Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Prospects of Anthriscus, Chaerophyllum, and Myrrhoides Species Utilization and Biofortification with Selenium

1 Federal Scientific Vegetable Center, Moscow, 143072, Russia

2 Nikitsky Botanic Gardens—National Scientific Center of RAS, Yalta, 298648, Russia

3 T.I. Vyazemsky Karadag Scientific Station—Nature Reserve of RAS—Branch of A. O. Kovalevsky Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas of RAS, Kurortnoe, 298188, Russia

4 Department of Ecology, Sergo Ordzhonikidzer Russian State Geological Exploration University, Moscow, 117485, Russia

5 Department of Food Technologies, ‘Ion Ionescu de la Brad’ Iasi University of Life Sciences, Iasi, 700490, Romania

6 Department of Agricultural Sciences, University of Naples Federico II, Portici, Naples, 80055, Italy

* Corresponding Author: Nadezhda Golubkina. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 4139-4153. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.072328

Received 24 August 2025; Accepted 22 October 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

Despite their remarkable content of biologically active compounds, highly valuable for human health, wild relatives of Umbelliferous plants show limited utilization. The aim of the present work was the evaluation of the antioxidant status of Anthriscus, Chaerophyllum, and Myrrhoides species gathered in different climatic zones (from Mediterranean to Arctic) and of their suitability to produce valuable functional food for optimizing the human Se status. Among the Crimean plants, A. sylvestris, C. bulbosis, and M. nososa showed the highest antioxidant status, while the lowest was recorded in A. cerefolium and A. caucalis, displaying a significant correlation between the antioxidant activity (AOA) and polyphenols (TP) (r = 0.93; p < 0.001). A positive correlation between the longitude and AOA, and TP was detected for A. sylvestris (r = 0.95 and r = 0.93, respectively; p < 0.001). The high adaptability and wide geographical distribution of the latter species, as well as its significant content in natural antioxidants, make it an interesting product for Se biofortification. Foliar supplementation of sodium selenate allowed to obtain a new functional food with high TP content (36.4 mg GAE g−1 d.w.), ascorbic acid (42 mg 100 g−1 f.w.), and AOA (72 mg GAE g−1 d.w.). Moreover, Se level exceeded 3 mg kg−1 d.w., which suggests the plant suitability for the human Se status optimization, especially in Se-deficient Arctic zone, particularly referring to Nikel settlement with relatively low levels of Se in human hair (377 ± 13 μg kg−1), bread (58 ± 3 μg kg−1), and freshwater fish (359 ± 22 μg kg−1). The high antioxidant status of Myrrhoides nodosa indicates the need for detailed investigation of plant biochemistry and the identification of its utilization prospects.Keywords

The need for new natural sources of antioxidants for the production of both biologically active food additives and raw material for the pharmaceutical industry suggests the need for underestimated edible wild plant species with interesting biochemical characteristics [1,2], capable of accumulating higher levels of vitamins, polyphenols, and other antioxidants, compared to the corresponding cultivated crops [3,4,5]. The mentioned approach is the basis for developing new functional foods along with medicinal drugs, generating related product commercialization [6]. Furthermore, specific investigations indicate high prospects of wild edible plant biofortification with Se [7,8], an essential trace element to humans, showing remarkable synergism with natural antioxidants [9,10] and able to protect the organism against cardiovascular, oncological, and viral diseases [11]. This is especially important due to the high frequency of Se deficiency within the population of many countries worldwide, leading to decreased longevity, depressed brain activity, immunodeficiency, and, consequently, to significant economic losses [11].

Inside the plant kingdom. Apiaceae species and, particularly, the genera Anthriscus, Chaerophyllum, and Myrrhoides are of special interest due to the wide spectrum of biologically active compounds, including essential oils, polyphenols, polysaccharides, vitamins, and minerals [12]. The mentioned family includes about 3780 plant species, belonging to 434 genera, with the predominant distribution in the Mediterranean region and south-western Asia [13,14]. Cultivated Apiaceae species are highly valued in human nutrition and medicine, contrary to the corresponding wild relatives, whose utilization is significantly restricted to local communities. Indeed, residents in the Mediterranean countries consume less than 50% of native wild edible umbellifer species, among which Anthriscus cerefolium (L.) Hoffm., Anthriscus sylvestris (L.) Hoffm., and Chaerofyllum bulbosis L. are rather popular [15]. The utilization of these plants in human nutrition is extremely low and depends on the local culture. In this respect, while Anthriscus sylvestris L. Hoffm. is commonly used in Bulgaria, Armenia, and Crete, and is highly valued in traditional medicine in Romania [16], it is considered a disturbing weed in Russia.

Anthriscus genus combines 14 plant species, among which A. cerefolium, A. caucasus M. Bieb., and A. sylvestris are the most widespread in the south of Russia. A. cerefolium is the only species widely cultivated in many countries in the world due to its unique biochemical composition determining aroma and taste, and application in traditional medicine [17]. Differently, the most typical peculiarity of A. sylvestris is its high environmental adaptability, allowing a wide distribution in Europe, Asia, Africa, New Zealand, and northern America, including Canada, Alaska [18], and the Island [19]. The antioxidant status and essential oil composition of Anthriscus species have been intensively studied, revealing their high medicinal and nutritional value [20]. The protection against bacterial infections, inflammation, and oncological diseases, along with immune-modulatory and cardio-protection effects [21,22], results in broad areas of their utilization. A. caucalis, or burr-chervil, is a less studied plant inhabiting predominantly lowland European and Mediterranean areas, and as alien in some regions of Asia, North and South America, New Zealand, and Tasmania, where most of investigations were devoted to the essential oil whose main component is represented by cis-chrysanthenyl acetate in samples from Europe and North America, and sesquitherpene hydrocarbons in those from China [23].

Chaerophyllum bulbosum, or turnip chervil, is a not very diffused biannual plant cultivated for its tubers containing up to 76% of starch [24] and high levels of essential oil in leaves [25].

Myrrhoides nodosa (L.) Cannon (synonyms are Physocaulis nodosus (L.) W.D.J. Koch and Chaerophyllum nodosum (L.) Crantz plants are the least studied chervil relatives belonging to Myrrhoides Heist. ex Fabr. Genus, found in European and Mediterranean countries, Central Asia, Iran, Caucasus, and the Crimea. The latter plant was introduced to Great Britain and the non-Mediterranean areas of France, but has never been used for medicinal purposes, though its essential oil has been characterized [26,27].

Up to date, no attempts have been made regarding the Se biofortification of Anthriscus, Myrrhoides, and Chaerophyllum species, many of which possess high antioxidant activity and a wide spectrum of biologically active antitumor, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory compounds [20,28,29,30,31]. The only exception is garden chervil A. cerefolium, which was recently the object of Se/I biofortification for obtaining the corresponding functional food product [7]. Theoretically, biofortification of the mentioned plants with Se, having similar biological properties, can increase the medicinal and nutritional properties of the resulting products, creating a new group of Se-enriched functional foods.

The aim of the present research was (1) the evaluation of genetic and environmental effects on antioxidant properties of five Apiaceae species, Anthriscus cerefolium, Anthriscus caucalis, Anthriscus sylvestris, Chaerophyllum bulbosum, and Myrrhoides nodosa, cultivated or wildly grown in different climatic zones (the Southern Coast of Crimea, Karelia, Moscow, and Murmansk regions of Russia) and (2) the selection of the most promising species for the Se biofortification among the mentioned wild representatives, for manufacturing product with high antioxidant activity, essential for the human Se status optimization.

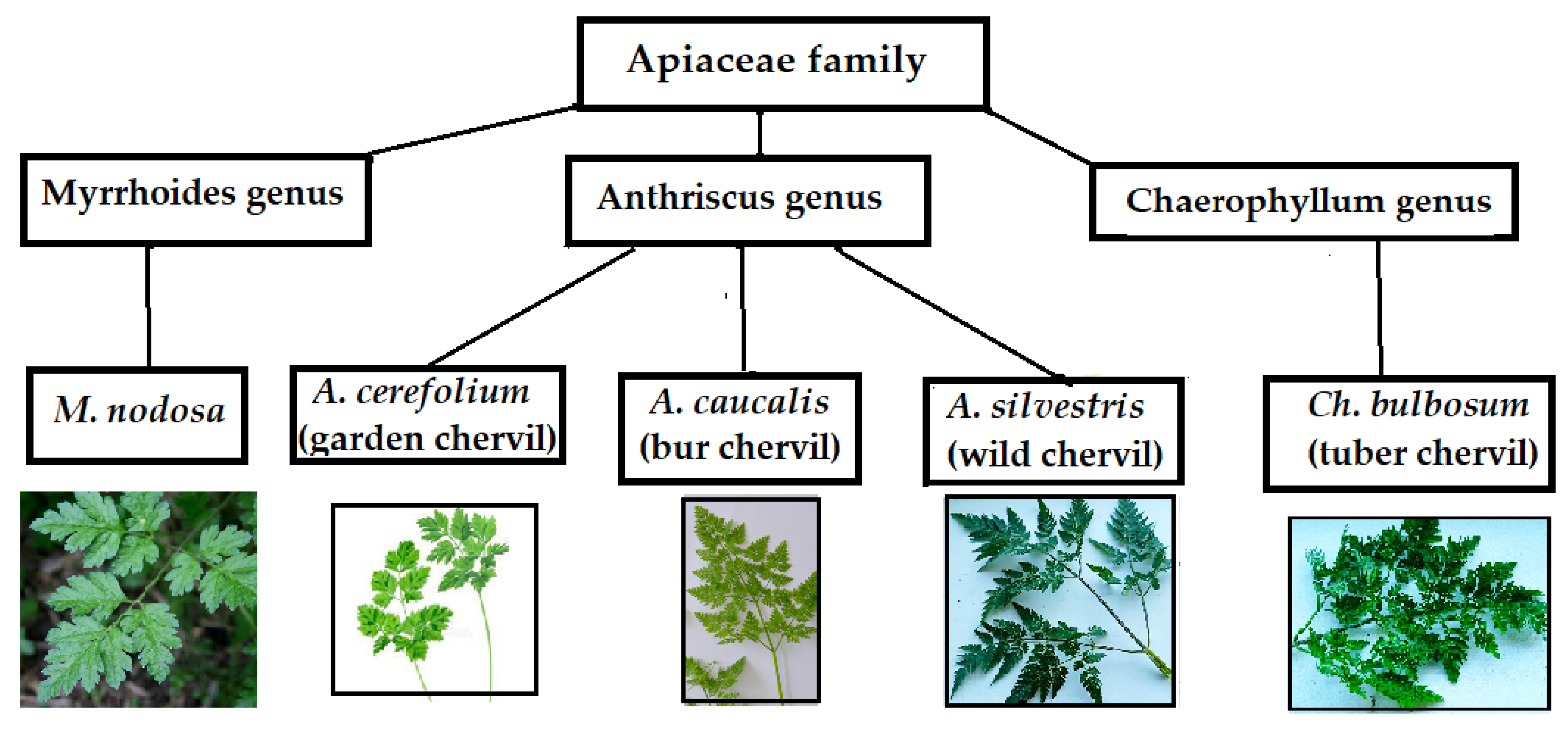

Three plant genera (Anthriscus, Chaerophyllum, and Myrrhoides) of the Apiaceae family with similar leaf architecture, including annual (A. cerefolium, A. caucalis, M. nodosa), biannual (C. bulbosum), and perennial (A. sylvestris) species were investigated (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Objects of investigation.

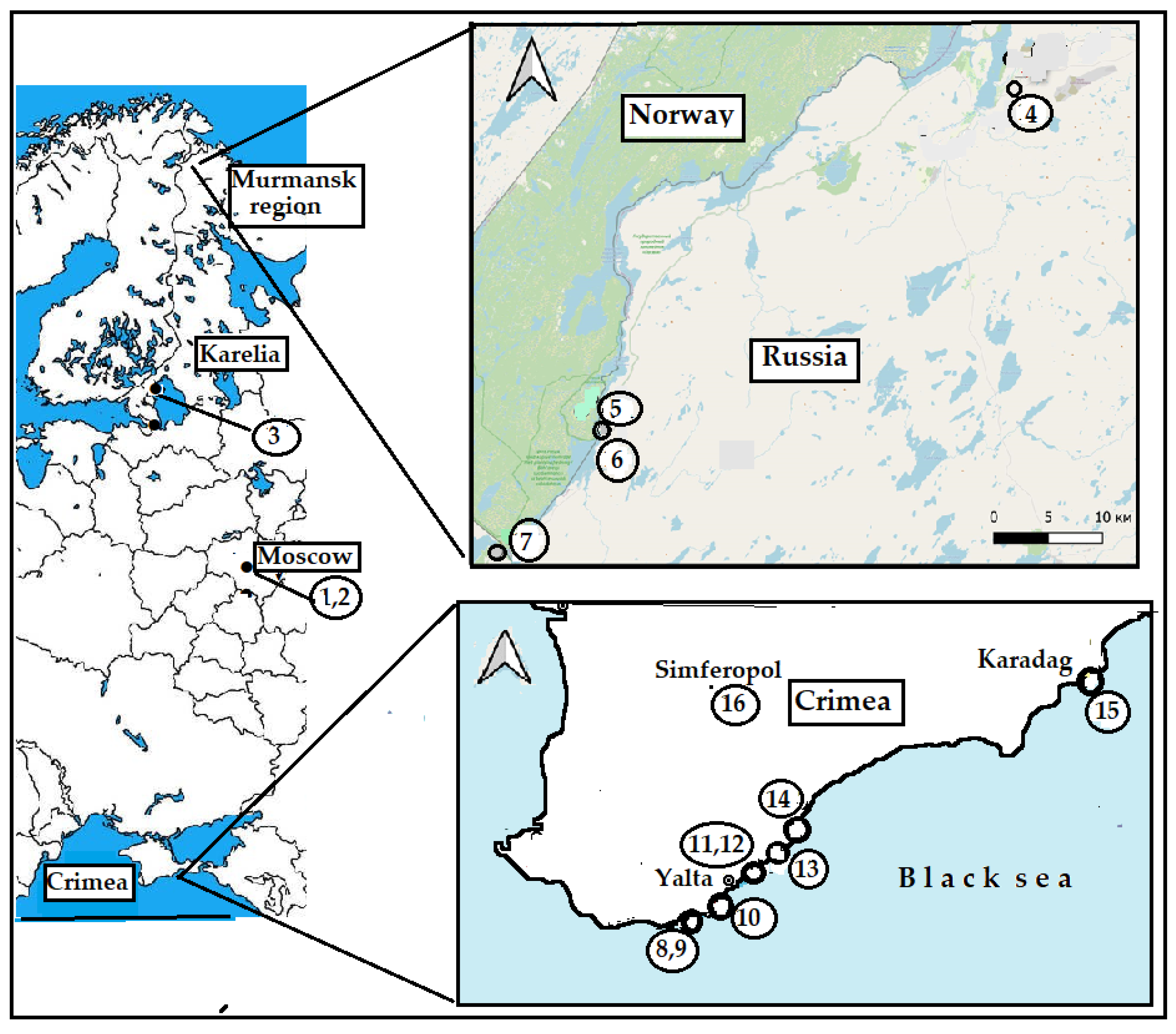

Samples of Anthriscus cerefolium wild relatives (Anthriscus sylvestris, Chaerophyllum bulbosum, Anthriscus caucalis, and Myrrhoides nodosa) were gathered in 2023–2024 at the territory of Moscow region and Crimea (Table 1), while cultivated species (Anthriscus cerefolium, cv. Ogorodnic, and Chaerophyllum bulbosum of Polish production) were produced in Moscow region at the experimental fields of Federal Scientific Vegetable Center (Table 1, Fig. 2).

To evaluate the effect of habitat on the antioxidant status of A. sylvestris, the latter was also gathered in Karelia and the Arctic region of European Russia (geographical coordinates of the sampling places are presented in Table 1).

Figure 2: Sampling places of Apiaceae species. The geographical coordinates and description of sampling places are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1: Objects of investigation and sampling places.

| Species | Region | No.** | Location | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthriscus cerefolium | Moscow* | 1 | Odintsovo | 55°39′31″ N, 37°12′23″ E |

| Anthriscus sylvestris | Moscow | 2 | Balashikha | 55°48′34″ N, 37°57′29″ E |

| Karelia | 3 | Kilpola island Ladoga lake | 61°12′59″ N, 29°55′56″ E | |

| Arctic | 4 | Nikel settlement | 69°24′29″ N, 30°13′14″ E | |

| 5 | Pasvik Nature Reserve | 69°08′16″ N, 29°14′37″ E | ||

| 6 | Pasvik Nature Reserve | 69°08′30″ N, 29°14′57″ E | ||

| 7 | Rayakoski settlement | 69°01′13″ N, 29°00′21″ E | ||

| Crimea | 10 | Oreanda, Krestovaya mountain | 44°27′30″ N, 34°08′10″ E | |

| 11 | Nikita | 44°30′51″ N, 34°14′07″ E | ||

| 12 | Nikita ash forest | 44°30′56″ N, 34°14′03″ E | ||

| 16 | Simpheropol | 44°57′25″ N, 34°06′38″ E | ||

| Anthriscus caucalis | Crimea | 8, 9 | Alupka Vorontsov park | 44°25′11″ N, 34°02′35″ E |

| 11 | Nikita | 44°30′51″ N, 34°14′07″ E | ||

| 14 | Gurzuf | 44°32′38″ N, 34°16′25″ E | ||

| Chaerophyllum bulbosum | Moscow* | 2 | Balashikha region | 55°48′34″ N, 37°57′29″ E |

| Crimea | 15 | Karadag Nature Reserve | 44°56′10″ N, 35°14′00″ E | |

| Myrrhoides nodosa | Crimea | 13 | Cape Martyan Nature Reserve | 44°30′38″ N, 34°15′25″ E |

Leaves of all plants investigated were harvested at the end of June in Moscow region, Crimea, and Karelia, and in the middle of August at the Arctic.

Garden and wild chervil plants (A. cerefolium, cultivar Ogorodnik, C. bulbosum, and A. sylvestris) were grown at the experimental fields of Federal Scientific Vegetable Center in 2023–2024 in clay-loam soil with pH 6.8, 2.1% organic matter, 1.32 mg-eq 100 g−1 hydrolytic acidity; 18.5 mg kg−1 mineral nitrogen; 21.3 mg kg−1 ammonium nitrogen; 402 mg kg−1 mobile phosphorous; 198 mg kg−1 exchangeable potassium; sum of absorbed bases 93.6%; cation exchange capacity 15 mg-eq 100 g−1 soil. No soil fertilization was practiced during the experiment, whereas the irrigation was activated when the soil humidity dropped to 75%.

A. cerefolium and C. bulbosum were sown on 10 May, while 2-year-old plants of wild A. sylvestris were transferred from the Balashikha park (55°48′34″ N 37°57′29″ E) to the experimental plot of 3 × 3 m2 with a 40 cm distance between plants.

At the 15th day of seedling development, A. cerefolium and A. sylvestris plants were sprayed with a 25 mg L−1 solution of sodium selenate, as in a previous investigation on A. cerefolium Se/I biofortification, which did not cause plant toxicity [7]. Foliar supply of Se was chosen as the most effective method of Se supply because of the significantly higher assimilation of this microelement compared to soil application [32]. Harvest was practiced 30 days after the vegetation beginning. Leaves were separated from plants, dried to constant weight in an oven at 70°C, and homogenized. The obtained powder was used for the determination of AOA and TP, while the ascorbic acid and photosynthetic pigments were determined on fresh homogenized leaves.

To determine the content of photosynthetic pigments, half a gram of dry samples was homogenized in a porcelain mortar with 10 mL of 96% ethanol. The homogenized sample mixture was quantitatively transferred to a volumetric flask, bringing the volume to 25 mL, and the mixture was filtered through filter paper. In the resulting solution, analyses of chlorophyll-a, chlorophyll-b, and carotene were performed through a spectrophotometer (Unico 2804 UV, USA). The calculation of chlorophyll and carotene concentrations was achieved using appropriate equations [33]: Ch-a = 13.36A664 − 5.19A649; Ch-b = 27.43A649 − 8.12A664; C c = (1000A470 − 2.13 Ch-a − 87.63 Ch-b)/209; where A = Absorbance at the wave length of 664, 649, and 470 nm, Ch-a = Chlorophyll a, Ch-b = Chlorophyll b and C c = Carotene.

The ascorbic acid content in leaves of A. cerefolium, A. sylvestris, and C. bulbosum plants was determined by visual titration of fresh leaf extracts in 3% trichloracetic acid with Tillman’s reagent [34]. Three grams of leaves were mixed with 5 mL of 3% trichloracetic acid and quantitatively transferred to a measuring cylinder. The volume was brought to 60 mL using 3% trichloracetic acid, and the mixture was filtered through a filter paper 15 min later. The concentration of the ascorbic acid was determined from the amount of Tillman’s reagent that went into the titration of the sample.

Total polyphenols were determined in 70% ethanol extract using the Folin–Ciocalteu colorimetric method as previously described [35]. One gram of dry homogenates was extracted with 20 mL of 70% ethanol at 80°C for 1 h. The mixture was cooled down and quantitatively transferred to a volumetric flask, and the volume was adjusted to 25 mL. The mixture was filtered through filter paper, and 1 mL of the resulting solution was transferred to a 25 mL volumetric flask, to which 2.5 mL of saturated Na2CO3 solution and 0.25 mL of diluted (1:1) Folin–Ciocalteu reagent were added. The volume was brought to 25 mL with distilled water. One hour later, the solutions were analyzed through a spectrophotometer (Unico 2804 UV, Suite E Dayton, NJ, USA), and the concentration of polyphenols was calculated according to the absorption of the reaction mixture at 730 nm. As an external standard, 0.02% gallic acid was used. The results were expressed as mg of Gallic Acid Equivalent per g of dry weight (mg GAE g−1 d.w.).

The antioxidant activity of samples was assessed using a redox titration method [35] via titration of 0.01 N KMnO4 solution with ethanolic extracts of dry samples, produced as described in the Section 2.2. The reduction of KMnO4 to colorless Mn+2 in this process reflects the quantity of antioxidants dissolvable in 70% ethanol. The values were expressed in mg Gallic Acid Equivalents (mg GAE g−1 d.w.).

Total Se content was analyzed using the microfluorimetric method [36]. Dried homogenized samples were digested via heating with a mixture of nitric and perchloric acids, subsequently selenate (Se + 6) was reduced to selenite (Se + 4) with a solution of 6 N HCl, and the resulting selenite was subjected to a complexation with 2,3-diaminonaphtalene to form piazoselenol. Calculation of the Se concentration was achieved by recording the piazoselenol fluorescence value in hexane at 519 nm-emission and 376 nm-excitation. Each determination was performed in triplicate. The precision of the results was verified using a reference standard of Se fortified mitsuba stem powder in each determination with a Se concentration of 1865 μg Kg−1 d.w. (Federal Scientific Vegetable Center).

The appropriate determination of organic Se was achieved analogously after removal of inorganic Se species with distilled water rinsing and precipitation of water soluble proteins with trichoracetic acid solution.

To evaluate the importance of Se-biofortified A. sylvestris utilization in the Arctic, the selenium status of Nikel residents (Murmansk region) was characterized by analyzing hair samples of 15 volunteers aged 30–46 (August 2024). Hair was washed with acetone to remove fat impurities, homogenized, and subjected to the Se analysis. Selenium concentrations were also determined in dried bread samples (n = 12) and muscles of fresh water whitefish (Coregonus pidschian) of the Paz River (n = 10).

The data were processed by the analysis of variance, and mean separations were performed through Duncan’s multiple range test, with reference to a 0.05 probability level, using the SPSS software version 29 (Armonk, NY, USA). Data expressed as percentages were subjected to angular transformation before processing.

The comparison of the polyphenol content (TP) and total antioxidant activity (AOA) between the examined species revealed great variations of the mentioned parameters depending on the genetic peculiarities and habitat (Table 2). Indeed, the AOA range indicated 5-time differences between the extreme AOA values (20.0–99.9 mg GAE g−1 d.w.), with the lowest level recorded in the Crimean A. caucalis and the highest in the Arctic A. sylvestris. A similar trend was shown by the polyphenol content, with an 8-time difference between the two mentioned species (4.4 to 36.6 mg GAE g−1 d.w.), suggesting that the Arctic and Karelian A. sylvestris proved the best source of phenolics and A. caucalus, and A. cerifolium the least rich in these compounds.

The highest diversity of Apiaceae species at the southern Crimean sea shore was demonstrated by AOA decrease from 65.1–70.9 mg GAE g−1 d.w. in M. nodosa and C. bulbosum to 30.0–63.1 mg GAE g−1 d.w. in A. sylvestris (mean value 44.7 mg GAE g−1 d.w.), and to 20.0–36.5 mg GAE g−1 d.w. in A. caucalis (mean value 26.5 mg GAE g−1 d.w.). The garden chervil A. cerefolium in the Moscow region was characterized by twice lower AOA, compared to A. sylvestris. The differences in antioxidant activity between the mentioned plants may relate to the corresponding annual/perennial growth cycle and half content of photosynthetic pigments in leaves of A. cerefolium [5]. Though A. caucalis is relatively abundant along the Crimean Sea shore, its antioxidant status was lower than that of the other species of the same genus.

Table 2: Total antioxidant activity (AOA) and total polyphenol content (TP) in cultivated chervil and its wild relatives.

| Species | Region | No on the Map | AOA | TP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg GAE g−1 d.w. | % from the AOA | ||||

| Anthriscus cerefolium | Moscow | 1 | 34.1 ± 3.1cd | 10.5 ± 1.0f | 30.8 |

| Anthriscus sylvestris | Moscow | 2 | 66.3 ± 6.2b | 25.2 ± 2.4c | 38.0 |

| Karelia | 3 | 93.6 ± 0.7a | 36.6 ± 1.9a | 39.1 | |

| Arctic | 4 | 88.3 ± 6.5a | 31.6 ± 1.9ab | 35.8 | |

| 5 | 99.9 ± 7.1a | 35.3 ± 2.0a | 35.3 | ||

| 6 | 86.3 ± 6.8a | 33.4 ± 1.9a | 38.7 | ||

| 7 | 99.6 ± 7.0a | 29.0 ± 1.8b | 29.2 | ||

| Crimea | 10 | 30.0 ± 1.3d | 15.0 ± 0.6e | 50.0 | |

| 11 | 63.1 ± 6.0b | 25.8 ± 2.5c | 40.9 | ||

| 12 | 41.7 ± 2.0c | 23.2 ± 1.1d | 55.6 | ||

| 16 | 43.8 ± 4.1c | 18.6 ± 1.8d | 42.5 | ||

| Anthriscus caucalis | Crimea | 8 | 20.0 ± 1.1f | 4.4 ± 0.1h | 22.0 |

| 9 | 23.0 ± 2.0ef | 7.1 ± 0.2g | 30.9 | ||

| 11 | 36.5 ± 3.5c | 13.4 ± 1.3e | 36.9 | ||

| 14 | 26.4 ± 2.5de | 9.8 ± 0.9f | 37.1 | ||

| Chaerophyllum bulbosum | Moscow | 2 | 67.8 ± 6.4b | 18.4 ± 1.8d | 27.1 |

| Crimea | 15 | 70.9 ± 6.9b | 25.5 ± 2.5c | 36.0 | |

| Myrrhoides nodosus | Crimea | 13 | 65.1 ± 6.4b | 28.9 ± 2.7bc | 44.4 |

Contrary, the high antioxidant status of M. nodosa in the Mediterranean zone, compared to A. caucalis and A. sylvestris, entails the importance of further investigations of this species nutritional and medicinal value aimed at widening the list of powerful antioxidant sources and improving the plant utilization. Notably, close values of antioxidant status were recorded in wild (Crimea) and cultivated (Moscow region) C. bulbosum. At present, the bulbs of the latter plant are rarely used in human nutrition [2], while the leaves have never been considered as a possible component of the human diet.

The wide spectrum of climatic differences between the chosen sampling places and the ubiquitous character of A., sylvestris distribution allowed us to reveal the effect of the environmental factors on the antioxidant status of plants. Indeed, the latitude range between 44°25′ to 69°42′ combines both the zone of Mediterranean climate (the Southern shore of Crimea with dark chestnut saline on Meikop clays), moderate continental climate of Moscow region (with sod-podzolic loamy soils), Karelia (with podzolic soils), and subarctic zone of Murmansk region (with tundra bog soils), i.e., regions greatly differing in terms of soil pH, mean annual temperature and precipitation, annual amount of total solar radiation (Table 3). According to the available data, the mean values of A. sylvestris total antioxidant activity were more than double in the Arctic region, compared to the Southern one (Table 2), in agreement with the above mentioned environmental characteristics. The measured parameters ranged in these regions from 4.3 to 8.0 (pH), 250 to 713 mm (precipitation), −3.1 to +13.5°C (mean annual temperature), and 70 to 118.3 kKal cm−2 (annual amount of total solar radiation) (Table 3). The neutral pH favourable for A. sylvestris growth [17] led to the tallest plants in the Moscow region (about 100 cm), while the mean height of wild chervil in the Arctic zone was about 30 cm (Pasvik Nature Research). The correlation coefficients between AOA, TP, and climate characteristics confirmed a powerful regulation effect of the environment on A. sylvestris antioxidant status and the existence of intensive oxidant stress in Arctic conditions, promoting the antioxidant biosynthesis in plants [3,37].

Table 3: Effect of climate parameter differences between the territories investigated.

| Region and Correlations | pH | Precipitation (mm) | Annual Air Temperature (°C) | Annual Amount of Total Solar Radiation (kKal cm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern shore of Crimea [38] | 7.8–8.0 | 596 | 13.5 | 118.3 |

| Moscow region [7] | 6.8–7.0 | 713 | 6.3 | 90 |

| Southern part of Karelia [39] | 4.5–5.5 | 611 | 2–3 | 80 |

| Arctic [40] | 4.3–4.5 | 350–428 | −3.1 | 70 |

| AOA correlation | −0.929a | −0.666c | −0.919b | −0.925a |

| TP correlation | −0.854a | −0.621d | −0.837a | −0.655c |

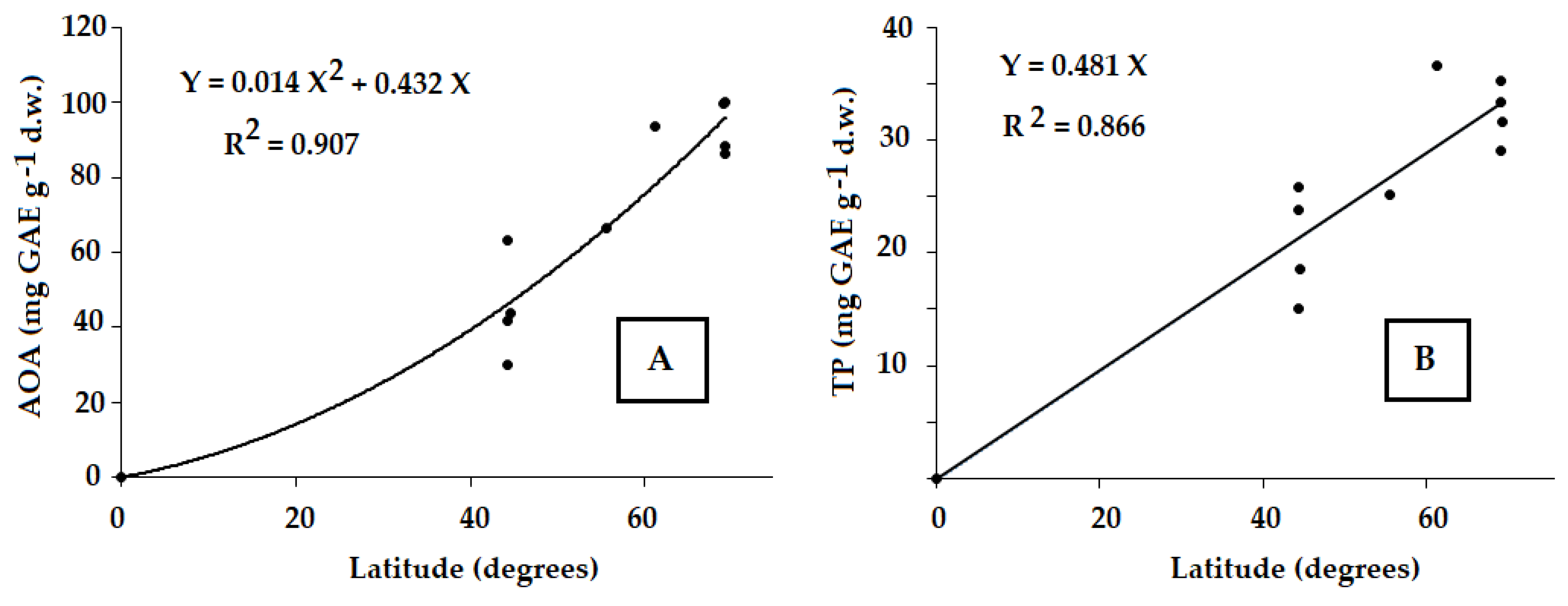

In this respect, latitude may be considered as an integral parameter governing climate and showing significant correlations with the wild chervil antioxidant status (Fig. 3A,B).

The revealed positive correlations between antioxidant status parameters (AOA and TP) of A. sylvestris leaves and the latitude (Fig. 3A,B) were in accordance with previous observations regarding the AOA and TP activation under the environmental stress applied [3,37,41,42]. The ubiquitous character of the revealed phenomenon entails high prospects of Arctic A. sylvestris utilization as a powerful source of natural antioxidants.

Figure 3: Relationship between the antioxidant activity (A) and polyphenol content (B) in A. sylvestris leaves and place of habitat (r = +0.952 and r = +0.931, respectively, p < 0.001; n = 10).

As far as the Crimean samples are concerned, the plants grown at the Nikita settlement (A. caucalis and A. sylvestris) demonstrated significantly higher local AOA and TP values, compared to those of other seashore habitats, which may relate to a local anthropogenic influence.

3.1.3 General Patterns of Antioxidant Accumulation

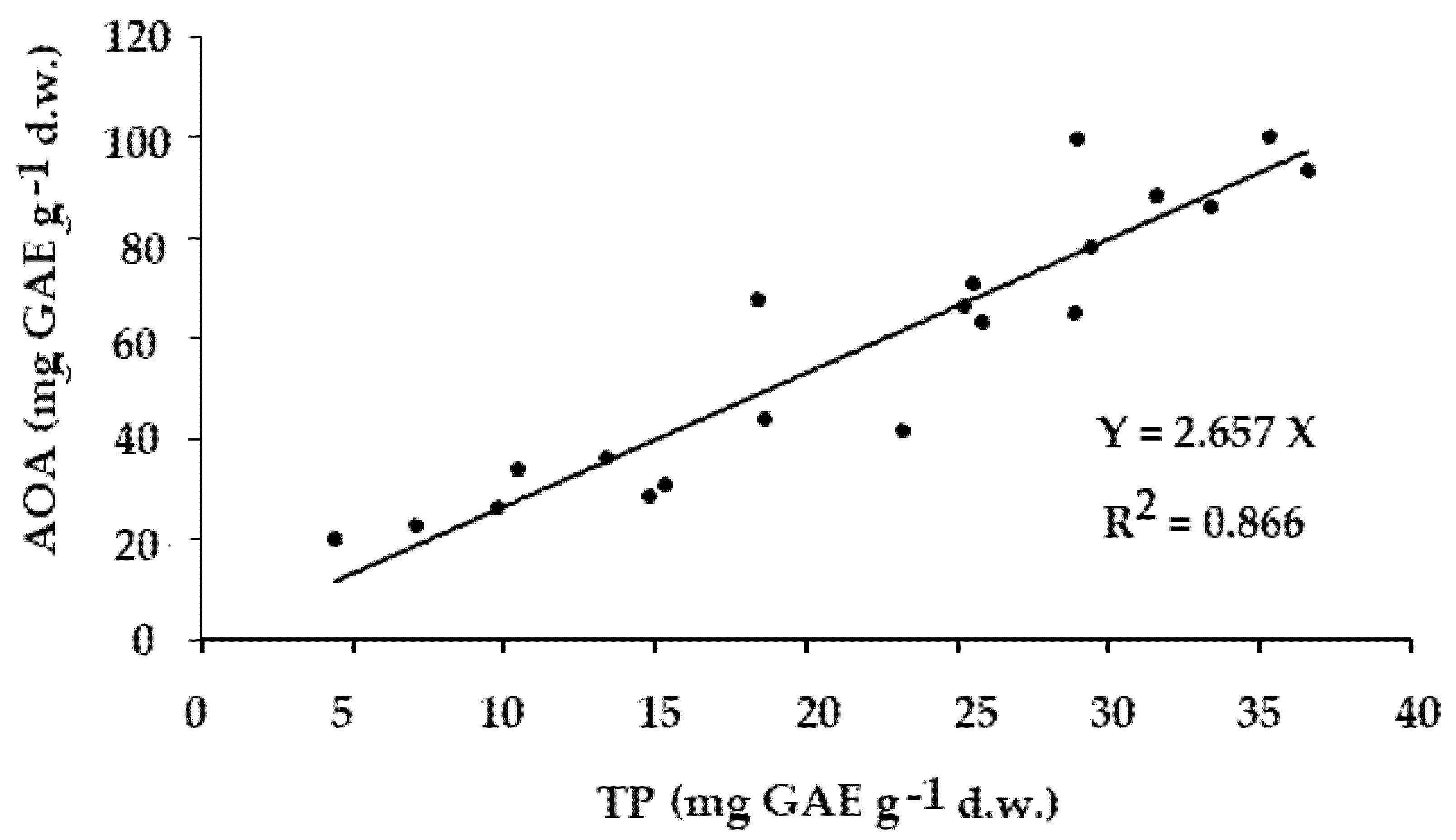

The results of the present research show the significant positive correlation between the total antioxidant activity (AOA) and polyphenol content in all the Apiaceae species examined (Fig. 4), consistently with previous reports [42].

Figure 4: Relationship between AOA and TP in leaves of all the Apiaceae species examined (r = 0.931; p < 0.001).

The same relationship has been recorded in other plant species: tree and shrub bark from 5 distinct geographical regions of Russia [42], Allium representatives [43], and mushrooms [40].

For the perspective of new functional food creation, the topic regarding the peculiarities and expediency of Se biofortification of edible wild plants arises [44]. Previous investigations indicated high prospects of Se-biofortified Allium ursinum [45], Azolla caroliniana [46], Portulaca olecracea [47], Taráxacum officinále [48], Plantago [47,49], and Rumex acetosa [47], etc. Contrary, wild A. sylvestris, A. caucalis, M. nodosa, and C. bulbosum have never been used for these purposes. In this respect, among the plants studied, A. sylvestris was chosen for Se foliar biofortification due to the chance to predict its antioxidant status in different geographical zones, as well as its high adaptability, wide habitat, and remarkable nutritional and medicinal value.

The production of functional food via plant biofortification with Se is one of the most interesting approaches for protecting human health and preventing hunger [39,46]. In this respect, wild relatives of agricultural crops are especially interesting due to their higher levels of adaptability and antioxidants [50]. Indeed, wild chervil (A. sylvestris) demonstrated unexpectedly great concentrations of total phenolics, ascorbic acid, and chlorophyll content, compared to garden chervil (A. cerefolium) (Table 4).

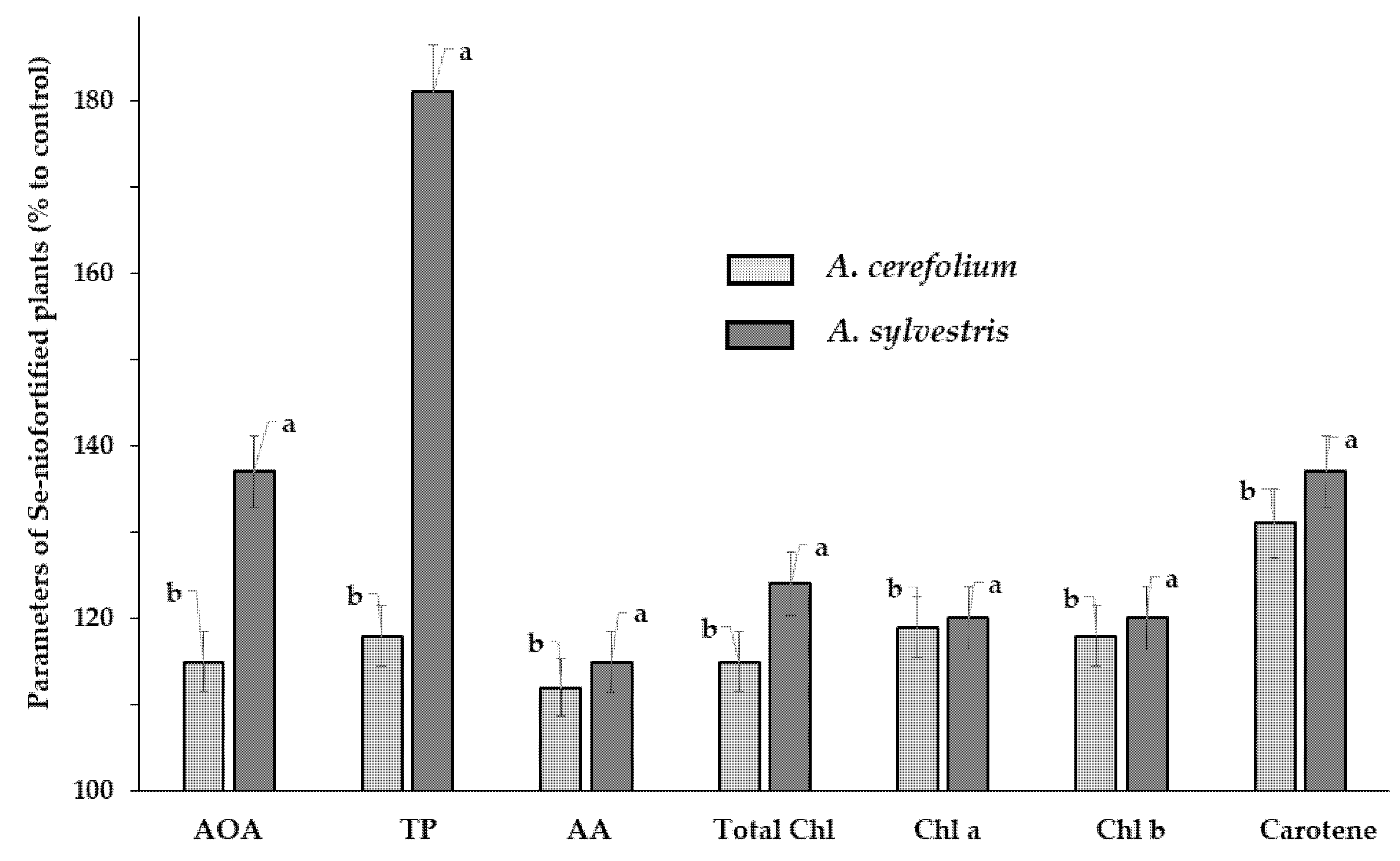

The comparison of foliar Se biofortification effect on wild A. sylvestris and cultivated A. cerefolium showed that, despite the higher initial antioxidant characteristics of A. sylvestris, compared to A. cerefolium, the mentioned plants displayed similar levels of resistance to Se treatment and increase of chlorophyll a, b, carotene, ascorbic acid, and Se biofortification (Table 4, Fig. 5). A beneficial effect of Se on the biosynthesis of plant antioxidants was recorded in many agricultural crops, suggesting the high prospect of Se biofortification [8,51]. Notably, in our research a significantly higher increase in the total antioxidant activity and polyphenol content was recorded in wild chervil under Se supplementation, compared to A. cerefolium, with values of 72.0 and 36.4 mg GAE g−1 d.w., respectively (Fig. 5). The data presented in Table 4 indicate that the consumption of 10 g of Se-fortified wild chervil powder may provide up to 60% of the Recommended Dietary Allowance for Se equal to 55 μg per day, not exceeding the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for adults of 400 μg [52]. Furthermore, the amount of organic Se in Se fortified plants was as high as 81.2% for Se biofortified A. sylvestris and 77.9% for A. cerefolium. These results are in accordance with the known ability of plants to use the external Se to synthesize various organic Se compounds, such as Se containing amino acids (selenomethionine, selenocysteine), the corresponding peptides, polysaccharides, etc., using the chemical similarity of Se and S [44]. As an essential microelement for human health, Se in the form of amino acids is incorporated into different enzymes, providing the antioxidant activity of glutathione peroxidases and thioredoxin reductase, participating in thyroid hormone metabolism in triiodothyronine deiodinases, ensuring Se transport in the form of selenoprotein P, regulating the inflammation processes in the form of selenoprotein S [10].

Table 4: Biochemical characteristics of control and Se biofortified A. sylvestris and A. cerefolium leaves.

| Parameter | A. sylvestris | A. cerefolium* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Se | Control | Se | |

| Dry matter (%) | 21.5 ± 1.6a | 24.4 ± 1.7a | 10.9 ± 0.9b | 11.1 ± 1.0b |

| Chlorophyll (mg g−1 f.w.) | 4.37 ± 0.39b | 5.44 ± 0.51a | 2.24 ± 0.20c | 2.58 ± 0.21c |

| Chlorophyll a (mg g−1 f.w.) | 2.73± 0.21b | 3.38± 0.30a | 1.58± 0.15d | 1.88± 0.19c |

| Chlorophyll b (mg g−1 f.w.) | 1.64± 0.13b | 2.06± 0.18a | 0.66± 0.06c | 0.78± 0.08c |

| Carotene (mg g−1 f.w.) | 0.43 ± 0.03c | 0.59 ± 0.04b | 0.59 ± 0.03b | 0.77 ± 0.04a |

| Ascorbic acid (mg 100 g−1 f.w.) | 38.0 ± 2.5a | 42.0 ± 3.1a | 28.0 ± 2.0b | 31.0 ± 2.1b |

| AOA (mg GAE g−1 d.w.) | 52.5 ± 4.5b | 72.0 ± 6.0a | 35.7 ± 3.0d | 40.9 ± 3.8c |

| TP (mg GAE g−1 d.w.) | 20.0 ± 1.7b | 36.4 ± 3.2a | 10.8 ± 0.9c | 12.7 ± 1.1c |

| Se (μg kg−1 d.w.) | 59 ± 5d | 3288 ± 191b | 110 ± 9c | 5150 ± 321a |

Figure 5: Antioxidant and chlorophyll differences between Se biofortified A. cerefolium and A. sylvestris and control. AOA: total antioxidant activity; TP: total polyphenol content; AA: ascorbic acid; Chl: chlorophyll. Values with the same letters do not differ statistically according to Duncan test at p < 0.05.

3.3 The Possible Role of Se-Fortified A. sylvestris for Human Health Protection in Arctic

From a practical point of view, the new Se-biofortified product shows the highest values of the AOA and TP content in plants from the Moscow region, similar to those recorded in the Arctic A. sylvestris. Future investigations may provide additional data, as the effect of altitude on the efficiency of Se biofortification in A. sylvestris in Arctic conditions has never been investigated previously. Supposedly, Se supply will further enhance plant tolerance to severe northern climate due to the antioxidant properties of Se, allowing to protect plants against all forms of oxidant stresses [8,51]. Moreover, rather high levels of Se may become significant for the northern zones of selenium deficient soil and low human Se status [53].

Indeed, epidemiological investigations in Nikel settlement indicated rather low Se levels in human hair: 377 ± 13 μg kg−1 d.w. on average (358–394 μg kg−1 d.w.; n = 15), along with low Se content in bread (58 ± 3 μg kg−1 d.w. on average; 54–63; n = 9) produced from grain of the neighboring Se-deficient regions and in whitefish muscles (Coregonus pidschian) of the Paz river (359 ± 22 μg kg−1 f.w.; n = 12). These results confirm the low Se status of the mentioned region and are in agreement with the previous investigations carried out in Syktyvkar, Komi republic (human serum Se concentration range of 54–91 μg L−1) [53] and the evaluation of Se content in whitefish from Arkhangelsk region (340 μg kg−1 f.w.; Pechora river; Narian-Mar; 67°38′16″ N.; 53°00′24″ E) [54].

A. sylvestris is widespread in the territory of the Pechenga district of Murmansk region, where the Nikel settlement is situated. According to our observation, this plant grows especially at unpolluted territories, with the exception of Nikel settlement, where imported soil has been used after the closure of Pechenganikel Cu/Ni smelting plant, which entails the possibility of A. sylvestris Se biofortified production in the Murmansk region, for the human Se status optimization. Unfortunately, no attempts have been made to assess the efficiency of plant Se biofortification in the Arctic zone, where severe climate may hamper plant growth and, therefore, the results may significantly differ from those obtained in the Moscow region; however, the latter hypothesis needs experimental confirmation.

The production of Se biofortified A. sylvestris plants may become important for the residents of other Se-deficient areas in Russia and other countries, due to the significant levels of antioxidants, sufficient Se levels predominantly in organic form, and low-cost technology of this new functional food. At present, A. sylvestris is used in salads, pastry, and soups [4,16], while the present results provide some new aspects of Se-enriched plant utilization as a spice and biologically active food additive.

A comparative assessment of the antioxidant status in Anthriscus, Chaerophyllum, and Myrrhoides species, grown in different climatic zones, revealed high prospects of A. sylvestris utilization to produce functional food beneficial for optimizing the human Se status and protection against oxidant stresses. The ubiquitous character of A. sylvestris distribution across different geographical zones, its high levels of adaptability, antioxidants, and efficiency of Se biofortification confirm the importance of this plant in human nutrition and health maintenance, especially in zones with remarkable oxidative stress and Se deficiency. A positive correlation between the antioxidant activity of wild chervil leaves and the habitat latitude shows its importance in the Arctic zone characterized by an increased environmental stress and low soil Se. Among the wild Apiaceae species from the Mediterranean zone, Myrrhoides nodosa may become another functional food ingredient due to its high antioxidant content, which suggests the need to deepen the investigation of this plant’s biochemistry and exploitation prospects.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The work was achieved according to the agreements between Federal Scientific Vegetable Center, Nikitsky Botanic Garden, and Karadag Nature Reserve, and state budget scientific theme numbers: FNNS-2025-0006, and 124030100098-0.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Nadezhda Golubkina, Viktor Kharchenko, and Gianluca Caruso; investigation: Anastasia Moldovan, Ekaterina Krainyuk, Lubov Riff, Vladimir Lapchenko, Helene Lapchenko, and Uliana Plotnoikova; methodology: Nadezhda Golubkina, Viktor Kharchenko, and Otilia Cristina Murariu; formal analysis: Nadezhda Golubkina and Vladimir Lapchenko; data curation: Helene Lapchenko and Lubov Riff; software: Ekaterina Krainyuk and Otilia Cristina Murariu; validation: Ekaterina Krainyuk and Lubov Riff; supervision: Nadezhda Golubkina; writing—original draft: Nadezhda Golubkina, Viktor Kharchenko, and Anastasia Moldovan; writing—review and editing: Nadezhda Golubkina and Gianluca Caruso. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Vanzani P , Rossetto M , De Marco V , Sacchetti LE , Paoletti MG , Rigo A . Wild Mediterranean plants as traditional food: a valuable source of antioxidants. J Food Sci. 2011; 76( 1): C46– C51. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01949.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Casas M , Vallès J , Gras A . Nutritional properties of wild edible plants with traditional use in the Catalan linguistic area: a first step for their relevance in food security. Foods. 2024; 13( 17): 2785. doi:10.3390/foods13172785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Rao MJ , Wu S , Duan M , Wang L . Antioxidant metabolites in primitive, wild, and cultivated Citrus and their role in stress tolerance. Molecules. 2021; 26( 19): 5801. doi:10.3390/molecules26195801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ozturk HI , Nas H , Ekinci M , Turan M , Ercisli S , Narmanlioglu HK , et al. Antioxidant activity, phenolic composition, and hormone content of wild edible vegetables. Horticulturae. 2022; 8( 5): 427. doi:10.3390/horticulturae8050427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kharchenko VA , Moldovan AI , Golubkina NA , Gins MS , Shafigullin DR . Comparative evaluation of several biologically active compounds content in Anthriscus sylvestris (L.) Hoffm. and Anthriscus cerefolium (L.) Hoffm. Veg Crops Russ. 2020;( 5): 81– 7. doi:10.18619/2072-9146-2020-5-81-87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Simopoulos AP . Omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants in edible wild plants. Biol Res. 2004; 37( 2): 263– 77. doi:10.4067/s0716-97602004000200013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Golubkina N , Moldovan A , Fedotov M , Kekina H , Kharchenko V , Folmanis G , et al. Iodine and selenium biofortification of chervil plants treated with silicon nanoparticles. Plants. 2021; 10( 11): 2528. doi:10.3390/plants10112528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Bandehagh A , Dehghanian Z , Gougerdchi V , Anwar Hossain M . Selenium: a game changer in plant development, growth, and stress tolerance, via the modulation in gene expression and secondary metabolite biosynthesis. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2023; 92( 8): 2301– 24. doi:10.32604/phyton.2023.028586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Andrés CMC , Pérez de la Lastra JM , Juan CA , Plou FJ , Pérez-Lebeña E . Antioxidant metabolism pathways in vitamins, polyphenols, and selenium: parallels and divergences. Int J Mol Sci. 2024; 25( 5): 2600. doi:10.3390/ijms25052600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Genchi G , Lauria G , Catalano A , Sinicropi MS , Carocci A . Biological activity of selenium and its impact on human health. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24( 3): 2633. doi:10.3390/ijms24032633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Thiviya P , Gamage A , Piumali D , Merah O , Madhujith T . Apiaceae as an important source of antioxidants and their applications. Cosmetics. 2021; 8( 4): 111. doi:10.3390/cosmetics8040111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sayed-Ahmad B , Talou T , Saad Z , Hijazi A , Merah O . The Apiaceae: ethnomedicinal family as source for industrial uses. Ind Crops Prod. 2017; 109: 661– 71. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.09.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Gangwar H , Kumari P , Jaiswal V . Phytochemically rich medicinally important plant families. In: Phytochemical genomics. Singapore: Springer; 2022. p. 35– 68. doi:10.1007/978-981-19-5779-6_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kozuharova E , Malfa GA , Acquaviva R , Valdes B , Aleksanyan A , Batovska D , et al. Wild species from the family Apiaceae, traditionally used as food in some Mediterranean countries. Plants. 2024; 13( 16): 2324. doi:10.3390/plants13162324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Velescu BS , Anuţa V , Niţulescu GM , Olaru OT , Ortan A , Ionescu D , et al. Pharmaceutical assessment of Romanian crops of Anthriscus sylvestris (Apiaceae) Farmacia. Farmacia. 2017; 65: 824– 31. [Google Scholar]

16. Vyas A , Shukla SS , Pandey R , Jain V , Joshi V , Gidwani B . Chervil: a multifunctional miraculous nutritional herb. Asian J Plant Sci. 2012; 11( 4): 163– 71. doi:10.3923/ajps.2012.163.171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Berežni S , Mimica-Dukić N , Domina G , Raimondo F , Orčić D . Anthriscus sylvestris—noxious weed or sustainable source of bioactive lignans? Plants. 2024; 13( 8): 1087. doi:10.3390/plants13081087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Luoma MO , Tamayo M , Sigurðsson S . Mapping wild chervil (Anthriscus sylvestris) and anise (Myrrhis odorata) in urban green spaces: a subarctic case study. Invasive Plant Sci Manag. 2025; 18( e3): 1– 13. doi:10.1017/inp.2024.39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Olaru O , Niţulescu G , Orțan A , Dinu-Pîrvu C . Ethnomedicinal, phytochemical and pharmacological profile of Anthriscus sylvestris as an alternative source for anticancer lignans. Molecules. 2015; 20( 8): 15003– 22. doi:10.3390/molecules200815003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bussmann RW , Batsatsashvili K , Kikvidze Z , Paniagua-Zambrana NY , Khutsishvili M , Maisaia I , et al. Anthriscus cerefolium (L.) hoffm. Anthriscus sylvestris (L.) hoffm. Apiaceae. In: Ethnobotany of the mountain regions of far eastern Europe. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 107– 12. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-28940-9_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kim SB , Lee AY , Chun JM , Lee AR , Kim HS , Seo YS , et al. Anthriscus sylvestris root extract reduces allergic lung inflammation by regulating interferon regulatory factor 4-mediated Th2 cell activation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019; 232: 165– 75. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2018.12.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Swor K , Satyal P , Setzer WN . The essential oil composition of Anthriscus caucalis M. bieb. (Apiaceae) growing wild in southwestern Idaho. Nat Prod Commun. 2023; 18( 7): 1– 5. doi:10.1177/1934578x231187699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ayala Garay OJ , Briard M , Péron JY , Planchot V . Chaerophyllum bulbosum: a new vegetable interesting for its root carbohydrate reserves. Acta Hortic. 2001; 598: 227– 34. doi:10.17660/actahortic.2003.598.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Molo Z , Tel-Çayan G , Deveci E , Öztürk M , Duru ME . Insight into isolation and characterization of compounds of Chaerophyllum bulbosum aerial part with antioxidant, anticholinesterase, anti-urease, anti-tyrosinase, and anti-diabetic activities. Food Biosci. 2021; 42: 101201. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2021.101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chizzola R . Essential oil composition of wild growing Apiaceae from Europe and the Mediterranean. Nat Prod Commun. 2010; 5( 9): 1477– 92. [Google Scholar]

26. Chizzola R . Composition of the essential oils from Anthriscus cerefolium var. trichocarpa and A. Caucalis growing wild in the urban area of Vienna (Austria). Nat Prod Commun. 2011; 6( 8): 1147– 50. [Google Scholar]

27. Bos R , Koulman A , Woerdenbag HJ , Quax WJ , Pras N . Volatile components from Anthriscus sylvestris (L.) hoffm. J Chromatogr A. 2002; 966( 1–2): 233– 8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(02)00704-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Jeong GS , Kwon OK , Park BY , Oh SR , Ahn KS , Chang MJ , et al. Lignans and coumarins from the roots of Anthriscus sylvestris and their increase of caspase-3 activity in HL-60 cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007; 30( 7): 1340– 3. doi:10.1248/bpb.30.1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang M , Ji X , Li Y , Chen X , Wu X , Tan R , et al. Anthriscus sylvestris: an overview on bioactive compounds and anticancer mechanisms from a traditional medicinal plant to modern investigation. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2024; 24( 12): 1162– 76. doi:10.2174/0113895575271848231116095447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Fejes S , Lemberkovics É , Balázs A , Apáti P , Kristó T , Szőke É , et al. Antioxidant activity of different compounds from Anthriscus cerefolium L. (Hoffm.). Acta Hortic. 2003, 597( 597): 191– 8. [Google Scholar]

31. Stamenković J , Petrović G . The utility and chemotaxonomic significance of volatiles for inferring phylogeny in Chaerophyllum (Apiaceae): Essential oil composition of Myrrhoides nodosa (L.) Cannon. Chem Biodivers. 2025; 10( 6): e202403267. doi:10.1002/cbdv.202403267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wang M , Zhou F , Cheng N , Chen P , Ma Y , Zhai H , et al. Soil and foliar selenium application: impact on accumulation, speciation, and bioaccessibility of selenium in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Front Plant Sci. 2022; 13: 988627. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.988627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Lichtenthaler HK . [34] Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. In: Plant cell membranes. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1987. p. 350– 82. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(87)48036-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. AOAC International, Latimer GW . Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: AOAC International; 2012. [Google Scholar]

35. Guide to Quality and Safety Contril Methods of Biologically Active Food Supplements. P 4.1.1672-03 Russian Ministry of Health. Moscow, 2024; 124–127. ISBN 5750804909 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: http://gost.gtsever.ru/Index2/1/4293855/4293855460.htm. [Google Scholar]

36. Alfthan G . A micromethod for the determination of selenium in tissues and biological fluids by single-test-tube fluorimetry. Anal Chim Acta. 1984; 165: 187– 94. doi:10.1016/S0003-2670(00)85199-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Hasanuzzaman M , Bhuyan MHMB , Zulfiqar F , Raza A , Mohsin SM , Al Mahmud J , et al. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under abiotic stress: revisiting the crucial role of a universal defense regulator. Antioxidants. 2020; 9( 8): 681. doi:10.3390/antiox9080681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Pavlova SA , Gorbachev VV , Sukhareva NA . Prerequisites for the sustainable development of horticulture in the Crimea. Int Res J. 2023; 6( 132): 48. [Google Scholar]

39. Morozova KV , Evseeva DA . Resources and morphological features of Anthriscus sylvesntis in communities of Karelia and the Murmansk region. J Appl Fund Res. 2025; 9: 10– 4. doi:10.17513/mjpfi.13752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Golubkina N , Plotnikova U , Koshevarov A , Sosna E , Hlebosolova O , Polikarpova N , et al. Nickel, Cu, Fe, Zn, and Se accumulation, and the antioxidant status of mushrooms grown in the Arctic under Ni/Cu pollution and in unpolluted areas. Stresses. 2025; 5( 2): 25. doi:10.3390/stresses5020025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Cannea FB , Padiglia A . Antioxidant defense systems in plants: mechanisms, regulation, and biotechnological strategies for enhanced oxidative stress tolerance. Life 2025; 15( 8): 1293. doi:10.3390/life15081293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Golubkina N , Plotnikova U , Lapchenko V , Lapchenko H , Sheshnitsan S , Amagova Z , et al. Evaluation of factors affecting tree and shrub bark’s antioxidant status. Plants. 2022; 11( 19): 2609. doi:10.3390/plants11192609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kovarovič J , Bystrická J , Fehér A , Lenková M . Evaluation and comparison of bioactive substabces in selected species of the genus Allium. Potravin Slovak J Food Sci. 2017; 11( 1): 702– 8. doi:10.5219/833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Spyro GP , Ntanasi T , Karavidas I , Marka S , Giannothanasis E , Vultaggio L , et al. Enhancing nutritional and functional properties of hydroponically grown underutilised leafy greens through selenium biofortification. Plants. 2025; 14: 2716. doi:10.3390/plants14172716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Amagova ZA , Matsadze VH , Golubkina NA , Seredin TM , Caruso G . Fortification of wild garlic with selenium. Veg Crops Russ. 2018;( 4): 76– 80. doi:10.18619/2072-9146-2018-4-76-80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Hassan AMA , Mostafa EM . Selenium invoked antioxidant defense system in Azolla caroliniana plant. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2016; 85( 1): 262– 9. doi:10.32604/phyton.2016.85.262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Puccinelli M , Pezzarossa B , Pintimalli L , Malorgio F . Selenium biofortification of three wild species, Rumex acetosa L., Plantago coronopus L., and Portulaca oleracea L., grown as microgreens. Agronomy. 2021; 11( 6): 1155. doi:10.3390/agronomy11061155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Žnidarčič D . Yield attributes of dandelion (Taraxacum officinale Web.) in response to foliar application with selenium. In: Proceedings of the 56th Croatian & 16th International Symposium on Agriculture; 2021 Sep 5–10; Vodice, Croatia. p. 408– 12. [Google Scholar]

49. Dey S , Sen R . Selenium biofortification improves bioactive composition and antioxidant status in Plantago ovata Forsk., a medicinal plant. Genes Environ. 2023; 45( 1): 38. doi:10.1186/s41021-023-00293-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Myrtsi ED , Evergetis E , Koulocheri SD , Haroutounian SA . Bioactivity of wild and cultivated legumes: phytochemical content and antioxidant properties. Antioxidants. 2023; 12( 4): 852. doi:10.3390/antiox12040852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Liu H , Xiao C , Qiu T , Deng J , Cheng H , Cong X , et al. Selenium regulates antioxidant, photosynthesis, and cell permeability in plants under various abiotic stresses: a review. Plants. 2022; 12( 1): 44. doi:10.3390/plants12010044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on Dietary Antioxidants and Related Compounds . Dietary reference intakes for vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

53. Parshukova O , Potolitsyna N , Shadrina V , Chernykh A , Bojko E . Features of selenium metabolism in humans living under the conditions of North European Russia. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2014; 87( 6): 607– 14. doi:10.1007/s00420-013-0895-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Sobolev N , Aksenov A , Sorokina T , Chashchin V , Ellingsen DG , Nieboer E , et al. Essential and non-essential trace elements in fish consumed by indigenous peoples of the European Russian Arctic. Environ Pollut. 2019; 253: 966– 73. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.07.072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools