Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Chitosan-Selenate Complex Improves Bioactive Profile and Antioxidant Response in Wheat Sprouts (Triticum aestivum L.)

1 Ingenieria en Biotecnología, Universidad Politécnica de Gómez Palacio (UPGOP). Carretera El Vergel-La Torreña km 0820, El Vergel, Gómez Palacio, 35120, Mexico

2 Postgrado en Ciencias en Producción Agropecuaria, Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Periférico Raúl López Sánchez and Carretera Santa Fe S/N, Torreón, 27010, Mexico

3 Departamento de Horticultura, Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Periférico Raúl López Sánchez and Carretera Santa Fe S/N, Torreón, 27010, Mexico

4 Agricultura Sustentable y Protegida, Universidad Tecnológica de Escuinapa, Camino al Guasimal S/N, Colonia Centro, Escuinapa de Hidalgo, 82400, Mexico

5 Departamento de Riego y Drenaje, Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Periférico Raúl López Sánchez and Carretera Santa Fe S/N, Torreón, 27010, Mexico

* Corresponding Author: Ricardo Israel Ramírez-Gottfried. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Molecular Insights of Plant Secondary Metabolites: Biosynthesis, Regulation, and Applications)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 3961-3973. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.072536

Received 29 August 2025; Accepted 14 November 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

Selenium (Se) deficiency is a global health problem affecting more than 500 million people; crop biofortification is a sustainable strategy for its mitigation. This study investigated the effect of the application of selenate nanoparticles (SeO42−) and the combination of selenate (SeO42−) and chitosan (CS) (forming a SeO42−-CS complex) on the antioxidant profile, growth, biomass, bioactive compounds, enzymes, and Se accumulation of wheat (Triticum spp.) sprouts. Fourteen treatments were applied using a factorial design combining seven concentrations and two formulations: SeO42− and SeO42−-CS. It was identified that chitosan increased Se uptake efficiency by 30% versus conventional selenate. The optimal dose for biomass was 0.15 mg L−1 of SeO42−-CS (+40% vs. control), while 0.25 mg L−1 maximized bioactive compounds (phenolics (25%) and flavonoids (21%)) as well as antioxidant capacity (26%) and enzymatic activity (SOD: 37%; POD: 41%). In addition, CS reduced Se phytotoxicity at doses ≥1.50 mg L−1, evidencing its dual role as a delivery vehicle and cell protector. These findings demonstrate that the SeO42−-CS hybrid system is a technologically viable and efficient alternative to traditional selenate for the production of biofortified sprouts. This strategy shows high potential for scaling up in the functional food industry and for application in agricultural regions with selenium-deficient soils.Keywords

Wheat (Triticum spp.) is one of the most important crops worldwide due to its nutritional value and its role as a basic source of food for millions of people [1]. The consumption of its sprouts is becoming popular due to their high nutritional value and functional properties [2]. The incorporation of sprouts in people’s daily diet is an attractive option to improve general health and prevent diseases, especially within the context of healthy and preventive diets [3]. Selenium (Se) is an essential trace element in human health. In plants, it stimulates aerial and root growth, and it triggers the antioxidant response. Deficiency of this element in humans causes negative effects such as cardiomyopathy and cancer-related problems [4].

Chitosan (CS), a natural cationic biopolymer obtained from the deacetylation of chitin, has been highlighted for its agricultural applications. Its ability to form complexes with metal micronutrients is an innovative strategy to improve their stability, bioavailability, and uptake in plants while acting as an elicitor of defense responses against abiotic stresses [5,6]. When it forms complexes with anions such as selenate (SeO42−), it can facilitate its transport across negatively charged cell membranes, potentially improving biofortification efficiency. SeO42− is not essential for most plants, yet it has shown beneficial effects by promoting growth and resistance to various conditions, although excessive concentration can be toxic [7].

Nanotechnology has shown great potential to transform various aspects of agriculture, from improving plant nutrition to protecting crops and improving the quality of agricultural products [8]. In this context, nanobiofortification is an innovative strategy that employs nanoparticles to increase the content of essential nutrients in plants, which benefits the productivity and nutritional quality of crops as well as human nutrition [9]. Nanobiofortification of sprouts with micronutrients such as selenate, zinc, and iron can significantly increase their nutrient content. This represents an affordable and sustainable solution to combat global micronutrient deficiency [10].

Therefore, the objective of this research was to evaluate the effects of applying selenate (SeO42−) and chitosan-selenate nanoparticles (SeO42−-CS) to wheat sprouts in terms of yield, bioactive compounds, antioxidant activity, and Se accumulation. We hypothesized that the formation of the SeO42−-CS complex would enhance selenium uptake and bioavailability, boost the synthesis of bioactive compounds and antioxidant response, and reduce the phytotoxicity of high selenate doses compared to the application of selenate alone.

2.1 Plant Material and Growing Conditions

The experiment was carried out in the Biotechnology Laboratory of the Polytechnic University of Gómez Palacio, Durango, Mexico (25°34′11.5′′ N, 103°29′53.5′′ W; 1120 m a.s.l.). Uniform Triticum aestivum L. seeds (“BORLAUG 100 F2014,” Nature Jim’s®, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) were selected, surface sterilized using 75% ethanol for five minutes, and subsequently rinsed four times with distilled water to ensure asepsis [11].

2.2 Preparation of Selenate Solutions and Selenate-Chitosan Complexes

A sodium selenate stock solution (Na2SeO4, ≥99%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was prepared in sterile distilled water. Chitosan (low molecular weight, ≥75% deacetylation, agricultural grade) was dissolved in 1% v/v acetic acid (50 mg mL−1), and pH was adjusted to 5.5 with 1 M NaOH. The selenate and chitosan solutions were combined under continuous stirring (200 rpm, 25°C) for 2 h to allow the formation of electrostatic complexes. Dynamic light scattering (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK) was used to determine the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential (152 ± 12 nm and +32.5 ± 2.1 mV, respectively), confirming the formation of a stable nanostructure suitable for plant uptake.

2.3 Germination Test and Growth Measurement

Fourteen treatments were established (Table 1), each consisting of ten seeds. The priming treatments were applied during the imbibition phase by immersing the seeds in darkness for 8 h in the respective treatment solutions [12]. After treatment, the seeds were placed in 200 mm glass Petri dishes containing two layers of Whatman® grade 1 filter paper moistened with 5 mL of distilled water. Plates were sealed and incubated at 25 ± 2°C and 60% RH with a 12 h photoperiod (HGZ-150 incubator, M®, Shanghai, China). Germination was monitored daily according to ISTA (2024) standards, with a seed considered germinated when the root length reached at least half the seed length [13].

Table 1: Treatments established with selenate (SeO42−) and selenate-chitosan (SeO42−-CS).

| Treatment | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Control = Distilled water |

| 2 | CS (50 mg mL−1) |

| 3 | SeO42− (0.10 mg mL−1) |

| 4 | SeO42− (0.50 mg mL−1) |

| 5 | SeO42− (1.00 mg mL−1) |

| 6 | SeO42− (1.50 mg mL−1) |

| 7 | SeO42− (2.00 mg mL−1) |

| 8 | SeO42− (2.50 mg mL−1) |

| 9 | SeO42−-CS (0.10 mg mL−1–50 mg mL−1) |

| 10 | SeO42−-CS (0.50 mg mL−1–50 mg mL−1) |

| 11 | SeO42−-CS (1.00 mg mL−1–50 mg mL−1) |

| 12 | SeO42−-CS (1.50 mg mL−1–50 mg mL−1) |

| 13 | SeO42−-CS (2.00 mg mL−1–50 mg mL−1) |

| 14 | SeO42−-CS (2.50 mg mL−1–50 mg mL−1) |

2.4 Parameters Evaluated in the Bioassay

Fifteen seedlings per treatment were separated into shoots and roots, weighed fresh, and oven-dried at 60°C (FDM®, Rome, Italy) to constant weight. Water content (WC, %) was calculated from the difference between fresh and dry weights (Eq. (1)).

2.4.2 Germination Percentage (G%)

Germination rate was determined seven days after sowing using the formula based on the total number of germinated seeds (Eq. (2)).

Initial germination counting occurred four days after sowing. Seeds with developed roots and plumules (average growth ≥ 2 cm) were recorded. The vigor index was calculated as: (Eq. (3)).

2.5 Extract Preparation and Bioactive Compound Analysis

Fresh samples (2 g) were homogenized with 10 mL of 80% ethanol under constant agitation for 24 h at 70 rpm and 5°C. Extracts were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min, with supernatants collected for subsequent analysis [14].

Phenolic content was determined by a modified Folin–Ciocalteu method [15] using gallic acid as a standard. Absorbance was measured at 760 nm in a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (TFS®, Durham, NC, USA), and results were expressed as mg GAE per 100 g fresh weight.

Flavonoids were quantified colorimetrically [16] using quercetin as a standard. The samples were analyzed in a spectrophotometer (TFS®, Durham, NC, USA) at 510 nm. Results were expressed as mg QE per 100 g fresh weight.

2.5.3 Antioxidant Capacity (DPPH Assay)

Antioxidant capacity was measured using the DPPH radical scavenging method [17]. The samples were analyzed in a spectrophotometer (TFS®, Durham, NC, USA) at 517 nm. Results were expressed as µM Trolox equivalent per 100 g fresh weight.

Glutathione content (mg 100 g−1 DW) was determined using the method described by [18]. Absorbance was recorded at 412 nm and expressed as mg 100 g−1 per kg dry weight.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity (EC 1.15.1.1) was measured using the Cayman® 706002 commercial kit (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). CAT (EC 1.11.1.6) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX) (EC 1.11.1.9) activities were determined according to [19,20], respectively, following standard absorbance-based protocols.

2.7 SeO42− Accumulation in Wheat Sprouts

Selenate concentration in shoots was quantified by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAS) with an air-acetylene flame (TFS®, Waltham, MA, USA) according to AOAC (1990). Values were expressed as µg Se per kg dry weight.

The data of the variables’ response to the factors under study, as well as their interactions, were analyzed by a two-way analysis of variance using Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 statistical software, and Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05) was used to compare the means.

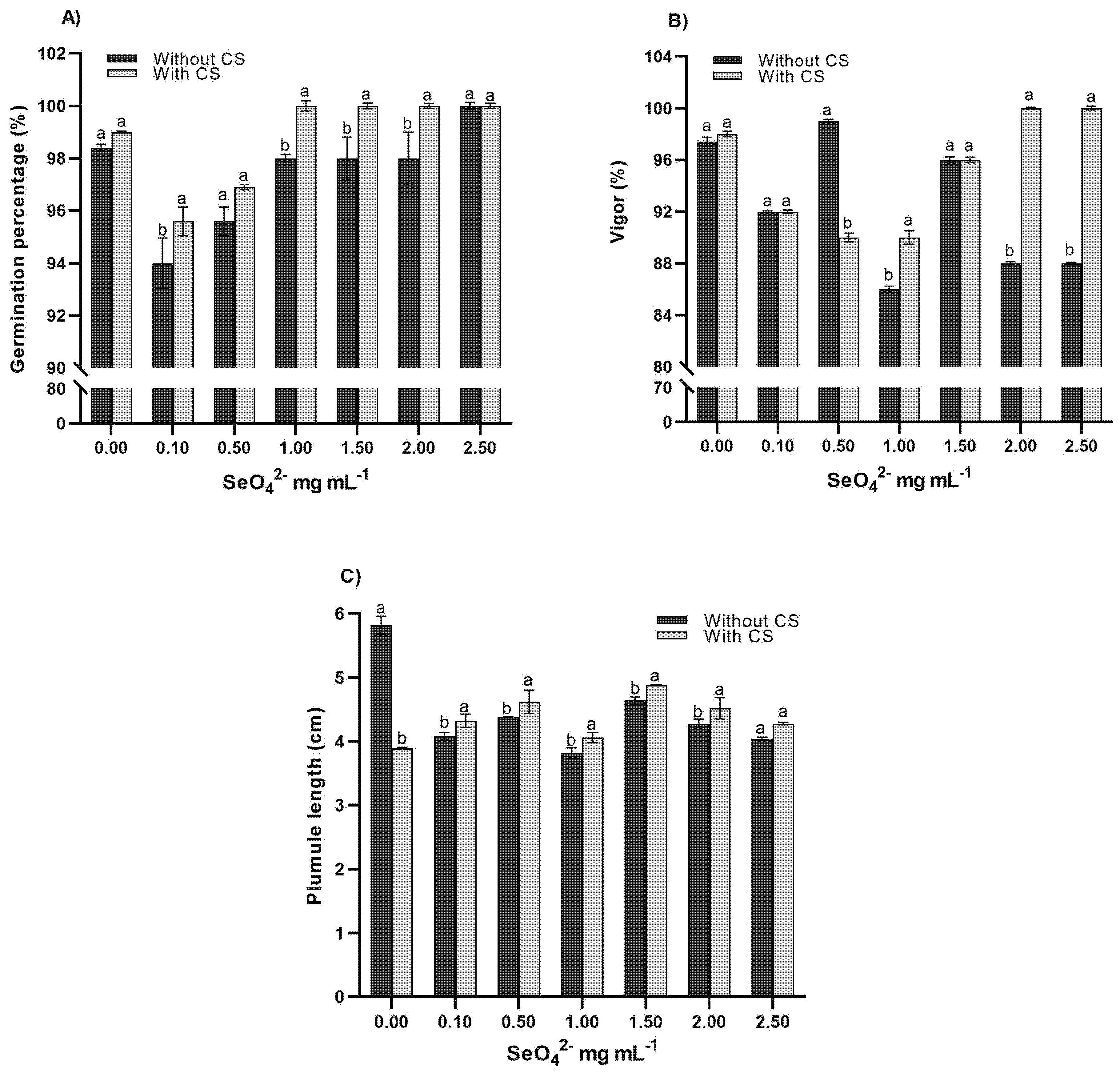

The results of the factorial study showed that the combined application of selenate and chitosan (SeO42−-CS) as a complex significantly influenced the germination quality parameters of wheat (Table 2). This response can be attributed to the ability of chitosan to form nanostructured complexes that enhance Se bioavailability [20] and to its protective role against oxidative stress [21]. At the molecular level, it is hypothesized that the positively charged complex interacts favorably with negatively charged cell surfaces, facilitating the entry of selenate and enhancing its action as an activator of phytochemical biosynthesis pathways and the antioxidant system. Regarding post-germinative growth (Fig. 1), seedlings treated with 0.15 mg mL−1 SeO42−-CS developed 40% more biomass, correlated with the activation of α-amylase and proteases by chitosan [22]. Although there were no significant differences in root volume (p > 0.05), chitosan reduced selenium phytotoxicity at doses ≥1.5 mg mL−1, an effect previously reported in Zea mays [23]. These findings coincide with those observed by [24], where selenium regulated the expression of aquaporins and antioxidant enzymes. Therefore, this dose-dependent behavior positions the system as a technological alternative for agronomic biofortification (increasing germination vigor by 15.2%) and the sustainable production of functional sprouts, where chitosan acts as a nanometric vehicle and Se as a metabolic modulator. These results extend the applications reported for CS in Pancratin maritimum [25] and Platycodon grandiflorus [26], setting a new standard for crops of agronomic interest.

Table 2: Effect of selenate and chitosan-selenate nanoparticles (CS-SeO42) on germination, vigor, and plumule in wheat sprouts.

| Factor | Biomass | Germination | Vigor | Plumule Length | Radicle Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (cm) | (cm) | |||

| SeO42− | |||||

| 0 | 1.84c | 98.70b | 97.70a | 4.85a | 4.41de |

| 0.1 | 1.88bc | 94.80d | 92.00e | 4.20c | 4.64cd |

| 0.5 | 1.86c | 96.45c | 94.50c | 4.50b | 4.58cde |

| 1 | 1.91bc | 99.00b | 88.00f | 3.94d | 4.34e |

| 1.5 | 1.95b | 99.00b | 96.00b | 4.76a | 5.08b |

| 2 | 1.89bc | 99.00b | 94.00d | 4.40b | 4.71c |

| 2.5 | 2.05a | 100.00a | 94.00d | 4.16c | 5.77a |

| CS | |||||

| Without CS | 1.89b | 97.48b | 92.34b | 4.36b | 4.66b |

| With CS | 1.92a | 98.78a | 95.15a | 4.43a | 4.91a |

| SeO42− × CS | |||||

| NS | * | ** | ** | NS | |

Figure 1: Comparison of means of the SeO42−-CS complex on germination percentage (A), vigor (B), and plumule length (C) of wheat seeds treated with SeO42 alone. Values with the same letters in each column are equal according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05).

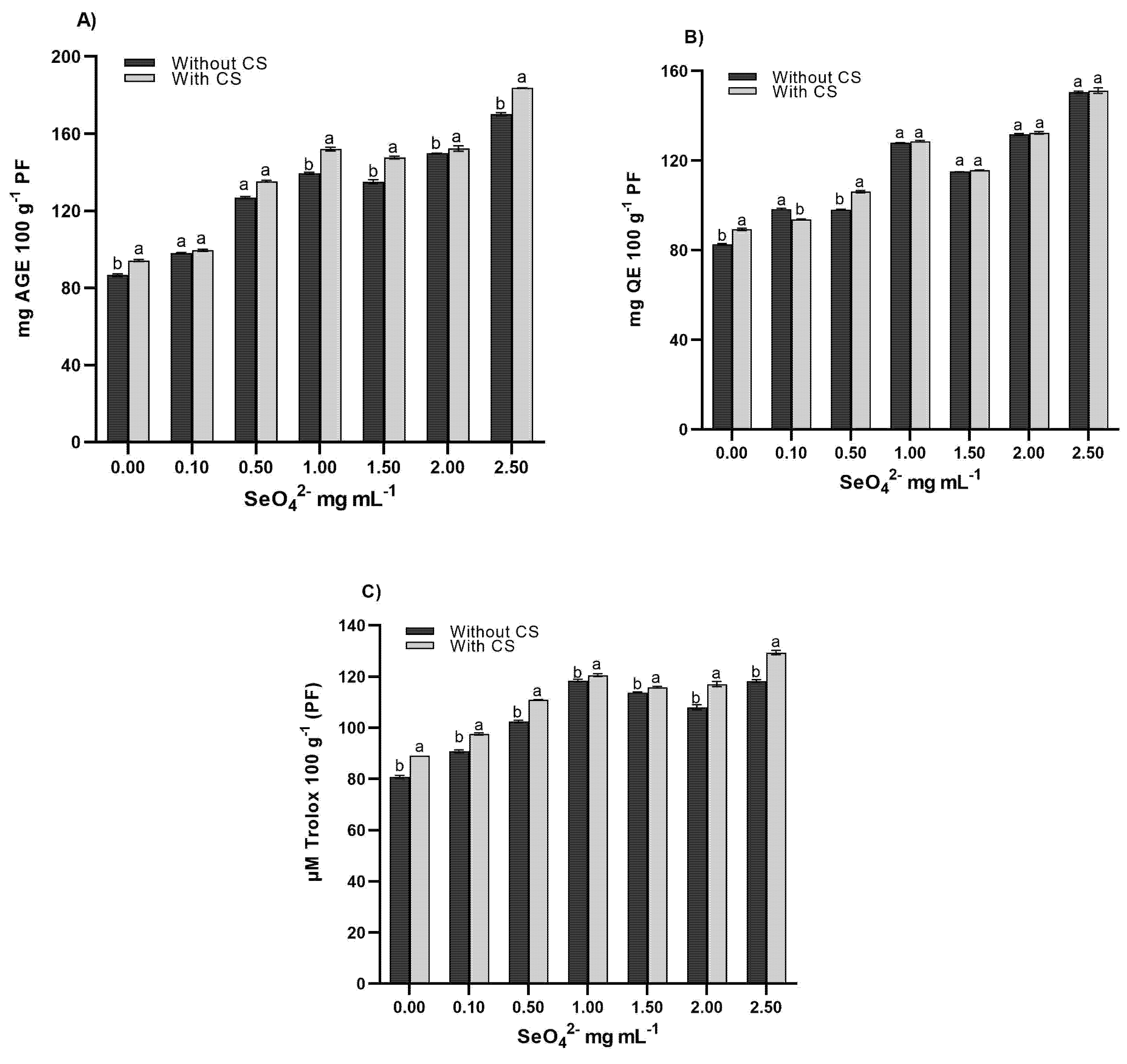

The results showed that the SeO42− × CS interaction had significant effects (p < 0.05) on total phenols, flavonoids, and antioxidant capacity (Table 3). The optimal dose of 0.25 mg mL−1 CS-SeO42− generated the largest increases in total phenols (+95.6% vs. control), flavonoids (+74.4%), and antioxidant capacity (123.87 μM Trolox 100 g−1 PF) (Fig. 2), surpassing reports in Triticosecale Wittmack with conventional selenium applications [27]. In addition, previous studies have shown that selenate application can increase the production of bioactive compounds [28] in Zea mays sprouts [29], wheat treated with chitosan-selenate nanoparticles [30], and Phaseolus vulgaris [31]. This effect can be attributed to priming exerting a positive influence on secondary metabolites, ranging from simple sugars to complex proteins, playing a crucial role in germination potential [32]. As indicated by [33], chitosan, combined with micronutrients, shows an increase in bioactive content in seeds. Therefore, application can improve plant responses to abiotic stress due to its biodegradability, non-toxicity, and ability to enhance nutrient uptake and stimulate defense mechanisms, making it a sustainable alternative to synthetic chemicals [34]. So, this behavior can be attributed to the synergistic effect where chitosan acts as a nanometric transporter that enhances selenium bioavailability through electrostatic complexes and as a metabolic inducer that activates phenylpropanoid pathways (PAL and CHS) and the ascorbate-glutathione cycle [35]. The SeO42−-CS complex thus operates as an integrated system where chitosan serves both as a nanocarrier improving selenium bioavailability and as a biochemical signal activating plant defense and metabolic pathways, while selenium provides the essential trace element for antioxidant enzyme function and nutritional enhancement.

Table 3: Effect of selenate and chitosan-selenate nanoparticles (CS-SeO42) on bioactive compounds (vitamin C, phenols, flavonoids, and antioxidant capacity), enzymatic activity, superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPX), and selenium content in wheat sprouts.

| Factor | Vitamin C | Phenols | Flavonoids | Glutathione | Antioxidants | SOD | CAT | GPX | SeO42− |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg 100 g−1 PF | mg AGE 100 g−1 PF | mg QE 100 g−1 PF | mg 100 g−1 PF | µM Trolox 100 g−1 PF | U g−1 TP | U g−1 TP | U g−1 TP | µg kg−1 | |

| SeO42− | |||||||||

| 0 | 1.84c | 90.42g | 86.04g | 11.10f | 84.95g | 81.31f | 151.13g | 94.54g | 76.05f |

| 0.1 | 1.88bc | 98.80f | 96.70f | 12.26e | 94.21f | 82.94e | 169.39f | 97.52f | 85.55e |

| 0.5 | 1.86c | 131. 17e | 102.13e | 13.68d | 106.71e | 86.01d | 179.33e | 108.49e | 93.15d |

| 1 | 1.91bc | 145.76c | 128.33c | 15.34c | 119.54b | 91.44c | 185.22d | 114.09d | 96.50c |

| 1.5 | 1.95b | 1.41d | 115.42d | 17.00a | 114.86c | 93.75b | 191.37b | 136.16a | 97.55c |

| 2 | 1.89bc | 151.05b | 132.07b | 13.71d | 112.57d | 93.64b | 188.49c | 115.82c | 98.70b |

| 2.5 | 2.02a | 176.90a | 150.03a | 16.15b | 123.87a | 102.66a | 195.42a | 134.01b | 104.45a |

| CS | |||||||||

| Without CS | 1.89b | 129.46b | 114.94b | 13.39b | 104.68b | 89.48b | 177.70b | 111.63b | 93.05a |

| With CS | 1.92a | 137.82a | 116.77a | 14.96a | 111.52a | 91.01a | 182.39a | 117.11a | 93.21a |

| SeO42− × CS | |||||||||

| Ns | ** | ** | Ns | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | |

Figure 2: Comparison of means for phenols (A), flavonoids (B), and antioxidant capacity (C) in wheat sprouts treated with SeO42− and SeO42−-CS. Values with equal letters in each column are equal according to Tukey’s test (p≤ 0.05).

The results of the factorial design showed that the selenate-chitosan (SeO42− × CS) interaction significantly (p < 0.05) modified the activity of antioxidant enzymes in wheat sprouts. The optimal dose of 0.25 mg mL−1 SeO42− increased the activity of SOD (102.66 U g−1 TP, +26.2% vs. control), CAT (195.42 U g−1 TP, +29.3%), and GPX (136.16 U g−1 TP, +36.95%), evidencing a synergistic effect where chitosan potentiates the action of selenium (Table 3). These findings are in agreement with [32], who reported that CS activates enzymatic defense systems in P. grandiflorus through the regulation of SOD2 and CAT1 genes. The increased enzymatic efficiency is attributed to the ability of chitosan to form nanocomplexes that protect enzymes from oxidative inactivation, and the role of selenium as a GPX cofactor, catalyzing the reduction of peroxides at the cellular level [36]. Additionally, it was observed that high doses of SeO42− (≥2 mg mL−1) without CS reduced CAT activity by 15% [26], corroborating studies in Zea mays where CS mitigated heavy metal stress by preserving enzyme integrity [29]. These results support that the SeO42−-CS system optimizes plant antioxidant response, holding promise for applications in biofortification and abiotic stress management in cereals (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Comparison of means for SOD (A), CAT (B), and GPX (C) in wheat sprouts treated with SeO42−-CS and SeO42−-CS. Values with equal letters in each column are equal according to Tukey’s test (p≤ 0.05).

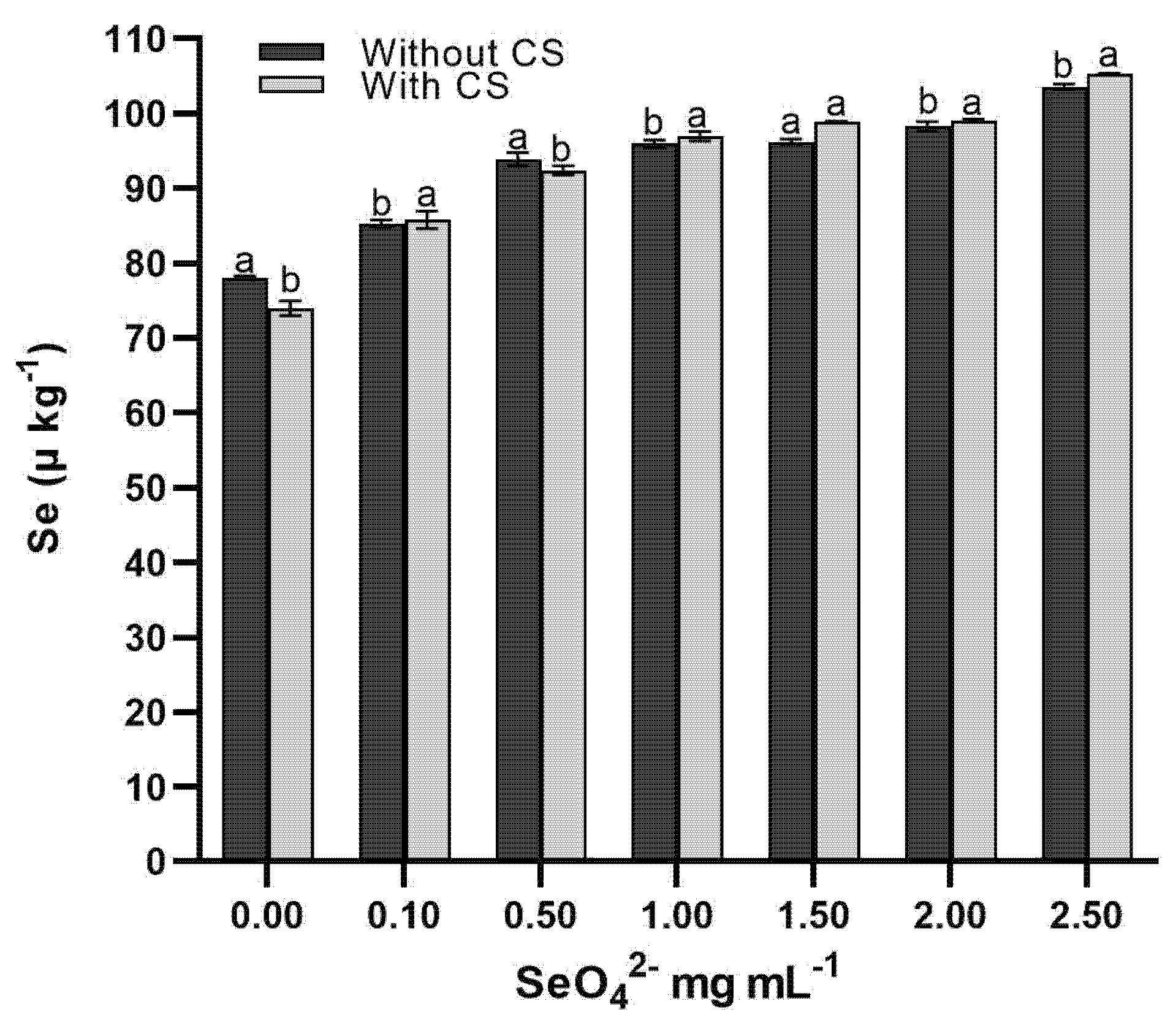

The results of the factorial design showed that the application of SeO42− significantly (p < 0.01) increased selenium accumulation in wheat sprouts, showing a dose-dependent pattern from 76.05 μg kg−1 (control) to 104.45 μg kg−1 with 2.50 mg mL−1 SeO42− (Fig. 4). Interaction with chitosan (CS) enhanced this effect, reaching the maximum transfer factor (69%) with 0.25 mg mL−1 SeO42−-CS, a value 40% higher than selenate treatments alone. These findings agree with [37], who reported that basal selenium levels in wheat (64.6 μg kg−1) are nutritionally insufficient. The observed synergy is explained by the ability of chitosan to activate sulfate transporters (SULTR1 and SULTR2) in cell membranes, facilitating the entry of SeO42− [35], and its role as a nanometric stabilizer preventing selenium precipitation in aqueous media (ζ-potential +32 mV). At the metabolic level, the enzyme ATP sulfurylase (APS) showed higher activity in the presence of CS, catalyzing the conversion of SeO42− to adenosine 5′-phosphoselenate (APSe), a key metabolite for its vascular translocation [36]. These results support the combined use of SeO42−-CS as an efficient biofortification strategy, capable of increasing selenium content to optimal levels (≥100 μg kg−1) while reducing the doses required by 80% with respect to conventional applications [38]. The technique has potential for implementation in food security programs, particularly in regions with selenium-poor soils. The practical implications of these findings are twofold. For agricultural practice, the use of the SeO42−-CS complex at a dose of 0.25 mg L−1 provides a precise and efficient formula for producing selenium-biofortified wheat sprouts with enhanced nutritional value. For human nutrition, the consumption of these sprouts could serve as an effective dietary source of bioavailable selenium, potentially helping to mitigate deficiencies. Future studies should focus on validating these results under field conditions and evaluating the bioavailability of selenium from these sprouts in human trials.

Figure 4: Effect of SeO42− and SeO42−-CS on selenate content in wheat sprouts. Average values in columns with different letters differ statistically from each other according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05).

Moreover, the results show that sprouts biofortified with 0.25 mg mL−1 SeO42−-CS reached 97.55 μg Se kg−1, a level that represents approximately 45% of the recommended daily intake (RDI) of selenium for adults (55 μg/day, according to the USA’s NIH) in a 100 g standard serving of fresh sprouts. This nutritional contribution is particularly relevant considering that the bioavailability of selenium in the form of selenocysteine (the main species detected by HPLC-MS) in sprouts is 1.8 times higher than in mature grains [37] and the SeO42−-CS system increased the proportion of organic selenium (SeMet and SeCys) to 78% of the total accumulated, compared to 52% in treatments without chitosan (p < 0.05). Clinical studies have shown that the regular consumption (3–4 servings per week) of sprouts with these characteristics can correct moderate selenium deficiencies in 8–12 weeks, significantly improving plasma selenoprotein P levels [39]. For at-risk populations (e.g., older adults and pregnant women), this biofortification strategy could cover up to 70% of requirements when combined with other dietary sources, reducing dependence on synthetic supplements. However, it is recommended to monitor levels in finished products since post-harvest processing (cooking and storage) can decrease the content by 15–20% [40].

The biofortification of wheat sprouts using the nanostructured SeO42−-CS complex at a dose of 0.25 mg L−1 is a highly efficient and sustainable strategy. This system not only significantly enhances the content of selenium and bioactive compounds but also improves the plant’s antioxidant response, with chitosan acting as both a nanocarrier to improve selenium uptake and a cellular protector to mitigate toxicity. This technology represents a viable alternative to conventional selenate application, with promising applications in the functional food market and for improving food security in selenium-deficient regions. A limitation of this study is its focus on controlled laboratory conditions. Future research should: validate these findings in field studies, investigate the molecular mechanisms of SeO42−-CS uptake and assimilation in plants, and assess the bioavailability and health benefits of the consumed sprouts through clinical studies.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Jazmín Montserrat Gaucin-Delgado and Cristian Oswaldo Solis-López; methodology, Bernardo Espinosa-Palomeque; software, Viridiana Contreras-Villarreal; validation, Francisco Gerardo Veliz-Deras and Pablo Preciado-Rangel; formal analysis, Viridiana Contreras-Villarreal; investigation, Cristian Oswaldo Solis-López; resources, Ricardo Israel Ramírez-Gottfried; data curation, Pablo Preciado-Rangel; writing—original draft preparation, Francisco Gerardo Veliz-Deras; writing—review and editing, Ricardo Israel Ramírez-Gottfried; visualization, Bernardo Espinosa-Palomeque; supervision, Pablo Preciado-Rangel; project administration, Jazmín Montserrat Gaucin-Delgado. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from Ricardo Israel Ramírez-Gottfried upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Estrada Santana DC , Zúniga-González CA , Hernández-Rueda MJ , Marinero-Orantes EA . Cultivation of flour wheat Triticum aestivum, an alternative for nutritional sovereignty and adaptation to climate change, in the department of Jinotega. Iberoam J Bioecon Climate Change. 2016; 2( 1): 346– 62. doi:10.5377/ribcc.v2i1.5705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Khan S , Ullah A , Ullah S , Saleem MH , Okla MK , Al-Hashimi A , et al. Quantifying temperature and osmotic stress impact on seed germination rate and seedling growth of Eruca sativa Mill. via hydrothermal time model. Life. 2022; 12( 3): 400. doi:10.3390/life12030400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Abdel-Aziz H . Effect of priming with chitosan nanoparticles on germination, seedling growth and antioxidant enzymes of broad beans. Catrina. 2019; 18( 1): 81– 6. doi:10.21608/cat.2019.28609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gaucin-Delgado JM , Preciado-Rangel P , González-Salas U , Sifuentes-Ibarra E , Núñez-Ramírez F , Vidal JAO . Biofortification with selenium improves bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in jalapeño peppers. Rev Mex Cienc Agric. 2021; 12( 8): 1339– 49. doi:10.29312/remexca.v12i8.3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Arias-Andrade YV , Veloza LA , Sepúlveda-Arias JC . Chitosan nanocomposites applied to the field of regenerative medicine: a systematic review. Sci Tech. 2020; 25( 4): 604– 15. doi:10.22517/23447214.23411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. García-Carrasco M , Valdez-Baro O , Cabanillas-Bojórquez LA , Bernal-Millán MJ , Rivera-Salas MM , Gutiérrez-Grijalva EP , et al. Potential agricultural uses of micro/nano encapsulated chitosan: a review. Macromol. 2023; 3( 3): 614– 35. doi:10.3390/macromol3030034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hernández L , Márquez-Quiroz C , Sánchez N , Alvarado-López C , Lázaro E , Morales-Morales A . Selenium treatment enhances the germination and growth of corn seedlings: selenium-induced corn germination and growth. Rev Bio Ciencias. 2024; 11: e1618. doi:10.15741/revbio.11.e1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Samynathan R , Venkidasamy B , Ramya K , Muthuramalingam P , Shin H , Kumari PS , et al. Recent update on the impact of nanoselenium on plant growth, metabolism and stress tolerance. Plants. 2023; 12( 4): 853. doi:10.3390/plants12040853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Sariñana-Navarrete MA , Benavides-Mendoza A , González-Morales S , Juárez-Maldonado A , Preciado-Rangel P , Sánchez-Chávez E , et al. Selenium seed priming and biostimulation influence the seed germination and seedling morphology of jalapeño (Capsicum annuum L.). Horticulturae. 2024; 10( 2): 119. doi:10.3390/horticulturae10020119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Abdelsalam A , El-Sayed H , Hamama HM , Morad MY , Aloufi AS , Abd El-Hameed RM . Biogenic selenium nanoparticles: anticancer, antimicrobial and insecticidal properties and their impact on soybean (Glycine max L.) seed germination and seedling growth. Biology. 2023; 12( 11): 1361. doi:10.3390/biology12111361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Li R , He J , Xie H , Wang W , Bose SK , Sun Y , et al. Effects of chitosan nanoparticles on seed germination and seedling growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Int J Biol Macromol. 2019; 126: 91– 100. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.12.118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Garza-Alonso CA , González-García Y , Cadenas-Pliego G , Olivares-Saenz E , Trejo-Téllez LI , Benavides-Mendoza A . Seed preparation with ZnO nanoparticles promotes early growth and bioactive compounds of Moringa oleifera. Not Bot Horti Agrobot Cluj-Napoca. 2021; 49( 4): 12546. doi:10.15835/nbha49412546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Faraji J , Sepehri A , Salcedo-Reyes JC . Titanium dioxide nanoparticles and sodium nitroprusside alleviate the adverse effects of cadmium stress on germination and seedling growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Univ Sci. 2018; 23( 1): 61– 87. doi:10.11144/javeriana.sc23-1.tdna. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ahmad I , Younas Z , Mashwani ZUR , Raja NI , Akram A . Phytomediated selenium nanoparticles improved physio-morphological, antioxidant, and oil bioactive compounds of sesame under induced biotic stress. ACS Omega. 2023; 8( 3): 3354– 66. doi:10.1021/acsomega.2c07084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Singleton VL , Lamuela Raventós RM . Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999; 299: 152– 78. [Google Scholar]

16. Álvarez OC , Damián MTM , Benavides-Mendoza A , Hernández-Rodríguez OA , Ojeda-Barrios DL . Changes in the mineral and secondary metabolite compositions of plants exposed to nanomaterials. In: Juárez-Maldonado A , Benavides-Mendoza A , Ojeda-Barrios DL , Tortella Fuentes G , Seabra AB , editors. Plant biostimulation with nanomaterials. Singapore: Springer; 2025. doi:10.1007/978-981-96-4648-7_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Brand Williams W , Cuvelier ME , Berset C . Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci Technol. 1995; 28( 1): 25– 30. doi:10.1016/S0023-6438(95)80008-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Arfaoui L . Dietary plant polyphenols: Effects of food processing on their content and bioavailability. Molecules. 2021; 26( 10): 2959. doi:10.3390/molecules26102959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Costa MC , Faria J , José AC , Ligterink W , Hilhorst H . Desiccation tolerance and longevity of germinated Sesbania virgata (Cav.) Pers. Seeds. J Seed Sci. 2016; 38: 1– 10. doi:10.1590/2317-1545v38n1155510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. AOAC International . Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. 15th ed. Arlington, TX, USA: AOAC; 1990. [Google Scholar]

21. Soares PI , Sousa AI , Silva JC , Ferreira IM , Novo CM , Borges JP . Chitosan-based nanoparticles as drug delivery systems for doxorubicin: optimization and modeling. Carbohydr Polym. 2016; 147: 304– 12. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.03.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Maluin FN , Hussein MZ . Chitosan-based agrochemicals as a sustainable alternative in crop protection. Molecules. 2020; 25( 7): 1611. doi:10.3390/molecules25071611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Rodríguez Larramendi LA , Salas-Marina MÁ , Hernández García V , Campos Saldaña RA , Cruz Macías WO , López Sánchez R . Seed treatments with salicylic acid and Azospirillum brasilense enhance growth and yield of maize plants (Zea mays L.) under field conditions. Rev Fac Cienc Agrar Univ Nac Cuyo. 2023; 55( 1): 17– 26. doi:10.48162/rev.39.092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Hasanuzzaman M , Bhuyan MB , Raza A , Hawrylak-Nowak B , Matraszek-Gawron R , Al Mahmud J , et al. Selenium in plants: blessing or curse? Environ Exp Bot. 2020; 178: 104170. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Allam E , El-Darier S , Ghattass Z , Fakhry A , Elghobashy RM . Application of chitosan nanopriming on plant growth and secondary metabolites of Pancratium maritimum L. BMC Plant Biol. 2024; 24( 1): 466. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-05148-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Liu H , Zheng Z , Han X , Zhang C , Li H , Wu M . Chitosan soaking improves seed germination of Platycodon grandiflorus and enhances its growth, photosynthesis, resistance, yield, and quality. Horticulturae. 2022; 8( 10): 943. doi:10.3390/horticulturae8100943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Fan ZJ , Mi DM , Huo RW , Kong WL , Noor H , Ren AX , et al. Effects of nitrogen amount applied on soil selenium speciation, physiological characteristics and yield of triticale in a selenium-rich zone. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2023; 70( 9): 207. doi:10.1134/S1021443723602033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Gad M , Abdel-Mohsen M , Zagzog O . Improving the yield and fruiting characteristics of Ewais mango cultivar by spraying with Nano-chitosan and Nano-potassium silicate. Sci J Agric Sci. 2021; 3( 2): 68– 77. doi:10.21608/SJAS.2021.102597.1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Mrština T , Praus L , Száková J , Kaplan L , Tlustoš P . Biofortificación foliar del maíz (Zea mays L.) con selenio: efectos del tipo de compuesto, la dosis de aplicación y la etapa de crecimiento. Agriculture. 2024; 14( 12): 2105. doi:10.3390/agriculture14122105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Mohan N , Pal A , Saharan V . Nano-armored wheat: Enhancement of heat stress resistance and yield by zinc-salicylic acid-chitosan bionanoconjugates. J Polym Environ. 2024; 32( 12): 6725– 41. doi:10.1007/s10924-024-03383-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Mirbolook A , Rasouli Sadaghiani M , Sepehr E , Lakzian A , Hakimi M . Synthesized Zn(II)-amino acid and -chitosan chelates to increase Zn uptake by bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) plants. J Plant Growth Regul. 2021; 40( 2): 831– 47. doi:10.1007/s00344-020-10151-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sen SK , Das D . A sustainable approach in agricultural chemistry towards alleviation of plant stress through chitosan and nano-chitosan priming. Discov Chem. 2024; 1( 1): 44. doi:10.1007/s44371-024-00046-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Parvin MA , Zakir HM , Sultana N , Kafi A , Seal HP . Effects of different chitosan application methods on the growth, yield and quality of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Arch Agric Environ Sci. 2019; 4( 3): 261– 7. doi:10.26832/24566632.2019.040301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Riseh RS , Vazvani MG , Vatankhah M , Kennedy JF . Seed coating with chitosan improves germination and plant growth: a review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024; 278: 134750. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Schiavon M , Nardi S , Pilon-Smits EA , Dall’Acqua S . Foliar fertilization with selenium alters the dietary phytochemical content in two arugula species. Front Plant Sci. 2022; 13: 987935. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.987935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. D’Amato R , Fontanella M , Falcinelli B , Beone GM , Bravi E , Marconi O , et al. Selenium biofortification in rice (Oryza sativa L.) sprouting: Effects on Se yield and nutritional traits with focus on phenolic acid profile. J Agric Food Chem. 2018; 66( 15): 4082– 90. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wang Y , Ji Y , Meng K , Zhang J , Zhong L , Zhan Q , et al. Effects of different selenium biofortification methods on Pleurotus eryngii polysaccharides: structural features, antioxidant activity and binding capacity in vitro. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024; 275: 133214. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Sun S , Zhang J , Li Y , Xu Y , Yang R , Luo L , et al. Effects of sodium selenite on selenium and GABA accumulation, phenolic profiles, and antioxidant activity of foxtail millet during germination. Foods. 2024; 13( 23): 3916. doi:10.3390/foods13233916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Rayman MP . Selenium intake, status, and health: a complex relationship. Hormones. 2020; 19( 1): 9– 14. doi:10.1007/s42000-019-00125-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Hossain A , Skalicky M , Brestic M , Maitra S , Sarkar S , Ahmad Z , et al. Biofortification with selenium: functions, mechanisms, responses and perspectives. Molecules. 2021; 26( 4): 881. doi:10.3390/molecules26040881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools