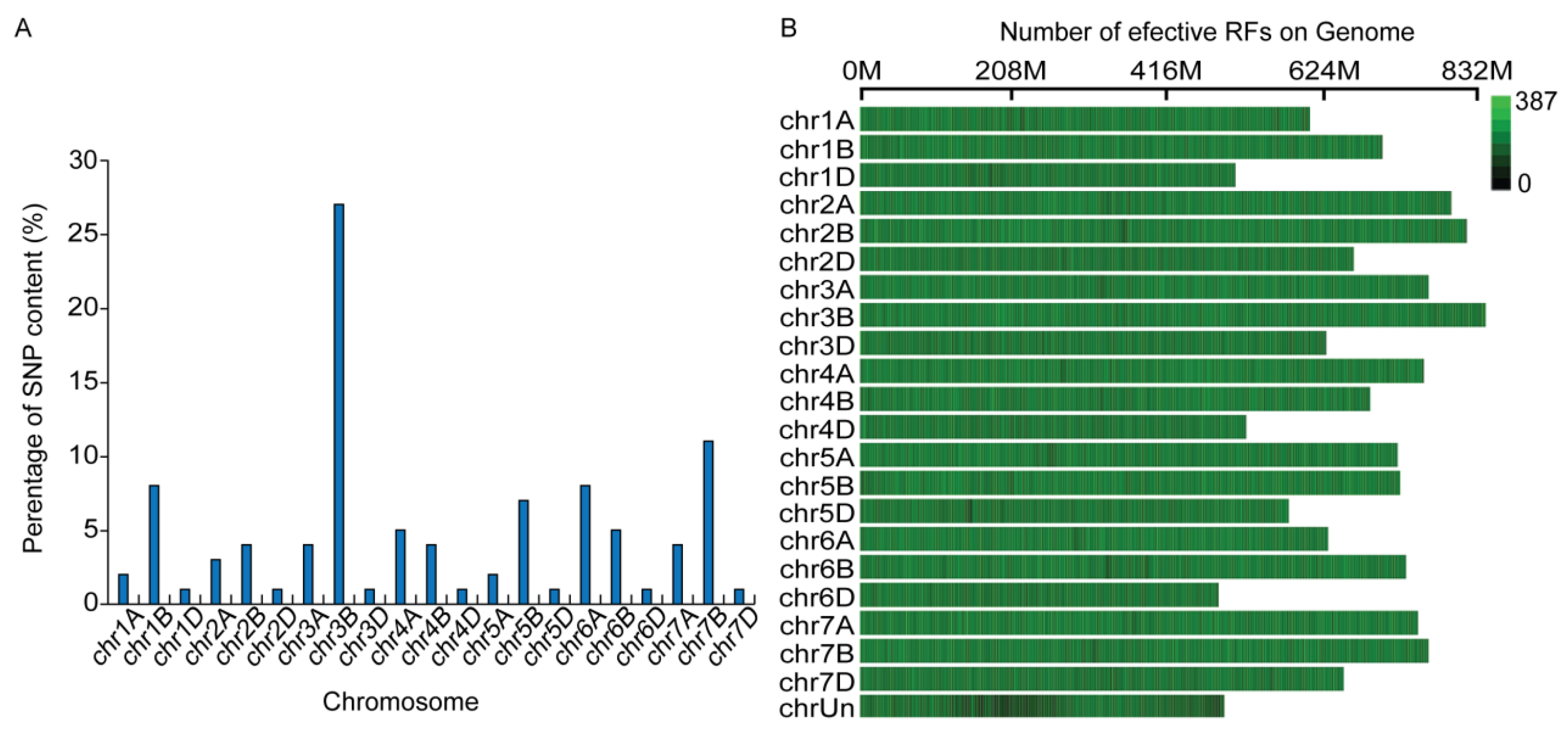

A total of 1,684,236,264 entries were obtained from the GBS analysis of 110 hybrid offspring (F2) and their two parental plants. Following a screening process, 311,065 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified in comparison to the Chinese spring wheat genome (IWGSC RefSeq v1.0). By applying genotype correction with smoothing statistics, we successfully identified 23,134 high-quality SNPs, which collectively constituted a genetic linkage map encompassing 21 chromosomes with a total length of 5402.12 cm. The distribution of SNPs across the 21 chromosomes was heterogeneous, ranging from 134 SNPs on chromosome 6D to 6288 SNPs on chromosome 3B. The number of SNPs identified per chromosome included 812 on chromosome 2B, 6288 on chromosome 3B, and 910 on chromosome 3A (Fig. 3A). Notably, SNPs associated with grain length and grain width exhibited the highest densities on chromosomes 2B, 3A, and 3B, with average mapping distances between SNP markers of 0.22 cm for chromosome 2B, 0.23 cm for chromosome 3A, and 0.12 cm for chromosome 3B, respectively (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3: (A) Distribution of the 23,134 high-quality SNPs per chromosome. (B) Percentage of candidate SNPs per chromosome (RF (restriction fragment): restriction enzyme fragment obtained after e-enzymatic digestion of the genome. Effective RF ave-length: The average length of the effective restriction enzyme fragment of this chromosome).

3.3 QTL Analysis for Grain Length and Grain Width

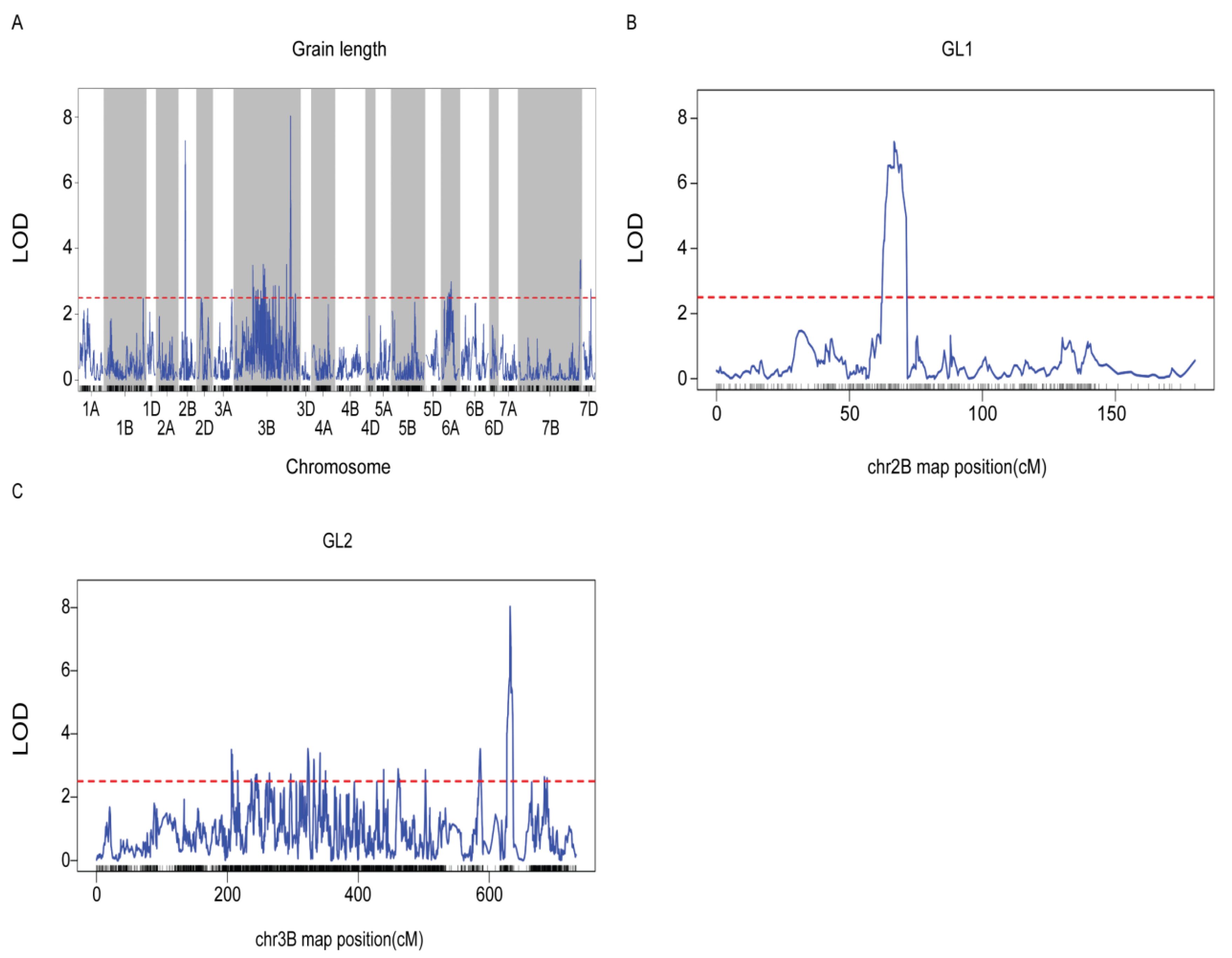

A QTL associated with grain length was identified on chromosomes 2B and 3B through QTL analysis, designated asGL (Fig. 3A). GL1 was localized within the credible interval defined by the markers chr2B-139159686 to chr2B-189796241 on chromosome 2B, exhibiting a logarithm of odds (LOD) value of 7.3 (Fig. 3B). Additionally, GL2 was positioned within the credible interval of markers chr3B-556884518 to chr3B-562389288 on chromosome 3B, with an LOD value of 8.0 (Fig. 3C). The genetic position of GL1 on chromosome 2B spanned from 63.6 to 70.4 (6.8 cm), based on the Chinese Spring reference genome, whereas on chromosome 3B, it ranged from 631.5 to 633.3 (1.8 cm). The GL1 and GL2 genes accounted for 37% of the phenotypic variance, indicating that the GL1 and GL2 genes associated with seed length are localized on chromosomes 2B and 3B, respectively.

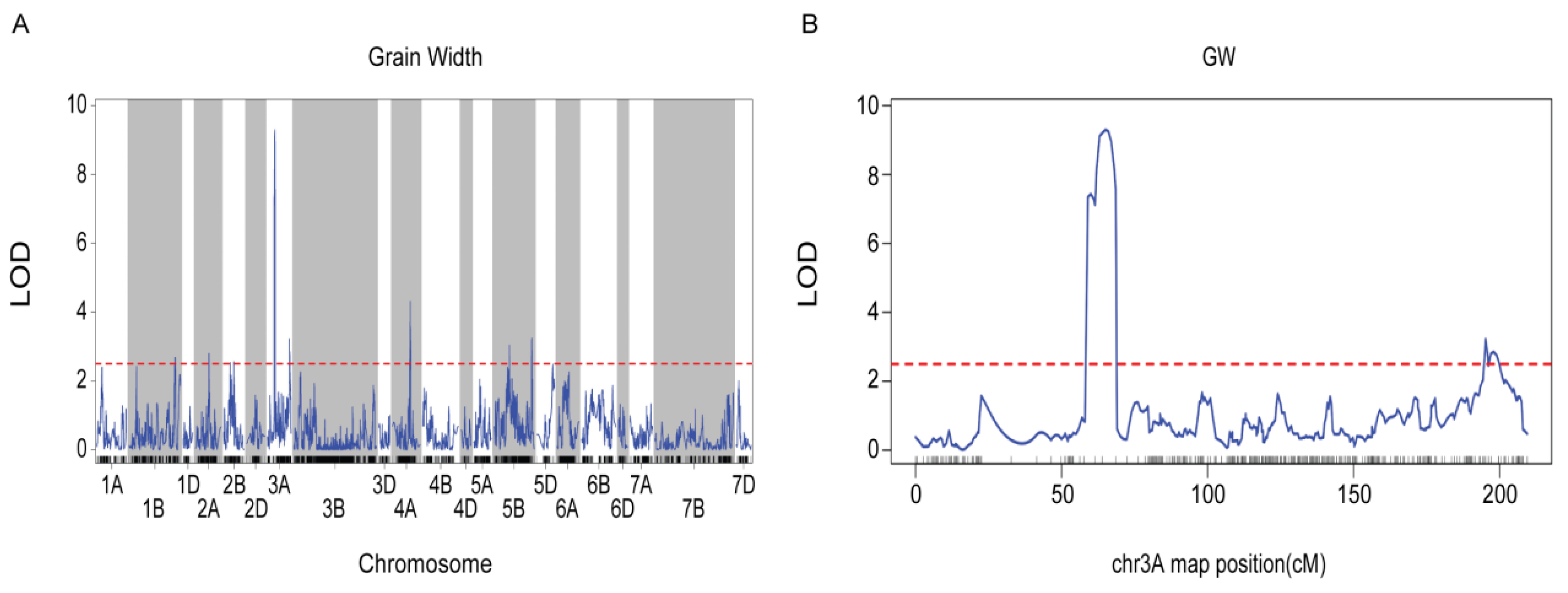

A QTL associated with grain width (GW) was identified on chromosome 3A, referred to as GW (Fig. 4A). This locus was localized within the credible interval defined by the markers chr3A-38579758 to chr3A-44154126 on chromosome 3A, exhibiting a logarithm of odds (LOD) value of 9.3. The genetic position of GW on chromosome 3A spanned from 61.4 to 68.5 (7.1 cm) (Fig. 4B). GW accounted for 24% of the phenotypic variance, indicating that the gene associated with grain length GW is localized on chromosome 3A.

Figure 4: (A) The LOD curve of GL on 21 chromosomes. (B) GL1 on the LOD curve of chromosome 2B. (C) GL2 is located on the LOD curve for chromosome 3B. Note: The blue curve represents the LOD values, while the red dashed line denotes the threshold LOD.

From the QTL analysis, we identified 57 putative annotated genes associated with grain width located within the interval of chromosome 3A (61.4–68.5 Mb). Among these candidate genes, two were potentially involved in regulating grain width, specifically those encoding proteins related to TOR 2 regulation and starch synthase (Table 1, Table 2, Tables S3 and S4). Furthermore, within the intervals of chromosomes 2B (63.6–70.4 Mb) and 3B (631.5–633.3 Mb), we identified 470 putative annotated genes related to grain length. Among these, eight candidate genes may be implicated in controlling grain length, including those encoding TOR 2 regulation-associated proteins gene, erect spike 2 protein (EP2) gene, fibroblast growth factor 6 (FGF6) gene, cellulose synthase-like protein (CSLD) gene, Rela/pot homologue 3 family proteins gene, and three other genes encoding GDSL esterase/lipase (GLIP) (see Tables S5 and S6).

Table 1: Predicted candidate genes of GL.

| Gene ID* | Start Position (bp) | Stop Position (bp) | Length (bp) | Gene Description/Predicted Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TraesCS2B01G170800 | 144,021,136 | 144,022,430 | 1294 | GDSL esterase/lipase |

| TraesCS2B01G170900 | 144,034,321 | 144,035,705 | 1384 | GDSL esterase/lipase |

| TraesCS2B01G171000 | 144,076,886 | 144,078,584 | 1698 | GDSL esterase/lipase |

| TraesCS2B01G182700 | 157,639,786 | 157,644,811 | 5025 | Cellulose synthase-like protein |

| TraesCS2B01G194900 | 171,995,910 | 172,003,669 | 7759 | Erect panicle 2 protein |

| TraesCS2B01G197300 | 175,067,745 | 175,071,145 | 3400 | Rela/spot homolog 3 family protein |

| TraesCS2B01G197700 | 175,454,756 | 175,455,112 | 356 | Fibroblast growth factor 6 |

| TraesCS2B01G207500 | 188,149,190 | 188,151,658 | 2468 | regulatory-associated protein of TOR 2 (RAPTOR2) |

Table 2: Predicted candidate genes of GW.

| Gene ID* | Start Position (bp) | Stop Position (bp) | Length (bp) | Gene Description/Predicted Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TraesCS3A01G070200 | 42,319,880 | 42,320,278 | 398 | Regulatory-associated protein of TOR 2 (RAPTOR2) |

| TraesCS3A01G071200 | 43,634,217 | 43,635,422 | 1205 | Starch synthase, chloroplastic/amyloplastic |

4.1 Application of GBS in Wheat Breeding

GBS technology facilitates the efficient customization of the library preparation process, thereby enhancing the acquisition of high-quality SNP data [37]. In a prior study, Arora et al. identified 17 SNPs associated with grain size traits through GBS markers distributed across all seven chromosomes of wheat. Notably, markers on chromosomes 6D, 5D, and 2D exhibited the most significant associations with these traits [38]. In contrast, Tekeu et al. conducted a genome-wide association analysis involving 228 hexaploid wheat varieties, uncovering genomic regions that regulate the variation in grain length and width. They identified seven SNPs associated with these traits, in addition to three QTL located on chromosomes 1D, 2D, and 4A [39].

In this study, we employed GBS to systematically analyze and localize the genes associated with grain length and grain width in F2 generation hybrid plants. We identified 23,134 high-quality SNP markers that spanned all 21 chromosomes of wheat through GBS sequencing and subsequently constructed a high-density genetic map utilizing these markers. Genetic mapping analysis revealed that SNP markers significantly associated with grain length and width exhibited the highest density on chromosomes 2B, 3A, and 3B (Fig. 3A,B). These findings provide crucial molecular marker information for the in-depth exploration of the genetic regulatory mechanisms underlying wheat grain size traits, thereby establishing a theoretical foundation for future identification and functional validation of candidate genes.

4.2 Application of QTLs in Wheat Breeding

Yield-related traits are crucial in wheat breeding. Previous studies have extensively investigated various quantitative trait loci (QTL) and genes associated with yield across diverse environmental conditions on 21 chromosomes of wheat [40]. Earlier work by Okamoto et al. identified genetic loci affecting grain size and morphological variation in hexaploid wheat, revealing quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for grain length and width on chromosomes 1D and 2D [41]. Likewise, Yan et al. reported genomic regions linked to grain size on chromosome 2D. [42]. In bread wheat, Kumari et al. identified two QTLs that regulate grain length on chromosomes 4A and 5A, while two QTLs affecting grain width were located on chromosomes 7D and 6A [43]. Conversely, a genome-wide association study conducted by Sehgal et al. on spring bread wheat revealed a yield-associated QTL situated within the 57.5 to 61.6 Mbps interval on chromosome 2B, which serves as a major pleiotropic QTL linked to TGW, grain width, harvest density, harvest index, and grain width/grain weight [44]. In a study by Yang [45], four loci on chromosomes 1A, 2B, 3A, and 5B were found to significantly influence TGW-related traits in an RIL (Recombinant Inbred Line) population from a Zhongmai 871×Zhongmai 895 cross. Additionally, Sabouri et al. identified qGL-3D and qGL-1D on chromosomes 3D, 1D, and 2A as QTLs controlling grain length, and qGW-2A on chromosome 2A as a QTL regulating grain width in two populations, Gonbad×Zagros and Gonbad×Kuhdasht [46].

In the present study, we systematically collated the physical positions of the identified QTLs with documented QTLs and genes utilizing the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC) reference genome assembly v1.0. Our analysis revealed that the grain length (GL) associated with the genes of the hybrid F2 population was localized on chromosome 2B (63.6–70.4 Mb) and chromosome 3B (631.5–633.3 Mb) (Fig. 4A–C), while the grain width (GW) of the genes of the hybrid population F2 was localized on chromosome 3A (61.4–68.5 Mb) (Fig. 5A,B). Notably, we identified novel QTLs on chromosome 3A that regulate grain width and on chromosome 3B that influence grain length. These findings diverge from those of previous studies and offer valuable insights into the genetic mechanisms governing grain length and width in wheat, which may be beneficial for future breeding programs.

Figure 5: (A) The LOD curve of GW on 21 chromosomes. (B) GW on the LOD curve of chromosome 3A. Note: The blue curve represents the LOD values, while the red dashed line denotes the threshold LOD.

4.3 Functional Prediction of Grain Length and Grain Width Candidate Genes

Within the genomic intervals of chromosome 2B (63.6–70.4 Mb) and chromosome 3B (631.5–633.3 Mb), we identified 470 putatively annotated genes associated with grain length (GL) (Fig. 4A–C, Table S5). Among these, eight were screened as candidate genes regulating grain length (Table 1). The TOR2 protein (RAPTOR2), encoded by the candidate gene TraesCS2B01G207500, influences plant growth and developmental processes by regulating lipid biosynthesis in chloroplast-like vesicle membranes, maintaining lipid homeostasis, and stabilizing the basal lamellipodia structure of vesicles [47]. FGF6 (encoded by TraesCS2B01G197700) modulates cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration [48]. The Rela/pot homologue 3 family of proteins, encoded by TraesCS2B01G197300, significantly influences photosynthetic activity, metabolite accumulation, and nutrient remobilization, thereby regulating plant growth and development [49]. Notably, EP2, encoded by TraesCS2B01G194900, primarily regulates spike morphology, including spike length and grain size; however, it has a limited effect on the number of grains per spike [50]. The CSLD protein, encoded by TraesCS2B01G182700, is instrumental in the biosynthesis of plant cell wall polysaccharides, particularly β-glucan, which in turn is essential for plant cell morphogenesis, bacterial biofilm formation, and fruiting body development. [51]. Furthermore, functional studies of GLIP proteins co-encoded by TraesCS2B01G170800, TraesCS2B01G170900, and TraesCS2B01G171000 in Arabidopsis thaliana have demonstrated that ectopic expression of cotton GhGLIP significantly increases seed size and weight [52]. Based on the evidence from the aforementioned studies, the proteins encoded by the eight candidate genes identified in this research have been shown to regulate plant growth and developmental processes. Therefore, we hypothesize that these genes may be associated with seed length in the Guizi 1×Zhongyan 96-3 cross.

Within the candidate interval of chromosome 3A (631.48178–633.33097 Mb), we identified 57 putatively annotated genes associated with grain width (Fig. 5A,B, Table S4). Among these, two genes were elected as candidates for regulating grain width: TOR 2 regulation-related protein (TraesCS3A01G070200) and starch synthase (TraesCS3A01G071200) (Table 2). Previous studies have demonstrated that TraesCS3A01G071200 encodes a starch synthase, which is involved in regulating starch granule formation in Arabidopsis chloroplasts [53]. Based on the evidence from these studies, the proteins encoded by the two candidate genes identified in this study are implicated in regulating plant growth and developmental processes. Therefore, we hypothesized that these genes may be associated with grain width in the Guizi 1×Zhongyan 96-3 cross.

In summary, although eight genes potentially involved in regulating wheat grain length and two that may influence wheat grain characteristics have been identified, the precise regulatory roles of these genes in wheat remain uncertain. Therefore, further transgenic experiments are required to functionally validate these candidate genes. Overall, this study provides a theoretical foundation and technical support for the genetic improvement, fine localization of QTLs, and subsequent screening and identification of candidate genes controlling wheat grain yield.

This study mapped the genetic loci controlling grain length and width in a segregating population derived from Guizi 1 and Zhongyan 96-3. Using genotyping-by-sequencing, a high-density linkage map containing 23,134 high-quality SNPs was constructed, enabling precise QTL localization. Two major QTLs related to grain length (GL1 on chromosome 2B and GL2 on chromosome 3B) and one QTL controlling grain width (GW on chromosome 3A) were identified. These loci explained a substantial portion of phenotypic variation, reflecting their strong genetic effects. Candidate genes associated with these intervals including TOR2 regulatory-associated proteins, EP2, FGF6, CSLD, RelA/pot homologue proteins, GLIP family members, and starch synthase represent promising regulators of grain development. Overall, these findings provide valuable molecular targets for improving grain size in wheat. The identified QTLs and candidate genes offer strong potential for marker-assisted selection and functional validation, supporting breeding programs aimed at increasing yield, enhancing grain morphology, and improving the commercial value of Guizi 1 and related germplasm.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: Funding for this project was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 32160456, 32360474, 32360486, and 32260496) and the Key Laboratory of Functional Agriculture of Guizhou Provincial Higher Education Institutions (Grant No. Qianjiaoji (2023) 007).

Author Contributions: Shaoyan Wu: Formal analysis, methodology, software, data curation, initial draft writing, writing review, and editing. Jie Tian: Formal analysis, methodology, software, data curation, writing review, and editing. Yiyan Wang: Methodology, data curation, writing review, and editing. Muhammad Arif: Methodology, data curation, writing review, and editing. Shuyao Wang: Methodology, data curation, writing review, and editing. Jing Wang: Methodology, data curation, writing review, and editing. Zhuoyao Yang: Methodology, data curation, writing review, and editing. Ruhong Xu: Validation, funding acquisition, writing review, and editing. Luhua Li: conceptualization, supervision, project management, funding acquisition, writing review, and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.072229/s1.

Abbreviations

| Abscisic acid | |

| Jasmonic acid | |

| Indole acetic acid | |

| Guizi 1 wheat | |

| Zhongyan 96-3 wheat | |

| Genotyping-by-sequencing | |

| Quantitative trait loci | |

| Recombinant inbred line |

References

1. Sehgal D , Dhakate P , Ambreen H , Shaik KHB , Rathan ND , Anusha NM , et al. Wheat omics: advancements and opportunities. Plants. 2023; 12( 3): 426. doi:10.3390/plants12030426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. CIMMYT (International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center). 2021 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.cimmyt.org/work/wheat-research. [Google Scholar]

3. Cao S , Xu D , Hanif M , Xia X , He Z . Genetic architecture underpinning yield component traits in wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2020; 133( 6): 1811– 23. doi:10.1007/s00122-020-03562-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bai X , Wu B , Xing Y . Yield-related QTLs and their applications in rice genetic improvement. J Integr Plant Biol. 2012; 54( 5): 300– 11. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7909.2012.01117.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang Y , Sun G . Molecular prospective on the wheat grain development. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2023; 43( 1): 38– 49. doi:10.1080/07388551.2021.2001784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Gasparis S , Miłoszewski MM . Genetic basis of grain size and weight in rice, wheat, and barley. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24( 23): 16921. doi:10.3390/ijms242316921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Cheng S , Feng C , Wingen LU , Cheng H , Riche AB , Jiang M , et al. Harnessing landrace diversity empowers wheat breeding. Nature. 2024; 632( 8026): 823– 31. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07682-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li N , Xu R , Li Y . Molecular networks of seed size control in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2019; 70: 435– 63. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-095851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chakravorty D , Trusov Y , Zhang W , Acharya BR , Sheahan MB , McCurdy DW , et al. An atypical heterotrimeric G-protein γ-subunit is involved in guard cell K+-channel regulation and morphological development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2011; 67( 5): 840– 51. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313x.2011.04638.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Pandey S , Vijayakumar A . Emerging themes in heterotrimeric G-protein signaling in plants. Plant Sci. 2018; 270: 292– 300. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang S , Wu K , Qian Q , Liu Q , Li Q , Pan Y , et al. Non-canonical regulation of SPL transcription factors by a human OTUB1-like deubiquitinase defines a new plant type rice associated with higher grain yield. Cell Res. 2017; 27( 9): 1142– 56. doi:10.1038/cr.2017.98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang M , Wu H , Su J , Wang H , Zhu Q , Liu Y , et al. Maternal control of embryogenesis by MPK6 and its upstream MKK4/MKK5 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2017; 92( 6): 1005– 19. doi:10.1111/tpj.13737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Xu R , Yu H , Wang J , Duan P , Zhang B , Li J , et al. A mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase influences grain size and weight in rice. Plant J. 2018; 95( 6): 937– 46. doi:10.1111/tpj.13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Su Z , Hao C , Wang L , Dong Y , Zhang X . Identification and development of a functional marker of TaGW2 associated with grain weight in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2011; 122( 1): 211– 23. doi:10.1007/s00122-010-1437-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang Y , Li D , Zhang D , Zhao X , Cao X , Dong L , et al. Analysis of the functions of TaGW2 homoeologs in wheat grain weight and protein content traits. Plant J. 2018; 94( 5): 857– 66. doi:10.1111/tpj.13903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hanif M , Gao F , Liu J , Wen W , Zhang Y , Rasheed A , et al. TaTGW6-A1, an ortholog of rice TGW6, is associated with grain weight and yield in bread wheat. Mol Breed. 2015; 36( 1): 1. doi:10.1007/s11032-015-0425-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang S , Wu K , Yuan Q , Liu X , Liu Z , Lin X , et al. Control of grain size, shape and quality by OsSPL16 in rice. Nat Genet. 2012; 44( 8): 950– 4. doi:10.1038/ng.2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jiang Y , Jiang Q , Hao C , Hou J , Wang L , Zhang H , et al. A yield-associated gene TaCWI, in wheat: its function, selection and evolution in global breeding revealed by haplotype analysis. Theor Appl Genet. 2015; 128( 1): 131– 43. doi:10.1007/s00122-014-2417-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hu M , Zhao X , Liu Q , Hong X , Zhang W , Zhang Y , et al. Transgenic expression of plastidic glutamine synthetase increases nitrogen uptake and yield in wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2018; 16( 11): 1858– 67. doi:10.1111/pbi.12921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ma L , Li T , Hao C , Wang Y , Chen X , Zhang X . TaGS5-3A, a grain size gene selected during wheat improvement for larger kernel and yield. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016; 14( 5): 1269– 80. doi:10.1111/pbi.12492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Dong L , Wang F , Liu T , Dong Z , Li A , Jing R , et al. Natural variation of TaGASR7-A1 affects grain length in common wheat under multiple cultivation conditions. Mol Breed. 2014; 34( 3): 937– 47. doi:10.1007/s11032-014-0087-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang Y , Shen C , Li G , Shi J , Yuan Y , Ye L , et al. MADS1-regulated lemma and awn development benefits barley yield. Nat Commun. 2024; 15: 301. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-44457-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Xiong D , Wang R , Wang Y , Li Y , Sun G , Yao S . SLG2 specifically regulates grain width through WOX11-mediated cell expansion control in rice. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023; 21( 9): 1904– 18. doi:10.1111/pbi.14102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang Y , Lv Y , Yu H , Hu P , Wen Y , Wang J , et al. GR5 acts in the G protein pathway to regulate grain size in rice. Plant Commun. 2024; 5( 1): 100673. doi:10.1016/j.xplc.2023.100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Jia M , Li Y , Wang Z , Tao S , Sun G , Kong X , et al. TaIAA21 represses TaARF25-mediated expression of TaERFs required for grain size and weight development in wheat. Plant J. 2021; 108( 6): 1754– 67. doi:10.1111/tpj.15541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Niaz M , Zhang L , Lv G , Hu H , Yang X , Cheng Y , et al. Identification of TaGL1-B1 gene controlling grain length through regulation of jasmonic acid in common wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023; 21( 5): 979– 89. doi:10.1111/pbi.14009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu H , Si X , Wang Z , Cao L , Gao L , Zhou X , et al. TaTPP-7A positively feedback regulates grain filling and wheat grain yield through T6P-SnRK1 signalling pathway and sugar-ABA interaction. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023; 21( 6): 1159– 75. doi:10.1111/pbi.14025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Li X , Qian X , Lv X , Wang X , Ji N , Zhang M , et al. Upregulated structural and regulatory genes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis for coloration of purple grains during the middle and late grain-filling stages. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2018; 130: 235– 47. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.07.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Li L , Yang S , Wang Z , Ren M , An C , Xiong F , et al. Physiological and cytological analyses of the thousand-grain weight in ‘Zhongyan96-3’ wheat. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023; 42( 4): 2212– 20. doi:10.1007/s00344-022-10694-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Favre F , Jourda C , Besse P , Charron C . Genotyping-by-sequencing technology in plant taxonomy and phylogeny. Methods Mol Biol. 2021; 2222: 167– 78. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-0997-2_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Elshire RJ , Glaubitz JC , Sun Q , Poland JA , Kawamoto K , Buckler ES , et al. A robust, simple genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach for high diversity species. PLoS One. 2011; 6( 5): e19379. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Li H , Handsaker B , Wysoker A , Fennell T , Ruan J , Homer N , et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009; 25( 16): 2078– 9. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. van Os H , Stam P , Visser RGF , van Eck HJ . SMOOTH: a statistical method for successful removal of genotyping errors from high-density genetic linkage data. Theor Appl Genet. 2005; 112( 1): 187– 94. doi:10.1007/s00122-005-0124-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Taylor J , Butler D . R package ASMap: efficient genetic linkage map construction and diagnosis. J Stat Soft. 2017; 79( 6): 1– 29. doi:10.18637/jss.v079.i06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Broman KW , Wu H , Sen Ś , Churchill GA . R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics. 2003; 19( 7): 889– 90. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Xu Y , La G , Fatima N , Liu Z , Zhang L , Zhao L , et al. Precise mapping of QTL for Hessian fly resistance in the hard winter wheat cultivar ‘Overland’. Theor Appl Genet. 2021; 134( 12): 3951– 62. doi:10.1007/s00122-021-03940-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Chung YS , Jun T , Kim C . Digestion efficiency differences of restriction enzymes frequently used for genotype-by-sequencing technology. Korean J Agric Sci. 2017; 44( 3): 318– 24. [Google Scholar]

38. Arora S , Singh N , Kaur S , Bains NS , Uauy C , Poland J , et al. Genome-wide association study of grain architecture in wild wheat Aegilops tauschii. Front Plant Sci. 2017; 8: 886. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Tekeu H , Ngonkeu ELM , Bélanger S , Djocgoué PF , Abed A , Torkamaneh D , et al. GWAS identifies an ortholog of the rice D11 gene as a candidate gene for grain size in an international collection of hexaploid wheat. Sci Rep. 2021; 11( 1): 19483. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-98626-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Dhakal S , Liu X , Chu C , Yang Y , Rudd JC , Ibrahim AMH , et al. Genome-wide QTL mapping of yield and agronomic traits in two widely adapted winter wheat cultivars from multiple mega-environments. PeerJ. 2021; 9: e12350. doi:10.7717/peerj.12350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Okamoto Y , Nguyen AT , Yoshioka M , Iehisa JCM , Takumi S . Identification of quantitative trait loci controlling grain size and shape in the D genome of synthetic hexaploid wheat lines. Breed Sci. 2013; 63( 4): 423– 9. doi:10.1270/jsbbs.63.423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Yan L , Liang F , Xu H , Zhang X , Zhai H , Sun Q , et al. Identification of QTL for grain size and shape on the D genome of natural and synthetic allohexaploid wheats with near-identical AABB genomes. Front Plant Sci. 2017; 8: 1705. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.01705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kumari S , Jaiswal V , Mishra VK , Paliwal R , Balyan HS , Gupta PK . QTL mapping for some grain traits in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2018; 24( 5): 909– 20. doi:10.1007/s12298-018-0552-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Sehgal D , Rosyara U , Mondal S , Singh R , Poland J , Dreisigacker S . Incorporating genome-wide association mapping results into genomic prediction models for grain yield and yield stability in CIMMYT spring bread wheat. Front Plant Sci. 2020; 11: 197. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.00197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Yang L , Zhao D , Meng Z , Xu K , Yan J , Xia X , et al. QTL mapping for grain yield-related traits in bread wheat via SNP-based selective genotyping. Theor Appl Genet. 2020; 133( 3): 857– 72. doi:10.1007/s00122-019-03511-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Sabouri H , Alegh SM , Sahranavard N , Sanchouli S . SSR linkage maps and identification of QTL controlling morpho-phenological traits in two Iranian wheat RIL populations. BioTech. 2022; 11( 3): 32. doi:10.3390/biotech11030032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Sun L , Yu Y , Hu W , Min Q , Kang H , Li Y , et al. Ribosomal protein S6 kinase1 coordinates with TOR-Raptor2 to regulate thylakoid membrane biosynthesis in rice. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipds. 2016; 1861( 7): 639– 49. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.04.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Smith J , Jerome-Majewska LA . Fibroblast growth factor 6. Differentiation. 2024; 137: 100780. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2024.100780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Dąbrowska GB , Turkan S , Tylman-Mojżeszek W , Mierek-Adamska A . In silico study of the RSH (RelA/SpoT homologs) gene family and expression analysis in response to PGPR bacteria and salinity in Brassica napus. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22( 19): 10666. doi:10.3390/ijms221910666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Zhu K , Tang D , Yan C , Chi Z , Yu H , Chen J , et al. Erect panicle2 encodes a novel protein that regulates panicle erectness in indica rice. Genetics. 2010; 184( 2): 343– 50. doi:10.1534/genetics.109.112045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Xu H , Chater KF , Deng Z , Tao M . A cellulose synthase-like protein involved in hyphal tip growth and morphological differentiation in Streptomyces. J Bacteriol. 2008; 190( 14): 4971– 8. doi:10.1128/JB.01849-07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Ma R , Yuan H , An J , Hao X , Li H . A Gossypium hirsutum GDSL lipase/hydrolase gene (GhGLIP) appears to be involved in promoting seed growth in Arabidopsis. PLoS One. 2018; 13( 4): e0195556. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0195556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Abt MR , Pfister B , Sharma M , Eicke S , Bürgy L , Neale I , et al. STARCH SYNTHASE5, a noncanonical starch synthase-like protein, promotes starch granule initiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2020; 32( 8): 2543– 65. doi:10.1105/tpc.19.00946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools